Transcriber’s Note

There were a number of spelling and typographical errors in the original text. Obvious printer's errors have been corrected silently. Variant and idiosyncratic spellings have been retained, especially for place names. at the end of this text. Footnotes have been moved to the end of the text, and are linked for the reader’s convenience.

A HISTORY OF

THE NATIONAL ROAD,

WITH

INCIDENTS, ACCIDENTS, AND ANECDOTES

THEREON.

ILLUSTRATED.

BY

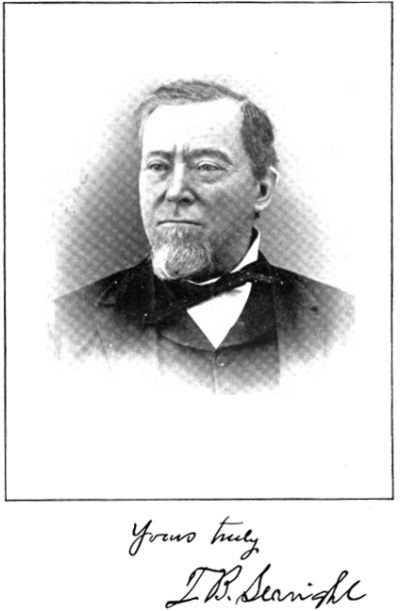

THOMAS B. SEARIGHT.

UNIONTOWN, PA:

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR.

1894.

Copyright, 1894, by T. B. Searight.

PRESSES OF

M. CULLATON & CO.,

RICHMOND, IND.

| Stanwood, Bar Harbor, Maine. September 8th, 1892. |

} |

Hon. T. B. Searight,

Uniontown, Pa.

My Dear Friend:—

I have received the sketches of the “Old Pike” regularly and have as regularly read them, some of them more than once, especially where you come near the Monongahela on either side of it, and thus strike the land of my birth and boyhood. I could trace you all the way to Washington, at Malden, at Centreville, at Billy Greenfield’s in Beallsville, at Hillsboro (Billy Robinson was a familiar name), at Dutch Charley Miller’s, at Ward’s, at Pancake, and so on—familiar names, forever endeared to my memory. I cherish the desire of riding over the “Old Pike” with you, but I am afraid we shall contemplate it as a scheme never to be realized.

Very sincerely,

Your friend,

JAMES G. BLAINE.

| CHAPTER I. | PAGES |

| Inception of the Road—Author’s Motive in Writing its History—No History of the Appian Way—A Popular Error Corrected—Henry Clay, Andrew Stewart, T. M. T. McKennan, General Beeson, Lewis Steenrod and Daniel Sturgeon—Their Services in Behalf of the Road, etc., etc. | 13-19 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Origin of the Fund for Making the Road—Acts for the Admission of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri, etc., etc. | 20-24 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Act of Congress Authorizing the Laying Out and Making of the Road | 25-27 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Special Message of President Jefferson—Communicating to Congress the First Report of the Commissioners—Uniontown left out, etc. | 28-35 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Pennsylvania grants Permission to make the Road through her Territory—Uniontown Restored, Gist left Out, and Washington, Pennsylvania, made a Point—Heights of Mountains and Hills—On to Brownsville and Wheeling, etc., etc. | 36-40 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury, called upon for Information Respecting the Fund Applicable to the Roads mentioned in the Ohio Admission Act—His Responses | 41-43 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| The Life of the Road Threatened by the Spectre of a Constitutional Cavil—President Monroe Vetoes a Bill for its Preservation and Repair—General Jackson has Misgivings—Hon. Andrew Stewart Comes to the Rescue | 44-51 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| State Authority Prevails—The Road Surrendered by Congress—The Erection of Toll Gates Authorized— Commissioners Appointed by the States to Receive the Road, etc., etc. | 52-56 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Plan of Repairs—The Macadam System Adopted—Mr. Stockton offers his services—Captain Delafield made Superintendent, etc., etc. | 57-63 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Lieut. Mansfield superseded by Capt. Delafield—The Turning of Wills Mountain, etc., etc. | 64-76 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| On with the Work—Wooden Bridges Proposed for the New Location up Wills Creek and Braddock’s Run—The War Department holds that Wooden Superstructures would be a Substantial Compliance with the Maryland Law—Cumberland to Frostburg, etc. | 77-86 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Gen. Lewis Cass, Secretary of War, Transmits a Report—More about the Wooden Bridges for the New Location near Cumberland, etc. | 87-94 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| The Iron Bridge over Dunlap’s Creek at Brownsville | 95-99 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Appropriations by Congress at Various Times for Making, Repairing, and Continuing the Road | 100-106 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Speech of Hon. T. M. T. McKennan | 107-108 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Life on the Road—Origin of the Phrase Pike Boys—Slaves Driven like Horses—Race Distinction at the Old Taverns—Old Wagoners—Regulars and Sharpshooters— Line Teams | 109-115 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Old Wagoners continued—Broad and Narrow Wheels— Peculiar Wagon—An Experiment and a Failure—Wagon Beds—Bell Teams | 116-119 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Old Wagoners continued | 120-126 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Old Wagoners continued—The Harness they Used, etc. | 127-133 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Old Wagoners continued—An Exciting Incident of the Political Campaign of 1840—All about a Petticoat—A Trip to Tennessee—Origin of the Toby Cigar—The Rubber—The Windup and Last Lay of the Old Wagoners | 134-145 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Stage Drivers, Stage Lines and Stage Coaches—The Postillion, etc. | 146-155 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Stages and Stage Drivers continued—Character of Drivers Defended—Styles of Driving—Classification of Drivers, etc. | 156-163 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The First Mail Coaches—The Stage Yard at Uniontown—Names of Coaches—Henry Clay and the Drivers—Jenny Lind and Phineas T. Barnum on the Road, etc., etc. | 164-174 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Stages and Stage Drivers continued—Gen. Taylor Approaching Cumberland—Early Coaches, etc. | 175-183 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Distinguished Stage Proprietors—Lucius W. Stockton, James Reeside, Dr. Howard Kennedy, William H. Stelle—Old Stage Agents—The Pony Express | 184-191 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers from Baltimore to Boonsboro—Pen Picture of an Old Tavern by James G. Blaine | 192-196 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Boonsboro to Cumberland | 197-203 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Cumberland to the Little Crossings—The City of Cumberland | 204-208 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Little Crossings to Winding Ridge—Grantsville | 209-213 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Winding Ridge to the Big Crossings—The State Line—How it is Noted | 214-219 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Big Crossings to Mt. Washington | 220-226 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Mt. Washington to Uniontown | 227-233 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Uniontown—The Town as it Appeared to Gen. Douglass in 1784—Its Subsequent Growth and Improvement, etc., etc. | 234-243 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Uniontown to Searights | 244-249 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Searights to Brownsville | 250-259 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Brownsville to Beallsville | 260-265 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Beallsville to Washington | 266-272 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Washington, Penn.—Washington and Jefferson College—The Female Seminary | 273-282 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—Washington to West Alexander | 283-289 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Old Taverns and Tavern Keepers continued—West Alexander to Wheeling | 290-297 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| West of Wheeling—Old Stage Lines Beyond the Ohio River—Through Indiana—The Road Disappears Among the Prairies of Illinois | 298-310 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| Superintendents under National and State Control—Old Mile Posts, etc. | 311-318 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| Old Contractors—Cost of the Road—Contractors for Repairs, etc. | 319-322 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| Thomas Endsley, William Sheets, W. M. F. Magraw, etc. | 323-328 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| Dumb Ike—Reminiscences of Uniontown—Crazy Billy, etc. | 329-338 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| The Trial of Dr. John F. Braddee for Robbing the U.S. Mails | 339-352 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| Visit of John Quincy Adams to Uniontown in 1837—Received by Dr. Hugh Campbell—The National Road a Monument of the Past—A Comparison with the Appian Way | 353-356 |

| CHAPTER APPENDIX. | |

| Digest of the Laws of Pennsylvania Relating to the Cumberland Road—Unexpended Balances in Indiana—Accounts of Two Old Commissioners—Rates of Toll—Letters of Albert Gallatin, Ebenezer Finley and Thomas A. Wiley—Curiosities of the Old Postal Service | 357-384 |

Inception of the Road—Author’s Motive in Writing its History—No History of the Appian Way—A Popular Error Corrected—Henry Clay, Andrew Stewart, T. M. T. McKennan, Gen. Beeson, Lewis Steenrod and Daniel Sturgeon—Their Services in Behalf of the Road—Braddock’s Road—Business and Grandeur of the Road—Old and Odd Names—Taverns—No Beer on the Road—Definition of Turnpike—An Old Legal Battle.

