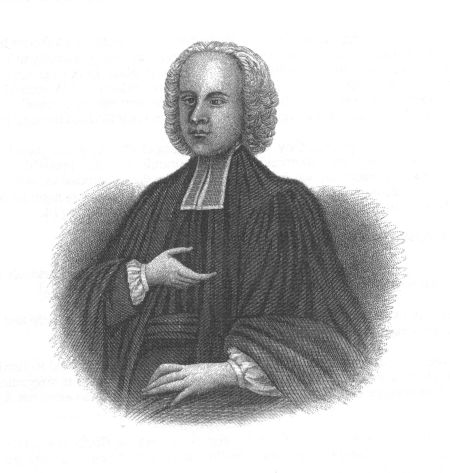

Revd. George Whitefield, B.A.

AGED 24

Engraved by J Cochran

NEW AND CHEAPER EDITION, UNABRIDGED,

In Three Volumes. Price 7s. 6d. each volume.

ELEGANTLY BOUND IN CLOTH, WITH ENGRAVED PORTRAITS.

THE LIFE AND TIMES

OF THE

REV. JOHN WESLEY, M.A.

BY THE REV. L. TYERMAN.

"It deserves the praise, not only of being the fullest biography of Wesley, but also of being eminently painstaking, veracious, and trustworthy."—The Edinburgh Review.

"Mr. Tyerman's volumes constitute by far the most exhaustive, as they are certainly the bulkiest, and from many points of view the most interesting, of the lives of Wesley. Mr. Tyerman's judgment is usually characterised by great clearness and good sense; his pen seems to be always governed by the desire to be fair and impartial, and for the first time our libraries receive a full and comprehensive memoir of the great religious teacher and ecclesiastical statesman."—The British Quarterly Review.

"The most copious account of the great evangelist's life and labours, and the noblest literary tribute to his memory, which has yet been offered to the world."—Methodist Recorder.

"The narratives of travel through England, Scotland, and Ireland, the records of evangelistic labour, the gradual building up of Wesleyanism as a system, form a history of great interest, and allure the reader on from chapter to chapter, with all the attraction of a romance. We cannot doubt that Mr. Tyerman's work, so rich and abundant in materials, will henceforth be regarded as the standard life of Wesley."—The Evangelical Magazine.

"We are thankful for a new and carefully revised edition of this very laborious, interesting, and important work, the value of which is great and obvious. The portraits as now rendered, are very striking and self-evidencing, and of real historical value."—Wesleyan Methodist Magazine.

"This is the most truthful, full, accurate, and painstaking of all the lives of Wesley."—The Methodist.

London:

HODDER & STOUGHTON, 27, Paternoster Row, E.C.

Revd. George Whitefield, B.A.

AGED 24

Engraved by J Cochran

B.A., OF PEMBROKE COLLEGE, OXFORD.

BY

AUTHOR OF

"THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REV. SAMUEL WESLEY, M.A., RECTOR OF EPWORTH;"

"THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE REV. JOHN WESLEY, M.A.;"

AND "THE OXFORD METHODISTS."

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL I.

London:

HODDER AND STOUGHTON,

27, PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C.

———

MDCCCLXXVI.

Hazell Watson, and Viney, Printers, London and Aylesbury.

Every one who wishes to understand and rightly estimate the Methodist movement of the last century, must, not only read the lives of the two Wesleys, but also, make himself acquainted with the history of Whitefield, and the career of the Methodist contemporaries of the illustrious trio.

John Wesley was Methodism's founder, and Charles its hymnologist. John Clayton became a man of mark among the High Church clergymen of the Episcopal Communion. James Hervey belonged to the Evangelical section of the Church of England, and, by his writings, influenced not a few of the country's aristocracy. Benjamin Ingham, by his preaching, left a deep impress on Yorkshire, and other parts of the North of England. John Gambold rendered inestimable service, in moderating and correcting the extravagances of the Moravian Brotherhood. Thomas Broughton gave an impetus to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, which is felt to the present day. Richard Hutchins, as Rector of Lincoln College, Oxford, helped to mould the character of students, who afterwards rose to great distinction. To each of these distinguished men, Providence assigned a sphere of unusual usefulness. They moved in different orbits, but all were made a blessing to the world.

George Whitefield was pre-eminently the outdoor preacher;—the[iv] most popular evangelist of the age;—a roving revivalist,—who, with unequalled eloquence and power, spent above thirty years in testifying to enormous crowds, in Great Britain and America, the gospel of the grace of God. Practically, he belonged to no denomination of Christians, but was the friend of all. His labours, popularity, and success were marvellous, perhaps unparalleled. All churches in England, Wales, Scotland, and the British settlements in America, were permanently benefited by his piety, his example, and the few great truths which he continually preached; whilst the Methodism organised by his friend Wesley—especially in the northern counties of the kingdom—was, by his itinerant services, promoted to a far greater extent than the Methodists have ever yet acknowledged.

The world has a right to know all that can be told of such a man. To say nothing of almost innumerable sketches, at least half a dozen lives of Whitefield have been already published. If the reader asks why I have dared to add to the number of these biographies? I answer, because I possessed a large amount of biographical material which previous biographers had not employed, and much of which seems to have been unknown to them. This is not an empty boast, as will be evident to every one who compares the present work with the lives of Whitefield which have preceded it.

In collecting materials for the "Life and Times of Wesley," and for the "Oxford Methodists," I met with much concerning Whitefield; and, since then, I have spared neither time, toil, nor money in making further researches relating to the great evangelist. With the exception of a few instances, all of which are acknowledged, my facts are taken from original sources; and, though to say so may savour of vanity, I believe there is now no information concerning Whitefield, of any public importance, which is not contained in the present volumes.

I have been obliged to employ a few of Whitefield's letters,[v] which I had previously published in the "Life and Times of Wesley." This was unavoidable; but the repetition is extremely limited, and is never used except when justice made it necessary.

Whitefield was a Calvinist: I am an Arminian; but the book is not controversial. Whitefield's sentiments and language have been honestly and truly quoted; and I have not attempted to refute his theological opinions. On such subjects, men, at present, must agree to differ.

The Life is not written with special regard to the interests of any Church whatever,—Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist, or even Methodist. Whitefield, indeed, called himself a member and minister of the Church of England; but, in reality, he belonged to the Church Catholic. He loved all who loved Jesus Christ, and was always ready to be their fellow-labourer. It is right to add, however, that, as a matter of fact, I have felt bound to shew that the friendship between Whitefield and the Wesleys was much more loving and constant than it has been represented by previous biographers; and that Whitefield's services to Methodism were more important than the public generally have imagined.

Without the least desire to depreciate any of the lives of Whitefield already published, I may be allowed to say, they are not without errors. Instead, however, of confuting the errors, one by one, as I have met with them, I have, as a rule, not noticed them; but have simply narrated facts, bearing on the respective cases, without comment and without colouring.

The foot-notes are more numerous than I like, and this has prevented my adding to their number by giving all the references for the statements I have made; but, if the truthfulness of any statement be called in question, it will be an easy task to adduce the authority in support of it. For the notices of American ministers and gentlemen, I am chiefly indebted to the "Biographical and Historical Dictionary" of the Rev. William Allen, D.D., President of Bowdoin College,[vi] and Member of the Historical Society of Maine, New Hampshire, and New York.

The book is neither artistic nor philosophic. I have merely done my utmost to collect information concerning Whitefield, and have related the facts as clearly, concisely, and honestly as I could. I have also, as far as possible, acted upon the principle of making Whitefield his own biographer. Perhaps, I ought to apologise for the introduction of such lengthened details concerning the first few years of Whitefield's public life. Apart from being influenced by the fact, that, it was during this eventful period that Whitefield's character was formed, and his unique mission among men determined, I was wishful to give to the Christian Church, at least, the substance of his Journals—Journals which, unlike those of his friend Wesley, have never been republished, and which, in consequence of their rareness, are almost quite unknown.

The two portraits are copied from original engravings, which Dr. Gillies, Whitefield's friend and first biographer, pronounced the most exact likenesses of the great preacher ever published.

Whitefield's power was not in his talents, nor even in his oratory, but in his piety. In some respects, he has had no successors; but in prayer, in faith, in religious experience, in devotedness to God, and in a bold and steadfast declaration of the few great Christian truths which aroused the churches and created Methodism,—he may have many. May Whitefield's God raise them up, and thrust them out! The Church and the world greatly need them.

