[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Orbit volume 1 number 2, 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

"Tell me what time is," said Harrigan one late summer afternoon in a Madison Street bar. "I'd like to know."

"A dimension," I answered. "Everybody knows that."

"All right, granted. I know space is a dimension and you can move forward or back in space. And, of course, you keep on aging all the time."

"Elementary," I said.

"But what happens if you can move backward or forward in time? Do you age or get younger, or do you keep the status quo?"

"I'm not an authority on time, Tex. Do you know anyone who traveled in time?"

Harrigan shrugged aside my question. "That was the thing I couldn't get out of Vanderkamp, either. He presumed to know everything else."

"Vanderkamp?"

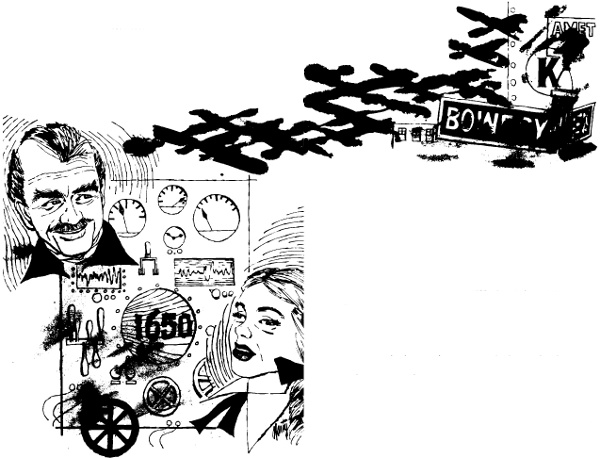

"He was another of those strange people a reporter always runs into. Lived in New York—downtown, near the Bowery. Man of about forty, I'd say, but a little on the old-fashioned side. Dutch background, and hipped on the subject of New Amsterdam, which, in case you don't know, was the original name of New York City."

"Don't mind my interrupting," I cut in. "But I'm not quite straight on what Vanderkamp has to do with time as dimension."

"Oh, he was touched on the subject. He claimed to travel in it. The fact is, he invented a time-traveling machine."

"You certainly meet the whacks, Tex!"

"Don't I!" He grinned appreciatively and leaned reminiscently over the bar. "But Vanderkamp had the wildest dreams of the lot. And in the end he managed the neatest conjuring trick of them all. I was on the Brooklyn Enterprise at that time; I spent about a year there. Special features, though I was on a reporter's salary. Vanderkamp was something of a local celebrity in a minor way; he wrote articles on the early Dutch in New York, the nomenclature of the Dutch, the history of Dutch place-names, and the like. He was handy with a pen, and even handier with tools. He was an amateur electrician, carpenter, house-painter, and claimed to be an expert in genealogy."

"And he built a time-traveling machine?"

"So he said. He gave me a rather hard time of it. He was a glib talker and half the time I didn't know whether I was coming or going. He kept me on my toes by taking for granted that I accepted his basic premises. I got next to him on a tip. He could be close-mouthed as a clam, but his sister let things slip from time to time, and on this occasion she passed the word to one of her friends in a grocery store that her brother had invented a machine that took him off on trips into the past. It seemed like routine whack stuff, but Blake, who decided what went into the Enterprise and what didn't, sent me over to Manhattan to get something for the paper, on the theory that since Vanderkamp was well-known in Brooklyn, it was good neighborhood copy.

"Vanderkamp was a sharp-eyed little fellow, about five feet or so in height, and I hit him at a good time. His sister said he had just come back from a trip—she left me to draw my own conclusions about what kind of trip—and I found him in a mild fit of temper. He was too upset, in fact, to be truculent, which was more like his nature.

"Was it true, I wanted to know, that he'd invented a machine that traveled in time?

"He didn't make any bones about it. 'Certainly,' he said. 'I've been using it for the last month, and if my sister hadn't decided to blab nobody would know about it yet. What about it?'

"'You believe it can take you backwards or forwards into the past or the future?'

"'Do I look crazy? I said so, didn't I?'

