The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Complete Opera Book, by Gustav Kobbé

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Complete Opera Book

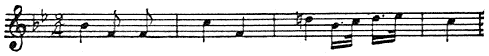

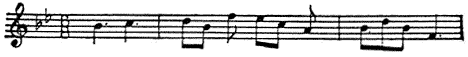

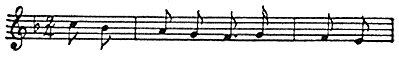

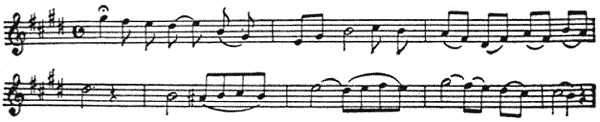

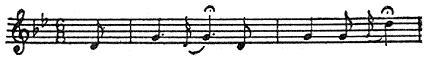

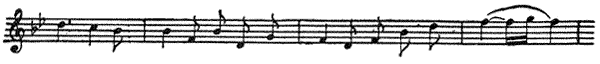

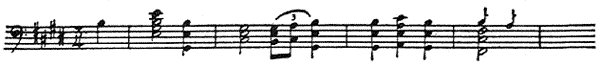

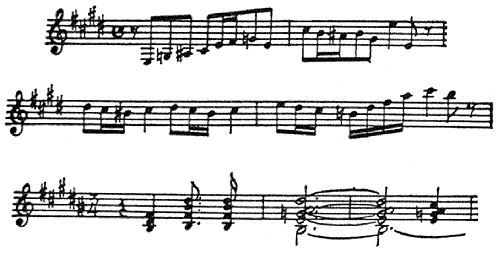

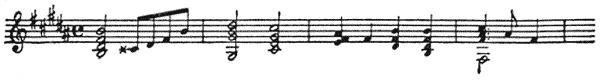

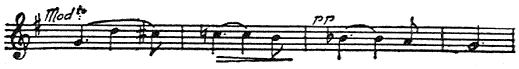

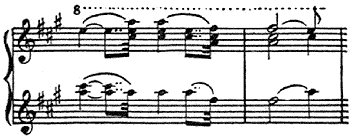

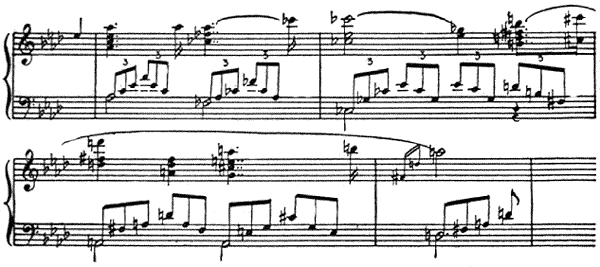

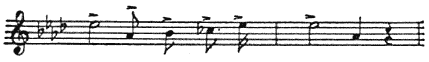

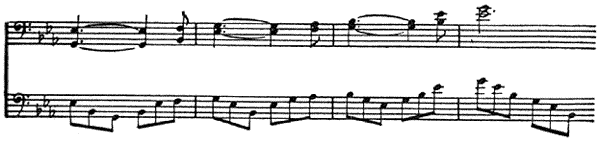

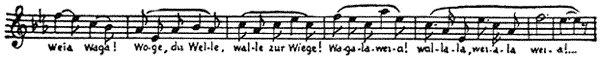

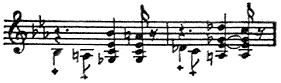

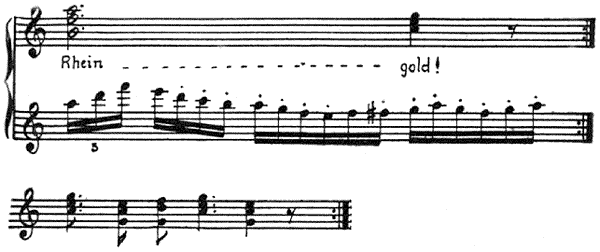

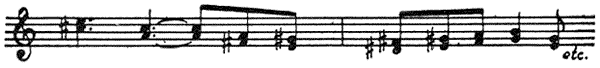

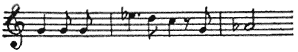

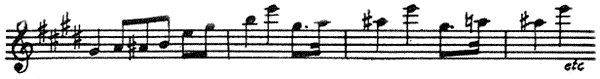

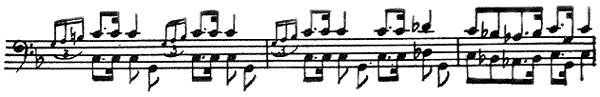

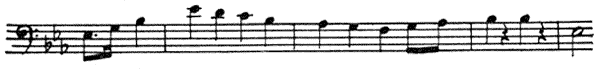

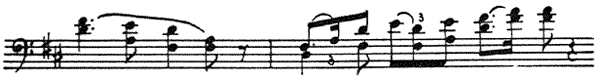

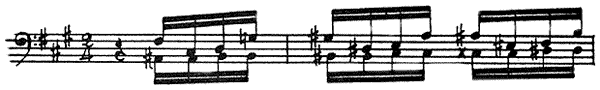

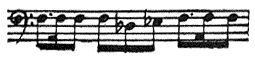

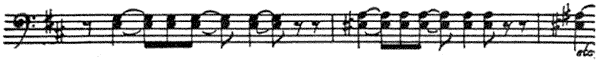

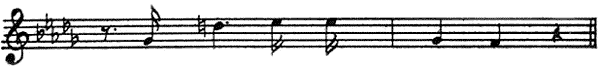

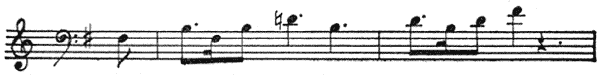

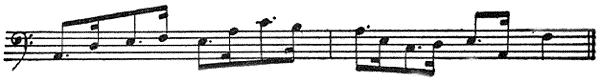

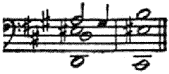

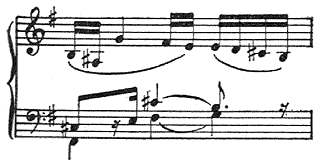

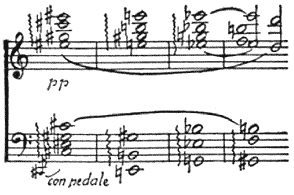

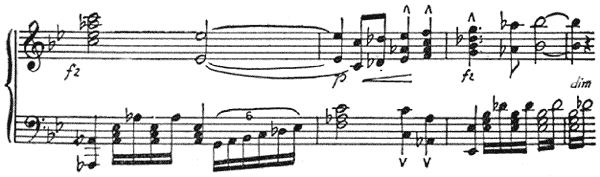

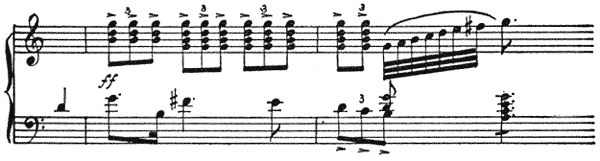

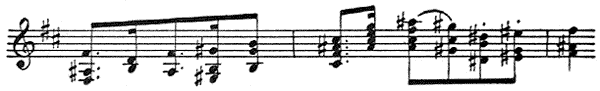

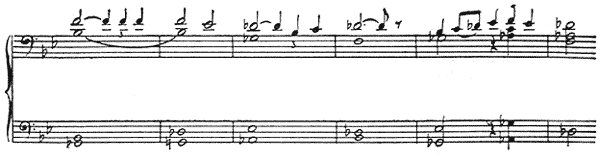

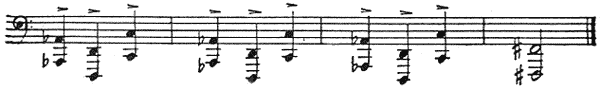

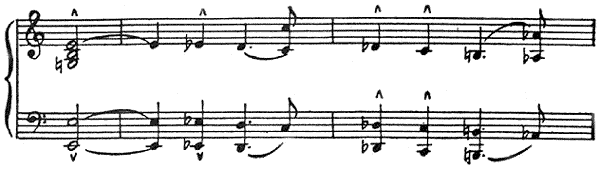

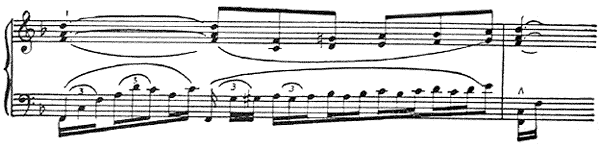

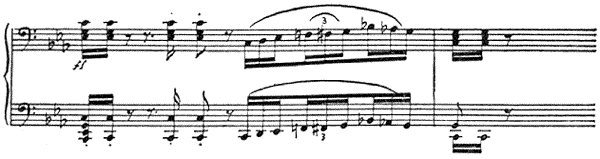

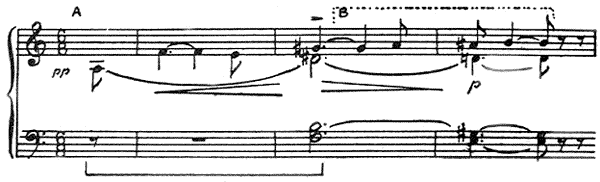

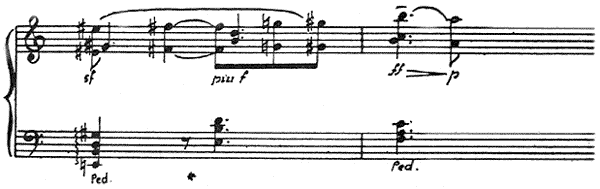

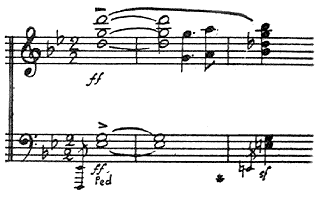

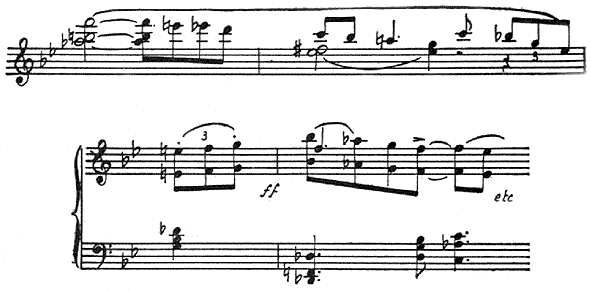

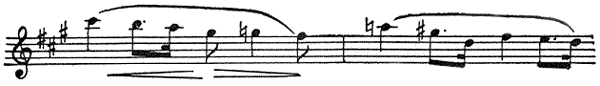

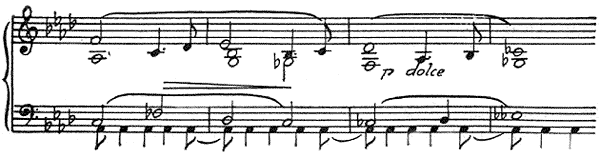

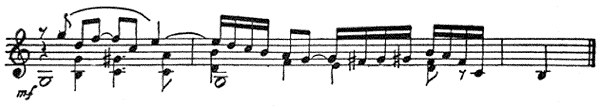

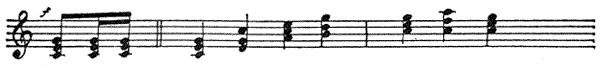

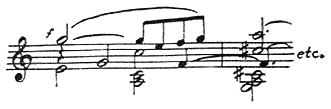

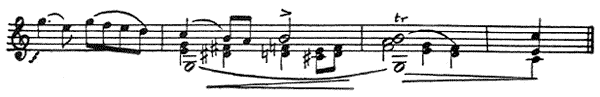

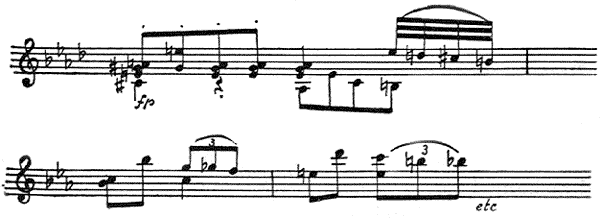

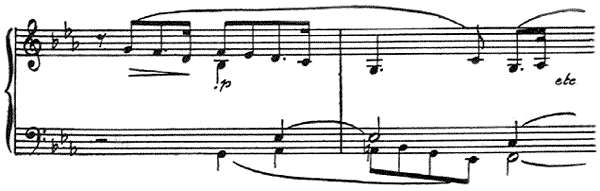

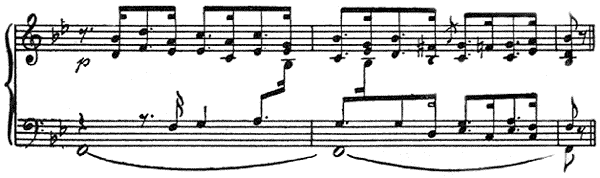

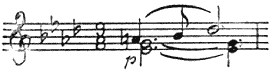

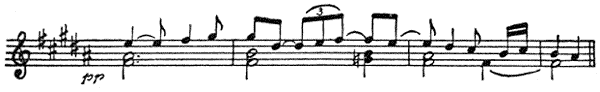

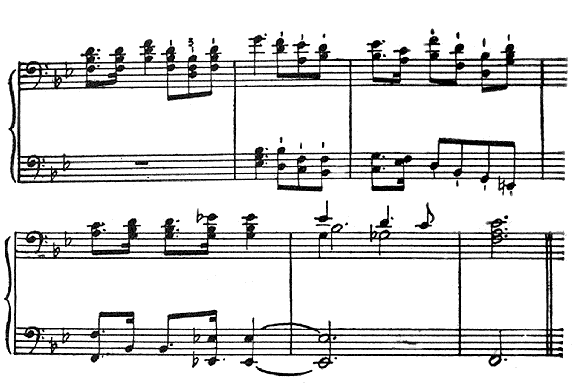

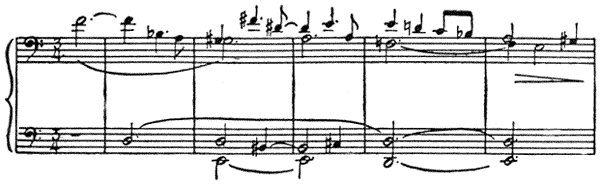

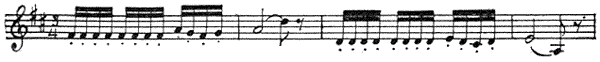

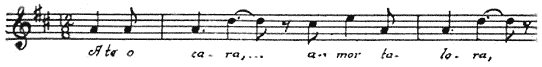

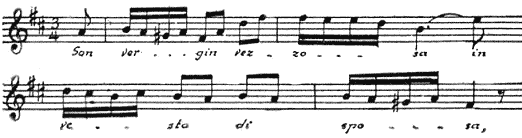

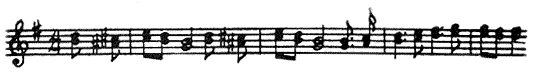

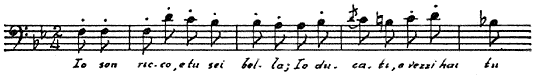

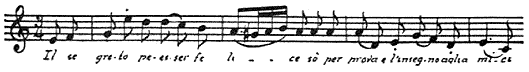

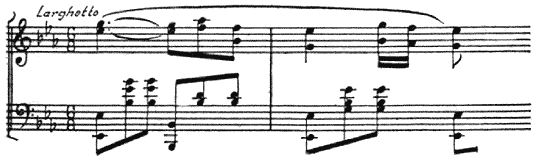

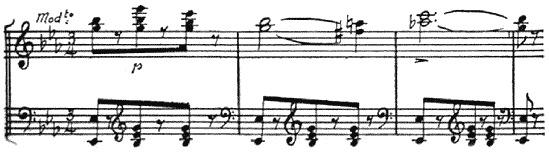

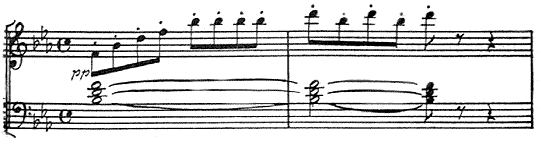

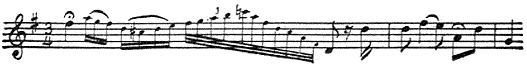

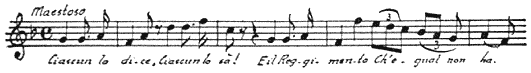

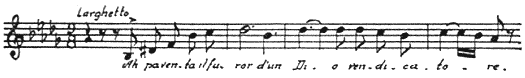

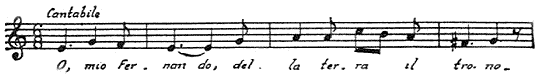

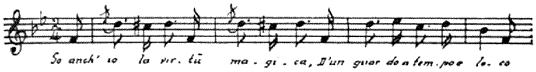

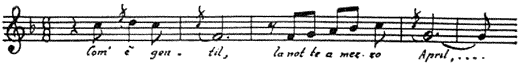

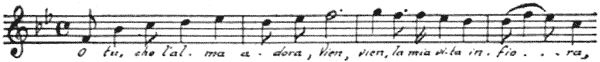

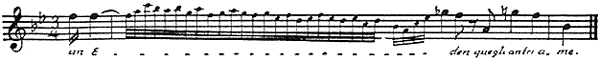

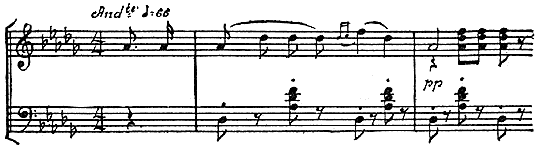

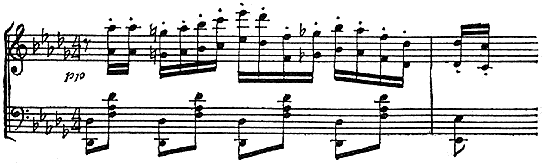

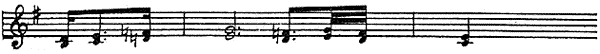

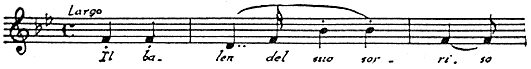

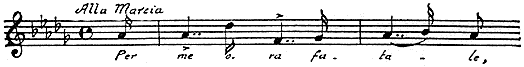

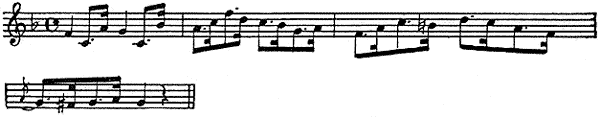

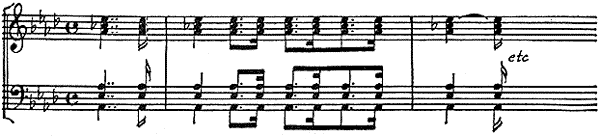

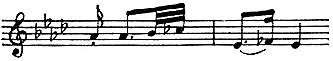

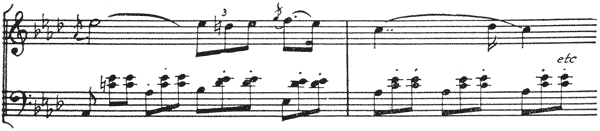

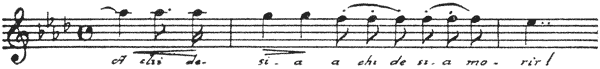

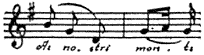

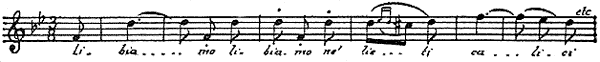

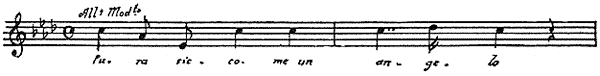

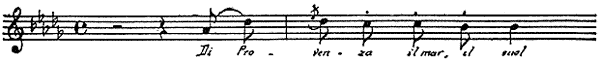

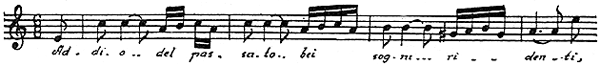

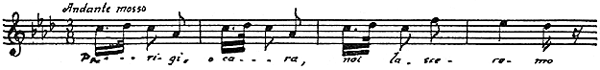

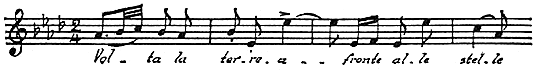

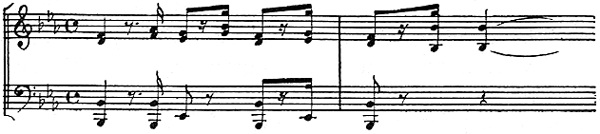

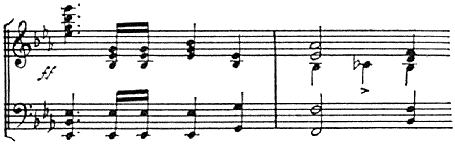

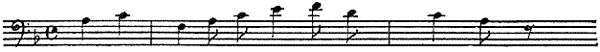

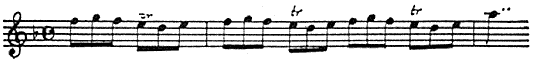

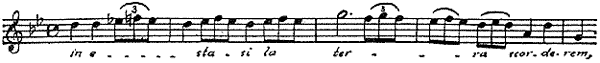

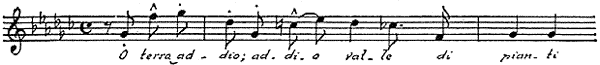

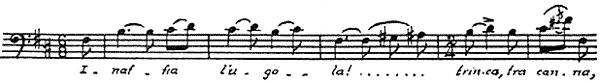

