THE

WITH A VOCABULARY OF THEIR LANGUAGE.

EDITED BY

MARTIN LUTHER

IN THE YEAR 1528.

NOW FIRST TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH, WITH

INTRODUCTION AND NOTES,

BY

JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN.

LONDON:

JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN, PICCADILLY.

1860.

S

a picture of the manners and customs of the

Vagabond population of Central Europe before

the Reformation, I think this little book, the

earliest of its kind, will be found interesting. The fact of

Luther writing a Preface and editing it gives it at once

some degree of importance, and excites the curiosity of the

student.

S

a picture of the manners and customs of the

Vagabond population of Central Europe before

the Reformation, I think this little book, the

earliest of its kind, will be found interesting. The fact of

Luther writing a Preface and editing it gives it at once

some degree of importance, and excites the curiosity of the

student.

In this country the Liber Vagatorum is almost unknown, and in Germany only a few scholars and antiquaries are acquainted with the book.

In translating it I have endeavoured as much as possible to preserve the spirit and peculiarities of the original. Some may object to the style as being too antique; but this garb I thought preserved a small portion of the originalPg vi quaintness, and was best suited to the period when it was written.

For several explanations of old German words, and other hints, I am indebted to a long notice of the Liber Vagatorum, which occurs in the “Wiemarisches Jahrbuch,” 10te, Band, 1856,—the only article of any moment that I know to have been written on the little book.

With respect to the facsimile woodcut, as it was too large to occupy a place on the title, as in the original (of 4to. size), it is here given as a frontispiece.

Perhaps some apology is required for the occasional use of plain-spoken, not to say coarse words. I can only urge, in justification of their adoption, that the nature of the subject would not admit of their being softened,—unless indeed at the expense of the narrative. As it is, I have sent forth this edition in very much more refined language than the great Reformer thought necessary when issuing the old German version.

J. C. H.

Piccadilly,

June 1, 1860.

| Page | |

REFACE | v ix |

Liber Vagatorum.—Various editions.—Gengenbach’s metrical version; Gödecke’s claim for the priority of this refuted | xv |

Martin Luther.—Occupied in the work of the Reformation.—Writes several popular pieces.—Edits the Liber Vagatorum | xix |

English Books on Vagabonds.—Harman’s Caveat for commen Cvrsetors.—The Fraternitye of Vacabondes.—Greene, Decker, and Shakespeare | xxiv |

Ancient Customs of English Beggars.—Licences with Seals.—Seals now disused.—Wandering Students or Vagabond Scholars | xxviii |

German Origin of tricks practised by English Vagabonds.—Masters [Pg viii]of the Black-Art.—Fawney Riggers.—Card-Sharpers.—Begging-Letter-Writers.—Shabby-Genteels.—Mechanics out of employ.—Shivering Jemmies.—Maimers of Children.—Borrowers of Children.—Simulated Fits.—Quack Doctors.—Treasure-Seekers.—Travelling Tinkers | xxxi |

Old German Cant Words | xxxvi |

| LIBER VAGATORUM | 1 |

| Luther’s Preface | 3 |

| Part I.—The several Orders of Vagabonds | 7 |

| Part II.—Notabilia relating to Beggars | 43 |

| Part III.—Vocabulary of Cant Words | 49 |

AGABONDS and Beggars are ancient

blots in the history of the world. Idleness,

I suppose, existed before civilization

began, but feigned distress must

certainly have been practised soon after.

AGABONDS and Beggars are ancient

blots in the history of the world. Idleness,

I suppose, existed before civilization

began, but feigned distress must

certainly have been practised soon after.

In the records of the Middle Ages enactments for the suppression and ordering of vagrancy continually occur. In this country, as we shall see directly, laws for its abolishment were passed at a very early date.

The begging system of the Friars, perhaps more than any other cause, contributed to swell the ranks of vagabonds. These religious mendicants, who had long been increasing in number and dissoluteness, gavePg x to beggars sundry lessons in hypocrisy, and taught them, in their tales of fictitious distress, how to blend the troubles of the soul with the infirmities of the body. Numerous systems of religious imposture were soon contrived, and mendicants of a hundred orders swarmed through the land. Things were at their worst, or rather both friars and vagabonds were in their palmiest days, towards the latter part of the fifteenth century, just before the suppression of the Religious Houses commenced, and immediately before the first symptoms of the Reformation showed themselves,—that great movement which was so soon to sweep one of the two pests away for ever.

In Schreiber’s account of the Bettler-industrie (begging practices) of Germany in the year 1475, he thus speaks of this golden age for mendicants.1 His theory, as to the origin of the complicated system of mendicity, is, perhaps, more fanciful than true, but Pg xihis account is nevertheless very interesting, and well worth extracting from.

“The beggars of Germany rejoiced in their Golden Age; it extended throughout nearly two centuries, from the invasions of the Turks until after the conclusion of the Swedish war (1450 to 1650). During this long period it was frequently the case that begging was practised less from necessity than for pleasure;—indeed, it was pursued like a regular calling. For poetry had estranged herself from the Nobility; knights no longer went out on adventures to seek giants and dragons, or to liberate the Holy Tomb; she had likewise become more and more alien to the Citizen, since he considered it unwise to brood over verses and rhymes, when he was called upon to calculate his profits in hard coin. Even the ‘Sons of the Muses,’ the Scholars, had become more prosaic, since there was so much to learn and so many universities to visit, and the masters could no longer wander from one country to another with thousands of pupils.

“Then poetry (as everything in human life gradually descends) began to ally herself with beggars and vagrants. That which formerly had been misfortune and misery became soon a sort of free art, which only retained the mask of misery in order to pursue its course more safely and undisturbed. Mendicity became a distinct institution, was divided into various branches, and was provided with a language of its own. Doubtless, besides the frequent wars, it was the Gipsies—appearing in Germany, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, in larger swarms than ever—who contributed greatly to this state of things. They formed entire tribes of wanderers, as free as the birds in the air, now dispersing themselves, now reuniting, resting whereever forests or moors pleased, or stupidity and superstition allured them, possessing nothing, but appropriating to themselves the property of everybody, by stratagem or rude force.

“In what manner and to what extent such beggary had grown up and branched off towards thePg xiii close of the fifteenth century, what artifices and even what language these beggars used to employ, is shown us in Johann Knebel’s Chronicles, the MSS. of which are preserved in the Library of the City and University of Bâle.”

These MSS. are very curious. They contain the proceedings of the Trials at Basle,2 in Switzerland, in 1475, when a great number of vagabonds, strollers, blind men, and mendicants of all orders, were arrested and examined. Johann Knebel was the chaplain of the cathedral there, and wrote them down at the time. From the reports of these trials it is believed the Liber Vagatorum was compiled; and it is also conjectured that, from the same rich source, Sebastian Brant, who just at that period had established himself at the University of Basle, where Pg xivhe remained until 1500, drew the vivid description of beggars and begging, to be found in his Ship of Fools.3

Knebel gives a long list of the different orders of beggars, and the names they were known by amongst themselves. This account is similar to, only not so spirited as that given in the Liber Vagatorum. The tricks and impostures are very nearly the same, together with the cant terms for the various tribes of mendicants. Knebel, speaking of the manner in which the tricks of these rogues were first found out, says:—“At those times a great number of knaves went about the country begging and annoying people. Of these several were caught, and they told how they and their fellow-knaves were known, and when and how they used to meet, what they were called, and they told also several of their cant words.”

HE Liber Vagatorum, or The Book of Vagabonds,

was probably written shortly after

1509, that year being mentioned in the

work; it is the earliest book on beggars and their

secret language of which we have any record,—preceding

by half a century any similar work issued in

this country.

HE Liber Vagatorum, or The Book of Vagabonds,

was probably written shortly after

1509, that year being mentioned in the

work; it is the earliest book on beggars and their

secret language of which we have any record,—preceding

by half a century any similar work issued in

this country.

Nothing is known of the author other than that it was written by one who styled himself a “Reverend Magister, nomine expertus in truffis,”—which proficiency in roguery, as Luther remarks, “the little book very well proves, even though he had not given himself such a name.”

None of the early impressions bears a date, but the first edition is known to have been printed at Augsburg, about the year 1512-14, by Erhart Öglin, or Ocellus.4 It is a small quarto, consisting of 12 leaves.