"Now, as a matter of fact, he did look crazy. Unlike most of the candidates for my file of queer people, Vanderkamp actually looked like a nut. He had a wild eye and a constantly working mouth; he blinked a good deal and stammered when he was excited. In features he was as Dutch as his name implied. Well, we talked back and forth for some time, but I stuck with him and in the end he took me out into a shed adjoining his house and showed me the contraption he'd built.

"It looked like a top. The first thing I thought of was Brick Bradford, and before I could catch myself, I'd asked, 'Is that pure Brick Bradford?'

"He didn't turn a hair. 'Not by a long shot,' he answered. 'H. G. Wells was there first. I owe it to Wells.'

"'I see,' I said.

"'The hell you do!' he shot back. 'You think I'm as nutty as a fruit-cake.'

"'The idea of time travel is a little hard to swallow,' I said.

"'Sure it is. But me, I'm doing it. So that's all there is to it.'

"'If you don't mind, Mr. Vanderkamp,' I said, 'I'm a dummy in scientific matters. I have all I can do to tell a nut from a bolt.'

"'That I believe,' he said.

"'So how do you time travel?'

"'Look,' he said, 'time is a dimension like space. You can go up or down this ruler,' he snatched a steel ruler and waved it in front of me, 'from any given point. But you move. In the dimension of time, you only seem to move. You stand still; time moves. Do you get it?'

"I had to confess that I didn't.

"He tried again, with obviously strained patience. Judging by what I could gather from what he said, it was possible for him—so he believed—to get into his machine, twirl a few knobs, push a few buttons, relax for any given period, and end up just where he liked—back in the past, or ahead in the future. But wherever he ended up, he was still in this same spot. In other words, whether he was back in 1492 or ahead in 2092, the place he got out of his time machine was still his present address.

"It was beyond me, frankly, but I figured that as long as he was a little touched, it wouldn't do any harm to humor him. I intimated that I understood and asked him where he'd been last.

"His face fell, his brow clouded, and he said, 'I've been ahead thirty years.' He shook his head angrily. 'What a time! I'll be seventy, and you won't even be that, Mr. Harrigan. But we'll be in the middle of the worst atomic war you ever dreamed about.'

"Now this was before Hiroshima, quite a bit. I didn't know what he was talking about, but it gives me a queer feeling now and then when I think of what he said, especially since it's still short of thirty years since that time.

"'It's no time to be living here,' he went on. 'Direct hits on the entire area. What would you do?'

"'I'd get out,' I said.

"'That's what I thought,' he said. 'But that kind of warfare carries a long way. A long way. And I'm a man who loves his comforts, reasonably. I don't intend to set up housekeeping in equatorial Africa or the forests of Brazil.'

"'What did you see thirty years from now, Mr. Vanderkamp?' I asked him.

"'Everything blown to hell,' he answered. 'Not a building in all Manhattan.' He leered and added, 'And everybody who'll be living here at that time will be scattered into the atmosphere in fragments no bigger than an amoeba.'

"'You fill me with anticipation,' I said.

"So I went back to my desk and wrote the story. You could guess what kind it had to be. 'Time Travel Is Possible, Says Amateur Scientist!'—that kind of thing. You can see it every week, in large doses, in the feature sections of some of the biggest chain papers. It went over like an average feature about life on the moon or prehistoric animals surviving in remote mountain valleys, or what have you. Just what Vanderkamp went back to after I left, I don't know, but I have an idea that he gave his sister a devil of a time."

Vanderkamp stalked into the house and confronted his sister.

"You see, Julie—a reporter. Can't you learn to hold your tongue?"

She threw him a scornful glance. "What difference does it make?" she cried. "You're gone all the time."

"Maybe I'll take you along sometime. Just wait."

"Wait, wait! That's all I've been doing. Since I was ten years old I've been waiting on you!"

"Oh, the hell with it!" He turned on his heel and left the house.

She followed him to the door and shouted after him, "Where are you going now?"

"To New Amsterdam for a little peace and quiet," he said testily.

