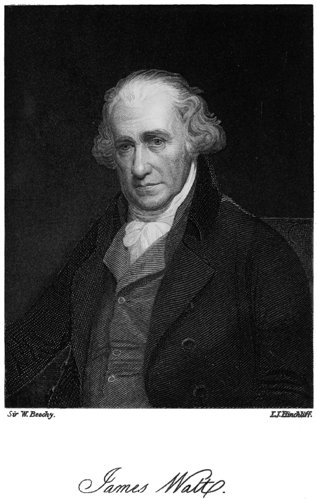

Sir W. Beechy.

I. J. Hinchliff.

James Watt.

Transcriber's note: Cover created by Transcriber and placed into the Public Domain.

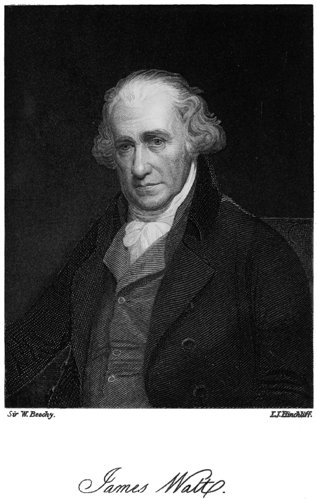

Sir W. Beechy.

I. J. Hinchliff.

James Watt.

By JOHN BECKMANN,

PROFESSOR OF ŒCONOMY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF GÖTTINGEN.

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN,

By WILLIAM JOHNSTON.

Fourth Edition,

CAREFULLY REVISED AND ENLARGED BY

WILLIAM FRANCIS, Ph.D., F.L.S.,

EDITOR OF THE CHEMICAL GAZETTE;

AND

J. W. GRIFFITH, M.D., F.L.S.,

LICENTIATE OF THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PHYSICIANS.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

HENRY G. BOHN, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN.

1846.

PRINTED BY RICHARD AND JOHN E. TAYLOR,

RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET.

Although the plan of this new edition of Beckmann’s ‘History of Inventions and Discoveries’ was to confine it to the subjects treated of in the original work, yet we feel it imperative to make an exception in favour of the Steam-Engine, the most important of all modern inventions.

The power of steam was not entirely unknown to the ancients, but before the æra rendered memorable by the discoveries of James Watt, the steam-engine, which has since become the object of such universal interest, was a machine of extremely limited power, inferior in importance and usefulness to most other mechanical agents used as prime movers. Hero of Alexandria, who lived about 120 years before the birth of Christ, has left us the description of a machine, in which a continued rotatory motion was imparted to an axis by a blast of steam issuing from lateral orifices in arms placed at right angles to it. About the beginning of the seventeenth century, a French engineer, De Caus, invented a machine by which a column of water might be raised by the pressure of steam confined in the vessel, above the water to be elevated; and in 1629, Branca, an Italian philosopher, contrived a plan of working several mills by a blast of steam against the vanes; from the descriptions, however, which have been left us of these contrivances, it does not appear that their projectors were acquainted with those physical properties of elasticity and condensation on which the power of steam as a mechanical agent depends.

In 1663, the celebrated Marquis of Worcester described in his Century of Inventions, an apparatus for raising watervi by the expansive force of steam only. From this work we extract the following short account of the first steam-engine. “68. An admirable and most forcible way to drive up water by fire; not by drawing or sucking it upwards, for that must be as the philosopher calleth it, intra sphæram activitatis, which is but at such a distance. But this way hath no bounder, if the vessel be strong enough: for I have taken a piece of whole cannon, whereof the end was burst, and filled it three-quarters full of water, stopping and screwing up the broken end as also the touch-hole; and making a constant fire under it, within twenty-four hours it burst and made a great crack; so that having a way to make my vessels so that they are strengthened by the force within them, and the one to fill after the other, I have seen the water run like a constant stream, forty feet high: one vessel of water rarefied by fire, driveth up forty of cold water; and a man that tends the work is but to turn two cocks, that one vessel of water being consumed, another begins to force and refill with cold water, and so successively; the fire being tended and kept constant, which the self-same person may likewise abundantly perform in the interim, between the necessity of turning the said cocks.”

The next name to be mentioned in connection with the progressive history of the invention of the steam-engine, is that of Denis Papin, a native of France, who, being banished from his country, was established Professor of Mathematics at the University of Marburg, by the Landgrave of Hesse. He first conceived the important idea of obtaining a moving power by means of a piston working in a cylinder (1688), and subsequently (1690) that of producing a vacuum in the cylinder by the sudden condensation of steam by cold. In accordance with these ideas he constructed a model consisting of a small cylinder, in which was inserted a solid piston, and beneath this a small quantity of water; on applying heat to the bottom of the cylinder, steam was generated, the elastic force of which raised the piston; the cylinder was then cooled by removing the fire, when the steam condensed and became again converted into water, thus creating a vacuum in the cylinder, into which the piston was forced by the pressure of the atmosphere; there is, however, no evidence of his having carriedvii that or any other machine into practical use, before machines worked by steam had been constructed elsewhere.

The first actual working steam-engine of which there is any record, was invented by Captain Savery an Englishman, to whom a patent was granted in 1698 for a steam-engine to be applied to the raising of water, &c. This gentleman produced a working-model before the Royal Society, as appears from the following extract from their Transactions:—“June 14th, 1699. Mr. Savery entertained the Royal Society with showing a small model of his engine for raising water by help of fire, which he set to work before them: the experiment succeeded according to expectation, and to their satisfaction.” This engine, which was used for some time to a considerable extent for raising water from mines, consisted of a strong iron vessel shaped like an egg, with a tube or pipe at the bottom, which descended to the place from which the water was to be drawn, and another at the top, which ascended to the place to which it was to be elevated. This oval vessel was filled with steam supplied from a boiler, by which the atmospheric air was first blown out of it. When the air was thus expelled, and nothing but pure steam left in the vessel, the communication with the boiler was cut off, and cold water poured on the external surface. The steam within was thus condensed and a vacuum produced, and the water drawn up from below in the usual way by suction. The oval steam-vessel was thus filled with water; a cock placed at the bottom of the lower pipe was then closed, and steam was introduced from the boiler into the oval vessel above the surface of the water. This steam being of high pressure, forced the water up the ascending tube, from the top of which it was discharged; and the oval vessel being thus refilled with steam, the vacuum was again produced by condensation, and the same process was repeated by using two oval steam-vessels, which would act alternately; one drawing water from below, while the other was forcing it upwards, by which an uninterrupted discharge of water was produced. Owing to the danger of explosion, from the high pressure of the steam which was used, and from the enormous waste of heat by unnecessary condensation, these engines soon fell into disuse.

Several ingenious men now turned their attention to the improvement of the steam-engine, with a view to reduce theviii consumption of fuel, which was found to be so immense as to preclude its use except under very favourable circumstances; and in 1705, Thomas Newcomen, a blacksmith or ironmonger, and John Cawley, a plumber and glazier, patented their atmospheric engine, in which at first condensation was effected by the affusion of cold water upon the external surface of the cylinder, which was introduced into a hollow casing by which it was surrounded. Having accidentally observed that an engine worked several strokes with unusual rapidity without the supply of condensing water, Newcomen found, on examining the piston, a hole in it through which the water poured on to keep it air-tight issued in the form of a little jet, and instantly condensed the steam under it; this led him to abandon the casing and to introduce a pipe furnished with a cock, into the bottom of the cylinder, by which water was supplied from a reservoir. Newcomen’s engine required the constant attendance of some person to open and shut the regulating and condensing valves, a duty which was usually entrusted to boys, called cock-boys. It is said that one of these boys, named Humphrey Potter, wishing to join his comrades at play, without exposing himself to the consequences of suspending the performance of the engine, contrived by attaching strings of proper length to the levers which governed the two cocks, to connect them with the beam, so that it should open and close the cocks as it moved up and down, with the most perfect regularity. By this simple contrivance the steam-engine for the first time became an automaton.

