The Project Gutenberg EBook of Mayne Reid, by Elizabeth Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

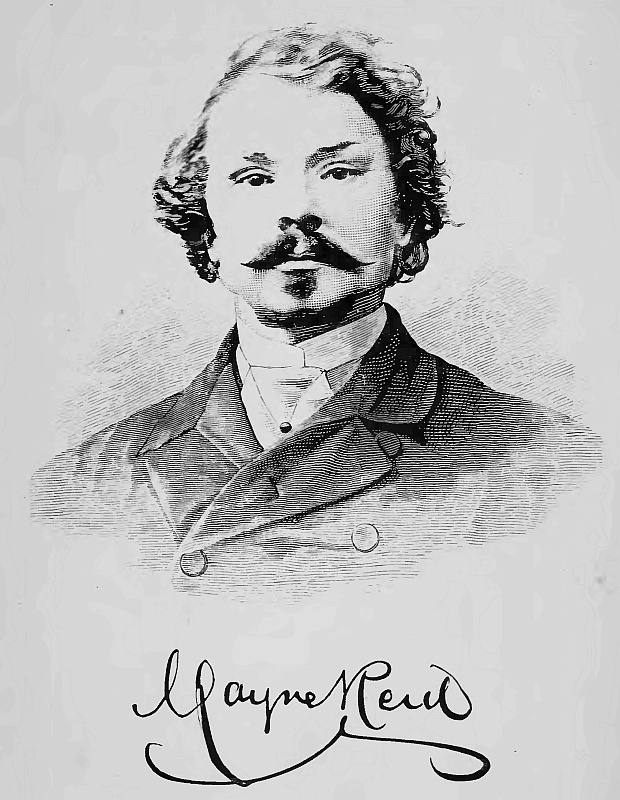

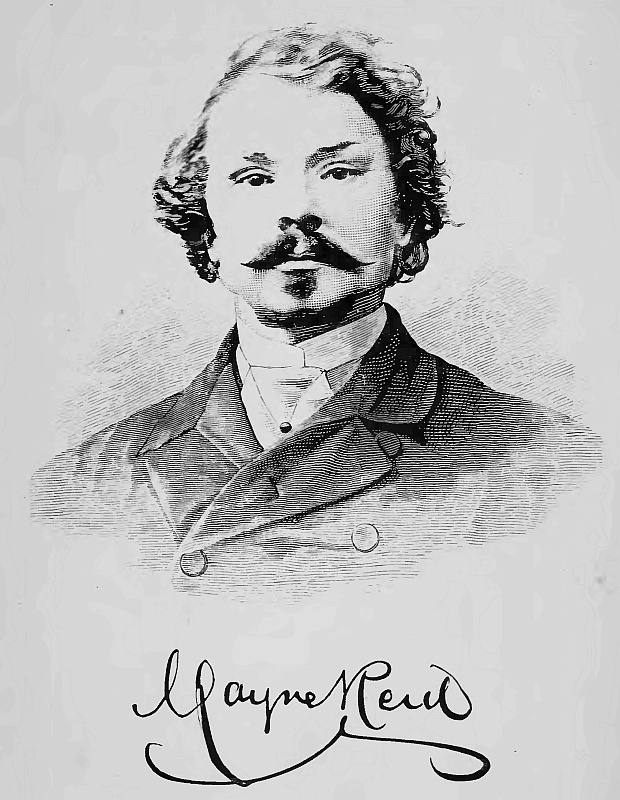

Title: Mayne Reid

A Memoir of his Life

Author: Elizabeth Reid

Release Date: March 21, 2011 [EBook #35648]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MAYNE REID ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Elizabeth Reid

"Mayne Reid"

"A Memoir of his Life"

Chapter One.

Early Life. Emigration to America. Edgar Allan Poe.

To most of the world, Captain Mayne Reid is known only as a writer of thrilling romances and works on natural history. It will appear in these pages that he was also distinguished as a man of action and a soldier, and the record of his many gallant deeds should still further endear him to the hearts of his readers.

He was born in the north of Ireland, in April, 1818, at Ballyroney, county Down, the eldest son of the Reverend Thomas Mayne Reid, Presbyterian minister, a man of great learning and ability. His mother was the daughter of the Reverend Samuel Rutherford, a descendant of the “hot and hasty Rutherford” mentioned in Sir Walter Scott’s “Marmion.”

One of Mayne Reid’s frequent expressions was: “I have all the talent of the Reids and all the deviltry of the Rutherfords.” He certainly may be said to have inherited at least the “hot and hasty temper” of his mother’s family, for his father, the Reverend Thomas Mayne Reid, was of a most placid disposition, much beloved by his parishioners, and a favourite alike with Catholics and Protestants. It used to be said of him by the peasantry, “Mr Reid is so polite he would bow to the ducks.” Several daughters had been born to them before the advent of their first son. He was christened Thomas Mayne, but in after life dropped the Thomas, and was known only as Mayne Reid. Other sons and daughters followed, but Mayne was the only one destined to figure in the world’s history.

Young Mayne Reid early evinced a taste for war. When a small boy he was often found running barefooted along the road after a drum and fife band, greatly to his mother’s dismay. She chided him, saying, “What will the folks think to see Mr Reid’s son going about like this?” To which young Mayne replied, “I don’t care. I’d rather be Mr Drum than Mr Reid.”

It was the ardent wish of both parents that their eldest son should enter the Church; and, at the age of sixteen, Mayne Reid was sent to college to prepare for the ministry of the Presbyterian Church, but after four years’ study, it was found that his inclinations were altogether opposed to this calling. He carried off prizes in mathematics, classics, and elocution; distinguished himself in all athletic sports; anything but theology. It is recorded, on one occasion when called upon to make a prayer, he utterly failed, breaking down at the first few sentences. It was called by his fellow-students “Reid’s wee prayer.”

Captain Mayne Reid has been heard to say, “My mother would rather have had me settle down as a minister, on a stipend of one hundred a year, than know me to be the most famous man in history.”

The good mother could never understand her eldest son’s ambition; but she was happy in seeing her second son, John, succeed his father as pastor of Closkilt, Drumgooland.

In the month of January, 1810, Mayne Reid first set foot in the new world—landing at New Orleans. We quote his own words: “Like other striplings escaped from college, I was no longer happy at home. The yearning for travel was upon me, and without a sigh I beheld the hills of my native land sink behind the black waves, not much caring whether I should ever see them again.”

Soon after landing, he thus expressed himself, showing how little store he set upon his classical training as a stock-in-trade upon which to begin the battle of life: “And one of my earliest surprises—one that met me on the very threshold of my Transatlantic existence—was the discovery of my own utter uselessness. I could point to my desk and say, ‘There lie the proofs of my erudition; the highest prizes of my college class.’ But of what use are they? The dry theories I had been taught had no application to the purposes of real life. My logic was the prattle of the parrot. My classic lore lay upon my mind like lumber; and I was altogether about as well prepared to struggle with life—to benefit either my fellow-men or myself—as if I had graduated in Chinese mnemonics. And, oh! ye pale professors, who drilled me in syntax and scansion, ye would deem me ungrateful indeed were I to give utterance to the contempt and indignation which I then felt for ye; then, when I looked back upon ten years of wasted existence spent under your tutelage; then, when, after believing myself an educated man, the illusion vanished, and I awoke to the knowledge that I knew nothing.”

We shall not here follow Mayne Reid through the ever varying scenes of this period—his life in Louisiana, encounters on the prairies with buffaloes, grizzly bears, and Indians on the war-path with their trophies of scalps; his excursions with trappers and Indians up the Red River, the Missouri, and Platte—for all of these are embodied in his writings, which contain more reality than romance.

Mayne Reid tried his hand at various occupations, both in the civilised and uncivilised life of the new world.

For a brief space he was “storekeeper” and “nigger driver,” then tutor in the family of Judge Peyton Robertson, of Tennessee. Soon tiring of this, he set up a school of his own in the neighbourhood, erecting a wooden building as school house, at his own expense. He was very popular as a teacher, but hunting in the backwoods being more to his taste, he soon went in quest of fresh sport.

At Cincinnati, Ohio, by way of a change, he joined a company of strolling players, but very soon convinced himself that play-acting was not his forte. This little episode in his life, the gallant Captain was anxious to keep from the knowledge of his family in Ireland. They, strict Presbyterians as they were, looked upon play-actors as almost lost to the evil one. However, the fact got into print some years later.

