| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

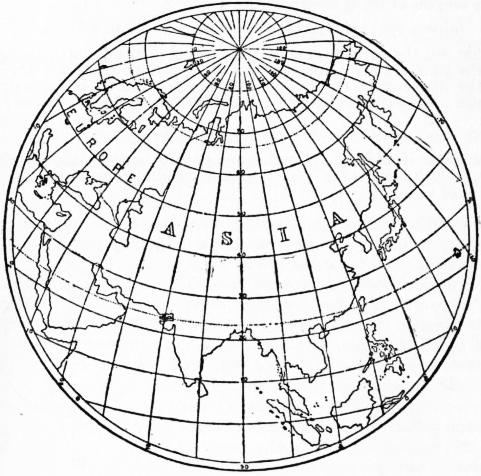

Articles in This Slice

MAP, a representation, on a plane and a reduced scale, of part or the whole of the earth’s surface. If specially designed to meet the requirements of seamen it is called a chart, if on an exceptionally large scale a plan. The words map and chart are derived from mappa and charta, the former being the Latin for napkin or cloth, the latter for papyrus or parchment. Maps were thus named after the material upon which they were drawn or painted, and it should be noted that even at present maps intended for use in the open air, by cyclists, military men and others, are frequently printed on cloth. In Italian, Spanish and Portuguese the word mappa has retained its place, by the side of carta, for marine charts, but in other languages both kinds of maps1 are generally known by a word derived from the Latin charta, as carte in French, Karte in German, Kaart in Dutch. A chart, in French, is called carte hydrographique, marine or des côtes; in Spanish or Portuguese carta de marear, in Italian carta da navigare, in German Seekarte (to distinguish it from Landkarte), in Dutch Zeekaart or Paskaart. A chart on Mercator’s projection is called Wassende graadkaart in Dutch, carte réduite in French. Lastly, a collection of maps is called an atlas, after the figure of Atlas, the Titan, supporting the heavens, which ornamented the title of Lafreri’s and Mercator’s atlases in the 16th century.

Classification of Maps.—Maps differ greatly, not only as to the scale on which they are drawn, but also with respect to the fullness or the character of the information which they convey. Broadly speaking, they may be divided into two classes, of which the first includes topographical, chorographical and general maps, the second the great variety designed for special purposes.

Topographical maps and plans are drawn on a scale sufficiently large to enable the draughtsman to show most objects on a scale true to nature.2 Its information should not only be accurate, but also conveyed intelligibly and with taste. Exaggeration, however, is not always to be avoided, for even on the British 1 in. ordnance map the roads appear as if they were 130 ft. in width.

Chorographical (Gr. χώρα, country or region) and general maps are either reduced from topographical maps or compiled from such miscellaneous sources as are available. In the former case the cartographer is merely called upon to reduce and generalize the information given by his originals, to make a judicious selection of place names, and to take care that the map is not overcrowded with names and details. Far more difficult is his task where no surveys are available, and the map has to be compiled from a variety of sources. These materials generally include reconnaissance survey of small districts, route surveys and astronomical observations supplied by travellers, and information obtained from native sources. The compiler, in combining these materials, is called upon to examine the various sources of information, and to form an estimate of their value, which he can only do if he have himself some knowledge of surveying and of the methods of determining positions by astronomical observation. A knowledge of the languages in which the accounts of travellers are written, and even of native languages, is almost indispensable. He ought not to be satisfied with compiling his map from existing maps, but should subject each explorer’s account to an independent examination, when he will frequently find that either the explorer himself, or the draughtsman employed by him, has failed to introduce into his map the whole of the information available. Latitudes from the observations of travellers may generally be trusted, but longitudes should be accepted with caution; for so competent an observer as Captain Speke placed the capital of Uganda in longitude 32° 44′ E., when its true longitude as determined by more trustworthy observations is 32° 26′ E., an error of 18′. Again, on the map illustrating Livingstone’s “Last Journals” the Luapula is shown as issuing from the Bangweulu in the north-west, when an examination of the account of the natives who carried the great explorer’s remains to the coast would have shown that it leaves that lake on the south.

The second group includes all maps compiled for special purposes. Their variety is considerable, for they are designed to illustrate physical and political geography, travel and navigation, trade and commerce, and, in fact, every subject connected with geographical distribution and capable of being illustrated by means of a map. We thus have (1) physical maps in great variety, including geological, orographical and hydrographical maps, maps illustrative of the geographical distribution of meteorological phenomena, of plants and animals, such as are to be found in Berghaus’s “Physical Atlas,” of which an enlarged English edition is published by J. G. Bartholomew of Edinburgh; (2) political maps, showing political boundaries; (3) ethnological maps, illustrating the distribution of the varieties of man, the density of population, &c.; (4) travel maps, showing roads or railways and ocean-routes (as is done by Philips’ “Marine Atlas”), or designed for the special use of cyclists or aviators; (5) statistical maps, illustrating commerce and industries; (6) historical maps; (7) maps specially designed for educational purposes.

Scale of Maps.—Formerly map makers contented themselves with placing upon their maps a linear scale of miles, deduced from the central meridian or the equator. They now add the proportion which these units of length have to nature, or state how many of these units are contained within some local measure of length. The former method, usually called the “natural scale,” may be described as “international,” for it is quite independent of local measures of length, and depends exclusively upon the size and figure of the earth. Thus a scale of 1 : 1,000,000 signifies that each unit of length on the map 630 represents one million of such units in nature. The second method is still employed in many cases, and we find thus:—

| 1 in. = 1 statute mile (of 63,366 in.) | corresponds to | 1 : 63,366 |

| 6 in. = 1 ” ” ” | ” | 1 : 10,560 |

| 1 in. = 5 chains (of 858 in.) | ” | 1 : 4,890 |

| 1 in. = 1 nautical mile (of 73,037 in.) | ” | 1 : 73,037 |

| 1 in. = 1 verst (of 42,000 in.) | ” | 1 : 42,000 |

| 2 Vienna in. = 1 Austrian mile (of 288,000 in.) | ” | 1 : 144,000 |

| 1 cm. = 500 metres (of 100 cm.) | ” | 1 : 50,000 |

In cases where the draughtsman has omitted to indicate the scale we can ascertain it by dividing the actual length of a meridian degree by the length of a degree measure upon the map. Thus a degree between 50° and 51° measures 111,226,000 mm.; on the map it is represented by 111 mm. Hence the scale is 1 : 1,000,000 approximately.

The linear scale of maps can obviously be used only in the case of maps covering a small area, for in the case of maps of greater extension measurements would be vitiated owing to the distortion or exaggeration inherent in all projections, not to mention the expansion or shrinking of the paper in the process of printing. As an extreme instance of the misleading character of the scale given on maps embracing a wide area we may refer to a map of a hemisphere. The scale of that map, as determined by the equator or centre meridian, we will suppose to be 1 : 125,000,000, while the encircling meridian indicates a scale of 1 : 80,000,000; and a “mean” scale, equal to the square root of the proportion which the area of the map bears to the actual area of a hemisphere, is 1 : 112,000,000. In adopting a scale for their maps, cartographers will do well to choose a multiple of 1000 if possible, for such a scale can claim to be international, while in planning an atlas they ought to avoid a needless multiplicity of scales.

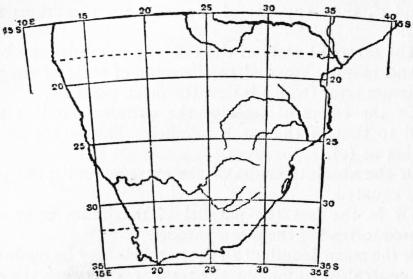

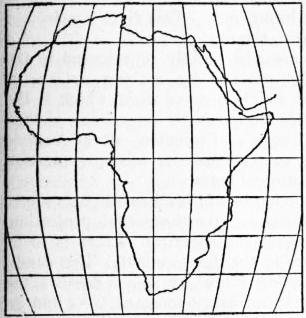

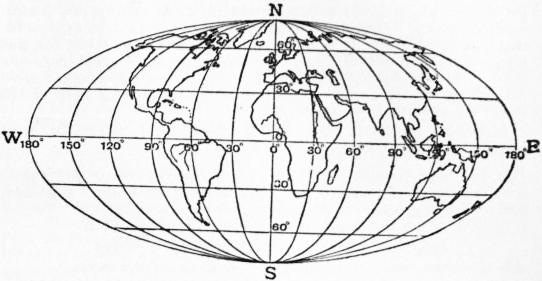

Map Projections are dealt with separately below. It will suffice therefore to point out that the ordinary needs of the cartographer can be met by conical projections, and, in the case of maps covering a wide area, by Lambert’s equal area projection. The indiscriminate use of Mercator’s projection, for maps of the world, is to be deprecated owing to the inordinate exaggeration of areas in high latitudes. In the case of topographical maps sheets bounded by meridians and parallels are to be commended.

The meridian of Greenwich has been universally accepted as the initial meridian, but in the case of most topographical maps of foreign countries local meridians are still adhered to—the more important among which are:—

| Paris (Obs. nationale) | 2° 20′ 14″ | E. of Greenwich. |

| Pulkova (St Petersburg) | 30° 19′ 39″ | E. ” |

| Stockholm | 18° 3′ 30″ | E. ” |

| Rome (Collegio Romano) | 12° 28′ 40″ | E. ” |

| Brussels (Old town) | 4° 22′ 11″ | E. ” |

| Madrid | 3° 41′ 16″ | W. ” |

| Ferro (assumed) | 20° 0′ 0″ | W. of Paris. |

The outline includes coast-line, rivers, roads, towns, and in fact all objects capable of being shown on a map, with the exception of the hills and of woods, swamps, deserts and the like, which the draughtsman generally describes as “ornament.” Conventional signs and symbols are universally used in depicting these objects.