It was in repairing a working model of a steam-engine on Newcomen’s principle for the lectures of the professor of natural philosophy at the University of Glasgow, that James Watt directed his mind to the prosecution of those inventions and beautiful contrivances, by which he gave to senseless matter an almost instinctive power of self-adjustment, with precision of action more than belongs to any animated being, and which have rendered his name celebrated over the world.

At the time of which we speak, Newcomen’s engine was of the last and most approved construction. The moving power was the weight of the air pressing on the upper surface of a piston working in a cylinder; steam being employed at the termination of each downward stroke to raise the piston withix its load of air up again, and then to form a vacuum by its condensation when cooled by a jet of cold water, which was thrown into the cylinder when the admission of steam was stopped. Upon repairing the model, Watt was struck by the incapability of the boiler to produce a sufficient supply of steam, though it was larger in proportion to the cylinder than was usual in working engines. This arose from the nature of the cylinder, which being made of brass, a better conductor of heat than cast-iron, and presenting, in consequence of its small size, a much larger surface in proportion to its solid content than the cylinders of working engines, necessarily cooled faster between the strokes, and therefore at every fresh admission consumed a greater proportionate quantity of steam. But being made aware of a much greater consumption of steam than he had imagined, he was not satisfied without a thorough inquiry into the cause. With this view he made experiments upon the merits of boilers of different constructions; on the effect of substituting a less perfect conductor, as wood, for the material of the cylinder; on the quantity of coal required to evaporate a given quantity of water; on the degree of expansion of water in the form of steam: and he constructed a boiler which showed the quantity of water evaporated in a given time, and thus enabled him to calculate the quantity of steam consumed at each stroke of the engine. This proved to be several times the content of the cylinder. He soon discovered that, whatever the size and construction of the cylinder, an admission of hot steam into it must necessarily be attended with very great waste, if in condensing the steam previously admitted, that vessel had been cooled down sufficiently to produce a vacuum at all approaching to a perfect one. If, on the other hand, to prevent this waste, he cooled it less thoroughly, a considerable quantity of steam remained uncondensed within, and by its resistance weakened the power of the descending stroke. These considerations pointed out a vital defect in Newcomen’s engine; involving either a loss of steam, and consequent waste of fuel; or a loss of power from the piston’s descending at every stroke through a very imperfect vacuum.

It soon occurred to Watt, that if the condensation were performed in a separate vessel, one great evil, the cooling of the cylinder, and the consequent waste of steam, would bex avoided. The idea once started, he soon verified it by experiment. By means of an arrangement of cocks, a communication was opened between the cylinder, and a distinct vessel exhausted of its air, at the moment when the former was filled with steam. The vapour of course rushed to fill up the vacuum, and was there condensed by the application of external cold, or by a jet of water; so that fresh steam being continually drawn off from the cylinder to supply the vacuum continually created, the density of that which remained might be reduced within any assignable limits. This was the great and fundamental improvement.

Still, however, there was a radical defect in the atmospheric engine, inasmuch as the air being admitted into the cylinder at every stroke, a great deal of heat was abstracted, and a proportionate quantity of steam wasted. To remedy this, Watt excluded the air from the cylinder altogether; and recurred to the original plan of making steam the moving power of the engine, not a mere agent to produce a vacuum. In removing the difficulties of construction which beset this new plan, he displayed great ingenuity and powers of resource. On the old plan, if the cylinder was not bored quite true, or the piston not accurately fitted, a little water poured upon the top rendered it perfectly air-tight, and the leakage into the cylinder was of little consequence, so long as the injection water was thrown into that vessel. But on the new plan, no water could possibly be admitted within the cylinder; and it was necessary, not merely that the piston should be air-tight, but that it should work through an air-tight collar, that no portion of the steam admitted above it might escape. This he accomplished by packing the piston and the stuffing-box, as it is called, through which the piston-rod works, with hemp. A further improvement consisted in equalising the motion of the engine by admitting the steam alternately above and below the piston, by which the power is doubled in the same space, and with the same strength of material. The vacuum of the condenser was perfected by adding a powerful pump, which at once drew off the condensed and injected water, and with it any portion of air which might find admission; as this would interfere with the action of the engine if allowed to accumulate. His last great change was to cut off the communication between the cylinder and the boiler, whenxi a portion only, as one-third or one-half, of the stroke was performed; leaving it to the expansive power of the steam to complete it. By this, œconomy of steam was obtained, together with the power of varying the effort of the engine according to the work which it has to do, by admitting the steam through a greater or smaller portion of the stroke.

These are the chief improvements which Watt effected at different periods of his life. He was born June 19, 1736, at Greenock, where he received the rudiments of his education. Having at an early age manifested a partiality for the practical part of mechanics, he went in his eighteenth year to London to obtain instruction in the profession of a mathematical instrument-maker, but remained there little more than a year, being compelled to return home on account of his health. In 1757, shortly after his return home, he was appointed instrument-maker to the University of Glasgow, and accommodated with premises within the precincts of that learned body. In 1763 he removed into the town of Glasgow, intending to practise as a civil engineer. His first patent is dated June 5, 1769, which parliament extended in 1775 for twenty-five years in consideration of the national importance of the inventions, and the difficulty and expense of introducing them to public notice. He died at his house at Heathfield in the county of Stafford, on the 25th of August, 1819, at the advanced age of eighty-four, after having realized an ample fortune, the well-earned reward of his industry and ability.

To enter into the history of the various applications of the steam-engine to the different branches of industry would carry us beyond the bounds of this work. “To enumerate its present effects,” says a well-known writer on the steam-engine1, “would be to count almost every comfort and every luxury of life. It has increased the sum of human happiness, not only by calling new pleasures into existence, but by so cheapening former enjoyments as to render them attainable by those who before could never have hoped to share them: the surface of the land, and the face of the waters are traversed with equal facility by its power; and by thus stimulating and facilitating the intercourse of nation with nation, and the commerce of people with people, it has knit togetherxii remote countries by bonds of amity not likely to be broken. Streams of knowledge and information are kept flowing between distant centres of population, those more advanced diffusing civilization and improvement among those that are more backward. The press itself, to which mankind owes in so large a degree the rapidity of their improvement in modern times, has had its power and influence increased in a manifold ratio by its union with the steam-engine. It is thus that literature is cheapened, and by being cheapened, diffused; it is thus that reason has taken the place of force, and the pen has superseded the sword; it is thus that war has almost ceased upon the earth, and that the differences which inevitably arise between people and people are for the most part adjusted by peaceful negotiation.”

1 Dr. Lardner.

It appears singular to us at present that it should have been once considered unlawful to receive interest for lent money; but this circumstance will excite no wonder when the reason of it is fully explained. The different occupations by which one can maintain a family without robbery and without war, were at early periods neither so numerous nor so productive as in modern times; those who borrowed money required it only for immediate use, to relieve their necessities or to procure the conveniences of life; and those who advanced it to such indigent persons did so either through benevolence or friendship. The case now is widely different. With the assistance of borrowed money people enter into business, and carry on trades, from which by their abilities, diligence, or good fortune, so much profit arises that they soon acquire more than is requisite for their daily support; and under these circumstances the lender may undoubtedly receive for the beneficial use of his money a certain remuneration, especially as he himself might have employed it to advantage; and as by lending it he runs the risk of losing either the whole or a part of his capital, or at least of not receiving it again so soon as he may have occasion for it.

Lending on interest, therefore, must have become more usual in proportion as trade, manufactures, and the arts were extended; or as the art of acquiring money by money became2 more common: but it long continued to be detested, because the ancient abhorrence against it was by an improper construction of the Mosaic law converted into a religious prejudice2, which, like many other prejudices more pernicious, was strengthened and confirmed by severe papal laws. The people, however, who often devise means to render the faults of their legislators less hurtful, concealed this practice by various inventions, so that neither the borrower nor lender could be punished, nor the giving and receiving of interest be prevented. As it was of more benefit than prejudice to trade, the impolicy of the prohibition became always more apparent; it was known that the new-invented usurious arts under which it was privately followed would occasion greater evils than those which had been apprehended from lending on interest publicly; it was perceived also that the Jews, who were not affected by papal maledictions, foreigners, and a few natives who had neither religion nor conscience, and whom the church wished least of all to favour, were those principally enriched by it.

In no place was this inconvenience more felt than at the Romish court, even at a time when it boasted of divine infallibility; and nowhere was more care employed to remove it. A plan, therefore, was at length devised, by which the evil, as was supposed, would be banished. A capital was collected from which money was to be lent to the poor for a certain period on pledges without interest. This idea was indeed not new; for such establishments had long before been formed and supported by humane princes. The emperor Augustus, we are told, converted into a fund the surplus of the money which arose to the State from the confiscated property of criminals, and lent sums from it, without interest, to those who could pledge effects equal to double the amount3. Tiberius also advanced a large capital, from which those were supplied with money for three years, who could give security on lands equivalent to twice the value4. Alexander Severus reduced the interest of money by lending it at a low rate, and advancing sums to the poor without interest to purchase lands, and agreeing to receive payment from the produce of them5.

3 These examples of the ancients were followed in modern Italy. In order to collect money, the popes conferred upon those who would contribute towards that object a great many fictitious advantages, which at any rate cost them nothing. By bulls and holy water they dispensed indulgences and eternal salvation; they permitted burthensome vows to be converted into donations to lending-houses; and authorised the rich who advanced them considerable sums to legitimate such of their children as were not born in wedlock. As an establishment of this kind required a great many servants, they endeavoured to procure these also on the same conditions; and they offered, besides the above-mentioned benefits, a great many others not worth notice, to those who would engage to discharge gratis the business of their new undertaking; but in cases of necessity they were to receive a moderate salary from the funds. This money was lent without interest for a certain time to the poor only, provided they could deposit proper pledges of sufficient value.

It was, however, soon observed that an establishment of this kind could neither be of extensive use nor of long duration. In order to prevent the secret lending of money, by the usurious arts which had begun to be practised, it was necessary that it should advance sums not only to those who were poor in the strictest sense of the word, but to those also who, to secure themselves from poverty, wished to undertake and carry on useful employments, and who for that purpose had need of capitals. However powerful the attractions might be, which, on account of the religious folly that then prevailed, induced people to make large contributions, they gradually lost their force, and the latter were lessened in proportion, especially as a spirit of reformation began soon after to break out in Germany, and to spread more and more into other countries. Even if a lending-house should not be exhausted by the maintenance of its servants, and various accidents that could not be guarded against, it was still necessary, at any rate, to borrow as much money at interest as might be sufficient to support the establishment. As it was impossible that it could relieve all the poor, the only method to be pursued was to prevent their increase, by encouraging trade, and by supplying those with money who wanted only a little to enable them to gain more, and who were in a condition and willing to pay a moderate4 interest. The pontiffs, therefore, at length resolved to allow the lending-houses to receive interest, not for the whole capitals which they lent, but only for a part, merely that they might raise as much money as might be sufficient to defray their expenses; and they now, for the first time, adopted the long-established maxim, that those who enjoy the benefits should assist to bear the burthen—a maxim which very clearly proves the legality of interest. When this opening was once made, one step more only was necessary to place the lending-houses on that judicious footing on which they would in all probability have been put by the inventor himself, had he not been under the influence of prejudice. In order that they might have sufficient stock in hand, it was thought proper to give to those who should advance them money a moderate interest, which they prudently concealed by blending it with the unavoidable expenses of the establishment, to which it indeed belonged, and which their debtors, by the practice a little before introduced, were obliged to make good. The lending-houses, therefore, gave and received interest. But that the odious name might be avoided, whatever interest was received, was said to be pro indemnitate; and this is the expression made use of in the papal bull.

All this, it must be confessed, was devised with much ingenuity: but persons of acuteness still discovered the concealed interest; and a violent contest soon arose respecting the legality of lending-houses, in which the greatest divines and jurists of the age took a part; and by which the old question, whether one might do anything wicked, or establish interest, in order to effect good, was again revived and examined. Fortunately for the pontifical court, the folly of mankind was still so great that a bull was sufficient to suppress, or at least to silence, the spirit of inquiry. The pope declared the holy mountains of piety, “sacri monti de pietà,” to be legal; and threatened those with his vengeance who dared to entertain any further doubts on the subject. All the cities now hastened to establish lending-houses; and their example was at length followed in other countries. Such, in a general view, is the history of these establishments: I shall now confirm it by the necessary proofs.

When under the appellation of lending-house we understand a public establishment where any person can borrow5 money upon pledges, either for or without interest, we must not compare it to the tabernæ argentariæ or mensæ nummulariæ of the Romans. These were banking-houses, at which the state and rich people caused their revenues to be paid, and on which they gave their creditors orders either to receive their debts in money, or to have the sums transferred in their own name, and to receive security for them. To assign over money and to pay money by a bill were called perscribere and rescribere; and an assignment or draft was called attributio. These argentarii, mensarii, nummularii, collybistæ and trapezitæ followed the same employment, therefore, as our cashiers or bankers. The former, like the latter, dealt in exchanges and discount; and in the same manner also they lent from their capital on interest, and gave interest themselves, in order that they might receive a greater. Those who among the ancients were enemies to the lending of money on interest brought these people into some disrepute; and the contempt entertained for them was probably increased by prejudice, though those nummarii who were established by government as public cashiers held so exalted a rank that some of them became consuls. Such banking-houses existed in the Italian States in the middle ages, about the year 1377. They were called apothecæ seu casanæ feneris6, and in Germany Wechselbanke, banks of exchange; but they were not lending-houses in the sense in which I here understand them.

Equally distinct also from lending-houses were those banks established in the fourteenth century, in many cities of Italy, such, for example, as Florence, in order to raise public loans. Those who advanced money on that account received an obligation and monthly interest, which on no pretext could be refused, even if the creditor had been guilty of any crime. These obligations were soon sold with advantage, but oftener with loss; and the price of them rose and fell like that of the English stocks, but not so rapidly; and theologists disputed whether one could with a safe conscience purchase an obligation at less than the stated value, from a proprietor who was obliged to dispose of it for ready specie. If the State6 was desirous or under the necessity of repaying the money, it availed itself of that regale called by Leyser regale falsæ monetæ, and returned the capital in money of an inferior value. This establishment was confirmed, at least at Florence, by the pontiff, who subjected those who should commit any fraud in it to ecclesiastical punishment and a fine, which was to be carried to the papal treasury: but long before that period the republic of Genoa had raised a loan by mortgaging the public revenues. I have been more particular on this subject, because Le Bret7 calls these banks, very improperly, lending-houses; and in order to show to what a degree of perfection the princely art of contracting and paying debts was brought so early as the fourteenth century.

Those who have as yet determined the origin of lending-houses with the greatest exactness, place it, as Dorotheus Ascanius, that is Matthias Zimmermann8, does, in the time of Pope Pius II. or Paul II., who filled the papal chair from 1464 to 1471; and the reason for supposing it to have been under the pontificate of the latter is, because Leo X. in his bull, which I shall quote hereafter, mentions that pope as the first who confirmed an establishment of this kind. As the above account did not appear to me satisfactory, and as I knew before that the oldest lending-houses in Italy were under the inspection of the Franciscans, I consulted the Annals of the Seraphic Order, with full expectation that this service would not be omitted in that work; and I indeed found in it more materials towards the history of lending-houses than has ever been collected, as far as I know, by any other person.