He threw open the thick-walled door of his time-machine and pulled it shut behind him. He sat down before the controls and began to chart his course for 1650. If his calculations were correct, he would shortly find himself in the vicinity of that sturdy if autocratic first citizen of the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant, as well as Governor Stuyvesant's friend and neighbor, Heinrich Vanderkamp. He gave not even a figurative glance over his shoulder before he started out.

When he emerged at last from his machine, he was in what appeared to be the backyard of a modest residence on a street which, though he did not know it, he suspected might be the Bouwerie. At the moment of his emergence, a tall, angular woman stood viewing him, open-mouthed and aghast, from the wooden stoop at the back door of her home. He looked at her in astonishment himself. The resemblance to his sister Julie was uncanny.

With only the slightest hesitation, he addressed her in fluent Dutch. "Pray do not be disturbed, young lady."

"A fine way for a gentleman to call!" she exclaimed in a voice considerably more forceful than her appearance. "I suppose my father sent you. And where did you get that outlandish costume?"

"I bought it," he answered, truthfully enough.

"A likely tale," she said. "And if my father sent you, just go back and tell him I'm satisfied the way I am. No woman needs a man to manage her."

"I don't have the honor of your father's acquaintance," he answered.

She gazed at him suspiciously from narrowed eyes. "Everyone in New Amsterdam knows Henrik Van Tromp. He's as unloved as yonder bumblebee. Stand where you are and say whence you came."

"I am a visitor in New Amsterdam," he said, standing obediently still. "I confess I don't know my way about very well, and I chose to stop at this attractive home."

"I know it's attractive," she said tartly. "And it's plain to see you're a stranger here, or you'd never be wearing such clothes. Or is it the fashion where you come from?" She gave him no opportunity to answer, but added, after a moment of indecision, "Well, you look respectable enough, though much like my rascally cousin Pieter Vanderkamp. Do you know him?"

"No."

"Well, no matter. He's much older than you—near forty blessed years. You're no more than twenty, I don't doubt."

Involuntarily Vanderkamp put his hand to his cheek, and smiled as he felt its smooth roundness. "You may be right, at that," he said cryptically.

"You might as well come in," she said grudgingly. "What with the traffic on the road outside, the Indians, and people who come in such flighty vehicles as yours, I might as well live in the heart of the colony."

He looked around. "And still," he said, "it is a pleasant spot—peaceful, comfortable. I'm sure a man could live out his days here in contentment."

"Oh, could he?" she said belligerently. "And where would I be while this went on?"

He gazed at her beetling nose, her jutting chin. "A good question," he muttered thoughtfully.

He followed her into the house. It was a treasury of antiquities, filling him with delight. Miss Anna Van Tromp offered him a cup of milk, which he accepted, thanking her profusely. She talked volubly, eyeing him all the while with the utmost curiosity, and he gathered presently that her father had made several attempts to marry her off, disapproving of her solitary residence so far from the center of the city; but she had frowned upon one and all of the suitors he had encouraged to call on her. She was undeniably impressive, almost formidable, he conceded privately, with a touch of the shrew and harridan. Life with Miss Anna Van Tromp would not be easy, he reflected. But then, life with his sister Julie was not easy, either. Miss Anna, however, had not to face atomic warfare; all she had to look forward to in fourteen years was surrender to the besieging British, which she would have no trouble in surviving.

He settled down to his ingratiating best and succeeded in making a most favorable impression on Miss Anna Van Tromp before at last he took his leave, carrying with him a fine, hand-wrought bowl with which the lady had presented him. He had a hunch he might come back. Of all the times he had visited since finishing the machine, he knew that old New Amsterdam in the 1650s was the one period most likely to keep him contented—provided Miss Van Tromp didn't turn out to be a nuisance. So he took careful note of the set of his controls, jotting them down so that he would not be likely to forget them.

It was late when he found himself back in his own time.

His sister was waiting up for him. "Two o'clock in the morning!" she screamed at him. "What are you doing to me? Oh, God, why didn't I marry when I had the chance, instead of throwing away my life on a worthless brother!"