The road which forms the subject of this volume, is the only highway of its kind ever wholly constructed by the government of the United States. When Congress first met after the achievement of Independence and the adoption of the Federal Constitution, the lack of good roads was much commented upon by our statesmen and citizens generally, and various schemes suggested to meet the manifest want. But, it was not until the year 1806, when Jefferson was President, that the proposition for a National Road took practical shape. The first step, as will hereinafter be seen, was the appointment of commissioners to lay out the road, with an appropriation of money to meet the consequent expense. The author of this work was born and reared on the line of the road, and has spent his whole life amid scenes connected with it. He saw it in the zenith of its glory, and with emotions of sadness witnessed its decline. It was a highway at once so grand and imposing, an artery so largely instrumental in promoting the early growth and development of our country’s wonderful resources, so influential in strengthening the bonds of the American Union, and at the same time so replete with important events and interesting incidents, that the writer of these pages has long cherished a hope that some capable hand would write its history and collect and preserve its legends, and no one having come forward to perform the task, he has ventured upon it himself, with unaffected diffidence and a full knowledge of his inability to do justice to the subject.

It is not a little singular that no connected history of the renowned Appian Way can be found in our libraries. Glimpses of its existence and importance are seen in the New Testament and in some old volumes of classic lore, but an accurate and complete history of its inception, purpose, construction and development, with the incidents, accidents and anecdotes, which of necessity were connected with it, seems never to have been written. This should not be said of the great National Road of the United States of America. The Appian Way has been called the Queen of Roads. We claim for our National highway that it was the King of Roads.

Tradition, cheerfully acquiesced in by popular thought, attributes to Henry Clay the conception of the National Road, but this seems to be error. The Hon. Andrew Stewart, in a speech delivered in Congress, January 27th, 1829, asserted that “Mr. Gallatin was the very first man that ever suggested the plan for making the Cumberland Road.” As this assertion was allowed to go unchallenged, it must be accepted as true, however strongly and strangely it conflicts with the popular belief before stated. The reader will bear in mind that the National Road and the Cumberland Road are one and the same. The road as constructed by authority of Congress, begins at the city of Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, and this is the origin of the name Cumberland Road. All the acts of Congress and of the legislatures of the States through which the road passes, and they are numerous, refer to it as the Cumberland Road. The connecting link between Cumberland and the city of Baltimore is a road much older than the Cumberland Road, constructed and owned by associations of individuals, and the two together constitute the National Road.

While it appears from the authority quoted that Henry Clay was not the planner of the National Road, he was undoubtedly its ablest and most conspicuous champion. In Mallory’s Life of Clay it is stated that “he advocated the policy of carrying forward the construction of the Cumberland Road as rapidly as possible,” and with what earnestness, continues his biographer, “we may learn from his own language, declaring that he had to beg, entreat and supplicate Congress, session after session, to grant the necessary appropriations to complete the road.” Mr. Clay said, “I have myself toiled until my powers have been exhausted and prostrated to prevail on you to make the grant.” No wonder Mr. Clay was a popular favorite along the whole line of the road. At a public dinner tendered him by the mechanics of Wheeling, he spoke of “the great interest the road had awakened in his breast, and expressed an ardent desire that it might be prosecuted to a speedy completion.” Among other things he said that “a few years since he and his family had employed the whole or greater part of a day in traveling the distance of about nine miles from Uniontown to Freeman’s,[A] on Laurel Hill, which now, since the construction of the road over the mountains, could be accomplished, together with seventy more in the same time,” and that “the road was so important to the maintenance of our Union that he would not consent to give it up to the keeping of the several States through which it passed.”

Hon. Andrew Stewart, of Uniontown, who served many years in Congress, beginning with 1820, was, next to Mr. Clay, the most widely known and influential congressional friend of the road, and in earnestness and persistency in this behalf, not excelled even by Mr. Clay. Hon. T. M. T. McKennan, an old congressman of Washington, Pennsylvania, was likewise a staunch friend of the road, carefully guarding its interests and pressing its claims upon the favorable consideration of Congress. Gen. Henry W. Beeson, of Uniontown, who represented the Fayette and Greene district of Pennsylvania in Congress in the forties, was an indomitable friend of the road. He stoutly opposed the extension of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad west of Cumberland, through Pennsylvania, and was thoroughly sustained by his constituents. In one of his characteristic speeches on the subject, he furnished a careful estimate of the number of horse-shoes made by the blacksmiths along the road, the number of nails required to fasten them to the horses’ feet, the number of bushels of grain and tons of hay furnished by the farmers to the tavern keepers, the vast quantity of chickens, turkeys, eggs and butter that found a ready market on the line, and other like statistical information going to show that the National Road would better subserve the public weal than a steam railroad. This view at the time, and in the locality affected, was regarded as correct, which serves as an illustration of the change that takes place in public sentiment, as the wheels of time revolve and the ingenuity of man expands. Lewis Steenrod, of the Wheeling district, was likewise an able and influential congressional friend of the road. He was the son of Daniel Steenrod, an old tavernkeeper on the road, near Wheeling; and the Cumberland, Maryland, district always sent men to Congress who favored the preservation and maintenance of the road. Hon. Daniel Sturgeon, who served as a senator of the United States for the State of Pennsylvania from 1840 to 1852, was also an undeviating and influential friend of the road. He gave unremitting attention and untiring support to every measure brought before the Senate during his long and honorable service in that body, designed to make for the road’s prosperity, and preserve and maintain it as the nation’s great highway. His home was in Uniontown, on the line of the road, and he was thoroughly identified with it alike in sentiment and interest. He was not a showy statesman, but the possessor of incorruptible integrity and wielded an influence not beneath that of any of his compeers, among whom were that renowned trio of Senators, Clay, Webster and Calhoun.

Frequent references will be made in these pages to the Old Braddock Road, but it is not the purpose of the writer to go into the history of that ancient highway. This volume is devoted exclusively to the National Road. We think it pertinent, however, to remark that Braddock’s Road would have been more appropriately named Washington’s Road. Washington passed over it in command of a detachment of Virginia troops more than a year before Braddock ever saw it. Mr. Veech, the eminent local historian, says that Braddock’s Road and Nemicolon’s Indian trail are identical, so that Nemicolon, the Indian, would seem to have a higher claim to the honor of giving name to this old road than General Braddock. However, time, usage and common consent unite in calling it Braddock’s Road, and, as a rule, we hold it to be very unwise, not to say downright foolishness, to undertake to change old and familiar names. It is difficult to do, and ought not to be done.

