Drida (Thryth) reproached for her Evil Deeds

Drida (Thryth) reproached for her Evil Deeds

From MS Cotton Nero D. I, fol. 11 b

"That is no way for a lady to behave." (Ne bið swylc cwēnlīc þēaw | idese tō efnanne:

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Beowulf, by R. W. Chambers

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Beowulf

An Introduction to the Study of the Poem with a Discussion

of the Stories of Offa and Finn

Author: R. W. Chambers

Release Date: October 23, 2010 [EBook #34117]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BEOWULF ***

Produced by Charlene Taylor, Ted Garvin, Keith Edkins and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net

Drida (Thryth) reproached for her Evil Deeds

Drida (Thryth) reproached for her Evil Deeds

From MS Cotton Nero D. I, fol. 11 b

"That is no way for a lady to behave." (Ne bið swylc cwēnlīc þēaw | idese tō efnanne:

BY

Dey mout er bin two deloojes: en den agin dey moutent.

Uncle Remus, The Story of the Deluge.

TO

Dear Prof. Lawrence,

When, more than four years ago, I asked you to allow me to dedicate this volume to you, it was as a purely personal token of gratitude for the help I had received from what you have printed, and from what you have written to me privately.

Since then much has happened: the debt is greater, and no longer purely personal. We in this country can never forget what we owe to your people. And the self-denial which led them voluntarily to stint themselves of food, that we in Europe might be fed, is one of many things about which it is not easy to speak. Our heart must indeed have been hardened if we had not considered the miracle of those loaves. But I fear that to refer to that great debt in the dedication to this little book may draw on me the ridicule incurred by the poor man who dedicated his book to the Universe.

Nevertheless, as a fellow of that College which has just received from an American donor the greatest benefaction for medical research which has ever been made in this country of ours, I may rejoice that the co-operation between our nations is being continued in that warfare against ignorance and disease which some day will become the only warfare waged among men.

Sceal hring-naca ofer heafu bringan

lāc ond luf-tācen. Ic þā lēode wāt

ge wið fēond ge wið frēond fæste geworhte,

ǣghwæs untǣle ealde wīsan.

R. W. C.

I have to thank various colleagues who have read proofs of this book, in whole or in part: first and foremost my old teacher, W. P. Ker; also Robert Priebsch, J. H. G. Grattan, Ernest Classen and two old students, Miss E. V. Hitchcock and Mrs Blackman. I have also to thank Prof. W. W. Lawrence of Columbia; and though there are details where we do not agree, I think there is no difference upon any important issues. If in these details I am in the right, this is largely due to the helpful criticism of Prof. Lawrence, which has often led me to reconsider my conclusions, and to re-state them more cautiously, and, I hope, more correctly. If, on the other hand, I am in the wrong, then it is thanks to Prof. Lawrence that I am not still more in the wrong.

From Axel Olrik, though my debt to him is heavy, I find myself differing on several questions. I had hoped that what I had to urge on some of these might have convinced him, or, better still, might have drawn from him a reply which would have convinced me. But the death of that great scholar has put an end to many hopes, and deprived many of us of a warm personal friend. It would be impossible to modify now these passages expressing dissent, for the early pages of this book were printed off some years ago. I can only repeat that it is just because of my intense respect for the work of Dr Olrik that, where I cannot agree with his conclusions, I feel bound to go into the matter at length. Names like those of Olrik, Bradley, Chadwick and Sievers carry rightly such authority as to make it the duty of those who differ, if only on minor details, to justify that difference if they can.

From Dr Bradley especially I have had help in discussing various of these problems: also from Mr Wharton of the British Museum, Prof. Collin of Christiania, Mr Ritchie Girvan of Glasgow, and Mr Teddy. To Prof. Brøgger, the Norwegian state-antiquary, I am indebted for permission to reproduce photographs of the {viii}Viking ships: to Prof. Finnur Jónsson for permission to quote from his most useful edition of the Hrólfs Saga and the Bjarka Rímur, and, above all, to Mr Sigfús Blöndal, of the Royal Library of Copenhagen, for his labour in collating with the manuscript the passages quoted from the Grettis Saga.

Finally, I have to thank the Syndics of the University Press for undertaking the publication of the book, and the staff for the efficient way in which they have carried out the work, in spite of the long interruption caused by the war.

R. W. C.

April 6, 1921.

| PAGE | |

| GENEALOGICAL TABLES | xii |

| PART I | |

| CHAPTER I. THE HISTORICAL ELEMENTS | |

| Section I. The Problem | 1 |

| Section II. The Geatas—their Kings and their Wars | 2 |

| Section III. Heorot and the Danish Kings | 13 |

| Section IV. Leire and Heorot | 16 |

| Section V. The Heathobeardan | 20 |

| Section VI. Hrothulf | 25 |

| Section VII. King Offa | 31 |

| CHAPTER II. THE NON-HISTORICAL ELEMENTS | |

| Section I. The Grendel Fight | 41 |

| Section II. The Scandinavian Parallels—Grettir and Orm | 48 |

| Section III. Bothvar Bjarki | 54 |

| Section IV. Parallels from Folklore | 62 |

| Section V. Scef and Scyld | 68 |

| Section VI. Beow | 87 |

| Section VII. The house of Scyld and Danish parallels—Heremod-Lotherus and Beowulf-Frotho | 89 |

| CHAPTER III. THEORIES AS TO THE ORIGIN, DATE AND STRUCTURE OF THE POEM | |

| Section I. Is Beowulf translated from a Scandinavian original? | 98 |

| Section II. The dialect, syntax and metre of Beowulf as evidence of its literary history | 104 |

| Section III. Theories as to the structure of Beowulf | 112 |

| Section IV. Are the Christian elements incompatible with the rest of the poem? | 121 |

| {x} PART II | |

| DOCUMENTS ILLUSTRATING THE STORIES IN BEOWULF, AND THE OFFA-SAGA | |

| A. The early Kings of the Danes, according to Saxo Grammaticus: Dan, Humblus, Lotherus and Scioldus; Frotho's dragon fight; Haldanus, Roe and Helgo; Roluo (Rolf Kraki) and Biarco (Bjarki); the death of Rolf | 129 |

| B. Extract from Hrólfs Saga Kraka, with translation (cap. 23) | 138 |

| C. Extracts from Grettis Saga, with translation: (a) Glam episode (caps. 32-35); (b) Sandhaugar episode (caps. 64-66) | 146 |

| D. Extracts from Bjarka Rímur, with translation | 182 |

| E. Extract from Þáttr Orms Stórólfssonar, with translation | 186 |

| F. A Danish Dragon-slaying of the Beowulf-type, with translation | 192 |

| G. The Old English Genealogies. I. The Mercian Genealogy. II. The stages above Woden: Woden to Geat and Woden to Sceaf | 195 |

| H. Extract from the Chronicle Roll | 201 |

| I. Extract from the Little Chronicle of the Kings of Leire | 204 |

| K. The Story of Offa in Saxo Grammaticus | 206 |

| L. From Skiold to Offa in Sweyn Aageson | 211 |

| M. Note on the Danish Chronicles | 215 |

| N. The Life of Offa I, with extracts from the Life of Offa II. Edited from two MSS in the Cottonian Collection | 217 |

| O. Extract from Widsith, II. 18, 24-49 | 243 |

| PART III | |

| THE FIGHT AT FINNSBURG | |

| Section I. The Finnsburg Fragment | 245 |

| Section II. The Episode in Beowulf | 248 |

| Section III. Möller's Theory | 254 |

| Section IV. Bugge's Theory | 257 |

| Section V. Some Difficulties in Bugge's Theory | 260 |

| Section VI. Recent Elucidations. Prof. Ayres' Comments | 266 |

| Section VII. Problems still outstanding | 268 |

| Section VIII. The Weight of Proof: the Eotens | 272 |

| Section IX. Ethics of the Blood Feud | 276 |

| {xi} Section X. An Attempt at Reconstruction | 283 |

| Section XI. Gefwulf, Prince of the Jutes | 286 |

| Section XII. Conclusion | 287 |

| Note. Frisia in the heroic age | 288 |

| PART IV | |

| APPENDIX | |

| A. A Postscript on Mythology in Beowulf. (1) Beowulf the Scylding and Beowulf son of Ecgtheow. (2) Beow | 291 |

| B. Grendel | 304 |

| C. The Stages above Woden in the West-Saxon Genealogy | 311 |

| D. Grammatical and literary evidence for the date of Beowulf. The relation of Beowulf to the Classical Epic | 322 |

| E. The "Jute-question" reopened | 333 |

| F. Beowulf and the Archaeologists | 345 |

| G. Leire before Rolf Kraki | 365 |

| H. Bee-wolf and Bear's son | 365 |

| I. The date of the death of Hygelac | 381 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY OF BEOWULF AND FINNSBURG | 383 |

