CONTENTS

CHAPTER THE FIRST. THE BRITONS—THE ROMANS—INVASION BY JULIUS CÆSAR.

CHAPTER THE THIRD. THE SAXONS—THE HEPTARCHY.

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. THE UNION OF THE HEPTARCHY UNDER EGBERT.

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. THE DANES—ALFRED.

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. FROM KING EDWARD THE ELDER TO THE NORMAN CONQUEST.

BOOK II. THE PERIOD FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TO THE DEATH OF KING JOHN.

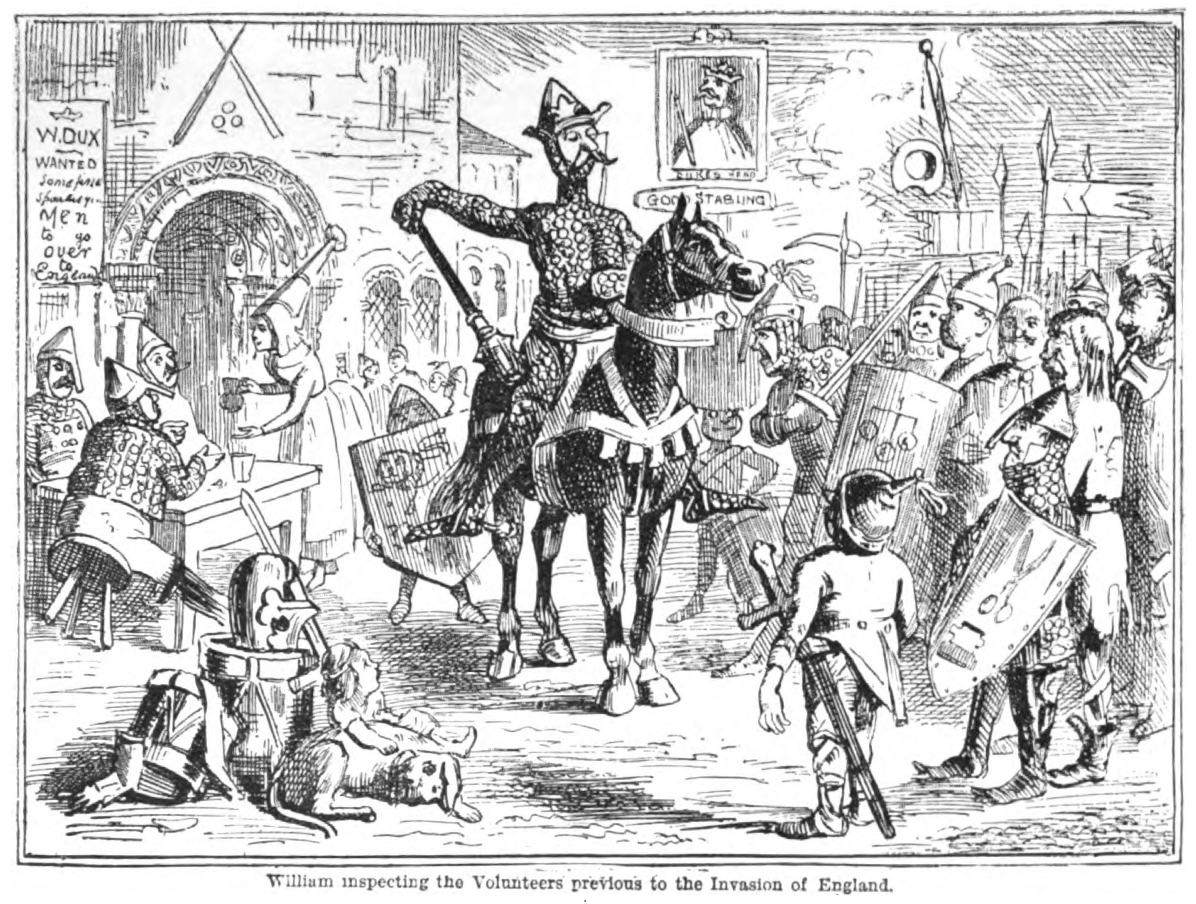

CHAPTER THE FIRST. WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR.

CHAPTER THE SECOND. WILLIAM RUFUS.

CHAPTER THE THIRD. HENRY THE FIRST, SURNAMED BEAUCLERC.

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. HENRY THE SECOND, SURNAMED PLANTAGENET.

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. RICHARD THE FIRST, SURNAMED COUR DE LION.

CHAPTER THE SEVENTH. JOHN, SURNAMED SANSTERRE, OR LACKLAND.

CHAPTER THE FIRST. HENRY THE THIRD, SURNAMED OF WINCHESTER.

CHAPTER THE SECOND. EDWARD THE FIRST, SURNAMED LONGSHANKS.

CHAPTER THE THIRD. EDWARD THE SECOND, SURNAMED OF CAERNARVON.

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. EDWARD THE THIRD.

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. RICHARD THE SECOND, SURNAMED OF BORDEAUX.

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. ON THE MANNERS, CUSTOMS, AND CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE.

CHAPTER THE FIRST. HENRY THE FOURTH, SURNAMED BOLINGBROKE.

CHAPTER THE SECOND. HENRY THE FIFTH, SURNAMED OF MONMOUTH.

CHAPTER THE THIRD. HENRY THE SIXTH, SURNAMED OF WINDSOR.

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. HENRY THE SIXTH, SURNAMED OF WINDSOR (CONTINUED).

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. EDWARD THE FOURTH.

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. EDWARD THE FIFTH.

CHAPTER THE SEVENTH. RICHARD THE THIRD.

CHAPTER THE EIGHTH. NATIONAL INDUSTRY.

CHAPTER THE NINTH. OF THE MANNERS, CUSTOMS, AND CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE.

BOOK V. FROM THE ACCESSION OF HENRY THE SEVENTH TO THE END OF THE REIGN OF ELIZABETH.

CHAPTER THE FIRST. HENRY THE SEVENTH.

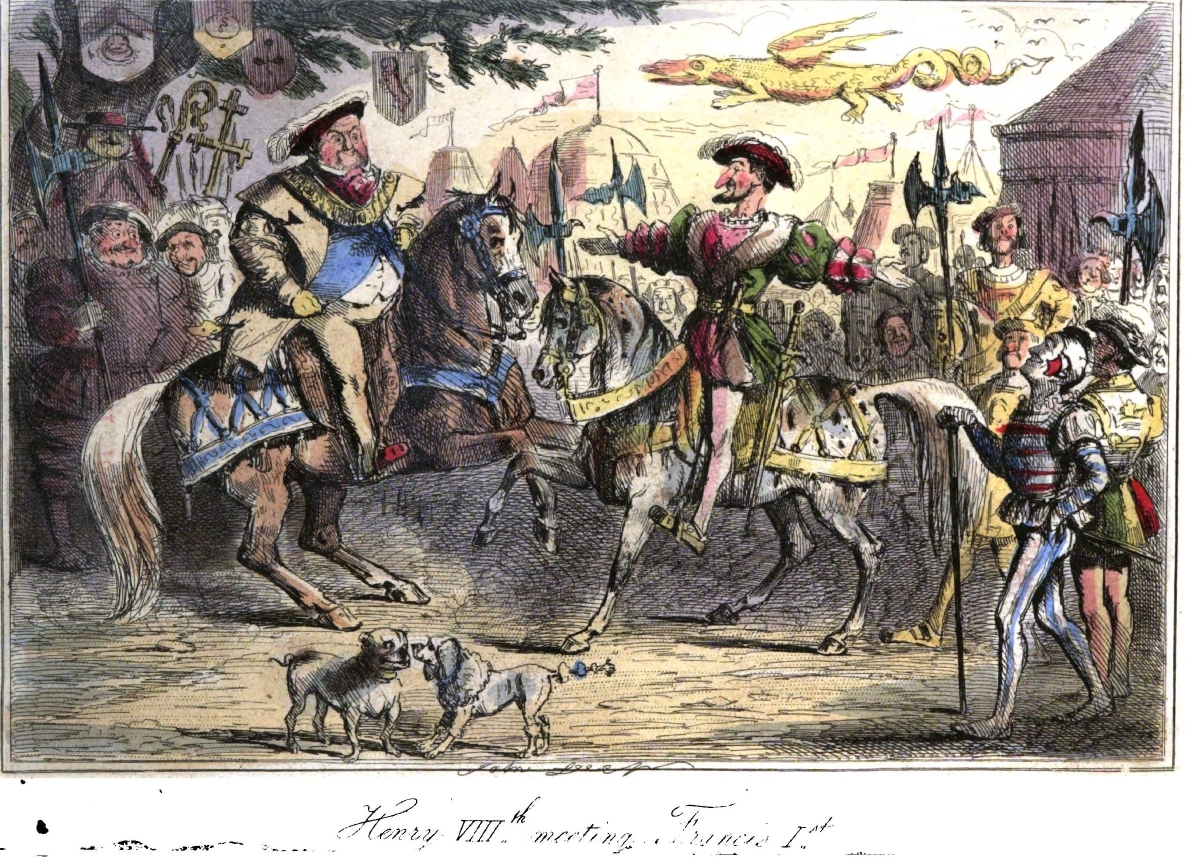

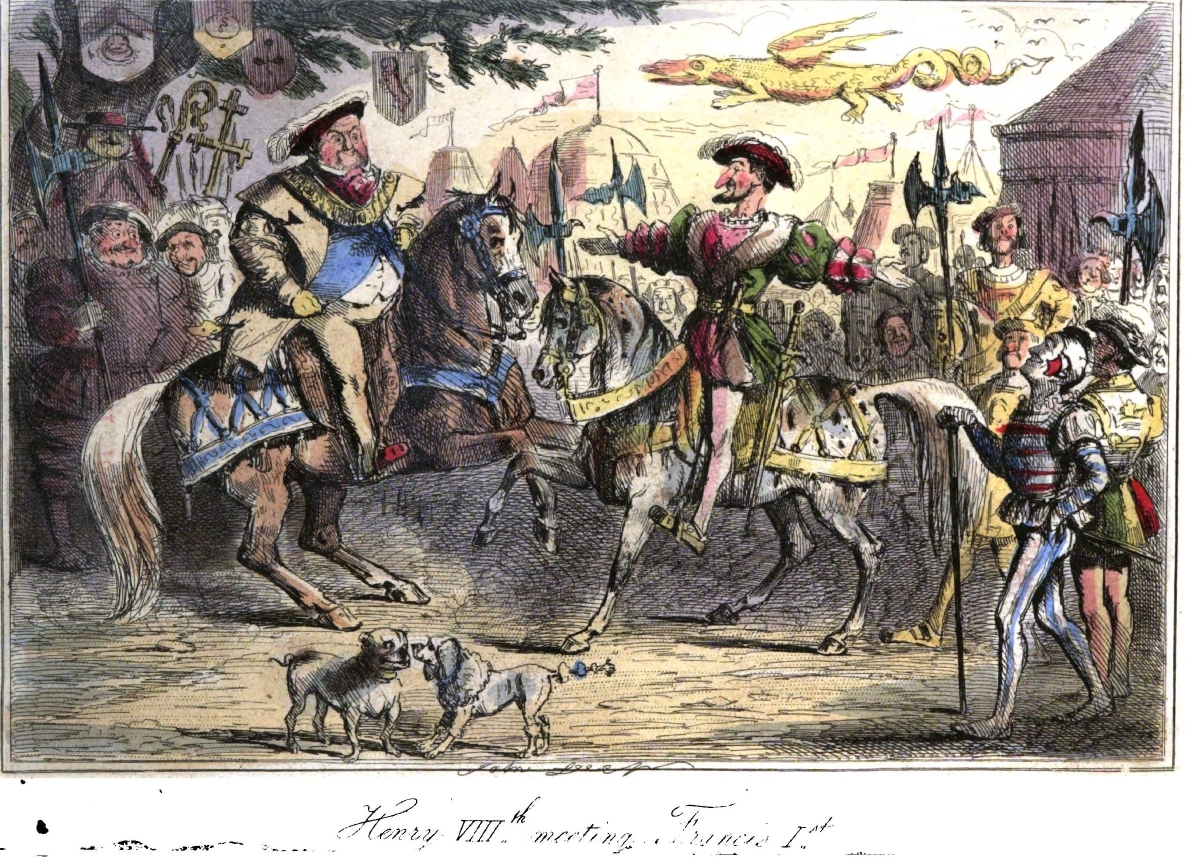

CHAPTER THE SECOND. HENRY THE EIGHTH.

