GROTTO DEL CANI.

p. 446.

Engraved for the Book of Curiosities.

p. 877.

THE

BOOK OF CURIOSITIES:

CONTAINING

TEN THOUSAND

WONDERS AND CURIOSITIES

OF

NATURE AND ART;

AND OF

Remarkable and Astonishing PLACES, BEINGS, ANIMALS, CUSTOMS,

EXPERIMENTS, PHENOMENA, etc., of both Ancient

and Modern Times, on all Parts of the GLOBE: comprising

Authentic Accounts of the most WONDERFUL

FREAKS of NATURE and ARTS of MAN.

BY THE REV. I. PLATTS.

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION.

COMPLETE IN ONE VOLUME.

PHILADELPHIA:

PUBLISHED BY LEARY & GETZ.

1854.

Abderites, or inhabitants of Abdera, curious account of, 45

Abstinence, wonders of, 67

Act of faith, 638

Adansonia; or, African calabash tree, 378

Agnesi, Maria Gaetana, account of, 120

Agrigentum, in Sicily, ruins of, 540

Air, its pressure and elasticity, 839

Alarm bird, 243

Alexandria, buildings and library of, 549

Alhambra, 559

Alligators, 164

American natural history, 182

Anagrams, 450

Andes, 415

Androides, 701

Anger, surprising effects of, 82

Animalcules, 357

Animal generation, curiosities respecting, 139

Animals, formation of, 142

Animals, preservation of, 144

Animals, destruction of, 150

Animal reproductions, 154

Animals and plants, winter sleep of, 808

Animals, remarkable strength of affection in, 184

Animals, surprising instances of sociality in, 185

Animals, unaccountable faculties possessed by some, 187

Animals, remarkable instances of fasting in, 189

Animal flower, 392

Anthropophagi, or men-eaters, account of, 75

Ants, curiosities of, 290

Ants, green, 311

Ants, white, or termites, 301

Ant, lion, 312

Ants, visiting, 312

Aphis, curiosities respecting, 331

Aqueducts, remarkable, 795

Arc, Joan of, 927

Ark of Noah, 582

Artificer, unfortunate, 745

Artificial figure to light a candle, 830

Asbestos, 402

Athos, mount, 423

Attraction, examples of, 837

Augsburg, curiosities of, 576

Aurora borealis, 684

Automaton, description of, 700

B

Babylon, 557

Bacon flitch, custom at Dunmow, Essex, 605

Balbeck, ancient ruins of, 538

Bannian tree, 374

Baptism, a curious one, 642

Baratier, John Philip, premature genius of, 125

Barometer, rules for predicting the weather by it, 864

Beards, remarks concerning, 31

Beaver, description of, 156

Beavers, habitations of the, 158

Bee, the honey, 265

Bees, wild, curiosities of, Clothier Bee, Carpenter Bee, Mason Bee, Upholsterer Bee, Leaf-cutter Bee, 277, 278, 279, 280

Bees, account of an idiot-boy and, 283

Bees, Mr. Wildman’s curious exhibitions of, explained, 283

Bells, baptism of, 639

Benefit of clergy, origin and history of, 623

Bird of Paradise, 230

Bird, singular account of one inhabiting a volcano in Guadalope, 246

Bird-catching fish, 196

Bird-catching, curious method of, 260

Birds, method of preserving, 865

Birds, hydraulic, 713

Birds, song of, 261

Birds’ nests, 251

Bisset, Samuel, the noted animal instructor, 124

Bletonism, 95

Blind clergyman of Wales, 903

Blind persons, astonishing acquisitions made by some, 46

Blind Jack of Knaresborough, 900

Blood, circulation of, 24

Blunders, book of, 761

Boa Constrictor, 217

Boat-fly, 342

Body, human, curiosities of the, 13

Bolea, Monte, 418

Books, curious account of the scarcity of, 757

Borrowdale, 458

Bottles, to uncork, 836

Boverick’s curiosities, 713

Bowthorpe oak, 382

Bread-fruit tree, 372

Bread, old, curious account of, 807

Brine, to ascertain the strength of, 839

Brown, Simon, and his curious dedication to queen Caroline, 108

Bunzlau curiosities, 714

Buonaparte, principal events in the life of, 126

Burning spring in Kentucky, 493

Burning and hot springs, 494, 495, 496, 497

Burning, extraordinary cures by, 792

Burning-glasses, 717

[Pg iv]

Bustard, the great, 243

Butterflies, beauty and diversities of, 344

Butterflies, to take an impression of their wings, 866

C

Camera obscura, to make, 830

Candiac, John Lewis, account of, 113

Candlemas-day, 632

Cannon, extraordinary, 807

Cards, origin of, 767

Carrier, or courier pigeon, 244

Carthage, ancient grandeur of, 542

Case, John, celebrated quack doctor, 113

Catching a hare, curious custom respecting, 601

Caterpillar, 219

Caterpillar-eaters, 220

Cave of Fingal, 452

Cave near Mexico, 457

Centaurs and Lapithæ, 785

Chameleon, particulars respecting, 175

Changeable flower, 387

Cheese-mite, curiosities respecting, 358

Chemical illuminations, 844

Chick, formation of in the egg, 249

Child, extraordinary arithmetical powers of a, 88

Chiltern hundreds, 634

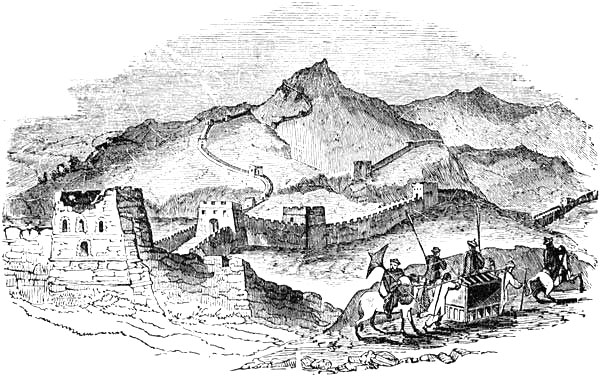

China, great wall of, 579

Chinese, funeral ceremonies of the, 610

Christmas-boxes, origin of, 633

Cinchona, or Peruvian bark, curious effects of, 390

Clepsydra, 706

Clock-work, extraordinary pieces of, 704

Clouds, electrified, terrible effects of, 656

Coal-pit, visit to one, 469

Cocoa-nut tree, 371

Coins of the kings of England, 814

Cold, surprising effects of extreme, 659

Colossus, 570

Colours, experiments on, 867

Colours, incapacity of distinguishing, 56

Combustion of the human body by the immoderate use of spirits, 97

Common house-fly, curiosities of the, 337

Company of Stationers, singular custom annually observed by the, 766

Conscience, instances of the power of, 84

Cormorant, 242

Coruscations, artificial, 849

Cotton wool, curious particulars of a pound weight of, 391

Countenance, human, curiosities of the, 18

Cromwell, A. M. of Hammersmith, a rich miser, 897

Creeds of the Jews, 775

Crichton, the admirable, 911

Crichup Linn, 797

Crocodile, 163

Crocodile, fossil, curiosity of, 165

Cuckoo, curiosities respecting, 240

Curfew bell, why so called, 635

Curious historical fact, 744

D

Dancer, Daniel, account of, 104

Dajak, inhabitants of Borneo, curious funeral ceremonies of, 612

Deaf, to make the, perceive sounds, 828

Deaths, poetical, grammatical, and scientific, 73

Death-watch, 347

Diamond mine, on the river Tigitonhonha, in the Brazilian territory, 460

Diamond, wonderful, 405

Diana, temple of, at Ephesus, 554

Dictionary, modern, 950

Dimensions, &c. of some of the largest trees growing in England, 382

Diseases peculiar to particular countries, 789

Dismal swamp, 798

Dog, remarkable, 194

Dog, curious anecdotes of a, 195

Dogs, sagacity of, 193

Dreams, instances of extraordinary, 70

Dwarfs, extraordinary, 40

E

Eagle, the golden, 237

Ear, curious structure of the, 22

Earl of Pembroke, curious extracts from the will of an, 773

Earth-eaters, 908

Earthquakes, and their causes, 499

Eating, singularities of different nations in, 595

Eclipses, 676

Eddystone rocks, 797

Egg, to soften an, 851

Electricity, illumination by, 793

Electrical experiments, 841

Elephant, account of an, 168

Elephant, docility of the, 170

Elwes, John, account of, 104

English ladies turned Hottentots, 744

Ephemeral flies, 343

Ephesus, temple of Diana at, 554

Escurial, 577

Etna, 443

Extraordinary custom, 601

Eye, curious formation of the, 20

F

Fact, the most extraordinary on record, 744

Fairy rings, 667

Falling stars, 681

Faquirs, travelling, 940

Fasting, extraordinary instances of, 65

Fata Morgana, 665

Feasts, among the ancients of various nations, 614

Female beauty and ornaments, 596

Fiery fountain, 844

Fire-balls, 655

Fire of London, 748

Fire, perpetual, 806

Fisher, Miss Clara, 905

Fishes, air bladder in, 201

Fishes, respiration in, 202

[Pg v]