|

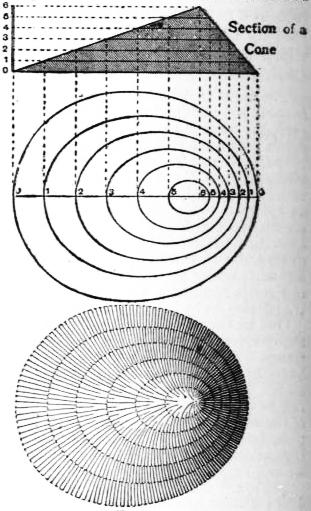

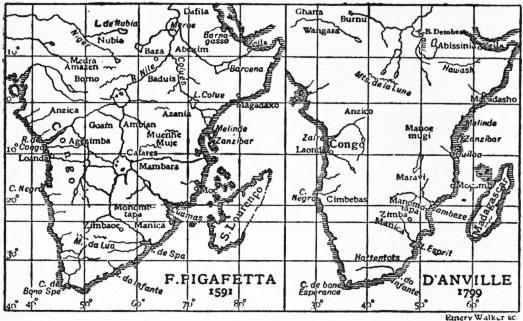

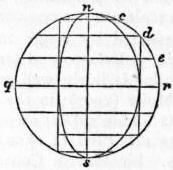

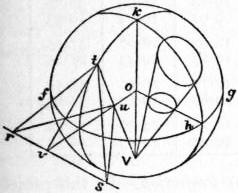

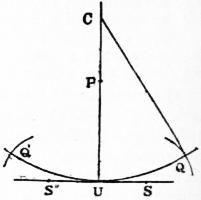

| Fig. 1. |

Delineation of the Ground.—The mole-hills and serrated ridges of medieval maps were still in almost general use at the close of the 18th century, and are occasionally met with at the present day, being cheaply produced, readily understood by the unlearned, and in reality preferable to the uncouth and misleading hatchings still to be seen on many maps. Far superior are those scenographic representations which enable a person consulting the map to identify prominent landmarks, such as the Pic du Midi, which rises like a pillar to the south of Pau, but is not readily discovered upon an ordinary map. This advantage is still fully recognized, for such views of distant hills are still commonly given on the margin of marine charts for the assistance of navigators; military surveyors are encouraged to introduce sketches of prominent landmarks upon their reconnaissance plans, and the general public is enabled to consult “Picturesque Relief Maps”—such as F. W. Delkeskamp’s Switzerland (1830) or his Panorama of the Rhine. Delineations such as these do not, however, satisfy scientific requirements. All objects on a map are required to be shown as projected horizontally upon a plane. This principle must naturally be adhered to when delineating the features of the ground. This was recognized by J. Picard and other members of the Academy of Science whom Colbert, in 1668, directed to prepare a new map of France, for on David Vivier’s map of the environs of Paris (1674, scale 1 : 86,400) very crude hachures bounding the rivers have been substituted for the scenographic hills of older maps. Little progress in the delineation of the ground, however, was made until towards the close of the 18th century, when horizontal contours and hachures regulated according to the angle of inclination of all slopes, were adopted. These contours intersect the ground at a given distance above or below the level of the sea, and thus bound a series of horizontal planes (see fig. 1). Contours of this kind were first utilized by M. S. Cruquius in his chart of the Merwede (1728); Philip Buache (1737) introduced such contours or isobaths (Gr. ἶσος, equal; βαθύς, deep) upon his chart of the Channel, and intended to introduce similar contours or isohypses (ὔψος, height) for a representation of the land. Dupain-Triel, acting upon a suggestion of his friend M. Ducarla, published his La France considérée dans les différentes hauteurs de ses plaines (1791), upon which equidistant contours at intervals of 16 toises found a place. The scientific value of these contoured maps is fully recognized. They not only indicate the height of the land, but also enable us to compute the declivity of the mountain slopes; and if minor features of ground lying between two contours—such as ravines, as also rocky precipices and glaciers—are indicated, as is done on the Siegfried atlas of Switzerland, they fully meet the requirements of the scientific man, the engineer and the mountain-climber. At the same time it cannot be denied that these maps, unless the contours are inserted at short intervals, lack graphic expression. Two methods are employed to attain this: the first distinguishes the strata or layers by colours; the second indicates the varying slopes by shades or hachures. The first of these methods yields a hypsographical, or—if the sea-bottom be included, in which case all contours are referred to a common datum line—a bathy hypsographical map. Carl Ritter, in 1806, employed graduated tints, increasing in lightness on proceeding from the lowlands to the highlands; while General F. von Hauslab, director of the Austrian Surveys, in 1842, advised that the darkest tints should be allotted to the highlands, so that they might not obscure details in the densely peopled plains. The desired effect may be produced by a graduation of the same colour, or by a polychromatic scale—such as white, pale red, pale brown, various shades of green, violet and purple, in ascending order. C. von Sonklar, in his map of the Hohe Tauern (1 : 144,000; 1864) coloured plains and valleys green; mountain slopes in five shades of brown; glaciers blue or white. E. G. Ravenstein’s map of Ben Nevis (1887) first employed the colours of the spectrum, viz. green to brown, in ascending order for the land; blue, indigo and violet for the sea, increasing in intensity with the height or the depth. At first cartographers chose their colours rather arbitrarily. Thus Horsell, who was the first to introduce tints 631 on his map of Sweden and Norway (1 : 600,000; 1835), coloured the lowlands up to 300 ft. in green, succeeded by red, yellow and white for the higher ground; while A. Papen, on his hypsographical map of Central Europe (1857) introduced a perplexing range of colours. At the present time compilers of strata maps generally limit themselves to two or three colours, in various shades, with green for the lowlands, brown for the hills and blue for the sea. On the international map of the world, planned by Professor A. Penck on a scale of 1 : 1,000,000, which has been undertaken by the leading governments of the world, the ground is shown by contours at intervals of 100 metres (to be increased to 200 and 500 metres in mountainous districts); the strata are in graded tints, viz. blue for the sea, green for lowlands up to 300 metres, yellow between 300 and 500 metres, brown up to 2000 metres, and reddish tints beyond that height.

|

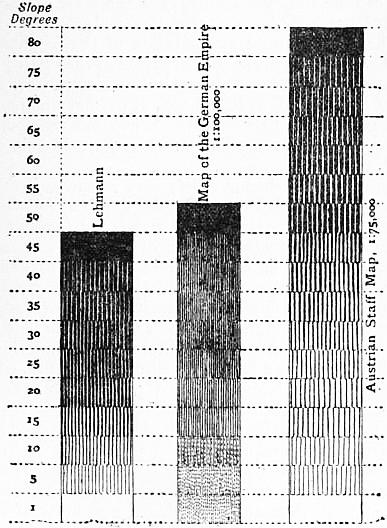

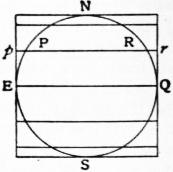

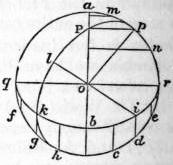

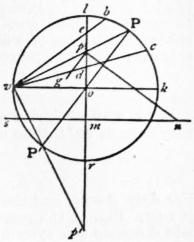

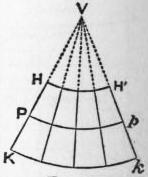

| Fig. 2. |

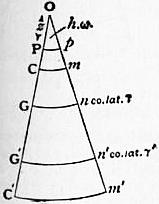

The declivities of the ground are still indicated in most topographical maps by a system of strokes or hachures, first devised by L. Chr. Müller (Plan und Kartenzeichnen, 1788) and J. G. Lehmann, who directed a survey of Saxony, 1780-1806, and published his Theorie der Bergzeichnung in 1799. By this method the slopes are indicated by strokes or hachures crossing the contour lines at right angles, in the direction of flowing water, and varying in thickness according to the degree of declivity they represent (cf. for example, the map of Switzerland in this work). The light is supposed to descend vertically upon the country represented, and in a true scale of shade the intensity increases with the inclination from 0° to 90°; but as such a scale does not sufficiently differentiate the lesser inclinations which are the most important, the author adopted a conventional scale, representing a slope of 45° or more, supposed to be inaccessible, as absolutely black, the level surfaces, which reflect all the light which falls upon them, as perfectly white, and the intervening slopes by a proportion between black and white, as in fig. 2. The main principles of this system have been maintained, but its details have been modified frequently to suit special cases. Thus the French survey commission of 1828 fixed the proportion of black to white at one and a half times the angle of slope; while in Austria, where steep mountains constitute an important feature, solid black has been reserved for a slope of 80°, the proportion of black to white varying from 80 : 0 (for 50°) to 8 : 72 (for 5°). On the map of Germany (1 : 100,000) a slope of 50° is shown in solid black while stippled hachures are used for gentle slopes up to 10°. Instead of shading lines following the greatest slopes, lines following the contours and varying in their thickness and in their intervals apart, according to the slope of the ground to be represented, may be employed. This method affords a ready and expeditious means of sketching the ground, if the draughtsman limits himself to characteristically indicating its features by what have been called “form lines.” This method can be recommended in the case of plotting the results of an explorer’s route, or in the case of countries of which we have no regular survey (cf. the map of Afghanistan in this work).

Instead of supposing the light to fall vertically upon the surface it is often supposed to fall obliquely, generally at an angle of 45° from the upper left-hand corner. It is claimed for this method that it affords a means of giving a graphic representation of Alpine districts where other methods of shading fail. The Dufour map of Switzerland (1 : 100,000) is one of the finest examples of this style of hill-shading. For use in the field, however, and for scientific work, a contoured map like Siegfried’s atlas of Switzerland, or, in the case of hilly country, a map shaded on the assumption of a vertical light, will prove more useful than one of these, notwithstanding that truth to nature and artistic beauty are claimed on their behalf.

Instead of shading by lines, a like effect may be produced by mezzotint shading (cf. the map of Italy, or other maps, in this work, on a similar method), and if this be combined with contour lines very satisfactory results can be achieved. If this tint be printed in grey or brown, isohypses, in black or red, show distinctly above it. The same combination is possible if hills engraved in the ordinary manner are printed in colours, as is done in an edition of the 1-inch ordnance map, with contours in red and hills hachured in brown.

Efforts have been made of late years to improve the available methods of representing ground, especially in Switzerland, but the so-called stereoscopic or relief maps produced by F. Becker, X. Imfeld, Kümmerly, F. Leuzinger and other able cartographers, however admirable as works of art, do not, from the point of utility, supersede the combination of horizontal contours with shaded slopes, such as have been long in use. There seems to be even less chance for the combination of coloured strata and hachures proposed by K. Peucker, whose theoretical disquisitions on aerial perspective are of interest, but have not hitherto led to satisfactory practical results.3

The above remarks apply more particularly to topographic maps. In the case of general maps on a smaller scale, the orographic features must be generalized by a skilful draughtsman and artist. One of the best modern examples of this kind is Vogel’s map of Germany, on a scale of 1 : 500,000.

Selection of Names and Orthography.—The nomenclature or “lettering” of maps is a subject deserving special attention. Not only should the names be carefully selected with special reference to the objects which the map is intended to serve, and to prevent overcrowding by the introduction of names which can serve no useful object, but they should also be arranged in such a manner as to be read easily by a person consulting the map. It is an accepted rule now that the spelling of names in countries using the Roman alphabet should be retained, with such exceptions as have been familiarized by long usage. In such cases, however, the correct native form should be added within brackets, as Florence (Firenze), Leghorn (Livorno), Cologne (Cöln) and so on. At the same time these corrupted forms should be eliminated as far as possible. Names in languages not using the Roman alphabet, or having no written alphabet should be spelt phonetically, as pronounced on the spot. An elaborate universal alphabet, abounding in diacritical marks, has been devised for the purpose by Professor Lepsius, and various other systems have been adopted for Oriental languages, and by certain missionary societies, adapted to the languages in which they teach. The following simple rules, laid down by a Committee of the Royal Geographical Society, will be found sufficient as a rule; according to this system the vowels are to be sounded as in Italian, the consonants as in English, and no redundant letters are to be introduced. The diphthong ai is 632 to be pronounced as in aisle; au as ow in how; aw as in law. Ch is always to be sounded as in church, g is always hard; y always represents a consonant; whilst kh and gh stand for gutturals. One accent only is to be used, the acute, to denote the syllable on which stress is laid. This system has in great measure been followed throughout the present work, but it is obvious that in numerous instances these rules must prove inadequate. The introduction of additional diacritical marks, such as ˉ and ˜, used to express quantity, and the diaeresis, as in aï, to express consecutive vowels, which are to be pronounced separately, may prove of service, as also such letters as ä, ö and ü, to be pronounced as in German, and in lieu of the French ai, eu or u.

The United States Geographic Board acts upon rules practically identical with those indicated, and compiles official lists of place-names, the use of which is binding upon government departments, but which it would hardly be wise to follow universally in the case of names of places outside America.

Measurement on Maps

Measurement of Distance.—The shortest distance between two places on the surface of a globe is represented by the arc of a great circle. If the two places are upon the same meridian or upon the equator the exact distance separating them is to be found by reference to a table giving the lengths of arcs of a meridian and of the equator. In all other cases recourse must be had to a map, a globe or mathematical formula. Measurements made on a topographical map yield the most satisfactory results. Even a general map may be trusted, as long as we keep within ten degrees of its centre. In the case of more considerable distances, however, a globe of suitable size should be consulted, or—and this seems preferable—they should be calculated by the rules of spherical trigonometry. The problem then resolves itself in the solution of a spherical triangle.

In the formulae which follow we suppose l and l′ to represent the latitudes, a and b the co-latitudes (90 − l or 90° − l′), and t the difference in longitude between them or the meridian distance, whilst D is the distance required.

If both places have the same latitude we have to deal with an isosceles triangle, of which two sides and the included angle are given. This triangle, for the convenience of calculation, we divide into two right-angled triangles. Then we have sin 1⁄2 D = sin a sin 1⁄2 t, and since sin a = sin (90° − l) = cos t, it follows that

sin 1⁄2 D = cos l sin 1⁄2 t.

If the latitudes differ, we have to solve an oblique-angled spherical triangle, of which two sides and the included angle are given. Thus,

| cos t = | cos D − cos a cos b |

| sin a sin b |

cos D = cos a cos b + sin a sin b cos t

= sin l sin l′ + cos l cos l′ cos t.

In order to adapt this formula to logarithms, we introduce a subsidiary angle p, such that cot p = cot l cos t; we then have

cos D = sin l cos (l′ − p) / sin p.

In the above formulae our earth is assumed to be a sphere, but when calculating and reducing to the sea-level, a base-line, or the side of a primary triangulation, account must be taken of the spheroidal shape of the earth and of the elevation above the sea-level. The error due to the neglect of the former would at most amount to 1%, while a reduction to the mean level of the sea necessitates but a trifling reduction, amounting, in the case of a base-line 100,000 metres in length, measured on a plateau of 3700 metres (12,000 ft.) in height, to 57 metres only.