| INDEX | 414 |

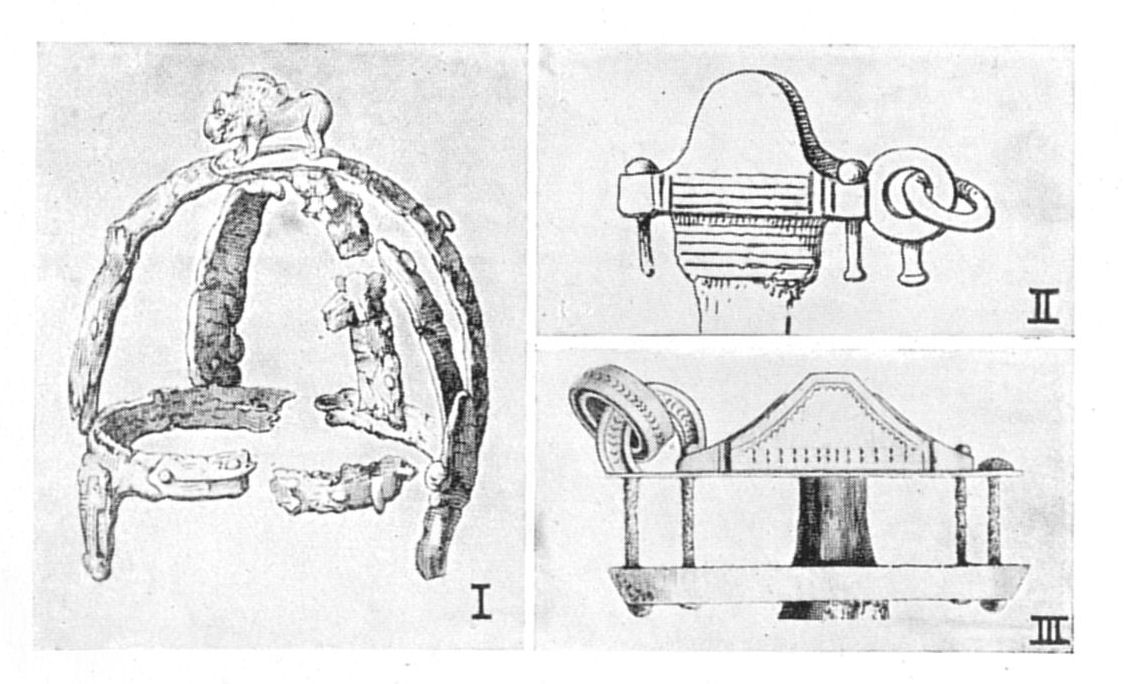

| PLATE | ||

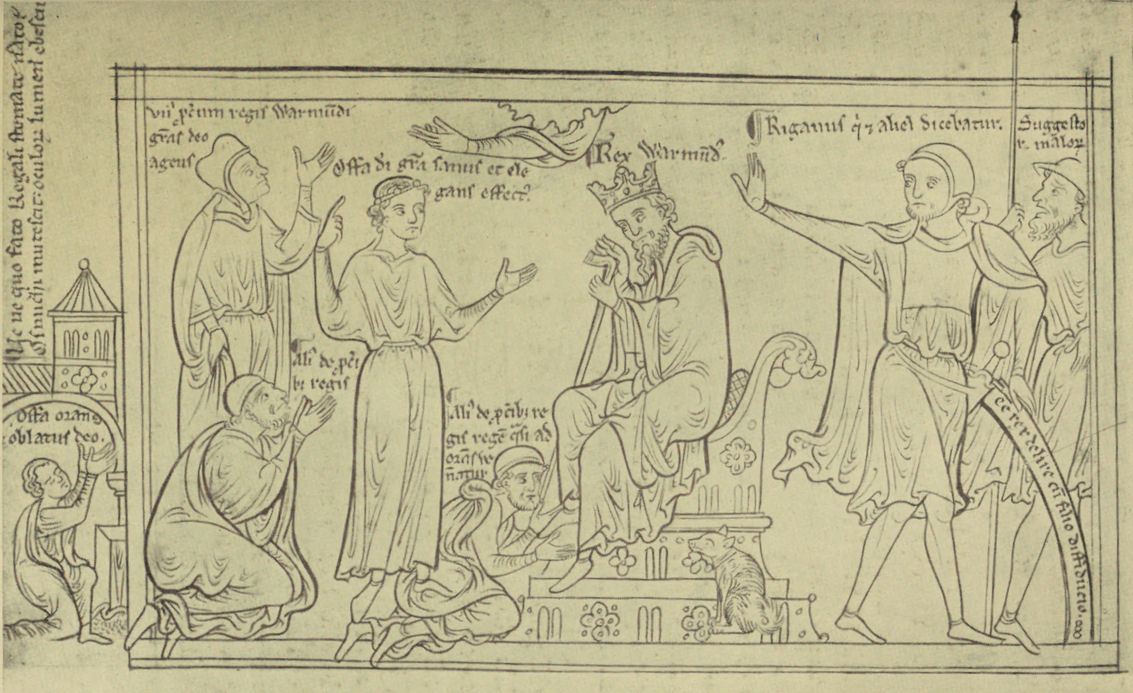

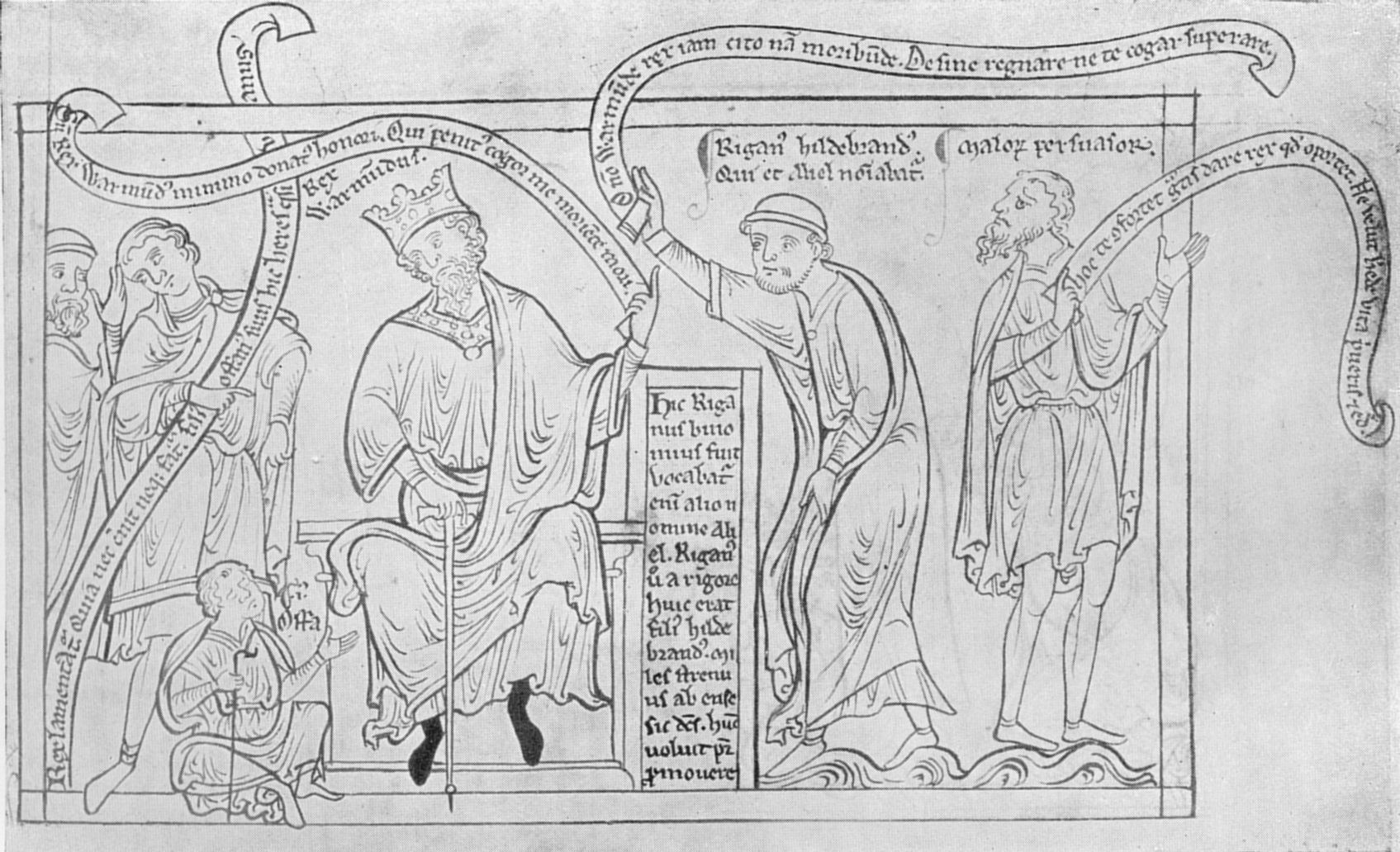

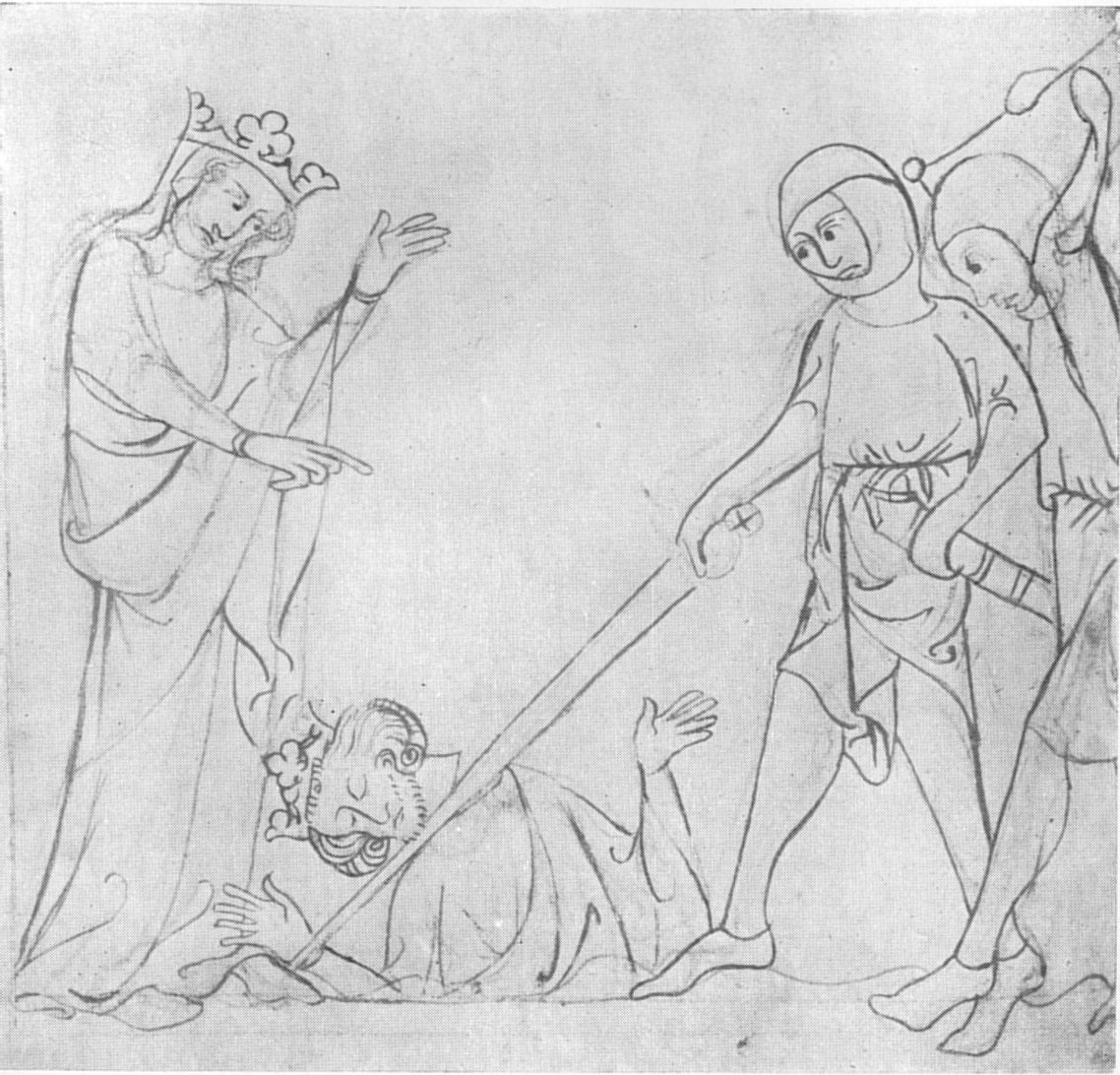

| I. | Drida (Thryth) reproached for her Evil Deeds | FRONTISPIECE |

| II. | Leire in the Seventeenth Century | TO FACE 16 |

| III. | Offa, miraculously restored, vindicates his Right. At the side, Offa is represented in Prayer | ,, ,, 34 |

