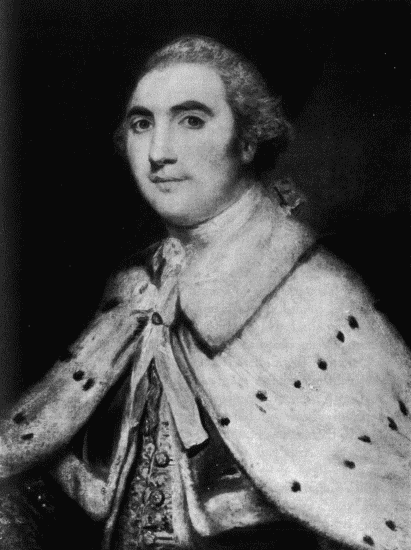

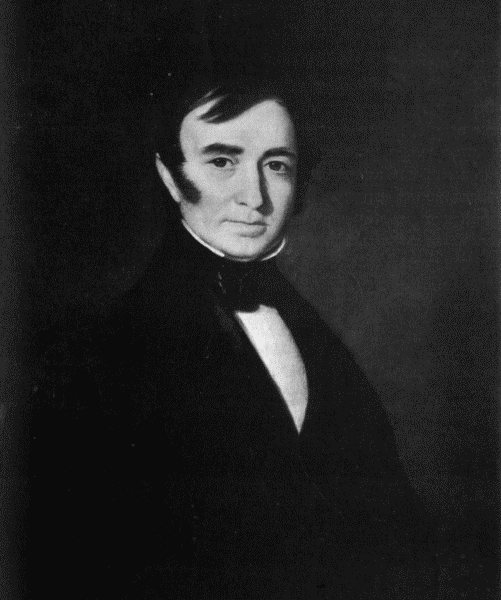

John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun (1705-1782). Governor-in-Chief of Virginia

and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in America, for whom

Loudoun County was named in 1757.

John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun (1705-1782). Governor-in-Chief of Virginia

and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in America, for whom

Loudoun County was named in 1757.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Legends of Loudoun, by Harrison Williams

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Legends of Loudoun

An account of the history and homes of a border county of

Virginia's Northern Neck

Author: Harrison Williams

Release Date: November 25, 2011 [EBook #38130]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEGENDS OF LOUDOUN ***

Produced by Mark C. Orton, Julia Neufeld and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun (1705-1782). Governor-in-Chief of Virginia

and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in America, for whom

Loudoun County was named in 1757.

John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun (1705-1782). Governor-in-Chief of Virginia

and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in America, for whom

Loudoun County was named in 1757.

Many causes have contributed to the great upsurge of interest now manifesting itself in Virginia's romantic history and in the men and women who made it. If, perhaps, the greatest and most potent of these forces is the splendid restoration of Williamsburg, her colonial capital, through the munificence of Mr. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., of New York, we must not lose sight of the part played by the reconstruction of her old historic highways and their tributary roads into the fine modern highway system which is today the Commonwealth's boast and pride; the systematic and constructive activities of the Virginia Commission of Conservation and Development of which the present chairman is the Hon. Wilbur C. Hall of Loudoun; and the excellent work done by the Garden Club of Virginia in holding its annual Garden Week celebration in each spring and the generous permission it obtains, from so many of the present owners of Virginia's historic old homes and gardens, for the public to visit and inspect them at that time and thus capture, if but for the moment, a sense of personal unity with Virginia's glamourous past.

The increasing flow of visitors to Loudoun and to Leesburg, its county seat, has developed a steadily growing demand for more information concerning the County's past and its charming old homes than has been available in readily accessible form. These visitors, in their quest, usually call at Leesburg's beautiful Thomas Balch Library which, during Garden Week, lends its facilities to Virginia's Garden Clubs for their Loudoun headquarters; and Miss Rebecca Harrison, its Librarian, has upon occasion found the lack of published information in convenient form somewhat a handicap in her always gracious efforts to welcome and inform our growing tide of visitors. Knowing as she did my lifelong interest in Colonial history and the lives and family stories of the men and women who enacted their parts therein (my sole qualification, if such in charity it may be called, for such a task) she, from time to time, had suggested that I prepare a book upon Loudoun, the people who built up the County and the old homes which they erected and in which[viii] they lived. The present volume has been written in an effort to respond to those requests. When some four years ago the work was contemplated, it was proposed to make it primarily a small, informal guidebook to Loudoun's older homes; but as my research into her earlier days progressed, I became deeply conscious that the people of Loudoun have forgotten much of her past that tenaciously and loyally should be remembered; and so the story of the County almost crowded out, beyond expectation, the story of the homes. It is hoped that, sometime in the future, another book pertaining wholly to these old plantations and their owners may be prepared and published.

Although there has been no very recent book devoted to her history, Loudoun has had her historians within and without her boundaries and, above all, has been fortunate in attracting the interest of that outstanding scholar and historian of the Northern Neck, the late Fairfax Harrison, Esq., whose beautiful country-seat of Belvoir is near by in the adjoining county of Fauquier. As the most casual reader of the following pages will quickly recognize, I have been under constant obligation, in the preparation of this work, to these earlier writers and can but here sincerely acknowledge the help I have derived from them.

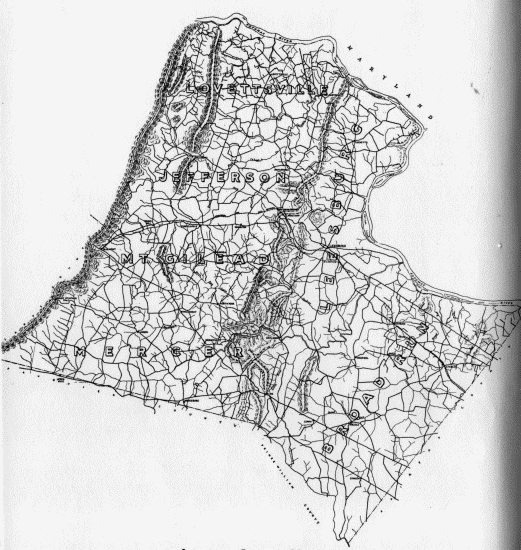

The first published history of Loudoun was written by Yardley Taylor, a Quaker of the upper country, prior to 1853 in which year it made its printed appearance. With it was published a map of the County prepared by him (for his vocation was that of a land-surveyor) and both map and book are highly creditable to their author. The book, however, is not very large and, concerning itself somewhat extensively with the topography, geology, etc. of the County, it has less to say of Loudoun's history than its admirers could wish. The map, embellished with cartouches of old buildings, was the first county map to be prepared in this part of Virginia and so accurate was it found to be that it was used by both Federals and Confederates in the devastating War Between the States. That war, with its aftermath, set back the cultural activities of Virginia for a full generation; thus it was not until 1909 that the next Loudoun history appears, this time by Mr. James W. Head of Leesburg.[ix] His volume is more comprehensive than Mr. Taylor's but, again, it covers far more than the County's history, including carefully prepared surveys of its minerals, soils, farm statistics, commercial activities, and many other interesting and closely related subjects. In 1926 Messrs. Patrick A. Deck and Henry Heaton published their Economic and Social Survey of Loudoun County which is somewhat similar in its scope to the work of Mr. Head but not so large a volume. In the meanwhile, however, in 1924, Mr. Fairfax Harrison, himself a scion of the Fairfax family, had privately published his comprehensive Landmarks of Old Prince William covering the early history of all the territory originally comprised in old Prince William County; and thereby built an enduring monument to his own erudition and industry that will stand as long as there remains a man or woman who retains an interest in the fairest part of the princely Colepeper-Fairfax Proprietary. It remains a pleasant and grateful memory that I had the benefit of Mr. Harrison's personal suggestions and advice, as well as access to the overflowing treasury of his published writings, in my preparation of this volume.

In addition to the authors named, much help was derived from Mr. John Alexander Binns' treatise on his agricultural experiments, from the war-books of Major General Henry Lee, Col. John S. Mosby, Col. E. V. White, Rev. J. J. Williamson, Captain F. M. Myers and Mr. Briscoe Goodhart, although in the case of the two latter authors their writings are measurably impaired by the rancour which controlled their pens. Dr. E. G. Swem's Virginia Historical Index was of constant assistance as were the publications of the Virginia Historical Society, those of the College of William and Mary and similar historical magazines as well as Virginia's Colonial records and the records of Loudoun County. The resources of the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution and those of our little Thomas Balch Library in Leesburg have all been available to me. In short, I had intended to append a bibliography of volumes consulted and relied upon for many of the views hereafter expressed; but when those volumes grew in number to five or six hundred I realized that limited space would permit no such project. Therefore[x] I have contented myself with frequently indicating in footnotes the principal sources from which my information has been derived.

