| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

LATIN LANGUAGE. 1. Earliest Records of its Area.—Latin was the language spoken in Rome and in the plain of Latium in the 6th or 7th century B.C.—the earliest period from which we have any contemporary record of its existence. But it is as yet impossible to determine either, on the one hand, whether the archaic inscription of Praeneste (see below), which is assigned with great probability to that epoch, represents exactly the language then spoken in Rome; or, on the other, over how much larger an area of the Italian peninsula, or even of the lands to the north and west, the same language may at that date have extended. In the 5th century B.C. we find its limits within the peninsula fixed on the north-west and south-west by Etruscan (see Etruria: Language); on the east, south-east, and probably north and north-east, by Safine (Sabine) dialects (of the Marsi, Paeligni, Samnites, Sabini and Picenum, qq.v.); but on the north we have no direct record of Sabine speech, nor of any non-Latinian tongue nearer than Tuder and Asculum or earlier than the 4th century B.C. (see Umbria, Iguvium, Picenum). We know however, both from tradition and from the archaeological data, that the Safine tribes were in the 5th century B.C. migrating, or at least sending off swarms of their younger folk, farther and farther southward into the peninsula. Of the languages they were then displacing we have no explicit record save in the case of Etruscan in Campania, but it may be reasonably inferred from the evidence of place-names and tribal names, combined with that of the Faliscan inscriptions, that before the Safine invasion some idiom, not remote from Latin, was spoken by the pre-Etruscan tribes down the length of the west coast (see Falisci; Volsci; also Rome: History; Liguria; Siculi).

2. Earliest Roman Inscriptions.—At Rome, at all events, it is clear from the unwavering voice of tradition that Latin was spoken from the beginning of the city. Of the earliest Latin inscriptions found in Rome which were known in 1909, the oldest, the so-called “Forum inscription,” can hardly be referred with confidence to an earlier century than the 5th; the later, the well-known Duenos (= later Latin bonus) inscription, certainly belongs to the 4th; both of these are briefly described below (§§ 40, 41). At this date we have probably the period of the narrowest extension of Latin; non-Latin idioms were spoken in Etruria, Umbria, Picenum and in the Marsian and Volscian hills. But almost directly the area begins to expand again, and after the war with Pyrrhus the Roman arms had planted the language of Rome in her military colonies throughout the peninsula. When we come to the 3rd century B.C. the Latin inscriptions begin to be more numerous, and in them (e.g. the oldest epitaphs of the Scipio family) the language is very little removed from what it was in the time of Plautus.

3. The Italic Group of Languages.—For the characteristics and affinities of the dialects that have just been mentioned, see the article Italy: Ancient Languages and Peoples, and to the separate articles on the tribes. Here it is well to point out that the only one of these languages which is not akin to Latin is Etruscan; on the other hand, the only one very closely resembling Latin is Faliscan, which with it forms what we may call the Latinian dialect of the Italic group of the Indo-European family of languages. Since, however, we have a far more complete knowledge of Latin than of any other member of the Italic group, this is the most convenient place in which to state briefly the very little that can be said as yet to have been ascertained as to the general relations of Italic to its sister groups. Here, as in many kindred questions, the work of Paul Kretschmer of Vienna (Einleitung in die Geschichte der griechischen Sprache, Göttingen, 1896) marked an important epoch in the historical aspects of linguistic study, as the first scientific attempt to interpret critically the different kinds of evidence which the Indo-European languages give us, not in vocabulary merely, but in phonology, morphology, and especially in their mutual borrowings, and to combine it with the non-linguistic data of tradition and archaeology. A certain number of the results so obtained have met with general acceptance and may be briefly treated here. It is, however, extremely dangerous to draw merely from linguistic kinship deductions as to racial identity, or even as to an original contiguity of habitation. Close resemblances in any two languages, especially those in their inner structure (morphology), may be due to identity of race, or to long neighbourhood in the earliest period of their development; but they may also be caused by temporary neighbourhood (for a longer or shorter period), brought about by migrations at a later epoch (or epochs). A particular change in sound or usage may spread over a whole chain of dialects and be in the end exhibited alike by them all, although the time at which it first began was long after their special and distinctive characteristics had become clearly marked. For example, the limitation of the word-accent to the last three syllables of a word in Latin and Oscan (see below)—a phenomenon which has left deep marks on all the Romance languages—demonstrably grew up between the 5th and 2nd centuries B.C.; and it is a permissible conjecture that it started from the influence of the Greek colonies in Italy (especially Cumae and Naples), in whose language the same limitation (although with an accent whose actual character was probably more largely musical) had been established some centuries sooner.

4. Position of the Italic Group.—The Italic group, then, when compared with the other seven main “families” of Indo-European 245 speech, in respect of their most significant differences, ranges itself thus:

(i.) Back-palatal and Velar Sounds.—In point of its treatment of the Indo-European back-palatal and velar sounds, it belongs to the western or centum group, the name of which is, of course, taken from Latin; that is to say, like German, Celtic and Greek, it did not sibilate original k and g, which in Indo-Iranian, Armenian, Slavonic and Albanian have been converted into various types of sibilants (Ind.-Eur.* kṃtom = Lat. centum, Gr. (ἑ)-κατόν, Welsh cant, Eng. hund-(red), but Sans. ṡatam, Zend satƏm); but, on the other hand, in company with just the same three western groups, and in contrast to the eastern, the Italic languages labialized the original velars (Ind.-Eur. * qod = Lat. quod, Osc. pod, Gr. ποδ-(απός), Welsh pwy, Eng. what, but Sans. kás, “who?”).

(ii.) Indo-European Aspirates.—Like Greek and Sanskrit, but in contrast to all the other groups (even to Zend and Armenian), the Italic group largely preserves a distinction between the Indo-European mediae aspiratae and mediae (e.g. between Ind.-Eur. dh and d, the former when initial becoming initially regularly Lat. f as in Lat. fēc-ī [cf. Umb. feia, “faciat”], beside Gr. ἔ-θηκ-α [cf. Sans. da-dhā-ti, “he places”], the latter simply d as in domus, Gr. δόμος). But the aspiratae, even where thus distinctly treated in Italic, became fricatives, not pure aspirates, a character which they only retained in Greek and Sanskrit.

(iii.) Indo-European ŏ.—With Greek and Celtic, Latin preserved the Indo-European ŏ, which in the more northerly groups (Germanic, Balto-Slavonic), and also in Indo-Iranian, and, curiously, in Messapian, was confused with ă. The name for olive-oil, which spread with the use of this commodity from Greek (ἔλαιϝον) to Italic speakers and thence to the north, becoming by regular changes (see below) in Latin first *ólaivom, then *óleivom, and then taken into Gothic and becoming alēv, leaving its parent form to change further (not later than 100 B.C.) in Latin to oleum, is a particularly important example, because (a) of the chronological limits which are implied, however roughly, in the process just described, and (b) of the close association in time of the change of o to a with the earlier stages of the “sound-shifting” (of the Indo-European plosives and aspirates) in German; see Kretschmer, Einleit. p. 116, and the authorities he cites.

(iv.) Accentuation.—One marked innovation common to the western groups as compared with what Greek and Sanskrit show to have been an earlier feature of the Indo-European parent speech was the development of a strong expiratory (sometimes called stress) accent upon the first syllable of all words. This appears early in the history of Italic, Celtic, Lettish (probably, and at a still later period) in Germanic, though at a period later than the beginning of the “sound-shifting.” This extinguished the complex system of Indo-European accentuation, which is directly reflected in Sanskrit, and was itself replaced in Latin and Oscan by another system already mentioned, but not in Latin till it had produced marked effects upon the language (e.g. the degradation of the vowels in compounds as in cōnficio from cón-facio, inclūdo from ín-claudo). This curious wave of accentual change (first pointed out by Dieterich, Kuhn’s Zeitschrift, i., and later by Thurneysen, Revue celtique, vi. 312, Rheinisches Museum, xliii. 349) needs and deserves to be more closely investigated from a chronological standpoint. At present it is not clear how far it was a really connected process in all the languages. (See further Kretschmer, op. cit. p. 115, K. Brugmann, Kurze vergleichende Grammatik (1902-1904), p. 57, and their citations, especially Meyer-Lübke, Die Betonung im Gallischen (1901).)

To these larger affinities may be added some important points in which the Italic group shows marked resemblances to other groups.

5. Italic and Celtic.—It is now universally admitted that the Celtic languages stand in a much closer relation than any other group to the Italic. It may even be doubted whether there was any real frontier-line at all between the two groups before the Etruscan invasion of Italy (see Etruria: Language; Liguria). The number of morphological innovations on the Indo-European system which the two groups share, and which are almost if not wholly peculiar to them, is particularly striking. Of these the chief are the following.

(i.) Extension of the abstract-noun stems in -ti- (like Greek φάτις with Attic βάσις, &c.) by an -n- suffix, as in Lat. mentio (stem mentiōn-) = Ir. (er-)mitiu (stem miti-n-), contrasted with the same word without the n-suffix in Sans. mati-, Lat. mens, Ind.-Eur. *mṇ-ti-. A similar extension (shared also by Gothic) appears in Lat. iuventū-t-, O. Ir. óitiu (stem oiliūt-) beside the simple -tu- in nouns like senātus.

(ii.) Superlative formation in -is-ṃmo- as in Lat. aegerrimus for *aegr-isṃmos, Gallic Οὐξισάμη the name of a town meaning “the highest.”

