HANDBOOK TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY

The National Gallery is open to the Public on week-days throughout the year. On MONDAYS, TUESDAYS, WEDNESDAYS, and SATURDAYS admission is free, and the Gallery is open during the following hours:—

| January | From 10A.M.until 4P.M. |

| February | From 10A.M. until dusk. |

| March | |

| April | From 10A.M.until 6 P.M. |

| May | |

| June | |

| July | |

| August | |

| September | |

| October | From 10A.M.until dusk. |

| November | |

| December |

On THURSDAYS and FRIDAYS (Students' Days) the Gallery is open to the Public on payment of Sixpence each person, from 11 A.M. to 4 P.M. in winter, and from 11 A.M. to 5 P.M. in summer.

On SUNDAYS the Gallery is open, free, from 2 P.M. till dusk, or 6 P.M. (according to the season).

☞ Persons desirous of becoming Students should address the Secretary and Keeper, National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, S.W.

The National Gallery of British Art ("Tate Gallery") is open under the same regulations, and during the same hours, as those given above, except that Students' Days are Tuesdays and Wednesdays.

COMPILED BY

E. T. COOK

WITH PREFACE BY JOHN RUSKIN, LL.D., D.C.L.

EIGHTH EDITION

MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED

ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON

1922

A picture which is worth buying is also worth seeing. Every noble picture is a manuscript book, of which only one copy exists, or ever can exist. A National Gallery is a great library, of which the books must be read upon their shelves (Ruskin: Arrows of the Chace, i. 71).

| PAGE | |

| Preface by John Ruskin | vii |

| General Introduction, with some Account of the National Gallery | x |

| Guide to the Gallery and Plan of the Rooms | xxv |

| Introductions to the Schools of Painting: | |

| The Early Florentine School | 1 |

| The Florentine School | 8 |

| The Sienese School | 14 |

| The Lombard School | 16 |

| The Ferrarese School | 19 |

| The Umbrian School | 22 |

| The Venetian School | 25 |

| The Paduan School | 32 |

| The Later Italian Schools | 34 |

| The Early Flemish and the German Schools | 38 |

| The Dutch School | 43 |

| The Later Flemish School | 47 |

| The Spanish School | 48 |

| The French School | 51 |

| Numerical Catalogue, with Biographical and Descriptive Notes | 55 |

| Pictures on Loan | 749 |

| Copies from Old Masters | 752 |

| The Arundel Society's Collection | 757 |

| Sculptures and Marbles | 770 |

| Appendix I. Index List of Painters (with the subjects of their pictures) | 771 |

| Appendix II. Index List of Pictures | 791 |

So far as I know, there has never yet been compiled, for the illustration of any collection of paintings whatever, a series of notes at once so copious, carefully chosen, and usefully arranged, as this which has been prepared, by the industry and good sense of Mr. Edward T. Cook, to be our companion through the magnificent rooms of our own National Gallery; without question now the most important collection of paintings in Europe for the purposes of the general student. Of course the Florentine School must always be studied in Florence, the Dutch in Holland, and the Roman in Rome; but to obtain a clear knowledge of their relations to each other, and compare with the best advantage the characters in which they severally excel, the thoughtful scholars of any foreign country ought now to become pilgrims to the Dome—(such as it is)—of Trafalgar Square.

We have indeed—be it to our humiliation remembered—small reason to congratulate ourselves on the enlargement of the collection now belonging to the public, by the sale of the former possessions of our nobles. But since the parks and castles which were once the pride, beauty, and political strength of England are doomed by the progress of democracy to be cut up into lots on building leases, and have their libraries and pictures sold at Sotheby's and Christie's, we may at least be thankful that the funds placed by the Government at the disposal of the Trustees for the National Gallery have permitted them to save so much from the wreck of English mansions and Italian monasteries, and enrich the recreations of our metropolis with graceful interludes by Perugino and Raphael.

It will be at once felt by the readers of the following catalogue that it tells them, about every picture and its painter, just the things they wished to know. They may rest satisfied also that it tells them these things on the best historical authorities, and that they have in its concise pages an account of the rise and decline of the arts of the Old Masters, and record of their personal characters and worldly state and fortunes, leaving nothing of authentic tradition, and essential interest, untold.

As a collection of critical remarks by esteemed judges, and of clearly formed opinions by earnest lovers of art, the little book possesses a metaphysical interest quite as great as its historical one. Of course[Pg ix] the first persons to be consulted on the merit of a picture are those for whom the artist painted it: with those in after generations who have sympathy with them; one does not ask a Roundhead or a Republican his opinion of the Vandyke at Wilton, nor a Presbyterian minister his impressions of the Sistine Chapel:—but from any one honestly taking pleasure in any sort of painting, it is always worth while to hear the grounds of his admiration, if he can himself analyse them. For those who take no pleasure in painting, or who are offended by its inevitable faults, any form of criticism is insolent. Opinion is only valuable when it

When I last lingered in the Gallery before my old favourites, I thought them more wonderful than ever before; but as I draw towards the close of life, I feel that the real world is more wonderful yet: that Painting has not yet fulfilled half her mission,—she has told us only of the heroism of men and the happiness of angels: she may perhaps record in future the beauty of a world whose mortal inhabitants are happy, and which angels may be glad to visit.

Division into Volumes.—In arrangement and, to some degree, in contents the Handbook in its present form differs from the earlier editions. Important changes have been made during the last few years in the constitution and scope of the National Gallery itself. The Gallery now consists of two branches controlled by a single Board of Trustees: (1) the "National Gallery" in Trafalgar Square; and (2) the "Tate Gallery" or, as it is officially called, the "National Gallery of British Art" on the Thames Embankment at Millbank.[1] At the former Gallery are hung all the pictures belonging to Foreign Schools. Pictures of the British Schools are hung partly in Trafalgar Square and partly at Millbank, and from time to time pictures are moved from one Gallery to the other. It has therefore been decided to divide the Handbook into volumes according to subject rather than according to position. Volume I. deals with the Foreign Schools (National Gallery); Volume II., with the British Schools (National Gallery and Tate Gallery). By this division the convenience of the books for purposes of reference or use in the Galleries will not be disturbed by future changes in the[Pg xi] allocation of British pictures between Trafalgar Square and Millbank respectively.

How to use the Handbook.—The one fixed point in the arrangement of the National Gallery is the numbering of the pictures. The numbers affixed to the frames, and referred to in the Official Reports and Catalogues, are never changed. This is an excellent rule, the observance of which, in the case of some foreign galleries, would have saved no little inconvenience to students and visitors. In the present, as in the preceding editions of the Handbook, advantage has been taken of this fixed system of numbering; and in the pages devoted to the Biographical and Descriptive Catalogue the pictures are enumerated in their numerical order. The introductory remarks on the chief Schools of Painting represented in the Gallery are brought together at the beginning of the book. The visitor who desires to make an historical study of the Collection may, if he will, glance first at the general introduction given to the pictures in each School; and then, as he makes his survey of the rooms devoted to the several Schools, note the numbers on the frames, and refer to the Numerical Catalogue following the series of introductions. On the other hand, the visitor who does not care to use the Handbook in this way has only to skip the preliminary chapters, and to pass at once, as he finds himself before this picture or that, to the Numerical Catalogue. For the convenience, again, of visitors or students desiring to find the works of some particular painter, the full and detailed Index of Painters, first introduced in the Third Edition, has here been retained. References to all the pictures by each painter, and to the page where some account of his life and work is given, will be found in this Index. Finally, a concise Numerical Index is given, wherein the reader may find at once the particulars of acquisition, the provenance, and other circumstances regarding every picture (by a foreign artist) in the possession of the National Gallery, wherever deposited.

