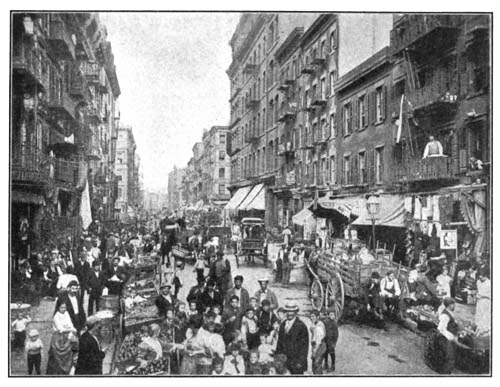

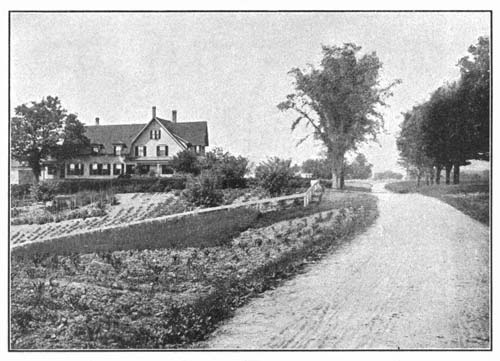

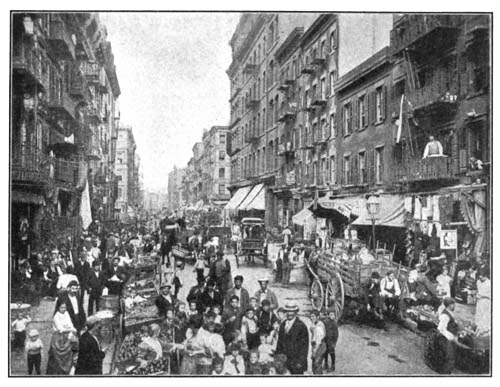

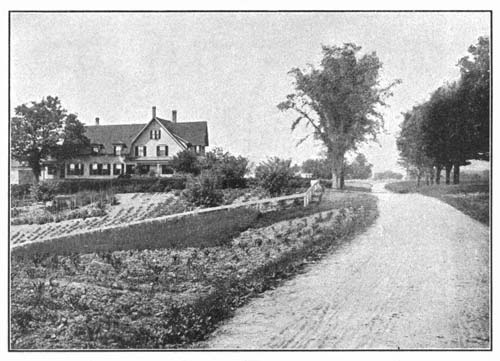

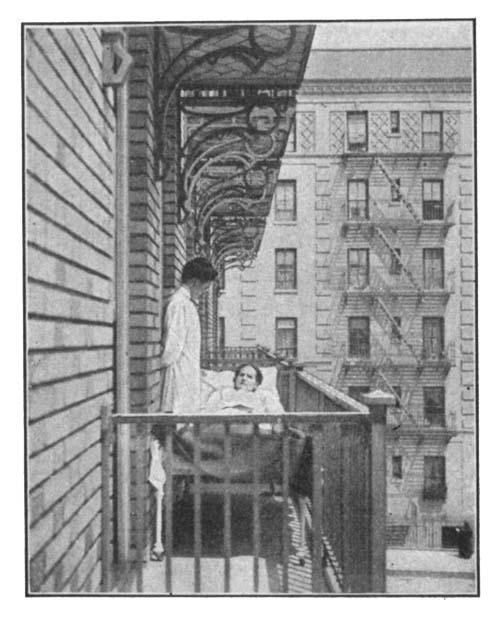

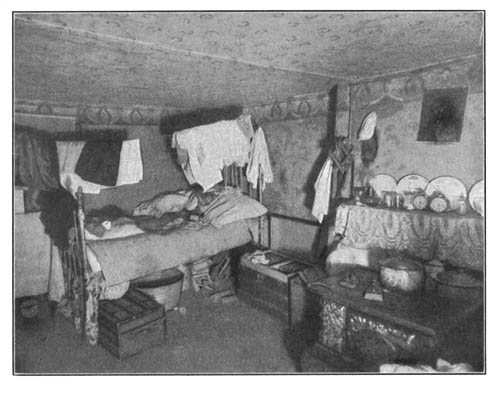

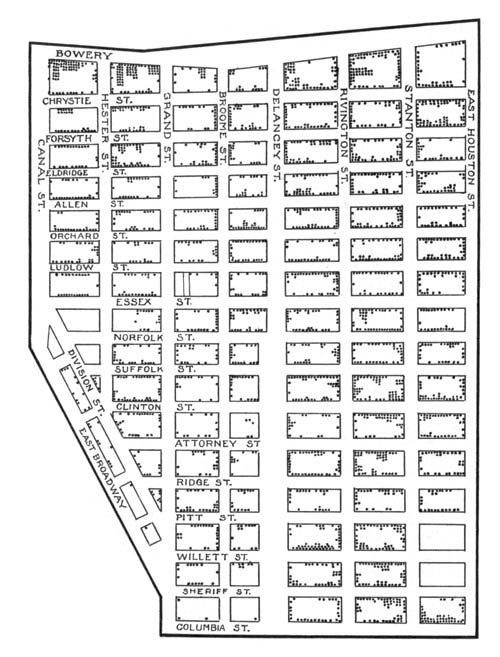

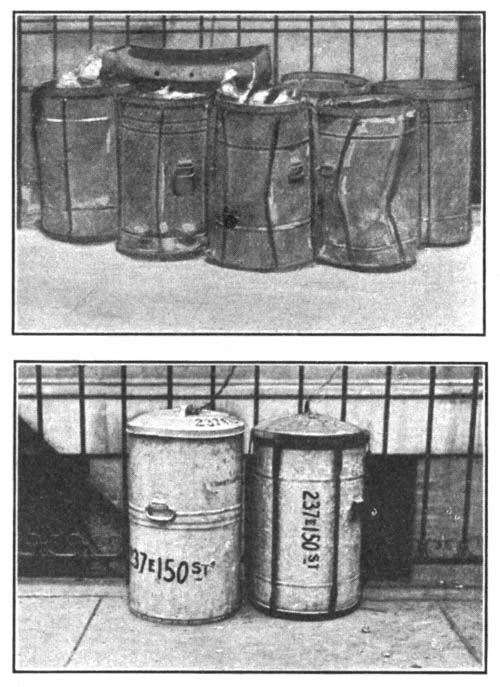

Compare the unfavorable artificial environment of a crowded city with the more favorable environment of the country.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Civic Biology, by George William Hunter

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Civic Biology

Presented in Problems

Author: George William Hunter

Release Date: June 11, 2012 [EBook #39969]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A CIVIC BIOLOGY ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Carol Ann Brown, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Compare the unfavorable artificial environment of a crowded city with the more favorable environment of the country.

BY

GEORGE WILLIAM HUNTER, A.M.

HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY, DE WITT

CLINTON

HIGH SCHOOL, CITY OF NEW YORK.

AUTHOR OF "ELEMENTS OF BIOLOGY," "ESSENTIALS

OF

BIOLOGY," ETC.

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

NEW YORK

CINCINNATI

CHICAGO

Copyright, 1914, by

GEORGE WILLIAM HUNTER.

Copyright, 1914, in Great Britain.

hunter, civic biology.

w. p. 3

Dedicated

to my

FELLOW TEACHERS

of the department of

biology

in the de witt clinton high school

whose capable, earnest, unselfish

and inspiring aid has made

this book possible

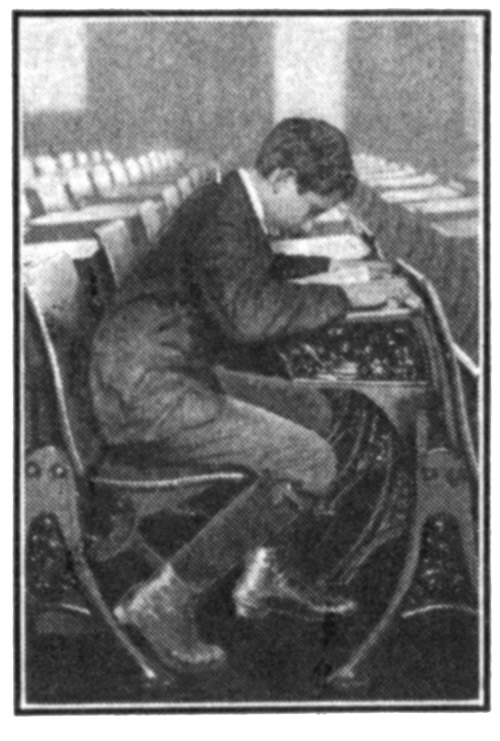

A course in biology given to beginners in the secondary school should have certain aims. These aims must be determined to a degree, first, by the capabilities of the pupils, second, by their native interests, and, third, by the environment of the pupils.

The boy or girl of average ability upon admission to the secondary school is not a thinking individual. The training given up to this time, with but rare exceptions, has been in the forming of simple concepts. These concepts have been reached didactically and empirically. Drill and memory work have been the pedagogic vehicles. Even the elementary science work given has resulted at the best in an interpretation of some of the common factors in the pupil's environment, and a widening of the meaning of some of his concepts. Therefore, the first science of the secondary school, elementary biology, should be primarily the vehicle by which the child is taught to solve problems and to think straight in so doing. No other subject is more capable of logical development. No subject is more vital because of its relation to the vital things in the life of the child. A series of experiments and demonstrations, discussed and applied as definite concrete problems which have arisen within the child's horizon, will develop power in thinking more surely than any other subject in the first year of the secondary school.

But in our eagerness to develop the power of logical thinking we must not lose sight of the previous training of our pupil. Up to this time the method of induction, that handmaiden of logical thought, has been almost unknown. Concepts have been formed deductively by a series of comparisons. All concepts have been handed down by the authority of the teacher or the text; the inductive search for the unknown is as yet a closed book. It is unwise, then, to directly introduce the pupil to the method of induction with a series of printed directions which, though definite in the mind of the teacher because of his wider horizon, mean [Pg 8]little or nothing as a definite problem to the pupil. The child must be brought to the appreciation of the problem through the deductive method, by a comparison of the future problem with some definite concrete experience within his own field of vision. Then by the inductive experiment, still led by a series of oral questions, he comes to the real end of the experiment, the conclusion, with the true spirit of the investigator. The result is tested in the light of past experiment and a generalization is formed which means something to the pupil.

For the above reason the laboratory problems, which naturally precede the textbook work, should be separated from the subject matter of the text. A textbook in biology should serve to verify the student's observations made in the laboratory, it should round out his concept or generalization by adding such material as he cannot readily observe and it should give the student directly such information as he cannot be expected to gain directly or indirectly through his laboratory experience. For these reasons the laboratory manual has been separated from the text.

"The laboratory method was such an emancipation from the old-time bookish slavery of pre-laboratory days that we may have been inclined to overdo it and to subject ourselves to a new slavery. It should never be forgotten that the laboratory is simply a means to the end; that the dominant thing should be a consistent chain of ideas which the laboratory may serve to elucidate. When, however, the laboratory assumes the first place and other phases of the course are made explanatory to it, we have taken, in my mind, an attitude fundamentally wrong. The question is, not what types may be taken up in the laboratory to be fitted into the general scheme afterwards, but what ideas are most worth while to be worked out and developed in the laboratory, if that happens to be the best way of doing it, or if not, some other way to be adopted with perfect freedom. Too often our course of study of an animal or plant takes the easiest rather than the most illuminating path. What is easier, for instance, particularly with large classes of restless pupils who apparently need to be kept in a condition of uniform occupation, than to kill a supply of animals, preferably as near alike as possible, and set the pupils to work drawing the dead remains? This method is usually supplemented by a series of questions concerning the remains which are sure to keep the pupils busy a while longer, perhaps until the bell strikes, and which usually are so planned as to anticipate any ideas that might naturally crop up in the pupil's mind during the drawing exercise.

[Pg 9]"Such an abuse of the laboratory idea is all wrong and should be avoided. The ideal laboratory ought to be a retreat for rainy days; a substitute for out of doors; a clearing house of ideas brought in from the outside. Any course in biology which can be confined within four walls, even if these walls be of a modern, well-equipped laboratory, is in some measure a failure. Living things, to be appreciated and correctly interpreted, must be seen and studied in the open where they will be encountered throughout life. The place where an animal or plant is found is just as important a characteristic as its shape or function. Impossible field excursions with large classes within school hours, which only bring confusion to inflexible school programs, are not necessary to accomplish this result. Properly administered, it is without doubt one of our most efficient devices for developing biological ideas, but the laboratory should be kept in its proper relation to the other means at our disposal and never be allowed to degenerate either into a place for vacuous drawing exercises or a biological morgue where dead remains are viewed."—Dr. H. E. Walter.

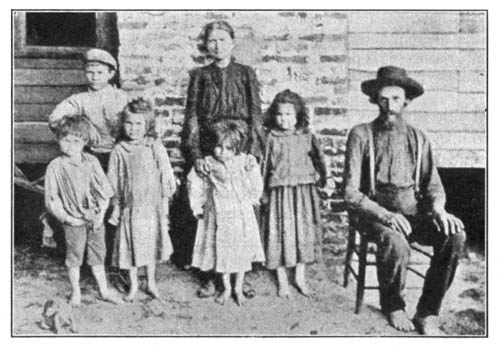

For the sake of the pupil the number of technical and scientific terms has been reduced to a minimum. The language has been made as simple as possible and the problems made to hinge upon material already known, by hearsay at least, to the pupil. So far as consistent with a well-rounded course in the essentials of biological science, the interests of the children have been kept in the foreground. In a recent questionnaire sent out by the author and answered by over three thousand children studying biology in the secondary schools of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York by far the greatest number gave as the most interesting topics those relating to the care and functions of the human body and the control and betterment of the environment. As would be expected, boys have different biological interests from girls, and children in rural schools wish to study different topics from those in congested districts in large communities. The time has come when we must frankly recognize these interests and adapt the content of our courses in biology to interpret the immediate world of the pupil.

With this end in view the following pages have been written. This book shows boys and girls living in an urban community how they may best live within their own environment and how they may coöperate with the civic authorities for the betterment of their environment. A logical course is built up around the [Pg 10]topics which appeal to the average normal boy or girl, topics given in a logical sequence so as to work out the solution of problems bearing on the ultimate problem of the entire course, that of preparation for citizenship in the largest sense.

Seasonal use of materials has been kept in mind in outlining this course. Field trips, when properly organized and later used as a basis for discussion in the classroom, make a firm foundation on which to build the superstructure of a course in biology. The normal environment, its relation to the artificial environment of the city, the relations of mutual give and take existing between plants and animals, are better shown by means of field trips than in any other way. Field and museum trips are enjoyed by the pupils as well. These result in interest and in better work. The course is worked up around certain great biological principles; hence insects may be studied when abundant in the fall in connection with their relations to green plants and especially in their relation to flowers. In the winter months material available for the laboratory is used. Saprophytic and parasitic organisms, wild plants in the household, are studied in their relations to mankind, both as destroyers of food, property and life and as man's invaluable friends. The economic phase of biology may well be taken up during the winter months, thus gaining variety in subject matter and in method of treatment. The apparent emphasis placed upon economic material in the following pages is not real. It has been found that material so given makes for variety, as it may be assigned as a topical reading lesson or simply used as reference when needed. Cyclic work in the study of life phenomena and of the needs of organisms for oxygen, food, and reproduction culminates, as it rightly should, in the study of life-processes of man and man's relation to his environment.

In a course in biology the difficulty comes not so much in knowing what to teach as in knowing what not to teach. The author believes that he has made a selection of the topics most vital in a well-rounded course in elementary biology directed toward civic betterment. The physiological functions of plants and animals, the hygiene of the individual within the community, conservation and the betterment of existing plant and animal products, the [Pg 11]big underlying biological concepts on which society is built, have all been used to the end that the pupil will become a better, stronger and more unselfish citizen. The "spiral" or cyclic method of treatment has been used throughout, the purpose being to ultimately build up a number of well-rounded concepts by constant repetition but with constantly varied viewpoint.

The sincere thanks of the author is extended to all who have helped make this book possible, and especially to the members of the Department of Biology in the De Witt Clinton High School. Most of the men there have directly or indirectly contributed their time and ideas to help make this book worth more to teachers and pupils. The following have read the manuscript in its entirety and have offered much valuable constructive criticism: Dr. Herbert E. Walter, Professor of Zoölogy in Brown University; Miss Elsie Kupfer, Head of the Department of Biology in Wadleigh High School; George C. Wood, of the Department of Biology in the Boys' High School, Brooklyn; Edgar A. Bedford, Head of Department of Biology in the Stuyvesant High School; George E. Hewitt, George T. Hastings, John D. McCarthy, and Frank M. Wheat, all of the Department of Biology in the De Witt Clinton High School.

Thanks are due, also, to Professor E. B. Wilson, Professor G. N. Calkins, Mr. William C. Barbour, Dr. John A. Sampson, W. C. Stevens, and C. W. Beebe, Dr. Alvin Davison, and Dr. Frank Overton; to the United States Department of Agriculture; the New York Aquarium; the Charity Organization Society; and the American Museum of Natural History, for permission to copy and use certain photographs and cuts which have been found useful in teaching. Dr. Charles H. Morse and Dr. Lucius J. Mason, of the De Witt Clinton High School, prepared the hygiene outline in the appendix. Frank M. Wheat and my former pupil, John W. Teitz, now a teacher in the school, made many of the line drawings and took several of the photographs of experiments prepared for this book. To them especially I wish to express my thanks.

At the end of each of the following chapters is a list of books which have proved their use either as reference reading for students or as aids to the teacher. Most of the books mentioned are within [Pg 12]the means of the small school. Two sets are expensive: one, The Natural History of Plants, by Kerner, translated by Oliver, published by Henry Holt and Company, in two volumes, at $11; the other, Plant Geography upon a Physiological Basis, by Schimper, published by the Clarendon Press, $12; but both works are invaluable for reference.

For a general introduction to physiological biology, Parker, Elementary Biology, The Macmillan Company; Sedgwick and Wilson, General Biology, Henry Holt and Company; Verworn, General Physiology, The Macmillan Company; and Needham, General Biology, Comstock Publishing Company, are most useful and inspiring books.

Two books stand out from the pedagogical standpoint as by far the most helpful of their kind on the market. No teacher of botany or zoölogy can afford to be without them. They are: Lloyd and Bigelow, The Teaching of Biology, Longmans, Green, and Company, and C. F. Hodge, Nature Study and Life, Ginn and Company. Other books of value from the teacher's standpoint are: Ganong, The Teaching Botanist, The Macmillan Company; L. H. Bailey, The Nature Study Idea, Doubleday, Page, and Company; and McMurry's How to Study, Houghton Mifflin Company. [Pg 13]

| chapter | page | |

|---|---|---|

| Foreword to Teachers | 7 | |

| I. | Some Reasons for the Study of Biology | 15 |

| II. | The Environment of Plants and Animals | 19 |

| III. | The Interrelations of Plants and Animals | 28 |

| IV. | The Functions and Composition of Living Things | 47 |

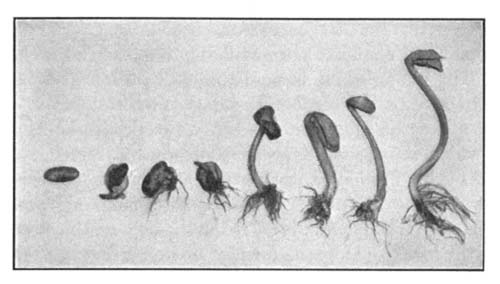

| V. | Plant Growth and Nutrition—The Causes of Growth | 58 |

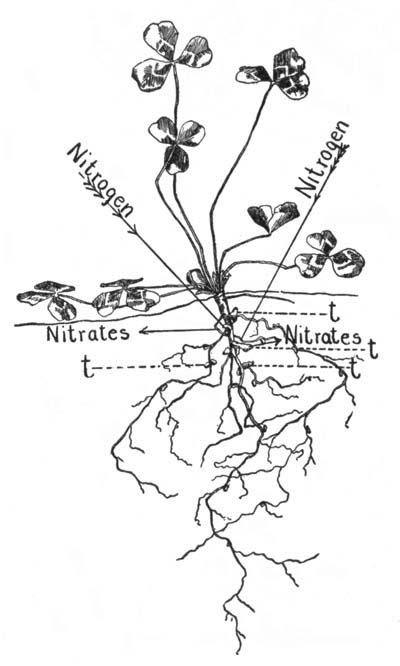

| VI. | The Organs of Nutrition in Plants—The Soil and its Relation to Roots | 71 |

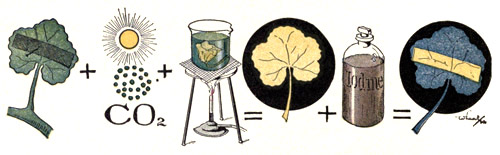

| VII. | Plant Growth and Nutrition—Plants make Food | 84 |

| VIII. | Plant Growth and Nutrition—The Circulation and Final Uses of Food by Plants | 97 |

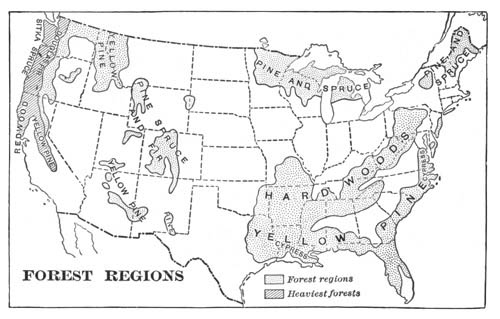

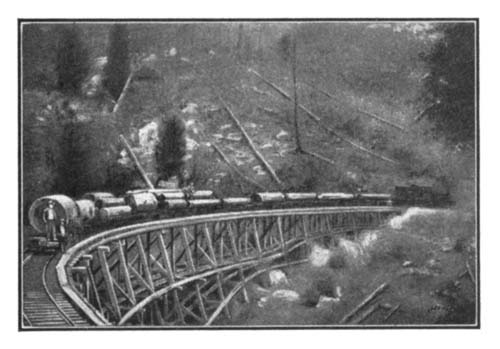

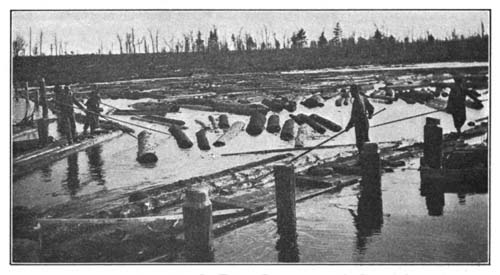

| IX. | Our Forests, their Uses and the Necessity of their Protection | 105 |

| X. | The Economic Relation of Green Plants to Man | 117 |

| XI. | Plants without Chlorophyll in their Relation to Man | 130 |

| XII. | The Relations of Plants to Animals | 159 |

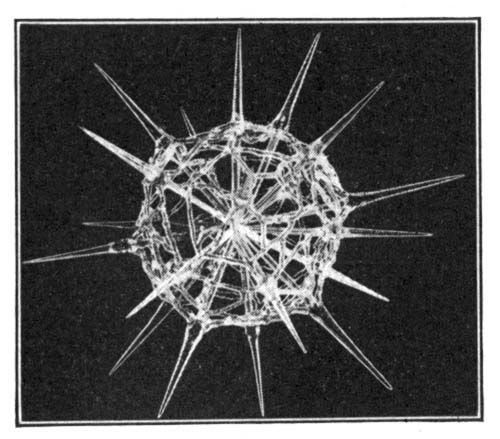

| XIII. | Single-Celled Animals considered as Organisms | 166 |

| XIV. | Division of Labor, the Various Forms of Plants and Animals | 173 |

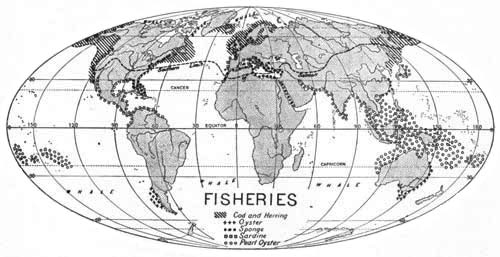

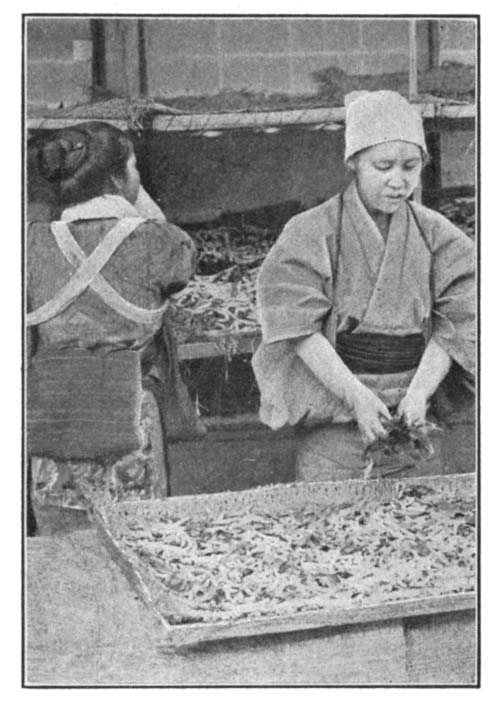

| XV. | The Economic Importance of Animals | 197 |

| XVI. | An Introductory Study of Vertebrates | 232 |

| XVII. | Heredity, Variation, Plant and Animal Breeding | 249 |

| XVIII. | The Human Machine and its Needs | 266 |

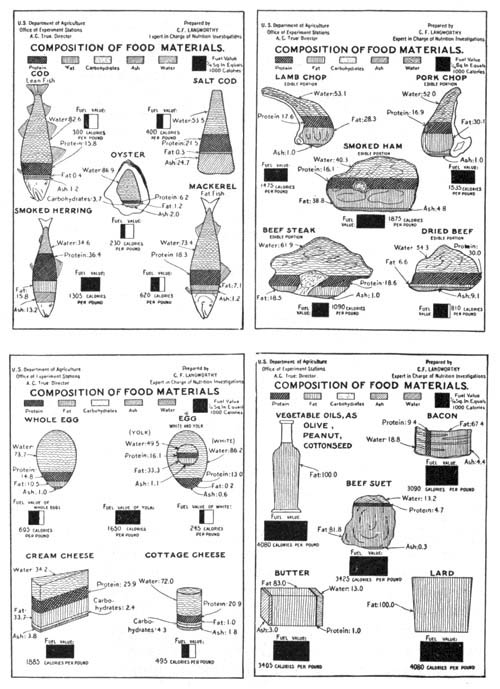

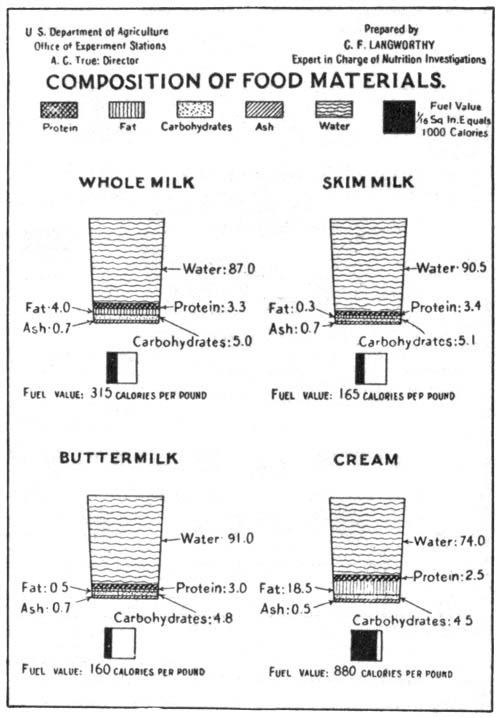

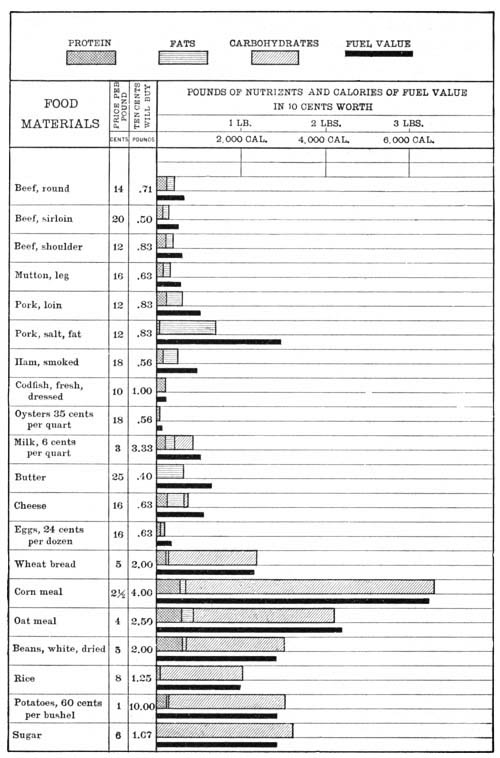

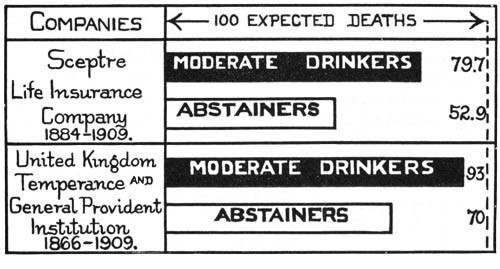

| XIX. | Foods and Dietaries | 272 |

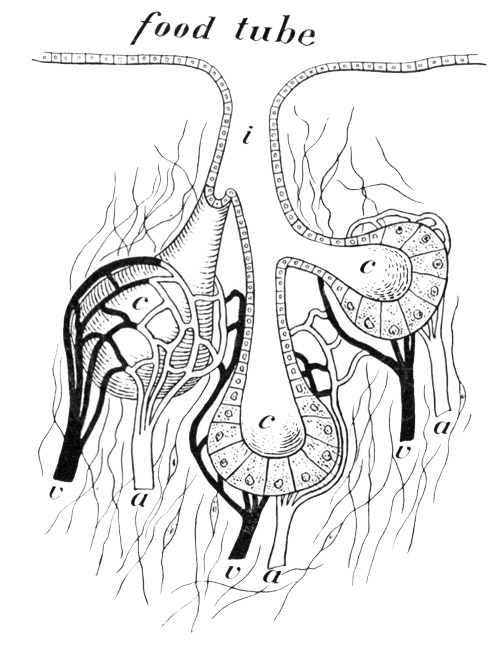

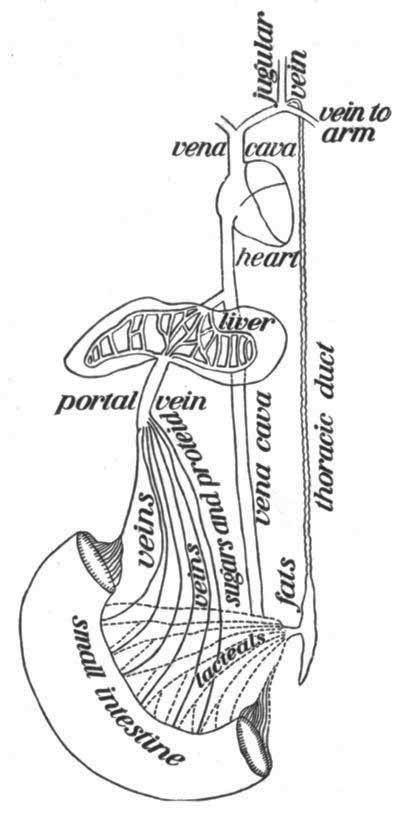

| XX. | Digestion and Absorption | 296 [Pg 14] |

| XXI. | The Blood and its Circulation | 313 |

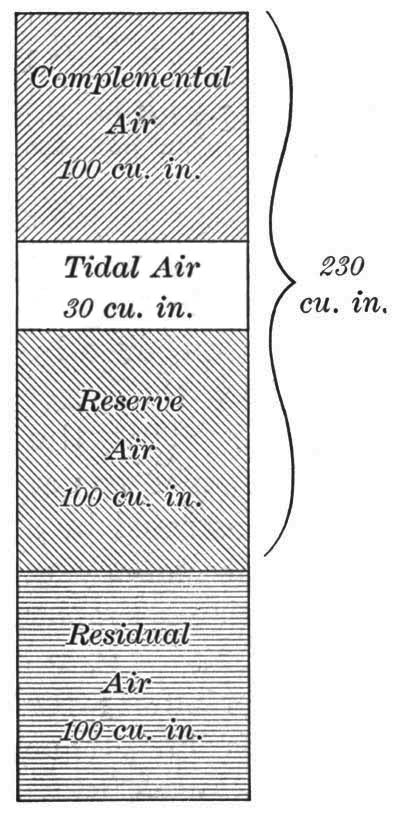

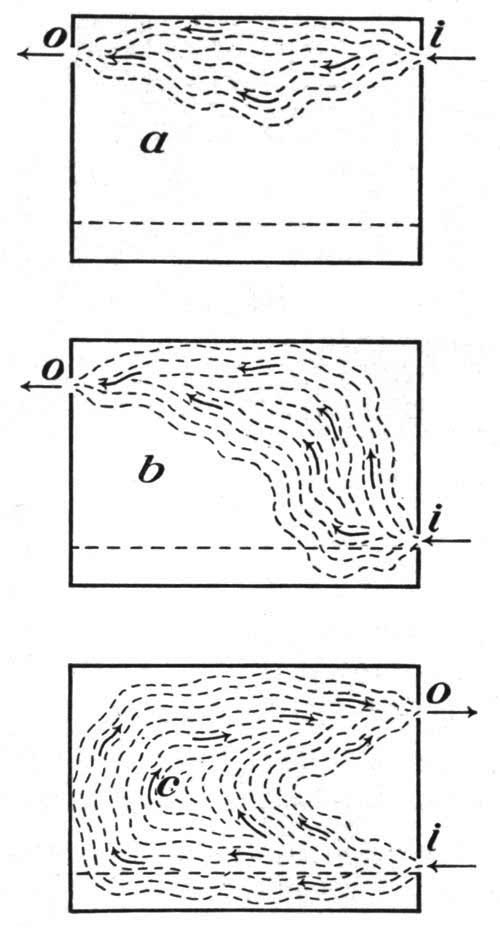

| XXII. | Respiration and Excretion | 329 |

| XXIII. | Body Control and Habit Formation | 348 |

| XXIV. | Man's Improvement of his Environment | 373 |

| XXV. | Some Great Names in Biology | 398 |

| APPENDIX | 407 | |

| Suggested Course with Time Allotment and Sequence of Topics for Course beginning in Fall | 407 | |

