The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 10, Slice 2, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 10, Slice 2

"Fairbanks, Erastus" to "Fens"

Author: Various

Release Date: June 17, 2011 [EBook #36452]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

FAIRBANKS, ERASTUS (1792-1864), American manufacturer, was born in Brimfield, Massachusetts, on the 28th of October 1792. He studied law but abandoned it for mercantile pursuits, finally settling in St Johnsbury, Vermont, where in 1824 he formed a partnership with his brother Thaddeus for the manufacture of stoves and ploughs. Subsequently the scales invented by Thaddeus were manufactured extensively. Erastus was a member of the state legislature in 1836-1838, and governor of Vermont in 1852-1853 and 1860-1861, during his second term rendering valuable aid in the equipment and despatch of troops in the early days of the Civil War. His son Horace (1820-1888) became president of E. & T. Fairbanks & Co. in 1874, and was governor of Vermont from 1876 to 1878.

His brother, Thaddeus Fairbanks (1796-1886), inventor, was born at Brimfield, Massachusetts, on the 17th of January 1796. He early manifested a genius for mechanics and designed the models from which he and his brother manufactured stoves and ploughs at St Johnsbury. In 1826 he patented a cast-iron plough which was extensively used. The growing of hemp was an important industry in the vicinity of St Johnsbury, and in 1831 Fairbanks invented a hemp-dressing machine. By the old contrivances then in use, the weighing of loads of hemp-straw was tedious and difficult, and in 1831 Fairbanks invented his famous compound-lever platform scale, which marked a great advance in the construction of machines for weighing bulky and heavy objects. He subsequently obtained more than fifty patents for improvements or innovations in scales and in machinery used in their manufacture, the last being granted on his ninetieth birthday. His firm, eventually known as E. & T. Fairbanks & Co., went into the manufacture of scales of all sizes, in which these inventions were utilized. He, with his brothers, Erastus and Joseph P., founded the St Johnsbury Academy. He died at St Johnsbury on the 12th of April 1886.

The latter’s son Henry, born in 1830 at St Johnsbury, Vermont, graduated at Dartmouth College in 1853 and at Andover Theological Seminary in 1857, and was professor of natural philosophy at Dartmouth from 1859 to 1865 and of natural history from 1865 to 1868. In the following year he patented a grain-scale and thenceforth devoted himself to the scale manufacturing business of his family. Altogether he obtained more than thirty patents for mechanical devices.

FAIRFAX, EDWARD (c. 1580-1635), English poet, translator of Tasso, was born at Leeds, the second son of Sir Thomas Fairfax of Denton (father of the 1st Baron Fairfax of Cameron). His legitimacy has been called in question, and the date of his birth has not been ascertained. He is said to have been only about twenty years of age when he published his translation of the Gerusalemme Liberala, which would place his birth about the year 1580. He preferred a life of study and retirement to the military service in which his brothers were distinguished. He married a sister of Walter Laycock, chief alnager of the northern counties, and lived on a small estate at Fewston, Yorkshire. There his time was spent in his literary pursuits, and in the education of his children and those of his elder brother, Sir Thomas Fairfax, afterwards baron of Cameron. His translation appeared in 1600,—Godfrey of Bulloigne, or the Recoverie of Jerusalem, done into English heroicall Verse by Edw. Fairefax, Gent., and was dedicated to the queen. It was enthusiastically received. In the same year in which it was published extracts from it were printed in England’s Parnassus. Edward Phillips, the nephew of Milton, in his Theatrum Poetarum, warmly eulogized the translation. Edmund Waller said he was indebted to it for the harmony of his numbers. It is said that it was King James’s favourite English poem, and that Charles I. entertained himself in prison with its pages. Fairfax employed the same number of lines and stanzas as his original, but within the limits of each stanza he allowed himself the greatest liberty. Other translators may give a more literal version, but Fairfax alone seizes upon the poetical and chivalrous character of the poem. He presented, says Mr Courthope, “an idea of the chivalrous past of Europe, as seen through the medium of Catholic orthodoxy and classical humanism.” The sweetness and melody of many passages are scarcely excelled even by Spenser. Fairfax made no other appeal to the public. He wrote, however, a series of eclogues, twelve in number, the fourth of which was published, by permission of the family, in Mrs Cooper’s Muses’ Library (1737). Another of the eclogues and a Discourse on Witchcraft, as it was acted in the Family of Mr Edward Fairfax of Fuystone in the county of York in 1621, edited from the original copy by Lord Houghton, appeared in the Miscellanies of the Philobiblon Society (1858-1859). Fairfax was a firm believer in witchcraft. He fancied that two of his children had been bewitched, and he had the poor wretches whom he accused brought to trial, but without obtaining a conviction. Fairfax died at Fewston and was buried there on the 27th of January 1635.

FAIRFAX OF CAMERON, FERDINANDO FAIRFAX, 2nd Baron (1584-1648), English parliamentary general, was a son of Thomas Fairfax of Denton (1560-1640), who in 1627 was 131 created Baron Fairfax of Cameron in the peerage of Scotland. Born on the 29th of March 1584, he obtained his military education in the Netherlands, and was member of parliament for Boroughbridge during the six parliaments which met between 1614 and 1629 and also during the Short Parliament of 1640. In May 1640 he succeeded his father as Baron Fairfax, but being a Scottish peer he sat in the English House of Commons as one of the representatives of Yorkshire during the Long Parliament from 1640 until his death; he took the side of the parliament, but held moderate views and desired to maintain the peace. In the first Scottish war Fairfax had commanded a regiment in the king’s army; then on the outbreak of the Civil War in 1642 he was made commander of the parliamentary forces in Yorkshire, with Newcastle as his opponent. Hostilities began after the repudiation of a treaty of neutrality entered into by Fairfax with the Royalists. At first he met with no success. He was driven from York, where he was besieging the Royalists, to Selby; then in 1643 to Leeds; and after beating off an attack at that place he was totally defeated on the 30th of June at Adwalton Moor. He escaped to Hull, which he successfully defended against Newcastle from the 2nd of September till the 11th of October, and by means of a brilliant sally caused the siege to be raised. Fairfax was victorious at Selby on the 11th of April 1644, and joining the Scots besieged York, after which he was present at Marston Moor, where he commanded the infantry and was routed. He was subsequently, in July, made governor of York and charged with the further reduction of the county. In December he took the town of Pontefract, but failed to secure the castle. He resigned his command on the passing of the Self-denying Ordinance, but remained a member of the committee for the government of Yorkshire, and was appointed, on the 24th of July 1645, steward of the manor of Pontefract. He died from an accident on the 14th of March 1648 and was buried at Bolton Percy. He was twice married, and by his first wife, Mary, daughter of Edmund Sheffield, 3rd Lord Sheffield (afterwards 1st earl of Mulgrave), he had six daughters and two sons, Thomas, who succeeded him as 3rd baron, and Charles, a colonel of horse, who was killed at Marston Moor. During his command in Yorkshire, Fairfax engaged in a paper war with Newcastle, and wrote The Answer of Ferdinando, Lord Fairfax, to a Declaration of William, earl of Newcastle (1642; printed in Rushworth, pt. iii. vol. ii. p. 139); he also published A Letter from ... Lord Fairfax to ... Robert, Earl of Essex (1643), describing the victorious sally at Hull.

FAIRFAX OF CAMERON, THOMAS FAIRFAX, 3rd Baron (1612-1671), parliamentary general and commander-in-chief during the English Civil War, the eldest son of the 2nd lord, was born at Denton, near Otley, Yorkshire, on the 17th of January 1612. He studied at St John’s College, Cambridge (1626-1629), and then proceeded to Holland to serve as a volunteer with the English army in the Low Countries under Sir Horace (Lord) Vere. This connexion led to one still closer; in the summer of 1637 Fairfax married Anne Vere, the daughter of the general.