(iii.) Genitive singular of the o-stems (second declension) in -ī Lat. agri, O. Ir. (Ogam inscriptions) magi, “of a son.”

(iv.) Passive and deponent formation in -r, Lat. sequitur = Ir. sechedar, “he follows.” The originally active meaning of this curious -r suffix was first pointed out by Zimmer (Kuhn’s Zeitschrift, 1888, xxx. 224), who thus explained the use of the accusative pronouns with these “passive” forms in Celtic; Ir. -m-berar, “I am carried,” literally “folk carry me”; Umb. pir ferar, literally ignem feratur, though as pir is a neuter word (= Gr. πῦρ) this example was not so convincing. But within a twelvemonth of the appearance of Zimmer’s article, an Oscan inscription (Conway, Camb. Philol. Society’s Proceedings, 1890, p. 16, and Italic Dialects, p. 113) was discovered containing the phrase ůltiumam (iůvilam) sakrafỉr, “ultimam (imaginem) consecraverint” (or “ultima consecretur”) which demonstrated the nature of the suffix in Italic also. This originally active meaning of the -r form (in the third person singular passive) is the cause of the remarkable fondness for the “impersonal” use of the passive in Latin (e.g., itur in antiquam silvam, instead of eunt), which was naturally extended to all tenses of the passive (ventum est, &c.), so soon as its origin was forgotten. Fuller details of the development will be found in Conway, op. cit. p. 561, and the authorities there cited (very little is added by K. Brugmann, Kurze vergl. Gramm. 1904, p. 596).

(v.) Formation of the perfect passive from the -to- past participle, Lat. monitus (est), &c., Ir. léic-the, “he was left,” ro-léiced, “he has been left.” In Latin the participle maintains its distinct adjectival character; in Irish (J. Strachan, Old Irish Paradigms, 1905, p. 50) it has sunk into a purely verbal form, just as the perfect participles in -us in Umbrian have been absorbed into the future perfect in -ust (entelust, “intenderit”; benust, “venerit”) with its impersonal passive or third plural active -us(s)so (probably standing for -ussor) as in benuso, “ventum erit” (or “venerint”).

To these must be further added some striking peculiarities in phonology.

(vi.) Assimilation of p to a qṷ in a following syllable as in Lat. quinque = Ir. cóic, compared with Sans. pánca, Gr. πέντε, Eng. five, Ind.-Eur. *penqe.

(vii.) Finally—and perhaps this parallelism is the most important of all from the historical standpoint—both Italic and Celtic are divided into two sub-families which differ, and differ in the same way, in their treatment of the Ind.-Eur. velar tenuis q. In both halves of each group it was labialized to some extent; in one half of each group it was labialized so far as to become p. This is the great line of cleavage (i.) between Latinian (Lat. quod, quandō, quinque; Falisc. cuando) and Osco-Umbrian, better called Safine (Osc. pod, Umb. panū- [for *pandō], Osc.-Umb. pompe-, “five,” in Osc. půmperias “nonae,” Umb. pumpeḓia-, “fifth day of the month”); and (ii.) between Goidelic (Gaelic) (O. Ir. cóic, “five,” maq, “son”; modern Irish and Scotch Mac as in MacPherson) and Brythonic (Britannic) (Welsh pump, “five,” Ap for map, as in Powel for Ap Howel).

The same distinction appears elsewhere; Germanic belongs, broadly described, to the q-group, and Greek, broadly described, to the p-group. The ethnological bearing of the distinction within Italy is considered in the articles Sabini and Volsci; but the wider questions which the facts suggest have as yet been only scantily discussed; see the references for the “Sequanian” dialect of Gallic (in the inscription of Coligny, whose language preserves q) in the article Celts: Language.

From these primitive affinities we must clearly distinguish the numerous words taken into Latin from the Celts of north Italy within the historic period; for these see especially an interesting study by J. Zwicker, De vocabulis et rebus Gallicis sive Transpadanis apud Vergilium (Leipzig dissertation, 1905).

6. Greek and Italic.—We have seen above (§ 4, i., ii., iii.) certain broad characteristics which the Greek and the Italic groups of language have in common. The old question of the degree of their affinity may be briefly noticed. There are deep-seated differences in morphology, phonology and vocabulary between the two languages—such as (a) the loss of the forms of the ablative in Greek and of the middle voice in Latin; (b) the decay of the fricatives (s, v, ḭ) in Greek and the cavalier treatment of the aspirates in Latin; and (c) the almost total discrepancy of the vocabularies of law and religion in the two languages—which altogether forbid the assumption that the two groups can ever have been completely identical after their first dialectic separation from the parent language. On the other hand, in the first early periods of that dialectic development in the Indo-European family, the precursors of Greek and Italic cannot have been separated by any very wide boundary. To this primitive neighbourhood may be referred such peculiarities as (a) the genitive plural feminine ending in -āsōm (Gr. -άων, later in various dialects -έων, -ῶν, -ᾶν; cf. Osc. egmazum “rerum”; Lat. mensarum, with -r- from -s-), (b) the feminine gender of many nouns of the -o- declension, cf. Gr. ἡ ὁδὸς, Lat. haec fāgus; and some important and ancient syntactical features, especially in the uses of the cases (e.g. (c) the genitive of price) of the (d) infinitive and of the (e) participles passive (though in 246 each case the forms differ widely in the two groups), and perhaps (f) of the dependent moods (though here again the forms have been vigorously reshaped in Italic). These syntactic parallels, which are hardly noticed by Kretschmer in his otherwise careful discussion (Einleit. p. 155 seq.), serve to confirm his general conclusion which has been here adopted; because syntactic peculiarities have a long life and may survive not merely complete revolutions in morphology, but even a complete change in the speaker’s language, e.g. such Celticisms in Irish-English as “What are you after doing?” for “What have you done?” or in Welsh-English as “whatever” for “anyhow.” A few isolated correspondences in vocabulary, as in remus from *ret-s-mo-, with ἐρετμός and in a few plant-names (e.g. πράσον and porrum), cannot disturb the general conclusion, though no doubt they have some historical significance, if it could be determined.

7. Indo-Iranian and Italo-Celtic.—Only a brief reference can here be made to the striking list of resemblances between the Indo-Iranian and Italo-Celtic groups, especially in vocabulary, which Kretschmer has collected (ibid. pp. 126-144). The most striking of these are rēx, O. Ir. rīg-, Sans. rāj-, and the political meaning of the same root in the corresponding verb in both languages (contrast regere with the merely physical meaning of Gr. ὀρέγνυμι); Lat. flāmen (for *flag-men) exactly = Sans. brahman- (neuter), meaning probably “sacrificing,” “worshipping,” and then “priesthood,” “priest,” from the Ind.-Eur. root *bhelgh-, “blaze,” “make to blaze”; rēs, rem exactly = Sans. rās, rām in declension and especially in meaning; and Ārio-, “noble,” in Gallic Ariomanus, &c., = Sans. ārya-, “noble” (whence “Aryan”). So argentum exactly = Sans. rajata-, Zend erezata-; contrast the different (though morphologically kindred) suffix in Gr. ἄργυρος. Some forty-two other Latin or Celtic words (among them crēdere, caesariēs, probus, castus (cf. Osc. kasit, Lat. caret, Sans. šiṣta-), Volcānus, Neptūnus, ensis, erus, pruina, rūs, novācula) have precise Sanskrit or Iranian equivalents, and none so near in any other of the eight groups of languages. Finally the use of an -r suffix in the third plural is common to both Italo-Celtic (see above) and Indo-Iranian. These things clearly point to a fairly close, and probably in part political, intercourse between the two communities of speakers at some early epoch. A shorter, but interesting, list of correspondences in vocabulary with Balto-Slavonic (e.g. the words mentīrī, rōs, ignis have close equivalents in Balto-Slavonic) suggests that at the same period the precursor of this dialect too was a not remote neighbour.

8. Date of the Separation of the Italic Group.—The date at which the Italic group of languages began to have (so far as it had at all) a separate development of its own is at present only a matter of conjecture. But the combination of archaeological and linguistic research which has already begun can have no more interesting object than the approximate determination of this date (or group of dates); for it will give us a point of cardinal importance in the early history of Europe. The only consideration which can here be offered as a starting-point for the inquiry is the chronological relation of the Etruscan invasion, which is probably referable to the 12th century B.C. (see Etruria), to the two strata of Indo-European population—the -CO- folk (Falisci, Marruci, Volsci, Hernici and others), to whom the Tuscan invaders owe the names Etrusci and Tusci, and the -NO- folk, who, on the West coast, in the centre and south of Italy, appear at a distinctly later epoch, in some places (as in the Bruttian peninsula, see Bruttii) only at the beginning of our historical record. If the view of Latin as mainly the tongue of the -CO- folk prove to be correct (see Rome: History; Italy: Ancient Languages and Peoples; Sabini; Volsci) we must regard it (a) as the southern or earlier half of the Italic group, firmly rooted in Italy in the 12th century B.C., but (b) by no means yet isolated from contact with the northern or later half; such is at least the suggestion of the striking peculiarities in morphology which it shares with not merely Oscan and Umbrian, but also, as we have seen, with Celtic. The progress in time of this isolation ought before long to be traced with some approach to certainty.

The History of Latin

9. We may now proceed to notice the chief changes that arose in Latin after the (more or less) complete separation of the Italic group whenever it came about. The contrasted features of Oscan and Umbrian, to some of which, for special reasons, occasional reference will be here made, are fully described under Osca Lingua and Iguvium respectively.

