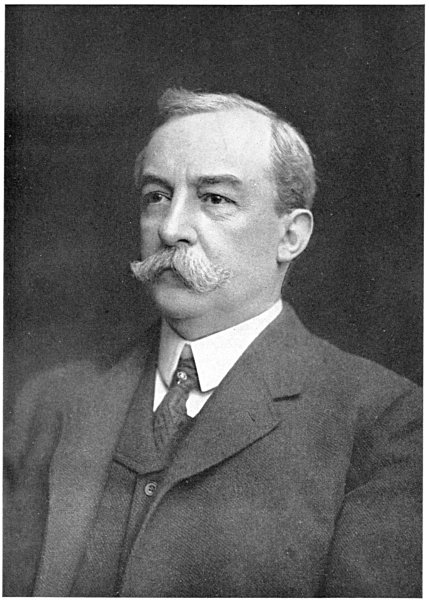

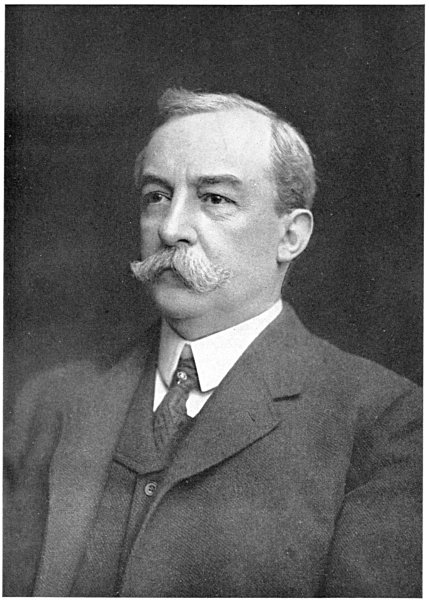

BERNARD N. BAKER

Baltimore, Md.

President, Second National Conservation Congress

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Proceedings of the Second National

Conservation Congress, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Proceedings of the Second National Conservation Congress

at Saint Paul, September 5-8, 1910

Author: Various

Release Date: May 5, 2011 [EBook #36031]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND ***

Produced by Bryan Ness, Stephen H. Sentoff and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BERNARD N. BAKER

Baltimore, Md.

President, Second National Conservation Congress

[Pg ii]

W. F. ROBERTS COMPANY

PRINTERS

WASHINGTON, D. C.

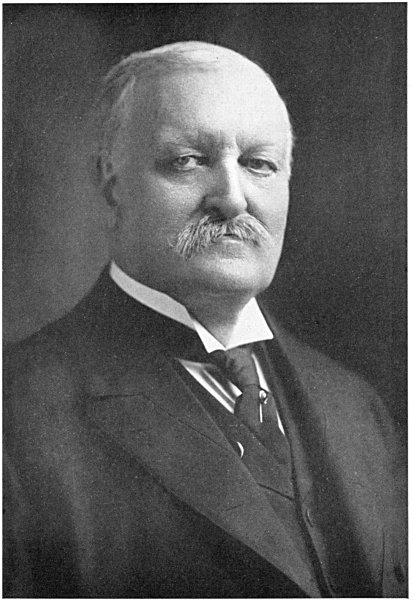

HON. J. B. WHITE

Kansas City, Mo.

Chairman, Executive Committee, Second National Conservation

Congress and Third National Conservation Congress

President

B. N. Baker, Baltimore

Executive Secretary

Thomas R. Shipp, Washington, D. C.

Secretary

L. Frank Brown, Seattle

Vice-Presidents

John Barrett, Washington, D. C.

James S. Whipple, Albany

E. J. Wickson, Berkeley

Alfred C. Ackerman, Athens, Ga.

Henry A. Barker, Providence

Executive Committee

J. B. White, Kansas City, Mo., Chairman

B. N. Baker, Baltimore

J. N. Teal, Portland, Ore.

A. B. Farquhar, York, Pa.

L. H. Bailey, Ithaca

Thomas Burke, Seattle

Henry E. Hardtner, Urania, La.

W. A. Fleming Jones, Las Cruces

Mrs Philip N. Moore, Saint Louis

Mrs J. Ellen Foster, Washington, D. C.

Local Board of Managers for the Saint Paul Congress

Hon. A. O. Eberhart, Chairman

Frank B. Kellogg, Vice-Chairman

J. S. Bell, Minneapolis

H. A. Tuttle, Minneapolis

George M. Gillette, Minneapolis

B. F. Nelson, Minneapolis

L. S. Donaldson, Minneapolis

Joseph H. Beek, Saint Paul

George H. Prince, Saint Paul

Reuben Warner, Saint Paul

Paul W. Doty, Saint Paul

Theodore W. Griggs, Saint Paul

W. C. Handy, Secretary

President

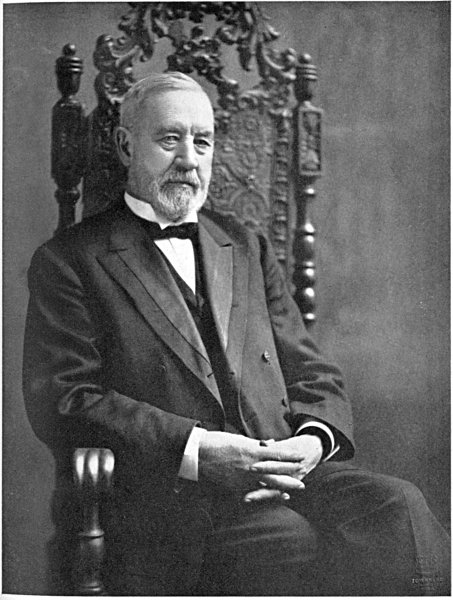

Henry Wallace, Des Moines

Executive Secretary

Thomas R. Shipp, Washington, D. C.

Treasurer

D. Austin Latchaw, Kansas City, Mo.

Recording Secretary

James C. Gipe, Clarks, La.

Executive Committee

J. B. White, Kansas City, Mo., Chairman

B. N. Baker, Baltimore

L. H. Bailey, Ithaca

James R. Garfield, Cleveland

Frank C. Goudy, Denver

W. A. Fleming Jones, Las Cruces

Mrs Philip N. Moore, Saint Louis

Walter H. Page, New York

George C. Pardee, Oakland, Cal.

Gifford Pinchot, Washington, D. C.

J. N. Teal, Portland, Ore.

E. L. Worsham, Atlanta

Vice-Presidents

Alabama, Hon. Albert P. Bush, Mobile; Alaska, Hon. James Wickersham, Fairbanks; Arizona, B. A. Fowler, Phenix; Arkansas, A. H. Purdue, Fayetteville; California, E. H. Cox, San Francisco; Colorado, Murdo Mackenzie, Trinidad; Columbia (District of), W J McGee, Washington; Connecticut, Rollin S. Woodruff, Hartford; Delaware, Hon. George Gray, Wilmington; Florida, Cromwell Gibbons, Jacksonville; Georgia, Hon. Jno. C. Hart, Union Point; Hawaii, Mrs Margaret R. Knudsen, Kanai; Idaho, James A. MacLean, University of Idaho; Illinois, Julius Rosenwald, Chicago; Indiana, F. J. Breeze, Lafayette; Iowa, Carl Leopold, Burlington; Kansas, W. R. Stubbs, Topeka; Kentucky, James K. Patterson, Lexington; Louisiana, Newton C. Blanchard, Shreveport; Maine, Bert M. Fernald, Augusta; Maryland, William Bullock Clark, Baltimore; Massachusetts, Frank W. Rane, Boston; Michigan, J. L. Snyder, Lansing; Minnesota, Ambrose Tighe, Saint Paul; Mississippi, A. W. Shands, Sardis; Missouri, Hermann Von Schrenk, Saint Louis; Montana, E. L. Norris, Helena; Nebraska, Dr F. A. Long, Madison; Nevada, Senator Francis G. Newlands, Reno; New Hampshire, George B. Leighton, Monadnock; New Jersey, Charles Lathrop Pack, Lakewood; New Mexico, W. A. Fleming Jones, Las Cruces; New York, R. A. Pearson, Albany; North Carolina, T. Gilbert Pearson, Greensboro; North Dakota, U. G. Larimore, Larimore; Ohio, James R. Garfield, Cleveland; Oklahoma, Benj. Martin, Jr., Muskogee; Oregon, J. N. Teal, Portland; Pennsylvania, William S. Harvey, Philadelphia; Philippine Islands, Maj. George P. Ahern, Manila; Porto Rico, Hon. Walter K. Landis, San Juan; Rhode Island, Henry A. Barker, Providence; South Carolina, E. J. Watson, Columbia; South Dakota, Ellwood C. Perisho, Vermillion; Tennessee, Herman Suter, Nashville; Texas, W. Goodrich Jones, Temple; Utah, Harden Bennion, Salt Lake City; Vermont, Fletcher D. Proctor, Proctor; Virginia, A. R. Turnbull, Norfolk; Washington, M. E. Hay, Olympia; West Virginia, A. B. Fleming, Fairmont; Wisconsin, Charles R. Van Hise, Madison; Wyoming, Bryant B. Brooks, Cheyenne; National Conservation Association, Gifford Pinchot, Washington.