| Suggested Syllabus for Course in Biology beginning in February and ending the Next January | 411 | |

| Hygiene Outline | 415 | |

| Weights, Measures, and Temperatures | 417 | |

| Suggestions for Laboratory Equipment | 418 | |

| INDEX | 419 | |

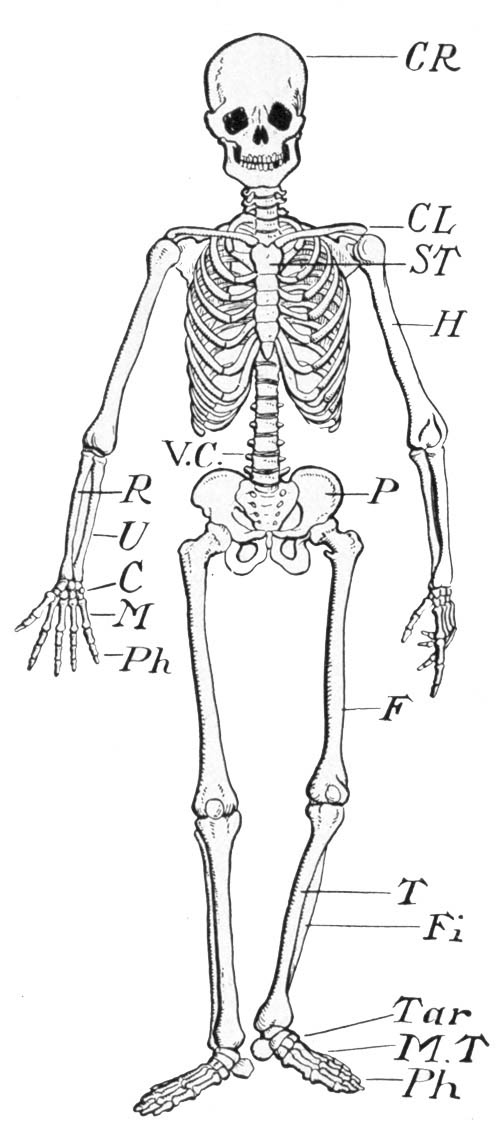

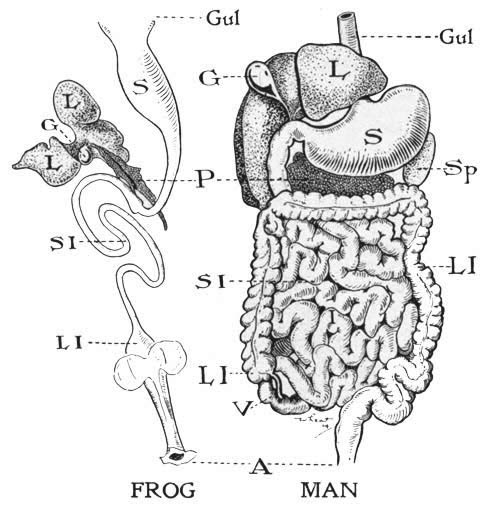

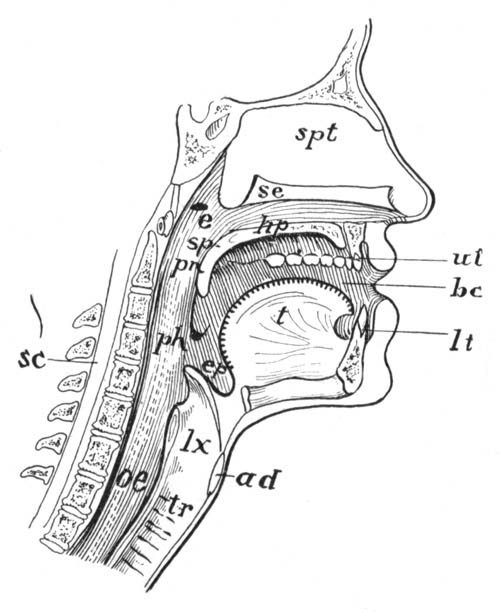

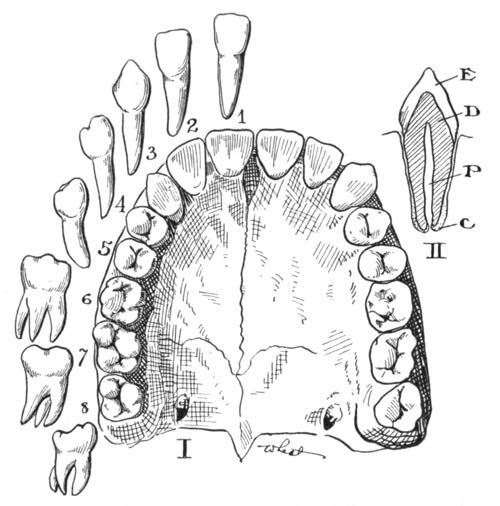

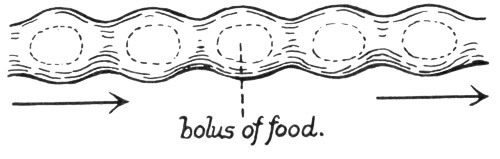

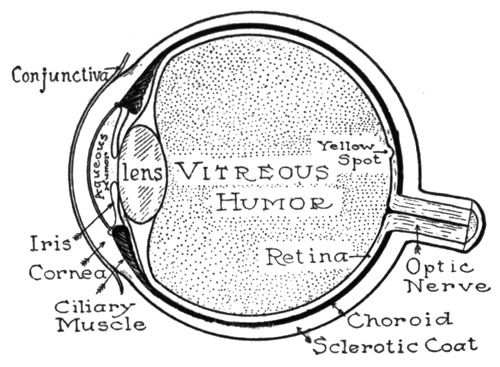

What is Biology?—Biology is the study of living beings, both plant and animal. Inasmuch as man is an animal, the study of biology includes the study of man in his relations to the plants and the animals which surround him. Most important of all is that branch of biology which treats of the mechanism we call the human body,—of its parts and their uses, and its repair. This subject we call human physiology.

Why study Biology?—Although biology is a very modern science, it has found its way into most high schools; and an increasingly large number of girls and boys are yearly engaged in its study. These questions might well be asked by any of the students: Why do I take up the study of biology? Of what practical value is it to me? Besides the discipline it gives me, is there anything that I can take away which will help me in my future life?

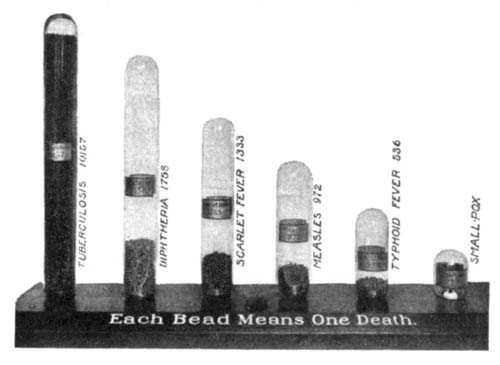

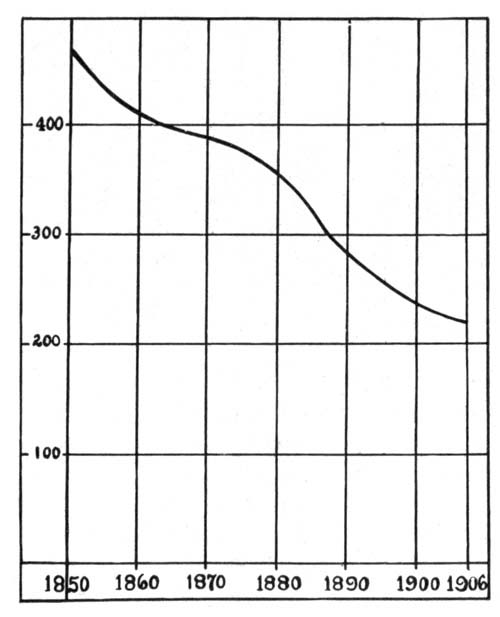

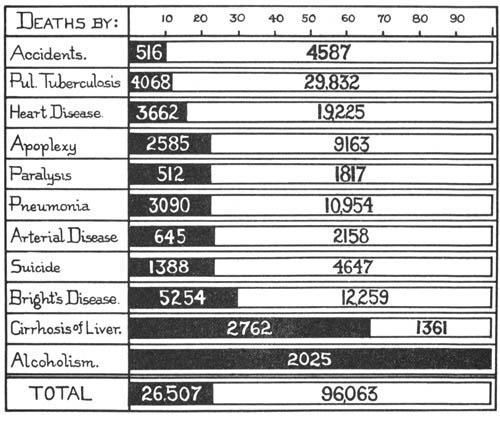

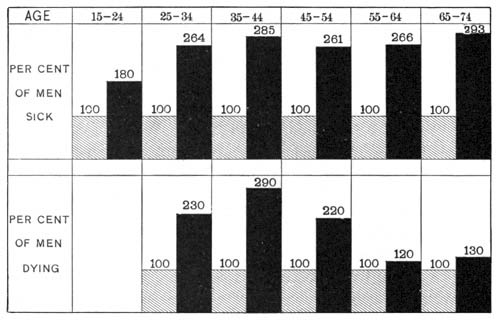

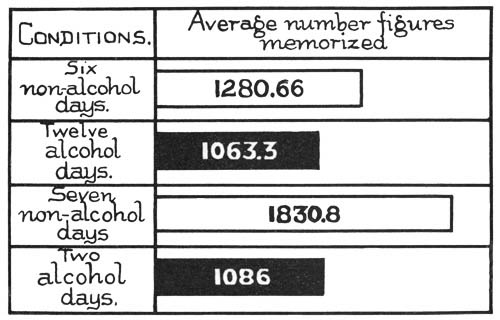

Human Physiology.—The answer to this question is plain. If the study of biology will give us a better understanding of our own bodies and their care, then it certainly is of use to us. That phase of biology known as physiology deals with the uses of the parts of a plant or animal; human physiology and hygiene deal with the uses and care of the parts of the human animal. The prevention of sickness is due in a large part to the study of hygiene. It is estimated that over twenty-five per cent of the deaths that occur yearly in this country could be averted if all people lived in a hygienic manner. In its application to the lives of each of us, as a member of our family, as a member of the school we attend, and as a future citizen, a knowledge of hygiene is of the greatest importance.

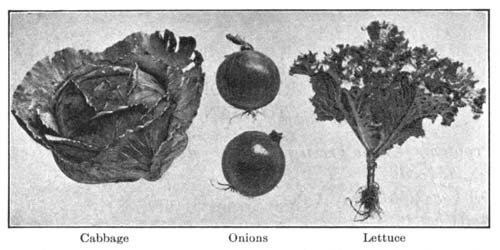

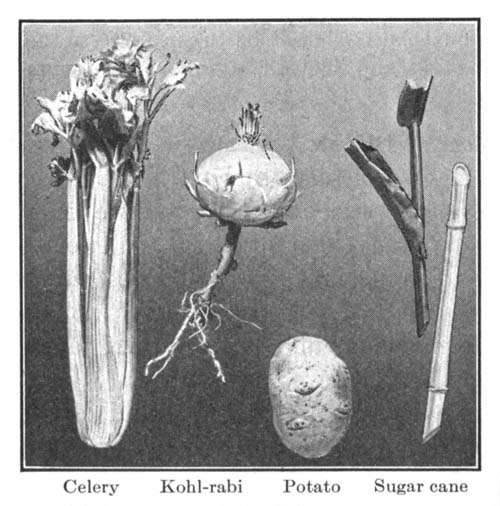

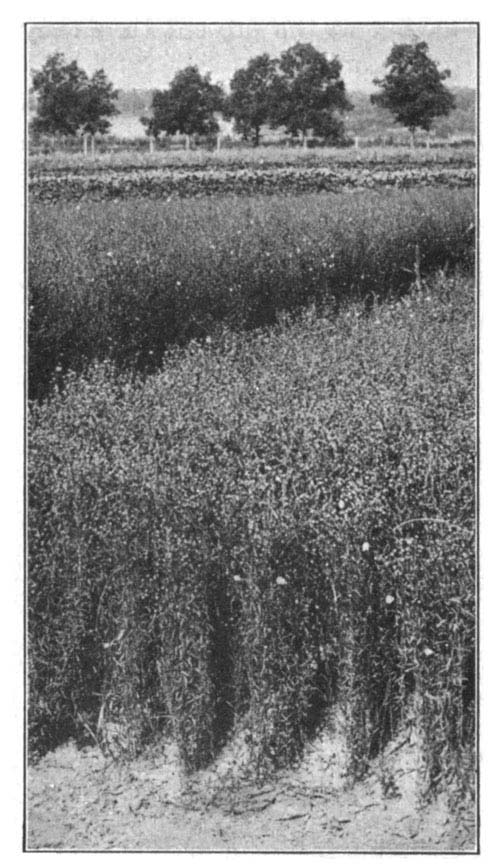

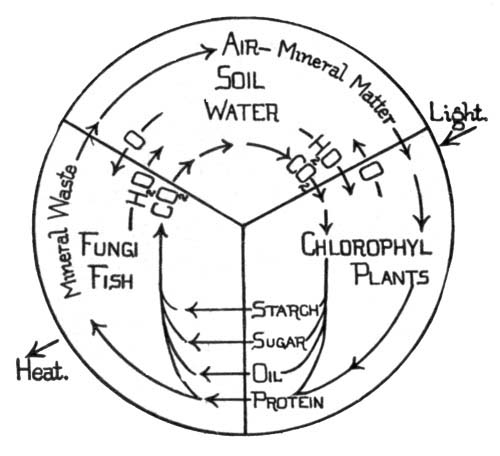

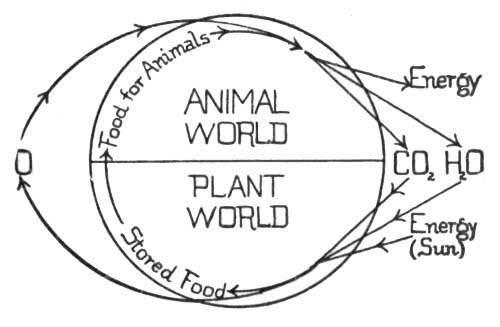

Relations of Plants to Animals.—But there are other reasons why an educated person should know something about biology. [Pg 16]We do not always realize that if it were not for the green plants, there would be no animals on the earth. Green plants furnish food to animals. Even the meat-eating animals feed upon those that feed upon plants. How the plants manufacture this food and the relation they bear to animals will be discussed in later chapters. Plants furnish man with the greater part of his food in the form of grains and cereals, fruits and nuts, edible roots and leaves; they provide his domesticated animals with food; they give him timber for his houses and wood and coal for his fires; they provide him with pulp wood, from which he makes his paper, and oak galls, from which he may make ink. Much of man's clothing and the thread with which it is sewed together come from fiber-producing plants. Most medicines, beverages, flavoring extracts, and spices are plant products, while plants are made use of in hundreds of ways in the useful arts and trades, producing varnishes, dyestuffs, rubber, and other products.

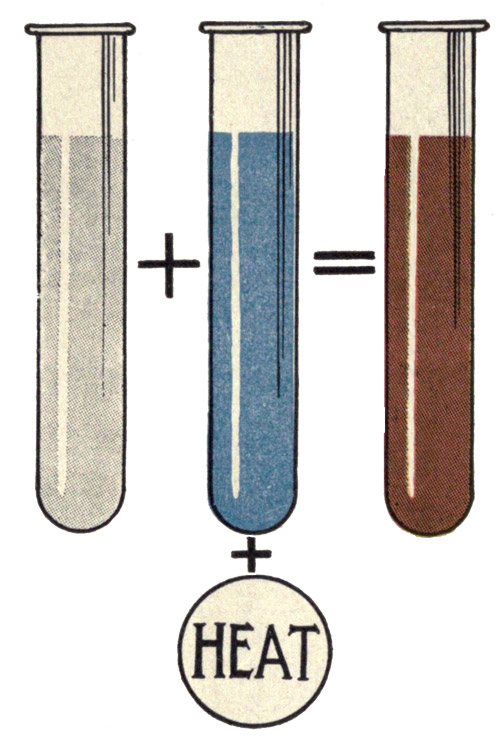

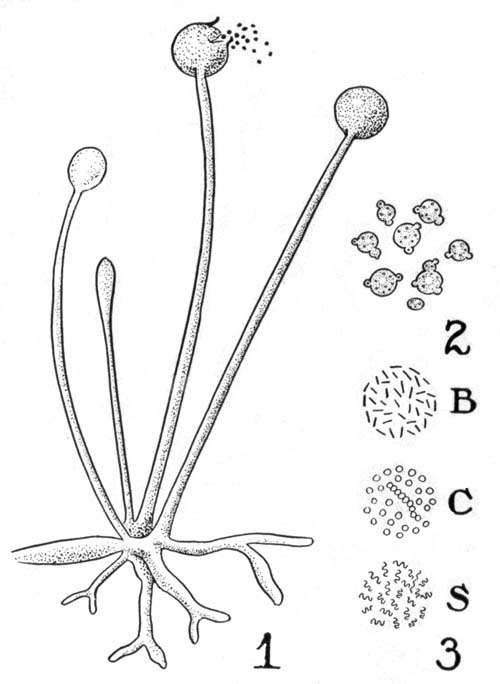

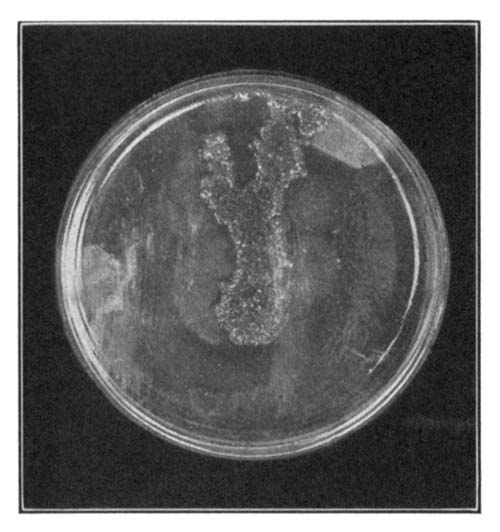

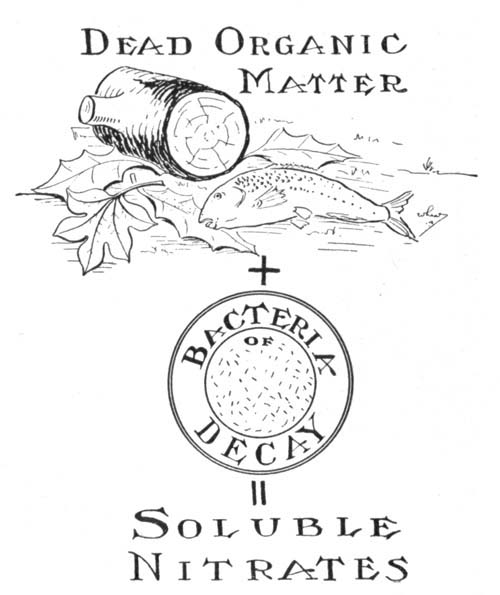

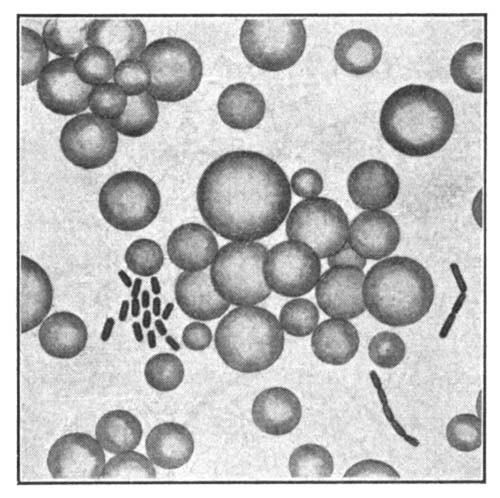

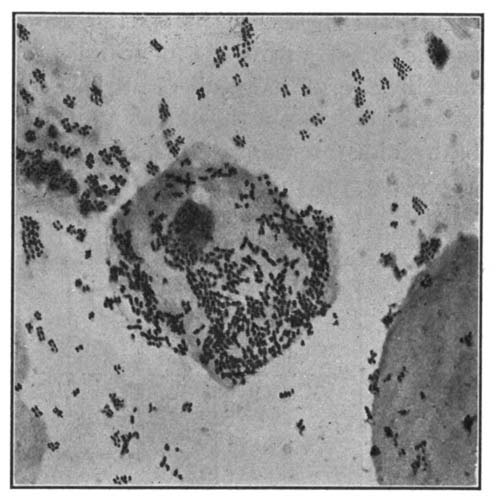

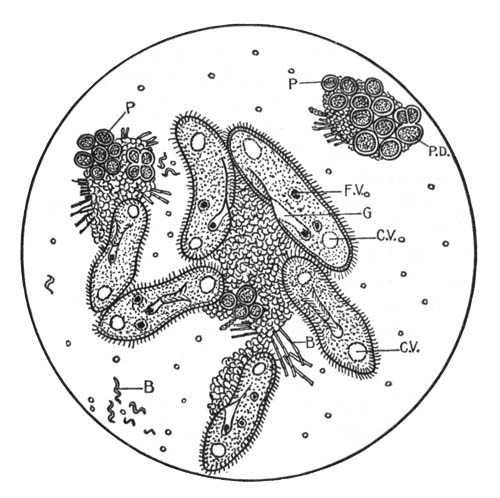

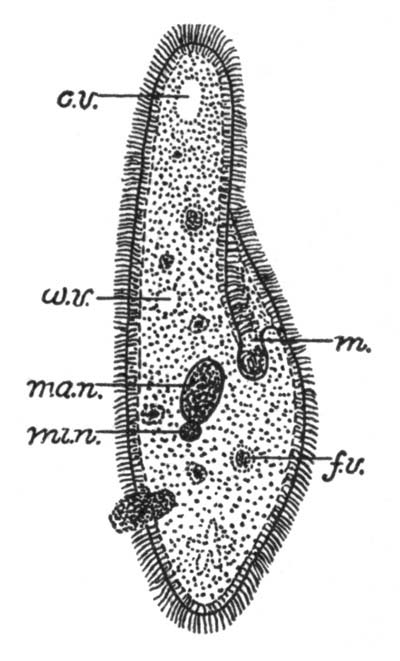

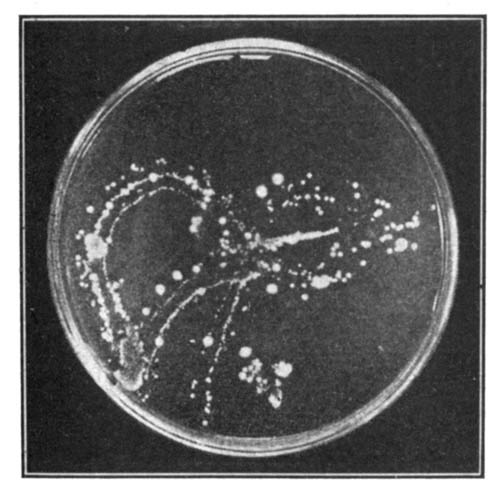

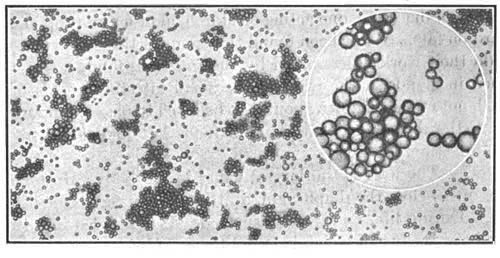

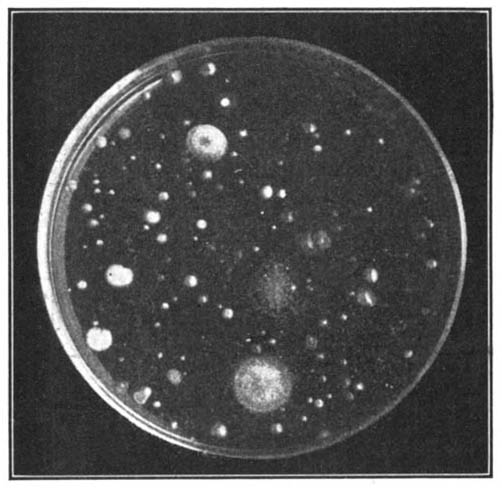

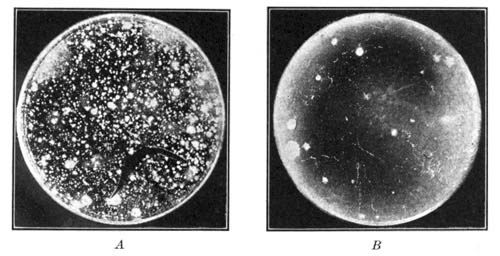

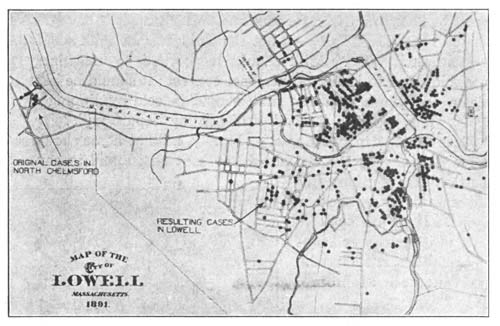

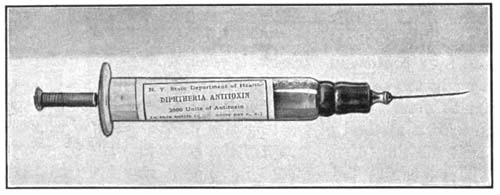

Bacteria in their Relation to Man.—In still another way, certain plants vitally affect mankind. Tiny plants, called bacteria, so small that millions can exist in a single drop of fluid, exist almost everywhere about us,—in water, soil, food, and the air. They play a tremendous part in shaping the destiny of man on the earth. They help him in that they act as scavengers, causing things to decay; thus they remove the dead bodies of plants and animals from the surface of the earth, and turn this material back to the ground; they assist the tanner; they help make cheese and butter; they improve the soil for crop growing; so the farmer cannot do without them. But they likewise sometimes spoil our meat and fish, and our vegetables and fruits; they sour our milk, and may make our canned goods spoil. Worst of all, they cause diseases, among others tuberculosis, a disease so harmful as to be called the "white plague." Fully one half of all yearly deaths are caused by these plants. So important are the bacteria that a subdivision of biology, called bacteriology, has been named after them, and hundreds of scientists are devoting their lives to the study of bacteria and their control. The greatest of all bacteriologists, Louis Pasteur, once said, "It is within the power of man to cause all parasitic diseases (diseases mostly caused by bacteria) to disappear [Pg 17]from the world." His prophecy is gradually being fulfilled, and it may be the lot of some boys or girls who read this book to do their share in helping to bring this condition of affairs about.

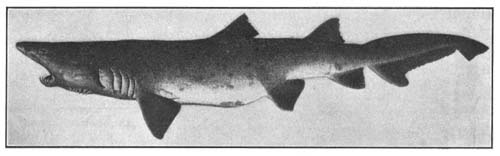

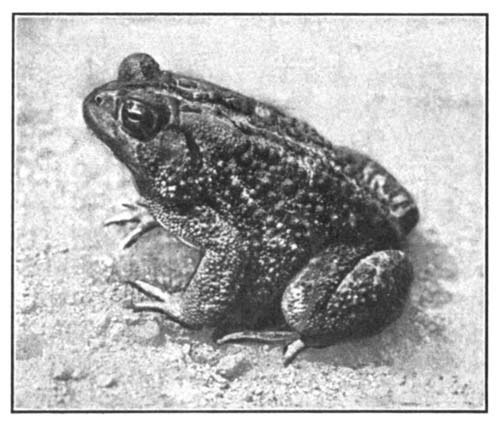

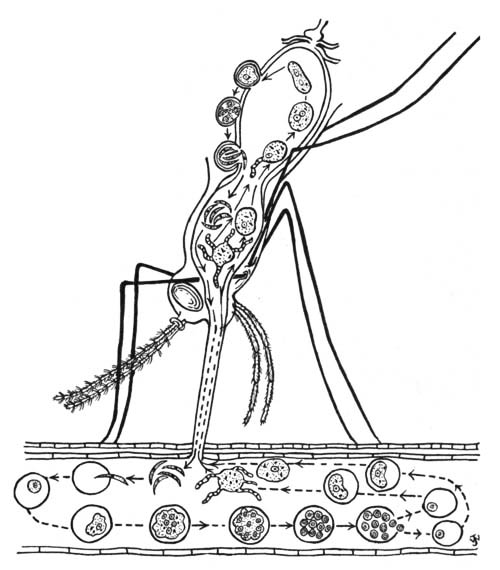

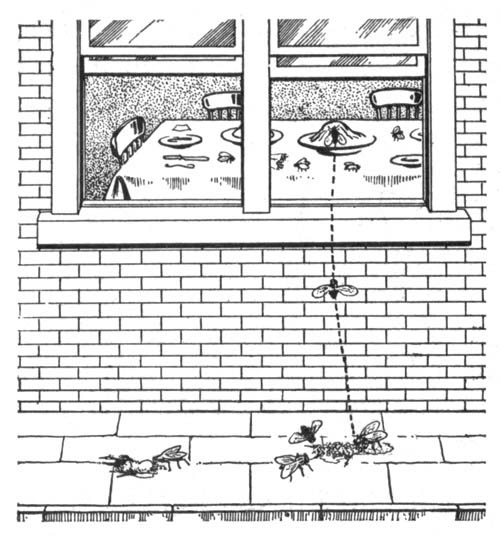

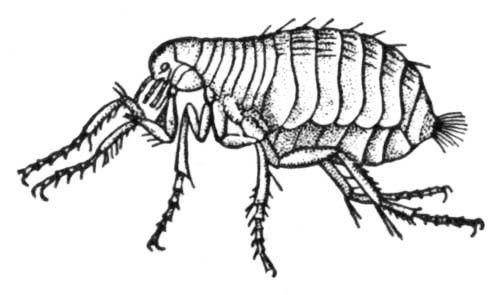

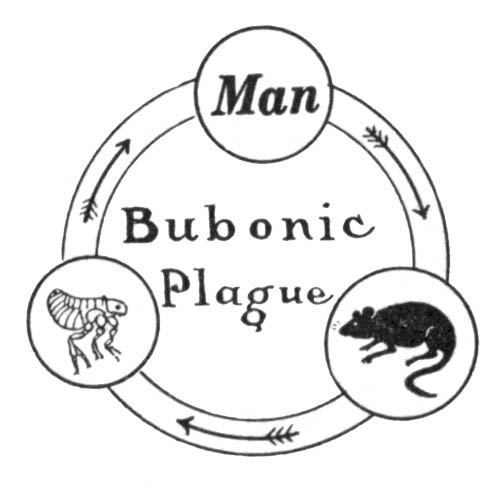

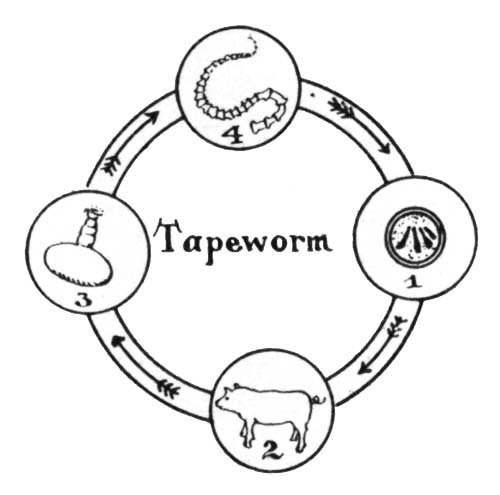

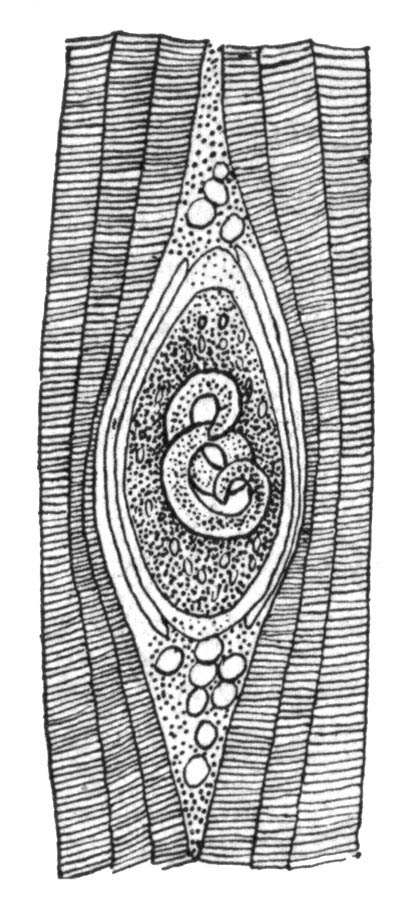

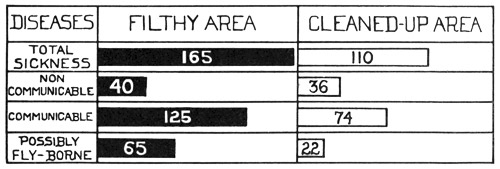

The Relation of Animals to Man.—Animals also play an important part in the world in causing and carrying disease. Animals that cause disease are usually tiny, and live in other animals as parasites; that is, they get their living from their hosts on which they feed. Among the diseases caused by parasitic animals are malaria, yellow fever, the sleeping sickness, and the hookworm disease. Animals also carry disease, especially the flies and mosquitoes; rats and other animals are also well known as spreaders of disease.

