Fig. 1.—Entrance to the Catacomb of St. Priscilla.

Transcriber’s Note:

This text includes characters that require UTF-8 (Unicode) file encoding: œ (oe ligature), διορθῶσαι or ϹΥΝΑΓΩΓ (Greek), and שָׁלוֹם (Hebrew). If any of these characters do not display properly--in particular, if the diacritic does not appear directly above the letter--or if marks highlighted in this paragraph appear as squares or garbage, make sure your text reader’s “character set” or “file encoding” is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You may also need to change the default font.

Additional notes are at the end of the book.

THE

AND

Their Testimony Relative to Primitive Christianity.

BY THE REV.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS.

London:

HODDER AND STOUGHTON,

27, PATERNOSTER ROW.

MDCCCLXXXVIII.

Hazell, Watson, and Viney, Ld. Printers, London and Aylesbury.

The present work, it is hoped, will supply a want long felt in the literature of the Catacombs. That literature, it is true, is very voluminous; but it is for the most part locked up in rare and costly folios in foreign languages, and inaccessible to the general reader. Recent discoveries have refuted some of the theories and corrected many of the statements of previous books in English on this subject; and the present volume is the only one in which the latest results of exploration are fully given, and interpreted from a Protestant point of view.

The writer has endeavored to illustrate the subject by frequent pagan sepulchral inscriptions, and by citations from the writings of the Fathers, which often throw much light on the condition of early Christian society. The value of the work is greatly enhanced, it is thought, by the addition of many hundreds of early Christian inscriptions carefully translated, a very large proportion of which have never before appeared in English. Those only who have given some attention to epigraphical studies can conceive the difficulty of this part of the work. The defacements of time, and frequently the original imperfection of the inscriptions and the ignorance of their writers, [Pg 6] demand the utmost carefulness to avoid errors of interpretation. The writer has been fortunate in being assisted by the veteran scholarship of the Rev. Dr. McCaul, well known in both Europe and America as one of the highest living authorities in epigraphical science, under whose critical revision most of the translations have passed. Through the enterprise of the publishers this work is more copiously illustrated, from original and other sources, than any other work on the subject in the language; thus giving more correct and vivid impressions of the unfamiliar scenes and objects delineated than is possible by any mere verbal description. References are given, in the foot-notes, to the principal authorities quoted, but specific acknowledgment should here be made of the author’s indebtedness to the Cavaliere De Rossi’s Roma Sotterranea and Inscriptiones Christianæ, by far the most important works on this fascinating but difficult subject.

Believing that the testimony of the Catacombs exhibits, more strikingly than any other evidence, the immense contrast between primitive Christianity and modern Romanism, the author thinks no apology necessary for the somewhat polemical character of portions of this book which illustrate that fact. He trusts that it will be found a contribution of some value to the historical defense of the truth against the corruptions and innovations of Popish error.

| CONTENTS. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Book First. | ||

| THE STRUCTURE AND HISTORY OF THE CATACOMBS. | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | The Structure of the Catacombs | 11 |

| II. | The Origin and Early History of the Catacombs | 49 |

| III. | The Disuse and Abandonment of the Catacombs | 120 |

| IV. | The Rediscovery and Exploration of the Catacombs | 150 |

| V. | The Principal Catacombs | 164 |

Book Second. | ||

| THE ART AND SYMBOLISM OF THE CATACOMBS. | ||

| I. | Early Christian Art | 203 |

| II. | The Symbolism of the Catacombs | 225 |

| III. | The Biblical Paintings of the Catacombs | 282 |

| IV. | Objects found in the Catacombs | 362 |

Book Third. | ||

| THE INSCRIPTIONS OF THE CATACOMBS. | ||

| I. | General Character of the Inscriptions | 395 |

| II. | The Doctrinal Teachings of the Inscriptions | 415 |

| III. | Early Christian Life and Character as read in the Catacombs | 453 |

| IV. | Ministry, Rites, and Institutions of the Primitive Church as Indicated in the Catacombs | 506 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Fig. | Page | |