Standing Committees

Forests—H. S. Graves, U. S. Forester, Washington, D. C., Chairman; E. M. Griffith, Madison, Wis.; E. T. Allen, Portland, Ore.; J. Lewis Thompson, Houston.

Lands—Governor W. R. Stubbs, Topeka, Chairman; Dwight B. Heard, Phenix; J. L. Snyder, Lansing; Murdo Mackenzie, Trinidad; Charles S. Barrett, Union City, Ga.

Waters—W J McGee, Washington, D. C., Chairman; E. A. Smith, Spokane; Henry A. Barker, Providence; J. N. Teal, Portland, Ore.; Herbert Knox Smith, Washington, D. C.

Minerals—Charles R. Van Hise, Madison, Chairman; Joseph A. Holmes, Washington, D. C.; D. W. Brunton, Denver; John Mitchell, New York; I. C. White, Morgantown, W. Va.

Vital Resources—Dr William H. Welch, Baltimore, Chairman; Professor Irving Fisher, New Haven; Dr H. W. Wiley, Washington, D. C.; Dr J. H. Kellogg, Battle Creek, Mich.; Walter H. Page, New York.

HENRY WALLACE

Des Moines, Iowa

President, Third National Conservation Congress

| page | ||

| CONSTITUTION | ix | |

| OPENING SESSION | 1 | |

| Invocation by Archbishop Ireland | 1 | |

| Greeting from Cardinal Gibbons | 3 | |

| Address by Governor Eberhart | 3 | |

| Welcome by Mayor Keller | 13 | |

| Address by President Taft | 14 | |

| SECOND SESSION | 34 | |

| Induction of Governor Stubbs as Chairman | 34 | |

| Address by Senator Nelson | 35 | |

| Address by Governor Noel | 48 | |

| Address by Governor Norris | 52 | |

| Address by Governor Deneen | 59 | |

| Address by Governor Hay | 64 | |

| Announcement by Professor Condra | 71 | |

| Address by Governor Brooks | 72 | |

| Remarks by Governor Stubbs | 75 | |

| Address by Governor Vessey | 77 | |

| THIRD SESSION | 79 | |

| Appointment of Credentials Committee | 79 | |

| Action on Constitution of the National Conservation Congress | 79 | |

| Remarks by Director-General Barrett | 80 | |

| Remarks by Governor Stubbs | 81 | |

| Invocation by Reverend Doctor Montgomery | 81 | |

| Address by Ex-President Roosevelt | 82 | |

| FOURTH SESSION | 93 | |

| Address by Miss Boardman | 94 | |

| Address by Commissioner Herbert Knox Smith | 101 | |

| Modification of Credentials Committee | 106 | |

| Address by Honorable James R. Garfield | 106 | |

| Address by Ex-Governor Pardee | 115 | |

| Remarks by Delegate Horr, of Washington | 120 | |

| Address by Ex-Governor Blanchard | 121 | |

| Address by William E. Smythe | 127 | |

| Address by Walter L. Fisher | 129 | |

| Address by Colonel James H. Davidson | 132 | |

| FIFTH SESSION | 134 | |

| Invocation by Bishop Edsall | 134 | |

| Address by President Finley | 135 | |

| Report of Credentials Committee | 145 | |

| Address by Senator Beveridge | 146 | |

| Response by Gifford Pinchot | 152 | |

| Address by President McVey | 152 | |

| Discussion by Chairman White | 158 | |

| Address by Mrs Welch, of the General Federation of Women's Clubs | 160 | |

| [Pg vi] | Address by Mrs Hoyle Tomkies, of the Women's National Rivers and Harbors Congress | 163 |

| Address by Mrs Sneath, of the General Federation of Women's Clubs | 166 | |

| Report by Mrs Howard, of the Daughters of the American Revolution | 167 | |

| SIXTH SESSION | 168 | |

| Induction of Senator Clapp as Chairman | 168 | |

| Address by President Craighead | 168 | |

| Postponement of Call of States | 171 | |

| Address by D. Austin Latchaw | 171 | |

| Address by James J. Hill | 177 | |

| Discussion by Henry Wallace | 188 | |

| Address by Secretary Wilson | 194 | |

| Discussion by Representative Stevens | 201 | |

| Address by Professor Bailey | 203 | |

| SEVENTH SESSION | 213 | |

| Address by Professor Graves | 214 | |

| Address by Alfred L. Baker | 222 | |

| Address by Frank H. Short | 226 | |

| Address by Director-General Barrett | 237 | |

| Address by Honorable Esmond Ovey | 243 | |

| Action on time for election and report of Resolutions Committee | 246 | |

| EIGHTH SESSION | 246 | |

| Appointment of Nominating Committee | 246 | |

| Induction of Governor Eberhart as Chairman | 246 | |

| Address by Dean Wesbrook | 247 | |

| Address by Wallace D. Simmons | 257 | |

| Address by Commissioner Elmer E. Brown | 264 | |

| Address by Mrs Scott, President of the Daughters of the American Revolution | 270 | |

| Action in memory of Mrs J. Ellen Foster | 276 | |

| Presentation by Mrs Howard to Gifford Pinchot | 276 | |

| Response by Mr Pinchot | 277 | |

| Address by Francis J. Heney | 278 | |

| Address by Gifford Pinchot | 292 | |

| Expression by Governor Eberhart | 298 | |

| Statement by Professor Condra | 298 | |

| CLOSING SESSION | 299 | |

| Commencement of Call of States | 299 | |

| Response by Delegate Harvey, of Pennsylvania | 299 | |

| Interlude by E. W. Ross, of Washington | 302 | |

| Report of Nominating Committee | 303 | |

| Nomination by Chairman White | 303 | |

| Second by Gifford Pinchot | 304 | |

| Election of and response by Henry Wallace as President | 305 | |

| Election of other Officers | 306 | |

| Resolution of thanks to retiring President Baker | 308 | |

| Response by Mr Baker | 308 | |

| Report of Resolutions Committee | 308 | |

| Adoption of Resolutions | 312 | |

| Interlude by E. W. Ross, of Washington | 312 | |

| Remarks by Delegate Horr, of Washington | 313 | |

| Ratification of Vice-Presidents | 313 | |

| [Pg vii] | Resolution in memory of Professor Green | 313 |

| Resumption of Call of States | 314 | |

| Response by Delegate Purdue, of Arkansas | 314 | |

| Response by Delegate Bannister, of Indiana | 314 | |

| Response by Delegate Miller, of Iowa | 314 | |

| Response by Delegate Young, of Kansas | 314 | |

| Response by Delegate Baker, of Maryland | 314 | |

| Response by Delegate Thorp, of Minnesota | 315 | |

| Response by State Geologist Lowe, of Mississippi | 315 | |

| Response by General Noble, of Missouri | 315 | |

| Response by Chairman White | 316 | |

| Response by Professor Condra, of Nebraska | 317 | |

| Response by a Delegate from New York | 318 | |

| Response by Delegate Nestos, of North Dakota | 318 | |

| Response by Delegate Krueger, of South Dakota | 319 | |

| Remarks by Delegate Johns, of Washington | 320 | |

| Privileged statement by Land Commissioner Ross, of Washington | 322 | |

| Response by Delegate Fowler, of Arizona | 324 | |

| Response by Delegate Hunt, of District of Columbia | 324 | |

| Response by Delegate Barker, of Rhode Island | 324 | |

| Response by Professor White, of West Virginia | 325 | |

| Response by Delegate Worsham, of Georgia | 325 | |

| Motion for adjournment by Delegate Martin, of Oklahoma | 326 | |

| SUPPLEMENTARY PROCEEDINGS | 327 | |

| Laws that should be Passed, by Senator Francis G. Newlands | 327 | |

| Conservation of the Nation's Resources, by Chairman J. B. White | 328 | |

| Practical Aspects of Conservation, by A. B. Farquhar | 331 | |

| Report from Arkansas, by Sid B. Redding | 333 | |

| Report from Colorado, by Frank C. Goudy | 334 | |

| Report from Florida, by Cromwell Gibbons | 335 | |

| Report from Idaho, by Jerome J. Day | 336 | |

| Report from Indiana, by A. E. Metzger | 336 | |

| Report from Iowa, by A. C. Miller | 337 | |

| Report from Louisiana, by Henry E. Hardtner | 339 | |

| Report from Maine, by Cyrus C. Babb | 341 | |

| Report from Massachusetts, by Frank William Rane and Henry H. Sprague | 343 | |

