Mrs. Bec. "I think it was perfectly hateful of Grace to send Lady Copperthwaite in to dinner before me, when she knows Sir John is only a sergeant, and my George is a Sub-Inspector!"

Vol. 148.

January 27, 1915.

"Herts are doing well," reports Lord Cavan in a letter from the Front received at Stevenage. Herts, in fact, are trumps.

* * *

In Germany it is now said that the Kaiser will receive Calais as a birthday present. In France, however, it is said that it will be Pas de Calais.

* * *

The English governess whose book Messrs. Chapman and Hall have just published says of the Kaiser:—"When he made a witticism he laughed out aloud, opening his mouth, throwing back his head slightly with a little jerk, and looking one straight in the eyes." It seems a lot of trouble to take to intimate that one has made a joke, but no doubt his hearers found it helpful.

* * *

Further details of the battle off the Falkland Islands are now to hand. Von Spee, the German Admiral, it seems, ordered "No quarter"—to which our men retorted, "Not half."

* * *

An Express correspondent reports from Belgium that the Germans now have a number of monitor-like vessels at Zeebrugge which have only one large gun and "sit low in the water." We trust our Navy may be relied upon to make them sit lower still.

* * *

With regard to the occupation of Swakopmund the Vossische Zeitung now says that this proceeding of war in South-West Africa is without significance. It seems rather churlish of our contemporary not to point this out until we have had the trouble of taking the place.

* * *

A Berlin despatch announces that Dr. Weill, the member of the Reichstag who entered the French army, has been deprived of his German nationality. We fear that Dr. Weill omitted some of the formalities.

* * *

We cannot blame the ex-Khedive for assuming that his life is of value. He is to direct operations in Egypt from Geneva.

* * *

"CARDINAL MERCIER

Belief that he does not enjoy

full Liberty."

These headlines are regrettable. They make it possible for the Germans to say, "What's the good of giving him full liberty if he does not enjoy it?"

* * *

On more than one occasion lately the Special Constables have bean called out only to kick their heels for a considerable time at the local police station. There is some grumbling as to this, it being felt that they might have been told, anyhow, to bring their knitting with them.

* * *

The Glasgow Evening Times must not be surprised if it loses a few subscribers among the members of the R.A.M.C. owing to the following answer to a correspondent in its issue of the 15th inst.:—"'18' (Falkirk)—Delicate lads are of little use in the Army. You might try the Royal Army Medical Corps."

* * *

With reference to the action brought by Sir Hiram Maxim to restrain an alleged nuisance from noise and vibration caused by a firm of builders, our sympathy certainly went out to the defendants, for who could have guessed that the inventor of the famous machine-gun would have a rooted objection to noise?

* * *

The new West London Police Court was opened last week, and is pronounced by its patrons to be both handsome and comfortable—a place, in fact, in which no one need feel ashamed to be seen. There is even a writing desk in the dock for the use of prisoners. When so many of them write memoirs for the Yellow Press this is a little convenience which will be much appreciated.

Mrs. Bec. "I think it was perfectly hateful of Grace to send Lady Copperthwaite in to dinner before me, when she knows Sir John is only a sergeant, and my George is a Sub-Inspector!"

THE MURDERERS.

(Lines addressed to their Master.)

THE FISH FAMINE.

It is only proper that an agitation should be on foot to compel the Government to take measures to prevent a further rise in the cost of bread, the food of the people.

But what is the Government prepared to do to remedy the present deplorable dearth in the food of the people's thinkers—fish?

Scientists, statisticians, fishmongers and other authorities tell us that for the development of the human brain there is nothing to compare with fish. Indeed, one has only to glance at the throng assembled in any popular fish-bar of a night to realise that the people of our country are alive to their need in this respect.

Consider what this shortage of fish must mean in the development of the intellectual life of the people of this country. How can we expect our parcels to be delivered intelligently, our gas-fittings to be adjusted properly, our bulbs to be planted effectively, if our carmen, our plumbers, our jobbing gardeners, and so forth, are deprived of their daily bloater or bloaters, as the case may be?

How can we hope that Mr. H. G. Wells, Mr. Arnold Bennett or even Lord Kitchener himself will continue to guide the nation effectively with the fish course obliterated from the menu?

What is the use of the Poet Laureate to the country if Billingsgate is inactive? And without Billingsgate how can our half-penny morning papers adjust their differences, or illuminating discussion among intellectuals be maintained?

How much longer will The Spectator and The Church Times be worth reading if the present scarcity of fish continues? Is a Hampstead thinkable without halibut?

A marked deterioration has already been noted in the quality of the discourses of the senior curate at one of our suburban churches. We may be capturing trade, and the position of our banks may be wonderfully sound; but against that must be recorded the lamentable fact that in a certain town in the Home Counties last week only twenty-two people attended a widely announced debate on the subject, "Have Cinema Pictures a more refining influence upon the Poor than Classical Poetry?"

THE BRITISH ARMY.

(As seen from Berlin.)

[The Socialist Vorwärts, which takes considerable pains to correct the mistakes of its contemporaries, solemnly rebukes journals which, it says, have described the Scots Greys as "the Scottish Regiment of the Minister Grey."—The Times.]

The desperate straits of the British are indicated by the statement that it has become necessary for what is called in England the "senior service" to take a hand in recruiting the junior, i.e. the British Army. We learn that the naval gunnery expert, Sir Percy Scott, has raised a regiment known as Scott's Guards.

It illustrates the difficulty which the British have in raising recruits, that the Government, now that it has acquired the railways, is ruthlessly compelling even the older servants to join the army. One section of these men, who hitherto have been occupied with flag and whistle, and have never been mounted in their lives, are being enlisted in a special battalion known as the Horse Guards, while, as the authorities themselves admit, the railways furnish whole regiments of the line. The War Office has even made up a force from the men who drive King George's trains, under the title of the Royal Engineers.

The British commemorate their generals in their regiments. For instance, the name of the Duke of Wellington is carried by the West Riding Regiment, which, as its name indicates, is a cavalry regiment; and the Gordon Highlanders—the Chasseurs Alpins of the British army—were founded to preserve the name of the late General Gordon.

The curious practice of bathing the body in cold water at the beginning of day, which is compulsory in the British army, is an old one, and is said to have been inaugurated by a royal regiment which even to-day commemorates the beginning of the odd habit in its title of Coldstreamers.

THE BELLS OF BERLIN.

(Which are said to be rung by order occasionally to announce some supposed German victory.)

[January 27th.

Emperor of Austria. "NOW WHAT DO WE REALLY WANT TO SAY?"

Sultan of Turkey. "WELL, OF COURSE WE COULDN'T SAY THAT; NOT ON HIS BIRTHDAY."

THE LAST FIGHT OF ALL.

THE WAR AND THE BOOKS.

"Nowhere," says a contemporary, "is the influence of the War more apparent than in the publishers' lists." We venture to anticipate a few items that are promised for this time next year:—

For Lovers of Bright Fiction. New German Fairy Tales. Selected from the Official Wireless. 550 pp., large quarto, 10s. 6d. The first review says, "Deliciously entertaining ... powers of imagination greatly above the ordinary. The story of "Hans across the Sea, or the Eagles in Egypt," will make you rock with laughter."

