The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 2, Slice 8, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 2, Slice 8

"Atherstone" to "Austria"

Author: Various

Release Date: November 13, 2010 [EBook #34312]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOLUME 2 SL 8 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

|

Transcriber’s note:

|

One typographical error has been corrected. It

appears in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME II SLICE VIII

Atherstone to Austria

Articles in This Slice

| ATHERSTONE, WILLIAM GUYBON | AUDEBERT, JEAN BAPTISTE |

| ATHERSTONE | AUDEFROI LE BATARD |

| ATHERTON | AUDIENCE |

| ATHETOSIS | AUDIFFRET-PASQUIER, EDMÉ ARMAND GASTON |

| ATHIAS, JOSEPH | AUDIT and AUDITOR |

| ATHLETE | AUDLEY, SIR JAMES |

| ATHLETIC SPORTS | AUDLEY, THOMAS AUDLEY |

| ATHLONE | AUDOUIN, JEAN VICTOR |

| ATHOL | AUDRAN |

| ATHOLL, EARLS AND DUKES OF | AUDRAN, EDMOND |

| ATHOLL | AUDREHEM, ARNOUL D’ |

| ATHOS | AUDUBON, JOHN JAMES |

| ATHY | AUE |

| ATINA | AUERBACH, BERTHOLD |

| ATITLÁN | AUERSPERG, ANTON ALEXANDER |

| ATKINSON, EDWARD | AUFIDENA |

| ATKINSON, SIR HARRY ALBERT | AUGEAS |

| ATLANTA | AUGER |

| ATLANTIC | AUGEREAU, PIERRE FRANÇOIS CHARLES |

| ATLANTIC CITY | AUGHRIM |

| ATLANTIC OCEAN | AUGIER, GUILLAUME VICTOR ÉMILE |

| ATLANTIS | AUGITE |

| ATLAS | AUGMENT |

| ATLAS MOUNTAINS | AUGMENTATION |

| ATMOLYSIS | AUGSBURG |

| ATMOSPHERE | AUGSBURG, CONFESSION OF |

| ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY | AUGSBURG, WAR OF THE LEAGUE OF |

| ATMOSPHERIC RAILWAY | AUGURS |

| ATOLL | AUGUST |

| ATOM | AUGUSTA (Georgia, U.S.A.) |

| ATONEMENT and DAY OF ATONEMENT | AUGUSTA (Maine, U.S.A.) |

| ATRATO | AUGUSTA (Sicily) |

| ATREK | AUGUSTA BAGIENNORUM |

| ATREUS | AUGUSTAN HISTORY |

| ATRI | AUGUSTA PRAETORIA SALASSORUM |

| ATRIUM | AUGUSTI, JOHANN CHRISTIAN WILHELM |

| ATROPHY | AUGUSTINE, SAINT (354-430) |

| ATROPOS | AUGUSTINE, SAINT (archbishop) |

| ATTA, TITUS QUINCTIUS | AUGUSTINIAN CANONS |

| ATTACAPA | AUGUSTINIAN HERMITS |

| ATTACHMENT | AUGUSTINIANS |

| ATTAINDER | AUGUSTOWO |

| ATTAINT, WRIT OF | AUGUSTUS |

| ATTALIA | AUGUSTUS I |

| ATTAR OF ROSES | AUGUSTUS II |

| ATTEMPT | AUGUSTUS III |

| ATTENTION | AUGUSTUSBAD |

| ATTERBOM, PER DANIEL AMADEUS | AUK |

| ATTERBURY, FRANCIS | AULARD, FRANÇOIS VICTOR ALPHONSE |

| ATTESTATION | AULIC COUNCIL |

| ATTHIS | AULIE-ATA |

| ATTIC | AULIS |

| ATTICA | AULNOY, MARIE CATHERINE LE JUMEL DE BARNEVILLE DE LA MOTTE |

| ATTIC BASE | AULOS |

| ATTICUS, TITUS POMPONIUS | AUMALE, HENRI EUGÈNE PHILIPPE LOUIS D’ORLÉANS |

| ATTICUS HERODES, TIBERIUS CLAUDIUS | AUMALE |

| ATTILA | AUMONT |

| ATTIS | AUNCEL |

| ATTLEBOROUGH | AUNDH |

| ATTOCK | AUNGERVYLE, RICHARD |

| ATTORNEY | AUNT SALLY |

| ATTORNEY-GENERAL | AURA |

| ATTORNMENT | AURANGABAD |

| ATTRITION | AURANGZEB |

| ATTWOOD, THOMAS (English composer) | AURAY |

| ATTWOOD, THOMAS (English political reformer) | AURELIA, VIA |

| ATWOOD, GEORGE | AURELIAN |

| AUBADE | AURELIANUS, CAELIUS |

| AUBAGNE | AURELLE DE PALADINES, LOUIS JEAN BAPTISTE D’ |

| AUBE | AUREOLA |

| AUBENAS | AURICH |

| AUBER, DANIEL FRANÇOIS ESPRIT | AURICLE |

| AUBERGINE | AURICULA |

| AUBERVILLIERS | AURIFABER |

| AUBIGNAC, FRANÇOIS HÉDELIN | AURIGA |

| AUBIGNÉ, CONSTANT D’ | AURILLAC |

| AUBIGNÉ, JEAN HENRI MERLE D’ | AURISPA, GIOVANNI |

| AUBIGNÉ, THÉODORE AGRIPPA D’ | AUROCHS |

| AUBIN | AURORA (Roman goddess) |

| AUBREY, JOHN | AURORA (Illinois, U.S.A.) |

| AUBURN (Maine, U.S.A.) | AURORA (Missouri, U.S.A.) |

| AUBURN (New York, U.S.A.) | AURORA (New York, U.S.A.) |

| AUBURN (colour) | AURORA POLARIS |

| AUBUSSON, PIERRE D’ | AURUNCI |

| AUBUSSON | AUSCULTATION |

| AUCH | AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS |

| AUCHMUTY, SIR SAMUEL | AUSSIG |

| AUCHTERARDER | AUSTEN, JANE |

| AUCHTERMUCHTY | AUSTERLITZ |

| AUCKLAND, GEORGE EDEN | AUSTIN, ALFRED |

| AUCKLAND, WILLIAM EDEN | AUSTIN, JOHN |

| AUCKLAND | AUSTIN, SARAH |

| AUCKLAND ISLANDS | AUSTIN, STEPHEN FULLER |

| AUCTION PITCH | AUSTIN (Minnesota, U.S.A.) |

| AUCTIONS and AUCTIONEERS | AUSTIN (Texas, U.S.A.) |

| AUCUBA | AUSTRALASIA |

| AUDAEUS | AUSTRALIA |

| AUDE (river of France) | AUSTRASIA |

| AUDE (department of France) | AUSTRIA |

845

ATHERSTONE, WILLIAM GUYBON (1813-1898), British

geologist, one of the pioneers in South African geology, was

born in 1813, in the district of Uitenhage, Cape Colony. Having

qualified as M.D. he settled in early life as a medical practitioner

at Grahamstown, subsequently becoming F.R.C.S. In 1839

his interest was aroused in geology, and from that date he

“devoted the leisure of a long and successful medical practice”

to the pursuit of geological science. In 1857 he published an

account of the rocks and fossils of Uitenhage (the latter described

more fully by R. Tate, Quart. Journal Geol. Soc., 1867). He also

obtained many fossil reptilia from the Karroo beds, and presented

specimens to the British Museum. These were described

by Sir Richard Owen. Atherstone’s identification in 1867 as a

diamond of a crystal found at De Kalk near the junction of the

Riet and Vaal rivers, led indirectly to the establishment of the

great diamond industry of South Africa. He encouraged the

workings at Jagersfontein, and he also called attention to the

diamantiferous neck at Kimberley. He was one of the founders

of the Geological Society of South Africa at Johannesburg in

1895; and for some years previously he was a member of the

Cape parliament. He died at Grahamstown, on the 26th of

June 1898.

See the obituary by T. Rupert Jones, Natural Science, vol. xiv.

(January 1899).

ATHERSTONE, a market-town in the Nuneaton parliamentary

division of Warwickshire, England, 102½ m. N.W. from London

by the London & North-Western railway. Pop. (1901) 5248.

It lies in the upper valley of the Anker, under well-wooded

hills to the west, and is on the Roman Watling Street, and the

Coventry canal. The once monastic church of St Mary is rebuilt,

excepting the central tower and part of the chancel. The chief

industry is hat-making. On the high ground to the west lie

ruins of the Cistercian abbey of Merevale, founded in 1149;

they include the gatehouse chapel, part of the refectory and

other remains exhibiting beautiful details of the 14th century.

Coal is worked at Baxterley, 3 m. west of Atherstone.

