This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Amenities of Literature

Consisting of Sketches and Characters of English Literature

Author: Isaac Disraeli

Release Date: June 1, 2011 [eBook #36298]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMENITIES OF LITERATURE***

| Transcriber’s note: | A few typographical errors have been corrected. They appear in the text like this, and the explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked passage. |

|

| London, Frederick Warne & Co. |

AMENITIES OF LITERATURE,

CONSISTING OF

SKETCHES AND CHARACTERS OF ENGLISH LITERATURE.

BY

ISAAC DISRAELI.

A New Edition,

EDITED BY HIS SON,

THE EARL OF BEACONSFIELD.

LONDON:

FREDERICK WARNE AND CO.,

BEDFORD STREET, STRAND.

LONDON:

BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO., PRINTERS, WHITEFRIARS.

PREFACE.

A history of our vernacular literature has occupied my studies for many years. It was my design not to furnish an arid narrative of books or of authors, but following the steps of the human mind through the wide track of Time, to trace from their beginnings the rise, the progress, and the decline of public opinions, and to illustrate, as the objects presented themselves, the great incidents in our national annals.

In the progress of these researches many topics presented themselves, some of which, from their novelty and curiosity, courted investigation. Literary history, in this enlarged circuit, becomes not merely a philological history of critical erudition, but ascends into a philosophy of books where their subjects, their tendency, and their immediate or gradual influence over the people discover their actual condition.

Authors are the creators or the creatures of opinion; the great form an epoch, the many reflect their age. With them the transient becomes permanent, the suppressed lies open, and they are the truest representatives of their nation for those very passions with which they are themselves infected. The pen of the ready-writer transmits to us the public and the domestic story, and thus books become the intellectual history of a people. As authors are scattered through all the ranks of society, among the governors and the governed, and the objects of their pursuits are usually carried on by their own peculiar idiosyncrasy, we are deeply interested in the secret connexion of the incidents of their lives with their intellectual habits. In the development of that predisposition which is ever working in characters of native force, all their felicities and their failures, and the fortunes which such men have shaped for themselves, and often for the world, we discover what is not found in biographical dictionaries, the history of the mind of the individual—and this constitutes the psychology of genius.

In the midst of my studies I was arrested by the loss of sight; the papers in this collection are a portion of my projected history.

The title prefixed to this work has been adopted to connect it with its brothers, the “Curiosities of Literature,” and “Miscellanies of Literature;” but though the form and manner bear a family resemblance, the subject has more unity of design.

The author of the present work is denied the satisfaction of reading a single line of it, yet he flatters himself that he shall not trespass on the indulgence he claims for any slight inadvertences. It has been confided to ONE whose eyes unceasingly pursue the volume for him who can no more read, and whose eager hand traces the thought ere it vanish in the thinking; but it is only a father who can conceive the affectionate patience of filial devotion.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| THE DRUIDICAL INSTITUTION | 1 |

| BRITAIN AND THE BRITONS | 12 |

| THE NAME OF ENGLAND AND OF THE ENGLISH | 24 |

| THE ANGLO-SAXONS | 28 |

| CÆDMON AND MILTON | 37 |

| BEOWULF; THE HERO-LIFE | 51 |

| THE ANGLO-NORMANS | 59 |

| THE PAGE, THE BARON, AND THE MINSTREL | 70 |

| GOTHIC ROMANCES | 81 |

| ORIGIN OF THE VERNACULAR LANGUAGES OF EUROPE | 96 |

| ORIGIN OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE | 111 |

| VICISSITUDES OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE | 128 |

| DIALECTS | 142 |

| MANDEVILLE; OUR FIRST TRAVELLER | 151 |

| CHAUCER | 158 |

| GOWER | 177 |

| PIERS PLOUGHMAN | 183 |

| OCCLEVE; THE SCHOLAR OF CHAUCER | 191 |

| LYDGATE; THE MONK OF BURY | 196 |

| THE INVENTION OF PRINTING | 203 |

| THE FIRST ENGLISH PRINTER | 214 |

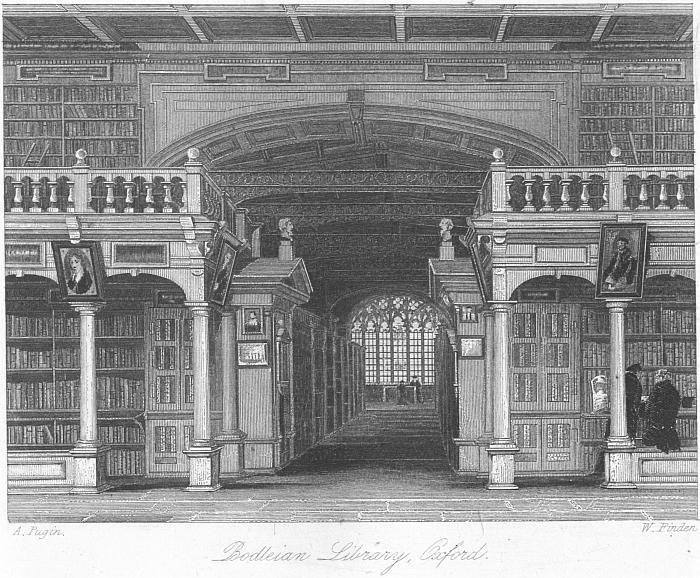

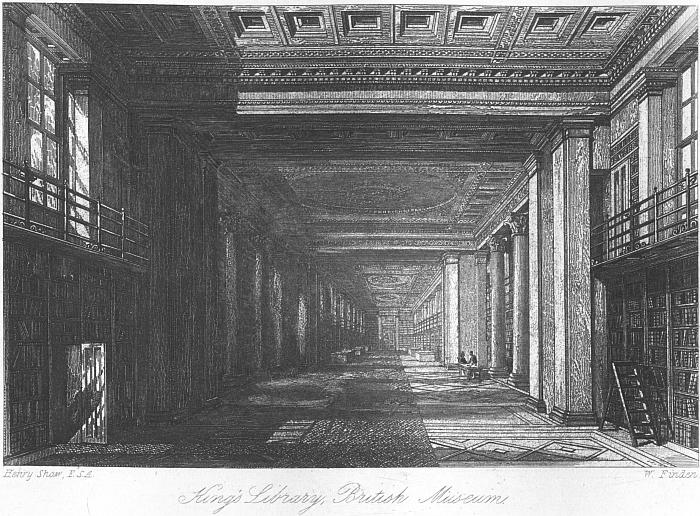

| EARLY LIBRARIES | 221 |

| HENRY THE SEVENTH | 228 |

| FIRST SOURCES OF MODERN HISTORY | 234 |

| ARNOLDE’S CHRONICLE | 240 |

| THE FIRST PRINTED CHRONICLE | 243 |

| HENRY THE EIGHTH; HIS LITERARY CHARACTER | 250 |

| BOOKS OF THE PEOPLE | 256 |

| THE DIFFICULTIES EXPERIENCED BY A PRIMITIVE AUTHOR | 268 |

| SKELTON | 276 |

| THE SHIP OF FOOLS | 285 |

| THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CHARACTER OF SIR THOMAS MORE | 289 |