L. Tyerman.

Stanhope House, Clapham Park, S.W.

October 16th, 1876.

| WHITEFIELD'S BOYHOOD. | |

| 1714 to 1732. | |

| PAGE | |

Whitefield's Genealogy—Autobiography—Birth—Wickedness—St. Mary de Crypt School—Tapster—Religious Feelings—Reformation—Dr. Adams—Sin and Penitence—An Orator | 1-13 |

| WHITEFIELD AT COLLEGE. | |

| 1732 to 1735. | |

Oxford Methodists—Pembroke College—Dr. Johnson—Whitefield a Servitor—Law's 'Serious Call'—Joins Oxford Methodists—Charles Wesley—Satanic Temptations—Introduced to John Wesley—Two Converts—Whitefield's Conversion—Religion of Oxford Methodists—The New Birth—Whitefield at Gloucester, etc. | 14-34 |

| WHITEFIELD ORDAINED. | |

| May 1735 to June 1736. | |

Ten Months' Interval—How spent—Efforts to be useful—Books read—Stage Entertainments—Visiting a Prisoner—Letter to Wesley—Anxiety respecting Ministerial Office—A Dream—Rev. Thomas Cole—Bishop Benson—Sir John Philips—Preparing for Ordination—Ordained—Whitefield's Autobiography | 35-46 |

| COMMENCEMENT OF MINISTRY. | |

| 1736. | |

A grand Day—First Sermon—Personal Appearance—Plain Speaking—Work at Oxford—First Visit to London—Letter to Wesley—Unknown Oxford Methodists—At Dummer—Resolves to go to Georgia—Letter to Charles Wesley | 47-63 |

| [viii]A YEAR OF PREACHING. | |

| 1737. | |

Whitefield's Popularity—Pious Clergymen—Dissenting Ministers—Abounding Wickedness—Dr. Isaac Watts—Infidelity—State of Dissenting Churches—National Impiety—Whitefield at Bristol—In London—At Stonehouse—Crowded Congregations—First Publication—New Birth—Rev. John Hutton—Preaching in London Churches—Opposition—Intercourse with Dissenters—First extempore Prayer—Picture taken—Marvellous commotion—Charity Schools—"Lecture Churches"—Charles Wesley—Poem on Whitefield—Weekly Miscellany—"The Oxford Methodists"—Whitefield and the Wesleys—Sermons published—The almost Christian—Terrific Preaching—Original Sin—Profane Swearing—First Farewell Sermon—Ignorant of Justification by Faith only—Preface to "Forms of Prayer" | 64-105 |

| FIRST VISIT TO AMERICA. | |

| 1738. | |

Collections for Poor of Georgia—Whitefield's Cargo—Notable Day—Embarks for Georgia—At Gravesend—At Margate—At Deal—Wesley's return to England—Eternity of Hell's Torments—At Gibraltar—Publication of Journal—Sermon on Drunkenness—Incidents of the Voyage—Ill of Fever—Farewell Sermon on Shipboard—America—The Indians—Georgia—Carolina—Emigrants to Georgia—First Services at Savannah—Tomo Chici—Charles Delamotte—Schools opened—Work at Savannah—The Saltzburghers—Visit to Frederica—Dead Infidel—Departure from Savannah—Reasons for return to England—Storms at Sea—Pastoral Epistle—Lands in Ireland—Bishop Burscough—Archbishop Boulter—Arrives in England—At Manchester—The Wesley Brothers—Churches closed—Hostile Publications—Last Week of 1738 | 106-154 |

| COMMENCEMENT OF OUTDOOR PREACHING. | |

| January to August, 1739. | |

Lovefeast at Fetter Lane—Conference at Islington—Ordained a Priest—Aristocratic Hearers—The Seward Family—Howell Harris—Scene at St. Margaret's, Westminster—Susannah Wesley on Whitefield—At Bath—At Bristol—The Poet Savage—Bristol Prison—Chancellor of Bristol Diocese—Letter to Bishop Butler—Religious Societies at Bristol—Begins Outdoor Preaching—First Visit to Wales—Interview with Howell Harris—Rev. Griffith Jones—Kingswood—Whitefield invites Wesley to Bristol—Kingswood School begun—Again in Wales—At Gloucester—Cheltenham—Benjamin Seward—Dean Kinchin—Vice-Chancellor of Oxford—[ix]At Islington—Dr. Trapp—Rev. Robert Seagrave—Outdoor Preaching in London—Newspaper Abuse—Contemporaneous Opinions of Whitefield—Reasons for Whitefield's Popularity—Joseph Humphreys—Joseph Periam—Itinerating—In London—Whitefield's Journals—Answer to Dr. Trapp—In Kent—Moravians—Scene in a Public House—Specimens of Preaching—The Wesleys become Outdoor Preachers—A Notable Sermon—Another Philippic—William Delamotte—William Seward—Letter to Wesley—Rev. Josiah Tucker—Dr. Skerret—Dr. Byrom—Ebenezer Blackwell—Constables and Magistrates—Whitefield and Wesley at Bristol—Letter to Bishop Benson—Quaker at Thornbury—Mayor of Basingstoke—A Friendly Quaker—Rev. Ralph Erskine—Last Sermons—Whitefield's Calvinism—Extracts from his Sermons—The Weekly Miscellany—The Craftsman—Rev. William Law and Dr. Warburton—Countess of Hertford—Pamphlets for and against Whitefield—Bishop Gibson's Pastoral Letter—Whitefield's Answer—Sermons Published—Extracts from them—Spiritual Pride—Catholic Spirit—Innocent Diversions—Self-righteousness—Entreaties—Whitefield's Oratory. | 155-306 |

| SECOND VISIT TO AMERICA. | |

| August 1739 to March 1741. | |

Whitefield asks Charles Wesley to be his Successor—Whitefield's Fellow-Voyagers—Letter to Ebenezer Blackwell—Extracts from other Letters—Letter to the Religious Societies—Arrival in America—Pennsylvania—Philadelphia—The Tennent Family—Whitefield at New York—Return to Philadelphia—Log College—Letter to Ralph Erskine—Gilbert Tennent—Scene in a Church—Leaving Philadelphia—Benjamin Franklin—Journey through Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas—Arrival at Savannah—The Orphan House—Stephens's Journal—Letters to Ralph Erskine and Gilbert Tennent—Letter to Slave-Owners—Plan of Orphan House—At Charleston—Commissary Garden—Oglethorpe snubs Whitefield—Letter to Wesley—Whitefield's Courtship—In Philadelphia—Franklin's Account of Whitefield—Great Work in Philadelphia—New Meeting House—Large Scheme—Letter to Ebenezer Blackwell—Itinerating—Many Adversaries—Moravian Settlement of Nazareth—William Seward—Enormous Labours—Marvellous Movements—Results in Philadelphia—Letter to William Seward—Missionary Advice—Calvinian Controversy—The Orphans Praying—Philip Henry Molther—Letters to Rev. G. Stonehouse, William Delamotte, and Wesley—Whitefield, practically, a Dissenter—Whitefield in Commissary Garden's Court—Whitefield out of Court—Reformation at Charleston—Election and Final Perseverance—Letter to Bishop of London—Rev. Nathaniel Clap—Boston—Labours in New England—"Washington's Elm"—Governor Belcher—Letter by Charles Wesley—[x]Sinless Perfection—William Delamotte—A Week's Work—Whitefield's Preaching in New England—Gilbert Tennent—Results in Boston—Visit to Jonathan Edwards—Whitefield on New England—"The Querists"—Letters—Whitefield and Wesley—Orphan-house Family—Jonathan Barber—The Savannah Club—Hugh Bryan—Whitefield before Magistrates—His influence in America—Hostile Publications—Nixon's Prophecy | 307-458 |

| WHITEFIELD'S RETURN TO ENGLAND IN 1741. | |

| March to July, 1741. | |

Letters—Wesley's Sermon on "Free Grace"—A Trying Time—Trouble at Kingswood—Letter to Wesley—First Methodist Newspaper—Old Friends divided—A Scene at the Foundery—Whitefield in Distress—Good News from America—Whitefield and Charles Wesley—Charles Wesley and the Calvinists—London Tabernacle—Rev. Daniel Rowlands—"Outward Enemies"—Help in Time of Need—Collections for Orphan House—Plan of action—Letter to Students | 459-496 |

| FIRST VISIT TO SCOTLAND. | |

| August to November, 1741. | |

Ebenezer and Ralph Erskine—"The Associate Presbytery"—The Sins of Scotland—The Erskines and the Methodists—Whitefield and the Erskines—Rupture with the Associate Presbytery—"A Warning," by Rev. Adam Gibb—"Act of the Associate Presbytery"—Aristocratic Friends—Letter to David Erskine—Tour in Scotland—Earl of Leven and Melville—Collections in Scotland—Strange Scene—Anecdotes—Religious Results in Scotland. | 497-529 |

| SEVEN MONTHS IN ENGLAND. | |

| November 1741 to June, 1742. | |

Whitefield's Marriage—His Wife—Christian Perfection—Good News from America—Racy Letter—The Welsh Evangelists—The Orphan House—Wesley's Publications—Calvinistic Controversy—Success—Whitefield's Journals and Letters—Letter to Lady Mary Hamilton—Desire for Christian Union—Scenes in Moorfields—Charles Square, Hoxton—Rev. John Meriton—Man of one Busine | 530-561 |

THE LIFE

OF

The REV. GEORGE WHITEFIELD, B.A.