It is rarely possible to fix with any precision the date at which a particular change began or was completed, and the most serviceable form for this conspectus of the development will be to present, under the heads of Phonology, Morphology and Syntax, the chief characteristics of Ciceronian Latin which we know to have been developed after Latin became a separate language. Which of these changes, if any, can be assigned to a particular period will be seen as we proceed. But it should be remembered that an enormous increase of exact knowledge has accrued from the scientific methods of research introduced by A. Leskien and K. Brugmann in 1879, and finally established by Brugmann’s great Grundriss in 1886, and that only a brief enumeration can be here attempted. For adequate study reference must be made to the fuller treatises quoted, and especially to the sections bearing on Latin in K. Brugmann’s Kurze vergleichende Grammatik (1902).

I. Phonology

10. The Latin Accent.—It will be convenient to begin with some account of the most important discovery made since the application of scientific method to the study of Latin, for, though it is not strictly a part of phonology, it is wrapped up with much of the development both of the sounds and, by consequence, of the inflexions. It has long been observed (as we have seen § 4, iv. above) that the restriction of the word-accent in Latin to the last three syllables of the word, and its attachment to a long syllable in the penult, were certainly not its earliest traceable condition; between this, the classical system, and the comparative freedom with which the word-accent was placed in pro-ethnic Indo-European, there had intervened a period of first-syllable accentuation to which were due many of the characteristic contractions of Oscan and Umbrian, and in Latin the degradation of the vowels in such forms as accentus from ad + cantus or praecipitem from prae + caput- (§ 19 below). R. von Planta (Osk.-Umbr. Grammatik, 1893, i. p. 594) pointed out that in Oscan also, by the 3rd century B.C., this first-syllable-accent had probably given way to a system which limited the word-accent in some such way as in classical Latin. But it remained for C. Exon, in a brilliant article (Hermathena (1906), xiv. 117, seq.), to deduce from the more precise stages of the change (which had been gradually noted, see e.g. F. Skutsch in Kroll’s Altertumswissenschaft im letzten Vierteljahrhundert, 1905) their actual effect on the language.

11. Accent in Time of Plautus.—The rules which have been established for the position of the accent in the time of Plautus are these:

(i.) The quantity of the final syllable had no effect on accent.

(ii.) If the penult was long, it bore the accent (amābấmus).

(iii.) If the penult was short, then

(a) if the ante-penult was long, it bore the accent (amấbimus);

(b) if the ante-penult was short, then

(i.) if the ante-ante-penult was long, the accent was on the ante-penult (amīcítia); but

(ii.) if the ante-ante-penult was also short, it bore the accent (cólumine, puéritia).

Exon’s Laws of Syncope.—With these facts are now linked what may be called Exon’s Laws, viz:—

In pre-Plautine Latin in all words or word-groups of four or more syllables whose chief accent is on one long syllable, a short unaccented medial vowel was syncopated; thus *quínquedecem became *quínqdecem and thence quíndecim (for the -im see § 19), *súps-emere became *súpsmere and that sūmere (on -psm- v. inf.) *súrregere, *surregémus, and the like became surgere, surgémus, and the rest of the paradigm followed; so probably validé bonus became valdé bonus, exterá viam became extrá viam; so *supo-téndo became subtendo (pronounced sup-tendo), *āridére, *avidére (from āridus, avidus) became ārdére, audére. But the influence of cognate forms often interfered; posterí-diē became postrídiē, but in posterórum, posterárum the short syllable was restored by the influence of the trisyllabic cases, pósterus, pósterī, &c., to which the law did not apply. Conversely, the nom. *áridor (more correctly at this period *āridōs), which would not have been contracted, followed the form of ārdórem (from *āridórem), ārdére, &c.

The same change produced the monosyllabic forms nec, ac, neu, seu, from neque, &c., before consonants, since they had no accent of their own, but were always pronounced in one breath with the following word, neque tántum becoming nec tantum, and the like. So in Plautus (and probably always in spoken Latin) the words nemp(e), ind(e), quipp(e), ill(e), are regularly monosyllables.

12. Syncope of Final Syllables.—It is possible that the frequent but far from universal syncope of final syllables in Latin (especially before -s, as in mēns, which represents both Gr. μένος and Sans. matís = Ind.-Eur. mṇtís, Eng. mind) is due also to this law operating on such combinations as bona mēns and the like, but this has not yet been clearly shown. In any case the effects of any such phonetic change have been very greatly modified by analogical changes. The Oscan and Umbrian syncope of short vowels before final s seems to be an independent change, at all events in its detailed working. The outbreak of the unconscious affection of slurring final syllables may have been contemporaneous.

13. In post-Plautine Latin words accented on the ante-antepenult:—

(i.) suffered syncope in the short syllable following the accented syllable (bálineae became bálneae, puéritia became puértia (Horace), cólumine, tégimine, &c., became cúlmine, tégmine, &c., beside the trisyllabic cólumen, tégimen) unless

(ii.) that short vowel was e or i, followed by another vowel (as in párietem, múlierem, Púteoli), when, instead of contraction, the accent shifted to the penult, which at a later stage of the language became lengthened, pariétem giving Ital. paréếte, Fr. paroi, Puteóli giving Ital. Pozzuốli.

The restriction of the accent to the last three syllables was completed by these changes, which did away with all the cases in which it had stood on the fourth syllable.

14. The Law of the Brevis Brevians.—Next must be mentioned another great phonetic change, also dependent upon accent, which had come about before the time of Plautus, the law long known to students as the Brevis Brevians, which may be stated as follows (Exon, Hermathena (1903), xii. 491, following Skutsch in, e.g., Vollmöller’s Jahresbericht für romanische Sprachwissenschaft, i. 33): a syllable long by nature or position, and preceded by a short syllable, was itself shortened if the word-accent fell immediately before or immediately after it—that is, on the preceding short syllable or on the next following syllable. The sequence of syllables need not be in the same word, but must be as closely connected in utterance as if it were. Thus mốdō became módŏ, vŏlūptấtēm became vŏlŭ(p)tấtem, quḯd ēst? became quid ĕst? either the s or the t or both being but faintly pronounced.

It is clear that a great number of flexional syllables so shortened would have their quantity immediately restored by the analogy of the same inflexion occurring in words not of this particular shape; thus, for instance, the long vowel of ấmā and the like is due to that in other verbs (pulsā, agitā) not of iambic shape. So ablatives like modö, sonō get back their -ō, while in particles like modo, “only,” quōmodo, “how,” the shortened form remains. Conversely, the shortening of the final -a in the nom. sing. fem. of the a-declension (contrast lūnă with Gr. χωρᾷ) was probably partly due to the influence of common forms like eă, bonă, mală, which had come under the law.

15. Effect on Verb Inflexion.—These processes had far-reaching effects on Latin inflexion. The chief of these was the creation of the type of conjugation known as the capio-class. All these verbs were originally inflected like audio, but the accident of their short root-syllable, (in such early forms as *fúgīs, *fugītṹrus, *fugīsếtis, &c., becoming later fúgĭs, fugĭtṹrus, fugĕrếtis) brought great parts of their paradigm under this law, and the rest followed suit; but true forms like fugīre, cupīre, morīri, never altogether died out of the spoken language. St Augustine, for instance, confessed in 387 A.D. (Epist. iii. 5, quoted by Exon, Hermathena (1901), xi. 383,) that he does not know whether cupi or cupiri is the pass. inf. of cupio. Hence we have Ital. fuggīre, morīre, Fr. fuir, mourir. (See further on this conjugation, C. Exon, l.c., and F. Skutsch, Archiv für lat. Lexicographie, xii. 210, two papers which were written independently.)

16. The question has been raised how far the true phonetic shortening appears in Plautus, produced not by word-accent but by metrical ictus—e.g. whether the reading is to be trusted in such lines as Amph. 761, which gives us dedisse as the first foot (tribrach) of a trochaic line “because the metrical ictus fell on the syllable ded-”—but this remarkable theory cannot be discussed here. See the articles cited and also F. Skutsch, Forschungen zu Latein. Grammatik und Metrik, i. (1892); C. Exon, Hermathena (1903) xii. p. 492, W. M. Lindsay, Captivi (1900), appendix.

In the history of the vowels and diphthongs in Latin we must distinguish the changes which came about independently of accent and those produced by the preponderance of accent in another syllable.

17. Vowel Changes independent of Accent.—In the former category the following are those of chief importance:—

(i.) ĭ became ĕ (a) when final, as in ant-e beside Gr. ἀντί, trīste besides trīsti-s, contrasted with e.g., the Greek neuter ἴδρι (the final -e of the infinitive—regere, &c.—is the -ĭ of the locative, just as in the so-called ablatives genere, &c.); (b) before -r- which has arisen from -s-, as in cineris beside cinis, cinisculus; serō beside Gr. ἴ(σ)ημι (Ind.-Eur. *si-sēmi, a reduplicated non-thematic present).

(ii.) Final ŏ became ĕ; imperative sequere = Gr. ἔπε(σ)ο; Lat. ille may contain the old pronoun *so, “he,” Gr. ὁ, Sans. sa (otherwise Skutsch, Glotta, i. Hefte 2-3).

