*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 46804 ***

BENTLEY'S

MISCELLANY.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY,

NEW BURLINGTON STREET.

1837.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY,

Dorset Street, Fleet Street.

[iii]

ADDRESS.

Twelve months have elapsed since we first took the

field, and every successive number of our Miscellany has

experienced a warmer reception, and a more extensive

circulation, than its predecessor.

In the opening of the new year, and the commencement

of our new volume, we hope to make many changes

for the better, and none for the worse; and, to show

that, while we have one grateful eye to past patronage,

we have another wary one to future favours; in short,

that, like the heroine of the sweet poem descriptive of

the faithlessness and perjury of Mr. John Oakhum, of

the Royal Navy, we look two ways at once.

It is our intention to usher in the new year with a

very merry greeting, towards the accomplishment of

which end we have prevailed upon a long procession of

distinguished friends to mount their hobbies on the[iv]

occasion, in humble imitation of those adventurous and

aldermanic spirits who gallantly bestrode their foaming

chargers on the memorable ninth of this present month,

while

"The stones did rattle underneath,

As if Cheapside were mad."

These, and a hundred other great designs, preparations,

and surprises, are in contemplation, for the fulfilment of

all of which we are already bound in two volumes cloth,

and have no objection, if it be any additional security

to the public, to stand bound in twenty more.

BOZ.

30th November, 1837.

[v]

CONTENTS

OF THE

SECOND VOLUME.

——————

| Songs of the Month—July, by "Father Prout;" August; September, by

"Father Prout;" October, by J.M.; November, by C.D.; December, by

Punch |

Pages 1, 109, 213, 321,

429, 533 |

| Papers by Boz: | |

| Oliver Twist, or the Parish Boy's Progress, |

2, 110, 215, 430, 534 |

| The Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything |

397 |

| Poetry by Mrs. Cornwell Baron Wilson: | |

| Elegiac Stanzas |

16 |

| Lady Blue's Ball |

380 |

| My Father's Old Hall |

453 |

| Fictions of the Middle Ages: The Butterfly Bishop, by Delta |

17 |

| A New Song to the Old Tune of Kate Kearney |

25 |

| What Tom Binks did when he didn't know what to do with himself |

26 |

| A Gentleman Quite |

36 |

| The Foster-Child |

37 |

| The White Man's Devil-house, by F.H. Rankin |

46 |

| A Lyric for Lovers |

50 |

| The Remains of Hajji Baba, by the Author of "Zohrab" |

51, 166 |

| Shakspeare Papers, by Dr. Maginn: |

| No. III. Romeo |

57 |

| IV. Midsummer Night's Dream—Bottom the Weaver |

370 |

| V. His Ladies—Lady Macbeth |

550 |

| The Piper's Progress, by Father Prout |

67 |

| Papers by J.A. Wade: | |

| No. II. Darby the Swift |

68 |

| III. The Darbiad |

464 |

| Song of the Old Bell |

196 |

| Serenade to Francesca |

239 |

| Phelim O'Toole's Nine Muse-ings on his Native County |

319 |

| Papers by Captain Medwin: | |

| The Duel |

76 |

| Mascalbruni |

254 |

| The Last of the Bandits |

585[vi] |

| The Monk of Ravenne |

81 |

| A Marine's Courtship, by M. Burke Honan |

82 |

| Family Stories, by Thomas Ingoldsby: | |

| No. VI. Mrs. Botherby's Story—The Leech of Folkestone |

91 |

| VII. Patty Morgan the Milkmaid's Story—Look at the Clock |

207 |

| What though we were Rivals of yore, by T. Haynes Bayly |

124 |

| Papers by the Author of "Stories of Waterloo:" | |

| Love in the City |

125 |

| The Regatta, No. I.: Run Across Channel |

299 |

| Legends—of Ballar; the Church of the Seven; and the Tory | |

| Islanders |

527 |

| Three Notches from the Devil's Tail, or the Man in the Spanish Cloak,

by the Author of "Reminiscences of a Monthly Nurse" |

135 |

| The Serenade |

149 |

| The Portrait Gallery, by the Author of "The Bee Hive" | |

| No. III. The Cannon Family |

150 |

| IV. Journey to Boulogne |

454 |

| A Chapter on Laughing |

163 |

| A Muster-chaunt for the Members of the Temperance Societies |

165 |

| My Uncle: a Fragment |

175 |

| Why the Wind blows round St. Paul's, by Joyce Jocund |

176 |

| Papers by C. Whitehead: | |

| Rather Hard to Take |

181 |

| The Narrative of John Ward Gibson |

240 |

| Nights at Sea, by the Old Sailor: |

| No. IV. The French Captain's Story |

183 |

| V. The French Captain's Story |

471 |

| VI. Jack among the Mummies |

610 |

| Midnight Mishaps, by Edward Mayhew |

197 |

| The Dream |

206 |

| Genius, or the Dog's-meat Dog, by Egerton Webbe |

214 |

| The Poisoners of the Seventeenth Century, by George Hogarth: | |

| No. I. The Marchioness de Brinvilliers |

229 |

| II. Sir Thomas Overbury |

322 |

| Smoke |

268 |

| Some Passages in the Life of a Disappointed Man |

270 |

| The Professor, by Goliah Gahagan |

277 |

| Biddy Tibbs, who cared for Nobody, by H. Holl |

288 |

| The Key of Granada |

303 |

| Glorvina, the Maid of Meath, by J. Sheridan Knowles |

304 |

| An Excellent Offer, by Marmaduke Blake |

340 |

| The Autobiography of a Good Joke |

354 |

| The Secret, by M. Paul de Kock |

360 |

| The Man with the Club-foot |

381 |

| A Remonstratory Ode to Mr. Cross on the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius,

by Joyce Jocund |

413[vii] |

| Memoirs of Beau Nash |

414 |

| Grub-street News |

425 |

| The Confessions of an Elderly Gentleman |

445 |

| The Relics of St. Pius |

462 |

| A few Inquiries |

470 |

| Lines occasioned by the Death of Count Borowlaski |

484 |

| A Chapter on Widows |

485 |

| Petrarch in London |

494 |

| Adventures in Paris, by Toby Allspy: | |

| The Five Floors |

No. I. 495; No. II. 575 |

| Martial in Town |

507 |

| Astronomical Agitation—Reform of the Solar System |

508 |

| The Adventures of a Tale, by Mrs. Erskine Norton |

511 |

| When and Why the Devil Invented Brandy |

518 |

| The Wit in spite of Himself, by Richard Johns |

521 |

| The Apportionment of the World, from Schiller |

549 |

| Ode to the Queen |

568 |

| Suicide |

569 |

| The Glories of Good Humour |

591 |

| Song of the Modern Time |

594 |

| Capital Punishments in London Eighty Years ago—Earl Ferrers |

595 |

| A Peter Pindaric to and of a Fog, by Punch |

606 |

| The Castle by the Sea |

623 |

| Legislative Nomenclature |

624 |

| Nobility in Disguise, by Dudley Costello |

626 |

| Another Original of "Not a Drum was heard," |

632 |

| Index |

633 |

[viii]

ILLUSTRATIONS.

BY GEORGE CRUIKSHANK.

| |

Page |

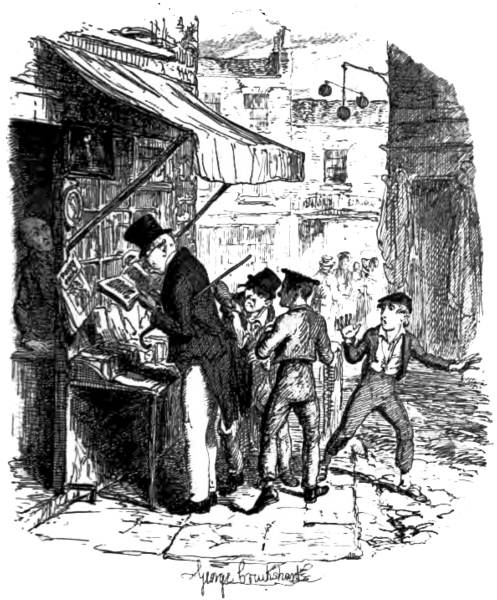

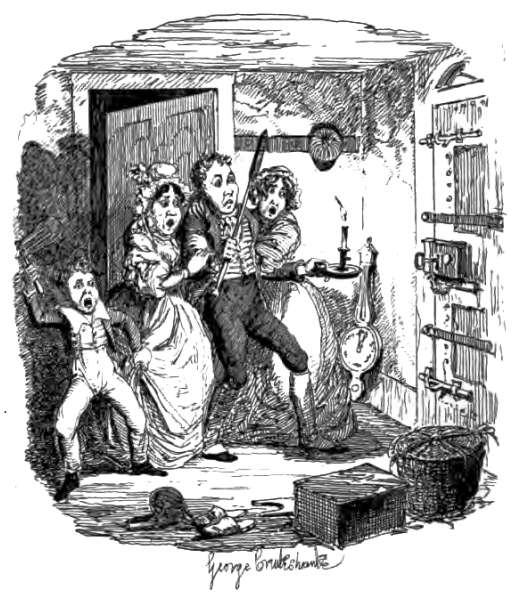

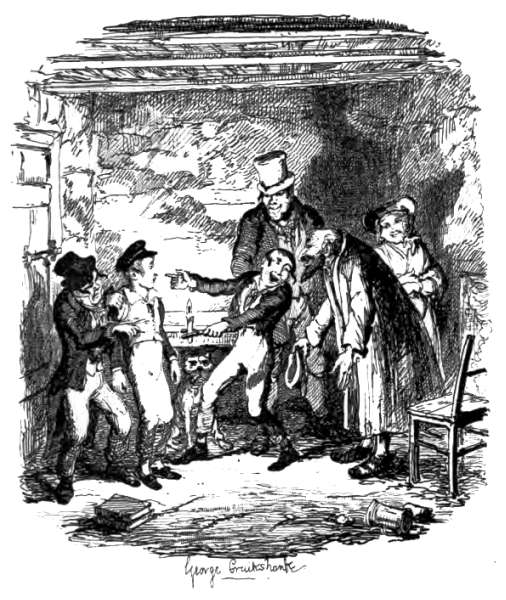

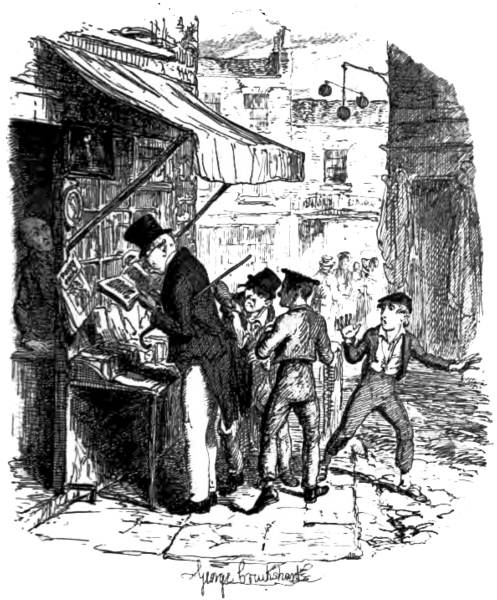

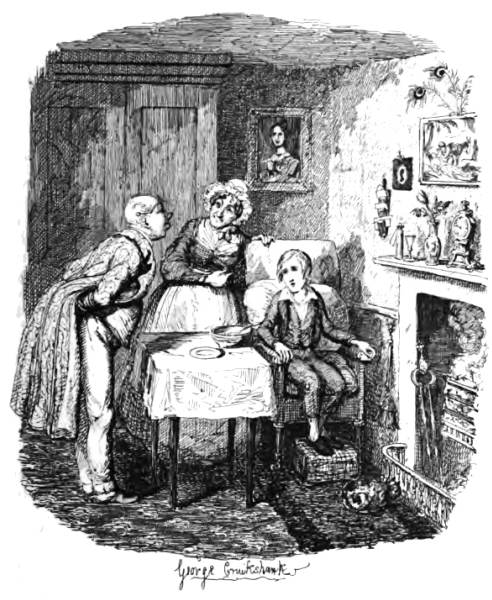

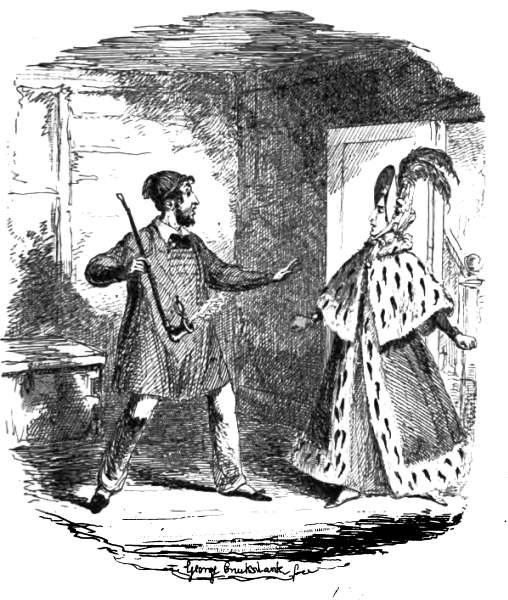

| Oliver Twist—The Dodger's way of going to work |

2 |

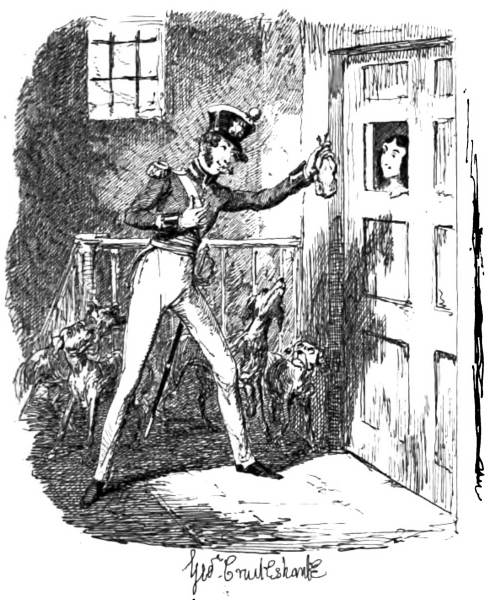

| A Marine's Courtship |

82 |

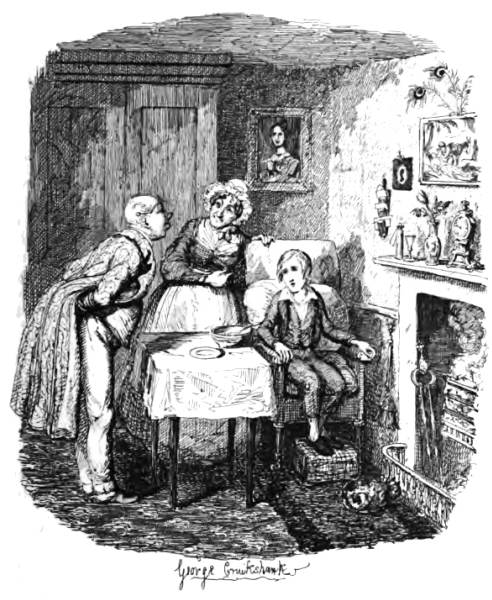

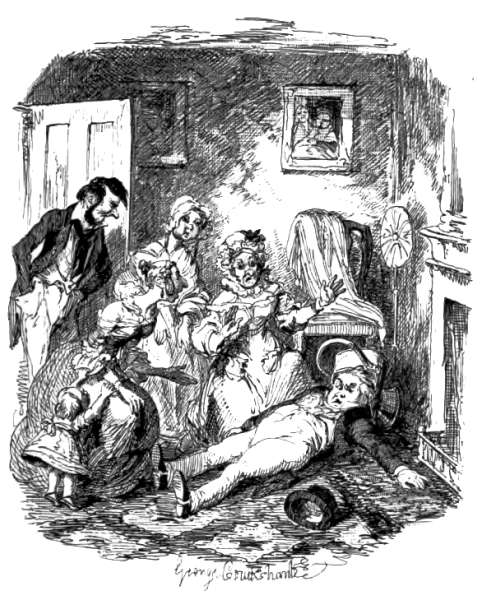

| Oliver Twist recovering from the fever |

110 |

| Midnight Mishaps |

197 |

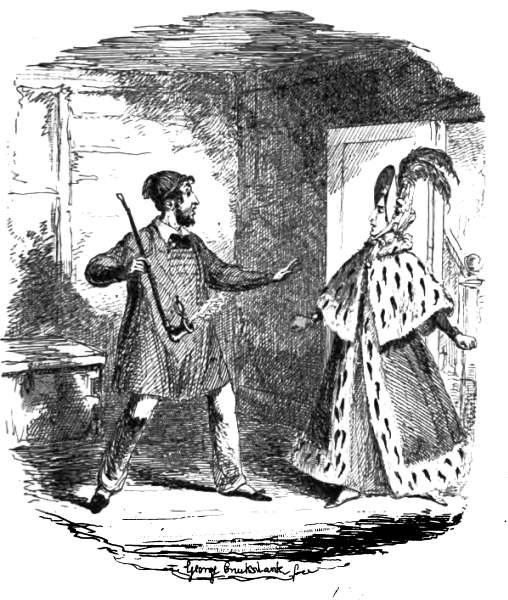

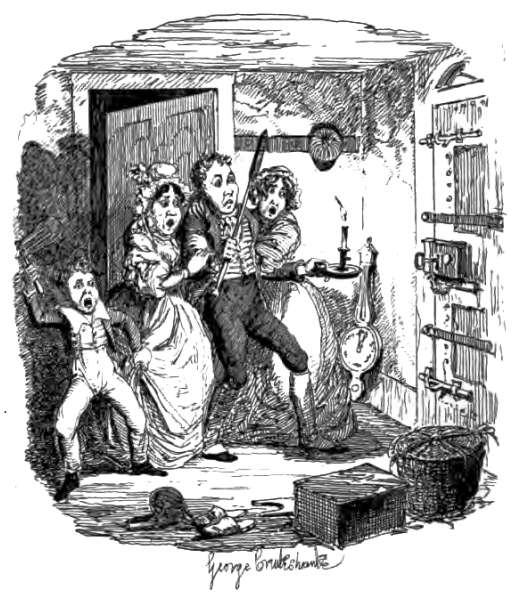

| Oliver Twist and his affectionate Friends |

215 |

| A Disappointed Man |

270 |

| The Autobiography of a Good Joke |

354 |

| The Secret |

360 |

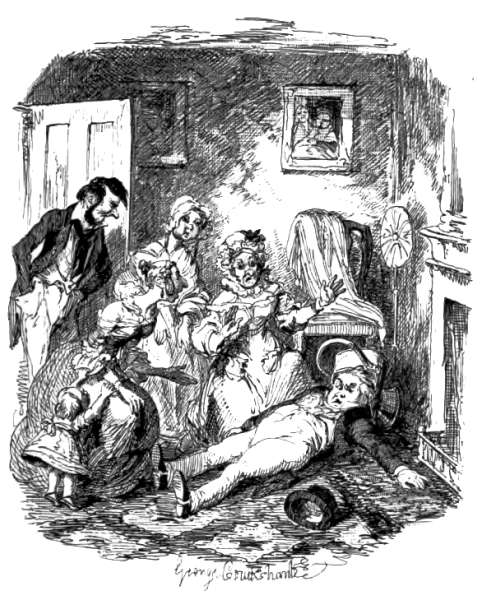

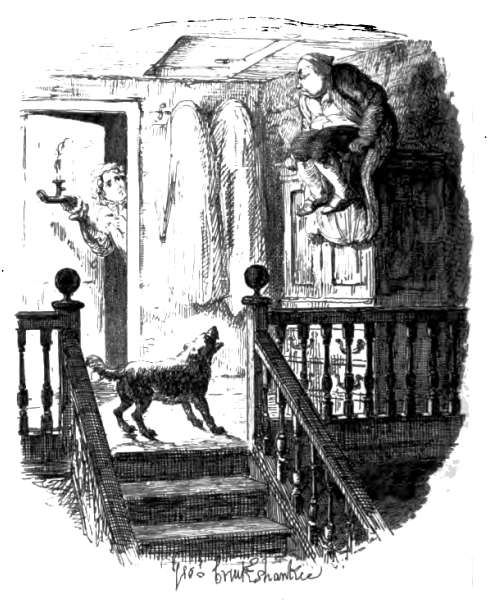

| Oliver Twist returns to the Jew's den |

430 |

| The Confessions of an Elderly Gentleman |

445 |

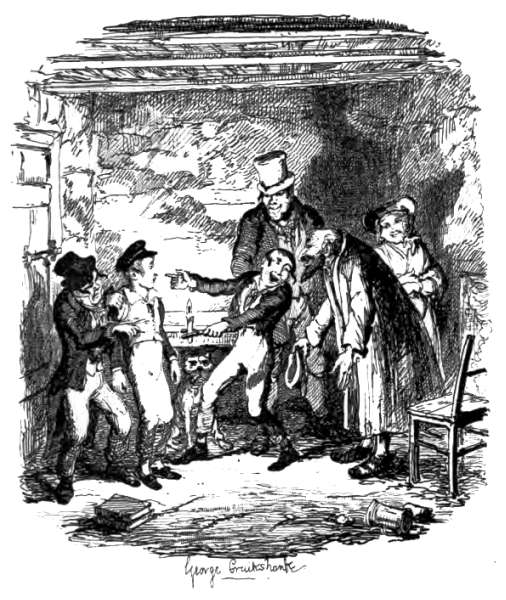

| Oliver Twist instructed by the Dodger |

533 |

| Jack among the Mummies |

610 |

|

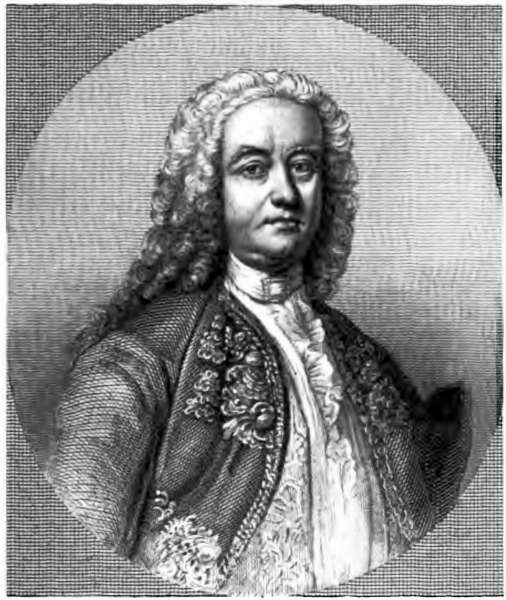

| Portrait of Beau Nash, by W. Greatbach |

414 |

BENTLEY'S MISCELLANY.

[1]

SONG OF THE MONTH. No. VII.

July, 1837.

BEING A BAPTISMAL CHAUNT FOR THE BIRTH OF OUR SECOND

VOLUME, AS SUNG (IN CHARACTER) BY FATHER PROUT.

(Tune "The groves of Blarney.")

"Ille ego qui quondam," &c. &c.—Æneid.

In the month of Janus,

When Boz to gain us,

Quite "miscellaneous,"

Flashed his wit so keen,

One, (Prout they call him,)

In style most solemn,

Led off the volume

Of his magazine.

Though Maga, 'mongst her

Bright set of youngsters,

Had many songsters

For her opening tome;

Yet she would rather

Invite "the Father,"

And an indulgence gather

From the Pope of Rome.

And, such a beauty

From head to shoe-tie,

Without dispute we

Found her first boy,

That she detarmined,

There's such a charm in 't,

The Father's sarmint

She'd again employ.

While other children

Are quite bewilderin',

'Tis joy that fill'd her in

This bantling; 'cause

What eye but glistens,

And what ear but listens,

When the clargy christens

A babe of Boz?

I've got a scruple

That this young pupil

Surprised its parent

Ere her time was sped;

Else I'm unwary,

Or, 'tis she's a fairy,

For in January

She was brought to bed.

This infant may be

A six months' baby,

But may his cradle

Be blest! say I;

And luck defend him!

And joy attend him!

Since we can't mend him,

Born in July.

He's no abortion,

But born to fortune,

And most opportune,

Though before his time;

Him, Muse, O! nourish,

And make him flourish

Quite Tommy-Moorish

Both in prose and rhyme!

I remember, also,

That this month they call so,

From Roman Julius

The "Cæsarian" styled;

Who was no gosling,

But, like this Boz-ling,

From birth a dazzling

And precocious child!

GOD SAVE THE QUEEN!

[2]

OLIVER TWIST;

OR, THE PARISH BOY'S PROGRESS.

BY BOZ.

ILLUSTRATED BY GEORGE CRUIKSHANK.

CHAPTER THE NINTH.

CONTAINING FURTHER PARTICULARS CONCERNING THE PLEASANT OLD

GENTLEMAN, AND HIS HOPEFUL PUPILS.

It was late next morning when Oliver awoke from a sound,

long sleep. There was nobody in the room beside, but the old

Jew, who was boiling some coffee in a saucepan for breakfast,

and whistling softly to himself as he stirred it round and

round with an iron spoon. He would stop every now and

then to listen when there was the least noise below; and, when

he had satisfied himself, he would go on whistling and stirring

again, as before.

Although Oliver had roused himself from sleep, he was not

thoroughly awake. There is a drowsy, heavy state, between

sleeping and waking, when you dream more in five minutes

with your eyes half open, and yourself half conscious of everything

that is passing around you, than you would in five

nights with your eyes fast closed, and your senses wrapt in

perfect unconsciousness. At such times, a mortal knows just

enough of what his mind is doing to form some glimmering

conception of its mighty powers, its bounding from earth and

spurning time and space, when freed from the irksome restraint

of its corporeal associate.

Oliver was precisely in the condition I have described. He

saw the Jew with his half-closed eyes, heard his low whistling,

and recognised the sound of the spoon grating against the

saucepan's sides; and yet the self-same senses were mentally