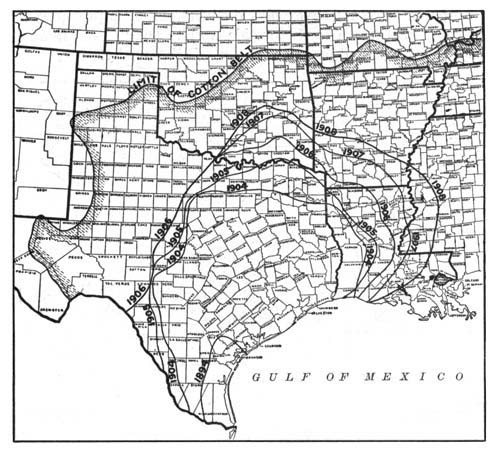

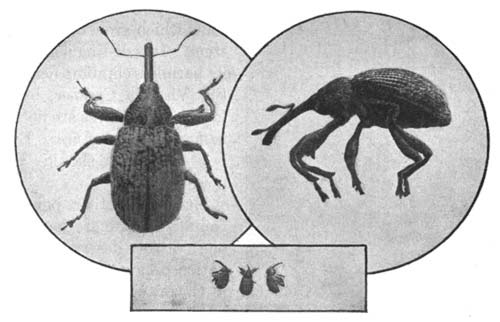

From a money standpoint, animals called insects do much harm. It is estimated that in this country alone they are annually responsible for $800,000,000 worth of damage by eating crops, forest trees, stored food, and other material wealth.

The Uses of Animals to Man.—We all know the uses man has made of the domesticated animals for food and as beasts of burden. But many other uses are found for animal products, and materials made from animals. Wool, furs, leather, hides, feathers, and silk are examples. The arts make use of ivory, tortoise shell, corals, and mother-of-pearl; from animals come perfumes and oils, glue, lard, and butter; animals produce honey, wax, milk, eggs, and various other commodities.

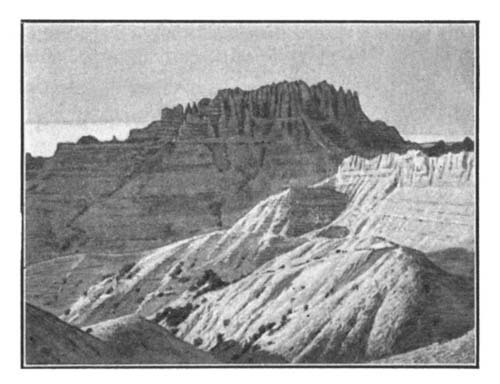

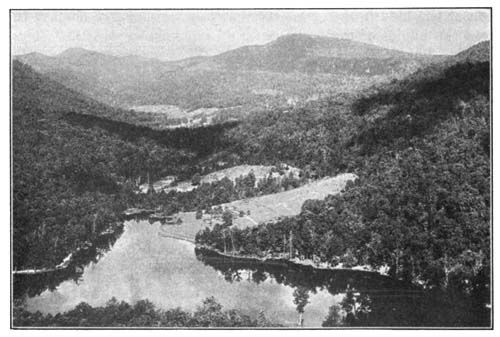

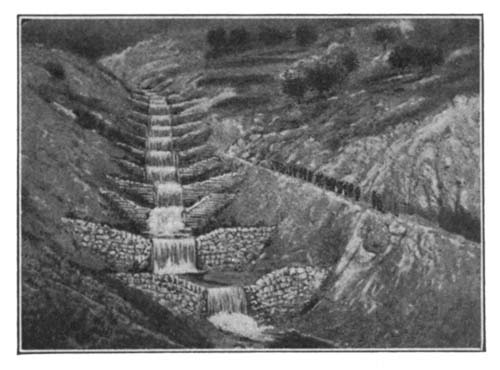

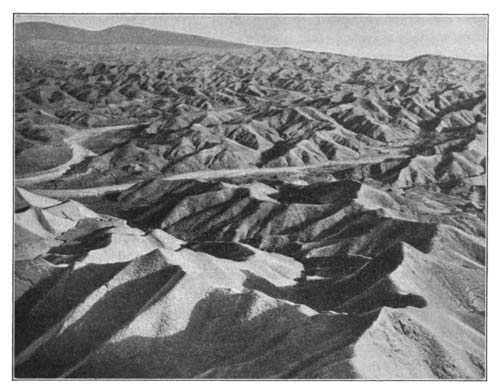

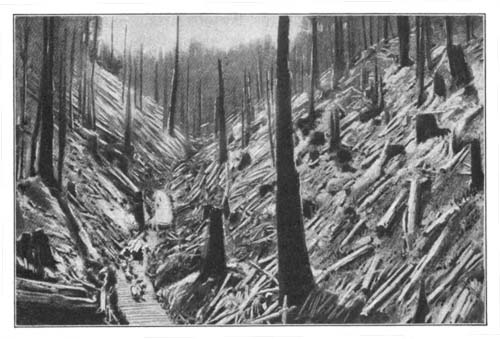

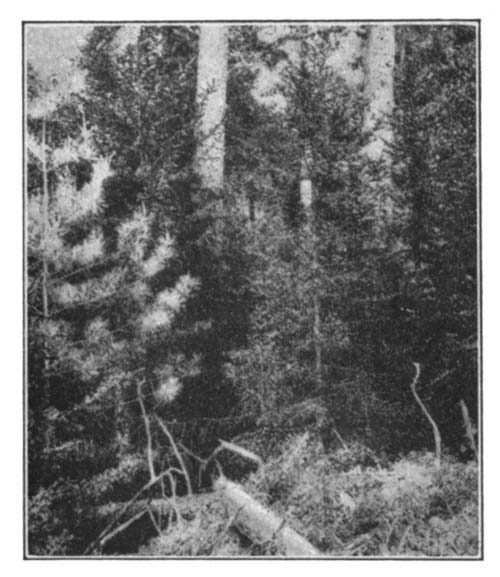

The Conservation of our Natural Resources.—Still another reason why we should study biology is that we may work understandingly for the conservation of our natural resources, especially of our forests. The forest, aside from its beauty and its health-giving properties, holds water in the earth. It keeps the water from drying out of the earth on hot days and from running off on rainy days. Thus a more even supply of water is given to our rivers, and thus freshets are prevented. Countries that have been deforested, such as China, Italy, and parts of France, are now subject to floods, and are in many places barren. On the forests depend our supply of timber, our future water power, and the future commercial importance of cities which, like New York, are located at the mouths of our navigable rivers.

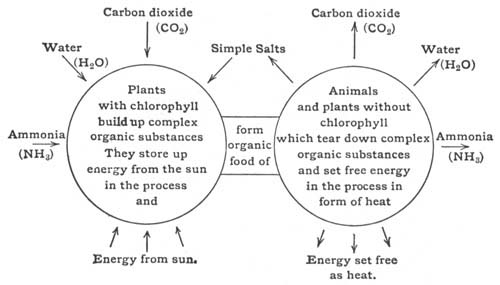

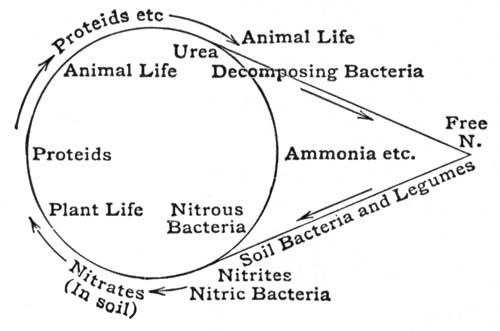

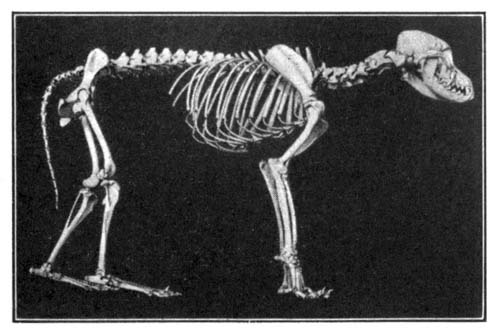

[Pg 18]Plants and Animals mutually Helpful.—Most plants and animals stand in an attitude of mutual helpfulness to one another, plants providing food and shelter for animals; animals giving off waste materials useful to plants in the making of food. We also learn that plants and animals need the same conditions in their surroundings in order to live: water, air, food, a favorable temperature, and usually light. The life processes of both plants and animals are essentially the same, and the living matter of a tree is as much alive as is the living matter in a fish, a dog, or a man.

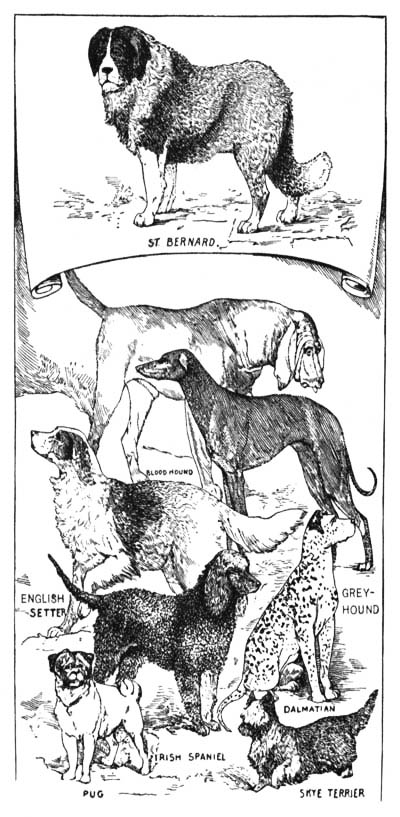

Biology in its Relation to Society.—Again, the study of biology should be part of the education of every boy and girl, because society itself is founded upon the principles which biology teaches. Plants and animals are living things, taking what they can from their surroundings; they enter into competition with one another, and those which are the best fitted for life outstrip the others. Animals and plants tend to vary each from its nearest relative in all details of structure. The strong may thus hand down to their offspring the characteristics which make them the winners. Health and strength of body and mind are factors which tell in winning.

Man has made use of this message of nature, and has developed improved breeds of horses, cattle, and other domestic animals. Plant breeders have likewise selected the plants or seeds that have varied toward better plants, and thus have stocked the earth with hardier and more fruitful domesticated plants. Man's dominion over the living things of the earth is tremendous. This is due to his understanding the principles which underlie the science of biology.

Finally the study of biology ought to make us better men and women by teaching us that unselfishness exists in the natural world as well as among the highest members of society. Animals, lowly and complex, sacrifice their comfort and their very lives for their young. In the insect communities the welfare of the individual is given up for the best interests of the community. The law of mutual give and take, of sacrifice for the common good, is seen everywhere. This should teach us, as we come to take our places in society, to be willing to give up our individual pleasure or selfish gain for the good of the community in which we live. Thus the application of biological principles will benefit society.

Problem.—To discover some of the factors of the environment of plants and animals.

(a) Environment of a plant.

(b) Environment of an animal.

(c) Home environment of a girl or boy.

Laboratory Suggestions

Laboratory demonstrations.—Factors of the environment of a living plant or animal in the vivarium.

Home exercise.—The study of the factors making up my own environment and how I can aid in their control.

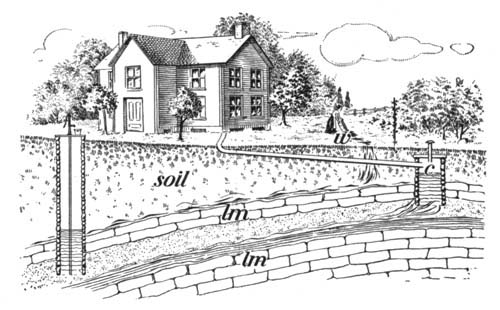

Environment.—Each one of us, no matter where he lives, comes in contact with certain surroundings. Air is everywhere around us; light is necessary to us, so much so that we use artificial light at night. The city street, with its dirty and hard paving stones, has come to take the place of the soil of the village or farm. Water and food are a necessary part of our surroundings. Our clothing, useful to maintain a certain temperature, must also be included. All these things—air, light, heat, water, food—together make up our environment.

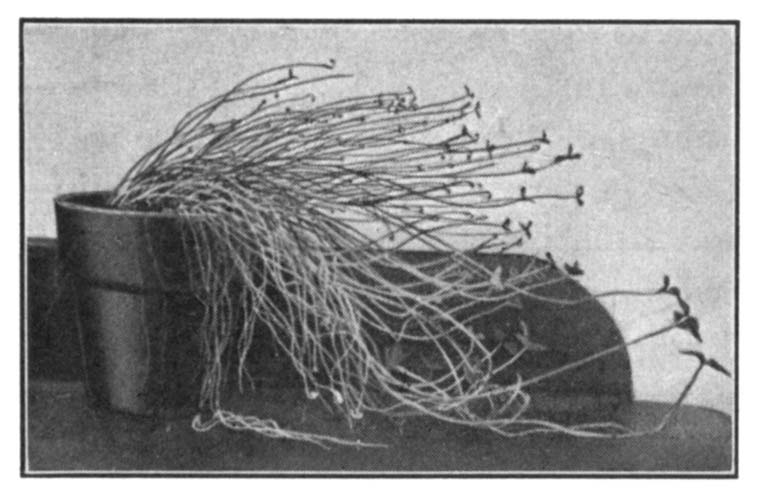

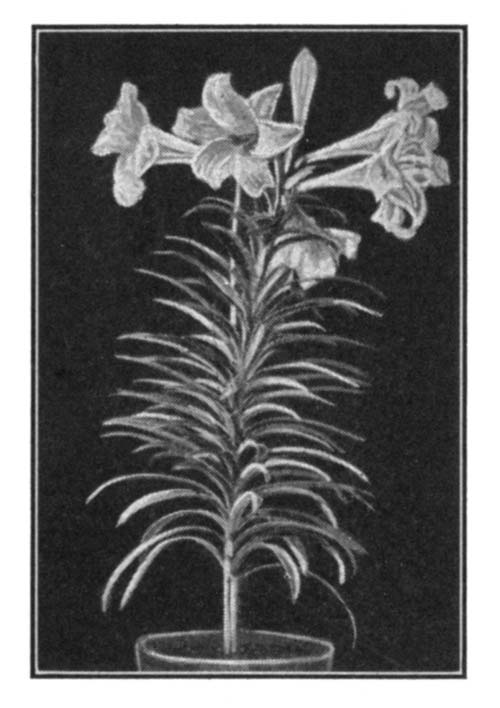

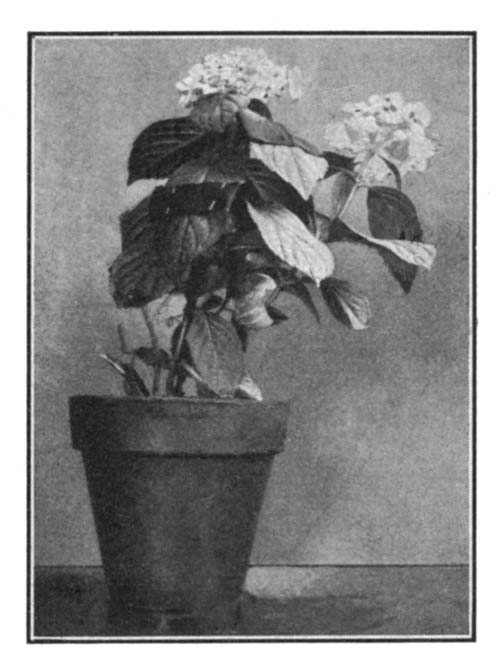

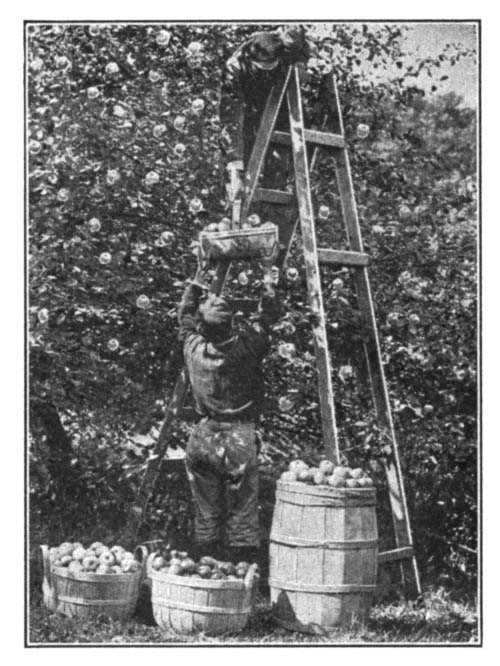

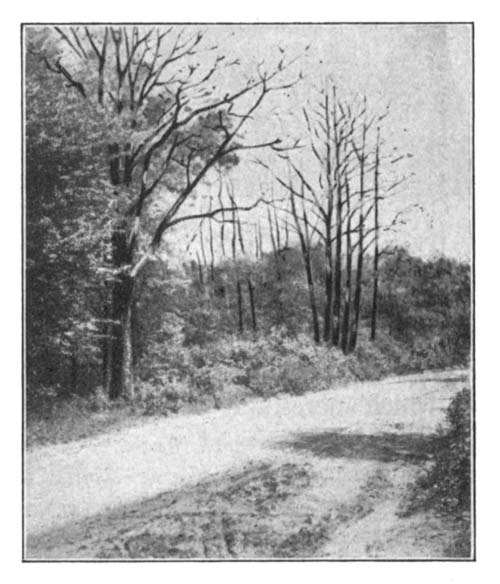

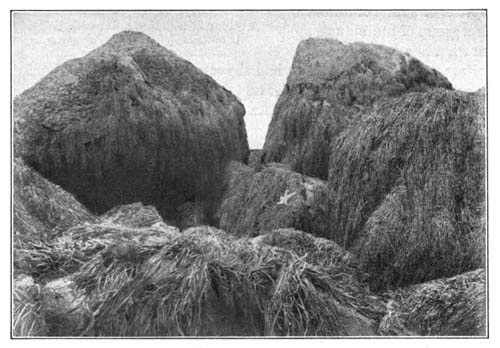

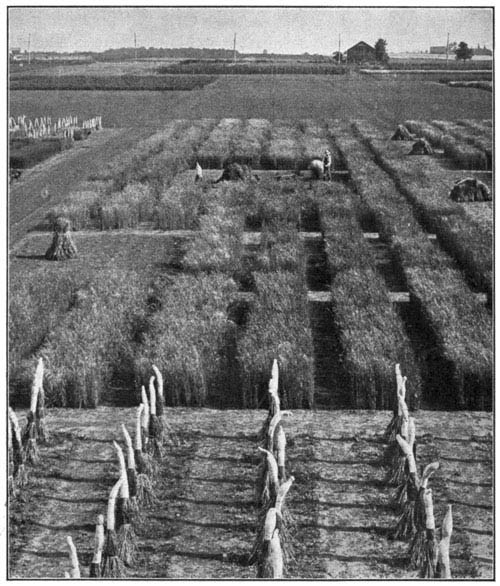

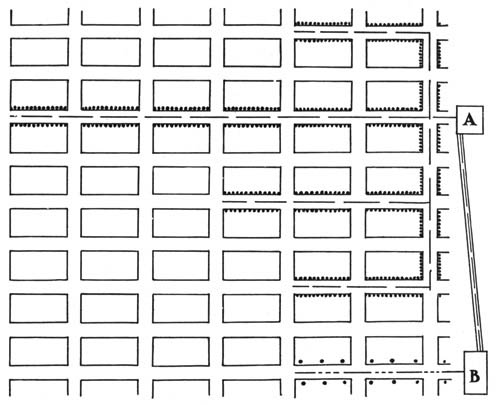

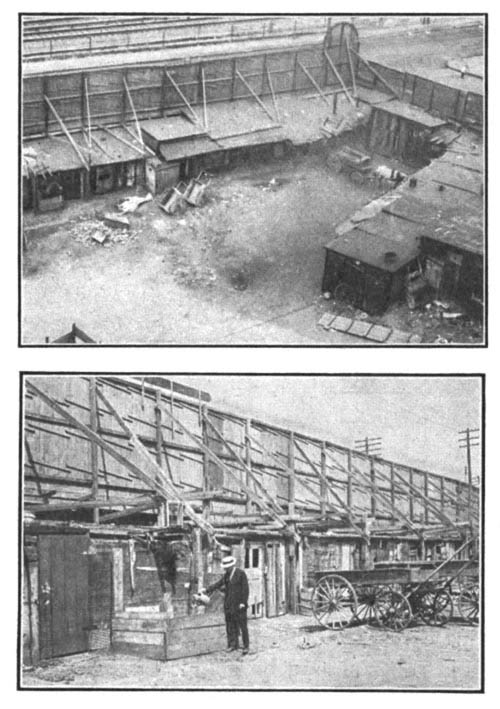

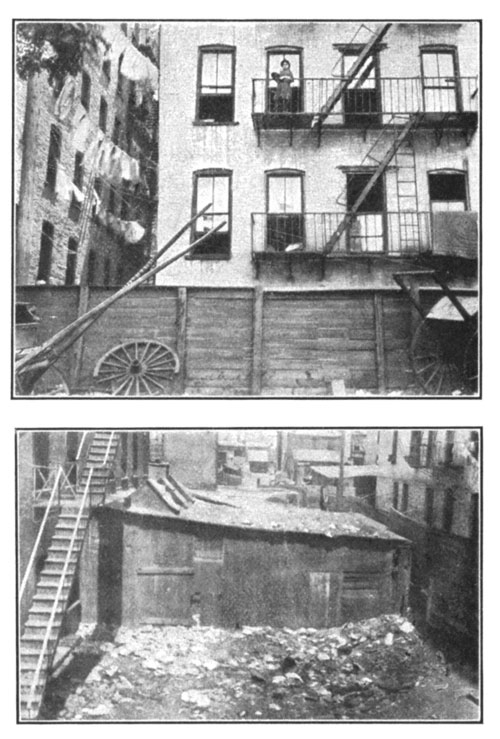

An unfavorable city environment.

All other animals, and all plants as well, are surrounded by and use practically the same things from their environment as we do. The potted plant in the window, the goldfish in the aquarium, your pet dog at home, all use, as we will later prove, the factors of their environment [Pg 20]in the same manner. Air, water, light, a certain amount of heat, soil to live in or on, and food form parts of the surroundings of every living thing.

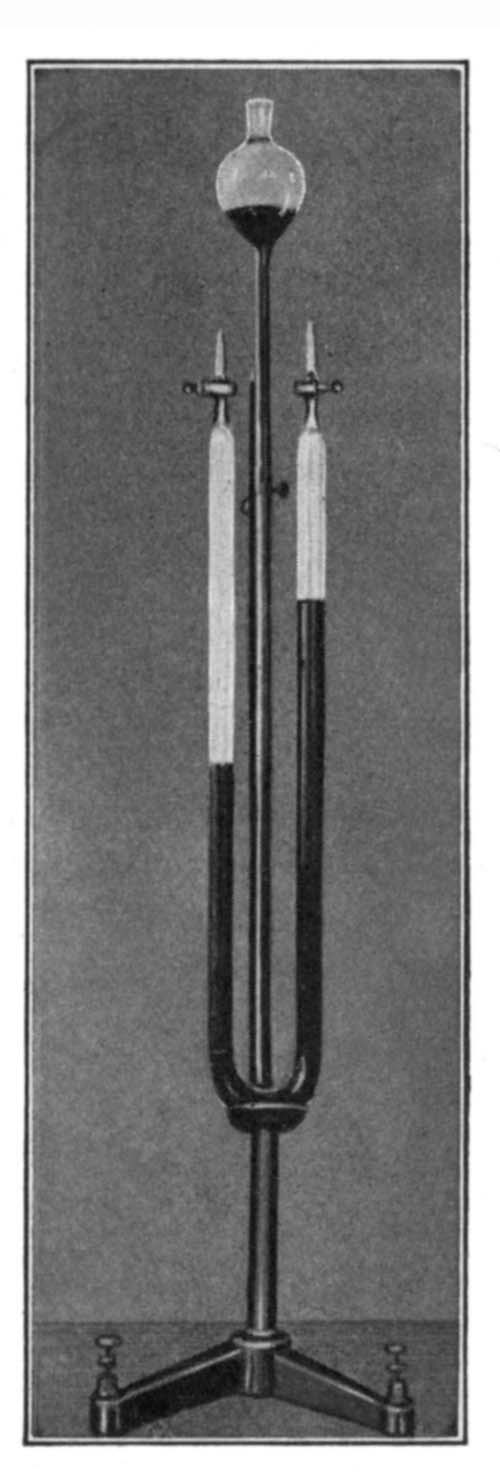

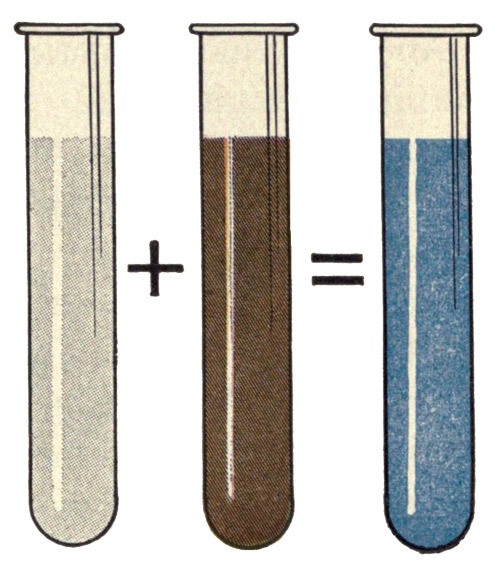

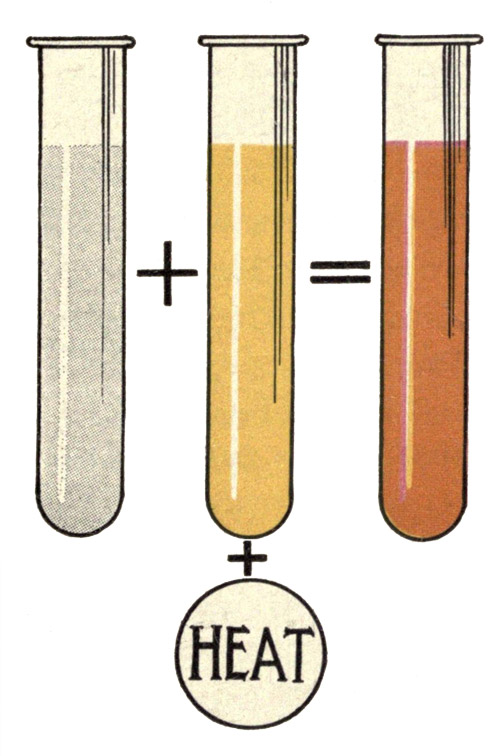

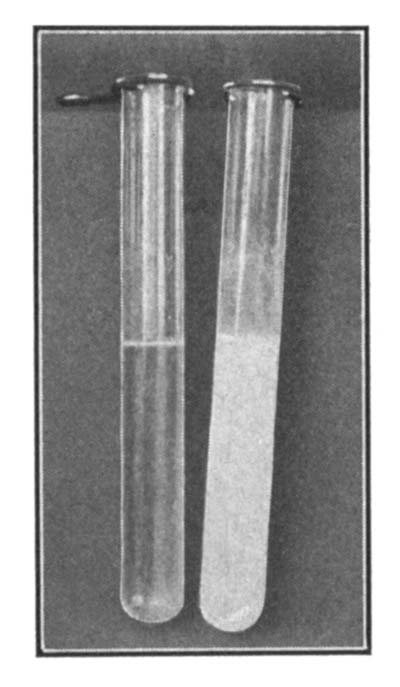

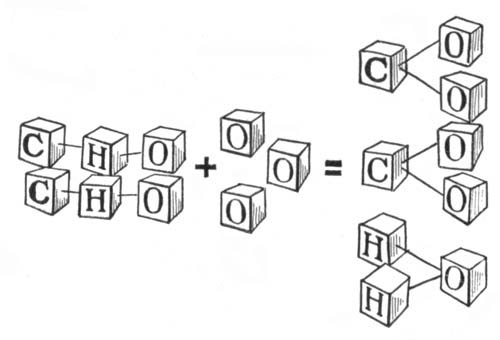

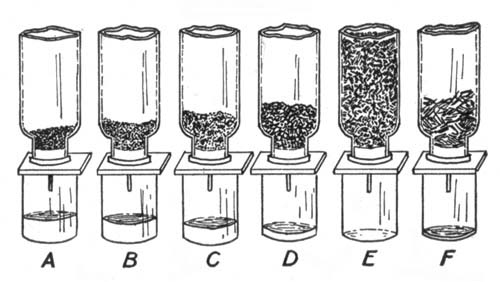

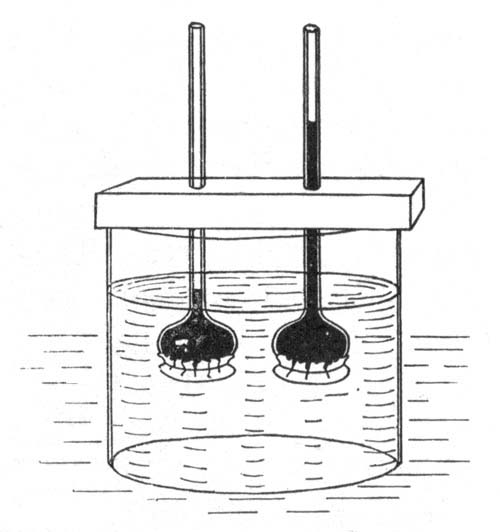

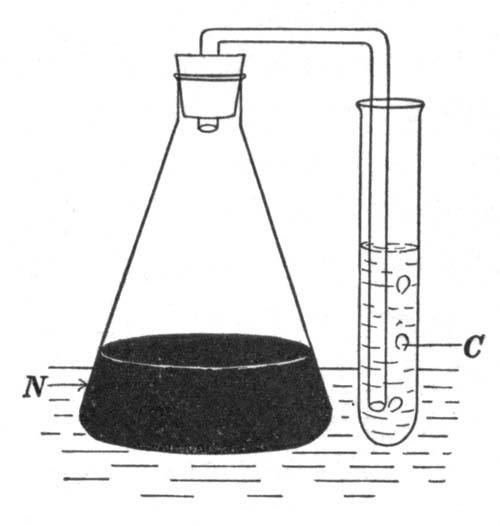

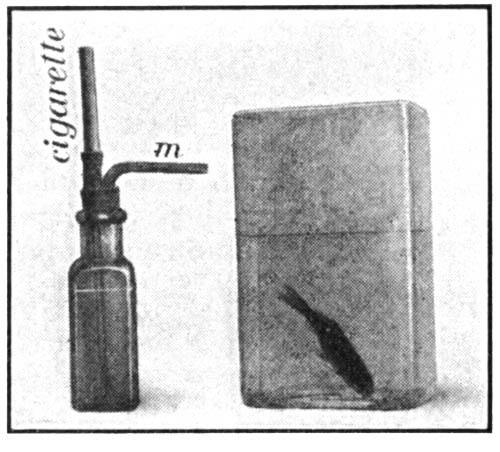

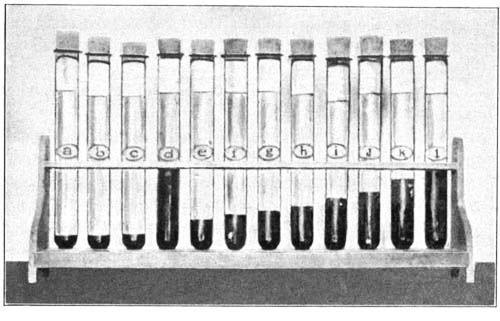

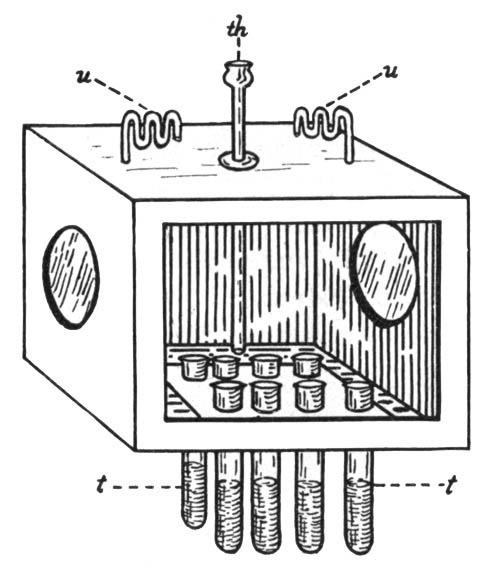

An experiment that shows the air contains about four fifths nitrogen.