(iii.) el became ol when followed by any sound save e, i or l, as in volō, volt beside velle; colō beside Gr. τέλλομαι, πολεῖν, Att. τέλος; colōnus for *quelōnus, beside inquilīnus for *en-quēlenus.

(iv.) e became i (i.) before a nasal followed by a palatal or velar consonant (tingo, Gr. τέγγω; in-cipio from *en-capio); (ii.) under certain conditions not yet precisely defined, one of which was i in a following syllable (nihil, nisi, initium). From these forms in- spread and banished en-, the earlier form.

(v.) The “neutral vowel” (“schwa Indo-Germanicum”) which arose in pro-ethnic Indo-European from the reduction of long ā, ē or ō in unaccented syllables (as in the -tós participles of such roots as stā-, dhē-, dō-, *stƏtós, *dhƏtós, *dƏtós) became a in Latin (status con-ditus [from *con-dhatos], datus), and it is the same sound which is represented by a in most of the forms of dō (damus, dabō, &c.).

(vi.) When a long vowel came to stand before another vowel in the same word through loss of ḭ or ṷ, it was always shortened; thus the -eō of intransitive verbs like candeō, caleō is for -ēḭō (where the ē is identical with the η in Gr. ἐφάνην, ἐμάνμν) and was thus confused with the causative -eiō (as in moneō, “I make to think,” &c.), where the short e is original. So audīuī became audīī and thence audiī (the form audīvī would have disappeared altogether but for being restored from audīveram, &c.; conversely audieram is formed from audiī). In certain cases the vowels contracted, as in trēs, partēs, &c. with -ēs from eḭes, *amō from amā(ḭ)ō.

18. Of the Diphthongs.

(vii.) eu became ou in pro-ethnic Italic, Lat. novus: Gr. νέος, Lat. novem, Umb. nuviper (i.e. noviper), “usque ad Changes of the diphthongs independent of accent. noviens”: Gr. (ἐν-)νέα; in unaccented syllables this -ov- sank to -u(v)- as in dếnuō from dế novō, suus (which is rarely anything but an enclitic word), Old Lat. sovos: Gr. ἑ(ϝ)ός.

(viii.) ou, whether original or from eu, when in one syllable became -ū-, probably about 200 B.C., as in dūcō, Old Lat. doucō, Goth, tiuhan, Eng. tow, Ind.-Eur. *deṷcō.

(ix.) ei became ī (as in dīcō, Old Lat. deico: Gr. δείκ-νυμι, fīdo: Gr. πείθομαι, Ind.-Eur. *bheidhō) just before the time of Lucilius, who prescribes the spellings puerei (nom. plur.) but puerī (gen. sing.), which indicates that the two forms were pronounced alike in his time, but that the traditional distinction in spelling had been more or less preserved. But after his time, since the sound of ei was merely that of ī, ei is continually used merely to denote a long ī, even where, as in faxeis for faxīs, there never had been any diphthongal sound at all.

(x.) In rustic Latin (Volscian and Sabine) au became ō as in the vulgar terms explōdere, plōstrum. Hence arose interesting doublets of meaning;—lautus (the Roman form), “elegant,” but lōtus, “washed”; haustus, “draught,” but hōstus (Cato), “the season’s yield of fruit.”

(xi.) oi became oe and thence ū some time after Plautus, as in ūnus, Old Lat. oenus: Gr. οἰνή “ace.” In Plautus the forms have nearly all been modernized, save in special cases, e.g. in Trin. i. 1, 2, immoene facinus, “a thankless task,” has not been changed to immune because that meaning had died out of the adjective so that immune facinus would have made nonsense; but at the end of the same line utile has replaced oetile. Similarly in a small group of words the old form was preserved through their frequent use in legal or religious documents where tradition was strictly preserved—poena, foedus (neut.), foedus (adj.), “ill-omened.” So the archaic and poetical moenia, “ramparts,” beside the true classical form mūnia, “duties”; the historic Poeni beside the living and frequently used Pūnicum (bellum)—an example which demonstrates conclusively (pace Sommer) that the variation between ū and oe is not due to any difference in the surrounding sounds.

(xii.) ai became ae and this in rustic and later Latin (2nd or 3rd century A.D.) simple ē, though of an open quality—Gr. αἴθος, αἴθω, Lat. aedēs (originally “the place for the fire”); the country forms of haedus, praetor were edus, pretor (Varro, Ling. Lat. v. 97, Lindsay, Lat. Lang. p. 44).

19. Vowels and Diphthongs in unaccented Syllables.—The changes of the short vowels and of the diphthongs in unaccented syllables are too numerous and complex to be set forth here. Some took place under the first-syllable system of accent, some later (§§ 9, 10). Typical examples are pepErci from *péparcai and ónustus from *ónostos (before two consonants); concIno from *cóncano and hospItIs from *hóstipotes, legImus beside Gr. λέγομεν (before one consonant); SicUli from *Siceloi (before a thick l, see § 17, 3); dilIgIt from *dísleget (contrast, however, the preservation of the second e in neglEgIt); occUpat from *opcapat (contrast accipit with i in the following syllable); the varying spelling in monumentum and monimentum, maxumus and maximus, points to an intermediate sound (ü) between u and i (cf. Quint. i. 4. 8, reading optumum and optimum [not opimum] with W. M. Lindsay, Latin Language §§ 14, 16, seq.), which could not be correctly represented in spelling; this difference may, however, be due merely to the effect of differences in the neighbouring sounds, an effect greatly obscured by analogical influences.

Inscriptions of the 4th or 3rd century, B.C. which show original -es and -os in final syllables (e.g. Venerĕs, gen. sing., nāvebos abl. pl.) compared with the usual forms in -is, -us a century later, give us roughly the date of these changes. But final -os, -om, remained after -u- (and v) down to 50 B.C. as in servos.

20. Special mention should be made of the change of -rĭ- and -ro- to -er- (incertus from *encritos; ager, ācer from *agros, *ācris; the 248 feminine ācris was restored in Latin (though not in North Oscan) by the analogy of other adjectives, like tristis, while the masculine ācer was protected by the parallel masculine forms of the -o- declension, like tener, niger [from *teneros, *nigros]).

21. Long vowels generally remained unchanged, as in compāgo, condōno.

22. Of the diphthongs, ai and oi both sank to ei, and with original ei further to ī, in unaccented syllables, as in Achivi from Gr. Ἀχαιϝοί, olīivom, earlier *oleivom (borrowed into Gothic and there becoming alēv) from Gr. ἔλαιϝον. This gives us interesting chronological data, since the el- must have changed to ol- (§ 16. 3) before the change of -ai- to -ei-, and that before the change of the accent from the first syllable to the penultimate (§ 9); and the borrowing took place after -ai- had become -ei-, but before -eivom had become -eum, as it regularly did before the time of Plautus.

But cases of ai, ae, which arose later than the change to ei, ī, were unaffected by it; thus the nom. plur. of the first declension originally ended in -ās (as in Oscan), but was changed at some period before Plautus to -ae by the influence of the pronominal nom. plur. ending -ae in quae? hae, &c., which was accented in these monosyllables and had therefore been preserved. The history of the -ae of the dative, genitive and locative is hardly yet clear (see Exon, Hermathena (1905), xiii. 555; K. Brugmann, Grundriss, 1st ed. ii. 571, 601).

The diphthongs au, ou in unaccented syllables sank to -u-, as in inclūdō beside claudō; the form clūdō, taken from the compounds, superseded claudo altogether after Cicero’s time. So cūdō, taken from incūdō, excūdō, banished the older *caudō, “I cut, strike,” with which is probably connected cauda, “the striking member, tail,” and from which comes caussa, “a cutting, decision, legal case,” whose -ss- shows that it is derived from a root ending in a dental (see §25 (b) below and Conway, Verner’s Law in Italy, p. 72).

Consonants.—Passing now to the chief changes of the consonants we may notice the following points:—

23. Consonant i (wrongly written j; there is no g-sound in the letter), conveniently written ḭ by phoneticians,

(i.) was lost between vowels, as in trēs for *treḭes, &c. (§ 17. 6);

(ii.) in combination: -mḭ- became -ni-, as in veniö, from Ind.-Eur. *Ƨṷ mḭo, “I come,” Sans. gam-, Eng. come; -nḭ- probably (under certain conditions at least) became -nd-, as in tendō beside Gr. τείνω, fendō = Gr. θείνω, and in the gerundive stem -endus, -undus, probably for -enḭos, -onḭos; cf. the Sanskrit gerundive in -an-īya-s; -gḭ-, -dḭ- became -ḭ- as in māior from *mag-ior, pēior from *ped-ior;

(iii.) otherwise -ḭ- after a consonant became generally syllabic (-iḭ-), as in capiō (trisyllabic) beside Goth. hafya.

24. Consonant u (formerly represented by English v), conveniently written ṷ,

(i.) was lost between similar vowels when the first was accented, as in audīui, which became audiī (§ 17 [6]), but not in amāuī, nor in avārus.

(ii.) in combination: dṷ became b, as in bonus, bellum, O. Lat. dṷonus, *dṷellum (though the poets finding this written form in old literary sources treated it as trisyllabic); pṷ-, fṷ-, bṷ-, lost the ṷ, as in ap-erio, op-erio beside Lith. -veriu, “I open,” Osc. veru, “gate,” and in the verbal endings -bam, -bō, from -bhṷ-ām, -bhṷō (with the root of Lat. fui), and fīo, du-bius, super-bus, vasta-bundus, &c., from the same; -sṷ- between vowels (at least when the second was accented) disappeared (see below § 25 (a), iv.), as in pruīna for prusuīna, cf. Eng. fros-t, Sans, pruṣvā, “hoar-frost.” Contrast Minérva from an earlier *menes-ṷā, sṷe-, sṷo-, both became so-, as in sorōor(em) beside Sans. svasār-am, Ger. schwes-t-er, Eng. sister, sordēs, beside O. Ger. swart-s, mod. schwarz. -ṷo- in final syllables became -u-, as in cum from quom, parum from parṷom; but in the declensional forms -ṷu- was commonly restored by the analogy of the other cases, thus (a) serṷos, serṷom, serṷī became (b) *serus, *serum, *serṷi, but finally (c) serṷus, serṷum, serṷi.

(iii.) In the 2nd century A.D., Lat. v (i.e. ṷ) had become a voiced labio-dental fricative, like Eng. v; and the voiced labial plosive b had broken down (at least in certain positions) into the same sound; hence they are frequently confused as in spellings like vene for bene, Bictorinus for Victorinus.

25. (a) Latin s

(i.) became r between vowels between 450 and 350 B.C. (for the date see R. S. Conway, Verner’s Law in Italy, pp. 61-64), as āra, beside O. Lat. āsa, generis from *geneses, Gr. γένεος; eram, erō for *esām, *esō, and so in the verbal endings -erām, -erō, -erim. But a considerable number of words came into Latin, partly from neighbouring dialects, with -s- between vowels, after 350 B.C., when the change ceased, and so show -s-, as rosa (probably from S. Oscan for *rodḭa “rose-bush” cf. Gr. ῥόδον), cāseus, “cheese,” miser, a term of abuse, beside Gr. μυσαρός (probably also borrowed from south Italy), and many more, especially the participles in -sus (fūsus), where the -s- was -ss- at the time of the change of -s- to -r- (so in causa, see above). All attempts to explain the retention of the -s- otherwise must be said to have failed (e.g. the theory of accentual difference in Verner’s Law in Italy, or that of dissimilation, given by Brugmann, Kurze vergl. Gram. p. 242).

(ii.) sr became þr (= Eng. thr in throw) in pro-ethnic Italic, and this became initially fr- as in frīgus, Gr. ῥῖγος (Ind.-Eur. *srīgos), but medially -br-, as in funebris, from funus, stem funes-.

(iii.) -rs-, ls- became -rr-, -ll-, as in ferre, velle, for *fer-se, *vel-se (cf. es-se).

(iv.) Before m, n, l, and v, -s- vanished, having previously caused the loss of any preceding plosive or -n-, and the preceding vowel, if short, was lengthened as in

prīmus from *prismos, Paelig. prismu, “prima,” beside pris-cus.

iūmentum from O. Lat. iouxmentum, older *ieugsmentom; cf. Gr. ζεῦγμα, ζύγον, Lat. iugum, iungo.

lūna from *leucsnā-, Praenest, losna, Zend raoχsna-; cf. Gr. λεῦκος, “white-ness” neut. e.g. λευκός, “white,” Lat. lūceō.

tēlum from *tēns-lom or *tends-lom, trānāre from *trāns-nāre.

sēvirī from *sex-virī, ēvehō from *ex-vehō, and so ē-mittō, ē-līdō, ē-numerō, and from these forms arose the proposition ē instead of ex.

(v.) Similarly -sd- became -d-, as in īdem from is-dem.

(vi.) Before n-, m-, l-, initially s- disappeared, as in nūbo beside Old Church Slavonic snubiti, “to love, pay court to”; mīror beside Sans, smáyatē, “laughs,” Eng. smi-le; lūbricus beside Goth, sliupan, Eng. slip.

(b) Latin -ss- arose from an original -t + t-, -d + t-, -dh + t- (except before -r), as in missus, earlier *mit-tos; tōnsus, earlier *tond-tos, but tonstrīx from *tond-trīx. After long vowels this -ss- became a single -s- some time before Cicero (who wrote caussa [see above], divissio, &c., but probably only pronounced them with -s-, since the -ss- came to be written single directly after his time).

26. Of the Indo-European velars the breathed q was usually preserved in Latin with a labial addition of -ṷ- (as in sequor, Gr. ἕπομαι, Goth, saihvan, Eng. see; quod, Gr. ποδ-(απός), Eng. what); but the voiced Ƨṷ remained (as -gu-) only after -n- (unguo beside Ir. imb, “butter”) and (as g) before r, l, and u (as in gravis, Gr. βαρύς; glans, Gr. βάλανος; legūmen, Gr. λοβός, λεβίνθος). Elsewhere it became v, as in veniō (see § 23, ii.), nūdus from *novedos, Eng. naked. Hence bōs (Sans. gāus, Eng. cow) must be regarded as a farmer’s word borrowed from one of the country dialects (e.g. Sabine); the pure Latin would be *vōs, and its oblique cases, e.g. acc. *vovem, would be inconveniently close in sound to the word for sheep ovem.

27. The treatment of the Indo-European voiced aspirates (bh, dh, ḡh Ƨh) in Latin is one of the most marked characteristics of the language, which separates it from all the other Italic dialects, since the fricative sounds, which represented the Indo-European aspirates in pro-ethnic Italic, remained fricatives medially if they remained at all in that position in Oscan and Umbrian, whereas in Latin they were nearly always changed into voiced explosives. Thus—

Ind.-Eur. bh: initially Lat. f- (ferō; Gr. φέρω).

medially Lat. -b- (tibi; Umb. tefe; Sans, tubhy-(am), “to thee”; the same suffix in Gr. βίη-φι, &c.).

Ind.-Eur. dh: initially Lat. f- (fa-c-ere, fē-c-ī; Gr. θετός (instead of *θατός), ἔθη-κα).

medially -d- (medius; Osc. mefio-; Gr. μέσσος, μέσος from *μεθιος); except after u (iubēre beside iussus for *ḭudh-tos; Sans. yốdhati, “rouses to battle”); before l (stabulum, but Umb. staflo-, with the suffix of Gr. οτέργηθρον, &c.); before or after r (verbum: Umb. verfale: Eng. word. Lat. glaber [v. inf].: Ger. glatt: Eng. glad).

Ind.-Eur. ḡh: initially h- (humī: Gr. χαμαί); except before -u- (fundo: Gr. χέ(ϝ)ω, χύτρα).

medially -h- (veho: Gr. ἔχω, ὄχος; cf. Eng. wagon); except after -n- (fingere: Osc. feiho-, “wall”: Gr. θιγγάνω: Ind.-Eur. dheiĝh-, dhinĝh-); and before l (fīg(u)lus, from the same root).

Ind.-Eur gṷh: initially f- (formus and furnus, “oven”, Gr. θερμός, θέρμη, cf. Ligurian Bormiō, “a place with hot springs,” Bormanus, “a god of hot springs”; fendō: Gr. θείνω, φόνος, πρόσ-φατος).

medially v, -gu- or -g- just as Ind.-Eur. Ƨṷ (ninguere, nivem beside Gr. νίφα, νείφει; frāgrāre beside Gr. ὀσφραίνομαι [ὀσ- for ods-, cf. Lat. odor], a reduplicated verb from a root Ƨṷhra-).

For the “non-labializing velars” (Hostis, conGius, Glaber) reference must be made to the fuller accounts in the handbooks.

28. Authorities.—This summary account of the chief points in Latin phonology may serve as an introduction to its principles, and give some insight into the phonetic character of the language. For systematic study reference must be made to the standard books, Karl Brugmann, Grundriss der vergleichenden Grammatik der Indo-Germanischen Sprachen (vol. i., Lautlehre, 2nd ed. Strassburg, 1897; Eng. trans. of ed. 1 by Joseph Wright, Strassburg, 1888) and his Kurze vergleichende Grammatik (Strassburg, 1902); these contain still by far the best accounts of Latin; Max Niederman, Précis de phonétique du Latin (Paris, 1906), a very convenient handbook, excellently planned; F. Sommer, Lateinische Laut- und Flexionslehre (Heidelberg, 1902), containing many new conjectures; W. M. Lindsay, The Latin Language (Oxford, 1894), translated into German (with corrections) by Nohl (Leipzig, 1897), a most valuable collection of material, especially from the ancient grammarians, but not always accurate in phonology; F. Stolz, vol. i. of a joint Historische Grammatik d. lat. Sprache by Blase, Landgraf, Stolz and others (Leipzig, 1894); Neue-Wagener, Formenlehre d. lat. Sprache (3 vols., 3rd ed. 249 Leipzig, 1888, foll.); H. J. Roby’s Latin Grammar (from Plautus to Suetonius; London, 7th ed., 1896) contains a masterly collection of material, especially in morphology, which is still of great value. W. G. Hale and C. D. Buck’s Latin Grammar (Boston, 1903), though on a smaller scale, is of very great importance, as it contains the fruit of much independent research on the part of both authors; in the difficult questions of orthography it was, as late as 1907, the only safe guide.

II. Morphology

In morphology the following are the most characteristic Latin innovations:—

29. In nouns.

(i.) The complete loss of the dual number, save for a survival in the dialect of Praeneste (C.I.L. xiv. 2891, = Conway, Ital. Dial. p. 285, where Q. k. Cestio Q. f. seems to be nom. dual); so C.I.L. xi. 67065, T. C. Vomanio, see W. Schulze, Lat. Eigennamen, p. 117.