| IV. | Drida (Thryth) arrives in the land of King Offa, "in nauicula armamentis carente" | ,, ,, 36 |

| V. | Riganus (or Aliel) comes before King Warmundus to claim that he should be made King in place of the incompetent Offa | ,, ,, 218 |

| VI. | Drida (Thryth) entraps Albertus (Æthelberht) of East Anglia, and causes him to be slain | ,, ,, 242 |

| VII. | The Gokstad Ship. The Oseberg Ship | ,, ,, 362 |

| VIII. | Southern Scandinavia in the Sixth Century. English Boar-Helmet and Ring-Swords | At end |

The names of the corresponding characters in Scandinavian legend are added in italics; first the Icelandic forms, then the Latinized names as recorded by Saxo Grammaticus.

(1) THE DANISH ROYAL FAMILY

Scyld Scēfing [Skjǫldr, Skyoldus]

|

Bēowulf [not the hero of the poem]

|

Healfdene [Halfdan, Haldanus]

|

.-------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

| | | |

Heorogār Hrōðgār [Hróarr[1], Roe], Hālga [Helgi, a daughter

[no Scandinavian mar. Wealhþēow Helgo] [Signy]

parallel] | |

| .-----------------------------. |

| | | | |

Heoroweard Hrēðrīc Hrōðmund Frēawaru Hrōðulf

[Hjǫrvarðr, [Hrærekr, mar. [Hrólfr

Hiarwarus: Røricus: Ingeld Kraki,

but not not Roluo]

recognized as recognized

belonging as a son of

to this family] Hroarr]

(2) THE GEAT ROYAL FAMILY

Hrēðel Wǣgmund

| |

.------------------------------------------. .-------------.

| | | | | |

Herebeald Hæðcyn Hygelāc, mar. Hygd a daughter, mar. Ecgþēow Wēohstān

| | |

.-----------------. Bēowulf Wīglāf

| |

a daughter, Heardrēd

mar. Eofor

(3) THE SWEDISH ROYAL FAMILY

Ongenþēow

|

.-------------------------------------.

| |

Onela Ōhthere [Óttarr]

[Áli, not recognized |

as belonging to this .---------------.

family] | |

Eanmund Ēadgils

[Aðils[2],

Athislus]

THE HISTORICAL ELEMENTS

Section I. The Problem.

The unique MS of Beowulf may be, and if possible should be, seen by the student in the British Museum. It is a good specimen of the elegant script of Anglo-Saxon times: "a book got up with some care," as if intended for the library of a nobleman or of a monastery. Yet this MS is removed from the date when the poem was composed and from the events which it narrates (so far as these events are historic at all) by periods of time approximately equal to those which separate us from the time when Shakespeare's Henry V was written, and when the battle of Agincourt was fought.

To try to penetrate the darkness of the five centuries which lie behind the extant MS by fitting together such fragments of illustrative information as can be obtained, and by using the imagination to bridge the gaps, has been the business of three generations of scholars distributed among the ten nations of Germanic speech. A whole library has been written around our poem, and the result is that this book cannot be as simple as either writer or reader might have wished.

The story which the MS tells us may be summarized thus: Beowulf, a prince of the Geatas, voyages to Heorot, the hall of Hrothgar, king of the Danes; there he destroys a monster Grendel, who for twelve years has haunted the hall by night and slain all he found therein. When Grendel's mother in revenge makes an attack on the hall, Beowulf seeks her out and kills her also in her home beneath the waters. He then {2}returns to his land with honour and is rewarded by his king Hygelac. Ultimately he himself becomes king of the Geatas, and fifty years later slays a dragon and is slain by it. The poem closes with an account of the funeral rites.

Fantastic as these stories are, they are depicted against a background of what appears to be fact. Incidentally, and in a number of digressions, we receive much information about the Geatas, Swedes and Danes: all which information has an appearance of historic accuracy, and in some cases can be proved, from external evidence, to be historically accurate.

Section II. The Geatas—their Kings and their Wars.

Beowulf's people have been identified with many tribes: but there is strong evidence that the Geatas are the Götar (O.N. Gautar), the inhabitants of what is now a portion of Southern Sweden, immediately to the south of the great lakes Wener and Wetter. The names Geatas and Gautar correspond exactly[3], according to the rules of O.E. and O.N. phonetic development, and all we can ascertain of the Geatas and of the Gautar harmonizes well with the identification[4].

We know of one occasion only when the Geatas came into violent contact with the world outside Scandinavia. Putting together the accounts which we receive from Gregory of Tours and from two other (anonymous) writers, we learn that a piratical raid was made upon the country of the Atuarii (the O.E. Hetware) who dwelt between the lower Rhine and what is now the Zuyder Zee, by a king whose name is spelt in a variety of ways, all of which readily admit of identification with that of the Hygelac of our poem[5]. From the land of the Atuarii this king carried much spoil to his ships; but, remaining on shore, he was overwhelmed and slain by the army which the {3}Frankish king Theodoric had sent under his son to the rescue of these outlying provinces; the plunderers' fleet was routed and the booty restored to the country. The bones of this gigantic king of the "Getae" [presumably = Geatas] were long preserved, it was said, on an island near the mouth of the Rhine.

Such is the story of the raid, so far as we can reconstruct it from monkish Latin sources. The precise date is not given, but it must have been between A.D. 512 and 520.

Now this disastrous raid of Hygelac is referred to constantly in Beowulf: and the mention there of Hetware, Franks and the Merovingian king as the foes confirms an identification which would be satisfactory even without these additional data[6].

Our authorities are:

(1) Gregory of Tours (d. 594):

His ita gestis, Dani cum rege suo nomine Chlochilaico evectu navale per mare Gallias appetunt. Egressique ad terras, pagum unum de regno Theudorici devastant atque captivant, oneratisque navibus tam de captivis quam de reliquis spoliis, reverti ad patriam cupiunt; sed rex eorum in litus resedebat donec naves alto mare conpraehenderent, ipse deinceps secuturus. Quod cum Theudorico nuntiatum fuisset, quod scilicet regio ejus fuerit ab extraneis devastata, Theudobertum, filium suum, in illis partibus cum valido exercitu et magno armorum apparatu direxit. Qui, interfecto rege, hostibus navali proelio superatis opprimit, omnemque rapinam terrae restituit.

The name of the vanquished king is spelt in a variety of ways: Chlochilaichum, Chrochilaicho, Chlodilaichum, Hrodolaicum.

See Gregorii episcopi Turonensis Historia Francorum, p. 110, in Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Scriptores rerum merovingicarum, I).

(2) The Liber Historiae Francorum (commonly called the Gesta Francorum):

In illo tempore Dani cum rege suo nomine Chochilaico cum navale hoste per alto mare Gallias appetent, Theuderico paygo [i.e. pagum] Attoarios vel alios devastantes atque captivantes plenas naves de captivis alto mare intrantes rex eorum ad litus maris resedens. Quod cum Theuderico nuntiatum fuisset, Theudobertum filium suum cum magno exercitu in illis partibus dirigens. Qui consequens eos, pugnavit cum eis caede magna atque prostravit, regem eorum interficit, preda tullit, et in terra sua restituit.

The Liber Historiae Francorum was written in 727, but although so much later than Gregory, it preserves features which are wanting in the earlier historian, such as the mention of the Hetware (Attoarii). Note too that the name of the invading king is given in a form which {4}approximates more closely to Hygelac than that of any of the MSS of Gregory: variants are Chrochilaico, Chohilaico, Chochilago, etc.

See Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Scriptores rerum merovingicarum, II, 274).

(3) An anonymous work On monsters and strange beasts, appended to two MSS of Phaedrus.

Et sunt [monstra] mirae magnitudinis: ut rex Huiglaucus qui imperavit Getis et a Francis occisus est. Quem equus a duodecimo anno portare non potuit. Cujus ossa in Reni fluminis insula, ubi in Oceanum prorumpit, reservata sunt et de longinquo venientibus pro miraculo ostenduntur.

This treatise was first printed (from a MS of the tenth century, in private possession) by J. Berger de Xivrey (Traditions tératologiques, Paris, 1836, p. 12). It was again published from a second MS at Wolfenbüttel by Haupt (see his Opuscula II, 223, 1876). This MS is in some respects less accurate, reading Huncglacus for Huiglaucus, and gentes for Getis. The treatise is assigned by Berger de Xivrey to the sixth century, on grounds which are hardly conclusive (p. xxxiv). Haupt would date it not later than the eighth century (II, 220).

The importance of this reference lies in its describing Hygelac as king of the Getae, and in its fixing the spot where his bones were preserved as near the mouth of the Rhine[7].

But if Beowulf is supported in this matter by what is almost contemporary evidence (for Gregory of Tours was born only some twenty years after the raid he narrates) we shall probably be right in arguing that the other stories from the history of the Geatas, their Danish friends, and their Swedish foes, told with what seems to be such historic sincerity in the different digressions of our poem, are equally based on fact. True, we have no evidence outside Beowulf for Hygelac's father, king Hrethel, nor for Hygelac's elder brothers, Herebeald and Hæthcyn; and very little for Hæthcyn's deadly foe, the Swedish king Ongentheow[8].

