Author of “The Round Towers of Ireland.”

THE ROUND TOWERS

OF IRELAND

OR

THE HISTORY OF THE TUATH-DE-DANAANS

BY

HENRY O’BRIEN

A NEW EDITION

WITH INTRODUCTION, SYNOPSIS, INDEX, ETC.

London: W. THACKER & CO., 2 Creed Lane, E.C.

Calcutta: THACKER, SPINK & CO.

1898

[All Rights Reserved]

750 Copies only of this Edition have been printed for Sale and the Type distributed, of which this is No. 324.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | vii |

| Synopsis | xxxvii |

| Dedication (First Edition) | lxi |

| Preface (First Edition) | lxiii |

| Dedication (Second Edition) | xciii |

| List of Illustrations | xcv |

| Author’s Text (Second Edition) | 1 |

| List of the Principal Irish Towers and Crosses | 525 |

| Index | 529 |

“When all is dark, who would object to a ray of light, merely because of the faulty or flickering medium by which it is transmitted? And if those round towers have been hitherto a dark puzzle and a mystery, must we scare away O’Brien, because he approaches with a rude and unpolished but serviceable lantern?”—Fraser’s Magazine for August 1835.

Henry O’Brien, the most daring and ingenious explorer of that recondite mystery, the origin and purpose of Irish Round Towers, was born in 1808. On both his father’s and his mother’s side he came of good descent,[1] being connected with two of the oldest and most influential families in the west of Ireland. At the time of his birth that branch of “the O’Briens” to which he belonged were settled in Kerry, where his father resided in a wild, mountainous district, known as Iveragh, forming a portion of the Marquis of Lansdowne’s Irish estates. That his family were in affluent circumstances is improbable, for up to the age of twelve the boy’s education seems to have been neglected in a way very uncommon with Irish people who are well off. “Though I could then tolerably well express myself in English,” he says,[2] referring to this portion of his life, “the train of my reflections always ran in Irish. From infancy I spoke that tongue; it was to me vernacular. I thought in Irish, I understood in Irish, and I composed in Irish”; and again, “I was twelve years of[Pg viii] age before ever I saw a Testament in any language.” From this unusual neglect, coupled with the fact of his becoming a private tutor soon after he had settled in London, and an obscure reference to certain “difficulties” at the outset of his career as an author, we are probably justified in assuming that money was a rather scarce commodity in the paternal home. There is, however, reason to suppose that when he had reached the age of twelve, or thereabouts, his education was taken in hand, though how, or by whom, does not appear. Evidence of his having been sent to school and placed under systematic and qualified instruction is not forthcoming. In fact, circumstances go to negative that supposition. His acquaintance with Greek and Latin authors seems to have been more extensive than accurate, and his quotations from them are marked by solecisms which any properly taught schoolboy would avoid, but in which the self-educated are prone to indulge. It is true that (at p. 481) he describes in terms of unqualified praise a “tutor” with whom he commenced the study of the Greek Testament; but there is internal evidence in the same passage that such praise was not wholly deserved, and that the tutor in question was certainly not the person referred to in Father Prout’s statement that O’Brien had been “brought up at the feet of the Rev. Charles Boyton.”[3] Mr. Boyton was at the time a highly distinguished Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, who, in addition to holding the position of Greek Lecturer at that University, was the most eminent mathematical “coach” of his day; and the only connection likely to have existed between him and young O’Brien was that of college-tutor and undergraduate[Pg ix] in statu pupillari. The probability is, therefore, that any instruction which the boy received at this early period of his life was of a very elementary character, and that his education was mainly conducted by himself, a probability which is certainly not discounted by the wide and promiscuous character of his reading. From the outset of his introduction to letters he is known to have been an omnivorous reader of all books that came in his way, nor was his mode of studying classical authors that by which the scholastic proficiency essential to aspirants for success at college examinations is usually attained. O’Brien did not resemble the ordinary boy-student, to whom Roman or Greek classics represent merely a given quantity of “text” possessing certain peculiarities of diction or allusion which have to be nicely dissected, analysed, and mastered, but who regards the subject-matter of each work as being of very minor importance. On the contrary, he manifestly read them as authors, or rather authorities upon the subjects with which they respectively dealt, paying, so far as we can perceive, little or no attention to the diction or distinctive literary character of their writings. The result was what might be expected. If, whilst an undergraduate of Dublin University, it be true that he was regarded by many of his fellow-students as a prodigy of learning, their seniors appear to have been less enthusiastic about his scholarship, for we have not been able to discover his name in the college archives.[4] Still, from the fact of his having obtained, after he took his degree in 1831, the appointment of private tutor to the sons of the then Master of the Rolls,[5] it is possible that he may have distinguished himself previously.

[Pg x]What seems absolutely certain is, that during his stay at the University he must have availed himself to the full of opportunities presented by the library for which Trinity College is famous. Here, no doubt, he laid the foundation of that Oriental learning in which he was second to no Irishman of his day, and probably to few Englishmen. It is hardly too much to say that in the early part of the century Orientalism was comparatively untrodden ground. Sir William Jones had indeed, many years before, thoroughly explored this field of knowledge, but the results of his splendid labours had not as yet been properly assimilated by the general mass of readers, or supplemented to any remarkable extent by other workers in the same field. Hence the scope of European knowledge of the East was by no means so extensive then as now; and an enthusiastic student thereof, which O’Brien undoubtedly was, had it in his power to acquire an almost complete mastery of the subject, so far as it was then known. It was one peculiarly fitted to his ardent, dreamy, and speculative nature. He read, he pondered, he divined, he foresaw. Dark places in the history of his own country began to grow clear in the light of this Eastern dawn. Hitherto, like so many of his compatriots, he had found no way of accounting for the extraordinary contrast between the distinctive superiority of “the Ireland that was” and the relative obscurity of “the Ireland that is.” To what, he must apparently have asked himself, was the fact to be attributed, that a people who in days of old were admittedly pre-eminent in learning and civilisation, should have afterwards lost all claim to such distinction; or how was it that, in a land covered with the ruins of structures evincing the ripest skill and most fanciful artistic device, architecture should have sunk to a level that was almost barbarous? Why was it that this decadence did not take place gradually, as one would expect, but was plainly the result of a sudden check that stopped the erection of such edifices at once and for ever? Why were the materials, structure, and conformation of the edifices in question so different from those of other[Pg xi] ancient buildings found in their immediate neighbourhood? Why had their sculptured ornamentation reference to what was unconnected with, nay even opposed to, the teachings of that religious faith to which its execution was attributed; and why did the peasantry, inheriting the tradition of bygone ages, not recognise them as identified with that religion? Questions like these are very stimulating to inquisitive young souls, which usually become fired with an ambition to solve them; and as O’Brien pored over Sir William Jones and The Asiatic Researches—not to mention his beloved, though decried, Herodotus—it was only natural that he should draw certain conclusions from the undoubted affinity that exists between the languages, folk-lore, customs, superstitions, and modes of thought of his own country and those of the Orient. Similar conclusions had forced themselves upon older people who did not possess a tithe of his Eastern lore. Moore, that versatile Anacreontic, in his ill-fitting disguise of an Edinburgh Reviewer, avowed “That there exist strong traces of an Oriental origin in the language, character, and movements of the Irish people, no fair inquirer into the subject will be inclined to deny;” and it is further instanced by the same reviewer how the famous traveller, Bishop Pococke, on visiting Ireland after his return from the East, was much struck with “the amazing conformity” he observed between the Irish and the Egyptians.[6] From early childhood the questions to which we have referred seem to have been present to O’Brien—even from the time when he gazed upon the stunted ruin of Bally-Carbery Round Tower, not far from his father’s house, and had been told by awestruck peasants that the real name of that desolate and unsightly object was Cathoir Ghall, or “The Temple of Delight” (p. 48). Since then he had seen other and complete round towers; had noticed that all were of the same peculiar shape, and possibly had detected for himself, or learned from other sources, the existence of that phallic analogy upon which he so strongly insists.[Pg xii] He must have read in Sir William Jones and elsewhere how, in Eastern lands, the idea which lay beneath this same analogy formed the basis of a widespread religious faith, and was expressed in structures devoted to public worship. His next step was, almost inevitably, one of conjecture. If, as the voice of national tradition asserted, the round towers are “temples,” and if certain analogous associations are connected with them, might they not have been temples of a kindred religious belief? Having settled this to his own satisfaction, the speculation would naturally rise—How came that particular form of belief to prevail in Ireland? Was it native to the soil; or if not, by whom was it introduced, and when? His book being mainly an answer to these questions, we need not continue to follow the various stages by which conjecture may have passed into theory, and theory into conviction. With men of O’Brien’s temperament the hypothetical interval is rarely of long duration. Before he had assumed the toga virilis of a full-fledged graduate, he probably felt confident that in an Eastern origin lay the true solution of the mystery of the round towers; and the more he studied the subject, the stronger grew his belief. Being an ambitious man, too, he had no intention to forego the honour which he was persuaded must accrue to the discoverer of this key to a problem that had baffled so many generations of inquirers, and longed for an opportunity to display his acquisition.