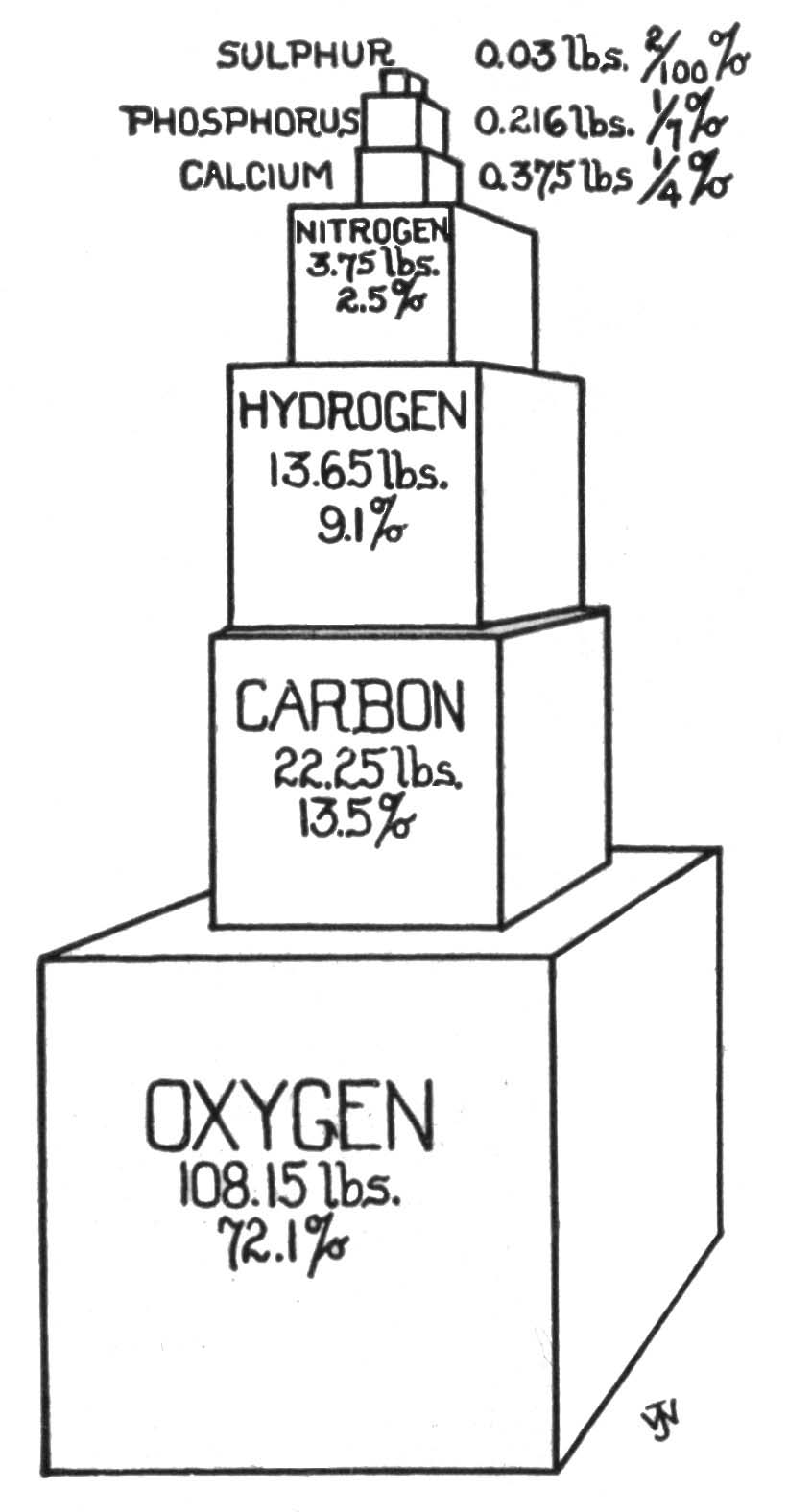

The Same Elements found in Plants and Animals as in their Environment.—It has been found by chemists that the plants and animals as well as their environment may be reduced to about eighty very simple substances known as chemical elements. For example, the air is made up largely of two elements, oxygen and nitrogen. Water, by means of an electric current, may be broken up into two elements, oxygen and hydrogen. The elements in water are combined to make a chemical compound. The oxygen and nitrogen of the air are not so united, but exist as separate gases. If we were to study the chemistry of the bodies of plants and animals and of their foods, we would find them to be made up of certain chemical elements combined in various complex compounds. These elements are principally carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and perhaps a dozen others in very minute proportions. But the same elements present in the living things might also be found [Pg 21]in the environment, for example, water, food, the air, and the soil. It is logical to believe that living things use the chemical elements in their surroundings and in some wonderful manner build up their own bodies from the materials found in their environment. How this is done we will learn in later chapters.

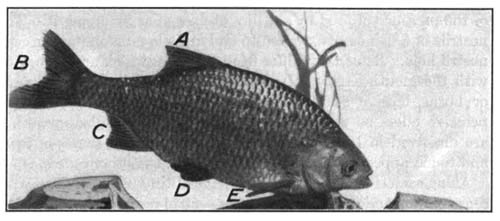

What Plants and Animals take from their Environment. Air.—It is a self-evident fact that animals need air. Even those living in the water use the air dissolved in the water. A fish placed in an air-tight jar will soon die. It will be proven later that plants also need air in order to live.

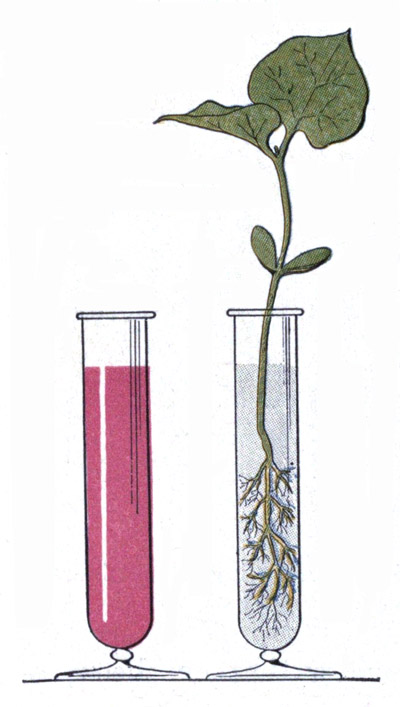

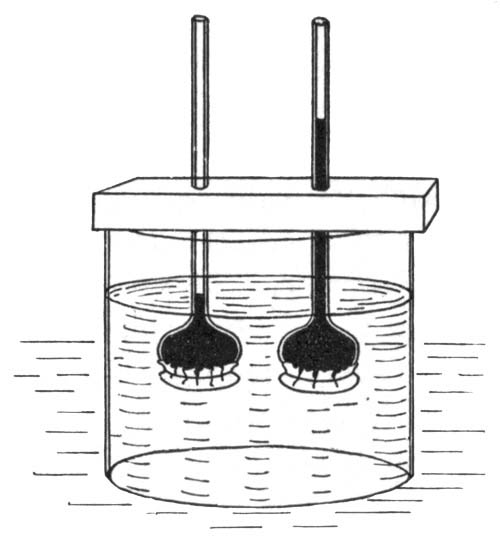

Apparatus for separating water by means of an electric current into the two elements, hydrogen and oxygen.

Chart to show the percentage of chemical elements in the human body.

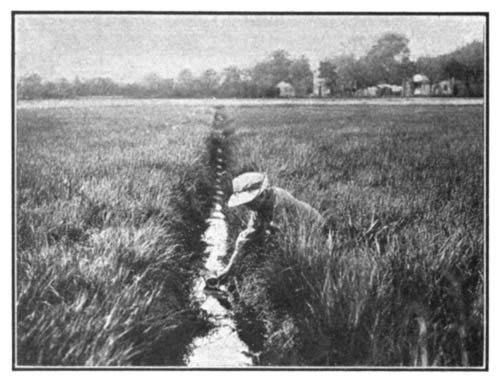

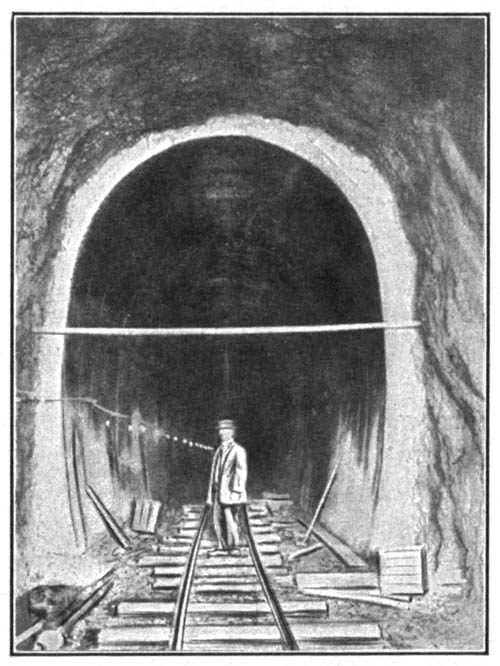

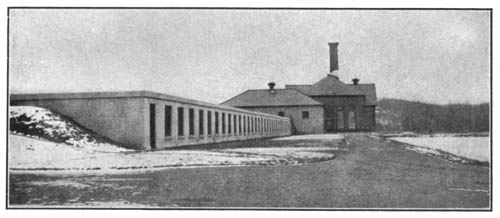

Water.—We all know that water must form part of the environment of plants and animals. It is a matter of common knowledge that pets need water to drink; so do other animals. Every one knows we must water a potted plant if we expect it to grow. Water is of so much importance to man that from the time of the Caesars until now he has spent enormous sums of money to bring pure water to his cities. The United States government is spending millions of dollars at the present time to bring by irrigation the water needed to support life in the western desert lands.

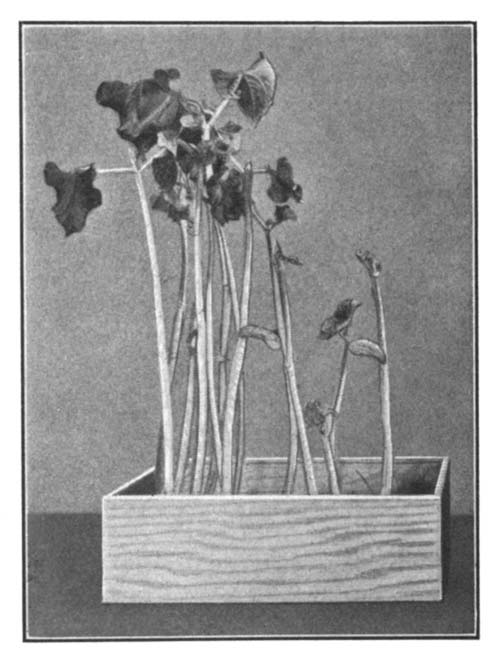

Light as Condition of the Environment.—Light is another important factor of the environment. A study of the leaves on any green plant growing near a window will convince one that such plants grow toward the light. All green plants are thus influenced by the sun. Other plants which are not green seem either indifferent or are negatively influenced (move away from) the source of light. Animals may or may not be attracted by light. A moth, for example, will fly toward a flame, an earthworm will move away from light. Some animals prefer a moderate or [Pg 22]weak intensity of light and live in shady forests or jungles, prowling about at night. Others seem to need much and strong light. And man himself enjoys only moderate intensity of light and heat. Look at the shady side of a city street on any hot day to prove this statement.

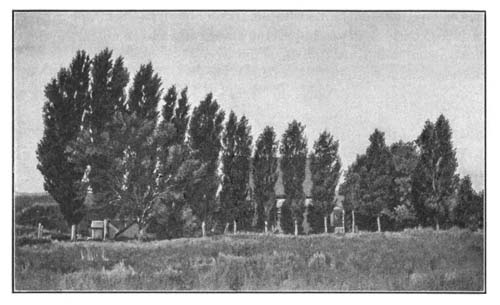

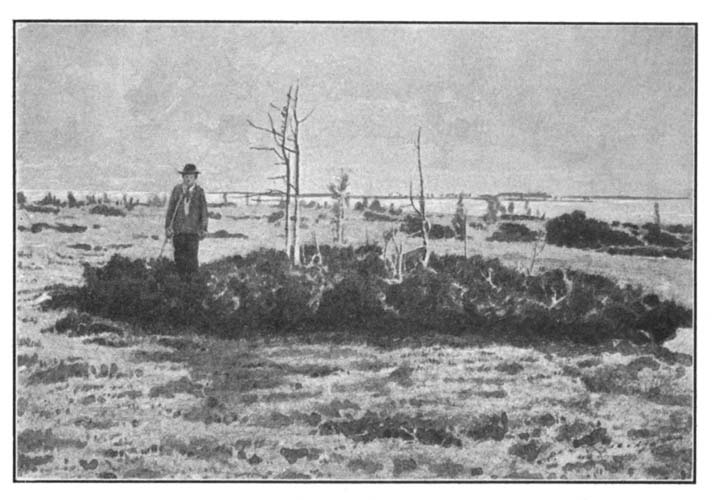

The effect of water upon the growth of trees. These trees were all planted at the same time in soil that is sandy and uniform. They are watered by a small stream which runs from left to right in the picture. Most of the water soaks into the ground before reaching the last trees.

The effect of light upon a growing plant.

Heat.—Animals and plants are both affected by heat or the absence of it. In cold weather green plants either die or their life activities are temporarily suspended,—the plant becomes dormant. Likewise small animals, such as insects, may be killed by cold or they may hibernate under stones or boards. Their life activities are stilled until the coming of warm weather. Bears [Pg 23]and other large animals go to sleep during the winter and awake thin and active at the approach of warm weather. Animals or plants used to certain temperatures are killed if removed from those temperatures. Even man, the most adaptable of all animals, cannot stand great changes without discomfort and sometimes death. He heats his houses in winter and cools them in summer so as to have the amount of heat most acceptable to him, i.e. about 70° Fahrenheit.

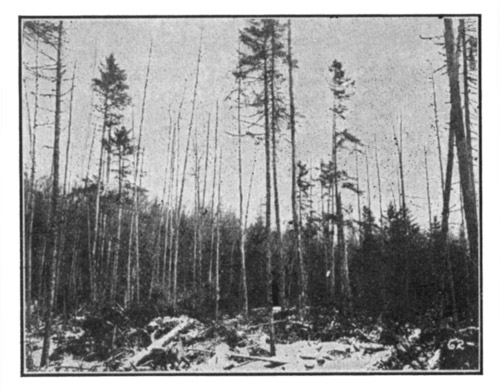

Vegetation in Northern Russia. The trees in this picture are nearly one hundred years old. They live under conditions of extreme cold most of the year.

The Environment determines the Kind of Animals and Plants within It.—In our study of geography we learned that certain luxuriant growths of trees and climbing plants were characteristic of the tropics with its moist, warm climate. No one would expect to find living there the hardy stunted plants of the arctic region. Nor would we expect to find the same kinds of animal life in warm regions as in cold. The surroundings determine the kind of living things there. Plants or animals fitted to live in a given locality will probably be found there if they have had an opportunity to [Pg 24]reach that locality. If, for example, temperate forms of life were introduced by man into the tropics, they would either die or they would gradually change so as to become fitted to live in their new environment. Sheep with long wool fitted to live in England, when removed to Cuba, where conditions of greater heat exist, soon died because they were not fitted or adapted to live in their changed environment.

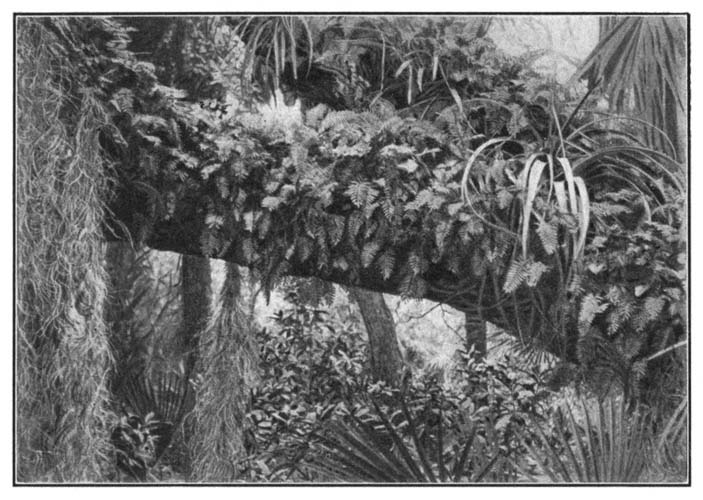

Plant life in a moist tropical forest. Notice the air plants to the left and the resurrection ferns on the tree trunk.

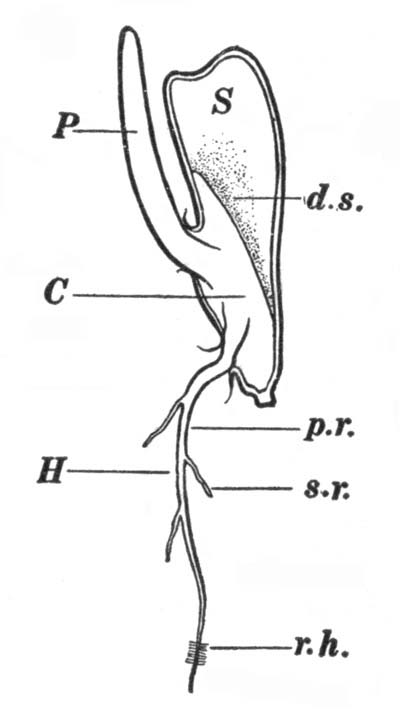

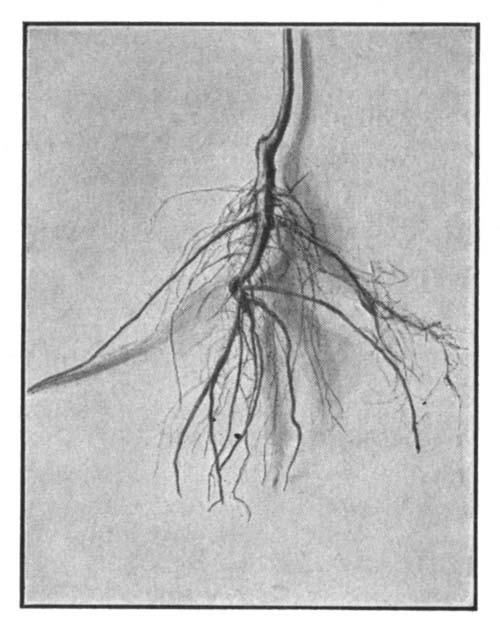

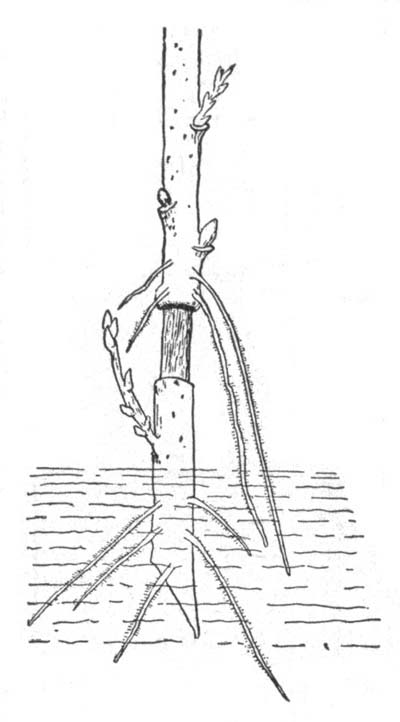

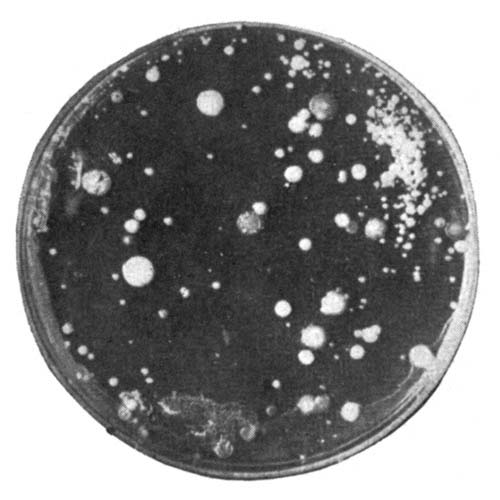

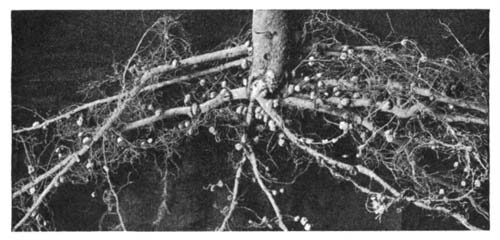

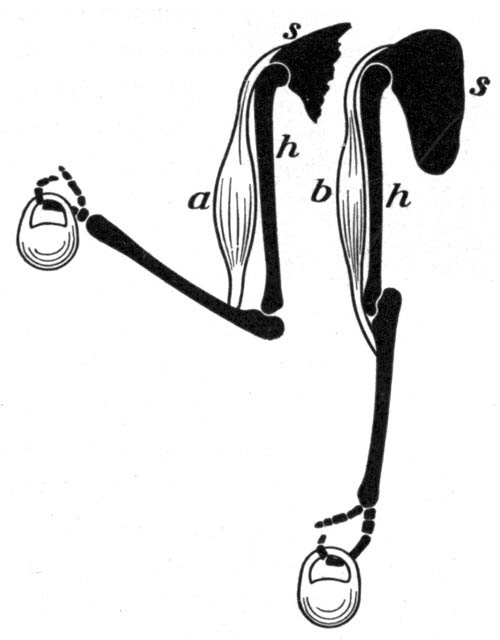

Adaptations.—Plants and animals are not only fitted to live under certain conditions, but each part of the body may be fitted to do certain work. I notice that as I write these words the fingers of my right hand grasp the pen firmly and the hand and arm execute some very complicated movements. This they are able to do because of the free movement given through the arrangement of the delicate bones of the wrist and fingers, their attachment to the bones of the arm, a wonderful complex of muscles which move the bones, and a directing nervous system which plans the work. Because of the peculiar fitness in the structure of the [Pg 25]hand for this work we say it is adapted to its function of grasping objects. Each part of a plant or animal is usually fitted for some particular work. The root of a green plant, for example, is fitted to take in water by having tiny absorbing organs growing from it, the stems have pipes or tubes to convey liquids up and down and are strong enough to support the leafy part of the plant. Each part of a plant does work, and is fitted, by means of certain structures, to do that work. It is because of these adaptations that living things are able to do their work within their particular environment.

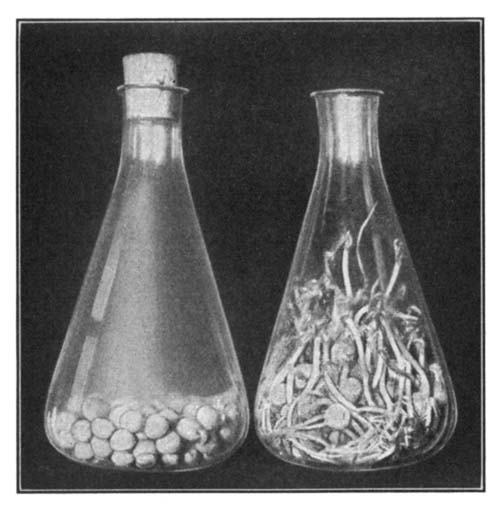

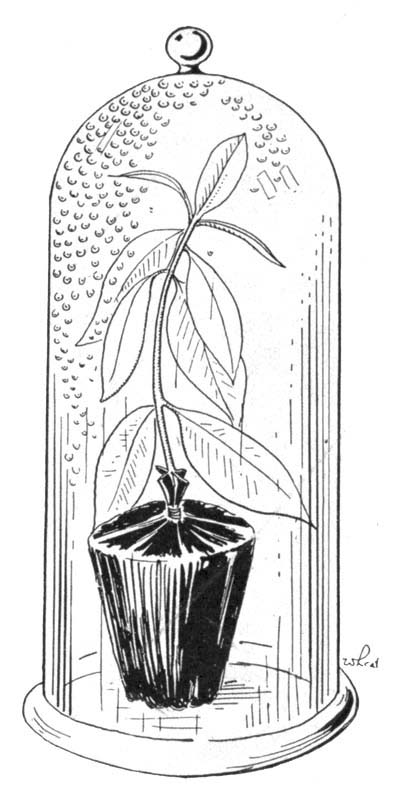

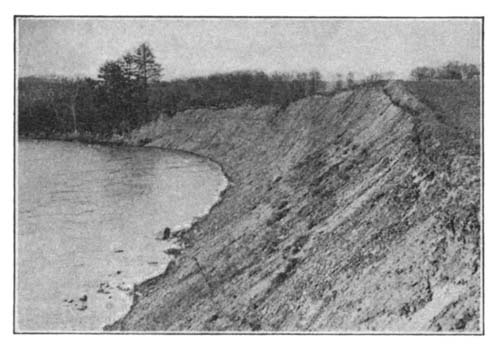

Plants and Animals and their Natural Environment.—Those of us who have tried to keep potted plants in the schoolroom know how difficult it is to keep them healthy. Dust, foreign gases in the air, lack of moisture, and other causes make the artificial environment in which they are placed unsuitable for them.

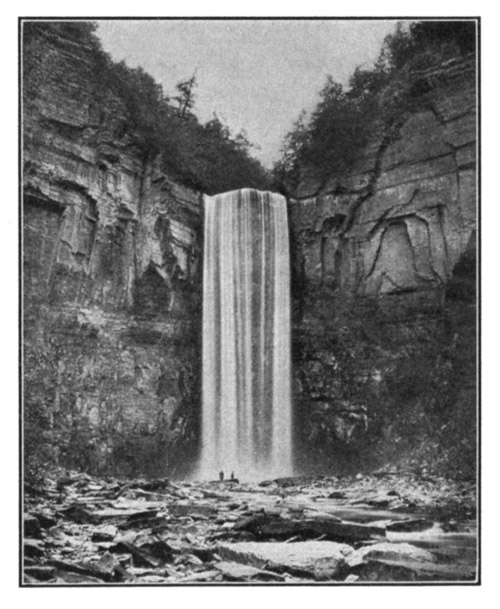

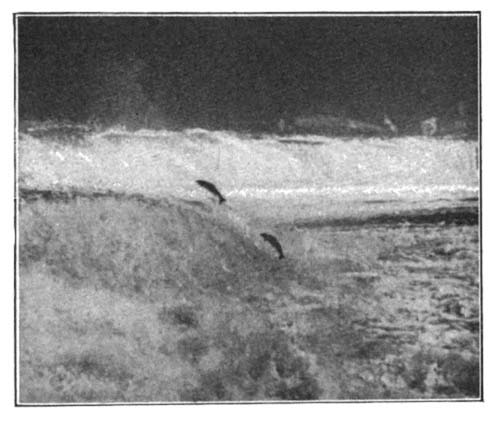

A natural barrier on a stream. No trout would be found above this fall. Why not?

A goldfish placed in a small glass jar with no food or no green water plants soon seeks the surface of the water, and if the water is not changed frequently so as to supply air the fish will die. Again the artificial environment lacks something that the fish needs. Each plant and animal is limited to a certain environment because of certain individual needs which make the surroundings fit for it to live in.

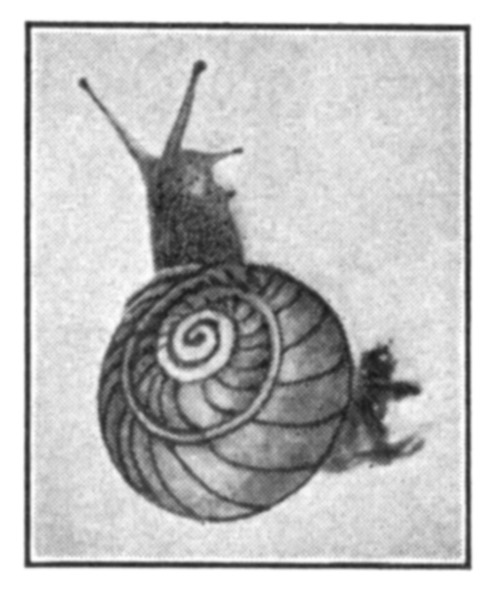

Changes in Environment.—Most plants and animals do not change their environment. Trees, green plants of all kinds, and some animals remain [Pg 26]fixed in one spot practically all their lives. Certain tiny plants and most animals move from place to place, either in air, water, on the earth or in the earth, but they maintain relatively the same conditions in environment. Birds are perhaps the most striking exception, for some may fly thousands of miles from their summer homes to winter in the south. Other animals, too, migrate from place to place, but not usually where there are great changes in the surroundings. A high mountain chain with intense cold at the upper altitudes would be a barrier over which, for example, a bear, a deer, or a snail could not travel. Fish like trout will migrate up a stream until they come to a fall too high for them to jump. There they must stop because their environment limits them.

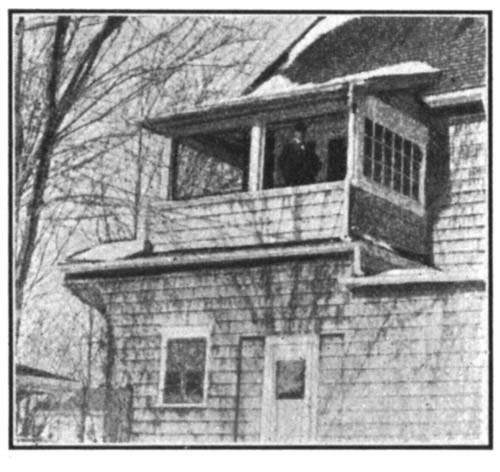

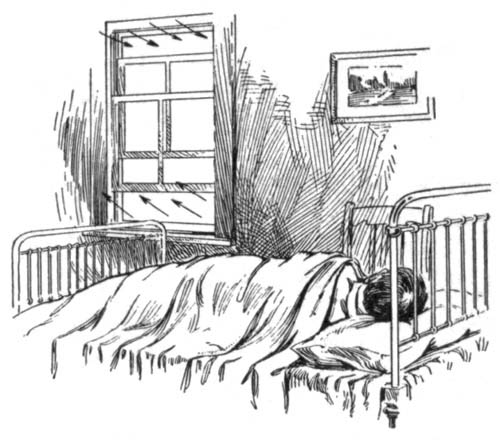

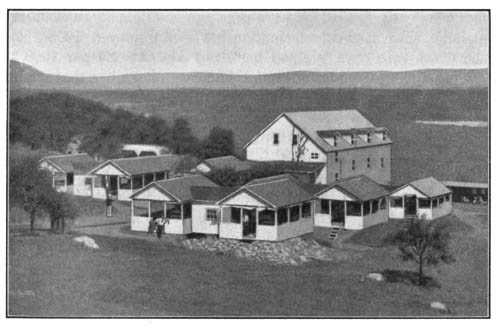

A new apartment house, with out-of-door sleeping porch.

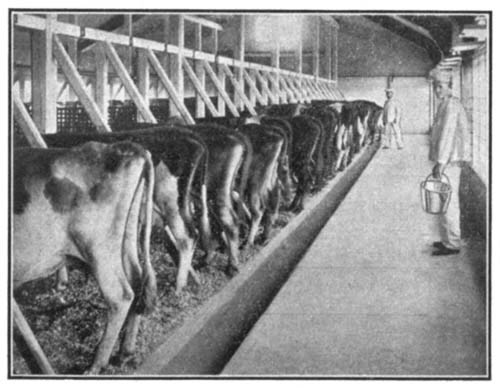

Man in his Environment.—Man, while he is like other animals in requiring heat, light, water, and food, differs from them in that he has come to live in a more or less artificial environment. Men who lived on the earth thousands of year ago did not wear clothes or have elaborate homes of wood or brick or stone. They did not use fire, nor did they eat cooked foods. In short, by slow degrees, civilized man has come to live in a changed environment from that of other animals. The living together of men in communities has caused certain needs to develop. Many things can be supplied in common, as water, milk, foods. Wastes of all kinds have to be disposed of in a town or city. Houses have come [Pg 27]to be placed close together, or piled on top of each other, as in the modern apartment. Fields and trees, all outdoor life, has practically disappeared. Man has come to live in an artificial environment.

Care and Improvement of One's Environment.—Man can modify or change his surroundings by making this artificial environment favorable to live in. He may heat his dwellings in winter and cool them in summer so as to maintain a moderate and nearly constant temperature. He may see that his dwellings have windows so as to let light and air pass in and out. He may have light at night and shade by day from intense light. He may have a system of pure water supply and may see that drains or sewers carry away his wastes. He may see to it that people ill with "catching" or infectious diseases are isolated or quarantined from others. This care of the artificial environment is known as sanitation, while the care of the individual for himself within the environment is known as hygiene. It will be the chief end of this book to show girls and boys how they may become good citizens through the proper control of personal hygiene and sanitation.

Reference Books

elementary

Hunter, Laboratory Problems in Civic Biology. American Book Company.

Hough and Sedgwick, Elements of Hygiene and Sanitation. Ginn and Company.

Jordan and Kellogg, Animal Life. Appleton.

Sharpe, A Laboratory Manual for the Solution of Problems in Biology, p. 95. American Book Company.

Tolman, Hygiene for the Worker. American Book Company.

advanced

Allen, Civics and Health. Ginn and Company.

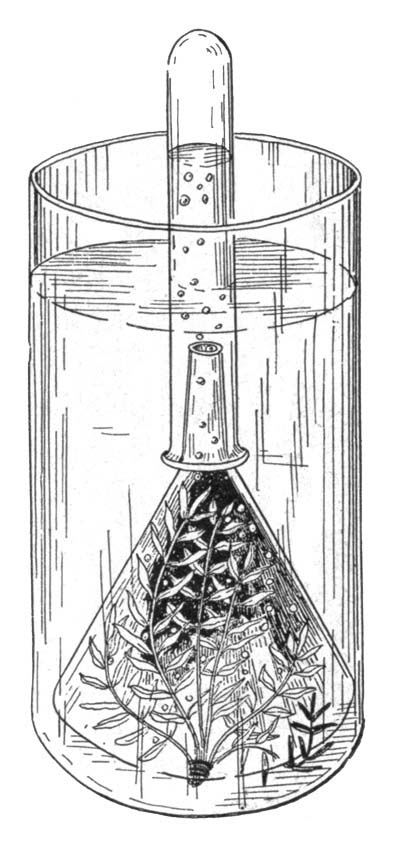

Problem.—To discover the general interrelations of green plants and animals.

(a) Plants as homes for insects.

(b) Plants as food for insects.

(c) Insects as pollinating agents.

Laboratory Suggestions

A field trip:—Object: to collect common insects and study their general characteristics; to study the food and shelter relation of plant and insects. The pollination of flowers should also be carefully studied so as to give the pupil a general viewpoint as an introduction to the study of biology.

Laboratory exercise.—Examination of simple insect, identification of parts—drawing. Examination and identification of some orders of insects.

Laboratory demonstration.—Life history of monarch and some other butterflies or moths.

Laboratory exercise.—Study of simple flower—emphasis on work of essential organs, drawing.

Laboratory exercise.—Study of mutual adaptations in a given insect and a given flower, e.g. butter and eggs and bumble bee.

Demonstration of examples of insect pollination.

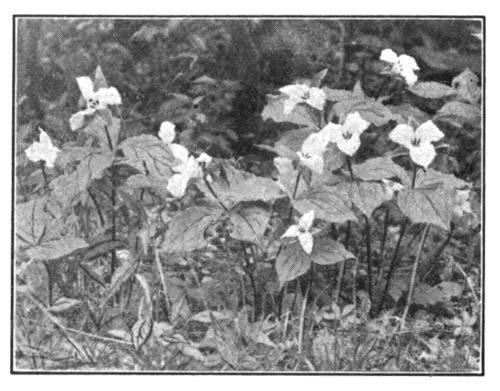

The Object of a Field Trip.—Many of us live in the city, where the crowded streets, the closely packed apartments, and the city playgrounds form our environment. It is very artificial at best. To understand better the normal environment of plants or animals we should go into the country. Failing in this, an overgrown city lot or a park will give us much more closely the environment as it touches some animals lower than man. We must then remember that in learning something of the natural environment of other living creatures we may better understand our own environment and our relation to it.

