The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 9, Slice 6, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 9, Slice 6

"English Language" to "Epsom Salts"

Author: Various

Release Date: February 17, 2011 [EBook #35306]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

Transcriber’s note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME IX SLICE VI

English Language to Epsom Salts

Articles in This Slice

| ENGLISH LANGUAGE | EPHEBI |

| ENGLISH LAW | EPHEMERIS |

| ENGLISH LITERATURE | EPHESIANS, EPISTLE TO THE |

| ENGLISHRY | EPHESUS |

| ENGRAVING | EPHESUS, COUNCIL OF |

| ENGROSSING | EPHOD |

| ENGYON | EPHOR |

| ENID | EPHORUS |

| ENIGMA | EPHRAEM SYRUS |

| ENKHUIZEN | EPHRAIM |

| ENNEKING, JOHN JOSEPH | EPHTHALITES |

| ENNIS | ÉPI |

| ENNISCORTHY | EPICENE |

| ENNISKILLEN, WILLIAM WILLOUGHBY COLE | EPICHARMUS |

| ENNISKILLEN | EPIC POETRY |

| ENNIUS, QUINTUS | EPICTETUS |

| ENNODIUS, MAGNUS FELIX | EPICURUS |

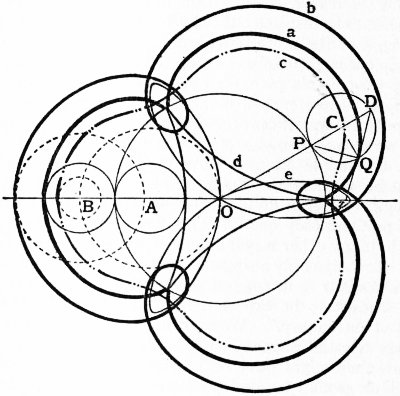

| ENNS | EPICYCLE |

| ENOCH | EPICYCLOID |

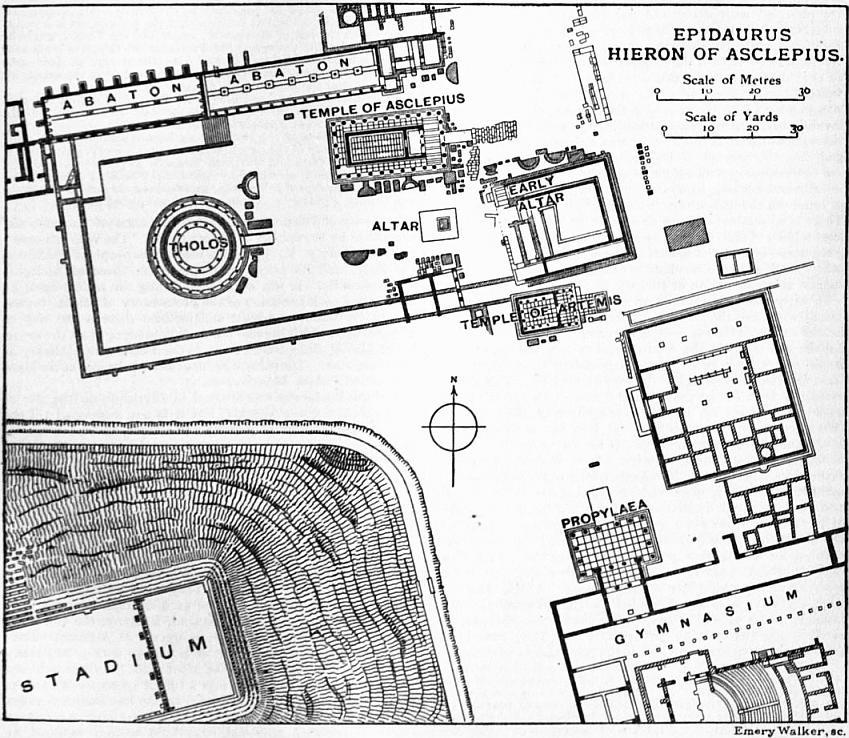

| ENOCH, BOOK OF | EPIDAURUS |

| ENOMOTO, BUYO | EPIDIORITE |

| ENOS | EPIDOSITE |

| ENRIQUEZ GOMEZ, ANTONIO | EPIDOTE |

| ENSCHEDE | EPIGONI |

| ENSENADA, CENON DE SOMODEVILLA | EPIGONION |

| ENSIGN | EPIGRAM |

| ENSILAGE | EPIGRAPHY |

| ENSTATITE | EPILEPSY |

| ENTABLATURE | EPILOGUE |

| ENTADA | EPIMENIDES |

| ENTAIL | ÉPINAL |

| ENTASIS | EPINAOS |

| ENTERITIS | ÉPINAY, LOUISE FLORENCE PÉTRONILLE TARDIEU D’ESCLAVELLES D’ |

| ENTHUSIASM | EPIPHANIUS, SAINT |

| ENTHYMEME | EPIPHANY, FEAST OF |

| ENTOMOLOGY | EPIRUS |

| ENTOMOSTRACA | EPISCOPACY |

| ENTRAGUES, CATHERINE HENRIETTE DE BALZAC D’ | EPISCOPIUS, SIMON |

| ENTRECASTEAUX, JOSEPH-ANTOINE BRUNI D’ | EPISODE |

| ENTRE MINHO E DOURO | EPISTAXIS |

| ENTREPÔT | EPISTEMOLOGY |

| ENTRE RIOS | EPISTLE |

| ENVOY | EPISTYLE |

| ENZIO | EPISTYLIS |

| ENZYME | EPITAPH |

| EOCENE | EPITHALAMIUM |

| EON DE BEAUMONT | EPITHELIAL, ENDOTHELIAL and GLANDULAR TISSUES |

| EÖTVÖS, JÓZSEF | EPITOME |

| EPAMINONDAS | EPOCH |

| EPARCH | EPODE |

| EPAULETTE | EPONA |

| ÉPÉE, CHARLES-MICHEL | EPONYMOUS |

| ÉPÉE-DE-COMBAT | EPPING |

| EPERJES | EPPS |

| ÉPERNAY | ÉPRÉMESNIL, JEAN JACQUES DUVAL D’ |

| ÉPERNON | EPSOM |

| EPHEBEUM | EPSOM SALTS |

587

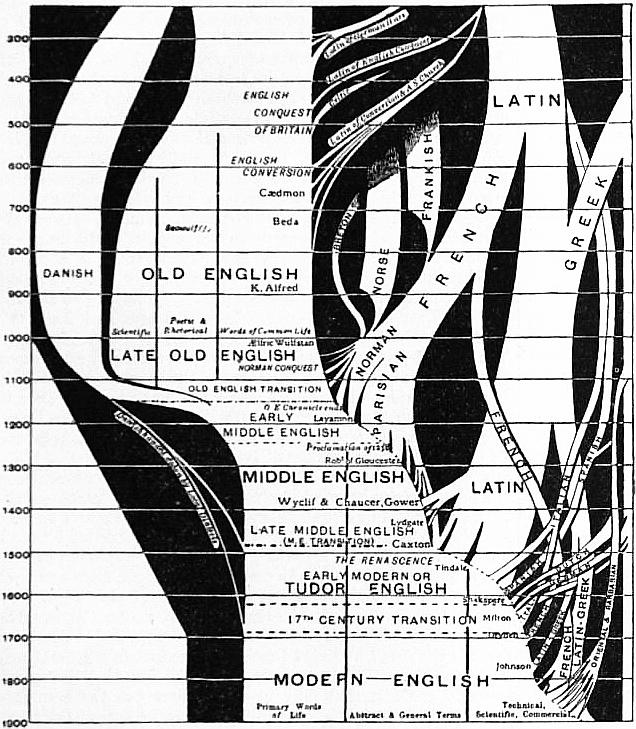

ENGLISH LANGUAGE. In its historical sense, the name

English is now conveniently used to comprehend the language

of the English people from their settlement in Britain to the

present day, the various stages through which it has passed being

distinguished as Old, Middle, and New or Modern English. In

works yet recent, and even in some still current, the term is

confined to the third, or at most extended to the second and third

of these stages, since the language assumed in the main the

vocabulary and grammatical forms which it now presents, the

oldest or inflected stage being treated as a separate language,

under the title of Anglo-Saxon, while the transition period which

connects the two has been called Semi-Saxon. This view had

the justification that, looked upon by themselves, either as

vehicles of thought or as objects of study and analysis, Old

English or Anglo-Saxon and Modern English are, for all practical

ends, distinct languages,—as much so, for example, as Latin and

Spanish. No amount of familiarity with Modern English,

including its local dialects, would enable the student to read

Anglo-Saxon, three-fourths of the vocabulary of which have

perished and been reconstructed within 900 years;1 nor would a

knowledge even of these lost words give him the power, since

the grammatical system, alike in accidence and syntax, would

be entirely strange to him. Indeed, it is probable that a modern

Englishman would acquire the power of reading and writing

French in less time than it would cost him to attain to the same

proficiency in Old English; so that if the test of distinct languages

be their degree of practical difference from each other,

it cannot be denied that “Anglo-Saxon” is a distinct language

from Modern English. But when we view the subject historically,

recognizing the fact that living speech is subject to continuous

change in certain definite directions, determined by the constitution

and circumstances of mankind, as an evolution or

development of which we can trace the steps, and that, owing

to the abundance of written materials, this evolution appears

so gradual in English that we can nowhere draw distinct lines

separating its successive stages, we recognize these stages as

merely temporary phases of an individual whole, and speak

of the English language as used alike by Cynewulf, by Chaucer,

by Shakespeare and by Tennyson.2 It must not be forgotten,

however, that in this wide sense the English language includes,

not only the literary or courtly forms of speech used at successive

periods, but also the popular and, it may be, altogether unwritten

dialects that exist by their side. Only on this basis, indeed, can

we speak of Old, Middle and Modern English as the same

language, since in actual fact the precise dialect which is now

the cultivated language, or “Standard English,” is not the

descendant of that dialect which was the cultivated language

or “Englisc” of Alfred, but of a sister dialect then sunk in comparative

obscurity,—even as the direct descendant of Alfred’s

Englisc is now to be found in the non-literary rustic speech

of Wiltshire and Somersetshire. Causes which, linguistically

588

considered, are external and accidental, have shifted the

political and intellectual centre of England, and along with it

transferred literary and official patronage from one form of

English to another; if the centre of influence had happened to

be fixed at York or on the banks of the Forth, both would

probably have been neglected for a third.

