TRANSCRIBER’S NOTES:

—Obvious print and punctuation errors were corrected.

—Table of Contents and List of Illustration were not in the original work; they have been produced and added by Transcriber.

THE

PRAIRIE–BIRD.

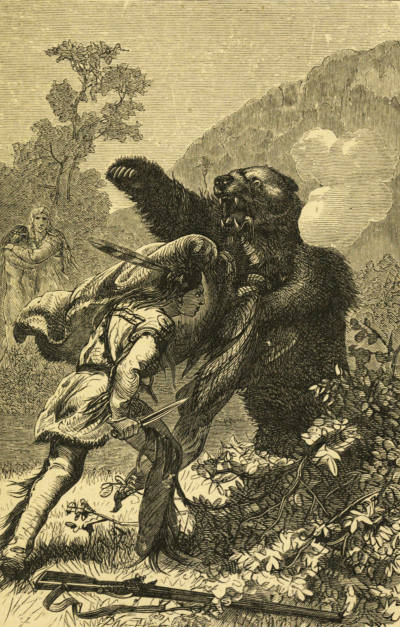

Monsieur Perrot is scalped

P. 276

THE

PRAIRIE–BIRD

BY THE

HON. CHARLES AUGUSTUS MURRAY.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY J. B. ZWECKER.

LONDON:

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & SONS,

THE BROADWAY, LUDGATE;

NEW YORK: 416, BROOME STREET.

PREFACE.

“I hate a Preface!” Such will probably be the reader’s exclamation on opening this volume. I will, however, pursue the subject a little further in the form of a dialogue.

Author.—“I entirely agree in your dislike of a Preface; for a good book needs none, and a dull book cannot be mended by it.”

Reader.—“If then you coincide in my opinion, why write a preface? Judging from appearances, your book is long enough without one!”

A.—“Do not be too severe; it is precisely because the road which we propose to travel together is of considerable extent, that I wish to warn you at the outset of the nature of the scenery, and the entertainment you are likely to meet with, in order that you may, if these afford you no attraction, turn aside and seek better amusement and occupation elsewhere.”

R.—“That seems plausible enough; yet, how can I be assured that the result will fulfil your promise? I once travelled in a stage coach, wherein was suspended, for the benefit of passengers, a coloured print of the watering–place which was our destination; it represented[vi] a magnificent hotel, with extensive gardens and shrubberies, through the shady walks of which, gaily attired parties were promenading on horseback and on foot. When we arrived, I found myself at a large, square, unsightly inn by the sea–side, where neither flower, shrub, nor tree was to be seen: and on inquiry, I was informed that the print represented the hotel as the proprietor intended it to be! Suppose I were to meet with a similar disappointment in my journey with you?”

A.—“I can at least offer you this comfort; that whereas you could not have got out of the stage half–way on the road without much inconvenience, you can easily lay down the book whenever you find it becoming tedious: if you seek for amusement only, you probably will be disappointed, because one of my chief aims has been to afford you correct information respecting the habits, condition, and character of the North American Indians and those bordering on their territory. I have introduced also several incidents founded on actual occurrences; and some of them, as well as of the characters, are sketched from personal observation.”

R.—“Indeed! you are then the individual who resided with the Pawnees, and published, a few years since, your Travels in North America. I suppose we may expect in these volumes a sort of pot–pourri, composed of all the notes, anecdotes, and observations which you could not conveniently squeeze into your former book?”

A. (looking rather foolish.)—“Although the terms in which you have worded your conjecture are not the most flattering, I own that it is not altogether without foundation; nevertheless, Gentle Reader——“

R.—“Spare your epithets of endearment, or at least reserve them until I have satisfied myself that I can reply in a similar strain.”

A.—“Nay, it is too churlish to censure a harmless courtesy that has been adopted even by the greatest dramatists and novelists from the time of Shakspeare to the present day.”

R.—“It may be so; permit me, however, to request, in the words of one of those dramatists to whom you refer, that you will be so obliging as to

‘Forbear the prologue,

And let me know the substance of thy tale!’”

The Orphan.

CONTENTS

FIRST VOLUME

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | In Which the Reader Will Find a Sketch of a Village in the West, and Will Be Introduced to Some of the Dramatis Personæ. | 1 |

| II. | Containing an Account of the Marriage of Colonel Brandon, and Its Consequences. | 8 |

| III. | Containing Some Further Account of Colonel and Mrs. Brandon, and of the Education of Their Son Reginald. | 15 |

| IV. | Containing Sundry Adventures of Reginald Brandon and His Friend Ethelston on the Continent; Also Some Further Proceedings at Squire Shirley’s; and the Return of Reginald Brandon to His Home.—in This Chapter the Sporting Reader Will Find an Example of an Unmade Rider On a Made Hunter. | 20 |

| V. | An Adventure in the Woods.—reginald Brandon Makes the Acquaintance of an Indian Chief. | 31 |

| VI. | Reginald and Baptiste Pay a Visit to War–eagle.—an Attempt at Treachery Meets With Summary Punishment. | 39 |

| VII. | Containing Some Particulars of the History of the Two Delawares and of Baptiste. the Latter Returns With Reginald to Mooshanne, the Residence of Colonel Brandon. | 50 |

| VIII. | Containing a Sketch of Mooshanne.—reginald Introduces His Sister to the Two Delawares. | 59 |

| IX. | How Reginald Brandon Returned to Mooshanne With His Sister, Accompanied by Wingenund; and What Befell Them On the Road. | 71 |

| X. | In Which the Reader Is Unceremoniously Transported to Another Element in Company With Ethelston; the Latter Is Left in a Disagreeable Predicament. | 79 |

| XI. | Ethelston’s Further Adventures at Sea, and How He Became Captor and Captive in a Very Short Space of Time. | 87 |

| XII. | Visit of Wingenund to Mooshanne.—he Rejoins War–eagle, And They Return to Their Band in the Far West.—m. Perrot Makes an Unsuccessful Attack on the Heart of a Young Lady. | 97 |

| XIII. | In Which the Reader Will Find That the Couch of an Invalid Has Perils Not Less Formidable Than Those Which Are to Be Encountered at Sea. | 107 |

| XIV. | Narrating the Trials and Dangers That Beset Ethelston; And How He Escaped from Them, and from the Island of Guadaloupe. | 117 |

| XV. | What Took Place at Mooshanne During the Stay of Ethelston In Guadaloupe.—departure of Reginald For the Far–west. | 128 |

| XVI. | The Escape of Ethelston from Guadaloupe, and the Consequences Which Ensued from That Expedition. | 136 |

| XVII. | Excursion on the Prairie.—the Party Fall in With a Veteran Hunter. | 148 |

| XVIII. | Reginald and His Party Reach the Indian Encampment. | 156 |

SECOND VOLUME

| I. | Reginald and His Party at the Indian Encampment. | 165 |

| II. | Reginald Holds a Conversation With the Missionary. | 173 |

| III. | An Arrival at Mooshanne.—a Calm Ashore After a Storm At Sea. | 181 |

| IV. | An Elk–hunt.—reginald Makes His First Essay in Surgery.—the Reader Is Admitted Into Prairie–bird’s Tent. | 193 |

| V. | Symptoms of a Rupture Between the Delawares and Osages.—mahéga Comes Forward in the Character of a Lover.—his Courtship Receives an Unexpected Interruption. | 212 |

| VI. | Ethelston Prepares to Leave Mooshanne.—mahéga Appears As An Orator, in Which Character He Succeeds Better Than in That of a Lover.—a Storm Succeeded by a Calm. | 222 |

| VII. | In Which the Reader Will Find a Moral Disquisition Somewhat Tedious, a True Story Somewhat Incredible, a Conference That Ends in Peace, and a Council That Betokens War. | 239 |

| VIII. | War–eagle and Reginald, With Their Party, Pursue the Dahcotahs. | 257 |

| IX. | A Deserted Village in the West.—mahéga Carries Off Prairie–bird, and Endeavours to Baffle Pursuit. | 264 |

| X. | An Ambuscade.—reginald Brandon Finds His Horse, and M. Perrot Nearly Loses His Head.—while Indian Philosophy Is Displayed in One Quarter, Indian Credulity Is Exhibited in Another. | 273 |

| XI. | Ethelston Visits St. Louis, Where He Unexpectedly Meets An Old Acquaintance, and Undertakes a Longer Journey Than He Had Contemplated. | 290 |

| XII. | The Osages Encamp Near the Base of the Rocky Mountains.—an Unexpected Visitor Arrives. | 297 |

| XIII. | War–eagle’s Party Follow the Trail.—a Skirmish and Its Results.—the Chief Undertakes a Perilous Journey Alone, And His Companions Find Sufficient Occupation During His Absence. | 307 |

| XIV. | An Unexpected Meeting.—reginald Prepares to Follow the Trail. | 328 |

| XV. | Showing How Wingenund Fared in the Osage Camp, and the Issue of the Dilemma in Which Prairie–bird Was Placed by Mahéga. | 337 |

| XVI. | Mahéga Finds the Bodies of His Two Followers Slain by War–eagle.—some Reflections on the Indian Character.—war–eagle Returns to His Friends, and the Osage Chief Pushes His Way Further Into the Mountains. | 347 |