Atherstone (Aderestone, Edridestone, Edrichestone), though not

mentioned in any pre-Conquest record, is of unquestionably ancient

origin. A Saxon barrow was opened near the town in 1824. It is

traversed by Watling Street, and portions of the ancient Roman

road have been discovered in modern times. Atherstone is mentioned

in Domesday among the possessions of Countess Godiva, the

widow of Leofric. In the reign of Henry III. it passed to the monks

of Bec in Normandy, who in 1246 obtained the grant of an annual

fair at the feast of the Nativity of the Virgin, and the next year of

a market every Tuesday. This market became so much frequented

846

that in 1319 a toll was levied upon all goods coming into the town,

in order to defray the cost of the repair to the roads necessitated

by the constant traffic, and in 1332 a similar toll was levied on all

goods passing over the bridge called Feldenbrigge near Atherstone.

The September fair and Tuesday markets are still continued. In

the reign of Edward III. a house of Austin Friars was founded at

Atherstone by Ralph Lord Basset of Drayton, which, however,

never rose to much importance, and at its dissolution in 1536 was

valued at 30 shillings and 3 pence only.

ATHERTON, or Chowbent, an urban district in the Leigh

parliamentary division of Lancashire, England, 13 m. W.N.W.

of Manchester on the London & North-Western and Lancashire

& Yorkshire railways. Pop. (1901) 16,211. The cotton factories

are the principal source of industry; there are also iron-works

and collieries. The manor was held by the local family of

Atherton from John’s reign to 1738, when it passed by marriage

to Robert Gwillym, who assumed that name. In 1797 his

eldest daughter and co-heiress married Thomas Powys, afterwards

the second Lord Lilford. Up to 1891 the lord of the manor

held a court-leet and court-baron annually in November, but

in that year Lord Lilford sold to the local board the market

tolls, stallages and pickages, and since this sale the courts have

lapsed. The earliest manufactures were iron and cotton. Silk-weaving,

formerly an extensive industry, has now almost

entirely decayed. The first chapel or church was built in 1645.

James Wood, who became Nonconformist minister in the chapel

at Atherton in 1691, earned fame and the familiar title of

“General” by raising a force from his congregation, uncouthly

armed, to fight against the troops of the Pretender (1715).

ATHETOSIS (Gr. ἄθετος, “without place”), the medical term

applied to certain slow, purposeless, deliberate movements of

the hands and feet. The fingers are separately flexed and

extended, abducted and adducted in an entirely irregular way.

The hands as a whole are also moved, and the arms, toes and feet

may be affected. The condition is usually due to some lesion of

the brain which has caused hemiplegia, and is especially common

in childhood. It is occasionally congenital (so called), and is

then due to some injury of the brain during birth. It is more

usually associated with hemiplegia, in which condition there is

first of all complete voluntary immobility of the parts affected:

but later, as there is a return of a certain amount of power over

the limbs affected, the slow rhythmic movements of athetosis

are first noticed. This never develops, however, where there is

no recovery of voluntary power. Its distribution is thus nearly

always hemiplegic, and it is often associated with more or less

mental impairment. The movements may or may not continue

during sleep. They cannot be arrested for more than a moment

by will power, and are aggravated by voluntary movements.

The prognosis is unsatisfactory, as the condition usually continues

unchanged for years, though improvement occasionally

occurs in slight cases, or even complete recovery.

ATHIAS, JOSEPH (d. 1700), Jewish rabbi and printer, was

born in Spain and settled in Amsterdam. His editions of the

Hebrew Bible (1661, 1667) are noted for beauty of execution

and the general correctness of the text. He also printed a

Judaeo-German edition of the Bible in 1679, a year after the

appearance of the edition by Uri Phoebus.

ATHLETE (Gr. ἀθλητής; Lat. athleta), in Greek and Roman

antiquities, one who contended for a prize (ἀθλον) in the games;

now a general term for any one excelling in physical strength.

Originally denoting one who took part in musical, equestrian,

gymnastic, or any other competitions, the name became restricted

to the competitors in gymnastic contests, and, later,

to the class of professional athletes. Whereas in earlier times

competitors, who were often persons of good birth and position,

entered the lists for glory, without any idea of material gain,

the professional class, which arose as early as the 5th century

B.C., was chiefly recruited from the lower orders, with whom the

better classes were unwilling to associate, and took up athletics

entirely as a means of livelihood. Ancient philosophers, moralists

and physicians were almost unanimous in condemning the profession

of athletics as injurious not only to the mind but also to

the body. The attack made upon it by Euripides in the fragment

of the Autolycus is well known. The training for the contests

was very rigorous. The matter of diet was of great importance;

this was prescribed by the aleiptes, whose duty it also was to

anoint the athlete’s body. At one time the principal food

consisted of fresh cheese, dried figs and wheaten bread. Afterwards

meat was introduced, generally beef, or pork; but the

bread and meat were taken separately, the former at breakfast,

the latter at dinner. Except in wine, the quantity was unlimited,

and the capacity of some of the heavy-weights must have been,

if such stories as those about Milo are true, enormous. In

addition to the ordinary gymnastic exercises of the palaestra,

the athletes were instructed in carrying heavy loads, lifting

weights, bending iron rods, striking at a suspended leather sack

filled with sand or flour, taming bulls, &c. Boxers had to practise

delving the ground, to strengthen their upper limbs. The competitions

open to athletes were running, leaping, throwing the

discus, wrestling, boxing and the pancratium, or combination

of boxing and wrestling. Victory in this last was the highest

achievement of an athlete, and was reserved only for men of

extraordinary strength. The competitors were naked, having

their bodies salved with oil. Boxers wore the caestus, a strap of

leather round the wrists and forearms, with a piece of metal

in the fist, which was sometimes employed with great barbarity.

An athlete could begin his career as a boy in the contests set

apart for boys. He could appear again as a youth against his

equals, and though always unsuccessful, could go on competing

till the age of thirty-five, when he was debarred, it being assumed

that after this period of life he could not improve. The most

celebrated of the Greek athletes whose names have been handed

down are Milo of Crotona, Hipposthenes, Polydamas, Promachus

and Glaucus. Cyrene, famous in the time of Pindar for its

athletes, appears to have still maintained its reputation to at

least the time of Alexander the Great; for in the British Museum

are to be seen six prize vases carried off from the games at

Athens by natives of that district. These vases, found in the

tombs, probably, of the winners, are made of clay, and painted

on one side with a representation of the contest in which they

were won, and on the other side with a figure of Pallas Athena,

with an inscription telling where they were gained, and in some

cases adding the name of the eponymous magistrate of Athens,

from which the exact year can be determined.

Amongst the Romans athletic contests had no doubt taken

place from the earliest times, but according to Livy (xxxix. 22)

professional Greek athletes were first introduced at Rome by

M. Fulvius Nobilior in 186 B.C. After the institution of the

Actian games by Augustus, their popularity increased, until

they finally supplanted the gladiators. In the time of the

empire, gilds or unions of athletes were formed, each with a

temple, treasury and exercise-ground of its own. The profession,

although it ranked above that of a gladiator or an actor, was

looked upon as derogatory to the dignity of a Roman, and it is

a rare thing to find a Roman name amongst the athletes on inscriptions.

The system was entirely, and the athletes themselves

nearly always, Greek. (See also Games, Classical.)

Krause, Gymnastik und Agonistik der Hellenen (1841); Friedländer,

Sittengeschichte Roms, ii.; Reisch, in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyc.

ATHLETIC SPORTS. Various sports were cultivated many

hundred years before the Christian era by the Egyptians and

several Asiatic races, from whom the early Greeks undoubtedly

adopted the elements of their athletic exercises (see Athlete),

which reached their highest development in the Olympic games,

and other periodical meetings of the kind (see Games, Classical).

The original Celtic inhabitants of Great Britain were an athletic

race, and the earliest monuments of Teutonic literature abound

in records of athletic prowess. After the Norman conquest of

England the nobles devoted themselves to the chase and to the

joust, while the people had their games of ball, running at the

quintain, fencing with club and buckler, wrestling and other

pastimes on green and river. The chroniclers of the succeeding

centuries are for the most part silent concerning the sports of

the folk, except such as were regarded as a training for war, as

archery, while they love to record the prowess of the kings and

847

their courts. Thus it is told of Henry V. that he “was so swift

a runner that he and two of his lords, without bow or other engine,

would take a wild buck in a large park.” Several romances of

the middle ages, quoted by Strutt (Sports and Pastimes of the

People of England), chronicle the fact that young men of good

family were taught to run, leap, wrestle and joust. In spite of

the general silence of the historians concerning the sports of the

people, it is evident that they were indulged in very largely,

since several English sovereigns found it necessary to curtail,

and even prohibit, certain popular pastimes, on the ground that

they seduced the people from the practice of archery. Thus

Edward III. prohibited weight-putting by statute. Nevertheless

a variety of this exercise, “casting of the barre,” continued to

be a popular pastime, and was afterwards one of the favourite

sports of Henry VIII., who attained great proficiency at it.

The prowess of the same monarch at throwing the hammer is a

matter of history, and his reign seems to have been at a time of

general athletic revival. We even find his secretary, Richard

Pace, advising the sons of noblemen to practise their sports and

“leave study and learning to the children of meaner people,”

and Sir William Forest, in his Poesye of Princeelye Practice, thus

admonishes his high-born readers:—

“In featis of maistries bestowe some diligence.