The English language, thus defined, is not “native” to

Britain, that is, it was not found there at the dawn of history,

but was introduced by foreign immigrants at a date many

centuries later. At the Roman Conquest of the island the

languages spoken by the natives belonged all (so far as is known)

to the Celtic branch of the Indo-European or Indo-Germanic

family, modern forms of which still survive in Wales, Ireland,

the Scottish Highlands, Isle of Man and Brittany, while one has

at no distant date become extinct in Cornwall (see Celt:

Language). Brythonic dialects, allied to Welsh and Cornish,

were apparently spoken over the greater part of Britain, as far

north as the firths of Forth and Clyde; beyond these estuaries

and in the isles to the west, including Ireland and Man, Goidelic

dialects, akin to Irish and Scottish Gaelic, prevailed. The long

occupation of south Britain by the Romans (A.D. 43-409)—a

period, it must not be forgotten, equal to that from the Reformation

to the present day, or nearly as long as the whole duration

of modern English—familiarized the provincial inhabitants with

Latin, which was probably the ordinary speech of the towns.

Gildas, writing nearly a century and a half after the renunciation

of Honorius in 410, addressed the British princes in that

language;3 and the linguistic history of Britain might have been

not different from that of Gaul, Spain and the other provinces

of the Western Empire, in which a local type of Latin, giving

birth to a neo-Latinic language, finally superseded the native

tongue except in remote and mountainous districts,4 had not

the course of events been entirely changed by the Teutonic

conquests of the 5th and 6th centuries.

The Angles, Saxons, and their allies came of the Teutonic

stock, and spoke a tongue belonging to the Teutonic or Germanic

branch of the Indo-Germanic (Indo-European) family, the same

race and form of speech being represented in modern times by

the people and languages of Holland, Germany, Denmark, the

Scandinavian peninsula and Iceland, as well as by those of

England and her colonies. Of the original home of the so-called

primitive Aryan race (q.v.), whose language was the parent

Indo-European, nothing is certainly known, though the subject

has called forth many conjectures; the present tendency is to

seek it in Europe itself. The tribe can hardly have occupied

an extensive area at first, but its language came by degrees to be

diffused over the greater part of Europe and some portion of

Asia. Among those whose Aryan descent is generally recognized

as beyond dispute are the Teutons, to whom the Angles and

Saxons belonged.

The Teutonic or Germanic people, after dwelling together in a

body, appear to have scattered in various directions, their

language gradually breaking up into three main groups, which

can be already clearly distinguished in the 4th century A.D.,

North Germanic or Scandinavian, West Germanic or Low and

High German, and East Germanic, of which the only important

representative is Gothic. Gothic, often called Moeso-Gothic, was

the language of a people of the Teutonic stock, who, passing

down the Danube, invaded the borders of the Empire, and

obtained settlements in the province of Moesia, where their

language was committed to writing in the 4th century; its

literary remains are of peculiar value as the oldest specimens, by

several centuries, of Germanic speech. The dialects of the

invaders of Britain belonged to the West Germanic branch, and

within this to the Low German group, represented at the present

day by Dutch, Frisian, and the various “Platt-Deutsch”

dialects of North Germany. At the dawn of history the forefathers

of the English appear to have been dwelling between

and about the estuaries and lower courses of the Rhine and the

Weser, and the adjacent coasts and isles; at the present day the

most English or Angli-form dialects of the European continent

are held to be those of the North Frisian islands of Amrum and

Sylt, on the west coast of Schleswig. It is well known that the

greater part of the ancient Friesland has been swept away by the

encroachments of the North Sea, and the disjecta membra of the

Frisian race, pressed by the sea in front and more powerful

nationalities behind, are found only in isolated fragments from the

Zuider Zee to the coasts of Denmark. Many Frisians accompanied

the Angles and Saxons to Britain, and Old English was

in many respects more closely connected with Old Frisian than

with any other Low German dialect. Of the Geatas, Eotas or

“Jutes,” who, according to Bede, occupied Kent and the Isle of

Wight, and formed a third tribe along with the Angles and

Saxons, it is difficult to speak linguistically. The speech of

Kent certainly formed a distinct dialect in both the Old English

and the Middle English periods, but it has tended to be assimilated

more and more to neighbouring southern dialects, and is at the

present day identical with that of Sussex, one of the old Saxon

kingdoms. Whether the speech of the Isle of Wight ever showed

the same characteristic differences as that of Kent cannot now be

ascertained, but its modern dialect differs in no respect from that

of Hampshire, and shows no special connexion with that of Kent.

It is at least entirely doubtful whether Bede’s Geatas came from

Jutland; on linguistic grounds we should expect that they

occupied a district lying not to the north of the Angles, but

between these and the old Saxons.

The earliest specimens of the language of the Germanic

invaders of Britain that exist point to three well-marked dialect

groups: the Anglian (in which a further distinction may be

made between the Northumbrian and the Mercian, or South-Humbrian);

the Saxon, generally called West-Saxon from the

almost total lack of sources outside the West-Saxon domain;

and the Kentish. The Kentish and West-Saxon are sometimes,

especially in later times, grouped together as southern dialects as

opposed to midland and northern. These three groups were

distinguished from each other by characteristic points of phonology

and inflection. Speaking generally, the Anglian dialects may

be distinguished by the absence of certain normal West-Saxon

vowel-changes, and the presence of others not found in West-Saxon,

and also by a strong tendency to confuse and simplify

inflections, in all which points, moreover, Northumbrian tended to

deviate more widely than Mercian. Kentish, on the other hand,

occupied a position intermediate between Anglian and West-Saxon,

early Kentish approaching more nearly to Mercian,

owing perhaps to early historical connexion between the two, and

late Kentish tending to conform to West-Saxon characteristics,

while retaining several points in common with Anglian. Though

we cannot be certain that these dialectal divergences date from a

period previous to the occupation of Britain, such evidence as

can be deduced points to the existence of differences already on

the continent, the three dialects corresponding in all likelihood

to Bede’s three tribes, the Angles, Saxons and Geatas.

As it was amongst the Engle or Angles of Northumbria that

literary culture first appeared, and as an Angle or Englisc dialect

was the first to be used for vernacular literature, Englisc came

eventually to be a general name for all forms of the vernacular

as opposed to Latin, &c.; and even when the West-Saxon of

Alfred became in its turn the literary or classical form of speech,

it was still called Englisc or English. The origin of the name

Angul-Seaxan (Anglo-Saxons) has been disputed, some maintaining

that it means a union of Angles and Saxons, others (with better

foundation) that it meant English Saxons, or Saxons of England

or of the Angel-cynn as distinguished from Saxons of the

Continent (see New English Dictionary, s.v.). Its modern use is

mainly due to the little band of scholars who in the 16th and

17th centuries turned their attention to the long-forgotten

language of Alfred and Ælfric, which, as it differed so greatly from

589

the English of their own day, they found it convenient to distinguish

by a name which was applied to themselves by those who

spoke it.5 To these scholars “Anglo-Saxon” and “English”

were separated by a gulf which it was reserved for later scholarship

to bridge across, and show the historical continuity of the

English of all ages.