To my acknowledgment of aid obtained from books, pamphlets, newspapers and magazines, official records and documents, must be added my appreciation of the help of many friends. Mr. Thomas M. Fendall of Morrisworth and Leesburg, of distinguished Virginia background himself, has made such careful and comprehensive studies of Loudoun's past that he was and is the logical prospective author of a book thereon; but his modesty equals his industry and scholarship to the very obvious loss, in this instance, to the County and its people. From him I have had such constant and constructive assistance and cheerful response to my frequent appeals that without his aid this book could not have attained its present form. To Loudoun's present County Clerk Mr. Edward O. Russell and to his deputy Miss Nellie Hammerley; to Mrs. John Mason; Mrs. E. B. White and Miss Elizabeth White of Selma; Mrs. Frederick Page; the Rev. G. Peyton Craighill, the present Rector of Shelburne Parish; the Rev. J. S. Montgomery; Miss Lilias Janney; Judge and Mrs. J. R. H. Alexander of Springwood; Mrs. Ashby Chancellor; Mrs. John D. Moore; Mr. Frank C. Littleton of Oak Hill, and his long studies of the history of that estate and of President Monroe; Trial Justice William A. Metzger; Mr. J. Ross Lintner, Loudoun's County Agent; Hon. Charles F. Harrison, Commonwealth's Attorney; Mr. Oscar L. Emerick, Superintendent of Schools, for permission to use the map of the County prepared by him; Mr. E. Marshall Rust; Mr. George Carter; Hon. Wilbur C. Hall and his efficient official staff; Mr. Valta Palma, Curator of the Rare Book Collection of the Library of Congress, and Mr. Hirst Milhollen of the Fine Arts Division of the same great institution; Mr. John T. Loomis, Managing Director of Loudermilk and Co. of Washington, as well as to very many others, my sincere thanks are again tendered for the valuable help they all so willingly have given me.

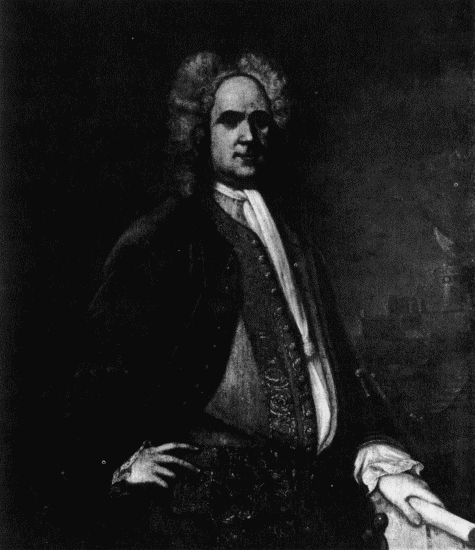

The illustrations used to embellish the text deserve a word of comment. The portrait of the Right Honourable John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun, Captain-General of the British forces in America and Governor-in-Chief of Virginia, in whose honour the County of[xi] Loudoun was named, is reproduced from an engraving that appeared in the London Magazine of October, 1757, when Loudoun was at the height of his career. It was copied from the engraving by Charles Spooner of an earlier painting of the Earl by the Scotch artist Allan Ramsay (1713-1784), who later became the principal portrait painter to King George III and his court. I have in my collection two copies of this London Magazine engraving, one of which I found in the hands of a dealer in New York and the other in London. No other copies, so far as I can learn, have recently been offered for sale.

The fine portrait of the Right Honourable William Petty-FitzMaurice, Earl of Shelburne and 1st Marquess of Landsdowne, for whom Shelburne Parish was named, is by Sir Joshua Reynolds and is now in the National Portrait Gallery in London to which it was presented by his son Henry, 3rd Marquess of Landsdowne, K. G., in June, 1858. I obtained an official photograph of this painting at the National Portrait Gallery in the summer of 1937, and permission to reproduce it in this book.

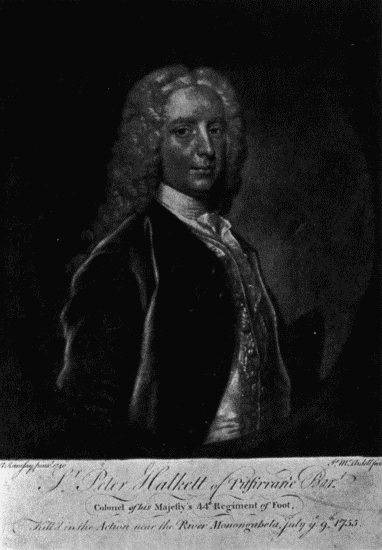

The portrait of Sir Peter Halkett, Baronet, of Pitfiranie, Scotland, who commanded that part of Braddock's army that passed through the present Loudoun on its way to the fatal battle near Fort DuQuesne, is from P. McArdell's engraving of the portrait painted by Allan Ramsay in 1740, and is considered by me one of my most fortunate discoveries.

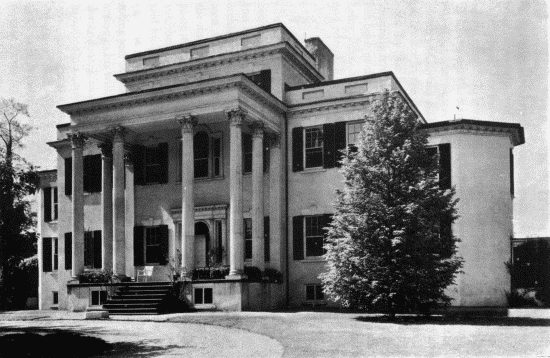

The pictures of Oak Hill in the body of the book and that of the meeting of the Middleburg Hunt on its spacious lawns, reproduced on the dust-jacket, are from the extensive collections of Mr. Frank C. Littleton. The original of the portrait of General George Rust of Rockland (1788-1857), builder of that cherished family seat in 1822, belongs to and is in the possession of a grandson, Mr. John Y. Rust of San Angelo, Texas, but a carefully executed copy hangs on Rockland's walls. During the two administrations of President Andrew Jackson, General Rust was in command of the United States Arsenal at nearby Harper's Ferry and for many years he was one of the most respected and influential of the County's citizens. The photograph of the original portrait herein used I owe to another grandson,[xii] Mr. E. Marshall Rust of Leesburg and Washington, as I do the picture of Rockland itself and that of the old John Janney residence in Leesburg, later so long the home of the late Mr. and Mrs. Thomas W. Edwards, the latter a sister of Mr. Rust. They were all photographed in this masterly fashion by Miss Frances Benjamin Johnston of Washington. The pictures of Foxcroft, Oak Hill and the old Valley Bank in Leesburg are from the Pictorial Archives of Early American Architecture in the Division of Fine Arts of the Library of Congress and the negatives are also the work of Miss Johnston.

Reproduction of the portrait of Nicholas Cresswell, the Journalist, is due to the courtesy of the Dial Press, of New York, publishers of the American edition of his journal. The original portrait is owned by Mr. Samuel Thorneley of Drayton House, near Chichester, West Sussex, England, a descendant of Cresswell's younger brother, Joseph Cresswell. The map of Loudoun is based on that prepared by Mr. Oscar L. Emerick in 1923, and is used by his kind permission.

And now, gentle reader, step with me into the pleasant land of Loudoun.

Roxbury Hall

Near Leesburg, Virginia

March, 1938.

| Preface | vii |

| The Earlier Indians | 1 |

| England Acquires Virginia | 10 |

| The Passing of the Indians | 20 |

| Settlement | 31 |

| The Melting Pot | 43 |

| Roads and Boundaries | 60 |

| Speculation and Development | 72 |

| The French and Indian War | 83 |

| Organization of Loudoun and the Founding of Leesburg | 97 |

| Adolescence | 114 |

| Revolution | 123 |

| The Story of John Champe | 142 |

| Early Federal Period | 159 |

| Maturity | 182 |

| Civil War | 198 |

| Recovery | 222 |

| Index | 235 |

| John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun Frontispiece | Face Page |