Important new work on Ornithology. British Birds, by One who Got Them. Being the experiences of a Slacker in the prime of life during the Great War. Crown octavo, 6s. Profusely illustrated with cuts.

Civilian Life From Within. The author, Mr. Jude Brown, has (for good reasons fully explained in the preface) remained a civilian during the past year. He is thus in a position to speak with authority upon a phase of life which most of his contemporary readers will either have forgotten or never known. Just as Service novels in the past used to appear full of the most absurd technical errors, so to-day many books that profess to deal with civilian life are disfigured by every kind of solecism. Mr. Brown, however, writes not as a gushing amateur but as one who knows. Order early.

Nephew. "I'm reading a very interesting book, Aunt, called 'Germany and the next war.'"

Aunt. "Well, my dear, I should have thought they had their hands full enough with the present one."

In a Good Cause.

Mr. Punch begs to call the attention of his readers to a sale which will take place at Christie's, on February 5th, of pictures by members of the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolours. The entire proceeds will be divided between the two allied societies, the Red Cross and the St. John Ambulance. The pictures are on exhibition at Messrs. Christie's, who are bearing all expenses and charging no commission.

A Birthday Wish: Jan. 27th:—

"We have the further intelligence that 80 Turkish transports have been sunk by the Russians in the North Sea. This last piece of information lacks official confirmation."

Dublin Evening Mail.

This continued official scepticism about the Russians is very disheartening.

"Sandringham is fifty miles due east of Yarmouth."—Liverpool Echo.

Rather a score off the Kaiser, who didn't realise it was a submarine job.

"Our Correspondent at Washington reports that the Press of the Eastern United States is unanimous in excoriating the German Air Raid."—The Times.

If only they would excoriate the Zeppelins themselves.

Manager (to dragon). "What's the meaning of this? Where's your hind legs?"

Dragon. "They've enlisted, Sir."

ON THE SPY-TRAIL.

I.

Jimmy had been saving up his pocket-money and his mother had begun to get rather anxious; she thought he must be sickening for something.

He was. It was for a dog, any dog, but preferably a very fierce bloodhound. He had already bought a chain; he had to have that because the dog he was going to buy would have to be held in by main force; it would have to be restrained.

But he didn't have to buy one after all; he had one transferred to him.

You see Jimmy was helping at a kind of bazaar in aid of the Belgian Refugees Fund. He had volunteered to help with the refreshment stall. There is a lot of work about a refreshment stall, Jimmy says. His work made him a bit husky, but he stuck to it and so it stuck to him.

He was very busy explaining the works of a cake to a lady when a man came up with something under his arm. It was a raffle. You paid threepence for a ticket, and would the lady like one?

The lady said she already had two tea-cosies at home; but the man explained that it was not a tea-cosy, it was a dog.

A dog! Perhaps a bloodhound! Jimmy trembled with excitement. Only threepence for a ticket, and he had a chance of winning it.

It seemed a faithful dog, Jimmy thought. It had a very good lick, too; it licked a sponge-cake off a plate, and would have licked quite a lot more from Jimmy's stall if it had had time.

Jimmy came third in the raffle.

But the man whose ticket won the dog said he didn't care for that kind of breed, by the look of it, and gave way in favour of the next.

The next man said he wasn't taking any shooting this year, and he stood aside. The dog was Jimmy's!!

With trembling hands he fastened on the chain—to restrain it. Then he asked the man whose ticket had won the raffle if it was really a prize bloodhound.

The man looked at the dog critically, and said it was either a prize bloodhound or a Scotch haggis; at any rate it was a very rare animal.

Jimmy asked if he would have to have a licence for it, but the man said it would be best to wait and see what it grew into. All good bloodhounds are like that, Jimmy says.

Jimmy ran all the way home: he couldn't run very fast, as the bloodhound tried to slide on its hind legs most of the way, it was so fierce.

Jimmy knows all about bloodhounds, how to train them. He is training his to track down German spies, amongst other things.

He knows a way so that if you say something—well, you don't exactly say it, you do it by putting your tongue into the place where your front tooth came out and then blowing—a really well-trained bloodhound will begin to shiver, and the hair on the back of his neck will go up. You then go and look for someone to help you to pull him off the German's throat, and ask the German his name and address, politely.

Jimmy taught his bloodhound to track clothes by letting it smell at a piece of cloth. It brought him a lot of clothes from nearly a quarter of a mile away. They were not the light clothes though, and Jimmy had to take them back. The woman wanted them—to wash over again, she said. She doesn't like bloodhounds much.

Jimmy says you ought to have the blood of the victim on the cloth.

Jimmy has trained his bloodhound to watch things. It is very good at watching. It watched a cat up a tree all one night, and never left off once: it is very faithful like that. And it bays quite well, without being taught to. It bayed up to four hundred and ten one night, and would have gone past that but a man opened a window and told it not to. He sent it a water-bottle to play with instead.

Jimmy's bloodhound is a splendid fighter. It fought a dog much bigger than itself and nearly choked it. The other dog was trying to swallow it, and Jimmy had to pull his dog out.

Jimmy says he has only once seen his bloodhound really frightened. It was when it followed Jimmy up into his bedroom, and saw itself in the mirror in the wardrobe. Jimmy says it was because it came upon itself too suddenly. It made it brood a great deal, and Jimmy had to give it a certain herb to reassure it.

Jimmy takes it out every day, searching for German spies. It goes round sniffing everywhere—in hopes. It is a very strong sniffer and full of zeal, and one day it did it.

A man was looking at a shop-window, where they sell sausages and pork pies. He was studying them, Jimmy says. Jimmy says he never would have guessed he was a German spy if his bloodhound hadn't sniffed him out. It walked round the man twice, and in doing so wrapped the chain round the man's legs. Jimmy says it was to cut off his retreat. The man moved backwards and stepped on the bloodhound's toe, and the bloodhound began to bay like anything. Jimmy says it showed the bloodhound was hot upon the scent.

It then sniffed a piece out of the man's trousers.

There was another man there; he was looking on and laughing. He said to Jimmy, "Pull in, sonny; you've got a bite."

But he stopped laughing when the German spy tripped up and fell on top of the bloodhound; for the German spy shouted out, "Ach, Himmel!" The man who was looking on shouted, "What ho!" and put all the fingers of both hands into his mouth and gave one terrific whistle. The bloodhound held on tightly underneath the German, baying faithfully, till the policeman came and forced them apart. The German spy never said anything to the policeman or to the man or to Jimmy, but it seemed he couldn't say enough to the bloodhound. He kept turning round to say things, as they came into his head, on his way to the police-station.

Jimmy asked the German if he could keep the piece of cloth his bloodhound had sniffed out.

Jimmy has made the piece of cloth into a kind of medal with a piece of wire, and has fastened it to the bloodhound's collar. Jimmy says if he gets a lot of pieces of cloth like this he is going to make a patchwork quilt for the bloodhound.

Jimmy's bloodhound is hotter than ever on the trail of German spies.

If you are good you shall hear more of it another time.