"Why don't you? It's not too late," he sighed wearily.

"How can you say that?" she snapped bitterly. "Here I am thirty nearly, and worn out from working for you. Who would marry me now? Oh, if only I could have another chance! If I could be young again, and do it all over, I'd know how to have a better life!"

In spite of his boredom with her, Vanderkamp felt the effect of this cry from a lonely heart. He looked at her pityingly; it was true, after all, that she had worked faithfully for him, without pay, since their parents died. "Take a look at this," he said gently, offering her the bowl.

"Hah! Can we eat bowls?"

He raised his eyes heavenward and went wearily to bed.

"I saw Vanderkamp again about a fortnight later," Harrigan went on. "Ran into him in a tavern on the Bowery. He recognized me and came over.

"'That was some story you did,' he said.

"'Been bothered by cranks?' I asked.

"'Hell, yes! Not too badly, though. They want to ride off somewhere just to get away. I get that feeling myself sometimes. But, tell me, have you seen the morning papers?'

"Now, by coincidence, the papers that morning had carried a story from some local nuclear physicist about the increasing probability that the atom would be smashed. I told him I'd seen it.

"'What did I tell you?' he said.

"I just smiled and asked where he'd been lately. He didn't hesitate to talk, perhaps because his sister had been giving him a hard time with her nagging. So I listened. It appeared, to hear him tell it, that he had been off visiting the Dutch in New Amsterdam. You could almost believe what he said, listening to him, except for that wild look he had. Anyway, he'd been in New Amsterdam about 1650, and he'd brought back a few trifling souvenirs of the trips. Would I like to see them? I said I would.

"I figured he'd got his hands on some nice antiques and wanted an appreciative audience. His sister wasn't home; so he took me around and showed me his pieces, one by one—a bowl, a pair of wooden candlesticks, wooden shoes, and more, all in all a fine collection. He even had a chair that looked pretty authentic, and I wondered where he'd dug up so many nice things of the New Amsterdam period—though, of course, I had to take his word as to where they belonged historically; I didn't know. But I imagine he got them somewhere in the city or perhaps up in the Catskill country.

"Well, after a while I got another look at his contraption. It didn't appear to have been moved at all; it was still sitting where it had been before, without a sign to say that it had been used to go anywhere, least of all into past time.

"'Tell me,' I said to him at last, 'when you go back in time do you get younger?'

"'Yes and no,' he said. 'Obviously.'

"It wasn't obvious to me, but I couldn't get any more than that out of him. The thing I couldn't figure out was the reason for his claim. He wasn't trying to sell anything to anybody, as far as I could see; he wasn't anxious to tell the world about his time-machine, either. He didn't mind talking in his oblique fashion about his trips. He did talk about New Amsterdam as if he had a pretty good acquaintance with the place. But then, he was known as a minor authority on the customs of the Dutch colony.

"He was touched, obviously. Just the same, he challenged me, in a way. I wanted to know something more about him, how his machine worked, how he took off, and so on. I made up my mind the next time I was in the neighborhood to look him up, hoping he wouldn't be home.

"When I made it, his sister was alone, and in fine fettle, as cantankerous as a flea-bitten mastiff.

"'He's gone again,' she complained bitterly.

"Clearly the two of them were at odds. I asked her whether she had seen him go. She hadn't; he had just marched out to his shop and that was an end to him as far as she was concerned.

"I haggled around quite a lot and finally got her permission to go out and see what I could see for myself. Of course, the shop was locked. I had counted on that and had brought along a handy little skeleton key. I was inside in no time. The machine wasn't there. Not a sign of it, or of Vanderkamp either.

"Now, I looked around all over, but I couldn't for the life of me figure out how he could have taken it out of that place; it was too big for doors or windows, and the walls and roof were solid and immovable. I figured that he couldn't have got such a large machine away without his sister's seeing him; so I locked the place up and went back to the house.

"But she was immovable; she hadn't seen a thing. If he had taken anything larger than pocket-size out of that shop of his, she had missed it. I could hardly doubt her sincerity. There was nothing to be had from that source; so I had no alternative but to wait for him another time."