| 1. | Entrance to Catacomb of St. Priscilla | 12 |

| 2. | Entrance to Catacomb of St. Prætextatus | 16 |

| 3. | Part of Callixtan Catacomb | 17 |

| 4. | Gallery with Tombs | 18 |

| 5. | Interior of Corridor | 20 |

| 6. | Loculi—Open and Closed | 23 |

| 7. | Tomb of Valeria | 24 |

| 8. | Arcosolium with Perforated Slab | 25 |

| 9. | Plan of Double Chamber | 26 |

| 10. | Section of Gallery and Cubicula | 27 |

| 11. | Suite of Chambers | 28 |

| 12. | Vaulted Chamber with Columns | 29 |

| 13. | Cubiculum with Arcosolia | 30 |

| 14. | Section of Catacomb of Callixtus | 32 |

| 15. | Cubicula with Luminare | 35 |

| 16. | Gallery in St. Hermes | 42 |

| 17. | Part of Wall of Gallery in St. Hermes | 42 |

| 18. | Slab in Jewish Catacomb | 51 |

| 19. | Epitaph of Martyrus | 66 |

| 20. | Reputed Martyr Symbol | 77 |

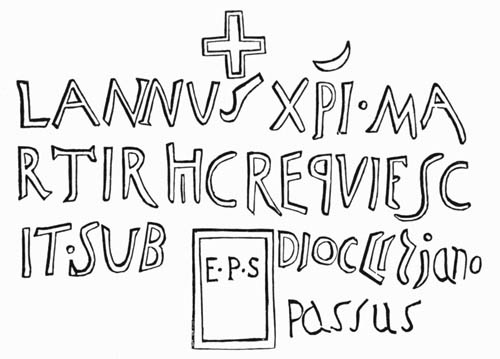

| 21. | Epitaph of Lannus, a Martyr | 98 |

| 22. | Secret Stairway in Catacomb of Callixtus | 101 |

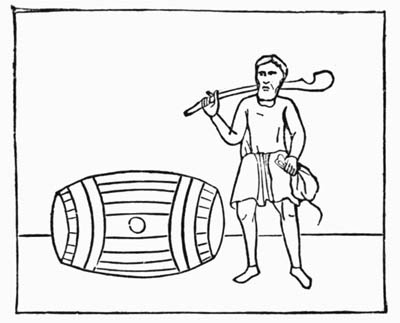

| 23. | Diogenes the Fossor | 133 |

| 24. | Fossor at Work | 134 |

| 25. | Tombs on Appian Way | 165 |

| 26. | Plan of Area in Callixtan Catacomb | 171 |

| 27. | Plan of Crypt of St. Peter and St. Paul | 187 |

| 28. | Crypt of St. Peter and St. Paul | 188 |

| 29. | Section of Catacomb of Helena | 191 |

| 30. | Entrance to Catacomb of St. Agnes | 195 |

| 31. | Mithraic Painting | 216 |

| 32. | Leaf Point | 227 |

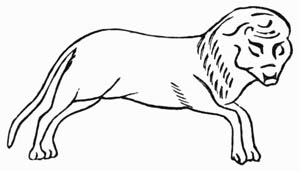

| 33. | Phonetic Symbol—Leo | 229 |

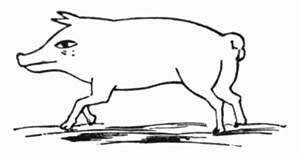

| 34. | Phonetic Symbol—Porcella | 230 |

| 35. | Phonetic Symbol—Nabira | 230 |

| 36. | Wool-comber’s Implements | 231 |

| 37. | Carpenter’s Implements | 231 |

| 38. | Vine Dresser’s Tomb | 232 |

| 39. | Symbolical Anchor | 234 |

| 40. | Symbolical Ship | 235 |

| 41. | Symbolical Palm and Crown | 236 |

| 42. | Symbolical Doves | 237 |

| 43. | Symbolical Dove | 238 |

| 44. | Doves and Vase | 238 |

| 45. | Locus Primi | 238 |

| 46. | Symbolical Peacock | 240 |

| 47. | The Good Shepherd | 245 |

| 48. | Good Shepherd with Syrinx | 246 |

| 49. | Symbolical Lamb | 249 |

| 50. | Symbolical Fish | 255[Pg 9] |

| 51. | Symbolical Fish | 256 |

| 52. | Fish and Anchor | 256 |

| 53. | Fish and Dove | 256 |

| 54. | Eucharistic Symbol | 256 |

| 55. | Constantinian Monogram | 265 |

| 56. | Early Christian Seal | 266 |

| 57. | Various Forms of Monogram | 267 |

| 58. | Epitaph of Tasaris | 267 |

| 59. | Opisthographæ | 268 |

| 60. | Early Christian Seal | 270 |

| 61. | Monogram and Cross | 270 |

| 62. | The Temptation and Fall | 284 |

| 63. | Adam and Eve Receiving their Sentence | 285 |

| 64. | Noah in the Ark | 286 |

| 65. | Noah in the Ark | 287 |

| 66. | Noah in the Ark, from Sarcophagus | 287 |

| 67. | Apamean Medal | 288 |

| 68. | Sacrifice of Isaac | 289 |

| 69. | Sacrifice of Isaac | 289 |

| 70. | Moses on Horeb | 290 |

| 71. | Moses Receiving the Law | 290 |

| 72. | Moses and the Baskets of Manna | 291 |

| 73. | Moses Striking the Rock | 291 |

| 74. | Moses Striking the Rock | 291 |

| 75. | The Sufferings of Job | 293 |

| 76. | Ascension of Elijah | 295 |

| 77. | The Three Hebrew Children | 296 |

| 78. | The Three Hebrew Children | 297 |

| 79. | The Three Hebrew Children | 298 |

| 80. | Daniel in the Lions’ Den | 299 |

| 81. | The Story of Jonah | 300 |

| 82. | Jonah, Moses, and Oranti | 301 |

| 83. | Jonah and the Great Fish | 302 |

| 84. | Noah and Jonah | 302 |

| 85. | Jonah’s Gourd | 304 |

| 86. | Adoration of Magi | 305 |

| 87. | Adoration of Magi | 306 |

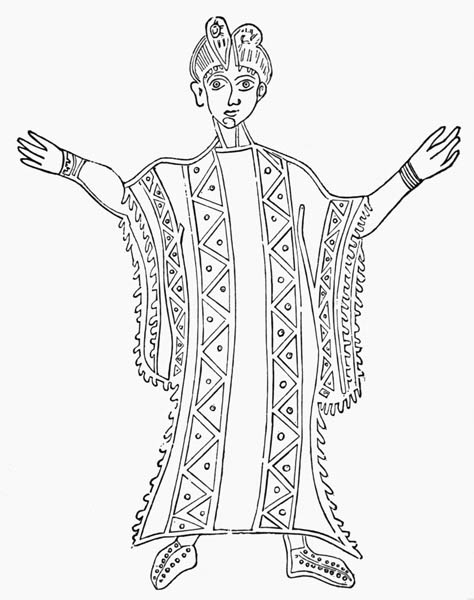

| 88. | Orante | 309 |

| 89. | Supposed Madonna | 311 |

| 90. | Earliest Madonna | 312 |

| 91. | Christ with the Doctors | 324 |

| 92. | Christ and the Woman of Samaria | 325 |

| 93. | Paralytic Carrying Bed | 325 |

| 94. | Woman with Issue of Blood | 326 |

| 95. | Miracle of Loaves and Fishes | 327 |

| 96. | Opening the Eyes of the Blind | 327 |

| 97. | Christ Blessing a Little Child | 328 |

| 98. | Lazarus (rude) | 330 |

| 99. | Lazarus (in fresco) | 330 |

| 100. | Lazarus (in relief) | 331 |

| 101. | Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem | 331 |

| 102. | Peter’s Denial of Christ | 332 |

| 103. | Pilate Washing his Hands | 333 |

| 104. | Sculptured Sarcophagus | 334 |

| 105. | Painted Chamber | 339 |

| 106. | Oldest Extant Head of Christ (mosaic) | 347 |

| 107. | God Symbolized by a Hand | 356 |

| 108. | God as Pope | 359 |

| 109. | Domestic Group in Gilt Glass | 366 |

| 110. | Reputed Martyr Relic | 371 |

| 111. | Reputed Martyr Symbol | 374 |

| 112. | Symbolical Lamp | 377 |

| 113. | Symbolical Lamp | 378 |

| 114. | Vases from the Catacombs | 381 |

| 115. | Amphora from the Catacombs | 382[Pg 10] |

| 116. | Earthen and Metal Vessels | 383 |

| 117. | Early Christian Ring | 385 |

| 118. | Early Christian Seal | 385 |

| 119. | Impressions of Seals | 386 |

| 120. | Children’s Toys | 387 |

| 121. | Statue of Good Shepherd | 390 |

| 122. | Epitaph of Gemella | 401 |

| 123. | Epitaph of Ligurius Successus | 402 |

| 124. | Epitaph of Domitius | 402 |

| 125. | Epitaph Inverted | 404 |

| 126. | Epitaph Reversed | 404 |

| 127. | Epitaph of Cassta | 405 |

| 128. | Triple Epitaph | 405 |

| 129. | Belicia | 500 |

| 130. | Chamber with Catechumens’ Seats | 531 |

| 131. | Baptismal Font | 537 |

| 132. | Baptism of Our Lord | 538 |

| 133. | Baptismal Scene | 539 |

| 134. | Fresco of Early Christian Agape | 546 |

STRUCTURE AND HISTORY OF THE CATACOMBS.

“Among the cultivated grounds not far from the city of Rome,” says the Christian poet Prudentius, “lies a deep crypt, with dark recesses. A descending path, with winding steps, leads through the dim turnings, and the daylight, entering by the mouth of the cavern, somewhat illumines the first part of the way. But the darkness grows deeper as we advance, till we meet with openings, cut in the roof of the passages, admitting light from above. On all sides spreads the densely-woven labyrinth of paths, branching into caverned chapels and sepulchral halls; and throughout the subterranean maze, through frequent openings, penetrates the light.”[1]

This description of the Catacombs in the fourth century is equally applicable to their general appearance in the nineteenth. Their main features are unchanged, although time and decay have greatly impaired their structure and defaced their beauty. These Christian cemeteries are situated chiefly near the great roads leading from the city, and, for the most part, within a circle of three miles from the walls. From this circumstance they have been compared to the “encampment of a Christian host besieging Pagan Rome, and driving inward its mines and trenches with an assurance of [Pg 13] final victory.” The openings of the Catacombs are scattered over the Campagna, whose mournful desolation surrounds the city; often among the mouldering mausolea that rise, like stranded wrecks, above the rolling sea of verdure of the tomb-abounding plain.[2] On every side are tombs—tombs above and tombs below—the graves of contending races, the sepulchres of vanished generations: “Piena di sepoltura è la Campagna.”[3]

How marvelous that beneath the remains of a proud pagan civilization exist the early monuments of that power before which the myths of paganism faded away as the spectres of darkness before the rising sun, and by which the religion and institutions of Rome were entirely changed.[4] Beneath the ruined palaces and temples, the crumbling tombs and dismantled villas, of the august mistress of the world, we find the most interesting relics of early Christianity on the face of the earth. In traversing these tangled labyrinths we are brought face to face with the primitive ages; we are present at the worship of the infant Church; we observe its rites; we study its institutions; we witness the deep emotions of the first believers as they commit their dead, often [Pg 14] their martyred dead, to their last long resting-place; we decipher the touching record of their sorrow, of the holy hopes by which they were sustained, of “their faith triumphant o’er their fears,” and of their assurance of the resurrection of the dead and the life everlasting. We read in the testimony of the Catacombs the confession of faith of the early Christians, sometimes accompanied by the records of their persecution, the symbols of their martyrdom, and even the very instruments of their torture. For in these halls of silence and gloom slumbers the dust of many of the martyrs and confessors, who sealed their testimony with their blood during the sanguinary ages of persecution; of many of the early bishops and pastors of the Church, who shepherded the flock of Christ amid the dangers of those troublous times; of many who heard the words of life from teachers who lived in or near the apostolic age, perhaps from the lips of the apostles themselves. Indeed, if we would accept ancient tradition, we would even believe that the bodies of St. Peter and St. Paul were laid to rest in those hallowed crypts—a true terra sancta, inferior in sacred interest only to that rock-hewn sepulchre consecrated evermore by the body of Our Lord. These reflections will lend to the study of the Catacombs an interest of the highest and intensest character.

It is impossible to discover with exactness the extent of this vast necropolis on account of the number and intricacy of its tangled passages. That extent has been greatly exaggerated, however, by the monkish ciceroni, who guide visitors through these subterranean labyrinths.[5] There are some forty-two of these cemeteries [Pg 15] in all now known, many of which are only partially accessible. Signor Michele De Rossi, from an accurate survey of the Catacomb of Callixtus, computes the entire length of all the passages to be eight hundred and seventy-six thousand mètres, or five hundred and eighty-seven geographical miles, equal to the entire length of Italy, from Ætna’s fires to the Alpine snows.

The entrance to the abandoned Catacomb is sometimes a low-browed aperture like a fox’s burrow, almost concealed by long and tangled grass, and overshadowed by the melancholy cypress or gray-leaved ilex. Sometimes an ancient arch can be discerned, as at the Catacomb of St. Priscilla,[6] or the remains of the chamber for the celebration of the festivals of the martyrs, as at the entrance of the Cemetery of St. Domitilla. In a few instances it is through the crypts of an ancient basilica, as at St. Sebastian, and sometimes a little shrine or oratory covers the descent, as at St. Agnes,[7] St. Helena,[8] and St. Cyriaca. In all cases there is a stairway, often long and steep, crumbling with time and worn with the feet of pious generations. The following illustration shows the entrance to the Catacomb of St. Prætextatus on the Appian Way, trodden in the primitive ages by the early martyrs and confessors, or perhaps by the armed soldiery of the oppressors, hunting to earth the persecuted flock of Christ. Here, too, in mediæval times, the [Pg 16] martial clang of the armed knight may have awaked unwonted echoes among the hollow arches, or the gliding footstep of the sandaled monk scarce disturbed the silence as he passed. In later times pilgrims from every land have visited, with pious reverence or idle curiosity, this early shrine of the Christian faith.

