*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 45978 ***

|

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Some typographical errors have been corrected;

a list follows the text.

Some illustrations

have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  will bring up a larger version of the image.

will bring up a larger version of the image.

Table of Contents

Index to Illustrations

Bibliography and references with abbreviations used

Index:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

U,

V,

W,

X,

Y,

Z

(etext transcriber's note) |

EDWARD STANIFORD ROGERS

State of New York—Department of Agriculture

Fifteenth Annual Report—Vol. 3—Part II

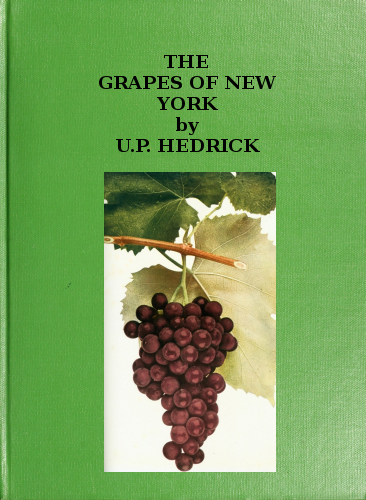

THE

GRAPES OF NEW YORK

BY

U. P. HEDRICK

ASSISTED BY

N. O. BOOTH

O. M. TAYLOR

R. WELLINGTON

M. J. DORSEY

Report of the New York Agricultural Experiment Station for the Year 1907

II

ALBANY

J. B. LYON COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS

1908

NEW YORK AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION,

Geneva, N. Y., December 31, 1907.

To the Honorable Board of Control of the New York Agricultural

Experiment Station:

Gentlemen.—I have the honor to submit herewith Part II of the report of

this institution for the year 1907, to be known as The Grapes of New

York. It is the second in the series of fruit publications which is now

being prepared under your authority.

This volume is the result of years of recorded observations by members

of the Station staff, to which has been added the collection of a large

amount of information from practical growers of the grape. Every effort

has been made to insure completeness and accuracy of statement, and to

make the work a reliable guide as to all the varieties of grapes that

are likely to meet the attention of New York grape-growers. It is

believed that this volume will occupy a useful place in grape literature

and will be serviceable to an important industry in this State.

W. H. JORDAN,

Director.

PREFACE

The purpose of The Grapes of New York is to record the state of

development of American grapes. The title implies that the work is being

done for a locality but in this matter New York is representative of the

whole country. The contents are: Brief historical narratives of Old

World and New World grapes; an account of the grape regions and of

grape-growing in New York, with statistics relating to the grape, wine

and grape juice industries in this State; a discussion of the species of

American grapes; and the synonymy, bibliography, economic status, and

full descriptions of all of the important varieties of American grapes.

In the footnotes will be found brief biographical sketches of those

persons who have contributed most to the evolution of the grape and to

grape-growing in America and some historical and descriptive notices of

certain things pertaining to the grape which do not belong in the text

and yet serve to give a better understanding of it or otherwise add to

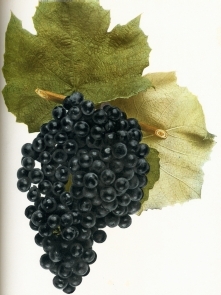

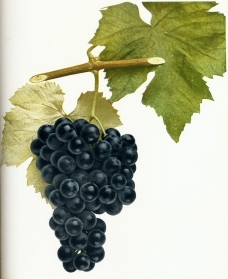

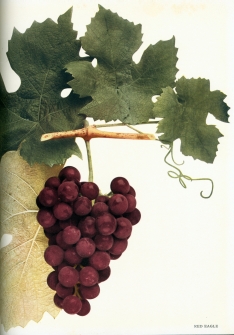

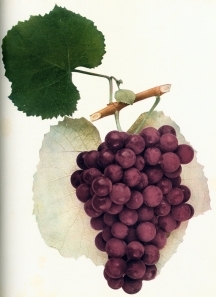

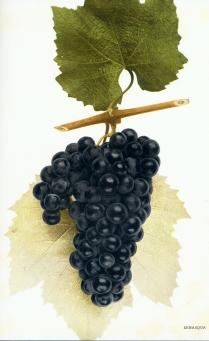

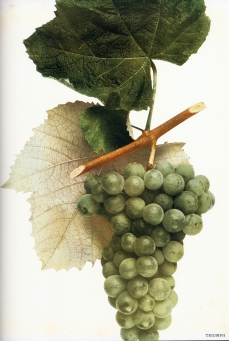

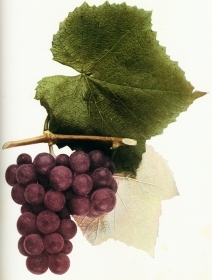

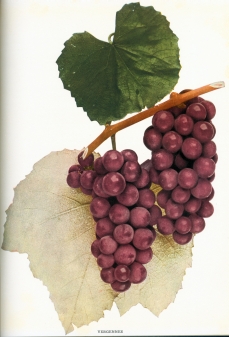

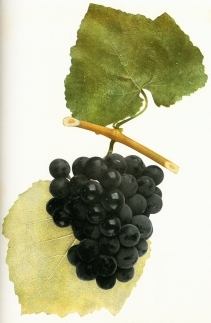

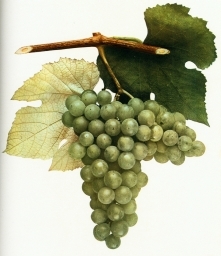

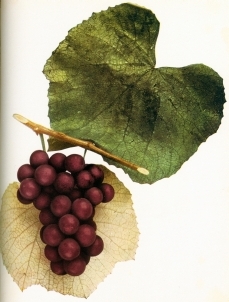

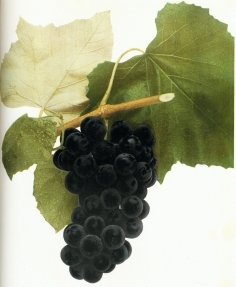

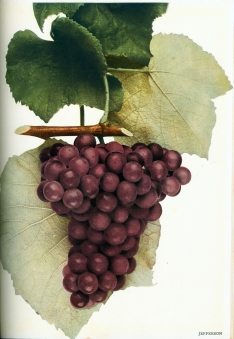

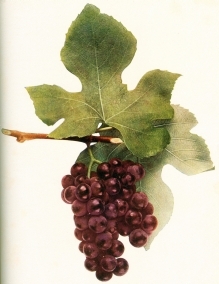

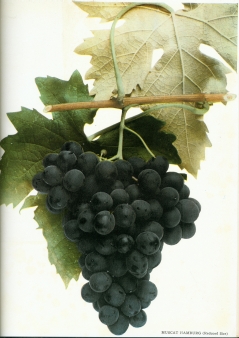

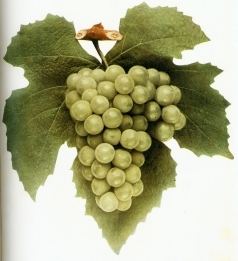

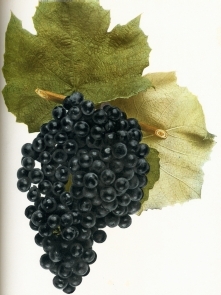

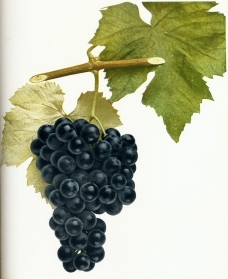

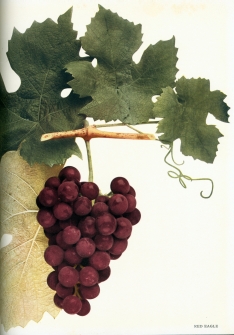

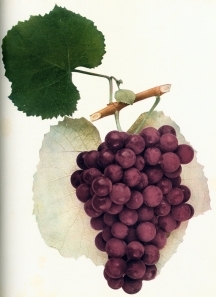

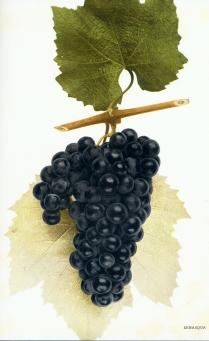

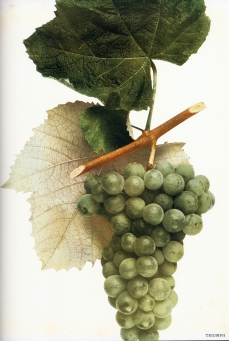

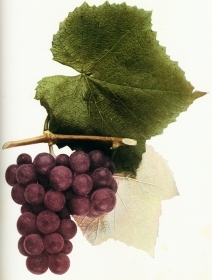

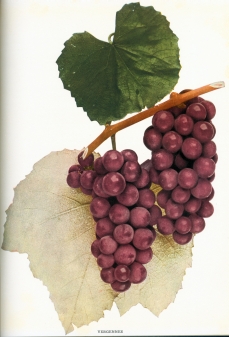

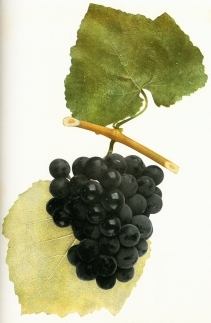

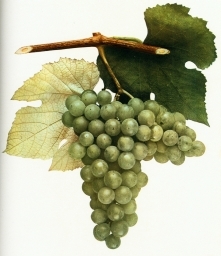

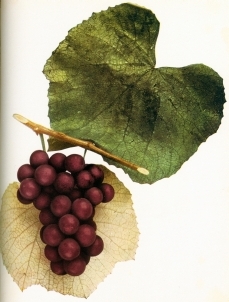

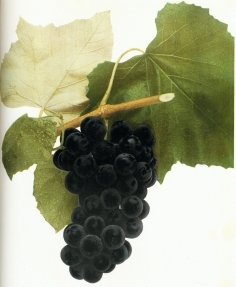

the completeness of the book. Color-plates are shown of varieties which

from various standpoints are considered most important.

In the brief account of the Old World grape there is little that is new.

Its history is on record from the earliest times in the literature of

nearly all civilized peoples. A few facts, selected here and there, have

been taken to serve as an introduction to the accounts of the New World

grapes. So, too, the history of the American grape has been written by

others and, here, only the main facts have been set down as recorded in

the score or more books dealing with this fruit. A few excursions have

been made in hitherto unexplored fields. The purpose of these historical

sketches is to give the reader a proper perspective of the work in hand.

The grape is probably influenced to a greater degree by soil, climate,

and culture than any other fruit, and a discussion of its status cannot

be complete without due consideration of the environment in which it is

growing. Hence there is included as full an account of grape-growing and

of the grape regions in New York as space permits. This part of the work

may serve the prospective planter somewhat in selecting soils and

locations but as it is not written with this as a chief end, it falls

far short of some of the standard treatises on grape culture in this

respect.

Comparatively few statistics are given, only those which are necessary

to show the volume of grape products and the extent of the vineyards in

the State and country at the present time. The figures for the whole

country are surpassed by those of no other native fruit, and only by

corn and tobacco among all the domesticated native plants.

The botany of the grape has been the most perplexing problem to deal

with in the preparation of this work. The variability of the grape is so

great, and the variations are so often toward closely related species,

that it is difficult to tell where one species ends and another begins.

This, of course, has led to differences in opinions. Then, too, the

several monographers have not had the same specimens to work with; men

do not have the same powers of discrimination; and the arrangement of

botanical groups, based upon the characters of the plants and the theory

of descent with adaptive modifications, is not governed by definite

rules; hence botanical divisions are arbitrary and differ with the

judgments of the botanists who make them. For these reasons we have as

many different arrangements of species of grapes as there are men who

have worked them over.

Since this work is not written from the standpoint of the botanist but

of the horticulturist, no effort has been made to revise the botany of

the grape. But it has been necessary to select some arrangement of

species in order to make such disposition of the cultivated varieties

that their characters and relationships can best be shown. In making a

choice of the several recent classifications of American grapes, three

main considerations have been in mind: First, that the arrangement

should separate the species in the genus freely, thus decreasing the

size of the groups so that they may be more easily studied. Second, that

it should show as clearly as possible the relationships of the various

groups and of their development—the evolution of the grape. Third, that

it be an arrangement in good standing with botanists and

horticulturists. After having examined all American classifications of

grapes and all recent European ones, Bailey’s classification, as set

forth in his monograph of the Vitaceae in Gray’s Synoptical Flora, in

the Evolution of our Native Fruits, and in the Cyclopedia of American

Horticulture, was adopted.

The Grapes of New York makes its chief contribution to the pomology of

the country in the description of varieties. The authors have tried to

study varieties from every point of view, not alone nor chiefly, it must

be said, with regard to their cultural value; for most of the varieties

pass out of cultivation and such information would be worthless within a

few years at most. But, rather, the effort has been to determine what

elementary or unit characters the grape possesses as shown in its

botanical and horticultural groups. The Twentieth Century begins with

the unanimous judgment of scientists that the characters of plants are

independent entities which are thrown into various relationships with

each other in individuals and groups of individuals. This conception of

unit characters lies at the foundation of plant improvement. We are but

beginning the breeding of American grapes and it has seemed to the

writer that the most important part of this undertaking is to discover

and record as far as possible these unit characters of grapes, thereby

aiding to furnish a foundation for grape-breeding. The great problem of

plant-breeding in the future will be to correlate the characters known

to exist in the plant being improved; we must know what these are before

we begin to combine and rearrange them.

The varieties are arranged alphabetically throughout, though, were

present knowledge exact enough, it would be far better to arrange them

in natural groups. Such a classification is probably possible, but it

remains for future workers to search out the relationships which the

structures and qualities of plant and fruit indicate and to group the

varieties naturally rather than alphabetically. Wherever possible in

this work, however, the relationships of varieties have been indicated

as fully as knowledge permits, thus making a start toward natural

classification.

In the lists of synonyms given, all known names for a variety used in

the American literature of the grape are brought together. These lists

ought to be useful in correcting and simplifying the nomenclature of the

grape which, like that of all of our fruits, is in more or less

confusion. It is hoped that the work may become a standard guide, for

some time to come at least, in the identification of varieties and in

nomenclature, and that it will aid originators of new grapes and

nurserymen in avoiding the duplication of names. In matters pertaining

to nomenclature, the revised rules of the American Pomological Society

have been followed, though in a few cases it has not seemed best to make

changes which their strict observance would have required. The necessity

for rules is shown by an examination of the synonymy of any considerable

number of varieties as given in the body of the work. In some cases

varieties have from ten to twenty names and very often different

varieties are found to have the same name. This chaotic condition is

confusing and burdensome and it has been one of the aims in the

preparation of the work to set straight the horticultural nomenclature

of the grape, thus lessening the difficulty and uncertainty of

identification and making the comparative study of varieties easier.

It would be impossible, and not worth while, could it be done, to give

all of the references to be found in even the standard grape literature.

Only such have been given as have been found useful by the writers or as

would serve to give the future student of the literature of grape

varieties a working basis.

A brief history of each variety is given so far as it can be determined

by correspondence and from grape literature. In these historical

sketches the originator and his method of work justly receive most

attention. The place, date and circumstances of origin, the distributor,

and the present distribution of the variety, are given when known and

are of about equal importance in the plan of this work.

The technical descriptions of grapes are all first-hand and made by

members of the present horticultural department of the Station from

living plants. But rarely has it been necessary to go to books for any

one character of a vine or fruit though the leading authorities have

been consulted in the final writing of the descriptions and

modifications made when the weight of authority has been against the

records of the Station. Some differences must be expected between

descriptions of varieties made in different years, different localities

and by different men. For most part the varieties described are growing

on the Station grounds but every opportunity has been taken to study

several specimens of each variety and especially of the fruit. In many

instances the descriptions have been submitted to the originators,

introducers, or to some recognized grape specialist.

A number of considerations have governed the selection of varieties for

full descriptions. These are: First, the value of a variety for the

commercial or amateur grower for any part of the State as determined by

the records of this Station, by reports collected from over 2000

grape-growers, and by published information from whatever source.

Second, the probable value of new sorts as determined by their behavior

elsewhere. Third, to show combinations of species or varieties, or new

characters hitherto unknown in fruit or vine, or to portray the range in

variation, or to suggest to the plant-breeder a course of future

development. Fourth, a few sorts have been described because of their

historical value—for the retrospection of the grape-grower of the

present and the future. It is needless to say that many of the varieties

described are worthless to the cultivator.

In all of the descriptions the effort has been to depict living plants

and not things existing only in books; to give a pen picture of them

that will show all of their characters. An attempt has been made, too,

to show the breeding of the plants, their relationships; to show what

combination of characters exist in the different groups of varieties; to

designate, as far as possible, the plastic types; in short to show

grapes as variable, plastic plants capable of further improvement and

not as unchangeable organisms restricted to definite forms.

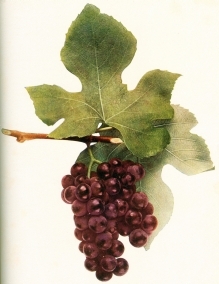

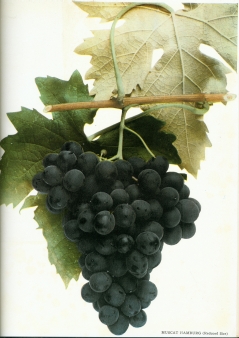

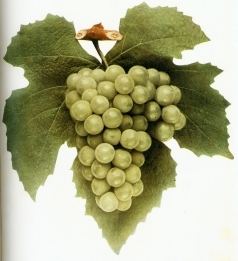

It is hoped that the color-plates will be of great service in

illustrating the text. All possible means at the command of photography

and color printing have been used to make them exact reproductions. The

specimens, too, have been selected with the utmost care. In preparing

these illustrations the thought has been that technical descriptions,

however simply written, are not easily understood, and that the readiest

means of comparison and identification for the average reader would be

found in the color-plates. Through these and the accompanying

descriptions it is hoped that all who desire may acquire, with time and

patience, a knowledge of the botanical characters of grapes and thereby

an understanding of the technical descriptions. The plates have been

made under the personal supervision of the writer.

With all care possible, due allowance must yet be made for the failure

to reproduce nature exactly in the color-plates. The plates are several

removes from the fruit. Four negatives were taken of each subject with

a color filter between the lens and the fruit. A copper plate was made

from each negative, one for each of the four colors, red, yellow, black

and blue. The color-plates in the book are composed of these four

colors, combined by the camera, the artist, the horticulturist and the

printer. With all of these agencies between the fruit and the

color-plate they could not be exact reproductions. It must ever be in

mind, too, that grapes grown in different localities vary more or less

in all characters and that the reproduction can represent the fruit from

but one locality. The specimens from which the plates were made came for

most part from the Station grounds. The illustrations are life size and

as far as possible from average specimens.

Acknowledgments are due to Professor Spencer A. Beach of Ames, Iowa,

who, while in charge of this Department previous to August, 1905, had

begun the collection and organization of information on grapes, much of

which has been used in this volume; to Mr. F. H. Hall, who as Station

Editor has read the manuscripts and proof sheets and given much valuable

assistance in organizing the information presented; to Zeese-Wilkinson &

Co., through whose zeal and painstaking skill the color-plates, which

add so much to the beauty and value of the book, have been made; and

lastly to the grape-growers of New York who have given information

whenever called upon and who have generously furnished grapes for

descriptive and photographic work.

U. P. HEDRICK,

Horticulturist, New York Agricultural Experiment Station.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| PAGE. |

| Preface

| v |

| Index to Illustrations

| xiii |

| Chapter I | —The Old World Grape | 1 |

| Chapter II | —American Grapes | 26 |

| Chapter III | —The Viticulture of New York | 68 |

| Chapter IV | —Species of American Grapes | 95 |

| Chapter V | —The Leading Varieties of American Grapes | 157 |

| Chapter VI | —The Minor Varieties of American Grapes | 433 |

| Bibliography and References

with Abbreviations Used | 531 |

| Index:

A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

U,

V,

W,

X,

Y,

Z | 537 |

INDEX TO ILLUSTRATIONS

{1}

THE GRAPES OF NEW YORK

CHAPTER I

THE OLD WORLD GRAPE

A single species of the grape is cultivated in the Old World. This is

Vitis vinifera, the grape of ancient and modern agriculture, the vine

of the allegories of sacred record and of the myths, fables and poetry

of the Old World countries. It is the vine which Adam and Eve cared

for:—

“* * * they led the vine

To wed his elm; * * *.” Milton.

It is the vine which Noah planted after the deluge; the vine of Judah

and Israel, and of the promised land. Dionysus of the Greeks, Bacchus of

the Romans, found the grape and devoted his life to spreading it; for

which he was raised to the rank of a deity—god of vines and vintages.

The history of this grape is as old as that of mankind. It has followed

civilized man from place to place throughout the world and is one of the

chief cultivated plants of temperate climates. This fruit of sacred and

profane literature has so impressed itself upon the human mind that when

we think or speak of the grape, or vine, it is the Old World species,

the vine of antiquity, that presents itself.

The history of the Old World grape goes back to prehistoric times. Seeds

of the grape are found in the remains of the Swiss lake dwellings of the

Bronze Period and entombed with the mummies of Egypt. Its printed

history is as old as that of man and is interwritten with it. According

to the botanists, the probable habitat of Vitis vinifera is the region

about the Caspian Sea.[1] From here it was carried eastward into Asia

and westward into Europe and Africa. It is probable that the

Phoenicians, the earliest navigators, tradesmen and colonizers on the

Mediterranean, carried it to the countries bordering on this sea. Grape

culture was developed in this{2} region a thousand years before Christ,

for Hesiod, who wrote at this time, gave directions for the care of the

vine which need to be changed but little for present practice in Europe.

Pliny, writing a thousand years after, quotes Hesiod as an authority on

vine culture. Vergil and Pliny, during Christ’s time, gave specific

directions for the care of the vine. Vergil describes fifteen varieties

while Pliny gives even fuller descriptions of ninety-one varieties and

distinguishes fifty kinds of wine.

The authentic written history of the grape and of its culture really

begins with Vergil. Many other writers, Greeks and Romans, had discussed

the vine, but none so fully nor so well as Vergil in his Georgics, of

which the parts having to do with the vine may still be read with profit

by the grape-grower; as, for example, the following[2] in which he tells

how to cultivate and train:—

“Be mindful, when thou hast entomb’d the shoot,

With store of earth around to feed the root;

With iron teeth of rakes and prongs, to move

The crusted earth, and loosen it above.

Then exercise thy sturdy steers to plow

Between thy vines, and teach the feeble row

To mount on reeds, and wands, and, upward led,

On ashen poles to raise their forky head,

On these new crutches let them learn to walk,

’Till, swerving upwards with a stronger stalk,

They brave the winds, and, clinging to their guide,

On tops of elms at length triumphant ride.”[3]

His directions for pruning are equally fitting for present practice:—

“But in their tender nonage, while they spread

Their springing leaves, and lift their infant head,

And upward while they shoot in open air,

Indulge their childhood, and the nurslings spare;{3}

Nor exercise thy rage on new-born life;

But let thy hand supply the pruning knife,

And crop luxuriant stragglers, nor be loth

To strip the branches of their leafy growth.

But when the rooted vines with steady hold

Can clasp their elms, then, husbandman, be bold

To lop the disobedient boughs, that strayed

Beyond their ranks; let crooked steel invade

The lawless troops, which discipline disclaim,

And their surperfluous growth with rigor tame.”

The history of the development of the vine from Vergil’s time through

the early centuries of the Christian Era and of the Middle Ages to our

own day, is largely the history of agriculture in the southern European

countries; for the vine during this period has been the chief cultivated

plant of the Greek and Latin nations. This history should furnish most

instructive lessons in grape-growing and in grape-breeding.

But interesting and profitable as a detailed account of the development

of the Old World grape would be, the brief outline in the few preceding

paragraphs must suffice for this work. The reader who desires further

information may find it in the agricultural literature in many languages

and dating back two thousand years.

