The Project Gutenberg EBook of Nooks and Corners of Old England, by Allan Fea This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Nooks and Corners of Old England Author: Allan Fea Release Date: September 11, 2012 [EBook #39685] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NOOKS AND CORNERS OF OLD ENGLAND *** Produced by Annie McGuire. This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print archive.

AUTHOR OF

"SECRET CHAMBERS AND HIDING PLACES" "PICTURESQUE OLD HOUSES"

"FLIGHT OF THE KING" ETC.

A recent glance over some old Ordnance Maps, the companions of many a ramble in the corners of Old England, has suggested the idea of jotting down a few fragmentary notes, which we trust may be of interest.

Upon a former occasion we wandered with pencil and camera haphazard off the beaten track mainly in the counties surrounding the great Metropolis; and though there are several tempting "Nooks" still near at hand, we have now extended our range of exploration.

We only trust the reader will derive a little of the pleasure we have found in compiling this little volume.

A. F.

At Huntingdon we are on familiar ground with Samuel Pepys. When he journeyed northwards to visit his parental house or to pay his respects to Lord Sandwich's family at Hinchinbrooke, he usually found suitable accommodation at "Goody Gorums" and "Mother" somebody else who lived over against the "Crown." Neither the famous posting-house the "George" nor the "Falcon" are mentioned in the Diary, but he speaks of the "Chequers"; however, the change of names of ancient hostelries is common, so in picturing the susceptible Clerk of the Admiralty chucking a pretty chambermaid under the chin in the old galleried yard of the "George," we may not be far out of our reckoning.

But altogether the old George Inn is somewhat disappointing. Its balustraded galleries are there sure enough, with t[Pg 2]he queer old staircase leading up to them in one of the corners; but it has the same burnished-up appearance of the courtyard of the Leicester Hospital at Warwick. How much more pleasing both would strike the eye were there less paint and varnish. The Inn has been refronted, and from the street has quite a modern appearance.

Huntingdon recalls the sterner name of Cromwell. Strange that this county, so proud of the Lord Protector (for has it not recently set up a gorgeous statue at St. Ives to his memory?), should still harbour red-hot Jacobites! According to The Legitimist Calendar, mysterious but harmless meetings are still held hereabouts on Oak Apple Day: a day elsewhere all but forgotten. Huntingdon was the headquarters of the Royalist army certainly upon many occasions, and when evil days fell upon the "Martyr King," some of his staunchest friends were here secretly working for his welfare.[1] When Charles passed through the town in 1644, the mayor, loyal to the back-bone, had prepared a speech to outrival the flowery welcome of his fellow-magistrates: "Although Rome's Hens," he said, "should daily hatch of its preposterous eggs, chrocodilicall chickens, yet under the Shield of Faith, by you our most Royal Sovereigne defended and by the King of Heavens as I stand and your most medicable councell, would we not be fearful t[Pg 3]o withstand them."[2] Though the sentence is somewhat involved, the worthy magnate doubtless meant well.

It was the custom, by the way, so Evelyn tells us, when a monarch passed through Huntingdon, to meet him with a hundred ploughs as a symbol of the fruitful soil: the county indeed at one time was rich in vines and hops, and has been described by old writers as the garden of England. Still here as elsewhere the farmers' outlook is a poor one to-day, although there are, of course, exceptions.

At historic Hinchinbrooke (on June 4, 1647), King Charles slept the first night after he was removed from Holdenby House by Cornet Joyce: the first stage of his progress to the scaffold. In the grounds of the old mansion, the monarch, when Prince of Wales, and little Oliver played together, for the owner in those days of the ancient seat of the Montagues and Cromwells was the future Protector's uncle and godfather. Upon one occasion the boys had a stand-up fight, and the commoner, the senior by only one year, made his royal adversary's nose bleed,—an augury for fatal events to follow. The story is told how little Oliver fell into the Ouse and was fished out by a Royalist piscatorial parson. Years afterwards, when the Protector revisited the scenes of his youth in the midst of his triumphant army, he[Pg 4] encountered his rescuer, and asked him whether he remembered the occurrence.

"Truly do I," was the prompt reply; "and the Lord forgive me, but I wish I'd let thee drown."

The Montagues became possessed of the estate in 1627. Pepys speaks of "the brave rooms and good pictures," which pleased him better than those at Audley End. The Diarist's parental house remains at Brampton, a little to the west of Huntingdon. In characteristic style he records a visit there in October 1667: "So away for Huntingdon mightily pleased all along the road to remember old stories, and come to Brampton at about noon, and there found my father and sister and brother all well: and here laid up our things, and up and down to see the gardens with my father, and the house; and do altogether find it very pretty, especially the little parlour and the summer-houses in the garden, only the wall do want greens up it, and the house is too low roofed; but that is only because of my coming from a house with higher ceilings."

Before turning our steps northwards, let us glance at the mediŠval bridge that spans the river Ouse, to Godmanchester, which is referred to by the thirteenth-century historian Henry of Huntingdon as "a noble city." But its nobility has long since departed, and some modern monstrosities in architecture make the old Tudo[Pg 5]r buildings which remain, blush for such brazen-faced obtrusion. Its ancient water-mill externally looks so dilapidated, that one would think the next "well-formed depression" from America would blow it to atoms. Not a bit of it. Its huge timber beams within, smile at such fears. It is a veritable fortress of timber. But although this solid wooden structure defies the worst of gales, there are rumours of coming electric tramways, and then, alas! the old mill will bow a dignified departure, and the curfew, which yet survives, will then also perhaps think it is time to be gone.

At Little Stukeley, on the Great North Road some three miles above Huntingdon, is a queer old inn, the "Swan and Salmon," bearing upon its sign the date 1676. It is a good example of the brickwork of the latter half of the seventeenth century. Like many another ancient hostelry on the road to York, it is associated with Dick Turpin's exploits; and to give colour to the tradition, mine host can point at a little masked hiding-place situated somewhere at the back of the sign up in its gable end. It certainly looks the sort of place that could relate stories of highwaymen; a roomy old building, which no doubt in its day had trap-doors and exits innumerable for the convenience of the gentlemen of the road.

A little off the ancient "Ermine Street," to the north-west of Stukeley, is the insignificant village of Coppingford, historically interesting from the fact that when Charles I. fled from Oxford in disguise in 1646, he stopped the night there at a little obscure cottage or alehouse, on his way to seek protection of the Scots at Southwell. "This day one hundred years ago," writes Dr. Stukeley in his Memoirs on May 3, 1746, "King Charles, Mr. John Ashburnham, and Dr. Hudson came from Coppingford in Huntingdonshire and lay at Mr. Alderman Wolph's house, now mine, on Barn Hill; all the day obscure." Hudson, from whom Sir Walter drew his character of Dr. Rochecliffe in Woodstock, records the fact in the following words: "We lay at Copingforde in Huntingdonshire one Sunday, 3 May; wente not to church, but I read prayers to the King; and at six at night he went to Stamforde. I writte from Copingforde to Mr. Skipwith for a horse, and he sente me one, which was brought to me at Stamforde. ——at Copingforde the King and me, with my hoste and hostis and two children, were by the fire in the hall. There was noe other chimney in the house."[3] The village of Little Gidding, still farther to the north-west, had often before been visited by Charles in connection with a religious establishment that had been founded there by the Ferrar family. A curious old silk[Pg 7] coffer, which was given by Charles to the nieces of the founder, Nicholas Ferrar, upon one of these occasions, some years ago came into the possession of our late queen, and is still preserved at Windsor.

A few miles to the north-east is Glatton, another remote village where old May-day customs yet linger. There are some quaint superstitions in the rural districts hereabouts. A favourite remedy for infectious disease is to open the window of the sickroom not so much to let in the fresh air as to admit the gnats, which are believed to fly away with the malady and die. The beneficial result is never attributed to oxygen!

The Roman road (if, indeed, it is the same, for some authorities incline to the opinion that it ran parallel at some little distance away) is unpicturesque and dreary. Towering double telegraph poles recur at set intervals with mathematical regularity, and the breeze playing upon the wires aloft brings forth that long-drawn melancholy wail only to make the monotony more depressing. Half a mile from the main road, almost due east of Glatton, stands Connington Hall, where linger sad memories of the fate of Mary Queen of Scots. When the castle of Fotheringay was demolished in 1625, Sir Robert Cotton had the great Hall in which she was beheaded removed here. The curious carved oak chair which was used by the poor Queen at Fotheringay until the day [Pg 8]of her death may now be seen in Connington Church, where also is the Tomb of Sir Robert, the founder of the famous Cottonian Library.