These orthodromic distances are of course shorter than those measured along a loxodromic line, which intersects all parallels at the same angle. Thus the distance between New York and Oporto, following the former (great circle sailing), amounts to 3000 m., while following the rhumb, as in Mercator sailing, it would amount to 3120 m.

These direct distances may of course differ widely with the distance which it is necessary to travel between two places along a road, down a winding river or a sinuous coast-line. Thus, the direct distance, as the crow flies, between Brig and the hospice of the Simplon amounts to 4.42 geogr. m. (slope nearly 9°), while the distance by road measures 13.85 geogr. m. (slope nearly 3°). Distances such as these can be measured only on a topographical map of a fairly large scale, for on general maps many of the details needed for that purpose can no longer be represented. Space runners for facilitating these measurements, variously known as chartometers, curvimeters, opisometers, &c., have been devised in great variety. Nearly all these instruments register the revolution of a small wheel of known circumference, which is run along the line to be measured.

The Measurement of Areas is easily effected if the map at our disposal is drawn on an equal area projection. In that case we need simply cover the map with a network of squares—the area of each of which has been determined with reference to the scale of the map—count the squares, and estimate the contents of those only partially enclosed within the boundary, and the result will give the area desired. Instead of drawing these squares upon the map itself, they may be engraved or etched upon glass, or drawn upon transparent celluloid or tracing-paper. Still more expeditious is the use of a planimeter, such as Captain Prytz’s “Hatchet Planimeter,” which yields fairly accurate results, or G. Coradi’s “Polar Planimeter,” one of the most trustworthy instruments of the kind.4

When dealing with maps not drawn on an equal area projection we substitute quadrilaterals bounded by meridians and parallels, the areas for which are given in the “Smithsonian Geographical Tables” (1894), in Professor H. Wagner’s tables in the geographical Jahrbuch, or similar works.

It is obvious that the area of a group of mountains projected on a horizontal plane, such as is presented by a map, must differ widely from the area of the superficies or physical surface of those mountains exposed to the air. Thus, a slope of 45° having a surface of 100 sq. m. projected upon a horizontal plane only measures 59 sq. m., whilst 100 sq. m. of the snowclad Sentis in Appenzell are reduced to 10 sq. m. A hypsographical map affords the readiest solution of this question. Given the area A of the plane between the two horizontal contours, the height h of the upper above the lower contour, the length of the upper contour l, and the area of the face presented by the edge of the upper stratum t·h = A1, the slope α is found to be tan α = h·l / (A − A1); hence its superficies, A = A2 sec α. The result is an approximation, for inequalities of the ground bounded by the two contours have not been considered.

The hypsographical map facilitates likewise the determination of the mean height of a country, and this height, combined with the area, the determination of volume, or cubic contents, is a simple matter.5

Relief Maps are intended to present a representation of the ground which shall be absolutely true to nature. The object, however, can be fully attained only if the scale of the map is sufficiently large, if the horizontal and vertical scales are identical, so that there shall be no exaggeration of the heights, and if regard is had, eventually, to the curvature of the earth’s surface. Relief maps on a small scale necessitate a generalization of the features of the ground, as in the case of ordinary maps, as likewise an exaggeration of the heights. Thus on a relief on a scale of 1 : 1,000,000 a mountain like Ben Nevis would only rise to a height of 1.3 mm.

The methods of producing reliefs vary according to the scale and the materials available. A simple plan is as follows—draw an outline of the country of which a map is to be produced upon a board; mark all points the altitude of which is known or can be estimated by pins or wires clipped off so as to denote the heights; mark river-courses and suitable profiles by strips of vellum and finally finish your model with the aid of a good map, in clay or wax. If contoured maps are available it is easy to build up a strata-relief, which facilitates the completion of the relief so that it shall be a fair representation of nature, which the strata-relief cannot claim to be. A pantograph armed with cutting-files6 which carve the relief out of a block of gypsum, was employed in 1893-1900 by C. Perron of Geneva, in producing his relief map of Switzerland on a scale of 1 : 100,000. After copies of such reliefs have been taken in gypsum, cement, statuary pasteboard, fossil dust mixed with vegetable oil, or some other suitable material, they are painted. If a number of copies is required it may be advisable to print a map of the country represented in colours, and either to emboss this map, backed with papier-mâché, or paste it upon a copy of the relief—a task of some difficulty. Relief maps are frequently objected to on 633 account of their cost, bulk and weight, but their great use in teaching geography is undeniable.

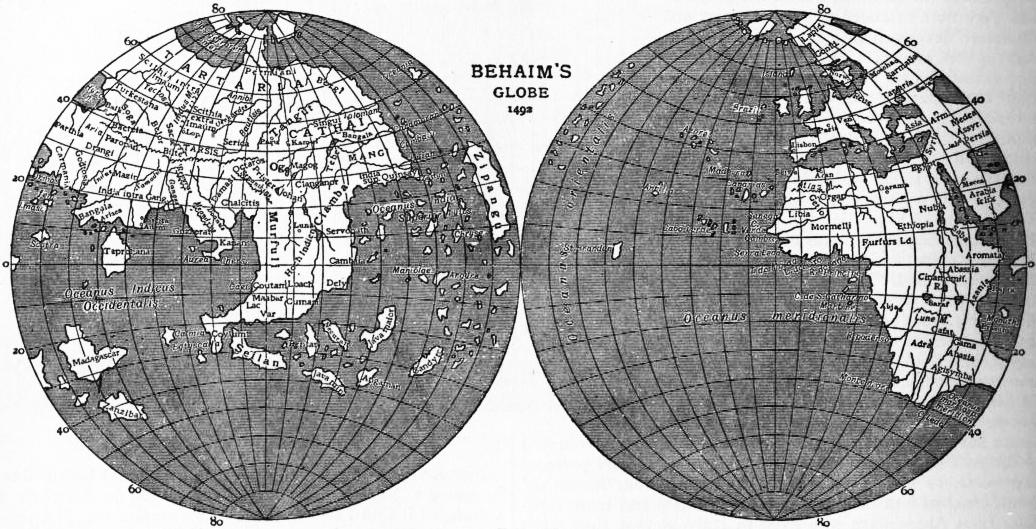

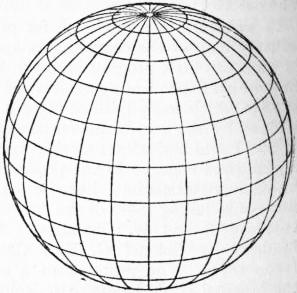

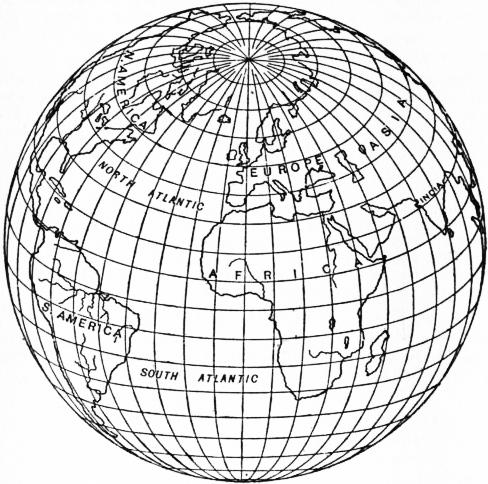

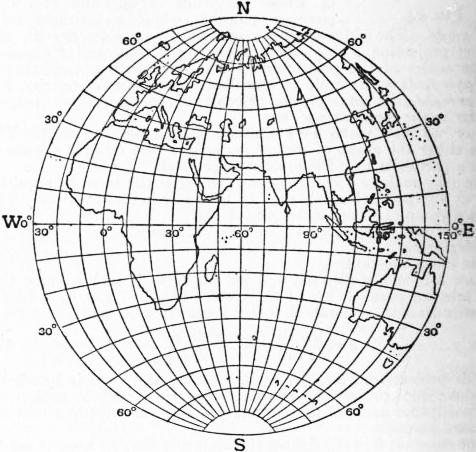

Globes.7—It is impossible to represent on a plane the whole of the earth’s surface, or even a large extent of it, without a considerable amount of distortion. On the other hand a map drawn on the surface of a sphere representing a terrestrial globe will prove true to nature, for it possesses, in combination, the qualities which the ingenuity of no mathematician has hitherto succeeded in imparting to a projection intended for a map of some extent, namely, equivalence of areas of distances and angles. Nevertheless, it should be observed that our globes take no account of the oblateness of our sphere; but as the difference in length between the circumference of the equator and the perimeter of a meridian ellipse only amounts to 0.16%, it could be shown only on a globe of unusual size.

The method of manufacturing a globe is much the same as it was at the beginning of the 16th century. A matrix of wood or iron is covered with successive layers of papers, pasted together so as to form pasteboard. The shell thus formed is then cut along the line of the intended equator into two hemispheres, they are then again glued together and made to revolve round an axis the ends of which passed through the poles and entered a metal meridian circle. The sphere is then coated with plaster or whiting, and when it has been smoothed on a lathe and dried, the lines representing meridians and parallels are drawn upon it. Finally the globe is covered with the paper gores upon which the map is drawn. The adaption of these gores to the curvature of the sphere calls for great care. Generally from 12 to 24 gores and two small segments for the polar regions printed on vellum paper are used for each globe. The method of preparing these gores was originally found empirically, but since the days of Albert Dürer it has also engaged the minds of many mathematicians, foremost among whom was Professor A. G. Kästner of Göttingen. One of the best instructions for the manufacture of globes we owe to Altmütter of Vienna.8

Larger globes are usually on a stand the top of which supports an artificial horizon. The globe itself rotates within a metallic meridian to which its axis is attached. Other accessories are an hour-circle, around the north pole, a compass placed beneath the globe, and a flexible quadrant used for finding the distances between places. These accessories are indispensable if it be proposed to solve the problems usually propounded in books on the “use of the globes,” but can be dispensed with if the globe is to serve only as a map of the world. The size of a globe is usually given in terms of its diameter. To find its scale divide the mean diameter of the earth (1,273,500 m.) by the diameter of the globe; to find its circumference multiply the diameter by π (3.1416).

Map Printing.—Maps were first printed in the second half of the 15th century. Those in the Rudimentum novitiarum published at Lübeck in 1475 are from woodcuts, while the maps in the first two editions of Ptolemy published in Italy in 1472 are from copper plates. Wood engraving kept its ground for a considerable period, especially in Germany, but copper in the end supplanted it, and owing to the beauty and clearness of the maps produced by a combination of engraving and etching it still maintains its ground. The objection that a copper plate shows signs of wear after a thousand impressions have been taken has been removed, since duplicate plates are readily produced by electrotyping, while transfers of copper engravings, on stone, zinc or aluminium, make it possible to turn out large editions in a printing-machine, which thus supersedes the slow-working hand-press.9 These impressions from transfers, however, are liable to be inferior to impressions taken from an original plate or an electrotype. The art of lithography greatly affected the production of maps. The work is either engraved upon the stone (which yields the most satisfactory result at half the cost of copper-engraving), or it is drawn upon the stone by pen, brush or chalk (after the stone has been “grained”), or it is transferred from a drawing upon transfer paper in lithographic ink. In chromolithography a stone is required for each colour. Owing to the great weight of stones, their cost and their liability of being fractured in the press, zinc plates, and more recently aluminium plates, have largely taken the place of stone. The processes of zincography and of algraphy (aluminium printing) are essentially the same as lithography. Zincographs are generally used for producing surface blocks or plates which may be printed in the same way as a wood-cut. Another process of producing such blocks is known as cerography (Gr. κηρός), wax. A copper plate having been coated with wax, outline and ornament are cut into the wax, the lettering is impressed with type, and the intaglio thus produced is electrotyped.10 Movable types are utilized in several other ways in the production of maps. Thus the lettering of the map, having been set up in type, is inked in and transferred to a stone or a zinc-plate, or it is impressed upon transfer-paper and transferred to the stone. Photographic processes have been utilized not only in reducing maps to a smaller scale, but also for producing stones and plates from which they may be printed. The manuscript maps intended to be produced by photographic processes upon stone, zinc or aluminium, are drawn on a scale somewhat larger than the scale on which they are to be printed, thus eliminating all those imperfections which are inherent in a pen-drawing. The saving in time and cost by adopting this process is considerable, for a plan, the engraving of which takes two years, can now be produced in two days. Another process, photo- or heliogravure, for obtaining an engraved image on a copper plate, was for the first time employed on a large scale for producing a new topographical map of the Austrian Empire in 718 sheets, on a scale of 1 : 75,000, which was completed in seventeen years (1873-1890). The original drawings for this map had to be done with exceptional neatness, the draughtsman spending twelve months on that which he would have completed in four months had it been intended to engrave the map on copper; yet an average chart, measuring 530 by 630 mm., which would have taken two years and nine months for drawing and engraving, was completed in less than fifteen months—fifty days of which were spent in “retouching” the copper plate. It only cost £169 as compared with £360 had the old method been pursued.