And in the last case, at any rate, such evidence might {5}fairly have been expected. For there are extant a very early Norse poem, the Ynglinga tal, and a much later prose account, the Ynglinga saga, enumerating the kings of Sweden. The Ynglinga tal traces back these kings of Sweden for some thirty reigns. Therefore, though it was not composed till some four centuries after the date to which we must assign Ongentheow, it should deal with events even earlier than the reign of that king: for, unless the rate of mortality among early Swedish kings was abnormally high, thirty reigns should occupy a period of more than 400 years. Nothing is, however, told us in the Ynglinga tal concerning the deeds of any king Angantyr—which is the name we might expect to correspond to Ongentheow[9].

But on the other hand, the son and grandson of Ongentheow, as recorded in Beowulf, do meet us both in the Ynglinga tal and in the Ynglinga saga.

According to Beowulf, Ongentheow had two sons, Onela and Ohthere: Onela became king of Sweden and is spoken of in terms of highest praise[10]. Yet to judge from the account given in Beowulf, the Geatas had little reason to love him. He had followed up the defeat of Hygelac by dealing their nation a second deadly blow. For Onela's nephews, Eadgils and Eanmund (the sons of Ohthere), had rebelled against him, and had taken refuge at the court of the Geatas, where Heardred, son of Hygelac, was now reigning, supported by Beowulf. Thither Onela pursued them, and slew the young king Heardred. Eanmund also was slain[11], then or later, but Eadgils escaped.

It is not clear from the poem what part Beowulf is supposed to have taken in this struggle, or why he failed to ward off disaster from his lord and his country. It is not even made clear whether or no he had to make formal submission to the hated Swede: but we are told that when Onela withdrew he succeeded to the vacant throne. In later days he took his revenge upon Onela. "He became a friend to Eadgils in his distress; he supported the son of Ohthere across the broad water with men, with warriors and arms: he wreaked his {6}vengeance in a chill journey fraught with woe: he deprived the king [Onela] of his life."

This story bears in its general outline every impression of true history: the struggle for the throne between the nephew and the uncle, the support given to the unsuccessful candidate by a rival state, these are events which recur frequently in the wild history of the Germanic tribes during the dark ages, following inevitably from the looseness of the law of succession to the throne.

Now the Ynglinga tal contains allusions to these events, and the Ynglinga saga a brief account of them, though dim and distorted[12]. We are told how Athils (=Eadgils) king of Sweden, son of Ottar (=Ohthere), made war upon Ali (=Onela). By the time the Ynglinga tal was written it had been forgotten that Ali was Athils' uncle, and that the war was a civil war. But the issue, as reported in the Ynglinga tal and Ynglinga saga, is the same as in Beowulf:

"King Athils had great quarrels with the king called Ali of Uppland; he was from Norway. They had a battle on the ice of Lake Wener; there King Ali fell, and Athils had the victory. Concerning this battle there is much said in the Skjoldunga saga."

From the Ynglinga saga we learn more concerning King Athils: not always to his credit. He was, as the Swedes had been from of old, a great horse-breeder. Authorities differed as to whether horses or drink were the death of him[13]. According to one account he brought on his end by celebrating, with immoderate drinking, the death of his enemy Rolf (the Hrothulf of Beowulf). According to another:

"King Athils was at a sacrifice of the goddesses, and rode his horse through the hall of the goddesses: the horse tripped under him and fell and threw the king; and his head smote a stone so that the skull broke and the brains lay on the stones, and that was his death. He died at Uppsala, and there was laid in mound, and the Swedes called him a mighty king."

There can, then, hardly be a doubt that there actually was such a king as Eadgils: and some of the charred bones which still lie within the gigantic "King's mounds" at Old Uppsala may well be his[14]. And, though they are not quite so well authenticated, there can also be little doubt as to the historic existence of Onela, Ohthere, and even of Ongentheow.

The Swedish Kings.

The account in the Ynglinga saga of the fight between Onela and Eadgils is as follows:

Aðils konungr átti deilur miklar við konung þann, er Áli hét inn upplenzki: hann var ór Nóregi. Þeir áttu orrostu á Vænis ísi; þar fell Áli konungr en Aðils hafði sigr; frá þessarri orrostu er langt sagt í Skjǫldunga sǫgu. (Ynglinga saga in Heimskringla, ed. Jónsson, Kjøbenhavn, 1893, I, 56.)

The Skjoldunga saga here mentioned is an account of the kings of Denmark. It is preserved only in a Latin abstract.

Post haec ortis inter Adilsum illum Sveciae regem et Alonem Opplandorum regem in Norvegia, inimicitiis, praelium utrinque indicitur: loco pugnae statuto in stagno Waener, glacie jam obducto. Ad illud igitur se viribus inferiorem agnoscens Rolphonis privigni sui opem implorat, hoc proposito praemio, ut ipse Rolpho tres praeciosissimas res quascunque optaret ex universo regno Sveciae praemii loco auferret: duodecim autem pugilum ipsius quilibet 3 libras auri puri, quilibet reliquorum bellatorum tres marcas argenti defecati. Rolpho domi ipse reses pugilos suos duodecim Adilso in subsidium mittit, quorum etiam opera is alioqui vincendus, victoriam obtinuit. Illi sibi et regi propositum praemium exposcunt, negat Adilsus, Rolphoni absenti ullum deberi praemium, quare et Dani pugiles sibi oblatum respuebant, cum regem suum eo frustrari intelligerent, reversique rem, ut gesta est, exponunt. (See Skjoldungasaga i Arngrim Jonssons Udtog, udgiven af Axel Olrik, Kjøbenhavn, 1894, p. 34 [116].)

There is also a reference to this battle on the ice in the Kálfsvísa, a mnemonic list of famous heroes and their horses. It is noteworthy that in this list mention is made of Vestein, who is perhaps the Wihstan of our poem, and of Biar, who has been thought (very doubtfully) to correspond to the O.E. Beaw.

Dagr reiþ Drǫsle en Dvalenn Móþne...

Ále Hrafne es til íss riþo,

enn annarr austr und Aþilse

grár hvarfaþe geire undaþr.

Bjǫrn reiþ Blakke en Biarr Kerte,

Atle Glaume en Aþils Slungne...

Lieder der Edda, ed. Symons and Gering, i, 221-2.

"Ale was on Hrafn when they rode to the ice: but another horse, a grey one, with Athils on his back, fell eastward, wounded by the spear." This, as Olrik points out, appears to refer to a version of the story in which Athils had his fall from his horse, not at a ceremony at Uppsala, but after the battle with Ali. (Heltedigtning, I, 203-4.)

For various theories as to the early history of the Swedish royal house, as recorded in Beowulf, see Weyhe, König Ongentheows Fall, in Engl. Stud., xxxix, 14-39; Schück, Studier i Ynglingatal (1905-7); Stjerna, Vendel och Vendelkråka, in A.f.n.F. XXI, 71, etc.

The Geatas.

The identification of Geatas and Götar has been accepted by the great majority of scholars, although Kemble wished to locate the Geatas in Schleswig, Grundtvig in Gotland, and Haigh in England. Leo was the first to suggest the Jutes: but the "Jute-hypothesis" owes its currency to the arguments of Fahlbeck (Beovulfsqvädet såsom källa för nordisk fornhistoria in the Antiqvarisk Tidskrift för Sverige, VIII, 2, 1). Fahlbeck's very inconclusive reasons were contested at the time by Sarrazin (23 etc.) and ten Brink (194 etc.) and the arguments against them have lately been marshalled by H. Schück (Folknamnet Geatas i den fornengelska dikten Beowulf, Upsala, 1907). It is indeed difficult to understand how Fahlbeck's theory came to receive the support it has had from several scholars (e.g. Bugge, P.B.B. XII, 1 etc.; Weyhe, Engl. Stud., XXXIX, 38 etc.; Gering). For his conclusions do not arise naturally from the O.E. data: his whole argument is a piece of learned pleading, undertaken to support his rather revolutionary speculations as to early Swedish history. These speculations would have been rendered less probable had the natural interpretation of Geatas as Götar been accepted. The Jute-hypothesis has recently been revived, with the greatest skill and learning, by Gudmund Schütte (Journal of English and Germanic Philology, XI, 574 etc.). But here again I cannot help suspecting that the wish is father to the thought, and that the fact that that eminent scholar is a Dane living in Jutland, has something to do with his attempt to locate the Geatas there. No amount of learning will eradicate patriotism.

The following considerations need to be weighed:

(1) Geatas etymologically corresponds exactly with O.N. Gautar, the modern Götar. The O.E. word corresponding to Jutes (the Iutae of Bede) should be, not Geatas, but in the Anglian dialect Eote, Iote, in the West Saxon Iete, Yte.

Now it is true that in one passage in the O.E. translation of Bede (I, 15) the word "Iutarum" is rendered Geata: but in the other (IV, 16) "Iutorum" is rendered Eota, Ytena. And this latter rendering is supported (a) by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Iotum, Iutna) and (b) by the fact that the current O.E. word for Jutes was Yte, Ytan, which survived till after the Norman conquest. For the name Ytena land was used for that portion of Hampshire which had been settled by the Jutes: William Rufus was slain, according to Florence of Worcester, in Ytene (which Florence explains as prouincia Jutarum).

From the purely etymological point of view the Götar-hypothesis, then, is unimpeachable: but the Jute-hypothesis is unsatisfactory, since it is based upon one passage in the O.E. Bede, where Jutarum is incorrectly rendered Geata, whilst it is invalidated by the other passage in the O.E. Bede, by the Chronicle and by Florence of Worcester, where Jutorum is correctly translated by Ytena, or its Anglian or Kentish equivalent Eota, Iotna.

(2) It is obvious that the Geatas of Beowulf were a strong and independent power—a match for the Swedes. Now we learn from Procopius that in the sixth century the Götar were an independent {9}and numerous nation. But we have no equal evidence for any similar preponderant Jutish power in the sixth century. The Iutae are indeed a rather puzzling tribe, and scholars have not even been able to agree where they dwelt.

The Götar on the other hand are located among the great nations of Scandinavia both by Ptolemy (Geog. II, 11, 16) in the second century and by Procopius (Bell. Gott. II, 15) in the sixth. When we next get clear information (through the Christian missionaries) both Götar and Swedes have been united under one king. But the Götar retained their separate laws, traditions, and voice in the selection of the king, and they were constantly asserting themselves during the Middle Ages. The title of the king of Sweden, rex Sveorum Gothorumque, commemorates the old distinction.

