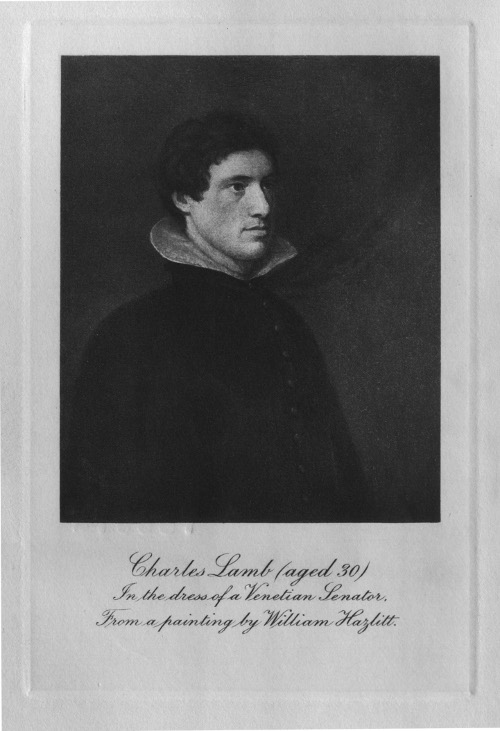

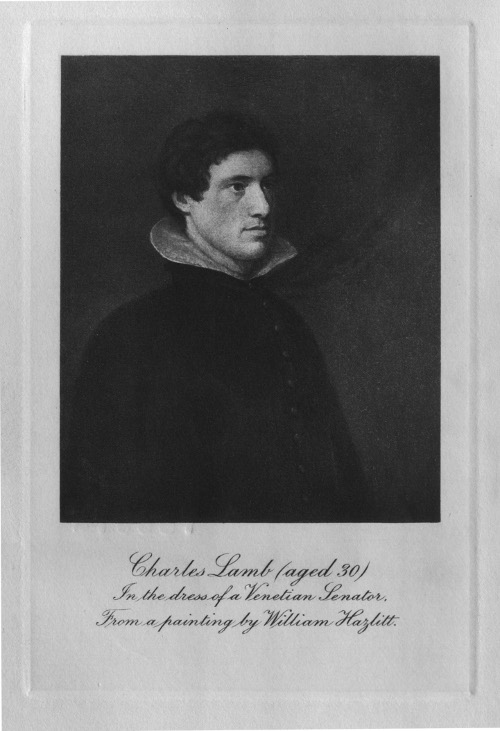

Charles Lamb (aged 30)

Charles Lamb (aged 30)In the dress of a Venetian Senator,

From a painting by William Hazlitt.

BY THE SAME EDITOR

and

The Pocket Edition of the Works of Charles Lamb: I. Miscellaneous Prose; II. Elia; III. Children's Books; IV. Poems and Plays; V. and VI. Letters.

Charles Lamb (aged 30)

Charles Lamb (aged 30)BY

CHARLES AND MARY LAMB

EDITED BY

E. V. LUCAS

WITH A FRONTISPIECE

METHUEN & CO LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published in this form (Fcap. 8vo) in 1912

This Work was first Published in Seven Volumes (Demy 8vo) in 1903-5

This edition is the same as that in seven large volumes published between 1903 and 1905, except that it has been revised and amended and arranged in more companionable shape. Some new matter is included; some doubtful matter has been removed; and the notes, although occasionally enriched, have been reduced in number and often condensed. For completer annotation as well as for portraits and accessory illustrations the old edition must be consulted.

The present volume contains all Lamb's prose, with the exception of his work for children, his full notes in the Dramatic Specimens and Garrick Extracts, his prose plays and the Elia essays. The contents have been arranged in their order of publication, the earliest dating from 1798, when Lamb was twenty-three, and the latest belonging to 1834, the year of his death—thus covering the whole of his literary life.

In Mr. Bedford's design for the cover of this edition certain Elian symbolism will be found. The upper coat of arms is that of Christ's Hospital, where Lamb was at school; the lower is that of the Inner Temple, where he was born and spent many years. The figures at the bells are those which once stood out from the façade of St. Dunstan's Church in Fleet Street, and are now in Lord Londesborough's garden in Regent's Park. Lamb shed tears when they were removed. The tricksy sprite and the candles (brought by Betty) need no explanatory words of mine.

E. V. L.

APPENDIX

Essays and Notes Not Certain To Be Lamb's, But Probably His

| Scraps of Criticism | 425 | 551 |

| The Miscellany | 427 | 552 |

| Review of Dibdin's Comic Tales | 429 | 552 |

| Dog Days | 430 | 553 |

| The Progress of Cant | 431 | 554 |

| Mr. Ephraim Wagstaff | 432 | 554 |

| Review of Moxon's Sonnets | 435 | 554 |

| NOTES | 437 | |

FRONTISPIECE

Charles Lamb (aged 30) in the Dress of a Venetian Senator

From A Painting By William Hazlitt Now in the National Portrait Gallery

(Written 1797-1798. First Edition 1798. Text of 1818)

It was noontide. The sun was very hot. An old gentlewoman sat spinning in a little arbour at the door of her cottage. She was blind; and her grandaughter was reading the Bible to her. The old lady had just left her work, to attend to the story of Ruth.

"Orpah kissed her mother-in-law; but Ruth clave unto her." It was a passage she could not let pass without a comment. The moral she drew from it was not very new, to be sure. The girl had heard it a hundred times before—and a hundred times more she could have heard it, without suspecting it to be tedious. Rosamund loved her grandmother.

The old lady loved Rosamund too; and she had reason for so doing. Rosamund was to her at once a child and a servant. She had only her left in the world. They two lived together.

They had once known better days. The story of Rosamund's parents, their failure, their folly, and distresses, may be told another time. Our tale hath grief enough in it.

It was now about a year and a half since old Margaret Gray had sold off all her effects, to pay the debts of Rosamund's father—just after the mother had died of a broken heart; for her husband had fled his country to hide his shame in a foreign land. At that period the old lady retired to a small cottage, in the village of Widford, in Hertfordshire.

Rosamund, in her thirteenth year, was left destitute, without fortune or friends: she went with her grandmother. In all this time she had served her faithfully and lovingly.

Old Margaret Gray, when she first came into these parts, had eyes, and could see. The neighbours said, they had been dimmed by weeping: be that as it may, she was latterly grown quite blind. "God is very good to us, child; I can feel you yet." This she would sometimes say; and we need not wonder to hear, that Rosamund clave unto her grandmother.

Margaret retained a spirit unbroken by calamity. There was a principle within, which it seemed as if no outward circumstances could reach. It was a religious principle, and she had taught it to Rosamund; for the girl had mostly resided with her grandmother from her earliest years. Indeed she had taught her all that she knew herself; and the old lady's knowledge did not extend a vast way.

Margaret had drawn her maxims from observation; and a pretty long experience in life had contributed to make her, at times, a little positive: but Rosamund never argued with her grandmother.

Their library consisted chiefly in a large family Bible, with notes and expositions by various learned expositors from Bishop Jewell downwards.

This might never be suffered to lie about like other books—but was kept constantly wrapt up in a handsome case of green velvet, with gold tassels—the only relick of departed grandeur they had brought with them to the cottage—every thing else of value had been sold off for the purpose above mentioned.

This Bible Rosamund, when a child, had never dared to open without permission; and even yet, from habit, continued the custom. Margaret had parted with none of her authority; indeed it was never exerted with much harshness; and happy was Rosamund, though a girl grown, when she could obtain leave to read her Bible. It was a treasure too valuable for an indiscriminate use; and Margaret still pointed out to her grandaughter where to read.

Besides this, they had the "Complete Angler, or Contemplative Man's Recreation," with cuts—"Pilgrim's Progress," the first part—a Cookery Book, with a few dry sprigs of rosemary and lavender stuck here and there between the leaves, (I suppose, to point to some of the old lady's most favorite receipts,) and there was "Wither's Emblems," an old book, and quaint. The old fashioned pictures in this last book were among the first exciters of the infant Rosamund's curi[Pg 3]osity. Her contemplation had fed upon them in rather older years.

