Please see Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

EDITED BY

EDMUND ROUTLEDGE.

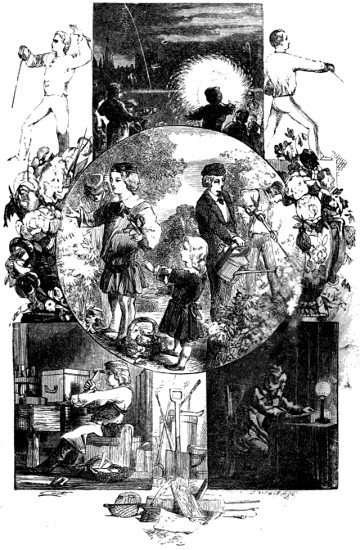

With more than Six Hundred Illustrations

FROM ORIGINAL DESIGNS.

LONDON:

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS,

THE BROADWAY, LUDGATE.

NEW YORK: 416, BROOME STREET.

1869.

R. Clay, Son, and Taylor, Printers,

Bread Street Hill, London.

The twelve years that have passed since the first edition of Every Boy’s Book was published, have brought so many changes in our national sports and pastimes, and have seen the introduction of so many new games, that it has been thought desirable to remodel this work, in order to bring it down to the requirements of the present time. In carrying out this plan effectually, Every Boy’s Book has been almost entirely rewritten; and scarcely anything now remains of the old work except the title.

All the articles that were in the former edition have been thoroughly revised, and papers on Boxing, Canoeing, Croquet, Fives, Golf, Rackets, Sliding, Billiards, Bagatelle, Dominoes, Spectrum Analysis, Canaries, Hedgehogs, Jackdaws, Jays, Magpies, Owls, Parrots, Ravens, Boats, Cryptography, Deaf and Dumb Alphabet, Dominoes, Mimicry and Ventriloquism, Shows, Stamp Collecting, and Tinselling, appear now for the first time.

In carrying out this work much valuable assistance has been given by Professor Pepper, the Rev. J. G. Wood, W. B. Tegetmeier, Clement Scott, Sidney Daryl, J. T. Burgess, Dr. Viner, Thomas Archer, W. Robinson of the Field, Cholmondeley Pennell, and other well-known writers on sports.

The articles at the end of this work on American Billiards, Base Ball, and the Canadian sport of La Crosse, have been contributed by Henry Chadwick, the leading authority on these games in America.

Christmas, 1868.

It would be impossible for a single author to produce a book of this description with a fair prospect of success, because it necessarily treats of many subjects; and a perfect acquaintance with some of the more important would occupy a lifetime. The reading and researches of one man would not be sufficiently extensive to embrace the rich variety of the materials required. Being fully convinced of this fact, the Publishers have endeavoured to obtain the aid of the most distinguished writers in the various departments of knowledge which the following pages are intended to illustrate. Thus each contributor, in furnishing his quota of information for the work, has been engaged in a congenial task, one best suited to his peculiar turn of mind, as well as to his individual acquirements, and one upon which he could, therefore, with the greatest ease and accuracy dilate. This brief explanation will show in what spirit the Publishers embarked in the undertaking; and the accompanying list of the writers may be received as a proof that they have succeeded in securing the services of the most competent authorities. With that portion of the book with which he was practically acquainted each of the following gentlemen has dealt: W. Martin, Esq., C. Baker, Esq., R. B. Wormald, Esq., J. F. Wood, Esq., A. McLaren, Esq., Stonehenge, author of “Rural Sports,” and the Rev. J. G. Wood, author of several works on Natural History, who also furnished some of the designs. The remaining illustrations are by William Harvey and Harrison Weir; and the credit for the able manner in which they have been engraved is due to the brothers Dalziel.

2, Farringdon Street,

February, 1856.

