THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD:

LEVI COFFIN RECEIVING A COMPANY OF FUGITIVES IN THE OUTSKIRTS OF CINCINNATI, OHIO.

(From a painting by C. T. Webber, Cincinnati, Ohio.)

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD:

LEVI COFFIN RECEIVING A COMPANY OF FUGITIVES IN THE OUTSKIRTS OF CINCINNATI, OHIO.

(From a painting by C. T. Webber, Cincinnati, Ohio.)

The

Underground Railroad

from Slavery to Freedom

A Comprehensive History

Wilbur H. Siebert

With an Introduction by

Albert Bushnell Hart

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

This Dover edition, first published in 2006, is an unabridged republication of The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom, originally published by The Macmillan Company, New York and London, in 1898. The original fold-out map facing page 113 has now been set into the book on three separate pages in the same location.

International Standard Book Number: 0-486-45039-2

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N. Y. 11501

BY ALBERT BUSHNELL HART

Of all the questions which have interested and divided the people of the United States, none since the foundation of the Federal Union has been so important, so far-reaching, and so long contested as slavery. During the first half of the nineteenth century the other great national questions were nearly all economic—taxation, currency, banks, transportation, lands,—and they had a strong material basis, a flavor of self-interest; but though slavery had also an economic side, the reasons for the onslaught upon it were chiefly moral. The first objection brought by the slave-power against the anti-slavery propaganda was the cry of the sacredness of vested and property rights against attack by sentimentalists; but what dignified the whole contest was the very fact that the sentiment for human rights was at the bottom of it, and that the abolitionists felt a moral responsibility even though property owners suffered. The slavery question, which in origin was sectional, became national as the moral issues grew clearer; and finally loomed up as the dominant question through the determination of both sides to use the power and prestige of the national government. From the moral agitation came also the personal element in the struggle, the development of strong characters, like Calhoun, Toombs, Stephens and Jefferson Davis on one side; like Lundy, Lovejoy, Garrison, Giddings, Sumner, Chase, John Brown and Lincoln on the other.

Among the many weak spots in the system of slavery none gave such opportunities to Northern abolitionists as the locomotive[viii] powers of the slaves; a "thing" which could hear its owner talking about freedom, a "thing" which could steer itself Northward and avoid the "patterollers," was a thing of impaired value as a machine, however intelligent as a human being. From earliest colonial times fugitive slaves helped to make slavery inconvenient and expensive. So long as slavery was general, every slaveholder in every colony was a member of an automatic association for stopping and returning fugitives; but, from the Revolution on, the fugitives performed the important function of keeping continually before the people of the states in which slavery had ceased, the fact that it continued in other parts of the Union. Nevertheless, though between 1777 and 1804 all the states north of Maryland threw off slavery, the free states covenanted in the Federal Constitution of 1787 to interpose no obstacle to the recapture of fugitives who might come across their borders; and thus continued to be partners in the system of slavery. From the first there was reluctance and positive opposition to this obligation; and every successful capture was an object lesson to communities out of hearing of the whipping-post and out of sight of the auction-block.

In aiding fugitive slaves the abolitionist was making the most effective protest against the continuance of slavery; but he was also doing something more tangible; he was helping the oppressed, he was eluding the oppressor; and at the same time he was enjoying the most romantic and exciting amusement open to men who had high moral standards. He was taking risks, defying the laws, and making himself liable to punishment, and yet could glow with the healthful pleasure of duty done.

To this element of the personal and romantic side of the slavery contest Professor Siebert has devoted himself in this book. The Underground Railroad was simply a form of combined defiance of national laws, on the ground that those laws were unjust and oppressive. It was the unconstitutional but logical refusal of several thousand people to[ix] acknowledge that they owed any regard to slavery or were bound to look on fleeing bondmen as the property of the slaveholders, no matter how the laws read. It was also a practical means of bringing anti-slavery principles to the attention of the lukewarm or pro-slavery people in free states; and of convincing the South that the abolitionist movement was sincere and effective. Above all, the Underground Railroad was the opportunity for the bold and adventurous; it had the excitement of piracy, the secrecy of burglary, the daring of insurrection; to the pleasure of relieving the poor negro's sufferings it added the triumph of snapping one's fingers at the slave-catcher; it developed coolness, indifference to danger, and quickness of resource.

The first task of the historian of the Underground Railroad is to gather his material, and the characteristic of this book is to consider the whole question on a basis of established facts. The effort is timely; for there are still living, or were living when the work began, many hundreds of persons who knew the intimate history of parts of the former secret system of transportation; the book is most timely, for these invaluable details are now fast disappearing with the death of the actors in the drama. Professor Siebert has rescued and put on record events which in a few years will have ceased to be in the memory of living men. He has done for the history of slavery what the students of ballad and folk-lore have done for literature; he has collected perishing materials.

Reminiscence is of course, standing alone, an insufficient basis for historical generalization. On that point Professor Siebert has been careful to explain his principle: he does not attempt to generalize from single memories not otherwise substantiated, but to use reminiscences which confirm each other, to search out telling illustrations, and to discover what the tendencies were from numerous contrasted testimonies. Actual contemporary records are scanty; a few are here preserved, such as David Putnam's memorandum, and Campbell's letter; and the crispness which they give to the[x] narrative makes us wish for more. The few available biographies, autobiographies, and contemporary memoirs have been diligently sought out and used; and no variety of sources has been ignored which seemed likely to throw light on the subject. The ground has been carefully traversed; and it is not likely that much will ever be added to the body of information collected by Professor Siebert. His list of sources, described in the introductory chapter and enumerated in the Appendices, is really a carefully winnowed bibliography of the contemporary materials on slavery.

The book is practically divided into four parts: the Railroad itself (Chapters ii, v); the railroad hands (Chapters iii, iv, vi); the freight (Chapters vii, viii); and political relations and effects (Chapters ix, x, xi). Perhaps one of the most interesting contributions to our knowledge of the subject is the account of the beginnings of the system of secret and systematic aid to fugitives. The evidence goes to show that there was organization in Pennsylvania before 1800; and in Ohio soon after 1815. The book thus becomes a much-needed guide to information about the obscure anti-slavery movement which preceded William Lloyd Garrison, and to some degree prepared the way for him; and it will prove a source for the historian of the influence of the West in national development. As yet we know too little of the anti-slavery movement which so profoundly stirred the Western states, including Kentucky and Missouri, and which came closely into contact with the actual conditions of slavery. As Professor Siebert points out, most of the early abolitionists in the West were former slaveholders or sons of slaveholders.

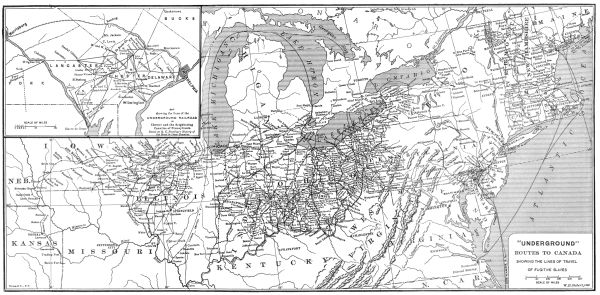

Professor Siebert has applied to the whole subject a graphic form of illustration which is at the same time a test of his conclusions. How can the scattered reminiscences and records of escapes in widely separated states be shown to refer to the results of one organized method? Plainly by applying them to the actual face of the country, so as to see[xi] whether the alleged centres of activity have a geographical connection. The painstaking map of the lines of the Underground Railroad "system" is an historical contribution of a novel kind; and it is impossible to gainsay its evidence, which is expounded in detail in one of the chapters of the book. The result is a gratifying proof of the usefulness of scientific methods in historical investigation; one who lived in an anti-slavery community before the Civil War is fascinated by tracing the hitherto unknown stretches north and south from the centre which he knew. The map bears testimony not only to the wide-spread practice of aiding fugitives, but to the devotion of the conductors on the Underground Railroad. How useful a section of Mr. Siebert's map would have been to the slave-catcher in the 50's, when so many strange negroes were appearing and disappearing in the free states! The facts presented in the brief compass of the map would have been of immense value also to the leaders of the Southern Confederacy in 1861, as a confirmation of their argument that the North would not perform its constitutional duty of returning the fugitives; yet there is no record in this book of the betraying of the secrets of the U. G. R. R. by any person in the service. The moral bond of opposition to the whole slave power kept men at work forwarding fugitives by a road of which they themselves knew but a small portion. The political philosophers who think that the Civil War might have been averted by timely concessions would do well to study this picture of the wide distribution of persons who saw no peace in slavery.

Amid all the varieties of anti-slavery men, from the Garrisonian abolitionist to faint-hearted slaveholders like James G. Birney, it is interesting to see how many had a share in the Underground Railroad; and how many earned a reputation as heroes. Professor Siebert has gathered the names of about 3,200 persons known to have been engaged in this work—a roll of honor for many American families. Everybody knew that the fugitives were aided by Fred[xii] Douglass, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Gerrit Smith, Joshua Giddings, John Brown, Levi Coffin, Thomas Garrett and Theodore Parker; but this book gives us some account of the interest of men like Thaddeus Stevens, not commonly counted among the sons of the prophets; and performs a special service to the student of history and the lover of heroic deeds, by the brief account of the services of obscure persons who deserve a place in the hearts of their countrymen. Men like Rev. George Bourne, Rev. James Duncan and Rev. John Rankin, years before Garrison's propaganda, had begun to speak and publish against slavery, and to prepare men's minds for a righteous disregard of Fugitive Slave Acts. Joseph Sider, with his carefully subdivided peddler's wagon, deserves a place alongside the better known Henry Box Brown. The thirty-five thousand stripes of Calvin Fairbank, seventeen years a convict in the Kentucky penitentiary, range him with Lovejoy as an anti-slavery martyr. Rev. Charles Torrey had in the work of rousing slaves to escape, the same devotion to a fatal duty as that which animated John Brown. And no one who has ever heard Harriet Tubman describe her part as "Moses" of the fugitives can ever forget that African prophetess, whose intense vigor is relieved by a shrewd and kindly humanity.

The quiet recital of the facts has all the charm of romance to the passengers on the Underground Railroad: whether travelling by night in a procession of covered wagons, or boldly by day in disguises; whether boxed up as so much freight, or riding on passes unhesitatingly given by abolitionist directors of railroads; the fugitives in these pages rejoice in their prospect of liberty. The road sign near Oberlin, of a tiger chasing a negro, was a white man's joke; but it was a negro who said, apropos of his master's discouraging account of Canada: "They put some extract onto it to keep us from comin'"; and neither Whittier in his poems, nor Harriet Beecher Stowe in her novels, imagined a more picturesque incident than the crossing of[xiii] the Detroit River by Fairfield's "gang" of twenty-eight rescued souls singing, "I'm on my way to Canada, where colored men are free," to the joyful accompaniment of their firearms.

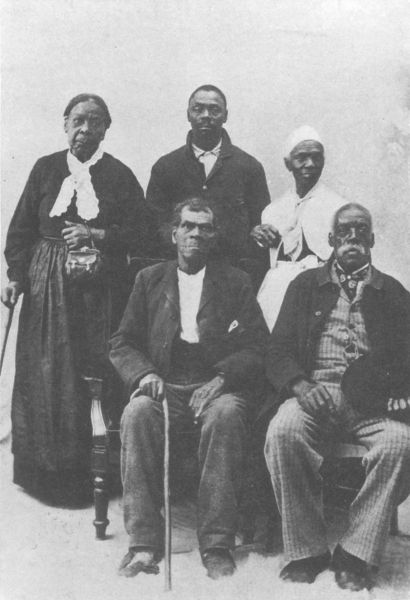

To the settlements of fugitives in Canada Professor Siebert has given more labor than appears in his book; for his own visits supplement the accounts of earlier investigators; and we have here the first complete account of the reception of the negroes in Canada and their progress in civilization.

Upon the general question of the political effects of the Underground Railroad, the book adds much to our information, by its discussion of the probable numbers of fugitives, and of the alarm caused in the slave states by their departure. The census figures of 1850 and 1860 are shown to be wilfully false; and the escape of thousands of persons seems established beyond cavil. Into the constitutional question of the right to take fugitives, the book goes with less minuteness, since it is intended to be a contribution to knowledge, and not an addition to the abundant literature on the legal side of slavery.

It has been the effort of Professor Siebert to furnish the means for settling the following questions: the origin of the system of aid to the fugitives, popularly called the Underground Railroad; the degree of formal organization; methods of procedure; geographical extent and relations; the leaders and heroes of the movement; the behavior of the fugitives on their way; the effectiveness of the settlement in Canada; the numbers of fugitives; and the attitude of courts and communities. On all these questions he furnishes new light; and he appears to prove his concluding statement that "the Underground Railroad was one of the greatest forces which brought on the Civil War and thus destroyed slavery."

| CHAPTER I | |

| Sources of the History of the Underground Railroad | |

| PAGE | |

| The Underground Road as a subject for research | 1 |

| Obscurity of the subject | 2 |

| Books dealing with the subject | 2 |

| Magazine articles on the Underground Railroad | 5 |

| Newspaper articles on the subject | 6 |

| Scarcity of contemporaneous documents | 7 |

| Reminiscences the chief source | 11 |

| The value of reminiscences illustrated | 12 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Origin and Growth of the Underground Road | |

| Conditions under which the Underground Road originated | 17 |

| The disappearance of slavery from the Northern states | 17 |

| Early provisions for the return of fugitive slaves | 19 |

| The fugitive slave clause in the Ordinance of 1787 | 20 |

| The fugitive slave clause in the United States Constitution | 20 |

| The Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 | 21 |

| The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 | 22 |

| Desire for freedom among the slaves | 25 |

| Knowledge of Canada among the slaves | 27 |

| Some local factors in the origin of the underground movement | 30 |

| The development of the movement in eastern Pennsylvania, in New Jersey, and in New York | 33 |

| The development of the movement in the New England states | 36 |

| The development of the movement in the West | 37 |

| The naming of the Road | 44 |

| [xvi]CHAPTER III | |

| The Methods of the Underground Railroad | |

| Penalties for aiding fugitive slaves | 47 |

| Social contempt suffered by abolitionists | 48 |

| Espionage practised upon abolitionists | 50 |

| Rewards for the capture of fugitives and the kidnapping of abolitionists | 52 |

| Devices to secure secrecy | 54 |

| Service at night | 54 |

| Methods of communication | 56 |

| Methods of conveyance | 59 |

| Zigzag and variable routes | 61 |

| Places of concealment | 62 |

| Disguises | 64 |

| Informality of management | 67 |

| Colored and white agents | 69 |

| City vigilance committees | 70 |

| Supplies for fugitives | 76 |

| Transportation of fugitives by rail | 78 |

| Transportation of fugitives by water | 81 |

| Rescue of fugitives under arrest | 83 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Underground Agents, Station-Keepers, or Conductors | |

| Underground agents, station-keepers, or conductors | 87 |

| Their hospitality | 87 |

| Their principles | 89 |

| Their nationality | 90 |

| Their church connections | 93 |

| Their party affinities | 99 |

| Their local standing | 101 |

| Prosecutions of underground operators | 101 |

| Defensive League of Freedom proposed | 103 |

| Persons of prominence among underground helpers | 104 |

| [xvii]CHAPTER V | |

| Study of the Map of the Underground Railroad System | |

| Geographical extent of underground lines | 113 |

| Location and distribution of stations | 114 |

| Southern routes | 116 |

| Lines of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York | 120 |

| Routes of the New England states | 128 |

| Lines within the old Northwest Territory | 134 |

| Noteworthy features of the general map | 139 |

| Complex routes | 141 |

| Broken lines and isolated place names | 141 |

| River routes | 142 |

| Routes by rail | 142 |

| Routes by sea | 144 |

| Terminal stations | 145 |

| Lines of lake travel | 147 |

| Canadian ports | 148 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Abduction of Slaves from the South | |

| Aversion among underground helpers to abduction of slaves | 150 |

| Abductions by negroes living along the northern border of the slave states | 151 |

| Abductions by Canadian refugees | 152 |

| Abductions by white persons in the South | 153 |

| Abductions by white persons of the North | 154 |

| The Missouri raid of John Brown | 162 |

| John Brown's great plan | 166 |

| Abductions attempted in response to appeals | 168 |

| Devotees of abduction | 178 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Life of the Colored Refugees in Canada | |

| Slavery question in Canada | 190 |

| Flight of slaves to Canada | 192 |

| Refugees representative of the slave class | 195 |

| [xviii]Misinformation about Canada among slaves | 197 |

| Hardships borne by Canadian refugees | 198 |

| Efforts toward immediate relief for fugitives | 199 |

| Attitude of the Canadian government | 201 |

| Conditions favorable to their settlement in Canada | 203 |

| Sparseness of population | 203 |

| Uncleared lands | 204 |

| Encouragement of agricultural colonies among refugees | 205 |

| Dawn Settlement | 205 |

| Elgin Settlement | 207 |

| Refugees' Home Settlement | 209 |

| Alleged disadvantages of the colonies | 211 |

| Their advantages | 212 |

| Refugee settlers in Canadian towns | 217 |

| Census of Canadian refugees | 220 |

| Occupations of Canadian refugees | 223 |

| Progress made by Canadian refugees | 224 |

| Domestic life of the refugees | 227 |

| School privileges | 228 |

| Organizations for self-improvement | 230 |

| Churches | 231 |

| Rescue of friends from slavery | 231 |

| Ownership of property | 232 |

| Rights of citizenship | 233 |

| Character as citizens | 233 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Fugitive Settlers in the Northern States | |

| Number of fugitive settlers in the North | 235 |

| The Northern states an unsafe refuge for runaway slaves | 237 |

| Reclamation of fugitives in the free states | 239 |

| Protection of fugitives in the free states | 242 |

| Object of the personal liberty laws | 245 |

| Effect of the law of 1850 on fugitive settlers | 246 |

| Underground operators among fugitives of the free states | 251 |

| [xix]CHAPTER IX | |

| Prosecutions of Underground Railroad Men | |

| Enactment of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 | 254 |

| Grounds on which the constitutionality of the measure was questioned | 254 |

| Denial of trial by jury to the fugitive slave | 255 |

| Summary mode of arrest | 257 |

| The question of concurrent jurisdiction between the federal and state governments in fugitive slave cases | 259 |

| The law of 1793 versus the Ordinance of 1787 | 261 |

| Power of Congress to legislate concerning the extradition of fugitive slaves denied | 263 |

| State officers relieved of the execution of the law by the Prigg decision, 1842 | 264 |

| Amendment of the law of 1793 by the law of 1850 | 265 |

| Constitutionality of the law of 1850 questioned | 267 |

| First case under the law of 1850 | 268 |

| Authority of a United States commissioner | 269 |

| Penalties imposed for aiding and abetting the escape of fugitives | 273 |

| Trial on the charge of treason in the Christiana case, 1854 | 279 |

| Counsel for fugitive slaves | 281 |

| Last case under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 | 285 |

| Attempted revision of the law | 285 |

| Destructive attacks upon the measure in Congress | 286 |

| Lincoln's Proclamation of Emancipation | 287 |

| Repeal of the Fugitive Slave Acts | 288 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Underground Railroad in Politics | |

| Valuation of the Underground Railroad in its political aspect | 290 |

| The question of the extradition of fugitive slaves in colonial times | 290 |

| Importance of the question in the constitutional conventions | 293 |

| Failure of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 | 294 |

| Agitation for a more efficient measure | 295 |

| Diplomatic negotiations for the extradition of colored refugees from Canada, 1826-1828 | 299 |

| The fugitive slave a missionary in the cause of freedom | 300 |

| [xx]Slave-hunting in the free states | 302 |

| Preparation for the abolition movement of 1830 | 303 |

| The Underground Railroad and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 | 308 |

| The law in Congress | 310 |

| The enforcement of the law of 1850 | 316 |

| The Underground Road and Uncle Tom's Cabin | 321 |

| Political importance of the novel | 323 |

| Sumner on the influence of escaped slaves in the North | 324 |

| The spirit of nullification in the North | 327 |

| The Glover rescue, Wisconsin, 1854 | 327 |

| The rendition of Burns, Boston, 1854 | 331 |

| The rescue of Addison White, Mechanicsburg, Ohio, 1857 | 334 |

| The Oberlin-Wellington rescue, 1858 | 335 |

| Obstruction of the Fugitive Slave Law by means of the personal liberty acts | 337 |

| John Brown's attempt Lo free the slaves | 338 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Effect of the Underground Railroad | |

| The Underground Road the means of relieving the South of many despairing slaves | 340 |

| Loss sustained by slave-owners through underground channels | 340 |

| The United States census reports on fugitive slaves | 342 |

| Estimate of the number of slaves escaping into Ohio, 1830-1860 | 346 |

| Similar estimate for Philadelphia, 1830-1860 | 346 |

| Drain on the resources of the depot at Lawrence, Kansas, described in a letter of Col. J. Bowles, April 4, 1859 | 347 |

| Work of the Underground Railroad as compared with that of the American Colonization Society | 350 |

| The violation of the Fugitive Slave Law a chief complaint of Southern states at the beginning of the Civil War | 351 |

| Refusal of the Canadian government to yield up the fugitive Anderson, 1860 | 352 |

| Secession of the Southern states begun | 353 |

| Conclusion of the fugitive slave controversy | 355 |

| General effect and significance of the controversy | 356 |

| The Underground Railroad: Levi Coffin receiving a company of fugitives in the outskirts of Cincinnati, Ohio | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Isaac T. Hopper | 17 |

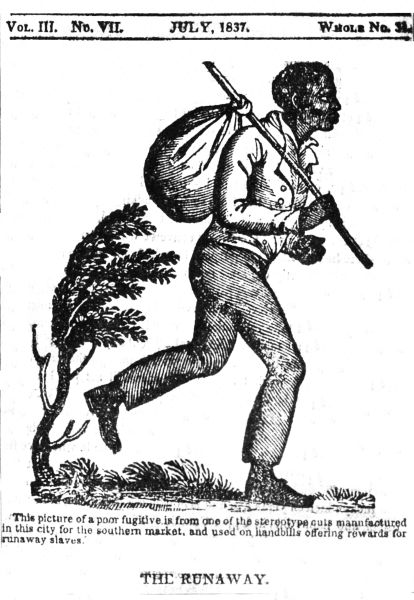

| The Runaway: a stereotype cut used on handbills advertising escaped slaves | 27 |

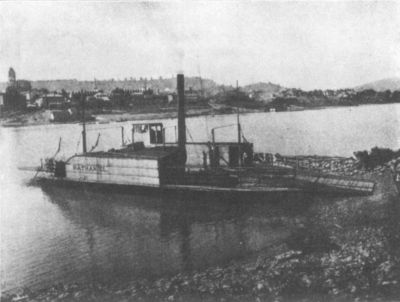

| Crossing-place on the Ohio River at Steubenville, Ohio | 47 |

| The Rankin House, Ripley, Ohio | 47 |

| Facsimile of an Underground Message | On page 57 |

| Barn of Seymour Finney, Detroit, Michigan | 65 |

| The Old First Church, Galesburg, Illinois | 65 |

| William Still | 75 |

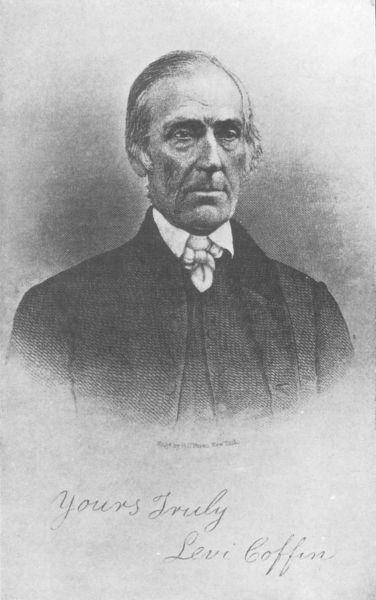

| Levi Coffin | 87 |

| Frederick Douglass | 104 |

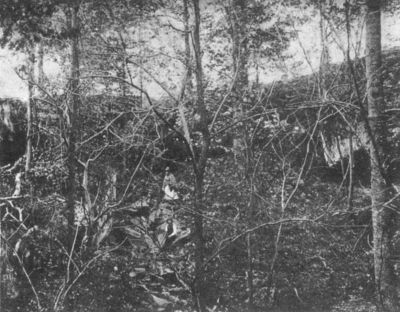

| Caves in Salem Township, Washington County, Ohio | 130 |

| House of Mrs. Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Valley Falls, Rhode Island | 130 |

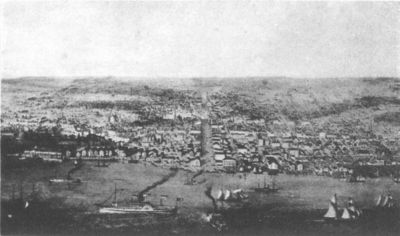

| The Detroit River at Detroit, Michigan | 147 |

| Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio | 147 |

| Ellen Craft as she escaped from Slavery | 163 |

| Samuel Harper and Wife | 163 |

| Dr. Alexander M. Ross | 180 |

| Harriet Tubman | 180 |

| Group of Refugee Settlers at Windsor, Ontario, C.W. | 190 |

| Theodore Parker | 205 |

| Thomas Wentworth Higginson | 205 |

| Dr. Samuel G. Howe | 205 |

| Benjamin Drew | 205 |

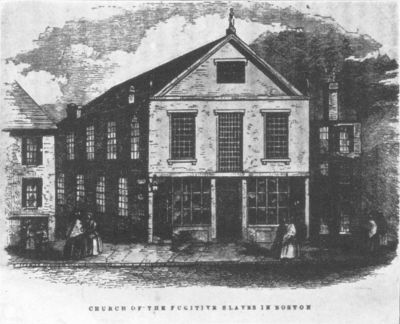

| Church of the Fugitive Slaves, Boston, Massachusetts | 235 |

| Salmon P. Chase | 254 |

| [xxii]Thomas Garrett | 254 |

| Rush R. Sloane | 282 |

| Thaddeus Stevens | 282 |

| J. R. Ware | 282 |

| Rutherford B. Hayes | 282 |

| Gerrit Smith | 290 |

| Joshua R. Giddings | 290 |

| Charles Sumner | 290 |

| Richard H. Dana | 290 |

| Bust of Rev. John Rankin | 307 |

| Harriet Beecher Stowe | 321 |

| Captain John Brown | 338 |

| Facsimile of a Leaf from the Diary of Daniel Osborn | On pages 344, 345 |

| MAPS | |

| Map of the Underground Railroad System | Facing page 113 |

| Map of Underground Lines in Southeastern Pennsylvania | " 113 |

| Map of Underground Lines in Morgan County, Ohio | On page 136 |

| Lewis Falley's Map of the Underground Routes of Indiana and Michigan | On page 138 |

| Map of an Underground Line through Livingston and La Salle Counties, Illinois | On page 139 |

| Map of Underground Lines through Greene, Warren and Clinton Counties, Ohio | On page 140 |

| APPENDICES | |

| Appendix A: Constitutional Provisions and National Acts relative to Fugitive Slaves, 1787-1850 | 359-366 |

| Appendix B: List of Important Fugitive Slave Cases | 367-377 |

| Appendix C: Figures from the United States Census Reports relating to Fugitive Slaves | 378, 379 |

| Appendix D: Bibliography | 380-402 |

| Appendix E: Directory of the names of Underground Railroad Operators and Members of Vigilance Committees | 403-439 |

This volume is the outgrowth of an investigation begun in 1892-1893, when the writer was giving a portion of his time to the teaching of United States history in the Ohio State University. The search for materials was carried on at intervals during several years until the mass of information, written and printed, was deemed sufficient to be subjected to the processes of analysis and generalization.

Patience and care have been required to overcome the difficulties attaching to a subject that was in an extraordinary sense a hidden one; and the author has constantly tried to observe those well-known dicta of the historian; namely, to be content with the materials discovered without making additions of his own, and to let his conclusions be defined by the facts, rather than seek to cast these "in the mould of his hypothesis."

Starting without preconceptions, the writer has been constrained to the views set forth in Chapters X and XI in regard to the real meaning and importance of the underground movement. And if it be found by the reader that these views are in any measure novel, it is hoped that the pages of this book contain evidence sufficient for their justification. There is something mysterious and inexplicable about the whole anti-slavery movement in the United States, as its history is generally recounted. According to the accepted view the anti-slavery movement of the thirties and the later decades has been considered as altogether distinct from the earlier abolition period in our history, both in principle and external features, and as separated from it by a[xxiv] considerable interval of time. The earlier movement is supposed to have died a natural death, and the later to have sprung into full life and vigor with the appearance of Garrison and the Liberator. Issue is made with this view in the following pages, where Macaulay's rational account of revolutions in general may, perhaps, be thought to find illustration. Macaulay says in one of his essays: "As the history of states is generally written, the greatest and most momentous revolutions seem to come upon them like supernatural inflictions, without warning or cause. But the fact is, that such revolutions are almost always the consequences of moral changes, which have gradually passed on the mass of the community, and which ordinarily proceed far before their progress is indicated by any public measure. An intimate knowledge of the domestic history of nations is therefore absolutely necessary to the prognosis of political events." Or, the essayist might have added, to a subsequent understanding of them.

It is impossible for the author to make acknowledgments to all who have contributed, directly and indirectly, to the promotion of his research. A liberal use of foot-notes suffices to reduce his obligations in part only. But, although the great balance of his indebtedness must stand against him, his special acknowledgments are due in certain quarters. The writer has to thank Professor J. Franklin Jameson of Brown University for calling his attention to a rare and important little book, which otherwise would almost certainly have escaped his notice. To Professor Eugene Wambaugh of the Harvard Law School he is indebted for the critical perusal of Chapter IX, on the Prosecutions of Underground Railroad Men,—a chapter based largely on reports of cases, and involving legal points about which the layman may easily go astray. The frequent citations of the monograph on Fugitive Slaves by Mrs. Marion G. McDougall attest the general usefulness of that book in the preparation of the present work. For personal encouragement in the undertaking[xxv] after the collection of materials had begun, and for assistance while the study was being put in manuscript, the author is most deeply indebted to Professor Albert Bushnell Hart, and the Seminary of American History in Harvard University, over which he and his colleague, Professor Edward Channing, preside. The proof-sheets of this book have been read by Mr. F. B. Sanborn, of Concord, Massachusetts, and, it is hardly necessary to add, have profited thereby in a way that would have been impossible had they passed under the eye of one less widely acquainted with anti-slavery times and anti-slavery people. More than to all others the author's gratitude is due to the members of his own household, without whose abiding interest and ready assistance in many ways this work could not have been carried to completion. It should be said that no responsibility for the use made of data or the conclusions drawn from them can justly be imposed upon those whose generous offices have kept these pages freer from discrepancies than they could have been otherwise.

It is a fortunate circumstance that, by the kindness of the artist, Mr. C. T. Webber, the reproduction of his painting entitled "The Underground Railroad" can appear as the frontispiece of this book. Mr. Webber was fitted by his intimate acquaintance with the Coffin family of Cincinnati, Ohio, and their remarkable record in the work of secret emancipation, to give a sympathetic delineation of the Underground Railroad in operation.

Ohio State University,

October, 1898.

THE

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

FROM

SLAVERY TO FREEDOM

Historians who deal with the rise and culmination of the anti-slavery movement in the United States have comparatively little to say of one phase of it that cannot be neglected if the movement is to be fully understood. This is the so-called Underground Railroad, which, during fifty years or more, was secretly engaged in helping fugitive slaves to reach places of security in the free states and in Canada. Henry Wilson speaks of the romantic interest attaching to the subject, and illustrates the coöperative efforts made by abolitionists in behalf of colored refugees in two short chapters of the second volume of his Rise and Fall of the Slave Power in America.[1] Von Holst makes several references to the work of the Road in his well-known History of the United States, and predicts that "The time will yet come, even in the South, when due recognition will be given to the touching unselfishness, simple magnanimity and glowing love of freedom of these law-breakers on principle, who were for the most part people without name, money, or higher education."[2] Rhodes in his great work, the History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850[2], mentions the system, but considers it only as a manifestation of popular sentiment.[3] Other writers give less space to an account of this enterprise, although it was one that extended throughout many Northern states, and in itself supplied the reason for the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, one of the most remarkable measures issuing from Congress during the whole anti-slavery struggle.

The explanation of the failure to give to this "institution" the prominence which it deserves, is to be found in the secrecy in which it was enshrouded. Continuous through a period of two generations, the Road spread to be a great system by being kept in an oblivion that its operators aptly designated by the figurative use of the word "underground." Then, too, it was a movement in which but few of those persons were involved whose names have been most closely associated in history with the public agitation of the question of slavery, or with those political developments that resulted in the destruction of slavery. In general the participants in underground operations were quiet persons, little known outside of the localities where they lived, and were therefore members of a class that historians find it exceedingly difficult to bring within their field of view.

Before attempting to prepare a new account of the Underground Railroad, from new materials, something should be said of previous works upon it, and especially of the seven books which deal specifically with the subject: The Underground Railroad, by the Rev. W. M. Mitchell; Underground Railroad Records, by William Still; The Underground Railroad in Chester and the Neighboring Counties of Pennsylvania, by R. C. Smedley; The Reminiscences of Levi Coffin; Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad, by Eber M. Pettit; From Dixie to Canada, by H. U. Johnson; and Heroes in Homespun, by Ascott R. Hope (a nom de plume for Robert Hope Moncrieff).

While several of these volumes are sources of original material, their value is chiefly that of collections of incidents, affording one an insight into the workings of the Underground[3] Railroad in certain localities, and presenting types of character among the helpers and the helped. In composition they are what one would expect of persons who lived simple, strenuous lives, who with sincerity record what they knew and experienced. They have not only the characteristics of a deep-seated, moral movement, they have also an undeniable value for historical purposes.

Mitchell's small volume of 172 pages was published in England in 1860. Its author was a free negro, who served as a slave-driver in the South for several years, then became a preacher in Ohio, and for twelve years engaged in underground work; finally, about 1855, he went to Toronto, Canada, to minister to colored refugees as a missionary in the service of the American Free Baptist Mission Society.[4] It was while soliciting money in England for the purpose of building a chapel and schoolhouse for his people in Toronto that he was induced to write his book. The range of experience of the author enabled him to relate at first hand many incidents illustrative of the various phases of underground procedure, and to give an account of the condition of the fugitive slaves in Canada.[5]

Still's Underground Railroad Records, a large volume of 780 pages, appeared in 1872, and a second edition in 1883. For some years before the War Mr. Still was a clerk in the office of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia; and from 1852 to 1860 he served as chairman of the Acting Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia, a body whose special business it was to harbor fugitives and help them towards Canada. About 1850 Mr. Still began to keep records of the stories he heard from runaways, and his book is mainly a compilation of these stories, together with some Underground Railroad correspondence. At the end there are some biographical sketches of persons more or less prominent in the anti-slavery cause. The book is a mine of material relating to the work of the Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia.

Operations carried on in an extended field of six or seven counties in southeastern Pennsylvania, over routes many of which led to the Quaker City, are recounted in Smedley's volume of 395 pages, published in 1883. The abundant reminiscences and short biographies were patiently gathered by the author from many aged participants in underground enterprises.

In his Reminiscences, a book of 732 pages, Levi Coffin, the reputed president of the Underground Railroad, relates his experiences from the time when he began, as a youth in North Carolina, to direct slaves northward on the path to liberty, till the time when, after twenty years of service in eastern Indiana and fifteen in Cincinnati, Ohio, he and his coworkers were relieved by the admission of slaves within the lines of the Union forces in the South. Mr. Coffin was a Quaker of the gentle but firm type depicted by Harriet Beecher Stowe in the character Simeon Halliday, of which he may have been the original. It need scarcely be said, therefore, that his autobiography is characterized by simplicity and candor, and supplies a fund of information in regard to those branches of the Road with which its author was connected.

Pettit's Sketches comprise a series of articles printed in the Fredonia (New York) Censor, during the fall of 1868, and collected in 1879 into a book of 174 pages. The author was for many years a "conductor" in southwestern New York, and most of the adventures narrated occurred within his personal knowledge.

Johnson's From Dixie to Canada is a little volume of 194 pages, in which are reprinted some of the many stories first published by him in the Lake Shore Home Magazine during the years 1883 to 1889 under the heading, "Romances and Realities of the Underground Railroad." The data that most of these tales embody were accumulated by research, and while the names of operators, towns and so forth are authentic, the writer allows himself the license of the story-teller instead of restricting himself to the simple recording of the information secured. His investigations have given him an acquaintance with the routes of northeastern Ohio and the adjacent portions of Pennsylvania and New York.

Hope's volume, published in 1894, does not increase the number of our sources of information, inasmuch as its materials are derived from Still's Underground Railroad Records and Coffin's Reminiscences. It was written by an Englishman apparently as a popular exposition of the hidden methods of the abolitionists.

To these books should be added a pamphlet of thirty pages, entitled The Underground Railroad, by James H. Fairchild, D.D., ex-President of Oberlin College, published in 1895 by the Western Reserve Historical Society.[6] The author had personal knowledge of many of the events he narrates and recounts several underground cases of notoriety; he thus affords a clear insight into the conditions under which secret aid came to be rendered to runaways.

It is surprising that a subject, the mysterious and romantic character of which might be supposed to appeal to a wide circle of readers, has not been duly treated in any of the modern popular magazines. During the last ten years a few articles about the Underground Railroad have appeared in The Magazine of Western History,[7] The Firelands Pioneer,[8] The Midland Monthly,[9] The Canadian Magazine of Politics, Science, Art and Literature[10] and The American Historical Review.[11] Three of these publications, the first two and the last, are of a special character; the other two, although they appeal to the general reader, cannot be said to have attempted more than the presentation of a few incidents out of the experience of certain underground helpers. From time to time the New England Magazine has given its readers glimpses of the Underground Road by its articles dealing with several well-known fugitive slave cases, and a biographical[6] sketch of the abductor Harriet Tubman.[12] But it would be quite impossible for any one to gain an adequate idea of the movement from the meagre accounts that have appeared in any of these magazines.

In contrast with the magazines, the newspapers have frequently published some of the stirring recollections of surviving abolitionists, but the result for the reader is usually that he learns only some anecdotes concerning a small section of the Road, without securing an insight into the real significance of the underground movement. Without undertaking here to print a full list of articles on the subject, it is worth while to notice a few newspapers in which series of sketches have appeared of more or less value in extending our geographical knowledge of the system, or in illustrating some important phase of its working. The New Lexington (Ohio) Tribune, from October, 1885, to February, 1886, contains a series of reminiscences, written by Mr. Thomas L. Gray, that supply interesting information about the work in southeastern Ohio. The Pontiac (Illinois) Sentinel, in 1890 and 1891, published fifteen chapters of "A History of Anti-Slavery Days" contributed by Mr. W. B. Fyffe, recording some episodes in the development of this Road in northeastern Illinois. The Sentinel, of Mt. Gilead, Ohio, in a series of articles, one of which appeared every week from July 13 to August 17, 1893, under the name of Aaron Benedict, affords a knowledge of the way in which the secret work was carried on in a typical Quaker community. In The Republican Leader, of Salem, Indiana, at various dates from Nov. 17, 1893, to April, 1894, E. Hicks Trueblood printed the results of some investigations begun at the instance of the author, which disclose the principal routes of south central Indiana. An account of the peculiar methods of the pedler Joseph Sider, an abductor of slaves, is also given by Mr. Trueblood. The Rev.[7] John Todd has preserved in the columns of the Tabor (Iowa) Beacon, in 1890 and 1891, some valuable reminiscences, running through more than twenty numbers of the paper, under the title, "The Early Settlement and Growth of Western Iowa"; several of these are devoted to fugitive slave cases.[13]

It is not surprising, in view of the unlawful nature of Underground Railroad service, that extremely little in the way of contemporaneous documents has descended to us even across the short span of a generation or two, and that there are few written data for the history of a movement that gave liberty to thousands of slaves. The legal restraints upon the rendering of aid to slaves bent on flight to Canada were, of course, ever present in the minds of those that pitied the bondman, whether a well-informed lawyer, like Joshua R. Giddings, or an illiterate negro, who, notwithstanding his fellow-feeling, was yet sufficiently sagacious to avoid the open violation of what others might call the law of the land. Therefore, written evidence of complicity was for the most part carefully avoided; and little information concerning any part of the work of the Underground Road was allowed to get into print. It is known that records and diaries were kept by certain helpers; and a few of the letters and messages that passed between station-keepers have been preserved. These sources of information are as valuable as they are rare: they would doubtless be more plentiful if the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 had not created such consternation as to lead to the destruction of most of the telltale documents.

The great collection of contemporaneous material is that of William Still, relating mainly to the work of the Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia. The motives and the methods of Mr. Still in keeping his register are given in the following words: "Thousands of escapes, harrowing separations, dreadful longings, dark gropings after lost parents, brothers, sisters, and identities, seemed ever to be pressing on my mind. While I knew the danger of keeping strict records, and while I did not then dream that in my day slavery would be blotted out,[8] or that the time would come when I could publish these records, it used to afford me great satisfaction to take them down fresh from the lips of fugitives on the way to freedom, and to preserve them as they had given them...."[14] When in 1852 Mr. Still became the chairman of the Acting Committee of Vigilance his opportunities were doubtless increased for obtaining histories of cases; and he was then directed as head of the committee "to keep a record of all their doings, ... especially of the money received and expended on behalf of every case claiming their interposition."[15] During the period of the War, Chairman Still concealed the records and documents he had collected in the loft of Lebanon Cemetery building, and although their publication became practicable when the Proclamation of Emancipation was issued, the Underground Railroad Records did not appear until 1872.[16]

Theodore Parker, the distinguished Unitarian clergyman of Boston, and one of the most active members of the Vigilance Committee of that city, kept memoranda of occurrences growing out of the attempted enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law in his neighborhood. He was outspoken in his opposition to the law, and was not less bold in gathering into a journal, along with newspaper clippings and handbills referring to the troubles of the time, manuscripts of his own bearing on the unlawful procedure of the Committee. This journal or scrap-book, given to the Boston Public Library in 1874 by Mrs. Parker,[17] was compiled day by day from March 15, 1851, to February 19, 1856, and throws much light on the rendition of the fugitives Burns and Sims.

John Brown, of Osawattomie, left a few notes of his memorable journey through Kansas and Iowa, on his way to Canada in the winter of 1858 and 1859, with a company of slaves rescued by him from bondage in western Missouri. On the back of the original draft of a letter written by Brown for the New York Tribune soon after the slaves had been taken from their[9] masters, appear the names of station-keepers of the Underground Railroad in eastern Kansas, and a record of certain expenditures forming, doubtless, a part of the cost of his trip.[18] When the fearless abductor arrived at Springdale, Iowa, late in February, he wrote to a friend in Tabor a statement concerning the "Reception of Brown and Party at Grinnell, Iowa, compared with Proceedings at Tabor," in which he set down in the form of items the substantial attentions he had received at the hands of citizens of Grinnell.[19] These meagre records, together with the letter written to the Tribune mentioned above, are all that Brown wrote, so far as known, giving explicit information in regard to an exploit that created a stir throughout the country.

Mr. Jirch Platt, of the vicinity of Mendon, Illinois, recorded his experiences as a station-keeper in a "sort of diary and farm record," and in a "blue-book," and appears to have been the only one of the underground helpers of Illinois that ventured to chronicle matters of this kind. The diary is still extant, and shows entries covering a period of more than ten years, closing with October, 1859; the following items will illustrate sufficiently the character of the record:—

"May 19, 1848. Hannah Coger arrived on the U. G. Railroad, the last $100.00 for freedom she was to pay to Thomas Anderson, Palmyra, Mo. The track is kept bright, it being the 3rd time occupied since the first of April...."

"Nov. 9, '54. Negro hoax stories have been very high in the market for a week past."

"Oct. 1859. U. G. R. R. Conductor reported the passage of five, who were considered very valuable pieces of Ebony, all designated by names, such as John Brooks, Daniel Brooks, Mason Bushrod, Sylvester Lucket and Hanson Gause. Have understood also that three others were ticketed about midsummer."

In Ohio, Daniel Osborn, of the Alum Creek Quaker Settlement, in the central part of the state, kept a diary, of[10] which to-day only a leaf remains. This bit of paper gives a record of the number of negroes passing through the Alum Creek neighborhood during an interval of five months, from April 14 to September 10, 1844, and is of considerable importance, because it supplies data that furnish, when taken in connection with other terms, the elements for an interesting computation of the number of slaves that escaped into Ohio.[20] In the correspondence of Mr. David Putnam, of Point Hamar, near Marietta, Ohio, there were found a few letters relating to the journeys of fugitives. That even these few letters remain is doubtless due to neglect or oversight on the part of the recipient. It is noticeable that some of them bear unmistakable signs of intended secrecy, the proper names having been blotted out, or covered with bits of paper.

Underground managers who were so indiscreet as to keep a diary or letters for a season, were induced to part with such condemning evidence under the stress of a special danger. Mr. Robert Purvis, of Philadelphia, states that he kept a record of the fugitives that passed through his hands and those of his coworkers in the Quaker City for a long period, till the trepidation of his family after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Bill in 1850 caused him to destroy it.[21] Daniel Gibbons, a Friend, who lived near Columbia in southeastern Pennsylvania, began in 1824 to keep a record of the number of fugitives he aided. He was in the habit of entering in his book the name of the master of each fugitive, the fugitive's own name and his age, and the new name given him. The data thus gathered came in time to form a large volume, but after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law Mr. Gibbons burned this book.[22] William Parker, the colored leader in the famous Christiana case, was found by a friend to have a large number of letters from escaped slaves hidden about his house at the time of the Christiana affair, September 11, 1851, and these fateful documents were quickly destroyed. Had they been discovered by the officers that visited Parker's[11] house, they might have brought disaster upon many persons.[23] Thus, the need of secrecy constantly served to prevent the making of records, or to bring about their early destruction. The written and printed records do give a multitude of unquestioned facts about the Underground Railroad; but when wishing to find out the details of rational management, the methods of business, and the total amount of traffic, we are thrown back on the recollections of living abolitionists as the main source of information; from them the gaps in the real history of the Underground Railroad must be filled, if filled at all.

It is with the aid of such memorials that the present volume has been written. Reminiscences have been gathered by correspondence and by travel from many surviving abolitionists or their families; and recollections of fugitive slave days have been culled from books, newspapers, letters and diaries. During three years of the five years of preparation the author's residence in Ohio afforded him opportunity to visit many places in that state where former employees of the Underground Railroad could be found, and to extend these explorations to southern Michigan, and among the surviving fugitives along the Detroit River in the Province of Ontario. Residence in Massachusetts during the years 1895-1897 has enabled him to secure some interesting information in regard to underground lines in New England. The materials thus collected relate to the following states: Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Vermont, besides a few items concerning North Carolina, Maryland and Delaware.

Underground operations practically ceased with the beginning of the Civil War. In view of the lapse of time, the reasons for trusting the credibility of the evidence upon which our knowledge of the Underground Road rests should be stated. Some of the testimony dealt with in this chapter was put in writing during the period of the Road's operation, or at the close of its activity, and, therefore, cannot be easily questioned. But it may be said that a large part of the[12] materials for this history were drawn from written and oral accounts obtained at a much later date; and that these materials, even though the honesty and fidelity of the narrators be granted, are worthy of little credit for historical purposes. Such a criticism would doubtless be just as applied to reminiscences purporting to represent particular events with great detail of narration, but clearly it would lose much of its force when directed against recollections of occurrences that came within the range of the narrator's experience, not once nor twice, but many times with little variation in their main features. It would be difficult to imagine an "old-time" abolitionist, whose faculties are in a fair state of preservation, forgetting that he received fugitives from a certain neighbor or community a few miles away, that he usually stowed them in his garret or his haymow, and that he was in the habit of taking them at night in all kinds of weather to one of several different stations, the managers of which he knew intimately and trusted implicitly. Not only did repetition serve to deepen the general recollections of the average operator, but the strange and romantic character of his unlawful business helped to fix them in his mind. Some special occurrences he is apt to remember with vividness, because they were in some way extraordinary. If it be argued that the surviving abolitionists are now old persons, it should not be forgotten that it is a fact of common observation that old persons ordinarily remember the occurrences of their youth and prime better than events of recent date. The abolitionists, as a class, were people whose remembrances of the ante-bellum days were deepened by the clear definition of their governing principles, the abiding sense of their religious convictions, and the extraordinary conditions, legal and social, under which their acts were performed. The risks these persons ran, the few and scattered friends they had, the concentration of their interests into small compass, because of the disdain of the communities where they lived, have secured to us a source of knowledge, the value of which cannot be lightly questioned. If there be doubt on this point, it must give way before the manner in which statements gathered from different localities during the last five years articulate[13] together, the testimony of different and sometimes widely separated witnesses combining to support one another.[24]

The elucidation by new light of some obscure matter already reported, the verification by a fresh witness of some fact already discovered, gives at once the rule and test of an investigation such as this. Out of many illustrations that might be given, the following are offered. Mr. J. M. Forsyth, of Northwood, Logan County, Ohio, writes under date September 22, 1894: "In Northwood there is a denomination known as Covenanters; among them the runaways were safe. Isaac Patterson has a cave on his place where the fugitives were secreted and fed two or three weeks at a time until the hunt for them was over. Then friends, as hunters, in covered wagons would take them to Sandusky. The highest number taken at one time was seven. The conductors were mostly students from Northwood. All I did was to help get up the team...."

The Rev. J. S. T. Milligan, of Esther, Pennsylvania, December 5, 1896, writes entirely independently: "In 1849 my brother ... and I went ... to Logan Co., Ohio, to conduct a grammar school ... at a place called Northwood. The school developed into a college under the title of Geneva Hall. J. R. W. Sloane[25] ... was elected President and moved to Northwood in 1851.... The region was settled by Covenanters and Seceders, and every house was a home for the wanderers. But there was a cave on the farm of a man by the name of Patterson, absolutely safe and fairly[14] comfortable for fugitives. In one instance thirteen fugitives, after resting in the cave for some days, were taken by the students in two covered wagons to Sandusky, some 90 miles, where I had gone to engage passage for them on the Bay City steamboat across the lake to Malden—where I saw them safely landed on free soil, to their unspeakable joy. Indeed, I thought one old man would have died from the gladness of his heart in being safe in freedom. I went from Belle Centre [near Northwood] by rail, and did not go with the land escort—but from what they told me of their experience, it was often amusing and sometimes thrilling. They were ostensibly a hunting party of 10 or 12 armed men.... The two covered wagons were a 'sanctum sanctorum' into which no mortal was allowed to peep.... The word of command, 'Stand back,' was always respected by those who were unduly intent upon seeing the thirteen deer ... brought from the woods of Logan and Hardin counties and being taken to Sandusky."

In the same letter Mr. Milligan corroborates some information secured from the Rev. R. G. Ramsey, of Cadiz, Ohio, August 18, 1892, in regard to an underground route in southern Illinois. Mr. Ramsey related that his father, Robert Ramsey, first engaged in Underground Railroad work at Eden, Randolph County, Illinois, in 1844, and that he carried it on at intervals until the War. "The fugitives," he said, "came up the river to Chester, Illinois, and there they started northeast on the state road, which followed an old Indian trail. The stations were each in a community of Covenanters, ..." and existed, according to his account, at Chester, Eden, Oakdale, Nashville and Centralia. "Besides my father," said Mr. Ramsey, "John Hood and two brothers, James B. and Thomas McClurkin, lived in Oakdale, where my father lived during the last thirty-five years of his life. He lived in Eden before this time...."[26] The Rev. Mr. Milligan writes as follows: "My father removed to Randolph Co., Ill., in 1847, and with Rev. Wm. Sloane ... and the Covenanter congregations under their ministry kept a very large depot wide open for slaves escaping from Missouri.[15] Scores at a time came to Sparta [the post-office of the Eden settlement mentioned above]—my father's region, were harbored there, ... and finally escorted to Elkhorn [about two miles from Oakdale], the region of Father Sloane, where they were sheltered and escorted ... to some friends in the region of Nashville, Ill., and thence north on the regular trail which I am not able further to locate. At Sparta, Coultersville and Elkhorn there was an almost constant supply of fugitives.... But ... few were ever gotten from the ægis of the Hayes and Moores and Todds and McLurkins and Hoods and Sloanes and Milligans of that region."

The evidence above quoted has the well-known value of two witnesses, examined apart, who corroborate each other; and it also illustrates the way in which the pieces of underground routes may be joined together. These letters, together with some additional testimony, enable us to trace on the map a section of a secret line of travel in southern Illinois.

Another example throws light on a channel of escape in northeastern Indiana. While Levi Coffin lived at Newport (now Fountain City), Indiana, he sometimes sent slaves northward by way of what he called "the Mississinewa route,"[27] from the Mississinewa River, near which undoubtedly it ran for a considerable distance. This road seems to have been called also the Grant County route. In the most general way only do these descriptions tell anything about the route. However, correspondence with several people of Indiana has brought it to light. One letter[28] informs us in regard to fugitives departing from Newport: "If they came to Economy they were sent to Grant Co...." Now, so far as known, Jonesboro' was the next locality to which they were usually forwarded, and the line from this point northward is given us by the Hon. John Ratliff, of Marion, Indiana, who had been over it with passengers. He says that the first station north of Jonesboro' was North Manchester, where "Morris" Place[16] was agent; the next station, Goshen, where Dr. Matchett harbored fugitives; and thence the line ran to Young's Prairie,[29] which is in Cass County, Michigan. The same section of Road, but with a few additional stations, is marked out by William Hayward. The additional stations may not have existed at the time when Mr. Ratliff served as a guide, or he may have forgotten to mention them. Mr. Hayward writes: "My cousin, Maurice Place, often brought carriage loads of colored people from North Manchester, Wabash Co., to my father's house, six miles west of Manchester on the Rochester road.... We would keep them ... until sometime in the night; then my father would go with them to Avery Brace's ... three miles ... north, through the woods. He took them ... seven miles farther ... to Chauncey Hurlburt's in Kosciusko Co.... They (the Hurlburts) took them twelve miles farther ... to Warsaw, to a man by the name of Gordon, and he took them to Dr. Matchett's in Elkhart Co., not far from Goshen. There were friends there to help them to Michigan."[30]

In weighing the testimony amassed, the author has had the advantage of personal acquaintance with many of those furnishing information; and the internal evidence of letters has been considered in estimating the worth of written testimony. Doubtless the work could have been more thoroughly executed, if the collection of materials had been systematically undertaken by some one a decade or two earlier. It is certain that it could not have been postponed to a later period. Since the inception of this research the ravages of time have greatly thinned the company of witnesses, who count it among their chiefest joys that they were permitted to live to see their country rid of slavery, and the negro race a free people.

ONE OF THE PIONEERS IN THE UNDERGROUND MOVEMENT IN

PHILADELPHIA AND NEW YORK.

Mr. Hopper is supposed to have resorted to underground methods as early as 1787.

The Underground Road developed in a section of country rid of slavery, and situated between two regions, from one of which slaves were continually escaping with the prospect of becoming indisputably free on crossing the borders of the other. Not a few persons living within the intervening territory were deeply opposed to slavery, and although they were bound by law to discountenance slaves seeking freedom, they felt themselves to be more strongly bound by conscience to give them help. Thus it happened that in the course of the sixty years before the outbreak of the War of the Rebellion the Northern states became traversed by numerous secret pathways leading from Southern bondage to Canadian liberty.

Slavery was put in process of extinction at an early period in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and the New England states. From the five and a fraction states created out of the Northwestern Territory slavery was excluded by the Ordinance of 1787. It is interesting to note how rapid was the progress of emancipation in the Northeastern states, where the conditions of climate, industry and public opinion were unfavorable to the continuance of slavery. In 1777 emancipation was begun by the action of Vermont, which upon its separation from New York adopted a constitution in which slavery was prohibited. Pennsylvania and Massachusetts took action three years later. Pennsylvania provided by statute for gradual abolition, and its example was followed by Rhode Island and Connecticut in 1784, by New York in 1799, and by New Jersey in 1804. Massachusetts was less direct, but not less effective, in securing the extinction of slavery; happily it had inserted in the declaration of[18] rights prefixed to its constitution: "All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights."[31] This clause received at a later time strict interpretation at the bar of the state supreme court, and slavery was held to have ceased with the year 1780.

There is little to be said about the remaining group of states with which we are here concerned. Their territorial organizations were effected under the provisions of the Ordinance of 1787. One of the most important of these provisions is as follows: "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said Territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted."[32] It was this feature, introduced into the great Ordinance by New England men, that rendered futile the many attempts subsequently made by Indiana Territory to have slavery admitted within its own boundaries by congressional enactment. "It is probable," says Rhodes, "that had it not been for the prohibitory clause, slavery would have gained such a foothold in Indiana and Illinois that the two would have been organized as slaveholding states."[33] The five states, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin were therefore admitted to the Union as free states. West of the Mississippi River there is one state, at least, that must be added to the group just indicated, namely, Iowa. Slaveholding was prevented within its domain by the Act of Congress of 1820, prohibiting slavery in the territory acquired under the Louisiana purchase north of latitude 36° 30', and several years before this law was abrogated Iowa had entered statehood with a constitution that fixed her place among the free commonwealths. The enfranchisement of this extended region was thus accomplished by state and national action. The ominous result was the establishment of a sweeping line of frontier between the slaveholding South and the non-slaveholding North, and thereby the propounding to the nation of a new question,[19] that of the status of fugitives in free regions. The elements were in the proper condition for the crystallization of this question.

The colonies generally had found it necessary to provide regulations in regard to fugitives and the restoration of them to their masters. Such provisions, it is probable, were reasonably well observed as long as runaways did not escape beyond the borders of the colonies to which their owners belonged; but escapes from the territory of one colony into that of another were at first left to be settled as the state of feeling existing between the two peoples concerned should dictate. In 1643 the New England Confederation of Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut and New Haven, unwilling to leave the subject of the delivery of fugitives longer to intercolonial comity, incorporated a clause in their Articles of Confederation providing: "If any servant runn away from his master into any other of these confederated Jurisdiccons, That in such case vpon the Certyficate of one Majistrate in the Jurisdiccon out of which the said servant fled, or upon other due proofs, the said servant shall be deliuered either to his Master or any other that pursues and brings such Certificate or proofe." About the same time an agreement was entered into between the Dutch at New Netherlands and the English at New Haven for the mutual surrender of fugitives, a step that was preceded by a complaint from the commissioners of the United Colonies to Governor Stuyvesant of New Netherlands, to the effect that the Dutch agent at Hartford was harboring one of their Indian slaves, and by the refusal to return some of Stuyvesant's runaway servants from New Haven until the redress of the grievance. It was only when some of the fugitives had been restored to New Netherlands, and a proclamation, issued in a spirit of retaliation by the Lords of the West India Company, forbidding the rendition of fugitive slaves to New Haven, had been annulled, that the agreement for the mutual surrender of runaways was made by the two parties. Negotiations in regard to fugitives early took place between Maryland and New Netherlands; at one time on account of the flight of some slaves from the Southern colony into the Northern colony, and later on account of the reversal of the[20] conditions. The temper of the Dutch when calling for their servants in 1659 was not conciliatory, for they threatened, if their demand should be refused, "to publish free liberty, access and recess to all planters, servants, negroes, fugitives, and runaways which may go into New Netherland." The escape of fugitives from the Eastern colonies northward to Canada was also a constant source of trouble between the French and the Dutch, and between the French and English.[34]

When, therefore, emancipation acts were passed by Vermont and four other states the new question came into existence. It presented itself also in the Western territories. The framers of the Northwest Ordinance found themselves confronted by the question, and they dealt with it in the spirit of compromise. They enacted a stipulation for the territory, "that any person escaping into the same, from whom labor or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original states, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or service aforesaid."[35]

Meanwhile the Federal Convention in Philadelphia had the same question to consider. The result of its deliberations on the point was not different from that of Congress expressed in the Ordinance. Among the concessions to slavery that the Federal Convention felt constrained to make, this provision found place in the Constitution: "No person held to service or labor in one state under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due."[36] Neither of these clauses appears to have been subjected to much debate, and they were adopted by votes that testify to their acceptableness; the former received the support of all members present but one, the latter passed unanimously.

In the sentiment of the time there seems to have been no[21] sense of humiliation on the part of the North over the conclusions reached concerning the rendition of escaped slaves. It had been seen by Northern men that the subject was one requiring conciliatory treatment, if it were not to become a block in the way of certain Southern states entering the Union; and, besides, the opinion generally prevailed that slavery would gradually disappear from all the states, and the riddle would thus solve itself.[37] The South was pleased, but apparently not exultant, over the supposed security gained for its slave property. General C. C. Pinckney, of South Carolina, probably expressed the view of most Southerners when he said that the terms for the security of slave property gained by his section were not bad, although they were not the best from the slaveholders' standpoint, and that they permitted the recapture of runaways in any part of America—a right the South had never before enjoyed.[38] In abstract law the rights of the slave-owner had in truth been well provided for. Especially deserving of note is the fact that a constitutional basis had been furnished for claims which, in case slavery did not disappear from the country—a contingency not anticipated by the fathers—might be insisted upon as having the fundamental and positive sanction of the government. But what would be the fate of the running slave was a matter with which, after all, private principles and sympathies, and not merely constitutional provisions, would have a good deal to do in each case.

For several years the stipulations for the rendition of fugitive slaves remained inoperative. At length, in 1791, a case of kidnapping occurred at Washington, Pennsylvania, and this served to bring the subject once more to the public mind. Early in 1793 Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Law.[39] This law provided for the reclamation of fugitives from justice and fugitives from labor. We are concerned, of course, with the latter class only. The sections of the act dealing with this division are too long to be here quoted:[22] they empowered the owner, his agent or attorney, to seize the fugitive and take him before a United States circuit or district judge within the state where the arrest was made, or before any local magistrate within the county in which the seizure occurred. The oral testimony of the claimant, or an affidavit from a magistrate in the state from which he came, must certify that the fugitive owed service as claimed. Upon such showing the claimant secured his warrant for removing the runaway to the state or territory from which he had fled. Five hundred dollars fine constituted the penalty for hindering arrest, or for rescuing or harboring the fugitive after notice that he or she was a fugitive from labor.

All the evidence goes to show that this law was ineffectual; Mrs. McDougall points out that two cases of resistance to the principle of the act occurred before the close of 1793.[40] Attempts at amendment were made in Congress as early as the winter of 1796, and were repeated at irregular intervals down to 1850. Secret or "underground" methods of rescue were already well understood in and around Philadelphia by 1804. Ohio and Pennsylvania, and perhaps other states, heeded the complaints of neighboring slave states, and gave what force they might to the law of 1793 by enacting laws for the recovery of fugitives within their borders. The law of Pennsylvania for this purpose was passed the same year in which Mr. Clay, then Secretary of State, began negotiations with England looking toward the extradition of slaves from Canada (1826); but it was quashed by the decision of the United States Supreme Court in the Prigg case in 1842.[41] By 1850 the Northern states were traversed by numerous lines of Underground Railroad, and the South was declaring its losses of slave property to be enormous.

The result of the frequent transgressions of the Fugitive Slave Law on the one hand and of the clamorous demand for a measure adequate to the needs of the South on the other, was the passage of a new Fugitive Recovery Bill in 1850.[42] The[23] increased rigor of the provisions of this act was ill adapted to generate the respect that a good law secures, and, indeed, must have in order to be enforced. The law contained features sufficiently objectionable to make many converts to the cause of the abolitionists; and a systematic evasion of the law was regarded as an imperative duty by thousands. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was based on the earlier law, but was fitted out with a number of clauses, dictated by a self-interest on the part of the South that ignored the rights of every party save those of the master. Under the regulations of the act the certificate authorizing the arrest and removal of a fugitive slave was to be granted to the claimant by the United States commissioner, the courts, or the judge of the proper circuit, district, or county. If the arrest were made without process, the claimant was to take the fugitive forthwith before the commissioner or other official, and there the case was to be determined in a summary manner. The refusal of a United States marshal or his deputies to execute a commissioner's certificate, properly directed, involved a fine of one thousand dollars; and failure to prevent the escape of the negro after arrest, made the marshal liable, on his official bond, for the value of the slave. When necessary to insure a faithful observance of the fugitive slave clause in the Constitution, the commissioners, or persons appointed by them, had the authority to summon the posse comitatus of the county, and "all good citizens" were "commanded to aid and assist in the prompt and efficient execution" of the law. The testimony of the alleged fugitive could not be received in evidence. Ownership was determined by the simple affidavit of the person claiming the slave; and when determined it was shielded by the certificate of the commissioner from "all molestation ... by any process issued by any court, judge, magistrate, or other person whomsoever." Any act meant to obstruct the claimant in his arrest of the fugitive, or any attempt to rescue, harbor, or conceal the fugitive, laid the person interfering liable "to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisonment not exceeding six months," also liable for "civil damages to the party injured in the sum of one thousand dollars for each fugitive so[24] lost." In all cases where the proceedings took place before a commissioner he was "entitled to a fee of ten dollars in full for his services," provided that a warrant for the fugitive's arrest was issued; if, however, the fugitive was discharged, the commissioner was entitled to five dollars only.[43]