Rosamund had not read many books besides these; or if any, they had been only occasional companions: these were to Rosamund as old friends, that she had long known. I know not whether the peculiar cast of her mind might not be traced, in part, to a tincture she had received, early in life, from Walton, and Wither, from John Bunyan, and her Bible.

Rosamund's mind was pensive and reflective, rather than what passes usually for clever or acute. From a child she was remarkably shy and thoughtful—this was taken for stupidity and want of feeling; and the child has been sometimes whipt for being a stubborn thing, when her little heart was almost bursting with affection.

Even now her grandmother would often reprove her, when she found her too grave or melancholy; give her sprightly lectures about good humour and rational mirth; and not unfrequently fall a crying herself, to the great discredit of her lecture. Those tears endeared her the more to Rosamund.

Margaret would say, "Child, I love you to cry, when I think you are only remembering your poor dear father and mother—I would have you think about them sometimes—it would be strange if you did not—but I fear, Rosamund; I fear, girl, you sometimes think too deeply about your own situation and poor prospects in life. When you do so, you do wrong—remember the naughty rich man in the parable. He never had any good thoughts about God, and his religion: and that might have been your case."

Rosamund, at these times, could not reply to her; she was not in the habit of arguing with her grandmother; so she was quite silent on these occasions—or else the girl knew well enough herself, that she had only been sad to think of the desolate condition of her best friend, to see her, in her old age, so infirm and blind. But she had never been used to make excuses, when the old lady said she was doing wrong.

The neighbours were all very kind to them. The veriest rustics never passed them without a bow, or a pulling off of the hat—some shew of courtesy, aukward indeed, but affectionate—with a "good morrow, madam," or "young madam," as it might happen.

Rude and savage natures, who seem born with a propensity[Pg 4] to express contempt for any thing that looks like prosperity, yet felt respect for its declining lustre.

The farmers, and better sort of people, (as they are called,) all promised to provide for Rosamund, when her grandmother should die. Margaret trusted in God, and believed them.

She used to say, "I have lived many years in the world, and have never known people, good people, to be left without some friend; a relation, a benefactor, a something. God knows our wants—that it is not good for man or woman to be alone; and he always sends us a helpmate, a leaning-place, a somewhat." Upon this sure ground of experience, did Margaret build her trust in Providence.

Rosamund had just made an end of her story, (as I was about to relate,) and was listening to the application of the moral, (which said application she was old enough to have made herself, but her grandmother still continued to treat her, in many respects, as a child, and Rosamund was in no haste to lay claim to the title of womanhood,) when a young gentleman made his appearance, and interrupted them.

It was young Allan Clare, who had brought a present of peaches, and some roses, for Rosamund.

He laid his little basket down on a seat of the arbour; and in a respectful tone of voice, as though he were addressing a parent, enquired of Margaret "how she did."

The old lady seemed pleased with his attentions—answered his enquiries by saying, that "her cough was less troublesome a-nights, but she had not yet got rid of it, and probably she never might; but she did not like to teaze young people with an account of her infirmities."

A few kind words passed on either side, when young Clare, glancing a tender look at the girl, who had all this time been silent, took leave of them with saying "I shall bring Elinor to see you in the evening."

When he was gone, the old lady began to prattle.

"That is a sweet dispositioned youth, and I do love him dearly, I must say it—there is such a modesty in all he says or does—he should not come here so often, to be sure, but I don't know how to help it; there is so much goodness in him, I can't find in my heart to forbid him. But, Rosamund, girl,[Pg 5] I must tell you beforehand; when you grow older, Mr. Clare must be no companion for you—while you were both so young, it was all very well—but the time is coming, when folks will think harm of it, if a rich young gentleman, like Mr. Clare, comes so often to our poor cottage.—Dost hear, girl? why don't you answer? come, I did not mean to say any thing to hurt you—speak to me, Rosamund—nay, I must not have you be sullen—I don't love people that are sullen."

And in this manner was this poor soul running on, unheard and unheeded, when it occurred to her, that possibly the girl might not be within hearing.

And true it was, that Rosamund had slunk away at the first mention of Mr. Clare's good qualities: and when she returned, which was not till a few minutes after Margaret had made an end of her fine harangue, it is certain her cheeks did look very rosy. That might have been from the heat of the day or from exercise, for she had been walking in the garden.

Margaret, we know, was blind; and, in this case, it was lucky for Rosamund that she was so, or she might have made some not unlikely surmises.

I must not have my reader infer from this, that I at all think it likely, a young maid of fourteen would fall in love without asking her grandmother's leave—the thing itself is not to be conceived.

To obviate all suspicions, I am disposed to communicate a little anecdote of Rosamund.

A month or two back her grandmother had been giving her the strictest prohibitions, in her walks, not to go near a certain spot, which was dangerous from the circumstance of a huge overgrown oak tree spreading its prodigious arms across a deep chalk-pit, which they partly concealed.

To this fatal place Rosamund came one day—female curiosity, we know, is older than the flood—let us not think hardly of the girl, if she partook of the sexual failing.

Rosamund ventured further and further—climbed along one of the branches—approached the forbidden chasm—her foot slipped—she was not killed—but it was by a mercy she escaped—other branches intercepted her fall—and with a palpitating heart she made her way back to the cottage.

It happened that evening, that her grandmother was in one of her best humours, caressed Rosamund, talked of old times,[Pg 6] and what a blessing it was they two found a shelter in their little cottage, and in conclusion told Rosamund, "she was a good girl, and God would one day reward her for her kindness to her old blind grandmother."

This was more than Rosamund could bear. Her morning's disobedience came fresh into her mind, she felt she did not deserve all this from Margaret, and at last burst into a fit of crying, and made confession of her fault. The old gentlewoman kissed and forgave her.

Rosamund never went near that naughty chasm again.

Margaret would never have heard of this, if Rosamund had not told of it herself. But this young maid had a delicate moral sense, which would not suffer her to take advantage of her grandmother, to deceive her, or conceal any thing from her, though Margaret was old, and blind, and easy to be imposed upon.

Another virtuous trait I recollect of Rosamund, and, now I am in the vein, will tell it.

Some, I know, will think these things trifles—and they are so—but if these minutiæ make my reader better acquainted with Rosamund, I am content to abide the imputation.

These promises of character, hints, and early indications of a sweet nature, are to me more dear, and choice in the selection, than any of those pretty wild flowers, which this young maid, this virtuous Rosamund, has ever gathered in a fine May morning, to make a posy to place in the bosom of her old blind friend.

Rosamund had a very just notion of drawing, and would often employ her talent in making sketches of the surrounding scenery.

On a landscape, a larger piece than she had ever yet attempted, she had now been working for three or four months. She had taken great pains with it, given much time to it, and it was nearly finished. For whose particular inspection it was designed, I will not venture to conjecture. We know it could not have been for her grandmother's.

One day she went out on a short errand, and left her landscape on the table. When she returned she found it gone.

Rosamund from the first suspected some mischief, but held her tongue. At length she made the fatal discovery. Margaret, in her absence, had laid violent hands on it; not knowing what it was, but taking it for some waste paper, had[Pg 7] torn it in half, and with one half of this elaborate composition had twisted herself up—a thread-paper!

Rosamund spread out her hands at sight of the disaster, gave her grandmother a roguish smile, but said not a word. She knew the poor soul would only fret, if she told her of it,—and when once Margaret was set a fretting for other people's misfortunes, the fit held her pretty long.

So Rosamund that very afternoon began another piece of the same size and subject; and Margaret, to her dying day, never dreamed of the mischief she had unconsciously done.

Rosamund Gray was the most beautiful young creature that eyes ever beheld. Her face had the sweetest expression in it—a gentleness—a modesty—a timidity—a certain charm—a grace without a name.

There was a sort of melancholy mingled in her smile. It was not the thoughtless levity of a girl—it was not the restrained simper of premature womanhood—it was something which the poet Young might have remembered, when he composed that perfect line,

She was a mild-eyed maid, and every body loved her. Young Allan Clare, when but a boy, sighed for her.

