The Project Gutenberg eBook, Gebir, and Count Julian, by Walter Savage Landor, Edited by Henry Morley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Gebir, and Count Julian Author: Walter Savage Landor Editor: Henry Morley Release Date: August 15, 2014 [eBook #4007] [The file was first posted on 14 October 2001] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GEBIR, AND COUNT JULIAN***

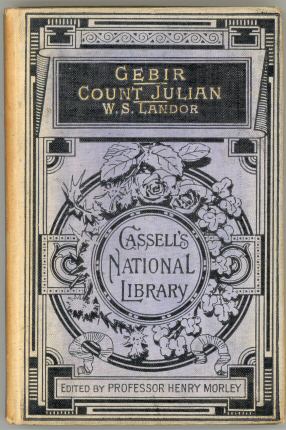

Transcribed from the 1887 Cassell & Company edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

CASSELL’S NATIONAL LIBRARY

BY

WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR.

CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited:

LONDON, PARIS,

NEW YORK &

MELBOURNE.

1887

Walter Savage Landor was born on the 30th of January, 1775, and died at the age of eighty-nine in September, 1864. He was the eldest son of a physician at Warwick, and his second name, Savage, was the family name of his mother, who owned two estates in Warwickshire—Ipsley Court and Tachbrook—and had a reversionary interest in Hughenden Manor, Buckinghamshire. To this property, worth £80,000, her eldest son was heir. That eldest son was born a poet, had a generous nature, and an ardent impetuous temper. The temper, with its obstinate claim of independence, was too much for the head master of Rugby, who found in Landor the best writer of Latin verse among his boys, but one ready to fight him over difference of opinion about a Latin quantity. In 1793 Landor went to Trinity College, Oxford. He had been got rid of at Rugby as unmanageable. After two years at Oxford, he was rusticated; thereupon he gave up his chambers, and refused to return. Landor’s father, who had been much tried by his unmanageable temper, then allowed him £150 a year to live with as he pleased, away from home. He lived in South Wales—at Swansea, Tenby, or elsewhere—and he sometimes went home to Warwick for short visits. In South Wales he gave himself to full communion with the poets and with Nature, and he fastened with particular enthusiasm upon Milton. Lord Aylmer, who lived near Tenby, was among his friends. Rose Aylmer, whose name he has made through death imperishable, by linking it with a few lines of perfect music, [6] lent Landor “The Progress of Romance,” a book published in 1785, by Clara Reeve, in which he found the description of an Arabian tale that suggested to him his poem of “Gebir.”

Landor began “Gebir” in Latin, then turned it into English, and then vigorously condensed what he had written. The poem was first published at Warwick as a sixpenny pamphlet in the year 1798, when Landor’s age was twenty-three. Robert Southey was among the few who bought it, and he first made known its power. In the best sense of the phrase, “Gebir” was written in classical English, not with a search for pompous words of classical origin to give false dignity to style, but with strict endeavour to form terse English lines of apt words well compacted. Many passages appear to have been half thought out in Greek or Latin, some, as that on the sea-shell (on page 19), were first written in Latin, and Landor re-issued “Gebir” with a translation into Latin three or four years after its first appearance.

“Gebir” was written nine years after the outbreak of the French Revolution, and at a time when the victories of Napoleon were in many minds associated with the hopes of man. In the first edition of the poem there were, in the nuptial voyage of Tamar, prophetic visions of the triumph of his race, in march of the French Republic from the Garonne to the Rhine—

“How grand a prospect opens! Alps

o’er Alps

Tower, to survey the triumphs that proceed.

Here, while Garumna dances in the gloom

Of larches, mid her naiads, or reclined

Leans on a broom-clad bank to watch the sports

Of some far-distant chamois silken haired,

The chaste Pyrené, drying up her tears,

Finds, with your children, refuge: yonder, Rhine

Lays his imperial sceptre at your feet.”

The hope of the purer spirits in the years of revolution, expressed by Wordsworth’s

“War shall cease,

Did ye not hear, that conquest is abjured?”

was in the first design of “Gebir,” and in those early years of hope Landor joined to the vision of the future for the sons of Tamar that,

“Captivity led captive, war

o’erthrown,

They shall o’er Europe, shall o’er earth extend

Empire that seas alone and skies confine,

And glory that shall strike the crystal stars.”

Landor was led by the failure of immediate expectation to revise his poem and omit from the third and the sixth books about one hundred and fifty lines, while adding fifty to heal over the wounds made by excision. As the poem stands, it is a rebuke of tyrannous ambition in the tale of Gebir, prince of Boetic Spain, from whom Gibraltar took its name. Gebir, bound by a vow to his dying father in the name of ancestral feud to invade Egypt, prepares invasion, but yields in Egypt to the touch of love, seeks to rebuild the ruins of the past, and learns what are the fruits of ambition. This he learns in the purgatory of conquerors, where he sees the figures of the Stuarts, of William the Deliverer, and of George the Third, “with eyebrows white and slanting brow,” intentionally confused with Louis XVI. to avoid a charge of treason. But the strength of Landor’s sympathy with the French Revolution and of his contempt for George III. was more evident in the first form of the poem. Parallel with the quenching in Gebir of the conqueror’s ambition, and with the ruin of his life and its new hope by the destroying powers that our misunderstandings of the better life bring into play, runs that part of the poem which shows Tamar, his brother, preparing to dwell with the sea nymph, the ideal, far away from all the struggle of mankind.

Recognition of the great beauty of Lander’s “Gebir” came first from Southey in “The Critical Review.” Southey found that the poem grew upon him, and became afterwards Landor’s lifelong friend. When Shelley was at Oxford in 1811, there were times when he would read nothing but “Gebir.” His friend Hogg says that when he went to Shelley’s rooms one morning to tell him something of importance, he could not draw his attention away from “Gebir.” Hogg impatiently threw the book out of window. It was brought back by a servant, and Shelley immediately fastened upon it again.

At the close of 1805 Landor’s father died, and the young poet became a man of property. In 1808 Southey and Landor first met. Their friendship remained unbroken. When Spain rose to throw off the yoke of Napoleon, Landor’s enthusiasm carried him to Corunna, where he paid for the equipment of a thousand volunteers, and joined the Spanish army of the North. After the Convention of Cintra he returned to England. Then he bought a large Welsh estate—Llanthony Priory—paid for it by selling other property, and began costly improvements. But he lived chiefly at Bath, where he married, in 1811, when his age was thirty-six, a girl of twenty. It was then that he began his tragedy of “Count Julian.” The patriotic struggle in Spain commended at the same time to Scott, Southey, and Landor the story of Roderick, the last of the Gothic kings, against whom, to avenge wrong done to his daughter, Count Julian called the Moors in to invade his country. In 1810 Southey was working at his poem of “Roderick the Last of the Goths,” in fellowship with his friend Landor, who was treating the same subject in his play. Scott’s “Roderick” was being printed so nearly at the same time with Landor’s play, that Landor wrote to Southey early in 1812 while the proof-sheets were coming to him: “I am surprised that Upham has not sent me Mr. Scott’s poem yet. However, I am not sorry. I feel a sort of satisfaction that mine is going to the press first, though there is little danger that we should think on any subject alike, or stumble on any one character in the same track.” De Quincey spoke of the hidden torture shown in Landor’s play to be ever present in the mind of Count Julian, the betrayer of his country, as greater than the tortures inflicted in old Rome on generals who had committed treason. De Quincey’s admiration of this play was more than once expressed. “Mr. Landor,” he said, “who always rises with his subject, and dilates like Satan into Teneriffe or Atlas when he sees before him an antagonist worthy of his powers, is probably the one man in Europe that has adequately conceived the situation, the stern self-dependency, and the monumental misery of Count Julian. That sublimity of penitential grief, which cannot accept consolation from man, cannot bear external reproach, cannot condescend to notice insult, cannot so much as see the curiosity of bystanders; that awful carelessness of all but the troubled deeps within his own heart, and of God’s spirit brooding upon their surface and searching their abysses; never was so majestically described.”

H. M.

I sing the fates of

Gebir. He had dwelt

Among those mountain-caverns which retain

His labours yet, vast halls and flowing wells,

Nor have forgotten their old master’s name

Though severed from his people here, incensed

By meditating on primeval wrongs,

He blew his battle-horn, at which uprose

Whole nations; here, ten thousand of most might

He called aloud, and soon Charoba saw

His dark helm hover o’er the land of Nile,

What should the virgin do? should royal knees

Bend suppliant, or defenceless hands engage

Men of gigantic force, gigantic arms?