[Pg 29] On any bright warm day in the fall we will find insects swarming everywhere in any vacant lot or the less cultivated parts of a city park. Grasshoppers, butterflies alighting now and then on the flowers, brightly marked hornets, bees busily working over the purple asters or golden rod, and many other forms hidden away on the leaves or stems of plants may be seen. If we were to select for observation some partially decayed tree, we would find it also inhabited. Beetles would be found boring through its bark and wood, while caterpillars (the young stages of butterflies or moths) are feeding on its leaves or building homes in its branches. Everywhere above, on, and under ground may be noticed small forms of life, many of them insects. Let us first see how we would go to work to identify some of the common forms we would be likely to find on plants. Then a little later we will find out what they are doing on these plants.

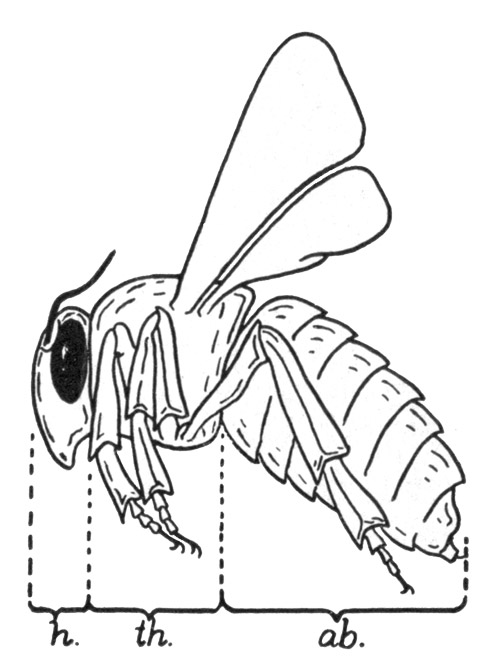

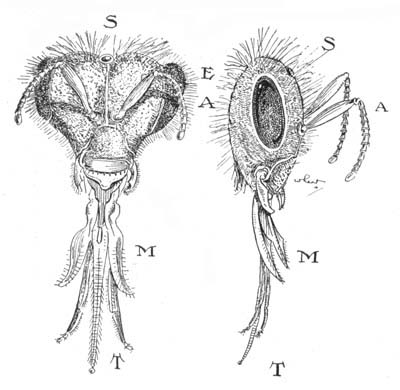

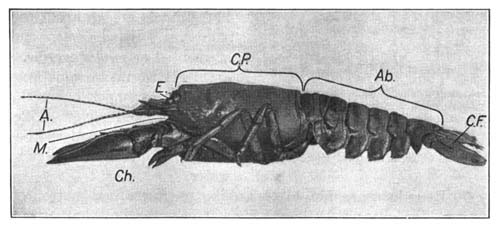

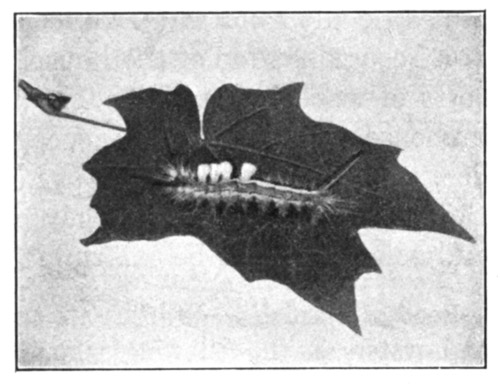

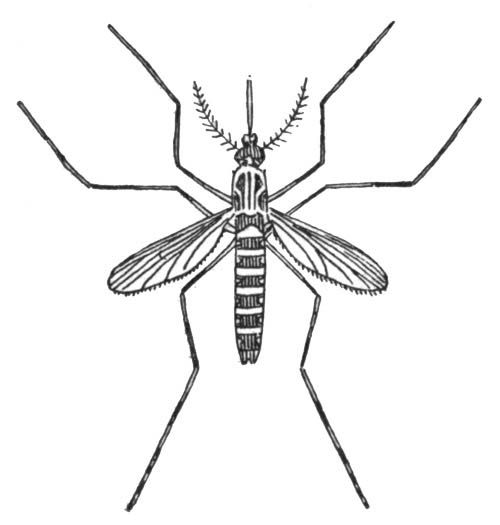

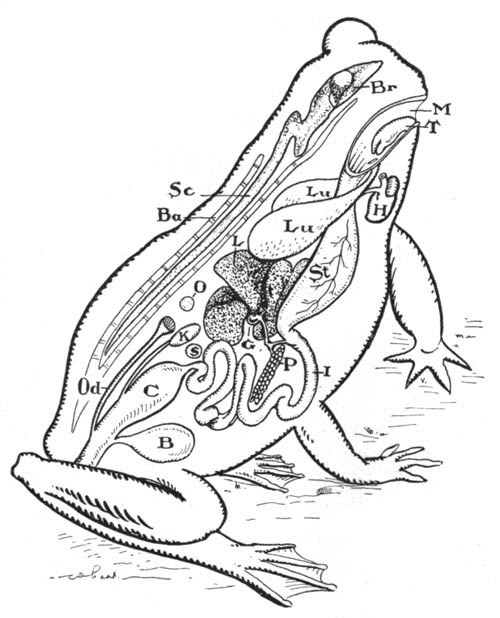

An insect viewed from the side. Notice the head, thorax, and abdomen. What other characters do you find?

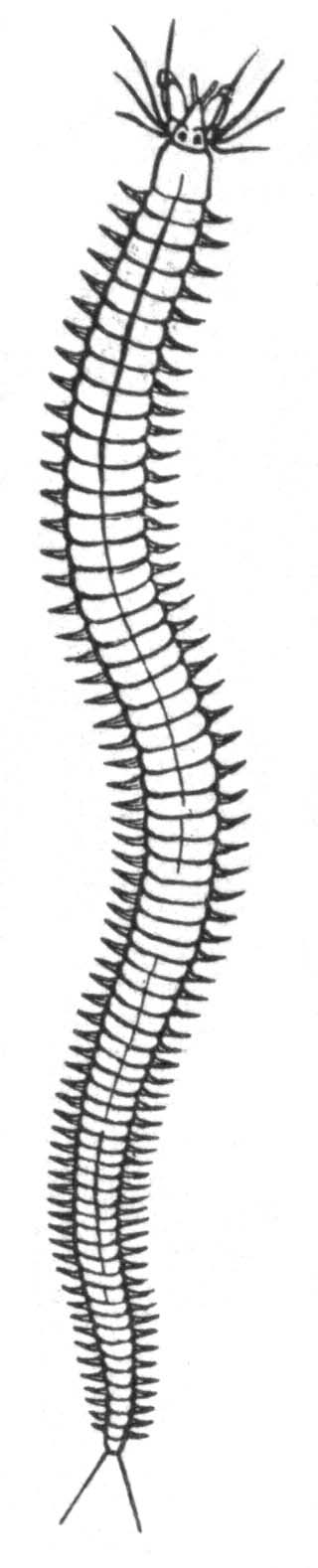

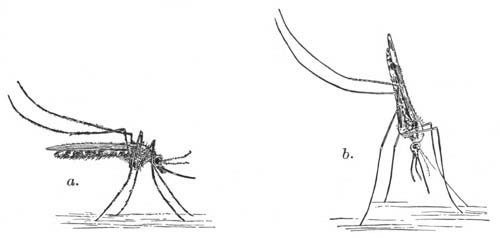

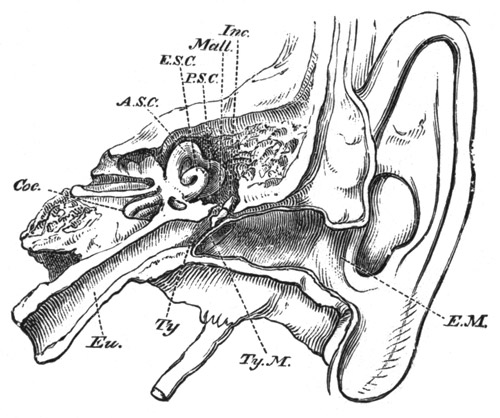

How to tell an Insect.—A bee is a good example of the group of animals we call insects. If we examine its body carefully, we notice that it has three regions, a front part or head, a middle part called the thorax, and a hind portion, jointed and hairy, the abdomen. We cannot escape noting the fact that this insect has wings with which it flies and that it also has legs. The three pairs of legs, which are jointed and provided with tiny hooks at the end, are attached to the thorax. Two pairs of delicate wings are attached to the upper or dorsal side of the thorax. The thorax and indeed the entire body, is covered with a hard shell of material similar to a cow's horn, there being no skeleton inside for the attachment of muscles. If we carefully watch the abdomen of a living bee, we notice it move up and down quite regularly. The animal is breathing through tiny breathing holes called spiracles, [Pg 30]placed along the side of the thorax and abdomen. Bees also have compound eyes. Wings are not found on all insects, but all the other characters just given are marks of the great group of animals we call insects.

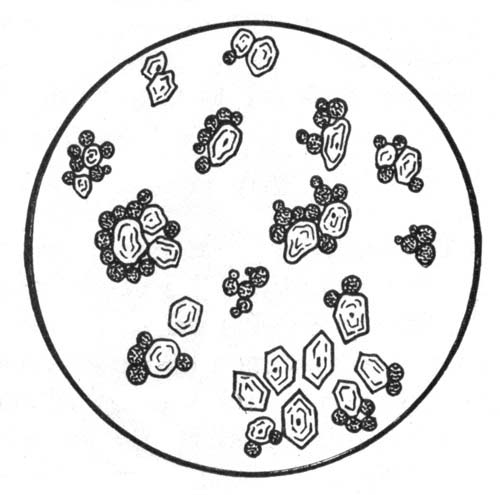

Part of the compound eye of an insect (highly magnified).

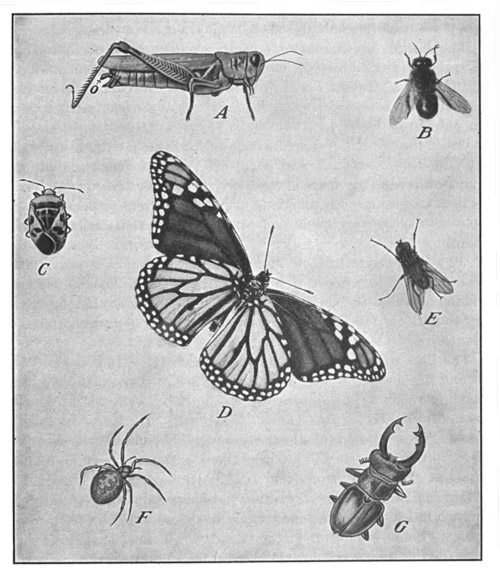

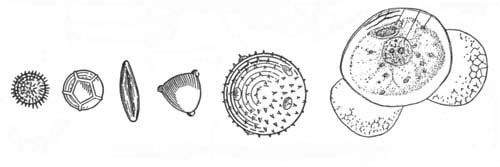

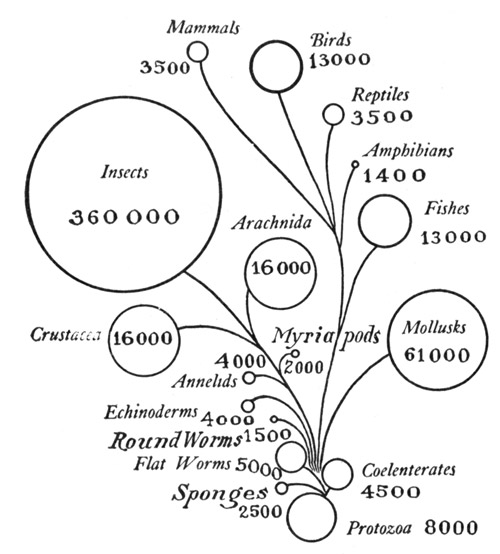

Forms to be looked for on a Field Trip.—Inasmuch as there are over 360,000 different species or kinds of insects, it is evident that it would be a hopeless task for us even to think of recognizing all of them. But we can learn to recognize a few examples of the common forms that might be met on a field trip. In the fields, on grass, or on flowering plants we may count on finding members from six groups or orders of insects. These may be known by the following characters.

The order Hymenoptera (membrane wing) to which the bees, wasps, and ants belong is the only insect group the members of which are provided with true stings. This sting is placed in a sheath at the extreme hind end of the abdomen. Other characteristics, which show them to be insects, have been given above.

Butterflies or moths will be found hovering over flowers. They belong to the order Lepidoptera (scale wings). This name is given to them because their wings are covered with tiny scales, which fit into little sockets on the wing much as shingles are placed on a roof. The dust which comes off on the fingers when one catches a butterfly is composed of these scales. The wings are always large and usually brightly colored, the legs small, and one pair is often inconspicuous. These insects may be seen to take liquid food through a long tubelike organ, called the proboscis, which they keep rolled up under the head when not in use. The young of the butterfly or moth are known as caterpillars and feed on plants by means of a pair of hard jaws.

Grasshoppers, found almost everywhere, and crickets, black grasshopper-like insects often found under stones, belong to the order Orthoptera (straight wings). Members of this group may usually be distinguished by their strong, jumping hind legs, by their chewing or biting mouth parts, and by the fact that the hind wings are folded up under the somewhat stiffer front wings. [Pg 31]

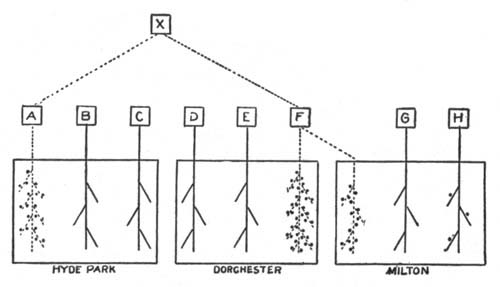

Forms of life to be met on a field trip. A, The red-legged locust, one of the Orthoptera; o, the egg-layer, about natural size. B, the honey bee, one of the Hymenoptera, about natural size. C, a bug, one of the Hemiptera, about natural size. D, a butterfly, an example of the Lepidoptera, slightly reduced. E, a house fly, an example of the Diptera, about twice natural size. F, an orb-weaving spider, about half natural size. (This is not an insect, note the number of legs.) G, a beetle, slightly reduced, one of the Coleoptera.

Another group of insects sometimes found on flowers in the fall are flies. They belong to the order Diptera (two wings). These insects are usually rather small and have a single pair of gauzy [Pg 32]wings. Flies are of much importance to man because certain of their number are disease carriers.

Bugs, members of the order Hemiptera (half wings), have a jointed proboscis which points backward between the front legs. They are usually small and may or may not have wings.

The beetles or Coleoptera (sheath wings), often mistaken for bugs by the uneducated, have the first pair of hardened wings meeting in a straight line in the middle of the back, the second pair of wings being covered by them. Beetles are frequently found on goldenrod blossoms in the fall.

Other forms of life, especially spiders, which have four pairs of walking legs, centipedes and millepedes, both of which are wormlike and have many pairs of legs, may be found.

Try to discover members of the six different orders named above. Collect specimens and bring them to the laboratory for identification.

Why do Insects live on Plants?—We have found insect life abundant on living green plants, some visiting flowers, others hidden away on the stalks or leaves of the plants. Let us next try to find out why insects live among and upon flowering green plants.

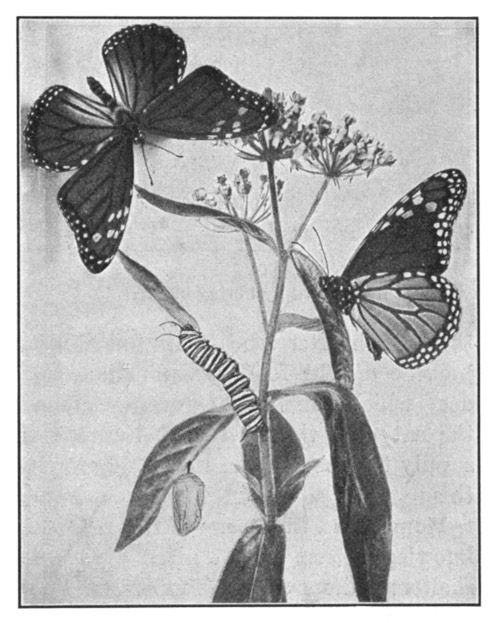

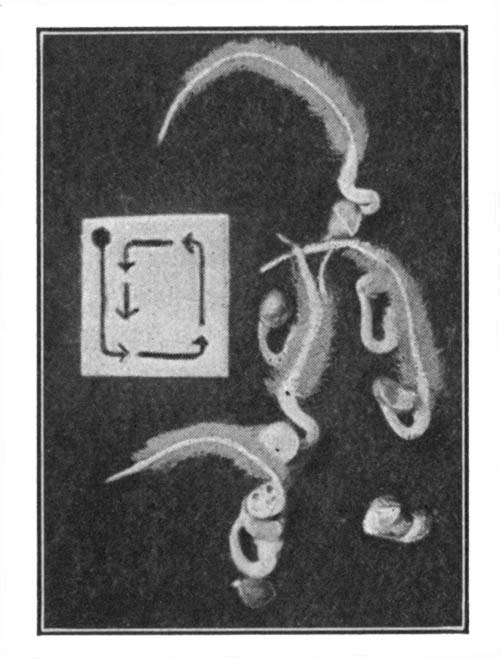

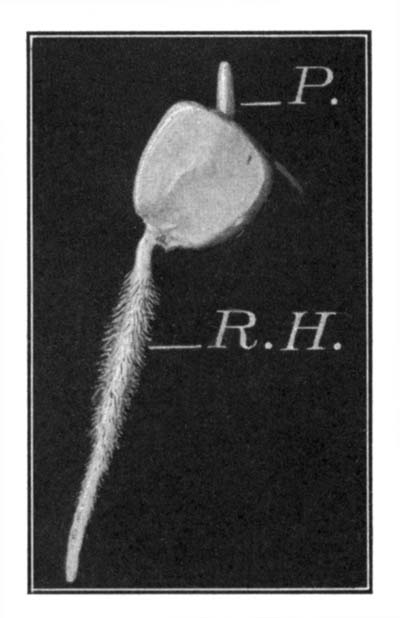

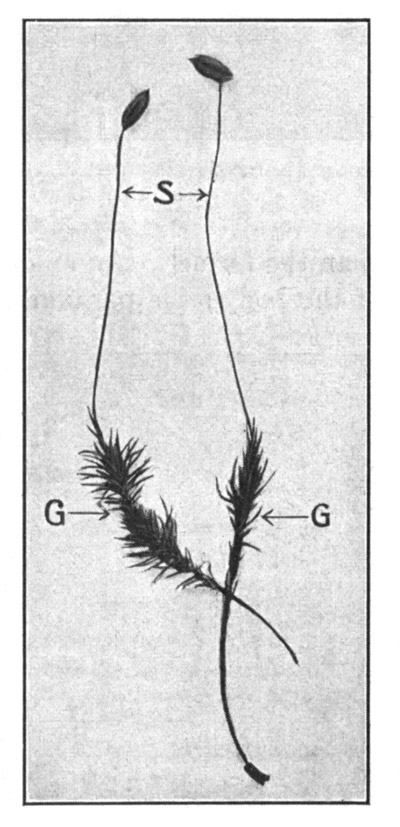

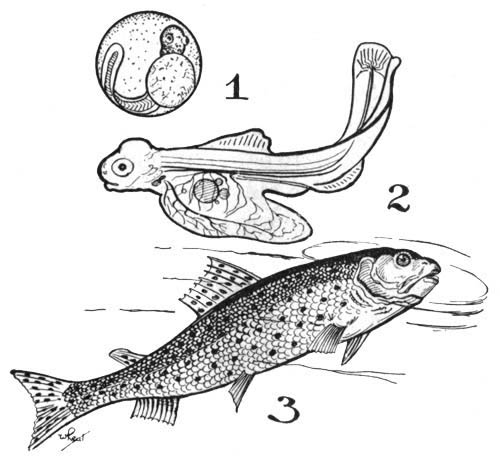

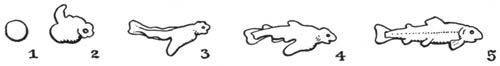

The Life History of the Milkweed Butterfly.—If it is possible to find on our trip some growing milkweed, we are quite likely to find hovering near, a golden brown and black butterfly, the monarch or milkweed butterfly (Anosia plexippus). Its body, as in all insects, is composed of three regions. The monarch frequents the milkweed in order to lay eggs there. This she may be found doing at almost any time from June until September.

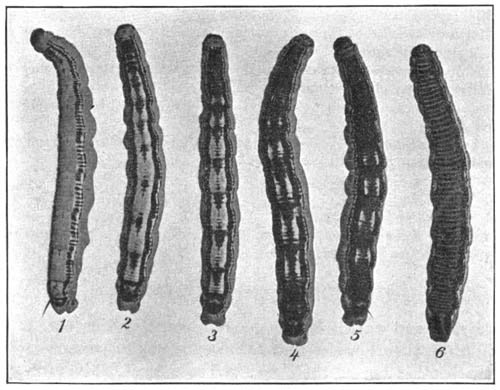

Egg and Larva.—The eggs, tiny hat-shaped dots a twentieth of an inch in length, are fastened singly to the underside of milkweed leaves. Some wonderful instinct leads the animal to deposit the eggs on the milkweed, for the young feed upon no other plant. The eggs hatch out in four or five days into rapid-growing wormlike caterpillars, each of which will shed its skin several times before it becomes full size. These caterpillars possess, in addition to the three pairs of true legs, additional pairs of prolegs or caterpillar legs. The animal at this stage is known as a larva.

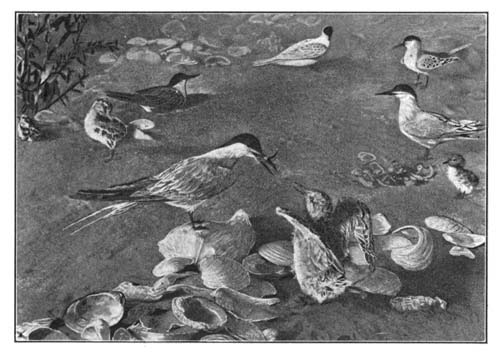

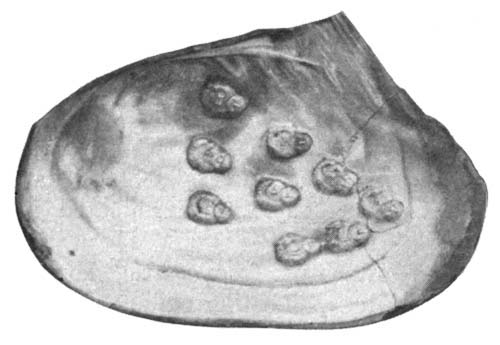

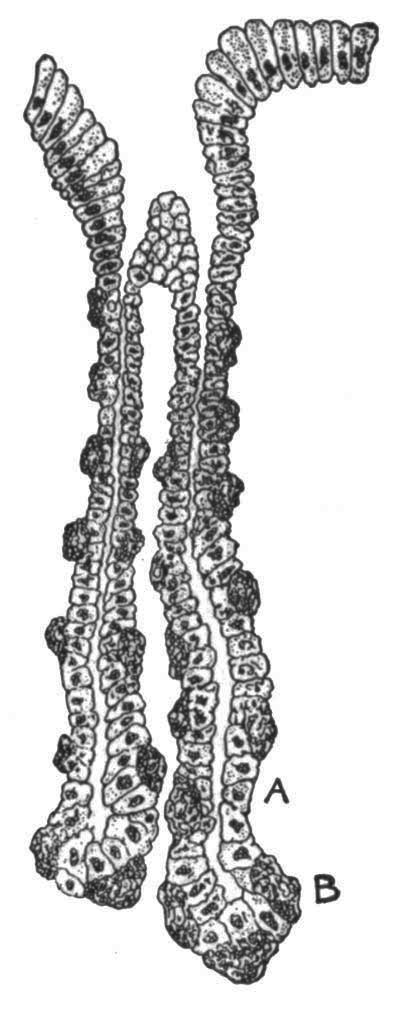

Monarch butterfly: adults, larvæ, and pupa on their food plant, the milkweed. (From a photograph loaned by the American Museum of Natural History.)

[Pg 33]Formation of Pupa.—After a life of a few weeks at most, the caterpillar stops eating and begins to spin a tiny mat of silk upon a leaf or stem. It attaches itself to this web by the last pair of prolegs, and there hangs in the dormant stage known as the chrysalis or pupa. This is a resting stage during which the body changes from a caterpillar to a butterfly.

The Adult.—After a week or more of inactivity in the pupa state, the outer skin is split along the back, and the adult butterfly emerges. At first the wings are soft and much smaller than in the adult. Within fifteen minutes to half an hour after the butterfly emerges, however, the wings are full-sized, having been pumped full of blood and air, and the little insect is ready after her wedding flight to follow her instinct to deposit her eggs on a milkweed plant.

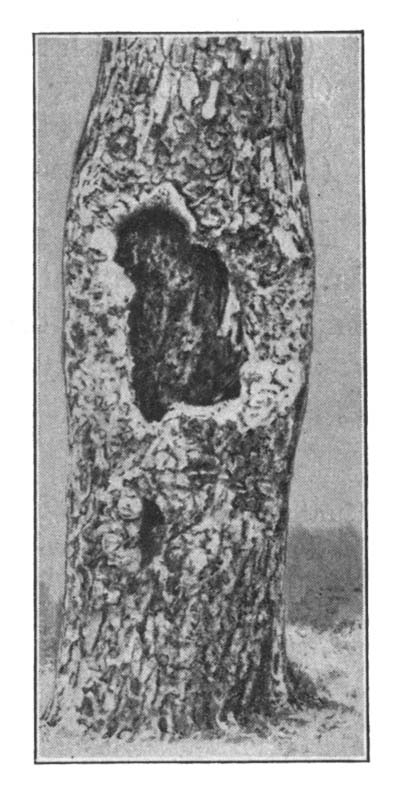

Plants furnish Insects with Food.—Food is the most important factor of any animal's environment. The insects which we have seen on our field trip feed on the green plants among which they live. Each insect has its own particular favorite food plant or plants, and in many cases the eggs of the insect are laid on the food plant so that the young may have food close at hand. Some insects prefer the rotted wood of trees. An American zoölogist, Packard, has estimated that over 450 kinds of insects live upon [Pg 34]oak trees alone. Everywhere animals are engaged in taking their nourishment from plants, and millions of dollars of damage is done every year to gardens, fruits, and cereal crops by insects.

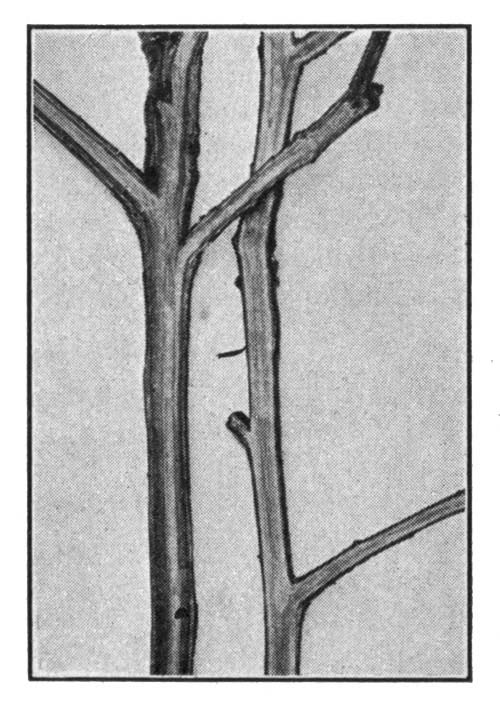

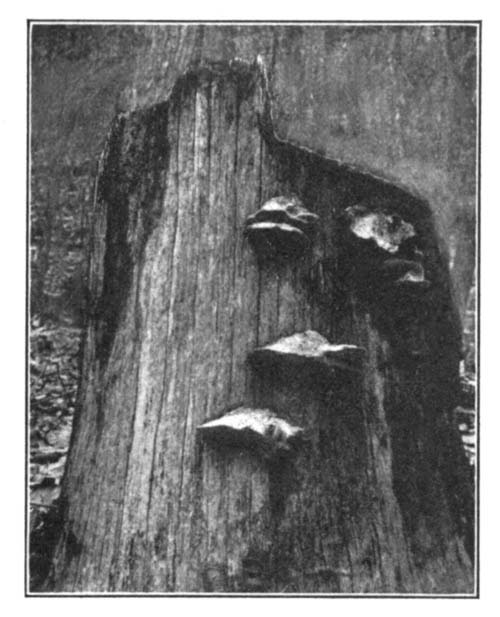

Damage done by insects. These trees have been killed by boring insects.

All Animals depend on Green Plants.—But insects in their turn are the food of birds; cats and dogs may kill birds; lions or tigers live on still larger defenseless animals as deer or cattle. And finally comes man, who eats the bodies of both plants and animals. But if we reduce this search after food to its final limit, we see that green plants provide all the food for animals. For the lion or tiger eats the deer which feeds upon grass or green shoots of young trees, or the cat eats the bird that lives on weed seeds. Green plants supply the food of the world. Later by experiment we will prove this.

Homes and Shelter.—After a field trip no one can escape the knowledge that plants often give animals a home. The grass shelters millions of grasshoppers and countless hordes of other small insects which can be obtained by sweeping through the grass with an insect net. Some insects build their homes in the trees or bushes on which they feed, while others tunnel through the wood, making homes there. Spiders build webs on plants, often using the leaves for shelter. Birds nest in trees, and many other wild animals use the forest as their home. Man has come to use all kinds of plant products to aid him in making his home, wood and various fibers being the most important of these.

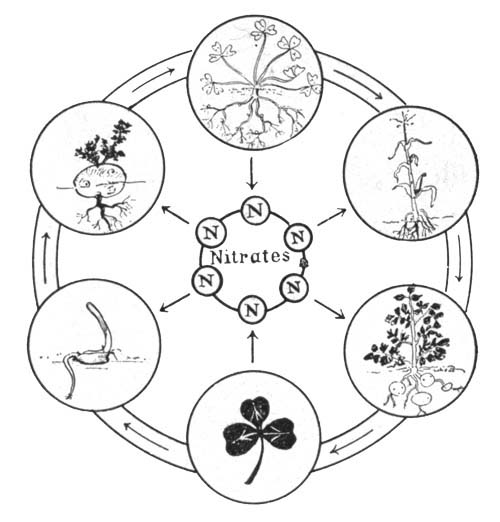

What do Animals do for Plants?—So far it has seemed that green plants benefit animals and receive nothing in return. We will later see that plants and animals together form a balance of life on the earth and that one is necessary for the other. Certain [Pg 35]substances found in the body wastes from animals are necessary to the life of a green plant.

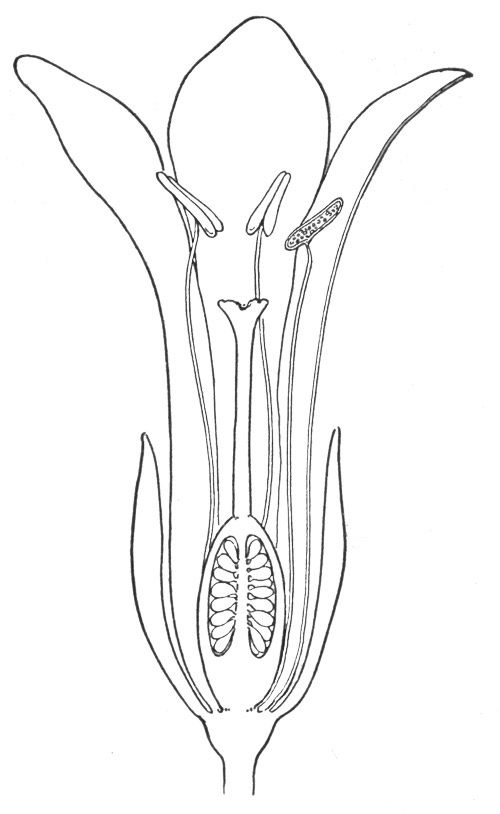

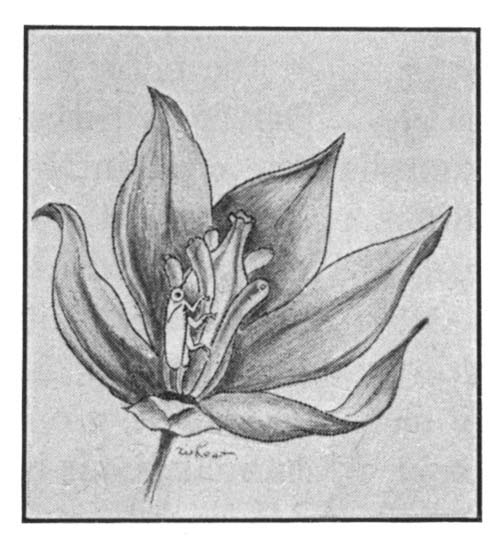

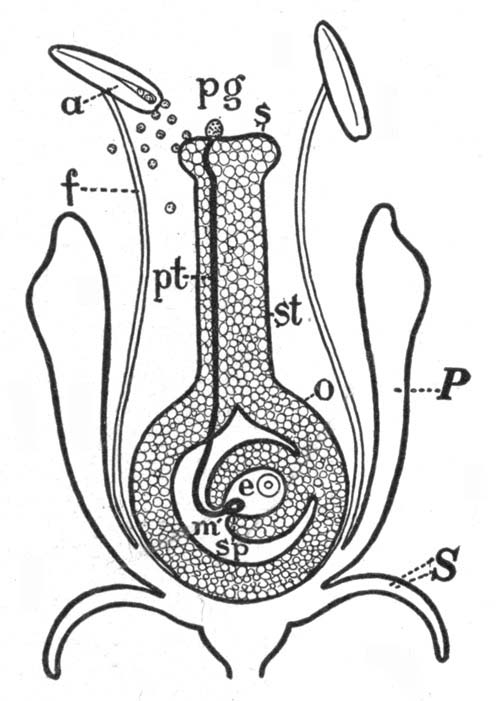

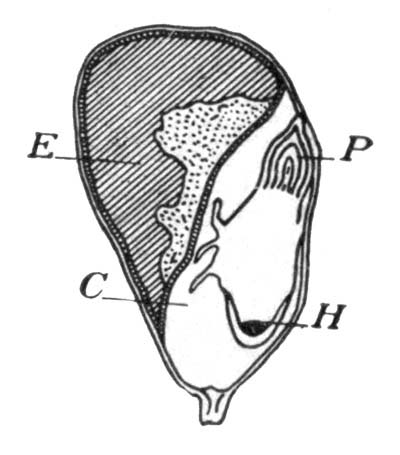

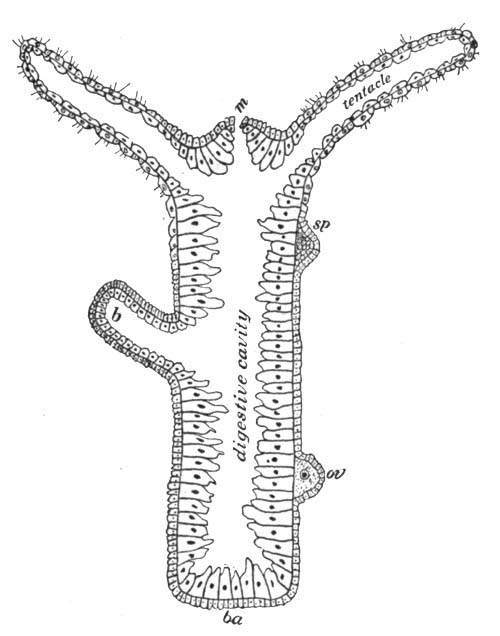

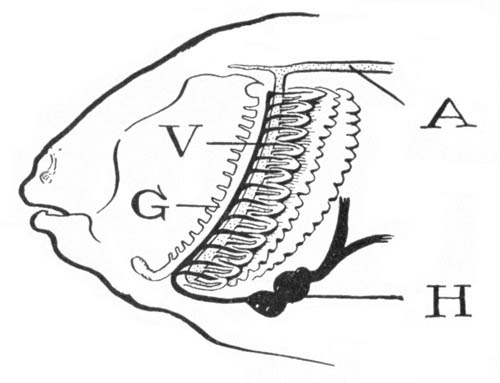

A section of a flower, cut lengthwise. In the center find the pistil with the ovary containing a number of ovules. Around this organ notice a circle of stalked structures, the stamens; the knobs at the end contain pollen. The outer circles of parts are called the petals and sepals, as we go from the inside outward.

