*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 45733 ***

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Famous Men and Great Events of the Nineteenth

Century, by Charles Morris

Transcriber’s Note

The many illustrations have been moved to fall on paragraph breaks.

As a result, on occasion, the pagination will be locally disrupted.

Between the Introduction and Chapter I there are two full-page

illustrations, but the pagination skips four pages. On the other hand

the illustrations between pp. 94 and 95 were not included in the

pagination. The occasional blank pages have been omitted. In any case,

the page numbers provided here reflect those which were printed.

Footnotes were relocated from the end of page to the end of the

text and linked for easy reference.

Please see the transcriber’s notes at the end of this text for a more

complete account of any other textual issues and their resolution.

THE MARVELOUS PROGRESS OF THE 19th CENTURY

The above symbolic picture, after the master painting

of Paul Sinibaldi, explains the secret of the

wonderful progress of the past 100 years. The genius

of Industry stands in the centre. To her right sits

Chemistry; to the left the geniuses of Electricity

with the battery, the telephone, the electric light;

there also are the geniuses of Navigation with the

propeller, and of Literature and Art, all bringing

their products to Industry who passes them through the

hands of Labor in the foreground to be fashioned for

the use of mankind.

THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF ONE HUNDRED YEARS

Famous Men And Great Events

of the Nineteenth Century

Embracing Descriptions of the Decisive Battles of the Century and

the Great Soldiers Who Fought Them; the Rise and Fall of Nations; the

Changes in the Map of the World, and the Causes Which Contributed

to Political and Social Revolutions; Discoverers and Discoveries;

Explorers of the Tropics and Arctics; Inventors and Their Inventions;

the Growth of Literature, Science and Art; the Progress of Religion,

Morals and Benevolence in All Civilized Nations.

By CHARLES MORRIS, LL. D.

Author of “The Aryan Race,” “Civilization, Its History, Etc.,”

“The Greater Republic,” Etc.

Embellished With Nearly 100 Full-Page Half-Tone Engravings,

Illustrating the Greatest Events of the Century, and 100 Portraits of

the Most Famous Men in the World.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1899, by

W. E. SCULL,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

LIST OF CHAPTERS AND SUBJECTS

| Introduction | PAGE |

|

A Bird’s-eye View—Tyranny and Oppression in the Eighteenth

Century—Government and the Rights of Man in 1900—Prisons

and Punishment in 1900—The Factory System and Oppression

of the Workingman—Suffrage and Human Freedom—Criminal

Law and Prison Discipline in 1800—The Era of Wonderful

Inventions—The Fate of the Horse and the Sail—Education,

Discovery and Commerce | 23 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The Threshold of the Century | |

|

The Age We Live in and its Great Events—True History and

the Things Which Make It—Two of the World’s Greatest

Events—The Feudal System and Its Abuses—The Climax of

Feudalism in France—The States General is Convened—The

Fall of the Bastille—King and Queen Under the

Guillotine—The Reign of Terror—The Wars of the French

Revolution—Napoleon in Italy and Egypt—England as a

Centre of Industry and Commerce—The Condition of the

German States—Dissension in Italy and Decay in Spain—The

Partition of Poland by the Robber Nations—Russia and

Turkey | 33 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Napoleon Bonaparte; The Man of Destiny | |

|

A Remarkable and Wonderful Career—The Enemies and Friends

of France—Movements of the Armies in Germany and

Italy—Napoleon Crosses the Alps at St. Bernard Pass—The

Situation in Italy—The Famous Field of Marengo—A

Great Battle Lost and Won—The Result of the Victory of

Marengo—Napoleon Returns to France—Moreau and the Great

Battle of Hohenlinden—The Peace of Luneville—The Peace

of Amiens—The Punishment of the Conspirators and the

Assassination of the Duke d’Enghien—Napoleon Crowned

Emperor of the French—The Great Works Devised By the New

Emperor | 44 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Europe in the Grasp of the Iron Hand | |

|

Great Preparations for the Invasion of England—Rapid March

on Austria—The Surrender of General Mack—The Eve Before

Austerlitz—The Dreadful Lake Horror—Treaty of Peace

With Austria—Prussian Armies in the Field—Defeat of the

Prussians at Jena and Auerstadt—Napoleon Divides the

Spoils of Victory—The Frightful Struggle at Eylau—The

Cost of Victory—The Total Defeat of the Russians—The

Emperors at Tilsit and the Fate of Prussia—The Pope a

Captive at Fontainebleau—Andreas Hofer and the War in

Tyrol—Napoleon Marches Upon Austria—The Battle of

Eckmuhl and the Capture of Ratisbon—The Campaign in

Italy—The Great Struggle of Essling and Aspern—Napoleon

Forced to His First Retreat—The Second Crossing of the

Danube—The Victory at Wagram—The Peace of Vienna—The

Divorce of Josephine and Marriage of Maria Louisa | 57 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Decline and Fall of Napoleon’s Empire | |

|

The Causes of the Rise and Decline of Napoleon’s Power—Aims

and Intrigues in Portugal and Spain—Spain’s Brilliant

Victory and King Joseph’s Flight—The Heroic Defence of

Saragossa—Wellington’s Career in Portugal and Spain—The

Invasion of Russia by the Grand Army—Smolensk Captured

and in Flames—The Battle of Borodino—The Grand Army

in the Old Russian Capital—The Burning of the Great

City of Moscow—The Grand Army Begins its Retreat—The

Dreadful Crossing of the Beresina—Europe in Arms Against

Napoleon—The Battle of Dresden, Napoleon’s Last Great

Victory—The Fatal Meeting of the Armies at Leipzig—The

Break-up of Napoleon’s Empire—The War in France and the

Abdication of the Emperor—Napoleon Returns From Elba—The

Terrible Defeat at Waterloo—Napoleon Meets His Fate | 83 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Nelson and Wellington, the Champions of England | |

|

England and France on Land and Sea—Nelson Discovers the

French Fleet in Aboukir Bay—The Glorious Battle of the

Nile—The Fleet Sails for Copenhagen—The Danish Line

of Defence—The Attack on the Danish Fleet—How Nelson

Answered the Signal to Cease Action—Nelson in Chase of

the French Fleet—The Allied Fleet Leaves Cadiz—Off Cape

Trafalgar—The “Victory” and Her Brilliant Fight—The Great

Battle and its Sad Disaster—Victory for England and Death

for Her Famous Admiral—The British in Portugal—The Death

of Sir John Moore—The Gallant Crossing of the Douro—The

Victory at Talavera and the Victor’s Reward—Wellington’s

Impregnable Lines at Torres Vedras—The Siege and Capture

of the Portuguese Fortresses—Wellington Wins at Salamanca

and Enters Madrid—Vittoria and the Pyrenees—The Gathering

of the Forces at Brussels—The Battlefield of Waterloo—The

Desperate Charges of the French—Blücher’s Prussians and

the Charge of Napoleon’s Old Guard | 101 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| From the Napoleonic Wars to the Revolution 1830 |

|

A Quarter Century of Revolution—Europe After Napoleon’s

Fall—The Work of the Congress—Italy, France and

Spain—The Rights of Man—The Holy Alliance—Revolution

in Spain and Naples—Metternich and His Congresses—How

Order Was Restored in Spain—The Revolution in Greece—The

Powers Come to the Rescue of Greece—The Spirit of

Revolution—Charles X. and His Attempt at Despotism—The

Revolution in Paris—Louis Phillippe Chosen as King—Effect

in Europe of the Revolution—The Belgian Uprising and

its Result—The Movements in Germany—The Condition of

Poland—The Revolt of the Poles—A Fatal Lack of Unity—The

Fate of Poland | 116 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Bolivar, the Liberator of Spanish America | |

|

How Spain Treated Her Colonies—The Oppression of the

People—Bolivar the Revolutionary Leader—An Attempt

at Assassination—Bolivar Returns to Venezuela—The

Savage Cruelty of the Spaniards—The Methods of General

Morillo—Paez the Guerilla and His Exploits—British

Soldiers Join the Insurgents—Bolivar’s Plan to Invade

New Granada—The Crossing of the Andes—The Terror of the

Mountains—Bolivar’s Methods of Fighting—The Victory at

Boyaca—Bolivar and the Peruvians—The Freeing of the Other

Colonies | 128 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Great Britain as a World Empire | |

|

Napoleonic Wars’ Influence—Great Awakening in Commerce—

Developments of the Arts—Growth of the Sciences—A Nation

Noted for Patriotism—National Pride—Conscious Strength—

Political Changes and Their Influence—Great Statesmen of

England | 141 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| The Great Reform Bill and the Corn Laws | |

|

Causes of Unrest—Demands of the People—The Struggle for

Reform in 1830—The Corn Laws—Free Trade in Great

Britain—Cobden the Apostle of Free Trade—Other Promoters

of Reform—England’s Enlarged Commerce | 147 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Turkey the “Sick Man” of Europe |

|

The Sultan’s Empire in 1800—Revolts in Her

Dependencies—Greece Gains Her Freedom—The Sympathy of

the Christian World—Russian Threats—The Crimean War and

its Heroes—The War of 1877—The Armenian Massacres—The

Nations Warn off Russia—War in Crete and Greece in

1897—The Tottering Nation of to-day—The “Sick Man” | 156 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The European Revolution of 1848 |

|

Corrupt Courts and Rulers—The Spirit of Liberty Among

the People—Bourbonism—Revolutionary Outbreak in

France—Spreads to Other Countries—The Struggle in

Italy—In Germany—The Revolt in Hungary—The Career of

Kossuth the Patriot, Statesman and Orator—His Visit

to America—Defeat of the Patriots by Austria and

Hungary—General Haynau the Cruel Tyrant—Later History of

Hungary | 167 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Louis Napoleon and the Second French Empire | |

|

The Power of a Great Name—The French People Love the

Name Napoleon—Louis Napoleon’s Personality—Elected

President—The Tricks of His Illustrious Ancestor

Imitated—Makes Himself Emperor—The War With

Austria—Sends an Army to Mexico—Attempt to Establish

an Empire in America—Maximilian Made Emperor in the New

World—His Sad Fate—War With Germany—Louis Napoleon

Dethroned | 178 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Garibaldi and the Unification of Italy | |

|

The Many Little States of Italy—Secret Movements for

Union—Mazzini the Revolutionist—Tyranny of Austria

and Naples—War in Sardinia—Victor Emanuel and Count

Cavour—Garibaldi in Arms—The French in Rome—Fall of the

Papal City—Rise of the New Italy—Naval War With Austria | 194 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Bismarck and the New Empire of Germany | |

|

The State of Prussia—Sudden Rise to Power—Bismarck Prime

Minister—War With Denmark—With Austria—With France—Metz

and Sedan—Von Moltke—The Fall of Paris—William I.