engaged at the same time, in busy action with almost everybody

he had ever known.

When the coffee was done, the Jew drew the saucepan to

the hob, and, standing in an irresolute attitude for a few minutes

as if he did not well know how to employ himself, turned

round and looked at Oliver, and called him by his name. He

did not answer, and was to all appearance asleep.

After satisfying himself upon this head, the Jew stepped

gently to the door, which he fastened; he then drew forth,

as it seemed to Oliver, from some trap in the floor, a small

box, which he placed carefully on the table. His eyes glistened

as he raised the lid and looked in. Dragging an old

chair to the table, he sat down, and took from it a magnificent

gold watch, sparkling with diamonds.

Oliver amazed at the Dodger's Mode of 'going

to work'

[3]

"Aha!" said the Jew, shrugging up his shoulders, and distorting

every feature with a hideous grin. "Clever dogs!

clever dogs! Staunch to the last! Never told the old parson

where they were; never peached upon old Fagin. And why

should they? It wouldn't have loosened the knot, or kept

the drop up a minute longer. No, no, no! Fine fellows!

fine fellows!"

With these, and other muttered reflections of the like nature,

the Jew once more deposited the watch in its place of safety.

At least half a dozen more were severally drawn forth from the

same box, and surveyed with equal pleasure; besides rings,

brooches, bracelets, and other articles of jewellery, of such magnificent

materials and costly workmanship that Oliver had no

idea even of their names.

Having replaced these trinkets, the Jew took out another,

so small that it lay in the palm of his hand. There seemed

to be some very minute inscription on it, for the Jew laid it

flat upon the table, and, shading it with his hand, pored over

it long and earnestly. At length he set it down as if despairing

of success, and, leaning back in his chair, muttered,

"What a fine thing capital punishment is! Dead men never

repent; dead men never bring awkward stories to light. The

prospect of the gallows, too, makes them hardy and bold. Ah,

it's a fine thing for the trade! Five of them strung up in a

row, and none left to play booty or turn white-livered!"

As the Jew uttered these words, his bright dark eyes which

had been staring vacantly before him, fell on Oliver's face;

the boy's eyes were fixed on his in mute curiosity, and, although

the recognition was only for an instant—for the briefest

space of time that can possibly be conceived,—it was enough

to show the old man that he had been observed. He closed

the lid of the box with a loud crash, and, laying his hand on a

bread-knife which was on the table, started furiously up. He

trembled very much though; for, even in his terror, Oliver

could see that the knife quivered in the air.

"What's that?" said the Jew. "What do you watch me

for? Why are you awake? What have you seen? Speak

out, boy! Quick—quick! for your life!"

"I wasn't able to sleep any longer, sir," replied Oliver,

meekly. "I am very sorry if I have disturbed you, sir."

"You were not awake an hour ago?" said the Jew, scowling

fiercely on the boy.

"No—no, indeed, sir," replied Oliver.

"Are you sure?" cried the Jew, with a still fiercer look than

before, and a threatening attitude.

"Upon my word I was not, sir," replied Oliver, earnestly.

"I was not, indeed, sir."

"Tush, tush, my dear!" said the Jew, suddenly resuming his

old manner, and playing with the knife a little before he laid it[4]

down, as if to induce the belief that he had caught it up in

mere sport. "Of course I know that, my dear. I only tried

to frighten you. You're a brave boy. Ha! ha! you're a

brave boy, Oliver!" and the Jew rubbed his hands with a

chuckle, but looked uneasily at the box notwithstanding.

"Did you see any of these pretty things, my dear?" said the

Jew, laying his hand upon it after a short pause.

"Yes, sir," replied Oliver.

"Ah!" said the Jew, turning rather pale. "They—they're

mine, Oliver; my little property. All I have to live

upon in my old age. The folks call me a miser, my dear,—only

a miser; that's all."

Oliver thought the old gentleman must be a decided miser

to live in such a dirty place, with so many watches; but,

thinking that perhaps his fondness for the Dodger and the

other boys cost him a good deal of money, he only cast a deferential

look at the Jew, and asked if he might get up.

"Certainly, my dear,—certainly," replied the old gentleman.

"Stay. There's a pitcher of water in the corner by the door.

Bring it here, and I'll give you a basin to wash in, my dear."

Oliver got up, walked across the room, and stooped for one

instant to raise the pitcher. When he turned his head, the

box was gone.

He had scarcely washed himself and made everything tidy by

emptying the basin out of the window, agreeably to the Jew's

directions, than the Dodger returned, accompanied by a very

sprightly young friend whom Oliver had seen smoking on the

previous night, and who was now formally introduced to him as

Charley Bates. The four then sat down to breakfast off the

coffee and some hot rolls and ham which the Dodger had

brought home in the crown of his hat.

"Well," said the Jew, glancing slyly at Oliver, and addressing

himself to the Dodger, "I hope you've been at work this

morning, my dears."

"Hard," replied the Dodger.

"As nails," added Charley Bates.

"Good boys, good boys!" said the Jew. "What have you

got, Dodger?"

"A couple of pocket-books," replied that young gentleman.

"Lined?" inquired the Jew with trembling eagerness.

"Pretty well," replied the Dodger, producing two pocket-books,

one green and the other red.

"Not so heavy as they might be," said the Jew, after looking

at the insides carefully; "but very neat, and nicely made. Ingenious

workman, ain't he, Oliver?"

"Very, indeed, sir," said Oliver. At which Mr. Charles

Bates laughed uproariously, very much to the amazement of

Oliver, who saw nothing to laugh at, in anything that had

passed.

[5]

"And what have you got, my dear?" said Fagin to Charley

Bates.

"Wipes," replied Master Bates: at the same time producing

four pocket-handkerchiefs.

"Well," said the Jew, inspecting them closely; "they're very

good ones,—very. You haven't marked them well, though,

Charley; so the marks shall be picked out with a needle, and

we'll teach Oliver how to do it. Shall us, Oliver, eh?—Ha!

ha! ha!"

"If you please, sir," said Oliver.

"You'd like to be able to make pocket-handkerchiefs as

easy as Charley Bates, wouldn't you, my dear?" said the Jew.

"Very much indeed, if you'll teach me, sir," replied Oliver.

Master Bates saw something so exquisitely ludicrous in this

reply that he burst into another laugh; which laugh meeting the

coffee he was drinking, and carrying it down some wrong channel,

very nearly terminated in his premature suffocation.

"He is so jolly green," said Charley when he recovered, as an

apology to the company for his unpolite behaviour.

The Dodger said nothing, but he smoothed Oliver's hair down

over his eyes, and said he'd know better by-and-by; upon

which the old gentleman, observing Oliver's colour mounting,

changed the subject by asking whether there had been much of

a crowd at the execution that morning. This made him wonder

more and more, for it was plain from the replies of the two boys

that they had both been there; and Oliver naturally wondered

how they could possibly have found time to be so very industrious.

When the breakfast was cleared away, the merry old gentleman

and the two boys played at a very curious and uncommon

game, which was performed in this way:—The merry old gentleman,

placing a snuff-box in one pocket of his trousers, a note-case

in the other, and a watch in his waistcoat-pocket, with a

guard-chain round his neck, and sticking a mock diamond pin

in his shirt, buttoned his coat tight round him, and, putting his

spectacle-case and handkerchief in the pockets, trotted up and

down the room with a stick, in imitation of the manner in which

old gentlemen walk about the streets every hour in the day.

Sometimes he stopped at the fire-place, and sometimes at the

door, making belief that he was staring with all his might into

shop-windows. At such times he would look constantly round

him for fear of thieves, and keep slapping all his pockets in

turn, to see that he hadn't lost anything, in such a very funny

and natural manner, that Oliver laughed till the tears ran down

his face. All this time the two boys followed him closely about,

getting out of his sight so nimbly every time he turned round,

that it was impossible to follow their motions. At last the

Dodger trod upon his toes, or ran upon his boot accidentally,

while Charley Bates stumbled up against him behind; and in[6]

that one moment they took from him with the most extraordinary

rapidity, snuff-box, note-case, watch-guard, chain, shirt-pin,

pocket-handkerchief,—even the spectacle-case. If the old gentleman

felt a hand in any one of his pockets, he cried out where

it was, and then the game began all over again.

When this game had been played a great many times, a

couple of young ladies came to see the young gentlemen, one of

whom was called Bet and the other Nancy. They wore a good

deal of hair, not very neatly turned up behind, and were rather

untidy about the shoes and stockings. They were not exactly

pretty, perhaps; but they had a great deal of colour in their

faces, and looked quite stout and hearty. Being remarkably

free and agreeable in their manners, Oliver thought them very

nice girls indeed, as there is no doubt they were.

These visitors stopped a long time. Spirits were produced, in

consequence of one of the young ladies complaining of a coldness

in her inside, and the conversation took a very convivial and

improving turn. At length Charley Bates expressed his opinion

that it was time to pad the hoof, which it occurred to Oliver

must be French for going out; for directly afterwards the

Dodger, and Charley, and the two young ladies went away

together, having been kindly furnished with money to spend, by

the amiable old Jew.

"There, my dear," said Fagin, "that's a pleasant life, isn't

it? They have gone out for the day."

"Have they done work, sir?" inquired Oliver.

"Yes," said the Jew; "that is, unless they should unexpectedly

come across any when they are out; and they won't

neglect it if they do, my dear, depend upon it."

"Make 'em your models, my dear, make 'em your models,"

said the Jew, tapping the fire-shovel on the hearth to add force

to his words; "do everything they bid you, and take their advice

in all matters, especially the Dodger's, my dear. He'll be

a great man himself, and make you one too, if you take pattern

by him. Is my handkerchief hanging out of my pocket, my

dear?" said the Jew, stopping short.

"Yes, sir," said Oliver.

"See if you can take it out, without my feeling it, as you saw

them do when we were at play this morning."

Oliver held up the bottom of the pocket with one hand as he

had seen the Dodger do, and drew the handkerchief lightly out

of it with the other.

"Is it gone?" cried the Jew.

"Here it is, sir," said Oliver, showing it in his hand.

"You're a clever boy, my dear," said the playful old gentleman,

patting Oliver on the head approvingly; "I never saw

a sharper lad. Here's a shilling for you. If you go on in

this way, you'll be the greatest man of the time. And now

come here, and I'll show you how to take the marks out of the

handkerchiefs."

[7]

Oliver wondered what picking the old gentleman's pocket in

play had to do with his chances of being a great man; but

thinking that the Jew, being so much his senior, must know

best, followed him quietly to the table, and was soon deeply

involved in his new study.

CHAPTER THE TENTH.

OLIVER BECOMES BETTER ACQUAINTED WITH THE CHARACTERS OF HIS NEW

ASSOCIATES, AND PURCHASES EXPERIENCE AT A HIGH PRICE. BEING A

SHORT BUT VERY IMPORTANT CHAPTER IN THIS HISTORY.

For eight or ten days Oliver remained in the Jew's room,

picking the marks out of the pocket-handkerchiefs, (of which a

great number were brought home,) and sometimes taking part

in the game already described, which the two boys and the Jew

played regularly every day. At length he began to languish

for the fresh air, and took many occasions of earnestly entreating

the old gentleman to allow him to go out to work with his

two companions.

Oliver was rendered the more anxious to be actively employed

by what he had seen of the stern morality of the old gentleman's

character. Whenever the Dodger or Charley Bates came

home at night empty-handed, he would expatiate with great

vehemence on the misery of idle and lazy habits, and enforce

upon them the necessity of an active life by sending them supperless

to bed: upon one occasion he even went so far as to

knock them both down a flight of stairs; but this was carrying

out his virtuous precepts to an unusual extent.

At length one morning Oliver obtained the permission he

had so eagerly sought. There had been no handkerchiefs to

work upon, for two or three days, and the dinners had been

rather meagre. Perhaps these were reasons for the old gentleman's

giving his assent; but, whether they were or no, he

told Oliver he might go, and placed him under the joint guardianship

of Charley Bates and his friend the Dodger.

The three boys sallied out, the Dodger with his coat-sleeves

tucked up and his hat cocked as usual, Master Bates sauntering

along with his hands in his pockets, and Oliver between them,

wondering where they were going, and what branch of manufacture

he would be instructed in first.

The pace at which they went was such a very lazy, ill-looking

saunter, that Oliver soon began to think his companions were

going to deceive the old gentleman, by not going to work at all.

The Dodger had a vicious propensity, too, of pulling the caps

from the heads of small boys and tossing them down areas;

while Charley Bates exhibited some very loose notions concerning

the rights of property, by pilfering divers apples and

onions from the stalls at the kennel sides, and thrusting them

into pockets which were so surprisingly capacious, that they[8]

seemed to undermine his whole suit of clothes in every direction.

These things looked so bad, that Oliver was on the point of

declaring his intention of seeking his way back in the best way

he could, when his thoughts were suddenly directed into another

channel by a very mysterious change of behaviour on the

part of the Dodger.

They were just emerging from a narrow court not far from

the open square in Clerkenwell, which is called, by some strange

perversion of terms, "The Green," when the Dodger made a

sudden stop, and, laying his finger on his lip, drew his companions

back again with the greatest caution and circumspection.

"What's the matter?" demanded Oliver.

"Hush!" replied the Dodger. "Do you see that old cove at

the book-stall?"

"The old gentleman over the way?" said Oliver. "Yes, I

see him."

"He'll do," said the Dodger.

"A prime plant," observed Charley Bates.

Oliver looked from one to the other with the greatest surprise,

but was not permitted to make any inquiries, for the two

boys walked stealthily across the road, and slunk close behind

the old gentleman towards whom his attention had been directed.

Oliver walked a few paces after them, and, not knowing

whether to advance or retire, stood looking on in silent

amazement.

The old gentleman was a very respectable-looking personage,

with a powdered head and gold spectacles; dressed in a bottle-green

coat with a black velvet collar, and white trousers: with

a smart bamboo cane under his arm. He had taken up a book

from the stall, and there he stood, reading away as hard as if

he were in his elbow-chair in his own study. It was very possible

that he fancied himself there, indeed; for it was plain, from

his utter abstraction, that he saw not the book-stall, nor the

street, nor the boys, nor, in short, anything but the book itself,

which he was reading straight through, turning over the leaves

when he got to the bottom of a page, beginning at the top line

of the next one, and going regularly on with the greatest interest

and eagerness.

What was Oliver's horror and alarm as he stood a few paces

off, looking on with his eye-lids as wide open as they would

possibly go, to see the Dodger plunge his hand into this old gentleman's

pocket, and draw from thence a handkerchief, which he

handed to Charley Bates, and with which they both ran away

round the corner at full speed!

In one instant the whole mystery of the handkerchiefs, and

the watches, and the jewels, and the Jew, rushed upon the boy's

mind. He stood for a moment with the blood tingling so

through all his veins from terror, that he felt as if he were in a

burning fire; then, confused and frightened, he took to his[9]

heels, and, not knowing what he did, made off as fast as he

could lay his feet to the ground.

This was all done in a minute's space, and the very instant

that Oliver began to run, the old gentleman, putting his hand

to his pocket, and missing his handkerchief, turned sharp

round. Seeing the boy scudding away at such a rapid pace, he

very naturally concluded him to be the depredator, and, shouting

"Stop thief!" with all his might, made off after him, book

in hand.

But the old gentleman was not the only person who raised

the hue and cry. The Dodger and Master Bates, unwilling to

attract public attention by running down the open street, had

merely retired into the very first doorway round the corner.

They no sooner heard the cry, and saw Oliver running, than,

guessing exactly how the matter stood, they issued forth with

great promptitude, and, shouting "Stop thief!" too, joined in

the pursuit like good citizens.

Although Oliver had been brought up by philosophers, he

was not theoretically acquainted with their beautiful axiom that

self-preservation is the first law of nature. If he had been,

perhaps he would have been prepared for this. Not being prepared,

however, it alarmed him the more; so away he went

like the wind, with the old gentlemen and the two boys roaring

and shouting behind him.

"Stop thief! stop thief!" There is a magic in the sound.

The tradesman leaves his counter, and the carman his waggon;

the butcher throws down his tray, the baker his basket, the milkman

his pail, the errand-boy his parcels, the schoolboy his

marbles, the paviour his pick-axe, the child his battledore:

away they run, pell-mell, helter-skelter, slap-dash, tearing, yelling,

and screaming, knocking down the passengers as they turn

the corners, rousing up the dogs, and astonishing the fowls; and

streets, squares, and courts re-echo with the sound.

"Stop thief! stop thief!" The cry is taken up by a hundred

voices, and the crowd accumulate at every turning. Away they

fly, splashing through the mud, and rattling along the pavements;

up go the windows, out run the people, onward bear the

mob: a whole audience desert Punch in the very thickest of the

plot, and, joining the rushing throng, swell the shout, and lend

fresh vigour to the cry, "Stop thief! stop thief!"

"Stop thief! stop thief!" There is a passion for hunting

something deeply implanted in the human breast. One wretched,

breathless child, panting with exhaustion, terror in his looks,

agony in his eye, large drops of perspiration streaming down his

face, strains every nerve to make head upon his pursuers; and as

they follow on his track, and gain upon him every instant, they

hail his decreasing strength with still louder shouts, and whoop

and scream with joy "Stop thief!"—Ay, stop him for God's

sake, were it only in mercy!

[10]

Stopped at last. A clever blow that. He's down upon the

pavement, and the crowd eagerly gather round him; each new

comer jostling and struggling with the others to catch a glimpse.

"Stand aside!"—"Give him a little air!"—"Nonsense! he don't

deserve it."—"Where's the gentleman?"—"Here he is, coming

down the street."—"Make room there for the gentleman!"—"Is

this the boy, sir?"—"Yes."

Oliver lay covered with mud and dust, and bleeding from the

mouth, looking wildly round upon the heap of faces that surrounded

him, when the old gentleman was officiously dragged

and pushed into the circle by the foremost of the pursuers, and

made this reply to their anxious inquiries.

"Yes," said the gentleman in a benevolent voice, "I am

afraid it is."

"Afraid!" murmured the crowd. "That's a good un."

"Poor fellow!" said the gentleman, "he has hurt himself."

"I did that, sir," said a great lubberly fellow stepping forward;

"and preciously I cut my knuckle agin' his mouth. I

stopped him, sir."

The fellow touched his hat with a grin, expecting something

for his pains; but the old gentleman, eyeing him with an expression

of disgust, looked anxiously round, as if he contemplated

running away himself; which it is very possible he might

have attempted to do, and thus afforded another chase, had not

a police officer (who is always the last person to arrive in such

cases) at that moment made his way through the crowd, and

seized Oliver by the collar. "Come, get up," said the man

roughly.

"It wasn't me indeed, sir. Indeed, indeed, it was two other

boys," said Oliver, clasping his hands passionately, and looking

round: "they are here somewhere."

"Oh no, they ain't," said the officer. He meant this to be

ironical; but it was true besides, for the Dodger and Charley

Bates had filed off down the first convenient court they came to.

"Come, get up."

"Don't hurt him," said the old gentleman compassionately.

"Oh no, I won't hurt him," replied the officer, tearing his

jacket half off his back in proof thereof. "Come, I know you;

it won't do. Will you stand upon your legs, you young devil?"

Oliver, who could hardly stand, made a shift to raise himself

upon his feet, and was at once lugged along the streets by the

jacket-collar at a rapid pace. The gentleman walked on with

them by the officer's side; and as many of the crowd as could,

got a little a-head, and stared back at Oliver from time to time.

The boys shouted in triumph, and on they went.

[11]

CHAPTER THE ELEVENTH

TREATS OF MR. FANG THE POLICE MAGISTRATE, AND FURNISHES A SLIGHT

SPECIMEN OF HIS MODE OF ADMINISTERING JUSTICE.

The offence had been committed within the district, and indeed

in the immediate neighbourhood of a very notorious metropolitan

police-office. The crowd had only the satisfaction of

accompanying Oliver through two or three streets, and down a

place called Mutton-hill, when he was led beneath a low archway

and up a dirty court into this dispensary of summary justice,

by the back way. It was a small paved yard into which

they turned; and here they encountered a stout man with a

bunch of whiskers on his face, and a bunch of keys in his hand.

"What's the matter now?" said the man carelessly.

"A young fogle-hunter," replied the man who had Oliver in

charge.

"Are you the party that's been robbed, sir?" inquired the

man with the keys.

"Yes, I am," replied the old gentleman; "but I am not sure

that this boy actually took the handkerchief. I—I'd rather not

press the case."

"Must go before the magistrate now, sir," replied the man.

"His worship will be disengaged in half a minute. Now, young

gallows."

This was an invitation for Oliver to enter through a door

which he unlocked as he spoke, and which led into a small stone

cell. Here he was searched, and, nothing been found upon him,

locked up.

This cell was in shape and size something like an area cellar,

only not so light. It was most intolerably dirty, for it was

Monday morning, and it had been tenanted since Saturday night

by six drunken people. But this is nothing. In our station-houses,

men and women are every night confined on the most

trivial charges—the word is worth noting—in dungeons, compared

with which, those in Newgate, occupied by the most atrocious

felons, tried, found guilty, and under sentence of death,

are palaces! Let any man who doubts this, compare the two.

The old gentleman looked almost as rueful as Oliver when

the key grated in the lock; and turned with a sigh to the book

which had been the innocent cause of all this disturbance.

"There is something in that boy's face," said the old gentleman

to himself as he walked slowly away, tapping his chin with

the cover of the book in a thoughtful manner, "something that

touches and interests me. Can he be innocent? He looked

like—By the bye," exclaimed the old gentleman, halting very

abruptly, and staring up into the sky, "God bless my soul!

where have I seen something like that look before?"

After musing for some minutes, the old gentleman walked

with the same meditative face into a back ante-room opening

from the yard; and there, retiring into a corner, called up before[12]

his mind's eye a vast amphitheatre of faces over which a

dusky curtain had hung for many years. "No," said the old

gentleman, shaking his head; "it must be imagination."

He wandered over them again. He had called them into

view, and it was not easy to replace the shroud that had so long

concealed them. There were the faces of friends and foes, and

of many that had been almost strangers, peering intrusively

from the crowd; there were the faces of young and blooming

girls that were now old women; there were others that the

grave had changed to ghastly trophies of death, but which the

mind, superior to his power, still dressed in their old freshness

and beauty, calling back the lustre of the eyes, the brightness

of the smile, the beaming of the soul through its mask of clay,

and whispering of beauty beyond the tomb, changed but to be

heightened, and taken from earth only to be set up as a light

to shed a soft and gentle glow upon the path to Heaven.

But the old gentleman could recall no one countenance of

which Oliver's features bore a trace; so he heaved a sigh over

the recollections he had awakened; and being, happily for himself,

an absent old gentleman, buried them again in the pages of

the musty book.

He was roused by a touch on the shoulder, and a request

from the man with the keys to follow him into the office. He

closed his book hastily, and was at once ushered into the imposing

presence of the renowned Mr. Fang.

The office was a front parlour, with a panneled wall. Mr.

Fang sat behind a bar at the upper end; and on one side the

door was a sort of wooden pen in which poor little Oliver was

already deposited, trembling very much at the awfulness of the

scene.

Mr. Fang was a middle-sized man, with no great quantity

of hair; and what he had, growing on the back and sides of his

head. His face was stern, and much flushed. If he were really

not in the habit of drinking rather more than was exactly

good for him, he might have brought an action against his

countenance for libel, and have recovered heavy damages.

The old gentleman bowed respectfully, and, advancing to

the magistrate's desk, said, suiting the action to the word,

"That is my name and address, sir." He then withdrew a pace

or two; and, with another polite and gentlemanly inclination of

the head, waited to be questioned.