Fishes, shower of, 203

Flea, account of a, 325

Flea, on the duration of the life of a, 328

Florence statues, 579

Fly, the common house, 337

Fly, the Hessian, 336

Fly, the May, 340

Fly, the vegetable, 341

Fly, the boat, 342

Flying, artificial, 716

Fountain trees, 375

Freezing mixture, to form, 859

Freezing, astonishing expansive force of, 661

Friburg, curiosities of, 575

Friendship, curious demonstrations of, 594

Friendship, true Roman, recipe for establishing, 951

Fright, or terror, remarkable effects of, 82

Frog, the common, 160

Frog-fish, 196

Frosts, remarkable, 533

Flower, the animal, 392

Fruits, injuries from swallowing the stones of, 791

Funeral ceremonies of the ancient Ethiopians, 609

Fungi, 395

G

Galley of Hiero, 584

Galvanism, 689

Gardens, floating, 580

Gardens, hanging, 558

Garter, origin of the order of the, 623

Gas lights, miniature, 836

Gauts, or Indian Appenines, 421

Giants, curious account of, 39

Giant’s causeway, 590

Gipsies, 732

Glaciers, 529

Glass, ductility of, 720

Glass, to cut, without a diamond, 833

Glass, to write on, by the sun’s rays, 858

Gluttony, instances of extraordinary, 64

Gold, remarkable ductility and extensibility of, 721

Graham, the celebrated Dr. 909

Gravity, experiments respecting the, 838

Great events from little causes, 746

Grosbeak, the social, 234

Grosbeak, the Bengal, 235

Grotto in South America, 445

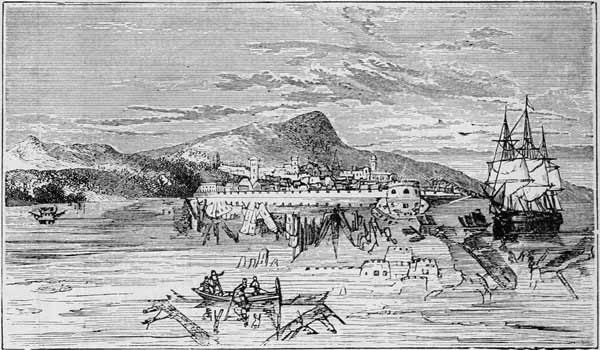

Grotto del Cani, 446

Grotto of Antiparos, 447

Grotto of Guacharo, 450

Growth, extraordinary instances of rapid, 37

Guinea, explanation of all the letters on a, 768

Gulf stream, 490

H

Hagamore, Rev. Mr. a most singular character, 896

Hail, surprising showers of, 518

Hair of the head, account of, 28

Hair, instances of the internal growth of, 30

Hair, ancient and modern opinions respecting the, 29

Halo, or corona, and similar appearances, 680

Hand-fasting, 609

Harmattan, 511

Harrison, a singular instance of parsimony, 903

Heat, diminished by evaporation, 839

Hecla, 442

Heidelberg clock, 705

Heinecken, Christian Henry, account of, 114

Hell, opinions respecting, 812

Henderson, John, the Irish Crichton, 883

Henry, John, singular character of, 107

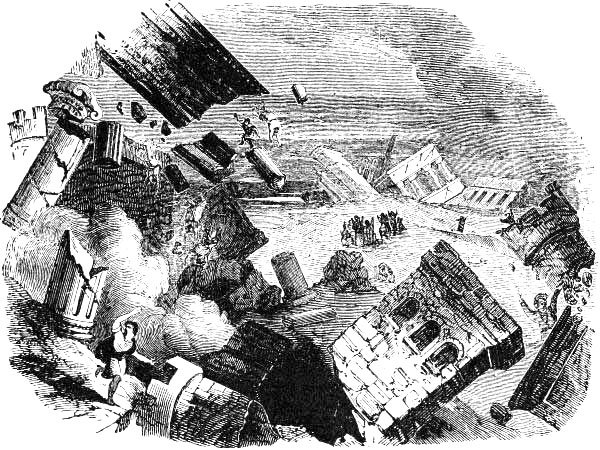

Herculaneum and Pompeii, 536

Herschel’s grand telescope, 713

Hessian fly, 339

Hobnails, origin of the sheriff’s counting, 622

Holland, North, curious practice in, 630

Honour, extraordinary instances of, 80

Horse, remarkable instances of sagacity in a, 192

Human heart, structure of the, 24

Humming bird, 236

Huntingdon, William, eccentric character of, 134

Hurricane, curious particulars respecting a, 511

Husband long absent, returned, 741

Hydra, or polypes, account of, 359

I

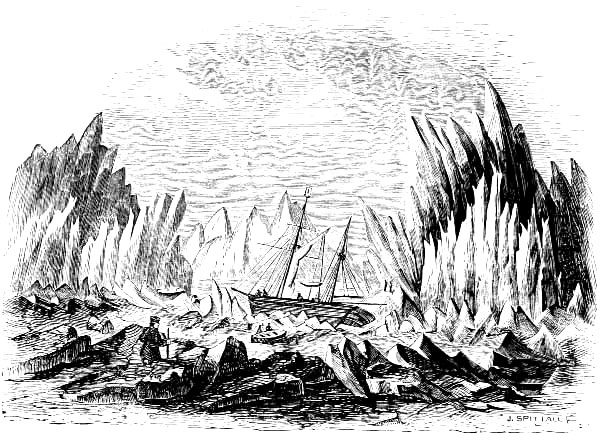

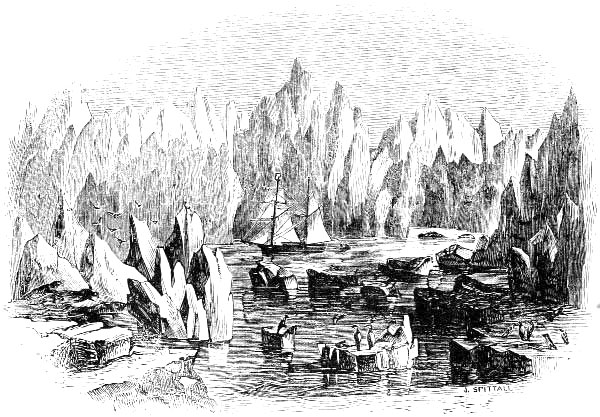

Ice, Greenland or polar, 525

Ice, tremendous concussions of fields of, 528

Ice, showers of, 533

Ignis Fatuus, 644

Improvement of the learned, 765

Incubus, or nightmare, 941

Indian jugglers, 897

Individuation, 780

Indulgences, Romish, 636

Ingratitude, shocking instances of, 78

Inks, various sympathetic, 853 to 857

Insects, metamorphoses of: the butterfly, the common fly, the grey-coated gnat, the shardhorn beetle, 345

Insects blown from the nose, —

Integrity, striking instances of, 77

Inverlochy castle, 574

Island, new, starting from the sea, 491

J

Jew’s harp, 795

John Bull, origin of the term of, 634

K

Killarney, the lake of, 487

Kimos, singular nation of dwarfs, 43

Knout, 804

Kraken, 210

L

Labrador stone, 402

Lady of the Lamb, 601

Lama, 810

[Pg vi]