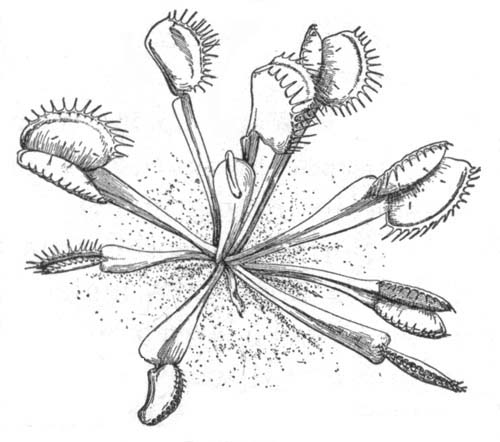

Insects and Flowers.—Certain other problems can be worked out in the fall of the year. One of these is the biological interrelations between insects and flowers. It is easy on a field trip to find insects lighting upon flowers. They evidently have a reason for doing this. To find out why they go there and what they do when there, it will be first necessary for us to study flowers with the idea of finding out what the insects get from them, and what the flowers get from the insects.

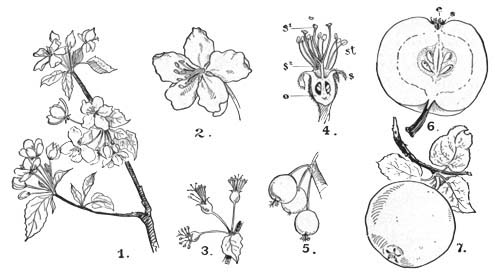

The Use and Structure of a Flower.—It is a matter of common knowledge that flowers form fruits and that fruits contain seeds. They are, then, very important parts of certain plants. Our field trip shows us that flowers are of various shapes, colors, and sizes. It will now be our problem first to learn to know the parts of a flower, and then find out how they are fitted to attract and receive insect visitors.

The Floral Envelope.—In a flower the expanded portion of the flower stalk, which holds the parts of the flower, is called the receptacle. The green leaflike parts covering the unopened flower are called the sepals. Together they form the calyx.

The more brightly colored structures are the petals. Together they form the corolla. The corolla is of importance, as we shall see later, in making the flower conspicuous. Frequently the petals or corolla have bright marks or dots which lead down to the base of the cup of the flower, where a sweet fluid called nectar is made and [Pg 36]secreted. It is principally this food substance, later made into honey by bees, that makes flowers attractive to insects.

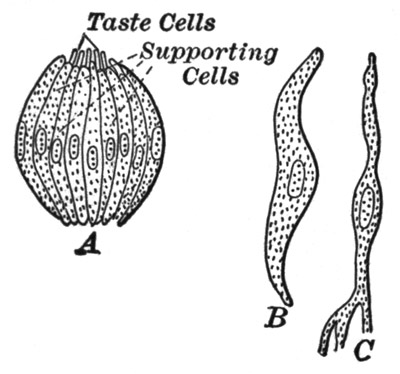

The Essential Organs.—A flower, however, could live without sepals or petals and still do the work for which it exists. Certain essential organs of the flower are within the so-called floral envelope. They consist of the stamens and pistil, the latter being in the center of the flower. The structures with the knobbed ends are called stamens. In a single stamen the boxlike part at the end is the anther; the stalk which holds the anther is called the filament. The anther is in reality a hollow box which produces a large number of little grains called pollen. Each pistil is composed of a rather stout base called the ovary, and a more or less lengthened portion rising from the ovary called the style. The upper end of the style, which in some cases is somewhat broadened, is called the stigma. The free end of the stigma usually secretes a sweet fluid in which grains of pollen from flowers of the same kind can grow.

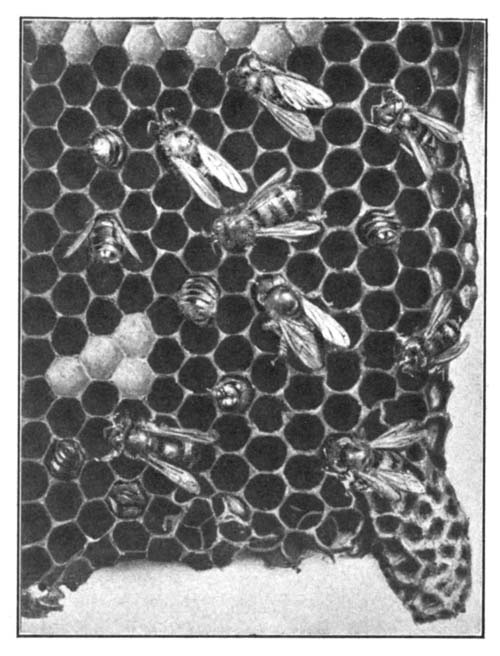

Insects as Pollinating Agents.—Insects often visit flowers to obtain pollen as well as nectar. In so doing they may transfer some of the pollen from one flower to another of the same kind. This transfer of pollen, called pollination, is of the greatest use to the plant, as we will later prove. No one who sees a hive of bees with their wonderful communal life can fail to see that these insects play a great part in the life of the flowers near the hive. A famous observer named Sir John Lubbock tested bees and wasps to see how many trips they made daily from their homes to the flowers, and found that the wasp went out on 116 visits during a working day of 16 hours, while the bee made but a few less visits, and worked only a little less time than the wasp worked. It is evident that in the course of so many trips to the fields a bee must light on hundreds of flowers.

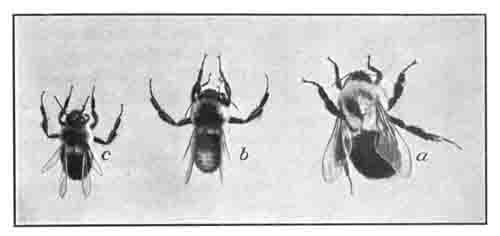

Bumblebees. a, queen; b, worker; c, drone.

Adaptations in a Bee.—If we look closely at the bee, we find the body and legs more or less covered with tiny hairs; especially are these hairs found on the legs. When a plant or animal structure is fitted to do a certain kind of work, we say it is adapted to do that work. The joints in the leg of the bee adapt it for complicated movements; the arrangement of stiff hairs along the edge of a concavity in one of the joints of the leg forms a structure well [Pg 37]adapted to hold pollen. In this way pollen is collected by the bee and taken to the hive to be used as food. But while gathering pollen for itself, the dust is caught on the hairs and other projections on the body or legs and is thus carried from flower to flower. The value of this to a flower we will see later.

Field Work.—Is Color or Odor in a Flower an Attraction to an Insect?—Sir John Lubbock tried an experiment which it would pay a number of careful pupils to repeat. He placed a few drops of honey on glass slips and placed them over papers of various colors. In this way he found that the honeybee, for example, could evidently distinguish different colors. Bees seemed to prefer blue to any other color. Flowers of a yellow or flesh color were preferred by flies. It would be of considerable interest for some student to work out this problem with our native bees and with other insects by using paper flowers and honey or sirup. Test the keenness of sight in insects by placing a white object (a white golf ball will do) in the grass and see how many insects will alight on it. Try to work out some method by which you can decide whether a given insect is attracted to a flower by odor alone.

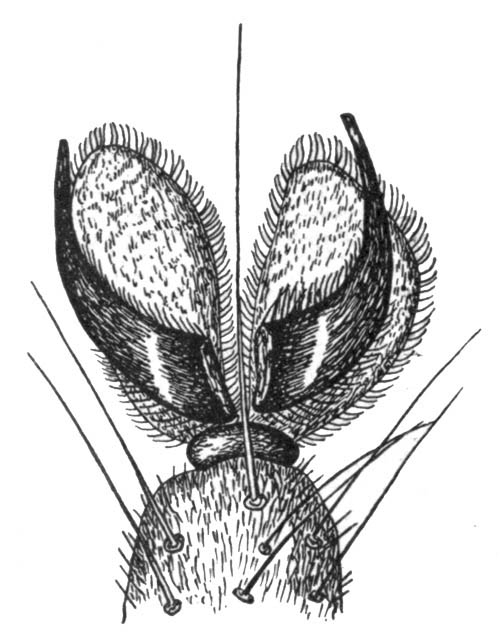

The Sight of the Bumblebee.—The large eyes located on the sides of the head are made up of a large number of little units, each of which is considered to be a very simple eye. The large eyes are therefore called the compound eyes. All insects are provided with compound eyes, with simple eyes, or in most cases with both. The simple eyes of the bee may be found by a careful observer between and above the compound eyes.[Pg 38]

The head of a bee. A, antennæ or "feelers"; E, compound eye; S, simple eye; M, mouth parts; T, tongue.

Insects can, as we have already learned, distinguish differences in color at some distance; they can see moving objects, but they do not seem to be able to make out form well. To make up for this, they appear to have an extremely well-developed sense of smell. Insects can distinguish at a great distance odors which to the human nose are indistinguishable. Night-flying insects, especially, find the flowers by the odor rather than by color.

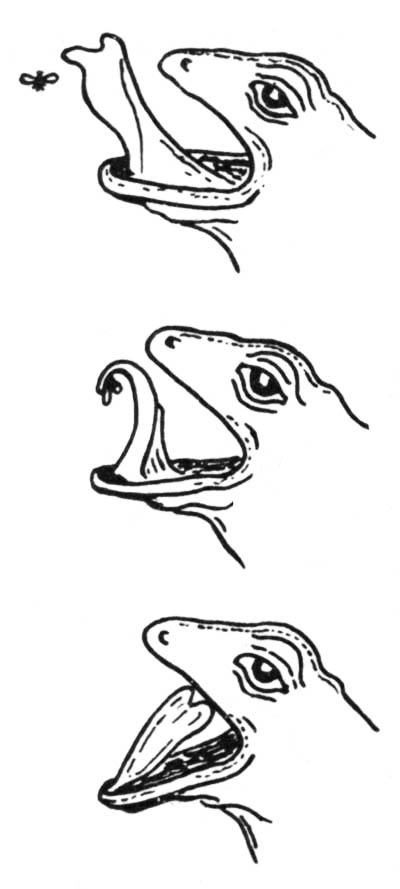

Mouth Parts of the Bee.—The mouth of the bee is adapted to take in the foods we have mentioned, and is used for the purposes for which man would use the hands and fingers. The honeybee laps or sucks nectar from flowers, it chews the pollen, and it uses part of the mouth as a trowel in making the honeycomb. The uses of the mouth parts may be made out by watching a bee on a well-opened flower.

Suggestions for Field Work.—In any locality where flowers are abundant, try to answer the following questions: How many bees visit the locality in ten minutes? How many other insects alight on the flowers? Do bees visit flowers of the same kinds in succession, or fly from one flower on a given plant to another on a plant of a different kind? If the bee lights on a flower cluster, does it visit more than one flower in the same cluster? How does a bee alight? Exactly what does the bee do when it alights?

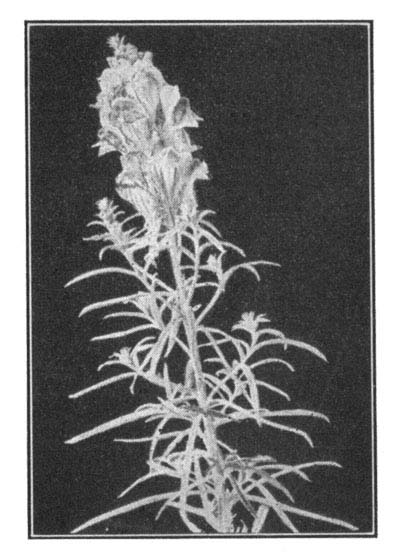

Butter and Eggs (Linaria vulgaris).—From July to October this very abundant weed may be found especially along roadsides [Pg 39]and in sunny fields. The flower cluster forms a tall and conspicuous cluster of orange and yellow flowers.

Flower cluster of "butter and eggs."

The corolla projects into a spur on the lower side; an upper two-parted lip shuts down upon a lower three-parted lip. The four stamens are in pairs, two long and two short.

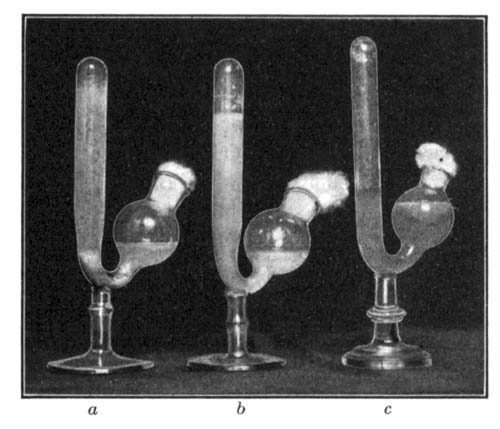

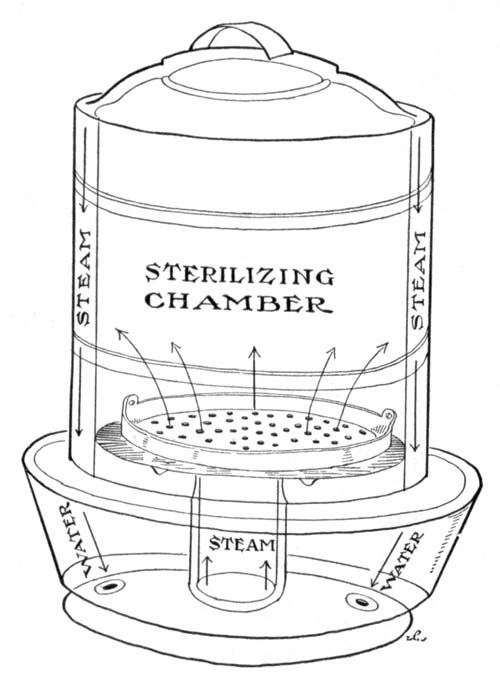

Diagram to show how the bee pollinates "butter and eggs." The bumblebee, upon entering the flower, rubs its head against the long pair of anthers (a), then continuing to press into the flower so as to reach the nectar at (N) it brushes against the stigma (S), thus pollinating the flower. Inasmuch as bees visit other flowers in the same cluster, cross-pollination would also be likely. Why?

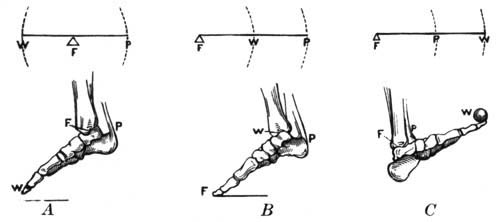

Certain parts of the corolla are more brightly colored than the rest of the flower. This color is a guide to insects. Butter and eggs is visited most by bumblebees, which are guided by the orange lip to alight just where they can push their way into the flower. The bee, seeking the nectar secreted in the spur, brushes his head and shoulders against the stamens. He may then, as he pushes down after nectar, leave some pollen upon the pistil, thus assisting in self-pollination. Visiting another flower of the cluster, it would be an easy matter accidentally to transfer [Pg 40]this pollen to the stigma of another flower. In this way pollen is carried by the insect to another flower of the same kind. This is known as cross-pollination. By pollination we mean the transfer of pollen from an anther to the stigma of a flower. Self-pollination is the transfer of pollen from the anther to the stigma of the same flower; cross-pollination is the transfer of pollen from the anthers of one flower to the stigma of another flower on the same or another plant of the same kind.

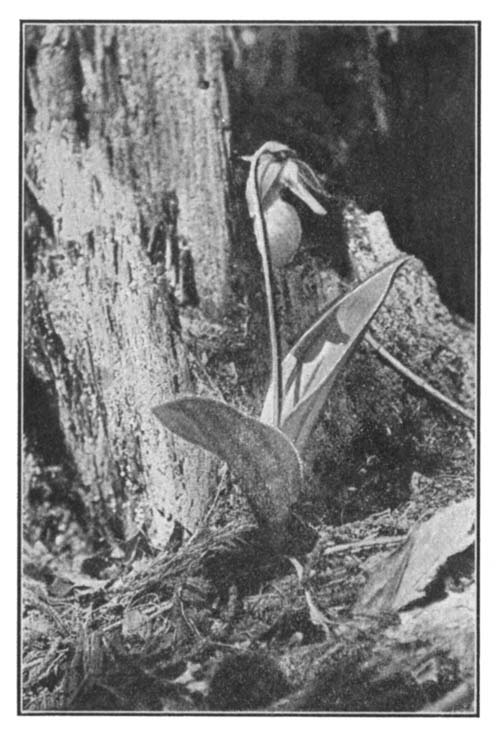

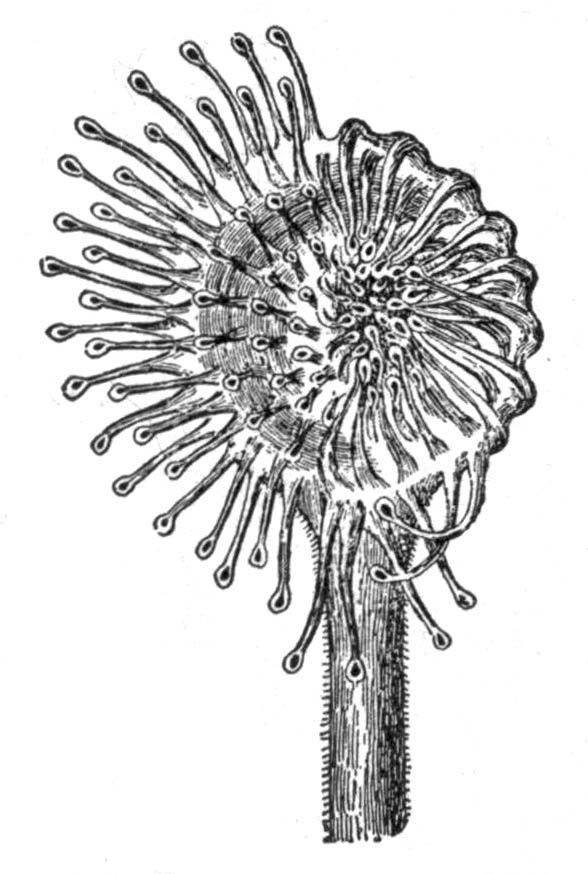

A wild orchid, a flower of the type from which Charles Darwin worked out his theory of cross-pollination by insects.

History of the Discoveries regarding Pollination of Flowers.—Although the ancient Greek and Roman naturalists had some vague ideas on the subject of pollination, it was not until the first part of the nineteenth century that a book appeared in which a German named Conrad Sprengel worked out the facts that the structure of certain flowers seemed to be adapted to the visits of insects. Certain facilities were offered to an insect in the way of easy foothold, sweet odor, and especially food in the shape of pollen and nectar, the latter a sweet-tasting substance manufactured by certain parts of the flower known as the nectar glands. Sprengel further discovered the fact that pollen could be and was carried by the insect visitors from the anthers of the flower to its stigma. It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century, however, that an Englishman, Charles Darwin, applied Sprengel's discoveries on the relation of insects to flowers by his investigations upon cross-pollination. The growth of the pollen on the stigma of the flower results eventually in the production of seeds, [Pg 41]and thus new plants. Many species of flowers are self-pollinated and do not do so well in seed production if cross-pollinated, but Charles Darwin found that some flowers which were self-pollinated did not produce so many seeds, and that the plants which grew from their seeds were smaller and weaker than plants from seeds produced by cross-pollinated flowers of the same kind. He also found that plants grown from cross-pollinated seeds tended to vary more than those grown from self-pollinated seed. This has an important bearing, as we shall see later, in the production of new varieties of plants. Microscopic examination of the stigma at the time of pollination also shows that the pollen from another flower usually germinates before the pollen which has fallen from the anthers of the same flower. This latter fact alone in most cases renders it unlikely for a flower to produce seeds by its own pollen. Darwin worked for years on the pollination of many insect-visited flowers, and discovered in almost every case that showy, sweet-scented, or otherwise attractive flowers were adapted or fitted to be cross-pollinated by insects. He also found that, in the case of flowers that were inconspicuous in appearance, often a compensation appeared in the odor which rendered them attractive to certain insects. The so-called carrion flowers, pollinated by flies, are examples, the odor in this case being like decayed flesh. Other flowers open at night, are white, and provided with a powerful scent. Thus they attract night-flying moths and other insects.

Other Examples of Mutual Aid between Flowers and Insects.—Many other examples of adaptations to secure cross-pollination by means of the visits of insects might be given. The mountain laurel, which makes our hillsides so beautiful in late spring, shows a remarkable adaptation in having the anthers of the stamens caught in little pockets of the corolla. The weight of the visiting insect on the corolla releases the anther from the pocket in which it rests so that it springs up, dusting the body of the visitor with pollen.

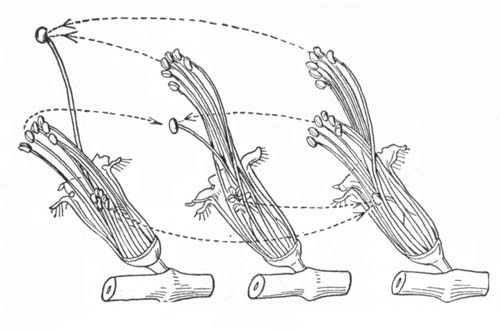

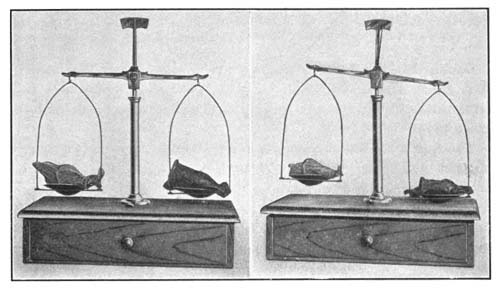

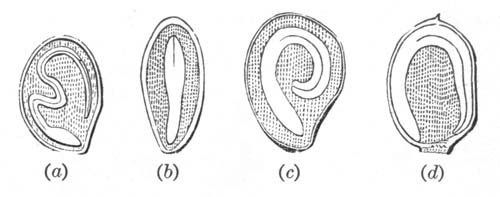

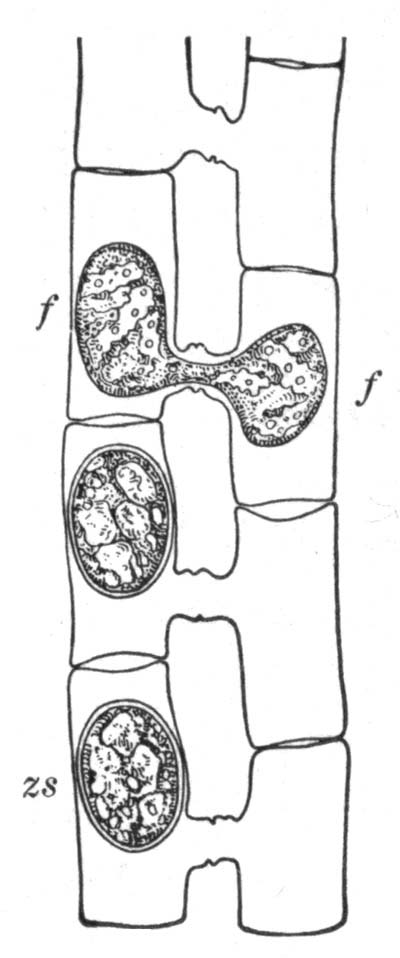

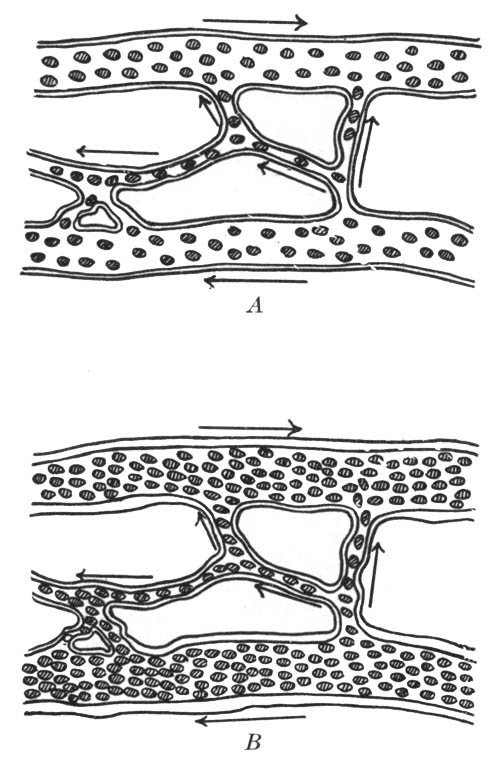

The condition of stamens and pistils on the spiked loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria).

In some flowers, as shown by the primroses or primula of our hothouses, the stamens and pistils are of different lengths in different flowers. Short styles and long or high-placed filaments are found in one flower, and long styles with short or low-placed filaments [Pg 42]in the other. Pollination will be effected only when some of the pollen from a low-placed anther reaches the stigma of a short-styled flower, or when the pollen from a high anther is placed upon a long-styled pistil. There are, as in the case of the loosestrife, flowers having pistils and stamens of three lengths. Pollen only grows on pistils of the same length as the stamens from which it came.

The milkweed or butterfly weed already mentioned is another example of a flower adapted to insect pollination.[1]

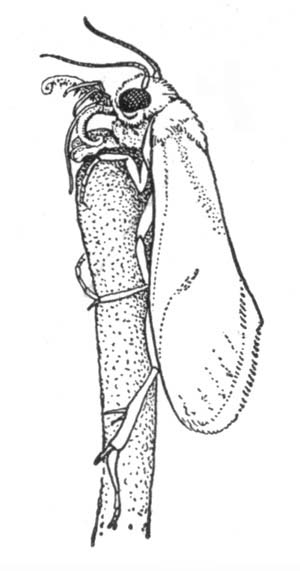

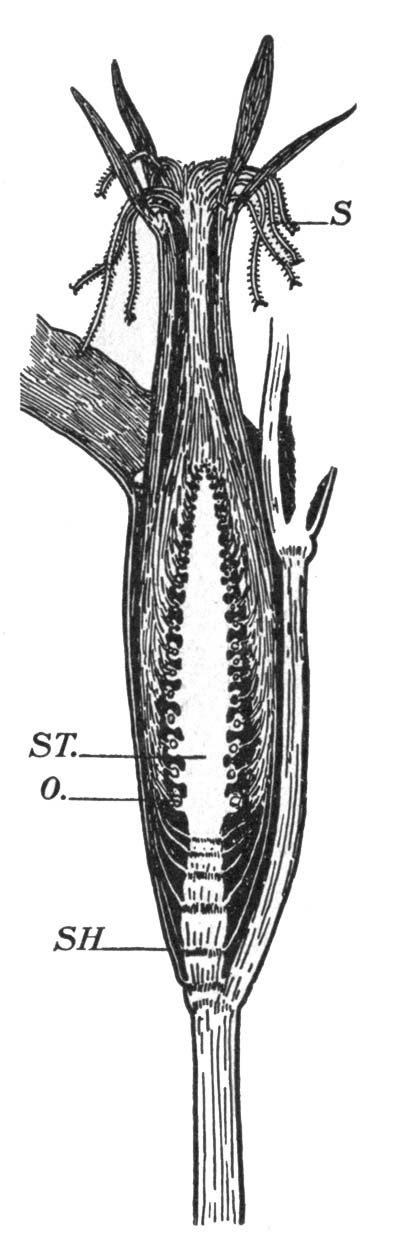

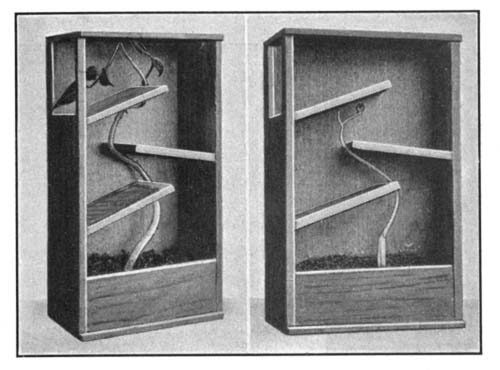

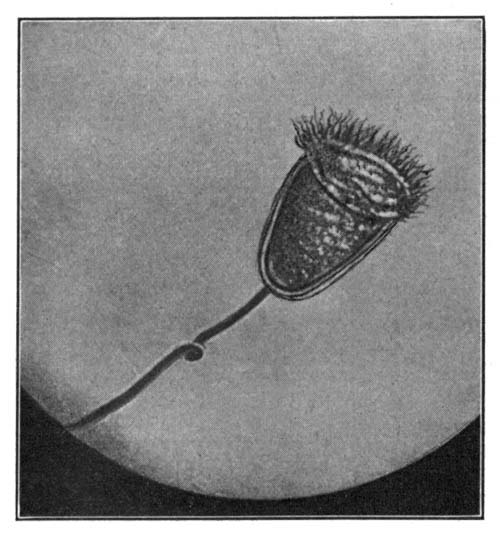

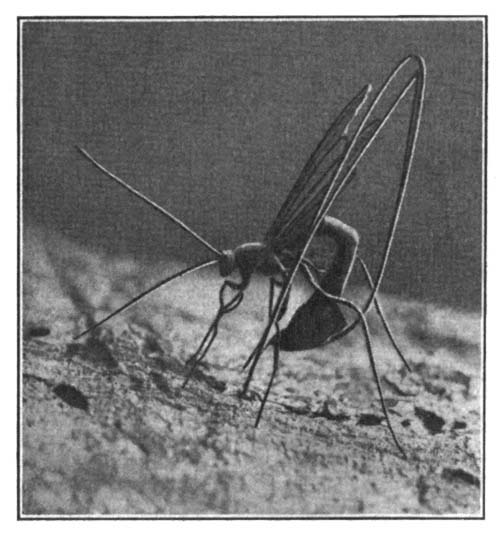

The pronuba moth within the yucca flower.

A very remarkable instance of insect help is found in the pollination of the yucca, a semitropical lily which lives in deserts (to be seen in most botanic gardens). In this flower the stigmatic surface is above the anther, and the pollen is sticky and cannot be transferred except by insect aid. This is accomplished in a remarkable manner. A little moth, called the pronuba, after gathering pollen from an anther, deposits an egg in the ovary of the pistil, and then rubs its load of pollen over the stigma of the flower. The young hatch out and feed on the young seeds which have grown because of the pollen placed on the stigma by the mother. The baby caterpillars [Pg 43]eat some of the developing seeds and later bore out of the seed pod and escape to the ground, leaving the plant to develop the remaining seeds without further molestation.

The pronuba pollinating the pistil of the yucca.

Pod of yucca showing where the young pronubas escaped.

The fig insect (Blastophaga grossorum) is another member of the insect tribe that is of considerable economic importance. It is only in recent years that the fruit growers of California have discovered that the fertilization of the female flowers is brought about by a gallfly which bores into the young fruit. By importing the gallflies it has been possible to grow figs where for many years it was believed that the climate prevented figs from ripening.

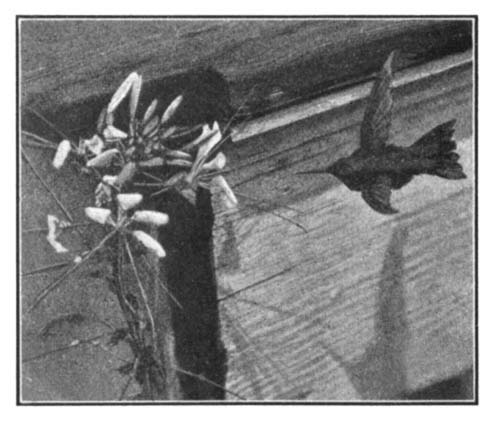

Other Flower Visitors.—Other insects besides those already mentioned are pollen carriers for flowers. Among the most useful are moths and butterflies. Projecting from each side of the head of a butterfly is a fluffy structure, the palp. This collects and carries a large amount of pollen, which is deposited upon the stigmas of other flowers when the butterfly pushes its head down into the flower tube after nectar. The scales and hairs on the wings, legs, and body also carry pollen.

A humming bird about to

cross-pollinate a

lily.

Flies and some other insects are agents in cross-pollination. Humming birds are also active agents in [Pg 44]some flowers. Snails are said in rare instances to carry pollen. Man and the domesticated animals undoubtedly frequently pollinate flowers by brushing past them through the fields.

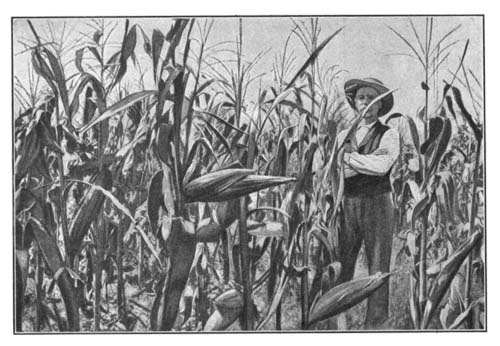

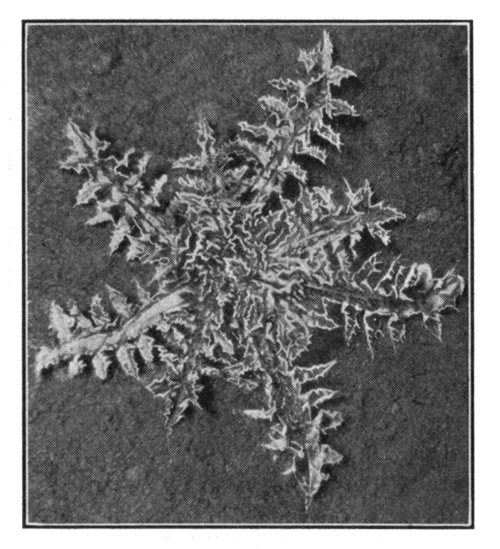

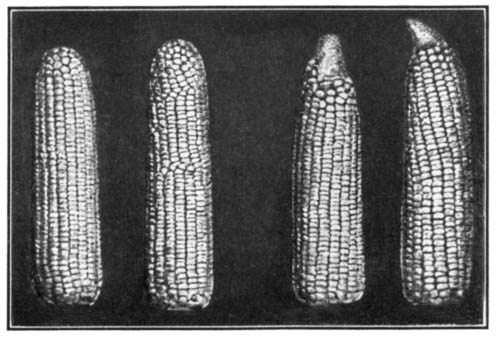

Pollination by the Wind.—Not all flowers are dependent upon insects or other animals for cross-pollination. Many of the earliest of spring flowers appear almost before the insects do. Such flowers are dependent upon the wind for carrying pollen from the stamens of one flower to the pistil of another. Most of our common trees, oak, poplar, maple, and others, are cross-pollinated almost entirely by the wind.

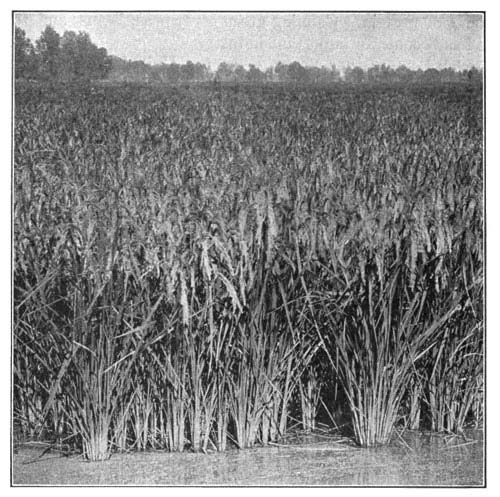

A cornfield showing staminate and pistillate flowers, the latter having become grains of corn. An ear of corn is a bunch of ripened fruits.

Flowers pollinated by the wind are generally inconspicuous and often lack a corolla. The anthers are exposed to the wind and provided with much pollen, while the surface of the stigma may be long and feathery. Such flowers may also lack odor, nectar, and bright color. Can you tell why?

Imperfect Flowers.—Some flowers, the wind-pollinated ones in particular, are imperfect; that is, they lack either stamens [Pg 45]or pistils. Again, in some cases, imperfect flowers having stamens only are alone found on one plant, while those flowers having pistils only are found on another plant of the same kind. In such flowers, cross-pollination must of necessity follow. Many of our common trees are examples.

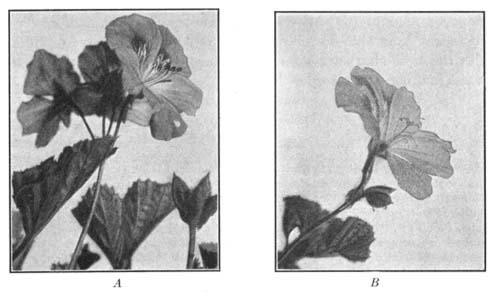

Other Cases.—The stamens and pistil ripen at different times in some flowers. The "Lady Washington" geranium, a common house plant, shows this condition. Here also cross-pollination must take place if seeds are to be formed.

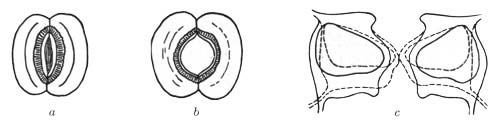

The flower of "Lady Washington" geranium, in which stamens and pistil ripen at different times, thus insuring cross-pollination. A, flower with ripe stamens; B, flower with stamens withered and ripe pistil.

Summary.—If we now collect our observations upon flowers with a view to making a summary of the different devices flowers have assumed to prevent self-pollination and to secure cross-pollination, we find that they are as follows:—

(1) The stamens and pistils may be found in separate flowers, either on the same or on different plants.

(2) The stamens may produce pollen before the pistil is ready to receive it, or vice versa.

(3) The stamens and pistils may be so placed with reference to each other that pollination can be brought about only by outside assistance. [Pg 46]

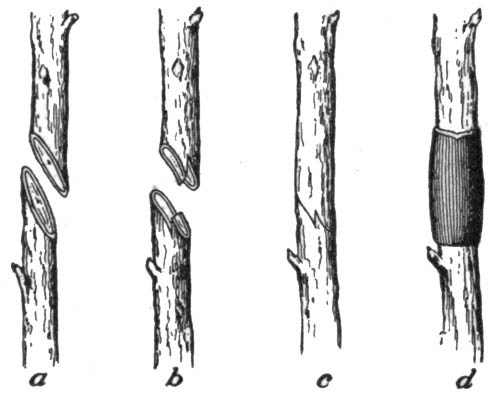

Artificial Cross-pollination and its Practical Benefits to Man.—Artificial cross-pollination is practiced by plant breeders and can easily be tried in the laboratory or at home. First the anthers must be carefully removed from the bud of the flower so as to eliminate all possibility of self-pollination. The flower must then be covered so as to prevent access of pollen from without; when the ovary is sufficiently developed, pollen from another flower, having the characters desired, is placed on the stigma and the flower again covered to prevent any other pollen reaching the flower. The seeds from this flower when planted may give rise to plants with the best characters of each of the plants which contributed to the making of the seeds.

[1] For an excellent account of cross-pollination of this flower, the reader is referred to W. C. Stevens, Introduction to Botany. Orchids are well known to botanists as showing some very wonderful adaptations. A classic easily read is Darwin, On the Fertilization of Orchids.

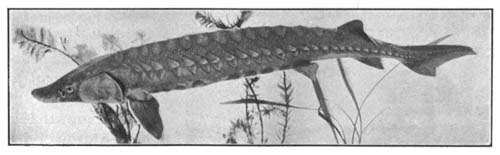

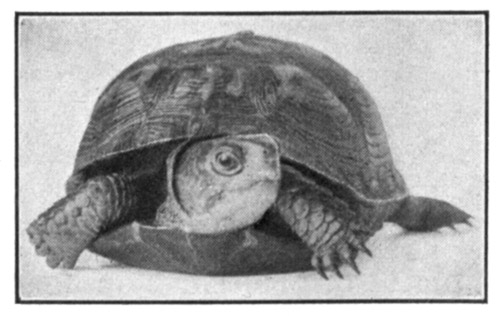

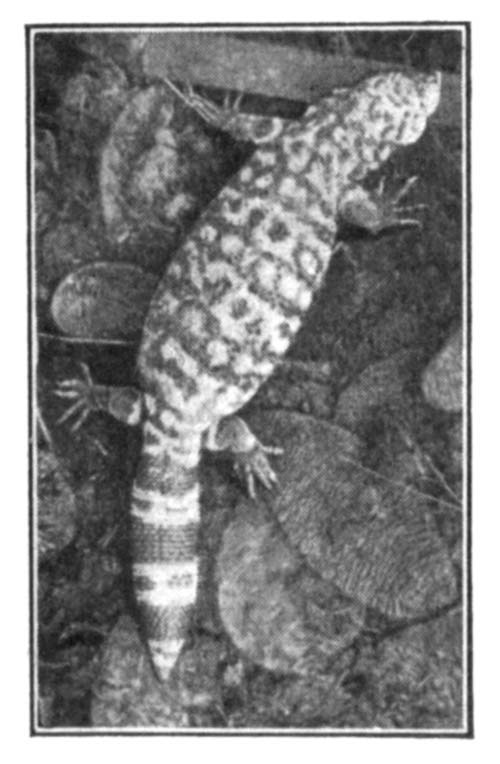

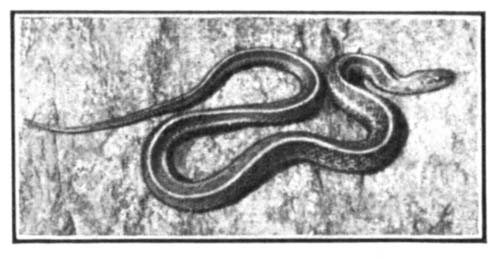

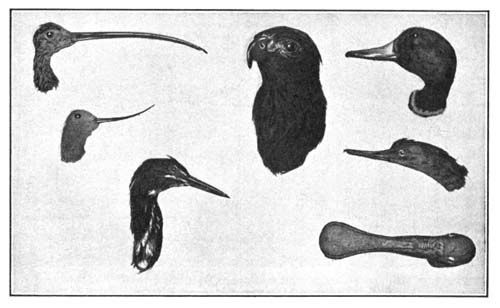

Reference Books

elementary

Hunter, Laboratory Problems in Civic Biology. American Book Company.

Andrews, A Practical Course in Botany, pages 214-249. American Book Company.

Atkinson, First Studies of Plant Life, Chaps. XXV-XXVI. Ginn and Company.

Coulter, Plant Life and Plant Uses, pages 301-322. American Book Company.

Dana, Plants and their Children, pages 187-255. American Book Company.

Lubbock, Flowers, Fruits, and Leaves, Part I. The Macmillan Company.

Needham, General Biology, pages 1-50. The Comstalk Publishing Company.

Newell, A Reader in Botany, Part II, pages 1-96. Ginn and Company.

Sharpe, A Laboratory Manual in Biology, pages 43-48. American Book Company.

advanced

Bailey, Plant Breeding. The Macmillan Company.

Campbell, Lectures on the Evolution of Plants. The Macmillan Company.

Coulter, Barnes, and Cowles, A Textbook of Botany, Part II. American Book Company.

Darwin, Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species, D. Appleton and Company.

Darwin, Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom, Chaps. I and II. D. Appleton and Company.

Darwin, Orchids Fertilized by Insects, D. Appleton and Company.

Lubbock, British Wild Flowers. The Macmillan Company.

Müller, The Fertilization of Flowers. The Macmillan Company.

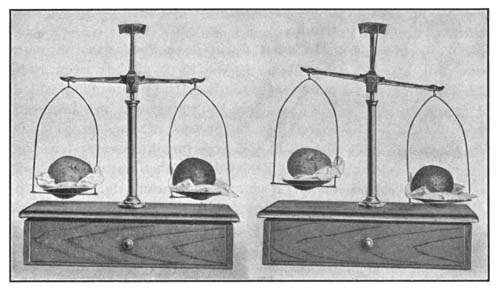

Problems.—To discover the functions of living matter.

(a) In a living plant.

(b) In a living animal.

Laboratory Suggestions

Laboratory study of a living plant.—Any whole plant may be used; a weed is preferable.

Laboratory demonstration or home study.—The functions of a living animal.

Demonstration.—The growth of pollen tubes.

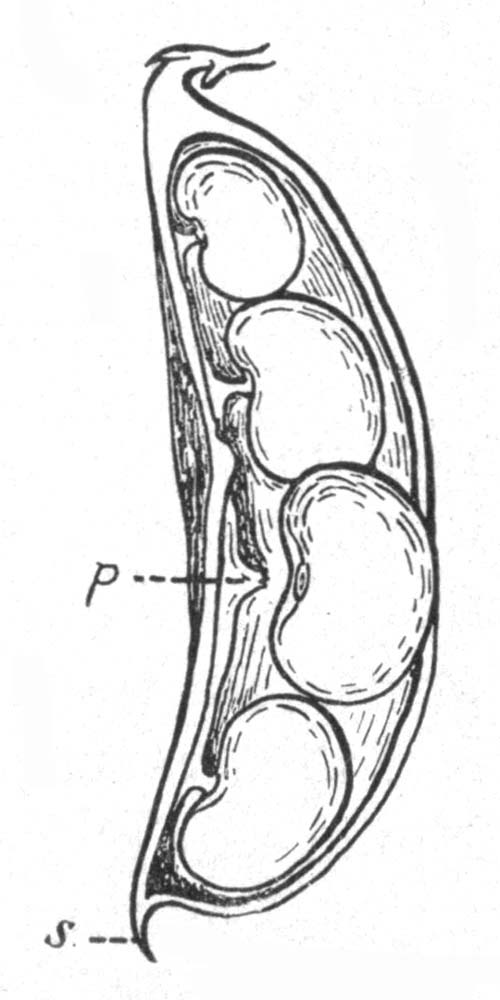

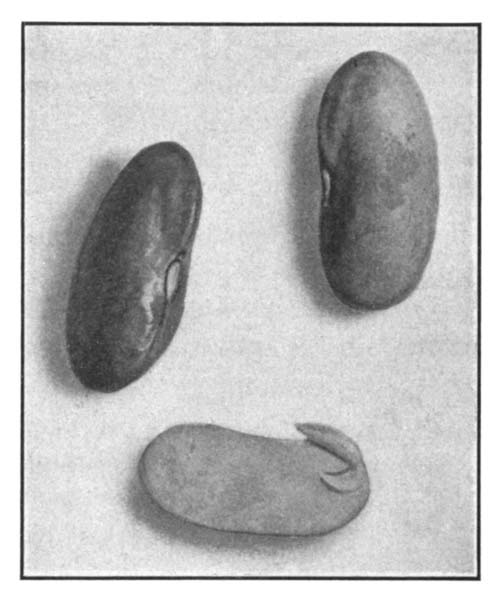

Laboratory exercise.—The growth of the mature ovary into the fruit, e.g. bean or pea pod.

A Living Plant and a Living Animal Compared.—A walk into the fields or any vacant lot on a day in the early fall will give us first-hand acquaintance with many common plants which, because of their ability to grow under somewhat unfavorable conditions, are called weeds. Such plants—the dandelion, butter and eggs, the shepherd's purse—are particularly well fitted by nature to produce many of their kind, and by this means drive out other plants which cannot do this so well. On these or other plants we find feeding several kinds of animals, usually insects.

If we attempt to compare, for example, a grasshopper with the plant on which it feeds, we see several points of likeness and difference at once. Both plant and insect are made up of parts, each of which, as the stem of the plant or the leg of the insect, appears to be distinct, but which is a part of the whole living plant or animal. Each part of the living plant or animal which has a separate work to do is called an organ. Thus plants and animals are spoken of as living organisms.

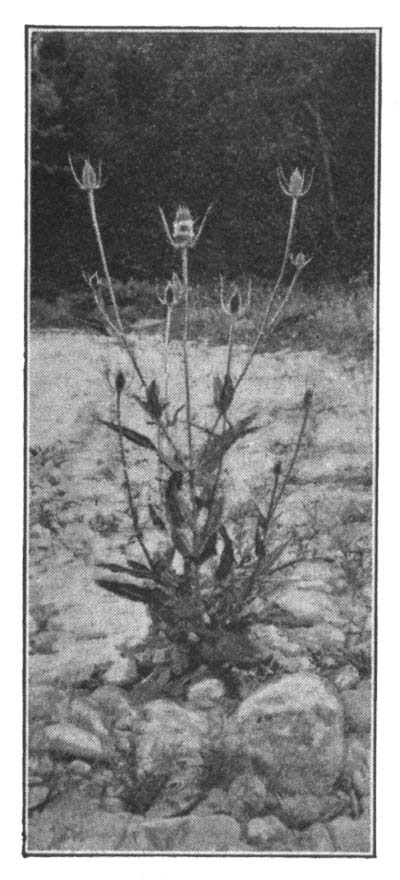

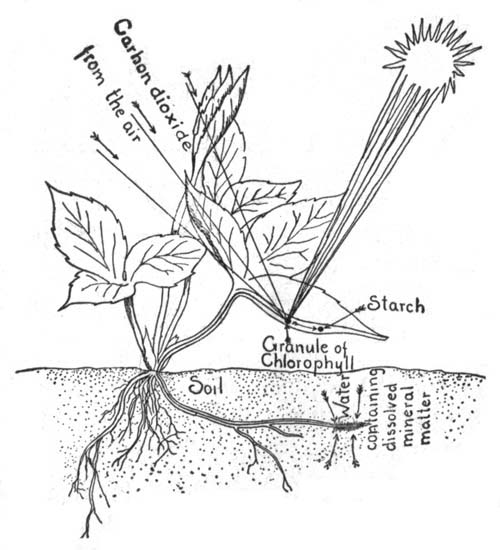

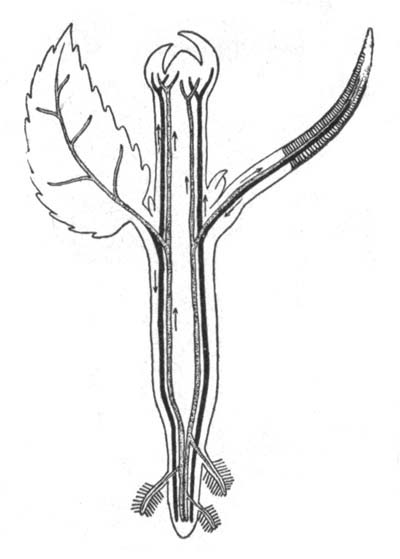

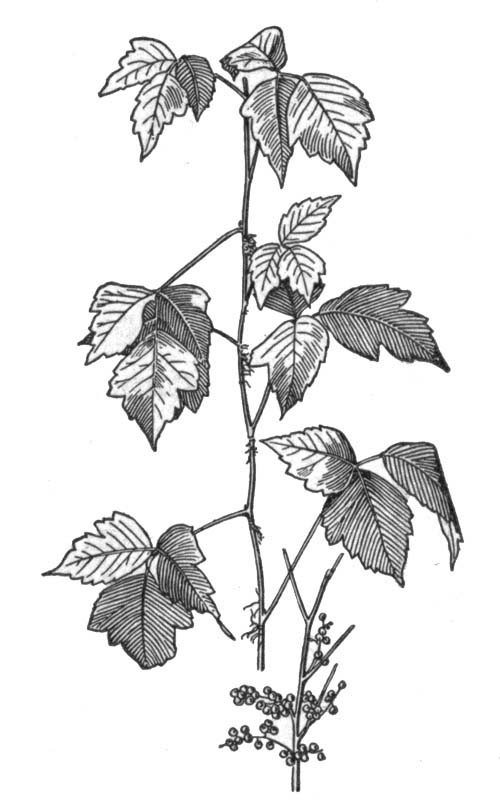

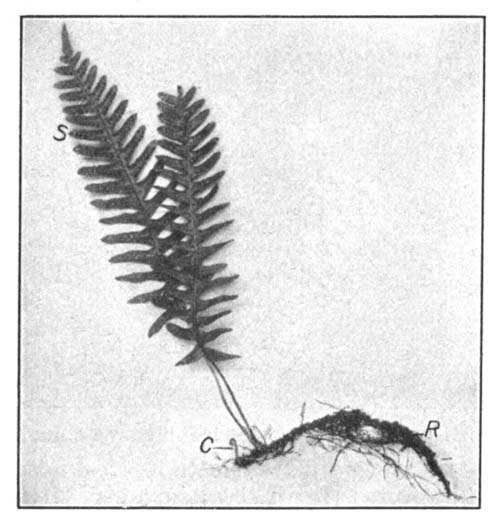

A weed—notice the unfavorable environment.

[Pg 48]Functions of the Parts of a Plant.—We are all familiar with the parts of a plant,—the root, stem, leaves, flowers, and fruit. But we may not know so much about their uses to the plant. Each of these structures differs from every other part, and each has a separate work or function to perform for the plant. The root holds the plant firmly in the ground and takes in water and mineral matter from the soil; the stem holds the leaves up to the light and acts as a pathway for fluids between the root and leaves; the leaves, under certain conditions, manufacture food for the plant and breathe; the flowers form the fruits; the fruits hold the seeds, which in turn hold young plants which are capable of reproducing adult plants of the same kind.

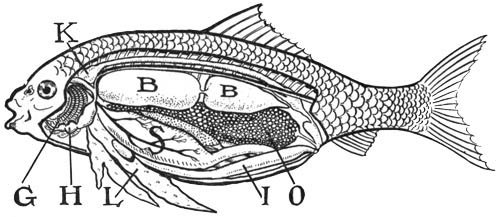

The Functions of an Animal.—As we have already seen, the grasshopper has a head, a jointed body composed of a middle and a hind part, three pairs of jointed legs, and two pairs of wings. Obviously, the wings and legs are used for movement; a careful watching of the hind part of the animal shows us that breathing movements are taking place; a bit of grass placed before it may be eaten, the tiny black jaws biting little pieces out of the grass. If disturbed, the insect hops away, and if we try to get it, it jumps or flies away, evidently seeing us before we can grasp it. Hundreds of little grasshoppers on the grass indicate that the grasshopper can reproduce its own kind, but in other respects the animal seems quite unlike the plant. The animal moves, breathes, feeds, and has sensation, while apparently the plant does none of these. It will be the purpose of later chapters to prove that the functions of plants and animals are in many respects similar and that both plants and animals breathe, feed, and reproduce.

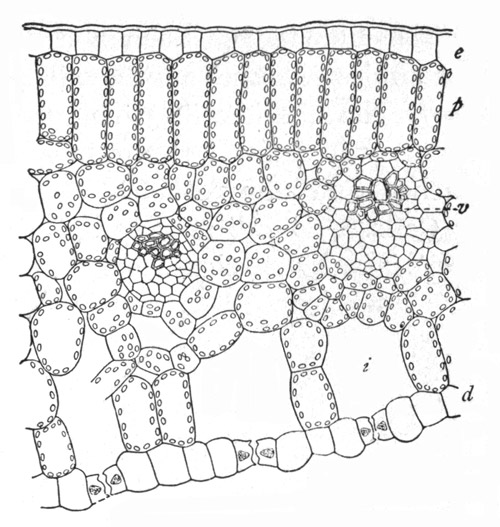

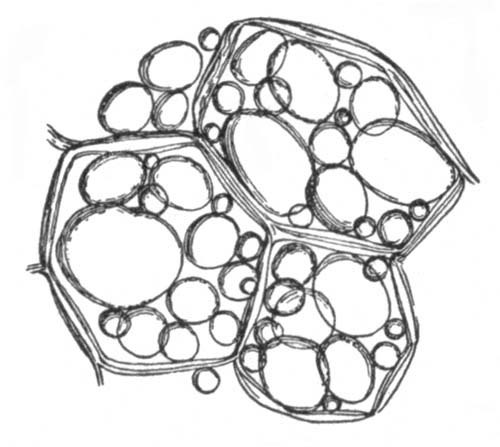

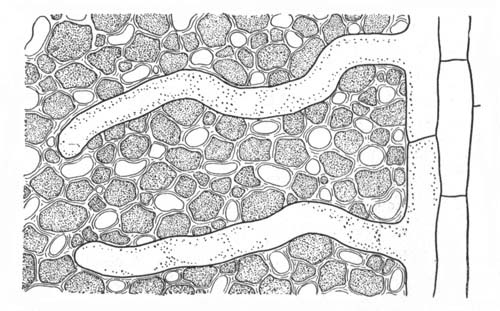

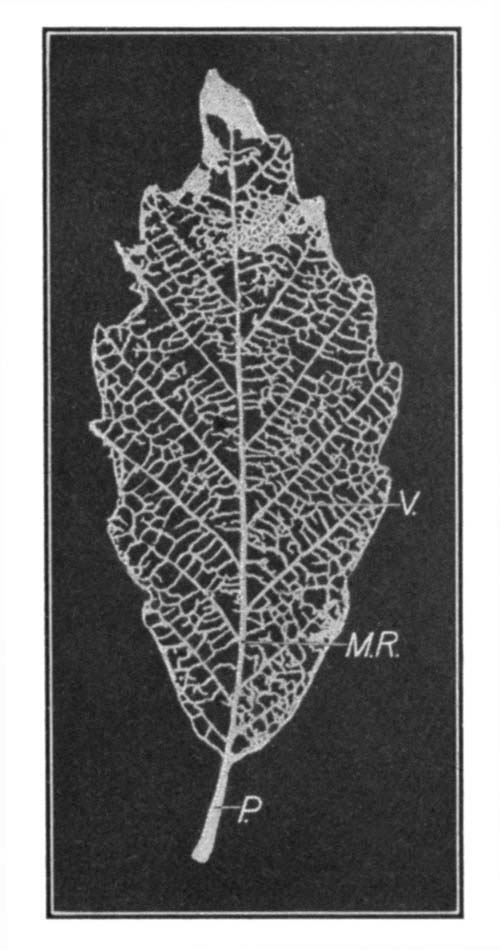

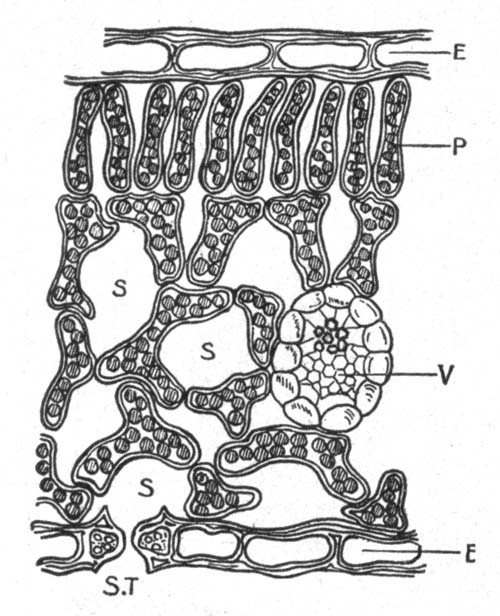

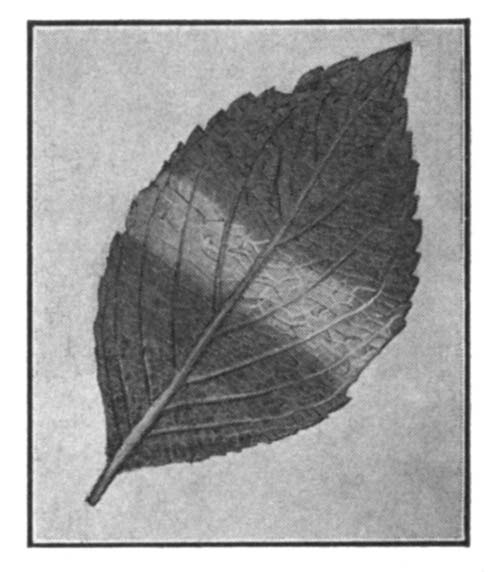

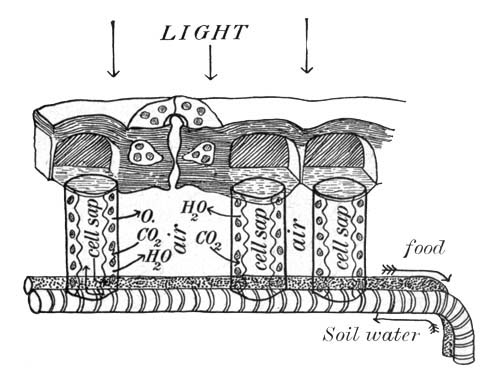

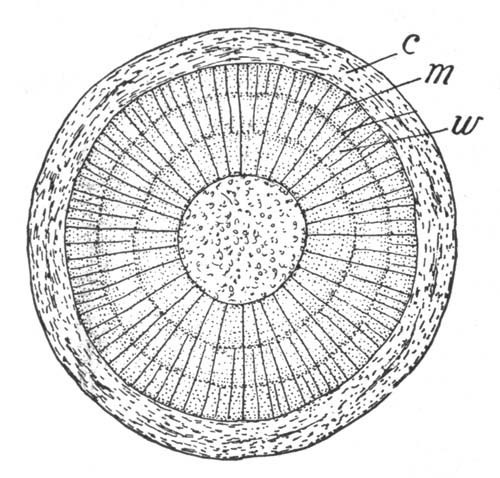

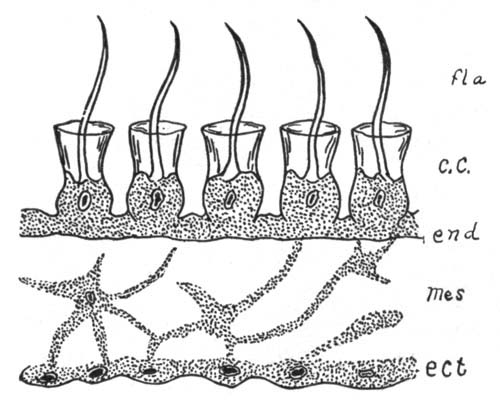

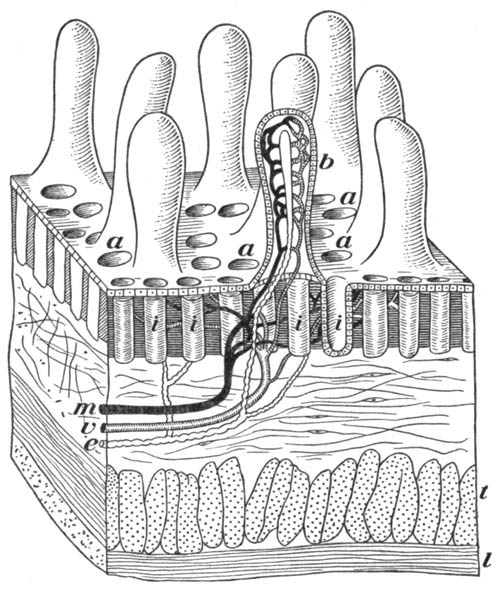

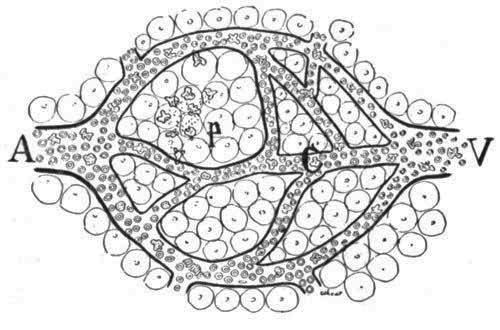

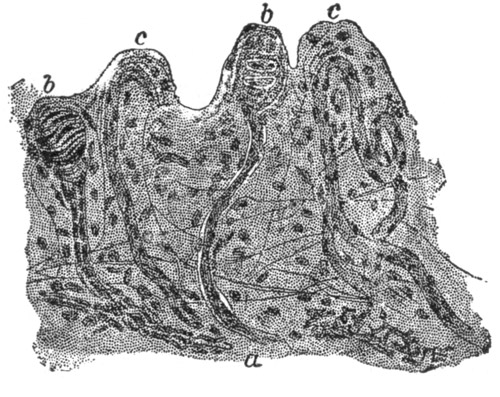

Section through the blade of a leaf. e, cells of the upper surface; d, cells of the lower surface; i, air spaces in the leaf; v, vein in cross sections; p, green cells.

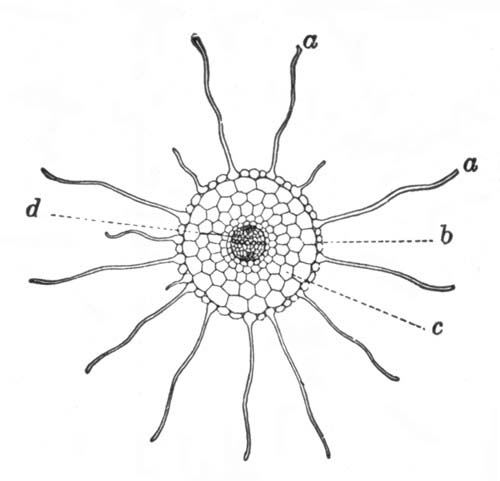

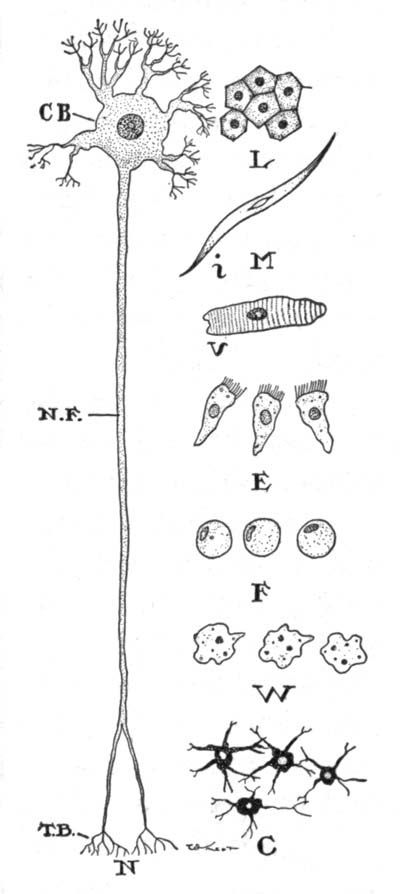

Organs.—If we look carefully at the organ of a plant called a leaf, we find that the materials of which it is composed do not appear [Pg 49]to be everywhere the same. The leaf is much thinner and more delicate in some parts than in others. Holding the flat, expanded blade away from the branch is a little stalk, which extends into the blade of the leaf. Here it splits up into a network of tiny "veins" which evidently form a framework for the flat blade somewhat as the sticks of a kite hold the paper in place. If we examine under the compound microscope a thin section cut across the leaf, we shall find that the veins as well as the other parts are made up of many tiny boxlike units of various sizes and shapes. These smallest units of building material of the plant or animal disclosed by the compound microscope are called cells. The organs of a plant or animal are built of these tiny structures.

