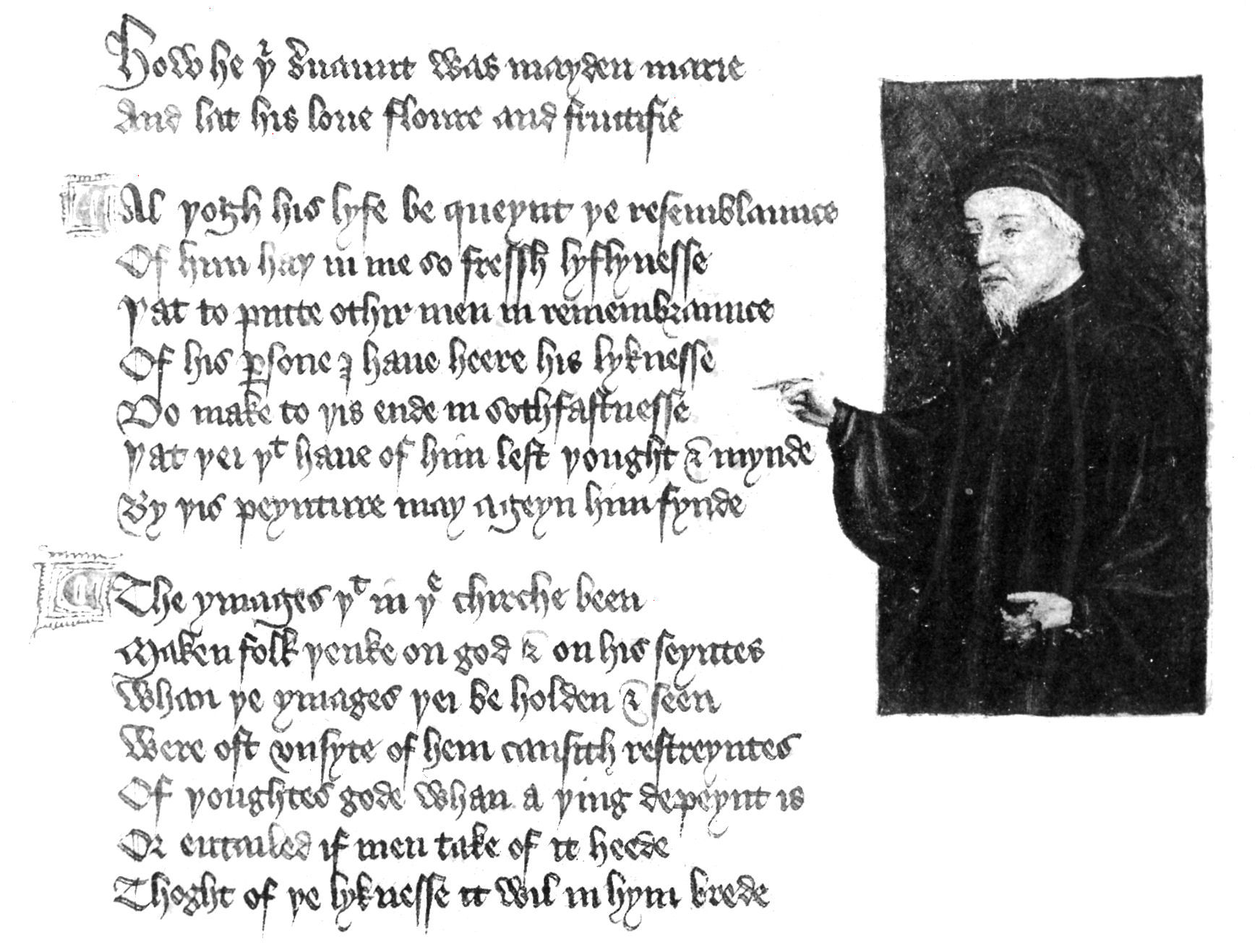

Vol. I. Frontispiece.

GEOFFREY CHAUCER: FROM MS. HARL. 4866

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. |

THE COMPLETE WORKS

OF

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

EDITED, FROM NUMEROUS MANUSCRIPTS

BY THE

Rev. WALTER W. SKEAT, M.A.

Litt.D., LL.D., D.C.L., Ph.D.

ELRINGTON AND BOSWORTH PROFESSOR OF ANGLO-SAXON

AND FELLOW OF CHRIST'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

*

ROMAUNT OF THE ROSE

MINOR POEMS

——'blanda sonantibus

Chordis carmina temperans.'

Boethius, De Cons. Phil. Lib. III. Met. 12.

'He temprede hise blaundisshinge songes by resowninge strenges.'

Chaucer's Translation.

SECOND EDITION

Oxford

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

MDCCCXCIX

Oxford

PRINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

BY HORACE HART, M.A.,

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

CONTENTS.

*** The Portrait of Chaucer in the frontispiece is noticed at p. lix.

| PAGE | ||

| General Introduction | vii | |

| Life of Chaucer | ix | |

| List of Chaucer's Works | lxii | |

| Errata and Addenda | lxiv | |

| Introduction to the Romaunt of the Rose.—§ 1. Why (the chief part of) the Romaunt of the Rose is not Chaucer's. § 2. The English Version of the Romaunt. § 3. Internal evidence. § 4. Dr. Lidner's opinion. § 5. Dr. Kaluza's opinion. The three Fragments. § 6. Discussion of Fragment B. Test. I.—Proportion of English to French. § 7. Test II.—Dialect. § 8. Test III.—The Riming of -y with -yë. § 9. Test IV.—Assonant Rimes. § 10. Result: Fragment B is not by Chaucer. § 11. Discussion of Fragment C. § 12. Rime-tests. § 13. Further considerations. § 14. Result: Fragment C is not by the author of Fragment B, and perhaps not by Chaucer. § 15. Discussion of Fragment A. (1) Rimes in -y. (2) Rimes in -yë § 16. No false rimes. § 17. The three Fragments seem to be all distinct. § 18. Fragment A is probably Chaucer's. § 19. Summary. § 20. Probability of the results. § 21. The external evidence. § 22. The Glasgow MS. § 23. Th.—Thynne's Edition; 1532. § 24. Reprints. § 25. The Present Edition. § 26. Some corrections. § 27. The French Text. §§ 28, 29. Brief Analysis of the French Poem: G. de Lorris. § 30. Jean de Meun; to the end of Fragment B. § 31. Gap in the Translation. § 32. Fragment C. § 33. Chaucer's use of 'Le Roman.' § 34. Méon's French text | 1 | |

| Introduction to the Minor Poems.—§ 1. Principles of selection. § 2. Testimony of Chaucer regarding his Works. § 3. Lydgate's List. § 4. Testimony of Shirley. § 5. Testimony of Scribes. § 6. Testimony of Caxton. § 7. Early Editions of Chaucer. § 8. Contents of Stowe's Edition (1561): Part I.—Reprinted Matter. § 9. Part II.—Additions by Stowe. § 10. Part I. discussed. § 11. Part II. discussed. § 12. Poems added by Speght. [vi] § 13. Poems added by Morris. § 14. Description of the MSS. List of the MSS. § 15. Remarks on the MSS. at Oxford. § 16. MSS. at Cambridge. § 17. London MSS. § 18. I.—A. B. C. § 19. II.—The Compleynt unto Pitè. § 20. III.—The Book of the Duchesse. § 21. IV.—The Compleynt of Mars. § 22. V.—The Parlement of Foules. § 23. VI.—A Compleint to his Lady. § 24. VII.—Anelida and Arcite. § 25. VIII. Chaucers Wordes unto Adam. § 26. IX.—The Former Age. § 27. X.—Fortune. § 28. XI.—Merciless Beauty. § 29. XII.—To Rosemounde. § 30. XIII.—Truth. § 31. XIV.—Gentilesse. § 32. XV.—Lak of Stedfastnesse. § 33. XVI—Lenvoy to Scogan. § 34. XVII.—Lenvoy to Bukton. § 35. XVIII.—Compleynt of Venus. § 36. XIX.—The Compleint to his Purse. § 37. XX.—Proverbs. § 38. XXI.—Against Women Unconstaunt. § 39. XXII.—An Amorous Complaint. § 40. XXIII.—Balade of Compleynt. § 41. Concluding Remarks | 20 | |

| The Romaunt of the Rose. | ||

| Fragment A. (with the French Text) | 93 | |

| Fragment B. (containing Northern forms) | 164 | |

| Fragment C. | 229 | |

| The Minor Poems. | ||

| I. | An A. B. C. (with the French original) | 261 |

| II. | The Compleynte unto Pitè | 272 |

| III. | The Book of the Duchesse | 277 |

| IV. | The Compleynt of Mars | 323 |

| V. | The Parlement of Foules | 335 |

| VI. | A Compleint to his Lady | 360 |

| VII. | Anelida and Arcite | 365 |

| VIII. | Chaucers Wordes unto Adam | 379 |

| IX. | The Former Age | 380 |

| X. | Fortune | 383 |

| XI. | Merciles Beautè | 387 |

| XII. | Balade to Rosemounde | 389 |

| XIII. | Truth | 390 |

| XIV. | Gentilesse | 392 |

| XV. | Lak of Stedfastnesse | 394 |

| XVI. | Lenvoy to Scogan | 396 |

| XVII. | Lenvoy to Bukton | 398 |

| XVIII. | The Compleynt of Venus (with the French original) | 400 |

| XIX. | The Compleint of Chaucer to his empty Purse | 405 |

| XX. | Proverbs of Chaucer | 407 |

| XXI. | Appendix: Against Women Unconstaunt | 409 |

| XXII. | An Amorous Complaint | 411 |

| XXIII. | A Balade of Compleynt | 415 |

| Notes to the Romaunt of the Rose | 417 | |

| Notes to the Minor Poems | 452 | |

GENERAL INTRODUCTION.