| Map of Loudoun County | 1 |

| Sir Alexander Spotswood | 20 |

| Sir Peter Halkett, Bart | 83 |

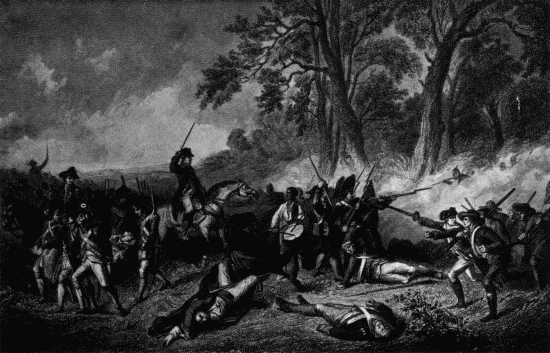

| The Fall of Braddock | 93 |

| William Petty-FitzMaurice | 116 |

| Nicholas Cresswell | 129 |

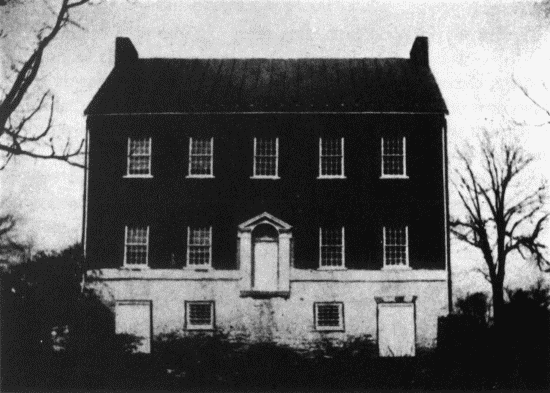

| Noland Mansion | 139 |

| Oatlands | 171 |

| Foxcroft | 173 |

| Rockland | 175 |

| General George Rust | 176 |

| Oak Hill | 178 |

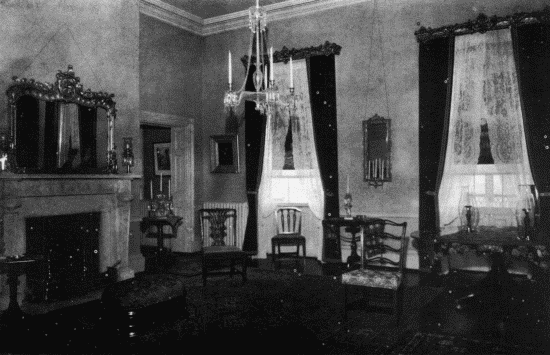

| Oak Hill, East Drawing Room | 179 |

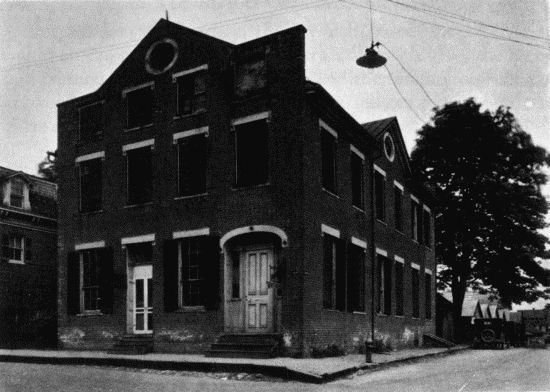

| Old Valley Bank | 203 |

| Battle of Ball's Bluff | 205 |

| Old John Janney House | 226 |

Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County, Virginia

The county of Loudoun, as now constituted, is an area of 525 square miles, lying in the extreme northwesterly corner of Virginia, in that part of the Old Dominion known as the Piedmont and of very irregular shape, its upper apex formed by the Potomac River on the northeast and the Blue Ridge Mountains on the northwest, pointing northerly. It is a region of equable climate, with a mean temperature of from 50 to 55 degrees, seldom falling in winter below fahrenheit zero nor rising above the upper nineties during its long summer, thus giving a plant-growing season of about two hundred days in each year.

The county exhibits the typical topography of a true piedmont, a rolling and undulating land broken by numerous streams and traversed by four hill-ranges—the Catoctin, the Bull Run and the Blue Ridge mountains and the so-called Short Hills. These ranges are of a ridge-like character, with no outstanding peaks, although occasionally producing well-rounded, cone-like points. The whole area is generously well watered not only by the Potomac, flowing for thirty-seven miles on its border and the latter's tributary Goose Creek crossing the southern portion of the county, but also by many smaller creeks or, as they are locally called, "runs"; and by such innumerable springs of most excellent potable water that few, if any, of the farm-fields lack a natural water supply for livestock. These conditions most happily combine to create a climate that for healthfulness and all year comfortable living is without peer on the eastern seaboard and, indeed, truthfully may be said to be among the best and most enjoyable east of the Mississippi.

Before the advent of the white man, the land was covered by a dense forest of oak, hickory, walnut, sycamore, locust, ash, pine, maple, poplar and other varieties of trees—not by any means unbroken, for here and there the Indian tribes that roamed the area, had burned out great clearings for grazing-grounds to entice the wild animals they hunted and in which the native grasses then quickly and indigenously sprang up; attracting particularly the buffalo, in[2] those days, and at least until as late as 1730, to be found in vast numbers all through the Piedmont region and always in the forefront as an unending supply of flesh-food to their Indian hunters. With the buffalo were great herds of "red and fallow deer" and wolves, foxes in abundance, bears in the mountains, opossum, racoons, and, along the streams, otter and beaver (later to be so greatly valued for their pelts) and whose presence, with that of other fur-bearing animals, was to have its influence on the history of the region.

When in 1607 the doughty Captain John Smith—in writing of any part of Virginia one sooner or later is certain to shake hands with that amourous hero—when Captain Smith made his first voyage to Virginia and came in contact with her aboriginees, the latter were, in a broad sense, of several stocks or nations, distinguishable principally by linguistic affinity and more or less common cultural idiosyncracies rather than by close alliances; and indeed frequently appearing to cherish their bitterest enmities among their own blood-kindred. Along the coast, in what we now know as Tidewater, the territory running from the Chesapeake to those rocky outcrops making waterfalls in all the great rivers flowing from Virginia into the Bay, the Indians were generally of the Algonquin stock, a tribe covering an enormous territory along the Atlantic seaboard from the neighborhood of Hudson's Bay southerly to at least the Carolinas but by no means monopolizing the regions where they were found.

To the north, in what is now New York, centred the Iroquoian tribes, with ramifications as far south as Virginia and North Carolina. Among these more southerly Indians of the Iroquoian stock were the fierce and powerful "Susquehannocks" along the river we still call by that name who later were to play a prominent rôle in our Loudoun yet to be; the Nottoways, occupying a part of southeastern Virginia; the Cherokees, occupying the area in Virginia and North Carolina west of the Blue Ridge, extending north as far as the Peaks of Otter near the headquarters of the James; and the Tuskaroras of famous and bloody memory, who were paramount in North Carolina until their conquest and all but annihilation by the English in[3] 1711. What were left of the fiercest and most implacable of the Tuskaroras after that crushing defeat, retreated to New York where, as the sixth nation they joined the Iroquois Confederacy of their near kinsmen of the Long House. A few of the more friendly were removed to a local reservation in 1717 but gradually, in small parties, says Mooney, they too moved to join their kindred in the north.

Both Algonquins and Iroquois were to be classed as barbarians rather than savages. The former have been described as having generally "found locations in permanent villages surrounded by extensive cornfields. They were primarily agriculturists or fishermen, to whom hunting was hardly more than a pastime and who followed the chase as a serious business only in the interval between the gathering of one crop and the sowing of the next." The Iroquois, who found their highest development in their confederacy of the Five Nations of the Long House in central New York (the Massawomecks so dreaded by the Powhattans and Manahoacs of Smith's narratives) were even further advanced. Described by historians as the Romans of America, they led all other Indians of what is now the United States in their powers of organization and extraordinary political development. They lived in cleverly and strongly palisaded villages and their agricultural activities, falling to the women's share of tribal work, were probably further advanced than those of any other Indians north of Mexico. Our earliest knowledge places them on the banks of the St. Lawrence, in the neighborhood of the present Montreal, whence they were driven by the neighboring Algonquins. Their defeat and expulsion to the south bred in them a deep determination for revenge. In the New York wilderness they developed and cultivated a passion for ruthless warfare and forming their famous Confederation somewhere about the year 1570, they rapidly became the most powerful Indian military force east of the Mississippi and a sombre threat and terror to the other Indian tribes far and wide.

In contrast to both Algonquins and Iroquois, the Siouan tribes who ranged the Piedmont country from the Potomac south, were primarily nomads—and nomads, observes Mooney, have short histories.[4] Modern scholarship inclines to place the origin of the great Siouan or Dakotan family possibly amidst the eastern foothills of the southern Alleghanies or at least as far east as Ohio, whence, after a long period, they probably were driven by the Iroquois and other enemies beyond the Mississippi. Being essentially nomadic, without permanent villages and relying on constant hunting for their food, following their game wherever it might lead, they necessarily ranged widely and covered broad areas. From the days of the earliest European invasion, locations of the Iroquois and Algonquin stock were known, but as the earliest English scouts and adventurers found no such long established villages in the Piedmont country, their tendency and following them, that of the early writers and historians, was to loosely assume that the Indians found there were, in common with their neighbours, either Algonquins or Iroquois. Later antiquarians and ethnologists seem to have followed their lead; with an exasperating paucity of record, tradition or material remains, there was but little on which to base knowledge of language, whence racial stock might be deduced. It was not until Horatio Hale announced, sixty years ago, his discovery of a Siouan language bordering the Atlantic coast and James Mooney, in 1894, published his Siouan Tribes of the East that these Indians of the northern Virginia Piedmont, known to be members of the Manahoac Confederacy, were identified as of the Siouan stock. They "consisted of perhaps a dozen tribes of which the names of eight have been preserved. With the exception of the Stegarake," writes Mooney, "all that is known of these was recorded by Smith, whose own acquaintance with them seems to have been limited to an encounter with a large hunting party in 1608."