The Catacombs are excavated in the volcanic rock which abounds in the neighborhood of Rome. It is a granulated, grayish breccia, or tufa, as it is called, of a coarse, loose texture, easily cut with a knife, and bearing still the marks of the mattocks with which it was dug. In the firmer volcanic rock of Naples the excavations are larger and loftier than those of Rome; but the latter, although they have less of apparent majesty, have more of funereal mystery. The Catacombs consist essentially of two parts—corridors and chambers, or cubicula. The corridors are long, narrow and intricate passages, [Pg 17] forming a complete underground net-work. They are for the most part straight, and intersect each other at approximate right angles. The accompanying map of part of the Catacomb of Callixtus will indicate the general plan of these subterranean galleries.

The main corridors vary from three to five feet in width, but the lateral passages are much narrower, often [Pg 18] affording room for but one person to pass. They will average about eight feet in height, though in some places as low as five or six, and in others, under peculiar circumstances, reaching to twelve or fifteen feet. The ceiling is generally vaulted, though sometimes flat; and the floor, though for the most part level, has occasionally a slight incline, or even a few steps, caused by the junction of areas of different levels, as hereafter explained. The walls are generally of the naked tufa, though sometimes plastered; and where they have given way are occasionally strengthened with masonry. At the corners of these passages there are frequently niches, in [Pg 19] which lamps were placed, without which, indeed, the Catacombs must have been an impenetrable labyrinth. Cardinal Wiseman recounts a touching legend of a young girl who was employed as a guide to the places of worship in the Catacombs because, on account of her blindness, their sombre avenues were as familiar to her accustomed feet as the streets of Rome to others.

Both sides of the corridors are thickly lined with loculi or graves, which have somewhat the appearance of berths in a ship, or of the shelves in a grocer’s shop; but the contents are the bones and ashes of the dead, and for labels we have their epitaphs. Figure 4 will illustrate the general character of these galleries and loculi.

The following engraving, after a sketch by Maitland, shows a gallery wider and more rudely excavated. On the right hand is seen a passage blocked up with stones, as was frequently done, to prevent accident. The daylight is seen pouring in at the further end of the gallery, as described by Prudentius,[9] and rendering visible the rifled graves.

It is evident that the principle followed in the formation of these galleries and loculi was the securing of the greatest amount of space for graves with the least excavation. Hence the passages are made as narrow as possible. The graves are also as close together as the friable nature of the tufa will permit, and are made to suit the shape of the body, narrow at the feet, broader at the shoulders, and often with a semi-circular excavation for the head, so as to avoid any superfluous removal of tufa. Sometimes the loculi were made large enough to hold two, three, or even four bodies, which were often [Pg 20] placed with the head of one toward the feet of the other, in order to economize space. These were called bisomi, trisomi, and quadrisomi, respectively. The graves were apparently made as required, probably with the corpse lying beside them, as some unexcavated spaces have been observed traced in outline with chalk or paint upon the walls. Almost every inch of available space is occupied, and sometimes, though rarely, graves are [Pg 21] dug in the floor. The loculi are of all sizes, from that of the infant of an hour to that of an adult man. But here, as in every place of burial, the vast preponderance of children’s graves is striking. How many blighted buds there are for every full-blown flower or ripened fruit!

Sometimes the loculi were excavated with mathematical precision. An example occurs in the Cemetery of St. Cyriaca, where at one end of a gallery is a tier of eight small graves for infants, then eight, somewhat larger, for children from about seven to twelve, then seven more, apparently for adult females, and lastly, a tier of six for full-grown men, occupying the entire height of the wall. Generally, however, a less regular arrangement was observed, and the graves of the young and old were intermixed, without any definite order.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to compute the number of graves in these vast cemeteries. Some seventy thousand have been counted, but they are a mere fraction of the whole, as only a small part of this great necropolis has been explored. From lengthened observation Father Marchi estimates the average number of graves to be ten, five on each side, for every seven feet of gallery. Upon this basis he computed the entire number in the Catacombs to be seven millions! The more accurate estimate of their extent made by Sig. Michele De Rossi would allow room for nearly four millions of graves, or, more exactly, about three million eight hundred and thirty-one thousand.[10] This seems [Pg 22] almost incredible; but we know that for at least three hundred years, or for ten generations, the entire Christian population of Rome was buried here. And that population, as we shall see, was, even at an early period, of considerable size. In the time of persecution, too, the Christians were hurried to the tomb in crowds. In this silent city of the dead we are surrounded by a “mighty cloud of witnesses,” “a multitude which no man can number,” whose names, unrecorded on earth, are written in the Book of Life. For every one who walks the streets of Rome to-day are hundreds of its former inhabitants calmly sleeping in this vast encampment of death around its walls—“each in his narrow cell forever laid.”[11] Till the archangel awake them they slumber. “It is scarcely known,” says Prudentius, “how full Rome is of buried saints—how richly her soil abounds in holy sepulchres.”

These graves were once all hermetically sealed by slabs of marble, or tiles of terra cotta. The former were generally of one piece, which fitted into a groove or mortice cut in the rock at the grave’s mouth, and were securely cemented to their places, as, indeed, was absolutely necessary, from the open character of the galleries in which the graves were placed. Sometimes fragments of heathen tombstones or altars were used for this purpose. The tiles were generally smaller, two or three being required for an adult grave. They were arranged in panels, and were cemented with plaster, on which a name or symbol was often rudely scratched with a trowel while soft, as in the following illustration. Most [Pg 23] of these slabs and tiles have disappeared, and many of the graves have long been rifled of their contents. In others may still be seen the mouldering skeleton of what was once man in his strength, woman in her beauty, or a child in its innocence and glee. The annexed engraving exhibits two graves, one of which is partially open, exposing the skeleton which has reposed on its rocky bed for probably over fifteen centuries.

If these bones be touched they will generally crumble into a white, flaky powder. D’Agincourt copied a tomb (Fig. 7) in which this “dry dust of death" still retained the outline of a human skeleton. Verily, “Pulvis et umbra sumus.” Sometimes, however, possibly from some constitutional peculiarity, the bones remain quite firm notwithstanding the lapse of so many centuries. De [Pg 24] Rossi states that he has assisted at the removal of a body from the Catacombs to a church two miles distant without the displacement of a single bone.[12] The age of the deceased and the nature of the ground also affect the condition in which the remains are found. Of the bodies of children nothing but dust remains. Where the pozzolana is damp, the bones are often well preserved; and where water has infiltrated, a partial petrifaction sometimes occurs.[13] Campana describes the opening of a hermetically sealed sarcophagus, which revealed the undisturbed body clad in funeral robes, and wearing the ornaments of life; but while he gazed it suddenly dissolved to dust before his eyes. Sometimes the sarcophagus was placed behind a perforated slab of marble, as shown in the following example, given by Maitland. The lower part of the slab is broken.

The other essential constituent of the Catacombs, besides the galleries already described, consists of the cubicula.[14] These are chambers excavated in the tufa on either side of [Pg 25] the galleries, with which they communicate by doors, as seen in Fig. 4. These often bear the character of family vaults, and are lined with graves, like the corridors without. They are generally square or rectangular, but sometimes octagonal or circular. They were probably used as mortuary chapels, for the celebration of funeral service, and for the administration of the eucharist near the tombs of the martyrs on the anniversaries of their death. They were too small to be used for regular worship, except perhaps in time of persecution. They are often not more than eight or ten feet square. Even the so-called “Papal Crypt,” a chamber of peculiar sanctity, is only eleven by fourteen [Pg 26] feet; and that of St. Cecilia adjoining it, one of a large size, is less than twenty feet square. Even the largest would not accommodate more than a few dozen persons. These chambers are generally facing one another on opposite sides of a gallery, as in the annexed plan of two cubicula in the Catacomb of Callixtus.

It is thought that in the celebration of worship one of these chambers was designed for men and the other for women. Sometimes separate passages to the chapels and distinct entrances to the Catacombs seem intended to facilitate this separation of the sexes. Sometimes three, or even as many as five, cubicula, as in one example in the Catacomb of St. Agnes, were placed on the same [Pg 27] axial line, and formed one continuous suite of chambers. The accompanying section of what is known as “The Chapel of Two Halls,” in the Catacomb of St. Prætextatus, illustrates this: A is the main gallery, D a large cubiculum known as “The Women’s Hall,” to the right, and to the left B, a hexagonal vaulted room with a smaller chamber, C, opening from it. The length of the entire range from G to F, according to the accurate measurement of M. Perret, is twenty-three and a half mètres, or nearly seventy-seven feet. The larger engraving (Fig. 11) gives a perspective view looking toward the left of the hexagonal chamber, (D. Fig. 10,) and the smaller one, C, opening from it. By means of these connected chambers the Christians were enabled in times of persecution to assemble for worship in these “dens and caves of the earth,” surrounded by the slumbering bodies of the holy dead.

