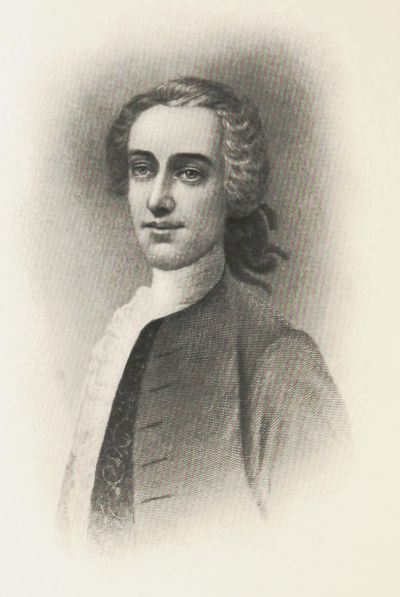

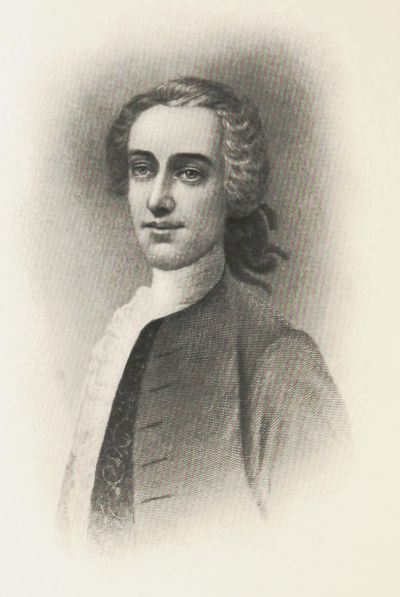

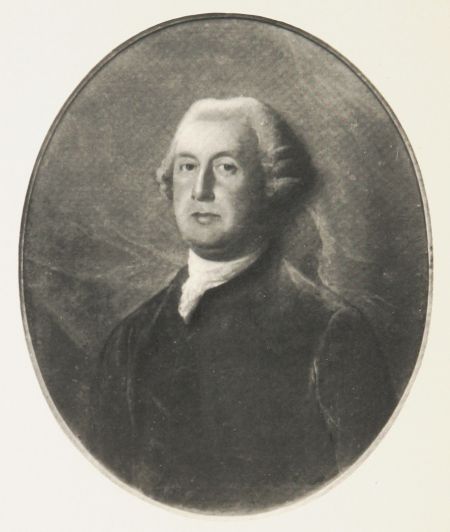

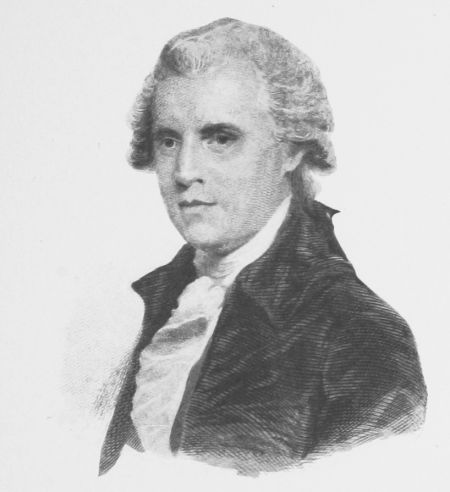

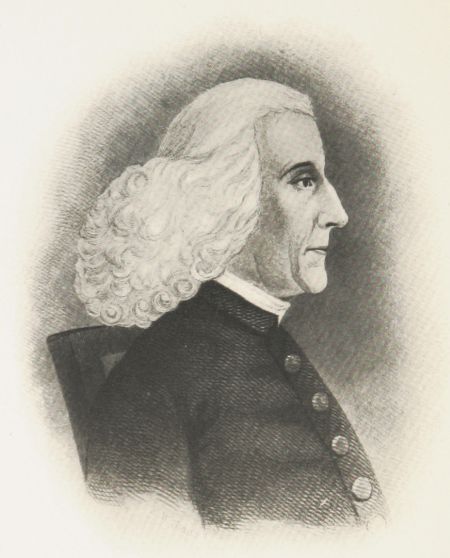

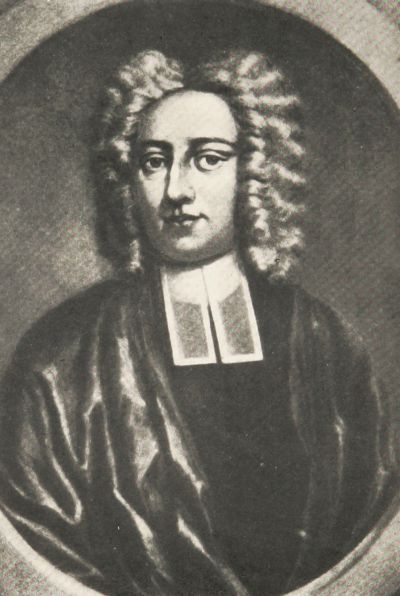

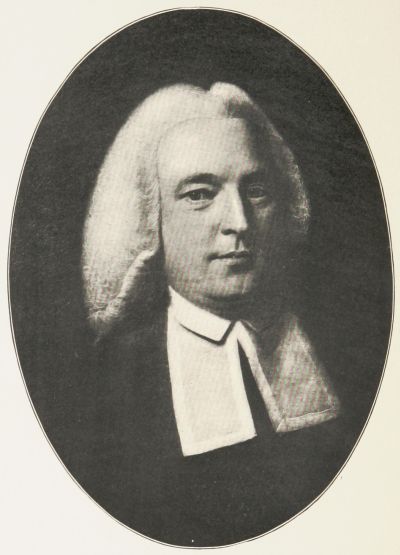

THOMAS HUTCHINSON.

THOMAS HUTCHINSON.Born in Boston, Sept. 9, 1711. Governor of Massachusetts 1771-4. Died in London

June 3, 1780.

Project Gutenberg's The Loyalists of Massachusetts, by James H. Stark

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: The Loyalists of Massachusetts

And the Other Side of the American Revolution

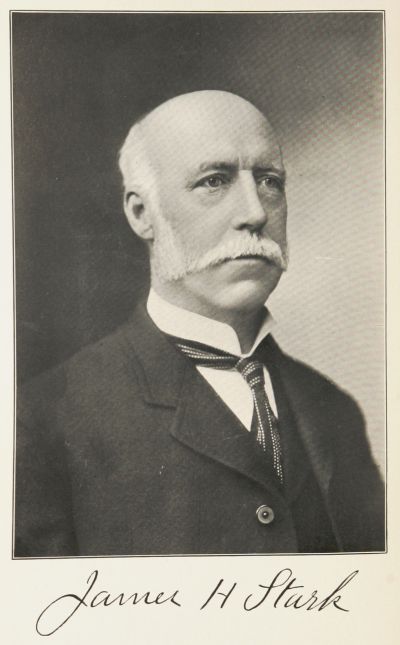

Author: James H. Stark

Release Date: March 31, 2012 [EBook #39316]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LOYALISTS OF MASSACHUSETTS ***

Produced by Andrew Wainwright, Jonathan Ingram and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THOMAS HUTCHINSON.

THOMAS HUTCHINSON.

"History makes men wise."—Bacon.

W. B. CLARKE CO.

26 Tremont Street

Boston

COPYRIGHTED 1907

BY

JAMES H. STARK

To

The Memory of the Loyalists

of

The Massachusetts Bay

WHOSE FAITHFUL SERVICES AND MEMORIES ARE NOW FORGOTTEN

BY THE NATION THEY SO WELL SERVED, THIS

WORK IS DEDICATED BY THE

AUTHOR

| INTRODUCTION | 5 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| THE FIRST CHARTER | 7 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE SECOND CHARTER | 16 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| CAUSES THAT LED TO THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION | 27 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| BOSTON MOBS AND THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE REVOLUTION | 40 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE LOYALISTS OF MASSACHUSETTS | 54 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE REVOLUTIONIST | 68 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| INDIANS IN THE REVOLUTION | 88 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE EXPULSION OF THE LOYALISTS AND THE SETTLEMENT OF CANADA | 93 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE WAR OF 1812 AND THE ATTEMPTED CONQUEST OF CANADA | 98 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE CIVIL WAR AND THE PART TAKEN BY GREAT BRITAIN IN SAME | 107 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| RECONCILIATION. THE DISMEMBERED EMPIRE REUNITED IN BONDS OF FRIENDSHIP. "BLOOD IS THICKER THAN WATER." | 113 |

| [ii]PART II | |

| BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES OF THE LOYALISTS OF MASS. | 122 |

| THE ADDRESS OF THE MERCHANTS AND OTHERS OF BOSTON TO GOVERNOR HUTCHINSON | 123 |

| ADDRESS OF THE BARRISTERS AND ATTORNEYS OF MASSACHUSETTS TO GOVERNOR HUTCHINSON | 125 |

| ADDRESS OF THE INHABITANTS OF MARBLEHEAD TO GOVERNOR HUTCHINSON | 127 |

| ADDRESS TO GOVERNOR HUTCHINSON FROM HIS FELLOW TOWNSMEN IN THE TOWN OF MILTON | 128 |

| ADDRESS PRESENTED TO GOVERNOR GAGE ON HIS ARRIVAL AT SALEM | 131 |

| ADDRESS TO GOVERNOR GAGE ON HIS DEPARTURE | 132 |

| LIST OF INHABITANTS OF BOSTON WHO REMOVED TO HALIFAX WITH THE ARMY MARCH, 1776 | 133 |

| MANDAMUS COUNSELLORS | 136 |

| THE BANISHMENT ACT OF MASSACHUSETTS | 137 |

| THE WORCESTER RESOLUTION RELATING TO THE ABSENTEES AND REFUGEES | 141 |

| THE CONFISCATION ACT | 141 |

| CONSPIRACY ACT | 141 |

| ABSENTEES ACT | 143 |

| BIOGRAPHIES | |

| THOMAS HUTCHINSON | 145 |

| LIST OF GOV. HUTCHINSON'S CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 174 |

| THOMAS HUTCHINSON, SON OF THE GOVERNOR | 175 |

| ELISHA HUTCHINSON | 177 |

| FOSTER HUTCHINSON | 177 |

| ELIAKIM HUTCHINSON | 178 |

| LIST OF ELIAKIM HUTCHINSON'S CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 180 |