As Smith's narrative, after its wont, paints a vivid picture of the Manahoacs, a picture which almost stands alone in the mist of conjecture and deductive reasoning making up what is left to us of them, it is well to quote it in full, bearing always in mind that while these people were found on the upper Rappahannock, we have excellent reason to believe that they also occupied all the land now within the bounds of Loudoun. As allied bands, without fixed[5] habitation, they wandered over the lands between Tidewater and the Blue Ridge, from the James to the Potomac.

The story is contained in Smith's Generall Historie of Virginia which states on its title page to be "by Captaine John Smith sometymes Governor in those Countryes & Admirall of New England." Chapter VI of the book, from which we quote, is however apparently signed by Anthony Bagnall, Nathaniel Powell and Anas Todhill who were three of Smith's companions on this adventure. Bagnall and Powell were among the six listed as "Gentlemen" in distinction to an additional six listed as "Souldiers," among the latter being Todhill.

On the 24th July, 1608, Smith and these twelve men set out on this second voyage of discovery along the shores of the Chesapeake Bay. Going as far north as the head of the Bay and the "Susquesahannock's" river and noting their many findings, they eventually, upon their return south, came to "the discovery of this river some call Rapahanock" up which they proceeded, with occasional brushes with the Indians along its banks. On their third day upon the river

"Wee sailed so high as our Boat would float, there setting up crosses, and graving our names in the trees. Our Sentinell saw an arrowe fall by him, though he had ranged up and downe more than an houre in digging in the earth, looking of stones, herbs, and springs, not seeing where a Salvage could well hide himselfe.

"Upon the alarum by that we had recovered our armes, there was about an hundred nimble Indians skipping from tree to tree, letting fly their arrows so fast as they could: the trees here served us for Baricadoes as well as they. But Mosco (their Indian guide) did us more service than we expected, for having shot away his quiver of Arrowes, he ran to the Boat for more. The Arrowes of Mosco at the first made them pause upon the matter, thinking by his bruit and skipping, there were many Salvages. About halfe an houre this continued, then they all vanished as suddenly as they approached. Mosco followed them so farre as he could see us, till they were out of sight. As we returned there lay a Salvage as dead, shot in the[6] knee, but taking him up we found he had life, which Mosco seeing, never was Dog more furious against a Beare, than Mosco was to have beat out his braines, so we had him to our Boat, where our Chirugian who went with us to cure our Captaines hurt of the Stingray, so dressed this Salvage that within an houre after he looked somewhat chearefully, and did eat and speake. In the meane time we contented Mosco in helping him to gather up their arrowes, which were an armefull, whereby he gloried not a little. Then we desired Mosco to know what he was, and what Countries were beyond the mountaines; the poore Salvage mildly answered he and all with him were of Hassinninga, where there are three Kings more like unto them, namely the King of Stegora, the King of Tauxuntania and the King of Shakahonea, that were coming to Mohaskahod, which is onely a hunting Towne, and the bounds betwixt the Kingdom of the Mannahocks, and the Nantaughtacunds, but hard by where we were. We demanded why they came in that manner to betray us, that came to them in peace, and to seeke their loves; he answered they heard we were a people come from under the world, to take their world from them. We asked him how many worlds he did know, he replyed, he knew no more than that which was under the skie that covered him, which were the Powhattans, with the Monacans, and the Massawomecks, that were higher up in the mountaines. Then we asked him what was beyond the mountaines, he answered the Sunne: but of anything els he knew nothing; because the woods were not burnt. These and many such questions we demanded, concerning the Massawomecks, the Monacans, their owne Country, and where were the Kings of Stegora, Tauxintania, and the rest. The Monacans he said were their neighbours and friends, and did dwell as they in the hilly Countries by small rivers, living upon rootes and fruits, but chiefly by hunting. The Massawomecks did dwell upon a great water and had many boats, & so many men that they made warre with all the world. For their Kings, they were gone every one a severall way with their men on hunting: But those with him came thither a fishing until they saw us, notwithstanding they would be altogether at night at Mahaskahod. For his relation we gave him many toyes, with perswasions to go with[7] us, and he as earnestly desired us to stay the coming of those Kings that for his good usage should be friends with us, for he was brother to Hassinninga. But Mosco advised us presently to be gone, for they were all naught, yet we told him we would not till it was night. All things we made ready to entertain what came, & Mosco was as dilligent in trimming his arrowes. The night being come we all imbarked, for the river was so narrow, had it biene light the land on the one side was so high, they might have done us exceeding much mischiefe. All this while the K. of Hassinninga was seeking the rest, and had consultation a good time what to doe. But by their espies seeing we were gone, it was not long before we heard their arrowes dropping on every side the Boat; we caused our Salvage to call unto them, but such a yelling and hallowing they made that they heard nothing but now and then a peece, ayming for neere as we could where we heard the most voyces. More than 12 miles they followed us in this manner; then the day appearing, we found ourselves in a broad Bay, out of danger of their shot, where we came to an anchor, and fell to breakfast. Not so much as speaking to them till the Sunne was risen; being well refreshed, we untyed our Targets[1] that covered us as a Deck, and all shewed ourselves with these shields on our armes, and swords in our hands, and also our prisoner Amoroleck; a long discourse there was betwixt his countrimen and him, how good we were, how well wee used him, how we had a Patawomeck with us, loved us as his life, that would have slaine him had we not preserved him, and that he should have his liberty would they be but friends; and to doe us any hurt it was impossible. Upon this they all hung their Bowes and Quivers upon the trees, and one came swimming aboard us with a Bow tyed on his head, and another with a Quiver of Arrowes, which they delivered to our Captaine as a present, the Captaine having used them so kindly as he could, told them the other three Kings should doe the like, and then the great King of our world should be their friend, whose men we were. It was no sooner demanded than performed, so upon a low Moorish poynt of Land we went to the Shore, where[8] those foure Kings came and received Amoroleck: nothing they had but Bowes, Arrowes, Tobacco-bags, and Pipes: what we desired, none refused to give us, wondering at every thing we had, and heard we had done: our Pistols they tooke for pipes, which they much desired, but we did content them with other Commodities, and so we left foure or five hundred of our merry Mannahocks, singing, dancing, and making merry and set sayle for Moraughtacund."

The spelling, punctuation and capitalization follow the text of the first edition (1624) in which, opposite page 41, is a map shewing apparently the Manahoacs (there spelled "Mannahoacks") in possession of the present Loudoun and the Monacans south of them, around the upper waters of the James.

With Smith's return to the mouth of the Rappahannock the mist descends again upon Loudoun for many years.

In 1669 and 1670, John Lederer made three journeys into the interior of Virginia. His first journey took him up the York River; his second, up the James; and the route of his third he describes as "from the Falls of the Rappahannock River to the top of the Apalataen Mountains." Although he obtained the consent of Sir William Berkeley before making his explorations, he seems to have incurred the ill-will of the Virginians themselves and by them was forced to flee to Maryland. There he met Sir William Talbot, who sympathized with and befriended him and translated his story of his travels from the latin in which it had been written. It was published in London in 1672 with a "foreword" by Talbot in Lederer's defense.

Of the "Indians then Inhabiting the western parts of Carolina and Virginia," Lederer says:

"The Indians now seated in these parts are none of those which the English removed from Virginia, but a people driven by the Enemy from the northwest, and invited to sit down here by an Oracle above four hundred years since, as they pretend for the ancient inhabitants of Virginia were far more rude and barbarous,[9] feeding only upon raw flesh and fish, until they taught them to plant corn, and shewed them the use of it."

Concerning the whole Piedmont region, called by Lederer "The Highlands" he writes:

"These parts were formerly possessed by the Tacci, alias Dogi, but they are extinct and the Indians now seated here, are distinguished into the several nations of Mahoc, Nuntaneuck, alias Nuntaly, Nahyssan, Sapon, Managog, Mangoack, Akernatatzy and Monakin &c. One language is common to them all, though they differ in dialects. The parts inhabited here are pleasant and fruitful because cleared of wood and laid open to the Sun."

Apparently in Lederer's "Monakins" and "Mangoacks" we may recognize Smith's "Monacans" and "Mannahocks" or "Mannahoacks"; but on his third or Rappahannock journey he does not speak of such Indians as he may have actually met. James Mooney thinks that by that time the Manahoacs may have been driven out of their earlier hunting grounds. The "Tacci, alias Dogi" described by Lederer are suggested by Mooney to have been only a mythic people, a race of monsters or unnatural beings, such as we find in the mythologies of all tribes and had no relation to the Doeg, named in the records of the Bacon rebellion in 1676, who were probably a branch of the Nanticoke.

What became of the Manahoacs? Did their pursuit of the game they hunted gradually draw them westward or were they, more probably, driven from the Piedmont country by their terrible foes the northern Iroquois, aided perhaps by the Susquehannocks who next appear upon the scene? But before taking up the story of the Iroquois and Susquehannock influence in Loudoun, we must turn to the English Kings and their grants of Virginia and particularly its Northern Neck, that spacious territory lying between the Rappahannock and Potomac, extending from the Chesapeake to a disputed western boundary.