| PART I. | |

| EASY GAMES WITHOUT TOYS. | |

| OUTDOOR. | |

| PAGE | |

| Hop, Step, and Jump | 1 |

| Hopping on the Bottle | 2 |

| Hop-Scotch | 2 |

| French and English | 3 |

| Drawing the Oven | 4 |

| I Spy | 4 |

| Pitch-Stone | 3 |

| Duck-Stone | 5 |

| Prisoner’s Base, or Prison Bars | 5 |

| Fox | 7 |

| Baste the Bear | 7 |

| Leap-Frog | 8 |

| Fly the Garter | 8 |

| Spanish Fly | 9 |

| Touch | 10 |

| Touch-Wood and Touch-Iron | 10 |

| Buck, Buck, how many Horns do I hold up? | 10 |

| Warning | 10 |

| Follow my Leader | 11 |

| The Fugleman | 11 |

| Hare and Hounds | 11 |

| Steeple Chase | 13 |

| Duck and Drake | 13 |

| Simon Says | 14 |

| King of the Castle | 14 |

| Battle for the Banner | 14 |

| Snow-Balls | 15 |

| Snow Castle | 16 |

| Snow Giant | 17 |

| Jack! Jack! show a Light! | 18 |

| Jingling | 19 |

| Jump little Nag-tail! | 19 |

| Jumping Rope | 20 |

| My Grandmother’s Clock | 20 |

| Rushing Bases | 21 |

| See-saw | 21 |

| Thread the Needle | 22 |

| Tom Tiddler’s Ground | 22 |

| Two to One | 22 |

| Walk, Moon, Walk! | 22 |

| Want a day’s work? | 23 |

| Will you List? | 23 |

| Whoop! | 24 |

| High Barbaree! | 24 |

| Bull in the Ring | 24 |

| Cock Fight | 25 |

| Dropping the Handkerchief | 25 |

| INDOOR. | |

| Blind Man’s Buff | 26 |

| Bob-Cherry | 26 |

| Buff | 27 |

| Concert | 27 |

| Consequences | 28 |

| Cross Questions & Crooked Answers | 28 |

| Dumb Motions | 29 |

| Family Coach | 29 |

| Frog in the Middle | 30 |

| The Four Elements | 31 |

| Hand | 31 |

| Hot Boiled Beans | 32 |

| Hot Cockles | 32 |

| How? Where? and When? | 32 |

| Hunt the Slipper | 33 |

| Hunt the Ring | 33 |

| Hunt the Whistle | 33 |

| Magic Music | 34 |

| Post | 34 |

| Proverbs | 35 |

| Puss in the Corner | 36 |

| Red-Cap and Black-Cap | 36 |

| Shadow Buff | 37 |

| Slate Games | 37 |

| Trades | 40 |

| Trussed Fowls | 40 |

| The Two Hats | 40 |

| What is my Thought like? | 41[viii] |

| EASY GAMES WITH TOYS. | |

| OUTDOOR. | |

| BALLS | 43 |

| Catch Ball | 43 |

| Doutee-Stool | 43 |

| Egg-Hat | 44 |

| Feeder | 44 |

| Monday, Tuesday | 45 |

| Nine-Holes | 46 |

| Northern Spell | 46 |

| Rounders | 46 |

| Sevens | 48 |

| Stool-Ball | 48 |

| Trap, Bat, and Ball | 48 |

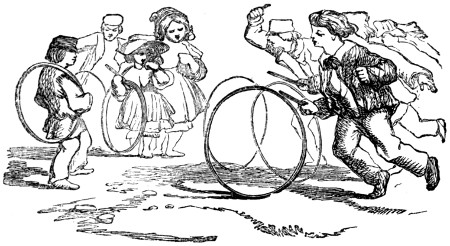

| HOOPS | 49 |

| The Hoop | 50 |

| Encounters | 50 |

| Hoop Race | 51 |

| Posting | 51 |

| Tournament | 52 |

| Turnpike | 52 |

| KITES | 53 |

| How to make a Kite | 53 |

| Flying the Kite | 54 |

| Messengers | 55 |

| Calico Kites | 55 |

| Fancy Kites | 55 |

| MARBLES | 57 |

| Bounce Eye | 58 |

| Conqueror | 58 |

| Die Shot | 58 |

| Eggs in the Bush | 59 |

| Increase Pound | 59 |

| Knock out, or Lag out | 59 |

| Long Taw | 60 |

| Nine-Holes, or Bridge Board | 60 |

| Odd or Even | 61 |

| Picking the Plums | 61 |

| The Pyramid | 61 |

| Ring Taw | 61 |

| Spans and Snops, and Bounce About | 62 |

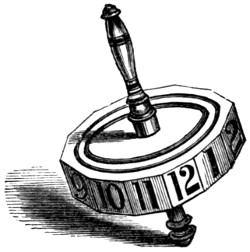

| Teetotum Shot | 62 |

| Three-Holes | 62 |

| Tipshares, or Handers | 63 |

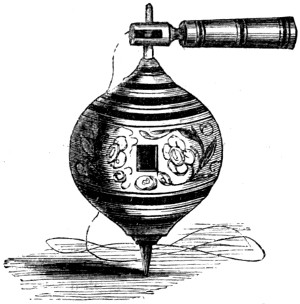

| TOPS | 64 |

| The Humming-top | 64 |

| Peg-top | 65 |

| Spanish Peg-top | 65 |

| The Whip-top | 65 |

| Chip-stone | 66 |

| Peg-in-the-Ring | 66 |

| MISCELLANEOUS TOYS | 68 |

| The Apple Mill | 68 |

| Aunt Sally | 68 |

| Baton | 69 |

| Cat | 69 |

| Cat and Mouse | 70 |

| Knock-’em-down | 71 |

| Pea-shooters | 71 |

| Quoits | 71 |

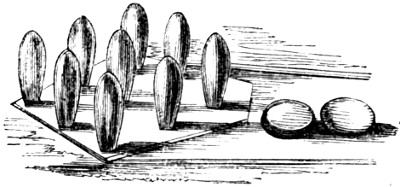

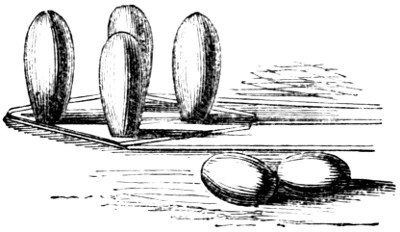

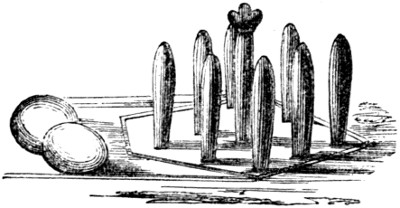

| Nine-pins | 72 |

| Skittles | 72 |

| Dutch-pins | 73 |

| Throwing the Hammer | 73 |

| The Boomerang | 74 |

| The Skip-jack, or Jump-jack | 74 |

| The Sling | 74 |

| Walking on Stilts | 76 |

| The Sucker | 76 |

| INDOOR. | |

| Battledore and Shuttlecock | 78 |

| Bandilor | 79 |

| Cup and Ball | 79 |

| The Cutwater | 79 |

| Fox and Geese | 80 |

| Goose | 81 |

| Head, Body, and Legs | 81 |

| Knuckle-bones | 82 |

| Merelles, or Nine Men’s Morris | 83 |

| Paper Dart | 83 |

| The Popgun | 84 |

| Push-pin | 84 |

| Schimmel | 84 |

| Spelicans | 86 |

[ix] |

|

| PART II. | |

| ATHLETIC SPORTS AND MANLY EXERCISES. | |

| ANGLING | 89 |

| A Word about Fish | 90 |

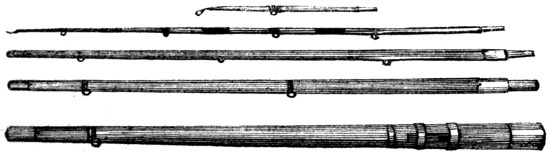

| About the Rod | 91 |

| Choosing the Rod | 91 |

| Lines or Bottoms | 92 |

| Shotting the Line | 93 |

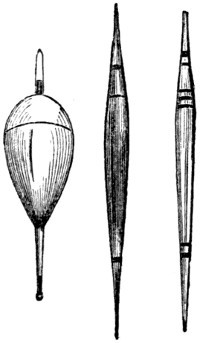

| The Float | 93 |

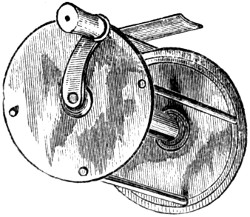

| Reels or Winches | 94 |

| Reel Lines | 94 |

| Hooks | 94 |

| How to bait a Hook | 95 |

| Baits | 95 |

| To Bait with Greaves | 97 |

| To Scour and Preserve Worms | 97 |

| The Plummet | 97 |

| Plumbing the Depth | 97 |

| Landing-hook and Landing-net | 98 |

| Clearing Ring and Line | 98 |

| Drag-hook | 98 |

| Bank Runner | 98 |

| Live-bait Kettle | 99 |

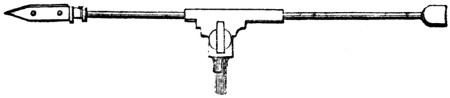

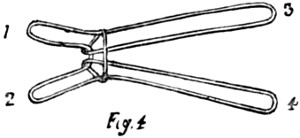

| Disgorger | 99 |

| Angling Axioms | 99 |

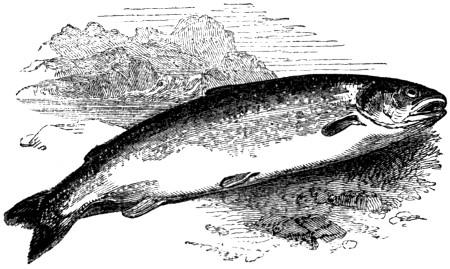

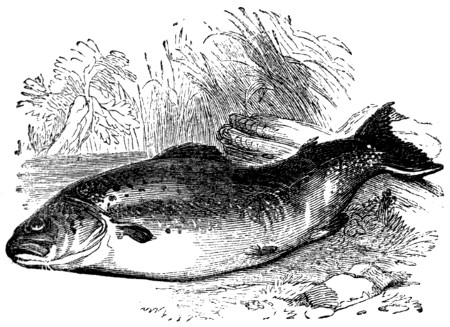

| Salmon | 100 |

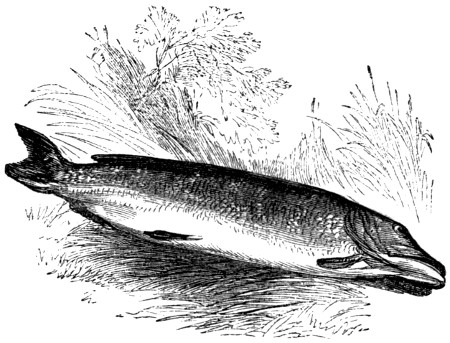

| Trout | 100 |

| Jack or Pike | 101 |

| Gudgeon | 103 |

| Roach | 104 |

| Dace | 105 |

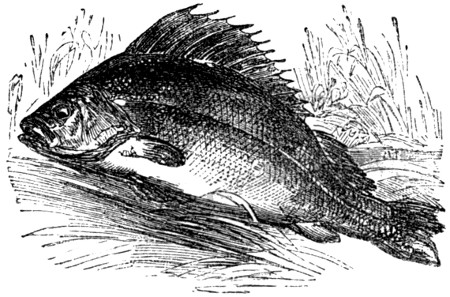

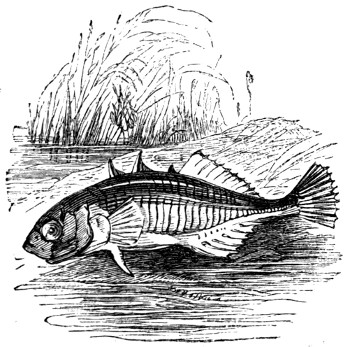

| Perch | 106 |

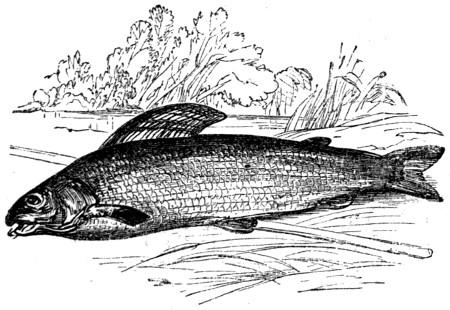

| Grayling | 107 |

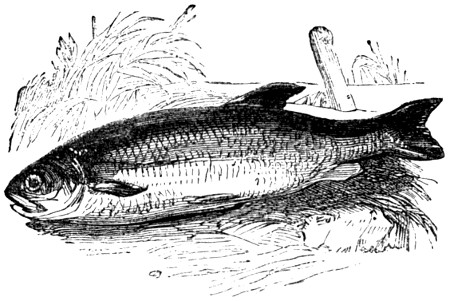

| Chub | 108 |

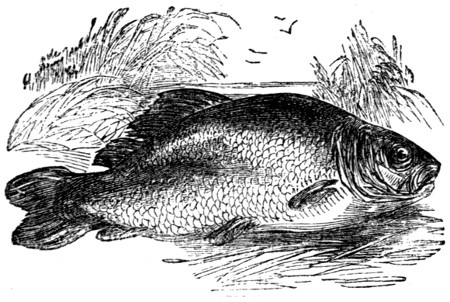

| Carp | 109 |

| Tench | 110 |

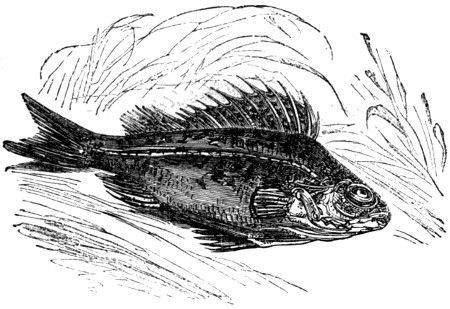

| Pope, or Ruff | 110 |

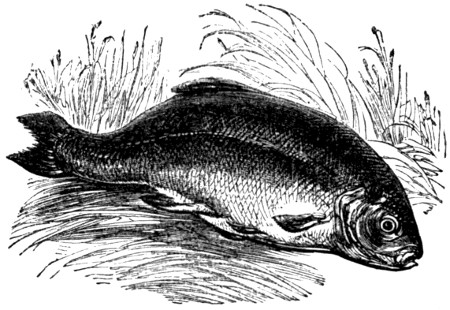

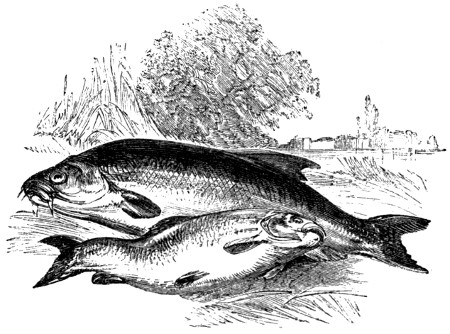

| Bream | 111 |

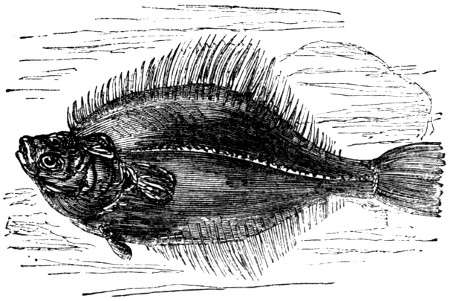

| Flounder | 111 |

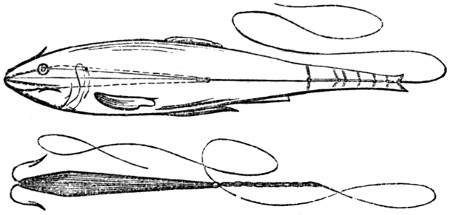

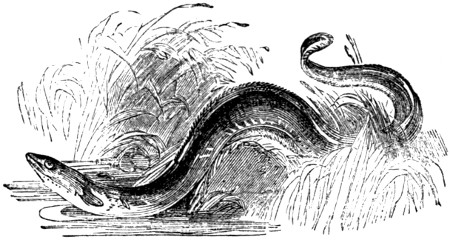

| Eels | 112 |

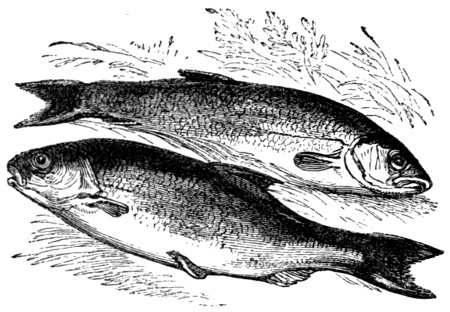

| Stickleback and Minnow | 113 |

| Barbel | 114 |

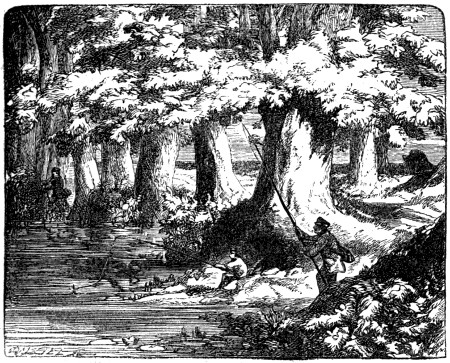

| Natural Fly-fishing, or Dipping | 115 |

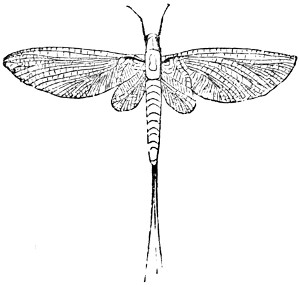

| Fly-fishing and Artificial Flies | 115 |