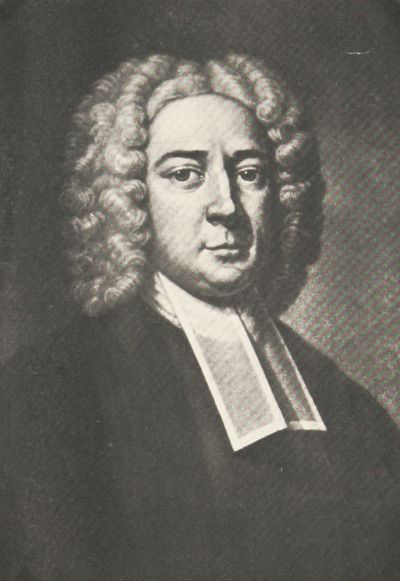

| ANDREW OLIVER—LIEUT. GOVERNOR | 181 |

| THOMAS OLIVER | 183 |

| PETER OLIVER—CHIEF JUSTICE | 188 |

| [iii]SIR FRANCIS BERNARD | 191 |

| SIR WILLIAM PEPPERRELL | 205 |

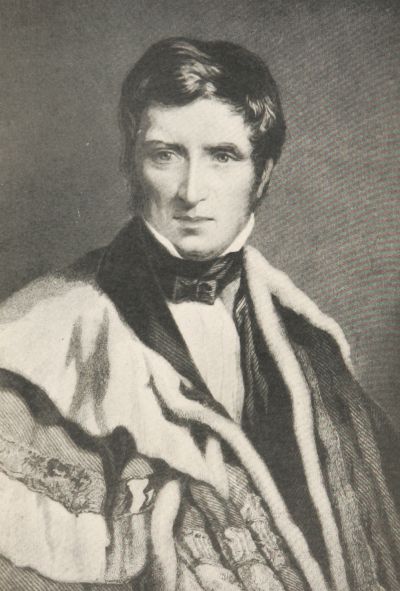

| JOHN SINGLETON COPLEY AND HIS SON LORD LYNDHURST | 216 |

| KING HOOPER OF MARBLEHEAD | 221 |

| WILLIAM BOWES | 224 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES OF WILLIAM BOWES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 225 |

| GENERAL TIMOTHY RUGGLES | 225 |

| THE FANEUIL FAMILY OF BOSTON | 229 |

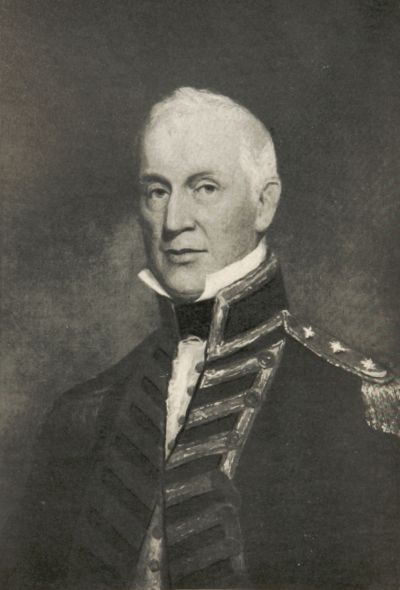

| THE COFFIN FAMILY OF BOSTON. ADMIRAL SIR ISAAC COFFIN SIR THOMAS ASTON COFFIN ADMIRAL FROMAN H. COFFIN GENERAL JOHN COFFIN | 233 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES OF JOHN COFFIN IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 246 |

| JUDGE SAMUEL CURWEN | 246 |

| JAMES MURRAY | 254 |

| SIR BENJAMIN THOMPSON—COUNT RUMFORD | 261 |

| COL. RICHARD SALTONSTALL | 272 |

| REV. MATHER BYLES | 275 |

| THE HALLOWELL FAMILY OF BOSTON | 281 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES OF BENJAMIN HALLOWELL IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 284 |

| THE VASSALLS | 285 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES OF JOHN VASSALL IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 290 |

| GENERAL ISAAC ROYALL | 290 |

| GENERAL WILLIAM BRATTLE | 294 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATE OF WILLIAM BRATTLE IN BOSTON | 297 |

| JOSEPH THOMPSON | 297 |

| COLONEL JOHN ERVING | 298 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES BELONGING TO COL. JOHN ERVING | 299 |

| MAJOR GENERAL SIR DAVID OCTHERLONY | 299 |

| JUDGE AUCHMUTY'S FAMILY | 301 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES OF ROBERT AUCHMUTY | 305 |

| COLONEL ADINO PADDOCK | 305 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES OF ADINO PADDOCK IN SUFFOLK COUNTY | 308 |

| [iv]THEOPHILUS LILLIE | 308 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO THEOPHILUS LILLIE | 313 |

| DR. SYLVESTER GARDINER | 313 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO SYLVESTER GARDINER | 317 |

| RICHARD KING | 317 |

| CHARLES PAXTON | 318 |

| JOSEPH HARRISON | 319 |

| CAPTAIN MARTIN GAY | 321 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO MARTIN GAY | 325 |

| DANIEL LEONARD | 325 |

| JUDGE GEORGE LEONARD | 332 |

| COLONEL GEORGE LEONARD | 333 |

| HARRISON GRAY—RECEIVER GENERAL OF MASSACHUSETTS | 334 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO HARRISON GRAY | 337 |

| REV. WILLIAM WALTER, RECTOR OF TRINITY CHURCH | 338 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO REV. WILLIAM WALTER | 342 |

| THOMAS AMORY | 343 |

| REV. HENRY CANER | 346 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO REV. HENRY CANER | 349 |

| FREDERICK WILLIAM GEYER | 350 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO FREDERICK WILLIAM GEYER | 351 |

| THE APTHORP FAMILY OF BOSTON | 351 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO CHARLES WARD APTHORP | 354 |

| THE GOLDTHWAITE FAMILY OF BOSTON | 355 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO JOSEPH GOLDTHWAIT | 361 |

| JOHN HOWE | 361 |

| SAMUEL QUINCY, SOLICITOR GENERAL | 364 |

| [v]COLONEL JOHN MURRAY | 376 |

| JUDGE JAMES PUTNAM, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MASSACHUSETTS BAY | 378 |

| JUDGE TIMOTHY PAINE | 382 |

| DR. WILLIAM PAINE | 385 |

| JOHN CHANDLER | 388 |

| JOHN GORE | 392 |

| JOHN JEFFRIES | 394 |

| THOMAS BRINLEY | 395 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO THOMAS BRINLEY | 397 |

| REV. JOHN WISWELL | 398 |

| HENRY BARNES | 399 |

| THOMAS FLUCKER, SECRETARY OF MASSACHUSETTS BAY | 402 |

| MARGARET DRAPER | 404 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO MARGARET DRAPER | 405 |

| RICHARD CLARKE | 405 |

| PETER JOHONNOT | 409 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO PETER JOHONNOT | 411 |

| JOHN JOY | 411 |

| RICHARD LECHMERE | 413 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO RICHARD LECHMERE | 414 |

| EZEKIEL LEWIS | 414 |

| BENJAMIN CLARK | 415 |

| LADY AGNES FRANKLAND | 417 |

| COLONEL DAVID PHIPS | 418 |

| THE DUNBAR FAMILY OF HINGHAM | 421 |

| EBENEZER RICHARDSON | 422 |

| COMMODORE JOSHUA LORING | 423 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO JOSHUA LORING | 426 |

| ROBERT WINTHROP | 426 |

| [vi]NATHANIEL HATCH | 429 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO NATHANIEL HATCH | 430 |

| CHRISTOPHER HATCH | 430 |

| WARD CHIPMAN | 431 |

| GOVERNOR EDWARD WINSLOW | 433 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO ISAAC WINSLOW | 439 |

| SIR ROGER HALE SHEAFFE, BARONET | 439 |

| JONATHAN SAYWARD | 443 |

| DEBLOIS FAMILY | 445 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO GILBERT DEBLOIS | 446 |

| LYDE FAMILY | 447 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO EDWARD LYDE | 447 |

| JAMES BOUTINEAU | 448 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO JAMES BOUTINEAU | 449 |

| COL. WILLIAM BROWNE | 449 |

| ARCHIBALD CUNNINGHAM | 451 |

| CAPTAIN JOHN MALCOMB | 451 |

| THE RUSSELL FAMILY OF CHARLESTOWN | 452 |

| EZEKIEL RUSSELL | 453 |

| JONATHAN SEWALL | 454 |

| CONFISCATED ESTATES IN SUFFOLK COUNTY BELONGING TO SAMUEL SEWALL | 457 |

| THOMAS ROBIE | 457 |

| BENJAMIN MARSTON | 459 |

| HON. BENJAMIN LYNDE, CHIEF JUSTICE OF MASSACHUSETTS | 462 |

| PAGAN FAMILY | 464 |

| THE WYER FAMILY OF CHARLESTOWN | 465 |

| JEREMIAH POTE | 467 |

| EBENEZER CUTLER | 468 |

| [vii]APPENDIX | |

| THE TRUE STORY CONCERNING THE KILLING OF THE TWO SOLDIERS AT CONCORD BRIDGE, APRIL 19, 1775. THE FIRST BRITISH SOLDIER KILLED IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR | 471 |

| THE ENGAGEMENT AT THE NORTH BRIDGE IN CONCORD WHERE THE TWO SOLDIERS WERE KILLED | 476 |

| PAUL REVERE, THE SCOUT OF THE REVOLUTION | 477 |

| WILLIAM FRANKLIN, SON OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN | 481 |

| THE ROYAL COAT OF ARMS | 482 |

| JUDGE MELLEN CHAMBERLAIN'S OPINION OF COLONEL THOMAS GOLDTHWAITE | 483 |

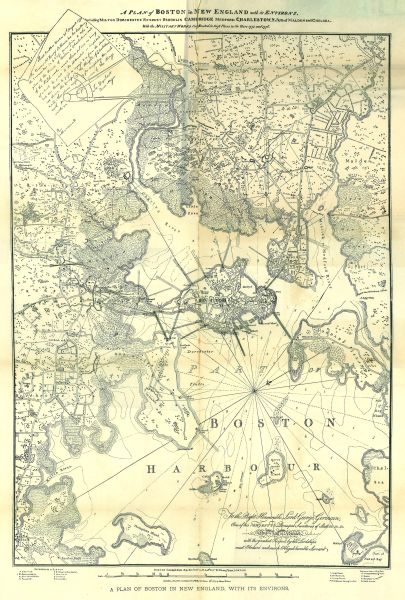

| NOTE ON PELHAM'S MAP OF BOSTON | 483 |

| NOTE ON GOV. JOHN WINTHROP | 483 |

| LIST OF LOYALISTS WHOSE NAMES OR BIOGRAPHIES ARE NOT FOUND IN THIS WORK | 484 |

| PELHAM'S MAP OF BOSTON IN POCKET IN THE BACK COVER. |

The author wishes to acknowledge the great assistance he has received from the New England Historic Genealogical Society, of which he has been a member for twenty-eight years,—whose library consisting of biographies and genealogies is the most complete in America. Other authorities consulted, have been the "Royalist" records in the original manuscript preserved in the archives of the State of Massachusetts, the Record Commissioners' Reports of the City of Boston, the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the numerous town histories, and ancient records published in recent years, to the most important of which he has acknowledged his obligations in the reference given, and also to the Boston Athenaeum for the use of their paintings and engravings, in making copies of same.