Now, it so happened that Mr. Fang was at that moment

perusing a leading article in a newspaper of the morning, adverting

to some recent decision of his, and commending him,

for the three hundred and fiftieth time, to the special and particular

notice of the Secretary of State for the Home Department.

He was out of temper, and he looked up with an angry

scowl.

"Who are you?" said Mr. Fang.

[13]

The old gentleman pointed with some surprise to his card.

"Officer!" said Mr. Fang, tossing the card contemptuously

away with the newspaper, "who is this fellow?"

"My name, sir," said the old gentleman, speaking like a gentleman,

and consequently in strong contrast to Mr. Fang,—"my

name, sir, is Brownlow. Permit me to inquire the name

of the magistrate who offers a gratuitous and unprovoked insult

to a respectable man, under the protection of the bench." Saying

this, Mr. Brownlow looked round the office as if in search of

some person who would afford him the required information.

"Officer!" said Mr. Fang, throwing the paper on one side,

"what's this fellow charged with?"

"He's not charged at all, your worship," replied the officer.

"He appears against the boy, your worship."

His worship knew this perfectly well; but it was a good

annoyance, and a safe one.

"Appears against the boy, does he?" said Fang, surveying

Mr. Brownlow contemptuously from head to foot. "Swear

him."

"Before I am sworn I must beg to say one word," said Mr.

Brownlow; "and that is, that I never, without actual experience,

could have believed——"

"Hold your tongue, sir!" said Mr. Fang peremptorily.

"I will not, sir!" replied the spirited old gentleman.

"Hold your tongue this instant, or I'll have you turned out

of the office!" said Mr. Fang. "You're an insolent impertinent

fellow. How dare you bully a magistrate!"

"What!" exclaimed the old gentleman, reddening.

"Swear this person!" said Fang to the clerk. "I'll not

hear another word. Swear him!"

Mr. Brownlow's indignation was greatly roused; but, reflecting

that he might only injure the boy by giving vent to it, he

suppressed his feelings, and submitted to be sworn at once.

"Now," said Fang, "what's the charge against this boy?

What have you got to say, sir?"

"I was standing at a book-stall—" Mr. Brownlow began.

"Hold your tongue, sir!" said Mr. Fang. "Policeman!—where's

the policeman? Here, swear this man. Now, policeman,

what is this?"

The policeman with becoming humility related how he had

taken the charge, how he had searched Oliver and found nothing

on his person; and how that was all he knew about it.

"Are there any witnesses?" inquired Mr. Fang.

"None, your worship," replied the policeman.

Mr. Fang sat silent for some minutes, and then, turning

round to the prosecutor, said, in a towering passion,

"Do you mean to state what your complaint against this

boy is, fellow, or do you not? You have been sworn. Now,

if you stand there, refusing to give evidence, I'll punish you

for disrespect to the bench; I will, by ——"

[14]

By what, or by whom, nobody knows, for the clerk and jailer

coughed very loud just at the right moment, and the former dropped

a heavy book on the floor; thus preventing the word from being heard—accidentally,

of course.

With many interruptions, and repeated insults, Mr. Brownlow contrived

to state his case; observing that, in the surprise of the moment,

he had run after the boy because he saw him running away, and expressing

his hope that, if the magistrate should believe him, although

not actually the thief, to be connected with thieves, he would deal as

leniently with him as justice would allow.

"He has been hurt already," said the old gentleman in conclusion.

"And I fear," he added, with great energy, looking towards the bar,—"I

really fear that he is very ill."

"Oh! yes; I dare say!" said Mr. Fang, with a sneer. "Come;

none of your tricks here, you young vagabond; they won't do. What's

your name?"

Oliver tried to reply, but his tongue failed him. He was deadly

pale, and the whole place seemed turning round and round.

"What's your name, you hardened scoundrel?" thundered Mr.

Fang. "Officer, what's his name?"

This was addressed to a bluff old fellow in a striped waistcoat, who

was standing by the bar. He bent over Oliver, and repeated the inquiry;

but finding him really incapable of understanding the question,

and knowing that his not replying would only infuriate the magistrate

the more, and add to the severity of his sentence, he hazarded a guess.

"He says his name's Tom White, your worship," said this kind-hearted

thief-taker.

"Oh, he won't speak out, won't he?" said Fang. "Very well, very

well. Where does he live?"

"Where he can, your worship," replied the officer, again pretending

to receive Oliver's answer.

"Has he any parents?" inquired Mr. Fang.

"He says they died in his infancy, your worship," replied the

officer, hazarding the usual reply.

At this point of the inquiry Oliver raised his head, and, looking

round with imploring eyes, murmured a feeble prayer for a draught

of water.

"Stuff and nonsense!" said Mr. Fang; "don't try to make a fool of

me."

"I think he really is ill, your worship," remonstrated the officer.

"I know better," said Mr. Fang.

"Take care of him, officer," said the old gentleman, raising his

hands instinctively; "he'll fall down."

"Stand away, officer," cried Fang savagely; "let him if he likes."

Oliver availed himself of the kind permission, and fell heavily to

the floor in a fainting fit. The men in the office looked at each other,

but no one dared to stir.

"I knew he was shamming," said Fang, as if this were incontestable

proof of the fact. "Let him lie; he'll soon be tired of that."

"How do you propose to deal with the case, sir?" inquired the

clerk in a low voice.

"Summarily," replied Mr. Fang. "He stands committed for three

months,—hard labour of course. Clear the office."

[15]

The door was opened for this purpose, and a couple of men were

preparing to carry the insensible boy to his cell, when an elderly man

of decent but poor appearance, clad in an old suit of black, rushed

hastily into the office, and advanced to the bench.

"Stop, stop,—don't take him away,—for Heaven's sake stop a

moment," cried the new-comer, breathless with haste.

Although the presiding geniuses in such an office as this, exercise

a summary and arbitrary power over the liberties, the good name,

the character, almost the lives of his Majesty's subjects, especially of

the poorer class, and although within such walls enough fantastic

tricks are daily played to make the angels weep thick tears of blood,

they are closed to the public, save through the medium of the daily

press. Mr. Fang was consequently not a little indignant to see an

unbidden guest enter in such irreverent disorder.

"What is this? Who is this? Turn this man out. Clear the

office," cried Mr. Fang.

"I will speak," cried the man; "I will not be turned out,—I saw

it all. I keep the book-stall. I demand to be sworn. I will not be

put down. Mr. Fang, you must hear me. You dare not refuse, sir."

The man was right. His manner was bold and determined, and

the matter was growing rather too serious to be hushed up.

"Swear the fellow," growled Fang with a very ill grace. "Now,

man, what have you got to say?"

"This," said the man: "I saw three boys—two others and the

prisoner here—loitering on the opposite side of the way, when this

gentleman was reading. The robbery was committed by another boy.

I saw it done, and I saw that this boy was perfectly amazed and stupified

by it." Having by this time recovered a little breath, the

worthy book-stall keeper proceeded to relate in a more coherent manner

the exact circumstances of the robbery.

"Why didn't you come here before?" said Fang after a pause.

"I hadn't a soul to mind the shop," replied the man; "everybody

that could have helped me had joined in the pursuit. I could get

nobody till five minutes ago, and I've run here all the way."

"The prosecutor was reading, was he?" inquired Fang, after another

pause.

"Yes," replied the man, "the very book he has got in his hand."

"Oh, that book, eh?" said Fang. "Is it paid for?"

"No, it is not," replied the man, with a smile.

"Dear me, I forgot all about it!" exclaimed the absent old gentleman,

innocently.

"A nice person to prefer a charge against a poor boy!" said Fang,

with a comical effort to look humane. "I consider, sir, that you

have obtained possession of that book under very suspicious and disreputable

circumstances, and you may think yourself very fortunate that

the owner of the property declines to prosecute. Let this be a lesson

to you, my man, or the law will overtake you yet. The boy is discharged.

Clear the office!"

"D—me!" cried the old gentleman, bursting out with the rage

he had kept down so long, "d—me! I'll——"

"Clear the office!" roared the magistrate. "Officers, do you

hear? Clear the office!"

The mandate was obeyed, and the indignant Mr. Brownlow was[16]

conveyed out, with the book in one hand and the bamboo cane in the

other, in a perfect phrenzy of rage and defiance.

He reached the yard, and it vanished in a moment. Little Oliver

Twist lay on his back on the pavement, with his shirt unbuttoned

and his temples bathed with water: his face a deadly white, and a

cold tremble convulsing his whole frame.

"Poor boy, poor boy!" said Mr. Brownlow bending over him.

"Call a coach, somebody, pray, directly!"

A coach was obtained, and Oliver, having been carefully laid on

one seat, the old gentleman got in and sat himself on the other.

"May I accompany you?" said the book-stall keeper looking in.

"Bless me, yes, my dear friend," said Mr. Brownlow quickly. "I

forgot you. Dear, dear! I've got this unhappy book still. Jump

in. Poor fellow! there's no time to lose."

The book-stall keeper got into the coach, and away they drove.

ELEGIAC STANZAS.

BY MRS. CORNWELL BARON WILSON.

Why mourn we for her, who in Spring's tender bloom,

And the sweet blush of womanhood, quitted life's sphere?

Why weep we for her? Thro' the gates of the tomb

She has pass'd to the regions undimm'd by a tear!

To the spirits' far land in the mansions above,

Unsullied, thus early her soul wing'd its flight;

While she bask'd in the beams of affection and love,

And knew not the clouds that oft shadow their light!

Fate's hand pluck'd the bud ere it blossom'd to fame,

No withering canker its leaflets had known;

The ministering angels her fellowship claim,

And rejoice o'er a spirit as pure as their own!

While she knew but life's purer and tenderer ties,

The guardian who watches life's path from our birth

Call'd home the bright being Heav'n form'd for the skies

Ere its bloom had been ting'd by the follies of earth!

Alas! while the light of her young spirit's flame

Shone a day-star of Hope to illumine us here,

The messenger-seraph too suddenly came,

And bore his bright charge to her own native sphere!