That opportunity soon came. In December 1830, the Royal Irish Academy offered the prize of a gold medal and fifty pounds to “the author of an approved essay on the Round Towers, in which it is expected that the characteristic architectural peculiarities belonging to all those ancient buildings now existing shall be noticed, and the uncertainty in which their origin and uses are involved be satisfactorily removed.” Unfortunately, the advertisement of this offer escaped O’Brien’s notice, and he did not join in the competition which it evoked. But on the 21st February 1832 the advertisement was repeated, and this time it caught his attention. It declared that none of the essays[Pg xiii] which had been sent in “satisfied the conditions of the question,” and extended the period of competition for another three months (i.e. until 1st June 1832), in the alleged hope “of receiving other essays on said subject,” and also for allowing the authors of the essays already sent in “to enlarge and improve them.” Considering the task that was set, new competitors were thus placed at a singular disadvantage—being expected to do in three months what the others had been unable to accomplish in two years. With all due respect to the Royal Irish Academy, it is difficult to believe that its members can have fully realised the nature of their own conditions. There still exist some scores of round towers in a more or less perfect state; and they are scattered all over Ireland, being situated for the most part in remote and not easily accessible places. The work of visiting and inspecting these—which was, surely, a necessary preliminary to describing “the characteristic architectural peculiarities belonging to all”—would require much time, after which candidates must apply themselves to the by no means trifling task of dispelling “the uncertainty in which their origin and use are involved,” and all within three short months.[7] O’Brien was not, however, to be deterred by considerations of time or space when confronted with such a chance of winning deathless fame. Besides, he was, in one respect at any rate, well equipped for the enterprise, having already made up his mind as to the “origin and uses” of the Round Towers. That he had examined them all is not to be supposed, nor is it at all likely that at his age he could have possessed sufficient technical knowledge of architecture, in its historical and scientific aspects, to profit much by their inspection. Still, he was probably acquainted with whatever had been written on that branch of the subject, and had actually made an examination of some towers, which[Pg xiv] would give him a fair general idea of the whole. Moreover, he had a formidable quantity of Eastern learning to fall back upon, in which latter respect he would have enjoyed an immense advantage over all other possible competitors, if his judges had only been qualified to appreciate that learning as it deserved. Be his equipment for the enterprise what it might, the enthusiastic young Irishman saw no rocks ahead, felt no mistrust, and rushed into the fray. “I grappled with the question,” he assures us, “with all the ardour of my nature; and, heaven and earth, night and day, in difficulties and in sorrow, I laboured until I finished my ‘essay’ against the appointed hour, when—a brain blow to their (sc. the Academy’s) expectation—I sent it in—fully satisfied, from the consciousness of its imperturbable axioms, that all the powers of error and wickedness combined could not withhold from it the suffrage of the advertised medal.”[8] The meaning of this passionate reference to malign influences in the background will appear later on; as yet, he had no cause for misgiving on the subject of fair play, and his overweening self-confidence precluded any anticipation of failure. Bad omens seem to have attended his venture from the very outset. The Academy had requested that each essay should be inscribed with some motto; and it would appear that the motto appended to O’Brien’s was “Φωνη εν τη ερεμω” (sic[9])—a sorry introduction to the notice of learned Academicians.

The heartburnings of suspense, with which most young authors are familiar, soon began. Four days after his essay had been sent in, the Academy issued a third advertisement, requiring all the essays to be taken back, and extending the period of preparation by an additional month, “so as to admit of the receiving of other essays on said subject, and for allowing the authors of essays already given in to improve and enlarge them.” O’Brien [Pg xv]afterwards saw fit to attribute this fresh delay to a cause very different from that alleged; but just then, being persuaded that his triumph was merely postponed, he reconciled himself as best he could to the infliction, and calmly waited for apotheosis. Six months more passed by—wearily enough, we may be sure; and then, one direful morning, just at the close of 1832, came news that the premiums had been adjudged as follows:—“£50 and the gold medal to George Petrie, and £20 to Henry O’Brien, Esq.”

It may be stated here that an additional premium of £100, which had been placed by Lord Cloncurry at the disposal of the Academy, was also awarded in its entirety to Mr. Petrie, and that the essay sent in by that gentleman was, by order of the Academy, printed in their Transactions. It further appears that O’Brien’s essay was at first accepted for publication in the Transactions, but afterwards rejected on the ground of having been made too lengthy by the insertion of additional matter, though in its most enlarged form it never attained to the dimensions of Mr. Petrie’s work, and, presumably, must have been smaller in its original than in its present shape. The true reason for its exclusion from the Transactions (as will, we think, appear from what follows) was that the Academy took offence at the way in which O’Brien received their decision. Nor was such resentment to be wondered at. So confidently had our author reckoned upon an overwhelming triumph for the revelation which, as we have seen, he believed to be not only unprecedented, but given to the world with flawless perfection of statement, that the award seems to have almost maddened him. Belonging to a race which has never been remarkable for the silent endurance of wrongs, he lost no time in giving expression to his feelings of disappointment. At first came distant mutterings of the storm that was brewing. “On hearing of the decision,” he informs us, “I wrote off to the secretary, tendering, in indignant irony, my thanks for their adjudication, taking care, however, to tell[Pg xvi] them that I had expected an issue more flattering to my hopes.” This dignified attitude having apparently failed to imbue the Academy with a desire to remedy his grievance, he flung off the mask of satire, and rushed into downright, unmistakable personalities of a kind rarely addressed to august and learned associations. He declared that, from information which had come to his knowledge, he was prepared to prove “that the Royal Irish Academy, at the very moment in which they published their second invitation (i.e. that by which the time for receiving essays was extended to 1st June 1832), had actually determined to award the gold medal and premium to one of their own Council.”[10] He then went on to denounce the successful essay as “a farrago of anachronisms and historical falsehoods.” He prophesied that when both essays were published, and the public given an opportunity of seeing “the truth,” in the shape of his own essay, there would be a general acclamation of “This alone is right.” He warned the Academy that, “though separated from them by a roaring sea” (he was living in London at the time), his eye was on their plans, and he demanded from them an opportunity for making his ascription of the Round Towers “a mathematical demonstration by all the varieties and modes of proof”; and further, that upon such demonstration they should at once award him the gold medal and premium, “or, if that could not be recalled, an equivalent gold medal and premium”—not that, as he is careful to assure them, this offer was to be construed as an admission that his original essay was not “all-sufficient, all-conclusive, all-illustrative, and all-convincing.” As was only to be expected, the reply sent to this challenge ran to the effect that, “whatever might be the merits of any additional matter supplied to them after the day appointed by advertisement, the Academy could not make any alteration or revocation of their award.” Then[Pg xvii] came the rejoinder,—“I do not want them either to ‘alter’ or ‘revoke’ their award; but simply to vote me ‘an equivalent gold medal and premium’ for my combined essay, or, if they prefer, the new portion of it. Should this be refused, I will put my cause into the hands of the great God who has enlightened me, and make Him the Umpire between me and the Academy.”[11] One is not surprised to learn that “no answer was received to this communication,” which, as already pointed out, may have afforded one of the reasons why the Academy declined to publish the essay in their Transactions. We may sympathise with O’Brien’s disappointment, and even go further in deprecation of the attitude assumed by the Academy; but it is impossible to deny that his conduct showed a want of dignity and common sense, excusable only on the ground of youth.

As regards the Academy’s decision, assuming that the competition was conducted fairly,—and, a priori, everything seemed in favour of that assumption,—it is not easy to see how it could well have been other than it was. With all possible admiration for O’Brien’s talents and learning, candour obliges us to own that his essay—taken merely as a literary performance—was inferior to that of his rival. Apart from the question as to whether his theory was the true one, and that of Dr. Petrie the reverse, the Academy were in a manner bound by regard for their own dignity, and by the literary standard then prevailing, to withhold the meed of their unqualified approval from a composition which violated in so many respects the established precedents of literary “form,” not to mention the canons of good taste. Besides, O’Brien was, in archæological matters, so far in advance of his generation, that a body of elderly gentlemen, who simply represented the standard of knowledge prevalent at the time, might well be excused for declining to follow him. They had, in fact, to decide between the respective merits of two[Pg xviii] essays,—one of which was well put together, conforming, at least in appearance, to the stipulated conditions, expressing the most approved views, bearing the marks of careful and systematic investigation and of superior technical knowledge, also of literary skill much above the average; the other, daring, novel, incoherent, propounding views which were not only unfamiliar, but even shocking, to grave and reverend seignors, rambling in method, deficient in proof, and slipshod in language. Was it not, then, almost inevitable that they should have preferred the former? But if one has to pronounce upon the way in which the competition was started, carried on, and finally decided, we are by no means sure that O’Brien had not some reason to complain. First of all, with regard to his charge of the Academy having awarded the prize to a member of their own Council, the evidence to support it is primâ facie strong. Upon turning to vol. xvi. of the Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy, we find the names of “The Committee of Antiquities of the Council” for the year 1830 (that in which the competition was first invited) given as follows:—“Isaac D’Olier, LL.D.; Thomas Herbert Orpen, M.D.; Hugh Ferguson, M.D.; Sir William Betham; John D’Alton, Esq.; George Petrie, Esq.; and the Rev. Cæsar Otway.” In the next volume of the Transactions, extending to 1837, the above list is given without any alteration, except that Mr. D’Alton’s name is omitted, that of the Dean of St. Patrick’s being substituted. From this the inference seems only natural that “George Petrie, Esq.,” was a member of the Council (being likewise, as we find, “antiquarian artist to the Academy”) at the time when the idea of offering a prize for an essay on the Round Towers was first started; that he continued to be a member while the competition was in progress, and was actually one when the said prize was adjudicated. Next, as to the charge that the Academy had predetermined to award the prize to a member of its own Council, we have the very compromising letter of the Rev. Mr. Otway (himself a member of the Council) to the editor of the Dublin Penny[Pg xix] Journal, which is cited in the Preface to the first edition of this work,[12] coupled with those repeated postponements of the date for sending in essays, which O’Brien assures us were inexplicable on any other ground than that of giving Mr. Petrie time to finish his essay. We are far from contending that the reasons adduced in support of both these charges should weigh against the high repute which the Royal Irish Academy has always enjoyed from the time of its foundation; still, it is impossible to deny that, in the absence of all satisfactory explanation,—at least so far as we have been able to discover any,—they wear a rather ugly look.