He also wishes to acknowledge the assistance rendered him by his daughter, Mildred Manton Stark, in preparing many of the biographies, also the assistance rendered by Mr. Thomas F. O'Malley, who prepared the very copious index to this work, which will, he thinks be appreciated by all historical students who may have occasion to use same.

| Thomas Hutchinson's Portrait, Opposite the title page. | |||

| James H. Stark, Portrait, | Opposite | Page | 7. |

| Landing of the Commissioners at Boston, 1664, | " | " | 13. |

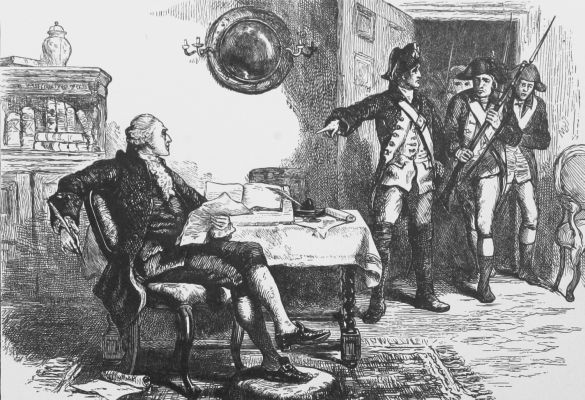

| Randolph threatened, | " | " | 15. |

| Proclaiming King William and Queen Mary, | " | " | 17. |

| Killing and scalping Father Rasle at Norridgewock, | " | " | 32. |

| Reading the Stamp Act in King street, opposite the State House, | " | " | 37. |