A couple of miles or so to the north is Stilton, which bears an air of decayed importance. A time-mellowed red-brick Queen Anne house, whose huge wooden supports, like cripples' crutches, keep it from toppling over, comes first in sight. In striking contrast, with its formal style of architecture, is the picturesque outline of the ancient inn beyond. A complicated flourish of ornamental ironwork, that would exasperate the most expert freehand draughtsman, supports the weather-beaten sign of solid copper. Upon the right-hand gable stands the date 1642, bringing with it visions of the coming struggle between King and Parliament. But the date is misleading, as may be seen from the stone groining upon the adjoining masonry. The main building was certainly erected quite a century earlier. Here and there modern windows have been inserted in place of the Tudor mullioned ones, as also have later doorways, for part of the building is now occupied as tenements. The archway leading into the courtyard has also been somewhat modernised, as may be judged from the corresponding internal arch, with its original curved dripstone[Pg 9] above.

We came upon this inn, tramping northwards in a bitter day in March. It looked homely and inviting, the waning sunlight tinting the stonework and lighting up the window casements. Enthusiastic with pleasing imaginings of panelled chambers and ghostly echoing corridors, we entered only to have our dreams speedily dispersed. In vain we sought for such a "best room" as greeted Mr. Chester at the "Maypole." There were no rich rustling hangings here, nor oaken screens enriched with grotesque carvings. Alas! not even a cheery fire of fagots. Nor, indeed, was there a bed to rest our weary bones upon. Spring cleaning was rampant, and the merciless east wind sweeping along the bare passages made one shudder more than usual at the thought of that terrible annual necessity (but the glory of energetic house-wives). But surely mine hostess of the good old days would have scrupled to thrust the traveller from her door: moreover to a house of refreshment, or rather eating-house, a stone's-throw off, uncomfortably near that rickety propped-up red-brick residence.

With visions of the smoking bowl and lavender-scented sheets dashed to the ground, we turned away. But, lo! and behold a good angel had come to the rescue. So absorbed had we been with the possibilities of the "Bell" that the "Angel" opposite had quite been overlooked. This rival inn of Georgian date furnished us with cosy quarters. From our flower-bedecked win[Pg 10]dow the whole front of the old "Bell" could be leisurely studied in all its varying stages of light and shade—an inn with a past; an object-lesson for the philosopher to ruminate upon. Yes, in its day one can picture scenes of lavish, shall we say Ainsworthian hospitality. There is a smack of huge venison pasties, fatted capons, and of roasted peacocks about this hoary hostel. And its stables; one has but to stroll up an adjacent lane to get some idea of the once vast extent of its outbuildings. The ground they covered must have occupied nearly half the village. Here was stabling for over eighty horses, and before the birth of trains, thirty-six coaches pulled up daily at the portal for hungry passengers to refresh or rest.

The famous cheese, by the way, was first sold at this inn; but why it was dubbed Stilton instead of Dalby in Leicestershire, where it was first manufactured, is a mystery. Like its vis-Ó-vis, the "Angel" is far different from what it was in its flourishing days. The main building is now occupied for other purposes, and its dignity has long since departed. To-day Stilton looks on its last legs. The goggled motor-fiend sweeps by to Huntingdon or Peterborough while Stilton rubs its sleepy eyes. But who can tell but that its fortunes may yet revive. Was not Broadway dying a natural death when Jonathan, who invar[Pg 11]iably tells us what treasures we possess, stepped in and made it popular? Some enterprising landlord might do worse than take the old "Bell" in hand and ring it to a profitable tune. But judging by appearances, visitors to-day, at least in March, are few and far between.

Half the charm of Stilton lies in the fact that there is no hurry. It is quite refreshing in these days of rush. For instance, you want to catch a train at Peterborough,—at least we did, for that was the handiest way of reaching Oundle, some seven miles to the west of Stilton as the crow flies. Sitting on thorns, we awaited the convenience of the horse as to whether his accustomed jog-trot would enable us to catch our train. We did catch it truly, but the anxiety was a terrible experience.

Oundle is full of old inns. The "Turk's Head," facing the church, is a fine and compact specimen of Jacobean architecture. It was a brilliant morning when we stood in the churchyard looking up at the ball-surmounted gables standing out in bold relief against the clear blue sky, while the caw of a colony of rooks sailing overhead seemed quite in harmony with the old-world surroundings.

More important and flourishing is the "Talbot," which looks self-conscious of the fact that in its walls are inc[Pg 12]orporated some of the remains of no less historic a building than Fotheringay Castle, whose moat and fragmentary walls are to be seen some three and a half miles to the north of the town. The fortress, with its sad and tragic memories of Mary Queen of Scots, was demolished after James came to the throne, and its fine oak staircase, by repute the same by which she descended to the scaffold, was re-erected in the "Talbot." The courtyard is picturesque. The old windows which light the staircase, which also are said to have come from Fotheringay, are angular at the base, and have an odd and pleasing appearance.

Two ancient almshouses, with imposing entrance gates, are well worth inspection. There is a graceful little pinnacle surmounting one of the gable ends, at which we were curiously gazing when one of the aged inmates came out in alarm to see if the chimney was on fire.

Fotheringay church, with its lantern tower and flying buttresses, is picturesquely situated close to the river Nene, and with the bridge makes a charming picture. The older bridge of Queen Mary's time was angular, with square arches, as may be seen from a print of the early part of the eighteenth century. In this is shown the same scanty remains of the historic Castle: a wall with a couple of Gothic doorways, all that survived of the formidable fortress that was the unfortunate queen's last prison-house. As at Cumnor, wher[Pg 13]e poor Amy Robsart was done to death in a manner which certainly Elizabeth hinted at regarding her troublesome cousin, there is little beyond the foundations from which to form an idea of the building. It was divided by a double moat, which is still to be seen, as well as the natural earthwork upon which the keep stood. The queen's apartments, that towards the end were stripped of all emblems of royalty, were situated above and to the south of the great hall, into which she had to descend by a staircase to the scaffold. Some ancient thorn trees now flourish upon the spot. The historian Fuller, who visited the castle prior to its demolition, found the following lines from an old ballad scratched with a diamond upon a window-pane of Mary's prison-chamber:

"From the top of all my trust

Mishap hath laid me in the dust."

Though Mary's mock trial took place at Fotheringay in the "Presence Chamber," she was actually condemned in the Star Chamber at Westminster; and it may here be stated that that fine old room may yet be seen not very many miles away, at Wormleighton, near the Northamptonshire border of south-east Warwickshire. A farmhouse near Fotheringay is still pointed out where the executioner lodged the night before the deed; and some claim[Pg 14] this distinction for the ancient inn in which are incorporated some remains of the castle.

As is known, the Queen of Scots' body was buried first in Peterborough Cathedral, whence it was removed to Westminster Abbey. There is a superstition in Northamptonshire that if a body after interment be removed, it bodes misfortune to the surviving members of the family. This was pointed out at the time to James I.; but superstitious as he was, he did not alter his plans, and the death of Prince Henry shortly afterwards seemed to confirm this belief.[4]

But there are other memories of famous names in history, for the head of the White Rose family, Richard of York, was buried in the church, and his duchess, Cecilia Neville, as well as Edward of York, whose death at Agincourt is immortalised by Shakespeare. When the older church was dismantled and the bodies removed to their present destination, a silver ribbon was discovered round the Duchess Cecilia's neck upon which a pardon from Rome was clearly written. The windows of the church once were rich in painted glass; and at the fine fifteenth-century font it is conjectured Richard III. was baptized, for he was born at the Castle. Crookback's badge, the boar, may still be seen in the church, and the Yorkist falcon and fetterlock are displayed on the summit o[Pg 15]f the vane upon the tower. Also some carved stalls, which came from here, in the churches of Tansor and Hemington to the south of Fotheringay, bear the regal badges and crest. The falcon and the fetterlock also occur in the monuments to the Dukes of York, which were rebuilt by Queen Elizabeth when the older tombs had fallen to decay. The allegiance to the fascinating Queen of Scots is far from dead, for in February 1902, and doubtless more recently, a gentleman journeyed specially from Edinburgh to Fotheringay to place a tribute to her martyrdom in the form of a large cross of immortelles bearing the Scots crown and Mary's monogram, and a black bordered white silk sash attached.