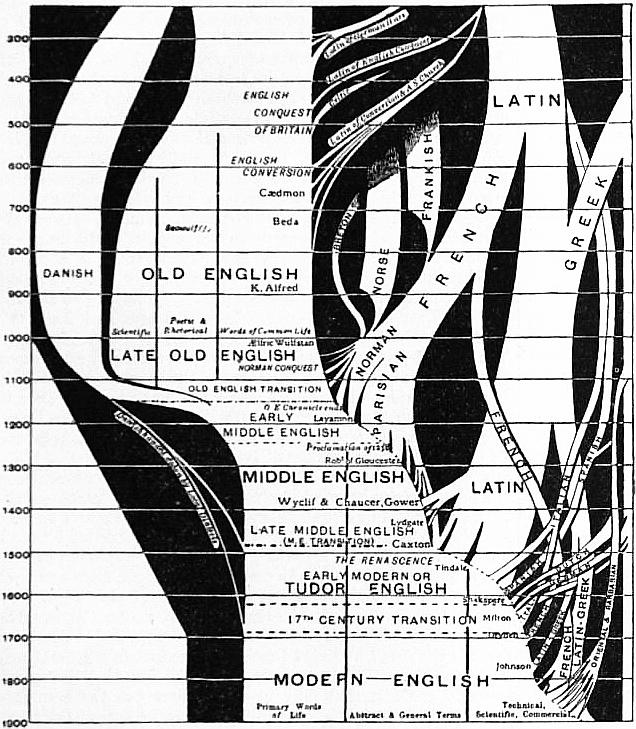

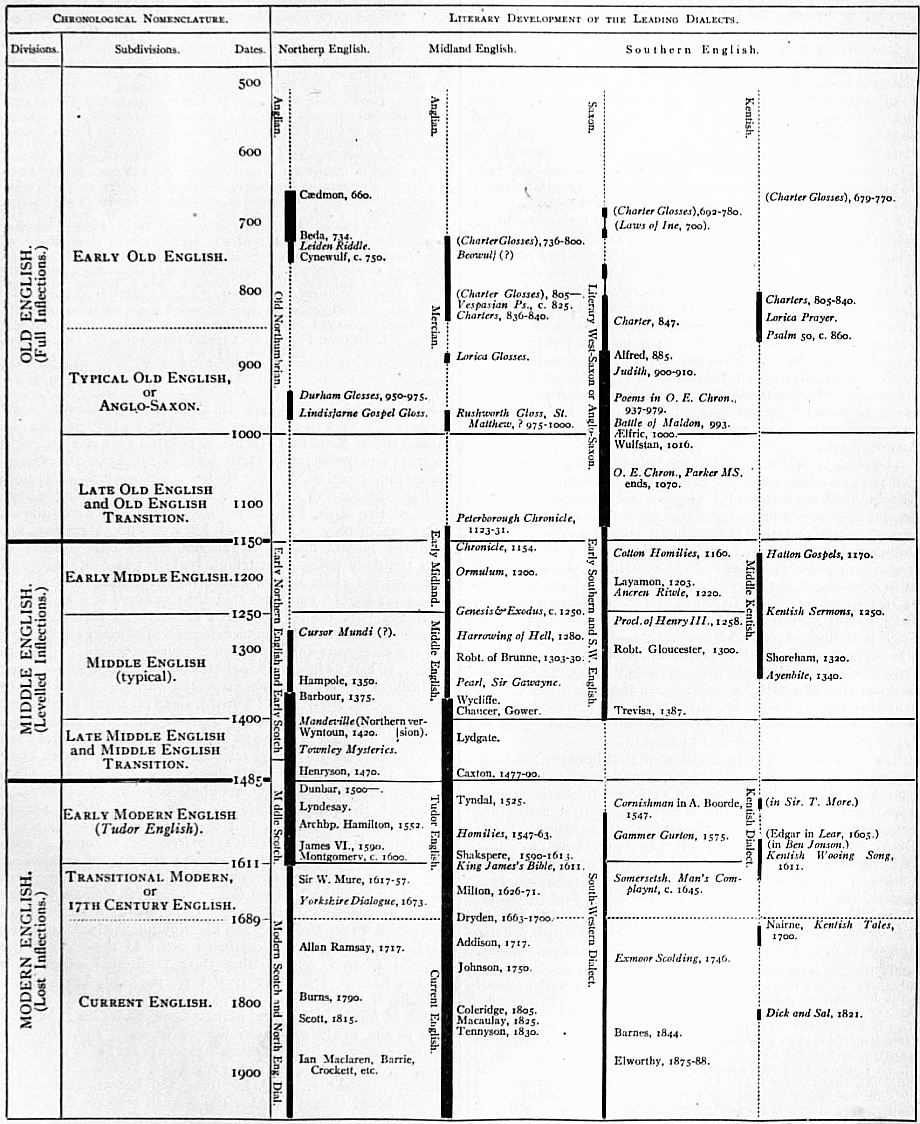

As already hinted, the English language, in the wide sense,

presents three main stages of development—Old, Middle and

Modern—distinguished by their inflectional characteristics.

The latter can be best summarized in the words of Dr Henry

Sweet in his History of English Sounds:6 “Old English is the

period of full inflections (nama, gifan, caru), Middle English of

levelled inflections (naame, given, caare), and Modern English of

lost inflections (name, give, care = nām, giv, cār). We have besides

two periods of transition, one in which nama and name exist side

by side, and another in which final e [with other endings] is

beginning to drop.” By lost inflections it is meant that only very

few remain, and those mostly non-syllabic, as the -s in stones and

loves, the -ed in loved, the -r in their, as contrasted with the Old

English stán-as, lufað, luf-od-e and luf-od-on, þá-ra. Each of

these periods may also be divided into two or three; but from

the want of materials it is difficult to make any such division for

all dialects alike in the first.

As to the chronology of the successive stages, it is of course

impossible to lay down any exclusive series of dates, since the

linguistic changes were inevitably gradual, and also made themselves

felt in some parts of the country much earlier than in others,

the north being always in advance of the midland, and the south

much later in its changes. It is easy to point to periods at which

Old, Middle and Modern English were fully developed, but much

less easy to draw lines separating these stages; and even if we

recognize between each part a “transition” period or stage, the

determination of the beginning and end of this will to a certain

extent be a matter of opinion. But bearing these considerations

in mind, and having special reference to the midland dialect

from which literary English is mainly descended, the following

may be given as approximate dates, which if they do not

demarcate the successive stages, at least include them:—

| Old English or Anglo-Saxon | to 1100 |

| Transition Old English (“Semi-Saxon”) | 1100 to 1150 |

| Early Middle English | 1150 to 1250 |

| (Normal) Middle English | 1250 to 1400 |

| Late and Transition Middle English | 1400 to 1485 |

| Early Modern or Tudor English | 1485 to 1611 |

| Seventeenth century transition | 1611 to 1688 |

| Modern or current English | 1689 onward |

Dr Sweet has reckoned Transition Old English (Old Transition)

from 1050 to 1150, Middle English thence to 1450, and Late or

Transition Middle English (Middle Transition) 1450 to 1500.

As to the Old Transition see further below.

The Old English or Anglo-Saxon tongue, as introduced into

Britain, was highly inflectional, though its inflections at the date

when it becomes known to us were not so full as those of the

earlier Gothic, and considerably less so than those of Greek and

Latin during their classical periods. They corresponded more

closely to those of modern literary German, though both in

nouns and verbs the forms were more numerous and distinct;

for example, the German guten answers to three Old English

forms,—gódne, gódum, gódan; guter to two—gódre, gódra;

liebten to two,—lufodon and lufeden. Nouns had four cases.

Nominative, Accusative (only sometimes distinct), Genitive,

Dative, the latter used also with prepositions to express locative,

instrumental, and most ablative relations; of a distinct instrumental

case only vestiges occur. There were several declensions of

nouns, the main division being that known in Germanic languages

generally as strong and weak,—a distinction also extending to

adjectives in such wise that every adjective assumed either the

strong or the weak inflection as determined by associated grammatical

forms. The first and second personal pronouns possessed

a dual number = we two, ye two; the third person had a complete

declension of the stem he, instead of being made up as now of the

three stems seen in he, she, they. The verb distinguished the

subjunctive from the indicative mood, but had only two inflected

tenses, present and past (more accurately, that of incomplete

and that of completed or “perfect” action)—the former also used

for the future, the latter for all the shades of past time. The order

of the sentence corresponded generally to that of German. Thus

from King Alfred’s additions to his translation of Orosius:

“Donne þy ylcan dæge hi hine to þæm ade beran wyllað þonne

todælað hi his feoh þaet þær to lafe bið æfter þæm gedrynce and

þæm plegan, on fif oððe syx, hwilum on ma, swa swa þaes feos

andefn bið” (“Then on the same day [that] they him to

the pile bear will, then divide they his property that there to

remainder shall be after the drinking and the sports, into five or

six, at times into more, according as the property’s value is”).

The poetry was distinguished by alliteration, and the abundant

use of figurative and metaphorical expressions, of bold compounds

and archaic words never found in prose. Thus in the following

lines from Beowulf (ed. Thorpe, l. 645, Zupitza 320):—

Stræt wæs stán-fáh, stig wisode

Gumum ætgædere. gúð-byrne scán

Heard hond-locen. hring-iren scir

Song in searwum, þa hie to sele furðum

In hyra gry′re geatwum gangan cwomon.

|

Trans.:—

The street was stone-variegated, the path guided

(The) men together; the war-mailcoat shone,

Hard hand-locked. Ring-iron sheer (bright ring-mail)

Sang in (their) cunning-trappings, as they to hall forth

In their horror-accoutrements going came.

|

The Old English was a homogeneous language, having very

few foreign elements in it, and forming its compounds and

derivatives entirely from its own resources. A few Latin

appellatives learned from the Romans in the German wars had

been adopted into the common West Germanic tongue, and are

found in English as in the allied dialects. Such were stræte

(street, via strata), camp (battle), cásere (Cæsar), míl (mile), pín

(punishment), mynet (money), pund (pound), wín (wine); probably

also cyriće (church), biscop (bishop), læden (Latin language), cése

(cheese), butor (butter), pipor (pepper), olfend (camel, elephantus),

ynce (inch, uncia), and a few others. The relations of the first

invaders to the Britons were to a great extent those of destroyers;

and with the exception of the proper names of places and prominent

natural features, which as is usual were retained by the

new population, few British words found their way into the Old

English. Among these are named broc (a badger), bréc (breeches),

clút (clout), púl (pool), and a few words relating to the employment

of field or household menials. Still fewer words seem to

have been adopted from the provincial Latin, almost the only

certain ones being castra, applied to the Roman towns, which

appeared in English as cæstre, ceaster, now found in composition as

-caster, -chester, -cester, and culina (kitchen), which gave cylen (kiln).

The introduction and gradual adoption of Christianity, brought

a new series of Latin words connected with the offices of the

church, the accompaniments of higher civilization, the foreign

productions either actually made known, or mentioned in the

Scriptures and devotional books. Such were mynster (monasterium),

munuc (monk), nunne (nun), maesse (mass), schol

(school), œlmesse (eleemosyna), candel (candela), turtle (turtur),

fic (ficus), cedar (cedrus). These words, whose number increased

from the 7th to the 10th century, are commonly called Latin

of the second period, the Latin of the first period including the

Latin words brought by the English from the continent, as well

as those picked up in Britain either from the Roman provincials

or the Welsh. The Danish invasions of the 8th and 10th centuries

590

resulted in the establishment of extensive Danish and Norwegian

populations, about the basin of the Humber and its tributaries,

and above Morecambe Bay. Although these Scandinavian

settlers must have greatly affected the language of their own

localities, but few traces of their influence are to be found in the

literature of the Old English period. As with the greater part

of the words adopted from the Celtic, it was not until after the

dominion of the Norman had overlaid all preceding conquests,

and the new English began to emerge from the ruins of the old,

that Danish words in any number made their appearance in

books, as equally “native” with the Anglo-Saxon.

The earliest specimens we have of English date to the end of

the 7th century, and belong to the Anglian dialect, and particularly

to Northumbrian, which, under the political eminence of

the early Northumbrian kings from Edwin to Ecgfrið, aided

perhaps by the learning of the scholars of Ireland and Iona, first

attained to literary distinction. Of this literature in its original

form mere fragments exist, one of the most interesting of which

consists of the verses uttered by Bede on his deathbed, and

preserved in a nearly contemporary MS.:—

Fore there neid faerae . naenig uuiurthit

thonc snotturra . than him tharf sie,

to ymb-hycggannæ . aer his hin-iongae,

huaet his gastae . godaes aeththa yflaes,

aefter deoth-daege . doemid uueorthae.

|

Trans.:—

Before the inevitable journey becomes not any

Thought more wise than (that) it is needful for him,

To consider, ere his hence-going,

What, to his ghost, of good or ill,

After death-day, doomed may be.

|

But our chief acquaintance with Old English is in its West-Saxon

form, the earliest literary remains of which date to the

9th century, when under the political supremacy of Wessex and

the scholarship of King Alfred it became the literary language

of the English nation, the classical “Anglo-Saxon.” If our

materials were more extensive, it would probably be necessary

to divide the Old English into several periods; as it is, considerable

differences have been shown to exist between the “early

West-Saxon” of King Alfred and the later language of the 11th

century, the earlier language having numerous phonetic and

inflectional distinctions which are “levelled” in the later, the

inflectional changes showing that the tendency to pass from the

synthetical to the analytical stage existed quite independently

of the Norman Conquest. The northern dialect, whose literary

career had been cut short in the 8th century by the Danish

invasions, reappears in the 10th in the form of glosses to the

Latin gospels and a service-book, often called the Ritual of

Durham, where we find that, owing to the confusion which had

so long reigned in the north, and to special Northumbrian

tendencies, e.g. the dropping of the inflectional n in both verbs

and nouns, this dialect had advanced in the process of inflection-levelling

far beyond the sister dialects of Mercian and the south,

so as already to anticipate the forms of Early Middle English.

Among the literary remains of the Old English may be mentioned

the epic poem of Beowulf, the original nucleus of which

has been supposed to date to heathen and even continental

times, though we now possess it only in a later form; the poetical

works of Cynewulf; those formerly ascribed to Cædmon; several

works of Alfred, two of which, his translation of Orosius and of

The Pastoral Care of St Gregory, are contemporary specimens

of his language; the Old English or Anglo-Saxon Chronicle;

the theological works of Ælfric (including translations of the

Pentateuch and the gospels) and of Wulfstan; and many works

both in prose and verse, of which the authors are unknown.

The earliest specimens, the inscriptions on the Ruthwell and

Bewcastle crosses, are in a Runic character; but the letters used

in the manuscripts generally are a British variety of the Roman

alphabet which the Anglo-Saxons found in the island, and which

was also used by the Welsh and Irish.7 Several of the Roman

letters had in Britain developed forms, and retained or acquired

values, unlike those used on the continent, in particular  (d f g r s t). The letters q and z were not used, q being represented

by cw, and k was a rare alternative to c; u or v was only

a vowel, the consonantal power of v being represented as in

Welsh by f. The Runes called thorn and wēn, having the consonantal

values now expressed by th and w, for which the Roman

alphabet had no character, were at first expressed by th, ð (a

contraction for ɣɣ or ɣh), and v or u; but at a later period the

characters þ and Þ were revived from the old Runic alphabet.

Contrary to Continental usage, the letters c and

(d f g r s t). The letters q and z were not used, q being represented

by cw, and k was a rare alternative to c; u or v was only

a vowel, the consonantal power of v being represented as in

Welsh by f. The Runes called thorn and wēn, having the consonantal

values now expressed by th and w, for which the Roman

alphabet had no character, were at first expressed by th, ð (a

contraction for ɣɣ or ɣh), and v or u; but at a later period the

characters þ and Þ were revived from the old Runic alphabet.

Contrary to Continental usage, the letters c and  (g) had

originally only their hard or guttural powers, as in the neighbouring

Celtic languages; so that words which, when the Continental

Roman alphabet came to be used for Germanic languages, had

to be written with k, were in Old English written with c, as

cêne = keen, cynd = kind.8 The key to the values of the letters,

and thus to the pronunciation of Old English, is also to be

found in the Celtic tongues whence the letters were taken.

(g) had

originally only their hard or guttural powers, as in the neighbouring

Celtic languages; so that words which, when the Continental

Roman alphabet came to be used for Germanic languages, had

to be written with k, were in Old English written with c, as

cêne = keen, cynd = kind.8 The key to the values of the letters,

and thus to the pronunciation of Old English, is also to be

found in the Celtic tongues whence the letters were taken.

The Old English period is usually considered as terminating

1120, with the death of the generation who saw the Norman

Conquest. The Conquest established in England a foreign

court, a foreign aristocracy and a foreign hierarchy.9 The

French language, in its Norman dialect, became the only polite

medium of intercourse. The native tongue, despised not only

as unknown but as the language of a subject race, was left to the

use of boors and serfs, and except in a few stray cases ceased to

be written at all. The natural results followed.10 When the

educated generation that saw the arrival of the Norman died

out, the language, ceasing to be read and written, lost all its

literary words. The words of ordinary life whose preservation

is independent of books lived on as vigorously as ever, but the

literary terms, those that related to science, art and higher

culture, the bold artistic compounds, the figurative terms of

poetry, were speedily forgotten. The practical vocabulary

shrank to a fraction of its former extent. And when, generations

later, English began to be used for general literature, the only

terms at hand to express ideas above those of every-day life

were to be found in the French of the privileged classes, of whom

alone art, science, law and theology had been for generations

the inheritance. Hence each successive literary effort of the

reviving English tongue showed a larger adoption of French

words to supply the place of the forgotten native ones, till by

the days of Chaucer they constituted a notable part of the

vocabulary. Nor was it for the time being only that the French

words affected the English vocabulary. The Norman French

words introduced by the Conquest, as well as the Central or

Parisian French words which followed under the early Plantagenets,

were mainly Latin words which had lived on among

the people of Gaul, and, modified in the mouths of succeeding

generations, had reached forms more or less remote from their

originals. In being now adopted as English, they supplied

precedents in accordance with which other Latin words might

be converted into English ones, whenever required; and long

before the Renascence of classical learning, though in much

greater numbers after that epoch, these precedents were freely

followed.

While the eventual though distant result of the Norman Conquest

was thus a large reconstruction of the English vocabulary,

591

the grammar of the language was not directly affected by it.

There was no reason why it should—we might almost add, no

way by which it could. While the English used their own words,

they could not forget their own way of using them, the inflections

and constructions by which alone the words expressed ideas—in

other words, their grammar; when one by one French words

were introduced into the sentence they became English by the

very act of admission, and were at once subjected to all the

duties and liabilities of English words in the same position. This

is of course precisely what happens at the present day: telegraph

and telegram make participle telegraphing and plural telegrams,

and naïve the adverb naïvely, precisely as if they had been in the

language for ages.