Of all his varied adventures, the Captain would never tell us of his failure in this one line of business, though he would dwell on his talent as “storekeeper” and schoolmaster.

Between the years 1842 and 1846 we hear of him as a poet, newspaper correspondent and editor. In the autumn of 1842 Mayne Reid had reached Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Here he contributed poetry to the Pittsburgh Chronicle, under the nom de plume of the “Poor Scholar.” In the spring of 1813 he settled in Philadelphia, and devoted all his energies to literature, the most ambitious of his efforts being a poem, “La Cubana,” published in “Godey’s Magazine.” Here he also produced a five-act tragedy “Love’s Martyr,” which is full of dramatic power.

During Mayne Reid’s residence in Philadelphia he made the acquaintance of the American poet, Edgar Allan Poe, and the following account of the poet’s life, written by Mayne Reid some years later, in defence of his much maligned friend, is of interest.

“Nearly a quarter of a century ago, I knew a man named Edgar Allan Poe. I knew him as well as one man may know another, after an intimate and almost daily association extending over a period of two years. He was then a reputed poet; I only an humble admirer of the Muses.

“But it is not of his poetic talent I here intend to speak. I never myself had a very exalted opinion of it—more especially as I knew that the poem upon which rests the head corner-stone of his fame is not the creation of Edgar Allan Poe, but of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. In ‘Lady Geraldine’s Courtship,’ you will find the original of ‘The Raven.’ I mean the tune, the softly flowing measure, the imagery and a good many of the words—even to the ‘rustling of the soft and silken curtain.’

“This does not seem like defending the dead poet, nor, as a poet, is his defence intended. I could do it better were I to speak of his prose, which for classic diction and keen analytic power has not been surpassed in the republic of letters. Neither to speak of his poetry, or his prose, have I taken up the pen; but of what is, in my opinion, of much more importance than either—his moral character. Contrary to my estimate, the world believes him to have been a great poet; and there are few who will question his transcendent talents as a writer of prose. But the world also believes him to have been a blackguard; and there are but few who seem to dissent from this doctrine.

“I am one of this few; and I shall give my reasons, drawing them from my own knowledge of the man. In attempting to rescue his maligned memory from the clutch of calumniators, I have no design to represent Edgar Allan Poe as a model of what man ought to be, either morally or socially. I desire to obtain for him only strict justice; and if this be accorded, I have no fear that those according it will continue to regard him as the monster he has been hitherto depicted. Rather may it be that the hideous garment will be transferred from his to the shoulders of his hostile biographer.

“When I first became acquainted with Poe he was living in a suburban district of Philadelphia, called ‘Spring Garden.’ I have not been there for twenty years, and, for aught I know, it may now be in the centre of that progressive city. It was then a quiet residential neighbourhood, noted as the chosen quarter of the Quakers.

“Poe was no Quaker; but, I remember well, he was next-door neighbour to one. And in this wise: that while the wealthy co-religionist of William Penn dwelt in a splendid four-story house, built of the beautiful coral-coloured bricks for which Philadelphia is celebrated, the poet lived in a lean-to of three rooms—there may have been a garret with a closet—of painted plank construction, supported against the gable of the more pretentious dwelling.

“If I remember aright, the Quaker was a dealer in cereals. He was also Poe’s landlord; and, I think, rather looked down upon the poet—though not from any question of character, but simply from his being fool enough to figure as a scribbler and a poet.

“In this humble domicile I can say that I have spent some of the pleasantest hours of my life—certainly some of the most intellectual. They were passed in the company of the poet himself and his wife—a lady angelically beautiful in person and not less beautiful in spirit. No one who remembers that dark-eyed, dark-haired daughter of Virginia—her own name, if I rightly remember—her grace, her facial beauty, her demeanour, so modest as to be remarkable—no one who has ever spent an hour in her company but will endorse what I have above said. I remember how we, the friends of the poet, used to talk of her high qualities. And when we talked of her beauty, I well knew that the rose-tint upon her cheek was too bright, too pure to be of earth. It was consumption’s colour—that sadly-beautiful light which beckons to an early tomb.

“In the little lean-to, besides the poet and his interesting wife, there was but one other dweller. This was a woman of middle age, and almost masculine aspect. She had the size and figure of a man, with a countenance that, at first sight, seemed scarce feminine. A stranger would have been incredulous—surprised, as I was—when introduced to her as the mother of that angelic creature who had accepted Edgar Poe as the partner of her life.

“Such was the relationship; and when you came to know this woman better, the masculinity of her person disappeared before the truly feminine nature of her mind; and you saw before you a type of those grand American mothers—such as existed in the days when block-houses had to be defended, bullets run in red-hot saucepans, and guns loaded for sons and husbands to fire them. Just such a woman was the mother-in-law of the poet Poe. If not called upon to defend her home and family against the assaults of the Indian savage, she was against that as ruthless, as implacable, and almost as difficult to repel—poverty. She was the ever-vigilant guardian of the house, watching it against the silent but continuous sap of necessity, that appeared every day to be approaching closer and nearer. She was the sole servant, keeping everything clean: the sole messenger, doing the errands, making pilgrimages between the poet and his publishers, frequently bringing back such chilling responses as ‘The article not accepted,’ or, ‘The cheque not to be given until such and such a day’—often too late for his necessities.

“And she was also messenger to the market; from it bringing back, not the ‘delicacies of the season,’ but only such commodities as were called for by the dire exigencies of hunger.

“And yet were there some delicacies. I shall never forget how, when peaches were in season and cheap, a pottle of these, the choicest gifts of Pomona, were divested of their skins by the delicate fingers of the poet’s wife, and left to the ‘melting mood,’ to be amalgamated with Spring Garden cream and crystallised sugar, and then set before such guests as came in by chance.

“Reader! I know you will acknowledge this to be a picture of tranquil domestic happiness; and I think you will believe me, when I tell you it is truthful. But I know also you will ask, ‘What has it to do with the poet?’ since it seems to reflect all the credit on his wife, and the woman who called him her son-in-law. For all yet said it may seem so; but I am now to say that which may give it a different aspect.

“During two years of intimate personal association with Edgar Allan Poe, I found in him the following phases of character, accomplishment and disposition:

“First: I discovered rare genius; not at all of the poetic order, not even of the fanciful, but far more of a practical kind, shown in a power of analytic reasoning such as few men possess, and which would have made him the finest detective policeman in the world. Vidocq would have been a simpleton beside him.

“Secondly: I encountered a scholar of rare accomplishments—especially skilled in the lore of Northern Europe, and more imbued with it than with the southern and strictly classic. How he had drifted into this speciality I never knew. But he had it in a high degree, as is apparent throughout all his writings, some of which read like an echo of the Scandinavian ‘Sagas.’

“Thirdly: I felt myself in communication with a man of original character, disputing many of the received doctrines and dogmas of the day; but only original in so far as to dispute them, altogether regardless of consequences to himself or the umbrage he gave to his adversaries.

“Fourthly: I saw before me a man to whom vulgar rumour had attributed those personal graces supposed to attract the admiration of women. This is the usual description given of him in biographical sketches. And why, I cannot tell, unless it has been done to round off a piquant paragraph. His was a face purely intellectual. Women might admire it, thinking of this; but it is doubtful if many of them ever fell, or could have fallen, in love with the man to whom it belonged. I don’t think many ever did. It was enough for one man to be beloved by one such woman as he had for his wife.

“Fifthly: I feel satisfied that Edgar Allan Poe was not, what his slanderers have represented him, a rake. I know he was not; but in truth the very opposite. I have been his companion in one or two of his wildest frolics, and can certify that they never went beyond the innocent mirth in which we all indulge when Bacchus gets the better of us. With him the jolly god sometimes played fantastic tricks—to the stealing away his brain, and sometimes, too, his hat—leaving him to walk bareheaded through the streets at an hour when the sun shone too clearly on his crown, then prematurely bald.

“While acknowledging this as one of Poe’s failings, I can speak truly of its not being habitual; only occasional, and drawn out by some accidental circumstance—now disappointment; now the concurrence of a social crowd, whose flattering friendship might lead to champagne, a single glass of which used to affect him so much that he was hardly any longer responsible for his actions, or the disposal of his hat.

“I have chronicled the poet’s crimes, all that I ever knew him to be guilty of, and, indeed, all that can be honestly alleged against him; though many call him a monster. It is time to say a word of his virtues. I could expatiate upon these far beyond the space left me; or I might sum them up in a single sentence by saying that he was no worse and no better than most other men.