From the historical point of view, then, the Götar comply with what we are told in Beowulf of the power of the Geatas much better than do the Jutes.

(3) Advocates of the Jute-hypothesis have claimed much support from the geographical argument that the Swedes and Geatas fight ofer sǣ (e.g. when Beowulf and Eadgils attack Onela, 2394). But the term sǣ is just as appropriate to the great lakes Wener and Wetter, which separated the Swedes from the Götar, as it is to the Cattegatt. And we have the evidence of Scandinavian sources that the battle between Eadgils and Onela actually did take place on the ice of lake Wener (see above, p. 6). Moreover the absence of any mention of ships in the fighting narrated in ll. 2922-2945 would be remarkable if the contending nations were Jutes and Swedes, but suits Götar and Swedes admirably: since they could attack each other by land as well as by water.

(4) There is reason to think that the old land of the Götar included a great deal of what is now the south-west coast of Sweden[15]. Hygelac's capital was probably not far from the modern Göteborg. The descriptions in Beowulf would suit the cliffs of southern Sweden well, but they are quite inapplicable to the sandy dunes of Jutland.

Little weight can, however, be attached to this last argument, as the cliffs of the land of the Geatas are in any case probably drawn from the poet's imagination.

(5) If we accept the identification Beowulf = Bjarki (see below, pp. 60-1) a further argument for the equation of Geatas and Götar will be found in the fact that Bjarki travels to Denmark from Gautland just as Beowulf from the land of the Geatas; Bjarki is the brother of the king of the Gautar, Beowulf the nephew of the king of the Geatas.

(6) No argument as to the meaning of Geatas can be drawn from the fact that Gregory calls Chlochilaicus (Hygelac) a Dane. For it is clear from Beowulf that, whatever else they may have been, the Geatas were not Danes. Either, then, Gregory must be misinformed, or he must be using the word Dane vaguely, to cover any kind of Scandinavian pirate.

(7) Probably what has weighed most heavily (often perhaps not consciously) in gaining converts to the "Jute-hypothesis" has been the conviction that "in ancient times each nation celebrated in song its own heroes alone." Hence one set of scholars, accepting the identification of the Geatas with the Scandinavian Götar, have argued that Beowulf is therefore simply a translation from a Scandinavian Götish original. Others, accepting Beowulf as an English poem, have {10}argued that the Geatas who are celebrated in it must therefore be one of the tribes that settled in England, and have therefore favoured the "Jute theory." But the a priori assumption that each Germanic tribe celebrated in song its own national heroes only is demonstrably incorrect[16].

But in none of the accounts of the warfare of these Scandinavian kings, whether written in Norse or monkish Latin, is there mention of any name corresponding to that of Beowulf, as king of the Geatas. Whether he is as historic as the other kings with whom in our poem he is brought into contact, we cannot say.

It has been generally held that the Beowulf of our poem is compounded out of two elements: that an historic Beowulf, king of the Geatas, has been combined with a mythological figure Beowa[17], a god of the ancient Angles: that the historical achievements against Frisians and Swedes belong to the king, the mythological adventures with giants and dragons to the god. But there is no conclusive evidence for either of these presumed component parts of our hero. To the god Beowa we shall have to return later: here it is enough to note that the current assumption that there was a king Beowulf of the Geatas lacks confirmation from Scandinavian sources.

And one piece of evidence there is, which tends to show that Beowulf is not an historic king at all, but that his adventures have been violently inserted amid the historic names of the kings of the Geatas. Members of the families in Beowulf which we have reason to think historic bear names which alliterate the one with the other. The inference seems to be that it was customary, when a Scandinavian prince was named in the Sixth Century, to give him a name which had an initial letter similar to that of his father: care was thus taken that metrical difficulties should not prevent the names of father and son being linked together in song[18]. In the case of Beowulf himself, however, this rule breaks down. Beowulf seems an intruder {11}into the house of Hrethel. It may be answered that since he was only the offspring of a daughter of that house, and since that daughter had three brothers, there would have been no prospect of his becoming king, when he was named. But neither does his name fit in with that of the other great house with which he is supposed to be connected. Wiglaf, son of Wihstan of the Wægmundingas, was named according to the familiar rules: but Beowulf, son of Ecgtheow, seems an intruder in that family as well.

This failure to fall in with the alliterative scheme, and the absence of confirmation from external evidence, are, of course, not in themselves enough to prove that the reign of Beowulf over the Geatas is a poetic figment. And indeed our poem may quite possibly be true to historic fact in representing him as the last of the great kings of the Geatas; after whose death his people have nothing but national disaster to expect[19]. It would be strange that this last and most mighty and magnanimous of the kings of the Geatas should have been forgotten in Scandinavian lands: that outside Beowulf nothing should be known of his reign. But when we consider how little, outside Beowulf, we know of the Geatic kingdom at all, we cannot pronounce such oblivion impossible.

What tells much more against Beowulf as a historic Geatic king is that there is always apt to be something extravagant and unreal about what the poem tells us of his deeds, contrasting with the sober and historic way in which other kings, like Hrothgar or Hygelac or Eadgils, are referred to. True, we must not disqualify Beowulf forthwith because he slew a dragon[20]. Several unimpeachably historical persons have done this: so sober an authority as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle assures us that fiery dragons were flying in Northumbria as late as A.D. 793[21].

But (and this is the serious difficulty) even when Beowulf is depicted in quite historic circumstances, there is still something unsubstantial about his actions. When, in the midst of the strictly historical account of Hygelac's overthrow, we are told that Beowulf swam home bearing thirty suits of armour, this is as fantastic as the account of his swimming home from Grendel's lair with Grendel's head and the magic swordhilt. We may well doubt whether there is any more kernel of historic fact in the one feat than in the other[22]. Again, we are told how Beowulf defended the young prince Heardred, Hygelac's son. Where was he, then, when Heardred was defeated and slain? To protect and if necessary avenge his lord upon the battlefield was the essential duty of the Germanic retainer. Yet Beowulf has no part to play in the episode of the death of Heardred. He is simply ignored till it is over. True, we are told that in later days he did take vengeance, by supporting the claims of Eadgils, the pretender, against Onela, the slayer of Heardred. But here again difficulties meet us: for the Scandinavian authorities, whilst they agree that Eadgils overthrew Onela by the use of foreign auxiliaries, represent these auxiliaries as Danish retainers, dispatched by the Danish king Hrothulf. The chief of these Danish retainers is Bothvar Bjarki, who, as we shall see later, has been thought to stand in some relation to Beowulf. But Bothvar is never regarded as king of the Geatas: and the fact remains that Beowulf is at variance with our other authorities in representing Eadgils as having been placed on the throne by a Geatic rather than by a Danish force. Yet this Geatic expedition against Onela is, with the exception of the dragon episode, the only event which our poem has to narrate concerning Beowulf's long reign of fifty years. And in other respects the reign is shadowy. Beowulf, we are told, came to the throne at a time of utter national distress; he had a long and prosperous reign, and became so powerful that he was able to dethrone the mighty[23] Swedish king Onela, and place in his stead the miserable fugitive[24] Eadgils. Yet, after this half century of success, the {13}kingdom is depicted upon Beowulf's death as being in the same tottering condition in which it stood at the time when he is represented as having come to the throne, after the fall of Heardred.

The destruction one after the other of the descendants of Hrethel sounds historic: at any rate it possesses verisimilitude. But the picture of the childless Beowulf, dying, after a glorious reign, in extreme old age, having apparently made no previous arrangements for the succession, so that Wiglaf, a youth hitherto quite untried in war, steps at once into the place of command on account of his valour in slaying the dragon—this is a picture which lacks all historic probability.

I cannot avoid a suspicion that the fifty years' reign of Beowulf over the Geatas may quite conceivably be a poetic fiction[25]; that the downfall of the Geatic kingdom and its absorption in Sweden were very possibly brought about by the destruction of Hygelac and all his warriors at the mouth of the Rhine.

Such an event would have given the Swedes their opportunity for vengeance: they may have swooped down, destroyed Heardred, and utterly crushed the independent kingdom of the Geatas before the younger generation had time to grow up into fighting men.

To the fabulous achievements of Beowulf, his fight with Grendel, Grendel's dam, and the dragon, it will be necessary to return later. As to his other feats, all we can say is that the common assumption that they rest upon an historic foundation does not seem to be capable of proof. But that they have an historic background is indisputable.

Section III. Heorot and the Danish Kings.

Of the Danish kings mentioned in Beowulf, we have first Scyld Scefing, the foundling, an ancient and probably a mythical figure, then Beowulf, son of Scyld, who seems an intruder among the Danish kings, since the Danish records know nothing {14}of him, and since his name does not alliterate with those of either his reputed father or his reputed son. Then comes the "high" Healfdene, to whom four children were born: Heorogar, Hrothgar, Halga "the good," and a daughter who was wedded to the Swedish king. Since Hrothgar is represented as an elder contemporary of Hygelac, we must date[26] Healfdene and his sons, should they be historic characters, between A.D. 430 and 520.

Now it is noteworthy that just after A.D. 500 the Danes first become widely known, and the name "Danes" first meets us in Latin and Greek authors. And this cannot be explained on the ground that the North has become more familiar to dwellers in the classical lands: on the contrary far less is known concerning the geography of the North Sea and the Baltic than had been the case four or five centuries before. Tacitus and Ptolemy knew of many tribes inhabiting what is now Denmark, but not of the Danes: the writers in Ravenna and Constantinople in the sixth century, though much less well informed on the geography of the North, know of the Danes as amongst the most powerful nations there. Beowulf is, then, supported by the Latin and Greek records when it depicts these rulers of Denmark as a house of mighty kings, the fame of whose realm spread far and wide. We cannot tell to what extent this realm was made by the driving forth of alien nations from Denmark, to what extent by the coming together (under the common name of Danes) of many tribes which had hitherto been known by other distinct names.

The pedigree of the house of Healfdene can be constructed from the references in Beowulf. Healfdene's three sons, Heorogar, Hrothgar, Halga, are presumably enumerated in order of age, since Hrothgar mentions Heorogar, but not Halga, as his senior[27]. Heorogar left a son Heoroweard[28], but it is in accordance with Teutonic custom that Hrothgar should have succeeded to the throne if, as we may well suppose, Heoroweard was too young to be trusted with the kingship.