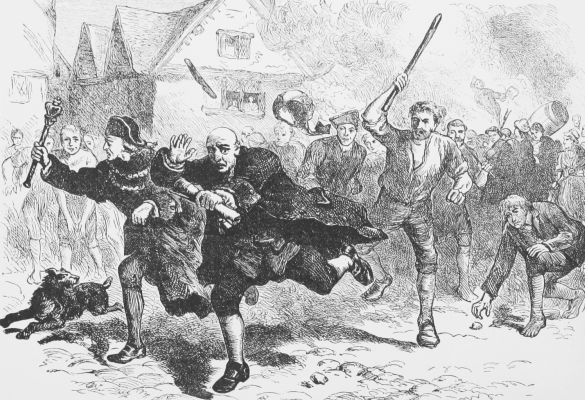

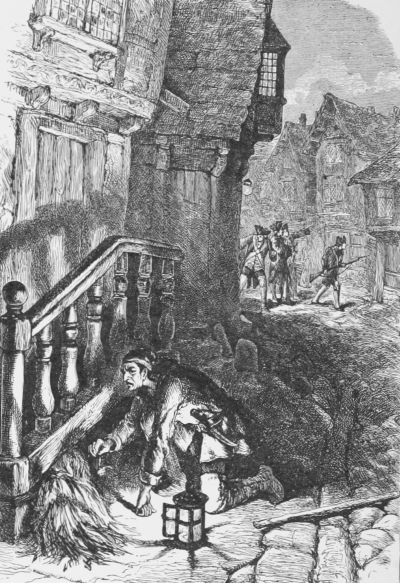

| Andrew Oliver, Stamp Collector attacked by the Mob, | " | " | 41. |

| Bostonians paying the Exciseman or Tarring and Feathering, | " | " | 49. |

| Colonel Mifflin's Interview with the Caughnawaga Indians, | " | " | 89. |

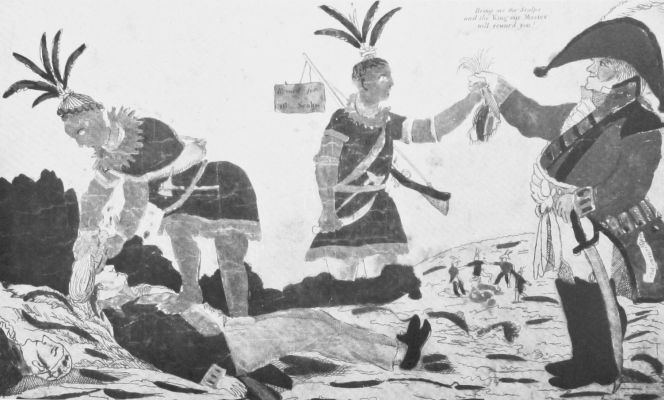

| Cartoon illustrating Franklin's diabolical Scalp story, | " | " | 91. |

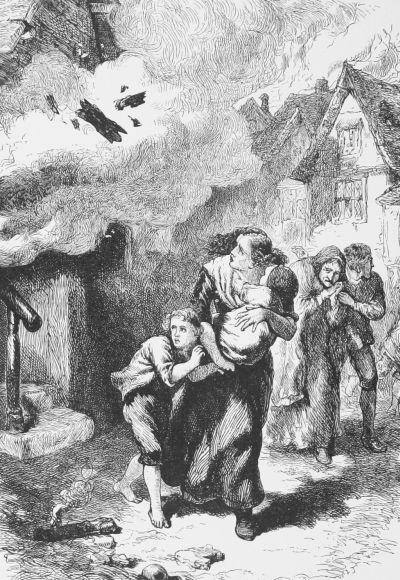

| Burning of Newark, Canada, by United States Troops, | " | " | 103. |

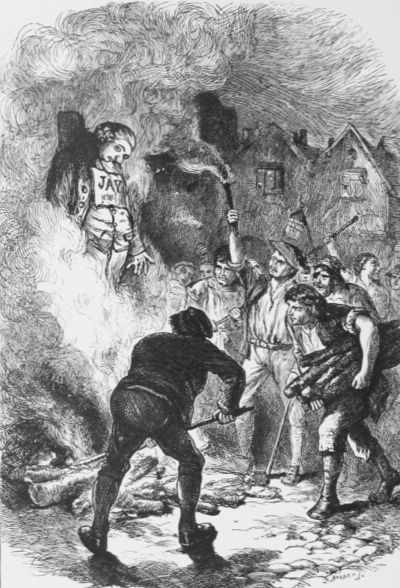

| Burning of Jay in Effigy, | " | " | 105. |

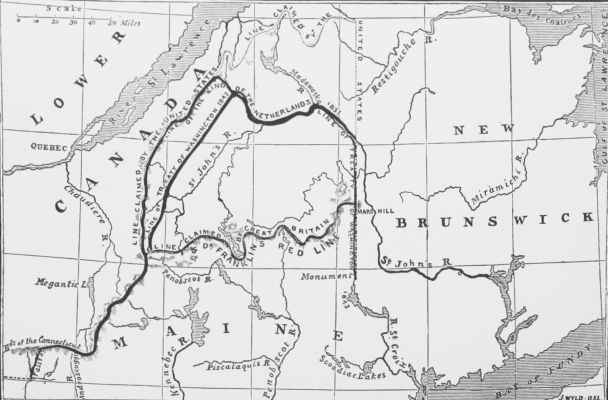

| Map, Boundary line between Maine and New Brunswick, | " | " | 115. |

| Governor Hutchinson's House Destroyed by the Mob, | Page | 155. | |

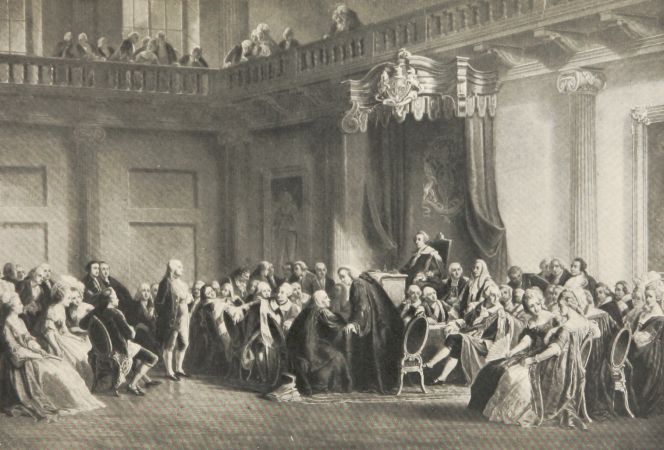

| Benjamin Franklin Before the Privy Council, | Opposite | Page | 165. |

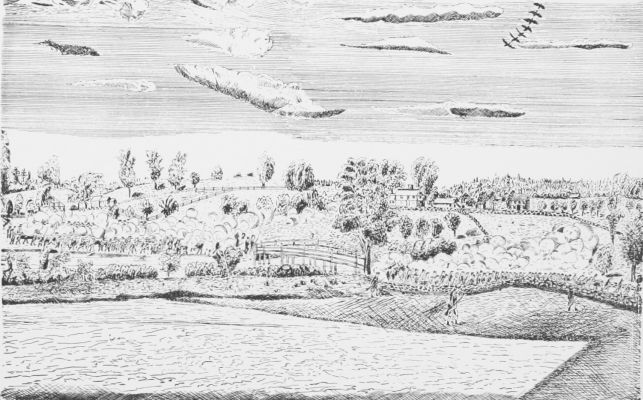

| Views from Governor Hutchinson's Field, | Page | 168. | |

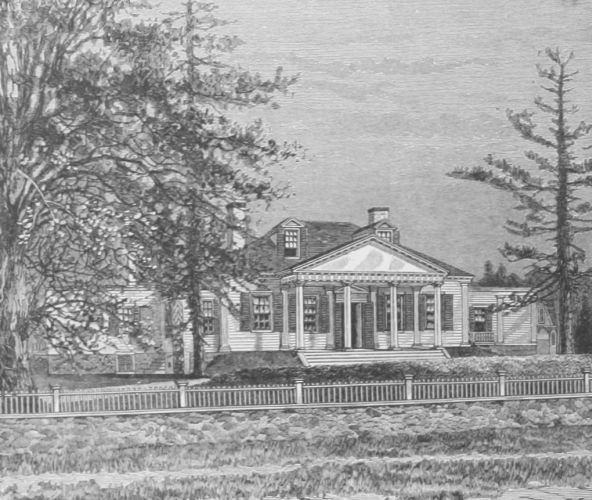

| Governor Hutchinson's House on Milton Hill, | " | 170. | |

| Inland View from Governor Hutchinson's House, | Page | 171. | |

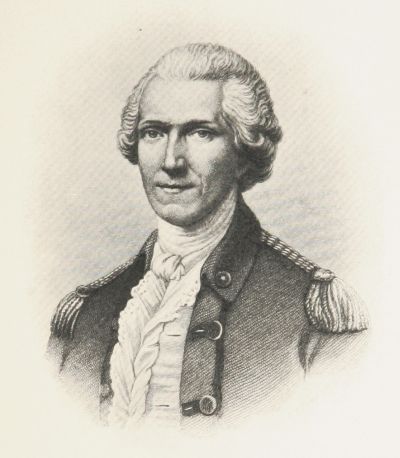

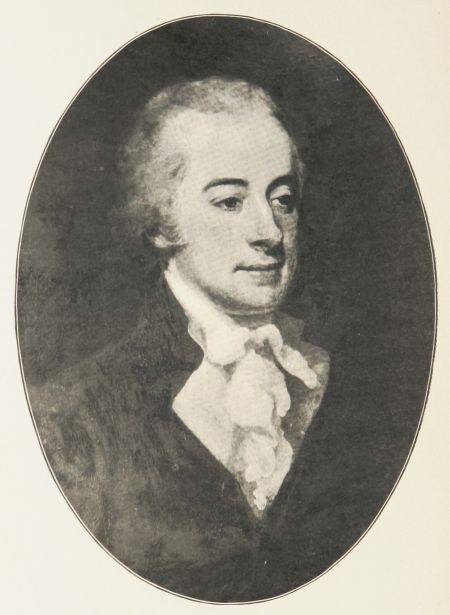

| Andrew Oliver, portrait, | Opposite | Page | 181. |

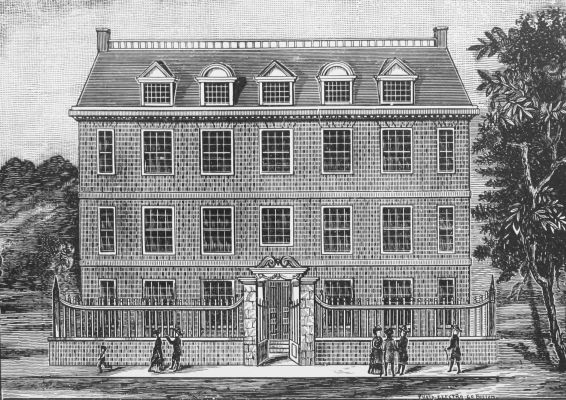

| Andrew Oliver Mansion, Washington street, Dorchester, | " | " | 183. |

| Thomas Oliver and John Vassall Mansion, Dorchester, | " | " | 185. |

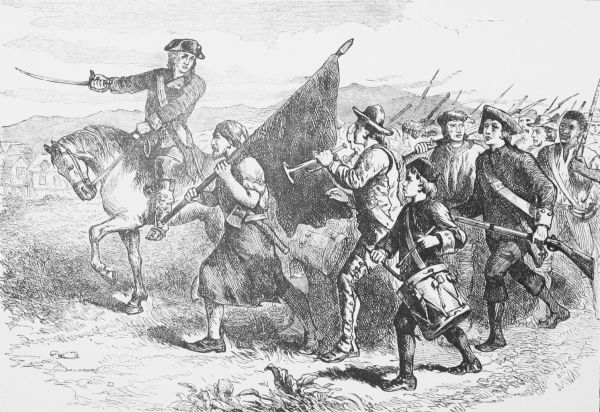

| Revolutionists Marching to Cambridge, | " | " | 187. |

| Sir Francis Bernard, Portrait, | " | " | 191. |

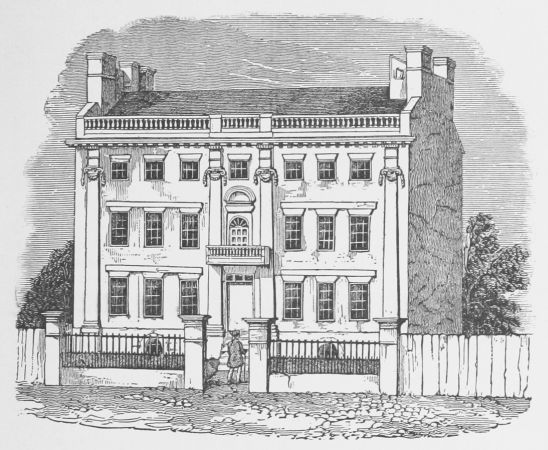

| Province House, | " | " | 195. |

| Pepperell House, | " | " | 210. |

| Reception of the American Loyalists in England, | Page | 214. | |

| Arrest of William Franklin by order of Congress, | Opposite | Page | 215. |

| John Singleton Copley, Portrait, | " | " | 218. |

| Lord Lyndhurst, Lord High Chancellor of England, Portrait, | " | " | 221. |

| King Hooper Mansion, Danvers, | " | " | 223. |

| Admiral Sir Isaac Coffin, Portrait, | " | " | 239. |

| Curwin House, Salem, | Page | 247. | |

| Samuel Curwin, Portrait, | Opposite | Page | 253. |

| Country Residence of James Smith, Brush Hill, Milton, | Page | 256. | |

| Birthplace of Benjamin Thompson, North Woburn, | " | 261. | |

| Sir Benjamin Thompson, Portrait, | Opposite | Page | 267. |

| Rev. Mather Byles, D. D., Portrait, | " | " | 277. |

| The Old Vassall House, Cambridge, | " | " | 285. |

| Colonel John Vassall's Mansion, Cambridge, | " | " | 289. |

| General Isaac Royall's Mansion, Medford, | " | " | 293. |

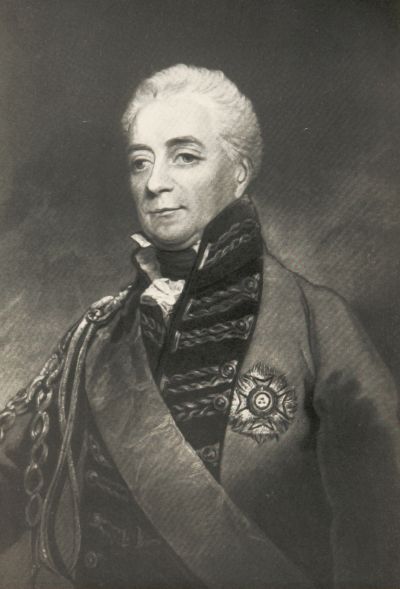

| Major General Sir David Ochterlony, Portrait, | " | " | 299. |

| British Troops preventing the destruction of New York, | " | " | 303. |

| Landing a Bishop, Cartoon, | " | " | 341. |

| Rev. Henry Caner, Portrait, | " | " | 349. |

| Leonard Vassall and Frederick W. Geyer Mansion, | " | " | 351. |

| Bishop's Palace, Residence of Rev. East Apthorp, | " | " | 353. |

| Samuel Quincy, Portrait, | " | " | 369. |

| Dr. John Jeffries, Portrait, | " | " | 395. |

| Clark-Frankland House, | " | " | 417. |

| Sir Roger Hale Sheaffe, Baronet, Portrait, | " | " | 439. |

| The Engagement at the North Bridge in Concord, | " | " | 471. |

| Monument to Commemorate the Skirmish at Concord Bridge, | " | " | 475. |

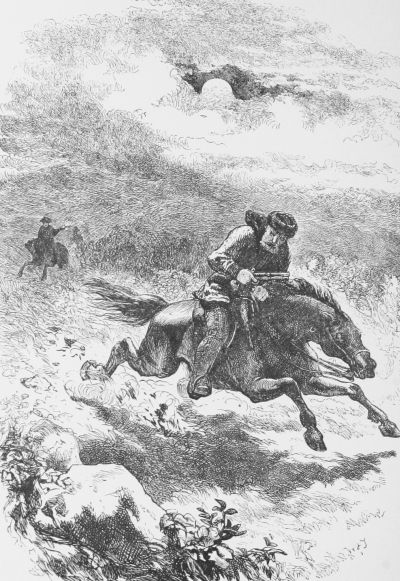

| Pursuit and Capture of Paul Revere, | " | " | 479. |

| Pelham Map of Boston, In the envelop of the back cover. |

At the dedication of the monument erected on Dorchester Heights to commemorate the evacuation of Boston by the British, the oration was delivered by that Nestor of the United States Senate, Senator Hoar.

In describing the government of the colonies at the outbreak of the Revolution, he made the following statement: "The government of England was, in the main, a gentle government, much as our fathers complained of it. Her yoke was easy and her burden was light; our fathers were a hundred times better off in 1775 than were the men of Kent, the vanguard of liberty in England. There was more happiness in Middlesex on the Concord, than there was in Middlesex on the Thames."[1] A few years later Hon. Edward B. Callender, a Republican candidate for mayor of Boston, in his campaign speech said: "I know something about how this city started. It was not made by the rich men or the so-called high-toned men of Boston—they were with the other party, with the king; they were Loyalists. Boston was founded by the ordinary man—by Paul Revere, the coppersmith; Sam Adams, the poor collector of the town of Boston, who did not hand over to the town even the sums he collected as taxes; by John Hancock, the smuggler of rum; by John Adams, the attorney, who naively remarked in his book that after the battle of Lexington they never heard anything about the suits against John Hancock. Those were settled."[2]

These words of our venerable and learned senator and our State Senator Edward B. Callender, seemed strangely unfamiliar to us who had derived our history of the Revolution from the school text-books. These had taught us that the Revolution was due solely to the oppression and tyranny of the British, and that Washington, Franklin, Adams, Hancock, Otis, and the host of other Revolutionary patriots, had in a[6] supreme degree all the virtues ever exhibited by men in their respective spheres, and that the Tories or Loyalists, such as Hutchinson, the Olivers, Saltonstalls, Winslows, Quincys and others, were to be detested and their memory execrated for their abominable and unpatriotic actions.

This led me to inquire and to examine whether there might not be two sides to the controversy which led to the Revolutionary War. I soon found that for more than a century our most gifted writers had almost uniformly suppressed or misrepresented all matter bearing upon one side of the question, and that it would seem to be settled by precedent that this nation could not be trusted with all portions of its own history. But it seemed to me that history should know no concealment. The people have a right to the whole truth, and to the full benefit of unbiased historical teachings, and if, in an honest attempt to discharge a duty to my fellow citizens, I relate on unquestionable authority facts that politic men have intentionally concealed, let no man say that I wantonly expose the errors of the fathers.

In these days we are recognizing more fully than ever the dignity of history, we are realizing that patriotism is not the sole and ultimate object of its study, but the search for truth, and abiding by the truth when found, for "the truth shall make you free" is an axiom that applies here as always.

Much of the ill will towards England which until recently existed in great sections of the American people, and which the mischief-making politician could confidently appeal to, sprung from a false view of what the American Revolution was, and the history of England was, in connection with it. The feeling of jealousy and anger, which was born in the throes of the struggle for independence, we indiscriminately perpetuated by false and superficial school text-books. The influence of false history and of crude one-sided history is enormous. It is a natural and logical step that when our children pass from our schoolroom into active life, feelings so born should die hard and at times become a dangerous factor in the national life, and it is not too much to say that the persistent ill will towards England as compared with the universal kindliness of English feeling towards us, is to be explained by the very different spirit in which the history of the American Revolution is taught in the schools of one country and in those of the other.

A nation's own experience should be its best political guide, but it is not certain that as a people we have improved by all the teachings of our own history, for the reason that our "patriot" writers and orators mostly bound their vision in retrospect by the revolutionary era. And yet, all beyond that is not dark, barren, and profitless to explore. It should be known that the most important truths on which our free forms of government now rest are not primarily the discoveries of the revolutionary sages.

Writing of the Revolution, Mr. John Adams, the successor of Washington, declared that it was his opinion that the Revolution "began as early as the first plantation of the country," and that "independence of church and state was the fundamental principle of the first colonization, has been its principle for two hundred years, and now I hope is past dispute. Who was the author, inventor, discoverer of independence? The only true answer must be, the first emigrants." Before this time he had declared that "The claim of the men of 1776 to the honor of first conceiving the idea of American independence or of first inventing the project of it, is ridiculous. I hereby disclaim all pretension to it, because it was much more ancient than my nativity."

