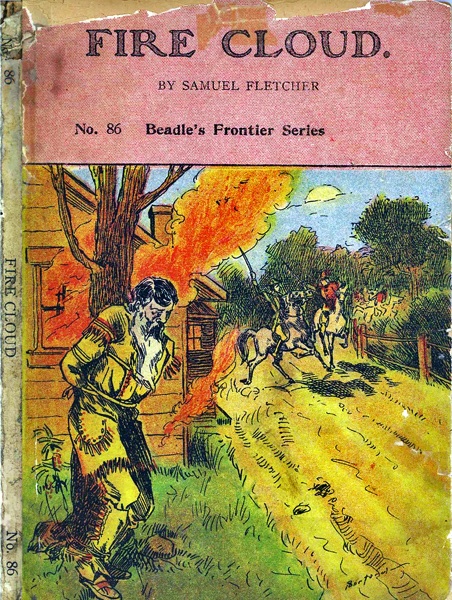

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Fire Cloud, by Samuel Fletcher

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Fire Cloud

The Mysterious Cave. A Story of Indians and Pirates.

Author: Samuel Fletcher

Release Date: August 8, 2011 [EBook #37006]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIRE CLOUD ***

Produced by Greg Weeks and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

(Printed in the United States of America)

FIRE CLOUD.

CHAPTER I.

Whether or not, the story which we are about to relate is absolutely true in every particular, we are not prepared to say. All we know about it is, that old Ben Miller who told it to our uncle Zeph, believed it to be true, as did uncle Zeph himself. And from all we can learn, uncle Zeph was a man of good judgment, and one not easily imposed upon.

And uncle Zeph said that he had known old people in his younger days, who stated that they had actually seen the cave where many of the scenes which we are about to relate occurred, although of late years, no traces of any kind could be discovered in the locality where it is supposed to have been situated.

His opinion was, that as great rocks were continually rolling down the side of the mountain at the foot of which the entrance to the cave was, some one or more of these huge boulders had fallen into the opening and completely closed it up.

But that such a cave did exist, he was perfectly satisfied, and that it would in all probability be again discovered at some future day, by persons making excavations in the side of the mountain. And lucky he thought would be the man who should make the discovery, for unheard of treasures he had no doubt would be found stowed away in the chinks and crevices of the rocks.

So much by way of introduction; as we have no intention to describe the cave until the proper time comes, we shall leave that part of the subject for the present, while we introduce the reader to a few of the principal personages of our narrative.

At a distance of some fifteen or twenty miles from the City of New York, on the Hudson river in the shadow of the rocks known as the Palisades, something near two hundred years ago, lay a small vessel at anchor.

The vessel as we have said was small. Not more than fifty or sixty tons burden, and what would be considered a lumbering craft now a days with our improved knowledge of ship building, would at that time be called a very fast sailor.

This vessel was schooner rigged, and every thing about her deck trim and in good order.

On the forecastle sat two men, evidently sailors, belonging to the vessel.

We say sailors, but in saying so we do not mean to imply that they resembled your genuine old salt, but something between a sailor and a landsman. They could hardly be called land lubbers, for I doubt if a couple of old salts could have managed their little craft better than they, while they, when occasion required, could work on land as well as water.

In fact they belonged to the class known as river boatmen, though they had no hesitation to venturing out to sea on an emergency.

The elder of these men, who might have seen some fifty years or more, was a short, thick set man with dark complexion, and small grey eyes overshadowed by thick, shaggy brows as black as night.

His mouth was large when he chose to open it, but his lips were thin and generally compressed.

He looked at you from under his eyebrows like one looking at you from a place of concealment, and as if he was afraid he would be seen by you.

His name was David Rider, but was better known among his associates under the title of Old Ropes.

The other was a man of about twenty-five or thirty, and was a taller and much better-looking man, but without anything very marked in his countenance. His name was Jones Bradley.

"I tell you what, Joe," said his companion, "I don't like the captain's bringin' of this gal; there can't no good come of it, and it may bring us into trouble."

"Bring us into trouble! everything that's done out of the common track, accordin' to you's a goin' to bring us into trouble. I'd like to know how bringing a pretty girl among us, is goin' to git us into trouble?"

"A pretty face is well enough in its way," said Old Ropes, "but a pretty face won't save a man from the gallows, especially if that face is the face of an enemy."

"By the 'tarnal, Ropes, if I hadn't see you fight like the very devil when your blood was up, I should think you was giten' to be a coward. How in thunder is that little baby of a girl goin' to git us into trouble?"

"Let me tell you," said Ropes, "that one pretty gal, if she's so minded, can do you more harm than half a dozen stout men that you can meet and fight face to face, and if you want to know the harm that's goin' to come to us in this case I'll show you."

"The gal, you know's the only daughter of old Rosenthrall. Why the captain stole her away, I don't know. Out of revenge for some slight or insult or other, I s'pose. Now the old man, as you're aware, knows more about our business than is altogether safe for us. As I said before, the gal's his only daughter, and he'll raise Heaven and earth but he'll have her again, and when he finds who's got her, do you suppose there'll be any safety for us here? No! no! if I was in the captain's place, I'd either send her back again, or make her walk the plank, as he did, you know who, and so get rid of her at once."

"As for walking the plank," said the young man, laying his hand on his companion's shoulder, danger or no danger, the man who makes that girl walk the plank, shall walk after, though it should be Captain Flint himself, or my name is not Jones Bradley."

"You talk like a boy that had fallen dead in love," said the other; "but anyhow, I don't like the captain's bringing the young woman among us, and so I mean to tell him the first chance I have."

"Well, now's your time," said Bradley, "for here comes the captain."

As he spoke, a man coming up from the cabin joined them. His figure, though slight, was firm and compact. He was of medium height; his complexion naturally fair, was somewhat bronzed by the weather, his hair was light, his eyes grey, and his face as a whole, one which many would at first sight call handsome. Yet it was one that you could not look on with pleasure for any length of time. There was something in his cold grey eye that sent a chill into your blood, and you could not help thinking that there was deceit, and falsehood in his perpetual smile.

Although his age was forty-five, there was scarcely a wrinkle on his face, and you would not take him to be over thirty.

Such was Captain Flint, the commander and owner of the little schooner Sea Gull.

"Captain," said Rider, when the other had joined the group; "Joe and I was talking about that gal just afore you came up, and I was a sayin' to him that I was afeard that she would git us into trouble, and I would speak to you about it."

"Well," said Captain Flint, after a moment's pause, "if this thing was an affair of mine entirely, I should tell you to mind your own business, and there the matter would end, but as it concerns you as well as me, I suppose you ought to know why it was done.

"The girl's father, as you know, has all along been one of our best customers. And we suppose that he was too much interested in our success to render it likely that he would expose any of our secrets, but since he's been made a magistrate, he has all at once taken it into his head to set up for an honest man, and the other day he not only told me that it was time I had changed my course and become a fair trader, but hinted that he had reason to suspect that we were engaged in something worse than mere smuggling, and that if we did not walk pretty straight in future, he might be compelled in his capacity of magistrate to make an example of us.

"I don't believe that he has got any evidence against us in regard to that last affair of ours, but I believe that he suspects us, and should he even make his suspicions public, it would work us a great deal of mischief, to say the least of it.

"I said nothing, but thinks I, old boy, I'll see if I can't get the upper hand of you. For this purpose I employed some of our Indian friends to entrap, and carry off the girl for me. I took care that it should be done in such a manner as to make her father believe that she was carried off by them for purposes of their own.

"Now, he knows my extensive acquaintance with all the tribes along the river, and that there is no one who can be of as much service to him in his efforts to recover his daughter, as I, so that he will not be very likely to interfere with us for some time to come.