O’Brien was resolved that, as the Academy would not publish his essay, he must do so himself; but in the meantime he had been engaged upon a translation of Dr. Villanueva’s Ibernia Phœnicia, which appeared in 1833. Personal liking for the author must have been his motive for undertaking this task, as his own views do not always harmonise with those of the Spanish savant; and certain letters which are quoted in the “Translator’s Preface” show that the two were very intimate. Having made this concession to friendship, he busied himself with the production of an enlarged and amended version of his essay. The first edition of this was published, early in 1834, by Whittaker & Co. of London, and J. Cumming of Dublin. It seems to have met with a ready sale, for a second edition appeared during the same year, bearing the imprint of Parbury & Allen, London, and J. Cumming, Dublin. Both editions are in octavo, and to outward appearance uniform, but differ in some respects. On the title-page of the first it is described as the “Prize Essay of the Royal Irish Academy, enlarged”—a description omitted in the second. Further, the title itself is given as “The Round Towers of Ireland (or the Mysteries of Freemasonry, of Sabaism, and of Budhism, for the first time unveiled)”; but the words within brackets are absent from the title-page of the second. A few corrections, too, appear in the latter[Pg xx] edition; but, upon the whole, it is not much more carefully edited than the first—the curious omission of chapters vii. and xxxii. being common to both. What is known in the book-trade as “The Long Preface,” together with an amusingly comprehensive “Dedication,” is omitted from the second edition, a much more commonplace dedication to the Marquis of Lansdowne (described, of course, as “The Mæcenas of his age”) being substituted for the latter. As the second, and last, edition is that which had the author’s latest revisions, it has been thought advisable to reproduce it in the present issue. No interference with its text has been attempted—typography and pagination being alike preserved. Nor has anything in the shape of comment been inserted. A few supplementary additions to the original work will probably not be considered out of place. Together with this Introduction, they comprise a “Synopsis,” of which the object is to assist readers in following the track of the main argument—not always an easy task in the face of the author’s numerous divagations, annotated lists of the principal Round Towers and crosses, and an Index to the body of the work.

The reception accorded to the book by those whose verdict was most important to its success, was decidedly hostile, and—what must have been especially galling to a man like O’Brien—took the shape of ridicule. Though it cannot be said that he had given no occasion for the latter, it is equally apparent that much of it was owing to ignorance; for there is not to be found among all the censorious judgments of those “irresponsible reviewers” a single attempt at sterling criticism. They attacked his style, and they laughed his theory out of court, but they never resorted to anything that deserved to be called refutation; and showed plainly by the character of their strictures that they were quite in the dark with respect to the nature of the evidence which he adduced in support of his statements. It was profanely said of the late Professor Jowett, that whatever he did not happen to know was held by him not to be knowledge; and such was the view which his[Pg xxi] critics seem to have taken of O’Brien’s dependence upon Eastern authorities, with which they themselves were unfamiliar. As occasionally happens in Irish affairs, a countryman of his own led the attack. In one of the weakest articles that ever appeared in the Edinburgh Review,[13] Moore, the poet, accused O’Brien of plagiarism and other misdeeds. Considering the extent of Moore’s acquaintance with Oriental literature, and the character of his mind, it is perhaps not surprising that he mistakes the whole drift of O’Brien’s argument, fails to perceive the force of those analogies upon which the latter chiefly relied, and, in fact, only succeeds in proving his own incapacity as a critic. But it is less conceivable that he should seek to overwhelm a young aspirant for literary honours, who was of his own nationality, and with whom he was on terms of at least nominal friendship, with unfounded charges and clumsy ridicule. The secret of this otherwise unaccountable severity is disclosed to us by “Father Prout,” in his article on “The Rogueries of Tom Moore.” From it we learn that Moore had endeavoured unsuccessfully to secure the co-operation of O’Brien in his forthcoming History of Ireland, and that, upon the negotiation falling through, a “coolness” ensued between the two. As “Father Prout” had the whole correspondence laid before him, the story does not rest upon O’Brien’s own version of what took place. But, be it reliable or not, there is no denying that the poet went out of his way—and out of his depth, too—in the effort to crush a young author, who might fairly be supposed to have some claim upon his sympathy. The scent which Moore thus struck was followed up by the whole critical pack. The Gentleman’s Magazine, for instance,[14] without attempting anything like serious criticism, quizzed O’Brien unmercifully. He [Pg xxii]committed the fatal indiscretion of sending a lengthy, but for him most temperate, reply, in which he is fain to cite the Freemason’s Quarterly Review as his solitary backer. The Gentleman’s Magazine reserved its answer until he was no more; when, in an obituary notice (November 1835), it flung back this retort: “Fondly imagining that he was the author of most profound discoveries, and as it were the discoverer of a new historical creed, Mr. O’Brien was always in a state of the highest excitement; and when his lucubrations were treated with ridicule instead of serious refutation, he was acutely irritated”—which last observation somehow reminds one of that fastidious man-o’-war’s man, who, whether the bo’sun “hit him high or hit him low,” took no pleasure in being flogged. In fact, there was no real scholarly criticism of the book from any quarter, though its eccentricities of style and treatment received due attention. Superficially regarded, indeed, it bristled with salient points for attack, and of these the gentlemen of the press naturally availed themselves. They described it as “wild and extravagant”—and no one could say them nay; but they failed to point out, probably because they failed to see, that under this same wildness and extravagance lay profound knowledge of a most unusual kind, powerful if somewhat erratic reasoning, and the only theory as to the genesis of ancient Irish proficiency in the arts of civilisation which is consistent with the traditions, customs, superstitions, folk-lore, and antiquities of the country.

O’Brien had now settled in London, where such time as could be spared from his tutorial duties was spent in the study of his favourite literature. It appears that he had at least two works then in contemplation—one a Dissertation on the Pyramids, partly written, and the other a Celtic Dictionary—which latter project excited the ribaldry, altogether unfounded,[15] of certain critics. His health, never strong, was now such as to cause some apprehension to his friends; still he was able to share the pleasures which London life affords. He went into the fashionable [Pg xxiii]world—which, by the way, does not appear to have taken him quite seriously, while acknowledging his talents and erudition. The Marquis of Lansdowne’s house was open to him; and mainly, no doubt, through the influence of that kindly nobleman, he was even presented at Court. The military career, for which, as he informs us (p. 130), he had a predilection second only to “his love for truth and the rectification of his country’s honour,” was no longer an object of ambition; and he may be regarded as having resigned himself contentedly to the peaceful avocations of a man of letters. Bad health, aggravated by his studious habits, seems indeed to have been the only drawback from which he suffered; but although this had previously excited the apprehension of his friends, it was without any immediate warning that the end came. He had been paying a visit to some acquaintances in the suburbs of London; had spent with them an evening, during which he displayed his usual cheerfulness and vivacity; had retired to rest without any symptoms of indisposition; and the next morning was found lifeless in his bed,—death having, to all appearance, taken place quite painlessly during sleep. By those who knew him he was mourned, and by none more sincerely than the genial “Father Prout,” who added the following postscript to his article on “The Rogueries of Tom Moore,” already in print when the news of his young friend’s death reached him:—

“Mem.—On the 28th of June 1835, died, at The Hermitage, Hanwell, Henry O’Brien, author of The Round Towers of Ireland. His portrait was hung up in the gallery of Regina on the 1st August following; and the functionary who exhibits the ‘Literary Characters’ dwelt thus on his merits:—