Anna Van Tromp, considerably chastened, watched her strange suitor—she looked upon all men as suitors, without exception; for so her father had conditioned her to do—as he reached into his sack and brought out another wonder.

"Now this," said Vanderkamp, "is an alarm clock. You wind it up like this, you see; set it, and off it goes. Listen to it ring! That will wake you up in the morning."

"More magic," she cried doubtfully.

"No, no," he explained patiently. "It is an everyday thing in my country. Perhaps some day you would like to join me in a little visit there, Anna?"

"Ja, maybe," she agreed, looking out the window to his weird and frightening carriage, which had no animal to draw it and which vanished so strangely, fading away into the air, whenever Vanderkamp went into it. "This clothes-washing machine you talk about," she admitted. "This I would like to see."

"I must go now," said Vanderkamp, gazing at her with well-simulated coyness. "I'll leave these things here with you, and I'll just take along that bench over there."

"Ja, ja," said Anna, blushing.

"Six of one and half a dozen of the other," muttered Vanderkamp, comparing Anna with his sister.

He got into his time-machine and set out for home in the twentieth century. There was some reluctance in his going. Here all was somnolent peace and quiet, despite the rigors of living; in his own time there were wars and turmoil and the ultimate threat of the greatest war of all. New Amsterdam had one drawback, however—the presence of Anna Von Tromp. She had grown fond of him, undeniably, perhaps because he was so much more interested in her circumstances than in herself. What was a man to do? Julie at one end, Anna at the other. But even getting rid of Julie would not allow him to escape the warfare to come.

He thought deeply of his problem all the way home.

When he got back, he found his sister waiting up, as usual, ready to deliver the customary diatribe.

He forestalled her. "I've been thinking things over, Julie. I believe you'd be much happier if you were living with brother Carl. I'll give you as much money as you need, and you can pack your things and I'll take you down to Louisiana."

"Take me!" she exclaimed. "How? In that crazy contraption of yours?"

"Precisely."

"Oh no!" she said. "You don't get me into that machine! How do I know what it will do to me? It's a time machine, isn't it? It might make an old hag of me—or a baby!"

"You said that you wanted to be young again, didn't you?" he said softly. "You said you'd like another chance...."

A faraway look came into her eyes. "Oh, if I only could! If I only could be a girl again, with a chance to get married...."

"Pack your things," Vanderkamp said quietly.

"It must have been all of a month before I saw Vanderkamp again," Harrigan continued, waving for another scotch and soda. "I was down in the vicinity on an assignment and I took a run over to his place.

"He was home this time. He came to the door, which he had chained on the inside. He recognized me, and it was plain at the same time that he had no intention of letting me in.

"I came right out with the first question I had in mind. 'The thing that bothers me,' I said to him, 'is how you get that time machine of yours in and out of that shed.'

"'Mr. Harrigan,' he answered, 'newspaper reporters ought to have at least elementary scientific knowledge. You don't. How in hell could even a time machine be in two places at once, I ask you? If I take that machine back three centuries, that's where it is—not here. And three centuries ago that shop wasn't standing there. So you don't go in or out; you don't move at all, remember? It's time that moves.'

"'I called the other day,' I went on. 'Your sister spoke to me. Give her my regards.'

"'My sister's left me,' he said shortly, 'to stew, as you might say, in my own time machine.'

"'Really?' I said. 'Just what do you have in mind to do next?'

"'Let me ask you something, Mr. Harrigan,' he answered. 'Would you sit around here waiting for an atomic war if you could get away?'

"'Certainly not,' I answered.

"'Well, then, I don't intend to, either.'

"All this while he was standing at the door, refusing to open it any wider or to let me in. He was making it pretty plain that there wasn't much he had to say to me. And he seemed to be in a hurry.

"'Remember me to the inquiring public thirty years hence, Mr. Harrigan,' he said at last, and closed the door.

"That was the last I saw of him."

