The Project Gutenberg EBook of Impertinent Poems, by Edmund Vance Cooke

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Impertinent Poems

Author: Edmund Vance Cooke

Illustrator: Gordon Ross

Release Date: September 20, 2010 [EBook #33770]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IMPERTINENT POEMS ***

Produced by Barbara Tozier, Bill Tozier, Josephine Paolucci

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net.

Page 57.

Page 57.

Impertinent Poems

By

Edmund Vance Cooke

Author of

"Chronicles of the Little Tot"

"Told to the Little Tot"

"Rimes to Be Read"

Etc.

With Illustrations by

Gordon Ross

Death comes with a crawl, or comes with a pounce,

And whether he's slow, or spry,

It isn't the fact that you're dead that counts

But only—how did you die?

New York

Dodge Publishing Company

220 East 23rd Street

Copyright, 1903, by

Edmund Vance Cooke

Copyright, 1907, by

Dodge Publishing Company

A PRE-IMPERTINENCE.

Anticipating the intelligent critic of "Impertinent Poems," it may well

be remarked that the chief impertinence is in calling them poems. Be

that as it may, the editors and publishers of "The Saturday Evening

Post," "Success" and "Ainslee's," and, in a lesser degree,

"Metropolitan," "Independent," "Booklovers'" and "New York Herald" share

with the author the reproach of first promoting their publicity. That

they are now willing to further reduce their share of the burden by

dividing it with the present publishers entitles them to the thanks of

the author and the gratitude of the book-buying public.

E. V. C.

INDEX.

PAGE

Are You You? 59

Better 83

Between Two Thieves 71

Blood is Red 33

Bubble-Flies, The 61

Choice, The 68

Conscience Pianissimo 47

Conservative, The 40

Critics, The 89

Dead Men's Dust 11

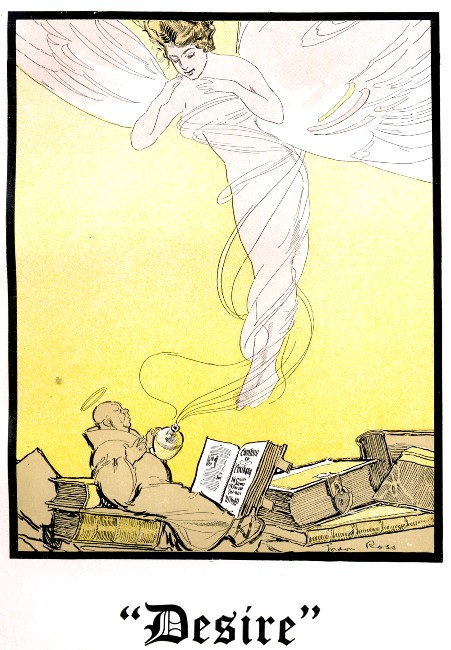

Desire 99

Diagnosis 35

Dilettant, The 38

Distance and Disenchantment 77

Don't Take Your Troubles to Bed 22

Don't You? 16

Eternal Everyday, The 21

Failure 23

Familiarity Breeds Contempt 95

Family Resemblance 79

First Person Singular, The 66

Forget What the Other Man Hath 85

Get Next 57

Good 24

Grill, The 30

How Did You Die? 103

Humbler Heroes 45

Hush 41

In Nineteen Hundred and Now 14

Island, The 43

Let's Be Glad We're Living 26

Move 55

Need 81

Pass 51

Plug 92

Price, The 60

Publicity 53

Qualified 63

Saving Clause, The 70

Song of Rest, A 97

Spectator, The 73

Spread Out 37

Squealer, The 75

Success 28

There Is, Oh, So Much 101

Vision, The 32

What Are You Doing? 65

What Sort Are You? 87

Whet, The 86

World Runs On, The 49

You Too 18

IMPERTINENT POEMS

[Pg 11]

DEAD MEN'S DUST.

You don't buy poetry. (Neither do I.)

Why?

You cannot afford it? Bosh! you spend

Editions de luxe on a thirsty friend.

You can buy any one of the poetry bunch

For the price you pay for a business lunch.

Don't you suppose that a hungry head,

Like an empty stomach, ought to be fed?

Looking into myself, I find this true,

So I hardly can figure it false in you.

[Pg 12]

And you don't read poetry very much.

(Such

Is my own case also.) "But," you cry,

"I haven't the time." Beloved, you lie.

When a scandal happens in Buffalo,

You ponder the details, con and pro;

If poets were pugilists, couldn't you tell

Which of the poets licked John L.?

If poets were counts, could your wife be fooled

As to which of the poets married a Gould?

And even my books might have some hope

If poetry books were books of dope.

"You're a little bit swift," you say to me,

"See!"

You open your library. There you show

Your "favorite poets," row on row,

Chaucer, Shakespeare, Tennyson, Poe,

A Homer unread, an uncut Horace,

A wholly forgotten William Morris.

My friend, my friend, can it be you thought

That these were poets whom you had bought?

These are dead men's bones. You bought their mummies

To display your style, like clothing dummies.

But when do they talk to you? Some one said

That these were poets which should be read,

So here they stand. But tell me, pray,

How many poets who live to-day

[Pg 13]

Have you, of your own volition, sought,

Discovered and tested, proved and bought,

With a grateful glow that the dollar you spent

Netted the poet his ten per cent.?

"But hold on," you say, "I am reading you."

True,

And pitying, too, the sorry end

Of the dog I tried this on. My friend,

I can write poetry—good enough

So you wouldn't look at the worthy stuff.

But knowing what you prefer to read

I'm setting the pace at about your speed,

Being rather convinced these truths will hold you

A little bit better than if I'd told you

A genuine poem and forgotten to scold you.

Besides, when I open my little room

And see my poets, each in his tomb,

With his mouth dust-stopped, I turn from the shelf

And I must scold you, or scold myself.

[Pg 14]

IN NINETEEN HUNDRED AND NOW.

Thomas Moore, at the present date,

Is chiefly known as "a ten-cent straight."

Walter, the Scot, is forgiven his rimes

Because of his tales of stirring times.

William Morris's fame will wear

As a practical man who made a chair.

And even Shakespere's memory's green

Less because he's read than because he's seen.

Then why should a poet make his bow

In the year of nineteen hundred and now?

Homer himself, if he could but speak,

Would admit that most of his stuff is Greek.

Chaucer would no doubt own his tongue

Was the broken speech of the land when young.

Shelley's a sealed-up book, and Byron

Is chiefly recalled as a masculine siren.

Poe has a perch on the chamber door,

But the populace read him "Nevermore."

Spenser fitted his day, as all allow,

But this is nineteen hundred and now.

Tennyson's chiefly given away

To callow girls on commencement day.

Alfred Austin, entirely solemn,

Is quoted most in the funny column.

Riley's Hoosiers have made their pile

And moved to the city to live in style.

[Pg 15]

Kipling's compared to "The Man Who Was,"

And the rest of us write with little cause,

Till publishers shy at talk of per cents.,

But offer to print "at author's expense."

O, once the "celestial fire" burned bright,

But the world now calls for electric light!

And Pegasus, too, is run by meter,

Being trolleyized to make him fleeter.

So I throw the stylus away and set

Myself at the typewriter alphabet

To spell some message I find within

Which shall also scratch your rawhide skin,

For you must read it, if I learn how

To write for nineteen hundred and now.

[Pg 16]

DON'T YOU?

When the plan which I have, to grow suddenly rich

Grows weary of leg and drops into the ditch,

And scheme follows scheme

Like the web of a dream

To glamor and glimmer and shimmer and seem,...

Only seem;

And then, when the world looks unfadably blue,

If my rival sails by

With his head in the sky,

And sings "How is business?" why, what do I do?

Well, I claim that I aim to be honest and true,

But I sometimes lie. Don't you?

[Pg 17]

When something at home is decidedly wrong,

When somebody sings a false note in the song,

Too low or too high,

And, you hardly know why,

But it wrangles and jangles and runs all awry,...

Aye, awry!

And then, at the moment when things are askew,

Some cousin sails in

With a face all a-grin,

And a "Do I intrude? Oh, I see that I do!"

Well, then, though I aim to be honest and true,

Still I sometimes lie. Don't you?

When a man whom I need has some foible or fad,

Not very commendable, not very bad;

Perhaps it's his daughter,

And some one has taught her

To daub up an "oil" or to streak up a "water";

What a "water"!

And her grass is green green and her sky is blue blue,

But her father, with pride,

In a stagey aside

Asks my "candid opinion." Then what do I do?

Well, I claim that I aim to be honest and true,

But I sometimes lie. Don't you?

[Pg 18]

YOU TOO.

Did you ever make some small success

And brag your little brag,

As if your breathing would impress

The world and fix your tag

Upon it, so that all might see

The label loudly reading, "ME!"

And when you thought you'd gained the height

And, sunning in your own delight,

You preened your plumes and crowed "All right!"

Did something wipe you out of sight?

Unless you did this many a time

You needn't stop to read this rime.

When I was mamma's little joy

And not the least bit tough,

I'd sometimes whop some other boy

(If he were small enough),

And for a week I'd wear a chip,

And at the uplift of a lip

I'd lord it like a pigmy pope,

Until, when I had run my rope,

Some bullet-headed little Swope

Would clean me out as slick as soap.

No doubt you were as bad, or worse,

Or else you had not read this verse.

Page 18.

Page 18.

[Pg 19]

All women were like pica print

When I was young and wise;

I'd read their very souls by dint

Of looking in their eyes.

And in those limpid souls I'd see

A very fierce regard for me.

And then—my, my, it makes me faint!—

Peroxide and a pinkish paint

Gave me the hard, hard heart complaint,

I saw the sham, I felt the taint,

Yet if she'd pat me once or twice,

I'd follow like a little fyce.

I never played a little game

And won a five or ten,

But, presto! I was not the same

As common makes of men.

Not Solomon and all his kind

Held half the wisdom of my mind.

And so I'd swell to twice my size,

And throw my hat across my eyes,

And chew a quill, and wear red ties,

And tip you off the stock to rise—

Until, at last, I'd have to steal

The baby's bank to buy a meal.

I speak as if these things remained

All in the perfect tense,

And yet I don't suppose I've gained

A single ounce of sense.

[Pg 20]

I scoff these tales of yesterday

In quite a supercilious way,

But by to-morrow I may bump

Into some newer game and jump!