The cubicula had vaulted roofs, and were sometimes plastered or cased with marble and paved with tiles, or, though rarely, with mosaic. These, however, were generally additions of later date than the original construction, as were also the semi-detached columns in the angles, with stucco capitals and bases, as indicated in Fig. 9, and shown more clearly in the following engraving, which is a perspective view of the lower chamber [Pg 29] in Fig. 9. The walls and ceiling were often covered with fresco paintings, frequently of elegant design, to be hereafter described.[15] Sometimes, as in some examples in the Catacomb of St. Agnes, tufa or marble seats are ranged around the chamber, and chairs are hewn out of the solid rock.[16] These chambers were used probably for the instruction of catechumens. Occasionally the cubiculum terminates in a semicircular recess, as in the upper chamber in Fig. 9. These probably gave rise to the apse in early Christian architecture, of which a good example is found in the Church of St. Clement, one of the most ancient Christian edifices in Rome. Niches and shelves for lamps, an absolute necessity in the perpetual darkness that there reigns, frequently occur, such as may be seen in Italian houses to-day. Without the least authority, some Roman Catholic writers have described [Pg 30] these as closets for priestly vestments and shelves for pictures.

A peculiar form of grave common in these chambers, as well as in the galleries, is that known as the arcosolium, or arched tomb. It consists of a recess in the wall, having a grave, often double or triple, excavated in the tufa, or built with masonry, like a solid sarcophagus, and closed with a marble slab. These are seen in the plan, Fig. 9, in the section, Fig. 10, at G and E in Fig. 15, and in perspective in Figs. 11 and 12. Sometimes the recess is rectangular instead of arched, and is then called by De Rossi sepolcro a mensa, or table tomb. Sometimes the arch was segmental, especially when constructed of masonry.[17] An example of both sorts is seen in the accompanying engraving of a cubiculum in the Catacomb of St. Prætextatus. The narrow door into the corridor is also seen, and the stucco capitals and bases of the columns. In course of time these arcosolia were [Pg 31] used as altars for the celebration of the eucharist, and eventually grave abuses arose from the superstitious veneration paid to the relics of the martyr or confessor interred therein. Frequently, also, the back of this arched recess was pierced with graves of a later date, often directly through a painting,[18] in order to obtain a resting place near the bodies of the saints.

Hitherto only one level of the Catacombs has been described, but frequently “beneath this depth there is a lower deep,” or even three or four tiers of galleries, excavated as the upper ones became filled with graves. Thus there are sometimes as many as five stories, or piani, as they are called, one beneath the other. These are carefully maintained horizontal, to avoid breaking through the floor of the one above or the roof of the one below, the danger of which would be very great if the strict level were departed from. For the same reason the different piani were generally separated by a thick stratum of solid tufa. The relative position of these levels is shown by the following engraving, reduced from De Rossi. It represents a section of the Crypt of St. Lucina, a part of the Cemetery of Callixtus. The dark colored stratum, marked I in the margin, is entirely made up of the débris of ancient monuments, buildings, and other materials accumulated in the course of ages in this place to the depth of eight feet. It has completely buried the ancient roads, except where excavated, as shown in the engraving. The next stratum, II, is of solid grayish tufa. In this the first level or piano, φ, is excavated. It is not more than twenty feet below the surface, and in many places only half that depth. Consequently its area is comparatively limited, because if extended it would have run out into the [Pg 32] open air, from the sloping of the ground in which it is dug. The next stratum, III, is softer and more easily worked, and therefore is that in which are found the most important and extensive piani of galleries. The cross sections P and X, and the longitudinal section υ, will show how the lower surface of the more solid stratum above was made the ceiling of these galleries, in order to lessen the danger of its falling. At B will be observed the employment of masonry to strengthen the [Pg 33] crumbling walls of the friable tufa. The descent of a few steps, some of which have been worn away, will also be noticed at U. At IV a more rocky stratum is found, called tufa lithoide, below which the ancient fossors[19] had to go to find suitable material for the excavation of the third piano. This was found in stratum V, in which are two piani at different levels. The lower one is not vertically beneath that here represented above it, but at some little distance. It is here shown, to exhibit at one view a section of all the stories of this Catacomb. The upper piano, g, consists of low and narrow galleries, but the lower one, marked Γ Γ Γ, seventy-one feet beneath the surface of the ground, is of great extent. Several of the loculi, it will be perceived, are built of masonry, in consequence of the crumbling nature of the soil. The three large arcosolia will also be observed. The floor of this piano rests on a somewhat firmer stratum, in which is still another level of galleries, Ω Ω Ω, ten feet lower down. This lower level is generally subject to inundation by water, in consequence of the periodical rising of the adjacent Almone, the level of which is shown at a depth of one hundred and four feet, and that of the Tiber at one hundred and thirty-one feet, below the surface.

To secure immunity from dampness, which would accelerate decomposition and corrupt the atmosphere, the Catacombs were generally excavated in high ground in the undulating hills around the city, never crossing the intervening depressions or valleys. There is, therefore, no connection between the different cemeteries except where they happen to be contiguous, nor, as has been asserted, with the churches of Rome. Where a [Pg 34] Catacomb has been excavated in low ground, as in the exceptional case of that of Castulo on the Via Labicana, the water has rendered it completely inaccessible.

Access to these different piani is gained by stairways, which are sometimes covered with tile or marble, or built with masonry, or by shafts. The awful silence and almost palpable darkness of these deepest dungeons is absolutely appalling. They are fitly described by the epithet applied by Dante to the realms of eternal gloom: loco d’ogni luce muto—a spot mute of all light. Here death reigns supreme. Not even so much as a lizard or a bat has penetrated these obscure recesses. Nought but skulls and skeletons, dust and ashes, are on every side. The air is impure and deadly, and difficult to breathe. “The cursed dew of the dungeon’s damp” distills from the walls, and a sense of oppression, like the patriarch’s “horror of great darkness,” broods over the scene.

The Catacombs were ventilated and partially lighted by numerous openings variously called spiragli, or breathing-holes, and luminari, or light-holes. They were also probably used for the removal of the excavated material from those parts remote from the entrance. They were even more necessary for the admission of air than of light. Were it not for these the number of burning lamps, the multitude of dead bodies, no matter how carefully the loculi were cemented, and the opening of bisomi, or double graves, for interments, would create an insupportable atmosphere. They were generally in the line of junction between two cubicula, a branch of the luminare entering each chamber, as shown in the accompanying section of a portion of the Catacomb of Sts. Marcellinus and Peter. Sometimes, indeed, four, or even more, cubicula were ventilated and partially lighted by the same shaft. De Rossi mentions one luminare in [Pg 35] the recently discovered Cemetery of St. Balbina, which is not square but hexagonal, or nearly so, and which divides into eight branches, illumining as many separate chambers or galleries. Sometimes a funnel-shaped luminare reaches to the lowest piano; but from the faint rays that feebly struggle to those gloomy depths there comes “no light, but rather darkness visible.” In the upper levels, however, some cubicula are well lighted by large openings. The brilliant Italian sunshine to-day lights up the pictured figures on the wall as it must have illumined with its strong Rembrandt light the fair brow of the Christian maiden, the silvery hair of the venerable pastor, or the calm face of the holy dead waiting for interment in those early centuries so long ago. These luminari are often two feet square at the top, and wider as they descend; sometimes they are cylindrical in shape, as in the Catacomb of St. Helena.[20] The external [Pg 36] openings, often concealed by grass and weeds, are very numerous throughout the Campagna near the city, and are often dangerous to the unwary rider. In almost every vineyard between the Pincian and Salarian roads they may be found, and through them an entrance into the Catacombs may frequently be effected. After the persecution had ceased, and there was no longer need for concealment, their number was increased, and they were made of a larger size, and frequently lined with masonry, or plastered and frescoed. In the Catacombs of St. Agnes and of Callixtus are several in a very good state of preservation.

We have already seen the contemporary account of the Catacombs by Prudentius, in the fourth century. Jerome also describes their appearance at the same period in words which are almost equally applicable to-day. “When I was a boy, being educated at Rome,” he says, “I used every Sunday, in company with others of my own age and tastes, to visit the sepulchres of the apostles and martyrs, and to go into the crypts dug in the heart of the earth. The walls on either side are lined with bodies of the dead, and so intense is the darkness as to seemingly fulfill the words of the prophet, ‘They go down alive to Hades.’ Here and there is light let in to mitigate the gloom. As we advance the words of the poet are brought to mind: ‘Horror on all sides; the very silence fills the soul with dread.’”[21]

It must not be supposed that the features above described [Pg 37] are always perfectly exhibited. They are often obscured and obliterated by the lapse of time, and by earthquakes, inundations, and other destructive agencies of nature. The stairways are often broken and interrupted, and the corridors blocked up by the falling in of the roof, where it has been carried too near the surface, or by the crumbling of the walls, and sometimes apparently by design during the age of persecution. The rains of a thousand winters have washed tons of earth down the luminari, destroyed the symmetry of the openings, and completely filled the galleries with débris. The natural dampness of the situation, and the smoke of the lamps of the early worshipers, or the torches of more recent visitors, and sometimes incrustations of nitre, have impaired or destroyed the beauty of many of the paintings. The hand of the spoiler has in many cases completed the work of devastation. The rifled graves and broken tablets show where piety or superstition has removed the relics of the dead, or where idle curiosity has wantonly mutilated their monuments.