| Materials for making Flies | 115 |

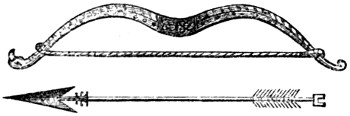

| ARCHERY | 121 |

| The Long-bow | 122 |

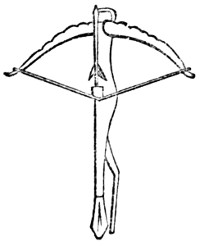

| The Cross-bow | 122 |

| Feats of the Bow | 123 |

| Length of Bows and Arrows, and how used in Ancient Times | 124 |

| Marks for Shooting at | 124 |

| Equipment for Archery | 125 |

| Ancient Directions for Archery | 125 |

| Decline of Archery | 125 |

| Modern Archery | 126 |

| The Bow | 126 |

| The String | 126 |

| Stringing the Bow | 127 |

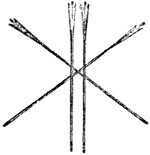

| The Arrows | 127 |

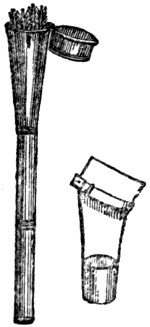

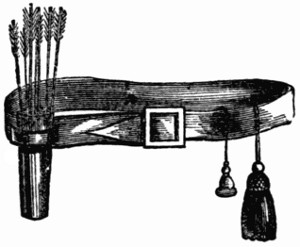

| The Quiver | 128 |

| The Tassel, Brace, Belt, and Pouch | 128 |

| Shooting Glove, and Grease Pot | 129 |

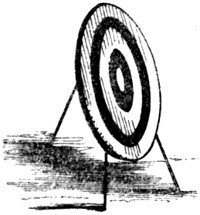

| The Target | 129 |

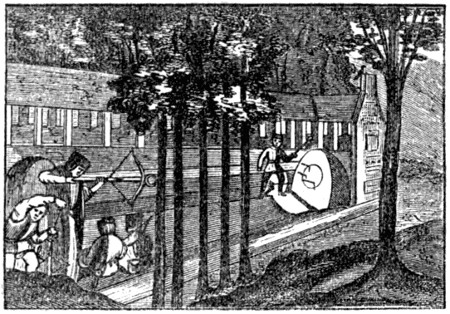

| Butts | 130 |

| How to draw the Bow | 130 |

| Flight Shooting | 131 |

| Clout Shooting | 131 |

| Roving | 131 |

| General Hints for Archers | 132 |

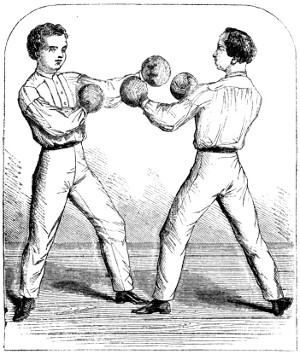

| BOXING | 133 |

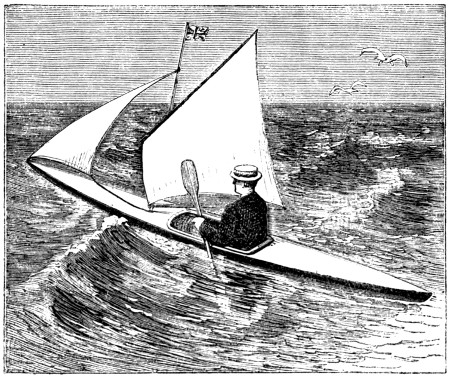

| CANOES AND CANOEING | 140 |

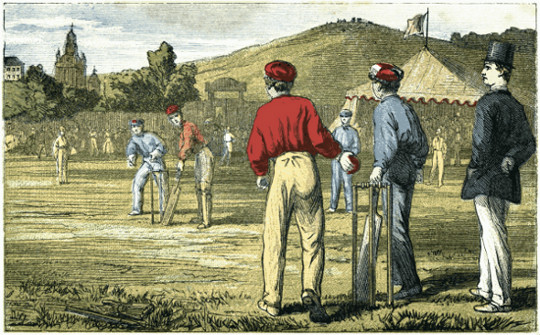

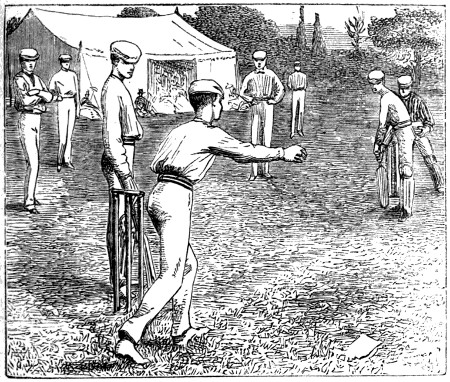

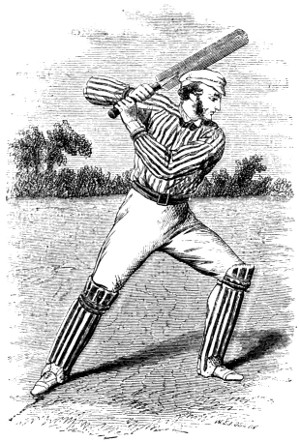

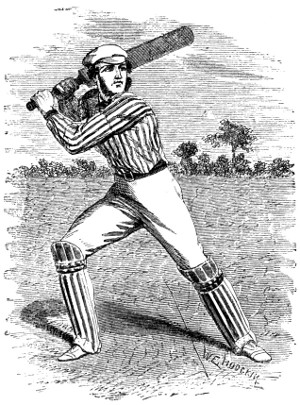

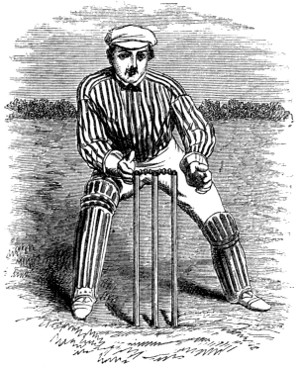

| CRICKET | 143 |

| The Bat | 145 |

| The Ball | 145 |

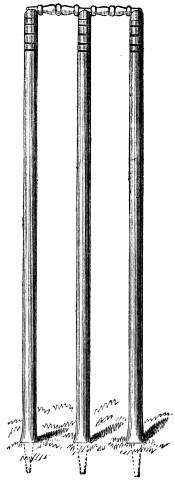

| The Stumps | 145 |

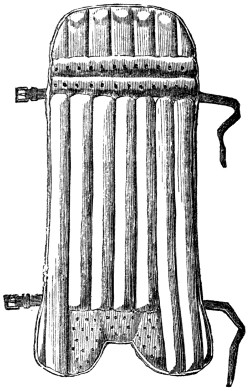

| Pads or Guards | 146 |

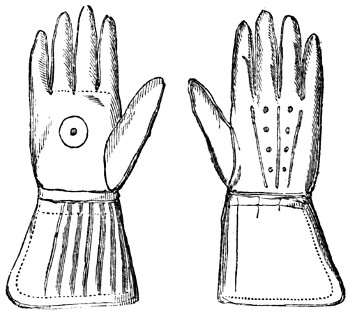

| Batting Gloves | 147 |

| Wicket-keeping Gloves | 148 |

| The Laws of Cricket | 148 |

| The Laws of Single Wicket | 152 |

| The Batsman.—Hints to Young Players | 153 |

| Fielding | 159 |

| Bowling | 162 |

| The Wicket-keeper | 165 |

| Long-stop | 166 |

| Point | 166 |

| Short-slip | 166 |

| Cover-point | 167 |

| Long-slip | 167 |

| Long-on | 167 |

| Long-off | 167 |

| Leg | 167 |

| Mid-wicket on and off | 167 |

| Third Man up | 167 |

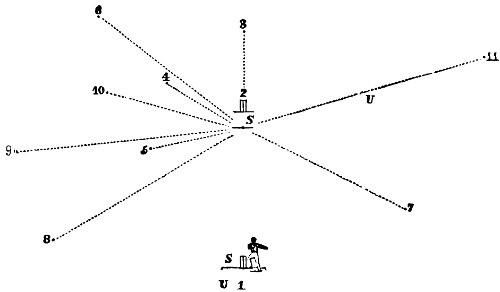

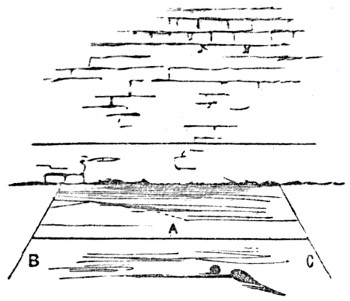

| Diagram I.—Fast Round-arm Bowling | 168 |

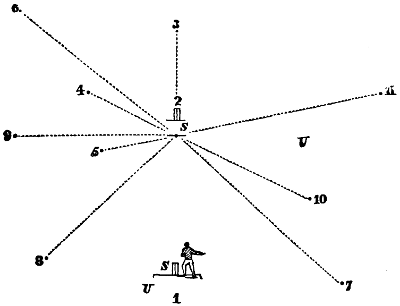

| Diagram II.—Medium Pace Round-arm Bowling | 169 |

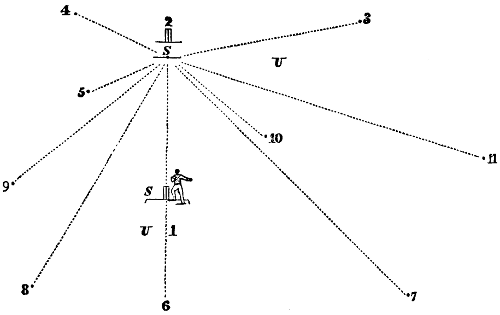

| Diagram III.—Slow Under-hand Bowling | 169 |

| CROQUET.—Materials of the Game | 170 |

| The Mallets | 170 |

| The Balls[x] | 171 |

| The Hoops | 171 |

| The Posts | 172 |

| Clips | 172 |

| Marking Board | 173 |

| Tunnel | 173 |

| The Cage | 173 |

| A Croquet Stand | 174 |

| How the Game is played | 174 |

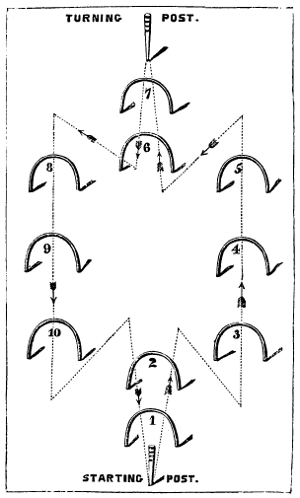

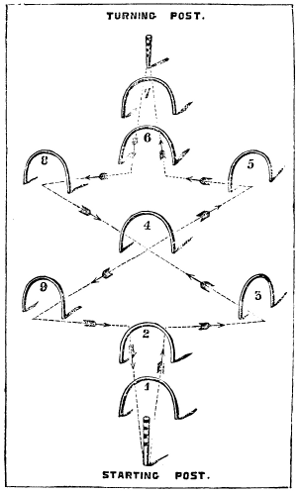

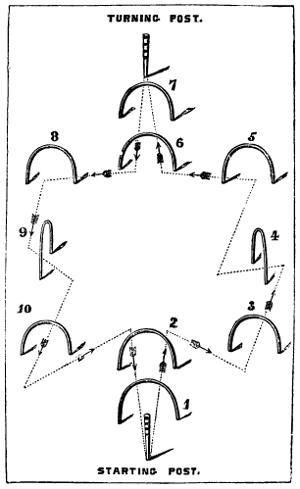

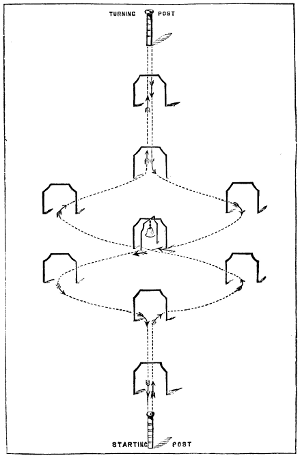

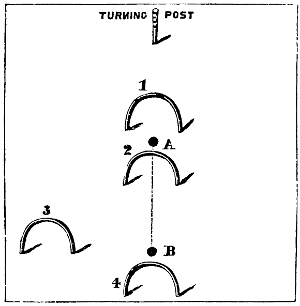

| Diagram, No. I. | 177 |

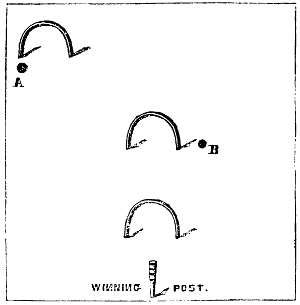

| Dia„ram, N„. II. | 178 |

| Dia„ram, N„. III. | 179 |

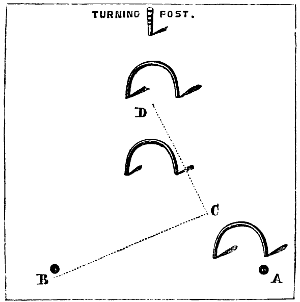

| Dia„ram, N„. IV. | 180 |

| Rules | 181 |

| Striking | 181 |

| Order of Playing | 181 |

| The Croquet | 182 |

| The Posts | 185 |

| The Rover | 185 |

| Hints to Young Players | 186 |

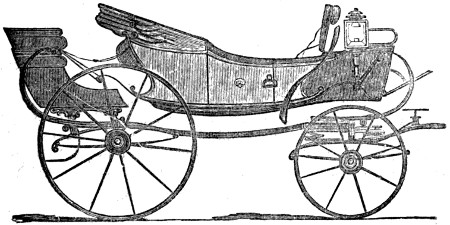

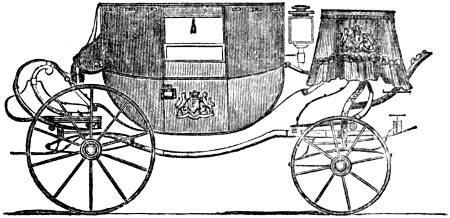

| DRIVING | 192 |

| Introduction | 192 |

| The Horse in Harness | 193 |

| The Horse | 194 |

| The Harness | 194 |

| The Carriage | 195 |

| Putting to | 196 |

| Directions for Driving | 196 |

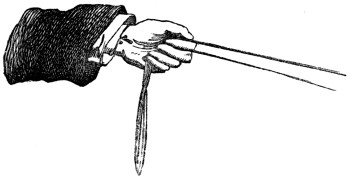

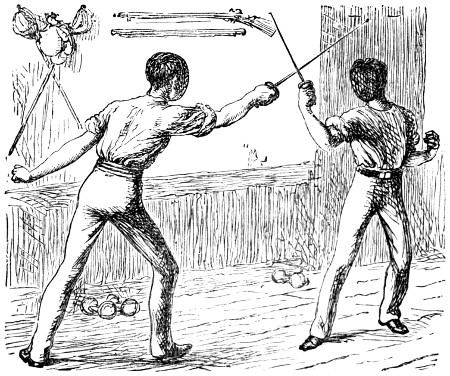

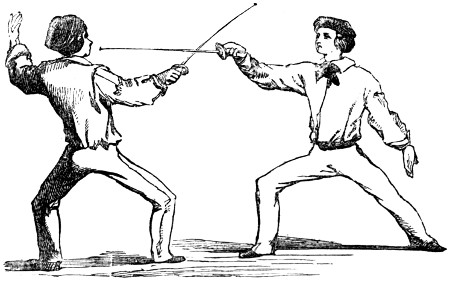

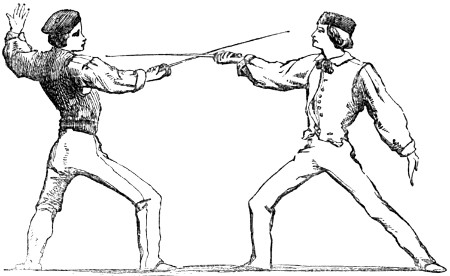

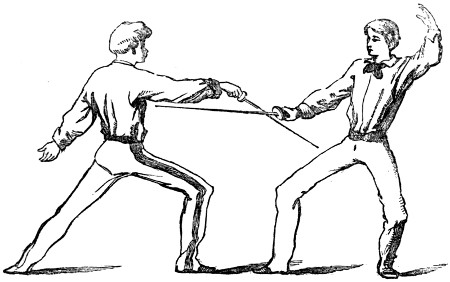

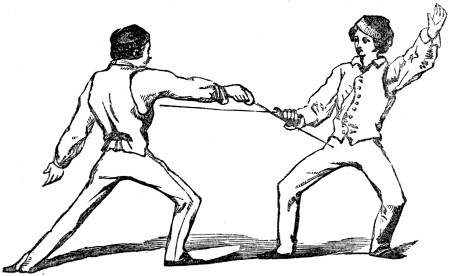

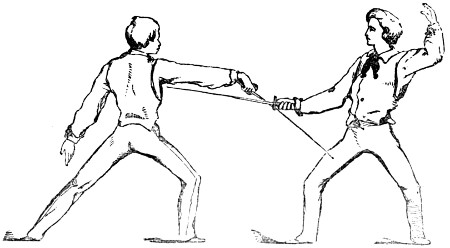

| FENCING | 198 |

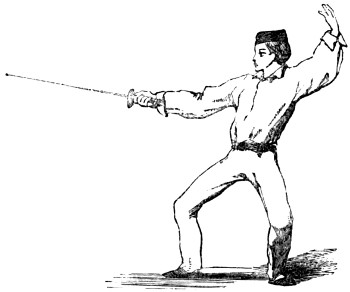

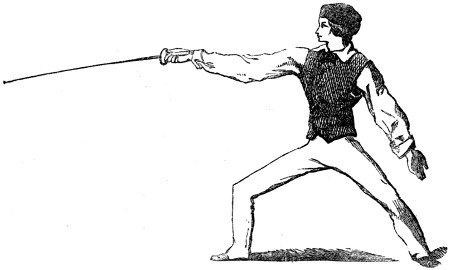

| The Guard | 199 |

| Advance | 200 |

| Retreat | 201 |

| The Longe | 201 |

| The Recover | 201 |

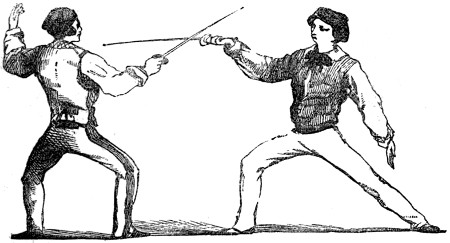

| The Engage | 202 |

| Parades | 202 |

| Quarte | 203 |

| Tierce | 203 |

| Seconde | 205 |

| Demi-Cercle | 205 |

| Octave | 206 |

| Contre-Parades | 206 |

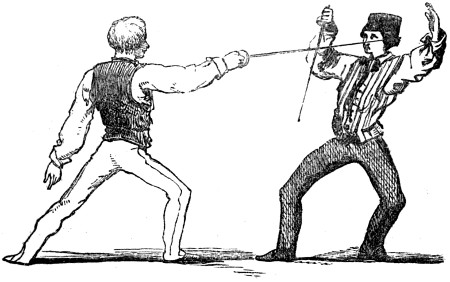

| Attacks | 207 |

| The Straight Thrust | 207 |

| The Disengagement | 207 |

| The One-Two | 208 |

| The Beat and Thrust | 208 |

| The Beat and Disengagement | 208 |

| Cut over the Point | 208 |

| Cut over the Disengagement | 208 |

| Double | 209 |

| All Feints | 209 |

| The Assault | 209 |

| General Advice | 210 |

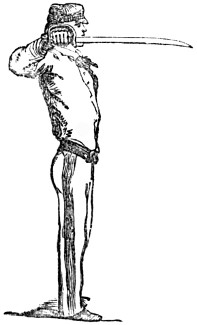

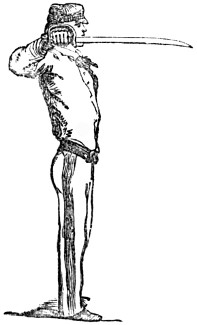

| BROADSWORDS | 210 |

| Positions | 211 |

| Target | 212 |

| Cuts and Guards | 213 |

| Cuts | 213 |

| Points | 214 |

| Guards | 215 |

| Parry | 215 |

| Hanging Guard | 216 |

| Inside Guard | 216 |

| Outside Guard | 217 |

| Attack and Defence | 217 |

| Draw Swords | 218 |

| Recover Swords | 219 |

| Carry Swords | 219 |

| Slope Swords | 219 |

| Return Swords | 219 |

| Practices | 220 |

| Second Practice | 220 |

| Third Practice | 220 |

| Fourth Practice | 221 |

| Fifth Practice | 221 |

| Fort and Feeble | 222 |

| Drawing Cut | 222 |

| General Advice | 222 |

| FIVES | 223 |

| FOOT-BALL | 224 |

| GOLFING | 226 |

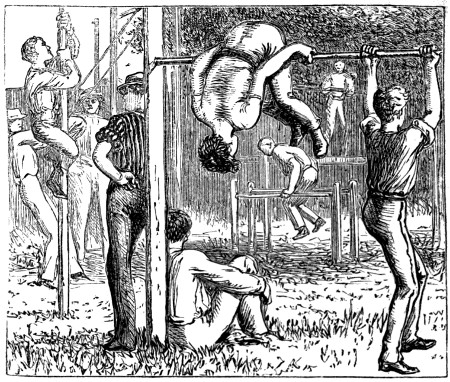

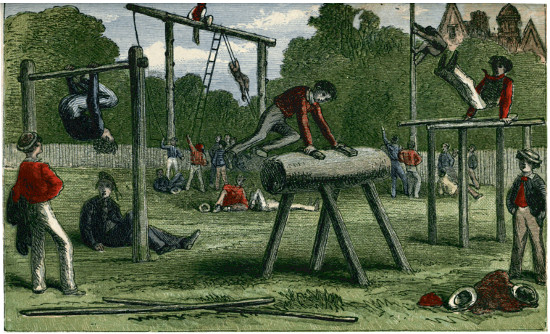

| GYMNASTICS | 228 |

| Introduction | 228 |

| Historical Memoranda | 229 |

| Modern Gymnastics | 230 |

| Walking | 230 |

| The Tip-toe March | 231 |

| Running | 232 |

| Jumping | 232 |

| Leaping | 233 |

| To climb up a Board | 234 |

| Climbing the Pole | 234 |

| Clim„ing t„e Rope | 235 |

| Clim„ing Trees | 235 |

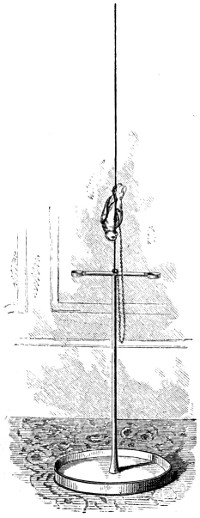

| The Giant Stride, or Flying Steps, and its capabilities | 235 |

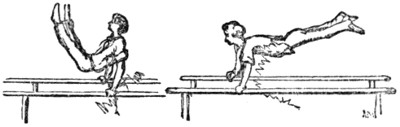

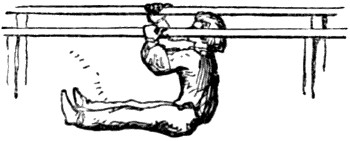

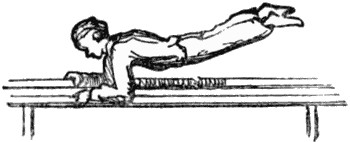

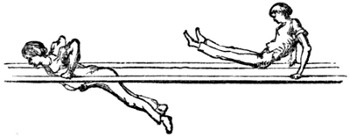

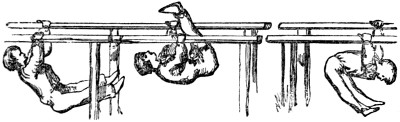

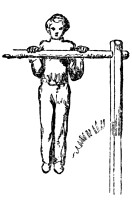

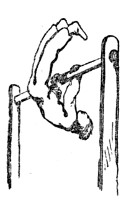

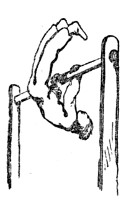

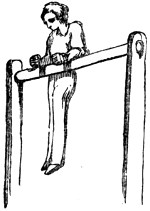

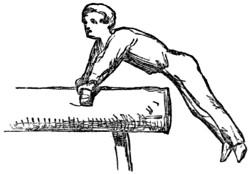

| Parallel Bars | 241 |

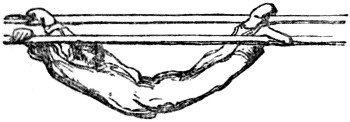

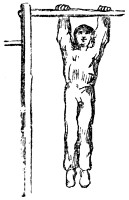

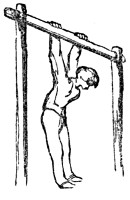

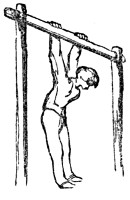

| The Horizontal Bar | 243 |

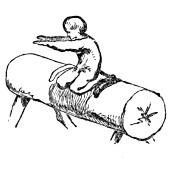

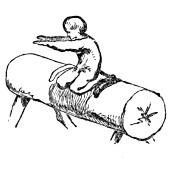

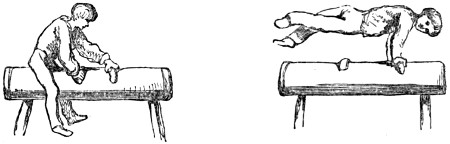

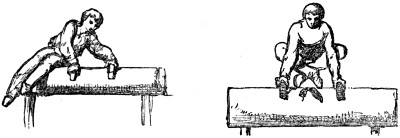

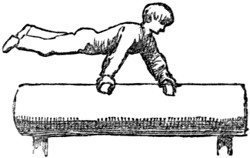

| The Horse | 246 |

| The Swing | 249 |

| Throwing the Javelin | 253 |

| The Trapeze, Single and Double | 254 |

| Tricks and Feats of Gymnastics | 262 |

| HOCKEY | 265 |

| RACKETS | 268 |

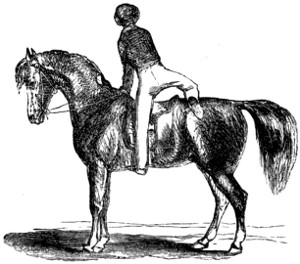

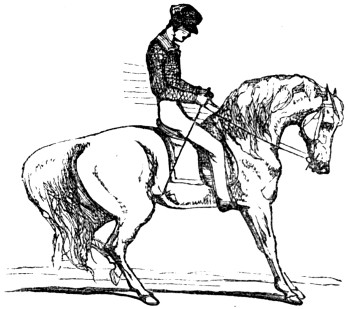

| RIDING | 270 |

| The Horse | 271 |

| The Marks of Age in the Horse | 271 |

| The Paces of the Horse | 272 |

| Terms used by Horsemen | 274 |

| Form of the Horse | 274 |

| Varieties of the Horse suitable for Boys | 274 |

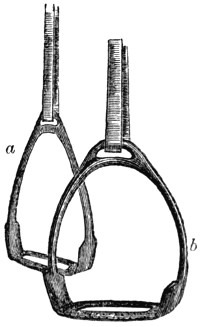

| The Accoutrements and Aids | 275 |

| Mounting | 277 |

| Dismounting | 278 |

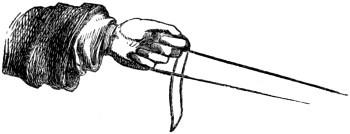

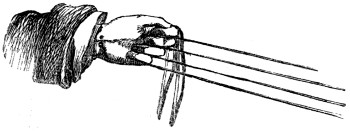

| The Management of the Reins | 278 |

| The Seat[xi] | 279 |

| The Control of the Horse | 280 |

| Management of the Walk | 280 |

| The Trot and Canter | 281 |

| The Management of the Gallop | 282 |

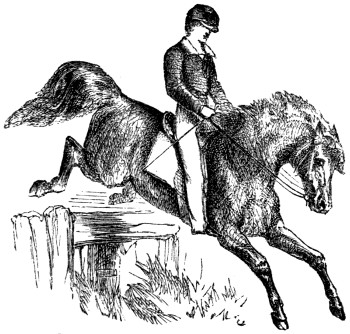

| Leaping | 282 |

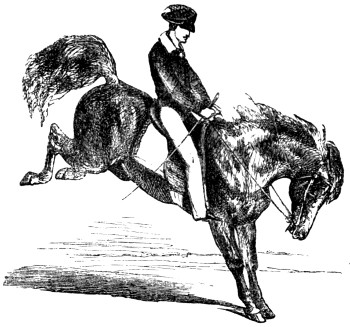

| Treatment of Vices | 284 |

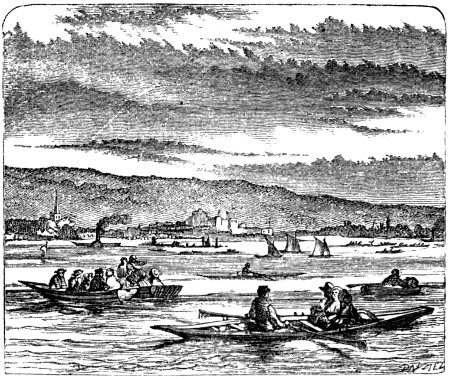

| ROWING | 288 |

| Historical Memoranda | 288 |

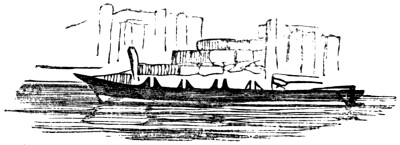

| Construction of Ancient Ships and Galleys | 289 |

| Roman Galleys, Ships, &c. | 290 |

| Of Boats | 291 |

| The Component Parts of Boats | 292 |

| The Oars and Sculls | 293 |

| Sea Rowing | 293 |

| River Rowing | 293 |

| Management of the Oar | 294 |

| The Essential Points in Rowing | 295 |

| Management of the Boat | 295 |

| Rowing together | 296 |

| Caution to Young Rowers | 296 |

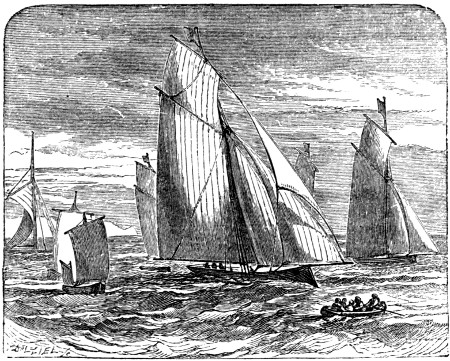

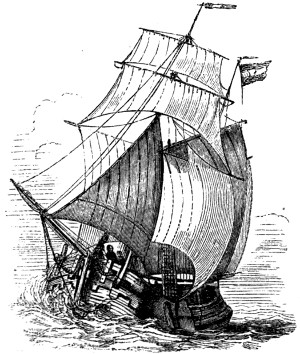

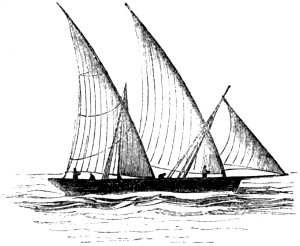

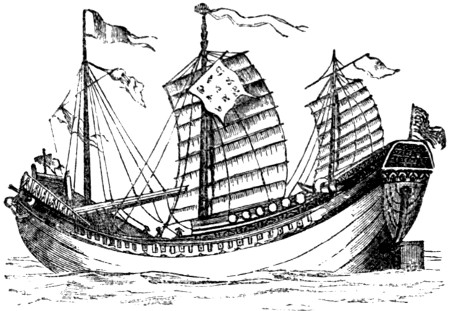

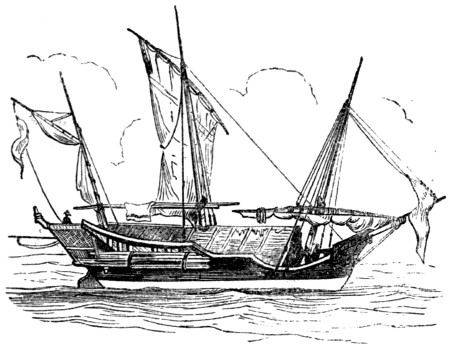

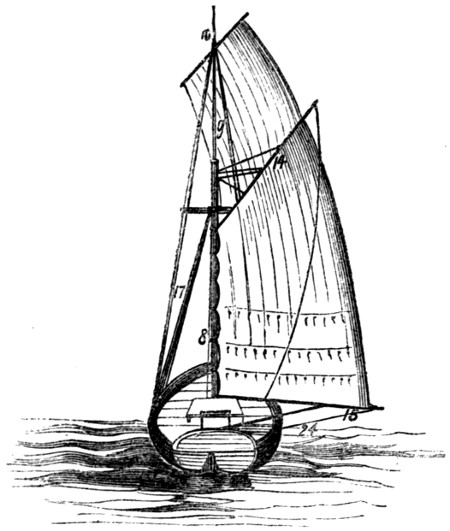

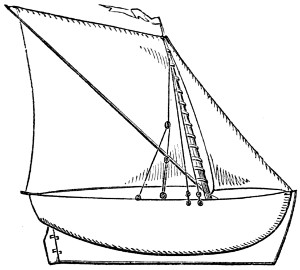

| SAILING | 297 |

| Characters of a Yacht | 301 |

| Various kinds of Yachts | 302 |

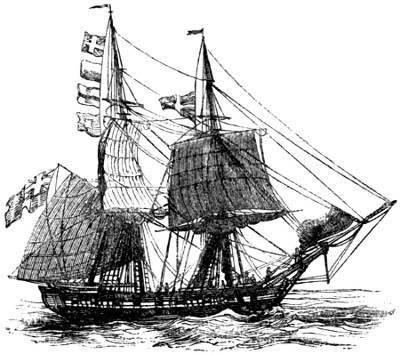

| Description of the Cutter Yacht | 303 |

| Construction of the Hull | 303 |

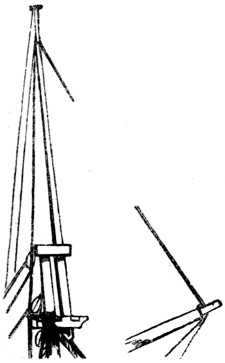

| Something about the Masts, Spars, Ropes, &c. | 306 |

| Sailing a Yacht | 308 |

| Bringing up | 310 |

| Making Snug | 310 |

| Going back | 310 |

| Jibing | 310 |

| Bringing up at Moorings | 310 |

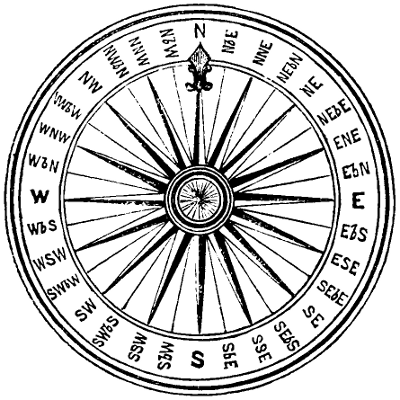

| Of the Mariners’ Compass, and various Nautical | |

| Terms | 311 |

| Cautions and Directions | 312 |

| Nautical Terms | 312 |

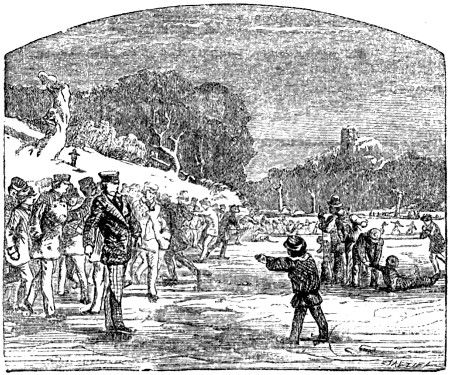

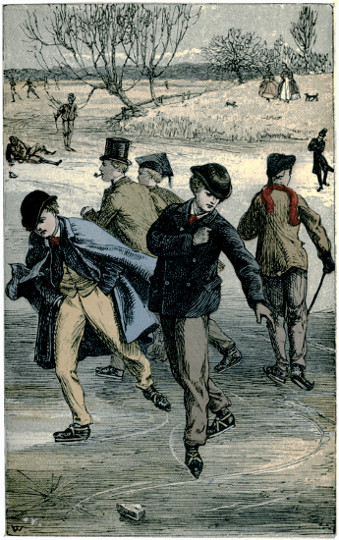

| SKATING | 316 |

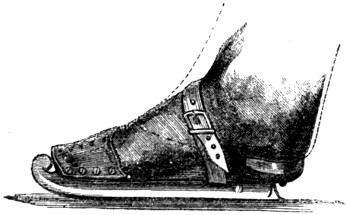

| The Skate | 317 |

| Putting on the Skates | 318 |

| How to start upon the Inside Edge | 319 |

| Movement on the Outside Edge | 319 |

| Forward Roll | 320 |

| The Dutch Roll | 320 |

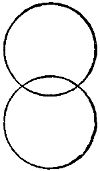

| The Figure of Eight | 321 |

| The Figure of Three | 321 |

| The Back Roll | 321 |

| General Directions to be followed by Persons learning to Skate | 322 |

| SLIDING | 323 |

| SWIMMING | 325 |

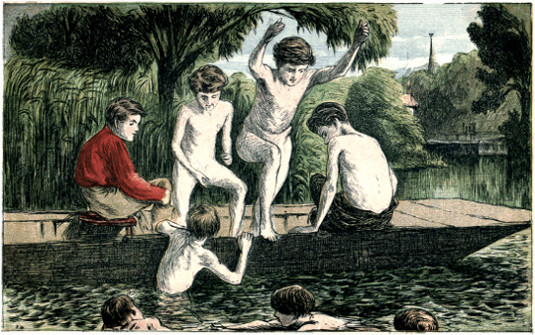

| Places and Times for Bathing and Swimming | 327 |

| Entering the Water | 328 |

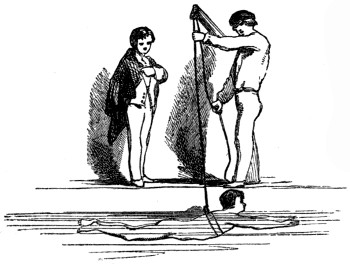

| Aids to Swimming | 328 |

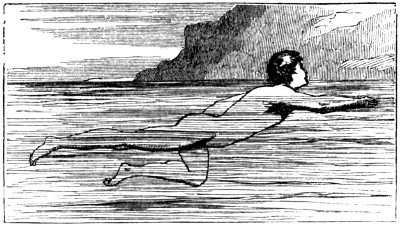

| Striking off and Swimming | 329 |

| How to manage the Legs | 330 |

| Plunging and Diving | 330 |

| Swimming under Water | 331 |

| Swimming on the Side | 332 |

| Swimming on the Back without employing the Feet | 332 |

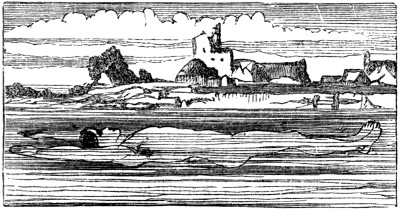

| Floating | 333 |

| Treading Water | 333 |

| The Fling | 333 |

| Swimming on the Back | 334 |

| Thrusting | 334 |

| The Double Thrust | 335 |

| To Swim like a Dog | 335 |

| The Mill | 335 |

| The Wheel backwards and forwards | 335 |

| To Swim with one Hand | 336 |

| Hand over Hand Swimming | 336 |

| Balancing | 336 |

| The Cramp | 337 |

| Saving from Danger | 337 |

| Sports and Feats in Swimming | 338 |

| Bernardi’s system of Upright Swimming | 338 |

| The Prussian System of Pfuel | 339 |

| TRAINING | 342 |

| PART III. | |

| SCIENTIFIC PURSUITS. | |

| ACOUSTICS | 347 |

| Difference between Sound and Noise | 347 |

| Sounds, how propagated | 347 |

| To show how Sound travels through a Solid | 347 |

| To show that Sound depends on Vibration | 347 |

| Musical Figures resulting from Sound | 347 |

| To make an Æolian Harp | 348 |

| The Invisible Girl | 348 |

| Ventriloquism | 349 |

| AERONAUTICS | 350 |

| Balloons | 350 |

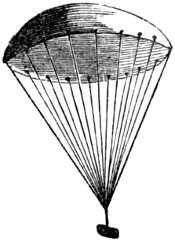

| How to make an Air-balloon | 351 |

| How to Fill a Balloon | 352 |

| To make Fire-Balloons | 352 |

| Parachutes[xii] | 352 |

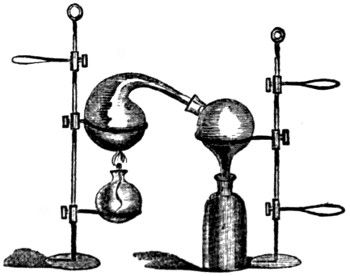

| CHEMISTRY | 353 |

| Gases | 357 |

| Oxygen Gas | 358 |

| Experiments | 359 |

| Nitrogen | 360 |

| Experiments | 361 |

| Atmospheric Air | 362 |

| Hydrogen | 364 |

| Experiments | 364 |

| Water | 365 |

| Experiment | 366 |

| Chlorine | 367 |

| Experiments | 368 |

| Muriatic Acid Gas, or Hydric Chloride | 369 |

| Experiments | 370 |

| Iodine | 371 |

| Experiments | 371 |

| Bromine | 371 |

| Experiments | 371 |

| Fluorine | 372 |

| Experiment | 372 |

| Carbon | 372 |

| Experiments | 373 |

| Carbon and Hydrogen | 374 |

| Experiment | 375 |

| Coal Gas | 376 |

| Experiment | 376 |

| Phosphorus | 377 |

| Experiments | 377 |

| Sulphur | 378 |

| Metals | 379 |

| Potassium | 381 |

| Experiments | 381, 382, 383 |

| Crystallization of Metals | 383 |

| Experiment | 383 |

| To form a Solid from two Liquids | 384 |