You'll think I am the only trump

In all the deck until—kerslump!

Unless you'll do the same some time,

Of course you haven't read this rime.

Page 21.

Page 21.

[Pg 21]

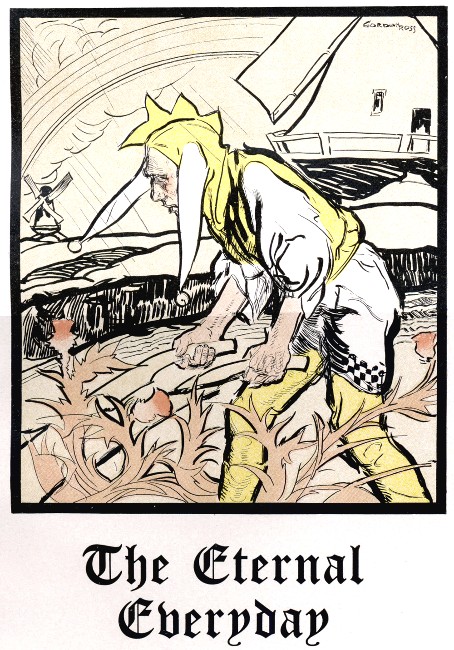

THE ETERNAL EVERYDAY.

O, one might be like Socrates

And lift the hemlock up,

Pledge death with philosophic ease,

And drain the untrembling cup;—

But to be barefoot and be great,

Most in desert and least in state,

Servant of truth and lord of fate!

I own I falter at the peak

Trod daily by the steadfast Greek.

O, one might nerve himself to climb

His cross and cruelly die,

Forgiving his betrayer's crime,

With pity in his eye;—

But day by day and week by week

To feel his power and yet be meek,

Endure the curse and turn the cheek,

I scarce dare trust even you to be

As was the Jew of Galilee.

O, one might reach heroic heights

By one strong burst of power.

He might endure the whitest lights

Of heaven for an hour;—

But harder is the daily drag,

To smile at trials which fret and fag,

And not to murmur—nor to lag.

The test of greatness is the way

One meets the eternal Everyday.

[Pg 22]

DON'T TAKE YOUR TROUBLES TO BED.

You may labor your fill, friend of mine, if you will;

You may worry a bit, if you must;

You may treat your affairs as a series of cares,

You may live on a scrap and a crust;

But when the day's done, put it out of your head;

Don't take your troubles to bed.

You may batter your way through the thick of the fray,

You may sweat, you may swear, you may grunt;

You may be a jack-fool if you must, but this rule

Should ever be kept at the front:—

Don't fight with your pillow, but lay down your head

And kick every worriment out of the bed.

That friend or that foe (which he is, I don't know),

Whose name we have spoken as Death,

Hovers close to your side, while you run or you ride,

And he envies the warmth of your breath;

But he turns him away, with a shake of his head,

When he finds that you don't take your troubles to bed.

[Pg 23]

FAILURE.

What is a failure? It's only a spur

To a man who receives it right,

And it makes the spirit within him stir

To go in once more and fight.

If you never have failed, it's an even guess

You never have won a high success.

What is a miss? It's a practice shot

Which a man must make to enter

The list of those who can hit the spot

Of the bull's-eye in the centre.

If you never have sent your bullet wide,

You never have put a mark inside.

What is a knock-down? A count of ten

Which a man may take for a rest.

It will give him a chance to come up again

And do his particular best.

If you never have more than met your match,

I guess you never have toed the scratch.

GOOD.

[Pg 24]

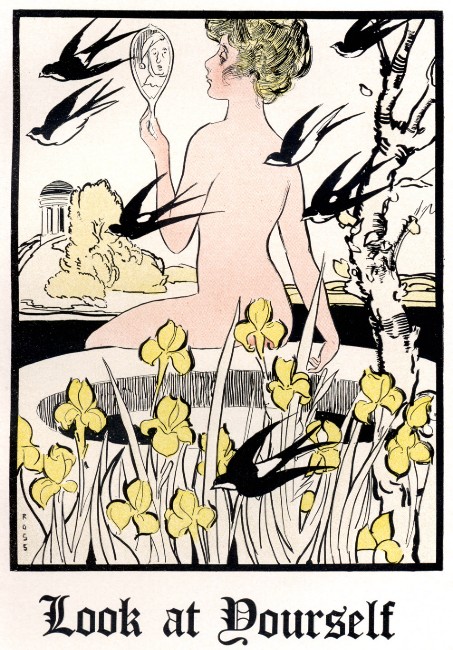

You look at yourself in the glass and say:

"Really, I'm rather distingué.

To be sure my eyes

Are assorted in size,

And my mouth is a crack

Running too far back,

And I hardly suppose

An unclassified nose

Is a mark of beauty, as beauty goes;

But still there's something about the whole

Suggesting a beauty of—well, say soul."

And this is the reason that photograph-galleries

Are able to pay employees' salaries.

Now, this little mark of our brotherhood,

By which each thinks that his looks are good,

Is laudable quite in you and me,

Provided we not only look, but be.

I look at my poem and you hear me say:

"Really, it's clever in its way.

The theme is old

And the style is cold.

These words run rude;

That line is crude;

And here is a rhyme

Which fails to chime,

And the metre dances out of time.

Page 24.

Page 24.

[Pg 25]

Oh, it isn't so bright it'll blind the sun,

But it's better than that by Such-a-one."

And this is the reason I and my creditors

Curse the "unreasoning whims" of editors,

And yet, if one writes for a livelihood,

He ought to believe that his work is good,

Provided the form that his vanity takes

Not only believes, but also makes.

And there is our neighbor. We've heard him say:

"Really, I'm not the commonest clay.

Brown got his dust

By betraying a trust;

And Jones's wife

Leads a terrible life;

While I have heard

That Robinson's word

Isn't quite so good as Gas preferred.

And Smith has a soul with seamy cracks,

For he talks of people behind their backs!"

And these are the reasons the penitentiary

Holds open house for another century.

True, we want no man in our neighborhood

Who doesn't consider his character good,

But then it ought to be also true

He not only knows to consider, but do.

[Pg 26]

LET'S BE GLAD WE'RE LIVING.

I.

Oh, let's be glad that we're living yet; you bet!

The sun runs round and the rain is wet

And the bird flip-flops its wing;

Tennis and toil bring an equal sweat;

It's so much trouble to frown and fret,

So easy to laugh and sing,

Ting ling!

So easy to laugh and sing!

(And yet, sometimes, when I sing my song,

I'm almost afraid my method is wrong.)

II.

Many have money which I have not, God wot!

But victual and keep are all they've got,

And the stars still dot the sky.

Heaven be praised that they shine so bright,

Heaven be praised for an appetite,

So who is richer than I?

Hi yi!

Say, who is richer than I?

(And yet I'm hoping to sell this screed

For several dollars I hardly need.)

III.

Ducats and dividends, stocks and shares, who cares?

Worry and property travel in pairs,

While the green grows on the tree.

A banquet's nothing more than a meal;

[Pg 27]

A trolley's much like an automobile,

With a transfer sometimes free,

Tra lee!

With a transfer sometimes free!

(And yet you're unwilling, I plainly see,

To leave the automobile to me.)

IV.

A note you give and a note you get; don't fret,

For they both may go to protest yet,

And the roses blow perfume.

Fortune is only a Dun report;

The Homestead Law and the Bankrupt Court

Have fostered many a boom,

Boom, boom!

Have fostered many a boom.

(But I see you smile in a rapturous way

On the man who is rated double A.)

V.

Life is a show for you and me; it's free!

And what you look for is what you see;

A hill is a humped-up hollow.

Riches are yours with a dollar bill;

A million's the same little digit still,

With nothing but naughts to follow,

So hollo!

There's nothing but naughts to follow.

(But you and I, as I've said before,

Could get along with a trifle more.)

[Pg 28]

SUCCESS.

It's little the difference where you arrive;

The serious question is how you strive.

Are you up to your eyes in a wild romance?

Does your lady lead you a dallying dance?

Do you question if love be fate, or chance?

Oh, the world will ask: "Did he get the girl?"

Though gentleman, coxcomb, clown or churl,

Master or menial of passion's whirl.

But it isn't that. The world will run

Though you never bequeath it daughter or son,

But what, O lover, will come to you

If you be not chivalrous, honest, true?

As far ahead as a man may think,

You can see your little soul shrivel and shrink.

It's not, "Do you win?"

It is, "What have you been?"

Are you stripped for the world-old, world-wide race

For the metal which shines like the sun's own face

Till it dazzles us blind to the mean and base?

Do you say to yourself, "When I have my hoard,

I will give of the plenty which I have stored,

If the Lord bless me, I will bless the Lord"?

And do you forget, as you pile your pelf,

What is the gift you are giving yourself?

Though your mountain of gold may dazzle the day,

Can you climb its height with your feet of clay?

[Pg 29]

Oh, it isn't the stamp on the metal you win;

It's the stamp on the metal you coin within.

It's not what you give;

It is "What do you live?"

Are you going to sail the polar seas

To the point of ninety-and-north degrees,

Where the very words in your larynx freeze?

Well, the mob may ask "Did he reach the pole?

Though fair, or foul, did he touch the goal?"

But if that be the spirit which stirs your soul,

Off, off from the land below the zeroes;

For you are not of the stuff of heroes.

Ho! many a man can lead men forth

To the fearsome end of the Farthest North,

But can you be faithful for woe or weal

In a land where nothing but self is leal?

Oh, it isn't "How far?"

It is what you are.

And it isn't your lookout where you arrive,

But it's up to you as to how you strive.

[Pg 30]

THE GRILL.

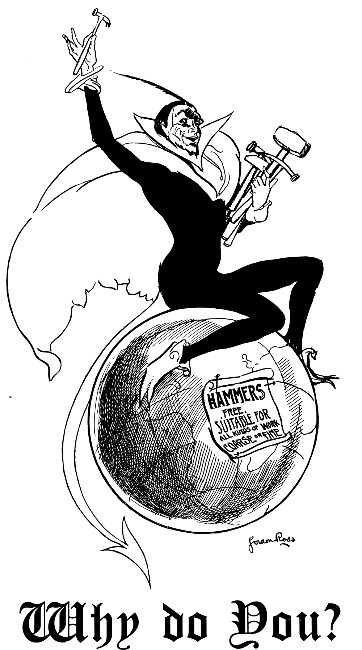

Why do you?