The present extent of the Catacombs is the result, not of primary intention, but of the contact of separate areas of comparatively limited original size, and the inosculation, as it were, of their distinct galleries. This is apparent from the fact that this contact and junction sometimes take place between areas of different levels, causing a break in their horizontal continuity, like the “faults” or dislocations common in geological strata. Sometimes, too, this junction between two adjacent areas takes place through a tier of graves, and evidently formed no part of the original design. These separate areas were originally, as we shall see in the following chapter, private burial places in the vineyards of wealthy Christian converts, and were early [Pg 38] made available for the interment of the poorer members of the infant Church. In accordance with a common Roman usage the ground thus set apart for the purpose of sepulture was placed under the protection of the law, and was accurately defined, to secure it from trespass or violation. While the protection of the law was enjoyed, the excavations were strictly confined within the limits of these areas, and lower piani were dug rather than transgress the boundary. But when that protection was withdrawn the galleries were horizontally extended, often for the purpose of facilitating escape, and connections were made with adjacent areas, till the whole became an intricate labyrinth of passages and chambers. These areas are still further distinguished by certain peculiarities in the inscriptions, cubicula, and paintings, and were greatly modified by subsequent constructions.

It has till recently been thought that the Catacombs were originally excavations made by the Romans for the extraction of sand and other building material, and afterward adopted by the Christians as places of refuge, and eventually of sepulture and worship. This opinion was founded on a few misunderstood classical allusions and statements in ancient ecclesiastial writers, and on a misinterpretation of certain accidental features of the Catacombs themselves. It was held, nevertheless, by such eminent authorities as Baronius, Severano, Aringhi, Bottari, D’Agincourt, and Raoul-Rochette. Padre Marchi first rejected this theory of construction, and the brothers De Rossi have completely refuted it. An examination of the material in which these sand pits and stone quarries and the Catacombs were respectively excavated, as well as of their structural differences, will show their entirely distinct character.

The surface of the Campagna, especially of that part [Pg 39] occupied by the Catacombs, is almost exclusively of volcanic origin. The most ancient and lowest stratum of this igneous formation is a compact conglomerate known as tufa lithoide. It was extensively quarried for building, and the massive blocks of the Cloaca Maxima and the ancient wall of Romulus attest the durability of its character. Upon this rest stratified beds of volcanic ashes, pumice, and scoria, often consolidated with water, but of a substance much less firm than that of the tufa lithoide, and called tufa granolare. In insulated beds, rarely of considerable extent, in this latter formation, occurs another material, known as pozzolana. It consists of volcanic ashes deposited on dry land, and still existing in an unconsolidated condition. This is the material of the celebrated Roman cement, which holds together to this day the massy structures of ancient Rome. It was conveyed for building purposes as far as Constantinople, and the pier on the Tiber from which it was shipped is still called the Porto di Pozzolana. It is in these latter deposits exclusively that the arenaria, or sand pits, are found. The tufa granolare is too firm, and contains too large a proportion of earth, to use as sand, and is yet too friable for building purposes. Yet it is in this material, entirely worthless for any economic use, that the Catacombs are almost exclusively excavated; while the tufa lithoide and the pozzolana are both carefully avoided where possible, the one as too hard and the other as too soft for purposes of Christian sepulture. Sometimes, indeed, as at the cemeteries of St. Pontianus and St. Valentinus, for special reasons, Catacombs were excavated in less suitable material; but still the substance removed—a shelly marl—was economically useless, and the galleries had to be supported by solid masonry. The tufa granolare, on the [Pg 40] contrary, was admirably adapted for the construction of these subterranean cemeteries. It could be easily dug with a mattock, yet was firm enough to be hollowed into loculi and chambers; and its porous character made the chambers dry and wholesome for purposes of assembly, which was of the utmost importance in view of the vast number of bodies interred in these recesses.

The differences of structure between the quarries or arenaria and the Catacombs are no less striking. To this day, the vast grottoes from which the material for the building of the Coliseum was hewn, most probably by the Jewish prisoners of Titus, may still be seen on the Cœlian hill. It is said that in those gloomy vaults were kept the fierce Numidian lions and leopards whose conflicts with the Christian martyrs furnished the savage pastime of the Roman amphitheatre. But nothing can less resemble the narrow and winding passages of the Catacombs than those tremendous caverns.

Nor is there any greater resemblance in the excavations of the arenaria. These are large and lofty vaults, from sixteen to twenty feet wide, the arch of which often springs directly from the floor, so as to give the largest amount of sand with the least labour of excavation. The object was to remove as much material as possible; hence there was often only enough left to support the roof. The spacious passages of the arenaria run in curved lines, avoiding sharp angles, so as to allow the free passage of the carts which carried away the excavated sand. In the Catacombs, on the contrary, as little material as possible was removed; hence the galleries are generally not more than three, or sometimes only two, feet wide, and run for the most part in straight lines, often crossing each other at quite acute angles, so that only very narrow carts can be used in [Pg 41] cleaning out the accumulated débris of centuries—a very tedious process, which greatly increases the cost of exploration. The walls, moreover, are always vertical, and the roof sometimes quite flat, or only slightly arched. The wide difference in the principle of construction is obvious. The great object in the Catacombs has been to obtain the maximum of wall-surface, for the interment of the dead in the loculi with which the galleries are lined throughout, with the minimum of excavation. The structural difference will at once be seen by comparing the irregular windings of the small arenarium represented in the upper part of Figs. 3 and 26 with the straight and symmetrical galleries of the adjacent Catacomb. Connected with the Catacomb of St. Agnes is an extensive arenarium, whose spacious, grotto-like appearance is very different from that of the narrow sepulchral galleries beneath. In the floor of this arenarium is a square shaft leading to the Catacomb, in which Dr. Northcote conjectures there was formerly a windlass for removing the excavated material. There are also footholes, for climbing the sides of the shaft, cut in the solid tufa, perhaps as a means of escape in the time of persecution. This arenarium, which was probably worked out and abandoned long before its connection with the Catacomb, may have been employed as a masked entrance to its crypts, when the more public one could not be safely used. Its spacious vaults may also have been a receptacle for the broken tufa removed from the galleries beneath.

Many of these arenaria may be observed excavated in the hill-sides near Rome; but except when incidentally forming part of a Catacomb, they have never been found to contain a single grave. Indeed, in consequence of the utter unfitness of the pozzolana for the [Pg 42] purposes of Christian sepulture, the intrusion of a deposit of that material into the area of a Catacomb prevented the extension or necessitated the diversion of its galleries. Moreover, where the attempt has been made to convert an arenarium into a Christian cemetery, the changes which have been made show conclusively its original unfitness for the latter purpose. The accompanying section of a gallery in the Catacomb of St. Hermes will exhibit the structural additions necessary to adopt an arenarium for Christian sepulture. The sides of the semi-eliptical vault had to be built up with brick-work, leaving only a narrow passage in the middle. The loculi were spaces left in the masonry, in which the mouldering skeletons may still be seen. The openings were closed with slabs in the usual manner, as shown in the elevation, (Fig. 17,) except at the top, where they cover the grave obliquely, like the roof of a house. The vault is often arched with brick-work, and at the [Pg 43] intersection of the galleries has sometimes to be supported by a solid pier of masonry. In part of an ancient arenarium converted into a cemetery in the Catacomb of St. Priscilla similar constructions may be seen. The long walls and numerous pillars of brick-work concealing and sustaining the tufa, and the irregular windings of the passages, show at once the vast difference between the arenarium and the Catacomb, and the immense labour and expense required to convert the former into the latter.

It has been urged in objection to this theory, that the difficulty of secretly disposing of at least a hundred millions of cubic feet of refuse material taken from the Catacombs must have been exceedingly great, unless it could be removed under cover of employment for some economic purpose. It will be shown, however, that secrecy was not always necessary, as has been assumed, but that, on the contrary, the Christian right of sepulture was for a long time legally recognized by the Pagan Emperors; and that the Catacombs continued to be publicly used for a considerable time after the establishment of Christianity on the throne of the Cæsars. During the exacerbations of persecution there is evidence that the excavated material was deposited in the galeries already filled with graves, or, as we have seen, in the spacious vaults of adjacent arenaria. If the Catacombs were merely excavations for sand or stone, as has been asserted, we ought to find many of their narrow galleries destitute of tombs, and many of the arenaria containing them; whereas every yard of the former is occupied with graves, and not a single grave is found in the latter, nor do they contain a single example of a mural painting or inscription. The conclusion is irresistible that the Catacombs proper were created exclusively [Pg 44] for the purpose of Christian burial, and in no case were of Pagan construction.

The erroneous theory here combated has arisen, as we have said, chiefly from certain classical allusions to the arenaria, and from passages in the ancient ecclesiastical records describing the burial places of the martyrs, as in cryptis arenariis, in arenario, or ad arenas. Some of these localities, however, have been identified beyond question, and found to consist merely of a sandy kind of rock, and not at all of the true pozzolana. In others a vein of pozzolana does actually occur in the Catacombs, or they are connected with ancient arenaria, as at St. Agnes and at Calixtus. In the other instances the localities are either yet unrecognized, or the expression merely implies that the cemetery was near the sand pits—juxta arenarium, or in loco qui dicitur ad Arenas.

The mere technical description of the Catacombs, however, gives no idea of the thrilling interest felt in traversing their long-drawn corridors and vaulted halls. As the pilgrim to this shrine of the primitive faith visits these chambers of silence and gloom, accompanied by a serge-clad, sandaled monk,[22] he seems like the Tuscan poet wandering through the realms of darkness with his shadowy guide.

“Ora sen’ va per un segreto calle

Tra l’ muro della terra.”[23]

His footsteps echo strangely down the distant passages and hollow vaults, dying gradually away in the solemn stillness of this valley of the shadow of death. The [Pg 45] graves yawn weirdly as he passes, torch in hand. The flame struggles feebly with the thickening darkness, vaguely revealing the unfleshed skeletons on either side, till its redness fades to sickly white, like that fioco lume,[24] that pale light, by which Dante saw the crowding ghosts upon the shores of Acheron. Deep mysterious shadows crouch around, and the dim perspective, lined with the sepuchral niches of the silent community of the dead, stretch on in an apparently unending vista. The very air seems oppressive and stifling, and laden with the dry dust of death. The vast extent and population of this great necropolis overwhelm the imagination, and bring to mind Petrarch’s melancholy line—

“Piena di morti tutta la campagna.”[25]

Almost appalling in its awe and solemnity is the sudden transition from the busy city of the living to the silent city of the dead; from the golden glory of the Italian sunlight to the funereal gloom of these sombre vaults. The sacred influence of the place subdues the soul to tender emotions. The fading pictures on the walls and the pious epitaphs of the departed breathe on every side an atmosphere of faith and hope, and awaken a sense of spiritual kinship that overleaps the intervening centuries. We speak with bated breath and in whispered tones, and thought is busy with the past. It is impossible not to feel strangely moved while gazing on the crumbling relics of mortality committed ages ago, with pious care and many tears, to their last, long rest.

“It seems as if we had the sleepers known.”[26]

[Pg 46] We see the mother, the while her heart is wrung with anguish, laying on its stony bed—rude couch for such a tender thing—the little form that she had cherished in her warm embrace. We behold the persecuted flock following, it may be, the mangled remains of the faithful pastor and valiant martyr for the truth, which at the risk of their lives they have stealthily gathered at dead of night. With holy hymns,[27] broken by their sobs, they commit his mutilated body to the grave, where after life’s long toil he sleepeth well. We hear the Christian chant, the funeral plaint, the pleading tones of prayer, and the words of holy consolation and of lofty hope with which the dead in Christ are laid to rest. A moment, and—the spell is broken, the past has vanished, and stern reality becomes again a presence. Ruin and desolation and decay are all around.

The exploration of these worse than Dædalian labyrinths is not unattended with danger. That intrepid investigator, Bosio, was several times well nigh lost in their mysterious depths. That disaster really happened to M. Roberts, a young French artist, whose adventure has been wrought into an exciting scene in Hans Andersen’s tale, “The Improvisatore,” and forms an episode in the Abbé de Lille’s poem, “L’Imagination.” Inspired by the enthusiasm of his profession, he attempted to explore one of the Catacombs, with nothing but a torch and a thread for a guide. As he wandered on through gallery and chamber, he became so absorbed in his study that, unawares, the thread slipped from his hand. On discovering his loss he tried, but in vain, to recover the clew. Presently his torch went out, and he was left in utter darkness, imprisoned in a living grave, surrounded by the relics of mortality. The silence was oppressive. [Pg 47] He shouted, but the hollow echoes mocked his voice. Weary with fruitless efforts to escape his dread imprisonment he threw himself in despair upon the earth, when, lo, something familiar touched his hand. Could he believe it? it was indeed the long lost clew by which alone he could obtain deliverance from this awful labyrinth. Carefully following the precious thread he reached at last the open air,

And never Tiber, rippling through the meads,

Made music half so sweet among its reeds;

And never had the earth such rich perfume,

As when from him it chased the odor of the tomb.[28]

Still more terrible in its wildness is an incident narrated by MacFarlane.[29] In the year 1798, after the return to Rome of the Republican army under Berthier, a party of French officers, atheistic disciples of Voltaire and Rousseau, and hardened by the orgies of the Revolution, visited the Catacombs. They caroused in the sepulchral crypts, and sang their bacchanalian songs among the Christian dead. They rifled the graves and committed sacrilege at the tombs of the saints. One of the number, a reckless young cavalry officer, “who feared not God nor devil, for he believed in neither,” resolved to explore the remoter galleries. He was speedily lost, and was abandoned by his companions. His excited imagination heightened the natural horrors of the scene. The grim and ghastly skeletons seemed an army of accusing spectres. Down the long corridors the wind mysteriously whispered, rising in inarticulate moanings and woeful sighs, as of souls in pain. The tones of the neighbouring convent bell, echoing through the stony [Pg 48] vaults, sounded loud and awful as the knell of doom. Groping blindly in the dark, he touched nothing but rocky walls or mouldering bones, that sent a thrill of horror through his frame. Though but a thin roof separated him from the bright sunshine and free air, he seemed condemned to living burial. His philosophical skepticism failed him in this hour of peril. He could no longer scoff at death as “un sommeil éternel.” The palimpsest of memory recalled with intensest vividness the Christian teachings of his childhood. His soul became filled and penetrated with a solemn awe. His physical powers gave way beneath the intensity of his emotion. He was rescued the next day, but was long ill. He rose from his bed an altered man. His life was thenceforth serious and devout. When killed in battle in Calabria seven years after, a copy of the Gospels was found next to his heart.

Even as late as 1837 a party of students with their professor, numbering in all some sixteen, or, as some say, nearly thirty, entered the Catacombs on a holiday excursion, to investigate their antiquities, but became entangled amid their intricacies. Diligent search was made, but no trace of them was ever found. In some silent crypt or darksome corridor they were slowly overtaken by the same torturing fate as that of Ugolino and his sons in the Hunger Tower of Pisa.[30] The passage by which they entered has been walled up, but the mystery of their fate will never be dispelled till the secrets of the grave shall be revealed.

Haud procul extremo culta ad pomœria vallo,

Mersa latebrosis crypta patet foveis...—Peristephanon, iv.

The origin of the word Catacombs is exceedingly obscure. Father Marchi derives it from κατὰ, down, and τύμβος, a tomb; or from κατὰ and κοιμάω, to sleep. Mommsen thinks it comes from κατὰ and cumbo, part of decumbo, to lie down. According to Schneider (Lex. Græk.) it is derived from κατὰ and κύμβη, a boat or canoe, from the resemblance of a sarcophagus to that object. The more probable derivation seems to the present writer to be from κατὰ and κύμβος, a hollow, as if descriptive of a subterranean excavation. The name was first given in the sixth century to a limited area beneath the Church of St. Sebastian: “Locus qui dicitur catacumbas.”—S. Greg., Opp., tom. ii, ep. 30. It was afterward generically applied to all subterranean places of sepulture. The earliest writers who mention those of Rome call them cryptæ, or crypts, or cæmeteria—whence our word cemetery, literally, sleeping places, from κοιμάω, to slumber. Similar excavations have been found in Syria, Asia Minor, Cyprus, Crete, the Ægean Isles, Greece, Sicily, Naples, Malta, and France.

[2] These great roads for miles are lined with the sepulchral monuments of Rome’s mighty dead, majestic even in decay. But only the wealthy could be entombed in those stately mausolea, or be wrapped in those “marble cerements.” For the mass of the population columbaria were provided, in whose narrow niches, like the compartments of a dove-cote—whence the name—the terra cotta urns containing their ashes were placed, sometimes to the number of six thousand in a single columbarium. They also contain sometimes the urns of the great.

[3] Ariosto, Orlando Furioso.

[4] Aringhi, in the elegant Latin ode prefixed to his great work, exclaims, “Sub Roma Romam quærito”—Beneath Rome I seek the true Rome.

[5] Even so accurate and philosophical a writer as the late Professor Silliman reports on their authority that the Catacombs extend twenty miles, to the port of Ostia, in one direction, and to Albano, twelve miles, in another. Visit to Europe, vol. i, p. 329. This is impossible, as will be shown, on account of the undulation of the ground, and the limited area of the volcanic tufa in which alone they can be excavated. The number of distinct Catacombs has also been magnified to sixty; and Father Marchi estimated the aggregate length of passages to be nine hundred miles.