For ’twas reported that nor sword sufficed,

Nor shield immense nor coat of massive mail,

But that upon their towering heads they bore

Each a huge stone, refulgent as the stars.

This told she Dalica, then cried aloud:

“If on your bosom laying down my head

I sobbed away the sorrows of a child,

If I have always, and Heaven knows I have,

Next to a mother’s held a nurse’s name,

Succour this one distress, recall those days,

Love me, though ’twere because you loved me then.”

But whether confident in magic rites

Or touched with sexual pride to stand implored,

Dalica smiled, then spake: “Away those fears.

Though stronger than the strongest of his kind,

He falls—on me devolve that charge; he falls.

Rather than fly him, stoop thou to allure;

Nay, journey to his tents: a city stood

Upon that coast, they say, by Sidad built,

Whose father Gad built Gadir; on this ground

Perhaps he sees an ample room for war.

Persuade him to restore the walls himself

In honour of his ancestors, persuade—

But wherefore this advice? young, unespoused,

Charoba want persuasions! and a queen!”

“O Dalica!” the shuddering maid

exclaimed,

“Could I encounter that fierce, frightful man?

Could I speak? no, nor sigh!”

“And canst thou

reign?”

Cried Dalica; “yield empire or comply.”

Unfixed though seeming fixed, her eyes downcast,

The wonted buzz and bustle of the court

From far through sculptured galleries met her ear;

Then lifting up her head, the evening sun

Poured a fresh splendour on her burnished throne—

The fair Charoba, the young queen, complied.

But Gebir when he heard of her approach

Laid by his orbéd shield, his vizor-helm,

His buckler and his corset he laid by,

And bade that none attend him; at his side

Two faithful dogs that urge the silent course,

Shaggy, deep-chested, crouched; the crocodile,

Crying, oft made them raise their flaccid ears

And push their heads within their master’s hand.

There was a brightening paleness in his face,

Such as Diana rising o’er the rocks

Showered on the lonely Latmian; on his brow

Sorrow there was, yet nought was there severe.

But when the royal damsel first he saw,

Faint, hanging on her handmaids, and her knees

Tottering, as from the motion of the car,

His eyes looked earnest on her, and those eyes

Showed, if they had not, that they might have loved,

For there was pity in them at that hour.

With gentle speech, and more with gentle looks

He soothed her; but lest Pity go beyond,

And crossed Ambition lose her lofty aim,

Bending, he kissed her garment and retired.

He went, nor slumbered in the sultry noon

When viands, couches, generous wines persuade

And slumber most refreshes, nor at night,

When heavy dews are laden with disease,

And blindness waits not there for lingering age.

Ere morning dawned behind him, he arrived

At those rich meadows where young Tamar fed

The royal flocks entrusted to his care.

“Now,” said he to himself, “will I repose

At least this burthen on a brother’s breast.”

His brother stood before him. He, amazed,

Reared suddenly his head, and thus began:

“Is it thou, brother! Tamar, is it thou!

Why, standing on the valley’s utmost verge,

Lookest thou on that dull and dreary shore

Where many a league Nile blackens all the sand.

And why that sadness? when I passed our sheep

The dew-drops were not shaken off the bar;

Therefore if one be wanting ’tis untold.”

“Yes, one is wanting, nor is that

untold.”

Said Tamar; “and this dull and dreary shore

Is neither dull nor dreary at all hours.”

Whereon the tear stole silent down his cheek,

Silent, but not by Gebir unobserved:

Wondering he gazed awhile, and pitying spake:

“Let me approach thee; does the morning light

Scatter this wan suffusion o’er thy brow,

This faint blue lustre under both thine eyes?”

“O brother, is this pity or reproach?”

Cried Tamar; “cruel if it be reproach,

If pity, oh, how vain!”

“Whate’er it be

That grieves thee, I will pity: thou but speak

And I can tell thee, Tamar, pang for pang.”

“Gebir! then more than brothers are we now!

Everything, take my hand, will I confess.

I neither feed the flock nor watch the fold;

How can I, lost in love? But, Gebir, why

That anger which has risen to your cheek?

Can other men? could you?—what, no reply!

And still more anger, and still worse concealed!

Are these your promises, your pity this?”

“Tamar, I well may pity what I feel—

Mark me aright—I feel for thee—proceed—

Relate me all.”

“Then will I all

relate,”

Said the young shepherd, gladdened from his heart.

“’Twas evening, though not sunset, and springtide

Level with these green meadows, seemed still higher.

’Twas pleasant; and I loosened from my neck

The pipe you gave me, and began to play.

Oh, that I ne’er had learnt the tuneful art!

It always brings us enemies or love!

Well, I was playing, when above the waves

Some swimmer’s head methought I saw ascend;

I, sitting still, surveyed it, with my pipe

Awkwardly held before my lips half-closed.

Gebir! it was a nymph! a nymph divine!

I cannot wait describing how she came,

How I was sitting, how she first assumed

The sailor; of what happened there remains

Enough to say, and too much to forget.

The sweet deceiver stepped upon this bank

Before I was aware; for with surprise

Moments fly rapid as with love itself.

Stooping to tune afresh the hoarsened reed,

I heard a rustling, and where that arose

My glance first lighted on her nimble feet.

Her feet resembled those long shells explored

By him who to befriend his steed’s dim sight

Would blow the pungent powder in the eye.

Her eyes too! O immortal gods! her eyes

Resembled—what could they resemble? what

Ever resemble those! E’en her attire

Was not of wonted woof nor vulgar art:

Her mantle showed the yellow samphire-pod,

Her girdle the dove-coloured wave serene.

‘Shepherd,’ said she, ‘and will you wrestle

now

And with the sailor’s hardier race engage?’

I was rejoiced to hear it, and contrived

How to keep up contention; could I fail

By pressing not too strongly, yet to press?

‘Whether a shepherd, as indeed you seem,

Or whether of the hardier race you boast,

I am not daunted, no; I will engage.

But first,’ said she, ‘what wager will you

lay?’

‘A sheep,’ I answered; ‘add whate’er you

will.’

‘I cannot,’ she replied, ‘make that return:

Our hided vessels in their pitchy round

Seldom, unless from rapine, hold a sheep.

But I have sinuous shells of pearly hue

Within, and they that lustre have imbibed

In the sun’s palace porch, where when unyoked

His chariot-wheel stands midway in the wave:

Shake one and it awakens, then apply

Its polished lips to your attentive ear,

And it remembers its august abodes,

And murmurs as the ocean murmurs there.

And I have others given me by the nymphs,

Of sweeter sound than any pipe you have.

But we, by Neptune, for no pipe contend—

This time a sheep I win, a pipe the next.’

Now came she forward eager to engage,

But first her dress, her bosom then surveyed,

And heaved it, doubting if she could deceive.

Her bosom seemed, enclosed in haze like heaven,

To baffle touch, and rose forth undefined:

Above her knees she drew the robe succinct,

Above her breast, and just below her arms.

‘This will preserve my breath when tightly bound,

If struggle and equal strength should so constrain.’

Thus, pulling hard to fasten it, she spake,

And, rushing at me, closed: I thrilled throughout

And seemed to lessen and shrink up with cold.

Again with violent impulse gushed my blood,

And hearing nought external, thus absorbed,

I heard it, rushing through each turbid vein,

Shake my unsteady swimming sight in air.

Yet with unyielding though uncertain arms

I clung around her neck; the vest beneath

Rustled against our slippery limbs entwined:

Often mine springing with eluded force

Started aside, and trembled till replaced:

And when I most succeeded, as I thought,

My bosom and my throat felt so compressed

That life was almost quivering on my lips,

Yet nothing was there painful! these are signs

Of secret arts and not of human might—

What arts I cannot tell—I only know

My eyes grew dizzy, and my strength decayed.

I was indeed o’ercome! with what regret,

And more, with what confusion, when I reached

The fold, and yielding up the sheep, she cried:

‘This pays a shepherd to a conquering maid.’

She smiled, and more of pleasure than disdain

Was in her dimpled chin and liberal lip,

And eyes that languished, lengthening, just like love.