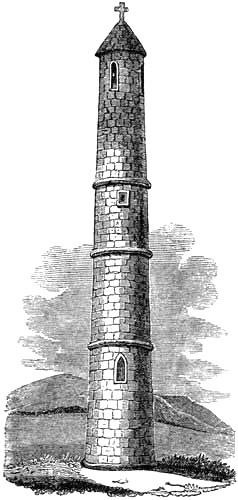

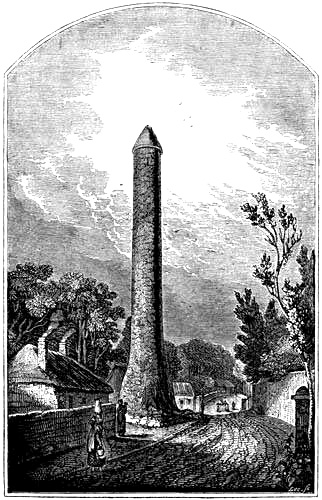

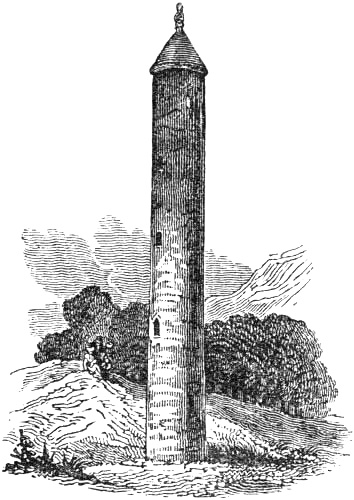

“In the village graveyard of Hanwell (ad viii. ab urbe lapidem) sleeps the original of yonder sketch.... Some time back we had our misgivings that the oil in his flickering lamp of life would soon dry up; still we were not prepared to hear of his light being thus abruptly extinguished. “One morn we missed him” from the accustomed table at the library of the British Museum, where the page of antiquity awaited his perusal; “another came—nor yet” was he to be seen behind the pile of Asiatic Researches, poring over his favourite Herodotus, or deep in the Zendavesta. “The next” brought tidings of his death. His book on the Round Towers has thrown more light on the early history of Ireland, and on the freemasonry of those [Pg xxiv]gigantic puzzles, than will ever shine from the cracked pitchers of the Royal Irish Academy, or the farthing candle of Tommy Moore.... No emblem will mark the sequestered spot where lies the Œdipus of the Round Towers riddle—no hieroglyphic.... But ye who wish for monuments to his memory, go to his native land, and there—circumspicite!—Glendalough, Devenish, Clondalkin, Inis-Scattery, rear their architectural cylinders; and each proclaims to the four winds of heaven ... the name of him who solved the problem of 3000 years, and who first disclosed the drift of these erections.... Suffice it to add that he fell a victim to the intense ardour with which he pursued the antiquarian researches that he loved.”

One portion at least of the good Father’s prophecy was amply fulfilled. In Irish Graves in England, by Michael M‘Donagh (Evening Telegraph Reprints: Dublin, 1888), a chapter on O’Brien contains these words:—

“His grave cannot now be identified in Hanwell churchyard. It was never marked by even a rude stone. In the register of burials the entry is: ‘No. 526, Henry O’Brien, Hanwell, July 2, years 26. Charles Birch, officiating clergyman.’ Tho number of the grave did not help towards its identification, and an examination of every stone did not result in the discovery of the name of O’Brien.”

So passed out of life a gifted young soul that had just begun to know the measure of its strength. Had O’Brien been spared, he might have taken the very highest rank among antiquarians and ethnologists; as it is, his fame must rest upon a single crude and imperfect work, written in haste, before his powers were fully ripe, or his learning properly assimilated. Beyond this, and his translation of Villanueva, he may be said to have left no trace behind. He had never married, though it is highly improbable that, with his ardent temperament, and that almost reverential admiration for the sex to which he gives frequent expression in The Round Towers, he could have reached the age of six-and-twenty heart-whole. From his portrait by Maclise (a copy of which forms the frontispiece to this volume), he must, one would think, have been a sufficiently personable man—though somewhat frail, and looking older than his years—not to have wooed in vain. But he has left no hint of a love affair, beyond occasional references to a mysterious “sorrow,” which may have been of this nature. No stain rests upon his memory; his habits were convivial,[Pg xxv] but not vicious; and he had a great reverence for his own religion, in no way weakened by his sympathy with other less perfect aspects of eternal truth. It may be said of him that he left the world without having done it any harm, and in the firm belief that he had nobly served the cause of human enlightenment,—which surely was no bad ending.

It is one thing to admit the ingenuity, or even the plausibility, of a writer’s views, and another to accept them as articles of belief. So far from claiming for O’Brien that he has completely solved the mystery of the Round Towers, we may even confess a doubt that the latter admits of any complete solution. Certain links in the chain of evidence are wanting, which, to all appearance, are not likely to be ever supplied. That, for instance, the Tuath-de-danaans came from Persia, bringing with them to Ireland their arts and their religion, is quite possible; but the absence of any reference to such migration in the more ancient Persian historians, where we should expect to find it; the want of some adequate explanation of the motives which could have led a highly-civilised people, accustomed to a luxurious climate, to prefer as their final settlement the bleak shores of a remote Atlantic island to the more temperate and, to an Eastern eye, more beautiful countries through which they must have passed on their way; the all but complete failure to point out the route which they followed in their quest of an asylum—these are gaps which require to be filled up before most of us will be prepared to accept their Eastern genealogy. Still, it must be confessed that O’Brien’s theory rests upon other and surer foundations, so far as its essential probability is concerned; also, that it is entertaining and suggestive to a degree which renders it, if not a profitable, at least a pleasing mental exercise.