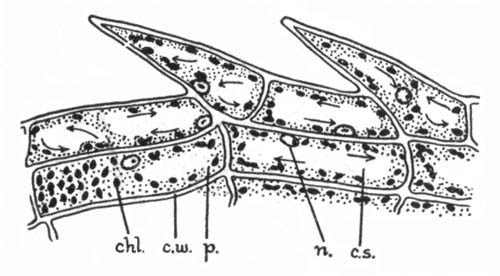

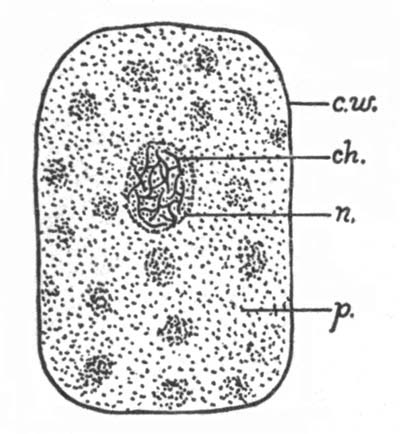

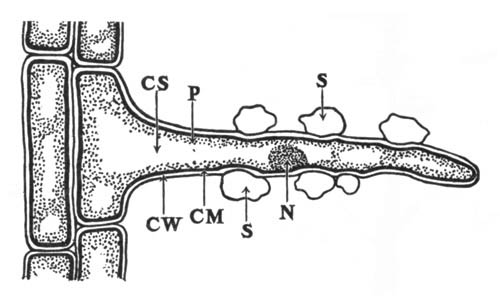

Several cells of Elodea, a water plant. chl., chlorophyll bodies; c.s., cell sap; c.w., cell wall; n., nucleus; p., protoplasm. The arrows show the direction of the protoplasmic movement.

Tissues.[2]—The cells which form certain parts of the veins, the flat blade, or other portions of the plant, are often found in groups or collections, the cells of which are more or less alike [Pg 50]in size and shape. Such a collection of cells is called a tissue. Examples of tissues are the cells covering the outside of the human body, the muscle cells, which collectively allow of movement, bony tissues which form the framework to which the muscles are attached, and many others.

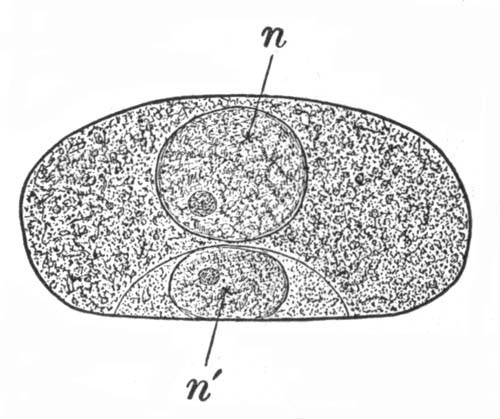

A cell. ch., chromosomes; c.w., cell wall; n., nucleus; p., protoplasm.

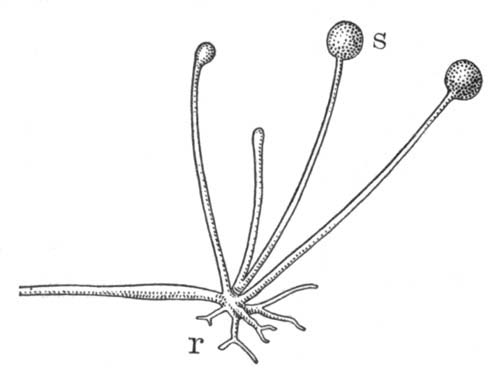

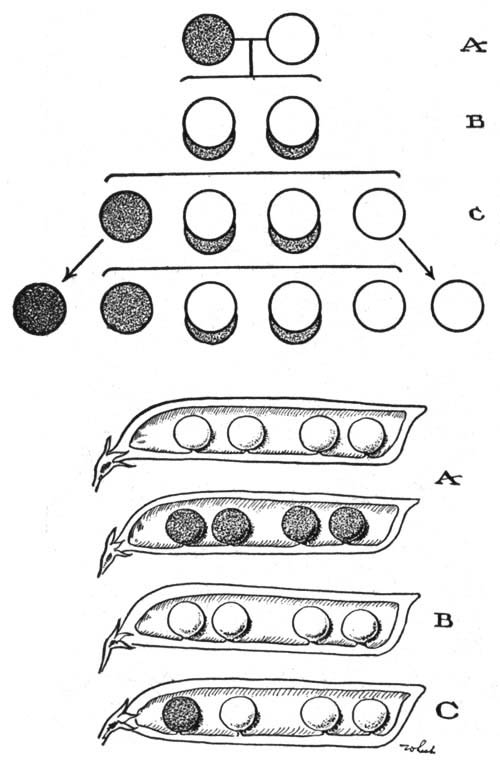

Cells.—A cell may be defined as a tiny mass of living matter containing a nucleus, either living alone or forming a unit of the building material of a living thing. The living matter of which all cells are formed is known as protoplasm (formed from two Greek words meaning first form). If we examine under a compound microscope a small bit of the water plant Elodea, we see a number of structures resembling bricks in a wall. Each "brick," however, is really a plant cell bounded by a thin wall. If we look carefully, we can see that the material inside of this wall is slowly moving and is carrying around in its substance a number of little green bodies. This moving substance is living matter, the protoplasm of the cell. The green bodies (the chlorophyll bodies) we shall learn more about later; they are found only in plant cells. All plant and animal cells appear to be alike in the fact that every living cell possesses a structure known as the nucleus (pl. nuclei), which is found within the body of the cell. This nucleus is not easy to find in the cells of Elodea. Within the nucleus of all cells are found certain bodies called chromosomes. These chromosomes in a given plant or animal are always constant in number. These chromosomes are supposed to be the bearers of the qualities which we believe can be handed down from plant to plant and from animal to animal, in other words, the inheritable qualities which make the offspring like its parents.

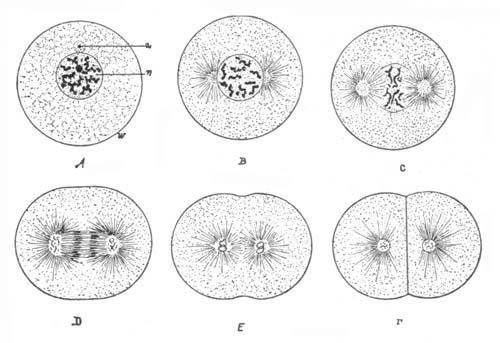

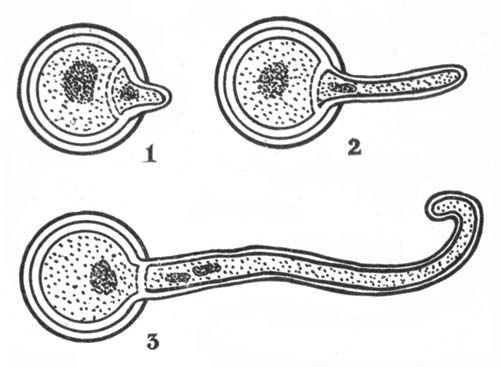

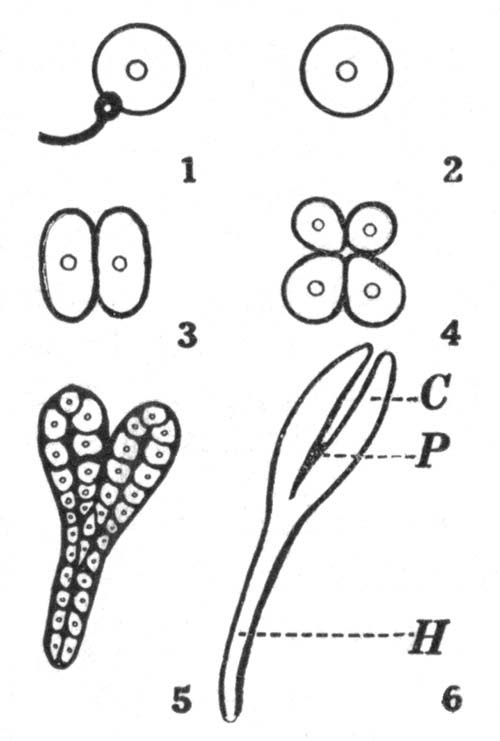

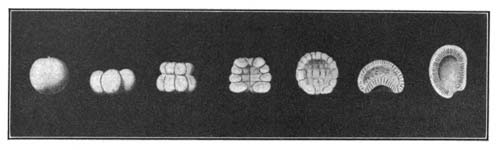

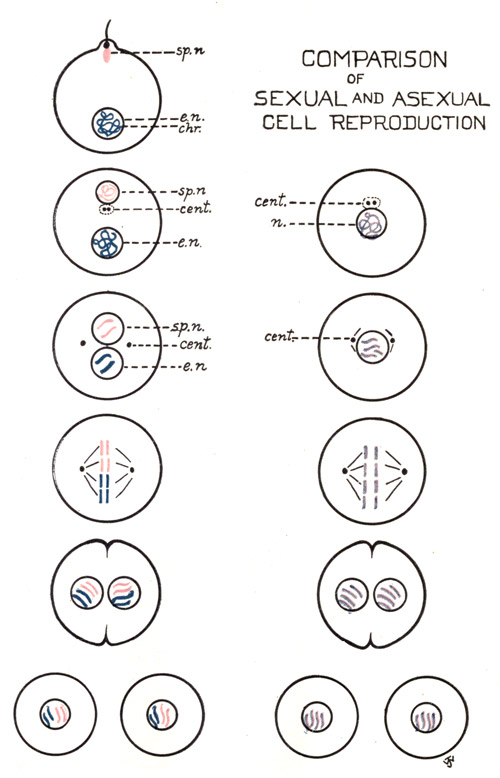

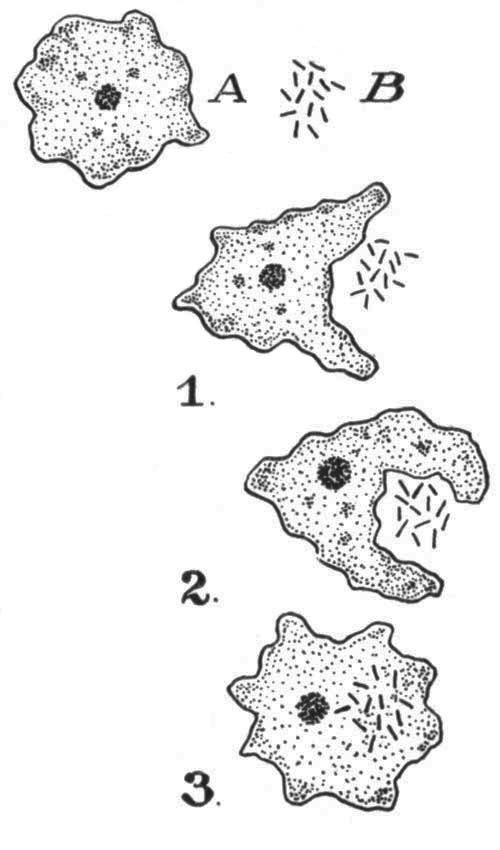

How Cells form Others.—Cells grow to a certain size and then split into two new cells. In this process, which is of very great importance in the growth of both plants and animals, the nucleus divides first. The chromosomes also divide, each splitting lengthwise and the parts going in equal numbers to each of the two cells [Pg 51]formed from the old cell. In this way the matter in the chromosomes is divided equally between the two new cells. Then the rest of the protoplasm separates, and two new cells are formed. This process is known as fission. It is the usual method of growth found in the tissues of plants and animals.

Stages in the division of one cell to form two. Which part of the cell divides first? What seems to become of the chromosomes?

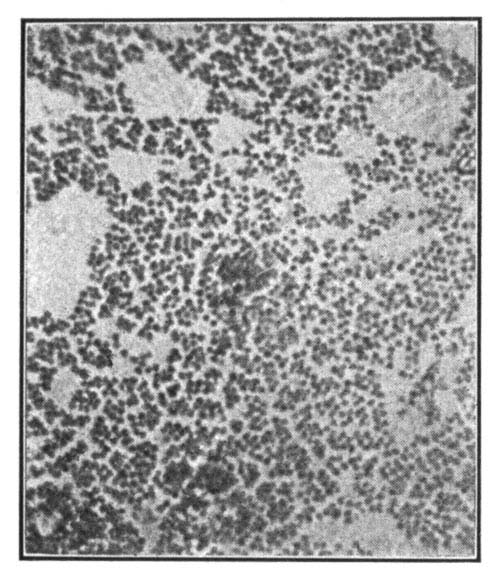

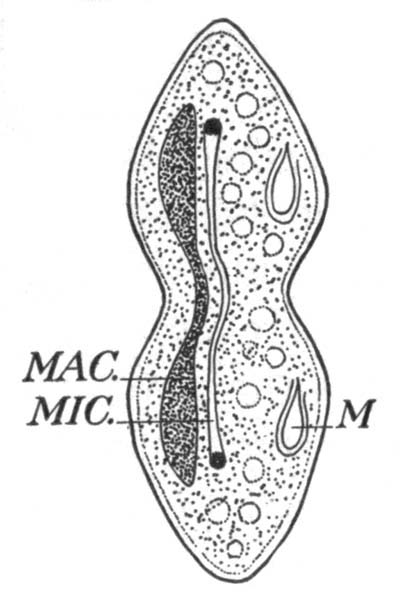

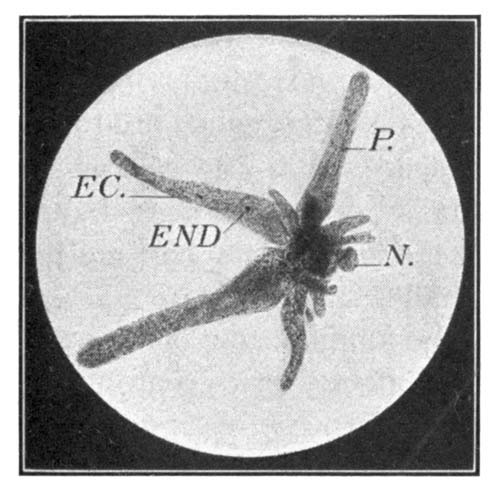

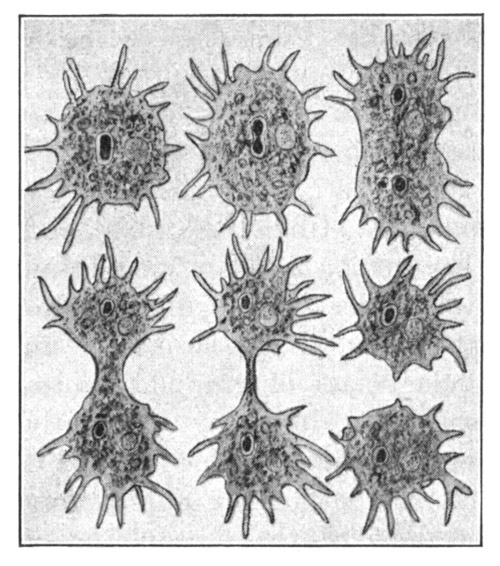

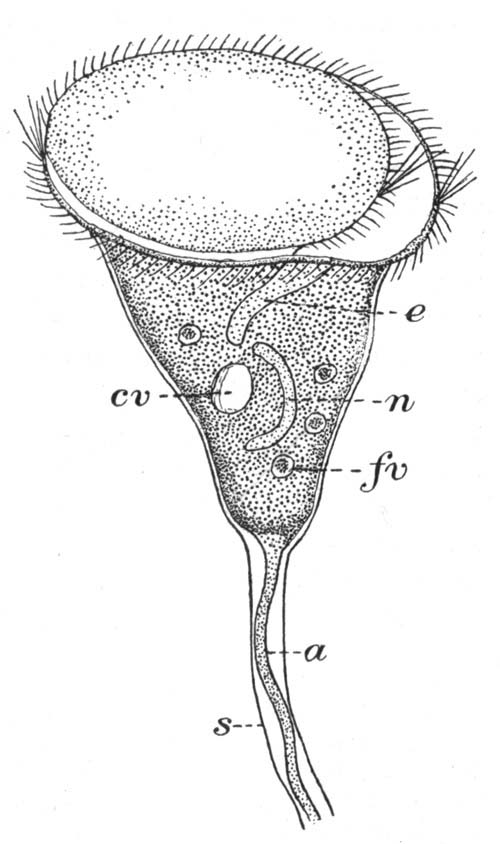

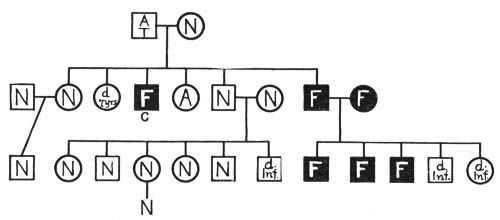

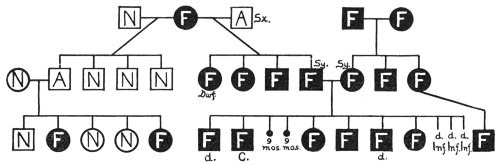

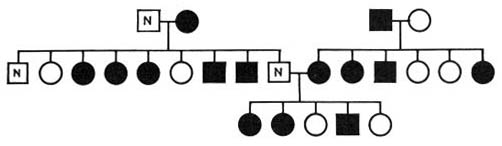

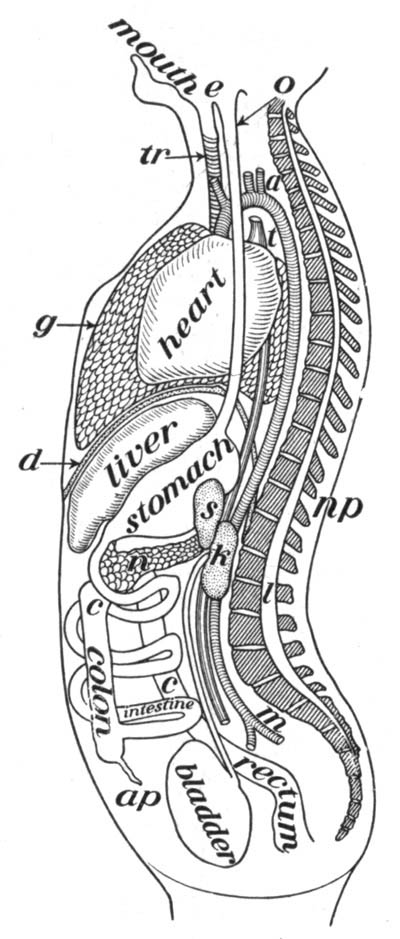

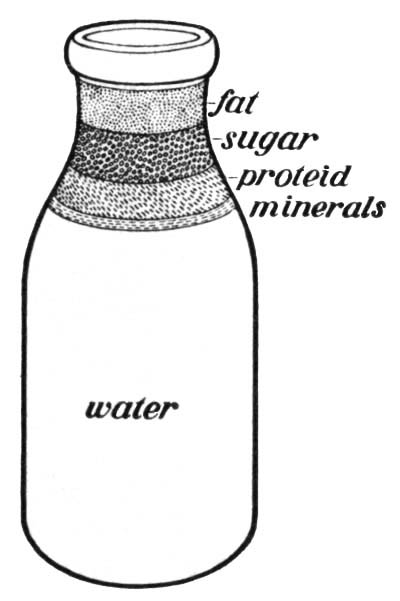

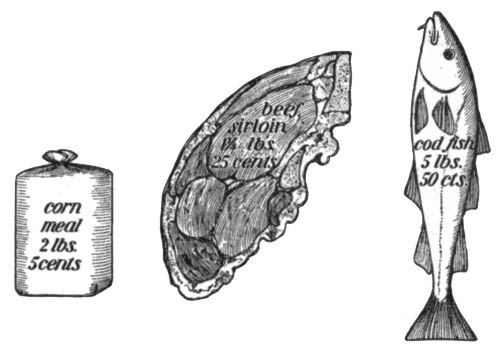

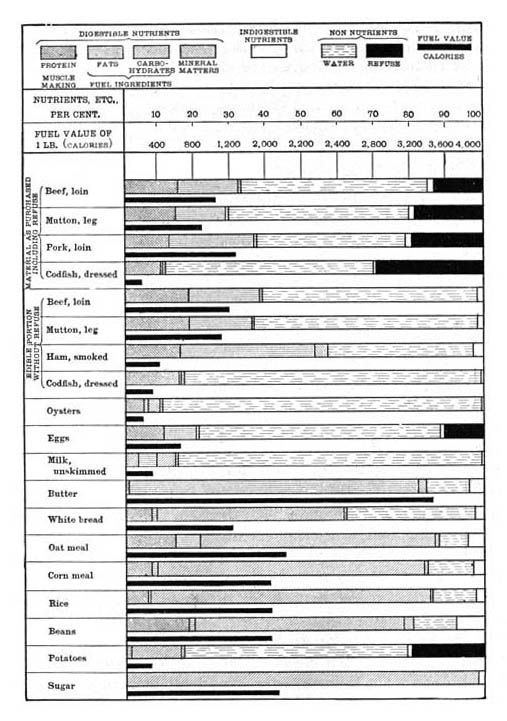

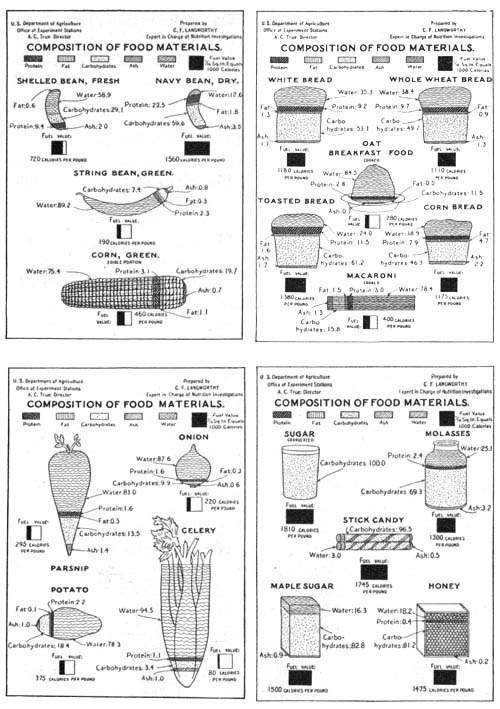

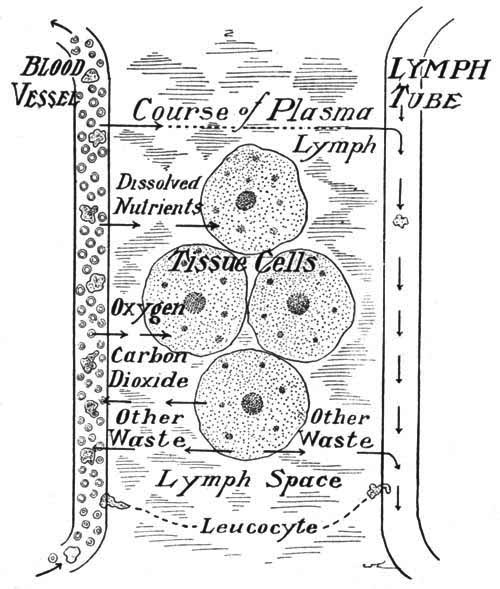

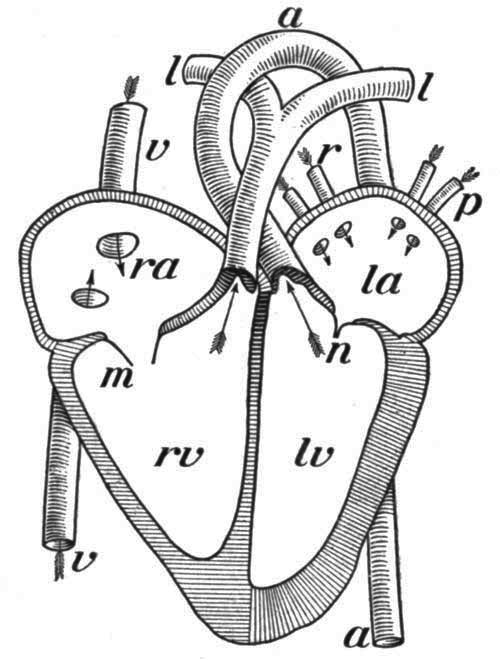

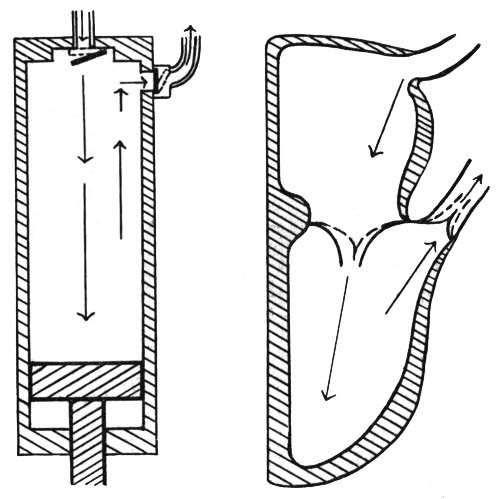

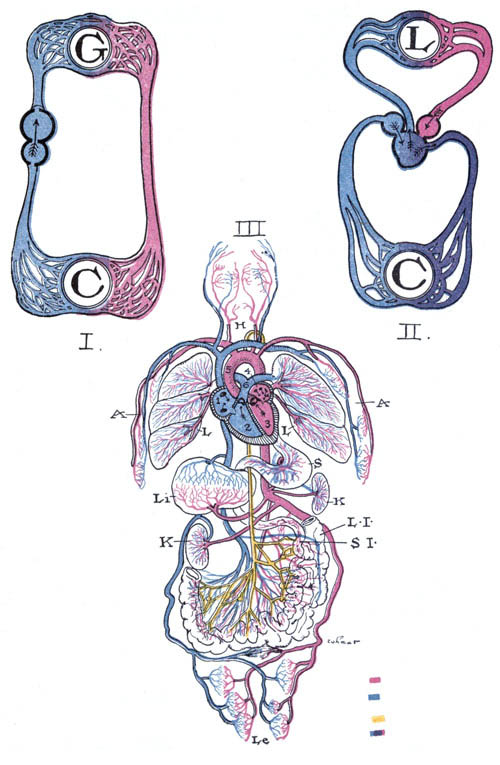

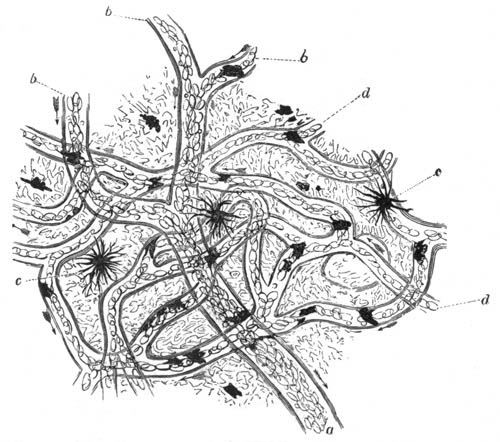

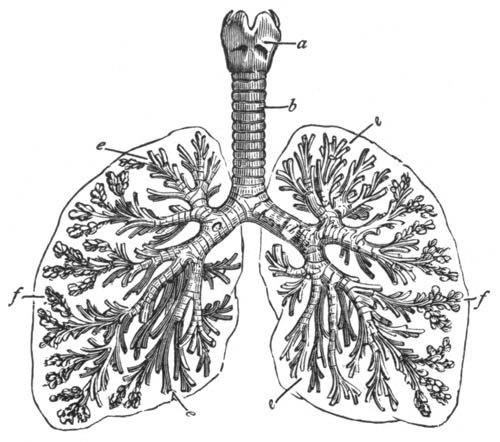

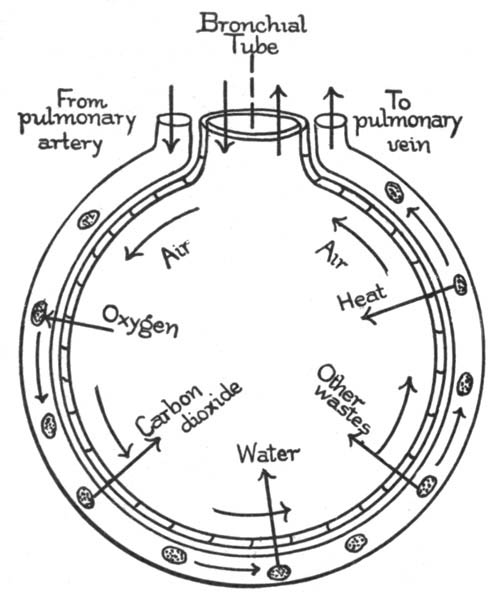

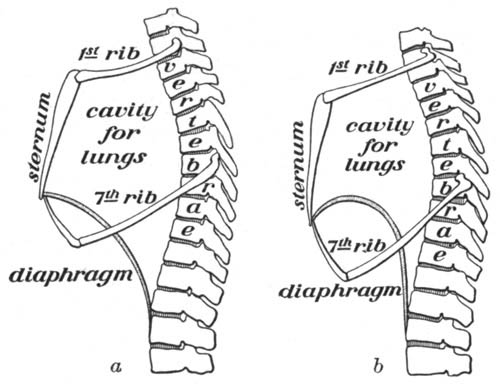

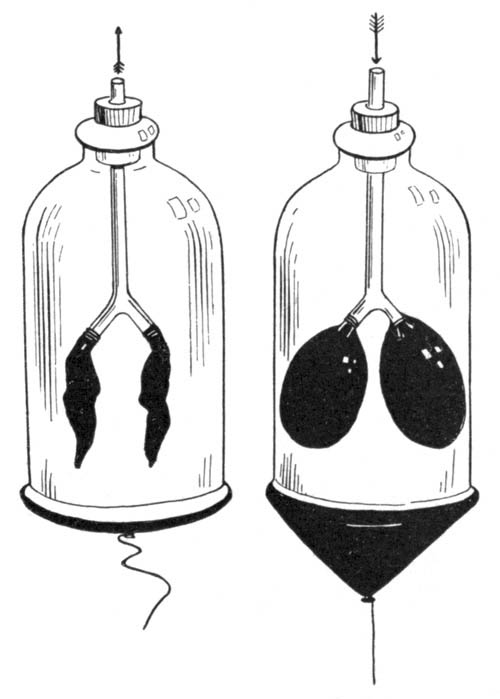

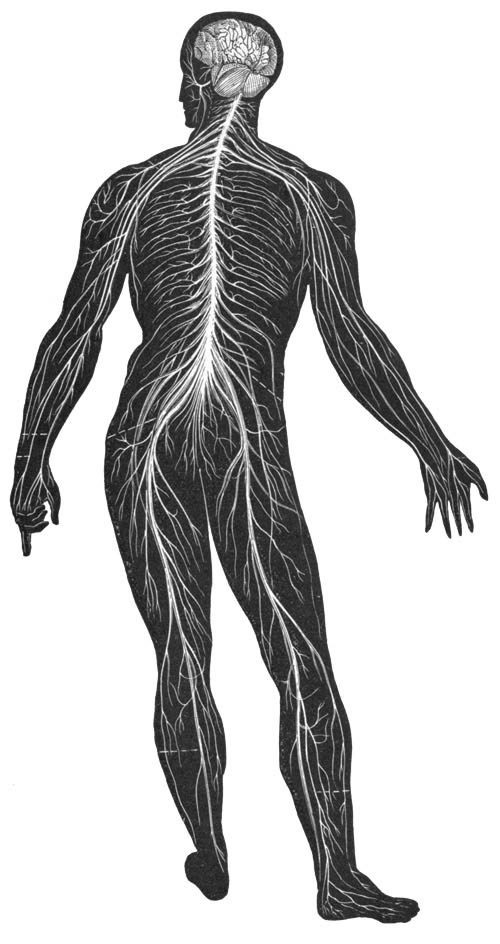

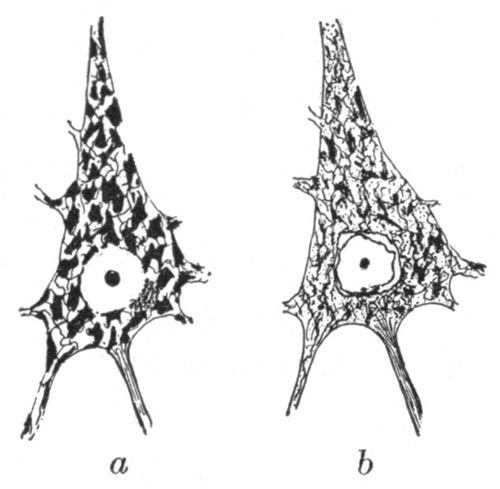

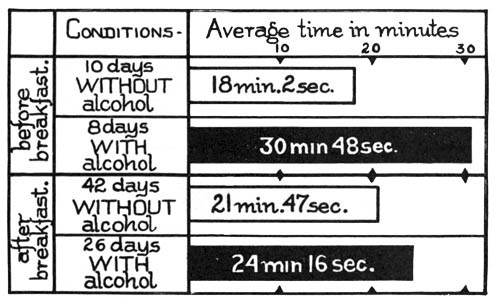

Cells of Various Sizes and Shapes.—Plant cells and animal cells are of very diverse shapes and sizes. There are cells so large that they can easily be seen with the unaided eye; for example, the root hairs of plants and eggs of some animals. On the other hand, cells may be so minute, as in the case of the plant cells named bacteria, that several million might be present in a few drops of milk. The forms of cells may be extremely varied in different tissues; they may assume the form of cubes, columns, spheres, flat plates, or may be extremely irregular in shape. One kind of tissue cell, found in man, has a body so small as to be quite invisible to the naked eye, although it has a prolongation several feet in length. Such are some of the cells of the nervous system of man and other large animals, as the ox, elephant, and whale.