It was the inestimable fortune of our ancestors to have been taught the difficulties of government in two distinct schools, under the Colonial and Provincial charters, known as the first and second charters. The Charter government as moulded and modelled by our ancestors, was as perfect as is our own constitution of today. It was as tender of common right, as antagonistic to special privilege to classes or interests, and as sensitive, too, to popular impulses, good or evil. And it is thus in all self-governing communities, that their weal or woe, being supposedly in their own keeping, the freest forms of delegated government written on parchment are in themselves no protection, but will be such instruments of blessing or of destruction as may best gratify the controlling influences or interests for the time being.

[8]In tracing the origin and development of the sentiment and the desires, the fears and the prejudices which culminated in the American Revolution, in the separation of thirteen colonies from Great Britain, it is necessary to notice the early settlement and progress of those New England colonies in which the seeds of that Revolution were first sown and nurtured to maturity. The Colonies of New England were the result of two distinct emigrations of English Puritans, two classes of Puritans, two distinct governments for more than sixty years—one class of these emigrants, now known as the "Pilgrim Fathers," having first fled from England to Holland, thence emigrated to New England in 1620 in "the Mayflower," and named their place of settlement "New Plymouth." Here they elected seven governors in succession, and existed under a self-constituted government for seventy years. The second class was called "Puritan Fathers." The first installment of their immigrants arrived in 1629, under Endicott, the ancestor of Mr. Joseph Chamberlain's wife. They were known as the "Massachusetts Bay Company," and their final capital was Boston, which afterwards became the capital of the Province and of the State.

The characteristics of the separate and independent governments of these two classes of Puritans were widely different. The one was tolerant, non-persecuting, and loyal to the King, during the whole period of its seventy years' existence; the other was an intolerant persecutor of all religionists who did not adopt its worship, and disloyal, from the beginning, to the government from which it held its Charter, and sedulously sowed and cultivated the seeds of disaffection and hostility to the Royal government until they grew and ripened into the harvest of the American Revolution.

English Puritanism, transferred from England to the head of Massachusetts Bay in 1629, presents the same characteristics which it developed in England. In Massachusetts it had no competitor, it developed its principles and spirit without restraint; it was absolute in power from 1629 to 1689. During these sixty years it assumed independence of the government to which it owed its corporate existence; it made it a penal crime for any immigrant to appeal to England against a local decision of courts or of government; it permitted no oath of allegiance to the King, nor the administration of the laws in his name; it allowed no elective franchise to any Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Baptist, Quaker or Papist. Every non-member of the Congregational church was compelled to pay taxes and bear all other Puritan burdens, but was allowed no representation by franchise, nor had he eligibility for any public office.

When the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Company emigrated from England, they professed to be members of the Church of England, but Endicott, who had imbibed views of church government and of forms of worship, determined not to perpetuate here the worship of the Established Church, to which he had professed to belong[9] when he left England, but to establish a new church with a new form of worship. He seemed to have brought over some thirty of the immigrants to his new scheme, but a majority either stood aloof from, or were opposed to his extraordinary proceeding. Among the most noted adherents of the old Church of the Reformation were two brothers, John and Samuel Brown, who refused to be parties to this new and locally devised church revolution, and resolved for themselves, their families, and such as thought with them, to continue to worship God according to the custom of their fathers.

It is the fashion of many American historians, as well as their echoes in England, to apply epithets of contumely or scorn to these men. Both the Browns were men of wealth, one a lawyer, the other a private gentleman, and both of them were of a social position in England much superior to that of Endicott. They were among the original patentees and first founders of the colony; they were church reformers, but neither of them a church revolutionist. The brothers were brought before the Governor, who informed them that New England was no place for such as they, and therefore he sent them both back to England, on the return of the ships the same year.

Endicott resolved to admit of no opposition. They who could not be terrified into silence were not commanded to withdraw, but were seized and banished as criminals.[3]

A year later John Winthrop was appointed to supersede Endicott as Governor. On his departure with a fleet of eleven ships from England an address to their "Fathers and Brethren of the Church of England" was published by Winthrop from his ship, the Arbella, disclaiming the acts of some among them hostile to the Church of England, declaring their obligations and attachment to it. He said: "We desire you would be pleased to take notice of the principles and body of our Company as those who esteem it an honor to call the Church of England, from whence we rise, our dear Mother, and cannot part from our native countrie, where she especially resideth, without much sadness of heart and many tears in our eyes." It might be confidently expected that Mr. Winthrop, after this address of loyalty and affection to his Father and Brethren of the Church of England, would, on his arrival at Massachusetts Bay, and assuming its government, have rectified the wrongs of Endicott and his party, and have secured at least freedom of worship to the children of his "dear Mother." But he did nothing of the kind; he seems to have fallen in with the very proceedings of Endicott which had been disclaimed by him in his address.

Thus was the first seed sown, which germinated for one hundred and thirty years, and then ripened in the American Revolution. It was the opening wedge which shivered the transatlantic branches from the parent stock. It was the consciousness of having abused the Royal confidence, and broken faith with their Sovereign, of having acted contrary[10] to the laws and statutes of England, that led the Government of Massachusetts Bay to resist and evade all inquiries into their proceedings; to prevent all evidence from being transmitted to England, and to punish as criminals all who should appeal to England against any of their proceedings; to claim, in short, independence and immunity from all responsibility to the Crown for anything they did or might do. This spirit of tyranny and intolerance, of proscription and persecution, caused all the disputes with the parent Government, and all the bloodshed on account of religion in Massachusetts, which its Government inflicted in subsequent years, in contradistinction to the Governments of Plymouth, Rhode Island, Connecticut and even Maryland.

The church government established by the Puritans at Boston was not a government of free citizens elected by a free citizen suffrage, or even of property qualification, but was the "reign of the church, the members of which constituted but about one-sixth of the population, five-sixths being mere helots bound to do the work and pay the taxes imposed upon them by the reigning church but denied all eligibility to any office in the Commonwealth." It was indeed such a "connection between church and state" as had never existed in any Protestant country; it continued for sixty years, until suppressed by a second Royal Charter, as will appear in the next chapter.

The Puritans were far from being the fathers of American Liberty. They neither understood nor practiced the first principles of civil and religious liberty nor the rights of British subjects as then understood and practiced in the land they had left "for conscience sake."

The first Charter obtained of Charles I. is still in existence, and can be seen in the Secretary's Office at the State House, Boston. A duplicate copy of this Charter was sent over in 1629 to Governor Endicott, at Salem, and is now in the Salem Athenæum.

If the conditions of the Charter had been observed the colonists would have been independent indeed, and would have enjoyed extraordinary privileges for those times. They would have had the freest government in the world. They were allowed to elect their own governor and members of the General Court, and the government of the Colony was but little different from that of the State today, so far as the rights conferred by the charter were concerned. The people were subjects of the Crown in name, but in reality were masters of their own public affairs. The number of the early emigrants to New England who renounced allegiance to the mother church was exceedingly small, for the obvious reason that it was at the same time a renunciation of their allegiance to the Crown. A company of restless spirits had been got rid of, and whether they conformed to all the laws of church and state or not, they were three thousand miles away and could not be easily brought to punishment even if they deserved it, or be made to mend the laws if they broke them. The restriction of subjecting those who wished to emigrate to the oaths of allegiance and supremacy did not last long.[11] Those who chose "disorderly to leave the Kingdom" did so, and thus what they gained in that kind of liberty is a loss to their descendants who happen to be antiquaries and genealogists.

Under the charter they were allowed to make laws or ordinances for the government of the plantation, which should not be repugnant to the laws of England; all subjects of King Charles were to be allowed to come here; and these emigrants and their posterity were declared "to be natural-born subjects, and entitled to the immunities of Englishmen." The time of the principal emigration was auspicious. The rise of the civil war in England gave its rulers all the work they could do at home. The accession of Oliver Cromwell to the Protectorate was regarded very favorably by the colonists, who belonged to the same political party, and they took advantage of this state of affairs to oppress all others who had opinions different from their own. The Quakers, both men and women, were persecuted, and treated with great severity; many were hung, a number of them were whipped at the cart's tail through the town, and then driven out into the wilderness; others had their ears cut off, and other cruelties were perpetrated of a character too horrible to be here related. It was in vain that these poor Quakers demanded wherein they had broken any laws of England. They were answered with additional stripes for their presumption, and not without good reason did they exclaim against "such monstrous illegality," and that such "great injustice was never heard of before." Magna Charta, they said, was trodden down and the guaranties of the Colonial Charter were utterly disregarded.

The following is a striking example of the very many atrocities committed by the authorities at that time: "Nicholas Upshall, an old man, full of years, seeing their cruelty to the harmless Quakers and that they had condemned some of them to die, bothe he and Elder Wiswell, or otherwise Deacon Wiswell, members of the church in Boston, bore their testimony in publick against their brethren's horrid cruelty to said Quakers. And Upshall declared, 'That he did look at it as a sad forerunner of some heavy judgment to follow upon the country.'... Which they took so ill at his hands that they fined him twenty pounds and three pound more at their courts, for not coming to this meeting and would not abate him one grote, but imprisoned him and then banished him on pain of death, which was done in a time of such extreme bitter weather for frost, and snow, and cold, that had not the Heathen Indians in the wilderness woods taken compassion on his misery, for the winter season, he in all likelihood had perished, though he had then in Boston a good estate, in houses and land, goods and money, as also wife and children, but not suffered to come unto him, nor he to them."[4]

After the death of Oliver Cromwell, Charles II. was proclaimed in London the lawful King of England, and the news of it in due time[12] reached Boston. It was a sad day to many, and they received the intelligence with sorrow and concern, for they saw that a day of retribution would come. But there was no alternative, and the people of Boston made up their minds to submit to a power they could not control. They, however, kept a sort of sullen silence for a time, but fearing this might be construed into contempt, or of opposition to the King, they formally proclaimed him, in August, 1661, more than a year after news of the Restoration had come. Meanwhile the Quakers in England had obtained the King's ear, and their representations against the government at Boston caused the King to issue a letter to the governor, requiring him to desist from any further proceedings against them, and calling upon the government here to answer the complaints made by the Quakers. A ship was chartered, and Samuel Shattock, who had been banished, was appointed to carry the letter, and had the satisfaction of delivering it to the governor with his own hand. After perusing it, Mr. Endicott replied, "We shall obey his Majesty's command," and then issued orders for the discharge of all Quakers then in prison. The requisition of the king for some one to appear to answer the complaints against the government of Boston, caused much agitation in the General Court; and when it was decided to send over agents, it was not an easy matter to procure suitable persons, so sensible was everybody that the complaints to be answered had too much foundation to be easily excused, or by any subterfuge explained away. It is worthy of note that the two persons finally decided upon (Mr. Bradstreet and Mr. Norton) were men who had been the most forward in the persecutions of the Quakers. And had it not been for the influence which Lord Saye and Seale of the king's Council, and Col. Wm. Crowne, had with Charles II., the colony would have felt his early and heavy displeasure. Col. Crowne was in Boston when Whalley and Goffe, the regicides, arrived here, and he could have made statements regarding their reception, and the persecution of the Quakers, which might have caused the king to take an entirely different course from the mild and conciliatory one which, fortunately for Boston, was taken. Having "graciously" received the letter from the hands of the agents, and, although he confirmed the Patent and Charter, objects of great and earnest solicitude in their letter to him, yet "he required that all their laws should be reviewed, and that such as were contrary or derogatory to the king's authority should be annulled; that the oath of allegiance should be administered; that administration of justice should be in the king's name; that liberty should be given to all who desired it, to use the Book of Common Prayer; in short, establishing religious freedom in Boston." This was not all—the elective franchise was extended "to all freeholders of competent estates," if they sustained good moral characters.