From the time it was thrown open to the public, in the year 1818, until the coming of railroads west of the Allegheny mountains, in 1852, the National Road was the one great highway, over which passed the bulk of trade and travel, and the mails between the East and the West. Its numerous and stately stone bridges with handsomely turned arches, its iron mile posts and its old iron gates, attest the skill of the workmen engaged on its construction, and to this day remain enduring monuments of its grandeur and solidity, all save the imposing iron gates, which have disappeared by process of conversion prompted by some utilitarian idea, savoring in no little measure of sacrilege. Many of the most illustrious statesmen and heroes of the early period of our national existence passed over the National Road from their homes to the capital and back, at the opening and closing of the sessions of Congress. Jackson, Harrison, Clay, Sam Houston, Polk, Taylor, Crittenden, Shelby, Allen, Scott, Butler, the eccentric Davy Crockett, and many of their contemporaries in public service, were familiar figures in the eyes of the dwellers by the roadside. The writer of these pages frequently saw these distinguished men on their passage over the road, and remembers with no little pride the incident of shaking hands with General Jackson, as he sat in his carriage on the wagon-yard of an old tavern. A coach, in which Mr. Clay was proceeding to Washington, was upset on a pile of limestone, in the main street of Uniontown, a few moments after supper at the McClelland house. Sam Sibley was the driver of that coach, and had his nose broken by the accident. Mr. Clay was unhurt, and upon being extricated from the grounded coach, facetiously remarked that: “This is mixing the Clay of Kentucky with the limestone of Pennsylvania.”

As many as twenty-four horse coaches have been counted in line at one time on the road, and large, broad-wheeled wagons, covered with white canvass stretched over bows, laden with merchandise and drawn by six Conestoga horses, were visible all the day long at every point, and many times until late in the evening, besides innumerable caravans of horses, mules, cattle, hogs and sheep. It looked more like the leading avenue of a great city than a road through rural districts.

The road had a peculiar nomenclature, familiar to the tens of thousands who traveled over it in its palmy days. The names, for example, applied to particular localities on the line, are of striking import, and blend harmoniously with the unique history of the road. With these names omitted, the road would be robbed of much that adds interest to its history. Among the best remembered of these are, The Shades of Death, The Narrows, Piney Grove, Big Crossings, Negro Mountain, Keyser’s Ridge, Woodcock Hill, Chalk Hill, Big Savage, Little Savage, Snake Hill, Laurel Hill, The Turkey’s Nest, Egg Nog Hill, Coon Island and Wheeling Hill. Rich memories cluster around every one of these names, and old wagoners and stage drivers delight to linger over the scenes they bring to mind.

The road was justly renowned for the great number and excellence of its inns or taverns. On the mountain division, every mile had its tavern. Here one could be seen perched on some elevated site, near the roadside, and there another, sheltered behind a clump of trees, many of them with inviting seats for idlers, and all with cheerful fronts toward the weary traveler. The sign-boards were elevated upon high and heavy posts, and their golden letters winking in the sun, ogled the wayfarer from the hot road-bed and gave promise of good cheer, while the big trough, overflowing with clear, fresh water, and the ground below it sprinkled with droppings of fragrant peppermint, lent a charm to the scene that was well nigh enchanting.

The great majority of the taverns were called wagon stands, because their patrons were largely made up of wagoners, and each provided with grounds called the wagon-yard, whereon teams were driven to feed, and rest over night. The very best of entertainment was furnished at these wagon stands. The taverns whereat stage horses were kept and exchanged, and stage passengers took meals, were called “stage houses,” located at intervals of about twelve miles, as nearly as practicable.

The beer of the present day was unknown, or if known, unused on the National Road during the era of its prosperity. Ale was used in limited quantities, but was not a favorite drink. Whisky was the leading beverage, and it was plentiful and cheap. The price of a drink of whisky was three cents, except at the stage houses, where by reason of an assumption of aristocracy the price was five cents. The whisky of that day is said to have been pure, and many persons of unquestioned respectability affirm with much earnestness that it never produced delirium tremens. The current coin of the road was the big copper cent of United States coinage, the “fippenny bit,” Spanish, of the value of six and one-fourth cents, called for brevity a “fip,” the “levy,” Spanish, of the value of twelve and a half cents, the quarter, the half dollar, and the dollar. The Mexican and Spanish milled dollar were oftener seen than the United States dollar. The silver five-cent piece and the dime of the United States coinage were seen occasionally, but not so much used as the “fip” and the “levy.” In times of stringency, the stage companies issued scrip in denominations ranging from five cents to a dollar, which passed readily as money. The scrip was similar to the postal currency of the war period, lacking only in the artistic skill displayed in the engraving of the latter. A hungry traveler could obtain a substantial meal at an old wagon stand tavern for a “levy,” and two drinks of whisky for a “fippenny bit.” The morning bill of a wagoner with a six-horse team did not exceed one dollar and seventy-five cents, which included grain and hay for the horses, meals for the driver, and all the drinks he saw proper to take.

The National Road is not in a literal sense a turnpike. A turnpike, in the original meaning of the word, is a road upon which pikes were placed to turn travelers thereon through gates, to prevent them from evading the payment of toll. Pikes were not used, or needed on the National Road. It was always kept in good condition, and travelers thereon, as a rule, paid the required toll without complaining. At distances of fifteen miles, on the average, houses were erected for toll collectors to dwell in, and strong iron gates, hung to massive iron posts, were established to enforce the payment of toll in cases of necessity. These toll houses were of uniform size, angular and round, west of the mountains constructed of brick, and through the mountains, of stone, except the one six miles west of Cumberland, which is of brick. They are all standing on their old sites at this date (1893), except the one that stood near Mt. Washington, and the one that stood near the eastern base of Big Savage Mountain. At the last mentioned point, the old iron gate posts are still standing, firmly rooted in their original foundations, and plastered all over with advertisements of Frostburg’s business houses, but the old house and the old gates have gone out of sight forever.

It is curious to note how the word turnpike has been perverted from its literal meaning by popular usage. The common idea is that a turnpike is a road made of stone, and that the use of stone is that alone which makes it a turnpike. The common phrase, “piking a road,” conveys the idea of putting stones on it, whereas in fact, there is no connection between a stone and a pike, and a road might be a turnpike without a single stone upon it. It is the contrivance to turn travelers through gates, before mentioned, that makes a turnpike. We recall but one instance of a refusal to pay toll for passing over the National Road, and that was a remarkable one. It grew out of a misconception of the scope of the act of Congress, providing for the exemption from toll of carriages conveying the United States mails. The National Road Stage Company, commonly called the “Old Line,” of which Lucius W. Stockton was the controlling spirit, was a contractor for carrying the mails, and conceived the idea that by placing a mail pouch in every one of its passenger coaches it could evade the payment of toll. Stage companies did not pay toll to the collectors at the gates, like ordinary travelers, but at stated periods to the Road Commissioner. At the time referred to, William Searight, father of the writer, was the commissioner in charge of the entire line of the road through the state of Pennsylvania, and it was fifty years ago. Upon presenting his account to Mr. Stockton, who lived at Uniontown, for accumulated tolls, that gentleman refused payment on the ground that all his coaches carried the mail, and were therefore exempt from toll. The commissioner was of opinion that the act of Congress could not be justly construed to cover so broad a claim, and notified Mr. Stockton that if the toll was not paid the gates would be closed against his coaches. Mr. Stockton was a resolute as well as an enterprising man, and persisted in his position, whereupon an order was given to close the gates against the passage of his coaches until the legal toll was paid. The writer was present, though a boy, at an execution of this order at the gate five miles west of Uniontown. It was in the morning. The coaches came along at the usual time and the gates were securely closed against them. The commissioner superintended the act in person, and a large number of people from the neighborhood attended to witness the scene, anticipating tumult and violence, as to which they were happily disappointed. The drivers accepted the situation with good nature, but the passengers, impatient to proceed, after learning the cause of the halt, paid the toll, whereupon the gates were thrown open, and the coaches sped on. For a considerable time after this occurrence an agent was placed on the coaches to pay the toll at the gates. Mr. Stockton instituted prosecutions against the commissioner for obstructing the passage of the United States mails, which were not pressed to trial, but the main contention was carried to the Supreme Court of the United States for adjudication on a case stated, and Mr. Stockton’s broad claim was denied, the court of last resort holding that “the exemption from tolls did not apply to any other property (than the mails) conveyed in the same vehicle, nor to any persons traveling in it, unless he was in the service of the United States and passing along the road in pursuance of orders from the proper authority; and further, that the exemption could not be claimed for more carriages than were necessary for the safe, speedy and convenient conveyance of the mail.” This case is reported in full in 3d Howard U. S. Reports, page 151 et seq., including the full text of Chief Justice Taney’s opinion, and elaborate dissenting opinions by Justices McClean and Daniel. The attorneys for the road in this controversy were Hon. Robert P. Flenniken and Hon. James Veech of Uniontown, and Hon. Robert J. Walker of Mississippi, who was Secretary of the Treasury in the cabinet of President Polk. After this decision, and by reason of it, the Legislature of Pennsylvania enacted the law of April 14th, 1845, still in force, authorizing the collection of tolls from passengers traveling in coaches which at the same time carried the mail.

Origin of the Fund for Making the Road.—Acts for the Admission of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Missouri—Report of a Committee of Congress as to the Manner of Applying the Ohio Fund—Distances from Important Eastern Cities to the Ohio River—The Richmond Route Postponed—The Spirit and Perseverance of Pennsylvania—Maryland, “My Maryland,” not behind Pennsylvania—Wheeling the Objective Point—Brownsville a Prominent Point—Rivers tend to Union, Mountains to Disunion.

Act of April 30, 1802, for the admission of Ohio, provides that one-twentieth part of the net proceeds of the lands lying within the said State sold by Congress, from and after the 30th of June next, after deducting all expenses incident to the same, shall be applied to laying out and making public roads leading from navigable waters emptying into the Atlantic to the Ohio, to the said State and through the same, such roads to be laid out under the authority of Congress, with the consent of the several States through which the road shall pass.

Act of April 19, 1816, for the admission of Indiana, provides that five per cent. of the net proceeds of lands lying within the said territory, and which shall be sold by Congress from and after the first day of December next, after deducting all expenses incident to the same, shall be reserved for making public roads and canals, of which three-fifths shall be applied to those objects within the said State under the direction of the Legislature thereof, and two-fifths to the making of a road or roads leading to the said State under the direction of Congress.

Act of April 18, 1818, for the admission of Illinois, provides that five per cent. of the net proceeds of the lands lying within the said State, and which shall be sold by Congress from and after the first day of January, 1819, after deducting all expenses incident to the same, shall be reserved for the purposes following, viz: Two-fifths to be disbursed under the direction of Congress in making roads leading to the State, the residue to be appropriated by the Legislature of the State for the encouragement of learning, of which one-sixth part shall be exclusively bestowed on a college or university.

Act of March 6, 1820, admitting Missouri, provides that five per cent. of the net proceeds of the sale of lands lying within the said Territory or State, and which shall be sold by Congress from and after the first day of January next, after deducting all expenses incident to the same, shall be reserved for making public roads and canals, of which three-fifths shall be applied to those objects within the State under the direction of the Legislature thereof, and the other two-fifths in defraying, under the direction of Congress, the expenses to be incurred in making a road or roads, canal or canals, leading to the said State.

No. 195.

NINTH CONGRESS—FIRST SESSION.

CUMBERLAND ROAD.

Communicated to the Senate December 19, 1805.

Mr. Tracy, from the committee to whom was referred the examination of the act entitled, “An act to enable the people of the eastern division of the territory northwest of the river Ohio to form a Constitution and State Government, and for the admission of such State into the Union on an equal footing with the original States, and for other purposes;” and to report the manner in which, in their opinion, the money appropriated by said act ought to be applied, made the following report:

That, upon examination of the act aforesaid, they find “the one-twentieth part, or five per cent., of the net proceeds of the lands lying within the State of Ohio, and sold by Congress from and after the 30th day of June, 1802, is appropriated for the laying out and making public roads leading from the navigable waters emptying into the Atlantic to the river Ohio, to said State, and through the same; such roads to be laid out under the authority of Congress, with the consent of the several States through which the road shall pass.”

They find that by a subsequent law, passed on the 3d day of March, 1803, Congress appropriated three per cent. of the said five per cent. to laying out and making roads within the State of Ohio, leaving two per cent. of the appropriation contained in the first mentioned law unexpended, which now remains for “the laying out, and making roads from the navigable waters emptying into the Atlantic to the river Ohio, to said State.”

They find that the net proceeds of sales of land in the State of Ohio,

| From 1st July, 1802, to June 30, 1803, both inclusive, were | $124,400 92 |

| From 1st July, 1803, to June 30, 1804 | 176,203 35 |

| From 1st July, 1804, to June 30, 1805 | 266,000 00 |

| From 1st July, 1805, to Sept. 30, 1805 | 66,000 00 |

| ————— | |

| Amounting, in the whole, to | $632,604 27 |

Two per cent. on which sum amounts to $12,652. Twelve thousand six hundred and fifty-two dollars were, therefore, on the 1st day of October last, subject to the uses directed by law, as mentioned in this report; and it will be discerned that the fund is constantly accumulating, and will, probably, by the time regular preparations can be made for its expenditure, amount to eighteen or twenty thousand dollars. The committee have examined, as far as their limited time and the scanty sources of facts within their reach would permit, the various routes which have been contemplated for laying out roads pursuant to the provisions of the act first mentioned in this report.

They find that the distance from Philadelphia to Pittsburg is 314 miles by the usual route, and on a straight line about 270.

From Philadelphia to the nearest point on the river Ohio, contiguous to the State of Ohio, which is probably between Steubenville and the mouth of Grave creek, the distance by the usual route is 360 miles, and on a straight line about 308.

From Baltimore to the river Ohio, between the same points, and by the usual route, is 275 miles, and on a straight line 224.

From this city (Washington) to the same points on the river Ohio, the distance is nearly the same as from Baltimore; probably the difference is not a plurality of miles.

From Richmond, in Virginia, to the nearest point on the river Ohio, the distance by the usual route is 377 miles; but new roads are opening which will shorten the distance fifty or sixty miles; 247 miles of the contemplated road, from Richmond northwesterly, will be as good as the roads usually are in that country, but the remaining seventy or eighty miles are bad, for the present, and probably will remain so for a length of time, as there seems to be no existing inducement for the State of Virginia to incur the expense of making that part of the road passable.

From Baltimore to the Monongahela river, where the route from Baltimore to the Ohio river will intersect it, the distance as usually traveled is 218 miles, and on a straight line about 184. From this point, which is at or near Brownsville, boats can pass down, with great facility, to the State of Ohio, during a number of months in every year.

The above distances are not all stated from actual mensuration, but it is believed they are sufficiently correct for the present purpose.

The committee have not examined any routes northward of that leading from Philadelphia to the river Ohio, nor southward of that leading from Richmond, because they suppose the roads to be laid out must strike the river Ohio on some point contiguous to the State of Ohio, in order to satisfy the words of the law making the appropriation; the words are: “Leading from the navigable waters emptying into the Atlantic, to the river Ohio, to the said State, and through the same.”