(ii.) The introduction of new forms in the gen. sing, of the -o- stems (dominī), of the -ā- stems (mēnsae) and in the nom. plural of the same two declensions; innovations mostly derived from the pronominal declension.

(iii.) The development of an adverbial formation out of what was either an instrumental or a locative of the -o- stems, as in longē. And here may be added the other adverbial developments, in -m (palam, sensim) probably accusative, and -iter, which is simply the accusative of iter, “way,” crystallized, as is shown especially by the fact that though in the end it attached itself particularly to adjectives of the third declension (molliter), it appears also from adjectives of the second declension whose meaning made their combination with iter especially natural, such as longiter, firmiter, largiter (cf. English straightway, longways). The only objections to this derivation which had any real weight (see F. Skutsch, De nominibus no- suffixi ope formatis, 1890, pp. 4-7) have been removed by Exon’s Law (§ 11), which supplies a clear reason why the contracted type constanter arose in and was felt to be proper to Participial adverbs, while firmiter and the like set the type for those formed from adjectives.

(iv.) The development of the so-called fifth declension by a re-adjustment of the declension of the nouns formed with the suffix -iē-: ia- (which appears, for instance, in all the Greek feminine participles, and in a more abstract sense in words like māteriēs) to match the inflexion of two old root-nouns rēs and diēs, the stems of which were originally rēḭ- (Sans. rās, rāyas, cf. Lat. reor) and diēṷ-.

(v.) The disuse of the -ti- suffix in an abstract sense. The great number of nouns which Latin inherited formed with this suffix were either (1) marked as abstract by the addition of the further suffix -ōn- (as in natio beside the Gr. γνὴσι-ος, &c.) or else (2) confined to a concrete sense; thus vectis, properly “a carrying, lifting,” came to mean “pole, lever”; ratis, properly a “reckoning, devising,” came to mean “an (improvised) raft” (contrast ratiō); postis, a “placing,” came to mean “post.”

(vi.) The confusion of the consonantal stems with stems ending in -ĭ-. This was probably due very largely to the forms assumed through phonetic changes by the gen. sing. and the nom. and acc. plural. Thus at say 300 B.C. the inflexions probably were:

| conson. stem | -ĭ- stem | |

| Nom. plur. | *rēg-ĕs | host-ēs |

| Acc. plur. | rĕg-ēs | host-īs |

The confusing difference of signification of the long -ēs ending led to a levelling of these and other forms in the two paradigms.

(vii.) The disuse of the u declension (Gr. ἡδύς, στάχυς) in adjectives; this group in Latin, thanks to its feminine form (Sans. fem. svādvī, “sweet”), was transferred to the i declension (suavis, gravis, levis, dulcis).

30. In verbs.

(i.) The disuse of the distinction between the personal endings of primary and secondary tenses, the -t and -nt, for instance, being used for the third person singular and plural respectively in all tenses and moods of the active. This change was completed after the archaic period, since we find in the oldest inscriptions -d regularly used in the third person singular of past tenses, e.g. deded, feced in place of the later dedit, fecit; and since in Oscan the distinction was preserved to the end, both in singular and plural, e.g. faamat (perhaps meaning “auctionatur”), but deded (“dedit”). It is commonly assumed from the evidence of Greek and Sanskrit (Gr. ἕστι, Sans. asti beside Lat. est) that the primary endings in Latin have lost a final -i, partly or wholly by some phonetic change.

(ii.) The non-thematic conjugation is almost wholly lost, surviving only in a few forms of very common use, est, “is”; ēst, “eats”; volt, “wills,” &c.

(iii.) The complete fusion of the aorist and perfect forms, and in the same tense the fusion of active and middle endings; thus tutudī, earlier *tutudai, is a true middle perfect; dīxī is an s aorist with the same ending attached; dīxit is an aorist active; tutudisti is a conflation of perfect and aorist with a middle personal ending.

(iv.) The development of perfects in -uī and -vī, derived partly from true perfects of roots ending in v or u, e.g. mōvī ruī. For the origin of monuī see Exon, Hermathena (1901), xi. 396 sq.

(v.) The complete fusion of conjunctive and optative into a single mood, the subjunctive; regam, &c., are conjunctive forms, whereas rexerim, rexissem are certainly and regerem most probably optative; the origin of amem and the like is still doubtful. Notice, however, that true conjunctive forms were often used as futures, regēs, reget, &c., and also the simple thematic conjunctive in forms like erō, rexerō, &c.

(vi.) The development of the future in -bo and imperfect in -bam by compounding some form of the verb, possibly the Present Participle with forms from the root of fuī, *amans-fuo becoming amabō, *amans-fṷām becoming amābam at a very early period of Latin; see F. Skutsch, Atti d. Congresso Storico Intern. (1903), vol. ii. p. 191.

(vii.) We have already noticed the rise of the passive in -r (§ 5 (d)). Observe, however, that several middle forms have been pressed into the service, partly because the -r- in them which had come from -s- seemed to give them a passive colour (legere = Gr. λέγε(σ)ο, Attic λέγου). The interesting forms in -minī are a confusion of two distinct inflexions, namely, an old infinitive in -menai, used for the imperative, and the participial -menoi, masculine, -menai, feminine, used with the verb “to be” in place of the ordinary inflexions. Since these forms had all come to have the same shape, through phonetic change, their meanings were fused; the imperative forms being restricted to the plural, and the participial forms being restricted to the second person.

31. Past Participle Passive.—Next should be mentioned the great development in the use of the participle in -tos (factus, fusus, &c.). This participle was taken with sum to form the perfect tenses of the passive, in which, thanks partly to the fusion of perfect and aorist active, a past aorist sense was also evolved. This reacted on the participle itself giving it a prevailingly past colour, but its originally timeless use survives in many places, e.g. in the participle ratus, which has as a rule no past sense, and more definitely still in such passages as Vergil, Georg. i. 206 (vectis), Aen. vi. 22 (ductis), both of which passages demand a present sense. It is to be noticed also that in the earliest Latin, as in Greek and Sanskrit, the passive meaning, though the commonest, is not universal. Many traces of this survive in classical Latin, of which the chief are

1. The active meaning of deponent participles, in spite of the fact that some of them (e.g. adeptus, ēmēnsus, expertus) have also a passive sense, and

2. The familiar use of these participles by the Augustan poets with an accusative attached (galeam indutus, traiectus lora). Here no doubt the use of the Greek middle influenced the Latin poets, but no doubt they thought also that they were reviving an old Latin idiom.

32. Future Participle.—Finally may be mentioned together (a) the development of the future participle active (in -ūrus, never so freely used as the other participles, being rare in the ablative absolute even in Tacitus) from an old infinitive in -ūrum (“scio inimicos meos hoc dicturum,” C. Gracchus (and others) apud Gell. 1. 7, and Priscian ix. 864 (p. 475 Keil), which arose from combining the dative or locative of the verbal noun in -tu with an old infinitive esom “esse” which survives in Oscan, *dictu esom becoming dicturum. This was discovered by J. P. Postgate (Class. Review, v. 301, and Idg. Forschungen iv. 252). (b) From the same infinitival accusative with the post-position -dō, meaning “to,” “for,” “in” (cf. quandō for *quam-do, and Eng. to, Germ, zu) was formed the so-called gerund agen-dō, “for doing,” “in doing,” which was taken for a Case, and so gave rise to the accusative and genitive in -dum and -dī. The form in -dō still lives in Italian as an indeclinable present participle. The modal and purposive meanings of -dō appear in the uses of the gerund.

The authorities giving a fuller account of Latin morphology are the same as those cited in § 28 above, save that the reader must consult the second volume of Brugmann’s Grundriss, which in the English translation (by Conway and Rouse, Strassburg, 1890-1896) is divided into volumes ii, iii. and iv.; and that Niedermann does not deal with morphology.

III. Syntax

The chief innovations of syntax developed in Latin may now be briefly noted.

33. In nouns.

(i.) Latin restricted the various Cases to more sharply defined uses than either Greek or Sanskrit; the free use of the internal accusative in Greek (e.g. ἁβρὸν βαίνειν, τυφλὸς τὰ ὦτα) is strange to Latin, save in poetical imitations of Greek; and so is the freedom of the Sanskrit instrumental, which often covers meanings expressed in Latin by cum, ab, inter.

(ii.) The syncretism of the so-called ablative case, which combines the uses of (a) the true ablative which ended in -d (O. Lat. praidād); (b) the instrumental sociative (plural forms like dominīs, the ending being that of Sans. çivāiş); and (c) the locative (noct-e, “at night”; itiner-e, “on the road,” with the ending of Greek ἐλπίδ-ι). The so-called absolute construction is mainly derived from the second of these, since it is regularly attached fairly closely to the subject of the clause in which it stands, and when accompanied by a passive participle most commonly denotes an action performed by that subject. But the other two sources cannot be altogether excluded (orto sole, “starting from sunrise”; campo patente, “on, in sight of, the open plain”).

34. In verbs.

(i.) The rich development and fine discrimination of the uses of the subjunctive mood, especially (a) in indirect questions (based on 250 direct deliberative questions and not fully developed by the time of Plautus, who constantly writes such phrases as dic quis es for the Ciceronian dic quis sis); (b) after the relative of essential definition (non is sum qui negem) and the circumstantial cum (“at such a time as that”). The two uses (a) and (b) with (c) the common Purpose and Consequence-clauses spring from the “prospective” or “anticipatory” meaning of the mood. (d) Observe further its use in subordinate oblique clauses (irascitur quod abierim, “he is angry because, as he asserts, I went away”). This and all the uses of the mood in oratio obliqua are derived partly from (a) and (b) and partly from the (e) Unreal Jussive of past time (Non illi argentum redderem? Non redderes, “Ought I not to have returned the money to him?” “You certainly ought not to have,” or, more literally, “You were not to”).

On this interesting chapter of Latin syntax see W. G. Hale’s “Cum-constructions” (Cornell University Studies in Classical Philology, No. 1, 1887-1889), and The Anticipatory Subjunctive (Chicago, 1894).

(ii.) The complex system of oratio obliqua with the sequence of tenses (on the growth of the latter see Conway, Livy II., Appendix ii., Cambridge, 1901).

(iii.) The curious construction of the gerundive (ad capiendam urbem), originally a present (and future?) passive participle, but restricted in its use by being linked with the so-called gerund (see § 32, b). The use, but probably not the restriction, appears in Oscan and Umbrian.

(iv.) The favourite use of the impersonal passive has already been mentioned (§ 5, iv.).

35. The chief authorities for the study of Latin syntax are: Brugmann’s Kurze vergl. Grammatik, vol. ii. (see § 28); Landgraf’s Historische lat. Syntax (vol. ii. of the joint Hist. Gram., see § 28); Hale and Buck’s Latin Grammar (see § 28); Draeger’s Historische lat. Syntax, 2 vols. (2nd ed., Leipzig, 1878-1881), useful but not always trustworthy; the Latin sections in Delbrück’s Vergleichende Syntax, being the third volume of Brugmann’s Grundriss (§ 28).

IV. Importation of Greek Words

36. It is convenient, before proceeding to describe the development of the language in its various epochs, to notice briefly the debt of its vocabulary to Greek, since it affords an indication of the steadily increasing influence of Greek life and literature upon the growth of the younger idiom. Corssen (Lat. Aussprache, ii. 814) pointed out four different stages in the process, and though they are by no means sharply divided in time, they do correspond to different degrees and kinds of intercourse.

(a) The first represents the period of the early intercourse of Rome with the Greek states, especially with the colonies in the south of Italy and Sicily. To this stage belong many names of nations, countries and towns, as Siculi, Tarentum, Graeci, Achivi, Poenus; and also names of weights and measures, articles of industry and terms connected with navigation, as mina, talentum, purpura, patina, ancora, aplustre, nausea. Words like amurca, scutula, pessulus, balineum, tarpessita represent familiarity with Greek customs and bear equally the mark of naturalization. To these may be added names of gods or heroes, like Apollo, Pollux and perhaps Hercules. These all became naturalized Latin words and were modified by the phonetic changes which took place in the Latin language after they had come into it (cf. §§ 9-27 supra). (b) The second stage was probably the result of the closer intercourse resulting from the conquest of southern Italy, and the wars in Sicily, and of the contemporary introduction of imitations of Greek literature into Rome, with its numerous references to Greek life and culture. It is marked by the free use of hybrid forms, whether made by the addition of Latin suffixes to Greek stems as ballistārius, hēpatārius, subbasilicānus, sycophantiōsus, cōmissārī or of Greek suffixes to Latin stems as plāgipatidas, pernōnides; or by derivation, as thermopōtāre, supparasītāri; or by composition as ineuschēmē, thyrsigerae, flagritribae, scrophipascī. The character of many of these words shows that the comic poets who coined them must have been able to calculate upon a fair knowledge of colloquial Greek on the part of a considerable portion of their audience. The most remarkable instance of this is supplied by the burlesque lines in Plautus (Pers. 702 seq.), where Sagaristio describes himself as

| Vaniloquidorus, Virginisvendonides, Nugipiloquides, Argentumexterebronides, Tedigniloquides, Nummosexpalponides, Quodsemelarripides, Nunquameripides. |

During this period Greek words are still generally inflected according to the Latin usage.

(c) But with Accius (see below) begins a third stage, in which the Greek inflexion is frequently preserved, e.g. Hectora, Oresten, Cithaeron; and from this time forward the practice wavers. Cicero generally prefers the Latin case-endings, defending, e.g., Piraeeum as against Piraeea (ad Att. vii. 3, 7), but not without some fluctuation, while Varro takes the opposite side, and prefers poëmasin to the Ciceronian poëmatis. By this time also y and z were introduced, and the representation of the Greek aspirates by th, ph, ch, so that words newly borrowed from the Greek could be more faithfully reproduced. This is equally true whatever was the precise nature of the sound which at that period the Greek aspirates had reached in their secular process of change from pure aspirates (as in Eng. ant-hill, &c.) to fricatives (like Eng. th in thin). (See Arnold and Conway, The Restored Pronunciation of Greek and Latin, 4th ed., Cambridge, 1908, p. 21.)

(d) A fourth stage is marked by the practice of the Augustan poets, who, especially when writing in imitation of Greek originals, freely use the Greek inflexions, such as Arcaděs, Tethŷ, Aegida, Echūs, &c. Horace probably always used the Latin form in his Satires and Epistles, the Greek in his Odes. Later prose writers for the most part followed the example of his Odes. It must be added, however, in regard to these literary borrowings that it is not quite clear whether in this fourth class, and even in the unmodified forms in the preceding class, the words had really any living use in spoken Latin.

V. Pronunciation

This appears the proper place for a rapid survey of the pronunciation1 of the Latin language, as spoken in its best days.

37. Consonants.—(i.) Back palatal. Breathed plosive c, pronounced always as k (except that in some early inscriptions—probably none much later, if at all later, than 300 B.C.—the character is used also for g) until about the 7th century after Christ. K went out of use at an early period, except in a few old abbreviations for words in which it had stood before a, e.g., kal. for kalendae. Q, always followed by the consonantal u, except in a few old inscriptions, in which it is used for c before the vowel u, e.g. pequnia. X, an abbreviation for cs; xs is, however, sometimes found. Voiced plosive g, pronounced as in English gone, but never as in English gem before about the 6th century after Christ. Aspirate h, the rough breathing as in English.

(ii.) Palatal.—The consonantal i, like the English y; it is only in late inscriptions that we find, in spellings like Zanuario, Giove, any definite indication of a pronunciation like the English j. The precise date of the change is difficult to determine (see Lindsay’s Latin Lang. p. 49), especially as we may, in isolated cases, have before us merely a dialectic variation; see Paeligni.

(iii.) Lingual.—r as in English, but probably produced more with the point of the tongue. l similarly more dental than in English. s always breathed (as Eng. ce in ice). z, which is only found in the transcription of Greek words in and after the time of Cicero, as dz or zz.

(iv.) Dental.—Breathed, t as in English. Voiced, d as in English; but by the end of the 4th century di before a vowel was pronounced like our j (cf. diurnal and journal). Nasal, n as in English; but also (like the English n) a guttural nasal (ng) before a guttural. Apparently it was very lightly pronounced, and easily fell away before s.

(v.) Labial.—Breathed, p as in English. Voiced, b as in English; but occasionally in inscriptions of the later empire v is written for b, showing that in some cases b had already acquired the fricative sound of the contemporary β (see § 24, iii.). b before a sharp s was pronounced p, e.g. in urbs. Nasal, m as in English, but very slightly pronounced at the end of a word. Spirant, v like the ou in French oui, but later approximating to the w heard in some parts of Germany, Ed. Sievers, Grundzüge d. Phonetik, ed. 4, p. 117, i.e. a labial v, not (like the English v) a labio-dental v.

(vi.) Labio-dental.—Breathed fricative, f as in English.

38. Vowels.—ā, ū, ī, as the English ah, oo, ee; ō, a sound coming nearer to Eng. aw than to Eng. ō; ē a close Italian ē, nearly as the a of Eng. mate, ée of Fr. passée. The short sound of the vowels was not always identical in quality with the long sound. ă was pronounced as in the French chatte, ŭ nearly as in Eng. pull, ĭ nearly as in pit, ŏ as in dot, ĕ nearly as in pet. The diphthongs were produced by pronouncing in rapid succession the vowels of which they were composed, according to the above scheme. This gives, au somewhat broader than ou in house; eu like ow in the “Yankee” pronunciation of town; ae like the vowel in hat lengthened, with perhaps somewhat more approximation to the i in wine; oe, a diphthongal sound approximating to Eng. oi; ui, as the French oui.

To this it should be added that the Classical Association, acting 251 on the advice of a committee of Latin scholars, has recommended for the diphthongs ae and oe the pronunciation of English i (really ai) in wine and oi in boil, sounds which they undoubtedly had in the time of Plautus and probably much later, and which for practical use in teaching have been proved far the best.