For details of the various methods of reproduction see Lithography; Process, &c.

History of Cartography

A capacity to understand the nature of maps is possessed even by peoples whom we are in the habit of describing as “savages.” Wandering tribes naturally enjoy a great advantage in this respect over sedentary ones. Our arctic voyagers—Sir E. W. Parry, Sir J. Ross, Sir F. L. MacClintock and others—have profited from rough maps drawn for them by Eskimos. Specimens of such maps are given in C. F. Hall’s Life with the Esquimaux (London, 1864). Henry Youle Hind, in his work on the Labrador Peninsula (London, 1863) praises the map which the Montagnais and Nasquapee Indians drew upon bark. Similar essays at map-making are reported in connexion with Australians, Maoris and Polynesians. Tupaya, a Tahitian, who accompanied Captain Cook in the “Endeavour” to Europe, supplied his patron with maps; Raraka drew a map in chalk of the Paumotu archipelago on the deck of Captain Wilkes’s vessel; the Marshall islanders, according to Captain Winkler (Marine Rundschau, Oct. 1893) possess maps upon which the bearings of the islands are indicated by small strokes. Far superior were the maps found among the semi-civilized Mexicans when the Spaniards first discovered and invaded their country. Among them were cadastral plans of villages, maps of the provinces of the empire of the Aztecs, of towns and of the coast. Montezuma presented Cortes with a map, painted on Nequen cloth, of the Gulf coast. Another map did the Conquistador good service on his campaign against Honduras (Lorenzana, Historia de nueva España, Mexico, 1770; W. H. Prescott, History of the Conquest of Mexico, New 634 York, 1843). Peru, the empire of the Incas, had not only ordinary maps, but also maps in relief, for Pedro Sarmiento da Gamboa (History of the Incas, translated by A. R. Markham, 1907) tells us that the 9th Inca (who died in 1191) ordered such reliefs to be produced of certain localities in a district which he had recently conquered and intended to colonize. These were the first relief maps on record. It is possible that these primitive efforts of American Indians might have been further developed, but the Spanish conquest put a stop to all progress, and for a consecutive history of the map and map-making we must turn to the Old World, and trace this history from Egypt and Babylon, through Greece, to our own age.

The ancient Egyptians were famed as “geometers,” and as early as the days of Rameses II. (Sesostris of the Greeks, 1333-1300 B.C.) there had been made a cadastral survey of the country showing the rows of pillars which separated the nomens as well as the boundaries of landed estates. It was upon a map based upon such a source that Eratosthenes (276-196 B.C.) measured the distance between Syene and Alexandria which he required for his determination of the length of a degree. Ptolemy, who had access to the treasures of the famous library of Alexandria was able, no doubt, to utilize these cadastral plans when compiling his geography. It should be noted that he places Syene only two degrees to the east of Alexandria instead of three degrees, the actual meridian distance between the two places; a difference which would result from an error of only 7° is the orientation of the map used by Ptolemy. Scarcely any specimens of ancient Egyptian cartography have survived. In the Turin Museum are preserved two papyri with rough drawings of gold mines established by Sesostris in the Nubian Desert.11 These drawings have been commented upon by S. Birch, F. Chabas, R. J. Lauth and other Egyptologists, and have been referred to as the two most ancient maps in existence. They can, however, hardly be described as maps, while in age they are surpassed by several cartographical clay tablets discovered in Babylonia. On another papyrus in the same museum is depicted the victorious return of Seti I. (1366-1333) from Syria, showing the road from Pelusium to Heroopolis, the canal from the Nile with crocodiles, and a lake (mod. Lake Timsah) with fish in it. Apollonius of Rhodes who succeeded Eratosthenes as chief librarian at Alexandria (196 B.C.) reports in his Argonautica (iv. 279) that the inhabitants of Colchis whom, like Herodotus (ii., 104) he looks upon as the descendants of Egyptian colonists, preserved, as heirlooms, certain graven tablets (κύρβεις) on which land and sea, roads and towns were accurately indicated.12 Eustathius (since 1160 archbishop of Thessalonica) in his commentary on Dionysius Periegetes, mentions route-maps which Sesostris caused to be prepared, while Strabo (i., 1. 5) dwells at length upon the wealth of geographical documents to be found in the library of Alexandria.

A cadastral survey for purposes of taxation was already at work in Babylonia in the age of Sargon of Akkad, 3800 B.C. In the British Museum may be seen a series of clay tablets, circular in shape and dating back to 2300 or 2100 B.C., which contain surveys of lands. One of these depicts in a rough way lower Babylonia encircled by a “salt water river,” Oceanus.

Development of Map-making among the Greeks.13—Ionian mercenaries and traders first arrived in Egypt, on the invitation of Psammetichus I. about the middle of the 7th century B.C. Among the visitors to Egypt, there were, no doubt, some who took an interest in the science of the Egyptians. One of the most distinguished among them was Thales of Miletus (640-543 B.C.), the founder of the Ionian school of philosophy, whose pupil, Anaximander (611-546 B.C.) is credited by Eratosthenes with having designed the first map of the world. Anaximander looked upon the earth as a section of a cylinder, of considerable thickness, suspended in the centre of the circular vault of the heavens, an idea perhaps borrowed from the Babylonians, for Job (xxvi. 7) already speaks of the earth as “hanging upon nothing.” Like Homer he looked upon the habitable world (οἰκουμένη) as being circular in outline and bounded by a circumfluent river. The geographical knowledge of Anaximander was naturally more ample than that of Homer, for it extended from the Cassiterides or Tin Islands in the west to the Caspian in the east, which he conceived to open out into Oceanus. The Aegean Sea occupied the centre of the map, while the line where ocean and firmament seemed to meet represented an enlarged horizon.

Anaximenes, a pupil of Anaximander, was the first to reject the view that the earth was a circular plane, but held it to be an oblong rectangle, buoyed up in the midst of the heavens by the compressed air upon which it rested. Circular maps, however, remained in the popular favour long after their erroneousness had been recognized by the learned.

Even Hecataeus of Miletus (549-472 B.C.), the author of a Periodos or description of the earth, of whom Herodotus borrowed the terse saying that Egypt was the gift of the Nile, retained this circular shape and circumfluent ocean when producing his map of the world, although he had at his disposal the results of the voyage of Scylax of Caryanda from the Indus to the Red Sea, of Darius’ campaign in Scythia (513), the information to be gathered among the merchants from all parts of the world who frequented an emporium like Miletus, and what he had learned in the course of his own extensive travels. Hecataeus was probably the author of the “bronze tablets upon which was engraved the whole circuit of the earth, the sea and rivers” (Herod, v. 49), which Aristagoras, the tyrant of Miletus, showed to Cleomenes, the king of Sparta, in 504, whose aid he sought in vain in a proposed revolt against Darius, which resulted disastrously in 494 in the destruction of Miletus. The map of the world brought upon the stage in Aristophanes’ comedy of The Clouds (423 B.C.), whereon a disciple of the Sophists points out upon it the position of Athens and of other places known to the audience, was probably of the popular circular type, which Herodotus (iv. 36) not many years before had derided and which was discarded by Greek cartographers ever after. Thus Democritus of Abdera (b. c. 450, d. after 360), the great philosopher and founder, with Leucippus, of the atomic theory, was also the author of a map of the inhabited world which he supposed to be half as long again from west to east, as it was broad.

Dicaearcus of Messana in Sicily, a pupil of Aristotle (326-296 B.C.), is the author of a topographical account of Hellas, with maps, of which only fragments are preserved; he is credited with having estimated the size of the earth, and, as far as known he was the first to draw a parallel across a map.14 This parallel, or dividing line, called diaphragm (partition) by a commentator, extended due east from the Pillars of Hercules, through the Mediterranean, and along the Taurus and Imaus (Himalaya) to the eastern ocean. It divided the inhabited world, as then known, into a northern and a southern half. In compiling his map he was able to avail himself of the information obtained by the bematists (surveyors who determined distances by pacing) who accompanied Alexander the Great on his campaigns; of the results of the voyage of Nearchus from the Indus to the Euphrates, and of the “Periplus” of Scylax of Caryanda, which described the coast from between India and the head of the Arabian Gulf. On the other hand he unwisely rejected the results of the observations for latitude made by Pytheas in 326 B.C. at his native town, Massilia, and during a subsequent voyage to northern Europe. In the end the map of Dicaearcus resembled that of Democritus.

Scientific geography profited largely from the labours of Eratosthenes of Cyrene, whom Ptolemy Euergetes appointed 635 keeper of the famous library of Alexandria in 247 B.C., and died in that city in 195 B.C. He won fame as having been the first to determine the size of the earth by a scientific method. Having determined the difference of latitude between Alexandria and Syene which he erroneously believed to lie on the same meridian, and obtained the distance of those places from each other from the surveys made by Egyptian geometers, he concluded that a degree of the meridian measured 700 stadia.15

Eratosthenes is the author of a treatise which deals systematically with the geographical knowledge of his time, but of which only fragments have been preserved by Strabo and others. This treatise was intended to illustrate and explain his map of the world. In this task he was much helped by the materials collected in his library. Among the travellers of whose information he was thus able to avail himself were Pytheas of Massilia, Patroclus, who had visited the Caspian (285-282 B.C.), Megasthenes, who visited Palibothra on the Ganges, as ambassador of Seleucus Nicator (302-291 B.C.), Timosthenus of Rhodes, the commander of the fleet of Ptolemy Philadelphus (284-246 B.C.) who wrote a treatise “On harbours,” and Philo, who visited Meroe on the upper Nile. His map formed a parallelogram measuring 75,800 stadia from Usisama (Ushant island) or Sacrum Promontorium in the west to the mouth of the Ganges and the land of the Coniaci (Comorin) in the east, and 46,000 stadia from Thule in the north to the supposed southern limit of Libya. Across it were drawn seven parallels, running through Meroe, Syene, Alexandria, Rhodes, Lysimachia on the Hellespont, the mouth of the Borysthenes and Thule, and these were crossed at right angles by seven meridians, drawn at irregular intervals, and passing through the Pillars of Hercules, Carthage, Alexandria, Thapsacus on the Euphrates, the Caspian gates, the mouth of the Indus and that of the Ganges. The position of all the places mentioned was supposed to have been determined by trustworthy authorities. The inhabited world thus delineated formed an island of irregular shape, surrounded on all sides by the ocean, the Erythrean Sea freely communicating with the western ocean. In his text Eratosthenes ignored the popular division of the world into Europe, Asia and Libya, and substituted for it a northern and southern division, divided by the parallel of Rhodes, each of which he subdivided into sphragides or plinthia—seals or plinths. The principles on which these divisions were made remain an enigma to the present day.

This map of Eratosthenes, notwithstanding its many errors, such as the assumed connexion of the Caspian with a northern ocean and the supposition that Carthage, Sicily and Rome lay on the same meridian, enjoyed a high reputation in his day. Even Strabo (c. 30 B.C.) adopted its main features, but while he improved the European frontier, he rejected the valuable information secured by Pytheas and retained the connexion between the Caspian and the outer ocean. In the extreme east his information extended no further than that of Eratosthenes, viz. to India and Taprobane (Ceylon) and the Sacae (Kirghiz).