"I have seen him since the affair happened, and condoled with him, of course.

"He believes that the Indian who stole his daughter was the chief Fire Cloud, in revenge for some insult received a number of years ago.

"This opinion I encouraged, as it answered my purpose exactly, and I promised to render all the assistance I could in his efforts to recover his child.

"This part of the country, as we all know, is getting too hot for us; we can't stand it much longer; if we can only stave off the danger until the arrival of that East Indiaman that's expected in shortly there'll be a chance for us that don't come more than once or twice in a lifetime.

"Let us once get the pick out of her cargo, and we shall have enough to make the fortunes of all of us, and we can retire to some country where we can enjoy our good luck without the danger of being interfered with. And then old Rosenthrall can have his daughter again and welcome provided he can find her.

"So you see that to let this girl escape will be as much as your necks are worth."

So saying, Captain Flint left his companions and returned to the cabin.

"Just as I thought," said Old Ropes, when the captain had gone, "if we don't look well to it this unlucky affair will be the ruin of us all."

CHAPTER II.

Carl Rosenthrall was a wealthy citizen of New York. That is, rich when we consider the time in which he lived, when our mammoth city was little more than a good-sized village, and quite a thriving trade was carried on with the Indians along the river, and it was in this trade chiefly, that Carl Rosenthrall and his father before him, had made nearly all the wealth which Carl possessed.

But Carl Rosenthrall's business was not confined to trading with the Indians alone, he kept what would now be called a country store. A store where everything almost could be found, from a plough to a paper of needles.

Some ten years previous to the time when the events occurred which are recorded in the preceding chapter, and when Hellena Rosenthrall was about six years old, an Indian chief with whom Rosenthrall had frequent dealings, and whose name was Fire Cloud, came in to the merchant's house when he was at dinner with his family, and asked for something to eat, saying that he was hungry.

Now Fire Cloud, like the rest of his race, had an unfortunate liking for strong drink, and was a little intoxicated, and Rosenthrall not liking to be intruded upon at such a time by a drunken savage, ordered him out of the house, at the same time calling him a drunken brute, and making use of other language not very agreeable to the Indian.

The chief did as he was required, but in doing so, he put his hand on his tomahawk and at the same time turned on Rosenthrall a look that said as well as words could say, "Give me but the opportunity, and I'll bury this in your skull."

The chief, on passing out, seated himself for a moment on the stoop in front of the house.

While he was sitting there, little Hellena, with whom he had been a favorite, having often seen him at her father's store, came running out to him with a large piece of cake in her hand, saying:

"Here, No-No, Hellena will give you some cake."

No-No was the name by which the Indian was known to the child, having learned it from hearing the Indian make use of the name no, no, so often when trading with her father.

The Indian took the proffered cake with a smile, and as he did so lifted the child up in his arms and gazed at her steadily for a few moments, as if he wished to impress every feature upon his memory, and then sat her down again.

He was just in the act of doing this when the child's father came out of the dining-room.

Rosenthrall, imagining that the Indian was about to kidnap his daughter, or do her some violence, rushed out ordering him to put the child down, and be off about his business.

It was the recollection of this circumstance, taken in connection with the fact that Fire Cloud had been seen in the city on the day on which his daughter had disappeared, which led Rosenthrall to fix upon the old chief as the person who had carried off Hellena.

This opinion, as we have seen, was encouraged by Captain Flint for reasons of his own.

The facts in the case were these.

Rosenthrall, as Captain Flint had said, although for a long time one of his best customers, knowing to, and winking at his unlawful doings, having been elected a magistrate took it in to his head to be honest.

He had made money out of his connection with the smuggler and pirate, and he probably thought it best to break off the connection before it should be too late, and he should be involved in the ruin which he foresaw Captain Flint was certain to bring upon himself if he continued much longer in the reckless course he was now pursuing.

All this was understood by Captain Flint, and it was as he explained to his men, in order to get the upper hand of Rosenthrall, and thus prevent the danger which threatened him from that quarter, he had caused Hellena to be kidnapped, and conveyed to their grand hiding place, the cave in the side of the mountain.

Rosenthrall at this time resided in a cottage on the banks of the river, a short distance from his place of business, the grounds sloping down to the water.

These grounds were laid out into a flower garden where there was an arbor in which Hellena spent the greater part of her time during the warm summer evenings.

It was while lingering in this arbor rather later than usual that she was suddenly pounced upon by the two Indians employed by Captain Flint for the purpose, and conveyed to his vessel, which lay at anchor a short distance further up the river.

Captain Flint immediately set sail with his unwilling passenger, and in a few hours afterwards she was placed in the cave under the safe keeping of the squaw who presided over that establishment.

If the reader would like to know what kind of a looking girl Hellena Rosenthrall was at this time, I would say that a merrier, more animated, if not a handsomer face he never looked upon. She was the very picture of health and fine spirits.

Her figure was rather slight, but not spare, for her form was compact and well rounded, and her movements were as light and elastic as those of a deer.

Her complexion was fair, one in which you might say without any streak of fancy, the lily was blended with the rose.

Her eyes were blue and her hair auburn, bordering on the golden, and slightly inclined to wave rather than to curl.

Her nose was of moderate size and straight, or nearly so.

Some would say that her mouth was rather large, but the lips were so beautifully shaped, and then when she smiled she displayed such an exquisite set of the purest teeth, setting off to such advantage the ruby tinting of the lips, you felt no disposition to find fault with it.

We have spoken of Hellena's look as being one of animation and high spirits, and such was its general character, but for some time past a shadow of gloom had come over it.

Hellena was subject to the same frailties which are common to her sex. She had fallen in love!

The object of her affections was a young man some two or three years older than herself, and at first nothing occurred to mar their happiness, for the parents of both were in favor of the match.

As they were both young, however, it was decided to postpone their union for a year.

In the meantime, Henry Billings, the intended bridegroom, should make a voyage to Europe in order to transact some business for his father, who was a merchant trading with Amsterdam.

The vessel in which he sailed never reached her place of destination.

It was known that she carried out a large amount of money sent by merchants in New York, as remittances to those with whom they had dealings in Europe. This, together with certain facts which transpired shortly after the departure of the vessel, led some people to suspect that she had met with foul play somewhere on the high seas; and that not very far from port either.

Hellena, who happened to be in her father's store one day when Captain Flint was there, saw on his finger a plain gold ring which she was sure had belonged to her lover.

This fact she mentioned to her father after the captain had gone.

Her father at that time ridiculed her suspicions. But he afterwards remembered circumstances connected with the departure of the vessel, and the movements of Captain Flint about the same time, which taken in connection with the discovery made by his daughter, did seem to justify the dark suspicions created in the mind of his daughter.

But how was he to act under the circumstance? As a magistrate, it was his business to investigate the matter. But then there was the danger should he attempt to do so, of exposing his own connection with the pirate.

He must move cautiously.

And he did move cautiously, yet not so cautiously but he aroused the suspicions of Captain Flint, who, as we have seen, in order to secure himself against the danger which threatened him in that quarter, had carried off the daughter of the merchant.

CHAPTER III.

When the vessel in which young Billings set sail started she had a fair wind, and was soon out in the open sea.

Just as night began to set in, a small craft was observed approaching them, and being a much faster sailor than the larger and heavily ladened ship, she was soon along-side.

When near enough to be heard, the commander of the smaller vessel desired the other to lay too, as he had important dispatches for him which had been forgotten.

The commander of the ship not liking to stop his vessel while under full sail merely for the purpose of receiving dispatches, offered to send for them, and was about lowering a boat for that purpose, when the other captain, who was none other than Captain Flint, declared that he could only deliver them in person.