LANDING OF THE COMMISSIONERS AT BOSTON, 1664.

LANDING OF THE COMMISSIONERS AT BOSTON, 1664.The return of the agents to New England, bearing such mandates from the king, was the cause of confusion and dismay to the whole country. Instead of being thankful for such lenity, many were full of resentment[13] and indignation, and most unjustly assailed the agents for failing to accomplish an impossibility.

Meanwhile four ships had sailed from Portsmouth, with about four hundred and fifty soldiers, with orders to proceed against the Dutch in the New Netherlands (New York), and then to land the commissioners at Boston and enforce the king's authority. The Dutch capitulated, and the expedition thus far was completely successful. The commissioners landed in Boston on Feb. 15th, 1664, and held a Court to correct whatever errors and abuses they might discover. The commission was composed of the following gentlemen: Col. Richard Nichols, who commanded the expedition; Sir Robert Carr, Col. Geo. Cartwright and Mr. Samuel Maverick. Maverick had for several years made his home on Noddle Island (now known as East Boston), but, like his friends, Blackstone of Beacon Hill and other of the earliest settlers, had been so harshly and ungenerously treated by the Puritan colonists of Boston that he was compelled to remove from his island domain. An early adventurous visitor to these shores mentions him in his diary as "the only hospitable man in all the country." These gentlemen held a commission from the king constituting them commissioners for visiting the colonies of New England, to hear and determine all matters of complaint, and to settle the peace and security of the country, any three or two of them being a quorum.

The magistrates of Boston having assembled, the commissioners made known their mission, and added that so far was the king from wishing to abridge their liberties, he was ready to enlarge them, but wished them to show, by proper representation of their loyalty, reasons to remove all causes of jealousy from their royal master. But it was of no avail; the word loyalty had been too long expunged from their vocabulary to find a place in it again. At every footstep the commissioners must have seen that whatever they effected, and whatever impressions they made, would prove but little better than footprints in the sand. The government thought best to comply with their requirements, so far, at least, as appearances were concerned. They therefore agreed that their allegiance to the king should be published "by sound of trumpet;" that Mr. Oliver Purchis should proclaim the same on horseback, and that Mr. Thomas Bligh, Treasurer, and Mr. Richard Wait, should accompany him; that the reading in every place should end with the words, "God save the King!" Another requirement of the commissioners was that the government should stop coining money; that Episcopalians should not be fined for non-attendance at the religious meetings of the community, as they had hitherto been; that they should let the Quakers alone, and permit them to go about their own affairs. These were only a part of the requirements, but they were the principal ones. Notwithstanding a pretended acquiescence on the part of the government to the requests of the commissioners, it was evident from the first that little could be effected by them from the evasive manner in which all their orders and[14] recommendations were accepted. At length the commissioners found it necessary to put the question to the Governor and Council direct, "Whether they acknowledged his Majesty's Commission?" The Court sent them a message, desiring to be excused from giving a direct answer, inasmuch as their charter was their plea. Being still pressed for a direct answer, they declared that "it was enough for them to give their sense of the powers granted them by charter, and that it was beyond their line to determine the power, intent, or purpose of his Majesty's commission." The authorities then issued a proclamation calling upon the people, in his Majesty's name (!), not to consent unto, or give approbation to the proceedings of the King's Commission, nor to aid or to abet them. This proclamation was published through the town by sound of trumpet, and, oddly enough, added thereto "God save the King." The commissioners then sent a threatening protest, saying they thought the king and his council knew what was granted to them in their charter; but that since they would misconstrue everything, they would lose no more of their labor upon them; at the same time assuring them that their denial of the king's authority, as vested in his commission, would be represented to his Majesty only in their own words. The conduct of Col. Nichols, at Boston, is spoken of in terms of high commendation; but Maverick, Carr and Cartwright are represented as totally unfitted for their business. It is, however, difficult to see how any commissioners, upon such an errand, could have given greater satisfaction; for a moment's consideration is sufficient to convince any one that the difficulty was not so much in the commissioners, as in their undertaking.

After the return of the commissioners to England the government continued their persecutions of the Quakers, Baptists, Episcopalians, and all others who held opinions differing from their own. The laws of England regulating trade were entirely disregarded; the reason alleged therefor being, "that the acts of navigation were an invasion of the rights and privileges of the subjects of his Majesty's colony, they not being represented in Parliament."

Again the king wrote to the authorities of Boston, requiring them not to molest the people, in their worship, who were of the Protestant faith, and directing that liberty of conscience should be extended to all. This letter was dated July 24th, 1679. It had some effect on the rulers; but they had become so accustomed to what they called interference from England, and at the same time so successful in evading it, that to stop now seemed, to the majority of the people, as well as the rulers, not only cowardly, but an unworthy relinquishment of privileges which they had always enjoyed, and which they were at all times ready to assert, as guaranteed to them in their charter. However, there was a point beyond which even Bostonians could not go, and which after-experience proved.

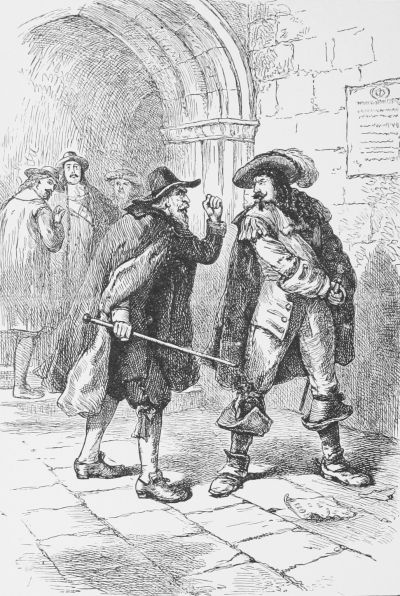

RANDOLPH THREATENED.

RANDOLPH THREATENED.Edward Randolph brought the king's letter to Boston, and was required to make a report concerning the state of affairs in the colony, and to see that the laws of England were properly executed; but he did[15] not fare well in his mission. He wrote home that every one was saying they were not subject to the laws of England, and that those laws were of no force in Massachusetts until confirmed by the Legislature of the colony.

Every day aggravated his disposition more strongly against the people, who used their utmost endeavors to irritate his temper and frustrate his designs. Any one supporting him was accounted an enemy of the country.

His servants were beaten while watching for the landing of contraband goods. Going on board a vessel to seize it, he was threatened to be knocked on the head, and the offending ship was towed away by Boston boats. Randolph returned to England, reporting that he was in danger of his life, and that the authorities were resolved to prosecute him as a subserver of their government. If they could, they would execute him; imprisonment was the least he expected. Well might the historian exclaim, as one actually did, "To what a state of degradation was a king of England reduced!" his commissioners, one after another, being thwarted, insulted and obliged to return home in disgrace, and his authority openly defied. What was the country to expect when this state of affairs should be laid before the king? A fleet of men-of-war to bring it to its duty? Perhaps some expected this; but there came again, instead, the evil genius of the colony, Edward Randolph, bringing from the king the dreaded quo warranto. This was Randolph's hour of triumph; he said "he would now make the whole faction tremble," and he gloried in their confusion and the success which had attended his efforts to humble the people of Boston. To give him consequence a frigate brought him, and as she lay before the town the object of her employment could not be mistaken. An attempt was made, however, to prevent judgment being rendered on the return of the writ of quo warranto. An attorney was sent to England, with a very humble address, to appease the king, and to answer for the country, but all to no purpose. Judgment was rendered, and thus ended the first charter of Massachusetts, Oct. 23rd, 1684.

Charles II. died Feb. 6th, 1685, and was succeeded by his brother, James II. News of this was brought to Boston by private letter, but no official notification was made to the governor. In a letter to him, however, he was told that he was not written to as governor, for as much as now he had no government, the charter being vacated. These events threw the people of Boston into great uncertainty and trouble as to what they were in future to expect from England. Orders were received to proclaim the new king, which was done "with sorrowful and affected pomp," at the town house. The ceremony was performed in the presence of eight military companies of the town, and "three volleys of cannon" were discharged. Sir Edmund Andros, the new Royal Governor, arrived in Boston Dec. 20th, 1686, and, as was to be expected, he was not regarded favorably by the people, especially as his first act after landing was a demand for the keys of the Old South Church "that they may say prayers there." Such a demand from the new governor could not be tolerated by the now superseded governing authority of Boston, and defy it they would. The Puritan oligarchy stoutly objected to being deprived of the right to withhold from others than their own sect the privileges of religious liberty. To enjoy religious liberty in full measure they had migrated from the home of their fathers, but in New England had become more intolerant than the church which they had abandoned, and became as arbitrary as the Spanish inquisition. Under direction of the king, Andros had come to proclaim the equality of Christian religion in the new colonies. Too evidently this was not what was wanted here.

At last came the news of the landing of the Prince of Orange in England and the abdication of James the Second. The people of Boston rose against Andros and his government and seized him and fifty of his associates and confined them in the "Castle" until February, 1690, when they were sent to England for trial; but having committed no offence, they were discharged. Andros was received so favorably at home that under the new administration he was appointed governor of Virginia and Maryland. He took over with him the charter of William and Mary college, and later laid the foundation stone of that great institution of learning.

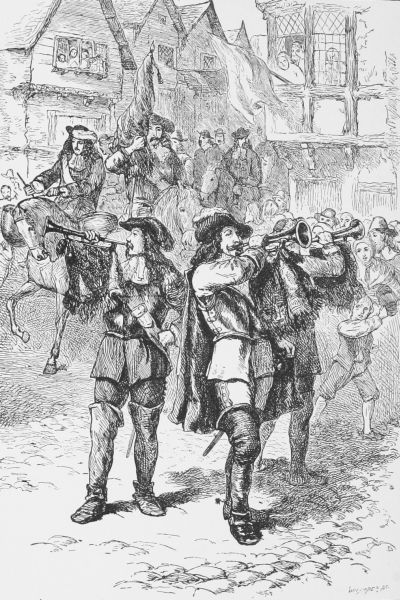

PROCLAIMING KING WILLIAM AND QUEEN MARY, 1689.