What's it to you?

I know you do, for I've seen the gruesome feeling simmer through you.

I've seen it rise behind your eyes

And take your features by surprise.

I've seen it in your half-hid grin

And the tilting-upness of your chin.

Good-natured though you are and fair, as you have often boasted,

Still you like to hear the other man artistically roasted.

Whenever the star secures the stage with the spotlight in the centre,

Why should the anvil chorus think it has the cue to enter?

Whenever the prima donna trills the E above the clef,

Why should the brasses orchestrate the bass in double f?

It's funny,

But it's even money,

You like to spy the buzzing fly in the other fellow's honey.

Though you have said that honest bread

Demands no honey on it spread,

Page 30.

Page 30.

[Pg 31]

And if we eat the crusty wheat

With appetite, it needs no sweet,

Still I have noticed you were not at all inclined to cry

Because the man the bees had blest was bothered with the fly.

Whenever the chef concocts a dish which sets the world to tasting,

Why does the cooking-school get out its recipes for basting?

Whenever a sprinter beats the bunch from the pistol-shot, why is it

The heavy hammer throwers get together for a visit?

Excuse me!

Did you accuse me

Of turning the spit a little bit myself? Why, you amuse me!

Didn't I scratch the sulphurous match

And blow the flame to make it catch?

Didn't you trot to get the pot

To heat the water good and hot?

Then, seizing on our victim, if we found no greater sin,

Didn't we call him "a lobster," and cheerfully chuck him in?

[Pg 32]

THE VISION.

At the door of Success, I've been tempted to knock

Both the door and the man who went through it,

But I find that the fellow was greasing the lock

All the time that he strove to undo it,

So I either stay out, or must look for the key

Which slipped back the bolt which impeded,

And I'm certain to find it, as soon as I see

The reason my rival succeeded.

Yes, I own when the man is a rank also-ran

That I feel quite pish-tushy and pooh-y,

And exclaim if he ever knew saw-dust from bran,

Well—I come from just west of St. Louis!

But then, in the winning he's made, there's a hope

That I may do even as he did,

So I swallow my sneer and I study his dope

To discover just why he succeeded.

I've been up in the air, I've been down in the hole,

(But always, let's hope, on the level,)

And I've been on my uppers—so meagre my sole

'Twould scarcely have tempted the devil!

But it's nothing to you what I am, or I was,

And no whit of your sympathy's needed,

For I'm certain to win in the long run, because

I shall see how my rival succeeded.

[Pg 33]

BLOOD IS RED.

Some of us don't drink, some of us do;

Some of us use a word or two.

Most of us, maybe, are half-way ripe

For deeds that would't look well in type.

All of us have done things, no doubt,

We don't very often brag about.

We are timidly good, we are badly bold,

But there's hope for the worst of us, I hold,

If there be a few things we didn't do,

For the reason that we so wanted to.

Some of us sin on a smaller scale.

(We don't mind minnows, we shy at a whale.)

We speak of a woman with half a sneer,

We sit on our hands when we ought to cheer.

The salad we mix in the bowl of the heart

We sometimes make a little too tart

For home consumption. We growl, we nag,

But we're not quite lost if we sometimes drag

The hot words back and make them mild

At the moment they fret to be running wild.

Don't pin your faith on the man or woman

Who never is tempted. We're mostly human.

And whoever he be who never has felt

The red blood sing in the veins and melt

The ice of convention, caste and creed,

To the very last barrier, has no need

[Pg 34]

To raise his brows at the rest of us.

It bides its time in the best of us,

And well for him if he do not do

That which the strength of him wants him to.

[Pg 35]

DIAGNOSIS.

You have a grudge against the man

Who did the thing you couldn't do.

You hatched the scheme, you laid the plan,

And yet you couldn't push it through.

You strained your soul and couldn't win;

He gave a breath and it was easy.

You smile and swallow your chagrin,

But, oh, the swallow makes you queasy.

I know your illness, for, you see,

The diet never pleases me.

Your dearest friend has made a strike,

Has placed his mark above the crowd,

Has won the thing which you would like

And you are glad for him, and proud.

Your tongue is swift, your cheek is red,

If some one speak to his detraction,

And yet, the fact the thing is said

Affords you half a satisfaction.

I see the workings of your mind

Because my own is so inclined.

You tell me fame is hollow squeak,

You say that wealth is carking care;

And to live care-free a single week

Is more than years of work and wear.

[Pg 36]

Alexander weeps his highest place,

Diogenes is happy sunning!

What matters it who wins the race

So you have had the joy of running?

And yet, you covet prize and pelf.

I know it, for I do, myself.

[Pg 37]

SPREAD OUT.

In politics I'm a—never mind,

And you are a—I don't care,

But, anyway, I am rather inclined

To suspect we are both unfair;

For I have called you a coward and slave

And you have dubbed me a fool and knave.

(Yet, perhaps I was right, for you surely abused

The right of free speech in the names you used!)

In business you figure—a profit, I guess,

And I charge you—as much as I dare,

And I grumble that you ought to do it for less,

And you ask if my price is fair.

But if I sold your goods and you sold mine,

I doubt if the prices would much decline.

(Though I must insist that I think I see

Where you'd still have a little advantage of me!)

In religion you are a—who cares what?

And I am a—what's the odds?

So why have I sneered at your holiest thought,

And why have you jeered at my gods?

For, thinking it over, I'm sure we two

Were doing the best that we honestly knew.

(Though, of course, I cannot escape a touch

Of suspicion that you never knew too much!)

[Pg 38]

THE DILETTANT.

To lie outright in the light of day

I'm not sufficiently skilful,

But I practice a bit, in an amateur way,

The lie which is hardly wilful;

The society lie and the business lie

And the lie I have had to double,

And the lie that I lie when I don't know why

And the truth is too much trouble.

For this I am willing to take your blame

Unless you have sometimes done the same.

To be a fool of an A1 brand

I'm not sufficiently clever,

But I often have tried my 'prentice hand

In a callow and crude endeavor;

A fool with the money for which I've toiled,

A fool with the word I've spoken,

And the foolish fool who is fooled and foiled

On a maiden's finger broken.

If you never yourself have made a slip,

I'm willing to watch you curl your lip.

And yet my blood and my bone resist

If you dub me fool and liar.

I set my teeth and double my fist

And my brow is flushed with fire.

[Pg 39]

You I deny and you I defy

And I vow I will make you rue it;

And I lie when I say that I never lie,

Which proves me a fool to do it!

You may jerk your thumb at me and grin

If liar and fool you never have been.

[Pg 40]

THE CONSERVATIVE.

At twenty, as you proudly stood

And read your thesis, "Brotherhood,"

If I remember right, you saw

The fatuous faults of social law.

At twenty-five you braved the storm

And dug the trenches of Reform,

Stung by some gadfly in your breast

Which would not let your spirit rest.

At thirty-five you made a pause

To sum the columns of The Cause;

You noted, with unwilling eye,

The heedless world had passed you by.

At forty you had always known

Man owes a duty to His Own.

Man's life is as man's life is made;

The game is fair, if fairly played.

At fifty, after years of stress

You bore the banner of Success.

All men have virtues, all have sins,

And God is with the man who wins.

At sixty, from your captured heights

You fly the flag of Vested Rights,

Bounded by bonds collectable,

And hopelessly respectable!

[Pg 41]

HUSH.

What's the best thing that you ever have done?

The whitest day,

The cleverest play

That ever you set in the shine of the sun?

The time that you felt just a wee bit proud

Of defying the cry of the cowardly crowd

And stood back to back with God?

Aye, I notice you nod,

But silence yourself, lest you bring me shame

That I have no answering deed to name.

What's the worst thing that ever you did?

The darkest spot,

The blackest blot

On the page you have pasted together and hid?

Ah, sometimes you think you've forgotten it quite,

Till it crawls in your bed in the dead of the night

And brands you its own with a blush.

What was it? Nay, hush!

Don't tell it to me, for fear it be known

That I have an answering blush of my own.

But whenever you notice a clean hit made,

Sing high and clear

The sounding cheer

You would gladly have heard for the play you played,

[Pg 42]

And when a man walks in the way forbidden,

Think you of the thing you have happily hidden

And spare him the sting of your tongue.

Do I do that which I've sung?

Well, it may be I don't and it may be I do,

But I'm telling the thing which is good for you!

[Pg 43]

THE ISLAND.

You, my friend, in your long-tailed coat,

With your white cravat at your withered throat,

Praying by proxy of him you hire,

Worshiping God with a quartet choir,

Bumping your head on the pew in front,

Assenting "Amen!" with an unctuous grunt,

Are you sure it is you

In the pew?

Look!

You're away on a lonely isle,

Where the scant breech-clout is the only style,

Where the day of the week forgets its name,

Where god and devil are all the same.

Look at yourself in your careless clout,

And tell me, then, would you be devout?

One on the island, one in the pew—

How do you know which is you?

You, dear maiden, with eyes askance

At the little soubrette and her daring dance,

Thanking God that His ways are wide

To allow you to pass on the other side,

You, as you ask, "Will the world approve?"

At the hint of a wabble out of the groove,

[Pg 44]

Look!

On that isle of the lonely sea

Are you, the saucy soubrette and he.

And the little grooves that you circle in

Are forever as though they never had been.

Now you are naked of soul and limb:

Will you say what you will not dare—for him?

Which of the women is real?

The one you appear, or the one you feel?

You, good sir, with your neck a-stretch,

As the van goes by with the prison wretch,

Asking naught of his ills or hurts,

Judging "he's getting his just deserts,"

Pluming yourself that the moral laws

Are centred in you as effect and cause.

Look!

At the island, and there you are

With the long, strong arm which reaches far,

And there are the natives who kneel and bow,

And where are your meum et tuum now?

Are you sure that the balance swings quite true?

Or does it a little incline to you?

Answer or not as you will, but oh,

I have an island, too, and so

I know, I know.

[Pg 45]

HUMBLER HEROES.

It might not be so difficult to lead the light brigade,

While the army cheered behind you, and the fifes and bugles played;

It might be rather easy, with the war-shriek in your ears,

To forget the bite of bullets and the taste of blood and tears.

But to be a scrubwoman, with four

Babies, or more,

Every day, every day setting your back

On the rack,

And all your reward forever not quite

A full bite

Of bread for your babies. Say!

In the heat of the day

You might be a hero to head a brigade,

But a hero like her? I'm afraid! I'm afraid!

It might be very feasible to force a great reform,

To saddle public passion and to ride upon the storm;

It might be somewhat simple to ignore the roar of wrath,

Because a second shout broke out to cheer you on your path.

But he who, alone and unknown, is true

To his view,

[Pg 46]

Unswerved by the crush of the mutton-browed,

Blatting crowd,

Unwon by the flabby-brained, blinking ease

Which he sees

Throned and anointed. Say!

At the height of the fray,

You might be the chosen to captain the throng:

But to stand all alone? How long? How long?

[Pg 47]

CONSCIENCE PIANISSIMO.

You are honest as daylight. You're often assured

That your word is as good as your note—unsecured.

We could trust you with millions unaudited, but——

(Tut, tut!

There is always a "but,"

So don't get excited,) I'm pained to perceive

It is seldom I notice you grumble or grieve

When the custom-house officer pockets your tip

And passes the contraband goods in your grip.

You would scorn to be shy on your ante, I'm certain,

But skinning your Uncle you're rather expert in.

Well, I'm proud that no taint of the sort touches me.

(For I've never been over the water, you see.)

Your yardstick's a yard and your goods are all wool;

Your bushel's four pecks and you measure it full.

You are proud of your business integrity, yet—

(Don't fret!

There is always a "yet,")

I never have noticed a sign of distress, or

Disturbance in you, when the upright assessor

Has listed your property somewhere about

Half what you would take were you selling it out.

You're as true to the world as the world to its axis,

But you chuckle to swear off your personal taxes.

[Pg 48]

As for me, I would scorn to do any such thing,

(Though I may have considered the question last spring.)

You have notions of right. You would count it a sin

To cheat a blind billionaire out of a pin.

You have a contempt for a pettiness, still—

(Don't chill!

There is always a "still,")

I never have noticed you storm with neglect

Because the conductor had failed to collect,

Or growl that the game wasn't run on the square

When your boy in the high school paid only half fare.

The voice of your conscience is lusty and audible,

But a railroad—good heavens! why, that's only laudable.

Of course, I am quite in a different class;

For me, it is painful to ride on a pass!

[Pg 49]

THE WORLD RUNS ON.

So many good people find fault with God,

Tho' admitting He's doing the best He can,

But still they consider it somewhat odd

That He doesn't consult them concerning his plan,

But the sun sinks down and the sun climbs back,

And the world runs round and round its track.

Or they say God doesn't precisely steer

This world in the way they think is best,

And if He would listen to them, He'd veer

A hair to the sou', sou'west by west.

But the world sails on and it never turns back

And the Mariner never makes a tack.

Or the same folk pray "O, if Thou please,

Dear God, be a little more circumspect;

Thou knowest Thy worm who is on his knees

Would not willingly charge thee with neglect,

But O, if indeed Thou knowest all things,

Why fittest Thou not Thy worm with wings?"

So many good people are quite inclined

To favor God with their best advices,

And consider they're something more than kind

In helping Him out of critical crises.

But the world runs on, as it ran before,

And eternally shall run evermore.

[Pg 50]

So many good people, like you and me,

Are deeply concerned for the sins of others

And conceive it their duty that God should be

Apprised of the lack in erring brothers.

And the myriad sun-stars seed the skies

And look at us out of their calm, clear eyes.

[Pg 51]

PASS.

Did somebody give you a pat on the back?

Pass it on!

Let somebody else have a taste of the snack,

Pass it on!

If it heightens your courage, or lightens your pack,

If it kisses your soul, with a song in the smack,

Maybe somebody else has been dressing in black;

Pass it on!

God gives you a smile, not to make it a yawn;

Pass it on!

Did somebody show you a slanderous mess?

Pass it by!

When a brook's flowing by, will you drink at the cess?

Pass it by!

Dame Gossip's a wanton, whatever her dress;

Her sire was a lie and her dam was a guess,

And a poison is in her polluting caress;

Pass it by!

Unless you're a porker, keep out of the sty.

Pass it by!

Did somebody give you an insolent word?

Pass it up!

'T is the creak of a cricket, the pwit of a bird;

Pass it up!

[Pg 52]

Shake your fist at the sea! Is its majesty blurred?

Blow your breath at the sky! Is its purity slurred?

But the shallowest puddle, how easily stirred!

Pass it up!

Does the puddle invite you to dip in your cup?

Pass it up!

[Pg 53]

PUBLICITY.

There's nothing like publicity

To further that lubricity

Which minted cartwheels need

To maximize their speed

In your direction.

True, some hydropathist of stocks,

Or one whose trade is picking locks,

May make objection:

Yet even those gentry always lurk

Where booming first has done its work.

Observe how oft some foreigner,

About the size of coroner,

Can sell L O R D

(Four letters, as you see,)

For seven numbers,

Because his trade-mark, thus devised,

Is advertised and advertised

Till it encumbers

The mental view, as though 't were some

Bald-headed brand of chewing-gum.

Study your own psychology!

See how some mere tautology

Of picture, or of print,

Has realized the glint

Of your good money.

[Pg 54]

How often have persistent views

Of one bare head sold you your shoes!

Which does seem funny;

And yet 'twas head-work, after all,

Which helped the shoe-man make his haul.

There's some obscure locality

In every man's mentality

Which, I am free to state,

I'd like to penetrate

For my felicity.

For now who gives a second look

When he perceives a POEM by Cooke?

But come publicity!

And then a poem by COOKE were seen

The first thing in the magazine!

Page 55.

Page 55.

[Pg 55]

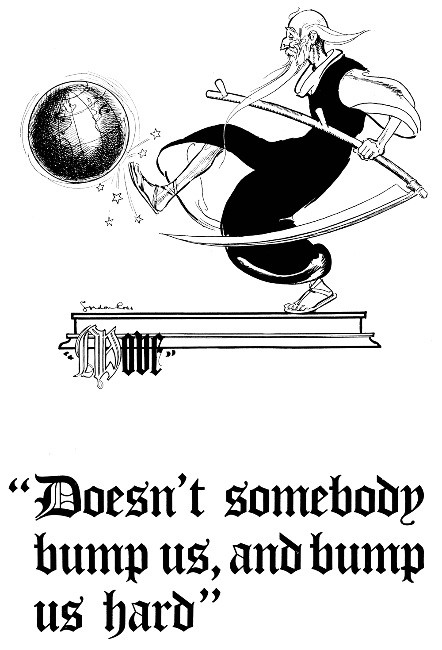

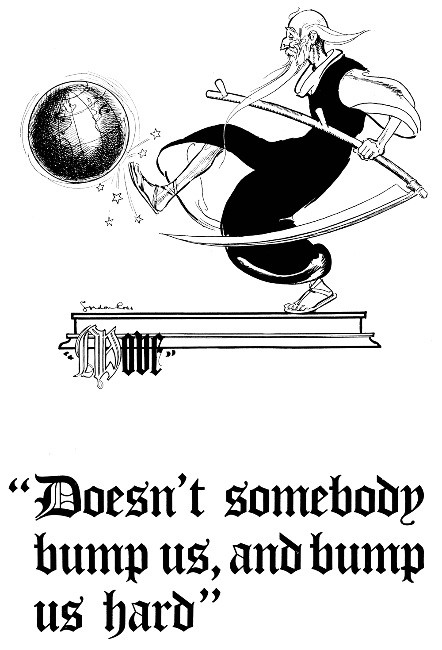

MOVE!

We are on the main line of a crowded track;

We've got to go forward; we can't go back

And run the risk of colliding:

We must make schedule, not now and again,

But always, forever and ever, amen!

Or else switch off on a siding.

If ever we loaf, like a car in the yard,

Doesn't somebody bump us, and bump us hard,

I wonder?

You've succeeded in building a pretty fair trade,

But can you sit down in the grateful shade

And kill time cutting up capers?

Or must you hustle and scheme and sweat,

Though the shine be fine or the weather be wet,

And keep your page in the papers?

If ever you fail to be pulling the strings,

Aren't some of your rivals around doing things,

I wonder?

You're a first-class salesman. You know your line;

Your house is good and your goods are fine,

So you fill your book with orders,

But can you get quit of the ball and chain,

Or are you in jail on a railroad train,

With blue-coated men for warders?

[Pg 56]

If you sent your samples and cut out the trip,

Wouldn't somebody else soon be lugging your grip,

I wonder?

You are starred on the bills and are chummy with fame;

The man on the corner could tell you your name

At three o'clock in the morning,

But can you depend on the mind of the mob?

Can you tell your press-agent to look for a job,

Or give your manager warning?

Should you lie down to sleep, with your laurels beneath,

Wouldn't somebody else soon be wearing your wreath,

I wonder?

Oh, I'm willing to work, but I wish I could lag,

Not feeling as if I were "it" for tag,

Or last in follow-my-leader;

There is only one spot where, I haven't a doubt,

Nobody will try to be crowding me out,

And that is under the cedar.

And even in that place, will Gabriel's trump

Come nagging along and be making me jump?

I wonder.

[Pg 57]

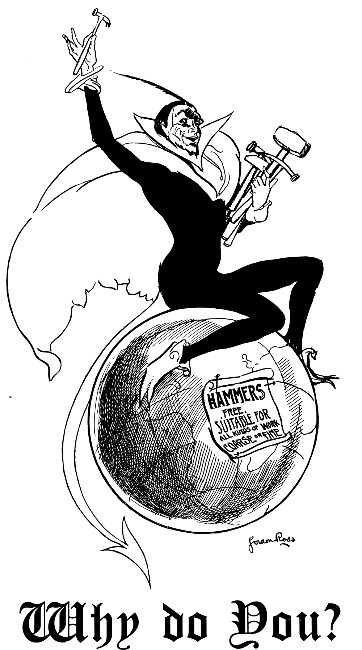

GET NEXT.

Chap. I., verse 1, is where you'll find

The text of what is in my mind

If, haply, you are so inclined.

Chap. I., verse 1—the primal rule

For saint or sinner, sage or fool,

No matter what his church or school.

Though you may call it slangy solely,

Though you may term it flippant wholly,

Truth still is truth and is not vexed;

I write this rhyme to prove the text—

Get Next.

