Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed. Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol (etext transcriber's note) |

THE

C H R O N I C L E S O F C R I M E.

The Man with the Carpet Bag.

Edited by Camden Pelham

OF THE INNER TEMPLE BARRISTER-AT LAW

with

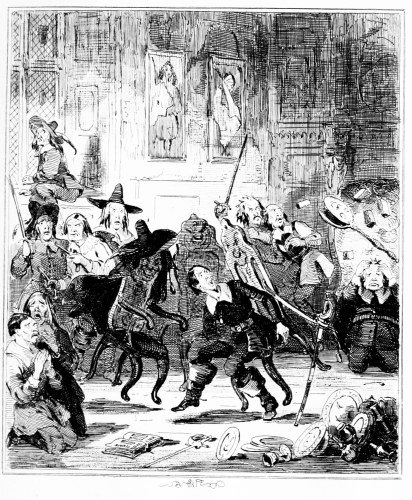

ILLUSTRATIONS FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS

BY PHIZ

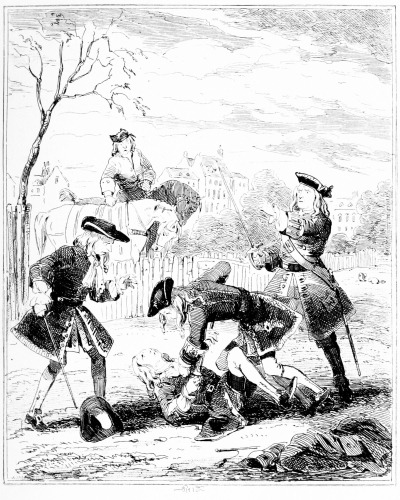

Escape of the Mayor of Bristol.

“His worship, seeing me, said, ‘For God’s sake, young man, assist me

COMPRISING

| COINERS. EXTORTIONERS. FORGERS. FRAUDULENT BANKRUPTS. FOOTPADS. HIGHWAYMEN. HOUSEBREAKERS. |

INCENDIARIES. IMPOSTORS. MURDERERS. MUTINEERS. MONEY-DROPPERS. |

PIRATES. PICKPOCKETS. RIOTERS. SHARPERS. TRAITORS. &c., &c. |

INCLUDING

A NUMBER OF CURIOUS CASES NEVER BEFORE PUBLISHED.

EMBELLISHED WITH FIFTY-TWO ENGRAVINGS,

FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS BY “PHIZ.”

BY CAMDEN PELHAM, ESQ.,

OF THE INNER TEMPLE, BARRISTER-AT-LAW.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

T. MILES & CO., 95, UPPER STREET.

1887.

FEW words are necessary to introduce to our readers a work, the character and the object of which are so legibly written upon its title-page. “Chronicles of Crime” must comprise details, not only interesting to every person concerned for the welfare of society, but useful to the world in pointing out the consequences of guilt to be equally dreadful and inevitable. It is to be regretted that in most of the works of the present day, little attention is paid to the ultimate moral or beneficial effects to be produced by them upon the public mind; and that while every effort is made to afford amusement, no care is taken to produce those general impressions, so necessary to the maintenance of virtue and good order. The advantages of precept are everywhere admitted and extolled; but still more effectual are the lessons which are taught through the influence of example, whose results are but too frequently fatal. The representation of guilt with its painful and degrading consequences, has been universally considered to be the best means of warning youth against the danger of temptation;—the benefits to be expected from example are too plainly exhibited by the infliction of punishment to need repetition; and the more generally the effects of crime are shown, and the more the horrors which precede{vi} detection and the deplorable fate of the guilty are made known, the greater is the probability that the atrocity of vice may be abated and the security of the public promoted.

Having said thus much in recommendation of the object of this work, a few words as to its precise character may be added. Amusement and instruction are alike the results which are hoped to be secured. It is admitted by men, whose desire it is to make themselves acquainted with human nature, that jails and other places of confinement afford them a wide field for contemplation. The study of life, in all its varieties, is one no less interesting than useful. The ingenuity of thieves, depicted in their crimes, is a theme upon which all have opportunities to remark, in their passage through a life of communication with the world; and no less worthy of observation are the offences of men, whose outrages or cruelties have rendered them amenable to the laws, framed for the protection of society. All afford matter of contemplation to the mind, most likely to be attended with useful results. It may be observed that to persons of vicious inclination, effects the opposite to those which are suggested may be produced; but an answer as conclusive as it is just may be given to any such remark. The consequences of crime are as clearly exhibited as its motives and its supposed advantages, and few are hardy enough to declare or to exhibit a carelessness for punishment, or a contempt for the bitter fruits of their misdeeds. Presenting an example, therefore, of peculiar usefulness, it is trusted that the work will be found no less interesting than instructive. Combining these two most important qualities to secure its success, it is hoped that the patronage afforded it will be at least commensurate with the pains which have been bestowed upon its production.{vii}

It will be observed that in the preparation of these pages much care has been taken to preserve those features only which are likely to be acceptable to society. The most scrupulous attention has been paid to the rejection of such instances of guilt, the circumstances of which might be deemed unfit for general perusal. In a compass so circumscribed as that to which the work is confined, it would be impossible to give the history of every criminal who has undergone punishment for his offences, during the period to which our Chronicles extend: neither is that the object of the work. It is intended to embrace within its limits all those cases which from their details present outlines of attraction. The earlier pages are derived from sources of information peculiarly within the reach of the Editor, while those of a later period are compiled from known authorities as accurate as they are complete.

The comparison of the offences, and of the punishments of the last century, with those of more recent date, will exhibit a marked distinction between the two periods, both as to the atrocity of the one, and the severity of the other. Those dreadful and frequent crimes, which would disgrace the more savage tribes, and which characterised the lives of the early objects of our criminal proceedings, are now no longer heard of; and those characters of blood, in which the pages of our Statute-book were formerly written, have been wiped away by improved civilisation and the milder feelings of the people. It is but just to say that the provisions of a wise Parliament have not been unattended with proper results. Humanity has been permitted to temper the stern demands of justice; and however atrocious, it must be admitted, some of the crimes may be which have been recently perpetrated, and however numerous the offenders-it cannot be denied that the{viii} general aspect of the state of crime in this country is now infinitely less alarming than formerly.

The necessity for punishment as the consequence of crime, can neither be doubted nor denied. Without it the bonds of society must be broken—government in no form could be upheld. If, then, example be the object of punishment, and peace and good order, nay, the binding together of the community, be its effects, how useful must be a work, whose intention is to hold out that example which must be presumed to be the foundation of a well-ordered society.

The cases will be found to be arranged chronologically, which, it is presumed, will afford the most satisfactory and the most easy mode of reference. This advantage is, however, increased by the addition of copious indices.

London, July 1, 1840.

Note.—The offence mentioned opposite to each name is that alleged against the person charged.