She went away; I on the wicker gate

Leant, and could follow with my eyes alone.

The sheep she carried easy as a cloak;

But when I heard its bleating, as I did,

And saw, she hastening on, its hinder feet

Struggle and from her snowy shoulder slip—

One shoulder its poor efforts had unveiled—

Then all my passions mingling fell in tears;

Restless then ran I to the highest ground

To watch her—she was gone—gone down the

tide—

And the long moonbeam on the hard wet sand

Lay like a jasper column half-upreared.”

“But, Tamar! tell me, will she not

return?”

“She will return, yet not before the moon

Again is at the full; she promised this,

Though when she promised I could not reply.”

“By all the gods I pity thee! go on—

Fear not my anger, look not on my shame;

For when a lover only hears of love

He finds his folly out, and is ashamed.

Away with watchful nights and lonely days,

Contempt of earth and aspect up to heaven,

Within contemplation, with humility,

A tattered cloak that pride wears when deformed,

Away with all that hides me from myself,

Parts me from others, whispers I am wise—

From our own wisdom less is to be reaped

Than from the barest folly of our friend.

Tamar! thy pastures, large and rich, afford

Flowers to thy bees and herbage to thy sheep,

But, battened on too much, the poorest croft

Of thy poor neighbour yields what thine denies.”

They hastened to the camp, and Gebir there

Resolved his native country to forego,

And ordered, from those ruins to the right

They forthwith raise a city: Tamar heard

With wonder, though in passing ’twas half-told,

His brother’s love, and sighed upon his own.

The Gadite men the

royal charge obey.

Now fragments weighed up from th’ uneven streets

Leave the ground black beneath; again the sun

Shines into what were porches, and on steps

Once warm with frequentation—clients, friends,

All morning, satchelled idlers all mid-day,

Lying half-up and languid though at games.

Some raise the painted pavement, some on wheels

Draw slow its laminous length, some intersperse

Salt waters through the sordid heaps, and seize

The flowers and figures starting fresh to view.

Others rub hard large masses, and essay

To polish into white what they misdeem

The growing green of many trackless years.

Far off at intervals the axe resounds

With regular strong stroke, and nearer home

Dull falls the mallet with long labour fringed.

Here arches are discovered, there huge beams

Resist the hatchet, but in fresher air

Soon drop away: there spreads a marble squared

And smoothened; some high pillar for its base

Chose it, which now lies ruined in the dust.

Clearing the soil at bottom, they espy

A crevice: they, intent on treasure, strive

Strenuous, and groan, to move it: one exclaims,

“I hear the rusty metal grate; it moves!”

Now, overturning it, backward they start,

And stop again, and see a serpent pant,

See his throat thicken, and the crispéd scales

Rise ruffled, while upon the middle fold

He keeps his wary head and blinking eye,

Curling more close and crouching ere he strike.

Go mighty men, invade far cities, go—

And be such treasure portions to your heirs.

Six days they laboured: on the seventh day

Returning, all their labours were destroyed.

’Twas not by mortal hand, or from their tents

’Twere visible; for these were now removed

Above, here neither noxious mist ascends

Nor the way wearies ere the work begin.

There Gebir, pierced with sorrow, spake these words:

“Ye men of Gades, armed with brazen

shields,

And ye of near Tartessus, where the shore

Stoops to receive the tribute which all owe

To Boetis and his banks for their attire,

Ye too whom Durius bore on level meads,

Inherent in your hearts is bravery:

For earth contains no nation where abounds

The generous horse and not the warlike man.

But neither soldier now nor steed avails:

Nor steed nor soldier can oppose the gods:

Nor is there ought above like Jove himself;

Nor weighs against his purpose, when once fixed,

Aught but, with supplicating knee, the prayers.

Swifter than light are they, and every face,

Though different, glows with beauty; at the throne

Of mercy, when clouds shut it from mankind,

They fall bare-bosomed, and indignant Jove

Drops at the soothing sweetness of their voice

The thunder from his hand; let us arise

On these high places daily, beat our breast,

Prostrate ourselves and deprecate his wrath.”

The people bowed their bodies and obeyed:

Nine mornings with white ashes on their heads,

Lamented they their toil each night o’erthrown.

And now the largest orbit of the year,

Leaning o’er black Mocattam’s rubied brow,

Proceeded slow, majestic, and serene,

Now seemed not further than the nearest cliff,

And crimson light struck soft the phosphor wave.

Then Gebir spake to Tamar in these words:

“Tamar! I am thy elder and thy king,

But am thy brother too, nor ever said,

‘Give me thy secret and become my slave:’

But haste thee not away; I will myself

Await the nymph, disguised in thy attire.”

Then starting from attention Tamar cried:

“Brother! in sacred truth it cannot be!

My life is yours, my love must be my own:

Oh, surely he who seeks a second love

Never felt one, or ’tis not one I feel.”

But Gebir with complacent smile replied:

“Go then, fond Tamar, go in happy hour—

But ere thou partest ponder in thy breast

And well bethink thee, lest thou part deceived,

Will she disclose to thee the mysteries

Of our calamity? and unconstrained?

When even her love thy strength had to disclose.

My heart indeed is full, but witness heaven!

My people, not my passion, fills my heart.”

“Then let me kiss thy garment,” said the

youth,

“And heaven be with thee, and on me thy grace.”

Him then the monarch thus once more addressed:

“Be of good courage: hast thou yet forgot

What chaplets languished round thy unburnt hair,

In colour like some tall smooth beech’s leaves

Curled by autumnal suns?”

How flattery

Excites a pleasant, soothes a painful shame!

“These,” amid stifled blushes Tamar

said,

“Were of the flowering raspberry and vine:

But, ah! the seasons will not wait for love;

Seek out some other now.”

They parted here:

And Gebir bending through the woodlands culled

The creeping vine and viscous raspberry,

Less green and less compliant than they were;

And twisted in those mossy tufts that grow

On brakes of roses when the roses fade:

And as he passes on, the little hinds

That shake for bristly herds the foodful bough,

Wonder, stand still, gaze, and trip satisfied;

Pleased more if chestnut, out of prickly husk

Shot from the sandal, roll along the glade.

And thus unnoticed went he, and untired

Stepped up the acclivity; and as he stepped,

And as the garlands nodded o’er his brow,

Sudden from under a close alder sprang

Th’ expectant nymph, and seized him unaware.

He staggered at the shock; his feet at once

Slipped backward from the withered grass short-grazed;

But striking out one arm, though without aim,

Then grasping with his other, he enclosed

The struggler; she gained not one step’s retreat,

Urging with open hands against his throat

Intense, now holding in her breath constrained,

Now pushing with quick impulse and by starts,

Till the dust blackened upon every pore.

Nearer he drew her and yet nearer, clasped

Above the knees midway, and now one arm

Fell, and her other lapsing o’er the neck

Of Gebir swung against his back incurved,

The swoll’n veins glowing deep, and with a groan

On his broad shoulder fell her face reclined.

But ah, she knew not whom that roseate face

Cooled with its breath ambrosial; for she stood

High on the bank, and often swept and broke

His chaplets mingled with her loosened hair.

Whether while Tamar tarried came desire,

And she grown languid loosed the wings of love,

Which she before held proudly at her will,

And nought but Tamar in her soul, and nought

Where Tamar was that seemed or feared deceit,

To fraud she yielded what no force had gained—

Or whether Jove in pity to mankind,

When from his crystal fount the visual orbs

He filled with piercing ether and endued

With somewhat of omnipotence, ordained

That never two fair forms at once torment

The human heart and draw it different ways,

And thus in prowess like a god the chief

Subdued her strength nor softened at her charms—

The nymph divine, the magic mistress, failed.

Recovering, still half resting on the turf,

She looked up wildly, and could now descry

The kingly brow, arched lofty for command.

“Traitor!” said she, undaunted, though

amaze

Threw o’er her varying cheek the air of fear,

“Thinkest thou thus that with impunity

Thou hast forsooth deceived me? dar’st thou deem

Those eyes not hateful that have seen me fall?

O heaven! soon may they close on my disgrace.

Merciless man, what! for one sheep estranged

Hast thou thrown into dungeons and of day

Amerced thy shepherd? hast thou, while the iron

Pierced through his tender limbs into his soul,

By threats, by tortures, torn out that offence,

And heard him (oh, could I!) avow his love?