The captain of the ship, though in no very good humor, finally consented to lay too, and the two vessels were soon lying along side of each other.

Now although while lying at, or about the wharves of New York, the two men already introduced to the reader apparently constituted the whole crew of Captain Flint's vessel, such was by no means the fact, for there were times when the deck of the little craft would seem fairly to swarm with stout, able-bodied fellows. And the present instance, Captain Flint had no sooner set foot upon the deck of the ship, than six or eight men fully armed appeared on the deck of the schooner prepared to follow him.

The first thing that Captain Flint did on reaching the deck of the ship was to strike the captain down with a blow from the butt of a large pistol he held in his hand. His men were soon at his side, and as the crew of the other vessel were unarmed, although defending themselves as well as they could, they were soon overpowered.

Several of them were killed on the spot, and those who were not killed outright, were only reserved for a more cruel fate.

The fight being over, the next thing was to secure the treasure.

This was a task of but little difficulty, for Flint had succeeded in getting one of his men shipped as steward on the ill-fated vessel.

One of those who had escaped the massacre was James Bradley. He had, by order of Captain Flint, been lashed to the mast at the commencement of the fight.

He had not received a wound. All the others who were not killed were more or less badly hurt.

These were unceremoniously compelled to walk the plank, and were drowned.

When it came to Billings' turn, there seemed to be some hesitation among the pirates subjecting him to the same fate as the others.

Jones Bradley, in a particular manner, was for sparing his life on condition that he would pledge himself to leave the country, never to return, and bind himself to eternal secrecy.

But this advice was overruled by Captain Flint himself, who declared he would trust no one, and that the young man should walk the plank as the others had done.

From this decision there was no appeal, and Henry Billings resigned himself to his fate.

Before going he said he would, as a slight favor, to ask of one of his captors.

And then pulling a plain gold ring off his finger, he said:

"It is only to convey this to the daughter of Carl Rosenthrall, if he can find means of doing so, without exposing himself to danger. I can hardly wish her to be made acquainted with my fate."

When he had finished, Captain Flint stepped up saying that he would undertake to perform the office, and taking the ring he placed it upon his own finger.

By this time it was dark. With a firm tread Billings stepped upon the plank, and the next moment was floundering in the sea.

The next thing for the pirates to do was to scuttle the ship, which they did after helping themselves to so much of the most valuable portion of the cargo as they thought they could safely carry away with them.

In about an hour afterwards the ship sank, bearing down with her the bodies of her murdered crew, and burying, as Captain Flint supposed, in the depths of the ocean all evidences of the fearful tragedy which had been enacted upon her deck.

The captain now directed his course homeward, and the next day the little vessel was lying in port as if nothing unusual had happened, Captain Flint pretending that he had returned from one of his usual trading voyages along the coast.

The intercourse between the new and the old world was not so frequent in those days as now. The voyages, too, were much longer than at present. So that, although a considerable time passed, bringing no tidings of the ill-fated vessel without causing any uneasiness.

But when week after week rolled by, and month followed month, and still nothing was heard from her, the friends of those on board began to be anxious about their fate.

At length a vessel which had sailed some days later than the missing ship, had reported that nothing had been heard from her.

The only hope now was that she might have been obliged by stress of weather to put in to some other port.

But after awhile this hope also was abandoned, and all were reluctantly compelled to come to the conclusion that she had foundered at sea, and that all on board had perished.

After lying a short time in port, Captain Flint set sail up the river under pretence of going on a trading expedition among the various Indian tribes.

But he ascended the river no further than the Highlands, and come to anchor along the mountain familiarly known as Butterhill, but which people of more romantic turn call Mount Tecomthe, in honor of the famous Indian chief of that name.

Having secured their vessel close to the shore, the buccaneers now landed, all save one, who was left in charge of the schooner.

Each carried with him a bundle or package containing a portion of the most valuable part of the plunder taken from the ship which they had so recently robbed.

Having ascended the side of the mountain for about two hundred yards, they came to what seemed to be a simple fissure in the rocks about wide enough to admit two men abreast.

This cleft or fissure they entered, and having proceeded ten or fifteen feet they came to what appeared to be a deep well or pit.

Here the party halted, and Captain Flint lighted a torch, and producing a light ladder, which was concealed in the bushes close by, the whole party descended.

On reaching the bottom of the pit, a low, irregular opening was seen in the side, running horizontally into the mountain.

This passage they entered, Indian file, and bending almost double.

As they proceeded the opening widened and grew higher, until it expanded into a rude chamber about twelve feet one way by fifteen feet the other.

Here, as far as could be seen, was a bar to all further progress, for the walls of the chamber appeared to be shut in on every side.

But on reaching the further side of the apartment, they stopped at a rough slab of stone, which apparently formed a portion of the floor of the cave.

Upon one of the men pressing on one end of the slab, the other rose like a trap door, disclosing an opening in the floor amply sufficient to admit one person, and by the light of the torch might be seen a rude flight of rocky stairs, descending they could not tell how far.

These were no doubt in part at least artificial.

The slab also had been placed over the hole by the pirates, or by some others like them who had occupied the cave before this time, by way of security, and to prevent surprise.

Captain Flint descended these steps followed by his men.

About twenty steps brought them to the bottom, when they entered another horizontal passage, and which suddenly expanded into a wide and lofty chamber.

Here the party halted, and the captain shouted at the top of his voice:

"What ho! there, Lightfoot, you she devil, why don't you light up!"

This rude summons was repeated several times before it received any answer.

At length an answer came in what was evidently a female voice, and from one who was in no very good humor: "Oh, don't you get into a passion now. How you s'pose I know you was coming back so soon."

"Didn't I tell you I'd be back to-day!" angrily asked Flint.

"Well, what if you did," replied the voice. "Do you always come when you says you will?"

"Well, no matter, let's have no more of your impudence. We're back bow, and I want you to light up and make a fire."

The person addressed was now heard retiring and muttering to herself.

In a few moments the hall was a blaze of light from lamps placed in almost every place where a lamp could be made to stand.

The scene that burst upon the sight was one of enchantment.

The walls and ceiling of the cavern seemed to be covered with a frosting of diamonds, multiplying the lamps a thousand fold, and adding to them all the colors of the rainbow.

Some of the crystals which were of the purest quartz hanging from the roof, were of an enormous size, giving reflections which made the brilliancy perfectly bewildering.

The floor of the cavern was covered, not with Brussels or Wilton carpets, but with the skins of the deer and bear, which to the tread were as pleasant as the softest velvet.

Around the room were a number of frames, rudely constructed to be sure, of branches, but none the less convenient on that account, over which skins were stretched, forming comfortable couches where the men might sleep or doze away their time when not actively employed.

Near the center of the room was a large flat stone rising about two feet above the floor. The top of this stone had been made perfectly level, and over it a rich damask cloth had been spread so as to make it answer all the purposes of a table. Boxes covered with skins, and packages of merchandise answered the purpose of chairs, when chairs were wanted.

"Where is the king, I should like to know?" said Captain Flint, looking with pride around the cavern now fully lighted up; "who can show a hall in his palace that will compare with this?"

"And where is the king that is half so independent as we are?" said one of the men.

"And kings we are," said Captain Flint; "didn't they call the Buccaneers Sea Kings in the olden time?"

"But this talking isn't getting our supper ready. Where has that Indian she-devil taken herself off again?"

The person here so coarsely alluded to, now made her appearance again, bearing a basket containing a number of bottles, decanters and drinking glasses.

She was not, to be sure, so very beautiful, but by no means so ugly as to deserve the epithet applied to her by Captain Flint.

She was an Indian woman, apparently thirty, or thirty-five years of age, of good figure and sprightly in her movements, which circumstance had probable gained for her among her own people, the name of Lightfoot.

She had once saved Captain Flint's life when a prisoner among the Indians, and fearing to return to her people, she had fled with him.

It was while flying in company with this Indian woman, that Captain Flint had accidently discovered this cave. And here the fugitives had concealed themselves for several days, until the danger which then threatened them had passed.

It was on this occasion that it occurred to the captain, what a place of rendezvous this cave would be for himself and his gang; what a place of shelter in case of danger; what a fine storehouse for the plunder obtained in his piratical expeditions!

He immediately set about fixing it up for the purpose; and as it would be necessary to have some one to take charge of things in his absence, he thought of none whom he could more safely trust with the service, than the Indian woman who had shared his flight.

From that time, the cave became a den of pirates, as it had probably at one time been a den of wild beasts.

Which was the better condition, we leave it for the reader to decide.

The only other occupant of the cave was a negro boy of about fourteen or fifteen years of age, known by the name of Black Bill.

He seemed to be a simple, half-witted, harmless fellow, and assisted Lightfoot in doing the drudgery about the place.

"What have you got in your basket, Lightfoot?" asked Captain Flint.

"Wine," replied the Indian.

"Away with your wine," said the captain; "we must have something stronger than that. Give us some brandy; some fire-water. Where's Black Bill?" he continued.

"In de kitchen fixin' de fire," said Lightfoot.

"All right, let him heat some water," said the captain; "and now, boys, we'll make a night of it," he said, turning to his men.

The place here spoken of by Lightfoot as the kitchen, was a recess of several feet in the side of the cave, at the back of which was a crevice or fissure in the rock, extending to the outside of the mountain.

This crevice formed a natural chimney through which the smoke could escape from the fire that was kindled under it.

The water was soon heated, the table was covered with bottles, decanters and glasses of the costliest manufacture. Cold meats of different kinds, and an infinite variety of fruits were produced, and the feasting commenced.

CHAPTER IV.

Yes, the pirate and his crew were now seated round the table for the purpose as he said, of making a night of it. And a set of more perfect devils could hardly be found upon the face of the earth.

And yet there was nothing about them so far as outward appearance was concerned, that would lead you to suppose them to be the horrible wretches that they really were.

With the exception of Jones Bradley, there was not one among them who had not been guilty of almost every crime to be found on the calender of human depravity.

For some time very little was said by any of the party, but after a while as their blood warmed under the influence of the hot liquor, their tongues loosened, and they became more talkative. And to hear them, you would think that a worthier set of men were no where to be found.

Not that they pretended to any extraordinary degree of virtue, but then they had as much as anyone else. And he who pretended to any more, was either a hypocrite or a fool.

To be sure, they robbed, and murdered, and so did every one else, or would if they found it to their interest to do so.

"Hallo! Tim," shouted one of the men to another who sat at the opposite side of the table; "where is that new song that you learned the other day?"

"I've got it here," replied the person referred to, putting his finger on his forehead.

"Out with it, then."

"Let's have it," said the other.

The request being backed by the others Tim complied as follows.

THE BUCCANEER.

Fill up the bowl,

Through heart and soul,

Let the red wine circle free,

Here's health and cheer,

To the Buccaneer,

The monarch of the sea!

The king may pride,

In his empire wide,

A robber like us is he,

With iron hand,

He robs on land,

As we rob on the sea.

The priest in his gown,

Upon us may frown,

The merchant our foe may be,

Let the judge in his wig,

And the lawyer look big,

They're robbers as well as we!

Then fill up the bowl,

Through heart and through soul,

Let the red wine circle free,

Drink health and cheer,

To the Buccaneer.

He's monarch of the sea.

"I like that song," said one of the men, whose long sober face and solemn, drawling voice had gained for him among his companions the title of Parson. "I like that song; it has the ring of the true metal, and speaks my sentiments exactly. It's as good as a sermon, and better than some sermons I've heard."

"It preaches the doctrine I've always preached, and that is that the whole world is filled with creatures who live by preying upon each other, and of all the animals that infest the earth, man is the worst and cruelest."

"What! Parson!" said one of the men, "you don't mean to say that the whole world's nothing but a set of thieves and murderers!"

"Yes; I do," said the parson; "or something just as bad."

"I'd like to know how you make that out," put in Jones Bradley. "I had a good old mother once, and a father now dead and gone. I own I'm bad enough myself, but no argument of yours parson, or any body else's can make me believe that they were thieves and murderers."

"I don't mean to be personal," said the parson, "your father and mother may have been angels for all I know, but I'll undertake to show that all the rest of the world, lawyers, doctors and all, are a set of thieves and murderers, or something just as bad."

"Well Parson, s'pose you put the stopper on there," shouted one of the men; "if you can sing a song, or spin a yarn, it's all right; but this ain't a church, and we don't want to listen to one of your long-winded sermons tonight."

"Amen!" came from the voices of nearly all present.

The Parson thus rebuked, was fain to hold his peace for the rest of the evening.

After a pause of a few moments, one of the men reminded Captain Flint, that he had promised to inform them how he came to adopt their honorable calling as a profession.

"Well," said the captain, "I suppose I might as well do it now, as at any other time; and if no one else has anything better to offer, I'll commence; and to begin at the beginning, I was born in London. About my schooling and bringing up, I haven't much to say, as an account of it would only be a bore.

"My father was a merchant and although I suppose one ought not to speak disrespectfully of one's father, he was, I must say, as gripping, and tight-fisted a man as ever walked the earth.

"I once heard a man say, he would part with anything he had on earth for money, but his wife. My father, I believe, would have not only parted with his wife and children for money, but himself too, if he had thought he should profit by the bargain.

"As might be expected, the first thing he tried to impress on the minds of his children was the necessity of getting money.

"To be sure, he did not tell us to steal, as the word is generally understood; for he wanted us to keep clear of the clutches of the law. Could we only succeed in doing this, it mattered little to him, how the desired object was secured.

"He found in me an easy convert to his doctrine, so far as the getting of money was concerned; but in the propriety of hoarding the money as he did when it was obtained, I had no faith.

"The best use I thought that money could be put too, was to spend it.

"Here my father and I were at swords' points, and had it not been that notwithstanding this failing, as he called it, I had become useful to him in his business, he would have banished me long before I took into my head to be beforehand with him, and become a voluntary exile from the parental roof.

"The way of it was this. As I have intimated, according to my father's notions all the wealth in the world was common property, and every one was entitled to all he could lay his hands on.

"Now, believing in this doctrine, it occurred to me that my father had more money than he could ever possibly make use of, and that if I could possess a portion of it without exposing myself to any great danger, I should only be carrying out his own doctrine.

"Acting upon this thought, I set about helping myself as opportunity offered, sometimes by false entries, and in various ways that I need not explain.

"This game I carried on for some time, but I knew that it would not last forever. I should be found out at last, and I must be out of the way before the crash came.

"Luckily a chance of escape presented itself.

"My father, in connection with two or three other merchants, chartered a vessel to trade among the West India islands.

"I managed to get myself appointed supercargo. I should now be out of the way when the discovery of the frauds which I had been practicing I knew must be made.

"As I had no intention of ever returning, my mind was perfectly at ease on this score.

"We found ready sale for our cargo, and made a good thing of it.

"As I have said, when I left home, it was with the intention of never returning, though what I should do while abroad I had not decided, but as soon as the cargo was disposed of, my mind was made up.

"I determined to turn pirate!

"I had observed on our outward passage, that our vessel, which was a bark of about two hundred tons burden, was a very fast sailor, and with a little fitting up, could be made just the craft we wanted for our purpose.

"During the voyage, I had sounded the hands in regard to my intention of becoming a Buccaneer. I found them all ready to join me excepting the first mate and the steward or cook, rather, a negro whose views I knew too well beforehand, to consult on the matter.

"As I knew that the ordinary crew of the vessel would not be sufficient for our purpose, I engaged several resolute fellows to join us, whom I prevailed on the captain to take on board as passengers.

"When we had been about a week out at sea and all our plans were completed, we quietly made prisoners of the captain and first mate, put them in the jolly boat with provisions to last them for several days, and sent them adrift. The cook, with his son, a little boy, would have gone with them, but thinking that they might be useful to us, we concluded to keep them on board.

"What became of the captain and mate afterwards, we never heard.

"We now put in to port on one of the islands where we knew we could do it in safety, and fitted our vessel up for the purpose we intended to use her.

"This was soon done, and we commenced operations.

"The game was abundant, and our success far exceeded our most sanguine expectations.

"There would be no use undertaking to tell the number of vessels, French, English, Spanish and Dutch, that we captured and sunk, or of the poor devils we sent to a watery grave.

"But luck which had favored us so long, at last turned against as.

"The different governments became alarmed for the safety of their commerce in the seas which we frequented, and several expeditions were fitted out for our special benefit.

"For a while we only laughed at all this, for we had escaped so many times, that we began to think we were under the protection of old Neptune himself. But early one morning the man on the look-out reported a sail a short distance to the leeward, which seemed trying to get away from us.

"It was a small vessel, or brig, but as the weather was rather hazy, her character in other respects he could not make out.

"We thought, however, that it was a small trading vessel, which having discovered us, and suspecting our character, was trying to reach port before we could overtake her.

"Acting under this impression, we made all sail for her.

"As the strange vessel did not make very great headway, an hour's sailing brought as near enough to give us a pretty good view of her, yet we could not exactly make out her character, yet we thought that she had a rather suspicious look. And still she appeared rather like a traveling vessel, though if so, she could not have much cargo on board, and as the seemed built for speed, we wondered why she did not make better headway.

"But we were not long left in doubt in regard to her real character, for all at once her port-holes which had been purposely concealed were unmasked, and we received a broadside from her just as we were about to send her a messenger from our long tom.

"This broadside, although doing us little other damage, so cut our rigging as to render our escape now impossible if such had been our intention. So after returning the salute we had received, in as handsome a manner as we could, I gave orders to bear down upon the enemy's ship, which I was glad to see had been considerably disabled by our shot. But as she had greatly the advantage of us in the weight of material, our only hope was in boarding her, and fighting it out hand to hand on her own deck.

"The rigging of the two vessels was soon so entangled as to make it impossible to separate them.

"In spite of all the efforts of the crew of the enemy's vessel to oppose us we were soon upon her deck. We found she was a Spanish brigantine sent out purposely to capture us.

"Her apparent efforts to get away from us had been only a ruse to draw us on, so as to get us into a position from which there could be no escape.

"I have been in a good many fights, but never before one like that.

"As we expected no quarter, we gave none. The crew of the Spanish vessel rather outnumbered us, but not so greatly as to make the contest very unequal. And in our case desperation supplied the place of numbers.

"The deck was soon slippery with gore, and there were but few left to fight on either side. The captain of the Spanish vessel was one of the first killed. Some were shot down, some were hurled over the deck in the sea, some had their skulls broken with boarding pikes, and there was not a man left alive of the Spanish crew; and of ours, I at first thought that I was the only survivor, when the negro cook who had been forgotten all the while, came up from the cabin of our brig, bearing in his arms his little son, of course unharmed, but nearly frightened to death. Strange as it may appear, it is nevertheless true, that with the exception of a few slight scratches, I escaped without a wound.

"To my horror I now discovered that both vessels were fast sinking. But the cook set me at my ease on that score, by informing me that there was one small boat that had not been injured. Into this we immediately got, after having secured the small supply of provisions and water within our reach, which from the condition the vessels were, was very small.

"We had barely got clear of the sinking vessels, when they both went down, leaving us alone upon the wide ocean without compass or chart; not a sail in sight, and many a long, long league from the nearest coast.

"For more than a week we were tossing about on the waves without discovering a vessel. At last I saw that our provisions were nearly gone. We had been on short allowance from the first. At the rate they were going, they would not last more than two days longer. What was to be done? Self preservation, they say is the first law of human nature; to preserve my own life, I must sacrifice my companions. The moment the thought struck me it was acted upon.

"Sam, the black cook, was sitting a straddle the bow of the boat; with a push I sent him into the sea. I was going to send his boy after him, but the child clung to my legs in terror, and just at that moment a sail hove in sight and I changed my purpose.

"Such a groan of horror as the father gave on striking the water I never heard before, and trust I shall never hear again."

"At that instant the whole party sprang to their feet as if started by a shock of electricity, while most fearful groan resounded through the cavern, repeated by a thousand echos, each repetition growing fainter, and fainter until seeming to lose itself in the distance.

"That's it, that's it," said the captain, only louder, and if anything more horrible.

"But what does all this mean?" he demanded of Lightfoot, who had joined the astonished group.

"Don't know," said the woman.

"Where's Black Bill?" next demanded the captain.

"Here I is," said the boy crawling out from a recess in the wall in which he slept.

"Was that you, Bill?" demanded his master.

"No; dis is me," innocently replied the darkey.

"Do you know what that noise was?" asked the captain.

"S'pose 'twas de debble comin' after massa," said the boy.

"What do you mean, you wooley-headed imp," said the captain; "don't you know that the devil likes his own color best? Away to bed, away, you rascal!"

"Well, boys," said Flint, addressing the men and trying to appear very indifferent, "we have allowed ourselves to be alarmed by a trifle that can be easily enough accounted for.

"These rocks, as you see, are full of cracks and crevices; there may be other caverns under, or about as, for all we know. The wind entering these, has no doubt caused the noise we have beard, and which to our imaginations, somewhat heated by the liquor we have been drinking, has converted into the terrible groan which has so startled us, and now that we know what it is, I may as well finish my story.

"As I was saying, a sail hove in sight. It was a vessel bound to this port. I and the boy were taken on board and arrived here in safety.

"This boy, whether from love or fear, I can hardly say, has clung to me ever since.

"I have tried to shake him off several times, but it was no use, he always returns.

"The first business I engaged in on arriving here, was to trade with the Indians; when having discovered this cave, it struck me that it would make a fine storehouse for persons engaged in our line of business. Acting upon this hint, I fitted it up as you see.

"With a few gold pieces which I had secured in my belt I bought our little schooner. From that time to the present, my history it as well known to you as to myself. And now my long yarn is finished, let us go on with our sport."

But to recall the hilarity of spirits with which the entertainment had commenced, was no easy matter.

Whether the captain's explanation of the strange noise was satisfactory to himself or not, it was by no means so to the men.

Every attempt at singing, or story telling failed. The only thing that seemed to meet with any favor was the hot punch, and this for the most part, was drank in silence.

After a while they slunk away from the table one by one, and fell asleep in some remote corner of the cave, or rolled over where they sat, and were soon oblivious to everything around them.

The only wakeful one among them was the captain himself, who had drank but little.

He sat by the table alone. He started up! Could he have dozed and been dreaming? but surely he heard that groan again!

In a more suppressed voice than before, and not repeated so many times, but the same horrid groan; he could not be mistaken, he had never heard anything else like it. The matter must be looked into.

CHAPTER V.

Although it was nearly true, as Captain Flint had told his men, that they were about as well acquainted with his history since he landed in this country as he was himself, such is not the case with the reader. And in order that he may be as well informed in this matter as they were, we shall now endeavor to fill up the gap in the narrative.

To the crew of the vessel who had rescued him and saved his life, Captain Flint had represented himself as being one of the hands of a ship which had been wrecked at sea, and from which the only ones who had escaped, were himself and two negros, one of whom was the father of the boy who had been found with him. The father of the boy had fallen overboard, and been drowned just before the vessel hove in sight.

This story, which seemed plausible enough, was believed by the men into whose hands they had fallen, and Flint and the negro, received every attention which their forlorn condition required. And upon arriving in port, charitable people exerted themselves in the captain's behalf, procuring him employment, and otherwise enabling him to procure an honest livelihood, should he so incline.

But honesty was not one of the captain's virtues.

He had not been long in the country before he determined to try his fortune among the Indians.

He adopted this course partly because he saw in it a way of making money more rapidly than in any other, and partly because it opened to him a new field of wild adventure.

Having made the acquaintance of some of the Indians who were in the habit of coming to the city occasionally for the purpose of trading, he accompanied them to their home in the wilderness, and having previously made arrangements with merchants in the city, among others Carl Rosenthrall, to purchase or dispose of his furs, he was soon driving a thriving business. In a little while he became very popular with the savages, joined one of the tribes and was made a chief.

This state of things however, did not last long. The other chiefs became jealous of his influence, and incited the minds of many of the people against him.

They said he cheated them in his dealings, that his attachment to the red men was all pretence. That he was a paleface at heart, carrying on trade with the palefaces to the injury of the Indians. Killing them with his fire water which they gave them for their furs.

In all this there was no little truth, but Flint, confident of his power over his new friends, paid no attention to it.

A crisis came at last.

One of the chiefs who had been made drunk by whiskey which he had received from Flint in exchange for a lot of beaver skins, accused the latter of cheating him; called him a paleface thief who had joined the Indians only for the purpose of cheating them.

Flint forgetting his usual caution took the unruly savage by the shoulders and thrust him out of the lodge.

In a few moments the enraged Indian returned accompanied by another, when the two attacked the white man with knives and tomahawks.

Flint saw no way but to defend himself single-handed as he was, against two infuriated savages, and to do to if possible without killing either.

This he soon discovered was impossible. The only weapon he had at command was a hunting knife, and he had two strong men to contend against. Fortunately for him, one of them was intoxicated.

As it was, the savage who had begun the quarrel, was killed, and the other so badly wounded that he died a few hours afterwards.

The enmity of the whole tribe was now aroused against Flint, by the unfortunate termination of this affair.

It availed him nothing to contend that he had killed the two in self defence, and that they begun the quarrel.

He was a white man, and had killed two Indians, and that was enough.

Besides, how did they know whether he told the truth or not?

He was a paleface, and palefaces had crooked tongues, and their words could not be depended upon. Besides their brethren were dead, and could not speak for themselves.

Finally it was decided in the grand council of the tribe that he should suffer death, and although they called him a paleface, as he had joined the tribe he should be treated as an Indian, and suffer death by torture in order that he might have an opportunity of showing how he could endure the most horrible torment without complaining.

The case of Flint now seemed to be a desperate one. He was bound hand and foot, and escape seemed out of the question.

Relief came from a quarter he did not anticipate.

The place where this took place was not on the borders of the great lakes where the tribe to which Flint had attached himself belonged, but on the shores of the Hudson river a few miles above the Highlands, where a portion of the tribe had stopped to rest for a few days, while on their way to New York, where they were going for the purpose of trading.

It happened that there was among them a woman who had originally belonged to one of the tribes inhabiting this part of the country, but who while young, had been taken prisoner in some one of the wars that were always going on among the savages. She was carried away by her captors, and finally adopted into their tribe.

To this woman Flint had shown some kindness, and had at several times made her presents of trinkets and trifles such as he knew would gratify an uncultivated taste. And which cost him little or nothing. He little thought when making these trifling presents the service he was doing himself.

Late in the night preceding the day on which he was to have been executed, this woman came into the tent where he lay bound, and cut the thongs with which he was tied, and telling him in a whisper to follow her, she led the way out.

With stealthy and cautious steps they made their way through the encampment, but when clear of this, they traveled as rapidly as the darkness of the night and the nature of the ground would admit of.

All night, and a portion of the next day they continued their journey. The rapidity with which she traveled, and her unhesitating manner, soon convinced Flint that she was familiar with the country.

Upon reaching Butterhill, or Mount Tecomthe, she led the way to the cave which we have already described.

After resting for a few moments in the first chamber, the Indian woman, who we may as well inform the reader was none other than our friend Lightfoot, showed Flint the secret door and the entrance to the grand chamber, which after lighting a torch made of pitch-pine, they entered.

"Here we are safe," said Lightfoot; "Indians no find us here."

The moment Flint entered this cavern it struck him as being a fine retreat for a band of pirates or smugglers, and for this purpose he determined to make use of it.

Lightfoot's knowledge of this cave was owing to the fact, that she belonged to a tribe to whom alone the secrets of the place were known. It was a tribe that had inhabited that part of the country for centuries. But war and privation had so reduced them, that there was but a small remnant of them left, and strangers now occupied their hunting grounds.

The Indians in the neighborhood knew of the existence of the cave, but had never penetrated farther than the first chamber, knowing nothing of the concealed entrance which led to the other. Having as they said, seen Indians enter it who never came out again, and who although followed almost immediately could not be found there, they began to hold it in a kind of awe, calling it the mystery or medicine cave, and saying that it was under the guardianship of spirits.

Although the remnants of the once powerful tribe to whom this cave had belonged, were now scattered over the country, there existed between them a sort of masonry by which the different members could recognise each other whenever they met.

Fire Cloud, the Indian chief, who has already been introduced to the reader, was one of this tribe.

Although the existence of the cave was known to the members of the tribe generally, the whole of its secrets were known to the medicine men, or priests only.

In fact it might be considered the grand temple where they performed the mystic rites and ceremonies by which they imposed upon the people, and held them in subjection.

Flint immediately set about fitting up the place for the purpose which he intended it.

To the few white trappers who now and then visited the district, the existence of the cave was entirely unknown, and even the few Indians who hunted and fished in the neighborhood, were acquainted only with the outer cave as before stated.

When Flint was fully satisfied that all danger from pursuit was over, he set out for the purpose of going to the city in order to perfect the arrangements for carrying out the project he had in view.

On passing out, the first object that met his view was his faithful follower Black Bill, siting at the entrance.

"How the devil did you get here!" was his first exclamation.

"Follered de Ingins what was a comin' arter massa," replied the boy.

Bill had followed his master into the wilderness, always like a body servant keeping near his person when not prevented by the Indians, which was the case while his master was a prisoner.

When the escape of Flint was discovered, he was free from restraint, and he, unknown to the party who had gone in pursuit, had followed them.

From the negro, Flint learned that the Indians had tracked him to the cave, but not finding him there, and not being able to trace him any further, they had given up the pursuit.

Flint thinking that the boy might be of service to him in the business he was about to enter upon, took him into the cave and put him in charge of Lightfoot.

On reaching the city, Flint purchased the schooner of which he was in command when first introduced to the reader.

It is said that, "birds of a feather flock together," and Flint having no difficulty gathering about him a number of kindred spirits, was soon in a condition to enter upon the profession as he called it, most congenial to his taste and habits.

CHAPTER VI.

When the crew of the schooner woke up on the morning following the night in which we have described in a previous chapter, they were by no means the reckless, dare-devil looking men they were when they entered the cave on the previous evening.

For besides the usual effects produced on such characters by a night's debauch, their countenances wore the haggard suspicious look of men who felt judgment was hanging over them; that they were in the hands of some mysterious power beyond their control. Some power from which they could not escape, and which sooner or later, would mete out to them the punishment they felt that they deserved.

They had all had troubled dreams, and several of them declared that they had heard that terrible groan during the night repeated if possible, in a more horrible manner than before.

To others the ghosts of the men they had lately murdered, appeared menacing them with fearful retribution.

As the day advanced, and they had to some extent recovered their spirits by the aid of their favorite stimulants, they attempted to laugh the matter off as a mere bugbear created by an imagination over heated by too great an indulgence in strong drink.

Although this opinion was not shared by Captain Flint, who had carefully abstained from over-indulgence, for reasons of his own, he encouraged it in his men.

But even they, while considering it necessary to remain quiet for a few days, to see whether or not, any harm should result to them, in consequence of their late attack on the merchant ship, none of them showed a disposition to pass another night in the cave.

Captain Flint made no objection to his men remaining outside on the following night, as it would give him the opportunity to investigate the matter, which he desired.

On the next night, when there was no one in the cavern but himself and the two who usually occupied it, he called Lightfoot to him, and asked her if she had ever heard any strange noises in the place before.

"Sometime heard de voices of the Indian braves dat gone to the spirit land," said the woman.

"Did you ever hear anything like the groan we heard last night?"

"Neber," said Lightfoot.

"What do you think it was?" asked the captain.

"Tink him de voice ob the great bad spirit," was the reply.

Captain Flint, finding that he was not likely to learn anything in this quarter that would unravel the mystery, now called the negro.

"Bill," he said, "did you ever hear that noise before?"

"Ony once, massa."

"When was that, Bill?"

"When you trow my—"

"Hold your tongue, you black scoundrel, or I'll break every bone in your body!" roared his master, cutting off the boy's sentence in the middle.

The boy was going to say:

"When you trow'd my fadder into the sea."

The captain now examined every portion of the cavern, to see if he could discover anything that could account for the production of the strange sound.

In every part he tried his voice, to see if he could produce those remarkable echoes, which had so startled him, on the previous night, but without success.

The walls, in various parts of the cavern, gave back echoes, but nothing like those of the previous night.

There were two recesses in opposite sides of the cave. The larger one of these was occupied by Lightfoot as a sleeping apartment. The other, which was much smaller, Black Bill made use of for the same purpose.

From these two recesses, the captain had everything removed, in order that he might subject them to a careful examination.

But with no better success than before.

He tried his voice here, as in other parts of the cavern, but the walls gave back no unusual echoes.

He was completely baffled, and, placing his lamp on the table, he sat down on one of the seats, to meditate on what course next to pursue.

Lightfoot and Bill soon after, at his request, retired.

He had been seated, he could not tell how long, with his head resting on his hands, when he was aroused by a yell more fearful, if possible, even than the groan that had so alarmed him on the previous night.

The yell was repeated in the same horrible and mysterious manner that the groan had been.

Flint sprang to his feet while the echoes were still ringing in his ears, and rushed to the sleeping apartment, first, to that of the Indian woman, and then, to that of the negro.

They both seemed to be sound asleep, to all appearance, utterly unconscious of the fearful racket that was going on around them.

Captain Flint, more perplexed and bewildered than ever, resumed his seat by the table; but not to sleep again that night, though the fearful yell was not repeated.

The captain prided himself on being perfectly free from all superstition.

He held in contempt the stories of ghosts of murdered men coming back to torment their murderers.

In fact, he was very much inclined to disbelieve in any hereafter at all, taking it to be only an invention of cunning priests, for the purpose of extorting money out of their silly dupes. But here was something, which, if not explained away, would go far to stagger his disbelief.

He was glad that the last exhibition had only been witnessed by himself, and that the men for the present preferred passing their nights outside; for, as he learned from Lightfoot, the noises were only during the night time.

This would enable him to continue his investigation without any interference on the part of the crew, whom he wished to keep in utter ignorance of what he was doing, until he had perfectly unraveled the mystery.

For this purpose, he gave Lightfoot and Black Bill strict charges not to inform the men of what had taken place during the night.

He was determined to pass the principal portion of the day in sleep, so as to be wide awake when the time should come for him to resume his investigations.

CHAPTER VII.

On the day after the first scene in the cave, late in the afternoon, three men sat on the deck of the schooner, as she lay in the shadow of forest covered mountain.

These were Jones Bradley, Old Ropes, and the man who went by the name of the Parson. They were discussing the occurrences of the previous night.

"I'm very much of the captains opinion," said the Parson, "that the noises are caused by the wind rushing through the chinks and crevices of the rocks."

"Yes; but, then, there wan't no wind to speak of, and how is the wind to make that horrible groan, s'pose it did blow a hurricane?" said Jones Bradley.

"Just so," said Old Ropes; "that notion about the wind makin' such a noise at that, is all bosh. My opinion is, that it was the voice of a spirit. I know that the captain laughs at all such things, but all his laughin' don't amount to much with one that's seen spirits."

"What! you don't mean to say that you ever actually see a live ghost?" asked the Parson.

"That's jist what I do mean to say," replied Old Ropes.

"Hadn't you been takin' a leetle too much, or wasn't the liquor too strong?" said the Parson.

"Well, you may make as much fun about it as you please," said Old Ropes; "but I tell you, that was the voice of a spirit, and, what's more, I believe it's either the spirit of some one that's been murdered in that cave, by some gang that's held it before, and buried the body over the treasure they've stowed away there, or else the ghost of some one's that's had foul play from the captain."

"Well," said the Parson, "if I thought there was any treasure there worth lookin' after, all the ghosts you could scare up wouldn't hinder me from trying to get at it."

"But, no matter about that; you say you see a live ghost once. Let's hear about that."

"I suppose," said Old Ropes, "that there aint no satisfaction in a feller's tellin' of things that aint no credit to him; but, howsomever, I might as well tell this, as, after all, it's only in the line of our business.

"You must know, then, that some five years ago, I shipped on board a brig engaged in the same business that our craft is.

"I needn't tell you of all the battles we were in, and all the prizes we made; but the richest prize that ever come in our way, was a Spanish vessel coming from Mexico, With a large amount of gold and silver on board.

"We attacked the ship, expecting to make an easy prize of her, but we were disappointed.

"The Spaniards showed fight, and gave us a tarnal sight of trouble. Several of our best men were killed.

"This made our captain terrible wrothy. He swore that every soul that remained alive on the captured vessel should be put to death.

"Now, it so happened that the wife and child (an infant,) of the captain of the Spanish vessel, were on board. When the others had all been disposed of, the men plead for the lives of these two. But our captain would not listen to it; but he would let us cast lots to see which of us would perform the unpleasant office.

"As bad luck would have it, the lot fell upon me. There was no shirking it.

"It must be done; so, the plank was got ready. She took the baby in her arms, stepped upon the plank, as I ordered her, and the next moment, she, with the child in her arms, sank to rise no more; but the look she gave me, as she went down, I shall never forget.

"It haunts me yet, and many and many is the time that Spanish woman, with the child in her arms, has appeared to me, fixing upon me the same look that she gave me, as she sank in the sea.

"Luck left us from that time; we never took a prize afterwards.

"Our Vessel was captured by a Spanish cruiser soon afterwards. I, with one other, succeeded in making our escape.

"The captain, and all the rest, who were not killed in the battle, were strung out on the yard-arm."

"Does the ghost never speak to you?" asked the Parson.

"Never," replied Old Ropes.

"I suppose that's because she's a Spaniard, and thinks you don't understand her language," remarked the Parson, sneeringly. "I wonder why this ghost of the cave don't show himself, and not try to frighten us with his horrible boo-wooing."

"Well, you may make as much fun as you please," replied Old Ropes; "but, mark my words for it, if the captain don't pay attention to the warning he has had, that ghost will show himself in a way that won't be agreeable to any of us."

"If he takes my advice, he'll leave the cave, and take up his quarters somewhere else."

"What! you don't mean to say you're afraid!" quietly remarked the Parson.

"Put an enemy before me in the shape of flesh and blood, and I'll show you whether I'm afeard, or not," said Old Ropes; "but this fighting with dead men's another affair. The odds is all agin you. Lead and steel wont reach 'em, and the very sight on 'em takes the pluck out of a man, whether he will or no.

"An enemy of real flesh and blood, when he does kill you, stabs you or shoots you down at once, and there's an end of it; but, these ghosts have a way of killing you by inches, without giving a fellow a chance to pay them back anything in return."

"It's pretty clear, anway, that they're a 'tarnal set of cowards," remarked the Parson.

"The biggest coward's the bravest men, when there's no danger," retorted Old Ropes.

To this, the Parson made no reply, thinking, probably, that he had carried the joke far enough, and not wishing to provoke a quarrel with his companion.

"As to the affair of the cave," said Jones Bradley; "I think very much as Old Ropes does about it. I'm opposed to troubling the dead, and I believe there's them buried there that don't want to be disturbed by us, and if we don't mind the warning they give us, still the worse for us."

"The captain don't seem to be very much alarmed about it," said the Parson; "for he stays in the cave. And, then, there's the Indian woman and the darkey; the ghost don't seem to trouble them much."

"I'll say this for Captain Flint," remarked Old Ropes, "if ever I knowed a man that feared neither man nor devil, that man is Captain Flint; but his time'll come yet."

"You don't mean to say you see breakers ahead, do you?" asked the Parson.

"Not in the way of our business, I don't mean," said Ropes; "but, I've had a pretty long experience in this profession, and have seen the finishing up of a good many of my shipmates; and I never know'd one that had long experience, that would not tell you that he had been put more in fear by the dead than ever he had by the living."

"We all seem to be put in low spirits by this afternoon," said the Parson; "s'pose we go below, and take a little something to cheer us up."

To this the others assented, and all three went below.

CHAPTER VIII.

All Captain Flint's efforts to unravel the mysteries of the cave were unsuccessful; and he was reluctantly obliged to give up the attempt, at least for the present; but, in order to quiet the minds of the crew, he told them that he had discovered the cause, and that it was just what he had supposed it to be.

As everything remained quiet in the cave for a long time after this, and the minds of the men were occupied with more important matters, the excitement caused by it wore off; and, in a while, the affair seemed to be almost forgotten.

And here we may as well go back a little in our narrative, and restore the chain where it was broken off a few chapters back.

When Captain Flint had purchased the schooner which he commanded, it was with the professed object of using her as a vessel to trade with the Indians up the rivers, and along the shore, and with the various seaports upon the coast.

To this trade it is true, he did to some extent apply himself, but only so far as it might serve as a cloak to his secret and more dishonorable and dishonest practices.

Had Flint been disposed to confine himself to the calling he pretended to follow, he might have made a handsome fortune in a short time, but that would not have suited the corrupt and desperate character of the man.

He was like one of those wild animals which having once tasted blood, have ever afterward an insatiable craving for it.

It soon became known to a few of the merchants in the city, among the rest Carl Rosenthrall, that Captain Flint had added to his regular business, that of smuggling.

This knowledge, however, being confined to those who shared the profits with him, was not likely to be used to his disadvantage.

After a while the whole country was put into a state of alarm by the report that a desperate pirate had appeared on the coast.

Several vessels which had been expected to arrive with rich cargoes had not made their appearance, although the time for their arrival had long passed. There was every reason to fear that they had been captured by this desperate stranger who had sunk them, killing all on board.

The captain of some vessels which had arrived in safety reported having been followed by a suspicious looking craft.

They said she was a schooner about the size of one commanded by Captain Flint, but rather longer, having higher masts and carrying more sail.

No one appeared to be more excited on the subject of the pirate, than Captain Flint. He declared that he had seen the mysterious vessel, had been chased by her, and had only escaped by his superior sailing.

Several vessels had been fitted out expressly for the purpose of capturing this daring stranger, but all to no purpose; nothing could be seen of her.

For a long time she would seem to absent herself from the coast, and vessels would come and go in safety. Then all of a sudden, she would appear again and several vessels would be missing, and never heard from more.

The last occurrence of this kind is the one which we have already given an account of the capturing and sinking of the vessel in which young Billings had taken passage for Europe.

We have already seen how Hellena Rosenthrall's having accidentally discovered her lover's ring on the finger of Captain Flint, had excited suspicions of the merchant's daughter, and what happened to her in consequence.

Captain Flint having made it the interest of Rosenthrall to keep his suspicions to himself if he still adhered to them, endeavored to convince him that his daughter was mistaken, and that the ring however much it might resemble the one belonging to her lover, was one which had been given to him by his own mother at her death, and had been worn by her as long as he could remember.

This explanation satisfied, or seemed to satisfy the merchant, and the two men appeared to be as good friends as ever again.

The sudden and strange disappearance of the daughter of a person of so much consequence as Carl Rosenthrall, would cause no little excitement in a place no larger than New York was at the time of which we write.

Most of the people agreed in the opinion with the merchant that the girl had been carried off by the Indian Fire Cloud, in order to avenge himself for the insult he had received years before. As we have seen, Captain Flint encouraged this opinion, and promised that in an expedition he was about fitting out for the Indian country, he would make the recovery of the young woman one of his special objects.

Flint knew all the while where Fire Cloud was to be found, and fearing that he might come to the city ignorant as he was of the suspicion he was laboring under, and thereby expose the double game he was playing, he determined to visit the Indian in secret, under pretence of putting him on his guard, but in reality for the purpose of saving himself.

He sought out the old chief accordingly, and warned him of his danger.

Fire Cloud was greatly enraged to think that he should be suspected carrying off the young woman.

"He hated her father," he said, "for he was a cheat, and had a crooked tongue. But the paleface maiden was his friend, and for her sake he would find her if she was among his people, and would restore her to her friends."

"If you enter the city of the palefaces, they will hang you up like a dog without listening to anything you have to say in your defence," said Flint.

"The next time Fire Cloud enters the city of the palefaces, the maiden shall accompany him," replied the Indian.

This was the sort of an answer that Flint wished, and expected, and he now saw that there was no danger to be apprehended from that quarter.

But if Captain Flint felt himself relieved from danger in this quarter, things looked rather squally in another. If he knew how to disguise his vessel by putting on a false bow so as to make her look longer, and lengthen the masts so as to make her carry more sail, he was not the only one who understood these tricks. And one old sailor whose bark had been chased by the strange schooner, declared that she very much resembled Captain Flint's schooner disguised in this way.

And then it was observed that the strange craft was never seen when the captain's vessel was lying in port, or when she was known to be up the river where he was trading among the Indians.

Another suspicious circumstance was, that shortly after the strange disappearance of a merchant vessel, Flint's schooner came into port with her rigging considerably damaged, as if she had suffered from some unusual cause. Flint accounted for it by saying that he had been fired into by the pirate, and had just escaped with the skin of his teeth.

These suspicions were at first spoken cautiously, and in whispers only, by a very few.

They came to the ears of Flint himself at last, who seeing the danger immediately set about taking measures to counteract it by meeting and repelling, what he pretended to consider base slanders invented by his enemies for the purpose of effecting his ruin.