What are the characters of the European grape and how does it differ

from the native grapes of America? The Old World grape is grown for

wine; the American grapes for the table. The differences in the fruit of

the vines of the two continents are largely the differences necessary

for the two distinct purposes for which they are grown. The varieties of

Vitis vinifera have a higher sugar and solid content than do those of

the American species. Because of this richness in sugar they not only

make better wine but keep much longer and can be made into raisins. The

American grapes do not keep well and do not make good raisins. Taken as

a whole the European varieties are better flavored, possessing a more

delicate and a richer vinous flavor, a more agreeable aroma, and they

lack the acidity and somewhat obnoxious foxy odor and taste of many

American varieties. It is true that there is a disagreeable astringency

in some Vinifera grapes and that many varieties are without character of

flavor, yet, all and all, the species produces by far the better

flavored fruit. On the other hand,{4} American table grapes are more

refreshing; one does not tire of them so quickly as they do not cloy the

appetite as do the richer grapes; and the unfermented juice makes a much

more pleasant drink. The characteristic flavor and aroma of the

varieties of Vitis labrusca, our most commonly cultivated native

species, are often described by the terms “foxy”[4] or “musky.” If not

too pronounced this foxiness is often very agreeable though, as with the

flavor in many exotic fruits, the liking for it must often be acquired,

and of course may never be acquired; yet the universal condemnation of

this taste by the French and some other Europeans is sheer prejudice.

The bunches and berries of the European grape are larger, more

attractive in appearance, and are borne in greater quantity, vine for

vine or acre for acre. The pulp and skin of the berries of Vitis

vinifera are less objectionable than those of any native species and

the pulp separates more easily from the seeds. The berries do not shell

from the stem nearly so quickly, hence the bunches ship better.

In comparing the vines, those of the Old World grape are more compact in

habit, make a shorter and stouter annual growth, therefore require less

pruning and training. The roots are fleshier, and more fibrous. The

species, taken as a whole, is adapted to far more kinds of soil, and to

much greater differences in environment, and is more easily propagated

from cuttings, than most of the species of American grapes. The

cultivated forms of the wild vines of this country have few points of

superiority over their{5} relative from the eastern hemisphere, but these

few are such as to make them now and probably ever the only grapes

possible to cultivate in America in the commercial vineyards east of the

Rocky Mountains. Indeed, but for the fortunate discovery that the vine

of Vitis vinifera could be grown on the roots of any one of several

species of the American grapes, the vineyards of the Old World grape

would have been almost wholly destroyed within the last half century

because of one of its weaknesses. This destructive agent is the

phylloxera,[5] a tiny plant louse working on the leaf and root of the

grape, which in a few years wholly destroys the European vine but does

comparatively little harm to most of the American vines. Three other

pests are much more harmful in the Old World vineyards than to the vines

of the New World; these are black-rot (Guignardia bidwellii (Ell.) V.

& R.), downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola (B. & C.) Berl. & De Toni),

and powdery mildew (Uncinula necator (Schw.) Burr.).

The susceptibility of the Old World grape to these parasites debars it

from cultivation in eastern America and so effectually that there is but

little hope of any pure-bred variety of it ever being grown in this

region. American viticulture must, therefore, depend upon the native

species for its varieties, though it may be hoped that by combining the

good qualities{6} of the foreign grape with those of one or several of the

species of this country, or by combining and rearranging the best

characters of the native species, we may in time secure varieties equal

in all respects to those of the Old World. The comparative resistance of

the American species to the phylloxera, the mildews, and black-rot has

been due to natural selection in the contest that has been waged for

untold ages between host and parasite. The fact that the native species

have been able to survive and thrive is a guarantee of the permanence of

the resistance thus acquired.

We have said that the Old World grape is debarred from cultivation in

eastern America. It is worth while considering how thorough the attempts

to grow it in this region have been and to give a more exact account of

the failures and their causes, for there are yet those who are

attempting its culture with the hope that we may sometime grow some

offshoot of Vitis vinifera in the region under consideration.

It is probable that the first European grapes planted in what is now

American soil, were grown by the Spanish padres at the old missions in

New Mexico, Arizona and California. Early accounts of some of these

missions speak of grapes which must have been planted before settlements

were made in eastern America. We need take no further account of these

vineyards except to say that in this region the European grape has

always been grown successfully, and that under the skilled hands of the

mission fathers, ever notable vineyardists and wine-makers, these early

plantings must have succeeded.

The English were the first to plant the Old World grape in the territory

in which this species fails because of the attacks of native parasites.

Lord Delaware seems to have been the original promoter of grape-growing

in the New World. In 1616 he wrote to the London Company urging the

culture of the grape as a possible source of revenue for the new

colony.[6] His letter seems to have been convincing, for it is on record

that the Company in 1619 sent a number of French vine-dressers and a

collection of the best{7} varieties of the grapes of France to Virginia.

The Colonial Assembly showed quite as much solicitude in encouraging the

cultivation of the vine as did the Company in London. The year of the

importation of vines and vine-dressers, 1619, the Assembly passed an act

compelling every householder to plant ten cuttings and to protect them

from injury and stated that the landowners were expected to acquire the

art of dressing a vineyard, either through instruction or by

observation. The Company, to increase the interest in vine-growing,

showed marked favors to all who undertook it with zealousness; promises

of servants, the most valuable gifts that could be made to the

colonists, were frequent. Under the impulse thus given vineyards were

planted containing as many as ten thousand vines.[7]

In spite of a rich soil, congenial climate, and skilled vine-dressers,

nothing of importance came from the venture, some of the historians of

the time attributing the failure to the massacre of 1622; others to poor

management of the vines; and still others to disagreements between the

English and their French vine-dressers, who, it was claimed, concealed

their knowledge because they worked as slaves. It is probable that the

latter explanation was fanciful but the former must have been real for

we are told that the farms and outlying settlements were abandoned after

the great massacre. But the colony could hardly have recovered from the

ravages of the Indians before efforts to force the colonists to grow

grapes were again made; for in 1623 the Assembly passed a law that for

every four men in the colony a garden should be laid off a part of which

was to be planted to vines.[8]

In 1639 the Assembly again tried to encourage vine-growing by

legislative enactment, this time with an act giving a premium to

successful grape-growers.[9] Later, about 1660, a premium of ten

thousand pounds of tobacco was offered in Virginia for each “two tunne

of wine” from grapes raised in the colony. Shortly after, some wine was

exported to England but{8} whether made from wild plants or cultivated

ones does not appear. In spite of the encouragement of legislative acts,

grape-growing did not flourish in Virginia.[10] The fact that tobacco

was a paying crop and more easily grown than the grape may have had

something to do with the failure to grow the latter. Or it may have been

that the cheapness of Madeira, “a noble strong drink,” as one of the

Colonial historians puts it, had a depressing influence on the industry.

But still more likely, the foreign plants did not thrive.

Encouragement of the home production of wine did not cease in Virginia

for at least one hundred and fifty years; for in 1769 an enactment of

the Assembly was passed to encourage wine-making in favor of one Andrew

Estave, a Frenchman. As a result of the act of this time, land was

purchased, buildings erected, and slaves and workmen with a complete

outfit for wine-making were furnished Estave. The act provided that if

he made within six years ten hogsheads of merchantable wine—land,

houses, slaves, the whole plant was to be given to him. It is stated

that this unusual subsidy is made “as a reward for so useful an

improvement.” Estave succeeded in making the wine but it was poor stuff

and he had difficulty in getting the authorities to turn over the

property which was to be his reward. This was finally done by an act of

the Assembly, however, the failure to make good wine being attributed by

all parties to the “unfitness of the land.”

An attempt was made to cultivate the European grape in Virginia early in

the eighteenth century on an extensive scale. Soon after taking office

as governor in 1710, Alexander Spotswood brought over a colony of{9}

Germans from the Rhine and settled them in Spottsylvania County on the

Rapidan river. The site of their village on this river is now marked by

a ford, Germania Ford, a name which is a record of the settlement. That

they grew grapes and made wine is certain, for the Governor’s “red and

white Rapidan, made by his Spottsylvania Germans” is several times

mentioned in the published journals and letters of the time. But the

venture did not make a deep nor lasting impress on the agriculture of

the colony.[11]

Several early attempts were made in the Carolinas and Georgia to grow

the Vinifera grape. It was thought, in particular, that the French

Huguenots who settled in these states in large numbers toward the close

of the seventeenth century would succeed in grape-growing but even these

skilled vine-growers failed. Their failures are recorded by Alexander

Hewitt in 1779 as follows: “European grapes have been transplanted, and

several attempts made to raise wine; but so overshaded are the vines

planted in the woods, and so foggy is the season of the year when they

ripen, that they seldom come to maturity, but as excellent grapes have

been raised in gardens where they are exposed to the sun, we are apt to

believe that proper methods have not been taken for encouraging that

branch of agriculture, considering its great importance in a national

view.” In Georgia, Abraham De Lyon, encouraged by the authorities of the

colony, imported vines from Portugal and planted them at Savannah early

in the eighteenth century but his attempt, though carried out on a small

scale in a garden, soon failed.

In Maryland, if the records are correct, a greater degree of success was

attained than in the states to the south. Lord Charles Baltimore, son of

the grantee of the territory, in 1662 planted three hundred acres of

land in St. Mary’s to vines. It is certain that he made and sold wine in

considerable quantities and the old chroniclers report that it was as

good as the best Burgundy. Efforts to grow the European grape in

Maryland continued until as late as 1828 when the Maryland Society for

Promoting the Culture of the Vine was incorporated by the State

Legislature.[12] The object of the Society was to “carry on experiments

in the cultivation of both the European and native grapes and to collect

and disseminate all{10} possible information upon this interesting

subject.” The organization was in existence for several years and

through its exertions practically all of the native sorts were tried in

or about Baltimore as well as many seedlings. Besides the achievements

of the Society as a body, their Secretary reports in 1831 that, through

the individual efforts of its members, there were then under cultivation

near the city of Baltimore several vineyards of from three to ten acres

each and a great number of smaller ones. This was several years after

the introduction of the Catawba and Isabella for which grape-growers in

other parts of the United States had largely given up the Vinifera

sorts. Seemingly in every part of the Union the grape of the Old World

was tried, not once only, but time and again before its culture could be

given up.

The Swedes made some attempts at an early day to grow grapes on the

Delaware. Queen Christina instructed John Printz, governor of New

Sweden, to encourage the “culture of the vine” and to give the industry

his personal attention. Later when New Sweden had become a part of

Pennsylvania, William Penn encouraged vine-growing by importing cuttings

of French and Spanish vines; and several experimental vineyards were set

out in the neighborhood of Philadelphia, but all efforts to establish

bearing plantations came to naught. Penn’s interest in grape-growing

seems to have been greatly stimulated by wine made by a friend of his

from native grapes which grew about Germantown.

There are no detailed accounts of grape-growing by the Dutch of New York

but the following taken from the writings of Jasper Dankers and Peter

Sluyter, two Hollanders who visited New York in 1679, soon after the

English took possession of New Netherland, indicates that there had been

attempts to cultivate grapes.[13] “I went along the shore to Coney

Island, which is separated from Long Island only by a creek, and around

the point, and came inside not far from a village called Gravesant,

and again home. We discovered on the roads several kinds of grapes still

on the vines, called speck (pork) grapes, which are not always good,

and these were not; although they were sweet in the mouth at first, they

made it disagreeable and stinking. The small blue grapes are better, and

their{11} vines grow in good form. Although they have several times

attempted to plant vineyards, and have not immediately succeeded, they,

nevertheless, have not abandoned the hope of doing so by and by, for

there is always some encouragement, although they have not, as yet,

discovered the cause of the failure.” The “speck” grape was without

question Vitis labrusca and the small blue grape was probably Vitis

riparia.

Thirty years before the visit of Dankers and Sluyter the people of New

Netherland addressed a remonstrance to the home government regarding

certain abuses in the colony. This document[14] is headed with a chapter

on the productions of New Netherland in which the wild grapes are

mentioned and their cultivation is suggested. “Almost the whole country,

as well the forest as the maize lands and flats, is full of vines, but

principally—as if they had been planted there—around and along the

banks of the brooks, streams and rivers which course and flow in

abundance very conveniently and agreeably all through the land. The

grapes are of many varieties; some white, some blue, some very fleshy

and fit only to make raisins of; some again are juicy, some very large,

others on the contrary small; their juice is pleasant and some of it

white, like French or Rhenish Wine; that of others, again, a very deep

red, like Tent; some even paler; the vines run far up the trees and are

shaded by their leaves, so that the grapes are slow in ripening and a

little sour, but were cultivation and knowledge applied here, doubtless

as fine Wines would then be made as in any other wine growing

countries.”

Nicolls, the first English governor of New York, greatly desired to grow

the vine for wine-making. In 1664 he granted Paul Richards a monopoly of

the industry for the colony stipulating that he could make and sell

wines free of impost and gave him the right to tax any person planting

vines in the colony five shillings per acre.[15] Richards lived in the{12}

city of New York but his vineyard, as indicated in the grant, was

located on Long Island. It may be assumed that this was the first

attempt to grow grapes commercially in the State of New York. It would

seem that the governor by granting a monopoly of the grape and wine

industry took the surest means of killing the infant industry. The Earl

of Bellomont, a later governor of the Colony, wrote to London with

assurances of a great future of viticulture in the Colony.[16] For over

a century after, there were spasmodic efforts to grow the Old World

grape in and about New York City, and at the beginning of the

Revolutionary War there were a few small vineyards and some wine-making

on Manhattan Island.

There were many attempts to grow foreign grapes in New England. John

Winthrop, governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony, had planted a vineyard

in one of the islands, known as “Governor’s Garden,” in Boston Harbor

before 1630. Vine-planters were sent to this colony in 1629.[17]{13} There

were plantations at the mouth of the Piscataqua in Maine as early or

before Winthrop’s plantings were made. In granting a charter to Rhode

Island in 1663, Charles II sought to encourage viticulture in that State

by offering liberal inducements to colonists who would grow grapes and

make wine.[18] But if grapes were grown, or wine made from the foreign

grape, no great degree of success was attained. Wine was made in plenty

from the wild grapes in all of the New England colonies so that it was

not because of Puritanical prejudices against wine that the grapes were

not grown. The glowing terms in which travelers returning to England

spoke of the native grapes and of the wine from them undoubtedly

stimulated those founding the colonies to make every effort to introduce

the cultivated grape even though the cold, bleak climate and thin soils

of this northern region were inhospitable to a plant which thrives best

in the sunny southern portions of Europe.

In only one of the states east of the Rockies is grape-growing recorded

to have gained even a foothold before the introduction of varieties of

native grapes. In this instance there is much doubt as to whether the

varieties grown were pure-bred Vitis vinifera. Louisiana, while owned

by France, grew grapes and made wine in such quantities, and the wine

was of such high quality, so several of the old chroniclers say, that

the French government forbade grape-growing in the colony. Since the

wine-making was in the hands of the Jesuits who had learned the art in

Europe, and since there were no cultivated varieties of native grapes at

that time of which there is record, the presumption among the early

writers was that these vineyards were of European grapes. Louisiana,

however, was a vast and undefined region and it is not known where these

oft-mentioned vineyards were located. It is probable in the light of

what we now know that these Louisiana Jesuits made wine from native

grapes either wild or cultivated.

The time covered so far is the two hundred years in which America was

being colonized. We have seen that all of our European forefathers

brought with them a love of the vine, or more correctly, a love of wine,

and{14} that throughout the period many experiments were made in all parts

of the eastern United States to grow varieties of Vitis vinifera. The

experiments were on a large scale and in the hands of expert

vine-growers, as well trained as their fellow colonists in South Africa,

New Zealand, Australia and South America, countries where the colonists

grew the Old World grapes as easily and as well as they are grown in the

most favored parts of Europe. It is certain that the failures recorded

for these two hundred years were not due to lack of effort on the part

of the settlers. We now pass to more recent efforts, even more

thoroughly carried out, to grow the grape of the Old World in this part

of the New World. The discussion of these later attempts cannot be full.

The reader can readily turn to the horticultural literature of the

century just closed and find much fuller records of them than space

permits in this work.

One of the first and most notable of the vineyards in the eighteenth

century was that of Colonel Robert Bolling of Buckingham County,

Virginia. An account of his undertaking written by one of the Bolling

family some years later reads as follows: “It is now but little known

that this gentleman had early turned his attention to the cultivation of

the vine, and had actually succeeded in procuring and planting a small

vineyard of four acres, of European grapes, at Chellow, the seat of his

residence: that he had so far accomplished his object as to have the

satisfaction of seeing his vines in a most flourishing condition, and

arrived at an age when they were just beginning to bear; promising all

the success that the most sanguine imagination could desire, when,

unfortunately for his family, and perhaps for his country, he departed

this life while in the Convention in Richmond, in July, 1775. Thus all

his fond anticipations of being enabled, in a short time, to afford to

his countrymen a practical demonstration of the facility and certainty

with which grapes might be raised, and wine made, in Virginia, were

suddenly frustrated; all his hopes and prospects blasted; and owing to

the general want of information, in the management of vines, among us at

that time; and the confusion produced by the war of the revolution,

which immediately followed, this promising and flourishing little

vineyard was totally neglected and finally perished.”[19]

{15}

At the time of Bolling’s death he was preparing to send to press a book

on grape-growing entitled A Sketch of Vine Culture. The book was never

printed but the manuscript was copied several times and parts of it were

printed contemporaneously in the Virginia Gazette, and subsequently in

the Bolling Memoirs and in the American Farmer.[20] Bolling’s book

was largely a compilation from European sources but it contained the

experiences and observations of the author in cultivating European

grapes in America and though not printed, was sufficiently distributed

through manuscript copies and through the papers and books mentioned

above, to give its author the honor of being the first American writer

on grapes.

In an essay on the cultivation of the vine published in the first volume

of the Transactions of the American Philosophical Society[21] printed

in Philadelphia in 1771, a Mr. Edward Antill of Shrewsbury, New Jersey,

gives explicit directions for grape-growing and wine-making.[22] Antill

describes only foreign varieties and leads the reader to infer, though

he does not say so, that he has grown many varieties of these grapes

successfully. But neither his essay, nor his efforts at grape-growing,

seemed to have stimulated a grape industry worthy of note. This essay of

Antill’s is the second American treatise on the cultivation of the grape

and was for many years the chief authority on grape-growing in America.

It is greatly to be regretted that a treatise which was to be quoted for

fifty years could not have been more meritorious. The eighty quarto

pages written by Antill give little real or trustworthy information. It

is a rambling discussion of European grapes, wine-making, the temperance

question, patriotism, “wellfare of country,” and “good of mankind”. He

quotes Columella, gives methods of curing grapes for raisins, and winds

up with a discussion of figs. Yet a hundred years ago it was the chief

work on grape-growing.

A Frenchman, Peter Legaux, founded a company in 1793 for the cultivation

of grapes at Spring Mill near Philadelphia. In 1800 he published{16} an

account of his venture.[23] A vineyard of European grapes was set out

and the prospects seemed favorable for the success of the undertaking.

But the grapes began to fail, dissensions arose among the stock-holders,

the vineyards were neglected and the company failed. Legaux speaks of

his experience in grape-growing as follows:[24] “But if the native

grapes of America are not the most eligible for vineyards, others are

now within the reach of its inhabitants. Some years since I procured

from France three hundred plants from the three kinds of grapes in the

highest estimation, of which are made Burgundy, Champagne and Bordeaux

wines. These three hundred plants have in ten years produced 100,000

plants; which, were the culture encouraged, would in ten years more,

produce upwards of thirty millions of plants; or enough to stock more

than 8000 acres, at 3600 plants to the acre, set about three feet and a

half apart. I have also about 3000 plants raised from a single plant

procured a few years since from the Cape of Good Hope, of the kind which

produces the excellent Constantia wines. The gentlemen who at different

times have done me the honour to taste these wines can bear testimony to

their good quality. Although made in the hottest season, (about the

middle of August) yet they were perfectly preserved without the addition

of a drop of brandy or any other spirit. And in this will consist one

excellency of the wines here recommended to the notice of my fellow

citizens; that being made wholly of{17} the juice of grapes, they will be

light, wholesome, and excite an agreeable cheerfulness, without

inflaming the blood, or producing the other ill effects of the strong

brandied wines, imported from the southern parts of Europe. Since 1793,

I have confined my attention chiefly to the multiplication of my vines,

to supply the demand for plants, and to furnish an extended vineyard

under my own direction, whenever my fellow citizens possessing pecuniary

means, should be inclined to encourage and support the attempt.”

Out of this venture, however, came the Alexander grape, an offspring of

a native species, and not, as Legaux held, a foreign variety, which, as

we shall see later, was the first variety to be grown on a commercial

scale in eastern America. Johnson,[25] writing of Legaux’s work with the

grape, says that in 1801 cuttings were sent from the Spring Mill

vineyards in quantities of fifteen hundred to Kentucky and Pennsylvania

and smaller quantities to Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Maryland,

Virginia and Ohio, and indicates that these cuttings in their turn were

multiplied so that many diverse experiments with foreign grapes arose

from Legaux’s efforts.

Chief of the experiments which Legaux’s partial success in vine-growing

stimulated was carried on in Kentucky by The Kentucky Vineyard Society

of which John James Dufour, a Swiss, was leader.[26] It was to this

Company that Legaux had sent the fifteen hundred cuttings mentioned

above as going to Kentucky. Before founding his grape colony, Dufour had

made a tour of inspection of all the vineyards that he could hear of in

what then constituted the United States. His account of what he saw,

given in his book The Vine Dresser’s Guide, is the most accurate

statement we have of grape-growing in America at the beginning of the

nineteenth century.

Dufour’s account, pages 18-24, runs as follows: “I went to see all the

vines growing that I could hear of, even as far as Kaskaskia, on the

borders of the Mississippi; because I was told, by an inhabitant of that

town, whom I met with at Philadelphia, that the Jesuits had there a very

successful vineyard,{18} when that country belonged to the French, and were

afterwards ordered by the French government to destroy it, for fear the

culture of the grapes should spread in America and hurt the wine trade

of France. As I had seen but discouraging plantations of vines on that

side of the Alleghany, and as the object of my journey to America, was

purposely to learn what could be done in that line of business; I was

desirous to see if the west would afford more encouragement. I resolved

therefore on a visit to see if any remains of the Jesuits’ vines were

still in being, and what sort of grapes they were; supposing very

naturally, that if they had succeeded as well as tradition reported,

some of them might possibly be found in some of the gardens there. But I

found only the spot where that vineyard had been planted, in a well

selected place, on the side of a hill to the north east of the town,

under a cliff. No good grapes, however were found either there, or in

any of the gardens of the country. * * * In my journeying down the Ohio,

I found at Marietta a Frenchman, who was making several barrels of wine

every year, out of grapes that were growing wild, and abundantly, on the

heads of the Islands of the Ohio River, known by the name of Sand

grapes, because they grow best on the gravels; a few plants of which are

now growing in one of our vineyards, given by the Harmonites under the

name of red juice. * * * The various attempts at vineyards that I heard

of, which I went to see, at Monticello, President Jefferson’s place;

which, in 1799, I perceived had been abandoned, or left without any care

for three or four years before, which proved evidently, that it had not

been profitable: At Spring Mill, on the Schuylkill, near Philadelphia,

planted by Mr. Legaux, a French gentleman, and afterwards supported by a

wealthy Society formed by subscription, at that City, for the express

purpose of trying to extend the culture of the grape. I saw that

vineyard in 1796, 1799 and 1806. On the estate of Mr. Caroll, of

Carollton, below Baltimore, in Maryland; whither I went on purpose from

Philadelphia in 1796, there was a small vineyard kept by a French

vinedresser, and where they had tried a few sorts of the indigenous

grapes. At the Southern Liberties of Philadelphia, I saw in 1806, a

plantation of a large assortment of the best species of French grapes;

which a French vinedresser had brought over the Atlantic. They were at

their 2d or 3d years: they had not been attacked by the sickness: their

nurse was{19} yet full of hope.—In 1796, I saw also, near the Susquehannah

river, not far from Middletown, a vineyard that had been planted by a

German; but who having died sometime before, the vineyard had been

wholly neglected. I was told, it had produced some wine; but it had

suffered so much delapidation, that I could not recognize the species of

grapes.”

With full knowledge of the failures of the past in growing grapes, and

after his disheartening visits to a score or more of worthless vineyards

planted with the grapes of his native country, Dufour embarked in the

Kentucky Vineyard Society enterprise and gave the Old World grapes a

thorough trial on an extensive scale, with an abundance of capital, and,

to care for the vines, as skilled labor as could be obtained in the

vineyards of Europe. As was the case with all past undertakings of the

kind so this one proved a failure. In the words of Dufour “a sickness

took hold of all our vines except a few stocks of Cape and Madeira

grapes.” The promoters became disheartened and the vineyard after being

cultivated for several years was abandoned.

Members of the colony, thinking that a more favorable location might be

found elsewhere in the valley of the Ohio, settled at Vevay, Indiana, in

1802. Dufour and several of his relatives were granted the privilege of

purchasing lands with extended credit by an act of Congress May 1st,

1802. They purchased 2500 acres at the location of the new colony in

Indiana and began anew the culture of the vine. For a time there was an

element of prosperity in the enterprise but the vines became diseased

and died, only one sort, the Cape or Alexander, gave returns for the

care bestowed and by 1835 the Vevay vineyards ceased to exist. Could

Dufour have foreseen the value of the native grapes for cultivation and

devoted the capital and energy spent on European sorts to the best wild

plants from the woods, grape culture in America would have been put

forward half a century.

Other experiments with Old World grapes were tried in 1803 by the

Harmonists, a religious-socialistic community founded in Germany, but

which finally settled in America. After temporary sojourns in other

settlements, the Harmonists founded a permanent colony in Pennsylvania

near Pittsburg. Here they planted ten acres of European grapes and grew

them with but temporary success, if any, for Dufour in 1826 visited the{20}

colony and says: “None of the imported grapes do well there except the

Black Juice, of which I saw but one plant; it is too small a bearer to

be worth nursing.”[27] Again there was disaster to an extensive

experiment in the hands of skilled men. Besides having tried grape

culture in Pennsylvania, the Harmonists made plantations at New Harmony,

Indiana, where they settled for a time; but exact accounts of this

experiment are wanting.

One other of the many organized attempts to grow the foreign grapes

needs mention. When the Napoleonic wars were over a number of

Bonaparte’s exiled officers came to America. They were impoverished, and

in order to help them, as well as to insure their becoming permanent

settlers in the United States, the exiles were organized by American

sympathizers into a society for the cultivation of the vine and the

olive. The society was organized in the early fall of 1816 in

Philadelphia and the remainder of the year was spent in prospecting for

a suitable location for the venture. The colony finally decided to

settle on the Tombigbee river in Alabama and petitioned Congress for a

grant of land in that region. In the end the refugees obtained a grant

from Congress of four contiguous townships, each six miles square[28]

for the culture of the vine and the olive.

In 1817, an installment of one hundred and fifty French settlers left

Philadelphia taking with them an assortment of grape and olive plants.

December 12, 1821, Charles Villars, one of the company, reported to the

American government[29] that there were then in the colony eighty-one

actual planters, 327 persons all told, with 1100 acres in full

cultivation, including 10,000 vines and that the company had spent about

$160,000 in the venture. Villars tells in full of the ups and downs of

the Society. It was apparent from the start that the olive could not be

grown. The history of the vineyards on the Tombigbee, as he tells it, is

but a record of misfortune. All efforts to cultivate the foreign vines

resulted only in failure. The few vines that the vintners made grow

yielded a scant crop of miserable quality which could not be made into

wine because of ripening in the heat of summer. The land was not adapted

to growing grapes. The Society, meeting failure at every turn, finally

disbanded and the colonists were scattered. For a{21} half century after,

there were records in the southern agricultural literature of the

attempts of stragglers or descendants of this colony to grow European

grapes in the South. Yet these grapes are not now cultivated in this

region, which seemingly has the climate and the soil of France.

The history of these French settlers on the Tombigbee is a most pathetic

one.[30] Many of the leaders had been officers of high rank in

Napoleon’s armies unaccustomed to field work and the hardships of a new

country. Here, in a rough and hardly explored country, part of which was

overflowed half of the year, visited by all the sicknesses inherent to

such a location, they passed several years in their attempts to grow

European grapes. Failure was predestined because of natural obstacles

which by this time were apparent, and was foreshadowed by so many

previous unsuccessful attempts that it would seem that this culminating

tragedy in growing European grapes could have been prevented. The

certain failure of the attempt makes all the more pathetic the story of

the Vine and Olive Colony on the Tombigbee.[31]

In closing the record of the Old World grape in America a few of the

later individual attempts to grow this grape must be recounted.

Three generations of Princes experimented with European grapes at the

famous Linnæan Botanic Garden, Flushing, Long Island. Wm. R. Prince[32]{22}

author of A Treatise on the Vine, devoted his life to promoting the

culture of the grape in America. He tried all of the European sorts

obtainable, “reared” as he tells us, “from plants imported direct from

the most celebrated collections in France, Germany, Italy, the Crimea,

Madeira, etc.; and above two hundred varieties are the identical kinds

which were cultivated at the Royal Garden of the Luxembourg at Paris, an

establishment formed by royal patronage for the purpose of concentrating

all the most valuable fruits of France, and testing their respective

merits.”[33] After nearly a half century of experimentation he gave up

the culture of foreign grapes and largely devoted the last years of his

life to growing and disseminating native varieties, exercising,

probably, a greater influence on the culture of American grapes than any

other of the many men who have helped improve the grapes of this

country.

Nicholas Longworth,[34] of Cincinnati, Ohio, experimented with the

European grapes for thirty years. His experience is best told in his own

words written in 1846: “I have tried the foreign grapes extensively for

wine at great expense for many years, and have abandoned them as unfit

for our climate. In the acclimation of plants I do not believe. The

white,{23} Sweetwater grape is not more hardy with me than it was thirty

years since, and does not bear as well. I have tried them in all soils

and with all exposures.

“I obtained 5,000 plants from Madeira, 10,000 from France; and one-half

of them, consisting of twenty varieties of the most celebrated wine

grapes from the mountains of Jura, in the extreme northern[35] part of

France, where the vine region ends; I also obtained them from the

vicinity of Paris, Bordeaux, and from Germany. I went to the expense of

trenching one hundred feet square on a side hill, placing a layer of

stone and gravel at the bottom, with a drain to carry off the water, and

to put in a compost of rich soil and sand three feet deep, and planted

on it a great variety of foreign wine grapes. All failed; and not a

single plant is left in my vineyards. I would advise the cultivation of

native grapes alone, and the raising of new varieties from their

seed.”[36]

The French Revolution drove a wealthy and educated Frenchman, M.

Parmentier, to New York at the beginning of the nineteenth century. He

planted about his place in Brooklyn a large garden in which there were

many grapes. This garden afterward became a commercial nursery from

which was distributed a considerable number of European grapes. Mr.

Robert Underhill at Croton Point on the Hudson was induced to plant a

vineyard of these but they soon went the way of all their kind, leaving

Mr. Underhill only a consuming desire to plant grapes. This desire bore

fruit, as we shall see. When the reign of terror had ceased, Parmentier

returned to France from whence he sent many grapes to friends in

America.{24} He left a lasting impress on the horticulture and viticulture

of America, through his experimental efforts with plants and his

contribution to American horticultural literature. The Underhills (the

father had been joined by his sons R. T. and W. A. Underhill) planted a

vineyard of Catawbas and Isabellas in 1827. These vineyards grew until

they covered seventy-five acres, the product of which was marketed in

the metropolis and nearby cities. The grapes from this vineyard often

sold for twenty-five cents a pound and supplied the whole market of the

region. The grape industry of the Hudson River Valley began with

Parmentier and the Underhills.

Another Frenchman, Alphonse Loubat, planted a vineyard of forty acres at

Utrecht, Long Island, containing about 150,000 plants of foreign

varieties. Here, we are told, “he strove against mildew and sun-scald

for several years, but had to yield at last, as the elements were too

much for human exertions to overcome.”[37] Loubat attempted to protect

his grapes from mildew by covering them with paper bags and was probably

the originator of the practice of bagging grapes.

Not infrequently one may still find some varieties of the Old World

grape grown out of doors with a fair degree of success in favored

locations but always by the amateur and never in a commercial vineyard.

These few pages rehearsing repeated failures without a single success,

serve to show the uselessness of attempting to grow foreign grapes in

eastern America. Their culture has been tried by thousands on a small

scale and by many individuals with experience, knowledge and capital on

a large scale. With all, the results have been the same; a year or two

of promise, then disease, dead vines and an abandoned vineyard.

The causes for these failures have been indicated. As Dufour says, “a

sickness takes hold of the vines.” Phylloxera, mildew, rot—native

parasites to which native grapes are comparatively immune—“take hold”

of the foreign sorts and they die.

It is probable, too, that our climate, at the North at least, is not

well suited to the production of the Old World grape. As a species, the

Vinifera grapes thrive best in climates equable in both temperature and

humidity.{25} The climate of eastern America is not equable; it alternates

between hot and cold, wet and dry. The range in both temperature and

humidity is far greater than in the grape-growing regions of Europe,

California, South Africa or Australia. The fleshy roots of Vitis

vinifera are more tender to cold than are those of the species of

northern United States and this would prevent its culture becoming very

general in many regions where native grapes can be grown.

It is only in the regions west of the Rocky Mountains, and more

particularly in California, that the varieties of Vinifera are

successfully grown in America. The great viticultural interests of the

far West are founded upon the success of this one species. The native

grapes can be grown but they cannot compete in California with Vitis

vinifera for any purpose. Nevertheless American species are

indispensable in this western region for stocks upon which to graft the

Vinifera varieties, and it is probable that the time is not far distant

when all California vines will be upon American roots. Within the

boundaries of latitude in which Vinifera varieties are grown west of the

Rocky Mountains the grape shows wonderful adaptability; it is found at

all elevations permitting fruit culture; it grows on practically all

soils; it thrives under irrigation or under dry farming; it is given

various kinds of treatment, including total neglect, and still thrives;

the number of varieties grown for wine, raisin and table grapes runs

into hundreds. The truly wonderful success met with in the cultivation

of this species west of the great continental divide makes all the more

remarkable the fact that in no place east of the divide will varieties

of it thrive.

We now pass to a consideration of the American grapes, their characters,

the early notices of them, their rise, their success, and their

future—a more pleasing task than to record disaster after disaster in

growing the grape of the Old World.{26}

CHAPTER II

AMERICAN GRAPES

The grape is preeminently a North American plant. The genus Vitis is a

large one, from thirty to fifty species being distinguished for the

world; more than half of these are found on this continent. But few

other plants in America, or in the world, inhabit such varied and such

extended areas. In North America wild grapes abound on the warm, dry

soils of New Brunswick and New England, about the Great Lakes in Canada

and in the United States, and on the fertile river banks and in the

valleys, rich woodlands and thickets of the eastern and southern States.

They thrive in the dry woods, sandy sea-plains, and reef-keys of the

Carolinas, Georgia and Florida where the vines of the Scuppernong often

run more than a hundred feet over trees and shrubs, rioting in natural

luxuriance. They flourish in the mountains and limestone hills of the

Virginias, Tennessee and Kentucky. They are not so common in the West,

yet found in almost all parts of Missouri and Arkansas, and from North

Dakota through Kansas to southern Texas. Some wild grape is found in

each of the Rocky Mountain States on plain or mountain, or in river

chasm or dry canon. Several species are found in New Mexico, Arizona and

California, where if they did not furnish the Spanish padres of Santa

Fe and San Diego with fruit for wine, they suggested to them the

planting of the first successful vineyards in the United States.

How did the grape spread from the Carolinas to California and from

subtropical Mexico to the barren plains of Central Canada? Why divide

into its manifold forms in the distribution? These questions are of

practical import to the grape-grower and breeder who seeks to improve

this fruit. The knowledge of the distribution and evolution of plants

obtained in the last half century is so complete that these questions

present few difficulties to the naturalist of today. In answering them

no one would now hold that the numerous species and their sub-divisions

were created separately for the regions in which they grow. All would

take the ground that the different wild forms come from one ancestral

species. We can waive the question as to what the original species was

and as to where it first grew.

It is certain that grapes have not been distributed over North America{27}

by the hand of man. Probably they have been growing in the regions where

they are now found since before the migration of the first savages. The

agents of distribution have been natural ones, such as animals, birds,

and lake and river currents. These have widened the area of a species to

limits imposed by the hostile action of other plants and of animals and

by geographical and physical conditions. As a species has encroached

upon a new region, climate, soil, all of the conditions of environment,

and the contest with other living things, have gradually modified its

characters until in time it became so changed that it constituted a new

species.

This descent from an original species with plants changed by environment

has given us, in America, types of the wild grape as widely diverse as

the regions they inhabit. The species found in the forests have

developed long slender trunks and branches in their struggle to attain

sunlight and air. At least two species are dwarf and shrubby, or

infrequently climbing, two to six feet high, growing in dry sands, on

rocky hills and mountains where roots must cling to rocks and penetrate

into interstices. Still another form runs on the ground and over low

bushes and is nearly evergreen, but in the herbarium can hardly be

distinguished from a grape whose habit of growth is strikingly

different. Some are long-lived, growing and bearing fruit for two or

more centuries, while others reach no greater age than the ordinary

shrub. Some have enormous stems, a foot or more in diameter, gnarled and

picturesque and supporting a great canopy of branch and foliage,[38]

while others are slender in stem and graceful, almost delicate, in

character of vine. Not less remarkable than the differences in structure

is the adaptability of the genus and some of the species to varied

climatic conditions. Several of the wild grapes develop full size and

display natural luxuriance and fruit-bearing qualities only in the

Middle States, but may{28} be found on dry, gravelly, wind-swept hills far

to the north or in some hot and humid atmosphere of the South, as if to

show indifference to wet or dry, heat or cold.

On the other hand there are many strong points of resemblance between

the score or more of species. The organs and characters that do not bear

the strain of changed environment, nor suffer in the perpetual warfare

of nature, are much the same in all of the species of Vitis. Thus the

structure of flowers, fruits and seeds is practically identical; all

have naked-tipped tendrils; leaves and leaf-buds are very similar; and

the various species usually hybridize freely. They are alike in the

unlikeness of individual plants in any of the species; that is, all of

the individuals of the genus are most variable and seeds taken from the

same vine may produce plants quite unlike one another and quite unlike

the parent.

These few facts regarding the evolution and distribution of American

grapes lead to two important conclusions:

First, the species are so distributed throughout the United States, and

individuals of the species grow in such abundance and luxuriance, as to

suggest that we shall be able to improve and domesticate some one or

more of them for all of the agricultural regions of the country. For it

is proved that nearly all of the wild grapes have horticultural

possibilities; and experience with many plants teaches that the

boundaries of areas inhabited by the wild species of a given region

coincide with those suited to the production of the domesticated plant

in that region. It is not possible to tell where the grape-growing

regions of the future are to be located; for species and individuals of

this fruit are so common that no one can say where the grape is most at

home in America.

Second, grapes are so variable and plastic in nature that, were it not

known from experience, it could be assumed that they would yield readily

to improvement. Besides being variable they hybridize freely and thus

the plant-breeder can obtain desirable starting points. There are

indications that some of the characters of grapes, at least, follow

Mendel’s Law, and when once these have been determined, and the more

important unit characters segregated and defined, it ought to be

possible to combine and rearrange the characters of this fruit with some

system and surely with more certainty than in the past.{29}

This brief introduction leads us to the consideration of American grapes

as cultivated plants. We have seen that it is an absolute impossibility

to grow the Old World grape in eastern America. The fruit-growers in

this great region are forced to plant the native grapes if any. It

required two hundred years to establish this fact and it is less than a

hundred years since grape-growers have generally acknowledged it as a

fact. What was known of American grapes during the two hundred years

wasted in attempting to grow the foreign Vinifera? And what has been

accomplished in a century in ameliorating the native grapes?

The earliest European visitors to the Atlantic seaboard delighted in the

wild grapes which they found everywhere and which reminded them of the

Old World vineyards. Had they never seen such a fruit, the wild grapes

could not long have escaped their attention; for the Indians knew and

used them as they did potatoes, corn, and tobacco. In the narratives of

the early voyages the grape is often in the lists of the resources and

treasures of the new-found continent. Unfortunately it was not

considered of great intrinsic value but only suggested to the explorers

that the grape of the old home might be grown in the new home. Could a

part of the exaggerated esteem given by the early European travelers and

home-seekers to sassafras, ginseng and other such plants, have been

bestowed upon the wild grapes which over-run the country, viticulture

would have taken rank with the tobacco, lumber and the fish industries

of the early settlers.

In the history of Vinland, or more properly Wineland, we find the {30}first

record of American grapes.[39] Biarni Heriulfsson, a Norseman, while

making a voyage from Iceland to Greenland, 986 A. D., was driven by a

storm to the coast of New England but did not touch land. Leif the

Lucky, son of Eric the Red, about 1000 A. D., visited the country

discovered by Biarni. One of Leif’s men, Tyrker, a German who “was born