THIRD VOLUME

| I. | War–eagle and His Party Reach the Deserted Camp of the Osages.—the Latter Fall in With a Strange Band of Indians, and Mahéga Appears in the Character of a Diplomatist. | 367 |

| II. | Containing Various Incidents That Occurred to the Party Following the Trail.—plots and Counterplots, and a Discussion Upon Oratory, Which Is Very Much Out of Place, And, Fortunately For the Reader, Is Not Very Long. | 385 |

| III. | A Scene in the Tent of Prairie–bird, Who Gives Some Good Advice, and Receives in a Short Space of Time More Than One Unexpected Visitor.—the Crows Led by Mahéga Attack The Delaware Camp by Night.—the Defeated Party Achieve a Kind of Triumph, and the Victors Meet With an Unexpected Loss. | 403 |

| IV. | The Negotiation Set on Foot by Reginald For the Release Of His Friends.—besha Becomes an Important Personage. | 422 |

| V. | David Muir and His Daughter Pay a Visit to Colonel Brandon.—the Merchant Becomes Ambitious; He Entertains Projects For Jessie’s Future Welfare, Which Do Not Coincide With That Young Lady’s Wishes. | 430 |

| VI. | Besha Pursues His Career As a Diplomatist.—an Agreeable Tete–a–tete Disagreeably Interrupted.—the Steps That Mahéga Took to Support His Declining Interests Among the Crows. | 440 |

| VII. | Wingenund Devises a Plan For the Liberation of His Friends, and Seeks to Obtain by Means Equally Unusual and Effective the Co–operation of the One–eyed Horse–dealer.—a Further March Into the Mountains.—wingenund Pays a Visit to His Friends, and the Latter Make Acquaintance With a Strange Character. | 460 |

| VIII. | The Root–digger Makes Friends With the Party.—an Adventure With a Grisly Bear.—the Conduct of War–eagle. | 478 |

| IX. | Mahéga Is Found in Strange Company, and Wingenund Defers, On Account of More Important Concerns, His Plan For the Liberation of His Friends.—a Council, a Combat, and a Skirmish, in Which Last the Crows Receive Assistance from A Quarter Whence They Least Expected It. | 487 |

| X. | Wingenund and His Friends Return Towards Their Camp.—a Serious Adventure and a Serious Argument Occur by the Way.—showing, Also, How the Extremes of Grief, Surprise, And Joy May Be Crowded Into the Space of a Few Minutes. | 507 |

| XI. | Containing a Treaty Between the Crows and Delawares, and The Death of an Indian Chief. | 527 |

| XII. | War–eagle’s Funeral.—the Party Commence Their Homeward Journey.—Besha Exerts His Diplomatic Talents For the Last Time, and Receives Several Rewards, With Some of Which He Would Willingly Have Dispensed. | 540 |

| XIII. | The Scene Is Shifted to the Banks of the Muskingum, and Prairie–bird Returns to the Home of Her Childhood. | 553 |

| Supplementary Chapter. | 557 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Monsieur Perrot Is Scalped | Facing | Page | i |

| Wingenund and Lucy | ” | ” | 70 |

| Prairie–bird and Mahéga | ” | ” | 218 |

| Reginald and the Crow Chief | ” | ” | 313 |

| Mahéga Spying the Camp of the Delawares | ” | ” | 398 |

| War–eagle and the Grizzly Bear | ” | ” | 482 |

THE

PRAIRIE–BIRD.

CHAPTER I.

IN WHICH THE READER WILL FIND A SKETCH OF A VILLAGE IN THE WEST, AND WILL BE INTRODUCED TO SOME OF THE DRAMATIS PERSONÆ.

There is, perhaps, no country in the world more favoured, in respect to natural advantages, than the state of Ohio in North America: the soil is of inexhaustible fertility; the climate temperate; the rivers, flowing into Lake Erie to the north, and through the Ohio into the Mississippi to the south–west, are navigable for many hundreds of miles; the forests abound with the finest timber, and even the bowels of the earth pay, in various kinds of mineral, abundant contribution to the general wealth: the southern frontier of the state is bounded by the noble river from which she derives her name, and which obtained from the early French traders and missionaries the well–deserved appellation of “La Belle Rivière.”

Towns and cities are now multiplying upon its banks; the axe has laid low vast tracts of its forest; the plough has passed over many thousand acres of the prairies which it fertilised; and crowds of steam–boats, laden with goods, manufactures, and passengers, from every part of the world, urge their busy way through its waters.

Far different was the appearance and condition of that region at the period when the events detailed in the following narrative occurred. The reader must bear in mind that, at the close of the last century, the vast tracts of forest and prairie now[2] forming the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, were all included in what was then called the North–west Territory; it was still inhabited by numerous bands of Indian tribes, of which the most powerful were the Lenapé, or Delawares, the Shawanons, the Miamies, and the Wyandotes, or Hurons.

Here and there, at favourable positions on the navigable rivers, were trading–posts, defended by small forts, to which the Indians brought their skins of bear, deer, bison, and beaver; receiving in exchange powder, rifles, paint, hatchets, knives, blankets, and other articles, which, although unknown to their forefathers, had become to them, through their intercourse with the whites, numbered among the necessaries of life. But the above–mentioned animals, especially the two last, were already scarce in this region; and the more enterprising of the hunters, Indian as well as white men, made annual excursions to the wild and boundless hunting–ground, westward of the Mississippi.

At the close of the eighteenth century, the villages and settlements on the north bank of the Ohio, being scarce and far apart, were built rather for the purpose of trading with the Indians than for agriculture or civilised industry; and their inhabitants were as bold and hardy, sometimes as wild and lawless, as the red men, with whom they were beginning to dispute the soil.

Numerous quarrels arose between these western settlers and their Indian neighbours; blood was frequently shed, and fierce retaliation ensued, which ended in open hostility. The half–disciplined militia, aided sometimes by regular troops, invaded and burnt the Indian villages; while the red men, seldom able to cope with their enemy in the open field, cut off detached parties, massacred unprotected families; and so swift and indiscriminate was their revenge, that settlements, at some distance from the scene of war, were often aroused at midnight by the unexpected alarm of the war–whoop and the fire–brand. There were occasions, however, when the Indians boldly attacked and defeated the troops sent against them; but General Wayne, having taken the command of the western forces (about four years before the commencement of our tale), routed them at the battle of the Miamies with great slaughter; after which many of them went off to the Missain plains, and those who remained no more ventured to appear in the field against the United States.

One of the earliest trading ports established in that region was Marietta, a pretty village situated at the mouth of the Muskimgum river, where it falls into the Ohio. Even so far back as the year 1799 it boasted a church; several taverns; a strong block–house, serving as a protection against an attack from the Indians; stores for the sale of grocery; and, in short, such a collection of buildings as has, in more than one instance in the western states of America, grown into a city with unexampled rapidity.

This busy and flourishing village had taken the lead, of all others within a hundred miles, in the construction of vessels for the navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi; nay, some of the more enterprising merchants there settled, had actually built, launched, and freighted brigs and schooners of sufficient burthen to brave the seas of the Mexican gulf; and had opened, in their little inland port, a direct trade with the West Indian islands, to which they exported flour, pork, maize, and other articles, their vessels returning laden with fruit, coffee, sugar, and rum.

The largest store in the village, situated in the centre of a row of houses fronting the river, was built of brick, and divided into several compartments, wherein were to be found all the necessaries of life,—all such at least as were called for by the inhabitants of Marietta and its neighbourhood; one of these compartments was crowded with skins and furs from the north–west, and with clothes, cottons, and woollen stuffs from England; the second with earthenware, cutlery, mirrors, rifles, stoves, grates, &c.; while in the third, which was certainly the most frequented, were sold flour, tea, sugar, rum, whiskey, gunpowder, spices, cured pork, &c.; in a deep corner or recess of the latter was a trap–door, not very often opened, but which led to a cellar, wherein was stored a reasonable quantity of Madeira and claret, the quality of which would not have disgraced the best hotel in Philadelphia.