The mercantile intercourse of the citizens of Ohio with those of the Atlantic States is chiefly in Philadelphia and Baltimore; not very extensive in the towns on the Potomac, within the District of Columbia, and still less with Richmond, in Virginia. At present, the greatest portion of their trade is with Philadelphia; but it is believed their trade is rapidly increasing with Baltimore, owing to the difference of distance in favor of Baltimore, and to the advantage of boating down the Monongahela river, from the point where the road strikes it, about 70 miles by water, and 50 by land, above Pittsburg.

The sum appropriated for laying out and making roads is so small that the committee have thought it most expedient to direct an expenditure to one route only. They have therefore endeavored to fix on that which, for the present, will be most accommodating to the citizens of the State of Ohio; leaving to the future benevolence and policy of congress, an extension of their operations on this or other routes, and an increase of the requisite fund, as the discoveries of experience may point out their expediency and necessity. The committee being fully convinced that a wise government can never lose sight of an object so important as that of connecting a numerous and rapidly increasing population, spread upon a fertile and extensive territory, with the Atlantic States, now separated from them by mountains, which, by industry and an expense moderate in comparison with the advantages, can be rendered passable.

The route from Richmond must necessarily approach the State of Ohio in a part thinly inhabited, and which, from the nature of the soil and other circumstances, must remain so, at least for a considerable time; and, from the hilly and rough condition of the country, no roads are or can be conveniently made, leading to the principal population of the State of Ohio.

These considerations have induced the committee to postpone, for the present, any further consideration of that route.

The spirit and perseverance of Pennsylvania are such, in the matter of road making, that no doubt can remain but they will, in a little time, complete a road from Philadelphia to Pittsburg, as good as the nature of the ground will permit. They are so particularly interested to facilitate the intercourse between their trading capital, Philadelphia, not only to Pittsburg, but also to the extensive country within that State, on the western waters, that they will, of course, surmount the difficulties presented by the Allegheny mountain, Chestnut Ridge and Laurel Hill, the three great and almost exclusive impediments which now exist on that route.

The State of Maryland, with no less spirit and perseverance, are engaged in making roads from Baltimore and from the western boundary of the District of Columbia, through Fredericktown, to Williamsport. Were the Government of the United States to direct the expenditure of the fund in contemplation upon either of these routes, for the present, in Pennsylvania or Maryland, it would, probably, so far interfere with the operations of the respective States, as to produce mischief instead of benefit; especially as the sum to be laid out by the United States is too inconsiderable, alone, to effect objects of such magnitude. But as the State of Maryland have no particular interest to extend their road across the mountains (and if they had it would be impracticable, because the State does not extend so far), the committee have thought it expedient to recommend the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, on the northerly bank of the Potomac, and within the State of Maryland, to the river Ohio, at the most convenient place between a point on the easterly bank of said river, opposite to Steubenville, and the mouth of Grave creek, which empties into said river Ohio a little below Wheeling, in Virginia. This route will meet and accommodate the roads leading from Baltimore and the District of Columbia; it will cross the Monongahela river, at or near Brownsville, sometimes called Redstone, where the advantage of boating can be taken; and from the point where it will probably intersect the river Ohio, there are now roads, or they can easily be made over feasible and proper ground, to and through the principal population of the State of Ohio.

Cumberland is situated at the eastern foot of the Allegheny mountains, about eighty miles from Williamsport, by the usual route, which is circuitous, owing to a large bend in the river Potomac, on the bank of which the road now runs, the distance on a straight line is not more than fifty or fifty-five miles, and over tolerable ground for a road, which will probably be opened by the State of Maryland, should the route be established over the mountains, as contemplated by this report.

From Cumberland to the western extremity of Laurel Hill, by the route now travelled, the distance is sixty-six miles, and on a straight line about fifty-five; on this part of the route, the committee suppose the first and very considerable expenditures are specially necessary. From Laurel Hill to the Ohio river, by the usual route, is about seventy miles, and on a straight line fifty-four or five; the road is tolerable, though capable of amelioration.

To carry into effect the principles arising from the foregoing facts, the committee present herewith a bill for the consideration of the Senate. They suppose that to take the proper measures for carrying into effect the section of the law respecting a road or roads to the State of Ohio, is a duty imposed upon Congress by the law itself, and that a sense of duty will always be sufficient to insure the passage of the bill now offered to the Senate. To enlarge upon the highly important considerations of cementing the union of our citizens located on the Western waters with those of the Atlantic States, would be an indelicacy offered to the understandings of the body to whom this report is addressed, as it might seem to distrust them. But from the interesting nature of the subject, the committee are induced to ask the indulgence of a single observation: Politicians have generally agreed that rivers unite the interests and promote the friendship of those who inhabit their banks; while mountains, on the contrary, tend to the disunion and estrangement of those who are separated by their intervention. In the present case, to make the crooked ways straight, and the rough ways smooth will, in effect, remove the intervening mountains, and by facilitating the intercourse of our Western brethren with those on the Atlantic, substantially unite them in interest, which, the committee believe, is the most effectual cement of union applicable to the human race.

All which is most respectfully submitted.

The Act of Congress Authorizing the Laying Out and Making of the Road.

An Act to Regulate the Laying Out and Making a Road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the President of the United States be, and he is hereby authorized to appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, three discreet and disinterested citizens of the United States, to lay out a road from Cumberland, or a point on the northern bank of the river Potomac, in the State of Maryland, between Cumberland and the place where the main road leading from Gwynn’s to Winchester, in Virginia, crosses the river, to the State of Ohio; whose duty it shall be, as soon as may be, after their appointment, to repair to Cumberland aforesaid, and view the ground, from the points on the river Potomac hereinbefore designated, to the river Ohio; and to lay out in such direction as they shall judge, under all circumstances the most proper, a road from thence to the river Ohio, to strike the same at the most convenient place, between a point on its eastern bank, opposite the northern boundary of Steubenville, in said State of Ohio, and the mouth of Grave creek, which empties into the said river a little below Wheeling, in Virginia.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That the aforesaid road shall be laid out four rods in width, and designated on each side by a plain and distinguishable mark on a tree, or by the erection of a stake or monument sufficiently conspicuous, in every quarter of a mile of the distance at least, where the road pursues a straight course so far or farther, and on each side, at every point where an angle occurs in its course.

Sec. 3. And be it further enacted, That the commissioners shall, as soon as may be, after they have laid out said road, as aforesaid, present to the President an accurate plan of the same, with its several courses and distances, accompanied by a written report of their proceedings, describing the marks and monuments by which the road is designated, and the face of the country over which it passes, and pointing out the particular parts which they shall judge require the most and immediate attention and amelioration, and the probable expense of making the same passable in the most difficult parts, and through the whole distance; designating the State or States through which said road has been laid out, and the length of the several parts which are laid out on new ground, as well as the length of those parts laid out on the road now traveled. Which report the President is hereby authorized to accept or reject, in the whole or in part. If he accepts, he is hereby further authorized and requested to pursue such measures, as in his opinion shall be proper, to obtain consent for making the road, of the State or States through which the same has been laid out. Which consent being obtained, he is further authorized to take prompt and effectual measures to cause said road to be made through the whole distance, or in any part or parts of the same as he shall judge most conducive to the public good, having reference to the sum appropriated for the purpose.

Sec. 4. And be it further enacted, That all parts of the road which the President shall direct to be made, in case the trees are standing, shall be cleared the whole width of four rods; and the road shall be raised in the middle of the carriageway with stone, earth, or gravel and sand, or a combination of some or all of them, leaving or making, as the case may be, a ditch or water course on each side and contiguous to said carriageway, and in no instance shall there be an elevation in said road, when finished, greater than an angle of five degrees with the horizon. But the manner of making said road, in every other particular, is left to the direction of the President.

Sec. 5. And be it further enacted, That said Commissioners shall each receive four dollars per day, while employed as aforesaid, in full for their compensation, including all expenses. And they are hereby authorized to employ one surveyor, two chainmen and one marker, for whose faithfulness and accuracy they, the said Commissioners, shall be responsible, to attend them in laying out said road, who shall receive in full satisfaction for their wages, including all expenses, the surveyor three dollars per day, and each chainman and the marker one dollar per day, while they shall be employed in said business, of which fact a certificate signed by said commissioners shall be deemed sufficient evidence.

Sec. 6. And be it further enacted, That the sum of thirty thousand dollars be, and the same is hereby appropriated, to defray the expense of laying out and making said road. And the President is hereby authorized to draw, from time to time, on the treasury for such parts, or at any one time, for the whole of said sum, as he shall judge the service requires. Which sum of thirty thousand dollars shall be paid, first, out of the fund of two per cent, reserved for laying out and making roads to the State of Ohio, by virtue of the seventh section of an act passed on the thirtieth day of April, one thousand eight hundred and two, entitled, “An act to enable the people of the eastern division of the territory northwest of the river Ohio to form a constitution and State government, and for the admission of such State into the Union on an equal footing with the original States, and for other purposes.” Three per cent. of the appropriation contained in said seventh section being directed by a subsequent law to the laying out, opening and making roads within the said State of Ohio; and secondly, out of any money in the treasury not otherwise appropriated, chargeable upon, and reimbursable at the treasury by said fund of two per cent. as the same shall accrue.

Sec. 7. And be it further enacted, That the President be, and he is hereby requested, to cause to be laid before Congress, as soon as convenience will permit, after the commencement of each session, a statement of the proceedings under this act, that Congress may be enabled to adopt such further measures as may from time to time be proper under existing circumstances.

| United States of America, Department of State. |

} |

To all to whom these presents shall come, Greeting:

I certify that hereto annexed is a true copy of an Act of Congress, approved March 29, 1806, the original of which is on file in this Department, entitled: “An Act to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio.”

In testimony whereof, I, James G. Blaine, Secretary of State of the United States, have hereunto subscribed my name and caused the seal of the Department of State to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this seventh day of March, A. D. 1891, and of the Independence of the United States the one hundred and fifteenth.

Special Message of President Jefferson—Communicating to Congress the First Report of the Commissioners—They View the Whole Ground—Solicitude of the Inhabitants—Points Considered—Cumberland the First Point Located—Uniontown Left Out—Improvement of the Youghiogheny—Distances—Connellsville a Promising Town—“A Well Formed, Stone Capped Road”—Estimated Cost, $6,000 per Mile, exclusive of Bridges.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:

In execution of the act of the last session of Congress, entitled, “An act to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio,” I appointed Thomas Moore, of Maryland, Joseph Kerr, of Ohio, and Eli Williams, of Maryland, commissioners to lay out the said road, and to perform the other duties assigned to them by the act. The progress which they made in the execution of the work, during the last season, will appear in their report now communicated to Congress; on the receipt of it, I took measures to obtain consent for making the road of the States of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia, through which the commissioners propose to lay it out. I have received acts of the Legislatures of Maryland and Virginia, giving the consent desired; that of Pennsylvania has the subject still under consideration, as is supposed. Until I receive full consent to a free choice of route through the whole distance, I have thought it safest neither to accept nor reject, finally, the partial report of the commissioners.

Some matters suggested in the report belong exclusively to the legislature.

The commissioners, acting by appointment under the law of Congress, entitled “An act to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio,” beg leave to report to the President of the United States, and to premise that the duties imposed by the law became a work of greater magnitude, and a task much more arduous, than was conceived before entering upon it; from which circumstance the commissioners did not allow themselves sufficient time for the performance of it before the severity of the weather obliged them to retire from it, which was the case in the first week of the present month (December). That, not having fully accomplished their work, they are unable fully to report a discharge of all the duties enjoined by the law; but as the most material and principal part has been performed, and as a communication of the progress already made may be useful and proper, during the present session of Congress, and of the Legislatures of those States through which the route passes, the commissioners respectfully state that at a very early period it was conceived that the maps of the country were not sufficiently accurate to afford a minute knowledge of the true courses between the extreme points on the rivers, by which the researches of the commissioners were to be governed; a survey for that purpose became indispensable, and considerations of public economy suggested the propriety of making this survey precede the personal attendance of the commissioners.

Josias Thompson, a surveyor of professional merit, was taken into service and authorized to employ two chain carriers and a marker, as well as one vaneman, and a packhorse man and horse, on public account; the latter being indispensable and really beneficial in excelerating the work. The surveyors’ instructions are contained in document No. 1, accompanying this report.

Calculating on a reasonable time for the performance of the instructions to the surveyor, the commissioners, by correspondence, fixed on the first day of September last, for their meeting at Cumberland to proceed in the work; neither of them, however, reached that place until the third of that month, on which day they all met.

The surveyor having, under his instructions, laid down a plat of his work, showing the meanders of the Potomac and Ohio rivers, within the limits prescribed for the commissioners, as also the road between those rivers, which is commonly traveled from Cumberland to Charleston, in part called Braddock’s road; and the same being produced to the commissioners, whereby straight lines and their true courses were shown between the extreme points on each river, and the boundaries which limit the powers of the commissioners being thereby ascertained, serving as a basis whereon to proceed in the examination of the grounds and face of the country; the commissioners thus prepared commenced the business of exploring; and in this it was considered that a faithful discharge of the discretionary powers vested by the law made it necessary to view the whole to be able to judge of a preference due to any part of the grounds, which imposed a task of examining a space comprehending upwards of two thousand square miles; a task rendered still more incumbent by the solicitude and importunities of the inhabitants of every part of the district, who severally conceived their grounds entitled to a preference. It becoming necessary, in the interim, to run various lines of experiment for ascertaining the geographical position of several points entitled to attention, and the service suffering great delay for want of another surveyor, it was thought consistent with the public interest to employ, in that capacity, Arthur Rider, the vaneman, who had been chosen with qualification to meet such an emergency; and whose service as vaneman could then be dispensed with. He commenced, as surveyor, on the 22d day of September, and continued so at field work until the first day of December, when he was retained as a necessary assistant to the principal surveyor, in copying field notes and hastening the draught of the work to be reported.

The proceedings of the commissioners are specially detailed in their general journal, compiled from the daily journal of each commissioner, to which they beg leave to refer, under mark No. 2.

After a careful and critical examination of all the grounds within the limits prescribed, as well as the grounds and ways out from the Ohio westwardly, at several points, and examining the shoal parts of the Ohio river as detailed in the table of soundings, stated in their journal, and after gaining all the information, geographical, general and special, possible and necessary, toward a judicial discharge of the duties assigned them, the commissioners repaired to Cumberland to examine and compare their notes and journals, and determine upon the direction and location of their route.

In this consultation the governing objects were:

1st. Shortness of distance between navigable points on the eastern and western waters.

2d. A point on the Monongahela best calculated to equalize the advantages of this portage in the country within reach of it.

3d. A point on the Ohio river most capable of combining certainty of navigation with road accommodation; embracing, in this estimate, remote points westwardly, as well as present and probable population on the north and south.

4th. Best mode of diffusing benefits with least distance of road.

In contemplating these objects, due attention was paid as well to the comparative merits of towns, establishments, and settlements already made, as to the capacity of the country with the present and probable population.