Primas namque fores summo tenus intrat hiatu

Illustratque dies limina vestibuli.—Peristephanon, ii.

[10] In the single crypt of St. Lucina, one hundred feet by one hundred and eighty, De Rossi counted over seven hundred loculi, and estimated that nearly twice as many were destroyed, giving a total of two thousand graves in this area. The same space, with our mode of interment, would not accommodate over half the number, even though placed as close together as possible, without any room for passages.

[11] Compare Bryant’s Thanatopsis:

“All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom.”

[12] Rom. Sott., ii, 127.

[13] D’Agincourt, Histoire de l’art par les Monumens, i, 20.

[14] Literally, little sleeping chambers, from cubo, I lie down. The same name was also given to the cells for meditation and prayer attached to the Church of Nola. Paulin., ep. 12, ad Sever.

[16] See Fig. 130 and context, where the entire subject is discussed.

[17] See in the Cemetery of St. Helena, Fig. 29.

[18] As in Fig. 12, and more strikingly in Fig. 76.

[19] An organized body of diggers, by whom the Catacombs were excavated. See Book III, chap. iv.

[21] “Dum essem Romæ puer, et liberalibus studiis erudirer, solebam cum cæteris ejusdem ætatis et propositi, diebus Dominicis sepulchra apostolorum et martyrum circuire, crebròque cryptas ingredi, quæ in terrarum profunda defossæ, ex utraque parte ingredientium per parietes corpora sepultorum, ... ‘Horror ubique animos, simul ipsa silentia terrent.’”—Hieron. in Ezech., Cap. xl.

[22] Unfortunately for Protestant visitors most of the Catacombs are open for inspection only on Sunday, when the work of exploration is suspended.

“And now through narrow, gloomy paths we go,

’Tween walls of earth and tombs.”—Inferno.

[24] “Com’io discerno per lo fioco lume.”—Inferno.

[25] “Full of the dead this far extending field.”

[26] Childe Harold, iv, 104.

[27] Hymnos et psalmos decantans.—Hieron., Vit. Pauli.

[28] From “L’Imagination,” by Abbé de Lille, MacFarlane’s translation.

[29] Catacombs of Rome. London, 1852. P. 94, et seq.

[30] Inferno, Canto xxxiii, vv. 21-75.

It is highly probable that the first Roman Catacombs were excavated by the Jews.[31] Many Hebrew captives graced the triumph of Pompey after his Syrian conquests, B. C. 62. The Jewish population increased by further voluntary accessions. They soon swarmed in that Trans-Tiberine region which formed the ancient Ghetto of Rome. They made many proselytes from paganism to the worship of the true God, and thus, to use the language of Seneca, “The conquered gave laws to their conquerors.”[32]

All the national customs and prejudices of the Jews were opposed to the Roman practice of burning the dead, which Tacitus asserts they never observed;[33] and they clung with tenacity to their hereditary mode of sepulture. Wherever they have dwelt they have left traces [Pg 50] of subterranean burial. The hills of Judea are honeycombed with sepulchral caves and galleries. Similar excavations have been found in the Jewish settlements of Asia Minor, the Ægean Isles, Sicily, and Southern Italy.[34] So also in Rome they sought to be separated in death, as in life, from the Gentiles among whom they dwelt. They had their Catacombs apart, in which not a single Christian or pagan inscription has been found. Bosio describes one such Catacomb, which he discovered on Monte Verde, which was much more ancient than the Christian Catacomb of St. Pontianus in the same vicinity. It was of very rude construction, and contained not a single Christian monument, but numerous slabs bearing the seven-branched Jewish candlestick, and one inscription on which the word ϹΥΝΑΓΩΓ—Synagogue—was legible.[35] It was situated near that Trans-Tiberine quarter of the city inhabited at the period of the Christian era by the numerous Jewish population of Rome. It cannot now, however, be identified, having been obliterated or concealed by the changes of the last two centuries. Maitland gives the following Jewish inscription from a MS. collection in Rome. The figure to the left may be a horn for replenishing the lamp with oil. The letters at the right are probably intended for the Hebrew word שָׁלוֹם, Shalom, or Peace, so common in its classical equivalent upon Christian tombs. The palm branch is a Pagan as well as Jewish and Christian symbol of victory. The central figure is a rude representation [Pg 51] of the seven-branched candlestick which appears also in bass-relief on the Arch of Titus at Rome.

In the year 1859 another Jewish Catacomb was discovered in the Vigna Randanini, on the Appian Way, about two miles from Rome. It has been minutely described by Padre Garrucci.[36] In this the graves and sarcophagi are sunk in the floor as well as in the walls. They are closed with terra cotta or marble slabs, and are otherwise similar to those of the Christian Catacombs. It contains several vaulted chambers, one of which has some very remarkable paintings of the seven-branched candlestick on the roof and walls. The same figure is frequently scratched on the mortar with which the graves are closed. The dove and olive branch and the palm are also frequently repeated. Although nearly two hundred inscriptions have been discovered, not one of either pagan or Christian character has been met with.

The names are sometimes strikingly Jewish in form, and where the epitaphs refer to the station of the deceased [Pg 52] it is always to officers of the synagogue, as ΑΡΚΟΝΤΕϹ, rulers, ΓΡΑΜΜΑΤΕΙϹ, scribes. The following examples are from the Kircherian Museum:

ΩΔΕ ΚΕΙΤΕ ϹΑΛΩ[ΜΗ] ΘΥΓΑΤΗΡ ΓΑΔΙΑ ΠΑΤΡΟϹ ϹΥΝΑΓΩΓΗϹ ΑΙΒΡΕΩΝ ΕΒΙΩϹΕΝ ΜΑ ΕΝ ΕΙΡΗΝΗ ΚΟΙΜΗϹΙϹ ΑΥΤΗϹ. Here lies Salome, daughter of Gadia, Father of the Synagogue of the Hebrews. She lived forty-one years. Her sleep is in peace. ΕΝΘΑΔΕ ΚΕΙΤΕ ΚΥΝΤΙΑΝΟϹ ΓΕΡΟΥϹΙΑΡΧΗϹ ϹΥΝΑΓΩΓΗϹ ΤΗϹ ΑΥΓΥϹΤΗϹΙΩΝ. Here lies Quintianus, Gerousiarch (that is, Chief Elder) of the Synagogue of the Augustenses. ΕΝΘΑΔΕ ΚΕΙΤΑΙ ΝΕΙΚΟΔΗΜΟϹ HΟ ΑΡΧΩΝ ϹΙΒΟΥΡΗϹΙΩΝ ΚΑΙ ΠΑϹΙ ΦΕΙΛΗΤΟϹ ΑΙΤΩΝ Λ ΗΜΕΡ ΜΒ ΘΑΡΙ ΑΒΛΑΒΙ ΝΕΩΤΕΡΕ ΟΥΔΕΙϹ ΑΘΑΝΑΤΟϹ. Here lies Nicodemus, ruler of the Severenses, and beloved of all; (aged) thirty years, forty-two days. Be of good cheer, O inoffensive young man! no one is exempt from death.

This inscription will recall another “ruler of the Synagogue” of the same name. Many of the sleepers in this Jewish Cemetery were evidently, from their names,[37] Greek or Latin proselytes. Sometimes, indeed, this is expressly asserted, as in the following:

Mannacivs sorori Crysidi dvlcissime proselyte.—Mannacius to his sweetest sister Chrysis, a proselyte.

It may be assumed that this Catacomb was exclusively Jewish, and we know, from the testimony of Juvenal[38] and others, that numbers of the Jews inhabited the adjacent part of Rome, about the Porta Capena and the valley of Egeria. It is not, however, certain whether it is the original type, or a later imitation, of the Christian cemetery. But the Jewish population must have had extra-mural places of sepulture before the Christian era; and it is probable that the early Jewish [Pg 53] converts to Christianity may have merely continued a mode of burial already in vogue, substituting the emblems of their newly adopted faith for those which they had forsaken; or, rather—for we find that they frequently retained certain Jewish symbols, as the dove, olive branch, and palm—supplementing them with the emblems of Christianity. De Rossi has expressed the opinion that the earliest mode of Christian burial was in sarcophagi, as in the Jewish cemetery above described.

The date of the planting of Christianity in Rome is uncertain. Probably some of the “strangers of Rome” who witnessed the miracle of the Pentecost, or, perhaps, the Gentile converts of the “Italian band” of Cornelius, brought the new evangel to their native city.[39] But certain it is that as early as A. D. 58 the faith of the [Pg 54] Roman Church was “spoken of throughout the whole world.” “Christianity,” says Tertullian, “grew up under the shadow of the Jewish religion, to which it was regarded as akin, and about the lawfulness of which there was no question;”[40] and it doubtless adopted the burial usages of Judaism.