A few miles to the west of this historic spot are the fine Tudor houses Deene and Kirby: the former still a palatial residence; the latter, alas! a ruin fast falling to decay. Deene, with its battlemented towers and turrets and buttressed walls, is a noble-looking structure, with numerous shields of arms and heraldic devices carved upon the masonry. These are of the great families, Brudenel, Montagu, Bruce, Bulstrode, etc., whose intermarriages are emblazoned in painted glass in the top of the mullioned windows of the hall. Sir Thomas Brudenel, the first Earl of Cardigan, who died three years after the Restoration, was a typical old cavalier afte[Pg 16]r the style of Sir Henry Lee in Woodstock; and in the manor are preserved many of his manuscripts written during his twenty years' confinement in the Tower. In the great hall there is a blocked-up entrance to a subterranean passage running towards Kirby, and through this secret despatches are said to have been carried in the time of the Civil War; and at the back of a fireplace in the same apartment is a hiding-place sufficiently large to contain a score of people standing up. One of the rooms is called Henry VII.'s room, as that monarch when Earl of Richmond is said to have ridden from Bosworth Field to seek refuge at Deene, then a monastery.

Among the numerous portraits are the Earl of Shrewsbury, who was slain by the second Duke of Buckingham in the notorious duel, and his wife Lady Anne Brudenel, who was daughter of the second Earl of Cardigan. Some time before the poor plain little duchess suspected that she had a formidable rival in the beautiful countess, she was returning from a visit to Deene to her house near Stamford, where her reckless husband just then found it convenient to hide himself, as a warrant for high treason was out against him, when she noticed a suspicious little cavalcade travelling in the same direction. Ordering the horses to be whipped up, she arrived in time to give the alarm. The duke had just set out for[Pg 17] Burleigh House with some ladies in his company, and, says Clarendon, the sergeant "made so good haste that he was in view of the coach, and saw the duke alight out of the coach and lead a lady into the house, upon which the door of the court was shut before he could get to it. He knocked loudly at that and other doors that were all shut, so that he could not get into the house though it were some hours before sunset in the month of May."[5] Pepys was strolling in the park and met Sergeant Bearcroft "who was sent for the Duke of Buckingham, to have brought his prisoner to the Tower. He come to towne this day and brings word that being overtaken and outrid by the Duchesse of Buckingham within a few miles of the duke's house of Westhorp, he believes she got thither about a quarter of an hour before him, and so had time to consider; so that when he came, the doors were kept shut against him. The next day, coming with officers of the neighbour market-town [Stamford] to force open the doors, they were open for him, but the duke gone, so he took horse presently and heard upon the road that the Duke of Buckingham was gone before him for London. So that he believes he is this day also come to towne before him; but no newes is yet heard of him."[6] Many blunders have been made in reference to the duke's hou[Pg 18]se of "Westhorp." Some have called it "Owthorp" and others "Westhorpe" in Suffolk, the demolished mansion of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk. The place referred to is really Wothorpe manor-house, the remains of which stand some two miles to the south of Stamford and ten to the north of Deene. The existing portion consists of four towers, the lower part of which is square and the upper octagonal, presumably having been at one time surmounted by cupolas. The windows are long and narrow, having only one mullion running parallel across. Beneath the moulding of the summit of each tower are circular loopholes. It is evidently of Elizabethan date, but much of the ornamental detail is lost in the heavy mantle of ivy and the trees which encircle it.

That that stately Elizabethan mansion, Kirby Hall (which is close to Deene), should ever have been allowed to fall to ruin is most regrettable and deplorable. It was one of John Thorpe's masterpieces, the architect of palatial Burleigh, of Holland House and Audley End, and other famous historic houses. He laid the foundation-stone in 1570, and that other great master Inigo Jones made additions in the reign of Charles I. The founder of Kirby was Sir Christopher Hatton, who is said to have first danced into the virgin queen's favour at a masque at[Pg 19] Court. The Earl of Leicester probably first was famous in this way, if we may judge from the quaint painting at Penshurst, where he is bounding her several feet into the air; but was not so accomplished as Sir Christopher, who in his official robes of Lord Chancellor danced in the Hall of the Inner Temple with the seals and mace of his office before him, an undignified proceeding, reminding one of the scene in one of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas.

Kirby must have been magnificent in its day; and when we consider that it was in occupation by the Chancellor's descendant, the Earl of Winchelsea, in 1830 or even later, one may judge by seeing it how rapidly a neglected building can fall into decay. Even in our own memory a matter of twenty years has played considerable havoc, and cleared off half the roof. Standing in the deserted weed-grown courtyard, one cannot but grieve to see the widespread destruction of such beautiful workmanship. The graceful fluted Ionic pilasters that intersect the lofty mullioned windows are falling to pieces bit by bit, and the fantastic stone pinnacles above and on the carved gable ends are disappearing one by one. But much of the glass is still in the windows, and some of the rooms are not all yet open to the weather, and the great hall and music gallery and the "Library" with fine bay window are both in [Pg 20]a fair state of preservation. Is it yet too much to hope that pity may be taken upon what is undoubtedly one of the finest Elizabethan houses in England? The north part of the Inner Court is represented in S. E. Waller's pathetic picture "The Day of Reckoning," which has been engraved.

Some three miles to the south of Kirby is the village of Corby, famous for its surrounding woods, and a curious custom called the "Poll Fair," which takes place every twenty years. Should a stranger happen to be passing through the village when the date falls due, he is liable to be captured and carried on a pole to the stocks, which ancient instrument of punishment is there, and put to use on these occasions. He may purchase his liberty by handing over any coin he happens to have. It certainly is a rather eccentric way of commemorating the charter granted by Elizabeth and confirmed by Charles II. by which the residents (all of whom are subjected to similar treatment) are exempt from market tolls and jury service.

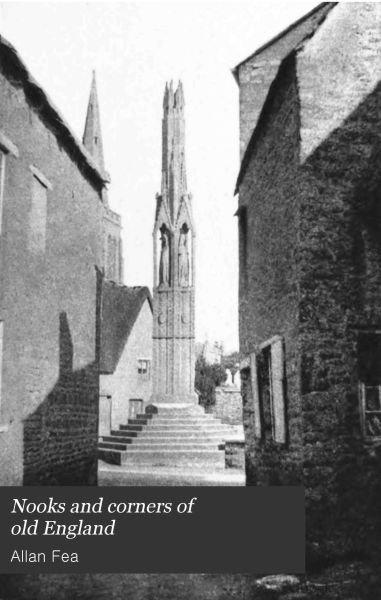

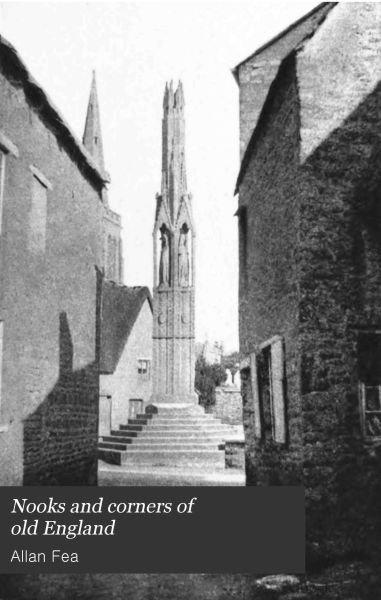

A pair of stocks stood formerly at the foot of the steps of the graceful Eleanor Cross at Geddington to the south of Corby. Of the three remaining memorials said to have been erected by Edward I. at every place where the coffin of his queen rested on its way from Hardeby in[Pg 21] Lincolnshire to Westminster Abbey, Geddington Cross is by far the most graceful and in the best condition. The other two are at Waltham and Northampton. Originally there were fifteen Eleanor crosses, including Hardeby, Lincoln, Stony Stratford, Woburn, Dunstable, St. Albans, Cheapside, and Charing Cross. The last two, the most elaborate of all, as is known, were destroyed by order of Lord Mayor Pennington in 1643 and 1647, accompanied by the blast of trumpets.

The idea of calling pretty little Mildenhall in north-west Suffolk a town, seems out of place. It is snug and sleepy and prosperous-looking, an inviting nook to forget the noise and bustle of a town in the ordinary sense of the word. May it long continue so, and may the day be long distant when that terrible invention, the electric tram, is introduced to spoil the peace and harmony. Mildenhall is one of those old-world places where one may be pretty sure in entering the snug old courtyard of its ancient inn, tha[Pg 23]t one will be treated rather as a friend than a traveller. Facing the "Bell" is the church, remarkable for the unique tracery of its early-English eastern window, and for its exceptionally fine open hammer-beam carved oak roof, with bold carved spandrels and large figures of angels with extended wings, and the badges of Henry V., the swan and antelope, displayed in the south aisle.