Over this multifarious property on sale presided David Muir, a bony, long–armed man, of about forty–five years of age, whose red bristly hair, prominent cheek bones, and sharp, sunken grey eyes, would, without the confirming evidence of his broad Scottish accent, have indicated to an experienced observer the country to which he owed his birth. In the duties of his employment, David was well seconded by his[4] helpmate, a tall, powerful woman, whose features, though strong and masculine, retained the marks of early beauty, and whose voice, when raised in wrath, reached the ears of every individual, even in the furthest compartment of the extensive store above described.

David was a shrewd, enterprising fellow, trustworthy in matters of business, and peaceable enough in temper; though in more than one affray, which had arisen in consequence of some of his customers, white men and Indians, having taken on the spot too much of his “fire–water,” he had shown that he was not to be affronted with impunity; nevertheless, in the presence of Mrs. Christie (so was his spouse called) he was gentle and subdued, never attempting to rebel against an authority which an experience of twenty years had proved to be irresistible. One only child, aged now about eighteen, was the fruit of their marriage; and Jessie Muir was certainly more pleasing in her manners and in her appearance than might have been expected from her parentage; she assisted her mother in cooking, baking, and other domestic duties; and, when not thus engaged, read or worked in a corner of the cotton and silk compartment, over which she presided. Two lads, engaged at a salary of four dollars a–week, to assist in the sale, care, and package of the goods, completed David’s establishment, which was perhaps the largest and the best provided that could be found westward of the Alleghany mountains.

It must not be supposed, however, that all this property was his own: it belonged for the most part to Colonel Brandon, a gentleman who resided on his farm, seven or eight miles from the village, and who entrusted David Muir with the entire charge of the stores in Marietta; the accounts of the business were regularly audited by the colonel once every year, and a fair share of the profits as regularly made over to David, whose accuracy and integrity had given much satisfaction to his principal.

Three of the largest trading vessels from the port of Marietta were owned and freighted by Colonel Brandon; the command and management of them being entrusted by him to Edward Ethelston, a young man who, being now in his twenty–eighth year, discharged the duties of captain and supercargo with the greatest steadiness, ability, and success.

As young Ethelston and his family will occupy a considerable[5] place in our narrative, it may be as well to detail briefly the circumstances which led to his enjoying so large a share of the Colonel’s affection and confidence.

About eleven years before the date mentioned as being that of the commencement of our tale, Colonel Brandon, having sold his property in Virginia, had moved to the north–west territory, with his wife and his two children, Reginald and Lucy. He had persuaded, at the same time, a Virginian friend, Digby Ethelston, who, like himself, was descended from an ancient royalist family in the mother country, to accompany him in this migration. The feelings, associations, and prejudices of both the friends had been frequently wounded during the war which terminated in the independence of the United States; for not only were both attached by those feelings and associations to the old country, but they had also near connections resident there, with whom they kept up a friendly intercourse.

It was not, therefore, difficult for Colonel Brandon to persuade his friend to join him in his proposed emigration. The latter, who was a widower, and who, like the colonel, had only two children, was fortunate in having under his roof a sister, who, being now past the prime of life, devoted herself entirely to the charge of her brother’s household. Aunt Mary (for she was known by no other name) expressed neither aversion nor alarm at the prospect of settling permanently in so remote a region; and the two families moved accordingly, with goods and chattels, to the banks of the Ohio.

The Colonel and his friend were both possessed of considerable property, a portion of which they invested in the fur companies, which at that time carried on extensive traffic in the north–west territory; they also acquired from the United States government large tracts of land at no great distance from Marietta, upon which each selected an agreeable site for his farm or country residence.

Their houses were not far apart, and though rudely built at first, they gradually assumed a more comfortable appearance; wings were added, stables enlarged, the gardens and peach–orchards were well fenced, and the adjoining farm–offices amply stocked with horses and cattle.

For two years all went on prosperously: the boys, Edward Ethelston and Reginald Brandon, were as fond of each other as their fathers could desire: the former, being three years[6] the senior, and possessed of excellent qualities of head and heart, controlled the ardent and somewhat romantic temper of Reginald: both were at school near Philadelphia: when on a beautiful day in June, Mr. Ethelston and Aunt Mary walked over to pay a visit to Mrs. Brandon, leaving little Evelyn (who was then about eight years old) with her nurse at home: they remained at Colonel Brandon’s to dine, and were on the point of returning in the afternoon, when a farm–servant of Mr. Ethelston’s rushed into the room where the two gentlemen were sitting alone; he was pale, breathless, and so agitated that he could not utter a syllable: “For heaven’s sake speak! What has happened?” exclaimed Colonel Brandon.

A dreadful pause ensued: at length, he rather gasped than said, “The Indians!” and buried his face in his hands, as if to shut out some horrid spectacle!

Poor Ethelston’s tongue clove to his mouth; the prescient agony of a father overcame him.

“What of the Indians, man?” said Colonel Brandon, angrily; “‘sblood, we have seen Indians enough hereabout before now;—what the devil have they been at?”

A groan and a shudder was the only reply.

The Colonel now lost all patience, and exclaimed, “By heavens, the sight of a red–skin seems to have frightened the fellow out of his senses! I did not know, Ethelston, that you trusted your farm–stock to such a chicken–heart as this!”

Incensed by this taunt, the rough lad replied, “Colonel for all as you be so bold, and have seen, as they say, a bloody field or two, you’d a’ been skeared if you’d a’ seen this job; but as for my being afeared of Ingians in an up and down fight, or in a tree skrimmage—I don’t care who says it—t’aint a fact.”

“I believe it, my good fellow,” said the Colonel; “but keep us no longer in suspense—say what has happened?”

“Why, you see, Colonel, about an hour ago, Jem and Eliab was at work in the ‘baccy–field behind the house, and nurse was out in the big meadow a walkin’ with Miss Evelyn, when I heard a cry as if all the devils had broke loose; in a moment, six or eight painted Ingians with rifles and tomahawks dashed out of the laurel thicket, and murdered poor Jem and Eliab before they could get at their rifles which stood[7] by the worm fence[1]; two of them then went after the nurse and child in the meadow, while the rest broke into the house, which they ransacked and set o’ fire!”

“But my child?” cried the agonised father.

“I fear it’s gone too,” said the messenger of this dreadful news. “I saw one devil kill and scalp the nurse, and t’other,”—here he paused, awe–struck by the speechless agony of poor Ethelston, who stood with clasped hands and bloodless lips, unable to ask for the few more words which were to complete his despair.

“Speak on, man, let us know the worst;” said the Colonel, at the same time supporting the trembling form of his unhappy friend.

“I seed the tomahawk raised over the sweet child, and I tried to rush out o’ my hidin’ place to save it, when the flames and the smoke broke out, and I tumbled into the big ditch below the garden, over head in water; by the time I got out and reached the place, the red devils were all gone, and the house, and straw, and barns all in a blaze!”

Poor Ethelston had only heard the first few words—they were enough—his head sunk upon his breast, his whole frame shuddered convulsively; and a rapid succession of inarticulate sounds came from his lips, among which nothing could be distinguished beyond “child,” “tomahawk,” “Evelyn.”

It is needless to relate in detail all that followed this painful scene; the bodies of the unfortunate labourers and of the nurse were found; all had been scalped; that of the child was not found; and though Colonel Brandon himself led a band of the most experienced hunters in pursuit, the trail of the savages could not be followed: with their usual wily foresight they had struck off through the forest in different directions, and succeeded in baffling all attempts at discovering either their route or their tribe. Messengers were sent to the trading–posts at Kaskaskia, Vincennes, and even to Genevieve, and St. Louis, and all returned dispirited by a laborious and fruitless search.

Mr. Ethelston never recovered this calamitous blow: several fits of paralysis, following each other in rapid succession, carried[8] him off within a few months. By his will he appointed a liberal annuity to Aunt Mary, and left the remainder of his property to his son Edward, but entirely under the control and guardianship of Colonel Brandon.

The latter had prevailed upon Aunt Mary and her young nephew to become inmates of his house; where, after the soothing effect of time had softened the bitterness of their grief, they found the comforts, the occupations, the endearments, the social blessings embodied in the word “home.” Edward became more fondly attached than ever to his younger companion Reginald; and Aunt Mary, besides aiding Mrs. Brandon in the education of her daughter, found time to knit, to hem, to cook, to draw, to plant vegetables, to rear flowers, to read, to give medicine to any sick in the neighbourhood, and to comfort all who, like herself, had suffered under the chastising hand of Providence.