Crowned Emperor—United Germany—Bismarck and the Young

Kaiser—Peculiarities of William II.—Germany of To-Day | 207 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Gladstone the Apostle of Liberalism in England | |

|

Sterling Character of the Man—His Steady Progress to

Power—Becomes Prime Minister—Home and Foreign Affairs

Under His Administration—His Long Contest With

Disraeli—Early Conservatism Later Liberalism—Home Rule

Champion—Result of Gladstone’s Labors | 243 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Ireland the Downtrodden | |

|

Ancient Ireland—English Domination—Oppression—Patriotic

Struggles Against English Rule—Robert Emmet and

His Sad Fate—Daniel O’Connell—Grattan, Curran and

Other Patriots—The Fenians—Gladstone’s Work for

Ireland—Parnell, the Irish Leader in Parliament—Ireland

of the Present | 259 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| England and Her Indian Empire | |

|

Why England Went to India—Lord Clive and the East India

Company—Sir Arthur Wellesley—Trouble With the

Natives—Subjugation of Indian States—The Great

Mutiny—Havelock—Relief of Lucknow—Repulse From

Afghanistan—Conquest of Burmah—Queen Victoria Crowned

Empress of India—What English Rule Has Done for the

Orient—A Vast Country Teeming With Population—Its

Resources and Its Prospects | 268 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Thiers, Gambetta and the Rise of the New French Republic | |

|

French Instability of Character—Modern Statesmen

of France—Thiers—MacMahon—Gambetta—The New

Republic—Leaders in Politics—Dangerous Powers of the

Army—Moral and Religious Decline—Law and Justice—The

Dreyfus Case as an Index to France’s National Character and

the Perils Which Beset the Republic | 277 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| Paul Kruger and South Africa | |

|

Review of the Boers—Their Establishment in Cape Colony—The

Rise and Progress of the Transvaal Republic—Diamond Mines

and Gold Discoveries—England’s Aggressiveness—The Career

of Cecil Rhodes—Attempt to Overthrow the Republic—The

Zulus and Neighboring Peoples—The Uitlanders—Political

Struggle of England and Paul Kruger—Chamberlain’s

Demands—The Boers’ Firm Stand—War of 1899 | 295 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| The Rise of Japan and the Decline of China | |

|

Former Cloud of Mystery Surrounding These Two Nations—Ancient

Civilizations—Closed Territory to the Outside World—Their

Ignorance of Other Nations—The Breaking Down of

the Walls in the Nineteenth Century—Japan’s Sudden

Rise to Power—Aptness to Learn—The Yankees of the

East—Conditions of Conservatism Holds on in China—Li

Hung Chang Rises into Prominence—The Corean Trouble—War

Between China and Japan—The Battle of Yalu River—Admiral

Ito’s Victory—Japanese Army Invades the Celestial

Empire—China Surrenders—European Nations Demand Open

Commerce—Threatened Partition | 309 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| The Era of Colonies | |

|

Commerce the Promoter of Colonization—England’s Wise

Policy—The Growth of Her Colonies Under Liberal

Treatment—India—Australia—Africa—Colonies of France

and Germany—Partition of Africa—Progress of Russia in

Asia—Aggressiveness of the Czar’s Government—The United

States Becomes a Colonizing Power—The Colonial Powers and

Their Colonies at the Close of the Century | 323 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| How the United States Entered the Century | |

|

A Newly Formed Country—Washington, the National Capital—Peace

With France—Nations of State Sovereignty—State

Legislatures and the National Congress—The Influence of

Washington—The Supreme Court and its Powers—Population

of Less Than Four Millions—No City of 50,000 Inhabitants

in America—Sparsely Settled Country—Savages—Trouble

With Algiers—War Declared by Tripoli—Thomas Jefferson

Elected President | 343 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| Expansion of the United States From Dwarf to Giant | |

|

Ohio Admitted in 1802—Louisiana Purchased From French

1803—Admission of the States—Florida Transferred to the

United States 1819—The First Railway in 1826—Indians

Cede Their Illinois Lands in 1830—Invention of Telegraph

1832—Fremont’s Expeditions to the Pacific Slope—Conquest

of Mexico—Our Domain Established From Ocean to Ocean

1848—The Purchase of Alaska From Russia 1867—Rapid

Internal Growth—Cities Spring up on the Plains—A

Marvelous Era of Peace—Through the Spanish-American War

Comes the Acquisition of First Tropical Territory—From

East to West America’s Domain Reaches Half-way Around the

World—Three Cities Each With Over 1,000,000 Inhabitants | 351 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| The Development of Democratic Institutions In America | |

|

Colonization and its Results—Religious Influences—Popular

Rights—Limitations—Colonial Legislatures—The Money

Question—Taxation—Confederation—The Franchise—Property

Qualifications—Growth of Western Ideas—Contrast Between

Institutions at the Beginning and Close of the Century | 361 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| America’s Answer to British Doctrine of Right of Search | |

|

Why the War of 1812 Was Fought—The Principles

Involved—Impressing American Sailors—Insults and

Outrages Resented—The “Chesapeake” and “Leopard”—Injury

to Commerce—Blockades—Embargo as Retaliation—Naval

Glory—Failure of Canadian Campaign—“Constitution” and

the “Guerriere”—The “Wasp” and the “Frolic”—Other

Sea Duels—Privateers—Perry’s Great Victory—Land

Operations—The “Shannon” and the “Chesapeake”—Lundy’s

Lane and Plattsburg—The Burning of Washington—Baltimore

Saved—Jackson’s Victory at New Orleans—Treaty of Peace | 369 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| The United States Sustains Its Dignity Abroad | |

|

First Foreign Difficulty—The Barbary States—Buying

Peace—Uncle Sam Aroused—Thrashes the Algerian

Pirates—A Splendid Victory—King Bomba Brought to

Terms—Austria and the Koszta Case—Captain Ingraham—His

Bravery—“Deliver or I’ll Sink You”—Austria Yields—The

Paraguayan Trouble—Lopez Comes to Terms—The Chilian

Imbroglio—Balmaceda—The Insult to the United

States—American Seamen Attacked—Matta’s Impudent

Letter—Backdown—Peace—All’s Well That Ends Well, Etc. | 382 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| Webster and Clay—The Preservation of the Union |

|

The Great Questions in American Politics in the First Half

of the Century—The Great Orators to Which They Gave

Rise—Daniel Webster—Henry Clay—John C. Calhoun

—Clay’s Compromise Measure on the Tariff Question—On

Slavery Extension—Webster and Calhoun and the Tariff

Question—Webster’s Reply to Hayne—The Union Must and

Shall be Preserved | 398 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| The Annexation of Texas and the War With Mexico | |

|

Texas as a Province of Mexico—Rebellion and War—The Alamo

Massacre—Rout of Mexicans at San Jacinto—Freedom

of Mexico—Annexation to the United States—The War

With Mexico—Taylor and Buena Vista—Scott and Vera

Cruz—Advance on and Capture of Mexico—Results of the War | 413 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| The Negro In America and the Slavery Conflict | |

|

The Negro in America—The First Cargo—Beginning of the Slave

Traffic—As a Laborer—Increase in Numbers—Slavery;

its Different Character in Different States—Political

Disturbances—Agitation and Agitators—John Brown—War and

How it Emancipated the Slave—The Free Negro—His Rapid

Progress | 425 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| Abraham Lincoln and the Work of Emancipation | |

|

Lincoln’s Increasing Fame—Comparison With Washington—The

Slave Auction at New Orleans—“If I Ever Get a Chance

to Hit Slavery, I Will Hit it Hard”—The Young

Politician—Elected Representative to Congress—His

Opposition to Slavery—His Famous Debates With Douglas—The

Cooper Institute Speech—The Campaign of 1860—The Surprise

of Lincoln’s Nomination—His Triumphant Election—Threats

of Secession—Firing on Sumter—The Dark Days of the

War—The Emancipation Question—The Great Proclamation—End

of the War—The Great Tragedy—The Beauty and Greatness of

His Character | 436 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| Grant and Lee and The Civil War | |

|

Grant a Man for the Occasion—Lincoln’s Opinion—“Wherever

Grant is Things Move”—“Unconditional Surrender”—“Not a

Retreating Man”—Lee a Man of Acknowledged Greatness—His

Devotion to Virginia—Great Influence—Simplicity of

Habits—Shares the Fare of His Soldiers—Lee’s Superior

Skill—Gratitude and Affection of the South—Great

Influence in Restoring Good Feeling—The War—Secession

Not Exclusively a Southern Idea—An Irrepressible

Conflict—Coming Events—Lincoln—A Nation in Arms—

Sumter—Anderson—McClellan—Victory and Defeat—“Monitor”

and “Merrimac”—Antietam—Shiloh—Buell—Grant—George H.

Thomas—Rosecrans—Porter—Sherman—Sheridan—Lee—

Gettysburg—A Great Fight—Sherman’s March—The

Confederates Weakening—More Victories—Appomattox—Lee’s

Surrender—From War to Peace | 449 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| The Indian in the Nineteenth Century | |

|

Our Relations and Obligations to the Indian—Conflict

between Two Civilizations—Indian Bureau—Government

Policy—Treaties—Reservation Plan—Removals Under

It—Indian Wars—Plan of Concentration—Disturbance

and Fighting—Plan of Education and Absorption—Its

Commencement—Present Condition of Indians—Nature of

Education and Results—Land in Severalty Law—Missionary

Effort—Necessity and Duty of Absorption | 468 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| The Development of the American Navy | |

|

The Origin of the American Navy—Sights on Guns and What They

Did—Opening Japan—Port Royal—Passing the Forts—The

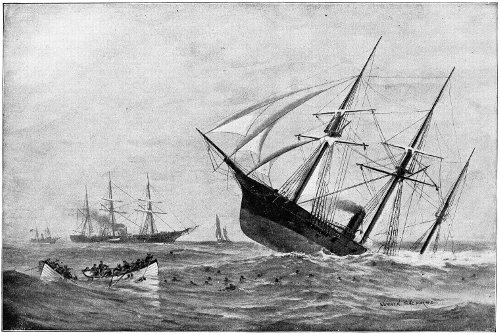

“Monitor” and “Merrimac”—In Mobile Bay—The “Kearsarge”

and the “Alabama”—Naval Architecture Revolutionized—The

Samoan Hurricane—Building a New Navy—Great Ships of

the Spanish American War—The Modern Floating Iron

Fortresses—New “Alabama” and “Kearsarge” | 482 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| America’s Conflict With Spain | |

|

A War of Humanity—Bombardment of Matanzas—Dewey’s Wonderful

Victory at Manila—Disaster to the “Winslow” at Cardenas

Bay—The First American Loss of Life—Bombardment of San

Juan, Porto Rico—The Elusive Spanish Fleet—Bottled-up in

Santiago Harbor—Lieutenant Hobson’s Daring Exploit—Second

Bombardment of Santiago and Arrival of the Army—Gallant

Work of the Rough Riders and the Regulars—Battles of San

Juan and El Caney—Destruction of Cervera’s Fleet—General

Shafter Reinforced in Front of Santiago—Surrender

of the City—General Miles in Porto Rico—An Easy

Conquest—Conquest of the Philippines—Peace Negotiations

and Signing of the Protocol—Its Terms—Members of the

National Peace Commission—Return of the Troops from Cuba

and Porto Rico—The Peace Commission in Paris—Conclusion

of its Work—Terms of the Treaty—Ratified by the Senate | 496 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| The Dominion of Canada | |

|

The Area and Population of Canada—Canada’s Early

History—Upper and Lower Canada—The War of 1812—John

Strachan and the Family Compact—A Religious

Quarrel—French Supremacy in Lower Canada—The Revolt of

1837—Mackenzie’s Rebellion—Growth of Population and

Industry—Organization of the Dominion of Canada—The

Riel Revolts—The Canadian Pacific Railway—The Fishery

Difficulties—The Fur-Seal Question—The Gold of

the Klondike—A Boundary Question—An International

Commission—The Questions at Issue—The Failure of

the Commission—Commerce of Canada with the United

States—Railway Progress in Canada—Manufacturing

Enterprise—Yield of Precious Metals—Extent and Resources

of the Dominion—The Character of the Canadian Population | 509 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| Livingstone, Stanley, Peary, Nansen and other Great Discoverers and