But indirectly the grammar was affected very quickly. In

languages in the inflected or synthetic stage the terminations

must be pronounced with marked distinctness, as these contain

the correlation of ideas; it is all-important to hear whether a

word is bonus or bonis or bonas or bonos. This implies a measured

and distinct pronunciation, against which the effort for ease and

rapidity of utterance is continually struggling, while indolence

and carelessness continually compromise it. In the Germanic

languages, as a whole, the main stress-accent falls on the radical

syllable, or on the prefix of a nominal compound, and thus at

or near the beginning of the word; and the result of this in

English has been a growing tendency to suffer the concluding

syllables to fall into obscurity. We are familiar with the cockney

winder, sofer, holler, Sarer, Sunder, would yer, for window, sofa,

holla, Sarah, Sunday, would you, the various final vowels sinking

into an obscure neutral one now conventionally spelt er, but

formerly represented by final e. Already before the Conquest,

forms originally hatu, sello, tunga, appeared as hate, selle, tunge,

with the terminations levelled to obscure ě; but during the

illiterate period of the language after the Conquest this careless

obscuring of terminal vowels became universal, all unaccented

vowels in the final syllable (except i) sinking into e. During

the 12th century, while this change was going on, we see a great

confusion of grammatical forms, the full inflections of Old English

standing side by side in the same sentence with the levelled ones

of Middle English. It is to this state of the language that the

names Transition and Period of Confusion (Dr Abbott’s appellation)

point; its appearance, as that of Anglo-Saxon broken down

in its endings, had previously given to it the suggestive if not

logical appellation of Semi-Saxon.

Although the written remains of the transition stage are few,

sufficient exist to enable us to trace the course of linguistic

change in some of the dialects. Within three generations after

the Conquest, faithful pens were at work transliterating the old

homilies of Ælfric, and other lights of the Anglo-Saxon Church,

into the current idiom of their posterity.11 Twice during the period,

in the reigns of Stephen and Henry II., Ælfric’s gospels were

similarly modernized so as to be “understanded of the people.”12

Homilies and other religious works of the end of the 12th century13

show us the change still further advanced, and the language

passing into Early Middle English in its southern form. While

these southern remains carry on in unbroken sequence the history

of the Old English of Alfred and Ælfric, the history of the northern

English is an entire blank from the 11th to the 13th century.

The stubborn resistance of the north, and the terrible retaliation

inflicted by William, apparently effaced northern English

culture for centuries. If anything was written in the vernacular

in the kingdom of Scotland during the same period, it probably

perished during the calamities to which that country was subjected

during the half-century of struggle for independence. In

reality, however, the northern English had entered upon its

transition stage two centuries earlier; the glosses of the 10th

century show that the Danish inroads had there anticipated the

results hastened by the Norman Conquest in the south.

Meanwhile a dialect was making its appearance in another

quarter of England, destined to overshadow the old literary

dialects of north and south alike, and become the English of the

future. The Mercian kingdom, which, as its name imports, lay

along the marches of the earlier states, and was really a congeries

of the outlying members of many tribes, must have presented

from the beginning a linguistic mixture and transition; and it is

evident that more than one intermediate form of speech arose

within its confines, between Lancashire and the Thames. The

specimens of early Mercian now in existence consist mainly

of glosses, in a mixed Mercian and southern dialect, dating from

the 8th century; but, in a 9th-century gloss, the so-called

Vespasian Psalter, representing what is generally held to be pure

Mercian. Towards the close of the Old English period we find

some portions of a gloss to the Rushworth Gospels, namely

St Matthew and a few verses of St John xviii., to be in Mercian.

These glosses, with a few charters and one or two small fragments,

represent a form of Anglian which in many respects stands

midway between Northumbrian and Kentish, approaching the

one or the other more nearly as we have to do with North

Mercian or South Mercian. And soon after the Conquest we

find an undoubted midland dialect in the transition stage from

Old to Middle English, in the eastern part of ancient Mercia, in

a district bounded on the south and south-east by the Saxon

Middlesex and Essex, and on the east and north by the East

Anglian Norfolk and Suffolk and the Danish settlements on the

Trent and Humber. In this district, and in the monastery of

Peterborough, one of the copies of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,

transcribed about 1120, was continued by two succeeding hands

to the death of Stephen in 1154. The section from 1122 to 1131,

probably written in the latter year, shows a notable confusion

between Old English forms and those of a Middle English, impatient

to rid itself of the inflectional trammels which were still,

though in weakened forms, so faithfully retained south of the

Thames. And in the concluding section, containing the annals

from 1132 to 1154, and written somewhere about the latter

year, we find Middle English fairly started on its career. A

specimen of this new tongue will best show the change that had

taken place:

1140 A.D.—And14 te eorl of Angæu wærd ded, and his sune Henri

toc to þe rice. And te cuen of France to-dælde fra þe king, and scæ

com to þe iunge eorl Henri. and he toc hire to wiue, and al Peitou

mid hire. þa ferde he mid micel færd into Engleland and wan castles—and

te king ferde agenes him mid micel mare ferd. þoþwæthere

fuhtten hi noht. oc ferden þe ærcebiscop and te wise men betwux

heom, and makede that sahte that te king sculde ben lauerd and king

wile he liuede. and æfter his dæi ware Henri king. and he helde him

for fader, and he him for sune, and sib and sæhte sculde ben betwyx

heom, and on al Engleland.15

With this may be contrasted a specimen of southern English,

from 10 to 20 years later (Hatton Gospels, Luke i. 4616):

Da cwæð Maria: Min saule mersed drihten, and min gast geblissode

on gode minen hælende. For þam þe he geseah his þinene

eadmodnysse. Soðlice henen-forð me eadige seggeð alle cneornesse;

for þam þe me mychele þing dyde se þe mihtyg ys; and his name is

halig. And his mildheortnysse of cneornisse on cneornesse hine ondraedende.

He worhte maegne on hys earme; he to-daelde þa

ofermode, on moda heora heortan. He warp þa rice of setlle, and

þa eadmode he up-an-hof. Hyngriende he mid gode ge-felde, and

þa ofermode ydele for-let. He afeng israel his cniht, and gemynde

his mildheortnysse; Swa he spræc to ure fæderen, Abrahame and

his sæde on a weorlde.

To a still later date, apparently close upon 1200, belongs the

versified chronicle of Layamon or Laweman, a priest of Ernely

on the Severn, who, using as his basis the French Brut of Wace,

expanded it by additions from other sources to more than twice

the extent: his work of 32,250 lines is a mine of illustration for

the language of his time and locality. The latter was intermediate

between midland and southern, and the language, though forty

years later than the specimen from the Chronicle, is much more

archaic in structure, and can scarcely be considered even as

Early Middle English. The following is a specimen (lines

9064-9079):

592

On Kinbelines daeie ... þe king wes inne Bruttene, com a

þissen middel aerde ... anes maidenes sune, iboren wes in Beþleem ... of

bezste alre burden. He is ihaten Jesu Crist ... þurh

þene halie gost, alre worulde wunne ... walden englenne; faeder

he is on heuenen ... froure moncunnes; sune he is on eorðen ... of

sele þon maeidene, & þene halie gost ... haldeð mid him

seoluen.

The Middle English was pre-eminently the Dialectal period

of the language. It was not till after the middle of the 14th

century that English obtained official recognition. For three

centuries, therefore, there was no standard form of speech which

claimed any pre-eminence over the others. The writers of each

district wrote in the dialect familiar to them; and between

extreme forms the difference was so great as to amount to

unintelligibility; works written for southern Englishmen had to

be translated for the benefit of the men of the north:—

“In sotherin Inglis was it drawin,

And turnid ic haue it till ur awin

Langage of þe northin lede

That can na nothir Inglis rede.”

Cursor Mundi, 20,064.

|

Three main dialects were distinguished by contemporary

writers, as in the often-quoted passage from Trevisa’s translation

of Higden’s Polychronicon completed in 1387:—

“Also Englysche men ... hadde fram þe bygynnynge þre maner

speche, Souþeron, Norþeron and Myddel speche (in þe myddel of

þe lond) as hy come of þre maner people of Germania.... Also

of þe forseyde Saxon tonge, þat ys deled a þre, and ys abyde scarslyche

wiþ feaw uplondysche men and ys gret wondur, for men of

þe est wiþ men of þe west, as hyt were under þe same part of heyvene,

acordeþ more in sounynge of sþeche þan men of þe norþ wiþ men of

þe souþ; þerfore hyt ys þat Mercii, þat buþ men of myddel Engelond,

as hyt were parteners of þe endes, undurstondeþ betre þe syde

longages Norþeron and Souþeron, þan Norþern and Souþern undurstondeþ

oyþer oþer.”