The Fairfaxes, father and son, though serving at first under Charles I. (Thomas commanded a troop of horse, and was knighted by the king in 1640), were opposed to the arbitrary prerogative of the crown, and Sir Thomas declared that “his judgment was for the parliament as the king and kingdom’s great and safest council.” When Charles endeavoured to raise a guard for his own person at York, intending it, as the event afterwards proved, to form the nucleus of an army, Fairfax was employed to present a petition to his sovereign, entreating him to hearken to the voice of his parliament, and to discontinue the raising of troops. This was at a great meeting of the freeholders and farmers of Yorkshire convened by the king on Heworth Moor near York. Charles evaded receiving the petition, pressing his horse forward, but Fairfax followed him and placed the petition on the pommel of the king’s saddle. The incident is typical of the times and of the actors in the scene. War broke out, Lord Fairfax was appointed general of the Parliamentary forces in the north, and his son, Sir Thomas, was made lieutenant-general of the horse under him. Both father and son distinguished themselves in the campaigns in Yorkshire (see Great Rebellion). Sometimes severely defeated, more often successful, and always energetic, prudent and resourceful, they contrived to keep up the struggle until the crisis of 1644, when York was held by the marquess of Newcastle against the combined forces of the English Parliamentarians and the Scots, and Prince Rupert hastened with all available forces to its relief. A gathering of eager national forces within a few square miles of ground naturally led to a battle, and Marston Moor (q.v.) was decisive of the struggle in the north. The younger Fairfax bore himself with the greatest gallantry in the battle, and though severely wounded managed to join Cromwell and the victorious cavalry on the other wing. One of his brothers, Colonel Charles Fairfax, was killed in the action. But the marquess of Newcastle fled the kingdom, and the Royalists abandoned all hope of retrieving their affairs. The city of York was taken, and nearly the whole north submitted to the parliament.

In the south and west of England, however, the Royalist cause was still active. The war had lasted two years, and the nation began to complain of the contributions that were exacted, and the excesses that were committed by the military. Dissatisfaction was expressed with the military commanders, and, as a preliminary step to reform, the Self-denying Ordinance was passed. This involved the removal of the earl of Essex from the supreme command, and the reconstruction of the armed forces of the parliament. Sir Thomas Fairfax was selected as the new lord general with Cromwell as his lieutenant-general and cavalry commander, and after a short preliminary campaign the “New Model” justified its existence, and “the rebels’ new brutish general,” as the king called him, his capacity as commander-in-chief in the decisive victory of Naseby (q.v.). The king fled to Wales. Fairfax besieged Leicester, and was successful at Taunton, Bridgwater and Bristol. The whole west was soon reduced.

Fairfax arrived in London on the 12th of November 1645. In his progress towards the capital he was accompanied by applauding crowds. Complimentary speeches and thanks were presented to him by both houses of parliament, along with a jewel of great value set with diamonds, and a sum of money. The king had returned from Wales and established himself at Oxford, where there was a strong garrison, but, ever vacillating, he withdrew secretly, and proceeded to Newark to throw himself into the arms of the Scots. Oxford capitulated, and by the end of September 1646 Charles had neither army nor garrison in England. In January 1647 he was delivered up by the Scots to the commissioners of parliament. Fairfax met the king beyond Nottingham, and accompanied him during the journey to Holmby, treating him with the utmost consideration in every way. “The general,” said Charles, “is a man of honour, and keeps his word which he had pledged to me.” With the collapse of the Royalist cause came a confused period of negotiations between the parliament and the king, between the king and the Scots, and between the Presbyterians and the Independents in and out of parliament. In these negotiations the New Model Army soon began to take a most active part. The lord general was placed in the unpleasant position of intermediary between his own officers and parliament. To the grievances, usual in armies of that time, concerning arrears of pay and indemnity for acts committed on duty, there was quickly added the political propaganda of the Independents, and in July the person of the king was seized by Joyce, a subaltern of cavalry—an act which sufficiently demonstrated the hopelessness of controlling the army by its articles of war. It had, in fact, become the most formidable political party in the realm, and pressed straight on to the overthrow of parliament and the punishment of Charles. Fairfax was more at home in the field than at the head of a political committee, and, finding events too strong for him, he sought to resign his commission as commander-in-chief. He was, however, persuaded to retain it. He thus remained the titular chief of the army party, and with the greater part of its objects 132 he was in complete, sometimes most active, sympathy. Shortly before the outbreak of the second Civil War, Fairfax succeeded his father in the barony and in the office of governor of Hull; In the field against the English Royalists in 1648 he displayed his former energy and skill, and his operations culminated in the successful siege of Colchester, after the surrender of which place he approved the execution of the Royalist leaders Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle, holding that these officers had broken their parole. At the same time Cromwell’s great victory of Preston crushed the Scots, and the Independents became practically all-powerful.

Milton, in a sonnet written during the siege of Colchester, called upon the lord general to settle the kingdom, but the crisis was now at hand. Fairfax was in agreement with Cromwell and the army leaders in demanding the punishment of Charles, and he was still the effective head of the army. He approved, if he did not take an active part in, Pride’s Purge (December 6th, 1648), but on the last and gravest of the questions at issue he set himself in deliberate and open opposition to the policy of the officers. He was placed at the head of the judges who were to try the king, and attended the preliminary sitting of the court. Then, convinced at last that the king’s death was intended, he refused to act. In calling over the court, when the crier pronounced the name of Fairfax, a lady in the gallery called out “that the Lord Fairfax was not there in person, that he would never sit among them, and that they did him wrong to name him as a commissioner.” This was Lady Fairfax, who could not forbear, as Whitelocke says, to exclaim aloud against the proceedings of the High Court of Justice. His last service as commander-in-chief was the suppression of the Leveller mutiny at Burford in May 1649. He had given his adhesion to the new order of things, and had been reappointed lord general. But he merely administered the affairs of the army, and when in 1650 the Scots had declared for Charles II., and the council of state resolved to send an army to Scotland in order to prevent an invasion of England, Fairfax resigned his commission. Cromwell was appointed his successor, “captain-general and commander-in-chief of all the forces raised or to be raised by authority of parliament within the commonwealth of England.” Fairfax received a pension of £5000 a year, and lived in retirement at his Yorkshire home of Nunappleton till after the death of the Protector. The troubles of the later Commonwealth recalled Lord Fairfax to political activity, and for the last time his appearance in arms helped to shape the future of the country, when Monk invited him to assist in the operations about to be undertaken against Lambert’s army. In December 1659 he appeared at the head of a body of Yorkshire gentlemen, and such was the influence of Fairfax’s name and reputation that 1200 horse quitted Lambert’s colours and joined him. This was speedily followed by the breaking up of all Lambert’s forces, and that day secured the restoration of the monarchy. A “free” parliament was called; Fairfax was elected member for Yorkshire, and was put at the head of the commission appointed by the House of Commons to wait upon Charles II. at the Hague and urge his speedy return. Of course the “merry monarch, scandalous and poor,” was glad to obey the summons, and Fairfax provided the horse on which Charles rode at his coronation. The remaining eleven years of the life of Lord Fairfax were spent in retirement at his seat in Yorkshire. He must, like Milton, have been sorely grieved and shocked by the scenes that followed—the brutal indignities offered to the remains of his companions in arms, Cromwell and Ireton, the sacrifice of Sir Harry Vane, the neglect or desecration of all that was great, noble or graceful in England, and the flood of immorality which, flowing from Whitehall, sapped the foundations of the national strength and honour. Lord Fairfax died at Nunappleton on the 12th of November 1671, and was buried at Bilborough, near York. As a soldier he was exact and methodical in planning, in the heat of battle “so highly transported that scarce any one durst speak a word to him” (Whitelocke), chivalrous and punctilious in his dealings with his own men and the enemy. Honour and conscientiousness were equally the characteristics of his private and public character. But his modesty and distrust of his powers made him less effectual as a statesman than as a soldier, and above all he is placed at a disadvantage by being both in war and peace overshadowed by his associate Cromwell.

Lord Fairfax had a taste for literature. He translated some of the Psalms, and wrote poems on solitude, the Christian warfare, the shortness of life, &c. During the last year or two of his life he wrote two Memorials which have been published—one on the northern actions in which he was engaged in 1642-1644, and the other on some events in his tenure of the chief command. At York and at Oxford he endeavoured to save the libraries from pillage, and he enriched the Bodleian with some valuable MSS. His only daughter, Mary Fairfax, was married to George Villiers, the profligate duke of Buckingham of Charles II.’s court.

His correspondence, edited by G.W. Johnson, was published in 1848-1849 in four volumes (see note thereon in Dict. Nat. Biogr., s.v.), and a life of him by Clements R. Markham in 1870. See also S.R. Gardiner, History of the Great Civil War (1893).

His descendant Thomas, 6th baron (1692-1782), inherited from his mother, the heiress of Thomas, 2nd Baron Culpepper, large estates in Virginia, U.S.A., and having sold Denton Hall and his Yorkshire estates he retired there about 1746, dying a bachelor. He was a friend of George Washington. Thomas found his cousin William Fairfax settled in Virginia, and made him his agent, and Bryan (1737-1802), the son of William Fairfax, eventually inherited the title, becoming 8th baron in 1793. His claim was admitted by the House of Lords in 1800. But it was practically dropped by the American family, until, shortly before the coronation of Edward VII., the successor in title was discovered in Albert Kirby Fairfax (b. 1870), a descendant of the 8th baron, who was an American citizen. In November 1908 Albert’s claim to the title as 12th baron was allowed by the House of Lords.

FAIRFIELD, a township in Fairfield county, Connecticut, U.S.A., near Long Island Sound, adjoining Bridgeport on the E. and Westport on the W. Pop. (1890) 3868; (1900) 4489 (1041 being foreign-born); (1910) 6134. It is served by the New York, New Haven & Hartford railway. The principal villages of the township are Fairfield, Southport, Greenfield Hill and Stratfield. The beautiful scenery and fine sea air attract to the township a considerable number of summer visitors. The township has the well-equipped Pequot and Fairfield memorial libraries (the former in the village of Southport, the latter in the village of Fairfield), the Fairfield fresh air home (which cares for between one and two hundred poor children of New York during each summer season), and the Gould home for self-supporting women. The Fairfield Historical Society has a museum of antiquities and a collection of genealogical and historical works. Among Fairfield’s manufactures are chemicals, wire and rubber goods. Truck-gardening is an important industry of the township. In the Pequot Swamp within the present Fairfield a force of Pequot Indians was badly defeated in 1637 by some whites, among whom was Roger Ludlow, who, attracted by the country, founded the settlement in 1639 and gave it its present name in 1645. Within its original limits were included what are now the townships of Redding (separated, 1767), Weston (1787) and Easton (formed from part of Weston in 1845), and parts of the present Westport and Bridgeport. During the colonial period Fairfield was a place of considerable importance, but subsequently it was greatly outstripped by Bridgeport, to which, in 1870, a portion of it was annexed. On the 8th of July 1779 Fairfield was burned by the British and Hessians under Governor William Tryon. Among the prominent men who have lived in Fairfield are Roger Sherman, the first President Dwight of Yale (who described Fairfield in his Travels and in his poem Greenfield Hill), Chancellor James Kent, and Joseph Earle Sheffield.

See Frank S. Child, An Old New England Town, Sketches of Life, Scenery and Character (New York, 1895); and Mrs E.H. Schenck, History of Fairfield (2 vols., New York, 1889-1905).

FAIRFIELD, a city and the county-seat of Jefferson county, Iowa, U.S.A., about 51 m. W. by N. of Burlington. Pop. (1890) 3391; (1900) 4689, of whom 206 were foreign-born and 54 were 133 negroes; (1905) 5009; (1910) 4970. Area, about 2.25 sq. m. Fairfield is served by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, and the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific railways. The city is in a blue grass country, in which much live stock is bred; and it is an important market for draft horses. It is the seat of Parsons College (Presbyterian, coeducational, 1875), endowed by Lewis Baldwin Parsons, Sr. (1798-1855), a merchant of Buffalo, N.Y. The college offers classical, philosophical and scientific courses, and has a school of music and an academic department; in 1907-1908 it had 19 instructors and 257 students, of whom 93 were in the college and 97 were in the school of music. Fairfield has a Carnegie library (1892), and a museum with a collection of laces. Immediately E. of the city is an attractive Chautauqua Park, of 30 acres, with an auditorium capable of seating about 4000 persons; and there is an annual Chautauqua assembly. The principal manufactures of Fairfield are farm waggons, farming implements, drain-tile, malleable iron, cotton gloves and mittens and cotton garments. The municipality owns its waterworks and an electric-lighting plant. Fairfield was settled in 1839; was incorporated as a town in 1847; and was first chartered as a city in the same year.

See Charles H. Fletcher, Jefferson County, Iowa: Centennial History (Fairfield, 1876).

FAIRHAVEN, a township in Bristol county, Massachusetts, U.S.A., on New Bedford Harbor, opposite New Bedford. Pop. (1890) 2919; (1900) 3567 (599 being foreign-born); (1905, state census) 4235; (1910) 5122. Area, about 13 sq. m. Fairhaven is served by the New York, New Haven & Hartford railway and by electric railway to Mattapoisett and Marion, and is connected with New Bedford by two bridges, by electric railway, and by the New York, New Haven & Hartford ferry line. The principal village is Fairhaven; others are Oxford, Naskatucket and Sconticut Neck. As a summer resort Fairhaven is widely known. Among the principal buildings are the following, presented to the township by Henry H. Rogers (1840-1909), a native of Fairhaven and a large stockholder and long vice-president of the Standard Oil Co.; the town hall, a memorial of Mrs Rogers, the Rogers public schools; the Millicent public library (17,500 vols. in 1908), a memorial to his daughter; and a fine granite memorial church (Unitarian) with parish house, a memorial to his mother; and there is also a public park, of 13 acres, the gift of Mr Rogers. From 1830 to 1857 the inhabitants of Fairhaven were chiefly engaged in whaling, and the fishing interests are still important. Among manufactures are tacks, nails, iron goods, loom-cranks, glass, yachts and boats, and shoes.

Fairhaven, originally a part of New Bedford, was incorporated as a separate township in 1812. On the 5th of September 1778 a fleet and armed force under Earl Grey, sent to punish New Bedford and what is now Fairhaven for their activity in privateering, burned the shipping and destroyed much of New Bedford. The troops then marched to the head of the Acushnet river, and down the east bank to Sconticut Neck, where they camped till the 7th of September, when they re-embarked, having meanwhile dismantled a small fort, built during the early days of the war, on the east side of the river at the entrance to the harbour. On the evening of the 8th of September a landing force from the fleet, which had begun to set fire to Fairhaven, was driven off by a body of about 150 minute-men commanded by Major Israel Fearing; and on the following day the fleet departed. The fort was at once rebuilt and was named Fort Fearing, but as early as 1784 it had become known as Fort Phoenix; it was one of the strongest defences on the New England coast during the war of 1812. The township of Acushnet was formed from the northern part of Fairhaven in 1860.

See James L. Gillingham and others, A Brief History of the Town of Fairhaven, Massachusetts (Fairhaven, 1903).

FAIRHOLT, FREDERICK WILLIAM (1814-1866), English antiquary and wood engraver, was born in London in 1814. His father, who was of a German family (the name was originally Fahrholz), was a tobacco manufacturer, and for some years Fairholt himself was employed in the business. For a time he was a drawing-master, afterwards a scene-painter, and in 1835 he became assistant to S. Sly, the wood engraver. Some pen and ink copies made by him of figures from Hogarth’s plates led to his being employed by Charles Knight on several of his illustrated publications. His first published literary work was a contribution to Hone’s Year-Book in 1831. His life was one of almost uninterrupted quiet labour, carried on until within a few days of death. Several works on civic pageantry and some collections of ancient unpublished songs and dialogues were edited by him for the Percy Society in 1842. In 1844 he was elected fellow of the Society of Antiquaries. He published an edition of the dramatic works of Lyly in 1856. His principal independent works are Tobacco, its History, and Association (1859); Gog and Magog (1860); Up the Nile and Home Again (1862); many articles and serials contributed to the Art Journal, some of which were afterwards separately published, as Costume in England (1846); Dictionary of Terms in Art (1854). These works are illustrated by numerous cuts, drawn on the wood by his own hand. His pencil was also employed in illustrating Evans’s Coins of the Ancient Britons, Madden’s Jewish Coinage, Halliwell’s folio Shakespeare and his Sir John Maundeville, Roach Smith’s Richborough, the Miscellanea Graphica of Lord Londesborough, and many other works. He died on the 3rd of April 1866. His books relating to Shakespeare were bequeathed to the library at Stratford-on-Avon; those on civic pageantry (between 200 and 300 volumes) to the Society of Antiquaries; his old prints and works on costume to the British Museum; his general library he desired to be sold and the proceeds devoted to the Literary Fund.

FAIRMONT, a city and the county-seat of Marion county, West Virginia, U.S.A., on both sides of the Monongahela river, about 75 m. S.E. of Wheeling. Pop. (1890) 1023; (1900) 5655, of whom 283 were negroes and 182 foreign-born; (1910) 9711. It is served by the Baltimore & Ohio railway. Among its manufactures are glass, machinery, flour and furniture, and it is an important shipping point for coal mined in the vicinity. The city is the seat of one of the West Virginia state normal schools. Fairmont was laid out as Middletown in 1819, became the county-seat of the newly established Marion county in 1842, received its present name about 1844, and was chartered as a city in 1899.

FAIR OAKS, a station on a branch of the Southern railway, 6 m. E. of Richmond, Virginia, U.S.A. It is noted as the site of one of the battles of the Civil War, fought on the 31st of May and the 1st of June 1862, between the Union (Army of the Potomac) under General G.B. McClellan and the Confederate forces (Army of Northern Virginia) commanded by General J.E. Johnston. The attack of the Confederates was made at a moment when the river Chickahominy divided the Federal army into two unequal parts, and was, moreover, swollen to such a degree as to endanger the bridges. General Johnston stationed part of his troops along the river to prevent the Federals sending aid to the smaller force south of it, upon which the Confederate attack, commanded by General Longstreet, was directed. Many accidents, due to the inexperience of the staff officers and to the difficulty of the ground, hindered the development of Longstreet’s attack, but the Federals were gradually driven back with a loss of ten guns, though at the last moment reinforcements managed to cross the river and re-establish the line of defence. At the close of the day Johnston was severely wounded, and General G.W. Smith succeeded to the command. The battle was renewed on the 1st of June but not fought out. At the close of the action General R.E. Lee took over the command of the Confederates, which he held till the final surrender in April 1865. So far as the victory lay with either side, it was with the Union army, for the Confederates failed to achieve their purpose of destroying the almost isolated left wing of McClellan’s army, and after the battle they withdrew into the lines of Richmond. The Union losses were 5031 in killed, wounded and missing; those of the Confederates were 6134. The battle is sometimes known as the battle of Seven Pines.

FAIRŪZĀBĀDĪ Ābū-ṭ-Ṭāhir ibn Ibrahīm Majd ud-Dīn ul-Fairūzābādī] (1329-1414), Arabian lexicographer, was born at Kārazīn near Shiraz. His student days were spent in Shiraz, Wāsiṭ, Bagdad and Damascus. He taught for ten years in 134 Jerusalem, and afterwards travelled in western Asia and Egypt. In 1368 he settled in Mecca, where he remained for fifteen years. He next visited India and spent some time in Delhi, then remained in Mecca another ten years. The following three years were spent in Bagdad, in Shiraz (where he was received by Timur), and in Ta’iz. In 1395 he was appointed chief cadi (qadi) of Yemen, married a daughter of the sultan, and died at Zabīd in 1414. During this last period of his life he converted his house at Mecca into a school of Mālikite law and established three teachers in it. He wrote a huge lexicographical work of 60 or 100 volumes uniting the dictionaries of Ibn Sīda, a Spanish philologist (d. 1066), and of Sajānī (d. 1252). A digest of or an extract from this last work is his famous dictionary al-Qāmūs (“the Ocean”), which has been published in Egypt, Constantinople and India, has been translated into Turkish and Persian, and has itself been the basis of several later dictionaries.

FAIRY (Fr. fée, faerie; Prov. fada; Sp. hada; Ital. fata; med. Lat. fatare, to enchant, from Lat. fatum, fate, destiny), the common term for a supposed race of supernatural beings who magically intermeddle in human affairs. Of all the minor creatures of mythology the fairies are the most beautiful, the most numerous, the most memorable in literature. Like all organic growths, whether of nature or of the fancy, they are not the immediate product of one country or of one time; they have a pedigree, and the question of their ancestry and affiliation is one of wide bearing. But mixture and connexion of races have in this as in many other cases so changed the original folk-product that it is difficult to disengage and separate the different strains that have gone to the making or moulding of the result as we have it.

It is not in literature, however ancient, that we must look for the early forms of the fairy belief. Many of Homer’s heroes have fairy lemans, called nymphs, fairies taken up into a higher region of poetry and religion; and the fairy leman is notable in the story of Athamas and his cloud bride Nephelē, but this character is as familiar to the unpoetical Eskimo, and to the Red Indians, with their bird-bride and beaver-bride (see A. Lang’s Custom and Myth, “The Story of Cupid and Psyche”). The Gandharvas of Sanskrit poetry are also fairies.

One of the most interesting facts about fairies is the wide distribution and long persistence of the belief in them. They are the chief factor in surviving Irish superstition. Here they dwell in the “raths,” old earth-forts, or earthen bases of later palisaded dwellings of the Norman period, and in the subterranean houses, common also in Scotland. They are an organized people, often called “the army,” and their life corresponds to human life in all particulars. They carry off children, leaving changeling substitutes, transport men and women into fairyland, and are generally the causes of all mysterious phenomena. Whirls of dust are caused by the fairy marching army, as by the being called Kutchi in the Dieri tribe of Australia. In 1907, in northern Ireland, a farmer’s house was troubled with flying stones (see Poltergeist). The neighbours said that the fairies caused the phenomenon, as the man had swept his chimney with a bough of holly, and the holly is “a gentle tree,” dear to the fairies. The fairy changeling belief also exists in some districts of Argyll, and a fairy boy dwelt long in a small farm-house in Glencoe, now unoccupied.

In Ireland and the west Highlands neolithic arrow-heads and flint chips are still fairy weapons. They are dipped in water, which is given to ailing cattle and human beings as a sovereign remedy for diseases. The writer knows of “a little lassie in green” who is a fairy and, according to the percipients, haunts the banks of the Mukomar pool on the Lochy. In Glencoe is a fairy hill where the fairy music, vocal and instrumental, is heard in still weather. In the Highlands, however, there is much more interest in second sight than in fairies, while in Ireland the reverse is the case. The best book on Celtic fairy lore is still that of the minister of Aberfoyle, the Rev. Mr Kirk (ob. 1692). His work on The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies, left in MS. and incomplete (the remainder is in the Laing MSS., Edinburgh University library), was published (a hundred copies) in 1815 by Sir Walter Scott, and in the Bibliothèque de Carabas (Lang) there is a French translation. Mr Kirk is said (though his tomb exists) to have been carried away by fairies. He appeared to a friend and said that he would come again, when the friend must throw a dirk over his shoulder and he would return to this world. The friend, however, lost his nerve and did not throw the dirk. In the same way a woman reappeared to her husband in Glencoe in the last generation, but he was wooing another lass and did not make any effort to recover his wife. His character was therefore lost in the glen.

It is clear that in many respects fairyland corresponds to the pre-Christian abode of the dead. Like Persephone when carried to Hades, or Wainamoïnen in the Hades of the Finns (Manala), a living human being must not eat in fairyland; if he does, he dwells there for ever. Tamlane in the ballad, however, was “fat and fair of flesh,” yet was rescued by Janet: probably he had not abstained from fairy food. He was to be given as the kane to Hell, which shows a distinction between the beliefs in hell and in the place of fairies.

It is a not uncommon theory that the fairies survive in legend from prehistoric memories of a pigmy people dwelling in the subterranean earth-houses, but the contents of these do not indicate an age prior to the close of the Roman occupation of Britain; nor are pigmy bones common in neolithic sepulchres. The “people of peace” (Daoine Shie) of Ireland and Scotland are usually of ordinary stature, indeed not to be recognized as varying from mankind except by their proceedings (see J. Curtin, Irish Folk-tales).

The belief in a species of lady fairies, deathly to their human lovers, was found by R.L. Stevenson to be as common in Samoa (see Island Nights’ Entertainments) as in Strathfinlas or on the banks of Loch Awe. In New Caledonia a native friend of J.J. Atkinson (author of Primal Law) told him that he had met and caressed the girl of his heart in the forest, that she had vanished and must have been a fairy. He therefore would die in three days, which (Mr Atkinson informs the writer) he punctually did. The Greek sirens of Homer are clearly a form of these deadly fairies, as the Nereids and Oreads and Naiads are fairies of wells, mountains and the sea. The fairy women who come to the births of children and foretell their fortunes (Fata, Moerae, ancient Egyptian Hathors, Fées, Dominae Fatales), with their spindles, are refractions of the human “spae-women” (in the Scots term) who attend at birth and derive omens of the child’s future from various signs. The custom is common among several savage races, and these women, represented in the spiritual world by Fata, bequeath to us the French fée, in the sense of fairy. Perrault also uses fée for anything that has magical quality; “the key was fée,” had mana, or wakan, savage words for the supposed “power,” or ether, which works magic or is the vehicle of magical influences.

Though the fairy belief is universally human, the nearest analogy to the shape which it takes in Scotland and Ireland—the “pixies” of south-western England—is to be found in Jān or Jinnis of the Arabs, Moors and people of Palestine. In stories which have passed through a literary medium, like The Arabian Nights, the geni or Jān do not so much resemble our fairies as they do in the popular superstitions of the East, orally collected. The Jān are now a subterranean commonwealth, now they reside in ruinous places, like the fairies in the Irish raths. Like the fairies they go about in whirls of dust, or the dust-whirls themselves are Jān. They carry off men and women “to their own herd,” in the phrase of Mr Kirk, and are kind to mortals who are kind to them. They chiefly differ from our fairies in their greater tendency to wear animal forms; though, like the fairies, when they choose to appear in human shape they are not to be distinguished from men and women of mortal mould. Like the fairies everywhere they have amours with mortals, such as that of the Queen of Faery with Thomas of Ercildoune. The herb rue is potent against them, as in British folk-lore, and a man long captive among the Jān escaped from them by observing their avoidance of rue, and by plucking two handfuls 135 thereof. They, like the British brownies (a kind of domesticated fairy), are the causes of strange disappearances of things. To preserve houses from their influences, rue, that “herb of grace,” is kept in the apartments, and the name of Allah is constantly invoked. If this is omitted, things are stolen by the Jān.

They often bear animal names, and it is dangerous to call a cat or dog without pointing at the animal, for a Jinni of the same name may be present and may take advantage of the invocation. A man, in fun, called to a goat to escort his wife on a walk: he did not point at the goat, and the wife disappeared. A Jinni had carried her off, and her husband had to seek her at the court of the Jān. Euphemistically they are addressed as mubārakin, “blessed ones,” as we say “the good folk” or “the people of peace.” As our fairies give gold which changes into withered leaves, the Jān give onion peels which turn into gold. Like our fairies the Jān can apply an ointment, kohl, to human eyes, after which the person so favoured can see Jān, or fairies, which are invisible to other mortals, and can see treasure wherever it may be concealed (see Folk-lore of the Holy Land, by J.E. Hanauer, 1907).

It is plain that fairies and Jān are practically identical, a curious proof of the uniformity of the working of imagination in peoples widely separated in race and religion. Fairies naturally won their way into the poetry of the middle ages. They take lovers from among men, and are often described as of delicate, unearthly, ravishing beauty. The enjoyment of their charms is, however, generally qualified by some restriction or compact, the breaking of which is the cause of calamity to the lover and all his race, as in the notable tale of Melusine. This fay by enchantment built the castle of Lusignan for her husband. It was her nature to take every week the form of a serpent from the waist below. The hebdomadal transformation being once, contrary to compact, witnessed by her husband, she left him with much wailing, and was said to return and give warning by her appearance and great shrieks whenever one of the race of Lusignan was about to die. At the birth of Ogier le Danois six fairies attend, five of whom give good gifts, which the sixth overrides with a restriction. Gervaise of Tilbury, writing early in the 13th century, has in his Otia Imperialia a chapter, De lamiis et nocturnis larvis, where he gives it out, as proved by individuals beyond all exception, that men have been lovers of beings of this kind whom they call Fadas, and who did in case of infidelity or infringement of secrecy inflict terrible punishment—the loss of goods and even of life. There seems little in the characteristics of these fairies of romance to distinguish them from human beings, except their supernatural knowledge and power. They are not often represented as diminutive in stature, and seem to be subject to such human passions as love, jealousy, envy and revenge. To this class belong the fairies of Boiardo, Ariosto and Spenser.

There is no good modern book on the fairy belief in general. Keightley’s Fairy Mythology is full of interesting matter; Rhys’s Celtic Mythology is especially copious about Welsh fairies, which are practically identical with those of Ireland and Scotland. The works of Mr Jeremiah Curtin and Dr Douglas Hyde are useful for Ireland; for Scotland, Kirk’s Secret Commonwealth has already been quoted. Scott’s dissertation on fairies in The Border Minstrelsy is rich in lore, though necessarily Scott had not the wide field of comparative study opened by more recent researches. There is a full description of French fairies of the 15th century in the evidence of Jeanne d’Arc at her trial (1431) in Quicherat’s Procès de Jeanne d’Arc, vol. i. pp. 67, 68, 187, 209, 212, vol. ii. pp. 390, 404, 450.

FAIRY RING, the popular name for the circular patches of a dark green colour that are to be seen occasionally on permanent grass-land, either lawn or meadow, on which the fairies were supposed to hold their midnight revels. They mark the area of growth of some fungus, starting from a centre of one or more plants. The mycelium produced from the spores dropped by the fungus or from the “spawn” in the soil, radiates outwards, and each year’s successive crop of fungi rises from the new growth round the circle. The rich colour of the grass is due to the fertilizing quality of the decaying fungi, which are peculiarly rich in nitrogenous substances. The most complete and symmetrical grass rings are formed by Marasmius orcades, the fairy ring champignon, but the mushroom and many other species occasionally form rings, both on grass-lands and in woods. Observations were made on a ring in a pine-wood for a period of nine years, and it was calculated that it increased from centre to circumference about 8½ in. each year. The fungus was never found growing within the circle during the time the ring was under observation, the decaying vegetation necessary for its growth having become exhausted.

FAITHFULL, EMILY (1835-1895), English philanthropist, was the youngest daughter of the Rev. Ferdinand Faithfull, and was born at Headley Rectory, Surrey, in 1835. She took a great interest in the conditions of working-women, and with the object of extending their sphere of labour, which was then painfully limited, in 1860 she set up in London a printing establishment for women. The “Victoria Press,” as it was called, soon obtained quite a reputation for its excellent work, and Miss Faithfull was shortly afterwards appointed printer and publisher in ordinary to Queen Victoria. In 1863 she began the publication of a monthly organ, The Victoria Magazine, in which for eighteen years she continuously and earnestly advocated the claims of women to remunerative employment. In 1868 she published a novel, Change upon Change. She also appeared as a lecturer, and with the object of furthering the interests of her sex, lectured widely and successfully both in England and the United States, which latter she visited in 1872 and 1882. In 1888 she was awarded a civil list pension of £50. She died in Manchester on the 31st of May 1895.

FAITH HEALING, a form of “mind cure,” characterized by the doctrine that while pain and disease really exist, they may be neutralized and dispelled by faith in Divine power; the doctrine known as Christian Science (q.v.) holds, however, that pain is only an illusion and seeks to cure the patient by instilling into him this belief. In the Christian Church the tradition of faith healing dates from the earliest days of Christianity; upon the miracles of the New Testament follow cases of healing, first by the Apostles, then by their successors; but faith healing proper is gradually, from the 3rd century onwards, transformed into trust in relics, though faith cures still occur sporadically in later times. Catherine of Siena is said to have saved Father Matthew from dying of the plague, but in this case it is rather the healer than the healed who was strong in faith. With the Reformation faith healing proper reappears among the Moravians and Waldenses, who, like the Peculiar People of our own day, put their trust in prayer and anointing with oil. In the 16th century we find faith cures recorded of Luther and other reformers, in the next century of the Baptists, Quakers and other Puritan sects, and in the 18th century the faith healing of the Methodists in this country was paralleled by Pietism in Germany, which drew into its ranks so distinguished a man of science as Stahl (1660-1734). In the 19th century Prince Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst, canon of Grosswardein, was a famous healer on the continent; the Mormons and Irvingites were prominent among English-speaking peoples; in the last quarter of the 19th century faith healing became popular in London, and Bethshan homes were opened in 1881, and since then it has found many adherents in England.

Under faith healing in a wider sense may be included (1) the cures in the temples of Aesculapius and other deities in the ancient world; (2) the practice of touching for the king’s evil, in vogue from the 11th to the 18th century; (3) the cures of Valentine Greatrakes, the “Stroker” (1629-1683); and (4) the miracles of Lourdes, and other resorts of pilgrims, among which may be mentioned St Winifred’s Well in Flintshire, Treves with its Holy Coat, the grave of the Jansenist F. de Paris in the 18th century, the little town of Kevelaer from 1641 onwards, the tombs of St Louis, Francis of Assisi, Catherine of Siena and others.

An animistic theory of disease was held by Pastor J. Ch. Blumhardt, Dorothea Trudel, Boltzius and other European faith healers. Used in this sense faith healing is indistinguishable from much of savage leech-craft, which seeks to cure disease by expelling the evil spirit in some portion of the body. Although 136 it is usually present, faith in the medicine man is not essential for the efficacy of the method. The same may be said of the lineal descendant of savage medicine—the magical leech-craft of European folk-lore; cures for toothache, warts, &c., act in spite of the disbelief of the sufferer; how far incredulity on the part of the healer would result in failure is an open question.

From the psychological point of view all these different kinds of faith healing, as indeed all kinds of mind cure, including those of Christian Science and hypnotism, depend on suggestion (q.v.). In faith healing proper not only are powerful direct suggestions used, but the religious atmosphere and the auto-suggestions of the patient co-operate, especially where the cures take place during a period of religious revival or at other times when large assemblies and strong emotions are found. The suggestibility of large crowds is markedly greater than that of individuals, and to this and the greater faith must be attributed the greater success of the fashionable places of pilgrimage.

See A.T. Myers and F.W.H. Myers in Proc. Soc. Psychical Research, ix. 160-209, on the miracles of Lourdes, with bibliography; A. Feilding, Faith Healing and Christian Science; O. Stoll, Suggestion und Hypnotismus in der Völkerpsychologie; article “Greatrakes” in Dict. Nat. Biog.

FAITHORNE, WILLIAM (1626 or 1627-1691), English painter and engraver, was born in London and was apprenticed to Robert Peake, a painter and printseller, who received the honour of knighthood from Charles I. On the outbreak of the Civil War he accompanied his master into the king’s service, and being made prisoner at Basinghouse, he was confined for some time to Aldersgate, where, however, he was permitted to follow his profession of engraver, and among other portraits did a small one of the first Villiers, duke of Buckingham. At the earnest solicitation of his friends he very soon regained his liberty, but only on condition of retiring to France. There he was so fortunate as to receive instruction from Robert Nanteuil. He was permitted to return to England about 1650, and took up a shop near Temple Bar, where, besides his work as an engraver, he carried on a large business as a printseller. In 1680 he gave up his shop and retired to a house in Blackfriars, occupying himself chiefly in painting portraits from the life in crayons, although still occasionally engaged in engraving. It is said that his life was shortened by the misfortunes, dissipation, and early death of his son William. Faithorne is especially famous as a portrait engraver, and among those on whom he exercised his art were a large number of eminent persons, including Sir Henry Spelman, Oliver Cromwell, Henry Somerset, the marquis of Worcester, John Milton, Queen Catherine, Prince Rupert, Cardinal Richelieu, Sir Thomas Fairfax, Thomas Hobbes, Richard Hooker, Robert second earl of Essex, and Charles I. All his works are remarkable for their combination of freedom and strength with softness and delicacy, and his crayon paintings unite to these the additional quality of clear and brilliant colouring. He is the author of a work on engraving (1622).

His son William (1656-1686), mezzotint engraver, at an early age gave promise of attaining great excellence, but became idle and dissipated, and involved his father in money difficulties. Among persons of note whose portraits he engraved are Charles II., Mary princess of Orange, Queen Anne when princess of Denmark, and Charles XII. of Sweden.

The best account of the Faithornes is that contained in Walpole’s Anecdotes of Painting. A life of Faithorne the elder is preserved in the British Museum among the papers of Mr Bayford, librarian to Lord Oxford, and an intimate friend of Faithorne.

FAIZABAD, a town of Afghanistan, capital of the province of Badakshan, situated on the Kokcha river. In 1821 it was destroyed by Murad Beg of Kunduz, and the inhabitants removed to Kunduz. But since Badakshan was annexed by Abdur Rahman, the town has recovered its former importance, and is now a considerable place of trade. It is the chief cantonment for eastern Afghanistan and the Pamir region, and is protected by a fort built in 1904.

FAJARDO, a district and town on the E. coast of Porto Rico, belonging to the department of Humacao. Pop. (1899) of the district, 16,782; and of the town, 3414. The district is highly fertile and is well watered, owing in great measure to its abundant rainfall. Sugar production is its principal industry, but some attention is also given to the growing of oranges and pineapples. The town, which was founded in 1774, is a busy commercial centre standing 1¼ m. from a large and well-sheltered bay, at the entrance to which is the cape called Cabeza de San Juan. It is the market town for a number of small islands off the E. coast, some of which produce cattle for export.

FAKHR UD-DĪN RĀZI (1149-1209), Arabian historian and theologian, was the son of a preacher, himself a writer, and was born at Rai (Rei, Rhagae), near Tehran, where he received his earliest training. Here and at Marāgha, whither he followed his teacher Majd ud-Dīn ul-Jilī, he studied philosophy and theology. He was a Shaf‘ite in law and a follower of Ash‘arī (q.v.) in theology, and became renowned as a defender of orthodoxy. During a journey in Khwarizm and Mawara’l-nahr he preached both in Persian and Arabic against the sects of Islam. After this tour he returned to his native city, but settled later in Herat, where he died. His dogmatic positions may be seen from his work Kitāb ul-Muḥassal, which is analysed by Schmölders in his Essai sur les écoles philosophiques chez les Arabes (Paris, 1842). Extracts from his History of the Dynasties were published by Jourdain in the Fundgruben des Orients (vol. v.), and by D.R. Heinzius (St Petersburg, 1828). His greatest work is the Mafātiḥ ul-Ghaib (“The Keys of Mystery”), an extensive commentary on the Koran published at Cairo (8 vols., 1890) and elsewhere; it is specially full in its exposition of Ash‘arite theology and its use of early and late Mu’tazilite writings.

For an account of his life see F. Wüstenfeld’s Geschichte der arabischen Ärzte, No. 200 (Göttingen, 1840); for a list of his works cf. C. Brockelmann’s Gesch. der arabischen Literatur, vol. 1 (Weimar, 1898), pp. 506 ff. An account of his teaching is given by M. Schreiner in the Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft (vol. 52, pp. 505 ff.).

FAKIR (from Arabic faqīr, “poor”), a term equivalent to Dervish (q.v.) or Mahommedan religious mendicant, but which has come to be specially applied to the Hindu devotees and ascetics of India. There are two classes of these Indian Fakirs, (1) the religious orders, and (2) the nomad rogues who infest the country. The ascetic orders resemble the Franciscans of Christianity. The bulk lead really excellent lives in monasteries, which are centres of education and poor-relief; while others go out to visit the poor as Gurus or teachers. Strict celibacy is not enforced among them. These orders are of very ancient date, owing their establishment to the ancient Hindu rule, followed by the Buddhists, that each “twice-born” man should lead in the woods the life of an ascetic. The second class of Fakirs are simply disreputable beggars who wander round extorting, under the guise of religion, alms from the charitable and practising on the superstitions of the villagers. As a rule they make no real pretence of leading a religious life. They are said to number nearly a million. Many of them are known as “Jogi,” and lay claim to miraculous powers which they declare have become theirs by the practice of abstinence and extreme austerities. The tortures which some of these wretches will inflict upon themselves are almost incredible. They will hold their arms over their heads until the muscles atrophy, will keep their fists clenched till the nails grow through the palms, will lie on beds of nails, cut and stab themselves, drag, week after week, enormous chains loaded with masses of iron, or hang themselves before a fire near enough to scorch. Most of them are inexpressibly filthy and verminous. Among the filthiest are the Aghoris, who preserve the ancient cannibal ritual of the followers of Siva, eat filth, and use a human skull as a drinking-vessel. Formerly the fakirs were always nude and smeared with ashes; but now they are compelled to wear some pretence of clothing. The natives do not really respect these wandering friars, but they dread their curses.

See John Campbell Oman, The Mystics, Ascetics and Saints of India (1903), and Indian Census Reports.

FALAISE, a town of north-western France, capital of an arrondissement in the department of Calvados, on the right bank of the Ante, 19 m. S. by E. of Caen by road. Pop. (1906) 137 6215. The principal object of interest is the castle, now partly in ruins, but formerly the seat of the dukes of Normandy and the birthplace of William the Conqueror. It is situated on a lofty crag overlooking the town, and consists of a square mass defended by towers and flanked by a small donjon and a lofty tower added by the English in the 15th century; the rest of the castle dates chiefly from the 12th century. Near the castle, in the Place de la Trinité, is an equestrian statue in bronze of William the Conqueror, to whom the town owed its prosperity. The churches of La Trinité and St Gervais combine the Gothic and Renaissance styles of architecture, and St Gervais also includes Romanesque workmanship. A street passes by way of a tunnel beneath the choir of La Trinité. Falaise has populous suburbs, one of which, Guibray, is celebrated for its annual fair for horses, cattle and wool, which has been held in August since the 11th century. The town is the seat of a subprefecture and has tribunals of first instance and commerce, a chamber of arts and manufacture, a board of trade-arbitrators and a communal college. Tanning and important manufactures of hosiery are carried on.

From 1417, when after a siege of forty-seven days it succumbed to Henry V., king of England, till 1450, when it was retaken by the French, Falaise was in the hands of the English.

FALASHAS (i.e. exiles; Ethiopic falas, a stranger), or “Jews of Abyssinia,” a tribe of Hamitic stock, akin to Galla, Somali and Beja, though they profess the Jewish religion. They claim to be descended from the ten tribes banished from the Holy Land. Another tradition assigns them as ancestor Menelek, Solomon’s alleged son by the queen of Sheba. There is little or no physical difference between them and the typical Abyssinians, except perhaps that their eyes are a little more oblique; and they may certainly be regarded as Hamitic. It is uncertain when they became Jews: one account suggests in Solomon’s time; another, at the Babylonian captivity; a third, during the 1st century of the Christian era. That one of the earlier dates is correct seems probable from the fact that the Falashas know nothing of either the Babylonian or Jerusalem Talmud, make no use of phylacteries (tefillin), and observe neither the feast of Purim nor the dedication of the temple. They possess—not in Hebrew, of which they are altogether ignorant, but in Ethiopic (or Geez)—the canonical and apocryphal books of the Old Testament; a volume of extracts from the Pentateuch, with comments given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai; the Te-e-sa-sa Sanbat, or laws of the Sabbath; the Ardit, a book of secrets revealed to twelve saints, which is used as a charm against disease; lives of Abraham, Moses, &c.; and a translation of Josephus called Sana Aihud. A copy of the Orit or Mosaic law is kept in the holy of holies in every synagogue. Various pagan observances are mingled in their ritual: every newly-built house is considered uninhabitable till the blood of a sheep or fowl has been spilt in it; a woman guilty of a breach of chastity has to undergo purification by leaping into a flaming fire; the Sabbath has been deified, and, as the goddess Sanbat, receives adoration and sacrifice and is said to have ten thousand times ten thousand angels to wait on her commands. There is a monastic system, introduced it is said in the 4th century A.D. by Aba Zebra, a pious man who retired from the world and lived in the cave of Hoharewa, in the province of Armatshoho. The monks must prepare all their food with their own hands, and no lay person, male or female, may enter their houses. Celibacy is not practised by the priests, but they are not allowed to marry a second time, and no one is admitted into the order who has eaten bread with a Christian, or is the son or grandson of a man thus contaminated. Belief in the evil eye or shadow is universal, and spirit-raisers, soothsayers and rain-doctors are in repute. Education is in the hands of the monks and priests, and is confined to boys. Fasts, obligatory on all above seven years of age, are held on every Monday and Thursday, on every new moon, and at the passover (the 21st or 22nd of April). The annual festivals are the passover, the harvest feast, the Baala Mazalat or feast of tabernacles (during which, however, no booths are built), the day of covenant or assembly and Abraham’s day. It is believed that after death the soul remains in a place of darkness till the third day, when the first sacrifice for the dead is offered; prayers are read in the synagogue for the repose of the departed, and for seven days a formal lament takes place every morning in his house. No coffins are used, and a stone vault is built over the corpse so that it may not come into direct contact with the earth.

The Falashas are an industrious people, living for the most part in villages of their own, or, if they settle in a Christian or Mahommedan town, occupying a separate quarter. They had their own kings, who, they pretend, were descended from David, from the 10th century until 1800, when the royal race became extinct, and they then became subject to the Abyssinian kingdom of Tigré. They do not mix with the Abyssinians, and never marry women of alien religions. They are even forbidden to enter the houses of Christians, and from such a pollution have to be purified before entering their own houses. Polygamy is not practised; early marriages are rare, and their morals are generally better than those of their Christian masters. Unlike most Jews, they have no liking for trade, but are skilled in agriculture, in the manufacture of pottery, ironware and cloth, and are good masons. Their numbers are variously estimated at from one hundred to one hundred and fifty thousand.

Bibliography.—M. Flad, Zwölf Jahre in Abyssinia (Basel, 1869), and his Falashas of Abyssinia, translated from the German by S.P. Goodhart (London, 1869); H.A. Stern, Wanderings among the Falashas in Abyssinia (London, 1862); Joseph Halévy, Travels in Abyssinia (trans. London, 1878); Morais, “The Falashas” in Penn Monthly (Philadelphia, 1880); Cyrus Adler, “Bibliography of the Falashas” in American Hebrew (16th of March 1894); Lewin, “Ein verlassener Bruderstamm,” in Bloch’s Wochenschrift (7th February 1902), p. 85; J. Faitlovitch, Notes d’un voyage chez les Falachas (Paris, 1905).

FALCÃO, CHRISTOVÃO DE SOUSA (? 1512-1557), Portuguese poet, came of a noble family settled at Portalegre in the Alemtejo, which had originated with John Falcon or Falconet, one of the Englishmen who went to Portugal in 1386 in the suite of Philippa of Lancaster. His father, João Vaz de Almada Falcão, was an upright public servant who had held the captaincy of Elmina on the West African coast, but died, as he had lived, a poor man. There is a tradition that in boyhood Christovão fell in love with a beautiful child and rich heiress, D. Maria Brandão, and in 1526 married her clandestinely, but parental opposition prevented the ratification of the marriage. Family pride, it is said, drove the father of Christovão to keep his son under strict surveillance in his own house for five years, while the lady’s parents, objecting to the youth’s small means, put her into the Cistercian convent of Lorvão, and there endeavoured to wean her heart from him by the accusation that he coveted her fortune more than her person. Their arguments and the promise of a good match ultimately prevailed, and in 1534 D. Maria left the convent to marry D. Luis de Silva, captain of Tangier, while the broken-hearted Christovão told his sad story in some beautiful lyrics and particularly in the eclogue Chrisfal. He had been the disciple and friend of the poets Bernardim Ribeiro and Sá de Miranda, and when his great disappointment came, Falcão laid aside poetry and entered on a diplomatic career. There is documentary evidence that he was employed at the Portuguese embassy in Rome in 1542, but he soon returned to Portugal, and we find him at court again in 1548 and 1551. The date of his death, as of his birth, is uncertain. Such is the story accepted by Dr Theophilo Braga, the historian of Portuguese literature, but Senhor Guimarães shows that the first part is doubtful, and, putting aside the testimony of a contemporary and grave writer, Diogo do Couto, he even denies the title of poet to Christovão Falcão, arguing from internal and other evidence that Chrisfal is the work of Bernardim Ribeiro; his destructive criticism is, however, stronger than his constructive work. The eclogue, with its 104 verses, is the very poem of saudade, and its simple, direct language and chaste and tender feeling, enshrined in exquisitely sounding verses, has won for its author lasting fame and a unique position in Portuguese literature. Its influence on later poets has been very considerable, and Camoens used several of the verses as proverbs.

The poetical works of Christovão Falcão were published anonymously, owing, it is supposed, to their personal nature and allusions, 138 and, in part or in whole, they have been often reprinted. There is a modern critical edition of Chrisfal and a Carta (letter) by A. Epiphanio da Silva Dias under the title Obras de Christovão Falcão (Oporto, 1893), and one of the Cantigas and Esparsas by the same scholar appeared in the Revista Lusitana, vol. 4, pp. 142-179 (Lisbon, 1896), under the name Fragmento de um Cancioneiro do Seculo XVI. See Bernardim Ribeiro e o Bucolismo, by Dr T. Braga (Oporto, 1897), and Bernardim Ribeiro (O Poeta Crisfal), by Delfim Guimarães (Lisbon, 1908).

FALCK, ANTON REINHARD (1777-1843), Dutch statesman, was born at Utrecht on the 19th of March 1777. He studied at the university of Leiden, and entered the Dutch diplomatic service, being appointed to the legation at Madrid. Under King Louis Napoleon he was secretary-general for foreign affairs, but resigned office on the annexation of the Batavian republic to France. He took a leading part in the revolt of 1813 against French domination, and had a considerable share in the organization of the new kingdom of the Netherlands. As minister of education under William I. he reorganized the universities of Ghent, Louvain and Liége and the Royal Academy of Brussels. Side by side with his activities in education he directed the departments of trade and the colonies. Falck was called in Holland the king’s good genius, but William I. presently tired of his counsels and he was superseded by Van Maanen. He was ambassador in London when the disturbances of 1830 convinced him of the necessity of the separation of Belgium from Holland. He consequently resigned his post and lived in close retirement until 1839, when he became the first Dutch minister at the Belgian court. He died at Brussels on the 16th of March 1843. Besides some historical works he left a correspondence of considerable political interest, printed in Brieven van A.R. Falck, 1795-1843 (2nd ed. The Hague, 1861), and Ambtsbrieven van A.R. Falck (ibid. 1878).

FALCÓN, the most northern state of Venezuela, with an extensive coast line on the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Venezuela. Pop. (1905 est.) 173,968. It lies between the Caribbean on the N. and the state of Lara on the S., with Zulia and the Gulf of Venezuela on the W. Its surface is much broken by irregular ranges of low mountains, and extensive areas on the coast are sandy plains and tropical swamps. The climate is hot, but, being tempered by the trade winds, is not considered unhealthy except in the swampy districts. The state is sparsely settled and has no large towns, its capital, Coro, being important chiefly because of its history, and as the entrepôt for an extensive inland district. The only port in the state is La Vela de Coro, on a small bay of the same name, 7 m. E. of the capital, with which it is connected by railway.

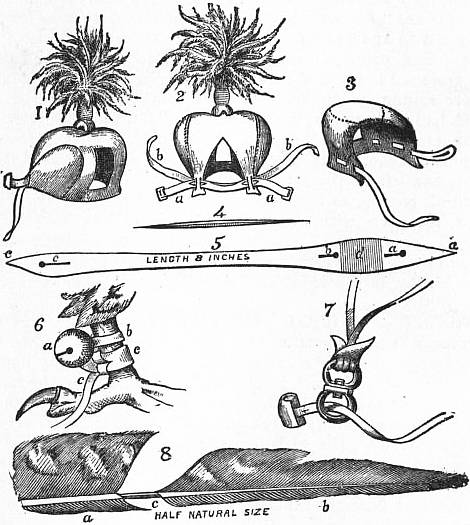

FALCON (Lat. Falco;1 Fr. Faucon; Teutonic, Falk or Valken), a word now restricted to the high-couraged and long-winged birds of prey which take their quarry as it moves; but formerly it had a very different meaning, being by the naturalists of the 18th and even of the 19th century extended to a great number of birds comprised in the genus Falco of Linnaeus and writers of his day,2 while, on the other hand, by falconers, it was, and still is, technically limited to the female of the birds employed by them in their vocation (see Falconry), whether “long-winged” and therefore “noble,” or “short-winged” and “ignoble.”

According to modern usage, the majority of the falcons, in the sense first given, may be separated into five very distinct groups: (1) the falcons pure and simple (Falco proper); (2) the large northern falcons (Hierofalco, Cuvier); (3) the “desert falcons” (Gennaea, Kaup); (4) the merlins (Aesalon, Kaup); and (5) the hobbies (Hypotriorchis, Boie). A sixth group, the kestrels (Tinnunculus, Vieillot), is often added. This, however, appears to have been justifiably reckoned a distinct genus.

|

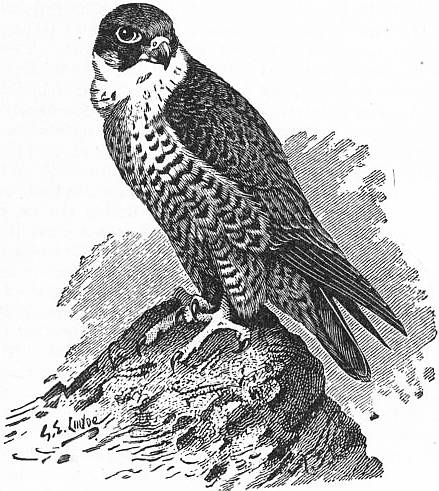

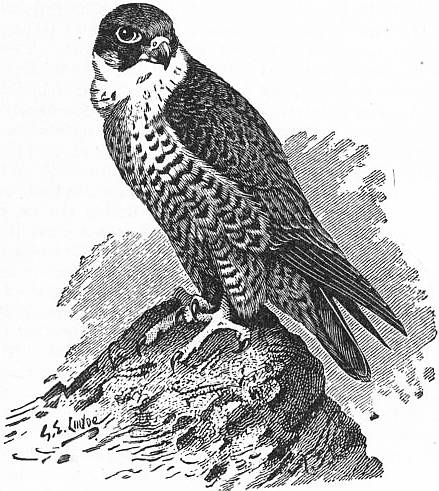

| Fig. 1.—Peregrine Falcon. |

The typical falcon is by common consent allowed to be that almost cosmopolitan species to which unfortunately the English epithet “peregrine” (i.e. strange or wandering) has been attached. It is the Falco peregrinus of Tunstall (1771) and of most recent ornithologists, though some prefer the specific name communis applied by J.F. Gmelin a few years later (1788) to a bird which, if his diagnosis be correct, could not have been a true falcon at all, since it had yellow irides—a colour never met with in the eyes of any bird now called by naturalists a “falcon.” This species inhabits suitable localities throughout the greater part of the globe, though examples from North America have by some received specific recognition as F. anatum (the “duck-hawk”), and those from Australia have been described as distinct under the name of F. melanogenys. Here, as in so many other cases, it is almost impossible to decide as to which forms should, and which should not, be accounted merely local races. In size not surpassing a raven, this falcon (fig. 1) is perhaps the most powerful bird of prey for its bulk that flies, and its courage is not less than its power. It is the species, in Europe, most commonly trained for the sport of hawking (see Falconry). Volumes have been written upon it, and to attempt a complete account of it is, within the limits now available, impossible. The plumage of the adult is generally blackish-blue above, and white, with a more or less deep cream-coloured tinge, beneath—the lower parts, except the chin and throat, being barred transversely with black, while a black patch extends from the bill to the ear-coverts, and descends on either side beneath the mandible. The young have the upper parts deep blackish-brown, and the lower white, more or less strongly tinged with ochraceous-brown, and striped longitudinally with blackish-brown. From Port Kennedy, the most northern part of the American continent, to Tasmania, and from the shores of the Sea of Okhotsk to Mendoza in the Argentine territory, there is scarcely a country in which this falcon has not been found. Specimens have been received from the Cape of Good Hope, and it is only a question of the technical differentiation of species whether it does not extend to Cape Horn. Fearless as it is, and adapting itself to almost every circumstance, it will form its eyry equally on the sea-washed cliffs, the craggy mountains, or (though more rarely) the drier spots of a marsh in the northern hemisphere, as on trees (says H. Schlegel) in the forests of Java or the waterless ravines of Australia. In the United Kingdom it was formerly very common, and hardly a high rock from the Shetlands to the Isle of Wight 139 but had a pair as its tenants. But the British gamekeeper has long held the mistaken faith that it is his worst foe, and the number of pairs now allowed to rear their brood unmolested in the British Islands is very small. Yet its utility to the game-preserver, by destroying every one of his most precious wards that shows any sign of infirmity, can hardly be questioned by reason, and G.E. Freeman (Falconry) has earnestly urged its claims to protection.3 Nearly allied to this falcon are several species, such as F. barbarus of Mauretania, F. minor of South Africa, the Asiatic F. babylonicus, F. peregrinator of India (the shaheen), and perhaps F. cassini of South America, with some others.

Next to the typical falcons comes a group known as the “great northern” falcons (Hierofalco). Of these the most remarkable is the gyrfalcon (F. gyrfalco), whose home is in the Scandinavian mountains, though the young are yearly visitants to the plains of Holland and Germany. In plumage it very much resembles F. peregrinus, but its flanks have generally a bluer tinge, and its superiority in size is at once manifest. Nearly allied to it is the Icelander (F. islandus), which externally differs in its paler colouring and in almost entirely wanting the black mandibular patch. Its proportions, however, differ a good deal, its body being elongated. Its country is shown by its name, but it also inhabits south Greenland, and not unfrequently makes its way to the British Islands. Very close to this comes the Greenland falcon (F. candicans), a native of north Greenland, and perhaps of other countries within the Arctic Circle. Like the last, the Greenland falcon from time to time occurs in the United Kingdom, but it is always to be distinguished by wearing a plumage in which at every age the prevailing colour is pure white. In north-eastern America these birds are replaced by a kindred form (F. labradorus), first detected by Audubon and subsequently recognized by Dresser (Orn. Miscell. i. 135). It is at once distinguished by its very dark colouring, the lower parts being occasionally almost as deeply tinted at all ages as the upper.

All the birds hitherto named possess one character in common. The darker markings of their plumage are longitudinal before the first real moult takes place, and for ever afterwards are transverse. In other words, when young the markings are in the form of stripes, when old in the form of bars. The variation of tint is very great, especially in F. peregrinus; but the experience of falconers, whose business it is to keep their birds in the very highest condition, shows that a falcon of either of these groups if light-coloured in youth is light-coloured when adult, and if dark when young is also dark when old-age, after the first moult, making no difference in the complexion of the bird. The next group is that of the so-called “desert falcons” (Gennaea), wherein the difference just indicated does not obtain, for long as the bird may live and often as it may moult, the original style of markings never gives way to any other. Foremost among these are to be considered the lanner and the saker (commonly termed F. lanarius and F. sacer), both well known in the palmy days of falconry, but only since about 1845 readmitted to full recognition. Both of these birds belong properly to south-eastern Europe, North Africa and south-western Asia. They are, for their bulk, less powerful than the members of the preceding group, and though they may be trained to high flights are naturally captors of humbler game. The precise number of species is very doubtful, but among the many candidates for recognition are especially to be named the lugger (F. jugger) of India, and the prairie falcon (F. mexicanus) of the western plains of North America.

The systematist finds it hard to decide in what group he should place two somewhat large Australian species (F. hypoleucus and F. subniger), both of which are rare in collections—the latter especially.

|

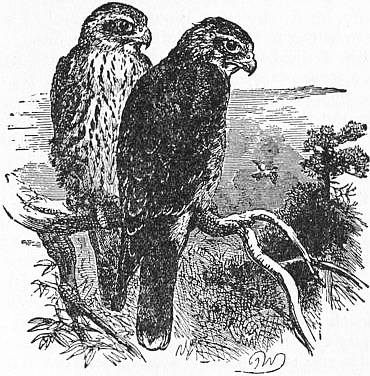

| Fig. 2.—Merlin. |