| Report from Missouri, by Hermann von Schrenk | 344 | |

| Report from Montana, by Rudolph von Tobel | 345 | |

| Report from New Mexico, by Colonel W. A. Fleming Jones | 347 | |

| Report from New York, by J. S. Whipple | 347 | |

| Special report from New York, by Henry H. Persons | 352 | |

| Report from North Dakota, by Professor Waldron | 362 | |

| Report from Ohio, by Professor Lazenby | 364 | |

| Report from Oklahoma, by Benj. Martin, Jr. | 365 | |

| Report from Oregon, by E. T. Allen | 367 | |

| Report from Rhode Island, by Henry A. Barker | 368 | |

| Report from South Carolina, by E. J. Watson | 369 | |

| Report from South Dakota, by Doane Robinson | 369 | |

| Report from Texas, by Will L. Sargent | 370 | |

| Report from Utah, by O. J. Salisbury | 372 | |

| Supplementary report from Utah, by E. T. Merritt | 372 | |

| Report from Vermont, by George Aitkin | 373 | |

| Report from Washington, by E. G. Griggs | 375 | |

| Report from West Virginia, by Hu Maxwell | 376 | |

| [Pg viii] | Report from Wisconsin, by E. M. Griffith | 377 |

| Report of the American Academy of Political and Social Science | 379 | |

| Report of the American Automobile Association | 380 | |

| Report of the American Civic Association | 383 | |

| Report of the American Forestry Association | 384 | |

| Report of the American Humane Association | 385 | |

| Report of the American Institute of Architects | 386 | |

| Report of the American Paper and Pulp Association | 388 | |

| Report of the American Medical Association | 389 | |

| Report of the American Railway Engineering and Maintenance of Way Association | 392 | |

| Report of the American Railway Master Mechanics' Association | 393 | |

| Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society | 394 | |

| Report of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks | 397 | |

| Report of the Carriage Builders' National Association | 410 | |

| Report of the Delaware State Federation of Women's Clubs | 411 | |

| Report of the Farmers' Union of America | 411 | |

| Report of the General Federation of Women's Clubs | 412 | |

| Report of the Lakes-to-Gulf Deep Waterway Association | 413 | |

| Report of the League of American Sportsmen | 415 | |

| Report of the National Board of Fire Underwriters | 416 | |

| Report of the National Board of Trade | 419 | |

| Report of the National Business League of America | 420 | |

| Report of the Missouri Valley River Improvement Association | 420 | |

| Report of the Upper Mississippi River Improvement Association | 421 | |

| Report of the Washington State Federation of Labor | 422 | |

| Report of the Western Forestry and Conservation Association | 423 | |

| Report of the United Mine Workers | 424 | |

| Timber Conservation, by George H. Emerson | 424 | |

| Forests and Stream-Flow, by William S. Harvey | 428 | |

| The Conservation of Minerals and Subterranean Waters, by George F. Kunz, Ph.D. | 429 | |

| The Question of Land Titles, by Franklin McCray | 430 | |

| INDEX | 431 | |

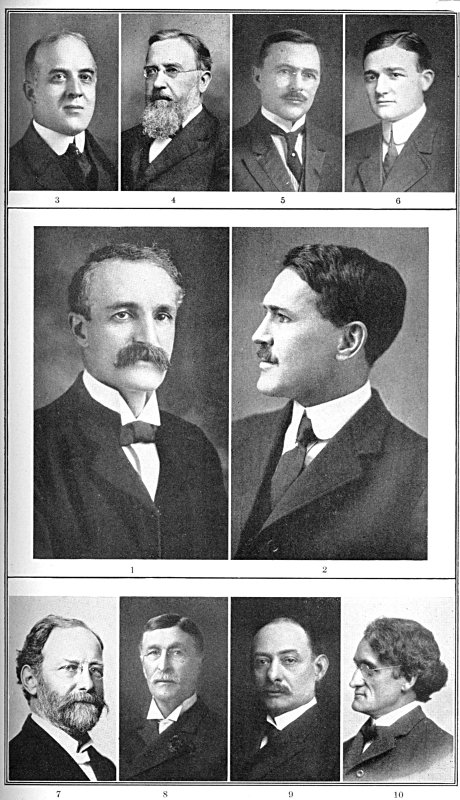

1. Gifford Pinchot, Vice-President (1910).

2. James R. Garfield, Vice-President (1910).

3. Henry A. Barker, Vice-President (1909-10).

4. A. B. Farquhar, Executive Committee (1909).

5. W. A. Fleming Jones, Vice-president (1910).

6. E. L. Worsham, Executive Committee (1910).

7. George C. Pardee, Executive Committee (1910).

8. J. N. Teal, Executive Committee (1909-10).

9. Walter H. Page, Executive Committee (1910).

10. L. H. Bailey, Executive Committee (1909-10).

Article 1—Name

This organization shall be known as the National Conservation Congress.

Article 2—Object

The object of the National Conservation Congress shall be: (1) to provide a forum for discussion of the resources of the United States as the foundation for the prosperity of the people, (2) to furnish definite information concerning the resources and their utilization, and (3) to afford an agency through which the people of the country may frame policies and principles affecting the wise and practical development, conservation, and utilization of the resources, to be put into effect by their representatives in State and Federal Governments.

Article 3—Meetings

Section 1. Regular annual meetings shall be held at such time and place as may be determined by the Executive Committee.

Section 2. Special meetings of the Congress, or its officers, committees, or boards, may be held subject to the call of the President of the Congress or the Chairman of the Executive Committee.

Article 4—Officers

Section 1. The officers of the Congress shall consist of a President, to be elected by the Congress; a Vice-President from each State, to be chosen by the respective State delegations, and from the National Conservation Association; an Executive Secretary; a Recording Secretary; and a Treasurer.

Section 2. The duties of these officers may at any time be prescribed by formal action of the Congress or Executive Committee. In the absence of such action their duties shall be those implied by their designations and established by custom. In addition, it shall be the duty of the Vice-Presidents to receive, from the State Conservation Commissions and other organizations concerned in Conservation, suggestions and recommendations, and report them to the Executive Committee of the Congress.

Section 3. The officers shall serve for one year, or until their successors are elected and qualify.

Article 5—Committees and Boards

Section 1. An Executive Committee of seven, in addition to which the President of the National Conservation Association and all ex-Presidents of the Congress shall be members ex-officio, shall be appointed by the President during each regular annual session to act for the ensuing year; its membership shall be drawn from different States, and not more than one of the appointed members shall be from any one State. The Executive Committee shall act for the Congress and shall be empowered to initiate action and meet emergencies. It shall report to each regular annual session.

Section 2. A Board of Managers shall be created in each city in which the next ensuing session of the Congress is to be held, preferably by leading organizations of citizens. The Board of Managers shall have power to raise and expend funds, to incur obligations on its own responsibility, and to appoint subordinate boards and committees, all with the approval of the Executive Committee of the Congress. It shall report to the Executive Committee at least two days before the opening of the ensuing session, and at such other times as the Congress or the Executive Committee may direct.

Section 3. A Committee on Credentials shall be appointed, consisting of five (5) members, by the President of the Congress not later than on the second day of each session of the Congress. It shall determine all questions raised by delegates as to representation, and shall report to the Congress from time to time as required by the President of the Congress.

Section 4. A Committee on Resolutions shall be created for each annual meeting of the Congress. A Chairman shall be appointed by the President. One member of the Committee shall be selected by each State represented in the Congress. The Committee shall report to the Congress not later than the morning of the last day of each annual meeting.

Section 5. Permanent Committees, consisting of five (5) members each, shall be appointed by the President of the Congress on each of the following five divisions of Conservation: Forests, Waters, Lands, Minerals, and Vital Resources. These committees shall, during the intervals between the annual meetings of the Congress, inquire into these respective subjects and prepare reports to be submitted on the request of the Executive Committee, and render such other assistance to the Congress as the Executive Committee may direct.

Section 6. By direction of the Congress, standing and special committees may be appointed by the President.

Section 7. The President shall be a member, ex-officio, of every committee of the Congress.

Article 6—Arrangements for Sessions

Section 1. The program for the session of each annual meeting of the Congress, including a list of speakers, shall be arranged by the Executive Committee. The entire program, including allotments of time to speakers and hours for daily sessions and all other arrangements concerning the program, shall be made by the Executive Committee.

Section 2. Unless otherwise ordered, the rules adopted for the guidance of the preceding Congress shall continue in force.

Article 7—Membership

Section 1. The personnel of the National Conservation Congress shall be as follows:

Officers and Delegates

Officers of the National Conservation Congress.

Fifteen Delegates appointed by the Governor of each State and Territory.

Five Delegates appointed by the Mayor of each city with a population of 25,000, or more.

Two Delegates appointed by the Mayor of each city with a population of less than 25,000.

Two Delegates appointed by each Board of County Commissioners.

Five Delegates appointed by each National Organization concerned in the work of Conservation.

Five Delegates appointed by each State or Interstate Organization concerned in the work of Conservation.

Three Delegates appointed by each Chamber of Commerce, Board of Trade, Commercial Club, or other local organization concerned in the work of Conservation.

Two Delegates appointed by each State or other University or College, and by each Agricultural College or Experiment Station.

Honorary Members

The President of the United States.

The Vice-President of the United States.

The Speaker of the House of Representatives.

The Cabinet.

The United States Senate and House of Representatives.

The Supreme Court of the United States.

The Representatives of Foreign Governments.

The Governors of the States and Territories.

The Lieutenant-Governors of the States and Territories.

The Speakers of State Houses of Representatives.

The State Officers.

The Mayors of Cities.

The County Commissioners.

The Presidents of State and other Universities and Colleges.

The Officers and Members of the National Conservation Association.

The Officers and Members of the National Conservation Commission.

The Officers and Members of the State Conservation Commissions and Associations.

Article 8—Delegations and State Officers

Section 1. The several Delegates from each State in attendance at any Congress shall assemble at the earliest practicable time and organize by choosing a Chairman and a Secretary. These Delegates, when approved by the Committee on Credentials, shall constitute the Delegation from that State.

Article 9—Voting

Section 1. Each member of the Congress shall be entitled to one vote on all actions taken viva voce.

Section 2. A division or call of States may be demanded on any action by a State delegation. On division, each Delegate shall be entitled to one vote; provided (1) that no State shall have more than twenty votes; and provided (2) that when a State is represented by less than ten Delegates, said Delegates may cast ten votes for such State.

Section 3. The term "State" as used herein is to be construed to mean either State, Territory, or Insular Possession.

Article 10—Amendments

This Constitution may be amended by a two-thirds vote of the Congress during any regular session, provided notice of the proposed amendment has been given from the Chair not less than one day or more than two days preceding; or by unanimous vote without such notice.

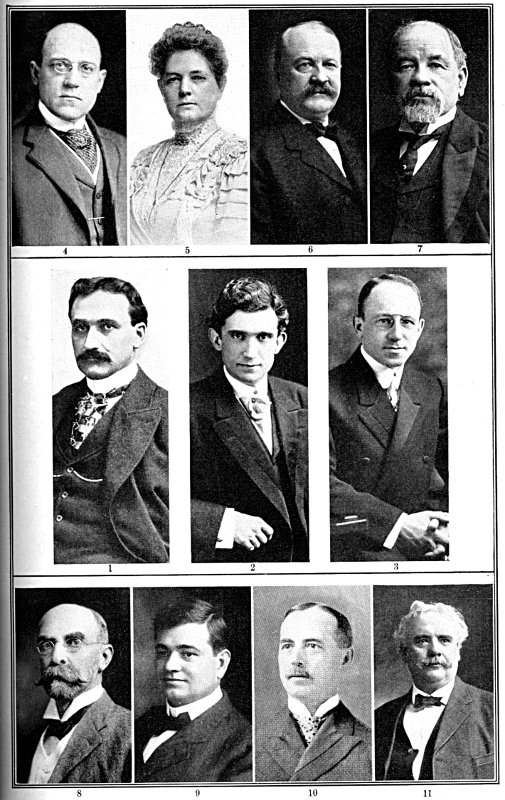

1. D. Austin Latchaw, Treasurer (1910).

2. Thomas R. Shipp, Executive Secretary (1909-10).

3. James C. Gipe, Recording Secretary (1910).

4. John Barrett, Vice-President (1909).

5. Mrs Philip N. Moore, Executive Committee (1909-10).

6. Frank C. Goudy, Executive Committee (1910).

7. Thomas Burke, Executive Committee (1909).

8. E. J. Wickson, Vice-President (1909).

9. Henry D. Hardtner, Vice-President (1909).

10. James S. Whipple, Vice-President (1909).

11. W J McGee, Vice-President (Editor of Proceedings).

The Congress convened in the Auditorium, Saint Paul, Minnesota, on the morning of September 5, 1910, President Baker in the chair, and was called to order on arrival of the President of the United States.

President Baker—Mr President, your Grace, Ladies and Gentlemen: The honor I have today in opening this great Congress is one that will always be highly treasured, for I feel that what we are trying to do is to make our country great and strong by men who see the Nation's wrongs and are giving their time to this great object. We are meeting today for the purpose of using our very best efforts to assist in protecting the interests of this great country in a way that will best protect every man and woman and child in his or her rights, with justice to all. That our great National resources are in danger of being wasted and not fully preserved for the future, I am satisfied is the thought of all the great minds assembled here today to take part in this Congress.

There is a Great High Power that rules and governs for the best in the world, and I now call upon His Grace, Archbishop Ireland, to open our Congress with an invocation to that Great Power for help, guidance, and direction.

Invocation

Almighty and eternal God. We bow before Thee in deep humility. Accept from us, we beseech Thee, from submissive minds and sincere hearts, adoration, praise, gratitude, love, and the promise of abiding recognition of Thy sovereignty and of loyal obedience to Thy laws.

O God, all things are Thine; all things were made by Thee; no thing that was made was made without Thee; "the heavens show forth Thy glory and the firmament declareth Thy power, day to day uttereth speech, night to night showeth knowledge," ever proclaiming that Thou are the Master, that things created are the scintillations of Thy power and wisdom. We are Thine, O God, Thee our Father and our Master; earth and skies are ours through gift of Thy munificence. "Till the earth," was it said to us, "and subdue it and dominate over the fishes of the sea and the fowls of the air and all living creatures that move upon the earth." Earth is ours, not, O Lord, that we use it at our [Pg 2]will and caprice, but that under Thy guidance we bid it turn to our best and truest welfare, to the best and truest welfare of our fellow-men, Thy children all; over all of whom spread Thy love and care.

Grant to us, O Lord, this morning wisdom in our counselings and deliberations, that the intents of Thy providence be our intents, and, Thy will the inspiration of our counselings and our actions.

We thank thee, O God, for the gift to us of America. As to few other lands, Thou hast been prodigal to America of gifts rich and rare. In America skies are serene and health-giving above us; beneath us fields are verdant and fertile; nowhere else are forests more fruitful, hills and mountains richer in imbedded treasure; nowhere else are lakes and rivers endowed with higher grandeur or more ready to proffer to man useful and ennobling service. Of America, through Thy munificence, O God, we are the caretakers. May we be wise and prudent in our duty. We pray that under Thy abiding watchfulness, through our intelligent industry, America grows ever in fairness and in wealth, and be the first and most beauteous of the stopping-places allowed to men in their pilgrimage toward their abiding home in heaven.

Bless, O Lord, America, and bless its people, that they be ever faithful to Thy laws; bless its citizenship, bless its Government, that the spirit of its freedom-giving institutions never die, never lessen in sweetness and in power; that here liberty be ever encircled in order, and order ever wreathed in liberty; that righteousness dominate and permeate prosperity; that whatever the laws we form may be scintillations of Thy own eternal laws—compliance with which is life and felicity, forgetfulness of which is misery and death to men and to nations.

And we pray Thee, O God, send down Thy blessing upon the President of the Republic, upon whose shoulders descends the chief responsibility of upholding the salvation and the dignity of America. We pray that Thou bestow upon him Thy precious blessing. The burthen is heavy, often the horizon is dark, often the polar star is hidden from which guidance might come; but in Thee, O God, he confideth,—send upon him the wisdom and the strength of Thy Holy Spirit, the wisdom that he may know, the power that he may do, ever Thy will. In Thee, O Lord, in Thy omnipotent hand—prompt to give aid in single-mindedness of purpose and in rectitude of intention—he puts his trust. Be Thou his teacher, be Thou his guide.

Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name. Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread, and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us, and lead us not into temptation but deliver us from all evil. Amen.

President Baker—Mr President, Ladies and Gentlemen: His Eminence, Cardinal Gibbons, sends you greeting:

Allow me to say how earnestly I wish the Congress every success in the much-needed work of National Conservation.

It is said that the French and Germans could subsist on what we waste; and I fear that to a stranger visiting our country it must seem that in a hundred years we have wasted more of our natural resources than the nations of Europe have done in all the centuries of their existence. But if we have been reckless in the past, wasting like vandals our rich inheritance, it is also most consoling and full of promise for the future that with the strong aid of our President, of Colonel Roosevelt, and of leading citizens in various parts of the country, we may look for a wiser use of our resources in the near future. And I am the more hopeful of a successful Congress from the fact that there is no political issue involved in the great subject before it which might threaten to divide our counsels and breed discontent, but that the sole motive that actuates the Congress is to conserve and increase our natural resources and thereby contribute to the material prosperity of our beloved country.

It is also decidedly my opinion that we should regard our natural resources as the patrimony of the Nation, a sacred trust committed to our keeping to be administered for the good of the whole people, and to be transmitted by us, as far as possible unimpaired, to our posterity. By husbanding and using economically the gifts of Nature, we shall have an abundant supply for our own times, and also make suitable provisions for the future. Mother Earth is not only a fruitful mother; she is also a grateful mother, and repays her children for every kindness and tenderness we exercise toward her. And there are also instances on record to show that she is relentless when she chastises.

Did my many duties allow, I should gladly take a more active part in the greatly needed Conservation labors. However, I trust you will feel assured of my entire sympathy and of the hope I confidently entertain of the very great benefits coming to us all as the fruitful result of these devoted laborers. James Card. Gibbons.

President Baker—Ladies and Gentlemen: The opening of the Congress today in Saint Paul is due largely to the kind assistance and friendly welcome of the Governor of Minnesota, His Excellency A. O. Eberhart, who will now extend you a welcome. (Great applause and cheers)

Governor Eberhart—Mr President, Members of the Congress, Ladies and Gentlemen: When I was invited to appear before this Congress and bid you welcome, it was suggested that I also outline what the people of Minnesota felt when they sought to have this splendid gathering at Saint Paul.

I am sure that no State or city could receive greater honor than to have the President of the United States come fifteen hundred miles to deliver the most important message on Conservation that has ever been presented to the people of this great country. (Applause) Yet [Pg 4]I am not going to take more than the twenty minutes allotted to assure you that the only interest this State has in the Conservation movement is that which every true friend of the movement stands for. Last night I cut out the meat of my remarks, this morning the bones, and now there is nothing left but the nerve, and I have scarcely enough "nerve" to deliver it. (Laughter and applause)

The Conservation of natural resources does not consist merely in the preservation of these resources for the benefit of future generations, but rather such present use thereof as will result in the greatest general good and yet maintain that productive power which insures continued future enjoyment. (Applause) While it is true that exhaustible resources like mineral wealth cannot be conserved for both future and present use, except by economic regulations and the prevention of wasteful methods, Conservation deals with their distribution in such a way as to prevent their control by grasping corporations and individuals, who would monopolize them for their own exclusive benefit at the expense of the general public. (Applause)

It follows necessarily that any theory of Conservation which does not provide for the present as well as the future does not cover the entire field and cannot possibly bring the best results. (Applause) From every economic standpoint it is desirable that the present generation should be preferred, since future discoveries and inventions may render present resources of less value and importance to the coming generations.

In its broadest sense the Conservation movement is not limited merely to the consideration of natural resources. Every great convention called to consider the problems involved has widened the scope of the movement so that today it includes the elimination of wasteful methods in almost every field of human activity and the conservation of all human endeavor so as to confer on all mankind the greatest blessings that a bounteous nature and twenty centuries of enlightenment can bestow.

Every consideration of natural resources for the purpose of eliminating wasteful methods, preserving and increasing productive power, as well as regulating operation and control, has for its ultimate object the conservation of human energy, health and life, the securing of equal opportunities for all, and such dissemination of knowledge as will guarantee the continual possession and enjoyment of these blessings. The subjects for consideration by this Congress should, therefore, include not only the restoration and increase of soil fertility, the protection and development of forests, mines and water-powers, the reclamation of arid and swamp lands by irrigation and drainage, the forestation of areas unsuited to farming, the control of rivers by reservoirs so as to prevent flooding, as well as the elimination of waste in the use of these resources, but also the problems of public comfort, health and life that are so intimately connected with all material and [Pg 5]intellectual development. (Applause) Many of these questions will concern home attractions and management, industrial education in the public schools, public highways, State advertising and settlement, pure food, public health, and sanitation.

By far the most important of all natural resources is the soil, and the maintenance and increase of its fertility must, therefore, be given the greatest consideration. (Applause) As long as food is necessary to human life, agriculture must continue to be the most vital industry of man, and the farm will be the most general and indispensable theater of his activity. We must have manufacture, art, schools, churches and government to round out our sphere of civilized existence, but the foundation of them all is the farm. (Applause) From the earth come all the materials for manufactures, the commodities of commerce, and ultimately the support of all human institutions. During the half century just past our country has devoted its energies to the development of manufacturing and commercial industries to such an extent that the scientific methods of agriculture necessary to insure not only the permanency of our institutions but the very existence of human life itself have been comparatively neglected. The pendulum is now swinging back to the farm, and our great Nation is becoming aroused to the fact that its most vital concern is the elimination of soil waste, the promotion of scientific methods of agriculture, and the conservation of that soil fertility which is the foundation of our entire social, political and commercial superstructure. (Applause)

This new birth of agricultural progress comes at a psychological moment. We have developed American manufactures until the $16,000,000,000 product of our mills and factories exceeds that of Germany, France, and the United Kingdom combined. (Applause) We have built railroads by liberal public and private enterprise until the United States has about one-half of all the railway mileage and tonnage of the world. We have developed banking enterprise and home trade until we have the greatest banking power on earth, and an internal commerce which far exceeds the entire foreign commerce of the globe. We have become the model of the world in our free public schools and our republican form of government. But while we have demonstrated the possession of the greatest agricultural resources on the globe, and have heretofore supplied the world's markets with an unparalleled volume of farm products, we have wasted a wealth that would maintain our population for centuries. The loss in farm values in nearly all of the older States, as shown by the census records from 1880 to 1900, varies from $1,000,000 to $160,000,000 in each State and aggregates the enormous total of more than $1,000,000,000. Is this not sufficient to arouse the entire Nation and cause such a wave of reform as will put into activity every agency and instrumentality for scientific and progressive methods of agricultural reconstruction?

The unprecedented agricultural growth of the United States, in spite of wasteful methods, has been caused by the extraordinary fertility of its virgin soil, the great inducement offered by States and Nation to promote settlement and cultivation, the rapid growth of favorable transportation facilities, as well as the great demand for agricultural products resulting from the rapid increase of population, wealth and commercial enterprise.

Minnesota affords a splendid illustration of this development process, and I trust that I may be pardoned for using my own State for that purpose, since I am best acquainted with her conditions, development, and resources. Of her 50,000,000 acres of land area, about one-half is actually tilled, constituting the field area of about 200,000 farms whose aggregate area, including lands not tilled, approximates 32,000,000 acres, or 160 acres each. Nearly 4,000,000 acres of her area are covered by 10,000 lakes. This vast farm area possesses a soil unsurpassed by any State or any country in the world. The great glacier of several thousand years ago was generous to Minnesota. Its fine glacial drift almost wholly covers the old rock formations. Coming from many regions and rock sources, it has given to the soil an excellent chemical composition. This, together with the vegetal mold, accumulated for ages, makes the very best of hospitable soils. The incomparable fertility of the Minnesota soil and its ability to withstand fifty years of starvation methods in cultivation is accounted for by the almost uniform mixture of vegetal mold with all kinds of decomposed rock drift, thus making it possible for less than half of the State to produce farm products aggregating the enormous total for 1909 of more than $427,000,000. (Applause) It accounts also for the fact that, while Minnesota, like all other States, during this period of fifty years has been rather mining the fertility out of her soil than cultivating it, she has withstood the consequent impoverishment without appreciable shrinkage in farm value. There is perhaps not a single representative in this distinguished assemblage who cannot recall the day when the virgin soil in his locality did not produce from 50 to 100 percent larger crops than it does today, when dense forests covered large tracts now a barren waste, and when the bosom of the earth contained untold millions of mineral wealth now represented on the surface by huge spoil-banks and sunken surfaces. We remember only too well when our fertile fields yielded thirty-five to forty bushels of wheat to the acre, and that the same fields produced only about twelve bushels five years ago. In nearly every community there is found that pathetic omen of decay, the deserted farm—even in this young State.

The economic importance of soil conservation is so great that it can scarcely be estimated. In making my estimates I have taken a very conservative view, and while no absolutely accurate figures can [Pg 7]be obtained, the few that I shall give will be found sufficiently reliable to establish the paramount value of soil conservation.

In Minnesota the low tide of soil impoverishment occurred about five years ago. At that time, after several years of apparently unsuccessful effort, the Agricultural College and schools, assisted by the State Farmers' Institutes and the press, succeeded in stemming the tide and arousing considerable interest in new methods of farming along more intelligent and intensive lines. Only within the last year, however, has progress been marked and rapid. When the first State Conservation Congress was called to meet in Saint Paul, March, 1909, nearly every township in the State was represented and all but two counties presented agricultural and industrial exhibits, attracting a total attendance of more than 150,000 people. The wonderful success of that Congress and the enthusiasm it stirred up all over the State gave a great impetus to this new era of agricultural reform in the entire Northwest and insured the complete success of this Congress from a local standpoint. Never before had 6,000 of the most progressive farmers of a State met for the purpose of discussing more intelligent methods of farming, as well as the suppression of wasteful methods in all fields of agricultural and industrial activity.

During the past short period of five years the average cereal yield of this State has been increased more than five bushels per acre; the corn belt has been extended northward more than 300 miles to the Canadian boundary by the production of hardy and early maturing varieties of corn, yielding the State last year over 60,000,000 bushels, and placing Minnesota among the dozen leading corn States of the Union. It is estimated that plant breeding and seed selection alone last year added about $15,000,000 to our agricultural products. The cereal production has also affected clover, timothy and other tame grasses, thus largely contributing to the growth of the dairy industry, which has been increased ten-fold in twenty years until it now yields the State $50,000,000 annually, several counties netting more than $1,000,000 each. Similar progress has been made in the live stock, fruit, and truck gardening industries, and it is safe to conclude that Minnesota has entered in earnest upon a complete plan of agricultural reconstruction.

But let us consider the opportunities for advancement that are still open, in order that we may determine the economy of soil conservation in terms of dollars and cents. The average yield of Minnesota wheat last season was seventeen bushels per acre. At the agricultural experiment stations the same wheat with improved seed selection and better preparation of soil by crop rotation and tillage yielded twenty-eight bushels per acre, climatic and soil conditions, as well as expense of tillage being otherwise similar, a difference in favor of intelligent farming approximating from five to eight dollars per acre, depending on local conditions. Assuming for the sake of [Pg 8]argument that the average difference in the State would not be more than four dollars per acre, it would still increase the agricultural net earning of the State on the basis of the present acreage $100,000,000 annually. These figures do not take into consideration the further increase of soil productivity by various methods of fertilization other than those resulting from planting crops which enrich the soil with nitrogen, phosphoric acid, potash and calcium, the essential elements of plant growth. Besides, I have not attempted to estimate the value of raising almost maximum yields, where weather conditions are unfavorable, by such drainage, preparation of soil, planting and tillage as will best suit local and climatic conditions. No crop emphasizes the value of seed selection in such unmistakable terms as corn. The average stand of this crop does not exceed 60 percent, which means that the farmer spends 40 percent of his time in the cornfield without result. By selecting the seed in the field at the proper season, testing each ear before planting, and separating with reference to size, so that as nearly as possible the planter will put three kernels in each hill, the stand can be increased to at least 95 percent. Applying this increase to the 2,000,000 acres of cornfield in Minnesota, it would add approximately 30,000,000 bushels with practically no additional cost of production. That the importance of this matter might be more firmly impressed upon the people of the State, I have issued a seed-corn proclamation designating the time when the seed-corn should be selected and calling the attention of the people to the feed value of the corn product as well as corn fodder, which is of utmost importance in a dry season like the one we are now experiencing. This proclamation has received extensive publicity, and it is safe to say that a large number of Minnesota's 200,000 farmers will heed the note of warning.

Of still more vital importance, if possible, is the maintenance and increase of soil fertility as a source of support for future generations. The soil is the only permanent asset of the farmer, and its net returns in crops constitute his annual dividends. Any impairment of this asset will not only reduce the dividends on which his support depends, but will destroy the productive power of the soil to such extent as to deprive future owners of the most essential means of livelihood. A loss of $1,000,000,000 in farm values, such as the older States have already suffered, does not mean merely that this vast sum of money has been wasted, but that its annual earning capacity on which thousands should depend for support has been entirely destroyed, and that these thousands have been forced to seek their sustenance from the fields of commerce and manufacture in the large cities. We enact stringent legislation to prevent the impairment of capital in our banking institutions to protect depositors from loss, but the working capital investment of millions in farm property on which all human institutions must necessarily depend for existence has not been safeguarded in any [Pg 9]manner whatsoever. Without any organized effort to interfere, we still permit millions of farmers to mine out the fertility of the soil, thus increasing the drudgery of farm life, reducing every source of farm income, converting the producers of the farm into consumers of the city, and thus contributing directly to the great increase in cost of living, the scarcity of farm labor, and the congested conditions that breed disease and crime in our large cities. Apply the situation to the country at large and you will find a situation that is simply appalling. There are approximately 500,000,000 acres under actual tillage in the United States. Instead of figuring four dollars per acre waste, which probably would be a fair average, we will place the loss at the extremely low estimate of one dollar. This will still make the total loss through wasteful farming methods in the United States reach the enormous total of $500,000,000 annually. In other words, if the loss were in fact not greater than one dollar per acre, which is unquestionably too low, and that rate could be maintained perpetually without an ultimate depletion of the soil, it would mean that a capital investment of $12,500,000,000 with an earning capacity of four percent per annum aggregating $500,000,000 annually, had been completely destroyed.

At the rate of two dollars per acre, which is a low average, we are every year wasting the income from $25,000,000,000, a sum so great as to be entirely beyond human comprehension. In many of the older States, where farms were sold forty years ago at $150 per acre, the same farms cannot be sold today for $25 per acre, sometimes less than the actual cash value of the buildings and other improvements, because the soil has been robbed of its fertility, making it impossible for the owner to earn the most meager living without restoring the vitality of the soil through expensive methods of fertilization.

It is not at all difficult to see how such wasteful methods of farming must affect the entire industrial situation. The younger generation, inspired with the hopes, aspirations, and energy of youth, stirred by the achievements, opportunities, and general prosperity of a truly great Nation, and encouraged by the possibilities of a liberal education, cannot afford to stake its future on the eking out of a mere existence under the shadow of a rapidly increasing farm mortgage or the threatening omen of a deserted homestead. All honor and credit to that farmer's boy who early realizes the handicap placed upon him by the impairment, and oftentimes utter destruction, of the only safe capital investment of the farmer—fertile and productive soil. Should we complain because he goes to the city to seek more inviting and attractive fields of existence after having been robbed of his only means of livelihood on the farm? This is the proper time for us to think it over. In the younger States, where soil mining has been of such short duration as to be incomplete, and the value of the land through settlement, city growth, and increased transportation [Pg 10]facilities is constantly growing, the young man, who has learned intelligent and progressive methods of farming, should have no fear as to the future, for he has the making of a safe investment; but the young lad who, without experience or training, unexpectedly finds himself possessor of a farm where land values have ceased to rise and the soil has been starved until it no longer can yield in abundance, has a white elephant on his hands, and the sooner he can be brought to the realization thereof the better for himself and the entire community.

Where a certain amount of labor should produce thirty bushels of wheat to the acre, it yields but ten, or even less; and when the farmer cultivates his corn, working ten hours per day, four hours thereof is spent in vain, because 40 percent of the field has no corn—not to speak of the poor quality of the corn grown on account of defective preparation of soil, poor tillage, and the lack of necessary nutritive elements within the soil itself. In addition, he has no knowledge as to diversified farming, the value of live stock, dairying, fruit-raising, truck-gardening, and many other means of livelihood which yield large incomes to the possessor of a well-managed farm, nor does he appreciate the enormous waste committed by unnecessary exposure to the elements of farm machinery and buildings.

The young lady faces a similar situation. Every field of employment bids her welcome at wages from $50 or more per month, and she has already achieved such abundant success in every line of human enterprise, and at the same time enjoyed all the pleasures and delights which bring cheer to the heart of the young, that she cannot afford to even hesitate. Should we complain if she refuses to stay on the farm and take her chances of marrying a $25 man and a ruined farm plastered all over with mortgages, and be chained in matrimonial bonds of lifelong drudgery to a devastated farm homestead, robbed of everything that contributes to the beautiful and good and true in a woman's life? (Great applause) There is only one answer, and its conclusions are just.

Though I have presented a sad picture, it is not pessimistic. The background is altogether cheerful. Two words express the most simple and effective remedy: intelligent farming. This will not only make farming profitable, but it will surround the home life on the farm with so many attractions as to remove all desire for the deceptive allurements of a city. Intelligent farming does not merely guarantee good dividends on a farm investment, but it builds good roads to save cost of transportation, consolidates rural schools where intelligent farming, industry and home economics can be taught by precept and example, beautifies the home and its surroundings and fills it with all the attractions that elevate manhood and womanhood, teaches the younger generation the dignity as well as reward of farm labor, and inspires the laborer with the hope of a bright future.

Drainage, farm settlement, good roads, forestry, transportation, industrial education, minerals, cheap heat and power resources, are all important factors in the Conservation movement. Minnesota has successfully drained about 3,000,000 acres in the northern part of the State at an average cost of two dollars per acre, and converted into meadows, grain and clover fields, celery and cranberry gardens, what only a year or two since was a rough wilderness. Every State should have some effective way of making these results known to prospective settlers through exhibits and judicious advertising. No State officer is in a position to bring greater returns to the State than the immigration commissioner, and it is to be regretted that his work is so often crippled by lack of sufficient appropriations.

In marketing produce, distributing material, fertilizer and machinery, the farmers of Minnesota haul annually approximately 20,000,000 wagon loads. Averaging the cost of each load over mostly unimproved roads at $1.50, the cost of highway transportation in the State aggregates $30,000,000. Most experts claim that uniformly good roads would reduce this cost one-half, but conceding for the sake of argument that the reduction would be only a third, the net saving to the farmers of the State in one year would be about $10,000,000. However, this is not the most important result. The building of good roads would build up farm intercommunication and promote the consolidation of rural school districts by making it possible to carry the pupils at all seasons of the year some distance over country roads to the school at a minimum cost.

Several of the north-central border States were the chief shippers of lumber only a few years ago. Now our great forests are largely depleted, and scientific deforestation has become an absolute necessity. One of the most important duties the States as well as the Nation have to perform is the transformation of this vast stumpage area into forests and farms. Practical and scientific reforestation should convert the lands unsuited for farming into forests, so that every acre would produce revenue and furnish some necessity of life. The dry season of 1910 has particularly emphasized another important duty in this connection, and that is the protection of our forests and settlers from fires. It is a well known fact that enough timber has been destroyed by fire within the last four months to pay for the adequate protection of all our forests for a period of ten years or more, not to mention the great loss of human life, which in itself imposes upon States and Nation the duty of protection. This Congress should be instrumental in stirring public sentiment to such an extent that the various legislatures and the Congress will take immediate steps to stop this needless and expensive waste.

Since mineral wealth is exhaustible, it follows that the interest of the people in this important resource should be guarded against the encroachments of greed with the utmost care. Minnesota furnishes [Pg 12]now one-half of all the iron-ore in the United States, and one-fourth of that of the world, exporting this year about 40,000,000 tons. It is estimated that not less than 2,000,000,000 tons of ore has been definitely located, and that the volume of the undeveloped properties is enormous. The State is the owner of very large quantities of ore, and the income from this source alone will increase the State school fund by at least $100,000,000.

No section of our country could profit more by water transportation than that tributary to this great mineral wealth. The canalization of the Mississippi river system with its 16,000 miles of streams would by cheap transportation bring together the coal fields of the central interior with the iron ore of the North, and produce in the Mississippi valley the greatest iron and steel industries of the world, besides opening up the greatest agricultural and industrial sections to the transportation facilities of the Panama canal.

No commercial nation can long retain supremacy unless it has unlimited supplies of cheap heat and power. In the north-central border States are located peat deposits that should furnish cheap heat and power for untold generations, Minnesota alone possessing more than 1,000,000 acres; and as the source of the three great watersheds of the country, with an elevation of about 1,500 feet over sea and gulf level, there is an abundance of water-power to turn the wheels of manufacture and commerce.

Time will not permit any consideration of the strictly human side of Conservation. We have saved millions of dollars annually by guarding against plant and animal disease, and are just beginning to take note of the untold millions wasted every month through neglect of preventable and curable disease, impure foods, defective sanitation and health inspection in homes and schools, unsuitable playgrounds for children, and the lack of safeguards against railway, mine and factory accidents, all of which come properly within the Conservation scope.

The splendid progress made by Minnesota and other States merely emphasizes the importance of the Conservation movement. Warned by the decay of older nations, we must act before the crisis of exhausted natural resources reaches our Nation and commonwealths. Indeed, warned by signs that are only too plain in our own midst, we must take decisive action without delay. Fortunately, we have passed the pioneer stage of development. Our Nation and commonwealths have all experienced many of the disasters resulting from the skimming of natural resources. Having discovered the vast mines of wealth which surround us everywhere, we must now and forever determine that ignorance, selfishness, and greed shall no longer control our governments and exhaust our resources. (Great applause and cheers)

The problems before us are not merely of tremendous importance, but they are also difficult as to solution. They frequently involve sharply conflicting claims and interests as between the Nation and the [Pg 13]various commonwealths. Every State as well as the Nation itself should have a distinct and separate department empowered to deal with all these problems. It matters but little how it should be designated, though it would serve all purposes best to be known as a Conservation Commission. But it is of vital importance that the agency should be given sufficient authority and funds, so as to enlist the strongest and best men in the Conservation service. That such commissions would have sufficient work, and that from an economic standpoint they would constitute good investments, there is and can be no question.

Minnesota, as a distinctly progressive State and a recognized leader in the Conservation movement, heartily welcomes this Congress with its noted guests and speakers. We have the special honor of entertaining and hearing the three truly great men who have contributed so much to the actual achievements of the Conservation movement, and they are the three most distinguished guests of this Congress, President Taft (applause and the Chautauqua salute), Colonel Roosevelt (applause and cheers), and James J. Hill. Minnesota appreciates this honor and will prove herself worthy thereof. As her Chief Executive, I earnestly hope that the deliberations of this Congress may bring results far beyond our hopes or expectations. I am intensely interested in the Conservation of our resources, and will use all my efforts in securing and enforcing the best possible legislation, believing firmly that the Conservation movement, as here outlined, will promote the general public welfare in a far greater degree than any other, and that it is destined to mark the twentieth century as an era of the greatest industrial achievement for the benefit of all mankind. The people of Minnesota feel keenly their duties and responsibilities with reference to their great heritage of unsurpassed natural resources, and will continue as leaders in the only movement that can insure the perpetuation of our country as the greatest agricultural, industrial and commercial nation in the world. On their behalf, I welcome you to the State. I thank you. (Applause)

President Baker—It is now my pleasure to call upon his Honor, Mayor Herbert E. Keller, who will welcome you on behalf of the great city of Saint Paul. (Great applause and cheers)

Mayor Keller—Mr President, Delegates to the Second National Conservation Congress, and Guests: Upon me, as Chief Executive of the city where this body will carry on its labors, the honor of welcoming you devolves. It is a great privilege and pleasure to discharge this duty, and yet my greeting can but inadequately convey to you the appreciation felt by all Saint Paul at being selected as the scene of this great Congress, whose deliberations mark the commencement of a new epoch in the history of our country. (Applause)

The Conservation to and by ourselves as trustees, and the dedication and perpetuation to our children and our children's children [Pg 14]as beneficiaries, of the tremendous natural resources of our country is a duty and trust too sacred and too imperative to be disregarded or lightly considered, once the situation stands revealed in its true light. It is purely and simply a proposition of the greatest good for the greatest number, and the sound judgment of a great people, with the patriotism and unselfish devotion to duty of the founders of our country ever before them, must and shall consider the greatest number to be the countless millions of population to follow after us, and to whom must be handed down a heritage not diminished or impoverished by us, the temporary executors.

We may be likened to children turned loose in some vast Midas treasurehouse and told to go where we would and take what we pleased. A knock at the doors of Congress, a State legislature, or a city council, gives the magical "Open Sesame!" And behold! the lavishing on some private interest or individual of a great National or State property or municipal right or franchise!

The Nation's bounty and generosity has been limitless, for the entire previous history of the whole world provides no precedent for a guide. But, fortunately, thoughtful minds began to work, awakened to what was being done, and the result is the present all-pervasive sentiment and determination to economize, to check improvidence and waste, and to establish a policy whereby future generations, as well as the present, may have equal opportunities to enjoy our natural benefits and advantages; and Conservation is now more than a mere issue: it is an assured, established, sane and universal desire to preserve and perpetuate for ourselves and posterity the treasures of our country.

And so I bid you welcome to the city of Saint Paul. May your labors be fruitful of great good. I know that your stay with us will be enjoyable. Our city limits may be somewhat circumscribed for the immense crowds here this week, but our hospitality and good wishes are as limitless as the ocean. (Applause)

President Baker—Fellow delegates, I am sure we all extend to his Honor, Mayor Keller, a hearty vote of thanks for what he has done in preparing for this Congress.

And now comes a privilege of which I am very proud—as a southern man all my life—that of presenting to you the President of this great Nation. (Great applause and cheers, the audience rising)

Ladies and Gentlemen: Before beginning my formal address, I should like to extend to the President and the Managers of this Congress, to Governor Eberhart, and to the Mayor of the city, my sincere [Pg 15]and cordial thanks for the opportunity to come here and address this magnificent audience, and to reach the people of the United States on a subject of the utmost interest to them and to every patriot. (Applause)

Conservation, as an economic and political term, has come to mean the preservation of our natural resources for economical use, so as to secure the greatest good to the greatest number.

In the development of this country, in the hardships of the pioneer, in the energy of the settler, in the anxiety of the investor for quick returns, there was very little time, opportunity, or desire to prevent waste of those resources supplied by nature which could not be quickly transmuted into money; while the investment of capital was so great a desideratum that the people as a community exercised little or no care to prevent the transfer of absolute ownership of many of the valuable natural resources to private individuals, without retaining some kind of control of their use. The impulse of the whole new community was to encourage the coming of population, the increase of settlement, and the opening up of business; and he who demurred in the slightest degree to any step which promised additional development of the idle resources at hand was regarded as a traitor to his neighbors and an obstructor to public progress. But now that the communities have become old, now that the flush of enthusiastic expansion has died away, now that the would-be pioneers have come to realize that all the richest lands in the country have been taken up, we have perceived the necessity for a change of policy in the disposition of our natural resources so as to prevent the continuance of the waste which has characterized our phenomenal growth in the past. Today we desire to restrict and retain under public control the acquisition and use by the capitalists of our natural resources.

The danger to the State and to the people at large from the waste and dissipation of our national wealth is not one which quickly impresses itself on the people of the older communities, because its most obvious instances do not occur in their neighborhood, while in the newer part of the country the sympathy with expansion and development is so strong that the danger is scoffed at or ignored. Among scientific men and thoughtful observers, however, the danger has always been present; but it needed some one to bring home the crying need for a remedy of this evil so as to impress itself on the public mind and lead to the formation of public opinion and action by the representatives of the people. Theodore Roosevelt (great and prolonged applause) took up the task in the last two years of his second administration, and well did he perform it. (Great and prolonged applause)

As President of the United States I have, as it were, inherited this policy, and I rejoice in my heritage (great applause). I prize my high opportunity to do all that an Executive can do to help a great [Pg 16]people to realize a great national ambition; for Conservation is National. It affects every man of us, every woman, every child. What I can do in the cause I shall do, not as President of a party, but as President of the whole people (enthusiastic applause and cheers). Conservation is not a question of politics, or of factions, or of persons. It is a question that affects the vital welfare of all of us—of our children and our children's children. I urge that no good can come from meetings of this sort unless we ascribe to those who take part in them, and who are apparently striving worthily in the cause, all proper motives (applause), and unless we judiciously consider every measure or method proposed with a view to its effectiveness in achieving our common purpose, and wholly without regard to who proposes it or who will claim credit for its adoption (great applause). The problems are of very great difficulty, and call for the calmest consideration and clearest foresight. Many of the questions presented have phases that are new in this country, and it is possible that in their solution we may have to attempt first one way and then another. What I wish to emphasize, however, is that a satisfactory conclusion can only be reached promptly if we avoid acrimony, imputations of bad faith and political controversy (cries of "Hear, hear," and great applause).

The public domain of the Government of the United States, including all the cessions from those of the thirteen States that made cessions to the United States, and including Alaska, amounts in all to about 1,800,000,000 acres. Of this there is left as purely Government property outside of Alaska something like 700,000,000 acres. Of this the national forest reserves in the United States proper embrace 144,000,000 acres. The rest is largely mountain or arid country, offering some opportunity for agriculture by dry farming and by reclamation, and containing metals as well as coal, phosphates, oils, and natural gas. Then the Government owns many tracts of land lying along the margins of streams that have water-power, the use of which is necessary in the conversion of the power into electricity and its transmission.

I shall divide my discussion under the heads of (1) agricultural lands; (2) mineral lands—that is, lands containing metalliferous minerals; (3) forest lands; (4) coal lands; (5) oil and gas lands; and (6) phosphate lands. I feel that it will conduce to a better understanding of the problems presented if I take up each class and describe, even at the risk of tedium, first, what has been done by the last Administration and the present one in respect to each kind of land; second, what laws at present govern its disposition; third, what was done by the present Congress in the matter; and fourth, the statutory changes proposed in the interest of Conservation.

AGRICULTURAL LANDS

Our land laws for the entry of agricultural lands are as follows:

The original Homestead Law, with the requirements of residence and cultivation for five years, much more strictly enforced now than ever before.

The Enlarged Homestead Act, applying to non-irrigable lands only, requiring five years' residence and continuous cultivation of one-fourth of the area.

The Desert-land Act, which requires on the part of the purchaser the ownership of a water-right and thorough reclamation of the land by irrigation, and the payment of $1.25 per acre.

The Donation or Carey Act, under which the State selects the land and provides for its reclamation, and the title vests in the settler who resides upon the land and cultivates it and pays the cost of the reclamation.

The National Reclamation Homestead Law, requiring five years' residence and cultivation by the settler on the land irrigated by the Government, and payment by him to the Government of the cost of the reclamation.

There are other acts, but not of sufficient general importance to call for mention unless it is the Stone and Timber Act, under which every individual, once in his lifetime, may acquire 160 acres of land, if it has valuable timber on it or valuable stone, by paying the price of not less than $2.50 per acre, fixed after examination of the stone or timber by a Government appraiser.

In times past, a great deal of fraud has been perpetrated in the acquisition of lands under this Act, but it is now being much more strictly enforced, and the entries made are so few in number that it seems to serve no useful purpose and ought to be repealed. (Applause)

The present Congress passed a bill of great importance, severing the ownership of coal by the Government in the ground from the surface and permitting homestead entries upon the surface of the land, which, when perfected, gives the settler the right to farm the surface, while the coal beneath the surface is retained in ownership by the Government and may be disposed of by it under other laws.

There is no crying need for radical reform in the methods of disposing of what are really agricultural lands. The present laws have worked well. The Enlarged Homestead Law has encouraged the successful farming of lands in the semi-arid regions. Of course the teachings of the Agricultural Department as to how these sub-arid lands may be treated and the soil preserved for useful culture are of the very essence of Conservation. Then the conservation of agricultural lands is shown in the reclamation of arid lands by irrigation, and I should devote a few words to what the Government has done and is doing in this regard.

By the Reclamation Act a fund has been created of the proceeds of the public lands of the United States with which to construct works for storing great bodies of water at proper altitudes from [Pg 18]which, by a suitable system of canals and ditches, the water is to be distributed over the arid and sub-arid lands of the Government to be sold to settlers at a price sufficient to pay for the improvements. Primarily the projects are and must be for the improvement of public lands. Incidentally, where private land is also within the reach of the water supply, the furnishing at cost of operation of this water to private owners by the Government is held by the federal Court of Appeals not to be a usurpation of power; but certainly this ought not to be done except from surplus water not needed for Government land. About thirty projects have been set on foot, distributed through the public-land States, in accordance with the Statute, by which allotments from the reclamation fund are required to be, as nearly as practicable, in proportion to the proceeds from the sale of the public lands in the respective States.

The total sum already accumulated in the reclamation fund is $60,273,258.22, and of that all but $6,491,955.34 has been expended. It became very clear to Congress at its last session, from the statements made by experts, that these thirty projects could not be promptly completed with the balance remaining on hand, or with the funds likely to accrue in the near future. It was found, moreover, that there are many settlers who have been led into taking up lands with the hope and understanding of having water furnished in a short time, who are left in a most distressing situation. I recommended to Congress that authority be given to the Secretary of the Interior to issue bonds in anticipation of the assured earnings by the projects, so that the projects, worthy and feasible, might be promptly completed and the settlers might be relieved from their present inconvenience and hardship (applause). In authorizing the issue of these bonds, Congress limited the application of their proceeds to those projects which a board of army engineers, to be appointed by the President, should examine and determine to be feasible and worthy of completion. The board has been appointed, and soon will make its report.

Suggestions have been made that the United States ought to aid in the drainage of swamp lands belonging to the States or private owners, because, if drained, they would be exceedingly valuable for agriculture and contribute to the general welfare by extending the area of cultivation. I deprecate the agitation in favor of such legislation. It is inviting the general Government into contribution from its treasury toward enterprises that should be conducted either by private capital or at the instance of the State (applause). In these days there is a disposition to look too much to the Federal Government for everything (applause). I am liberal in the construction of the Constitution with reference to Federal power (applause); but I am firmly convinced that the only safe course for us to pursue is to hold fast to the limitations of the Constitution, and to regard as sacred the powers of the States (great applause and cheers). We have made wonderful progress, [Pg 19]and at the same time have preserved with judicious exactness the restrictions of the Constitution. There is an easy way in which the Constitution can be violated by Congress without judicial inhibition, to-wit, by appropriations from the National treasury for unconstitutional purposes. It will be a sorry day for this country if the time ever comes when our fundamental compact shall be habitually disregarded in this manner. (Applause)

MINERAL LANDS

By mineral lands, I mean those lands bearing metals, or what are called metalliferous minerals.