| PAGE | |

| Adams, Agnes. Forgery | 505 |

| Alden, Martha. Murder | 445 |

| Allen, George. Murder | 444 |

| Allen, William. Returned Transport | 330 |

| Armitage, Richard. Forgery | 506 |

| Aslett, Robert. Embezzlement | 410 |

| Atkins, James, alias Hill, alias Jack the Painter. Arson | 269 |

| Attaway, James. Burglary | 226 |

| Aram, Eugene. Murder | 168 |

| Avershaw, Lewis Jeremiah. Murder | 347 |

| Bailey, Richard. Burglary | 226 |

| Balfour, Alexander. Murder | 3 |

| Balmerino, Lord. Treason | 107 |

| Baltimore, Lord. Rape | 213 |

| Barrington, George, alias Waldron. Pickpocket | 363 |

| Bateman, Mary. Murder | 458 |

| Bellingham, John. Murder | 527 |

| Benson, Mary, alias Phipoe. Murder | 358 |

| Birmingham Riots (1780) | 326 |

| Blackburn, Joseph. Forgery | 575 |

| Blake, Joseph, alias Blueskin. Burglary | 35 |

| Blandy, Mary. Parricide | 148 |

| Bodkin, John, and Dominick. Murder | 105 |

| Bolland, James. Forgery | 229 |

| Bounty, Mutiny of | 328 |

| Bourne, John. Conspiracy | 332 |

| Bradford, Jonathan. Murder | 107 |

| Briant, Mary. Returned Transport | 330 |

| Bristol, Countess of, alias Duchess of Kingston. Bigamy | 250 |

| Broadric, Ann. Murder | 343 |

| Brown, Nicol. Murder | 157 |

| Brown, Joseph. Murder | 456 |

| Brownrigg, Elizabeth. Murder | 204 |

| Burt, Samuel. Forgery | 316 |

| Burgh, Rev. Richard. Conspiracy | 332 |

| Butcher, John. Returned Transport | 330 |

| Butterworth, William. Murder | 342 |

| Buxton, James. Murder | 202 |

| Caddell, George. Murder | 7 |

| Cameron, Dr. Archibald. Treason | 154 |

| Campbell, Alexander. Murder | 452 |

| Campbell, Mungo. Murder | 227 |

| Carr, John. Forgery | 124 |

| Carroll, Barney. Cutting and Maiming | 197 |

| Carson, Thomas. Murder | 590 |

| Caulfield, Frederick. Murder | 141 |

| Chandler, William. Perjury | 145 |

| Charteris, Col. Francis. Rape | 76 |

| Clayton, John. Burglary | 522 |

| Cobby, John. Murder | 127 |

| Colley, Thomas. Murder | 138 |

| Cook, Thomas. Murder | 8 |

| Cooke, Arundel. Cutting and Maiming | 31 |

| Cooper, James. Murder | 454 |

| Couchman, Samuel. Mutiny | 131 |

| Coyle, Richard. Piracy | 84 |

| Cox, Jane. Murder | 507 |

| Cummings, John. Conspiracy | 332 |

| Crosswell, John. Conspiracy | 49 |

| Dagoe, Hannah. Robbery{x} | 197 |

| Davis, James. Conspiracy | 332 |

| Dawson, Daniel. Poisoning Race-horses | 524 |

| Dawson, James. Treason | 122 |

| De Butte, Louis, alias Mercier. Murder | 272 |

| De la Motte, Francis Henry. Treason | 301 |

| Derwentwater, Earl Of. Treason | 19 |

| Despard, Col. Edward Marcus. Treason | 389 |

| Dignum, David Brown. Fraud | 268 |

| Diver, Jenny, alias Mary Young. Pickpocket | 96 |

| Dixon, Margaret. Murder | 71 |

| Dodd, Dr. William. Forgery | 274 |

| Donally, James. Robbery | 292 |

| Downie, David. Treason | 335 |

| Dramatti, John Peter. Murder | 9 |

| Drew, Charles. Parricide | 102 |

| Duncan, William. Murder | 436 |

| Durnford, Abraham. Robbery | 292 |

| Elby, William. Murder | 10 |

| Emmet, Robert. Treason | 382 |

| Farmery, William. Murder | 236 |

| Farrell, James, alias Buck. Murder | 202 |

| Favey, James, alias O’Coigley. Treason | 360 |

| Fenning, Elizabeth. Murder | 569 |

| Ferguson, Richard, alias Galloping Dick. Robbery | 371 |

| Ferrers., Earl. Murder | 181 |

| Fleet Marriages | 159 |

| Foster, George. Murder | 380 |

| Francis, John. Treason | 389 |

| Fryer, James. Burglary | 288 |

| Gadesby, William. Robbery | 325 |

| Galloping Dick, alias Richard Ferguson. Robbery | 371 |

| Gardelle, Theodore. Murder | 188 |

| Gentleman Harry, alias Henry Sterne. Robbery | 315 |

| Gidley, George. Murder | 199 |

| Goodere, Capt. Samuel. Murder | 103 |

| Gordon, Thomas. Murder | 318 |

| Gow, John. Piracy | 72 |

| Grant, Jeremiah. Burglary | 588 |

| Gregg, William. Treason | 12 |

| Grierson, Rev. Jno., unlawful performance of the Marriage Ceremony | 159 |

| Griffenburg, Elizabeth. Accessory to a Rape | 213 |

| Griffiths, William. Robbery | 234 |

| Guest, William. Diminishing the Coin of the Realm | 203 |

| Hackman, the Rev. James. Murder | 289 |

| Hadfield, James. Treason | 370 |

| Hatfield, John. Forgery | 394 |

| Haggerty, Owen. Murder | 437 |

| Hamilton, Col. John. Manslaughter | 16 |

| Hammond, John. Murder | 127 |

| Hardwick, James. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Harris, Samuel. Murder | 311 |

| Harvey, Anne. Accessory To a Rape | 213 |

| Hawden, John. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Hawes, Nathaniel. Robbery | 28 |

| Hayden, James. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Hayes, Catherine. Murder | 65 |

| Haywood, Richard. Robbery | 417 |

| Heald, Joseph. Murder | 378 |

| Hebberfield, William. Forgery | 521 |

| Henderson, Matthew. Murder | 116 |

| Henley, John. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Hill, James, alias Jack the Painter | 269 |

| Hodges, Joseph. Cross-dropping | 351 |

| Holloway, John. Murder | 437 |

| Holmes, John. Body-stealing | 273 |

| Horne, William Andrew. Murder | 179 |

| Horner, Thomas. Burglary | 288 |

| Housden, Jane. Murder | 18 |

| Hunter, the Rev. Thomas. Murder | 1 |

| Hutchinson, Amy. Murder | 133 |

| Jackson, the Rev. Mr. Treason | 346 |

| Jack the Painter, alias Hill. Arson | 269 |

| Jacobs, Simon. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Jeffries, Elizabeth. Murder | 152 |

| Jenkins, William. Burglary | 522 |

| Jennison, Francis. Murder | 342 |

| Jobbins, William. Arson | 324 |

| Johnson, William. Murder | 18 |

| Jones, Laurence. Robbery | 333 |

| Kearinge, Matthew. Arson & Murder{xi} | 453 |

| Keele, Richard. Murder | 18 |

| Kendall, Richard. Robbery | 552 |

| Kenmure, Lord. Treason | 19 |

| Kidd, Capt. John. Piracy | 4 |

| Kilmarnock, Earl Of. Treason | 107 |

| King, William. Cutting and Maiming | 197 |

| Kingston, Duchess of, alias Countess of Bristol. Bigamy. | 250 |

| Knight, Thomas. Mutiny | 131 |

| Lancey, Capt. John. Arson | 156 |

| Layer, Christopher. Treason | 32 |

| Lazarus, Jacob. Murder | 227 |

| Le Maitre, Peter. Stealing | 267 |

| Leonard, John. Rape | 235 |

| Lilly, Nathaniel. Returned Transport | 330 |

| Lisle, alias Major J. G. Semple. Swindling | 564 |

| London, Riots of | 295 |

| Lovat, Lord. Treason | 118 |

| Lowe, Edward. Arson | 324 |

| Lowther, William. Murder | 18 |

| Luddites, The | 549 |

| Magnis, Harriet. Child-stealing | 510 |

| Mahony, Matthew. Murder | 103 |

| Malcolm, Sarah. Murder | 79 |

| Male, Samuel. Robbery | 236 |

| Marrs, Murder of the | 513 |

| Martin, James. Returned Transport | 330 |

| Massey, Capt. John. Piracy | 30 |

| Mathison, James. Forgery | 295 |

| Mayne, Robert. Mutiny | 196 |

| M‘Can, Townley. Conspiracy | 332 |

| M‘Canelly, John. Burglary | 151 |

| Merritt, Amos. Burglary | 237 |

| Mercier, Francis, alias De Butte. Murder | 272 |

| Metyard, Sarah, and Sarah Morgan. Murder | 210 |

| Mills, John. Murder | 132 |

| Mills, Richard. Murder | 127 |

| M‘Ilvena, Michael. Unlawfully performing the Marriage Ceremony | 560 |

| Mitchell, Samuel Wild. Murder | 415 |

| Mitchell, James. Murder | 562 |

| M‘Kinlie, Peter. Murder | 199 |

| M‘Naughton, John. Murder | 191 |

| Morgan, Edward. Murder and Arson | 158 |

| Morgan, John. Mutiny | 131 |

| Morgan, Luke. Burglary | 151 |

| Mutiny of the Bounty | 328 |

| Mutiny at the Nore | 353 |

| Newton, William. Robbery | 300 |

| Nicholson, Philip. Murder | 555 |

| Nore, Mutiny at | 353 |

| North, John. Murder | 311 |

| O’Coigley, James, alias Favey. Treason | 360 |

| Page, William. Robbery | 165 |

| Paleotti, Marquis de. Murder | 25 |

| Palmer, John. Burglary | 448 |

| Parker, Richard. Mutiny | 353 |

| Parsons, William. Returned Transport | 142 |

| Patch, Richard. Murder | 430 |

| Perfect, Henry. Fraud | 419 |

| Perreau, Robert and Daniel. Forgery | 244 |

| Phillips, Thomas. Robbery | 27 |

| Phillips, Morgan. Murder and Arson | 294 |

| Phillips, John. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Phipoe, Maria Theresa, alias Mary Benson. Murder | 358 |