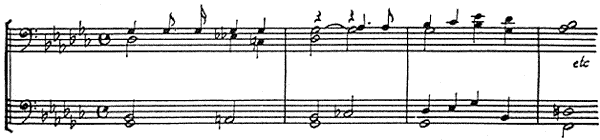

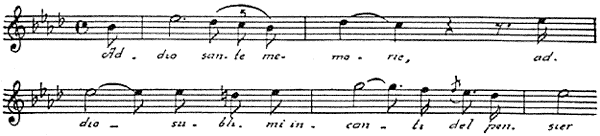

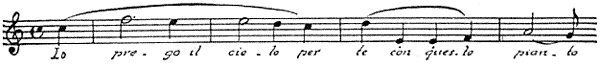

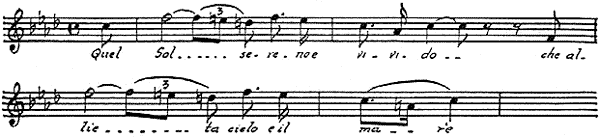

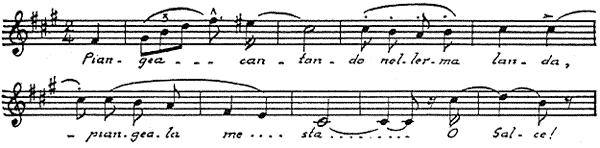

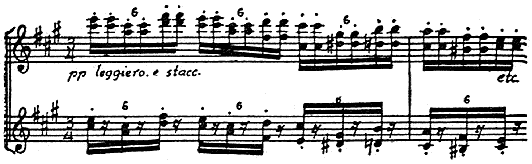

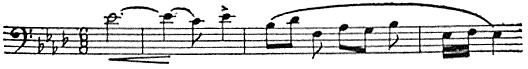

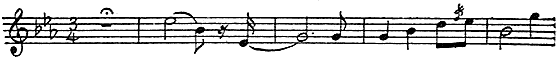

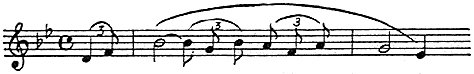

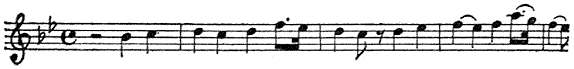

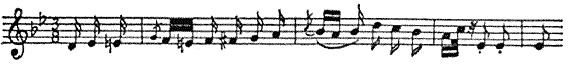

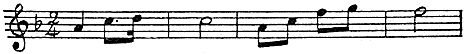

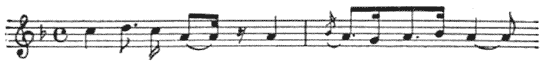

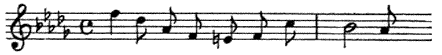

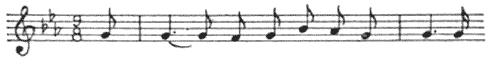

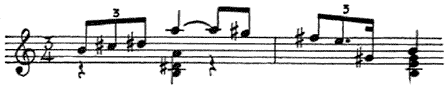

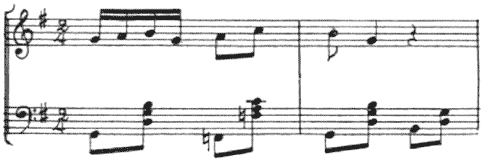

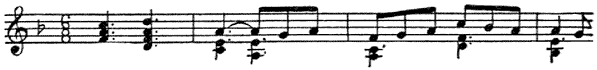

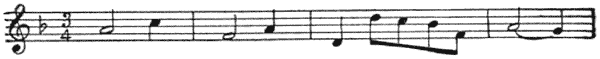

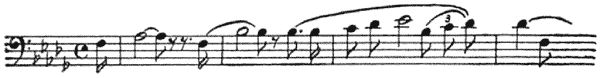

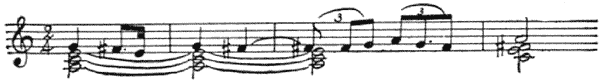

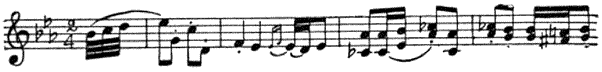

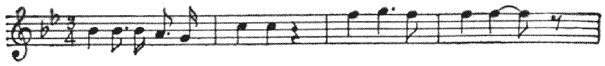

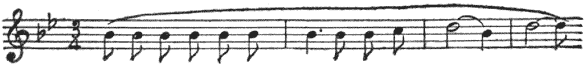

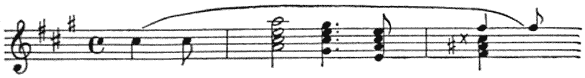

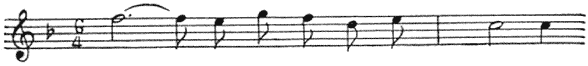

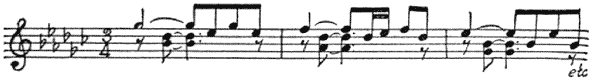

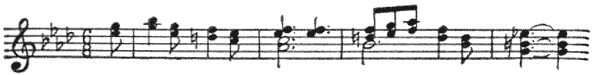

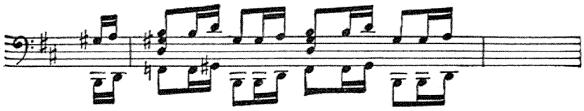

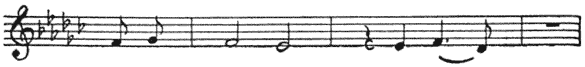

The Stories of the Operas, together with 400 of the Leading

Airs and Motives in Musical Notation

Author: Gustav Kobbé

Release Date: August 19, 2012 [EBook #40540]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE COMPLETE OPERA BOOK ***

Produced by Charlene Taylor, Linda Cantoni, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Notes

The Complete Opera Book has been an important opera reference work since its first publication in 1919. It has been revised and updated a number of times, most famously by George Lascelles, 7th Earl of Harewood, and most recently in 1997.

This e-book was prepared from the 1919 first edition. Gustav Kobbé was killed in a sailing accident in 1918 and apparently did not have the opportunity to make corrections before the book was published. There are consequently numerous typographical, spelling, and formatting errors and inconsistencies in the first edition, the most obvious of which have been corrected without note in this e-book. Ambiguous errors are marked with red dotted underlining in the HTML version; hover the mouse over the underlined text to see a pop-up Transcriber's Note. A Transcriber's Errata List of these notes is also provided at the end of this file. The author's deliberate interchanges of foreign words or names and their equivalents in English or other languages have been preserved as they appear in the original. Misplaced Table of Contents and index entries have been moved to their proper places.

Photograph illustrations have been moved so as not to break up the flow of the text and may not appear on the page indicated in the List of Illustrations, which in this e-book contains links to the illustrations themselves, rather than to the pages.

Click on the [Listen] link to download and hear a midi file (or MP3 file, where noted) of the music. Obvious errors in the music notation have been corrected in the sound files, and the corrections are noted in the titles of the corresponding music images. If you are reading this e-book in any format other than HTML, you will not be able to hear the music.

By Gustav Kobbé

All-of-a-Sudden Carmen

The Complete Opera Book

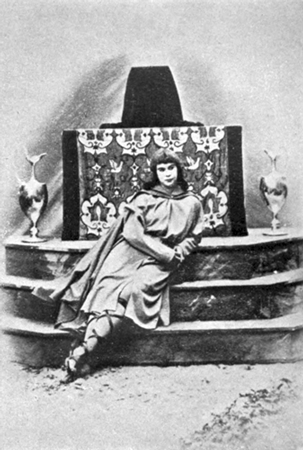

Copyright photo by Mishkin

Mary Garden as Sapho

Author of “Wagner’s Music-Dramas Analysed,”

“All-of-a-Sudden Carmen,” etc.

Illustrated with One Hundred Portraits in Costume and

Scenes from Opera

G.P. Putnam’s Sons

New York and London

The Knickerbocker Press

1919

Copyright, 1919

BY

GUSTAV KOBBÉ

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

Copyright photo by Pirie MacDonald

GUSTAV KOBBÉ

Through the thoughtfulness of William J. Henderson I was asked to supply material for The Complete Opera Book, which was missing at the time of Mr. Kobbé's death.

In performing my share of the work it has been my endeavor to confine myself to facts, rather than to intrude with personal opinions upon a work which should stand as a monument to Mr. Kobbé's musical knowledge and convictions.

Katharine Wright.