Explorers | |

|

Ignorance of the Earth’s Surface at the Beginning of

the Century—Notable Fields of Nineteenth Century

Travel—Famous African Travelers—Dr. Livingstone’s

Missionary Labors—Discovery of Lake Ngami—Livingstone’s

Journey from the Zambesi to the West Coast—The

Great Victoria Falls—First Crossing of the

Continent—Livingstone discovers Lake Nyassa—Stanley in

Search of Livingstone—Other African Travelers—Stanley’s

Journeys—Stanley Rescues Emin Pasha—The Exploration

of the Arctic Zone—The Greely Party—The Fatal

“Jeanette” Expedition—Expeditions of Professor

Nordenskjöld—Peary Crosses North Greenland—Nansen and his

Enterprise—Andrée’s Fatal Balloon Venture | 523 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| Robert Fulton, George Stephenson, and the Triumphs of Invention |

|

Anglo-Saxon Activity in Invention—James Watt and the

Steam Engine—Labor-Saving Machinery of the Eighteenth

Century—The Steamboat and the Locomotive—The First

Steamboat Trip up the Hudson—Development of Ocean

Steamers—George Stephenson and the Locomotive—First

American Railroads—Development of the Railroad—Great

Railroad Bridges—The Electric Steel Railway—The

Bicycle and the Automobile—Marvels in Iron and

Woodworking—Progress in Illumination and Heating—Howe and

the Sewing Machine—Vulcanization of Rubber—Morse and the

Telegraph—The Inventions of Edison—Marconi and Wireless

Telegraphy—Increase of Working Power of the Farmer—The

American Reapers and Mowers—Commerce of the United States | 535 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

| The Evolution in Industry and the Revolt Against Capital | |

|

Mediæval Industry—Cause of Revolution in the Labor

System—Present Aspect of the Labor Question—The

Trade Union—The International Workingmen’s

Association—The System of the Strike—Arbitration

and Profit Sharing—Experiments and Theories in

Economies—Co-operative Associations—The Theories

of Socialism and Anarchism—Secular Communistic

Experiments—Development of Socialism—Growth of the

Socialist Party—The Development of the Trust—An

Industrial Revolution | 554 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | |

| Charles Darwin and the Development of Science | |

|

Scientific Activity of the Nineteenth Century—Wallace’s

“Wonderful Century”—Useful and Scientific Steps of

Progress—Foster’s Views of Recent Progress—Discoveries

in Astronomy—The Spectroscope—The Advance of

Chemistry—Light and its Phenomena—Heat as a Mode of

Motion—Applications of Electricity—The Principles

of Magnetism—Progress in Geology—The Nebular and

Meteoric Hypotheses—Biological Sciences—Discoveries in

Physiology—Pasteur and His Discoveries—Koch and the

Comma Bacillus—The Science of Hygiene—Darwin and Natural

Selection | 569 |

| CHAPTER XL | |

| Literature and Art in the Nineteenth Century | |

|

Literary Giants of Former Times—The Standing of the Fine Arts

in the Past and the Present—Early American Writers—The

Poets of the United States—American Novelists—American

Historians and Orators—The Poets of Great Britain—British

Novelists and Historians—Other British Writers—French

Novelists and Historians—German Poets and Novelists—The

Literature of Russia—The Authors of Sweden, Norway and

Denmark—Writers of Italy—Other Celebrated Authors—The

Novel and its Development—The Text-Book and Progress of

Education—Wide-spread use of Books and Newspapers | 591 |

| CHAPTER XLI | |

| The American Church and the Spirit of Human Brotherhood | |

|

Division of Labor—American Type of Christianity—Distinguishing

Feature of American Life—The Sunday-school System—The Value

of Religion in Politics—Missionary Activity—New Religious

Movements—The Movement in Ethics—Child Labor in

Factories—Prevention of Cruelty to Animals—Prison

Reform—Public Executions—The Spirit of Sympathy—The Growth

of Charity—An Advanced Spirit of Benevolence | 605 |

| CHAPTER XLII | |

| The Dawn of the Twentieth Century | |

|

The Century’s Wonderful Stages—Progress in Education—The

Education of Women—Occupation and Suffrage

for Women—Peace Proposition of the Emperor of

Russia—The Peace Conference at The Hague—Progress in

Science—Political Evolution—Territorial Progress of the

Nations—Probable Future of English Speech—A Telephone

Newspaper—Among the Dull-Minded Peoples—Limitations to

Progress—Probable Lines of Future Activity—Industry in

the Twentieth Century—The King, the Priest and the Cash

Box—The New Psychology | 617 |

LIST OF FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

| | PAGE |

| Progress of the Nineteenth Century | Frontispiece |

| Duke of Chartres at the Battle of Jemappes | 21 |

| Battle of Chateau-Gontier | 22 |

| Death of Marat | 31 |

| Last Victims of the Reign of Terror | 32 |

| Marie Antoinette Led to Execution | 37 |

| The Battle of Rivoli | 38 |

| Napoleon Crossing the Alps | 47 |

| Napoleon and the Mummy of Pharaoh | 48 |

| Napoleon Bonaparte | 53 |

| The Meeting of Two Sovereign | 54 |

| The Death of Admiral Nelson | 59 |

| Murat at the Battle of Jena | 60 |

| The Battle of Eylau | 69 |

| The Battle of Friedland | 70 |

| The Order to Charge at Friedland | 79 |

| Napoleon and the Queen of Prussia at Tilsit | 80 |

| Marshal Ney Retreating from Russia | 89 |

| General Blücher’s Fall at Ligny | 90 |

| The Battle of Dresden, August 26 and 27, 1813 | 94 |

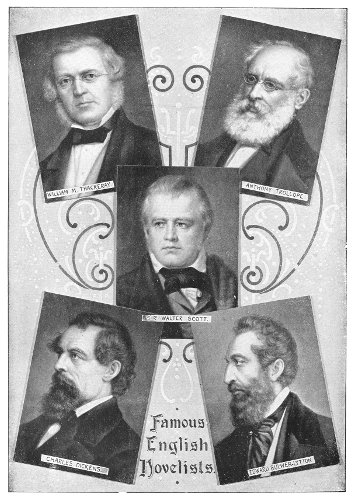

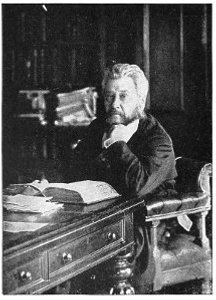

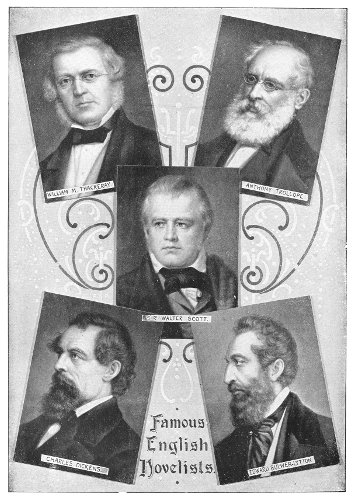

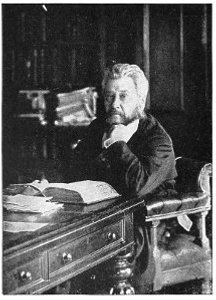

| Famous English Novelists | 95 |

| The Eve of Waterloo | 99 |

| Wellington at Waterloo Giving the Word to Advance | 100 |

| Retreat of Napoleon from Waterloo | 109 |

| The Remnant of an Army | 110 |

| Illustrious Leaders of England’s Navy and Army | 119 |

| James Watt, the Father of the Steam Engine | 120 |

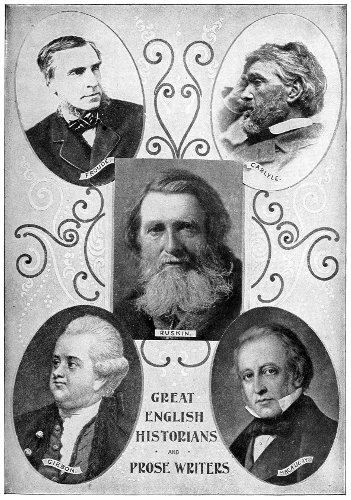

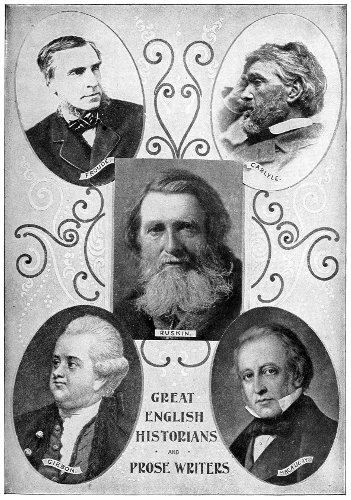

| Great English Historians and Prose Writers | 129 |

| Famous Popes of the Century | 130 |

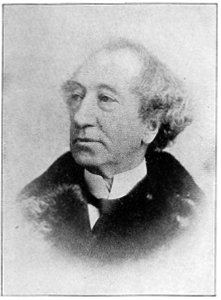

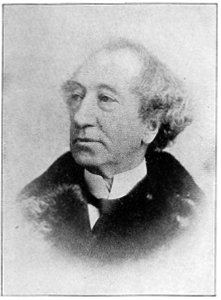

| Great English Statesmen (Plate I) | 139 |

| Britain’s Sovereign and Heir Apparent to the Throne | 140 |

| Popular Writers of Fiction In England | 149 |

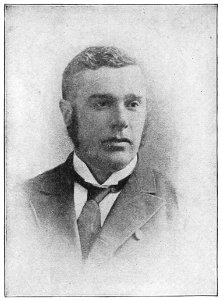

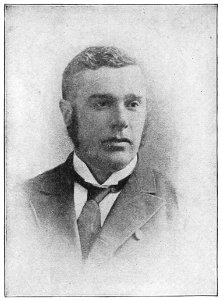

| Great English Statesmen (Plate II) | 150 |

| Potentates of the East | 159 |

| Landing in the Crimea and the Battle of Alma | 160 |

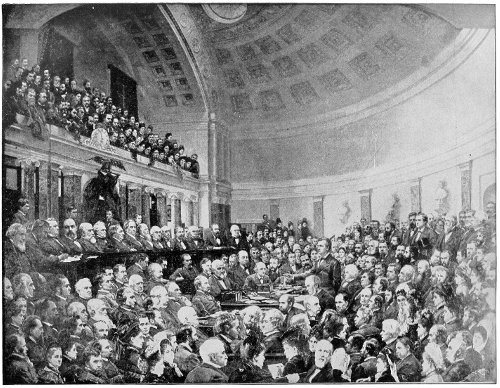

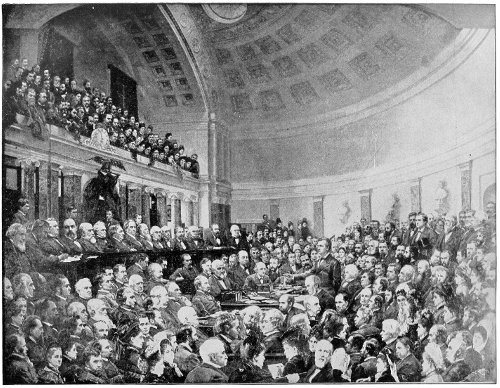

| The Congress at Berlin, June 13, 1878 | 169 |

| The Wounding of General Bosquet | 170 |

| The Battle of Champigny | 179 |

| Noble Sons of Poland and Hungary | 180 |

| Noted French Authors | 189 |

| Napoleon III. at the Battle of Solferino | 190 |

| Great Italian Patriots | 199 |

| The Zouaves Charging the Barricades at Mentana | 200 |

| Noted German Emperors | 209 |

| Renowned Sons of Germany | 210 |

| The Storming of Garsbergschlosschen | 219 |

| Crown Prince Frederick at the Battle of Froschwiller | 220 |

| Present Kings of Four Countries | 229 |

| Great Men of Modern France | 230 |

| Russia’s Royal Family and Her Literary Leader | 257 |

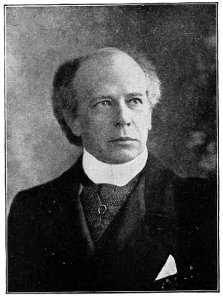

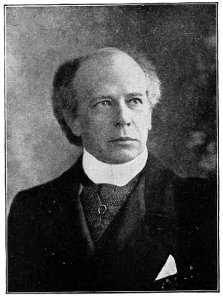

| Four Champions of Ireland’s Cause | 258 |

| Dreyfus, His Accusers and Defenders | 281 |

| The Dreyfus Trial | 282 |

| The Bombardment of Alexandria | 291 |

| Battle Between England and the Zulus, South Africa | 292 |

| The Battle of Majuba Hill, South Africa | 301 |

| Two Opponents in the Transvaal War | 302 |

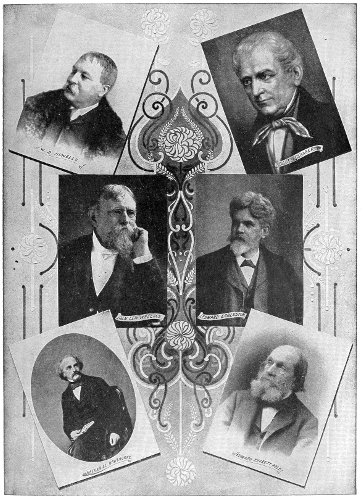

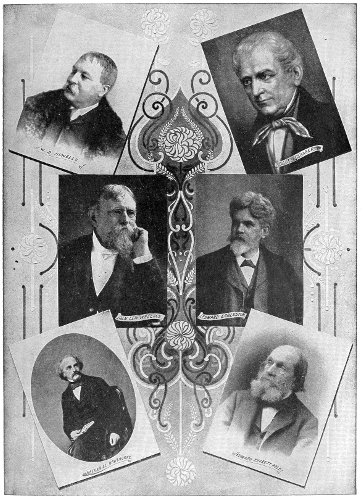

| Typical American Novelists | 307 |

| Two Powerful Men of the Orient | 308 |

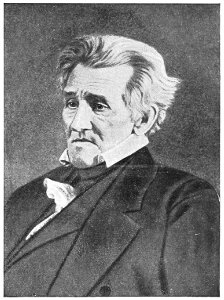

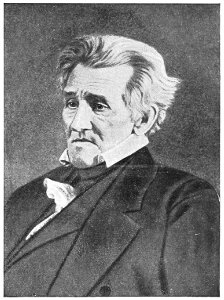

| Four American Presidents | 409 |

| Great American Orators and Statesmen | 410 |

| The Battle of Resaca de la Palma | 419 |

| Great American Historians and Biographers | 420 |

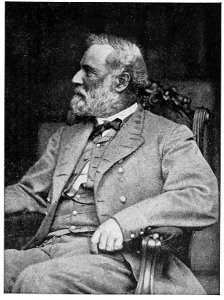

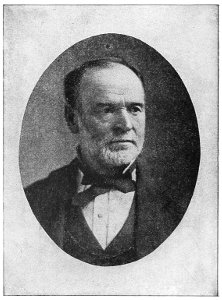

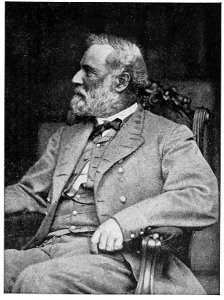

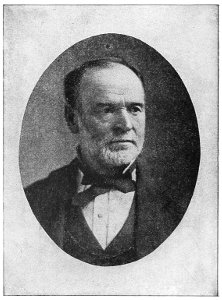

| Great Men of the Civil War in America | 445 |

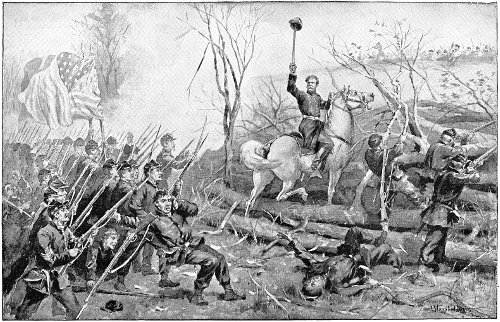

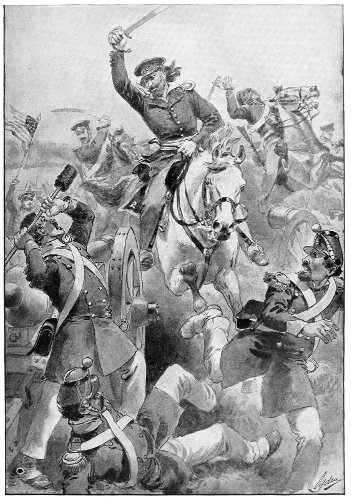

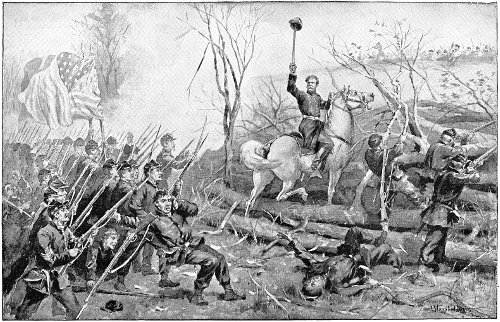

| The Attack on Fort Donelson | 446 |

| General Lee’s Invasion of the North | 455 |

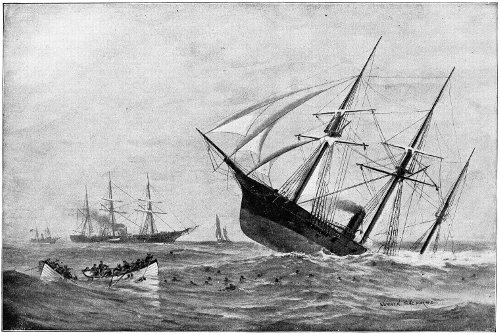

| The Sinking of the Alabama, etc. | 456 |

| The Surrender of General Lee | 465 |

| The Electoral Commission Which Decided Upon Election of

President Hayes | 466 |

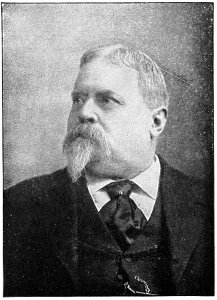

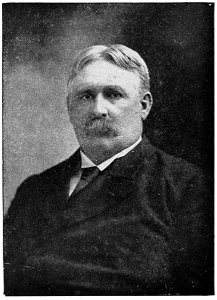

| Prominent American Political Leaders | 475 |

| Noted American Journalists and Magazine Contributors | 476 |

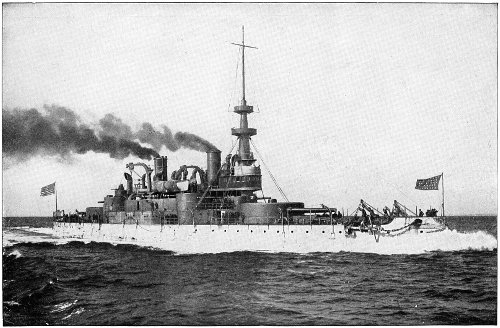

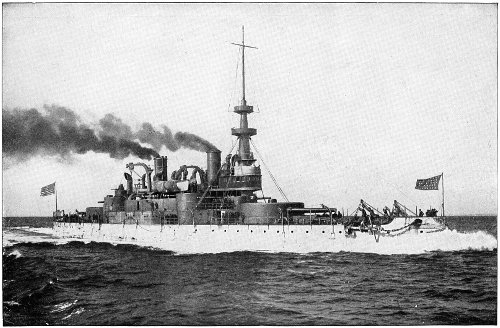

| The U.S. Battleship “Oregon” | 483 |