Yet mourn not for her, who, in Spring's tender bloom,

Has made life a desert to those left behind;

Like the rose-leaf, tho' wither'd, still yielding perfume,

In our hearts, ever fragrant, her memory is shrin'd!

[17]

FICTIONS OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

BY DELTA.

THE BUTTERFLY BISHOP.

Amongst the numerous grievances complained of, during the reigns

of the Anglo-Norman sovereigns, none gave more uneasiness than the

inhuman severity of the forest-laws; they disgusted those nobles not

in the confidence of the monarch, oppressed the people, and impoverished

the country.

The privilege of hunting in the royal forests was confined to the

king and his favourites, who spent the greater portion of their time,

not engaged in active warfare, in that diversion; many of them pursued

wild beasts with greater fury than they did enemies of their

country, and became as savage as the very brutes they hunted.

The punishment for hunting or destroying game in royal forests, or

other property belonging to the crown, was very severe: the offender

was generally put to death; but, if he could afford to pay an enormous

mulct to the king, the sentence was commuted either to dismemberment

or tedious imprisonment.

The propensity of the dignified clergy to follow secular pastimes,

especially that of hunting, is well known: they were ambitious to surpass

the laity in the number and splendid livery of their huntsmen, and

to excel in making the woods resound with the echo of their bugles;

many of them are recorded for their skill in the aristocratic and manly

amusement of the chase. Few persons, however, either ecclesiastic

or secular, equalled Peter de Roches, Bishop of Winchester, in

his fondness for, and prowess in, the chase.

Peter had spent the prime of his life as a soldier,[1] and having

rendered King John essential service in such capacity, that monarch

conferred upon him the lucrative office of Bishop of Winchester, and

he thenceforth became a curer of souls instead of a destroyer of

bodies.

Peter's appointment as a bishop afforded him ample time to devote

to the fascinating employment of chasing the "full-acorned boar" and

stealthy fox: he thought the hunter's shout, the winding notes of the

clanging horn, and the joyous bark of the hounds, much sweeter music

than the nasal chaunt of the drowsy monks.

It happened one day that Peter, (who was, according to the Chronicle

of Lanercost,[2] a proud and worldly man,—as was too often the

case with bishops of that period,) with a bugle dangling at his belt,

and mounted upon a fiery steed, attended by a vast retinue of men,

horses, and hounds, was in hot pursuit of a wary old fox; his courser,—more

fleet than the mountain roe, scarce bruising the grass with his

iron-shod hoofs,—like Bucephalus of Macedon, took fright at his own

shadow, and became unmanageable; nor were all the skill and spur

of the rider able to check his impetuous speed: the harder the bishop

pulled, the more unruly became his steed; the bridle now suddenly[18]

snapped in twain, and the bishop was left to the fate that awaited him.

Velocipede, for so the horse was called, now seemed exultingly to

bound over the deepest ditches, and to clear the highest thorny-twining

hedge with the greatest ease: nothing could moderate his

foaming rage; he resembled more the far-famed Pegasus of Medusan

blood, than the palfrey of a gentle bishop. The retinue, and eager

hounds, notwithstanding their utmost endeavour to keep pace with

their master, were left far behind.

Peter, having no control over his flying barbary, awaited with

truly apostolic calmness and gravity the issue of his wondrous ride,

seriously expecting every minute a broken neck or leg; or, perchance,

to have his preaching spoilt by the dislocation of a jaw-bone.—Such

thoughts will frequently obtrude themselves into the minds of

men encompassed with similar difficulties, let their presence of mind

be never so great.

After half an hour's ride in such unepiscopal speed, which can

only be compared to that of a steam-engine upon the Manchester

railroad, Velocipede suddenly stopped before a magnificent castle

with frowning battlements and a gloomy moat. The bishop, wondering

at what he saw, was struck dumb with astonishment; for he

well knew that so extensive a castle had not hitherto existed in his

diocese, nor did he know of any such in England. Velocipede seemed

also at his wits' end, and commenced frisking and gamboling

about; and, in making a devotional curvet to the castle, threw the

gallant, but unprepared bishop, over his head. Peter was either

stunned or entranced by the fall,—whether his senses ever returned

the reader must determine for himself when he has perused what

follows: the bishop, however, always declared that he was never

senseless, and that he could preach as well after, as before his fall.

No sooner was the bishop safely located upon the verdant down

by the reverential feelings of the awe-struck Velocipede, than the

castle's drawbridge fell, and an aged seneschal, of rubicund-tinted

face, with at least fifty liveried lackeys in fanciful suits, ran to assist

the bishop, and help him to regain his legs.

By the aid of a restorative cordial the bishop was resuscitated, and,

upon coming to himself, was welcomed by the seneschal to the castle

of Utopia.

The bishop looked aghast.

"My lord bishop," said the seneschal, "the king, our master, has

been long expecting you; he is all impatient to embrace you: hasten,

my lord, hasten your steps into the castle; the wines are cooled, the

supper is ready; oh, such a supper! my mouth waters at the very

smell thereof! Four wild turkeys smoke upon the spit, seven bitterns,

six-and-twenty grey partridges, two-and-thirty red-legged

ones, sixteen pheasants, nine woodcocks, nineteen herons, two-and-thirty

rooks, twenty ring-doves, sixty leverets, twelve hares, twenty

rabbits, and an ocean of Welsh ones, (enough to surfeit all the mice,

and kill every apoplectic person in the world,) twenty kids, six roebucks,

eight he-goats, fifteen sucking wild-boars, a flock of wild-ducks,

to say nothing of the sturgeons, pikes, jacks, and other fish, both

fresh and saltwater, besides ten tons of the most exquisite native

oysters: and then there are flagons, goblets, and mead-cups overflowing

with frothy ale, exhilarating wine, and goodly mead, all[19]

longing to empty their contents into our parched and ready stomachs,

which are unquenchable asbestos; for we drink lustily, my lord, and

eat powdered beef salted at Shrovetide, to season our mouths, and

render them rabid for liquid in the same proportion as a rabid dog

avoids it."

The seneschal here paused to take breath, for his description of the

supper exhausted the wind-trunk of his organ; and the bishop, seizing

the opportunity of its being replenished, said,

"Peace, hoary dotard! thou hast mistaken thy man; I am Peter

de Roches, Bishop of Winchester, and Protector of England during

the king's sojourn abroad."

"You need not tell me what I already know," replied the seneschal;

"though, it seems, I must again remind you that my lord the king

awaits your coming within the castle walls, and has prepared a sumptuous

supper, with all manner of good cheer, to greet you."

"Supper!" said the bishop in astonishment, "I have not yet

dined; besides I never eat supper."

"The devil take your inhuman fashion, then!" replied the seneschal:

"in extreme necessity I might forego a dinner, provided I

had eaten an overwhelming breakfast; but I would as soon die as

go without my supper. To go to bed without supper is a base and

aristocratic custom; I say it is an error offensive to nature, and nature's

dictates; all fasting is bad save breakfasting. That wicked

pope who first invented fasting ought to have been baked alive in

the papal kitchen."

To the latter part of the seneschal's speech the bishop mentally

assented; but he merely said,

"Go to, thou gorged dullard, and tell thy master to gormandize

without me."

"Well, go I suppose I must, if you will not come," returned the

seneschal, "for I cannot longer tarry here. Ah, Sir Bishop, did you

feel the gnawings of my stomach, you would be glad to throw some

food to the hungry mastiff that seems feeding upon my very vitals!"

"Hold thy balderdash!" said the bishop, who had become very

irritated, and would have sworn, had it been etiquette to do so in

those days, at the effusive and edacious harangue of the seneschal.

"Verily, thy hunger and thirst have gotten the better of thy wits!

Whence comest thou?"

"From within the pincernary of that castle, where I have been

indefatigably filling the goblets," answered the seneschal, smacking

his lips. "Sitio! sitio! my parched mouth moistens at the thought!

Oh! the lachryma Christi, the nectar, the ambrosia, and the true Falernian!

Ah! Sir Bishop, some persons drink to quench their thirst,

but I drink to prevent it."

"Pshaw!" said the bishop, "the wine that thou hast already

drunken hath fuddled thy brains."

"By a gammon of the saltest bacon!" returned the seneschal, "I

have more sense of what is good in my little finger than your reverence

has in your whole pate, or you would not stand shilly-shambling

here whilst so goodly a supper waits within."

The bishop was highly incensed at the seneschal's reflection upon

his pate, and would have followed, had he dared, the slashing example

of his namesake, and have smitten off the ear of this high-priest[20]

of the pantry; (for he always wore a sword, even in the pulpit,

firmly believing in the efficacy of cold steel, knowing from experience

that it would make a deeper and more lasting impression upon

human obduracy than the most eloquent preaching;) but the bishop

was deterred by prudential reflections from such sanguinary vengeance.

How long the confabulation between the bishop and the loquacious

seneschal would have lasted, and to what extent the patience of

the former might have been tried, it would at this remote period

be difficult to determine, especially as the Lanercost Chronicle does

not inform us. At any rate, it was cut shorter than it would have

been, by the approach of twenty youthful knights, clad in superb

armour, and riding upon horses caparisoned in most costly and gorgeous

trappings; they dismounted, and made a low obeisance. The

bishop returned it as lowly as bishops generally do, unless they are

bowing to the premier during the vacancy of an archbishoprick. The

knights advanced; but Peter remained as firm and majestic as the

rock of Gibraltar.

"Sir Bishop," said the chief of the knights, a youth with a most

beautiful and smiling face, "we are come to request your speedy

attendance upon our lord the king, who with any other than yourself

would have been much displeased at your perverse absence, after you

have been bidden by the steward of the household."

The bishop rubbed, shut, and opened his eyes.—"Am I bewitched,"

thought he to himself, "or do I dream?"

"Neither the one nor the other," said the knight, who perfectly

understood the bishop's cogitations.

"No? What, then, does all this mean?" inquired the bishop.

"When did my lord the king return from Picardy?"

"Proceed into the castle," replied the knight, "and let him answer

for himself."

"If these people consider this a joke," thought the bishop, "I by

no means think it one. At all events, come what come may, I will

follow up this strange adventure, and be even with these gentlemen.