Hipparchus, the famous astronomer, on the other hand, (c. 150 B.C.) proved a somewhat captious critic. He justly objected to the arbitrary network of the map of Eratosthenes. The parallels or climata16 drawn through places, of which the longest day is of equal length and the decimation (distance) from the equator is the same, he maintained, ought to have been inserted at equal intervals, say of half an hour, and the meridians inserted on a like principle. In fact, he demanded that maps should be based upon a regular projection, several descriptions of which he had adopted for his star maps. He moreover accuses Eratosthenes, (whose determination of a degree he accepts without hesitation) with trusting too much to hypothesis in compiling his map instead of having recourse to latitudes and longitudes deduced by astronomical observations. Such observations, however, were but rarely available at the time. A few latitudes had indeed been observed, but although Hipparchus had shown how longitudes could be determined by the observation of eclipses, this method was in reality not available for want of trustworthy time-keepers. The determination of an ocean surrounding the inhabited earth he declared to be based on a mere hypothesis and that it would be equally allowable to describe the Erythraea as a sea surrounded by land. Hipparchus is not known to have compiled a map himself.

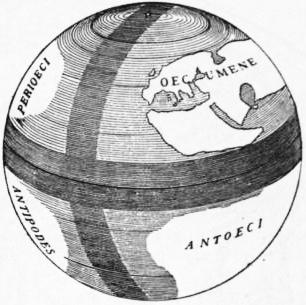

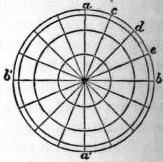

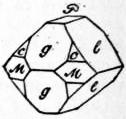

About the same time Crates of Mallus (d. 145 B.C.) embodied the views of the Stoic school of philosophy in a globe which has become typical as one of the insignia of royalty. On this globe an equatorial and a meridional ocean divide our earth into four quarters, each inhabited, thus anticipating the discovery of North and South America and Australia.17

|

| Fig. 2.—The Globe of Crates of Mallus. |

The period between Eratosthenes and Marinus of Tyre was one of great political importance. Carthage had been destroyed (146 B.C.), Julius Caesar had carried on his campaign in Gaul (58-51 B.C.), Egypt had been occupied (30 B.C.), Britannia conquered (A.D. 41-79), and the Roman empire had attained its greatest extent and power under the emperor Trajan (A.D. 98-117). But although military operations added to our knowledge of the world, scientific cartography was utterly neglected.

Among Greek works written during this period there are several which either give us an idea of the maps available at that time, or furnish information of direct service to the compiler of a map. Among the latter a Periplus or coastal guide of the Erythrean Sea, which clearly reveals the peninsular shape of India (A.D. 90) and Arrian’s Periplus Ponti Euxeni (A.D. 131) which Festus Avienus translated into Latin. Among travellers Eudoxus of Cyzicus occupies a foremost rank, since, between 115-87 B.C. he visited India and the east coast of Africa, which subsequently he attempted in vain to circumnavigate by 636 following the route of Hanno, along the west coast. Among geographers should be mentioned Posidonius (135-51), the head of the Stoic school of Rhodes, who is stated to be responsible for having reduced the length of a degree to 500 stadia; Artemidorus of Ephesus, whose “Geographumena” (c. 100 B.C.) are based upon his own travels and a study of itineraries, and above all, Strabo, who has already been referred to. Among historians who looked upon geography as an important aid in their work are numbered Polybius (c. 210-120 B.C.), Diodorus Siculus (c. 30 B.C.) and Agathachidus of Cnidus (c. 120 B.C.) to whom we are indebted for a valuable account of the Erythrean Sea and the adjoining parts of Arabia and Ethiopia. The Periegesis of Dionysius of Alexandria is a popular description of the world in hexameters, of no particular scientific value (c. A.D. 130). He as well as Artemidorus and others accepted a circular or ellipsoidal shape of the world and a circumfluent ocean; Strabo alone adhered to the scientific theories of Eratosthenes.

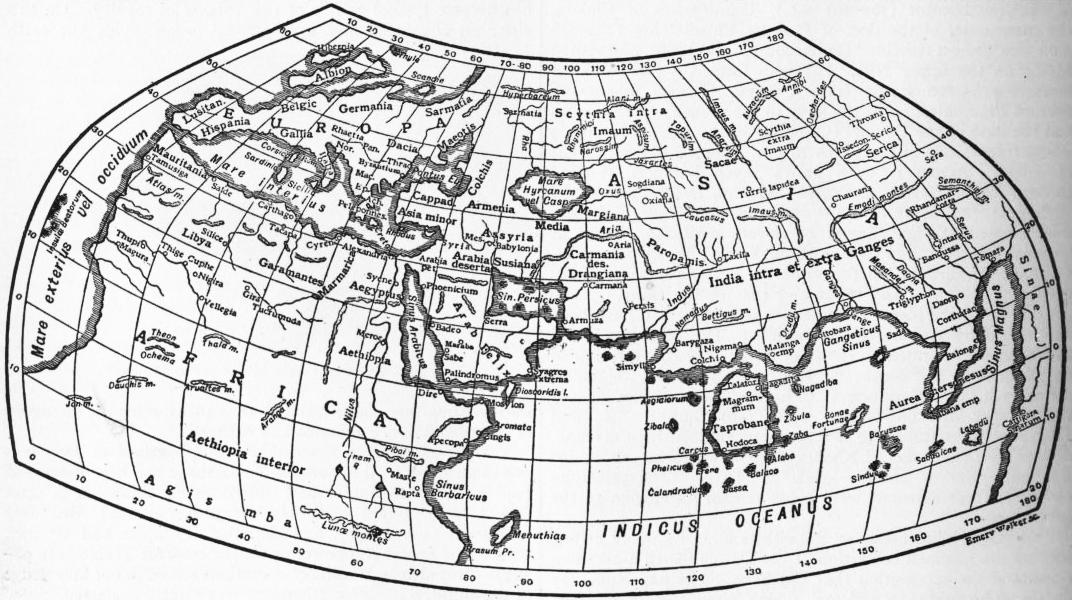

|

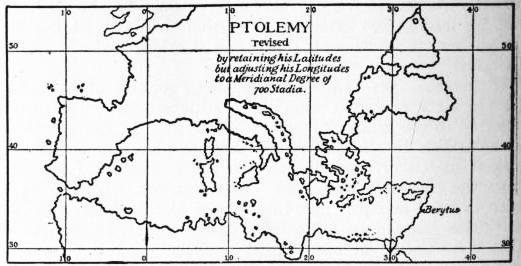

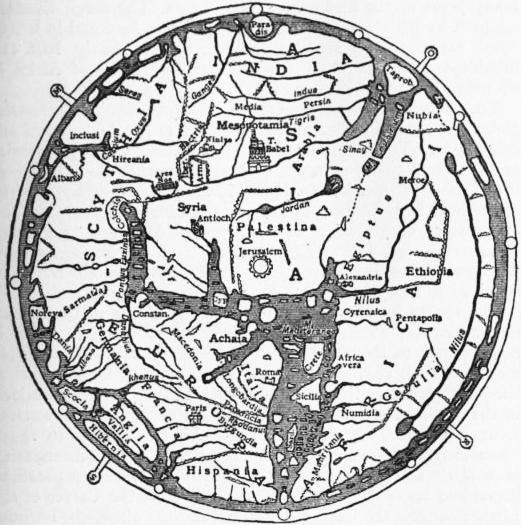

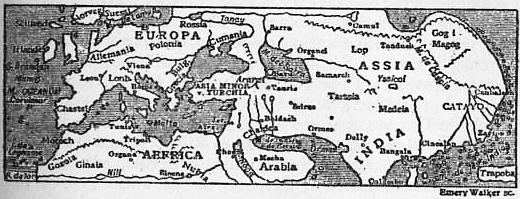

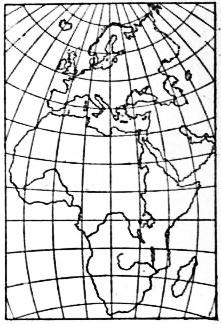

| Fig. 3.—Ptolemy’s Map. |

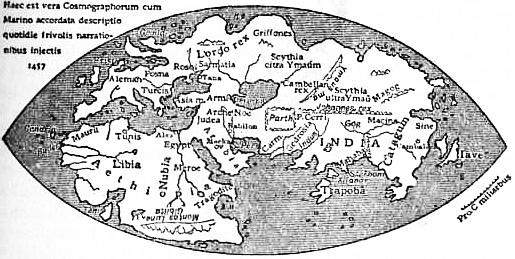

The credit of having returned to the scientific principles innovated by Eratosthenes and Hipparchus is due to Marinus of Tyre (c. A.D. 120) which, though no longer occupying the pre-eminent position of former times, was yet an emporium of no inconsiderable importance, having extensive connexions by sea and land. The map of Marinus and the descriptive accounts which accompanied it have perished, but we learn sufficient concerning them from Ptolemy to be able to appreciate their merits and demerits. Marinus was the first who laid down the position of places on a projection according to their latitude and longitude, but the projection used by him was of the rudest. Parallels and meridians were represented by straight lines intersecting each other at right angles, the relative proportions between degrees of longitude and latitude being retained only along the parallel of Rhodes. The distortion of the countries represented would thus increase with the distance, north and south, from this central parallel. The number of places whose position had been determined by astronomical observation was as yet very small, and the map had thus to be compiled mainly from itineraries furnished by travellers or the dead reckoning of seamen. The errors due to an exaggeration of distances were still further increased on account of his assuming a degree to be equal to 500 stadia, as determined by Posidonius, instead of accepting the 700 stadia of Eratosthenes. He was thus led to assume that the distance from the first meridian drawn through the Fortunate islands to Sera (mod. Si-ngan-fu), the capital of China, was equal to 225°, which Ptolemy reduced to 177°, but which in reality only amount to 126°. A like overestimate of the distances covering the march of Julius Maternus to Agisymba, which Marinus places 24° south of the equator, a latitude which Ptolemy reduces to 18°, but which is probably no farther south than lat. 12° N. The map of Marinus was accompanied by a list of places arranged according to latitude and longitude. It must have been much in demand, for three editions of it were prepared. Masudi (10th century) saw a copy of it and declared it to be superior to Ptolemy’s map.

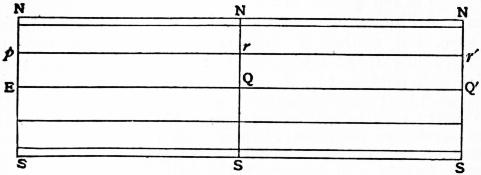

|

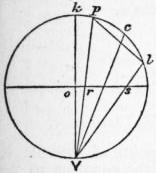

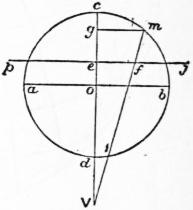

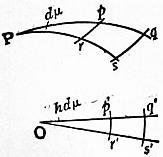

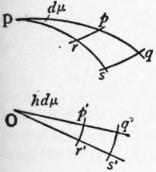

| Fig. 4. |

Ptolemy (q.v.) was the author of a Geography18 (c. A.D. 150) in eight books. “Geography,” in the sense in which he uses the term, signifies the delineation of the known world, in the shape of a map, while chorography carries out the same objects in fuller detail, with regard to a particular country. In Book I. he deals with the principles of mathematical geography, map projections, and sources of information with special reference to his predecessor Marinus. Books II. to VII. form an index to the maps. They contain about 8000 names, with their latitudes and longitudes, and with their aid it is possible to reconstruct the maps. These maps existed, as a matter of course, before such an index could be compiled, but it is doubtful whether the maps in our available manuscript, which are attributed to Agathodaemon, are copies of Ptolemy’s originals or have been compiled, after their loss, from this index. Book VIII. gives further details with reference to the principal towns of each map, as to geographical position, length of day, climata, &c.

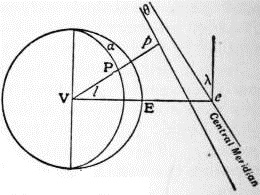

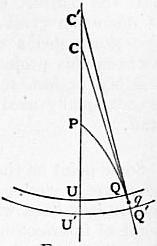

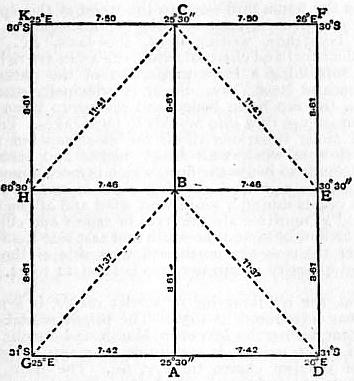

Ptolemy’s great merit consists in having accepted the views of Hipparchus with respect to a projection suited for a map of the world. Of the two projections proposed by him one is a modified conical projection with curved parallels and straight meridians; in the second projection (see fig. 3) both parallels and meridians are curved. The correct relations in the length of degrees of latitude and longitude are maintained in the first case along the latitude of Thule and the equator, in the second along the parallel of Agisymba, the equator and the parallels of Meroe, Syene and Thule. Following Hipparchus he divided the equator into 360° drawing his prime meridian through the Fortunate Islands (Canaries). The 26 special maps are drawn on a rectangular projection. As a map compiler Ptolemy does not take a high rank. In the main he copied Marinus whose work he revised and supplemented in some points, but he failed to realize the peninsular shape of India, erroneously exaggerated the size of Taprobane (Ceylon), and suggested that the Indian Ocean had no connexion with the western ocean, but formed Mare Clausum. Ptolemy knew but of a few latitudes which had been determined by actual observation, while of three longitudes resulting from simultaneous observation of eclipses he unfortunately accepted the least satisfactory, namely, that which placed Arbela 45° to the east of Carthage, while the actual meridian distance only amounts to 34°. An even graver source of error was Ptolemy’s acceptance of a degree of 500 instead of 700 stadia. The extent to which the more correct proportion would have affected the delineation of the Mediterranean is illustrated by fig. 4. But in spite of his errors the scientific method pursued by Ptolemy was correct, and though he was neglected by the Romans and during the middle ages, once he had become known, in the 15th century, he became the teacher of the modern world.

Map-Making among the Romans.—We learn from Cicero, Vitruvius, Seneca, Suetonius, Pliny and others, that the Romans had both general and topographical maps. Thus, Varro (De rustici) mentions a map of Italy engraved on marble, in the temple of Tellus, Pliny, a map of the seat of war in Armenia, of the time of the emperor Nero, and the more famous map of the Roman Empire which was ordered to be prepared for Julius Caesar (44 B.C.), but only completed in the reign of Augustus, who placed a copy of it, engraved in marble, in the Porticus of his sister Octavia (7 B.C.). M. Vipsanius Agrippa, the son-in-law of Augustus (d. 12 B.C.), who superintended the completion of this famous map, also wrote a commentary illustrating it, quotations from which of Ammianus Marcellinus of Antioch (d. 330), Pliny and others, afford the only means of judging of its character. The map is supposed to be based upon actual surveys or rather reconnaissances, and if it be borne in mind that the Roman Empire at that time was traversed in all directions by roads furnished with mile-stones, that the Agrimensores employed upon such a duty were skilled surveyors, and that the official reports of the commanders of military expeditions and of provincial governors were available, this map, as well as the provincial maps upon which it was based, must have been a work of superior excellence, the loss of which is much to be regretted. A copy of it may possibly have been utilized by Marinus and Ptolemy in their compilations. The Romans have been reproached for having neglected the scientific methods of map-making advocated by Hipparchus. Their maps, however, seem to have met the practical requirements of political administration and of military undertakings.

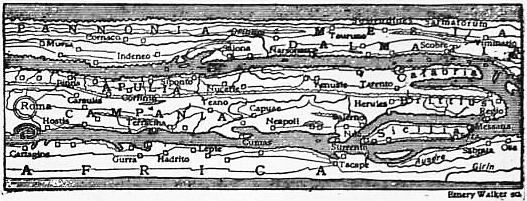

Only two specimens of Roman cartography have come down to us, viz. parts of a plan of Rome, of the time of the emperor 637 Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211), now in the Museo Capitolino, and an itinerarium scriptum, or road map of the world, compressed within a strip 745 mm. in length and 34 mm. broad. Of its character the reduced copy of one of its 12 sections (fig. 5) conveys an idea. The map, apparently of the 3rd century, was copied by a monk at Colmar, in 1265, who fortunately contented himself with adding a few scriptural names, and having been acquired by the learned Conrad Peutinger of Augsburg it became known as Tabula peutingeriana. The original is now in the imperial library of Vienna.19

|

| Fig. 5.—A Section of Peutinger’s Tabula. |

|

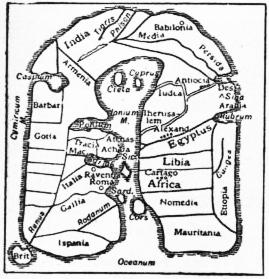

| Fig. 6.—The World according to Cosmas Indicopleustes (535). |

|

| Fig. 7.—Map of Albi (8th century). |

Map-Making in the Middle Ages.—In scientific matters the early middle ages were marked by stagnation and retrogression. The fathers of the church did not encourage scientific pursuits, which Lactantius (4th century) declared to be unprofitable. The doctrine of the sphericity of the earth was still held by the more learned, but the heads of the church held it to be unscriptural. Pope Zachary, when in 741 he condemned the views of Virgilius, the learned bishop of Salzburg, an Irishman who had been denounced as a heretic by St Boniface, declares it to be perversa et iniqua doctrina. Even after Gerbert of Aurillac, better known as Pope Sylvester II. (999-1063), Adam of Bremen (1075), Albertus Magnus (d. 1286), Roger Bacon (d. 1294), and indeed all men of leading had accepted as a fact and not a mere hypothesis the geocentric system of the universe and sphericity of the globe, the authors of maps of the world, nearly all of whom were monks, still looked in the main to the Holy Scriptures for guidance in outlining the inhabited world. We have to deal thus with three types of these early maps, viz. an oblong rectangular, a circular and an oval type, the latter being either a compromise between the two former, or an artistic development of the circular type. In every instance the inhabited world is surrounded by the ocean. The authors of rectangular maps look upon the Tabernacle as an image of the world at large, and believe that such expressions as the “four corners of the earth” (Isa. x. 12), could be reconciled only with a rectangular world. On the other hand there was the expression “circuit of the earth” (Isa. xl. 22), and the statement (Ezek. v. 5) that “God had set Jerusalem in the midst of the nations and countries.” In 638 nearly every case the East occupies the top of the map. Neither parallels nor meridians are indicated, nor is there a scale. Other features frequently met with are the Paradise in the Far East, miniatures of towns, plants, animals, human beings and monsters, and an indication of the twelve winds around the margin.

|

| Fig. 8.—Anglo-Saxon Map of the World (9th century). |

The oldest rectangular map of the world is contained in a most valuable work written by Cosmas, an Alexandrian monk, surnamed Indicopleustes, after returning from a voyage to India (535 A.D.), and entitled Christian Topography. According to Cosmas (fig. 6) the inhabited earth has the shape of an oblong rectangle surrounded by an ocean which breaks in in four great gulfs—the Roman or Mediterranean, the Arabian, Persian and Caspian Sea. Beyond this ocean lies another world, which was occupied by man before the Deluge, and within which Cosmas placed the Terrestrial Paradise. Above this rise the walls of the heavens like unto the tent of the Tabernacle. Far more simple is a small map of the world of the 8th century found in a codex in the library of Albi, an archiepiscopal seat in the department of Tarn. Its scanty nomenclature is almost wholly derived from the “Historiae adversum paganos” of Paulus Orosius (418). Far greater interest attaches to the so-called Anglo-Saxon Map of the World in the British Museum (Cotton MSS.), where it is bound up in a codex which also contains a copy of the Periegesis of Priscianus. Map and Periegesis are copies by the same hand, but no other connexion exists between them. More than half the nomenclature of the map is derived from Orosius, an annotated Anglo-Saxon version of which had been produced by King Alfred (871-901). The Anglo-Saxons of the time were of course well acquainted with Island (first thus named in 870) Slesvic and Norweci (Norway), and there is no need to have recourse to Adam of Bremen (1076) to account for their presence upon this map. The broad features of the map were derived no doubt from an older document which may likewise have served as the basis for the map of the world engraved on silver for Charlemagne, and was also consulted by the compilers of the Hereford and Ebstorf maps (see fig. 11).

|

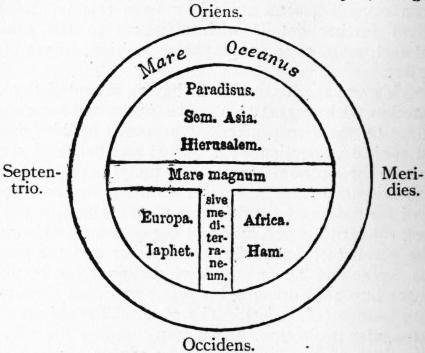

| Fig. 9.—T map from Isidor of Seville’s Origines. |

The map or diagram of which Leonardo Dati in his poem on the Sphere (Della Spera) wrote in 1422 “un T dentre a uno O mostra il disegno” (a T within an O shows the design) is one of the most persistent types among the circular or wheel maps of the world. It perpetuates the tripartite division of the world by the ancient Greeks and survives in the Royal Orb. A diagram of this description will be found in Isidor of Seville’s Origines (630), see fig. 9.

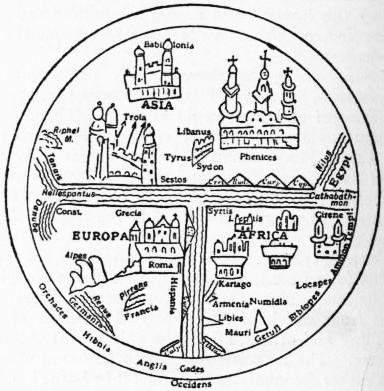

T maps of more elaborate design illustrate the MS. copies of Sallust’s Bellum jugurthinum; one of these taken from a codex of the 11th century in the Leipzig town library is shown in fig. 10.

|

| Fig. 10.—Map illustrating Sallust’s Bellum jugurthinum (11th century, Leipzig). |

The outlines of several medieval maps resemble each other to such an extent that there can be no doubt that they are derived from the same original source. This source by some authors is assumed to have been the official map of the Roman Empire, but if we compare the crude outline given to the Mediterranean with the more correct delineation of Ptolemy, who was certainly in a position to avail himself of these official sources, such an assumption is untenable. The earliest delineation of the description has already been referred to as the Anglo-Saxon map of the world. Next in the order of age, follows the oval map which Henry, canon of Mayence Cathedral, dedicated to Mathilda, consort of the emperor Henry V. (1110). Of far greater importance is the map seen in Hereford Cathedral. It is the work of Richard of Haldingham, and has a diameter of 134 cm. (53 ins.). The “survey” ordered by Julius Caesar is referred to in the legend, evidently derived from the Cosmography of 639 Aethicus a work widely read at the time, but this does not prove that the author was able to avail himself of a map based upon that survey. A map essentially identical with that of Hereford, but larger—its diameter is 15.6 cm. (6 in.), and consequently fuller of information—was discovered in 1830 in the old monastery of Ebstorf in Hanover. Its date is 1484. Both maps abound in miniature pictures of towns, animals, fabulous beings and other subjects. The Hereford map is surmounted by a picture of the Day of Judgment. Similar in design, though much smaller of scale and oval in form, are the maps which illustrate the popular Polychronicon of Ranulf Higden, a monk of St Werburgh’s Abbey of Chester (d. 1363).

|

| Fig. 11.—The Hereford Map (c. 1280). |

|

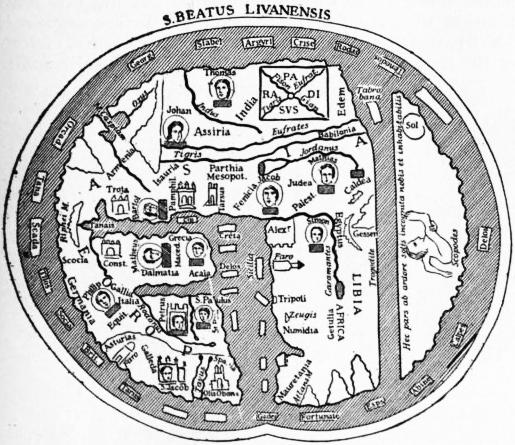

| Fig. 12.—The Map of Beatus (776). |

Pomponius Mela tells us that beyond the Ethiopian Ocean which sweeps round Africa in the south and the uninhabitable torrid zone, there lies an alter orbis, or fourth part of the world inhabited by Antichthones. On a diagram illustrating the origines of Isidore of Seville (d. 636) this country is shown, but is described as a terra inhabitabilis. It is shown likewise upon a number of maps which illustrate the Commentaries on the Apocalypse, by Beatus, a Benedictine monk of the abbey of Valcavado at the foot of the hills of Liebana in Asturia (776).