PROCLAIMING KING WILLIAM AND QUEEN MARY, 1689.Andros has never received justice from Massachusetts historians. Before his long public career ended he had been governor of every Royal[17] Province in North America. His services were held in such high esteem that he was honored with office by four successive monarchs.

It is gratifying to notice that at last his character and services are beginning to be better appreciated in the provinces over which he ruled, and we may hope that in time the Andros of partisan history will give place, even in the popular narratives of colonial affairs, to the Andros who really existed, stern, proud and uncompromising it is true, but honest, upright and just; a loyal servant of the crown and a friend to the best interests of the people.

Not only were the governor and all of his adherents arrested and thrown into jail, but Captain George, of the Rose frigate, being found on shore, was seized by a party of ship carpenters and handed over to the guard.

So strong was the feeling against the prisoners that it was found necessary to guard them against the infuriated people, lest they should be torn into pieces by the mob. The insurrection was completely successful, and the result was that the resumption of the charter was once more affirmed. A general court was formed after the old model, and the venerable Bradstreet was made governor. Nothing now seemed wanting to the popular satisfaction but favorable news from England, and that came in a day or two. On the 26th of May, 1689, a ship arrived from the old country with an order to the Massachusetts authorities to proclaim King William and Queen Mary. This was done on the 29th, and grave, Puritanical Boston went wild with joy, and all thanked God that a Protestant sovereign once more ruled in England. This has been said to have been the most joyful news ever before received in Boston.

May 14, 1692, Sir William Phipps, a native of Massachusetts, arrived in Boston from England, bringing with him the new Charter of the province, and a commission constituting him governor of the same. Unfortunately he countenanced and upheld the people in their delusion respecting witchcraft, and confirmed the condemnation and execution of the victims. The delusion spread like flames among dry leaves in autumn, and in a short time the jails in Boston were filled with the accused. During the prevalence of this moral disease, nineteen persons in the colony were hanged, and one pressed to death. At last the delusion came to an end, and the leaders afterwards regretted the part they had taken in it.

The new Charter of Massachusetts gave the Province a governor appointed by the Crown. While preserving its assembly and its town organization, it tended to encourage and develop, even in that fierce democracy, those elements of a conservative party which had been called into existence some years before by the disloyalty and tyranny of the ecclesiastical oligarchy.

Thus, side by side with a group of men who were constantly regretting their lost autonomy, and looking with suspicion and prejudice at every action of the royal authorities, there arose another group of[18] men who constantly dwelt upon the advantages they derived from their connection with the mother country. The Church of England also had at last waked up to a sense of the spiritual needs of its children beyond the seas. Many of the best of the laity forsook their separatist principles and returned to the historic church of the old home. This influence tended inevitably to maintain and strengthen the feeling of national unity in those of the colonists who came under the ministration of the church. In all the Royal Provinces there was an official class gradually growing up, that was naturally imperial rather than local in its sympathy. The war with the French, in which colonists fought side by side with "regulars" in a contest of national significance, tended upon the whole to intensify the sense of imperial unity.

"The people of Massachusetts Bay were never in a more easy and happy situation than at the conclusion of the war with France in 1749. By generous reimbursement of the whole charge of £183,000 incurred by the expedition against Cape Breton, the English government set the Province free from a heavy debt by which it must otherwise have remained involved, and enabled by it to exchange a depreciating paper medium, which had long been the sole instrument of trade, for a stable medium of gold and silver. Soon the advantage of this relief from the heavy burden of debt was apparent in all branches of their commerce, and excited the envy of other colonies, in each of which paper was the principal currency."[5]

The early part of the eighteenth century was filled with wars: France, England and Spain were beginning to overrun the interior of North America. Spain claimed a zone to the south, and France a vast territory to the north and west of the English colonies. Each of the three countries sought aid from the savage to carry on its enterprises and depredations. While the English colonies were beset on the north by the French, on the south by the Spaniards, on the west by native Indians along the Alleghany Mountains, and were compelled to depend on the "wooden walls of England" for the protection of their coasts, they were then remarkably loyal to the Crown of England. Their representative assemblies passed obsequious resolutions expressing loyalty and gratitude to the King, and the people; and erected his statue in a public place. This feeling of loyalty remained in the minds of a large majority of the people down to the battle of Lexington.

In May, 1756, the English government, goaded by the constantly continued efforts of the French to ignore her treaty obligations in Acadia, and her ever-harrassing, irritating "pin-pricks" on the frontiers of the English colonies, declared war against France. Long before this official declaration the two countries had been, on this continent, in a state of active but covert belligerency. Preparations for an inevitable conflict were being made by both sides. French intrigue and French treachery were met with English determination to defend the rights of the mother[19] country and of her children here. Money was pledged to the colonies to aid in equipping militia for active service, and the local governments and the inhabitants of every province became as enthusiastic as the home government in the prosecution of war.

On the northern and western borders of New England and of New York, along the thin fringe of advanced English settlements bordering Pennsylvania and Virginia, Indians had long been encouraged or employed in savage raids, and in Nova Scotia, which, by the treaty of Utrecht had been ceded to England, systematic opposition to English occupation was constantly kept up.

Intriguing agents of the French government, soldiers, priests of the "Holy Catholic" church—all were active in a determined effort to check and finally crush out the menacing influence and prosperity of the growing English colonies.

The ambushing and slaughter of Braddock's force on the Monongahela, the removal of Acadians from Annapolis Valley, the defeat of Dieskau at Crown Point, the siege and occupation of Fort Beausejour, all occurred before the formal declaration of war. Clouds were gathering. Men of fighting age of the English colonies volunteered in thousands; British regiments, seasoned in war, were brought from the old country to the new, and with them and after them came ships innumerable. A fight for life of the English colonies was at hand. The brood of the mistress of the seas must not be driven into the ocean. France must be compelled to give pledges for the performance of her treaty engagements or find herself without a foothold in the country.

With the hour came the man. Under the direction of the greatest war minister England had ever seen, or has since seen, William Pitt, the "Great Commoner," war on France was begun in earnest.

At first a few successes were achieved by the French commanders. Fort William Henry, with its small garrison, surrendered to Montcalm, and Abercrombie's expedition to Fort Ticonderoga was a disastrous failure. But the tide of battle soon turned.

The beginning of the end came in 1758. Louisbourg, the great fortress which France had made "The Gibraltar of the West," became a prize to the army and navy of Britain. New England soldiers formed a part of the investing force on land, and their record in the second capture of Louisbourg was something to be proud of. Fort Frontenac, on Lake Ontario, was taken, together with armed vessels and a great collection of stores and implements of war. Fort Duquesne, a strongly fortified post of the French, whose site is now covered by the great manufacturing city of Pittsburgh, surrendered to a British force. For many years after it was known as Fort Pitt, so called in honor of the great minister under whose compelling influence the war against France had become so mighty a success.

In 1759, General Wolfe, who had been the leading spirit in the siege of Louisbourg, was placed in command of an expedition for the capture[20] of Quebec. Next after Louisbourg, Quebec was by nature and military art the strongest place in North America. The tragic story of the capture of Quebec has been so often told that it is not necessary for us to repeat it here.

Of the long, impatient watch by Wolfe, from the English fleet, for opportunity to disembark his small army, drifting with the tides of the St. Lawrence, passing and repassing the formidable citadel, the stealthy midnight landing at the base of a mighty cliff, the hard climb of armed men up the wooded height, and the assembly, in early morning mist, on the Plains of Abraham, are not for us to write of here. In the glowing pages of Parkman all this is so thrillingly described that we need not say more of the most dramatic and most pathetic story in all American history, than that Quebec fell, and with it, in short time, fell the whole power of France in North America.

In the following year (September 8, 1760), Montreal, the last stronghold of the French in Canada, capitulated to Sir Jeffrey Amherst, who had ascended the St. Lawrence with a force of about 10,000 men, comprising British regiments of the line artillery, rangers and provincial regiments from New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. The provincial contingent numbered above four thousand.

With the fall of Montreal the seven years' fight for supremacy was ended.

Such a defeat to proud France was a bitter experience, and definite settlement of the terms of peace, which Great Britain was able to dictate, was not made until, on the 10th of February, 1763, the treaty of Paris was signed.

By this treaty to Great Britain was ceded all Canada, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton and the West India Islands of Dominica, St. Vincent, Tobago and Grenada. Minorca was restored to Great Britain, and to her also was given the French possession of Senegal in Western Africa. In India, where the French had obtained considerable influence, France was bound by this treaty to raise no fortifications and to keep no military force in Bengal. To remove the annoyance which Florida had long been to the contiguous English colonies, that province of Spain was transferred to the English in exchange for Havana, which had been only recently wrested from the occupation of Spain by the brilliant victory of Pocock and Albamarle.

And so 1763 saw the British flag peacefully waving from the Gulf of Mexico to the northern shores of Hudson's Bay. The coast of the Atlantic was protected by the British navy, and the colonists had no longer foreign enemies to fear.

For this relief the colonists gave warm thanks to the king and to parliament. Massachusetts voted a costly monument in Westminster Abbey in memory of Lord Howe, who had fallen in the campaign against Canada. The assembly of the same colony, in a joyous address to the governor, declared that without the assistance of the parent state the colonies[21] must have fallen a prey to the power of France, and that without money sent from England the burden of the war would have been too great to bear. In an address to the king they made the same acknowledgment, and pledged themselves to demonstrate their gratitude by every possible testimony of duty and loyalty. James Otis expressed the common sentiment of the hour when, upon being chosen moderator of the first town meeting held in Boston after the peace, he declared: "We in America have certainly abundant reason to rejoice. Not only are the heathen driven out, but the Canadians, much more formidable enemies, are conquered and become fellow subjects. The British dominion and power can now be said literally to extend from sea to sea and from the Great River to the ends of the earth." And after praising the wise administration of His Majesty, and lauding the British constitution to the skies, he went on to say: "Those jealousies which some weak and wicked minds endeavored to infuse with regard to these colonies, had their birth in the blackness of darkness, and it is a great pity that they had not remained there forever. The true interests of Great Britain and her plantation are mutual, and what God in his providence has united, let no man dare attempt to pull asunder."

In June, 1763, a confederation, including several Indian tribes, suddenly and unexpectedly swept over the whole western frontier of Pennsylvania and Virginia. They murdered almost all the English settlers who were scattered beyond the mountains, surprised every British fort between the Ohio and Lake Erie, and closely blockaded Forts Detroit and Pitt. In no previous war had the Indians shown such skill, tenacity, and concert, and had there not been British troops in the country the whole of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Maryland would have been overrun.

The war lasted fourteen months, and most of the hard fighting was done by English troops, assisted by militia from some of the Southern colonies. General Amherst called upon the New England colonies to help their brethren, but his request was almost disregarded. Connecticut sent 250 men, but Massachusetts, being beyond the zone of immediate danger, would give no assistance. After a war of extreme horror, peace was signed September, 1764. In a large degree by the efforts of English soldiers Indian territory was rolled back, and one more great service was rendered by England to her colonies, and also the necessity was shown for a standing army.[6]

The "French and Indian War," as it was commonly called, waged with so much energy and success, doubled the national debt of England and made taxation oppressive in that country. The war had been waged mainly for the benefit of the colonists, and as it was necessary to maintain a standing army to protect the conquered territory, it was considered but reasonable that part of the expense should be borne by the Americans. This was especially so in view that the conquest of Canada had[22] been a prime object of statesmen and leading citizens of the colonies for many years.