Too ryde, runne, lepe, or caste by violence

Stone, barre or plummett, or such other thinge,

It not refuseth any prince or kynge.”

|

Mr Montague Shearman, to whose volume on Athletics in the

Badminton series the reader is referred, notes that Sir Thomas

Elyot, who wrote at about the same period, deprecated too much

study and flogging for schoolboys, saying: “A discrete master

may with as much or more ease both to himself and his scholler

lead him to play at tennis or shoote.” Elyot recommends the

perusal of Galen’s De sanitate tuenda, and suggests as suitable

athletic exercises within doors “deambulations, labouryng with

poyses made of ledde, lifting and throwing the heavy stone or

barre, playing at tennis,” and dwells upon “rennyng” as a

“good exercise and laudable solace.” It is probable that the

disciples of the “new learning,” who had become prominent

in Sir Thomas’s time, endeavoured to combat the influence of

athletic exercises, their point of view being exemplified by the

dictum of Roger Ascham, who, in his Toxophilus, declares that

“running, leaping and quoiting be too vile for scholars.”

In the 16th century the great football match played annually

at Chester was abolished in favour of a series of foot-races, which

took place in the presence of the mayor. A list of the common

sports of that time is contained in some verses by Randel Holme,

a minstrel of the North country, and makes mention of throwing

the sledge, jumping, “wrastling,” stool-ball (cricket), running,

pitching the bar, shooting, playing loggets, “nine holes or ten

pins,” “football by the shinnes,” leap-frog, morris, shove-groat,

leaping the bonfire, stow-ball (golf), and many other outdoor

and indoor sports, some of them now obsolete. Shakespeare and

the other Elizabethan poets abound in allusions to sport, which

formed an important feature in school life and at every fair.

The Stuart kings were warm encouragers of sport, the Basilikon

Doron of James I., written for his son, containing a

recommendation to the young prince to practise “running, leaping,

wrestling, fencing, dancing, and playing at the caitch, or tennise,

archerie, palle-malle, and such like other fair and pleasant field

games.”

An extraordinary variety of sports has been popular in Great

Britain with high and low for the past five centuries, no other

country comparing with it in this respect. Nor have Ireland

and Scotland lagged behind England in athletic prowess. Indeed,

so far as history and legend record, Ireland boasts of by far the

most ancient organized sports known, the Tailtin Games, or

Lugnasad, traditionally established by Lugaid of the Long Arm,

one of the gods of Dia and Ana, in honour of his foster-mother

Tailti, some three thousand years ago. For many centuries these

games, and others like them, were kept up in Ireland, and though

the almost constant wars which harried the country finally

destroyed their organization, yet the Irish have always been,

and still are, a very important factor in British athletics, as well

as in America and the colonies.

The Scottish people have, like the Irish, ever delighted in feats

of strength and skill, especially the Celtic highlanders, the

character of whose country and mode of life have, however,

prevented organized athletics from attaining the same prominence

as in England. Nevertheless, the celebrated Highland games

held at Braemar, Bridge of Allan, Luss, Aboyne and other places

have served to bring into prominence many athletes of the first

class, although the records, on account of the roughness of the

grounds, have not generally vied with those made farther south.

The Briton does not lose his love of sport upon leaving his

native soil, and the development of athletics in the United

States and the British colonies has kept step with that of the

mother-land. Upon the continent of Europe sports have

occupied a more or less prominent place in the life of the nations,

but their development has been but an echo of that in Great

Britain. A great advance, however, has been made since the

institution of the modern Olympic games.

About the year 1812 the Royal Military College at Sandhurst

inaugurated regular athletic sports, but the example was not

followed until about 1840, when Rugby, Eton, Harrow, Shrewsbury

and the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich came to

the front, the “Crick Run” at Rugby having been started in

1837. At the two great English universities there were no

organized sports of any kind until 1850, when Exeter College,

Oxford, held a meeting; this example has been followed, one

after the other, by the other colleges of both institutions. The

first contest between Oxford and Cambridge occurred at Oxford

in 1864, the programme consisting of eight events, of which four

were won by each side. The same year saw the first contest of

the Civil Servants, still an annual event.

In 1866 the Amateur Athletic Club was formed in London for

“gentlemen amateurs,” most of its members being old university

men. Its first championship meeting, held in that year, was the

beginning of a series afterwards continued to the present day by

the Amateur Athletic Association, founded in 1880, which has

jurisdiction over British athletic sports. The most important

individual English athletic organization is the London Athletic

Club, which antedated the Amateur Athletic Club, and whose

meetings have always been the most important events except

the championships.

In America a revival of interest in athletic sports took place

about the year 1870. Ten years later was formed the National

Association of Amateur Athletes of America, which, in 1888,

became the Amateur Athletic Union. This body controls

athletics throughout the United States, and is allied with the

Canadian Amateur Athletic Association. It is supreme in

matters of amateur status, records and licensing of meetings,

and has control over the following branches of sport: basket-ball,

billiards, boxing, fencing (in connexion with the Amateur

Fencers’ League of America), gymnastics, hand-ball (fives),

running, jumping, walking, weight-putting (hammer, shot,

discus, weights), hurdle-racing, lacrosse, pole-vaulting, swimming,

tugs-of-war and wrestling. The Amateur Athletic Union has

eight sectional groups, and is allied with the Intercollegiate

Association of Amateur Athletes of America (founded 1876) and

the Western Intercollegiate Association. The first American

intercollegiate athletic meeting took place at Saratoga in 1873,

only three universities competing, though the next year there

were eight and in 1875 thirteen. Professional athletes in America

are confined almost entirely to base-ball, boxing, bicycling,

wrestling and physical training.

The Canadian athletic championships are held independently

of the American. Annual championship meetings are also held

in South Africa, New Zealand and the different states of Australia.

For the Australasian championships New Zealand joins with

Australia.

The organization of university sports in America differs from

that at Oxford and Cambridge, where there is no official control

on the part of the university authorities, and where a man is

eligible to represent his college or university while in residence.

848

In nearly all American universities and colleges athletic and other

sports are under the general control of faculty committees, to

which the undergraduate athletic committees are subordinate,

and which have the power to forbid the participation of any

student who has not attained a certain standard of scholarship.

For some years prior to 1906 no student of an American university

was allowed to represent his university in any sport for longer

than four years. Early in that year, however, many of the

most important institutions, including Harvard, Yale, Princeton

and Pennsylvania, entered upon a new agreement, that only

students who have been in residence one year should play in

’varsity teams in any branch of athletics and that no student

should play longer than three years. This, together with many

other reformatory changes, was directly due to a widespread

outcry against the growing roughness of play exhibited in

American football, basket-ball, hockey and other sports, the too

evident desire to win at all hazards, the extraordinary luxury of

the training equipment, and the enormous gate-receipts of many

of the large institutions—the Yale Athletic Association held a

surplus of about $100,000 (£20,000) in December 1905, after

deducting immense amounts for expenses. The new rule against

the participation of freshmen in ’varsity sports was to discourage

the practice of offering material advantages of different kinds to

promising athletes, generally those at preparatory schools, to

induce them to become students at certain universities.

At the present day athletic sports are usually understood to

consist of those events recognized in the championship programmes

of the different countries. Those in the competitions

between Oxford and Cambridge are the 100 yards, 440 yards,

880 yards, 1-mile and 3-mile runs; 120 yards hurdle-race;

high and long jumps; throwing the hammer; and putting the

weight (shot). To the above list the English A.A.A. adds the

4-mile and 10-mile runs; the 2-mile and 7-mile walking races;

the 2-mile steeplechase; and the pole-vault. The American

intercollegiate programme is identical with that of the Oxford-Cambridge

meeting, except that a 2-mile run takes the place of

the 3-mile, and the pole-vault is added. The American A.A.U.

programme includes the 100 yards, 220 yards, 440 yards, 880

yards, 1-mile and 5-mile runs; 120 yards high-hurdle race;

220 yards low-hurdle race; high and broad (long) jumps; throwing

the hammer; throwing 56-℔ weight; putting 16-℔ shot;

throwing the discus; and pole-vault. Of these the running

contests are called “track athletics,” and the rest “field”

events.