| To form a Liquid from two Solids | 384 |

| Experiments | 384 |

| Changes of Colour produced by Colourless Liquids | 385 |

| ELECTRICITY | 386 |

| Simple Means of producing Electricity | 386 |

| Attraction and Repulsion exhibited | 387 |

| How to make an Electrical Machine | 388 |

| The Conductor | 389 |

| The Plate Electrical Machine | 389 |

| How to draw Sparks from the tip of the Nose | 389 |

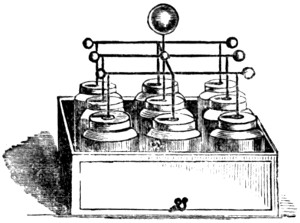

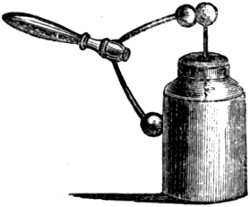

| How to charge a Leyden Jar | 390 |

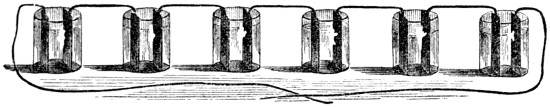

| The Electrical Battery | 390 |

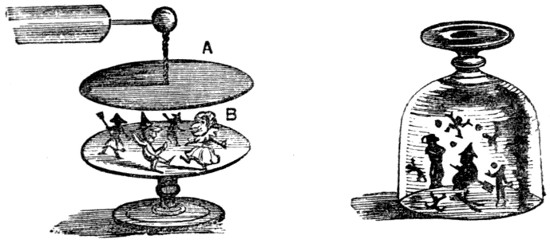

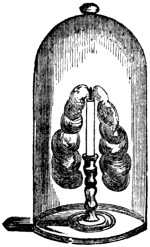

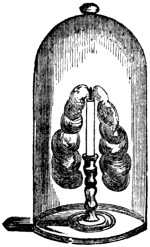

| Dancing Balls and Dolls | 391 |

| The Electrical Kiss | 391 |

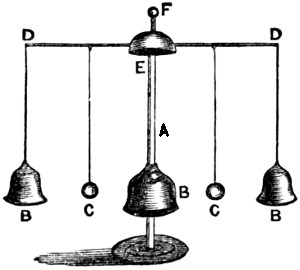

| Ringing Bells | 391 |

| Working Power of Electricity | 392 |

| The Electrified Wig | 392 |

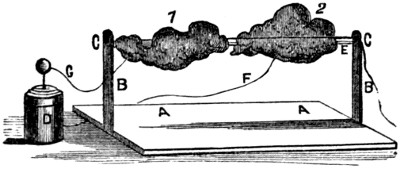

| Imitation Thunder Clouds | 393 |

| The Lightning Stroke imitated | 393 |

| The Sportsman | 394 |

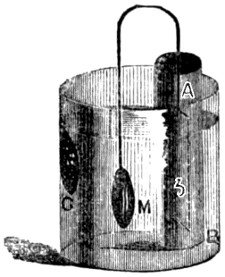

| GALVANISM, or Voltaic Electricity | 395 |

| Origin of Galvanism | 395 |

| Simple Experiment to excite Galvanic Action | 396 |

| With Metal Plates in Water | 396 |

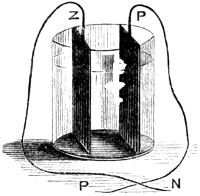

| To make a Magnet by the Voltaic Current | 397 |

| Effects of Galvanism on a Magnet | 397 |

| Change of Colour by Galvanism | 397 |

| The Galvanic Shock | 398 |

| The Electrotype | 398 |

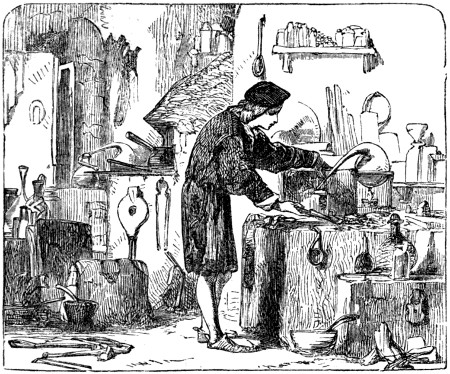

| How to make an Electrotype Apparatus | 398 |

| To obtain the Copy of a Coin or Medal | 399 |

| HEAT | 399 |

| Heat or Caloric | 399 |

| Expansion | 402 |

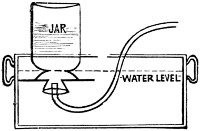

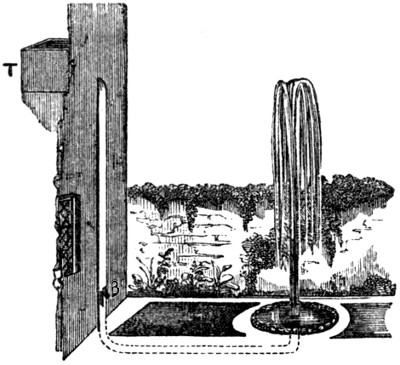

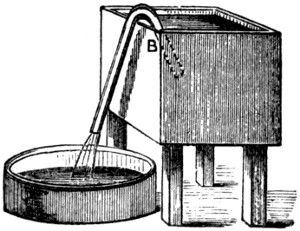

| HYDRAULICS | 404 |

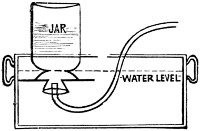

| The Syphon | 405 |

| The Pump | 405 |

| The Hydraulic Dancer | 406 |

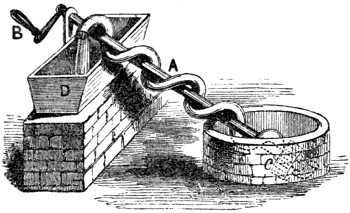

| The Water Snail or Archimedean Screw | 407 |

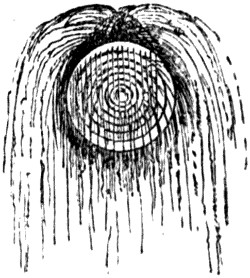

| MAGNETISM | 408 |

| Relation of Magnetism to Electricity | 408 |

| To make Artificial Magnets | 409 |

| How to Magnetise a Poker | 409 |

| To show Magnetic Repulsion and Attraction | 409 |

| North and South Poles of the Magnet | 410 |

| Polarity of the Magnet | 410 |

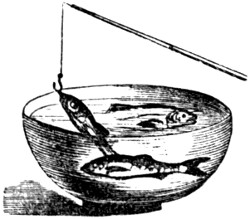

| The Magnetic Fish | 410 |

| The Ma„netic Swan | 411 |

| To suspend a Needle in the Air by Magnetism | 411 |

| To make Artificial Magnets without the aid either of Natural Loadstones or Artificial Magnets | 411 |

| Horse-shoe Magnets | 412 |

| Experiment to show that soft Iron possesses Magnetic Properties while it remains in the vicinity of a Magnet | 412 |

| Electro-Magnetism | 413 |

| Power of the Electro-Magnet | 413 |

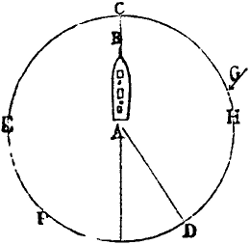

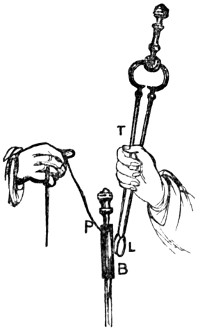

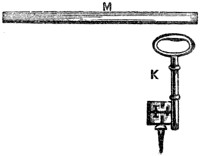

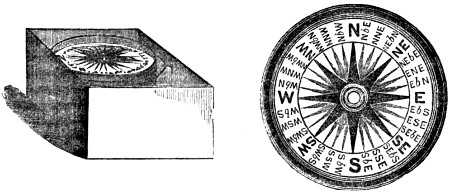

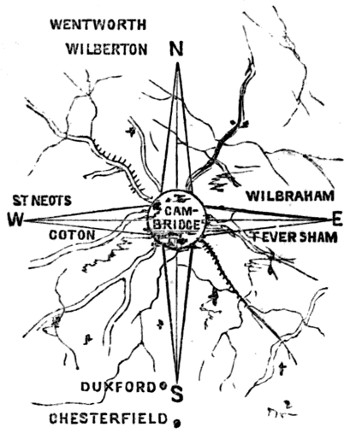

| The Mariner’s Compass, and Experiments with a Pocket Compass | 413 |

| Variation of the Needle | 414 |

| Dip of the Needle | 414 |

| Useful Amusement with the Pocket Compass | 414 |

| Interesting Particulars concerning the Magnet | 415 |

| MECHANICS | 417 |

| Experiment of the Law of Motion | 417 |

| Balancing | 418 |

| The Prancing Horse | 418 |

| To construct a Figure, which being placed upon a curved surface and inclined in any position, shall, when left to itself, return to its former position[xiii] | 418 |

| To make a Carriage run in an inverted position without falling | 418 |

| To cause a Cylinder to roll by its own weight up-hill | 418 |

| The Balanced Stick | 419 |

| The Chinese Mandarin | 419 |

| To make a Shilling turn on its edge on the point of a Needle | 419 |

| The Dancing Pea | 420 |

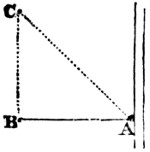

| Obliquity of Motion | 420 |

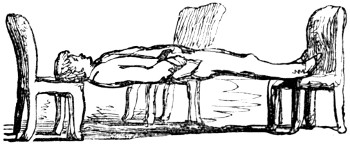

| The Bridge of Knives | 421 |

| The Toper’s Tripod | 421 |

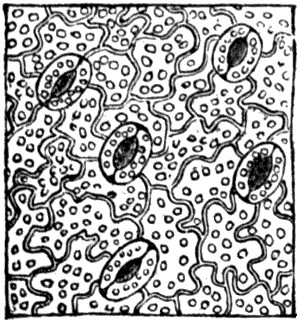

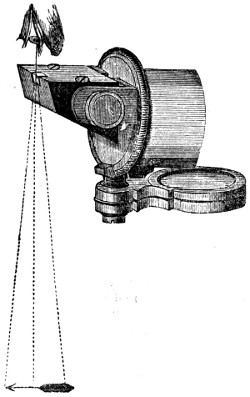

| THE MICROSCOPE | 422 |

| The Compound Microscope | 432 |

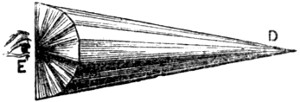

| OPTICS AND OPTICAL AMUSEMENTS | 455 |

| Light as an Effect | 455 |

| Refraction | 456 |

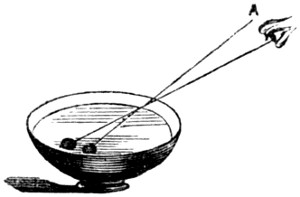

| The Invisible Coin made Visible | 456 |

| The Multiplying Glass | 457 |

| Transparent Bodies | 457 |

| The Prism | 457 |

| Composition of Light | 457 |

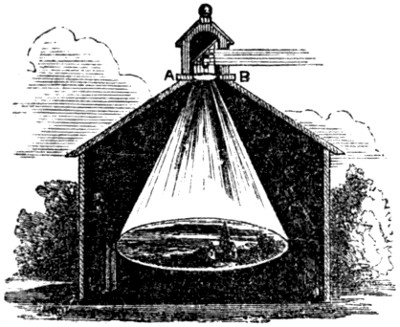

| A Natural Camera Obscura | 458 |

| Bullock’s-eye Experiment | 458 |

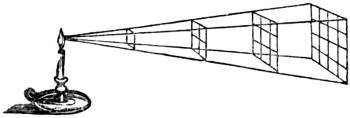

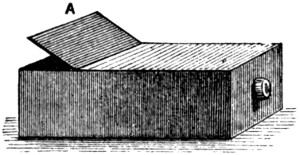

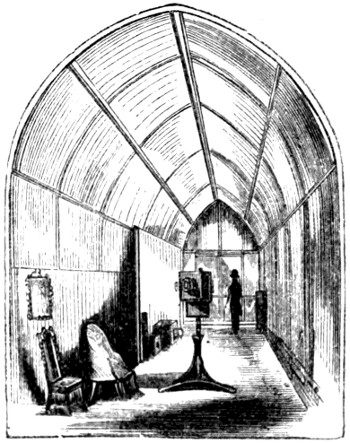

| The Camera Obscura | 458 |

| The Camera Lucida | 459 |

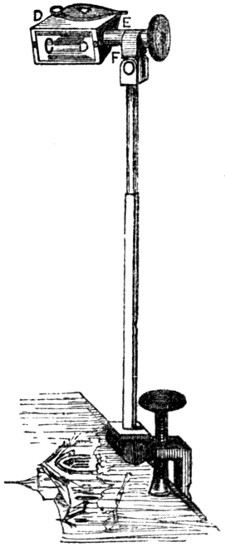

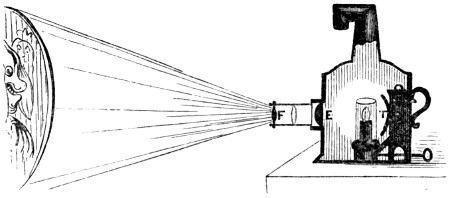

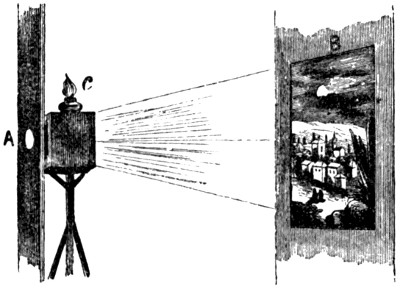

| The Magic Lantern | 460 |

| Painting the Slides | 460 |

| To exhibit the Magic Lantern | 461 |

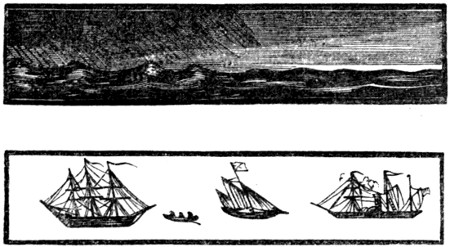

| Effects of the Magic Lantern | 461 |

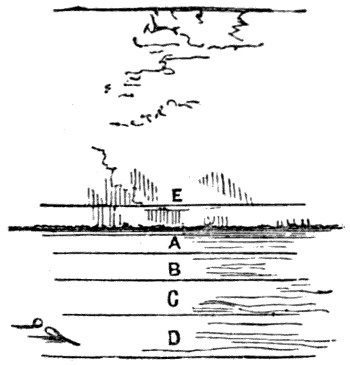

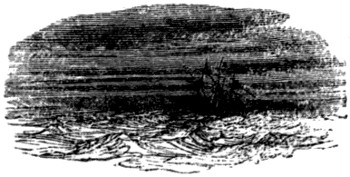

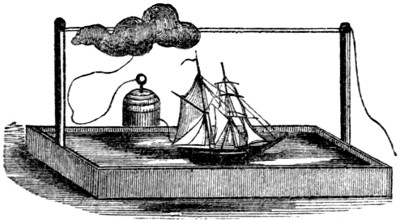

| Tempest at Sea | 461 |

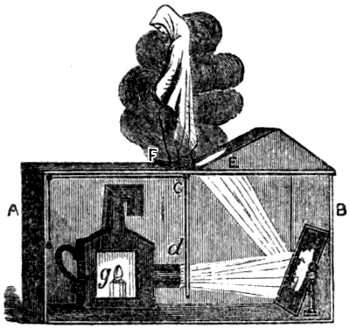

| The Phantasmagoria | 462 |

| Dissolving Views | 462 |

| How to raise a Ghost | 462 |

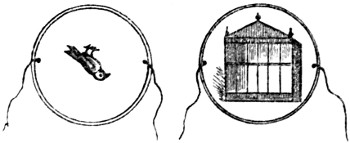

| The Thaumatrope | 463 |

| The Bird in the Cage | 463 |

| Construction of the Phantasmacope | 464 |

| Curious Optical Illusions | 464, 465 |

| The Picture in the Air | 465 |

| Breathing Light and Darkness | 466 |

| To show that Rays of Light do not obstruct each other | 466 |

| Optics of a Soap-bubble | 467 |

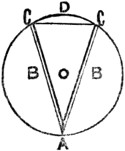

| The Kaleidoscope | 467 |

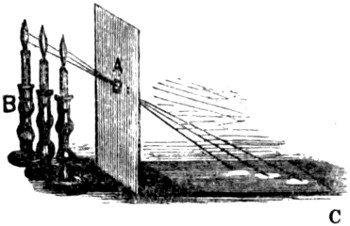

| Simple Solar Microscope | 468 |

| Anamorphoses | 468 |

| The Cosmorama | 470 |

| Distorted Landscapes | 470 |

| PHOTOGRAPHY | 472 |

| How to make the Negative on Glass, using Collodion bromoiodized for Iron development | 472 |