New York, 1919.

| PAGE | |

| Mary Garden as Sapho | Frontispiece |

| Louise Homer as Orpheus in "Orpheus and Eurydice" | 10 |

| Hempel (Susanna), Matzenauer (The Countess), and Farrar (Cherubino) in "Le Nozze di Figaro" | 26 |

| Scotti as Don Giovanni | 34 |

| Sembrich as Zerlina in "Don Giovanni" | 35 |

| Scotti as Don Giovanni | 42 |

| Alten and Goritz as Papagena and Papageno in "The Magic Flute" | 43 |

| Matzenauer as Fidelio | 56 |

| Farrar as Elizabeth in "Tannhäuser" | 108 |

| "Tannhäuser," Finale, Act II. Tannhäuser (Maclennan), Elizabeth (Fornia), Wolfram (Dean), The Landgrave (Cranston) | 109 |

| Sembach as Lohengrin | 122 |

| Schumann-Heink as Ortrud in "Lohengrin" | 123 |

| Emma Eames as Elsa in "Lohengrin" | 128 |

| Louise Homer as Fricka in "The Ring of the Nibelung" | 129 |

| Lilli Lehmann as Brünnhilde in "Die Walküre" | 166 |

| "The Valkyr" Act I. Hunding (Parker), Sieglinde (Rennyson), and Siegmund (Maclennan) | 167-xvi- |

| Fremstad as Brünnhilde in "Die Walküre" | 172 |

| Fremstad as Sieglinde in "Die Walküre" | 173 |

| Weil as Wotan in "Die Walküre" | 178 |

| "Die Walküre" Act III. Brünnhilde (Margaret Crawford) | 179 |

| Édouard de Reszke as Hagen in "Götterdämmerung" | 210 |

| Jean de Reszke as Siegfried in "Götterdämmerung" | 211 |

| Nordica as Isolde | 228 |

| Lilli Lehmann as Isolde | 236 |

| Jean de Reszke as Tristan | 237 |

| Gadski as Isolde | 242 |

| Ternina as Isolde | 243 |

| Emil Fischer as Hans Sachs in "Die Meistersinger" | 248 |

| Weil and Goritz as Hans Sachs and Beckmesser in "Die Meistersinger" | 249 |

| The Grail-Bearer | 272 |

| Winckelmann and Materna as Parsifal and Kundry | 273 |

| Scaria as Gurnemanz | 273 |

| Sammarco as Figaro in "The Barber of Seville" | 298 |

| Galli-Curci as Rosina in "The Barber of Seville" | 302 |

| Sembrich as Rosina in "The Barber of Seville" | 303 |

| Hempel (Adina) and Caruso (Nemorino) in "L'Elisir d'Amore" | 336 |

| Caruso as Edgardo in "Lucia di Lammermoor" | 348 |

| Galli-Curci as Lucia in "Lucia di Lammermoor" | 349 |

| Galli-Curci as Gilda in "Rigoletto" | 392 |

| Caruso as the Duke in "Rigoletto" | 393-xvii- |

| The Quartet in "Rigoletto." The Duke (Sheehan), Maddalena (Albright), Gilda (Easton), Rigoletto (Goff) | 400 |

| Riccardo Martin as Manrico in "Il Trovatore" | 401 |

| Schumann-Heink as Azucena in "Il Trovatore" | 410 |

| Galli-Curci as Violetta in "La Traviata" | 411 |

| Farrar as Violetta in "La Traviata" | 420 |

| Scotti as Germont in "La Traviata" | 421 |

| Emma Eames as Aïda | 442 |

| Saléza as Rhadames in "Aïda" | 443 |

| Louise Homer as Amneris in "Aïda" | 448 |

| Rosina Galli in the Ballet of "Aïda" | 449 |

| Alda as Desdemona in "Otello" | 460 |

| Amato as Barnaba in "La Gioconda" | 461 |

| Caruso as Enzo in "La Gioconda" | 488 |

| Louise Homer as Laura in "La Gioconda" | 489 |

| Plançon as Saint Bris in "The Huguenots" | 508 |

| Jean de Reszke as Raoul in "The Huguenots" | 509 |

| Ober and De Luca; Caruso and Hempel in "Martha" | 548 |

| Plançon as Méphistophélès in "Faust" | 549 |

| Galli-Curci as Juliette in "Roméo et Juliette" | 578 |

| Calvé as Carmen with Sparkes as Frasquita, and Braslau as Mercedes | 579 |

| Caruso as Don José in "Carmen" | 590 |

| Caruso as Don José in "Carmen" | 591 |

| Calvé as Carmen | 594 |

| Amato as Escamillo in "Carmen" | 595-xviii- |

| Gadski as Santuzza in "Cavalleria Rusticana" | 614 |

| Bori as Iris | 615 |

| Caruso as Canio in "I Pagliacci" | 630 |

| Farrar as Nedda in "I Pagliacci" | 631 |

| Farrar as Mimi in "La Bohème" | 644 |

| Café Momus Scene, "La Bohème." Act II. Mimi (Rennyson), Musette (Joel), Rudolph (Sheehan) | 645 |

| Cavalieri as Tosca | 656 |

| Scotti as Scarpia | 657 |

| Emma Eames as Tosca | 660 |

| Caruso as Mario in "Tosca" | 661 |

| Farrar as Tosca | 664 |

| "Madama Butterfly." Act I. (Francis Maclennan, Renée Vivienne, and Thomas Richards) | 665 |

| Farrar as Cio-Cio-San in "Madama Butterfly" | 668 |

| Destinn as Minnie, Caruso as Johnson, and Amato as Jack Rance in "The Girl of the Golden West" | 669 |

| Alda as Francesca, and Martinelli as Paolo in "Francesca da Rimini" | 682 |

| Bori and Ferrari-Fontana in "The Love of Three Kings" | 683 |

| Farrar as Catherine in "Mme. Sans-Gêne" | 710 |

| Galli-Curci as Lakmé | 711 |

| Caruso as Samson in "Samson and Dalila" | 726 |

| Mary Garden as Grisélidis | 727 |

| Mary Garden as Thaïs | 730 |

| Farrar and Amato as Thaïs and Athanaël | 731-xix- |

| Farrar as Thaïs | 734 |

| Farrar and Amato as Thaïs and Athanaël | 735 |

| Caruso as Des Grieux in "Manon" | 738 |

| Mary Garden in "Le Jongleur de Nôtre Dame" | 739 |

| Mary Garden as Louise | 750 |

| Lucienne Bréval as Salammbô | 751 |

| Mary Garden as Mélisande in "Pelléas and Mélisande" | 754 |

| Farrar as the Goose Girl in "Königskinder" | 776 |

| Van Dyck and Mattfeld as Hänsel and Gretel | 777 |

| Mary Garden as Salome | 802 |

| Hempel as the Princess and Ober as Octavian in "Der Rosenkavalier" | 803 |

| Scene from the Ballet in "Prince Igor" (with Rosina Galli) | 820 |

| Anna Case as Feodor, Didur as Boris, and Sparkes as Xenia in "Boris Godounoff" | 821 |

THERE are three great schools of opera,—Italian, French, and German. None other has developed sufficiently to require comment in this brief chapter.

Of the three standard schools, the Italian is the most frankly melodious. When at its best, Italian vocal melody ravishes the senses. When not at its best, it merely tickles the ear and offends common sense. "Aïda" was a turning point in Italian music. Before Verdi composed "Aïda," Italian opera, despite its many beauties, was largely a thing of temperament, inspirationally, but often also carelessly set forth. Now, Italian opera composers no longer accept any libretto thrust at them. They think out their scores more carefully; they produce works in which due attention is paid to both vocal and orchestral effect. The older composers still represented in the repertoire are Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi. The last-named, however, also reaches well over into the modern school of Italian opera, whose foremost living exponent is Puccini.

Although Rameau (1683-1764), whose "Castor and Pollux" held the stage until supplanted by Gluck's works, was a native of France, French opera had for its founder the Italian, Lully; and one of its chief exponents was the German, Meyerbeer. Two foreigners, therefore, have had-2- a large share in developing the school. It boasts, however, many distinguished natives—Halévy, Auber, Gounod, Bizet, Massenet.

In the French school of opera the instrumental support of the voice is far richer and the combination of vocal and instrumental effect more discriminating than in the old school of Italian opera. A first cousin of Italian opera, the French, nevertheless, is more carefully thought out, sometimes even too calculated; but, in general, less florid, and never indifferent to the librettist and the significance of the lines he has written and the situations he has evoked. Massenet is, in the truest sense, the most recent representative of the school of Meyerbeer and Gounod, for Bizet's "Carmen" is unique, and Débussy's "Pelléas et Mélisande" a wholly separate manifestation of French art for the lyric stage.

The German school of opera is distinguished by a seriousness of purpose that discards all effort at vocal display for itself alone, and strives, in a score, well-balanced as between voice and orchestra, to express more forcibly than could the spoken work, the drama that has been set to music.

An opera house like the Metropolitan, which practically has three companies, presents Italian, French, and German operas in the language in which they were written, or at least usually does so. Any speaker before an English-speaking audience can always elicit prolonged applause by maintaining that in English-speaking countries opera should be sung in English. But, in point of fact, and even disregarding the atrocities that masquerade as translations of opera into English, opera should be sung in the language in which it is written. For language unconsciously affects, I might even say determines, the structure of the melody.

Far more important than language, however, is it that opera be sung by great artists. For these assimilate music-3- and give it forth in all its essence of truth and beauty. Were great artists to sing opera in Choctaw, it would still be welcome as compared with opera rendered by inferior interpreters, no matter in what language.

GLUCK'S "Orfeo ed Euridice" (Orpheus and Eurydice), produced in 1762, is the oldest opera in the repertoire of the modern opera house. But when you are told that the Grand Opéra, Paris, was founded by Lully, an Italian composer, in 1672; that Italians were writing operas nearly a century earlier; that a German, Reinhard Keiser (1679-1739), is known to have composed at least 116 operas; and that another German, Johann Adolph Hasse, composed among his operas, numbering at least a hundred, one entitled "Artaxerxes," two airs from which were sung by Carlo Broschi every evening for ten years to soothe King Philip V. of Spain;—you will realize that opera existed, and even flourished before Gluck produced his "Orpheus and Eurydice."

Opera originated in Florence toward the close of the sixteenth century. A band of composers, enthusiastic, intellectual, aimed at reproducing the musical declamation which they believed to have been characteristic of the representation of Greek tragedy. Their scores were not melodious, but composed in a style of declamatory recitative highly dramatic for its day. What usually is classed as the first opera, Jacopo Peri's "Dafne," was privately performed in the Palazzo Corsi, Florence, in 1597. So great was its success that Peri was commissioned, in 1600, to write a similar work for the festivities incidental to the marriage of Henry IV. of France with Maria de Medici, and composed "Euridice," said to have been the first opera ever produced in public.

The new art form received great stimulus from Claudio Monteverdi, the Duke of Mantua's director of music, who composed "Arianna" (Ariadne) in honor of the marriage of Francesco Gonzaga with Margherita, Infanta of Savoy. The scene in which Ariadne bewails her desertion by her lover was so dramatically written (from the standpoint of the day, of course) that it produced a sensation. The permanency of opera was assured, when Monteverdi brought out, with even greater success, his opera "Orfeo," which showed a further advance in dramatic expression, as well as in the treatment of the instrumental score. This composer invented the tremolo for strings—marvellous then, commonplace now, and even reprehensible, unless employed with great skill.

Monteverdi's scores contained, besides recitative, suggestions of melody. The Venetian composer, Cavalli, introduced melody more conspicuously into the vocal score in order to relieve the monotonous effect of a continuous recitative, that was interrupted only by brief melodious phrases. In his airs for voice he foreshadowed the aria form, which was destined to be freely developed by Alessandro Scarlatti (1659-1725). Scarlatti was the first to introduce into an opera score the ritornello—the instrumental introduction, interlude, or postlude to a composition for voice. Indeed, Scarlatti is regarded as the founder of what we call Italian opera, the chief characteristic of which is melody for the voice with a comparatively simple accompaniment.

By developing vocal melody to a point at which it ceased to be dramatically expressive, but degenerated into mere voice pyrotechnics, composers who followed Scarlatti laid themselves open to the charge of being too subservient to the singers, and of sacrificing dramatic truth and depth of expression to the vanity of those upon the stage. Opera became too much a series of show-pieces for its interpreters.-6- The first practical and effective protest against this came from Lully, who already has been mentioned. He banished all meaningless embellishment from his scores. But in the many years that intervened between Lully's career and Gluck's, the abuse set in again. Then Gluck, from copying the florid Italian style of operatic composition early in his career, changed his entire method as late as 1762, when he was nearly fifty years old, and produced "Orfeo ed Euridice." From that time on he became the champion for the restoration of opera to its proper function as a well-balanced score, in which the voice, while pre-eminent, does not "run away with the whole show."

Indeed, throughout the history of opera, there have been recurring periods, when it has become necessary for composers with the true interest of the lyric stage at heart, to restore the proper balance between the creator of a work and its interpreters, in other words to prevent opera from degenerating from a musical drama of truly dramatic significance to a mere framework for the display of vocal pyrotechnics. Such a reformer was Wagner. Verdi, born the same year as Wagner (1813), but outliving him nearly twenty years, exemplified both the faults and virtues of opera. In his earlier works, many of which have completely disappeared from the stage, he catered almost entirely to his singers. But in "Aïda" he produced a masterpiece full of melody which, while offering every opportunity for beautiful singing, never degenerates into mere vocal display. What is here said of Verdi could have been said of Gluck. His earlier operas were in the florid style. Not until he composed "Orpheus and Eurydice" did he approach opera from the point of view of a reformer. "Orpheus" was his "Aïda."

Regarding opera Gluck wrote that "the true mission of music is to second the poetry, by strengthening the expression of the sentiments and increasing the interest of the-7- situations, without interrupting and weakening the action by superfluous ornaments in order to tickle the ear and display the agility of fine voices."

These words might have been written by Richard Wagner, they express so well what he accomplished in the century following that in which Gluck lived. They might also have been penned by Verdi, had he chosen to write an introduction to his "Aïda," "Otello," or "Falstaff"; and they are followed by every successful composer of grand opera today—Mascagni, Leoncavallo, Puccini, Massenet, Strauss.

In fact, however much the public may be carried away temporarily by astonishing vocal display introduced without reason save to be astonishing, the fate of every work for the lyric stage eventually has been decided on the principle enunciated above. Without being aware of it, the public has applied it. For no matter how sensationally popular a work may have been at any time, it has not survived unless, consciously or unconsciously, the composer has been guided by the cardinal principle of true dramatic expression.

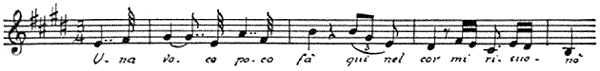

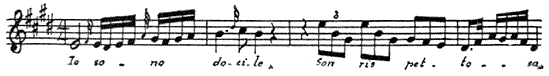

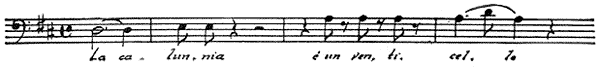

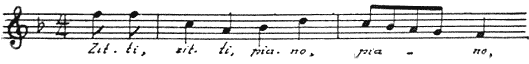

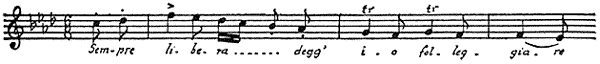

Finally, I must not be misunderstood as condemning, at wholesale, vocal numbers in opera that require extraordinary technique. Scenes in opera frequently offer legitimate occasion for brilliant vocal display. Witness the arias of the Queen of the Night in "The Magic Flute," "Una voce poco fa" in "The Barber of Seville," "Ah! non giunge" in "Sonnambula," the mad scene in "Lucia," "Caro nome" in "Rigoletto," the "Jewel Song" in "Faust," and even Brünnhilde's valkyr shout in "Die Walküre"—works for the lyric stage that have escorted thousands of operatic scores to the grave, with Gluck's gospel on the true mission of opera for a funeral service.

GLUCK is the earliest opera composer represented in the repertoire of the modern opera house. In this country three of his works survive. These are, in the order of their production, "Orfeo ed Euridice" (Orpheus and Eurydice), "Armide," and "Iphigénie en Tauride" (Iphigenia in Tauris). "Orpheus and Eurydice," produced in 1762, is the oldest work of its kind on the stage. It is the great-great-grandfather of operas.

Its composer was a musical reformer and "Orpheus" was the first product of his musical reform. He had been a composer of operas in the florid vocal style, which sacrificed the dramatic verities to the whims, fancies, and ambitions of the singers, who sought only to show off their voices. Gluck began, with his "Orpheus," to pay due regard to true dramatic expression. His great merit is that he accomplished this without ignoring the beauty and importance of the voice, but by striking a correct balance between the vocal and instrumental portions of the score.

Simple as his operas appear to us today, they aroused a strife comparable only with that which convulsed musical circles during the progress of Wagner's career. The opposition to his reforms reached its height in Paris, whither he went in 1772. His opponents invited Nicola Piccini, at that time famous as a composer of operas in the florid Italian style, to compete with him. So fierce was the war-9- between Gluckists and Piccinists, that duels were fought and lives sacrificed over the respective merits of the two composers. Finally each produced an opera on the subject of "Iphigenia in Tauris." Gluck's triumphed, Piccini's failed.

Completely victorious, Gluck retired to Vienna, where he died, November 25, 1787.

Opera in three acts. Music by Christoph Willibald Gluck; book by Raniero di Calzabigi. Productions and revivals. Vienna, October 5, 1762; Paris, as "Orphée et Eurydice," 1774; London, Covent Garden, June 26, 1860; New York, Metropolitan Opera House, 1885 (in German); Academy of Music, American Opera Company, in English, under Theodore Thomas, January 8, 1886, with Helene Hastreiter, Emma Juch, and Minnie Dilthey; Metropolitan Opera House, 1910 (with Homer, Gadski, and Alma Gluck).

Characters

| Orpheus | Contralto |

| Eurydice | Soprano |

| Amor, God of Love | Soprano |

| A Happy Shade | Soprano |

Shepherds and Shepherdesses, Furies and Demons, Heroes and Heroines in Hades.

Time—Antiquity.

Place—Greece and the Nether Regions.