Suppose I sought some lonely height

And dipped a stylus in the light

Of welding worlds and sought to write

Upon the highest, deepest blue

My message to Sam Smith and you.

The chances are it would not do.

You would not risk your neck to read

My much too altitudinous screed,

And I, chagrined and half-perplexed,

Had missed you when I missed my text—

Get Next.

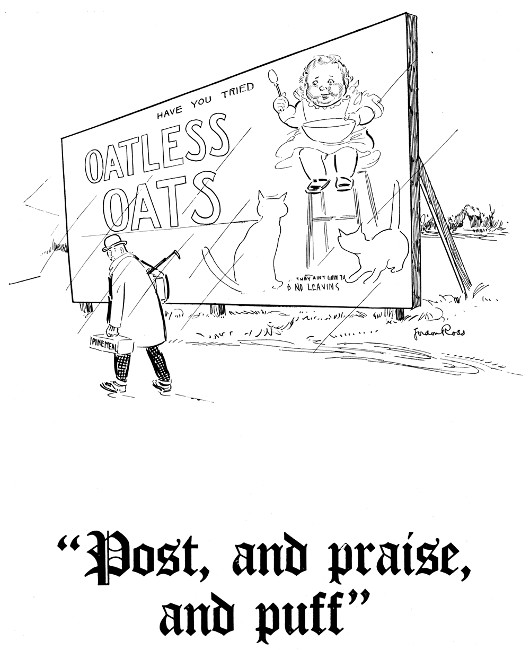

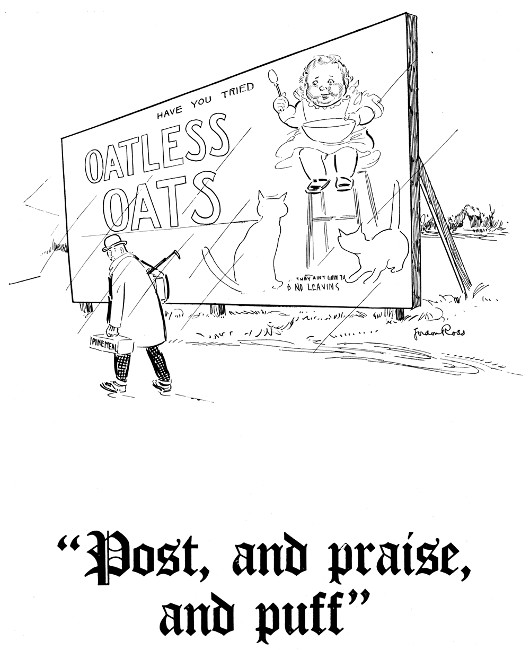

Suppose you have a breakfast food

Which you conceive I should include

Within my lat-and-longitude.

[Pg 58]

'T is not enough to have the stuff,

But you must post, and praise, and puff,

Until I memo. on my cuff,

Among my most important notes—

Be sure to bring home Oatless Oats.

And then you know that I'm annexed,

Because you followed out the text—

Get Next.

Get next! get next! and hold it true

There's one you must get nextest to,

And that important one is you.

Be not of those who, uncommuned

With their own skins, have all but swooned

From some imaginary wound,

But strip the rags from off your soul

And find you are not maimed, but whole!

'T is but a flea-bite which has vexed

As soon as you've applied the text—

Get Next.

Page 58.

Page 58.

Page 59.

Page 59.

[Pg 59]

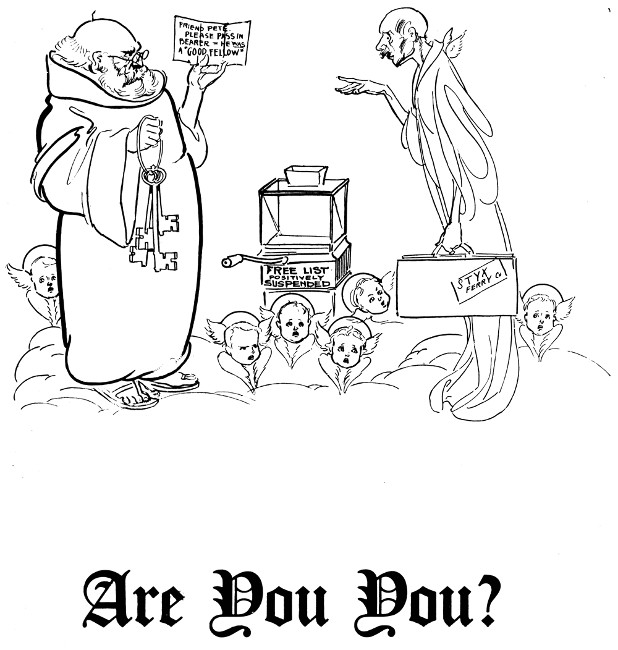

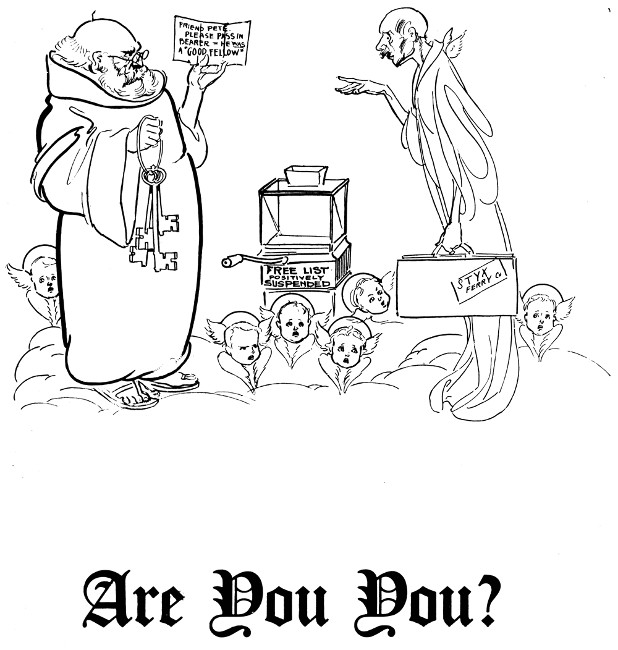

ARE YOU YOU?

Are you a trailer, or are you a trolley?

Are you tagged to a leader through wisdom and folly?

Are you Somebody Else, or You?

Do you vote by the symbol and swallow it "straight"?

Do you pray by the book, do you pay by the rate?

Do you tie your cravat by the calendar's date?

Do you follow a cue?

Are you a writer, or that which is worded?

Are you a shepherd, or one of the herded?

Which are you—a What or a Who?

It sounds well to call yourself "one of the flock,"

But a sheep is a sheep after all. At the block

You're nothing but mutton, or possibly stock.

Would you flavor a stew?

Are you a being and boss of your soul?

Or are you a mummy to carry a scroll?

Are you Somebody Else, or You?

When you finally pass to the heavenly wicket

Where Peter the Scrutinous stands on his picket,

Are you going to give him a blank for a ticket?

Do you think it will do?

[Pg 60]

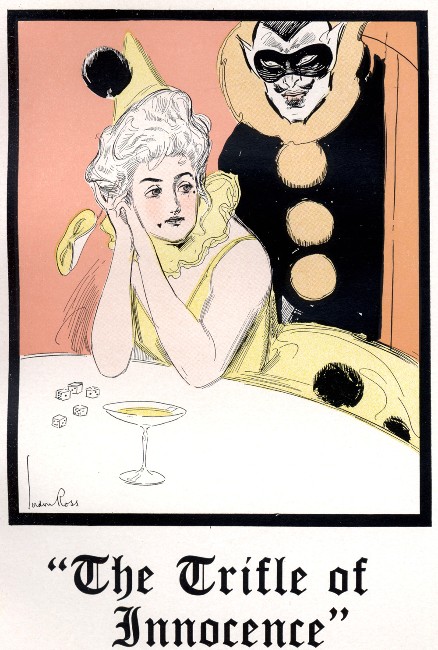

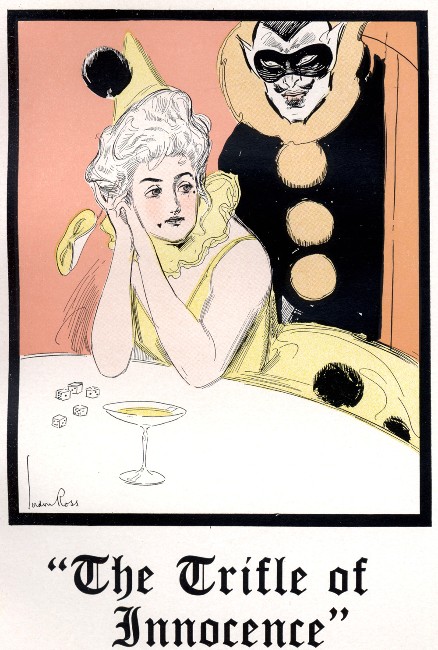

THE PRICE.

In, or under, or over the earth,

What will fill you, and what suffice?

No matter how mean, or much its worth,

It is yours if you pay the price.

Never a thing may a man attain,

But gain pays loss, or loss pays gain.

Lady of riches, riot and rout,

Fair of flesh and sated of sense,

Nothing in life you need do without

Except the trifle of innocence.

Counterfeit kisses you paid, and got

Just what you paid for—which is what?

Man of adroitness, place and power,

Trampled above and torn below;

Set in the light of your noonday hour,

Playing a part in the public show;

Fooling the mob that the mob be ruled:

You know which is the greater fooled.

Artist of pencil, or paint, or pen,

Reed, or string, or the vocal note,

Making the soul to suffer again

And the wild heart clutch the throat;

Ever your fancy has paid in fact;

You rack my soul, as yours was racked.

Page 60.

Page 60.