George Whitefield was born in the Bell Inn, Gloucester, on the 16th day of December (O.S.), 1714.

His genealogy, as given by his first biographer, Dr. Gillies, is brief, but not without interest:—

"The Rev. Mr. Samuel Whitefield, great-grandfather of George, was born at Wantage, and was rector of North Ledyard,[1] in Wiltshire. He removed afterwards to Rockhampton, in Gloucestershire. He had five daughters—two of whom were married to clergymen, Mr. Perkins and Mr. Lovingham; and two sons—Samuel, who succeeded his father in the cure of Rockhampton, and died without issue; and Andrew, who was a private gentleman, and lived retired upon his estate. Andrew had fourteen children, of whom Thomas was the eldest.

"Thomas was first bred to the employment of a wine-merchant in Bristol, but afterwards kept the Bell Inn, in the city of Gloucester. In Bristol he married Elizabeth Edwards, who was related to the Blackwells and the Dimours of that city; by whom he had six sons and one daughter.

"Elizabeth, the daughter, was twice reputably married at Bristol. John lies interred with the family in St. Mary de Crypt Church, in Gloucester. Joseph died an infant. Andrew settled in trade at Bristol, and died in the twenty-eighth year of his age. James was captain of a ship, and died suddenly at Bath. George was the youngest of the family, and, at his death, left two surviving brothers, Thomas and Richard.

"The father died in December, 1716, when George was only two years old. The mother continued a widow seven years, and was then married to Mr. Longden, an ironmonger in Gloucester, by whom she had no issue. She died in December, 1751, in the seventy-first year of her age."

So much for pedigree. Though Whitefield's ancestry was far from aristocratic, it was not ignoble.

Nothing is known of the years of Whitefield's boyhood, except what is furnished by himself. In the year 1740, he published an octavo pamphlet of seventy-six pages, entitled "A Short Account of God's Dealings with the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield, A.B., Late of Pembroke College, Oxford: from his Infancy to the Time of his entering into Holy Orders." This was written on board the Elizabeth, during his first voyage to America, and contains not a few unguarded and objectionable expressions—expressions which brought upon him the ridicule of his enemies, and which he himself afterwards regretted. In 1756, he "revised, corrected, and abridged" this imprudent publication; and, in the Preface, confessed that "many mistakes were rectified," and "many passages, that were justly exceptionable, erased."

In the present work, Whitefield, as far as possible, is made to be his own biographer; and though, perhaps, it is scarcely fair to print again what he himself erased, yet, as the sentences and paragraphs which he subsequently omitted were the occasion of many of the virulent attacks made upon him by his earliest opponents, these attacks cannot be properly understood without the text from which they had their origin.

Besides this, the publication in question is now extremely scarce. Not one in a thousand of Whitefield's admirers has ever seen it. It has never been re-published in its entirety since it was first issued, in the year 1740. It exhibits, not only Whitefield's honesty, but his weaknesses and faults, at the early age of twenty-five; and, without it, the reader cannot have a full and correct conception of[3] Whitefield's character at the commencement of his marvelous and illustrious career.

For such reasons, the pamphlet of 1740 is here given in its completeness, without abridgment and without revision. The words and passages, however, which he himself, in 1756, altered or erased, will be marked by being enclosed in brackets, or by notes.

Another remark must be added. What Whitefield says of his boyhood's wickedness must be received with caution. To exalt the grace of God in his conversion, he seemed desirous to magnify his own depravity and sin. Without intentional exaggeration, he, perhaps, makes himself worse than he really was. At all events, the following extract from his preface deserves attention:—

"In the accounts of good men which I have read, I have observed that the writers of them have been partial. They have given us the bright, but not the dark side of their character. This, I think, proceeded from a kind of pious fraud, lest mentioning persons' faults should encourage others in sin. It cannot, I am sure, proceed from the wisdom which cometh from above. The sacred writers give an account of their failings as well as their virtues. Peter is not ashamed to confess that, with oaths and curses, he thrice denied his Master; nor do the Evangelists make any scruple of telling us, that out of Mary Magdalene Jesus Christ cast seven devils.

"I have, therefore, endeavoured to follow their good example. I have simply told what I was by nature, as well as what I am by grace. I am not over cautious as to any supposed consequences, since none can be hurt by these but such as hold the truth in unrighteousness. To the pure all things will be pure.

"As I have often wished, when in my best frames, that the first years of my life might be put down as a blank, and had no more in remembrance, so I could almost wish now to pass them over in silence. But as they will, in some degree, illustrate God's dealings with me in my riper years, I shall, as I am able, give the following brief account of them."

After this exordium, which the reader will find useful in interpreting what follows, Whitefield proceeds with the first section of his autobiography.

"I was born in Gloucester, in the month of December, 1714. [My father and mother kept the Bell Inn. The former died when I was two years old; the latter is now alive, and has often told me how she endured fourteen weeks' sickness after she brought me into the world; but was[4] used to say, even when I was an infant, that she expected more comfort from me than any other of her children. This, with the circumstance of my being born in an inn, has been often of service to me in exciting my endeavours to make good my mother's expectations, and so follow the example of my dear Saviour, who was born in a manger belonging to an inn.

"My very infant years must necessarily not be mentioned; yet, I can remember such early stirrings of corruption in my heart, as abundantly convinces me that I was conceived and born in sin,—that in me dwelleth no good thing by nature, and that if God had not freely prevented me by His grace, I must have been for ever banished from His presence.]

"I can truly say, I was froward from my mother's womb. I was so brutish as to hate instruction, and used purposely to shun all opportunities of receiving it. I can date some very early acts of uncleanness. [I soon gave pregnant proofs of an impudent temper.] Lying, filthy talking, and foolish jesting I was much addicted to [even when very young]. Sometimes I used to curse, if not swear. Stealing from my mother I thought no theft at all, and used to make no scruple of taking money out of her pocket before she was up. I have frequently betrayed my trust, and have more than once spent money I took in the house, in buying fruits, tarts, etc., to satisfy my sensual appetite. Numbers of Sabbaths have I broken, and generally used to behave myself very irreverently in God's sanctuary. Much money have I spent in plays, and in the common entertainments of the age. Cards and reading romances were my heart's delight. Often have I joined with others in playing roguish tricks, but was generally, if not always, happily detected. For this, I have often since, and do now, bless and praise God.

"It would be endless to recount the sins and offences of my younger days. They are more in number than the hairs of my head. My heart would fail me at the remembrance of them, was I not assured that my Redeemer liveth, ever to make intercession for me. However the young man in the Gospel might boast how he had kept the commandments from his youth, with shame and confusion of face I confess that I have broken them all from my youth. Whatever foreseen fitness for salvation others may talk of and glory in, I disclaim any such thing. If I trace myself from my cradle to my manhood, I can see nothing in me but a fitness to be damned. [I speak the truth in Christ, I lie not.] If the Almighty had not prevented me by His grace, and wrought most powerfully upon my soul, quickening me by His free Spirit when dead in trespasses and sins, I had now been either sitting in darkness and in the shadow of death, or condemned, as the due reward of my crimes, to be for ever lifting up my eyes in torments.

"But such was the free grace of God to me, that though corruption worked so strongly in my soul, and produced such early and bitter fruits, yet I can recollect very early movings of the blessed Spirit upon my heart, sufficient to satisfy me that God loved me with an everlasting love, and separated me even from my mother's womb for the work to which He afterwards was pleased to call me.

"I had some early convictions of sin; and once, I remember, when some persons, as they frequently did, made it their business to tease me, I immediately retired to my room, and kneeling down, with many tears, prayed over that psalm wherein David so often repeats these words—'But in the name of the Lord will I destroy them.' I was always fond of being a clergyman, and used frequently to imitate the ministers reading prayers, etc. Part of the money I used to steal from my parent I gave to the poor, and some books I privately took from others, for which I have since restored fourfold, I remember were books of devotion.

"My mother was very careful of my education, and always kept me in my tender years [for which I never can sufficiently thank her] from intermeddling in the least with the public business.

"About the tenth year of my age, it pleased God to permit my mother to marry a second time. It proved what the world would call an unhappy match as for temporals, but God overruled it for good. [It set my brethren upon thinking more than otherwise they would have done, and made an uncommon impression upon my own heart in particular.]

"When I was about twelve, I was placed at a school called St. Mary de Crypt, in Gloucester—the last grammar school I ever went to. Having a good elocution and memory, I was remarked for making speeches before the Corporation, at their annual visitation.[2] But I cannot say I felt any drawings of God upon my soul for a year or two, saving that I laid out some of the money that was given me, on one of those forementioned occasions, in buying Ken's 'Manual for Winchester Scholars'—a book that had much affected me when my brother used to read it in my mother's troubles, and which, for some time after I bought it, was of great benefit to my soul.

"During the time of my being at school, I was very fond of reading plays, and have kept from school for days together to prepare myself for acting them. My master, seeing how mine and my schoolfellows' vein ran, composed something of this kind for us himself, and caused[6] me to dress myself in girl's clothes, which I had often done, to act a part before the Corporation. The remembrance of this has often covered me with confusion of face, and I hope will do so, even to the end of my life.

["And I cannot but here observe, with much concern of mind, how this way of training up youth has a natural tendency to debauch the mind, to raise ill passions, and to stuff the memory with things as contrary to the Gospel of Jesus Christ as light to darkness, heaven to hell. However, though the first thing I had to repent of was my education in general, yet I must always acknowledge my particular thanks are due to my master, for the great pains he took with me and his other scholars, in teaching us to speak and write correctly.]

"Before I was fifteen, having, as I thought, made a sufficient progress in the classics, and, at the bottom, longing to be set at liberty from the confinement of a school, I one day told my mother, 'Since her circumstances would not permit her to give me an University education, more learning I thought would spoil me for a tradesman; and, therefore, I judged it best not to learn Latin any longer.' She at first refused to consent, but my corruptions soon got the better of her good nature. Hereupon, for some time, I went to learn to write only. But my mother's circumstances being much on the decline, and being tractable that way, I from time to time began to assist her occasionally in the public-house, till at length I put on my blue apron and my snuffers,[3] washed mops, cleaned rooms, and, in one word, became professed and common drawer for nigh a year and a half.

"[But He who was with David when he was following the sheep big with young, was with me even here. For] notwithstanding I was thus employed in a common inn, and had sometimes the care of the whole house upon my hands, yet I composed two or three sermons, and dedicated one of them in particular to my elder brother. One time, I remember, I was much pressed to self-examination, and found myself very unwilling to look into my heart. Frequently I read the Bible when sitting up at night. Seeing the boys go by to school has often cut me to the heart. And a dear youth, now with God, would often come entreating me, when serving at the bar, to go to Oxford. My general answer was, 'I wish I could.'

"After I had continued about a year in this servile employment, my mother was obliged to leave the inn. My brother, who had been bred up for the business, married; whereupon all was made over to him; and, I being accustomed to the house, it was agreed that I should continue there as an assistant. [But God's thoughts were not as our thoughts.

"By His good Providence] it happened that my sister-in-law and I could by no means agree; [and at length the resentment grew to such an height, that my proud heart would scarce suffer me to speak to her for three weeks together. But notwithstanding I was much to blame, yet I used to retire and weep before the Lord, as Hagar when flying from her[7] mistress Sarah—little thinking that God by this means was forcing me out of the public business, and calling me from drawing wine for drunkards, to draw water out of the wells of salvation for the refreshment of His spiritual Israel.]

"After continuing for a long while under this burden of mind, I at length resolved, thinking my absence would make all things easy, to go away. Accordingly, by the advice of my brother and consent of my mother, I went to see my elder brother, then settled at Bristol.

"Here God was pleased to give me great foretastes of His love,[4] and fill me with such unspeakable raptures, particularly once in St. John's Church, that I was carried out beyond myself. I felt great hungerings and thirstings after the blessed Sacrament, and wrote many letters to my mother, telling her I would never go into the public employment again. Thomas à Kempis was my great delight, and I was always impatient till the bell rang to call me to tread the courts of the Lord's house. But in the midst of these illuminations, something surely whispered, 'This will not last.'

"And, indeed, so it happened. For—oh that I could write it in tears of blood!—when I left Bristol, as I did in about two months, and returned to Gloucester, I changed my devotion with my place. Alas! all my fervour went off: I had no inclination to go to church, or draw nigh unto God. In short, my heart, though I had so lately tasted of His love, was far from Him.

"However, I had so much religion left, as to persist in my resolution not to live in the inn; and therefore my mother gave me leave, though she had but a little income, to have a bed upon the ground, and live at her house, till Providence should point out a place for me.

"Having now, as I thought, nothing to do, it was a proper season for Satan to tempt me. Much of my time I spent in reading plays, and in sauntering from place to place. I was careful to adorn my body, but took little pains to deck and beautify my soul. Evil communications with my old schoolfellows soon corrupted my good manners. By seeing their evil practices, the sense of the Divine presence[5] I had vouchsafed unto me insensibly wore off my mind, and I at length fell into abominable secret sin, the dismal effects of which I have felt, and groaned under ever since.

"[But God, whose gifts and callings are without repentance, would let nothing pluck me out of His hands, though I was continually doing despite to the Spirit of Grace. He saw me with pity and compassion, when lying in my blood. He passed by me; He said unto me, Live; and even gave me some foresight of His providing for me.

"One morning, as I was reading a play to my sister, said I, 'God intends something for me which we know not of. As I have been diligent in business, I believe many would gladly have me for an apprentice, but[8] every way seems to be barred up, so that I think God will provide for me some way or other that we cannot apprehend.'

"How I came to say these words I know not. God afterwards showed me they came from Him.] Having thus lived with my mother for some considerable time, a young student, who was once my schoolfellow, and then a servitor of Pembroke College, Oxford, came to pay my mother a visit. Amongst other conversation, he told her how he had discharged all college expenses that quarter, and received a penny. Upon that my mother immediately cried out, 'This will do for my son.' Then, turning to me, she said, 'Will you go to Oxford, George?' I replied, 'With all my heart.' Whereupon, having the same friends that this young student had, my mother, without delay, waited on them. They promised their interest to get me a servitor's place in the same college. She then applied to my old master, who much approved of my coming to school again.

"In about a week I went and re-entered myself, [and being grown much in stature, my master addressed me thus: 'I see, George, you are advanced in stature, but your better part must needs have gone backwards.' This made me blush. He set me something to translate into Latin; and though I had made no application to my classics for so long a time, yet I had but one inconsiderable fault in my exercises. This, I believe, somewhat surprised my master then, and has afforded me matter of thanks and praise ever since.

"Being re-settled at school, I spared no pains to go forward in my book.] God was pleased to give me His blessing, and I learned much faster than I did before. But all this while I continued in [secret] sin; and, at length, got acquainted with such a set of debauched, abandoned, atheistical youths, that if God, by His free, unmerited, and especial grace, had not delivered me out of their hands, I should long since have sat in the scorner's chair [and made a mock at sin]. By keeping company with them, my thoughts of religion grew more and more like theirs. I went to public service only to make sport and walk about. I took pleasure in their lewd conversation. I began to reason as they did [and to ask why God had given me passions, and not permitted me to gratify them? Not considering that God did not originally give us these corrupt passions, and that He had promised help to withstand them, if we would ask it of Him. In short, I soon made a great proficiency in the school of the devil. I affected to look rakish], and was in a fair way of being as infamous as the worst of them.

"But, oh stupendous love! God even here stopped me, when running on in a full career to hell. For, just as I was upon the brink of ruin, He gave me such a distaste of their principles and practices, that I discovered them to my master, who soon put a stop to their proceedings.

"Being thus delivered out of the snare of the devil, I began to be more and more serious, and felt God, at different times, working powerfully and convincingly upon my soul. One day in particular, as I was coming downstairs, and overheard my friends speaking well of me, God so deeply convinced me of hypocrisy, that, though I had formed frequent but ineffectual[9] resolutions before, yet I had then power given me over my secret and darling sin. Notwithstanding, some time after being overtaken in liquor, as I have been twice or thrice in my lifetime, Satan gained his usual advantage over me again,—an experimental proof to my poor soul, how that wicked one makes use of men as machines, working them up to just what he pleases [when by intemperance they have chased away the Spirit of God from them].

"Being now near the seventeenth year of my age, I was resolved to prepare myself for the holy sacrament, which I received on Christmas Day. I began now to be more and more watchful over my thoughts, words, and actions. I kept the following Lent, fasting Wednesday and Friday, thirty-six hours together. My evenings, when I had done waiting upon my mother, were generally spent in acts of devotion, reading 'Drelincourt on Death,' and other practical books, and I constantly went to public worship twice a day. Being now upper-boy, by God's help, I made some reformation amongst my schoolfellows. I was very diligent in reading and learning the classics, and in studying my Greek Testament, but was not yet convinced of the absolute unlawfulness of playing at cards, and of reading and seeing plays, though I began to have some scruples about it.

"Near this time, I dreamed that I was to see God on Mount Sinai, but was afraid to meet Him. This made a great impression upon me; and a gentlewoman to whom I told it said, 'George, this is a call from God.'

["Still I grew more serious after this dream; but yet hypocrisy crept into every action. As once I affected to look more rakish, I now strove to appear more grave than I really was. However, an uncommon concern and alteration were visible in my behaviour, and I often used to find fault with the lightness of others.

"One night, as I was going on an errand for my mother, an unaccountable but very strong impression was made upon my heart that I should preach quickly. When I came home, I innocently told my mother what had befallen me; but she, like Joseph's parents when he told them his dream, turned short upon me, crying out, 'What does the boy mean? Pri'thee hold thy tongue,' or something to that purpose. God has since shown her from whom that impression came.]

"For a twelvemonth, I went on in a round of duties, receiving the sacrament monthly, fasting frequently, attending constantly on public worship, and praying often more than twice a day in private. One of my brothers used to tell me he feared this would not hold long, and that I should forget all when I came to Oxford. This caution did me much service, for it set me upon praying for perseverance; and, under God, the preparation I made in the country was a preservative against the manifold temptations which beset me at my first coming to that seat of learning.

"Being now near eighteen years old, it was judged proper for me to go to the University. God had [sweetly] prepared my way. The friends before applied to recommended me to the master of Pembroke College.[10] Another friend took up £10 upon bond, which I have since repaid, to defray the first expense of entering; and the master,[6] contrary to all expectations, admitted the servitor immediately."

Thus ends Whitefield's history of his own boyhood. His confession of youthful wickedness is more minute than profitable. It was scarcely wise for a young evangelist of twenty-five, who had attained an unexampled popularity, and thereby brought upon himself the rancour of envious observers, to print such an enumeration of juvenile sins and follies. Indeed, the wisdom of doing this may be justly questioned in any case. A man may and ought to confess to God; but he is under no obligation to confess to men like himself. As already stated, the foregoing details would not have been reproduced in the present work, had it not been that this was necessary to exhibit the imprudent ingenuousness of the youthful preacher, and to show that his own unguarded writings fairly exposed him to some of the bitter pamphleteering with which he was soon attacked. Augustine had written similar Confessions, and so also had Jean Jacques Rousseau; but the world is none the better because Augustine and Rousseau made the world their father confessor. Whitefield's enemies were not slow to use the advantage against him with which he had furnished them; and, even nine years after the publication of his pamphlet, he had to pay a penalty for some of its well-meant, but inconsiderate expressions. "Mr.[11] Whitefield's account of God's dealings with him," said Dr. Lavington, Bishop of Exeter, "is such a boyish, ludicrous, filthy, nasty, and shameless relation of himself, as quite defiles paper, and is shocking to decency and modesty. 'Tis a perfect jakes of uncleanness."[7] The reader, with the "account" unabridged before him, can easily form an opinion of the truthfulness, or rather free-tongued censure, of Whitefield's episcopal castigator. Whitefield assigned a reason for what he did; and, though the sufficiency of that reason may not be admitted, yet all will give Whitefield credit for sincerity and good intentions, and no spiritually minded man will laugh at the penitential spirit which the confessions unquestionably evince.

As in the case of many others, Whitefield's boyhood was a strange admixture of sin and penitence. At intervals, we find the boy a liar, a petty thief, a pretended rake, a dandy, and almost an infidel; and then we find him spending his scantily collected pence in buying the manual of Bishop Ken; composing sermons; delighting in Thomas à Kempis; reading books like Drelincourt's "Christian Defence against the Fears of Death;" promoting a reformation of manners among the boys in the school of St. Mary de Crypt; religiously watching over his own thoughts, words, and actions; praying in private; worshipping in public; receiving the sacrament once a month; and, during Lent and at other times, frequently fasting for eighteen hours together. The Oxford Methodists, of whom perhaps he had never heard, were now approaching the very climax of their ascetic practices; and the quondam tapster of the Bell Inn, Gloucester, by a strange experience, was prepared to join them. Bad companions had nearly ruined him; but now his companions were to be of another sort.

In the midst of all his wickedness and youthful frolics, Whitefield displayed an undauntedness which helped to make him what he afterwards became. His educational advantages were not great. Unlike the Wesleys, his home was not favourable to his mental improvement. The public-house in which he was born and bred was widely different[12] from the Epworth parsonage. Practically he was fatherless whilst the Wesley brothers had for a father a man who, though sometimes improvident in attending convocations and in the publishing of books, had, in learning, but few superiors, and, as a clergyman of the Church of England, was excelled by none. Whitefield's mother was, evidently, an affectionate, sensible, and worthy woman; but, in most respects, immeasurably inferior to Susannah Wesley. Besides having had the unspeakable advantages of their Epworth home-education, John Wesley was privileged to spend five years and a half at the Charterhouse, London; and his brother Charles about the same length of time in the equally famed school of Westminster. On the other hand, Whitefield had no education, worth mentioning, until he was twelve years old; from twelve to fifteen he spent in the school of St. Mary de Crypt, partly in acquiring learning and partly in acting plays; from fifteen to seventeen, he was chiefly employed as tapster in his mother's tavern; and then came the turning-point of his existence. After listening to the story of the poor servitor of Pembroke College, who, by serving others, had paid all his college expenses, and had saved a penny, Whitefield's mother said, "George, will you go to Oxford?" "Yes," said George, "with all my heart." And, within a week, he was again at the school of St. Mary de Crypt; and, within a year, an undergraduate of an Oxford college. George's decision, prompt action, and hard-working ambition displayed pluck, not unworthy of the man, who, in later years, braved brutal mobs with heroic boldness, and who, when the present comforts of oceanic travelling were things unthought about, again and again crossed the turbulent Atlantic; and, constrained by the love of Christ his Saviour, tramped American woods and swamps, seeking sinners, and trying to save them.

One other fact is noticeable. From childhood George Whitefield was an orator. A hundred and fifty years ago dramatic performances appear to have been an important part of the education of the public schools of England. Thus it was in the Westminster School, where Charles Wesley was "put forward to act dramas," because of his lively cleverness; and thus it was at St. Mary de Crypt,[13] Gloucester, where Whitefield, on account of his "good elocution and memory," was "remarked for making speeches before the Corporation at their annual visitation;" and where the master of the school composed dramatical pieces in which Whitefield and his schoolfellows might display their histrionic genius and powers. The marvellously exciting eloquence of Whitefield was not so much an acquirement as a gift of nature; and this helps to explain his inordinate delight in theatrical literature, previous to his conversion.

Whitefield went to Oxford towards the end of the year 1732. Twelve years before this, Wesley had been admitted to Christ-Church College, and in the interval had been elected Fellow of Lincoln College, had taken his Master of Arts degree, and had been ordained deacon and also priest. Charles Wesley had been six years at Christ-Church, and was now Bachelor of Arts, and a College Tutor. Willam Morgan, one of the first of the Oxford Methodists, died a few weeks before Whitefield entered Pembroke College. For three years past, Clayton had been at Brasenose. Ingham had already spent two years at Queen's. In 1726, Gambold had been admitted as servitor in Christ Church, and in 1733 was ordained by Bishop Potter. Hervey, born in the same year as Whitefield, had, in 1731, become undergraduate in Lincoln College, where Wesley was Tutor. Broughton was in Exeter College. Kinchin was a Fellow of Corpus Christi. For twelve years, Hutchins had been Fellow of Lincoln, where also, for some time past, Whitelamb and Westley Hall had been studying, to the content of Wesley.

These were the chief of the Oxford Methodists. Whitefield, a boy not yet eighteen years of age, was the last to enter the University, and the last of the illustrious ones to join their godly brotherhood. For three years, the "Holy Club" had been notorious among their fellows; but, up to the present, Whitefield had never seen them.

Pembroke College, founded in 1624, had a Master, fourteen Fellows, twenty-four Scholars, and several Exhibitioners, being in all about sixty. As already stated, Whitefield was admitted as a servitor,—a lowly, but not necessarily dishonourable[15] position. Half a century before, Wesley's father had "footed it" to Oxford, with forty-five shillings in his purse, and had been received as servitor of Exeter College, in which, during his five years' residence, five shillings was the only assistance he received from his family and friends. And now Wesley's great coadjutor entered Pembroke in the same capacity, and in about the same penniless condition.

It is a fact worth noticing, that Samuel Johnson left Pembroke College only twelve months previous to Whitefield's admission; and that the poet Shenstone entered at the same time Whitefield did. At that period, some of the college tutors were so inefficient, that Johnson declared, concerning one of them, Mr. Jorden, that "he scarcely knew a noun from an adverb." The Rev. Dr. Adams, however, who succeeded Jorden in 1731, was a man of another stamp; and Johnson used to boast of the many eminent men who had been educated at Pembroke. "Sir," he used to say, with a smile of sportive triumph, when mentioning how many of the English poets had been trained in Pembroke College, "Sir, we are a nest of singing birds."[8]

Whitefield spent four years at Oxford—from 1732 to 1736. How did he employ his time, and what were the results? For the reasons previously assigned, the history of this important period shall be given in his own language, without any abridgment or alteration whatever. With perfect artlessness, he writes as follows:—

"Soon after my admission to Pembroke College, I found my having been used to a public-house was now of service to me. For many of the servitors being sick at my first coming up, by my diligent and ready attendance I ingratiated myself into the gentlemen's favour so far, that many, who had it in their power, chose me to be their servitor.

"This much lessened my expense; and, indeed, God was so gracious, that, with the profits of my place, and some little presents made me by my kind tutor, for almost the first three years I did not put all my relations together to above £24 expense.[9] [And it has often grieved my soul to see so many young students spending their substance in extravagant living, and hereby entirely unfitting themselves for the prosecution of their proper[16] studies.] I had not been long at the University before I found the benefit of the foundation I had laid in the country for a holy[10] life. I was quickly solicited to join in their excess of riot with several who lay in the same room. God, in answer to prayers before put up, gave me grace to withstand them; and once, in particular, it being cold, my limbs were so benumbed by sitting alone in my study, because I would not go amongst them, that I could scarce sleep all night. But I soon found the benefit of not yielding; for when they perceived they could not prevail, they let me alone as a singular, odd fellow.

["All this while I was not fully satisfied of the sin of playing at cards and reading plays, till God, upon a fast-day, was pleased to convince me. For, taking a play to read a passage out of it to a friend, God struck my heart with such power, that I was obliged to lay it down again; and—blessed be His name!—I have not read any such book since.

"Before I went to the University, I met with Mr. Law's 'Serious Call to a Devout Life,' but had not then money to purchase it. Soon after my coming up to the University, seeing a small edition of it in a friend's hand, I soon procured it. God worked powerfully upon my soul, as He has since upon many others, by that and his other excellent treatise upon 'Christian Perfection.']

"I now began to pray and sing psalms thrice every day, besides morning and evening, and to fast every Friday, and to receive the sacrament at a parish church near our college, and at the castle, where the despised Methodists used to receive once a month.

"The young men so called[11] were then much talked of at Oxford. I had heard of, and loved them before I came to the University; and so strenuously defended them when I heard them reviled by the students, that they began to think that I also in time should be one of them.

"For above a twelvemonth my soul longed to be acquainted with some of them, and I was strongly pressed to follow their good example, when I saw them go through a ridiculing crowd to receive the holy Eucharist at St. Mary's. At length, God was pleased to open a door. It happened that a poor woman in one of the workhouses had attempted to cut her throat, but was happily prevented. Upon hearing of this, and knowing that both the Mr. Wesleys were ready to every good work, I sent a poor aged apple-woman of our college to inform Mr. Charles Wesley of it, charging her not to discover who sent her. She went; but, contrary to my orders, told my name. He having heard of my coming to the castle and a parish church sacrament, and having met me frequently walking by myself, followed the woman when she was gone away, and sent an invitation to me by her, to come to breakfast with him the next morning.

"I thankfully embraced the opportunity; [and, blessed be God! it was one of the most profitable visits I ever made in my life. My soul, at that time, was athirst for some spiritual friends to lift up my hands when they hung down, and to strengthen my feeble knees. He soon discovered[17] it, and, like a wise winner of souls, made all his discourses tend that way. And, when he had] put into my hand Professor Frank's treatise against the 'Fear of Man,' [and a book entitled 'The Country Parson's Advice to his Parishioners,' the last of which was wonderfully blessed to my soul, I took my leave.]

"In a short time, he let me have another book entitled, 'The Life of God in the Soul of Man; [and, though I had fasted, watched, and prayed, and received the sacrament so long, yet I never knew what true religion was, till God sent me that excellent treatise by the hands of my never-to-be-forgotten friend].

"At my first reading it, I wondered what the author meant by saying, 'That some falsely placed religion in going to church, doing hurt to no one, being constant in the duties of the closet, and now and then reaching out their hands to give alms to their poor neighbours.' 'Alas!' thought I, 'if this be not religion, what is?' God soon showed me; for in reading a few lines further, that 'true religion was a union of the soul with God, and Christ formed within us,' a ray of Divine light was instantaneously darted in upon my soul, and, from that moment, but not till then, did I know that I must be a new creature.

"Upon this, [like the woman of Samaria when Christ revealed Himself to her at the well,] I had no rest [in my soul] till I wrote letters to my relations, telling them there was such a thing as the new birth. I imagined they would have gladly received it. But, alas! my words seemed to them as idle tales. They thought that I was going beside myself, and, by their letters, confirmed me in the resolutions I had taken not to go down into the country, but continue where I was, lest that, by any means, the good work which God had begun in my soul might be made of none effect.[12]

"From time to time Mr. Wesley permitted[13] me to come unto him, and instructed me as I was able to bear it. By degrees, he introduced me to the rest of his Christian brethren.[14] [They built me up daily in the knowledge and fear of God, and taught me to endure hardness like a good soldier of Jesus Christ.]

"I now began, like them, to live by rule, and to pick up the very fragments of my time, that not a moment of it might be lost. Whether I ate or drank, or whatsoever I did, I endeavoured to do all to the glory of God. Like them, having no weekly sacrament, although the rubric required it, at our own college, I received every Sunday at Christ Church. I joined with them in [keeping the stations by] fasting Wednesdays and Fridays [and left no means unused, which I thought would lead me nearer to Jesus Christ.

"Regular retirement, morning and evening, at first I found some difficulty in submitting to; but it soon grew profitable and delightful. As I grew ripe for such exercises, I was, from time to time] engaged to visit[18] the sick and the prisoners, and to read to poor people, till I made it a custom, as most of us did, to spend an hour every day in doing acts of charity.

"The course of my studies I soon entirely changed. Whereas, before I was busied in studying the dry sciences, and books that went no farther than the surface, I now resolved to read only such as entered into the heart of religion, and which led me directly into an experimental knowledge of Jesus Christ, and Him crucified. [The lively oracles of God were my soul's delight. The book of the Divine laws was seldom out of my hands: I meditated therein day and night; and, ever since that, God has made my way signally prosperous, and given me abundant success.

"God enabled me to do much good to many, as well as to receive much from the despised Methodists, and made me instrumental in converting one who is lately come out into the Church, and, I trust, will prove a burning and shining light.

"Several short fits of illness was God pleased to visit and to try me with, after my first acquaintance with Mr. Wesley. My new convert was a helpmeet for me in those and in all other circumstances; and, in company with him and several other Christian friends, did I spend many sweet and delightful hours. Never did persons, I believe, strive more earnestly to enter in at the strait gate. They kept their bodies under even to an extreme. They were dead to the world, and willing to be accounted as the dung and offscouring of all things, so that they might win Christ. Their hearts glowed with the love of God, and they never prospered so much in the inward man, as when they had all manner of evil spoken against them falsely without.

"Many came amongst them for a while, who, in time of temptation, fell away. The displeasure of a tutor or head of a college, the changing of a gown from a lower to a higher degree—above all, a thirst for the praise of men, more than that which cometh from God, and a servile fear of contempt—caused numbers, that had set their hands to the plough, shamefully to look back. The world, and not themselves, gave them the title of Methodists, I suppose, from their custom of regulating their time, and planning the business of the day every morning. Mr. John and Charles Wesley were two of the first that thus openly dared to confess Christ; and they, under God, were the spiritual fathers of most of them. They had the pleasure of seeing the work of the Lord prosper in their hands before they went to Georgia. Since their return, the small grain of mustard-seed has sprung up apace. It has taken deep root. It is growing into a great tree. Ere long, I trust, it will fill the land, and numbers of souls will come from the east and from the west, from the north and from the south, and lodge under the branches of it.

"But to return. While I was thus comforted on every side by daily conversing with so many Christian friends, God was pleased to permit Satan to sift me like wheat. A general account of which I shall, by the Divine assistance, give in the following section.

"At my first setting out, in compassion to my weakness, I grew in[19] favour both with God and man, and used to be much lifted up with sensible devotion, especially at the blessed sacrament. But when religion began to take root in my heart, and I was fully convinced my soul must totally be renewed ere it could see God, I was visited with outward and inward trials.]

"The first thing I was called to give up for God was what the world calls my fair reputation. I had no sooner received the sacrament publicly on a weekday at St. Mary's, but I was set up as a mark for all the polite students that knew me to shoot at. [By this they knew that I was commenced Methodist; for though there is a sacrament at the beginning of every term, at which all, especially the seniors, are by statute obliged to be present, yet so dreadfully has that once faithful city played the harlot, that very few masters, and no undergraduates but the Methodists, attended upon it.

"Mr. Charles Wesley, whom I must always mention with the greatest deference and respect, walked with me, in order to confirm me, from the church even to the college. I confess, to my shame, I would gladly have excused him; and the next day, going to his room, one of our Fellows passing by, I was ashamed to be seen to knock at his door. But, blessed be God! this fear of man gradually wore off. As I had imitated Nicodemus in his cowardice, so, by the Divine assistance, I followed him in his courage. I confessed the Methodists more and more publicly every day. I walked openly with them, and chose rather to bear contempt with those people of God, than to enjoy the applause of almost-Christians for a season.]

"Soon after this, I incurred the displeasure of the master of the college, who frequently chid, and once threatened to expel me, if I ever visited the poor again. Being surprised by this treatment,[15] I spake unadvisedly with my lips, and said, if it displeased him, I would not. My conscience soon pricked me for this sinful compliance. I immediately repented, and visited the poor the first opportunity, [and told my companions, if ever I was called to a stake for Christ's sake, I would serve my tongue as Archbishop Cranmer served his hand, namely, make that burn first.]

"My[16] tutor, being a worthy man, did not oppose me [much, but thought, I believe, that I went a little too far. He lent me books, gave me money, visited me, and furnished me with a physician when sick. In short, he behaved in all respects like a father; and I trust God will remember him for good, in answer to the many prayers I have put up in his behalf.

"My relations were quickly alarmed at the alteration of my behaviour, conceived strong prejudices against me, and for some time counted my life madness.] I daily underwent some contempt at college. Some have thrown dirt at me; others by degrees took away their pay from me; and two friends that were dear unto me grew shy of and forsook me, [when they saw me resolved to deny myself, take up my cross daily, and follow Jesus Christ. But our Lord, by His Spirit, soon convinced me that I must[20] know no one after the flesh; and I soon found that promise literally fulfilled, 'That no one hath left father or mother, brethren or sisters, houses or lands, for Christ's sake and the Gospel's, but he shall receive a hundredfold in this life, with persecution, as well as eternal life in the world to come.'

"These, though little, were useful trials. They inured me to contempt, lessened self-love, and taught me to die daily.] My inward sufferings were of a more uncommon nature. [Satan seemed to have desired me in particular to sift me as wheat. God permitted him for wise reasons, I have seen already, namely, that His future blessings might not prove my ruin.

"From my first awakenings to the divine life, I felt a particular hungering and thirsting after the humility of Jesus Christ. Night and day I prayed to be a partaker of that grace, imagining that the habit of humility would be instantaneously infused into my soul. But as Gideon taught the men of Succoth with thorns, so God, if I am yet in any measure blessed with true poverty of spirit, taught it me by the exercise of strong temptations.

"I observed before how I used to be favoured with sensible devotion; those] comforts were soon withdrawn, and a horrible fearfulness and dread permitted to overwhelm my soul. [One morning in particular, rising from my bed, I felt an unusual impression and weight upon my breast, attended with inward darkness. I applied to my friend, Mr. Charles Wesley. He advised me to keep upon my watch, and referred me to a chapter in Kempis. In a short time I perceived this load gradually increase, till it almost weighed me down, and fully convinced me that Satan had as real a possession of, and power given over, my body, as he had once over Job's.] All power of meditating, or even thinking, was taken from me. My memory quite failed me. My whole soul was barren and dry, and I could fancy myself to be like nothing so much as a man locked up in iron armour. Whenever I kneeled down, I felt great[17] heavings in my body, and have often prayed under the weight of them till the sweat came through me. [At this time, Satan used to terrify me much, and threatened to punish me if I discovered his wiles. It being my duty, as servitor, in my turn to knock at the gentlemen's rooms by ten at night, to see who were in their rooms, I thought the devil would appear to me every stair I went up. And he so troubled me when I lay down to rest, that for some weeks I scarce slept above three hours at a time.]

"God only knows how many nights I have lain upon my bed groaning under the weight I felt, [and bidding Satan depart from me in the name of Jesus.] Whole days and weeks have I spent in lying prostrate on the ground,[18] [and begging for freedom from those proud hellish thoughts that used to crowd in upon and distract my soul. But God made Satan drive out Satan; for these thoughts and suggestions created such a self-abhorrence[21] within me, that I never ceased wrestling with God till He blessed me with a victory over them. Self-love, self-will, pride, and envy so buffeted me in their turns, that I was resolved either to die or conquer. I wanted to see sin as it was, but feared, at the same time, lest the sight of it should terrify me to death.

"Whilst my inward man was thus exercised, my outward man was not unemployed. I soon found what a slave I had been to my sensual appetite, and now resolved to get the mastery over it by the help of Jesus Christ.] Accordingly, by degrees, I began to leave off eating fruits and such like, and gave the money I usually spent in that way to the poor. Afterward, I always chose the worst sort of food, though my place furnished me with variety. I fasted twice a week. My apparel was mean. I thought it unbecoming a penitent to have his hair powdered. I wore woollen gloves, a patched gown, and dirty shoes;[19] and [though I was then convinced that the kingdom of God did not consist in meats and drinks, yet I resolutely persisted in these voluntary acts of self-denial, because I found them great promoters of the spiritual life.]

"For many months, I went on in this[20] state, [faint, yet pursuing, and travelling along in the dark, in hope that the star I had before once seen would hereafter appear again. During this season I was very active;] but finding pride creeping in at the end of almost every thought, word, and action, and meeting with Castaniza's 'Spiritual Combat,' in which he says 'that he that is employed in mortifying his will was as well employed as though he was converting Indians,' or words to that effect, Satan so imposed upon my understanding, that he persuaded me to shut myself up in my study till I could do good[21] [with a single eye], lest, in endeavouring to save others as I did now, I should at last, by pride and self-complacence, lose myself.

["Henceforward, he transformed himself into an angel of light, and worked so artfully, that I imagined the good, and not the evil, spirit suggested to me everything I did.

"His main drift was to lead me into a state of quietism (he generally ploughed with God's heifer); and when the Holy Spirit put into my heart good thoughts or convictions, he always drove them to extremes. For instance, having out of pride put down in my diary what I gave away, Satan tempted me to lay my diary quite aside. When Castaniza[22] advised to talk but little, Satan said I must not talk at all. So that I, who used to be the most forward in exhorting my companions, have sat whole nights almost without speaking at all. Again, when Castaniza advised to endeavour after a silent recollection and waiting upon God, Satan told me[22] I must leave off all forms, and not use my voice in prayer at all. The time would fail me to recount all the instances of this kind in which he had deceived me. But when matters came to an extreme, God always showed me my error, and by His Spirit pointed out a way for me to escape.

"The devil also sadly imposed upon me in the matter of my college exercises. Whenever I endeavoured to compose my theme, I had no power to write a word, nor so much as to tell my Christian friends of my inability to do it. Saturday being come, which is the day the students give up their compositions, it was suggested to me that I must go down into the hall, and confess I could not make a theme, and so publicly suffer, as if it were, for my Master's sake. When the bell rung to call us, I went to open the door to go down stairs, but feeling something give me a violent inward check, I entered my study, and continued instant in prayer, waiting the event. For this my tutor fined me half a crown. The next week Satan served me in like manner again; but now having got more strength, and perceiving no inward check, I went into the hall. My name being called, I stood up and told my tutor I could not make a theme. I think he fined me a second time; but, imagining that I would not willingly neglect my exercise, he afterward called me into the common room, and kindly enquired whether any misfortune had befallen me, or what was the reason I could not make a theme. I burst into tears, and assured him that it was not out of contempt of authority, but that I could not act otherwise. Then, at length, he said he believed I could not; and, when he left me, told a friend, as he very well might, that he took me to be really mad. This friend, hearing from my tutor what had happened, came to me, urging the command of Scripture, to be subject to the higher powers. I answered, 'Yes; but I had a new revelation.' Lord, what is man?

"As I daily got strength, by continued, though almost silent, prayer in my study, my temptations grew stronger also, particularly for two or three days before deliverance came.]

"Near five or six weeks I had now spent in my study, except when[23] I was obliged to go out. During this time I was fighting with my corruptions, and did little else besides kneeling down by my bedside, feeling, as it were, a heavy pressure upon my body, as well as an unspeakable oppression of mind, yet offering up my soul to God to do with me as it pleased Him. It was now suggested to me that Jesus Christ was among the wild beasts when He was tempted, and that I ought to follow His example; and being willing, as I thought, to imitate Jesus Christ, after supper I went into Christ Church walk, near our college, and continued in silent prayer under one of the trees [for near two hours, sometimes lying flat on my face, sometimes] kneeling upon my knees, [all the while filled with fear and concern lest some of my brethren should be overwhelmed with pride. The night being stormy, it gave me awful thoughts of the day of judgment. I continued, I think,] till the great bell rung for retirement to[23] the college, not without finding some reluctance in the natural man against staying so long in the cold.

["The next night I repeated the same exercise at the same place. But the hour of extremity being now come, God was pleased to make an open show of those diabolical devices by which I had been deceived.]

"By this time, I had left off keeping my diary, using my forms, or scarce my voice in prayer, visiting prisoners, etc. Nothing remained for me to leave, unless I forsook public worship, but my religious friends. Now it was suggested that I must leave them also for Christ's sake. This was a sore trial; but rather than not be, as I fancied, Christ's disciple, I resolved to renounce them, though as dear to me as my own soul. Accordingly, the next day being Wednesday, whereon we kept one of our weekly fasts, instead of meeting with my brethren as usual, I went out into the fields, and prayed silently by myself. Our evening meeting I neglected also, and went not to breakfast, according to appointment, with Mr. Charles Wesley the day following. This, with many other concurring circumstances, made my honoured friend, Mr. Charles Wesley, suspect something more than ordinary was the matter. He came to my room, [soon found out my case,] apprised me of my danger if I would not take advice, and recommended me to his brother John, Fellow of Lincoln College, as more experienced[24] [in the spiritual life]. God gave me—[blessed be His holy name]—a teachable temper, and I waited upon his brother, with whom from that time I had the honour of growing intimate. He advised me to resume all my externals, though not to depend on them in the least. From time to time he gave me directions as my [various and] pitiable state required; [and, at length, by his excellent advice and management of me, under God, I was delivered from those wiles of Satan. 'Praise the Lord, O my soul, and all that is within me praise His holy name!']

["During this and all other seasons of temptation my soul was inwardly supported with great courage and resolution from above. Every day God made me willing to renew the combat, and though my soul, when quite empty of God, was very prone to seek satisfaction in the creature, and sometimes I fell into sensuality, yet I was generally enabled to wait in silence for the salvation of God, or to persist in prayer till some beams of spiritual light and comfort were vouchsafed me from on high. Thomas à Kempis, since translated and published by Mr. John Wesley; Castaniza's Combat; and the Greek Testament, every reading of which I endeavoured to turn into a prayer, were of great help and furtherance to me. On receiving the holy sacrament, especially before trials, I have found grace in a very affecting manner, and in abundant measure, sometimes imparted to my soul,—an irrefragable proof to me of the miserable delusion of the author of that work called, 'The Plain Account of the Sacrament,' which sinks that holy ordinance into a bare memorial, who, if he obstinately refuse the instruction of the Most High, will doubtless, without repentance, bear his punishment, whosoever he be.]

"To proceed—I had now taken up my externals again;[25] [and though Satan for some weeks had been biting my heel, God was pleased to show me that I should soon bruise his head.] A few days after, as I was walking along, I met with a poor woman whose husband was then in [Bocardo, or] Oxford Town-Gaol, [which I constantly visited.] Seeing her much discomposed, I enquired the cause. She told me, not being able to bear the crying of her children, ready to perish for hunger, and having nothing to relieve them, she had been to drown herself, but was mercifully prevented, and said she was coming to my room to inform me of it. I gave her some immediate relief, and desired her to meet me at the prison with her husband in the afternoon. She came, and there God visited them both by His free grace. She was powerfully quickened from above; and when I had done reading, he also came to me like the trembling gaoler, and, grasping my hand, cried out, 'I am upon the brink of hell!'. From this time forward, both of them grew in grace. God, by His providence, soon delivered him from his confinement. Though notorious offenders against God and one another before, yet now they became helpmeets for each other in the great work of their salvation. They are both now living, and, I trust, will be my joy and crown of rejoicing in the great day of our Lord Jesus.

"Soon after this, [the holy season of] Lent came on, which our friends kept very strictly, eating no flesh during the six weeks, except on Saturdays and Sundays. I abstained frequently on Saturdays also, and ate nothing on the other days, except on Sunday, but sage-tea without sugar, and coarse bread. I constantly walked out in the cold mornings till part of one of my hands was quite black. This, with my continued abstinence and inward conflicts, at length so emaciated my body, that, at Passion-week, finding I could scarce creep upstairs, I was obliged to inform my kind tutor of my condition, who immediately sent for a physician to me.

"This caused no small triumph amongst the collegians, who began to cry out, 'What is his fasting come to now?' [But I rejoiced in this reproach, knowing that, though I had been imprudent, and lost much of my flesh, yet, I had nevertheless increased in the spirit.]

["This fit of sickness continued upon me for seven weeks, and a glorious visitation it was.[26] The blessed Spirit was all this time purifying my soul. All my former gross and notorious, and even my heart sins also, were now set home upon me, of which I wrote down some remembrance immediately, and confessed them before God morning and evening. Though weak, I often spent two hours in my evening retirements, and prayed over my Greek Testament and Bishop Hall's most excellent 'Contemplations' every hour that my health would permit.] About the end of the seven weeks,[27] [and after I had been groaning under an unspeakable[25] pressure both of body and mind for above a twelvemonth, God was pleased to set me free in the following manner. One day, perceiving an uncommon drought and a disagreeable clamminess in my mouth, and using things to allay my thirst, but in vain, it was suggested to me that when Jesus Christ cried out, 'I thirst,' His sufferings were near at an end. Upon which I cast myself down on the bed, crying out, 'I thirst! I thirst!' Soon after this, I found and felt in myself that I was delivered from the burden that had so heavily oppressed me. The spirit of mourning was taken from me, and I knew what it was truly to rejoice in God my Saviour, and, for some time, could not avoid singing psalms wherever I was; but my joy gradually became more settled, and, blessed be God, has abode and increased in my soul, saving a few casual intermissions, ever since.

"Thus were the days of my mourning ended. After a long night of desertion and temptation, the star, which I had seen at a distance before, began to appear again, and the day star arose in my heart. Now did the Spirit of God take possession of my soul, and, as I humbly hope, seal me unto the day of redemption."]