I have not a bishop's garment," said he, addressing the seneschal;

"how can I appear before the king, accoutred as I am?"

"Knowing how much you are addicted to hunting," returned the

seneschal, "the king will assuredly receive you in your usual costume."

"Tut, fool!" said the bishop sneeringly; "do you forget, or has

your time been so engrossed with epicurean pursuits, that you have

not learnt how a guest, though bidden, was punished because he attended

a supper-party without a proper garment? Find me a becoming

dress, and I will instantly attend his highness' pleasure."

"If you will condescend to follow me," said the youthful knight,

"a sacerdotal dress shall be procured for you."

The bishop, nodding assent, was then conducted in solemn silence

into the wardrobe of the castle, where the obsequious attendants soon

arrayed him in a dress fit for a bishop to sit with the king at supper in.

It was not such unpretending costume as that in which bishops are at

present apparelled; but robes of the tinctured colours of the East,

which were more apt to remind both the wearer and the beholders of

mundane pomps and vanities, than of the humility and simplicity of[21]

Christianity. The alb was of most dazzling white, the dalmatica of

gold tissue, the stole was embroidered with precious stones, and the

chasuble, of purple velvet wrought with orfraise, was also studded

with costly orient gems.

The bishop thus splendidly accoutred was conducted with great

state and solemnity into the banqueting-room, one of the most magnificent

and spacious of the kind. It excelled everything he had ever

before seen: odoriferous and fragrant perfumes, fit for a Peri[3] to feed

on, saluted his nose; his sight was dazzled by splendid and radiant

illuminations, the most exquisite music stole upon his ear, and laughter

and mirth seemed to be universal; every face (there were many

hundreds in the room) was decked with a smile; there wanted but

one thing to complete the enchantment of the scene,—the light of

woman's laughing eye.

As the bishop entered the hall, five hundred harpers in an instant

twanged their harps; and the air resounded with trumpets, clarions,

fifes, and other musical instruments, not omitting the hollow drum.

The bishop, being tainted with the superstitious feelings of the age,

easily persuaded himself that he was in an enchanted palace; he

therefore determined to conform to every custom that prevailed in

the assembled company, and by that means he hoped to ingratiate

himself with the presiding spirit. When he had reached the centre

of the hall, the king (he wore a robe of rich crimson velvet, furred

with ermine, over a dalmatica flowered with gold, rubies, emeralds,

pearls, and diamonds, and on his head was a splendid crown beyond

estimation,) descended from a throne of the purest crystal, and advanced

to meet the bishop. As he passed the obsequious nobles, he

received their servile adulation with a smile, and, extending his arms,

folded the bishop in a royal embrace. The latter surveyed with some

awe the brawny shoulders of the king, and regarded with much

respect the amber-coloured locks hanging in great profusion down his

musculous back. The bishop thought that the aquiline nose, the

expansive brow, the large clear azure eye, and the ruddy complexion

of his host, about as much resembled those of his own monarch as a

terrible-looking bull-dog does a snarling mongrel. But he kept his

complimentary thoughts of his host to himself, as he was not at any

time of a communicative spirit,—he was a proud, not a vain man,—and

he moreover did not know how his compliment might be received.

The king handed the bishop to the upper end of the hall, and

placed him at his right hand. No sooner were they seated than

twenty trumpeters, in a gallery at the lower end of the room, blew,

as the signal for supper to be served up, three such electrifying blasts,

that, had the building not been as substantial as beautiful, it must

have been shaken.

As the loquacious seneschal, in tempting the bishop to quicken his

steps to supper, has put us in possession of many of the various

articles provided for this festive entertainment, we shall not weary

our reader by recapitulating them; but content ourselves with stating[22]

that, in addition to the solid fare, there were exquisite and delicate

fruits and viands, with wines and liqueurs of the choicest quality and

flavour. The supper-service was of the most superb description,

frosted silver and burnished gold; the goblets, vases, and wine-cups

were of crystal, mounted in gold richly carved. Such a feast the

bishop had never seen or tasted; and yet he was, like many of his

predecessors and successors too, perfectly familiar with the charms

of eating and drinking.

Nothing produces good-fellowship, intimacy, and conviviality more

than a good supper. We do not mean the cold, formal, and pompous

supper given to a fashionable party of the present day; but such as

were peculiar to by-gone days, when the table groaned under hot and

solid joints, and the company, with good appetites as provocatives,

ate and drank right heartily,—when glee and joy sat merrily upon

every face, and the glass went briskly round. Even misanthropes or

proud men could not be insensible to such festive scenes; their hearts

would necessarily warm as the exhilarating wine washed away their

gloomy and proud thoughts.

The bishop soon became familiar with his host, ate, drank, laughed,

and was merry; (we will not so scandalise the Bench as to presume

that he was drunk, although the Chronicle of Lanercost insinuates as

much;) the conversation was brilliant, the wit bright and poignant,

and the repartees flashed, and often rebounded upon the discharger.

To put a direct or pointed question at any time is, to say the least

of it, ungentlemanly; it very often gives dire offence, is seldom

admired or tolerated even by your most intimate acquaintance; and

men are seldom guilty of it, unless in their cups, or with a desire of

insulting:—how unpalatable must it be to royalty! As we know

it was the bishop's desire to keep upon good terms with his host,

it is but natural to infer that he would not intentionally insult him by

any rude question. If, therefore, any rudeness occurred on the part

of the bishop, it is charitable to set it down to inebriation, or perhaps

to the bishop's habit of putting questions in the confessional.

To the ineffable surprise of the king, the bishop was so injudicious

as to ask his host, in the most direct and pointed manner, who he

was, and whence he came there.

No sooner had the bishop attempted to satisfy his prying curiosity

by what appeared to him a very natural question, than the hall shook

as if Nature were indignant at his presumptuous inquiry; the whole

place was filled with an effulgent lambent light so brilliant, that it

entirely eclipsed the blaze of the variegated lamps that burned in the

hall; a low murmuring wind followed. The king's eyes seemed to

flash liquid fire as he answered, "Know me for what I am,—Arthur,

formerly lord of the whole monarchy of Britain, son of the mighty

Pendragon, and the illustrious founder of the Order of the Round

Table."

The bishop, having a firm heart and buxom valour, was far from

being daunted, as most men in a similar situation would have been,

and he inquired whether the story then current was true, that King Arthur

was not dead, but had been carried away by fairies into some

pleasant place, where he was to remain for a time, and then return

again and reign in as great authority as ever; or whether he died by

the sword-wounds he received from the sons of the king of the Picts;[23]

and if so, whether his soul was saved, and come to revisit this sublunary

world. The bishop, meditating authorship, asked a thousand

other questions relative to the immortality of the soul; and so subtle

were they, that, had they been put in these days of sciolism and charlatanry,

his fame would have been as brilliant, lasting, and deserved

as that of the noble editor of Paley's Theology.

Whether King Arthur did not choose to satisfy the bishop's curiosity,

or whether, judging from the usual depth of the human mind,

he thought the immortality of the soul a subject too deep and mystic

for such moonshine treatises as have been written concerning it, the

Chronicle of Lanercost does not inform us. It merely states, that to all

the bishop's searching questions Arthur only replied, "Verè expecto misericordiam

Dei magnam." He had no sooner uttered those words than

a roar, like the falling of mighty waters such as Niagara's was heard,

and from the incense-altar another blaze of transcendent light issued:

the whole assembly, excepting the bishop, prostrated themselves and

chaunted a hymn, which he, mistaking for a bacchanal-venatical chorus,

heartily joined in. Upon this outrage of public decency, the chaunt

instantly terminated with a crash resembling what is ignorantly called

the falling of a thunderbolt; the altar again smoked, and horrible

and clamorous noises issued therefrom, like the bellowing of buffaloes,

the howling of wolves, the snarling and barking of hounds, the neighing

of horses, the halloo of huntsmen, and the blasts of brazen trumpets,

all in heterogeneous mingle. The smoke gradually assumed the

appearance of a host of hunters; one of them, evidently their chief,

fixed his glaring eyes upon the bishop, and frowned awfully. The

bishop did not admire the looks of the hunter-chief, and even winced

a little when he raised his ghastly arm, (as a self-satisfied orator does

when about to enforce some appalling clap-trap sentiment,) and said

in a gruff growl, "I am Nimrod, of hunting fame, and such a hunter

was I as the world had not before, or since, or will ever have again.

Yet was I no monopolizer of game, or murderer of men to preserve it,

as some have unjustly charged me. I loved the chase, and taught my

subjects to love it too; but thou, oh Bishop Peter, hast been a cruel

hunter, and strict preserver of game. The tongues thou hast dilacerated,

the ears and noses thou hast cut off, and the wretches thou

hast slain, form an awful catalogue of cruelty, and one that will require

tears of blood to wash out. Hearken to the lamentations of thy

victims, and the bewailings of the widows and orphans thy cruelty

hath made! Hadst thou not been so peerless and bold a hunter, I

should not have condescended to warn you of the terrible fate you

will experience in the world to come, unless you mend your ways.

Lover and encourager that I was, and interested as I still am in that

manly sport, I would sooner that it were entirely lost to the world

than it should be disgraced by human bloodshed. List, I say, to

the cries of the victims whom thou hast sacrificed at the altar of

Diana, thy divinity!" Loud lamentations were now heard, and a hideous

group of dismembered menacing ghosts flitted rapidly before

the bishop's wondering sight. He closed his eyes to avoid their

angry looks; one writer insinuates that he swooned, but we think

that unlikely. Be it, however, as it may, upon his opening his eyes

he neither saw Nimrod, his crew, nor any of the victims of the forest-laws.

They had every one of them disappeared!

[24]

King Arthur, like a brave and magnanimous prince, soon forgot and

forgave the bishop's want of good breeding in asking impertinent

questions; though he severely chid him for having split so many

human noses, and dismembered Christians without the slightest remorse,

for so trifling an offence as infraction of the forest-laws: and

that, too, within the very precinct of Winchester Castle, where the

Round Table was preserved. The bishop thought those offences anything