Such were the circumstances which (eleven years before the commencement of this narrative) had led to the affectionate and paternal interest which the Colonel felt for the son of his friend, and which was increased by the high and estimable qualities gradually developed in Edward’s character. Before proceeding further in our tale, it is necessary to give the reader some insight into the early history of Colonel Brandon himself, and into those occurrences in the life of his son Reginald which throw light upon the events hereafter to be related.

CHAPTER II.

CONTAINING AN ACCOUNT OF THE MARRIAGE OF COLONEL BRANDON, AND ITS CONSEQUENCES.

George Brandon was the only son of a younger brother, a scion of an ancient and distinguished family: they had been, for the most part, staunch Jacobites, and George’s father lost the greater part of his property in a fruitless endeavour to support the ill–timed and ill–conducted expedition of Charles Edward, in 1745.

After this he retired to the Continent and died, leaving to[9] his son little else besides his sword, a few hundred crowns, and an untarnished name. The young man returned to England; and, being agreeable, accomplished, and strikingly handsome, was kindly received by some of his relations and their friends.

During one of the visits that he paid at the house of a neighbour in the country, he fell desperately in love with Lucy Shirley, the daughter of the richest squire in the country, a determined Whig, and one who hated a Jacobite worse than a Frenchman. As George Brandon’s passion was returned with equal ardour, and the object of it was young and inexperienced as himself, all the obstacles opposed to their union only served to add fuel to the flame; and, after repeated but vain endeavours on the part of Lucy Shirley to reconcile her father, or her only brother, to the match, she eloped with her young lover; and, by a rapid escape into Scotland, where they were immediately married, they rendered abortive all attempt at pursuit.

It was not long before the young couple began to feel some of the painful consequences of their imprudence. The old squire was not to be appeased; he would neither see his daughter, nor would he open one of the many letters which she wrote to entreat his forgiveness: but, although incensed, he was a proud man and scrupulously just in all his dealings: Lucy had been left 10,000l. by her grand–mother, but it was not due to her until she attained her twenty–first year, or married with her father’s consent. The squire waved both these conditions; he knew that his daughter had fallen from a brilliant sphere to one comparatively humble. Even in the midst of his wrath he did not wish her to starve, and accordingly instructed his lawyer to write to Mrs. Brandon, and to inform her that he had orders to pay her 500l. a–year, until she thought fit to demand the payment of the principal.

George and his wife returned, after a brief absence, to England, and made frequent efforts to overcome, by entreaty and submission, the old squire’s obduracy; but it was all in vain: neither were they more successful in propitiating the young squire, an eccentric youth, who lived among dogs and horses, and who had imbibed from his father an hereditary taste for old port, and an antipathy to Jacobites. His reply to a letter which George wrote, entreating his good offices in effecting a reconciliation between Lucy and her father, will serve[10] better than an elaborate description to illustrate his character; it ran as follows:—

“Sir,

“When my sister married a Jacobite, against Father’s consent, she carried her eggs to a fool’s market, and she must make the best of her own bargain. Father isn’t such a flat as to be gulled with your fine words now: and tho’ they say I’m not over forw’rd in my schoolin’, you must put some better bait on your trap before you catch

“Marmaduke Shirley, Jun.”

It may well be imagined, that after the receipt of this epistle George Brandon did not seek to renew his intercourse with Lucy’s brother: but as she had now presented him with a little boy, he began to meditate seriously on the means which he should adopt to better his fortunes.

One of his most intimate and esteemed friends, Digby Ethelston, being, like himself, a portionless member of an ancient family, had gone out early in life to America, and had, by dint of persevering industry, gained a respectable competence: while in the southern colonies he had married the daughter of an old French planter, who had left the marquisate to which he was entitled in his own country, in order to live in peace and quiet among the sugar–canes and cotton–fields of Louisiana. Ethelston had received with his wife a considerable accession of fortune, and they were on the eve of returning across the Atlantic, her husband having settled all the affairs which had brought him to England.

His representations of the New World made a strong impression on the sanguine mind of George Brandon, and he proposed to his wife to emigrate with their little one to America. Poor Lucy, cut off from her own family, and devoted to her husband, made no difficulty whatever, and it was soon settled that they should accompany the Ethelstons.

George now called upon Mr. Shirley’s solicitor, a dry, matter–of–fact, parchment man, to inform him of their intention, and of their wish that the principal of Lucy’s fortune might be paid up. The lawyer took down a dusty box of black tin whereon was engraved “Marmaduke Shirley, Esq., Shirley Hall, No. 7.”; and after carefully perusing a paper of instructions, he said, “Mrs. Brandon’s legacy shall be paid[11] up, sir, on the 1st of July, to any party whom she may empower to receive it on her behalf, and to give a legal discharge for the same.”

“And pray, sir,” said George, hesitating, “as we are going across the Atlantic, perhaps never to return, do you not think Mr. Shirley would see his daughter once before she sails, to give her his blessing?”

Again the man of parchment turned his sharp nose towards the paper, and having scanned its contents, he said, “I find nothing, sir, in these instructions on that point. Good morning, Mr. Brandon.—James, show in Sir John Waltham.”

George walked home dispirited, and the punctual solicitor failed not to inform the squire immediately of the young couple’s intended emigration, and the demand for the paying up of the sum due to Lucy. In spite of his long–cherished prejudices against George Brandon’s Jacobite family, and his anger at the elopement, he was somewhat softened by time, by what he heard of the blameless life led by the young man, and by the respectful conduct that the latter had evinced towards his wife’s family; for it had happened on one occasion that some of his young companions had thought fit to speak of the obstinacy and stinginess of the old squire: this language George had instantly and indignantly checked, saying, “My conduct in marrying his daughter against his consent, was unjustifiable: though he has not forgiven her, has he behaved justly and honourably. Any word spoken disrespectfully of my wife’s father, I shall consider a personal insult to myself.”

This had accidentally reached the ears of the old squire; and though still too proud and too obstinate to agree to any reconciliation, he said to the solicitor: “Perkins, I will not be reconciled to these scapegraces; I will have no intercourse with them, but I will see Lucy before she goes; she must not see me. Arrange it as you please: desire her to come to your house to sign the discharge for the 10,000l., in person; you can put me in a cupboard, in the next room; where you will; a glass door will do;—you understand?”

“Yes, sir. When?”

“Oh, the sooner the better; whenever the papers are ready.”

“It shall be done, sir.” And thus the interview closed.

Meantime George made one final effort in a letter, which he addressed to the squire, couched in terms at once manly and respectful; owning the errors that he had committed, but hoping that forgiveness might precede this long, this last separation.

This letter was returned to him unopened; and, in order to conceal from Lucy the grief and mortification of his high and wounded spirit, he was obliged to absent himself from home for many hours; and when he did return, it was with a clouded brow.

Certainly the fate of this young couple, though not altogether prosperous, was in one particular a remarkable exception to the usual results of a runaway match; they were affectionately and entirely devoted to each other: and Lucy, though she had been once, and only once, a disobedient daughter, was the most loving and obedient of wives.

The day fixed for her signature arrived. Mr. Perkins had made all his arrangements agreeably to his wealthy client’s instructions; and when, accompanied by her husband, she entered the solicitor’s study, she was little conscious that her father was separated from her only by a frail door, which being left ajar, he could see her, and hear every word that she spoke.

Mr. Perkins, placing the draft of the discharge into George Brandon’s hand, together with the instrument whereby his wife was put in possession of the 10,000l., said to him, “Would it not be better, sir, to send for your solicitor to inspect these papers on behalf of yourself and Mrs. Brandon, before she signs the discharge?”

“Allow me to inquire, sir,” replied George, “whether Mr. Shirley has perused these papers, and has placed them here for his daughter’s signature?”

“Assuredly, he has, sir,” said the lawyer, “and I have too, on his behalf; you do not imagine, sir, that my client would pay the capital sum without being certain that the discharge was regular and sufficient!”

“Then I am satisfied, sir,” said George, with something of disdain expressed on his fine countenance. “Mr. Shirley is a man of honour, and a father; whatever he has sent for his daughter’s signature will secure her interests as effectually as if a dozen solicitors had inspected it.”

At the conclusion of this speech, a sort of indistinct hem proceeded from the ensconced squire; to cover which, Mr.[13] Perkins said, “But, sir, it is not usual to sign papers of this consequence without examining them.”