| In the War-Room at Washington | 484 |

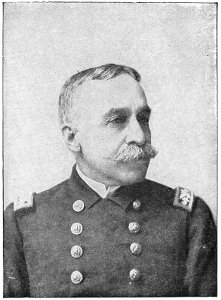

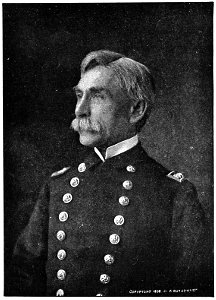

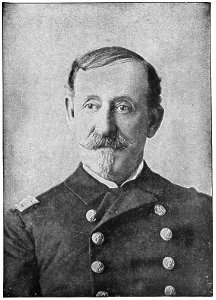

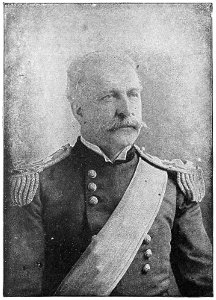

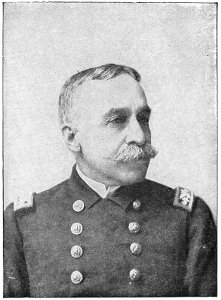

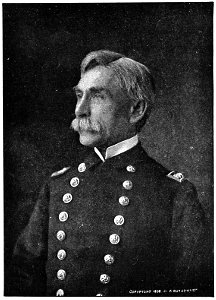

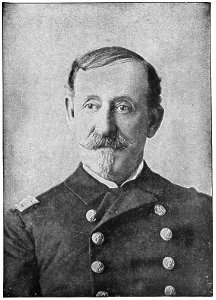

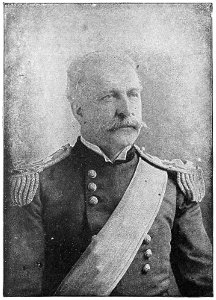

| Leading Commanders of the American Navy, Spanish-American War | 487 |

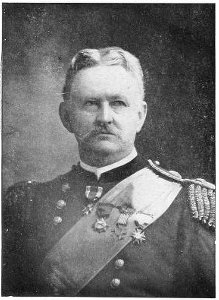

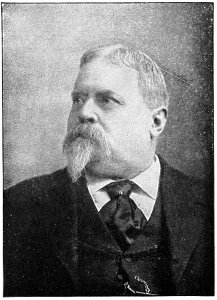

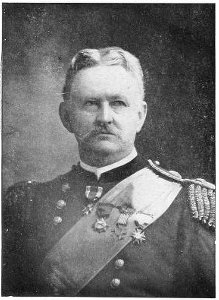

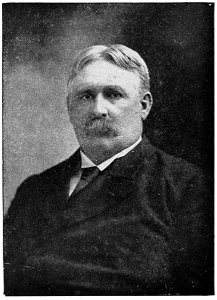

| Leading Commanders of the American Army | 488 |

| Prominent Spaniards in 1898 | 497 |

| Popular Heroes of the Spanish-American War | 498 |

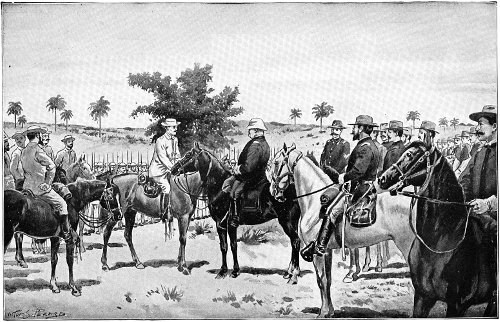

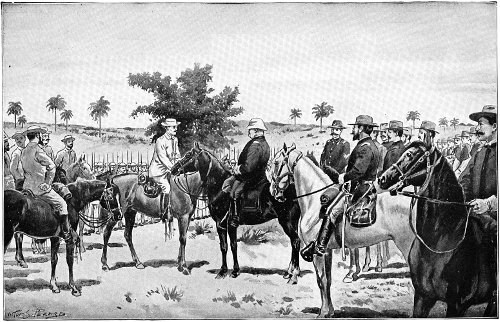

| The Surrender of Santiago | 501 |

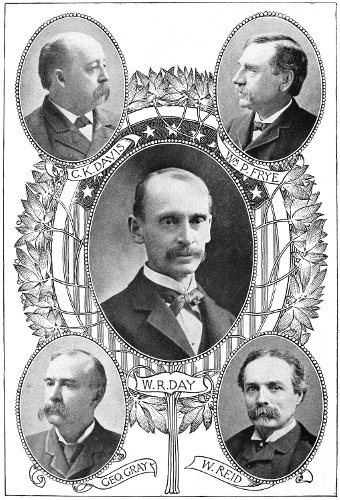

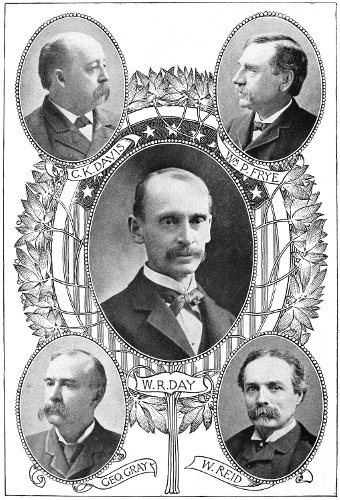

| United States Peace Commissioners of the Spanish-American War | 502 |

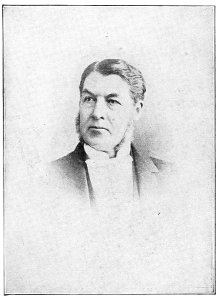

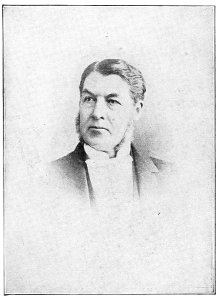

| Illustrious Sons of Canada | 521 |

| Great Explorers in the Tropics and Arctics | 522 |

| Inventors of the Locomotive and the Electric Telegraph | 539 |

| Edison Perfecting the First Phonograph | 540 |

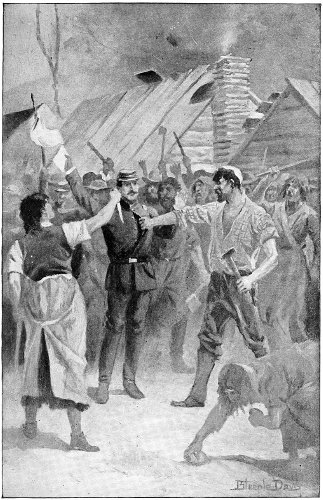

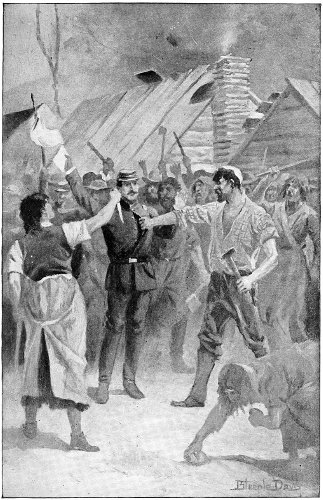

| The Hero of the Strike, Coal Creek, Tenn. | 557 |

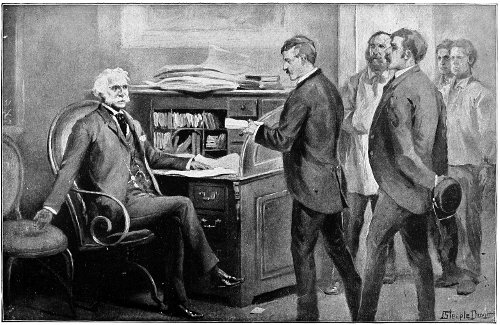

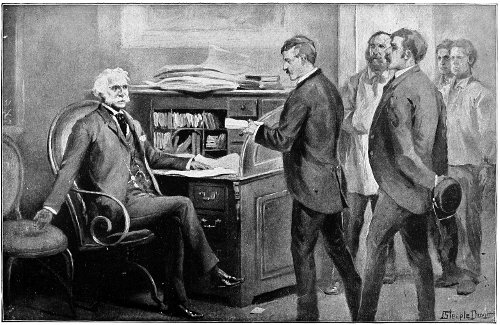

| Arbitration | 558 |

| Illustrious Men of Science in the Nineteenth Century | 575 |

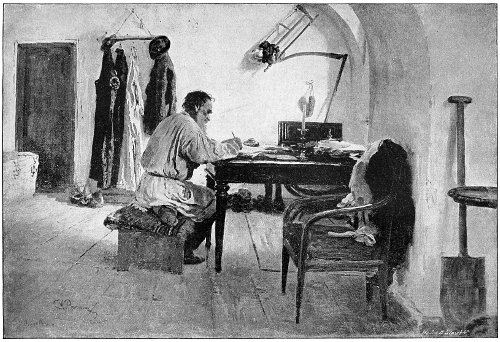

| Pasteur in His Laboratory | 576 |

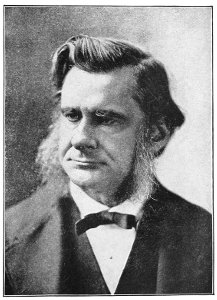

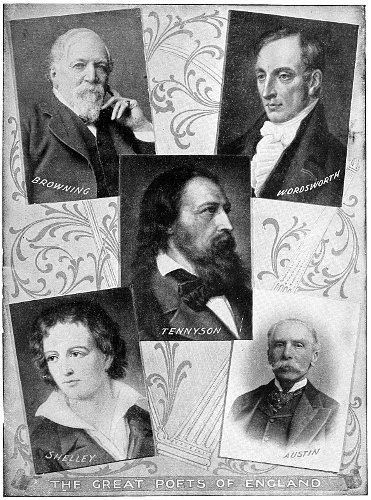

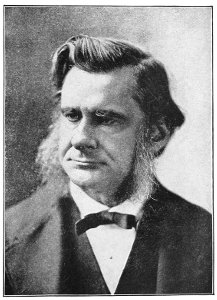

| Great Poets of England | 589 |

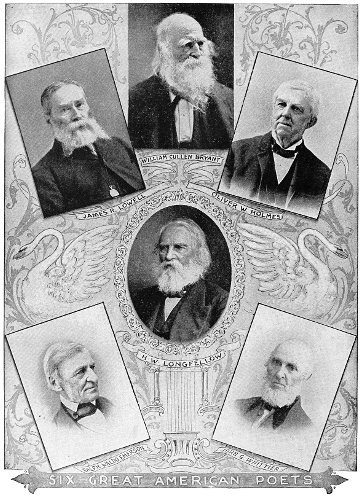

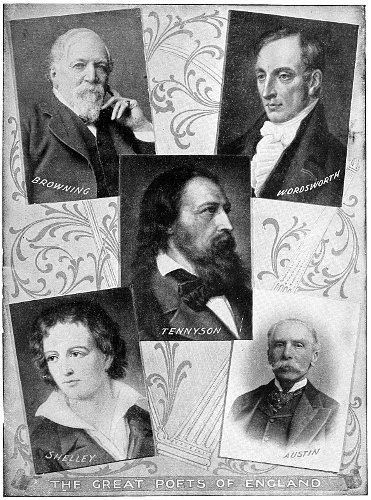

| Great American Poets | 590 |

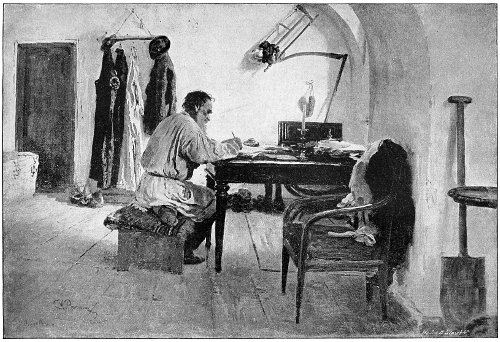

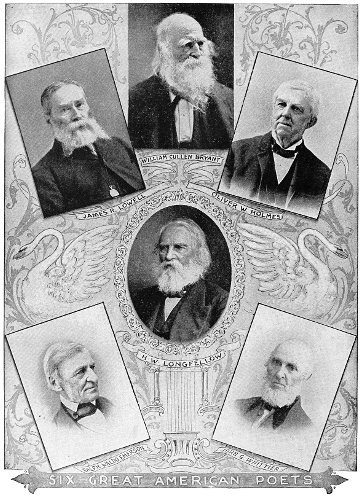

| Count Tolstoi at Literary Work | 603 |

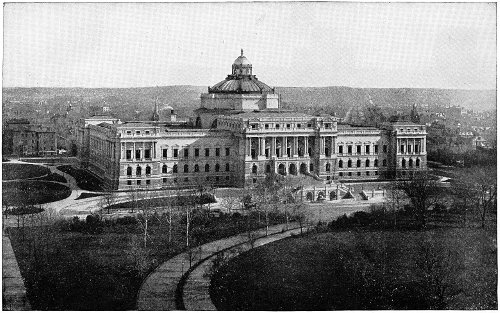

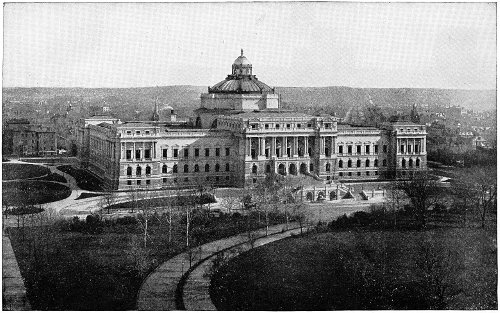

| New Congressional Library at Washington, D. C. | 604 |

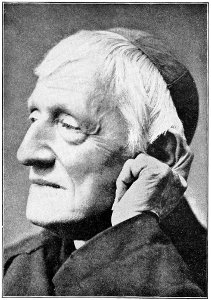

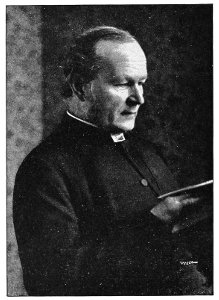

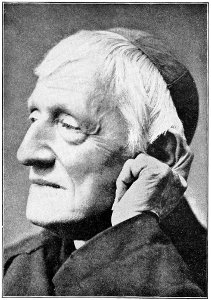

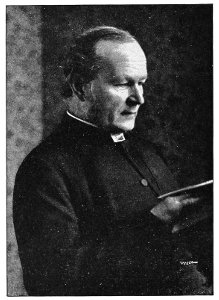

| Famous Cardinals of the Century | 615 |

| Noted Preachers and Writers of Religious Classics | 616 |

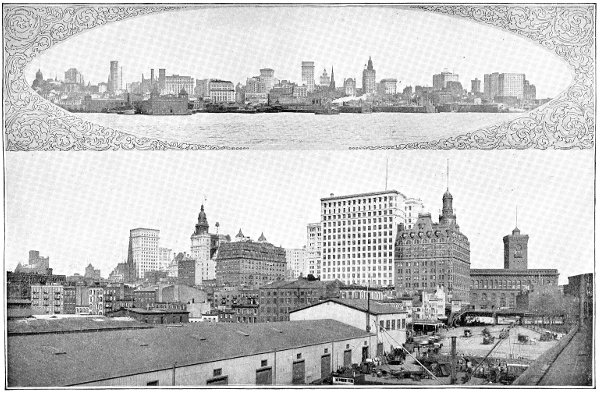

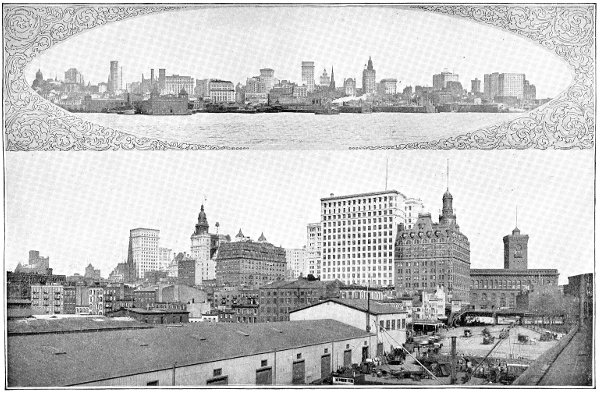

| Greater New York | 629 |

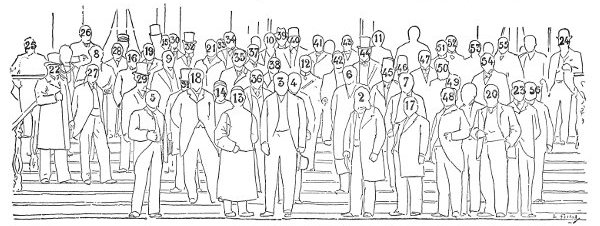

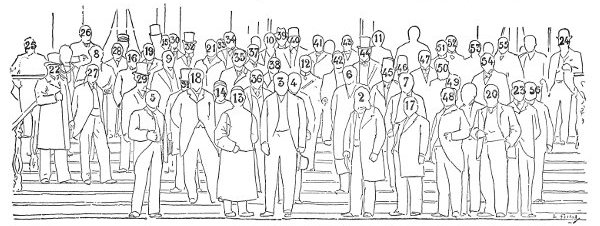

| Delegates to the Universal Peace Conference at The Hague, 1899 | 630 |

| Key to above | 631 |

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF PORTRAITS

| | PAGE |

| Abbott, Lyman | 476 |

| Adams, John Quincy | 409 |

| Agassiz, Louis | 575 |

| Aguinaldo, Emilio | 308 |

| Albert Edward, (Prince of Wales) | 140 |

| Austin, Alfred | 589 |

| Balfour, A. J. | 150 |

| Bancroft, George | 420 |

| Barrie, James M. | 149 |

| Beecher, Henry Ward | 410 |

| Besant, Walter | 149 |

| Bismarck, Karl Otto Von | 210 |

| Black, William | 149 |

| Blaine, James G. | 475 |

| Blanco, Ramon | 497 |

| Bright, John | 139 |

| Browning, Robert | 589 |

| Bryan, William Jennings | 475 |

| Bryant, William Cullen | 590 |

| Bryce, James | 150 |

| Caine, T. Hall | 149 |

| Carlyle, Thomas | 129 |

| Cervera, (Admiral) | 497 |

| Chamberlain, Joseph | 302 |

| Christian IX, (King of Denmark) | 229 |

| Clay, Henry | 410 |

| Cleveland, Grover | 475 |

| Cooper, James Fenimore | 307 |

| Dana, Charles A. | 476 |

| Darwin, Charles | 575 |

| Davis, Cushman K. | 502 |

| Davis, Richard Harding | 476 |

| Davitt, Michael | 258 |

| Day, William R. | 502 |

| DeLesseps, Ferdinand | 230 |

| Depew, Chauncey M. | 410 |

| Dewey, George | 487 |

| Dickens, Charles | 95 |

| Disraeli, Benjamin | 139 |

| Dreyfus, (Captain), Alfred | 281 |

| Doyle, A. Conan | 149 |

| Drummond, Henry | 616 |

| Dumas, Alexander | 189 |

| DuMaurier, George | 149 |

| Eggleston, Edward | 307 |

| Emerson, Ralph Waldo | 590 |

| Esterhazy, Count Ferdinand W. | 281 |

| Everett, Edward | 410 |

| Farrar, Frederick W., (Canon) | 616 |

| Francis Joseph, (Emperor of Austria) | 229 |

| Froude, Richard H. | 129 |

| Frye, William P. | 502 |

| Gambetta, Leon | 230 |

| Garibaldi, Guiseppe | 199 |

| Gibbon, Edward | 129 |

| Gladstone, William Ewart | 139 |

| Gough, John B. | 410 |

| Grady, Henry W. | 410 |

| Grant, Ulysses S. | 445 |

| Gray, George | 502 |

| Greeley, Horace | 476 |

| Hale, Edward Everett | 307 |

| Halstead, Murat | 476 |

| Hawthorne, Nathaniel | 307 |

| Hawthorne, Julian | 476 |

| Healy, T. M. | 258 |

| Henry, Patrick | 410 |

| Henry, Lieutenant-Colonel | 281 |

| Hobson, Richmond Pearson | 498 |

| Holmes, Oliver Wendell | 590 |

| Howells, William Dean | 307 |

| Hugo, Victor | 189 |

| Humbert, (King of Italy) | 229 |

| Humboldt, F. H. Alexander von | 575 |

| Huxley, Thomas H. | 575 |

| Jackson, Andrew | 409 |

| Jefferson, Thomas | 409 |

| Kipling, Rudyard | 149 |

| Kosciusko, Thaddeus | 180 |

| Kossuth, Louis | 180 |

| Kruger, Paul | 302 |

| Labori, Maitre | 281 |

| Laurier, Sir Wilfrid | 521 |

| Lee, Robert E. | 445 |

| Lee, Fitzhugh | 488 |

| Leo XIII., (Pope) | 130 |

| Li Hung Chang | 308 |

| Lincoln, Abraham | 445 |

| Livingstone, David | 522 |

| Longfellow, Henry W. | 590 |

| Loubet (President of France) | 230 |

| Lowell, James Russell | 590 |

| Lytton, (Lord) Bulwer | 95 |

| McCarthy, Justin | 150 |

| Macaulay, Thomas B. | 129 |

| MacDonald, Sir John A. | 521 |

| MacDonald, George | 149 |

| McKinley, William | 475 |

| McMaster, John B. | 420 |

| Manning, Henry Edward (Cardinal) | 615 |

| Mercier, (General of French Army) | 281 |

| Merritt, Wesley | 488 |

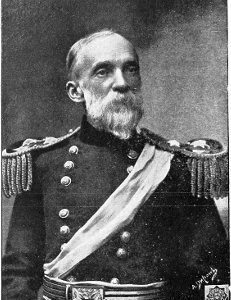

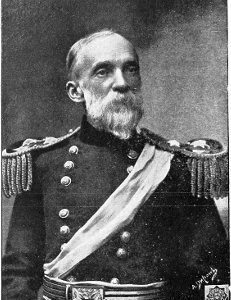

| Miles, Nelson A. | 488 |

| Moltke, H. Karl B. von | 210 |

| Morley, John | 150 |

| Morse, Samuel F. B. | 539 |

| Motley, John L. | 420 |

| Nansen, (Dr.) Frithiof | 522 |

| Napoleon Bonaparte | 53 |

| Nelson, (Lord) Horatio | 119 |

| Newman, John Henry (Cardinal) | 615 |

| Nicholas II. and Family, (Czar of Russia) | 257 |

| O’Brien, William | 258 |

| Oscar II., (King of Sweden and Norway) | 229 |

| Otis, Elwell S. | 498 |

| Parnell, Charles Stewart | 258 |

| Parton, James | 420 |

| Pasteur, Louis, in his Laboratory | 576 |

| Peary, Lieutenant R. E. | 522 |

| Phillips, Wendell | 410 |

| Pitt, William, (Earl of Chatham) | 139 |

| Pius IX., (Pope) | 130 |

| Prescott, William H. | 420 |

| Reid, Whitelaw | 476 |

| Rios, Montero | 497 |

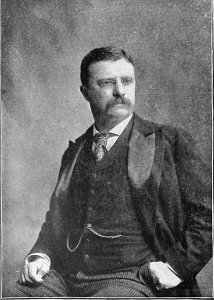

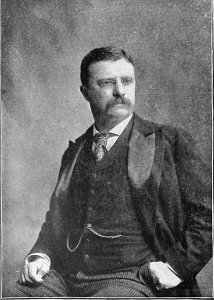