The younger brother Halga is never mentioned during Beowulf's visit to Heorot, and the presumption is that he is already dead.

The Hrothulf who, both in Beowulf and Widsith, is linked with King Hrothgar, almost as his equal, is clearly the son of Halga: for he is Hrothgar's nephew[29], and yet he is not the son of Heorogar[30]. The mention of how Hrothgar shielded this Hrothulf when he was a child confirms us in the belief that his father Halga had died early. Yet, though he thus belongs to the youngest branch of the family, Hrothulf is clearly older than Hrethric and Hrothmund, the two sons of Hrothgar, whose youth, in spite of the age of their father, is striking. The seat of honour occupied by Hrothulf[31] is contrasted with the undistinguished place of his two young cousins, sitting among the giogoth[32]. Nevertheless Hrothgar and his wife expect their son, not their nephew, to succeed to the throne[33]. Very small acquaintance with the history of royal houses in these lawless Teutonic times is enough to show us that trouble is likely to be in store.

So much can be made out from the English sources, Beowulf and Widsith. Turning now to the Scandinavian records, we find much confusion as to details, and as to the characters of the heroes: but the relationships are the same as in the Old English poem.

Heorogar is, it is true, forgotten; and though a name Hiarwarus is found in Saxo corresponding to that of Heoroweard, the son of Heorogar, in Beowulf, this Hiarwarus is cut off from the family, now that his father is no longer remembered. Accordingly the Halfdan of Danish tradition (Haldanus in Saxo's Latin: = O.E. Healfdene) has only two sons, Hroar {16}(Saxo's Roe, corresponding to O.E. Hrothgar) and Helgi (Saxo's Helgo: = O.E. Halga). Helgi is the father of Rolf Kraki (Saxo's Roluo: = O.E. Hrothulf), the type of the noble king, the Arthur of Denmark.

And, just as Arthur holds court at Camelot, or Charlemagne is at home ad Ais, à sa capele, so the Scandinavian traditions represent Rolf Kraki as keeping house at Leire (Lethra, Hleiðar garðr).

Accounts of all these kings, and above all of Rolf Kraki, meet us in a number of Scandinavian documents, of which three are particularly important:

(1) Saxo Grammaticus (the lettered), the earlier books of whose Historia Danica are a storehouse of Scandinavian tradition and poetry, clothed in a difficult and bombastic, but always amusing, Latin. How much later than the English these Scandinavian sources are, we can realize by remembering that when Saxo was putting the finishing touches to his history, King John was ruling in England.

There are also a number of other Danish-Latin histories and genealogies.

(2) The Icelandic Saga of Rolf Kraki, a late document belonging to the end of the middle ages, but nevertheless containing valuable matter.

(3) The Icelandic Skjoldunga saga, extant only in a Latin summary of the end of the sixteenth century.

Section IV. Leire and Heorot.

The village of Leire remains to the present day. It stands near the north coast of the island of Seeland, some five miles from Roskilde and three miles from the sea, in a gentle valley, through the midst of which flows a small stream. The village itself consists of a tiny cluster of cottages: the outstanding feature of the place is formed by the huge grave mounds scattered around in all directions.

The tourist, walking amid these cottages and mounds, may feel fairly confident that he is standing on the site of Heorot.

There are two distinct stages in this identification: it must be proved (a) that the modern Leire occupies the site of the Leire (Lethra) where Rolf Kraki ruled, and (b) that the Leire of Rolf Kraki was built on the site of Heorot.

(a) That the modern Leire occupies the site of the ancient Leire has indeed been disputed[34], but seems hardly open to doubt, in view of the express words of the Danish chroniclers[35]. It is true that the mounds, which these early chroniclers probably imagined as covering the ashes of 'Haldanus' or 'Roe,' and which later antiquaries dubbed with the names of other kings, are now thought to belong, not to the time of Hrothgar, but to the Stone or Bronze Ages. But this evidence that Leire was a place of importance thousands of years before Hrothgar or Hrothulf were born, in no wise invalidates the overwhelming evidence that it was their residence also.

The equation of the modern Leire with the Leire of Rolf Kraki we may then accept. We cannot be quite so sure of our thesis (b): that the ancient Leire was identical with the site where Hrothgar built Heorot. But it is highly probable: for although Leire is more particularly connected with the memory of Rolf Kraki himself, we are assured, in one of the mediæval Danish chronicles, that Leire was the royal seat of Rolf's predecessors as well: of Ro (Hrothgar) and of Ro's father: and that Ro "enriched it with great magnificence[36]." Ro also, according to this chronicler, heaped a mound at Leire over the grave of his father, and was himself buried at Leire under another mound.

Now since the Danish tradition represents Hrothgar as enriching his royal town of Leire, whilst English tradition commemorates him as a builder king, constructing a royal hall "greater than the sons of men had ever heard speak of"—it becomes very probable that the two traditions are reflections of the same fact, and that the site of that hall was Leire. That Heorot, the picturesque name of the hall itself, should, in English tradition, have been remembered, whilst that of the town where it was built had been forgotten, is natural[37]. For {18}though the names of heroes survived in such numbers, after the settlement of the Angles in England, it was very rarely indeed, so far as we can judge, that the Angles and Saxons continued to have any clear idea concerning the places which had been familiar to their forefathers, but which they themselves had never seen.

Further, the names of both Hrothgar and Hrothulf are linked with Heorot in English tradition in the same way as those of Roe and Rolf are with Leire in Danish chronicles.

Yet there is some little doubt, though not such as need seriously trouble us, as to this identification of the site of Heorot with Leire. Two causes especially have led students to doubt the connection of Roe (Hrothgar) with Leire, and to place elsewhere the great hall Heorot which he built.

In the first place, Rolf Kraki came to be so intimately associated with Leire that his connection overshadowed that of Roe, and Saxo even goes so far in one place as to represent Leire as having been founded by Rolf[38]. In that case Leire clearly could not be the place where Rolf's predecessor built his royal hall. But that Saxo is in error here seems clear, for elsewhere he himself speaks of Leire as being a Danish stronghold when Rolf was a child[39].

In the second place, Roe is credited with having founded the neighbouring town of Roskilde (Roe's spring)[40] so that some have wished to locate Heorot there, rather than at Leire, five miles to the west. But against this identification of Heorot with Roskilde it must be noted that Roe is said to have built Roskilde, not as a capital for himself, but as a market-place for the merchants: there is no suggestion that it was his royal town, though in time it became the capital, and its cathedral is still the Westminster Abbey of Denmark.

What at first sight looks so much in favour of our equating {19}Roskilde with Heorot—the presence in its name of the element Ro (Hrothgar)—is in reality the most suspicious thing about the identification. There are other names in Denmark with the element Ro, in places where it is quite impossible to suppose that the king's name is commemorated. Some other explanation of the name has therefore to be sought, and it is very probable that Roskilde meant originally not "Hrothgar's spring," but "the horses' spring," and that the connection with King Ro is simply one of those inevitable pieces of popular etymology which take place so soon as the true origin of a name is forgotten[41].

Leire has, then, a much better claim than Roskilde to being the site of Heorot: and geographical considerations confirm this. For Heorot is clearly imagined by the poet of Beowulf as being some distance inland; and this, whilst it suits admirably the position of Leire, is quite inapplicable to Roskilde, which is situated on the sea at the head of the Roskilde fjord[42]. Of course we must not expect to find the poet of Beowulf, or indeed any epic poet, minutely exact in his geography. At the same time it is clear that at the time Beowulf was written there were traditions extant, dealing with the attack made upon Heorot by the ancestral foes of the Danes, a tribe called the Heathobeardan. These accounts of the fighting around Heorot must have preserved the general impression of its situation, precisely as from the Iliad we know that Troy is neither on the sea nor yet very remote from it. A poet would draw on his imagination for details, but would hardly alter a feature like this.

In these matters absolute certainty cannot be reached: but we may be fairly sure that the spot where Hrothgar built his "Hart-Hall" and where Hrothulf held that court to which the North ever after looked for its pattern of chivalry was {20}Leire, where the grave mounds rise out of the waving cornfields[43].

Section V. The Heathobeardan.

Now, as Beowulf is the one long Old English poem which happens to have been preserved, we, drawing our ideas of Old English story almost exclusively from it, naturally think of Heorot as the scene of the fight with Grendel.

But in the short poem of Widsith, almost certainly older than Beowulf, we have a catalogue of the characters of the Old English heroic poetry. This catalogue is dry in itself, but is of the greatest interest for the light it throws upon Old Germanic heroic legends and the history behind them. And from Widsith it is clear that the rule of Hrothgar and Hrothulf at Heorot and the attack of the Heathobeardan upon them, rather than any story of monster-quelling, was what the old poets more particularly associated with the name of Heorot. The passage in Widsith runs:

"For a very long time did Hrothgar and Hrothwulf, uncle and nephew, hold the peace together, after they had driven away the race of the Vikings and humbled the array of Ingeld, had hewed down at Heorot the host of the Heathobeardan."

The details of this war can be reconstructed, partly from the allusions in Beowulf, partly from the Scandinavian accounts. The Scandinavian versions are less primitive and historic. They have forgotten all about the Heathobeardan as an independent tribe, and, whilst remembering the names of the leading chieftains on both sides, they see in them members of two rival branches of the Danish royal house.

We gather from Beowulf that for generations a blood feud has raged between the Danes and the Heathobeardan. Nothing is told us in Beowulf about the king Healfdene, except that he {21}was fierce in war and that he lived to be old. From the Scandinavian stories it seems clear that he was concerned in the Heathobard feud. According to some later Scandinavian accounts he was slain by Frothi (=Froda, whom we know from Beowulf to have been king of the Heathobeardan) and this may well have been the historic fact[44]. How Hroar and Helgi (Hrothgar and Halga), the sons of Halfdan (Healfdene), evaded the pursuit of Frothi, we learn from the Scandinavian tales; whether the Old English story knew anything of their hair-breadth escapes we cannot tell. Ultimately, the saga tells us, Hroar and Helgi, in revenge for their father's death, burnt the hall over the head of his slayer, Frothi[45]. To judge from the hints in Beowulf, it would rather seem that the Old English tradition represented this vengeance upon Froda as having been inflicted in a pitched battle. The eldest brother Heorogar—known only to the English story—perhaps took his share in this feat. But, after his brothers Heorogar and Halga were dead, Hrothgar, left alone, and fearing vengeance in his turn, strove to compose the feud by wedding his daughter Freawaru to Ingeld, the son of Froda. So much we learn from the report which Beowulf gives, on his return home, to Hygelac, as to the state of things at the Danish court.