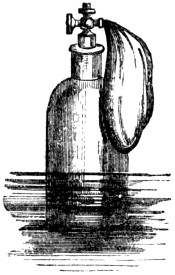

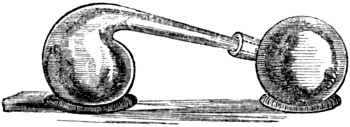

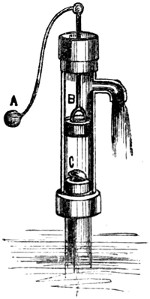

| PNEUMATICS | 477 |

| Weight of the Air Proved by a pair of Bellows | 477 |

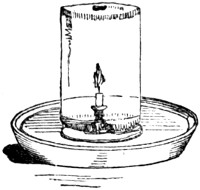

| The Pressure of the Air shown by a Wine-glass | 478 |

| Another Experiment | 478 |

| Elasticity of the Air | 478 |

| Reason for this | 479 |

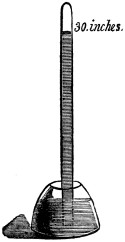

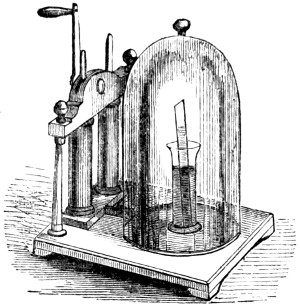

| The Air-Pump | 479 |

| To prove that Air has Weight | 479 |

| To prove Air elastic | 480 |

| Sovereign and Feather | 480 |

| Air in the Egg | 480 |

| The Descending Smoke | 480 |

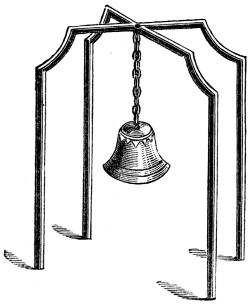

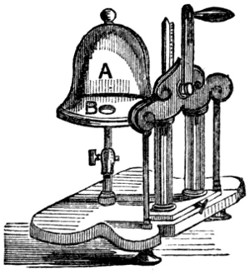

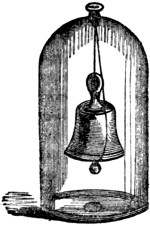

| The Soundless Bell | 481 |

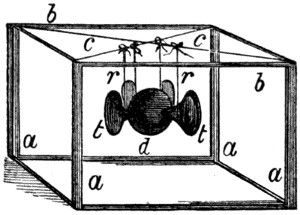

| The Floating Fish | 481 |

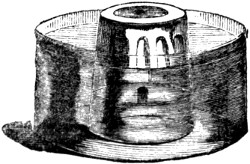

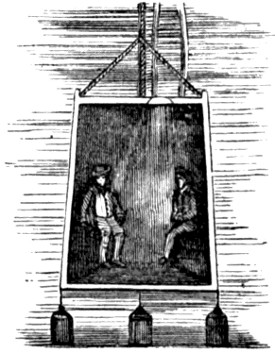

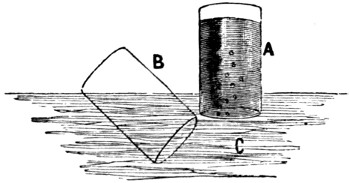

| The Diving Bell | 482 |

| Experiments | 482, 484, 485 |

| With Ice or Snow | 485 |

| Without Snow or Ice | 485 |

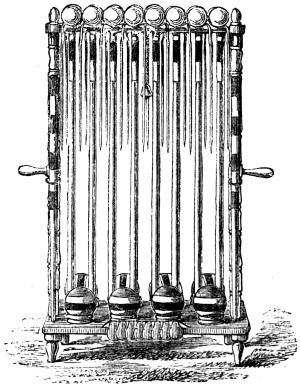

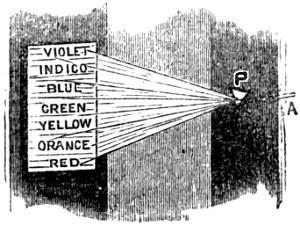

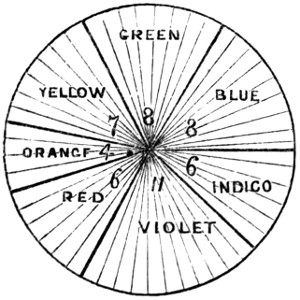

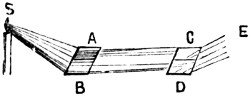

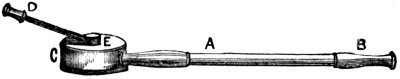

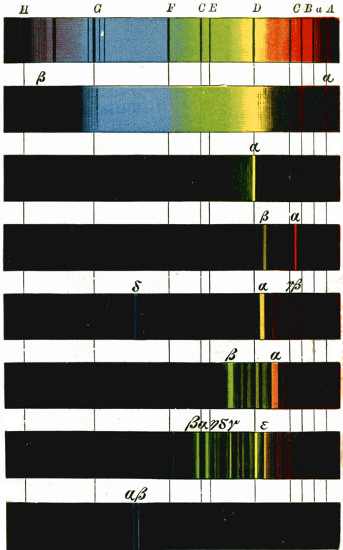

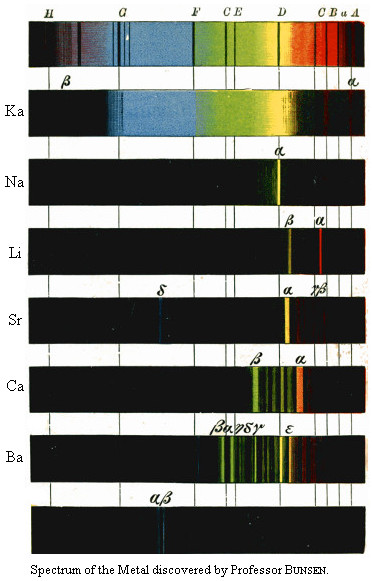

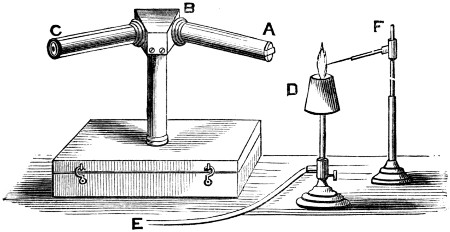

| SPECTRUM ANALYSIS | 486 |

| How to use the Spectroscope | 488 |

| To obtain the Bright Lines in the Spectrum given by any Substance | 488 |

| Professor Stokes’ Absorption Bands | 489 |

| To Map out any Spectrum | 489 |

| PART IV. | |

| DOMESTIC PETS. | |

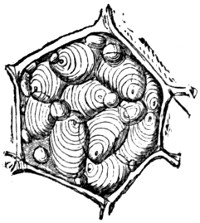

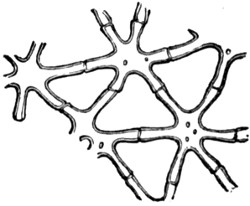

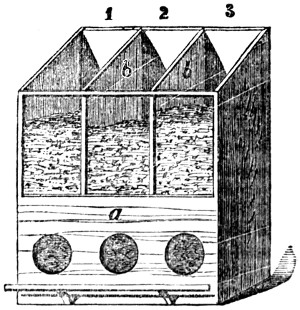

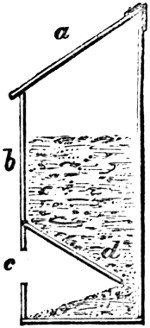

| BEES AND BEE-KEEPING | 493 |

| THE CANARY | 497 |

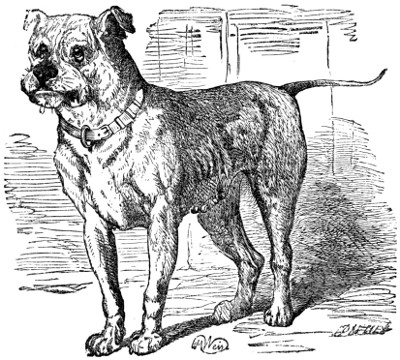

| DOGS | 506 |

| GOLD AND SILVER FISH | 516 |

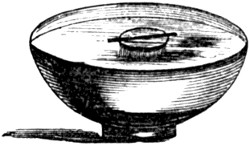

| Glasses | 517 |

| Feeding | 517 |

| Diseases | 517 |

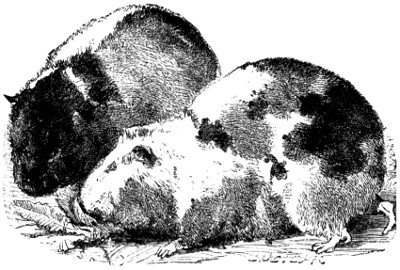

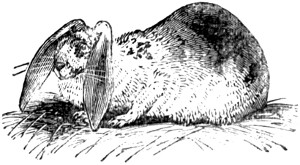

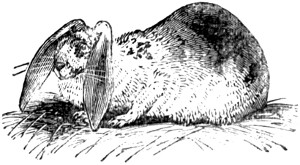

| THE GUINEA PIG | 518 |

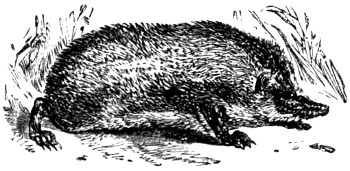

| THE HEDGEHOG | 520 |

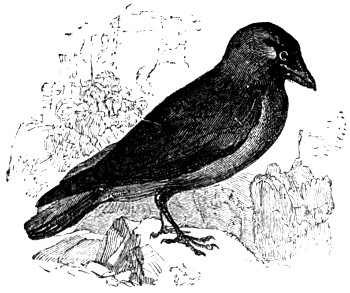

| THE JACKDAW | 521 |

| THE JAY | 523 |

| THE MAGPIE | 524 |

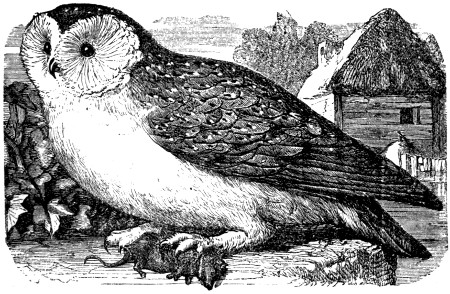

| OWLS | 526 |

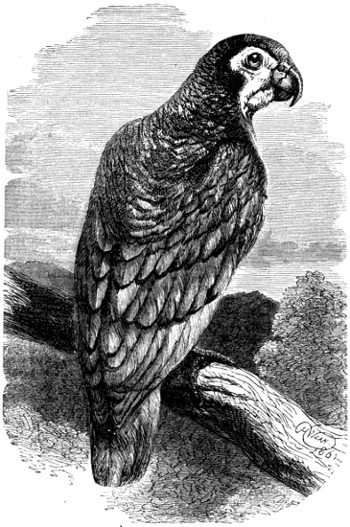

| THE PARROT | 532 |

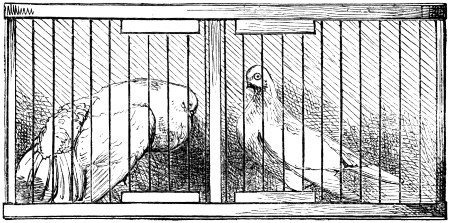

| PIGEONS | 541 |

| Varieties of Pigeons | 545 |

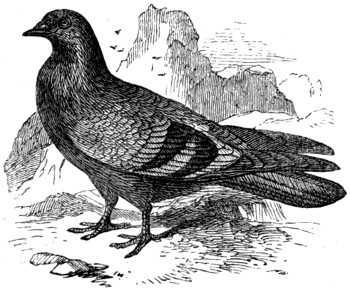

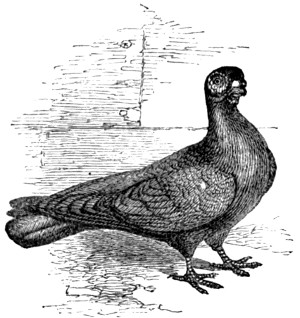

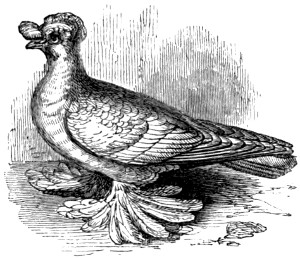

| Blue Rock Dove | 545 |

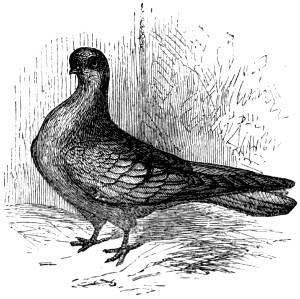

| The Antwerp, or Smerle[xiv] | 546 |

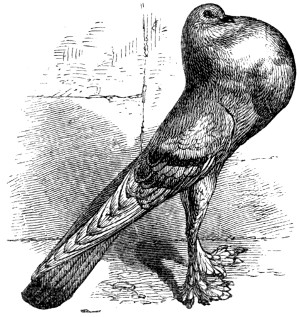

| The Pouter | 547 |

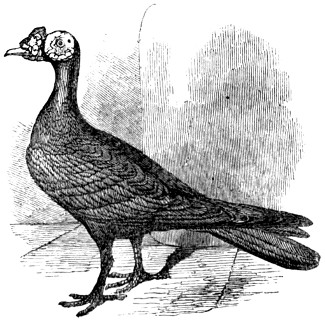

| The Carrier | 548 |

| The Dragon | 549 |

| The Tumbler | 549 |

| The Barb | 550 |

| The Owl | 551 |

| The Turbit | 551 |

| The Fantail | 551 |

| The Trumpeter | 552 |

| The Jacobin | 553 |

| POULTRY | 554 |

| Fowls | 554 |

| Fattening | 555 |

| Laying | 555 |

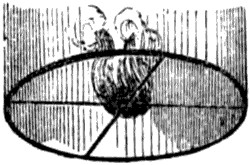

| Hatching | 555 |

| Rearing of Chickens | 556 |

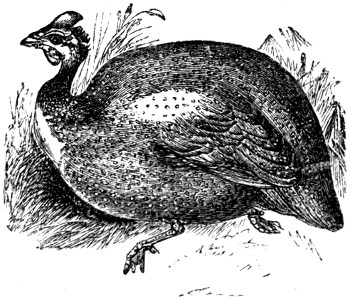

| The Pintado, or Guinea Fowl | 557 |

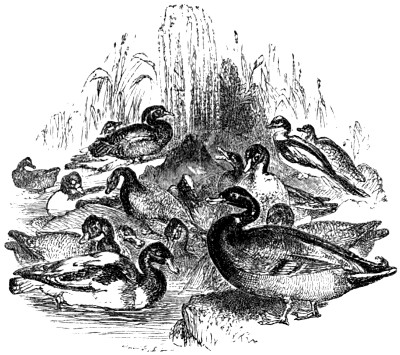

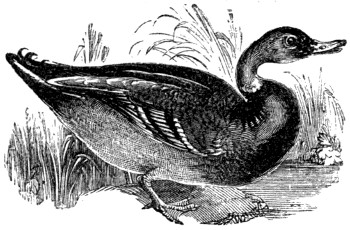

| Ducks | 558 |

| THE RABBIT | 560 |

| THE RAVEN | 570 |

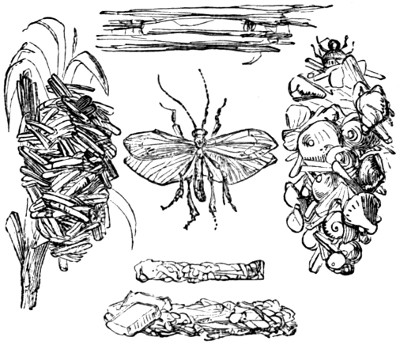

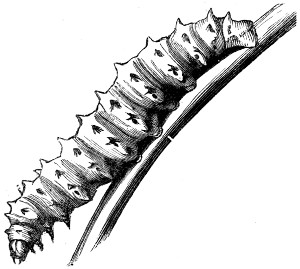

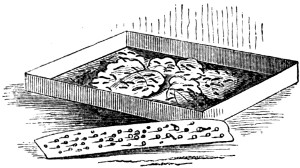

| SILKWORMS | 574 |

| Food of the Silkworm | 576 |

| Hatching, Feeding, and Temperature | 576 |

| Moultings | 577 |

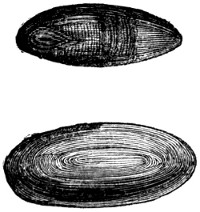

| The Cocoon | 577 |

| The Aurelia | 578 |

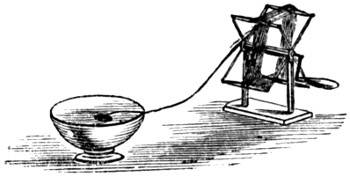

| Winding the Silk | 578 |

| The Moth | 578 |

| General Remarks | 579 |

| THE SQUIRREL | 580 |

| WHITE MICE | 587 |

| PART V. | |

| MISCELLANEOUS. | |

| BAGATELLE | 591 |

| English Bagatelle | 591 |

| The French Game | 591 |

| Sans Egal | 591 |

| The Cannon Game | 592 |

| Mississippi | 592 |

| BILLIARDS | 593 |

| The Angles of the Table | 597 |

| The American Game | 602 |

| Pyramids, or Pyramid Pool | 602 |

| Winning and Losing Carambole Game | 602 |

| Pool | 603 |

| Italian Skittle Pool | 604 |

| BOAT-BUILDING | 605 |

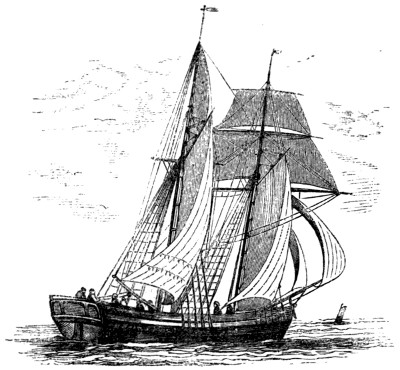

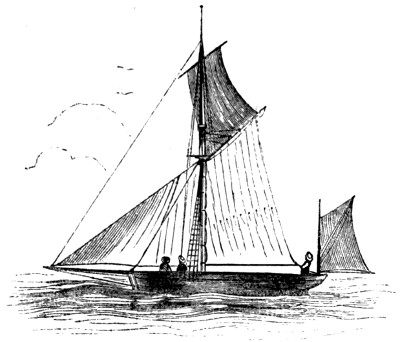

| Cutter | 606 |

| Smack | 607 |

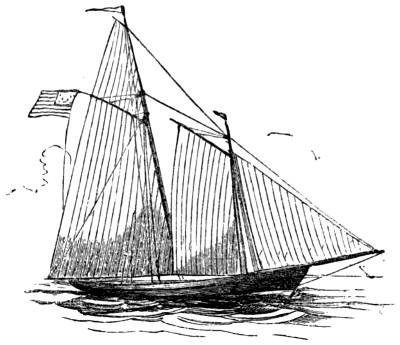

| Schooner | 607 |

| Lugger | 608 |

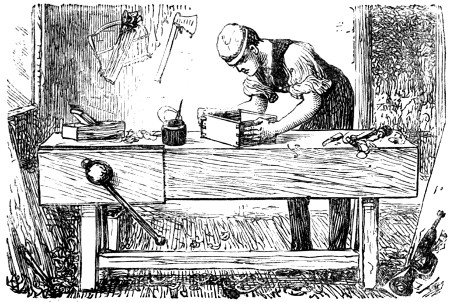

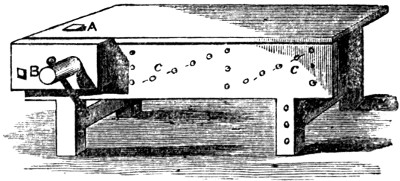

| CARPENTERING | 609 |

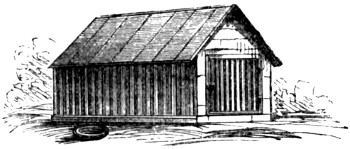

| The Shop and Bench | 609 |

| Of Planes | 610 |

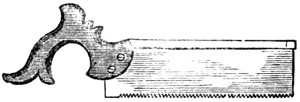

| Saws | 611 |

| The Spoke Shave | 613 |

| Stock and Bits | 613 |

| How to make a Wheelbarrow | 613 |

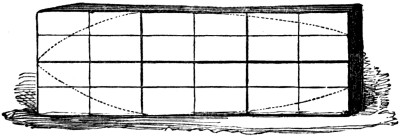

| The Way to make a Box | 615 |

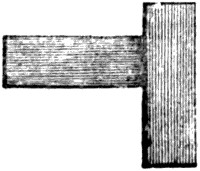

| To cut the Dovetails | 615 |

| The Bottom of the Box | 616 |

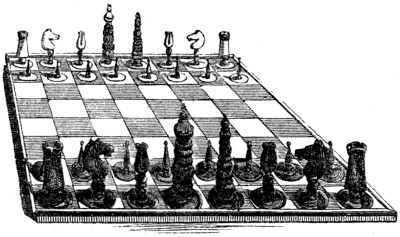

| THE GAME OF CHESS | 617 |

| The Laws of the Game | 618 |

| The King’s Knight’s opening | 620 |

| Game I.—Philidor’s Defence | 621 |

| Ga„e II.—Petroff’sDef„ | 622 |

| Variation A. on White’s 5th Move | 622 |

| Game III.—The Giuoco Piano | 622 |

| Variation A. on White’s 6th Move | 622 |

| Game IV.—The Evans’ Gambit | 623 |

| Variation A. on White’s 9th Move | 623 |

| Vari„tion B. on „hite’„ 9th „ | 624 |

| Vari„tion A. on Black’s 10th Move | 624 |

| The Gambit declined | 625 |

| Game V.—Ruy Lopez Knight’s Game | 626 |

| Variation B. on Black’s 3rd Move | 627 |

| Vari„tion C. on „lack„ 3rd „ | 627 |

| Game VI.—The Scotch Gambit | 627 |

| Variation A. on Black’s 4th Move | 628 |

| The King’s Bishop’s Opening | 630 |

| Game I.—The Lopez Gambit | 630 |

| Variation A. on White’s 4th Move | 631 |

| Game II.—The Double Gambit | 631 |

| Game III. | 631 |

| Variation A. on Black’s 4th Move | 632 |

| The King’s Gambit | 632 |

| Game I. | 632 |

| The Salvio Gambit | 633 |

| Variation A. on Black’s 4th Move | 633 |

| Game II.—The Muzio Gambit | 633 |

| Game I.—The Allgaier Gambit | 635 |

| Game II. | 635 |

| Game I.—The Bishop’s Gambit | 636 |

| Game II. | 636 |

| The Gambit refused | 638 |

| Game I. | 638 |

| Game II. | 639 |

| The Centre Gambit | 639 |

| Game I. | 639 |

| Variation A. on Black’s 3rd Move | 640 |

| Game II. | 640 |

| The Queen’s Gambit | 641 |

| Game I.[xv] | 641 |

| Variation A. on Black’s 3rd Move | 641 |

| Game II. | 642 |

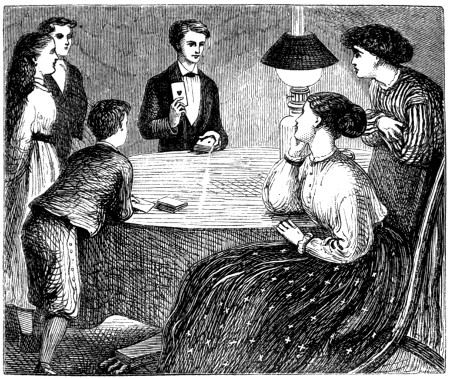

| THE YOUNG CONJURER | 643 |

| Sleight of Hand | 645 |

| The Flying Shilling | 645 |

| Another Method | 646 |

| The Beads and Strings | 646 |

| To get a Ring out of a Handkerchief | 647 |

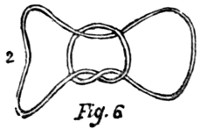

| To tie a Knot in a Handkerchief which cannot be drawn tight | 647 |

| The Three Cups | 648 |

| To tie a Handkerchief round your Leg, and get it off without untying the Knot | 648 |

| The Magic Bond | 649 |

| The Old Man and his Chair | 649 |

| To tie a Knot on the Left Wrist without letting the Right Hand approach it | 651 |

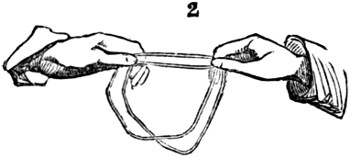

| The Handcuffs | 651 |

| To pull a String through your Button-hole | 652 |

| The Cut String restored | 652 |

| The Gordian Knot | 653 |

| The Knot loosened | 653 |

| To put Nuts into your Ear | 654 |

| To crack Walnuts in your Elbow | 654 |

| To take Feathers out of an empty Handkerchief | 654 |

| Tricks requiring Special Apparatus | 654 |

| The Die Trick | 655 |

| The Penetrative Pence | 656 |

| The Doll Trick | 657 |

| The Flying Coins | 657 |

| The Vanished Groat | 658 |

| The Restored Document | 658 |

| The Magic Rings | 658 |

| The Fish and Ink Trick | 659 |

| The Cannon Balls | 659 |

| The Shilling in the Ball of Cotton | 660 |

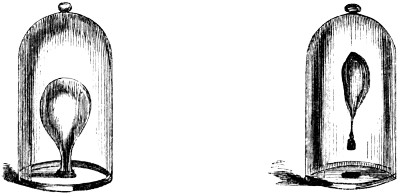

| The Egg and Bag Trick | 660 |

| The Dancing Egg | 661 |

| Bell and Shot | 661 |

| The Burned Handkerchief restored | 662 |

| The Fire-Eater | 662 |

| Tricks with Cards | 663 |

| To make the Pass | 663 |

| To tell a Card by its Back | 664 |

| The Card named without being Seen | 664 |

| The Card told by the Opera Glass | 664 |

| The Four Kings | 666 |

| Audacity | 666 |

| The Card found at the Second Guess | 666 |

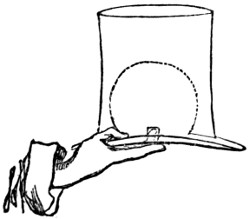

| The Card found under the Hat | 667 |

| To call the Cards out of the Pack | 667 |

| Heads and Tails | 667 |

| The Surprise | 668 |

| The Revolution | 668 |

| The Slipped Card | 668 |

| The Nailed Card | 668 |

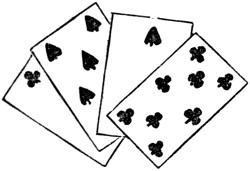

| To ascertain the Number of Points on three Unseen Cards | 669 |

| To tell the Numbers on two Unseen Cards | 669 |

| The Pairs repaired | 669 |

| The Queen digging for Diamonds | 670 |

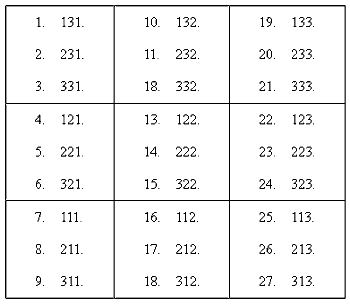

| The Triple Deal | 670 |

| The Quadruple Deal | 671 |

| Tricks with Cards that require Apparatus | 671 |

| The Cards in the Vase | 671 |

| The Metamorphosis | 672 |

| To change a Card in a Person’s Hand | 673 |

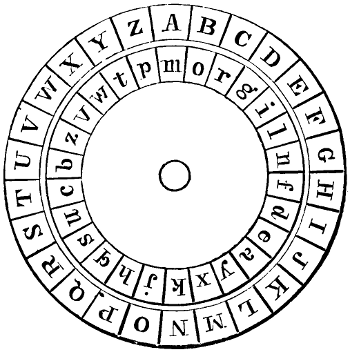

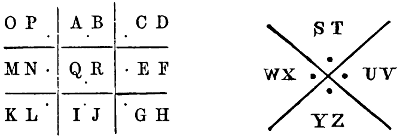

| CRYPTOGRAPHY | 674 |

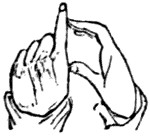

| THE DEAF AND DUMB ALPHABET | 682 |

| The Alphabet | 682 |

| The Numbers | 685 |

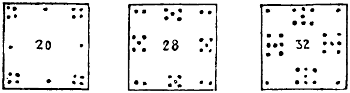

| DOMINOES | 685 |

| The ordinary Boy’s Game | 686 |

| All Fives | 687 |

| The Matadore Game | 687 |

| All Threes | 687 |

| Tidley-Wink | 688 |

| The Fortress | 688 |

| Whist Dominoes | 688 |

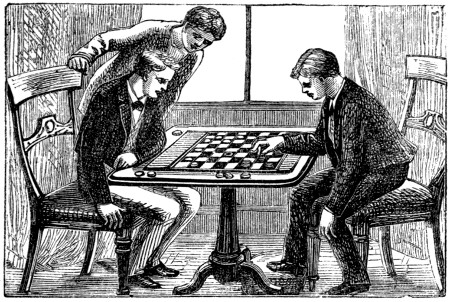

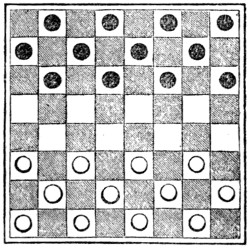

| DRAUGHTS | 689 |

| How to play the Game | 690 |

| The Moves | 690 |

| Laws of the Game | 690 |

| Games for Practice | 691 |

| Game I. | 691 |

| Game II. | 692 |

| FIREWORKS | 693 |

| Gunpowder | 693 |

| How to make Touch-paper | 694 |

| Cases for Squibs, Flower-pots, Rockets, Roman Candles, &c. | 694 |

| To choke the Cases | 694 |

| Composition for Squibs, &c. | 694 |

| How to fill the Cases | 695 |

| To make Crackers | 695 |

| Roman Candles and Stars | 695 |

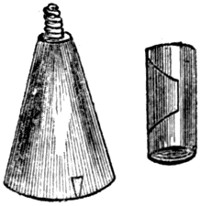

| Rockets | 696 |

| Rains | 696 |

| Catherine Wheels | 696 |

| Various Coloured Fires | 696 |

| Crimson Fire | 696 |

| Blue„ | 697 |

| Green „ | 697 |

| Purple „ | 697 |

| White„ | 697 |

| Spur„ | 697 |

| Blue Lights | 697 |

| Port or Wild Fires | 697 |

| Slow Fire for Wheels | 697 |

| Dead Fire for Wheels | 697 |

| Cautions | 697 |

| To make an Illuminated Spiral Wheel | 698 |

| The Grand Volute | 698 |

| A brilliant Yew-tree[xvi] | 699 |

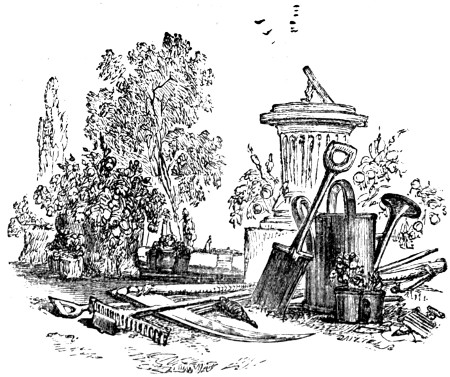

| GARDENING | 700 |

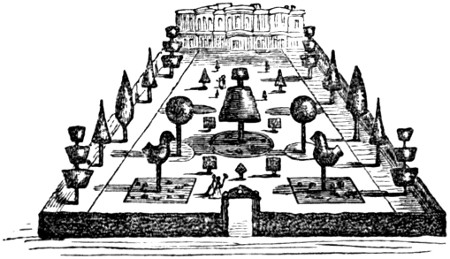

| On Laying out a Small Garden | 702 |

| Planting the Ground with Trees, Flowers, &c. | 703 |

| The Noblest Kind of Gardening for Boys | 703 |

| The Boy’s Flower Garden | 710 |

| T„e Bo„y’ Fruit Garden | 717 |

| Cropping the Ground | 719 |

| Digging | 719 |

| Hoeing | 720 |

| Raking | 720 |

| Weeding | 720 |

| Sowing Seeds | 721 |

| Transplanting | 721 |

| Watering | 722 |

| Various Modes of Propagation | 723 |

| Layers | 723 |

| Pipings | 723 |

| Grafting | 724 |

| Tongue-Grafting | 724 |

| Budding | 725 |

| Inarching | 725 |

| Grafting Clay | 726 |

| Pruning | 726 |

| Training | 726 |

| Insects and Depredators | 727 |

| Protection from Frost | 727 |

| The Young Gardener’s Calendar for the Work to be done in all the Months of the Year | 728 |

