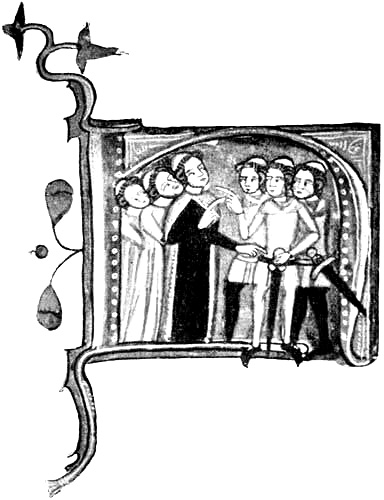

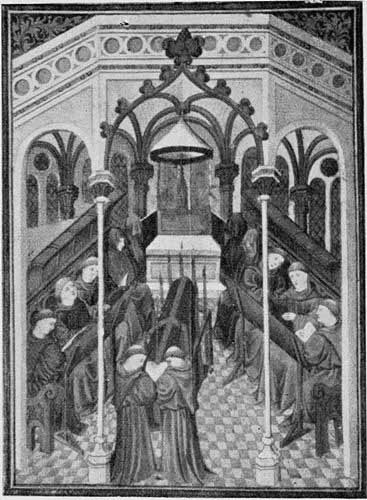

FROM THE XV. CENT. MS., EGERTON 2019, f. 142.

PARISH PRIESTS

AND THEIR PEOPLE

IN THE

MIDDLE AGES IN ENGLAND.

BY THE

REV. EDWARD L. CUTTS, D.D.,

AUTHOR OF “TURNING POINTS OF ENGLISH CHURCH HISTORY,”

“A DICTIONARY OF THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND,”

“A HANDY BOOK OF THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND,” ETC.

PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OE THE TRACT COMMITTEE.

LONDON:

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE.

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.

43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C.

BRIGHTON: 129, NORTH STREET.

New York: E & J. B. YOUNG AND CO.

1898.

great mass of material has of late years been brought within reach of

the student, bearing upon the history of the religious life and customs of

the English people during the period from their conversion, in the sixth

and seventh centuries, down to the Reformation of the Church of England in

the sixteenth century; but this material is still to be found only in

great libraries, and is therefore hardly within reach of the general

reader.

great mass of material has of late years been brought within reach of

the student, bearing upon the history of the religious life and customs of

the English people during the period from their conversion, in the sixth

and seventh centuries, down to the Reformation of the Church of England in

the sixteenth century; but this material is still to be found only in

great libraries, and is therefore hardly within reach of the general

reader.

The following chapters contain the results of some study of the subject among the treasures of the library of the British Museum; much of those results, it is believed, will be new, and all, it is hoped, useful, to the large number of general readers who happily, in these days, take an intelligent interest in English Church history.

The book might have been made shorter and lighter by giving fewer extracts from the original[Pg vi] documents; but much of the history is new, and it seemed desirable to support it by sufficient evidence. The extracts have been, as far as possible, so chosen that each shall give some additional incidental touch to the filling up of the general picture.

The photographic reproductions of illuminations from MSS. of various dates, illustrating ecclesiastical ceremonies and clerical costumes, are enough in themselves to give a certain value to the book which contains and describes them.

The writer is bound to make grateful acknowledgment of his obligations to the Bishop of Oxford, who, amidst his incessant occupations, was so kind to an old friend as to read through the rough proof of the book, pointing out some corrigenda, making some suggestions, and indicating some additional sources of information; all which, while it leaves the book the better for what the bishop has done for it, does not make him responsible for its remaining imperfections.

The writer has also to express his thanks to the Rev. Professor Skeat, Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Cambridge, and to the Rev. Dr. Cunningham, formerly Professor of Economic Science, K.C.L., for their kind replies to inquiries on matters on which they are authorities; and to some others who kindly looked over portions of the book dealing with matters of which they have special knowledge.

| CHAPTER I. |

| OUR HEATHEN FOREFATHERS. |

| The land only partially reclaimed, 1—The Anglo-Saxon conquest, 2—Civil constitution, 4—Religion, 7—Structural temples, 8—Priests, 11. |

| CHAPTER II. |

| THE CONVERSION OF THE ENGLISH. |

| Conversion of the heptarchic kingdoms, 14—Its method, 16—Illustrations from the history of Jutland, Norway, etc., 17—The cathedral centres, 20—Details of mission work, 21—Mission stations, 24. |

| CHAPTER III. |

| THE MONASTIC PHASE OF THE CHURCH. |

| Multiplication of monasteries, 28: in Kent, 29; Northumbria, 29; East Anglia, 31; Wessex, 31; Mercia, 31—List of other Saxon monasteries, 33—Constitution of the religious houses, 35—Their destruction by the Danes, 37—Rebuilding in the reigns of Edgar and Canute, 37. |

| [Pg viii] |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| DIOCESAN AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION. |

| Character of the new converts, 38—Coming of Archbishop Theodore, 40—Union of the Heptarchic Churches, 41—Subdivision of dioceses, 41—Introduction of the parochial system, 43—Northumbria made a second province, 49—Multiplication of parishes, 50—Different classes of churches, 53—Number of parishes at the Norman Conquest, 54. |

| CHAPTER V. |

| THE SAXON CLERGY. |

| Laws of the heptarchic kingdoms: of Ethelbert, 57; of Ine, 57; of Wihtred, 57—Council of Clovesho (747), 60—Laws of Alfred, 65; of Athelstan, 66—Canons of Edgar, 66—Laws of Ethelred, 72—Canons of Elfric, 74—Privilege of sanctuary, 75—Tithe and other payments, 78—Observance of Sunday and holy days, 79—Slavery, 81—Manumission, 81. |

| CHAPTER VI. |

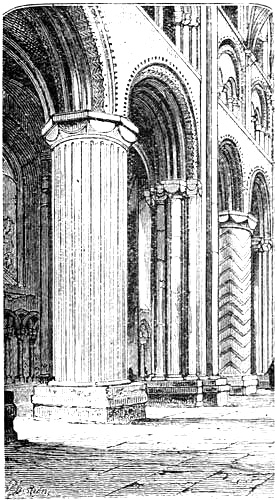

| THE NORMAN CONQUEST. |

| Foreign bishops and abbots introduced, 84—Parochial clergy undisturbed, 85—Papal supremacy, 85—Separation of civil and ecclesiastical Courts, 86—Norman cathedrals and churches, 87—Revival of monasticism, 90—Appropriation of parochial benefices, 91. |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| THE FOUNDATION OF VICARAGES. |

| Mode of appropriation of parishes, 95—Evil results, 97—Ordination of vicarages, 98—Its conditions, 99—Not always fulfilled, 108—Abuses, 109. |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| PAROCHIAL CHAPELS. |

| Chapels-of-ease for hamlets, 110—Some of them elevated into churches, 110—Rights of mother churches safeguarded, 121—Free chapels, 123. |

| [Pg ix] |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| THE PARISH PRIEST—HIS BIRTH AND EDUCATION. |

| Saxon clergy largely taken from the higher classes, 127—The career opened up by the Church to all classes, 129; even to serfs, 130—Education of the clergy, 131—The Universities, 136—Schools of thought, 136—The scholastic theology, 137—The contemplative, 138—Oxford: its colleges, 140—The students, 141—Ordination, 144—Institution, 146. |

| CHAPTER X. |

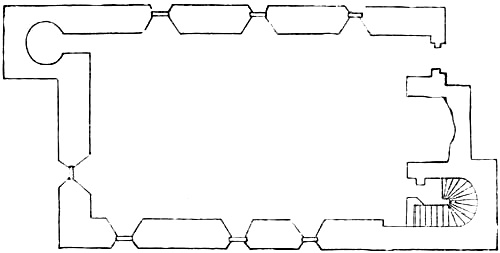

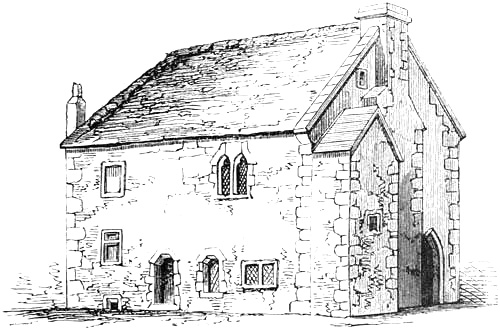

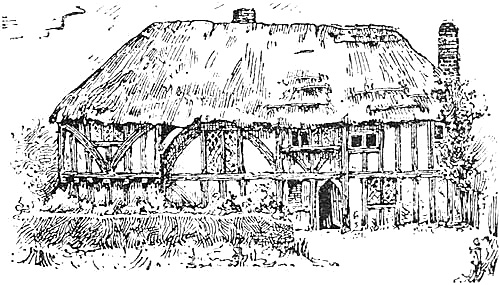

| PARSONAGE HOUSES. |

| Like lay houses, 149—Examples at West Dean and Alfriston, Sussex, 152—Descriptions of: at Kelvedon, 154; Kingston-on-Thames, Bulmer, Ingrave, 155; Ingatestone, 156; Little Bromley, North Benfleet, 157; West Hanningfield, 158—Hospitality, 158—Smaller houses, 160—Dilapidations, 162. |

| CHAPTER XI. |

| FURNITURE AND DRESS. |

| Sumptuary laws, 164—Disregard of them, 167—Contemporary pictures, 169—Extracts from wills, 172—Introduction of sober colours, 174—Wills, 175. |