“Lucy, my dear,” said George, turning with a smile of affectionate confidence to his wife; “to oblige Mr. Perkins, I will read through these two papers attentively: sit down for a minute, as they are somewhat long:” so saying, he applied himself at once to his task.

Meantime Lucy, painfully agitated and excited, made several attempts to address Mr. Perkins; but her voice failed her, as soon as she turned her eyes upon that gentleman’s rigid countenance: at length, however, by a desperate effort, she succeeded in asking, tremulously, “Mr. Perkins, have you seen my father lately?”

“Yes, ma’am,” said the lawyer nibbing his pen.

“Oh! tell me how he is!—Has the gout left him?—Can he ride to the farm as he used?”

“He is well, madam, very well, I believe.”

“Shall you see him soon again, sir?”

“Yes, madam, I must show him these papers, when signed.”

“Oh! then, tell him, that his daughter, who never disobeyed him but once, has wept bitterly for her fault; that she will probably never see him again, in this world; that she blesses him in her daily prayers. Oh! tell him, I charge you as you are a man, tell him, that I could cross the ocean happy—that I could bear years of sickness, of privation, happy—that I could die happy, if I had but my dear, dear father’s blessing.” As she said this, the young wife had unconsciously fallen upon one knee before the man of law, and her tearful eyes were bent upon his countenance in earnest supplication.

Again an indistinct noise, as of a suppressed groan or sob, was heard from behind the door, and the solicitor wiping his spectacles and turning away his face to conceal an emotion of which he felt rather ashamed, said: “I will tell him all you desire, madam; and if I receive his instructions to make any communication in reply, I will make it faithfully, and without loss of time.”

“Thank you, thank you a thousand times,” said Lucy: and resuming her seat, she endeavoured to recover her composure.

George had by this time run his eye over the papers; and although he had overheard his wife’s appeal to the solicitor, he would not interrupt her, nor throw any obstacle in the way of an object which he knew she had so much at heart. “I am perfectly satisfied, sir,” said he; “you have nothing to do but to provide the witnesses, and Mrs. Brandon will affix her signature.”

Two clerks of Mr. Perkins’ were accordingly summoned, and the discharge having been signed in their presence, they retired. Mr. Perkins now drew another paper from the leaves of a book on his table, saying: “Mr. Brandon, the discharge being now signed and attested, I have further instructions from Mr. Shirley to inform you, that although he cannot alter his determination of refusing to see his daughter, or holding any intercourse with yourself, he is desirous that you should not in America find yourself in straitened circumstances; and has accordingly authorised me to place in your hands this draft upon his banker for 5000l.”

“Mr. Perkins,” said George, in a tone of mingled sadness and pride; “in the payment of the 10,000l., my wife’s fortune, Mr. Shirley, though acting honourably, has only done justice, and has dealt as he would have dealt with strangers; had he thought proper to listen to my wife’s, or to my own repeated entreaties for forgiveness and reconciliation, I would gratefully have received from him, as from a father, any favour that he wished to confer on us; but, sir, as he refuses to see me under his roof, or even to give his affectionate and repentant child a parting blessing, I would rather work for my daily bread than receive at his hands the donation of a guinea.”

As he said this, he tore the draft and scattered its shreds on the table before the astonished lawyer. Poor Lucy was still in tears, yet one look assured her husband that she felt with him. He added in a gentler tone, “Mr. Perkins, accept my acknowledgments for your courtesy;” and, offering his arm to Lucy, turned to leave the room.

CHAPTER III.

CONTAINING SOME FURTHER ACCOUNT OF COLONEL AND MRS. BRANDON, AND OF THE EDUCATION OF THEIR SON REGINALD.

While the scene described in the last chapter was passing in the lawyer’s study, stormy and severe was the struggle going on in the breast of the listening father; more than once he had been on the point of rushing into the room to fold his child in his arms; but that obstinate pride, which causes in life so many bitter hours of regret, prevented him, and checked the natural impulse of affection: still, as she turned with her husband to leave the room, he unconsciously opened the door on the lock of which his hand rested, as he endeavoured to get one last look at a face which he had so long loved and caressed. The door being thus partially opened, a very diminutive and favourite spaniel, that accompanied him wherever he went, escaped through the aperture, and, recognising Lucy, barked and jumped upon her in an ecstasy of delight.

“Heavens!” cried she, “it is—it must be Fan!” At another time she would have fondly caressed it, but one only thought now occupied her: trembling on her husband’s arm, she whispered, “George, papa must be here.” At that moment her eye caught the partially opened door, which the agitated squire still held, and breaking from her husband, she flew as if by instinct into the adjacent room, and fell at her father’s feet.

Poor Mr. Perkins was now grievously disconcerted; and calling out, “This way, madam, this way; that is not the right door,” was about to follow, when George Brandon, laying his hand upon the lawyer’s arm, said, impressively,

“Stay, sir; that room is sacred!” and led him back to his chair. His quick mind had seized in a moment the correctness of Lucy’s conjecture, and his good feeling taught him that no third person, not even he, should intrude upon the father and the child.

The old squire could not make a long resistance when the gush of his once loved Lucy’s tears trickled upon his hand, and while her half–choked voice sobbed for his pardon and his blessing; it was in vain that he summoned all his pride, all[16] his strength, all his anger; Nature would assert her rights; and in another minute his child’s head was on his bosom, and he whispered over her, “I forgive you, Lucy: may God bless you, as I do!”

For some time after this was the interview prolonged, and Lucy seemed to be pleading for some boon which she could not obtain; nevertheless, her tears, her old familiar childish caresses, had regained something of their former dominion over the choleric but warm–hearted squire; and in a voice of joy that thrilled even through the quiet man of law, she cried, “George! George, come in!” He leaped from his seat, and in a moment was at the feet of her father. There, as he knelt by Lucy’s side, the old squire put one hand upon the head of each, saying, “My children, all that you have ever done to offend me is forgotten: continue to love and to cherish each other, and may God prosper you with every blessing!” George Brandon’s heart was full: he could not speak; but straining his wife affectionately to his bosom, and kissing her father’s hand, he withdrew into a corner of the room, and for some minutes remained oppressed by emotions too strong to find relief in expressions.

We need not detail at length the consequences of this happy and unexpected reconciliation. The check was re–written, was doubled, and was accepted. George still persevered in his wish to accompany his friend to Virginia; where, Ethelston assured him, that with his 20,000l. prudently managed, he might easily acquire a sufficient fortune for himself and his family.

How mighty is the power of circumstance; and upon what small pivots does Providence sometimes allow the wheels of human fortune to be turned! Here, in the instance just related, the blessing or unappeased wrath of a father, the joy or despair of a daughter, the peace or discord of a family, all, all were dependent upon the bark and caress of a spaniel! For that stern old man had made his determination, and would have adhered to it, if Lucy had not thus been made aware of his presence, and, by her grief aiding the voice of nature, overthrown all the defences of his pride.

It happened that the young squire was at this time in Paris, his father having sent him thither to see the world and learn to fence. A letter was, however, written by Lucy, announcing[17] to him the happy reconciliation, and entreating him to participate in their common happiness.

The arrangements for the voyage were soon completed; the cabin of a large vessel being engaged to convey the whole party to Norfolk in Virginia. The old squire offered no opposition, considering that George Brandon was too old to begin a profession in England, and that he might employ his time and abilities advantageously in the New World.

We may pass over many of the ensuing years, the events of which have little influence on our narrative, merely informing the reader that the investment of Brandon’s money, made by the advice of Ethelston, was prosperous in the extreme. In the course of a year or two, Mrs. Brandon presented her lord with a little girl, who was named after herself. In the following year, Mrs. Ethelston had also a daughter: the third confinement was not so fortunate, and she died in childbed, leaving, to Ethelston, Edward, then about nine, and little Evelyn a twelvemonth old.

It was on this sad occasion that he persuaded his sister to come out from England to reside with him, and take care of his motherless children: a task that she undertook and fulfilled with the love and devotion of the most affectionate mother.

In course of time the war broke out which ended in the independence of the colonies. During its commencement, Brandon and Ethelston both remained firm to the crown; but as it advanced, they became gradually convinced of the impolicy and injustice of the claims urged by England. Brandon having sought an interview with Washington, the arguments, and the character, of that great man decided him: he joined the Independent party, obtained a command, and distinguished himself so much as to obtain the esteem and regard of his commander. As soon as peace was established, he had, for reasons before stated, determined to change his residence, and persuaded Ethelston to accompany him with his family.