| Phipps, Thomas, Sen. and Jun. Forgery | 319 |

| Picton, Thomas. Unlawfully Applying The Torture | 423 |

| Porteous, Captain John. Murder | 81 |

| Porter, Solomon. Murder | 227 |

| Price, John. Murder | 26 |

| Price, George. Murder | 87 |

| Price, Charles. Forgery | 312 |

| Probin, Richard. Cross-dropping | 351 |

| Quintin, St., Richard. Murder | 199 |

| Rann, John, alias Sixteen-stringed Jack. Robbery | 242 |

| Ratcliffe, Charles. Treason | 118 |

| Richardson, John. Piracy | 84 |

| Riots, Birmingham (1780) | 326 |

| Riots of London | 295 |

| Roach, Philip. Piracy | 34 |

| Ross, Norman. Murder | 136 |

| Rowan, Archibald Hamilton. Sedition{xii} | 340 |

| Rudd, Margaret Caroline. Forgery | 249 |

| Ryan, John. Arson and Murder | 453 |

| Ryland, William Wynne. Forgery | 308 |

| Sawyer, William. Murder | 566 |

| Scoldwell, Charles. Stealing | 350 |

| Semple, Major J. G. Swindling | 564 |

| Sheeby, Father. Murder | 202 |

| Sheppard, James. Treason | 24 |

| Sheppard, John. Burglary | 38 |

| Simmons, Thomas. Murder | 450 |

| Sixteen-stringed Jack. Robbery | 242 |

| Sligo, the Marquis of. Enticing Seamen from H.M. Navy | 526 |

| Smith, John. Robbery | 11 |

| Smith, John. Mutiny | 196 |

| Smith, Robert. Robbery | 379 |

| Smith, Francis. Murder | 399 |

| Solomons, John. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Spencer, Barbara. Coining | 27 |

| Spiggot, William. Robbery | ib. |

| Sterne, Henry, alias Gentleman Harry. Robbery | 315 |

| Swan, John. Murder | 152 |

| Tapner, Benjamin. Murder | 127 |

| Terry, John. Murder | 378 |

| Thomas, Charles. Forgery | 506 |

| Thornhill, Richard. Manslaughter | 15 |

| Tilley, William. Conspiracy | 349 |

| Townley, Francis. Treason | 122 |

| Trusty, Christopher. Returned Transport | 310 |

| Turpin, Richard. Robbery | 89 |

| Tyrie, David. Treason | 307 |

| Underwood, Thomas. Robbery | 325 |

| Vaux, James Hardy. Privately Stealing | 481 |

| Waldron, George, alias Barrington. Pickpocket | 363 |

| Wall, Joseph. Murder | 374 |

| Walsh, Benjamin. Felony | 511 |

| Watt, Robert. Treason | 335 |

| Weil, Levi and Asher. Murder | 227 |

| White, Huffey. Robbery | 552 |

| White, Charles. Murder | 103 |

| Whiting, Michael. Murder | 509 |

| Whitmore, John, alias Old Dash. Rape | 504 |

| Wild, Jonathan. Receiving Stolen Goods | 51 |

| Wilkinson, the Rev. Mr. Unlawfully performing the Marriage Ceremony | 208 |

| Wilkes, John. Sedition | 220 |

| Williamson, John. Murder | 208 |

| Williamsons, Murder of the | 513 |

| Williams, Peter. Body-stealing | 273 |

| Williams, Renwick. Cutting and Maiming | 320 |

| Winton, Earl of. Treason | 19 |

| Woodburne, John. Cutting and Maiming | 31 |

| Wood, Joseph. Robbery | 325 |

| Wood, John. Treason | 389 |

| York, William. Murder | 127 |

| Young, Mary, alias Jenny Diver. Pickpocket | 96 |

| Zekerman, Andrew. Murder | 199 |

THE case of this criminal, who was executed in the year 1700, for the barbarous murder of his two pupils, the children of a gentleman named Gordon, an eminent merchant, and a baillie, or alderman of the City of Edinburgh, is the first on our record; and, certainly, for its atrocity, deserves to be placed at the head of the list of offences which follows its melancholy recital. From the title of the offender, it will be seen that he was a preacher of the word of God; and that a person in his situation in life should suffer so ignominious an end for such a crime, is indeed extraordinary; but how much more horrible is the fact which is related to us, that on the scaffold, when all hope of life and of repentance was past, he expressed his disbelief in that God whom it was his profession to uphold, and whose omnipotence it had been his duty to teach!

The malefactor, it would appear, was born of most respectable parents, his father being a rich farmer in the county of Fife, and at an early age he was sent to the University of St. Andrew’s for his education. His success in the pursuit of classical knowledge soon enabled him to take the degree of Master of Arts, and his subsequent study of divinity was attended with as favourable results. Upon his quitting college, in accordance with the practice of the time he entered the service of Mr. Gordon in the capacity of chaplain, in which situation it became his duty to instruct the sons of his employer, children respectively of the ages of eight and ten years. The family consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Gordon, the two boys, their sister (a girl younger than themselves), Mr. Hunter, a young woman who attended upon Mrs. Gordon, and the usual menial servants. The attention of Hunter was attracted by the comeliness of the lady’s-maid, and a connexion of a criminal nature was soon commenced between them. The accidental discovery of this intrigue by the three children, was the ultimate cause of the deliberate murder of two of them by their tutor.

The young woman and Hunter had retired to the apartment of the latter, but, having omitted to fasten the door, the children entered and saw enough to excite surprise in their young minds. In their conversation{2} subsequently at meal-time, they said so much as convinced their parents of what had taken place, and the servant-girl was instantly dismissed; while the chaplain, who had always been considered to be a person of mild and amiable disposition and of great genius, was permitted to remain, upon his making such amends to the family as were in his power, by apologising for his indiscretion. From this moment, however, an inveterate hatred for the children arose in his breast, and he determined to satisfy his revenge upon them by murdering them all. Chance for some time marred his plans, but he was at length enabled to put them into execution as regarded the two boys. It appears that he was in the habit of taking them to walk in the fields before dinner, and the girl on such occasions usually accompanied them, but at the time at which the murder of her brothers was perpetrated she was prevented from going with them. They were at the country-seat of Mr. Gordon, situated at a short distance only from Edinburgh, and an invitation having been received for the whole family to dine in that city, Mrs. Gordon desired that all the children might accompany her and her husband. The latter, however, opposed the execution of this plan, and the little girl only was permitted to go with her parents. The intention of the murderer to destroy all the children was by this means frustrated; but he still persevered in his bloody purpose with regard to the sons of his benefactor, whom he determined to murder while they were yet in his power. Proceeding with them in their customary walks, they all sat down together to rest; but the boys soon quitted their tutor to catch butterflies, and to gather the wild flowers which grew in abundance around them. Their murderer was at that moment engaged in preparing the weapon for their slaughter, and presently calling them to him, he reprimanded them for disclosing to their parents the particulars of the scene which they had witnessed, and declared his intention to put them to death. Terrified by this threat, they ran from him; but he pursued and overtook them, and then throwing one of them on the ground and placing his knee on his chest, he soon despatched his brother by cutting his throat with a penknife. This first victim disposed of, he speedily completed his fell purpose, with regard to the child whose person he had already secured. The deed, it will be observed, was perpetrated in open day; and it would have been remarkable, indeed, if, within half a mile of the chief city of Scotland, there had been no human eye to see so horrible an act. A gentleman who was walking on the Castle Hill had a tolerable view of what passed, and immediately ran to the spot where the deceased children were lying; giving the alarm as he went along, in order that the murderer might be secured. The latter, having accomplished his object, proceeded towards the river to drown himself, but was prevented from fulfilling his intention; and having been seized, he was soon placed in safe custody, intelligence of the frightful event being meanwhile conveyed to the parents of the unhappy children.

The prisoner was within a few days brought to trial, under the old Scottish law, by which it was provided that a murderer, being found with the blood of his victim on his clothes, should be prosecuted in the Sheriff’s Court, and executed within three days. The frightful nature of the case rendered it scarcely uncharitable to pursue a law so vigorous according to its letter, and a jury having been accordingly impanelled, the prisoner was brought to trial, and pleaded guilty, adding the horrible announcement of his regret that Miss Gordon had escaped from his revenge. The sentence{3} of death was passed upon the culprit by the sheriff, but it was directed to be carried into effect with the additional terms, that the prisoner should first have his right hand struck off; that he should then be drawn up to the gibbet, erected near the locality of the murder, by a rope; and that after execution, he should be hanged in chains, between Edinburgh and Leith, the weapon of destruction being passed through his hand, which should be advanced over his head, and fixed to the top of the gibbet. The sentence, barbarous as it may now appear, was carried into full execution on the 22nd of August, 1700; and frightful to relate, he, who in life had professed to be a teacher of the Gospel, on his scaffold declared himself to be an Atheist. His words were, “There is no God—or if there be, I hold him in defiance.” The body of the executed man, having been at first suspended in chains according to the precise terms of his sentence, was subsequently, at the desire of Mr. Gordon, removed to the outskirts of the village of Broughton, near Edinburgh.

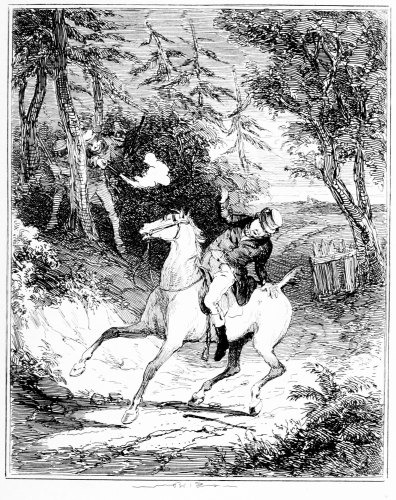

THE case of this criminal is worthy of some attention, from the very remarkable circumstances by which it was attended. The subject of this sketch was born in 1687, at the seat of his father, Lord Burley, near Kinross; and having studied successively at Orwell, near the place of his birth, and at St. Andrews, so successfully as to obtain considerable credit, he returned home, being intended by his father to join the army of the Duke of Marlborough, then in Flanders. Here he became enamoured of Miss Robertson, the governess of his sisters, however; and in order to break off the connexion he was sent to make the tour through France and Italy, the young lady being dismissed from the house of her patron. Balfour, before his quitting Scotland, declared his intention, if ever the young lady should marry, to murder her husband; but deeming this to be merely an empty threat, she was, during his absence, united to a Mr. Syme, with whom she went to live at Inverkeithing. On his return to his father’s house, he learned this fact, and immediately proceeded to put his threat into execution. Mrs. Syme, on seeing him, remembering his expressed determination, screamed with affright; but her husband, unconscious of offence, advanced to her aid, and in the interim, Balfour entering the room, shot him through the heart. The offender escaped, but was soon afterwards apprehended near Edinburgh; and being tried, was convicted and sentenced to be beheaded by the maiden[1], on account of the nobility of his family.{4}

The subsequent escape of the criminal from an ignominious end is not the least remarkable part of his case. The scaffold was actually erected for the purpose of his execution; but on the day before it was to take place his sister went to visit him, and, being very like him in face and stature, they changed clothes, and he escaped from prison. His friends having provided horses for him, he proceeded to a distant village, where he lay concealed until an opportunity was eventually offered him of quitting the kingdom. His father died in the reign of Queen Anne, but he had first obtained a pardon for his son, who succeeded to the title and honours of the family, and died in the year 1752, sincerely penitent for his crime.

THE first-named subject of this memoir was born at Greenock, in Scotland, and was bred to the sea; and quitting his native land at an early age, he resided at New York, where he eventually became possessed{5} of a small vessel, with which he traded among the pirates, and obtained a complete knowledge of their haunts. His ruling passion was avarice, although he was not destitute of that courage which became necessary in the profession in which he eventually embarked. His frequent remarks upon the subject of piracy, and the facility with which it might be checked, having attracted the attention of some considerable planters, who had recently suffered from the depredations of the marauders who infested the seas of the West Indies, obtained for him a name which eventually proved of great service to him. The constant and daring interruptions offered to trading ships, encouraged as they were by the inhabitants of North America, who were not loath to profit by the irregularities of the pirates, having attracted the attention of the Government, the Earl of Bellamont, an Irish nobleman of distinguished character and abilities, was sent out to take charge of the government of New England and New York, with special instructions upon the subject of these marine depredators. Colonel Livingston, a gentleman of property and consideration, was consulted upon the subject by the governor; and Kidd, who was then possessed of a sloop of his own, was recommended as a fit person to be employed against the pirates. The suggestion met the approbation of Lord Bellamont; but the unsettled state of public affairs rendered the further intervention of Government impossible; and a private company, consisting of the Duke of Shrewsbury, the Lord Chancellor Somers, the Earls of Romney and Oxford, Colonel Livingston, and other persons of rank, agreed to raise 6000l. to pay the expenses of a voyage, the purpose of which was to be directed to the removal of the existing evil; and it was agreed that the Colonel and Capt. Kidd, who was to have charge of the expedition, should receive one-fifth of the profits. A commission was then prepared for Kidd, directing him to seize and take pirates, and to bring them to justice; but the further proceedings of the Captain, and of his officers, were left unprovided for.

A vessel was purchased and manned, and she sailed under the name of the “Adventure,” from London for New York, at the end of the year 1695. A French ship was seized as a prize during the voyage; and the vessel subsequently proceeded to the Madeira Islands, to Buonavista, and St. Jago, and thence to Madagascar, in search of further spoil. A second prize was subsequently made at Calicut, of a vessel of 150 tons burden, which was sold at Madagascar; and, at the termination of a few weeks, the “Adventure” made prize of the “Quedah Merchant,” a vessel of 400 tons burden, commanded by an Englishman named Wright, and officered by two Dutch mates and a French gunner, and whose crew consisted of Moors. The captain having carried this vessel into Madagascar, he burned the “Adventure,” and then proceeded to divide the lading of the prize with his crew, taking forty shares for himself.

He seems now to have determined to act entirely apart from his owners, and he accordingly sailed in the “Quedah Merchant” to the West Indies. At Anguilla and St. Thomas’s, he was refused refreshments; but he eventually succeeded in obtaining supplies at Mona, between Porto Rico and Hispaniola, through the instrumentality of an Englishman named Button. This man, who thus at first affected to be friendly to the pirate, soon showed the extent to which his friendship was to be relied upon. He sold a sloop to Kidd, in which the latter sailed, leaving the “Quedah{6} Merchant” in his care; but on proceeding to Boston, New England, he found his friend there before him, having disposed of the “Quedah Merchant” to the Spaniards, and having besides given information of his piratical expedition. He was now immediately seized by order of Lord Bellamont, before whom he endeavoured to justify his proceedings, by contending that he had taken none but lawful prizes; but his lordship transmitted an account of the whole transaction to England, requiring that a ship might be sent to convey Kidd home, in order that he might be punished. A great clamour arose upon this, and attempts were made to show that the proceedings of the pirate had been connived at by the projectors of the undertaking, and a motion was made in the House of Commons, that “The letters-patent granted to the Earl of Bellamont and others, respecting the goods taken from pirates, were dishonourable to the king, against the law of nations, contrary to the laws and statutes of this realm, an invasion of property, and destructive to commerce.” Though a negative was put on this motion, yet the enemies of Lord Somers and the Earl of Oxford continued to charge those noblemen with giving countenance to pirates; and it was even insinuated that the Earl of Bellamont was not less culpable than the actual offenders. Another motion was in consequence made to address his Majesty, that “Kidd might not be tried till the next session of parliament; and that the Earl of Bellamont might be directed to send home all examinations and other papers relative to the affair.” This was carried, and the king complied with the request which was made. As soon as Kidd arrived in England, he was sent for, and examined at the bar of the house, with a view to show the guilt of the parties who had been concerned in sending him on the expedition; but nothing arose to criminate any of those distinguished persons. Kidd, who was in some degree intoxicated, made a contemptible appearance at the bar of the house; and a member, who had been one of the most earnest to have him examined, violently exclaimed, “I thought the fellow had been only a knave, but unfortunately he happens to be a fool likewise.” Kidd was at length tried at the Old Bailey, and was convicted on the clearest evidence; but neither at that time, nor afterwards, did he charge any of his employers with being privy to his infamous proceedings.

He was executed with one of his companions, at Execution Dock, on the 23d of May, 1701. After he had been tied up to the gallows, the rope broke, and he fell to the ground; but being immediately tied up again, the Ordinary, who had before exhorted him, desired to speak with him once more; and, on this second application, entreated him to make the most careful use of the few further moments thus providentially allotted to him for the final preparation of his soul to meet its important change. These exhortations appeared to have the wished-for effect; and he died, professing his charity to all the world, and his hopes of salvation through the merits of his Redeemer.

The companion in crime of this malefactor, and his companion also at the gallows, was named Darby Mullins. He was born in a village in the north of Ireland, about sixteen miles from Londonderry; and having resided with his father, and followed the business of husbandry till he was about eighteen, the old man then died, and the young one went to Dublin: but he had not been long there before he was enticed to go to the West Indies, where he was sold to a planter, with whom he resided four years.{7} At the expiration of that term he became his own master, and followed the business of a waterman, in which he saved money enough to purchase a small vessel, in which he traded from one island to another, till the time of the earthquake at Jamaica in the year 1691, from the effects of which he was preserved in a miraculous manner. He afterwards went to Kingston, where he kept a punch-house, and then proceeding to New York, he married; but at the end of two years his wife dying, he unfortunately fell into company with Kidd, and joined him in his piratical practices. He was apprehended, with his commander, and, as we have already stated, suffered the extreme penalty of the law with him.

THIS delinquent was a native of Bromsgrove, in Worcestershire, where he was articled to an apothecary. Having served his time, he proceeded to London to complete his studies in surgery, and he then entered the service of Mr. Randall, a surgeon at Worcester, as an assistant. He was here admired for his extremely amiable character, as well as for the abilities which he possessed; and he married the daughter of his employer, who, however, died in giving birth to her first child. He subsequently resided with Mr. Dean, a surgeon at Lichfield; and during his employment by that gentleman he became enamoured of his daughter, and would have been married to her, but for the commission of the crime which cost him his life.

It would appear that he had become acquainted with a young woman named Elizabeth Price, who had been seduced by an officer in the army, and who supported herself by her skill in needle-work, residing near Mr. Caddell’s abode. An intimacy subsisted between them, the result of which was the pregnancy of Miss Price; and she repeatedly urged her paramour to marry her. Mr. Caddell resisted her importunities for a considerable time, until at last Miss Price, hearing of his paying his addresses to Miss Dean, became more importunate than ever, and threatened, in case of his non-compliance with her wishes, to put an end to all his prospects with that young lady, by discovering everything that had passed between them. Hereupon Caddell formed the horrid resolution of murdering Miss Price. He accordingly called on her on a Saturday evening, and requested that she would walk in the fields with him on the afternoon of the following; day, in order to adjust the plan of their intended marriage. Thus deluded, she met him at the time appointed, on the road leading towards Burton-upon-Trent, at the Nag’s Head public-house, and accompanied her supposed lover into the fields. They walked about till towards evening, when they sat down under the hedge, and after a little conversation, Caddell suddenly pulled out a knife, cut the wretched woman’s throat, and made his escape. In the distraction of his mind, he left behind him the knife with which he had perpetrated the deed, together with his case of instruments. On his returning home it was observed that he appeared exceedingly confused, though the reason of the perturbation of his mind could not be guessed at; but, on the following morning, Miss Price being found murdered in the field, great{8} numbers of people went to see the body. Among them was the woman of the house where she lodged, who recollected that she had said she was going to walk with Mr. Caddell; and then the instruments were examined, and were known to have belonged to him. He was in consequence taken into custody, and committed to the gaol of Stafford; and, being soon afterward tried, was found guilty, condemned, and executed at Stafford on the 21st of July, 1701.

THE death of this person exhibits the singular fatality which attends some men who have been guilty of crime. Cook was the son of a butcher, who was considered a person of respectability, residing at Gloucester. He was apprenticed to a barber-surgeon in London; but running away before his time had expired, he entered the service of one of the pages of honour to William III.; but he soon after quitted this situation to set up at Gloucester as a butcher, upon the recommendation of his mother.

Restless, however, in every station of life, he repaired to London, where he commenced prize-fighter at May-fair; which, at this time, was a place greatly frequented by prize-fighters, thieves, and women of bad character. Here puppet-shows were exhibited, and it was the favourite resort of all the profligate and abandoned, until at length the nuisance increased to such a degree, that Queen Anne issued her Proclamation for the Suppression of Vice and Immorality, with a particular view to this fair; in consequence of which the justices of peace issued their warrant to the high constable, who summoned all the inferior constables to his assistance. When they came to suppress the fair, Cook, with a mob of about thirty soldiers, and other persons, stood in defiance of the peace-officers, and threw brickbats at them, by which some of them were wounded. Cooper, a constable, being the most active, Cook drew his sword and stabbed him in the belly, and he died of the wound at the expiration of four days. Hereupon Cook fled to Ireland, and, as it was deposed upon his trial, while he was in a public house, he swore in a profane manner, for which the landlord censured him, and told him there were persons in the house who would take him in custody for it; to which he answered, “Are there any of the informing dogs in Ireland? we in London drive them; for at a fair called May-fair, there was a noise which I went out to see—six soldiers and myself—the constables played their parts with their staves, and I played mine; and, when the man dropped, I wiped my sword, put it up, and went away.”

The fellow was, subsequently, taken into custody, and sent to Chester, whence being removed to London, he was tried at the Old Bailey, was convicted, and received sentence of death.

After conviction he solemnly denied the crime for which he had been condemned, declaring that he had no sword in his hand on the day the constable was killed, and was not in company with those who killed him. Having received the sacrament on the 21st of July, 1703, he was taken from Newgate to be carried to Tyburn; but, when he had got to High{9} Holborn, opposite Bloomsbury, a respite arrived for him till the following Friday. On his return to Newgate he was visited by numbers of his acquaintance, who rejoiced on his narrow escape. On Friday he received another respite till the 11th of August, but on that day he was executed.

THIS unfortunate man was the son of Protestant parents, and was born at Saverdun, in the county of Foix, and province of Languedoc, in France. He received a religious education; but when he arrived at years of maturity, he left his own country, and went into Germany, where he served as a horse-grenadier under the Elector of Brandenburgh, who was afterwards King of Prussia. When he had been in this condition about a year, he came over to England, and entered into the service of Lord Haversham, and afterwards enlisted as a soldier in the regiment of Colonel de la Melonière. Having made two campaigns in Flanders, the regiment was ordered into Ireland, where it was dismissed from farther service; in consequence of which Dramatti obtained his discharge.

He now became acquainted with a widow, between fifty and sixty years of age, who pretended that she had a great fortune, and was allied to the royal family of France; and he soon married her, not only on account of her supposed wealth and rank, but also of her understanding English and Irish, thinking it prudent to have a wife who could speak the language of the country in which he proposed to spend the remainder of his life. As soon as he discovered that his wife had no fortune, he went to London and offered his services to Lord Haversham, and was again admitted as one of his domestics. His wife, unhappy on account of their separate residence, wished to live with him at Lord Haversham’s, which he would not consent to, saying, that his lordship did not know he was married.

The wife now began to evince the jealousy of her disposition, and frequent quarrels took place between them, because he was unable to be with her so frequently as she desired.

At length, on the 9th of June, 1703, Dramatti was sent to London from his master’s house at Kensington, and calling upon his wife at her lodgings near Soho-square, she endeavoured to prevail upon him to stay with her. This, however, he refused; and finding that he was going home, she went before him, and stationed herself at the Park-gate. On his coming up, she declared that he should go no further, unless she accompanied him; but he quitted her abruptly, and went onwards to Chelsea. She pursued him to the Bloody Bridge, and there seized him by the neckcloth, and would have strangled him, but that he beat her off with his cane. He then attacked her with his sword; and having wounded her in so many places as to conclude that he had killed her, his passion immediately began to subside, and, falling on his knees, he devoutly implored the pardon of God for the horrid sin of which he had been guilty. He went on to Kensington, where his fellow-servants observing that his clothes were bloody, he{10} said he had been attacked by two men in Hyde Park, who would have robbed him of his clothes, but that he defended himself, and broke the head of one of them.

The real fact, however, was subsequently discovered; and Dramatti being taken before a magistrate, to whom he confessed his crime, the body of his wife was found in a ditch between Hyde Park and Chelsea, and a track of blood was seen to the distance of twenty yards; at the end of which a piece of a sword was found sticking in a bank, which fitted the other part of the sword in the prisoner’s possession. The circumstances attending the murder being proved to the satisfaction of the jury, the culprit was found guilty, condemned, and, on the 21st of July, 1703, was executed at Tyburn.

THIS young man was born in the year 1667, at Deptford, in Kent, and served his time with a blockmaker at Rotherhithe, during which he became acquainted with some women of ill fame. After the term of his apprenticeship had expired, he kept company with young fellows of such bad character, that he found it necessary to enter on board a ship to prevent worse consequences. Having returned from sea, he enlisted as a soldier; but while in this situation he committed many small thefts, in order to support the women with whom he was connected. At length he deserted from the army, assumed a new name, and prevailed on some of his companions to engage in housebreaking.

Detection soon terminated his career, and in September 1704, he was indicted for robbing the house of —— Barry, Esq. of Fulham, and murdering his gardener. Elby, it seems, having determined on robbing the house, arrived at Fulham soon after midnight, and had wrenched open one of the windows, at which he was getting in, when the gardener, awaking, came down to prevent the intended robbery with a light in his hand. Elby, terrified lest he should be known, seized a knife and stabbed him to the heart, and the poor man immediately fell dead at his feet. This done, he broke open a chest of drawers, and stole about two hundred and fifty pounds, with which he repaired to his associates in London.

The murder soon became the subject of very general conversation, and Elby being at a public-house in the Strand, it was mentioned, and he became so alarmed on seeing one of the company rise and quit the house, that he suddenly ran away, without paying his reckoning. The landlord was enraged at his being cheated; and learning his address from one of his companions, he caused him to be apprehended, and he was eventually committed for trial on suspicion of being concerned in the robbery and murder.

On his trial he steadily denied the perpetration of the crimes with which he was charged; and his conviction would have been very doubtful, had not a woman with whom he cohabited become an evidence, and sworn that he came from Fulham with the money the morning after the commission of the fact. Some other persons also deposed that they saw him come{11} out of Mr. Barry’s house on the morning the murder was committed; and he was found guilty, and having received sentence of death, was executed at Fulham, on the 13th September, 1704, and was hung in chains near the same place.

THOUGH the crimes committed by this man were not particularly atrocious, nor his life sufficiently remarkable for a place in this work, yet the circumstances attending his fate at the place of execution are perhaps more singular than any we may have to record. He was the son of a farmer at Malton, about fifteen miles from the city of York, who bound him apprentice to a packer in London, with whom he served his time, and afterwards worked as a journeyman. He then went to sea on board a man-of-war, and was at the expedition against Vigo; but on his return from that service he was discharged. He afterwards enlisted as a soldier in the regiment of Guards commanded by Lord Cutts; but in this station he soon made bad connexions, and engaged with some of his dissolute companions as a housebreaker. On the 5th of December, 1705, he was arraigned on four different indictments, on two of which he was convicted. While he lay under sentence of death, he seemed very little affected with his situation, absolutely depending on a reprieve, through the interest of his friends. An order, however, came for his execution on the 24th day of the same month, in consequence of which he was carried to Tyburn, where he performed his devotions, and was turned off in the usual manner; but when he had hung near fifteen minutes, the people present cried out, “A reprieve!” Hereupon the malefactor was cut down, and, being conveyed to a house in the neighbourhood, he soon revived, upon his being bled, and other proper remedies applied.

When he perfectly recovered his senses, he was asked what were his feelings at the time of execution; to which he repeatedly replied, in substance, as follows:—“That when he was turned off, he, for some time, was sensible of very great pain, occasioned by the weight of his body, and felt his spirits in a strange commotion, violently pressing upwards; that having forced their way to his head, he, as it were, saw a great blaze, or glaring light, which seemed to go out at his eyes with a flash, and then he lost all sense of pain. That after he was cut down, and began to come to himself, the blood and spirits, forcing themselves into their former channels, put him, by a sort of pricking or shooting, to such intolerable pain, that he could have wished those hanged who had cut him down.” From this circumstance he was called “Half-hanged Smith.” After this narrow escape from the grave, Smith pleaded to his pardon on the 20th of February, and was discharged; yet such was his propensity to evil deeds, that he returned to his former practices, and, being apprehended, was again tried at the Old Bailey, for housebreaking; but some difficulties arising in the case, the affair was left to the opinion of the twelve judges, who determined in favour of the prisoner. After this second extraordinary escape, he was a third time indicted; but the prosecutor happening to die before the day{12} of trial, he once more obtained that liberty which his conduct showed had not deserved.

We have no account of what became of this man after this third remarkable incident in his favour; but Christian charity inclines us to hope that he made a proper use of the singular dispensation of Providence evidenced in his own person.

It was not infrequently the case, that, in Dublin, men were formerly seen walking about who, it was known, had been sentenced to suffer the extreme penalty of the law, and upon whom, strange as it may appear to unenlightened eyes, the sentence had been carried out. The custom until lately was, that the body should hang only half an hour; and, in a mistaken lenity, the sheriff, in whose hands was entrusted the execution of the law, would look away, after the prisoner had been turned off, while the friends of the culprit would hold up their companion by the waistband of his breeches, so that the rope should not press upon his throat. They would, at the expiration of the usual time, thrust their “deceased” friend into a cart, in which they would gallop him over all the stones and rough ground they came near, which was supposed to be a never-failing recipe, in order to revive him, professedly, and indeed in reality, with the intention of “waking” him. An anecdote is related of a fellow named Mahony, who had been convicted of the murder of a Connaught-man, in one of the numerous Munster and Connaught wars, and whose execution had been managed in the manner above described; who, being put into the cart in a coffin by his Munster friends, on his way home was so revived, and so overjoyed at finding himself still alive, that he sat upright and gave three hearty cheers, by way of assuring his friends of his safety. A “jontleman” who was shocked at this indecent conduct in his defunct companion, and who was, besides, afraid of their scheme being discovered and thwarted, immediately, with the sapling which he carried, hit him a thump on the head, which effectually silenced his self-congratulations. On their arrival at home, they found that the “friendly” warning which had been given to the poor wretch, had been more effectual than the hangman’s rope; and the wailings and lamentations which had been employed at the place of execution to drown the encouraging cries of the aiders of the criminal’s escape, were called forth in reality at his wake on the same night. It was afterwards a matter of doubt whether the fellow who dealt the unfortunate blow ought not to have been charged with the murder of his half-hanged companion; but “a justice” being consulted, it was thought no one could be successfully charged with the murder of a man who was already dead in law.

THE treason of which this offender was convicted was that of “adhering to the Queen’s enemies, and giving them aid, without the realm,” which was made a capital offence by the statute of Edward III.

It appears that Gregg was a native of Montrose, in Scotland, and having received such instruction as the grammar-schools of the place afforded, he{13}

completed his education at Aberdeen university, where he pursued these studies which were calculated to fit him for the profession of the church, for which he was intended. London, however, held forth so many attractions to his youthful eye, that the wishes of his relatives were soon overruled; and having visited that city, with good introductions, he was, after some time, appointed secretary to the ambassador at the court of Sweden. But while performing the duties of his office, he was guilty of so many and so great excesses, that he was at length compelled to retire, and London once more became his residence. His good fortune placed him in a situation alike honourable and profitable, but his dishonest and traitorous conduct in his employment, was such as to cost him his life, and to involve his employers in political difficulties of no ordinary kind. Having been engaged by Mr. Secretary Harley, minister of the reigning sovereign, Queen Anne, to write despatches, he took advantage of the knowledge which he thus gained, and voluntarily opened a communication with the enemies of his country. England, it will be remembered, was at this time in a situation of no ordinary difficulty; and the position of her Majesty’s ministers, harassed as they were by the opposition of their political antagonists, was rendered even more difficult by the disclosures of their traitorous servant.

We shall take the advantage afforded us by Bishop Burnet’s History, of laying before our readers a more authentic account of this transaction than is given by the usual channels of information to which we have access. He says, “At this time two discoveries were made very unlucky for Mr. Harley: Tallard wrote often to Chamillard, but he sent the letters open to the secretary’s office, to be perused and sealed up, and so be conveyed by the way of Holland. These were opened upon some suspicion in Holland, and it appeared that one in the secretary’s office put letters in them, in which, as he offered his services to the courts of France and St. Germains, so he gave an account of all transactions here. In one of these he sent a copy of the letter that the Queen was to write in her own hand to the Emperor; and he marked what parts were drawn by the secretary, and what additions were made to it by the lord treasurer. This was the letter by which the Queen pressed the sending Prince Eugene into Spain; and this, if not intercepted, would have been at Versailles many days before it could reach Vienna.

“He who sent this wrote, that by this they might see what service he could do them, if well encouraged. All this was sent over to the Duke of Marlborough; and, upon search, it was found to be written by one Gregg, a clerk, whom Harley had not only entertained, but had taken into a particular confidence, without inquiring into the former parts of his life; for he was a vicious and necessitous person, who had been secretary to the Queen’s envoy in Denmark, but was dismissed by him for his ill qualities. Harley had made use of him to get him intelligence, and he came to trust him with the perusal and sealing up of the letters, which the French prisoners, here in England, sent over to France; and by that means he got into the method of sending intelligence thither. He, when seized on, either upon remorse or hopes of pardon, confessed all, and signed his confession: upon that he was tried, and, pleading guilty, was condemned as a traitor, for corresponding with the Queen’s enemies.

“At the same time Valiere and Bara, whom Harley had employed as{14} his spies to go often over to Calais, under the pretence of bringing him intelligence, were informed against, as spies employed by France to get intelligence from England, who carried over many letters to Calais and Boulogne, and, as was believed, gave such information of our trade and convoys, that by their means we had made our great losses at sea. They were often complained of upon suspicion, but they were always protected by Harley; yet the presumptions against them were so violent, that they were at last seized on, and brought up prisoners.”

The Whigs took such advantage of this circumstance, that Mr. Harley was obliged to resign; and his enemies were inclined to carry matters still further, and were resolved, if possible, to find out evidence enough to affect his life. With this view, the House of Lords ordered a committee to examine Gregg and the other prisoners, who were very assiduous in the discharge of their commission, as will appear by the following account, written by the same author:—

“The Lords who were appointed to examine Gregg could not find out much by him: he had but newly begun his designs of betraying secrets, and he had no associates with him in it. He told them that all the papers of state lay so carelessly about the office that every one belonging to it, even the door-keepers, might have read them all. Harley’s custom was to come to the office late on post-nights, and, after he had given his orders, and wrote his letters, he usually went away, and left all to be copied out when he was gone. By that means he came to see every thing, in particular the Queen’s letter to the Emperor. He said he knew the design on Toulon in May last, but he did not discover it; for he had not entered on his ill practices till October. This was all he could say.

“By the examination of Valiere and Bara, and of many others who lived about Dover, and were employed by them, a discovery was made of a constant intercourse they were in with Calais, under Harley’s protection. They often went over with boats full of wool, and brought back brandy, though both the import and export were severely prohibited. They, and those who belonged to the boats carried over by them, were well treated on the French side at the governor’s house, or at the commissary’s: they were kept there till their letters were sent to Paris, and till returns could be brought back, and were all the while upon free cost. The order that was constantly given them was, that if an English or Dutch ship came up with them, they should cast their letters into the sea, but that they should not do it when French ships came up with them: so they were looked on by all on that coast as the spies of France. They used to get what information they could, both of merchant-ships and of the ships of war that lay in the Downs, and upon that they usually went over; and it happened that soon after some of those ships were taken. These men, as they were Papists, so they behaved themselves insolently, and boasted much of their power and credit.

“Complaints had been often made of them, but they were always protected; nor did it appear that they ever brought any information of importance to Harley but once, when, according to what they swore, they told him that Fourbin was gone from Dunkirk, to lie in wait for the Russian fleet, which proved to be true; he both went to watch for them, and he took the greater part of the fleet. Yet, though this was a single piece of intelligence that they ever brought, Harley took so little notice of{15} it, that he gave no advertisement to the Admiralty concerning it. This particular excepted, they only brought over common news, and the Paris Gazeteer. These examinations lasted for some weeks; when they were ended, a full report was made of them to the House of Lords, and they ordered the whole report, with all the examinations, to be laid before the Queen.”

Upon the conviction of Gregg, both houses of parliament petitioned the Queen that he might be executed; and, on the 28th April, 1708, he was accordingly hanged at Tyburn.

While on the scaffold, he delivered a paper to the sheriffs of London and Middlesex, in which he acknowledged the justice of his sentence, declared his sincere repentance of all his sins, particularly that lately committed against the Queen, whose forgiveness he devoutly implored. He also expressed his wish to make all possible reparation for the injuries he had done; and testified the perfect innocence of Mr. Secretary Harley, whom he declared to have been no party to his proceedings. He professed that he died a member of the Protestant church; and declared that the want of money to supply his extravagances had tempted him to commit the fatal crime, which cost him his life.

It is a remarkable circumstance in the life of this offender, that while he was corresponding with the enemy, and taking measures to subvert the government, he had no predilection in favour of the Pretender. On the contrary, he declared, while he was under sentence of death, that “he never thought he had any right to the throne of these realms.”

THIS was a case which arose out of the practice of duelling, which has always existed almost peculiarly among the higher classes of society. Mr. Thornhill and Sir Cholmondeley Deering having dined together on the 7th of April, 1711, in company with several other gentlemen, at the Toy at Hampton Court, a quarrel arose, during which Sir Cholmondeley struck Mr. Thornhill. A scuffle ensuing, the wainscot of the room broke down, and Thornhill falling, the other stamped on him, and beat out some of his teeth. The company now interposed, and Sir Cholmondeley, convinced that he had acted improperly, declared that he was willing to ask pardon; but Mr. Thornhill said, that asking pardon was not a proper retaliation for the injury that he had received; adding, “Sir Cholmondeley, you know where to find me.” Soon after this the company broke up, and the parties went home in different coaches, without any farther steps being taken towards their reconciliation.

On the next day, the following letter was written by Mr. Thornhill:—

“April 8th, 1711.

“Sir,—I shall be able to go abroad to-morrow morning, and desire you will give me a meeting with your sword and pistols, which I insist on. The worthy gentleman who brings you this will concert with you the time{16} and place. I think Tothill Fields will do well; Hyde Park will not at this time of year, being full of company.

“I am your humble servant,

“Richard Thornhill.”

On the 9th of April, Sir Cholmondeley went to the lodgings of Mr Thornhill, and the servant showed him to the dining-room. He ascended with a brace of pistols in his hands; and soon afterwards, Mr. Thornhill coming to him, asked him if he would drink tea, but he declined. A hackney-coach was then sent for, and the gentlemen rode to Tothill Fields, where, unattended by seconds, they proceeded to fight their duel. They fired their pistols almost at the same moment, and Sir Cholmondeley, being mortally wounded, fell to the ground. Mr, Thornhill, after lamenting the unhappy catastrophe, was going away, when a person stopped him, told him he had been guilty of murder, and took him before a justice of the peace, who committed him to prison.

On the 18th of May, Mr. Thornhill was indicted at the Old Bailey sessions for the murder; and the facts already detailed having been proved, the accused called several witnesses to show how ill he had been used by Sir Cholmondeley; that he had languished some time of the wounds he had received; during which he could take no other sustenance than liquids, and that his life was in imminent danger. Several persons of distinction swore that Mr. Thornhill was of a peaceable disposition, and that, on the contrary, the deceased was of a remarkably quarrelsome temper; and it was also deposed, that Sir Cholmondeley, being asked if he came by his hurt through unfair usage, replied, “No; poor Thornhill! I am sorry for him; this misfortune was my own fault, and of my own seeking. I heartily forgive him, and desire you all to take notice of it, that it may be of some service to him, and that one misfortune may not occasion another.”

The jury acquitted Mr. Thornhill of the murder, but found him guilty of manslaughter; in consequence of which he was burnt in the hand.

THERE was no occurrence which at the time occupied so much of the public attention, and excited so much general interest, as the duel which took place in the year 1711, between the Duke of Hamilton and Lord Mohun; in which, unhappily, both the principals fell.

The gentleman who is the subject of the present notice, was the second of the noble duke, and appears to have been connected with him by the ties of relationship. At the sessions held at the Old Bailey, on the 11th of September, he was indicted for the murder of Charles Lord Mohun, Baron of Oakhampton, on the 15th of November preceding; and at the same time he was indicted for abetting Charles Lord Mohun, and George Macartney, Esq., in the murder of James, Duke of Hamilton and Brandon. Colonel Hamilton pleaded not guilty; and evidence was then adduced, which showed that Lord Mohun having met the Duke of Hamilton at the chambers{17} of a master in chancery, on Thursday the 13th of November, a misunderstanding arose between them respecting the testimony of a witness.

On the return home of his lordship, he directed that no person should be admitted to him, except Mr. Macartney; and subsequently he went with that gentleman to a tavern. The Duke of Hamilton and his second, Colonel Hamilton, were also at the tavern; and from thence they all proceeded to Hyde Park. The only evidence which exhibited the real circumstances immediately attending the duel, was that of William Morris, a groom, who deposed that, “as he was walking his horses towards Hyde Park, he followed a hackney-coach with two gentlemen in it, whom he saw alight by the Lodge, and walk together towards the left part of the ring. They were there about a quarter of an hour, when he saw two other gentlemen come to them; and, after having saluted each other, one of them, who he was since told was the Duke of Hamilton, threw off his cloak; and one of the other two, who he now understands was Lord Mohun, his surtout coat, and all immediately drew. The duke and lord pushed at each other but a very little while, when the duke closed, and took the lord by the collar, who fell down and groaned, and the duke fell upon him. That just as Lord Mohun was dropping, he saw him lay hold of the duke’s sword, but could not tell whether the sword was at that time in his body; nor did he see any wound given after the closing, and was sure Lord Mohun did not shorten his sword. He declared he did not see the seconds fight; but they had their swords in their hands, assisting their lords.”

It further appeared that the bodies of the deceased noblemen were examined by Messrs. Boussier and Amie, surgeons; and that in that of the duke, a wound was found between the second and third ribs on his right side; and also that there were wounds in his right arm, which had cut the artery and one of the small tendons, as well as others in his right and left leg. There was also a wound in his left side between his second and third ribs, which ran down into his body, and pierced the midriff and caul: but it appeared that the immediate cause of the sudden death of his grace was the wound in his arm. It was further proved, as regarded the body of Lord Mohun, that there was a wound between the short ribs, quite through his belly, and another about three inches deep in the upper part of his thigh; a large wound, about four inches wide, in his groin, a little higher, which was the cause of his immediate death; and another small wound on his left side; and that the fingers of his left hand were cut.