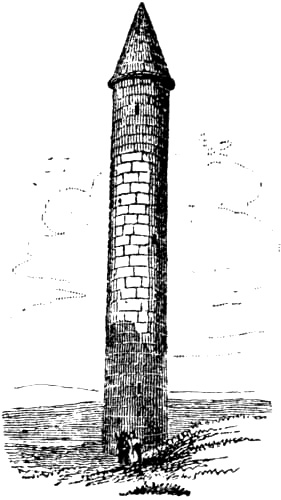

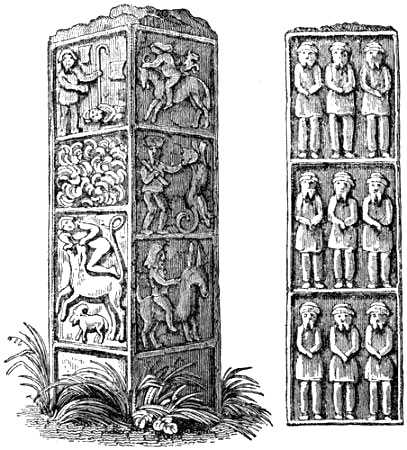

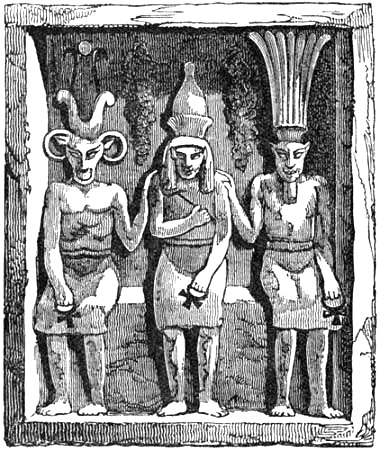

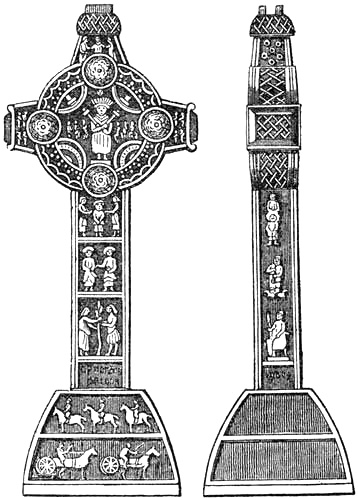

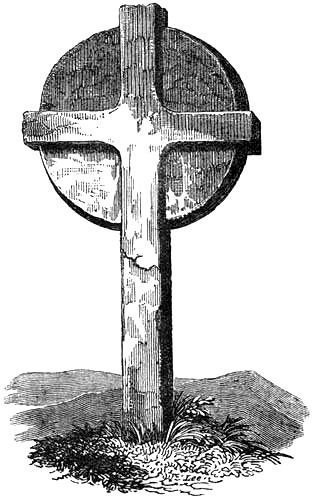

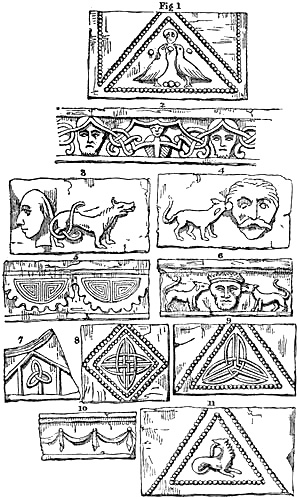

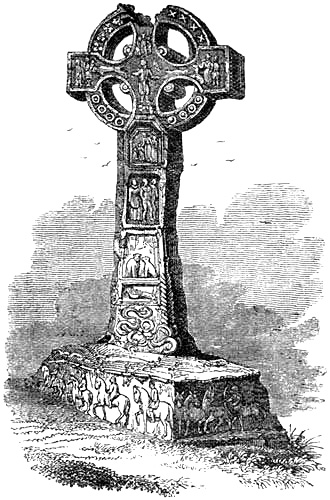

The Origin of the Round Towers (the first branch of the question proposed by the Royal Irish Academy) is really only part of a much wider problem which had long engaged the attention of earnest, capable, and industrious archæologists, with whose names the reader of this work[Pg xxvi] is likely to become only too familiar. The Round Towers are merely one class of more or less elaborate architectural or monumental remains, scattered all over Ireland, and bearing unmistakable signs of a very remote antiquity.[16] That these remains are inseparably connected in time and origin, seems to be proved by the fact that no writer upon the subject of the Round Towers had hitherto been able to treat of the latter exclusively, without taking into consideration the “crosses” or “temples,” or other subdivisions of the whole, and that neither Dr. Petrie nor his rival claimed exemption from the same necessity. A great portion of their respective works on the Round Towers is devoted, for instance, to a consideration of other antiquities; and what is perhaps the most valuable part of O’Brien’s,—namely, that upon which his assumption of a pagan origin chiefly rests,—is the result of investigation into the nature of that symbolism for which the sculptured crosses are so remarkable. It seemed, in fact, impossible for those who studied the subject carefully to resist the conclusion that all these remains belong to a period when Ireland was inhabited by a race which differed in many respects from the Irish of a later date. In Dr. Petrie’s opinion, that race consisted of the early Christian missionaries and their proselytes; in O’Brien’s, it belonged to an era far antecedent to Christianity itself; and so far, he is at one with the leading authorities who preceded him. Limiting his statement to the Round Towers, Dr. Petrie informs us[17] that, up to the time at which he undertook to decide the matter, two theories prevailed as to the “origin” of these structures: (1) That they were erected by the Danes; (2) that they were of Phœnician origin. But O’Brien discards the Danes altogether, and only allows a very subordinate part indeed to the Phœnicians, namely, that of having, as sea-carriers, assisted to convey the Tuath-de-danaans to Ireland. For[Pg xxvii] the grounds upon which Dr. Petrie attributes an exclusively Christian origin to the Round Towers inquirers must be referred to the body of his work, where they will find it most ingeniously, if not quite ingenuously, argued at much length that these structures were erected between the fifth and thirteenth centuries of our era by Christian founders. An outline of his rival’s argument to the contrary is given in the annexed “Synopsis.” The difference between the respective methods of the two theorists is very marked, and here the advantage does not rest with O’Brien. Petrie is calm, precise, authoritative; O’Brien fervid, rambling, and passionately expostulative. That the former has failed to prove his case, and that the latter has to some extent succeeded in doing so, may, or may not, be the fact; but it must be admitted that, if O’Brien was the more successful, he was not the more dexterous combatant. It has been frequently, and perhaps not without justice, remarked that “Irishmen have a way of blundering upon the truth”; and from the eccentric fashion in which he sets about proving his contention, some may argue that O’Brien’s success merely affords an instance of this national peculiarity. But it would be hardly fair to do so in the case of an author who is acknowledged to have prepared himself for his task by careful study of the authorities bearing upon its subject, and whose “discovery,” as he calls it, is expressly founded on the results of that preparation. In this latter respect he presents a marked contrast to his somewhat dictatorial rival, who is wont to treat the exercise of private judgment by those who happen to differ from himself as a species of lèse-majesté.[18] On the other hand,[Pg xxviii] O’Brien is always imploring the reader to follow his argument step by step. “Here,” he ever seems to be urging, “are the plain, unvarnished facts; here, the incontestable authorities; with these staring you in the face, surely you cannot think of denying that such and such an inference is unavoidable?” His reasons may not be always of the best; but, such as they are, he gives them freely. Of the two methods, the public, who are usually impressed by self-assertion, preferred the former; and “Dr. Petrie’s epoch-making book” was by general consent allowed to have “settled the question of the Round Towers for ever.” This comforting belief remained undisturbed for more than a quarter of a century, when, in the year 1867, a book appeared which challenged its infallibility. The author, a Mr. Marcus Keane, seems to have started upon an investigation of Irish ruins from sheer curiosity, and with a dispassionate intention to see and judge for himself. He was certainly not actuated by any wish to decry the merits of Petrie’s work, to which he confesses his great obligations, and which he appears to have taken at first as his guide. But, having carefully examined bit by bit the ancient architecture still remaining in most of the Irish counties, and having tested Petrie’s statements by personal investigation on the spot, he reluctantly confessed that he had lost faith in the latter. “After much consideration,” he declares,[19] “I have been forced to the conclusion ... that the generally received theory is[Pg xxix] not supported by sufficient evidence. My conviction of the heathen origin of these ruins has been strengthened in proportion to the increased knowledge which I have acquired by examination of the ruins themselves.... Not only the Round Towers, but also the crosses and stone-roofed churches are entirely of heathen origin.” Further, on all essential points he found himself in agreement with O’Brien, the difference between them, in respect of the particular form of paganism to which those remains owe their existence, being so trifling as hardly to merit notice. Of course, we do not undertake to say that he is right: the question is one upon which people have always differed hitherto, and which will probably be a subject of variance until the end of time. But it seems to us that the dispassionate, almost reluctant, judgment of this competent, methodical, and eminently fair observer, who approached his subject, not when controversy was raging, but after a sufficient number of years had elapsed to admit of prejudice dying out, is entitled to carry more than ordinary weight, where the object is to arrive at a conclusion based upon a study of unvarnished facts.

Up to this point the question may be said to have been regarded solely from the architectural point of view, which is not the most favourable for O’Brien; though, considering his necessarily limited knowledge in that respect, he must be admitted to have made out a fairly strong case. It is where the argument hinges upon analogies between Irish and Eastern symbolism that we have him at his best. Here all the resources of his great Oriental learning come into play, and may be said fairly to have turned the scale in his favour. Indeed, it is perfectly astonishing, considering that his book was written more than sixty years ago, when he was himself a mere youth, how nearly it reaches the level attained by modern research. In proof of this, it may be as well to refer, by way of example, to one of the latest authoritative treatises on the subject of Symbolism, that written by Count Goblet D’Alviella[20] (Hibbert Lecturer[Pg xxx] for 1891, and member of the Royal Academy of Belgium), together with its learned “Introduction” by Sir George Birdwood, K.C.I.E.; and we do so with the less hesitation because, as neither of these writers indulges in more than a passing reference to Ireland, no suspicion of a wish to strengthen their inferences by making out a pagan origin for Irish antiquities can attach to them. The reader who consults these authorities will find that they go far to support O’Brien’s interpretation of the symbolic ornamentation of Irish towers and crosses; that they perfectly coincide with his views on the nature of Sabaic paganism; and generally with his theory, that where symbolism of this character is found existing in Western lands, it must have been introduced there from an Eastern source. A few sentences taken almost at random from the Introduction to Count D’Alviella’s work, as well as from the book itself, may be adduced in support of this assertion. Thus, having stated that “the religious symbols common to the different historical races of mankind have not originated independently among them, but have, for the most part, been carried from the one to the other in the course of their migrations of conquests and commerce”; that “the more notable of these symbols were carried over the world in the footsteps of Buddhism”; that they were at first but “the obvious ideograph of the phenomena of nature that made the deepest impression on Asiatic man”; that the Sabæans were “the Chaldæan worshippers of the Host (Saba) of Heaven,”[21] it goes on to say: “Without doubt, the symbols that have attracted in the highest degree the veneration of the multitude have been the representative signs of gods, often uncouth and indecent; but what have the gods themselves ever been, except the more or less imperfect symbols of the Being transcending all definition whom the human conscience has more and more clearly divined through and above all these gods?” How, it may be asked, does this differ from O’Brien’s description of the nature of that “Budh” who forms the[Pg xxxi] central idea around which he groups the minor significances of Irish Sabaism? Again we read: “It is sentiment, and, above all, religious sentiment, that resorts largely to symbolism; and in order to place itself in more intimate communication with the being or abstraction it desires to approach. To that end men are everywhere seen either choosing natural or artificial objects to remind them of the Great Hidden One.[22]... There exists a symbolism so natural that ... it constitutes a feature of humanity in a certain phase of development; ... for example, the representations of the sun by a disc or radiating face, of the moon by a crescent; ... of the generative forces of nature by phallic emblems.”[23] Might we not fancy that this was written by O’Brien? Again: “What theories have not been built upon the existence of the equilateral cross as an object of veneration?... Orthodox writers have protested against the claim of attributing a pagan origin to the cross of the Christians, because earlier creeds had included cruciform signs in their symbolism. And the same objection might be urged against those who seek for Christian infiltrations in certain other religions under the pretext that they possess the sign of the Redemption.” Is not this O’Brien’s argument in a nutshell? Then we have an entire chapter (iv.), entitled “Symbolism and Mythology of the Tree,” the substance of which he may be said to have anticipated; and so on, all through the book. It is needless to multiply quotations; those already given suffice to show that, in its essential character, O’Brien’s argument, so far as it relies upon symbolism, is corroborated by those in the front rank of modern archæologists.

It must, however, be confessed that O’Brien is not always so much in harmony with modern thought, and that his reasoning from analogies of language appears to us, occasionally, neither sound nor ingenuous. Perhaps it would be more correct to say that he sometimes, without meaning deception, allows enthusiasm to entice him across[Pg xxxii] the line between fact and fiction. In this respect he is not, perhaps, less scrupulous than the average etymologist; but even admitting the veniality of his offence, it seems to us that the philological is the weakest portion of his book. In his hands Grimm’s then recently discovered “law of the mutation of consonants” was, as we think, too often strained to cover most questionable derivations, nor did he shrink, apparently, from coining forms of words to suit his purpose. As instances of this we may point to his otherwise skilful treatment of the name Hibernia at p. 128, where, without any authority that we are aware of, he employs the form νηος for υῆσος, evidently with a view to strengthen his case; also, to his wonderful evolution of the word Lingam, at p. 284. But whilst the reader will probably accept his statements on this head with caution, admiration of his skill in detecting analogies which only require pointing out to secure our assent, cannot be withheld. That he had in him the making of a great philologist, is beyond question; and that in course of time, had his life been spared, he would have made this branch of his argument really formidable, is very probable. Even as it stands, we may be undervaluing its merit: philology is not an exact science, and one can rarely be sure of one’s ground therein from day to day. But, judging the matter by such light as we possess, it seems to us that the least valuable part of O’Brien’s book is that upon which he evidently prided himself most: others may, possibly on better grounds, be of a different opinion, and we gladly leave this portion of the book to speak for itself.

It may, we think, be said without injustice, that when dealing with that part of the question which related to the uses of the Round Towers, O’Brien was more successful in upsetting the theories of other people than in establishing his own. The purposes for which preceding antiquarians had severally claimed that the towers were built are almost endless; but Dr. Petrie has summarised the most prominent of them as follows:[24]—(1) Fire-temples; (2) places from[Pg xxxiii] which to proclaim the Druidical festivals; (3) Gnomons, or astronomical observatories; (4) Phallic emblems, or Buddhist temples; (5) Anchorite towers, or Stylite columns; (6) Penitential prisons; (7) Belfries; (8) Keeps, or Monastic Castles; (9) Beacons and Watch-towers. Both he and O’Brien agree in holding that the Round Towers were not appropriated to any one of these purposes exclusively, though they might have been used for two or more of them. It is with regard to the selection of these latter that the authors differ—Petrie adopting views (7), (8), (9); O’Brien, view (3), but with much reservation; view (4) absolutely, and adding another view of his own, namely, that they were sometimes devoted to memorial or sepulchral uses. It has been mentioned already that Moore charged him with plagiarism in respect of his adoption of view (4); but, like other charges from the same quarter, the assertion rests upon unstable grounds. O’Brien made no secret of the fact that on many points he shared the views of General Vallancey, for whom he invariably expresses respect, and even admiration; but he is careful to explain that, where their judgments happen to coincide, it is for very different reasons. “I wish it to be emphatically laid down,” he says in one place, “that I do not tread in General Vallancey’s footsteps.... I have taken the liberty to chalk out my own road”; and, in another, “Though his perseverance had rendered him (Vallancey) the best Irishian of his age, and of many ages before him, yet he has committed innumerable blunders.” This goes to show that he was unlikely to adopt any theory merely because Vallancey held it; and to have arrived at the same conclusion by a wholly different road was surely not “plagiarism.” What is more, a reference to the published works of General Vallancey,[25] or even to[Pg xxxiv] such extracts from them as may be found in Dr. Petrie’s book, will, if we are not mistaken, give rise to some doubt of that author having ever distinctly maintained the Eastern, or pagan, origin of the Round Towers. His views are, however, so nebulous and shifting, that it is difficult to say whether he committed himself to any positive theory on the subject. Starting with the conjecture that the Round Towers may have been the work of “Phœnicians or Indo-Scythians,” he is soon found attributing them to certain “African sea-champions,” who, in his opinion, were the “Pheni,” being likewise, as he goes on to inform us, “a Pelasgic tribe.” Next, he declares that it was the Fomorians who, having conquered Ireland, “taught the inhabitants to build Round Towers”; but he afterwards seems to discard this theory in favour of a “Danish” origin, and ends, to all appearance, by resigning himself to the notion that they may, after all, have been built by “Christian” settlers. Nor are his speculations as to the purpose of those structures less varied and conflicting. At one time he maintains that they were undoubtedly “fire-temples”; at another, that they were “belfries”; and yet again, that they were “beacons.” But—what is especially remarkable in connection with the charge of plagiarism—he never, so far as we can discover, attributes to them a “phallic” significance. Upon the whole, then, it seems rather unreasonable to accuse anybody of having borrowed theories from an author who practically had none; and the probability is that, without having read General Vallancey’s works, Moore had, from hearsay, formed a vague general notion of their contents, which notion he, in the capacity of an irresponsible and not over-scrupulous reviewer, ventured to utilise for paying off old scores. Be that as it may, we are not prepared to urge that, upon the evidence, O’Brien’s theory as to the phallic emblemism of the Round[Pg xxxv] Towers—whether he borrowed it from Vallancey or not[26]—absolutely deserves credence. Like his ascription of an Eastern origin to the Tuath-de-danaans, it is one of those things which, so far as we can see, are incapable of proof. Still, it cannot be said that there is any inherent impossibility in the notion; in fact, assuming that the Round Towers were built by an Eastern colony, there is much in its favour. For, as all who are acquainted with our Indian Empire must be well aware, phallic symbols are there regarded with a veneration which in its character is entirely free from associations that appear to be inseparable from them elsewhere. The East and West have taken different views as to the light in which the physical agency by which divine creative power has chosen to perpetuate life should be regarded; and to the Hindoo mind, for instance, there is nothing inconsistent with the highest moral purity in worshipping an idealised representation of the generative principle. A similar belief, on O’Brien’s showing, prevailed in ancient Persia,—indeed, but for its existence there, the Tuath-de-danaans’ immigration into Ireland could hardly have taken place,—so that colonisers from that country, if any such colonisation ever took place, were likely to have introduced corresponding typical representations wherever they settled. Hence the theory of the Eastern origin of the Round Towers and that of their phallic significance are mutually interdependent. Further than this it is useless to go. The probability of either theory is a matter that, if we are not mistaken, most readers will determine for themselves, without much respect to authority; nor has any author who tries to establish a hypothesis on evidence the bearing of which upon the subject is in itself hypothetical, a right to complain that this should be so. O’Brien has been in a manner forced to rely upon such evidence all through his book, and the latter suffers in consequence. To our[Pg xxxvi] thinking, those portions of it are usually the most convincing where, discarding authority for the most part, he relies upon his own native shrewdness. His attack upon the “belfry” theory is one instance of this. Another is the way in which he combats Montmorency’s notion, that the towers may have been intended as places of shelter, for persons or property, from hostile invasion. Almost equally effective is his refutation of the hackneyed argument, that because Round Towers are usually (not invariably, as some assert) found in the vicinity of ecclesiastical buildings, they must necessarily be of Christian origin; though here, as in the case of the “belfry” theory, he might, we think, have insisted more upon the curious circumstance that Christians should have discontinued building them as soon as Christianity was firmly established in Ireland, but before the country had been reduced to a peaceful or settled condition. If such adjuncts to churches were needed up to the thirteenth century, there is nothing in the history of Ireland for the next three centuries, at least, which shows that they might have been dispensed with. To account for their disappearance by representing it as a consequence of the transition from Romanesque to Gothic architecture, which took place about the twelfth century, is to beg the whole question; for it assumes that the Round Towers are Romanesque—a point on which we take leave to think that opinions are much divided, as indeed they appear to be upon almost every topic connected with the subject-matter of this very remarkable book.

W. H. C.

London, 1897.

(Pp. 1-15)

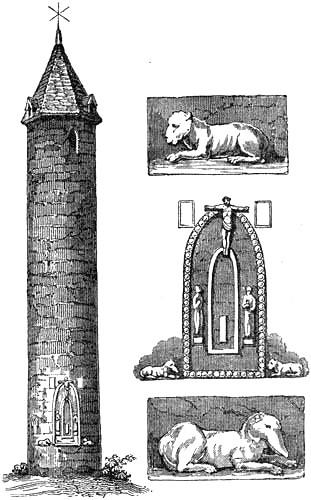

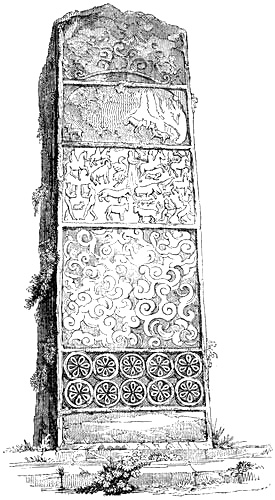

The book opens with a preliminary statement, in general terms, of the object which its author has in view. It is to prove that the round towers date from a more remote antiquity than that usually assigned to them; that they were, in fact, erected long before Christianity reached these islands, and even before the date of the Milesian and Scandinavian invasions. In support of this view, he contrasts the materials, architecture, and costliness of their construction with those of the early Christian churches usually found in their vicinity (cf. p. 514), and accounts for the contiguity of the latter by stating that the Christian missionaries selected, as the sites of their churches, localities previously consecrated to religious use, in order that they might thereby “conciliate the prejudices of those whom they would fain persuade”; whilst he points out that a Christian origin has not been claimed for Cromleachs and Mithratic caves, in the vicinity of which ecclesiastical remains likewise abound. On the other hand, he insists that the general structure and decorative symbolism of the round towers is clearly indicative of pagan times and a pagan origin, more especially of that primitive form of paganism which, originating in Chaldea, diffused itself eastward until it overspread a considerable part of Asia, and which is known as Sabaism. Dissenting from the theories of his predecessors in the same field of inquiry, he rejects the various theories that the round towers were intended as “purgatorial columns,” or “beacons,” or[Pg xxxviii] “belfries,” or “dungeons,” or “anchorite-cells,” or “places of retreat” in the case of hostile invasion, or “depositories” for State records, Church utensils, or national treasures; and he states as his conviction, based on examination of their structure, that it was not the intention of their founders to limit their use to any one specific purpose.

(Pp. 16-32)

Following up this line of argument, he attacks Montmorency, who had maintained that the founders of the round towers were “primitive Cœnobites and bishops, munificently supported in the undertaking by the newly-converted kings and toparchs; the builders and architects being those monks and pilgrims who, from Greece and Rome, either preceded or accompanied the early missionaries of the fifth and sixth centuries.” Reserving a detailed refutation of this theory for subsequent chapters, he contents himself for the present with showing that it rests upon mere assumption, which is not borne out by the evidence adduced in corroboration thereof; and exposes the fallacy of Montmorency’s argument, that pre-Christian Ireland was in a state of barbarism which precluded the possibility of such structures as the round towers being erected by its inhabitants. He further deals with the objections, that the bards do not allude to these towers as existent in their time, that those undoubtedly ancient excavations, the Mithratic caves, are never found in the vicinity of round towers, and that the limited nature of their accommodation made them serviceable only for some such purpose as that of a belfry or dungeon. With Vallancey’s views he finds himself more in sympathy, but is unable to adopt them unreservedly—preferring, as he puts it, to chalk out his own road.