Harrigan finished his scotch and soda appreciatively and looked around for the bartender.

"Did he take off then?" I asked.

"Like a rocket," said Harrigan. "Queerest thing was that there wasn't a trace of him. The machine was gone, too—the same way as the last time, without a disturbance in the shop. He and his machine had simply vanished off the face of the earth and were never heard from again.

"Matter of fact, though," Harrigan went on thoughtfully, "Vanderkamp's disappearance wasn't the really queer angle on the pitch. The other thing broke in the papers the week after he left. The neighbors got pretty worked up about it. They called the police to tell them that Vanderkamp's sister Julie was back, only she was off her nut—and a good deal changed in appearance, too.

"Gal going blarmy was no news, of course, but that last bit about her appearance—they said she looked about twenty years older, all of a sudden—sort of rang a bell. So I went over there. It was Julie, all right; at least, she looked a hell of a lot like Julie had when I last saw her—provided you could grant that a woman could age twenty years in the few weeks it had been. And she was off her rocker, sure enough—or hysterical. Or at least madder than a wet hen. She made out like she couldn't speak a word of English, and they finally had to get an interpreter to understand her. She wouldn't speak anything but Dutch—and an old-fashioned kind, too.

"She made a lot of extravagant claims and kept insisting that she would bring the whole matter up in a complaint before Governor Stuyvesant. Said she wasn't Julie Vanderkamp, by God, but was named Anna Van Tromp—which is an old Dutch name thereabouts—and claimed that she had been abducted from her home on the Bowery. We pointed out the Third Avenue El and told her that was the Bowery, but she just sniffed and looked at us as though we were crazy."

I toyed with my drink. "You mean you actually listened to the poor girl's story?" I asked.

"Sure," Harrigan said. "Maybe she was as crazy as a bedbug, but I've listened to whackier stories from supposedly sane people. Sure, I listened to her." He paused thoughtfully for a moment, then went on.

"She claimed that this fellow Vanderkamp had come to her house and filled her with a lot of guff about the wonderful country he lived in, and how she ought to let him take her to see it. Apparently he waxed especially eloquent about an automatic washing-machine and dryer, and that had fascinated her, for some reason. Then, she said, he'd brought a ten-year-old girl along—though where in the world old Vanderkamp could have picked up a tot like that is beyond me—and the kid had added her blandishments to the plot. Between them, they had managed to lure her into the old guy's machine. From what she said, it was obviously the time machine she was talking about, and if she was Julie there was no reason why she shouldn't know about it. But she talked as though it was a complete mystery to her, as though she'd no idea what the purpose of it was. Well, anyway, here she was—and very unhappy, too. Wanted to go back to old New Amsterdam, but bad.

"It was a beautiful act, even if she was nuts. The strange thing was, though, that there were some things even a gal going whacky couldn't explain. For instance, the house was filled with what the experts said were priceless antiques from Dutch New Amsterdam, of the period just prior to the British siege. You'd think those things would make poor Julie feel more at home, seeing as she claimed to belong in that period, but apparently they just made her homesick. And, curiously enough, all the modern gadgets were gone. All those handy little items that make the twentieth century so livable had been taken away—including the washing-machine and dryer, by the way. Julie—or Anna, as she called herself—claimed that Vanderkamp had taken it back with him, wherever he'd gone to, after he'd brought her there."

"Poor woman," I said sympathetically. "They toted her off to the booby hatch, I suppose."

"No...." Harrigan said slowly. "They didn't, as a matter of fact. Since she was harmless, they let her stay in the house a while. Which was a mistake, it seems. Of course, she wasn't from the seventeenth century. That's impossible. All the same—." He broke off abruptly and stared moodily into his glass.

"What happened to her?" I asked.

"She was found one morning about two weeks after she got there," he said. "Dead. Electrocuted. It seems she'd stuck her finger into a light socket while standing in a bathtub full of water. An accident, obviously. As the Medical Examiner said, it was an accident any six-year-old child would have known enough about electricity to avoid.

"That is," Harrigan added, "a twentieth-century child...."