CHAPTER THE THIRD. HENRY THE EIGHTH (CONTINUED).

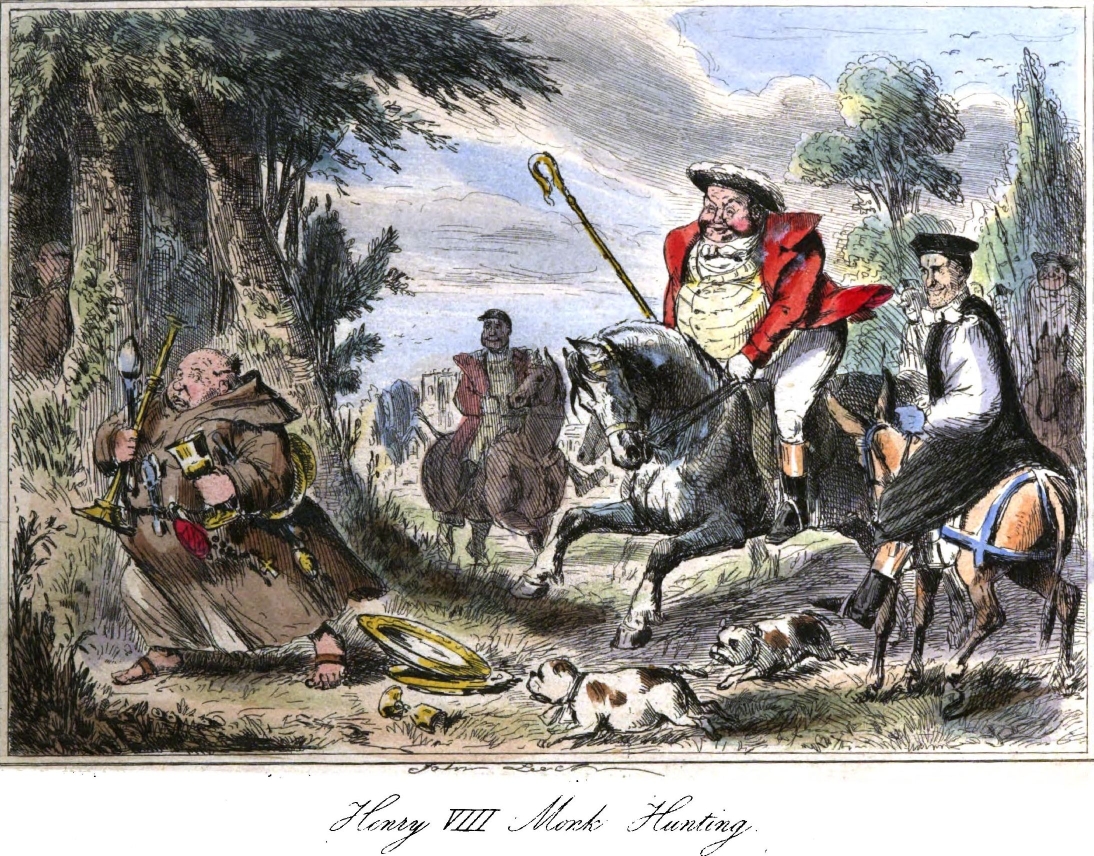

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. HENRY THE EIGHTH (CONTINUED.)

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. HENRY THE EIGHTH (CONCLUDED).

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. EDWARD THE SIXTH.

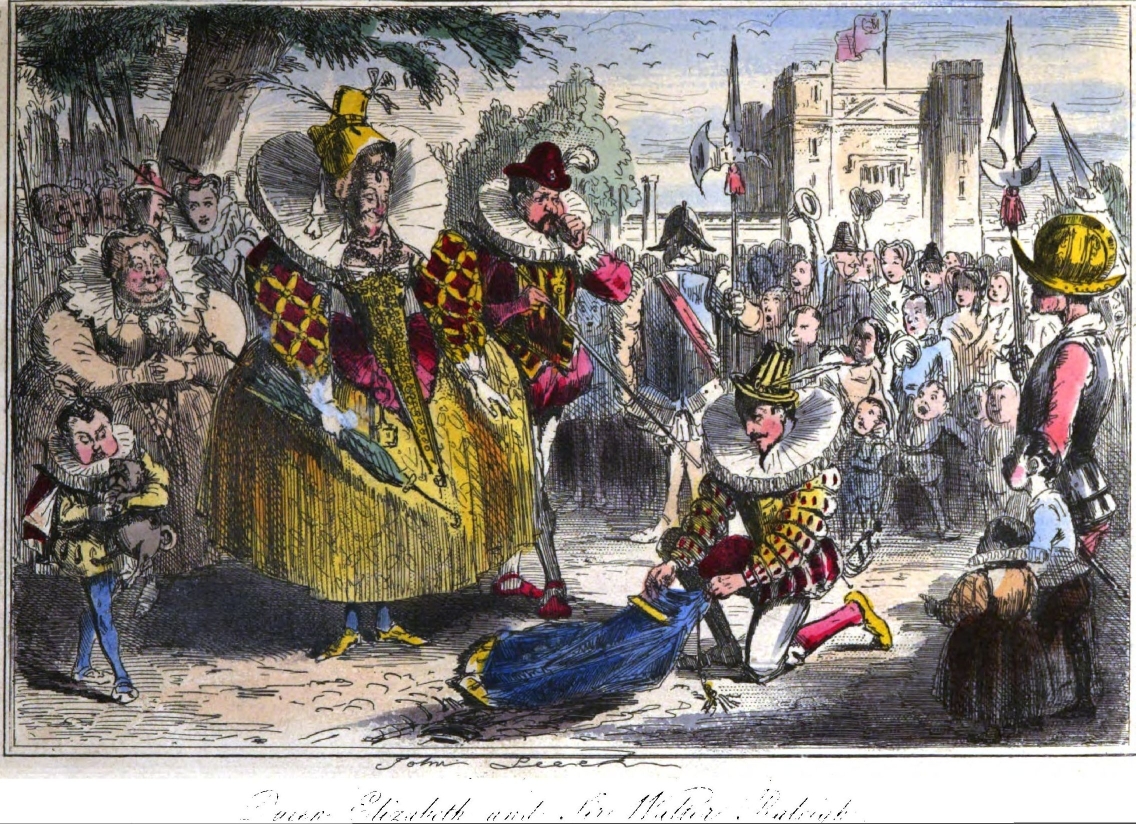

CHAPTER THE EIGHTH. ELIZABETH.

CHAPTER THE NINTH. ELIZABETH (CONTINUED).

CHAPTER THE TENTH. ELIZABETH (CONCLUDED).

CHAPTER THE FIRST. JAMES THE FIRST.

CHAPTER THE SECOND. JAMES THE FIRST (CONTINUED).

CHAPTER THE THIRD. CHARLES THE FIRST.

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. CHARLES THE FIRST (CONTINUED).

CHAPTER THE FIFTH CHARLES THE FIRST (CONCLUDED).

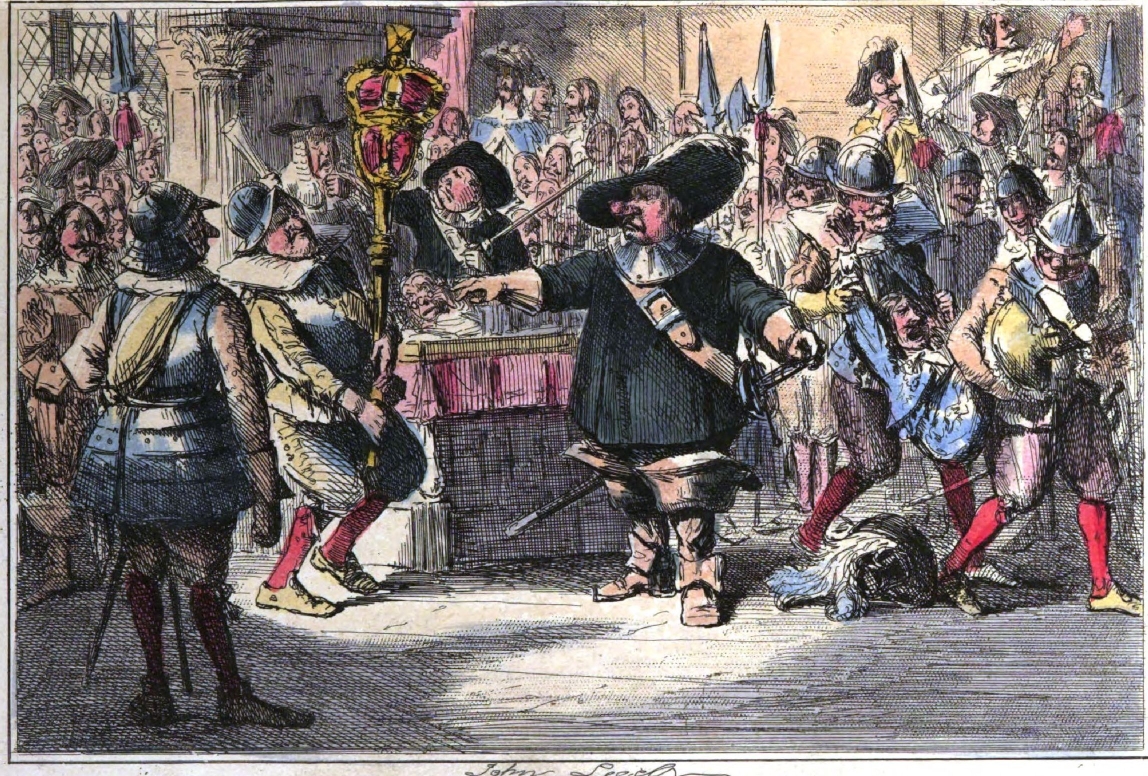

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. THE COMMONWEALTH.

CHAPTER THE SEVENTH. RICHARD CROMWELL.

BOOK VII. THE PERIOD FROM THE RESTORATION OF CHARLES THE SECOND TO THE REVOLUTION.

CHAPTER THE FIRST. CHARLES THE SECOND.

CHAPTER THE SECOND. CHARLES THE SECOND (CONTINUED).

CHAPTER THE THIRD. CHARLES THE SECOND (CONTINUED).

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. JAMES THE SECOND.

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. LITERATURE, SCIENCE, FINE ARTS, MANNERS, CUSTOMS, AND CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE.

BOOK VIII. THE PERIOD FROM THE REVOLUTION TO THE ACCESSION OF GEORGE THE THIRD.

CHAPTER THE FIRST. WILLIAM AND MARY.

CHAPTER THE SECOND. WILLIAM THE THIRD.

CHAPTER THE THIRD. QUEEN ANNE.

CHAPTER THE FOURTH. GEORGE THE FIRST.

CHAPTER THE FIFTH. GEORGE THE SECOND.

CHAPTER THE SIXTH. GEORGE THE SECOND (CONCLUDED).

IN commencing this work, the object of the Author was, as he stated in the Prospectus, to blend amusement with instruction, by serving up, in as palatable a shape as he could, the facts of English History. He pledged himself not to sacrifice the substance to the seasoning; and though he has certainly been a little free in the use of his sauce, he hopes that he has not produced a mere hash on the present occasion. His object has been to furnish something which may be allowed to take its place as a standing dish at the library table, and which, though light, may not be found devoid of nutriment. That food is certainly not the most wholesome which is the heaviest and the least digestible.

Though the original design of this History was only to place facts in an amusing light, without a sacrifice of fidelity, it is humbly presumed that truth has rather gained than lost by the mode of treatment that has been adopted. Persons and tilings, events and characters, have been deprived of their false colouring, by the plain and matter-of-fact spirit in which they have been approached by the writer of the "Comic History of England." He has never scrupled to take the liberty of tearing off the masks and fancy dresses of all who have hitherto been presented in disguise to the notice of posterity. Motives are treated in these pages as unceremoniously as men; and as the human disposition was much the same in former times as it is in the present day, it has been judged by the rules of common sense, which are alike at every period.

Some, who have been accustomed to look at History as a pageant, may think it a desecration to present it in a homely shape, divested of its gorgeous accessories. Such persons as these will doubtless feel offended at finding the romance of history irreverently demolished, for the sake of mere reality. They will-perhaps honestly though erroneously-accuse the author of a contempt for what is great and good; but the truth is, he has so much real respect for the great and good, that he is desirous of preventing the little and bad from continuing to claim admiration upon false pretences.

IT has always been the good fortune of the antiquarian who has busied himself upon the subject of our ancestors, that the total darkness by which they are overshadowed, renders it impossible to detect the blunderings of the antiquarian himself, who has thus been allowed to grope about the dim twilight of the past, and entangle himself among its cobwebs, without any light being thrown upon his errors.

But while the antiquarians have experienced no obstruction from others, they have managed to come into collision among themselves, and have knocked their heads together with considerable violence in the process of what they call exploring the dark ages of our early history. We are not unwilling to take a walk amid the monuments of antiquity, which we should be sorry to run against or tumble over for want of proper light; and we shall therefore only venture so far as we can have the assistance of the bull's-eye of truth, rejecting altogether the allurements of the Will o' the Wisp of mere probability. It is not because former historians have gone head oyer heels into the gulf of conjecture, that we are to turn a desperate somersault after them. *

* Some historians tell us that the most conclusive evidence of things that have happened is to be found in the reports of the Times. This source of information is, however, closed against us, for the Times, unfortunately, had no reporters when these isles were first inhabited.

The best materials for getting at the early history of a country are its coins, its architecture, and its manners. The Britons, however, had not yet converted the Britannia metal—for which their valour always made them conspicuous—into coins, while their architecture, to judge from the Druidical remains, was of the wicket style, consisting of two or three stones stuck upright in the earth, with another stone laid at the top of them; after the fashion with which all lovers of the game of cricket are of course familiar. As this is the only architectural assistance we are likely to obtain, we decline entering upon the subject through such a gate; or, to use an expression analogous to the pastime to which we have referred, we refuse to take our innings at such a wicket. We need hardly add, that in looking to the manners of our ancestors for enlightenment, we look utterly in vain, for there is no Druidical Chesterfield to afford us any information upon the etiquette of that distant period. There is every reason to believe that our forefathers lived in an exceedingly rude state; and it is therefore perhaps as well that their manners—or rather their want of manners—should be buried in oblivion.

It was formerly very generally believed that the first population of this country descended from Æneas, the performer of the most filial act of pick-a-back that ever was known; and that the earliest Britons were sprung from his grandson—one Brutus, who, preserving the family peculiarity, came into this island on the shoulders of the people. * Hollinshed, that greatest of antiquarian gobemouches, has not only taken in the story we have just told, but has added a few of his own ingenious embellishments. He tells us that Brutus fell in with the posterity of the giant Albion, who was put to death by Hercules, whose buildings at Lambeth are the only existing proofs of his having ever resided in this country.

* The story of Brutus and the Trojans has been told in such a variety of ways, that it is difficult to make either head or tail of it. Geoffrey of Monmouth says that Brutus found Britain deserted, except by a few giants—from which it is to be presumed that Brutus landed at Greenwich about the time of the fair. Perhaps the introduction of troy-weight into our arithmetic may be traced to the immigration of the Trojans, who were very likely to adopt the measures—and why not the weights—with which they had been familiar.

Considering it unprofitable to dwell any longer on those points, about which all writers are at loggerheads, we come at once to that upon which they are all agreed, which is, that the first inhabitants were a tribe of Celtæ from the Continent: that, in fact, the earliest Englishmen were all Frenchmen; and that, however bitter and galling the fact may be, it is to Gaul that we owe our origin. We ought perhaps to mention that Cæsar thinks our sea-ports were peopled by Belgic invaders, from Brussels, thus causing a sprinkling of Brussels sprouts among the native productions of England.

The name of our country—Britannia—has also been the subject of ingenious speculation among the antiquarians. To sum up all their conjectures into one of our own, we think they have succeeded in dissolving the word Britannia into Brit, or Brick, and tan, which would seem to imply that the natives always behaved like bricks in tanning their enemies. The suggestion that the syllable tan, means tin, and that Britannia is synonymous with tin land, appears to be rather a modern notion, for it is only in later ages that Britannia has become emphatically the land of tin, or the country for making money.

The first inhabitants of the island lived by pasture, and not by trade. They as yet knew nothing of the till, but supported themselves by tillage. Their dress was picturesque rather than elegant. A book of truly British fashions would be a great curiosity in the present day, and we regret that we have no Petit Courier des Druides, or Celtic Belle Assemblée, to furnish figurines of the costume of the period. Skins, however, were much worn, for morning as well as for evening dress; and it is probable that even at that early age ingenuity may have been exercised to suggest new patterns for cow cloaks and other varieties of the then prevailing articles of the wardrobe.

The Druids, who were the priests, exercised great ascendancy over the people, and often claimed the spoils of war, together with other property, under the plea of offering up the proceeds as a sacrifice to the divinities. These treasures, however, were never accounted for; and it is now too late for the historians to file, as it were, a bill in equity to inquire what has become of them.

Cæsar, who might have been so called from his readiness to seize upon everything, now turned his eyes and directed his arms upon Britain. According to some he was tempted by the expectation of finding pearls, which he hoped to get out of the oysters, and he therefore broke in upon the natives with considerable energy.

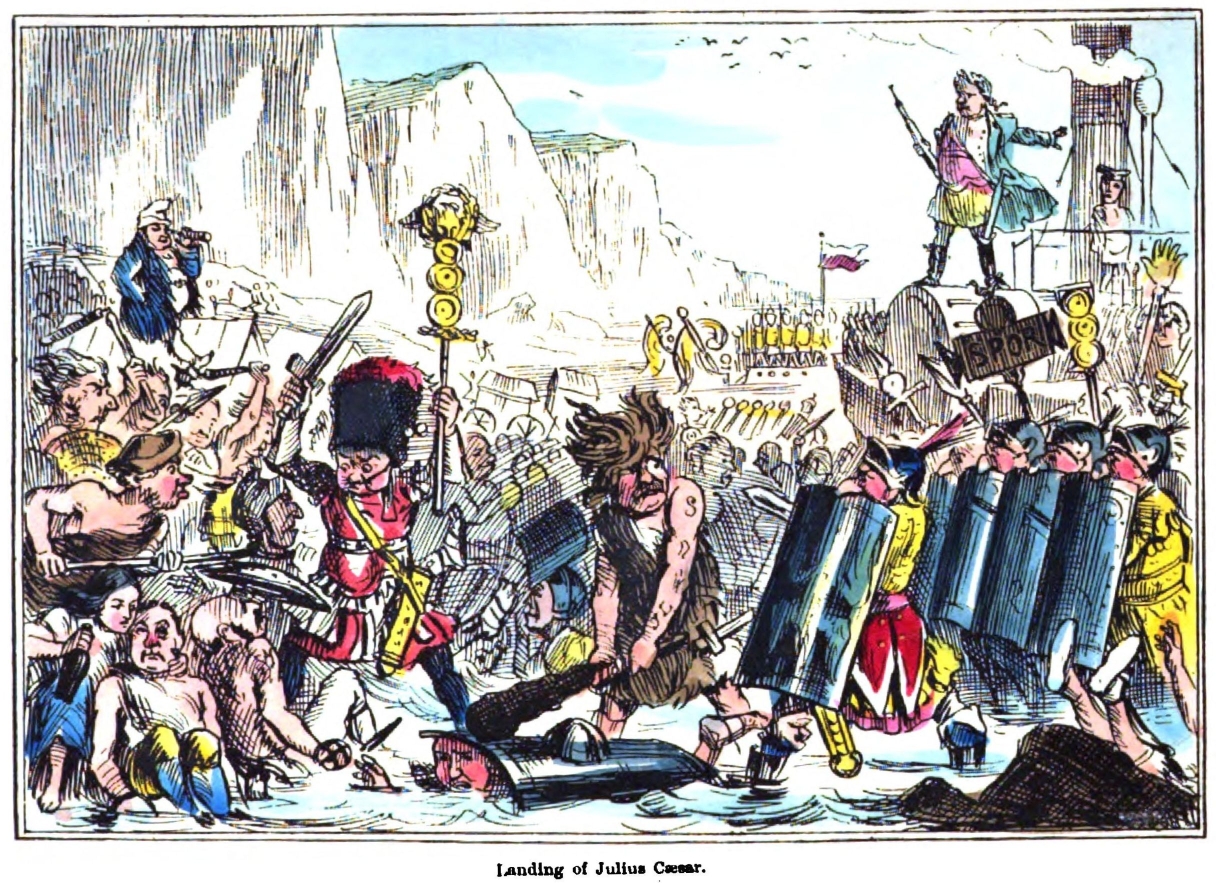

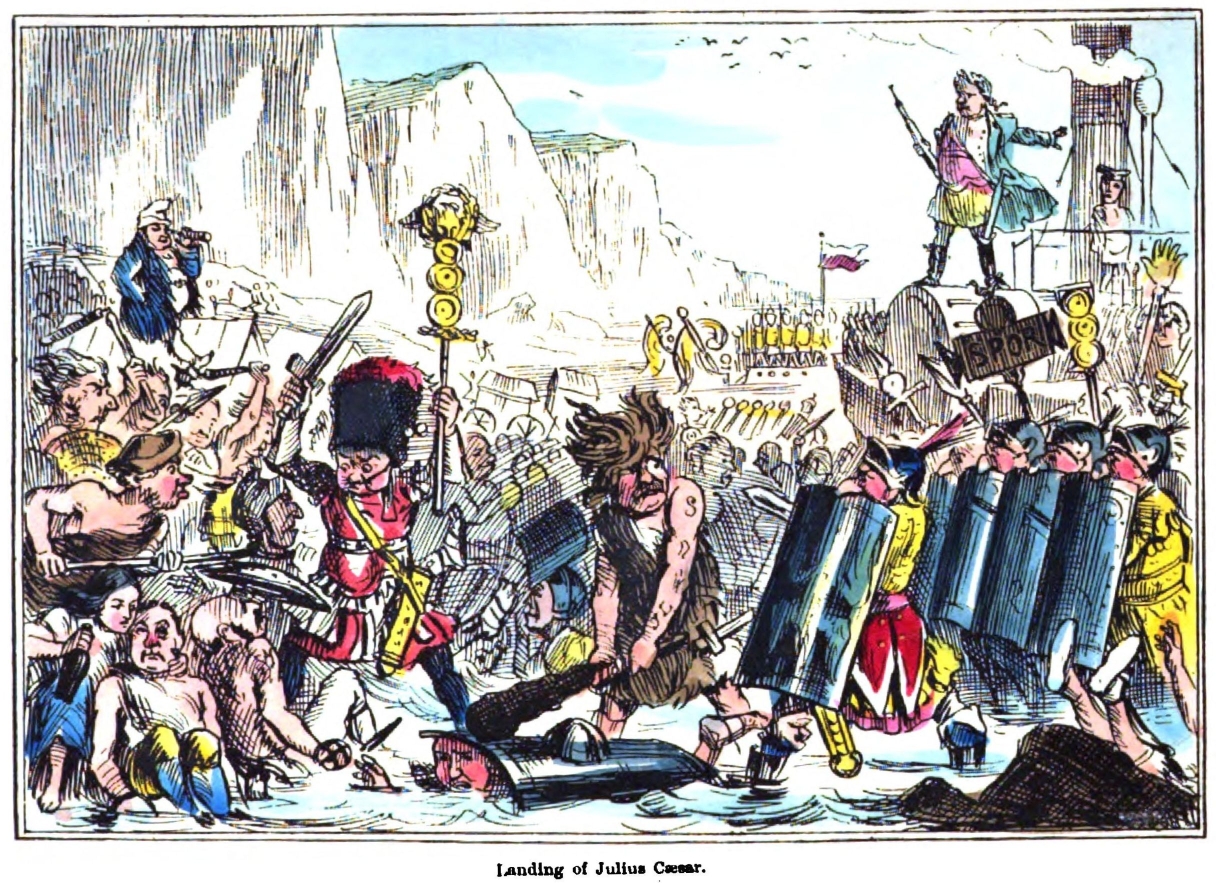

Whatever Caesar looking for the Pearls for which Britain was formerly celebrated, may have been Caesar's motives the fact is pretty well ascertained, that at about ten o'clock one fine morning in August—some say a quarter past—he reached the British coast with 12,000 infantry, packed in eighty vessels. He had left behind him the whole of his cavalry—the Roman horse-marines—who were detained by contrary winds on the other side of the sea, and though anxious to be in communication with their leader, they never could get into the right channel. At about three in the afternoon, Cæsar having taken an early dinner, began to disembark his forces at a spot called to this day the Sandwich Flats, from the people having been such flats as to allow the enemy to effect a landing. While the Roman soldiers were standing shilly-shallying at the side of their vessels, a standard-bearer of the tenth legion, or, as we should call him, an ensign in the tenth, jumped into the water, which was nearly up to his knees, and addressing a claptrap to his comrades as he stood in the sea, completely turned the tide in Caesar's favour. After a severe shindy on the shingles, the Britons withdrew, leaving the Romans masters of the beach, where Cæsar erected a marquee for the accommodation of his cohorts. The natives sought and obtained peace, which had no sooner been concluded, than the Roman horse-marines were seen riding across the Channel. A tempest, however, arising, the horses were terrified, and the waves beginning to mount, added so much to the confusion, that the Roman cavalry were compelled to back to the point they started from. The same storm gave a severe blow to the camp of Cæsar, on the beach, dashing his galleys and transports against the rocks which they were sure to split upon. Daunted by these disasters, the invaders, after a few breezes with the Britons, took advantage of a favourable gale to return to Gaul, and thus for a time the dispute appeared to have blown over.

Cæsar's thoughts, however, still continued to run in one, namely, the British, Channel. In the spring of the ensuing year, he rigged out 800 ships, into which he contrived to cram 32,000 men, and with this force he was permitted to land a second time by those horrid flats at Sandwich. The Britons for some time made an obstinate resistance in their chariots, but they ultimately took a fly across the country, and retreated with great rapidity. Cæsar had scarcely sat down to breakfast the next morning when he heard that a tempest had wrecked all his vessels. At this intelligence he burst into tears, and scampered off to the sea coast, with all his legions in full cry, hurrying after him.

The news of the disaster turned out to be no exaggeration, for there were no penny-a-liners in those days; and, having carried his ships a good way inland, where they remained like fish out of water, he set out once more in pursuit of the enemy. The Britons had, however, made the most of their time, and had found a leader in the person of Gassivelaunus, alias Caswallon, a quarrelsome old Gelt, who had so frequently thrashed his neighbours, that he was thought the most likely person to succeed in thrashing the Romans. This gallant individual was successful in a few rough off handed engagements; but when it came to the fancy work, where tactics were required, the disciplined Roman troops were more than a match for him. His soldiers having been driven back to their woods, he drove himself back in his chariot to the neighbourhood of Chertsey, where he had a few acres of ground, which he called a Kingdom. He then stuck some wooden posts in the middle of the Thames, as an impediment to Cæsar, who, in the plenitude of his vaulting ambition, laid his hands on the posts and vaulted over them.

The army of Cassivelaunus being now disbanded, his establishment was reduced to 4000 chariots, which he kept up for the purpose of harassing the Romans. As each chariot required at least a pair of horses, his 4000 vehicles, and the enormous stud they entailed, must have been rather more harassing to Cassivelaunus himself than to the enemy.

This extremely extravagant Celt, who had long been the object of the jealousy of his neighbours, was now threatened by their treachery. The chief of the Trinobantes, who lived in Middlesex, and were perhaps the earliest Middlesex magistrates, sent ambassadors to Cæsar, promising submission. They also showed him the way to the contemptible cluster of houses which Cassivelaunus dignified with the name of his capital. It was surrounded with a ditch, and a rampart made chiefly of mud, the article in which military engineering seemed to have stuck at that early period. Cassivelaunus was driven by Cæsar from his abode, constructed of clay and felled trees, and so precipitate was the flight of the Briton, that he had only time to pack up a few necessary articles, leaving everything else to fall into the hands of the enemy.

The Roman General, being tired of his British campaign, was glad to listen to the overtures of Cassivelaunus; but these overtures consisted of promissory notes, which were never realised. The Celt undertook to transmit an annual tribute to Cæsar, who never got a penny of the money; and the hostages he had carried with him to Gaul became a positive burden to him, for they were never taken out of pawn by their countrymen. It is believed that they were ultimately got rid of at a sale of unredeemed pledges, where they were put up in lots of half a dozen, and knocked down as slaves to the highest bidder.

Before quitting the subject of Caesar's invasion, it may be interesting to the reader to know something of the weapons with which the early Britons attempted to defend themselves. Their swords were made of copper, and generally bent with the first blow, which must have greatly straitened their aggressive resources, for the swords thus followed their own bent, instead of carrying out the intentions of the persons using them. This provoking pliancy of the material must often have made the soldier as ill-tempered as his own weapon. The Britons carried also a dirk, and a spear, the latter of which they threw at the foe, as an effectual means of pitching into him. A sort of reaping-hook was attached to their chariot wheels, and was often very useful in reaping the laurels of victory.

For nearly one hundred years after Cæsar's invasion, Britain was undisturbed by the Romans, though Caligula, that neck-or-nothing tyrant, as his celebrated wish entitles him to be called, once or twice had his eye upon it. The island, however, if it attracted the Imperial eye, escaped the lash, during the period specified.

IT was not until ninety-seven years after Cæsar had seized upon the island that it was unceremoniously clawed by the Emperor Claudius. Kent and Middlesex fell an easy prey to the Roman power; nor did the brawny sons of Canterbury—since so famous for its brawn—succeed in repelling the enemy. Aulus Plautius, the Roman general, pursued the Britons under that illustrious character, Caractus. He retreated towards Lambeth Marsh, and the swampy nature of the ground gave the invaders reason to feel that it was somewhat too

"Far into the bowels of the land They had march'd on without impediment."

Vespasian, the second in command, made a tour in the Isle of Wight, then called Vectis, where he boldly took the Bull by the horns, and seized upon Cowes with considerable energy. Still, little was done till Ostorius Scapula—whose name implies that he was a sharp blade—put his shoulder to the wheel, and erected a line of defences—a line in which he was so successful that it may have been called his peculiar forte—to protect the territory that had been acquired.

After a series of successes, Ostorius having suffocated every breath of liberty in Suffolk, and hauled the inhabitants of Newcastle over the coals, drove the people of Wales before him like so many Welsh rabbits; and even the brave Caractacus was obliged to fly as well as he could, with the remains of one of the wings of the British army. He was taken to Rome with his wife and children, in fetters, but his dignified conduct procured his chains to be struck off, and from this moment we lose the chain of his history.

Ostorius, who remained in Britain, was so harassed by the natives that he was literally worried to death; but in the reign of Nero (a.d. 59), Suetonius fell upon Mona, now the Isle of Anglesey, where the howlings, cries, and execrations of the people were so awful, that the name of Mona was singularly appropriate. Notwithstanding, however, the terrific oaths of the natives, they could not succeed in swearing away the lives of their aggressors. Suetonius, having made them pay the penalty of so much bad language, was called up to London, then a Roman colony; but he no sooner arrived in town, than he was obliged to include himself among the departures, in consequence of the fury of Boadicea, that greatest of viragoes and first of British heroines. She reduced London to ashes, which Suetonius did not stay to sift; but he waited the attack of Boadicea a little way out of town, and pitched his tent within a modern omnibus ride of the great metropolis. His fair antagonist drove after him in her chariot, with her two daughters, the Misses Boadicea, at her side, and addressed to her army some of those appeals on behalf of "a British female in distress," which have since been adopted by British dramatists. The valorous old vixen was, however, defeated; and rather than swallow the bitter pill which would have poisoned the remainder of her days, she took a single dose and terminated her own existence.

Suetonius soon returned with his suite to the Continent, without having finished the war; for it was always a characteristic of the Britons, that they never would acknowledge they had had enough at the hands of an enemy. Some little time afterwards, we find Cerealis engaged in one of those attacks upon Britain which might be called serials, from their frequent repetition; and subsequently, about the year 75 or 78, Julius Frontinus succeeded to the business from which so many before him had retired with very little profit.

The general, however, who cemented the power of Rome—or, to speak figuratively, introduced the Roman cement among the Bricks or Britons—was Julius Agricola, the father-in-law of Tacitus, the historian, who has lost no opportunity of puffing most outrageously his undoubtedly meritorious relative.