VI. The Language As Recorded

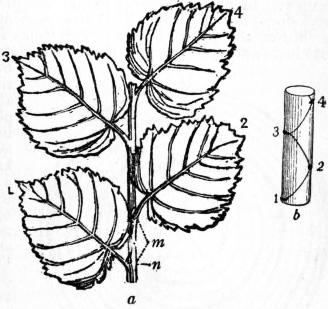

39. Passing now to a survey of the condition of the language at various epochs and in the different authors, we find the earliest monument of it yet discovered in a donative inscription on a fibula or brooch found in a tomb of the 7th century B.C. at Praeneste. It runs “Manios med fhefhaked Numasioi,” i.e. “Manios made me for Numasios.” The use of f (fh) to denote the sound of Latin f supplied the explanation of the change of the symbol f from its Greek value (= Eng. w) to its Latin value f, and shows the Chalcidian Greek alphabet in process of adaptation to the needs of Latin (see Writing). The reduplicated perfect, its 3rd sing. ending -ed, the dative masculine in -oi (this is one of the only two recorded examples in Latin), the -s- between vowels (§ 25, 1), and the -a- in what was then (see §§ 9, 10) certainly an unaccented syllable and the accusative med, are all interesting marks of antiquity.2

40. The next oldest fragment of continuous Latin is furnished

by a vessel dug up in the valley between the Quirinal and the

Viminal early in 1880. The vessel is of a dark brown clay, and

consists of three small round pots, the sides of which are connected

together. All round this vessel runs an inscription,

in three clauses, two nearly continuous, the third written below;

the writing is from right to left, and is still clearly legible; the

characters include one sign not belonging to the later Latin

alphabet, namely  for R, while the M has five strokes and the

Q has the form of a Koppa.

for R, while the M has five strokes and the

Q has the form of a Koppa.

The inscription is as follows:—

“iovesat deivos qoi med mitat, nei ted endo cosmis virco sied, asted noisi opetoitesiai pacari vois.

dvenos med feced en manom einom duenoi ne med malo statod.”

The general style of the writing and the phonetic peculiarities make it fairly certain that this work must have been produced not later than 300 B.C. Some points in its interpretation are still open to doubt,3 but the probable interpretation is—

“Deos iurat ille (or iurant illi) qui me mittat (or mittant) ne in te Virgo (i.e. Proserpina) comis sit, nisi quidem optimo (?) Theseae (?) pacari vis. Duenos me fecit contra Manum, Dueno autem ne per me malum stato (= imputetur, imponatur).”

“He (or they) who dispatch me binds the gods (by his offering) that Proserpine shall not be kind to thee unless thou wilt make terms with (or “for”) Opetos Thesias (?). Duenos made me against Manus, but let no evil fall to Duenos on my account.”

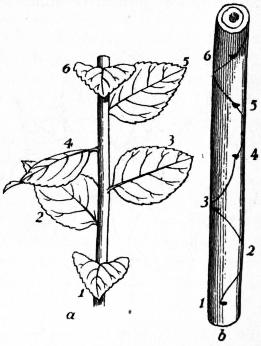

41. Between these two inscriptions lies in point of date the famous stele discovered in the Forum in 1899 (G. Boni, Notiz. d. scavi, May 1899). The upper half had been cut off in order to make way for a new pavement or black stone blocks (known to archaeologists as the niger lapis) on the site of the comitium, just to the north-east of the Forum in front of the Senate House. The inscription was written lengthwise along the (pyramidal) stele from foot to apex, but with the alternate lines in reverse directions, and one line not on the full face of any one of the four sides, but up a roughly-flattened fifth side made by slightly broadening one of the angles. No single sentence is complete and the mutilated fragments have given rise to a whole literature of conjectural “restorations.”

R. S. Conway examined it in situ in company with F. Skutsch in

1903 (cf. his article in Vollmöller’s Jahresbericht, vi. 453), and the

only words that can be regarded as reasonably certain are regei

(regi) on face 2, kalatorem and iouxmenta on face 3, and iouestod

(iusto) on face 4.4 The date may be said to be fixed by the variation of

the sign for m between  and

and  (with

(with  for r) and other alphabetic

indications which suggest the 5th century B.C. It has been suggested

also that the reason for the destruction of the stele and the repavement

may have been either (1) the pollution of the comitium by the

Gallic invasion of 390 B.C., all traces of which, on their departure,

could be best removed by a repaving; or (2) perhaps more probably,

the Augustan restorations (Studniczka, Jahresheft d. Österr. Institut,

1903, vi. 129 ff.).

for r) and other alphabetic

indications which suggest the 5th century B.C. It has been suggested

also that the reason for the destruction of the stele and the repavement

may have been either (1) the pollution of the comitium by the

Gallic invasion of 390 B.C., all traces of which, on their departure,

could be best removed by a repaving; or (2) perhaps more probably,

the Augustan restorations (Studniczka, Jahresheft d. Österr. Institut,

1903, vi. 129 ff.).

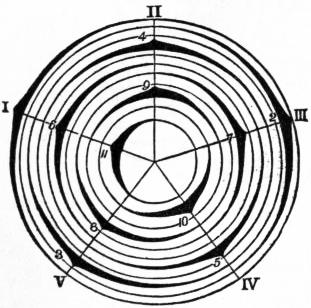

42. Of the earlier long inscriptions the most important would be the Columna Rostrata, or column of Gaius Duilius (q.v.), erected to commemorate his victory over the Carthaginians in 260 B.C., but for the extent to which it has suffered from the hands of restorers. The shape of the letters plainly shows that the inscription, as we have it, was cut in the time of the empire. Hence Ritschl and Mommsen pointed out that the language was modified at the same time, and that, although many archaisms have been retained, some were falsely introduced, and others replaced by more modern forms. The most noteworthy features in it are—C always written for G (Ceset = gessit), single for double consonants (clases-classes), d retained in the ablative (e.g., in altod marid), o for u in inflexions (primos, exfociont = exfugiunt), e for i (navebos = navibus, exemet = exemit); of these the first is probably an affected archaism, G having been introduced some time before the assumed date of the inscription. On the other hand, we have praeda where we should have expected praida; no final consonants are dropped; and the forms -es, -eis and -is for the accusative plural are interchanged capriciously. The doubts hence arising preclude the possibility of using it with confidence as evidence for the state of the language in the 3rd century B.C.

43. Of unquestionable genuineness and the greatest value are the Scipionum Elogia, inscribed on stone coffins, found in the monument of the Scipios outside the Capene gate (C.I.L.1 i. 32). The earliest of the family whose epitaph has been preserved is L. Cornelius Scipio Barbatus (consul 298 B.C.), the latest C. Cornelius Scipio Hispanus (praetor in 139 B.C.); but there are good reasons for believing with Ritschl that the epitaph of the first was not contemporary, but was somewhat later than that of his son (consul 259 B.C.). This last may therefore be taken as the earliest specimen of any length of Latin and it was written at Rome; it runs as follows:—

| honcoino . ploirume . cosentiont . r[omai] duonoro . optumo . fuise . uiro [virorum] luciom . scipione . filios . barbati co]nsol . censor . aidilis . hic . fuet a [pud vos] he]c . cepit . corsica . aleriaque . urbe[m] de]det . tempestatebus . aide . mereto[d votam]. |

The archaisms in this inscription are—(1) the retention of o for u in the inflexion of both nouns and verbs; (2) the diphthongs oi (= later u) and ai (= later ae); (3) -et for -it, hec for hic, and -ebus for -ibus; (4) duon- for bon; and (5) the dropping of a final m in every case except in Luciom, a variation which is a marked characteristic of the language of this period.

44. The oldest specimen of the Latin language preserved to us in any literary source is to be found in two fragments of the Carmina Saliaria (Varro, De ling. Lat. vii. 26, 27), and one in Terentianus Scaurus, but they are unfortunately so corrupt as to give us little real information (see B. Maurenbrecher, Carminum Saliarium reliquiae, Leipzig, 1894; G. Hempl, American Philol. Assoc. Transactions, xxxi., 1900, 184). Rather better evidence is supplied in the Carmen Fratrum Arvalium, which was found in 1778 engraved on one of the numerous tablets recording the transactions of the college of the Arval brothers, dug up on the site of their grove by the Tiber, 5 m. from the city of Rome; but this also has been so corrupted in its oral tradition that even its general meaning is by no means clear (C.I.L.1 i. 28; Jordan, Krit. Beiträge, pp. 203-211).

45. The text of the Twelve Tables (451-450 B.C.), if preserved in its integrity, would have been invaluable as a record of antique Latin; but it is known to us only in quotations. R. Schoell, whose edition and commentary (Leipzig, 1866) is the most complete, notes the following traces, among others, of an archaic syntax: (1) both the subject and the object of the verb are often left to be understood from the context, e.g. ni it antestamino, igitur, em capito; (2) the imperative is used even for permissions, “si volet, plus dato,” “if he choose, he may give him more”; (3) the subjunctive is apparently never used in conditional, 252 only in final sentences, but the future perfect is common; (4) the connexion between sentences is of the simplest kind, and conjunctions are rare. There are, of course, numerous isolated archaisms of form and meaning, such as calvitur, pacunt, endo, escit. Later and less elaborate editions are contained in Fontes Iuris Romani, by Bruns-Mommsen-Gradenwitz (1892); and P. Girard, Textes de droit romain (1895).

46. Turning now to the language of literature we may group the Latin authors as follows:—5

I. Ante-Classical (240-80 B.C.).—Naevius (? 269-204), Plautus (254-184), Ennius (239-169), Cato the Elder (234-149), Terentius (? 195-159), Pacuvius (220-132), Accius (170-94), Lucilius (? 168-103).

II. Classical—Golden Age (80 B.C.-A.D. 14).—Varro (116-28), Cicero (106-44), Lucretius (99-55), Caesar (102-44), Catullus (87-? 47), Sallust (86-34), Virgil (70-19), Horace (65-8), Propertius (? 50- ?), Tibullus (? 54-? 18), Ovid (43 B.C.-A.D. 18), Livy (59 B.C.-A.D. 18).