Lambert, Daniel, account of, 887

Lamps, remarkable, 805

Lamp, phosphoric, 844

Lanterns, feast of, 621

Laocoon, monument of, 556

Leaves, to take an impression of them, 866

Letter, curious, from Pomare, king of Otaheite, to the Missionary Society, 773

Libraries, celebrated, 760

Light produced under water, 850

Lightning, extraordinary properties and effects of, 651

Lightning, to produce artificial, 844

Liquids, to produce changeable-coloured, 858

Liquids, to exchange two in different bottles, 872

Literary labour and perseverance, 756

Lizard, imbedded in coal, 225

Locusts, and their uses in the creation, 349

London, compendious description of, 813

London, intellectual improvement in, 761

Longevity, extraordinary instances of, 96

Louse, 328

Love-letter, and answer, curious, 774

Luminous insects, 319

M

M‘Avoy, Miss Margaret, 919

Maelstrom, 489

Magdalen’s hermitage, 575

Magic oracle, 845

Magical bottle, 851

Magical drum, 806

Magnetism, 693

Magnetic experiments, 848

Magnify, to, small objects, 882

Mahometan paradise, 811

Maiden, 599

Mammoth, or Fossil Elephant, found in Siberia, 170

Man with the iron mask, 727

Mandrake, 387

Marmot, or the Mountain Rat of Switzerland, 167

Marriage custom of the Japanese, 604

Marriage ceremonies, curious, in different nations, 602

Masons, free and accepted, 737

Mathematical talent, curious instance of, 93

Matrimonial ring, 608

Matter, divisibility of, 793

May-fly, 340

May poles and garlands, the origin of, 629

Memnon, palace of, 552

Memory, remarkable instance of, 86

Metals, different, to discover, 828

Metals, mixed, to detect, 871

Metcalf, John, alias Blind Jack of Knaresborough, 900

Microscopic experiments, 859

Migration of birds, 253

Mills, remarkable, 799

Mint of Segovia, 799

Miraculous vessel, 852

Mirage, account of, 521

Miners, curious effects of, 833

Mite, the cheese, curiosities respecting, 358

Mock suns, 673

Mocking bird of America, 233

Mole, the common, 159

Money, test of good or bad, 834

Monkey, sagacity of a, 192

Monsoons, or trade winds, 512

Monster, 777

Montague, Edward Wortley, 110

Mont Blanc, in Switzerland, 427

Moon, account of three volcanoes in the, 682

Morland, George, account of, 114

Moscow, great bell of, 726

Mosquitoes, and their uses, 355

Mourning, ancient modes of, 613

Mountains, natural descriptions of, 406

Mountains Written, Mountains of Inscription, or Jibbel El Mokatteb, 422

Mount Snowden, excursion to the top of, 412

Mud and Salt, volcanic eruptions of, in the island of Java, 467

Murdering statue, 801

Museum, 566

Mushroom, 395

Mushroom-stone, 402

N

Names, curious, adopted in the civil war, 772

Naphtha springs, 492

National debt, singular calculation respecting, 816

Natural productions, resembling artificial compositions, 804

Natural history, curious facts in, 247

Nautilus, 197

Navigation, perfection of, 481

Needles, 722

Needle’s eye, 459

News, origin of the word, 762

Newspapers, origin of, 762

New studies in old age, instances of, 763

New year’s gifts, origin of, 633

Niagara, and its falls, 485

Nicholas Pesce, 117

Nitre caves of Missouri, 457

Nokes, Edward, a miser, 888

Numbers, remarkable instance of skill in, 86

Numbers, curious arrangements of, 868, 871

Nuns, particulars respecting, 811

Nuovo, Monte, 419

O

Oak-tree, remarkable account of, 380

Oakham, custom at, 630

Obelisk, remarkable, near Forres, in Scotland, 573

Okey Hole, 458

Orang-Outang, 178

Origin of ‘That’s a Bull,’ 635

Origin of the old adage respecting St. Swithin, and rainy weather, 635

Ornithorhynchus paradoxus, 166

Ostrich, curiosities of the, 231

Owl, adventure of an, 247

[Pg vii]

P

Pausilippo, 419

Peacock, the common, 226

Peak in Derbyshire, description of, 409

Peeping Tom of Coventry, 740

Peg, to make a, to fit three differently shaped holes, 872

Pelican, the great, 229

Penance, curious account of a, 643

Performances of a female, blind almost from her infancy, 53

Persons born defective in their limbs, wonderful instances of adroitness of, 54

Peruke, 783

Peru, mines of, 465

Pesce, Nicholas, extraordinary character of, 117

Pharos of Alexandria, 549

Phosphoric fire, sheet of, 669

Phosphorus, 670

Pichinca, 415

Pico, 422

Pigeon, wild, its multiplying power, 245

Pigeon, carrier, or courier, 244

Pin-making, 721

Pitch-wells, 468

Plague, dreadful instances of the, in Europe, 747

Plant, curious, 386

Plants, curious dissemination of, 366

Plants upon the earth, prodigious number of, 367

Plough-Monday, origin of, 632

Poison-eater, remarkable account of, 94

Pompey’s pillar, 547

Pope Joan, 931

Portland vase, 800

Praxiteles’ Venus, 712

Praying machines of Kalmuck, 642

Price, Charles, the renowned swindler, 889

Prince Rupert’s drops, 853

Prolificness, extraordinary instances of, 37

Psalmanazar, George, noted impostor, 112

Pulpit, curious, 801

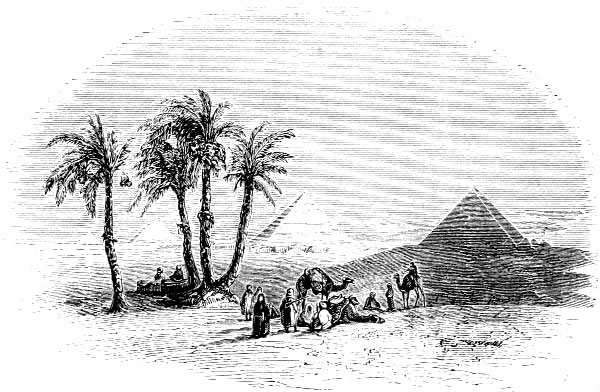

Pyramids of Egypt, 544

Q

Quaint lines, 772

Queen Charlotte, curious address to, 769

Queen, a blacksmith’s wife become a, 749

Queen Elizabeth’s dinner, curious account of the ceremonies at, 749

Queen Elizabeth, quaint lines on, 772

R

Recreations, amusing, in optics, &c. 873 to 882

Recreations, amusing, with numbers, 820 to 827

Religion, celebrated speech on, 944

Reproduction, 781

Repulsion, examples of, 837

Respiration, interesting facts concerning, 26

Revivified rose, 858

Rhinoceros, 162

Rings, on the origin of, 606

Rosin bubbles, 851

Royal progenitors, 744

Ruin at Siwa in Egypt, 534

S

Salutation, various modes of, 598

Sand-floods, account of, 521

Savage, Richard, extraordinary character of, 128

Scaliot’s lock, 712

Scarron, Paul, account of, 119

Schurrman, Anna Maria, 123

Scorpion, 213

Sea, curiosities of the, 471

Sea, on the saltness of, 476

Sea, to measure the depth of the, 829

Sea serpent, American, 218

Seal, common account of, 180

Seal, ursine, 181

Seeds, germination of, 365

Sensibility of plants, 368

Sensitive plant, 369

Seraglio, 564

Serpents, fascinating power of, 219

Sexes, difference between the, 34

Sexes at birth, comparative number of the, 36

Shark, 198

Sheep, extraordinary adventures of one, 190

Shelton oak, description of, 382

Ship worm, 224

Ship at sea, to find the burden of a, 829

Shoes, curiosities respecting, 724

Shoe-makers, literary, 764

Shower of gossamers, curious phenomenon of a, 523

Shrovetide, 630

Silk-mill at Derby, 800

Silk stockings, electricity of, 842

Silkworm, 220

Singular curiosity, 405

Skiddaw, 414

Sleep-walker, 69

Sleeping woman of Dunninald, 70

Smeaton, John, 113

Sneezing, curious observations on, 33

Snow grotto, 451

Solfatara, the lake of, 488

Sound, experiments on, 840

Spectacle of a sea-fight at Rome, 711

Spectacles, a substitute for, 807

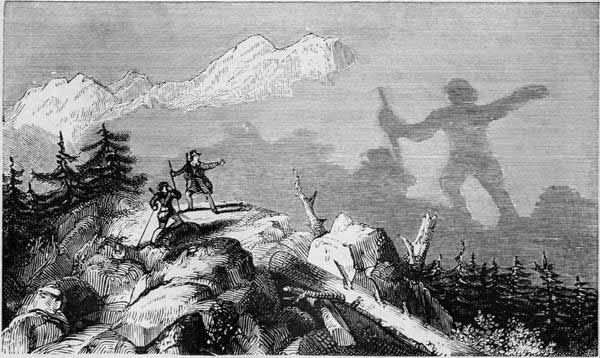

Spectre of the Broken, 420

Spider, curiosities of the, 314

Spider, tamed, 316

Spider, ingenuity of a, 316

Spider, curious anecdote of a, 318

Spirits of wine, to ascertain the strength of, 839

Spontaneous inflammations, 786

Sports, book of, 766

’Squire, old English, 925

Stalk, animated, 392

Star, falling or shooting, 401

Stephenson, the eccentric, 895

[Pg viii]