Following a brief and solemn prelude, the curtain rises on Act I, showing a grotto with the tomb of Eurydice. The beautiful bride of Orpheus has died. Her husband and friends are mourning at her tomb. During an affecting aria and chorus ("Thou whom I loved") funeral honours are paid to the dead bride. A second orchestra, behind the scenes, echoes, with charming effect, the distracted husband's evocations to his bride and the mournful measures of the chorus, until, in answer to the piercing cries of Orpheus-10- and the exclamatory recitative, "Gods, cruel gods," Amor appears. He tells the bereaved husband that Zeus has taken pity on him. He shall have permission to go down into Hades and endeavour to propitiate Pluto and his minions solely through the power of his music. But, should he rescue Eurydice, he must on no account look back at her until he has crossed the Styx.

Upon that condition, so difficult to fulfil, because of the love of Orpheus for his bride, turns the whole story. For should he, in answer to her pleading, look back, or explain to her why he cannot do so, she will immediately die. But Orpheus, confident in his power of song and in his ability to stand the test imposed by Zeus and bring his beloved Eurydice back to earth, receives the message with great joy.

"Fulfil with joy the will of the gods," sings Amor, and Orpheus, having implored the aid of the deities, departs for the Nether World.

Copyright Photo by Dupont

Louise Homer as Orpheus in “Orpheus and Eurydice”

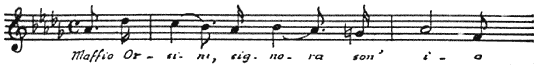

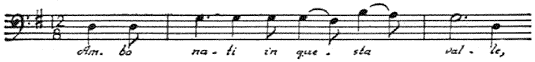

Act I. Entrance to Hades. When Orpheus appears, he is greeted with threats by the Furies. The scene, beginning with the chorus, "Who is this mortal?" is still considered a masterpiece of dramatic music. The Furies call upon Cerberus, the triple-headed dog monster that guards the entrance to the Nether World, to tear in pieces the mortal who so daringly approaches. The bark of the monster is reproduced in the score. This effect, however, while interesting, is but a minor incident. What lifts the scene to its thrilling climax is the infuriated "No!" which is hurled at Orpheus by the dwellers at the entrance to Hades, when, having recourse to song, he tells of his love for Eurydice and his grief over her death and begs to be allowed to seek her. He voices his plea in the air, "A thousand griefs, threatening shades." The sweetness of his music wins the sympathy of the Furies. They allow him to enter the Valley of the Blest, a beautiful spot where the good spirits in Hades find rest. (Song for Eurydice and her companions, "In this-11- tranquil and lovely abode of the blest.") Orpheus comes seeking Eurydice. His recitative, "What pure light!" is answered by a chorus of happy shades, "Sweet singer, you are welcome." To him they bring the lovely Eurydice. Orpheus, beside himself with joy, but remembering the warning of Amor, takes his bride by the hand and, with averted gaze, leads her from the vale.

She cannot understand his action. He seeks to soothe her injured feelings. (Duet: "On my faith relying.") But his efforts are vain; nor can he offer her any explanation, for he has also been forbidden to make known to her the reason for his apparent indifference.

Act III. A wood. Orpheus, still under the prohibition imposed by the gods, has released the hand of his bride and is hurrying on in advance of her urging her to follow. She, still not comprehending why he does not even cast a glance upon her, protests that without his love she prefers to die.

Orpheus, no longer able to resist the appeal of his beloved bride, forgets the warning of Amor. He turns and passionately clasps Eurydice in his arms. Immediately she dies.

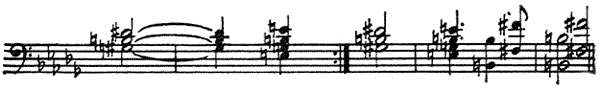

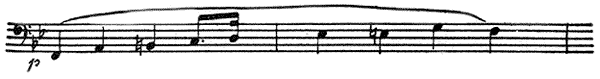

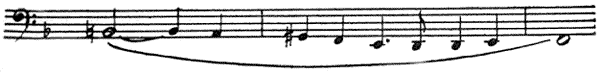

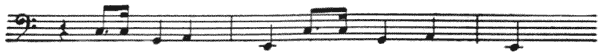

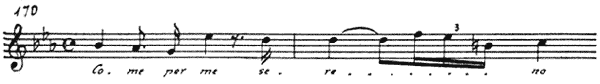

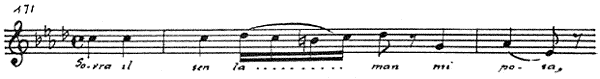

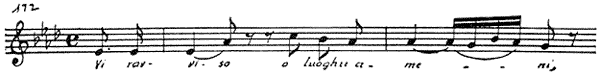

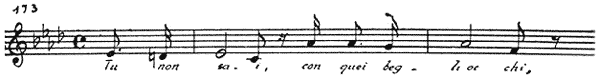

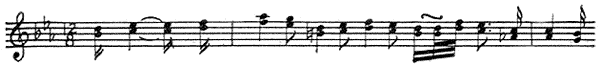

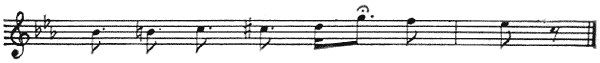

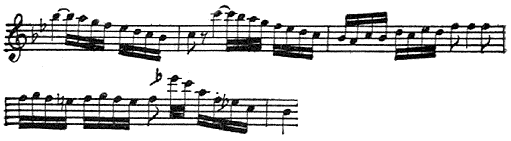

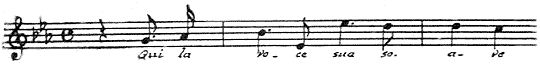

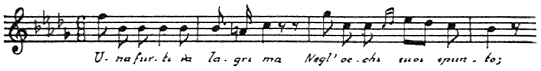

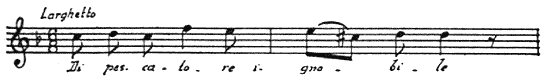

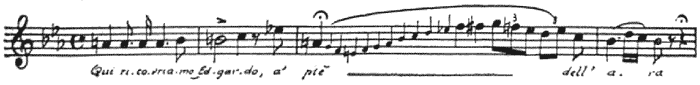

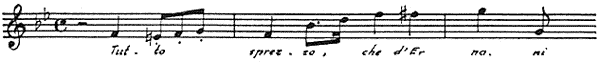

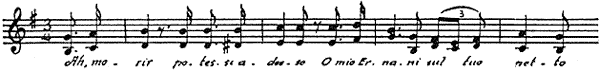

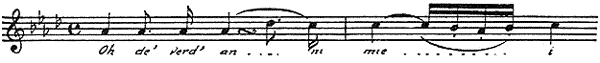

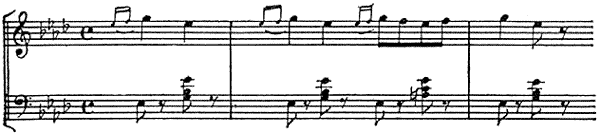

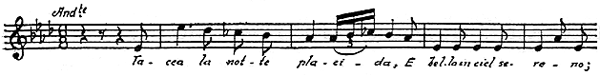

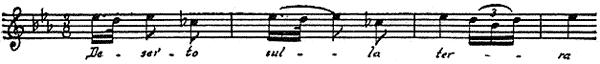

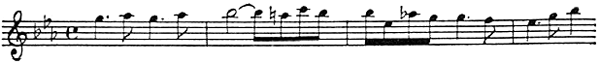

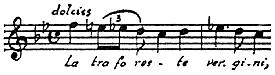

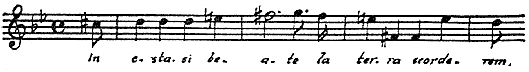

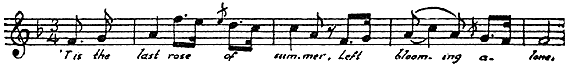

It is then that Orpheus intones the lament, "Che farò senza Euridice" (I have lost my Eurydice), that air in the score which has truly become immortal and by which Gluck, when the opera as a whole shall have disappeared from the stage, will still be remembered.

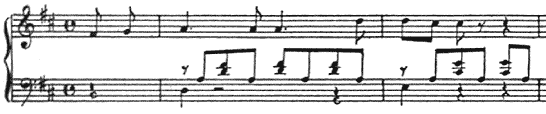

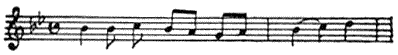

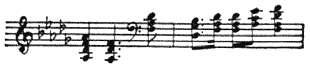

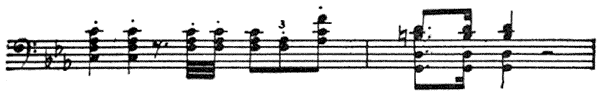

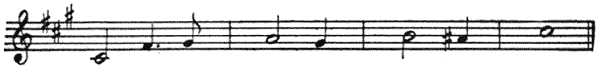

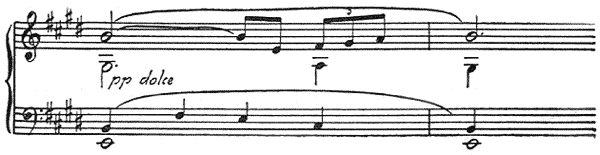

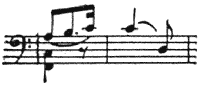

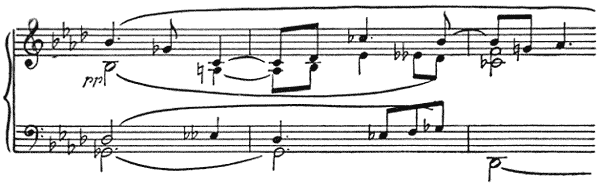

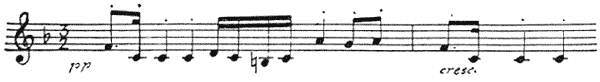

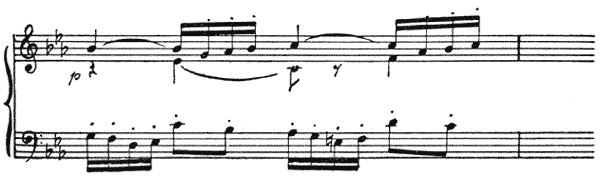

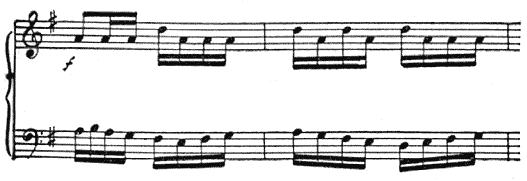

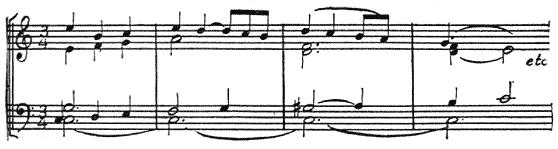

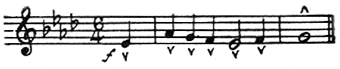

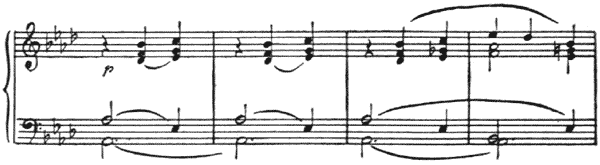

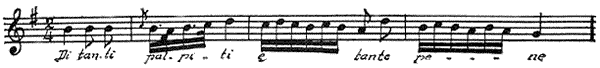

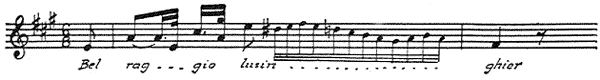

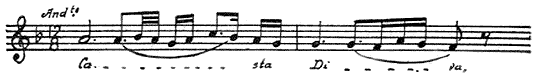

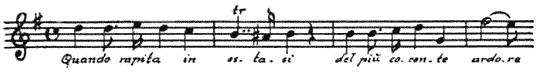

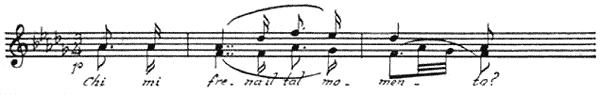

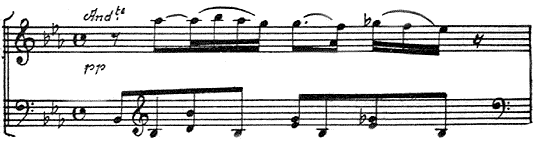

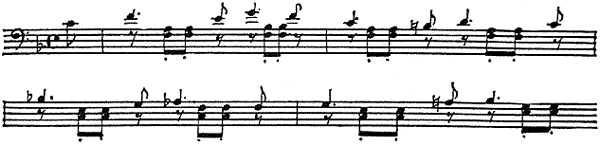

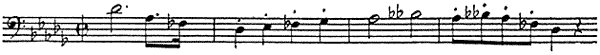

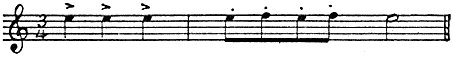

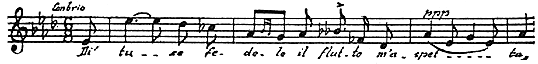

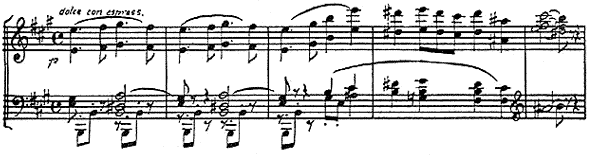

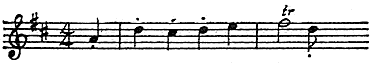

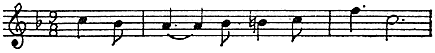

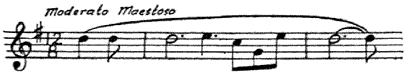

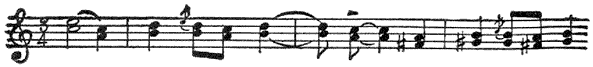

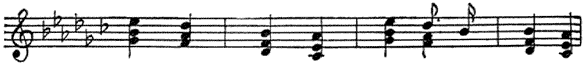

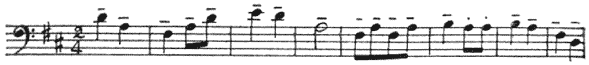

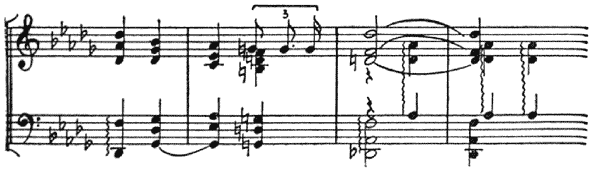

[Listen]

"All forms of language have been exhausted to praise the stupor of grief, the passion, the despair expressed in this sublime number," says a writer in the Clément and-12- Larousse Dictionnaire des Opéras. It is equalled only by the lines of Virgil:

|

Vox ipsa et frigida lingua, "Ah! miseram Eurydicen," anima fugiente, vocabat; "Eurydicen;" toto referabant flumine ripae. [E'en then his trembling tongue invok'd his bride; With his last voice, "Eurydice," he cried, "Eurydice," the rocks and river banks replied. Dryden.] |

In fact it is so beautiful that Amor, affected by the grief of Orpheus appears to him, touches Eurydice and restores her to life and to her husband's arms.

The legend of "Orpheus and Eurydice" as related in Virgil's Georgics, from which are the lines just quoted is one of the classics of antiquity. In "Orfeo ed Euridice" Gluck has preserved the chaste classicism of the original. Orpheus was the son of Apollo and the muse Calliope. He played so divinely that trees uprooted themselves and rocks were loosened from their fastnesses in order to follow him. His bride, Eurydice, was the daughter of a Thracian shepherd.

The rôle of Orpheus was written for the celebrated male contralto Guadagni. For the Paris production the composer added three bars to the most famous number of the score, the "Che farò senza Euridice," illustrated above. These presumably were the three last bars, the concluding phrases of the peroration of the immortal air. He also was obliged to transpose the part of Orpheus for the tenor Legros, for whom he introduced a vocal number not only entirely out of keeping with the rôle, but not even of his own composition—a bravura aria from "Tancred," an opera by the obscure Italian composer Fernandino Bertoni. It is believed that the tenor importuned Gluck for something that would show off his voice, whereupon the composer handed him the-13- Bertoni air. Legros introduced it at the end of the first act, where to this day it remains in the printed score.