Say, hast thou? cruel, hateful!—ah my fears!

I feel them true! speak, tell me, are they true?”

She blending thus entreaty with reproach

Bent forward, as though falling on her knee

Whence she had hardly risen, and at this pause

Shed from her large dark eyes a shower of tears.

Th’ Iberian king her sorrow thus consoled.

“Weep no more, heavenly damsel, weep no more:

Neither by force withheld, or choice estranged

Thy Tamar lives, and only lives for thee.

Happy, thrice happy, you! ’tis me alone

Whom heaven and earth and ocean with one hate

Conspire on, and throughout each path pursue.

Whether in waves beneath or skies above

Thou hast thy habitation, ’tis from heaven,

From heaven alone, such power, such charms, descend.

Then oh! discover whence that ruin comes

Each night upon our city, whence are heard

Those yells of rapture round our fallen walls:

In our affliction can the gods delight,

Or meet oblation for the nymphs are tears?”

He spake, and indignation sank in woe.

Which she perceiving, pride refreshed her heart,

Hope wreathed her mouth with smiles, and she exclaimed:

“Neither the gods afflict you, nor the nymphs.

Return me him who won my heart, return

Him whom my bosom pants for, as the steeds

In the sun’s chariot for the western wave,

The gods will prosper thee, and Tamar prove

How nymphs the torments that they cause assuage.

Promise me this! indeed I think thou hast,

But ’tis so pleasing, promise it once more.”

“Once more I promise,” cried the

gladdened king,

“By my right hand and by myself I swear,

And ocean’s gods and heaven’s gods I adjure,

Thou shalt be Tamar’s, Tamar shalt be thine.”

Then she, regarding him long fixed, replied:

“I have thy promise, take thou my advice.

Gebir, this land of Egypt is a land

Of incantation, demons rule these waves;

These are against thee, these thy works destroy.

Where thou hast built thy palace, and hast left

The seven pillars to remain in front,

Sacrifice there, and all these rites observe.

Go, but go early, ere the gladsome Hours,

Strew saffron in the path of rising Morn,

Ere the bee buzzing o’er flowers fresh disclosed

Examine where he may the best alight

Nor scatter off the bloom, ere cold-lipped herds

Crop the pale herbage round each other’s bed,

Lead seven bulls, well pastured and well formed,

Their neck unblemished and their horns unringed,

And at each pillar sacrifice thou one.

Around each base rub thrice the black’ning blood,

And burn the curling shavings of the hoof;

And of the forehead locks thou also burn:

The yellow galls, with equal care preserved,

Pour at the seventh statue from the north.”

He listened, and on her his eyes intent

Perceived her not, and she had disappeared—

So deep he pondered her important words.

And now had morn arisen and he performed

Almost the whole enjoined him: he had reached

The seventh statue, poured the yellow galls,

The forelock from his left he had released

And burnt the curling shavings of the hoof

Moistened with myrrh; when suddenly a flame

Spired from the fragrant smoke, nor sooner spired

Down sank the brazen fabric at his feet.

He started back, gazed, nor could aught but gaze,

And cold dread stiffened up his hair flower-twined;

Then with a long and tacit step, one arm

Behind, and every finger wide outspread,

He looked and tottered on a black abyss.

He thought he sometimes heard a distant voice

Breathe through the cavern’s mouth, and further on

Faint murmurs now, now hollow groans reply.

Therefore suspended he his crook above,

Dropped it, and heard it rolling step by step:

He entered, and a mingled sound arose

Like one (when shaken from some temple’s roof

By zealous hand, they and their fretted nest)

Of birds that wintering watch in Memnon’s tomb,

And tell the halcyons when spring first returns.

Oh, for the spirit

of that matchless man

Whom Nature led throughout her whole domain,

While he embodied breathed etherial air!

Though panting in the play-hour of my youth

I drank of Avon too, a dangerous draught,

That roused within the feverish thirst of song,

Yet never may I trespass o’er the stream

Of jealous Acheron, nor alive descend

The silent and unsearchable abodes

Of Erebus and Night, nor unchastised

Lead up long-absent heroes into day.

When on the pausing theatre of earth

Eve’s shadowy curtain falls, can any man

Bring back the far-off intercepted hills,

Grasp the round rock-built turret, or arrest

The glittering spires that pierce the brow of Heaven?

Rather can any with outstripping voice

The parting sun’s gigantic strides recall?

Twice sounded Gebir! twice th’ Iberian

king

Thought it the strong vibration of the brain

That struck upon his ear; but now descried

A form, a man, come nearer: as he came

His unshorn hair grown soft in these abodes

Waved back, and scattered thin and hoary light.

Living, men called him Aroar, but no more

In celebration or recording verse

His name is heard, no more by Arnon’s side

The well-walled city which he reared remains.

Gebir was now undaunted—for the brave

When they no longer doubt no longer fear—

And would have spoken, but the shade began,

“Brave son of Hesperus! no mortal hand

Has led thee hither, nor without the gods

Penetrate thy firm feet the vast profound.

Thou knowest not that here thy fathers lie,

The race of Sidad; theirs was loud acclaim

When living, but their pleasure was in war;

Triumphs and hatred followed: I myself

Bore, men imagined, no inglorious part:

The gods thought otherwise, by whose decree

Deprived of life, and more, of death deprived,

I still hear shrieking through the moonless night

Their discontented and deserted shades.

Observe these horrid walls, this rueful waste!

Here some refresh the vigour of the mind

With contemplation and cold penitence:

Nor wonder while thou hearest that the soul

Thus purified hereafter may ascend

Surmounting all obstruction, nor ascribe

The sentence to indulgence; each extreme

Has tortures for ambition; to dissolve

In everlasting languor, to resist

Its impulse, but in vain: to be enclosed

Within a limit, and that limit fire;

Severed from happiness, from eminence,

And flying, but hell bars us, from ourselves.

Yet rather all these torments most endure

Than solitary pain and sad remorse

And towering thoughts on their own breast o’er-turned

And piercing to the heart: such penitence,

Such contemplation theirs! thy ancestors

Bear up against them, nor will they submit

To conquering Time the asperities of Fate;

Yet could they but revisit earth once more,

How gladly would they poverty embrace,

How labour, even for their deadliest foe!

It little now avails them to have raised

Beyond the Syrian regions, and beyond

Phoenicia, trophies, tributes, colonies:

Follow thou me—mark what it all avails.”

Him Gebir followed, and a roar confused

Rose from a river rolling in its bed,

Not rapid, that would rouse the wretched souls,

Nor calmly, that might lull then to repose;

But with dull weary lapses it upheaved

Billows of bale, heard low, yet heard afar.

For when hell’s iron portals let out night,

Often men start and shiver at the sound,

And lie so silent on the restless couch

They hear their own hearts beat. Now Gebir breathed

Another air, another sky beheld.

Twilight broods here, lulled by no nightingale

Nor wakened by the shrill lark dewy-winged,

But glowing with one sullen sunless heat.

Beneath his foot nor sprouted flower nor herb

Nor chirped a grasshopper. Above his head

Phlegethon formed a fiery firmament:

Part were sulphurous clouds involving, part

Shining like solid ribs of molten brass;

For the fierce element which else aspires

Higher and higher and lessens to the sky,

Below, earth’s adamantine arch rebuffed.

Gebir, though now such languor held his limbs,

Scarce aught admired he, yet he this admired;

And thus addressed him then the conscious guide.

“Beyond that river lie the happy fields;

From them fly gentle breezes, which when drawn

Against yon crescent convex, but unite

Stronger with what they could not overcome.

Thus they that scatter freshness through the groves

And meadows of the fortunate, and fill

With liquid light the marble bowl of earth,

And give her blooming health and spritely force,

Their fire no more diluted, nor its darts

Blunted by passing through thick myrtle bowers,

Neither from odours rising half dissolved,

Point forward Phlegethon’s eternal flame;

And this horizon is the spacious bow

Whence each ray reaches to the world above.”

The hero pausing, Gebir then besought

What region held his ancestors, what clouds,

What waters, or what gods, from his embrace.

Aroar then sudden, as though roused, renewed.

“Come thou, if ardour urges thee and force

Suffices—mark me, Gebir, I unfold

No fable to allure thee—on! behold

Thy ancestors!” and lo! with horrid gasp

The panting flame above his head recoiled,

And thunder through his heart and life blood throbbed.

Such sound could human organs once conceive,

Cold, speechless, palsied, not the soothing voice

Of friendship or almost of Deity

Could raise the wretched mortal from the dust;

Beyond man’s home condition they! with eyes

Intent, and voice desponding, and unheard

By Aroar, though he tarried at his side.

“They know me not,” cried Gebir, “O my

sires,

Ye know me not! they answer not, nor hear.

How distant are they still! what sad extent

Of desolation must we overcome!

Aroar, what wretch that nearest us? what wretch

Is that with eyebrows white, and slanting brow?

Listen! him yonder who bound down supine,

Shrinks yelling from that sword there engine-hung;

He too among my ancestors?”

“O King!

Iberia bore him, but the breed accursed

Inclement winds blew blighting from north-east.”

“He was a warrior then, nor feared the

gods?”

“Gebir, he feared the Demons, not the Gods;

Though them indeed his daily face adored,

And was no warrior, yet the thousand lives

Squandered as stones to exercise a sling!

And the tame cruelty and cold caprice—

Oh, madness of mankind! addressed, adored!

O Gebir! what are men, or where are gods!

Behold the giant next him, how his feet

Plunge floundering mid the marshes yellow-flowered,

His restless head just reaching to the rocks,

His bosom tossing with black weeds besmeared,

How writhes he twixt the continent and isle!

What tyrant with more insolence e’er claimed

Dominion? when from the heart of Usury

Rose more intense the pale-flamed thirst for gold?

And called forsooth Deliverer! False or fools

Who praised the dull-eared miscreant, or who hoped

To soothe your folly and disgrace with praise!

Hearest thou not the harp’s gay simpering

air

And merriment afar? then come, advance;

And now behold him! mark the wretch accursed

Who sold his people to a rival king—

Self-yoked they stood two ages unredeemed.”

“Oh, horror! what pale visage rises there?

Speak, Aroar! me perhaps mine eyes deceive,

Inured not, yet methinks they there descry

Such crimson haze as sometimes drowns the moon.

What is yon awful sight? why thus appears

That space between the purple and the crown?”

“I will relate their stories when we reach

Our confines,” said the guide; “for thou, O king,

Differing in both from all thy countrymen,

Seest not their stories and hast seen their fates.

But while we tarry, lo again the flame

Riseth, and murmuring hoarse, points straighter, haste!

’Tis urgent, we must hence.”

“Then, oh, adieu!”

Cried Gebir, and groaned loud, at last a tear

Burst from his eyes turned back, and he exclaimed,

“Am I deluded? O ye powers of hell,

Suffer me—Oh, my fathers!—am I torn—”

He spake, and would have spoken more, but flames

Enwrapped him round and round intense; he turned,

And stood held breathless in a ghost’s embrace.

“Gebir, my son, desert me not! I heard

Thy calling voice, nor fate withheld me more:

One moment yet remains; enough to know

Soon will my torments, soon will thine, expire.

Oh, that I e’er exacted such a vow!

When dipping in the victim’s blood thy hand,

First thou withdrew’st it, looking in my face

Wondering; but when the priest my will explained,

Then swearest thou, repeating what he said,

How against Egypt thou wouldst raise that hand

And bruise the seed first risen from our line.

Therefore in death what pangs have I endured!

Racked on the fiery centre of the sun,

Twelve years I saw the ruined world roll round.

Shudder not—I have borne it—I deserved

My wretched fate—be better thine—farewell.”

“Oh, stay, my father! stay one moment more.

Let me return thee that embrace—’tis past—

Aroar! how could I quit it unreturned!

And now the gulf divides us, and the waves

Of sulphur bellow through the blue abyss.

And is he gone for ever! and I come

In vain?” Then sternly said the guide, “In

vain!

Sayst thou? what wouldst thou more? alas, O prince,

None come for pastime here! but is it nought

To turn thy feet from evil? is it nought

Of pleasure to that shade if they are turned?

For this thou camest hither: he who dares

To penetrate this darkness, nor regards

The dangers of the way, shall reascend

In glory, nor the gates of hell retard

His steps, nor demon’s nor man’s art prevail.

Once in each hundred years, and only once,

Whether by some rotation of the world,

Or whether willed so by some power above,

This flaming arch starts back, each realm descries

Its opposite, and Bliss from her repose

Freshens and feels her own security.”

“Security!” cried out the Gadite king,

“And feel they not compassion?”

“Child of Earth,”

Calmly said Aroar at his guest’s surprise,

“Some so disfigured by habitual crimes,

Others are so exalted, so refined,

So permeated by heaven, no trace remains

Graven on earth: here Justice is supreme;

Compassion can be but where passions are.

Here are discovered those who tortured Law

To silence or to speech, as pleased themselves:

Here also those who boasted of their zeal

And loved their country for the spoils it gave.

Hundreds, whose glitt’ring merchandise the lyre

Dazzled vain wretches drunk with flattery,

And wafted them in softest airs to Heav’n,

Doomed to be still deceived, here still attune

The wonted strings and fondly woo applause:

Their wish half granted, they retain their own,

But madden at the mockery of the shades.

Upon the river’s other side there grow

Deep olive groves; there other ghosts abide,

Blest indeed they, but not supremely blest.

We cannot see beyond, we cannot see

Aught but our opposite, and here are fates

How opposite to ours! here some observed

Religious rites, some hospitality:

Strangers, who from the good old men retired,

Closed the gate gently, lest from generous use

Shutting and opening of its own accord,

It shake unsettled slumbers off their couch:

Some stopped revenge athirst for slaughter, some

Sowed the slow olive for a race unborn.

These had no wishes, therefore none are crowned;

But theirs are tufted banks, theirs umbrage, theirs

Enough of sunshine to enjoy the shade,

And breeze enough to lull them to repose.”

Then Gebir cried: “Illustrious host,

proceed.

Bring me among the wonders of a realm

Admired by all, but like a tale admired.

We take our children from their cradled sleep,

And on their fancy from our own impress

Etherial forms and adulating fates:

But ere departing for such scenes ourselves

We seize their hands, we hang upon their neck,

Our beds cling heavy round us with our tears,

Agony strives with agony—just gods!

Wherefore should wretched mortals thus believe,

Or wherefore should they hesitate to die?”

Thus while he questioned, all his strength

dissolved

Within him, thunder shook his troubled brain,

He started, and the cavern’s mouth surveyed

Near, and beyond his people; he arose,

And bent toward them his bewildered way.

The king’s lone road, his visit, his

return,

Were not unknown to Dalica, nor long

The wondrous tale from royal ears delayed.

When the young queen had heard who taught the rites

Her mind was shaken, and what first she asked

Was, whether the sea-maids were very fair,

And was it true that even gods were moved

By female charms beneath the waves profound,

And joined to them in marriage, and had sons—

Who knows but Gebir sprang then from the gods!

He that could pity, he that could obey,

Flattered both female youth and princely pride,

The same ascending from amid the shades

Showed Power in frightful attitude: the queen

Marks the surpassing prodigy, and strives

To shake off terror in her crowded court,

And wonders why she trembles, nor suspects

How Fear and Love assume each other’s form,

By birth and secret compact how allied.

Vainly (to conscious virgins I appeal),

Vainly with crouching tigers, prowling wolves,

Rocks, precipices, waves, storms, thunderbolts,

All his immense inheritance, would Fear

The simplest heart, should Love refuse, assail:

Consent—the maiden’s pillowed ear imbibes

Constancy, honour, truth, fidelity,

Beauty and ardent lips and longing arms;

Then fades in glimmering distance half the scene,

Then her heart quails and flutters and would fly—

’Tis her belovéd! not to her! ye Powers!

What doubting maid exacts the vow? behold

Above the myrtles his protesting hand!

Such ebbs of doubt and swells of jealousy

Toss the fond bosom in its hour of sleep

And float around the eyelids and sink through.

Lo! mirror of delight in cloudless days,

Lo! thy reflection: ’twas when I exclaimed,

With kisses hurried as if each foresaw

Their end, and reckoned on our broken bonds,

And could at such a price such loss endure:

“Oh, what to faithful lovers met at morn,

What half so pleasant as imparted fears!”

Looking recumbent how love’s column rose

Marmoreal, trophied round with golden hair,

How in the valley of one lip unseen

He slumbered, one his unstrung low impressed.

Sweet wilderness of soul-entangling charms!

Led back by memory, and each blissful maze

Retracing, me with magic power detain

Those dimpled cheeks, those temples violet-tinged,

Those lips of nectar and those eyes of heaven!

Charoba, though indeed she never drank

The liquid pearl, or twined the nodding crown,

Or when she wanted cool and calm repose

Dreamed of the crawling asp and grated tomb,

Was wretched up to royalty: the jibe

Struck her, most piercing where love pierced before,

From those whose freedom centres in their tongue,

Handmaidens, pages, courtiers, priests, buffoons.

Congratulations here, there prophecies,

Here children, not repining at neglect

While tumult sweeps them ample room for play,

Everywhere questions answered ere begun,

Everywhere crowds, for everywhere alarm.

Thus winter gone, nor spring (though near) arrived,

Urged slanting onward by the bickering breeze

That issues from beneath Aurora’s car,

Shudder the sombrous waves; at every beam

More vivid, more by every breath impelled,

Higher and higher up the fretted rocks

Their turbulent refulgence they display.

Madness, which like the spiral element

The more it seizes on the fiercer burns,

Hurried them blindly forward, and involved

In flame the senses and in gloom the soul.

Determined to protect the country’s gods

And asking their protection, they adjure

Each other to stand forward, and insist

With zeal, and trample under foot the slow;

And disregardful of the Sympathies

Divine, those Sympathies whose delicate hand

Touching the very eyeball of the heart,

Awakens it, not wounds it nor inflames,

Blind wretches! they with desperate embrace

Hang on the pillar till the temple fall.

Oft the grave judge alarms religious wealth

And rouses anger under gentle words.

Woe to the wiser few who dare to cry

“People! these men are not your enemies,

Inquire their errand, and resist when wronged.”

Together childhood, priesthood, womanhood,

The scribes and elders of the land, exclaim,

“Seek they not hidden treasure in the tombs?

Raising the ruins, levelling the dust,

Who can declare whose ashes they disturb!

Build they not fairer cities than our own,

Extravagant enormous apertures

For light, and portals larger, open courts

Where all ascending all are unconfined,

And wider streets in purer air than ours?

Temples quite plain with equal architraves

They build, nor bearing gods like ours embossed.

Oh, profanation! Oh, our ancestors!”

Though all the vulgar hate a foreign face,

It more offends weak eyes and homely age,

Dalica most, who thus her aim pursued.

“My promise, O Charoba, I perform.

Proclaim to gods and men a festival

Throughout the land, and bid the strangers eat;

Their anger thus we haply may disarm.”

“O Dalica,” the grateful queen replied,

“Nurse of my childhood, soother of my cares,

Preventer of my wishes, of my thoughts,

Oh, pardon youth, oh, pardon royalty!

If hastily to Dalica I sued,

Fear might impel me, never could distrust.

Go then, for wisdom guides thee, take my name,

Issue what most imports and best beseems,

And sovereignty shall sanction the decree.”

And now Charoba was alone, her heart

Grew lighter; she sat down, and she arose,

She felt voluptuous tenderness, but felt

That tenderness for Dalica; she praised

Her kind attention, warm solicitude,

Her wisdom—for what wisdom pleased like hers!

She was delighted; should she not behold

Gebir? she blushed; but she had words to speak,

She formed them and re-formed them, with regret

That there was somewhat lost with every change;

She could replace them—what would that avail?—

Moved from their order they have lost their charm.

While thus she strewed her way with softest words,

Others grew up before her, but appeared

A plenteous rather than perplexing choice:

She rubbed her palms with pleasure, heaved a sigh,

Grew calm again, and thus her thoughts revolved—

“But he descended to the tombs! the thought

Thrills me, I must avow it, with affright.

And wherefore? shows he not the more beloved

Of heaven? or how ascends he back to day?

Then has he wronged me? could he want a cause

Who has an army and was bred to reign?

And yet no reasons against rights he urged,

He threatened not, proclaimed not; I approached,

He hastened on; I spake, he listened; wept,

He pitied me; he loved me, he obeyed;

He was a conqueror, still am I a queen.”

She thus indulged fond fancies, when the sound

Of timbrels and of cymbals struck her ear,

And horns and howlings of wild jubilee.

She feared, and listened to confirm her fears;

One breath sufficed, and shook her refluent soul.

Smiting, with simulated smile constrained,

Her beauteous bosom, “Oh, perfidious man!

Oh, cruel foe!” she twice and thrice exclaimed,

“Oh, my companions equal-aged! my throne,

My people! Oh, how wretched to presage

This day, how tenfold wretched to endure!”

She ceased, and instantly the palace rang

With gratulation roaring into rage—

’Twas her own people. “Health to Gebir!

health

To our compatriot subjects! to our queen!

Health and unfaded youth ten thousand years!”

Then went the victims forward crowned with flowers,

Crowned were tame crocodiles, and boys white-robed

Guided their creaking crests across the stream.

In gilded barges went the female train,

And hearing others ripple near, undrew

The veil of sea-green awning: if they found

Whom they desired, how pleasant was the breeze!

If not, the frightful water forced a sigh.

Sweet airs of music ruled the rowing palms,

Now rose they glistening and aslant reclined,

Now they descended, and with one consent

Plunging, seemed swift each other to pursue,

And now to tremble wearied o’er the wave.

Beyond and in the suburbs might be seen

Crowds of all ages: here in triumph passed

Not without pomp, though raised with rude device,

The monarch and Charoba; there a throng

Shone out in sunny whiteness o’er the reeds.

Nor could luxuriant youth, or lapsing age

Propped by the corner of the nearest street,

With aching eyes and tottering knees intent,

Loose leathery neck and worm-like lip outstretched,

Fix long the ken upon one form, so swift

Through the gay vestures fluttering on the bank,

And through the bright-eyed waters dancing round,

Wove they their wanton wiles and disappeared.

Meantime, with pomp august and solemn, borne

On four white camels tinkling plates of gold,

Heralds before and Ethiop slaves behind,

Each with the signs of office in his hand,

Each on his brow the sacred stamp of years,

The four ambassadors of peace proceed.

Rich carpets bear they, corn and generous wine,

The Syrian olive’s cheerful gift they bear,

With stubborn goats that eye the mountain tops

Askance and riot with reluctant horn,

And steeds and stately camels in their train.

The king, who sat before his tent, descried

The dust rise reddened from the setting sun.

Through all the plains below the Gadite men

Were resting from their labour; some surveyed

The spacious site ere yet obstructed—walls

Already, soon will roofs have interposed;

Some ate their frugal viands on the steps

Contented; some, remembering home, prefer

The cot’s bare rafters o’er the gilded dome,

And sing, for often sighs, too, end in song:

“In smiling meads how sweet the brook’s repose,

To the rough ocean and red restless sands!

Where are the woodland voices that increased

Along the unseen path on festal days,

When lay the dry and outcast arbutus

On the fane step, and the first privet-flowers

Threw their white light upon the vernal shrine?”

Some heedless trip along with hasty step

Whistling, and fix too soon on their abodes:

Haply and one among them with his spear

Measures the lintel, if so great its height

As will receive him with his helm unlowered.

But silence went throughout, e’en thoughts

were hushed,

When to full view of navy and of camp

Now first expanded the bare-headed train.

Majestic, unpresuming, unappalled,

Onward they marched, and neither to the right

Nor to the left, though there the city stood,

Turned they their sober eyes; and now they reached

Within a few steep paces of ascent

The lone pavilion of the Iberian king.

He saw them, he awaited them, he rose,

He hailed them, “Peace be with you:” they replied,

“King of the western world, be with you peace.”

Once a fair city,

courted then by king,

Mistress of nations, thronged by palaces,

Raising her head o’er destiny, her face

Glowing with pleasure and with palms refreshed,

Now pointed at by Wisdom or by Wealth,

Bereft of beauty, bare of ornaments,

Stood in the wilderness of woe, Masar.

Ere far advancing, all appeared a plain;

Treacherous and fearful mountains, far advanced.

Her glory so gone down, at human step

The fierce hyena frighted from the walls

Bristled his rising back, his teeth unsheathed,

Drew the long growl and with slow foot retired.

Yet were remaining some of ancient race,

And ancient arts were now their sole delight:

With Time’s first sickle they had marked the hour

When at their incantation would the Moon

Start back, and shuddering shed blue blasted light.

The rifted rays they gathered, and immersed

In potent portion of that wondrous wave,

Which, hearing rescued Israel, stood erect,

And led her armies through his crystal gates.

Hither (none shared her way, her counsel none)

Hied the Masarian Dalica: ’twas night,

And the still breeze fell languid on the waste.

She, tired with journey long and ardent thoughts

Stopped; and before the city she descried

A female form emerge above the sands.

Intent she fixed her eyes, and on herself

Relying, with fresh vigour bent her way;

Nor disappeared the woman, but exclaimed,

One hand retaining tight her folded vest,

“Stranger, who loathest life, there lies Masar.

Begone, nor tarry longer, or ere morn

The cormorant in his solitary haunt

Of insulated rock or sounding cove

Stands on thy bleachéd bones and screams for prey.

My lips can scatter them a hundred leagues,

So shrivelled in one breath as all the sands

We tread on could not in as many years.

Wretched who die nor raise their sepulchre!

Therefore begone.”

But Dalica unawed

(Though in her withered but still firm right-hand

Held up with imprecations hoarse and deep

Glimmered her brazen sickle, and enclosed

Within its figured curve the fading moon)

Spake thus aloud. “By yon bright orb of Heaven,

In that most sacred moment when her beam

Guided first thither by the forkéd shaft,

Strikes through the crevice of Arishtah’s

tower—”

“Sayst thou?” astonished cried the

sorceress,

“Woman of outer darkness, fiend of death,

From what inhuman cave, what dire abyss,

Hast thou invisible that spell o’erheard?

What potent hand hath touched thy quickened corse,

What song dissolved thy cerements, who unclosed

Those faded eyes and filled them from the stars?

But if with inextinguished light of life

Thou breathest, soul and body unamerced,

Then whence that invocation? who hath dared

Those hallowed words, divulging, to profane?”

Dalica cried, “To heaven, not earth,

addressed,

Prayers for protection cannot be profane.”

Here the pale sorceress turned her face aside

Wildly, and muttered to herself amazed;

“I dread her who, alone at such an hour,

Can speak so strangely, who can thus combine

The words of reason with our gifted rites,

Yet will I speak once more.—If thou hast seen

The city of Charoba, hast thou marked

The steps of Dalica?”

“What then?”

“The tongue

Of Dalica has then our rites divulged.”

“Whose rites?”

“Her sister’s,

mother’s, and her own.”

“Never.”

“How sayst thou never? one

would think,

Presumptuous, thou wert Dalica.”

“I am,

Woman, and who art thou?”

With close embrace,

Clung the Masarian round her neck, and cried:

“Art thou then not my sister? ah, I fear

The golden lamps and jewels of a court

Deprive thine eyes of strength and purity.

O Dalica, mine watch the waning moon,

For ever patient in our mother’s art,

And rest on Heaven suspended, where the founts

Of Wisdom rise, where sound the wings of Power;

Studies intense of strong and stern delight!

And thou too, Dalica, so many years

Weaned from the bosom of thy native land,

Returnest back and seekest true repose.

Oh, what more pleasant than the short-breathed sigh

When laying down your burden at the gate,

And dizzy with long wandering, you embrace

The cool and quiet of a homespun bed.”

“Alas,” said Dalica, “though all

commend

This choice, and many meet with no control,

Yet none pursue it! Age by Care oppressed

Feels for the couch, and drops into the grave.

The tranquil scene lies further still from Youth:

Frenzied Ambition and desponding Love

Consume Youth’s fairest flowers; compared with Youth

Age has a something something like repose.

Myrthyr, I seek not here a boundary

Like the horizon, which, as you advance,

Keeping its form and colour, yet recedes;

But mind my errand, and my suit perform.

Twelve years ago Charoba first could speak:

If her indulgent father asked her name,

She would indulge him too, and would reply

‘What? why, Charoba!’ raised with sweet surprise,

And proud to shine a teacher in her turn.

Show her the graven sceptre; what its use?

’Twas to beat dogs with, and to gather flies.

She thought the crown a plaything to amuse

Herself, and not the people, for she thought

Who mimic infant words might infant toys:

But while she watched grave elders look with awe

On such a bauble, she withheld her breath;

She was afraid her parents should suspect

They had caught childhood from her in a kiss;

She blushed for shame, and feared—for she believed.

Yet was not courage wanting in the child.

No; I have often seen her with both hands

Shake a dry crocodile of equal height,

And listen to the shells within the scales,

And fancy there was life, and yet apply

The jagged jaws wide open to her ear.

Past are three summers since she first beheld

The ocean; all around the child await

Some exclamation of amazement here:

She coldly said, her long-lashed eyes abased,

‘Is this the mighty ocean? is this

all!’

That wondrous soul Charoba once possessed,

Capacious then as earth or heaven could hold,

Soul discontented with capacity,

Is gone, I fear, for ever. Need I say

She was enchanted by the wicked spells

Of Gebir, whom with lust of power inflamed

The western winds have landed on our coast?

I since have watched her in each lone retreat,

Have heard her sigh and soften out the name,

Then would she change it for Egyptian sounds

More sweet, and seem to taste them on her lips,

Then loathe them—Gebir, Gebir still returned.

Who would repine, of reason not bereft!

For soon the sunny stream of youth runs down,

And not a gadfly streaks the lake beyond.

Lone in the gardens, on her gathered vest

How gently would her languid arm recline!

How often have I seen her kiss a flower,

And on cool mosses press her glowing cheek!

Nor was the stranger free from pangs himself.

Whether by spell imperfect, or while brewed

The swelling herbs infected him with foam,

Oft have the shepherds met him wandering

Through unfrequented paths, oft overheard

Deep groans, oft started from soliloquies

Which they believe assuredly were meant

For spirits who attended him unseen.

But when from his illuded eyes retired

That figure Fancy fondly chose to raise,

He clasped the vacant air and stood and gazed;

Then owning it was folly, strange to tell,

Burst into peals of laughter at his woes.

Next, when his passion had subsided, went

Where from a cistern, green and ruined, oozed

A little rill, soon lost; there gathered he

Violets, and harebells of a sister bloom,

Twining complacently their tender stems

With plants of kindest pliability.

These for a garland woven, for a crown

He platted pithy rushes, and ere dusk

The grass was whitened with their roots nipped off.

These threw he, finished, in the little rill

And stood surveying them with steady smile:

But such a smile as that of Gebir bids

To Comfort a defiance, to Despair

A welcome, at whatever hour she please.

Had I observed him I had pitied him;

I have observed Charoba, I have asked

If she loved Gebir.

‘Love him!’ she

exclaimed

With such a start of terror, such a flush

Of anger, ‘I love Gebir? I in love?’

And looked so piteous, so impatient looked—

And burst, before I answered, into tears.

Then saw I, plainly saw I, ’twas not love;

For such her natural temper, what she likes

She speaks it out, or rather she commands.

And could Charoba say with greater ease

Bring me a water-melon from the Nile,’

Than, if she loved him, ‘Bring me him I love.’

Therefore the death of Gebir is resolved.”

“Resolved indeed,” cried Myrthyr, nought

surprised,

“Precious my arts! I could without

remorse

Kill, though I hold thee dearer than the day,

E’en thee thyself, to exercise my arts.

Look yonder! mark yon pomp of funeral!

Is this from fortune or from favouring stars?

Dalica, look thou yonder, what a train!

What weeping! Oh, what luxury! Come, haste,

Gather me quickly up these herbs I dropped,

And then away—hush! I must unobserved

From those two maiden sisters pull the spleen:

Dissemblers! how invidious they surround

The virgin’s tomb, where all but virgins weep.”

“Nay, hear me first,” cried Dalica;

“’tis hard

To perish to attend a foreign king.”

“Perish! and may not then mine eye alone

Draw out the venom drop, and yet remain

Enough? the portion cannot be perceived.”

Away she hastened with it to her home,

And, sprinkling thrice flesh sulphur o’er the hearth,

Took up a spindle with malignant smile,

And pointed to a woof, nor spake a word;

’Twas a dark purple, and its dye was dread.

Plunged in a lonely house, to her unknown,

Now Dalica first trembled: o’er the roof

Wandered her haggard eyes—’twas some relief.