Steel, to melt, 830

Stick, to break a, on two wine-glasses, 871

Stone, the meteoric, 401

Stone, the Labrador, 402

Stone, the changeable, 404

Stone-eater, remarkable account of, 94

Stonehenge, 592

Storks, 229

Storm, singular effects of a, 519

Strasburg clock, 705

Sugar, antiquity of, 390

Sulphur mountains, 424

Sun, diminution of the, 673

Sun, spots in the, 671—to shew ditto, 852

Surgical operation, extraordinary, 791

Swine’s concert, 750

Sword-swallowing, 62

Sympathetic inks, 853 to 857

T

Tallow-tree, 378

Tantalus’ cup, 852

Tape-worm, 222

Tea, Chinese method of preparing, 388

Telegraph, 708

Temple of Tentira, in Egypt, 550

Tenures, curious, 628

Thermometrical experiments, 863

Thermometer, moral and physical, 817

Thread burnt, not broken, 844

Thunder powder, 836

Thunder rod, 654

Tides, 479

Titles of books, 755

Toad, common, description of, 161

Topham, Thomas, character of, 115

Tornado, description of a, 510

Torpedo, 200

Tortoise, the common, 176

Tree of Diana, 852

Trees, account of a country, in which the inhabitants reside in, 45

U

Unbeliever’s creed, 776

Unfortunate artificer, 745

Unicorn, 179

Upas, or poison tree, 383

V

Valentine’s-day, origin of, 632

Van Butchell, Mrs. preservation of her corpse, 902

Vegetable kingdom, curiosities in the, 363

Vegetables, number of known, 367

Vegetable fly, 341

Velocity of the wind, 517

Ventriloquism, 58

Vesuvius, 434, 947

Vicar of Bray, 748

Voltaic pile, to make a cheap, 847

Vulture, Egyptian, 228

Vulture, secretary, 228

W

Wasp, curiosities respecting the, 285

Watch, the mysterious, 835

Watches, invention of, 707

Water, to boil without heat, 835

Water, to weigh, 834

Water, to retain, in an inverted glass, 835

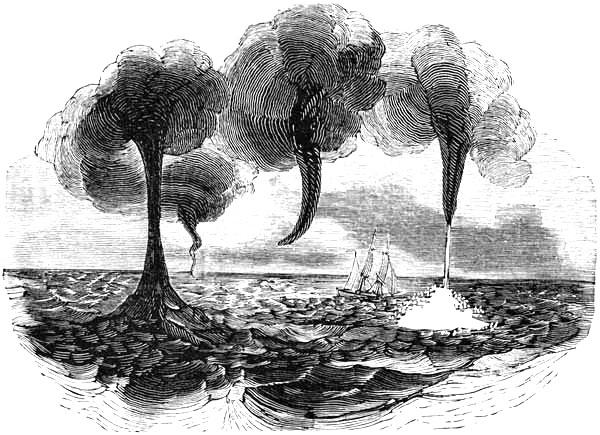

Waterspout, 663

Waves stilled by oil, 480

Weaving engine, 712

Whale, great northern, or Greenland, 204

Whale fishery, 208

Whig and Tory, explanation of the terms, 776

Whirlpool near Sudero, 489

Whirlwinds of Egypt, 509

Whispering places, and extraordinary echoes, 802

Whitehead’s ship, 712

Whittington, Sir Richard, 932

Wild man, account of a, 76

Wind, velocity of, 517

Winds, remarkable, in Egypt, 507

Wine cellar, curious, 799

Winter in Russia, 524

Wolby, Henry, extraordinary character of, 105

Women with beards, curious account of, 32

Wooden eagle, and iron fly, 711

Writing, origin of the materials of, 751

Writing, minute, 753

X

Xerxes’ bridge of boats over the Hellespont, 586

Z

Zeuxis, celebrated painter, 116.

| “Ye curious minds, who roam abroad, And trace Creation’s wonders o’er! Confess the footsteps of the God, And bow before him, and adore.” |

It was well observed by Lord Bacon, that “It would much conduce to the magnanimity and honour of man, if a collection were made of the extraordinaries of human nature, principally out of the reports of history; that is, what is the last and highest pitch to which man’s nature, of itself, hath ever reached, in all the perfection of mind and body. If the wonders of human nature, and virtues as well of mind as of body, were collected into a volume, they might serve as a calendar of human triumphs.”

The present work not only embraces the Curiosities of human nature, but of Nature and Art in general, as well as Science and Literature. Surrounded with wonders, and lost in admiration, the inquisitive mind of man is ever anxious to know the hidden springs that put these wonders in motion; he eagerly inquires for some one to take him by the hand, and explain to him the curiosities of the universe. And though the works of the Lord, like his nature and attributes, are great, and past finding out, and we cannot arrive at the perfection of science, nor discover the secret impulses which nature obeys, yet can we by reading, study, and investigation, dissipate much of the darkness in which we are enveloped, and dive far beyond the surface of this multifarious scene of things—The noblest employment of the human [Pg x]understanding is, to contemplate the works of the great Creator of the boundless universe; and to trace the marks of infinite wisdom, power, and goodness, throughout the whole. This is the foundation of all religious worship and obedience; and an essential preparative for properly understanding, and cordially receiving, the sublime discoveries and important truths of divine revelation. “Every man,” says our Saviour, “that hath heard, and hath learned of the Father, cometh unto me.” And no man can come properly to Christ, or, in other words, embrace the christian religion, so as to form consistent views of it, and enter into its true spirit, unless he is thus drawn by the Father through a contemplation of his works. Such is the inseparable connection between nature and grace.

A considerable portion of the following pages is devoted to Curiosities in the works of Nature, or, more properly, the works of God, for,

“Nature is but an effect, and God the cause.”

The Deity is the

“Father of all that is, or heard, or hears!

Father of all that is, or seen, or sees!

Father of all that is, or shall arise!

Father of this immeasurable mass

Of matter multiform; or dense, or rare;

Opaque, or lucid; rapid, or at rest;

Minute, or passing bound! In each extreme

Of like amaze, and mystery, to man.”

The invisible God is seen in all his works.

“God is a spirit, spirit cannot strike

These gross material organs: God by man

As much is seen, as man a God can see.

In these astonishing exploits of power

What order, beauty, motion, distance, size!

Concertion of design, how exquisite!

How complicate, in their divine police!

Apt means! great ends! consent to general good!”

[Pg xi]This work also presents to the reader, a view of the great achievements of the human intellect, in the discoveries of science; and the wonderful operations of the skill, power, and industry of man in the invention and improvement of the arts, in the construction of machines, and in the buildings and other ornaments the earth exhibits, as trophies to the glory of the human race.

But we shall now give the reader a short sketch of what is provided for him in the following pages. The work is divided into eighty-seven chapters. The Curiosities respecting Man occupy eleven chapters. The next four chapters are devoted to Animals; then two to Fishes; one to Serpents and Worms; three to Birds; eleven to Insects; six to Vegetables; three to Mountains; two to Grottos, Caves, &c.; one to Mines; two to the Sea; one to Lakes, Whirlpools, &c.; one to Burning Springs; one to Earthquakes; one to Remarkable Winds; one to Showers, Storms, &c.; one to Ice; one to Ruins; four to Buildings, Temples, and other Monuments of Antiquity; and one to Basaltic and Rocky Curiosities. The fifty-eighth chapter is devoted to the Ark of Noah—the Galley of Hiero—and the Bridge of Xerxes. The next six chapters detail at length the various Customs of Mankind in different parts of the World, and also explain many Old Adages and Sayings. The next five chapters exhibit a variety of curious phenomena in nature, such as the Ignis Fatuus; Thunder and Lightning; Fire Balls; Water Spouts; Fairy Rings; Spots in the Sun; Volcanoes in the Moon; Eclipses; Shooting Stars; Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights; &c. &c. The seventieth chapter is on Galvanism. The seventy-first on Magnetism. The next three chapters delineate the principal Curiosities respecting the Arts. Then follow five chapters on some of the principal Curiosities in History; three on the Curiosities of Literature; and five on Miscellaneous Curiosities. An Appendix is added, containing a number of easy, innocent, amusing Experiments and Recreations.

[Pg xii]This is “A New Compilation,” inasmuch as not one article is taken from any book bearing the title of Beauties, Wonders, or Curiosities. The Compiler trusts the work will afford both entertainment and instruction for the leisure hour, of the Philosopher or the Labourer, the Gentleman or the Mechanic. In short, all classes may find in the present work something conducive to their pleasure and improvement, in their hours of seriousness, as well as those of gaiety; and it will afford a constant source of subjects for interesting and agreeable conversation.

THE

BOOK OF CURIOSITIES.

CURIOSITIES RESPECTING MAN.

The Human Body—the Countenance—the Eye—the Ear—the Heart—the Circulation of the Blood—Respiration—the Hair of the Head—the Beard—Women with Beards—Sneezing.

| “Come, gentle reader, leave all meaner things To low ambition, and the pride of kings. Let us, since life can little more supply Than just to look about us, and to die; Expatiate free o’er all this scene of Man, A mighty maze! but not without a plan. A wild, where weeds and flow’rs promiscuous shoot; Or garden, tempting with forbidden fruit. Together let us beat this ample field, Try what the open, what the covert yield; The latent tracts, the giddy heights, explore, Of all who blindly creep, or sightless soar: Eye nature’s walks, shoot folly as it flies, And catch the manners living as they rise; Laugh where we must, be candid where we can, But vindicate the ways of God to man.” |

We shall, in the first place, enter on the consideration of The Curiosities of the Human Body.—The following account is abridged from the works of the late Drs. Hunter and Paley.

Dr. Hunter shows that all the parts of the human frame are requisite to the wants and well-being of such a creature as man. He observes, that, first the mind, the thinking immaterial agent, must be provided with a place of immediate residence, which shall have all the requisites for the union of spirit and body; accordingly, she is provided with the brain, where she dwells as governor and superintendant of the whole fabric.

In the next place, as she is to hold a correspondence with all the material beings around her, she must be supplied with organs fitted to receive the different kinds of impression which[Pg 14] they will make. In fact, therefore, we see that she is provided with the organs of sense, as we call them: the eye is adapted to light; the ear to sound; the nose to smell; the mouth to taste; and the skin to touch.