After the dreadful domestic calamity mentioned in the first chapter, and the untimely death of Ethelston, Colonel Brandon sent Edward, the son of his deceased friend, to a distant relative in Hamburgh, desiring that every care might be given to give him a complete mercantile and liberal education, including two years’ study at a German university.

Meanwhile the old Squire Shirley was dead; but his son[18] and successor had written, after his own strange fashion, a letter to his sister, begging her to send over her boy to England, and he would “make a man of him.” After duly weighing this proposal, Colonel and Mrs. Brandon determined to avail themselves of it; and Reginald was accordingly sent over to his uncle, who had promised to enter him immediately at Oxford.

When Reginald arrived, Marmaduke Shirley turned him round half a dozen times, felt his arms, punched his ribs, looked at his ruddy cheeks and brown hair, that had never known a barber, and exclaimed to a brother sportsman who was standing by, “D—n if he ain’t one of the right sort! eh, Harry?” But if the uncle was pleased with the lad’s appearance, much more delighted was he with his accomplishments: for he could walk down any keeper on the estate, he sat on a horse like a young centaur, and his accuracy with a rifle perfectly confounded the squire. “If this isn’t a chip of the old block, my name isn’t Marmaduke Shirley,” said he; and for a moment a shade crossed his usually careless brow, as he remembered that he had wooed, and married, and been left a childless widower.

But although, at Shirley Hall, Reginald followed the sports of the field with the ardour natural to his age and character, he rather annoyed the squire by his obstinate and persevering attention to his studies at college: he remembered that walking and shooting were accomplishments which he might have acquired and perfected in the woods of Virginia; but he felt it due to his parents, and to the confidence which they had reposed in his discretion, to carry back with him some more useful knowledge and learning.

With this dutiful motive, he commenced his studies; and as he advanced in them, his naturally quick intellect seized on and appreciated the beauties presented to it. Authors, in whose writings he had imagined and expected little else but difficulties, soon became easy and familiar; and what he had imposed upon himself from a high principle as a task, proved, ere long, a source of abundant pleasure.

In the vacations he visited his good–humoured uncle, who never failed to rally him as a “Latin–monger” and a book–worm: but Reginald bore the jokes with temper not less merry than his uncle’s; and whenever, after a hard run, he[19] had “pounded” the squire or the huntsman, he never failed to retaliate by answering the compliments paid him on his riding with some such jest as, “Pretty well for a book–worm, uncle.” It soon became evident to all the tenants, servants, and indeed to the whole neighbourhood, that Reginald exercised a despotic influence over the squire, who respected internally those literary attainments in his nephew which he affected to ridicule.

When Reginald had taken his degree, which he did with high honour and credit, he felt an ardent desire to visit his friend and school–fellow, Edward Ethelston, in Germany: he was also anxious to see something of the Continent, and to study the foreign languages. This wish he expressed without circumlocution to the squire, who received the communication with undisguised disapprobation: “What the devil can the boy want to go abroad for? not satisfied with wasting two or three years poking over Greek, Latin, mathematics, and other infernal ‘atics’ and ‘ologies,’ now you must go across the Channel to eat sour–krout, soup–maigre, and frogs! I won’t hear of it, sir;” and in order to keep his wrath warm, the squire poked the fire violently.

In spite of this determination, Reginald, as usual, carried his point, and in a few weeks was on board a packet bound for Hamburgh, his purse being well filled by the squire, who told him to see all that could be seen, and “not to let any of those Mounseers top him at any thing.” Reginald was also provided with letters of credit to a much larger amount than he required; but the first hint which he gave of a wish to decline a portion of the squire’s generosity raised such a storm, that our hero was fain to submit.

CHAPTER IV.

CONTAINING SUNDRY ADVENTURES OF REGINALD BRANDON AND HIS FRIEND ETHELSTON ON THE CONTINENT; ALSO SOME FURTHER PROCEEDINGS AT SQUIRE SHIRLEY’S; AND THE RETURN OF REGINALD BRANDON TO HIS HOME.—IN THIS CHAPTER THE SPORTING READER WILL FIND AN EXAMPLE OF AN UNMADE RIDER ON A MADE HUNTER.

Reginald having joined his attached and faithful friend Ethelston at Hamburgh, the young men agreed to travel together; and the intimacy of their early boyhood ripened into a mature friendship, based upon mutual esteem. In personal advantages, Reginald was greatly the superior; for although unusually tall and strongly built, such was the perfect symmetry of his proportions, that his height, and the great muscular strength of his chest and limbs, were carried off by the grace with which he moved, and by the air of high breeding by which he was distinguished: his countenance was noble and open in expression; and though there was a fire in his dark eye which betokened passions easily aroused, still there was a frankness on the brow, and a smile around the mouth, that told of a nature at once kindly, fearless, and without suspicion.

Ethelston, who was, be it remembered, three years older than his friend, was of middle stature, but active, and well proportioned: his hair and eyebrows were of the jettest black, and his countenance thoughtful and grave; but there was about the full and firm lip an expression of determination not to be mistaken. Habits of study and reflection had already written their trace upon his high and intellectual brow; so that one who saw him for the first time might imagine him only a severe student; but ere he had seen him an hour in society, he would pronounce him a man of practical and commanding character. The shade of melancholy, which was almost habitual on his countenance, dated from the death of his father, brought prematurely by sorrow to his grave, and from the loss of his little sister, to whom he had been tenderly attached. The two friends loved each other with the affection of brothers; and after the separation of the last few years, each found in the other newly developed qualities to esteem.

The state of Europe during the autumn of 1795 not being favourable for distant excursions, Ethelston contented himself with showing his friend all objects worthy of his attention in the north of Germany, and at the same time assisted him in attaining its rich though difficult language. By associating much, during the winter, with the students from the universities, Reginald caught some of their enthusiasm respecting the defence of their country from the arms of the French republic: he learnt that a large number of Ethelston’s acquaintances at Hamburgh had resolved in the spring to join a corps of volunteers from the Hanseatic towns, destined to fight under the banner of the Archduke Charles: to their own surprise, our two friends were carried away by the stream, and found themselves enrolled in a small but active and gallant band of sharpshooters, ordered to act on the flank of a large body of Austrian infantry. More than once the impetuous courage of Reginald had nearly cost him his life; and in the action at Amberg, where the Archduke defeated General Bernadotte, he received two wounds, such as would have disabled a man of less hardy constitution. It was in vain that Ethelston, whose bravery was tempered by unruffled coolness, urged his friend to expose himself less wantonly; Reginald always promised it, but in the excitement of the action always forgot the promise.

After he had recovered from his wounds, his commanding officer, who had noticed his fearless daring, a quality so valuable in the skirmishing duty to which his corps were appointed, sent for him, and offered to promote him. “Sir,” said Reginald, modestly, “I thank you heartily, but I must decline the honour you propose to me. I am too inexperienced to lead others; my friend and comrade, Ethelston, is three years my senior; in action he is always by my side, sometimes before me; he has more skill or riper judgment; any promotion, that should prefer me before him, would be most painful to me.” He bowed and withdrew. On the following day, the same officer, who had mentioned Reginald’s conduct to the Archduke, presented both the friends, from him, with a gold medal of the Emperor; a distinction the more gratifying to Reginald, from his knowledge that he had been secretly the means of bringing his friend’s merit into the notice of his commander.

They served through the remainder of that campaign, when[22] the arms of the contending parties met with alternate success: towards its close, the Archduke having skilfully effected his object of uniting his forces to the corps d’armée under General Wartenleben, compelled the French to evacuate Franconia, and to retire towards Switzerland.

This retreat was conducted with much skill by General Moreau; several times did the French rear–guard make an obstinate stand against the pursuers, among whom Reginald and his comrades were always the foremost. On one occasion, the French army occupied a position so strong that they were not driven from it without heavy loss on both sides; and even after the force of numbers had compelled the main body to retire, there remained a gallant band who seemed resolved to conquer or die upon the field. In vain did the Austrian leaders, in admiration of their devoted valour, call to them to surrender: without yielding an inch of ground, they fell fighting where they stood. Reginald made the most desperate efforts to save their young commander, whose chivalrous appearance and brilliantly decorated uniform made him remarkable from a great distance: several times did he strike aside a barrel pointed at the French officer; but it was too late; and when at length, covered with dust, and sweat, and blood, he reached the spot, he found the young hero, whom he had striven to save, stretched on the ground by several mortal wounds in his breast; he saw, however, Reginald’s kind intention, smiled gratefully upon him, waved his sword over his head, and died.