The title:—

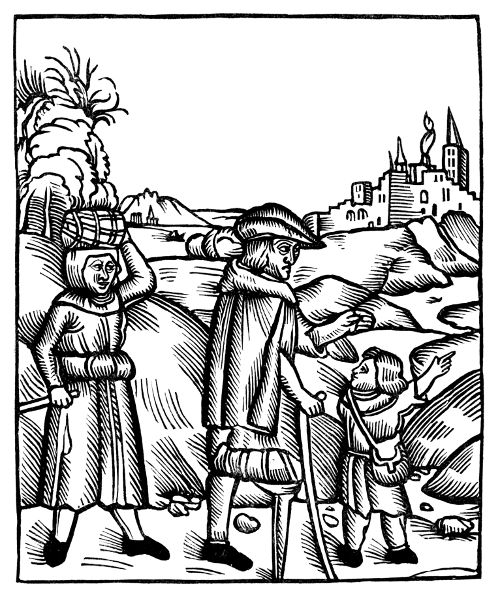

is printed in red. The title-page of this, as of most of the early editions, is embellished with a woodcut,—a facsimile of which is given in this translation. The picture, representing a beggar and his family, explains itself. At the foot of the title is printed, in black:—Getrucht zu Augspurg durch Erhart Öglin. The little book was frequently reprinted without any other variations than printers’ blunders (one edition having an error in the first word, Lieber Vagatorum) until 1528, when Luther edited an edition,5 supplying a preface, and correcting some of the passages. In 1529 another edition, with Luther’s preface, appeared at Wittemberg,6 and from this, comparing it occasionally with the first Pg xviiedition by Ocellus, the present English version has been made. Nearly all the editions contain the same matter; nor do those issued under Luther’s authority furnish us with additional information. With regard to the Vocabulary, however, I have made, in a few instances, slight variations, as given in two editions of the Liber Vagatorum, preserved in the Library at Munich. Wherever there was a marked divergence in style I have adopted that as my text which seemed to be the most characteristic for the fifteenth and the commencement of the sixteenth centuries, and which is mostly to be found in the better class MSS. and works of that period.

I should state, however, before proceeding further, that a metrical version of the Liber Vagatorum, in 838 verses, appeared about 1517-18, written by Pamphilus Gengenbach, including a vocabulary of the beggars’ cant. Although Karl Gödecke, in his work, Ein Beitrag zur Deutschen Literatur Geschichte der Reformations zeit (Hannover, Carl Rümpler, 1855), has stated thatPg xviii Gengenbach’s poetical version preceded the smaller prose account, it is impossible, upon examining the two publications, to agree with him on this point. Gengenbach’s book certainly did not appear till after 1517, and the direct copies from the Liber Vagatorum, in matter and manner, are too frequent to admit for one moment of the supposition of their being accidental. The cant terms, too, are incorrectly given, and altogether the work bears the appearance of hasty and piratical compilation. It never met with that popularity which the author anticipated, and probably never crossed the frontiers of Switzerland.

The latest prose edition of the Liber Vagatorum was issued towards the close of the seventeenth century. The title ran:—Expertus in truffis. Of False Beggars and their knaveries. A pretty little book, made more than a century and a half since, together with a Vocabulary of some old cant words that occur therein, newly edited. Anno 1668 (12o. pp. 160).

HAT Luther should have written a Preface

to so undignified a little work as The

Book of Vagabonds seems remarkable. At

this period (1528-9) he was in the midst of his labours,

surrounded with difficulties and cares, and

with every moment of his time fully occupied. The

Protest of Spires had just been signed by the first

Protestants. Melancthon, in great affliction at the

turbulent state of affairs, was running from city to

city; and all Germany was alarmed to hear that the

dreaded Turks were preparing to make battle before

Vienna. Yet, the centre of all this agitation, engaged

in directing and assisting his followers, Luther found

time to write several popular pieces, and kept, we are

told, the book-hawkers of Augsburg and Spires busy

in supplying them to the people. These Christian

pamphlets, D’Aubigné informs us, were eagerly

sought for and passed through numberless editions.

It was not the peasants and townspeople only who

read them, but nobles and princes. Luther intendedPg xx

that they should be popular. He knew better than

any man of his time how to captivate the reader and

fix his attention. His little books were short, easy

to read, full of homely sayings and current phrases,

and ornamented with curious engravings. They

were generally written, too, in Latin and German,

to suit both the educated and the unlettered. One

was entitled, The Papacy with its Members painted

and described by Dr. Luther. In it figured the

Pope, the cardinal, and all the religious orders.

Under the picture of one of the orders were these

lines:—

HAT Luther should have written a Preface

to so undignified a little work as The

Book of Vagabonds seems remarkable. At

this period (1528-9) he was in the midst of his labours,

surrounded with difficulties and cares, and

with every moment of his time fully occupied. The

Protest of Spires had just been signed by the first

Protestants. Melancthon, in great affliction at the

turbulent state of affairs, was running from city to

city; and all Germany was alarmed to hear that the

dreaded Turks were preparing to make battle before

Vienna. Yet, the centre of all this agitation, engaged

in directing and assisting his followers, Luther found

time to write several popular pieces, and kept, we are

told, the book-hawkers of Augsburg and Spires busy

in supplying them to the people. These Christian

pamphlets, D’Aubigné informs us, were eagerly

sought for and passed through numberless editions.

It was not the peasants and townspeople only who

read them, but nobles and princes. Luther intendedPg xx

that they should be popular. He knew better than

any man of his time how to captivate the reader and

fix his attention. His little books were short, easy

to read, full of homely sayings and current phrases,

and ornamented with curious engravings. They

were generally written, too, in Latin and German,

to suit both the educated and the unlettered. One

was entitled, The Papacy with its Members painted

and described by Dr. Luther. In it figured the

Pope, the cardinal, and all the religious orders.

Under the picture of one of the orders were these

lines:—

“Not one of these orders,” said Luther to the reader, “thinks either of faith or charity. This one wears the tonsure, the other a hood, this a cloak, that a robe. One is white, another black, a third gray, and a fourth blue. Here is one holding a looking-glass, there one with a pair of scissors. Each has his playthings.... Ah! these are the palmer-worms, the locusts, the canker-worms, andPg xxi the caterpillars which, as Joel saith, have eaten up all the earth.”7

In this style Luther addressed his readers—scourging the Pope, his cardinals, and all their emissaries. But another class of “locusts” besides these appeared to him to require sweeping away,—these were the beggars and vagabonds who imitated the Mendicant Friars in wandering up and down the country, with lying tales of distress, either of mind or body. As he says in his Preface, explaining the reason of his connection with the book, “I thought it a good thing that such a work should not only be published, but that it should become known everywhere, in order that men can see and understand how mightily the devil rules in this world; and I have also thought how such a book may help mankind to be wise, and on the look out for him, viz. the devil.”

Luther further adds—not forgetting, in passing, to give a blow to Papacy—“Princes, lords, counsellors of state, and everybody should be prudent, and cautious in dealing with beggars, and learn that, Pg xxiiwhereas people will not give and help honest paupers and needy neighbours, as ordained by God, they give, by the persuasion of the devil, and contrary to God’s judgment, ten times as much to vagabonds and desperate rogues,—in like manner as we have hitherto done to monasteries, cloisters, churches, chapels, and Mendicant Friars, forsaking all the time the truly poor.”

This was Luther’s object in affixing his name to the little book. He saw that the Friars, Beggars, and Jews were eating up his country, and he thought that a graphic account of the various orders of vagrants, together with a list of their secret or cant words, issued under the authority of his name, would put people on their guard, and help to suppress the wretched system.

Luther’s statement as to his own experience with these rogues is very naïve—“I have myself of late years,” he remarks, “been cheated and slandered by such tramps and liars more than I care to confess.”

Both priests and beggars regarded him with a peculiar aversion, and many were the nicknames andPg xxiii vulgar terms applied to him. The slang language of the day, therefore, was not unknown to Luther.

At page 204 of Williams’ Lectures on Ecclesiastical History, 4to. (apparently privately printed for the use of the students of St. Begh’s College,) is the following foot-note:—

Of the violence with which Luther’s enemies attacked his character, and strove to render his name and memory odious to the people, we have an example in the following production of a French Jesuit, Andreas Frusius, printed at Cologne, 1582:—

Elogium Martini Lutheri, ex ipsius Nomine et Cognomine.

Depinget et dignis te nemo coloribus unquam;

Nomen ego ut potero sic celebrabo tuum.

Magnicrepus

Ambitiosus

Ridiculus

Tabificus

Impius

Nyctocorax

Ventosus

Schismaticus

Lascivus

Ventripotens

Tartareus

Heresiarcha

Erro

Retrogradus

Vesanus

SacrilegusMendax

Atrox

Rhetor

Tumidus

Inconstans

Nebulo

Vanus

Stolidus

Leno

Vultur

Torris

Horrendus

Execrandus

Reprobus

Varius

SatanasMorofus

Astutus

Rabiosus

Tenebrosus

Impostor

Nugator

Vilis

Seductor

Larvatus

Vinosus

Tempestas

Hypocrita

Effrons

Resupinus

Veterator

SentinaMorio

Apostata

Rabula

Transfuga

Iniquus

Noxa

Vulpecula

Simia

Latro

Vappa

Tarbo

Hydra

Effronis

Rana

Vipera

SophistaMonstrum

Agaso

Raptor

Turpis

Ineptus

Nefandus

Vecors

Scurra

Lanista

Voluptas

Tyrannus

Hermaphroditus

Eriunis

Rebellis

Virus

Scelestu

Each column is an acrostic of the name Martinvs Luthervs, making 80 scurrilous epithets.

MUST now say something about the little

books on vagabonds which appeared in

this country fifty years after the Liber Vagatorum

had become popular in Germany. The first

and principal of these was edited by Thomas Harman,

a gentleman who lived in the days of Queen

Elizabeth, and who appears to have spent a considerable

portion of his time in ascertaining the artifices

and manœuvres of rogues and beggars. From a close

comparison of his work with the Liber Vagatorum, I

have little hesitation in saying that he obtained the

idea and general arrangement, together with a good

deal of the matter, from the German work edited by

Luther. The title of Harman’s book is:—A

Caueat for Cvrsetors vulgarely Called Vagabones, set

forth for the vtilitie and profit of his naturell countrey.

MUST now say something about the little

books on vagabonds which appeared in

this country fifty years after the Liber Vagatorum

had become popular in Germany. The first

and principal of these was edited by Thomas Harman,

a gentleman who lived in the days of Queen

Elizabeth, and who appears to have spent a considerable

portion of his time in ascertaining the artifices

and manœuvres of rogues and beggars. From a close

comparison of his work with the Liber Vagatorum, I

have little hesitation in saying that he obtained the

idea and general arrangement, together with a good

deal of the matter, from the German work edited by

Luther. The title of Harman’s book is:—A

Caueat for Cvrsetors vulgarely Called Vagabones, set

forth for the vtilitie and profit of his naturell countrey.

This first appeared in 1566. It was very popular, and soon ran through four editions, the lastPg xxv being “augmented and enlarged by the first author thereof, with the tale of the second taking of the counterfeit Crank, and the true report of his behaviour and punishment, most marvellous to the hearer or reader thereof.”

The dates of the four editions are—

| William Gryffith | 1566 |

| Wilib.lliamib. | 1567 |

| . . . . . . . . | 1567 |

| Henry Middleton | 1573 |

The printer of the third edition is not known. The book is dedicated, somewhat inconsistently, considering the nature of the subject, to Elizabeth, Countess of Shrewsbury. It gives, like the Liber Vagatorum, short but graphic descriptions of the different kinds of beggars, and concludes with a cant dictionary.

The next work on this subject which appeared in England was published nine years later:—

The Fraternitye of Vacabondes, with a Description of the crafty Company of Cousoners and Shifters;Pg xxvi whereunto also is adioyned the XXV Orders of Knaues, other wise called a Quartern of Knaues. Confirmed for ever by Cocke Lorell. (London by John Awdeley, 4to. 1575.)8

Some have conjectured that it was an original compilation by Audley, the printer; but this little book, perhaps more than Harman’s, shows traces of the German work. The “XXV Orders of Knaues” is nearly the number described in the Liber Vagatorum, and the tricks, and description of beggars’ dresses in both are very similar. There are the rogues with patched cloaks, who begged with their wives and “doxies;” those with forged licenses and letters, who pretended to collect for hospitals; those afflicted with the falling sickness, a numerous number; some without tongues, carrying letters, pretending they have been signed and sealed by the authorities of the towns from whence they came; Pg xxviiothers, “freshe-water mariners,” with tales of a dreadful shipwreck, and many more, all described in similar words, whether in the pages of the Liber Vagatorum, Harman, or Audley. It is reasonable to suppose, therefore, that the German account, being in the hands of the people abroad half a century before anything of the kind was issued here, copies must have found their way to England, and that from these the other two were in a great measure derived.

I might remark that other accounts of English vagabonds were published soon after this. The subject had become popular, and a demand for books of the kind was the result. Harrison, who wrote the Description of England, prefixed to Holinshed’s Chronicle (1577), describes the different orders of beggars. Greene, about 1592, wrote several works, based mainly on old Harman’s book; and Decker, twenty years later, provided a similar batch, giving an account of the vagabonds and loose characters of his day.

Shakespeare, too, and other dramatists of the period, introduced beggars and mendicants into their plays in company with the Gipsies, with whom, in a great measure, in this country they were allied.

MONGST those passages which refer to

the customs and tricks of beggars, in the

Liber Vagatorum, there are few which

receive illustration by a reference to the early laws

and statutes of this country.

MONGST those passages which refer to

the customs and tricks of beggars, in the

Liber Vagatorum, there are few which

receive illustration by a reference to the early laws

and statutes of this country.

The licenses, or “letters with seals,” so frequently alluded to, and which were granted to deserving poor people by the civil authorities, are mentioned as customary in this country in the Act for the ordering of Vagrants, passed in the reign of Henry VIII. (1531). It appears that the parish officers were compelled by this statute to make inquiry into the condition of the poor, and to ascertain who were really impotent and who were impostors. To aPg xxix person actually in want liberty was given to beg within a certain district, “and further,” says the Act, “there shall be delivered to every such person a letter containing the name of that person, witnessing that he is authorized to beg, and the limits within which he is appointed to beg, the same letter to be sealed with the seal of the hundred, rape, wapentake, city, or borough, and subscribed with the name of one of the said justices or officers aforesaid.”

I need scarcely remark that a seal in those days, when but few public functionaries could write, was looked upon as the badge of authority and genuineness, and that as the art of writing became more general autograph signatures supplanted seals. An English vagabond in the time of Elizabeth, when speaking of his passport, called it his JARKE, or JARKEMAN, viz. his sealed paper. His descendant of the present century would term it his LINES, viz. his written paper. The cant term JARKE is almost obsolete, but the powerful magic of a bigPg xxx seal is still remembered and made use of by the tribe of cadgers. When a number of them at the present day wait upon a farmer with a fictitious paper, authorizing them to collect subscriptions for the sufferers in some dreadful colliery accident, the document, covered with apparently genuine signatures, is generally garnished with a huge seal.

In Germany it was the custom (alluded to at page 34) for the priests or clerks to read these licenses to beg from the pulpit, that the congregation might know which of the poor people who waited at their doors were worthy of alms. Sometimes, as in the case of the Dützbetterin, or false “lying-in-woman,” an anecdote of whom is told here, the priests were deceived by counterfeit documents.

At page 17 reference is made to the wandering students who used to trudge over the country and sojourn for a time at any school charitable enough to take them in. These, in their journeys, often fell in with rogues and tramps, and sometimes joinedPg xxxi them in their vagabond calling, in which case they obtained for themselves the title of Kammesierers, or “Learned Beggars.” Now these same vagabond scholars were to be met with in this country in the time of Henry VIII,—and in Ireland, I believe, so late as the last century. Examining again the Act for Vagrants, 1531, we find that it was usual and customary for poor scholars from Oxford and Cambridge to tramp from county to county. The statute provided them with a document, signed by the commissary, chancellor, or vice-chancellor, which acted as their passport. When found without this license they were treated as vagrants, and whipped accordingly.

T is remarkable that many of the tricks

and manœuvres to obtain money from the

unthinking but benevolent people of Luther’s

time should have been practised in this country

at an early date, and that they should still be foundPg xxxii

amongst the arts to deceive thoughtless persons

adopted by rogues and tramps at the present day.

The stroller, or “Master of the Black Art,” described

at page 19, is yet occasionally heard of in

our rural districts. The simple farmer believes him

to be weather and cattle wise, and should his crops

be backward, or his cow “Spot,” not “let down

her milk,” with her accustomed readiness, he crosses

the fellow’s hand with a piece of silver, in order that

things may be righted.

T is remarkable that many of the tricks

and manœuvres to obtain money from the

unthinking but benevolent people of Luther’s

time should have been practised in this country

at an early date, and that they should still be foundPg xxxii

amongst the arts to deceive thoughtless persons

adopted by rogues and tramps at the present day.

The stroller, or “Master of the Black Art,” described

at page 19, is yet occasionally heard of in

our rural districts. The simple farmer believes him

to be weather and cattle wise, and should his crops

be backward, or his cow “Spot,” not “let down

her milk,” with her accustomed readiness, he crosses

the fellow’s hand with a piece of silver, in order that

things may be righted.

The Wiltners, or finders of pretended silver fingers, noticed at page 45, are now-a-days represented by the “Fawney Riggers,” or droppers of counterfeit gold rings,—described in Mayhew’s London Labour, and other works treating of the ways of vagabonds.

“Card-Sharpers,” or Joners, mentioned at page 47, are, unfortunately for the pockets of the simple, still to be met with on public race-courses and at fairs.

The over-Sönzen-goers, or pretended distressedPg xxxiii gentry, who went about “neatly dressed,” with false letters, would seem to have been the original of our modern “Begging-Letter-Writers.”

Those half-famished looking impostors, with clean aprons, or carefully brushed threadbare coats, who stand on the curbs of our public thoroughfares, and beg with a few sticks of sealing-wax in their hands, were known in Luther’s time as Goose-shearers. As the reader will have experienced only too frequently, they have, when pretending to be mechanics out of employ, a particularly unpleasant practice of following people, and detailing, in half-despairing, half-threatening sentences, the state of their pockets and their appetites. It appears they did the same thing more than three centuries ago.

Another class, known amongst London street-folk as “Shivering-Jemmies,”—fellows who expose themselves, half-naked, on a cold day, to excite pity and procure alms—were known in Luther’s time as Schwanfelders,—only in those days, people being not quite so modest as now, they stripped themPg xxxivselves entirely naked before commencing to shiver at the church-doors.

Those wretches, who are occasionally brought before the police magistrates, accused of maiming children, on purpose that they may the better excite pity and obtain money, are, unfortunately, not peculiar to our civilized age. These fellows committed like cruelties centuries ago.

Borrowers of children, too,—those pretended fathers of numerous and starving families of urchins, now often heard howling in the streets on a wet day, the children being arranged right and left according to height,—existed in the olden time,—only then the loan was but for All Souls’, or other Feast Day, when the people were in a good humour.

The trick of placing soap in the mouth to produce froth, and falling down before passers-by as though in a fit, common enough in London streets a few years ago, is also described as one of the old manœuvres of beggars.9

Travelling quack-doctors, against whom Luther cautions his readers, were common in this country up to the beginning of the present century.10 And it is not long ago since the credulous countrymen in our rural districts, were cheated by fellows—“wise-men” they preferred being termed—who pretended to divine dreams, and say under which tree or wall the hidden treasure, so plainly seen by Hodge in his sleep carefully deposited in a crock, was to be found. This pleasant idea of a pot full of gold, being buried near everybody, seems to have possessed people in all ages. In Luther’s time the nobility and clergy appear to have been sadly troubled with it, and it is very amusing to learn that so simple in this respect were the latter, that after they had given “gold and silver” to the cunning treasure-seeker, this worthy would insist upon their offering up masses in order that the digging might be attended with success!

And lastly, the travelling tinkers,—who appear to Pg xxxvihave had no better name for honesty in the fifteenth century than they have now,—“going about breaking holes in people’s kettles to give work to a multitude of others,” says the little book.

ITH regard to the Rothwelsch Sprache, or

cant language used by these vagrants, it

appears, like nearly all similar systems of

speech, to be founded on allegory. Many of the

terms, as in the case of the ancient cant of this country,

appear to be compound corruptions,—two or

more words, in ordinary use, twisted and pronounced

in such a way as to hide their original meaning.

As Luther states, in his preface, the Hebrew appears

to be a principal element. Occasionally a term

from a neighbouring country, or from a dead language

may be observed, but not frequently. As

they occur in the original I have retained those cant

words which are to be found here and there in the

text. Perhaps it would have rendered a perusal lessPg xxxvii

tedious had they been placed as foot-notes; but I

preferred to adhere to the form in which Luther was

content the little book should go forth to the world.

The simple form of these secret terms has generally

been given, there being no established rule for their

inflection. In a few instances I found myself unable

to give English equivalents to the cant words

in the Vocabulary, so was compelled to leave them

unexplained, but with the old German meanings

(not easy to be unravelled) attached.

ITH regard to the Rothwelsch Sprache, or

cant language used by these vagrants, it

appears, like nearly all similar systems of

speech, to be founded on allegory. Many of the

terms, as in the case of the ancient cant of this country,

appear to be compound corruptions,—two or

more words, in ordinary use, twisted and pronounced

in such a way as to hide their original meaning.

As Luther states, in his preface, the Hebrew appears

to be a principal element. Occasionally a term

from a neighbouring country, or from a dead language

may be observed, but not frequently. As

they occur in the original I have retained those cant

words which are to be found here and there in the

text. Perhaps it would have rendered a perusal lessPg xxxvii

tedious had they been placed as foot-notes; but I

preferred to adhere to the form in which Luther was

content the little book should go forth to the world.

The simple form of these secret terms has generally

been given, there being no established rule for their

inflection. In a few instances I found myself unable

to give English equivalents to the cant words

in the Vocabulary, so was compelled to leave them

unexplained, but with the old German meanings

(not easy to be unravelled) attached.

John Camden Hotten.

Piccadilly, June, 1860.

Printed at Wittemberg in the year

M.D.XXIX.

HIS little book about the knaveries of beggars

was first printed by one who called

himself Expertus in Truffis, that is, a

fellow right expert in roguery,—which

the little work very well proves, even though he had

not given himself such a name.

HIS little book about the knaveries of beggars

was first printed by one who called

himself Expertus in Truffis, that is, a

fellow right expert in roguery,—which

the little work very well proves, even though he had

not given himself such a name.

But I have thought it a good thing that such a book should not only be printed, but that it should become known everywhere, in order that men may see and understand how mightily the devil rules in this world; and I have also thought how such a book may help mankind to be wise, and on the look out for him, viz. the devil. Truly, such Beggars’ Cant has come from the Jews, for many Hebrew words occur in the Vocabulary, as any one who understands that language may perceive.

But the right understanding and true meaning of the book is, after all, this, viz. that princes, lords, counsellors of state, and everybody should be prudent, and cautious in dealing with beggars, and learn that, whereas people will not give and help honest paupers and needy neighbours, as ordained by God, they give, by the persuasion of the devil, and contrary to God’s judgment, ten times as much to Vagabonds and desperate rogues,—in like manner as we have hitherto done to monasteries, cloisters, churches, chapels, and mendicant friars, forsaking all the time the truly poor.

For this reason every town and village should know their own paupers, as written down in the Register, and assist them. But as to outlandish and strange beggars they ought not to be borne with, unless they have proper letters and certificates; for all the great rogueries mentioned in this book are done by these. If each town would only keep an eye upon their paupers, such knaveries would soon be at an end. I have myself of late years been cheated and befooled by suchPg 5 tramps and liars more than I wish to confess. Therefore, whosoever hears these words let him be warned, and do good to his neighbour in all Christian charity, according to the teaching of the commandment.

SO HELP US GOD! ![]()

THE BOOK OF VAGABONDS AND BEGGARS.

ERE follows a pretty little book, called

Liber Vagatorum, written by a high

and worthy master, nomine Expertus in

Truffis, to the praise and glory of

God, sibi in refrigerium et solacium, for all persons’

instruction and benefit, and for the correction and

conversion of those that practise such knaveries as

are shown hereafter; which little book is divided

into three parts. Part the first shows the several

methods by which mendicants and tramps get theirPg 8

livelihood; and is subdivided into XX chapters, et

paulo plus,—for there are XX ways, et ultra,

whereby men are cheated and fooled. Part the

second gives some notabilia which refer to the

means of livelihood afore mentioned. The third

part presents a Vocabulary of their language or

gibberish, commonly called Red Welsh, or Beggar-lingo.

ERE follows a pretty little book, called

Liber Vagatorum, written by a high

and worthy master, nomine Expertus in

Truffis, to the praise and glory of

God, sibi in refrigerium et solacium, for all persons’

instruction and benefit, and for the correction and

conversion of those that practise such knaveries as

are shown hereafter; which little book is divided

into three parts. Part the first shows the several

methods by which mendicants and tramps get theirPg 8

livelihood; and is subdivided into XX chapters, et

paulo plus,—for there are XX ways, et ultra,

whereby men are cheated and fooled. Part the

second gives some notabilia which refer to the

means of livelihood afore mentioned. The third

part presents a Vocabulary of their language or

gibberish, commonly called Red Welsh, or Beggar-lingo.

HE first chapter is about Bregers. These

are beggars who have neither the signs

of the saints about them, nor other good

qualities, but they come plainly and simply to

people and ask an alms for God’s, or the Holy

Virgin’s sake:—perchance honest paupers with

young children, who are known in the town or

village wherein they beg, and who would, I doubtPg 9

not, leave off begging if they could only thrive by

their handicraft or other honest means, for there is

many a godly man who begs unwillingly, and feels

ashamed before those who knew him formerly

when he was better off, and before he was compelled

to beg. Could he but proceed without he

would soon leave begging behind him.

HE first chapter is about Bregers. These

are beggars who have neither the signs

of the saints about them, nor other good

qualities, but they come plainly and simply to

people and ask an alms for God’s, or the Holy

Virgin’s sake:—perchance honest paupers with

young children, who are known in the town or

village wherein they beg, and who would, I doubtPg 9

not, leave off begging if they could only thrive by

their handicraft or other honest means, for there is

many a godly man who begs unwillingly, and feels

ashamed before those who knew him formerly

when he was better off, and before he was compelled

to beg. Could he but proceed without he

would soon leave begging behind him.

Conclusio: To these beggars it is proper to give,

for such alms are well laid out.

The next chapter is about the Stabülers.

These are vagrants who tramp through

the country from one Saint to another,

their wives (KRÖNERIN) and children (GATZAM)

going (ALCHEN) with them. Their hats (WETTERHAN)

and cloaks (WINTFANG) hang full of signs

of all the saints,—the cloak (wintfang) being made

(VETZEN) out of a hundred pieces. They go toPg 10

the peasants who give them bread (LEHEM DIPPEN);

and each of these Stabülers has six or

seven sacks, and carries a pot, plate, spoon, flask,

and whatever else is needed for the journey with

him. These same Stabülers never leave off

begging, nor do their children, from their infancy

to the day of their death—for the beggar’s staff

keeps the fingers (GRIFFLING) warm—and they

neither will nor can work, and their children (GATZAM)

grow up to be harlots and harlotmongers

(GLIDEN und GLIDESVETZER), hangmen and flayers

(ZWICKMEN und KAVELLER). Also, whithersoever

these Stabülers come, in town or country, they

beg; at one house for God’s sake, at another for

St. Valentine’s sake, at a third for St. Kürine’s, sic

de aliis, according to the disposition of the people

from whom they seek alms. For they do not adhere

to one patron or trust to one method alone.

The next chapter is about the Stabülers.

These are vagrants who tramp through

the country from one Saint to another,

their wives (KRÖNERIN) and children (GATZAM)

going (ALCHEN) with them. Their hats (WETTERHAN)

and cloaks (WINTFANG) hang full of signs

of all the saints,—the cloak (wintfang) being made

(VETZEN) out of a hundred pieces. They go toPg 10

the peasants who give them bread (LEHEM DIPPEN);

and each of these Stabülers has six or

seven sacks, and carries a pot, plate, spoon, flask,

and whatever else is needed for the journey with

him. These same Stabülers never leave off

begging, nor do their children, from their infancy

to the day of their death—for the beggar’s staff

keeps the fingers (GRIFFLING) warm—and they

neither will nor can work, and their children (GATZAM)

grow up to be harlots and harlotmongers

(GLIDEN und GLIDESVETZER), hangmen and flayers

(ZWICKMEN und KAVELLER). Also, whithersoever

these Stabülers come, in town or country, they

beg; at one house for God’s sake, at another for

St. Valentine’s sake, at a third for St. Kürine’s, sic

de aliis, according to the disposition of the people

from whom they seek alms. For they do not adhere

to one patron or trust to one method alone.

Conclusio: Thou mayest give to them if thou wilt,

for they are half bad and half good,—not all bad,

but most part.

HE iijrd chapter is about the Lossners.

These are knaves who say they have lain

in prison vi or vij years, and carry the

chains with them wherein they lay as captives

among the infidel (id est, in the SONNENBOSS,

i.e. brothel) for their christian faith; item, on the

sea in galleys or ships enchained in iron fetters;

item, in a strong tower for innocence’ sake; and

they have forged letters (LOE BSAFFOT), as from

the princes and lords of foreign lands, and from

the towns (KIELAM) there, to bear witness to their

truth, tho’ all the time they are deceit and lies

(GEVOPT und GEVERBT),—— for vagabonds may

be found everywhere on the road who can make

(VETZEN) any seal they like—— and they say they

have vowed to Our Lady at Einsiedlin (in the

DALLINGER’S BOSS, i.e. harlot’s house), or to some

Pg 12other Saint (in the SCHÖCHERBOSS, i.e. beer-house),

according to what country they are in, a pound of

wax, a silver crucifix, or a chasuble; and they say

they have been made free through that vow, and,

when they had vowed, the chains opened and

broke, and they departed safe and without harm.

Item, some carry iron fastenings, or coats of mail

(PANZER) with them, et sic de aliis. Nota: They

have perchance bought (KÜMMERT) the chains;

perchance they had them made (VETZEN); perchance

stolen (GEJENFT) them from the church

(DIFTEL) of St. Lenhart.

HE iijrd chapter is about the Lossners.

These are knaves who say they have lain

in prison vi or vij years, and carry the

chains with them wherein they lay as captives

among the infidel (id est, in the SONNENBOSS,

i.e. brothel) for their christian faith; item, on the

sea in galleys or ships enchained in iron fetters;

item, in a strong tower for innocence’ sake; and

they have forged letters (LOE BSAFFOT), as from

the princes and lords of foreign lands, and from

the towns (KIELAM) there, to bear witness to their

truth, tho’ all the time they are deceit and lies

(GEVOPT und GEVERBT),—— for vagabonds may

be found everywhere on the road who can make

(VETZEN) any seal they like—— and they say they

have vowed to Our Lady at Einsiedlin (in the

DALLINGER’S BOSS, i.e. harlot’s house), or to some

Pg 12other Saint (in the SCHÖCHERBOSS, i.e. beer-house),

according to what country they are in, a pound of

wax, a silver crucifix, or a chasuble; and they say

they have been made free through that vow, and,

when they had vowed, the chains opened and

broke, and they departed safe and without harm.

Item, some carry iron fastenings, or coats of mail

(PANZER) with them, et sic de aliis. Nota: They

have perchance bought (KÜMMERT) the chains;

perchance they had them made (VETZEN); perchance

stolen (GEJENFT) them from the church

(DIFTEL) of St. Lenhart.

Conclusio: To such vagrants thou shalt give

nothing, for they do nought but deceive (VOPPEN)

and cheat (VERBEN) thee; not one in a thousand

speaks the truth.

HE iiijth is about the Klenkners. These

are the beggars who sit at the church-doors,

and attend fairs and church gatherings

with sore and broken legs; one has no foot,

another no shank, a third no hand or arm. Item,

some have chains lying by them, saying they have

lain in captivity for innocence’ sake, and commonly

they have a St. Sebastianum or St. Lenhartum

with them, and they pray and cry with a loud

voice and noisy lamentations for the sake of the

Saints, and every third word one of them speaks

(BARL) is a lie (GEVOP), and the people who give

alms to him are cheated (BESEFELT),—inasmuch

as his thigh or his foot has rotted away in prison

or in the stocks for wicked deeds. Item, one’s

hand has been chopped off in the quarrels over

dice or for the sake of a harlot. Item, many a one

ties a leg up or besmears an arm with salves, orPg 14

walks on crutches, and all the while as little ails

him as other men. Item, at Utenheim there was a

priest by name Master Hans Ziegler (he holds

now the benefice of Rosheim), and he had his niece

with him. One upon crutches came before his

house. His niece carried him a piece of bread.

He said, “Wilt thou give me nought else?” She

said, “I have nought else.” He replied, “Thou

old priest’s harlot! wilt thou make thy parson

rich?” and swore many oaths as big as he could

utter them. She cried and came into the room and

told the priest. The priest went out and ran after

him. The beggar dropped his crutches and fled so

fast that the parson could not catch him. A short

time afterwards the parson’s house was burnt down;

he said the Klenkner did it. Item, another true

example: at Schletstat, one was sitting at the church-door.

This man had cut the leg of a thief from

the gallows. He put on the dead leg and tied his

own leg up. He had a quarrel with another beggar.

This latter one ran off and told the townPg 15serjeant.

When he saw the serjeant coming he fled

and left the sore leg behind him and ran out of the

town—a horse could hardly have overtaken him.

Soon afterwards he hung on the gallows at Achern,

and the dry leg beside him, and they called him

Peter of Kreuzenach. Item, they are the biggest

blasphemers thou canst find who do such things;

and they have also the finest harlots (GLIDEN), they

are the first-comers at fairs and church-celebrations,

and the last-goers therefrom.

HE iiijth is about the Klenkners. These

are the beggars who sit at the church-doors,

and attend fairs and church gatherings

with sore and broken legs; one has no foot,

another no shank, a third no hand or arm. Item,

some have chains lying by them, saying they have

lain in captivity for innocence’ sake, and commonly

they have a St. Sebastianum or St. Lenhartum

with them, and they pray and cry with a loud

voice and noisy lamentations for the sake of the

Saints, and every third word one of them speaks

(BARL) is a lie (GEVOP), and the people who give

alms to him are cheated (BESEFELT),—inasmuch

as his thigh or his foot has rotted away in prison

or in the stocks for wicked deeds. Item, one’s

hand has been chopped off in the quarrels over

dice or for the sake of a harlot. Item, many a one

ties a leg up or besmears an arm with salves, orPg 14

walks on crutches, and all the while as little ails

him as other men. Item, at Utenheim there was a

priest by name Master Hans Ziegler (he holds

now the benefice of Rosheim), and he had his niece

with him. One upon crutches came before his

house. His niece carried him a piece of bread.

He said, “Wilt thou give me nought else?” She

said, “I have nought else.” He replied, “Thou

old priest’s harlot! wilt thou make thy parson

rich?” and swore many oaths as big as he could

utter them. She cried and came into the room and

told the priest. The priest went out and ran after

him. The beggar dropped his crutches and fled so

fast that the parson could not catch him. A short

time afterwards the parson’s house was burnt down;

he said the Klenkner did it. Item, another true

example: at Schletstat, one was sitting at the church-door.

This man had cut the leg of a thief from

the gallows. He put on the dead leg and tied his

own leg up. He had a quarrel with another beggar.

This latter one ran off and told the townPg 15serjeant.

When he saw the serjeant coming he fled

and left the sore leg behind him and ran out of the

town—a horse could hardly have overtaken him.

Soon afterwards he hung on the gallows at Achern,

and the dry leg beside him, and they called him

Peter of Kreuzenach. Item, they are the biggest

blasphemers thou canst find who do such things;

and they have also the finest harlots (GLIDEN), they

are the first-comers at fairs and church-celebrations,

and the last-goers therefrom.

Conclusio: Give them a kick on their hind parts if thou canst, for they are nought but cheats (BESEFLER) of the peasants (HANZEN) and all other men.

Example: One was called Uz of Lindau. He

was at Ulm, in the hospital there, for xiiij days,

and on St. Sebastian’s day he lay before a church,

his hands and thighs tied up, nevertheless he could

use both legs and hands. This was betrayed to the

constables. When he saw them coming he fled

from the town,—a horse could hardly have ran

faster.

HE vth chapter is about Dobissers. These

beggars (STIRNENSTÖSSER, i.e. spurious

anointers) go hostiatim from house to house,

and touch the peasant and his wife (HANZ und HANZIN)

with the Holy Virgin, or some other Saint, saying

that it is the Holy Virgin from the chapel,—and

they pass themselves off for friars from the same

place. Item, that the chapel was poor and they

beg linen-thread for an altar-cloth (id est, a gown

[CLAFFOT] for a harlot [SCHREFEN]). Item, fragments

of silver for a chalice (id est, to spend it in

drinking [VERSCHÖCHERN] or gambling [VERJONEN]).

Item, towels for the priests to dry their

hands upon, (id est, to sell [VERKÜMMERN] them).

Item, there are also Dobissers, church-beggars, who

have letters with seals, and beg alms to repair a

Pg 17ruined chapel (DIFTEL), or to build a new church.

Verily, such friars do make collections for an edificium—viz.

one which lies not far below the nose, and

is called St. Drunkard’s chapel.

HE vth chapter is about Dobissers. These

beggars (STIRNENSTÖSSER, i.e. spurious

anointers) go hostiatim from house to house,

and touch the peasant and his wife (HANZ und HANZIN)

with the Holy Virgin, or some other Saint, saying

that it is the Holy Virgin from the chapel,—and

they pass themselves off for friars from the same

place. Item, that the chapel was poor and they

beg linen-thread for an altar-cloth (id est, a gown

[CLAFFOT] for a harlot [SCHREFEN]). Item, fragments

of silver for a chalice (id est, to spend it in

drinking [VERSCHÖCHERN] or gambling [VERJONEN]).

Item, towels for the priests to dry their

hands upon, (id est, to sell [VERKÜMMERN] them).

Item, there are also Dobissers, church-beggars, who

have letters with seals, and beg alms to repair a

Pg 17ruined chapel (DIFTEL), or to build a new church.

Verily, such friars do make collections for an edificium—viz.

one which lies not far below the nose, and

is called St. Drunkard’s chapel.

Conclusio: As to these Dobissers, give them

nought, for they cheat and defraud thee. If from

a church that lies ij or iij miles from thee people

come and beg, give them as much as thou wilt or

canst.

HE vjth chapter is about the Kammesierers.

These beggars are young scholars or young

students, who do not obey their fathers

and mothers, and do not listen to their masters’ teaching,

and so depart, and fall into the bad company

of such as are learned in the arts of strolling and

tramping, and who quickly help them to lose all

they have by gambling (VERJONEN), pawning (VERSENKEN),Pg 18

or selling (VERKÜMMERN) it, with drinking

(VERSCHÖCHERN) and revelry. And when they

have nought more left, they learn begging, and KAMMESIERING,

and to cheat the farmers (HANZEN-BESEFLEN);

and they KAMESIER as follows: Item, that they

come from Rome (id est, from the brothel [SONNENBOSS]),

studying to become priests (on the gallows,

i.e. DOLMAN); item, one is acolitus, another is epistolarius,

the third evangelicus, and a fourth clericus

(GALCH); item, they have nought on earth but the

alms wherewith people help them, and all their

friends and family have long been called away by

death’s song. Item, they ask linen cloth for an alb

(id est, for a harlot’s shift, i.e. GLIDEN HANFSTAUDEN).

Item, money, that they may be consecrated at

next Corpus Christi day (id est, in a SONNENBOSS, i.e.

brothel), and whatever they get by cheating and

begging they lose in gambling (VERJONEN), or with

strumpets, or spend it in drink (VERSCHOCHERNS

und VERBOLENS). Item, they shave tonsures on their

heads, although they are not ordained and have noPg 19

church document (FORMAT), though they say they

have, and they are altogether a bad lot (LOE VOT).

HE vjth chapter is about the Kammesierers.

These beggars are young scholars or young

students, who do not obey their fathers

and mothers, and do not listen to their masters’ teaching,

and so depart, and fall into the bad company

of such as are learned in the arts of strolling and

tramping, and who quickly help them to lose all

they have by gambling (VERJONEN), pawning (VERSENKEN),Pg 18

or selling (VERKÜMMERN) it, with drinking

(VERSCHÖCHERN) and revelry. And when they

have nought more left, they learn begging, and KAMMESIERING,

and to cheat the farmers (HANZEN-BESEFLEN);

and they KAMESIER as follows: Item, that they

come from Rome (id est, from the brothel [SONNENBOSS]),

studying to become priests (on the gallows,

i.e. DOLMAN); item, one is acolitus, another is epistolarius,

the third evangelicus, and a fourth clericus

(GALCH); item, they have nought on earth but the

alms wherewith people help them, and all their

friends and family have long been called away by

death’s song. Item, they ask linen cloth for an alb

(id est, for a harlot’s shift, i.e. GLIDEN HANFSTAUDEN).

Item, money, that they may be consecrated at

next Corpus Christi day (id est, in a SONNENBOSS, i.e.

brothel), and whatever they get by cheating and

begging they lose in gambling (VERJONEN), or with

strumpets, or spend it in drink (VERSCHOCHERNS

und VERBOLENS). Item, they shave tonsures on their

heads, although they are not ordained and have noPg 19

church document (FORMAT), though they say they

have, and they are altogether a bad lot (LOE VOT).

Conclusio: As to these Kammesierers give them

nought, for the less thou givest them the better it

is for them, and the sooner they must leave off.

They have also forged FORMATÆ (literæ).

HE vijth chapter is about Vagrants. These

are beggars or adventurers who wear yellow

garments, come from Venusberg, know the

black art, and are called rambling scholars. These

same when they come into a house speak thus:—“Here

comes a rambling scholar, a magister of

the seven free arts (id est, the various ways of cheating

[BESEFLEN] the farmers [HANZEN]), an exorciser

of the devil for hail, for storm, and for witchcraft.”

Then he utters some magical words and crosses his

breast ii or iij times, and speaks thus:—

HE vijth chapter is about Vagrants. These

are beggars or adventurers who wear yellow

garments, come from Venusberg, know the

black art, and are called rambling scholars. These

same when they come into a house speak thus:—“Here

comes a rambling scholar, a magister of

the seven free arts (id est, the various ways of cheating

[BESEFLEN] the farmers [HANZEN]), an exorciser

of the devil for hail, for storm, and for witchcraft.”

Then he utters some magical words and crosses his

breast ii or iij times, and speaks thus:—

and many more precious words. Then the farmers (HANZEN) think it all true, and are glad that he is come, and are sorry they have never seen a wandering scholar before, and speak to the vagrant:—“This or that has happened to me, can you help me? I would willingly give you a florin or ij”—and he says “Yes,” and cheats the farmers (BESEFELTDEN den HANZEN ums MESS) out of their money. And after these experiments they depart. The farmers suppose that by their talking they can drive the devil away, and can help them from any trouble that has befallen them. Thou canst ask them nothing but they will perform thee an experiment therewith; that is, they can cheat and defraud thee of thy money.

Conclusio: Beware of these Vagrants, for wherewith

they practise is all lies.

HE viijth chapter is about the Grantners.

These are the beggars who say in the

farm-houses (HANSEN-BOSS):—“Oh, dear

friend, look at me, I am afflicted with the falling

sickness of St. Valentine, or St. Kurinus, or St. Vitus,

or St. Antonius, and have offered myself to the

Holy Saint (ut supra) with vj pounds of wax, with an

altar cloth, with a silver salver (et cetera), and must

bring these together from pious people’s offerings and

help; therefore I beg you to contribute a heller, a

spindleful of flax, a ribbon, or some linen yarn for

the altar, that God and the Holy Saint may protect

you from misery and disease and the falling sickness.”

Nota: A false (LOE) trick.

HE viijth chapter is about the Grantners.

These are the beggars who say in the

farm-houses (HANSEN-BOSS):—“Oh, dear

friend, look at me, I am afflicted with the falling

sickness of St. Valentine, or St. Kurinus, or St. Vitus,

or St. Antonius, and have offered myself to the

Holy Saint (ut supra) with vj pounds of wax, with an

altar cloth, with a silver salver (et cetera), and must

bring these together from pious people’s offerings and

help; therefore I beg you to contribute a heller, a

spindleful of flax, a ribbon, or some linen yarn for

the altar, that God and the Holy Saint may protect

you from misery and disease and the falling sickness.”

Nota: A false (LOE) trick.

Item, some fall down before the churches, or in other places with a piece of soap in their mouths, whereby the foam rises as big as a fist, and they prickPg 22 their nostrils with a straw, causing them to bleed, as though they had the falling-sickness. Nota: this is utter knavery. These are villanous vagrants that infest all countries. Item, there are many who speak (BARLEN) thus:—“Listen to me, dear friends, I am a butcher’s son, a tradesman. And it happened some time since that a vagrant came to my father’s house and begged for St. Valentine’s sake; and my father gave me a penny to give to him. I said, ‘father, it is knavery.’ My father told me to give it to him, but I gave it him not. And since that hour I have been afflicted with the falling-sickness, and I have made a vow to St. Valentine of iij pounds of wax and a High Mass, and I beg and pray pious folks to help me, because I have made this vow; otherwise I should have substance enough for myself. Therefore I ask of you an offering and help that the dear holy St. Valentine may guard and protect you evermore.” Nota: what he says is all lies. Item, he has been more than xx years collecting for his iij pounds of wax and the mass, and has been gambling (VERJONEN),Pg 23 bibbling (VERSCHÖCHERN), and rioting (VERBOLEN) with it. And there are many that use other and more subtle words than those given in this book. Item, some have a written testimony (BSAFFOT) that it is all true.

Conclusio: If any of the Grantners cometh

before thine house, and simply beggeth for God’s

sake, and speaketh not many, nor flowery words, to

them thou shalt give, for there are many men who

have been afflicted with the sickness by the Saints;

but as to those Grantners who use many words,

speak of great wonders, tell you that they have

made vows, and can altogether skilfully use their

tongues—these are signs that they have followed this

business for a long time, and, I doubt not, they are

false and not to be trusted. As to him who believes

them, they take a nut off his tree. Take care

of such, and give them nothing.

HE ixth chapter is about the Dutzers.

These are beggars who have been ill for a

long time, as they say, and have promised

a difficult pilgrimage to this or that Saint (ut supra

in precedenti capitulo) for three whole and entire

alms every day, that they, thereby, must go each

day from door to door until they find three pious

men who will give them three entire alms. Thus

speaketh a pious man unto them: “What is an entire

alms?” Whereat the Dutzer replieth: “A

‘plaphart’ (blaffard), whereof I must have three

every day, and take no less, for without that the

pilgrimage is no good.” Some go for iij pennies,

some for one penny, et in toto nihil. And the alms

they “must have from a good and correct man.”

Such is the vanity of women, rather than be called

impious they give a double “blaffard,” and send

the Dutzer one to another, who uses many other

Pg 25

words which I cannot make bold to repeat. Item,

they would take a hundred “blaffards” and more a

day if they were given them, and what they say

is all lies (GEVOPT). Item, this also is DUTZING, viz.

when a beggar comes to thine house and speaks:

“Good woman, might I ask you for a spoonful of

butter; I have many young children, and I want the

wherewith to cook soup for them?” Item, for an

egg (BETZAM): “I have a child bedridden now these

seven days.” Item, for a mouthful of wine, “for I

have a sick wife,” et sic de aliis. This is called

DUTZING.

HE ixth chapter is about the Dutzers.

These are beggars who have been ill for a

long time, as they say, and have promised

a difficult pilgrimage to this or that Saint (ut supra

in precedenti capitulo) for three whole and entire

alms every day, that they, thereby, must go each

day from door to door until they find three pious

men who will give them three entire alms. Thus

speaketh a pious man unto them: “What is an entire

alms?” Whereat the Dutzer replieth: “A

‘plaphart’ (blaffard), whereof I must have three

every day, and take no less, for without that the

pilgrimage is no good.” Some go for iij pennies,

some for one penny, et in toto nihil. And the alms

they “must have from a good and correct man.”