Her yellow hair fell in bright and curling clusters, like

Her voice was trembling and musical. A graceful diffidence pleaded for her whenever she spake—and, if she said but little, that little found its way to the heart.

Young, and artless, and innocent, meaning no harm, and thinking none; affectionate as a smiling infant—playful, yet inobtrusive, as a weaned lamb—every body loved her. Young Allan Clare, when but a boy, sighed for her.

The moon is shining in so brightly at my window, where I write, that I feel it a crime not to suspend my employment awhile to gaze at her.

See how she glideth, in maiden honor, through the clouds, who divide on either side to do her homage.

Beautiful vision!—as I contemplate thee, an internal harmony is communicated to my mind, a moral brightness, a tacit analogy of mental purity; a calm like that we ascribe in fancy to the favored inhabitants of thy fairy regions, "argent fields."

I marvel not, O moon, that heathen people, in the "olden times," did worship thy deity—Cynthia, Diana, Hecate. Christian Europe invokes thee not by these names now—her idolatry is of a blacker stain: Belial is her God—she worships Mammon.

False things are told concerning thee, fair planet—for I will ne'er believe, that thou canst take a perverse pleasure in distorting the brains of us poor mortals. Lunatics! moonstruck! Calumny invented, and folly took up, these names. I would hope better things from thy mild aspect and benign influences.

Lady of Heaven, thou lendest thy pure lamp to light the way to the virgin mourner, when she goes to seek the tomb where her warrior lover lies.

Friend of the distressed, thou speakest only peace to the lonely sufferer, who walks forth in the placid evening, beneath thy gentle light, to chide at fortune, or to complain of changed friends, or unhappy loves.

Do I dream, or doth not even now a heavenly calm descend from thee into my bosom, as I meditate on the chaste loves of Rosamund and her Clare?

Allan Clare was just two years elder than Rosamund. He was a boy of fourteen, when he first became acquainted with her—it was soon after she had come to reside with her grandmother at Widford.

He met her by chance one day, carrying a pitcher in her hand, which she had been filling from a neighbouring well—the pitcher was heavy, and she seemed to be bending with its weight.

Allan insisted on carrying it for her—for he thought it a sin, that a delicate young maid, like her, should be so employed, and he stand idle by.

Allan had a propensity to do little kind offices for every body—but at the sight of Rosamund Gray his first fire was[Pg 9] kindled—his young mind seemed to have found an object, and his enthusiasm was from that time forth awakened. His visits, from that day, were pretty frequent at the cottage.

He was never happier than when he could get Rosamund to walk out with him. He would make her admire the scenes he admired—fancy the wild flowers he fancied—watch the clouds he was watching—and not unfrequently repeat to her poetry, which he loved, and make her love it.

On their return, the old lady, who considered them yet as but children, would bid Rosamund fetch Mr. Clare a glass of her currant wine, a bowl of new milk, or some cheap dainty, which was more welcome to Allan than the costliest delicacies of a prince's court.

The boy and girl, for they were no more at that age, grew fond of each other—more fond than either of them suspected.

And thus,

A circumstance had lately happened, which in some sort altered the nature of their attachment.

Rosamund was one day reading the tale of "Julia de Roubigné"—a book which young Clare had lent her.

Allan was standing by, looking over her, with one hand thrown round her neck, and a finger of the other pointing to a passage in Julia's third letter.

"Maria! in my hours of visionary indulgence, I have sometimes painted to myself a husband—no matter whom—comforting me amidst the distresses, which fortune had laid upon us. I have smiled upon him through my tears; tears, not of anguish, but of tenderness;—our children were playing around us, unconscious of misfortune; we had taught them to be humble, and to be happy; our little shed was reserved to us, and their smiles to cheer it.—I have imagined the luxury of such a scene, and affliction became a part of my dream of happiness."

The girl blushed as she read, and trembled—she had a[Pg 10] sort of confused sensation, that Allan was noticing her—yet she durst not lift her eyes from the book, but continued reading, scarce knowing what she read.

Allan guessed the cause of her confusion. Allan trembled too—his colour came and went—his feeling became impetuous—and, flinging both arms round her neck, he kissed his young favourite.

Rosamund was vexed and pleased, soothed and frightened, all in a moment—a fit of tears came to her relief.

Allan had indulged before in these little freedoms, and Rosamund had thought no harm of them—but from this time the girl grew timid and reserved—distant in her manner, and careful of her behaviour, in Allan's presence—not seeking his society as before, but rather shunning it—delighting more to feed upon his idea in absence.

Allan too, from this day, seemed changed: his manner became, though not less tender, yet more respectful and diffident—his bosom felt a throb it had till now not known, in the society of Rosamund—and, if he was less familiar with her than in former times, that charm of delicacy had superadded a grace to Rosamund, which, while he feared, he loved.

There is a mysterious character, heightened indeed by fancy and passion, but not without foundation in reality and observation, which true lovers have ever imputed to the object of their affections. This character Rosamund had now acquired with Allan—something angelic, perfect, exceeding nature.

Young Clare dwelt very near to the cottage. He had lost his parents, who were rather wealthy, early in life; and was left to the care of a sister, some ten years older than himself.

Elinor Clare was an excellent young lady—discreet, intelligent, and affectionate. Allan revered her as a parent, while he loved her as his own familiar friend. He told all the little secrets of his heart to her—but there was one, which he had hitherto unaccountably concealed from her—namely, the extent of his regard for Rosamund.

Elinor knew of his visits to the cottage, and was no stranger to the persons of Margaret and her grandaughter. She had several times met them, when she had been walking with her brother—a civility usually passed on either side—but Elinor avoided troubling her brother with any unseasonable questions.

Allan's heart often beat, and he has been going to tell his[Pg 11] sister all—but something like shame (false or true, I shall not stay to enquire) had hitherto kept him back—still the secret, unrevealed, hung upon his conscience like a crime—for his temper had a sweet and noble frankness in it, which bespake him yet a virgin from the world.

There was a fine openness in his countenance—the character of it somewhat resembled Rosamund's—except that more fire and enthusiasm were discernible in Allan's—his eyes were of a darker blue than Rosamund's—his hair was of a chesnut colour—his cheeks ruddy, and tinged with brown. There was a cordial sweetness in Allan's smile, the like to which I never saw in any other face.

Elinor had hitherto connived at her brother's attachment to Rosamund. Elinor, I believe, was something of a physiognomist, and thought she could trace in the countenance and manner of Rosamund qualities, which no brother of her's need be ashamed to love.

The time was now come, when Elinor was desirous of knowing her brother's favorite more intimately—an opportunity offered of breaking the matter to Allan.

The morning of the day, in which he carried his present of fruit and flowers to Rosamund, his sister had observed him more than usually busy in the garden, culling fruit with a nicety of choice not common to him.

She came up to him, unobserved, and, taking him by the arm, enquired, with a questioning smile—"What are you doing, Allan? and who are those peaches designed for?"

"For Rosamund Gray"—he replied—and his heart seemed relieved of a burthen, which had long oppressed it.

"I have a mind to become acquainted with your handsome friend—will you introduce me, Allan? I think I should like to go and see her this afternoon."

"Do go, do go, Elinor—you don't know what a good creature she is—and old blind Margaret, you will like her very much."

His sister promised to accompany him after dinner; and they parted. Allan gathered no more peaches, but hastily cropping a few roses to fling into his basket, went away with it half filled, being impatient to announce to Rosamund the coming of her promised visitor.

When Allan returned home, he found an invitation had been left for him, in his absence, to spend that evening with a young friend, who had just quitted a public school in London, and was come to pass one night in his father's house at Widford, previous to his departure the next morning for Edinburgh University.

It was Allan's bosom friend—they had not met for some months—and it was probable, a much longer time must intervene, before they should meet again.

Yet Allan could not help looking a little blank, when he first heard of the invitation. This was to have been an important evening. But Elinor soon relieved her brother, by expressing her readiness to go alone to the cottage.

"I will not lose the pleasure I promised myself, whatever you may determine upon, Allan—I will go by myself rather than be disappointed."

"Will you, will you, Elinor?"

Elinor promised to go—and I believe, Allan, on a second thought, was not very sorry to be spared the aukwardness of introducing two persons to each other, both so dear to him, but either of whom might happen not much to fancy the other.

At times, indeed, he was confident that Elinor must love Rosamund, and Rosamund must love Elinor—but there were also times in which he felt misgivings—it was an event he could scarce hope for very joy!

Allan's real presence that evening was more at the cottage than at the house, where his bodily semblance was visiting—his friend could not help complaining of a certain absence of mind, a coldness he called it.

It might have been expected, and in the course of things predicted, that Allan would have asked his friend some questions of what had happened since their last meeting, what his feelings were on leaving school, the probable time when they should meet again, and a hundred natural questions which friendship is most lavish of at such times; but nothing of all this ever occurred to Allan—they did not even settle the method of their future correspondence.

The consequence was, as might have been expected, Allan's friend thought him much altered, and, after his departure, sat down to compose a doleful sonnet about a "faithless friend."[Pg 13]—I do not find that he ever finished it—indignation, or a dearth of rhymes, causing him to break off in the middle.

In my catalogue of the little library at the cottage, I forgot to mention a book of Common Prayer. My reader's fancy might easily have supplied the omission—old ladies of Margaret's stamp (God bless them) may as well be without their spectacles, or their elbow chair, as their prayer book—I love them for it.

Margaret's was a handsome octavo, printed by Baskerville, the binding red, and fortified with silver at the edges. Out of this book it was their custom every afternoon to read the proper psalms appointed for the day.

The way they managed was this: they took verse by verse—Rosamund read her little portion, and Margaret repeated hers, in turn, from memory—for Margaret could say all the Psalter by heart, and a good part of the Bible besides. She would not unfrequently put the girl right when she stumbled or skipped. This Margaret imputed to giddiness—a quality which Rosamund was by no means remarkable for—but old ladies, like Margaret, are not in all instances alike discriminative.

They had been employed in this manner just before Miss Clare arrived at the cottage. The psalm they had been reading was the hundred and fourth—Margaret was naturally led by it into a discussion of the works of creation.

There had been thunder in the course of the day—an occasion of instruction which the old lady never let pass—she began—

"Thunder has a very awful sound—some say, God Almighty is angry whenever it thunders—that it is the voice of God speaking to us—for my part, I am not afraid of it"—

And in this manner the old lady was going on to particularise, as usual, its beneficial effects, in clearing the air, destroying of vermin, &c. when the entrance of Miss Clare put an end to her discourse.

Rosamund received her with respectful tenderness—and, taking her grandmother by the hand, said, with great sweetness, "Miss Clare is come to see you, grandmother."

"I beg pardon, lady—I cannot see you—but you are[Pg 14] heartily welcome—is your brother with you, Miss Clare? I don't hear him."—

"He could not come, madam, but he sends his love by me."

"You have an excellent brother, Miss Clare—but pray do us the honor to take some refreshment—Rosamund"——

And the old lady was going to give directions for a bottle of her currant wine—when Elinor, smiling, said "she was come to take a cup of tea with her, and expected to find no ceremony."

"After tea, I promise myself a walk with you, Rosamund, if your grandmother can spare you."—Rosamund looked at her grandmother.

"O, for that matter, I should be sorry to debar the girl from any pleasure—I am sure it's lonesome enough for her to be with me always—and if Miss Clare will take you out, child, I shall do very well by myself till you return—it will not be the first time, you know, that I have been left here alone—some of the neighbours will be dropping in bye and bye—or, if not, I shall take no harm."

Rosamund had all the simple manners of a child—she kissed her grandmother, and looked happy.

All tea-time the old lady's discourse was little more than a panegyric on young Clare's good qualities. Elinor looked at her young friend, and smiled. Rosamund was beginning to look grave—but there was a cordial sunshine in the face of Elinor, before which any clouds of reserve, that had been gathering on Rosamund's soon brake away.

"Does your grandmother ever go out, Rosamund?"

Margaret prevented the girl's reply, by saying—"my dear young lady, I am an old woman, and very infirm—Rosamund takes me a few paces beyond the door sometimes—but I walk very badly—I love best to sit in our little arbour, when the sun shines—I can yet feel it warm and cheerful—and, if I lose the beauties of the season, I shall be very happy if you and Rosamund can take delight in this fine summer evening."

"I shall want to rob you of Rosamund's company now and then, if we like one another. I had hoped to have seen you, madam, at our house. I don't know whether we could not make room for you to come and live with us—what say you to it?—Allan would be proud to tend you, I am sure; and Rosamund and I should be nice company."

Margaret was all unused to such kindnesses, and wept—Margaret had a great spirit—yet she was not above accepting an obligation from a worthy person—there was a delicacy in Miss Clare's manner—she could have no interest, but pure goodness, to induce her to make the offer—at length the old lady spake from a full heart.

"Miss Clare, this little cottage received us in our distress—it gave us shelter when we had no home—we have praised God in it—and, while life remains, I think I shall never part from it—Rosamund does every thing for me—"

"And will do, grandmother, as long as I live;"—and then Rosamund fell a crying.

"You are a good girl, Rosamund, and if you do but find friends when I am dead and gone, I shall want no better accommodation while I live—but, God bless you, lady, a thousand times, for your kind offer."

Elinor was moved to tears, and, affecting a sprightliness, bade Rosamund prepare for her walk. The girl put on her white silk bonnet; and Elinor thought she had never beheld so lovely a creature.

They took leave of Margaret, and walked out together—they rambled over all Rosamund's favourite haunts—through many a sunny field—by secret glade or woodwalk, where the girl had wandered so often with her beloved Clare.

Who now so happy as Rosamund? She had oft-times heard Allan speak with great tenderness of his sister—she was now rambling, arm in arm, with that very sister, the "vaunted sister" of her friend, her beloved Clare.

Not a tree, not a bush, scarce a wild flower in their path, but revived in Rosamund some tender recollection, a conversation perhaps, or some chaste endearment. Life, and a new scene of things, were now opening before her—she was got into a fairy land of uncertain existence.

Rosamund was too happy to talk much—but Elinor was delighted with her when she did talk:—the girl's remarks were suggested, most of them, by the passing scene—and they betrayed, all of them, the liveliness of present impulse:—her conversation did not consist in a comparison of vapid feeling, an interchange of sentiment lip-deep—it had all the freshness of young sensation in it.

Sometimes they talked of Allan.

"Allan is very good," said Rosamund, "very good indeed[Pg 16] to my grandmother—he will sit with her, and hear her stories, and read to her, and try to divert her a hundred ways. I wonder sometimes he is not tired. She talks him to death!"

"Then you confess, Rosamund, that the old lady does tire you sometimes."

"Oh no, I did not mean that—it's very different—I am used to all her ways, and I can humour her, and please her, and I ought to do it, for she is the only friend I ever had in the world."

The new friends did not conclude their walk till it was late, and Rosamund began to be apprehensive about the old lady, who had been all this time alone.

On their return to the cottage, they found that Margaret had been somewhat impatient—old ladies, good old ladies, will be so at times—age is timorous and suspicious of danger, where no danger is.

Besides, it was Margaret's bed-time, for she kept very good hours—indeed, in the distribution of her meals, and sundry other particulars, she resembled the livers in the antique world, more than might well beseem a creature of this.

So the new friends parted for that night—Elinor having made Margaret promise to give Rosamund leave to come and see her the next day.

Miss Clare, we may be sure, made her brother very happy, when she told him of the engagement she had made for the morrow, and how delighted she had been with his handsome friend.

Allan, I believe, got little sleep that night. I know not, whether joy be not a more troublesome bed-fellow than grief—hope keeps a body very wakeful, I know.

Elinor Clare was the best good creature—the least selfish human being I ever knew—always at work for other people's good, planning other people's happiness—continually forgetful to consult for her own personal gratifications, except indirectly, in the welfare of another—while her parents lived, the most attentive of daughters—since they died, the kindest of sisters—I never knew but one like her.

It happens that I have some of this young lady's letters in my possession—I shall present my reader with one of them.[Pg 17] It was written a short time after the death of her mother, and addressed to a cousin, a dear friend of Elinor's, who was then on the point of being married to Mr. Beaumont, of Staffordshire, and had invited Elinor to assist at her nuptials. I will transcribe it with minute fidelity.

Elinor Clare to Maria Leslie

Widford, July the —, 17—.

Health, Innocence, and Beauty, shall be thy bridemaids, my sweet cousin. I have no heart to undertake the office. Alas! what have I to do in the house of feasting?

Maria! I fear lest my griefs should prove obtrusive. Yet bear with me a little—I have recovered already a share of my former spirits.

I fear more for Allan than myself. The loss of two such parents, with so short an interval, bears very heavy on him. The boy hangs about me from morning till night. He is perpetually forcing a smile into his poor pale cheeks—you know the sweetness of his smile, Maria.

To-day, after dinner, when he took his glass of wine in his hand, he burst into tears, and would not, or could not then, tell me the reason—afterwards he told me—"he had been used to drink Mamma's health after dinner, and that came in his head and made him cry." I feel the claims the boy has upon me—I perceive that I am living to some end—and the thought supports me.

Already I have attained to a state of complacent feelings—my mother's lessons were not thrown away upon her Elinor.

In the visions of last night her spirit seemed to stand at my bed-side—a light, as of noon day, shone upon the room—she opened my curtains—she smiled upon me with the same placid smile as in her life-time. I felt no fear. "Elinor," she said, "for my sake take care of young Allan,"—and I awoke with calm feelings.

Maria! shall not the meeting of blessed spirits, think you, be something like this?—I think, I could even now behold my mother without dread—I would ask pardon of her for all my past omissions of duty, for all the little asperities in my tem[Pg 18]per, which have so often grieved her gentle spirit when living. Maria! I think she would not turn away from me.

Oftentimes a feeling, more vivid than memory, brings her before me—I see her sit in her old elbow chair—her arms folded upon her lap—a tear upon her cheek, that seems to upbraid her unkind daughter for some inattention—I wipe it away and kiss her honored lips.

Maria! when I have been fancying all this, Allan will come in, with his poor eyes red with weeping, and taking me by the hand, destroy the vision in a moment.

I am prating to you, my sweet cousin, but it is the prattle of the heart, which Maria loves. Besides, whom have I to talk to of these things but you—you have been my counsellor in times past, my companion, and sweet familiar friend. Bear with me a little—I mourn the "cherishers of my infancy."

I sometimes count it a blessing, that my father did not prove the survivor. You know something of his story. You know there was a foul tale current—it was the busy malice of that bad man, S——, which helped to spread it abroad—you will recollect the active good nature of our friends W—— and T——; what pains they took to undeceive people—with the better sort their kind labours prevailed; but there was still a party who shut their ears. You know the issue of it. My father's great spirit bore up against it for some time—my father never was a bad man—but that spirit was broken at the last—and the greatly-injured man was forced to leave his old paternal dwelling in Staffordshire—for the neighbours had begun to point at him.—Maria! I have seen them point at him, and have been ready to drop.

In this part of the country, where the slander had not reached, he sought a retreat—and he found a still more grateful asylum in the daily solicitudes of the best of wives.

"An enemy hath done this," I have heard him say—and at such times my mother would speak to him so soothingly of forgiveness, and long-suffering, and the bearing of injuries with patience; would heal all his wounds with so gentle a touch;—I have seen the old man weep like a child.

The gloom that beset his mind, at times betrayed him into scepticism—he has doubted if there be a Providence! I have heard him say, "God has built a brave world, but methinks he has left his creatures to bustle in it how they may."

At such times he could not endure to hear my mother talk[Pg 19] in a religious strain. He would say, "Woman, have done—you confound, you perplex me, when you talk of these matters, and for one day at least unfit me for the business of life."

I have seen her look at him—O God, Maria! such a look! it plainly spake that she was willing to have shared her precious hope with the partner of her earthly cares—but she found a repulse—

Deprived of such a wife, think you, the old man could have long endured his existence? or what consolation would his wretched daughter have had to offer him, but silent and imbecile tears?

My sweet cousin, you will think me tedious—and I am so—but it does me good to talk these matters over. And do not you be alarmed for me—my sorrows are subsiding into a deep and sweet resignation. I shall soon be sufficiently composed, I know it, to participate in my friend's happiness.

Let me call her, while yet I may, my own Maria Leslie! Methinks, I shall not like you by any other name. Beaumont! Maria Beaumont! it hath a strange sound with it—I shall never be reconciled to this name—but do not you fear—Maria Leslie shall plead with me for Maria Beaumont.

And now, my sweet Friend,

God love you, and your

Elinor Clare.

I find in my collection several letters, written soon after the date of the preceding, and addressed all of them to Maria Beaumont.—I am tempted to make some short extracts from these—my tale will suffer interruption by them—but I was willing to preserve whatever memorials I could of Elinor Clare.

From Elinor Clare to Maria Beaumont

(AN EXTRACT)

——"I have been strolling out for half an hour in the fields; and my mind has been occupied by thoughts, which Maria has a right to participate. I have been bringing my mother to my recollection. My heart ached with the remem[Pg 20]brance of infirmities, that made her closing years of life so sore a trial to her.

I was concerned to think, that our family differences have been one source of disquiet to her. I am sensible that this last we are apt to exaggerate after a person's death—and surely, in the main, there was considerable harmony among the members of our little family—still I was concerned to think, that we ever gave her gentle spirit disquiet.

I thought on years back—on all my parents' friends—the H——s, the F——s, on D—— S——, and on many a merry evening, in the fire-side circle, in that comfortable back parlour—it is never used now.—

O ye Matravises[1] of the age, ye know not what ye lose, in despising these petty topics of endeared remembrance, associated circumstances of past times;—ye know not the throbbings of the heart, tender yet affectionately familiar, which accompany the dear and honored names of father or of mother.

Maria! I thought on all these things; my heart ached at the review of them—it yet aches, while I write this—but I am never so satisfied with my train of thoughts, as when they run upon these subjects—the tears, they draw from us, meliorate and soften the heart, and keep fresh within us that memory of dear friends dead, which alone can fit us for a re-admission to their society hereafter."

[1] This name will be explained presently.

(From another Letter)

——"I had a bad dream this morning—that Allan was dead—and who, of all persons in the world, do you think, put on mourning for him? Why, Matravis.—This alone might cure me of superstitious thoughts, if I were inclined to them; for why should Matravis mourn for us, or our family?—Still it was pleasant to awake, and find it but a dream.—Methinks something like an awaking from an ill dream shall the Resurrection from the Dead be.—Materially different from our accustomed scenes, and ways of life, the World to come may possibly not be—still it is represented to us under the notion of a Rest, a Sabbath, a state of bliss."

(From another Letter)

——"Methinks, you and I should have been born under the same roof, sucked the same milk, conned the same hornbook, thumbed the same Testament, together:—for we have been more than sisters, Maria!

Something will still be whispering to me, that I shall one day be inmate of the same dwelling with my cousin, partaker with her in all the delights, which spring from mutual good offices, kind words, attentions in sickness and in health,—conversation, sometimes innocently trivial, and at others profitably serious;—books read and commented on, together; meals ate, and walks taken, together,—and conferences, how we may best do good to this poor person or that, and wean our spirits from the world's cares, without divesting ourselves of its charities. What a picture I have drawn, Maria!—and none of all these things may ever come to pass."

(From another Letter)

——"Continue to write to me, my sweet cousin. Many good thoughts, resolutions, and proper views of things, pass through the mind in the course of the day, but are lost for want of committing them to paper. Seize them, Maria, as they pass, these Birds of Paradise, that show themselves and are gone,—and make a grateful present of the precious fugitives to your friend.

To use a homely illustration, just rising in my fancy,—shall the good housewife take such pains in pickling and preserving her worthless fruits, her walnuts, her apricots, and quinces—and is there not much spiritual housewifery in treasuring up our mind's best fruits,—our heart's meditations in its most favored moments?

This said simile is much in the fashion of the old Moralizers, such as I conceive honest Baxter to have been, such as Quarles and Wither were, with their curious, serio-comic, quaint emblems. But they sometimes reach the heart, when a more elegant simile rests in the fancy.

Not low and mean, like these, but beautifully familiarized to our conceptions, and condescending to human thoughts and notions, are all the discourses of our Lord—conveyed in parable, or similitude, what easy access do they win to the heart,[Pg 22] through the medium of the delighted imagination! speaking of heavenly things in fable, or in simile, drawn from earth, from objects common, accustomed.

Life's business, with such delicious little interruptions as our correspondence affords, how pleasant it is!—why can we not paint on the dull paper our whole feelings, exquisite as they rise up?"

(From another Letter)

——"I had meant to have left off at this place; but, looking back, I am sorry to find too gloomy a cast tincturing my last page—a representation of life false and unthankful. Life is not all vanity and disappointment—it hath much of evil in it, no doubt; but to those who do not misuse it, it affords comfort, temporary comfort, much—much that endears us to it, and dignifies it—many true and good feelings, I trust, of which we need not be ashamed—hours of tranquillity and hope.—But the morning was dull and overcast, and my spirits were under a cloud. I feel my error.

Is it no blessing, that we two love one another so dearly—that Allan is left me—that you are settled in life—that worldly affairs go smooth with us both—above all, that our lot hath fallen to us in a Christian country? Maria! these things are not little. I will consider life as a long feast, and not forget to say grace."

(From another Letter)

——"Allan has written to me—you know, he is on a visit at his old tutor's in Gloucestershire—he is to return home on Thursday—Allan is a dear boy—he concludes his letter, which is very affectionate throughout, in this manner—

'Elinor, I charge you to learn the following stanza by heart—

'The lines are in Burns—you know, we read him for the first time together at Margate—and I have been used to refer them to you, and to call you, in my mind, Glencairn—for you were always very, very good to me. I had a thousand failings, but you would love me in spite of them all. I am going to drink your health.'"

I shall detain my reader no longer from the narrative.

They had but four rooms in the cottage. Margaret slept in the biggest room up stairs, and her grandaughter in a kind of closet adjoining, where she could be within hearing, if her grandmother should call her in the night.

The girl was often disturbed in that manner—two or three times in a night she has been forced to leave her bed, to fetch her grandmother's cordials, or do some little service for her—but she knew that Margaret's ailings were real and pressing, and Rosamund never complained—never suspected, that her grandmother's requisitions had any thing unreasonable in them.

The night she parted with Miss Clare, she had helped Margaret to bed, as usual—and, after saying her prayers, as the custom was, kneeling by the old lady's bed-side, kissed her grandmother, and wished her a good night—Margaret blessed her, and charged her to go to bed directly. It was her customary injunction, and Rosamund had never dreamed of disobeying.

So she retired to her little room. The night was warm and clear—the moon very bright—her window commanded a view of scenes she had been tracing in the day-time with Miss Clare.

All the events of the day past, the occurrences of their walk, arose in her mind. She fancied she should like to retrace those scenes—but it was now nine o'clock, a late hour in the village.

Still she fancied it would be very charming—and then her grandmother's injunction came powerfully to her recollection—she sighed, and turned from the window—and walked up and down her little room.

Ever, when she looked at the window, the wish returned.[Pg 24] It was not so very late. The neighbours were yet about, passing under the window to their homes—she thought, and thought again, till her sensations became vivid, even to painfulness—her bosom was aching to give them vent.

The village clock struck ten!—the neighbours ceased to pass under the window. Rosamund, stealing down stairs, fastened the latch behind her, and left the cottage.

One, that knew her, met her, and observed her with some surprize. Another recollects having wished her a good night. Rosamund never returned to the cottage!

An old man, that lay sick in a small house adjoining to Margaret's, testified the next morning, that he had plainly heard the old creature calling for her grandaughter. All the night long she made her moan, and ceased not to call upon the name of Rosamund. But no Rosamund was there—the voice died away, but not till near day-break.

When the neighbours came to search in the morning, Margaret was missing! She had straggled out of bed, and made her way into Rosamund's room—worn out with fatigue and fright, when she found the girl not there, she had laid herself down to die—and, it is thought, she died praying—for she was discovered in a kneeling posture, her arms and face extended on the pillow, where Rosamund had slept the night before—a smile was on her face in death.

Fain would I draw a veil over the transactions of that night—but I cannot—grief, and burning shame, forbid me to be silent—black deeds are about to be made public, which reflect a stain upon our common nature.

Rosamund, enthusiastic and improvident, wandered unprotected to a distance from her guardian doors—through lonely glens, and wood walks, where she had rambled many a day in safety—till she arrived at a shady copse, out of the hearing of any human habitation.

Matravis met her.—"Flown with insolence and wine," returning home late at night, he passed that way!

Matravis was a very ugly man. Sallow-complexioned! and, if hearts can wear that colour, his heart was sallow-complexioned also.

A young man with gray deliberation! cold and systematic[Pg 25] in all his plans; and all his plans were evil. His very lust was systematic.

He would brood over his bad purposes for such a dreary length of time, that it might have been expected, some solitary check of conscience must have intervened to save him from commission. But that Light from Heaven was extinct in his dark bosom.

Nothing that is great, nothing that is amiable, existed for this unhappy man. He feared, he envied, he suspected; but he never loved. The sublime and beautiful in nature, the excellent and becoming in morals, were things placed beyond the capacity of his sensations. He loved not poetry—nor ever took a lonely walk to meditate—never beheld virtue, which he did not try to disbelieve, or female beauty and innocence, which he did not lust to contaminate.

A sneer was perpetually upon his face, and malice grinning at his heart. He would say the most ill-natured things, with the least remorse, of any man I ever knew. This gained him the reputation of a wit—other traits got him the reputation of a villain.

And this man formerly paid his court to Elinor Clare!—with what success I leave my readers to determine.—It was not in Elinor's nature to despise any living thing—but in the estimation of this man, to be rejected was to be despised—and Matravis never forgave.

He had long turned his eyes upon Rosamund Gray. To steal from the bosom of her friends the jewel they prized so much, the little ewe lamb they held so dear, was a scheme of delicate revenge, and Matravis had a two-fold motive for accomplishing this young maid's ruin.

Often had he met her in her favorite solitudes, but found her ever cold and inaccessible. Of late the girl had avoided straying far from her own home, in the fear of meeting him—but she had never told her fears to Allan.

Matravis had, till now, been content to be a villain within the limits of the law—but, on the present occasion, hot fumes of wine, co-operating with his deep desire of revenge, and the insolence of an unhoped for meeting, overcame his customary prudence, and Matravis rose, at once, to an audacity of glorious mischief.

Late at night he met her, a lonely, unprotected virgin—no friend at hand—no place near of refuge.

Rosamund Gray, my soul is exceeding sorrowful for thee—I loath to tell the hateful circumstances of thy wrongs. Night and silence were the only witnesses of this young maid's disgrace—Matravis fled.

Rosamund, polluted and disgraced, wandered, an abandoned thing, about the fields and meadows till day-break. Not caring to return to the cottage, she sat herself down before the gate of Miss Clare's house—in a stupor of grief.

Elinor was just rising, and had opened the windows of her chamber, when she perceived her desolate young friend.—She ran to embrace her—she brought her into the house—she took her to her bosom—she kissed her—she spake to her; but Rosamund could not speak.

Tidings came from the cottage. Margaret's death was an event, which could not be kept concealed from Rosamund. When the sweet maid heard of it, she languished, and fell sick—she never held up her head after that time.

If Rosamund had been a sister, she could not have been kindlier treated, than by her two friends.

Allan had prospects in life—might, in time, have married into any of the first families in Hertfordshire—but Rosamund Gray, humbled though she was, and put to shame, had yet a charm for him—and he would have been content to share his fortunes with her yet, if Rosamund would have lived to be his companion.

But this was not to be—and the girl soon after died. She expired in the arms of Elinor—quiet, gentle, as she lived—thankful, that she died not among strangers—and expressing by signs, rather than words, a gratitude for the most trifling services, the common offices of humanity. She died uncomplaining; and this young maid, this untaught Rosamund, might have given a lesson to the grave philosopher in death.

I was but a boy when these events took place. All the village remember the story, and tell of Rosamund Gray, and old blind Margaret.

I parted from Allan Clare on that disastrous night, and set out for Edinburgh the next morning, before the facts were commonly known—I heard not of them—and it was four months before I received a letter from Allan.

"His heart" he told me "was gone from him—for his sister had died of a phrensy fever!"—not a word of Rosamund in the letter—I was left to collect her story from sources which may one day be explained.

I soon after quitted Scotland, on the death of my father, and returned to my native village. Allan had left the place, and I could gain no information, whether he were dead or living.

I passed the cottage. I did not dare to look that way, or to enquire who lived there.—A little dog, that had been Rosamund's, was yelping in my path. I laughed aloud like one mad, whose mind had suddenly gone from him—I stared vacantly around me, like one alienated from common perceptions.

But I was young at that time, and the impression became gradually weakened, as I mingled in the business of life. It is now ten years since these events took place, and I sometimes think of them as unreal. Allan Clare was a dear friend to me—but there are times, when Allan and his sister, Margaret and her grandaughter, appear like personages of a dream—an idle dream.

Strange things have happened unto me—I seem scarce awake—but I will recollect my thoughts, and try to give an account of what has befallen me in the few last weeks.

Since my father's death our family have resided in London. I am in practice as a surgeon there. My mother died two years after we left Widford.

A month or two ago I had been busying myself in drawing up the above narrative, intending to make it public. The employment had forced my mind to dwell upon facts, which had begun to fade from it—the memory of old times became vivid, and more vivid—I felt a strong desire to revisit the scenes of my native village—of the young loves of Rosamund and her Clare.

A kind of dread had hitherto kept me back; but I was restless now, till I had accomplished my wish. I set out one morning to walk—I reached Widford about eleven in the forenoon—after a slight breakfast at my inn—where I was mortified to perceive, the old landlord did not know me again[Pg 28]—(old Thomas Billet—he has often made angle rods for me when a child)—I rambled over all my accustomed haunts.

Our old house was vacant, and to be sold. I entered, unmolested, into the room that had been my bed-chamber. I kneeled down on the spot where my little bed had stood—I felt like a child—I prayed like one—it seemed as though old times were to return again—I looked round involuntarily, expecting to see some face I knew—but all was naked and mute. The bed was gone. My little pane of painted window, through which I loved to look at the sun, when I awoke in a fine summer's morning, was taken out, and had been replaced by one of common glass.

I visited, by turns, every chamber—they were all desolate and unfurnished, one excepted, in which the owner had left a harpsichord, probably to be sold—I touched the keys—I played some old Scottish tunes, which had delighted me when a child. Past associations revived with the music-blended with a sense of unreality, which at last became too powerful—I rushed out of the room to give vent to my feelings.

I wandered, scarce knowing where, into an old wood, that stands at the back of the house—we called it the Wilderness. A well-known form was missing, that used to meet me in this place—it was thine, Ben Moxam—the kindest, gentlest, politest, of human beings, yet was he nothing higher than a gardener in the family. Honest creature, thou didst never pass me in my childish rambles, without a soft speech, and a smile. I remember thy good-natured face. But there is one thing, for which I can never forgive thee, Ben Moxam—that thou didst join with an old maiden aunt of mine in a cruel plot, to lop away the hanging branches of the old fir trees.—I remember them sweeping to the ground.

I have often left my childish sports to ramble in this place—its glooms and its solitude had a mysterious charm for my young mind, nurturing within me that love of quietness and lonely thinking, which have accompanied me to maturer years.

In this Wilderness I found myself after a ten years' absence. Its stately fir trees were yet standing, with all their luxuriant company of underwood—the squirrel was there, and the melancholy cooings of the wood-pigeon—all was as I had left it—my heart softened at the sight—it seemed, as though my character had been suffering a change, since I forsook these shades.

My parents were both dead—I had no counsellor left, no experience of age to direct me, no sweet voice of reproof. The Lord had taken away my friends, and I knew not where he had laid them. I paced round the wilderness, seeking a comforter. I prayed, that I might be restored to that state of innocence, in which I had wandered in those shades.

Methought, my request was heard—for it seemed as though the stains of manhood were passing from me, and I were relapsing into the purity and simplicity of childhood. I was content to have been moulded into a perfect child. I stood still, as in a trance. I dreamed that I was enjoying a personal intercourse with my heavenly Father—and, extravagantly, put off the shoes from my feet—for the place where I stood, I thought, was holy ground.

This state of mind could not last long—and I returned, with languid feelings to my Inn. I ordered my dinner—green peas and a sweetbread—it had been a favorite dish with me in my childhood—I was allowed to have it on my birth days. I was impatient to see it come upon table—but, when it came, I could scarce eat a mouthful—my tears choaked me. I called for wine—I drank a pint and a half of red wine—and not till then had I dared to visit the church-yard, where my parents were interred.

The cottage lay in my way—Margaret had chosen it for that very reason, to be near the church—for the old lady was regular in her attendance on public worship—I passed on—and in a moment found myself among the tombs.

I had been present at my father's burial, and knew the spot again—my mother's funeral I was prevented by illness from attending—a plain stone was placed over the grave, with their initials carved upon it—for they both occupied one grave.

I prostrated myself before the spot—I kissed the earth that covered them—I contemplated, with gloomy delight, the time when I should mingle my dust with their's—and kneeled, with my arms incumbent on the grave-stone, in a kind of mental prayer—for I could not speak.

Having performed these duties, I arose with quieter feelings, and felt leisure to attend to indifferent objects.—Still I continued in the church-yard, reading the various inscriptions, and moralizing on them with that kind of levity, which will not unfrequently spring up in the mind, in the midst of deep melancholy.

I read of nothing but careful parents, loving husbands, and dutiful children. I said jestingly, where be all the bad people buried? Bad parents, bad husbands, bad children—what cemeteries are appointed for these? do they not sleep in consecrated ground? or is it but a pious fiction, a generous oversight, in the survivors, which thus tricks out men's epitaphs when dead, who, in their life-time, discharged the offices of life, perhaps, but lamely?—Their failings, with their reproaches, now sleep with them in the grave. Man wars not with the dead. It is a trait of human nature, for which I love it.

I had not observed, till now, a little group assembled at the other end of the church-yard; it was a company of children, who were gathered round a young man, dressed in black, sitting on a grave-stone.

He seemed to be asking them questions—probably, about their learning—and one little dirty ragged-headed fellow was clambering up his knees to kiss him.—The children had been eating black cherries—for some of the stones were scattered about, and their mouths were smeared with them.

As I drew near them, I thought I discerned in the stranger a mild benignity of countenance, which I had somewhere seen before—I gazed at him more attentively—

It was Allan Clare! sitting on the grave of his sister.

I threw my arms about his neck. I exclaimed "Allan"—he turned his eyes upon me—he knew me—we both wept aloud—it seemed, as though the interval, since we parted, had been as nothing—I cried out, "come, and tell me about these things."

I drew him away from his little friends—he parted with a show of reluctance from the church-yard—Margaret and her grandaughter lay buried there, as well as his sister—I took him to my Inn—secured a room, where we might be private—ordered fresh wine—scarce knowing what I did, I danced for joy.

Allan was quite overcome, and taking me by the hand he said, "this repays me for all."

It was a proud day for me—I had found the friend I thought dead—earth seemed to me no longer valuable, than as it contained him; and existence a blessing no longer than while I should live to be his comforter.

I began, at leisure, to survey him with more attention.[Pg 31] Time and grief had left few traces of that fine enthusiasm, which once burned in his countenance—his eyes had lost their original fire, but they retained an uncommon sweetness and, whenever they were turned upon me, their smile pierced to my heart.

"Allan, I fear you have been a sufferer." He replied not, and I could not press him further. I could not call the dead to life again.

So we drank, and told old stories—and repeated old poetry—and sang old songs—as if nothing had happened.—We sat till very late—I forgot that I had purposed returning to town that evening—to Allan all places were alike—I grew noisy, he grew cheerful—Allan's old manners, old enthusiasm, were returning upon him—we laughed, we wept, we mingled our tears, and talked extravagantly.

Allan was my chamber-fellow that night—and lay awake, planning schemes of living together under the same roof, entering upon similar pursuits;—and praising God, that we had met.

I was obliged to return to town the next morning, and Allan proposed to accompany me.—"Since the death of his sister," he told me, "he had been a wanderer."

In the course of our walk he unbosomed himself without reserve—told me many particulars of his way of life for the last nine or ten years, which I do not feel myself at liberty to divulge.

Once, on my attempting to cheer him, when I perceived him over thoughtful, he replied to me in these words:—

"Do not regard me as unhappy, when you catch me in these moods. I am never more happy than at times, when, by the cast of my countenance, men judge me most miserable.

"My friend, the events, which have left this sadness behind them, are of no recent date. The melancholy, which comes over me with the recollection of them, is not hurtful, but only tends to soften and tranquillize my mind, to detach me from the restlessness of human pursuits.

"The stronger I feel this detachment, the more I find myself drawn heavenward to the contemplation of spiritual objects.

"I love to keep old friendships alive and warm within me, because I expect a renewal of them in the World of Spirits.

"I am a wandering and unconnected thing on the earth. I have made no new friendships, that can compensate me for[Pg 32] the loss of the old—and the more I know mankind, the more does it become necessary for me to supply their loss by little images, recollections, and circumstances, of past pleasures.

"I am sensible that I am surrounded by a multitude of very worthy people, plain-hearted souls, sincere, and kind.—But they have hitherto eluded my pursuit, and will continue to bless the little circle of their families and friends, while I must remain a stranger to them.

"Kept at a distance by mankind, I have not ceased to love them—and could I find the cruel persecutor, the malignant instrument of God's judgments on me and mine, I think I would forgive, and try to love him too.

"I have been a quiet sufferer. From the beginning of my calamities it was given to me, not to see the hand of man in them. I perceived a mighty arm, which none but myself could see, extended over me. I gave my heart to the Purifier, and my will to the Sovereign Will of the Universe. The irresistible wheels of destiny passed on in their everlasting rotation,—and I suffered myself to be carried along with them without complaining."

Allan told me, that for some years past, feeling himself disengaged from every personal tye, but not alienated from human sympathies, it had been his taste, his humour he called it, to spend a great portion of his time in hospitals and lazar houses.

He had found a wayward pleasure, he refused to name it a virtue, in tending a description of people, who had long ceased to expect kindness or friendliness from mankind, but were content to accept the reluctant services, which the often-times unfeeling instruments and servants of these well-meant institutions deal out to the poor sick people under their care.

It is not medicine, it is not broths and coarse meats, served up at a stated hour with all the hard formalities of a prison,—it is not the scanty dole of a bed to die on—which dying man requires from his species.

Looks, attentions, consolations,—in a word, sympathies, are what a man most needs in this awful close of mortal sufferings. A kind look, a smile, a drop of cold water to[Pg 33] the parched lip—for these things a man shall bless you in death.

And these better things than cordials did Allan love to administer—to stay by a bed-side the whole day, when something disgusting in a patient's distemper has kept the very nurses at a distance—to sit by, while the poor wretch got a little sleep—and be there to smile upon him when he awoke—to slip a guinea, now and then, into the hands of a nurse or attendant—these things have been to Allan as privileges, for which he was content to live, choice marks, and circumstances, of his Maker's goodness to him.

And I do not know whether occupations of this kind be not a spring of purer and nobler delight (certainly instances of a more disinterested virtue) than arises from what are called Friendships of Sentiment.

Between two persons of liberal education, like opinions, and common feelings, oftentimes subsists a Vanity of Sentiment, which disposes each to look upon the other as the only being in the universe worthy of friendship, or capable of understanding it,—themselves they consider as the solitary receptacles of all that is delicate in feeling, or stable in attachment:—when the odds are, that under every green hill, and in every crowded street, people of equal worth are to be found, who do more good in their generation, and make less noise in the doing of it.

It was in consequence of these benevolent propensities, I have been describing, that Allan oftentimes discovered considerable inclinations in favor of my way of life, which I have before mentioned as being that of a surgeon. He would frequently attend me on my visits to patients; and I began to think, that he had serious intentions of making my profession his study.

He was present with me at a scene—a death-bed scene—I shudder when I do but think of it.

I was sent for the other morning to the assistance of a gentleman, who had been wounded in a duel,—and his wounds by unskilful treatment had been brought to a dangerous crisis.

The uncommonness of the name, which was Matravis[Pg 34] suggested to me, that this might possibly be no other than Allan's old enemy. Under this apprehension, I did what I could to dissuade Allan from accompanying me—but he seemed bent upon going, and even pleased himself with the notion, that it might lie within his ability to do the unhappy man some service. So he went with me.

When we came to the house, which was in Soho-Square, we discovered that it was indeed the man—the identical Matravis, who had done all that mischief in times past—but not in a condition to excite any other sensation than pity in a heart more hard than Allan's.

Intense pain had brought on a delirium—we perceived this on first entering the room—for the wretched man was raving to himself—talking idly in mad unconnected sentences,—that yet seemed, at times, to have a reference to past facts.

One while he told us his dream. "He had lost his way on a great heath, to which there seemed no end—it was cold, cold, cold—and dark, very dark—an old woman in leading-strings, blind, was groping about for a guide"—and then he frightened me,—for he seemed disposed to be jocular, and sang a song about "an old woman clothed in grey," and said "he did not believe in a devil."

Presently he bid us "not tell Allan Clare"—Allan was hanging over him at that very moment, sobbing.—I could not resist the impulse, but cried out, "this is Allan Clare—Allan Clare is come to see you, my dear Sir."—The wretched man did not hear me, I believe, for he turned his head away, and began talking of charnel houses, and dead men, and "whether they knew anything that passed in their coffins."

Matravis died that night.

Extracted from a common-place book, which belonged to Robert Burton, the famous Author of The Anatomy of Melancholy

(1800. First Published 1802. Text of 1818)

I Democritus Junior have put my finishing pen to a tractate De Melancholia, this day December 5, 1620. First, I blesse the Trinity, which hath given me health to prosecute my worthlesse studies thus far, and make supplication, with a Laus Deo, if in any case these my poor labours may be found instrumental to weede out black melancholy, carking cares, harte-grief, from the mind of man. Sed hoc magis volo quam expecto.

I turn now to my book, i nunc liber, goe forth, my brave Anatomy, child of my brain-sweat, and yee, candidi lectores, lo! here I give him up to you, even do with him what you please, my masters. Some, I suppose will applaud, commend, cry him up (these are my friends) hee is a flos rarus, forsooth, a none-such, a Phœnix, (concerning whom see Plinius and Mandeuille, though Fienus de monstris doubteth at large of such a bird, whom Montaltus confuting argueth to have been a man malæ scrupulositatis, of a weak and cowardlie faith: Christopherus a Vega is with him in this.) Others again will blame, hiss, reprehende in many things, cry down altogether, my collections, for crude, inept, putid, post cœnam scripta, Coryate could write better upon a full meal, verbose, inerudite, and not sufficiently abounding in authorities, dogmata, sentences of learneder writers which have been before me, when as that first named sort clean otherwise judge of my labours to bee nothing else but a messe of opinions, a vortex attracting indiscriminate, gold, pearls, hay, straw, wood, excrement, an exchange, tavern, marte, for foreigners to congregate, Danes, Swedes, Hollanders, Lombards, so many strange faces, dresses, salutations, languages, all which Wolfius behelde with great content upon the Venetian Rialto, as he describes diffusedly in his book the world's Epitome, which Sannazar[Pg 36] so bepraiseth, e contra our Polydore can see nothing in it; they call me singular, a pedant, fantastic, words of reproach in this age, which is all too neoteric and light for my humour.