But even without the example of the Jews the Roman Christians would naturally revolt from the pagan custom of burning the dead, with its accompanying idolatrous usages,[41] and would prefer burial, after the manner of their Lord. They showed a tender care for the remains of the dead, under a vivid impression of the communion of saints and the resurrection of the body. They seemed to regard the sepulchre as “God’s cabinet or shrine, where he pleases to lay up the precious relics of his dear saints until the jubilee of glory.”[42] Even the Jews designated the grave as Beth-ha-haim, the “house of the living,” rather than the house of the dead. It is probable, therefore, that the origin of the Christian Catacombs dates from the death of the first Roman believer in Christ.

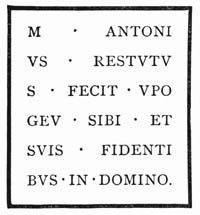

Many of the Catacombs were probably begun as [Pg 55] private sepulchres for single families; indeed, some such tombs have been discovered in the vicinity of Rome, which never extended beyond a single chamber. They were excavated in the gardens or vineyards of the wealthy converts to Christianity, in imitation of that rock-hewn sepulchre consecrated by the body of Christ. The following inscription, which may still be seen in the most ancient part of the Catacombs of Sts. Nereus and Achilles, seem to refer to such a family tomb. Another inscription, found in the Catacomb of St. Nicomedes, restricts the use of the sepulchre to the original owner, and those of his dependents who belong to his religion—AT [AD] RELIGIONEM PERTINENTES MEAM.

M. Antonius Res[ti]tutus made [this] hypogeum for himself and his [relatives] who believe in the Lord.[43]

The names of many of the burial crypts commemorate these original owners. Among others those of Lucina, Priscilla, and Domitilla are considered to belong to the First Century, and the two former to the times of the Apostles. Some of these may have been originally designed, or afterwards opened, for the reception of the poor belonging to the Church; and thus the Catacombs would be indefinitely extended till they attained their present dimensions. Tertullian [Pg 56] expressly declares that the provision made for the poor included that for their burial—egenis humandis.[44]

There is reason to believe that, even from the very first, the Christian Church at Rome contained not a few who were of noble blood and of high rank. In one of the apostolic epistles Paul conveys the salutation of Pudens, a Roman Senator, of Linus, reputed the first Roman bishop, and of Claudia, daughter of a British king;[45] and we know that even in the Golden House of Nero, the scene of that colossal orgy whose record pollutes the pages of Suetonius and Tacitus, were disciples of the crucified Nazarene. In remarkable confirmation of this fact is the discovery in the recent explorations of the ruins of the Imperial Palace of several Christian memorials, including one of those lamps adorned with evangelical symbols, so common in the Catacombs. Much of the evidence on this subject has been lost by the zealous destruction of ecclesiastical records during the terrible Diocletian persecution; but from inscriptions in the Catacombs, and from the incidental allusions [Pg 57] of early writers, we learn that persons of the highest position, and even members of the Imperial family, were associated with the Christians in life and in death. Some of the noblest names of Rome occur in funeral epitaphs in some of the most ancient galleries of the Catacombs. There is evidence that even during the first century some who stood near the throne became converts to Christianity, and even died as martyrs for the faith.[46]

But doubtless the preservation and advancement of true religion was better secured amid the dark recesses of the Catacombs, during the fiery persecutions that befel the Church, than it would have been in the sunshine of imperial favour, in an age and court unparalleled for their corruptions. The sad decline of Christianity after the accession of Constantine makes it a matter of congratulation that in the earlier ages it was kept pure by the wholesome breezes of adversity.

The new religion, notwithstanding all the efforts that were made for its suppression, rapidly spread, even in the high places of the earth. “We are but of yesterday,” writes Tertullian at the close of the second century, “yet we fill every city, town, and island of the empire. We abound in the very camps and castles, in the council chamber and the palace, in the senate [Pg 58] and the forum; only your temples and theatres are left.”[47]

It is evident from an examination of the earliest Catacombs that they were not the offspring of fear on the part of the Christians. There was no attempt at secrecy in their construction. They were, like the pagan tombs, situated on the high roads entering the city. Their entrances were frequently protected and adorned by elegant structures of masonry, such as that which is still visible at the Catacomb of St. Domitilla on the Via Ardeatina;[48] and their internal decorations and frescoes, which in the most ancient examples are of classic taste and beauty, were manifestly not executed by stealth and in haste, but in security and at leisure.

There was, in classic times, a sacred character attached to all places set apart for the purposes of sepulture. They enjoyed the especial protection of the law, and were invested with a sort of religious sanctity.[49] This protection was asserted in many successive edicts, and the heaviest penalties were inflicted on the violators of tombs, as guilty of sacrilege.[50] Reverence for the sepulchres of the dead was regarded by the ancient mind as a religious virtue; and the neglect of the ancestral tomb even involved disability for municipal office.[51]

[Pg 59] Being situated along the public highway, these pagan tombs were liable to various pollutions, to which numerous inscriptions refer. Hence the frequent CAVE VIATOR—“Traveller, beware!”—so common in classic epitaphs. The SCRIPTOR PARCE HOC OPVS—“Writer, spare this work”—sometimes met with, is, as Kenrick well remarks,[52] not the address of an author to a critic, but of a relative of the deceased, entreating the wall-scribbler not to disfigure a tomb. Electioneering notices were sometimes written upon these wayside monuments—a practice which is deprecated in the following: CANDIDATVS FIAT HONORATVS ET TV FELIX SCRIPTOR SI HIC NON SCRIPSERIS—“May your candidate be honoured and yourself happy, O writer, if you write not on this tomb!” INSCRIPTOR, ROGO TE VT TRANSEAS MONVMENTVM—“Inscriber, I pray you pass by this monument.”

As these sepulchral areas, often of considerable extent, were taken from the fields in the vicinity of a great city, where the land was very valuable for the purpose of tillage, they were in continual danger of invasion from the cupidity of the heirs or of adjacent land-owners, but for this legal protection. On many of the cippi, or funereal monuments, which line the public roads in the vicinity of Rome, the extent of these areas is set forth. Some of them are quite small, as is indicated in the following inscription: TERRENVM SACRATVM LONGVM P[EDES] · X · LAT · P[EDES] · X · FODERE NOLI · NE SACRILEGIVM COMMITTAS[52a]—“A consecrated plot of earth, ten feet long and ten feet broad. Do not dig here, lest you commit sacrilege.”

More generally the size of the area is expressed, as [Pg 60] in the following: IN FRONTE P[EDES] · IX IN AGRO P[EDES] · X; that is, “Frontage on the road, nine feet; depth in the field, ten feet.” This area, small as it is, was designed for several families. The limited space occupied by the cinerary urns rendered this quite possible. Frequently, however, the size was much larger. An area one hundred and twenty-five feet square would be of very moderate extent. Horace mentions one one thousand feet by three hundred,[53] and sometimes they greatly exceed this, as one on the Via Labicana, five hundred by eighteen hundred feet, or over twenty English acres. There were also frequently exhedræ, or seats by the wayside, for passers-by, who were sometimes exhorted to pause and read the inscription, or to pour a libation for the dead, as in the following: SISTE VIATOR TV QVI VIA FLAMINIA TRANSIS, RESTA AC RELEGE—“Stop, traveller, who passest by on the Flaminian Way; pause and read, and read again!” MISCE BIBE DA MIHI—“Mix, drink, and give to me.” VIATORES SALVETE ET VALETE—“Travellers, hail and farewell.”

These burial plots were incapable of alienation or transfer from the families for whom they were originally set apart; who are sometimes enumerated in the inscription, or more generally expressed by the formulæ, SIBI SVISQVE FECIT, SIBI ET POSTERIS SVIS, or with the addition, LIBERTIS LIBERTABVSQVE POSTERISQVE, that is, “He made this for himself and his family,” or “for himself and his descendants;” also “for his freedmen and freedwomen and their descendants.” Sometimes this limitation is plainly asserted to be, VT NE VNQVAM [Pg 61] DE NOMINE FAMILIAE NOSTRAE HOC MONVMENTVM EXEAT—“That this monument may not go out of the name of our family.” The cupidity of the inheritor of the estate is especially guarded against by the ever-recurring formula, H · M · H · N · S ·, that is, Hoc monumentum hæredem non sequitur—“This monument descends not to the heir.” Sometimes within a stately mausoleum reposed in solitary magnificence the dust of a single individual, who in sullen exclusiveness declares in his epitaph that he has no associate even in the grave, or that he made his tomb for himself alone—IN HOC MONVMENTO SOCIVM HABEO NVLLVM, or, HOC SOLO SIBI FECIT.

The violation of the monument is earnestly deprecated in numerous inscriptions in some such terms as these: ROGO PER DEOS SVPEROS INFEROSQVE NE VELITIS OSSA MEA VIOLARE—“I beseech you, by the supernal and infernal gods, that you do not violate my bones.” Sometimes this petition is accompanied by an imprecation of divine vengeance if it should be neglected, as, QVI VIOLAVERIT DEOS SENTIAT IRATOS—“May he feel the wrath of the gods[54] who shall have violated [this tomb.]” Another invokes the fearful curse, QVISQVIS HOC SVSTVLERIT AVT LAESERIT VLTIMVS SVORVM MORIATVR[55]—“Whoever shall take away or injure this [tomb] let him die the last of his race.”