Such is the vanity of women, rather than be called

impious they give a double “blaffard,” and send

the Dutzer one to another, who uses many other

Pg 25

words which I cannot make bold to repeat. Item,

they would take a hundred “blaffards” and more a

day if they were given them, and what they say

is all lies (GEVOPT). Item, this also is DUTZING, viz.

when a beggar comes to thine house and speaks:

“Good woman, might I ask you for a spoonful of

butter; I have many young children, and I want the

wherewith to cook soup for them?” Item, for an

egg (BETZAM): “I have a child bedridden now these

seven days.” Item, for a mouthful of wine, “for I

have a sick wife,” et sic de aliis. This is called

DUTZING.

Conclusio: Give nought whatsoever to those

Dutzers who say that they have taken a vow not

to gather more per diem than iij or iiij entire alms,

ut supra. They are half good (HUNT), and half

bad (LÖTSCH); but the greater part bad.

HE xth chapter is about the Schleppers.

These are Kammesierers who pretend to

be priests. They come to the houses with

a famulus or discipulus who carries a sack after

them, and speak thus:—“Here comes a consecrated

man, named Master George Kessler, of Kitzebühel

(or what else he likes to call himself) and I am of

such-and-such a village, or of such-and-such a family

(naming a family which they know), and I will

officiate at my first mass on such-and-such a day in

that village, and I was consecrated for the altar in

such-and-such a town at such-and-such a church,

and there is no altar cloth, nor is there a missal, et

cetera, and I cannot afford them without much help

from all men; for mark, whosoever is commended

for an offering in the angel’s requiem, or for as

many pennies as he gives, so many souls will be released

amongst his deceased kindred.” Item, theyPg 27

receive also the farmer (HANZ) and his wife

(HANZIN) into a brotherhood, which they say had

bestowed on it grace and a great indulgence from

the bishop who is to erect the altar. Thus men

are moved to pity; one gives linen yarn, another

flax or hemp; one table cloths, or towels, or old

silver plate; and the Schleppers say that they are

not a brotherhood like the others who have questionerer,

and who come every year, but that they

will come no more (for if they came again they

would certainly be drowned [GEFLÖSSELT]). Item,

this manner is greatly practised in the Black

Forest, and in the country of Bregenz, in Kurwalen,

and in the Bar, and in the Algen, and on the

Adige, and in Switzerland, where there are not many

priests, and where the churches are far distant from

each other,—as are also the farms.

HE xth chapter is about the Schleppers.

These are Kammesierers who pretend to

be priests. They come to the houses with

a famulus or discipulus who carries a sack after

them, and speak thus:—“Here comes a consecrated

man, named Master George Kessler, of Kitzebühel

(or what else he likes to call himself) and I am of

such-and-such a village, or of such-and-such a family

(naming a family which they know), and I will

officiate at my first mass on such-and-such a day in

that village, and I was consecrated for the altar in

such-and-such a town at such-and-such a church,

and there is no altar cloth, nor is there a missal, et

cetera, and I cannot afford them without much help

from all men; for mark, whosoever is commended

for an offering in the angel’s requiem, or for as

many pennies as he gives, so many souls will be released

amongst his deceased kindred.” Item, theyPg 27

receive also the farmer (HANZ) and his wife

(HANZIN) into a brotherhood, which they say had

bestowed on it grace and a great indulgence from

the bishop who is to erect the altar. Thus men

are moved to pity; one gives linen yarn, another

flax or hemp; one table cloths, or towels, or old

silver plate; and the Schleppers say that they are

not a brotherhood like the others who have questionerer,

and who come every year, but that they

will come no more (for if they came again they

would certainly be drowned [GEFLÖSSELT]). Item,

this manner is greatly practised in the Black

Forest, and in the country of Bregenz, in Kurwalen,

and in the Bar, and in the Algen, and on the

Adige, and in Switzerland, where there are not many

priests, and where the churches are far distant from

each other,—as are also the farms.

Conclusio: To these Schleppers, or Knaves, give nothing, for it would be badly laid out.

Exemplum, One was called Mansuetus; he also

invited the farmers to his first mass at St. Gallen;Pg 28

and when they came to St. Gallen they sought for

him in the cathedral, but found him not. After

their meal they discovered him in a brothel (SONNENBOSS),

but he escaped.

HE xith chapter is of the Gickisses, or Blind

Beggars. Mark: there are three kinds of

blind men who wander about. Some are

called BLOCHARTS, id est, blind men—made blind by

the power of God,—they go on a pilgrimage, and

when they come into a town they hide their round

hats, and say to the people they have been stolen

from them, or lost at the places where they had

sheltered themselves, and one of them often collects

ten or xx caps, and then sells them. Some are

called blind who have lost their sight by evil-doings

and wickednesses. They wander about in the country

and carry with them pictures of devils, and repairPg 29

to the churches, and pretend they had been at

Rome, to Saint James, and other distant places, and

speak of great signs and wonders that had taken

place, but it is all lies and deception. Some of the

blind men are called BROKEN WANDERERS (Bruch

Umbgeen). These are such as have been blinded

ten years or more; they take cotton, and make the

cotton bloody, and then with a kerchief tie this

over their eyes, and say that they have been mercers

or pedlers, and were blinded by wicked men

in a forest, that they were tied fast to a tree and so

remained three or four days, and, but for a merciful

passer-by, they would have miserably perished;—and

this is called BROKEN WANDERING.

HE xith chapter is of the Gickisses, or Blind

Beggars. Mark: there are three kinds of

blind men who wander about. Some are

called BLOCHARTS, id est, blind men—made blind by

the power of God,—they go on a pilgrimage, and

when they come into a town they hide their round

hats, and say to the people they have been stolen

from them, or lost at the places where they had

sheltered themselves, and one of them often collects

ten or xx caps, and then sells them. Some are

called blind who have lost their sight by evil-doings

and wickednesses. They wander about in the country

and carry with them pictures of devils, and repairPg 29

to the churches, and pretend they had been at

Rome, to Saint James, and other distant places, and

speak of great signs and wonders that had taken

place, but it is all lies and deception. Some of the

blind men are called BROKEN WANDERERS (Bruch

Umbgeen). These are such as have been blinded

ten years or more; they take cotton, and make the

cotton bloody, and then with a kerchief tie this

over their eyes, and say that they have been mercers

or pedlers, and were blinded by wicked men

in a forest, that they were tied fast to a tree and so

remained three or four days, and, but for a merciful

passer-by, they would have miserably perished;—and

this is called BROKEN WANDERING.

Conclusio: Know them well before thou givest to

them; my advice is only give to those thou knowest.

HE xijth chapter is about the Schwanfelders,

or Blickschlahers. These are

beggars who, when they come to a town,

leave their clothes at the hostelry, and sit down

against the churches naked, and shiver terribly before

the people that they may think they are suffering

from great cold. They prick themselves with nettle-feed

and other things, whereby they are made to

shake. Some say they have been robbed by wicked

men; some that they have lain ill and for this reason

were compelled to sell their clothes. Some say

they have been stolen from them; but all this is

only that people should give them more clothes,

when they sell (VERKÜMMERN) them, and spend the

money with lewd women (VERBOLENS) and gambling

(VERJONENS).

HE xijth chapter is about the Schwanfelders,

or Blickschlahers. These are

beggars who, when they come to a town,

leave their clothes at the hostelry, and sit down

against the churches naked, and shiver terribly before

the people that they may think they are suffering

from great cold. They prick themselves with nettle-feed

and other things, whereby they are made to

shake. Some say they have been robbed by wicked

men; some that they have lain ill and for this reason

were compelled to sell their clothes. Some say

they have been stolen from them; but all this is

only that people should give them more clothes,

when they sell (VERKÜMMERN) them, and spend the

money with lewd women (VERBOLENS) and gambling

(VERJONENS).

Conclusio: Beware of these Schwanfelders for

it is all knavery, and give them nothing, whether they

be men or women, (unless) thou knowest them well.

HE xiijth chapter is about the Voppers.

These beggars are for the most part women,

who allow themselves to be led in

chains as if they were raving mad; they tear their

shifts from their bodies, in order that they may deceive

people. There are also some that do both,

VOPPERY and DUTZING, together. This is VOPPING,

viz. when one begs for his wife’s or any other person’s

sake and says she has been possessed of a devil

(tho’ there is no truth in it), and he has vowed to

some Saint (whom he names), and must have xij

pounds of wax or other things whereby the person