In a corner of the little market-square is a curious hexagonal timber market-cross of this monarch's time, roofed with slabs of lead set diagonally, and adding to the picturesque effect. The centre part runs through the roof to a considerable height, and is surmounted by a weather-cock. Standing beneath the low-pitched roof, one may get a good idea of the massiveness of construction of these old Gothic structures; an object-lesson to the jerry builder of to-day. The oaken supports are relieved with graceful mouldings.

Within bow-shot of the market-cross is the gabled Jacobean manor-house of the Bunburys, a weather-worn wing of which abuts upon the street. The family name recalls associations with the beautiful sisters whom Goldsmith dubbed "Little Comedy" and the "Jessamy Bride." The original "Sir Joshua" of these ladies may be seen at Barton Hall, another seat of the Bunburys a few miles away, where they played good-natured pract[Pg 24]ical jokes upon their friend the poet. In a room of the Mildenhall mansion hangs a portrait of a less beautiful woman, but sufficiently attractive to meet with the approval of a critical connoisseur. When the Merry Monarch took unto himself a wife, this portrait of the little Portuguese woman was sent for him to see; and presumably it was flattering, for when Catherine arrived in person, his Majesty was uncivil enough to inquire whether they had sent him a bat instead of a woman.

A delightful walk by shady lanes and cornfields, and along the banks of the river Lark, leads to another fine old house, Wamil Hall, a portion only of the original structure; but it would be difficult to find a more pleasing picture than is formed by the remaining wing. It is a typical manor-house, with ball-surmounted gables, massive mullioned windows, and a fine Elizabethan gateway in the lofty garden wall, partly ivy-grown, and with the delicate greys and greens of lichens upon the old stone masonry.

In a south-easterly direction from Mildenhall there is charming open heathy country nearly all the way to West Stow Hall, some seven or eight miles away. The remains of this curious old structure consist principally of the gatehouse, octagonal red-brick towers surmounted by ornamen[Pg 25]tal cupolas with a pinnacled step-gable in the centre and the arms of Mary of France beneath it, and ornamental Tudor brickwork above the entrance. The passage leading from this entrance to the main structure consists of an open arcade, and the upper portion and adjoining wing are of half-timber construction. This until recently has been cased over in plaster; but the towers having become unsafe, some restorations have been absolutely necessary, the result of which is that the plaster is being stripped off, revealing the worn red-brick and carved oak beams beneath. Moreover, the moat, long since filled up, is to be reinstated, and, thanks to the noble owner, Lord Cadogan, all its original features will be most carefully brought to light. In a room above are some black outline fresco paintings of figures in Elizabethan costume, suggestive of four of the seven ages of man. Most conspicuous is the lover paying very marked attentions to a damsel who may or may not represent Henry VIII.'s sister at the time of her courtship by the valiant Brandon, Duke of Suffolk; anyway the house was built by Sir John Crofts, who belonged to the queen-dowager's household, and he may have wished to immortalise that romantic attachment. A gentleman with a parrot-like hawk upon his wrist says by an inscription, "Thus do I all the day"; while the lover observes, "Thus do I while I may." A third person, presumably getting on in years, says with a si[Pg 26]gh, "Thus did I while I might"; and he of the "slippered pantaloon" age groans, "Good Lord, will this world last for ever!" In a room adjoining, we were told, Queen Elizabeth slept during one of her progresses through the country, or maybe it was Mary Tudor who came to see Sir John; but the "White Lady" who issues from one of the rooms in the main building at 12 o'clock p.m. so far has not been identified.

In his lordship's stables close by we had the privilege of seeing "a racer" who had won sixteen or more "seconds," as well as a budding Derby winner of the future. Culford is a stately house in a very trim and well-cared-for park. It looks quite modern, but the older mansion has been incorporated with it. In Charles II.'s day his Majesty paid occasional visits to Culford en route from Euston Hall to Newmarket, and Pepys records an incident there which was little to his host's (Lord Cornwallis') credit. The rector's daughter, a pretty girl, was introduced to the king, whose unwelcome attentions caused her to make a precipitate escape, and, leaping from some height, she killed herself, "which, if true," says Pepys, "is very sad." Certainly Charles does not show to advantage in Suffolk. The Diarist himself saw him at Little Saxham Hall[7] (to the south-west of Culford), the seat of Lord Crofts, going to bed, after a heavy drinking bout with his boon companions[Pg 27] Sedley, Buckhurst, and Bab May.

The church is in the main modern, but there is a fine tomb of Lady Bacon, who is represented life-size nursing her youngest child, while on either side in formal array stand her other five children. Her husband is reclining full length at her feet.

Hengrave Hall, one of the finest Tudor mansions in England, is close to Culford. Shorn of its ancient furniture and pictures (for, alas! a few years ago there was a great sale here), the house is still of considerable interest; but the absence of colour—its staring whiteness and bare appearance—on the whole is disappointing, and compared with less architecturally fine houses, such as Kentwell or Rushbrooke, it is inferior from a picturesque point of view. Still the outline of gables and turreted chimneys is exceptionally fine and stately. It was built between the years 1525 and 1538. The gatehouse has remarkable mitre-headed turrets, and a triple bay-window bearing the royal arms of France and England quarterly, supported by a lion and a dragon. The entrance is flanked on either side by an ornamental pillar similar in character to the turrets. The house was formerly moated and had a drawbridge, as at Helmingham in this county. These were done a[Pg 28]way with towards the end of the eighteenth century, when a great part of the original building was demolished and the interior entirely reconstructed. The rooms included the "Queen's Chamber," where Elizabeth slept when she was entertained here after the lavish style at Kenilworth in 1578, by Sir Thomas Kytson. From the Kitsons, Hengrave came to the Darcys and Gages.

In the vicinity of Bury there are many fine old houses, but for historical interest none so interesting as Rushbrooke Hall, which stands about the same distance from the town as Hengrave in the opposite direction, namely, to the south-west. It is an Elizabethan house, with corner octagonal turrets to which many alterations were made in the next century: the windows, porch, etc., being of Jacobean architecture. It is moated, with an array of old stone piers in front, upon which the silvery green lichen stands out in harmonious contrast with the rich purple red of the Tudor brickwork. The old mansion is full of Stuart memories. Here lived the old cavalier Henry Jermyn, Earl of St. Albans, who owed his advancement to Queen Henrietta Maria, to whom he acted as secretary during the Civil War, and to whom he was privately married[Pg 29] when she became a widow and lived in Paris. He was a handsome man, as may be judged from his full-length portrait here by Vandyck, though he is said to have been somewhat ungainly. In the "State drawing-room," where the maiden queen held Court when she visited the earl's ancestor Sir Robert Jermyn in 1578, may be seen two fine inlaid cabinets of wood set with silver, bearing the monogram of Henrietta Maria. Jermyn survived his royal wife the dowager-queen over fourteen years. Evelyn saw him a few months before he died. "Met My Lord St. Albans," he says, "now grown so blind that he could not see to take his meat. He has lived a most easy life, in plenty even abroad, whilst His Majesty was a sufferer; he has lost immense sums at play, which yet, at about eighty years old, he continues, having one that sits by him to name the spots on the cards. He eat and drank with extraordinary appetite. He is a prudent old courtier, and much enriched since His Majesty's return."[8]

Charles I.'s leather-covered travelling trunk is also preserved at Rushbrooke as well as his night-cap and night-shirt, and the silk brocade costume of his great-grandson, Prince Charles Edward. An emblem of loyalty to the Stuarts also may be seen in the great hall, a bas-relief in plaster representing Charles II. concealed in the Boscobel oak. Many of the bedrooms remain such as they were two hundred years ago, with thei[Pg 30]r fine old tapestries, faded window curtains, and tall canopied beds. One is known as "Heaven" and another as "Hell," from the rich paintings upon the walls and ceilings. The royal bedchamber, Elizabeth's room, contains the old bed in which she slept, with its velvet curtains and elaborately worked counter-pane. The house is rich in portraits, and the walls of the staircase are lined from floor to ceiling with well-known characters of the seventeenth century, from James I. to Charles II.'s confidant, Edward Progers, who died in 1714, at the age of ninety-six, of the anguish of cutting four new teeth.[9] Here also is Agnes de Rushbrooke, who haunts the Hall. There is a grim story told of her body being cast into the moat; moreover, there is a certain bloodstain pointed out to verify the tale.