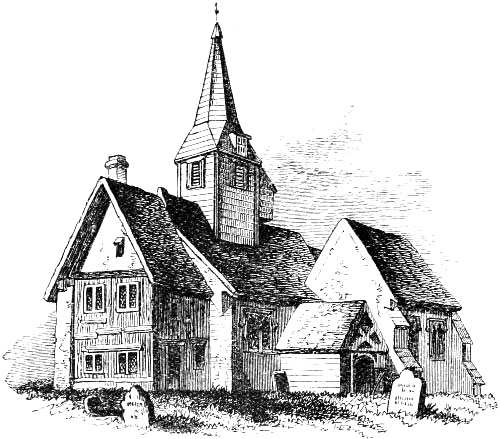

| CHAPTER XII. |

| FABRIC AND FURNITURE OF CHURCHES, AND OFFICIAL VESTMENTS. |

| Grandeur of the churches compared with domestic buildings, 184—Furniture of churches, 187, 190—List of necessary things, 189—Clerical vestments: pallium, chasuble, 191; stole, maniple, amice, dalmatic, 192; cope, surplice, 193; amyss, 194—Fanciful symbolism, 196; a bishop in “full canonicals,” 198. |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

| THE PUBLIC SERVICES IN CHURCH. |

| Matins, mass, and evensong, 200—Sunday attendance, 201—Communion, 200—Laxity of practice, 204—Week-day services, 205—The Bidding Prayer, 207—Bede Roll, 211—Chantry services, 212. |

| [Pg x] |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

| PREACHING AND TEACHING. |

| Not neglected, 214—Manuals of teaching, 214; Archbishop Peckham’s, 216—Helps for preachers, 223—Analysis of sin, 226; Arbor Virtutum, 229; Arbor Viciorum, 230—Types and antitypes, 231. |

| CHAPTER XV. |

| INSTRUCTIONS FOR PARISH PRIESTS. |

| Analysis of a book of that title by John Myrk, 232—The personal character and conduct which befit a priest, 233—A parish priest’s duties, 234—Non-communicating attendance at Holy Communion, 235, note—The “holy loaf,” 235—Behaviour of the people in church, 236—The people’s way of joining in the mass, 236—Behaviour in churchyard, 238—Visitation of the sick, 239. |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

| POPULAR RELIGION. |

| Education more common than is supposed, 241—Books for the laity in French and English, 242—Creed and Vision of “Piers Plowman,” the tracts of Richard of Hampole and Wiclif, 242—“Lay Folks’ Mass-book,” 243—Primers, 249—Religious poetry: Cædmon, 250; “The Love of Christ for Man’s Soul,” 255; “The Complaint of Christ,” 256. |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

| THE CELIBACY OF THE CLERGY. |

| Object of the obligation, 258—Opposition to it, 259—Introduced late in the Saxon period, 260—Endeavour to enforce it in Norman and later times, 261—Evasion of the canons, 268—Legal complications, 270—Popular view, 271—Disabilities of sons of the clergy, 273—Dispensations for it, 275. |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

| VISITATION ARTICLES AND RETURNS. |

| Visitation of parishes, 279—Visitation questions, 280—Examples from returns to the questions, 285—Popular estimation of the clergy, 289. |

| [Pg xi] |

| CHAPTER XIX. |

| PROVISION FOR OLD AGE. |

| Assistant chaplain, 290—Coadjutor assigned, 291—A leprous vicar, 294—Retirement on a pension, 295—A retiring vicar builds for himself a “reclusorium” in the churchyard, 295—Parish chaplain retires on a pension, 296—Death and burial, 296. |

| CHAPTER XX. |

| THE PARISH CLERK. |

| Ancient office, 298—Its duties, 299—Stipend, 301—Sometimes students for orders, 302—Gilds of parish clerks, 303—Chaucer’s parish clerk, 304. |

| CHAPTER XXI. |

| CUSTOMS. |

| Sanctuary for persons, 306; and property, 307—Belonged to some persons, 308—Pilgrimage, 308—Special ceremonies, 311—Lights, 311—Miracles and passion plays, 315—Fairs, markets, and sports in the churchyard, 316—Church ales, 317. |

| CHAPTER XXII. |

| ABUSES. |

| Papal invasions of the rights of patronage, 319—The intrusion of foreigners into benefices, 320—Abuse of patronage by the Crown, 321—Pluralities, 323—Farming of benefices, 324—Holding of benefices by men in minor orders, 324—Absenteeism, 330—Serfdom, 332. |

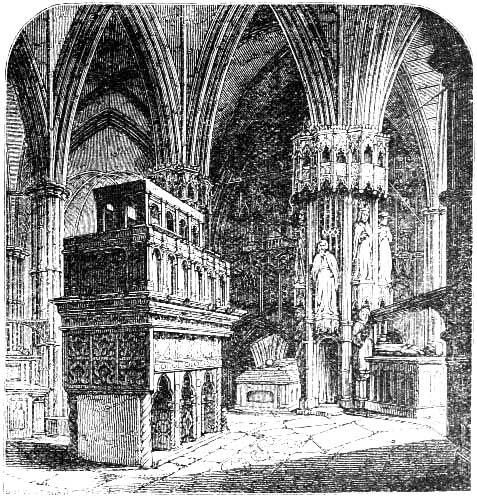

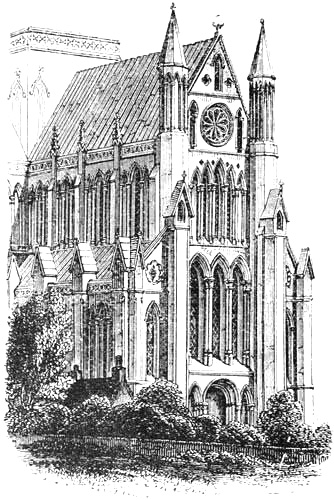

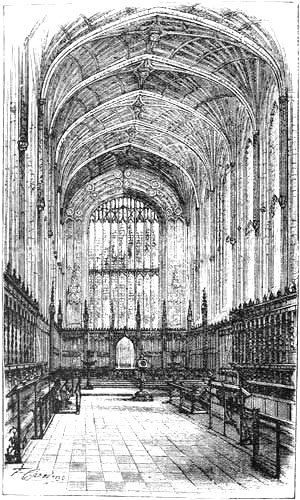

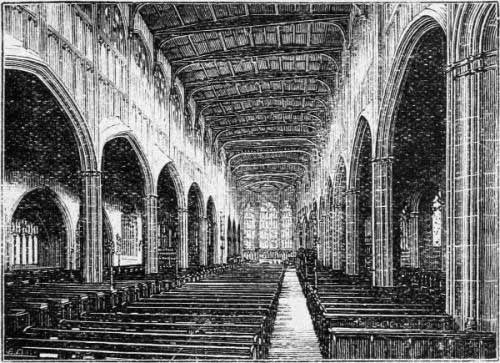

| CHAPTER XXIII. |

| THE CATHEDRAL. |

| Served by secular canons, 334—Organization of its clerical staff, 334—The dignitaries, 335—The dean and chapter, 335—Monastic cathedral, 336—Archdeacons, 337—Synods and visitations, 337—Lincoln Cathedral, 338—Bishop’s palace, 339—The close, 340—Residentiary houses, 341—Vicars’ court, 341—Chantries, 342—Chapter house, 342—Common room, 344—The first dean and [Pg xii]canons, 343—Revenues of the bishop, 344; of the dean and dignitaries, 345; of the prebendaries, 350; of the archdeacons, 353; of the vicars choral, 354; of the chantry priests, 355; of the choristers, 356—Lay officers, 356—Chichester Cathedral, 359—Revenues of bishop, dean, dignitaries, prebendaries, archdeacons, and vicars choral, 360-362—Prince bishops, 363. |

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

| MONKS AND FRIARS. |

| Character of the monks, 365—Place of the monasteries in social life, 366—Influence upon the parishes, 369—Friars, their origin; organization, 370—Work, 373—Rivalry with parish clergy, 374—Character, 377—Faults of the system, 378. |

| CHAPTER XXV. |

| THE “TAXATIO” OF POPE NICHOLAS IV. |

| Origin of firstfruits and tenths, 380—Taxation of a specimen deanery, 381—Number of parishes, 384—Value of parochial benefices, 386—Number of clergy, 389. |

| CHAPTER XXVI. |

| THE “VALOR ECCLESIASTICUS” OF HENRY VIII. |

| Number of parishes, 394—Income, 395—Sources of income, 397—Comparative value of money in 1292, 1534, and 1890, 404—Economical status of parochial clergy, 406. |

| CHAPTER XXVII. |

| DOMESTIC CHAPELS. |

| Early existence, 408—Saxon, 409—Norman, 409—Edwardian, 410—Later, 411. |

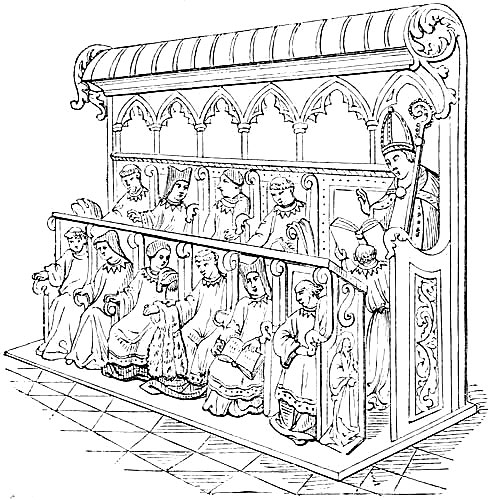

| CHAPTER XXVIII. |

| THE CHANTRY. |

| Characteristic work of the centuries, 438—Definition of a chantry, 438—“Brotherhood” of the religious houses, 439—A chantry a kind of monument, 441—Began in thirteenth century, 442—Their distribution over the country, 443—Foundation deed of Daundy’s[Pg xiii] chantry, 444—Chantry of the Black Prince, 446—Burghersh chantry, 447—Chantry of Richard III., 447; of Henry VII., 447—Parochial benefices appropriated to chantries, 449—Nomination to, 451—Chantry chapels within the church, 453; at Winchester, 453; Tewkesbury, 454—Additions to the fabric of the church, 454—Separate building in the churchyard, 455—Temporary chantries for a term of years, 457—Mortuary services, 458—Remuneration of chantry priests, 461—Number of cantarists, 464—Their character, 465—Hour of their services, 466—Some chantries were chapels-of-ease, 467—Some were grammar schools, 469. |

| CHAPTER XXIX. |

| GILDS. |

| Definition, 473—Trade gilds, 475—Religious gilds, 476—For the augmentation of Divine service, 478—For the maintenance of bridges, roads, chantries, 478—Services, 479—Social gilds, 482—Methods of obtaining better services and pastoral care, 483. |

| CHAPTER XXX. |

| THE MEDIÆVAL TOWNS. |

| Description of, 486—Parochial history of the towns, 489—Peculiar jurisdictions, the origin of town parishes, 490—Norwich, 490—London, 492—Exeter, 497—Bristol, 499—York, 503—Ipswich, 506—Burton, 508—St. Edmund’s Bury, 510—St. Albans, 513—Manchester, 514—Rotherham, 516—Sheffield, 519—Newark, 523—Recluses, 526—Bridge-chapels, 527—London Bridge, 529. |

| CHAPTER XXXI. |

| DISCIPLINE. |

| Definition, 531—Exercise of, in Saxon times, 532—Norman and subsequent times, 533—Examples of, among the clergy, 533, 537—Laity, 535—Resistance to, pictorial illustrations, 543—General sentences of excommunication, 544. |

| CHAPTER XXXII. |

| RELIGIOUS OPINIONS. |

| Schools of thought: progressive, 546; and conservative, 547—Religious character of the centuries: twelfth, 547; thirteenth, 548; fourteenth, 549; Chaucer’s “Poore parson;” fifteenth, 552. |

| [Pg xiv] |

| APPENDIX I. |

| The history of the parish of Whalley, 557. |

| APPENDIX II. |

| Comparative view of the returns of the “Taxatio,” the “Valor,” and the modern “Clergy List” in the two rural deaneries of Barstaple, Essex, 562; and Brigg, Canterbury, 564. |

| APPENDIX III. |

| References to pictorial illustrations in MSS. in the British Museum, 567. |

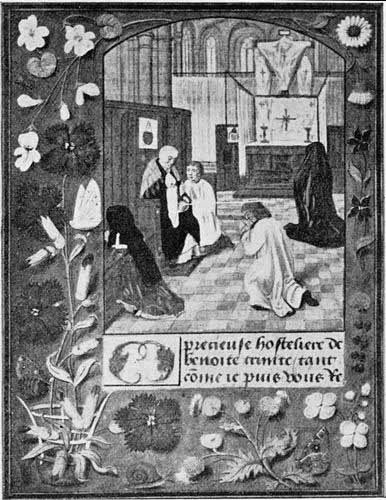

| Burial of the Dead | Frontispiece |

The illustration taken from a French MS. of the middle of the fifteenth century [Egerton 2019, f. 142, British Museum] will reward a careful study. Begin with the two pictures introduced into the broad ornamental border at the bottom of the page. On the left are a pope, an emperor, a king, and queen; on the right Death, on a black horse, hurling his dart at them.