The excitement of the battle was over; and leaning on his sword, Reginald still bent over the noble form and marble features of the young warrior at his feet; and he sighed deeply when he thought how suddenly had this flower of manly beauty been cut down. “Perhaps,” said he, half aloud, “some now childless mother yet waits for this last prop of her age and name; or some betrothed lingers at her window, and wonders why he so long delays.”

Ethelston was at his side, his eyes also bent sadly upon the same object: the young friends interchanged a warm and silent grasp of the hand, each feeling that he read the heart of the other! At this moment, a groan escaped from a wounded man, who was half buried under the bleeding bodies of his comrades: with some difficulty Reginald dragged him out from below them, and the poor fellow thanked him for his humanity:[23] he had only received a slight wound on the head from a spent ball, which had stunned him for the time; but he soon recovered from its effects, and looking around, he saw the body of the young commander stretched on the plain.

“Ah, mon pauvre Général!” he exclaimed: and on further inquiry, Reginald learnt that it was indeed the gallant, the admired, the beloved General Marceau, whose brilliant career was thus untimely closed.

“I will go,” whispered Ethelston, “and bear these tidings to the Archduke; meantime, Reginald, guard the honoured remains from the camp–spoiler and the plunderer.” So saying he withdrew: and Reginald, stooping over the prostrate form before him, stretched it decently, closed the eyes, and, throwing a mantle over the splendid uniform, sat down to indulge in the serious meditations inspired by the scene.

He was soon aroused from them by the poor fellow whom he had dragged forth, who said to him, “Sir, I yield myself your prisoner.”

“And who are you, my friend?”

“I was courier, valet, and cook to M. de Vareuil, aide–de–camp to the General Marceau; both lie dead together before you.”

“And what is your name, my good fellow?”

“Gustave Adolphe Montmorenci Perrot.”

“A fair string of names, indeed,” said Reginald, smiling. “But pray, Monsieur Perrot, how came you here? are you a soldier as well as a courier?”

“Monsieur does me too much honour,” said the other, shrugging his shoulders. “I only came from the baggage–train with a message to my master, and your avant–garde peppered us so hotly that I could not get back again. I am not fond of fighting: but somehow, when I saw poor Monsieur de Vareuil in so sad a plight, I did not wish to leave him.”

Reginald looked at the speaker, and thought he had never seen in one face such a compound of slyness and honesty, drollery and sadness. He did not, however, reply, and relapsed into his meditation. Before five minutes had passed, Monsieur Perrot, as if struck by a sudden idea, fell on his knees before Reginald, and said,

“Monsieur has saved my life—will he grant me yet one favour?”

“If within my power,” said Reginald, good–humouredly.

“Will Monsieur take me into his service? I have travelled over all Europe; I have lived long in Paris, London, Vienna; I may be of use to Monsieur; but I have no home now.”

“Nay, but Monsieur Perrot, I want no servant; I am only a volunteer with the army.”

“I see what Monsieur is,” said Perrot, archly, “in spite of the dust and blood with which he is disfigured. I will ask no salary; I will share your black bread, if you are poor, and will live in your pantry, if you are rich: I only want to serve you.”

Monsieur Perrot’s importunity overruled all the objections that Reginald could raise; and he at last consented to the arrangement, provided the former, after due reflection, should adhere to his wish.

Ethelston meanwhile returned with the party sent by the Archduke to pay the last token of respect to the remains of the youthful General. They were interred with all the military honours due to an officer whose reputation was, considering his years, second to none in France, save that of Napoleon himself.

After the ceremony, Monsieur Perrot, now on parole not to bear arms against Austria, obtained leave to return to the French camp for a week, in order to “arrange his affairs,” at the expiration of which he promised to rejoin his new master. Ethelston blamed Reginald for his thoughtlessness in engaging this untried attendant. The latter, however, laughed at his friend, and said, “Though he is such a droll–looking creature, I think there is good in him; at all events, rest assured I will not trust him far without trial.”

A few weeks after these events, General Moreau having effected his retreat into Switzerland, an armistice was concluded on the Rhine between the contending armies; and Reginald could no longer resist the imperative commands of his uncle to return to Shirley Hall. Monsieur Gustave Adolphe Montmorenci Perrot had joined his new master, with a valise admirably stocked, and wearing a peruke of a most fashionable cut. Ethelston shrewdly suspected that these had formed part of Monsieur de Vareuil’s wardrobe, and his dislike of Reginald’s foppish valet was not thereby diminished.

On the route to Hamburgh the friends passed through many places where the luxuries, and even the necessaries of life, had been rendered scarce by the late campaign. Here Perrot was in his element; fatigue seemed to be unknown to him; he was always ready, active, useful as a courier, and unequalled as a cook or a caterer; so that Ethelston was compelled to confess, that if he only proved honest, Reginald had indeed found a treasure.

At Hamburgh the two friends took an affectionate farewell, promising to meet each other in the course of the following year on the banks of the Ohio. Reginald returned to his uncle, who stormed dreadfully when he learnt that he had brought with him a French valet, and remained implacable, in spite of the circumstances under which he had been engaged; until one morning, when a footman threw down the tray on which he was carrying up the squire’s breakfast of beef–steaks and stewed kidneys, half an hour before “the meet” at his best cover–side. What could now be done? The cook was sulky, and sent word that there were no more steaks nor kidneys to be had. The squire was wrath and hungry. Reginald laughed, and said, “Uncle, send for Perrot.”

“Perrot be d—d!” cried the squire. “Does the boy think I want some pomatum? What else can that coxcomb give me?”

“May I try him, uncle?” said Reginald, still laughing.

“You may try him: but if he plays any of his jackanapes pranks, I’ll tan his hide for him, I promise you!”

Reginald having rung for Perrot, pointed to the remains of the good things which a servant was still gathering up, and said to him, “Send up breakfast for Mr. Shirley and myself in one quarter of an hour from this minute: you are permitted to use what you find in the larder; but be punctual.”

Perrot bowed, and, without speaking, disappeared.

“The devil take the fellow! he has some sense,” said the angry squire; “he can receive an order without talking; one of my hulking knaves would have stood there five minutes out of the fifteen, saying, ‘Yes, sir; I’ll see what can be done;’ or, ‘I’ll ask Mr. Alltripe,’ or some other infernal stuff. Come, Reginald, look at your watch. Let us stroll to the stable; we’ll be back to a minute; and if that fellow plays any of his French tricks upon me, I’ll give it him.” So saying, the[26] jolly squire cut the head off one of his gardener’s favourite plants with his hunting whip, and led the way to the stable.

We may now return to Monsieur Perrot, and see how he set about the discharge of his sudden commission; but it may be necessary, at the same time, to explain one or two particulars not known to his master or to the squire. Monsieur Perrot was very gallant, and his tender heart had been smitten by the charms of Mary, the still–room maid; it so happened on this very morning that he had prepared slyly, as a surprise, a little déjeûner à la fourchette, with which he intended to soften Mary’s obduracy. We will not inquire how he had obtained the mushroom, the lemon, and the sundry other good things with which he was busily engaged in dressing a plump hen–pheasant, when he received the above unexpected summons. Monsieur Perrot’s vanity was greater than either his gourmandise or his love; and, without hesitation, he determined to sacrifice to it the hen–pheasant: his first step was to run to the still–room; and having stolen a kiss from Mary, and received a box on the ear as a reward, he gave her two or three very brief but important hints for the coffee, which was to be made immediately; he then turned his attention to the hen–pheasant, sliced some bacon, cut up a ham, took possession of a whole basket of eggs, and flew about the kitchen with such surprising activity, and calling for so many things at once, that Mr. Alltripe left his dominion, and retired to his own room in high dudgeon.

Meanwhile the squire, having sauntered through the stables with Reginald, and enlightened him with various comments upon the points and qualities of his favourite hunters, took out his watch, and exclaimed, “The time is up, my boy; let us go in and see what your precious mounseer has got for us.” As they entered the library, Monsieur opened the opposite door, and announced breakfast as quietly and composedly as if no unusual demand had been made upon his talents. The squire led the way into the breakfast–room, and was scarcely more surprised than was Reginald himself at the viands that regaled his eye on the table. In addition to the brown and white loaves, the rolls, and other varieties of bread, there smoked on one dish the delicate salmi of pheasant, on another the squire’s favourite dish of bacon, with poached eggs, and on a third a most tempting omelette au jambon.

Marmaduke Shirley opened his eyes and mouth wide with astonishment, as Monsieur Perrot offered him, one after another, these delicacies, inquiring, with undisturbed gravity, if “Monsieur desired any thing else? as there were other dishes ready below?”