Further, she must be furnished with organs of communication between herself in the brain, and those organs of sense; to give her information of all the impressions that are made upon them; and she must have organs between herself in the brain, and every other part of the body, fitted to convey her commands and influence over the whole. For these purposes the nerves are actually given. They are soft white chords which rise from the brain, the immediate residence of the mind, and disperse themselves in branches through all parts of the body. They convey all the different kinds of sensations to the mind in the brain; and likewise carry out from thence all her commands to the other parts of the body. They are intended to be occasional monitors against all such impressions as might endanger the well-being of the whole, or of any particular part; which vindicates the Creator of all things, in having actually subjected us to those many disagreeable and painful sensations which we are exposed to from a thousand accidents in life.

Moreover, the mind, in this corporeal system, must be endued with the power of moving from place to place; that she may have intercourse with a variety of objects; that she may fly from such as are disagreeable, dangerous, or hurtful; and pursue such as are pleasant and useful to her. And accordingly she is furnished with limbs, with muscles and tendons, the instruments of motion, which are found in every part of the fabric where motion is necessary.

But to support, to give firmness and shape to the fabric; to keep the softer parts in their proper places; to give fixed points for, and the proper directions to its motions, as well as to protect some of the more important and tender organs from external injuries, there must be some firm prop-work interwoven through the whole. And in fact, for such purposes the bones are given.

The prop-work is not made with one rigid fabric, for that would prevent motion. Therefore there are a number of bones.

These pieces must all be firmly bound together, to prevent their dislocation. And this end is perfectly well answered by the ligaments.

The extremities of these bony pieces, where they move and rub upon one another, must have smooth and slippery surfaces for easy motion. This is most happily provided for, by the cartilages and mucus of the joints.

The interstices of all these parts must be filled up with some soft and ductile matter, which shall keep them in their[Pg 15] places, unite them, and at the same time allow them to move a little upon one another; these purposes are answered by the cellular membrane, or edipose substance.

There must be an outward covering over the whole apparatus, both to give it compactness, and to defend it from a thousand injuries; which, in fact, are the very purposes of the skin and other integuments.

Say, what the various bones so wisely wrought?

How was their frame to such perfection brought?

What did their figures for their uses fit,

Their numbers fix, and joints adapted knit;

And made them all in that just order stand,

Which motion, strength, and ornament, demand?

Blackmore.

Lastly, the mind being formed for society and intercourse with beings of her own kind, she must be endued with powers of expressing and communicating her thoughts by some sensible marks or signs, which shall be both easy to herself, and admit of great variety. And accordingly she is provided with the organs and faculty of speech, by which she can throw out signs with amazing facility, and vary them without end.

Thus we have built up an animal body, which would seem to be pretty complete; but as it is the nature of matter to be altered and worked upon by matter, so in a very little time such a living creature must be destroyed, if there is no provision for repairing the injuries which she must commit upon herself, and those which she must be exposed to from without. Therefore a treasure of blood is actually provided in the heart and vascular system, full of nutritious and healing particles; fluid enough to penetrate into the minutest parts of the animal; impelled by the heart, and conveyed by the arteries, it washes every part, builds up what was broken down, and sweeps away the old and useless materials. Hence we see the necessity or advantage of the heart and arterial system.

What more there was of the blood than enough to repair the present damages of the machine, must not be lost, but should be returned again to the heart; and for this purpose the venous system is provided. These requisites in the animal explain the circulation of the blood, a priori.[1]

All this provision, however, would not be sufficient; for the store of blood would soon be consumed, and the fabric would break down, if there was not a provision made by fresh supplies. These, we observe, in fact, are profusely scattered round her in the animal and vegetable kingdoms; and she is furnished with hands, the fittest instruments that could be contrived for gathering them, and for preparing them in their varieties for the mouth.

[Pg 16]But these supplies, which we call food, must be considerably changed; they must be converted into blood. Therefore she is provided with teeth for cutting and bruising the food, and with a stomach for melting it down; in short, with all the organs subservient to digestion: the finer parts of the aliments only can be useful in the constitution; these must be taken up and conveyed into the blood, and the dregs must be thrown off. With this view, the intestinal canal is provided. It separates the nutritious parts, which we call chyle, to be conveyed into the blood by the system of the absorbent vessels; and the coarser parts pass downwards to be ejected.

We have now got our animal not only furnished with what is wanting for immediate existence, but also with powers of protracting that existence to an indefinite length of time. But its duration, we may presume, must necessarily be limited; for as it is nourished, grows, and is raised up to its full strength and utmost perfection; so it must in time, in common with all material beings, begin to decay, and then hurry on into final ruin.

Thus we see, by the imperfect survey which human reason is able to take of this subject, that the animal man must necessarily be complex in his corporeal system, and in its operations.

He must have one great and general system, the vascular, branching through the whole circulation: another, the nervous, with its appendages—the organs of sense, for every kind of feeling: and a third, for the union and connection of all these parts.

Besides these primary and general systems, he requires others, which may be more local or confined: one, for strength, support, and protection,—the bony compages: another, for the requisite motions of the parts among themselves, as well as for moving from place to place,—the muscular system: another to prepare nourishment for the daily recruit of the body,—the digestive organs.

Dr. Paley observes, that, of all the different systems in the human body, the use and necessity are not more apparent, than the wisdom and contrivance which have been exerted, in putting them all into the most compact and convenient form: in disposing them so, that they shall mutually receive from, and give helps to one another: and that all, or many of the parts, shall not only answer their principal end or purpose, but operate successfully and usefully in a variety of secondary ways. If we consider the whole animal machine in this light, and compare it with any machine in which human art has exerted its utmost, we shall be convinced, beyond the possibility of doubt, that there are intelligence and power far surpassing what humanity can boast of.

[Pg 17]One superiority in the natural machine is peculiarly striking.—In machines of human contrivance or art, there is no internal power, no principle in the machine itself, by which it can alter and accommodate itself to injury which it may suffer, or make up any injury which admits of repair. But in the natural machine, the animal body, this is most wonderfully provided for, by internal powers in the machine itself; many of which are not more certain and obvious in their effects, than they are above all human comprehension as to the manner and means of their operation. Thus, a wound heals up of itself; a broken bone is made firm again by a callus; a dead part is separated and thrown off; noxious juices are driven out by some of the emunctories; a redundancy is removed by some spontaneous bleeding; a bleeding naturally stops of itself; and the loss is in a measure compensated, by a contracting power in the vascular system, which accommodates the capacity of the vessels to the quantity contained. The stomach gives intimation when the supplies have been expended; represents, with great exactness, the quantity and quality, of what is wanted in the present state of the machine; and in proportion as she meets with neglect, rises in her demand, urges her petition in a louder tone, and with more forcible arguments. For its protection, an animal body resists heat and cold in a very wonderful manner, and preserves an equal temperature in a burning and in a freezing atmosphere.

A farther excellence or superiority in the natural machine, if possible, still more astonishing, more beyond all human comprehension, than what we have been speaking of, is the distinction of sexes, and the effects of their united powers. Besides those internal powers of self-preservation in each individual, when two of them, of different sexes, unite, they are endued with powers of producing other animals or machines like themselves, which again are possessed of the same powers of producing others, and so of multiplying the species without end. These are powers which mock all human invention or imitation. They are characteristics of the Divine Architect.—Thus far Paley.

Galen takes notice, that there are in the human body above 600 muscles, in each of which there are, at least, 10 several intentions, or due qualifications, to be observed; so that, about the muscles alone, no less than 6000 ends and aims are to be attended to! The bones are reckoned to be 284; and the distinct scopes or intentions of these are above 40—in all, about 12,000! and thus it is, in some proportion, with all the other parts, the skin, ligaments, vessels, and humours; but more especially with the several vessels, which do, in regard to their great variety, and multitude of their several intentions, very much exceed the homogeneous parts.

[Pg 18]

——————————How august,

How complicate, how wonderful, is man!

How passing wonder He who made him such!—

From different natures marvellously mixt;—

Though sully’d and dishonour’d, still DIVINE!

Young.

“Come! all ye nations! bless the Lord,

To him your grateful homage pay:

Your voices raise with one accord,

Jehovah’s praises to display.

From clay our complex frames he moulds,

And succours us in time of need:

Like sheep when wandering from their folds,

He calls us back, and does us feed.

Then thro’ the world let’s shout his praise,

Ten thousand million tongues should join,

To heav’n their thankful incense raise,

And sound their Maker’s love divine.

When rolling years have ceas’d their rounds,

Yet shall his goodness onward tend;

For his great mercy has no bounds,

His truth and love shall never end!”

So curious is the texture or form of the human body in every part, and withal so “fearfully and wonderfully made,” that even atheists, after having carefully surveyed the frame of it, and viewed the fitness and usefulness of its various parts, and their several intentions, have been struck with wonder, and their souls kindled into devotion towards the all-wise Maker of such a beautiful frame. And so convinced was Galen of the excellency of this piece of divine workmanship, that he is said to have allowed Epicurus a hundred years to find out a more commodious shape, situation, or texture, for any one part of the human body! Indeed, no understanding can be so low and mean, no heart so stupid and insensible, as not plainly to see, that nothing but Infinite Wisdom could, in so wonderful a manner, have fashioned the body of man, and inspired into it a being of superior faculties, whereby He teacheth us more than the beasts of the field, and maketh us wiser than the fowls of the heaven.