When the tenor Nourrit sang the rôle many years later, he substituted the far more appropriate aria, "Ô transport, ô désordre extrême" (O transport, O ecstasy extreme) from Gluck's own "Echo and Narcissus."

But that the opera, as it came from Gluck's pen, required nothing more, appeared in the notable revival at the Théâtre Lyrique, Paris, November, 1859, under Berlioz's direction, when that distinguished composer restored the rôle of Orpheus to its original form and for a hundred and fifty nights the celebrated contralto, Pauline Viardot-Garcia, sang it to enthusiastic houses.

The best production of the work in this country was that of the American Opera Company. It was suited, as no other opera was, to the exact capacity of that ill-starred organization. The representation was in four acts instead of three, the second act being divided into two, a division to which it easily lends itself.

The opera has been the object of unstinted praise. Of the second act the same French authority quoted above says that from the first note to the last, it is "a complete masterpiece and one of the most astonishing productions of the human mind. The chorus of demons, 'What mortal dares,' in turn questions, becomes wrathful, bursts into a turmoil of threats, gradually becomes tranquil and is hushed, as if subdued and conquered by the music of Orpheus's lyre. What is more moving than the phrase 'Laissez-vous toucher par mes pleurs'? (A thousand griefs, threatening shades.) Seeing a large audience captivated by this mythological subject; an audience mixed, frivolous and unthinking, transported and swayed by this scene, one recognizes the real power of music. The composer conquered his hearers as his Orpheus succeeded in subduing the Furies. Nowhere, in no work, is the effect more gripping. The scene in the-14- Elysian fields also has its beauties. The air of Eurydice, the chorus of happy shades, have the breath of inalterable calm, peace and serenity."

Gaetano Guadagni, who created the rôle of Orpheus, was one of the most famous male contralti of the eighteenth century. Händel assigned to him contralto parts in the "Messiah" and "Samson," and it was Gluck himself who procured his engagement at Vienna. The French production of the opera was preceded by an act of homage, which showed the interest of the French in Gluck's work. For while it had its first performance in Vienna, the score was first printed in Paris and at the expense of Count Durazzo. The success of the Paris production was so great that Gluck's former pupil, Marie Antoinette, granted him a pension of 6,000 francs with an addition of the same sum for every fresh work he should produce on the French stage.

The libretto of Calzabigi was, for its day, charged with a vast amount of human interest, passion, and dramatic intensity. In these particulars it was as novel as Gluck's score, and possibly had an influence upon him in the direction of his operatic reforms.

Opera in five acts by Gluck; words by François Quinault, founded on Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered.

Produced, Paris, 1777, at the Académie de Musique; New York, Metropolitan Opera House, November 14, 1910, with Fremstad, Caruso, Homer, Gluck, and Amato.

Characters

| Armide, a Sorceress, Niece of Hidraot | Soprano | ||||

| Phenice | } | her attendants | { | Soprano | |

| Sidonie | } | { | Soprano | ||

| Hate, a Fury | Soprano | ||||

| Lucinde | } | apparitions | { | Soprano | |

| Mélisse | } | { | Soprano-15- | ||

| Renaud (Rinaldo), a Knight of the Crusade under Godfrey of Bouillon | Tenor | ||||

| Artemidore, Captive Knight Delivered by Renaud | Tenor | ||||

| The Danish Knight | } | Crusaders | { | Tenor | |

| Ubalde | } | { | Bass | ||

| Hidraot, King of Damascus | Bass | ||||

| Arontes, leader of the Saracens | Bass | ||||

| A Naiad, a Love | Apparitions | ||||

Populace, Apparitions and Furies.

Time—First Crusade, 1098.

Place—Damascus.

Act I. Hall of Armide's palace at Damascus. Phenice and Sidonie are praising the beauty of Armide. But she is depressed at her failure to vanquish the intrepid knight, Renaud, although all others have been vanquished by her. Hidraot, entering, expresses a desire to see Armide married. The princess tells him that, should she ever yield to love, only a hero shall inspire it. People of Damascus enter to celebrate the victory won by Armide's sorcery over the knights of Godfrey. In the midst of the festivities Arontes, who has had charge of the captive knights, appears and announces their rescue by a single warrior, none other than Renaud, upon whom Armide now vows vengeance.

Act II. A desert spot. Artemidore, one of the Christian knights, thanks Renaud for his rescue. Renaud has been banished from Godfrey's camp for the misdeed of another, whom he will not betray. Artemidore warns him to beware the blandishments of Armide, then departs. Renaud falls asleep by the bank of a stream. Hidraot and Armide come upon the scene. He urges her to employ her supernatural powers to aid in the pursuit of Renaud. After the king has departed, she discovers Renaud. At her behest apparitions, in the disguise of charming nymphs, shepherds and shepherdesses, bind him with garlands of flowers. Armide now approaches to slay her sleeping enemy with a dagger, but, in the act of striking him, she is overcome with love for him, and bids the apparitions-16- transport her and her hero to some "farthest desert, where she may hide her weakness and her shame."

Act III. Wild and rugged landscape. Armide, alone, is deploring the conquest of her heart by Renaud. Phenice and Sidonie come to her and urge her to abandon herself to love. They assure her that Renaud cannot fail to be enchanted by her beauty. Armide, reluctant to yield, summons Hate, who is ready to do her bidding and expel love from her bosom. But at the critical moment Armide cries out to desist, and Hate retires with the threat never to return.

Act IV. From yawning chasms and caves wild beasts and monsters emerge in order to frighten Ubalde and a Danish Knight, who have come in quest of Renaud. Ubalde carries a magic shield and sceptre, to counteract the enchantments of Armide, and to deliver Renaud. The knights attack and vanquish the monsters. The desert changes into a beautiful garden. An apparition, disguised as Lucinde, a girl beloved by the Danish Knight, is here, accompanied by apparitions in various pleasing disguises. Lucinde tries to detain the knight from continuing upon his errand, but upon Ubalde touching her with the golden sceptre, she vanishes. The two then resume their journey to the rescue of Renaud.

Act V. Another part of the enchanted garden. Renaud, bedecked with garlands, endeavours to detain Armide, who, haunted by dark presentiment, wishes to consult with the powers of Hades. She leaves Renaud to be entertained by a company of happy Lovers. They, however, fail to divert the lovelorn warrior, and are dismissed by him. Ubalde and the Danish Knight appear. By holding the magic shield before Renaud's eyes, they counteract the passion that has swayed him. He is following the two knights, when Armide returns and vainly tries to detain him. Proof against her blandishments, he leaves her to-17- seek glory. Armide deserted, summons Hate to slay him. But Hate, once driven away, refuses to return. Armide then bids the Furies destroy the enchanted palace. They obey. She perishes in the ruins. (Or, according to the libretto, "departs in a flying car"—an early instance of aviation in opera!)

There are more than fifty operas on the subject of Armide. Gluck's has survived them all. Nearly a century before his opera was produced at the Académie, Paris, that institution was the scene of the first performance of "Armide et Renaud," composed by Lully to the same libretto used by Gluck, Quinault having been Lully's librettist in ordinary.

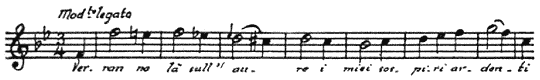

"Armide" is not a work of such strong human appeal as "Orpheus"; but for its day it was a highly dramatic production; and it still admits of elaborate spectacle. The air for Renaud in the second act, "Plus j'observe ces lieux, et plus je les admire!" (The more I view this spot the more charmed I am); the shepherd's song almost immediately following; Armide's air at the opening of the third act, "Ah! si la liberté me doit être ravie" (Ah! if liberty is lost to me); the exquisite solo and chorus in the enchanted garden, "Les plaisirs ont choisi pour asile" (Pleasure has chosen for its retreat) are classics. Several of the ballet numbers long were popular.

In assigning to a singer of unusual merit the ungrateful rôle of the Danish Knight, Gluck said: "A single stanza will compensate you, I hope, for so courteously consenting to take the part." It was the stanza, "Nôtre général vous rappelle" (Our commander summons you), with which the knight in Act V recalls Renaud to his duty. "Never," says the relater of the anecdote, "was a prediction more completely fulfilled. The stanza in question produced a sensation."

Opera in four acts by Gluck, words by François Guillard.

Produced at the Académie de Musique, Paris, May 18, 1779; Metropolitan Opera House, New York, November 25, 1916, with Kurt, Weil, Sembach, Braun, and Rappold.

Characters

| Iphigénie, Priestess of Diana | Soprano |

| Orestes, her Brother | Baritone |

| Pylades, his Friend | Tenor |

| Thoas, King of Scythia | Bass |

| Diana | Soprano |

Scythians, Priestesses of Diana.

Time—Antiquity, after the Trojan War.

Place—Tauris.

Iphigénie is the daughter of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae. Agamemnon was slain by his wife, Clytemnestra, who, in turn, was killed by her son, Orestes. Iphigénie is ignorant of these happenings. She has been a priestess of Diana and has not seen Orestes for many years.

Act I. Before the atrium of the temple of Diana. To priestesses and Greek maidens, Iphigénie tells of her dream that misfortune has come to her family in the distant country of her birth. Thoas, entering, calls for a human sacrifice to ward off danger that has been foretold to him. Some of his people, hastily coming upon the scene, bring with them as captives Orestes and Pylades, Greek youths who have landed upon the coast. They report that Orestes constantly speaks of having committed a crime and of being pursued by Furies.

Act II. Temple of Diana. Orestes bewails his fate. Pylades sings of his undying friendship for him. Pylades is separated from Orestes, who temporarily loses his mind. Iphigénie questions him. Orestes, under her influence, becomes calmer, but refrains from disclosing his identity.-19- He tells her, however, that he is from Mycenae, that Agamemnon (their father) has been slain by his wife, that Clytemnestra's son, Orestes, has slain her in revenge, and is himself dead. Of the once great family only a daughter, Electra, remains.

Act III. Iphigénie is struck with the resemblance of the stranger to her brother and, in order to save him from the sacrifice demanded by Thoas, charges him to deliver a letter to Electra. He declines to leave Pylades; nor until Orestes affirms that he will commit suicide, rather than accept freedom at the price of his friend's life, does Pylades agree to take the letter, and then only because he hopes to bring succour to Orestes.

Act IV. All is ready for the sacrifice. Iphigénie has the knife poised for the fatal thrust, when, through an exclamation uttered by Orestes, she recognizes him as her brother. The priestesses offer him obeisance as King. Thoas, however, enters and demands the sacrifice. Iphigénie declares that she will die with her brother. At that moment Pylades at the head of a rescue party enters the temple. A combat ensues in which Thoas is killed. Diana herself appears, pardons Orestes and returns to the Greeks her likeness which the Scythians had stolen and over which they had built the temple.

Gluck was sixty-five, when he brought out "Iphigénie en Tauride." A contemporary remarked that there were many fine passages in the opera. "There is only one," said the Abbé Arnaud. "Which?"—"The entire work."

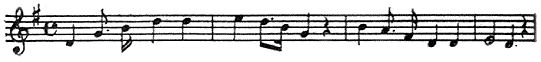

The mad scene for Orestes, in the second act, has been called Gluck's greatest single achievement. Mention should also be made of the dream of Iphigénie, the dances of the Scythians, the air of Thoas, "De noirs pressentiments mon âme intimidée" (My spirit is depressed by dark forebodings); the air of Pylades, "Unis dès la plus tendre enfance" (United since our earliest infancy); Iphigénie's "Ô mal-20-heureuse (unhappy) Iphigénie," and "Je t'implore et je tremble" (I pray you and I tremble); and the hymn to Diana, "Chaste fille de Latone" (Chaste daughter of the crescent moon).

Here may be related an incident at the rehearsal of the work, which proves the dramatic significance Gluck sought to impart to his music. In the second act, while Orestes is singing, "Le calme rentre dans mon cœur," (Once more my heart is calm), the orchestral accompaniment continues to express the agitation of his thoughts. During the rehearsal the members of the orchestra, not understanding the passage, came to a stop. "Go on all the same," cried Gluck. "He lies. He has killed his mother!"

Gluck's enemies prevailed upon his rival, Piccini, to write an "Iphigénie en Tauride" in opposition. It was produced in January, 1781, met with failure, and put a definite stop to Piccini's rivalry with Gluck. At the performance the prima donna was intoxicated. This caused a spectator to shout:

"'Iphigénie en Tauride!' allons donc, c'est 'Iphigénie en Champagne!'" (Iphigenia in Tauris! Do tell! Shouldn't it be Iphigenia in Champagne?)

The laugh that followed sealed the doom of the work.

The Metropolitan production employs the version of the work made by Richard Strauss, which involves changes in the finales of the first and last acts. Ballet music from "Orfeo" and "Armide" also is introduced.

THE operas of Gluck supplanted those of Lully and Rameau. Those of Mozart, while they did not supplant Gluck's, wrested from them the sceptre of supremacy. In a general way it may be said that, before Mozart's time, composers of grand opera reached back to antiquity and mythology, or to the early Christian era, for their subjects. Their works moved with a certain restricted grandeur. Their characters were remote.

Mozart's subjects were more modern, even contemporary. Moreover, he was one of the brightest stars in the musical firmament. His was a complete and easy mastery of all forms of music. "In his music breathes the warm-hearted, laughter-loving artist," writes Theodore Baker. That is a correct characterization. "The Marriage of Figaro" is still regarded as a model of what a comic grand opera, if so I may call it, should be. "Don Giovanni," despite its tragic dénouement, sparkles with humour, and Don Giovanni himself, despite the evil he does, is a jovial character. "The Magic Flute" is full of amusing incidents and, if its relationship to the rites of freemasonry has been correctly interpreted, was a contemporary subject of strong human interest, notwithstanding its story being laid in ancient Egypt. In fact it may be said that, in the evolution of opera, Mozart was the first to impart to it a strong human interest with humour playing about it like sunlight.

The libretto of "The Marriage of Figaro" was derived from a contemporary French comedy; "Don Giovanni," though its plot is taken from an old Spanish story, has in its principal character a type of libertine, whose reckless daring inspires loyalty not only in his servant, but even in at least one of his victims—a type as familiar to Mozart's contemporaries as it is to us; the probable contemporary significance of "The Magic Flute" I have already mentioned, and the point is further considered under the head of that opera.

For the most part as free from unnecessary vocal embellishments as are the operas of Gluck, Mozart, being the more gifted composer, attained an even higher degree of dramatic expression than his predecessor. May I say that he even gave to the voice a human clang it hitherto had lacked, and in this respect also advanced the art of opera? By this I mean that, full of dramatic significance as his voice parts are, they have, too, an ingratiating human quality which the music of his predecessor lacks. In plasticity of orchestration his operas also mark a great advance.

Excepting a few works by Gluck, every opera before Mozart and the operas of every composer contemporary with him, and for a considerable period after him, have disappeared from the repertoire. The next two operas to hold the stage, Beethoven's "Fidelio" (in its final form) and Rossini's "Barber of Seville" were not produced until 1814 and 1816—respectively twenty-three and twenty-five years after Mozart's death.

That Mozart was a genius by the grace of God will appear from the simple statement that his career came to an end at the age of thirty-five. Compare this with the long careers of the three other composers, whose influence upon opera was supreme—Gluck, Wagner, and Verdi. Gluck died in his seventy-third year, Wagner in his seven-23-tieth, and Verdi in his eighty-eighth. Yet the composer who laid down his pen and went to a pauper's grave at thirty-five, contributed as much as any of these to the evolution of the art of opera.

Opera in four acts by Mozart; words by Lorenzo da Ponte, after Beaumarchais. Produced at the National Theatre, Vienna, May 1, 1786, Mozart conducting. Académie de Musique, Paris, as "Le Mariage de Figaro" (with Beaumarchais's dialogue), 1793; as "Les Noces de Figaro" (words by Barbier and Carré), 1858. London, in Italian, King's Theatre, June 18, 1812. New York, 1823, with T. Phillips, of Dublin, as Figaro; May 10, 1824, with Pearman as Figaro and Mrs. Holman, as Susanna; January 18, 1828, with Elizabeth Alston, as Susanna; all these were in English and at the Park Theatre. (See concluding paragraph of this article.) Notable revivals in Italian, at the Metropolitan Opera House: 1902, with Sembrich, Eames, Fritzi Scheff, de Reszke, and Campanari; 1909, Sembrich, Eames, Farrar, and Scotti; 1916, Hempel, Matzenauer, Farrar, and Scotti.