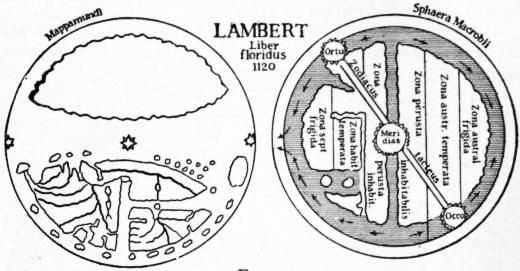

Our little map (fig. 12) is taken from a copy of Beatus’ work made in 1203, and preserved at Burgo de Osma in Castille. Similar maps illustrating the Commentaries exist at St Sever (1050), Paris (1203), and Tunis; others are rectangular, the oldest being in Lord Ashburnham’s library (970). Beatus, too, describes the southern land as inhabitabilis. The habitable world is divided among the twelve apostles, whose portraits are given. On the maps illustrating the encyclopaedic Liber floridus by Lambert, a canon of St Omer (1120), this south land “unknown to the sons of Adam,” is stated to be inhabited “according to the philosophers” by Antipodes. Lambert, indeed, seems to have believed in the sphericity of the earth. Fig. 13 shows his map of the world reduced from a MS. at Wolfenbüttel, to which is added a diagram of the zones from a MS. at Ghent, which illustrates Macrobius’ commentary on Cicero’s Somnium Scipionis. Diagrams illustrating the division of the world into climata, are to be found in the opus majus of Roger Bacon (d. 1294) and in Cardinal Pierre d’Ailly’s De imagine Mundi (1410).

|

| Fig. 13. |

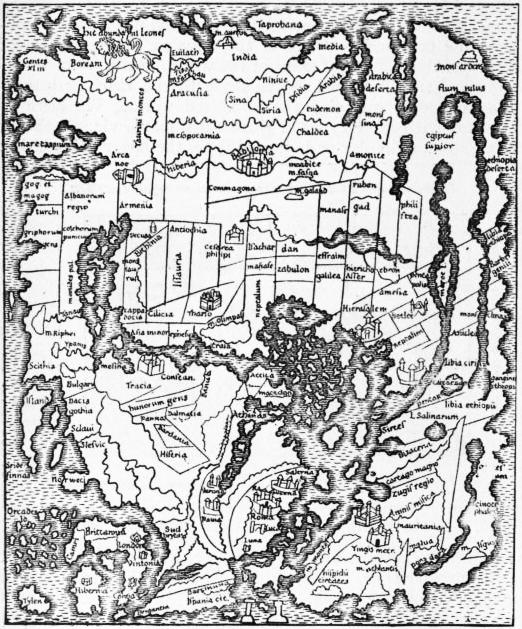

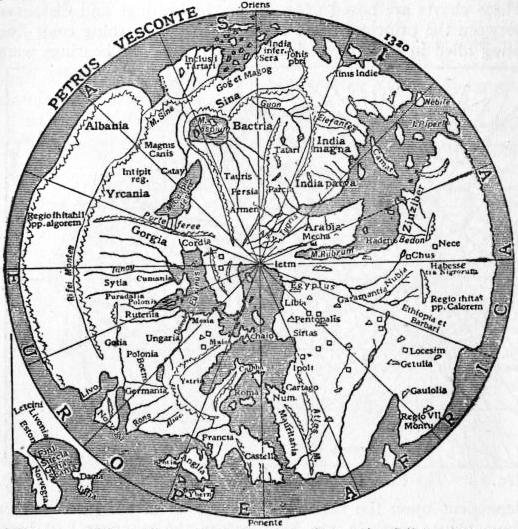

Among countries represented on a larger scale on maps, Palestine not unnaturally occupies a prominent place in this age of pilgrimages and crusades (1095-1291). The maps which accompany St Jerome’s translation of the Onomasticon of St Eusebius (388). The same subject is illustrated by a picture-map in mosaic, portions of which were discovered in 1896 on the floor of the church of Madaba to the east of the Dead Sea. This is the oldest original of a map in existence, for it dates back to the 6th century. Among more recent maps of Palestine, that by Petrus Vesconte (1320) is greatly superior to the earlier maps. It illustrates Marino Sanuto’s Secreta fidelium crucis, in which its author vainly appeals to Christendom to undertake another crusade. One of the earliest plans of Jerusalem is contained in Gesta Francorum, a history of the Crusades up to 1106, based upon information furnished by Fulcherius of Chartres (c. 1109).

|

| Fig. 14.—Matthew of Paris (1236-1259). |

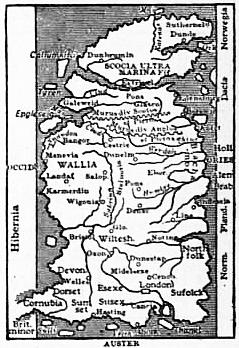

There existed, no doubt, special maps of European countries, but the only documents of that description are two maps of Great Britain, the one of the 12th century, the other by Matthew of Paris, the famous historiographer of the monastery of St Albans (1236-1259).20

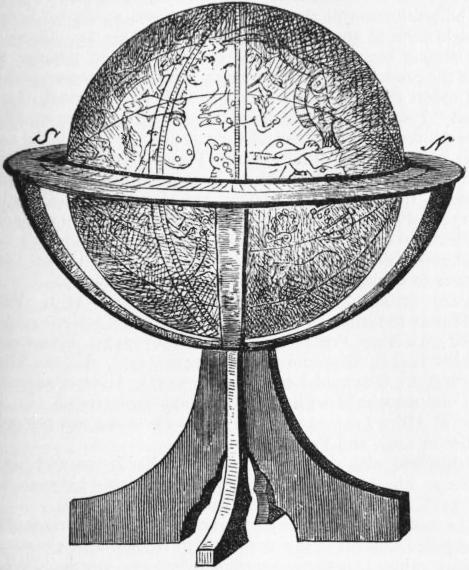

Celestial globes were known in the time of Bede; they formed part of the educational apparatus of the monastic schools. Gerbert of Aurillac is known to have made such globes (929). Their manufacture is described by Alphonso the Wise (1252), as also in De sphaera solida of G. Campanus of Novara (1303). Terrestrial globes, however, are not referred to.

Map-making among the Arabians and other Nations of the East.—Bagdad early became a famous seat of learning. Indian astronomers found apt pupils there among the Arabs; the works of 640 Ptolemy were translated into Arabic, and in 827, in the reign of the caliph Abdullah al Mamun, an arc of the meridian was measured in the plain of Mesopotamia. Most famous among these Arabian astronomers were Al Batani (d. 998), Ibn Yunis of Cairo (d. 1008), Zarkala (Azarchel), who determined the meridian distance between his observatory in Toledo and Bagdad to amount to 51° 30′, an error of 3° only, as compared with Ptolemy’s error of 18°, and Abul Hassan (1230) who reduced the great axis of the Mediterranean to 44°.

|

| Fig. 15.—Idrisi (1154). |

|

| Fig. 16.—Idrisi (1154). |

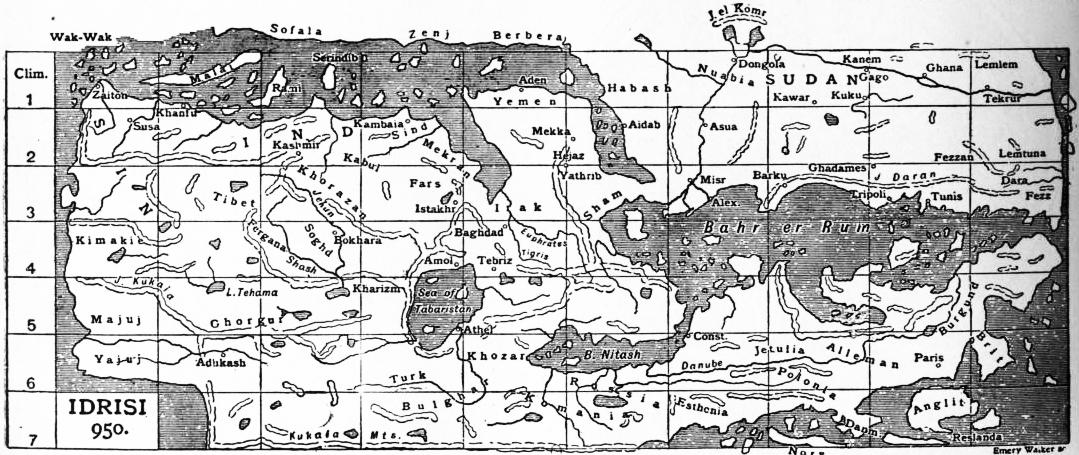

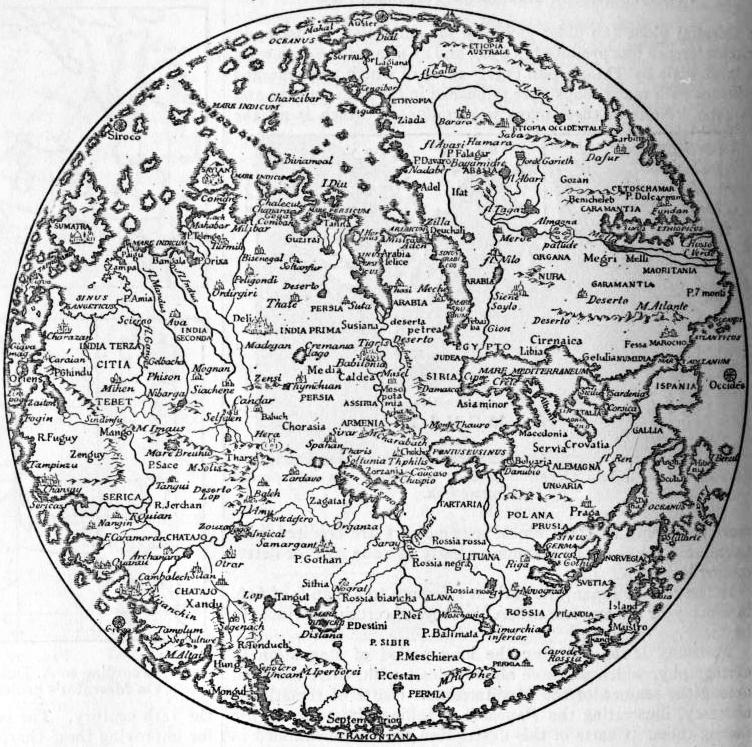

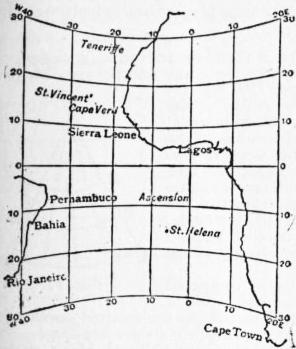

Further materials serviceable to the compilers of maps were supplied by numerous Arabian travellers and geographers, among whom Masudi (915-940), Istakhri (950), Ibn Haukal (942-970), Al Biruni (d. 1038), Ibn Batuta (1325-1356) and Abul Feda (1331-1370), occupy a foremost place, yet the few maps which have reached us are crude in the extreme. Masudi, who saw the maps in the Horismos or Rasm el Ard, a description of the world by Abu Jafar Mahommed ben Musa of Khiva, the librarian of the caliph el Mamun (833), declares them to be superior to the maps of Ptolemy or Marinus, but maps of a later date by Istakhri (950) or Ibn al Wardi (1349) are certainly of a most rudimentary type. Nor can Idrisi’s map of the world, which was engraved for King Roger of Sicily upon a silver plate, or the rectangular map in 70 sheets which accompanies his geography (Nushat-ul Mushtat) take rank with Ptolemy’s work. These maps are based upon information collected during many years at the instance of King Roger. The seven climates adopted by Idrisi are erroneously supposed to be equal in latitudinal extent. The Mediterranean occupies nearly half the inhabited world in longitude, and the east coast of Africa is shown as if it extended due east.

The Arabians are not known to have produced a terrestrial globe, but several of their celestial globes are to be found in our collections. The oldest of these globes was made at Valentia, and is now in the museum of Florence. Another globe (of 1225) is at Velletri; a third by Ibn Hula of Mosul (1275) is the property of the Royal Asiatic Society of London; a fourth (1289) from the observatory of Maragha, in the Dresden Museum, two globes of uncertain age at Paris (see fig. 17) and another in London. All these globes are of metal (bronze), or they might not have survived so many years.