Mighty in her military strength and with an all but inexhaustible wealth pouring into her coffers from her American conquests, Spain stood as a very colossus over the Europe of the sixteenth century; and England, watching and fearing her hostile growth, grimly determined that she too, should have her share of that fabulous new world and its treasure. So deeply planted and so greatly grew this determination that it eventually became a part of England's public policy and in June, 1578, the great Elizabeth, with her eyes on the American coast, issued letters patent to Sir Humphrey Gilbert, and after Gilbert's death reissued them on the 25th March, 1584, to his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh, to discover, have, hold and occupy forever, such "remote heathern and barbarous lands, countries and territories not actually possessed by any Christian prince, nor inhabited by Christian people." As by its terms the new grant was to continue but for "the space of six yeares and no more," it was clear that advantage of its provisions should be taken with promptness; and Raleigh was not a man given to delay or indecision. He had been making his preparations; hardly more than a month elapsed before an expedition of two ships captained by Philip Amidas and Arthur Barlow set sail from England, bound for America. On the 4th of the following July, having landed on an island off the coast of the present Carolinas, these men raised the English flag and formally declared the sovereignty of England and its Queen. They brought home with them such glowing accounts of their discovery that Elizabeth was moved to bestow upon all the coast the name of Virginia—the land of the Virgin Queen. Two more attempts were made to establish permanent settlements in the neighborhood and although both failed, enough had been done to found a claim of English ownership and dominion, a claim which covered the entire coast from the French settlements in the north to the Spanish settlements upon the Florida peninsula, and thus the original Virginia became coextensive with England's pretensions on the North American continent.[11] It is true that Spain then claimed the entire coast under a Papal Bull but Papal Bulls meant very little to Elizabeth or to her pugnacious sea-rovers. One of the many curiosities of history is that neither Raleigh nor his captains ever saw the soil of that part of America which was to become the Virginia we know, nor did the Queen who named it ever have knowledge of its physical characteristics, its resources or its inhabitants. In short, Virginia proper was neither to be discovered nor have its first precarious settlement until after Elizabeth's death.

After these first abortive attempts to found English settlements under his patent, Raleigh, on the 7th March, 1589, assigned it and all his rights thereunder to a company of merchants and adventurers who were resolved to proceed with the enterprise. These assigns, after the death of Elizabeth, became the leaders in seeking from King James I "leave to deduce a colony in Virginia." That monarch, says Bancroft, "promoted the noble work by readily issuing an ample patent" and on the 10th day of April, 1606, signed and affixed his seal to the first Charter of an English colony in America under which permanent settlement was to be effected. This charter declared the boundaries of Virginia to extend from the 34th to the 45th parallels of longitude and authorized the planting of two colonies. The first of these, to be founded by the London Company, largely made up of men of that city, was designated a "First Colony" to be established in the southerly portion of England's claim; the right to establish a "Second Colony" to be planted in the north, went to the Plymouth Company, whose membership, headed by Sir Ferdinando Gorges, Governor of the garrison of Plymouth in Devonshire, came principally from the west of England. Under this Charter the King named the first "Council for all matters which shall happen in Virginia;" under it the London Company dispatched the expedition of three ships in command of Sir Christopher Newport and having Captain John Smith among its members; and under it and the Second Charter (of 1609) the infant colony was governed until, in the year 1624, the Charter was revoked and the Crown took over the affairs of the Colony.

[12]Until the troubled reign of the first Charles, the growth of Virginia's population had been very slow. It was not until the defeat of the Royalists in 1645 by the forces of the Parliament and the King's execution in January, 1649, that the first great increase in population occurred. In a pamphlet published in London in that latter year, by an unknown author, it is stated that her population was at that time 15,000 English and 300 negroes and these were scattered along the lower portions of the James and the York and the shores of the Chesapeake. Then the defeated Cavaliers began to arrive in such great numbers that by 1670 Sir William Berkeley estimated that 32,000 free whites, 6,000 indentured servants and 2,000 negroes were there. Many of the old population and the newer arrivals as well, were pressing northward to the land between the mouth of Rappahannock and that of the Potomac which in 1647 had been organized into a new county, under the name of Northumberland, to include all the lands lying between those latter rivers and running westerly to a still indefinite boundary. This was new territory recently, and still very sparsely, settled by the English and even as late as 1670 it was contemporaneously estimated that the Indians between the two rivers had nearly 200 warriors.

Although the Stuarts had been deposed in England and the younger Charles forced to fly to the Continent, he was still King in Virginia with loyal and devoted subjects. It was under such conditions that Charles, actuated not only by a desire to reward certain of his Cavalier adherents who were sharing his exile, but also to create a refuge for others of his followers from the ire and oppression of the triumphant Roundheads, granted by charter dated the 18th day of September, 1649, the whole domain between the Rappahannock and Potomac to seven of his faithful lieges who, during the Civil War, had fought valiantly in the Stuart cause. These men were described in the charter, still preserved in the British Museum, as Ralph Lord Hopton, Baron of Stratton; Henry Lord Jermyn, Baron of St. Edmund's Bury; John Lord Colepeper, Baron of Thoresway; Sir John Berkeley, Sir William Morton, Sir Dudley Wyatt and Thomas Colepeper Esq. And thus, says Fairfax Harrison, "the[13] proprietary of the Northern Neck of Virginia came into existence."

He notes that of the patentees Lord Jermyn, after the Restoration, became Earl of St. Albans and Sir John Berkeley, Baron Berkeley of Stratton. "The only conditions" quotes Head "attached to the conveyance of the domain, the equivalent of a principality, were that one-fifth of all the gold and one-tenth of all the silver, discovered within its limits should be reserved for the royal use and that a nominal rent of a few pounds sterling should be paid into the treasury at Jamestown each year."

But to receive a grant of this splendid Proprietary from a fugitive and powerless King was one thing and to reduce it to actual possession was another and very different one. Charles might and did consider himself King in both England and Virginia and the ruling Virginians might and did consider themselves his very loyal and obedient subjects; but unfortunately for the seven Cavalier patentees of the Northern Neck, the Parliament and Cromwell took a radically different view of the matter and, even more unfortunately, were in a position to enforce that view. No sooner had the representatives of the new Proprietors come to Virginia and were duly welcomed by the royalist Governor Sir William Berkeley, than a Parliamentary fleet of warships arrived from England, deposed the Governor, set up the rule of Parliament in 1652 and abruptly ended, for the time being, the patentees' hopes of gaining possession of their new grant.

There was little to be done by these Cavaliers while Parliament and Cromwell ruled. And then the wheel of history, after its fashion, completed another cycle. On the 3rd September, 1658, Cromwell died and soon the ruthless and efficient but never very cheerful control of England by the Puritans came to an end. In 1659 word came to Virginia of the resignation of Richard Cromwell and the Puritan Governor Mathews dying about the same time, the Virginia Assembly in March, 1660, proceeded to elect Sir William Berkeley to be their Governor again. On the 8th of the following May, Charles II was proclaimed King in England and in September a royal commission for Berkeley, already elected by the Assembly, arrived, the[14] Virginians themselves welcoming the restoration of Stuart rule with great enthusiasm.

The owners of the patent of the Northern Neck believed that their patience was at length to be rewarded. Again they sent a representative to Virginia, this time with instructions from King to Governor to give his aid to the Proprietors to obtain possession of their domain. But during all the years of their forced inactivity, the settlement of Virginia had gone on apace. What had been in 1649 a thinly settled frontier, shewed now a largely increased population and land grants to these new settlers had been freely issued by Virginia's government. Many of those newly seated in the Northern Neck were very influential men and in their opposition to the claims of the patentees received popular sympathy and encouragement. As a result, Berkeley found himself confronted by a Council which obstructed his every effort to carry out the King's instructions and the endeavours of the Proprietors to gain possession of their grant being completely blocked, they were obliged to appeal to the home government for relief. The outcome of negotiations between them and Francis Moryson, then representing Virginia in London, was that the patent of 1649 was surrendered by its holders for a new grant carrying on its face substantial limitations of the earlier patent. This new grant was dated the 8th day of May, 1669, almost twenty years after the first, and contained provisions recognizing the title to lands already seated or occupied under other authority; generally limiting the Proprietors' title to such other lands as should be "inhabited or planted" within the ensuing twenty-one years, together with a constructive recognition of the political jurisdiction of the Virginia government within the Proprietary.[2]

This appeared a reasonably satisfactory compromise of the controversy to both sides. But suddenly in February, 1673, Charles made a grant of all Virginia to the Earl of Arlington and Lord Colepeper to hold for thirty-one years at an annual rent of forty shillings to be paid at Michaelmas. Thus was Virginia rewarded for her faithful[15] loyalty to the Stuarts. When the news came to Jamestown the Colony flamed with resentment and anger; and now Berkeley and his Council were in hearty accord with the wrathful indignation of the Colonists. Even though the King had not intended to interfere with the title of individual planters in possession of their land, his action threw the whole situation, and particularly in the Northern Neck, into turmoil and confusion. Exasperation was directed against the holders of the Charter of 1669 as well as those of 1673 and again the original patentees appealed to the Privy Council for relief. Again the King sought to help them but by this time they had grown weary of the long controversy and indicated their willingness to sell out their rights to the Colony; before an agreement could be reached, Bacon's Rebellion flared up and the whole subject was again in abeyance.

We must now return to the Indians. The Dutch settlements along the Hudson had early developed a very lucrative and active trade with their native neighbours, particularly the Iroquois, who brought to them furs for which they were given European manufactures, especially spirits and firearms and when, in 1664, the English conquered and took possession of these Hudson settlements, they continued the Dutch trade and friendship with the Iroquois. To obtain furs, the hunters and warriors of the Five Nations ranged further and further afield and before long were in bitter conflict with the Susquehannocks who had their headquarters and principal stronghold fifty or sixty miles above the present Port Deposit in Maryland on the east bank of that river from which they derived their name. They were mighty men and warriors, these Susquehannocks. All the early English who mention them pay tribute to their splendid strength and stature. Smith who, it will be remembered, came in contact with them before his skirmish with the Manahoacs, said of them that "such great and well proportioned men are seldom seen, for they seem like giants to the English, yea to their neighbours." And in 1666 Alsop wrote that the Christian inhabitants of Maryland regarded them as "the most noble and[16] heroic nation of Indians that dwelt upon the confines of America.... Men, women and children both summer and winter went practically naked," and adds, among other details, that they painted their faces in red, green, white and black stripes; that the hair of their heads was black, long and coarse but that the hair growing on other parts of their bodies was removed by pulling it out hair by hair; and that some tattooed their bodies, breasts and arms with outlines. Our American soil, from the beginning, appears to have favoured the art of the barber and beauty-shop.

From the English in Maryland these Susquehannocks acquired guns and ammunition and thus were able to hold their own with their Iroquois foe for over twenty years of the harshest warfare. But the Iroquois were relentless and though repulsed again and again, returned year after year to the attack. The Susquehannocks finally weakened by an epidemic of smallpox, were overcome, the Iroquois captured their main stronghold and completely overthrew their power. Fugitive bands of Susquehannocks, nominally friendly to the English of Maryland and Virginia, then roamed the western frontiers of those colonies and along both banks of the Potomac, still harassed by pursuing bands of Senecas.

Under such conditions it was not long before they came in open conflict with the English settlers, some say through Indian thefts, others because the English attacked a party of them, mistaking them for pilfering Algonquin Doegs. The fighting, once begun, spread rapidly and the settlers on their exposed frontiers, denied practical assistance by the Virginia Governor Berkeley and his colleagues (whom rumor said were making such substantial profits from the Indian trade that they were loath to antagonize the Indians by sending organized forces against them) turned for leadership to Nathaniel Bacon, a young planter of gentle birth, not long come out from England. Bacon was a natural leader, their cause was popular and soon Virginia found herself in the midst of an Indian war and a rebellion against the Jamestown government as well. Bacon led his men to victory over both Indians and Governor but suddenly dying from a dysentery or from poison—to this day the cause of his[17] death is surrounded by uncertainty—the "rebellion collapsed with surprising suddenness," his former followers were overcome by the Governor with the aid of English troops and Berkeley proceeded to wreak a vindictive and merciless revenge.

Meanwhile knowledge of the turmoil had reached England and the King sent Commissioners to Virginia to investigate the causes of the trouble and Berkeley's wholesale executions and confiscations of estates. These men made a fair report of their findings to the King, which, added to the many complaints from the families of Berkeley's victims, caused Charles to exclaim: "As I live, that old fool has taken more lives in that naked country than I have done for the murder of my father." In the spring of 1677 the royal order for Berkeley's removal arrived and he sailed for England in an attempt to justify himself in an audience with Charles, his departure being "joyfully celebrated with bonfires and salutes of the cannon" by the Virginians. But in England he found that the King, resentful at his abuse of power, avoided meeting him and in July the old man fell ill and died, his end hastened, it is said, by his vexation and chagrin over the King's attitude.

Upon the death of Berkeley, the King appointed Lord Colepeper Governor of Virginia. As he was not ready nor, possibly, inclined to go immediately to his post, the King issued a special commission to Sir Herbert Jeffries, who had been one of his emissaries to investigate Berkeley, as Lieutenant Governor in immediate charge of affairs. Jeffries ruled until his death in 1678 when he was succeeded by Sir Henry Chicheley as Deputy Governor under an old Commission issued to him as early as 1674. Colepeper did not personally take charge on Virginia's soil until 1680, and then but for a brief period, soon returning to England and remaining there over two years. It was not until December, 1682, that we again find him in Virginia.

Colepeper, it will be remembered, was not only by inheritance a part owner of the patents of 1649 and 1669 to the Northern Neck but he was coproprietor with Arlington under the grant of 1673 of all Virginia and now in his own person Governor of the Colony as well. For good measure, his cousin, Alexander Colepeper, was also[18] an owner by inheritance of a share in the grants of 1649 and 1669. It was apparent that he was in a position at long last to turn his Virginia interests to account; but in doing so he sought to make the new dispensation as personally profitable to his rapacious self as possible. Therefore he opened negotiations with his old associates, by 1681 had succeeded in buying most of them out, and declared himself sole owner of all these grants, although his cousin still owned his one-sixth interest. But the King had become annoyed at his conduct and the stories of his rapacity and, seeking an opportunity to punish him, seized upon the pretext that he had been absent from his post without leave. On this charge he, in 1682, was deprived of his office as Governor. Two years later (1684) Colepeper sold out his rights under the so-called Arlington Charter of 1673 to the English Crown for a pension of £600 a year for twenty-one years. He tried also to sell to Virginia his rights to the Northern Neck under the Charter of 1669, but in that transaction he was unsuccessful. A curiously ironic fate seemed intent upon keeping the Northern Neck Proprietary, reward of Cavalier loyalty and devotion, as an inheritance for the still unborn sixth Lord Fairfax, scion and representative of the family of two of the most able of the Parliamentary leaders.

Although Bacon and his men, when they took the field in 1676, had thoroughly disciplined the Indians in Virginia, the Iroquois and the Susquehannocks still entered Piedmont and roamed its forests. The Iroquois are believed to have driven out the Manahoacs and their kinsmen prior to 1670 and certainly claimed their lands by conquest; not coveting them for settlement but for hunting and particularly for such furs as they could trap and collect in a land plentiful of beaver and otter. The Virginians built forts at the navigation heads of the great rivers for the protection of settlers; but the northern Indians passed beyond and between them and not only attacked the tributary Virginia Algonquin tribes, from time to time, but were frequently in conflict with the English as well. Lord Howard of Effingham, successor to Colepeper as Governor, met Governor Dongan of New York in July, 1684, and with him closed a treaty with the Iroquois whereby the latter were to call out of Virginia[19] and Maryland "all their young braves who had been sent thither for war; they were to observe profound peace with the friendly Indians; they were to make no incursions upon the whites in either state; and when they marched southward they were not to approach near to the heads of the great rivers on which plantations had been made."[3] But the treaty also contained a provision that the Iroquois, when in Virginia, should "Keep at the Foot of the Mountains" which seemed to acknowledge their right to be there and so continued the Indian menace to such settlers as pushed into Piedmont. Nevertheless the frontier forts of the Virginians were allowed to fall into disuse, the Colony depending on companies of armed and mounted rangers to patrol the back country and keep the Indians in order, and there seemed some prospect of peace though the outlying plantations, long keyed up to Indian alarms, remained alert and watchful. However for awhile there was less Indian trouble in the upper country and then a new alarm occurred, resulting in the first recorded exploration of the present Loudoun.

Sir Alexander Spotswood

Sir Alexander Spotswood

When Smith came to Virginia, there was an Indian tribe of the Algonquin stock called by him the Nacothtanks, a name later evolving into Anacostans, which occupied the land about the present city of Washington and some years later having moved its principal village southward to the banks of the Piscataway Creek, thereafter was known by the name of that stream. A daughter of their so called "Emperor" or Chief, having been converted to Christianity, married Giles Brent of Maryland and with him moved across the Potomac to land he acquired on the north shore of Aquia Creek, then still in a frontier wilderness. The Susquehannocks, at the time of their outbreak in 1675, had sought refuge within the fort of the Piscataways but had been refused asylum, the Piscataways remaining loyal to their Maryland neighbours and aiding them in the fighting. In consequence the Susquehannocks bore these lower river Indians bitter hatred. When the Iroquois completed their conquest of the Susquehannocks and reduced them to vassalage, they embraced their side of the quarrel. Toward all the tribes of the east the attitude of the Iroquois was simple, consistent and uncompromising. Rule or ruin, subjugation or extinction, was the harsh choice offered and there was no alternative for these others save in remotest flight. To protect the Piscataways, the Marylanders gave them a reservation amidst their settlements. Blocked and perhaps made jealous by this move, the Iroquois changed from force to guile, seeking every opportunity to turn them against their Maryland protectors and, it is thought, eventually in 1697, persuading them to move across the Potomac into the forests of the Virginia piedmont where they camped for a while near what is now The Plains in Fauquier County. It was not long before white hunters or friendly Indians brought the news to the settlements and the Virginians, still having sporadic troubles with the Iroquois and Susquehannocks in these backwoods, viewed the incursion of another tribe with great alarm. They immediately sought to induce the newcomers to return to Maryland but this they suavely, though none[21] the less stubbornly, refused to do. At length in 1699, feeling the loss of their normal and accustomed diet of fish, they, of their own accord, broke up their camp and traversing the forests of the present Loudoun, settled on what has since been known as Conoy Island in the Potomac at the Point of Rocks. There had recently occurred several murders of English settlers by Indians, probably roving Iroquois; and Stafford County—which some years before, had come into existence to cover this upper country and was to include all this northern piedmont wilderness until through increasing settlement, it was separately formed into Prince William County in 1731—was again in fine ferment over the whole Indian menace. By direction of Governor Nicholson, the county sent two of its officers, Burr Harrison of Chipawansic and Giles Vandercastel whose plantation was on the upper Accotink, to summon the "Emperor" of the Conoy Piscataways to Williamsburg. Mounted on horseback and, we may believe well armed, the two intrepid emissaries promptly set out upon their mission, travelling it is thought, an Indian trail about a mile or more south of the Potomac, which is in its course approximately followed by the present Alexandria Pike, and fording as well as they could the various creeks which run into that stream from the south. The Governor had ordered that they keep a record of their journey and a description of their route and the land traversed and complying with those instructions they wrote the first detailed description of any part of Loudoun. Their report exactly complied with the Governor's orders as to its scope and became a document of primary importance in Loudoun's history. It reads:

"In obedience to His Excellency's command and an order of this Corte bearing date the 12th day of this Instance, April," (1699) "We, the subscribers have beene with the Emperor of Piscataway, att his forte, and did then Comand him, in his Maj'tys name, to meet his Excellency in a General Assembly of this his Maj'ties most Ancient Colloney and Dominion of Virginia, the ffirst of May next or two or three days before, with sume of his great men. As soone as we had delivered his Excellency's Commands, the Emperor summons all his Indians thatt was then at the forte—being in all about[22] twenty men. After consultation of almost two oures, they told us they were very bussey and could not possibly come or goe downe, but if his Excellency would be pleased to come to him, sume of his great men should be glad to see him, and then his Ex-lly might speake whatt he hath to say to him if Excellency could nott come himself, then to send sume of his great men, ffor he desired nothing butt peace.

"They live on an Island in the middle of the Potomack River, its aboutt a mile long or something Better, and aboute a quarter of a mile wide in the Broaddis place. The forte stands att ye upper End of the Island butt nott quite ffinished, & theire the Island is nott above two hundred and ffifty yards over; the bankes are about 12 ffoot high, and very heard to asend. Just at ye lower end of the Island is a Lower Land, and Little or noe Bank; against the upper end of the Island two small Island, the one on Marriland side, the other on this side, which is of about fore acres of Land, & within two hundred yards of the fforte, the other smaller and sumthing nearer, both ffirme land, & from the maine to the fforte is aboute foure hundred yards att Leaste—not ffordable Excepte in a very dry time; the fforte is about ffifty or sixty yardes square and theire is Eighteene Cabbins in the fforte and nine Cabbins without the forte that we Could see. As for Provitions they have Corne, they have Enuf and to spare. We saw noe straing Indians, but the Emperor sayes that the Genekers Lives with them when they att home; also addes that he had maid peace with all ye Indians Except the ffrench Indians; and now the ffrench have a minde to Lye still themselves; they have hired theire Indians to doe mischief. The Distance from the inhabitance is about seventy miles, as we conceave by our Journeys. The 16th of this Instance April, we sett out from the Inhabitance, and ffound a good Track ffor five miles, all the rest of the days's Jorney very Grubby and hilly, Except sum small patches, but very well for horses, tho nott good for cartes, and butt one Runn of any danger in a ffrish, and then very bad; that night lay at the sugar land, which Judge to be forty miles. The 17th day we sett ye River by a small Compasse, and found it lay up N.[23] W. B. N., and afterwards sett it ffoure times, and always ffound it neere the same Corse. We generally kept about one mile ffrom the River, and a bout seven or Eight miles above the sugar land, we came to a broad Branch of a bout fifty or sixty yards wide, a still or small streeme, it tooke our horses up to the Belleys, very good going in and out; about six miles ffarther came to another greate branch of about sixty or seventy yeards wide, with a strong streeme, making ffall with large stones that caused our horses sume times to be up to theire Bellyes, and sume times nott above their Knees; So we conceave it a ffreish, then not ffordable, thence in a small Track to a smaller Runn, a bout six miles, Indeferent very, and soe held on till we came within six or seven miles of the forte or Island, and then very Grubby, and greate stones standing Above the ground Like heavy cocks—they hold for three or ffoure miles; and then shorte Ridgges with small Runns, untill we came to ye forte or Island. As for the number of Indeens, there was att the fforte about twenty men & aboute twenty women and abbout Thirty children & we mett sore. We understand theire is in the Inhabitance a bout sixteene. They informed us there was sume outt a hunting, butt we Judge by theire Cabbins theire cannot be above Eighty or ninety bowmen in all. This is all we Can Report, who subscribes ourselves

"Yo'r Ex'lly Most Dutifull Servants

This "Sugar land" where our emissaries spent the first night of their journey, and the Sugarland Run passing through and named from it, are frequently referred to in the early records and the mouth of the Run became in 1798 the starting point of Loudoun's corrected southern boundary line with Fairfax. They derived their name from the groves of sugar maples found growing there which, with the use of their sap, were well known to the Indians from earliest times. In 1692 David Strahane "Lieut. of the Rangers of Pottomack" tells in his journal that while patrolling the upper woods, he and his men on the 22nd September "Ranged due North till we[24] came to a great Runn that made into the sugar land, & we marcht down it about 6 miles & ther we lay that night." The wording quite clearly shows that the sugar land was then well known to the whites.

Although, as their report shews, Vandercastel and Harrison reached their goal and duly delivered their message, the Piscataways did not then or later comply with the Governor's pressing invitation. That their attitude was not prompted by defiance but rather by worried caution based on their appreciation of the manifold difficulties of their then relations with the whites, is indicated by the report of two other English envoys who, later in the same year, were sent by the authorities to Conoy. These men, Giles Tillett and David Straughan, kept a journal from which we learn that in November, 1699, they in their turn reached the fort and found that "one Siniker" (i.e. Seneca or Iroquois) was among the Piscataways who had had trouble with "strange Indians" who they called Wittowees and that the "Suscahannes" had captured and brought two of these Wittowees to the fort. The "Emperor" received the Englishmen very kindly and told them that he was then willing to "come to live amongst the English againe but he was afeared the sstrange Indians would follow them and due mischief amongst the English, and he should be blamed for it, soe he must content himselfe to live there." He accused the French of stirring up these "strange Indians" and "presents his services to the Gove'n'r, and thanks him for his Kindness to send men to see him to know how he did."

Our friend the Emperor shews his knowledge of statecraft. Doubtless he continued to find plausible reasons for holding on to Conoy where he and his people complacently continued to remain until after the Spotswood-Iroquois Treaty of 1722 which had such a broad effect on Loudoun and which we shall presently consider. During this long occupation of the island, the Piscataways finished building and occupied their fort and village and to this day evidence of their tenure, in arrowheads and other objects, is still, from time to time, discovered.

The journey of Harrison and his companion Vandercastel is important[25] to Loudoun not only because it resulted in the first known description of any of the topography of what is now that county, but also because it marks the first definitely known white exploration of the locality above the Sugarland Run and while unknown English hunters may have theretofore penetrated some part of Loudoun's wilderness, these men were, it is believed, the first whites named and recorded who ever trod Loudoun's soil above the Sugarland. Vandercastel's connection with our story then ends; but Burr Harrison became the progenitor of one of the most prominent and respected families of the county which has now been identified with its best life for five generations. He had been baptized in St. Margaret's, Westminster, in 1637 and came with his father Cuthbert Harrison of Ancaster, Yorkshire, to Virginia some time prior to 1669 when Burr, with others, patented land on Asmale Creek near Occoquan. Afterward, but before 1679, he acquired land on the Chipawansic, presumably from Gerrard Broadhurst. Therefore, to distinguish him and his descendants from the other numerous and not necessarily related Virginia Harrisons, he and they were thenceforward usually known as the Harrisons of Chipawansic. It was not, however, until 1811 that Burr Harrison's descendants in the male line took up their permanent residence in Loudoun; in that year the widow of his great-great-grandson Mathew Harrison moved with her children to Morrisworth, an estate seven miles southeast of Leesburg, now the home of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Fendall, which had come to her from her family the Ellzeys of Dumfries, and there she continued to live until her death.

In the year 1712 another courageous adventurer sought out Conoy. The Swiss Baron Christopher de Graffenreid had been interested in forming a colony of Germans, refugees from the lower Palatinate, at New Bern in North Carolina and also having obtained authority to make a settlement on the Shenandoah in Virginia's remote frontier, he proceeded to explore the neighbourhood. He followed the Potomac up to Conoy Island and drew a map of the surroundings. This map notes the great number of wild fowl on the river, particularly at the mouth of Goose Creek. "There is in winter," he wrote, "such[26] a prodigious number of swans, geese and ducks on this river from Canavest to the Falls that the Indians make a trade of their feathers." Such a description is enough to reduce to envious inanition our Loudoun Nimrod of today whose occasional reward of a few wild ducks may at rare intervals reach the hardly hoped for bagging of a single wild goose, as a rule now far too alert and wary to alight in their spring and fall flights over the county. The wild swan has, alas, wholly disappeared.

De Graffenreid's reference to the vast number of wild fowl on the upper Potomac, in those early days, has abundant confirmation from others. So numerous were the wild geese that the Indians called the river above the falls "Cohongarooton" or Goose River and the English at first gave it the same name; applying the name Potomac to only so much of the stream as lay between the falls and the bay. It was not until well after 1730 that the whole river was generally called by the latter name.

The "Canavest" referred to by de Graffenreid was the village of the Piscataways on Conoy and in his journal he describes it as "a very pleasant and enchanting spot about forty miles above the falls of the Potomac, we found a troop of savages there ... we made an alliance, however with these Indians of Canavest, a very necessary thing in connection with the mines which we hoped to find in that vicinity, as well as on account of the establishment which we had resolved to make in these parts of our small Bernese colony which we were waiting for. After that we visited those beautiful spots of the country, those enchanted islands in the Potomac above the falls." De Graffenreid's "mines" and "establishments" were to be over the Blue Ridge in the nearby Shenandoah Valley; but he shrewdly recognized the advisability of making friends with a tribe so firmly and strategically planted as he found at the settlement on Conoy. As to his "enchanted islands," those contiguous to the Loudoun bank of the Potomac long have had Loudoun owners and seem to its people to be sentimentally part of her domain; as a matter of cold fact and colder law, they lie within the bounds of Maryland; for in 1776 the long dispute over the sovereignty of the[27] Potomac was settled by a clause in Virginia's Constitution of that year relinquishing jurisdiction.

Two years before de Graffenreid's expedition, there arrived in Virginia as Lieutenant Governor, Colonel (afterward Sir) Alexander Spotswood, the most alert, devoted and able ruler the Colony had had since Smith—a man "who still enjoys an almost unrivalled distinction among Virginia's Colonial Governors"[4] and, says Howison, whose "chief advantage consisted in his social and moral character, in which aspect it would not be easy to find one of whom might be truly asserted so much that is good and so little that is evil."[5] Spotswood came to love Virginia as though it were his native land and great was the moral debt the Colony, and especially the counties created from its old frontier, came to owe to his strong and conscientious administration. Under a vicious practice by that time obtaining in England, the titular governship of Virginia had been held, since 1697, by George Hamilton Douglas, Earl of Orkney, who though never setting foot in the Colony, drew £1,200 of the annual salary of £2,000 attached to the office until his death in 1737; and thus Spotswood, preëminent among Virginia's rulers, served but under a lieutenant-governor's commission. A great-grandson of John Spottiswoode, Archbishop of St. Andrew's and Lord High Chancellor of Scotland, who lies buried in Henry VII's Chapel in Westminster Abbey, Spotswood descended from an old and aristocratic Scottish family, whose progenitor, a cadet of the great house of Gordon, married an heiress of the ancient race of Spottiswoode which took its name from the Barony of Spottiswoode in the Parish of Gordon, County of Berwick. Born in 1676 in Tangier where his father Robert Spotswood then served as physician to the English Governor and garrison, Spotswood "a tall robust man with gnarled and wrinkled face and an air of dignity and power"[6] had, in 1704, fought valiantly under Marlborough and had been desperately wounded in the battle of Blenheim. He brought with him recognition of the right of Virginians to the writ of Habeas[28] Corpus, which though, since Magna Carta, the common heritage of every free-born Englishman, had not theretofore run in Virginia. Had this been his all, Virginia would have been his debtor; in the event it was but an augury of many benefactions to follow.

From the first, Spotswood shewed a keen and enlightened interest in the problems of the frontier. His efforts to expand the settlements westerly and to subdue the Indians did not always meet with co-operation from the Virginia legislature, controlled by representatives of the more protected and densely settled tidewater sections, whose people, the "Tuckahoes" as they were called, were frequently unresponsive to the plight of those in the upper country; and from time to time Spotswood's impatience with his legislators boiled up into strong and bluntly worded reproof. To one of his assemblies, recalcitrant in Indian affairs, he addressed his well remembered words of dismissal: "In fine I cannot but attribute these miscarriages to the people's mistaken choice of a set of representatives whom Heaven has not ... endowed with the ordinary qualifications requisite to legislators; and therefore I dissolve you." A few Spotswoods, scattered here and there in the seats of the mighty of our modern America, might not prove inefficacious.

In May, 1717, we find him reporting upon the Indian situation to Paul Methuen, the then English Secretary of State, that though the English had carefully kept the terms of Lord Howard's Treaty of 1685, the Iroquois "had committed divers hostilitys on our ffrontiers, in 1713 they rob-d our Indian Traders of a considerable cargo of Goods, the same year they murdered a Gent'n of Acco't near his out Plantations; they carried away some slaves belonging to our Inhabitants, and now threaten not only to destroy our Tributary Indians but the English also in their neighbourhood." He adds that such conduct requires "some Reparation" and asks the Secretary to instruct the Governor of New York to cause his Iroquois to "forebear hostilitys on the King's subjects of the neighbouring Colonies and likewise any nation of Indians under their protection."[7]

Neither by temperament nor training was Spotswood a man to acquiesce in such conditions. After consulting with and urging co-operation upon the Governors of Maryland and Pennsylvania, he set out in the winter of 1717-'18 for New York "to demand something more substantial than the bare promises of the Chief men of those Indians, w'ch they are always very liberal of, in expectation of presents from the English, while at the same time their young men are committing their usual depredations upon ye Frontiers of these Southern Governments." He was fortunate in arriving in New York "very opportunely to prevent the march of a Great Body of those Indians w'ch I had Advice on the Road was intended chiefly against the Tributaries of this Governm't, and the Governor of New York's Messengers overtook them upon their march and obtained their promise to Abstain from any hostilitys on the English Governments."

It being late in the season for a conference with the Sachems of the Long House and the New York Assembly being in the "height of its business and like to make a larger session than ordinary," Spotswood arranged, through the Governor of New York, preliminary negotiations with the Indians and returned to his Virginia.

The discussions thus begun dragged along during the ensuing five years. At length, in 1721, the Iroquois sent their representatives to Williamsburg with more definite proposals and in May, 1722, the General Assembly passed an act reciting in detail the terms on which the treaty would be made.[8] Later in the summer Spotswood, with certain of his Council, went to New York on a man-of-war and thence proceeding to Albany (where he was joined by the Governor of Pennsylvania) the new treaty was closed after the usual endless speech making and other ceremony. By its terms the Iroquois were prohibited from ever again crossing the Potomac or the Blue Ridge "without the license or passport of the Governor or commander-in-chief of the province of New York, for the time being"; and the Virginia tributary Indians were similarly prohibited[30] from crossing the same boundaries. Moreover, there were provisions that should any Indians—Iroquois or tributary—ignore the prohibition, they were, upon capture and conviction, to be punishable by death or transportation to the West Indies, there to be sold as slaves. There was added a clause rewarding him who captured an Indian found in Virginia without permission, with 1,000 pounds of tobacco when the latter should be condemned to death; or, if he should be condemned to transportation, the captor should "have the benefit of selling and disposing of the said Indian, and have and receive to his own use, the money arising from such sale."

There was nothing ambiguous in this treaty's terms; the Iroquois in signing it realized that their Piedmont hunting grounds were lost to them and that the sportive raids of their war parties below the Potomac were ended.

And now Spotswood's consulship had reached its end. His enemies in London and Williamsburg had been industriously intriguing and upon his return he found he had been superseded. He had acquired a vast estate of over 45,000 acres in the Piedmont forests and to settle and improve those lands he proceeded to devote his great and able energies. But he had far from retired from his public labours. As Postmaster General for the American Colonies he, by 1738, developed a regular mail service from New England to the James; and was about to sail as a major-general on Admiral Vernon's expeditions against Carthagena when he suddenly died. He was buried on his estate, Temple Farm, near Yorktown, where latterly he had made his home. It was in his mansion there, then owned by his eldest daughter Ann Catherine and her husband M. Bernard Moore, Senior, that many years later the negotiations for the surrender of Lord Cornwallis to General Washington closed the American Revolution.