As complaints against usury, which was practised by many Christians, but particularly by the Jews, became louder and7 more public in Italy in the fifteenth century, Barnabas Interamnensis, probably of Terni, first conceived the idea of establishing a lending-house. This man was originally a physician; had been admitted to the degree of doctor; was held in great respect on account of his learning; became a Minorite, or Franciscan; acquired in that situation every rank of honour, and died, in the first monastery of this order at Assisi (in monte Subasio9), in the year 1474. While he was employed in preaching under Pope Pius II. at Perugia, in the territories of the Church, and observed how much the poor were oppressed by the usurious dealings of the Jews, he made a proposal for raising a capital by collections, in order to lend from it on pledges to the indigent, who should give monthly, for the use of the money borrowed, as much interest as might be necessary to pay the servants employed in this establishment, and to support it. Fortunatus de Copolis, an able jurist of Perugia, who after the death of his wife became also a Franciscan, approved of this plan, and offered to assist in putting it into execution. To be assured in regard to an undertaking which seemed to approach so near to the lending on interest, both these persons laid their plan before the university of that place, and requested to know whether such an establishment could be allowed; and an answer being given in the affirmative, a considerable sum was soon collected by preaching, so that there was a sufficiency to open a lending-house. Notwithstanding this sanction, many were displeased with the design, and considered the receiving of interest, however small it might be, as a species of usury. Those who exclaimed most against it were the Dominicans (ex ordine Prædicatorum): and they seem to have continued to preach in opposition to it, till they were compelled by Leo X. to be silent; while the Franciscans, on the other hand, defended it,8 and endeavoured to make it be generally adopted. The dispute became more violent when, at the end of a year, after all expenses were paid, a considerable surplus was found remaining; and as the managers did not know how to dispose of it, they at length thought proper to divide it amongst the servants, because no fixed salaries had been appointed for them. Such was the method first pursued at Perugia; but in other places the annual overplus was employed in a different manner. The particular year when this establishment began to be formed I have nowhere found marked; but as it was in the time of Pius II., it must have been in 1464, or before that period10. It is very remarkable that this pontiff confirmed the lending-house at Orvieto (Urbs Vetus) so early as the above year; whereas that at Perugia was sanctioned, for the first time, by Pope Paul II. in 1467. It is singular also that Leo X., in his confirmation of this establishment, mentions Paul II., Sixtus IV., Innocent VIII., Alexander VI. and Julius II.; but not Pius II. Pope Sixtus IV., as Wadding says, confirmed in 1472 the lending-house at Viterbo, which had, however, been begun so early as 1469, by Franciscus de Viterbo, a Minorite11.

In the year 1479 Sixtus IV. confirmed the lending-house which had been established at Savona, the place of his birth, upon the same plan as that at Perugia. The bull issued for this purpose is the first pontifical confirmation ever printed12; for that obtained for Perugia was not, as we are told by the editor, to be found in the archives there in 1618, the time when the other was printed. I have never found the confirmation9 of those at Orvieto and Viterbo. Ascianus sought for them, but without success, in Bullarium Magnum Cherubini, and they are not mentioned by Sixtus. This pontiff, in his bull, laments that the great expenses to which he was subjected did not permit him to relieve his countrymen with money, but that he would grant to the lending-house so many spiritual advantages, as should induce the faithful to contribute towards its support; and that it was his desire that money should be lent from it to those who would assist gratis during a year in the business which it required. If none could be found to serve on these conditions, a moderate salary was to be given. He added a clause also respecting pledges; but passed over in silence that the debtors were to contribute anything for the support of the institution by paying interest, which Barnabas, whose name does not occur in the bull, introduced however at Perugia, and which the pope tacitly approved.

The greater part of the lending-houses in Italy were established in the fifteenth and following centuries by the Minorites Marcus Bononiensis, Michael a Carcano13, Cherubinus Spoletanus, Jacobus de Marchia, Antonius Vercellensis, Angelus a Clavasio, and above all, Bernardinus Tomitano, named also Feltrensis and Parvulus. This man was born at Feltri, in the country of Treviso, in the year 1439. His father was called Donato Tomitano, and his mother Corona Rambaldoni; they were both of distinguished families, though some assert that he was of low extraction, and a native of Tomi, a small place near Feltri, on which account he got the name of Tomitano. The name of Parvulus arose from his diminutive stature, which he sometimes made a subject of pleasantry14. This much at any rate is certain, that he had received a good education. In 1456, when seventeen years of age, he suffered his instructors, contrary to the inclination of his father, to carry him to Padua, to be entered in the order of the Minorites; and on this occasion he changed his christian-name Martin into Bernardinus. As he was a good speaker, he was10 employed by his order in travelling through Italy and preaching. He was heard with applause, and in many parts the people almost paid him divine honours. The chief object of his sermons was to banish gaming, intemperance, and extravagance of dress; but he above all attacked the Jews, and excited such a hatred against them, that the governments in many places were obliged to entreat or to compel him either to quit their territories or not to preach in opposition to these unfortunate people, whom the crowds he collected threatened to massacre; and sometimes when he visited cities where there were rich Jews and persons who were connected with them in trade, he was in danger of losing even his own life. Taking advantage of this general antipathy to the Jews, he exerted himself, after the example of Barnabas, his brother Minorite, to get lending-houses established, and died at Pavia in the year 1494. The Minorites played a number of juggling tricks with his body, pretending that it performed miracles, by which means they procured him a place in the catalogue of the saints; and to render his name still more lasting, some of his sermons have been printed among the works of the writers of the Franciscan order15.

The lending-houses in Italy, with the origin of which I am acquainted, are as follows:—The lending-house at Perugia was inspected in 1485 by Bernardinus, who enlarged its capital.

The same year he established one at Assisi, which was confirmed by Pope Innocent, and which was visited and improved by its founder in 148716.

In the year 1486, after much opposition, he established a lending-house at Mantua, and procured for it also the pope’s sanction17. Four years after, however, it had declined so much, that he was obliged to preach in order to obtain new donations to support it.

At Florence he met with still more opposition; for the rich Jews bribed the members of the government, who wished in appearance to favour the establishment of the lending-house, to which they had consented eighteen years before,11 while they secretly thwarted it; and some boys having once proceeded, after hearing a sermon, to attack the houses of the Jews, the Minorites were ordered to abstain from preaching and to quit the city18. It was however completely established; but by the Dominican Hieronymus Savonarola19.

In the year 1488 Bernardinus established a lending-house at Parma, and procured for it the pope’s sanction, as well as for one at Cesena, where the interest was defined to be “pro salariis officialium et aliis montis oneribus perferendis.” About the conclusion of this year he was at the other end of Italy, where he re-established the lending-house at Aquila in the kingdom of Naples20.

In the year following he established one at Chieti (Theate) in the same kingdom, another at Rieti (Reate) in the territories of the Church, a third at Narni (Narnia)21; and a fourth at Lucca, which was confirmed by the bishop, notwithstanding the opposition of the Jews, who did every thing in their power to prevent it.

In the year 1490 a lending-house was established at Piacenza (Placentia) by Bernardinus, who at the same time found one at Genoa which had been established by the before-mentioned Angelus a Clavasio22. At this period also a lending-house was established at Verona23, and another at Milan by the Minorite Michael de Aquis.

In 1491 a lending-house was established at Padua, which was confirmed by Pope Alexander VI. in 149324; and another was established at Ravenna25.

In 1492 Bernardinus reformed the lending-house at Vicenza, where, in order to avoid the reproach of usury, the artifice was employed of not demanding any interest, but admonishing the borrowers that they should give a remuneration according to their piety and ability. As people were by these means induced to pay more interest than what was legally required at other lending-houses, Bernardinus caused this method to be abolished26. He established a lending-house also the same year in the small town of Campo S. Pietro,12 not far from Padua, and expelled the Jews who had lent upon pledges. At this period there were lending-houses at Bassano, a village in the county of Trevisi, and also at Feltri, which he inspected and improved27.

In the year 1493 Bernardinus caused a lending-house to be established at Crema, in the Venetian dominions; another at Pavia, where he requested the opinion of the jurists, whom he was happy to find favourable to his design; and likewise a third at Gubbio, in the territories of the Church. At the same time another Franciscan established at Cremona a mons frumenti pietatis, from which corn was lent out on interest to necessitous persons; and it appears that there had been an institution of the like kind before at Parma28.

In the year 1494, Bernardinus, a short time before his death, assisted to establish a lending-house at Montagnana, in the Venetian territories29, and to improve that at Brescia, which was likely to decay, because the servants had not fixed salaries30. The same year another Franciscan established the lending-house at Modena.

In the year 1506 Pope Julius II. confirmed the lending-house at Bologna. That of Trivigi was established in 1509; and in 1512, Elizabeth of the family of Gonzaga, as widow of duke Guido Ubaldus, established the first lending-house in the duchy of Urbino at Gubbio, and procured permission for it to coin money31.

The historical account I have here given, displays in the strongest light the great force of prejudice, and particularly of the prejudice of ecclesiastics. Notwithstanding the manifest advantages with which lending-houses were attended, and though a great part of them had been already sanctioned by the infallible court of Rome, many, but chiefly Dominicans, exclaimed against these institutions, which they did not call montes pietatis, but impietatis. No opposition gave the Minorites so much uneasiness as that of the Dominican Thomas de Vio, who afterwards became celebrated as a cardinal under the name of Cajetanus. This monk, while he taught at Pavia13 in 1498, wrote a treatise De Monte Pietatis32, in which he inveighed bitterly against taking pledges and interest, even though the latter was destined for the maintenance of the servants. The popes, he said, had confirmed lending-houses in general, but not every regulation that might be introduced into them, and had only given their express approbation of them so far as they were consistent with the laws of the church. These words, he added, had been wickedly left out in the bulls which had been printed; but he had heard them, and read them, in the confirmation of the lending-house at Mantua. I indeed find that these words are not in the copy of that bull given in Wadding, which is said to have been taken from the original; nor in the still older confirmation of the lending-house at Savona. But even were they to be found there, this would not justify Cajetan’s opposition, as the pope in both these bulls recommended the plan of the lending-house at Perugia to be adopted, of which receiving interest formed a part. Bernardinus de Bustis33, a Minorite, took up the cause in opposition to Cajetan, and, according to Wadding’s account, with rather too much vehemence. Among his antagonists were Barrianus and Franc. Papafava, a jurist of Padua34. As this dispute was revived with a great deal of warmth in the beginning of the sixteenth century, it was at length terminated by Pope Leo X., who in the tenth sitting of the council of the Lateran declared by a particular bull that lending-houses were legal and useful; that all doubts to the contrary were sinful, and that those who wrote against them should be placed in a state of excommunication35. The whole assembly, except one archbishop, voted in favour of14 this determination; and it appears from a decree of the council of Trent, that it also acknowledged their legality, and confirmed them36. Notwithstanding this decision, there were still writers who sometimes condemned them; and who did not consider all the decrees, at least the above one of the Lateran council, as agreeable to justice. Among these was Dominicus de Soto, a Dominican. All opposition, however, in the course of time subsided, and in the year 1565, Charles Borromeo, the pope’s legate at the council of Milan, ordered all governments and ecclesiastics to assist in establishing lending-houses37.

Of the lending-houses established after this period in Italy, I shall mention those only of Rome and Naples. It is very remarkable that the pope’s capital should have been without an institution of this kind till the year 1539, and that it should have been formed by the exertions of Giovanni Calvo, a Franciscan. Paul III., in his bull of confirmation, ordered that Calvo’s successors in rank and employment should always have the inspection of it, because the Franciscans had taken the greatest pains to endeavour to root out usury38.

The lending-house at Naples was first established in 1539 or 1540. Two rich citizens, Aurelio Paparo, and Leonardo or Nardo di Palma, redeemed all the pledges which were at that time in the hands of the Jews, and offered to deliver them to the owners without interest, provided they would return the money which had been advanced on them. More opulent persons soon followed their example; many bequeathed large sums for this benevolent purpose; and Toledo, the viceroy, who drove the Jews from the kingdom, supported it by every method possible. This lending-house, which has indeed undergone many variations, is the largest in Europe; and it contains such an immense number of different articles, many of them exceedingly valuable, that it may be considered as a repository of the most important part of the moveables of the whole nation. About the year 1563, another establishment of the like kind was formed under the title of banco de’ poveri.15 At first this bank advanced money without interest, only to relieve confined debtors; afterwards, as its capital increased, it lent upon pledges, but not above the sum of five ducats without interest. For larger sums the usual interest was demanded39.

At what time the first lending-house was established at Venice I have not been able to learn40. This State seems to have long tolerated the Jews; it endeavoured to moderate the hatred conceived against these people, and gave orders to Bernardinus to forbear preaching against them41. It appears to me in general, that the principal commercial cities of Italy were the latest to avail themselves of this invention; because they knew that to regulate interest by law, where trade was flourishing, would be ineffectual or useless; or because the rich Jew merchants found means to prevent it.

The name mons pietatis, of which no satisfactory explanation has been as yet given, came with the invention from Italy, and is equally old, if not older. Funds of money formed by the contributions of different persons, for some end specified, were long before called montes. In the first centuries of the Christian æra, free gifts were collected and preserved in churches by ecclesiastics, partly for the purpose of defraying the expense of divine service, and partly to relieve the poor. Such capitals, which were considered as ecclesiastical funds, were by Prudentius, in the beginning of the fifth century, called montes annonæ and arca numinis42. Tertullian calls them deposita pietatis43; and hence has been formed montes pietatis. At any rate I am of opinion that the inventor chose and adopted this name in order to give his institution a sacred or religious appearance, and to procure it more approbation and support.

I find however that those banks employed in Italy, during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, to borrow money in16 the name of States, for which the public revenues were mortgaged and interest paid, were also called montes44. In this sense the word is used by Italian historians of much later times; and those are greatly mistaken, who, with Ascian and many others, consider all these montes as real lending-houses. These loan-banks or montes received various names, sometimes from the princes who established them, sometimes from the use to which the money borrowed was applied, and sometimes from the objects which were mortgaged. Of this kind were the mons fidei, or loan opened by Pope Clement VII. in the year 1526, for defending his capital45; the mons aluminarius, under Pope Pius IV., for which the pontifical alum-works were pledged; the mons religionis, under Pius V., for carrying on the war against the Turks; and the montes farinæ, carnium, vini, &c., when the duties upon these articles were pledged as a security. To facilitate these loans, every condition that could induce people to advance money was thought of. Sometimes high interest was given, if the subscribers agreed that it should cease, and the capital fall to the bank after their death; and sometimes low interest was given, but the security was heritable and could be transferred at pleasure. The former were called montes vacabiles, and the latter montes non vacabiles. Sometimes the State engaged to pay back the capital at the end of a certain period, such for example as nine years, as was the case in regard to the mons novennalis, under Paul IV.; or it reserved to itself the option of returning the money at such a period as it might think proper, and sometimes the capital was sunk and the interest made perpetual. The first kind were called montes redimibiles, and the second irredimibiles46. One can here clearly discover the origin of life-rents, annuities, tontines, and government securities; but the further illustration of this subject I shall leave to those who may wish to employ their talents on a history of national debts. I have introduced these remarks, merely to rectify a mistake which has become almost general, and which occasioned some difficulties to me in this research; and I shall only observe further, that the popes gave to their17 loans, in order to raise their sinking credit, many of those spiritual advantages which they conferred on the montes pietatis. This error therefore was more easily propagated, as both were called montes; and hence it has happened that Ascianus and others assert that many lending-houses were misapplied by the popes in order to raise public loans.

From the instances here adduced, one may see that the first lending-houses were sanctioned by the pontiffs, because they only could determine to the Catholics in what cases it was lawful for them to receive interest. This circumstance seems to have rendered the establishment of them out of Italy difficult. At any rate the Protestants were at first averse to imitate an institution which originated at the court of Rome, and which, according to the prevailing prejudice of the times, it alone could approve; and from the same consideration they would not adopt the reformation which had been made in the calendar.

The first mention of a lending-house in Germany, which I have as yet met with, is to be found in the permission granted by the emperor Maximilian I. to the citizens of Nuremberg, in the year 1498, to drive the Jews from the city, and to establish an exchange-bank. The permission further stated, “That they should provide for their bank proper managers, clerks, and other persons to conduct it according to their pleasure, or as necessity might require; that such of their fellow-citizens as were not able to carry on their trades, callings, and occupations without borrowing and without pledging their effects, should, on demand, according to their trade and circumstances, receive money, for which pledges, caution and security should be taken; that at the time of payment a certain sum should be exacted by way of interest; that the clerks and conductors of the bank should receive salaries for their service from the interest; and that if any surplus remained it should be employed for the common use of the city of Nuremberg, like any other public fund.”

It here appears that the lending-houses in Germany were first known under the name of exchange-banks, by which was before understood any bank where money was lent and exchanged; but it does not thence follow, as Professor Fischer thinks47, that they were an Italian invention. The citizens of18 Nuremberg had not then a lending-house, nor was one established there till the year 1618. At that period they procured from Italy copies of the regulations drawn up for various houses of this kind, in order to select the best. Those of the city of Augsburg however were the grounds on which they built, and they sent thither the persons chosen to manage their lending-house, that they might make themselves fully acquainted with the nature of the establishment at that place48. In the year 1591, the magistrates of Augsburg had prohibited the Jews to lend money, or to take pledges; at the same time they granted 30,000 florins as a fund to establish a lending-house, and the regulations of it were published in 160749.

In the Netherlands, France and England, lending-houses were first known under the name of Lombards, the origin of which is evident. It is well known that in the thirteenth and following centuries many opulent merchants of Italy, which at those periods was almost the only part of Europe that carried on an extensive trade, were invited to these countries, where there were few mercantile people able to engage deeply in commerce. For this reason they were favoured by governments in most of the large cities; but in the course of time they became objects of universal hatred, because they exercised the most oppressive usury, by lending at interest and on pledges. They were called Longobardi or Lombardi, as whole nations are often named after a part of their country, in the same manner as all the Helvetians are called Swiss, and the Russians sometimes Moscovites. They were, however, called frequently also Caorcini, Caturcini, Caursini, Cawarsini, Cawartini, Bardi, and Amanati; names, which in all probability arose from some of their greatest houses or banks. We know, at any rate, that about those periods the family of the Corsini were in great consideration at Florence. They had banks in the principal towns for lending money; they demanded exorbitant interest; and they received pledges at a low value, and retained them as their own property if not redeemed at the stated time. They eluded the prohibition19 of the church against interest when they found it necessary, by causing the interest to be previously paid as a present or a premium; and it appears that some sovereigns borrowed money from them on these conditions. In this manner did Edward III. king of England, when travelling through France in the year 1329, receive 5000 marks from the bank of the Bardi, and give then in return, by way of acknowledgement, a bond for 700050. When complaints against the usurious practices of these Christian Jews became too loud to be disregarded, they were threatened with expulsion from the country, and those who had rendered themselves most obnoxious on that account, were often banished, so that those who remained were obliged to conduct themselves in their business with more prudence and moderation. It is probable that the commerce of these countries was then in too infant a state to dispense altogether with the assistance of these foreigners. In this manner were they treated by Louis IX. in 1268, and likewise by Philip the Bold; and sometimes the popes, who would not authorise interest, lent their assistance by prohibitions, as was the case in regard to Henry III. of England in 1240.

In the fourteenth century, the Lombards in the Netherlands paid to government rent for the houses in which they carried on their money transactions, and something besides for a permission. Of this we have instances at Delft in 1313, and at Dordrecht in 134251. As in the course of time the original Lombards became extinct, these houses were let, with the same permission, for the like employment52; but governments at length fixed the rate of interest which they ought to receive, and established regulations for them, by which usurious practices were restrained. Of leases granted on such conditions, an instance occurs at Delft in the year 1655. In 1578, William prince of Orange recommended to the magistrates of Amsterdam Francis Masasia, one of the Lombards, as they were then called, in order that he might obtain for him permission to establish a lending-house53, as many obtained permission to keep billiard-tables, and Jews letters of protection. In the year 1611, the proprietor of20 such a house at Amsterdam, who during the latter part of his lease had gained by his capital at least thirty-three and a half per cent., offered a very large sum for a renewal of his permission; but in 1614, the city resolved to take the lombard or lending-house into their own hands, or to establish one of the same kind. However odious this plan might be, a dispute arose respecting the legality of it, which Marets54 and Claude Saumaise endeavoured to support. The public lending-house or lombard at Brussels was established in 1619; that at Antwerp in 1620, and that at Ghent in 1622. All these were established by the archduke Albert, when he entered on the governorship, with the advice of the archbishop of Mechlin; and on this occasion the architect Wenceslaus Coberger was employed, and appointed inspector-general of all the lending-houses in the Spanish Netherlands55. Some Italians assert that the Flemings were the first people who borrowed money on interest for their lending-houses; and they tell us that this practice began in the year 161956. We are assured also, that after a long deliberation at Brussels, it was at length resolved to receive money on interest at the lending-houses. It however appears certain that in Italy this was never done, or at least not till a late period, and that the capitals of the lending-houses there were amassed without giving interest.

This beneficial institution was always opposed in France; chiefly because the doctors of the Sorbonne could not divest themselves of the prejudice against interest; and some in modern times who undertook there to accommodate people with money on the like terms, were punished by government57. A lending-house however was established at Paris under Louis XIII., in 1626; but the managers next year were obliged to abandon it58. In 1695, some persons formed a capital at Marseilles for the purpose of establishing one there according to the plan of those in Italy59. The present mont de piété at Paris, which has sometimes in its possession forty casks filled with gold watches that have been pledged, was, by royal command, first established in 177760.

21 [The following is the rate of profit or interest which pawnbrokers in this country are entitled to charge per calendar month. For 2s. 6d. one halfpenny; 5s. one penny; 7s. 6d. three halfpence; 10s. twopence; 12s. 6d. twopence halfpenny; 15s. threepence; 17s. 6d. threepence halfpenny; £1 fourpence; and so on progressively and in proportion for any sum not exceeding 40s. For every sum exceeding 40s. and not exceeding 42s. eightpence; and for every sum exceeding 42s. and not exceeding £10, threepence to every pound, and so on in proportion for any fractional sum. Where any intermediate sum lent on a pledge exceeds 2s. 6d. and does not exceed 40s., a sum of fourpence may be charged in proportion to each £1. Goods pawned are forfeited on the expiration of a year, exclusive of the date of pawning. But it has been held that the property is not transferred, but that the pawnbroker merely has a right to sell the article; and consequently that, on a claim after this period, with tender of principal and interest, the property must be restored if unsold (Walker v. Smith, 5 Barn. and Ald. 439). Pledges must not be taken from persons intoxicated or under twelve years of age. In Great Britain pawnbrokers must take out a license, which costs £15 within the limits of the old twopenny-post, and £7 10s. in other parts. No license is required in Ireland. A second license, which costs £5 15s., is required to take in pledge articles of gold and silver.

From 1833 to 1838 the number of pawnbrokers in the metropolitan district increased from 368 to 386; in the rest of England and Wales, from 1083 to 1194; and in Scotland, from 52 to 88; making a total of 1668 establishments, paying £15,419 for their licenses, besides the licenses which many of them take out as dealers in gold and silver. The business of a pawnbroker was not known in Glasgow until August 1806, when an itinerant English pawnbroker commenced business in a single room, but decamped at the end of six months; and his place was not supplied until June 1813, when the first regular office was established in the west of Scotland for receiving goods in pawn. Other individuals soon entered the business, and the practice of pawning had become so common, that in 1820, in a season of distress, 2043 heads of families pawned 7380 articles, on which they raised £739 5s. 6d. Of these heads of families 1375 had never applied for or received22 charity of any description; 474 received occasional aid from the relief committee, and 194 were paupers. The capital invested in this business in 1840 was about £26,000. Nine-tenths of the articles pledged are redeemed within the legal period. There are no means of ascertaining the exact number of pawnbrokers’ establishments in the large towns of England. In 1831, the number of males above the age of twenty employed in those at Manchester was 107; at Liverpool, 91; Birmingham, 54; Bristol, 33; Sheffield, 31.

The following curious return was made by a large pawnbroking establishment at Glasgow to Dr. Cleland, who read it before the British Association in 1836. The list comprised the following articles:—539 men’s coats, 355 vests, 288 pairs of trowsers, 84 pairs of stockings, 1980 women’s gowns, 540 petticoats, 132 wrappers, 123 duffies, 90 pelisses, 240 silk handkerchiefs, 294 shirts and shifts, 60 hats, 84 bed-ticks, 108 pillows, 262 pairs of blankets, 300 pairs of sheets, 162 bed-covers, 36 tablecloths, 48 umbrellas, 102 bibles, 204 watches, 216 rings, and 48 Waterloo medals. There were about thirty pawnbrokers in Glasgow in 1840. In the manufacturing districts, during the prevalence of strikes, or in seasons of commercial embarrassment, many hundreds of families pawn the greater part of their wearing apparel and household furniture. The practice of having recourse to the pawnbrokers on such occasions is quite of a different character from the habits of dependence into which many of the working classes suffer themselves to fall, and who, “on being paid their wages on the Saturday, are in the habit of taking their holiday clothes out of the hands of the pawnbroker to enable them to appear respectably on the Sabbath, and on the Monday following they are again pawned and a fresh loan obtained to meet the exigencies of their families for the remainder of the week.” It is on these transactions and on such as arise out of the desire of obtaining some momentary gratification that the pawnbrokers make their large profits. It is stated in one of the reports on the poor laws that a loan of threepence, if redeemed the same day, pays annual interest at the rate of 5200 per cent.; weekly, 866 per cent.;

4d., annual interest 3900 per cent., or 650 p. c. weekly;

12d., annual interest 1300 per cent., or 216 p. c. weekly.

It is stated that on a capital of sixpence thus employed (in23 weekly loans), pawnbrokers make in twelve months 2s. 2d.; on five shillings they gain 10s. 4d.; on ten shillings, 22s. 3¼d.; and on twenty shillings lent in weekly loans of sixpence, they more than double their capital in twenty-seven weeks, and should the goods pawned remain in their hands for the term of twelve months (which seldom occurs), they then frequently derive 100 per cent.61]

2 J. D. Michaelis, in Syntagma Commentationum, ii. p. 9; and his Mosaisches Recht. iii. p. 86.

3 Sueton. Vita Augusti, cap. 41.

4 Taciti Annal. vi. 17.—Sueton. Vita Tiberii, cap. 48.—Dio Cassius, lviii. 21.

5 Ælius Lamprid. Vita Alex. Severi, cap. 21.

6 M. Manni circa i sigilli antichi dei secoli bassi, vol. xxvii. p. 86. The author here quotes from an ancient city-book the following passage:—“Franciscus fenerator pro se et apotheca seu casana fenoris, quam tenebat in via Quattro Pagoni,” &c.

7 Algemeine Welthistorie, xlv. p. 10.

8 This theologian, born at Eperies in Hungary in 1625, was driven from his native country on account of his religion, and died superintendant at Meisse in 1689. He wrote, besides other works, Dorothei Asciani Montes Pietatis Romanenses, historice, canonice, et theologice detecti. Lipsiæ, 1670, 4to. This book is at present very scarce. I shall take this opportunity of mentioning also the following, because many who have written on lending-houses have quoted it, though they never saw it:—Montes Pietatis Romanenses, das ist, die Berg der Fromheit oder Gottesforcht in der Stadt Rom. Durch Elychnium Gottlieb. Strasburg, 1608, 8vo. It contains nothing of importance that may not be found in Ascianus.

9 Of this Barnabas I know nothing more than what I have here extracted from Waddingii Annales Minorum, tom. xiv. p. 93. Wadding refers to Marian. lib. v. c. 40. § 17; and Marc. 3. p. lib. 5. cap. 58. The former is Marianus Florentinus, whose Fasciculus Chronicoram Ordinis Minorum, which consists of five books, was used in manuscript by Wadding, in composing his large work, and in my opinion has never been printed. Marc. is Marcus Ulyssoponensis, whose Chronica Ordinis Minorum I have not been able to procure, though it is translated into several languages. See Waddingii Scriptores Ordinis Minorum. Romæ 1650, fol. pp. 248, 249.

10 This is confirmed by M. B. Salon, in t. 2. Contr. de Justit. et Jure, in ii. 2 Thom. Aquin. qu. 88. art. 2. controv. 27: “Hujus modi mons non erat in usu apud antiquos. Cœpit fere a 150 annis, tempore Pii II.” In C. L. Richard’s Analysis Conciliorum Generalium et Particularium, Venetiis, 1776, 4 vol. fol. iv. p. 98, I find that the first lending-house at Perugia was established in the year 1450; but Pius II., under whose pontificate it appears by various testimonies to have been founded, was not chosen pope till the year 1458.

11 Bussi, Istoria della città di Viterbo. In Roma, 1742, fol. p. 271.

12 It may be found in Bolle et Privilegi del Sacro Monte della Pietà di Roma. In Roma, 1618: ristampati l’anno 1658. This collection is commonly bound up with the following work, which was printed in the same year and again reprinted: Statuti del Sacro Monte della Pietà di Roma. This bull is inserted entire by Ascianus, p. 719, but in the Collection of the pontifical bulls it is omitted.

13 This Michael travelled and preached much in company with Bernardinus, and died at Como in 1485.—Wadding, xiv. p. 396.

14 The Piccolimini, nephews of the pope, having once paid their respects to him at Siena, he told them he was their namesake.—Wadding, xiv. p. 447.

15 Waddingii Scriptores Ordinis Minorum, p. 58. Fabricii Biblioth. Mediæ et Infimæ Æt. i. p. 586.

16 Wadding, xiv. pp. 398, 433.

17 It may be found entire in Wadding, xiv. p. 411. It was ordered that the pledges should be worth double the sum lent, and that they should be sold if not redeemed within a year.

18 Wadding, xiv. p. 446.

19 D. Manni circa i Sigilli Antichi, tom. xxvii. p. 92, where much information respecting this subject may be found.

20 Wadding, xiv. p. 451.

21 Ibid. pp. 462, 465.

22 Ibid. xiv. pp. 480, 481.

23 Ibid. p. 517.

24 Ibid. xiv. pp. 93, 482.

25 Ibid. p. 514.

26 Ibid. xv. pp. 6, 65.

27 Wadding, xv. pp. 7, 9, 12.

28 Ibid. xv. pp. 37, 45, 46.

29 Ibid. xv. 67.

30 Ibid. xv. p. 68. Bernardinus considered the giving of wages as a necessary evil.

31 Della Zecca di Gubbio, e delle Geste de’ Conti e Duchi di Urbino; opera di Rinaldo Reposati. Bologna, 1772, 4to.

32 It is to be found in the well-known large collection of juridical writings quoted commonly under the title Tractatus Tractatuum. Venetiis, 1584, fol. p. 419, vol. vi. part 1. It has also been printed separately.

33 His works were printed together, in folio, at Brescia in 1588.

34 The work of the former appeared in 1496. The writings of both are printed in the work of Ascianus, or Zimmermann, which has been often quoted already.

35 This bull, which forms an epoch in the history of lending-houses, may be found in S. Lateranen. Concilium Novissimum. Romæ, 1521, fol. This scarce work, which I have now before me, is inserted entire in Harduini Acta Conciliorum, tom. ix. Parisiis, 1714, fol. The bull may be found p. 1773. It may be found also in Bullarium Magnum Cherubini, i. p. 560; Waddingii Annal. Minor. xv. p. 470; Ascianus, p. 738; and Beyerlinck’s Theatrum Vitæ Hum. v. p. 603.

36 This is the conclusion formed by Richard, in Analysis Conciliorum, because in sess. 22, cap. 8, lending-houses are reckoned among the pia loca, and the inspection of them assigned to the bishops.

37 Waddingii Annal. Minor. xv. p. 471.

38 Ibid. xvi. p. 444; Ascianus, p. 766.

39 (Summonte) Historia de Napoli, 1749, 4to, vol. iv. p. 179.—Giannone, vol. iv.—De’ Banchi di Napoli, da Michele Rocco. Neap. 1785, 3 vols. 8vo, i. p. 151.

40 Vettor Sandi, in Principi di Storia civile della Republica di Venezia. In Venezia 1771, 4to, vol. ii. p. 436. The author treats expressly of the institution of this bank, but the year when it commenced is not mentioned.

41 Waddingii Annal. Minor. xv. p. 67.

42 Hymnus ii. honorem Laurentii. The poet relates, that in the third century the pagan governor of the city demanded the church treasure from Laurentius the deacon.

43 This passage, with which Senkenberg was not acquainted, may be found in Tertullian’s Apolog. cap. 39, edition of De la Cerda, p. 187.

44 This word however is not to be found in the Glossarium Manuale.

45 See the bull in Bullarium Magnum, n. 17.

46 See Petr. Gregorius Tholosanus de Republica. Francof. 1609, 4to, lib. xiii. c. 16, p. 566; and Ascianus, p. 753.

47 Geschichte des Teutschen Handels, ii. p. 454.

48 Gokink’s Journal für Teutschland, 1784, i. p. 504, where may be found the first and the newest regulations respecting the lending-house at Nuremberg.

49 Stettens Geschichte der Stadt Augsburg. Frankf. 1742, 2 vols. 4to, i. p. 720, 789, 833.

50 Fœdera, vol. iv. p. 387.

51 Beschryving der Stadt Delft. 1729, fol. p. 553.

52 Salmasius de Fœnore trapezitico. Lugd. 1640, 8vo, p. 744.

53 De Koophandel van Amsterdam. Rott. 1780, 8vo, i. p. 221.

54 S. de Marets Diss. de trapezitis.

55 Beyerlinck, Magnum Theatrum Vitæ, tom. v. p. 602.

56 Richard, Analysis Concilior. iv. p. 98.

57 Turgot, Mem. sur le prêt à intérest, &c. Par. 1789, 8vo.

58 Sauval, Hist. de la Ville de Paris.

59 Rufel, Hist. de la Ville de Marseille; 1696. fol. ii. p. 99.

60 Tableau de Paris. Hamb. 1781. 8vo, i. p. 78.

61 Waterston’s Cyclopædia of Commerce.

As those metals earliest known, viz. copper, iron, gold, silver, lead, quicksilver and tin, received the same names as the nearest heavenly bodies, which appear to us largest, and have been distinguished by the like characters, two questions arise: Whether these names and characters were given first to the planets or to the metals? When, where, and on what account were they made choice of; and why were the metals named after the planets, or the planets after the metals? The latter of these questions, in my opinion, cannot be answered with any degree of certainty; but something may be said on the subject, which will not, perhaps, be disagreeable to those fond of such researches, and who have not had an opportunity of examining it.

That the present usual names were first given to the heavenly bodies, and at a later period to the metals, is beyond all doubt; and it is equally certain that they came from the Greeks to the Romans, and from the Romans to us. It can be proved also that older nations gave other names to these heavenly bodies at much earlier periods. The oldest appellations, if we may judge from some examples still preserved, seem to have originated from certain emotions which these bodies excited in the minds of men; and it is not improbable that the planets were by the ancient Egyptians and Persians named after their gods, and that the Greeks only adopted or translated into their own language the names which those nations had given them62. The idea that each planet was the24 residence of a god, or that they were gods themselves, has arisen, according to the most probable conjecture, from rude nations worshiping the sun, which, on account of his beneficent and necessary influence over all terrestrial bodies, they considered either as the deity himself, or his abode, or, at any rate, as a symbol of him. In the course of time, when heroes and persons who by extraordinary services had rendered their names respected and immortal, received divine honours, particular heavenly bodies, of which the sun, moon and planets seemed the fittest, were also assigned to these divinities63. By what laws this distribution was made, and why one planet was dedicated to Saturn and not to another, Pluche did not venture to determine: and on this point the ancients themselves are not all agreed64. When the planets were once dedicated to the gods, folly, which never stops where it begins, proceeded still further, and ascribed to them the attributes and powers for which the deities, after whom they were named, had been celebrated in the fictions of their mythologists. This in time laid the foundation of astrology; and hence the planet Mars, like the deity of that name, was said to cause and to be fond of war; and Venus to preside over love and its pleasures.

The next question is, Why were the metals divided in the like manner among the gods, and named after them? Of all the conjectures that can be formed in answer to this question, the following appears to me the most probable. The number of the deified planets made the number seven so sacred to the Egyptians, Persians and other nations, that all those things which amounted to the same number, or which could be divided by it without a remainder, were supposed to have an affinity or a likeness to and connexion with each other65. The seven metals, therefore, were considered as having some relationship to the planets, and with them to the gods, and were accordingly named after them. To each god was assigned a metal, the origin and use of which was under his particular providence and government; and to each25 metal were ascribed the powers and properties of the planet and divinity of the like name; from which arose, in the course of time, many of the ridiculous conceits of the alchemists.

The oldest trace of the division of the metals among the gods is to be found, as far as I know, in the religious worship of the Persians. Origen, in his Refutation of Celsus, who asserted that the seven heavens of the Christians, as well as the ladder which Jacob saw in his dream, had been borrowed from the mysteries of Mithras, says, “Among the Persians the revolutions of the heavenly bodies were represented by seven stairs, which conducted to the same number of gates. The first gate was of lead; the second of tin; the third of copper; the fourth of iron; the fifth of a mixed metal; the sixth of silver, and the seventh of gold. The leaden gate had the slow tedious motion of Saturn; the tin gate the lustre and gentleness of Venus; the third was dedicated to Jupiter; the fourth to Mercury, on account of his strength and fitness for trade; the fifth to Mars; the sixth to the Moon, and the last to the Sun66.” Here then is an evident trace of metallurgic astronomy, as Borrichius calls it, or of the astronomical or mythological nomination of metals, though it differs from that used at present. According to this arrangement, tin belonged to Jupiter, copper to Venus, iron to Mars, and the mixed metal to Mercury. The conjecture of Borrichius, that the transcribers of Origen have, either through ignorance or design, transposed the names of the gods, is highly probable: for if we reflect that in this nomination men at first differed as much as in the nomination of the planets, and that the names given them were only confirmed in the course of time, of which I shall soon produce proofs, it must be allowed that the causes assigned by Origen for his nomination do not well agree with the present reading, and that they appear much juster when the names are disposed in the same manner as that in which we now use them67.

26 This astrological nomination of metals appears to have been conveyed to the Brahmans in India; for we are informed that a Brahman sent to Apollonius seven rings, distinguished by the names of the seven stars or planets, one of which he was to wear daily on his finger, according to the day of the week68. This can be no otherwise explained than by supposing that he was to wear the gold ring on Sunday; the silver one on Monday; the iron one on Tuesday, and so of the rest. Allusion to this nomination of the metals after the gods occurs here and there in the ancients. Didymus, in his Explanation of the Iliad, calls the planet Mars the iron star. Those who dream of having had anything to do with Mars are by Artemidorus threatened with a chirurgical operation, for this reason, he adds, because Mars signifies iron69. Heraclides says also in his allegories, that Mars was very properly considered as iron; and we are told by Pindar that gold is dedicated to the sun70.

Plato likewise, who studied in Egypt, seems to have admitted27 this nomination and meaning of the metals. We are at least assured so by Marsilius Ficinus71; but I have been able to find no proof of it, except where he says of the island Atlantis, that the exterior walls were covered with copper and the interior with tin, and that the walls of the citadel were of gold. It is not improbable that Plato adopted this Persian or Egyptian representation, as he assigned the planets to the demons; but perhaps it was first introduced into his system only by his disciples72. They seem, however, to have varied from the nomination used at present; as they dedicated to Venus copper, or brass, the principal component part of which is indeed copper; to Mercury tin; and to Jupiter electrum. The last-mentioned metal was a mixture of gold and silver; and on this account was probably considered to be a distinct metal, because in early periods mankind were unacquainted with the art of separating these noble metals73.