The charts in use of the medieval navigators of the Indian Ocean—Arabs, Persians or Dravidas—were equal in value if not superior to the charts of the Mediterranean. Marco Polo mentions such charts; Vasco da Gama (1498) found them in the hands of his Indian pilot, and their nature is fully explained in the Mohit or encyclopaedia of the sea compiled from ancient sources by the Turkish admiral Sidi Ali Ben Hosein in 1554.21 These charts are covered with a close network of lines intersecting each other at right angles. The horizontal lines are parallels, depending upon the altitude of the pole star, the Calves of the Little Bear and the Barrow of the Great Bear above the horizon. This altitude was expressed in isbas or inches each equivalent to 1° 42′ 50″. Each isba was divided into zams or eights. The interval between two parallels thus only amounted to 12′ 51″. These intervals were mistaken by the Portuguese occasionally for degrees, which account for Malacca, which is in lat. 2′ 13″ N., being placed on Cantino’s Chart (1502) in lat. 14′ S. It may have been a map of this kind which accounts for Ptolemy’s moderate exaggerations of the size of Taprobana (Ceylon). A first meridian, separating a leeward from a windward region, passed through Ras Kumhari (Comorin) and was thus nearly identical with the first meridian of the Indian astronomers which passed through the sacred city of Ujjain (Ozere of Ptolemy) or the meridian of Azin of the Arabs. Additional meridians were drawn at intervals of zams, supposed to be equal to three hours’ sail.

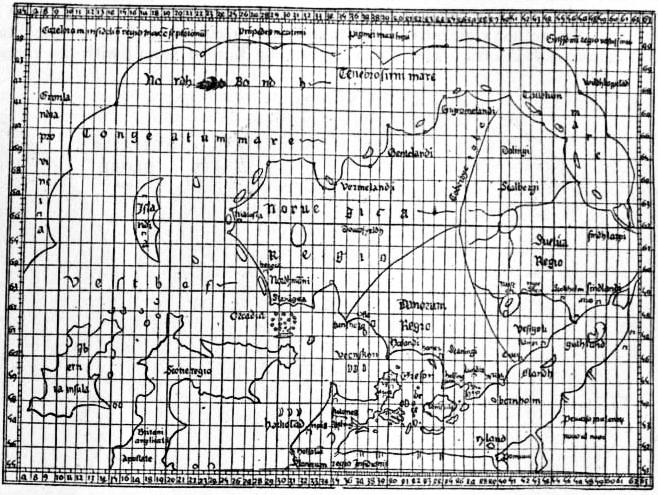

In China, maps in the olden time were engraved on bronze 641 or stone, but after the 10th century they were printed from wood-blocks. Among the more important productions of more recent times, may be mentioned a map of the empire, said to be based upon actual surveys by Yhang (721), who also manufactured a celestial globe (an older globe by Ho-shing-tien, 4 metres in circumference, was produced in 450), and an atlas of the empire on a large scale by Thu-sie-pun (1311-1312) of which new enlarged editions with many maps were published in the 16th century and in 1799. None of these maps was graduated, which is all the more surprising as the Chinese astronomers are credited with having made use of the gnomon as early as 1000 B.C. for determining latitudes.

|

| Fig. 17.—Globe in Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris |

|

| Fig. 18.—The Indian Ocean according to Mohit, as interpreted by Dr Tomaschek. |

In the case of Japan, the earliest reference to a map is of 646, in which year the emperor ordered surveys of certain provinces to be made.

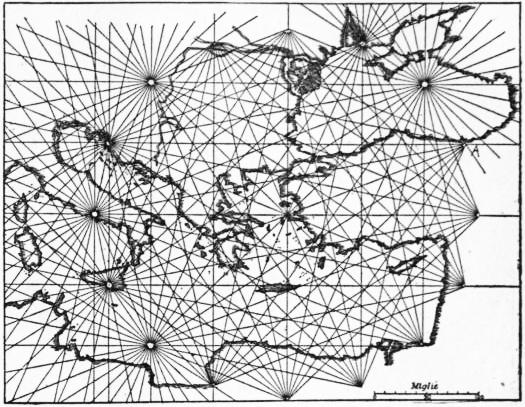

Portolano Maps.—During the long period of stagnation in cartography, which we have already dealt with, there survived among the seamen of the Mediterranean charts of remarkable accuracy, illustrating the Portolani or sailing directories in use among them. Charts of this description are first mentioned in connexion with the Crusade of Louis XI. in 1270, but they originated long before that time, and in the eastern part of the Mediterranean they embody materials available even in the days before Ptolemy, while the correct delineation of the west seems to be of a later date, and may have been due to Catalan seamen. These charts are based upon estimated bearings and distances between the principal ports or capes, the intervening coast-line being filled in from more detailed surveys. The bearings were dependent upon the seaman’s observation of the heavens, for these charts were in use long before the compass had been introduced on board ship (as early as 1205, according to Guiot de Provins) although it became fully serviceable only after the needle had been attached to the compass card, an improvement probably introduced by Flavio Gioja of Amalfi in the beginning of the 14th century. The compass may of course have been used for improving these charts, but they originated without its aid, and it is therefore misleading to describe them as Compass or Loxodromic charts, and they are now known as Portolano charts.

|

| Fig. 19.—The Eastern Mediterranean, by Petrus Vesconte (1311). |

|

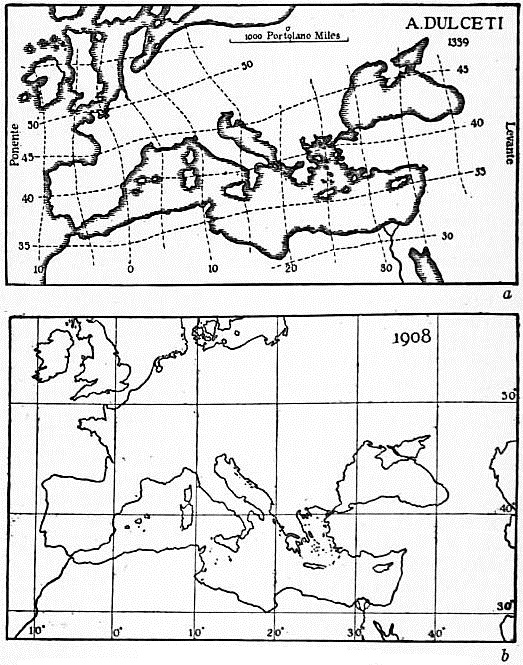

| Fig. 20.—The Mediterranean. |

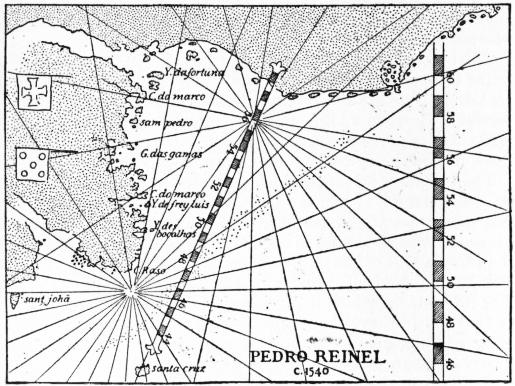

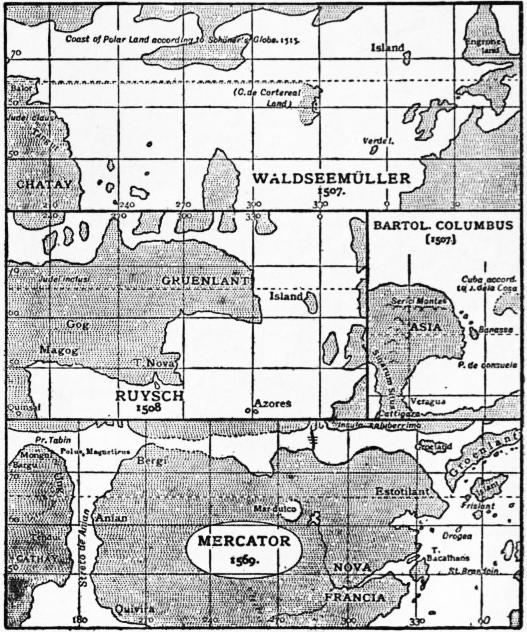

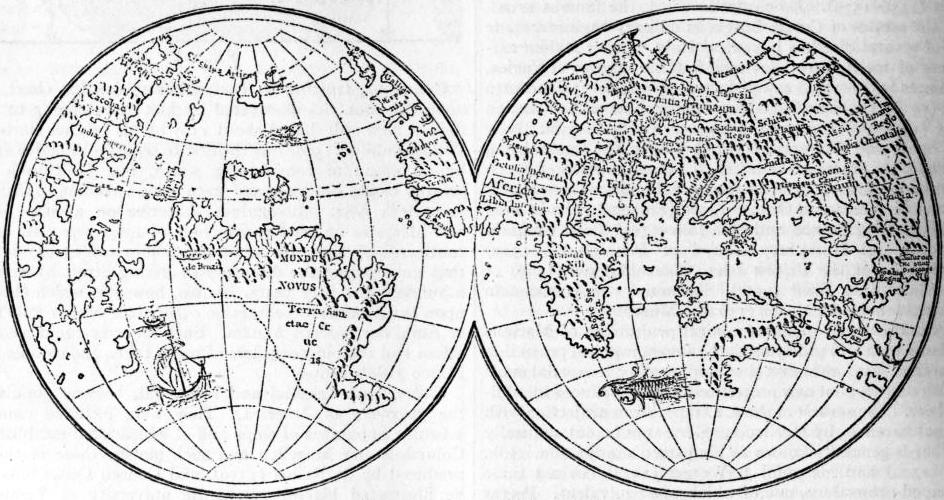

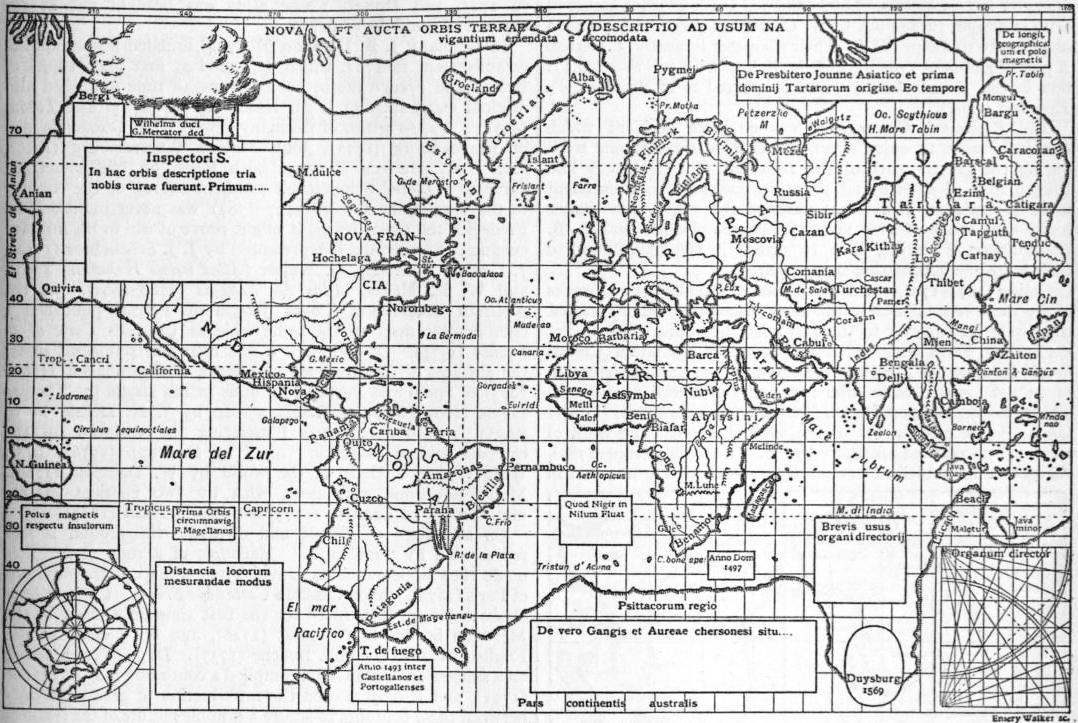

| a, According to A. Dulceti, 1339, and b, On Mercator’s projection, according to modern maps. |