[Pg 61]

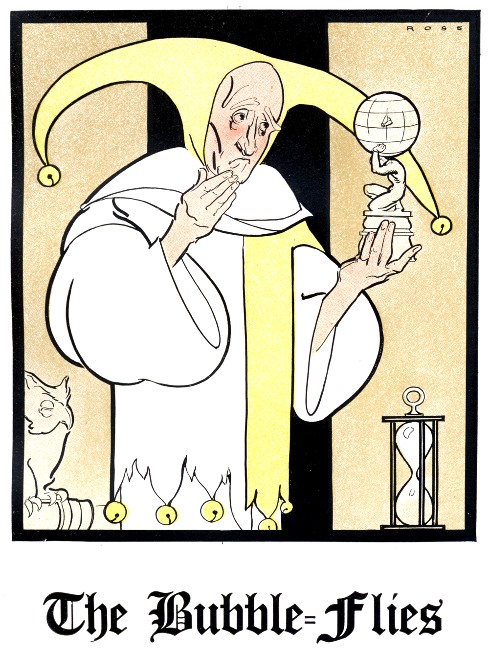

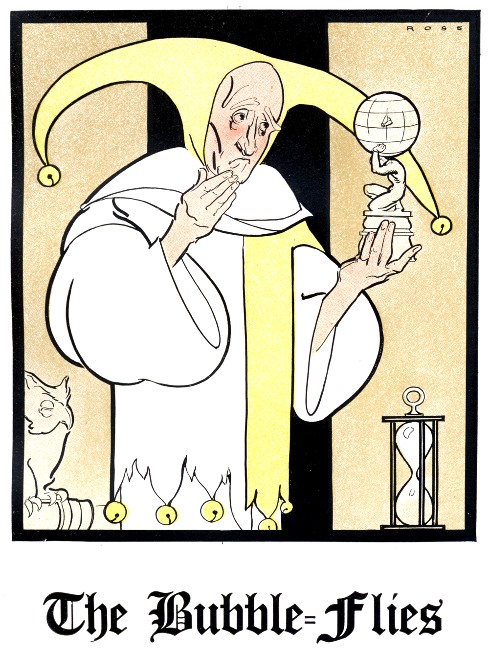

THE BUBBLE-FLIES.

Let me read a homily

Concerning an anomaly

I view

In you.

Whatever you are striving for,

Whatever you are driving for,

'T is not alone because you crave

To be successful that you slave

To swim upon the topmost wave.

You care less what your station is,

But more what your relation is.

To be a bit above the rest!

To be upon, or of, the crest!

Ah! that is where the trouble lies

Which stirs you little bubble-flies.

(I sneer these sneers, but just the same

I keep my fingers in the game.)

See! you have eat-and-drinkables

And portables and thinkables

And yet

You fret.

For what? Let's reach the heart of you

And see the funny part of you.

For what? I find the soul and seed

Of it is not your lack or need,

Or even merely vulgar greed.

[Pg 62]

Gold? You may have a store of it,

But someone else has more of it.

Fame? Pretty things are said of you,

But—some one is ahead of you.

Place? You disprize your easy one

For some one's high and breezy one.

(I smile these smiles to soothe my soul,

But squint one eye upon the goal.)

Tell me! what's your capacity

Compared to your voracity?

I guess

'T is less.

And so I strike these attitudes

And tender you these platitudes;—

Not wishing wealth, or spurning it,

Not hoarding it, or burning it

Is equal to the earning it.

Life's race is in the riding it,

Not in the word deciding it.

And after all is said and uttered

The keenest taste is bread-and-buttered.

(And yet—and yet—my palate aches

For pallid pie and pasty cakes!)

Page 61.

Page 61.

[Pg 63]

QUALIFIED.

I love to see my friend succeed;

I love to praise him; yes, indeed!

And so, no doubt, do you.

But will you tell me why it is

The praise we parcel out as his

So often goes askew,

And ends by running in the rut

Of "if," "except" or "but"?

"Boggs is a clever chap. His trade

Is doubling yearly, and he's made

A fortune all right, but——"

"Sharp is elected. Well, I say!

He'll hit a high mark yet, some day,

If——" (here one eye is shut).

"Such acting! Why, I laughed and wept!

Fobb's art is great—except."

"Miss Hautton has such queenly grace.

And then her figure and her face!

She'd be a beauty if——"

"And Mrs. Follol entertains

With so much taste and so much pains;

But——" (here a little sniff).

"And Mrs. Caste has ever kept

The narrow path—except."

[Pg 64]

I wish some man were great and good

That I might praise him all I could

And never add a "but."

I would that some would value me

And never hint what I would be

"If"—but why cavil? Tut!

Eternal justice still is kept

And Heaven is good—except!

Page 65.

Page 65.

[Pg 65]

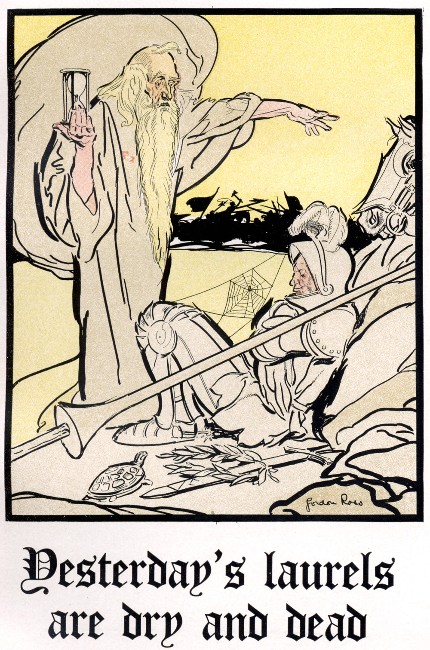

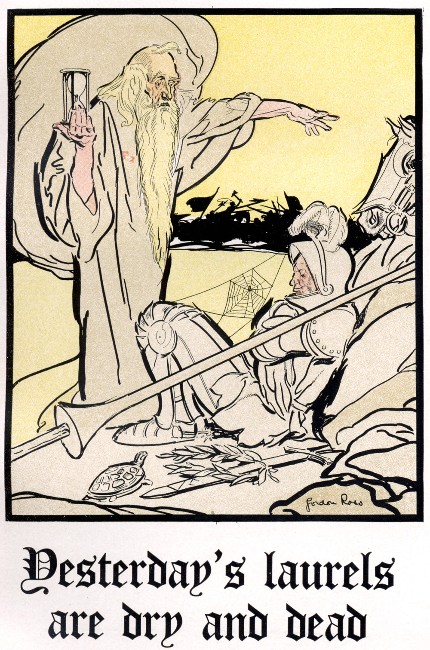

WHAT ARE YOU DOING?

Do you lazily nurse your knee and muse?

Do you contemplate your conquering thews

With a critical satisfaction?

But yesterday's laurels are dry and dead

And to-morrow's triumph is still ahead;

To-day is the day for action.

Yesterday's sun: is it shining still?

To-morrow's dawn: will its coming fill

To-day, if to-day's light fail us?

Not so. The past is forever past;

To-day's is the hand which holds us fast,

And to-morrow may never hail us.

The present and only the present endures,

So it's hey for to-day! for to-day is yours

For the goal you are still pursuing.

What you have done is a little amount;

What you will do is of lesser account,

But the test is, what are you doing?

[Pg 66]

THE FIRST PERSON SINGULAR.

McUmphrey's a fellow who's lengthy on lungs.

Backed up by the smoothest of ball-bearing tongues,

And his topic—himself—is worth talking about,

But he works it so much he has frazzled it out.

He never will give me my half of a chance

To chip in my own little, clever romance

In the first person singular. Yes, and they say,

He offended you, too, in a similar way.

Cousin Maud tells her illnesses, ancient and recent,

In a most minute way which is almost indecent!

Vivisecting herself, with some medical chatter,

She serves us her portions—as if on a platter,

Never noting how I am but waiting to stir

My dregs of diseases to offer to her.

And I hear (such a joke!) that your chronic gastritis

Stands silent forever before her nephritis.

Mrs. Henderson's Annie goes out every night,

And Bertha, before her, was simply a fright,

While Agnes broke more than the worth of her head,

And Maggie—well, some things are better unsaid.

Such manners to talk of her help—when she knows

My wife's simply aching to tell of our woes!

And I hear that she never lets you get a start

On your story of Rosy we all know by heart.

[Pg 67]

You'd hardly believe that I've heard Bunson tell

The Flea-Powder Frenchman and Razors to Sell,

The One-Legged Goose and that old What You Please—

And even, I swear it, The Crow and the Cheese.

And he sprang that old yarn of He Said 't was His Leg,

When you wanted to tell him Columbus's Egg,

While I wanted to tell my own whimsical tale

(Which I recently wrote) of The Man in the Whale!

[Pg 68]

THE CHOICE.

The little it takes to make life bright,

If we open our eyes to get it!

And the trifle which makes it black as night,

If we close our lids and let it!

Behold, as the world goes whirling by,

It is gloomy, or glad, as it fits your eye.

As it fits your eye, and I mean by that

You find what you look for mostly;

You can feed your happiness full and fat,

You can make your miseries ghostly,

Or you can forget every joy you own

By coveting something beyond your zone.

In the storms of life we can fret the eye

Where the guttering mud is drifted,

Or we can look to the world-wide sky

Where the Artist's scenes are shifted.

Puddles are oceans in miniatures,

Or merely puddles; the choice is yours.

We can strip our niggardly souls so bare

That we haggle a penny between us;

Or we can be rich in a common share

Of the Pleiades and Venus.

You can lift your soul to its outermost look,

Or can keep it packed in a pocketbook.

[Pg 69]

We may follow a phantom the arid miles

To a mountain of cankered treasure,

Or we can find, in a baby's smiles,

The pulse of a living pleasure.

We may drink of the sea until we burst,

While the trickling spring would have quenched our thirst.

[Pg 70]

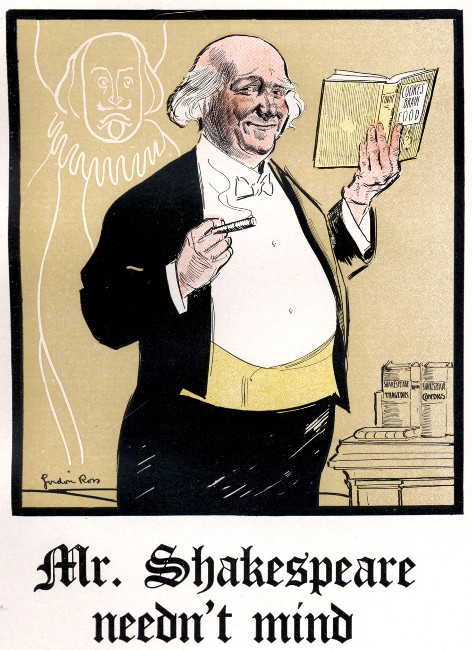

THE SAVING CLAUSE.