“Other dishes! why, man, here’s a breakfast for a court of aldermen,” said the squire; and having ascertained that the things were as agreeable to the taste as to the eye, and that the coffee was more clear and high–flavoured than he had ever tasted before, he seized his nephew’s hand, saying, “Reginald, my boy, I give in; your Master Perrot’s a trump, and no man shall ever speak a word against him in this house! A rare fellow!” Here he took another turn at the omelette; “hang me if he shan’t have a day’s sport;” and the squire chuckling at the idea that had suddenly crossed him, rang the bell violently: “Tell Repton,” said he to the servant who entered, “to saddle ‘Rattling Bess,’ for Monsieur Perrot, and to take her to the cover–side with the other horses at ten.”

“She kicks a bit at starting,” added he to Reginald; “but she’s as safe as a mill; and though she rushes now and then at the fences, she always gets through or over ‘em.”

Now it was poor Perrot’s turn to be astonished. To do him justice, he was neither a bad horseman (as a courier) nor a coward; but he had never been out with hounds, and the enumeration of “Rattling Bess’” qualities did not sound very attractive to his ear: he began gently to make excuses, and to decline the proposed favour: he had not the “proper dress:”—“he had much to do for Monsieur’s wardrobe at home:” but it was all to no purpose, the squire was determined; Repton’s coat and breeches would fit him, and go he must.

With a rueful look at his master, Perrot slunk off, cursing in his heart the salmi and the omelette, which had procured him this undesired favour: but he was ordered to lose no time in preparing himself; so he first endeavoured to get into Mr. Repton’s clothes: that proved impossible, as Mr. R. had been a racing jockey, and was a feather–weight, with legs like nutcrackers. Having no time for deliberation, Monsieur Perrot drew from his valise the courier suit which he had worn in France; and to the surprise of the whole party assembled at the door, he appeared clad in a blue coat turned up with yellow, a cornered hat, and enormous boots, half a foot higher than[28] his knees. He was ordered to jump up behind the squire’s carriage, and away they went to the cover–side, amid the ill–suppressed titter of the grooms and footmen, and the loud laughter of the maids, whose malicious faces, not excepting that of Mary, were at the open windows below.

When they reached the place appointed for “the meet,” and proceeded to mount the impatient horses awaiting them, Perrot eyed with no agreeable anticipation the long ears of Rattling Bess laid back, and the restless wag of her rat–tail, and he ventured one more attempt at an escape. “Really, sir,” said he to the squire, “I never hunted, and I don’t think I can manage that animal; she looks very savage.”

“Never mind her, Monsieur Perrot,” said the squire, enjoying the poor valet’s ill–dissembled uneasiness. “She knows her business here as well as any whipper–in or huntsman; only let her go her own way, and you’ll never be far from the brush.”

“Very well,” muttered Perrot; “I hope she knows her business; I know mine, and that is to keep on her back, which I’ll do as well as I can.”

The eyes of the whole field were upon this strangely attired figure; and as soon as he got into the saddle, “Rattling Bess” began to kick and plunge violently: we have said that he was not in some respects a bad horseman; and although in this, her first prank, he lost one of his stirrups, and his cornered hat fell off, he contrived to keep both his seat and his temper: while the hounds were drawing the cover, one of the squire’s grooms restored the hat, and gave him a string wherewith to fasten it, an operation which he had scarcely concluded, when the inspiring shouts of “Tally ho,” “Gone away,” “Forward,” rang on his ears. “Rattling Bess” seemed to understand the sounds as well as ever alderman knew a dinner–bell; and away she went at full gallop, convincing Monsieur Perrot, after an ineffectual struggle of a few minutes on his part, that both the speed and direction of her course were matters over which he could not exercise the smallest influence.

On they flew, over meadow and stile, ditch and hedge, nothing seemed to check Rattling Bess; and while all the field were in astonished admiration at the reckless riding of the strange courier, that worthy was catching his breath, and muttering[29] through his teeth, “Diable d’animal, she have a mouth so hard, like one of Mr. Alltripe’s bif–steak,—she know her business—and a sacré business it is—holà there! mind yourself!” shouted he, at the top of his voice, to a horseman whose horse had fallen in brushing through a thick hedge, and was struggling to rise on the other side just as Rattling Bess followed at tremendous speed over the same place; lighting upon the hind–quarters of her hapless predecessor, and scraping all the skin off his loins, she knocked the rider head over heels into the ploughed field, where his face was buried a foot deep in dirty mould: by a powerful effort she kept herself from falling, and went gallantly over the field; Perrot still muttering, as he tugged at the insensible mouth, “She know her business, she kill dat poor devil in the dirt, she kill herself and me too.”

A few minutes later, the hounds, having overrun the scent, came to a check, and were gathered by the huntsman into a green lane, from whence they were about to “try back” as Rattling Bess came up at unabated speed. “Hold hard there, hold hard!” shouted at once the huntsman, the whips, and the few sportsmen who were up with the hounds. “Where the devil are you going, man?” “The fox is viewed back.” “Halloo!—you’re riding into the middle of the pack.” These and similar cries scarcely had time to reach the ears of Perrot, ere “Rattling Bess” sprang over the hedge into a green lane, and coming down upon the unfortunate dogs, split the head of one, broke the back of another, and, laming two or three more, carried her rider over the opposite fence, who, still panting for breath, with his teeth set, muttered, “She know her business, sacré animal.”

After crossing two more fields, she cleared a hedge, so thick that he could not see what was on the other side; but he heard a tremendous crash, and was only conscious of being hurled with violence to the ground: slowly recovering his senses, he saw Rattling Bess lying a few yards from him, bleeding profusely; and his own ears were saluted by the following compassionate inquiry from the lips of a gardener, who was standing over him, spade in hand: “D—n your stupid outlandish head, what be you a doin’ here?”

The half–stunned courier, pointing to Rattling Bess, replied: “She know her business.”

The gardener, though enraged at the entire demolition of his melon–bed, and of sundry forced vegetables under glass, was not an ill–tempered fellow in the main; and seeing that the horse was half killed, and the rider, a foreigner, much bruised, he assisted poor Perrot to rise; and having gathered from him that he was in the service of rich Squire Shirley, rendered all the aid in his power to him and to Rattling Bess, who had received some very severe cuts from the glass.

When the events of the day came to be talked over at the Hall, and it proved that it was the squire himself whom Perrot had so unceremoniously ridden over,—that the huntsman would expect some twenty guineas for the hounds killed or maimed—that the gardener would probably present a similar or a larger account for a broken melon–bed and shivered glass—and that Rattling Bess was lame for the season, the squire did not encourage much conversation on the day’s sport; the only remark that he was heard to make, being, “What a fool I was to put a frog–eating Frenchman on an English hunter!”

Monsieur Perrot remained in his room for three or four days, not caring that Mary should see his visage while it was adorned with a black eye and an inflamed nose.

Soon after this eventful chase, Reginald obtained his uncle’s leave to obey his father’s wishes by visiting Paris for a few months. His stay there was shortened by a letter which he received from his sister Lucy, announcing to him his mother’s illness; on the receipt of which he wrote a few hurried lines of explanation to his uncle, and sailed by the first ship for Philadelphia, accompanied by the faithful Perrot, and by a large rough dog of the breed of the old Irish wolf–hound, given to him by the squire.

On arriving, he found his mother better than he had expected; and, as he kissed off the tears of joy which Lucy shed on his return, he whispered to her his belief that she had a little exaggerated their mother’s illness, in order to recall him. After a short time, Ethelston also returned, and joined the happy circle assembled at Colonel Brandon’s.

It was now the spring of 1797, between which time and that mentioned as the date of our opening chapter, a period of nearly two years, nothing worthy of peculiar record occurred. Reginald kept up a faithful correspondence with his kind uncle, whose letters showed how deeply he felt his nephew’s[31] absence. Whether Monsieur Perrot interchanged letters with Mary, or consoled himself with the damsels on the banks of the Ohio, the following pages may show. His master made several hunting excursions, on which he was always accompanied by Baptiste, a sturdy backwoodsman, who was more deeply attached to Reginald than to any other being on earth; and Ethelston had, as we have before explained, undertaken the whole charge of his guardian’s vessels, with one of the largest of which he was, at the commencement of our tale, absent in the West India Islands.

CHAPTER V.

AN ADVENTURE IN THE WOODS.—REGINALD BRANDON MAKES THE ACQUAINTANCE OF AN INDIAN CHIEF.