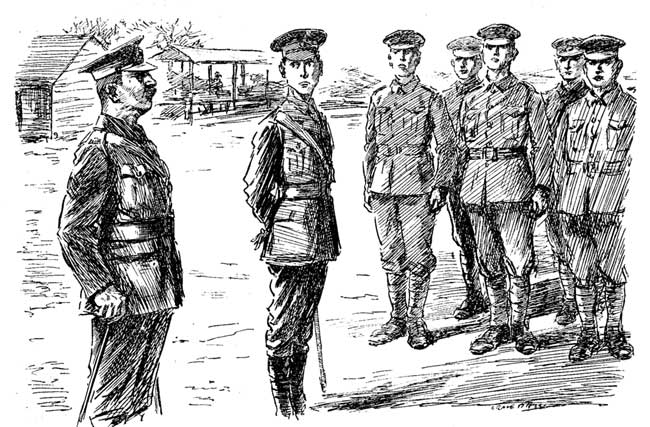

Nervous Subaltern (endeavouring to explain the mysteries of drill). "Forming Fours—when the squad wishes to form fours, the even numbers take——"

Sergeant-major. "As you were! A squad of recruits never wishes to do nothing, Sir!"

AS GOOD AS A MILE.

As this happened over a month ago, it is disclosing no military secret to say that the North Sea was extraordinarily calm. It was neither raining nor sleeting nor blowing; indeed the sun was actually visible, an alcoholic-visaged sun, glowing like a stage fire through a frosty haze. From the cruiser that was steaming slowly ahead, with no apparent object beyond that of killing time, the only break to be seen in the smoky blue of the sea was the dull copper reflection on one-half of its wake; and that somehow attracted no comment from the man on the look-out. Bits of flotsam nevertheless, however harmlessly flotsam, were recorded on their appearance in a penetrating mechanical sing-song, with a strong Cockney accent, as were the occasional glimpses of the shores of Norway.

All that could manage it were on deck, enjoying the unusual freedom from oilskins. The captain was assuring the commander that the safest way of avoiding a cold was to sit in a draught with a wet shirt on; a marine was having a heated argument with a petty officer as to whether the remnants of the German Navy would be destroyed or taken over at the end of the War; the torpedo-lieutenant was telling the A. P. what jolly scenery there was from here if only one could see it, and pronouncing his conviction that it was mere beef and not real reindeer that they had given him for lunch at the hotel up the fjord; while the A. P. was mentally calculating the chances of the old man's coming down handsomely enough to allow his honeymoon to run to Norway when the war was over.

"Periscope on the port bow, Sir!" It disappeared in the spray of half-a-dozen shells, and emerged unharmed for an instant before it dipped; but a rapidly-forming line of torpedo-bubbles showed that the submarine too had seen, and had made answer after its fashion.

People who ought to know assure us that the truly great often regret their days of obscurity; certainly the captain now wished that he were still merely the lieutenant-commander of a T.B. Then he could have turned nearly parallel to the course of the torpedo, and tried for a ram. With the heavier and slower ship there was no room or time for such a manœuvre; it was full speed ahead or astern. The torpedo was well-aimed, and, seeing from its track that it would meet their course ahead, he rang full speed astern. The ship quivered distressingly, and the water boiled beneath her stern. There was nothing left to do but wait and trust to the propellers.

Ranks and ratings alike clustered to the side, watching those bubbles with a curiously dispassionate interest; but for the silence they might have been a crowd of tourists assembled to see a whale. One low "Six to four against the torpedo" was heard; and a sub with a pathetically incipient beard asked for a match in a needlessly loud tone. The bubbles drew near, very near, and were hidden from all but one or two beneath the bow; hands gripped the rails rather tightly, and then once more the line of bubbles appeared, now to the starboard. Men turned and looked at each other curiously as if they were new acquaintances; one or two shook hands rather shamefacedly; and the sub who had asked for a match found that his cigarette wanted another.

And from the look-out, in the same mechanical sing-song, came "Torpedo passed ahead, Sir!"

AS WE HATE IT.

["Mr. Stanley Cooke will begin his tour with Caste at the Royal, Salisbury, on Monday. The old piece, we understand, has been altered so as to allow of references to current events in the War. Sam Gerridge now enlists in the last Act, and appears in khaki."—The Stage.

Not to be outdone, Mr. Punch begs to present scenes from his new version of As You Like It.]

Act I.

An open place (with goal-posts at each end).

Enter from opposite turnstiles Duke Frederick and Rosalind (with Celia).

Duke. How now, daughter and cousin? Are you crept hither to see the football?

Rosalind. Ay, my lord, so please you give us leave.

Duke. You will take little delight in it, I can tell you. I only came myself from—er—duty. It's disgraceful to think that our able-bodied young men should waste their time kicking a ball about in this crisis. I would enlist myself if only I were ten years younger.

Celia (thoughtfully). I know a man just about your age who——

Duke (hastily). Besides, I have a weak heart.

[Shout. Orlando kicks a goal.

Rosalind. Who is that excellent young man?

Duke. Orlando. I have tried to persuade him to go, but he will not be entreated. Speak to him, ladies; see if you can move him.

[Whistle. Time. Arden Wednesday is defeated 2-1. Orlando approaches.

Rosalind. Young man, are you aware that there is a war on?

Orlando. Yes, lady.

Rosalind (alarmed). Why want you a moustache, young man?

Rosalind (sighing). Celia, my dear, I've made a fool of myself again.

Celia. It looks like it. You're always so hasty.

Rosalind (casually). I wonder where the Fifth Battalion is training?

Celia. Somewhere in the Forest, I expect.

Rosalind. Alas, what danger will it be to us

Maids as we are to travel forth so far!

Celia. I'll put myself into a Red Cross dress.

Rosalind. I do not like the Red Cross uniform.

Celia. You could be photographed ten times a day:

"The Lady Rosalind a Red Cross Nurse."

Rosalind. I like it not. Nay, I will be a Scout.

Celia. What shall I call thee when thou art a Scout?

Rosalind. I'll have no worse a name than Archibald.

The Boy Scout Archibald. And what of you?

Celia. Something that hath a reference to my state;

No longer Celia now, but Helia.

Rosalind. Help!

Act II.

An open place in the Forest.

A Voice. Platoon! Properly at ease there, blank you! 'Tn-shun! Dis-miss!

Enter Amiens, Jaques and others.

Jaques. More, more, I prithee, more.

Amiens. It will make you melancholy, Corporal Jaques.

Jaques. I want to be melancholy. Any man would be melancholy when his officer's moustache falls off on parade.

Amiens. A white one too—a regular Landsturmer. And yet he's not an old man, Corporal.

Jaques. Ay, it's a melancholy business. Come, warble.

Jaques (getting up). A melancholy business. Amiens, my lad, I feel the old weakness coming over me.

Amiens (alarmed). You're going to recite, Corporal?

Jaques. Yes, I'm going to recite. (Sighs.)

Amiens. Fight against it, Corporal, fight against it! It didn't matter in the old civilian days, long ago; but think if it suddenly seized you when we were going into action!

Jaques. I know, I know. I've often thought of it. But when once it gets hold of me——(Pleadingly) This will only be a very little one, Amiens.... H'r'm!

[Exit hurriedly, followed by the others.

Enter Rosalind and Celia.

Celia. Is that your own, dear?

Rosalind. I found it on a tree. There's lots more.... Oh, Celia, listen! It ends up:

Celia, it must be Orlando! He has penetrated my disguise and he forgives me!

[Enter Orlando from left at the head of his men.

Orlando (to his platoon). Halt! Eyes right! (Advancing to Rosalind.) Lady, you gave me a feather once. I have lost it. Can you give me another one? My Colonel says I must have a moustache.

Rosalind. Alas, Sir, I have no others.

Orlando (firmly). Very well. Then there's only one thing for me to do. I shall have to join the Navy.

He does so, thus providing a naval Third Act.... And so eventually to the long-wished-for end.

THE LATEST IRISH GRIEVANCE.

A Milesian Medley.

[The Earl of Aberdeen on his promotion in the peerage has adopted the style of Marquess of Aberdeen and Tara.]

"Grease Spots on Milk.—Take a lump of magnesia, and, having wetted it, rub it over the grease-marks. Let it dry, and then brush the powder off, when the spots will be found to have disappeared."—North Wilts Herald.

They didn't. Perhaps we had the wrong kind of milk.

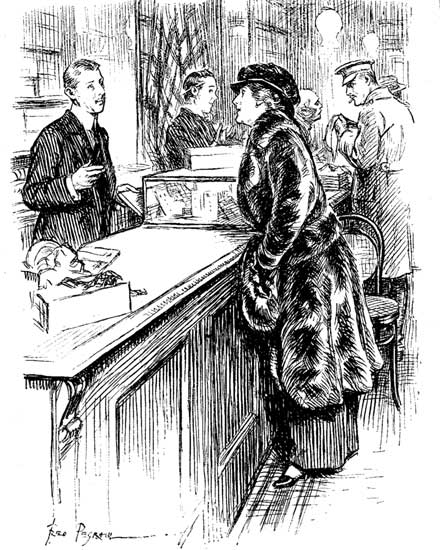

Lady. "I want some studs, please, for my son."

Shopman. "Yes, Madam—for the front?"

Lady. "No—home defence."

A TERRITORIAL IN INDIA.

II.

My dear Mr. Punch,—I think I see now the reason for the wholesale transference of our Battalion to clerical duties as described in my last letter. We are being "trained for the Front in the shortest possible time." That much is certain, because it is in the official documents. Clearly, then, we are to form a new arm. Each man will be posted in a tree with a type-*writer before him. The enemy, approaching, will hear from all sides a continuous tap-tapping and will fly in disorder, imagining that he is being assailed by a new kind of machine-gun.

Did I tell you that we are living in a tent? Four of us occupy one tent; that is to say, we occupy that portion of it which is not required by some five hundred millions of ants. I arrived at this figure in the same way that other scientists count microbes—by multiplying the number on a square inch by the superficial area in inches of the tent. Ants are voracious brutes. In five minutes they can eat a loaf of bread, two pounds of treacle, a tin of oatmeal (unopened), eight bananas, a shaving brush and a magazine. So at least we were assured by our colleagues in the office, some of whom have been in India for many years and therefore ought to know.

When we leave the tent to step across into the office some of the more friendly of the ants accompany us and indulge in playful little pranks. Only this morning one of them, while my back was turned, upset a bottle of ink over a document I had just completed.

We keep alive our military ardour in[Pg 70] our spare time by waging war upon this enemy. Their strategy resembles that of the Germans. They rely upon masses, and every day their losses are appalling. But, unlike the Germans, they seem to have unlimited reserves to draw upon. I foresee the day when we shall be driven out and they will be left masters of the field.

But enough of ants, which are becoming a bore. I have verified the theory that human nature is the same all the world over. When I was at home for that last forty-eight hours' leave before we sailed for India, five of us returned to the camp on Salisbury Plain by motor, and on our way we stopped at a country inn. Doubtless our big khaki overcoats and sunburnt faces gave us a more soldierly appearance than the length of our military training warranted, and an elderly countryman seated on a bench inside, regarding us with interest, asked me if we were off to the front. "Well," I said, "we're going to India first, and after a few months we are to return to the Front." Plainly our friend was in a difficulty. He was a patriot. One could see that he longed intensely, ardently, to express his appreciation of our action in volunteering, but he could not find the appropriate words. There was a long pause. Then a light of inspiration shone on his countenance. He had found it. His hand dived into his pocket. "Here," he said, "have some nuts."

So in India. We have another patriot here in our "boy" Mahadoo, who for two rupees a week acts as our valet, footman, housemaid, kitchenmaid, chambermaid, boots, errand boy and washerwoman. "And the sahib will fight the Germans?" he asked me the other day. "I hope so," I replied; "in a few months." One could see that he too experienced the difficulty of adequate expression. Then his hand went to his turban and he produced a small slab of English chocolate. "For you, rajah," he said, and, standing to attention, he saluted like a soldier. And I believe there was a lump in his honest dusky throat.

Life can be very difficult when you have only one uniform, and that an Indian summer one. I realised the other day that the dreaded hour had arrived when mine must be purified. Accordingly I gave Mahadoo instructions to wash it, and went into the office in pyjamas. So far so good. An hour later came an order from the D.A.Q.M.G. that I was to go into the town to cash a cheque. My uniform lay on the grass outside the tent, clean but wet. I was a soldier. I must obey orders unquestioningly. What was to be done?

Well, I pondered; it is a soldier's business unflinchingly to brave danger and hardship. I must go into the town in pyjamas and run stolidly the gauntlet of curious glances and invidious remarks. The bank lay in the centre of the European quarter. Very well, I must do my duty nevertheless. I was a soldier.

So I wrung out my uniform, changed into it and caught a severe cold.

I suppose they don't give V.C.'s till you have actually figured on the battlefield.

Yours ever,

One of the Punch Brigade.

"Why is everybody making such a fuss with that rather ordinary-looking little person?"

"My dear! She has a cellar."

Another Impending Apology.

"NEW BANKING DEPARTURE.

Sir Edward Holden Redeems His Promise."

The Emperor. "WHAT! NO BABES, SIRRAH?"

The Murderer. "ALAS! SIRE, NONE."

The Emperor. "WELL, THEN, NO BABES, NO IRON CROSSES."

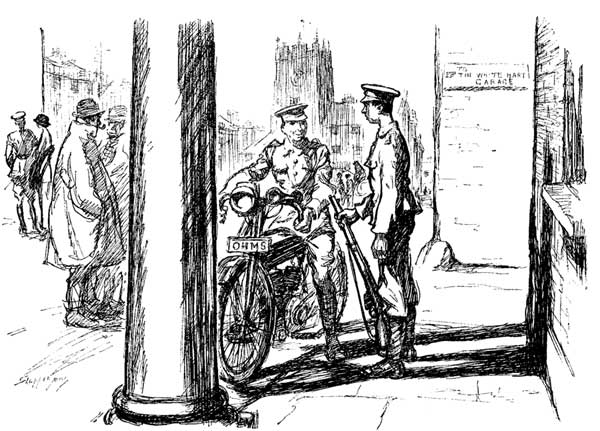

Cyclist. "I have a despatch for the officer in command. Can I see him?"