——————Thrice happy men,

And sons of men, whom God hath thus advanc’d;

Created in his image, here to dwell,

And worship him; and, in return, to rule

O’er all his works.

Milton.

We now proceed to consider The Curiosities of the Human Countenance.—On this subject we shall derive considerable assistance from the same German philosopher that was quoted in the last section. Indeed, we shall make a liberal use of Sturm’s Reflections in our delineations of the Curiosities of the human frame.

[Pg 19]The exterior of the human body at once declares the superiority of man over all living creatures. His Face, directed towards the heavens, prepares us to expect that dignified expression which is so legibly inscribed upon his features; and from the countenance of man we may judge of his important destination, and high prerogatives. When the soul rests in undisturbed tranquillity, the features of the face are calm and composed; but when agitated by emotions, and tossed by contending passions, the countenance becomes a living picture, in which every sensation is depicted with equal force and delicacy. Each affection of the mind has its particular impression, and every change of countenance denotes some secret emotion of the heart. The Eye may, in particular, be regarded as the immediate organ of the soul; as a mirror, in which the wildest passions and the softest affections are reflected without disguise. Hence it may be called with propriety, the true interpreter of the soul, and organ of the understanding. The colour and motions of the eye contribute much to mark the character of the countenance. The human eyes are, in proportion, nearer to one another than those of any other living creatures; the space between the eyes of most of them being so great, as to prevent their seeing an object with both their eyes at the same time, unless it is placed at a great distance. Next to the eyes, the eye-brows tend to fix the character of the countenance. Their colour renders them particularly striking; they form the shade of the picture, which thus acquires greater force of colouring. The eye-lashes, when long and thick, give beauty and additional charms to the eye. No animals, but men and monkeys, have both eye-lids ornamented with eye-lashes; other creatures having them only on the lower eye-lid. The eye-brows are elevated, depressed, and contracted, by means of the muscles upon the forehead, which forms a very considerable part of the face, and adds much to its beauty when well formed: it should neither project much, nor be quite flat; neither very large, nor small; beautiful hair adds much to its appearance. The Nose is the most prominent, and least moveable part of the face; hence it adds more to the beauty than the expression of the countenance. The Mouth and Lips are, on the contrary, extremely susceptible of changes; and, if the eyes express the passions of the soul, the mouth seems more peculiarly to correspond with the emotions of the heart. The rosy bloom of the lips, and the ivory white of the teeth, complete the charms of the human face divine.

Another Curiosity on this subject is, the wonderful diversity of traits in the human countenance. It is an evident proof of the admirable wisdom of God, that though the bodies of men are so similar to each other in their essential parts,[Pg 20] there is yet such a diversity in their exterior, that they can be readily distinguished without the liability of error. Amongst the many millions of men existing in the universe, there are no two that are perfectly similar to each other Each one has some peculiarity pourtrayed in his countenance, or remarkable in his speech; and this diversity of countenance is the more singular, because the parts which compose it are very few, and in each person are disposed according to the same plan. If all things had been produced by blind chance, the countenances of men might have resembled one another as nearly as balls cast in the same mould, or drops of water out of the same bucket: but as that is not the case, we must admire the infinite wisdom of the Creator, which, in thus diversifying the traits of the human countenance, has manifestly had in view the happiness of men; for if they resembled each other perfectly, they could not be distinguished from one another, to the utter confusion and detriment of society. We should never be certain of life, nor of the peaceable possession of our property; thieves and robbers would run little risk of detection, for they could neither be distinguished by the traits of their countenance, nor the sound of their voice. Adultery, and every crime that stains humanity, might be practiced with impunity, since the guilty would rarely be discovered; and we should be continually exposed to the machinations of the villain, and the malignity of the coward: we could not shelter ourselves from the confusion of the mistake, nor from the treachery and fraud of the deceitful; all the efforts of justice would be useless, and commerce would be the prey of error and uncertainty: in short, the uniformity and perfect similarity of faces would deprive society of its most endearing charms, and destroy the pleasure and sweet gratification of individual friendship.

We may well exclaim with a celebrated writer,—

“What a piece of work is man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculties! in form, and moving, how express and admirable! in action, how like an angel! in apprehension, how like a god!”

The next subject is, The Curious Formation of the Eye.—The Eye infinitely surpasses all the works of man’s industry. Its structure is one of the most wonderful things the human understanding can become acquainted with; the most skilful artist cannot devise any machine of this kind which is not infinitely inferior to the eye; whatever ability, industry, and attention he may devote to it, he will not be able to produce a work that does not abound with the imperfections incident to the works of men. It is true, we cannot perfectly become acquainted with all the art the Divine [Pg 21]Wisdom has displayed in the structure of this beautiful organ; but the little that we know suffices to convince us of the admirable intelligence, goodness, and power of the Creator. In the first place, how fine is the disposition of the exterior parts of the eye, how admirably it is defended! Placed in durable orbits of bone, at a certain depth in the skull, they cannot easily suffer any injury; the over-arching eye-brows contribute much to the beauty and preservation of this exquisite organ; and the eye-lids more immediately shelter it from the glare of light, and other things which might be prejudicial; inserted in these are the eye-lashes, which also much contribute to the above effect, and also prevent small particles of dust, and other substances, striking against the eye.[2] The internal structure is still more admirable. The globe of the eye is composed of tunics, humours, muscles, and vessels; the coats are the cornea, or exterior membrane, which is transparent anteriorly, and opake posteriorly; the charoid, which is extremely vascular; the uvea, with the iris, which being of various colours, gives the appearance of differently coloured eyes; and being perforated, with the power of contraction and dilatation, forms the pupil; and, lastly, the retina, being a fine expansion of the optic nerve, upon it the impressions of objects are made. The humours are the aqueous, lying in the forepart of the globe, immediately under the cornea; it is thin, liquid, and transparent; the crystalline, which lies next to the aqueous, behind the uvea, opposite to the pupil, it is the least of the humours, of great solidity, and on both sides convex; the vitreous, resembling the white of an egg, fills all the hind part of the cavity of the globe, and gives the spherical figure to the eye. The muscles of the eye are six, and by the excellence of their arrangement it is enabled to move in all directions. Vision is performed by the rays of light falling on the pellucid and convex cornea of the eye, by the density and convexity of which they are united into a focus, which passes the aqueous humours, and pupil of the eye, to be more condensed by the crystalline lens. The rays of light thus concentrated, penetrate the vitreous humour, and stimulate the retina upon which the images of objects, painted in an inverse direction, are represented to the mind through the medium of the optic nerves.

[Pg 22]

————————The visual orbs

Remark, how aptly station’d for their task;

Rais’d to th’ imperial head’s high citadel,

A wide extended prospect to command.

See the arch’d outworks of impending lids,

With hairs, as palisadoes fenc’d around

To ward annoyance from without.

Bally.

Again:—

Who form’d the curious organ of the eye,

And cloth’d it with its various tunicles,

Of texture exquisite; with crystal juice

Supply’d it, to transmit the rays of light;

Then plac’d it in its station eminent,

Well fenc’d and guarded, as a centinel

To watch abroad, and needful caution give?

Needler.

The next subject is, The Curious Structure of the Ear.

The channel’d ear, with many a winding maze,

How artfully perplex’d, to catch the sound.

And from her repercussive caves augment!

Bally.

Dark night, that from the eye his function takes,

The ear more quick of apprehension makes;

Wherein it doth impair the seeing sense,

It pays the Hearing—double recompense.

Shakspeare.

