CONTENTS

Preface 3

Contents 5

PART I.

HOME AND ITS EMPLOYMENTS.

House Cleaning—Repairing Furniture—Cleaning Stoves and

Grates—Mending Glass, China, &c.—Coloring and Polishing

Furniture, &c.—Removing unpleasant Odors—Fires—Water and

Cisterns—Carriages and Harness—Washing—To remove Stains—To

clean Silks, Lace, &c.—Paste, Glue, and Cement—Dyeing—Blacking

for Boots, Shoes, &c.—To destroy Insects—The

Kitchen, &c.

Page 9 to 88

PART II.

HEALTH AND BEAUTY.

Rules for the preservation of Health—Simple Recipes efficacious

in common diseases and slight injuries—Burns and Scalds—Fevers—Plasters,

Blisters, Ointments, &c.—Poisons and Antidotes—Baths

and Bathing—The Toilet, or hints for the preservation

of Beauty—The Dressing-Table

Page 89 to 150

PART III.

HOME PURSUITS AND DOMESTIC ARTS.

Needle-work—Explanation of Stitches—Preparation of House-Linen—Patchwork—Silk

Embroidery—Fancy-work—Ink—Birds,

Fish, Flowers, &c.—House-Plants—Window-Plants—To

manage a Watch

Page 151 to 187

PART IV.

DOMESTIC ECONOMY, AND OTHER MATTERS WORTH KNOWING.

Teas—Coffee—Various Recipes for making Essences, &c.—Preserving

Fruit, Vegetables, Herbs, &c.—Hints to Farmers—Management

of a Horse—Raising Poultry—Preservation from

Fire—Drowning—Suffocation—Thunderstorms

Page 188 to 209

PART V.

MISTRESS, MOTHER, NURSE, AND MAID.

Of the Table—On the management of Infants, young Children,

and the Sick—Qualifications of a good Nurse—Food for the Sick

and for Children—Drinks for the Sick—Simple mixtures—Rules

for Women Servants

Page 210 to 264

PART VI.

HINTS ABOUT AGRICULTURE, GARDENING, DOMESTIC ANIMALS, &c.

Manure—Soil—Hay—Grains—Vegetables—To destroy Insects—Vermin—Weeds—Cows,

Calves, Sheep, &c.—Gardening—The

Orchard—Timber—Building—Bees

Page 265 to 318

PART VII.

MISCELLANEOUS.

Choice and cheap Cookery—New Receipts—Southern Dishes—Cakes,

Bread, Pies, and Puddings—Home-made Wines, Mead,

Nectar, &c.—Washing—Hints on Diet, Exercise, and Economy—Painting—Books—Periodicals

and Newspapers

Page 319 to 384

PART VIII.

ELEGANT AND INGENIOUS ARTS.

Water-Colors used in Drawing—Directions for mixing Colors—Wash

Colors for Maps—To paint Flowers, Birds, Landscapes,

&c., in Water-Colors—Potichomanie—Grecian Painting—Diaphanic

Feather Flowers—Sea-Weeds—Botanical Specimens, Leaf

Impressions, &c.—Transferring to Glass, Wood, &c.—Emblematic

Stones—Staining Stone, Wood, &c.—Ornamental Leather work—Dyeing—

Games—Evening Pastime

Page 385 to 431

[7]

PART IX.

WORK IN DOORS AND OUT.

Household maxims—Household receipts for many things—Care

of Furs—Wise economy—Things to know—Cleanliness—Prevention

of accidents—Domestic hints—More hints on Agriculture—Cattle—Gardening—Drying Herbs—Properties

and uses of Vegetables—Vegetables to cultivate—Fruit Trees and Fruit—Vermin

on Trees

Page 431 to 484

PART X.

PERSONAL MATTERS.

Dress of Ladies—Dress of a Gentleman—Manners—Rules of

Etiquette—Dinner Parties—Balls and Evening Parties—Courtship

and Marriage—Marriage Ceremony—After Marriage—Directions

to a Wife—Directions to a Husband—Our House—Conversation—Rules

of Conduct

Page 484 to 533

PART XI.

HEALTH AND WEALTH.

Preservation of Health—Baths—Exercise—Terms expressing the

properties of medicines—Ointments and Cerates—Embrocations

and Liniments—Enemas—Poultices—Special rules for the prevention

of Cholera—Rules for a Sick Room—Domestic Surgery—Bandages—Riches—Temperance—Way

to Wealth

Page 533 to 590

PART XII.

THE FAMILY AT HOME.

A good Table—Bread, &c.—Meats—Vegetables—Household

management—Beverages—Useful Receipts for Family Practice—Miscellaneous

Receipts, Rules, &c.—Dietetic maxims—Hints

to Mechanics and Workmen—Maxims and Morals for all Men—Home

Industry for Young Ladies—Pets—Swimming—Riding—Home

Counsels—Parlor Amusements—The training of Daughters,

&c.—Sentiments of Flowers—Signs of the Weather—Air—Its

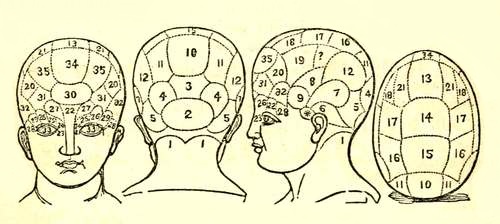

effects on Life—Importance of Laws—Phrenology—Synopsis of

American History—Words of Washington—Useful Family Tables

Page 590 to 699

Index 703

MRS. HALE'S

RECEIPTS FOR THE MILLION,

CONTAINING

FOUR THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED AND FORTY-FIVE

RECEIPTS, FACTS, ETC.

PART I.

HOME AND ITS EMPLOYMENTS.

House cleaning—Repairing Furniture—Washing—Mending Glass, China, &c.—Dyeing—Blacking for Boots, Shoes, &c.—To destroy Insects—The Kitchen, &c.

1. House Cleaning.—The spring is more particularly the time for house-cleaning; though, of course, it requires attention monthly.

Begin at the top of the house; first take up the carpets, and, if they require it, let them be scoured; or as carpets are sometimes injured by scouring, they may be well beaten, and if necessary, washed with soda and water.

Remove all the furniture from the room, have the chimneys swept where fires have been kept, and clean and blacken the grates. Wrap old towels, (they should be clean), around the bristles of the broom, and sweep lightly the ceiling and paper; or, if requisite, the paper should be cleaned with bread, as elsewhere directed. Then wash the paint with a flannel or sponge, and soap and water, and, as fast as one person cleans, another should follow, and with clean cloths, wipe the paint perfectly dry. Let the windows be cleaned, and scour the floor. Let the furniture be well rubbed; and the floor being dry, and the carpets laid down, the furniture may be replaced. The paper should be swept every three months.

2. To clean Bed-rooms.—In cleaning bed-rooms infested with bugs, take the bedsteads asunder, and wash every part of them,[10] but especially the joints, with a strong solution of corrosive sublimate in spirits of turpentine; as the sublimate is a fatal poison, the bottle containing the above solution should be labelled "Poison;" it should be used very carefully, and laid on with a brush kept for the purpose. Bugs can only be removed from walls by taking down the paper, washing them with the above poison, and re-papering.

In bed-rooms with fires, a whisk-brush is best to clear the curtains and hangings from dust.

To remove grease or oil from boards, drop on the spots spirits of turpentine before the floor is scoured.

The house-maid should be provided with a box, with divisions, to convey her various utensils, as brushes, black lead, &c., from room to room, and a small mat to kneel upon while cleaning the grate.

3. Scouring Bed-rooms.—This should never be done in winter if it can be avoided, as it is productive of many coughs and colds. If inevitable, a dry day should be selected, and the windows and doors should be left wide open till dusk. A fire ought always to be made in the room after cleaning.

4. To clean Carpets.—Before sweeping a carpet, sprinkle over it a few handfuls of waste tea-leaves. A stiff hair-broom or brush should be used, unless the carpet be very dirty, when a whisk or carpet-broom should be used first, followed by another made of hair to take off the loose dirt. The frequent use of a stiff broom soon injures the beauty of the best carpet. An ordinary clothes-brush is best adapted for superior carpets.

When Brussels carpets are very much soiled, take them up and beat them perfectly free from dust. Have the floor thoroughly scoured and dry, and nail the carpet firmly down to it. If still soiled, take a pailful of clean, cold water, and put into it about three gills of ox-gall. Take another pail, with clean, cold water only; now rub with a soft scrubbing-brush some of the ox-gall water on the carpet, which will raise a lather. When a convenient-sized portion is done, wash the lather off with a clean linen cloth dipped in the clean water. Let this water be changed frequently. When all the lather has disappeared, rub the part with a clean, dry cloth. After all is done, open the window to allow the carpet to dry. A carpet treated in this manner, will be greatly refreshed in color, particularly the greens. Kidderminster[11] carpets will scarcely bear the above treatment without becoming so soft as speedily to become dirty again. This may, in some measure, be prevented by brushing them over with a hot, weak solution of size in water, to which a little alum has been added. Curd soap dissolved in hot water, may be used instead of ox-gall, but it is more likely to injure the colors, if produced by false dyes. Where there are spots of grease in the carpeting, they may be covered with curd soap dissolved in boiling water, and rubbed with a brush until the stains are removed, when they must be cleaned with warm water as before. The addition of a little gall to the soap renders it more efficacious.

The carpets should be nailed on the full stretch, else they will shrink.

Fullers' earth is also used for cleaning carpets; and alum, or soda, dissolved in water, for reviving the colors.

5. To clean Turkey Carpets.—To revive the color of a Turkey carpet, beat it well with a stick till the dust is all got out; then, with a lemon or sorrel juice, take out the spots of ink, if the carpet be stained with any; wash it in cold water, and afterwards shake out all the water from the threads of the carpet. When it is thoroughly dry, rub it all over with the crumb of a hot wheaten loaf; and, if the weather is very fine, hang it out in the open air a night or two.

6. Cheap Carpeting.—Sew together strips of the cheapest cotton cloth, of the size of the room, and tack the edges to the floor. Then paper the cloth, as you would the sides of a room, with any sort of room paper. After being well dried, give it two coats of varnish, and your carpet is finished. It can be washed like carpets, without injury, retains its gloss, and, on chambers or sleeping rooms, where it will not meet rough usage, will last for two years, as good as new.

7. To beat a Carpet.—Hang the carpet upon a clothes-line, or upon a stout line between two trees; it should then be beaten on the wrong side, by three or four persons, each having a pliable stick, with cloth tied strongly in a knob on the end, in order to prevent the carpet from being torn, or the seams split, by the sharp end of the stick. When thoroughly beaten on the wrong side, the carpet should be turned, and beaten on the right side.

8. Floor or Oil Cloths.—Floor-cloths should be chosen that are painted on a fine cloth, which is well covered with the color, and the patterns on which do not rise much above the ground, as they wear out first. The durability of the cloth will depend much on these particulars, but more especially on the time it has been painted, and the goodness of the colors. If they have not been allowed sufficient time for becoming thoroughly hardened, a very little use will injure them; and, as they are very expensive articles, care in preserving them is necessary. It answers to keep them some time before they are used, either hung up in a dry barn where they will have air, or laid down in a spare room.

When taken up for the winter, they should be rolled round a carpet-roller, and observe not to crack the paint by turning the edges in too suddenly.

Old carpets answer extremely well, painted and seasoned some months before laid down. If for passages, the width must be directed when they are sent to the manufactory, as they are cut before painting.

9. To clean Floor cloths.—Sweep, then wipe them with a flannel; and when all dust and spots are removed, rub with a waxed flannel, and then with a dry plain one; but use little wax, and rub only enough with the latter to give a little smoothness, or it may endanger falling.

Washing now and then with milk, after the above sweeping and dry-rubbing them, gives as beautiful a look, and they are less slippery.

10. Method of Cleaning Paper-hangings.—Cut into eight half quarters a large loaf, two days old; it must neither be newer nor staler. With one of these pieces, after having blown off all the dust from the paper to be cleaned, by means of a good pair of bellows, begin at the top of the room, holding the crust in the hand, and wiping lightly downward with the crumb, about half a yard at each stroke, till the upper part of the hangings is completely cleaned all round. Then go round again, with the like sweeping stroke downwards, always commencing each successive course a little higher than the upper stroke had extended, till the bottom be finished. This operation, if carefully performed, will frequently make very old paper look almost equal to new.

Great caution must be used not by any means to rub the paper hard, nor to attempt cleaning it the cross, or horizontal way. The dirty part of the bread, too, must be each time cut away, and the pieces renewed as soon as it may become necessary.

11. To clean Paint.—Never use a cloth, but take off the dust with a little long-haired brush, after blowing off the loose parts with the bellows. With care, paint will look well for a long time, if guarded from the influence of the sun. When soiled, dip a sponge or a bit of flannel into soda and water, wash it off quickly, and dry immediately, or the soda will eat off the color. Some persons use strong soap and water, instead.

When the wainscot requires scouring, it should be done from the top downwards, and the water be prevented from running on the unclean parts as much as possible, or marks will be made which will appear after the whole is finished. One person should dry with old linen, as fast as the other has scoured off the dirt, and washed off the soap.

12. To give to Boards a beautiful appearance.—After washing them very nicely with soda and warm water and a brush, wash them with a very large sponge and clean water. Both times observe to leave no spot untouched; and clean straight up and down, not crossing from board to board; then dry with clean cloths, rubbed hard up and down in the same way.

The floors should not be often wetted, but very thoroughly when done; and once a-week dry-rubbed with hot sand and a heavy brush the right way of the boards.

The sides of stairs or passages on which are carpets or floor-cloths, should be washed with sponge instead of linen or flannel, and the edges will not be soiled. Different sponges should be kept for the above two uses; and those and the brushes should be well washed when done with, and kept in dry places.

12a. To extract Oil from Boards or Stone.—Make a strong ley of pearlashes and soft water, and add as much unslaked lime as it will take up; stir it together, and then let it settle a few minutes; bottle it, and stop close; have ready some water to lower it as used, and scour the part with it. If the liquor should lie long on the boards, it will draw out the color of them; therefore do it with care and expedition.

13. To scour Boards.—Mix together one part lime, three parts common sand, and two parts soft soap; lay a little of this on the scrubbing-brush, and rub the board thoroughly. Afterwards rinse with clean water, and dry with a clean coarse cloth. This will keep the boards a good color: it is also useful in keeping away vermin. For that object, early in the spring, beds should be taken down, and furniture in general removed and examined; bed-hangings and window-curtains, if not washed, should be shaken and brushed; and the joints of bedsteads, the backs of drawers, and indeed, every part of furniture, except polished mahogany, should be carefully cleaned with the above mixture, or with equal parts of lime and soft soap, without any sand. In old houses, where there are holes in the boards, which often abound with vermin, after scrubbing in, as far as the brush can reach, a thick plaster of the above should be spread over the holes, and covered with paper. When these things are timely attended to, and combined with general cleanliness, vermin may generally be kept away, even in crowded cities.

14. To wash Stone Stairs and Halls.—Wash them first with hot water and a clean flannel, and then wash them over with pipe-clay mixed in water. When dry, rub them, with a coarse flannel.

15. To take Oil and Grease out of Floors and Stone Halls.—Make a strong infusion of potash with boiling water; add to it as much quick-lime as will make it of the consistence of thick cream; let it stand a night, then pour off the clear part, which is to be bottled for use. When wanted, warm a little of it; pour it upon the spots, and after it has been on them for a few minutes, scour it off with warm water and soap, as it is apt to discolor the boards when left too long on them. When put upon stone, it is best to let it remain all night; and if the stain be a bad one, a little powdered hot lime may be put upon it before the infusion is poured on.

16. To clean Marble.—Muriatic acid, either diluted or pure, as occasion may require, proves efficacious. If too strong, it will deprive the marble of its polish, which may be easily restored by the use of a piece of felt, with some powder of putty or tripoli, with either, making use of water.

17. To clean Marble. Another way.—Mix ¼ lb. of soft soap with the same of pounded whiting, 1 oz. of soda, and a piece of stone-blue the size of a walnut; boil these together for ¼ of an hour; whilst hot, rub it over the marble with a piece of flannel, and leave it on for 24 hours; then wash it off with clean water, and polish the marble with a piece of coarse flannel, or what is better, a piece of an old hat.

18. To take Stains out of Marble.—Mix unslaked lime in finest powder with stringent soap-ley, pretty thick, and instantly with a painter's brush lay it on the whole of the marble. In two months' time wash it off perfectly clean; then have ready a fine thick lather of soft soap, boiled in soft water; dip a brush in it, and scour the marble. This will, with very good rubbing, give a beautiful polish.

19. To take Iron-stains out of Marble.—An equal quantity of fresh spirit of vitriol and lemon-juice being mixed in a bottle, shake it well; wet the spots, and in a few minutes rub with soft linen till they disappear.

20. Mixture for cleaning Stone Stairs, Hall Pavements, &c.—Boil together half a pint each of size and stone-blue water, with two table-spoonfuls of whiting, and two cakes of pipe-makers' clay, in about two quarts of water. Wash the stones over with a flannel slightly wetted in this mixture; and when dry, rub them with flannel and a brush. Some persons recommend beer, but water is much better for the purpose.

21. To Color or Paper the Walls of Rooms.—If a ceiling or wall is to be whitewashed or colored, the first thing to be done is, to wash off the dirt and stains with a brush and clean water, being careful to move the brush in one direction, up and down, and not all sorts of ways, or the work will look smeary afterwards. When dry, the ceiling is ready for whitewash, which is to be made by mixing whiting and water together, till quite smooth, and as thick as cream. Dissolve half-an-ounce of glue in a teacupful of water, stir it into the whitewash. This size, as it is called, prevents the white or color rubbing off the wall, and a teacupful is enough for a gallon of wash. Stone color is made by mixing a little yellow ochre and blue black with the size, and then stirring it into the whitewash; yellow or red ochre are also[16] good colors, and, with vermilion or indigo, any shade may be prepared, according to taste.

If paper is to be used, the wall must be washed with clean water, as above explained; and while wet, the old color must be scraped off with a knife, or a smooth-edged steel scraper of any sort. It will be best to wet a yard or two at a time, and then scrape. Next, wash the wall all over with size, made with an ounce of glue to a gallon of water; and when this is dry, the wall is ready for the paper. This must be cut into lengths according to the different parts of the room; one edge of the plain strip must be cut off close to the pattern, and the other left half an inch wide. If the paper is thick, it should lie a minute or two after it is pasted; but if thin, the sooner it is on the wall, the better. Begin by placing the close-cut edge of the paper at one side of the window, stick it securely to meet the ceiling, let it hang straight, and then press it down lightly and regularly with a clean cloth. The close-cut edge of the next length will cover the half-inch left on the first one, and so make a neat join; and in this way you may go all round the room, and finish at the other side of the window.

22. Damp Walls.—Damp may be prevented from exuding from walls by first drying them thoroughly, and then covering them with the following mixture: In a quart of linseed oil, boil three ounces of litharge, and four ounces of resin. Apply this in successive coats, and it will form a hard varnish on the wall after the fifth coating.

23. To clean Moreen Curtains.—Having removed the dust and clinging dirt as much as possible with a brush, lay the curtain on a large table, sprinkle on it a little bran, and rub it round with a piece of clean flannel; when the bran and flannel become soiled, use fresh, and continue rubbing till the moreen looks bright, which it will do in a short time.

24. To clean Calico Furniture.—Shake off the loose dust; then lightly brush with a small, long-haired furniture-brush; after which wipe it closely with clean flannels, and rub it with dry bread.

If properly done, the curtains will look nearly as well as at first; and, if the color be not light, they will not require washing for years.

Fold in large parcels, and put carefully by.

While the furniture remains up, it should be preserved from the sun and air as much as possible, which injure delicate colors; and the dust may be blown off with bellows.

By the above mode curtains may be kept clean, even to use with the linings newly dipped.

25. Making Beds.—Close or press bedsteads are ill adapted for young persons or invalids; when their use is unavoidable, the bed-clothes should be displaced every morning, and left for a short time before they are shut up.

The windows of bed-rooms should be kept open for some hours every day, to carry off the effluvia from the bed-clothes; the bed should also be shaken up, and the clothes spread about, in which state the longer they remain, the better.

The bed being made, the clothes should not be tucked in at the sides or foot, as that prevents any further purification taking place, by the cool air passing through them.

A warming-pan should be chosen without holes in the lid. About a yard of moderately-sized iron chain, made red hot and put into the pan, is a simple and excellent substitute for coals.

26. To Detect Dampness in Beds.—Let the bed be well warmed, and immediately after the warming-pan is taken out, introduce between the sheets, in an inverted position, a clean glass goblet: after it has remained in that situation a few minutes, examine it; if found dry and not tarnished with steam, the bed is perfectly safe; and vice versa. In the latter case, it will be best to sleep between the blankets.

27. Beech-tree Leaves.—The leaves of the beech-tree, collected at autumn, in dry weather, form an admirable article for filling beds for the poor. The smell is grateful and wholesome; they do not harbor vermin, are very elastic, and may be replenished annually without cost.

28. Useful Hints relative to Bed-clothes, Mattresses, Cushions, &c.—The purity of feathers and wool employed for mattresses and cushions ought to be considered as a first object of salubrity. Animal emanations may, under many circumstances, be prejudicial to the health; but the danger is still greater, when[18] the wool is impregnated with sweat of persons who have experienced putrid and contagious diseases. Bed-clothes, and the wool of mattresses, therefore, cannot be too often beat, carded, cleaned, and washed. This is a caution which cannot be too often recommended.

It would be very easy in most situations, and very effectual, to fumigate them with muriatic gas.

29. To clean Feathers of their Oil.—In each gallon of clean water mix a pound of quick-lime, and when the undissolved lime settles in fine powder, pour off the lime-water for use. Having put the feathers to be cleaned into a tub, pour the clear lime-water upon them, and stir them well about; let them remain three or four days in the lime-water, which should then be separated from them by laying them in a sieve. The feathers should next be washed in clean water, and dried upon fine nets; they will then only require beating, to get rid of the dust, previous to use.

To restore the spring of damaged feathers, it is only necessary to dip them in warm water for a short time.

30. To purify Wool infested with Insects.—The process of purification consists in putting into three pints of boiling water a pound and a half of alum, and as much cream of tartar, which are diluted in twenty-three pints more of cold water. The wool is then left immersed in this liquor during some days, after which it is washed and dried. After this operation, it will no longer be subject to be attacked by insects.

31. To clean Looking-glasses.—Keep for this purpose a piece of sponge, a cloth, and a silk handkerchief, all entirely free from dirt, as the least grit will scratch the fine surface of the glass. First, sponge it with a little spirit of wine, or gin and water, so as to clean off all spots; then, dust over it powder-blue, tied in muslin, rub it lightly and quickly off with the cloth, and finish by rubbing it with the silk handkerchief. Be careful not to rub the edges of the frames.

32. To preserve Gilding, and clean it.—It is impossible to prevent flies from staining the gilding without covering it; before which, blow off the light dust, and pass a feather or clean brush[19] over it, but never touch it with water; then, with strips of paper, or rather gauze, cover the frames of your glasses, and do not remove till the flies are gone.

Linen takes off the gilding and deadens its brightness; it should, therefore, never be used for wiping it.

A good preventive against flies is, to boil three or four leeks in a pint of water, and then with a gilding-brush wash over the glasses and frames with the liquid, and the flies will not go near the articles so washed. This will not injure the frames in the least. Stains or spots may be removed by gently wiping them with cotton dipped in sweet oil.

33. To retouch the rubbed parts of a Picture-frame.—Give the wood a coating of size made by dissolving isinglass with a weak spirit. When nearly dry, lay on some gold leaf; and polish, when quite dry, with an agate burnisher, or any similar substance.

34. Furniture Oil.—Put into a jar one pint of linseed oil into which stir one ounce of powdered rose pink, and one ounce of alkanet root, beaten in a mortar: set the jar in a warm place for a few days, when the oil will be deeply colored, and the substances having settled, the oil may be poured off, and will be excellent for darkening new mahogany.

35. Furniture Paste.—Put turpentine into a glazed pot, and scrape beeswax into it, which stir about till the liquid is of the thickness of cream; it will then be good for months, if kept clean; and furniture cleaned with the liquid thus made, will not receive stains so readily as when the turpentine and wax are heated over the fire; which plan is, besides, very dangerous; but if the heating be preferred, place the vessel containing the wax and turpentine in another containing boiling water.

36. French Polish for Furniture.—To one pint of spirits of wine, add half an ounce of gum-shellac, half an ounce of gum-lac, a quarter of an ounce of gum-sandarac; place the whole in a gentle heat, frequently shaking it, till the gums are dissolved, when it is fit for use. Make a roller of list, put a little of the polish upon it, and cover that with a piece of soft linen rag, which must be lightly touched with cold-drawn linseed oil. Rub the wood in a circular direction, not covering too large a[20] space at a time, till the pores of the wood are sufficiently filled up. After this, rub in the same manner spirits of wine, with a small portion of the polish added to it; and a most brilliant polish will be produced. If the article should have been polished with wax, it will be necessary to clean it off with fine glass paper.

37. Another Polish and Varnish.—The only way to preserve polish on rosewood French-polished furniture, is to keep it continually rubbed with a chamois leather and a silk handkerchief. We have no better remedy to offer for scratches on the wood than filling them in with a little oil covered with alkanet-root. The following varnish for furniture not French-polished, has been highly recommended: Melt one part of virgin white wax with eight parts of petroleum; lay a slight coat of this mixture on the wood with a fine brush while warm; the oil will then evaporate, and leave a thin coat of wax, which should afterwards be polished with a coarse woolen cloth.

38. Polish for Dining Tables.—Is to rub them with cold-drawn linseed oil, thus: Put a little in the middle of a table, and then with a piece of linen (never use woolen) cloth rub it well all over the table; then take another piece of linen and rub it for ten minutes, then rub it till quite dry with another cloth. This must be done every day for some months, when you will find your mahogany acquire a permanent and beautiful lustre, unattainable by any other means, and equal to the finest French polish; and if the table is covered with the table-cloth only, the hottest dishes will make no impression upon it; and when once this polish is produced, it will only require dry rubbing with a linen cloth for about ten minutes, twice in a week, to preserve it in the highest perfection; which never fails to please your employers; and remember, that to please others is always the surest way to profit yourself.

If the appearance must be more immediately produced, take some Furniture Paste.

39. Varnished Furniture.—This may be finished off so as to look equal to the best French polished wood, in the following manner, which is also suitable to other varnished surfaces. Take two ounces of Tripoli powder, put it into an earthen pot, with just enough water to cover it; then take a piece of white[21] flannel, lay it over a piece of cork or rubber, and proceed to polish the varnish, always wetting it with the Tripoli and water. It will be known when the process is finished by wiping a part of the work with a sponge, and observing whether there is a fair, even gloss. When this is the case, take a bit of mutton suet and fine flour, and clean the work.

Frames of varnished wood may be cleaned to look new, by careful washing with a sponge and soap and water, but nothing stronger should be used.

40. Varnish for Violins, &c.—Take a gallon of rectified spirits of wine, twelve ounces of mastic, and a pint of turpentine varnish; put them all together in a tin can, and keep it in a very warm place, shaking it occasionally till it is perfectly dissolved; then strain it, and it is fit for use. If you find it necessary, you may dilute it with turpentine varnish. This varnish is also very useful for furniture of plum-tree, mahogany, or rosewood.

41. White Varnish.—The white varnish used for toys is made of sandarac, eight ounces; mastic, two ounces; Canada balsam, four ounces; alcohol, one quart. This is white, drying, and capable of being polished when hard. Another varnish for objects of the toilet, such as work-boxes, card-cases, &c., is made of gum sandarac, six ounces; elemi (genuine), four ounces: anime, one ounce; camphor, half an ounce; rectified spirit, one quart. Melt slowly. These ingredients may, of course, be lessened in proportion.

42. To remove Ink-spots from Mahogany.—Drop on the spots a very small quantity of spirits of salt; rub it with a feather or piece of flannel, taking care not to let the spirit reach the fingers or clothes; in four or five minutes, wash it off with water.

Or, mix a teaspoonful of burnt alum, powdered, with a quarter of an ounce of oxalic acid, in half a pint of cold water; to be used by wetting a rag with it, and rubbing it on the ink-spots.

Or, crumple a piece of blotting-paper, so as to make it firm, wet it, and with it rub the ink-spot firmly and briskly, when it will disappear; and the white mark from the operation may be immediately removed by rubbing it with a cloth.

43. Or:—Dilute ½ a teaspoonful of oil of vitriol with a large spoonful of water, and touch the part with a feather; watch it, for if it stays too long, it will leave a white mark. It is, therefore, better to rub it quickly, and repeat if not quite removed.

44. To clean Chairs.—Scrape down one or two ounces of beeswax, put it into a jar, and pour as much spirits of turpentine over it as will cover it: let it stand till dissolved. Put a little upon a flannel or bit of green baize, rub it upon the chairs, and polish them with a brush. A very small portion of finely-powdered white rosin may be mixed with the turpentine and wax.

45. To clean and restore the Elasticity of Cane Chair Bottoms, Couches, &c.—Turn up the chair bottom, &c., and with hot water and a sponge wash the cane work well, so that it may be well soaked; should it be dirty, you must add soap; let it dry in the air, and you will find it as tight and firm as when new, providing the cane is not broken.

46. Blacking for Leather Seats, &c.—Beat well the yolks of two eggs, and the white of one; mix a tablespoonful of gin and a teaspoonful of sugar, thicken it with ivory black, add it to the eggs, and use as common blacking; the seats or cushions being left a day or two to harden.

47. To prevent Hinges Creaking.—Rub them with soft soap, or a feather dipped in oil.

48. Swallows' Nests.—To prevent swallows building under eaves, or in window corners, rub the places with oil or soft soap.

49. To clean Polished Grates and Irons.—Make into a paste with cold water, four pounds of putty-powder and one of finely-powdered whiting; rub off carefully the spots from the irons, and with a dry clean duster rub the irons with the mixture always in the same direction till bright and clear. Plain dry whiting will keep it highly polished if well attended to every day. The putty mixture should be used only to remove spots.

50. To clean the Back of the Grate, the inner Hearth, and the fronts of Cast-Iron Stoves.—Mix black lead and whites of eggs well beaten together; dip a painter's brush, and wet all over, then rub it bright with a hard brush.

51. To remove the Black from the Bright Bars of Polished Stoves in a few minutes.—Rub them well with some of the following[23] mixture on a bit of broadcloth; when the dirt is removed, wipe them clean, and polish with glass (not sand) paper.

52. For Mixture:—Boil slowly one pound of soft soap in two quarts of water to one quart. Of this jelly take three or four spoonfuls, and mix to a consistence with emery.

53. To clean Bright Stoves.—There are many ways of cleaning a stove, but if the ornamental parts be neglected, rust will soon disfigure the surface, and lead to incalculable trouble. Emery dust, moistened into a paste with sweet oil, should be kept in a little jar; this should be applied on a bung, up and down, never crossways, until marks or burns disappear. A dry leather should then remove the oil, and a polish should afterwards be given with putty powder on a dry clean leather.

54. Another way to clean Grates.—The best mixture for cleaning bright stove-grates is rotten-stone and sweet oil: they require constant attention, for, if rust be once suffered to make its appearance, it will become a toil to efface it. Polished fire-irons, if not allowed to rust by neglect, will require merely rubbing with leather; and the higher the polish, the less likely they are to rust. If the room be shut up for a time, and the grates be not used, to prevent their rusting, cover them with lime and sweet oil.

Bright fenders are cleaned as stoves; cast-iron fenders require black lead; they should not, however, be cleaned in the sitting-room, as the powdered lead may fly about and injure carpets and furniture. A good plan is to send cast-iron fenders to be bronzed or lackered by the iron-monger; they will then only require brushing, to free the dust from the ornamental work. The bright top of a fender should be cleaned with fine emery-paper.

55. To prevent Fire-Irons becoming Rusty.—Rub them with sweet oil, and dust over them unslaked lime. If they be rusty, oil them for two or three days, then wipe them dry, and polish with flour emery, powdered pumice-stone, or lime. A mixture of tripoli with half its quantity of sulphur, will also remove rust; as will emery mixed with soft soap, boiled to a jelly. The last mixture is also used for removing the fire-marks from bright bars.

56. To Color the Backs of Chimneys with Lead Ore.—Clean them with a very strong brush, and carefully rub off the dust and rust; pound about a quarter of a pound of lead ore into a fine powder, and put it into a vessel with half a pint of vinegar, then apply it to the back of the chimney with a brush. When it is made black with this liquid, take a dry brush, dip it in the same powder without vinegar; then dry and rub it with this brush, till it becomes as shining as glass.

57. To blacken the fronts of Stone Chimney-pieces.—Mix oil-varnish with lamp-black, and a little spirit of turpentine to thin it to the consistence of paint. Wash the stone with soap and water very clean; then sponge it with clear water; and when perfectly dry, brush it over twice with this color, letting it dry between the times. It looks extremely well. The lamp-black must be sifted first.

58. Composition that will effectually prevent Iron, Steel, &c., from rusting.—This method consists in mixing, with fat oil varnish, four-fifths of well rectified spirit of turpentine. The varnish is to be applied by means of a sponge; and articles varnished in this manner will retain their metallic brilliancy, and never contract any spots of rust. It may be applied to copper, and to the preservation of philosophical instruments; which, by being brought into contact with water, are liable to lose their splendor, and become tarnished.

59. To keep Arms and polished Metal from Rust.—Dissolve one ounce of camphor in two pounds of hog's lard, observing to take off the scum; then mix as much black lead as will give the mixture an iron color. Fire-arms, &c., rubbed over with this mixture, and left with it on twenty-four hours, and then dried with a linen cloth, will keep clean for many months.

60. To preserve Irons from Rust.—Melt fresh mutton-suet, and smear over the iron with it while hot; then dust it well with unslaked lime pounded and tied up in a muslin. Irons so prepared will keep many months. Use no oil for them but salad-oil, there being water in all other.

Fire-irons should be wrapped in baize, and kept in a dry place, when not used.

61. To prevent polished Hardware and Cutlery from taking Rust.—Case-knives, snuffers, watch-chains, and other small articles made of steel, may be preserved from rust, by being carefully wiped after use, and then wrapped in coarse brown paper, the virtue of which is such, that all hardware goods from Sheffield, Birmingham, &c., are always wrapped in the same.

62. Another way.—Beat into three pounds of fresh hog's-lard two drachms of camphor till it is dissolved; then add as much black lead as will make it the color of broken steel. Dip a rag in it, and rub it thick on the stove, &c., and the steel will never rust, even if wet. When it is to be used, the grease must be washed off with hot water, and the steel be dried before polishing.

63. To take Rust out of Steel.—Cover the steel with sweet oil well rubbed on it, and in forty-eight hours use unslaked lime finely powdered, to rub until all the rust disappears.

64. To clean Plate.—See that the plate is quite free from grease, by having been washed, if necessary, in warm soap and water. Then mix some whiting with water, and with a sponge rub it well on the plate, which will take the tarnish off, making use of a brush not too hard, to clean the intricate parts. Next, take some rouge-powder, mix it with water to about the thickness of cream, and with a small piece of leather (which should be kept for that purpose only) apply the rouge. This, with a little rubbing, will produce a most beautiful polish. This is the actual manner in which silversmiths clean their plate.

65. The common method of cleaning Plate.—First wash it well with soap and warm water; when perfectly dry, mix together a little whiting and sweet oil, so as to make a soft paste; then take a piece of flannel, rub it on the plate, then with a leather, and plenty of dry whiting, rub it clean off again; then with a clean leather and a brush, finish it.

66. An easy way to clean Plate.—A flannel and soap, and soft water, with proper rubbing, will clean plate nicely. It should be wiped dry with a good-sized piece of soft leather.

67. Plate Powder.—In most of the articles sold as plate powders,[26] under a variety of names, there is an injurious mixture of quicksilver, which is said sometimes so far to penetrate and render silver brittle, that it will even break with a fall. Whiting, properly purified from sand, applied wet, and rubbed till dry, is one of the easiest, safest, and certainly the cheapest of all plate powders: jewelers and silversmiths, for small articles, seldom use any thing else. If, however, the plate be boiled a little in water, with an ounce of calcined hartshorn in powder to about three pints of water, then drained over the vessel in which it was boiled, and afterwards dried by the fire, while some soft linen rags are boiled in the liquid till they have wholly imbibed it; these rags will, when dry, not only assist to clean the plate, which must afterwards be rubbed bright with leather, but also serve admirably for cleaning brass locks, finger-plates, &c.

68. To cleanse Gold.—Wash the article in warm suds made of delicate soap and water, with ten or fifteen drops of sal-volatile. (The sal-volatile will render the metal brittle. This hint may be used or left, at pleasure.)

69. To clean Brass and Copper.—Rub it over slightly with a bit of flannel dipped in sweet oil; next, rub it hard with another bit dipped in finely-powdered rotten stone; then make it clean with a soft linen cloth, and finish by polishing it with a plate-leather.

70. Obs.—The inside of brass or copper vessels should be scoured with fullers' earth and water, and set to dry, else the tinning will be injured.

71. Another way to clean Brass and Copper.—Put one pennyworth of powdered rotten stone into a dry, clean quart bottle; nearly fill it up with cold soft water; shake it well, and add one penny-worth of vitriol. Rub it on with a rag, and dry it with a clean, soft cloth, and then polish it with a plate-leather. This mixture will keep for a long time, and becomes better the longer it is kept. But the first method gives the most lasting polish, as well as the finest color.

72. To clean Brass Ornaments.—Wash the ornament in a strong solution of boiled roche-alum, in the proportion of an[27] ounce to a pint of water. When dry, rub them with fine tripoli powder.

73. Polishing Paste for Britannia metal, tins, brasses, and coppers, is composed of rotten-stone, soft soap, and oil of turpentine.

The stone must be powdered and sifted through a muslin or hair sieve: mix with it as much soft soap as will bring it to the stiffness of putty: to about half-a-pound of this, add two ozs. of oil of turpentine. It may be made up in balls, or put in gallipots; it will soon become hard, and will keep any length of time. Method of using:—The articles to be polished should be perfectly freed from grease and dirt. Moisten a little of the paste with water, smear it over the metal, then rub briskly with dry rag or wash-leather, and it will soon bear a beautiful polish.

74. To clean Britannia metal.—Rub the article with a piece of flannel moistened with sweet oil; then apply a little pounded rotten-stone or polishing paste with the finger, till the polish is produced; then wash the article with soap and hot water, and when dry, rub with soft wash-leather, and a little fine whiting.

75. To clean Pewter.—Scour it with fine white sand, and strong ley made with wood-ashes, soda, or pearl-ash; then rinse the pewter in clean water, and set it to drain. The best method, however, is to use the oil of tartar and sand.

76. To clean Tin Covers.—Get the finest whiting; mix a little of it powdered with the least drop of sweet oil, rub the covers well with it, and wipe them clean; then dust over them some dry whiting in a muslin bag, and rub bright with dry leather. This last is to prevent rust, which the cook must guard against by wiping them dry, and putting them by the fire when they come from the parlor; for if but once hung up damp, the inside will rust.

77. Safe Method of cleaning Tea-urns.—In an earthen gallipot put one ounce of bees'-wax, cut up in small pieces; set it by the fireside, until perfectly melted and quite hot, very near boiling heat; remove the jar from the fire, and stir into it rather[28] less than a table-spoonful of salad oil, and rather more than a table-spoonful of best spirits of turpentine; continue stirring till well mixed and nearly cold; fill the urn with boiling water so as to make it thoroughly hot, apply a thin coating of the above mixture, and rub with a soft cloth, till all stickiness is removed, then polish with a clean rag and a little crocus powder.

N. B.—The crocus powder must be very fine, so as to sift through muslin.

78. To clean Gilt or Lacquered Articles.—Brush them with warm soap and water, wipe them, and set them before the fire to dry; finish with a soft cloth. By this simple means may be cleaned ormolu and French gilt candelabra, branches, and lamps; mosaic gold and gilt jewelry, toys and ornaments. Care is requisite in brushing the dirt from fine work, and finishing it quite dry. Any thing stronger than soap, as acids, pearl-ash, or soda, will be liable to remove the lacquer.

To polish inlaid Brass Ornaments.—Mix powdered tripoli and linseed oil, and dip in it a piece of hat, with which rub the brass; then, if the wood be ebony, or dark rosewood, polish it with elder ashes in fine powder.

79. To clean Lacquer.—Make a paste of starch, one part; powdered rotten-stone, twelve parts; sweet oil, two parts; oxalic acid, one part; water to mix.

80. To clean Door-plates.—To clean brass-plates on doors, so as not to injure the paint at the edges, cut the size of the plate out of a large piece of mill-board, place it against the door, and rub the plate with rotten-stone, or crocus and sweet oil, upon leather.

81. To clean Mother-o'-pearl.—Wash in whiting and water. Soap destroys the brilliancy.

82. To clean Knives and Forks.—Hold the knives straightly on the board, and pass them backward and forward in as straight a line as possible. Forks should be cleaned with a stick covered with buff-leather, and finished with a brush. The best article for cleaning is the powder of the well-known Flanders bricks.

83. Of Knife-boards.—A knife-board properly made, should consist of an inch-deal-board, five feet long, with a hole at one end by which it is to be hung up when not in use. At this end, the left hand, and close to the front edge, should be fastened a stiff brush for cleaning forks. At the other end should be a box, with the open end towards the hand, and a sliding lid; this should contain a bath-brick, leathers for forks, &c., so that the materials for cleaning may be shut in and hung up with the board.

Or, cover a smooth board free from knots, with thick buff-leather, on which spread, the thickness of a shilling, the following paste:—emery, one ounce; crocus, three ounces; mixed with lard or sweet oil. This composition will not only improve the polish, but also the edges of the knives.

84. To re-fasten the loose handles of Knives and Forks.—Make a cement of common brick-dust and rosin, melted together. Seal-engravers understand this receipt.

85. Metal Kettles and other Vessels.—The crust on boilers and kettles arises from the hardness of the water boiled in them. Its formation may be prevented by keeping in the vessel a marble, or a potato tied in a piece of linen.

Tin-plate vessels are cleanly and convenient; but, unless carefully dried after washing, they will soon rust in holes.

Iron coal-scoops are liable to rust from the damp of the coals.

If cold water be thrown on cast-iron when hot (as the back of a grate), it will crack. Cast-iron articles are brittle, and cannot be repaired.

The tinning of copper-saucepans should be kept perfect, clean, and dry: in which case they may be used with safety.

Copper pans, if put away damp, will become coated with poisonous crust, or verdigris, as will also a boiling-copper, if left wet. When used for cooking, and not properly cleaned, copper vessels have occasioned death to persons partaking of soup which had been warmed in a pan infected with verdigris.

Untinned copper or brass vessels are at all times dangerous: it is absurd to suppose, that if the copper or brass pan be scoured bright and clean, there is little or no danger, for this makes but a trifling difference; such vessels for culinary purposes ought to be banished for ever from the kitchen.

A polished silver or brass tea-urn will keep the water hotter[30] than one of a dull brown color, such as is most commonly used. The more of the surface of a kettle that is polished, the sooner will water boil in it, as the part coated with soot drives off rather than retains heat.

A polished metal tea-pot is preferable to one of earthenware; because the earthen pot retains the heat only one-eighth of the time that a silver or polished metal pot will; consequently, the latter will best draw the tea.

A German saucepan is best adapted for boiling milk in: this is a saucepan glazed with white earthenware, instead of being tinned in the usual manner; the glaze prevents the tendency to burn, which, it is well known, milk possesses.

A stewpan, made as the German saucepan, is preferable to a metal preserving-pan; simple washing keeps it sweet and clean, and neither color nor flavor can by any chance be communicated to the article boiled in it.

Ornamental furniture, inlaid with brass or buhl, should not be placed very near the fire, as the metal when it becomes warm expands, and, being then too large for the space in which it was laid, starts from the wood.

"German silver" will not rust; but it does not contain a particle of silver, it being only white copper. If left in vinegar, or any acid mixture, it will become coated with verdigris. Salt should never be left in silver cellars, else the metal will be much injured.

86. To clean Glasses.—Glasses should be first washed in warm clean soap-suds, and rinsed in fresh cold water; wipe off the wet with one cloth, and finish them with another.

87. Cleaning Decanters.—Those encrusted with dregs of port wine, can be readily freed from stain by washing them with the refuse of the teapot, leaves and all. Dip the decanter into a vessel containing warm water, to prevent the hot tea-leaves from cracking the glass, then empty the teapot into the decanter, and shake it well. The tannin of the tea has a chemical affinity for the crust on the glass.

88. To clean Decanters.—Put into them broken egg-shells, pieces of coarse brown or blotting paper, with pearlash, and nearly fill them with lukewarm water; shake them well for a few minutes, or, if very dirty, leave them for some hours, when[31] rinse the decanters with cold water. The settlement of the crust of wine in decanters, may be best prevented by rinsing at night, with cold water, all the decanters used during the day. To clean the outer work of decanters, rub it with a damp sponge dipped in whiting; then brush it well, rinse the vessel in cold water, drain, and finish with a fine dry cloth.

89. To remove Crust from Glass.—It often happens that glass vessels used for flowers and other purposes, receive an unsightly crust hard to be removed by scouring. The best method is to wash it with a little diluted spirit of salts, which will soon loosen it.

90. To cleanse Bottles.—To cleanse bottles with bad smells, put into them pieces of blotting or brown paper, and fill up with water; shake the bottles, and leave them for a day or two, when, if they be not sweetened, repeat the process, and rinse with pure water.

91. To restore the Lustre of Glasses tarnished by Age or Accident.—Strew on them powdered fuller's-earth, carefully cleared from sand, &c., and rub them carefully with a linen cloth. Oxide of tin (putty) would perhaps be better.

92. To clean China.—China is best cleaned, when very dirty, with finely-powdered fuller's-earth and warm water; afterwards rinsing it well in clean water. A little clean soft soap may be added to the water instead of fuller's-earth. The same plan is recommended for cleaning glass.

93. To clean Alabaster.—Remove any spots of grease with spirit of turpentine: then dip the article in water for about ten minutes, rub it with a painter's brush and let it dry; finish by rubbing it with a soft brush dipped into dry and fine plaster of Paris.

94. To bleach Ivory.—Ivory that has become discolored, may be brought to a pure whiteness by exposing it to the sun under glasses; having first brushed the ivory with pumice-stone, burnt and made into a paste with water. To conceal the cracks in antique ivory, brush out the dust with warm water and soap, and then place the ivory under glass. It should be daily exposed[32] to the sun, and turned from time to time, that it may become equally bleached.

95. Glazed Vessels.—The glazing of stone ware is sometimes very imperfect: to test it, nearly fill the vessel with vinegar, into which put some fat of beef, salted; boil for half an hour, and set it by for a day, when, if the glazing be imperfect, small black particles of lead will be seen at the bottom of the vessel.

96. Use of Candle Snuffs for cleaning Glass.—Candle snuffs are generally thrown away as useless; they are, however, of great utility for cleaning mirrors and windows, especially the former. For this purpose take a small quantity of the burnt snuffs and rub them with a soft cloth upon the surface of the mirror. In a short time a splendid polish will appear, superior to that obtained by other means. We know those who clean the whole of the windows in a large house with snuffs; and we are told that not only are the windows cleaned much better but also much quicker than by the ordinary methods.

A Razor Strop Paste is also made of candle-snuffs, and answers very well. It consists in simply rubbing a small quantity of the snuffs upon the strop; this imparts a keener edge to the razor than when no such paste is employed. Mechi's celebrated Magic Razor Strop Paste is certainly an excellent article, but we question whether it be much superior to the ordinary and common-place substance now recommended.

97. To loosen the Glass Stopples of Smelling Bottles and Decanters.—With a feather rub a drop or two of olive oil round the stopple, close to the mouth of the bottle or decanter, which must be then placed before the fire, at the distance of a foot or eighteen inches; in which position the heat will cause the oil to spread downward between the stopple and the neck. When the bottle or decanter has grown warm, gently strike the stopple on one side, and on the other, with any light wooden instrument; then try it with the hand. If it will not yet move, place it again before the fire, adding, if you choose, another drop of oil. After a while strike again as before; and by persevering in this process, however tightly the stopple may be fastened in, you will at length succeed in loosening it.

98. Or, knocking the stopper gently with a piece of wood, first on one side, then on the other, will generally loosen it. If this method does not succeed, a cloth wetted with hot water and applied to the neck, will sometimes expand the glass sufficiently to allow the stopper to be easily withdrawn.

99. Crockery and Glass.—Crockery and glass, to be used for holding hot water, are best seasoned by boiling them, by putting the articles in a saucepan of cold water over the fire, and letting the water just boil; the saucepan should then be removed, and the articles should be allowed to remain in it till the water is cold. Some kind of pottery is best seasoned by soaking in cold water.

Choose thin rather than thick glasses, as the thin glass is less likely to be broken by boiling water than that which is thicker; for, thin glass allows the heat to pass through it in least time. The safest plan is to pour boiling water very slowly into cold glasses.

As boiling water will often break cold glass, so a cold liquid will break hot glass; thus wine, if poured into decanters that have been placed before the fire, will frequently break them.

Glass dishes and stands made in moulds are much cheaper than others, and they have a good appearance, if not placed near cut-glass.

Lamp-glasses are often cracked by the flame being too high when they are first placed round it; the only method of preventing which is to lower the flame before the glass is put on the lamp, and to raise the flame gradually as the glass heats.

100. Polished Tea Urns preferable to varnished ones.—Polished tea urns may be kept boiling with a much less expense of spirits of wine, than such as are varnished; and the cleaner and brighter the dishes, and covers for dishes, which are used for bringing food to table, and for keeping it hot, the more effectually will they answer that purpose.

101. Japanned Candlesticks and Tea-Trays, and Paper work.—To remove grease from these, let the water be just warm enough to melt it; then wipe them with a cloth, and if they look smeared, sprinkle a little flour on them, and wipe it clean off. Wax candles should not be burned in the candlesticks, as the wax cannot be taken off without injuring the varnish.[34] Paper work is liable to break if let fall, or if boiling water be poured on it.

102. To clean Lamps.—Bronzed lamps should be wiped carefully; if oil be frequently spilled over them, it will cause the bronzing to be rubbed off sooner than it would disappear by wear. Brass lamps are best cleaned with crocus or rotten-stone and sweet oil. Lackered lamps may be washed with soap and water, but should not be touched with acid or very strong ley, else the lacker will soon come off. When lamps are foul inside, wash them with potash and water, rinse them well, set them before the fire, and be sure they are dry before oil is again put into them.

Lamps will have a less disagreeable smell, if, before using, the cottons be dipped in hot vinegar, and dried.

To clean ground-glass shades, wash the insides carefully with weak soap and water, lukewarm, rub them very lightly and dry with a soft cloth.

103. To make economical Wicks for Lamps.—When using a lamp with a flat wick, if you take a piece of clean cotton stocking, it will answer the purpose as well as the cotton wicks which are sold in the shops.

104. Wax Candles.—Should they get dirty and yellow, wet them with a piece of flannel dipped in spirits of wine.

105. Blowing out a Candle.—There is one small fact in domestic economy which is not generally known; but which is useful, as saving time, trouble, and temper. If a candle be blown out holding it above you, the wick will not smoulder down, and may therefore be easily lighted again; but if blown upon downwards, the contrary is the case.

106. Plain Hints about Candles.—Candles improve by keeping a few months. Those made in winter are the best. The most economical, as well as the most convenient plan, is to purchase them by the box, keeping them always in a cool, dry place. If wax candles become discolored or soiled, they may be restored by rubbing them over with a clean flannel slightly dipped in spirits of wine. Candles are sometimes difficult to light. They will ignite instantly, if, when preparing them for[35] the evening, you dip the top in spirits of wine, shortly before they are wanted. Light them always with a match, and do not hold them to the fire, as that will cause the tops to melt and drip. Always hold the match to the side of the wick, and not over the top. If you find the candles too small for the candlesticks, always wrap a small piece of white paper round the bottom end, not allowing the paper to appear above the socket. Cut the wicks to a convenient length for lighting (nearly close); for if the wick is too long at the top, it will be very difficult to ignite, and will also bend down, and set the candle to running. Glass receivers, for the droppings of candles, are very convenient, as well as ornamental. The pieces of candles that are left each evening should be placed in a tin box kept for that purpose, and used for bed lights.

107. To make an improved Candle.—Make the wicks about half the usual size, and wet them with spirits of turpentine; dry them, before dipping, in the sunshine, or in some favorable place, and the candles will be more durable, emit a steadier and clearer blaze, and be in every way superior to those made in the ordinary way.

108. Quicksilver.—Tallow will take up quicksilver. Vinegar kills it.

109. To give any Close-grained Wood the appearance of Mahogany.—The surface of the wood must first be planed smooth, and then rubbed with weak aquafortis; after which it is to be finished with the following varnish:—To three pints of spirit of wine is to be added four ounces and a half of dragon's blood and an ounce of soda, which have been previously ground together; after standing some time, that the dragon's blood may dissolve, the varnish is to be strained, and laid on the wood with a soft brush. This process is to be repeated, and then the wood possesses the perfect appearance of mahogany. When the polish diminishes in brilliancy, it may be speedily restored by rubbing the article with linseed oil.

110. To Darken Mahogany.—Drop a nodule of lime in a basin of water, and wash the mahogany with it.

111. To make Imitation Rosewood.—Brush the wood over with a strong decoction of logwood, while hot; repeat this process[36] three or four times; put a quantity of iron-filings amongst vinegar; then with a flat open brush, made with a piece of cane, bruised at the end, or split with a knife, apply the solution of iron-filings and vinegar to the wood in such a manner as to produce the fibres of the wood required. After it is dry, the wood must be polished with turpentine and bees'-wax.

112. Imitation of Ebony.—Pale-colored woods are stained in imitation of ebony by washing them with, or steeping them in a strong decoction of logwood or galls, allowing them to dry, and then washing them over with a solution of the sulphate or acetate of iron. When dry, they are washed with clean water, and the process repeated, if required. They are, lastly, polished or varnished.

113. Cheap Coloring for Rooms.—Boil any quantity of potatoes, bruise them, and pour on them boiling water until a pretty thick mixture is obtained, which is to be passed through a sieve; then mix whiting with boiling water, and add it to the potato mixture. To color it, add either of the ochres, lampblack, &c.

114. Cheap Paint.—Tar mixed with yellow ochre makes an excellent green paint, for coarse wood-work, iron fencing, &c.

115. Weather-proof Composition.—Mix a quantity of sand with double the quantity of wood ashes, well sifted, and three times as much slaked lime; grind these with linseed oil, and use the composition as paint; the first coat thin, the second thick; and in a short time it will become so hard as to resist weather and time.

Or, slake lime in tar, and into it dip sheets of the thickest brown paper, to be laid on in the manner of slating.

116. Artificial Marble.—Soak in a solution of alum a quantity of plaster of Paris. Bake it in an oven, and grind it to a powder. When wanted, mix it with water to about the consistency of plaster. It sets into an exceedingly hard composition, and takes a high polish. It may be mixed with various colored minerals or ochres to represent the various marbles, and is a valuable receipt.

117. To give Wooden Stairs the Appearance of Stone.—Paint the stairs, step, by step, with white paint, mixed with strong drying oil. Strew it thick with silver sand.

It ought to be thoroughly dry next morning, when the loose sand is to be swept off. The painting and sanding is to be repeated, and when dry, the surface is to be done over with pipe-clay, whiting, and water; which may be boiled in an old saucepan, and laid on with a bit of flannel, not too thick, otherwise it will be apt to scale off.

A penny cake of pipe-clay, which must be scraped, is the common proportion to half a lump of whiting.

The pipe-clay and whiting is generally applied once a week, but that might be done only as occasion requires.

118. Lime for Cottage Walls, &c.—Take a stone or two of unslaked white lime, and dissolve it in a pail of cold water. This, of course, is whitewash. The more lime used, the thicker it will be; but the consistence of cream is generally advisable. In another vessel dissolve some green vitriol in hot water. Add it, when dissolved, to the whitewash, and a buff is produced. The more vitriol used, the darker it will be. Stir it well up, and use it in the same way as whitewash, having first carefully got off all the old dirt from the walls. Two or three coats are usually given. For a border at top and base, use more vitriol, to make it darker than the walls. If you have stencil-plates, you can use it with them. This is cheap, does not rub off like ochre, and is pure and wholesome, besides being disinfecting.

119. A White for Inside Painting, which dries in about four hours, and leaves no smell.—Take one gallon of spirits of turpentine, and two pounds of frankincense; let them simmer over a clear fire till dissolved, then strain and bottle it. Add one quart of this mixture to a gallon of bleached linseed oil, shake them well together, and bottle them likewise. Grind any quantity of white-lead very fine with spirits of turpentine, then add a sufficient quantity of the last mixture to it, till you find it fit for laying on. If it grows thick in working, it must be thinned with spirit of turpentine; it gives a flat, or dead white.

120. A Green Paint for Garden Stands, Trellisses, &c.—Take mineral green, and white lead ground in turpentine; mix up the quantity you wish with a small quantity of turpentine-varnish;[38] this serves for the first coat; for the second, put as much varnish in your mixture as will produce a good gloss; if you desire a brighter green, add a small quantity of Prussian blue, which will much improve the beauty of the color.

121. Cheap and beautiful Green.—The cost of this paint is less than one-fourth of oil color, and the beauty far superior. Take four pounds of Roman vitriol, and pour on it a tea-kettleful of boiling water; when dissolved, add two pounds of pearl-ash, and stir the mixture well with a stick until the effervescence cease; then add a quarter of a pound of pulverized arsenic, and stir the whole together. Lay it on with a paint brush, and if the wall has not been painted before, at least two, or even three coats, will be requisite. If a pea-green is required, put in less, and if an apple-green, more, of the yellow arsenic.

122. To Destroy the Smell of Fresh Paint.—Mix chloride of lime with water, with which damp some hay, and strew it upon the floor.

123. To take the Smell of Paint from Rooms.—Let three or four broad tubs, each containing about eight gallons of water, and one ounce of vitriolic acid, be placed in the new painted room near the wainscot; this water will absorb and retain the effluvia from the paint in three days, but the water should be renewed each day during that time.

124. To remove Unpleasant Odors.—The unpleasant smell of new paint is best removed by time and atmospheric ventilation; but tubs of water placed in the apartment, will act more rapidly; with this inconvenience, however, that the gloss of the paint will be destroyed. Unpleasant smells from water-closets, or all articles of furniture connected with them, may be modified by the application of lime-water, to which may be added the soap-suds that have been used in washing, which neutralize the pungently offensive salts; a little quick-lime put into a night-chair will destroy all disagreeable effluvia. Aromatic pastiles of the following composition may be burned with great success: take of camphor, flowers of benzoin, powdered charcoal, powdered cascarilla bark, powdered Turkey myrrh, and powdered nitre, each equal quantities; beat them with syrup sufficient to form a mass, and divide into pastiles of a conical shape. They[39] may be mixed up with spirit of turpentine (the rectified oil) or anything that is inflammable. Syrup does best, as it is most adhesive.

125. To prevent disagreeable Smells from Privies, Night Chairs, &c.—Milk of lime (water in which lime has been slaked, and which is whitened by the fine particles of that substance) must be mixed with a ley of ashes, or soapy water that has been used in washing, then thrown into the sink of the privy; it will destroy the offensive smell. By these means, for the value of a few pence, any collection of filth whatever may be neutralized.

For the night-chair of sick persons, put within the vessel half a pound of quicklime, half an ounce of powdered sal-ammoniac, and water one pint: this will prevent any disagreeable odor.

126. Remarks.—Quicklime, or even lime just slaked, answers the purpose without any addition. It is the only thing used in camps, particularly in hot countries, to keep the ditches from creating contagion.

127. To clean Books or Prints.—Ink spots may be removed by oxalic acid dissolved in water, and carefully applied with a hair pencil. To remove oil or grease, warm the spot, lay over it blotting paper, and upon it the heated blade of a knife, when the blotting-paper will absorb the grease; then apply spirits of turpentine, with a hair pencil, and restore the whiteness of the paper with spirits of wine.

128. To preserve Books.—A few drops of any perfumed oil will secure libraries from the consuming effects of mouldiness and damp. Russian leather which is perfumed with the tar of the birch-tree, never moulds; and merchants suffer large bales of this article to lie in the London Docks in the most careless manner, knowing that it cannot sustain any injury from damp.

129. To clean Oil Paintings.—Clean the picture well with a sponge, dipped in warm beer; after it has become perfectly dry, wash it with a solution of the finest gum-dragon, dissolved in pure water. Never use blue starch, which tarnishes and eats out the coloring; nor white of eggs, which casts a thick varnish over pictures, and only mends bad ones by concealing the faults of the coloring.

130. To Light a Coal Fire.—A considerable saving of time and trouble might often be effected, if housemaids would attend to the following rules in lighting a fire:—Clear the grate well from ashes and cinders; then lay at the bottom of it a few lumps of fresh coal, about the size of ducks' eggs, so as not wholly to obstruct the air passing between the bars on which they are placed. This done, put a small quantity of waste paper or shavings next upon the coal; then a few sticks or pieces of split wood placed carefully above it, so that they may not project between the bars; then a layer of the cinders you have before taken from the grate; and next a few lumps of coal on the top. Take care to complete this process before applying the light, which may easily be done afterwards by means of a lucifer match, and you will seldom fail to have a good fire in a few minutes.

Nothing is easier than to light a fire in the way here recommended, but the coals and cinders must be laid in place by hand, and not thrown in anyhow with the shovel. If the kindling wood be green or damp, it should be dried over night, as a more miserable task cannot be attempted than to light a fire with damp materials.

131. Another Way.—To light a fire from one already kindled, put three or four pieces of charcoal between the bars of the grate; then lay a few pieces of fresh coal upon the bottom of the grate in which the second fire is to be made, and place upon them, crosswise, the lighted pieces of charcoal; cover them with pieces of fresh coal, and blow them with the hand-bellows, when the charcoal will set fire to the fresh coal, and a brisk fire will be made in a few minutes. On the contrary, if we light a fire with wood, some time must elapse before it can safely be blown.

132. Economy in Fuel.—A saving of nearly one-third of the coal consumed may be made by the following easy means:—Let the coal ashes, which are usually thrown into the dust bin, be preserved in a corner of the coal hole, and make your servants add to them from your coal heap an equal part of the small coal or slack, which is too small to be retained in the grate, and pour a small quantity of water upon the mixture. When you make up your fire, place a few round coals in front, and throw some of this mixture behind; it saves the trouble of sifting your ashes, gives a warm and pleasant fire, and a very small part only will remain unburnt.

133. Fire Balls.—Mix one bushel of small coal, or saw-dust, or both, with two bushels of sand, and one bushel and a half of clay; make the mixture into balls with water, and pile them in a dry place, to harden them. A fire cannot be lighted with these balls; but when it burns strong, put them on above the top bar, and they will keep up a strong heat.

134. To prevent the ill effects of Charcoal.—Set over the burning charcoal a vessel of boiling water, the steam of which will prevent danger from the fumes.

135. Method of sweeping Chimneys without employing Children, and the danger attending the old Method pointed out.—Procure a rope for the purpose, twice the length of the height of the chimney; to the middle of it tie a bush (broom furze, or any other), of sufficient size to fill the chimney; put one end of the rope down the chimney (if there be any windings in it, tie a bullet or round stone to the end of the rope), and introduce the wood end of the bush after the rope has descended into the chamber; then let a person pull it down. The bush, by the elasticity of its twigs, brushes the sides of the chimney as it descends, and carries the soot with it. If necessary, the person at the top, who has hold of the other end of the rope, draws the bush up again; but, in this case, the person below must turn the bush, to send the wood end foremost, before he calls to the person at top to pull it up.

Many people, who are silent to the calls of humanity, are yet attentive to the voice of interest: chimneys cleansed in this way never need a tenth part of the repairs required where they are swept by children, who being obliged to work themselves up by pressing with their feet and knees on one side, and their back on the other, often force out the bricks which divide the chimneys. This is one of the causes why, in many houses, a fire in one apartment always fills the adjoining ones with smoke, and sometimes even the neighboring house. Nay, some houses have even been burnt by this means; for a foul chimney, taking fire, has been frequently known to communicate, by these apertures, to empty apartments, or to apartments filled with timber, where, of course, it was not thought necessary to make any examination, after extinguishing the fire in the chimney where it began.

136. To revive a dull Fire.—Powdered nitre, strewed on the fire, is the best bellows that can be used.

137. Fires, Stoves, &c.—It is wasteful to wet small coal, though it is commonly thought to make a fire last longer: in truth, it wastes the heat, and for a time makes a bad fire.

A close stove intended to warm an apartment should not have a polished surface, else it will keep in the heat; whereas, if of rough and unpolished cast iron, the heat will be dispersed through the room.

Long, shallow grates, are uneconomical, as the body of the coal in them is not soon heated, and requires to be oftener replenished to keep up the fire.

A good fire should be bright without being too hot: the best and quickest mode of making up a neglected fire is to stir out the ashes, and with the tongs fill up the spaces between the bars with cinders or half-burnt coals: this method will soon produce a glowing fire. If coke can be mixed with coals, the fire will require extra attention: coke, however, makes too much dust for fires in the best rooms.

138. Water.—Hard water by boiling may be brought nearly to the state of soft. A piece of chalk put into spring water will soften it.

Rain, or the softest water, is better adapted than any other for washing and cleaning; but it must be filtered for drinking in large towns, as it becomes impure from the roofs and plaster of houses. The best water has the greatest number of air bubbles when poured into a glass. Hard water will become thick and foul sooner than soft water.

139. To purify Water for drinking.—Filter river water through a sponge, more or less compressed, instead of stone or sand, by which the water is not only rendered more clear, but wholesome; for sand is insensibly dissolved by the water, so that in four or five years it will have lost a fifth part of its weight. Powder of charcoal should be added to the sponge when the water is foul, or fetid. Those who examine the large quantity of terrene matter on the inside of tea-kettles will be convinced all water should be boiled before drunk.

140. Or, take a large flower-pot, and put either a piece of sponge or some cleanly-washed moss over the hole at the bottom.[43] Fill the pot three-quarters with a mixture of equal parts of clean sharp sand, and charcoal in pieces the size of peas. On this lay a piece of linen or woollen cloth, large enough to hang over the sides of the pot. Pour the water to be filtered into the basin formed by the cloth, and it will come out pure through the sponge or moss at the bottom.