| Roosevelt, Theodore | 498 |

| Ruskin, John | 129 |

| Sagasta, Praxedes Mateo | 497 |

| Sampson, William T. | 487 |

| Schley, Winfield Scott | 487 |

| Scott, Sir Walter | 95 |

| Shafter, William R. | 488 |

| Shah of Persia | 150 |

| Shaw, Albert W. | 476 |

| Shelley, Percy B. | 589 |

| Sherman, William T. | 445 |

| Spurgeon, Charles H. | 616 |

| Stanley, Henry M. | 522 |

| Stephenson, George | 539 |

| Stevenson, Robert Louis | 149 |

| Sultan of Turkey | 159 |

| Taylor, Zachary | 409 |

| Tennyson, Alfred | 589 |

| Thackeray, William Makepeace | 95 |

| Thiers, Louis Adolphe | 230 |

| Thompson, Hon. J. S. D. | 521 |

| Tolstoi, Count Lyof Nikolaievitch | 603 |

| Trollope, Anthony | 95 |

| Tupper, Sir Charles | 521 |

| Victor Emmanuel (King of Italy) | 199 |

| Victoria (Queen of England) | 140 |

| Wallace, General Lew | 307 |

| Watson, John (Ian Maclaren) | 616 |

| Watson, John Crittenden | 487 |

| Watt, James | 120 |

| Watterson, Henry W. | 476 |

| Webster, Daniel | 410 |

| Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, (Duke) | 119 |

| Wheeler, Joseph | 498 |

| Whittier, John G. | 590 |

| William I., Emperor of Germany | 209 |

| William II., Emperor of Germany | 209 |

| Wordsworth, William | 589 |

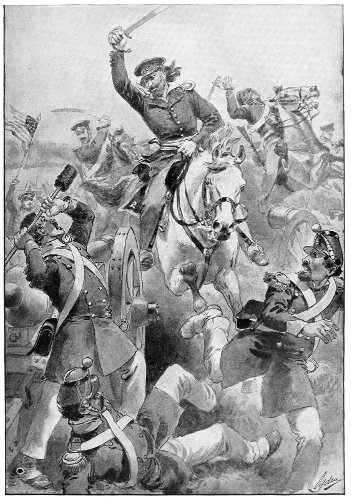

THE DUKE OF CHARTRES AT THE BATTLE OF JEMAPPES—

(from the original painting by A. Le Dres)

At Jemappes, in November, 1792, a battle was fought

between the French and Austrians. The Duke of Chartres

was Chief Lieutenant under General Dumouriez and

commanded the centre of attack. In 1830 the Duke was

made King of France, and on account of his peaceful

reign was known as the “Citizen’s King.” In 1848 he

abdicated the throne and soon after Napoleon III

became President of the new Republic.

BATTLE OF CHATEAU-GONTIER

(Reign of Terror, 1792)

INTRODUCTION.

It is the story of a hundred years that we propose to give; the record

of the noblest and most marvelous century in the annals of mankind.

Standing here, at the dawn of the Twentieth Century, as at the summit

of a lofty peak of time, we may gaze far backward over the road we have

traversed, losing sight of its minor incidents, but seeing its great

events loom up in startling prominence before our eyes; heedless of

its thronging millions, but proud of those mighty men who have made

the history of the age and rise like giants above the common throng.

History is made up of the deeds of great men and the movements of grand

events, and there is no better or clearer way to tell the marvelous

story of the Nineteenth Century than to put upon record the deeds of

its heroes and to describe the events and achievements in which reside

the true history of the age.

First of all, in this review, it is important to show in what the

greatness of the century consists, to contrast its beginning and

its ending, and point out the stages of the magnificent progress it

has made. It is one thing to declare that the Nineteenth has been

the greatest and most glorious of the centuries; it is another and

more arduous task to trace the development of this greatness and the

culmination of this career of glory. This it is that we shall endeavor

to do in the pages of this work. All of us have lived in the century

here described, many of us through a great part of it, some of us,

possibly, through the whole of it. It is in the fullest sense our own

century, one of which we have a just right to feel proud, and in whose

career all of us must take a deep and vital interest.

A Bird’s-Eye View

Before entering upon the history of the age it is well to take a

bird’s-eye view of it, and briefly present its claims to greatness.

They are many and mighty, and can only be glanced at in these

introductory pages; it would need volumes to show them in full. They

cover every field of human effort. They have to do with political

development, the relations of capital and labor, invention, science,

literature, production, commerce, and a dozen other life interests, all

of which will be considered in this work. The greatness of the world’s

progress can be most clearly shown by pointing out the state of affairs

in the several branches of human effort at the opening and closing of

the century and placing them in sharp contrast. This it is proposed to

do in this introductory sketch.

Tyranny and Oppression in the Eighteenth Century

A hundred years ago the political aspect of the world was remarkably

different from what it is now. Kings, many of them, were tyrants;

peoples, as a rule, were slaves—in fact, if not in name. The absolute

government of the Middle Ages had been in a measure set aside, but

the throne had still immense power, and between the kings and the

nobles the people were crushed like grain between the upper and nether

millstones. Tyranny spread widely; oppression was rampant; poverty was

the common lot; comfort was confined to the rich; law was merciless;

punishment for trifling offences was swift and cruel; the broad

sentiment of human fellowship had just begun to develop; the sun of

civilization shone only on a narrow region of the earth, beyond which

barbarism and savagery prevailed.

In 1800, the government of the people had just fairly begun. Europe had

two small republics, Switzerland and the United Netherlands, and in the

West the republic of the United States was still in its feeble youth.

The so-called republic of France was virtually the kingdom of Napoleon,

the autocratic First Consul, and those which he had founded elsewhere

were the slaves of his imperious will. Government almost everywhere

was autocratic and arbitrary. In Great Britain, the freest of the

monarchies, the king’s will could still set aside law and justice in

many instances and parliament represented only a tithe of the people.

Not only was universal suffrage unknown, but some of the greatest

cities of the kingdom had no voice in making the laws.

Government and the Rights of Man in 1900

In 1900, a century later, vast changes had taken place in the political

world. The republic of the United States had grown from a feeble infant

into a powerful giant, and its free system of government had spread

over the whole great continent of America. Every independent nation of

the West had become a republic and Canada still a British colony, was a

republic in almost everything but the name. In Europe, France was added

to the list of firmly-founded republics, and throughout that continent,

except in Russia and Turkey, the power of the monarchs had declined,

that of the people had advanced. In 1800, the kings almost everywhere

seemed firmly seated on their thrones. In 1900, the thrones everywhere

were shaking, and the whole moss-grown institution of kingship was

trembling over the rising earthquake of the popular will.

Suffrage and Human Freedom

The influence of the people in the government had made a marvelous

advance. The right of suffrage, greatly restricted in 1800, had

become universal in most of the civilized lands at the century’s end.

Throughout the American continent every male citizen had the right of

voting. The same was the case in most of western Europe, and even in

far-off Japan, which a century before had been held under a seemingly

helpless tyranny. Human slavery, which held captive millions upon

millions of men and women in 1800, had vanished from the realms of

civilization in 1900, and a vigorous effort was being made to banish

it from every region of the earth. As will be seen from this hasty

retrospect, the rights of man had made a wonderful advance during the

century, far greater than in any other century of human history.

Criminal Law and Prison Discipline in 1800

In the feeling of human fellowship, the sentiment of sympathy and

benevolence, the growth of altruism, or love for mankind, there had

been an equal progress. At the beginning of the century law was stern,

justice severe, punishment frightfully cruel. Small offences met with

severe retribution. Men were hung for a dozen crimes which now call for

only a light punishment. Thefts which are now thought severely punished

by a year or two in prison then often led to the scaffold. Men are hung

now, in the most enlightened nations, only for murder. Then they were

hung for fifty crimes, some so slight as to seem petty. A father could

not steal a loaf of bread for his starving children except at peril of

a long term of imprisonment, or, possibly, of death on the scaffold.

And imprisonment then was a different affair from what it is now. The

prisons of that day were often horrible dens, noisome, filthy, swarming

with vermin, their best rooms unfit for human residence, their worst

dungeons a hell upon earth. This not only in the less advanced nations,

but even in enlightened England. Newgate Prison, in London, for

instance, was a sink of iniquity, its inmates given over to the cruel

hands of ruthless gaolers, forced to pay a high price for the least

privilege, and treated worse than brute cattle if destitute of money

and friends. And these were not alone felons who had broken some of the

many criminal laws, but men whose guilt was not yet proved, and poor

debtors whose only crime was their misfortune. And all this in England,

with its boast of high civilization. The people were not ignorant of

the condition of the prisons; Parliament was appealed to a dozen times

to remedy the horrors of the jails; yet many years passed before it

could be induced to act.

Prisons and Punishment in 1900

Compare this state of criminal law and prison discipline with that

of the present day. Then cruel punishments were inflicted for small

offences; now the lightest punishments compatible with the well-being

of the community are the rule. The sentiment of human compassion has

become strong and compelling; it is felt in the courts as well as among

the people; public opinion has grown powerful, and a punishment to-day

too severe for the crime would be visited with universal condemnation.

The treatment of felons has been remarkably ameliorated. The modern

prison is a palace as compared with that of a century ago. The terrible

jail fever which swept through the old-time prisons like a pestilence,

and was more fatal to their inmates than the gallows, has been stamped

out. The idea of sanitation has made its way into the cell and the

dungeon, cleanliness is enforced, the frightful crowding of the past is

not permitted, prisoners are given employment, they are not permitted

to infect one another with vice or disease, kindness instead of cruelty

is the rule, and in no direction has the world made a greater and more

radical advance.

The Factory System and the Oppression of the

Workingman

A century ago labor was sadly oppressed. The factory system had

recently begun. The independent hand and home work of the earlier

centuries was being replaced by power and machine work. The

steam-engine and the labor-saving machine, while bringing blessings to

mankind, had brought curses also. Workmen were crowded into factories

and mines, and were poorly paid, ill-treated, ill-housed, over-worked.

Innocent little children were forced to perform hard labor when they

should have been at play or at school. The whole system was one of

white slavery of the most oppressive kind.

To-day this state of affairs no longer exists. Wages have risen, the

hours of labor have decreased, the comfort of the artisan has grown,

what were once luxuries beyond his reach have now become necessaries

of life. Young children are not permitted to work, and older ones not

beyond their strength. With the influences which have brought this

about we are not here concerned. Their consideration must be left to

a later chapter. It is enough here to state the important development

that has taken place.

Perhaps the greatest triumph of the nineteenth century has been in

the domain of invention. For ages past men have been aiding the work

of their hands with the work of their brains. But the progress of

invention continued slow and halting, and many tools centuries old were

in common use until the nineteenth century dawned. The steam-engine

came earlier, and it is this which has stimulated all the rest. A power

was given to man enormously greater than that of his hands, and he at

once began to devise means of applying it. Several of the important

machines used in manufacture were invented before 1800, but it was

after that year that the great era of invention began, and words are

hardly strong enough to express the marvelous progress which has since

taken place.

The Era of Wonderful Inventions

To attempt to name all the inventions of the nineteenth century would

be like writing a dictionary. Those of great importance might be named

by the hundreds; those which have proved epoch-making by the dozens. To

manufacture, to agriculture, to commerce, to all fields of human labor,

they extend, and their name is legion. Standing on the summit of this

century and looking backward, its beginning appears pitifully poor and

meager. Around us to-day are hundreds of busy workshops, filled with

machinery, pouring out finished products with extraordinary speed, men

no longer makers of goods, but waiters upon machines. In the fields the

grain is planted and harvested, the grass cut and gathered, the ground

ploughed and cultivated, everything done by machines. Looking back for

a century, what do we see? Men in the fields with the scythe and the

sickle, in the barn with the flail, working the ground with rude old

ploughs and harrows, doing a hundred things painfully by hand which now

they do easily and rapidly by machines. Verily the rate of progress on

the farm has been marvelous.

The Fate of the Horse and the Sail

The above are only a few of the directions of the century’s progress.

In some we may name, the development has been more extraordinary

still. Let us consider the remarkable advance in methods of travel.

In the year 1800, as for hundreds and even thousands of years before,

the horse was the fastest means known of traveling by land, the

sail of traveling by sea. A hundred years more have passed over our

heads, and what do we behold? On all sides the powerful, and swift

locomotive, well named the iron-horse, rushes onward, bound for the

ends of the earth, hauling men and goods to right and left with a speed

and strength that would have seemed magical to our forefathers. On

the ocean the steam engine performs the same service, carrying great

ships across the Atlantic in less than a week, and laughing at the

puny efforts of the sail. The horse, for ages indispensable to man, is

threatened with banishment. Electric power has been added to that of

steam. The automobile carriage is coming to take the place of the horse

carriage. The steam plough is replacing the horse plough. The time

seems approaching when the horse will cease to be seen in our streets,

and may be relegated to the zoological garden.

In the conveyance of news the development is more like magic than fact.

A century ago news could not be transported faster than the horse could

run or the ship could sail. Now the words of men can be carried through

space faster than one can breathe. By the aid of the telephone a man

can speak to his friend a thousand miles away. And with the phonograph

we can, as it were, bottle up speech, to be spoken, if desired, a

thousand years in the future. Had we whispered those things to our

forefathers of a century past we should have been set down as wild

romancers or insane fools, but now they seem like every-day news.

These are by no means all the marvels of the century. At its beginning

the constitution of the atmosphere had been recently discovered. In

the preceding period it was merely known as a mysterious gas called

air. To-day we can carry this air about in buckets like so much water,

or freeze it into a solid like ice. In its gaseous state it has long

been used as the power to move ships and windmills. In its liquid state

it may also soon become a leading source of power, and in a measure

replace steam, the great power of the century before.

Education, Discovery and Commerce

In what else does the beginning of the twentieth stand far in advance

of that of the nineteenth century? We may contrast the tallow candle

with the electric light, the science of to-day with that of a century

ago, the methods and the extension of education and the dissemination

of books with those of the year 1800. Discovery and colonization of the

once unknown regions of the world have gone on with marvelous speed.

The progress in mining has been enormous, and the production of gold

in the nineteenth century perhaps surpasses that of all previous time.

Production of all kinds has enormously increased, and commerce now

extends to the utmost regions of the earth, bearing the productions of

all climes to the central seats of civilization, and supplying distant

and savage tribes with the products of the loom and the mine.

Such is a hasty review of the condition of affairs at the end of the

nineteenth century as compared with that existing at its beginning. No

effort has been made here to cover the entire field, but enough has

been said to show the greatness of the world’s progress, and we may

fairly speak of this century as the Glorious Nineteenth.

DEATH OF MARAT

Never was there a more worthy act of murder than that

of the monster Marat, the most savage of the leaders

of the Reign of Terror, by the knife of the devoted

maiden, Charlotte Corday. She boldly avowed her guilt

and its purpose, and suffered death by the guillotine,

July 17, 1793.

THE LAST VICTIMS OF THE REIGN OF TERROR—

(FROM THE PAINTING BY MULLER)

CHAPTER I.

The Threshold of the Century.

The Age we Live in and its Great Events

After its long career of triumph and disaster, glory and shame, the

world stands to-day at the end of an old and the beginning of a new

century, looking forward with hope and backward with pride, for it has

just completed the most wonderful hundred years it has ever known, and

has laid a noble foundation for the twentieth century, now at its dawn.

There can be no more fitting time than this to review the marvelous

progress of the closing century, through a portion of which all of

us have lived, many of us through a great portion of it. Some of the

greatest of its events have taken place before our own eyes; in some of

them many now living have borne a part; to picture them again to our

mental vision cannot fail to be of interest and profit to us all.

True History and the Things which Make it

When, after a weary climb, we find ourselves on the summit of a lofty

mountain, and look back from that commanding altitude over the ground

we have traversed, what is it that we behold? The minor details of the

scenery, many of which seemed large and important to us as we passed,

are now lost to view, and we see only the great and imposing features

of the landscape, the high elevations, the town-studded valleys, the

deep and winding streams, the broad forests. It is the same when,

from the summit of an age, we gaze backward over the plain of time.

The myriad of petty happenings are lost to sight, and we see only the

striking events, the critical epochs, the mighty crises through which

the world has passed. These are the things that make true history, not

the daily doings in the king’s palace or the peasant’s hut. What we

should seek to observe and store up in our memories are the turning

points in human events, the great thoughts which have ripened into

noble deeds, the hands of might which have pushed the world forward

in its career; not the trifling occurrences which signify nothing,

the passing actions which have borne no fruit in human affairs. It is

with such turning points, such critical periods in the history of the

nineteenth century, that this work proposes to deal; not to picture the

passing bubbles on the stream of time, but to point out the great ships

which have sailed up that stream laden deep with a noble freight.

This is history in its deepest and best aspect, and we have set our

camera to photograph only the men who have made and the events which

constitute this true history of the nineteenth century.

Two of the World’s Greatest Events

On the threshold of the century with which we have to deal two grand

events stand forth; two of those masterpieces of political evolution

which mold the world and fashion the destiny of mankind. These are,

in the Eastern hemisphere, the French Revolution; in the Western

hemisphere, the American Revolution and the founding of the republic

of the United States. In the whole history of the world there are no

events that surpass these in importance, and they may fitly be dwelt

upon as main foundation stones in the structure we are seeking to

build. The French Revolution shaped the history of Europe for nearly a

quarter century after 1800. The American Revolution shaped the history

of America for a still longer period, and is now beginning to shape

the history of the world. It is important therefore that we dwell on

those two events sufficiently to show the part they have played in the

history of the age. Here, however, we shall confine our attention to

the Revolution in France. That in America must be left to the American

section of our work.

The Feudal System and Its Abuses

The Mediæval Age was the age of Feudalism, that remarkable system of

government based on military organization which held western Europe

captive for centuries. The State was an army, the nobility its captains

and generals, the king its commander-in-chief, the people its rank and

file. As for the horde of laborers, they were hardly considered at all.

They were the hewers of wood and drawers of water for the armed and

fighting class, a base, down-trodden, enslaved multitude, destitute of

rights and privileges, their only mission in the world to provide food

for and pay taxes to their masters, and often doomed to starve in the

midst of the food which their labor produced.

France, the country in which the Feudal system had its birth, was

the country in which it had the longest lease of life. It came down

to the verge of the nineteenth century with little relief from its

terrible exactions. We see before us in that country the spectacle of a

people steeped in misery, crushed by tyranny, robbed of all political

rights, and without a voice to make their sufferings known; and of an

aristocracy lapped in luxury, proud, vain, insolent, lavish with the

people’s money, ruthless with the people’s blood, and blind to the

spectre of retribution which rose higher year by year before their eyes.

One or two statements must suffice to show the frightful injustice that

prevailed. The nobility and the Church, those who held the bulk of

the wealth of the community, were relieved of all taxation, the whole

burden of which fell upon the mercantile and laboring classes—an

unfair exaction that threatened to crush industry out of existence. And

to picture the condition of the peasantry, the tyranny of the feudal

customs, it will serve to repeat the oft-told tale of the peasants who,

after their day’s hard labor in the fields, were forced to beat the

ponds all night long in order to silence the croaking of the frogs that

disturbed some noble lady’s slumbers. Nothing need be added to these

two instances to show the oppression under which the people of France

lay during the long era of Feudalism.

The Climax of Feudalism in France

This era of injustice and oppression reached its climax in the closing

years of the eighteenth century, and went down at length in that

hideous nightmare of blood and terror known as the French Revolution.

Frightful as this was, it was unavoidable. The pride and privilege of

the aristocracy had the people by the throat, and only the sword or

the guillotine could loosen their hold. In this terrible instance the

guillotine did the work.

It was the need of money for the spendthrift throne that precipitated

the Revolution. For years the indignation of the people had been

growing and spreading; for years the authors of the nation had been

adding fuel to the flame. The voices of Voltaire, Rousseau and a dozen

others had been heard in advocacy of the rights of man, and the people

were growing daily more restive under their load. But still the lavish

waste of money wrung from the hunger and sweat of the people went on,

until the king and his advisers found their coffers empty and were

without hope of filling them without a direct appeal to the nation at

large.

The States General is Convened

It was in 1788 that the fatal step was taken. Louis XVI, King of

France, called a session of the States General, the Parliament of the

kingdom, which had not met for more than a hundred years. This body

was composed of three classes, the representatives of the nobility, of

the church, and of the people. In all earlier instances they had been

docile to the mandate of the throne, and the monarch, blind to the

signs of the times, had no thought but that this assembly would vote

him the money he asked for, fix by law a system of taxation for his

future supply, and dissolve at his command.

He was ignorant of the temper of the people. They had been given a

voice at last, and were sure to take the opportunity to speak their

mind. Their representatives, known as the Third Estate, were made

up of bold, earnest, indignant men, who asked for bread and were

not to be put off with a crust. They were twice as numerous as the

representatives of the nobles and the clergy, and thus held control

of the situation. They were ready to support the throne, but refused

to vote a penny until the crying evils of the State were reformed.

They broke loose from the other two Estates, established a separate

parliament under the name of the National Assembly, and begun that

career of revolution which did not cease until it had brought monarchy

to an end in France and set all Europe aflame.

The Fall of the Bastille

The court sought to temporize with the engine of destruction which it

had called into existence, prevaricated, played fast and loose, and

with every false move riveted the fetters of revolution more tightly

round its neck. In July, 1789, the people of Paris took a hand in the

game. They rose and destroyed the Bastille, that grim and terrible

State prison into which so many of the best and noblest of France had

been cast at the pleasure of the monarch and his ministers, and which

the people looked upon as the central fortress of their oppression and

woe.

With the fall of the Bastille discord everywhere broke loose, the

spirit of the Revolution spread from Paris through all France, and the

popular Assembly, now the sole law-making body of the State, repealed

the oppressive laws of which the people complained, and with a word

overturned abuses many of which were a thousand years old. It took

from the nobles their titles and privileges, and reduced them to the

rank of simple citizens. It confiscated the vast landed estates of the

church, which embraced nearly one-third of France. It abolished the

tithes and the unequal taxes, which had made the clergy and nobles rich

and the people poor. At a later date, in the madness of reaction, it

enthroned the Goddess of Reason and sought to abolish religion and all

the time-honored institutions of the past.

The Revolution grew, month by month and day by day. New and more

radical laws were passed; moss-grown abuses were swept away in an

hour’s sitting; the king, who sought to escape, was seized and held as

a hostage; and war was boldly declared against Austria and Prussia,

which showed a disposition to interfere. In November, 1792, the

French army gained a brilliant victory at Jemmapes, in Belgium, which

eventually led to the conquest of that kingdom by France. It was the

first important event in the career of victory which in the coming

years was to make France glorious in the annals of war.

MARIE ANTOINETTE LED TO EXECUTION

The hapless wife of Louis XVI, of France, imprisoned

during the Revolution in the prisons of the Temple and

Conciergerie, separated from her family and friends,

and treated to great indignities, died at length under

the knife of the guillotine, October 16, 1793.

THE BATTLE OF RIVOLI

Rivoli is a village of Venetia, Italy, on the western

bank of the Adige; population, about 1,000. On January

14 and 15, 1797, Napoleon Bonaparte here, in his first

campaign as commander-in-chief, gained a great victory

over the Austrians commanded by Alvinczy, who lost

20,000 prisoners.

King and Queen Under the Guillotine

The hostility of the surrounding nations added to the revolutionary

fury in France. Armies were marching to the rescue of the king, and

the unfortunate monarch was seized, reviled and insulted by the mob,

and incarcerated in the prison called the Temple. The queen, Marie

Antoinette, daughter of the Emperor of Austria, was likewise haled from

the palace to the prison. In the following year, 1793, king and queen

alike were taken to the guillotine and their royal heads fell into

the fatal basket. The Revolution was consummated, the monarchy was at

an end, France had fallen into the hands of the people, and from them

it descended into the hands of a ruthless and blood-thirsty mob.

The Reign of Terror

At the head of this mob of revolutionists stood three men, Danton,

Marat, and Robespierre, the triumvirate of the Reign of Terror, under

which all safety ceased in France, and all those against whom the

least breath of suspicion arose were crowded into prison, from which

hosts of them made their way to the dreadful knife of the guillotine.

Multitudes of the rich and noble had fled from France, among them

Lafayette, the friend and aid of Washington in the American Revolution,

and Talleyrand, the acute statesman who was to play a prominent part in

later French history.

Marat, the most savage of the triumvirate, was slain in July, 1793,

by the knife of Charlotte Corday, a young woman of pious training,

who offered herself as the instrument of God for the removal of this

infamous monster. His death rather added to than stayed the tide of

blood, and in April, 1794, Danton, who sought to check its flow, fell

a victim to his ferocious associate. But the Reign of Terror was

nearing its end. In July the Assembly awoke from its stupor of fear,

Robespierre was denounced, seized, and executed, and the frightful

carnival of bloodshed came to an end. The work of the National Assembly

had been fully consummated; Feudalism was at an end, monarchy in France

had ceased, and a republic had taken its place, and a new era for

Europe had dawned.

The Wars of the French Revolution

Meanwhile a foreign war was being waged. England had formed a coalition

with most of the nations of Europe, and France was threatened by land

with the troops of Holland, Prussia, Austria, Spain and Portugal,

and by sea with the fleet of Great Britain. The incompetency of her

assailants saved her from destruction. Her generals who lost battles

were sent to prison or to the guillotine, the whole country rose as one

man in defence, and a number of brilliant victories drove her enemies

from her borders and gave the armies of France a position beyond the

Rhine.

These wars soon brought a great man to the front, Napoleon Bonaparte,

a son of Corsica, with whose nineteenth century career we shall deal

at length in the following chapters, but of whose earlier exploits

something must be said here. His career fairly began in 1794, when,

under the orders of the National Convention—the successor of the

National Assembly—he quelled the mob in the streets of Paris with

loaded cannon and put a final end to the Terror which had so long

prevailed.

Placed at the head of the French army in Italy, he quickly astonished

the world by a series of the most brilliant victories, defeating the

Austrians and the Sardinians wherever he met them, seizing Venice, the

city of the lagoon, and forcing almost all Italy to submit to his arms.

A republic was established here and a new one in Switzerland, while

Belgium and the left bank of the Rhine were held by France.

Napoleon in Italy and Egypt.

His wars here at an end, Napoleon’s ambition led him to Egypt,

inspired by great designs which he failed to realize. In his absence

anarchy arose in France. The five Directors, then at the head of the

Government, had lost all authority, and Napoleon, who had unexpectedly

returned, did not hesitate to overthrow them and the Assembly which

supported them. A new government, with three Consuls at its head, was

formed, Napoleon as First Consul holding almost royal power. Thus

France stood in 1800, at the end of the Eighteenth Century.

England as a Centre of Industry and Commerce.

In the remainder of Europe there was nothing to compare with the

momentous convulsion which had taken place in France. England had gone

through its two revolutions more than a century before, and its people

were the freest of any in Europe. Recently it had lost its colonies

in America, but it still held in that continent the broad domain of

Canada, and was building for itself a new empire in India, while

founding colonies in twenty other lands. In commerce and manufactures

it entered the nineteenth century as the greatest nation on the earth.

The hammer and the loom resounded from end to end of the island, mighty

centres of industry arose where cattle had grazed a century before,

coal and iron were being torn in great quantities from the depths of

the earth, and there seemed everywhere an endless bustle and whirr.

The ships of England haunted all seas and visited the most remote

ports, laden with the products of her workshops and bringing back raw

material for her factories and looms. Wealth accumulated, London became

the money market of the world, the riches and prosperity of the island

kingdom were growing to be a parable among the nations of the earth.

On the continent of Europe, Prussia, which has now grown so great,

had recently emerged from its mediæval feebleness, mainly under the

powerful hand of Frederick the Great, whose reign extended until 1786,

and whose ambition, daring, and military genius made him a fitting

predecessor of Napoleon the Great, who so soon succeeded him in the

annals of war. Unscrupulous in his aims, this warrior king had torn

Silesia from Austria, added to his kingdom a portion of unfortunate

Poland, annexed the principality of East Friesland, and lifted Prussia

into a leading position among the European states.

The Condition of the German States

Germany, now—with the exception of Austria—a compact empire, was

then a series of disconnected states, variously known as kingdoms,

principalities, margravates, electorates, and by other titles, the

whole forming the so-called Holy Empire, though it was “neither

holy nor an empire.” It had drifted down in this fashion from the

Middle Ages, and the work of consolidation had but just begun, in the

conquests of Frederick the Great. A host of petty potentates ruled the

land, whose states, aside from Prussia and Austria, were too weak to

have a voice in the councils of Europe. Joseph II., the titular emperor

of Germany, made an earnest and vigorous effort to combine its elements

into a powerful unit; but he signally failed, and died in 1790, a

disappointed and embittered man.

Austria, then far the most powerful of the German states, was from 1740

to 1780 under the reign of a woman, Maria Theresa, who struggled in

vain against her ambitious neighbor, Frederick the Great, his kingdom

being extended ruthlessly at the expense of her imperial dominions.

Austria remained a great country, however, including Bohemia and

Hungary among its domains. It was lord of Lombardy and Venice in Italy,

and was destined to play an important but unfortunate part in the

coming Napoleonic wars.

Dissension in Italy and Decay in Spain

The peninsula of Italy, the central seat of the great Roman Empire,

was, at the opening of the nineteenth century, as sadly broken up

as Germany, a dozen weak states taking the place of the one strong

one that the good of the people demanded. The independent cities of

the mediæval period no longer held sway, and we hear no more of wars

between Florence, Genoa, Milan, Pisa and Rome; but the country was

still made up of minor states—Lombardy, Venice and Sardinia in the

north, Naples in the south, Rome in the centre, and various smaller

kingdoms and dukedoms between. The peninsula was a prey to turmoil and

dissension. Germany and France had made it their fighting ground for

centuries, Spain had filled the south with her armies, and the country

had been miserably torn and rent by these frequent wars and those

between state and state, and was in a condition to welcome the coming

of Napoleon, whose strong hand for the time promised the blessing of

peace and union.

Spain, not many centuries before the greatest nation in Europe, and,

as such, the greatest nation on the globe, had miserably declined in

power and place at the opening of the nineteenth century. Under the

emperor Charles I. it had been united with Germany, while its colonies

embraced two-thirds of the great continent of America. Under Philip

II. it continued powerful in Europe, but with his death its decay set

in. Intolerance checked its growth in civilization, the gold brought

from America was swept away by more enterprising states, its strength

was sapped by a succession of feeble monarchs, and from first place it