Although the ear, with regard to beauty, yields to the eye, its conformation is not less perfect, nor less worthy of the Creator. The position of the ear bespeaks much wisdom; for it is placed in the most convenient part of the body, near to the brain, the common seat of all the senses. The exterior form of the ear merits considerable attention; its substance is between the flexible softness of flesh, and the firmness of bone, which prevents the inconvenience that must arise from its being either entirely muscular or wholly formed of solid bone. It is therefore cartilaginous, possessing firmness, folds, and smoothness, so adapted as to reflect sound; for the chief use of the external part is to collect the vibrations of the air, and transmit them to the orifice of the ear. The internal structure of this organ is still more remarkable. Within the cavity of the ear is an opening, called the meatus auditorius, or auditory canal, the entrance to which is defended by small hairs, which prevent insects and small particles of extraneous matter penetrating into it; for which purpose there is also secreted a bitter ceruminous matter, called ear-wax. The auditory canal is terminated obliquely by a membrane, generally known by the name of drum, which instrument it in some degree resembles; for within the cavity of the auditory canal is a kind of bony ring, over which the membrana tympani is stretched. In contact with this membrane, on the inner side, is a small bone (malleus) against which it strikes[Pg 23] when agitated by the vibrations of sound. Connected with these are two small muscles: one, by stretching the membrane, adapts it to be more easily acted upon by soft and low sounds; the other, by relaxing, prepares it for those which are very loud. Besides the malleus, there are some other very small and remarkable bones, called incus, or the anvil, as orbiculare, or orbicular bone, and the stapes, or stirrup: their use is, to assist in conveying the sounds received upon the membrana tympani. Behind the cavity of the drum, is an opening, called the Eustachian tube, which begins at the back part of the mouth with an orifice, which diminishes in size as the tube passes towards the ear, where it becomes bony; by this means, sounds may be conveyed to the ear through the mouth, and it facilitates the vibrations of the membrane by the admission of air. We may next observe the cochlea, which somewhat resembles the shell of a snail, whence its name; its cavity winds in a spiral direction, and is divided into two by a thin spiral lamina: and lastly is the auditory nerve, which terminates in the brain. The faculty of hearing is worthy of the utmost admiration and attention: by putting in motion a very small portion of air, without even being conscious of its moving, we have the power of communicating to each other our thoughts, desires, and conceptions. But to render the action of air in the propagation of sound more intelligible, we must recollect that the air is not a solid, but a fluid body. Throw a stone into a smooth stream of water, and there will take place undulations, which will be extended more or less according to the degree of force with which the stone was impelled. Conceive then, that when a word is uttered in the air, a similar effect takes place in that element, as is produced by the stone in the water. During the action of speaking, the air is expelled from the mouth with more or less force; this communicates to the external air which it meets, an undulatory motion; and these undulations of the air entering the cavity of the ear, the external parts of which are peculiarly adapted to receive them, strike upon the membrane, or drum, by which means it is shaken, and receives a trembling motion: the vibration is communicated to the malleus, the bone immediately in contact with the membrane, and from it to the other bones; the last of which, the stapes or stirrup, adhering to the fenestra ovalis, or oval orifice, causes it to vibrate; the trembling of which is communicated to a portion of water contained in the cavity called the vestibulum, and in the semicircular canals, causing a gentle tremor in the nervous expansion contained therein, which is transmitted to the brain; and the mind is thus informed of the presence of sound, and feels a sensation proportioned to the force or to the weakness of the impression[Pg 24] that is made. Let us rejoice that we possess the faculty of hearing; for without it, our state would be most wretched and deplorable; in some respects, more sorrowful than the loss of sight; had we been born deaf, we could not have acquired knowledge sufficient to enable us to pursue any art or science. Let us never behold those who have the misfortune to be deaf, without endeavoring better to estimate the gift of which they are deprived, and which we enjoy; or without praising the goodness of God, which has granted it to us: and the best way we can testify our gratitude is, to make a proper use of this important blessing.

We now proceed to a more particular description of The Curiosities of the Human Heart; and the Circulation of the Blood.

———Though no shining sun, nor twinkling star

Bedeck’d the crimson curtains of the sky;

Though neither vegetable, beast, nor bird,

Were extant on the surface of this ball,

Nor lurking gem beneath; though the great sea

Slept in profound stagnation, and the air

Had left no thunder to pronounce its Maker:

Yet Man at home, within himself might find

The Deity immense, and in that frame

So fearfully, so wonderfully made!

See and adore his providence and power.

Smart.

With what admirable skill and inimitable structure is formed that muscular body, situated within the cavity of the chest, and called the human heart! Its figure is somewhat conical, and it is externally divided into two parts: the base, which is uppermost, and attached to vessels; and the apex, which is loose and pointing to the left side, against which it seems to beat. Its substance is muscular, being composed of fleshy fibres, interwoven with each other. It is divided internally into cavities, called auricles and ventricles; from which vessels proceed to convey the blood to the different parts of the body. The ventricles are situated in the substance of the heart, and are separated from each other by a thick muscular substance; they are divided into right and left, and each communicates with its adjoining auricle, one of which is situated on each side the base of the heart. The right auricle receives the blood from the head and superior parts of the body, by means of a large vein; and in the same manner the blood is returned to it from the inferior parts, by all the veins emptying their stores into one, which terminates in this cavity; which, having received a sufficient portion of blood, contracts, and by this motion empties itself into the right ventricle, which also contracting, propels the blood into an artery, which immediately conveys it into the lungs, where[Pg 25] it undergoes certain changes, and then passes through veins into the left auricle of the heart, thence into the left ventricle, by the contraction of which it is forced into an artery, through whose ramifications it is dispersed to all parts of the body, from which it is again returned to the right auricle; thus keeping up a perpetual circulation, for, whilst life remains, the action of the heart never ceases. In a state of health the heart contracts about seventy times in a minute, and is supposed, at each contraction, to propel about two ounces of blood; to do which, the force it exerts is very considerable, though neither the quantity of force exerted, nor of blood propelled, is accurately determined. The heart comprises within itself a world of wonders, and whilst we admire its admirable structure and properties, we are naturally led to consider the wisdom and power of Him who formed it, from whom first proceeded the circulation of the blood, and the pulsations of the heart; who commands it to be still, and the functions instantly cease to act.

This important secret of the circulation of blood in the human body was brought to light by William Harvey, an English physician, a little before the year 1600: and when it is considered thoroughly, it will appear to be one of the most stupendous works of Omnipotence.

The blood, the fountain whence the spirits flow,

The generous stream that waters every part,

And motion, vigour, and warm life conveys

To every particle that moves or lives,

——————through unnumber’d tube.

Pour’d by the heart, and to the heart again

Refunded.—————

Armstrong.

Who in the dark the vital flame illum’d,

And from th’ impulsive engine caused to flow

Th’ ejaculated streams through many a pipe

Arterial with meand’ring lapse, then bring

Refluent their purple tribute to their fount:

Who spun the sinews’ branchy thread, and twin’d

The azure veins in spiral knots, to waft

Life’s tepid waves all o’er; or, who with bones

Compacted, and with nerves the fabric strung:

Their specious form, their fitness, which results

From figure and arrangement, all declare

Th’ Artificer Divine!

Bally.

Again:—

———The nerves, with equal wisdom made.

Arising from the tender brain, pervade

And secret pass in pairs the channel’d bone.

And thence advance through paths and roads unknown.

Form’d of the finest complicated thread,

The num’rous cords are through the body spread.

These subtle channels, such is every nerve,

For vital functions, sense, and motion serve;—

They help to labour and concoct the food,

Refine the chyle, and animate the blood.

Blackmore.

We now proceed to some Curious and Interesting Facts concerning Respiration, or the Act of Breathing.

Anatomists have, not unaptly, compared the lungs to a sponge; containing, like it, a great number of small cavities, and being also capable of considerable compression and expansion. The air cells of the lungs open into the windpipe, by which they communicate with the external atmosphere: the whole internal structure of the lungs is lined by a transparent membrane, estimated by Haller at only the thousandth part of an inch in thickness; but whose surface, from its various convolutions, measures fifteen square feet, which is equal to the external surface of the body. On this extensive and thin membrane innumerable branches of veins and arteries are distributed, some of them finer than hairs; and through these vessels all the blood in the system is successively propelled, by an extremely curious and beautiful mechanism, which will be described in some future article.

The capacity of the lungs varies considerably in different individuals.[3] On a general average, they may be said to contain about 280 cubic inches, or nearly five quarts of air. By each inspiration about forty cubic inches of air are received into the lungs, and at each expiration the same quantity is discharged. If, therefore, we calculate that twenty respirations take place in a minute, and forty cubic inches to be the amount of each inspiration, it follows, that in one minute, we inhale 800 cubic inches; in an hour, the quantity of air inspired will be 48,000 cubic inches; and in the twenty-four hours, it will amount to 1,152,000 cubic inches. This quantity of air will almost fill 78 wine hogsheads, and would weigh nearly 53 pounds. From this admirable provision of nature, by which the blood is made to pass in review, as it were, of this immense quantity of air, and over so extensive a surface, it seems obvious, that these two fluids are destined to exert some very important influence on each other; and it has been proved, by a very decisive experiment of Dr. Priestley’s, that the extremely thin membrane, which is alone interposed, does not prevent the exercise of the chemical affinity which prevails between the air which is received in the lungs, and the blood which is incessantly circulating through them. It must surely, therefore, be of the first importance to health, that the fluid of which we hourly inhale, at least, three hogsheads, should not be contaminated by the suspension of noxious effluvia.

[Pg 27]The purity of the atmosphere may be impaired either by the operation of what some denominate natural causes, or by the influence of circumstances resulting from our social condition. Its chemical constitution is changed by respiration; the vital principle is destroyed, and its place supplied by a highly poisonous gas.

The emanations from the surface of our bodies contribute, in a still greater degree, to vitiate the atmosphere, and to render it less fit for the healthful support of life. Many of the organs which compose our wonderfully complicated frame are engaged in discharging the constituent parts of our bodies, which, by the exercise of the various animal functions, are become useless, and, if retained, would become noxious. Physiologists have instituted a variety of experiments, to ascertain the amount of the exhalations from the surface of the body. Sanctorius, an eminent Italian physician, from a series of experiments performed during a period of thirty years, estimates it as greater than the aggregate of all our other discharges. From his calculations it would appear, that if we take of liquid and solid food eight pounds in the twenty-four hours, that five pounds are discharged by perspiration alone, within that period; and of this, the greater part is what has been denominated insensible perspiration, from its not being cognizable to the senses. We may estimate the discharge from the surface of the body, by sensible and insensible perspiration, as from half an ounce to four ounces per hour.