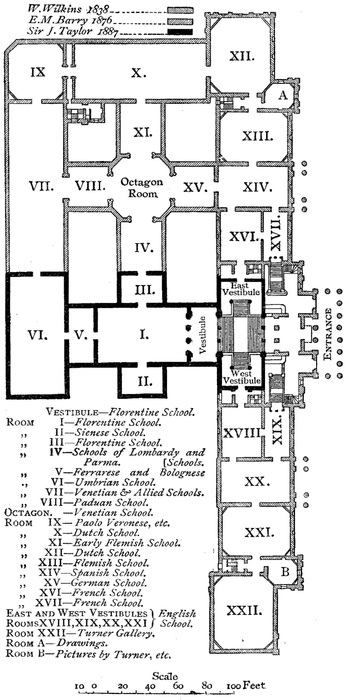

History of the National Gallery.—"For the purposes of the general student, the National Gallery is now," said Mr. Ruskin in 1888, "without question the most important collection of paintings in Europe." Forty years before he said of the same Gallery that it was "an European jest." The growth of the Gallery from jest to glory[2] may be traced in[Pg xii] the final index to this book, where the pictures are enumerated in the order of their acquisition. Many incidents connected with the acquisition of particular pictures will also be found chronicled in the Catalogue[3]; but it may here be interesting to summarise the history of the institution. The National Gallery of England dates from the year 1824, when the Angerstein Collection of thirty-eight pictures was purchased. They were exhibited for some years in Mr. Angerstein's house in Pall Mall; for it was not till 1832 that the building in which the collection is now deposited was begun. This building, which was designed expressly for the purpose by William Wilkins, R.A., was opened to the public in 1838.[4] At that time, however, the Gallery comprised only six rooms, the remaining space in the building being devoted to the Royal Academy of Arts—whose inscription may still be seen above a disused doorway to the right of the main entrance. In 1860 the first enlargement was made—consisting of one new room. In 1869 the Royal Academy removed to Burlington House, and five more rooms were gained for the National Gallery. In 1876 the so-called "New Wing" was added, erected from a design by E. M. Barry, R.A. In that year the whole collection was for the first time housed under a single roof. The English School had, since its increase in 1847 by the Vernon gift, been exhibited first at Marlborough House (up to 1859), and afterwards at South Kensington. In 1884 a further addition of five rooms was commenced under the superintendence of Sir John Taylor, of Her Majesty's Office of Works; these rooms (numbered I., II., III., V., VI. on the plan), with a new staircase and other improvements, were opened to the public in 1887; and the Gallery then consisted of twenty-two rooms, besides ample accommodation [Pg xiii]for the offices of the Director and the convenience of the students.[5] A further extension of the Gallery, on the site of St. George's Barracks, was completed in 1911; this consisted of six new rooms.[6] At the same time the older portions of the building were reconstructed, in order to make it fire-proof. The rearrangement of the Gallery is described below (p. xxv).

Growth of the Collection.—This growth in the Galleries has, however, barely sufficed to keep pace with the growth of the pictures. In 1838 the total number of national pictures was still only 150. In 1875 the number was 926. In 1911 the number of pictures, etc. (exclusive of the Turner water-colours) vested in the Trustees of the Gallery was nearly 2870. This result has been due to the combination of private generosity and State aid which is characteristic of our country. The Vernon gift of English pictures in 1847 added over 150 at a stroke. Ten years later Turner's bequest added (besides some 19,000 drawings in various stages of completion) 100 pictures. In 1876 the Wynn Ellis gift of foreign pictures added nearly another hundred. In 1910 the bequest of Mr. George Salting added 192 pictures (160 foreign and 32 British). Particulars of other gifts and bequests may be gathered from the Appendix. Parliamentary grants have of late years been supplemented by private subscriptions and bequests. In 1890 Messrs. N. M. Rothschild and Sons, Sir Edward Guinness, Bart. (now Lord Iveagh), and Mr. Charles Cotes, each contributed £10,000 towards the purchase of three important pictures (1314-5-6); whilst in 1904, Mr. Astor, Mr. Beit, Lord Burton, Lord Iveagh, Mr. Pierpont Morgan, and Lady Wantage subscribed £21,000 to supplement a Government grant for the purchase of Titian's "Portrait of Ariosto" (1944). In 1903 a "National Art-Collections Fund" was established for organising private benefactions to the Galleries and Museums of the United Kingdom; it was through this agency that the famous "Venus" by Velazquez (2057), in 1906, and the still more famous "Christina, Duchess of Milan," by Holbein (2475), in 1909, were added to the National Gallery. The same Fund contributed also to the [Pg xiv]purchase in 1911, of the Castle Howard Mabuse (2790). Mr. Francis Clarke bequeathed £23,104, and Mr. T. D. Lewis £10,000, the interest upon which sums was to be expended in pictures. Mr. R. C. Wheeler left a sum of £2655, the interest on which was to purchase English pictures. Mr. J. L. Walker left £10,000, not to form a fund, but to be spent on "a picture or pictures." In 1903 a large bequest was made to the Gallery by Colonel Temple West. The will was disputed; but by the settlement ultimately effected (1907, 1908) a sum of £99,909 was received, of which the interest is available for the purchase of pictures. In 1906 Mr. C. E. G. Mackerell made a bequest, and this will also was disputed. By the settlement (1908) a sum of £2859 was received, and a further sum will be forthcoming at the expiration of certain life-interests, of which sums, again, the interest will be available for the purchase of pictures. Appendix II. shows the pictures acquired from these several funds. This growth of the Gallery by private gift and public expenditure concurrently accords with the manner of its birth. One of the factors which decided Lord Liverpool in favour of the purchase of Mr. Angerstein's Collection was the generous offer of a private citizen—Sir George Beaumont.

Value of the Pictures.—Sir George's gift, as we shall see from a little story attaching to one of his pictures (61), was not of that which cost him nothing in the giving. The generosity of private donors, which that little story places in so pleasing and even pathetic a light, has been accompanied by public expenditure at once liberal and prudent. The total cost of the collection so far has been about £900,000[7]; at present prices there is little doubt that the pictures so acquired could be sold for several times that sum. It will be seen in the following pages that there have been some bad bargains; but these mostly belong to the period when responsibility was divided, in an undefined way, between the Trustees and the Keeper. The present organisation of the Gallery dates from 1855, when, as the result of several Commissions and Committees, a Treasury Minute was drawn up—appointing a Director to preside over the Gallery, and placing an annual grant of money at his disposal.[8] The [Pg xv]curious reader may trace the use of this discretion made by successive Directors in the table of prices given in the final index—a table which would afford material for an instructive history of recent fashions in art. The annual grant has from time to time been supplemented by special grants, of which the most notable were those for the Peel Collection, the Blenheim pictures, the Longford Castle pictures, two new Rembrandts (1674-5), Titian's "Ariosto" (1944), Holbein's "Duchess of Milan" (2475), and Mabuse's "Adoration of the Magi" (2790) respectively. The Peel Collection consisted of seventy-seven pictures. The vote was proposed in the House of Commons on March 20, 1871, and in supporting it the late Sir W. H. Gregory (one of the Trustees of the Gallery) alluded to "the additional interest connected with the collection, for it was the labour of love of one of our greatest English Statesmen, and it was gratifying to see that the taste of the amateur was on a par with the sagacity of the minister, for throughout this large collection there could hardly be named more than two or three pictures which were not of the very highest order of merit." The price paid for this collection, £70,000, was exceedingly moderate.[9] The "princely" price given for the two Blenheim pictures is more open to exception; but if the price was unprecedented, so also was the sale of so superb a Raphael in the present day unprecedented.

Features of the Collection.—The result of the expenditure with which successive Parliaments have thus supplemented private gifts has been to raise the National Gallery to a position second to that of no single collection in the world. The number of pictures now on view in Trafalgar Square, exclusive of the water-colours, is about 1600.[10] This number is very [Pg xvi]much smaller than that of the galleries at Dresden, Madrid, and Paris—the three largest in the world. On the other hand no foreign gallery has been so carefully acquired, or so wisely weeded, as ours. An Act was passed in 1856 authorising the sale of unsuitable works, whilst another passed in 1883 sanctioned the thinning of the Gallery in favour of Provincial collections. There are still many serious gaps. In the Italian School we have no work by Masaccio—the first of the naturalisers in landscape; only one doubtful example of Palma Vecchio, the greatest of the Bergamese painters; no first-rate portrait by Tintoret. The French School is little represented—an omission which is, however, splendidly supplied in the Wallace Collection at Hertford House, now the property of the nation. In the National Gallery itself there is no picture by "the incomparable Watteau," the "prince of Court painters." The specimens of the Spanish School are few in number, though Velazquez is now finely represented; whilst amongst the old masters of our own British School there are many gaps for some future Vernon or Tate to fill up. But on the other hand we can set against these deficiencies many painters who, and even schools which, can nowhere—in one place—be so well studied as in Trafalgar Square. The works of Crivelli—one of the quaintest and most charming of the earlier Venetians—which hang together in one room; the works of the Brescian School, including those of its splendid portrait painters—Moroni and Il Moretto; the series of Raphaels, showing each of his successive styles; and in the English School the unrivalled and incomparable collection of Turners,—are amongst the particular glories of the National Collection. Historically the collection is remarkably instructive. This is a point which successive Directors have, on the recommendation of Royal Commissions, kept steadily in view; and which has been very clearly shown since the successive re-arrangements of the Gallery after the extension in 1887.