It has been said on good authority that Franklin brought about the expedition against Canada that ended with Wolfe's victory on the Plains of Abraham. In all companies and on all occasions he had urged conquest of Canada as an object of the utmost importance. He said it would inflict a blow upon the French power in America from which it would never recover, and would have lasting influence in advancing the prosperity of the British colonies. Franklin was one of the shrewdest statesmen of the age. After egging England on to the capture of Canada from the French, and then removing the most dreaded enemy of the colonies, he won the confidence of the court and people of France, and obtained their aid to deprive England of the best part of a continent. He was genial, thrifty, and adroit, and his jocose wisdom was never more tersely expressed than when he advised the signers of the Declaration of Independence to "hang together or they would hang separately."

At the conclusion of the Peace of Paris in 1763, Great Britain had ceased to be an insular kingdom, and had become a world-wide empire, consisting of three grand divisions: the British Islands, India, and a large part of North America. In Ireland an army of ten or twelve thousand men were maintained by Irish resources, voted by an Irish Parliament and available for the general defence of the empire. In India a similar army was maintained by the despotic government of the East India Company. English statesmen believed that each of these great parts of the empire should contribute to the defence of the whole, and that unless they should do so voluntarily it was their opinion, in which the great lawyers of England agreed, that power to force contributions resided in the Imperial Parliament at Westminster, and should be exercised. It was thought that an army of ten thousand men was necessary to protect the territory won from France and to keep the several tribes of American Indians in subjection, especially as it was believed that the French would endeavor to recapture Canada at the first opportunity.

Americans, it should be remembered, paid no part of the interest on the national debt of England, amounting to one hundred and forty million pounds, one-half of which had been contracted in the French and Indian war. America paid nothing to support the navy that protected its coasts, although the American colonies were the most prosperous and lightly taxed portion of the British Empire. Grenville, Chancellor of the Exchequer, asked the Americans to contribute one hundred thousand pounds a year, about one-third of the expense of maintaining the proposed army, and about one-third of one percent of the sum we now pay each year for pensions. He promised distinctly that the army should never be required to serve except in America and the West India islands, but he could not persuade the colonists to agree among themselves on a practical plan for raising the money, and so it was proposed to resort to taxation by act[23] of Parliament. At the time he made this proposal he assured the Americans that the proceeds of the tax should be expended solely in America, and that if they would raise the money among themselves in their own way he would be satisfied. He gave them a year to consider the proposition. At the end of the year they were as reluctant as ever to tax themselves for their own defence or submit to taxation by act of Parliament. Then the stamp act was passed—it was designed to raise one hundred thousand pounds a year, and then the trouble began that led to the dismemberment of the empire. Several acute observers had already predicted that the triumph of England over France would be soon followed by a revolt of the colonies. Kalm, the Swedish traveller, contended in 1748 that the presence of the French in Canada, by making the English colonists depend for their security on the support of the mother country, was the main cause of the submission of the colonies. A few years later Argenson, who had left some of the most striking political predictions upon record, foretold in his Memoirs that the English colonies in America would one day rise against the mother country, that they would form themselves into a republic and astonish the world by their prosperity. The French ministers consoled themselves for the Peace of Paris by the reflection that the loss of Canada was a sure prelude to the independence of the colonies, and Vergennes, the sagacious French ambassador at Constantinople, predicted to an English traveller, with striking accuracy, the events that would occur. "England," he said, "will soon repent having removed the only check that would keep her colonies in awe. They stand no longer in need of her protection; she will call upon them to contribute towards supporting the burden they have helped to bring on her, and they will answer by striking off all dependence."[7]

It is not to be supposed that Englishmen were wholly blind to this danger. One of the ablest advocates of the retention of Canada was Lord Bath, who published a pamphlet on the subject, which had a very wide influence and a large circulation.[8] There were, however, some politicians who maintained that it would be wiser to restore Canada and to retain Guadaloupe, St. Lucia, and Martinique. This view was supported with distinguished talent in an anonymous reply to Lord Bath.

This writer argued "that we had no original right to Canada, and that the acquisition of a vast, barren, and almost uninhabited country lying in an inhospitable climate, and with no commerce except that of furs and skins, was economically far less valuable to England than the acquisition of Guadaloupe, which was one of the most important of the sugar islands. The acquisition of these islands would give England the control of the West Indies, and it was urged that an island colony is more advantageous than a continental one, for it is necessarily more dependent upon the mother country. In the New England provinces there are already colleges and academies where the American youths can receive[24] their education. America produces or can easily produce almost everything she wants. Her population and her wealth are rapidly increasing, and as the colonies recede more and more from the sea, the necessity of their connection with England will steadily diminish. They will have nothing to expect, they must live wholly by their own labor, and in process of time will know little, inquire little, and care little, about the mother country. If the people of our colonies find no check from Canada they will extend themselves almost without bounds into inland parts. What the consequences will be to have a numerous, hardy, independent people, possessed of a strong country, communicating little, or not at all, with England, I leave to your own reflections. By eagerly grasping at extensive territory we may run the risk, and that, perhaps, in no distant period, of losing what we now possess. The possession of Canada, far from being necessary to our safety, may in its consequences be even dangerous. A neighbor that keeps us in some awe is not always the worst of neighbors; there is a balance of power in America as well as in Europe."[9]

These views are said to have been countenanced by Lord Hardwicke, but the tide of opinion ran strongly in the opposite direction; the nations had learned to look with pride and sympathy upon that greater England which was growing up beyond the Atlantic, and there was a desire, which was not ungenerous or ignoble, to remove at any risk the one obstacle to its future happiness. These arguments were supported by Franklin, who in a remarkable pamphlet sketched the great undeveloped capabilities of the colonies, and ridiculed the "visionary fear" that they would ever combine against England. "This jealousy of each other," he said, "is so great that, however necessary a union of the colonies has long been for their common defence and security against their enemies, yet they have never been able to effect such a union among themselves. If they cannot agree to unite for defence against the French and Indians, can it reasonably be supposed there is any danger of their uniting against their own nation, which protects and encourages them, with which they have so many connections and ties of blood, interest, and affection, and which it is well known, they all love much more than they love one another."[10]

Within a few years after Franklin made this statement he did more than any other man living to carry into effect the "visionary fear" which he had ridiculed.

The denial that independence was the object sought for was constant and general. To obtain concessions and to preserve connection with the empire was affirmed everywhere. John Adams, the successor of Washington to the presidency, years after the peace of 1783 went farther than this, for he said, "There was not a moment during the Revolution when I would not have given everything I possessed for a restoration[25] to the state of things before the contest began, provided we could have had a sufficient security for its continuance."

In the summer of 1774, Franklin assured Chatham that there was no desire among the colonists for independence. He said: "Having more than once travelled almost from one end of the continent to the other, and kept a variety of company, eating and conversing with them freely, I have never heard in any conversation from any person, drunk or sober, the least wish for a separation or a hint that such a thing would be advantageous to America."

Mr. Jay is quite as explicit: "During the course of my life," said he, "and until the second petition of Congress in 1775, I never did hear an American of any class or of any description express a wish for the independence of the colonies."

Mr. Jefferson affirmed: "What eastward of New York might have been the disposition towards England before the commencement of hostilities I know not, but before that I never heard a whisper of a disposition to separate from Great Britain, and after that its possibility was contemplated with affliction by all."

Washington in 1774 fully sustains their declarations, and in the "Fairfax County Resolves" it was complained that "malevolent falsehoods" were propagated by the ministry to prejudice the mind of the king, particularly that there is an intention in the American colonies to set up for independent state.

Mr. Madison says: "It has always been my impression that a re-establishment of the colonial relations to the mother country, as they were previous to the controversy, was the real object of every class of the people till they despaired of obtaining redress for their grievances."

This feeling among the revolutionists is corroborated by DuPortail, a secret agent of the French government. In a letter dated 1778 he says: "There is a hundred times more enthusiasm for the revolution in a coffee-house at Paris than in all the colonies united. This people, though at war with the English, hate the French more than they hate them; we prove this every day, and notwithstanding everything that France has done or can do for them, they will prefer a reconciliation with their ancient brethren. If they must needs be dependent, they had rather be so on England."

Again, as late as March, 1775, only a month before the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington, John Adams wrote: "That there are any that hunt after independence is the greatest slander on the Province."

This feeling must have arisen from gratitude for the protection afforded by the mother country, or at least satisfaction with the relations then existing. It is true, as has been shown in a previous chapter, that for some years before the English Revolution, and for some years after the accession of William and Mary, the relations of the colonies to England had been extremely tense, but in the long period of unbroken Whig rule which followed, most of the elements of discontent had subsided.[26] The wise neglect of Walpole and Newcastle was eminently conducive to colonial interests. The substitution in several colonies of royal for proprietary government was very popular. There were slight differences in the colonial forms of government, but everywhere the colonists paid their governor and their other officials. In nearly every respect they governed themselves, under the shadow of British dominion, with a liberty not equalled in any other portion of the civilized globe; real constitutional liberty was flourishing in the English colonies when all European countries and their colonies were despotically governed. The circumstances and traditions of the colonists had made them extremely impatient of every kind of authority, but there is no reason for doubting that they were animated by a real attachment to England. Their commercial intercourse, under the restructions of the navigation laws, was mainly with her. Their institutions, their culture, their religion, their ideas were derived from English sources. They had a direct interest in the English war against France and Spain. They were proud of their English lineage, of English growth in greatness, and of English liberty. On this point there is a striking answer made by Franklin in his crafty examinations before the House of Commons in February, 1766. In reply to the question, "What was the temper of America towards Great Britain before the year 1763?" he said, "The best in the world. They submitted willingly to the government of the crown, and paid their courts obedience to the Acts of Parliament. Numerous as the people are in the several old provinces, they cost you nothing in forts, citadels, garrisons, or armies to keep them in subjection, they were governed by this country at the expense only of a little pen, ink, and paper; they were led by a thread. They had not only a respect, but an affection for Great Britain, for its laws, its customs, and manners, and even a fondness for its fashions that greatly increased the commerce. Natives of Britain were always treated with particular regard; to be an 'Old England' man was of itself a character of some respect and gave a kind of rank among us." In reply to the question, "What is their temper now?" he said, "Very much altered." It is interesting to inquire what happened during the three years intervening to change the temper of the colonists.

One of the principal causes that led to the American Revolution was the question of what was lawful under the constitution of the British empire, and what was expedient under the existing circumstances of the colonies. It was the contention of the American Whigs that the British parliament could not lawfully tax the colonies, because by so doing it would be violating an ancient maxim of the British constitution: "No taxation without representation."