| January | 728 |

| February | 729 |

| March | 729 |

| April | 729 |

| May | 730 |

| June | 730 |

| July | 731 |

| August | 731 |

| September | 731 |

| October | 732 |

| November | 732 |

| December | 732 |

| MIMICRY AND VENTRILOQUISM | 733 |

| PUZZLES | 736 |

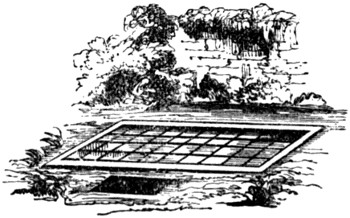

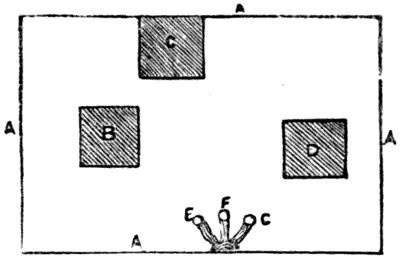

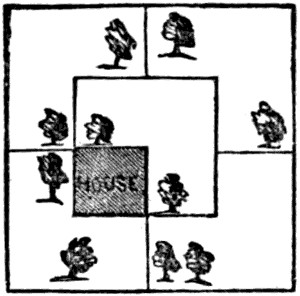

| The Divided Garden | 736 |

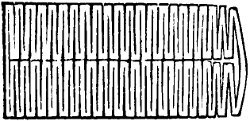

| The Vertical Line Puzzle | 736 |

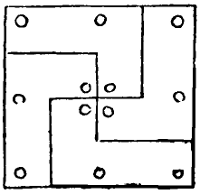

| The Cardboard Puzzle | 736 |

| The Button Puzzle | 736 |

| The Circle Puzzle | 737 |

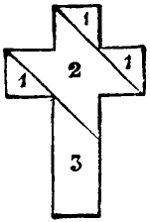

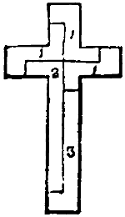

| The Cross Puzzle | 737 |

| Three-Square Puzzle | 737 |

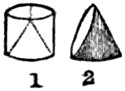

| Cylinder Puzzle | 737 |

| The Nuns | 738 |

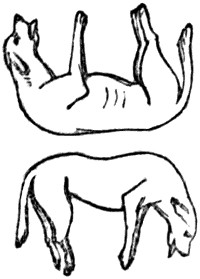

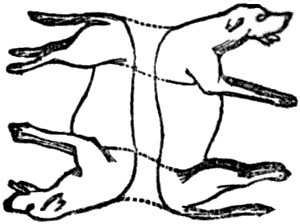

| The Dog Puzzle | 738 |

| Cutting out a Cross | 738 |

| Another Cross Puzzle | 738 |

| The Fountain Puzzle | 738 |

| The Cabinet-maker’s Puzzle | 739 |

| The String and Balls Puzzle | 739 |

| The Double-headed Puzzle | 739 |

| The Row of Halfpence | 740 |

| Typographical Advice | 740 |

| The Landlord made to Pay | 740 |

| Father and Son | 740 |

| Answers to Puzzles | 741 |

| The Divided Garden | 741 |

| Vertical Line Puzzle | 741 |

| Cut Card Puzzle | 741 |

| Button Puzzle | 741 |

| Circle Puzzle | 741 |

| The Cross Puzzle | 742 |

| Three-Square Puzzle | 742 |

| Cylinder Puzzle | 742 |

| The Nuns’ Puzzle | 742 |

| The Dog’s Puzzle | 742 |

| Cutting out a Cross Puzzle | 743 |

| Another Cross Puzzle | 743 |

| The Fountain Puzzle | 743 |

| The Cabinet-maker’s Puzzle | 743 |

| String and Balls Puzzle | 744 |

| Double-Headed Puzzle | 744 |

| The Row of Halfpence | 744 |

| Typographical Puzzle | 745 |

| The Landlord made to Pay | 745 |

| Father and Son | 745 |

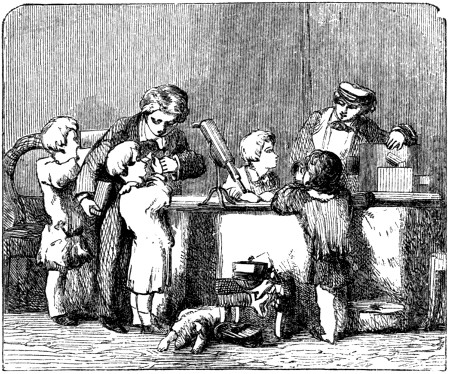

| SHOWS | 746 |

| Punch and Judy | 746 |

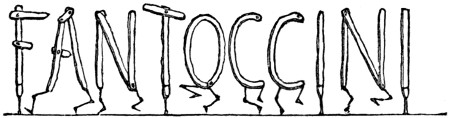

| Fantoccini | 749 |

| The Sailor | 751 |

| The Juggler | 751 |

| The Headless Man | 751 |

| The Milkwoman | 751 |

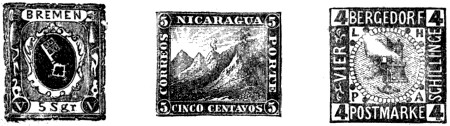

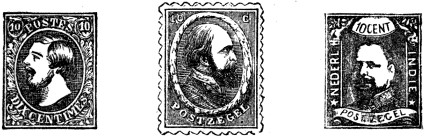

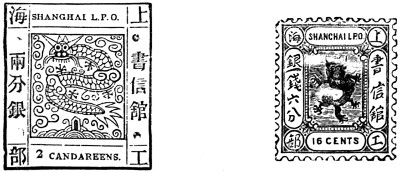

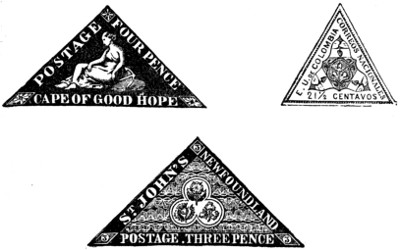

| POSTAGE-STAMP COLLECTING, or Philately | 752 |

| TINSELLING | 768 |

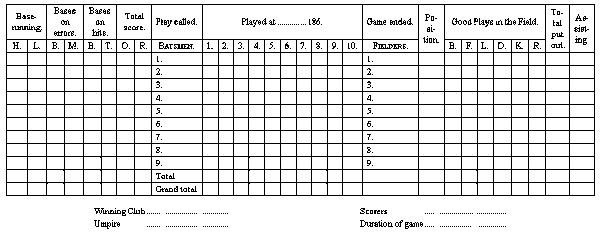

| THE AMERICAN GAME OF BASE-BALL | 769 |

| American Billiards | 797 |

| La Crosse | 812 |

Make a mark on the ground at a place called the “starting point.” At ten yards’ distance from this make another, called the “spring.” Then let the players arrange themselves at the starting point, and in succession run to the second mark called the spring. From the spring make first a hop on one leg, from this make a long step, and from the step a long jump. Those who go over the greatest space of ground are of course the victors.

Various games are in vogue among boys, in which hopping on one foot is the principal object. Among these is one which not only assists in strengthening the limbs, but also teaches the performers the useful art of balancing themselves upon a movable substance. A wooden bottle, a round wooden log, or something of that description, is laid upon the ground, a mark is made at a certain distance, and the players have to hop from the mark upon the bottle, and retain their possession while they count a number agreed upon. In the olden times of Greece, this was considered an exercise of sufficient importance to give it a place at the public games. The performer in this case had to hop upon inflated leather bags, carefully greased, and of course, by their inevitable upsettings and floundering, caused great amusement to the spectators. The sports took place on the Dionysia, or festivals of Bacchus, when the vintage was gathered in, and the victor was appropriately rewarded with a cask of wine. The rustics in many parts of England introduce a modification of this game in their rural festivals. Two men place themselves opposite to each other, the right knee of each being supported on a wooden cylinder, while the remaining foot is totally unsupported. When they are fairly balanced, they grasp each other by the shoulders, and endeavour to cast their opponent to the ground, while themselves retain their position upon their fickle support.

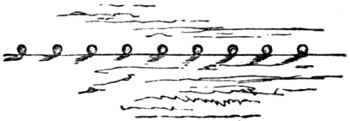

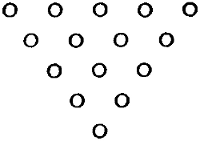

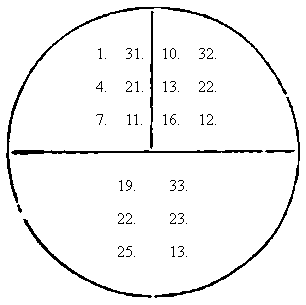

This is a game played by hopping on one foot and kicking an oyster-shell or piece of tile from one compartment to the other, without halting the lifted foot, except in one case, to the ground, and without suffering the shell or tile to rest on any of the lines. A diagram is first drawn similar to the subjoined. It consists of twelve compartments, each being numbered, and at its further end the pleasant and inviting picture of a plum pudding with knife and fork therein stuck. In commencing the game, the players take their stand at the place marked by a star, and “quoit” for innings. The object is, that of doing what every boy is supposed to like above all things to do, i. e. “pitch into the pudding,” and he who can do this, and go nearest to the plum in the centre, plays first.

Method of Playing.—The winner begins by throwing his shell into No. 1; he then hops into the space, and kicks the tile out to the star *; he next throws the tile into No. 2, kicks it from No. 2 to No. 1, and thence out. He then throws it into No. 3, kicks it[3] from 3 to 2, from 2 to 1, and out. He next throws it into No. 4, kicks it from 4 to 3, from 3 to 2, from 2 to 1, and out; and so he proceeds till he has passed the cross and comes to No. 7, when he is permitted to rest himself, by standing with one foot in No. 6 and the other in No. 7; but he must resume hopping before he kicks the tile home. He then passes through the beds 8, 9, 10 and 11, as he did those of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, &c., and so on, till he gets to plum pudding, when he may rest, and placing his tile on the plum, he is required, while standing on one foot, to kick it with such force as to send it through all the other beds to * at one kick. If one player throws his tile into the wrong compartment, or when he is kicking it out, he loses his innings, as he does also if the tile or his foot at any time rests on a line, or if he kicks his tile out of the diagram.

This is an old Greek game, and, like very many simple boys’ games, has retained its popularity to the present day. Its Greek name was rather a jaw-cracking one, but may be literally translated by “Pully-haully.” It consists of two parties of boys, who are chosen on different sides by lots. One party takes hold of one end of a strong rope, and the other party of the other end. A mark being made midway between the parties, each strives to pull the other over it, and those who are so pulled over, lose the game.

In this game, two leaders should be appointed, who must calculate the powers of their own side, and concert plans accordingly. The leader of either side should have a code of signals, in order to communicate with his own friends, that he may direct them when to stop, when to slacken, or when to pull hard. So important is the leader’s office, that a side with a good leader will always vanquish a much superior force which has no commander to guide it. For example, when all the boys are pulling furiously at the rope, the leader of one side sees that his opponents are leaning back too much, depending on their weight more than on their strength. He immediately gives the signal to slacken, when down go half the enemy on their backs, and are run away with merrily by the successful party, who drag them over the mark with the greatest ease. Or if the enemy begins to be wearied with hard pulling, an unanimous tug will often bring them upright, while they are off their guard, and once moved, the victory is easily gained. We have seen, assisted, and led this game hundreds of times, and never failed to find it productive of very great amusement. No knots are to be permitted on the rope, nor is the game to be considered as won, unless the entire side has been dragged over the line.

This is a game not very dissimilar to the preceding, but not so much to be recommended, as the clothes are very apt to be torn, and[4] if the players engage too roughly, the wrists are not unfrequently injured. The method of playing the game is as follows:—Several boys seat themselves in a row, clasping each other round the waist, thus fantastically representing a batch of loaves. Two other players then approach, representing the baker’s men, who have to detach the players from each other’s hold. To attain this object, they grasp the wrists of the second boy, and endeavour to pull him away from the boy in front of him. If they succeed, they pass to the third, and so on until they have drawn the entire batch. As sometimes an obstinate loaf sticks so tight to its companion, that it is not torn away without bringing with it a handful of jacket or other part of the clothing, the game ought not to be played by any but little boys.

This is a capital game for the summer months. The players divide themselves into two parties, one party remaining at a spot called “Bounds,” and concealing their faces, while the other party goes out and hides. After waiting for a few minutes, the home party shouts, “Coming, coming, coming.” After a short pause they repeat the cry, and after another short interval they again shout, “Coming.” If any out-player is not concealed, he may cry, “No,” and a few minutes more are allowed. At the last shout, the home players, leaving one to guard bounds, sally forth in search of their hidden companions. Directly one of the seekers sees one of the hiders, he shouts, “I Spy,” and runs home as fast as he can, pursued by the one he has found, who tries to touch him before he can reach bounds. If he succeeds, the one so touched is considered taken, and stands aside. If the hiding party can touch three, or more, if especially agreed upon, they get their hide over again. The object of the hiders is to intercept the seekers, and prevent them from reaching bounds without being touched. The worst player is left at the bounds, in order to warn his companions, which he does by the word “Home,” as any hider may touch any seeker.

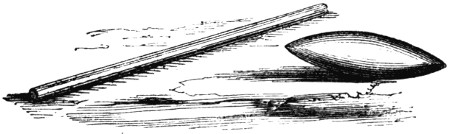

This game is played by two boys, each of whom takes a smooth round pebble. One player then throws his pebble about twenty feet before him, and the next tries to strike it with his stone, each time of striking counting as one. If the two pebbles are near enough for the player to place one upon the other with his hand, he is at perfect liberty to do so. It is easy enough to play at this game when the pebbles are at some distance apart; but when they lie near each other, it is very difficult to take a good aim, and yet send one’s own pebble beyond the reach of the adversary’s aim. Two four-pound cannon balls are the best objects to pitch, as they roll evenly, and do not split, as pebbles always do when they get a hard knock.

This game may be played by any number of players. A large stone is selected, and placed on a particular spot, and the players first “Pink for Duck,” that is, they each throw their stones up to the mark, and the one who is farthest from it becomes “Duck.” The Duck places his stone on the other, while the rest of the players return to the bounds, and in succession pitch their stones at his with the endeavour to knock it off. If this is accomplished, Duck must immediately replace it, and the throwers must pick up their stones and run to the bounds. As soon as Duck has replaced his stone, he runs after any of the other players, and if he can succeed in catching or merely touching any one of them, the player so touched becomes Duck.

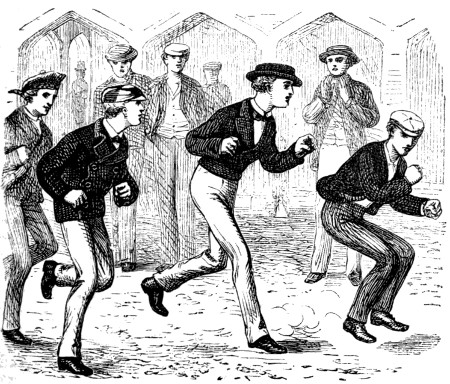

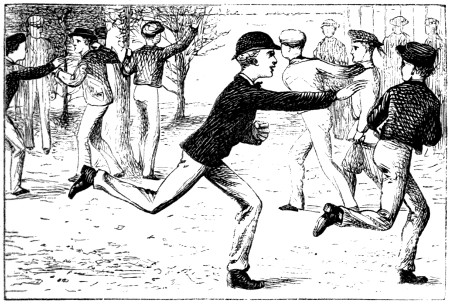

This is a most delightful game, and is a very great favourite among boys of all classes. It is commenced by choosing Captains, which is either done by lot or by the “sweet voices” of the youths. If by lot, a number of straws of different lengths are put in a bunch, and those who draw from one end, the other being hidden, the two longest straws, are the two “Captains;” each of which has the privilege of choosing his men: the drawer of the longest of the two straws has the first choice. When this has been arranged each Captain selects, alternately, a boy till the whole are drawn out.

This method is, however, often attended with considerable inconvenience, as it is not impossible that the lots may fall on the two worst players. It is very much better to let the boys choose the two[6] Captains, as the two best players will then assuredly be elected, and most of the success of the game depends on the Captains.

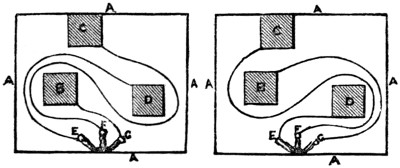

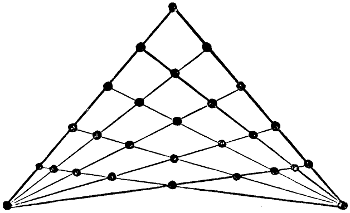

The leaders being thus chosen, the next point is to mark out the homes and prisons. First, two semicircles are drawn, large enough to hold the two parties, the distance between the semicircles being about twenty paces. These are the “homes,” or “bounds.” Twenty paces in front of these, two other semicircles, of a rather larger size, are marked out. These are the prisons; the prison of each party being in a line with the enemy’s home. These preliminaries being settled, the sides draw lots; the side drawing the longest straw having to commence the game. The Captain of side A orders out one of his own side, usually a poor player, who is bound to run at least beyond the prisons before he returns. Directly he has started, the Captain of side B sends out one of his men to pursue, and, if possible, to touch him before he can regain his own home. If this is accomplished, the successful runner is permitted to return home scathless, while the vanquished party must go to the prison belonging to his side; from which he cannot stir, until some one from his own side releases him, by touching him in spite of the enemy. This is not an easy task; as, in order to reach the prison, the player must cross the enemy’s home. It is allowable for the prisoner to stretch his hand as far towards his rescuer as possible, but he must keep some part of his body within the bounds; and if several prisoners are taken, it is sufficient for one to remain within the prison, while the rest, by joining hands, make a chain towards the boy who is trying to release them. When this is accomplished, both the prisoner and his rescuer return home, no one being able to touch them until they have reached their home and again started off. But the game is not only restricted to the two originally sent out. Directly Captain A sees his man pressed by his opponent, he sends out a third, who is in his turn pursued by another from side B; each being able to touch any who have preceded, but none who have left their home after him. The game soon becomes spirited; prisoners are made and released, the two Captains watching the game, and rarely exposing themselves, except in cases of emergency, but directing the whole proceedings. The game is considered won, when one party has succeeded in imprisoning the whole of the other side. Much depends upon the Captains, who sometimes, by a bold dash, rescue the most important of their prisoners, and thereby turn the fate of the battle; or, when the attention of the opposite side is occupied by some hardly-contested struggle, send some insignificant player to the rescue; who walks quietly up to the prison, and unsuspectedly lets out the prisoners one by one. No player is permitted to touch more than one person until he has returned to his home; when he can sally out again armed with fresh strength, like Antæus of old, who could not be conquered at wrestling, because whenever he touched the ground his strength was renewed by his mother Earth.

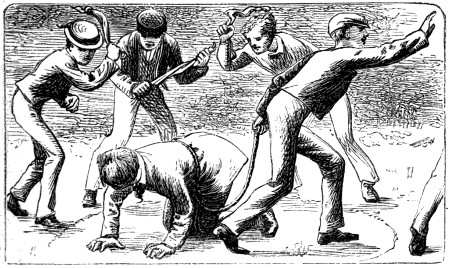

This game was extensively played at the school where our boyhood was passed; but we never saw it elsewhere. It used to afford us such amusement in the long summer evenings, that it deserves a place in this collection of sports. One player is termed Fox, and is furnished with a den, where none of the players may molest him. The other players arm themselves with twisted or knotted handkerchiefs, (one end to be tied in knots of almost incredible hardness,) and range themselves round the den waiting for the appearance of the Fox. He being also armed with a knotted handkerchief, hops out of his den. When he is fairly out, the other players attack him with their handkerchiefs, while he endeavours to strike one of them without putting down his other foot. If he does so he has to run back as fast as he can, without the power of striking the other players, who baste him the whole way. If, however, he succeeds in striking one without losing his balance, the one so struck becomes Fox; and, as he has both feet down, is accordingly basted to his den. The den is useful as a resting-place for the Fox, who is often sorely wearied by futile attempts to catch his foes.

This is a funny game. The players generally draw lots for the first Bear, who selects his own Keeper. The Bear kneels on the ground, and his Keeper holds him with a rope about four feet long, within a circle of about five feet in diameter. The other players tie knots in their handkerchiefs, and begin to strike or baste the Bear, by running close to, or into the ring. Should the Keeper touch any of the boys while they are at this sport without dragging the Bear out of the[8] ring, or should the Bear catch hold of any player’s leg, so as to hold him fast, the player so touched or caught becomes Bear. The second Bear may select his Keeper as before, and the play continues.

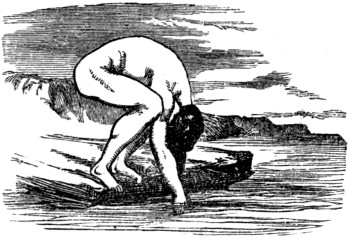

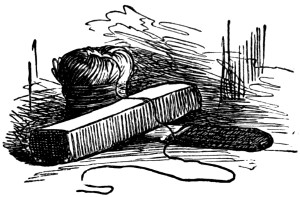

AN INSTRUMENT OF TORTURE.

This is an excellent game of agility, and very simple. It consists of any number of players; but from six to eight is the most convenient number. Having by agreement or lots determined who shall give the first “back,” one player so selected places himself in position, with his head inclined and his shoulders elevated, and his hands resting on his knees, at ten yards’ distance from the other players; one of whom immediately runs and leaps over him,—having made his leap, he sets a back at the same distance forward from the boy over whom he has just leaped. The third boy leaps over the first and second boy, and sets a “back” beyond the second; and the fourth boy leaps over the first, second, and third, and sets a “back” beyond the third, and so on till the players are out. The game may continue for any length of time, and generally lasts till the players are tired; but the proper rule should be, that all who do not go clean over should be out. Those who “make backs” should stand perfectly stiff and firm; and those who “make leaps” should not rest in their flight heavily upon the shoulders of their playmates, so as to throw them down, which is not fair play.

Chalk or make a line, or, as it is usually termed, “a garter,” on the ground; on this line one of the players must place himself and bend down as in leap-frog, while the other players in rotation leap over him, the last one as he flies over calling out “Foot it.” If he should fail in giving this notice, he is out, and must take the other boy’s place at the garter. The boy, immediately the word is given, rises, and places his right heel close to the middle of the left foot; he next moves the left forwards and places that heel close up to the[9] toes of his right foot, and bends down as before. This movement is called a “step,” and is repeated three times. The other players should fly from the garter each time a step is made, and the last player must invariably call out “Foot it” as he leaps over. After making the three “steps,” the player giving the back takes a short run, and, from the spot where he made his last step to, jumps as far forwards as he possibly can, and bends down again; the others jump from the garter and then fly over. Should any of the players be unable to jump easily over the one giving the back, but rather slide down upon, or ride on him, the player so failing must take the other’s place at the garter, and the game be begun again; if, also, through the impetus acquired in taking the jump from the garter, a player should happen to place his hands on the back of the player bending down, and then withdraw them in order to take the spring over, he is out, and must take his turn at the garter. It is usual, in some places, for the boy giving the back to take a hop, step, and a jump after he has footed it three times, the other players doing the same, and then flying over.