| THE EARL OF SURREY AND SIR THOMAS WYATT | 303 |

| THE SPOLIATION OF THE MONASTERIES | 316 |

| A CRISIS AND A REACTION; ROBERT CROWLEY | 322 |

| PRIMITIVE DRAMAS | 339 |

| THE REFORMER BISHOP BALE; AND THE ROMANIST JOHN HEYWOOD, THE COURT JESTER | 353 |

| ROGER ASCHAM | 359 |

| PUBLIC OPINION | 368 |

| ORTHOGRAPHY AND ORTHOEPY | 381 |

| THE ANCIENT METRES IN MODERN VERSE | 393 |

| ORIGIN OF RHYME | 399 |

| RHYMING DICTIONARIES | 403 |

| THE ARTE OF ENGLISH POESIE | 405 |

| THE DISCOVERIE OF WITCHCRAFT | 413 |

| THE FIRST JESUITS IN ENGLAND | 423 |

| HOOKER | 439 |

| SIR PHILIP SIDNEY | 451 |

| SPENSER | 460 |

| THE FAERY QUEEN | 475 |

| ALLEGORY | 487 |

| THE FIRST TRAGEDY AND THE FIRST COMEDY | 502 |

| THE PREDECESSORS AND CONTEMPORARIES OF SHAKESPEARE | 514 |

| SHAKESPEARE | 529 |

| THE “HUMOURS” OF JONSON | 578 |

| DRAYTON | 584 |

| THE PSYCHOLOGICAL HISTORY OF RAWLEIGH | 590 |

| THE OCCULT PHILOSOPHER, DR. DEE | 617 |

| THE ROSACRUSIAN FLUDD | 642 |

| BACON | 650 |

| THE FIRST FOUNDER OF A PUBLIC LIBRARY | 661 |

| EARLY WRITERS, THEIR DREAD OF THE PRESS,—THE TRANSITION TO AUTHORS BY PROFESSION | 670 |

| THE AGE OF DOCTRINES | 681 |

| PAMPHLETS | 685 |

| THE OCEANA OF HARRINGTON | 692 |

| THE AUTHOR OF “THE GROUNDS AND REASONS OF MONARCHY” | 709 |

| COMMONWEALTH | 712 |

| THE TRUE INTELLECTUAL SYSTEM OF THE UNIVERSE | 714 |

| DIFFICULTIES OF THE PUBLISHERS OF CONTEMPORARY MEMOIRS | 724 |

| THE WAR AGAINST BOOKS | 738 |

AMENITIES OF LITERATURE.

THE DRUIDICAL INSTITUTION.

England, which has given models to Europe of the most masterly productions in every class of learning and every province of genius, so late as within the last three centuries was herself destitute of a national literature. Even enlightened Europe itself amid the revolving ages of time is but of yesterday.

How “that was performed in our tongue, which may be compared or preferred, either to insolent Greece or haughty Rome,”1 becomes a tale in the history of the human mind.

In the history of an insular race and in a site so peculiar as our own, a people whom the ocean severed from all nations, where are we to seek for our Aborigines? A Welsh triad, and a Welsh is presumed to be a British, has commemorated an epoch when these mighty realms were a region of impenetrable forests and impassable morasses, and their sole tenants were wolves, bears, and beavers, and wild cattle. Who were the first human beings in this lone world?

Every people have had a fabulous age. Priests and poets invented, and traditionists expatiated; we discover gods who seem to have been men, or men who resemble gods; we read in the form of prose what had once been a poem; imaginations so wildly constructed, and afterwards as strangely allegorised, served as the milky food of the children of society, quieting their vague curiosity, and circumscribing the illimitable unknown. The earliest epoch of society is unapproachable to human inquiry. Greece, with all her ambiguous poetry, was called “the 2 mendacious;” credulous Rome rested its faith on five centuries of legends; and our Albion dates from that unhistorical period when, as our earliest historian, the Monk of Monmouth, aiming at probability, affirms, “there were but a few giants in the land,”2 and these the more melancholy Gildas, to familiarise us with hell itself, accompanied by “a few devils.” Every people however long acknowledged, with national pride, beings as fabulous, in those tutelary heroes who bore their own names.

The landing of Brutus with his fugitive Trojans on “the White Island,” and here founding a “Troynovant,” was one of the results of the immortality of Homer, though it came reflected through his imitator Virgil, whose Latin in the mediæval ages was read when Greek was unknown. The landing of Æneas on the shores of Italy, and the pride of the Romans in their Trojan ancestry, as their flattering Epic sanctioned, every modern people, in their jealousy of antiquity, eagerly adopted, and claimed a lineal descent from some of this spurious progeny of Priam. The idle humour of the learned flattered the imaginations of their countrymen; and each, in his own land, raised up a fictitious personage who was declared to have left his name to the people. The excess of their patriotism exposed their forgeries, while every pretended Trojan betrayed a Gothic name. France had its Francion, Ireland its Iberus, the Danes their Danus, and the Saxons their Saxo. The descent of Brutus into Britain is even tenderly touched by so late a writer as our Camden; for while he abstains from affording us either denial or assent, he expends his costly erudition in furnishing every refutation which had been urged against the preposterous 3 existence of these fabulous founders of every European people.

Such is the corruption of the earliest history, either to gratify the idle pride of a people, or to give completeness to inquiries extending beyond human knowledge. Even Buchanan, to gratify the ancestral vanity of his countrymen, has recorded the names of three hundred fabulous monarchs, and presents a nomenclature without an event; and in his classical latinity we must silently drop a thousand unhistorical years. Even Henry and Whitaker, in the gravity of English history, sketched the manners and the characteristics of an unchronicled generation from the fragmentary romances of Ossian.

Cæsar imagined that the inhabitants of the interior of Britain, a fiercer people than the dwellers on the coasts, were an indigenous race. But the philosophy of Cæsar did not exceed that of Horace and Ovid, who conceived no other origin of man than Mater Terra. Man indeed was formed out of “the dust of the ground,” but the Divine Spirit alone could have dictated the history of primeval man in the solitude of Eden. To Cæsar was not revealed that man was an oriental creature; that a single locality served as the cradle of the human race; and that the generations of man were the offspring of a single pair, when once “the whole earth was of one language and of one speech.” “And there is no antiquity but this that can tell any other beginning,” exclaims our honest Verstegan, exulting in his Teutonic blood, while furnishing an extraordinary evidence of the retreat of Tuisco and his Teutons from the conspiracy against the skies.3

The dispersion of Babel, and, consequently, the diversity of languages, is the mysterious link which connects sacred and profane history. There is but a single point whence human nature begins—the universe has been populated by migrations. Wherever the human being is found, he has been transplanted; however varied in structure and dissimilar in dialect, the first inhabitants of every land were not born there: unlike plants and animals, which seem coeval with the region in which they are found, never removing from the soil they occupy. Thus the miracle of Holy Writ solves the enigmas of philosophical theories; of more than one Adam, of distinct stocks of mankind, and of the mechanism of language—vague conjectures, and contested opinions! which have left us without even a conception how the human being is white, or tawny, or sable; or how the first letters of the alphabet are Aleph and Bêt, or Alpha and Beta, or A and B!

In tracing the origin of nations later speculators have therefore more discreetly, though not wanting in hardy conjectures or fanciful affinities, conducted people after people, from the mysterious fount of human existence in the Asian region. Through countless centuries they have followed the myriads who, propelling each other, took the right or the left, as chance led them: vanished nations may have received names which they themselves might not have recognised. Kelt or Kimmerian, Scandinavian or Goth, Phœnician or Iberian, have been hurried to the Isles of Britain. Their tale is older, though less “divine,” than the tale of Troy; and the difficulty remains to unravel the reality of the fabulous. The learned have rarely satisfied their consciences in arranging their dates in the confusion of unnoted time; nor in that other confusion of races, often mingling together under one common appellative, have they always agreed in assigning that ancient people who were the progenitors of the modern nation; and the aborigines have been more than once described as “an ancient people whose name is unknown.” 5 In the pride of erudition, and the irascibility of confutation, they have involved themselves in interminable discussions, yet one might be seduced to adopt any hypothesis, for more or less each bears some ambiguous evidence, or some startling circumstance sufficient to rock the dreaming antiquary, and to kindle the bitter blood of pedantic patriots. The origin of the population of Europe and the first inhabitants of our British Isles has produced some antiquarian romances, often ingenious and amusing, till the romances turn out to be mere polemics, and give us angry words amid the most quaint fancies. This theme, still continued, becomes a cavern of antiquity, where many waving their torches, the light has sometimes fallen on an unperceived angle; but the scattered light has shown the depth and the darkness.

Among those shadows of time we grasp at one certainty. Whoever might be the first-comers to this solitary island, when we obtain any knowledge of the inhabitants, we are struck by their close resemblance to those tribes of savage life whom our navigators have discovered, and who are now found in almost a primitive state among that innumerable cluster of what has recently been designated the Polynesian Isles. The aborigines of Britain took the same modes of existence, and fell into similar customs. We discover their rude population divided into jealous tribes, in perpetual battle with one another; they lived in what Hobbes has called the status belli, with no notion of the meum and tuum; in the same community of their women as was found in Otaheite;4 and with the same ignorance of property, when its representative in some form was not 6 yet invented. Our aborigines resembled these races even in their personal appearance; a Polynesian chief has been drawn and coloured after the life, and the figure exhibits the perfect picture of an ancient Briton, almost naked, the body painted red; the British savage chose blue, and made deep incisions in the flesh to insert his indelible woad.5 The fierce eye, and the bearded lip, with the long hair scattered to the waist, exhibit the Briton as he was seen by Cæsar, and, a century afterwards, as the British monarch Caractacus appeared before the Emperor Claudius at Rome: his sole ornaments consisted of an iron collar, and an iron girdle; but as his naked majesty had his skin painted with figures of animals, however rudely, this was probably a distinctive dress of British royalty. These Britons lived in thick woods, herding among circular huts of reed, as we find other tribes in this early state of society; and submissive to the absolute dominion of a priesthood of magicians, as we find even among the Esquimaux; and performing sanguinary rites, similar to those of the ancient Mexicans: we are struck with the conviction that men in a parallel condition remain but uniform beings.

It seems a solecism in the intellectual history of man to discover among such a semi-barbarous people a government of sages, who, we are assured, “invented and taught such philosophy and other learning as were never read of nor heard of by any men before.”6 This paradoxical incident deepens in mystery when we are to be 7 taught that the druidical institution of Britain was Pythagorean, or patriarchal, or Brahminical. The presumed encyclopedic knowledge which this order possessed, and the singular customs which they practised, have afforded sufficient analogies and affinities to maintain the occult and remote origin of Druidism. Nor has this notion been the mere phantom of modern system-makers. It was a subject of inquiry among the ancients whether the Druids had received their singular art of teaching by secret initiation, and the prohibition of all writing, with their doctrine of the pre-existence and transmigration of souls, from Pythagoras; or, whether this philosopher in his universal travels had not alighted among the Druids, and had passed through their initiation?7 This discussion is not yet obsolete, and it may still offer all the gust of novelty. A Welsh antiquary, according to the spirit of Welsh antiquity, insists that the Druidical system of the Metempsychosis was conveyed to the Brahmins of India by a former emigration from Wales; but the reverse may have occurred, if we trust the elaborate researches which copiously would demonstrate that the Druids were a scion of the oriental family.8 Every point of the Druidical history, from its mysterious antiquity, may terminate with reversing the proposition. A recent writer confidently intimated that the knowledge of Druidism must be searched for in the Talmudical writings; but another, in return, asserts that the Druids were older than the Jews.

Whence and when the British Druids transplanted themselves to this lone world amid the ocean, bringing with them all the wisdom of far antiquity, to an uncivilized race, is one of those events in the history of man which no historian can write. It is evident that they long preserved what they had brought; since the Druids 8 of Gaul were fain to resort to the Druids of Britain to renovate their instruction.

The Druids have left no record of themselves; they seem to have disdained an immortality separate from the existence of their order; but the shadow of their glory is reflected for ever in the verse of Lucan, and the prose of Cæsar. The poet imagined that if the knowledge of the gods was known to man, it had been alone revealed to these priests of Britain. The narrative of the historian is comprehensive, but, with all the philosophical cast of his mind and the intensity of his curiosity, Cæsar was not a Druid;9 and only a Druid could have written—had he dared!—on Druidheacht—a sacred, unspeakable word at which the people trembled in their veneration.

The British Druids constituted a sacred and a secret society, religious, political, and literary. In the rude mechanism of society in a state of pupilage, the first elements of government, however gross, or even puerile, were the levers to lift and to sustain the unhewn masses of the barbaric mind. Invested with all privileges and immunities, amid that transient omnipotence which man in his first feeble condition can confer, the wild children of society crouched together before those illusions which superstition so easily forges; but the supernatural dominion lay in the secret thoughts of the people; the marauder had not the daring to touch the open treasure as it lay in the consecrated grove; and a single word from a Druid for ever withered a human being, “cut down like grass.” The loyalty of the land was a religion of wonder and fear, and to dispute with a Druid was a state crime.

They were a secret society, for whatever was taught was forbidden to be written; and not only their doctrines and their sciences were veiled in this sacred obscurity, but 9 the laws which governed the community were also oral. For the people, the laws, probably, were impartially administered; for the Druids were not the people, and without their sympathies, these judges at least sided with no party. But if these sages, amid the conflicting interests of the multitude, seemed placed above the vicissitudes of humanity, their own more solitary passions were the stronger, violently compressed within a higher sphere: ambition, envy, and revenge, those curses of nobler minds, often broke their dreams. The election of an Arch-Druid was sometimes to be decided by a battle. Some have been chronicled by a surname which indicates a criminal. No king could act without a Druid by his side, for peace or war were on his lips; and whenever the order made common cause, woe to the kingdom!10 It was a terrible hierarchy. The golden knife which pruned the mistletoe beneath the mystic oak, immolated the human victim.

The Druids were the common fathers of the British youth, for they were the sole educators; but the genius of the order admitted of no inept member. For the acolyte unendowed with the faculty of study all initiation ceased; nature herself had refused this youth the glory of Druidism; but he was taught the love of his country. The Druidical lyre kindled patriotism through the land, and the land was saved—for the Druids!

The Druidical custom of unwritten instruction was ingeniously suggested by Cicero, as designed to prevent their secret doctrines from being divulged to those unworthy or ill fitted to receive them, and to strengthen the memory of their votaries by its continued exercise; but we may suspect, that this barbarous custom of this most ancient sodality began at a period when they themselves neither read nor wrote, destitute of an alphabet of their own; for when the Druids had learned from the Greeks their characters, they adopted them in all their public and private affairs. We learn that the Druidical sciences were contained in twenty thousand verses, which were to prompt their perpetual memory. Such traditional science could not be very progressive; what was to be got by rote no disciple would care to consider obsolete, and a century 10 might elapse without furnishing an additional couplet. The Druids, like some other institutions of antiquity, by not perpetuating their doctrines, or their secrets, in this primeval state of theology and philosophy, by writing, have effectually concealed their own puerile simplicity. But the monuments of a people remain to perpetuate their character. We may judge of the genius or state of the Druidical arts and sciences by such objects. We are told that the Druids were so wholly devoted to nature, that they prohibited the use of any tool in the construction of their rude works; all are unhewn masses, or heaps of stones; such are their cairns and cromleches and corneddes, and that wild architecture whose stones hang on one another, still frowning on the plains of Salisbury.11 A circle of stones marked the consecrated limits of the Druidical tribunal; and in the midst a hillock heaped up for the occasion was the judgment-seat. Here, in the open air, in “the eye of light and the face of the sun,” to use the bardic style, the decrees were pronounced, and the Druids harangued the people. Such a scene was exhibited by the Hebrew patriarchs, from whom some imagined these Druids descended; but whether or not the Celtic be of this origin we must not decide by any analogous manners or customs, because these are nearly similar, wherever we trace a primitive race—so uniform is nature, till art, infinitely various, conceals nature herself.

In the depth of antiquity, misty superstition and pristine tradition gave a false magnitude to the founders of human knowledge; and our own literary historians who have been over-curious about “the Genesis” of their antiquities, have inveigled us into the mystic groves of Druidism in all their cloudy obscurity. The “Antiquities of the University of Oxford” open with “the Originals of Learning in this Nation;” and our antiquary discerns the first shadowings of the University of Oxford in “the universal knowledge” of the Druidical institution in “ethics, politics, civil law, divinity, and poetry.” Such are the reveries of an antiquary.

1 Ben Jonson.

2 The existence of these giants was long historical, and their real origin was in the fourth verse of the fifth chapter of Genesis, which no commentator shall ever explain. Aylet Sammes in his “Britannia Antiqua Illustrata, or the Antiquities of Ancient Britain derived from the Phœnicians,” has particularly noticed “two teeth of a certain giant, of such a huge bigness, that two hundred such teeth as men now-a-days have might be cut out of them.” Becanus and Camden had however observed, that “the bones of sea-fish had been taken for giants’ bones;—but can it be rationally supposed that men ever entombed fishes?” triumphant in his arguments, exclaims Aylet Sammes. The revelations of geology had not yet been surmised, even by those who had discovered that giants were but sea-fish. So progressive is all human knowledge.

3 The miraculous event was perpetuated by the whole Teutonic people, “while it was fresh in their memories,” as our honest Saxon asserts; hence to this day we in our Saxon English, and our Teutonic kinsmen and neighbours in their idiom, describe a confusion of idle talk by the term of Babel, now written from our harsh love of supernumerary consonants Babble; and any such workmen of Babel are still indicated as Babblers.—“A Restitution of Decayed Intelligence,” 138, 4to. Antwerp, 1605.

The erudite Menage offers a memorable evidence of the precarious condition of etymology when it connects things which have no other affinity than that which depends on sounds. See his “Dictionnaire Etymologique, ou Origines de la Langue Françoise,” ad verbum Babil. Not satisfied with the usual authorities deduced from Babel, this verbal sage appeals to us English to demonstrate the natural connexion between Babbling and Childishness; for thus he has shrewdly opined “The English in this manner have Babble and Baby!”

After all the convulsion of lips at Babel, and confusion among the etymologists, the word is Hebrew, which with a few more such are found in many languages.

4 Julia, the empress of Severus, once in raillery remonstrated with a British female against this singular custom, which annulled every connubial tie. The British woman, whose observation had evidently been enlarged during her visit to Rome, retorted by her disdain of the more polished corruption of the greater nation. “We British women greatly differ from the Roman ladies, for we follow in public the men whom we esteem the most worthy, while the Roman women yield themselves secretly to the vilest of men.”

Such was the noble sentiment which broke forth from a lady of savage education—it was, however, but a savage’s view of social life. This female Briton had not felt how much remained of life which she had not taken into her view; when the attractions of her sex had ceased, and the season of flowers had passed, she was left without her connubial lord amid a progeny who had no father.

5 This practice of savage races may have originated in a natural circumstance. The naked body by this slight covering is protected from the atmosphere, from insects, and other inconveniences to which the unclothed are exposed. But though it may not have been considered merely as personal finery, which seems sometimes to have been the case, it became a refinement of barbarism when they painted their bodies frightfully to look terrible to the enemy.

6 See Mr. Tate’s twelve questions about the Druids, with Mr. Jones’s answers; a learned Welsh scholar who commented on the ancient laws of his nation.—Toland’s “History of the Druids.”

A later Welsh scholar affirms, “beyond all doubt there has been an era when science diffused a light among the Cymry—in a very early period of the world.”—Owen’s “Heroic Elegies of Llywarç Hen.” Preface, xxi.

This style is traditional and still kept up among Welsh and Irish scholars, who seem familiar with an antiquity beyond record.

7 Toland’s “History of the Druids” in his Miscellaneous Works, ii. 163.

8 “The Celtic Druids, or an Attempt to show that the Druids were the Priests of Oriental Colonies, who emigrated from India.” By Godfrey Higgins, Esq. London, 1829.

This is a quarto volume abounding with recondite researches and many fancies. It is more repulsive, by the absurd abuse of “the Christian priests who destroyed their (the Druids’) influence, and unnerved the arms of their gallant followers.” There are philosophical fanatics!

9 Cæsar was a keen observer of the Britons. He characterizes the Kentish men, Ex his omnibus longè sunt humanissimi,—“Of all this people the Kentish are far the most humane.” Cæsar describes the British boats to have the keel and masts of the lightest wood, and their bodies of wicker covered with leather; and the hero and sage was taught a lesson by the barbarians, for Cæsar made use of these in Spain to transport his soldiers,—a circumstance which Lucan has recorded. In the size and magnitude of Britain, confiding to the exaggerated accounts of the captives, he was mistaken; but he acknowledges, that many things he heard of, he had not himself observed.

10 Toland’s “Hist. of the Druids,” 56.

11 The origin of Stonehenge is as unknown as that of the Pyramids. As it is evident that those huge masses could not have been raised and fixed without the machinery of art, Mr. Owen, the Welsh antiquary, infers, that this building, if such it may be called, could not have been erected till that later period when the Druidical genius declined and submitted to Christianity, and the Druids were taught more skilful masonry in stone, though without mortar. It has been, however, considered, that those masses which have been ascribed to the necromancer Merlin, or the more ancient giants, might have been the work of the Britons themselves, who, without our knowledge of the mechanical powers in transporting or raising ponderous bodies, it is alleged, were men of mighty force and stature, whose co-operation might have done what would be difficult even to our mechanical science. The lances, helmets, and swords of these Britons show the vast size and strength of those who wore them. The native Americans, as those in Peru, unaided by the engines we apply to those purposes, have raised up such vast stones in building their temples as the architect of the present time would not perhaps hazard the attempt to remove. “Essays by a Society at Exeter,” 114.

BRITAIN AND THE BRITONS.

Britain stood as the boundary of the universe, beyond Which all was air and water—and long it was ere the trembling coasters were certain whether Britain was an island or a continent, a secret probably to the dispersed natives themselves. It was the triumphant fleet of Agricola, nearly a century after the descent of Cæsar, which, encircling it, proclaimed to the universe that Britain was an island. From that day Albion has lifted its white head embraced by the restless ocean, but often betrayed by that treacherous guardian, she became the possession of successive races.

Nations have derived their names from some accidental circumstance; some peculiarity marking their national character, or descriptive of the site of their country. The names of our island and of our islanders have exercised the inquiries, and too often the ingenuity, of our antiquarian etymologists. There are about half a hundred origins of the name of Britain; some absurd, many fanciful, all uncertain.1 Our primitive ancestors distinguished themselves, in pride or simplicity, as Brith and Brithon; Brith signified stained, and Brithon, a stained man, according to Camden.2 The predilection for colouring their bodies induced the civilized Romans to designate the people who were driven to the Caledonian forests as Picts, or a painted people.

That the native term of Brith or Brithon, by its curt harshness, would clash on the modulating ear of the Greek voyager, or the Latin poet, seems probable, for by them it was amplified. And thus we owe to sonorous antiquity the name now famous as their own, for Britannia first appeared in their writings, bequeathed to us by the masters of the world as their legacy of glory.

To the knowledge of the Romans the island exceeded in magnitude all other islands; and they looked on this land with pride and anxiety, while they dignified Britain as the “Roman island.” The Romans even personified the insular Genius with poetic conceptions. Britannia is represented as a female seated on a rock, armed with a spear, or leaning on a prow, while the ship beside her attests her naval power. We may yet be susceptible of the prophetic flattery, when we observe the Roman has also seated her on a globe, with the symbol of military power, and the ocean rolling under her feet.3

The tale of these ancient Britons who should have been our ancestors is told by the philosophical historian of antiquity. Under successive Roman governors they still remained divided by native factions: “A circumstance,” observes Tacitus, “most useful for us, among such a powerful people, where each combating singly, all are subdued.” A century, as we have said, had not elapsed from the landing of Cæsar to the administration of Agricola. That enlightened general changed the policy of former governors; he allured the Britons from their forest retreats and reedy roofs to partake of the pleasures of a Roman city—to dwell in houses, to erect lofty temples, and to indulge in dissolving baths. The barbarian who had scorned the Roman tongue now felt the ambition of Roman eloquence; and the painted Briton of Cæsar was enveloped in the Roman toga. Severus, in another century after Agricola, as an extraordinary evidence of his successful government, appealed to Britain—“Even the Britons are quiet!” exclaimed the emperor. The tutelary genius of Rome through four centuries preserved Britain—even from the Britons themselves; but the Roman policy was fatal to the national character, and when the day arrived that 14 their protector forsook them, the Britons were left among their ancient discords: for provincial jealousies, however concealed by circumstances, are never suppressed; the fire lives in its embers ready to be kindled.

The island of Britain, itself not extensive, was broken into petty principalities: we are told that there were nearly two hundred kinglings, the greater part of whom did not presume to wear crowns. Sometimes they united in their jealousies of some paramount tyrant, but they raged among themselves; and the passion of Gildas has figured them as “the Lioness of Devonshire” encountering a “Lion’s Whelp” in Dorsetshire, and “the Bear-baiter,” trembling before his regal brother, “the Great Bull-dog.” “These kings were not appointed by God,” exclaims the British Jeremiah; he who wrote under the name of Gildas. Thus the Britons formed a powerless aggregate, and never a nation. The naked Irish haunted their shores, covering their sea with piracy; and the Picts rushed from their forests—giants of the North who, if Gildas does not exaggerate, even dragged down from their walls the amazed Britons. Such a people in their terrified councils were to be suppliants to the valour of foreigners; from that hour they were doomed to be chased from their natal soil. They invited, or they encouraged, another race to become their mercenaries or their allies. The small and the great from other shores hastened to a new dominion. Britain then became “a field of fortune to every adventurer when nothing less than kingdoms were the prize of every fortunate commander.”4

We have now the history of a people whose enemies inhabited their ancient land: the flame and the sword ceaselessly devouring the soil; their dominion shrinking in space, and the people diminishing in number; victory for them was fatal as defeat. The disasters of the Britons pursued them through the despair of almost two centuries; it would have been the history of a whole people ever retreating, yet hardly in flight, had it been written. Shall we refuse, on the score of their disputed antiquity the evidence of the Welsh bards? The wild grandeur of the melancholy poetry of those ancient Britons attests the 15 reality of their story and the depth of their emotions.5

We have spun the last thread of our cobweb, and we know not on what points it hangs, such irreconcileable hypotheses are offered to us by our learned antiquaries, whenever they would account for the origin or the disappearance of a whole people. The mystery deepens, and the confusion darkens amid contradictions and incredibilities, when the British historian contemplates in the perspective the Fata Morgana of another Britain on the opposite shores of the ancient Armorica, another Britain in La Brétagne.