Beowulf is depicted as carrying a very sage head upon his young shoulders, and he gives evidence of his astuteness by predicting[46] that the peace which Hrothgar has purchased will not be lasting. Some Heathobard survivor of the fight in which Froda fell, will, he thinks, see a young Dane in the retinue of Freawaru proudly pacing the hall, wearing the treasures which his father had won from the Heathobeardan. Then the old warrior will urge on his younger comrade "Canst thou, my lord, tell the sword, the dear iron, which thy father carried to the fight when he bore helm for the last time, when the Danes slew him and had the victory? And now the son {22}of one of these slayers paces the hall, proud of his arms, boasts of the slaughter and wears the precious sword which thou by right shouldst wield[47]."

Such a reminder as this no Germanic warrior could long resist. So, Beowulf thinks, the young Dane will be slain; Ingeld will cease to take joy in his bride; and the old feud will break out afresh.

That it did so we know from Widsith, and from the same source we know that this Heathobard attack was repulsed by the combined strength of Hrothgar and his nephew Hrothulf.

But the tragic figure of Ingeld, hesitating between love for his father and love for his wife, between the duty of vengeance and his plighted word, was one which was sure to attract the interest of the old heroic poets more even than those of the victorious uncle and nephew. In the eighth century Alcuin, the Northumbrian, quotes Ingeld as the typical hero of song. Writing to a bishop of Lindisfarne, he reproves the monks for their fondness for the old stories about heathen kings, who are now lamenting their sins in Hell: "in the Refectory," he says, "the Bible should be read: the lector heard, not the harper: patristic sermons rather than pagan songs. For what has Ingeld to do with Christ[48]?" This protest testifies eloquently to the popularity of the Ingeld story, and further evidence is possibly afforded by the fact that few heroes of story seem to have had so many namesakes in Eighth Century England.

What is emphasized in Beowulf is not so much the struggle in the mind of Ingeld as the stern, unforgiving temper of the grim old warrior who will not let the feud die down; and this is the case also with the Danish versions, preserved to us in the Latin of Saxo Grammaticus. In two songs (translated by Saxo into "delightful sapphics") the old warrior Starcatherus stirs up Ingellus to his revenge:

"Why, Ingeld, buried in vice, dost thou delay to avenge thy father? Wilt thou endure patiently the slaughter of thy righteous sire?...

Whilst thou takest pleasure in honouring thy bride, laden with gems, and bright with golden vestments, grief torments us, coupled with shame, as we bewail thine infamies.

Whilst headlong lust urges thee, our troubled mind recalls the fashion of an earlier day, and admonishes us to grieve over many things.

For we reckon otherwise than thou the crime of the foes, whom now thou holdest in honour; wherefore the face of this age is a burden to me, who have known the old ways.

By nought more would I desire to be blessed, if, Froda, I might see those guilty of thy murder paying the due penalty of such a crime[49]."

Starkath came to be one of the best-known figures in Scandinavian legend, the type of the fierce, unrelenting warrior. Even in death his severed head bit the earth: or according to another version "the trunk fought on when the head was gone[50]." Nor did the Northern imagination leave him there. It loved to follow him below, and to indulge in conjectures as to his bearing in the pit of Hell[51].

Who the Heathobeardan were is uncertain. It is frequently argued that they are identical with the Longobardi; that the words Heatho-Bard and Long-Bard correspond, just as we get sometimes Gar-Dene, sometimes Hring-Dene. (So Heyne; Bremer in Pauls Grdr. (2) III, 949 etc.) The evidence for this is however unsatisfactory (see Chambers, Widsith, 205). Since the year 186 A.D. onwards the Longobardi were dwelling far inland, and were certainly never in a position from which an attack upon the Danes would have been practicable. If, therefore, we accept the identification of Heatho-Bard and Long-Bard, we must suppose the Heathobeardan of Beowulf to have been not the Longobardi of history, but a separate portion of the people, which had been left behind on the shores of the Baltic, when the main body went south. But as we have no evidence for any such offshoot from the main tribe, it is misleading to speak of the Heathobeardan as identical with the Longobardi: and although the similarity of one element in the name suggests some primitive relationship, that relationship may well have been exceedingly remote[52].

It has further been proposed to identify the Heathobeardan with the Heruli[53]. The Heruli came from the Scandinavian district, overran Europe, and became famous for their valour, savagery, and value as light-armed troops. If the Heathobeardan are identical with the Heruli, and if what we are told of the customs of the Heruli is true, Freawaru was certainly to be pitied. The Heruli were accustomed to put to death their sick and aged: and to compel widows to commit suicide.

The supposed identity of the Heruli with the Heathobeardan is however very doubtful. It rests solely upon the statement of Jordanes that they had been driven from their homes by the Danes (Dani ... Herulos propriis sedibus expulerunt). This is inconclusive, since the growth of the Danish power is likely enough to have led to collisions with more than one tribe. In fact Beowulf tells us that Scyld "tore away the mead benches from many a people." On the other hand the dissimilarity of names is not conclusive evidence against the identification, for the word Heruli is pretty certainly the same as the Old English Eorlas, and is a complimentary nick-name applied by the tribe to themselves, rather than their original racial designation.

Nothing, then, is really known of the Heathobeardan, except that evidence points to their having dwelt somewhere on the Baltic[54].

The Scandinavian sources which have preserved the memory of this feud have transformed it in an extraordinary way. The Heathobeardan came to be quite forgotten, although maybe some trace of their name remains in Hothbrodd, who is represented as the foe of Roe (Hrothgar) and Rolf (Hrothulf). When the Heathobeardan were forgotten, Froda and Ingeld were left without any subjects, and naturally came to be regarded, like Healfdene and the other kings with whom they were associated in story, as Danish kings. Accordingly the tale developed in Scandinavian lands in two ways. Some documents, and especially the Icelandic ones[55], represent the struggle as a feud between two branches of the Danish royal house. Even here there is no agreement who is the usurper and who the victim, so that sometimes it is Froda and sometimes Healfdene who is represented as the traitor and murderer.

But another version[56]—the Danish—whilst making Froda and Ingeld into Danish kings, separates their story altogether from that of Healfdene and his house: in this version the quarrel is still thought of as being between two nations, not as between the rightful heir to the throne and a treacherous and relentless usurper. Accordingly the feud is such as may be, at any rate temporarily, laid aside: peace between the contending parties is not out of the question. This version therefore preserves much more of the original character of the story, for it remains the tale of a young prince who, willing to marry into the house of his ancestral foes and to forgive and forget the old feud, is stirred by his more unrelenting henchman into taking vengeance for his father. But, owing to the prince having come to be represented as a Dane, patriotic reasons have suggested to the {25}Danish poets and historians a quite different conclusion to the story. Instead of being routed, Ingeld, in Saxo, is successful in his revenge.

See Neckel, Studien über Froði in Z.f.d.A. XLVIII, 182: Heusler, Zur Skiöldungendichtung in Z.f.d.A. XLVIII, 57: Olrik, Skjoldungasaga, 1894, 112 [30]; Olrik, Heltedigtning, II, 11 etc.: Olrik, Sakses Oldhistorie, 222-6: Chambers, Widsith, pp. 79-81.]

Section VI. Hrothulf.

Yet, although the Icelandic sources are wrong in representing Froda and Ingeld as Danes, they are not altogether wrong in representing the Danish royal house as divided against itself. Only they fail to place the blame where it really lay. For none of the Scandinavian sources attribute any act of injustice or usurpation to Rolf Kraki. He is the ideal king, and his title to the throne is not supposed to be doubtful.

Yet we saw that, in Beowulf, the position of Hrothulf is represented as an ambiguous one[57], he is the king's too powerful nephew, whose claims may prejudice those of his less distinguished young cousins, the king's sons, and the speech of queen Wealhtheow is heavy with foreboding. "I know," she says, "that my gracious Hrothulf will support the young princes in honour, if thou, King of the Scyldings, shouldst leave the world sooner than he. I ween that he will requite our children, if he remembers all which we two have done for his pleasure and honour, being yet a child[58]." Whilst Hrethric and Hrothmund, the sons of King Hrothgar, have to sit with the juniors, the giogoth[59], Hrothulf is a man of tried valour, who sits side by side with the king: "where the two good ones sat, uncle and nephew: as yet was there peace between them, and each was true to the other[60]."

Again we have mention of "Hrothgar and Hrothulf. Heorot was filled full of friends: at that time the mighty Scylding folk in no wise worked treachery[61]." Similarly in Widsith the mention of Hrothgar and Hrothulf together seems to stir the poet to dark sayings. "For a very long time did Hrothgar and Hrothulf, uncle and nephew, hold the peace together[62]."

The statement that "as yet" or "for a very long time" or "at that time" there was peace within the family, necessarily implies that, at last, the peace was broken, that Hrothulf quarrelled with Hrothgar, or strove to set aside his sons[63].

Further evidence is hardly needed; yet further evidence we have: by rather complicated, but quite unforced, fitting together of various Scandinavian authorities, we find that Hrothulf deposed and slew his cousin Hrethric.

Saxo Grammaticus tells us how Roluo (Rolf = O.N. Hrolfr, O.E. Hrothulf) slew a certain Røricus (or Hrærek = O.E. Hrethric) and gave to his own followers all the plunder which he found in the city of Røricus. Saxo is here translating an older authority, the Bjarkamál (now lost), and he did not know who Røricus was: he certainly did not regard him as a son or successor of Roe (Hrothgar) or as a cousin of Roluo (Hrothulf). "Roluo, who laid low Røricus the son of the covetous Bøkus" is Saxo's phrase (qui natum Bøki Røricum stravit avari). This would be a translation of some such phrase in the Bjarkamál as Hræreks bani hnøggvanbauga, "the slayer of Hrærek Hnoggvanbaugi[64]."

But, when we turn to the genealogy of the Danish kings[65], we actually find a Hrærekr Hnauggvanbaugi given as a king of Denmark about the time of Roluo. This Røricus or Hrærekr who was slain by Roluo was then, himself, a king of the Danes, and must, therefore, have preceded Roluo on the throne. But in that case Røricus must be son of Roe, and identical with his namesake Hrethric, the son of Hrothgar, in Beowulf. For no one but a son of King Roe could have had such a claim to the throne as to rule between that king and his all powerful nephew Roluo[65].