Characters

| Count Almaviva | Baritone |

| Figaro, his valet | Baritone |

| Doctor Bartolo, a Physician | Bass |

| Don Basilio, a music-master | Tenor |

| Cherubino, a page | Soprano |

| Antonio, a gardener | Bass |

| Don Curzio, counsellor at law | Tenor |

| Countess Almaviva | Soprano |

| Susanna, her personal maid, affianced to Figaro | Soprano |

| Marcellina, a duenna | Soprano |

| Barbarina, Antonio's daughter | Soprano |

Time—17th Century.

Place—The Count's château of Aguas Frescas, near Seville.

"Le Nozze di Figaro" was composed by Mozart by command of Emperor Joseph II., of Austria. After con-24-gratulating the composer at the end of the first performance, the Emperor said to him: "You must admit, however, my dear Mozart, that there are a great many notes in your score." "Not one too many, Sire," was Mozart's reply.

(The anecdote, it should be noted, also, is told of the first performance of Mozart's "Così Fan Tutte.")

No opera composed before "Le Nozze di Figaro" can be compared with it for development of ensemble, charm and novelty of melody, richness and variety of orchestration. Yet Mozart composed this score in a month. The finale to the second act occupied him but two days. In the music the sparkle of high comedy alternates with the deeper sentiment of the affections.

Michael Kelly, the English tenor, who was the Basilio and Curzio in the original production, tells in his memoirs of the splendid sonority with which Benucci, the Figaro, sang the martial "Non più andrai" at the first orchestral rehearsal. Mozart, who was on the stage in a crimson pelisse and cocked hat trimmed with gold lace, kept repeating sotto voce, "Bravo, bravo, Benucci!" At the conclusion the orchestra and all on the stage burst into applause and vociferous acclaim of Mozart:

"Bravo, bravo, Maestro! Viva, viva, grande Mozart!"

Further, the Reminiscences of Kelly inform us of the enthusiastic reception of "Le Nozze di Figaro" upon its production, almost everything being encored, so that the time required for its performance was nearly doubled. Notwithstanding this success, it was withdrawn after comparatively few representations, owing to Italian intrigue at the court and opera, led by Mozart's rival, the composer Salieri—now heard of only because of that rivalry. In Prague, where the opera was produced in January, 1787, its success was so great that Bondini, the manager of the company, was able to persuade Mozart to compose-25- an opera for first performance in Prague. The result was "Don Giovanni."

The story of "Le Nozze di Figaro" is a sequel to that of "The Barber of Seville," which Rossini set to music. Both are derived from "Figaro" comedies by Beaumarchais. In Rossini's opera it is Figaro, at the time a barber in Seville, who plays the go-between for Count Almaviva and his beloved Rosina, Dr. Bartolo's pretty ward. Rosina is now the wife of the Count, who unfortunately, is promiscuous in his attentions to women, including Susanna, the Countess's vivacious maid, who is affianced to Figaro. The latter and the music-master Basilio who, in their time helped to hoodwink Bartolo, are in the service of the Count, Figaro having been rewarded with the position of valet and majordomo. Bartolo, for whom, as formerly, Marcellina is keeping house, still is Figaro's enemy, because of the latter's interference with his plans to marry Rosina and so secure her fortune to himself. The other characters in the opera also belong to the personnel of the Count's household.

Aside from the difference between Rossini's and Mozart's scores, which are alike only in that each opera is a masterpiece of the comic sentiment, there is at least one difference between the stories. In Rossini's "Barber" Figaro, a man, is the mainspring of the action. In Mozart's opera it is Susanna, a woman; and a clever woman may possess in the rôle of protagonist in comedy a chicness and sparkle quite impossible to a man. The whole plot of "Le Nozze di Figaro" plays around Susanna's efforts to nip in the bud the intrigue in which the Count wishes to engage her. She is aided by the Countess and by Figaro; but she still must appear to encourage while evading the Count's advances, and do so without offending him, lest both she and her affianced be made to suffer through his disfavour. In the libretto there is much that is risqué,-26- suggestive. But as the average opera-goer does not understand the subtleties of the Italian language, and the average English translation is too clumsy to preserve them, it is quite possible—especially in this advanced age—to attend a performance of "Le Nozze di Figaro" without imperilling one's morals.

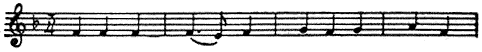

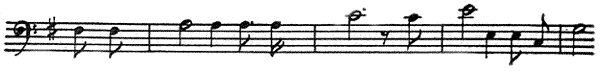

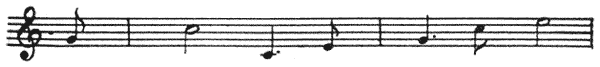

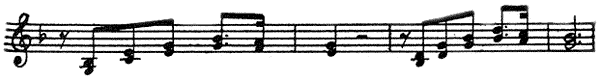

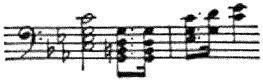

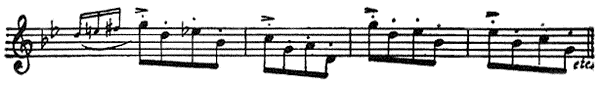

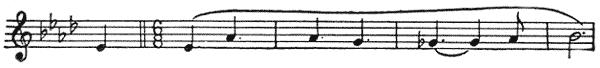

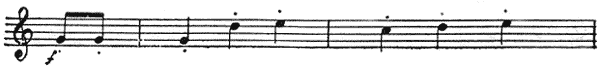

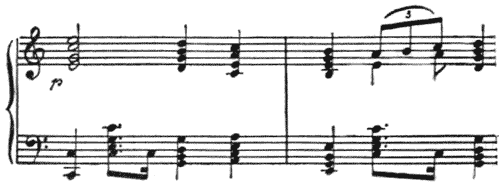

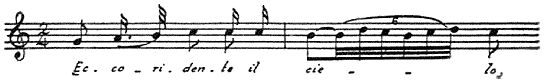

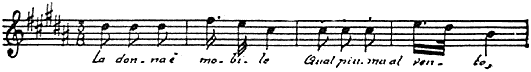

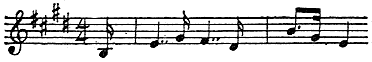

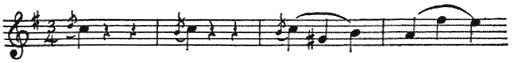

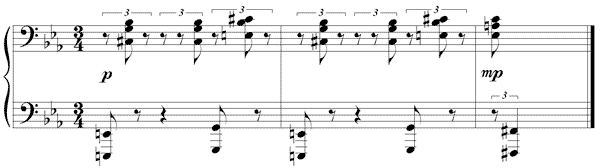

There is a romping overture. Then, in Act I, we learn that Figaro, Count Almaviva's valet, wants to get married. Susanna, the Countess's maid, is the chosen one. The Count has assigned to them a room near his, ostensibly because his valet will be able to respond quickly to his summons. The room is the scene of this Act. Susanna tells her lover that the true reason for the Count's choice of their room is the fact that their noble master is running after her. Now Figaro is willing enough to "play up" for the little Count, if he should take it into his head "to venture on a little dance" once too often. ("Se vuol ballare, Signor Contino!")

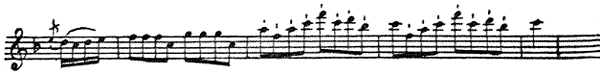

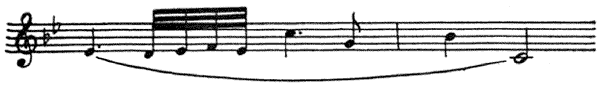

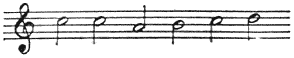

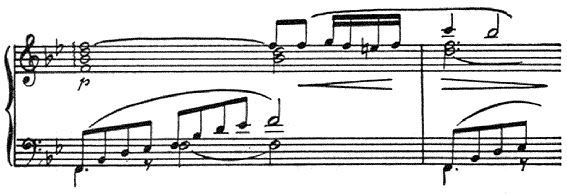

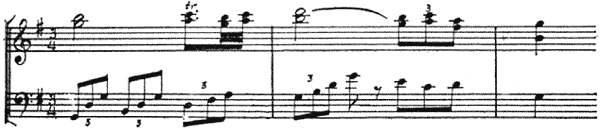

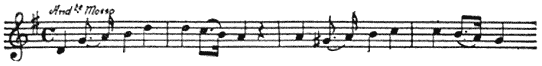

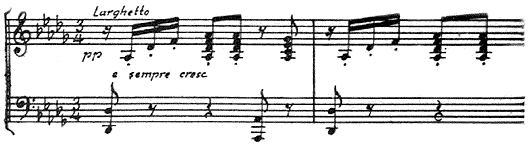

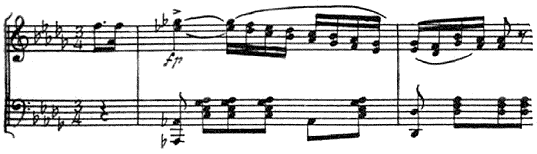

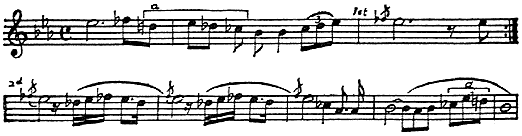

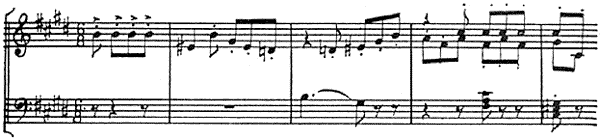

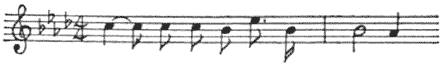

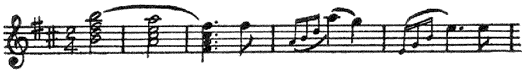

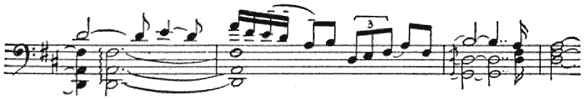

[Listen]

Unfortunately, however, Figaro himself is in a fix. He has borrowed money from Marcellina, Bartolo's housekeeper, and he has promised to marry her in case of his inability to repay her. She now appears, to demand of Figaro the fulfilment of his promise. Bartolo encourages her in this, both out of spite against Figaro and because he wants to be rid of the old woman, who has been his mistress and even borne him a son, who, however, was kidnapped soon after his birth. There is a vengeance aria for Bartolo, and a spiteful duet for Marcellina and Susanna, beginning: "Via resti servita, madama brillante" (Go first, I entreat you, Miss, model of beauty!).

Photo by White

Hempel (Susanna), Matzenauer (the Countess), and Farrar (Cherubino)

in “Le Nozze di Figaro”

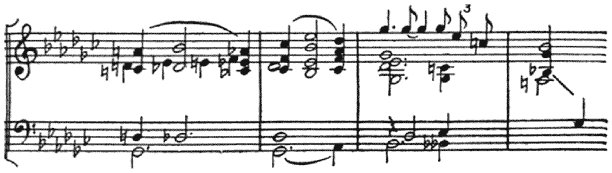

The next scene opens between the page, Cherubino, a-27- boy in love with every petticoat, and Susanna. He begs Susanna to intercede for him with the Count, who has dismissed him. Cherubino desires to stay around the Countess, for whom he has conceived one of his grand passions. "Non so più cosa son, cosa faccio"—(Ah, what feelings now possess me!). The Count's step is heard. Cherubino hides himself behind a chair, from where he hears the Count paying court to Susanna. The voice of the music-master then is heard from without. The Count moves toward the door. Cherubino, taking advantage of this, slips out from behind the chair and conceals himself in it under a dress that has been thrown over it. The Count, however, instead of going out, hides behind the chair, in the same place where Cherubino has been. Basilio, who has entered, now makes all kinds of malicious remarks and insinuations about the flirtations of Cherubino with Susanna and also with the Countess. The Count, enraged at the free use of his wife's name, emerges from behind the chair. Only the day before, he says, he has caught that rascal, Cherubino, with the gardener's daughter Barbarina (with whom the Count also is flirting). Cherubino, he continues, was hidden under a coverlet, "just as if under this dress here." Then, suiting the action to the words, by way of demonstration, he lifts the gown from the chair, and lo! there is Cherubino. The Count is furious. But as the page has overheard him making love to Susanna, and as Figaro and others have come in to beg that he be forgiven, the Count, while no longer permitting him to remain in the castle, grants him an officer's commission in his own regiment. It is here that Figaro addresses Cherubino in the dashing martial air, "Non più andrai, farfallone amoroso" (Play no more, the part of a lover).

Act II. Still, the Count, for whom the claims of Marcellina upon Figaro have come in very opportunely, has not given consent for his valet's wedding. He wishes to-28- carry his own intrigue with Susanna, the genuineness of whose love for Figaro he underestimates, to a successful issue. Susanna and Figaro meet in the Countess's room. The Countess has been soliloquizing upon love, of whose fickleness the Count has but provided too many examples.—"Porgi amor, qualche ristoro" (Love, thou holy, purest passion.) Figaro has contrived a plan to gain the consent of the Count to his wedding with Susanna. The valet's scheme is to make the Count ashamed of his own flirtations. Figaro has sent a letter to the Count, which divulges a supposed rendezvous of the Countess in the garden. At the same time Susanna is to make an appointment to meet the Count in the same spot. But, in place of Susanna, Cherubino, dressed in Susanna's clothes, will meet the Count. Both will be caught by the Countess and the Count thus be confounded.

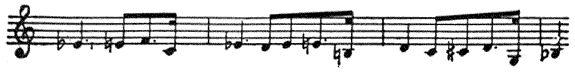

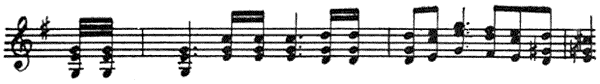

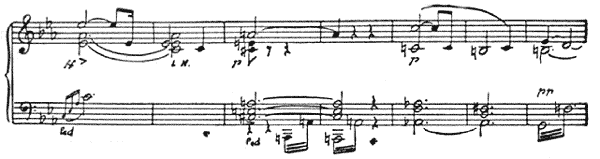

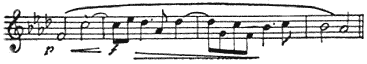

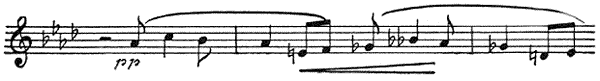

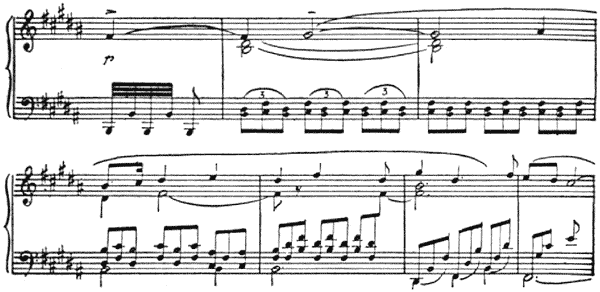

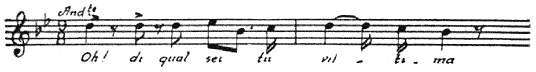

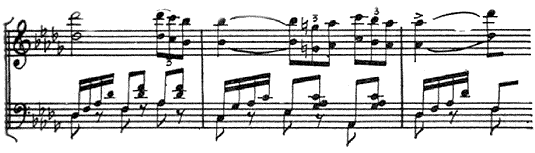

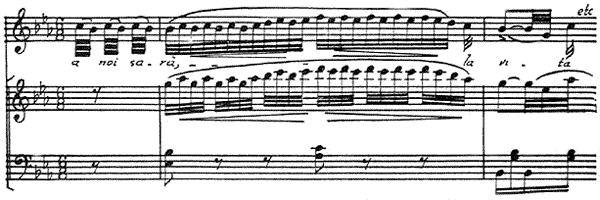

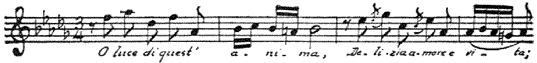

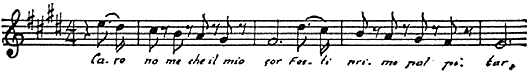

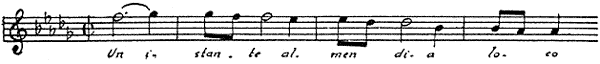

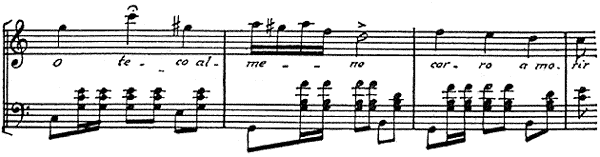

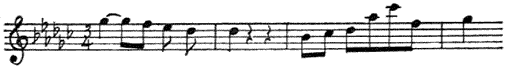

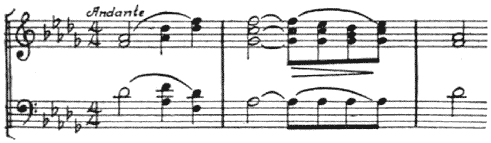

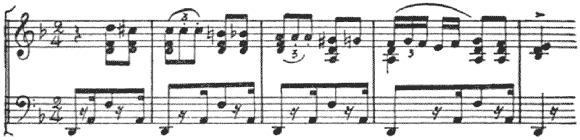

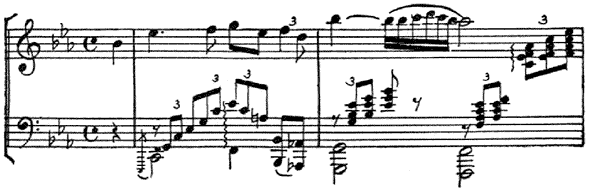

Cherubino is then brought in to try on Susanna's clothes. He sings to the Countess an air of sentiment, one of the famous vocal numbers of the opera, the exquisite: "Voi che sapete, che cosa è amor" (What is this feeling makes me so sad).