Scope of the Handbook.—It is in order to help visitors to take full advantage of the opportunities thus afforded for historical study that I have furnished some general introductions to the various Schools of Painting represented in the National Gallery. With regard to the notes in the Numerical Catalogue, my object has been to interest the daily increasing numbers of the general public who visit the National Gallery.[Pg xvii] The full inventories and other details, which are necessary for the identification of pictures, and which are most admirably given in the (unabridged) Official Catalogue—would obviously be out of place in a book designed for popular use. Nor, secondly, would any elaborate technical criticism have been in keeping—even had it been in my power to offer it—with a guide intended for unprofessional readers. C. R. Leslie, the father of the present Academician, tells how he "spoke one day to Stothard of his touching picture of a sailor taking leave of his wife or sweetheart. 'I am glad you like it, sir,' said Stothard; 'it was painted with japanner's gold size.'" I have been mainly concerned with the sentiment of the pictures, and have for the most part left the "japanner's gold size" alone.

Mr. Ruskin's Notes.—It had often occurred to me, as a student of Mr. Ruskin's writings, that a collection of his scattered notes upon painters and pictures now in the National Gallery would be of great value. I applied to Mr. Ruskin in the matter, and he readily permitted me to make what use I liked of any, or all, of his writings. The generosity of this permission, which was supplemented by constant encouragement and counsel, makes me the more anxious to explain clearly the limits of his responsibility for the book. He did not attempt to revise, or correct, either my gleanings from his own books, or the notes added by myself from other sources. Beyond his general permission to me to reprint his past writings, Mr. Ruskin had, therefore, no responsibility for this compilation whatever. I should more particularly state that the pages upon the Turner Gallery in the Second Volume were not even glanced at by him. The criticisms from his books there collected represent, therefore, solely his attitude to Turner at the time they were severally written. But, subject to this deduction, the passages from Ruskin arranged throughout the following pages will, I hope, enable the Handbook to serve a second purpose. Any student who goes through the Gallery under Ruskin's guidance—even at second-hand—can hardly fail to obtain some insight into the system of art-teaching embodied in his works. The full exposition of that system must still be studied in the original text-books, but here the reader may find a series of examples and illustrations which will perhaps make the study more vivid and actual.

Attribution of Pictures.—In the matter of attributions, the rule, in the successive editions of this Handbook, has been to follow the authority of the Official Labels and Catalogues. Criticism has been very busy of late years with the traditional attribution of pictures in our Gallery, and successive Directors introduce their several, and sometimes contradictory, opinions on such points. Thus more than One Old Master hitherto supposed to be represented in the Gallery has been banished, and others, whose fame had not previously been bruited abroad, have been credited with familiar masterpieces. Thus—to notice some of the changes made by Sir Edward Poynter (Catalogue of 1906)—among the Venetians, Bastiani and Catena have come into favour. To Bastiani was given the picture of "The Doge Giovanni Mocenigo" (750) which for forty years has been exhibited as a work by Carpaccio; that charming painter now disappears from the National Gallery. To Catena is attributed the "St. Jerome" (694), which for several decades had been cited as peculiarly characteristic of Bellini. To Catena also is given the "Warrior in Adoration" (234). In this case Catena's gain is Giorgione's loss. But elsewhere Giorgione has received compensation for disturbance. To him has been given the "Adoration of the Magi" (1160), which some critics attributed to Catena. The beautiful "Ecce Homo" (1310), which was sold as a Carlo Dolci and bought by Sir Frederick Burton as a Bellini, was ascribed by Sir Edward Poynter to Cima. One of the minor Venetians—Basaiti, who enjoyed a high reputation at the National Gallery—was deprived of the pretty "Madonna of the Meadow" (599), which went to swell the opulent record of Bellini. Among the Florentines, a newcomer is Zenobio Macchiavelli, to whom is attributed an altar-piece (586) formerly catalogued under the name of Fra Filippo Lippi. Cosimo Rosselli, hitherto credited with a large "St. Jerome in the Desert" (227), now disappears; it was labelled "Tuscan School," and was any one's picture. The attribution of pictures belonging to the group of the two Lippis and Botticelli is still very uncertain. A note on these critical diversities will be found under No. 293. Among alterations in other schools we may note the substitution of Zurbaran for Velazquez as the painter of "The Nativity," No. 232; the attribution to Patinir, the Fleming, of a landscape formerly labelled "Venetian School" (1298); and the discovery of Jacob van Oost as the painter of a charming "Portrait of a[Pg xix] Boy" (1137), which, but for an impossibility in the dates, might well continue to pass as Isaac van Ostade's.

Such were the principal changes made in the ascriptions of the pictures during Sir Edward Poynter's directorate. His successor, Sir Charles Holroyd, has recently made many others, as shown in the following list:

97 (P. Veronese), now described as "after Veronese."

215, 216 (School of T. Gaddi), now assigned to Lorenzo Monaco (see 1897).

227 (Florentine School), now assigned to Francesco Botticini (a Tuscan painter of the 15th century).

276 (School of Giotto), now assigned to Spinello Aretino; for whom, see 581.

296 (Florentine School), now assigned to Verrocchio; see below, p. 262.

568 (School of Giotto), now assigned to Angelo di Taddeo Gaddi, a pupil of Giotto's chief disciple, Taddeo Gaddi (for whom, see p. 211).

579 (School of Taddeo Gaddi), now assigned to Niccolo di Pietro Gerini, a painter of Florence who was inscribed in the guild in 1368 and died in 1415. Our picture is dated 1387.

579A (School of Taddeo Gaddi), now assigned to Gaddi's pupil, Giovanni da Milano.

581 (Spinello Aretino), now assigned to Orcagna; for whom, see 569.

585 (Umbrian School), now assigned to "School of Pollajuolo"; for whom, see 292.

591 (Benozzo Gozzoli), now described as "School of Benozzo."

592 (Filippino Lippi), now assigned to Botticelli; see below, p. 294 n.

599 (Giovanni Bellini), now re-assigned to Basaiti; see below, p. 299.

636 (Titian or Palma). After a period of ascription to Titian, this portrait is now re-assigned to Palma; see below, p. 315.

650 (Angelo Bronzino), now assigned to his pupil, Alessandro Allori (Florentine: 1535-1607).

654 (School of Roger van der Weyden), now assigned to School of Robert Campin; for whom, see 2608.

655 (Bernard van Orley), now ascribed to Ambrosius Benson; born in Lombardy, painted in Bruges, living in 1545.

658 (after Schongauer), now assigned to School of Campin. The picture ascribed to the "Master of Flémalle," as referred to in the text (p. 328), is now No. 2608 (also now assigned to Campin).

659 (Johann Rottenhammer), now assigned to Jan Brueghel, the younger (1601-1667), a scholar of Brueghel, the elder.

664 (Roger van der Weyden), now assigned to Dierick Bouts; for whom, see 2595.

670 (Angelo Bronzino), now described as "School of Bronzino."

696 (Flemish School), now assigned to Petrus Cristus; for whom, see 2593.

704 (Bronzino), now described as "School of Bronzino."

709 (Flemish School), now assigned to Memlinc; for whom, see 686.

713 (Jan Mostaert), now assigned to Jan Prevost (Flemish: 1462-1529), a painter of Bruges and a friend of Albert Dürer.

714 (Cornelis Engelbertsz), now assigned to Bernard van Orley; for whom, see 655.

715 (Joachim Patinir), now assigned to Quentin Metsys; for whom, see 295.

750 (Lazzaro Bastiani), now described as "School of Gentile Bellini"; for whom, see 1213.

774 (Flemish School), now assigned to Dierick Bouts; for whom, see 2595.

779, 780 (Borgognone), now described as "School of Borgognone."

781 (Florentine School), now attributed to Botticini.

782 (Botticelli), now described as "School of Botticelli."

808 (Giovanni Bellini), now assigned to Gentile Bellini; see below, p. 422 n.

916 (School of Botticelli), now assigned to Jacopo del Sellaio; for whom, see 2492.

943 (Flemish School), now assigned to D. Bouts.

1017 (Flemish School), now assigned to Josse de Momper; see below, p. 489.

1033 (Filippino Lippi), now assigned to Botticelli; see below, p. 494.

1048 (Italian), now assigned to Scipione Pulzone; see below, p. 505.

1078, 1079 (Flemish School), now "attributed to Gerard David"; for whom, see 1045.

1080 (School of the Rhine), now assigned to Flemish School.

1083 (Flemish School), now assigned to Albrecht Bouts (a son of D. Bouts), who died in 1549.

1085 (School of the Rhine), now assigned to Geertgen Tot Sint Jans (Dutch: 15th century). This painter was a pupil of Albert van Ouwater; he established himself at Haarlem in a convent belonging to the Knights of St. John (whence his name, Gerard of St. John's). His works were seen and admired by Dürer.

1086 (Flemish School), now assigned to the "School of Robert Campin"; for whom, see 2608.

1109A (Mengs). To this picture the number 1099 (noted in previous editions of this Handbook as having been missed in the official numbering) is now given.

1121 (Venetian School), now assigned to Catena; for whom, see 234.

1124 (Filippino Lippi), now described as "School of Botticelli."

1126 (Botticelli), now assigned to Botticini; see on this subject p. 536 n.

1160 (School of Giorgione), now assigned to Giorgione himself.

1199 (Florentine School), now assigned to Pier Francesco Fiorentino; a Tuscan painter of the 15th century.

1376 (Velazquez), now "ascribed to Velazquez."

1412 (Filippino Lippi), now described as "School of Botticelli."

1419 (Flemish School), now assigned to Early French School. The picture formed part of a diptych; the companion picture was in the Dudley Collection (No. 29 in the sale catalogue of 1892, where an illustration of it was given). In this the choir of St. Denis is shown. There are two portraits by the same hand at Chantilly.

1433 (Flemish School), now assigned to Roger van der Weyden; for whom, see 664.

1434 (Velazquez), now "ascribed to Velazquez," and it is added that the picture has been attributed to Luca Giordano (Neapolitan: 1632-1705).

1440 (Giovanni Bellini), now assigned to Gentile Bellini; for whom, see 1213.

1468 (Spinello Aretino), now assigned to Jacopo di Cione, the younger brother of Andrea Cione (called Orcagna); he was still living in 1394.

1652 This picture has hitherto been assigned to the British School (and therefore included in vol. ii. of the Handbook), and called a portrait of Katharine Parr. It is now discovered to belong to the Dutch School and to be a "portrait of Madame van der Goes."

1699 (Jan Vermeer), now "attributed to Vermeer."

1842 (Tuscan School), now "attributed to Stefano di Giovanni," known as Sassetta (Sienese: 1392-1450).

1870 "Angels with Keys," by Sebastiano Conca (Neapolitan: 1679-1764). Lent by the Victoria and Albert Museum.

1903 (Jan Fyt), now assigned to Pieter Boel (Flemish: 1622-1674), of Antwerp, who became official painter to Louis XIV.

It will be observed that critical fashions are unstable, and that in several cases Sir Edward Poynter's changes have been reversed. The recent alterations were made just as this edition of the Handbook was going to press. The ascriptions in the body of my Catalogue remain, therefore, in conformity with the Official Catalogue of 1906 which embodied Sir Edward Poynter's views. The lists of painters and pictures at the end (Appendix I. and II.) have, on the other hand, been revised in accordance with Sir Charles Holroyd's alterations.

Additional Notes.—In the notes upon the pictures, a large number of additional remarks have been introduced since this Handbook first appeared. These, it is hoped, may serve here[Pg xxii] and there to deepen the visitor's impression, to suggest fresh points of view, to open up incidental sources of interest. Attention may be called, by way of example, under this head, to several notes upon the designs depicted on the dresses, draperies, and backgrounds of the Italian pictures. These designs, sometimes invented by the artists themselves and sometimes copied from actual stuffs, form a series of examples which illustrate the "art fabrics" of the best period of Italian decorative art, and which might well give hints for the decoration of textile fabrics to-day.[11] Another incidental source of interest in a collection of pictures such as ours, is the historical development of art as it may be traced in the several representations of the same subject by different painters, in successive periods, and in different schools. Such comparisons are instructive to those interested alike in the evolution of art and in the history of religious ideas. In the art of mediæval Christendom we find an unwritten theology, a popular figurative teaching of the sublime story of Christianity blended with the traditions of many generations. On the walls of the National Gallery we may see a series of typical scenes from the Annunciation to the Passion, from the childhood of Christ to His Death, Resurrection, and Ascension, together with ideal forms of apostles and saints. These pictures, contemplated in sequence and compared with one another, afford, as a writer in the Dublin Review (October 1888) has pointed out, a large and interesting field for thought. Very interesting it is also to trace the different types which prevail in the different schools. Thus at Florence, the Madonna is a tender, shrinking, delicate maiden. At Venice, she is a calm, serene, and pure-spirited mother. The Florentine "handmaiden of the Lord" often wears a mystic, and almost always an intellectual air. The Venetian type, seen at its central perfection in Bellini, has a neck firm as a column; the child is nude and plays with a flower or fruit; grandeur of mien and a noble type of motherhood are the ideals the Venetian painters set before themselves. The Lombard Madonna is less spiritual and severe than the Florentine. A refined worldly beauty replaces here the poetic idealism of the Tuscan artists. With the Umbrian painters the model of the Madonna is usually a softly-rounded and very girlish maiden. A certain mystic pensiveness informs her [Pg xxiii]features. Her feet tread this earth, but her soul is absorbed in the contemplation of the infinite.[12] A study of the successive characteristics of Raphael's Madonnas, passing from the vaguely divine to the frankly human, would form material for a volume in itself.[13] In another department of the painter's art, the comparative method of study is no less suggestive. It is one of the most curious points of interest in any large collection of pictures to notice the different impressions that the same elements of natural scenery make upon different painters. As figure painting came to be perfected, some adequate suggestion of landscape background was required. Giotto and Orcagna first attempted to give resemblance to nature in this respect. Subsequent painters carried the attempt to greater success, but it was long before landscape for its own sake obtained attention. When it did, the preferences of individual painters, now freed from conventionalism, found abundant scope, as we may see by pausing in succession before the flowery meadows of the "primitives," the "fiery woodlands of Titian," the savage crags of Salvator Rosa, the "saffron skies of Claude."[14] These are some of the incidental points of interest upon which additional notes have been supplied in recent editions. Many others will be discovered by the patient reader of the following pages.

Notices of Painters.—Lastly, the biographical and critical notices of the painters have been revised and expanded since the first appearance of the book. Many have been re-written throughout, nearly all have been re-cast, and a good many references to pictures in other galleries and countries have been introduced. The important accession to the National Gallery of the Arundel Society's unique collection of copies from the old masters affords an opportunity even to the untraveled visitor to become acquainted, in some sort, with the most famous wall-paintings of Italy. Mr. Ruskin, by whose death the National Gallery lost one of its best and oldest friends, once expressed a hope to me that the notices of the painters [Pg xxiv]given in this Handbook would be found useful by some readers not only as a companion in Trafalgar Square, but also for other galleries, at home and abroad. Nobody can know better than the compiler how far Mr. Ruskin's kindness led him in the direction of over-indulgence.

I can only hope that the later editions have been made—largely owing to the suggestions of critics and private correspondents—a little more deserving of the kind reception which, now for a period of nearly twenty-five years, has been given by the public to my Handbook.

May 1912.

[1] The Tate Gallery is ten minutes' drive or twenty minutes' walk from Trafalgar Square. It is reached in a straight line by Whitehall, Parliament Street, past the Houses of Parliament, Millbank Street, and Grosvenor Road.

[2] Mr. Ruskin himself was converted by the acquisition of the great Perugino (No. 288). In congratulating the Trustees on their acquisition of this "noble picture," he wrote: "It at once, to my mind, raises our National Gallery from a second-rate to a first-rate collection. I have always loved the master, and given much time to the study of his works; but this is the best I have ever seen" (Notes on the Turner Gallery, p. 89 n.).

[3] See, for instance, Nos. 10, 61, 193, 195, 479 and 498, 757, 790, 896, 1131, and 1171.

[4] The exterior of the building is not generally considered an architectural success, and the ugliness of the dome is almost proverbial. But it should be remembered that the original design included the erection of suitable pieces of sculpture—such as may be seen in old engravings of the Gallery, made from the architect's drawings—on the still vacant pedestals.

[5] The several extensions of the Gallery are shown in the plan on a later page.

[6] The total number should thus be 28; but in the reconstruction four smaller rooms were thrown into two larger ones. The plan thus shows 25 numbered rooms and one called the "Dome."

[7] This sum only includes amounts paid out of Parliamentary grants or other National Gallery funds or special contributions.

[8] In 1894, however, an alteration was made in the Minute, and the responsibility for purchases was vested in the Director and the Trustees jointly.

[9] Sir William Gregory relates in his Autobiography the following story: "In 1884, when the Trustees were endeavouring to secure some of the pre-eminently fine Rubenses from the Duke of Marlborough, Alfred Rothschild met me in St. James's Street, and said, 'If you think the Blenheim Rubenses are more important than your Dutch pictures to the Gallery, and that you cannot get the money from the Government, I am prepared to give you £250,000 for the Peel pictures; and I will hold good to this offer till the day after to-morrow.'"

[10] Of the 1170 pieces thus unaccounted for (the total number belonging to the Trustees being roughly 2870) the greater number are at Millbank. Others are on loan to provincial institutions (see App. II.).

[11] With this object in view, several of them have been published with descriptive letterpress by Mr. Sydney Vacher.

[12] These contrasts were worked out and illustrated by Mr. Grant Allen in his papers on "The Evolution of Italian Art" in the Pall Mall Magazine for 1895.

[13] See Raphael's Madonnas, by Karl Károly, 1894.

[14] Ruskin's Modern Painters is of course the great book on this subject. The evolution of "Landscape in Art" has been historically treated by Mr. Josiah Gilbert in a work thus entitled, which contains numerous illustrations from the National Gallery.

The pictures in the National Gallery are hung methodically, so far as the wall-space and other circumstances will admit, in order to illustrate the different schools of painting, and to facilitate their historical study. Introductions to the several Foreign Schools of Painting, thus arranged, will be found in the following pages together with references to many of the chief painters in each school who are represented in the Gallery. Introductory remarks on the British School and British Painters will be found in Volume II.

At the present time (May 1912) the arrangement of the Gallery is in a transitional state, as some of the Rooms are still in process of reconstruction or rearrangement. When this work is finished, the arrangement of the whole Gallery will, it is expected, be as shown below:—

Archaic Greek Portraits: North Vestibule.

Italian Schools:—

Early Tuscan: North Vestibule.

Florentine and Sienese: Rooms I., II., V.

[Pg xxvi]Florentine (later): Room III.

Milanese: Room IV.

Umbrian: Room VI.

Venetian: Room VII.

Venetian (later): Room IX.

Paduan: Room VIII.

Venice, etc.: the Dome.

Brescian and Bergamese: Room XV.

Bolognese: Room XXV.

Late Italian: Room XXIII.

Schools of the Netherlands and Germany:—

Early Netherlands: Room XI.

Later Flemish (Rubens, etc.): Room X.

Dutch (landscape: Ruysdael, etc.): Room XII.

Dutch (Rembrandt): Room XIII.

Dutch: Room XIV.

German: Room XXIV.

Spanish School: Room XVI.

French School: Rooms XVII., XVIII.

British Schools:—

Hogarth, etc.: Room XXII.

Reynolds, Gainsborough, etc.: Room XXI.

Romney, Morland, etc.: Room XX.

Turner: Room XIX.

The rooms on the ground floor, hitherto occupied by the Turner Water-Colours (now for the most part removed to the Tate Gallery: see Vol. II.), will be arranged with pictures of minor importance, with the Arundel Society's collection and other copies, and with photographs and other aids to study.

It should, however, be understood that the scheme of arrangement set out above is provisional, and may be modified. It is also possible that the numbering of the rooms may be altered. Should this be the case, the visitor would have no difficulty in marking the changes on the Plan.

PLAN OF THE ROOMS.

"The early efforts of Cimabue and Giotto are the burning messages of prophecy, delivered by the stammering lips of infants"

(Ruskin: Modern Painters, vol. i. pt. i. sec. i. ch. ii. § 7).

On entering the Gallery from Trafalgar Square, and ascending the main staircase, the visitor reaches the North Vestibule. What, he may be inclined to ask, is there worth looking at in the quaint and gaunt pictures around him here? The answer is a very simple one. This vestibule is the nursery of Italian art. Here is the first stammering of infant painting. Accustomed as we are at the present day to so much technical skill even in the commonest works of art, we may be inclined to think that the art of painting—the art of giving the resemblances of things by means of colour laid on to wood or canvas—is an easy one, of which men have everywhere and at all times possessed the mastery. But this of course is not the case. The skill[Pg 2] of to-day is the acquired result of long centuries of gradual improvement; and the pictures in this vestibule bear the same relation to the pictures of our own time as the stone huts of our forefathers to the Gallery in which we stand. The poorness of the pictures here is the measure of the richness of others. To feel the full greatness of Raphael's Madonna (1171), one should first pause awhile before the earliest Italian picture here (564), the gaunt and forbidding Madonna by

But even in the earliest efforts of infancy, there is a certain amount of inherited gift. First of all, therefore, one should look at a specimen of such art as Italians had before them when they first began to paint for themselves. With the fall of the Roman Empire and the invasion of the Goths, the centre of civilisation shifted to the capital of the Eastern Church, Byzantium (Constantinople). The characteristics of Byzantine art may be seen in a Greek picture (594). The history of early Italian art is the history of the effort to escape from the swaddling clothes of this rigid Byzantine School. The effort was of two kinds: first the painters had to see nature truly, instead of contenting themselves with fixed symbols—art had to become "natural," instead of "conventional." Secondly, having learned to see truly, they had to learn how to give a true resemblance of what they saw; how to exhibit things in relief, in perspective, and in illumination. In relief: that is, they had to learn to show one thing as standing out from another; in perspective: that is, to show things as they really look, instead of as we infer they are; in illumination: that is, to show things in the colours they assume under such and such[Pg 3] lights. The first distinct advance was made by Cimabue and Giotto at Florence, but contemporaneous with them was the similar work of Duccio and his successors at Siena, whose pictures should be studied in this connection. Various stages in the advance will be pointed out under the pictures themselves; and the student of art will perhaps find the same kind of pleasure in tracing the painter's progress as grown-up people feel in watching the gradual development of children.

But there is another kind of interest also. Wordsworth says that children are the best philosophers; and in the case of art at any rate there is some truth in what he says, for "this is a general law, that supposing the intellect of the workman the same, the more imitatively complete his art, the less he will mean by it; and the ruder the symbol, the deeper is its intention" (Ruskin's Lectures on Art, § 19). The more complete his powers of imitation become, the more intellectual interest he takes in the expression, and the less therefore in the thing meant. What then is the meaning of these early pictures? To answer this question, we must go back to consider what it was that gave the original impulse to the revival of art in Italy. To this revival two circumstances contributed. First, no school of painting can exist until society is comparatively rich, until there is wealth enough to support a class of men with leisure to produce beautiful things. Such an increase of wealth took place at Florence in the thirteenth century: the gay and courteous life of the Florentines at that time was ready for the adornment of art. The particular direction which art took was due to the religious revival, headed by St. Francis and St. Dominic, which occurred at the same time. Churches were everywhere built, and on the church walls frescoes were wanted, alike to satisfy the growing sense of beauty and to assist in teaching Christian doctrine. These early pictures are thus[Pg 4] to be considered as a kind of painted preaching. The story of Cimabue's great picture (see No. 565) well illustrates the double origin of the revival of art. It was to its place above the altar in the great Dominican church of Sta. Maria Novella at Florence that the picture was carried in triumphal procession; whilst the fact that a whole city should thus have turned out to rejoice over the completion of a picture, proves "the widespread sensibility of the Florentines to things of beauty, and shows the sympathy which, emanating from the people, was destined to inspire and brace the artist for his work" (Symonds: Renaissance, iii. 137).[15] The history of Giotto is no less significant. It was for the walls of the church of St. Francis at Assisi that his greatest work was done. It was there that he at once pondered over the meaning of the Christian faith (with what result is shown by Ruskin in Fors Clavigera and elsewhere), and learned the secret of giving the resemblance of the objects of that faith in painting. Thus, then, we arrive at the second source of interest in these old pictures of Florence—rude and foolish as they sometimes seem. "Those were noble days for the painter, when the whole belief of Christendom, grasped by his own faith, and firmly rooted in the faith of the people round him, as yet unimpaired by alien emanations from the world of classic culture, had to be set forth for the first time in art. His work was then a Bible, a compendium of grave divinity and human history, a book embracing all things needful for the spiritual and civil life of man. He spoke to men who could not read, for whom there were no printed pages, but whose hearts received his teaching through the eye. Thus painting was not then what it is now, a decoration of existence, but a potent and efficient agent in the education of the race" (ibid. p. 143). The message which these painters had to [Pg 5]deliver was painted on the walls of churches or civic buildings; and it is only there—at Assisi, and Padua, and Florence, and Siena—that they can be properly read. But from such scraps and fragments as are here preserved, one may learn, as it were, the alphabet, and catch the necessary point of view.

But why, it may be asked, did painting come to its new birth first at Florence, rather than elsewhere in Italy? The first answer is that painting thus arose at Florence because it was there that a new style of building at this time arose. The painters were wanted, as we have seen, to decorate the churches, and in those days there was no sharp distinction between the arts. Not only were architects sculptors, but they were often painters and goldsmiths as well. Giotto and Orcagna are instances of this union of the arts. But why did the new style of building arise specially in Florence? The answer to this is twofold: first, the Florentines inherited the artistic gifts and faculties of the Etruscan (Tuscan) race. Even in late Florentine pictures, pure Etruscan design will often be found surviving (see 586). Secondly, in the middle of the thirteenth century new art impulse came from the North in the shape of a northern builder, who, after building Assisi, visited Florence and instructed Arnolfo in Gothic, as opposed to Greek architecture. Thus there met the two principles of art—the Norman (or Lombard), vigorous and savage; the Greek (or Byzantine), contemplative but sterile. The new spirit in Florence "adopts what is best in each, and gives to what it adopts a new energy of its own, ... collects and animates the Norman and Byzantine tradition, and forms out of the perfected worship and work of both, the honest Christian faith and vital craftsmanship of the world.... Central stood Etruscan Florence: agricultural in occupation, religious in thought, she directed the industry of the Northman into the[Pg 6] arts of peace; kindled the dreams of the Byzantine with the fire of charity. Child of her peace, and exponent of her passion, her Cimabue became the interpreter to mankind of the meaning of the Birth of Christ" (Ariadne Florentina, ch. ii.; Mornings in Florence, ii. 44, 45).

☞ In the left-hand corner of the Vestibule will be found a very remarkable series of archaic Greek portraits dating from the second or third century A.D. (Nos. 1260-1270).

The architecture of the Entrance Hall and Vestibule is worth some attention, for here is the finest collection of marbles in London. Many distant parts of the world have contributed to it. The Alps, from a steep face of mountain 2000 feet high on the Simplon Pass, send the two massive square pillars of light green "cipollino" which form the approach to the Vestibule from the Square. Their carved capitals are of alabaster from Derbyshire, whilst the bases on which they stand are of Corrennie granite from near Aberdeen. The square blocks of bluish gray beneath the upper columns come from New Zealand. Ascending the stone steps, the visitor should notice the side walls, built up of squares of "giallo antico," which was brought from the quarry at Simittu, in the territory of Tunis. It had long been known that Rome was full of the beautiful "giallo antico," sometimes yellow, sometimes rosy in colour, but always of exquisite texture and even to work. It had come from the province of Africa; and the quarry was rediscovered by a Belgian engineer working on the railway then being made from Tunis to the Algerian frontier. He observed at Simittu a half-consumed mountain with[Pg 7] gaps clearly marked, from which the last monoliths had been cut, and the work of the Romans was presently resumed by a Belgian Company. No more beautiful specimen of the "giallo antico" similar to that used in Augustan Rome could be desired than slabs in the entrance to the National Gallery. The cornice above the "giallo antico" walls is of "pavonazzetto" from the Apennines, near Pisa, and the same marble forms the base of the red columns. These splendid columns come from quarries near Chenouah, just west of Algiers, which were first opened by the French some years ago. Red Etruscan is the unmeaning trade name of this jasper-like stone, which is also used for door frames in many of the new rooms with very sumptuous effect.

[15] My references to this book are to the new edition of 1897.

"This is the way people look when they feel this or that—when they have this or that other mental character: are they devotional, thoughtful, affectionate, indignant, or inspired? are they prophets, saints, priests, or kings? then—whatsoever is truly thoughtful, affectionate, prophetic, priestly, kingly—that the Florentine School lived to discern and show; that they have discerned and shown; and all their greatness is first fastened in their aim at this central truth—the open expression of the living human soul" (Ruskin: Two Paths, § 21).

"Great nations write their autobiographies in three manuscripts;—the book of their deeds, the book of their words, and the book of their art. Not one of these books can be understood unless we read the two others; but of the three, the only quite trustworthy one is the last." The reason for this faithfulness in the record of art is twofold. The art of any nation can only be great "by the general gifts and common sympathies of the race;" and secondly, "art is always instinctive, and the honesty or pretence of it therefore open to the day" (St. Mark's Rest, Preface). It has been seen from the remarks already made how Floren[Pg 9]tine art in its infancy was thus in a certain sense a record of the times out of which it sprang. In the later pictures, we may trace some of the developments which characterised the inner history of Florence in succeeding stages. The first thing that will strike any one who takes a general look at the early Florentine pictures and then at the later, is the fact that easel pictures have now superseded fragments of fresco and altar-pieces. Here at once we see reflected two features of the time of the Renaissance. Pictures were no longer wanted merely for church decoration and Scripture teaching; there was a growing taste for beautiful things as household possessions. And then also the influence of the church itself was declining; the exclusive place hitherto occupied by religion as a motive for art was being superseded by the revival of classical learning. Benozzo Gozzoli paints the Rape of Helen, Botticelli paints Mars and Venus, Piero di Cosimo paints the Death of Procris, and Pollajuolo the story of Apollo and Daphne. The Renaissance was, however, "a new birth" in another way than this; it opened men's eyes not only to the learning of the ancient world, but to the beauties of the world in which they themselves lived. In previous times the burden of serious and thoughtful minds had been, "The world is very evil, the times are waxing late;" the burden of the new song is, "The world is very beautiful." Thus we see the painters no longer confined to a fixed cycle of subjects represented with the traditional surroundings, but ranging at will over everything that they found beautiful or interesting around them. And above all they took to representing the noblest embodiment of life—the human form. Some attempts at portraiture may be perceived in the saints of the earliest pictures; but here we find professed portraits on every wall. This indeed was one of the chief glories of the Florentine School—"the open expression of the living human soul." This widening and secularising of art did not pass in Florence, as we know, without a protest; and here, too, history is painted on the walls. Some of the protest was silent, as Angelico's, who painted on through[Pg 10] a later generation in the old spirit; some of it was vocal, in the fiery eloquence of Savonarola, whose influence may be seen in Botticelli's work (1034).

But the development went on, all protests notwithstanding; for as the life of every nation runs its appointed course, so does its art; and the second point of interest in studying a school of painting is to watch its successive periods of birth, growth, maturity, and decay. In no school is this development so completely marked as in the Florentine, which for this reason, as well as for its priority in time, and therefore influence on succeeding schools, takes precedence of all others. The first period—covering roughly the fourteenth century, called the Giottesque, from its principal master—is that in which the thing told is of more importance than the manner of telling it, and in which the religious sentiment dominated the plastic faculty. In the second period, covering roughly the fifteenth century, and called by the Italians the period of the quattro-centisti,[16] the artist, beginning as we have seen to look freely at the world around him, begins also to study deeply with a view to represent nature more exactly. One may see the new passion for the scientific study of the art in Paolo Uccello (583), who devoted himself to perspective; and in Pollajuolo (292), who first studied anatomy from the dead body. It is customary to group the Florentine artists of this scientific and realistic period under three heads, according to the main tendencies which they severally exhibit. The first group aimed especially at "action, movement, and the expression of intense passions." The artist who stands at the head of this group, Masaccio, is, unhappily, not represented in the National Gallery, but the descent from him is represented by Fra Filippo Lippi, Pesellino, Botticelli, Filippino Lippi. The second group aimed rather at "realistic probability, and correctness in hitting off the characteristics of individual things," and is represented by Cosimo Rosselli, Piero di Cosimo, Ghirlandajo, [Pg 11]Andrea del Sarto, Francia Bigio. Thirdly, some of the Florentine School were directly influenced by the work of contemporary sculptors. Chief amongst this group are Pollajuolo, Verocchio, himself a sculptor, and Lorenzo di Credi. We come now to the third stage in the Florentine, as in every other vital school of painting. This period witnesses the perfection of the technical processes of the art, and the attempt of the painter to "raise forms, imitated by the artists of the preceding period from nature, to ideal beauty, and to give to the representations of the sentiments and affections the utmost grace and energy." The great Florentine masters of this culminating period are Leonardo da Vinci and Michael Angelo. The former is especially typical of this stage of development. "When a nation's culture has reached its culminating point, we see everywhere," says Morelli,[17] "in daily life as well as in literature and art, that grace[18] comes to be valued more than character. So it was in Italy during the closing decades of the fifteenth century and the opening ones of the sixteenth. To no artist was it given to express this feeling so fully as to the great Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps the most richly gifted man that mother Nature ever made. He was the first who tried to express the smile of inward happiness, the sweetness of the soul." But this culminating period of art already contained within it the germs of decay. The very perfection of the technical processes of painting caused in all, except painters of the highest mental gifts, a certain deadness and coldness, such as Browning makes Andrea del Sarto (1487-1531) be conscious of in his own works; the "faultless painter" as compared with others less technically perfect but more full of soul (see under 690). Moreover the very fascination of the [Pg 12]great men, the pleasure in imitating their technical skill, led to decay. Grace soon passed into insipidity, and the dramatic energy of Michael Angelo into exaggerated violence. One mannerism led to another until the school of the "Eclectics" sought to unite the mannerisms of all, and Italian art, having run its course, became extinct.[19]

The growth and decay of painting described above is connected by Ruskin with a corresponding growth and decay in religion. He divides the course of mediæval art into two stages: the first stage (covering the first two periods above) "is that of the formation of conscience by the discovery of the true laws of social order and personal virtue, coupled with sincere effort to live by such laws as they are discovered. All the Arts advance steadily during this stage of national growth, and are lovely, even in their deficiencies, as the buds of flowers are lovely by their vital force, swift change, and continent beauty. The next stage is that in which the conscience is entirely formed, and the nation, finding it painful to live in obedience to the precepts it has discovered, looks about to discover, also, a compromise for obedience to them. In this condition of mind its first endeavour is nearly always to make its religion pompous, and please the gods by giving them gifts and entertainments, in which it may piously and pleasurably share itself; so that a magnificent display of the powers of art it has gained by sincerity, takes place for a few years, and is then followed by their extinction, rapid and complete exactly in the degree in which the nation resigns itself to hypocrisy. The works of Raphael, Michael Angelo, and Tintoret, belong to this period of compromise in the career of the greatest nation of the world; and are the most splendid efforts yet made by human creatures to maintain the dignity of states with beautiful colours, and defend the doctrines of theology with anatomical designs." It is easy [Pg 13]to see how the progress in realism led to a decline in religion. "The greater the (painter's) powers became, the more (his) mind was absorbed in their attainment, and complacent in their display. The early arts of laying on bright colours smoothly, of burnishing golden ornaments, or tracing, leaf by leaf, the outlines of flowers, were not so difficult as that they should materially occupy the thoughts of the artist, or furnish foundation for his conceit; he learned these rudiments of his work without pain, and employed them without pride, his spirit being left free to express, so far as it was capable of them, the reaches of higher thought. But when accurate shade, and subtle colour, and perfect anatomy, and complicated perspective, became necessary to the work, the artist's whole energy was employed in learning the laws of these, and his whole pleasure consisted in exhibiting them. His life was devoted, not to the objects of art, but to the cunning of it; and the sciences of composition and light and shade were pursued as if there were abstract good in them;—as if, like astronomy or mathematics, they were ends in themselves, irrespective of anything to be effected by them. And without perception, on the part of any one, of the abyss to which all were hastening, a fatal change of aim took place throughout the whole world of art. In early times art was employed for the display of religious facts; now, religious facts were employed for the display of art. The transition, though imperceptible, was consummate; it involved the entire destiny of painting. It was passing from the paths of life to the paths of death" (Relation between Michael Angelo and Tintoret, pp. 8, 9, and Modern Painters, vol. iii. pt. iv. ch. iv. § 11. See also under No. 744).

[16] It should be noted that the Italian terms quattro-cento and cinque-cento correspond with our fifteenth (1400-1500) and sixteenth (1500-1600) centuries respectively.

[17] Italian Masters in German Galleries, p. 124. My references to this work are to Mrs. Richter's translation, 1883; in the case of Morelli's Borghese and Doria-Pamfili Galleries in Rome, they are to Miss Ffoulkes's translation, 1892.

[18] Well said: but it remains to be asked, whether the "grace" sought is modest, or wanton: affectionate, or licentious (J. R.).

[19] Not by its own natural course or decay; but by the political and moral ruin of the cities by whose virtue it had been taught, and in whose glory it had flourished. The analysis of the decline of religious faith quoted below does not enough regard the social and material mischief which accompanied that decline (J. R.)

"Since we are teachers to unlearned men, who know not how to read, of the marvels done by the power and strength of holy religion, ... and since no undertaking, however small, can have a beginning or an end without these three things,—that is, without the power to do, without knowledge, and without true love of the work; and since in God every perfection is eminently united; now, to the end that in this our calling, however unworthy it may be, we may have a good beginning and a good ending in all our works and deeds, we will earnestly ask the aid of the Divine grace, and commence by a dedication to the honour of the Name, and in the Name of the most Holy Trinity" (Extract from the Statutes of the Painters' Guild of Siena, 1355).

The school of Siena, though in the main closely resembling that of Florence, has yet an independent origin and a distinct character. There is a "Madonna" at Siena, painted in 1281, which is decidedly superior to such work as Margaritone's (564). But the start which Siena obtained at first was soon lost; and at a time when Florentine art was finding new directions, that at Siena was running still in the old grooves. This was owing to the markedly religious character of its painting, shown in the tone of the statutes above quoted. Such religious fervour seems at first sight inconsistent with the character of a people who were famed for factious quarrels and[Pg 15] delicate living.[20] But "the contradiction is more apparent than real. The people of Siena were highly impressible and emotional, quick to obey the promptings of their passion, whether it took the form of hatred or of love, of spiritual fervour or of carnal violence. The religious feeling was a passion with them, on a par with all the other movements of their quick and mobile temperament."[21] Sienese art reflects this spirit; it is like the religion of their St. Catherine, rapt and ecstatic. The early Florentine pictures are not very dissimilar; but in Siena the same kind of art lasted much longer. In the work, for instance, of Matteo di Giovanni (see 1155), there is still the same expression of religious ecstasy, and the same prodigal use of gold in the background, as marked the works of the preceding century; yet he was contemporary with the Florentine Botticelli, who introduced many new motives into art. Matteo was the best Sienese painter of the fifteenth century, and with him the independent school of Siena comes to an end. Girolamo del Pacchia (246) betrays the influence of Florence; whilst Il Sodoma (1144), who settled at Siena and had many pupils, was not a native, and shows in his style no affinity with the true Sienese School. Peruzzi (218), on the other hand, was a native of Siena, but belongs in his artistic development to the Roman School.

[20] See Dante, Inferno xxix. 121. There was, moreover, in Siena a "Prodigal Club," and a poet of the day wrote a series of sonnets (translated by D. G. Rossetti) "Unto the blithe and lordly fellowship."

[21] History of the Renaissance in Italy, iii. 161.

Painters of "the loveliest district of North Italy, where hills, and streams, and air, meet in softest harmonies" (Ruskin: Queen of the Air, § 157).

The loose use of the term "school" has caused much confusion in the history and criticism of art. Sometimes the term is used with reference only to the place where such and such painters principally worked. Thus Raphael and Michael Angelo, together with their followers, are sometimes called the "Roman School." But Rome produced no great native painters; she was merely a centre to which painters were drawn from elsewhere. So too when the phrase "Milanese School" occurs, it generally means Leonardo da Vinci and his immediate pupils, because, though a Florentine, he taught at Milan. Sometimes, again, the term "school" is used as mere geographical expression. Thus under "Lombard School" are often included the painters of Parma, simply because Parma is contiguous to Lombardy. A third use of the term school, however, is that in which it means "a definite quality, native to the district, shared through many generations by all its[Pg 17] painters, and culminating in a few men of commanding genius." Such a definite quality is generally marked by "a special collection of traditions, and processes, a particular method, a peculiar style in design, and an equally peculiar taste in colouring—all contributing to the representation of a national ideal existing in the minds of the artists of the same country at the same time." This is the use of the term which is suggested by the main arrangement of the National Gallery, and which is at once the most instructive and the most interesting.

Following this principle in the case of the present chapter, we must first dispose of the "pseudo-Lombards"—the Cremonese, namely, and Correggio. The pictures belonging to artists of Cremona are, as will be seen below, practically Venetian. Correggio and his imitator Parmigiano are more difficult to deal with. The truth is that Correggio stands very much apart (see under 10); but if he must be labelled, it seems best to follow Morelli and class him, on the score of his early training, with the Ferrarese. Coming now to the genuine Lombard School, one sees by looking round the room that it is by no means identical with Leonardo da Vinci. He himself was a Florentine, who settled at Milan, and whose powerful individuality exercised a strong influence on succeeding painters there. But before his coming, there was a native Lombard School—with artists scattered about in the towns and villages around Milan, and with a distinct style of its own. Long before Leonardo came to settle at Milan, the Lombard Madonnas—with their long oval faces and somewhat simpering smile—have already what we now describe as a "Leonardesque character." Among technical points we may notice as characteristic of the Lombard School, in its earlier phases, a partiality for sombre tints and high finish in the rendering of detail. In spirit the School is characterised by great simplicity of feeling. It will be noticed that among the Milanese pictures there are few with any allegorical or mythological subject. Even after Leonardo came to Milan, bringing with him new motives and a wide curiosity, the native Lombard masters, such as Luini and[Pg 18] Gaudenzio Ferrari, adhered in the main to sacred subjects. The Lombard School, it should be observed, was late in arising. The building of Milan Cathedral and the Certosa of Pavia in the first part of the fifteenth century directed the art-impulse of the time rather to sculpture, and it was not till about 1450 that Vincenzo Foppa came from Brescia and established the principal school of painting at Milan. Other schools started with spiritual aims, which wore off, as it were, under the new pleasure of sharpening their means of execution; but the Lombards first took up the art when it had already been reduced to a science. And then most of the painters were natives, not of some large capital, but of small towns or country villages. Thus Luini was born on the Lago Maggiore, and the traditions of his life all murmur about the lake district. But he learned technique at Milan; and thus came to "stand alone," adds Ruskin, "in uniting consummate art power with untainted simplicity of religious imagination" (see references under 18).

With regard to the historical development of the school, it was founded, as we have seen, by Vincenzo Foppa, "the Mantegna of the Lombard School." Borgognone, his pupil, was its Perugino. Then came Leonardo from Florence, and the school divides into two sets—those who were immediately and directly his imitators, and those who, whilst feeling his influence, yet preserved the independent Lombard traditions. The visitor will have no difficulty in recognising the pictures of Beltraffio, Oggionno, and Martino Piazza as belonging to the former class. Solario, Luini, and Lanini are more independent. Lastly Sodoma, a pupil of Leonardo, went off to Siena and established a second Sienese School there, which is represented at the National Gallery by Peruzzi (218).

"One may almost apply to the School of Ferrara the proud boast of its ducal House of Este—

The Schools of Ferrara and Bologna, which, as will be seen, are substantially one and the same, are interesting both for themselves and for their influence on others. Two of the greatest of all Italian painters—Correggio and Raphael—may be claimed as "guests," as it were, of "this lordly" school. Correggio's master was Francesco Bianchi of Ferrara, a scholar of Cosimo Tura, and may possibly have afterwards studied under Francia at Bologna;[22] whilst as for Raphael, his master, Timoteo Viti, was also a pupil of Francia. The important influence of this school is natural enough, for the Ferrarese appear to have had much innate genius for art, and there is a note of unmistakable originality in their work.

"The Art of the Emilia, the region that lies between the river Po and the Apennines, has been unduly neglected. Here there once dwelt a vigorous and gifted race, as original[Pg 20] in their way as the Umbrians, Tuscans or Venetians, who found means of self-expression in form and colour under the political security of the Court of Este, and whose art forms an organic whole with stages of development and decay, characteristically differing, like their dialect, from that of other parts of Italy.... The traveller visiting the now deserted city of Ferrara, who meditates on its records of the past, may still in fancy see erected again the triumphal arches which welcomed emperors, popes and princes in the 'quattro-cento'; the gilded barges ascending the river to the city; the platforms draped with the arras, on which were woven in gold and silk stories of cavaliers in tilt and tourney; the duke in his robes, stiff with brocade of gold and covered with gems, bearing a jewelled sceptre in his hand; the magnificently caparisoned steeds; the princesses who came in their chariots of triumph, to be brides of the house of Este.... To trace the various processes, alike of thought, feeling and technique, which have gone to the making of a masterpiece of Correggio, L'Ortolano or Dosso is a fascinating pursuit. Only through knowledge of the tentative efforts of their predecessors at the splendid jovial court of the Este, is it possible to get a total impression. Born, as elsewhere, in bondage to rigid types and forms of composition, Ferrarese genius began by being profoundly dramatic and realistic. The masters of 1450 to 1475, well grounded in geometry, perspective and anatomy, painted rather what they saw than what they felt. Their aim was to conventionalise Nature rather than to transfigure her, and truth was more to them than beauty. The next generation, 1475 to 1500, developed technique so as to express movement and emotion, tempered by the eternal charm of antique ideals, till upon this sure foundation there arose men of high imagination and sentiment, who grasped and solved the mysteries of tone and colour, as distinguished from a brilliant palette" (R. H. Benson and A. Venturi in Burlington Fine Arts Club's Catalogue, 1894). Of the first or Giottesque period of the school no pictures survive, and the founder of the school, so far as we can now study it, is Cosimo Tura, who occupies[Pg 21] the same place in the art of Ferrara as Piero della Francesca occupied in that of Umbria, or Mantegna in that of Padua. Look at his picture (772): one sees at once that here is something different from other pictures, one feels that one would certainly be able to recognise that "rugged, gnarled, and angular" but vigorous style again. Doubtless there was some Flemish influence upon the school (see the notes on Tura, No. 772); and doubtless also the Ferrarese were influenced by the neighbouring school of Squarcione at Padua. But the pictures of Tura are enough to show how large an original element of native genius there was. The later developments of this genius are well illustrated in this room, with the important exception that Dosso Dossi, the greatest colourist amongst the Ferrarese masters, is very incompletely represented. His best works are to be seen at Ferrara, Dresden, Florence, and the Borghese Palace. He has been called "the Titian of the Ferrarese School," just as Lorenzo Costa has been called its Perugino and Garofalo its Raphael. Such phrases are useful as helping the student to compare corresponding pictures in different schools, and thus to appreciate their characteristics.

The early Bolognese School does not really exist except as an offshoot of the Ferrarese. Marco Zoppo (590) was "no better," says Morelli, "than a caricature of his master, Squarcione, and besides, he spent the greater part of his life at Venice;" whilst Lippo Dalmasii (752) was very inferior to contemporary artists elsewhere. The so-called earlier Bolognese School was really founded by the Ferrarese Francesco Cossa and Lorenzo Costa, who moved to Bologna about 1480, and the latter of whom "set up shop" with Francia in that town (see under 629). Remarks on the later "Eclectic" School of Bologna, formed by the Carracci, may more conveniently be deferred (see p. 35)

[22] See for Correggio's connection with the Ferrarese-Bolognese School, Morelli's German Galleries, pp. 120-124.

"More allied to the Tuscan than to the Venetian spirit, the Umbrian masters produced a style of genuine originality. The cities of the Central Apennines owed their specific quality of religious fervour to the influences emanating from Assisi, the headquarters of the cultus of St. Francis. This pietism, nowhere else so paramount, except for a short period in Siena, constitutes the individuality of Umbria" (J. A. Symonds: Renaissance in Italy, iii. 133).