The present edition of Chaucer contains an entirely new Text, founded solely on the manuscripts and on the earliest accessible printed editions. For correct copies of the manuscripts, I am indebted, except in a few rare instances, to the admirable texts published by the Chaucer Society.

In each case, the best copy has been selected as the basis of the text, and has only been departed from where other copies afforded a better reading. All such variations, as regards the wording of the text, are invariably recorded in the footnotes at the bottom of each page; or, in the case of the Treatise on the Astrolabe, in Critical Notes immediately following the text. Variations in the spelling are also recorded, wherever they can be said to be of consequence. But I have purposely abstained from recording variations of reading that are certainly inferior to the reading given in the text.

The requirements of metre and grammar have been carefully considered throughout. Beside these, the phonology and spelling of every word have received particular attention. With the exception of reasonable and intelligible variations, the spelling is uniform throughout, and consistent with the highly phonetic system employed by the scribe of the very valuable Ellesmere MS. of the Canterbury Tales. The old reproach, that Chaucer's works are chiefly remarkable for bad spelling, can no longer be fairly made; since the spelling here given is a fair guide to the old pronunciation of nearly every word. For further particulars, see the Introduction to vol. iv. and the remarks on Chaucer's language in vol. v.

The present edition comprises the whole of Chaucer's Works, whether in verse or prose, together with a commentary (contained in the Notes) upon every passage which seems to present any difficulty or to require illustration. It is arranged in six volumes, as follows.

Vol. I. commences with a Life of Chaucer, containing all the known facts and incidents that have been recorded, with [viii]authorities for the same, and dates. It also contains the Romaunt of the Rose and the Minor Poems, with a special Introduction and illustrative Notes. The Introduction discusses the genuineness of the poems here given, and explains why certain poems, formerly ascribed to Chaucer with more rashness than knowledge, are here omitted.

The attempt to construct a reasonably good text of the Romaunt has involved great labour; all previous texts abound with corruptions, many of which have now for the first time been amended, partly by help of diligent collation of the two authorities, and partly by help of the French original.

Vol. II. contains Boethius and Troilus, each with a special Introduction. The text of Boethius is much more correct than in any previous edition, and appears for the first time with modern punctuation. The Notes are nearly all new, at any rate as regards the English version.

The text of Troilus is also a new one. The valuable 'Corpus MS.' has been collated for the first time; and several curious words, which have been hitherto suppressed because they were not understood, have been restored to the text, as explained in the Introduction. Most of the explanatory Notes are new; others have appeared in Bell's edition.

Vol. III. contains The House of Fame, the Legend of Good Women, and the Treatise on the Astrolabe; with special Introductions. All these have been previously edited by myself, with Notes. Both the text and the Notes have been carefully revised, and contain several corrections and additions. The latter part of the volume contains a discussion of the Sources of the Canterbury Tales.

Vol. IV. contains the Canterbury Tales, with the Tale of Gamelyn appended. The MSS. of the Canterbury Tales, and the mode of printing them, are discussed in the Introduction.

Vol. V. contains a full Commentary on the Canterbury Tales, in the form of Notes. Such as have appeared before have been carefully revised; whilst many of them appear for the first time. The volume further includes all necessary helps for the study of Chaucer, such as remarks on the pronunciation, grammar, and scansion.

Vol. VI. contains a Glossarial Index and an Index of Names.

LIFE OF GEOFFREY CHAUCER.

*** Many of the documents referred to in the foot-notes are printed at length in Godwin's Life of Chaucer, 2nd ed. 1804 (vol. iv), or in the Life by Sir H. Nicolas. The former set are marked (G.); the latter set are denoted by a reference to 'Note A,' or 'Note B'; &c.

§ 1. The name Chaucer, like many others in England in olden times, was originally significant of an occupation. The Old French chaucier (for which see Godefroy's Old French Dictionary) signified rather 'a hosier' than 'a shoemaker,' though it was also sometimes used in the latter sense. The modern French chausse represents a Low Latin calcia, fem. sb., a kind of hose, closely allied to the Latin calceus, a shoe. See Chausses, Chaussure, in the New English Dictionary.

It is probable that the Chaucer family came originally from East Anglia. Henry le Chaucier is mentioned as a citizen of Norfolk in 1275; and Walter le Chaucer as the same, in 1292[1]. But Gerard le Chaucer, in 1296, and Bartholomew le Chaucer, in 1312-3, seem to have lived near Colchester[2].

In several early instances, the name occurs in connexion with Cordwainer Street, or with the small Ward of the City of London bearing the same name. Thus, Baldwin le Chaucer dwelt in 'Cordewanerstrete' in 1307; Elyas le Chaucer in the same, in 1318-9; Nicholas Chaucer in the same, in 1356; and Henry Chaucer was a man-at-arms provided for the king's service by Cordwanerstrete Ward[3]. This is worthy of remark, because, as [x]we shall see presently, both Chaucer's father and his grandmother once resided in the same street, the northern end of which is now called Bow Lane, the southern end extending to Garlick Hithe. (See the article on Cordwainer Street Ward in Stowe's Survey of London.)

§ 2. Robert le Chaucer. The earliest relative with whom we can certainly connect the poet is his grandfather Robert, who is first mentioned, together with Mary his wife, in 1307, when they sold ten acres of land in Edmonton to Ralph le Clerk, for 100s.[4] On Aug. 2, 1310, Robert le Chaucer was appointed 'one of the collectors in the port of London of the new customs upon wines granted by the merchants of Aquitaine[5].' It is also recorded that he was possessed of one messuage, with its appurtenances, in Ipswich[6]; and it was alleged, in the course of some law-proceedings (of which I have more to say below), that the said estate was only worth 20 shillings a year. He is probably the Robert Chaucer who is mentioned under the date 1310, in the Early Letter-books of the City of London[7].

Robert Chaucer was married, in or before 1307 (see above), to a widow named Maria or Mary Heyroun[8], whose maiden name was probably Stace[9]; and the only child of whom we find any mention was his son and heir, named John, who was the poet's father. At the same time, it is necessary to observe that Maria had a son still living, named Thomas Heyroun, who died in 1349[10]. [xi]

John Chaucer was born, as will be shewn, in 1312; and his father Robert died before 1316 (Close Rolls, 9 Edw. II., p. 318).

§ 3. Richard le Chaucer. Some years after Robert's death, namely in 1323[11], his widow married for the third time. Her third husband was probably a relative (perhaps a cousin) of her second, his name being Richard le Chaucer, a vintner residing in the Ward of Cordwainer Street; respecting whom several particulars are known.

Richard le Chaucer was 'one of the vintners sworn at St. Martin's, Vintry, in 1320, to make proper scrutiny of wines[12]'; so that he was necessarily brought into business relations with Robert, whose widow he married in 1323, as already stated.

A plea held at Norwich in 1326, and entered on mem. 13 of the Coram Rege Roll of Hilary 19 Edw. II.[13], is, for the present purpose, so important that I here quote Mr. Rye's translation of the more material portions of it from the Life-Records of Chaucer (Chaucer Soc.), p. 125:—

'London.—Agnes, the widow of Walter de Westhale, Thomas Stace, Geoffrey Stace, and Laurence 'Geffreyesman Stace[14],' were attached to answer Richard le Chaucer of London and Mary his wife on a plea that whereas the custody of the heir and land of Robert le Chaucer, until the same heir became of full age, belonged to the said Richard and Mary (because the said Robert held his land in socage, and the said Mary is nearer in relationship to the heir of the said Robert,) and whereas the said Richard and Mary long remained in full and peaceful seizin of such wardship, the said Agnes, Thomas, Geoffrey, and Laurence by force and arms took away John, the son and heir of the said Robert, who was under age and in the custody of the said Richard and Mary, and married him[15] against the will of the said R. and M. and of the said heir, and also did other unlawful acts against the said R. and M., to the grave injury of the said R. and M., and against the peace.

'And therefore the said R. and M. complain that, whereas the custody of the land and heir of the said Robert, viz. of one messuage with its appurtenances in Ipswich, until the full age of, &c., belonged, &c., ... because the said Robert held the said messuage in socage, and the said Mary is nearer in relationship to the said Robert, viz. mother of the said heir, and formerly [xii]the wife of the said Robert, and (whereas) the said R. and M. remained in full and peaceful seizin of the said wardship for a long while, viz. for one year; they, the said Agnes, T., G., and L., on the Monday [Dec. 3] before the feast of St. Nicholas, in the eighteenth year of the present king [1324], ... stole and took away by force and arms ... the said John, son and heir of the said Robert, who was under age, viz. under the age of fourteen years, and then in the wardship of the said R. and M. at London, viz. in the Ward of Cordwanerstrete, and married him to one Joan, the daughter of Walter de Esthale [error for Westhale], and committed other unlawful acts, &c.

'Wherefore they say they are injured, and have suffered damage to the extent of 300l.'

The defence put in was—

'That, according to the customs of the borough of Ipswich ... any heir under age when his heirship shall descend to him shall remain in the charge of the nearest of his blood, but that his inheritance shall not descend to him till he has completed the age of twelve years ... and they say that the said heir of the said Robert completed the age of twelve years before the suing out of the said writ[16].'

And it was further alleged that the said Agnes, T., G., and L. did not cause the said heir to be married.

'Most of the rest of the membrane,' adds Mr. Rye, 'is taken up with a long technical dispute as to jurisdiction, of which the mayor and citizens of London apparently got the best; for the trial came on before R. Baynard and Hamo de Chikewell [Chigwell] and Nicholas de Farndon (the two latter sitting on behalf of the City) at St. Martin's the Great (le Grand), London, on the Sunday [Sept. 7, 1326] next before the Nativity of the B.V.M. [Sept. 8]; when, the defendants making default, a verdict was entered for the plaintiffs for 250l. damages.'

Further information as to this affair is given in the Liber Albus, ed. Riley, 1859, vol. i. pp. 437-444. A translation of this passage is given at pp. 376-381 of the English edition of the same work, published by the same editor in 1861. We hence learn that the Staces, being much dissatisfied with the heavy damages which they were thus called upon to pay, attainted Richard le Chaucer and his wife, in November, 1328, of committing perjury in the above-mentioned trial. But it was decided that attaint does not lie as to the verdict of a jury in London; a decision so important that the full particulars of the trial and of this appeal were carefully preserved among the city records. [xiii]

Mr. Rye goes on to give some information as to a third document relating to the same affair. It appears that Geoffrey Stace next 'presented a petition to parliament (2 Edw. III., 1328, no. 6), praying for relief against the damages of 250l., which he alleged were excessive, on the ground that the heir's estate was only worth 20s. a year[17]. This petition sets out all the proceedings, referring to John as "fuiz [fiz] et heire Robert le Chaucier," but puts the finding of the jury thus: "et trove fu qu'ils avoient ravi le dit heire, mes ne mie mariee," and alleges that "le dit heire est al large et ove [with] les avantditz Richard et Marie demourant et unkore dismarie."' The result of this petition is unknown.

From the above particulars I draw the following inferences.

The fact that Mary le Chaucer claimed to be nearer in relationship to the heir (being, in fact, his mother) than the Staces, clearly shews that they also were very near relations. We can hardly doubt that the maiden name of Mary le Chaucer was Stace, and that she was sister to Thomas and Geoffrey Stace.

In Dec. 1324, John le Chaucer was, according to his mother's statement, 'under age'; i. e. less than fourteen years old. According to the Staces, he had 'completed the age of twelve before the suing out, &c.' We may safely infer that John was still under twelve when the Staces carried him off, on Dec. 3, 1324. Hence he was born in 1312, and we have seen that his father Robert married the widow Maria Heyroun not later than 1307 (§ 2). She was married to Richard in 1323 (one year before 1324), and she died before 1349, as Richard was then a widower.

The attempt to marry John to Joan de Westhale (probably his cousin) was unsuccessful. He was still unmarried in Nov. 1328, and still only sixteen years old. This disposes at once of an old tradition, for which no authority has ever been discovered, that the poet was born in 1328. The earliest date that can fairly be postulated for the birth of Geoffrey is 1330; and even then his father was only eighteen years old.

We further learn from Riley's Memorials of London (Pref. p. xxxiii), that Richard Chaucer was a man of some wealth. He was assessed, in 1340, to lend 10l. towards the expenses of the French war; and again, in 1346, for 6l. and 1 mark towards [xiv]the 3,000l. given to the king. In 1345, he was witness to a conveyance of a shop situated next his own tenement and tavern in La Reole or Royal Street, near Upper Thames Street.

The last extant document relative to Richard Chaucer is his will. Sir H. Nicolas (Life of Chaucer, Note A) says that the will of Richard Chaucer, vintner, of London, dated on Easter-day (Apr. 12), 1349, was proved in the Hustings Court of the City of London by Simon Chamberlain and Richard Litlebury, on the feast of St. Margaret (July 20), in the same year. He bequeathed his tenement and tavern, &c., in the street called La Reole, to the Church of St. Aldermary in Bow Lane, where he was buried; and left other property to pious uses. The will mentions only his deceased wife Mary and her son Thomas Heyroun; and appointed Henry at Strete and Richard Mallyns his executors[18]. From this we may infer that his stepson John was, by this time, a prosperous citizen, and already provided for.

The will of Thomas Heyroun (see the same Note A) was dated just five days earlier, April 7, 1349, and was also proved in the Hustings Court. He appointed his half-brother, John Chaucer, his executor; and on Monday after the Feast of St. Thomas the Martyr[19] in the same year, John Chaucer, by the description of 'citizen and vintner, executor of the will of my brother Thomas Heyroun,' executed a deed relating to some lands. (Records of the Hustings Court, 23 Edw. III.)

It thus appears that Richard Chaucer and Thomas Heyroun both died in 1349, the year of the first and the most fatal pestilence.

§ 4. John Chaucer. Of John Chaucer, the poet's father, not many particulars are known. He was born, as we have seen, about 1312, and was not married till 1329, or somewhat later. His wife's name was Agnes, described in 1369 as the kinswoman (consanguinea) and heiress of the city moneyer, Hamo de Copton, who is known to have owned property in Aldgate[20]. He was [xv]a citizen and vintner of London, and owned a house in Thames Street[21], close to Walbrook, a stream now flowing underground beneath Walbrook Street[22]; so that it must have been near the spot where the arrival platform of the South-Eastern railway (at Cannon Street) now crosses Thames Street. In this house, in all probability, Chaucer was born; at any rate, it became his own property, as he parted with it in 1380. It is further known that John and Agnes Chaucer were possessed of a certain annual quit-rent of 40d. sterling, arising out of a tenement in the parish of St. Botolph-without-Aldgate[23].

In 1338 (on June 12), John Chaucer obtained letters of protection, being then on an expedition to Flanders, in attendance on the king[24]. Ten years later, in the months of February and November, 1348, he is referred to as being deputy to the king's butler in the port of Southampton[25]. In 1349, as we have seen, he was executor to the will of his half-brother, Thomas Heyroun. There is a mention of him in 1352[26]. His name appears, together with that of his wife Agnes, in a conveyance of property dated Jan. 16, 1366[27]; but he died shortly afterwards, aged about fifty-four. His widow married again in the course of a few months; for she is described in a deed dated May 6, 1367, as being then the wife of Bartholomew atte Chapel, citizen and vintner of London, and lately wife of John Chaucer, citizen and vintner[28]. The date of her death is not known.

§ 5. Chaucer's Early Years. The exact date of Geoffrey's birth is not known, and will probably always remain a subject of dispute. It cannot, as we have seen, have been earlier than [xvi]1330; and it can hardly have been later than 1340. That it was nearer to 1340 than 1330, is the solution which best suits all the circumstances of the case. Those who argue for an early date do so solely because the poet sometimes refers to his 'old age'; as for example in the Envoy to Scogan, 35-42, written probably in 1393; and still earlier, probably in 1385, Gower speaks, in the epilogue to the former edition of his Confessio Amantis, of the 'later age' of Chaucer, and of his 'dayes olde'; whereas, if Chaucer was born in 1340, he was, at that time, only forty-five years old. But it is essential to observe that Gower is speaking comparatively; he contrasts Chaucer's 'later age' with 'the floures of his youth,' when he 'fulfild the land,' in sundry wise, 'of ditees and of songes glade.' And, in spite of all the needless stress that has been laid upon such references as the above, we must, if we really wish to ascertain the truth without prejudice, try to bear in mind the fact that, in the fourteenth century, men were deemed old at an age which we should now esteem as almost young. Chaucer's pupil, Hoccleve, describes himself as worn out with old age, and ready to die, at the age of fifty-three; all that he can look forward to is making a translation of a treatise on 'learning to die.'

'Of age am I fifty winter and thre;

Ripeness of dethe fast vpon me hasteth.'

Hoccleve's Poems, ed. Furnivall, p. 119[29].

And further, if, in order to make out that Chaucer died at the age of nearly 70, we place his birth near the year 1330, we are at once confronted with the extraordinary difficulty, that the poet was already nearly 39 when he wrote 'The Book of the Duchesse,' certainly one of the earliest of his poems that have been preserved, and hardly to be esteemed as a highly satisfactory performance. But as the exact date still remains uncertain, I can only say that we must place it between 1330 and 1340. The reader can incline to whichever end of the decade best pleases him. I merely record my opinion, for what it is worth, that 'shortly before 1340' fits in best with all the facts. [xvii]

The earliest notice of Geoffrey Chaucer, on which we can rely, refers to the year 1357. This discovery is due to Mr. (now Dr.) E. A. Bond, who, in 1851, found some fragments of an old household account which had been used to line the covers of a MS. containing Lydgate's Storie of Thebes and Hoccleve's De Regimine Principum, and now known as MS. Addit. 18,632 in the British Museum. They proved to form a part of the Household Accounts of Elizabeth, Countess of Ulster, wife of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the third son of King Edward III., for the years 1356-9[30]. These Accounts shew that, in April, 1357, when the Countess was in London, an entire suit of clothes, consisting of a paltock or short cloak, a pair of red and black breeches, and shoes, was provided for Geoffrey Chaucer at a cost of 7s., equal to about 5l. of our present money. On the 20th of May another article of dress was purchased for him in London. In December of the same year (1357), when the Countess was at Hatfield (near Doncaster) in Yorkshire, her principal place of residence, we find a note of a donation of 2s. 6d. to Geoffrey Chaucer for necessaries at Christmas. It further appears that John of Gaunt, the Countess's brother-in-law, was a visitor at Hatfield at the same period; which indicates the probable origin of the interest in the poet's fortunes which that illustrious prince so frequently manifested, during a long period of years.

It is further worthy of remark that, on several occasions, a female attendant on the Countess is designated as 'Philippa Pan', which is supposed to be the contracted form of Panetaria, i. e. mistress of the pantry. 'Speculations suggest themselves,' says Dr. Bond, 'that the Countess's attendant Philippa may have been Chaucer's future wife.... The Countess died in 1363, ... and nothing would be more likely than that the principal lady of her household should have found shelter after her death in the family of her husband's mother,' i. e. Queen Philippa. It is quite possible; it is even probable.

Perhaps it was at Hatfield that Chaucer picked up some knowledge of the Northern dialect, as employed by him in the Reves Tale. The fact that the non-Chaucerian Fragment B of the Romaunt of the Rose exhibits traces of a Northern dialect is [xviii]quite a different matter; for Fragment A, which is certainly Chaucer's, shews no trace of anything of the kind. What was Chaucer's exact position in the Countess of Ulster's household, we are not informed. If he was born about 1340, we may suppose that he was a page; if several years earlier, he would, in 1357, have been too old for such service. We only know that he was attached to the service of Lionel, duke of Clarence, and of the Countess of Ulster his wife, as early as the beginning of 1357, and was at that time at Hatfield, in Yorkshire. 'He was present,' says Dr. Bond, 'at the celebration of the feast of St. George, at Edward III's court, in attendance on the Countess, in April of that year; he followed the court to Woodstock; and he was again at Hatfield, probably from September, 1357, to the end of March, 1358, and would have witnessed there the reception of John of Ghent, then Earl of Richmond.' We may well believe that he accompanied the Countess when she attended the funeral of Queen Isabella (king Edward's mother), which took place at the Church of the Friars Minors, in Newgate Street, on Nov. 27, 1358.

§ 6. Chaucer's first expedition. 1359-60. A year later, in November, 1359, Chaucer joined the great expedition of Edward III. to France. 'There was not knight, squire, or man of honour, from the age of twenty to sixty years, that did not go[31].' The king of England was 'attended by the prince of Wales and three other sons,' including 'Lionel, earl of Ulster[32]'; and we may be sure that Chaucer accompanied his master prince Lionel. The march of the troops lay through Artois, past Arras to Bapaume; then through Picardy, past Peronne and St. Quentin, to Rheims, which Edward, with his whole army, ineffectually besieged for seven weeks. It is interesting to note that the army must, on this occasion, have crossed the Oise, somewhere near Chauny and La-Fère, which easily accounts for the mention of that river in the House of Fame (l. 1928); and shews the uselessness of Warton's suggestion, that Chaucer learnt the name of that river by studying Provençal poetry! In one of the numerous skirmishes that took place, Chaucer had the misfortune to be taken prisoner. This appears from his own evidence, in the 'Scrope and Grosvenor' trial, referred to below under the date [xix]of 1386; he then testified that he had seen Sir Richard Scrope wearing arms described as 'azure, a bend or,' before the town of 'Retters,' an obvious error for Rethel[33], not far from Rheims; and he added that he 'had seen him so armed during the whole expedition, until he (the said Geoffrey) was taken.' See the evidence as quoted at length at p. xxxvi. But he was soon ransomed, viz. on March 1, 1360; and the King himself contributed to his ransom the sum of 16l.[34] According to Froissart, Edward was at this time in the neighbourhood of Auxerre[35].

After a short and ineffectual siege of Paris, the English army suffered severely from thunder-storms during a retreat towards Chartres, and Edward was glad to make peace; articles of peace were accordingly concluded, on May 8, 1360, at Bretigny, near Chartres. King John of France was set at liberty, leaving Eltham on Wednesday, July 1; and after stopping for three nights on the road, viz. at Dartford, Rochester, and Ospringe, he arrived at Canterbury on the Saturday[36]. On the Monday he came to Dover, and thence proceeded to Calais. And surely Chaucer must have been present during the fifteen days of October which the two kings spent at Calais in each other's company; the Prince of Wales and his two brothers, Lionel and Edmund, being also present[37]. On leaving Calais, King John and the English princes 'went on foot to the church of our Lady of Boulogne, where they made their offerings most devoutly, and afterward returned to the abbey at Boulogne, which had been prepared for the reception of the King of France and the princes of England[38].' [xx]

On July 1, 1361, prince Lionel was appointed lieutenant of Ireland, probably because he already bore the title of Earl of Ulster. It does not appear that Chaucer remained in his service much longer; for he must have been attached to the royal household not long after the return of the English army from France. In the Schedule of names of those employed in the Royal Household, for whom robes for Christmas were to be provided, Chaucer's name occurs as seventeenth in the list of thirty-seven esquires. The list is not dated, but is marked by the Record Office '? 40 Edw. III,' i. e. 1366[39]. However, Mr. Selby thinks the right date of this document is 1368.

§ 7. Chaucer's Marriage: Philippa Chaucer. In 1366, we find Chaucer already married. On Sept. 12, in that year, Philippa Chaucer received from the queen, after whom she was doubtless named, a pension of ten marks (or 6l. 13s. 4d.) annually for life, perhaps on the occasion of her marriage; and we find her described as 'una domicellarum camerae Philippae Reginae Angliae[40].' The first known payment on behalf of this pension is dated Feb. 19, 1368[41]. Nicolas tells us that her pension 'was confirmed by Richard the Second; and she apparently received it (except between 1370[42] and 1373, in 1378, and in 1385, the reason of which omissions does not appear) from 1366 until June 18, 1387. The money was usually paid to her through her husband; but in November, 1374, by the hands of John de Hermesthorpe, and in June, 1377 (the Poet being then on his mission in France), by Sir Roger de Trumpington, whose wife, Lady Blanche de Trumpington, was [then], like herself[43], in the service of the Duchess of Lancaster.' As no payment appears after June, 1387, we may conclude that she died towards the end of that year[44]. [xxi]

Philippa's maiden name is not known. She cannot be identified with Philippa Picard, because both names, viz. Philippa Chaucer and Philippa Picard, occur in the same document[45]. Another supposition identifies her with Philippa Roet, on the assumption that Thomas Chaucer, on whose tomb appear the arms of Roet, was her son. This, as will be shewn hereafter, is highly probable, though not quite certain.

It is possible that she was the same person as Philippa, the 'lady of the pantry,' who has been already mentioned as belonging to the household of the Countess of Ulster. If so, she doubtless entered the royal household on the Countess's death in 1363, and was married in 1366, or earlier. After the death of the queen in 1369 (Aug. 15), we find that (on Sept. 1) the king gave Chaucer, as being one of his squires of lesser degree, three ells of cloth for mourning; and, at the same time, six ells of cloth, for the same, to Philippa Chaucer[46].

In 1372, John of Gaunt married (as his second wife) Constance, elder daughter of Pedro, king of Castile; and in the same year (Aug. 30), he granted Philippa Chaucer a pension of 10l. per annum, in consideration of her past and future services to his dearest wife, the queen of Castile[47]. Under the name of Philippa Chaucy (as the name is also written in this volume), the duke presented her with a 'botoner,' apparently a button-hook, and six silver-gilt buttons as a New Year's gift for the year 1373[48]. In 1374, on June 13, he granted 10l. per annum to his well-loved Geoffrey Chaucer and his well-beloved Philippa, for their service to Queen Philippa and to his wife the queen [i. e. of Castile], to be received at the duke's manor of the Savoy[49]. In 1377, on May 31, payments were made to Geoffrey Chaucer, varlet, of an annuity of 20 marks that day granted, and of 10 marks to Philippa Chaucer (granted to her for life) as being one of the damsels of the chamber to the late queen, by the hands of [xxii]Geoffrey Chaucer, her husband[50]. In 1380, the duke gave Philippa a silver hanap (or cup) with its cover, as his New Year's gift; and a similar gift in 1381 and 1382[51]. A payment of 5l. to Geoffrey 'Chaucy' is recorded soon after the first of these gifts. In 1384, the sum of 13l. 6s. 8d. (20 marks) is transmitted to Philippa Chaucer by John Hinesthorp, chamberlain[52]. The last recorded payment of a pension to Philippa Chaucer is on June 18, 1387; and it is probable, as said above, that she died very shortly afterwards.

Sir H. Nicolas mentions that, in 1380-2, Philippa Chaucer was one of the three ladies in attendance on the Duchess of Lancaster, the two others being Lady Senche Blount and Lady Blanche de Trompington; and that in June, 1377, as mentioned above, her pension was paid to Sir Roger de Trumpington, who was Lady Blanche's husband. This is worth a passing notice; for it clearly shews that the poet was familiar with the name of Trumpington, and must have known of its situation near Cambridge. And this may account for his laying the scene of the Reves Tale in that village, without necessitating the inference that he must have visited Cambridge himself. For indeed, it is not easy to see why the two 'clerks' should have been benighted there; the distance from Cambridge is so slight that, even in those days of bad roads, they could soon have returned home after dark without any insuperable difficulty.

§ 8. 1367. To return to Chaucer. In 1367, we find him 'a valet of the king's household'; and by the title of 'dilectus valettus noster,' the king, in consideration of his former and his future services, granted him, on June 20, an annual salary of 20 marks (13l. 6s. 8d.) for life, or until he should be otherwise provided for[53]. Memoranda are found of the payment of this pension, in half-yearly instalments, on November 6, 1367, and May 25, 1368[54]; but not in November, 1368, or May, 1369. The next entry as to its payment is dated October, 1369[55]. As to the [xxiii]duties of a valet in the royal household, see Life-Records of Chaucer, part ii. p. xi. Amongst other things, he was expected to make beds, hold torches, set boards (i. e. lay the tables for dinner), and perform various menial offices.

§ 9. 1368. The note that he received his pension, in 1368, on May 25, is of some importance. It renders improbable a suggestion of Speght, that he accompanied his former master, Lionel, Duke of Clarence, to Italy in this year. Lionel set off with an unusually large retinue, about the 10th of May[56], and passed through France on his way to Italy, where he was shortly afterwards married, for the second time, to Violante, daughter of Galeazzo Visconti. But his married life was of short duration; he died on Oct. 17 of the same year, not without suspicion of poison. His will, dated Oct. 3, 1368, is given in Testamenta Vetusta, ed. Nicolas, p. 70. It does not appear that Chaucer went to Italy before 1372-3; but it is interesting to observe that, on his second journey there in 1378, he was sent to treat with Barnabo Visconti, Galeazzo's brother, as noted at p. xxxii.

§ 10. 1369. In this year, Chaucer was again campaigning in France. An advance of 10l. is recorded as having been made to him by Henry de Wakefeld, the Keeper of the King's Wardrobe; and he is described as 'equitanti de guerre (sic) in partibus Francie[57].' In the same year, there is a note that Chaucer was to have 20s. for summer clothes[58].

This year is memorable for the last of the three great pestilences which afflicted England, as well as other countries, in the fourteenth century. Queen Philippa died at Windsor on Aug. 15; and we find an entry, dated Sept. 1, that Geoffrey Chaucer, a squire of less estate, and his wife Philippa, were to have an allowance for mourning[59], as stated above. Less than a month later, the Duchess Blaunche died, on Sept. 12; and her death was [xxiv]commemorated by the poet in one of the earliest of his extant poems, the Book of the Duchesse (see p. 277).

§ 11. 1370-1372. In the course of the next ten years (1370-80), the poet was attached to the court, and employed in no less than seven diplomatic services. The first of these occasions was during the summer of 1370, when he obtained the usual letters of protection, dated June 10, to remain in force till the ensuing Michaelmas[60]. That he returned immediately afterwards, appears from the fact that he received his half-yearly pension in person on Tuesday, the 8th of October[61]; though on the preceding occasion (Thursday, April 25), it was paid to Walter Walssh instead of to himself[62].

In 1371 and 1372, he received his pension himself[63]. In 1372 and 1373 he received 2l. for his clothes each year. This was probably a customary annual allowance to squires[64]. A like payment is again recorded in 1377.

Towards the end of the latter year, on Nov. 12, 1372, Chaucer, being then 'scutifer,' or one of the king's esquires, was joined in a commission with James Provan and John de Mari, the latter of whom is described as a citizen of Genoa, to treat with the duke, citizens, and merchants of Genoa, for the purpose of choosing an English port where the Genoese might form a commercial establishment[65]. On Dec. 1, he received an advance of 66l. 13s. 4d. towards his expenses[66]; and probably left England before the close of the year.

§ 12. 1373. Chaucer's First Visit to Italy. All that is known of this mission is that he visited Florence as well as Genoa, and that he returned before Nov. 22, 1373, on which day he received his pension in person[67]. It further appears that his [xxv]expenses finally exceeded the money advanced to him; for on Feb. 4, 1374, a further sum was paid to him, on this account, of 25l. 6s. 8d.[68] It was probably on this occasion that Chaucer met Petrarch at Padua, and learnt from him the story of Griselda, reproduced in the Clerkes Tale. Some critics prefer to think that Chaucer's assertions on this point are to be taken as imaginative, and that it was the Clerk, and not himself, who went to Padua; but it is clear that in writing the Clerkes Tale, Chaucer actually had a copy of Petrarch's Latin version before him; and it is difficult to see how he came by it unless he obtained it from Petrarch himself or by Petrarch's assistance. For further discussion of this point, see remarks on the Sources of the Clerkes Tale, in vol. iii., and the notes in vol. v.[69] We must, in any case, bear in mind the important influence which this mission to Italy, and a later one in 1378-9 to the same country, produced upon the development of his poetical writings.

It may be convenient to note here that Petrarch resided chiefly at Arquà, within easy reach of Padua, in 1370-4. His death took place there on July 18, 1374, soon after Chaucer had returned home.

§ 13. 1374. We may fairly infer that Chaucer's execution of this important mission was satisfactorily performed; for we find that on the 23rd of April, 1374, on the celebration at Windsor of the festival of St. George, the king made him a grant of a pitcher of wine daily, to be received in the port of London from the king's butler[70]. This was, doubtless, found to be rather a troublesome gift; accordingly, it was commuted, in 1378 (April 18), for the annual sum of 20 marks (13l. 6s. 8d.)[71]. The original grant was made 'dilecto Armigero nostro, Galfrido Chaucer.' [xxvi]

On May 10, in the same year, the corporation of London granted Chaucer a lease for his life of the dwelling-house situate above the city-gate of Aldgate, on condition that he kept the same in good repair; he seems to have made this his usual residence till 1385, and we know that he retained possession of it till October, 1386[72].

Four weeks later, on June 8, 1374, he was appointed Comptroller of the Customs and Subsidy of wools, skins, and tanned hides in the Port of London, with the usual fees. Like his predecessors, he was to write the rolls of his office with his own hand, to be continually present, and to perform his duties personally (except, of course, when employed on the King's service elsewhere); and the other part of the seal called the 'coket' (quod dicitur coket) was to remain in his custody[73]. The warrant by which, on June 13, 1374, the Duke of Lancaster granted him 10l. for life, in consideration of the services of himself and his wife, has been mentioned at p. xxi. In the same year, he received his half-yearly pension of 10 marks as usual; and again in 1375.

§ 14. 1375. On Nov. 8, 1375, his income was, for a time, considerably increased. He received from the crown a grant of the custody of the lands and person of Edmond, son and heir of Edmond Staplegate of Kent[74], who had died in 1372[75]; this he retained for three years, during which he received in all, for his wardship and on Edmond's marriage, the sum of 104l. This is ascertained from the petition presented by Edmond de Staplegate to Richard II. at his coronation, in which he laid claim to be permitted to exercise the office of chief butler to the king[76]. And further, on Dec. 28, 1375, he received a grant from the king of the custody of five 'solidates' of rent for land at Soles, in Kent, during the minority of William de Solys, then an infant aged 1 year, son and heir of John Solys, deceased; together with a fee due on the marriage of the said heir[77]. But the value of this grant cannot have been large. [xxvii]

§15. 1376. In 1376, on May 31, he received at the exchequer his own half-yearly pension of ten marks and his wife's of five marks, or 10l. in all (see Notes and Queries, 3rd Ser. viii. 63); and in October he received an advance from the exchequer of 50s. on account of his pension[78]. He also duly received his annuity of 10l. from the duke of Lancaster (Oct. 18, 1376, and June 12, 1377)[79].

In the same year, we also meet with the only known record connected with Chaucer's exercise of the Office of Comptroller of the Customs. On July 12, 1376, the King granted him the sum of 71l. 4s. 6d., being the value of a fine paid by John Kent, of London, for shipping wool to Dordrecht without having paid the duty thereon[80].

Towards the end of this year, Sir John Burley and Geoffrey Chaucer were employed together on some secret service (in secretis negociis domini Regis), the nature of which is unknown; for on Dec. 23, 1376, Sir John 'de Burlee' received 13l. 6s. 8d., and Chaucer half that sum, for the business upon which they had been employed[81].

§16. 1377. On Feb. 12, 1377, Chaucer was associated with Sir Thomas Percy (afterwards Earl of Worcester) in a secret mission to Flanders, the nature of which remains unknown; and on this occasion Chaucer received letters of protection during his mission, to be in force till Michaelmas in the same year[82]. Five days later, on Feb. 17, the sum of 33l. 6s. 8d. was advanced to Sir Thomas, and 10l. to Chaucer, for their expenses[83]. They started immediately, and the business was transacted by March 25; and on April 11 Chaucer himself received at the exchequer the sum of 20l. as a reward from the king for the various journeys which he had made abroad upon the king's [xxviii]service (pro regardo suo causâ diuersorum viagiorum per ipsum Galfridum factorum, eundo ad diuersas partes transmarinas ex precepto domini Regis in obsequio ipsius domini Regis)[84].

While Sir Thomas Percy and Chaucer were absent in Flanders, viz. on Feb. 20, 1377, the Bishop of Hereford, Lord Cobham, Sir John Montacu (i. e. Montague), and Dr. Shepeye were empowered to treat for peace with the French King[85]. Their endeavours must have been ineffectual; for soon after Chaucer's return, viz. on April 26, 1377, Sir Guichard d'Angle and several others were also appointed to negotiate a peace with France[86]. Though Chaucer's name does not expressly appear in this commission, he was clearly in some way associated with it; for only six days previously (Apr. 20), letters of protection were issued to him, to continue till Aug. 1, whilst he was on the king's service abroad[87]; and on April 30, he was paid the sum of 26l. 13s. 4d. for his wages on this occasion[88]. We further find, from an entry in the Issue Roll for March 6, 1381 (noticed again at p. xxix), that he was sent to Moustrell (Montreuil) and Paris, and that he was instructed to treat for peace.

This is clearly the occasion to which Froissart refers in the following passage. 'About Shrovetide[89], a secret treaty was formed between the two kings for their ambassadors to meet at Montreuil-sur-Mer; and the king of England sent to Calais sir Guiscard d'Angle, Sir Richard Sturey, and sir Geoffrey Chaucer. On the part of the French were the lords de Coucy and de la Rivieres, sir Nicholas Bragues and Nicholas Bracier. They for a long time discussed the subject of the above marriage [the marriage of the French princess with Richard, prince of Wales]; and the French, as I was informed, made some offers, but the others demanded different terms, or refused treating. These lords returned therefore, with their treaties, to their sovereigns; and [xxix]the truces were prolonged to the first of May.'—Johnes, tr. of Froissart, bk. i. c. 326.

I think Sir H. Nicolas has not given Froissart's meaning correctly. According to him, 'Froissart states that, in Feb. 1377, Chaucer was joined with Sir Guichard d'Angle, &c., to negociate a secret treaty for the marriage of Richard, prince of Wales, with Mary, daughter of the king of France,' &c.; and that the truce was prolonged till the first of May. And he concludes that Froissart has confused two occasions, because there really was an attempt at a treaty about this marriage in 1378 (see below). It does not appear that Froissart is wrong. He merely gives the date of about Shrovetide (Feb. 10) as the time when 'a secret treaty was formed'; and this must refer to the ineffectual commission of Feb. 20, 1377. After this 'the king of England' really sent 'Sir Guiscard d'Angle' in April; and Chaucer either went with the rest or joined them at Montreuil. Neither does it appear that discussion of the subject of the marriage arose on the English side; it was the French who proposed it, but the English who declined it, for the reason that they had received no instructions to that effect. On the other hand, the English ambassadors, having been instructed to treat for peace, procured, at any rate, a short truce. This explanation seems to me sufficient, especially as Froissart merely wrote what he had been informed; he was not present himself. The very fact that the marriage was proposed by the French on this occasion explains how the English came to consider this proposal seriously in the following year.

Fortunately, the matter is entirely cleared up by the express language employed in the Issue Roll of 4 Ric. II., under the date Mar. 6, as printed in Nicolas, Note R; where the object of the deliberations at Montreuil is definitely restricted to a treaty for peace, whilst the proposal of marriage (from the English side) is definitely dated as having been made in the reign of Richard, not of Edward III. The words are: 'tam tempore regis Edwardi ... in nuncium eiusdem ... versus Moustrell' et Parys ... causa tractatus pacis ... quam tempore domini regis nunc, causa locutionis habite de maritagio inter ipsum dominum regem nunc et filiam eiusdem aduersarii sui Francie.'

The princess Marie, fifth daughter of Charles V., was born in 1370 (N. and Q., 3 S. vii. 470), and was therefore only seven years [xxx]old in 1377; and died in the same year. It is remarkable that Richard married Isabella, daughter of Charles VI., in 1396, when she was only eight.

It is worth notice that Stowe, in his Annales, p. 437, alludes to the same mission. He mentions, as being among the ambassadors, 'the Earle of Salisbury and Sir Richard Anglisison a Poyton [can this be Sir Guiscard D'Angle?], the Bishop of Saint Dauids, the Bishop of Hereford, [and] Geffrey Chaucer, the famous Poet of England.' See Life-Records of Chaucer, p. 133, note 3.

The payments made to Chaucer by John of Gaunt on May 31 of this year have been noticed above in § 7, at p. xxi.

The long reign of Edward III. terminated on June 21, 1377, during which Chaucer had received many favours from the king and the Duke of Lancaster, and some, doubtless, from Lionel, Duke of Clarence. At the same time, his wife was in favour with the queen, till her death in August, 1369; and afterwards, with the second duchess of Lancaster. The poet was evidently, at this time, in easy circumstances; and it is not unlikely that he was somewhat lavish in his expenditure. The accession of Richard, at the early age of eleven, made no difference to his position for some nine years; but in 1386, the adverse supremacy of Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, caused him much pecuniary loss and embarrassment for some time, and he frequently suffered from distress during the later period of his life.

§ 17. Chaucer's earlier poems: till the death of Edward III. It is probable that not much of Chaucer's extant poetry can be referred to the reign of Edward III. At the same time, it is likely that he wrote many short pieces, in the form of ballads, complaints, virelayes, and roundels, which have not been preserved; perhaps some of them were occasional pieces, and chiefly of interest at the time of writing them. Amongst the lost works we may certainly include his translation of 'Origenes upon the Maudelayne,' 'The Book of the Lion,' all but a few stanzas (preserved in the Man of Lawes Tale) of his translation of Pope Innocent's 'Wrecched Engendring of Mankinde,' and all but the first 1705 lines of his translation of Le Roman de la Rose. His early work entitled 'Ceyx and Alcioun' is partly preserved in the Book of the Duchesse, written in 1369-70. His A. B. C. is, perhaps, his earliest extant complete poem.

It seems reasonable to date the poems which show a strong [xxxi]Italian influence after Chaucer's visit to Italy in 1373. The Compleint to his Lady is, perhaps, one of the earliest of these; and the Amorous Complaint bears so strong a resemblance to it that it may have been composed nearly at the same time. The Complaint to Pity seems to belong to the same period, rather than, as assumed in the text, to a time preceding the Book of the Duchesse. The original form of the Life of St. Cecily (afterwards the Second Nonnes Tale) is also somewhat early, as well as the original Palamon and Arcite, and Anelida. I should also include, amongst the earlier works, the original form of the Man of Lawes Tale (from Anglo-French), of the Clerkes Tale (from Petrarch's Latin), and some parts of the Monkes Tale. But the great bulk of his poetry almost certainly belongs to the reign of Richard II. See the List of Works at p. lxii.

§ 18. 1377. (CONTINUED). In the commencement of the new reign, Chaucer was twice paid 40s. by the keeper of the king's Wardrobe, for his half-yearly allowance for robes as one of the (late) king's esquires[90]. He also received 7l. 2s. 6½d. on account of his daily allowance of a pitcher of wine, calculated from October 27, 1376, to June 21, 1377, the day of king Edward's death[91].

§ 19. 1378. In 1378, on Jan. 16, Chaucer was again associated with Sir Guichard d'Angle (created Earl of Huntingdon at the coronation of the new king), with Sir Hugh Segrave, and Dr. Skirlawe, in a mission to France to negotiate for the king's marriage with a daughter of the king of France[92]; this is in accordance with a suggestion which, as noted at p. xxix., originated with the French. The negotiations came, however, to no result.

On Mar. 9, 1378, Geoffrey Chaucer and John Beauchamp are mentioned as sureties for William de Beauchamp, Knight, in a business having respect to Pembroke Castle[93].

On Mar. 23, 1378, Chaucer's previous annuity of 20 marks was confirmed to him by letters patent[94]; on April 18, his previous grant of a pitcher of wine was commuted for an annual sum of [xxxii]twenty marks[95]; and, on May 14, he received 20l. for the arrears of his pension, and 26s. 8d. in advance, for the current half-year[96].

Chaucer's second visit to Italy: Barnabo Visconti. On May 10, 1378, he received letters of protection, till Christmas[97]; on May 21, he procured letters of general attorney, allowing John Gower (the poet) and Richard Forrester to act for him during his absence from England[98]; and on May 28, he received 66l. 13s. 4d. for his wages and the expenses of his journey, which lasted till the 19th of September[99]. All these entries refer to the same matter, viz. his second visit to Italy. On this occasion, he was sent to Lombardy with Sir Edward Berkeley, to treat with Barnabo Visconti, lord of Milan, and the famous free-lance Sir John Hawkwood, on certain matters touching the king's expedition of war (pro certis negociis expeditionem guerre regis tangentibus); a phrase of uncertain import. This is the Barnabo Visconti, whose death, in 1385, is commemorated by a stanza in the Monkes Tale, B 3589-3596. Of Sir John Hawkwood, a soldier of fortune, and the most skilful general of his age, a memoir is given in the Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, vol. vi. pp. 1-35. The appointment of Gower as Chaucer's attorney during his absence is of interest, and shews the amicable relations between the two poets at this time. For a discussion of their subsequent relations, see Sources of the Canterbury Tales, vol. iii. § 38, p. 413.

§ 20. 1379-80. In 1379 and 1380, the notices of Chaucer refer chiefly to the payment of his pensions. In 1379, he received 12l. 13s. 4d. with his own hands on Feb. 3[100]; on May 24, he received the sums of 26s. 4d. and 13l. 6s. 4d. (the latter on account of the original grant of a pitcher of wine), both by assignment[101], which indicates his absence from London at the time; [xxxiii]and on Dec. 9 he received, with his own hands, two sums of 6l. 13s. 4d. each on account of his two pensions[102]. In 1380, on July 3, he received the same by assignment[103]; and on Nov. 28, he received the same with his own hands[104], together with a sum of 14l. for wages and expenses in connexion with his mission to Lombardy in 1378[104], in addition to the 66l. 13s. 4d. paid to him on May 28 of that year. He also received 5l. from the Duke of Lancaster on May 11 (N. and Q., 7 S. v. 290).

By a deed dated May 1, 1380, a certain Cecilia Chaumpaigne, daughter of the late William Chaumpaigne and Agnes his wife, released to Chaucer all her rights of action against him 'de raptu meo[105].' We have no means of ascertaining either the meaning of the phrase, or the circumstances referred to. It may mean that Chaucer was accessory to her abduction, much as Geoffrey Stace and others were concerned in the abduction of the poet's father; or it may be connected with the fact that his 'little son Lowis' was ten years old in 1391, as we learn from the Prologue to the Treatise on the Astrolabe.

§ 21. 1381. On March 6, Chaucer received 22l. for his services in going to Montreuil and Paris in the time of the late king, i. e. in 1377, in order to treat for peace; as well as for his journey to France in 1378 to treat for a marriage between king Richard and the daughter of his adversary (adversarii sui)[106]. The Treasury must, at this time, have been slack in paying its just debts. On May 24, he and his wife received their usual half-yearly pensions[107].

By a deed dated June 19, 1380, but preserved in the Hustings Roll, no. 110, at the Guildhall, and there dated 5 Ric. II. (1381-2), Chaucer released his interest in his father's house to Henry Herbury, vintner, in whose occupation it then was; and it is here that he describes himself as 'me Galfridum Chaucer, [xxxiv]filium Johannis Chaucer, Vinetarii Londonie [108].' This is the best authority for ascertaining his father's name, occupation, and abode. Towards the close of the year we find the following payments to him; viz. on Nov. 16, sums of 6l. 13s. 4d. and 6s. 8d.; on Nov. 28, the large sum of 46l. 13s. 4d., paid to Nicholas Brembre and John Philipot, Collectors of Customs, and to Geoffrey Chaucer, Comptroller of the Customs; and on Dec. 31, certain sums to himself and his wife[109].

§ 22. 1382. We have seen that, in 1378, an ineffectual attempt was made to bring about a marriage between the king and a French princess. In 1382, the matter was settled by his marriage with Anne of Bohemia, who exerted herself to calm the animosities which were continually arising in the court, and thus earned the title of the 'good queen Anne.' It was to her that Chaucer was doubtless indebted for some relaxation of his official duties in February, 1385, as noted below.

On May 8, 1382, Chaucer's income was further increased. Whilst retaining his office of Comptroller of the Customs of Wools, the duties of which he discharged personally, he was further appointed Comptroller of the Petty Customs in the Port of London, and was allowed to discharge the duties of the office by a sufficient deputy[110]. The usual payments of his own and his wife's pensions were made, in this year, on July 22 and Nov. 11. On Dec. 10, a payment to him is recorded, in respect of his office as Comptroller of the Customs [111].

§ 23. 1383. In 1383, the recorded payments are: on Feb. 27, 6s. 8d.; on May 5, his own and his wife's pensions; and on Oct. 24, 6l. 13s. 4d. for his own pension[112]. Besides these, is the following entry for Nov. 23: 'To Nicholas Brembre and John Philipot, Collectors of Customs, and Geoffrey Chaucer, Comptroller; money delivered to them this day in regard of the assiduity, labour, and diligence brought to bear by them on the duties of their office, for the year late elapsed, 46l. 13s. 4d.'; [xxxv]being the same amount as in 1381[113]. It is possible that the date Dec. 10, on which he tells us that he began his House of Fame, refers to this year.

§ 24. 1384. In 1384, on Apr. 30, he received his own and his wife's pensions[114]. On Nov. 25, he was allowed to absent himself from his duties for one month, on account of his own urgent affairs; and the Collectors of the Customs were commanded to swear in his deputy[115]. On Dec. 9, one Philip Chaucer is referred to as Comptroller of the Customs, but Philip is here an error for Geoffrey, as shewn by Mr. Selby[116].

§ 25. 1385. In 1385, a stroke of good fortune befell him, which evidently gave him much relief and pleasure. It appears that Chaucer had asked the king to allow him to have a sufficient deputy in his office as Comptroller at the Wool Quay (in French, Wolkee) of London[117]. And on Feb. 17, he was released from the somewhat severe pressure of his official duties (of which he complains feelingly in the House of Fame, 652-660) by being allowed to appoint a permanent deputy[118]. He seems to have revelled in his newly-found leisure; and we may fairly infer from the Prologue to the Legend of Good Women, which seems to have been begun shortly afterwards, that he was chiefly indebted for this favour to the good queen Anne. (See the Introduction to vol. iii. p. xix.) On April 24, he received his own pensions as usual, in two sums of 6l. 13s. 4d. each; and, on account of his wife's pension, 3l. 6s. 8d.[119]

§ 26. 1386. In 1386, as shewn by the Issue Rolls, he received his pensions as usual. In other respects, the year was eventful. Chaucer was elected a knight of the shire[120] for the county of Kent, with which he would therefore seem to have had some connexion, perhaps by the circumstance of residing at [xxxvi]Greenwich (see § 32). He sat accordingly in the parliament which met at Westminster on Oct. 1, and continued its sittings till Nov. 1. He and his colleague, William Betenham, were allowed 24l. 8s. for their expenses in coming to and returning from the parliament, and for attendance at the same; at the rate of 8s. a day for 61 days[121]. The poet was thus an unwilling contributor to his own misfortunes; for the proceedings of this parliament were chiefly directed against the party of the duke of Lancaster, his patron, and on Nov. 19 the king was obliged to grant a patent by which he was practically deprived of all power. A council of regency of eleven persons was formed, with the duke of Gloucester at their head; and the partisans of John of Gaunt found themselves in an unenviable position. Among the very few persons who still adhered to the king was Sir Nicholas Brembre[122], Chaucer's associate in the Customs (see note above, Nov. 23, 1383); and we may feel confident that Chaucer's sympathies were on the same side. We shall presently see that, when the king regained his power in 1389, Chaucer almost immediately received a valuable appointment.

It was during the sitting of this parliament, viz. on Oct. 15, that Chaucer was examined at Westminster in the case of Richard, lord Scrope, against the claim of Sir Robert Grosvenor, as to the right of bearing the coat of arms described as 'azure, a bend or.' The account of Chaucer's evidence is given in French[123]; the following is a translation of it, chiefly in the words of Sir H. Nicolas:—

'Geoffrey Chaucer, Esquire, of the age of 40 years and upwards, armed for 27 years, produced on behalf of Sir Richard Scrope, sworn and examined.

'Asked, whether the arms, "azure, a bend or," belonged or ought to belong to the said Sir Richard of right and heritage? Said—Yes, for he had seen them armed in France before the town of Retters[124], and Sir Henry Scrope armed in the same arms with a white label, and with a banner, and the said Sir Richard armed in the entire arms, Azure, a bend Or, and he had so seen them armed during the whole expedition, till the said Geoffrey was taken.

'Asked, how he knew that the said arms appertained to the said Sir Richard? [xxxvii]Said—by hearsay from old knights and squires, and that they had always continued their possession of the said arms; and that they had always been reputed to be their arms, as the common fame and the public voice testifies and had testified; and he also said, that when he had seen the said arms in banners, glass, paintings, and vestments, they were commonly called the arms of Scrope.

'Asked, if he had ever heard say who was the first ancestor of the said Sir Richard who first bore the said arms? Said—No; nor had he ever heard otherwise than that they were come of old ancestry and of old gentry, and that they had used the said arms.

'Asked, if he had ever heard say how long a time the ancestors of the said Sir Richard had used the said arms? Said—No; but he had heard say that it passed the memory of man.

'Asked, if he had ever heard of any interruption or claim made by Sir Robert Grosvenor or by his ancestors or by any one in his name, against the said Sir Richard or any of his ancestors? Said—No; but said, that he was once in Friday Street, London, and, as he was walking in the street, he saw a new sign, made of the said arms, hanging out; and he asked what inn it was that had hung out these arms of Scrope? And one answered him and said—No, sir; they are not hung out as the arms of Scrope, nor painted for those arms; but they are painted and put there by a knight of the county of Chester, whom men call Sir Robert Grosvenor; and that was the first time that he had ever heard speak of Sir Robert Grosvenor, or of his ancestors, or of any one bearing the name of Grosvenor.'

The statement that Chaucer was, at this time, of the age of 'forty and upwards' (xl. ans et plus) ought to be of assistance in determining the date of his birth; but it has been frequently discredited on the ground that similar statements made, in the same account, respecting other persons, can easily be shewn to be incorrect. It can hardly be regarded as more than a mere phrase, expressing that the witness was old enough to give material evidence. But the testimony that the witness had borne arms for twenty-seven years (xxvii. ans) is more explicit, and happens to tally exactly with the evidence actually given concerning the campaign of 1359; a campaign which we may at once admit, on his own shewing, to have been his first. Taken in connexion with his service in the household of the Countess of Ulster, where his position was probably that of page, we should expect that, in 1359, he was somewhere near 20 years of age, and born not long before 1340. It is needless to discuss the point further, as nothing will convince those who are determined to make much of Chaucer's allusions to his 'old age' (which is, after all, a personal affair), and who cannot understand why Hoccleve should speak of himself as 'ripe for death' when he was only fifty-three. [xxxviii]

It was during the session of this same parliament (Oct. 1386) that Chaucer gave up the house in Aldgate which he had occupied since May, 1374; and the premises were granted by the corporation to one Richard Forster, possibly the same person as the Richard Forrester who had been his proxy in 1378[125]. In this house he must have composed several of his poems; and, in particular, The Parlement of Foules, The House of Fame, and Troilus, besides making his translation of Boethius. The remarks about 'my house' in the Prologue to the Legend of Good Women, 282, are inconsistent with the position of a house above a city-gate. If, as is probable, they have reference to facts, we may suppose that he had already practically resigned his house to his friend in 1385, when he was no longer expected to perform his official duties personally.

Meanwhile, the duke of Gloucester was daily gaining ascendancy; and Chaucer was soon to feel the resentment of his party. On Dec. 4, 1386, he was deprived of his more important office, that of Comptroller of the Customs of Wool, and Adam Yerdeley was appointed in his stead. Only ten days later, on Dec. 14, he lost his other office likewise, and Henry Gisors became Comptroller of the Petty Customs[126]. This must have been a heavy loss to one who had previously been in good circumstances, and who seems to have spent his money rather freely[127]. He was suffered, however, to retain his own and his wife's pensions, as there was no pretence for depriving him of them.

§ 27. 1387. In 1387, the payment of his wife's pension, on June 18, appears for the last time[128]. It cannot be doubted that she died during the latter part of this year. In the same year, [xxxix]and in the spring of 1388, he received his own pensions, as usual[129]; but his wife's pension ceased at her death, at a time when his own income was seriously reduced.

§ 28. 1388. In 1388, on May 1, the grants of his two annual pensions, of 20 marks each, were cancelled at his own request, and assigned, in his stead, to John Scalby[130]. The only probable interpretation of this act is that he was then hard pressed for money, and adopted this ready but rather rash method for obtaining a considerable sum at once. He retained, however, the pension of 10l. per annum, granted him by the duke of Lancaster in 1374. Chaucer was evidently a hard worker and a practical man. We have every reason for believing that he performed his duties assiduously, as he himself asserts; and the loss of his offices in Dec. 1386 must have occasioned a good deal of enforced leisure. This explains at once why the years 1387 and 1388 were, as appears from other considerations, the most active time of his poetical career; he was then hard at work on his Canterbury Tales. And though the loss of his wife, at the close of 1387, must have caused a sad interruption in his congenial task, we can hardly wonder if, after a reasonable interval, he resumed it; it was perhaps the best thing that he could do.

§ 29. 1389. This period of almost complete leisure came to an end in July, 1389; owing, probably, to the fact that the king, on May 3 in that year, suddenly took the government into his own hands. The influence of the duke of Gloucester was on the wane; the duke of Lancaster returned to England; and the cloud that had lain over Chaucer's fortunes was once more dispersed. His public work required some attention, though he was allowed to have a deputy, and the time devoted to the Canterbury Tales was diminished. It is doubtful whether, with the exception of a few occasional pieces, Chaucer wrote much new poetry during the last ten years of his life.

On July 12, Chaucer received the valuable appointment of Clerk of the King's Works at the palace of Westminster, the [xl]Tower of London, the Mews at Charing Cross, and other places. Among them are mentioned the Castle of Berkhemsted (Berkhamstead, Herts.), the King's manors of Kennington (now in London), Eltham (Kent), Clarendon (near Salisbury), Sheen (now Richmond, Surrey)[131], Byfleet (Surrey), Childern Langley (i. e. King's Langley, Hertfordshire), and Feckenham (Worcestershire); also the Royal lodge of Hatherbergh in the New Forest, and the lodges in the parks of Clarendon, Childern Langley, and Feckenham. He was permitted to execute his duties by deputy, and his salary was 2s. per day, or 36l. 10s. annually, a considerable sum[132]. A payment to Chaucer, as Clerk of the Works, is recorded only ten days later (July 22); and we find that, about this time, he issued a commission to one Hugh Swayn to provide materials for the king's works at Westminster, Sheen, and elsewhere[133].

§ 30. 1390. In 1390, on March 13, Chaucer was appointed on a commission, with five others, to repair the banks of the Thames between Woolwich and Greenwich (at that time, probably, his place of residence); but was superseded in 1391[134].

In the same year, Chaucer was entrusted with the task of putting up scaffolds in Smithfield for the king and queen to see the jousts which took place there in the month of May; this notice is particularly interesting in connexion with the Knightes Tale (A 1881-92). The cost of doing this, amounting to 8l. 12s. 6d., was allowed him in a writ dated July 1, 1390; and he received further payment at the rate of 2s. a day[135].

About this time, in the 14th year of king Richard (June 22, 1390-June 21, 1391), he was appointed joint forester, with Richard Brittle, of North Petherton Park, in Somersetshire, by the earl of March, the grandson of his first patron, Prince Lionel. Perhaps in consequence of the death of Richard Brittle, he was made sole forester in 21 Ric. II. (1397-8) by the countess of March; and he probably held the appointment till his death in 1400. No appointment, however, is known to have been then [xli]made, and we find that the next forester, appointed in 4 Hen. V. (1416-17), was no other than Thomas Chaucer, who may have been his son[136]. It is perhaps worthy of remark that some of the land in North Petherton, as shewn by Collinson, descended to Emma, third daughter of William de Placetis, which William had the same office of 'forester of North Petherton' till his death in 1274; and this Emma married John Heyron, who died in 1326-7, seised of lands at Enfield, Middlesex, and at Newton, Exton, and North Petherton, in the county of Somerset (Calend. Inquis. post Mortem, 1806, vol. i. p. 333; col. 1). If this John Heyron was related to the Maria Heyron who was Chaucer's grandmother, there was perhaps a special reason for appointing Chaucer to this particular office.

On July 12, 1390, he was ordered to procure workmen and materials for the repair of St. George's Chapel, Windsor, then in a ruinous condition; this furnishes a very interesting association[137].

On Sept. 6, 1390, a curious misfortune befell the poet. He was robbed twice on the same day, by the same gang of robbers; once of 10l. of the king's money, at Westminster, and again of 9l. 3s. 2d., of his horse, and of other property, near the 'foul oak' (foule ok) at Hatcham, Surrey (now a part of London, approached by the Old Kent Road, and not far from Deptford and Greenwich). One of the gang confessed the robberies; and Chaucer was forgiven the repayment of the money[138].

§ 31. 1391. In 1391, on Jan. 22, Chaucer appointed John Elmhurst as his deputy, for superintending repairs at the palace of Westminster and the tower of London; this appointment was confirmed by the king[139]. It was in this year that he wrote his Treatise on the Astrolabe, for the use of his son Lowis. By this time, the Canterbury Tales had ceased to make much progress. For some unknown reason, Chaucer lost his appointment in the [xlii]summer; for on June 17, a writ was issued, commanding him to give up to John Gedney[140] all his rolls, &c. connected with his office[141]; and on Sept. 16, we find, accordingly, that the office was held by John Gedney[142]; nevertheless, payments to Chaucer as 'late Clerk of the Works' occur on Dec. 16, 1391, Mar. 4 and July 13, 1392, and even as late as in 1393[143].

§ 32. 1392-3. Chaucer was now once more without public employment. No doubt the Canterbury Tales received some attention, and perhaps we may assign to this period various alterations in the original plan of the poem. The author must by this time have seen the necessity of limiting each of his characters to the telling of one Tale only. The Envoy to Scogan and the Complaint of Venus were probably written in 1393. According to a note written opposite l. 45 of the former poem, Chaucer was then residing at Greenwich, a most convenient position for frequent observation of pilgrims on the road to Canterbury. See §§ 26 and 30.

§ 33. 1394. Chaucer was once more a poor man, although, as a widower, his expenses may have been less. Probably he endeavoured to draw attention to his reduced circumstances, or Henry Scogan may have done so for him, in accordance with the poet's suggestion in l. 48 of the Envoy just mentioned. In 1394, on Feb. 28, he obtained from the king a grant of 20l. per annum for life, payable half-yearly at Easter and Michaelmas, being 6l. 13s. 8d. less than the pensions which he had disposed of in 1388[144]; but the first payment was not made till Dec. 20, when he received 10l. for the half-year from Easter to Michaelmas, and the proportional sum of 1l. 16s. 7d. for the month of March[145].

§ 34. 1395. The difficulties which Chaucer experienced at this time, as to money matters, are clearly illustrated during the year 1395. In this year he applied for a loan from the exchequer, in advance of his pension, no less than four times. In this way he borrowed 10l. on April 1; 10l. on June 25; 1l. 6s. 8d. on [xliii]Sept. 9; and 8l. 6s. 8d. on Nov. 27. He repaid the first of these loans on May 28; and the second was covered by his allowance at Michaelmas. He must also have repaid the small third loan, as the account was squared by his receipt of the balance of 1l. 13s. 4d. (instead of 10l.) on March 1, 1396[146]. All the sums were paid into his own hands, so that he was not far from home in 1395. The fact that he borrowed so small a sum as 1l. 6s. 8d. is significant and saddening.

In 19 Ric. II. (June, 1395-June, 1396), Chaucer was one of the attorneys of Gregory Ballard, to receive seizin of the manor of Spitalcombe, and of other lands in Kent[147].

§ 35. 1396. In 1396, as noted above, he received the balance of his first half-year's pension on March 1. The second half-year's pension was not paid till Dec. 25[148]. The Balades of Truth, Gentilesse, and Lak of Stedfastnesse possibly belong to this period, but some critics would place the last of these somewhat earlier.

§ 36. 1397. In 1397, the payment of the pension was again behindhand; there seems to have been some difficulty in obtaining it, due, probably, to the lavish extravagance of the king. Instead of receiving his half-yearly pension at Easter, Chaucer received it much later, and in two instalments; viz. 5l. on July 2, and 5l. on Aug. 9. But after this, things mended; for his Michaelmas pension was paid in full, viz. 10l., on Oct 26[149]. It was received for him by John Walden, and it is probable that at this time he was in infirm health.