[Listen]

The Countess, examining his officer's commission, finds that the seal to it has been forgotten. While in the midst of these proceedings someone knocks. It is the Count. Consternation. Cherubino flees into the Countess's room and Susanna hides behind a curtain. The evident embarrassment of his wife arouses the suspicions of her husband, who, gay himself, is very jealous of her. He tries the door Cherubino has bolted from the inside, then goes off to get tools to break it down with. He takes his wife with him. While he is away, Cherubino slips out and leaps out of a window into the garden. In his place,-29- Susanna bolts herself in the room, so that, when the Count breaks open the door, it is only to discover that Susanna is in his wife's room. All would be well, but unfortunately Antonio, the gardener, enters. A man, he says, has jumped out of the Countess's window and broken a flowerpot. Figaro, who has come in, and who senses that something has gone wrong, says that it was he who was with Susanna and jumped out of the window. But the gardener has found a paper. He shows it. It is Cherubino's commission. How did Figaro come by it? The Countess whispers something to Figaro. Ah, yes; Cherubino handed it to him in order that he should obtain the missing seal.

Everything appears to be cleared up when Marcellina, accompanied by Bartolo, comes to lodge formal complaint against Figaro for breach of promise, which for the Count is a much desired pretext to refuse again his consent to Figaro's wedding with Susanna. These, the culminating episodes of this act, form a finale which is justly admired, a finale so gradually developed and so skilfully evolved that, although only the principals participate in it, it is as effective as if it employed a full ensemble of soloists, chorus, and orchestra worked up in the most elaborate fashion. Indeed, for effectiveness produced by simple means, the operas of Mozart are models.

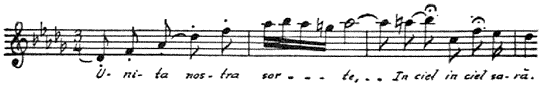

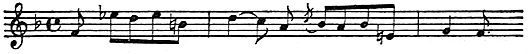

But to return to the story. At the trial in Act III, between Marcellina and Figaro, it develops that Figaro is her long-lost natural son. Susanna pays the costs of the trial and nothing now seems to stand in the way of her union with Figaro. The Count, however, is not yet entirely cured of his fickle fancies. So the Countess and Susanna hit upon still another scheme in this play of complications. During the wedding festivities Susanna is to contrive to send secretly to the Count a note, in which she invites him to meet her. Then the Countess, dressed in Susanna's clothes, is to meet him at the place named. Figaro knows-30- nothing of this plan. Chancing to find out about the note, he too becomes jealous—another, though minor, contribution to the mix-up of emotions. In this act the concoction of the letter by the Countess and Susanna is the basis of the most beautiful vocal number in the opera, the "letter duet" or Canzonetta sull'aria (the "Canzonetta of the Zephyr")—"Che soave zeffiretto" (Hither gentle zephyr); an exquisite melody, in which the lady dictates, the maid writes down, and the voices of both blend in comment.

[Listen]

The final Act brings about the desired result after a series of amusing contretemps in the garden. The Count sinks on his knees before his Countess and, as the curtain falls, there is reason to hope that he is prepared to mend his ways.

Regarding the early performances of "Figaro" in this country, these early performances were given "with Mozart's music, but adapted by Henry Rowley Bishop." When I was a boy, a humorous way of commenting upon an artistic sacrilege was to exclaim: "Ah! Mozart improved by Bishop!" I presume the phrase came down from these early representations of "The Marriage of Figaro." Bishop was the composer of "Home, Sweet Home." In 1839 his wife eloped with Bochsa, the harp virtuoso, afterwards settled in New York, and for many years sang in concert and taught under the name of Mme. Anna Bishop.

Opera in two acts by Mozart; text by Lorenzo da Ponte. Productions, Prague, Oct. 29, 1787; Vienna, May 17, 1788; London, April 12, 1817; New York, Park Theatre, May 23, 1826.

Original title: "Il Dissoluto Punito, ossia il Don Giovanni" (The-31- Reprobate Punished, or Don Giovanni). The work was originally characterized as an opera buffa, or dramma giocoso, but Mozart's noble setting lifted it out of that category.

Characters

| Don Pedro, the Commandant | Bass |

| Donna Anna, his daughter | Soprano |

| Don Ottavio, her betrothed | Tenor |

| Don Giovanni | Baritone |

| Leporello, his servant | Bass |

| Donna Elvira | Soprano |

| Zerlina | Soprano |

| Masetto, betrothed to Zerlina | Tenor |

"Don Giovanni" was presented for the first time in Prague, because Mozart, satisfied with the manner in which Bondini's troupe had sung his "Marriage of Figaro" a little more than a year before, had agreed to write another work for the same house.

The story on which da Ponte based his libretto—the statue of a murdered man accepting an insolent invitation to banquet with his murderer, appearing at the feast and dragging him down to hell—is very old. It goes back to the Middle Ages, probably further. A French authority considers that da Ponte derived his libretto from "Le Festin de Pierre," Molière's version of the old tale. Da Ponte, however, made free use of "Il Convitato di Pietra" (The Stone-Guest), a libretto written by the Italian theatrical poet Bertati for the composer Giuseppe Gazzaniga. Whoever desires to follow up this interesting phase of the subject will find the entire libretto of Bertati's "Convitato" reprinted, with a learned commentary by Chrysander, in volume iv of the Vierteljahrheft für Musikwissenschaft (Music Science Quarterly), a copy of which is in the New York Public Library.

Mozart agreed to hand over the finished score in time for the autumn season of 1787, for the sum of one hundred-32- ducats ($240). Richard Strauss receives for a new opera a guarantee of ten performances at a thousand dollars—$10,000 in all—and, of course, his royalties thereafter. There is quite a distinction in these matters between the eighteenth century and the present. And what a lot of good a few thousand dollars would have done the impecunious composer of the immortal "Don Giovanni!" Also, one is tempted to ask oneself if any modern ten thousand dollar opera will live as long as the two hundred and forty dollar one which already is 130 years old.

Bondini's company, for which Mozart wrote his masterpiece of dramatic music, furnished the following cast: Don Giovanni, Signor Bassi, twenty-two years old, a fine baritone, an excellent singer and actor; Donna Anna, Signora Teresa Saporiti; Donna Elvira, Signora Catarina Micelli, who had great talent for dramatic expression; Zerlina, Signora Teresa Bondini, wife of the manager; Don Ottavio, Signor Antonio Baglioni, with a sweet, flexible tenor voice; Leporello, Signor Felice Ponziani, an excellent basso comico; Don Pedro (the Commandant), and Masetto, Signor Giuseppe Lolli.

Mozart directed the rehearsals, had the singers come to his house to study, gave them advice how some of the difficult passages should be executed, explained the characters they represented, and exacted finish, detail, and accuracy. Sometimes he even chided the artists for an Italian impetuosity, which might be out of keeping with the charm of his melodies. At the first rehearsal, however, not being satisfied with the way in which Signora Bondini gave Zerlina's cry of terror from behind the scenes, when the Don is supposed to attempt her ruin, Mozart left the orchestra and went upon the stage. Ordering the first act finale to be repeated from the minuet on, he concealed himself in the wings. There, in the peasant dress of Zerlina, with its short skirt, stood Signora Bondini, waiting-33- for her cue. When it came, Mozart quickly reached out a hand from his place of concealment and pinched her leg. She gave a piercing shriek. "There! That is how I want it," he said, emerging from the wings, while the Bondini, not knowing whether to laugh or blush, did both.

One of the most striking features of the score, the warning words which the statue of the Commandant, in the plaza before the cathedral of Seville, utters within the hearing of Don Giovanni and Leporello, was originally accompanied by the trombones only. At rehearsal in Prague, Mozart, not satisfied with the way the passage was played, stepped over toward the desks at which the trombonists sat.

One of them spoke up: "It can't be played any better. Even you couldn't teach us how."

Mozart smiled. "Heaven forbid," he said, "that I should attempt to teach you how to play the trombone. But let me have the parts."

Looking them over he immediately made up his mind what to do. With a few quick strokes of the pen, he added the wood-wind instruments as they are now found in the score.

It is well known that the overture of "Don Giovanni" was written almost on the eve of the first performance. Mozart passed a gay evening with some friends. One of them said to him: "Tomorrow the first performance of 'Don Giovanni' will take place, and you have not yet composed the overture!" Mozart pretended to get nervous about it and withdrew to his room, where he found music-paper, pens, and ink. He began to compose about midnight. Whenever he grew sleepy, his wife, who was by his side, entertained him with stories to keep him awake. It is said that it took him but three hours to produce this overture.

The next evening, a little before the curtain rose, the copyists finished transcribing the parts for the orchestra.-34- Hardly had they brought the sheets, still wet, to the theatre, when Mozart, greeted by enthusiastic applause, entered the orchestra and took his seat at the piano. Although the musicians had not had time to rehearse the overture, they played it with such precision that the audience broke out into fresh applause. As the curtain rose and Leporello came forward to sing his solo, Mozart laughingly whispered to the musicians near him: "Some notes fell under the stands. But it went well."

The overture consists of an introduction which reproduces the scene of the banquet at which the statue appears. It is followed by an allegro which characterizes the impetuous, pleasure-seeking Don, oblivious to consequences. It reproduces the dominant character of the opera.

Without pause, Mozart links up the overture with the song of Leporello. The four principal personages of the opera appear early in the proceedings. The tragedy which brings them together so soon and starts the action, gives an effective touch of fore-ordained retribution to the misdeeds upon which Don Giovanni so gaily enters. This early part of the opera divides itself into four episodes. Wrapped in his cloak and seated in the garden of a house in Seville, Spain, which Don Giovanni, on amorous adventure bent, has entered secretly during the night—it is the residence of the Commandant—Leporello is complaining of the fate which makes him a servant to such a restless and dangerous master. "Notte e giorno faticar" (Never rest by day or night), runs his song.

Copyright photo by Dupont

Scotti as Don Giovanni

Don Giovanni hurriedly issues from the house, pursued by Donna Anna. There follows a trio in which the wrath of the insulted woman, the annoyance of the libertine, and the cowardice of Leporello are expressed simultaneously and in turn in manner most admirable. The Commandant, attracted by the disturbance, arrives, draws his sword, and a duel ensues. In the unequal combat between the-35- aged Commandant and the agile Don, the Commandant receives a fatal wound. The trio which follows between Don Giovanni, the dying Commandant, and Leporello is a unique passage in the history of musical art. The genius of Mozart, tender, profound, pathetic, religious, is revealed in its entirety. Written in a solemn rhythm and in the key of F minor, so appropriate to dispose the mind to a gentle sadness, this trio, which fills only eighteen measures, contains in a restricted outline, but in master-strokes, the fundamental idea of this mysterious drama of crime and retribution. While the Commandant is breathing his last, emitting notes broken by long pauses, Donna Anna, who, during the duel between her father and Don Giovanni, has hurried off for help, returns accompanied by her servants and by Don Ottavio, her affianced. She utters a cry of terror at seeing the dead body of her father. The recitative which expresses her despair is intensely dramatic. The duet which she sings with Don Ottavio is both impassioned and solicitous, impetuous on her part, solicitous on his; for the rôle of Don Ottavio is stamped with the delicacy of sentiment, the respectful reserve of a well-born youth who is consoling the woman who is to be his wife. The passage, "Lascia, O cara, la rimembranza amara!" (Through love's devotion, dear one) is of peculiar beauty in musical expression.

After Donna Anna and Don Ottavio have left, there enters Donna Elvira. The air she sings expresses a complicated nuance of passion. Donna Elvira is another of Don Giovanni's deserted ones. There are in the tears of this woman not only the grief of one who has been loved and now implores heaven for comfort, but also the indignation of one who has been deserted and betrayed. When she cries with emotion: "Ah! chi mi dice mai quel barbaro dov'è?" (In memory still lingers his love's delusive sway) one feels that, in spite of her outbursts of anger, she is ready to for-36-give, if only a regretful smile shall recall to her the man who was able to charm her.

Don Giovanni hears from afar the voice of a woman in tears. He approaches, saying: "Cerchiam di consolare il suo tormento" (I must seek to console her sorrow). "Ah! yes," murmurs Leporello, under his breath: "Così ne consolò mille e otto cento" (He has consoled fully eighteen hundred). Leporello is charged by Don Giovanni, who, recognizing Donna Elvira, hurries away, to explain to her the reasons why he deserted her. The servant fulfils his mission as a complaisant valet. For it is here that he sings the "Madamina" air, which is so famous, and in which he relates with the skill of a historian the numerous amours of his master in the different parts of the world.

The "Air of Madamina," "Madamina! il catalogo"—(Dear lady, the catalogue) is a perfect passage of its kind; an exquisite mixture of grace and finish, of irony and sentiment, of comic declamation and melody, the whole enhanced by the poetry and skill of the accessories. There is nothing too much, nothing too little; no excess of detail to mar the whole. Every word is illustrated by the composer's imagination without his many brilliant sallies injuring the general effect. According to Leporello's catalogue his master's adventures in love have numbered 2065. To these Italy has contributed 245, Germany 231, France 100, Turkey 91, and Spain, his native land, 1003. The recital enrages Donna Elvira. She vows vengeance upon her betrayer.

Copyright photo by Dupont

Sembrich as Zerlina in “Don Giovanni”

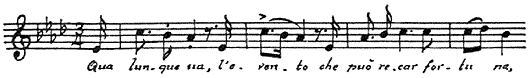

The scene changes to the countryside of Don Giovanni's palace near Seville. A troop of gay peasants is seen arriving. The young and pretty Zerlina with Masetto, her affianced, and their friends are singing and dancing in honour of their approaching marriage. Don Giovanni and Leporello join this gathering of light-hearted and simple-37- young people. Having cast covetous eyes upon Zerlina, and having aroused her vanity and her spirit of coquetry by polished words of gallantry, the Don orders Leporello to get rid of the jealous Masetto by taking the entire gathering—excepting, of course, Zerlina—to his château. Leporello grumbles, but carries out his master's order. The latter, left alone with Zerlina, sings a duet with her which is one of the gems, not alone of this opera, but of opera in general: "Là ci darem la mano!" (Your hand in mine, my dearest). Donna Elvira appears and by her denunciation of Don Giovanni, "Ah! fuggi il traditore," makes clear to Zerlina the character of her fascinating admirer. Donna Anna and Don Ottavio come upon the stage and sing a quartette which begins: "Non ti fidar, o misera, di quel ribaldo cor" (Place not thy trust, O mourning one, in this polluted soul), at the end of which Donna Anna, as Don Giovanni departs, recognizes in his accents the voice of her father's assassin. Her narrative of the events of that terrible night is a declamatory recitative "in style as bold and as tragic as the finest recitatives of Gluck."