Go on to the initial D of the Psalm Dilexi quoniam exaudiet Dominus vocem: “I am well pleased that the Lord hath heard the voice of my complaint.” It represents a canon in surplice and canon’s fur hood, giving absolution to a penitent who has been confessing to him (note the pattern of the hanging at the back of the canon’s seat). Next consider the picture in the middle of the border on the right. It represents the priest in surplice and stole, with his clerk in albe kneeling behind him and making the responses, administering the last Sacrament to the dying person lying on the bed. Next turn to the picture in the left-hand top corner of a woman in mourning, with an apron tied about her, arranging the grave-clothes about the corpse, and about to envelope it in its shroud. In the opposite corner, three clerks in surplice and cope stand at a lectern singing the Psalms for the departed; the pall which covers the coffin may be indistinctly made out, and the great candlesticks with lighted candles on each side of it. All these scenes lead us up to the principal subject, which is the burial. The scene is a graveyard (note the grave crosses) surrounded by a cloister, entered by a gate tower; the gables, chimneys, and towers of a town are seen over the cloister roof; note the skulls over the cloister arches, as though the space between the groining and the timber roof were used as a charnel house. The priest is asperging the corpse with holy water as the rude sextons lower the body into the grave. Note that it is not enclosed in a coffin—that was not used until comparatively recent times. He is assisted by two other priests, all three vested in surplices and black copes with a red-and-gold border; the clerk holds the holy-water vessel. Three mourners in black cloak and hood stand behind. The story is not yet finished. Above is seen our Lord in an opening through a radiant cloud which sheds its beams of light over the scene; the departed soul [de—parted = separated from the body] is mounting towards its Lord with an attitude and look of rapture; Michael the Archangel is driving back with the spear of the cross the evil angel disappointed of his prey. Lastly, study the beautiful border. Is it fanciful to think that the artist intended the vase of flowers standing upon the green earth as a symbol of resurrection, and the exquisite scrolls and twining foliage and many-coloured blossoms which surround the sad scenes of death, to symbolize the beauty and glory which surround those whom angels shall wait upon in death, and carry them to Paradise?

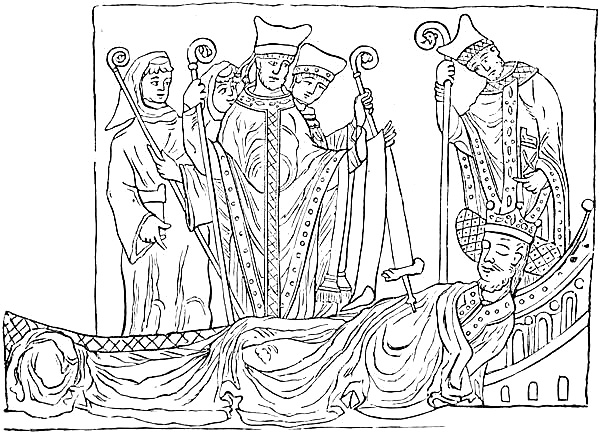

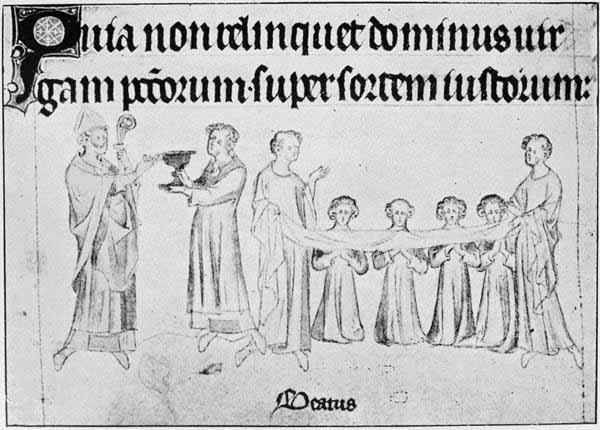

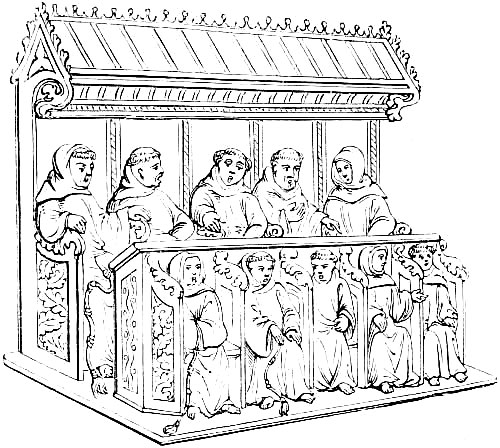

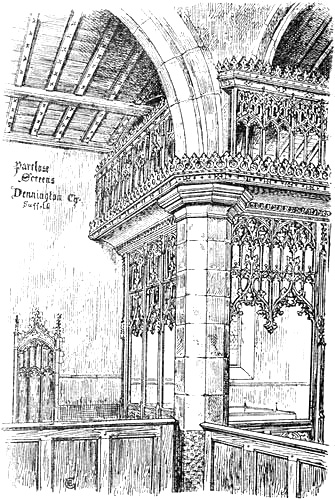

| Ordination of a Priest, Late 12th Century | 94 |

Gives the Eucharistic vestments of bishop and priest, a priest in cope and others in albes, the altar and its coverings, and two forms of chalice.

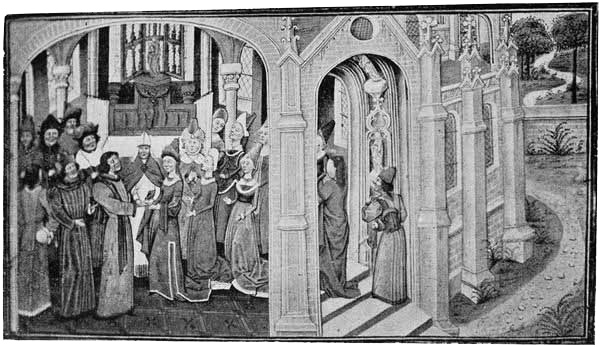

| Ordination of a Deacon, A.D. 1520 | 146 |

Gives the vestments of that period. The man in the group behind the bishop, who is in surplice and hood and “biretta,” is probably the archdeacon. Note the one candle on the altar, the bishop’s chair, the piscina with its cruet, and the triptych.

| (1) An Archdeacon Lecturing a Group of Clergymen on their Secular Habits and Weapons, 14th Century | 174 |

He is habited in a red tunic and cap, the clergy in blue tunic and red hose and red tunic and blue hose.

| (2) An Archdeacon’s Visitation | 174 |

| A Clerical Procession | 190 |

The illustration is taken from a French Pontifical of the 14th century in the British Museum [Tiberius, B. viii.], and represents part of the ceremonial of the anointing and crowning of a king of France. We choose it because it gives in one view several varieties of clerical costume. There was very little difference between French and English vestments, e.g. the only French characteristic here is that the bishop’s cope is embroidered with fleur-de-lys. On the left of the picture is the king, and behind him officers of state and courtiers. An ecclesiastical procession has met him at the door of the Cathedral of Rheims, and the archbishop, in albe, cope, and mitre, is sprinkling him with holy water; the clerk bearing the holy-water pot, and the cross-bearer, and the thurifer swinging his censer, are immediately behind him. Then come a group of canons. One is clearly shown, and easily recognized by the peculiar horned hood with its fringe of “clocks.” Lastly are a group of bishops, the most conspicuous bearing in his hands the ampulla, which contains the holy oil for the anointing.

The photograph fails here as in other cases to give the colours which define the costumes clearly and give brilliancy to the picture. The king’s tunic is crimson, and that of the nobleman behind him blue. The archbishop has a cope of blue semée with gold fleur-de-lys; the water-bearer, a surplice so transparent that the red tunic beneath gives it a pink tinge; the cross-bearer, a blue dalmatic lined with red over a surplice; the canon a pink cope over a white surplice, and black hood. The first bishop wears a cope of blue, the second of red, the third of pink. The background is diapered blue and red with a gold pattern. The wall of the building is blue with a gold pattern; the altar-cloth, red and blue with gold embroidery.

| Interior of a Church at the Time of Mass | 204 |

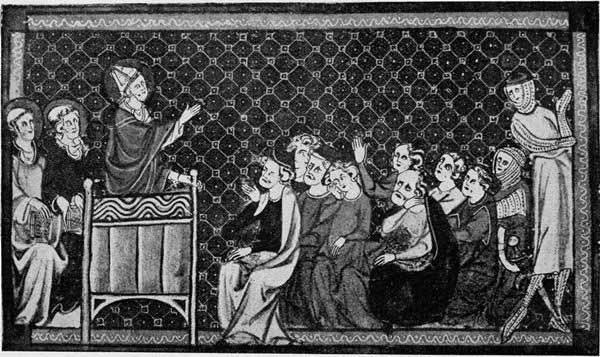

| A Sermon | 215 |

The bishop in blue chasuble and white mitre, people in red and blue tunics, two knights in chain armour, late 13th century.

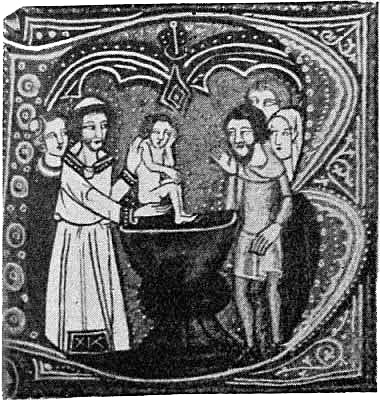

| (1) Baptism by Affusion | 233 |

The male sponsor holds the child over the font, while the priest pours water over its head from a shallow vessel. He wears a long full surplice, his stole is yellow semée with small crosses and fringed. The parish clerk stands behind him, 15th century.

| (2) Baptism by Immersion | 233 |

Here the priest wears an albe apparelled and girded, and an amice, but no stole; the sitting posture of the child occurs in other representations, 14th century.