International athletic contests of any importance have, with

the exception of the modern Olympic games, invariably taken

place between Britons, Americans and Canadians, the continental

European countries having as yet produced few track or

field athletes of the first class, although the interest in sports

in general has greatly increased in Europe during the last ten

years. In 1844 George Seward, an American professional runner,

visited England and competed with success against the best

athletes there; and in 1863 Louis Bennett, called “Deerfoot,” a

full-blooded Seneca Indian, repeated Seward’s triumphs, establishing

running records up to 12 miles. In 1878 the Canadian,

C.C. McIvor, champion sprinter of America, went to England,

but failed to beat his British professional rivals. In 1881

L.E. Myers of New York and E.E. Merrill of Boston competed

successfully in England, Myers winning every short-distance

championship except the 100-yards, and Merrill all the walking

championships save the 7-miles. The same year W.C. Davies

of England won the 5-mile championship of America, but, like

several other British runners who have had success in America,

he competed under the colours of an American club. In 1882 the

famous English runner, W.G. George, ran against Myers in

America in races of 1 mile, ¾ mile and ½ mile, winning over the

first two distances. In 1884 Myers again went to England and

made new British records over 500, 600, 800 and 1000 yards,

and world’s records over ½ mile and 1200 yards. The next year

he won both the British ¼-mile and ½-mile championships. The

same year a team of Irish athletes, among them W.J.M. Barry,

won several Canadian championships. In 1888 a team of the

Manhattan Athletic Club, New York, competed in England with

fair success, and during the same season an Irish team from

the Gaelic Athletic Association visited America without much

success. In 1890 a team from the Salford Harriers was invited to

America by the Manhattan Athletic Club, but the evidently

commercial character of the enterprise caused its failure. One

of the Harriers, E.W. Parry, won the American steeplechase

championship. The next year saw another visit to Europe

of the Manhattan athletes, who had fair success in England and

won every event at Paris. In 1895 the London Athletic Club

team competed in New York against the New York Athletic

Club, but lost every one of the eleven events, several new records

being established. During the previous summer (1894) occurred

the first of the international matches between British and

American universities which still retain their place as the most

interesting athletic event. In that contest, which took place at

Queen’s Club, London, Oxford beat Yale by 5½ to 3½ events.

The next summer Cambridge, as the champion English university,

visited America and was beaten by Yale (3 to 8). In 1899 both

British universities competed at Queen’s Club against the combined

athletes of Harvard and Yale, who were beaten by the odd

event. The return match took place between the same universities

at New York in the summer of 1901, the Americans

winning 6 to 3 events. In 1904 Harvard and Yale beat Oxford

and Cambridge at Queen’s Club by the same score.

Outside Great Britain and America the most important

athletic events are undoubtedly the revived Olympic games.

They were instituted by delegates from the different nations who

met in Paris on the 16th of June 1894, principally at the instigation

of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the result being the formation

of an International Olympic Games Committee with Baron de

Coubertin at its head, which resolved that games should be held

every fourth year in a different country. The first modern

Olympiad took place at Athens, 6th to 12th April 1896, in the

ancient stadium, which was rebuilt through the liberality of a

Greek merchant and seated about 45,000 people. The programme

of events included the usual field and track sports, gymnastics,

wrestling, pole-climbing, lawn tennis, fencing, rifle and revolver

shooting, weight-lifting, swimming, the Marathon race and

bicycle racing. Among the contestants were representatives of

nearly every European nation, besides Americans and Australians.

Great Britain took little direct interest in the occasion and was

inadequately represented, but the United States sent five men

from Boston and four from Princeton University, who, though

none of them held American championships, succeeded in

winning every event for which they were entered. The Marathon

race of 42 kilometres (26 miles), commemorative of the famous

run of the Greek messenger to Athens with the news of the

victory of Marathon, was won by a Greek peasant. The second

Olympiad was held in Paris in June 1900. Again Great Britain

was poorly represented, but American athletes won eighteen

of the twenty-four championship events. The third Olympiad

was held at St Louis in the summer of 1904 in connexion with

the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, its success being due in

great measure to James E. Sullivan, the physical director of the

Exposition, and Caspar Whitney, the president of the American

Olympic Games Committee. The games were much more

numerous than at the previous Olympiads, including sports of

all kinds, handicaps, inter-club competitions, and contests for

aborigines. In the track and field competitions the American

athletes won every championship except weight-throwing

(56 ℔) and lifting the bar. The sports of the savages, among

whom were American Indians, Africans of several tribes, Moros,

Patagonians, Syrians, Ainus and Filipinos, were disappointing;

their efforts in throwing the javelin, shooting with bow and

arrow, weight-lifting, running and jumping, proving to be

feeble compared with those of white races. The Americanized

Indians made the best showing.

The Greeks, however, were not altogether satisfied with the

cosmopolitan character of the revival of these celebrated games

of their ancestors, and resolved to give the revival a more

definitely Hellenic stamp by intercalating an additional series,

849

to take place at Athens, in the middle of the quadrennial period.

Their action was justified by the success which attended the

first of this additional series at Athens in 1906. This success

may have been partly due to the personal interest taken in the

games by the king and royal family of Greece, and to the presence

of King Edward VII., Queen Alexandra, and the prince and

princess of Wales; but to whatever cause it should be assigned

it was generally acknowledged that neither in France nor in

America had the games acquired the same prestige as those

held on the classical soil of Greece. In 1906 the governments

of Germany, France and the United States made considerable

grants of money to defray the expenses of the competitors

from those countries. These games aroused much more interest

in England than the earlier ones in the series, but though upwards

of fifty British competitors took part in the contests, they were

by no means representative in all cases of the best British

athletics. The American representatives were slightly less

numerous, but they were more successful. It was noteworthy

that no British or Americans took part in the rowing races in the

Bay of Phalerum, nor in the tennis, football or shooting competitions.

The Marathon race, by far the most important

event in the games, was won in 1906 by a British athlete,

M.D. Sherring, a Canadian by birth. The Americans won a total

of 75 prizes, the British 39, and the Swedes and Greeks each 28.

The games of the 4th Olympiad (1908) were held in London

in connexion with the Franco-British Exhibition of that year.

An immense sensation was caused by the finish for the Marathon

race from Windsor Castle to the stadium in the Exhibition

grounds in London. The first competitor to arrive was the

Italian, Dorando Pietri, whose condition of physical collapse

was such that, appearing to be on the point of death, he had to

be assisted over the last few yards of the course. He was therefore

disqualified, and J. Hayes, an American, was adjudged the

winner; a special prize was presented to the Italian by Queen

Alexandra. In the whole series of contests the United Kingdom

made 38 wins, the Americans 22, and the Swedes 7. In the

Olympic games proper, British athletes, including two wins by

colonials from Canada and Africa, scored 25 successes, and the

Americans 18. In the track events 8 wins fell to the British,

including two Colonials, and 6 to American athletes; but the

latter gained complete supremacy in the field events, of which

they won 9, while British competitors secured only two of minor

importance.

For records, &c., see the annual Sporting and Athletic Register; for

the Olympic games see Theodore Andrea Cook’s volume, published

in connexion with the Olympiad of 1908.

ATHLONE, a market-town of Co. Westmeath, Ireland, on

both banks of the Shannon. Pop. of urban district (1901)

6617. The urban district, under the Local Government (Ireland)

Act 1900, is wholly in county Westmeath, but the same area is

divided by the Shannon between the parliamentary divisions of

South Westmeath and South Roscommon. Athlone is 78 m.

W. from Dublin by the Midland Great Western railway, and

is also served by a branch from Portarlington of the Great

Southern & Western line, providing an alternative and somewhat

longer route from the capital. The main line of the

former company continues W. to Galway, and a branch

N.W. serves counties Roscommon and Mayo. The Shannon

divides the town into two portions, known as the Leinster side

(east), and the Connaught side (west), which are connected by a

handsome bridge opened in 1844. There is a swivel railway

bridge. The rapids of the Shannon at this point are obviated

by means of a lock communication with a basin, which renders

the navigation of the river practicable above the town. The

steamers of the Shannon Development Company ply on the

river, and some trade by water is carried on with Limerick,

and with Dublin by the river and the Grand and Royal canals.

Athlone is an important agricultural centre, and there are

woollen factories. The salmon fishing both provides sport and

is a source of commercial wealth. There are two parish churches,

St Mary and St Peter, both erected early in the 19th century,

of which the first has near it an isolated church tower of earlier

date. There are three Roman Catholic chapels, a court-house

and other public offices. Early remains include portions of the

castle, of the town walls (1576), of the abbey of St Peter and of a

Franciscan foundation. On several islands of the picturesque

Lough Ree, to the north, are ecclesiastical and other remains.

The military importance of Athlone dates from the erection

of the castle and of a bridge over the river by John de Grey,

bishop of Norwich and justiciar of Ireland, in 1210. It became

the seat of the presidency of Connaught under Elizabeth, and

withstood a siege by the insurgents in 1641. In the war of

1688 the possession of Athlone was considered of the greatest

importance, and it consequently sustained two sieges, the first

by William III. in person, which failed, and the second by

General Godart van Ginkel (q.v.), who, on the 30th of June

1691, in the face of the Irish, forded the river and took possession

of the town, with the loss of only fifty men. Ginkel was subsequently

created earl of Athlone, and his descendants held the

title till it became extinct in 1844. In 1797 the town was

strongly fortified on the Roscommon side, the works covering

15 acres and containing two magazines, an ordnance store, an

armoury with 15,000 stands of arms and barracks for 1500 men.

The works are now dismantled. Athlone was incorporated by

James I., and returned two members to the Irish parliament,

and one member to the imperial parliament till 1885.

ATHOL, a township of Worcester county, northern Massachusetts,

U.S.A., having an area of 35 sq. m. Pop. (1900) 7061,

of whom 986 were foreign-born; (1910 U.S. census) 8536.

Its surface is irregular and hilly. The village of Athol is on

Miller’s river, and is served by the Boston & Albany and the

Boston & Maine railways. The streams of the township furnish

good water-power, and manufactures of varied character are

its leading interests. Athol was first settled in 1735, and was

incorporated as a township in 1762. It was named by its

largest landowner Col. James Murray, after the ancestral home

of the Murrays, dukes of Atholl.

See L.B. Caswell, Athol, Mass., Past and Present (Athol, 1899).

ATHOLL, EARLS AND DUKES OF. The Stewart line of the

Scottish earls of Atholl, which ended with the 5th Stewart earl

in 1595, the earldom reverting to the crown, had originated

with Sir John Stewart of Balveny (d. 1512), who was created

earl of Atholl about 1457 (new charter 1481). The 5th earl’s

daughter, Dorothea, married William Murray, earl of Tullibardine

(cr. 1606), who in 1626 resigned his earldom in favour

of Sir Patrick Murray, on condition of the revival of the earldom

of Atholl in his wife and her descendants. The earldom thus

passed to the Murray line, and John Murray, their only son

(d. 1642), was accordingly acknowledged as earl of Atholl (the

1st of the Murrays) in 1629.

John Stewart, 4th earl of Atholl, in the Stewart line (d. 1579),

son of John, 3rd earl, and of Grizel, daughter of Sir John Rattray,

succeeded his father in 1542. He supported the government

of the queen dowager, and in 1560 was one of the three nobles

who voted in parliament against the Reformation and the

Confession of Faith, and declared their adherence to Roman

Catholicism. Subsequently, however, he joined the league

against Huntly, whom with Murray and Morton he defeated

at Corrichie in October 1562, and he supported the projected

marriage of Elizabeth with Arran. On the arrival of Mary from

France in 1561 he was appointed one of the twelve privy councillors,

and on account of his religion obtained a greater share

of the queen’s favour than either Murray or Maitland. He was

one of the principal supporters of the marriage with Darnley,

became the leader of the Roman Catholic nobles, and with

Lennox obtained the chief power in the government, successfully

protecting Mary and Darnley from Murray’s attempts to regain

his ascendancy by force of arms. According to Knox he openly

attended mass in the queen’s chapel, and was especially trusted

by Mary in her project of reinstating Roman Catholicism. The

fortress of Tantallon was placed in his keeping, and in 1565 he

was made lieutenant of the north of Scotland. He is described

the same year by the French ambassador as “très grand catholique

hardi et vaillant et remuant, comme l’on dict, mais de nul

850

jugement et expérience.” He had no share in the murders of

Rizzio or Darnley, and after the latter crime in 1567, he joined

the Protestant lords against Mary, appeared as one of the leaders

against her at Carberry Hill, and afterwards approved of her

imprisonment at Lochleven Castle. In July he was present at the

coronation of James, and was included in the council of regency

on Mary’s abdication. He, however, was not present at Langside

in May 1568, and in July became once more a supporter of Mary,

voting for her divorce from Bothwell (1569). In March 1570 he

signed with other lords the joint letter to Elizabeth asking for

the queen’s intercession and supporting Mary’s claims, and was

present at the convention held at Linlithgow in April in opposition

to the assembly of the king’s party at Edinburgh. In 1574

he was proceeded against as a Roman Catholic and threatened

with excommunication, subsequently holding a conference with

the ministers and being allowed till midsummer to overcome

his scruples. He had failed in 1572 to prevent Morton’s appointment

to the regency, but in 1578 he succeeded with the earl of

Argyll in driving him from office. On the 24th of March James

took the government into his own hands and dissolved the

regency, and Atholl and Argyll, to the exclusion of Morton,

were made members of the council, while on the 29th Atholl

was appointed lord chancellor. Subsequently, on the 24th of

May, Morton succeeded in getting into Stirling Castle and in

regaining his guardianship of James. Atholl and Argyll, who

were now corresponding with Spain in hopes of assistance from

that quarter, then advanced to Stirling with a force of 7000 men,

when a compromise was arranged, the three earls being all

included in the government. While on his way from a banquet

held on the 20th of April 1579 on the occasion of the reconciliation,

Atholl was seized with sudden illness, and died on the 25th,

not without strong suspicions of poison. He was buried at St.

Giles’s cathedral in Edinburgh. He married (1) Elizabeth,

daughter of George Gordon, 4th earl of Huntly, by whom he had

two daughters, and (2) Margaret, daughter of Malcolm Fleming,

3rd Lord Fleming, by whom, besides three daughters, he had

John, 5th earl of Atholl, at whose death in 1595 the earldom

in default of male heirs reverted to the crown.

John Murray, 1st earl of Atholl in the Murray line (see above),

died in 1642. On the outbreak of the civil war he called out the

men of Atholl for the king, and was imprisoned by the marquess

of Argyll in Stirling Castle in 1640.

John Murray, 2nd earl and 1st marquess of Atholl (1631-1703),

son of the 1st earl and of Jean, daughter of Sir Duncan Campbell

of Glenorchy, was born on the 2nd of May 1631. In 1650 he

joined in the unsuccessful attempt to liberate Charles II. from

the Covenanters, and in 1653 was the chief supporter of Glencairn’s

rising, but was obliged to surrender with his two regiments

to Monk on the 2nd of September 1654. At the restoration

Atholl was made a privy councillor for Scotland and sheriff of

Fife, in 1661 lord justice-general of Scotland, in 1667 a commissioner

for keeping the peace in the western Highlands, in 1670

colonel of the king’s horseguards, in 1671 a commissioner of the

exchequer, and in 1672 keeper of the privy seal in Scotland and

an extraordinary lord of session. In 1670 he became earl of

Tullibardine by the death of his cousin James, 4th earl, and on

the 7th of February 1676 he was created marquess of Atholl,

earl of Tullibardine, viscount of Balquhidder, Lord Murray,

Balvenie and Cask. He at first zealously supported Lauderdale’s

tyrannical policy, but after the raid of 1678, called the “Highland

Host,” in which Atholl was one of the chief leaders, he joined

in the remonstrance to the king concerning the severities inflicted

upon the Covenanters, and was deprived of his office of justice-general

and passed over for the chancellorship in 1681. In 1679,

however, he was present at the battle of Bothwell Brig; in July

1680 he was made vice-admiral of Scotland, and in 1681 president

of parliament. In 1684 he was appointed lord-lieutenant of

Argyll, and invaded the country, capturing the earl of Argyll

after his return from abroad in June 1685 at Inchinnan. The

excessive severities with which he was charged in this campaign

were repudiated with some success by him after the Revolution.1

The same year he was reappointed lord privy seal, and in 1687

was made a knight of the Thistle on the revival of the order.

At the Revolution he wavered from one side to the other, showing

no settled purpose but waiting upon the event, but finally in

April 1689 wrote to William to declare his allegiance, and in May

took part in the proclamation of William and Mary as king and

queen at Edinburgh. But on the occasion of Dundee’s insurrection

he retired to Bath to drink the waters, while the bulk of his

followers joined Dundee and brought about in great measure

the defeat of the government troops at Killiecrankie. He was

then summoned from Bath to London and imprisoned during

August. In 1690 he was implicated in the Montgomery plot and

subsequently in further Jacobite intrigues. In June 1691 he

received a pardon, and acted later for the government in the

pacification of the Highlands. He died on the 6th of May 1703.

He married Amelia, daughter of James Stanley, 7th earl of Derby

(through whom the later dukes of Atholl acquired the sovereignty

of the Isle of Man), and had, besides one daughter, six

sons, of whom John became 2nd marquess and 1st duke of Atholl;

Charles was made 1st earl of Dunmore, and William married

Margaret, daughter of Sir Robert Nairne, 1st Lord Nairne,

becoming in her right 2nd Lord Nairne.

John Murray, 2nd marquess and 1st duke of Atholl (1660-1724),

was born on the 24th of February 1660, and was styled during

his father’s lifetime Lord Murray, till 1696, when he was created

earl of Tullibardine. He was a supporter of William and the

Revolution in 1688, taking the oaths in September 1689, but was

unable to prevent the majority of his clan, during his father’s

absence, from joining Dundee under the command of his brother

James. In 1693 as one of the commissioners he showed great

energy in the examination into the massacre of Glencoe and in

bringing the crime home to its authors. In 1694 he obtained a

regiment, in 1695 was made sheriff of Perth, in 1696 secretary

of state, and from 1696 to 1698 was high commissioner. In the

latter year, however, he threw up office and went into opposition.

At the accession of Anne he was made a privy councillor, and in

1703 lord privy seal for Scotland. The same year he succeeded

his father as 2nd marquess of Atholl, and on the 30th of June he

was created duke of Atholl, marquess of Tullibardine, earl of

Strathtay and Strathardle, Viscount Balquhidder, Glenalmond

and Glenlyon, and Lord Murray, Balvenie and Gask. In 1704

he was made a knight of the Thistle. In 1703-1704 an unsuccessful

attempt was made by Simon, Lord Lovat, who used the duke

of Queensberry as a tool, to implicate him in a Jacobite plot

against Queen Anne; but the intrigue was disclosed by Robert

Ferguson, and Atholl sent a memorial to the queen on the

subject, which resulted in Queensberry’s downfall. But he fell

nevertheless into suspicion, and was deprived of office in October

1705, subsequently becoming a strong antagonist of the government,

and of the Hanoverian succession. He vehemently opposed

the Union during the years 1705-1707, and entered into a project

for resisting by force and for holding Stirling Castle with the aid

of the Cameronians, but nevertheless did not refuse a compensation

of £1000. According to Lockhart, he could raise 6000 of

the best men in the kingdom for the Jacobites. On the occasion,

however, of the invasion of 1708 he took no part, on the score of

illness, and was placed under arrest at Blair Castle. On the

downfall of the Whigs and the advent of the Tories to power,

Atholl returned to office, was chosen a representative peer in

the Lords in 1710 and 1713, in 1712 was an extraordinary lord

of session, from 1713 to 1714 was once more keeper of the privy

seal, and from 1712 to 1714 was high commissioner. On the

accession of George I. he was again dismissed from office, but at

the rebellion of 1715, while three of his sons joined the Jacobites,

he remained faithful to the government, whom he assisted in

various ways, on the 4th of June 1717 apprehending Robert

Macgregor (Rob Roy), who, however, succeeded in escaping.

He died on the 14th of November 1724. He married (1)

Catherine, daughter of William Douglas, 3rd duke of Hamilton,

by whom, besides one daughter, he had six sons, of whom John

was killed at Malplaquet in 1709, William was marquess of

Tullibardine, and James succeeded his father as 2nd duke on

851

account of the share taken by his elder brother in the rebellion;

and (2) Mary, daughter of William, Lord Ross, by whom he had

three sons and several daughters.

The Atholl Chronicles have been privately printed by the 7th duke

of Atholl (b. 1840). See also S. Cowan, Three Celtic Earldoms (1909).

1 A. Lang, Hist. of Scotland, iii. 407.

ATHOLL, or Athole, a district in the north of Perthshire,

Scotland, covering an area of about 450 sq. m. It is bounded

on the N. by Badenoch, on the N.E. by Braemar, on the E. by

Forfarshire, on the S. by Breadalbane, on the W. and N.W.

by Lochaber. The Highland railway bisects it diagonally from

Dunkeld to the borders of Inverness-shire. It is traversed by

the Grampian mountains and watered by the Tay, Tummel,

Garry, Tilt, Bruar and other streams. Glen Garry and Glen

Tilt are the chief glens, and Loch Rannoch and Loch Tummel

the principal lakes. The population mainly centres around

Dunkeld, Pitlochry and Blair Atholl. The only cultivable soil

occurs in the valleys of the large rivers, but the deer-forest and

the shootings on moor and mountain are among the most

extensive in Scotland. It is said to have been named Athfotla

(Atholl) after Fotla, son of the Pictish king Cruithne, and was

under the rule of a Celtic mormaer (thane or earl) until the

union of the Picts and Scots under Kenneth Macalpine in 843.

The duke of Atholl’s seats are Blair Castle and Dunkeld House.

What is called Atholl brose is a compound, in equal parts, of

whisky and honey (or oatmeal), which was first commonly used

in the district for hoarseness and sore throat.

ATHOS (Gr. Ἄγιον Ὄρος; Turk. Aineros; Ital. Monte Santo),

the most eastern of the three peninsular promontories which

extend, like the prongs of a trident, southwards from the

coast of Macedonia (European Turkey) into the Aegean Sea.

Before the 19th century the name Athos was usually confined

to the terminal peak of the promontory, which was itself known

by its ancient name, Acte. The peak rises like a pyramid, with

a steep summit of white marble, to a height of 6350 ft., and can

be seen at sunset from the plain of Troy on the east, and the

slopes of Olympus on the west. On the isthmus are distinct

traces of the canal cut by Xerxes before his invasion of Greece

in 480 B.C. The peninsula is remarkable for the beauty of its

scenery, and derives a peculiar interest from its unique group of

monastic communities with their medieval customs and institutions,

their treasures of Byzantine art and rich collections of

documents. It is about 40 m. in length, with a breadth varying

from 4 to 7 m.; its whole area belongs to the various monasteries.

It was inhabited in the earliest times by a mixed Greek and

Thracian population; of its five cities mentioned by Herodotus

few traces remain; some inscriptions discovered on the sites

were published by W.M. Leake (Travels in N. Greece, 1835,

iii. 140) and Kinch. The legends of the monks attribute the

first religious settlements to the age of Constantine (274-337),

but the hermitages are first mentioned in historical documents

of the 9th century. It is conjectured that the mountain was at

an earlier period the abode of anchorites, whose numbers were

increased by fugitives from the iconoclastic persecutions (726-842).

The “coenobian” rule to which many of the monasteries

still adhere was established by St Athanasius, the founder of the

great monastery of Laura, in 969. Under a constitution approved

by the emperor Constantine Monomachos in 1045, women and

female animals were excluded from the holy mountain. In

1060 the community was withdrawn from the authority of the

patriarch of Constantinople, and a monastic republic was

practically constituted. The taking of Constantinople by the

Latins in 1204 brought persecution and pillage on the monks;

this reminded them of earlier Saracenic invasions, and led them

to appeal for protection to Pope Innocent III., who gave them

a favourable reply. Under the Palaeologi (1260-1453) they

recovered their prosperity, and were enriched by gifts from

various sources. In the 14th century the peninsula became the

chosen retreat of several of the emperors, and the monasteries

were thrown into commotion by the famous dispute over the

mystical Hesychasts.

Owing to the timely submission of the monks to the Turks

after the capture of Salonica (1430), their privileges were respected

by successive sultans: a tribute is paid to the Turkish government,

which is represented by a resident kaimakam, and the

community is allowed to maintain a small police force. Under

the present constitution, which dates from 1783, the general

affairs of the commonwealth are entrusted to an assembly

(σύναξις) of twenty members, one from each monastery; a

committee of four members, chosen in turn, styled epistatae

(ἐπιστάται), forms the executive. The president of the committee

(ὁ πρῶτος) is also the president of the assembly, which holds its

sittings in the village of Karyes, the seat of government since

the 10th century. The twenty monasteries, which all belong

to the order of St Basil, are: Laura (ἡ Λαῦρα), founded in 963;

Vatopédi (Βατοπέδιον), said to have been founded by the

emperor Theodosius; Rossikon (Ῥωσσικόν), the Russian

monastery of St Panteleïmon; Chiliándari (Χιλιαντάριον:

supposed to be derived from χίλιοι ἄνδρες or χίλια λεοντάρια),

founded by the Servian prince Stephen Nemanya (1159-1195);

Iveron (ἡ μονὴ τῶν Ἰβήρων), founded by Iberians, or Georgians;

Esphigmenu (τοῦ Ἐσφιγμένου: the name is derived from the confined

situation of the monastery); Kutlumush (Κουτλουμούση);

Pandocratoros (τοῦ Παντοκράτορος); Philotheu (Φιλοθέου);

Caracallu (τοῦ Καρακάλλου); St Paul (τοῦ ἁγίου Παύλου);

St Denis (τοῦ ἁγίου Διονυσίου); St Gregory (τοῦ ἁγίου Γρηγορίου); Simópetra (Σιμόπετρα); Xeropotámu (τοῦ Ξηροποτάμου); St Xenophon (τοῦ ἁγίου Ξενοφῶντος); Dochiaríu

(Δοχειαρείου); Constamonítu (Κωνσταμονίτου); Zográphu

(τοῦ Ζωγράφου); and Stavronikítu (τοῦ Σταυρονικίτου, the last

built, founded in 1545). The “coenobian” monasteries (κοινόβια),

each under the rule of an abbot (ἡγοόμενος), are subjected

to severe discipline; the brethren are clothed alike, take their

meals (usually limited to bread and vegetables) in the refectory,

and possess no private property. In the “idiorrhythmic”

monasteries (ἰδιόρρυθμα), which are governed by two or three

annually elected wardens (ἐπίτροποι), a less stringent rule

prevails, and the monks are allowed to supplement the fare of

the monastery from their private incomes. Dependent on the

several monasteries are twelve sketae (σκῆται) or monastic

settlements, some of considerable size, in which a still more

ascetic mode of life prevails: there are, in addition, several

farms (μετοχία), and many hundred sanctuaries with adjoining

habitations (κελλία) and hermitages (ἀσκητήρια). The

monasteries, with the exception of Rossikón (St Panteleïmon) and the

Serbo-Bulgarian Chiliándari and Zográphu, are occupied exclusively

by Greek monks. The large skete of St Andrew and

some others belong to the Russians; there are also Rumanian

and Georgian sketae. The great monastery of Rossikón, which

is said to number about 3000 inmates, has been under a Russian

abbot since 1875; it is regarded as one of the principal centres

of the Russian politico-religious propaganda in the Levant.

The tasteless style of its modern buildings is out of harmony with

the quaint beauty of the other monasteries. Furnished with

ample means, the Russian monks neglect no opportunity of

adding to their possessions on the holy mountain; their encroachments

are resisted by the Greek monks, whose wealth, however,

was much diminished by the secularization of their estates in

Rumania (1864). The population of the holy mountain numbers

from 6000 to 7000; about 3000 are monks (καλόγεροι), the

remainder being lay brothers (κοσμικοί). The monasteries,

which are all fortified, generally consist of large quadrangles

enclosing churches; standing amid rich foliage, they present a

wonderfully picturesque appearance, especially when viewed

from the sea. Their inmates, when not engaged in religious

services, occupy themselves with husbandry, fishing and

various handicrafts; the standard of intellectual culture is not

high. A large academy, founded by the monks of Vatopedi in

1749, for a time attracted students from all parts of the East,

but eventually proved a failure, and is now in ruins. The

muniment rooms of the monasteries contain a marvellous series

of documents, including chrysobulls of various emperors and

princes, sigilla of the patriarchs, typica, iradés and other

documents, the study of which will throw an important light

on the political and ecclesiastical history and social life of the

852

East from the middle of the 10th century. Up to comparatively

recent times a priceless collection of classical manuscripts was

preserved in the libraries; many of them were destroyed during

the War of Greek Independence (1821-1829) by the Turks, who

employed the parchments for the manufacture of cartridges;

others fell a prey to the neglect or vandalism of the monks, who,

it is said, used the material as bait in fishing; others have been

sold to visitors, and a considerable number have been removed

to Moscow and Paris. The library of Simopetra was destroyed

by fire in 1891, and that of St Paul in 1905. There is now little

hope of any important discovery of classical manuscripts. The

codices remaining in the libraries are for the most part theological

and ecclesiastical works. Of the Greek manuscripts, numbering

about 11,000, 6618 have been catalogued by Professor Spyridion

Lambros of Athens; his work, however, does not include the

MSS. in some of the sketae, or those in the libraries of Laura and

Vatopedi, of which catalogues (hitherto unpublished) have been

prepared by resident monks. The canonic MSS. only of Vatopedi

and Laura have been catalogued by Benessevich in the supplement

to vol. ix. of the Bizantiyskiy Vremennik (St Petersburg,

1904). The Slavonic and Georgian MSS. have not been catalogued.

Apart from the illuminated MSS., the mural paintings,

the mosaics, and the goldsmith’s work of Mount Athos are of

infinite interest to the student of Byzantine art. The frescoes

in general date from the 15th or 16th century: some are attributed

by the monks to Panselinos, “the Raphael of Byzantine

painting,” who apparently flourished in the time of the Palaeologi.

Most of them have been indifferently restored by local artists,

who follow mechanically a kind of hieratic tradition, the principles

of which are embodied in a work of iconography by the monk

Dionysius, said to have been a pupil of Panselinos. The same

spirit of conservatism is manifest in the architecture of the

churches, which are all of the medieval Byzantine type. Some

of the monasteries were seriously damaged by an earthquake

in 1905.

Authorities.—R.N.C. Curzon, Visits to Monasteries in the Levant

(London, 1849); J.P. Fallmerayer, Fragmenta aus dem Orient

(Stuttgart and Tübingen, 1845);

V. Langlois, Le Mont Athos et ses monastères, with a complete bibliography

(Paris, 1867);

Duchesne and Bayet, Mémoirs sur une mission en Macédoine et au Mont Athos

(Paris, 1876);

Texier and Pullan, Byzantine Architecture (London, 1864);

H. Brockhaus, Die Kunst in den Athosklöstern (Leipzig, 1891);

A. Riley, Athos, or the Mountain of the Monks (London, 1887);

S. Lambros, Catalogue of the Greek Manuscripts on Mount Athos

(2 vols., Cambridge, 1895 and 1900);

M.I. Gedeon, ὁ Ἄθως (Constantinople, 1885);

P. Meyer, “Beiträge zur Kenntniss der neueren Geschichte und des gegenwärtigen

Zustandes der Athosklöster,” in Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte, 1890;

Die Haupturkunden für die Geschichte der Athosklöster (Leipzig, 1894);

G. Millet, J. Pargoire and L. Petit,

Recueil des inscriptions chrétiennes de l’Athos (Paris, 1904);

H. Gelzer, Vom Heiligen Berge und aus Makedonien (Leipzig, 1904);

K. Vlachu (Blachos), Ἡ Χερσόνησος τοῦ Ἁγίου Ὄρους (Athens, 1903);

G. Smurnakes, Τὸ Ἅγιον Ὄρος Ἀρχαιολογία ὄρους Ἀθῶ, (Athens, 1904).

(J. D. B.)

ATHY (pronounced Athý), a market-town of Co. Kildare,

Ireland, in the south parliamentary division, 45 m. S.W. of

Dublin on a branch of the Great Southern & Western railway.

Pop. of urban district (1901) 3599. It is intersected by the

river Barrow, which is here crossed by a bridge of five arches.

The crossing of the river here was guarded and disputed from

the earliest times, and the name of the town is derived from

a king of Munster killed here in the 2nd century. There are

picturesque remains of Woodstock Castle of the 12th or 13th

century, and White Castle built in 1506, and rebuilt in 1575 by

a member of the family whose name it bears, and still occupied.

Both were erected to defend the ford of the Barrow. There are

also an old town gate, and an ancient cemetery with slight

monastic remains. Previous to the Union Athy returned two

members to the Irish parliament. The trade, chiefly in grain,

is aided by excellent water communication, by a branch of the

Grand Canal to Dublin, and by the river Barrow, navigable

from here to Waterford harbour.

ATINA, the name of three ancient towns of Italy.

1. A town (mod. Àtena) of Lucania, upon the Via Popillia,

7 m. N. of Tegianum, towards which an ancient road leads, in

the valley of the river now known as Diano. Its ancient importance

is vouched for by its walls of rough cyclopean work, which

may have had a total extent of some 2 m. (see G. Patroni in

Notizie degli scavi, 1897, 112; 1901, 498). The date of these

walls has not as yet been ascertained, recent excavations, which

led to the discovery of a few tombs in which the earliest objects

showing Greek influence may go back to the 7th century B.C.,

not having produced any decisive evidence on the point. To

the Roman period belong the remains of an amphitheatre and

numerous inscriptions.

2. A town (mod. Atina) of the Volsci, 12 m. N. of Casinum,

and about 14 m. E. of Arpinum, on a hill 1607 ft. above sea-level.

The walls, of carefully worked polygonal blocks of stone, are

still preserved in parts, and the modern town does not fill the

whole area which they enclose. Cicero speaks of it as a prosperous

country town, which had not as yet fallen into the hands of large

proprietors; and inscriptions show that under the empire it was

still flourishing. One of these last is a boundary stone relating

to the assignation of lands in the time of the Gracchi, of which

six other examples have been found in Campania and Lucania.

3. A town of the Veneti, mentioned by Pliny, H.N. iii. 131.

ATITLÁN, or Santiago de Atitlán, a town in the department

of Sololá, Guatemala, on the southern shore of Lake Atitlán.

Pop. (1905) about 9000, almost all Indians. Cotton-spinning

is the chief industry. Lake Atitlán is 24 m. long and 10 m. broad,

with 64 m. circumference. It occupies a crater more than

1000 ft. deep and about 4700 ft. above sea-level. The peaks of

the Guatemala Cordillera rise round it, culminating near its

southern end in the volcanoes of San Pedro (7000 ft.) and Atitlán

(11,719 ft.). Although the lake is fed by many small mountain

torrents, it has no visible outlet, but probably communicates

by an underground channel with one of the rivers which drain

the Cordillera. Mineral springs abound in the neighbourhood.

The town of Sololá (q.v.) is near the north shore of the lake.

ATKINSON, EDWARD (1827-1905), American economist,

was born at Brookline, Massachusetts, on the 10th of February

1827. For many years he was engaged in managing various

business enterprises, and became, in 1877, president of the

Boston Manufacturers’ Mutual Fire Insurance Company, a post

which he held till his death. He was a strong controversialist

and a prolific writer on such economic subjects as banking,

railways, cotton manufacture, the tariff and free trade, and the

money question. He was appointed in 1887 a special commissioner

to report upon the status of bimetallism in Europe. He also

made a special study of mill construction and fire prevention,

and invented an improved cooking apparatus, called the

“Aladdin oven.” He was an active supporter of anti-imperialism.

He died at Boston on the 11th of December 1905.

His principal works were

Right Methods of Preventing Fires in Mills (1881);

Distribution of Products (1885);

Industrial Progress of the Nation (1889);

Taxation and Work (1892);

Science of Nutrition (10th ed., 1898).

ATKINSON, SIR HARRY ALBERT (1831-1892), British

colonial statesman, prime minister and speaker of the legislative

council, New Zealand, was born at Chester in 1831, and in 1855

emigrated to Taranaki, New Zealand, where he became a farmer.