(Pp. 33-47)

Continuing his attack upon Montmorency, the author points out that the towers erected elsewhere by Cœnobite associations are always square, not round, and that any argument based upon the elevated position of the entrances to both classes of edifices would apply equally to the pyramids. He shows that the round towers could not have been intended as places of refuge, or as depositories of ecclesiastical treasures, and adduces historical proof that the structures known as “belfries” were wholly different. Alluding to the supposed band of voluntary Cœnobite workmen under Saint Abban, he points out that their building operations must necessarily have been carried on in the midst of a raging war; that although they must have availed themselves of native assistance in the work, yet the Irish of the early Christian period betray not the slightest knowledge of the art of building; that the building of round towers ceased quite suddenly, almost immediately after the introduction of Christianity; that the native Irish have never attributed these towers to such an origin; that, so far from being, as Montmorency alleges, assisted by the munificence of native princes, the Cœnobite monks must have had to deal with absolute pagans, who would regard their labour with anything but approval; and that the fact of “kills,” or remains of Christian churches, being found in the vicinity of Cromleachs, Mithratic caves, and round towers is simply the result of the reverence felt by the pagan converts for the scenes and associations of their old belief, and affords no ground for supposing that the churches were coeval with the latter. Subsequently (at p. 514) he cites the instance of a round tower without any church near it.

(Pp. 48-62)

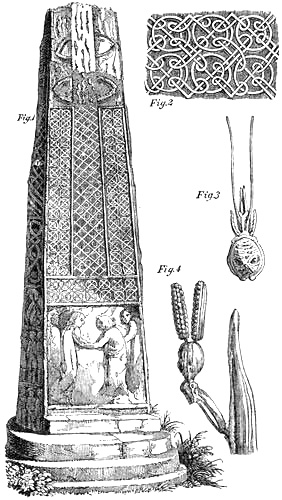

In tracing the origin and purpose of the round towers, our author is led to consider the names given them in ancient records and Irish folk-lore. The stunted ruin of Bally-Carbery Round Tower, near his own birthplace, was, he found, known to the peasantry as the “Cathoir ghall,” i.e. “the temple of brightness or delight,” whilst both in the Annals of the Four Masters, the Ulster Annals, and the Annals of Innisfallen these towers are included in the generic name Fiadh-Neimhedh, as contrasted with the names Cloic teacha and Erdam applied to “belfries,” thus showing that the two kinds of structures are perfectly distinct. He finds that Fiadh-Nemeadth in all preceding writers on the subject is held to apply specifically to the round towers, though some of these writers (e.g. Colgan and O’Connor) have wrested its meaning to support their own particular views, and the true import of this term he subsequently explains to be “consecrated Lingams” (p. 105), or phallic temples. The “belfry” and the gnomon, or “celestial index,” theories are thus exploded. From historical evidence he is further led to assume that Ireland is identical with the Insula Hyperboreorum of the ancients, and that the legendary mission of the Boreadan Abaris[27] to Delos took place during the Scythian occupation of Ireland. This friendly communication between the ancient Irish and the Greeks he attributes to their having sprung from a common stock—the Pelasgi and the Tuath-de-danaans belonging to “the same time as the Indo-Scythæ, or Chaldean Magi.” He traces briefly the relations between the Tuath-de-danaan settlers in Ireland and their Scythian (or Milesian) conquerors, and shows that to the former is due the high state of civilisation and learning for which ancient Ireland was distinguished, and which degenerated under Scythian[Pg xli] rule; and concludes with a general statement as to the prevalence of Sabaic worship therein, and the phallic configuration of the round towers.

(Pp. 63-76)

Being now fairly launched on the subject of Sabaism, or worship of natural manifestations of the divine energy, he traces its origin, development, and decadence into idolatry. Amid the heterogeneous confusion of beliefs that seem to have sprung up among the descendants of Noah, Nimrod introduced the worship of the sun as a deity, but only as a part of that general Sabaism which included the whole “host of heaven” as objects of worship, and recognised the Godhead, of which they were simply manifestations, under the names of Baal and Moloch. Gradually, the creature was substituted for the Creator, and their names, especially the former (Bolati), were applied to the sun, “as the source and dispenser of all earthly favours,” while to the moon was attributed a corresponding reverence under the name Baaltis, though in both cases the object of internal regard was intended to be Nature, or “the fructifying germ of universal generativeness.” From the tendency of man to the concrete, this central idea was soon lost sight of, and the material element put in its place—hence came Fire-worship. Originating in Chaldea, this degenerated form of Sabaism in course of time spread eastward until it reached Persia, where eventually there seems to have been a reversion to the principle which underlay it, i.e. that of generation and nutrition, in which form it afterwards extended to India. Though fire was the ostensible object of worship, the sun and moon, from which that worship originated, were regarded and reverenced as “the procreative causes of general fecundity,” with which was coupled the notion of regeneration after dissolution of the body. Hence when, as will appear hereafter, Eastern Sabaism was introduced into Ireland by the Tuath-de-danaans,[Pg xlii] the round towers created by them as temples of their worship had both a phallic and sepulchral meaning.

(Pp. 77-90)

That purer form of Sabaism in which the central idea of “the All-good and All-great One” predominated over materialism, seems to have prevailed in ancient Egypt, and to a more definite extent in India, whilst in both these countries, and also in Ireland, its material side led to the cultivation of astronomy. Hence the pyramids of Egypt, the pagodas of India, and the round towers of Ireland had both a religious and a scientific purpose. There is no ground, however, for supposing that the round towers were “fire-temples.” Though temples of the latter kind undoubtedly exist in Ireland, their structure is altogether different, and they evidently belong to a later period, showing, in fact, traces of an Italian origin. Fire-worship was probably introduced into Italy from Greece, where it had been practised by the old Pelasgic stock, who, on their expulsion from Thessaly, settled in Etruria, bringing their worship with them.

(Pp. 91-106)

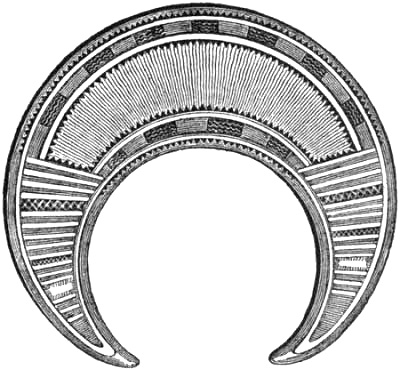

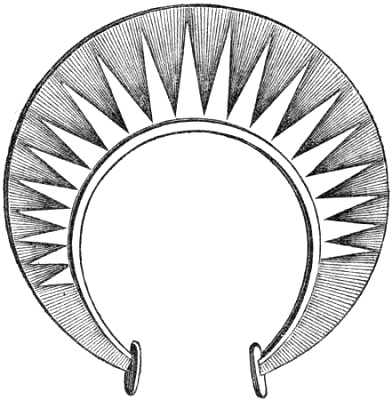

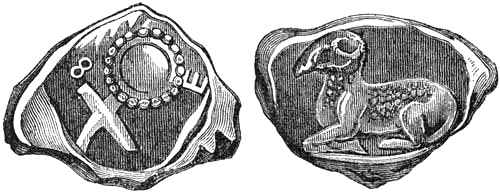

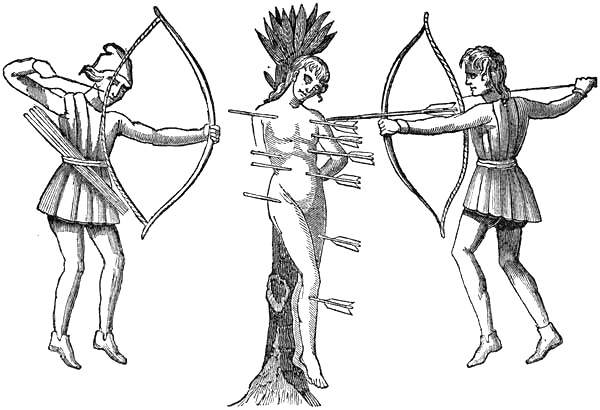

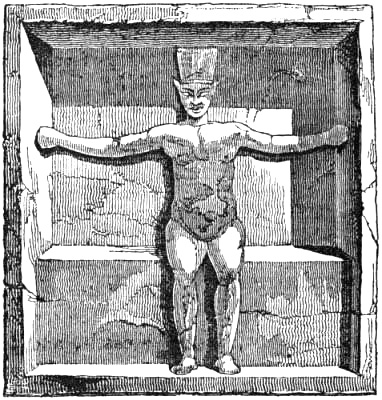

From a careful study of Eastern records and Sabaism, the author is led to take up the position that the round towers were constructed by early Indian colonists of Ireland (the Tuath-de-danaans), in honour of “the fructifying principle of nature,” of which the sun and moon are representative. The emblem of this principle was the phallus in the case of the sun, and the crescent in that of the moon. The round tower was simply a monumental phallus, which fact is taken to explain the terms “Cathoir ghall” and “Fidh-Nemphed” to which he alludes in chap. iv.; whilst the crescent ornament by which many of these[Pg xliii] towers were surmounted is symbolical of the female nature. A corroboration of this theory is found in the circumstance that the name Budh, by which these towers are “critically and accurately designated, signifies in Irish, first, the sun, and secondly, what φαλλός, phallus, does in Greek and Latin,” a view which is supported by the analogy of Egyptian sun and moon worship.