In the course of arrangement, and in its order, the first point located for the route was determined and fixed at Cumberland, a decision founded on propriety, and in some measure on necessity, from the circumstance of a high and difficult mountain, called Nobley, laying and confining the east margin of the Potomac so as to render it impossible of access on that side without immense expense, at any point between Cumberland and where the road from Winchester to Gwynn’s crosses, and even there the Nobley mountain is crossed with much difficulty and hazard. And this upper point was taxed with another formidable objection; it was found that a high range of mountains, called Dan’s, stretching across from Gwynn’s to the Potomac, above this point, precluded the opportunity of extending a route from this point in a proper direction, and left no alternative but passing by Gwynn’s; the distance from Cumberland to Gwynn’s being upward of a mile less than from the upper point, which lies ten miles by water above Cumberland, the commissioners were not permitted to hesitate in preferring a point which shortens the portage, as well as the Potomac navigation.

The point on the Potomac being viewed as a great repository of produce, which a good road will bring from the west of Laurel Hill, and the advantages which Cumberland, as a town, has in that respect over an unimproved place, are additional considerations operating forcibly in favor of the place preferred.

In extending the route from Cumberland, a triple range of mountains, stretching across from Jenings’ run in measure with Gwynn’s, left only the alternative of laying the road up Will’s creek for three miles, nearly at right angles with the true course, and then by way of Jenings’ run, or extending it over a break in the smallest mountain, on a better course by Gwynn’s, to the top of Savage mountain; the latter was adopted, being the shortest, and will be less expensive in hill-side digging over a sloped route than the former, requiring one bridge over Will’s creek and several over Jenings’ run, both very wide and considerable streams in high water; and a more weighty reason for preferring the route by Gwynn’s is the great accommodation it will afford travelers from Winchester by the upper point, who could not reach the route by Jenings’ run short of the top of Savage, which would withhold from them the benefit of an easy way up the mountain.

It is, however, supposed that those who travel from Winchester by way of the upper point to Gwynn’s, are in that respect more the dupes of common prejudice than judges of their own case, as it is believed the way will be as short, and on much better ground, to cross the Potomac below the confluence of the north and south branches (thereby crossing these two, as well as Patterson’s creek, in one stream, equally fordable in the same season), than to pass through Cumberland to Gwynn’s. Of these grounds, however, the commissioners do not speak from actual view, but consider it a subject well worthy of future investigation. Having gained the top of Allegany mountain, or rather the top of that part called Savage, by way of Gwynn’s, the general route, as it respects the most important points, was determined as follows, viz.:

From a stone at the corner of lot No. 1, in Cumberland, near the confluence of Will’s creek and the north branch of the Potomac river; thence extending along the street westwardly, to cross the hill lying between Cumberland and Gwynn’s, at the gap where Braddock’s road passes it; thence near Gwynn’s and Jesse Tomlinson’s, to cross the big Youghiogheny near the mouth of Roger’s run, between the crossing of Braddock’s road and the confluence of the streams which form the Turkey foot; thence to cross Laurel Hill near the forks of Dunbar’s run, to the west foot of that hill, at a point near where Braddock’s old road reached it, near Gist’s old place, now Colonel Isaac Meason’s, thence through Brownsville and Bridgeport, to cross the Monongahela river below Josias Crawford’s ferry; and thence on as straight a course as the country will admit to the Ohio, at a point between the mouth of Wheeling creek and the lower point of Wheeling island.

In this direction of the route it will lay about twenty-four and a half miles in Maryland, seventy-five miles and a half in Pennsylvania, and twelve miles in Virginia; distances which will be in a small degree increased by meanders, which the bed of the road must necessarily make between the points mentioned in the location; and this route, it is believed, comprehends more important advantages than could be afforded in any other, inasmuch as it has a capacity at least equal to any other in extending advantages of a highway, and at the same time establishes the shortest portage between the points already navigated, and on the way accommodates other and nearer points to which navigation may be extended, and still shorten the portage.

It intersects Big Youghiogheny at the nearest point from Cumberland, then lies nearly parallel with that river for the distance of twenty miles, and at the west foot of Laurel Hill lies within five miles of Connellsville, from which the Youghiogheny is navigated; and in the same direction the route intersects at Brownsville the nearest point on the Monongahela river within the district.

The improvement of the Youghiogheny navigation is a subject of too much importance to remain long neglected; and the capacity of that river, as high up as the falls (twelve miles above Connellsville), is said to be equal, at a small expense, with the parts already navigated below. The obstructions at the falls, and a rocky rapid near Turkey Foot, constitute the principal impediments in that river to the intersection of the route, and as much higher as the stream has a capacity for navigation; and these difficulties will doubtless be removed when the intercourse shall warrant the measure.

Under these circumstances the portage may be thus stated:

From Cumberland to Monongahela, 66½ miles. From Cumberland to a point in measure with Connellsville, on the Youghiogheny river, 51½ miles. From Cumberland to a point in measure with the lower end of the falls of Youghiogheny, which will lie two miles north of the public road, 43 miles. From Cumberland to the intersection of the route with the Youghiogheny river, 34 miles.

Nothing is here said of the Little Youghiogheny, which lies nearer Cumberland; the stream being unusually crooked, its navigation can only become the work of a redundant population.

The point which this route locates, at the west foot of Laurel Hill, having cleared the whole of the Allegheny mountain, is so situated as to extend the advantages of an easy way through the great barrier, with more equal justice to the best parts of the country between Laurel Hill and the Ohio. Lines from this point to Pittsburg and Morgantown, diverging nearly at the same angle, open upon equal terms to all parts of the Western country that can make use of this portage; and which may include the settlements from Pittsburg, up Big Beaver to the Connecticut reserve, on Lake Erie, as well as those on the southern borders of the Ohio and all the intermediate country.

Brownsville is nearly equi-distant from Big Beaver and Fishing creek, and equally convenient to all the crossing places on the Ohio, between these extremes. As a port, it is at least equal to any on the Monongahela within the limits, and holds superior advantages in furnishing supplies to emigrants, traders, and other travelers by land or water.

Not unmindful of the claims of towns and their capacity of reciprocating advantages on public roads, the commissioners were not insensible of the disadvantage which Uniontown must feel from the want of that accommodation which a more southwardly direction of the route would have afforded; but as that could not take place without a relinquishment of the shortest passage, considerations of public benefit could not yield to feelings of minor import. Uniontown being the seat of justice for Fayette county, Pennsylvania, is not without a share of public benefits, and may partake of the advantages of this portage upon equal terms with Connellsville, a growing town, with the advantage of respectable water-works adjoining, in the manufactory of flour and iron.

After reaching the nearest navigation on the western waters, at a point best calculated to diffuse the benefits of a great highway in the greatest possible latitude east of the Ohio, it was considered that, to fulfill the objects of the law, it remained for the commissioners to give such a direction to the road as would best secure a certainty of navigation on the Ohio at all seasons, combining, as far as possible, the inland accommodation of remote points westwardly. It was found that the obstructions in the Ohio, within the limits between Steubenville and Grave creek, lay principally above the town and mouth of Wheeling; a circumstance ascertained by the commissioners in their examination of the channel, as well as by common usage, which has long given a decided preference to Wheeling as a place of embarcation and port of departure in dry seasons. It was also seen that Wheeling lay in a line from Brownsville to the centre of the State of Ohio and Post Vincennes. These circumstances favoring and corresponding with the chief objects in view in this last direction of the route, and the ground from Wheeling westwardly being known of equal fitness with any other way out from the river, it was thought most proper, under these several considerations, to locate the point mentioned below the mouth of Wheeling. In taking this point in preference to one higher up and in the town of Wheeling, the public benefit and convenience were consulted, inasmuch as the present crossing place over the Ohio from the town is so contrived and confined as to subject passengers to extraordinary ferriage and delay, by entering and clearing a ferry-boat on each side of Wheeling island, which lies before the town and precludes the opportunity of fording when the river is crossed in that way, above and below the island. From the point located, a safe crossing is afforded at the lower point of the island by a ferry in high, and a good ford at low water.

The face of the country within the limits prescribed is generally very uneven, and in many places broken by a succession of high mountains and deep hollows, too formidable to be reduced within five degrees of the horizon, but by crossing them obliquely, a mode which, although it imposes a heavy task of hill-side digging, obviates generally the necessity of reducing hills and filling hollows, which, on these grounds, would be an attempt truly Quixotic. This inequality of the surface is not confined to the Allegheny mountain; the country between the Monongahela and Ohio rivers, although less elevated, is not better adapted for the bed of a road, being filled with impediments of hills and hollows, which present considerable difficulties, and wants that super-abundance and convenience of stone which is found in the mountain.

The indirect course of the road now traveled, and the frequent elevations and depressions which occur, that exceed the limits of the law, preclude the possibility of occupying it in any extent without great sacrifice of distance, and forbid the use of it, in any one part, for more than half a mile, or more than two or three miles in the whole.

The expense of rendering the road now in contemplation passable, may, therefore, amount to a larger sum than may have been supposed necessary, under an idea of embracing in it a considerable part of the old road; but it is believed that the contrary will be found most correct, and that a sum sufficient to open the new could not be expended on the same distance of the old road with equal benefit.

The sum required for the road in contemplation will depend on the style and manner of making it; as a common road cannot remove the difficulties which always exist on deep grounds, and particularly in wet seasons, and as nothing short of a firm, substantial, well-formed, stone-capped road can remove the causes which led to the measure of improvement, or render the institution as commodious as a great and growing intercourse appears to require, the expense of such a road next becomes the subject of inquiry.

In this inquiry the commissioners can only form an estimate by recurring to the experience of Pennsylvania and Maryland in the business of artificial roads. Upon this data, and a comparison of the grounds and proximity of the materials for covering, there are reasons for belief that, on the route reported, a complete road may be made at an expense not exceeding six thousand dollars per mile, exclusive of bridges over the principal streams on the way. The average expense of the Lancaster, as well as Baltimore and Frederick turnpike, is considerably higher; but it is believed that the convenient supply of stone which the mountain affords will, on those grounds, reduce the expense to the rate here stated.

As to the policy of incurring this expense, it is not the province of the commissioners to declare; but they cannot, however, withhold assurances of a firm belief that the purse of the nation cannot be more seasonably opened, or more happily applied, than in promoting the speedy and effectual establishment of a great and easy road on the way contemplated.

In the discharge of all these duties, the commissioners have been actuated by an ardent desire to render the institution as useful and commodious as possible; and, impressed with a strong sense of the necessity which urges the speedy establishment of the road, they have to regret the circumstance which delays the completion of the part assigned them. They, however, in some measure, content themselves with the reflection that it will not retard the progress of the work, as the opening of the road cannot commence before spring, and may then begin with marking the way.

The extra expense incident to the service from the necessity (and propriety, as it relates to public economy,) of employing men not provided for by law, will, it is hoped, be recognized, and provision made for the payment of that and similar expenses, when in future it may be indispensably incurred.

The commissioners having engaged in a service in which their zeal did not permit them to calculate the difference between their pay and the expense to which the service subjected them, cannot suppose it the wish or intention of the Government to accept of their services for a mere indemnification of their expense of subsistence, which will be very much the case under the present allowance; they, therefore, allow themselves to hope and expect that measures will be taken to provide such further compensation as may, under all circumstances, be thought neither profuse nor parsimonious.

The painful anxiety manifested by the inhabitants of the district explored, and their general desire to know the route determined on, suggested the measure of promulgation, which, after some deliberation, was agreed on by way of circular letter, which has been forwarded to those persons to whom precaution was useful, and afterward sent to one of the presses in that quarter for publication, in the form of the document No. 3, which accompanies this report.

All which is, with due deference, submitted.

Pennsylvania Grants Permission to Make the Road Through Her Territory—Uniontown Restored, Gist Left Out, and Washington, Pennsylvania, Made a Point—Simon Snyder, Speaker of the House—Pressly Carr Lane, a Fayette County Man, Speaker of the Senate, and Thomas McKean, Governor—A Second Special Message From President Jefferson, and a Second Report of the Commissioners—Heights of Mountains and Hills—On to Brownsville and Wheeling—An Imperious Call Made on Commissioner Kerr.

An Act authorizing the President of the United States to open a road through that part of this State lying between Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, and the Ohio river.

Whereas, by an Act of the Congress of the United States, passed on the twenty-ninth day of March, one thousand eight hundred and six, entitled “An act to regulate the laying out and making a road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio,” the President of the United States is empowered to lay out a road from the Potomac river to the river Ohio, and to take measures for making the same, so soon as the consent of the legislatures of the several States through which the said road shall pass, could be obtained: And whereas, application hath been made to this legislature, by the President of the United States, for its consent to the measures aforesaid: Therefore,

Section 1. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, in General Assembly met, and it is hereby enacted by the authority of the same, That the President of the United States be, and he is hereby authorized to cause so much of the said road as will be within this State, to be opened so far as it may be necessary the same should pass through this State, and to cause the said road to be made, regulated and completed, within the limits, and according to the intent and meaning of the before recited Act of Congress in relation thereto; Provided, nevertheless, That the route laid down and reported by the commissioners to the President of the United States, be so altered as to pass through Uniontown, in the county of Fayette, and Washington, in the county of Washington, if such alteration can, in the opinion of the President, be made, consistently with the provisions of an act of Congress passed March 29th, 1806, but if not, then over any ground within the limit of this State, which he may deem most advantageous.

Sec 2. And be it further enacted by the authority aforesaid, That such person or persons as are or shall be appointed for the purpose of laying out and completing the said road, under the authority of the United States, shall have full power and authority to enter upon the lands through which the same may pass, and upon any land near or adjacent thereto, and therefrom to take, dig, cut and carry away such materials of earth, stone, gravel, timber and sand as may be necessary for the purpose of completing, and for ever keeping in repair, said road; Provided, That such materials shall be valued and appraised, in the same manner as materials taken for similar purposes, under the authority of this Commonwealth are by the laws thereof, directed to be valued and appraised, and a certificate of the amount thereof shall, by the person or persons appointed, or hereafter to be appointed under the authority of the United States for the purpose aforesaid, be delivered to each party entitled thereto, for any materials to be taken by virtue of this act, to entitle him, her or them to receive payment therefor from the United States.

Approved, the ninth day of April, one thousand eight hundred and

seven.

THOMAS M’KEAN.

TENTH CONGRESS—FIRST SESSION.

Communicated to Congress February 19, 1808.

To the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States:

The States of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia having, by their several acts consented that the road from Cumberland to the State of Ohio, authorized by the act of Congress of March 29, 1806, should pass through those States, and the report of the commissioners communicated to Congress with my message of January 31, 1807, having been duly considered, I have approved of the route therein proposed for the said road as far as Brownsville, with a single deviation since located, which carries it through Uniontown.

From thence the course to the Ohio, and the point within the legal limits at which it shall strike that river, is still to be decided.

In forming this decision, I shall pay material regard to the interests and wishes of the populous parts of the State of Ohio, and to a future and convenient connection with the road which is to lead from the Indian boundary near Cincinnati, by Vincennes, to the Mississippi, at St. Louis, under authority of the act of April 21, 1806. In this way we may accomplish a continuous and advantageous line of communication from the seat of the General Government to St. Louis, passing through several very interesting points, to the Western country.

I have thought it advisable, also, to secure from obliteration the trace of the road so far as it has been approved, which has been executed at such considerable expense, by opening one-half of its breadth through its whole length.

The report of the commissioners herewith transmitted will give particular information of their proceedings under the act of March 29, 1806, since the date of my message of January 31, 1807, and will enable Congress to adopt such further measures, relative thereto, as they may deem proper under existing circumstances.