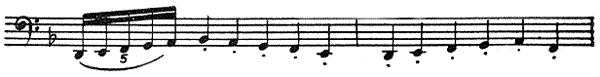

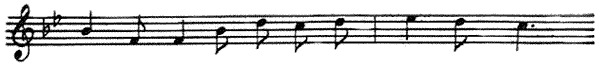

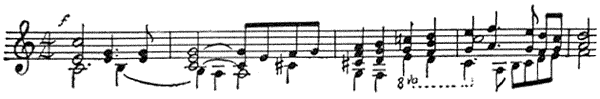

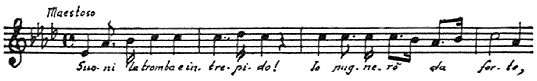

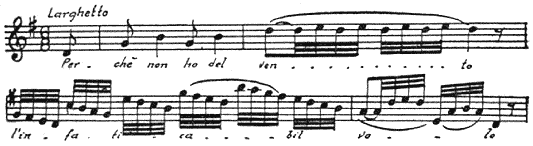

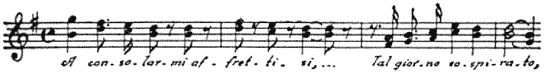

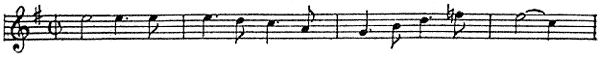

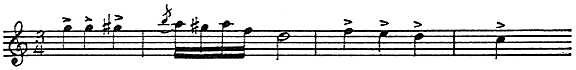

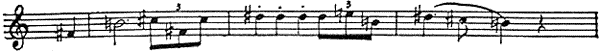

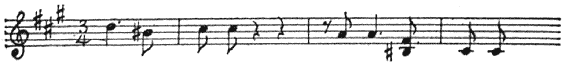

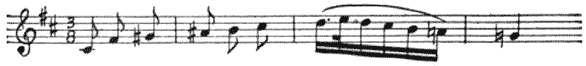

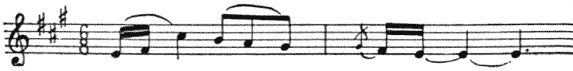

Don Giovanni orders preparations for the festival in his palace. He gives his commands to Leporello in the "Champagne aria," "Finch' han dal vino" (Wine, flow a fountain), which is almost breathless with exuberance of anticipated revel. Then there is the ingratiating air of Zerlina begging Masetto's forgiveness for having flirted with the Don, "Batti, batti, o bel Masetto" (Chide me, chide me, dear Masetto), a number of enchanting grace, followed by a brilliantly triumphant allegro, "Pace, pace o vita mia" (Love, I see you're now relenting).

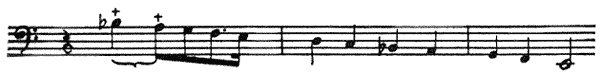

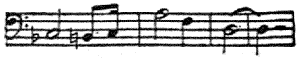

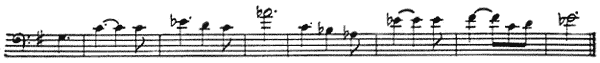

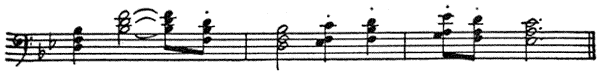

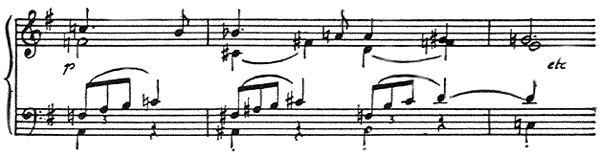

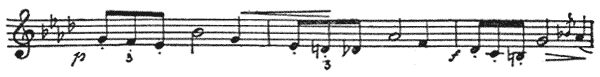

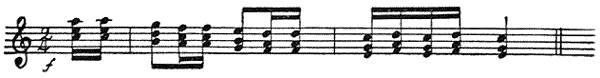

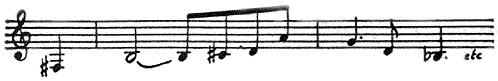

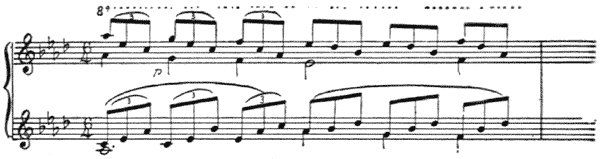

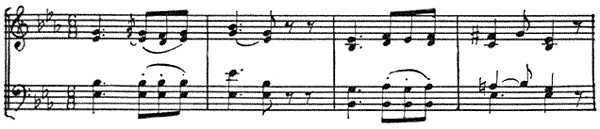

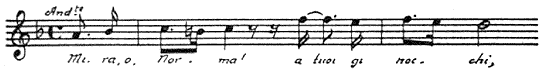

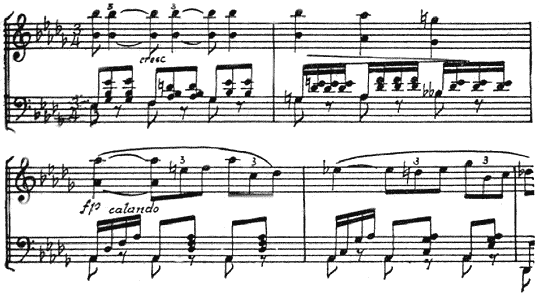

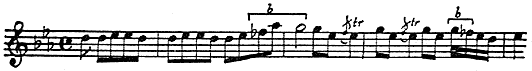

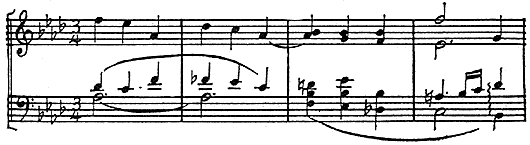

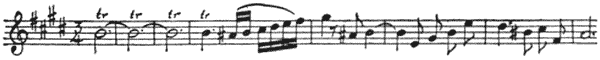

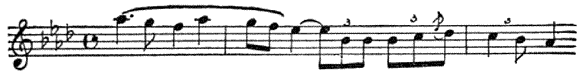

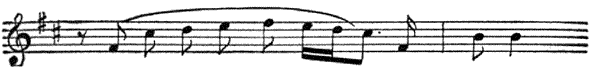

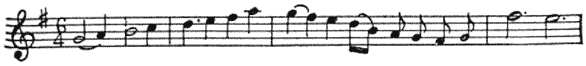

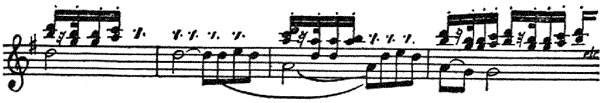

[Listen]

The finale to the first act of "Don Giovanni" rightly passes for one of the masterpieces of dramatic music. Lepo-38-rello, having opened a window to let the fresh evening air enter the palace hall, the violins of a small orchestra within are heard in the first measures of the graceful minuet. Leporello sees three maskers, two women and a man, outside. In accordance with custom they are bidden to enter. Don Giovanni does not know that they are Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and Don Ottavio, bent upon seeking the murderer of the Commandant and bringing him to justice. But even had he been aware of their purpose it probably would have made no difference, for courage this dissolute character certainly had.

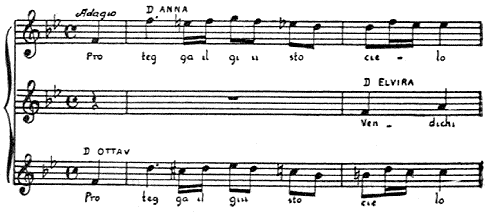

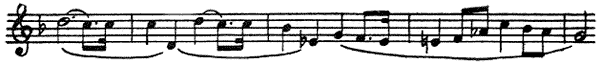

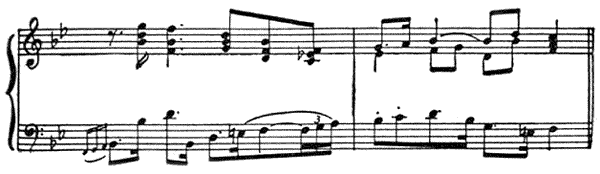

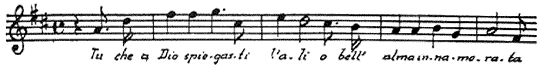

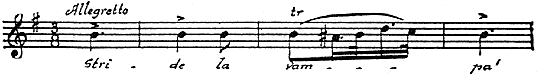

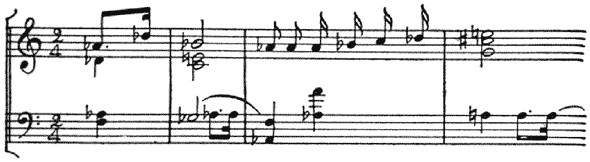

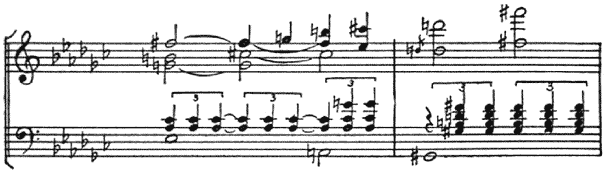

After a moment of hesitation, after having taken council together, and repressing a movement of horror which they feel at the sight of the man whose crimes have darkened their lives, Donna Elvira, Donna Anna, and Don Ottavio decide to carry out their undertaking at all cost and to whatever end. Before entering the château, they pause on the threshold and, their souls moved by a holy fear, they address Heaven in one of the most touching prayers written by the hand of man. It is the number known throughout the world of music as the "Trio of the Masks," "Protegga, il giusto cielo"—(Just Heaven, now defend us)—one of those rare passages which, by its clearness of form, its elegance of musical diction, and its profundity of sentiment, moves the layman and charms the connoisseur.

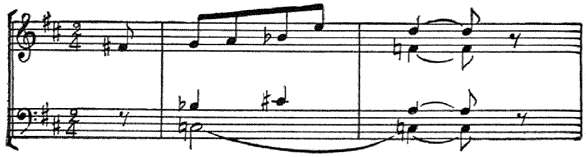

[Listen]

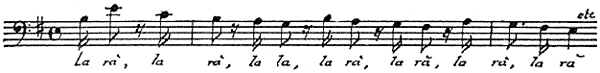

D ANNA

Protegga il giusto cielo

D ELVIRA

Vendichi

D OTTAV

Protegga il giusto cielo

The festivities begin with the familiar minuet. Its graceful rhythm is prolonged indefinitely as a fundamental-39- idea, while in succession, two small orchestras on the stage, take up, one a rustic quadrille in double time, the other a waltz. Notwithstanding the differences in rhythm, the three dances are combined with a skill that piques the ear and excites admiration. The scene would be even more natural and entertaining than it usually is, if the orchestras on the stage always followed the direction accordano (tune up) which occurs in the score eight bars before each begins to play its dance, and if the dances themselves were carried out according to directions. Only the ladies and gentlemen should engage in the minuet, the peasants in the quadrille; and before Don Giovanni leads off Zerlina into an adjoining room he should have taken part with her in this dance, while Leporello seeks to divert the jealous Masetto's attention by seizing him in an apparent exuberance of spirits and insisting on dancing the waltz with him. Masetto's suspicions, however, are not to be allayed. He breaks away from Leporello. The latter hurries to warn his master. But just as he has passed through the door, Zerlina's piercing shriek for help is heard from within. Don Giovanni rushes out, sword in hand, dragging out with him none other than poor Leporello, whom he has opportunely seized in the entrance, and whom, under pretence that he is the guilty party, he threatens to kill in order to turn upon him the suspicion that rests upon himself. But this ruse fails to deceive any one. Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and Don Ottavio unmask and accuse Don Giovanni of the murder of the Commandant, "Tutto già si sà" (Everything is known and you are recognized). Taken aback, at first, Don Giovanni soon recovers himself. Turning, at bay, he defies the enraged crowd. A storm is rising without. A storm sweeps over the orchestra. Thunder growls in the basses, lightning plays on the fiddles. Don Giovanni, cool, intrepid, cuts a passage through the crowd upon which, at the same time,-40- he hurls his contempt. (In a performance at the Academy of Music, New York, about 1872, I saw Don Giovanni stand off the crowd with a pistol.)

The second act opens with a brief duet between Don Giovanni and Leporello. The trio which follows: "Ah! taci, ingiusto core" (Ah, silence, heart rebellious), for Donna Elvira, Leporello, and Don Giovanni, is an exquisite passage. Donna Elvira, leaning sadly on a balcony, allows her melancholy regrets to wander in the pale moonlight which envelops her figure in a semi-transparent gloom. In spite of the scene which she has recently witnessed, in spite of wrongs she herself has endured, she cannot hate Don Giovanni or efface his image from her heart. Her reward is that her recreant lover in the darkness below, changes costume with his servant and while Leporello, disguised as the Don, attracts Donna Elvira into the garden, the cavalier himself addresses to Zerlina, who has been taken under Donna Elvira's protection, the charming serenade: "Deh! vieni alla finestra" (Appear, love at thy window), which he accompanies on the mandolin, or should so accompany, for usually the accompaniment is played pizzicato by the orchestra.

As the result of complications, which I shall not attempt to follow, Masetto, who is seeking to administer physical chastisement to Don Giovanni, receives instead a drubbing from the latter.

Zerlina, while by no means indifferent to the attentions of the dashing Don, is at heart faithful to Masetto and, while I fancy she is by no means obtuse to the humorous aspect of his chastisement by Don Giovanni, she comes trippingly out of the house and consoles the poor fellow with the graceful measures of "Vedrai carino, se sei buonino" (List, and I'll find love, if you are kind love).

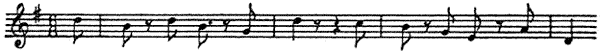

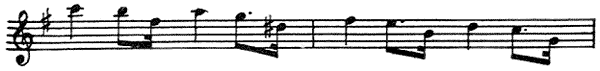

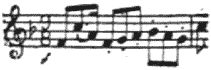

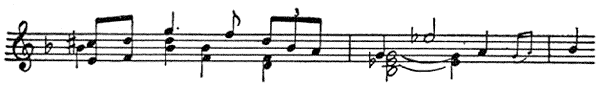

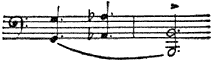

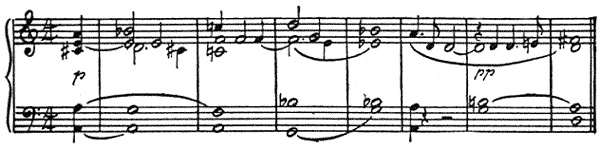

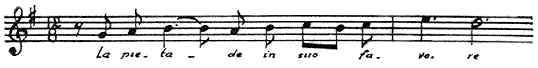

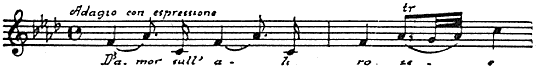

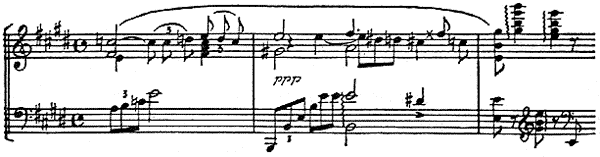

Shortly after this episode comes Don Ottavio's famous air, the solo number which makes the rôle worth while,-41- "Il mio tesoro intanto" (Fly then, my love, entreating). Upon this air praise has been exhausted. It has been called the "pietra di paragone" of tenors—the touchstone, the supreme test of classic song.

[Listen]

Retribution upon Don Giovanni is not to be too long deferred. After the escapade of the serenade and the drubbing of Masetto, the Don, who has made off, chances to meet in the churchyard (or in the public square) with Leporello, who meanwhile has gotten rid of Donna Elvira. It is about two in the morning. They see the newly erected statue to the murdered Commandant. Don Giovanni bids it, through Leporello, to supper with him in his palace. Will it accept? The statue answers, "Yea!" Leporello is terrified. And Don Giovanni?