The massy stones, though hewn most roughly, showed

The hand of man had once at least been there:

But from this object sinking back amazed,

Her bosom lost all consciousness, and shook

As if suspended in unbounded space.

Her thus entranced the sister’s voice recalled.

“Behold it here dyed once again! ’tis done.”

Dalica stepped, and felt beneath her feet

The slippery floor, with mouldered dust bestrewn;

But Myrthyr seized with bare bold-sinewed arm

The grey cerastes, writhing from her grasp,

And twisted off his horn, nor feared to squeeze

The viscous poison from his glowing gums.

Nor wanted there the root of stunted shrub

Which he lays ragged, hanging o’er the sands,

And whence the weapons of his wrath are death:

Nor the blue urchin that with clammy fin

Holds down the tossing vessel for the tides.

Together these her scient hand combined,

And more she added, dared I mention more.

Which done, with words most potent, thrice she dipped

The reeking garb; thrice waved it through the air:

She ceased; and suddenly the creeping wool

Shrunk up with crispèd dryness in her hands.

“Take this,” she cried, “and Gebir is no

more.”

Now to Aurora borne

by dappled steeds,

The sacred gate of orient pearl and gold,

Smitten with Lucifer’s light silver wand,

Expanded slow to strains of harmony:

The waves beneath in purpling rows, like doves

Glancing with wanton coyness tow’rd their queen,

Heaved softly; thus the damsel’s bosom heaves

When from her sleeping lover’s downy cheek,

To which so warily her own she brings

Each moment nearer, she perceives the warmth

Of coming kisses fanned by playful dreams.

Ocean and earth and heaven was jubilee.

For ’twas the morning pointed out by Fate

When an immortal maid and mortal man

Should share each other’s nature knit in bliss.

The brave Iberians far the beach o’erspread

Ere dawn with distant awe; none hear the mew,

None mark the curlew flapping o’er the field;

Silence held all, and fond expectancy.

Now suddenly the conch above the sea

Sounds, and goes sounding through the woods profound.

They, where they hear the echo, turn their eyes,

But nothing see they, save a purple mist

Roll from the distant mountain down the shore:

It rolls, it sails, it settles, it dissolves—

Now shines the nymph to human eye revealed,

And leads her Tamar timorous o’er the waves.

Immortals crowding round congratulate

The shepherd; he shrinks back, of breath bereft:

His vesture clinging closely round his limbs

Unfelt, while they the whole fair form admire,

He fears that he has lost it, then he fears

The wave has moved it, most to look he fears.

Scarce the sweet-flowing music he imbibes,

Or sees the peopled ocean; scarce he sees

Spio with sparkling eyes, and Beroe

Demure, and young Ione, less renowned,

Not less divine, mild-natured; Beauty formed

Her face, her heart Fidelity; for gods

Designed, a mortal too Ione loved.

These were the nymphs elected for the hour

Of Hesperus and Hymen; these had strewn

The bridal bed, these tuned afresh the shells,

Wiping the green that hoarsened them within:

These wove the chaplets, and at night resolved

To drive the dolphins from the wreathéd door.

Gebir surveyed the concourse from the tents,

The Egyptian men around him; ’twas observed

By those below how wistfully he looked,

From what attention with what earnestness

Now to his city, now to theirs, he waved

His hand, and held it, while they spake, outspread.

They tarried with him, and they shared the feast.

They stooped with trembling hand from heavy jars

The wines of Gades gurgling in the bowl;

Nor bent they homeward till the moon appeared

To hang midway betwixt the earth and skies.

’Twas then that leaning o’er the boy beloved,

In Ocean’s grot where Ocean was unheard,

“Tamar!” the nymph said gently, “come awake!

Enough to love, enough to sleep, is given,

Haste we away.” This Tamar deemed deceit,

Spoken so fondly, and he kissed her lips,

Nor blushed he then, for he was then unseen.

But she arising bade the youth arise.

“What cause to fly?” said Tamar; she replied,

“Ask none for flight, and feign none for delay.”

“Oh, am I then deceived! or am I cast

From dreams of pleasure to eternal sleep,

And, when I cease to shudder, cease to be!”

She held the downcast bridegroom to her breast,

Looked in his face and charmed away his fears.

She said not “Wherefore leave I then embraced

You a poor shepherd, or at most a man,

Myself a nymph, that now I should deceive?”

She said not—Tamar did, and was ashamed.

Him overcome her serious voice bespake.

“Grief favours all who bear the gift of tears!

Mild at first sight he meets his votaries

And casts no shadow as he comes along:

But after his embrace the marble chills

The pausing foot, the closing door sounds loud,

The fiend in triumph strikes the roof, then falls

The eye uplifted from his lurid shade.

Tamar, depress thyself, and miseries

Darken and widen: yes, proud-hearted man!

The sea-bird rises as the billows rise;

Nor otherwise when mountain floods descend

Smiles the unsullied lotus glossy-haired.

Thou, claiming all things, leanest on thy claim

Till overwhelmed through incompliancy.

Tamar, some silent tempest gathers round!”

“Round whom?” retorted Tamar;

“thou describe

The danger, I will dare it.”

“Who will dare

What is unseen?”

“The man that is

unblessed.”

“But wherefore thou? It threatens not

thyself,

Nor me, but Gebir and the Gadite host.”

“The more I know, the more a wretch am

I.”

Groaned deep the troubled youth, “still thou

proceed.”

“Oh, seek not destined evils to divine,

Found out at last too soon! cease here the search,

’Tis vain, ’tis impious, ’tis no gift of

mine:

I will impart far better, will impart

What makes, when winter comes, the sun to rest

So soon on ocean’s bed his paler brow,

And night to tarry so at spring’s return.

And I will tell sometimes the fate of men

Who loosed from drooping neck the restless arm

Adventurous, ere long nights had satisfied

The sweet and honest avarice of love;

How whirlpools have absorbed them, storms o’er-whelmed,

And how amid their struggles and their prayers

The big wave blackened o’er the mouths supine:

Then, when my Tamar trembles at the tale,

Kissing his lips half open with surprise,

Glance from the gloomy story, and with glee

Light on the fairer fables of the gods.

Thus we may sport at leisure where we go

Where, loved by Neptune and the Naiad, loved

By pensive Dryad pale, and Oread

The spritely nymph whom constant Zephyr wooes,

Rhine rolls his beryl-coloured wave; than Rhine

What river from the mountains ever came

More stately! most the simple crown adorns

Of rushes and of willows interwined

With here and there a flower: his lofty brow

Shaded with vines and mistletoe and oak

He rears, and mystic bards his fame resound.

Or gliding opposite, th’ Illyrian gulf

Will harbour us from ill.” While thus she spake,

She touched his eyelashes with libant lip,

And breathed ambrosial odours, o’er his cheek

Celestial warmth suffusing: grief dispersed,

And strength and pleasure beamed upon his brow.

Then pointed she before him: first arose

To his astonished and delighted view

The sacred isle that shrines the queen of love.

It stood so near him, so acute each sense,

That not the symphony of lutes alone,

Or coo serene or billing strife of doves,

But murmurs, whispers, nay the very sighs

Which he himself had uttered once, he heard.

Next, but long after and far off, appear

The cloud-like cliffs and thousand towers of Crete,

And further to the right, the Cyclades:

Phoebus had raised and fixed them, to surround

His native Delos and aërial fane.

He saw the land of Pelops, host of gods,

Saw the steep ridge where Corinth after stood

Beckoning the serious with the smiling arts

Into the sunbright bay; unborn the maid

That to assure the bent-up hand unskilled

Looked oft, but oftener fearing who might wake.

He heard the voice of rivers; he descried

Pindan Peneus and the slender nymphs

That tread his banks but fear the thundering tide;

These, and Amphrysos and Apidanus

And poplar-crowned Spercheus, and reclined

On restless rocks Enipeus, whore the winds

Scattered above the weeds his hoary hair.

Then, with Pirene and with Panope,

Evenus, troubled from paternal tears,

And last was Achelous, king of isles.

Zacynthus here, above rose Ithaca,

Like a blue bubble floating in the bay.

Far onward to the left a glimmering light

Glanced out oblique, nor vanished; he inquired

Whence that arose, his consort thus replied—

“Behold the vast Eridanus! ere long

We may again behold him and rejoice.

Of noble rivers none with mightier force

Rolls his unwearied torrent to the main.”

And now Sicanian Etna rose to view: