*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 48800 ***

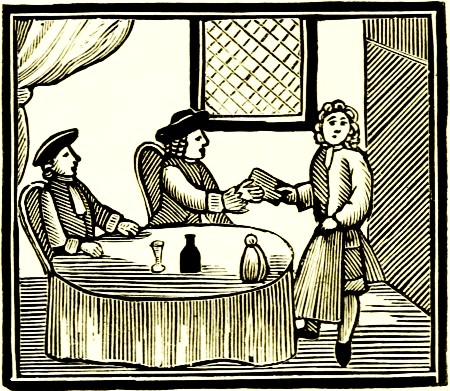

A CHAPMAN.

From "The Cries and Habits of the City of London," by M. Lauron, 1709.

CHAP-BOOKS

OF

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

WITH

FACSIMILES, NOTES, AND INTRODUCTION

BY

JOHN ASHTON

London

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY

1882

(All rights reserved)

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES.

Page vi

INTRODUCTION.

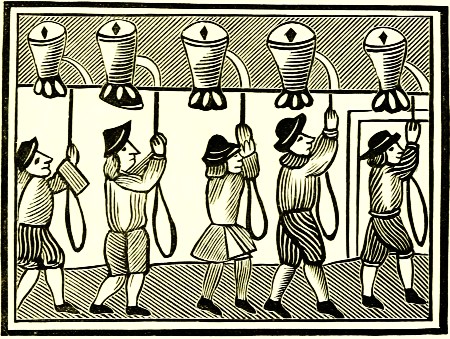

Although these Chap-books are very curious, and on many

accounts interesting, no attempt has yet been made to place

them before the public in a collected form, accompanied by the

characteristic engravings, without which they would lose much

of their value. They are the relics of a happily past age, one

which can never return, and we, in this our day of cheap,

plentiful, and good literature, can hardly conceive a time when

in the major part of this country, and to the larger portion of its

population, these little Chap-books were nearly the only mental

pabulum offered. Away from the towns, newspapers were

rare indeed, and not worth much when obtainable—poor little

flimsy sheets such as nowadays we should not dream of

either reading or publishing, with very little news in them, and

that consisting principally of war items, and foreign news,

whilst these latter books were carried in the packs of the

pedlars, or Chapmen, to every village, and to every home.

Previous to the eighteenth century, these men generally

carried ballads, as is so well exemplified in the "Winter's Tale,"

in Shakespeare's inimitable conception, Autolycus. The

servant (Act iv. sc. 3) well describes his stock: "He hath songs,

for man, or woman, of all sizes; no milliner can so fit his

customers with gloves. He has the prettiest love songs for

maids; so without bawdry, which is strange; with such delicate

burdens of 'dildos' and 'fadings:' 'jump her' and 'thump

her;' and where some stretch-mouthed rascal would, as it

were, mean mischief, and break a foul gap into the matter, he

makes the maid to answer, 'Whoop, do me no harm, good

man;' puts him off, slights him, with 'Whoop, do me no

Page vii

harm, good man.'" And Autolycus, himself, hardly exaggerates

the style of his wares, judging by those which have come down

to us, when he praises the ballads: "How a usurer's wife was

brought to bed of twenty money-bags at a burden; and how

she longed to eat adders' heads, and toads carbonadoed;" and

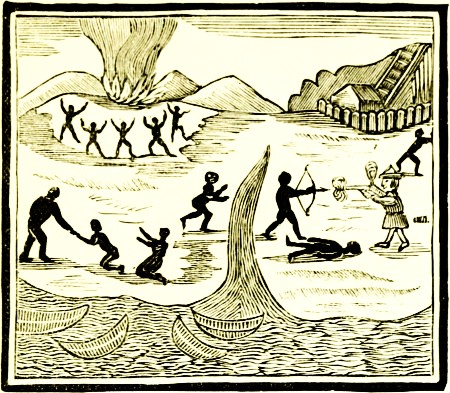

"of a fish, that appeared upon the coast, on Wednesday the

fourscore of April, forty thousand fathom above water, and

sung this ballad against the hard hearts of maids;" for the

wonders of both ballads, and early Chap-books, are manifold,

and bear strange testimony to the ignorance, and credulity, of

their purchasers. These ballads and Chap-books have, luckily

for us, been preserved by collectors, and although they are

scarce, are accessible to readers in that national blessing, the

British Museum. There the Roxburghe, Luttrell, Bagford, and

other collections of black-letter ballads are easily obtainable

for purposes of study, and, although the Chap-books, to the

uninitiated (owing to the difficulties of the Catalogue), are not

quite so easy of access, yet there they exist, and are a splendid

series—it is impossible to say a complete one, because some

are unique, and are in private hands, but so large, especially

from the middle to the close of the last century, as to be

virtually so.

I have confined myself entirely to the books of the last

century, as, previous to it, there were few, and almost all black-letter

tracts have been published or noted; and, after it, the

books in circulation were chiefly very inferior reprints of those

already published. As they are mostly undated, I have found

some difficulty in attributing dates to them, as the guides,

such as type, wood engravings, etc., are here fallacious, many—with

the exception of Dicey's series—having been printed with

old type, and any wood block being used, if at all resembling

the subject. I have not taken any dated in the Museum

Catalogue as being of this present century, even though internal

evidence showed they were earlier. The Museum dates are

admittedly fallacious and merely approximate, and nearly all

are queried. For instance, nearly the whole of the beautiful

Aldermary Churchyard (first) editions are put down as

Page viii

1750?—a manifest impossibility, for there could not have been

such an eruption of one class of publication from one firm

in one year—and another is dated 1700?, although the book

from which it is taken was not published until 1703. Still, as

a line must be drawn somewhere, I have accepted these quasi

dates, although such acceptation has somewhat narrowed my

scheme, and deprived the reader of some entertainment, and

I have published nothing which is not described in the Museum

Catalogue as being between the years 1700 and 1800.

In fact, the Chap-book proper did not exist before the

former date, unless the Civil War and political tracts can be so

termed. Doubtless these were hawked by the pedlars, but they

were not these pennyworths, suitable to everybody's taste, and

within the reach of anybody's purse, owing to their extremely

low price, which must, or ought to have, extracted every available

copper in the village, when the Chapman opened his budget

of brand-new books.

In the seventeenth, and during the first quarter of the

eighteenth century, the popular books were generally in 8vo

form, i.e. they consisted of a sheet of paper folded in eight, and

making a book of sixteen pages; but during the other seventy-five

years they were almost invariably 12mo, i.e. a sheet folded

into twelve, and making twenty-four pages. After 1800 they

rapidly declined. The type and wood blocks were getting worn

out, and never seem to have been renewed; publishers got less

scrupulous, and used any wood blocks without reference to the

letter-press, until, after Grub Street authors had worked their

wicked will upon them, Catnach buried them in a dishonoured

grave.

But while they were in their prime, they mark an epoch in

the literary history of our nation, quite as much as the higher

types of literature do, and they help us to gauge the intellectual

capacity of the lower and lower middle classes of the last

century.

The Chapman proper, too, is a thing of the past, although

we still have hawkers, and the travelling "credit drapers," or

"tallymen," yet penetrate every village; but the Chapman,

Page ix

as described by Cotsgrave in his "Dictionarie of the French

and English Tongues" (London, 1611), no longer exists. He

is there faithfully portrayed under the heading "Bissoüart, m.

A paultrie Pedlar, who in a long packe or maund (which he

carries for the most part open, and (hanging from his necke)

before him) hath Almanacks, Bookes of News, or other trifling

ware to sell."

Shakespeare uses the word in a somewhat different sense,

making him more of a general dealer, as in "Love's Labour's

Lost," Act ii. sc. I:

"Princess of France. Beauty is bought by judgment of the eye,

Not uttered by base sale of Chapmen's tongues."

And in "Troilus and Cressida," Act iv. sc. I:

"Paris. Fair Diomed, you do as Chapmen do,

Dispraise the thing that you desire to buy."

Unlike his modern congener, the colporteur, the Chapman's

life seems to have been an exceptionally hard one,

especially if we can trust a description, professedly by one of

the fraternity, in "The History of John Cheap the Chapman,"

a Chap-book published early in the present century. He

appears, on his own confession, to have been as much of a

rogue as he well could be with impunity and without absolutely

transgressing the law, and, as his character was well known,

very few roofs would shelter him, and he had to sleep in barns,

or even with the pigs. He had to take out a licence, and was

classed in old bye-laws and proclamations as "Hawkers,

Vendors, Pedlars, petty Chapmen, and unruly people." In

more modern times the literary Mercury dropped the somewhat

besmirched title of Chapmen, and was euphoniously

designated the "Travelling," "Flying," or "Running Stationer."

Little could he have dreamed that his little penny books

would ever have become scarce, and prized by book collectors,

and fetch high prices whenever the rare occasion happened

that they were exposed for sale. I have taken out the prices

paid in 1845 and 1847 for nine volumes of them, bought at

Page x

as many different sales. These nine volumes contain ninety-nine

Chap-books, and the price paid for them all was

£24 13s. 6d., or an average of five shillings each—surely not

a bad increment in a hundred years on the outlay of a penny;

but then, these volumes were bought very cheaply, as some of

their delighted purchasers record.

The principal factory for them, and from which certainly

nine-tenths of them emanated, was No. 4, Aldermary Churchyard,

afterwards removed to Bow Churchyard, close by. The

names of the proprietors were William and Cluer Dicey—afterwards

C. Dicey only—and they seem to have come from Northampton,

as, in "Hippolito and Dorinda," 1720, the firm is

described as "Raikes and Dicey, Northampton;" and this connection

was not allowed to lapse, for we see, nearly half a

century later, that "The Conquest of France" was "printed

and sold by C. Dicey in Bow Church Yard: sold also at his

Warehouse in Northampton."

From Dicey's house came nearly all the original Chap-books,

and I have appended as perfect a list as I can make,

amounting to over 120, of their publications. Unscrupulous

booksellers, however, generally pirated them very soon after

issue, especially at Newcastle, where certainly the next largest

trade was done in this class of books. The Newcastle editions

are rougher in every way, in engravings, type, and paper, than

the very well got up little books of Dicey's, but I have frequently

taken them in preference, because of the superior

quaintness of the engravings.

After the commencement of the present century reading

became more popular, and the following, which are only the

names of a few places where Chap-books were published, show

the great and widely spread interest taken in their production:—Edinburgh,

Glasgow, Paisley, Kilmarnock, Penrith, Stirling,

Falkirk, Dublin, York, Stokesley, Warrington, Liverpool, Banbury,

Aylesbury, Durham, Dumfries, Birmingham, Wolverhampton,

Coventry, Whitehaven, Carlisle, Worcester, Cirencester,

etc., etc. And they flourished, for they formed nearly the sole

literature of the poor, until the Penny Magazine and Chambers's

Page xi

penny Tracts and Miscellanies gave them their deathblow, and

relegated them to the book-shelves of collectors.

That these histories were known and prized in Queen

Anne's time, is evidenced by the following quotation from the

Weekly Comedy, January 22, 1708:—"I'll give him Ten of

the largest Folio Books in my Study, Letter'd on the Back, and

bound in Calves Skin. He shall have some of those that are the

most scarce and rare among the Learned, and therefore may be

of greater use to so Voluminous an Author; there is 'Tom

Thumb'

with Annotations and Critical Remarks, two volumes in folio.

The 'Comical Life and Tragical Death of the Old Woman that

was Hang'd for Drowning herself in Ratcliffe High-Way:' One

large Volume, it being the 20th Edition, with many new

Additions and Observations. 'Jack and the Gyants;' formerly

Printed in a small Octavo, but now Improv'd to three Folio

Volumes by that Elaborate Editor, Forestus, Ignotus Nicholaus

Ignoramus Sampsonius; then there is 'The King and the Cobler,'

a Noble piece of Antiquity, and fill'd with many Pleasant

Modern Intrigues fit to divert the most Curious."

And Steele, writing in the Tatler, No. 95, as Isaac

Bickerstaff, and speaking of his godson, a little boy of eight

years of age, says, "I found he had very much turned his

studies, for about twelve months past, into the lives and adventures

of Don Bellianis of Greece, Guy of Warwick, The Seven

Champions, and other historians of that age.... He would

tell you the mismanagements of John Hickerthrift, find fault

with the passionate temper in Bevis of Southampton and loved

St. George for being Champion of England."

As before said, their great variety adapted them for every

purchaser, and they may be roughly classed under the following

heads:—Religious, Diabolical, Supernatural, Superstitious,

Romantic, Humorous, Legendary, Historical, Biographical,

and Criminal, besides those which cannot fairly be put in any

of the above categories; and under this classification and in

this sequence I have taken them. The Religious, strictly so

called, are the fewest, the subjects, such as "Dr. Faustus,"

etc., connected with his Satanic Majesty being more exciting,

Page xii

and probably paying better; whilst the Supernatural, such as

"The Duke of Buckingham's Father's Ghost," "The Guildford

Ghost," etc., trading upon man's credulity and his love of the

marvellous, afford a far larger assortment. About the same

amount of popularity may be given to the Superstitious Chap-books—those

relating to fortune telling and the interpretation

of Dreams and Moles, etc. But they were nothing like the

favourites those of the Romantic School were. These dear

old romances, handed down from the days when printing

was not—some, like "Jack the Giant Killer," of Norse extraction;

others, like "Tom Hickathrift," "Guy of Warwick,"

"Bevis of Hampton," etc., records of the doughty deeds of

local champions; and others, again, "Reynard the Fox,"

"Valentine and Orson," and "Fortunatus," of foreign birth—hit

the popular taste, and many were the editions of them.

Naturally, however, the Humorous stories were the prime

favourites. The Jest-books, pure and simple, are, from their

extremely coarse witticisms, utterly incapable of being reproduced

for general reading nowadays, and the whole of them

are more or less highly spiced; but even here were shades

of humour to suit all classes, from the solemn foolery of the

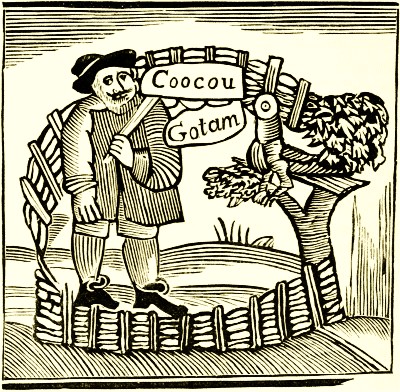

"Wise Men of Gotham," or the "World turned upside down,"

to the rollicking fun of "Tom Tram," "The Fryer and the

Boy," or "Jack Horner." In reading these books we must not,

however, look upon them from our present point of view.

Whether men and women are better now than they used to be,

is a moot point, but things used to be spoken of openly, which

are now never whispered, and no harm was done, nor offence

taken; so the broad humour of the jest-books was, after

all, only exuberant fun, and many of the bonnes histoires are

extremely laughable, though to our own thinking equally indelicate.

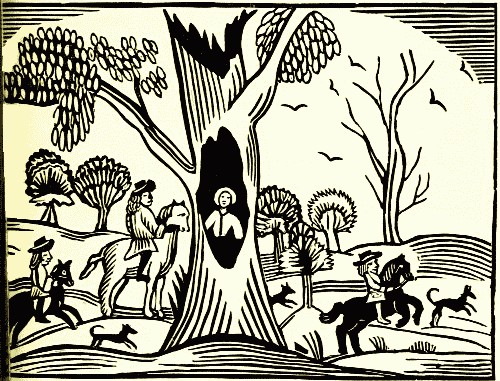

The old legends still held sway, and I have given

four—"Adam Bell," "Robin Hood," "The Blind Beggar of

Bethnal Green," and "The Children in the Wood"—all of them

remarkable for their illustrations. History has a wide range

from "Fair Rosamond," to "The Royal Martyr," Charles I.,

whilst, naturally, such books as "Robinson Crusoe," "George

Page xiii

Barnwell," and a host of criminal literature found ready

purchasers.

I have not included Calendars, and I have purposely avoided

Garlands, or Collections of ballads, which equally come under

the category of Chap-books. I should have liked to have

noticed more of them, but the exigencies of publishing have

prevented it; still, those I have taken seem to me to be the

best fitted for the purpose I had in view, which was to give

a fairly representative list: and I hope I have succeeded in

producing a book at once both amusing and instructive, besides

having rescued these almost forgotten booklets from the limbo

into which they were fast descending.

Page xiv

CONTENTS.

| |

PAGE |

| The History of Joseph and his Brethren |

1 |

| The Holy Disciple |

25 |

| The Wandering Jew |

28 |

| The Gospel of Nicodemus |

30 |

The Unhappy Birth, Wicked Life, and Miserable Death of that

Vile Traytor and Apostle Judas Iscariot |

32 |

| A Terrible and Seasonable Warning to Young Men |

33 |

| The Kentish Miracle |

34 |

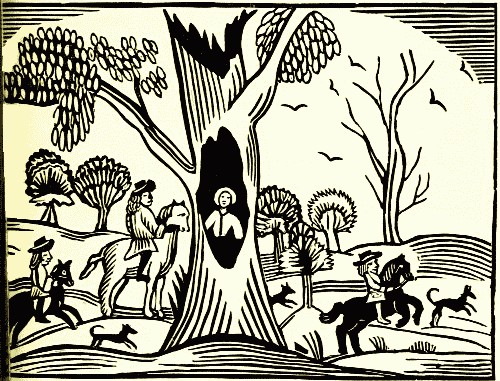

| The Witch of the Woodlands |

35 |

| The History of Dr. John Faustus |

38 |

| The History of the Learned Friar Bacon |

53 |

| A Timely Warning to Rash and Disobedient Children |

56 |

| Bateman's Tragedy |

57 |

| The Miracle of Miracles |

60 |

| A Wonderful and Strange Relation of a Sailor |

61 |

| The Children's Example |

62 |

| A New Prophesy |

64 |

| God's Just Judgment on Blasphemers |

65 |

| A Dreadful Warning to all Wicked and Forsworn Sinners |

66 |

| A Full and True Relation of one Mr. Rich Langly, a Glazier |

67 |

A Full, True and Particular Account of the Ghost or Apparition

of the Late Duke of Buckingham's Father |

68 |

| The Portsmouth Ghost |

70 |

| The Guilford Ghost |

72 |

| The Wonder of Wonders |

74 |

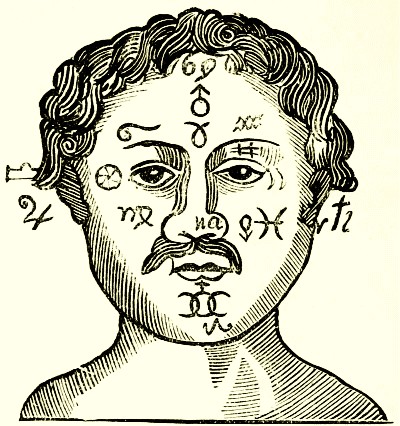

| Dreams and Moles |

78 |

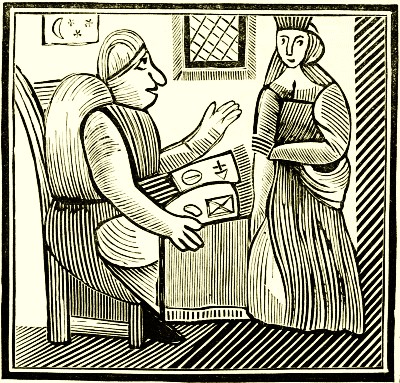

| The Old Egyptian Fortune-Teller's Last Legacy |

79 |

| A New Fortune BookPage xv |

83 |

| The History of Mother Bunch of the West |

84 |

| The History of Mother Shipton |

88 |

| Nixon's Cheshire Prophecy |

92 |

| Reynard the Fox |

95 |

| Valentine and Orson |

109 |

| Fortunatus |

124 |

| Guy, Earl of Warwick |

138 |

The History of the Life and Death of that Noble Knight

Sir Bevis of Southampton |

156 |

| The Life and Death of St. George |

163 |

| Patient Grissel |

171 |

| The Pleasant and Delightful History of Jack and the Giants |

184 |

| A Pleasant and Delightful History of Thomas Hickathrift |

192 |

| Tom Thumb |

206 |

| The Shoemaker's Glory |

222 |

| The Famous History of the Valiant London Prentice |

227 |

| The Lover's Quarrel |

230 |

| The History of the King and the Cobler |

233 |

| The Friar and Boy |

237 |

| The Pleasant History of Jack Horner |

245 |

| The Mad Pranks of Tom Tram |

248 |

| The Birth, Life, and Death of John Franks |

253 |

| Simple Simon's Misfortunes |

258 |

| The History of Tom Long the Carrier |

263 |

| The World turned Upside Down |

265 |

A Strange and Wonderful Relation of the Old Woman who was

Drowned at Ratcliffe Highway |

273 |

| The Wise Men of Gotham |

275 |

| Joe Miller's Jests |

288 |

| A Whetstone for Dull Wits |

295 |

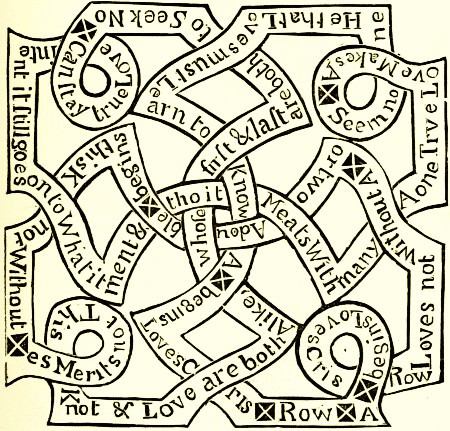

| The True Trial of Understanding |

304 |

| The Whole Trial and Indictment of Sir John Barleycorn, Knt. |

314 |

| Long Meg of Westminster |

323 |

| Merry Frolicks |

337 |

| The Life and Death of Sheffery Morgan |

341 |

| The Welch Traveller |

344 |

| Joaks upon JoaksPage xvi |

349 |

The History of Adam Bell, Clim of the Clough, and William of

Cloudeslie |

353 |

| A True Tale of Robin Hood |

356 |

| The History of the Blind Begger of Bednal Green |

360 |

| The History of the Two Children in the Wood |

369 |

| The History of Sir Richard Whittington |

376 |

| The History of Wat Tyler and Jack Straw |

382 |

| The History of Jack of Newbury |

384 |

| The Life and Death of Fair Rosamond |

387 |

| The Story of King Edward III. and the Countess of Salisbury |

390 |

| The Conquest of France |

392 |

| The History of Jane Shore |

393 |

The History of the Most Renowned Queen Elizabeth and her Great

Favourite the Earl of Essex |

396 |

| The History of the Royal Martyr |

398 |

| England's Black Tribunal |

403 |

| The Foreign Travels of Sir John Mandeville |

405 |

| The Surprizing Life and Most Strange Adventures of Robinson

Crusoe |

417 |

| A Brief Relation of the Adventures of M. Bamfyeld Moore Carew |

423 |

| The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders |

427 |

| Youth's Warning-piece |

429 |

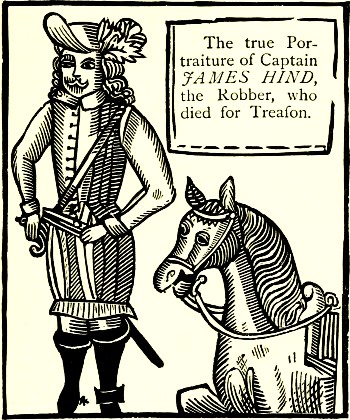

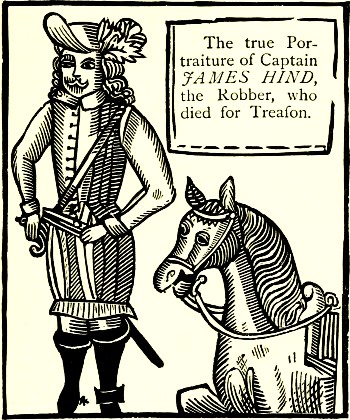

| The Merry Life and Mad Exploits of Capt. James Hind |

433 |

| The History of John Gregg |

437 |

| The Bloody Tragedy |

439 |

| The Unfortunate Family |

440 |

| The Horrors of Jealousie |

441 |

| The Constant, but Unhappy Lovers |

442 |

| A Looking Glass for Swearers, etc. |

443 |

| Farther, and More Terrible Warnings from God |

444 |

| The Constant Couple |

446 |

| The Distressed Child in the Wood |

447 |

| The Lawyer's Doom |

448 |

| The Whole Life and Adventures of Miss Davis |

449 |

| The Life and Death of Christian Bowman |

453 |

| The Drunkard's Legacy |

455 |

| Good News for EnglandPage xvii |

458 |

| A Dialogue between a Blind Man and Death |

459 |

| The Devil upon Two Sticks |

461 |

| Æsop's Fables |

463 |

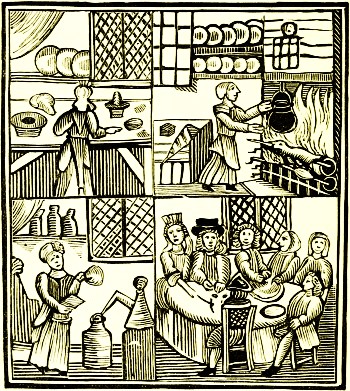

| A Choice Collection of Cookery Receipts |

472 |

| The Pleasant History of Taffy's Progress to London |

475 |

The Whole Life, Character, and Conversation of that Foolish

Creature called Granny |

478 |

| A York Dialogue between Ned and Harry |

479 |

| The French King's Wedding |

481 |

| Appendix |

483 |

Page 1

CHAP-BOOKS

OF

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

THE HISTORY OF

JOSEPH AND HIS BRETHREN.

The first printed metrical history of this Biblical episode is the

book printed by Wynkyn de Worde, a book of fourteen leaves,

and entitled "Thystorie of Jacob and his twelue Sones.

Empȳrted at Lōdon in Fletestrete at the sygne of the Sonne by

Wynkyn de Worde" (no date). It is chiefly remarkable in connection

with this book, as mentioning Chapmen.

"Now leaue we of them & speak we of the Chapman

That passed ouer the sea into Egipt land.

But truely ere that he thether came

The wind stiffly against them did stand;

And yet at the last an hauen they fand.

The Chapman led Joseph with a rope in the streat

Him for to bye came many a Lord great."

A metrical edition is still used in the performance of a sort of

miracle play, entitled "Joseph and his Brothers. A Biblical

Drama or Mystery Play." 1864. London and Derby.

The action of this piece is reported to be somewhat ludicrous,

Page 2

the performers being in their everyday dress, or, rather, in

their Sunday attire. There is no scenery, and very little life or

motion in connection with the dialogue, the quality of which

may be judged by the following specimen:—

"(Joseph, weeping, offers Benjamin his goblet.)

Here, my son,

Drink from my Cup; the sentiment shall be

'Health and long life to your aged father.'

(Benjamin drinks.)

Now sing me one of your Hebrew Songs

To any National Air; for we in Egypt

Know little of the music of Chanaan.

Benjamin. If such be your wish, I'll sing the song

I often sing to soothe my father's breast

When he is sad with memory of the past.

(He sings.) Air, 'Phillis is my only joy,' etc.:—

Joseph was my favourite boy,

Rachel's firstborn Son and pride:

His father's hope, his father's joy,

Begotten in life's eventide," etc.

Page 3

THE HISTORY

OF

Joseph and his Brethren,

WITH

Jacob's Journey into Egypt,

AND

HIS DEATH AND FUNERAL.

Illustrated with Twelve Cuts.

JOSEPH BROUGHT BEFORE PHAROAH.

Printed and Sold in Aldermary Church Yard,

Bow Lane, London.

Page 4

THE HISTORY OF

JOSEPH AND HIS BRETHREN.

JACOB'S LOVE TO JOSEPH, WITH JOSEPH'S FIRST

DREAM.

In Canaan's fruitful land there liv'd of late,

Old Isaac's heir blest with a vast estate;

Near Hebron Jacob sourjourned all alone,

A stranger in the land that was his own:

Dear to his God, for humbly he ador'd him,

As Isaac did, and Abraham before him.

And as he was of worldly wealth possest,

So with twelve sons the good old man was blest,

Amongst all whom none his affections won,

So much as Joseph, Rachel's first-born son,

He in his bosom lay, still next his heart,

And with his Joseph would by no means part:

He was the lad on whom he most did doat,

And gave to him a many colour'd coat.

This made his bretheren at young Joseph grudge,

And thought their father loved him too much.

At Jacob's love their hatred did encrease,

That they could hardly speak to him in peace.

But Joseph, (in whose heart the filial fear

Of his Creator early did appear)

Not being conscious to himself at all,

He had done ought to move his brethren's gall,

}Did unto them a dream of his relate,

Which (tho' it did increase his bretheren's hate,

Did plainly shew forth Joseph's future state

This is the dream, said Joseph, I did see:

The Corn was reap'd, and binding sheaves are we,

Page 5

When my sheaf only was on a sudden found,

Both to arise and stand upon the ground.

}Then yours arose, which round about were laid,

And unto mine a low obeisance made,

Is this your dream, his brethren said?

Can your ambitious thoughts become so vain,

To think that you shall o'er your brethren reign?

Or that we unto you shall tribute pay,

And at your feet our servile necks should lay?

Believe us brother, this youll never see,

But your aspiring will your ruin be.

Thus Joseph's bretheren talk'd, and if before

They hated him, they did it now much more;

The father lov'd him, and the lad they thought,

Took more upon him, than indeed he ought.

But they who judge a matter e'er the time,

Are oftentimes involved in a crime:

'Tis therefore best for us to wait and see

What the issue of mysterious things will be;

For those that judge by meer imagination,

Will find things contrary to their expectation.

Page 6

JOSEPH'S SECOND DREAM.

How bold is innocence! how fix'd it grows!

It fears no seeming friends nor real foes.

'Tis conscious of no guilt, nor base designs,

And therefore forms no plots nor countermines:

But in the paths of virtue walks on still,

And as it does none, so it fears no ill.

Just so it was with Joseph: lately he

Had dream'd a dream, and was so very free,

He to his bretheren did the dream reveal,

At which their hatred scarce they could conceal.

But Joseph not intending any ill,

Dream'd on again, and told his bretheren still.

Methought as on my slumb'ring bed I lay,

I saw a glorious light more bright than day:

The sun and moon, those glorious lamps of heaven,

With glittering stars in number seven,

Came all to me, on purpose to adore me,

And every one of them bow'd down before me:

And each one when they had thus obedience made,

Withdrew, nor for each other longer staid.

When Joseph thus his last dream had related,

Then he was by his bretheren much more hated.

Page 7

This dream young Joseph to his father told,

Who when he heard it, thinking him too bold,

Rebuk'd him thus: What dream is this I hear?

You are infatuated, child I fear,

Must I, your mother, and your bretheren too,

Become your slaves and bow down to you.

Thus Jacob chid him, for at present he,

Saw not so far into futurity:

Yet he did wonder how things might succeed,

And what for Joseph providence decreed,

For well he thought those dreams wa'nt sent in vain

Yet knew not how he should these dreams explain.

For those things oft are hid from human eyes,

Which are by him that rules above the skies

Firmly decreed; which when they come to know,

The beauty of the work will plainly shew,

And all those bretheren which now Joseph hate,

Shall then bow down to his superior fate:

Old Jacob therefore, just to make a shew,

As if he was displeased with Joseph too,

Thus seem'd to chide young Joseph, but indeed

To his strange dreams he gave no little heed;

Tho' how to interpret them he could not tell,

Yet in the meanwhile he observ'd them well.

How great's the difference 'twixt a father's love,

And brethren's hatred may be seen above.

}They hate their brother for his dreams, but he,

Observes his words, and willing is to see

What the event in future times may be.

JOSEPH PUT INTO A PIT BY HIS BRETHEREN.

When envy in the heart of man does reign,

To stifle its effects proves oft in vain.

Like fire conceal'd, which none at first did know,

It soon breaks out and breeds a world of woe:

Page 8

Young Joseph this by sad experience knew,

And his brethren's envy made him find it true:

For they, as in the sequel we shall see,

Resolv'd upon poor Joseph's tragedy;

That they together at his dream might mock,

Which they almost effected, when their flock

In Sechem's fruitful field they fed, for there

Was Joseph sent to see how they did fare:

Joseph his father readily obeys,

And on the pleasing message goes his ways.

Far off they know, and Joseph's coming note,

For he had on his many colour'd coat;

Which did their causeless anger set on fire,

And they against Joseph presently conspire:

Lo yonder doth the dreamer come they cry,

Now lets agree and act this tragedy.

And when we've slain him in some digged pit

Let's throw his carcase, and then cover it,

And if our father ask for him, we'll say,

We fear he's kill'd by some wild beast of prey.

}This Reuben heard, who was to save him bent,

And therefore said, (their purpose to prevent,)

To shed his blood I'll ne'er give my consent;

But into some deep pit him let us throw,

And what we've done there's none will know.

Page 9

This Reuben said his life for to defend,

Till he could home unto his father send.

To Reuben's proposition they agree,

And what came of it we shall quickly see.

Joseph by this time to his brethren got,

And now affliction was to be his lot;

They told him all his dreams would prove a lye,

For in a pit he now should starve and die.

}Joseph for his life did now entreat and pray,

But to his tears and prayers they answered Nay,

And from him first his coat they took away.

}Then into an empty pit they did him throw,

And there left Joseph almost drown'd in woe,

While they to eating and to drinking go.

See here the vile effects of causeless rage,

In what black crimes does it oftimes engage.

Nearest relations! setting bretheren on

To work their brother's dire destruction.

But now poor Joseph in the pit doth lie,

'Twill be his bretheren's turn to weep and cry.

JOSEPH SOLD INTO EGYPT.

As Joseph in the Pit condemn'd to die,

So did his grandfather on the altar lie,

Page 10

The wood was laid, a sacrificing knife,

Was lifted up to take poor Isaac's life.

But heaven that ne'er design'd the lad should die,

Stopt the bold hand, and shew'd a lamb just by,

Thus in like manner did the all-wise decree,

His brethrens plots should disappointed be:

}For while within the Pit poor Joseph lay,

And they set down to eat and drink and play,

And with rejoicing revel out the day:

}Some Ishmaelitish merchants strait drew near,

Who to the land of Egypt journeying were,

To sell some balm and myrrh, and spices there.

This had on Judah no impressions made,

And therefore to his bretheren thus he said,

Come Sirs, to kill young Joseph is not good,

What profit will it be to spill his blood?

How are we sure his death we shall conceal?

The birds of air this murder will reveal.

Come let's to Egypt sell him for a slave,

And we for him some money sure may have;

So from his blood our hands shall be clear,

And we for him have no cause for fear.

To this advice they presently agreed,

And Joseph from the Pit was drawn with speed:

For twenty pieces they their brother sell

To the Ishmaelites, and thought their bargain well.

And thus they to their brother bid adieu,

For he was quickly carried out of view.

Reuben this time was absent, and not told

That Joseph was took out of the pit and sold,

He therefore to the pit return'd, that he

Might sit his father's Joy at liberty.

}But when, alas! he found he was not there,

He was so overcome with black despair,

To rend his garments he could not forbear;

Then going to his bretheren thus said he,

Poor Joseph's out, and whither shall I flee?

Page 11

But they, not so concern'd, still kill'd a goat,

And in its blood they dipt poor Joseph's coat,

And that they all suspicion might prevent,

It by a stranger to their father sent,

Saying, We've found, and brought this coat to know

Whether 'tis thy son Joseph's coat or no.

This brought sad floods of tears from Jacob's eyes,

Ah! 'tis my son's, my Joseph's coat he cries:

Ah! woe is me, thus wretched and forlorn,

For my poor Joseph is in pieces torn:

}His sons and daughters comfort him in vain,

He can't but mourn while he thinks Joseph slain,

And yet those sons won't fetch him back again.

JOSEPH AND HIS MISTRESS.

How much for Joseph's loss old Jacob griev'd,

It was not now his time to be reliev'd:

And therefore let's to Egypt turn our thought,

Where we shall find young Joseph sold and bought,

By Potiphar a Captain of the Guard;

Sudden the change, but yet I can't say hard;

For Joseph mercy in this change did spy,

And thought it better than i' th' pit to lie;

And well might Joseph be therewith content,

For God was with him where so 'er he went;

Page 12

And tho' he did him with afflictions try,

He gave him favour in his master's eye,

For he each work he undertook did bless,

And crown'd his blessing with a good success.

So that his master then him steward made,

And Joseph's orders were by all obey'd:

In which such diligence and care he took,

His master needed after nothing look.

But his estate poor Joseph long can't hold,

His Mistress love so hot, made his master's cold,

For Joseph was so comely, young and wise,

His mistress on him cast her lustful eyes;

Joseph perceiv'd it, yet no notice took,

Nor scarcely on her did he dare to look.

This vex't her so, she could no more forbear,

But unto Joseph did the same declare;

Joseph with grief the unwelcome tidings heard,

But he his course by heavens directions steer'd.

And therefore to his mistress thus did say,

O mistress I must herein disobey;

My master has committed all to me,

That is within his house, save only thee:

And if I such a wickedness should do,

I should offend my God and master too;

And justly should I forfeit my own life,

To wrong my master's bed, debauch his wife.

But tho' he thus had given her denial,

She was resolv'd to make a further trial,

She saw he minded not whate'er she said,

And therefore now another plot she laid.

Joseph one day some business had to do,

When none was in the house beside them two,

When casting off all shame, and growing bold,

Of Joseph's upper garment she takes hold;

Now Joseph you shall lie with me, said she,

For there is none in the house but you and me;

But while she held his cloak to make him stay,

Page 13

He left it with her, and made haste away;

On this her lust to anger turns, and she,

Cries out help! help! Joseph will ravish me,

Whose raging lust I hardly could withstand!

But fled, and left his garment in my hand.

JOSEPH CAST INTO THE DUNGEON.

Poor Joseph's innocence was no defence,

Against this brazen strumpet's impudence,

She first accus'd, and that she might prevail,

She to her husband thus then told her tale.

Hast thou this servant hither brought that he

Might make a mock upon my chastity?

What tho' he's one come from the Hebrew Stock,

Shall he thus at my virtue make a mock?

}For if I once should yield to throw't away

On such a wretch.—O think what you would say?

And yet he sought to do't this very day.

But when he did this steady virtue find,

Then fled, and left his garment here behind.

No wonder if this story so well told

Stirr'd up his wrath, and made his love turn cold;

He strait believ'd all that his wife had said,

And Joseph was unheard in prison laid.

Page 14

Joseph must now again live underground,

And in a dungeon have his virtue crown'd,

But tho' in prison cast and bound in chains,

His God is with him, and his friend remains;

So here he with the gaoler favour finds,

That whatsoe'er he does he never minds:

The Gaoler knew his God was with him still,

And therefore lets him do whate'er he will.

King Pharoah's butler and his baker too

Under their Princes great displeasure grew

And therefore both of them were put in ward,

As prisoners to the captain of the guard

Where Joseph lay; to whom they did declare,

Their case, he serving them whilst they were there.

One night, a several dream to each befel,

But what it signify'd they could not tell.

Joseph perceiving they were very sad,

Demanded both the Dreams that they had had,

On which they each their dream to Joseph told,

Who strait the meaning of it did unfold.

}The butler in three days restor'd shall be,

The baker should be hang'd upon a tree,

But when this comes to pass remember me,

Said he to the Butler, for here I am thrown,

And charg'd with crimes that are to me unknown,

In three days time (such was their different case)

The Baker hang'd, the Butler gains his place;

And he again held Pharoh's cup in his hand,

And stood before him as he us'd to stand.

And yet for all that he to Joseph said,

Joseph in prison two years longer staid,

In all which time he ne'er of Joseph thought,

Tho' he his help so earnestly besought.

So in affliction promises we make,

But when that's o'er forget whate'er we speak.

Page 15

JOSEPH'S ADVANCEMENT.

More than two years Joseph in prison lay,

Yet had no prospect of the happy day

Of his release; nor any means could see,

By which he could be set at liberty;

But God who sent him thither to be try'd,

In his due time his mercy magnify'd.

For as King Pharaoh lay upon his bed,

He had strange things which troubled his head,

He saw seven well fed kine rise out of Neal,

And seven lean ones eat them in a meal.

Again he saw seven ears of corn that stood

Upon one stalk, and were both rank and good:

Yet these were eaten up as the kine before,

By seven ears very lean and poor.

What this imported Pharoah fain would know,

But none there were that could the meaning show.

This to the Butler's mind poor Joseph brought,

Who till this day of him had never thought.

Great Prince! I call to mind my faults this day,

And well remember when in gaol I lay,

I and the Baker each our dreams did tell,

Which a young Hebrew slave expounded well:

Page 16

I was advanc'd and executed he,

Both which the Hebrew servant said should be.

Go, said the King, and bring him hither strait,

I for his coming with impatience wait.

Joseph was put in hastily no doubt,

And now more hastily was he brought out.

His prison garment now aside was laid,

And being shav'd was with new cloaths array'd;

To Pharaoh being brought, canst thou, said he,

The dream I've dream'd expound me?

'Tis not me, great Sir, Joseph reply'd,

To say that I could do't were too much pride,

And so 'twould be for any that doth live,

But God to Pharaoh will an answer give.

Then Pharaoh did at large his dreams relate,

And Joseph shew'd him Egypt's future fate.

Seven years of plenty should to Egypt come,

In which they scarce could get their harvests in.

Which by seven years of dearth eat up should be;

As were the fair kine by the lean he see.

For Famine Sir, said he, provide therefore,

And in the years of Plenty lay up store.

What Joseph said, seem'd good in Pharoh's eyes,

Who did esteem him of all men most wise:

Since God, said Pharoah has shewn this to thee,

Thou shalt thro' all the land be next to me.

Then made him second in his chariot ride,

And bow the knee before him all men cry'd.

JOSEPH'S BRETHEREN COME INTO EGYPT TO BUY CORN.

Now Joseph's Lord of Egypt, all things there

Are by the King committed to his care:

The plenteous years come on as Joseph told,

The earth produces more than barns can hold:

New store-houses were in each city made,

Where all the corn about it up was laid,

Page 17

Till he had gotten such a numerous store,

That it was vain to count it any more.

But famine does to plenty next succeed,

And in all lands but Egypt there was need;

For they neglecting to lay up such store,

Had spent their Stock, and soon became so poor,

That in the land of Egypt there was bread,

By fame's loud trump, thro' every land was spread.

Old Jacob heard it, and to his sons thus said.

Why look you thus, as if you was afraid?

There's Corn in Egypt, therefore go and try,

That we may eat and live, not starve and die.

Joseph's ten bretheren straitway thither went,

Their corn in Canaan being almost spent.

This Joseph knew, for him they came before,

As being Lord of all the Egyptian store;

And as they came to him did each one bow,

But little thought he'd been the Dreamer now.

From whence came you? said Joseph as they stood,

My Lord say they from Canaan to buy food.

I don't believe it, said Joseph very high,

I rather think you came the land to spy,

That you abroad its nakedness may tell,

Come, come, I know your purpose very well;

Page 18

Let not, say they, my Lord, his servants blame,

For only to buy food thy servants came.

Said Joseph sternly, Tell me not those lies,

For by the life of Pharaoh ye are spies.

We are twelve bretheren, sir, they then reply'd,

Sons of one man, of whom one long since dy'd:

And with our father we the youngest left,

So that he might not be of him bereft.

Hereby said Joseph 'twill be prov'd I trow,

Whether what I have said be true or now.

Your younger brother fetch, make no replies,

For if you don't, by Pharoah's life ye are spies.

On this they unto prison all were brought,

Where how they us'd their brother oft they thought.

When they in prison three days time had staid,

He sent for them and this proposal made,

They to their father should the corn convey,

And Simeon should with him a prisoner stay;

Until they brought their youngest brother there,

Which should to him their innocence declare.

This they agreed to, and were sent away,

Whilst Simeon did behind in prison stay.

BENJAMIN BROUGHT TO JOSEPH.

Old Jacob's sons came back to him, report,

How they were us'd at the Egyptian court:

Taken for spies, and Simeon left behind,

Till Benjamin shall make the man more kind.

This news old Jacob griev'd unto the heart,

Who by no means with Benjamin would part;

But when the want of corn did pinch them sore,

And they were urg'd to go again for more;

They told their father they were fully bent,

To go no more except their brother went.

Then take your brother and arise and go,

Said good old Jacob, and the man will show

Page 19

You favour, that you may all safe return,

And I no more my children's loss may mourn.

Then taking money and rich presents too,

To Joseph they their younger brother shew.

Then he his steward straitway did enjoin

To bring those men to his house with him to dine.

When Joseph came, he kindly to them spake,

When they to him did low obeysance make,

He ask'd their welfare, and desir'd to tell

Whether their father was alive and well.

They answer'd Yea, he did in health remain,

And to the ground bow'd down their heads again.

Then Benjamin he by the hand did take,

And said, Is this the youth of whom ye spake,

Then God be gracious unto thee my son,

To whom he said; which when as soon as done,

Into his chamber strait he went to weep,

For he his countenance could hardly keep.

Then coming out, and sitting down to meet,

He made his bretheren all sit down to eat:

He sent to each a mess of what was best,

But Benjamin's was larger than the rest.

Then what he further did design to do,

He call'd his servant, and to him did shew;

Page 20

Put in each sack as much corn as they'll hold,

And in the mouth of each return his gold,

And see that you take my silver cup,

And in the sack of the youngest put it up.

The steward fill'd the sack as he was bid,

And in the mouth of each their money hid.

Then on the morrow morning merry hearted

With this their good success they all departed;

But Joseph's steward quickly spoil'd their laughter,

Who by his master's orders strait went after,

And to the eleven brethren thus he spake,

Is this the return you to my master make?

Could you not be contented with the wine,

But steal the Cup in which he does divine?

This is unkind. And therefore I must say

You've acted very foolishly to day.

JOSEPH MAKES HIMSELF KNOWN TO HIS BRETHEREN.

The steward's words put them into a fright,

They wonder'd at his speech, as well they might

Why does my Lord this charge against us bring;

For God forbid we e'er should do this thing:

The money that within our sacks we found,

We brought from Canaan; then what ground

Page 21

Have you to think, or to suppose that we

Of such a crime as this should guilty be.

With whatsoever man this cup is found,

Both let him die, and we'll be also bound

As slaves unto my Lord. Let it so be,

Reply'd the steward, we shall quickly see

Whether it is so or not; then down they took*

And when the steward he had search'd them round,

Within the sack of Benjamin the cup was found.

To Joseph therefore they straitway repair,

To whom he said as soon as they came there,

How durst you take this silver cup of mine

Did you not think that I could well divine?

To whom Judah said, My Lord we've nought to say

But at your feet as slaves ourselves we lay.

No, no, said Joseph, there's for that no ground,

He is my slave with whom the cup is found.

Then Judah unto Joseph drew more near,

And said, O let my Lord and Master hear:

If we without the lad should back return,

Our father would for ever grieve and mourn,

And his grey hairs with sorrows we should bring

Unto the grave, if we should do this thing;

For when your servants father would at home

Have kept the lad, I begg'd that he might come,

And said, If I return him not to thee,

Then let the blame for ever lay on me.

Now therefore let him back return again,

And in his stead thy servant will remain,

And how shall I that piercing sight endure,

Which will I know my father's death procure.

This speech of Judah touch'd good Joseph so,

That he bid all his servants out to go.

He and his brethren being all alone,

He unto them himself did thus make known.

Page 22

I am Joseph:—Is my father alive?

But to return an answer none did strive;

For at his presence they were troubled all,

Which made him thus unto his brethren call,

}I am your brother Joseph, him whom ye

To Egypt sold; but do not troubled be;

For what you did heaven did before decree.

Then he his brother Benjamin did kiss,

Wept on his neck, and so did he on his,

Then kist his bretheren, wept on them likewise,

So that among them there were no dry eyes.

JOSEPH SENDS FOR HIS FATHER WHO COMES TO EGYPT.

}Then Joseph to his bretheren thus did say,

Unto my father pray make haste away,

Take food and waggons here, and do not stay,

They went, and Jacob's spirits did revive,

To hear his dearest Joseph was alive,

It is enough, then did old Jacob cry,

I'll go and see my Joseph e'er I die;

And he had reason for resolving so,

For God appear'd to him and bid him go.

Then into Egypt Jacob went with speed,

Both he, his wives, his sons, and all their seed.

Page 23

And being for the land of Goshen bent,

Joseph himself before him did present.

Great was their Joy they on that meeting shew'd,

And each the others cheeks with tears bedew'd.

Then Joseph did his aged father bring

Into the royal presence of the King,

Whom Jacob blest, and Pharaoh lik'd him well,

And bid him in the land of Goshen dwell.

JACOB'S DEATH AND BURIAL.

Jacob now having finished his last stage,

And come to the end of earthly pilgrimage.

Was visited by his son Joseph, who

Brought with him Ephraim and Manassah too.

When Jacob saw them, who are these said he?

The sons said Joseph, God has given me

Then Jacob blest them both, and his sons did call,

To shew to each what should to them befal.

Then giving orders unto Joseph where

He would be buried, left to him that care;

Then yielded up the ghost upon his bed

And to his people he was gathered.

Then Joseph for his burial did provide,

And with a numerous retinue did ride,

Page 24

Of his own children and Egyptians too,

That their respect to Joseph might shew,

And with a mighty mourning did inter

Old Jacob in his fathers sepulchre.

FINIS.

Page 25

THE HOLY DISCIPLE;

OR, THE

History of Joseph of Arimathea.

Wherein is contained a true Account of his Birth; his Parents; his

Country; his Education; his Piety; and his begging of Pontius Pilate the

Body of our blessed Saviour, after his Crucifixion, which he buried in a

new Sepulchre of his own. Also the Occasion of his coming to England,

where he first preached the Gospel at Glastenbury, in Somersetshire, where

is still growing that noted White Thorn which buds every Christmas day in

the morning, blossoms at Noon, and fades at Night, on the Place where he

pitched his Staff in the Ground. With a full Relation of his Death and

Burial.

TO WHICH IS ADED,

Meditations on the Birth, Life, Death, and

Resurrection of our Lord and Saviour

Jesus Christ.

Newcastle: Printed in this present Year.

Page 26

THE HOLY DISCIPLE;

OR, THE

HISTORY OF JOSEPH OF ARIMATHEA.

The text of this book is simply an amplification of the title-page,

which is sufficient for its purpose in this work. The

legend of his planting his staff, which produced the famous

Glastonbury Thorn, is very popular and widespread. The

writer remembers in the winter of 1879, when living in Herefordshire,

on Old Christmas Day (Twelfth Day), people coming

from some distance to see one of these trees blossom at

noon. Unfortunately they were disappointed. Loudon, in his

"Arboretum Britannicum," v. 2, p. 833, says, "Cratægus præcox,

the early flowering, or Glastonbury, Thorn, comes into leaf in

January or February, and sometimes even in autumn; so that

occasionally, in mild seasons, it may be in flower on Christmas

Day. According to Withering, writing about fifty years ago, this

tree does not grow within the ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, but

stands in a lane beyond the churchyard, and appears to be a

very old tree. An old woman of ninety never remembered it

otherwise than it now appears. This tree is probably now

dead; but one said to be a descendant of the tree which,

according to the Romish legend, formed the staff of Joseph of

Arimathea, is still existing within the precincts of the ancient

abbey of Glastonbury. It is not of great age, and may probably

have sprung from the root of the original tree, or from a

truncheon of it; but it maintains the habit of flowering in the

winter, which the legend attributes to its supposed parent. A

correspondent (Mr. Callow) sent us on December 1, 1833, a

Page 27

specimen, gathered on that day, from the tree at Glastonbury,

in full blossom, having on it also ripe fruit; observing that the

tree blossoms again in the month of May following, and that it

is from these later flowers that the fruit is produced. Mr.

Baxter, curator of the Botanic Garden at Oxford, also sent us a

specimen of the Glastonbury Thorn, gathered in that garden

on Christmas Day, 1834, with fully expanded flowers and ripe

fruit on the same branch. Seeds of this variety are said to

produce only the common hawthorn; but we have no doubt

that among a number of seedlings there would, as in similar

cases, be found several plants having a tendency to the same

habits as the parent. With regard to the legend, there is

nothing miraculous in the circumstances of a staff, supposing it

to have been of hawthorn, having, when stuck in the ground,

taken root and become a tree; as it is well known that the

hawthorn grows from stakes and truncheons. The miracle of

Joseph of Arimathea is nothing compared with that of Mr.

John Wallis, timber surveyor of Chelsea, author of 'Dendrology,'

who exhibited to the Horticultural and Linnæan Societies, in

1834, a branch of hawthorn, which, he said, had hung for

several years in a hedge among other trees; and, though without

any root, or even touching the earth, had produced, every

year, leaves, flowers, and fruit!"

Of St. Joseph himself, Alban Butler gives a very meagre

account, not even mentioning his death or place of burial;

so that, outside Glastonbury, we may infer he had small reputation.

We must not, however, forget that he is supposed to

have brought the Holy Grail into England.

Wynkyn de Worde printed a book called "The Life of

Joseph of Armathy," and Pynson printed two—one "De

Sancto Joseph ab Arimathia," 1516, and "The Lyfe of Joseph

of Arimathia," 1520.

Page 28

THE

WANDERING JEW;

OR, THE

SHOEMAKER OF JERUSALEM.

Who lived when our Lord and Saviour

Jesus Christ was Crucified,

And by Him Appointed to Wander until He comes again.

With his Travels, Method of Living, and a

Discourse with some Clergymen about

the End of the World.

Printed and Sold in Aldermary Church-Yard,

Bow Lane, London.

Page 29

THE WANDERING JEW.

This version is but a catchpenny, and principally consists

of a fanciful dialogue between the Wandering Jew and a

clergyman. This famous myth seems to have had its origin

in the Gospel of St. John (xxi. 22), which, although it does

not refer to him, evidently was the source of the idea of his

tarrying on earth until the second coming of our Saviour. The

legend is common to several countries in Europe, and we, in

these latter days, are familiar with it in Dr. Croly's "Salathiel,"

"St. Leon," "Le Juif Errant," and "The Undying One." It

is certain it was in existence before the thirteenth century, for it

is given in Roger of Wendover, 1228, as being known; for an

Armenian archbishop, who was then in England, declared that

he knew him. His name is generally received as Cartaphilus,

but he was known, in different countries and ages, also as

Ahasuerus, Josephus, and Isaac Lakedion. The usual legend is

that he was Pontius Pilate's porter, and when they were dragging

Jesus out of the door of the judgment-hall, he struck him on the

back with his fist, saying, "Go faster, Jesus, go faster: why

dost thou linger?" Upon which Jesus looked at him with a

frown, and said, "I, indeed, am going; but thou shalt tarry

till I come." He was afterwards converted and baptized by

the name of Joseph. He is believed every hundred years to

have an illness, ending in a trance, from which he awakes

restored to the age he was at our Saviour's Crucifixion. Many

impostors in various countries have personated him.

Page 30

THE

GOSPEL OF

NICODEMUS.

In thirteen Chapters.

- 1. Jesus Accused of the Jews before Pilate.

- 2. Some of them spake for him.

- 3. Pilate takes Counsel of Ancient Lawyers, etc.

- 4. Nicodemus speaks to Pilate for Jesus.

- 5. Certain Jews shew Pilate the Miracles which Christ had done

to some of them.

- 6. Pilate commands that no villains should put him to his

Passion, but only Knights.

- 7. Centurio tells Pilate of the Wonders that were done at

Christ's Passion; and of the fine Cloth of Syndonia.

- 8. The Jews conspire against Nicodemus and Joseph.

- 9. One of the Knights that kept the Sepulchre of our Lord,

came and told the Master of the Law, that our Lord was

gone into Gallilee.

- 10. Three men who came from Gallilee to Jerusalem say they

saw Jesus alive.

- 11. The Jews chuse eight men who were Joseph's friends, to

desire him to come to them.

- 12. Joseph tells of divers dead Men risen, especially of Simon's

two sons, Garius and Levicius.

- 13. Nicodemus and Joseph tell Pilate all that those two Men

had said; and how Pilate treated with the Princes of

the Law.

Newcastle: Printed in this present Year.

Page 31

This is a translation by John Warren, priest, of this apocryphal

Gospel, of which the frontispiece is a summary, and varies very

little from that given by Hone, who, in his prefatory notice

says, "Although this Gospel is, by some among the learned,

supposed to have been really written by Nicodemus, who

became a disciple of Jesus Christ, and conversed with him;

others conjecture it was a forgery towards the close of the third

century, by some zealous believer, who, observing that there

had been appeals made by the Christians of the former Age, to

the Acts of Pilate, but that such Acts could not be produced,

imagined it would be of service to Christianity to fabricate and

publish this Gospel; as it would both confirm the Christians

under persecution, and convince the Heathens of the truth of

the Christian religion.... Whether it be canonical or not, it

is of very great antiquity, and is appealed to by several of the

ancient Christians."

Wynkyn de Worde published several editions of it—in

1509, 1511, 1512, 1518, 1532—and his headings of the chapters

differ very slightly from those already given.

Page 32

The unhappy Birth, wicked Life, and miserable

Death of that vile Traytor and Apostle

JUDAS ISCARIOT,

Who, for Thirty Pieces of Silver betrayed his Lord and

Master

JESUS CHRIST.

SHEWING

- 1. His Mother's Dream after Conception, the Manner of his Birth; and

the evident Marks of his future shame.

- 2. How his Parents, inclosing him in a little chest, threw him into the

Sea, where he was found by a King on the Coast of Iscariot, who

called him by that Name.

- 3. His advancement to be the King's Privy Counsellor; and how he unfortunately

killed the King's Son.

- 4. He flies to Joppa; and unknowingly, slew his own Father, for which

he was obliged to abscond a Second Time.

- 5. Returning a Year after, he married his own Mother, who knew him to

be her own Child, by the particular marks he had, and by his own

Declaration.

- 6. And lastly, seeming to repent of his wicked Life, he followed our Blessed

Saviour, and became one of his Apostles; But after betrayed him

into the Hands of the Chief Priests for Thirty Pieces of Silver, and

then miserably hanged himself, whose Bowels dropt out of his Belly.

TO WHICH IS ADDED,

A Short RELATION of the Sufferings of Our

BLESSED REDEEMER,

Also the Life and miserable Death of

PONTIUS PILATE,

Who condemn'd the Lord of Life to Death.

Being collected from the Writings of Josephus Sozomenus,

and other Ecclesiastical Historians.

Durham: Printed and Sold by Isaac Lane.

Page 33

A Terrible and seasonable Warning

to young Men.

Being a very particular and True Relation of one Abraham Joiner a young

Man about 17 or 18 Years of Age, living in Shakesby's Walks in Shadwell,

being a Ballast Man by Profession, who on Saturday Night last pick'd up a leud

Woman, and spent what Money he had about him in Treating her, saying

afterwards, if she wou'd have any more he must go to the Devil for it, and

slipping out of her Company, he went to the Cock and Lyon in

King Street, the Devil appear'd to him, and gave him a Pistole, telling him

he shou'd never want for Money, appointing to meet him the next Night at the

World's End at Stepney; Also how his Brother perswaded him to throw the Money away,

which he did; but was suddenly taken in a very strange manner; so that they

were fain to send for the Reverend Mr. Constable and other Ministers to pray

with him; he appearing now to be very Penitent; with an Account of the

Prayers and Expressions he makes use of under his Affliction, and the prayers

that were made for him to free him from this violent Temptation.

The Truth of which is sufficiently attested in the Neighbourhood, he lying

now at his mother's house, etc.

London: Printed for J. Dutton, near Fleet Street.

Page 34

THE

KENTISH MIRACLE

Or, a Seasonable Warning to all

Sinners

SHEWN IN

The Wonderful Relation of one Mary Moore, whose Husband

died some time ago, and left her with two Children, who was

reduced to great Want; How she wandered about the Country

asking Relief, and went two Days without any food. How

the Devil appeared to her, and the many great Offers he made

to her to deny Christ, and enter into his Service; and how

she confounded Satan by powerful Arguments. How she

came to a Well of Water, when she fell down on her Knees to

pray to God, that he would give that Vertue to the Water that

it might refresh and satisfy her Children's Hunger; with an

Account how an Angel appeared to her and relieved her; also

declared many things that shall happen in the Month of March

next; shewing likewise what strange and surprizing Accidents

shall happen by means of the present War; and concerning a

dreadful Earthquake, etc.

Edinburgh: Printed in the Year 1741.

Page 35

THE

Witch of the Woodlands;

OR, THE

COBLER'S NEW TRANSLATION.

Here Robin the Cobler for his former Evils,

Is punish'd bad as Faustus with his Devils.

Printed and Sold in Aldermary Church Yard,

Bow Lane, London.

Page 36

Here the old Witches dance, and then agree,

How to fit Robin for his Lechery;

First he is made a Fox and hunted on,

'Till he becomes an Horse, an Owl, a Swan.

At length their Spells of Witchcraft they withdrew,

But Robin still more hardships must go through;

For e'er he is transform'd into a Man,

They make him kiss their bums and glad he can.

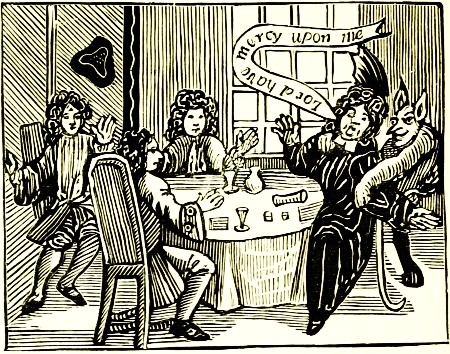

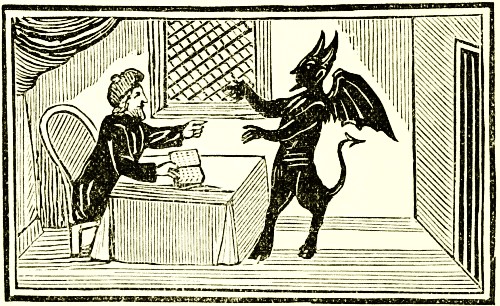

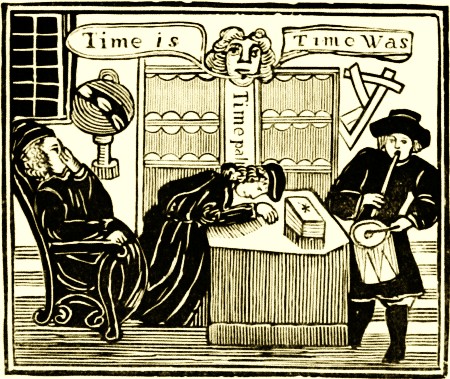

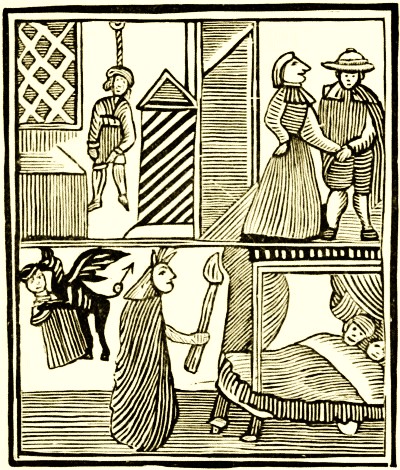

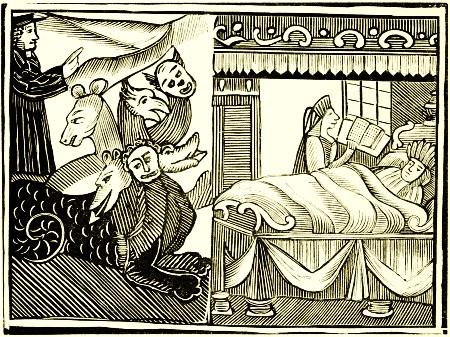

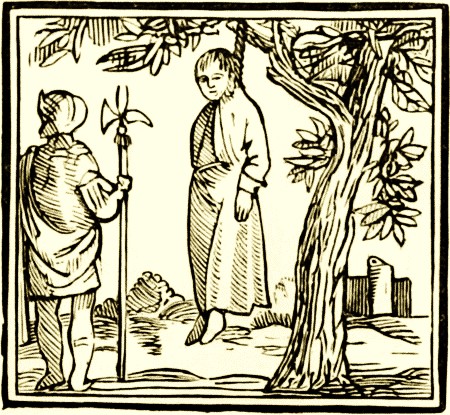

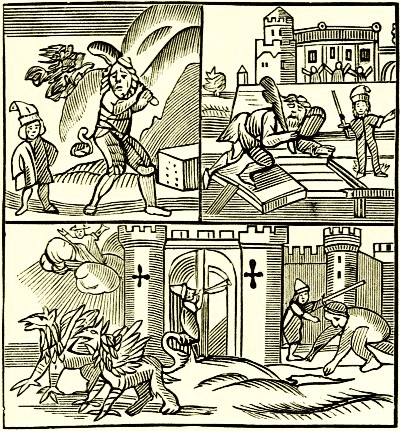

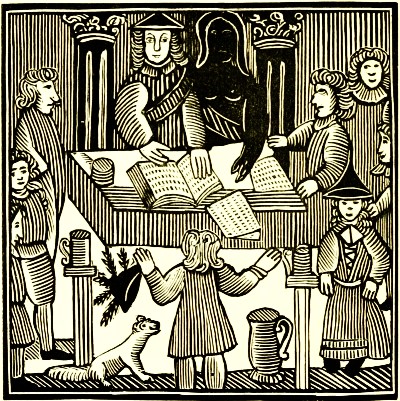

This is the argument of the story, which is too broad in its

humour to be reprinted, but the following two illustrations show

the popular idea of his Satanic Majesty and his dealings with

witches.

Page 37

Page 38

THE HISTORY OF

DR. JOHN FAUSTUS.

There is very little similarity between this history and Goethe's

beautiful drama. This is essentially vulgar, and perfectly fitted

for the popular taste it catered for; but we, who are familiar

with Goethe's masterpiece, can hardly read it without a

shudder. It has been given at length, because it is a type of

its class.

The History of Faust (who, as far as one can learn, existed

early in the sixteenth century) has been repeatedly written,

especially in Germany, where it first appeared in 1587, published

at Frankfurt-on-the-Main, and it was soon translated

into English by P. K. Gent. Marlowe produced his "Tragicall

History of D. Faustus" in 1589, and in an entry in the Register

of the Stationers' Company it appears that in the year 1588 "A

Ballad of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, the great Congerer,"

was licensed to be printed,* so that it soon became well

rooted in England. It has been a favourite theme with dramatists

and musicians, and has even been the subject of a

harlequinade, "The Necromancer; or Harlequin Dr. Faustus"

(London, 1723). It was a popular Chap book, and many versions

were published of it in various parts of the country.

J. O. Halliwell Phillips, Esq., has an English edition of Faustus

printed 1592, unknown to Herbert or Lowndes.

| Rox. II. 235 and |

643 m. 10, |

the date of both being attributed 1670. (return) |

| 55. |

Page 39

THE HISTORY

OF

Dr. John Faustus,

SHEWING

How he sold himself to the Devil to have power to do what

he pleased for twenty-four years.

ALSO

STRANGE THINGS DONE BY HIM AND HIS SERVANT

MEPHISTOPHOLES.

With an Account how the Devil came for him, and tore him in Pieces.

Printed and Sold in Aldermary Church Yard

Bow Lane, London.

Page 40

THE HISTORY OF

DR. JOHN FAUSTUS.

Chap. 1.

The Doctor's Birth and Education.

Dr. John Faustus was born in Germany: his father was

a poor labouring man, not able to give him any manner of

education; but he had a brother in the country, a rich man,

who having no child of his own, took a great fancy to his

nephew, and resolved to make him a scholar. Accordingly

he put him to a grammar school, where he took learning

extraordinary well; and afterwards to the University to study

Divinity. But Faustus, not liking that employment, betook

himself to the study of Necromancy and Conjuration, in

which arts he made such a proficiency, that in a short time

none could equal him. However he studied Divinity so

far, that he took his Doctor's Degree in that faculty; after

which he threw the scripture from him, and followed his

own inclinations.

Page 41

Chap. 2.

Dr. Faustus raises the Devil, and afterwards makes

him appear at his own House.

Faustus whose restless mind studied day and night, dressed

his imagination with the wings of an eagle, and endeavoured

to fly all over the world, and see and know the secrets of

heaven and earth. In short he obtained power to command

the Devil to appear before him whenever he pleased.

One day as Dr. Faustus was walking in a wood near

Wirtemberg in Germany, having a friend with him who was

desirous to see his art, and requested him to let him see if

he could then and there bring Mephistopholes before them.

The Doctor immediately called, and the Devil at the first

summons made such a hedious noise in the wood as if

heaven and earth were coming together. And after this made

a roaring as if the wood had been full of wild beasts. Then

the Doctor made a Circle for the Devil, which he danced

round with a noise like that of ten thousand waggons running

upon paved stones. After this it thundered and lightened

as if the world had been at an end.

Faustus and his friend, amazed at the noise, and frighted

at the devil's long stay, would have departed; but the Devil

cheared them with such musick, as they never heard before.

This so encouraged Faustus, that he began to command

Page 42

Mephistopholes, in the name of the prince of Darkness, to

appear in his own likeness; on which in an instant hung

over his head a mighty dragon.—Faustus called him again,

as he was used, after which there was a cry in the wood as

if Hell had been opened, and all the tormented souls had

been there—Faustus in the mean time asked the devil many

questions, and commanded him to shew a great many tricks.

Chap. 3.

Mephistopholes comes to the Doctor's House; and

of what passed between them.

Faustus commanded the spirit to meet him at his own

house by ten o'clock the next day. At the hour appointed

he came into his chamber, demanding what he would have?

Faustus told him it was his will and pleasure to conjure him

to be obedient to him in all points of these articles, viz.

- First, that the Spirit should serve him in all things he

asked, from that time till death.

- Secondly, whosoever he would have, the spirit should

bring him.

- Thirdly. Whatsoever he desired for to know he should

tell him.

The Spirit told him he had no such power of himself,

until he had acquainted his prince that ruled over him.

For, said he, we have rulers over us, who send us out

Page 43

and call us home when they will; and we can act no farther

than the power we receive from Lucifer, who you know for his

pride was thrust out of heaven. But I can tell you no more,

unless you bind yourself to us—I will have my request replied

Faustus, and yet not be damned with you—Then said the spirit,

you must not, nor shall not have your desire, and yet thou art

mine and all the world cannot save thee from my power. Then

get you hence, said Faustus, and I conjure thee that thou come

to me at night again.

Then the spirit vanished, and Doctor Faustus began to consider

by what means he could obtain his desires without binding

himself to the Devil.

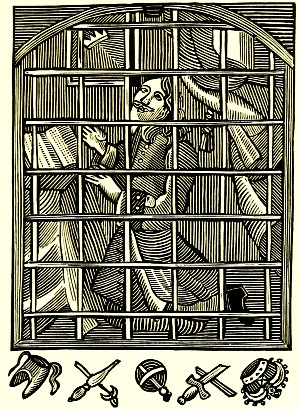

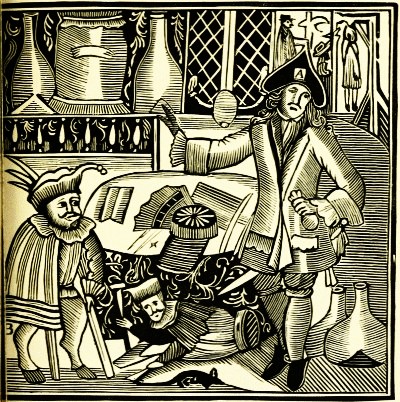

This is a rough copy of the frontispiece to Gent's translation,

ed. 1648.

While Faustus was in these cogitations, night drew on, and

then the spirit appeared, acquainting him that now he had

orders from his prince to be obedient to him, and to do for him

what he desired, and bid him shew what he would have.—Faustus

replied, His desire was to become a Spirit, and that

Mephistopholes should always be at his command; that whenever

he pleased he should appear invisible to all men.—The

Spirit answered his request should be granted if he would sign

the articles pronounced to him viz, That Faustus should give

Page 44

himself over body and soul to Lucifer, deny his Belief, and

become an enemy to all good men; and that the writings

should be made with his own blood.—Faustus agreeing to all

this, the Spirit promised he should have his heart's desire, and

the power to turn into any shape, and have a thousand spirits

at command.

Chap. 4.

Faustus lets himself blood, and makes himself over

to the Devil.

The Spirit appearing in the morning to Faustus, told him, That

now he was come to see the writing executed and give him

power. Whereupon Faustus took out a knife, pricked a vein

in his left arm, and drew blood, with which he wrote as follows:

"I, John Faustus, Doctor in Divinity, do openly acknowlege

That in all my studying of the course of nature and the elements,

I could never attain to my desire; I finding men unable

to assist me, have made my addresses to the Prince of Darkness,

and his messenger Mephistopholes, giving them both soul

and body, on condition that they fully execute my desires; the

which they have promised me. I do also further grant by these

presents, that if I be duly served, when and in what place I

command, and have every thing that I ask for during the space

of twenty four years, then I agree that at the expiration of the

said term, you shall do with Me and Mine, Body and Soul, as

Page 45

you please. Hereby protesting, that I deny God and Christ

and all the host of heaven. And as for the further consideration

of this my writing, I have subscribed it with my own hand,

sealed it with my own seal, and writ it with my own blood.

John Faustus."

No sooner had Faustus sent his name to the writing, but

his spirit Mephistopholes appeared all wrapt in fire, and out of

his mouth issued fire; and in an instant came a pack of hounds

in full cry. Afterwards came a bull dancing before him, then a

lion and a bear fighting. All these and many spectacles more

did the Spirit present to the Doctor's view, concluding with

all manner of musick, and some hundreds of spirits dancing

before him.—This being ended, Faustus looking about saw

seven sacks of silver, which he went to dispose of, but could

not handle himself, it was so hot.

This diversion so pleased Faustus, that he gave Mephistopholes

the writing he had made, and kept a copy of it in his

own hands. The Spirit and Faustus being agreed, they dwelt

together, and the devil was never absent from his councils.

Page 46

Chap. 5.

How Faustus served the Electoral Duke of Bavaria.

Faustus having sold his soul to the Devil, it was soon reported

among the neighbours, and no one would keep him company,

but his spirit, who was frequently with him, playing of strange

tricks to please him.

Not far from Faustus's house lived the Duke of Bavaria,

the Bishop of Saltzburg, and the Duke of Saxony, whose houses

and cellars Mephistopholes used to visit, and bring from thence

the best provision their houses afforded.

One day the Duke of Bavaria had invited most of the

gentry of that country to dinner, in an instant came Mephistopholes

and took all with him, leaving them full of admiration.

If at any time Faustus had a mind for wild or tame fowl,

the Spirit would call whole flocks in at the window. He also

taught Faustus to do the like so that no locks nor bolts could

hinder them.

The devil also taught Faustus to fly in the air, and act many

things that are incredible, and too large for this book to contain.

Chap. 6.

Faustus Dream of Hell, and what he saw there.

After Faustus had had a long conference with the Spirit concerning

the fall of Lucifer, the state and condition of the fallen

angels, he in a dream saw Hell and the Devils.

Having seen this sight he marvelled much at it, and having

Mephistopholes on his side, he asked him what sort of people

they was who lay in the first dark pit? Mephistopholes told

him they were those who pretended to be physicians, and had

poisoned many thousands in trying practices; and now said

the spirit, they have the very same administered unto them

which they prescribed to others, though not with the same

Page 47

effect; for here, said he, they are denied the happiness to die.—Over

their heads were long shelves full of vials and gallipots

of poison.

Having passed by them, he came to a long entry exceeding