The modern study of these Middle English dialects, initiated by

the elder Richard Garnett, scientifically pursued by Dr Richard

Morris, and elaborated by many later scholars, both English and

German, has shown that they were readily distinguished by the

conjugation of the present tense of the verb, which in typical

specimens was as follows:—-

| Southern. |

| Ich singe. | We singeþ. |

| Þou singest. | Ȝe singeþ. |

| He singeþ. | Hy singeþ. |

| Midland. |

| Ich, I, singe. | We singen. |

| Þou singest. | Ȝe singen. |

| He singeþ. | Hy, thei, singen. |

| Northern. |

| Ic. I, sing(e) (I þat singes). | We sing(e). We þat synges. |

| Þu singes. | Ȝe sing(e), Ȝe foules synges. |

| He singes. | Thay sing(e). Men synges. |

Of these the southern is simply the old West-Saxon, with the

vowels levelled to e. The northern second person in -es preserves

an older form than the southern and West-Saxon -est; but the

-es of the third person and plural is derived from an older -eth, the

change of -th into -s being found in progress in the Durham

glosses of the 10th century. In the plural, when accompanied by

the pronoun subject, the verb had already dropped the inflections

entirely as in Modern English. The origin of the -en plural in the

midland dialect, unknown to Old English, is probably an instance

of form-levelling, the inflection of the present indicative being

assimilated to that of the past, and the present and past subjunctive,

in all of which -en was the plural termination. In the

declension of nouns, adjectives and pronouns, the northern

dialect had attained before the end of the 13th century to the

simplicity of Modern English, while the southern dialect still

retained a large number of inflections, and the midland a considerable

number. The dialects differed also in phonology, for while

the northern generally retained the hard or guttural values of

k, g, sc, these were in the two other dialects palatalized before

front vowels into ch, j and sh. Kirk, chirche or church, bryg,

bridge; scryke, shriek, are examples. Old English hw was written

in the north qu(h), but elsewhere wh, often sinking into w.

The original long á in stán, már, preserved in the northern stane,

mare, became ō elsewhere, as in stone, more. So that the north

presented a general aspect of conservation of old sounds with the

most thorough-going dissolution of old inflections; the south, a

tenacious retention of the inflections, with an extensive evolution

in the sounds. In one important respect, however, phonetic decay

was far ahead in the north: the final e to which all the old vowels

had been levelled during the transition stage, and which is a distinguishing

feature of Middle English in the midland and southern

dialects, became mute, i.e., disappeared, in the northern dialect

before that dialect emerged from its three centuries of obscuration,

shortly before 1300. So thoroughly modern had its form consequently

become that we might almost call it Modern English, and

say that the Middle English stage of the northern dialect is lost.

For comparison with the other dialects, however, the same

nomenclature may be used, and we may class as Middle English

the extensive literature which northern England produced

during the 14th century. The earliest specimen is probably the

Metrical Psalter in the Cotton Library,17 copied during the reign of

Edward II. from an original of the previous century. The

gigantic versified paraphrase of Scripture history called the

Cursor Mundi,18 is held also to have been composed before 1300.

The dates of the numerous alliterative romances in this dialect

have not been determined with exactness, as all survive in later

copies, but it is probable that some of them were written before

1300. In the 14th century appeared the theological and

devotional works of Richard Rolle the anchorite of Hampole, Dan

Jon Gaytrigg, William of Nassington, and other writers whose

names are unknown; and towards the close of the century,

specimens of the language also appear from Scotland both in

official documents and in the poetical works of John Barbour,

whose language, barring minute points of orthography, is

identical with that of the contemporary northern English

writers. From 1400 onward, the distinction between northern

English and Lowland Scottish becomes clearly marked.

In the southern dialect one version of the work called the

Ancren Riwle or “Rule of Nuns,” adapted about 1225 for a small

sisterhood at Tarrant-Kaines, in Dorsetshire, exhibits a dialectal

characteristic which had probably long prevailed in the south,

though concealed by the spelling, in the use of v for f, as valle

fall, vordonne fordo, vorto for to, veder father, vrom from. Not

till later do we find a recognition of the parallel use of z for s.

Among the writings which succeed, The Owl and the Nightingale of

Nicholas de Guildford, of Portesham in Dorsetshire, before 1250,

the Chronicle of Robert of Gloucester, 1298, and Trevisa’s

translation of Higden, 1387, are of special importance in illustrating

the history of southern English. The earliest form of

Langland’s Piers Ploughman, 1362, as preserved in the Vernon

MS., appears to be in an intermediate dialect between southern

and midland.19 The Kentish form of southern English seems to

have retained specially archaic features; five short sermons in

it of the middle of the 13th century were edited by Dr Morris

(1866); but the great work illustrating it is the Ayenbite of Inwyt

(Remorse of Conscience), 1340,20 a translation from the French

by Dan Michel of Northgate, Kent, who tells us—

“Þet þis boc is y-write mid engliss of Kent;

Þis boc is y-mad uor lewede men,

Vor uader, and uor moder, and uor oþer ken,

Ham uor to berȝe uram alle manyere zen,

Þet ine hare inwytte ne bleue no uoul wen.”

|

In its use of v (u) and z for ƒ and s, and its grammatical inflections,

it presents an extreme type of southern speech, with

peculiarities specially Kentish; and in comparison with contemporary

Midland English works, it looks like a fossil of two

centuries earlier.

Turning from the dialectal extremes of the Middle English to

the midland speech, which we left at the closing leaves of the

593

Peterborough Chronicle of 1154, we find a rapid development of

this dialect, which was before long to become the national

literary language. In this, the first great work is the Ormulum,

or metrical Scripture paraphrase of Orm or Ormin, written about

1200, somewhere near the northern frontier of the midland area.

The dialect has a decided smack of the north, and shows for the

first time in English literature a large percentage of Scandinavian

words, derived from the Danish settlers, who, in adopting

English, had preserved a vast number of their ancestral forms of

speech, which were in time to pass into the common language, of

which they now constitute some of the most familiar words.

Blunt, bull, die, dwell, ill, kid, raise, same, thrive, wand, wing,

are words from this source, which appear first in the work of

Orm, of which the following lines may be quoted:—

“Þe Judewisshe folkess boc

hemm seȝȝde, þatt hemm birrde

Twa bukkes samenn to þe preost

att kirrke-dure brinngenn;

And teȝȝ þa didenn bliþeliȝ,

swa summ þe boc hemm tahhte,

And brohhtenn tweȝȝenn bukkess þær

Drihhtin þærwiþþ to lakenn.

And att21 te kirrke-dure toc

þe preost ta tweȝȝenn bukkess,

And o þatt an he leȝȝde þær

all þeȝȝre sake and sinne,

And lét itt eornenn for þwiþþ all

út inntill wilde wesste;

And toc and snaþ þatt oþerr bucc

Drihhtin þaerwiþþ to lakenn.

All þiss wass don forr here ned,

and ec forr ure nede;

For hemm itt hallp biforenn Godd

to clennssenn hemm of sinne;

And all swa maȝȝ itt hellpenn þe

ȝiff þatt tu willt [itt] follȝhenn.

Ȝiff þatt tu willt full innwarrdliȝ

wiþþ fulle trowwþe lefenn

All þatt tatt wass bitacnedd tær,

to lefenn and to trowwenn.”

Ormulum, ed. White, l. 1324.

|

The author of the Ormulum was a phonetist, and employed a

special spelling of his own to represent not only the quality but

the quantities of vowels and consonants—a circumstance which

gives his work a peculiar value to the investigator. He is

generally assumed to have been a native of Lincolnshire or Notts,

but the point is a disputed one, and there is somewhat to be said

for the neighbourhood of Ormskirk in Lancashire.

It is customary to differentiate between east and west midland,

and to subdivide these again into north and south. As was

natural in a tract of country which stretched from Lancaster to

Essex, a very considerable variety is found in the documents

which agree in presenting the leading midland features, those of

Lancashire and Lincolnshire approaching the northern dialect

both in vocabulary, phonetic character and greater neglect of

inflections. But this diversity diminishes as we advance.

Thirty years after the Ormulum, the east midland rhymed

Story of Genesis and Exodus22 shows us the dialect in a more

southern form, with the vowels of modern English, and from

about the same date, with rather more northern characteristics,

we have an east midland Bestiary.

Different tests and different dates have been proposed for

subdividing the Middle English period, but the most important

is that of Henry Nicol, based on the observation that in the

early 13th century, as in Ormin, the Old English short vowels

in an open syllable still retained their short quantity, as năma,

ŏver, mĕte; but by 1250 or 1260 they had been lengthened to

nā-me, ō-ver, mē-te, a change which has also taken place at a

particular period in all the Germanic, and even the Romanic

languages, as in buō-no for bŏ-num, pā-dre for pă-trem, &c. The

lengthening of the penult left the final syllable by contrast

shortened or weakened, and paved the way for the disappearance

of final e in the century following, through the stages nă-me,

nā-mĕ, nā-m’, nām, the one long syllable in nām(e) being the

quantitative equivalent of the two short syllables in nă-mĕ;

hence the notion that mute e makes a preceding vowel long,

the truth being that the lengthening of the vowel led to the e

becoming mute.

After 1250 we have the Lay of Havelok, and about 1300 the

writings of Robert of Brunne in South Lincolnshire. In the

14th century we find a number of texts belonging to the western

part of the district. South-west midland is hardly to be distinguished

from southern in its south-western form, and hence texts

like Piers Plowman elude any satisfactory classification, but

several metrical romances exhibit what are generally considered

to be west midland characteristics, and a little group of poems,

Sir Gawayne and the Grene Knighte, the Pearl, Cleanness and

Patience, thought to be the work of a north-west midland writer

of the 14th century, bear a striking resemblance to the modern

Lancashire dialect. The end of the century witnessed the prose

of Wycliff and Mandeville, and the poetry of Chaucer, with

whom Middle English may be said to have culminated, and in

whose writings its main characteristics as distinct from Old and

Modern English may be studied. Thus, we find final e in full

use representing numerous original vowels and terminations as

Him thoughtè that his hertè woldè brekè,

in Old English—

Him þuhte þæt his heorte wolde brecan,

which may be compared with the modern German—

Ihm däuchte dass sein Herze wollte brechen.

In nouns the -es of the plural and genitive case is still syllabic—

Reede as the berstl-es of a sow-es eer-es.

Several old genitives and plural forms continued to exist,

and the dative or prepositional case has usually a final e.

Adjectives retain so much of the old declension as to have -e

in the definite form and in the plural—

The tend-re cropp-es and the yong-e sonne.

And smal-e fowl-es maken melodie.

|

Numerous old forms of comparison were in use, which have

not come down to Modern English, as herre, ferre, lenger, hext = higher,

farther, longer, highest. In the pronouns, ich lingered

alongside of I; ye was only nominative, and you objective;

the northern thei had dispossessed the southern hy, but her and

hem (the modern ’em) stood their ground against their and them.

The verb is I lov-e, thou lov-est, he lov-eth; but, in the plural,

lov-en is interchanged with lov-e, as rhyme or euphony requires.

So in the plural of the past we love-den or love-de. The infinitive

also ends in en, often e, always syllabic. The present participle,

in Old English -ende, passing through -inde, has been confounded

with the verbal noun in -ynge, -yng, as in Modern English. The

past participle largely retains the prefix y- or i-, representing

the Old English ge-, as in i-ronne, y-don, Old English zerunnen,

zedón, run, done. Many old verb forms still continued in

existence. The adoption of French words, not only those of

Norman introduction, but those subsequently introduced under

the Angevin kings, to supply obsolete and obsolescent English

ones, which had kept pace with the growth of literature since

the beginning of the Middle English period, had now reached

its climax; later times added many more, but they also dropped

some that were in regular use with Chaucer and his contemporaries.

Chaucer’s great contemporary, William Langland, in his

Vision of William concerning Piers the Ploughman, and his

imitator the author of Pierce the Ploughman’s Crede (about 1400)

used the Old English alliterative versification for the last time

in the south. Rhyme had made its appearance in the language

shortly after the Conquest—if not already known before; and

in the south and midlands it became decidedly more popular

than alliteration; the latter retained its hold much longer in the

north, where it was written even after 1500: many of the

northern romances are either simply alliterative, or have both

alliteration and rhyme. To these characteristics of northern

and southern verse respectively Chaucer alludes in the prologue

of the “Persone,” who, when called upon for his tale said:—

594

“But trusteth wel; I am a sotherne man,

I cannot geste rom, ram, ruf, by my letter.

And, God wote, rime hold I but litel better:

And therefore, if you list, I wol not glose,

I wol you tell a litel tale in prose.”

|

The changes from Old to Middle English may be summed up

thus: Loss of a large part of the native vocabulary, and

adoption of French words to fill their place; not infrequent

adoption of French words as synonyms of existing native ones;

modernization of the English words preserved, by vowel change

in a definite direction from back to front, and from open to

close, ā, becoming ō,, original ē, ō tending to ee, oo, monophthongization

of the old diphthongs eo, ea, and development of new

diphthongs in connexion with g, h, and w; adoption of French

orthographic symbols, e.g. ou for ū,, qu, v, ch, and gradual loss

of the symbols ɔ, þ, ð, Þ; obscuration of vowels after the accent,

and especially of final a, o, u to ĕ; consequent confusion and loss

of old inflections, and their replacement by prepositions, auxiliary

verbs and rules of position; abandonment of alliteration for

rhyme; and great development of dialects, in consequence of

there being no standard or recognized type of English.

But the recognition came at length. Already in 1258 was

issued the celebrated English proclamation of Henry III., or

rather of Simon de Montfort in his name, which, as the only

public recognition of the native tongue between William the

Conqueror and Edward III., has sometimes been spoken of as

the first specimen of English. It runs:—

“Henri þurȝ godes fultume king on Engleneloande Lhoauerd

on Yrloande. Duk on Normandie on Aquitaine and eorl on Aniow.

Send igretinge to alle hise holde ilærde and ileawede on Huntendoneschire.

þæt witen ȝe wel alle þæt we willen and vnnen þæt þæt vre

rædesmen alle oþer þe moare dæl of heom þæt beoþ ichosen þurȝ us

and þurȝ þæt loandes folk on vre kuneriche. habbeþ idon and schullen

don in þe worþnesse of gode and on vre treowþe. for þe freme of þe

loande. þurȝ þe besiȝte of þan to-foren-iseide redesmen. beo stedefæst

and ilestinde in alle þinge a buten ænde. And we hoaten alle vre

treowe in þe treowþe þæt heo vs oȝen. þæt heo stedefæstliche healden

and swerien to healden and to werien þo isetnesses þæt ben imakede

and beon to makien þurȝ þan to-foren iseide rædesmen. oþer þurȝ

þe moare dæl of heom alswo alse hit is biforen iseid. And þæt æhc

oþer helpe þæt for to done bi þan ilche oþe aȝenes alle men. Riȝt

for to done and to foangen. And noan ne nime of loande ne of eȝte.

wherþurȝ þis besiȝte muȝe beon ilet oþer iwersed on onie wise.’ And

ȝif oni oþer onie cumen her onȝenes; we willen and hoaten þæt alle

vre treowe heom healden deadliche ifoan. And for þæt we willen

þæt þis beo stedefæst and lestinde; we senden ȝew þis writ open

iseined wiþ vre seel. to halden amanges ȝew ine hord. Witnesse vs

seluen æt Lundene. þane Eȝtetenþe day. on þe Monþe of Octobre In

þe Two-and-fowertiȝþe ȝeare of vre cruninge. And þis wes idon

ætforen vre isworene redesmen....

“And al on þo ilche worden is isend in to æurihce oþre shcire ouer

al þære kuneriche on Engleneloande. and ek in tel Irelonde.”

The dialect of this document is more southern than anything

else, with a slight midland admixture. It is much more archaic

inflectionally than the Genesis and Exodus or Ormulum; but it

closely resembles the old Kentish sermons and Proverbs of

Alfred in the southern dialect of 1250. It represents no doubt

the London speech of the day. London being in a Saxon county,

and contiguous to Kent and Surrey, had certainly at first a

southern dialect; but its position as the capital, as well as its

proximity to the midland district, made its dialect more and

more midland. Contemporary London documents show that

Chaucer’s language, which is distinctly more southern than

standard English eventually became, is behind the London

dialect of the day in this respect, and is at once more archaic

and consequently more southern.

During the next hundred years English gained ground steadily,

and by the reign of Edward III. French was so little known in

England, even in the families of the great, that about 1350

“John Cornwal, a maystere of gramere, chaungede þe lore

(= teaching) in gramere scole and construccion of [i.e. from]

Freynsch into Englysch”;23 and in 1362-1363 English by

statute took the place of French in the pleadings in courts of

law. Every reason conspired that this “English” should be

the midland dialect. It was the intermediate dialect, intelligible,

as Trevisa has told us, to both extremes, even when these failed

to be intelligible to each other; in its south-eastern form, it was

the language of London, where the supreme law courts were,

the centre of political and commercial life; it was the language

in which the Wycliffite versions had given the Holy Scriptures

to the people; the language in which Chaucer had raised English

poetry to a height of excellence admired and imitated by contemporaries

and followers. And accordingly after the end of

the 14th century, all Englishmen who thought they had anything

to say to their countrymen generally said it in the midland

speech. Trevisa’s own work was almost the last literary effort

of the southern dialect; henceforth it was but a rustic patois,

which the dramatist might use to give local colouring to his

creations, as Shakespeare uses it to complete Edgar’s peasant

disguise in Lear, or which 19th century research might disinter

to illustrate obscure chapters in the history of language. And

though the northern English proved a little more stubborn, it

disappeared also from literature in England; but in Scotland,

which had now become politically and socially estranged from

England, it continued its course as the national language of the

country, attaining in the 15th and 16th centuries a distinct

development and high literary culture, for the details of which

readers are referred to the article on Scottish Language.

The 15th century of English history, with its bloody French

war abroad and Wars of the Roses at home, was a barren period

in literature, and a transition one in language, witnessing the

decay and disappearance of the final e, and most of the syllabic

inflections of Middle English. Already by 1420, in Chaucer’s

disciple Hoccleve, final e was quite uncertain; in Lydgate it

was practically gone. In 1450 the writings of Pecock against

the Wycliffites show the verbal inflections in -en in a state of

obsolescence; he has still the southern pronouns her and hem

for the northern their, them:—

“And here-aȝens holi scripture wole þat men schulden lacke þe

coueryng which wommen schulden haue, & thei schulden so lacke bi

þat þe heeris of her heedis schulden be schorne, & schulde not growe

in lengþe doun as wommanys heer schulde growe....

“Also here-wiþal into þe open siȝt of ymagis in open chirchis,

alle peple, men & wommen & children mowe come whanne euere þei

wolen in ech tyme of þe day, but so mowe þei not come in-to þe vce of

bokis to be delyuered to hem neiþer to be red bifore hem; & þerfore,

as for to soone & ofte come into remembraunce of a long mater bi

ech oon persoon, and also as forto make þat þe mo persoones come

into remembraunce of a mater, ymagis & picturis serven in a

specialer maner þan bokis doon, þouȝ in an oþer maner ful substanciali

bokis seruen better into remembrauncing of þo same

materis þan ymagis & picturis doon; & þerfore, þouȝ writing is

seruen weel into remembrauncing upon þe bifore seid þingis, ȝit

not at þe ful: Forwhi þe bokis han not þe avail of remembrauncing

now seid whiche ymagis han.”24

The change of the language during the second period of

Transition, as well as the extent of dialectal differences, is

quaintly expressed a generation later by Caxton, who in the

prologue to one of the last of his works, his translation of Virgil’s

Eneydos (1490), speaks of the difficulty he had in pleasing all

readers:—

“I doubted that it sholde not please some gentylmen, whiche late

blamed me, sayeng, yt in my translacyons I had ouer curyous termes,

whiche coud not be vnderstande of comyn peple, and desired me to

vse olde and homely termes in my translacyons. And fayn wolde I

satysfy euery man; and so to doo, toke an olde boke and redde

therein; and certaynly the englysshe was so rude and brood that I

coude not wele vnderstande it. And also my lorde abbot of Westmynster

ded do shewe to me late certayn euydences wryton in olde

englysshe for to reduce it in to our englysshe now vsid. And certaynly

it was wreton in suche wyse that it was more lyke to dutche

than englysshe; I coude not reduce ne brynge it to be vnderstonden.

And certaynly, our langage now vsed varyeth ferre from that whiche

was vsed and spoken whan I was borne. For we englysshemen ben

borne vnder the domynacyon of the mone, whiche is neuer stedfaste,

but euer wauerynge, wexynge one season, and waneth and dycreaseth

another season. And that comyn englysshe that is spoken in one

shyre varyeth from a nother. In so much that in my days happened

that certayn marchauntes were in a shipe in tamyse, for to haue

sayled ouer the sea into zelande, and for lacke of wynde thei taryed

atte forlond, and wente to lande for to refreshe them. And one of

theym named sheffelde, a mercer, cam in to an hows and axed for

mete, and specyally he axyd after eggys, And the goode wyf answerde,

that she coude speke no frenshe. And the marchaunt was angry,

595

for he also coulde speke no frenshe, but wolde haue hadde egges;

and she vnderstode hym not. And thenne at laste a nother sayd

that he wolde haue eyren; then the good wyf sayd that she vnderstod

hym wel. Loo! what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte,

egges or eyren? certaynly, it is harde to playse euery man, by

cause of dyuersite & chaunge of langage. For in these dayes, euery

man that is in ony reputacyon in his countre wyll vtter his comynycacyon

and maters in suche maners & termes that fewe men shall

vnderstonde theym. And som honest and grete clerkes haue ben

wyth me, and desired me to wryte the moste curyous termes that I

coude fynde. And thus bytwene playn, rude and curyous, I stande

abasshed; but in my Iudgemente, the comyn termes that be dayli

vsed ben lyghter to be vnderstonde than the olde and auncyent

englysshe.”

In the productions of Caxton’s press we see the passage from

Middle to Early Modern English completed. The earlier of

these have still an occasional verbal plural in -n, especially in

the word they ben; the southern her and hem of Middle English

vary with the northern and Modern English their, them. In the

late works, the older forms have been practically ousted, and

the year 1485, which witnessed the establishment of the Tudor

dynasty, may be conveniently put as that which closed the

Middle English transition, and introduced Modern English.

Both in the completion of this result, and in its comparative

permanence, the printing press had an important share. By its

exclusive patronage of the midland speech, it raised it still

higher above the sister dialects, and secured its abiding victory.

As books were multiplied and found their way into every corner

of the land, and the art of reading became a more common

acquirement, the man of Northumberland or of Somersetshire

had forced upon his attention the book-English in which alone

these were printed. This became in turn the model for his own

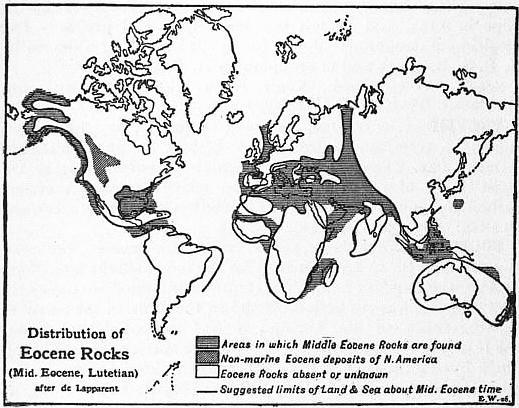

writings, and by-and-by, if he made any pretensions to education,

of his own speech. The written form of the language also tended

to uniformity. In previous periods the scribe made his own

spelling with a primary aim at expressing his own speech, according

to the particular values attached by himself or his contemporaries

to the letters and combinations of the alphabet,

though liable to disturbance in the most common words and

combinations by his ocular recollections of the spelling of others.

But after the introduction of printing, this ocular recognition

of words became ever more and more an aim; the book addressed

the mind directly through the eye, instead of circuitously

through eye and ear; and thus there was a continuous tendency

for written words and parts of words to be reduced to a single

form, and that the most usual, or through some accident the best

known, but not necessarily that which would have been chosen

had the ear been called in as umpire. Modern English spelling,

with its rigid uniformity as to individual results and whimsical

caprice as to principles, is the creation of the printing-office, the

victory which, after a century and a half of struggle, mechanical

convenience won over natural habits. Besides eventually

creating a uniformity in writing, the introduction of printing

made or at least ratified some important changes. The British

and Old English form of the Roman alphabet has already been

referred to. This at the Norman Conquest was superseded by

an alphabet with the French forms and values of the letters.

Thus k took the place of the older c before e and i; qu replaced

cw; the Norman w took the place of the wén (Þ), &c.; and hence

it has often been said that Middle English stands nearer to Old

English in pronunciation, but to Modern English in spelling.

But there were certain sounds in English for which Norman

writing had no provision; and for these, in writing English, the

native characters were retained. Thus the Old English g ( ),

beside the sound in go, had a guttural sound as in German tag,

Irish magh, and in certain positions a palatalized form of this

approaching y as in you (if pronounced with aspiration hyou or

ghyou). These sounds continued to be written with the native

form of the letter as burȝ, ȝour, while the French form was used

for the sounds in go, age,—one original letter being thus represented

by two. So for the sounds of th, especially the sound in

that, the Old English thorn (þ) continued to be used. But as

these characters were not used for French and Latin, their use

even in English became disturbed towards the 15th century,

and when printing was introduced, the founts, cast for continental

languages, had no characters for them, so that they were dropped

entirely, being replaced, ȝ by gh, yh, y, and þ by th. This was a

real loss to the English alphabet. In the north it is curious that

the printers tried to express the forms rather than the powers of

these letters, and consequently ȝ was represented by z, the black

letter form of which was confounded with it, while the þ was

expressed by y, which its MS. form had come to approach or in

some cases simulate. So in early Scotch books we find zellow, ze,

yat, yem = yellow, ye, that, them; and in Modern Scottish, such

names as Menzies, Dalziel, Cockenzie, and the word gaberlunzie,

in which the z stands for y.

),

beside the sound in go, had a guttural sound as in German tag,

Irish magh, and in certain positions a palatalized form of this

approaching y as in you (if pronounced with aspiration hyou or

ghyou). These sounds continued to be written with the native

form of the letter as burȝ, ȝour, while the French form was used

for the sounds in go, age,—one original letter being thus represented

by two. So for the sounds of th, especially the sound in

that, the Old English thorn (þ) continued to be used. But as

these characters were not used for French and Latin, their use

even in English became disturbed towards the 15th century,

and when printing was introduced, the founts, cast for continental

languages, had no characters for them, so that they were dropped

entirely, being replaced, ȝ by gh, yh, y, and þ by th. This was a

real loss to the English alphabet. In the north it is curious that

the printers tried to express the forms rather than the powers of

these letters, and consequently ȝ was represented by z, the black

letter form of which was confounded with it, while the þ was

expressed by y, which its MS. form had come to approach or in

some cases simulate. So in early Scotch books we find zellow, ze,

yat, yem = yellow, ye, that, them; and in Modern Scottish, such

names as Menzies, Dalziel, Cockenzie, and the word gaberlunzie,

in which the z stands for y.

Modern English thus dates from Caxton. The language had

at length reached the all but flectionless state which it now

presents. A single older verbal form, the southern -eth of the

third person singular, continued to be the literary prose form

throughout the 16th century, but the northern form in -s was

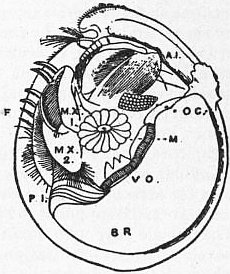

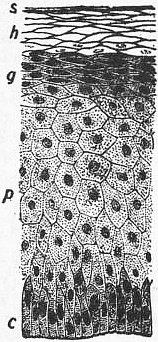

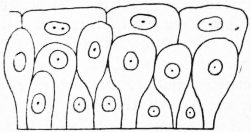

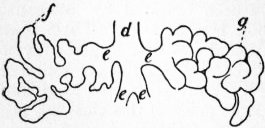

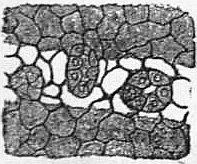

intermixed with it in poetry (where it saved a syllable), and