The exhalations from the lungs and the skin are, to a certain extent, offensive even in the most healthy individuals; but when proceeding from those labouring under disease, they are in a state very little removed from putrefaction.

Animal miasmata, like all other poison, become more active in proportion to the quantity which we imbibe. When, therefore, the air is stagnant, and when many individuals contribute their respective supplies of effluvia to vitiate it, the atmosphere necessarily becomes satured with the poison; and when inhaled, conveys it in a more virulent and concentrated state to the extensive and delicate surface of the lungs.

The collection of animal effluvia in confined places, is the source of the generation and diffusion of febrile infection: but when the miasmata are respired, in a diluted state, the ill effects which they produce, though slower in their operation, are equally certain. They, to a certain extent, pollute the fountain of life, and ultimately break down the vigour of the most robust frame; impairing the action of the digestive organs, engendering the whole train of nervous disorders, and rendering the body more susceptible of disease.

The lungs and the skin may equally become the means of introducing poisonous or infectious matter into the [Pg 28]constitution. The venom of a poisonous animal, the matter of small-pox, and many other contagions, produce their influence through the medium of the skin. Infectious diseases are communicated by the reception of air in our lungs, impregnated with contagious matter. The influence of the constant respiration of air in any degree impure, is fully evinced in the pallid countenances and languid frames of those who live in confined and ill-ventilated places; and the health of all classes of society suffers precisely in proportion to the susceptibility of their constitutions, and according to the greater or less impurities of the air which they habitually respire.

Of the offensive nature of animal effluvia, the senses of every one who enters a crowded assembly, must immediately convince him. When, therefore, we reflect on the state of the air which we breathe in churches, theatres, schools, and all crowded assemblies; and when we consider the amount of the exhalations emitted by each individual, and the very offensive nature of those emitted by many; and when, on the other hand, we take into consideration the importance of air to life, and the great quantity of this fluid which we daily respire, we must be naturally led to the adoption of such measures as would secure in our private dwellings, as well as in our public buildings, a full and unintermitting supply of fresh atmospheric air.

It is curious to observe the influence of habit, in reconciling us to many practices which would otherwise be considered in the highest degree offensive. Thus, while, with a fastidious delicacy, we avoid drinking from a cup which has been already pressed to the lips of our friends, we feel no hesitation in receiving into our lungs an atmosphere contaminated by the breath and exhalations of every promiscuous assembly.

“Were once the energy of air deny’d,

The heart would cease to pour its purple tide

The purple tide forget its wonted play,

Nor back again pursue its curious way.”

The next Subject of Curiosity we shall consider, is, The Hair of the Head.

If we consider the curious structure, and different uses of the hair of our heads, we shall find them very well worth our attention, and discover in them proofs of the wisdom and power of God.

In each entire hair we perceive with the naked eye, an oblong slender filament, and a bulb at the extremity thicker and more transparent than the rest of the hair. The filament forms the body of the hair, and the bulb the root. The large hairs have their root, and even part of the filament, enclosed in a small membraneous vessel or capsule. The size of this[Pg 29] sheath is proportionate to the size of the root, being always rather larger, that the root may not be too much confined, and that some space may remain between it and the capsule. The root or bulb has two parts, the one external, the other internal. The external is a pellicle composed of small laminæ; the internal is a glutinous fluid, in which some fibres are united; it is the marrow of the root. From the external part of the bulb proceed five, and sometimes, though rarely, six small white threads, very delicate and transparent, and often twice as long as the root. Besides these threads, small knots are seen rising in different places; they are viscous, and easily dissolved by heat. From the interior part of the bulb proceeds the body of the hair, composed of three parts; the external sheath, the interior tubes, and the marrow.

When the hair has arrived at the pore of the skin through which it is to pass, it is strongly enveloped by the pellicle of the root, which forms here a very small tube. The hair then pushes the cuticle before it, and makes of it an external sheath, which defends it at the time when it is still very soft. The rest of the covering of the hair, is a peculiar substance, and particularly transparent at the point. In a young hair this sheath is very soft, but in time becomes so hard and elastic, that it springs back with some noise when it is cut. It preserves the hair a long time. Immediately beneath the sheath are several small fibres, which extend themselves along the hair from the root to the extremity. These are united amongst themselves, and with the sheath that is common to them, by several elastic threads; and these bundles of fibres form together a tube filled with two substances; the one fluid, the other solid; and these constitute the marrow of the hair.

The wonders of creating power are seen in every thing, even in the hair that adorns our surface.

All are but parts of one stupendous whole,

Whose body Nature is, and God the soul.

That, chang’d thro’ all, and yet in all the same;

Great in the earth, as in th’ ethereal frame;

Warms in the sun, refreshes in the breeze,

Glows in the stars, and blossoms in the trees,

Lives thro’ all life, extends thro’ all extent,

Spreads undivided, operates unspent;

Breathes in our soul, informs our mortal part,

As full, as perfect, in a hair as heart;

As full, as perfect, in vile Man that mourns,

As the rapt seraph that adores and burns:

To him no high, no low, no great, no small;

He fills, he bounds, connects, and equals all.

Pope.

We shall now introduce to our readers some Ancient and Modern Opinions respecting the Hair.

The ancients held the hair a sort of excrement, fed only[Pg 30] with excrementitious matters, and no proper part of a living body. They supposed it generated of the fuliginous parts of the blood, exhaled by the heat of the body to the surface, and then condensed in passing through the pores. Their chief reasons were, that the hair being cut, will grow again, even in extreme old age, and when life is very low; that in hectic and consumptive people, where the rest of the body is continually emaciating, the hair thrives; nay, that it will even grow again in dead carcases. They added, that hair does not feed and grow like the other parts, by introsusception, i. e. by a juice circulating within it, but, like the nails, by juxtaposition. But the moderns are agreed, that every hair properly and truly lives, and receives nutriment to fill it, like the other parts; which they prove hence, that the roots do not turn grey in aged persons sooner than the extremities, but the whole changes colour at once; which shews that there is a direct communication, and that all the parts are affected alike. In strict propriety, however, it must be allowed, that the life and growth of hairs is of a different kind from that of the rest of the body, and is not immediately derived therefrom, or reciprocated therewith. It is rather of the nature of vegetation. They grow as plants do, or as some plants shoot from the parts of others; from which, though they draw their nourishment, yet each has, as it were, its distinct life and economy. They derive their food from some juices in the body, but not from the nutritious juices of the body; whence they may live, though the body be starved. Wulferus, in the Philosophical Collections, gives an account of a woman buried at Nurenberg, whose grave being opened forty-three years after her death, hair was found issuing forth plentifully through the clefts of the coffin. The cover being removed, the whole corpse appeared in its perfect shape; but, from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot, covered over with thick-set hair, long and curled. The sexton going to handle the upper part of the head with his fingers, the whole fell at once, leaving nothing in his hand but a handful of hair: there was neither skull nor any other bone left: yet the hair was solid and strong. Mr. Arnold, in the same collection, gives a relation of a man hanged for theft, who, in a little time, while he yet hung upon the gallows, had his body strangely covered over with hair.

Before we dismiss this subject, we shall give the following curious Instances of the Internal Growth of Hair.

Though the external surface of the body is the natural place for hairs, we have many well-attested instances of their being found also on the internal surface. Amatus Lusitanus mentions a person who had hair upon his tongue. Pliny and Valerius Maximus say, that the heart of Aristomenes the[Pg 31] Messenian, was hairy. Cællus Rhodiginus relates the same of Hermogenes the rhetorician; and Plutarch, of Leonidas king of Sparta. Hairs are said to have been found in the breasts of women, and to have occasioned the distemper called trichiasis; but some authors are of opinion, that these are small worms, and not hairs. There have been, however, various and indisputable evidences of hairs found in the kidneys, and voided by natural discharge. Hippocrates says, that the glandular parts are the most subject to hair; but bundles of hair have been found in the muscular parts of beef, and in parts of the human body equally firm. Hair has been often found in abscesses and imposthumations. Schultetus, opening the abdomen of a human body, found twelve pints of water, and a large lock of hair swimming loosely in it. It has, however, been found on examination, that some of the internal parts of the body are more subject to an unnatural growth of hair than others. This has long been known to anatomists; and many memorable instances have been recorded by Dr. Tyson, and others. In some animals, hairs of a considerable length have been discovered growing in the internal parts; and on several occasions, they have been found lying loosely in the cavities of the veins. There are instances of mankind being affected in the same manner. Cardan relates, that he found hair in the blood of a Spaniard; Slonatius, in that of a gentlewoman of Cracovia; and Schultetus declares, from his own observation, that those people, who are afflicted with the plica polonica, have very often hair in their blood.

We shall, in the next place, call the reader’s attention to some Curious Remarks concerning the Beard.