The defence made by the prisoner was, that “the duke called him to go abroad with him, but he knew not anything of the matter till he came into the field.”

Some Scottish noblemen, and other gentlemen of rank, gave Mr. Hamilton a very excellent character, asserting that he was brave, honest, and inoffensive; and the jury, having considered of the affair, gave a verdict of “Manslaughter;” in consequence of which the prisoner prayed the benefit of the statute, which was allowed him.

At the time the lives of these noblemen were thus unfortunately sacrificed, many persons thought they fell by the hands of the seconds; and some writers on the subject subsequently affected to be of the same opinion: but nothing appears in the written or printed accounts of the transaction, nor did anything arise on the trial, to warrant so ungenerous a suspicion; it is therefore but justice to the memory of all the parties to discredit such insinuations.{18}

WILLIAM LOWTHER was a native of Cumberland, and being bound to the master of a Newcastle ship which traded to London, he became acquainted with low abandoned company in the metropolis. Richard Keele was a native of Hampshire, and served his time to a barber at Winchester; and on coming to London, he married and settled in his own business in Rotherhithe: but not living happily with his wife, he parted from her, cohabited with another woman, and associated with a number of disorderly people.

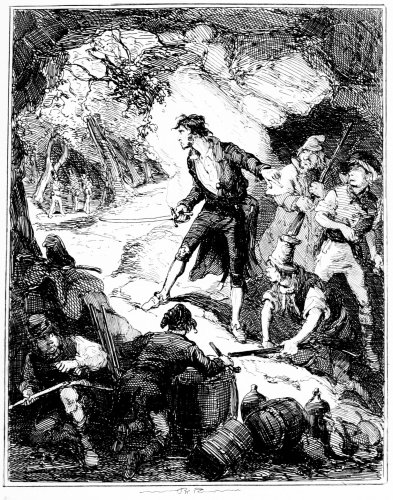

On the 10th of December, 1713, they were indicted at the Old Bailey, for assisting Charles Houghton in the murder of Edward Perry. The case was as follows:—The prisoners, together with two other desperate offenders, of the name of Houghton and Cullum, having been convicted of felony at the Old Bailey, were sentenced to be kept to hard labour in Clerkenwell Bridewell for two years. On their being carried thither, Mr. Boreman, the keeper, thought it necessary to put them in irons, to prevent their escape. This they all refused to submit to; and Boreman having ordered the irons, they broke into the room where the arms were deposited, seized what they thought fit, and then attacked the keeper and his assistants, and cruelly beat them. Lowther bit off part of a man’s nose. At this time, Perry, one of the turnkeys, was without the gate, and desired the prisoners to be peaceable; but, advancing towards them, he was stabbed by Houghton, and, during the fray, Houghton was shot dead. The prisoners being at length victorious, many of them made their escape; but the neighbours giving their assistance, Keele and Lowther, and several others, were taken and convicted on the clearest evidence.

Some time after conviction, a smith went to the prison to take measure of them for chains, in which they were to be hung, pursuant to an order from the secretary of state’s office; but they for some time resisted him in this duty.

On the morning of execution (the 13th December, 1713), they were carried from Newgate to Clerkenwell Green, and there hanged on a gallows; after which, their bodies were put in a cart, drawn by four horses, decorated with plumes of black feathers, and hung in chains.

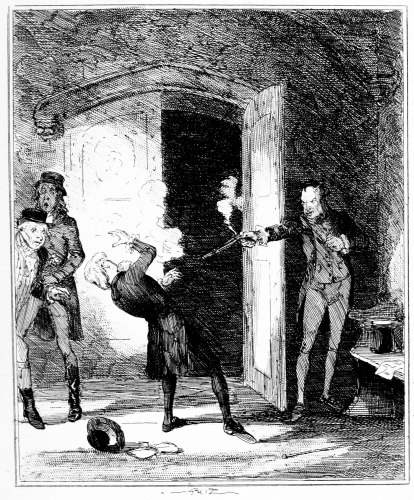

IT is not a little remarkable that two instances should have occurred within so short a space of time as nine months, in which the officers of the Crown should have fallen victims to the exertions which they were compelled to make in the discharge of their duties. The male prisoner in this case, William Johnson, was a native of Northamptonshire, where he served his time to a butcher, and, removing to London, he opened a shop in Newport{19} Market; but business not succeeding to his expectation, he pursued a variety of speculations, until at length he sailed to Gibraltar, where he was appointed a mate to one of the surgeons of the garrison. Having saved some money at this place, he came back to his native country, where he soon spent it, and then had recourse to the highway for a supply. Being apprehended in consequence of one of his robberies, he was convicted, but received a pardon. Previously to this he had been acquainted with Jane Housden, his fellow in crime, who had been tried and convicted of coining, but had obtained a pardon; but who, in September, 1714, was again in custody for a similar offence. On the day that she was to be tried, and just as she was brought down to the bar of the Old Bailey, Johnson called to see her; but Mr. Spurling, the head turnkey, telling him that he could not speak to her till her trial was ended, he instantly drew a pistol, and shot Spurling dead on the spot, in the presence of the court and all the persons attending to hear the trials, Mrs. Housden at the same time encouraging him in the perpetration of this singular murder. The event had no sooner happened, than the judges, thinking it unnecessary to proceed on the trial of the woman for coining, ordered both the parties to be tried for the murder; and there being many witnesses to the deed, they were convicted, and received sentence of death. From this time to that of their execution, which took place September 19th 1714, and even at the place of their death, they behaved as if they were wholly insensible of the enormity of the crime which they had committed; and notwithstanding the publicity of their offence, they had the confidence to deny it to the last moment of their lives: nor did they show any signs of compunction for their former sins. After hanging the usual time, Johnson was hung in chains near Holloway, between Islington and Highgate.

THE circumstances attending the crime of these individuals, intimately connected as they were with the history of the Royal Family of England, must be too well known to require them to be minutely repeated. On the accession of George the First to the throne of Great Britain, the question of the right of succession of King James the Third, as he was termed, which had long been secretly agitated, began to be referred to more openly; and his friends, finding themselves in considerable force in Scotland, sent an invitation to him in France, where he had taken refuge, to join them, for the purpose of making a demonstration, and of endeavouring to assume by force, that which was denied him as of right. The noblemen, whose names appear at the head of this article, were not the least active in their endeavours to support the title of the Pretender, by enlisting men under his standard; and their proceedings, although conducted with all secrecy, were soon made known to the government. The necessary steps were immediately taken for quelling the anticipated rebellion; and many persons were apprehended on suspicion of secretly aiding the rebels, and were committed to gaol.{20}

Meanwhile the Earl of Mar, the chief supporter of the Pretender, was in open rebellion at the head of an army of 3000 men, which was rapidly increasing, marching from town to town in Scotland, proclaiming the Pretender as King of England and Scotland, by the title of James III. An attempt was made by stratagem to surprise the castle of Edinburgh; and with this object, some of the king’s soldiers were base enough to receive a bribe to admit those of the Earl of Mar, who were, by means of ladders of rope, to scale the walls, and surprise the guard; but the Lord Justice Clerk, having some suspicion of the treachery, seized the guilty, and many of them were executed.

The rebels were greatly chagrined at this failure of their attempt; and the French king, Louis XIV., from whom they hoped for assistance, dying about this time, the leaders became disheartened, and contemplated the abandonment of their project, until their king could appear in person among them.

They were aided, however, by the discontent which showed itself in another quarter. In Northumberland the spirit of rebellion was fermented by Thomas Forster, then one of the members of parliament for that county; who, being joined by several noblemen and gentlemen, attempted to seize the large and commercial town of Newcastle, but was driven back by the friends of the government. Forster now set up the standard of the Pretender, and proclaimed him the lawful king of Great Britain and Scotland, wherever he went; and, eventually joining the Scotch rebels, he marched with them to Preston, in Lancashire. They were there attacked by Generals Carpenter and Wills, who succeeded in routing them, and in making 1500 persons prisoners; amongst whom were the Earl of Derwentwater and Lord Widrington, English peers; and the Earls of Nithisdale, Winton, and Carnwarth, Viscount Kenmore, and Lord Nairn, Scotch peers.

These noblemen, with about three hundred more rebels, were conveyed to London; while the remainder, taken at the battle of Preston, were sent to Liverpool, and its adjacent towns. At Highgate, the party intended for trial in London was met by a strong detachment of foot-guards, who tied them back to back, and placed two on each horse; and in this ignominious manner were they held up to the derision of the populace, the lords being conveyed to the Tower, and the others to Newgate and other prisons.