Agricola certainly did considerable havoc in Britain. He sent the Scotch reeling oyer the Grampian Hills, and led the Caledonians a pretty dance.

Portrait of Julius Agricola. He ran UP a kind of rampart between the Friths of Clyde and Forth, from which he could come forth at his leisure and complete the conquest of Caledonia. In the sixth year of his campaign, a.d. 83, he crossed the Frith of Forth, and came opposite to Fife, which was played upon by the whole of his band with considerable energy. Having wintered in Fife, upon which he levied contributions to a pretty tune, he moved forward in the summer of the next year, a.d. 84, from Glen Devon to the foot of the Grampians. He here encountered Galgacus and his host, who made a gallant resistance; but the Scottish chief was soon left to reckon without his host, for all his followers fled like lightning, and it has been said that their bolting came upon him like a thunderbolt.

Agricola having thoroughly beaten the Britons—on the principle, perhaps, that there is nothing so impressible as wax—began to think of instructing them. He had given them a few lessons in war which they were not likely to forget, and he now thought of introducing among their chiefs a tincture of polite letters, commencing of course with the alphabet. The Britons finding it as easy as A, B, C, began to cultivate the rudiments of learning, for there is a spell in letters of which few can resist the influence. They assumed the toga, which, on account of the comfortable warmth of the material, they very quickly cottoned; they plunged into baths, and threw themselves into the capacious lap of luxury.

For upwards of thirty years Britain remained tranquil, but in the reign of Hadrian, a.d. 120, the Caledonians, whose spirit had been "scotched, not killed," became exceedingly turbulent. Hadrian, who felt his weakness, went to the wall of Agricola, * which was rebuilt in order to protect the territory the Romans had acquired. Some years afterwards the power of the empire went into a decline, which caused a consumption at home of many of the troops that had been previously kept for the protection of foreign possessions. Britain took this opportunity of revolting, and in the year 207, the Emperor Severus, though far advanced in years and a martyr to the gout, determined to march in person against the barbarians. He had no sooner set his foot on English ground than his gout caused him to feel the greatest difficulties at every step, and having been no less than four years getting to York, he knocked up there, a.d. 211, and died in a dreadful hobble. Caracalla, son and successor to the late Emperor Severus, executed a surrender of land to the Caledonians for the sake of peace, and being desirous of administering to the effects of his lamented governor in Rome, left the island for ever.

* The remains of this wall are still in existence, to furnish food for the Archeologians who occasionally feast on the bricks, which have become venerable with the crust of ages. A morning roll among the mounds in the neighbourhood where this famous wall once existed, is considered a most delicate repast to the antiquarian.

The history of Britain for the next seventy years may be easily written, for a blank page would tell all that is known respecting it. In the partnership reign of Dioclesian and Maximian, a.d. 288, "the land we live in" turns up again, under somewhat unfavourable circumstances, for we find its coasts being ravaged about this time by Scandinavian and Saxon pirates. Carausius, a sea captain, and either a Belgian or Briton by birth, was employed against the pirates, to whom, in the Baltic sound, he gave a sound thrashing. Instead, however, of sending the plunder home to his employers, he pocketed the proceeds of his own victories, and the Emperors, growing jealous of his power, sent instructions to have him slain at the earliest convenience. The wily sailor, however, fled to Britain, where he planted his standard, and where the tar, claiming the natives as his "messmates," induced them to join him in the mess he had got into. The Roman eagles were put to flight, and both wings of the imperial army exhibited the white feather. Peace with Carausius was purchased by conceding to him the government of Britain and Boulogne, with the proud title of Emperor.

The assumption of the rank of Emperor of Boulogne seems to us about as absurd as usurping the throne of Broadstairs, or putting on the imperial purple at Herne Bay; but Carausius having been originally a mere pirate, was justly proud of his new dignity. Having swept the seas, he commenced scouring the country, and his victories were celebrated by a day's chairing, at which he assisted as the principal figure in a procession of unexampled pomp and pageantry. The throne, however, is not an easy fauteuil, and Carausius had scarcely had time to throw himself back in an attitude of repose, when he was murdered at Eboracum (York) (a.d. 297), by one Alectus, his confidential friend and minister. In accordance with the custom of the period, that the murderer should succeed his victim, Alectus ruled in Britain until he, in his turn, was slain at the instigation of Constantius Chlorus, who became master of the island. That individual died at York (a.d. 306), where his son Constantine, afterwards called the Great, commenced his reign, which was a short and not a particularly merry one, for after experiencing several reverses in the North, he quitted the island, which, until his death in 337, once more enjoyed tranquillity.

Rome, which had so long been mighty, was like a cheese in the same condition, rapidly going to decay, and she found it necessary to practise what has been termed "the noble art of self-defence," which is admitted on all hands to be the first law of Nature. Britain they regarded as a province, which it was not their province to look after. It was consequently left as pickings for the Picts, * nor did it come off scot free from the Scots, who were a tribe of Celtæ from Ireland, and who consequently must be regarded as a mixed race of Gallo-Hibernian Caledonians. They had, in fact, been Irishmen before they had been Scotchmen, and Frenchmen previous to either. Such were the translations that occurred even at that early period in the greatest drama of all—the drama of history.

* "The Picts," says Dr. Henry, "were so called from Pictich, a plunderer, and not from picti, painted." History, in assigning the latter origin to their name, has failed to exhibit them in their true colours.

Britain continued for years suspended like a white hart—a simile justified by its constant trepidation and alarm—with which the Romans and others might enjoy an occasional game at bob-cherry. Maximus (a.d. 382) made a successful bite at it, but turning aside in search of the fruits of ambition elsewhere, the Scots and Picts again began nibbling at the Bigaroon that had been the subject of so much snappishness.

The Britons being shortly afterwards left once more to themselves, elected Marcus as their sovereign (a.d. 407); but monarchs in those days were set up like the king of skittles, only to be knocked down again. Marcus was accordingly bowled out of existence by those who had raised him; and one, Gratian, having succeeded to the post of royal ninepin, was in four months as dead as the article to which we have chosen to compare him. After a few more similar ups and downs, the Romans, about the year 420, nearly five centuries after Cæsar's first invasion, finally cried quits with the Britons by abandoning the island.

In pursuing his labours over the few ensuing years, the author would be obliged to grope in the dark; but history is not a game at blind-man's-buff, and we will never condescend to make it so. It is true, that with the handkerchief of obscurity bandaging our eyes, we might turn round in a state of rigmarole, and catch what we can; but as it would be mere guesswork by which we could describe the object of which we should happen to lay hold, we will not attempt the experiment.

It is unquestionable that Britain was a prey to dissensions at home and ravages from abroad, while every kind of faction—except satisfaction—was rife within the island.

Such was the misery of the inhabitants, that they published a pamphlet called "The Groans of the Britons" (a.d. 441), in which they invited Ætius, the Roman consul, to come over and turn out the barbarians, between whom and the sea, the islanders were tossed like a shuttlecock knocked about by a pair of battledores. Ætius, in consequence of previous engagements with Attila and others, was compelled to decline the invitation, and the Britons therefore had a series of routs, which were unattended by the Roman cohorts.

The southern part of the island was now torn between a Roman faction under Aurelius Ambrosius, and a British or "country party," at the head of which was Vortigern. The latter is said to have called in the Saxons; and it is certain that (a.d. 449) he hailed the two brothers Hengist and Horsa, * who were cruising as Saxon pirates in the British Channel. These individuals being ready for any desperate job, accepted the invitation of Vortigern, to pass some time with him in the Isle of Thanet. They were received as guests by the people of Sandwich, who would as soon have thought of quarrelling with their bread and butter as with the friends of the gallant Vortigern. From this date commences the Saxon period of the history of Britain.

* Horen, means a horse; and the white horse, even now, appears as the ensign of Kent, as it once did on the shield of the Saxons. It is probable that when Horsa came to London, he may have put up somewhere near the present site of the White Horse Cellar. Vide "Palgrave's Rise and Progress of the English Commonwealth."

IN obedience to custom, the etymologists have been busy with the word Saxon, which they have derived from seax, a sword, and we are left to draw the inference that the Saxons were very sharp blades; a presumption that is fully sustained by their fierce and warlike character. Their chief weapons were a battleaxe and a hammer, in the use of which they were so adroit that they could always hit the right nail upon the head, when occasion required. Their shipping had been formerly exceedingly crazy, and indeed the crews must have been crazy to have trusted themselves in such fragile vessels. The bottoms of the boats were of very light timber, and the sides consisted of wicker, so that the fleet must have combined the strength of the washing-tub with the elegant lightness of the clothes' basket. Like their neighbours the wise men of Gotham, or Gotha, who went to sea in a bowl, the Saxons had not scrupled to commit themselves to the mercy of the waves, in these unsubstantial cockle-shells. The boatbuilders, however, soon took rapid strides, and improved their craft by mechanical cunning.

Another fog now comes over the historian, but the gas of sagacity is very useful in dispelling the clouds of obscurity. It is said that Hengist gave an evening party to Vortigern, who fell in love with Bowena, the daughter of his host—a sad flirt, who, throwing herself on her knee, presented the wine-cup to the king, wishing him, in a neat speech, all health and happiness. Vortigern's head was completely turned by the beauty of Miss Bowena Hengist, and the strength of the beverage she had so bewitchingly offered him.

A story is also told of a Saxon soirée having been given by Hengist to the Britons, to which the host and his countrymen came, with short swords or knives concealed in their hose, and at a given signal drew their weapons upon their unsuspecting guests. Many historians have doubted this dreadful tale, and it certainly is scarcely credible that the Saxons should have been able to conceal in their stockings the short swords or carving-knives, which must have been very inconvenient to their calves. Stonehenge is the place at which this cruel act of the hard-hearted and stony Hengist is reported to have occurred; and as antiquarians are always more particular about dates when they are most likely to be wrong, the 1st of May has been fixed upon as the very day on which this horrible réunion was given. It has been alleged, that Vortigern, in order to marry Bowena, settled Kent upon Hengist; but it is much more probable that Hengist settled himself upon Kent without the intervention of any formality.

It is certain that he became King of the County, to which he affixed Middlesex, Essex, and a part of Surrey; so that, as sovereigns went in those early days, he could scarcely be called a petty potentate. The success of Hengist induced several of his countrymen, after his death, to attempt to walk in his shoes; but it has been well and wisely said, that in following the footsteps of a great man an equally capacious understanding is requisite.

The Saxons who tried this experiment were divided into Saxons proper, Angles, and Jutes, who all passed under the common appellation of Angles and Saxons. The word Angles was peculiarly appropriate to a people so naturally sharp, and the whole science of mathematics can give us no angles so acute as those who figured in the early pages of our history.

In the year 447, Ella the Saxon landed in Sussex with his three sons, and drove the Britons into a forest one hundred and twenty miles long and thirty broad, according to the old writers, but in our opinion just about as broad as it was long, for otherwise there could have been no room for it in the place where the old writers have planted it. Ella, however, succeeded in clutching a very respectable slice, which was called the kingdom of South Saxony, which included Surrey, Sussex, and the New Forest; while another invading firm, under the title of Cerdic and Son, started a small vanquishing business in the West, and by conquering Hampshire and the Isle of Wight, founded the kingdom of Wessex. Cerdic was considerably harassed by King Arthur of fabulous fame, whose valour is reported to have been such, that he fought twelve battles with the Saxons, and was three times married. His first and third wives were carried away from him, but on the principle that no news is good news, the historians tell us that as there are no records of his second consort, his alliance with her may perhaps have been a happy one. The third and last of his spouses ran off with his nephew Mordred, and the enraged monarch having met his ungrateful kinsman in battle, they engaged each other with such fury, that, like the Kilkenny cats, they slew one another.

About the year 527, Greenwine landed on the Essex flats, which he had no trouble in reducing, for he found them already on a very low level. In 547, Ida, with a host of Angles, began fishing for dominion off Flamborough head, where he effected a landing. He however settled on a small wild space between the Tyne and the Tees, a tiny possession, in which he was much teased by the beasts of the forest, for the place having been abandoned, Nature had established a Zoological Society of her own in this locality. The kingdom thus formed was called Bernicia, and as the place was full of wild animals, it is not improbable that the British Lion may have originally come from the place alluded to.

Ella, another Saxon prince, defeated Lancashire and York, taking the name of King of the Deiri, and causing the inhabitants to lick the dust, which was the only way they could find of repaying the licking they had received from their conqueror. Ethelred, the grandson of Ida, having married the daughter of Ella, began to cement the union in the old-established way, by robbing his wife's relations of all their property. He seized on the kingdom of his brother-in-law, and added it to his own, uniting the petty monarchies of Deiri and Bemicia into the single sovereignty of Northumberland.

Such were the several kingdoms which formed the Heptarchy. Arithmeticians will probably tell us that seven into one will never go; but into one the seven did eventually go by a process that will be shown in the ensuing chapter.

IF it be a sound philosophical truth, that two of a trade can never agree, we may take it for granted that, à fortiori, seven in the same business will be perpetually quarrelling. Such was speedily the case with the Saxon princes; and it is not improbable that the disturbed condition, familiarly known as a state of sixes and sevens, may have derived its title from the turmoils of the seven Saxon sovereigns, during the existence of the Heptarchy. Nothing can exceed the entanglement into which the thread of history was thrown by the battles and skirmishes of these princes. The endeavour to lay hold of the thread would be as troublesome as the process of looking for a needle, * not merely in a bottle of hay, but in the very bosom of a haystack. Let us, however, apply the magnet of industry, and test the alleged fidelity of the needle to the pole by attempting to implant in the head of the reader a few of the points that seem best adapted for striking him.

* "A needle in a bottle of hay," is an old English phrase, of which we cannot trace the origin. Bottled hay must have been sad dry stuff, but it is possible the wisdom of our ancestors may have induced them to bottle their grass as we in the present day bottle our gooseberries.

We will take a run through the whole country as it was then divided, and will borrow from the storehouse of tradition the celebrated pair of seven-leagued boots, for the purpose of a scamper through the seven kingdoms of the Heptarchy.

We will first drop in upon Kent, whose founder, Hengist, had no worthy successor till the time of Ethelbert. This individual acted on the principle of give and take, for he was always taking what he could, and giving battle. He seated himself by force on the throne of Mercia, into which he carried his arms, as if the throne of Kent had not afforded him sufficient elbow-room. This, however, he resigned to Webba, the rightful heir: but poor Webba (query Webber) was kept like a fly in a spider's web, as a tributary prince to the artful Ethelbert. This monarch's reign derived, however, its real glory from the introduction of Christianity and the destruction of many Saxon superstitions. He kept up a friendly correspondence with Gregory, the punster pope, and author of the celebrated jeu de mot on the word Angli, in the Roman market-place.*

* The pun in question is almost too venerable for repetition, but we insert it in a note, as no History of England seems to be complete without it. The pope, on seeing the British children exposed for sale in the market-place at Rome, said they would not be Angles but Angels if they had been Christians. Non Angli sed Angeli forent si fuissent Christiani.

Ethelbert died in 616, having been not only king of Kent, but having filled the office of Bretwalda, a name given to the most influential—or, as we should call him, the president or chairman—of the sovereigns of the Heptarchy. His son, Eadbald, who succeeded, failed in supporting the fame of his father. It would be useless to pursue the catalogue of Saxons who continued mounting and dismounting the throne of Kent—one being no sooner down than another came on—in rapid succession. It was Egbert, king of Wessex, who, in the year 723, had the art to seat himself on all the seven thrones at once; an achievement which, considering the ordinary fate of one who attempts to preserve his balance upon two stools, has fairly earned the admiration of posterity.

Let us now take a skip into Northumberland—formed by Ethelred in the manner we have already alluded to, out of the two kingdoms of Deiri and Bemicia—which, though not enough for two, constituted for one a very respectable sovereignty. The crown of Northumberland seems to have been at the disposal of any one who thought it worth his while to go and take it; provided he was prepared to meet any little objections of the owner by making away with him. In this manner, Osred received his quietus from Kenred, a kinsman, who was killed in his turn by another of the family: and, after a long series of assassinations, the people quietly submitted to the yoke of Egbert.

The kingdom of East Anglia presents the same rapid panorama of murders which settled the succession to all the Saxon thrones; and Mercia, comprising the midland counties, furnishes all the materials for a melodrama. Offa, one of its most celebrated kings, had a daughter, Elfrida, to whom Ethelbert, the sovereign of the East Angles, had made honourable proposals, and had been invited to celebrate his nuptials at Hereford. In the midst of the festivities Offa asked Ethelbert into a back room, in which the latter had scarcely taken a chair when his head was unceremoniously removed from his shoulders by the father of his intended.

Offa having extinguished the royal family of East Anglia, by snuffing out the chief, took possession of the kingdom. In order to expiate his crime he made friends with the pope, and exacted a penny from every house possessed of thirty pence, or half-a-crown a year, which he sent as a proof of penitence to the Roman pontiff. Though at first intended by Offa as an offering, it was afterwards claimed as a tribute, under the name of Peter's Pence, which were exacted from the people; and the custom may perhaps have originated the dishonourable practice of robbing Paul for the purpose of paying Peter.

After the usual amount of slaughter, one Wiglaff mounted the throne, which was in a fearfully rickety condition. So unstable was this undesirable piece of Saxon upholstery that Wiglaff had no sooner sat down upon it than it gave way with a tremendous crash, and fell into the hands of Egbert, who was always ready to seize the remaining stock of royalty that happened to be left to an unfortunate sovereign on the eve of an alarming sacrifice.

The kingdom of Essex can boast of little worthy of narration, and in looking through the Venerable Bede, we find a string of names that are wholly devoid of interest.

The history of Sussex is still more obscure, and we hasten to Wessex, where we find Brihtric, or Beortric, sitting in the regal armchair that Egbert had a better right to occupy. The latter fled to the court of Offa, king of Mercia, to whom the former sent a message, requesting that Egbert's head might be brought back by return, with one of Offa's daughters, whom Beortric proposed to marry. The young lady was sent as per invoice, for she was rather a burden on the Mercian court; but Egbert's head, being still in use, was not duly forwarded.

Feeling that his life was a toss up, and that he might lose by heads coming down, Egbert wisely repaired to the court of the Emperor Charlemagne. There he acquired many accomplishments, took lessons in fencing, and received that celebrated French polish of which it may be fairly said in the language of criticism, that "it ought to be found on every gentleman's table."

Mrs. Beortric managed to poison her husband by a draft not intended for his acceptance, and presented by mistake, which caused a vacancy in the throne of Wessex. Egbert having embraced the opportunity, was embraced by the people, who received him with open arms, on his arrival from France, and hailed him as rightful heir to the Wessexian crown, which he had never been able to get out of his head, or on to his head, until the present favourable juncture. In a few years he got into hostilities with the Mercians, who being, as we are told by the chroniclers, "fat, corpulent, and short-winded," soon got the worst of it. The lean and active droops of Egbert prevailed over the opposing cohorts, who were at once podgy and powerless. As they advanced to the charge, they were met by the blows of the enemy, and as "it is an ill wind that blows nobody good," so the very ill wind of the Mercians made good for the soldiers of Egbert, who were completely victorious.

Mercia was now subjugated; Kent and Essex were soon subdued; the East Angles claimed protection; Northumberland submitted; Sussex had for some time been swamped; and Wessex belonged to Egbert by right of succession. Thus, about four hundred years after the arrival of the Saxons, the Heptarchy was dissolved, in the year 827, after having been in hot water for centuries. It was only when the spirit of Egbert was thrown in, that the hot water became a strong and wholesome compound.

CARCELY had unanimity begun to prevail in England, when the country was invaded by the Danes, whose desperate valour there was no disdaining. Some of them, in the year 832, landed on the coast, committed a series of ravages, and escaped to their ships without being taken into custody. Egbert encountered them on one occasion at Char-mouth, in Dorsetshire, but having lost two bishops—who, by the bye, had no business in a fight—he was glad to make the best of his way home again.

The Danes, or Northmen, having visited Cornwall, entered into an alliance with some of the Briks, or Britons, of the neigh-bourhood, and marched into Devonshire; but Egbert, collecting the cream of the Devonshire youth, poured it down upon the heads of his enemies. According to some historians, Egbert met with considerable resistance, and it has even been said that the Devonshire cream experienced a severe clouting. It is certainly sufficient to make the milk of human kindness curdle in the veins when we read the various recitals of Danish ferocity. Egbert, however, was successful at the battle of Hengsdown Hill, where many were put to the sword, by the sword being put to them, in the most unscrupulous manner. This was the last grand military drama in which Egbert represented the hero. He died in 836, after a long reign, which had been one continued shower of prosperity.

Ethelwolf, the eldest son of Egbert, now came to the throne, but misunderstanding the maxim, Divide et impera, he began to divide his kingdom, as the best means of ruling it, and gave a slice consisting of Kent and its dependencies to his son Athelstane.

The Scandinavian pirates having no longer an opponent like Egbert, ravaged Wessex; sailed up the Thames, which, if they could, they would have set on fire; gave Canterbury, Rochester, and London a severe dose, in the shape of pillage; and got into the heart of Surrey, which lost all heart on the approach of the enemy. Ethelwolf, however, taking with him his second son Ethelbald, met them at Okely—probably in the neighbourhood of Oakley Street—and at a place still retaining the name of the New Cut, made a fearful incision into the ranks of the enemy. The Danes retired to settle in the isle of Thanet, to repose after the settling they had received in Surrey, at the hands of the Saxons. Notwithstanding the state of his kingdom, Ethelwolf found time for an Italian tour, and taking with him his fourth son, Alfred the Great—then Alfred the Little, for he was a child of six—started to Rome, on that very vague pretext, a pilgrimage. He spent a large sum of money abroad, gave the Pope an annuity for himself, and another to trim the lamps of St. Peter and St. Paul, which has given rise to the celebrated jeu de mot that, "instead of roaming about and getting rid of his cash in trimming foreign lamps, he ought to have remained at home for the purpose of trimming his enemies."

On his return through France, he fell in love with Judith, the daughter of Charles the Bald, the king of the Franks, who probably gave a good fortune to the bride, for Charles being known as the bald, must of course have been without any heir apparent. When Ethelwolf arrived at home with his new wife, he found his three sons, or as he had been in the habit of calling them, "the boys,"—indignant at the marriage of their governor. According to some historians and chroniclers, Osburgha, his first wife, was not dead, but had been simply "put away" to make room for Judith. It certainly was a practice of the kings in the middle age, and particularly if they happened to be middle-aged kings, to "put away" an old wife; but the real difficulty must have been where on earth to put her. If Osburgha consented quietly to be laid upon the shelf, she must have differed from her sex in general.

Athelstane being dead, Ethelbald was now the king's eldest son, and had made every arrangement for a fight with his own father for the throne, when the old gentleman thought it better to divide his crown than run the risk of getting it cracked in battle. "Let us not split each other's heads, my son," he affectingly exclaimed, "but rather let us split the difference." Ethelbald immediately cried halves when he found his father disposed to cry quarter, and after a short debate they came to a division. The undutiful son got for himself the richest portion of the kingdom of Wessex, leaving his unfortunate sire to sigh over the eastern part, which was the poorest moiety of the royal property. The ousted Ethelwolf did not survive more than two years the change which had made him little better than half-a-sove-reign, for he died in 867, and was succeeded by his son Ethelbald. This person was, to use an old simile, as full of mischief "as an egg is full of meat," and indeed somewhat fuller, for we never yet found a piece of beef, mutton, or veal, in the whole course of our oval experience. Ethelbald, however, reigned only two years, having first married and subsequently divorced his father's widow Judith, whose venerable parent Charles the Bald, was happily indebted to his baldness for being spared the misery of having his grey hairs brought down in sorrow to the grave by the misfortunes of his daughter. This young lady, for she was still young in spite of her two marriages, her widowhood, and divorce, had retired to a convent near Paris, when a gentleman of the name of Baldwin, belonging to an old standard family, ran away with her. He was threatened with excommunication by the young lady's father, but treating the menaces of Charles the Bald as so much balderdash, Mr. Baldwin sent a herald to the Pope, who allowed the marriage to be legally solemnised.

We have given a few lines to Judith because, by her last marriage, she gave a most illustrious line to us; for her son having married the youngest daughter of Alfred the Great, was the ancestor of Maud, the wife of William the Conqueror.

Ethelbald was succeeded by Ethelbert, whose reign, though it lasted only five years, may be compared to a rain of cats and dogs, for he was constantly engaged in quarrelling. The Danes completely sacked and ransacked Winchester, causing Ethelbert to exclaim, with a melancholy smile, to one of his courtiers, "This is indeed the bitterest cup of sack I ever tasted." He died in 866 or 867, and was succeeded by his brother Ethelred, who found matters arrived at such a pitch, that he fought nine pitched battles with the Danes in less than a twelvemonth. He died in the year 871, of severe wounds, and the crown fell from his head on to that of his younger brother Alfred. The regal diadem was sadly tarnished when it came to the young king, who resolved that it should not long continue to lack lacker; and by his glorious deeds he soon restored the polish that had been rubbed off by repeated leathering. He had scarcely time to sit down upon the throne when he was called into the field to fulfil a very particular engagement with the Danes at Wilton. They were compelled to stipulate for a safe retreat, and went up to London for the winter, where they so harassed Burrhed the king of Mercia, in whose dominions London was situated, that the poor fellow ran down the steps of his throne, left his sceptre in the regal hall, and, repairing to Rome, finished his days in a cloister.

The Danes still continued the awful business of dyeing and scouring, for they scoured the country round, and dyed it with the blood of the inhabitants. Alfred, finding himself in the most terrible straits, conceived the idea of getting out of the straits by means of ships, of which he collected a few, and for a time he went on swimmingly.

He taught Britannia her first lesson in ruling the waves, by destroying the fleet of Guthrum the Dane, who had promised to make his exit from the kingdom on a previous defeat, but by a disgraceful quibble he had, instead of making his exit, retired to Exeter. From this place he now retreated, and took up his quarters at Gloucester, while Alfred, it being now about Christmas time, had repaired to spend the holidays at Chippenham. It was on Twelfth-night, which the Saxons were celebrating no doubt with cake and wine, when a loud knocking was heard at the gate, and on some one going to answer the door, Guthrum and his Danes rushed in with overwhelming celerity. Alfred, who had been probably favouring the company with a song—for he was fond of minstrelsy—made an involuntary shake on hearing the news, and ran off, followed by a small band, in an allegro movement, which almost amounted to a galop.

The Saxon monarch finding himself deserted by his coward subjects, and without an army, broke up his establishment, dismissed every one of his servants, and, exchanging his regal trappings for a bag of old clothes, went about the country in various disguises. He had taken refuge as a peasant in the hut of a swineherd or pig-driver, whose wife had put some cakes on the fire to toast, and had requested Alfred to turn them while she was otherwise employed in trying to turn a penny.

His Majesty being bent upon his bow, never thought of the cakes, which were burnt up to a cinder, and the old woman, looking as black as the cakes themselves, taunted the king with the smallness of the care he took, and the largeness of his appetite. "You can eat them fast enough," she exclaimed, "and I think you might have given the cakes a turn." * "I acknowledge my fault," replied Alfred, "for you and your husband have done me a good turn, and one good turn, I am well aware, deserves another."

* Though all the historians have given this anecdote, they vary in the words attributed to the old woman, and make no allusion to the reply of Alfred. So accomplished a monarch would hardly have found nothing at all to say for himself; and though he did not turn the cakes, he most probably turned the conversation in the manner we have described.

The monarch retired to a swamp, which he called AEthelingay—now Athelney—or the Isle of Nobles, and some of his retainers, who stuck to their sovereign through thick and thin, joined him in the morasses and marshes he had selected for his residence. Alfred did not despair, though in the middle of a swamp he had no good ground for hope, until he heard that Hubba, the Dane, after making a hubbub in Wales, had been killed by a sudden sally in an alley near the mouth of the Tau, in Devonshire. Alfred, on this intelligence, left his retreat, and having recourse to his old clothes bag, disguised himself as the "Wandering Minstrel," in which character he made a very successful appearance at the camp of Guthrum. The jokes of Alfred, though they would sound very old Joe Millerisms in the present day, were quite new at that remote period, and the Danes were constantly in fits; so that the Saxon king was preparing, by splitting their sides, to eventually break up the ranks of his enemy. He could also sing a capital song, which with his comic recitations, conundrums, and charades, rendered him a general favourite; and his vocal powers may be said to have been instrumental to the accomplishment of his object.

Having returned to his friends, he led them forth against Guthrum, who retreated to a fortified position with a handful of men, and Alfred, by a close blockade, took care not to let the handful of men slip through his fingers.

Guthrum, tired of the raps on the knuckles he had received, threw himself on the kind indulgence of a British public, and appeared before the Saxon king in the character of an apologist. Alfred's motto was, "Forget and Forgive;" but he wisely insisted on the Danes embracing Christianity, knowing that if their conversion should be sincere, they would never be guilty of any further atrocities. He stood godfather himself to Guthrum, who adopted the old family name of Athelstane, and all animosities were forgotten in the festivities of a general christening. A partition of the kingdom took place, and Alfred gave a good share, including all the east side of the island, to his new godson. The Danes settled tranquilly in their new possessions, though in the very next year (879), a small party sailed up the Thames and landed on the shores of Fulham; but finding the hardy sons of that suburban coast in a posture of defence, the Northmen took to their heels, or rather to their keels, by returning to their vessels. The would-be invaders repaired to Ghent to try their luck in the Low Countries, for which their ungentle-manly conduct in violating their treaties most peculiarly fitted them.

Alfred employed the period of peace in building and in law, both of which are generally ruinous, but which were exceedingly profitable in his judicious hands. He restored London, over which he placed his son-in-law, Ethelred, as Earl Eolderman or Alderman, and he established a regular militia all over the country, who, if they resembled the militia of modern times, must have kept away the invaders by placing them in the position familiarly known as "more frightened than hurt."

In the year 893, however, the Danes under Hasting, having ravaged all France, and eaten up every morsel of food they could find in that country, were compelled to come over to England in search of a meal. A portion of the invaders in two hundred and fifty ships, landed near Romney Marsh, at a river called Limine, and there being no one to oppose them in Limine, they proceeded to Appledore. Hasting, with eighty sail, took Milton; but he was soon routed out, and cutting across the Thames, he removed to Banfleet, which was only "over the way;" where he was broken in upon by Alderman Ethelred at the head of some London citizens. The cockney cohorts seized the wife and two sons of Hasting, who would have been killed but for the magnanimity of Alfred, though it has been hinted that in sending them back to his foe, the Saxon king calculated that as women and children are only in the way when business is going forward, their presence might add to the embarrassments of the Danish chieftain. That such was really the case, may be gleaned from the fact that on a subsequent occasion Hasting and his followers were compelled to leave their wives and families behind them in the river Lea, into which the Danish fleet had sailed when Alfred ingeniously drew all the water off, and left the enemy literally aground. This manouvre was accomplished partially by digging three channels from the Lea to the Thames, and partially by the removal of the water in buckets, though the bucket got very frequently kicked by those engaged in this perilous enterprise.

The river Lea would have been sufficiently deep for the purposes of Hasting had not Alfred been deeper still, and the fleet, which had been the floating capital of the Danes, became a deposit in the banks for the benefit of the Saxons. In the spring of 897 Hasting quitted England; but several pirates remained; and two ships being taken at the Isle of Wight, Alfred, on being asked what should be done with the crews, exclaimed, "Oh! they may go and be hanged at Winchester!" The king's orders having been taken literally, the marauders were carried to Winchester, and hanged accordingly.

Alfred, having tranquillised the country, died in the year 901, after a glorious reign of nearly thirty years, and is known to this day as Alfred the Great, an epithet which has never yet been earned by one of his successors.

The character of this prince seems to have been as near perfection as possible. His reputation as a sage has not been injured by time, nor has the mist of ages obscured the brightness of his military glory. He was a lover of literature, and a constant reader of every magazine of knowledge that he could lay his hands upon. An anecdote is told of his mother, Osburgha, having bought a book of Saxon poetry, illustrated according to the taste of our own times, with numerous drawings. Alfred and his brothers were all exclaiming, "Oh give it me!" with infantine eagerness, when his parent hit on the expedient of promising that he who could read it first should receive it as a present. Alfred, proceeding on the modern principle of acquiring "Spanish without a Master," and "French comparatively in no time," succeeded in picking up Anglo-Saxon in six self-taught lessons. He accordingly won the book, which was, no doubt, of a nature well calculated to "repay perusal."

Nor were war and literature the only pursuits in which Alfred indulged; but he added the mechanical arts to his other accomplishments. The sun-dial was probably known to Alfred; but that acute prince soon saw, or, rather, found from not seeing, that a sun-dial in the dark was worse than useless. Not content with being always alive to the time of day, he became desirous of knowing the time of night, and used to burn candles of a certain length with notches in them to mark the hours. * These were indeed melting moments, but the wind often blew the candles out, or caused them to burn irregularly. Sometimes they would get very long wicks, and, if every one had gone to bed, no one being up to snuff, might render the long wicks rather dangerous. In this dilemma he asked himself what could be done, and his friend Asser, the monk, having said half sportively, "Ah! you are on the horns of a dilemma," Alfred enthusiastically replied, "I have it; yes; I will turn the horns to my own advantage, and make a horn lanthorn." Thus, to make use of a figure of a recent writer, Alfred never found himself in a difficulty without, somehow or other, making light of it.

* The practice of telling the time by burning candles was ingenious, but could not have been always convenient. It must have been very awkward when a thief got into one of the candles, thus exposing time to another thief besides procrastination. After Alfred's invention of the lanthorn, it might have been worn as a watch, in the same manner as the modern policeman wears the bull's-eye.

He founded the navy, and, besides being the architect of his own fortunes, he studied architecture for the benefit of his subjects, for he caused so many houses to be erected, that during his reign the country seemed to be let out on one long building lease. He revised the laws, and his system of police was so good, that it has been said any one might have hung out jewels on the highway without any fear of their being stolen. Much, however, depends on the kind of jewellery then in use, for some future historian may say of the present generation, that such was its honesty, precious stones,—that is to say, precious large stones,—might be left in the streets without any one offering to take them up and walk away with them.

Alfred gave encouragement not only to native, but to foreign talent, and sent out Swithelm, bishop of Sherbum, to India, by what is now called the overland journey, and the good bishop was therefore the original Indian male—or Saxon Waghom. He brought from India several gems, and a quantity of pepper—the gems being generously given by Alfred to his friends, and the pepper freely bestowed on his enemies.

He died on the 26th of October, 901, in the fifty-third year of his age, and thirtieth of his reign, having fought in person fifty-six times; so that his life must have been one continued round of sparring with one or other of his enemies. All the chroniclers and historians have agreed in pronouncing unqualified praise upon Alfred; and unless puffing had reached a perfection, and acquired an effrontery which it has scarcely shown in the present day, he must be considered a paragon of perfection who never yet had a parallel. It is certain we have had but one Alfred, from the Saxon period to the present; but we have now a prospect of another, who, let us hope, may evince, at some future time, something more than a merely nominal resemblance to him who has been the subject of this somewhat lengthy chapter.

N the death of Alfred, his second son, Edward, took possession of the throne, when he was served with a notice of ejectment by his cousin Ethelwald. Preparations were made for commencing and defending an action at Wimbum, when Ethelwald, intimidated by the strength of his opponent, declined to go on with the proceedings, and judgment, as in case of a nonsuit, was claimed on Edward's behalf. Subsequently, however, Ethelwald moved, apparently with a view to a new trial, towards Bury, where some of the Kentish men had ventured; and an action having come off, he incurred very heavy damage, which ended in his paying the costs of the day with his own existence. Edward derived much aid from Ethelfleda, a sister, who acted as a sister, by assisting him in his wars against his enemies. This energetic specimen of the British female inherited all the spirit of her father, as well as his mantle, which we find in looking into our own Mackintosh. * She is called "The Lady of Mercia" by the old chroniclers; but as she was always foremost in a fight, there seems something slyly satirical in giving the name of lady to a person of the most fearfully unladylike propensities. She beat the Welsh unmercifully, filling their country with wailings as well as covering their backs with wails, and she took prisoner the king's wife, with whom it may be presumed she came furiously to the scratch before the capture was accomplished. Ethelfleda died in the year 920, and her brother in 925, the latter being succeeded by his natural son, Athelstane, who had no sooner got the crown on his head, than he found several persons preparing to have a snatch at it. He, however, defeated all his enemies, and devoted his time to polishing his throne, adding lustre to his crown, and giving brightness to his sceptre. It was in this reign that England first became an asylum for foreign refugees, to whom Athelstane always extended his hospitality. Louis d'Outremer, the French king, and several Celtic princes of Armorica or Brittany, played at hide-and-seek in London lodgings, while keeping out of the way of their rebellious subjects.

* Sir James Mackintosh's "History of England," Vol. I. chap, ii., p. 49,

It is probable that the part of the metropolis called Little Britain, may have derived its name from the princes having established a little Brittany of their own in that locality. Athelstane appears also to have taken a limited number of pupils into his own palace to board and educate, for Harold, the king of Norway, consigned his son Haco to the care and tuition of the Saxon monarch.

Athelstane died in the year 940, in his forty-seventh year, and was succeeded by Edmund the Atheling, a youth of eighteen, whose taste for elegance and splendour obtained for him the name of the Magnificent. He gave very large dinner parties to his nobles, and at one of these his eye fell upon one Leof, a notorious robber, returned from banishment, one of the Saxon swell mob who had been transported, but had escaped; and who, from some remissness on the part of the police, had obtained admission to the palace. Edmund commanded the proper officer to turn him out, but Leof—tempted no doubt by the sideboard of plate—insisted on remaining at the banquet. Edmund, who, as the chroniclers tell us, was heated by wine, jumped up from his seat, and forgetting the king in the constable, seized Leof by his collar and his hair, intending to turn him out neck and crop. Leof still refusing to "move on," the impetuous Edmund commenced wrestling with the intruder, who, irritated at a sudden and severe kick on his shins, drew a dagger from under his cloak, and stabbed the sovereign in a vital part. The nobles, who had formed a circle round the combatants, and had been encouraging their king with shouts of "Bravo, Edmund!"

"Give it him, your majesty!" were so infuriated at the foul play of the thief, and his un-English recourse to the knife, that they fell upon him at once, and cut him literally to pieces.

Edred, the brother and successor of Edmund, though not twenty-three years of age, was in a wretched state of health when he came to the throne. He had lost his teeth, and of course had none to show when threatened by his enemies; and he was so weak in the feet, that he literally seemed to be without a leg to stand upon. Nevertheless he succeeded in vanquishing the Danes, who could not hurt a hair of his head; but, as the chroniclers tell us that every bit of his hair had fallen off, his security in this respect is easily accounted for. The vigour that marked his reign has, however, been attributed to Dunstan, the abbot, who now began to figure as a political character.

Edred soon died, and left the kingdom to his little brother Edwy, a lad of fifteen, who soon married Elgiva, a young lady of good family, and took his wife's mother home to live with them. On the day of his coronation he had given a party, and the gentlemen, including Odo, Archbishop of Canterbury, and Dunstan, the monk, were still sitting over their wine, when Edwy slipped out to join the ladies. Odo and Dunstan, who were both six-bottle men, became angry at the absence of their royal host, and the latter, at the suggestion of the former, went staggering after the king to lug him back to the banquet-room. Edwy was quietly seated with his wife and her mother in the boudoir—for it being a gentlemen's party, no ladies seem to have been among the guests—and the monk, hiccuping out some gross abuse of the queen and her mamma, collared the young king, who was dragged back to the wine-table.

Though this outrage may have been half festive, interlarded with exclamations of "Come along, old boy," "Don't leave us, old chap," and other similar phrases of social familiarity, Edwy never forgave the monk, whom he called upon to account for money received in his late capacity of treasurer to the royal household. Dunstan being what is usually termed a "jolly dog," and a "social companion," was of course most irregular in money matters; and finding it quite impossible to make out his books, he ran away to avoid the inconvenience of a regular settlement.

Dunstan, nevertheless, resolved to pay his royal master off on the first opportunity; and a rising having been instigated by his friend and pot-companion, Archbishop Odo, Edgar, the brother of Edwy, was declared independent sovereign of the whole of the island north of the Thames. Dunstan returned from his brief exile; but, in the mean time, Edwy had been deprived of his wife, Elgiva, by forcible abduction, at the instigation of the odious Odo. The lovely unfortunate had her face branded with a hot iron, and the most cruel means were taken to deprive her of the beauty which was supposed to be the cause of her ascendancy over the heart of her royal husband. Some historians have attributed this outrage to the designs of Dunstan, and among the many irons that monk was known to have had in the fire, may have been the very irons with which this horrible barbarity was perpetrated. Her scars were, however, obliterated by some Kalydor known at the time, and probably the invention of some knightly Sir Rowland of that early era. She was on the point of rejoining Edwy at Gloucester, when she was savagely murdered by the enemies of her husband, who did not long survive her, for in the following year, 958, he perished either by assassination or a broken heart.

Edgar, a mere lad, of whom Dunstan had made a ladder for his own ambition, now succeeded to his brother's dignities, if a series of nothing but indignities can deserve to be so called. The wily monk had now become Archbishop of Canterbury, and encouraged the new king to make royal progresses among his subjects, in the course of which he is said to have gone up on the river Dee, in an eight-oared cutter, rowed by eight crowned sovereigns. In this illustrious water party Kenneth, king of Scotland, pulled the stroke oar, their majesties of Cumbria, Anglesey, Galloway, Westmere, and the three Welsh sovereigns, making up the remainder of the royal crew, over which Edgar himself presided as coxswain.

Though the young king gave great satisfaction in his public capacity, his private character was exceedingly reprehensible. His inconstancy towards the fair got him into sad disgrace, and his friend Dunstan on one occasion administered to him a severe reprimand. The monk, however, finished by fining him a crown, prohibiting him from putting on, during a period of seven years, that very uncomfortable article of the regalia. As the head is proverbially uneasy which wears a crown, the sentence passed upon the king must have been a boon rather than a punishment.

Among the events connected with the reign of Edgar, his marriage with Elfrida must always stand conspicuous. He had heard much of a provincial beauty, the daughter of Olgar, or Ordgar, Earl of Devonshire, and the king sent his favourite, the Earl of Athelwold, to see this rustic belle, with a view of ascertaining whether the flower would be worth transplanting to the palace of the sovereign. Athelwold, on seeing the young lady, fell in love with her himself, from her extreme beauty; but wrote up to Edgar, declaring that she might well be called "the mistress of the village plain," for her plainness was absolutely painful; and indeed he added in a P.S., "She is so disfigured by a squint, as to give me the idea of the very squintes-sence of ugliness." Athelwold attributed her reputation for beauty to her fortune, and declared that her money turned her red hair into golden locks, causing her to be well "worthy the attention of Persons about to Marry."

Edgar soon gave his consent to Athelwold's espousing the lady, on the ground of her being a good match for him; but she proved more than a match for him a short time afterwards. Edgar, at the expiration of the honeymoon, proposed to visit his friend, who made excuses as long as he could, inasmuch that he was seldom at home, and that he could not exactly say when his majesty would be sure of catching him. The king, however, good-naturedly promising to be satisfied with pot-luck, fixed a day for his visit; ana Athelwold, confessing all to his wife, begged her to disguise her charms, by putting on her shabbiest gown, and to behave herself in such a manner as to make the king believe he had lost nothing in not having married her.

"I should like to see myself appearing as a dowdy before my sovereign," was the lady's feminine reply, and she paid more than usual attention to her toilette in order to attract the favourable notice of Edgar. The monarch finding himself deceived by Athelwold, asked him to come and hunt in a wood, when, without any preliminary beating about the bush, and exclaiming, "You made game of me, thus do I make game of you," he stabbed the unfortunate earl, and returned home to marry his widow. Edgar did not live many years after this ungentlemanly conduct, but died at the early age of two-and-thirty. Though he had been favourable to priestcraft, and patronised the cunning foxes of the Church, he was an enemy to wolves, and offered so much per head for all that were killed, until the race was exterminated, and the cry of "Wolf" became synonymous with a false alarm of danger.

Edgar was succeeded (a.d. 975) by Edward, his son by his first wife, who was not more than fourteen or fifteen years old; and thus, at that age before which an individual in the present day is not legally qualified to drive a cab, this royal hobbledehoy assumed the reins of government. His mother-in-law, Elfrida, endeavoured to grasp them for her own son Ethelred, an infant of six, but Dunstan having at that moment the whip hand, prevented her from reaching the point she was driving at.