Kerr wrote a book, and a good book, too;

At least I[A] managed to read it through

Without finding very much room for blame,

And a good many other folks did the same.

But when any one asked me[A]: "Have you read?"

Or: "How do you like?" I[A] only said:

"Very good, very good! and I'm glad enough;

For his other writings are horrible stuff."

Banks wrote a play, and it had a run.

(That's a good deal more than ever I've[A] done.)

The interest held with hardly a lag

From the overture to the final tag.

But when any one asked me[A]: "Have you seen?"

Or: "What do you think?" I[A] looked serene

And remarked: "Oh, a pretty good thing of its kind,

But I guess Mr. Shakespeare needn't mind!"

Phelps made a machine; 't was smooth as grease.

(I[A] couldn't invent its smallest piece

In a thousand years.) It was tried and tried,

Until everybody was satisfied.

But when any one asked me[A]: "Will it pay?"—

"Is it really good?"—I[A] could only say:

"It's a marvelous thing! Why, it almost thinks!

And Phelps is a wonder—too bad he drinks!"

Page 70.

Page 70.

[Pg 71]

BETWEEN TWO THIEVES.

Sure! I am one who disbelieves

In thieves;

At which you interrupt to cry

"Aye, aye, and I."

Hmf! you're so sudden to agree.

Suppose we see.

I know a thief. No matter whether

I ought to know a thief, or not.

Perhaps "we went to school together;"

That old excuse is worked a lot.

One day he "copped a rummy's leather,"

Which means—I hate to tell you what.

It's such a vulgar thing to steal

A drunkard's purse to buy a meal.

"Hey, pal," said he, "come help me dine;

I've hit a pit and got the swag;

To-day, Delmonico's is mine;

To-morrow once again a vag.

Come on and tell me all the stunts

Of all the boys who knew me—once."

"Did I go with him?" I did not.

Would you have gone? Could you be bought

By dinners—when the trail was hot

And any hour he might be caught?

[Pg 72]

I know a thief, whose operations

Are colored by a kindly law.

Your income and a beggar's rations

Contribute to his cunning claw;

Cities and counties, courts and nations

Pay portion to his monstrous maw.

He gave a dinner not long since

In honor of some played-out Prince.

The decorations, ah, how chaste!

And how delicious was the wine!

For Mrs. Thief has perfect taste

And Mr. Thief knows how to dine.

And so the world has long agreed

Quite to forgive, forget—and feed.

But really I was shocked to see

How many decent folks could be

Induced to come and bow the knee;

I think you were my vis-a-vis.

Yes, yes, I quite despise him, too,

Like you;

And (though it's not a thing to brag)

I somehow like the vag.

But, oh, the difference one perceives

Between two thieves!

[Pg 73]

THE SPECTATOR.

Look at the man with the crown

Weighing him down.

Plumed and petted,

Galled and fretted!

Why do you eye him askance

With a quiver of hate in your glance?

Why not conceive him as human,

Nursed at the breast of a woman,

Growing, mayhap, as he could,

Not as he would?

How are you sure you would be

Better and wiser than he?

Look at the woman whose eye

Follows you by.

Silked and satined,

Scented, fattened!

Why does the half smile slip

Into a sneer on your lip?

You pity her? Ah, but the fashion

Of your complacent compassion.

Pity her! yet you have said,

"Better the creature were dead.

What is there left here for her

But to err?"

Thus would you make the world right,

Hiding its ills from your sight.

[Pg 74]

Look at the man with the pack

Breaking his back.

Ragged, squalid,

Wretched, stolid.

And you are sorry, you say,

(Much as you are at a play.)

But do you say to him, "Brother,

Twin-born son of our mother

What were the word, or the deed

Fitting your need?"

Or, as he slouches by,

Do you breathe "God be praised, I am I?"

Page 74.

Page 74.

[Pg 75]

THE SQUEALER.

Of course some people are born so bright

That no matter what one may say, or write,

The theme is old and the lesson is trite,

Which is what you may say, as these lines unreel

And I mildly suggest it is better to feel

Than to squeal.

Everybody knows that? Yes, it's certain they do,

Everybody, that is, with exception of two,

Of whom I am one and the other is you.

But for us the lesson is still remote,

Although we commit it and cite it and quote

It by rote.

But still when you thrill with the thudding thump

From the fist of the fellow you tried to bump

And the world looks hard at the swelling lump,

There's a strong temptation to open your door

And invite the public to hear you roar

That you're sore.

And again, tho' 'tis plain as the printed page:—

"Keep your hand on the lever and watch the gauge

When the fire-pot's full and the boilers rage,"

How often the steam-pressure grows and grows

And before the engineer cares or knows,

Up she goes.

[Pg 76]

So why should you fret if I send you to school

Again to consider the sapient rule

That Wisdom is Silence and Speech is a Fool.

Close up! and a year from to-day you will kneel

And thank the good Lord that you knew how to feel

And not squeal.

[Pg 77]

DISTANCE AND DISENCHANTMENT.

He was playing New York, and on Broadway at that;

I was playing in stock, in Chicago.

I heard that his Hamlet fell fearfully flat;

He heard I was fierce, as Iago.

Each looked to the other exceedingly small;

We were too far apart, that is all.

You, too, if your vision is ever reflective,

Have noticed your rival is small in perspective.

I heard him in Memphis (a chance matinée);

He heard me (one Sunday) in Dallas.

His critics, I swore, never witnessed the play;

He vowed mine were prompted by malice.

A pleasanter fellow I cannot recall.

We were closer together; that's all.

And your rival, too, if you once see him clearly,

Is clever, or how could he rival you, nearly?

In Seattle they said he was greater than Booth,

(Or in Portland, perhaps; I've forgotten);

I said 'twas ungracious to speak the plain truth,

But his work in the first act was rotten.

I had only intended to speak of the thrall

Of his wonderful fifth act; that's all.

But when a man's praised far ahead of his talents,

I guess you say something to even the balance.

[Pg 78]

In Atlanta I heard a remark that he made

And again in Mobile, Alabama;—

That he hardly thought Shakespeare was meant to be played

Like a ten-twenty-thirt' melodrama.

Oh, well, there was one honey-drop in the gall;

The fellow was jealous; that's all.

And you, too, have found, when a friendship is broken,

That his words are worse than the ones you have spoken.

Page 77.

Page 77.

[Pg 79]

FAMILY RESEMBLANCE.

I used to boost the P. and P.,

Designed to run from sea to sea,

From Portland, Ore., to Portland, Me.,

But which, as all the maps agree,

Begins somewhere in Minnesota

And peters out in North Dakota.

You gibed because I used to mock

Its streaks of rust and rolling-stock,

Its schedule and its G. P. A.

(Who took your Annual away,)

But lately you seem much inclined

To own a sudden change of mind.

Ah, me,

You're much like other folks, I see.

I much admired the book reviews

Of Quillip of the Daily News.

I laughed to see him put the screws

On some sprig of the late Who's-Whos,

Tear off his verbiage and skin him

To show the little there was in him.

You said the book he wrote himself

Lay stranded on the dealer's shelf

And wasn't worthy a critique;

(Just what he said of mine last week).

Perhaps your reasoning was strong

[Pg 80]

And you were right and I was wrong.

Heigho!

I'm very much like you, I know.

O'Brien's zeal ran almost daft

In its antipathy to graft.

He raked the practice fore and aft;

Lord! how his sulphurous breath would waft

"Eternal and infernal tarmint

To ivery grasping, grafting, varmint."

The worst of these upon the planet,

He said, were those who wanted granite

In public buildings,—"yis, begorry!"

(O'Brien owns a sandstone quarry.)

Of course I'd hate to see it tested,

But would he be less interested

In civic virtue—uninvested?

Oh, dear!

O'Brien's much like us, I fear.

[Pg 81]

NEED.

Don't you remember how you and I

Held a property nobody wanted to buy

In San José,

Until one day

A man came along from Franklin, Pa.?

And didn't we jump till we happened to find

The chap wasn't going it wholly blind,

But all the rest of the block was bought

And he simply had to have our lot.

Well, didn't our land go up in price

Till double the figures would scarce suffice?

And don't we sometimes figure and fret

How he got the best of us, even yet?

Don't you remember the perfect plan

You had, which needed another man

To make it win,

To jump right in

And everlasting make things spin?

And you said I had the requisite dash

And also the trifle of hoarded cash.

Was I glad to get in? Well, yes, indeed!

Until I saw the compelling need

Which had brought you to me, and then, "Ho! ho!

None of that for me, nay, not for Joe."

And I'm always provoked when I think you made

The plan get along without my aid.

[Pg 82]

Don't you remember the time we met

At Des Moines, or was it at Winterset?

But anyway, you

Were feeling blue

And tickled to see me through and through.

And "Come, let's open a bottle of—ink,"

Said you, "and see if it's good to drink."

But weren't you sorry because you spoke

When I had to tell you I was "broke"?

Oh, you lent me the saw-buck, I know, but still

I fancied your ardor had taken a chill.

And you've never been able to quite forget

That once I was "broke," and in your debt.

[Pg 83]

BETTER.

There's only one motto you need

To succeed:

"Better."

To other man's winning? Then you

Must do

Better.

From the baking of bread

To the breaking a head,

From rhyming a ballad

To sliming a salad,

From mending of ditches

To spending of riches,

Follow the rule to the uttermost letter:

"Better!"

Of course you may say but a few

Can do

Better;

And you're going to strive

So that all may thrive

Better.

And it's right you are

To follow the star,

Set in the heavens, afar, afar;

But still with your eyes

On the skies

It is wise

[Pg 84]

To be riding a mule,

Or guiding a school,

Thatching a hovel

Or hatching a novel,

Foretelling weather,

Or selling shoe-leather;

And remember you must

Be doing it just

A wee dust

Better.

And 'tis quite

As right

For you to cite

That the author might,

Or ought, to write

A heavenly sight

Better!

For which sharp word I am much your debtor,

Knowing none other could file my fetter

Better.

Page 85.

Page 85.

[Pg 85]

FORGET WHAT THE OTHER MAN HATH.

What do I care for your four-track line?

I have a country path;

And this is the message I've taken for mine:—

"Forget what the other man hath."

What do I care for your giant trees?

I'd rather whittle a lath,

And my motto helps me to take my ease;—

"Forget what the other man hath."

What do I care for your Newport beach?

A tub's as good for a bath.

And I keep my solace in constant reach:—

"Forget what the other man hath."

What do I care for your automobile?

I'm saving repairs and wrath,

My proverb goes well with an old style wheel;—

"Forget what the other man hath."

What do I care if you scorn my rime?

For this is its aftermath;—

It sounds so well I shall try, (sometime,)

To "forget what the other man hath!"

[Pg 86]

THE WHET.

The day that I loaf when I ought to employ it

Has, somehow, the flavor which makes me enjoy it.

So the man with no work

He may joyously shirk

I envy no more than I do the Grand Turk.

He most is in need of a holiday, who,

In this workaday world, has no duty to do.

The dollar you waste when you ought not to spend it

Buys something no plutocrat's millions could lend it,

For if once you exhaust

All your care of the cost,

Full half of the pleasure of purchase is lost,

So I trust you are one who is wise in discerning

The value of spending is most in the earning.

My little success which was nearest complete

Was that which I tore from the teeth of defeat,

And the man who can hit

With his wisdom and wit

Without any effort, I envy no whit.

The genius whose laurels grow always the greenest

Finds pleasure in plenty, but misses the keenest.

[Pg 87]

WHAT SORT ARE YOU?

"How much do you want for your A. Street lot?"

Said a real estate man to me.

I looked as if I were lost in thought

And then I replied: "Let's see;—

Black's sold last year at fifty the foot

And without using algebra that should put

My figure at sixty now, I guess,

Or a trifle more, or a trifle less."

I was anxious to sell at fifty straight,

Or I might have been glad of forty-eight.

Oh, yes, I'm a bit of a bluff, it's true;

What sort of a bluff are you?

"And what do you think of these railroad rates?"

The man with a bald brow said,

"For you have travelled through all the states

And have heard a good deal and read."

"The railroad lines," I wisely replied

"Are the lines with which our trade is tied,

And the wretches who take their rebates set

New knots in the bonds under which we fret."

But, now I remember, I once rode free

And forgot that the road rebated me!

Oh, yes, I'm a bit of a bluff, its true;

How much of a bluff are you?

[Pg 88]

"You've been to hear 'Siegfried' and found it fine?"

Cried a classical friend one day.

"I'm sure your impressions accord with mine,

But I want your own words and way.

And, oh, "the tone-color beats belief,"

And, oh, "dynamics," and oh, "motif,"

And "chiar-oscura, how finely abstruse,"

And oh, la-la-la, and oh, well, what's the use?

For the only thing I understood in the play

Was that dippy, old dragon of papier-maché.

Oh, yes, I'm a bit of a bluff, it's true;

What style of a bluff are you?

"And the senator should, you believe, be returned?"

Said a newspaper-man to me.

"He's as rotten a rascal as ever burned,"

I said. "May I quote?" asked he.

"Oh, no," I replied, "if you're going to quote,

Just remark that his friends are regretting to note

That the exigencies of the party case

Indicate that he shouldn't re-enter the race."

For the senator sometime may possibly be

Interviewed by a newspaper-man about me.

No, none of these cases may quite fit you,

But what sort of a bluff are you?

Page 88.

Page 88.

[Pg 89]

THE CRITICS.

As a matter of fact,

I am sure I can act,

And so,

When I go,

To the show,

Not the art of an Irving

Seems wholly deserving,

And though Booth were the star

He'd have many a jar,

If he heard the critique

Which I frequently speak,

As you

Do,

Too.

Written deep in my heart

Is a knowledge of art,

For why?

I've an eye

Like a die.

And where Raphael's paint

Has bedizened some saint,

I note his perspective

Is sadly defective,

And you? O, I know

[Pg 90]

When you've looked on Corot

The same

Blame

Came.

And the world would have gained

If my voice had been trained,

For my ear

Is severe,

As I hear

De Reszke and Patti.

(I've heard 'em sing "ratty!")

And the crowd has yelled "Bis!"

When a call for police

Should have shortened the score.

Was there ever a more

Absurd

Word

Heard?

And I feel, now and then,

I could handle a pen,

For indeed,

As I heed

What I read,

I observe many faults;

Homer nods, Shakespere halts,

Dante's sad, Pope is trite,

Poe's mechanic, Holmes light,

[Pg 91]

Yet so easy to do

Is the thing, even you

Might

Write

Quite

Bright!

[Pg 92]

PLUG.

As you haven't asked me for advice, I'll give it to you now:

Plug!

No matter who or what you are, or where you are, the how

Is plug.

You may take your dictionary, unabridged, and con it through,

You may swallow the Britannica and all its retinue,

But here I lay it f. o. b.—the only word for you

Is plug.

Are you in the big procession, but away behind the band?

Plug!

On the cobble, or asphaltum, in the mud or in the sand,

Plug!

Oh, you'll hear the story frequently of how some clever man

Cut clean across the country, so that now he's in the van;

You may think that you will do it, but I don't believe you can,

So plug!

Page 92.

Page 92.

[Pg 93]

Are you singing in the chorus? Do you want to be a star?

Plug!

You may think that you're a genius, but I don't believe you are,

So plug!

Oh, you'll hear of this or that one who was born without a name,

Who slept eleven hours a day and dreamed the way to fame,

Who simply couldn't push it off, so rapidly it came!

But plug.

Are you living in the valley? Do you want to reach the height?

Plug!

Where the hottest sun of day is and the coldest stars of night?

Plug!

Oh, it may be you're a fool, but if a fool you want to be,

If you want to climb above the crowd so every one can see

Just how a fool may look when he is at his apogee,

Why, plug!

Can you make a mile a minute? Do you want to make it two?

Plug!

[Pg 94]

Are you good and up against it? Well, the only thing to do

Is plug.

Oh, you'll find some marshy places, where the crust is pretty thin,

And when you think you're gliding out, you're only sliding in,

But the only thing for you to do is think of this and grin,

And plug.

There's many a word that's prettier that hasn't half the cheer

Of plug.

It may not save you in a day, but try it for a year.

Plug!

And to show you I am competent to tell you what is what,

I assure you that I never yet have made a centre shot,

Which surely is an ample demonstration that I ought

To plug.

[Pg 95]

FAMILIARITY BREEDS CONTENT.

I.

You sometimes think you'd like to be

John D.?

And not a man you know would dare

To josh you on your handsome hair,

Or say, "Hey, John, it's rather rude

To boost refined and jump on crude,

To help Chicago University,

Or bull the doctrine of—immersity."

II.

You wouldn't care to be the Pope,

I hope?

With not a chum to call your own,

To hale you up by telephone,

With, "Say, old man, I hope you're free

To-night. Bring Mrs. Pope to tea.

Let some one else lock up the pearly

Gateway to-night and get here early!"

III.

Perhaps you sometimes deem the Czar

A star?

With not a palm in all the land

To strike his fairly, hand to hand,

With not a man in all the pack

To fetch a hand against his back

[Pg 96]

And cry, "Well met, Old Nick, come out

And let us trot the kids about.

Tut, man! you needn't look so pale,

A red flag means an auction sale."

IV.

I'll bet even Shakespeare's name was "Will,"

Until

He was so dead that he was great,

For fame can only isolate.

And better than "The Immortal Bard"

Were "Hello, Bill," and "Howdy, pard!"

Would he have swapped his comrades' laughter

For all the praise of ages after?

[Pg 97]

A SONG OF REST.

I have sung the song of striving,

Of the struggling, of arriving,

Of making of one's self a horse and mounting him and driving!

But now, let's cease;

Let's look for peace.

Let's forget the mark of money,

Let's forget the love of fame.

Life is ours and skies are sunny;

What is worry but a name?

Let's sit down and whiff and whittle,

Let us loaf and laugh a little.

(Here the youngest spoiled the rime

By running to me for a dime.)

I have sung the joy of doing,

Of the pleasure of pursuing,

And how life is like a woman and our role and rule is wooing,

But now, O let

Us cease to fret!

Let us cease our vain desiring;

Water's better than Cliquot;

What is honor but perspiring?

Wealth's another name for woe.

Let us spread out in the clover,

Just too lazy to turn over,—

[Pg 98]

(Here my wife brought in the news:

All the children need new shoes.)

I have sung the song of action,

Of the sweet of satisfaction

Of pounding, pounding, pounding opposition to a fraction,

But now, let's quit;

Let's rest a bit.

Money only makes us greedy,

Life's success is but a taunt.

He alone is never needy

Who has learned to laugh at want.

Let us loaf and laugh and wallow;

Too much work to even swallow—

(Here's the mail and bills are curses;

I must try to sell these verses.)

[Pg 99]

DESIRE.

Oh, the ripe, red apple which handily hung

And flaunted and taunted and swayed and swung,

Till it itched your fingers and tickled your tongue,

For it was juicy and you were young!

But you held your hands and you turned your head,

And you thought of the switch which hung in the shed,

And you didn't take it (or so you said),

But tell me—didn't you want to?

Oh, the rounded maiden who passed you by,

Whose cheek was dimpled, whose glance was shy,

But who looked at you out of the tail of her eye,

And flirted her skirt just a trifle high!

Oh, you were human and not sedate,

But you thought of the narrow way and straight,

And you didn't follow (or so you state),

But tell me—didn't you want to?

Oh, the golden chink and the sibilant sign

Which sang of honey and love and wine,

Of pleasure and power when the sun's a-shine

And plenty and peace in the day's decline!

Oh, the dream was schemed and the play was planned;

You had nothing to do but to reach your hand,

But you didn't (or so I understand),

But tell me—didn't you want to?

[Pg 100]

Oh, you wanted to, yes; and hence you crow

That the Want To within you found its foe

Which wanted you not to want to, and so

You were able to answer always "No."

So you tell yourself you are pretty fine clay

To have tricked temptation and turned it away;

But wait, my friend, for a different day!

Wait till you want to want to!

Page 99.

Page 99.

[Pg 101]

THERE IS, OH, SO MUCH.

There is oh, so much for a man to be

In nineteen hundred and now.

He may cover the world like the searching sea

In nineteen hundred and now.

He may be of the rush of the city's roar

And his song may sing where the condors soar,

Or may dip to the dark of Labrador,

In nineteen hundred and now.

There is oh, so much for a man to do

In nineteen hundred and now.

He may sort the suns of Andromeda through

In nineteen hundred and now.