Then there is the old ballroom, and the Roman Catholic chapel, now a billiard-room, and the library, rich in ancient manuscripts and elaborate carvings by Grinling Gibbons. The old gardens also are quite in character with the house, with its avenues of hornbeams known as Lovers' Walk, and the site of the old labyrinth or maze.

Leaving Rushbrooke with its Stuart memories, our way lies to the south-east; but to the south-west there are also many places [Pg 31]of interest, such as Hardwick, Hawstead, Plumpton, etc. At the last-named place, in an old house with high Mansard roofs resembling a French chateau, lived an eccentric character of whom many anecdotes are told, old Alderman Harmer, one of which is that in damp weather he used to sit in a kind of pulpit in one of the topmost rooms, with wooden boots on!

For the remains of Hawstead Place, once visited in State by Queen Elizabeth, who dropped her fan in the moat to test the gallantry of her host, we searched in vain. A very old woman in mob-cap in pointing out the farm so named observed, "T'were nowt of much account nowadays, tho' wonderful things went on there years gone by." This was somewhat vague. We went up to the house and asked if an old gateway of which we had heard still existed. The servant girl looked aghast. Had we asked the road to Birmingham she could scarcely have been more dumbfounded. "No, there was no old gateway there," she said. We asked another villager, but he shook his head. "There was a lady in the church who died from a box on the ear!" This was scarcely to the point, and since we have discovered that the ancient Jacobean gateway is at Hawstead Place after all, we cannot place the Suffolk rustic intelligence above the average. It is in the kitchen garden, and in the alcoves of the pillars are[Pg 32] moulded bricks with initials and hearts commemorating the union of Sir Thomas Cullum with the daughter of Sir Henry North. The moat is still to be seen, but the bridge spanning it has given way. The principal ruins of the old mansion were removed about a century ago.

Gedding Hall, midway between Bury and Needham Market, is moated and picturesque, and before it was restored must have been a perfect picture, for as it is now it just misses being what it might have been under very careful treatment. A glaring red-brick tower has been added, which looks painfully new and out of keeping; and beneath two quaint old gables, a front door has been placed which would look very well in Fitz-John's Avenue or Bedford Park, but certainly not here. When old houses are nowadays so carefully restored so that occasionally it is really difficult to see where the old work ends and the new begins, one regrets that the care that is being bestowed upon West Stow could not have been lavished here.

We come across another instance of bad restoration at Bildeston. There is a good old timber house at the top of the village street which, carefully treated, would have been a delight to the eye; but the carved oak corner-post has been enveloped in hideous yellow brickwork in such a fashion that one would rather have wished the place had been pulled down. But at the farther end of the village[Pg 33] there is another old timber house, Newbury Farm, with carved beams and very lofty porch, which affords a fine specimen of village architecture of the fifteenth century. Within, there is a fine black oak ceiling of massive moulded beams, a good example of the lavish way in which oak was used in these old buildings.

Hadleigh is rich in seventeenth-century houses with ornamental plaster fronts and carved oak beams and corbels. One with wide projecting eaves and many windows bears the date 1676, formed out of the lead setting of the little panes of glass. Some bear fantastical designs upon the pargeting, half obliterated by continual coats of white or yellow wash, with varying dates from James I. to Dutch William.

A lofty battlemented tower in the churchyard, belonging to the rectory, was built towards the end of the fifteenth century by Archdeacon Pykenham. Some mural paintings in one of its rooms depict the adjacent hills and river and the interior of the church, and a turret-chamber has a kind of hiding-place or strong-room, with a stout door for defence. Not far from this rectory gatehouse is a half-timber building almost contemporary, with narrow Gothic doors, made up-to-date with an art[Pg 34]istic shade of green. The exterior of the church is fine, but the interior is disappointing in many ways. It was restored at that period of the Victorian era when art in the way of church improvement had reached its lowest ebb. But the church had suffered previously, for a puritanical person named Dowsing smashed the majority of the painted windows as "superstitious pictures." Fortunately some fine linen panelling in the vestry has been preserved. The old Court Farm, about half a mile to the north of the town, has also suffered considerably; for but little remains beyond the entrance gate of Tudor date. By local report, Cromwell is here responsible; but the place was a monastery once, and Thomas Cromwell dismantled it. It would be interesting to know if the Lord Protector ever wrote to the editor of the Weekly Post, to refute any connection with his namesake of the previous century. Though the "White Lion" Inn has nothing architecturally attractive, there is an old-fashioned comfort about it. The courtyard is festooned round with clematis of over a century's growth, and in the summer you step out of your sleeping quarters into a delightful green arcade. The ostler, too, is a typical one of the good old coaching days, and doubtless has a healthy distaste for locomotion by the means of petrol.

The corner of the county to the south-east of Hadleigh, and bounded by the rivers Stour and Orwell, could have no better r[Pg 35]ecommendation for picturesqueness than the works of the famous painter Constable. He was never happier than at work near his native village, Flatford, where to-day the old mill affords a delightful rural studio to some painters of repute. The old timber bridge and the willow-bordered Stour, winding in and out the valley, afford charming subjects for the brush; and Dedham on the Essex border is delightful. Gainsborough also was very partial to the scenery on the banks of the Orwell.

In the churchyard of East Bergholt, near Flatford, is a curious, deep-roofed wooden structure, a cage containing the bells, which are hung upside down. Local report says that his Satanic Majesty had the same objection to the completion of the sacred edifices that he had for Cologne Cathedral, consequently the tower still remains conspicuous by its absence. The "Hare and Hounds" Inn has a finely moulded plaster ceiling. It is worthy of note that the Folkards, an old Suffolk family, have owned the inn for upwards of six generations.

Little and Great Wenham both possess interesting manor-houses: the former particularly so, as it is one of the earliest specimens of domestic architecture in the kingdom, or at least the first house where Flemish bricks were used in construction. For this reason, no doubt, trippers from Ipswich [Pg 36]are desirous of leaving the measurements of their boots deep-cut into the leads of the roof with their initials duly recorded. Naturally the owner desires that some discrimination be now shown as to whom may be admitted. The building is compact, with but few rooms; but the hall on the first floor and the chapel are in a wonderfully good state of repair,—indeed the house would make a much more desirable residence than many twentieth-century dwellings of equal dimensions. Great Wenham manor-house is of Tudor date, with pretty little pinnacles at the corners of gable ends which peep over a high red-brick wall skirting the highroad.

From here to Erwarton, which is miles from anywhere near the tongue of land dividing the two rivers, some charming pastoral scenery recalls peeps we have of it from the brush of Constable. At one particularly pretty spot near Harkstead some holiday folks had assembled to enjoy themselves, and looked sadly bored at a company of Salvationists who had come to destroy the peace of the scene.

Erwarton Hall is a ghostly looking old place, with an odd-shaped[Pg 37] early-Jacobean gateway, with nine great pinnacles rising above its roof. It faces a wide and desolate stretch of road, with ancient trees and curious twisted roots, in front, and a pond: picturesque but melancholy looking. The house is Elizabethan, of dark red-brick, and the old mullioned windows peer over the boundary-wall as if they would like to see something of the world, even in this remote spot. In the mansion, which this succeeded, lived Anne Boleyn's aunt, Amata, Lady Calthorpe, and here the unfortunate queen is said to have spent some of the happiest days of girlhood,—a peaceful spot, indeed, compared with her subsequent surroundings. Local tradition long back has handed down the story that it was the queen's wish her heart should be buried at Erwarton; and it had well-nigh been forgotten, when some sixty-five years ago a little casket was discovered during some alterations to one of the walls of the church. It was heart-shaped, and contained but dust, and was eventually placed in a vault of the Cornwallis family. Sir W. Hastings D'Oyly, Bart., in writing an interesting article upon this subject a few years back,[10] pointed out that it has never been decided where Anne Boleyn's remains actually are interred, though they were buried, of course, in the first instance by her brother, Viscount Rochford, in the Tower. There are erroneous traditions, both at Salle in Norfolk and Horndon-on-the-Hill in Essex, that Anne Boleyn was buried there. There are some fine old monuments in the Erwarton church, a cross-legged cr[Pg 38]usader, and a noseless knight and lady, with elaborate canopy, members of the Davilliers family. During the Civil War five of the bells were removed from the tower and broken up for shot for the defence of the old Hall against the Parliamentarians. At least so goes the story. An octagonal Tudor font is in a good state of preservation, and a few old rusty helmets would look better hung up on the walls than placed upon the capital of a column.

The story of Anne Boleyn's heart recalls that of Sir Nicholas Crispe, whose remains were recently reinterred when the old London church of St. Mildred's in Bread Street was pulled down. The heart of the cavalier, who gave large sums of money to Charles I. in his difficulties, is buried in Hammersmith Old Church, and by the instructions of his will the vessel which held it was to be opened every year and a glass of wine poured upon it.

Some curious vicissitudes are said to have happened to the heart of the great Montrose. It came into the possession of Lady Napier, his nephew's wife, who had it embalmed and enclosed in a steel case of the size of an egg, which opened with a spring, made from the blade of his sword, and the relic was given by her to the then Marchioness of Montrose. Soon afterwards it was lost, but eventually traced to a collection of curios in Holland, and retu[Pg 39]rned into the possession of the fifth Lord Napier, who gave it to his daughter. When she married she went to reside in Madeira, where the little casket was stolen by a native, under the belief that it was a magic charm, and sold to an Indian chief, from whom it was at length recovered; but the possessor in returning to Europe in 1792, having to spend some time in France during that revolutionary period, thought it advisable to leave the little treasure in possession of a lady friend at Boulogne; but as luck would have it, this lady died unexpectedly, and no clue was forthcoming as to where she had hidden the relic.

But a still more curious story is told of the heart of Louis XIV. An ancestor of Sir William Harcourt, at the time of the French Revolution had given to him by a canon of St. Denis the great monarch's heart, which he had annexed from a casket at the time the royal tombs were demolished by the mob. It resembled a small piece of shrivelled leather, an inch or so long. Many years afterwards the late Dr. Buckland, Dean of Westminster, during a visit to the Harcourts was shown the curiosity. We will quote the rest in Mr Labouchere's words, for he it was who related the story in Truth. "He (Dr. Buckland) was then very old. He had some reputation as a man of science, and the scientific spirit moved him to wet his finger, rub it on the heart, and put the finger to his mouth. After that, before he could be stopped, he put the heart in his mouth and swallowed it, whether by accident or design will never be known. Very shortly afterwards he died and was buried in[Pg 40] Westminster Abbey. It is impossible that he could ever have digested the thing. It must have been a pretty tough organ to start with, and age had almost petrified it. Consequently the heart of Louis XIV. must now be reposing in Westminster Abbey enclosed in the body of an English dean."

Wells-next-the-Sea, on the north coast of Norfolk, sounds attractive, and looks attractive on the map; but that is about all that can be said in its favour, for a more depressing place would be difficult to find. Even Holkham, with all its art treasures, leaves a pervading impression of chill and gloom. The architects of the middle of the eighteenth century had no partiality for nooks and corners in the mansions they designed. Vastness and discomfort seems to have been their principal aim. Well might the noble earl for whom it was built have observed, "It is a melancholy thing to stand alone in one's own country." The advent of the motor car must indeed be welcome, to bring the place in touch with life.

We were attracted to the village of Stiffkey, to the east of Wells, mainly by a magazine article fresh in our memory, of some of its peculiarities, conspicuous among which was its weird red-headed inhabitants. The race of people, however, must have died out, for what few villagers we encountered were very ordinary ones: far from ill-favoured. Possibly they still invoke the aid of the local "wise woman," as they do in many other parts of Norfolk, so therein they are no further behind the times than their neighbours.

We heard of an instance farther south, for example, where the head of an establishment, as was his wont, having disposed of his crop of potatoes, disappeared for a week with the proceeds; and return[Pg 42]ing at length in a very merry condition, his good wife, in the hopes of frightening him, unknown to him removed his watch from his pocket. Next morning in sober earnest he went with his sole remaining sixpence to consult the wise woman of the village, who promptly told him the thief was in his own house. Consequently the watch was produced, and the lady who had purloined it, instead of teaching a lesson, was soundly belaboured with a broom-handle!

Stiffkey Hall is a curious Elizabethan gabled building with a massive flint tower, built, it is said, by Sir Nathaniel Bacon, the brother of the philosopher, but it never was completed. Far more picturesque and interesting are the remains of East Barsham manor-house, some seven miles to the south of Wells. Although it contained some of the finest ornamental Tudor brickwork in England when we were there, and possibly still, the old place could have been had for a song. It had the reputation of being haunted, and was held in awe. The gatehouse, bearing the arms and ensigns of Henry VIII., reminds one of a bit of Hampton Court, and the chimneys upon the buildings on the northern side of the Court are as fine as those [Pg 43]at Compton Wyniates. The wonder is that in these days of appreciation of beautiful architecture nobody has restored it back into a habitable mansion. That such ruins as this or Kirby Hall or Burford Priory should remain to drop to pieces, seems a positive sin. A couple of miles to the west of Barsham is Great Snoring, whose turreted parsonage is also rich in early-Tudor moulded brickwork, as is also the case at Thorpland Hall to the south.

One grieves to think that the old Hall of the Townshends on the other side of Fakenham has been shorn of its ancestral portraits. What a splendid collection, indeed, was this, and how far more dignified did the full-length Elizabethan warriors by Janssen look here than upon the walls at Christie's a year or so ago. The famous haunted chambers have a far less awe-inspiring appearance than some other of the bedrooms with their hearse-like beds and nodding plumes. We do not know when the "Brown Lady" last made her appearance, but there are rumours that she was visible before the decease of the late Marquis Townshend. Until then the stately lady in her rich brown brocade had absented herself for half a century. She had last introduced herself unbecoming a modest ghost, to two gentlemen visitors of a house party who were sitting up late at night. One of these gentlemen, a Colonel Loftus, afterwards made a sketch of her from memory which possibly is still in existence.

Walsingham, midway between Fakenham and Wells, is a quaint old town; its timber houses and its combined Gothic well, lock-up, and cross in the market-place giving it quite a mediŠval aspect. Before the image of Our Lady of Walsingham was consigned to the flames by Wolsey's confidential servant Cromwell, the pilgrimages to the Priory were in every respect as great as those to Canterbury, and the "way" through Brandon and Newmarket may be traced like that in Kent. Notwithstanding the fact that Henry VIII. himself had been a barefoot pilgrim, and had bestowed a costly necklace on the image, his gift as well as a host of other riches from the shrine came in very handy at the Dissolution. A relic of Our Lady's milk enclosed in crystal, says Erasmus, was occasionally like chalk mixed with the white of eggs. It had been brought from Constantinople in the tenth century; but this and a huge bone of St Peter's finger, of course, did not survive. The site of the chapel, containing the altar where the pilgrims knelt, stood somewhere to the north-west of the ruins of the Priory. These are approached from the street through a fine old early fifteenth-century gateway. The picturesque remains of the refectory date from the previous century, the western window being a good example of the purest Gothic. The old pilgrims' entrance was in "Knight Street," which derives its name from the miracle of a horseman who had sought sanctuary passing through the extraordinarily narrow limits of the wicket. Henry III. is said to have set the fashion for walking to Walsingham, and we strongly recommend[Pg 45] the tourists of to-day, who may find themselves stranded at Wells-next-the-Sea, to do likewise.

The little seaside resort Mundesley is an improvement on Wells; but dull as it is now, what must it have been in Cowper's time: surely a place ill-calculated to improve the poor poet's melancholia! There is little of interest beyond the ruined church on the cliffs and the Rookery Farm incorporated in the remains of the old monastery. A priest's hole is, or was not long since, to be seen in one of the gabled roofs. The churches of Trunch and Knapton to the south-west both are worth a visit for their fine timber roofs. The font at Trunch is enclosed by a remarkable canopy of oak supported by graceful wooden pillars from the floor. It is probably of early-Elizabethan date, and is certainly one of the most remarkable baptistries in the country. Here and in other parts of Norfolk when there are several babies to be christened the ceremony is usually performed on the girls last, as otherwise when they grew up they would develop beards!

Ten miles to the south-west as the crow flies is historic Blickling, one of the reputed birthplaces of the ill-fated Anne Boleyn. By some accounts Luton Hoo in Bedfordshire claims her nativity as well as Rochford Hall in Essex and Hever Castle in Kent; but, though Hever is the only building that will go back to that date, she probably was born in the older Hall of Blickling, the present mansion dating only from the reign of James I.

Upon the occasion of our visit the house was closed, so we can only speak of the exterior, and of the very extensive gardens, where in vain we sought the steward, who was said to be somewhere on the premises.

The rampant bulls, bearing shields, perched on the solid piers that guard the drawbridge across the moat, duly impress one with the ancestral importance of the Hobarts, whose arms and quarterings, surmounted by the helmet and ancient crest, adorn the principal entrance. Like Hatfield and Bramshill, the mellowed red-brick gives it a charm of colour which only the lapse of centuries will give; and though not so old as Knole or Hatfield, the main entrance is quite as picturesque. The gardens, however, immediatel[Pg 47]y surrounding the Hall look somewhat flat in comparison.

Although Henry VIII. did the principal part of his courting at Hever, it was at Blickling that he claimed his bride, and by some accounts was married to her there and not at Calais. The old earl, the unfortunate queen's father, survived her only two years; and after his death the estate was purchased by Sir Henry Hobart,[11] who built the present noble house. Among the relics preserved at Blickling of the unhappy queen are her morning-gown and a set of night-caps, and her toilet case containing mirrors, combs, etc. Sir John the third baronet entertained Charles II. and his queen here in 1671, upon which occasion the host's son and heir, then aged thirteen, was knighted. The royal visit is duly recorded in the parish register as follows: "King Charles the Second, with Queene Katherine, and James, Duke of Yorke, accompanied with the Dukes of Monmouth, Richmond, and Buckingham, and with divers Lords, arrived and dined at Sir John Hubart's, at Blicklinge Hall, the King, Queene, Duke of Yorke, and Duchesse of Richmond, of Buckingham etc., in[Pg 48] the great dining-roomes, the others in the great parloure beneath it, upon Michmasday 1671. From whence they went, the Queene to Norwich, the King to Oxneads and lodged there, and came through Blicklinge the next day about one of the clock, going to Rainham to the Lord Townsends."[12]

Queen Catherine slept that night and the following in the Duke's Palace at Norwich, but joined her royal spouse at lunch at Oxnead, which fine Elizabethan house has, alas! been pulled down, and the statues and fountain from there are now at Blickling. "Next morne (being Saterday)," writes a local scribe in 1671, "her Maty parted so early from Norwich as to meet ye King againe at Oxnead ere noone; Sr Robt Paston haveing got a vast dinner so early ready, in regard that his Maty was to goe that same afternoone (as he did) twenty myles to supper to the Ld Townshend's, wher he stayd all yesterday, and as I suppose, is this evening already return'd to Newmarket, extremely well satisfied with our Lord Lieuts reception.... Her Maty haveinge but seven myles back to Norwich that night from Sr Robt Pastons was pleased for about two houres after dinner to divert herselfe at cards with the Court ladies and my Lady Paston, who had treated her so well and yet returned early to Norwich that eveninge to the same qu[Pg 49]arters as formerly; and on Sunday morne (after her devotions perform'd and a plentifull breakfast) shee tooke coach, extreamely satisfied with the dutifull observances of all this countie and city, and was conducted by the Ld Howard and his sonnes as far as Attleburough where fresh coaches atended to carry her back to the Rt Hoble the Ld Arlington's at Euston."[13]

Sidelights of this royal progress are obtained from the diarist Evelyn and Lord Dartmouth. Among the attractions provided for the king's amusement at Euston was the future Duchess of Portsmouth. The Duchess of Richmond (La belle Stuart), in the queen's train, must have been reminded how difficult had been her position before she eloped with her husband four years previously. For the duke's sake let us hope he was as overcome as his Majesty when the latter let his tongue wag with more than usual freedom during the feast at Raynham. "After her marriage," says Dartmouth, speaking of the duchess, "she had more complaisance than before, as King Charles could not forbear telling the Duke of Richmond, when he was drunk at Lord Townshend's in Norfolk." Evelyn did not think much of the queen's lodgings at Norwich, which he describes as "an old wretched building," partly rebuilt in brick, standing in the market-place, which in his opinion would have been better had it been demolished and erected s[Pg 50]omewhere else.

Not far from Blickling to the north-east is Mannington Hall, a mansion built in the reign of Henry VI., which possesses one of the best authenticated ghost stories of modern times. The story is the more interesting as it is recorded by that learned and delightful chronicler Dr. Jessop, chaplain to His Majesty the King. The strange experiences of his visit in October 1879 are duly recorded in the AthenŠeum of the following January. The rest of the household had retired to rest, and Dr. Jessop was sitting up making extracts from some rare books in an apartment adjoining the library. Absorbed in his study, time had slipped away and it was after one o'clock. "I was just beginning to think that my work was drawing to a close," says the doctor, "when, as I was actually writing, I saw a large white hand within a foot of my elbow. Turning my head, there sat a figure of a somewhat large man, with his back to the fire, bending slightly over the table, and apparently examining the pile of books that I had been at work upon. The man's face was turned away from me, but I saw his closely-cut, reddish brown hair, his ear and shaved cheek, the eyebrow, the corner of his right eye, the side of the forehead, and the large high chee[Pg 51]kbone. He was dressed in what I can only describe as a kind of ecclesiastical habit of thick corded silk, or some such material, close up to the throat, and a narrow rim or edging of about an inch broad of satin or velvet serving as a stand-up collar and fitting close to the chin. The right hand, which had first attracted my attention, was clasping, without any great pressure, the left hand; both hands were in perfect repose, and the large blue veins of the right hand were conspicuous. I remember thinking that the hand was like the hand of Velasquez's magnificent 'Dead Knight' in the National Gallery. I looked at my visitor for some seconds, and was perfectly sure that he was a reality. A thousand thoughts came crowding upon me, but not the least feeling of alarm or even of uneasiness. Curiosity and a strong interest were uppermost. For an instant I felt eager to make a sketch of my friend, and I looked at a tray on my right for a pencil: then thought, 'Upstairs I have a sketch-book; shall I fetch it?' There he sat and I was fascinated, afraid not of his staying, but lest he should go. Stopping in my writing, I lifted my left hand from the paper, stretched it out to a pile of books and moved the top one. I cannot explain why I did this. My arm passed in front of the figure, and it vanished. Much astonished, I went on with my writing perhaps for another five minutes, and had actually got to the last few words of the extract when the figure appeared again, exactly in the same place and attitude as before. I saw the hand close to my own; I turned my head again to e[Pg 52]xamine him more closely, and I was framing a sentence to address to him when I discovered that I did not dare to speak. I was afraid of the sound of my own voice! There he sat, and there sat I. I turned my head again to my work, and finished the two or three words still remaining to be written. The paper and my notes are at this moment before me, and exhibit not the slightest tremor or nervousness. I could point out the words I was writing when the phantom came, and when he disappeared. Having finished my task I shut the book and threw it on the table: it made a slight noise as it fell—the figure vanished." Not until now did the doctor feel nervous, but it was only for a second. He replaced the books in the adjoining room, blew out the candles on the table, and retired to his rooms marvelling at his calmness under such strange circumstances.

The old-fashioned town Wymondham, to the south-west of Norwich, contains an interesting church and market-cross, and one or two fine Gothic houses, all in good preservation. But stay, the quaint octagonal Jacobean timber structure in the market-place was holding forth a petition for contributions, as it was feeling somewhat decrepit. This was six or seven years ago, so probably by now it has entered upon a new lease of life. How much more picturesque are these old timbered structures than the jubilee clock-towers which have sprung up in many old-fashioned towns, putting everything out of harmony. But few towns are proud of their old buildings. They must be up to date with flaring red-brick, and electric tramways, and down comes everything with any claim to antiquity, without a thought of its past associations or picturesque value. But let us hope that Wymondham may be exempt from these terrible tramways for many years to come, as its population is, or[Pg 53] was, decreasing.

The abbey and the church appear to have got rather mixed up; but having come to a satisfactory arrangement, present a most pleasing group, and, in the twilight, with two lofty towers and a ruined archway, it looks far more like a castle on the Rhine than a church in Norfolk. The effect doubtless would be heightened if we could see the rebel Kett dangling in chains from the tower as he did in the reign of Bloody Mary. The timber roof is exceptionally fine, with its long array of carved oak bosses and projecting angels.

Near Wymondham is the moated Hall of Stanfield, picturesque with its numerous pinnacles. Here the heroine of the delightful romance Kenilworth was born in 1532; but poor Amy's marriage, far from being secret, was celebrated with great pomp at Sheen in Surrey in 1550, and is recorded in the Diary of Edward VI. now in the British Museum. "Lydcote," the old house in North Devon where she lived for some years, was pulled down not many years ago. Her bedstead from there we[Pg 54] believe is still preserved at Great Torrington Rectory.

Somewhat similar to Stanfield, though now only a farmhouse, is the very pretty old Tudor house Hautboys Hall. It stands a few miles to the south-east of Oxnead.

Of all the moated mansions in Norfolk, Oxburgh Hall, near Stoke Ferry, is the most interesting, and is a splendid example of the fortified manor-house of the end of the fifteenth century, and it is one of the few houses in England that have always been occupied by one family. Sir Edmund Bedingfield built it in the reign of Richard III., and Sir Richard Bedingfield resides there at the present time. The octagonal towers which flank the entrance gate rise from the broad moat to a considerable height. There is a quaint projecting turret on the eastern side which adds considerably to the picturesque outline of stepped gables and quai[Pg 55]nt battlements. High above the ponderous oak gates the machicolation behind the arch that joins the towers shows ample provision for a liberal supply of molten lead, and in an old guard-room may be seen the ancient armour and weapons to which the retainers of the Hall were wont to have recourse in case of siege. The room recalls somehow the defence of the tower of Tillietudlem in Old Mortality, and one can picture the little household guard running the old culverins and sakers into position on the battlements.

The great mullioned window beneath the Tudor arch and over the entrance gate belongs to the "King's room," a fine old tapestried chamber containing the bed, with green and gold hangings, where Henry VII. slept; and it is no difficult matter to repeople it in the imagination with the inhabitants of that time in their picturesque costumes. There is a richness in the colouring of the faded tapestry and hangings in contrast with the red-brick Tudor fireplace far more striking than if the restorer had been allowed a liberal hand. It is like a bit of Haddon, and such rooms are as rarely met with nowadays as unrestored churches. The remarkable hiding-place at Oxburgh we have described in detail elsewhere.[14] It is situated in the little projecting turret of the eastern tower, and is so cleverly constr[Pg 56]ucted beneath the solid brick floor, that no one would believe until they saw the solid masonry move upwards that there was sufficient space beneath to conceal a man. The Bedingfields are an old Roman Catholic family, and it is usually in the mansions of those of that faith that these ingenious contrivances are to be seen.

A priest's hole was discovered quite recently in Snowre Hall, a curious Tudor house some ten miles to the west of Oxburgh. It is entered through a shaft from the roof, and measures five feet by six feet and four feet high, and beneath it is an inner and smaller hiding-place. Mr. Pratt (in whose family the house has been for two centuries) when he made the discovery had to remove four barrow-loads of jackdaws' nests. The discovery of this secret room is an interesting sequel to the fact that on April 29, 1646, Charles I. slept at Snowre Hall. It will be remembered that before he delivered himself up to the Scots army, he spent some days wandering about the eastern counties in disguise, like his son did in the western counties five years later. The owner of the house in those days was a Mr. Ralph Skipwith, who, to put the spies that were lurking about the vicinity off the track, provided th[Pg 57]e king with his own grey riding-jacket in place of the clergyman's black coat he was wearing, for that disguise had been widely advertised by his enemies. Dr. Hudson, who was acting as scout, joined Charles and his companion, Mr. Ashburnham, at Downham Market, where the "King's Walk" by the town side, where they met, may still be seen. It is recorded by Dr. Stukeley that Charles scratched some motto or secret instructions to his friends on a pane of glass in the Swan Inn, where he put up awaiting Hudson's return from Southwell. The fugitives proceeded thence to the Cherry Inn at Mundford, some fourteen miles from Downham, and back to Crimplesham, where they halted at an inn to effect the disguise above referred to. The regicide Miles Corbet, who was on the track with Valentine Walton, gave information as follows:

"Since our coming to Lyn we have done what service we were able. We have taken some examinations, and it doth appeare to us that Mr. Hudson, the parson that came from Oxford with the king, was at Downham in Norfolk with two other gentlemen upon Thursday the last of April. We cannot yet learn where they were Friday night; but Saturday morning, the 2 of May they came to a blind alehouse at Crimplesham, about 8 miles from Lyn. From thence Mr. Hudson did ride on Saturday to Downham again, and there [Pg 58]two soldiers met with him, and had private speech with him. Hudson was then in a scarlet coat. Ther he met with Mr. Ralf Skipwith of his former acquaintance, and with him he did exchange his horse; and Skipwith and the said Hudson did ride to Southrie ferrie a privat way to go towards Ely; and went by the way to Crimplesham, and ther were the other two—one in a parsons habit, which by all description was the king. Hudson procured the said Skipwith to get a gray coat for the Dr. (as he called the king), which he did. And ther the king put off his black coat and long cassock, and put on Mr. Skipwith his gray coat. The king bought a new hat at Downham, and on Saturday went into the Isle of Ely. Wherever they came they were very private and always writing. Hudson tore some papers when they came out of the house. Hudson did enquire for a ship to go to the north or Newcastel, but[Pg 59] could get none. We hear at the same time there were 6 soldiers and officers as is thought at Oxborough at another blind alehouse."[15]

It is worthy of remark that Miles Corbet, whom Pepys saw on the morning of April 19, 1662, looking "very cheerful" upon his way to Tyburn, was a native of Norfolk, and his monument may be seen in Sprowston Church near Norwich.

The "Swan" at Downham still exists, but it was modernised some fifteen years ago. It would be interesting to know what became of the historical pane of glass.

The outline of Warwickshire is something in the form of a turnip, and the stem of it, which, like an isthmus, projects into Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, contains many old-world places.

Long Compton, the most southern village of all, is grey and straggling and picturesque, with orchards on all sides, and a fine old church, amid a group of thatched cottages, whose interior was restored or mangled at a period when these things were not done with much antiquarian taste. We have pleasant recollections of a sojourn at the "Old Red Lion," where mine host in 1880, a typical Warwickshire farmer, was the most hospitable and cheery to [Pg 61]be found in this or any other county: an innkeeper of the old school that it did one's heart good to see.

But this welcome house of call is by no means the only Lion of the neighbourhood, for on the ridge of the high land which forms the boundary of Oxfordshire are the "Whispering Knights," the "King's Stone," and a weird Druidical circle. These are the famous Rollright Stones, about which there is a story that a Danish prince came over to invade England, and when at Dover he consulted the oracle as to the chances of success. He was told that

"When Long Compton you shall see,

You shall King of England be."

Naturally he and his soldiers made a bee-line for Long Compton, and, arriving at the spot where the circle is now marked by huge boulders, he was so elated that he stepped in advance of his followers, who stood round him, saying, "It is not meet that I should remain among my subjects, I will go before." But for his conceit some unkind spirit turned the whole party into stone, which doesn't seem [Pg 62]quite fair. "King's Stone" stands conspicuous from the rest on the other side of the road, and, being very erect, looks as if the prince still prided himself upon his folly. The diameter of the circle is over a hundred feet. In an adjoining field is a cluster of five great stones. These are the "Whispering Knights"; and the secret among themselves is that they will not consent to budge an inch, and woe to the farmer who attempts to remove them. The story goes that one of the five was once carted off to make a bridge; but the offender had such a warm time of it that he speedily repented his folly and reinstated it.

There is a delightful walk across the fields from Long Compton to Little Compton, with a glorious prospect of the Gloucestershire and Warwickshire hills. This village used to be in the former county, but now belongs to Warwickshire. Close to the quaint saddle-back towered church stands the gabled Elizabethan manor-house, with the Juxon arms carved over the entrance. Its exterior has been but little altered since the prelate lived here in retirement after the execution of Charles I. A gruesome relic was kept in one of the rooms, the block upon which the poor monarch's head was severed. This and King Charles' chair and some of the archbishop's treasured books disappeared from the manor-house after the death of his descendant Lady Fane. Internally the house has been much altered, but there are many nooks and corners to ca[Pg 63]rry the memory back to the hunting bishop, for his pack of hounds was one of the best managed in the country. Upon one occasion a complaint was made to the Lord Protector that Juxon's hounds had followed the scent through Chipping Norton churchyard at the time of a puritanical assembly there. But Oliver would hear none of it, and only replied, "Let the bishop enjoy his hunting unmolested."