(Pp. 107-126)

Having thus committed himself to the view that the paganism which founded the Irish Round Towers was a religion of which Budh (i.e. the sun and the phallus) was the central idea, and which, therefore, resembled in its essence the faiths of India and Egypt, the author proceeds to trace the origin of this religion. In India the latter is known as Buddhism, or that form of Sabaism taught by Buddha; but the author is persuaded that there never was such a person as Buddha—at least, when the religion first shot into life, which was almost as early as the creation of man—though in later times several enthusiasts assumed that name. The origin of the religion was, in fact, “an abstract thought,” which cannot easily be expressed in words until it is reduced to the materialised forms of that practical Sabaism which each nation framed for itself, and which consisted in the worship of generative and productive power under its various manifestations. Hence the objects of worship ranged from the sun and moon even to agricultural operations, and, of course, included sexual physiology. Indian Buddhism worshipped the Lingam (or phallus) as the emblem ofBudh (i.e. the Sun), but without any sensual alloy in such reverence, which, in fact, necessitated the observance of a strict moral code. Among other requirements of this code was the performance of works of charity, Dana (i.e. the giving of alms), and the religionists were hence called Danaans or Almoners. The bearing of all this upon Irish paganism is explained by referring to the[Pg xliv] intimate connection that in early times existed between Ireland and the East, from whence its Tuath-de-danaan colonists were derived. The name Erin, together with its Greek form Ierne, and its Latin transmutation Hibernia, is shown to be identical with Iran, the ancient name of Persia, which, modified into Irin, was applied by the Greek historians to the “Sacred Island” of the West, and recognised by Gildas and Ordericus Vitalis as the established designation of Ireland in their time.

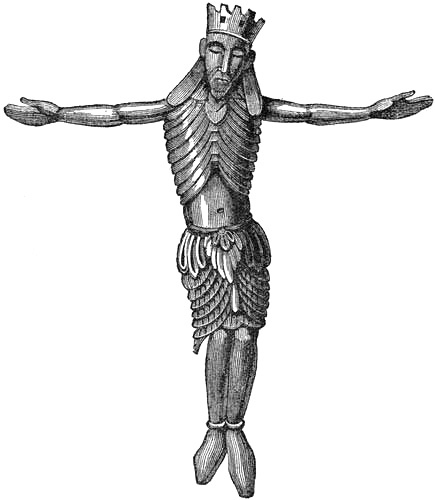

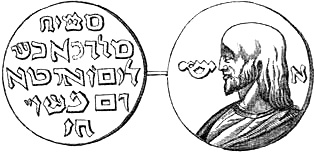

(Pp. 127-141)

Developing this last argument, our author shows that, while Iran (or “the sacred land”) was a name applied to both Persia and Ireland, the form Irin (Sacred Island) is exclusively applied to Ireland, and that Irc, Eri, Ere, and Erin are but modifications of the latter. The Greeks commuted this name of Irin into Ierne, which is merely a translation (ἱερός + νῆσος); and the Latins, by putting an H for the rough breathing of ἱερός, and interpolating a b for sound’s sake, transformed the latter into Hibernia, the meaning “Sacred Island” being preserved. But by its own inhabitants it continued to be known as Fuodhla, Fudh-Inis, and Inis-na-Bhfiodhbhadh, names associating the worship which prevailed therein with the profession of the worshippers, for they respectively denote the land or island of Fuodh or Budh and Budhism. The Budh here mentioned was identical with the phallic deity worshipped by the Tuath-de-danaans under the name of Buodh (known also as Moriagan and Fareagh or Phearagh), which name the Scythian invaders afterwards adopted as their war-cry (Boo or A-boo). The peculiar tenets of Irish Budhism were embodied in a mass of literature committed to the flames by Saint Patrick; but the history of pagan Ireland still survives in MSS. scattered over Europe, whilst an image of Buodh, or Fareagh, bearing a close resemblance to those of the Eastern Buddha, and to the idols of Matambo[Pg xlv] “whose priests are sorcerers or magicians” (afterwards shown to be the meaning of Tuath-de-danaans), has been unearthed at Roscommon, and is now in the Museum of Trinity College, Dublin.

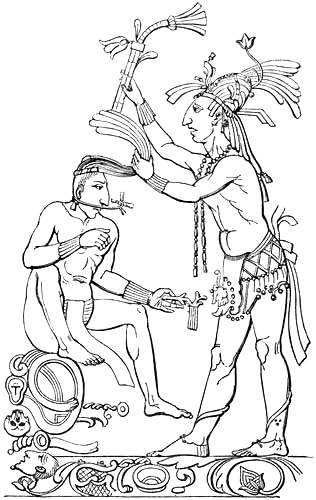

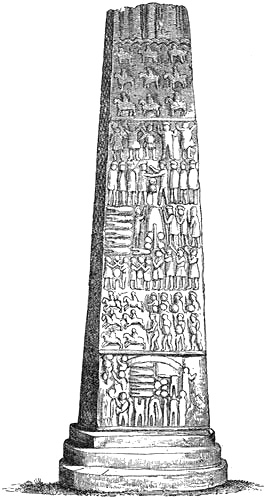

(Pp. 142-156)

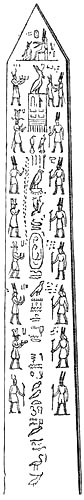

From India our author now diverges to Egypt. The similarity between the regal title “Pharaoh” and Phearagh or Fareagh just mentioned is accounted for by the invasion of Egypt by the Uksi, or Hyksos (Royal Shepherds or Shepherd Kings), who, according to Manetho, came “from the East.” The Indian Vedas, which corroborate his account, term them Pali, or “shepherds”; and the rigorous nature of their sway accounts for the dislike manifested by the Egyptians towards the Israelites, who were a pastoral people. That they introduced their form of worship into Egypt, is shown by the description which Herodotus gives of the rites, ceremonies, and usages of the Egyptian priests, resembling those practised by the Brahmins. Historical evidence points to the erection by them of the greater pyramids, also to their introduction of those magical arts for which the Egyptians became notorious. This latter fact brings the Uksi into connection with the Tuath-de-danaans (whose name is indicative of proficiency in magic), and serves to strengthen the author’s opinion that both belonged to the same Chaldean stock.

(Pp. 157-166)

The pyramids of Egypt may be said to correspond, with one significant difference, to the round towers of Ireland. Both are characterised by the highest architectural skill; both are constructed with an evident reference to astronomical purposes; both afford indications that they were inter alia appropriated to sepulture; and both are [Pg xlvi]distinctively of phallic or, more strictly, Sabaic import. But in this last feature a divergence becomes evident. The symbolism of the principle of “generative production” common to both is in the form of the pyramid more emblematic of the female nature (see pp. 267-269), whilst the round towers typify the male—a divergence which the author subsequently treats in more detail. To it may be due the circumstance that these excavations or “wells” which exist beneath the pyramids have not hitherto been found under round towers.

(Pp. 167-176)

In connection with the last paragraph, attention is, however, drawn to the fact that round towers have usually been erected in the vicinity of water; and that this may have been owing to a real, though less dominant, veneration of the female principle, is probable from the extensive use of bathing in the worship of Astarte, the representative of that principle whose peculiar emblemism is apparent in the ornamentation of the round towers. Traces of the apparatus for a bell found on the summit of one of the latter edifices affords no proof of its original purpose as a belfry. For though bells were used in pagan ceremonials, they were not rung to summon worshippers; and the fact may have been that, after their conversion to Christianity, the Irish applied round towers occasionally to the only purpose for which they could then be used in connection with public worship.

(Pp. 177-192)

Recurring to the affinity of Ireland with ancient Persia (Iran), the history of the latter country is traced from its settlement by the Aryans. According to tradition preserved in the collection of sacred books known as the Zendavesta, the original seat of that people was the [Pg xlvii]Eriene-Veedjo, a district situated in the north-western highlands of Asia, of great fertility, and enjoying a singularly mild climate, having seven months of summer and five of winter. Then “the death-dealing Ahriman smote it with the plague of cold, so that it came to have ten months of winter and only two of summer”; and was in consequence deserted by its inhabitants, who gradually overspread the low-lying countries, as far south as the Indus, including Fars, as Persia was then termed. They were a vigorous and energetic race these Aryans, who soon became dominant in their new quarters, substituting the name of their own country (Iran, or the sacred land, formed from the ancient Zend Eriene) for that of Fars, and founding a dynasty, or rather succession of dynasties, which superseded the government formerly in existence. The mixture of races led to a certain diversity of language, and thus originated the Zend and Pahlavi or Sanskrit dialects, which bear a remarkable affinity to Irish (cf. Palaver). There was further a diversity of religions, the old religion of Hushang, a predecessor of Zoroaster, being professed by many long after fire-worship became the dominant faith of Persia.

(Pp. 193-210)