“I have known him to be for a whole month closeted in his own house—the little ‘shanty’ supported against the gable of the rich Quaker—all the time hard at work with his pen, poorly paid, and hard driven to keep the wolf from his slightly-fastened door, intruded on only by a few select friends, who always found him, what they knew him to be, a generous host, an affectionate son-in-law and husband; in short, a respectable gentleman.

“In the list of literary men, there has been no such spiteful biographer as Dr Rufus Griswold, and never such a victim of posthumous spite as poor Edgar Allan Poe.”

Mayne Reid left Philadelphia in the spring of 1846, spending the summer at Newport, Rhode Island, as correspondent to the New York Herald, under the name of “Ecolier.” In September of the same year he was in New York, and had secured a post on Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, but in November he abandoned the pen for the sword.

The following extract from a letter of Mayne Reid to his father tells something of his life in Philadelphia:

“Headquarters, U.S. Army,

“City of Mexico,

“January 20th, 1848.

“Can I expect that my silence for several years will be pardoned? When I last wrote you I made a determination that our correspondence, on my side at least, should cease until I had made myself worthy of continuing that correspondence. Since then circumstances have enabled me to take rank among men—to prove myself not unworthy of that gentle blood from which I am sprung. Oh, how my heart beats at the renewal of those tender ties—paternal, fraternal, filial affection; those golden chains of the heart so long, so sadly broken.

“If I mistake not, my last letter to you was written in the city of Pittsburgh. I was then on my way from the West to the cities of the Atlantic. Shortly after I reached Philadelphia, where for a while my wild wanderings ceased. In this city I devoted myself to literature, and for a period of two or three years earned a scanty but honourable subsistence with my pen. My genius, unfortunately for my purse, was not of that marketable class which prostitutes itself to the low literature of the day. My love for tame literature enabled me to remain poor—ay, even obscure, if you will—though I have the consolation of knowing that there are understandings, and those, too, of a high order, who believe that my capabilities in this field are not surpassed, if equalled, by any writer on this continent. This is the under-current of feeling regarding me in the United States; the current, I am happy to say, that runs in the minds of the educated and intelligent. Perhaps in some future day this under-current may break through the surface, and shine the brighter for having been so long concealed.

“But I have now neither time nor space for theories. Facts will please you better, my dear father and best friend. During my trials as a writer, my almost anonymous productions occasionally called forth warm eulogies from the press. A little gold rubbed into the palm of an editor would have made them wonders! During this time I made many friends, but none of that class who were able and willing to lift me from the sink of poverty.

“There are no Maecenases in the United States. I found none to forge golden wings for me, that I might fly to the heights of Parnassus. During this probation I frequently sent you papers and magazines, containing my productions, generally, I believe, under the nom de plume of ‘The Poor Scholar.’ Have these missiles ever reached you? As I have said, for three or four years I struggled on through this life of literature, and amid the charlatanism and quackery of the age I found I must descend to the everyday nothings of the daily press. I edited, corresponded, became disgusted. The war broke out with Mexico. I flung down the pen and took up the sword. I entered the regiment of New York Volunteers as a 2nd lieutenant, and sailing—”

The letter is torn here, and the remaining portion has unfortunately been lost. The regiment in which Mayne Reid obtained a commission was the 1st New York Volunteers, the first regiment raised in New York for the Mexican War, and of which Ward B. Burnett was colonel. Mayne Reid sailed with his regiment in December, 1846, for Vera Cruz.

Chapter Two.

The Mexican War.

Shortly before his death Captain Mayne Reid conceived the idea of publishing his recollections of the Mexican war, and had commenced to roughly sketch out two or three chapters entitled “Mexican War Memories.” From these the following account in his own words is taken. The ink was scarcely dry on the last pages when he took to the bed from which he never more arose.

“During the first months of 1847, the look-out sentinel stationed on the crenated parapet of San Juan d’Ulloa must have seen an array of ships unusual in numbers for that coast, so little frequented by mariners: equally unusual in the kind of craft and the men on board. For, in addition to the half-score ships flying the flags of different nations, some at anchor close to the Castle, some under the lee of Sacrificios Isle, there was a stream of other craft out in the offing, not at anchor or lying to, but passing coastwise up and down, beyond the most distant range of cannon shot: craft of every size and speciality, schooners, brigs, barques and square-rigged three-masters, from a 200-ton sloop to a ship of as many thousands. Not armed vessels either, though every one of them was loaded to the water-line either with armed and uniformed men or the materials of war; in the large ones a whole regiment of soldiers, in the less, half a regiment, a consort ship containing the other half, and in some but two or three companies, all they were capable of accommodating. Some carried cavalrymen with their horses, others artillerymen with their mounts and batteries, while a large number were but laden with the senseless material of war-tents, waggons, the effects coming under the head of commissariat and quartermaster stores. Not one out of twenty of these vessels was an actual man-of-war. But one might be seen leading and guiding a group of the others, as if their convoy to some known pre-arranged destination. Just this were they doing, escorting the transport ships to their anchorage pre-determined.

“Two such anchorages were there, quite thirty miles apart from one another, though in the diaphanous atmosphere of the Vera Cruz coast a bird of eagle eye soaring midway between could command a view of both. The one northernmost was the Isle of Lobos; that south, Punta Anton Lizardo. To the first I shall take the reader, as to it I was first taken myself.

“Lobos Islet lies off the Vera Cruz coast, opposite the town of Tuxpan, and about two miles. It is of circular form, and, if I remember rightly, about a half-mile in diameter. Its availability as an anchorage comes from a surrounding of coral reefs, with a gap in its northern side that admits ships into water the breakers cannot disturb. Chiefly is it a harbour of refuge against the dreaded norther of the Caribbean coast, and a vessel caught in one of these might run for it; but not likely, unless her papers were not presentable to the Vera Cruz custom house. If they were, the shelter under Sacrificios would be safer, and easily reached. In later times the contrabandist a is the man who has most availed himself of the advantages of Lobos, and in times more remote the filibusters; the Tuxpan fishermen also occasionally beach their boats upon it. But that neither buccaneer, smuggler, nor fisherman had frequented it lately, we had proof given us at landing on its shore by its real denizens, the birds. These—several species of sea-fowl—were so tame they flew screaming over the heads of the soldiers, so close that many were knocked down by their muskets. They became shy enough anon.

“We found the island covered all over with a thick growth of chapparal; it could not be called forest, as the tallest of the trees was but some fifteen or twenty feet in height. The species were varied, most of them of true tropical character, and amongst them was one that attracted general attention as being the ‘india-rubber tree’. Whether it was the true siphonica elastica I cannot say, though likely it was that or an allied species.

“A peculiarity of this isle, and one making it attractive to contrabandista and filibusters, is that fresh water is found on it. Near its summit centre, not over six feet above the ocean level, is a well or hole, artificially dug out in the sand, some six feet deep. The water in this rises and falls with the tide, a law of hydraulics not well understood. Its taste is slightly brackish, but for all that was greatly relished by us—possibly from having been so long upon the cask-water of the transport ships. Near this well we found an old musket and loading pike, rust-eaten, and a very characteristic souvenir of the buccaneers; also the unburied skeleton of a man, who may have been one of their victims.

“The troops landed on Lobos were the 1st New York Volunteers, S. Carolina, 1st and 2nd Pennsylvania, etc, etc. One of the objects in this debarkation was to give these new regiments an opportunity for drilling, such as the time might permit, before making descent upon the Mexican coast. But there was no drill-ground there, as we saw as soon as we set foot on shore—not enough of open space to parade a single regiment in line, unless it were formed along the ribbon of beach.

“On discovery of this want, there followed instant action to supply it—a curious scene, hundreds of uniformed men plying axe and chopper, hewing and cutting, even the officers with their sabres slashing away at the chapparal of Lobos Island: a scene of great activity, and not without interludes of amusement, as now and then a snake, scorpion, or lizard, dislodged from its lair and attempting escape, drew a group of relentless enemies around it.

“In fine, enough surface was cleared for camp and parade-ground. Then up went soldiers’ bell-tents and officers’ marquees, in company rows and regimental, each regiment occupying its allotted ground.

“The old buccaneers may have caroused in Lobos, but never could they have been merrier than we, nor had they ampler means for promoting cheer, even though resting there after a successful raid. Both our sutlers and the skippers of our transport ships, with a keen eye to contingencies, were well provided with stores of the fancy sort; many the champagne cork had its wire fastenings cut on Lobos, and probably now, in that bare isle, would be found an array of empty bottles lying half buried in the sand.

“Any one curious about the life we led on Lobos Island will find some detailed description of it in a book I have written called ‘The Rifle Rangers,’ given to the public as a romance, yet for all more of a reality.

“Our sojourn there was but brief, ending in a fortnight or so, still it may have done something to help out the design for which it was made. It got several regiments of green soldiers through the ‘goose-step,’ and, better still, taught them the ways of camp and campaigning life.

“Mems.—A fright from threatened small-pox, trouble with insects, scorpions and little crabs. Also curious case of lizard remaining on my tent ridge pole for days without moving. No wonder at Shakespeare’s ‘Chameleon feeding on air.’ Amusements, stories, and songs; mingling of mariners with soldiers. Norther just after landing, well protected under Lobos.

“La Villa Rica de Vera Cruz (the rich city of the True Cross), viewed from the sea, presents a picture unique and imposing. It vividly reminded me of the vignette engravings of cities in Goldsmith’s old geography, from which I got my earliest lessons about foreign lands. And just as they were bordered by the engraver’s lines, so is Vera Cruz embraced by an enceinte of wall. For it is a walled city without suburbs, scarce a building of any kind beyond the parapet and fosse engirdling it. Roughly speaking, its ground plan is a half circle, having the sea-shore for diameter, this not more than three-quarters of a mile in length. There is no beach or strand intervening between the houses and the sea, the former overlooking the latter, and protected from its wash by a breakwater buttress.

“The architecture is altogether unlike that of an American or English seaport of similar size. Substantially massive, yet full of graceful lines, most of the private dwellings are of the Hispano-Moriscan order, flat-roofed and parapetted, while the public buildings, chiefly the churches, display a variety of domes, towers and turrets worthy of Inigo Jones or Christopher Wren.

“From near the centre of the semicircle a pier or mole, El Muello, projects about a hundred yards into the sea, and on this all visiting voyagers have to make landing, as at its inner end stands the custom house (aduana). Fronting this on an islet, or rather a reef of coral rocks, stands the fortress castle of San Juan d’Ulloa, off shore about a quarter of a mile. It is a low structure with the usual caramite coverings and crenated parapet, surmounted by a watch and flag-tower.

“The anchorage near it is neither good nor ample, better being found under the lee of Sacrificios, a small treeless islet lying south of it nearly a league, and, luckily for us, beyond the range of Ulloa’s guns, as also those of a fort at the southern extremity of the city.

“Hundreds of ships may ride there in safety, though not so many nor so safe as at Anton Lizardo. Perhaps never so many, nor of such varied kind, were brought to under it as on March 9th, 1847.

“The surf boats are worthy of a word, as without them our beaching would have been difficult and dangerous, if not impossible. They were of the whale boat speciality, and, as I remember, of two sizes. The larger were built to carry two hundred men, the smaller half this number. Most of them were brought to Anton Lizardo in two large vessels, and so hastily had they been built and dispatched, that there had not been time to paint them, all appearing in that pale slate colour known to painters as the priming coat. Of course none had any decking, only the thwarts.

“The commander-in-chief had made requisition for 150 of these boats, though only sixty-nine arrived at Anton Lizardo in time to serve the purpose they were intended for.

“The capture of Vera Cruz was an event alike creditable to the army and navy of the United States, for both bore part in it; and creditable not only on account of the courage displayed, but the strategic skill. It was, in truth, one of those coups in which boldness was backed up by intelligence even to cunning, this last especially shown in the way we effected a landing.

“The fleet, as already said, lay at Anton Lizardo, each day receiving increase from new arrivals. When at length all that were expected had come to anchor there, the final preparations were made for descent upon the land of Montezuma, and all we now waited for was a favouring wind. I do not remember how many steam vessels we had, but I think only two or three. Could we have commanded the services of a half-score steam tugs, the landing might have been effected at an earlier date.

“The day came when the wind proved all that was wanted. A light southerly breeze, blowing up coast almost direct for Vera Cruz, had declared itself before sunrise, and by earliest daybreak all was activity. Alongside each transport ship, as also some of the war vessels, would be seen one or more of the great lead-coloured boats already alluded to, with streams of men backing down the man-ropes and taking seat in them. These men were soldiers in uniform and full marching order. Knapsacks strapped on, haversacks filled and slung, cartouche box on hip, and gun in hand. In perfect order was the transfer made from ship to boat, and, when in the boats, each company had its own place as on a parade-ground. Where it was a boat that held two companies, one occupied the forward thwarts, the other the stern, their four officers—captain, first lieutenant, second and brevet—conforming to their respective places.

“But there were other than soldiers in the boat, each having its complement of sailors from the ships.

“A gun from the ship that carried our commander-in-chief gave the signal for departure from Punta Anton Lizardo, and while its boom was still reverberating, ship after ship was seen to spread sail; then, one after another, under careful pilotage, slipped out through the roadway of the coral reef, steaming up coast straight for Vera Cruz, the doomed city.

“While sweeping up the coast, I can perfectly remember what my own feelings were, and how much I admired the strategy of the movement. Who should get credit for it I cannot tell. But I can hardly think that Winfield Scott’s was the head that planned this enterprise, my after experience with this man guiding me to regard him as a soldier incapable—in short, such as late severe critics have called him, ‘fuss and feathers.’ ‘The hasty plate of soup’ was then ringing around his name. Whoever planned it is deserving of great praise. Its ingenuity, misleading our enemy, lay in making the latter believe that we intended to make landing at Anton Lizardo. Hence all his disposable force that could be spared from the garrison of Vera Cruz was there to oppose us. And when our ships hastily drew in anchor and went straight for Vera Cruz, as hawks at unprotected quarry, these detached garrison troops saw the mistake they had made. The coast road from Vera Cruz to Anton Lizardo is cut by numerous streams, all bridgeless. To cross them safely needed taking many a roundabout route—so many that the swiftest horse could not reach Vera Cruz so soon as our slowest ship, and we were there before them. We did not aim to enter the port nor come within range of its defending batteries, least of all those of San Juan d’Ulloa. The islet of Sacrificios, about a league from the latter, whose southern end affords sheltering anchorage, was the point we aimed at; and there our miscellaneous flotilla became concentrated, some of the ships dropping anchor, others remaining adrift. Then the beaching boats, casting off hawsers, were rowed straight for the shore, some half mile off. A shoal strand it was, where a boat’s keel touched bottom long before reaching dry land. That in which I was did so, and well do I remember how myself and comrades at once sprang over the gunwales, and, waist deep, waded out to the sand-strewn shore.

“There we encountered no enemy—nothing to obstruct us. All the antagonism we met with or saw was a stray shot or two from some long-range guns mounted on the parapet of the most southern fort of the city. But we had now our feet sure planted on the soil of Mexico.”

Chapter Three.

Fighting in Mexico.

I give now some accounts written by Mayne Reid of the various engagements of the American army in Mexico. Some of these were written from the seat of war, and others subsequently.

“The capture of Vera Cruz was an affair of artillery. The city was bombarded for several days by a semicircle of batteries placed upon the sandhills in its rear. It at length surrendered, and with it the celebrated castle of San Juan d’Ulloa.

“During the siege a few of us who were fond of fighting found opportunities of being shot at in the back country. The sandhills—resembling Murlock Banks, only more extensive—form a semicircle round Vera Cruz. The city itself, compactly built, and of picturesque appearance, stands upon a low sandy plain—semicircular, of course—the sea-shore being the boundary diameter. Behind the hills of sand, for leagues inward, extends a low jungly country, covered with the forests of tropical America. This, like all the coast lands of Mexico, is called the tierra caliente (hot land). This region is far from being uninhabited. These thickets have their clearings and their cottages, the latter of the most temporary construction that may serve the wants of man in a climate of almost perpetual summer. There are also several villages scattered through this part of the tierra caliente.

“During the siege the inhabitants of these cottages (ranchos) and villages banded together under the name jarochos or guerrilleros, but better known to our soldiers by the general title rancheros, and kept up a desultory warfare in our rear, occasionally committing murders on straggling parties of soldiers who had wandered from our lines.

“Several expeditions were sent out against them, but with indifferent success. I was present in many of these expeditions, and on one occasion, when in command of about thirty men, I fell in with a party of guerrilleros nearly a hundred strong, routed them, and, after a straggling fight of several hours, drove them back upon a strong position, the village of Medellini. In this skirmish I was fired at by from fifty to a hundred muskets and escopettes, and, although at the distance of not over two hundred yards, had the good fortune to escape being hit.

“One night I was sent in command of a scouting party to reconnoitre a guerilla camp supposed to be some five miles away in the country. It was during the mid-hours of the night, but under one of those brilliant moonlights for which the cloudless sky of Southern Mexico is celebrated. Near the edge of an opening—the prairie of Santa Fé—our party was brought suddenly to a halt at the sight of an object that filled every one of us with horror. It was the dead body of a soldier, a member of the corps to which the scouting party belonged. The body lay at full length upon its back; the hair was clotted with blood and standing out in every direction; the teeth were clenched in agony; the eyes glassy and open, as if glaring upon the moon that shone in mid-heaven above. One arm had been cut off at the elbow, while a large incision in the left breast showed where the heart had been torn out, to satisfy the vengeance of an inhuman enemy. There were shot wounds and sword cuts all over the body, and other mutilations made by the zopilotes and wolves. Notwithstanding all, it was recognised as that of a brave young soldier, who was much esteemed by his comrades, and who for two days had been missing from the camp. He had imprudently strayed beyond the line of pickets, and fallen into the hands of the enemy’s guerrilleros.

“The men would not pass on without giving to his mutilated remains the last rites of burial. There was neither spade nor shovel to be had; but fixing bayonets, they dug up the turf, and depositing the body, gave it such sepulture as was possible. One who had been his bosom friend, cutting a slip from a bay laurel close by, planted it in the grave. The ceremony was performed in deep silence, for they knew that they were on dangerous ground, and that a single shout or shot at that moment might have been the signal for their destruction.

“I afterwards learnt that this fiendish act was partly due to a spirit of retaliation. One of the American soldiers, a very brutal fellow, had shot a Mexican, a young Jarocho peasant, who was seen near the roadside chopping some wood with his macheté. It was an act of sheer wantonness, or for sport, just as a thoughtless boy might fire at a bird to see whether he could kill it. Fortunately the Mexican was not killed, but his elbow was shattered by the shot so badly that the whole arm required amputation. It was the wantonness of the act that provoked retaliation; and after this the lex talionis became common around Vera Cruz, and was practised in all its deadly severity long after the place was taken. Several other American soldiers, straying thoughtlessly beyond the lines, suffered in the same way, their bodies being found mutilated in a precisely similar manner. Strange to say, the man who was the cause of this vengeance became himself one of its victims. Not then, at Vera Cruz, but long afterwards, in the Valley of Mexico; and this was the strangest part of it. Shortly after the American army entered the capital, his body was found in the canal of Las Vigas, alongside the ‘Chinampas,’ or floating gardens, gashed all over with wounds, made by the knives of assassins, and mutilated just as the others had been. It might have been a mere coincidence, but it was supposed at the time that the one-armed Jarocho must have followed him up, with that implacable spirit of vengeance characteristic of his race, until at length, finding him alone, he had completed his vendetta.

“Vera Cruz being taken, we marched for the interior. Puente Nacional, the next strong point, had been fortified, but the enemy, deeming it too weak, fell back upon Cerro Gordo, another strong pass about twenty miles from the former. Here they were again completely routed, although numbering three times our force. In this action I was cheated out of the opportunity of having my name recorded, by the cowardice or imbecility of the major of my regiment, who on that day commanded the detachment of which I formed part. In an early part of the action I discovered a large body of the enemy escaping through a narrow gorge running down the face of a high precipice. The force which this officer commanded had been sufficient to have captured these fugitives, but he not only refused to go forward, but refused to give me a sufficient command to accomplish the object. I learnt afterwards that Santa Anna, commander-in-chief of the Mexican army, had escaped by this gorge.

“After the victory of Cerro Gordo, the army pushed forward to Jalapa, a fine village half-way up the table-lands. After a short rest here we again took the road, and crossing a spur of the Cordilleras, swept over the plains of Perote, and entered the city of Puebla. Yes, with a force of 3,000 men, we entered that great city, containing a population of at least 75,000. The inhabitants were almost paralysed with astonishment and mortification at seeing the smallness of our force. The balconies, windows and house-tops were crowded with spectators; and there were enough men in the streets—had they been men—to have stoned us to death. At Puebla we halted for reinforcements a period of about two months.

“In the month of August, 1847, we numbered about 12,000 effective men, and leaving a small garrison here, with the remainder—10,000—we took the road for the capital. The city of Mexico lies about eighty miles from Puebla. Half-way, another spur of the Andes must be crossed. On the 10th of August, with an immense siege and baggage-train, we moved over these pine-clad hills, and entered the Valley of Mexico. Here halt was made for reconnaissance, which lasted several days. The city stands in the middle of a marshy plain interspersed with lakes, and is entered by eight roads or causeways. These were known to be fortified, but especially that which leads through the gate San Lazaro, on the direct road to Puebla. This was covered by a strong work on the hill El Piñol, and was considered by General Scott as next to impregnable. To turn this, a wide diversion to the north or south was necessary. The latter was adopted, and an old road winding around Lake Chalco—through the old town of that name, and along the base of the southern mountain ridge—was found practicable.

“We took this road, and after a slow march of four days our vanguard debouched on the great National Road, which rounds southward from the city of Mexico to Acapulco. This road was also strongly fortified, and it was still further resolved to turn the fortifications on it by making more to the west. San Augustin de las Cuenas, a village five leagues from Mexico on the National Road, became the point of reserve. On the 19th of August, General Worth moved down the National Road, as a feint to hold the enemy in check at San Antonio (strongly fortified) while the divisions of Generals Worth and Twiggs, with the brigade of Shields—to which I was attached—commenced moving across the Pedregal, a tract of country consisting of rocks, jungle and lava, and almost impassable. On the evening of the 19th, we had crossed the Pedregal, and became engaged with a strong body of the enemy under General Valencia, at a place called Contreras. Night closed on the battle, and the enemy still held his position.

“It rained all night; we sat, not slept, in the muddy lanes of a poor village, San Geronimo—a dreadful night. Before daybreak, General Persifer Smith, who commanded in this battle, had taken his measures, and shortly after sunrise we were at it again. In less than an hour that army ‘of the north,’ as Valencia’s division was styled, being men of San Luis Potosi and other northern States, the flower of the Mexican army, was scattered and in full flight for the city of Mexico.

“This army was 6,000 strong, backed by a reserve of 6,000 more under Santa Anna himself. The reserve did not act, owing, it was said, to some jealousy between Valencia and Santa Anna. In this battle we captured a crowd of prisoners and twenty seven pieces of artillery.

“The road, as we supposed, was now open to the city; a great mistake, as the sharp skirmishes which our light troops encountered as we advanced soon led us to believe. All at once we stumbled upon the main body of the enemy, collected behind two of the strongest field works I have ever seen, in a little village called Cherubusco.

“The road to the village passed over a small stream spanned by a bridge, which was held in force by the Mexicans, and it soon became evident that, unless something like a flank movement were made, they would not be dislodged. The bridge was well fortified and the army attacked fruitlessly in front.

“General Shields’ brigade was ordered to go round by the hacienda of Los Portales and attack the enemy on the flank. They got as far as the barns at Los Portales, but would go no farther. They were being shot down by scores, and the men eagerly sought shelter behind walls or wherever else it could be found. Colonel Ward B. Burnett made a desperate attempt to get the companies together, but it was unsuccessful, and he himself fell, badly wounded.

“The situation had become very critical. I was in command of the Grenadier Company of New York Volunteers, and saw that a squadron of Mexican lancers were getting ready to charge, and knew that if they came on while the flanking party were in such a state of disorganisation the fight would end in a rout. On the other hand, if we charged on them, the chances were the enemy would give way and run. In any case, nothing could be worse than the present state of inaction and slaughter.

“The lieutenant-colonel of the South Carolina Volunteers—their colonel, Butler, having been wounded, was not on the field—was carrying the blue palmetto flag of the regiment. I cried out to him:

“‘Colonel, will you lead the men on a charge?’

“Before he could answer, I heard something snap, and the colonel fell, with one leg broken at the ankle by a shot. I took the flag, and as the wounded officer was being carried off the field, he cried:

“‘Major Gladden, take the flag. Captain Blanding, remember Moultrie, Loundes and old Charleston!’

“Hurrying back to my men, reaching them on the extreme right, I rushed on in front of the line, calling out: ‘Soldiers, will you follow me to the charge?’

“‘Ve vill!’ shouted Corporal Haup, a Swiss. The order to charge being given, away we went, the Swiss and John Murphy, a brave Irishman, being the first two after their leader—myself.

“The Mexicans seeing cold steel coming towards them with such gusto, took to their heels and made for the splendid road leading to the city of Mexico, which offered unequalled opportunities for flight.

“A broad ditch intervened between the highway and the field across which we were charging. Thinking this was not very deep, as it was covered with a green scum, I plunged into it. It took me nearly up to the armpits, and I struggled out all covered with slime and mud. The men avoided my mishap, coming to the road by a dryer but more roundabout path.

“As we got on the road Captain Phil Kearney came thundering over the bridge with his company, all mounted on dappled greys. The gallant Phil had a weakness for dappled greys. As they approached I sang out: ‘Boys, have you breath enough left to give a cheer for Captain Kearney?’

“Phil acknowledged the compliment with a wave of his sword, as he went swinging by towards the works the enemy had thrown up across this road. Just as he reached this spot, the recall bugle sounded, and at that moment Kearney received the shot that cost him an arm.

“Disregarding the bugle call, we of the infantry kept on, when a rider came tearing up, calling upon us to halt.

“‘What for?’ I cried.

“‘General Scott’s orders.’

“‘We shall rue this halt,’ was my rejoinder. ‘The city is at our mercy; we can take it now, and should.’

“Lieutenant-Colonel Baxter, then in command of the New York Volunteers, called out:

“‘For God’s sake, Mayne Reid, obey orders, and halt the men.’

“At this appeal I faced round to my followers, and shouted ‘Halt!’

“The soldiers came up abreast of me, and one big North Irishman cried:

“‘Do you say halt?’

“I set my sword towards them, and again shouted ‘Halt!’ This time I was obeyed, the soldiers crying out:

“‘We’ll halt for you, sir, but for nobody else.’”

Chapter Four.

The Assault on Chapultepec.

Captain Mayne Reid continues the account: “Thus was the American army halted in its victorious career on the 20th of August. Another hour, and it would have been in the streets of Mexico. The commander-in-chief, however, had other designs; and with the bugle recall that summoned the dragoons to retire, all hostile operations ended for the time. The troops slept upon the field.

“On the following day the four divisions of the American army separated for their respective headquarters in different villages. Worth crossed over to Tacubaya, which became the headquarters of the army; Twiggs held the village of San Angel; Pillow rested at Miscuac, a small Indian village between San Angel and Tacubaya, while the Volunteer and Marine division fell back on San Augustine. An armistice had been entered into between the commanders-in-chief of the two armies.

“This armistice was intended to facilitate a treaty of peace; for it was thought that the Mexicans would accept any terms rather than see their ancient city at the mercy of a foreign army. No doubt, however, a great mistake was made, as the armistice gave the crafty Santa Anna a chance to fortify an inner line of defence, the key to which was the strong Castle of Chapultepec, which had to be taken three weeks later with the loss of many brave men.

“The commissioners of both governments met at a small village near Tacubaya, and the American commissioner demanded, as a necessary preliminary to peace, the cession of Upper and Lower California, all New Mexico, Texas, parts of Sonora, Coahuila and Tamaulipas. Although this was in general a wild, unsettled tract of country, yet it constituted more than one-half the territory of Mexico, and the Mexican commissioners would not, even if they dared, agree to such a dismemberment. The armistice was therefore abortive, and on the 6th of September, the American commander-in-chief sent a formal notice to the enemy that it had ceased to exist. This elicited from Santa Anna an insulting reply, and on the same day the enemy was seen in great force to the left of Tacubaya, at a building called Molino del Rey, which was a large stone mill, with a foundry, belonging to the government, and where most of their cannon had been made. It is a building notorious in the annals of Mexican history as the place where the unfortunate Texan prisoners suffered the most cruel treatment from their barbarous captors. It lies directly under the guns of Chapultepec, from which it is distant about a quarter of a mile, and it is separated from the hill of Chapultepec by a thick wood of almond trees.

“On the afternoon of the 7th of September, Captain Mason, of the Engineers, was sent to reconnoitre the enemy’s position. His right lay at a strong stone building, with bastions, at some distance from Molino del Rey, while his left rested in the works around the latter.

“The building on the right is called Casa Mata. It is to be presumed that this position of the enemy was taken to prevent our army from turning the Castle of Chapultepec and entering the city by the Tacubaya road and the gate San Cosme. All the other garitas, Piedas, Nino Perdido, San Antonio and Belen were strongly fortified, and guarded by a large body of the enemy’s troops. Having in all at this time about 30,000 men, they had no difficulty in placing a strong guard at every point of attack.

“On the 7th General Worth was ordered to attack and carry the enemy’s lines at Molino del Rey. His attack was to be planned on the night of the 7th and executed on the morning of the 8th.

“On the night of the 7th the 1st Division, strengthened by a brigade of the 3rd, moved forward in front of the enemy. The dispositions made were as follows:

“It was discovered that the weakest point of the enemy’s lines was at a place about midway between the Casa Mata and Molino del Rey. This point, however, was strengthened by a battery of several guns.

“An assaulting party of 500 men, commanded by Major Wright, were detailed to attack the battery, after it had been cannonaded by Captain Huger with the battering guns. To the right of this assaulting party Garland’s brigade took position within supporting distance.

“On our left, and to the enemy’s right, Clark’s brigade, commanded by Brevet-Colonel Mackintosh, with Duncan’s battery, were posted; while the supporting brigade from Pillow’s division lay between the assaulting column and Clark’s brigade.

“At break of day the action commenced. Huger, with the 24th, opened on the enemy’s centre. Every discharge told; and the enemy seemed to retire. No answer was made from his guns. Worth, becoming at length convinced—fatal conviction—that the works in the centre had been abandoned, ordered the assaulting column to advance.

“These moved rapidly down the slope, Major Wright leading. When they had arrived within about half musket shot the enemy opened upon this gallant band the most dreadful fire it has ever been the fate of a soldier to sustain. Six pieces from the field battery played upon their ranks; while the heavy guns from Chapultepec, and nearly six thousand muskets from the enemy’s entrenchments, mowed them down in hundreds. The first discharge covered the ground with dead and dying. One half the command at least fell with this terrible cataract of bullets. The others, retiring for a moment, took shelter behind some magney, or, in fact, anything that would lend a momentary protection.

“The light battalion and the 11th Infantry now came to their relief, and springing forward amid the clouds of smoke and deadly fire, the enemy’s works were soon in our possession. At the same time the right and left wing had become hotly engaged with the left and right of the enemy. Garland’s brigade, with Duncan’s battery, after driving out a large body of infantry, occupied the mills, while the command of Colonel Mackintosh attacked the Casa Mata.

“This building proved to be a strong work with deep ditches and entrenchments. The brigade moved rapidly forward to assault it, but on reaching the wide ditch the tremendous fire of muskets to which they were exposed, as well as the heavy guns from the Castle, obliged them to fall back on their own battery.

“Duncan now opened his batteries upon this building, and with such effect that the enemy soon retreated from it, leaving it unoccupied.

“At this time the remaining brigade of Pillow’s division, as well as that of Twiggs’, came on the ground, but they were too late. The enemy had already fallen back, and Molino del Rey and the Casa Mata were in possession of the American troops. The latter was shortly after blown up, and all the implements in the foundry, with the cannon moulds, having been destroyed, our army was ordered to return to Tacubaya.

“Thus ended one of the most bloody and fruitless engagements ever fought by the American army. Six hundred and fifty of our brave troops were either killed or wounded, while the loss of the enemy did not amount to more than half this number.

“The fatal action at Molino del Rey cast a gloom over the whole army. Nothing had been gained. The victorious troops fell back to their former positions, and the vanquished assumed a bolder front, celebrating the action as a victory. The Mexican commander gave out that the attack was intended for Chapultepec, and had consequently failed. This, among his soldiers, received credence and doubled their confidence; we, on the other hand, called it a victory on our side. Another such victory and the American army would never have left the Valley of Mexico.

“On the night of the 11th of September, at midnight, two small parties of men were seen to go out from the village of Tacubaya, moving silently along different roads. One party directed itself along an old road toward Molino del Rey, and about half-way between the village and this latter point halted. The other moved a short distance along the direct road to Chapultepec and halted in like manner. They did not halt to sleep; all night long these men were busy piling up earth, filling sand-bags, and laying the platforms of a gun battery.

“When day broke these batteries were finished, their guns in position, and, much to the astonishment of the Mexican troops, a merry fire was opened upon the Castle. This fire was soon answered, but with little effect. By ten o’clock another battery from Molino del Rey, with some well-directed shots from a howitzer at the same point, seemed to annoy the garrison exceedingly.

“A belt of wood lies between the Castle and Molino del Rey on the south. A stone wall surrounds these woods. Well-garrisoned, Chapultepec would be impregnable. The belief is that 1,000 Americans could hold it against all Mexico. They might starve them out, or choke them with thirst, but they could not drive them out of it. There are but few fortresses in the world so strong in natural advantages.

“During the whole of the 12th the shot from the American batteries kept playing upon the walls of the Castle, answered by the guns of the fortress, and an incessant fire of musketry was kept up by the skirmishing party in the woods of Molino del Rey. Towards evening the Castle began to assume a battered and beleaguered appearance. Shot and shell had made ruin on every point, and several of the enemy’s guns were dismounted.

“To enumerate the feats of artillerists on this day would fill a volume. A twenty-pound shot from a battery commanded by Captain Huger and Lieutenant Hagney entered the muzzle of one of the enemy’s howitzers and burst the piece. It was not a chance shot. This battery was placed on the old road between Tacubaya and Molino del Rey. The gate of the Castle fronts this way, and the Calzada, or winding road from the Castle to the foot of the hill, was exposed to the fire. As the ground lying to the north and east of Chapultepec was still in possession of the enemy, a constant intercourse was kept up with the Castle by this Calzada.

“On the morning of the 11th, however, when Huger’s and Hagney’s battery opened, the Calzada became a dangerous thoroughfare. The latter officer found that his shot thrown on the face of the road ricochetted upon the walls with terrible effect, and consequently most of his shots were aimed at this point. It was amusing to see the Mexican officers who wished to enter or go out of the Castle wait until Hagney’s guns were discharged, and then gallop over the Calzada as if the devil were after them.

“A Mexican soldier at the principal gate was packing a mule with ordnance.

“‘Can you hit that fellow, Hagney?’ was asked.

“‘I’ll try,’ was the quiet and laconic reply. The long gun was pointed and levelled. At this moment the soldier stooped by the side of the mule in the act of tightening the girth. ‘Fire!’ said Hagney, and almost simultaneous with the shot a cloud of dust rose over the causeway. When this cleared away the mule was seen running wild along the Calzada, while the soldier lay dead by the wall.

“On the day when Chapultepec was stormed, September 13th, 1847, I was in command of the Grenadier Company of 2nd New York Volunteers—my own—and a detachment of United States Marines, acting with us as light infantry, my orders being to stay by and guard the battery we had built on the south-eastern side of the Castle during the night of the 11th. It was about a thousand yards from, and directly in front of, the Castle’s main gate, through which our shots went crashing all the day. The first assault had been fixed for the morning of the 13th, a storming party of 500 men, or ‘forlorn hope,’ as it was called, having volunteered for this dangerous duty. These were of all arms of the service, a captain of regular infantry having charge of them, with a lieutenant of Pennsylvanian Volunteers as his second in command.

“At an early hour the three divisions of our army, Worth’s, Pillow’s and Quitman’s, closed in upon Chapultepec, our skirmishers driving the enemy’s outposts before them; some of these retreating up the hill and into the Castle, others passing around it and on towards the city.

“It was now expected that our storming party would do the work assigned to it, and for which it had volunteered. Standing by our battery, at this time necessarily silent, with the artillery and engineer officers who had charge of it, Captain Huger and Lieutenant Hagney, we three watched the advance of the attacking line, the puffs of smoke from musketry and rifles indicating the exact point to which it had reached. Anxiously we watched it. I need not say, nor add, that our anxiety became apprehension when we saw that about half-way up the slope there was a halt, something impeding its forward movement. I knew that if Chapultepec were not taken, neither would the city, and failing this, not a man of us might ever leave the Valley of Mexico alive.

“Worth’s injudicious attempt upon the intrenchments of Molino del Rey—to call it by no harsher name—our first retreat during the campaign, had greatly demoralised our men, while reversely affecting the Mexicans, inspiring them with a courage they had never felt before. And there were 30,000 of these to our 6,000—five to one—to say nothing of a host of rancheros in the country around and leperos in the city, all exasperated against us, the invaders. We had become aware, moreover, that Alvarez with his spotted Indians (pintos) had swung round in our rear, and held the mountain passes behind us, so that retreat upon Puebla would have been impossible. This was not my belief alone, but that of every intelligent officer in the army: the two who stood beside me feeling sure of it as myself. This certainty, combined with the slow progress of the attacking party, determined me to participate in the assault. As the senior engineer officer out-ranked me, it was necessary I should have his leave to forsake the battery—now needing no further defence—a leave freely and instantly given, with the words: ‘Go, and God be with you!’

“The Mexican flag was still waving triumphantly over the Castle, and the line of smoke-puffs had not got an inch nearer it; nor was there much change in the situation when, after a quick run across the intervening ground with my following of volunteers and marines, we came up with the storming party at halt, and irregularly aligned along the base of the hill. For what reason they were staying there we knew not at the time, but I afterwards heard it was some trouble about scaling ladders. I did not pause then to inquire, but, breaking through their line with my brave followers, pushed on up the slope. Near the summit I found a scattered crowd of soldiers, some of them in the grey uniform of the Voltigeur Regiment; others, 9th, 14th and 15th Infantry. They were the skirmishers, who had thus far cleared the way for us, and far ahead of the ‘forlorn hope.’ But beyond lay the real area of danger, a slightly sloping ground, some forty yards in width, between us and the Castle’s outward wall—in short, the glacis. It was commanded by three pieces of cannon on the parapet, which, swept it with grape and canister as fast as they could be loaded and fired. There seemed no chance to advance farther without meeting certain death. But it would be death all the same if we did not—such was my thought at that moment.

“Just as I reached this point there was a momentary halt, which made it possible to be heard; and the words I then spoke, or rather shouted, are remembered by me as though it were but yesterday:

“‘Men! if we don’t take Chapultepec, the American army is lost. Let us charge up to the walls.’

“A voice answered: ‘We’ll charge if any one leads us.’

“Another adding: ‘Yes, we’re ready!’

“At that instant the three guns on the parapet belched forth their deadly showers almost simultaneously. My heart bounded with joy at hearing them go off thus together—it was our opportunity; and, quickly comprehending it, I leaped over the scarp which had sheltered us, calling out:

“‘Come on; I’ll lead you!’

“It did not need looking back to know that I was followed. The men I had appealed to were not the men to stay behind, else they would not have been there, and all came after.

“When about half-way across the open ground I saw the parapet crowded with Mexican artillerists in uniforms of dark blue with crimson facings, each musket in hand, and all aiming, as I believed, at my own person. On account of a crimson silk sash I was wearing, they no doubt fancied me a general at least. The volley was almost as one sound, and I avoided it by throwing myself flat along the earth, only getting touched on one of the fingers of my sword-hand, another shot passing through the loose cloth of my overalls. Instantly on my feet again, I made for the wall, which I was scaling, when a bullet from an escopette went tearing through my thigh, and I fell into the ditch.”

Even as he lay wounded in the ditch, brave Mayne Reid painfully raised himself, addressing the men and encouraging them. Above the din of musketry his voice was heard.

“‘For God’s sake, men, don’t leave that wall.’

“Only a few scattered shots were fired after this. The scaling ladders came up, and some scores of men went swarming over the parapet and Chapultepec was taken.

“The second man up to the walls of the Castle was Corporal Haup, the Swiss, when he fell, shot through the face, over the body of Mayne Reid, covering the latter with his blood. The poor fellow endeavoured to roll himself off, saying, ‘I’m not hurt so badly as you.’ But he was dead before Mayne Reid was carried off the field.

“Mayne Reid’s lieutenant, Hypolite Dardonville, a brave young Frenchman, dragged the Mexican flag down from its staff, planting the Stars and Stripes in its place—the standard of the New York regiment.

“The contest was not yet over. The advantage must be followed up, and the city entered. Worth’s division obliquing to the right followed the enemy on the Tabuca Road, and through the gate of San Cosme; while the volunteers, with the rifle and one or two other regiments, detached from the division of General Twiggs, were led along the aqueduct towards the citadel and the gate of Belen. Inch by inch did these gallant fellows drive back their opponents; and he who led them, the veteran Quitman, was ever foremost in the fight.

“A very storm of bullets rained along this road, and hundreds of brave men fell to rise no more; but when night closed the gates of Belen and San Cosme were in possession of the Americans.

“During the still hours of midnight the Mexican army, to the number of some 20,000, stole out of the city and took the road for Guadaloupe.

“Next morning at daybreak, the remnant of the American army, in all less than 3,000 men, entered the city without further opposition, and formed up in the Grand Plaza. Ere sunrise the American star-spangled banner floated proudly over the Palace of Moctezuma, and proclaimed that the city of the Aztecs was in possession of the Americans.

“Chapultepec was in reality the key to the city. If the former were not captured, the latter in all probability would not have been taken at that time, or by that army.

“The city of Mexico stands on a perfectly level plain, where water is reached by digging but a few inches below the surface; this everywhere around its walls, and for miles on every side.

“It does not seem to have occurred to military engineers that a position of this kind is the strongest in the world; the most difficult to assault and easiest to defend. It only needs to clear the surrounding terrain of houses, trees, or aught that might give shelter to the besiegers, and obstruct the fire of the besieged. As in the wet ground trenching is impossible, there is no other way of approach. Even a charge by cavalry going at full gallop must fail; they would be decimated, or utterly destroyed, long before arriving at the entrenched line.

“These were the exact conditions under which Mexico had to be assaulted by the American army. There were no houses outside of the city walls, no cover of any kind, save rows of tall poplar trees lining the sides of the outgoing roads, and most of these had been cut down. How then was the place to be stormed, or rather approached within storming distance? The eyes of some skilled American engineers rested upon the two aqueducts running from Chapultepec into the suburbs of the city. Their mason work, with its massive piers and open arches between, promised the necessary cover for skirmishers, to be supported by close following battalions.

“And they did afford this very shelter, enabling the American army to capture the city of Mexico. But to get at the aqueducts Chapultepec need to be first taken, otherwise the besiegers would have had the enemy both in front and rear. Hence the desperate and determined struggle at the taking of the Castle, and the importance of its succeeding. Had it failed, I have no hesitation in giving my opinion that no American who fought that day in the Valley of Mexico would ever have left it alive. Scott’s army was already weakened by the previous engagements, too much so to hold itself three days on the defensive. Retreat would have been not disastrous, but absolutely impossible. The position was far worse than that of Lord Sale, in the celebrated Cabool expedition. All the passes leading out of the valley by which the Americans might have attempted escape were closed by columns of cavalry. The Indian general, Alvarez, with his host of spotted horsemen, the Pintos of the Acapulco region, had occupied the main road by Rio Frio the moment after the Americans marched in. No wonder these fought on that day as for very life. Every intelligent soldier among them knew that in their attack upon Chapultepec there were but two alternatives: success and life, or defeat and death.”

The following are extracts from dispatches and official documents:

From Major-General Winfield Scott, commander-in-chief.

“September 18, 1847.

“The following are the officers and corps most distinguished in these brilliant operations... Particularly a detachment under Lieutenant Reid, New York Volunteers, consisting of a company of the same, with one of marines.”

From Major-General G.J. Pillow, commanding division.

“September 18, 1847.

“Lieutenant Reid, in command of the one company of the New York Regiment and one of marines, came forward in advance of the other troops of this command, Quitman’s, participated in the assault and was severely wounded.”

From Major-General J.A. Quitman, commanding division.

“September 29, 1847.

“Two detachments from my command not heretofore mentioned in this report should be noticed. Captain Gallagher and Lieutenant Reid, who, with their companies of New York Volunteers, had been detailed on the morning of the 12th, by General Shields, to the support of our battery, Number 2, well performed the service. The former, by the orders of Captain Huger, was detained at that battery during the storming of Chapultepec. The latter, a brave and energetic young officer, being relieved from the battery on the advance to the Castle, hastened to the assault, and was among the first to ascend the crest of the hill, where he was severely wounded... The gallant New York Regiment claims for their standard the honour of being the first waved from the battlements of Chapultepec.”

From Brigadier-General Shields.

“September 25, 1847.

“The New York flag and Company B of that regiment, under the command of a gallant young officer, Lieutenant Reid, were among the first to mount the ramparts of the Castle, and then display the Stars and Stripes to the admiration of the army.”

From Captain Huger, chief of ordnance.

“September 20, 1847.

“As there were two companies in support of batteries 2 and 3, I now allowed one of them, commanded by Lieutenant Reid, New York Volunteers, his command, composed of volunteers and marines, to join its proper division, and he gallantly pushed up the hill and joined it during the storming of the Castle.”

From Colonel Ward B. Burnett, commanding New York Regiment.

“Order Number 35.

“The following promotions and appointments having been made ‘upon good and sufficient recommendations’ will be obeyed and respected accordingly:

“2nd Lieutenant Mayne Reid, of Company B, to be 1st lieutenant of Company G, vice Innes, promoted.”

Chapter Five.

He is Mourned as Dead.

It was reported that Lieutenant Mayne Reid had died of his wounds. This intelligence reached his family in Ireland, who mourned him as dead until the joyful contradiction arrived. It may be interesting as evidence of his reputation at this time to give an extract from a contemporary notice in the Newport News.

“The lamented Lieutenant Reid.

“Lieutenant Reid has been in this country some five or six years, and during that time has been mostly connected with the press, either as an associate editor or correspondent; in this last capacity, he passed the summer of 1846 in Newport, R.I., engaged in writing letters to the New York Herald, under the signature of ‘Ecolier.’ It was at this time that we became acquainted with him, and there are many others in the community who will join us in bearing testimony to his worth as a man, all of whom will be grieved at the announcement of his death. He returned to New York about the first of September, and shortly after sailed for Mexico with his regiment. He was at the battle of Monterey, and distinguished himself in that bloody affair. We published a little poem from his pen, entitled ‘Monterey,’ about three months ago, which will undoubtedly be remembered by our readers; towards the close of the poem, was this stanza:

“‘We were not many - we who pressed

Beside the brave who fell that day;

But who of us has not confessed

He’d rather share their warrior rest,

Than not have been at Monterey?’

“Alas! for human glory! The departed, probably, little thought at the time he penned the above lines that he should so soon be sharing ‘their warrior rest.’ At the storming of Chapultepec he was severely wounded, and died soon after from his wounds. He was a man of singular talents, and gave much promise as a writer. His temperament was exceedingly nervous, and his fancy brilliant. His best productions may be found in ‘Godey’s Book,’ about three or four years ago, under the signature of ‘Poor Scholar.’ It is mournful that talents like his should be so early sacrificed, and that his career should be so soon closed, far—very far—from the land of his birth and the bosom of his home, as well as the land of his adoption. But thus it is! When the day arrives for our army to return, if it ever does, it will present a sad spectacle. The ranks will be thinned, and hearts made sorrowful at their coming that hoped to rejoice in the fullest fruition of gladness. Many a gallant spirit has fallen to rise no more; and the wild note of the bugle cannot awake them to duty, or the sweeter call of friendship and home. The triumphs may be as splendid as ever crowned a human effort, but they have been purchased at the price of noble lives, and too dearly not to mingle the tear of sorrow with the shout of joy.”

The verses by Captain Mayne Reid referred to are:

Monterey.

We were not many - we who stood

Before the iron sleet that day—

Yet many a gallant spirit would

Give half his years if he but could

Have been with us at Monterey.

Now here, now there, the shot it hailed

In deadly drifts of fiery spray,

Yet not a single soldier quailed,

When wounded comrades round them wailed

Their dying shouts at Monterey.

And on - still on our columns kept,

Through walls of flame, its withering way;

Where fell the dead, the living stept,

Still charging on the guns which swept

The slippery streets of Monterey.

The foe himself recoiled aghast,

When, striking where he strongest lay,

We swooped his flanking batteries past,

And braving full their murderous blast,

Stormed home the towers of Monterey.

Our banners on those turrets wave,

And there our evening bugles play;

Where orange boughs above their grave

Keep green the memory of the brave

Who fought and fell at Monterey.

We were not many - we who pressed

Beside the brave who fell that day;

But who of us has not confessed

He’d rather share their warrior rest,

Than not have been at Monterey?

At a public dinner held in the city of Columbus, Ohio, to celebrate the capture of Mexico, Mayne Reid’s memory was toasted, and the following lines, by a young poetess of Ohio, were recited with great effect:

Dirge.

Gone - gone - gone,

Gone to his dreamless sleep;

And spirits of the brave,