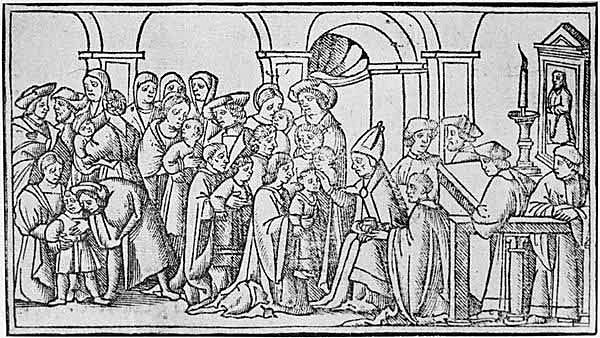

| Confirmation. (From a printed Pontifical, A.D. 1520) | 238 |

The bishop wears albe, dalmatic, cope, and mitre, the other clergy surplice and “biretta.”

| (1) Priest in Surplice, carrying Ciborium through the Street to a Sick Person, preceded by the Parish Clerk with Taper and Bell | 240 |

The ciborium, partly covered with a cloth, as in the illustration, which the priest carries, is silvered in the original illustration, and consequently comes out very imperfectly in the photograph.

| (2) | Priest, attended by Clerk, giving the Last Sacrament, 14th Century | 240 |

| Bishop and Deacon in Albe and Tunic, administering Holy Communion | 246 |

Two clerics in surplice hold the housel cloth to catch any of the sacred elements which might accidentally fall.

| Confession at the Beginning of Lent | 334 |

The priest in furred cope, the rood veiled; the altar has a red frontal. The two men are in blue habit. The woman on the right is all in black; the other, kneeling at a bench on the left, is in red gown and blue hood.

| Marriage | 410 |

It represents the marriage of the Count Waleran de St. Pol with the sister of Richard, King of England. The count is in a blue robe, the princess in cloth of gold embroidered with green; the groomsman in red, the man behind him in blue, the prince in the background in an ermine cape. The ladies attending the princess wear cloth of gold, blue, green, etc.; the bishop is vested in a light green cope over an apparelled rochet, and a white mitre. The bishop (and in other representations of marriage) takes hold of the wrists of the parties in joining their hands.

| Vespers of the Dead | 458 |

The mourners in black cloaks are at the east end of the stalls; the pall over the coffin is red with a gold cross; the hearse has about eighteen lighted tapers; the ecclesiastics seem to be friars in dark brown habit (Franciscans).

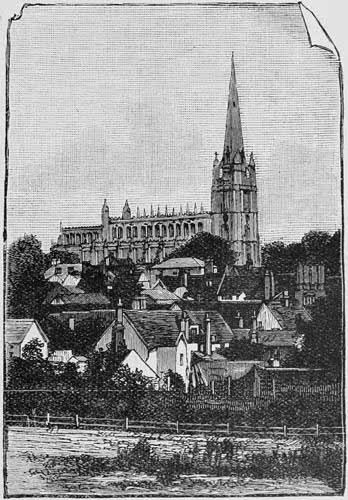

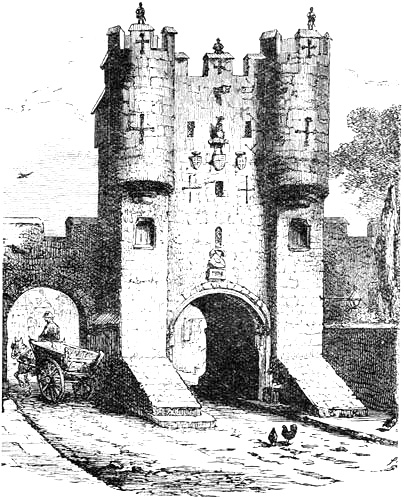

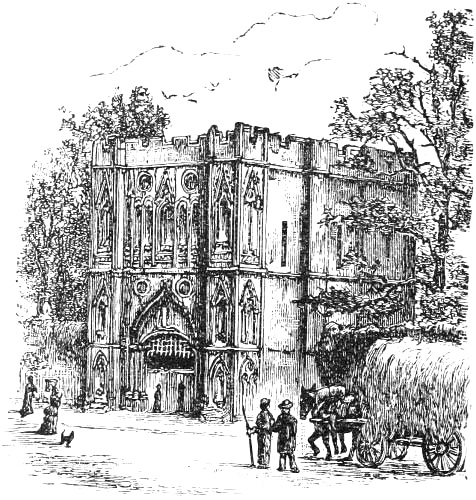

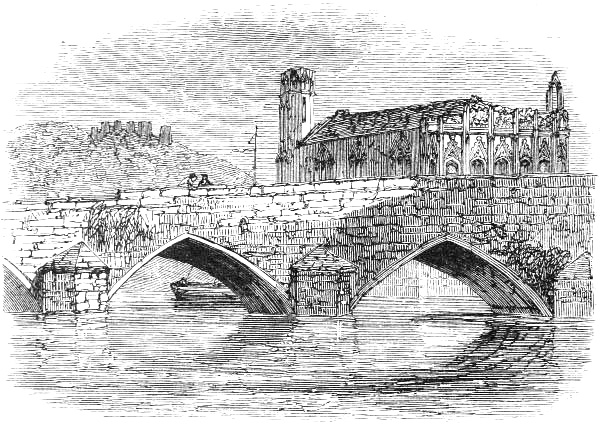

| Mediæval Norwich. (From Braun’s “Theatrum”) | 492 |

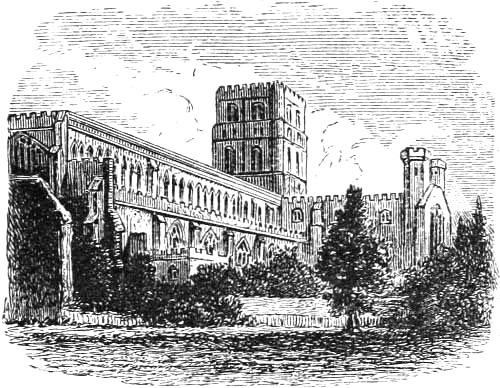

| Mediæval Exeter. (From Braun’s “Theatrum”) | 498 |

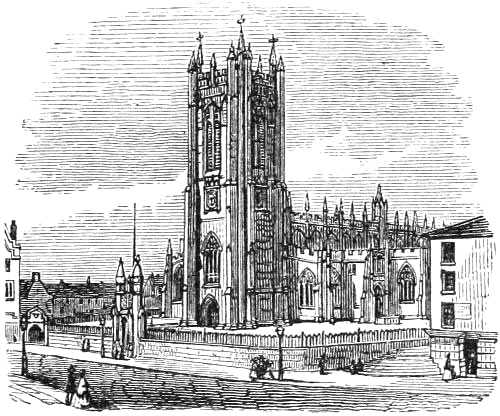

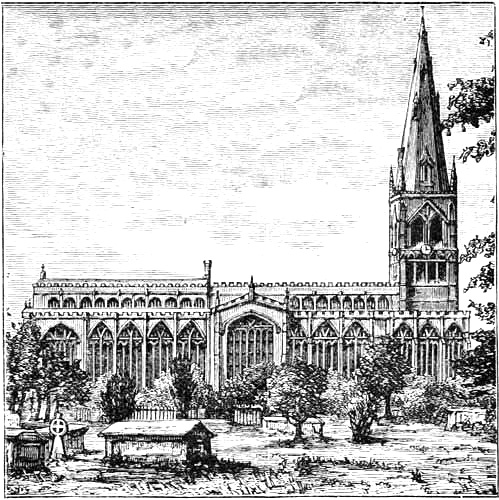

| Mediæval Bristol. (From Braun’s “Theatrum”) | 500 |

| Knights doing Penance at the Shrine of St. Edmund | 535 |

The abbot is vested in a gorgeous cope and mitre; one of the monks behind him also wears a cope over his monk’s habit.

References to other pictorial illustrations in MSS. in the British Museum are given in Appendix III., p. 567.

PARISH PRIESTS AND THEIR PEOPLE.

OUR HEATHEN FOREFATHERS.

hen we have the pleasure of taking our Colonial visitors on railway

journeys across the length and breadth of England, and they see

cornfields, meadows, pastures, copses, succeed one another for mile after

mile, with frequent villages and country houses, what seems especially to

strike and delight them is the thoroughness and finish of the cultivation;

England seems to them, they say, like a succession of gardens, or, rather,

like one great garden. This is the result, we tell them, of two thousand

years of cultivation by an ever-increasing population.

hen we have the pleasure of taking our Colonial visitors on railway

journeys across the length and breadth of England, and they see

cornfields, meadows, pastures, copses, succeed one another for mile after

mile, with frequent villages and country houses, what seems especially to

strike and delight them is the thoroughness and finish of the cultivation;

England seems to them, they say, like a succession of gardens, or, rather,

like one great garden. This is the result, we tell them, of two thousand

years of cultivation by an ever-increasing population.

[Pg 2]On the other hand, we are helped to understand what the land was like at the time of the settlement in it of our Saxon forefathers, by the descriptions which our Colonial friends give us of their surroundings in Australia or Africa, where the general face of the country is still in its primeval state, the settlements of men are dotted sparsely here and there, the flocks and herds roam over “bush” or “veldt,” and only just so much of the land about the settlements is roughly cultivated as suffices the wants of the settlers.

For in England, in those remote times of which we have first to speak, the land was, for the most part, unreclaimed. If we call to mind that the English population about the end of the sixth century could only have been about a million souls—200,000 families—we shall realize how small a portion of the land they could possibly have occupied. A large proportion of the country was still primeval forest, there were extensive tracts of moorland, the low-lying districts were mere and marsh, the mountainous districts wild and desolate. The country harboured wolf and bear, wild cattle and swine, beaver and badger, wild cat, fox, and marten, eagle, hawk, and heron, and other creatures, most of which have entirely disappeared, though some linger on, interesting survivals, in remote corners of the land.

Their possession of the country by the English was the result of recent, slow and desultory conquest. Independent parties of adventurers from the country round about the mouth of the Elbe had crossed the German Ocean in their keels, landed on the coast, or[Pg 3] rowed up the rivers, and pushed their way slowly against a tenacious resistance. Then, when a party of the invaders had made good their conquest, came its division among the conquerors.

Our own history tells us so little of the details of the Anglo-Saxon conquest, that we have to call in what we know of the manners of their Teutonic neighbours and Scandinavian relatives to help us to understand it. The late Sir W. Dasent, in his “Burnt Njal,” says that the Norse Viking, making an invasion with a view not to a mere raid, but to a permanent settlement, would lay claim to the whole valley drained by the river up which he had rowed his victorious keels; or, landing on the coast, would climb some neighbouring height, point out the headlands which he arbitrarily assigned as his boundaries on the coast, and claim all the hinterland which he should be able to subdue. The chief would allot extensive tracts to the subordinate leaders; and the freemen would be settled, after their native custom of village communities, upon the most fertile portions of the soil which their swords had helped to win. In the broad alluvial lands of the river valleys there would be ample space for several neighbouring townships; in forest clearings or fertile dales the townships would be scattered at more or less wide intervals. The unallotted lands belonged to the general community; it was Folk land, and its allotment from time to time, probably, in theory needed confirmation by a Folk-mote, but was practically made by the supreme chief.

[Pg 4]Every township possessed a tract of arable land, which was divided by lot yearly among the families of the freemen; a tract of meadow, which was reserved for hay, cultivated and harvested by the common labour; a wide expanse of pasture, into which each family had the right to turn a fixed number of cattle and sheep; and into the forest, a fixed number of swine to feed on the acorns, mast, and roots.[1] The people were rude agriculturists, not manufacturers, not traders, not civilized enough to profit by the civilization which the Romans had established in the country; they stormed and sacked the towns, and left them deserted, and selected only the most fertile spots for occupation.

It is a subject of dispute among our most learned historians to what extent the native Britons were slain or retired before the invaders, or to what extent they were taken as captives, or reappeared from their fastnesses after the slaughter was over, to be the slaves of the conquerors. When we first get glimpses of the situation of things after the conquest, we find that the British language and religion have disappeared from the Saxon half of the country; and this implies the disappearance of the great body of the people. The fact of the continuance of some ancient place-names, chiefly of great natural features, as hills and rivers, and of a few British words for things for which the Teutons had no names, would be sufficiently accounted for by the survival of a very small remnant.

[Pg 5]In their native seats the social condition of these Angle and Saxon freemen was patriarchal and primitive; they venerated their chiefs as Woden-born; they elected one of them as their leader in battle; but they did not obey them as their subjects. On questions of general importance the chiefs and wise men advised the Folk-mote, and the people said “Aye” or “No.” But their circumstances in their new conquests led to changes. It was necessary to maintain some sort of permanent military organization not only for the defence of their new possessions, and the extension of their conquests against the old inhabitants of the island, but also against the encroachments of rival tribes of their own countrymen. And a supreme chief, to whom all paid a kind of religious veneration, who exercised permanent military authority over lesser chiefs and people, soon became a king; limited, however, in power by the ancient institutions of the Council of the wise men, and the assent or dissent of the Folk-mote.

The several parties of invaders gradually extended their conquests until they met, and then made treaties or fought battles with one another, until, finally, by the end of the sixth century, they had organized themselves into seven independent kingdoms.

The freemen of each Township managed their own affairs in a town meeting; a number of neighbouring townships were grouped into what was called by the Saxons south of the Humber a Hundred, by the Angles north of the Humber a Wapentake; and each township sent four or five of its freemen to[Pg 6] represent it in the Hundred-mote every three months. Three times a year, in summer, autumn, and midwinter, a general meeting of the freemen was held—a Folk-mote—at some central place; to which every township was required to send so many footmen armed with sword, spear, and shield, and so many horsemen properly equipped. At these Folk-motes affairs of general interest were determined, justice was administered by the chief and priests,[2] and probably it was at these meetings that the great acts of national worship were celebrated. Except for these periodical meetings, the scattered townships existed in great isolation. A striking illustration of this isolation is afforded by laws of Wihtred of Kent and of Ine of the West Saxons, which enact—or perhaps merely record an ancient unwritten law—that if any stranger approached a township off the highway without shouting or sounding a horn to announce his coming, he might be slain as a thief, and his relatives have no redress. A subsequent law of Edgar[3] enacts that if he have with him an ox or a dog, with a bell hanging to his neck, and sounding at every step, that should be taken as sufficient warning, otherwise he must sound his horn. The local exclusiveness produced by this isolation, the suspicion and dislike of strangers, survive to this day in secluded villages in the wilder parts of the country.

These Teutonic tribes were heathen at the time of[Pg 7] their coming into the land. Of their religion and its observances our own historians have given no detailed account, and few incidental notices. Our names for the days of the week, Sun-day, Moon-day, Tuisco’s-day, Woden’s-day, Thor’s-day, Frya’s-day, Saeter’s-day, make it certain that our Anglo-Saxon ancestors worshipped the same gods as their Scandinavian neighbours, and probable that their religion as a whole was similar. Their supreme god was Odin or Woden, with whom were associated the twelve Æsir and their goddess-wives, and a multitude of other supernatural beings. In their belief in an All-father, superior to all the gods and goddesses—we recognize a relic of an earlier monotheism. They had structural temples, and in connection with their temples they had idols, priests, altars, and sacrifices. They believed in the immortality of the soul, in an intermediate state, and a final heaven and hell. The souls of the brave and good, they believed, went to Asgard, the abode of the Æsir; there the warriors all day enjoyed the fierce delight of combat, and in the evening all their wounds healed, and they spent the night in feasting in Valhalla, the hall of the gods; the wicked went to Niflheim, a place of pain and terror. But the time would come when the earth, and sun, and stars, and Valhalla, and the gods, and giants, and elves, should be consumed in a great and general conflagration, and then Gimli and Nastrond, the eternal heaven and hell, should be revealed. Gimli—a new earth adorned with green meadows, where the fields bring forth without culture, and calamities[Pg 8] are unknown; where there is a palace more shining than the sun, and where religious and well-minded men shall abide for ever; Nastrond—a place full of serpents who vomit forth venom, in which shall wade evil men and women, and murderers and adulterers.

A knowledge of their religious customs would help us to judge what hindrance they opposed to the reception of the system of the Christian Church; or, on the other hand, what facilities they offered for the substitution of one for the other; but it is only from the assumption that the religious customs of our English ancestors were similar to those of the Norsemen that we are able to form to ourselves any conception on the subject.

In Iceland, conformably to the constitution of its government, each several district (the island was divided into four districts) had its priest who not only presided over the religious rites of the people, but also directed the deliberations of the people when their laws were made, and presided over the administration of justice (Neander, “Church Hist.,” v. 418).

Sir W. Dasent says that after the Norse conqueror had marked out his boundaries and settled his people on their holdings, and chosen a site for his own rude timber hall, he erected in its neighbourhood a temple in which his followers might worship the gods of their forefathers, and that this was one means of maintaining their habitual attachment to his leadership.[4] The evidence leads to the conclusion that both Scandinavians and Teutons had very few[Pg 9] structural temples, perhaps only one to each tribe or nation; and perhaps only three great annual occasions of tribal or national worship. We get a glimpse of one of these structural temples in the story of the conversion of Norway.[5] The great temple at Mære, in the Drontheim district, contained wooden images of the gods; the people assembled there thrice a year at midwinter, spring, and harvest; the people feasted on horseflesh slain in sacrifice, and wine blessed in the name and in honour of the gods; and human victims were sometimes offered.

The English townships, generally, it is probable, had no structural temples, but sacred places of resort, as an open space in the forest, or a hilltop, or a striking mass of rock, or a notable tree or well. The religious observances at such places would probably not be a regular worship of the gods, but such superstitions as the passing of children through clefts in rocks and trees, dropping pins into wells, and others; these superstitions survived for centuries, for they are forbidden by a law of Canute,[6] and one of them, the[Pg 10] consultation of wells, so late as by a canon of Archbishop Anselm;[7] and, in spite of laws, and canons, and civilization, and a thousand years of Christianity, some of them survive among the peasantry of remote districts to this very day.

In the “Ecclesiastical History” of Bede, we find notices of only three structural heathen temples in England. The first is that at Godmundingham, which Coifi, the chief of the king’s priests, with the assent of King Edwin and his counsellors and thanes, defiled and destroyed on the acceptance of Christianity at the preaching of Paulinus. Of this we read that it had a fanum, enclosed with septis, which contained idola and aras;[8] and since the temple was set on fire and thus destroyed, it seems likely that the fanum was of timber. The second temple named is the building east of Canterbury, in which King Ethelbert was accustomed to worship while yet a heathen, which, on the king’s conversion, was consecrated as a church and dedicated to St. Pancras, and was soon afterwards incorporated into the monastery of SS. Peter and Paul built on the site. This was probably a stone building, and recent researches have brought to light what are possibly remains of it. The third temple is that in which Redwald, King of the East Anglians,[Pg 11] after his conversion at the Court of Ethelbert, worshipped Christ at one altar, while his queen continued the old heathen worship at another altar in the same building. It will be observed that all these were the temples of kings, and this accords with the supposition that such structural temples existed only in the chief places for worship of tribes and nations; just as the twelve tribes of Israel had only one great national temple, while they had numerous altars on the “high places” all over the country.[9]

Again, there is a remarkable absence all through the history of any mention of, or allusion to, the existence of a priesthood ministering among the people. The only priest clearly mentioned is the worldly-minded Coifi spoken of above, but as he is mentioned as “the chief of the king’s priests,” we assume that[Pg 12] there was a staff of them, probably attached to the king’s temple at Godmundingham. We suppose that Ethelbert of Kent, and Redwald of East Anglia, would also have a priest or priests attached to their temples; but we find no trace or indication of any others.

This all tends to confirm our belief that there were few structural temples, one for each kingdom, or perhaps one for each of the great tribes which had coalesced into a kingdom; and that the priests were only a small staff attached to each of these temples; while all the rest of the temples were open-air places to which the neighbouring inhabitants resorted for minor observances, without the assistance of any formal priesthood.

Another possible source of information on the subject is the ancient place-names. Godmundingham naturally invites consideration, and looks promising at first sight; but analyzed and interpreted it means the home of the sons of Godmund, and Godmund merely means “protection of God” as a name.[10]

The Saxon word Hearh[11] means either a temple or an idol.[12] Hearga is the word by which the fanum at Godmundingham and Redwald’s fanum is translated in Alfred’s version of Bede. It seems possible that this word may be the root of such place-names as[Pg 13] Harrow-on-the-Hill, Harrowgate, Yorks, and Harrowden, Northants. Such place-names as Wednesbury, Wedensfield, Satterthwaite, Satterleigh, Baldersby, Balderstone, Bulderton, and those of which Thor or Thur is the first syllable, may possibly indicate places where a temple or an idol or well has existed of Woden, or Saeter, or Baldur, or Thor; as Thrus Kell (Thor’s Well) in Craven.[13]

THE CONVERSION OF THE ENGLISH.

he history of the conversion of our heathen forefathers has happily been

told so often in recent times that it is not necessary to repeat it here.

It is sufficient for our purpose to recall to mind how when Augustine and

his Italian company came to Kent, they addressed themselves to King

Ethelbert, who had married a Christian princess of the House of Clovis,

and were permitted by him to settle and preach in his kingdom; how King

Oswald, on his recovery of his ancestral kingdom of Northumbria, sent to

the Fathers of Iona, among whom he had learnt Christianity during his

exile, for missionaries to convert his people; how Sigebert, King of the

East Saxons, and Peada, sub-King of the Middle Angles in Mercia, obtained

missionaries from Northumbria; how Sigebert, King of the East Angles,

invited Bishop Felix to give to his people the religion and civilization

which he had learnt in exile in Burgundy; how the Italian Bishop[Pg 15] Birinus

came to the Court of King Cynegils, and converted him, and taught among

the men of Wessex; and, finally, how Wilfrid of York began the conversion

of the South Saxons.

he history of the conversion of our heathen forefathers has happily been

told so often in recent times that it is not necessary to repeat it here.

It is sufficient for our purpose to recall to mind how when Augustine and

his Italian company came to Kent, they addressed themselves to King

Ethelbert, who had married a Christian princess of the House of Clovis,

and were permitted by him to settle and preach in his kingdom; how King

Oswald, on his recovery of his ancestral kingdom of Northumbria, sent to

the Fathers of Iona, among whom he had learnt Christianity during his

exile, for missionaries to convert his people; how Sigebert, King of the

East Saxons, and Peada, sub-King of the Middle Angles in Mercia, obtained

missionaries from Northumbria; how Sigebert, King of the East Angles,

invited Bishop Felix to give to his people the religion and civilization

which he had learnt in exile in Burgundy; how the Italian Bishop[Pg 15] Birinus

came to the Court of King Cynegils, and converted him, and taught among

the men of Wessex; and, finally, how Wilfrid of York began the conversion

of the South Saxons.

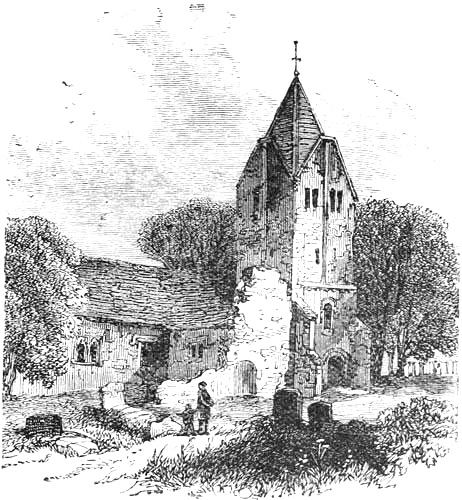

The Ruined Cathedral, Iona.

In the Apostolic Age, the conversion of people in a condition of ancient civilization began among the lower classes of the people, and ascended slowly man by man through the higher classes, and it was three hundred years before the conversion of the Emperor Constantine made Christianity the religion of the empire. In the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, the work began in every case with the kings and the higher classes of the people; and the people under their leadership abandoned their old religion and accepted Christianity as the national[Pg 16] religion, and put themselves under the teaching of the missionaries, as a general measure of national policy.

The explanation of this probably is that their Teutonic kinsmen, Goths, Burgundians, and Franks, who had carved for themselves kingdoms out of the body of the Roman empire, having accepted the religion and the civilization of the people they had conquered, were growing rapidly in prosperity and the arts of civilized life. Christianity was the religion of the new Teutonic civilization, and heathenism was a part of the old state of barbarism. The Angles and Saxons, when they fastened upon this derelict province of the empire, were too barbarous to appreciate civilization, and destroyed it; but by the time that they had been settled for some generations in their new seats they had outgrown their old wild heathenism; and their kings had become sufficiently politic to desire to learn how to raise the new kingdoms which they governed to an equality with those of the kindred Continental nations. Hence, some of the heptarchic kings sought for Christian teachers to help them, and others were willing to receive them when they offered themselves.

Our previous study of the organization, religion, and customs of the people will help us to understand the process of the revolution. The kings, when converted, put the matter before the constitutional council of chiefs and wise men, and with their assent, and perhaps after a reference of the question to a folk-mote, formally adopted the new religion. The history which Bede gives of the first acceptance of Christianity in Northumbria, under the teaching of[Pg 17] Paulinus, affords a profoundly interesting example of the process—the long hesitation of the king, the discussion in the witan, the general acceptance of the new faith, the zeal of the chief priest in destroying the national temple, the flocking of the people to the preaching of Paulinus, and their baptism in multitudes in the neighbouring rivers.

In no instance were the missionaries persecuted; in no instance did the kings coerce their people into the acceptance of the new religion.[14] In such a wholesale transition from one religion to another, it is not surprising that there occurred partial and temporary relapses, as in Kent and Essex, on the death of King Ethelbert, 616, in Wessex on the death of Cynegils, 643, and again in Essex, after the plague of 664; still less surprising that old superstitions retained their hold of the minds of a rude and ignorant people for centuries.[15]

[Pg 18 & 19]If we are right in our conjectures that every kingdom had a national temple at the principal residence of the king with a small staff of priests, and a few smaller temples with their priests under the patronage of some of the subordinate chiefs, and that these temples were resorted to by the people for special acts of common worship at the great festivals three or four times in the course of the year, then it would not be difficult for the new religion[Pg 20] to supply to the people all that they had been accustomed to of religious observances. Churches on the sites of the old temples, with their clergy, and services on the great festivals of the Christian year, would satisfy the customs of the people; and, in fact, the circumstances of the Christian missionaries led in the first instance to arrangements of this nature.

In every kingdom the king, who had been the patron of the old religion, took the new teachers under his protection, and made provision for their maintenance by the donation of an estate in land with farmers and slaves upon it; thus Ethelbert gave to Augustine a church and house in Canterbury, and land outside the city for a site for his monastery, and estates at Reculver and elsewhere for maintenance; Oswald gave to Aidan the isle of Lindisfarne, under the shadow of his principal residence at Bamborough; Ethelwalch gave Wilfred eighty-seven hides at Selsey, and Wilfrid began his work, as probably the other missionary bishops did, by emancipating his slaves and baptizing them; Cynegils, on his baptism, gave Birinus lands round Winchester, and his son Coinwalch endowed the church there with three manors; a little later, Wulfhere of Mercia gave Chad a wild tract of a hundred thousand acres between Lichfield and Ecclesfield. This was the “establishment” and beginning of the “endowment” of the Church in England.

The bishop in every kingdom first built a church and set up Divine service, then simultaneously set up a school, and invited the king and chiefs to send[Pg 21] their sons to be educated. Aidan took twelve youths of noble birth as his pupils, and added slaves whom he purchased. The young men of noble families showed themselves eager to avail themselves of the teaching and training of the missionaries, and readily offered themselves to training for Holy Orders. The ladies at first, before there were monasteries for women in England, went to the monasteries at Brie and Chelles near Paris, and at Andelys near Rouen, which were under the government of members of the Frankish royal families. From his central station the bishop went out and sent his priests on missionary journeys to the neighbouring townships, to teach and baptize.

We know that all the first missionary bishops, except Felix and Birinus, and perhaps they also, and most of their clergy, had been trained in the monastic life of that time, so that it was natural to them to live in community, under the rule of a superior, a very simple and regular life, with frequent offices of prayer, and duties carefully defined, and scrupulously fulfilled; a beautiful object-lesson on the Christian life for the study of the king and his household, and the people round about the bishop’s town.

Bede gives some interesting stories which illustrate this early phase of the English conversion. He tells us how Paulinus preached all day long to the people at Yeverin and Catterick[16] in Northumbria, and at Southwell[17] in Lindsey, and baptized the people by hundreds in the neighbouring rivers. He tells us[Pg 22] how Aidan preached to Oswald’s Court and people, and the King interpreted for him;[18] how Aidan travelled through the country on foot, accompanied by a group of monks and laymen, meditating on the scriptures, or singing psalms as they went;[19] not that he needed to travel on foot, for King Oswin had given him a fine horse which he might use in crossing rivers, or upon any urgent necessity; but a short time after, a poor man meeting him, and asking alms, the good bishop bestowed upon him the horse with its royal trappings.[20] We learn from the same authority that the company which attended a missionary bishop in his progress through the country were not always singing psalms as they went. Herebald, a pupil of St. John of Beverley, relates how one day as that bishop and his clergy and pupils were journeying, they came to a piece of open ground well adapted for galloping their horses, and the young men importuned the bishop for permission to try their speed, which he reluctantly granted; and so they ran races till Herebald was thrown, and, striking his head against a stone, lay insensible; whereupon they pitched a tent over him.[21]

An “interior” picture is afforded by a sentence in the life of Boniface,[22] who was afterwards to be the Apostle of Germany. When the itinerant teachers used to come to the township in which Winfrid’s father was the principal proprietor, they were [Pg 23]hospitably entertained at his father’s house; and the child would presently talk with them as well as he could, at such an early age (six or seven years), about heavenly things, and inquire what might hereafter profit himself and his weakness (A.D. 680).

Finally Bede sums up the work of this period. “The religious habit was at that period in great veneration; so that wheresoever any clergyman or monk happened to come, he was joyfully received by all persons as God’s servant; and if they chanced to meet him on the way, they ran to him, and, bowing, were glad to be signed with his hand, or blessed with his mouth. On Sundays they flocked eagerly to the Church or the monasteries, not to feed their bodies, but to hear the Word of God; and if any priest happened to come into a village, the inhabitants flocked together to hear the word of life; for the priests and clergymen went into the village on no other account than to preach, baptize, visit the sick, and, in short, to take care of souls.”[23]

So Cuthbert, a little later, not only afforded counsels and an example of regular life to his monastery, “but often went out of the monastery, sometimes on horseback, but oftener on foot, and repaired to the neighbouring towns, where he preached the way to such as were gone astray; which had been also done by his predecessor Boisil in his time. He was wont chiefly to visit the villages seated high among the rocky uncouth mountains, whose poverty and barbarity made them inaccessible[Pg 24] to other teachers. He would sometimes stay away from the monastery one, two, three weeks, and even a whole month among the mountains, to allure the rustic people by his eloquent preaching to heavenly employments.”[24]

It seems likely that the itinerating missionaries, on arriving at a township, would seek out the chief man, first to ask hospitality from him, and next to engage his interest with the people to assemble together at some convenient place to hear his preaching. When the people were converted, he would make arrangements for periodical visits to them for Divine service, and the “convenient place” would become their outdoor church; and there is good reason to believe that in many cases a cross of stone or wood, whichever was the most accessible material, was erected to mark and hallow the place.[25]

Even after a priest was permanently settled, and a church built at the ville of the lord of the land, the scattered hamlets on the estate would still, perhaps for centuries, have only open-air stations for prayer. It is very possible that some of these were the places[Pg 25] where the people, while unconverted, had been used to assemble for their ancient religious ceremonies.

Saxon Cross at Ruthwell, c. 680 A.D.

(For its history and description, see “Theodore

and Wilfrid,” by the Bishop of Bristol.)

[Pg 26]Some of the Saxon churchyard crosses which still remain, as at Whalley, Bakewell, Eyam, etc., possibly were station crosses. Possibly the well which exists in some churches and churchyards, and the yew tree of vast antiquity found in many churchyards, would carry us back, if we knew their story, to pre-Christian times and heathen ceremonials.

Churchyard Cross, Eyam, Derbyshire.

In time a church or chapel was built in this accustomed place of assembly, as we shall find in a later chapter. But here we have to throw out a conjecture as to an intermediate state of things between the open-air station and the structural church. We have before us the curious fact that usually the rector of a church is liable for the repair of the chancel, and the people for the repair of the nave. This seems to point to the fact that the forerunner of the rector built the first chancel, and left the people to build the nave; and we suggest the following explanation; at first in the worship of these stations, a temporary table was placed on trestles, and a “portable altar” upon that, and so the holy mysteries were celebrated. But in rainy weather[Pg 27] this was inconvenient and unseemly; and the rector of the parish provided a kind of little chapel for the protection of the altar and ministrant; indeed, there is an ancient foreign canon which requires rectors to do so. Then the parishioners, for their own shelter from the weather, built a nave on to the chancel, communicating with it by an arch through which the congregation could conveniently see and hear the service.

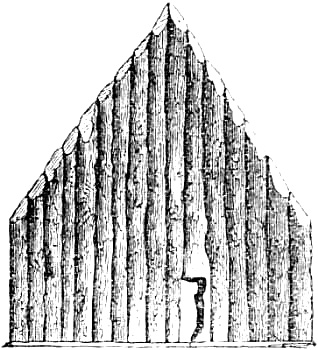

Base of Acca’s Cross, c. 740 A.D., from

“Theodore and Wilfrid,” by the Bishop of Bristol. S.P.C.K.

THE MONASTIC PHASE OF THE CHURCH.

e have seen how the bishops who introduced the Christian Faith into the

heptarchic kingdoms established themselves and their clergy as religious

communities, on the lands, and with the means which the kings gave them,

built their churches and schools, and made them the centres of their

evangelizing work. The next stage in the work was the multiplication of

similar centres. The princes and ealdormen who were in subordinate

authority over subdivisions of a kingdom would have two motives for

desiring to have such establishments beside them. First they had very

likely in some cases been the patrons of a temple or an idol, and a

priest, near their principal residence, and would desire to maintain their

influence over their dependents and neighbours by keeping up a similar

place of religious worship for them. Secondly, as enlightened men and

zealous converts, they would be glad to have near them some of these new

teachers of[Pg 29] religion and civilization, and to establish one of these

centres of light and leading to the neighbouring country. The bishops also

obtained grants of land from the king in suitable places, in order to

found on them new centres of evangelization.

e have seen how the bishops who introduced the Christian Faith into the

heptarchic kingdoms established themselves and their clergy as religious

communities, on the lands, and with the means which the kings gave them,

built their churches and schools, and made them the centres of their

evangelizing work. The next stage in the work was the multiplication of

similar centres. The princes and ealdormen who were in subordinate

authority over subdivisions of a kingdom would have two motives for

desiring to have such establishments beside them. First they had very

likely in some cases been the patrons of a temple or an idol, and a

priest, near their principal residence, and would desire to maintain their

influence over their dependents and neighbours by keeping up a similar

place of religious worship for them. Secondly, as enlightened men and

zealous converts, they would be glad to have near them some of these new

teachers of[Pg 29] religion and civilization, and to establish one of these

centres of light and leading to the neighbouring country. The bishops also

obtained grants of land from the king in suitable places, in order to

found on them new centres of evangelization.

Thus in Kent, Ethelbert founded the monastery of SS. Peter and Paul, which is better known to us as St. Augustine’s (A.D. 603), and his son Eadbald founded an offshoot from it at Dover (630). In 633 the latter king founded a nunnery at Folkestone as a provision for his daughter Eanswitha, who became its first abbess. And when, in the same year, his sister Ethelburga arrived as a refugee from Northumbria, he made provision for her by the gift of an estate at Lyminge, where the widowed queen founded a monastery. On the death of Earconbert, 664, Sexburga, his widow, built for herself a nunnery in the Isle of Sheppy. Sexburga was succeeded at Sheppy by her daughter Eormenhilda, and she by her daughter Werburga. Eormenburga, granddaughter of King Eadbald, built a nunnery, of which she was the first abbess, in the Isle of Thanet; and was succeeded by her daughter St. Mildred. Lastly, King Egbert, in 669, gave Reculver to his mass-priest, Bass, that he might build a minster thereon.

In Northumbria, King Edwin built a church at York. Oswald gave Aidan the Isle of Lindisfarne as the site of a religious house to be a centre of missionary work in Northumbria. Aidan encouraged Hieu, the first nun of the Northumbrian[Pg 30] race, to organize a small nunnery on the north bank of the Wear, and to remove thence to Hartlepool; there she was succeeded by Hilda, the grand-niece of King Edwin, who subsequently removed to Whitby. Besides organizing that famous double house, Hilda founded Hackness and several other cells on estates of the abbey. The nunnery at Coldingham was founded by Ebba, sister of King Oswald, who was herself the first abbess. King Oswy, on the eve of battle with Penda (655), vowed, in case of victory, to dedicate his infant daughter Elfleda to God, and to give twelve estates to build monasteries. In fulfilment of his vow, he gave Elfleda into the charge of Hilda, at Hartlepool (655), and gave six estates in Bernicia and six in Deira, each of ten families (= hides of land), of which probably Whitby was one, and perhaps Ripon and Hexham were others. Benedict Biscop, a man of noble if not royal descent, received grants of land from King Egfrid to found his famous monastery at Wearmouth in 674, and eleven years later (685) at Jarrow. King Oswy built a monastery at Gilling to atone for the crime of the slaughter of his brother there (642), that prayer might be daily offered up for the souls of both the slain and the slayer. King Ethelwald, son of Oswald and sub-king of Deira, gave Bishop Cedd of the East Saxons a site for a monastery at Lastingham, Yorkshire, that he might himself sometimes resort to it for prayer, and might be buried there. Cedd left the monastery, on his death, to his brother Chadd, afterwards Bishop of[Pg 31] Lichfield. Wulfhere, King of Mercia, gave Chadd fifty hides of land for the endowment of his abbey at Barton-on-Humber.

In the fen country of the Girvii, between Mercia and East Anglia, the two kings, Peada of Mercia, and Oswy of the East Angles, concurred in the foundation of a monastery at Medeshamsted (Peterborough, 655), and this was followed by the foundation of Croyland (716) and Thorney (682). When Etheldreda, the daughter of Anna, King of the East Angles, and virgin wife of Egfrid of Northumbria, at length obtained her husband’s leave to enter upon the religious life, she built herself a double monastery on her own estate in the Isle of Ely (673). On her death, she was succeeded as abbess by her sisters Sexburga, Eormenhilda and Werburga, each of whom had previously been abbesses at Sheppy.

Among the West Saxons, a small community of Irish monks, at Malmesbury (675), was enlarged by Aldhelm, a man of royal extraction, into a great centre of religion and learning; and he and Bishop Daniel founded a number of small monasteries, as Nutcelle (700) and Bradfield, up and down that kingdom.[26]

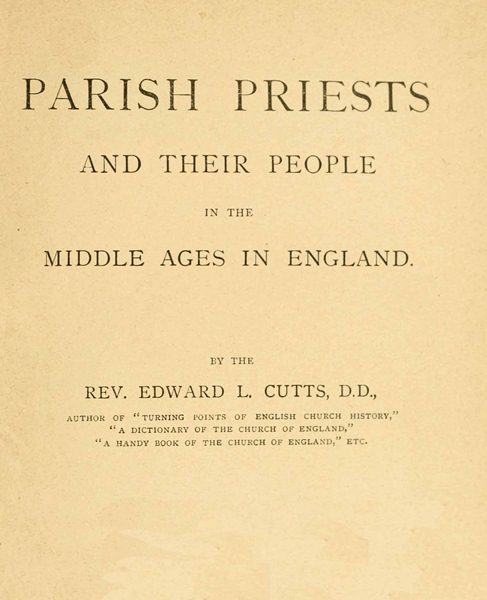

Saxon Church at Bradford-on-Avon.

(Probably one of Bishop Aldhelm’s churches.)

The four priests whom Peada, the son of Penda, on his conversion, took back with him from Northumbria to his Princedom of the Middle Angles, lived together in community for some years, till, by the death of [Pg 33]Penda, his son attained the Kingship of Mercia, and then Diuma was consecrated Bishop of the Mercians, and established his see at Lichfield. Earconwald (who was afterwards Bishop of London, 674), a man of noble birth, built a monastery for himself at Chertsey in Surrey, and a nunnery at Barking in Essex, for his sister Ethelberga. “The vales of Worcestershire and Gloucestershire were famous for the multitude and grandeur of their monastic institutions.” A monastic cell is said to have been founded at Tewkesbury in 675, and one at Deerhurst, by Ethelmund the ealdorman, at a still earlier date. Osric, the Prince of Wiccii, was probably the founder of St. Peter’s Nunnery, Gloucester, and of Bath Abbey. Apparently his brother Oswald founded Pershore Abbey; and their sister Cyneburga was the first Abbess of Gloucester. Saxulph, Bishop of Lichfield, founded a little religious house of St. Peter, at Worcester, which became the see of the first Bishop of Worcester, when that diocese was founded by Archbishop Theodore (680). Egwine, Bishop of Worcester, founded a monastery at Evesham (702), and laying down his bishopric, retired thither to spend the remainder of his life as its abbot.[27]

The following names will nearly complete the list of religious houses up to the end of the eighth century: Abingdon, 675; Acle, seventh century;[Pg 34] Amesbury, 600; Bardney, seventh century; Bedrichsworth (St. Edmunds), 630; Bosham, 681; Bredon, 761; Caistor, 650; Carlisle, 686; Clive, 790; Cnobheresbury (Burgh Castle), 637; Congresbury, 474; Dacor, seventh century; Derauuda, 714; Dereham, 650; Finchale, seventh century; Fladbury, 691; Gateshead, seventh century; Glastonbury, fifth century; Ikanho (Boston), 654; Ithanacester, 630; Kempsey, 799; Kidderminster, 736; Leominster, 660; Oundle, 711; Oxford St. Frideswide, 735; Partney, seventh century; Petrocstow, sixth century; Peykirk, eighth century; Redbridge, Hants. (Hreutford), 680; Repton, 660; Rochester, 600; St. Albans, 793; York St. Mary’s, 732; Selsey, 681; Sherborne, 671; Stamford, 658; Stone, Staff., 670; Stratford-on-Avon, 703; Tetbury, 680; Tilbury, 630; Tinmouth, 633; Walton, Yorks., 686; Wedon, 680; Wenloch, 680; Westminster, 604; Wilton, 773; Wimborne, 713; Winchcombe, 787; Winchester, 646; Withington, seventh century.[28]

The fashion of founding religious houses spread among the smaller landowners, and some begged land of the king on which to found them.

Some of these religious houses were great and solemn monasteries, like those of Italy and France, with noble churches and frequent services; and their inmates lived a secluded life, devoted to learning, meditation, and prayer. St. Augustine’s monastery at Canterbury was the earliest of them. Benedict[Pg 35] Biscop’s monasteries at Wearmouth and Jarrow, and Wilfrid’s at Ripon and Hexham, and others, were of this type.

The life of these greater monasteries was led according to a strict and ascetic rule. St. Augustine would certainly adopt at Canterbury the rule which his master, Gregory, had drawn up for his own house of St. Andrew on the Cœlian Hill. Benedict Biscop built his houses and framed his rule after repeated visits to Italy and France and a careful study of the most famous of their religious communities; Wilfrid would certainly introduce a similar rule into the monasteries over which he presided; these would follow the main lines of the Benedictine rule; though that, in its entirety, was not introduced till the reformation of the monasteries in the time of King Egbert and Archbishop Dunstan. The monastery at Lindisfarne would naturally follow the customs of Iona and the less rigid life of the Scottish religious houses; and is to be regarded rather as a citadel of Christian learning, and a centre of evangelization, than as a place devoted to seclusion and contemplation. The other religious houses which owed their existence to the missionaries from Lindisfarne would be likely to follow its customs.

Some of the smaller religious houses were conducted on the same lines of strict ascetic discipline as the greater monasteries; but in many of them the life was little more “regular” or ascetic than that of an ordinary household—say that of a church dignitary—scrupulous in the attendance of all its members at[Pg 36] the daily services in the oratory, and in the strict decorum of their daily life. This opened an easy door to abuse, and in a short time the discipline of many of the monasteries had become very lax.

One remarkable feature of these early monasteries is that many of them were hereditary properties, and the rule over them often descended from father to son and from mother to daughter. We have seen the successions in the Kentish monasteries and at Ely from sister to sister and from mother to daughter. Cedd bequeathed his monastery of Lastingham to his brother Chad. Benedict Biscop saw the danger of the custom, and declared that he would not transfer his monasteries to his own brother unless he was a fit person to be abbot. Whitgils built a small church and monastery at Spurnhead in Holderness, and left them to his heirs; they came at last, by legitimate succession, to no less distinguished a person than Alcuin; who was, therefore, not only Abbot of Tours, with its vast territory on which there were 200,000 serfs, but also of this little monastery in his native country. Hedda, who styles himself mass-priest, in 790 bequeathed his patrimonial inheritance, consisting of two large parcels of land, with a minster on one of them, limiting the succession of the latter to clergymen of his family considered capable of ruling a minster according to ecclesiastical law, and in default of such heir, it was to go to Worcester Cathedral, where he had been bred and schooled (“Cod. Dipl.,” i. 206).[29]

[Pg 37]It is easy to understand how it was that in process of time many of these semi-secular religious houses passed easily into the status of parochial rectories; and, on the other hand, how a rectory, which often had a number of chaplains and clerks to assist the rector in ministering to the mother church and its outlying chapels, came to be called a “minster.”

In the Danish invasions and occupations, most of these religious houses were plundered and ruined, the greater houses were not at once reoccupied on the restoration of order, and most of the smaller houses disappeared.

In the course of the revival of religion in the reign of Edgar under the influence of Dunstan, it was the boast of the king and his ecclesiastical advisers that they had restored not less than forty of the old monasteries, and brought them to the discipline of the Benedictine rule. A few monasteries were restored or founded after that time, notably by Canute at Bury St. Edmunds, and at Hulme in Norfolk, and by Edward the Confessor at Westminster; but at the time of the Conquest there were probably not more than about fifty monasteries in the country of any account; and in the latter part of the period the monastic zeal of Dunstan’s revival had cooled down to a level of average religiousness.

DIOCESAN AND PAROCHIAL ORGANIZATION.

he English Conversion forms a remarkable chapter in the general history

of Christian missions; the piety, simplicity, zeal, and unselfishness of

the missionaries are beyond praise; not less remarkable is the earnestness

with which the English embraced the new faith and the civilization which

came together with it. The fact bears witness to the intellectual and

moral qualities of the people that in the very first generation of

converts there were men of learning and character like Wilfrid and

Benedict Biscop, like the pupils of Hilda of Whitby, like Ithamar and

Deusdedit in Kent, worthy of taking place among the bishops and abbots of

their time.

he English Conversion forms a remarkable chapter in the general history

of Christian missions; the piety, simplicity, zeal, and unselfishness of

the missionaries are beyond praise; not less remarkable is the earnestness

with which the English embraced the new faith and the civilization which

came together with it. The fact bears witness to the intellectual and

moral qualities of the people that in the very first generation of

converts there were men of learning and character like Wilfrid and

Benedict Biscop, like the pupils of Hilda of Whitby, like Ithamar and

Deusdedit in Kent, worthy of taking place among the bishops and abbots of

their time.

The royal and noble ladies who played so important a part, in the influence they exercised in affairs, or in the foundation and rule of religious houses which trained bishops and priests, present a spectacle,[Pg 39] almost unparalleled in history, of which their descendants may well be proud.

The English kings and nobles put themselves frankly under the guidance of their teachers not only in religion and literature, but in the arts of civilization. The three codes of law which have remained to us—the first written laws of the English race—carry proof on the face of them that they were compiled under the influence of the Christian teachers. The princes sought their counsel in the Witenagemot, and put them beside the secular judges in the administration of justice at the hundred and folk motes. “In a single century England became known to Christendom as a fountain of light, as a land of learned men, of devout and unwearied missions, of strong, rich, and pious kings.”[30]

By the third quarter of the seventh century the first fervour of the English conversion had cooled down, and circumstances produced a kind of crisis. One of those plagues which at intervals ravaged mediæval Europe—it was called the Yellow Pest—during the summer of 664 swept over England from south to north. Earconbert, King of Kent, and Deusdedit, the first native bishop of the Kentish men, died on the same day; Damian, Bishop of Rochester, probably died a little before his brother of Canterbury. In the north, Tuda, recently appointed Bishop of Northumbria, died, and Cedd, Bishop of the East Saxons, then staying at his monastery of Lastingham. The half of the East Saxons who were under the rule[Pg 40] of the sub-king Sighere, thinking the pest a result of the anger of the ancient gods, apostatized from the faith. The differences between the two “schools of thought,” the Continental in the south of the country, and the Scotic in the north, were causing friction and inconvenience, so much so that the bishops elect of the Continental school hesitated to receive consecration from the bishops of the Celtic school; Wilfrid of York had at this very time gone to seek consecration from the Frankish bishops. In this crisis, Oswy, King of Northumbria, agreed with Egbert, who succeeded Earconbert in Kent, to send a priest acceptable to both schools to Rome, to study things in that centre of Western Christendom, to get consecration from the Bishop of Rome, and then to return and reduce the ecclesiastical affairs of England to a common order. Wighard, a Kentish priest, sent in pursuance of this wise plan, died in Rome; and, to save time, at the request of the English Churches, Vitalian, the Bishop of Rome, selected Theodore of Tarsus, a learned priest of the Greek Church, consecrated him, and sent him to be archbishop of the English.

With Theodore (668-690) begins a new chapter in our history. His antecedents, as a member of the Eastern Church, eminently qualified him to look impartially upon the two schools, the Italian and the Scotic, into which the religious world of England was divided, and to address himself with broad views of ecclesiastical polity to the task of organizing the Heptarchic Churches into a harmonious province of the Catholic Church.

[Pg 41]In 673, at the instance of Theodore, and under the presidency of Hlothere, King of Kent, a synod was held at Hertford, attended by all the English bishops but one, and by the kings and many of the principal nobles and clergy, at which the independent national Churches agreed to unite in an Ecclesiastical Province, with the Bishop of Canterbury as its metropolitan; it was further agreed that the bishops and clergy should meet in synod twice a year, once always in August at Clovesho, the other was probably left to the convenience of the moment as to time and place, but was usually held at Cealchyth. Augustine and his successors at Canterbury had never been practically more than bishops of the Kentish men, with the titular distinction of archbishop which Gregory gave them. Theodore, says Bede, was the first archbishop whom the Churches of the English obeyed. This gave Theodore the authority necessary for the carrying out of his plans for the peace and progress of the Church.

One feature of Theodore’s policy was the breaking up of some of the larger sees. This was not done without opposition. There was much to be said in favour of the idea of “one king one bishop;” it fell in with the political organization and it had the prestige of ancient use. But Theodore, looking at the subject from his point of view, as the ruler of an ecclesiastical province, saw the desirableness of breaking it up into dioceses of more manageable size. He was opposed by Wilfrid of York, who resented the diminution of his great position as Bishop of the Northumbrian[Pg 42] kingdom, by the division of the diocese into four, York, Lindisfarne, Hexham, and Whithern; but his opposition was overborne by the firmness of the King of Northumbria and the archbishop. Wilfrid carried his complaint to Rome, which is the first example of an appeal from the English to the Roman Court, and raises the question of the relations of the English Church to the Bishop of Rome. It is sufficient to say here in reference to the Roman decision in Wilfrid’s favour on this and subsequent occasions, that neither Archbishop Theodore, nor the clergy, nor the king and thanes of the Witan, showed any disposition to accept the intervention of the Bishop of Rome, or to defer to his judgment in the matter; and that Wilfrid was punished by the king with imprisonment and exile for his contumacy.

The Bishop of Mercia, backed by the king, resisted the subdivision of that vast diocese; and it was not until after Theodore’s death that his plan was carried into effect of dividing it into four, Lichfield, Hereford, Worcester, Leicester, with Sidnacester for Lindsey, recently reconquered from Northumbria. It was not till 705 that the great diocese of Wessex was divided into two, Winchester and Sherburn, and further subdivided in the time of Alfred the Great by the erection of sees for Somerset, Wilts, and Devon. A new English see in Cornwall, on its conquest by Athelstan, completed the list of Saxon bishoprics.

The annual meeting of the Churches in synods was a very important consequence of their organization into a province. Kings and their councillors[Pg 43] and great thanes came to the synods, as well as bishops and clergy. It is probable that the laymen had no formal voice in the ecclesiastical legislation, but their attestation and assent would add to the authority of the acts of the councils in the estimation of the people. The general synods would promote the regular holding of diocesan synods.[31] One direct result of these frequent assemblies would be to give a stimulus to the work of the Church all over the land. Another incidental result would be to afford a stable centre of affairs, and to promote the growth of a sentiment of nationality. Political affairs were in a state of great disturbance. In some of the kingdoms rival pretenders waged civil war, and now one, now another won the throne, while the bishop maintained his position undisturbed. Nations warred against one another, now Mercia reduced other kingdoms to dependence, and again Wessex asserted a supremacy over others; but the synods continued to unite the bishops and clergy of the kingdoms south of the Thames in frequent consultation for the common good.

Theodore’s idea in setting himself to divide the national bishoprics was to multiply episcopal centres of orderly Church life, adequate to the needs of the Christian flock. The settling of priests among the scattered people to take pastoral charge of them[Pg 44] was a natural sequel to the former movement. The practical way of effecting it was to induce the landowners to accept and make provision for a resident priest who should have the pastoral care of their households and people.