In 1860 the Waitara war broke out, and from its outset Atkinson,

who had been selected as a captain of the New Plymouth Volunteers,

distinguished himself by his contempt for appearances

and tradition, and by the practical skill, energy and courage

which he showed in leading his Forest Rangers in the tiresome

and lingering bush warfare of the next five years. For this work

he was made a major of militia, and thanked by the government.

Elected to the house of representatives in 1863, he joined Sir

Frederick Weld’s ministry at the end of November 1864 as

minister of defence, and, during eleven months of office, was

identified with the well-known “self-reliance” policy, a proposal

to dispense with imperial regulars, and meet the Maori with

colonials only. Parliament accepted this principle, but turned

out the Weld ministry for other reasons. For four years Atkinson

was out of parliament; in October 1873 he re-entered it, and

a year later became minister of lands under Sir Julius Vogel.

853

Ten months later he was treasurer, and such was his aptitude

for finance that, except during six months in 1876, he thenceforth

held that post whenever his party was in power. From

October 1874 to January 1891 Atkinson was only out of office

for about five years. Three times he was premier, and he was

always the most formidable debater and fighter in the ranks

of the Conservative opponents of the growing Radical party

which Sir George Grey, Sir Robert Stout and John Ballance led

in succession. It was he, who was mainly responsible for the

abolition of the provinces into which the colony was divided

from 1853 to 1876. He repealed the Ballance land-tax in 1879,

and substituted a property-tax. He greatly reduced the cost

of the public service in 1880, and again in 1888. In both these

years he raised the customs duties, amongst other taxes, and

gave them a quasi-protectionist character. In 1880 he struck

10% off all public salaries and wages; in 1887 he reduced the

salary of the governor by one-third, and the pay and number

of ministers and members of parliament. By these resolute steps

revenue was increased, expenditure checked, and the colony’s

finance reinstated. Atkinson was an advocate of compulsory

national assurance, and the leasing as opposed to the selling of

crown lands. Defeated in the general election of December 1890,

he took the appointment of speaker of the legislative council.

There, while leaving the council chamber after the sitting of the

28th of June 1892, he was struck down by heart disease and

died in a few minutes. Though brusque in manner and never

popular, he was esteemed as a vigorous, upright and practical

statesman. He was twice married, and had seven children, of

whom three sons and a daughter survived him.

(W. P. R.)

ATLANTA, the capital and the largest city of Georgia, U.S.A.,

and the county-seat of Fulton county, situated at an altitude of

1000-1175 ft., in the N.W. part of the state, near the

Chattahoochee river. Pop. (1860) 9554; (1880) 37,409; (1890)

65,533; (1900) 89,872, of whom 35,727 were negroes and

2531 were foreign-born; (1910) 154,839. It is served by the

Southern, the Central of Georgia, the Georgia, the Seaboard

Air Line, the Nashville, Chattanooga & St Louis (which enters

the city over the Western & Atlantic, one of its leased lines),

the Louisville & Nashville, the Atlanta, Birmingham & Atlantic,

and the Atlanta & West Point railways. These railway

communications, and the situation of the city (on the Piedmont

Plateau) on the water-parting between the streams flowing into

the Atlantic Ocean and those flowing into the Gulf of Mexico,

have given Atlanta its popular name, the “Gate City of the

South.” Atlanta was laid out in the form of a circle, the radius

being 1¾ m. and the centre the old railway station, the Union

Depot (the new station is called the Terminal); large additions

have been made beyond this circle, including West End, Inman

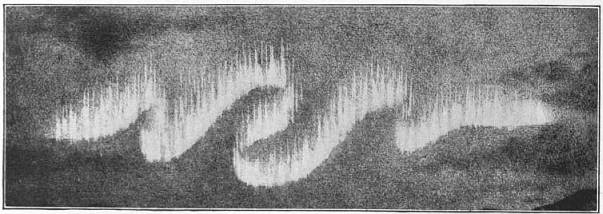

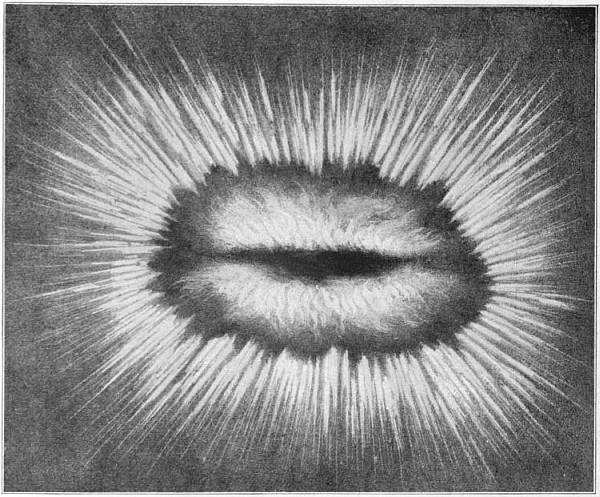

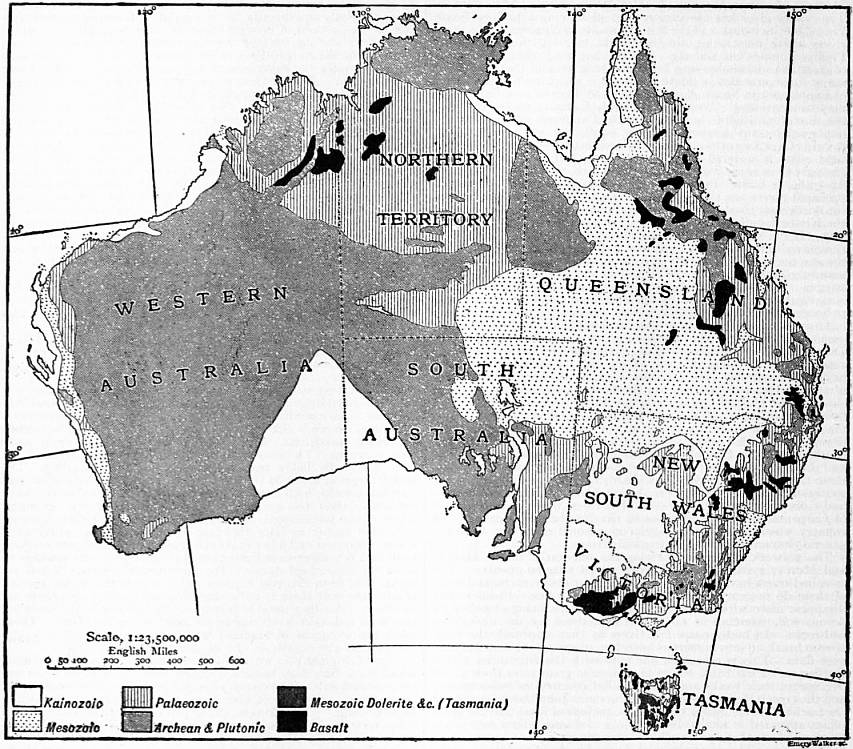

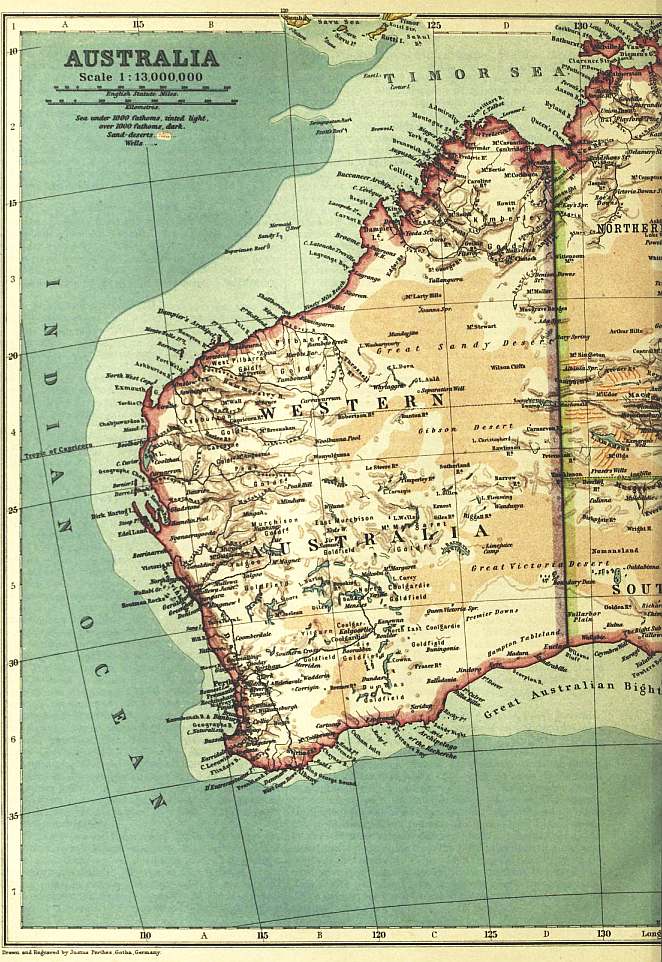

Park on the east, and North Atlanta. Among the best residence