The ancient Armorica was a district extending from the Loire to the Seine, about sixty leagues, and except on the land side, which joined Poictou, is encircled by the ocean. Composed of several small states, in the decline of the Roman empire they shook off the Roman yoke, and their independence was secured by the obscurity of their sequestered locality.

The tale runs that Maximus, having engaged his provincial Britons in his ambitious schemes, rewarded their military aid by planting them in one of these Armorican communities. To give colour to this tradition, the story adds that this Roman general had a considerable interest in Wales, “having married the daughter of a powerful chieftain, whose chapel at Carnarvon is still shown.”6 16 The marriage of this future Roman emperor with a Welsh princess would serve as an embellishment to a Welsh genealogy. This event must have occurred about the year 384. When the Britons were driven out of their country by faithless allies, Armorica would offer an easy refuge for fugitives; there they found brothers already settled, or friends willing to receive them.7

In this uncertainty of history, amid the dreams of theoretical antiquaries, we cannot doubt that at some time there was a powerful colony of Britons in Armorica; they acquired dominion as well as territory. They changed that masterless Armorican state to which they were transplanted from an aristocracy into a monarchy—that government to which they had been accustomed; they consecrated the strange land by the baptism of their own national name, and to this day it is called Brétagne, or Britain; and surely the Britons carried with them all their home-affections, for they made the new country an image of the old: not only had they stamped on it the British name, but the Britons of Cornwall called a considerable district by their own provincial name, known in France as “Le Pays de Cornouaille;” and their speech perpetuated their vernacular Celtic. At the siege of Belleisle in 1756, the honest Britons of the principality among our soldiers were amazed to find that they and the peasants of Brittany were capable of conversing together. This expatriation reminds us of the emotions of the first settlers in the New World. Ancient Spain reflected herself in her New Spain; and our first emigrants called their “plantations” “New England;” distributing local names borrowed from the land of their birth—undying memorials of their parent source!

This singular event in the civil annals of the ancient Britons has given rise to a circumstance unparalleled in the literary history of every people, for it has often involved in a mysterious confusion a part of our literary and historical antiquities. The Britain in France is not always discriminated from our own; and this double Britain at times becomes provokingly mystifying. Two eminent antiquaries, 17 Douce and Ritson, sometimes conceived that Bretagne meant England; a circumstance which might upset a whole hypothesis.

In the fastnesses of Wales, on the heights of Caledonia, and on the friendly land of Armorica, are yet tracked the fugitive and ruined Britons. It is most generally conceded that they retreated to the western coasts of England, and that, often discomfited, they took their last refuge in those “mountain heights” of Cambria.

Their shadowy Arthur has left an undying name in romance, and is a nonentity in history. Whether Arthur was a mortal commander heading some kings of Britain, or whether religion and policy were driven to the desperate effort for rallying their fugitives by a national name, and “a hope deferred,” like the Sebastian of Portugal, this far-famed chieftain could never have been a fortunate general; he displayed his invincibility but in some obscure and remote locality; he struck no terror among his enemies, for they have left his name unchronicled: nor living, have the bards distinguished his pre-eminence. “The grave of Arthur is a mystery of the world,” exclaimed Taliessin, the great bard of the Britons. But the mortal who vanished in the cloud of conflict had never seen death; and to the last the Britons awaited for the day of their Redeemer when Arthur should return in his immortality, accompanied by “the Flood-King of the Deluge,” from the Inys Avallon, the Isle of the Mystic Apple-tree, their Eden or their Elysium. Arthur was a myth, half Christian and half Druidical. In Armorica, as in Wales, his coming was long expected, till “Espérance brétonne” became proverbial for all chimerical hopes.

Thus the aborigines of this island vanished, but their name is still attached to us. The Anglo-Saxons became our progenitors, and the Saxon our mother-tongue. Yet so complex and incongruous is the course of time, that we still call ourselves Britons, and “true Britons;” and the land we dwell in Great Britain. Nor is it less remarkable, that the days of the Christian week commemorate the names of seven Saxon idols.8 There are improbabilities and incongruities 18 in authentic history as hard to reconcile as any we meet with in wild romance.

During six centuries the Saxons and the Normans combined to banish from the public mind the history of the Britons: it was lost; it did not exist even among the Britons in Wales. In the reign of Henry the First, an Archdeacon of Oxford, who was that king’s justiciary, being curious in ancient histories, opportunely brought out of “Britain in France,” “a very ancient book in the British tongue.” This book, which still forms the gordian knot of the antiquary, he confided to the safe custody and fertile genius of Geoffry, the Monk of Monmouth. It contained a regular story of the British kings, opening with Brute, the great grandson of Priam in this airy generation; kings who, Geoffry “had often wondered, were wholly unnoticed by Gildas and Bede.” “Yet,” adds our historian, “their deeds were celebrated by many people in a pleasant manner, and by heart, as if they had been written.” This remarkable sentence aptly describes that species of national songs which the early poets have always provided for the people, traditions which float before history is written. Whether this very ancient British book, almost five centuries old, was a volume of these poetical legends, which our historian might have arranged into that “regular history” which is furnished by his Latin prose version, we are left without the means of ascertaining, since it proved to be the only copy ever found, and was never seen after the day of the translation. The Monk of Monmouth does not arrogate to himself any other merit than that of a faithful translator, and with honest simplicity warns of certain additions, which, even in a history of two thousand years contained in a small volume, were found necessary.

We are told that the Britons who passed over into France carried with them “their archives.” But there were other Britons who did not fly to the sixty leagues of Armorica; and of these the only “archives” we hear of are those which the romancers so perpetually assure us may be consulted at Caerleon, or some other magical residence of the visionary Arthur. The Armorican colony must have formed but a portion of the Britons; and it would be unreasonable to suppose, that these fugitives 19 could by any human means sequestrate and appropriate for themselves the whole history of the nation, without leaving a fragment behind. Yet nothing resembling the Armorican originals has been traced among the Welsh. Our Geoffry modestly congratulates his contemporary annalists, while he warns them off the preserve where lies his own well-stocked game. And thus he speaks:—“The history of the kings who were the successors in Wales of those here recorded, I leave to Karadoc of Lancarven, as I do also the kings of the Saxons to William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon; hut I advise them to be silent concerning the British kings, since they have not that book written in the British tongue which Walter, Archdeacon of Oxford, brought out of Britain.” Well might Geoffry exult. He possessed the sole copy ever found in both the Britains.

The British history is left to speak for itself in a great simplicity of narrative, where even the supernatural offers no obstacle to the faith of the historian—a history which might fascinate a child as well as an antiquary. These remote occurrences are substantiated by the careful dates of a romantic chronology. Events are recorded which happened when David reigned in Judea, and Sylvius Latinus in Italy, and Gad, Nathan, and Asaph prophesied in Israel. And the incidents of Lear’s pathetic story occurred when Isaiah and Hosea flourished, and Rome was built by the two brothers. It tells of one of the British monarchs, how the lady of his love was concealed during seven years in a subterraneous palace. On his death, his avengeful queen cast the mother and her daughter into the river which still bears that daughter’s name, Sabrina, or the Severn, and was not forgotten by Drayton. Another incident adorns a canto of Spenser; the Lear came down to Shakspeare, as the fraternal feuds of Ferrex and Porrex created our first tragedy by Sackville. There are other tales which by their complexion betray their legendary origin.

Whatever assumed the form of history was long deemed authentic; and such was the authority of this romance of Geoffry, that when Edward the First claimed the crown of Scotland in his letter to the pope, he founded his right on a passage in Geoffry’s book; doubtless this very passage 20 was held to be as veracious by the Scots themselves, only that on this occasion they decided to fight against the text. Four centuries after Geoffry had written, when Henry the Seventh appointed a commission to draw up his pedigree, they traced the royal descent from the imaginary Brutus, and reckoning all Geoffry’s British kings in the line—the fairies of history—made the English monarch a descendant in the hundredth degree. We now often hear of “the fabulous” History of Geoffry of Monmouth; but neither his learned translator in 1718, nor the most eminent Welsh antiquaries, attach any such notion to a history crowded with domestic events, and with names famous yet unknown.

After the lapse of so many centuries, the scrutinising investigation of a thoughtful explorer in British antiquities has demonstrated, through a chain of recondite circumstances, that this History of Geoffry of Monmouth, and its immediate predecessor, the celebrated Chronicle of the pseudo-Archbishop Turpin, were sent forth on the same principle on which to this day we publish party pamphlets, to influence the spirit of two great nations opposed in interest and glory to each other; in a word, that they were two Tales of a Tub thrown out to busy those mighty whales, France and England.9

One great result of their successful grasp of the popular feelings could never have been contemplated by these grave forgers of fabulous history. The Chronicle of Archbishop Turpin and the British History of Geoffry of Monmouth became the parents of those two rival families of romances which commemorate the deeds of the Paladins of Charlemagne, and the Knights of Arthur, the delight of three centuries.

The Welsh of this day possess very ancient manuscripts, which they cherish as the remains of the ancient Britons. These preserve the deep strains of poets composed in triumph or in defeat, the poetry of a melancholy race. Gray first attuned the Cymry harp to British notes, more poetical than the poems themselves, while others have devoted their pens to translation, unhappily not always master of the language of their version. These manuscripts 21 contain also a remarkable body of fiction in the Mabinogion, or juvenile amusements, a collection of prose tales combining the marvellous and the imaginative. Some are chivalric and amatory, stamped with the manners and customs of the middle ages; others apparently of a much higher antiquity, like all such national remains, are considered mythological; some there are not well adapted, perhaps, to the initiation of youth. Obviously they are nothing more than short romances; but we are solemnly assured that the Mabinogion abound with occult mysteries, and that simple fiction only served to allure the British neophyte to bardic mysticism. A learned writer, who is apt to view old things in a new light, and whose boldness invigorates the creeping toil of the antiquary, reveals the esoteric doctrine—“the childhood alluded to in their title is an early and preparatory stage of initiation; they were calculated to inflame curiosity, to exercise ingenuity, and lead the aspirant gradually into a state of preparation for things which ears not long and carefully disciplined were unfit to hear.”10

Every people have tales which do not require to be written to be remembered, whose shortness is the salt which preserves them through generations. Our ancestors 22 long had heard of “Breton lays” and “British tales,” from the days of Chaucer to those of Milton; but it was reserved for our own day to ascertain the species, and to possess those forgotten yet imaginative effusions of the ancient Celtic genius. Our literary antiquaries have discovered reposing among the Harleian manuscripts the writings of Marie de France,11 an Anglo-Norman poetess, who in the thirteenth century versified many old Breton lais, which, she says, “she had heard and well remembered.” Who can assure us whether this Anglo-Norman poetess gathered her old tales, for such she calls them, in the French Britain or the English Britain, where she always resided?

It is among the Welsh we find a singular form of artificial memory which can be traced among no other people. These are their TRIADS. Though unauthorized by the learned in Celtic antiquities, I have sometimes fancied that in the form we may possess a relic of druidical genius. A triad is formed by classing together three things, neither more nor less, but supposed to bear some affinity, though a fourth or fifth might occur with equal claim to be admitted into the category.12 To connect three things together apparently analogous, though in reality not so, sufficed for the stores of knowledge of a Triadist; but to fix on any three incidents for an historical triad discovered a very narrow range of research; and if designed as an artificial memory, three insulated facts, deprived of dates or descriptions or connexion, neither settled the chronology, nor enlarged the understanding. It is, however, worthy of remark, that when the Triad is of an ethical cast, the number three may compose an excellent aphorism; for three things may be predicated with poignant concision, when they relate to our moral qualities, or to the intellectual faculties: in this capricious form the Triad has often afforded an enduring principle of human conduct, or 23 of critical discrimination; for our feelings are less problematical than historical events, and more permanent than the recollection of three names.13

1 See the opening of Speed’s “Chronicle.”

2 The historian of our land in the solemnity of his high office, unwilling that an obscure Welsh prince named Prydain should have left his immemorable name to this glorious realm, as a Welsh triad professes, was delighted to draw the national name out of the native tongue, appositely descriptive of the prevalent custom. But when, seduced by this syren of etymology, our grave Camden, to display the passion of a painted people for colours, collects a long list of ancient British names of polysyllabic elongation, and culls from each a single syllable which by its sound he conceives alludes to blue, or red, or yellow, our sage, in proving more than was requisite, has encumbered his cause, and has thrown suspicion over the whole. The doom of the etymologist, so often duped by affinity of sounds, seems to have been that of our judicious Camden.

3 Evelyn’s “Numismata.” Pinkerton has engraven ten of these Britannias struck by the Romans in his “Essay on Medals.”

4 Milton.

5 See Mr. Turner’s able “Vindication of the Genuineness of the Ancient British Bards.”

6 Warton draws his knowledge from Rowland’s “Mona Antiqua;” Geoffry of Monmouth would have extended his inquiry. Camden, judicious as he was, has actually bestowed the kingdom, as well as the princess, on this Roman general; and Gibbon has sarcastically noticed that Camden has been authority for all “his blind followers.” The source of this sort of history lies in the volume of the “Monk of Monmouth,” where Gibbon might have found the number of the numerous army of Maximus. Rowland’s “Mona Antiqua Restaurata” is one of the most extraordinary pieces of our British Antiquities. It is written with the embrowned rust of our old English Antiquaries, where nothing on a subject seems to be omitted; but our author, unlike his contemporary antiquaries, is sceptical even on his own acquisitions; he asserts little and assumes nothing. One may conceive the native simplicity of an author, who having to describe the Isle of Anglesey, opens his work with the history of Chaos itself, to explain by the division of land and water the origin of islands. I have heard that this learned antiquary never travelled from his native island.

7 “L’Art de vérifier les Dates,” article Brétagne, is thrown into utter confusion. It seems, however, to indicate that there were many migrations; but all is indistinct or uncertain.

8 Verstegan has finely engraved these idols in his “Restitution,” so delighted was this Teutonic Christian with these hideous absurdities of his pagan ancestors, and so proud of his Saxon descent.

9 Turner’s “History of England during the Middle Ages,” iv. 326.

10 “Britannia after the Romans.” The literary patriotism of Wales has been more remarkable among humble individuals than among the squirearchy, if we except the ardent Pennant. Mr. Owen Jones, an honest furrier in Thames-street, kindled by the love of father-land, offered the Welsh public a costly present of the “Archæology of Wales,” containing the bardic poetry, genealogies, triads, chronicles, &c. in their originals: the haughty descendant of the Cymry disdained to translate for the Anglo-Saxon. To Mr. William Owen the lore of Cambria stands deeply indebted for his persevering efforts. Under the name of Meirion he long continued his literal versions of the Welsh bards in the early volumes of the “Monthly Magazine;” he has furnished a Cambrian biography and a dictionary.

Some years ago, a learned Welsh scholar, Dr. Owen Pughe, issued proposals to publish the “Mabinogion,” accompanied by translations, on the completion of a subscription list sufficient to indemnify the costs of printing.—See Mr. Crofton Croker’s interesting work on “Fairy Legends,” vol. iii. He appealed in vain to the public, but the whole loss remains with them. Recently a munificent lady [Lady Charlotte Guest] has resumed the task, and has presented us in the most elegant form with two tales such as ladies read. Since this note was written several cheering announcements of some important works have been put forth. [Many have since been published.]

11 See Warton and Ellis. “Poésies de Marie de France” have been published by M. de Roquefort, Paris, 1820.

12 “The translators do the triadist an injustice in rendering Tri by ‘The Three’ when he has put no The at all. The number was accounted fortunate, and they took a pleasure in binding up all their ideas into little sheaves or fasciculi of three; but in so doing they did not mean to imply that there were no more such.”—“Britannia after the Romans.”

13 As these artificial associations, like the topics invented by the Roman rhetoricians, have been ridiculed by those who have probably formed their notions from unskilful versions, I select a few which might enter into the philosophy of the human mind. They denote a literature far advanced in critical refinement, and appear to have been composed from the sixth to the twelfth century.

“The three foundations of genius; the gift of God, human exertion, and the events of life.”

“The three first requisites of genius; an eye to see nature, a heart to feel it, and a resolution that dares follow it.”

“The three things indispensable to genius; understanding, meditation, and perseverance.”

“The three things that improve genius; proper exertion, frequent exertion, and successful exertion.”

“The three qualifications of poetry; endowment of genius, judgment from experience, and felicity of thought.”

“The three pillars of judgment; bold design, frequent practice, and frequent mistakes.”

“The three pillars of learning; seeing much, suffering much, and studying much.” See Turner’s “Vindication of the Ancient British Bards.”—Owen’s “Dissertation on Bardism, prefixed to the Heroic Elegies of Llywarç Hen.”

THE NAME OF ENGLAND AND OF THE ENGLISH.

Two brothers and adventurers of an obscure Saxon tribe raised their ensign of the White Horse on British land: the visit was opportune, or it was expected—this remains a state secret. Welcomed by the British monarch and his perplexed council amid their intestine dissensions, as friendly allies, they were renowned for their short and crooked swords called Seax, which had given the generic name of Saxons to their tribe.

These descendants of Woden, for such even the petty chieftains deemed themselves, whose trade was battle and whose glory was pillage, showed the spiritless what men do who know to conquer, the few against the many. They baffled the strong and they annihilated the weak. The Britons were grateful. The Saxons lodged in the land till they took possession of it. The first Saxon founded the kingdom of Kent; twenty years after, a second in Sussex raised the kingdom of the South-Saxons; in another twenty years appeared the kingdom of the West-Saxons. It was a century after the earliest arrival that the great emigration took place. The tribe of the Angles depopulated their native province and flocked to the fertile island, under that foeman of the Britons whom the bards describe as “The Flame Bearer,” and “The Destroyer.” Every quality peculiar to the Saxons was hateful to the Britons; even their fairness of complexion. Taliessin terms Hengist “a white-bellied hackney,” and his followers are described as of “hateful hue and hateful form.” The British poet delights to paint “a Saxon shivering and quaking, his white hair washed in blood;” and another sings how “close upon the backs of the pale-faced ones were the spear-points.”1

Already the name itself of Britain had disappeared among the invaders. Our island was now called “Saxony beyond the Sea,” or “West Saxon land;” and when the 25 expatriated Saxons had alienated themselves from the land of their fathers, those who remained faithful to their native hearths perhaps proudly distinguished themselves as “the old Saxons,” for by this name they were known by the Saxons in Britain.

Eight separate but uncertain kingdoms were raised on the soil of Britain, and present a moveable surface of fraternal wars and baffled rivals. There was one kingdom long left kingless, for “No man dared, though never so ambitious, to take up the sceptre which many had found so hot; the only effectual cure of ambition that I have read”—these are the Words of Milton. Finally, to use the quaint phrase of the Chancellor Whitelock, “the Octarchy was brought into one.” At the end of five centuries the Saxons fell prostrate before a stronger race.

But of all the accidents and the fortunes of the Saxon dynasty, not the least surprising is that an obscure town in the duchy of Sleswick, Anglen, is commemorated by the transference of its name to one of the great European nations. The Angles, or Engles, have given their denomination to the land of Britain—Engle-land is England, and the Engles are the English.2

How it happened that the very name of Britain was abolished, and why the Anglian was selected in preference to the more eminent race, may offer a philosophical illustration of the accidental nature of LOCAL NAMES.

There is a tale familiar to us from youth, that Egbert, the more powerful king of the West Saxons, was crowned the first monarch of England, and issued a decree that this kingdom of Britain should be called England; yet an event so strange as to have occasioned the change of the name of the whole country remains unauthenticated by any of the original writers of our annals.3 No record 26 attests that Egbert in a solemn coronation assumed the title of “King of England.” His son and successor never claimed such a legitimate title; and even our illustrious Alfred, subsequently, only styled himself “King of the West Saxons.”

The story, however, is of ancient standing; for Matthew of Westminster alludes to a similar if not the same incident, namely, that by “a common decree of all the Saxon kings, it was ordained that the title of the island should no longer be Britain, from Brute, but henceforward be called from the English, England.” Stowe furnishes a positive circumstance in this obscure transaction—“Egbert caused the brazen image of Cadwaline, King of the Britons, to be thrown down.” The decree noticed by Matthew of Westminster, combined with the fact of pulling down the statue of a popular British monarch, betrays the real motive of this singular national change: whether it were the suggestion of Egbert, or the unanimous agreement of the assembled monarchs who were his tributary kings, it was a stroke of deep political wisdom; it knitted the members into one common body, under one name, abolishing, by legislative measures, the very memory of Britain from the land. Although, therefore, no positive evidence has been produced, the state policy carries an internal evidence which yields some sanction to the obscure tradition.

It is a nicer difficulty to account for the choice of the Anglian name. It might have been preferred to distinguish the Saxons of Britain from the Saxons of the Continent; or the name was adopted, being that of the far more numerous race among these people. Four kingdoms of the octarchy were possessed by the Angles. Thus doubtful and obscure remains the real origin of our national name, which hitherto has hinged on a suspicious fact.

The casual occurrence of the Engles leaving their name to this land has bestowed on our country a foreign designation; and—for the contingency was nearly occurring—had the kingdom of Northumbria preserved its ascendancy 27 in the octarchy, the seat of dominion had been altered. In that case, the Lowlands of Scotland would have formed a portion of England; York would have stood forth as the metropolis of Britain, and London had been but a remote mart for her port and her commerce. Another idiom, perhaps, too, other manners, had changed the whole face of the country. We had been Northmen, not Southerns; our neighbourhood had not proved so troublesome to France. But the kingdom of Wessex prevailed, and became the sole monarchy of England, Such local contingencies have decided the character of a whole people.4

The history of LOCAL NAMES is one of the most capricious and fortuitous in the history of man; the etymologist must not be implicitly trusted, for it is necessary to be acquainted with the history of a people as much as the history of languages, to be certain of local derivations. We have recently been cautioned by a sojourner in the most ancient of kingdoms,5 not too confidently to rely on etymology, or to assign too positively any reason for the origin of LOCAL NAMES. No etymologist could have accounted for the name of our nation had he not had recourse to our annals. Sir Walter Raleigh, from his observations in the New World, has confirmed this observation by circumstances which probably remain unknown to the present inhabitants. The actual names given to those places in America which they still retain, are nothing more than the blunders of the first Europeans, demanding by signs and catching at words by which neither party were intelligible to one another.6

1 “Britannia after the Romans,” 62, 4to.

2 It is a singular circumstance that our neighbours have preserved the name of our country more perfectly than we have done by our mutilated term of England, for they write it with antiquarian precision, Angle-terre—the land of the Angles. Our counties bear the vestiges of these Saxons expelling or exterminating the native Britons, as our pious Camden ejaculates, “by God’s wonderful providence.”

3 The diligent investigator of the history of our Anglo-Saxons concludes that this unauthorised tale of the coronation and the decree of Egbert is unworthy of credence.

Camden, in his first edition, had fixed the date of the change of the name as occurring in the year 810; in his second edition he corrected it to 800. Holinshed says about 800. Speed gives a much later date, 819. It is evident that these disagreeing dates are all hazarded conjectures.

4 Mitford’s “Harmony of Language,” 429. I might have placed this possible circumstance in the article “A History of Events which have not happened,” in “Curiosities of Literature.”

5 Sir Gardner Wilkinson, in the curious volume of his recondite discoveries in the land of the Pyramids.

6 “History of the World,” 167, fol. 1666. We have also a curious account of the ancient manner of naming persons and places among our own nation in venerable Lambarde’s “Perambulations of Kent,” 349, 453.

THE ANGLO-SAXONS.

The history and literature of England are involved in the transactions of a people who, living in such remote times at the highest of their fortunes, never advanced beyond a semi-civilization. But political freedom was the hardy and jealous offspring nursed in the forests of Germany; there was first heard the proclamation of equal laws, and there a people first assumed the name of Franks or Freemen. Our language, and our laws, and our customs, originate with our Teutonic ancestors; among them we are to look for the trunk, if not the branches, of our national establishments. In the rude antiquities of the Anglo-Saxon church, our theoretical inquirers in ecclesiastical history trace purer doctrines and a more primitive discipline; and in the shadowy Witenagemot, the moveable elements of the British constitution: the language and literature of England still lie under their influence, for this people everywhere left the impression of a strong hand.

The history of the Anglo-Saxons as a people is without a parallel in the annals of a nation. Their story during five centuries of dominion in this land may be said to have been unknown to generations of Englishmen; the monuments of their history, the veritable records of their customs and manners, their polity, their laws, their institutions, their literature, whatever reveals the genius of a people, lie entombed in their own contemporary manuscripts, and in another source which we long neglected—in those ancient volumes of their northern brothers, who had not been idle observers of the transactions of England, which seems often to have been to them “the land of promise.” The Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, those authentic testimonies of the existence of the nation, were long dispersed, neglected, even unintelligible, disfigured by strange characters, and obscured by perplexing forms of diction. The language as well as the writing had passed away; all had fallen into desuetude; and no one suspected 29 that the history of a whole people so utterly cast into forgetfulness could ever be written.

But the lost language and the forgotten characters antiquity and religion seemed to have consecrated in the eyes of the learned Archbishop Matthew Parker, who was the first to attempt their restitution by an innocent stratagem. To his edition of Thomas Walsingham’s History in 1574, his Grace added the Life of Alfred by this king’s secretary, Asser, printed in the Saxon character; we are told, as “an invitation to English readers to draw them in unawares to an acquaintance with the handwriting of their ancestors.”1 “The invitation” was somewhat awful, and whether the guests were delighted or dismayed, let some Saxonist tell! Spelman, the great legal archæologist, was among the earliest who ventured to search amid the Anglo-Saxon duskiness, at a time when he knew not one who could even interpret the writing. This great lawyer had been perplexed by many barbarous names and terms which had become obsolete; they were Saxon. He was driven to the study; and his “Glossary” is too humble a title for that treasure of law and antiquity, of history and of disquisition, which astonished the learned world at home and abroad—while the unsold copies during the life of the author checked the continuation; so few was the number of students, and few they must still be; yet the devotion of its votary was not the less, for he had prepared the foundation of a Saxon professorship. Spelman was the father; but he who enlarged the inheritance of these Anglo-Saxon studies, appeared in the learned Somner; and though he lived through distracted times which loved not antiquity, the cell of the antiquary was hallowed by the restituted lore. Hickes, in his elaborate “Thesaurus,” displayed a literature which had never been read, and which he himself had not yet learned to read. These were giants; their successors were dwarfs who could not add to their stores, and little heeded their possessions. Few rarely succeeded in reading the Saxon; and at that day, about the year 1700, no printer could cast the types, which were deemed barbarous, or, as the antiquary Rowe Mores expresses it, “unsightly to 30 politer eyes.” A lady—and she is not the only one who has found pleasure in studying this ancient language of our country—Mrs. Elstob, the niece of Hickes, patronised by a celebrated Duchess of Portland, furnished several versions; but the Saxon Homilies she had begun to print, for some unknown cause, were suspended: the unpublished but printed sheets are preserved at our National Library. These pursuits having long languished, seemed wholly to disappear from our literature.

None of our historians from Milton to Hume ever referred to an original Saxon authority. They took their representations from the writings of the monks; but the true history of the Anglo-Saxons was not written in Latin. It was not from monkish scribes, who recorded public events in which the Saxons had no influence, that the domestic history of a race dispossessed of all power could be drawn, and far less would they record the polity which had once constituted their lost independence. The annalist of the monastery, flourishing under another dynasty, placed in other times and amid other manners, was estranged from any community of feeling with a people who were then sunk into the helots of England. Milton, in his history of Britain, imagined that the transactions of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, or Octarchy, would be as worthless “to chronicle as the wars of kites or crows flocking and fighting in the air.” Thus a poet-historian can veil by a brilliant metaphor the want of that knowledge which he contemns before he has acquired—this was less pardonable in a philosopher; and when Hume observed, perhaps with the eyes of Milton, that “he would hasten through the obscure and uninteresting period of Saxon Annals,” however cheering to his reader was the calmness of his indolence, the philosopher, in truth, was wholly unconscious that these “obscure and uninteresting annals of the Anglo-Saxons” formed of themselves a complete history, offering new results for his profound and luminous speculations on the political state of man. Genius is often obsequious to its predecessors, and we track Burke in the path of Hume; and so late as in 1794, we find our elegant antiquary, Bishop Percy, lamenting the scanty and defective annals of the Anglo-Saxons; naked 31 epitomes, bare of the slightest indications of the people themselves. The history of the dwellers in our land had hitherto yielded no traces of the customs and domestic economy of the nation; all beyond some public events was left in darkness and conjecture.

We find Ellis and Ritson still erring in the trackless paths. All this national antiquity was wholly unsuspected by these zealous investigators. In this uncertain condition stood the history of the Anglo-Saxons, when a new light rose in the hemisphere, and revealed to the English public a whole antiquity of so many centuries. In 1805, for the first time, the story and the literature of the Anglo-Saxons was given to the country. It was our studious explorer, Sharon Turner, who first opened these untried ways in our national antiquities.2

Anglo-Saxon studies have been recently renovated, but unexpected difficulties have started up. A language whose syntax has not been regulated, whose dialects can never be discriminated, and whose orthography and orthoepy seem irrecoverable, yields faithless texts when confronted; and treacherous must be the version if the construction be too literal or too loose, or what happens sometimes, ambiguous. Different anglicisers offer more than one construction.3

It is now ascertained that the Anglo-Saxon manuscripts are found in a most corrupt state.4 This fatality was occasioned by the inattention or the unskilfulness of the caligrapher, whose task must have required a learned pen. 32 The Anglo-Saxon verse was regulated by a puerile system of alliteration,5 and the rhythm depended on accentuation. Whenever the strokes, or dots, marking the accent or the pauses are omitted, or misplaced, whole sentences are thrown into confusion; compound words are disjoined, and separate words are jumbled together. “Nouns have been mistaken for verbs, and particles for nouns.”

These difficulties, arising from unskilful copyists, are infinitely increased by the genius of the Anglo-Saxon poets themselves. The tortuous inversion of their composition often leaves an ambiguous sense: their perpetual periphrasis; their abrupt transitions; their pompous inflations, and their elliptical style; and not less their portentous metaphorical nomenclature where a single object must be recognised by twenty denominations, not always appropriate, and too often clouded by the most remote and dark analogies6—all these have perplexed the most 33 skilful judges, who have not only misinterpreted passages, but have even failed to comprehend the very subject of their original. This last circumstance has been remarkably shown in the fate of the heroic tale of Beowulf. When it first fell to the hard lot of Wanley, the librarian of the Earl of Oxford, to describe “The Exploits of Beowulf,” he imagined, or conjectured, that it contained “the wars which this Dane waged against the reguli, or petty kings of Sweden.” He probably decided on the subject by confining his view to the opening page, where a hero descends from his ship—but for a very different purpose from a military expedition. Fortunately Wanley lauded the manuscript as a “tractatus nobilissimus,” and an “egregium exemplum” of the Anglo-Saxon poetry. Probably this manuscript remained unopened during a century, when Sharon Turner detected the error of Wanley, but he himself misconceived the design of these romantic “Exploits.” Yet this diligent historian carefully read and analysed this heroic tale. Conybeare, who had fallen into the same erroneous conception, at length caught up a clue in this labyrinth; and finally even a safer issue has been found, though possibly not without some desperate efforts, by the version of Mr. Kemble.

Even the learned in Saxon have not always been able to distinguish this verse from prose; the verse unmarked by rhyme being written continuously as prose.7 A diction turgid and obscure was apparent; but in what consisted the art of the poet, or the metrical system, long baffled the most ingenious conjectures. Ritson, in his perplexity, described this poetry or metre as a “rhymeless sort of poetry, a kind of bombast or insane prose, from 34 which it is very difficult to be distinguished.” Tyrwhit and Ellis remained wholly at a loss to comprehend the fabric of Anglo-Saxon poesy. Hickes, in the fascination of scholarship, had decided that it proceeded on a metrical system of syllabic quantities, and surmounted all difficulties by submitting the rhythmical cadences of Gothic poesy to the prosody of classical antiquity. This was a literary hallucination, and a remarkable evidence of a favourite position maintained merely by the force of prepossession.