Sentry (a raw one). "Yus. Shall I fetch un out to 'ee?"

ACCOUNT RENDERED.

Mr. Punch, Sir,—Can you inform me if the Government may be relied upon to pay compensation to all who suffer loss or damage as a result of the War? If so, will you be good enough to advise me how to proceed to get payment for the following items of my own personal loss?

| 1. | Damage to Dresden ornament due to maid's sudden alarm while dusting it, on hearing the newspaper boy call (as she thought) "Jellicoe sunk" | £2 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. | Loss of profits on a potential deal, due to my arriving late in the City on the morning of January 5th as a consequence of an argument on London Bridge with that ass Maralang on matters relating to the War. | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. | Expenses incurred by (a) spraining the great toe of my right foot, (b) spoiling one pair of trousers, and (c) grazing my forehead, in the course of field operations with my drilling corps, to which I belong only because of the War | 4 | 14 | 6 |

| 4. | Loss of office-boy's services for one week as a result of damage he received from a taxi-cab while waiting at Charing Cross for Zeppelins to appear | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| 5. | Breakage of glass in my greenhouse on Boxing Day, caused by my son's defective aim with the 5 mm. air-gun presented to him on Christmas Day by me, a gift inspired directly by the War | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 6. | Undoubted loss of expected and indeed practically promised legacy from my Aunt Margaret, caused by an ill-considered criticism I passed upon a belt she had knitted for a soldier at the Front; legacy estimated at not less than £2000. I am, however, prepared to accept cash down | 500 | 0 | 0 |

| ———— | ||||

| Total | £570 | 6 | 6 | |

| Yours obediently, | Computator. | |||

"A marriage has been arranged between Capt. Stokes, 4th (Queen's Own) Hussars, of St. Botolph's, and Mrs. Stokes and Miss Evelyn Wardell and Mrs. John Vaughan of Brynwern, Newbridge-on-Wye."—Welshman.

We hope that without offence we may congratulate him.

"PRIVATE STILLS IN FRANCE."

Daily News.

He is only one of thousands.

A QUESTION OF TACTICS.

Poor Jones! I often think of him—a patriot of the super-dreadnought type, with an apoplectic conviction that the whole conduct of the War, on the part of the Allies, had been from the outset a series of gigantic mistakes. "I don't believe in all this spade and chess-board work," he used to growl; "up and at'em, that's my motto. Magnificent fighting material we've got at the Front, but what we want is brains, Sir, brains to use it." And then (though I could never understand why he did this) he would tap his own forehead.

At the end of October we all agreed not to argue with Jones any more. Peters, who in his younger days very nearly qualified for the medical profession, said that for short-necked, wine-coloured persons like our friend anything in the nature of a heated discussion might easily lead to fatal results. So partly out of consideration for the Empire, which we felt could not afford in the present crisis to lose a single man, even Jones, partly out of consideration for Mrs. Jones (though here we were perhaps influenced by a sentiment of mistaken kindness), and partly out of consideration for ourselves we decided to avoid the topic of the War when conversing with Jones.

It proved very difficult to carry out our resolution. When a man is determined to discuss the War, the whole War, and nothing but the War, with everybody he meets, it is hard to side-track him. You can, of course, after listening to his views on coast defences, endeavour to turn the conversation by saying, "Yes, certainly; and by the way, speaking of Sheringham, I have an uncle, a retired minor canon of Exeter, who still deprecates the custom of mixed bathing"; or, "I quite agree with you, and that reminds me, have you heard that all the best people on the Essex coast are insuring against twins this season?" But even efforts like these are often of little avail. There is only one really effective course to pursue, and that is to avoid your adversary altogether. This was what we had to do with poor Jones.

One morning during the second week in November I was walking down the High Street, when I espied Jones conversing with a friend outside the butcher's. He was gesticulating with a newspaper in his hand and wore an angry expression. Knowing that there was not a moment to be lost, I dived into the nearest shop.

"Yes, Sir?"

There are, I doubt not, some who find a peculiar charm in the voice of the young female haberdasher; but I am not of them. It is a dreadful thing to be alone in a ladies' and children's outfitter's; these establishments are apt to contain so many articles that no self-respecting man should know anything about. As I realised where I was I shuddered.

"Yes, Sir?" said the voice again.

I gazed stonily from the fair young thing across the counter to a group of her sisters in the background, who had paused in their play to watch in silent reproach the rude disturber of their maiden peace.

"Yes, Sir?" said the voice once more. There was a note of weariness in it now, a far-off hint of unshed tears.

Suddenly my eye caught a label on a bale. I decided to plunge.

"A yard of cream wincey," I said firmly.

The ice was broken. She smiled; her sisters in the background smiled; and I sank relieved upon the nearest chair. Obviously I had picked a winner; it seemed that cream wincey was a thing no man need blush to buy. I watched her fold up the material and enclose it in brown paper, and resolved to send it to my married sister at Ealing. And then a terrible thing happened. As I rose to take my parcel I saw Jones standing just outside on the pavement, talking earnestly to the Vicar. I sat down again.

"And the next thing?" murmured the voice seductively.

I looked at her in despair. But even as I did so my second inspiration came. "A yard of cream wincey," I said.

One fleeting, startled, curious glance she gave me; then without a word she proceeded to comply with my request. I waited, with one eye on her deftly-moving fingers, the other on Jones and the Vicar. And, as I waited, I resolved, come what might, to see the thing through.

She finished all too soon, handed me my second parcel and repeated her question. I repeated my order.

I have never spoken to anyone of what I went through during the next three-quarters of an hour. My own recollection of it is very vague. Through a sort of mist I see a figure in a chair facing a damsel who cuts off and packs up endless yards of cream wincey till there rises between them on the counter a stockade of brown-paper parcels. I see the other young female haberdashers, her companions, gathering timidly round, an awed joy upon their faces. Finally I see the figure rise and stumble blindly into the street beneath an immense burden of small packages all identical in size and shape. I can remember no more.

On the following day I went down to Devonshire for a rest, and stayed there till my system was clear of cream wincey. The first man I met on my return was Peters.

"Have you heard about Jones?" he asked.

"No," I replied.

"He's gone," said Peters solemnly.

A thrill of hope shot through me. "To the Front?" I asked.

"No, not exactly; to a convalescent home."

"Dear, dear!" I exclaimed, "how very sudden! What was it?"

"German measles," said Peters, "and a mistake in tactics. If he had only waited to let them come out into the open the beggars could have been cut off all right in detachments. But you remember Jones's theory; he never believed in finesse. So he went for them to suppress them en masse, and they retreated into the interior, concentrated their forces and compelled him to surrender on their own terms."

"Poor old Jones!" I murmured sadly.

| Englishman (accidentally trodden on). "What the— D—n you, Sir! Can't you—— | "——Oh, pardon, Monsieur! Vive la Belgique!" |

From an examination paper:—

"A periscope is not a thing what a doctor uses."

THE FOOD PROBLEM.

Greenwood is one of those intolerable men who always rise to an occasion. He is the kind of man who rushes to sit on the head of a horse when it is down. I can even picture him sitting on the bonnet of an overturned motor-'bus and shouting, "Now all together!" to the men who are readjusting it.

We were going down to business when Perkins introduced a new grievance against the Censor.

"Whatever do they allow this rot about food prices in the paper for?" he began. "It unsettles women awfully. Now my wife is insisting on having her housekeeping allowance advanced twenty-five per cent. I tell you she'd never have known anything about the advances if they hadn't been put before her in flaring type."

The general opinion of the compartment seemed to be that the Censor had gravely neglected his duty.

"I agreed with my wife," said Blair, who is a shrewd Scotchman, "and told her that she must have an extra two pounds a month. Now a twenty-five per cent. advance would have meant five pounds a month. Luckily Providence fashioned women without an idea of arithmetic."

Most of us looked as if we wished we had thought of this admirable idea.

"My wife drew my attention to the paper," said Greenwood loftily. "I did not argue the point with her. Finance is not woman's strong point. I rang for the cook at once."

Everyone looked admiringly at the hero who had dared to face his cook.

"I said to her," continued Greenwood, "'Cook, get the Stores price-list for to-day and serve for dinner precisely the things that have not advanced. You understand? That will do.' So you see the matter was settled."

"Er, what did your wife say?" asked Perkins.

"Say! What could she say? Here was the obvious solution. And I have noticed that women always lose their heads in an emergency. They never rise to the occasion."

The next morning I met Greenwood again.

"By the way," I asked, "did you have a good dinner yesterday?"

Greenwood looked me straight in the eyes. There is a saying that a liar cannot look you straight in the eyes. Discredit it. "The dinner was excellent," he replied. "I wish you had been there to try it. And every single thing at pre-war prices."

But that night I came across Mrs. Greenwood as she emerged from a Red Cross working party loaded with mufflers and mittens.

"Glad to hear these hard times don't affect your household," I began diplomatically.

Mrs. Greenwood smiled. "What has Oswald been telling you?"

"Nothing, except that he had an excellent dinner yesterday."

"I wasn't there," said Mrs. Greenwood; "I went to my mother's. You see, Cook conscientiously followed Oswald's instructions. He had sardines, Worcester sauce, macaroni, and tinned pork and beans. I can't make out quite which of the two was the first to give notice afterwards. Perhaps it was what you call a dead heat. Only, unless Oswald shouted, 'Take a month's notice,' when he heard the cook's step in the hall, I am inclined to think that Cook got there first."

Now in the train I recommend tinned pork and beans with Worcester sauce as a cheap and nourishing food in war-time.

Greenwood says nothing but glares at me. For once in his life he cannot rise to the occasion.

"I pity the pore chaps that 'aven't got out 'ere. London streets, this time o' year, with the drizzle and slush must be awful."

Rural Intelligence.

"Wanted, an all-round Man for sheep and cows who can build and thatch."

The Rugby Advertiser.

Men we do not play billiards with.—I.

M. Take Jonescu.[Pg 76]

UNWRITTEN LETTERS TO THE KAISER.

No. XIV.

(From the Grand Duke Nicholas, Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Armies.)

Sir,—It is pleasant in the midst of this welter of war to remember the days when your nation and mine were at peace, and when it was possible for each of us to inspect the troops of the other without running the risk of having our heads blown off by gigantic shells fired at the distance of several miles. What splendid reviews were those you used to hold on the Tempelhofer Feld! What a feeling of almost irresistible power was inspired by those solid regiments manœuvring and marching past under the eyes of their supreme War-lord! I think the intoxication of that sight was too great for you. You were not one of those calm ones who can be secure through the mere possession of strength. You had it, but at last came a point when you felt that it was all useless to you unless you employed it. So you urged on Austria in her unhappy policy of quasi-Bismarckian adventure; you cast to the winds every prompting of prudence and humanity; you imagined that other nations, because they were slow to take offence, could be bullied and hectored with impunity; you flung your defiance east and west, and in a moment of passion made war against all those who had striven for peace, but were not prepared to cling to it at the price of dishonour.

And thus began the disappointments which have settled upon you like a cloud. For, after all, war is entirely different from a review or from the most skilful peace-manœuvres. In manœuvres everything can be comfortably arranged beforehand. There are no bullets and no shells, and at the end a Kaiser can place himself at the head of many thousands of cavalry and can execute a charge that will resound for days through the columns of the newspapers. But in war there is a real enemy who has guns and bayonets and knows how to use them. All the colour that fascinates a shallow mind has to be put aside. There are deaths and wounds and sickness, and in the endurance of these and in the courage that surmounts all difficulties and dangers the dingiest regiment may make as brave a show as those which used to practise the parade-march over the review-field. I rather doubt if you had thought of all this—now had you?

Moreover our Russians, though they may look rough and though you may accuse them of ignorance, are no whit inferior to the most cultivated German professor in their patriotism and in their stern resolution to die rather than submit to defeat. They do not boast themselves to be learned men, but, on the other hand, it is not they who have made Louvain a city of ruins. They fight fiercely against men who have arms in their hands, but they have not executed innocent hostages, nor have they used warships and airships to massacre women and children. In these particulars they are willing to grant you and your Germans an unquestioned supremacy. If that be the civilisation to which your philosophers and poets have brought you, I can only say that we shall endeavour to rub along without such philosophers and poets; and I must beg you not to attempt to convert our Cossacks to your views. Being simple folk and straightforward, they might resent violently your efforts to give them the enlightenment of the Germans.

All this sounds like preaching, and Heaven knows I do not want to preach to you. You have hardened your heart, and I suppose you must go through this bitter business to the end. Let me rather tell you that, rough and unlearned as we are, we are making excellent progress in our fighting. So far we have once more foiled your Hindenberg's attack on Warsaw. We have an earnest hope that we shall be able to make your troops highly uncomfortable in the North, while towards the South we have been dealing quite faithfully with the Austrians. The Caucasus is filled with Turks dead or flying from our troops. As to Serbia—but I feel it would be scarcely polite to mention this stiff-necked country. It must be galling for your ally to have to fight a people so small in numbers but so great in their unconquerable resolution. Was it in order that Austrian troops might be chased headlong from Belgrade that you went to war?

I am, with all possible respect, your devoted enemy,

THE BREAKING POINT.

Mr. Punch's "Notice."

The Treasurer of The National Anti-vivisection Society writes to complain that we spoke last week of "The Anti-vivisection Society," when we were referring to "The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection." He protests that his Society "does not enjoy being confused with the British Union in this manner," and concludes by saying: "It is hard on us to be given no credit by Mr. Punch for being reasonable people and for refraining from this particular agitation,"—the agitation, that is, against the anti-typhoid inoculation of our troops.

Lady (about to purchase military headgear, to her husband). "I know it's more expensive than the others, dear, but—well, you see, you're too old to enlist, and I really feel we ought to do something!"

BY THE SEA.

"Jolly good luck," Miss Vesta Tilley used to sing, "to the girl who loves a soldier!" The sentiment is not less true to-day than when, too long ago, the famous male impersonator first uttered it. But there is no need to be actually the warrior's lover. To be his companion merely on a walk is to reap benefits, too, as I have been observing on the promenade of —— (a marine town whose name is, for tactical reasons, suppressed). At —— the girls whose good fortune it is to have for an acquaintance a lieutenant or captain have just now a great time, for the town has suddenly become a veritable Chatham, and the promenade is also a Champ de Mars. All the week it is the scene of military evolutions, a thought too strenuous for the particular variety of jolly good luck of which I am thinking; but there's a day which comes betwixt the Saturday and Monday when hard work gives way to rest, and then——!

For then this promenade, two or three miles long, is thronged by the military—privates, usually in little bands of threes and fours, and officers, mostly accompanied by pretty girls. And the demeanour of some of the younger of these officers is a great deal better worth watching than the sullen winter sea or the other more ordinary objects of the seaside. For they are there, some of them (bless their hearts!), for the pleasure of being saluted, and their pretty friends enjoy the reflected glory too. Some high-spirited ones among the satellites even go so far as noticeably to count the salutes which a walk yields. And I daresay they pit their bag against those of others. Their heroes probably vote such a competition bad form, and yet I doubt if they are really deeply resentful, and I guess that the young Roberts and the young Wolseley and the young Wellington all passed through similar ecstasies when they were first gazetted.

It was while walking behind one such happy little group that I made the discovery—a discovery to me, who am hopelessly a civilian, but no new thing I daresay to most people—that the saluting soldier must employ the hand which is farthest away from the officer whom he is saluting, and that is why some use the right and some the left—a discrepancy which plunged me into the gravest fears as to Lord Kitchener's fitness to control our army, until I realised the method underlying.

I noticed too that there is a good deal of difference both in saluting and in acknowledging salutes, and I overheard the fair young friend of one lieutenant adjuring him to be a little more genial in his attitude to the nice men who were bringing their arms and hands up with such whipcord tenseness in his honour.

"On another occasion one of our officers was pursued by an albatross which succeeded in crossing our lines."

Victoria Daily Colonist.

Joy of the Ancient Mariner on hearing, that his King and Country want him.

AT THE PLAY.

"Kings and Queens."

Just as Thomas Carlyle, out of his superior knowledge of the proletariat, informed us that, if you pricked it, it would bleed, so Mr. Rudolf Besier, fortified by intimacy with Court life, confides to us on the programme (in quotation) that Kings and Queens "have five fingers on each hand and take their meals regularly." But unless we are to get a little sacrilegious fun (such as Captain Marshall gave us) out of the contrast between the human nature of Royalties and the formalities which govern them as by divine right, there is not much object in raising a vulgar domestic scandal to the dignity of Court circles. True, the higher claims of kingship did enter into the question in the case of Richard VIII., whose heart was badly torn between his duty to his people and his passion for his wife; but for the rest, and apart from the mere properties (human or inanimate) of a royal palace, we might have been concerned with an ordinary middle-class interior complicated by a residential mother-in-law.

King Richard VIII. (Mr. Arthur Wontner), referring to his mother, Queen Elizabeth (Miss Frances Ivor). "Keep her away from me, or I shall kill her!"

Emperor Frederick IV. (Sir George Alexander). "Tut, tut! Something must be done. We can't permit matricide at the St. James's Theatre."

The causes of the misunderstanding (partially shared by myself) between the King and his Consort were some four or five. There was the Dowager Queen—a constant obsession—who stood for the extreme of propriety. She ought, of course, to have had a palace of her own. There was the young King, upon whom she rigorously imposed her own standards of living. There was the young Queen with a harmless taste for the natural gaiety of youth. Not designed by nature for the wearing of the purple, she had been taken from a nice country home, where there were birds and flowers and mountains. She kept saying to herself:—

But, since she couldn't do that, she clamoured for pretty frocks, and for the right to choose her own friends. Among these was an American Marquise of so doubtful a record that her name had to be deleted from the list of guests commanded to the State Ball. I was greatly disappointed not to meet her. Then there was a royal female Infant (deceased), who should of course have been a boy. Her contribution to the general discomfort, though pressed upon us with fearless reiteration, was always outside the grasp of my intelligence. Neither of her parents seemed to share my hope that they might possibly live to beget other offspring, including even a male child.

Lastly, there was a vagrant troubadour with a gift for the pianoforte. He was called Prince Louis, and firmly held the opinion that he alone appreciated the Queen's qualities and could offer her a suitable solace. He had his simple dramatic uses, and by an elopement (as innocent, on her part, as it was arbitrary) enabled the lady to return to the arms of her desperate husband, for whom it appears that she had always entertained a profound adoration. What they all really needed for the correction of their little egoisms was a Big War. That is the only lesson that I could draw from Mr. Besier's play, and I don't believe he meant me to draw even that.

Such originality as it offered was to be found in the soul of the young King, with its distraction between two loyalties; its despairing conviction that virtue as its own reward was not good enough; its threatened rebound to the primrose paths which his father of never-to-be-forgotten memory had trodden before him. Mr. Arthur Wontner looked the part and played it with a very quiet dignity.

Sir George Alexander, as an imperial uncle, of no particular nationality, filled his familiar rôle of amicus curiæ; a man of sixty and much dalliance in the past, but with his heart—what was left of it—in the right place. His facial growth (a little in the manner of Mr. Maurice Hewlett) suited him well—far better indeed than the frock coat of the final Act. He was admirable throughout (except in one rather stuffy homily where he was not quite certain of his own views); but I could have done with much more of those lighter phases in which he excels. It was the same with the pleasant humour of Miss Frances Ivor as the Queen-Mother, which was sadly curtailed. Miss Marie Löhr played the young Queen with extraordinary sincerity, notably in one of the many scenes in which she lamented her lost child. Here, if this tedious baby had not failed to touch my imagination, I must have been honestly moved. If we suffered any doubt as to the reality of her grief, this was due to the disturbing beauty of the frocks in which she gave utterance to it. Anyhow they totally failed to support the charge of dowdiness which had been freely brought against the Queen-Mother's régime.

Finally, that native air of frank loyalty which Mr. Ben Webster's gifts as an actor are impotent to disguise gave the lie to his thankless part as Prince Louis. Nor did the superiority of his morning-coat go well with the sinister touch of melodrama in his set speeches. The villain of the piece should not have been plus royaliste que le roi, who was content to wear a lounge serge suit.

If Mr. Besier's play achieves the popular favour of which, as I understand, it has already secured the promise, it will not be on account of its intrinsic merits, though it has its good points; it will be due in part to the excellence of the performance, and in part to that innocent snobbery which is latent in the typical British bosom.

I ought to add that I think I asked Mr. Besier long ago to try and make a better bow to his audience. Well, he hasn't paid any attention to my request.

"Our World Famous Toilet Cream

IMPROVES THE COMPLEXION

of all Local Chemists and Stores."

We do not worry about the complexion of the Stores but we are glad for the local Chemists.

Officer (to trooper, whom he has recently had occasion to reprimand severely). "Why did you not salute?"

Trooper. "I thocht me an' you wisna' on speakin' ter-rms the noo."

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

I confess that I was at first a little alarmed by the title of Friendly Russia (Fisher Unwin). A book with a name like that, with, moreover, an "introduction"—and one by no less a person than Mr. H. G. Wells—seemed to threaten ponderous things, maps probably, and statistics and unpronounceable towns. Never was there a greater mistake. What Mr. Denis Garstin has put into his entertaining pages is simply the effect produced by a previously unknown country upon the keen and receptive mind of a young man who is fortunately able to translate his impressions into vigorous and picturesque language. I have met few travel books so unpretentious, none that gives more vividly the feeling of "going there oneself" that must be the final test of success. The last few years have made a happy change in the popular English conception of Russia. Even before the War, our old melodramatic idea, that jumble of bombs and spies and sledge-hunting wolves, had begun to give place to a slightly apologetic admiration. Now, of course, we are all Russophil; but for the understanding proper to that love there can be no better introduction than Mr. Garstin's pleasant book. Spend with him a happy summer by the waters of the Black Sea; share, along with his humour, his appreciation of that life of contented simplicity, where easy-going and hospitable families are ruled by the benevolent despotism of equally easy-going domestics (O knouts, O servitude!), where the casual caller "drops in" for a month or more, and where everyone knows everything about everybody and nobody minds. By way of contrast to this, the latter part of the book contains, in "Russia at War," some chapters of an even closer appeal. You will read here, not unmoved, of how that terrible week of suspense came upon the soul of a people, of the fusion of all discordant factions into one army intent only upon the Holy War. There is encouragement and a heartening certainty of triumph in this that should be an unfailing remedy for pessimism.

None of your confounded subtleties and last cries in Mrs. Latham's Extravagance (Chapman and Hall). An unvarnished tale, rather, fashioned according to the naïve method of simple enumeration and bald assertion, with such subsidiary trifles as characterisation left to the discretion and imaginative capacity of the reader. Christopher Sheffield, an artist, post-cubist brand, married his model, a dipsomaniac as it happened. Whereupon he implored Katherine to share his life, which, to keep him from going down-hill, she very generously did, it being explicitly understood that she was to have the reversion of Mrs. Sheffield's marriage lines. Christopher, however, becomes infatuated with the widow Latham—who had married a rich old gentleman for his money, while in love with Lord Ronald Eckington, then the penniless fourth son of a marquis, now the celebrated and well-paid photographer, "Mr. Lestocq"—so that when Sheffield's model wife dies, he, instead of doing the right thing by Katherine, suggests settling the matter on a basis of five-hundred or (at a push) five-fifty a year. Naturally she draws herself up very cold and proud and refuses the compensation. And then, with[Pg 80] a hardihood and success which nothing in this ingenuous narrative sufficiently explains, the Honourable Lavinia Elliston, Lord Ronald and the extravagant Mrs. Latham rush in to patch up the Christopher-Katherine alliance. I don't suspect Mr. Thomas Cobb of thinking that people really do things quite like this, but probably he found that his characters took the bits between their teeth—as they well might. Lord Ronald's share in the transaction seemed particularly gratuitous. I can only think that since moving in photographic circles he had discarded his high patrician polish in favour of a distinctly mat surface. He didn't marry the widow Latham because he hated the thought of touching old man Latham's money. She, discovering this, disposed of the whole of it in a few months of gloriously expensive living and giving. This, by the way, was her "Extravagance," which of course brought the happy ending. O, Mr. Cobb!

The king of curmudgeons could not complain when Mrs. Conyers is described as "one of the most entertaining hunting novelists of the day," but when Messrs. Methuen call her book (A Mixed Pack) "a collection of Irish sporting stories" I may at least be allowed to wonder at the inadequacy of their description. For the fact of the matter is that a third part of this volume, and by no means the worst part, is concerned with little Mr. Jones, a traveller in the firm of Amos and Samuel Mosenthal, who were dealers in precious stones and about as Irish and as sporting as their names suggest. Mr. Jones, in the opinion of the Mosenthals, was the simplest soul that they had ever entrusted with jewels of great value. Although the tales of apparent simpletons who outwit crafty villains are becoming tedious in their frequency, I can still congratulate Mrs. Conyers upon the thrills and shudders that she gets into these stories of robbery and torture. Not for a moment do I believe in Mr. Jones, but for all that I take the little man to my heart. As for the tales of sport, it is enough to say that they are written with so much wit and verve that even I, who am commonly suffocated with boredom when I have to listen to a hunting story, found them quite pleasant to read.

My expectations of enjoyment on opening The Whalers (Hodder and Stoughton) were nil, for the tales of whaling to which from time to time I have been compelled to listen have produced sensations which can only be described as nauseating. Somewhere, somehow, I knew that brave men risked their lives in gaining a precarious livelihood from blubber, but I was more than content to hear no further details either of them or their captures. Let me acknowledge, then, that Mr. J. J. Bell has persuaded me, against my will, of the romance and fascination of the whalers' calling. The twelve stories—or perhaps they ought to be called sketches—in this book contain plenty that is romantic and practically nothing that is repulsive. "There is," the author says with engaging frankness, "much that is slow in whaling. On the whole there is more anxiety than excitement, more labour than sport." Not for me is it to contradict such an authority, but even granted that he is right the fact remains that no one can justly complain of a lack of excitement in these stories, though complaints may legitimately be made that their pathos is sometimes allowed to drop into sentimentality. "The Herr Professor—an Interlude" deserves an especial word of praise, for it proves again that Mr. Bell, when not occupied in other directions, can be simply and delightfully funny.

At the War Office. "Oh, please could you tell me how to find Lord Kitchener's room? I want to see him particularly, and I won't keep him long. It's just to write his favourite author and flower in my album."

It must have happened to all of us to be hailed by some friend with the greeting, "I've got the funniest story to tell you; it'll make you scream," and to listen thereafter to something that produced nothing but irritated perplexity. Then, if the friend were a valued one, with a record of genuine humour, we would perhaps evoke with difficulty a polite snigger, and so break from the encounter. Well, this is very much what I cannot, help feeling about The Phantom Peer (Chapman And Hall). I have had such entertainment from Mr. Edwin Pugh in the past that I prepared for this Extravanganza (his own term) in a mood of smiling anticipation. But from the first page to the last it had me beat. Fun is the last subject in the world upon which one should dare to dogmatize; and to others, more fortunate, the thing may bring laughter. I can only envy them. It is not that I complain of the impossibility of the plot. Extravaganza covers a multitude of coincidences. When Johnnie Shotter was persuaded to take the name and personality of an imaginary Lord Counterpound, I bore without a murmur the immediate arrival on the scene of an actual holder of that very title. It was the dreariness of the resulting muddle that baffled me. To make matters worse the intrigue, such as it is, breaks off abruptly for several chapters in the middle, to permit the introduction of what appears to be an attempted satire upon forcible feeding. At the end, one of the chief male characters turns out to be a woman; but as none of them was anything but a knock-jointed puppet jumping upon ill-concealed wires the transformation was just academically uninteresting. I am sorry, Mr. Pugh, but even for your sake I can only say, "Tell us a better one next time!"

From the letter of an American restaurateur to a new arrival from England:—

"Dear Sir,—Before I chef—one Italian noble family—now come America—start the business my own—house top side this paper. Everybody speaks it me. Lunches and Dinners worth two (2) times. I delighted preparation for you—no charge extra—only notification me few hours behind. I build for clientelle intellectual—they more appreciation my art."