This game is capable of being varied to any extent by an ingenious boy, but it is generally played in the following way:—One boy, selected by chance, sets a back, as in “fly the garter,” and another is chosen leader. The game is commenced by the leader leaping over the one who gives the back, and the other players follow in succession; the leader then leaps back, and the others follow; then they all go over in a cross direction, and return, making, in all, four different ways. The leader then takes his cap in both hands, and leaves it on the boy’s back while he is “overing,” and his followers perform the same trick; in returning, the last man takes the lead, and removes his cap without disturbing the others, and each boy does the same: this trick is repeated in a cross direction. The next trick is throwing up the cap just before overing, and catching it before it falls; the next, reversing the cap on the head, and so balancing it while overing, without ever touching it with the hands; both tricks must be performed while leaping the four different ways. The leader, with his cap still balanced, now overs, and allows his cap to drop on the opposite side; the others do likewise, but they must be careful not to let their caps touch the others, nor to let their feet touch any of the caps in alighting; the leader now stoops down, picks up his cap with his teeth, and throws it over his head and the boy’s back; he then leaps after his cap, but avoids touching it with his feet. The other players follow him as before. The next trick is “knuckling,”—that is to say, overing with the hands clenched; the next, “slapping,” which is performed by placing one hand on the boy’s back, and hitting him with the other, while overing; the last, “spurring,” or touching him up with the heel. All these tricks must be performed in the four different[10] directions, and any boy failing to do them properly goes down, and the game begins afresh.

This is a brisk game, and may be played by any number of boys. One of the players being chosen as Touch, it is his business to run about in all directions after the other players, till he can touch one, who immediately becomes Touch in his turn. Sometimes when the game is played it is held as a law that Touch shall have no power over those boys who can touch iron and wood. The players then, when out of breath, rush to the nearest iron or wood they can find, to render themselves secure. Cross-touch is sometimes played, in which, whenever another player runs between Touch and the pursued, Touch must immediately leave the one he is after to follow him. But this rather confuses, and spoils the game.

These games are founded on the above. When the boys pursued by Touch can touch either wood or iron they are safe, the rule being that he must touch them as they run from one piece of wood or iron to another.

This is a very good game for three boys. The first is called the Buck, the second the Frog, and the third the Umpire. The boy who plays the Buck gives a back with his head down, and rests his hands on some wall or paling in front of him. The Frog now leaps on his back, and the Umpire stands by his side: the Frog now holds up one, two, three, five, or any number of fingers, and cries, “Buck! Buck! how many horns do I hold up?” The Buck then endeavours to guess the right number; if he succeeds, the Frog then becomes Buck, and in turn jumps on his back. The Umpire determines whether Buck has guessed the numbers rightly or not. In some places it is the custom to blindfold the Buck, in order to prevent him seeing. This plan, however, is scarcely necessary.

This is an excellent game for cold weather. It may be played by any number of boys. In playing it “loose bounds” are made near a wall or fence, about four feet wide and twelve long. One of the boys is selected, who is called the Cock, who takes his place within the bounds; the other players are called the Chickens, who distribute themselves in various parts of the playground. The Cock now clasps his hands together, and cries, “Warning once, warning twice, a bushel of wheat, and a bushel of rye, when the Cock crows out jump I.” He then, keeping his hands still clasped before him, runs after the other players; when he touches one, he and the player so touched[11] immediately make for the bounds; the other players immediately try to capture them before they get there; if they succeed, they are privileged to get upon their backs and ride them home. The Cock and his Chick now come out of the bounds hand-in-hand, and try to touch some other of the players; the moment they do this they break hands, and they and the player now touched run to the bounds as before, while the other players try to overtake them, so as to secure the ride. The three now come from the bounds in the same manner, capture or touch a boy, and return. If, while trying to touch the other boys, the players when sallying from the grounds break hands before they touch any one, they may immediately be ridden, if they can be caught before they reach the bounds. Sometimes when three players have been touched the Cock is allowed to join the out party, but this is of no advantage in playing the game.

This may be played by any number of boys: one being selected as the Leader, and the others are the Followers. The Followers arrange themselves in a line behind the Leader, who immediately begins to progress, and the others are bound to follow him. The fun of this sport is in the Leader carrying his Followers into “uncouth places,” over various “obstacles,” such as hedges, stiles, gate-posts, &c., through “extraordinary difficulties,” as ditches and quagmires,—every player being expected to perform his feats of agility; and those who fail are obliged to go last, and bear the emphatic name of the “Ass.” The game lasts till the Leader gives up, or the boys are all tired out.

This is a game something like the above. It consists of the Fugleman and his Squad. The Fugleman places himself in a central spot, and arranges his Squad before him in a line. He then commences with various odd gestures, which all the Squad are bound to imitate. He moves his head, arms, legs, hands, feet, in various directions, sometimes sneezes, coughs, weeps, laughs, and bellows, all of which the Squad are to imitate. Sometimes this is a most amusing scene, and provokes great laughter. Those who are observed to laugh, however, are immediately ordered to stand out of the line, and when half the number of players are so put out, the others are allowed to ride them three times round the playground, while the Fugleman with a knotted handkerchief accelerates their motions.

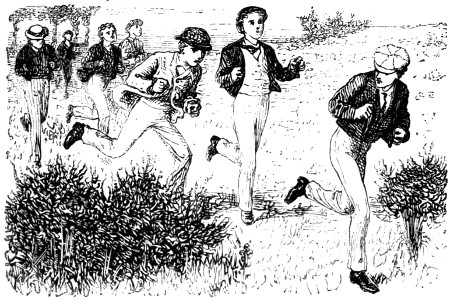

This is perhaps the very best game that can be introduced into a school. The principle of it is very simple, that one boy represents the Hare and runs away, while the others represent the Hounds and pursue him. The proper management of the game, however, requires[12] some skill. When we were at school in the north, this game was extensively played; and in more recent times, when we ourselves were masters instead of scholars, we reduced the game to a complete system. The first thing to be done is to choose a Hare, or if the chase is to be a long one, two Hares are required. The Hare should not be the best runner, but should be daring, and at the same time prudent, or he may trespass into forbidden lands, and thereby cause great mischief. A Huntsman and Whipper-in are then chosen. The Huntsman should be the best player, and the Whipper-in second best. Things having advanced so far, the whole party sally forth. The Hare is furnished with a large bag of white paper torn into small squares, which he scatters on the ground as he goes. An arrangement is made that the Hare shall not cross his path, nor return home until a certain time; in either of which cases he is considered caught. The Hounds also are bound to follow the track or “scent” implicitly, and not to make short cuts if they see the Hare. The Hare then starts, and has about seven minutes’ grace, at the expiration of which time the Huntsman blows a horn with which he is furnished, and sets off, the Hounds keeping nearly in Indian file, the Whipper-in bringing up the rear. The Huntsman is also furnished with a white flag, the Whipper-in with a red one, the staves being pointed and shod with metal. Off they go merrily enough, until at last the Huntsman loses the scent. He immediately shouts “Lost!” on which the Whipper-in sticks his flag in the ground where the scent was last seen, and the entire line walks or runs round it in a circle, within which they are tolerably sure to find the track. The Huntsman in the meanwhile has stuck his flag in the ground, and examines the country to see in what direction the Hare is likely to have gone.[13] When the track is found, the player who discovers it shouts Tally ho! the Huntsman takes up his flag, and ascertains whether it is really the track or not. If so, he blows his horn again, the Hounds form in line between the two flags, and off they go again. It is incredible how useful the two flags are. Many a Hare has been lost because the Hounds forgot where the last track was seen, and wasted time in searching for it again. Moreover, they seem to encourage the players wonderfully. We used often to make our chases fourteen or fifteen miles in length; but before such an undertaking is commenced, it is necessary to prepare by a series of shorter chases, which should however be given in an opposite direction to the course fixed upon for the grand chase, as otherwise the tracks are apt to get mixed, and the Hounds are thrown out. The Hare should always carefully survey his intended course a day or two previously, and then he will avoid getting himself into quagmires, or imprisoned in the bend of a river. A pocket compass is a most useful auxiliary, and prevents all chance of losing the way, a misfortune which is not at all unlikely to happen upon the Wiltshire downs or among the Derbyshire hills.

This is a trial of speed and agility, and may be played by any number of boys. It consists in the boys agreeing upon some distant object for a mark, such as a conspicuous tree, or house, or steeple. The players then start off in whatever direction they please, each one being at liberty to choose his own course. In a long run of a mile or so it very often happens that hedges, ditches, and other obstructions, have to be got over, which adds great interest to the play, and the best climbers and jumpers are the most likely to come in victors. He who comes in first to the appointed object is called the King, the second the Duke, the third the Marquis, the fourth the Viscount, the fifth the Earl, the sixth the Knight. The last receives the dignified appellation of the Snail, and the last but one the Tortoise.

At Oxford there were in our undergraduate days two clubs for the purpose of Steeple-chasing, one named the Kangaroo Club, and the other the Charitable Grinders, whose performances over hedges and ditches were really astonishing. There was also a club which kept a set of beagles, and used to hunt a red herring with intense perseverance.

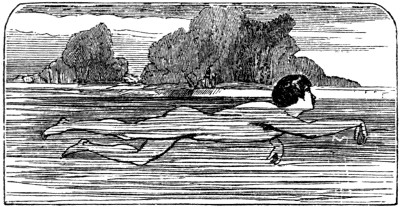

This is a very simple sport, but necessarily restricted to those spots where there is a river, or a pond of some magnitude. It consists in throwing oyster-shells, flat stones, or broken tiles along the water, so as to make them hop as often as possible. One hop is called Dick, the second Duck, and the third Drake. The sea-shore is a capital place for this sport, as, if the player can only succeed in making the stone touch the top of a wave, it is tolerably certain[14] to make a succession of hops from wave to wave. If a rifle-bullet is shot along the water, it will go a great distance, making very long hops, and splashing up the water at every bound. In war, this method of firing at an enemy that lies low is extensively made use of, and is called “ricochet practice.” It is also much used in naval warfare.

This, if well managed, is a very comical game. The players are arranged as in Fugleman, the player who enacts Simon standing in front. He and all the other players clench their fists, keeping the thumb pointed upwards. No player is to obey his commands unless prefaced with the words, “Simon says.” Simon is himself subjected to the same rules. The game commences by Simon commanding,—“Simon says, turn down:” on which he turns his thumbs downwards, followed by the other players. He then says, “Simon says, turn up,” and brings his hands back again. When he has done so several times, and thinks that the players are off their guard, he merely gives the word, “Turn up,” or “Turn down,” without moving his hands. Some one, if not all, is sure to obey the command, and is subject to a forfeit. Simon is also subject to a forfeit, if he tells his companions to turn down while the thumbs are already down, or vice versâ. With a sharp player enacting Simon, the game is very spirited.

This is a very good game, and to play it properly there must be in the centre of the playground a small hill or hillock. One player, selected by choice or lot, ascends this hill, and is called the King; and the object of the other players is to pull or push him from his elevation, while he uses his endeavours to keep his “pride of place.” Fair pulls and fair pushes are only allowed at this game; the players must not take hold of any part of the clothes of the King, and must confine their grasps to the hand, the leg, or the arm. If a player violates these rules, he is to sit down upon the ground, and is called “Dummy.” The player who succeeds in dethroning the King, takes his place, and is subjected to the like attacks.

This game is to be played from a mound, the same as the above, and it may consist of any number of players. Each party selects a Captain, and having done this, divide themselves into Attackers and Defenders. The defending party provide themselves with a small flag, which is fixed on a staff on the top of the mound, and then arrange themselves on its side and at its base, so as to defend it from the attacks of their opponents, who advance towards the hillock, and endeavour to throw down those that oppose them. Those that are so thrown on either side, are called “dead men,” and must lie quiet till[15] the game is finished, which is concluded either when all the attacking party are dead, or the banner is carried off by one of them. The player who carries off the banner is called the Knight, and is chosen Captain for the next game.

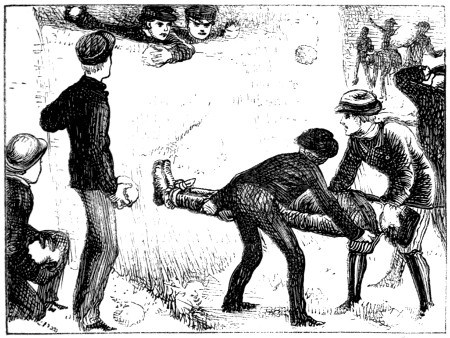

Every boy has played at snow-balls, from the time that his little fingers were first able to grasp and mould a handful of snow. Elderly gentlemen know to their cost how apt the youthful friend is to hurl very hard snow-balls, which appear to pick out the tenderest parts of his person, generally contriving to lodge just at the juncture of the chin and the comforter, or coming with a deafening squash in the very centre of his ear. Even the dread policeman does not always escape; and when he turns round, indignant at the temporary loss of his shiny hat, he cannot recognise his assailant in the boy who is calmly whistling the last new nigger-song, as he saunters along, with both his hands in his pockets. The prudent schoolmaster will also not venture too near the playground, unless he has provided himself with an umbrella. It is rather a remarkable fact, that whenever a Grammar-school and a National-school are within a reasonable distance of each other, they are always at deadly feud. So it was at the school where our youthful days were passed. One winter’s morning, just after school had opened, the door was flung violently open, and a party of National-school boys hurled a volley of snow-balls at the head-master. He, after the door had been secured, remarked in a particularly mild voice,—“Now, boys, if I had been at school, and[16] my schoolmaster had been assaulted by National-school boys, I should have gone out and given them a thrashing. Remember, I do not at all advise you to do so, but merely mention the course that I should have adopted under such circumstances. We will resume lessons at three.” So saying, he took off his gown, put on his hat and gloves, and walked out to see the fun. Now, the prospect of a morning’s holiday would have made us attack a force of twenty times our number, but as they only out-numbered us threefold, we commenced a pursuit without hesitation. After a sharp engagement, we drove them back to their own schoolroom. The cause of their yielding was, that they threw at random among us, whereas each of our balls was aimed at the face of an opponent, and we very seldom missed. When they had reached their school, they closed and barred their door; at which we made such a battering, that their master, a large negro, rushed out upon us, vowing vengeance, and flourishing a great cane. He was allowed to proceed a few yards from the door, when one snow-ball took off his hat, and two more lodged in his face. He immediately went to the right-about, and made for the school, which he reached under an avalanche of snow. We pursued, but he had succeeded in fastening the door, and we could not open it for some time. When we did, the school was deserted; not a boy was to be seen. There was no back entrance to account for their disappearance, and we were completely puzzled. At last, when we had quieted down a little, a murmuring was heard apparently below our feet, and on examination we found that the entire school had taken shelter in the coal-cellar. We made a dash at the door (a trap-door), and in spite of the showers of coal that came from below, fastened and padlocked the door, carefully throwing the key among a clump of fir-trees, where it was not likely to be found. Having achieved this victory, we had a snow-ball match among ourselves, and then returned to school. About five o’clock, in rushed the black schoolmaster, who had only just been liberated by the blacksmith, and who came to complain of our conduct. So far, however, from obtaining any satisfaction, he was forced to apologise for the conduct of his boys.

The object of this game is, that a castle of snow is built, which is attacked by one party and defended by the other. The method of building the castle is as follows:—A square place is cleared in the snow, the size of the projected castle. As many boys as possible then go to some distance from the cleared square, and commence making snow-balls, rolling them towards the castle. By the time that they have reached it, each ball is large enough to form a foundation-stone. By continuing this plan, the walls are built about five feet six inches high, a raised step running round the interior, on which, the defenders stand while hurling the balls against their opponents. In the centre are deposited innumerable snow-balls,[17] ready made; and a small boy is usually pressed into the service, to make snow-balls as fast as they are wanted. If the weather is very cold, some water splashed over the castle hardens and strengthens it considerably. The architect of the castle must not forget to leave space for a door.

This is made in the same way as the snow castle, that is, by rolling large snow-balls to the place where the giant is to be erected, and then piled up and carved into form. He is not considered completed until two coals are inserted for eyes, and until he is further decorated with a pipe and an old hat. When he is quite finished, the juvenile sculptors retire to a distance, and with snow-balls endeavour to knock down their giant, with as much zest as they exhibited in building him. If a snow giant is well made, he will last until the leaves are out, the sun having but little power on so large a mass of hard snow. There is a legend extant respecting the preservation of snow through the warmer parts of the year. A certain Scotch laird had for a tenant a certain farmer. The laird had been requested by influential personages to transfer the farm to another man directly the lease was run out. The farmer’s wife, hearing of this from some gossip of hers, went to her landlord, and besought him to grant a renewal of the lease. When she called, he was at dinner with a numerous party of friends, and replied in a mocking tone, that the lease should be renewed when she brought him a snow-ball in July. She immediately called upon the guests to bear witness to the offer, and went home.[18] In due time the winter came, and with it the snow. One day, her husband, an excellent labourer, but not over bright, asked her why she was wasting so much meal. At that time, she had taken a large vessel of meal to a valley, and was pouring it into the space between two great stones. Upon the meal she placed a large quantity of snow, which she stamped down until it was hard. Upon this she poured more meal, and placed upon the meal a layer of straw. The whole affair was then thickly covered over with straw and reeds. To her husband, who thought she had fairly lost her senses, she deigned no reply, except that the meal would repay itself. So affairs went on until July, when the good dame, hearing that her landlord had invited a large party to dine with him, many of whom had been at the party when the promise was made, proceeded to the store of snow, which she found about half diminished. The remainder she kneaded hard, and put it in a wheelbarrow, well covered with straw, which she rolled up to the laird’s own house. When once there, she took out her snow-ball, and presenting it to her landlord, before all his guests, demanded the renewal of her lease. It may be satisfactory to know, that the laird, struck with her ingenuity and perseverance, at once granted her request.

This game can only be played in the dusk of evening, when all the surrounding objects are lost in the deepening gloom. The players divide into two parties, and toss up for innings, which being gained, the winners start off to hide themselves, or get so far away that the others cannot see them; the losers remaining at the home. One of the hiding party is provided with a flint and steel, which, as soon as they are all ready, he strikes together; the sparks emitted guide the seekers as to what direction they must proceed in, and they must endeavour to capture the others ere they reach home; if they cannot[19] touch more than two of the boys, the hiders resume their innings, and the game continues as before. It is most usual, however, for the boys at the home to call out, “Jack, Jack! show a light!” before the possessor of the flint and steel does so. When one party is captured, the flint and steel must be given up to the captors, that they may carry on the game as before.

The jingling match is a common diversion at country wakes and fairs, and is often played by schoolboys. The match should be played on a soft grass-plot within a large circle, enclosed with ropes. The players rarely exceed nine or ten. All of these, except one of the most active, who is the “jingler,” have their eyes blindfolded with handkerchiefs. The jingler holds a small bell in his hand, which he is obliged to keep ringing incessantly so long as the play continues, which is commonly about twenty minutes. The business of the jingler is to elude the pursuit of his blindfolded companions, who follow him by the sound of the bell in all directions, and sometimes oblige him to exert his utmost abilities to effect his escape, which must be done within the boundaries of the rope, for the laws of the sport forbid him to pass beyond it. If he be caught in the time allotted for the continuance of the game, the person who caught him wins the match; if, on the contrary, they are not able to take him, he is proclaimed the winner.