It is difficult, perhaps, to state this argument in a way which will be convincing to those who are not acquainted with Saxo's method of working. To those who realize how he treats {27}his sources, it will be clear that Røricus is the son of Roe, and is slain by Roluo. Translating the words into their Old English equivalents, Hrethric, son of Hrothgar, is slain by Hrothulf.

The forebodings of Wealhtheow were justified.

Hrethric is then almost certainly an actual historic prince who was thrust from the throne by Hrothulf. Of Hrothmund[66], his brother, Scandinavian authorities seem to know nothing. He is very likely a poetical fiction, a duplicate of Hrethric. For it is very natural that in story the princes whose lives are threatened by powerful usurpers should go in pairs. Hrethric and Hrothmund go together like Malcolm and Donalbain. Their helplessness is thus emphasized over against the one mighty figure, Rolf or Macbeth, threatening them[67].

Yet this does not prove Hrothmund unhistoric. On the contrary it may well happen that the facts of history will coincide with the demands of well-ordered narrative, as was the case when Richard of Gloucester murdered two young princes in the Tower.

Two other characters, who meet us in Beowulf, seem to have some part to play in this tragedy.

It was a maxim of the old Teutonic poetry, as it is of the British Constitution, that the king could do no wrong: the real fault lay with the adviser. If Ermanaric the Goth slew his wife and his son, or if Irminfrid the Thuringian unwisely challenged Theodoric the Frank to battle, this was never supposed to be due solely to the recklessness of the monarch himself—it was the work of an evil counsellor—a Bikki or an Iring. Now we have seen that there is mischief brewing in Heorot—and we are introduced to a counsellor Unferth, the thyle or official spokesman and adviser of King Hrothgar. And Unferth is evil. His jealous temper is shown by the hostile and inhospitable reception which he gives to Beowulf. And Beowulf's reply gives us a hint of some darker stain: "though {28}thou hast been the slayer of thine own brethren—thy flesh and blood: for that thou shalt suffer damnation in hell, good though thy wit may be[68]." One might perhaps think that Beowulf in these words was only giving the "countercheck quarrelsome," and indulging in mere reckless abuse, just as Sinfjotli (the Fitela of Beowulf) in the First Helgi Lay hurls at his foes all kinds of outrageous charges assuredly not meant to be taken literally. But, as we learn from the Helgi Lay itself, the uttering of such unfounded taunts was not considered good form; whilst it seems pretty clear that the speech of Beowulf to Unferth is intended as an example of justifiable and spirited self-defence, not, like the speech of Sinfjotli, as a storehouse of things which a well-mannered warrior should not say.

Besides, the taunt of Beowulf is confirmed, although but darkly, by the poet himself, in the same passage in which he has recorded the fears of Wealhtheow lest perhaps Hrothulf should not be loyal to Hrothgar and his issue: "Likewise there Unferth the counsellor sat at the foot of the lord of the Scyldingas: each of them [i.e. both Hrothgar and Hrothulf] trusted to his spirit: that his courage was great, though he had not done his duty by his kinsmen at the sword-play[69]."

But, granting that Unferth has really been the cause of the death of his kinsmen, some scholars have doubted whether we are to suppose that he literally slew them himself. For, had that been the case, they urge, he could not be occupying a place of trust with the almost ideal king Hrothgar. But the record of the historians makes it quite clear that murder of kin did happen, and that constantly[70]. Amid the tragic complexities of heroic life it often could not be avoided. The comitatus-system, by which a man was expected to give unflinching support to any chief whose service he had entered, must often have resulted in slaughter between men united by very close bonds of kin or friendship. Turning from history to saga, we find some of the greatest heroes not free from the stain. Sigmund, {29}Gunnar, Hogni, Atli, Hrothulf, Heoroweard, Hnæf, Eadgils, Hæthcyn, Ermanaric and Hildebrand were all marred with this taint, and indeed were, in many cases, rather to be pitied than blamed. I doubt, therefore, whether we need try and save Unferth's character by suggesting that the stern words of the poet mean only that he had indirectly caused the death of his brethren by failing them, in battle, at some critical moment[71]. I suspect that this, involving cowardice or incompetence, would have been held the more unpardonable offence, and would have resulted in Unferth's disgrace. But a man might well have slain his kin under circumstances which, while leaving a blot on his record, did not necessitate his banishment from good society. All the same, the poet evidently thinks it a weakness on the part of Hrothgar and Hrothulf that, after what has happened, they still put their trust in Unferth.

Here then is the situation. The king has a counsellor: that counsellor is evil. Both the king and his nephew trust the evil counsellor. A bitter feud springs up between the king and his nephew. That the feud was due to the machinations of the evil adviser can hardly be doubted by those who have studied the ways of the old Germanic heroic story. But it is only an inference: positive proof we have none.

Lastly, there is Heoroweard. Of him we are told in Beowulf very little. He is son of Heorogar (or Heregar), Hrothgar's elder brother, who was apparently king before him, but died young[72]. It is quite natural, as we have seen, that, if Heoroweard was too young for the responsibility when his father died, he should not have succeeded to the throne. What is not so natural is that he does not inherit his father's arms, which one might reasonably have supposed Hrothgar would have preserved, to give to him when he came of age. Instead, Hrothgar gives them to Beowulf[73]. Does Hrothgar deliberately avoid doing honour to Heoroweard, because he fears that any distinction conferred upon him would strengthen a rival {30}whose claims to the throne might endanger those of his own sons? However this may be, in any future struggle for the throne Heoroweard may reasonably be expected to play some part.

Turning now to Saxo, and to the Saga of Rolf Kraki, we find that Rolf owed his death to the treachery of one whose name corresponds exactly to that of Heoroweard—Hiarwarus (Saxo), Hjǫrvarthr (Saga). Neither Saxo nor the Saga thinks of Hiarwarus as the cousin of Rolf Kraki: they do not make it really clear what the cause of his enmity was. But they tell us that, after a banquet, he and his men treacherously rose upon Rolf and his warriors. The defence which Rolf and his men put up in their burning hall: the loyalty and defiance of Rolf's champions, invincible in death—these were amongst the most famous things of the North; they were told in the Bjarkamál, now unfortunately extant in Saxo's paraphrase only.

But the triumph of Hiarwarus was brief. Rolf's men all fell around him, save the young Wiggo, who had previously, in the confidence of youth, boasted that, should Rolf fall, he would avenge him. Astonished at the loyalty of Rolf's champions, Hiarwarus expressed regret that none had taken quarter, declaring that he would gladly accept the service of such men. Whereupon Wiggo came from the hiding-place where he had taken refuge, and offered to do homage to Hiarwarus, by placing his hand on the hilt of his new lord's sword: but in doing so he drove the point through Hiarwarus, and rejoiced as he received his death from the attendants of the foe he had slain. It shows how entirely the duty of vengeance was felt to outweigh all other considerations, that this treacherous act of Wiggo is always spoken of with the highest praise.

For the story of the fall of Rolf and his men see Saxo, Book II (ed. Holder, pp. 55-68): Saga of Rolf Kraki, caps. 32-34: Skjoldunga Saga (ed. Olrik, 1894, 36-7 [118-9]).

How the feud between the different members of the Danish family forms the background to Beowulf was first explained in full detail by Ludvig Schrøder (Om Bjovulfs-drapen. Efter en række foredrag på folke-höjskolen i Askov, Kjøbenhavn, 1875). Schrøder showed how the bad character of Unferth has its part to play: "It is a weakness in Hrothgar that he entrusts important office to such a man—a {31}weakness which will carry its punishment." Independently the domestic feud was demonstrated again by Sarrazin (Rolf Krake und sein vetter im Beowulfliede: Engl. Stud. XXIV, 144-5). The story has been fully worked out by Olrik (Heltedigtning, 1903, I, 11-18 etc.).

These views have been disputed by Miss Clarke (Sidelights, 102), who seems to regard as "hypotheses" of Olrik data which have been ascertained facts for more than a generation. Miss Clarke's contentions, however, appear to me to be based upon a misunderstanding of Olrik.

Section VII. King Offa.

The poem, then, is mainly concerned with the deeds of Geatic and Danish kings: only once is reference made to a king of Anglian stock—Offa.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us of several kings named Offa, but two only concern us here. Still remembered is the historic tyrant-king who reigned over Mercia during the latter half of the eighth century, and who was celebrated through the Middle Ages chiefly as the founder of the great abbey of St Albans. This Offa is sometimes referred to as Offa the Second, because he had a remote ancestor, Offa I, who, if the Mercian pedigree can be trusted, lived twelve generations earlier, and therefore presumably in the latter half of the fourth century. Offa I, then, must have ruled over the Angles whilst they were still dwelling in Angel, their continental home, in or near the modern Schleswig.

Now the Offa mentioned in Beowulf is spoken of as related to Garmund and Eomer (MS geomor). This, apart from the abundant further evidence, is sufficient to identify him with Offa I, who was, according to the pedigree, the son of Wærmund and the grandfather of Eomer.

This Offa I, king of Angel, is referred to in Widsith. Widsith is a composite poem: the passage concerning Offa, though not the most obviously primitive portion of it, is, nevertheless, early: it may well be earlier than Beowulf. After a list of famous chieftains we are told:

Offa ruled Angel, Alewih the Danes; he was the boldest of all these men, yet did he not in his deeds of valour surpass Offa. But Offa gained, first of men, by arms the greatest of kingdoms whilst yet a boy; no one of equal age ever did greater deeds of valour in battle with his single sword: he drew the boundary against the Myrgingas at Fifeldor. The boundaries were held afterwards by the Angles and the Swæfe as Offa struck it out.

Much is obscure here: more particularly our ignorance as to the Myrgingas is to be regretted: but there is reason for thinking that they were a people dwelling to the south of the old continental home of the Angles.

After the lapse of some five centuries, we get abundant further information concerning Offa. The legends about him, though carried to England by the Anglian conquerors, must also have survived in the neighbourhood of his old kingdom of Angel: for as Angel was incorporated into the Danish kingdom, so these stories became part of the stock of Danish national legend. Offa came to be regarded as a Danish king, and his story is told at length by the two earliest historians of Denmark, Sweyn Aageson and Saxo Grammaticus. In Saxo the story runs thus: