The Project Gutenberg EBook of Harper's Round Table, July 2, 1895, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Harper's Round Table, July 2, 1895 Author: Various Release Date: July 1, 2010 [EBook #33046] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HARPER'S ROUND TABLE, JULY 2, 1895 *** Produced by Annie McGuire

| A MISPLACED "FOURTH." |

| SNOW-SHOES AND SLEDGES. |

| OAKLEIGH. |

| THE KNAVE OF HEARTS |

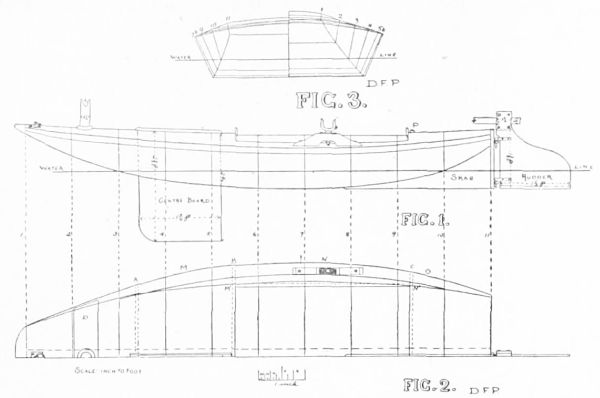

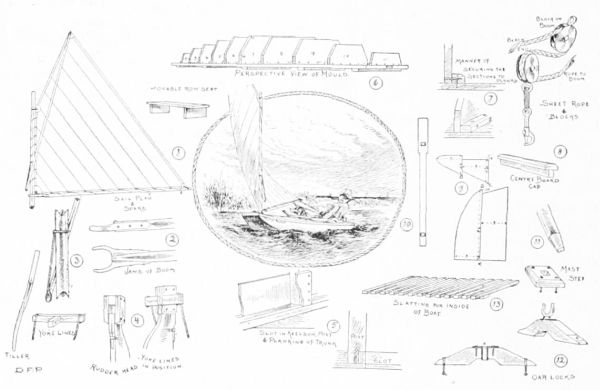

| HOW TO BUILD AN INEXPENSIVE SHOOTING-BOAT. |

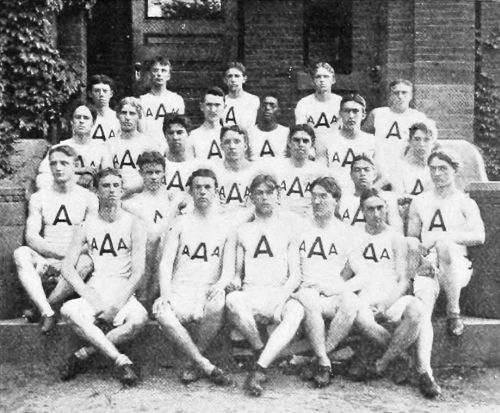

| INTERSCHOLASTIC SPORT |

| THE PUDDING STICK |

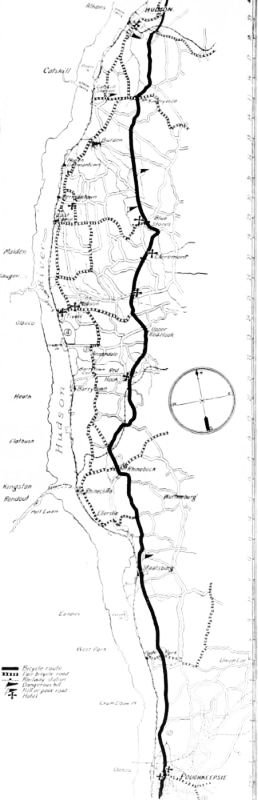

| BICYCLING |

| THE CAMERA CLUB |

| STAMPS |

Copyright, 1895, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| PUBLISHED WEEKLY. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, JULY 2, 1895. | FIVE CENTS A COPY. |

| VOL. XVI.—NO. 818. | TWO DOLLARS A YEAR. |

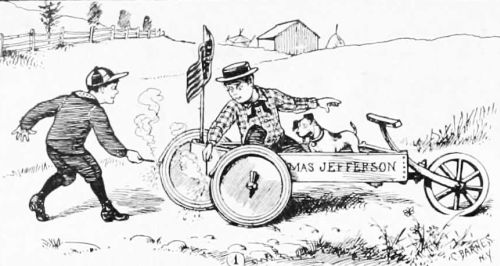

The male population of Middleton, Ohio, in the early summer of 186- appeared to consist altogether of old men and boys. True, a few young men, most of them dressed in blue coats with brass buttons, were to be seen on the streets, but nearly all of them carried their arms in slings, and one tall lad of twenty, who had once been the best runner in the village, hobbled along on crutches, with an empty trouser leg pinned up at the knee.

One bright morning three Middleton boys were sitting astride the top rail of a zigzag fence that ran along a hillside at the edge of a thicket of underbrush. A long Kentucky rifle lay across a near-by log. One of the boys held in his hand a glass bottle slopped with a bit of rag. Another had on a leather belt with "U.S." on the brass plate—upside down. The third boy was digging at the rail with a dull jackknife.

"I came near to running away and goin' as a drummer-boy," said the youngster with the belt, "but they wouldn't take me on account of my age. I'll be old enough this fall," he added. "Then you'll see."

"Your mother wouldn't let you go, Skinny," said the boy with the bottle. "She told Grandad that two was enough."

"Father'd let me go if he warn't with Sherman," said Skinny, "and brother Bill said I drummed good enough."

"My father wants me to stay home and look after ma," the second boy sighed. There had been no news of his father for six months, now.

"I've got a letter from Alfred, written jes before he was taken prisoner, I guess," said the third boy, closing his knife. He drew out of his pocket an envelope with the picture of an American flag on it.

"Go on and read it to us," said the oldest boy, wriggling himself up closer. And Hosmer Curtis began—following the words with his thumb:

"Crumms's Landing.

"Dear Brother,—I wish I was to home to-night, with you all sitting in the kitchen, and mother reading to us the way she used to, rather than being here. I am writing this by moonlight mostly, as it is getting late. We have[Pg 666] had a big fight all day, but drove the Rebs back across a crick into a swamp, where we captured a lot of them stuck in the mud. I am dreadful sorry to say that Tom Ditchard was killed. Poor Tom! I suppose the home papers will tell all about it; he was shot fording the crick. I have his watch; he gave it to me to bring back home. I hope I shall do so. To-morrow we will move westward to head off Morgan, I guess; I hope we won't march far, for my boots are all worn out, and my feet are sore. But I am well; love to all, and kiss mother. I wrote her two days ago.

"Your affec brother,

Alfred.

"P.S.—The Fourth of July will soon be here. I suppose you will have no fireworks, though perhaps we shall. Good-by."

"I don't know as I'd like to be a soldier," said the boy with the gunpowder bottle—he was also the proud possessor of the long rifle. "'Tisn't so much fun, I guess. Think so, Skinny?"

"You're a 'fraid-cat," returned the boy with the belt. "That's what you are, Will Tevis."

The other flushed, but said nothing; he was by far the smallest of the three.

"How do you know Alfred was captured?" said the thin one, after a silence of a minute.

"He was on the missing list—that's all we know," said Hosmer, putting the letter back into his pocket.

"It will be the Fourth in two days, now," remarked Skinny, as if to change the subject. "But I hain't heard any talk about any celebration."

"Let's have one all to ourselves," suggested Hosmer.

"What with?" asked the smallest boy. "I guess this is all the gunpowder there is in town." He held up the bottle. "'Tain't more'n three charges, anyhow," he added.

"I know where there's all the powder you want to look at," said the thin warrior, who jumped suddenly down from the fence. "Oh! and I say, you know the two old iron cannon—if we could only get them out—hey?"

"They're locked up in the engine-house," rejoined Master Tevis.

"What's the matter with an anvil? It makes a lot of noise," suggested Hosmer. "Where do you get the powder, Skinny?"

"Skinny," whose real name was Ambrose F. Skinner, Jun., assumed a very mysterious air.

"Now, listen, and I'll tell you," he said. "You remember when they had that smash up on the railroad last week—don't you?"

"You mean the train going South to the army?" asked Hosmer.

"Yep, that's it. Happened last Thursday," responded Ambrose, growing excited. "Well! they ran two banged-up cars back on the siding above the river-bridge, and left 'em. I guess they forgot, p'r'aps. But the worst-busted car is loaded with powder. I saw the barrels: one of them had a big hole in it. I say, come along, I'll show you. 'Tain't far."

"Come on; let's!" was the united answer. The two listeners jumped to the ground, and Master Tevis picked up the rifle. Then the three struck off across the hill, and walked along a path through the thicket of scrub-oak.

In a few minutes the boys were standing beside two heavy freight-cars on a crooked timber switch. The end of one had been broken in as if by a collision, and the trucks of both were injured.

Skinny climbed into the wrecked car, and lifted the end of a tarpauling that covered some barrels.

"There you are," he said, triumphantly. "All the powder you want—nuff to blow up the town."

"I don't suppose they'll let 'em stay here very long," said Hosmer.

"But they can't send them South on the road now," remarked Tevis. "The big bridge is down ten miles below—heard tell of it last night. They will have to go back the other way; not a train's been through for forty hours."

Tevis's grandfather was the station-agent at Middleton, and he spoke with an air of certain knowledge.

"Come, hand up your bottle and we will fill her up," said Skinner, extending his hand.

Will Tevis paused. "I say, fellows," he said, "I don't think it would be right. Do you, Hosmer?"

"A bottleful would never be missed," interposed Skinny. "There's more'n that spilled here on the floor. We must celebrate the Fourth. Why not, boys? Eh!"

It was evident that Master Skinner's intentions were liable to change, however, and that some scruples were arising even in his mind, for he said, testily,

"You're a 'fraid-cat, Will Tevis."

The latter put down the rifle. "If you say that again, Ambrose Skinner, I'll fight you," he said.

"Oh, come, don't talk like that," said Hosmer, quietly. "Will is right, Skinny; we oughtn't to touch the powder. It belongs to Uncle Sam."

"He would not miss a handful," said Skinny, shame-facedly. Then he added, "I guess you are right, though, come to think. Let's go back to the village; it's most four o'clock."

The boys walked down the grade. A mile away was a wooden box-bridge with a carriageway on one side and the single track on the other. It spanned a deep and swiftly running stream that opened into the Ohio River a few leagues below. It was here the accident had taken place.

As they came into the village street they saw that a crowd had collected around the post-office.

"News from the front!" shouted Tevis, in the familiar words they had so often heard; and the trio started forward on a run.

On the outside of the post-office shutters was a big placard drawn hastily up in red ink:

These words stared them in the face. The news had come by telegram from Turkeyville; but soon after the line had ceased to work, and no particulars could be obtained. It was late that night when the boys went to bed. The morrow was to be an eventful one for Middleton, and there was a feeling of uneasiness in the air.

The next day was the 3d of July.

Will Tevis was awakened by a tremendous clangor of bells.

"Fire!" shouted Will, making one dive from the bed to the window.

He opened the shutters with a crash; but not a sign of smoke was there to be seen. What could it mean?

"Sounds like the Fourth," he said, leaning over the sill and craning his neck to right and left.

The Tevis house was far up the slope, on which the village stood, and Will could look down one of the long streets. He saw people running from the houses and heading for the Court-house square.

He hurried on his clothes, jumped down the back stairs, and rushed to the street, joining his grandfather on the way. At the gate as they turned into the dusty road they met Ambrose Skinner.

"Heard the news?" he yelled, as he approached.

"What is it? Has any one surrendered?" asked old Mr. Tevis, breathlessly.

"No!" shouted Skinny, at the top of his lungs, although he was quite near. "The Rebels are coming! I'm off to summon Judge Black. They're going to hold a meeting at the Court-house." On he ran.

Grandfather Tevis surprised himself, for in his excitement he had struck into a long swinging gait that compelled Will to his best efforts to keep up.

At the square all was confusion. The Middleton "Home Guards" were there, forty-eight in number, composed mostly of men who were too old for service. There was not a leader among them.

Mr. Tevis forced his way into a room on the ground-floor of the Court-house. Somebody held up his hand to enjoin silence.

"They are receiving a telegram from Dresden down the[Pg 667] river," whispered a short, pale-faced man, in Mr. Tevis's ear.

There was a single wire connecting Middleton with Dresden, twenty-one miles to the westward. The nervous operator was translating the dots and dashes into words.

"The-rebels-are-in-full-sight-now-entering-the-town. The-home-guards-have-run-away." Then there was a pause. "The-rebels-are-breaking-into-the-stores. They-have-not-come-to-the-rail-way-station-yet."

"He is a brave man to stick to his post so," said Mr. Tevis, out loud.

"Hush," said the pale-faced man; "here he comes again."

"Tick-a-tick," began the instrument. "A-battery-of-artillery-is-with-them. They-are-here-at-the-station. I—" The instrument stopped suddenly.

"Something has happened," said the operator, breathlessly.

"Call him up," said some one.

"He does not answer," said the operator, after a few minutes. But as he spoke a slow ticking came from the receiver.

"Hello!" it spelled, laboriously.

"That isn't Jed Worth," said the operator. "Some one else has got hold of the wire."

"Hold on; ask who it is," said Mr. Tevis.

Then an idea came in Will Tevis' head, and he spoke up. "Ask if it is Frank," he said.

"What for?" inquired the operator, with his fingers on the key.

"Because if they answer yes, you will know they are trying to fool you," he said.

There was a murmur of approval.

"Is-that-you-Frank?" telegraphed the operator.

"Yes," came the unhesitating answer.

"Ask him if he has seen anything of the Rebs," suggested Mr. Tevis.

"No," was the response to this inquiry, "not one."

"He's a pretty good liar," said the pale-faced man, half to himself. The instrument began to work again.

"Are there any troops at Middleton," slowly asked the Reb operator down the line.

An answer was clicked back hastily.

"I told him that we had a regiment and two batteries of artillery," whispered the young man at the desk, smiling.

"Why under the sun didn't you make it an army corps," said Mr. Tevis.

The operator tried again, but no answer came. Dresden had switched off for good. A bustle and a cheer outside in the square showed that something was going forward. Judge Black had arrived. The Judge was a veteran of the Mexican war; his age alone had prevented him from accepting a commission in the army; but the village had a great respect for his military knowledge. He was offered the command of the forces by the Mayor; about four hundred had gathered; but there were no more than seventy muskets, with less than four rounds apiece. A search of the town shops disclosed the fact that there were but ten pounds of good powder to be had. Now "Skinny" came to the rescue with the same words he had used on the day before.

"I know where there's all the powder you want," he said, and he told of the freight-car on the siding. Despite the broken truck it was brought down the grade to the station, and two barrels were unloaded.

"Why not blow up the bridge?" suggested Will to his grandfather in a whisper, which the Judge overheard.

"We may have to come to that," said the Judge, turning.

"We'll leave that to the last, though. Now we must throw up intrenchments, and mount our two field-pieces. What's in those crates?"

"Uniforms, by jingo!" said a man inside the car.

"Get them out," said the Judge; "our forces must be uniformed. Have those mounted scouts been sent out?" he added.

"Yes, sir," said the Mayor; "an hour ago."

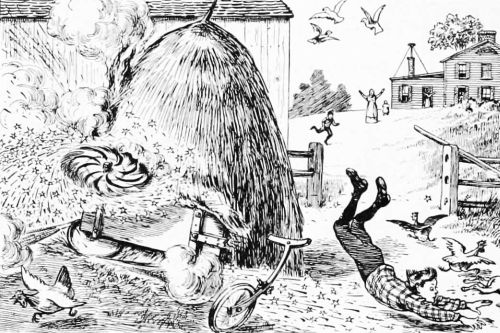

In a short time the slope below Middleton presented a curious sight; four hundred men and boys dressed in new uniforms with shining brass buttons were digging a long trench that stretched from the railway track to a steep bluff on the east. The old iron guns were in a position to command the bridge and the further bank. The freight-car with over two tons of gunpowder on board was anchored firmly in the centre of the bridge.

One man was left at the bridge to fire the train of powder if the enemy advanced. About four o'clock a very respectable fortification had been made at the bottom of the hill, and the few guns were distributed along it. The little army paused to rest. The women and children had long ago been sent north across the hills. At half past four a man on horseback thundered across the bridge; he was closely followed by two others.

"The Rebs are coming!" they shouted. "Thousands of them."

In fact, almost at their heels rose a cloud of dust, and two or three cavalrymen rode out on the bank of the river. They appeared surprised at the line of earthworks, and the blue coats that here and there showed plainly. In a few minutes more the bank was lined with rebel horsemen.

"Why doesn't he light the fuse?" said the Commander-in-chief, nervously looking toward the bridge.

As he spoke a man ran up the track from the bridge; he turned and looked back two or three times as if expecting something to happen. But nothing happened.

"It failed to go off," said the man, out of breath, as he jumped into the trench.

The Judge scowled at him. "Let go that battery," he said. "Commence firing."

At the first discharge one of the old cannons burst, luckily hurting no one, and the straggling volley that followed only showed to the enemy the weakness of their opponents. A rebel with a powerful field-glass had climbed a tree and taken in the situation. The enemy was preparing for an advance. That was evident.

"Hang that fool!" said the Judge; "if he'd kept his wits about him, we'd be safe. I don't believe he waited to strike a match. They could never ford the river."

But he or no one else had seen a figure in a uniform much too big for his small body steal across the track and crawl on all-fours down the embankment on the further side. All at once they saw him emerge into sight and dive into the shallow of the bridge. It was Will Tevis.

Just as the cavalry were preparing to charge, he came into sight again, running swiftly down the middle of the track. A faint smoke arose from the bridge entrance, several shots were fired at him; but on he came. The intrenchments now broke out into flame just as there came a terrific roar, a bursting rending sound, and the bridge disappeared. Will Tevis in the ill-fitting uniform was a hero. The rebels were forced to keep the other side of the swollen river, but exchanged shots for some time before they drew away.

Coming up the hill late in the evening Hosmer and Will met Skinny. "Where have you been?" they asked.

"Up in town looking for a drum," Skinny replied, flushing. "Will, I 'pologize for callin' you a 'fraid-cat."

The next day there was again no powder in the village; but Judge Black made a speech which began, "On this glorious occasion."

"I wish we had some fireworks for to-night," said Hosmer, after the old veteran had concluded.

"Never mind that, boys," said Grandfather Tevis, who had overheard. "You boys had your Fourth yesterday."

The things on which we are apt to set the highest value in this world are those that we have lost, and even our friends are, as a rule, most highly appreciated after they have been taken from us. Thus, in the present instance, Phil and Serge had so sincerely mourned the loss of their quaint but loyal comrade, that his restoration to them alive[Pg 668] and well, "hearty and hungry," as he himself expressed it, filled them with unbounded joy. They hung about him, and lovingly brushed the snow from his fur clothing, and plied him with many questions.

Even Nel-te showed delight at the return of his big playmate by cuddling up to him, and stroking his weather-beaten cheeks, and confiding to him how very hungry he was.

"Me too, Cap'n Kid!" exclaimed Jalap Coombs; "and I must say you're a mighty tempting mossel to a man as nigh starved as I be. Jest about boiling age, plump and tender. Cap'n Kid, look out, for I'm mighty inclined to stow ye away."

"Try this instead," laughed Phil, holding out a chunk of frozen pemmican that he had just chopped off. "We're in the biggest kind of luck to-day," he continued. "I didn't know there was a mouthful of anything to eat on this sledge, and here I've just found about five pounds of pemmican. It does seem to me the very best pemmican that was ever put up, too, and I only wonder that we didn't eat it long ago. I'm going to get my aunt Ruth to make me a lot of it just as soon as ever I get home."

As they sat before the fire on a tree felled and stripped of its branches for the purpose, and munched frozen pemmican, and took turns in sipping strong unsweetened tea from the only cup now left to them, Jalap Coombs described his thrilling experiences of the preceding night.

According to his story, one of his dogs gave out, and he stopped to unharness it with the hope that it would still have strength to follow the sledge. While he was thus engaged the storm broke, the blinding rush of snow swept over the mountains, and as he looked up he found to his dismay that the other sledge was already lost to view. He at once started to overtake it, urging on the reluctant dogs by every means in his power; but after a few minutes of struggle against the furious gale, they lay down and refused to move. After cutting their traces that they might follow him if they chose, the man set forth alone, with bowed and uncertain steps, on a hopeless quest for his comrades. He did not find them, as we know, though once he heard a faint cry from off to one side. Heading in that direction, the next thing he knew he had plunged over the precipice, and found himself sliding, rolling, and bounding downward with incredible velocity.

"The trip must have lasted an hour or more," said Jalap Coombs, soberly, in describing it, "and when I finally brung up all standing, I couldn't make out for quite a spell whether I were still on top of the earth, or had gone plumb through to the other side. I knowed every rib and timber of my framing were broke, and every plank started; but somehow I managed to keep my head above water, and struck out for shore. I made port under a tree, and went to sleep. When I woke at the end of the watch, I found all hatches closed and battened down. So I were jest turning over again when I heerd a hail, and knowed I were wanted on deck. And, boys, I've had happy moments in my life, but I reckon the happiest of 'em all were when I broke out and seen you two with the kid, standing quiet and respectful, and heerd ye saying, 'Good-morning, sir, and hoping you've passed a quiet night,' like I were a full-rigged cap'n."

"As you certainly deserve to be, Mr. Coombs," laughed Phil, "and as I believe you will be before long, for I don't think we can be very far from salt water at this moment."

"It's been seeming to me that I could smell it!" exclaimed the sailorman, eagerly sniffing the air as he spoke. "And, ef you're agreeable, sir, I moves that we set sail for it at once. My hull's pretty well battered and stove in, but top works is solid, standing and running rigging all right, and I reckon by steady pumping we can navigate the old craft to port yet."

"All aboard, then! Up anchor, and let's be off!" shouted Phil, so excited at the prospect of a speedy termination to their journey that he could not bear a moment's longer delay in attaining it.

So they set merrily and hopefully forth, and followed the windings of the valley, keeping just beyond the forest edge. In summer-time they would have found it filled with impassable obstacles—huge bowlders, landslides, a network of logs and fallen trees, and a roaring torrent; but now it was packed with snow to such an incredible depth that all these things lay far beneath their feet and the way was made easy.

By nightfall they had reached the mouth of the valley, and saw, opening before them, one so much wider that it reminded them of the broad expanse of the frozen Yukon. The course of this new valley was almost north and south, and they felt certain that it must lead to the sea. In spite of their anxiety to follow it, darkness compelled them to seek a camping-place in the timber. That evening they ate all that remained of their pemmican, excepting a small bit that was reserved for Nel-te's breakfast.

They made up, as far as possible, for their lack of food by building the most gorgeous camp-fire of the entire journey. They felled several green trees close together, and placed it on them so that it should not melt its way down out of sight through the deep snow. Then they felled dead trees and cut them into logs. These, together with dead branches, they piled up, until they had a structure forty feet long by ten feet high. They set fire to it with the last match in their possession, and as the flames gathered headway and roared and leaped to the very tops of the surrounding trees even Phil was obliged to acknowledge that at last he was thoroughly and uncomfortably warm.

The following morning poor Jalap was so stiff and lame that his face was contorted with pain when he attempted to rise. "Never mind," he cried, cheerily, as he noted Phil's anxious expression. "I'll fetch it. Just give me a few minutes' leeway."

And sure enough in a few minutes he was on his feet rubbing his legs, stretching his arms, and twisting his body "to limber up the j'ints." Although in a torment of pain he soon declared himself ready for the day's tramp, and they set forth. Ere they had gone half a mile, however, it was evident that he could walk no further. The pain of the effort was too great even for his sturdy determination, and, when he finally sank down with a groan, the boys helped him on the sledge, and attached themselves to its pulling-bar with long thongs of rawhide.

The two stalwart young fellows, together with three dogs made a strong team, but the snow was so soft, and their load so heavy, that by noon they had not made more than ten miles. They had, however, reached the end of their second valley, and came upon a most extraordinary scene. As far as the eye could reach on either side stretched a vast plain of frozen whiteness. On its further border, directly in front of them, but some ten miles away, rose a chain of mountains bisected by a deep wide cut like a gateway.

"It must be an arm of the sea, frozen over and covered with snow," said Phil.

"But," objected Serge, "on this coast no such body of salt water stays frozen so late in the season; for we are well into April now, you know."

"Then it is a great lake."

"I never heard of any lake on this side of the mountains."

"I don't reckon it's the sea; but salt water's mighty nigh," said Jalap Coombs, sniffing the air as eagerly as a hound on the scent of game.

"Whatever it is," said Phil, "we've got to cross it, and I am going to head straight for that opening."

So they again bent to their traces, and a few hours later had crossed the great white plain, and were skirting the base of a mountain that rose on their left. Its splintered crags showed the dull red of iron rust wherever they were bare of snow, and only thin fringes of snow were to be seen in its more sheltered gorges.

Suddenly Phil halted, his face paled, and his lips quivered with emotion. "The sea!" he gasped. "Over there, Serge!"

Jalap Coombs caught the words, and was on his feet in an instant, all his pain forgotten in a desire to once more catch a glimpse of his beloved salt water.

"Yes," replied Serge, after a long look. "It certainly is a narrow bay. How I wish we knew what one! But, Phil![Pg 669] what is that, down there near the foot of the cliffs? Is it—can it be—a house?"

"Where?" cried Phil. "Yes, I see! I do believe it is! Yes, it certainly is a house."

That little house nestling at the base of a precipitous mountain, and still nearly a mile away, was just then a more fascinating sight to our half-starved, toil-worn travellers than even the sea itself, and filled with a hopeful excitement they hastened toward it. It was probably a salmon cannery or saltery, or a trading-post. At any rate the one house they had discovered was that of a white man; for it had a chimney, and none of the Tlingits or natives of southern Alaska build chimneys.

While Phil and Jalap Coombs were full of confidence that a few minutes more would find them in a settlement of white men, Serge was greatly puzzled, and, though he said little, kept up a deal of thinking as he tugged at the rawhide sledge-trace. He felt that he ought to know the place, for he did not believe they were one hundred miles from Sitka; but he could not remember having heard of any white settlement on that part of the coast, except at the Chilkat cannery, and this place did not correspond in any particular with what he had heard of that.

At length they rounded the last low spur of the ridge, and came upon the house only a few rods away. For a few moments they stood motionless, regarding it in silence, and with a bitter disappointment. It was roughly but substantially constructed of sawed lumber, had a shingled roof, two glass windows, a heavy door, and a great outside chimney of rough stone. But it was closed and deserted. No hospitable smoke curled from its chimney, there was no voice of welcome nor sign of human presence. Nor was there another building of any kind in sight.

"I suppose we may as well keep on and examine the interior, now that we've come so far," said Phil, in a disgusted tone that readily betrayed his feelings. "There doesn't seem to be any one around to prevent us. I only wish there was."

So they pushed open the door, which was fastened but not locked, and stepped inside. The cabin contained but a single large room furnished with several sleeping bunks, a stout table, and a number of seats, all home-made from unplaned lumber. Much rubbish, including empty bottles and tin cans, was scattered about; but it was evident that everything of value had been removed by the last occupants. The chief feature of the room was an immense and rudely artistic fire-place at its farther end. Above this hung a smooth board skilfully decorated with charcoal sketches, and bearing the legend "Camp Muir."

As Serge caught sight of this he uttered an exclamation. "Now I know where we are!" he cried. "Come with me, Phil, and I will show you one of the grand sights of the world."

With this he dashed out of the door, and ran toward the beach ridge behind which the cabin stood. Phil followed, wondering curiously what his friend could mean. As they reached the low crest of the ridge he understood; for outspread before him, bathed in a rosy light by the setting sun, was a spectacle that tourists travel from all parts of the world to gaze upon.

A precipitous line of ice cliffs of marble whiteness or heavenly blue, two miles long and hundreds of feet in height, carved into spires, pinnacles, minarets, and a thousand other fantastic shapes, rose in frozen majesty at the head of a little bay whose waters washed the beach at their feet. Ere either of the boys could find words to express his delight and wonder, a huge mass of the lofty wall broke away and plunged into the sea, with a thunderous roar that echoed and re-echoed from the enclosing mountains. For a moment it disappeared in a milky cloud of foam and spray. Then it shot up from the depths like some stupendous submarine monster, and with torrents of water streaming from it in glittering cascades, floated on the heaving surface a new-born iceberg.

"It must be a glacier," said Phil, in an awe-stricken tone.

"It is a glacier," answered Serge, triumphantly, "and one of the most famous in the world, for it is the Muir, which is larger and contains more ice than all the eleven hundred glaciers of Switzerland put together. That cabin is the one occupied by John Muir and his companions when they explored it in 1890. To think that we should have come down one of its branches, and even crossed the great glacier itself without knowing what it was! I believe we would have known it, though, if the snow hadn't[Pg 670] been so deep as to alter the whole character of its surface."

"If this is the Muir Glacier," reflected Phil, "I don't see but what we are in a box. We must be to the westward of Chilkat."

"Yes," said Serge. "It lies to the eastward of those mountains."

"Which don't look as though they would be very easy even for us to climb, while I know we couldn't get Jalap and Nel-te over them. I don't suppose any tourist steamers will be visiting this place for some time, either."

"Not for two months at least," replied Serge.

"Which is longer than we can afford to wait without provisions or supplies of any kind. So we shall have to get away, somehow, and pretty quickly too. It doesn't look as though we could follow the coast any further, though; for just below here the cliffs seem to rise sheer from the water."

"No," said Serge, "we can't. We can only get out by boat or by scaling the mountains."

"In which case we shall starve to death before we have a chance to do either," retorted Phil, gloomily, "for we are pretty nearly starved now. In fact, old man, it looks as though the good fortune that has stood by us during the whole of this journey had deserted us at its very end."

By this time the boys had strolled back to the cabin, which was left by the setting sun in a dark shadow. As they turned its corner they came upon Nel-te standing outside clapping his chubby hands, and gazing upward in an ecstasy of delight. Following the child's glance Phil uttered a startled exclamation, and sprang through the doorway. A moment later he emerged, rifle in hand.

High up on a shoulder of the mountain, hundreds of feet above the cabin, sharply outlined against the sky, and bathed in the full glory of the setting sun, a mountain-goat, with immensely thick hair of snowy white, and sharp black horns, stood as motionless as though carved from marble. Blinded by the sunlight, and believing himself to be surrounded by a solitude untenanted by enemies, he saw not the quietly moving figures in the dim shadows beneath him.

Twice did Phil raise his rifle, and twice did he lower it, so tremulous was he with excitement, and a knowledge that four human lives depended on the result of his shot. The third time he took a quick aim and fired. As the report echoed sharply from the beetling cliffs, the stricken animal gave a mighty leap straight out into space, and came whirling downward like a great white bird with broken wings. He struck twice, but bounded off each time, and finally lay motionless, buried in the snow at the very foot of the mountain that had been his home.

"Seeing as how we hain't got no fire nor no matches I reckon we'll eat our meat raw like the Huskies," said Jalap Coombs, dryly, a little later, as they began to skin and cut up the goat.

"Whew!" ejaculated Phil. "I never thought of that but I know how to make a fire with the powder from a cartridge, if one of you can furnish a bit of cotton cloth."

"It seems a pity to waste a cartridge," said Serge, "when we haven't but three or four left, and a single one has just done so much for us. I think I can get fire in a much more economical way."

"How?" queried Phil.

"Ye won't find no brimstone nor yet feathers here," suggested Jalap Coombs, with a shake of his head.

"Never mind," laughed Serge; "you two keep on cutting up the goat, and by the time your job is completed I think I can promise that mine will be." So saying, Serge entered the cabin and closed the door.

In a pile of rubbish he had noticed several small pieces of wood, and a quantity of very dry botanical specimens, some of which bore fluffy seed-vessels that could be used as tinder. He selected a bit of soft pine, and worked a hole in it with the point of his knife. Next he whittled out a thick pencil of the hardest wood he could find, sharpened one end and rounded the other. In a block of hard wood he dug a cavity, into which the rounded top of the pencil would fit. He found a section of barrel hoop, and strung it very loosely with a length of rawhide from a dog harness, so as to make a small bow. Finally he took a turn of the bow-string about the pencil, fitted the point into the soft pine that rested on the floor, and the other end into the hard wood block on which he leaned his breast.

SERGE'S METHOD OF LIGHTING A FIRE.

SERGE'S METHOD OF LIGHTING A FIRE.

With one hand he now drew the bow swiftly to and fro, causing the pencil to revolve with great rapidity, and with the other he held a small quantity of tinder close to its point of contact with the soft pine. The rapid movement of the pencil produced a few grains of fine sawdust, and this shortly began to smoke with the heat of the friction. In less than one minute the sawdust and tinder were in a glow that a breath fanned into a flame, and there was no longer any doubt about a fire.[2]

That evening, as our friends sat contentedly in front of a cheerful blaze, after a more satisfactory meal than they had enjoyed for many a day, Jalap Coombs remarked that he only wanted one more thing to make him perfectly happy.

"Same here," said Phil. "What's your want?"

"A pipeful of tobacco," replied the sailor, whose whole smoking outfit had been lost with his sledge.

"All I want," laughed Phil, "is to know how and when we are to get out of this trap and continue our journey to Sitka. I hate the thought of spending a couple of months here, even if there are plenty of goats."

"I can't think of anything else we can do," said Serge, thoughtfully.

And yet those who were to rescue them from their perplexing situation were within five miles of them at that very moment.

They were all in the "long parlor" after tea. It was a beautiful room, extending the length of the house, and it was large enough to contain four windows and two fire-places. The paper on the walls was old-fashioned—indeed, it had been there when the children's grandmother was a girl, and the furniture was of equally early date.

It was all handsome, but shabby-looking. A few dollars wisely spent would have made a vast difference in its appearance; but, unfortunately, there were never any dollars to spare.

Jack had resumed the argument. "Nonsense, nonsense, Jack!" said Mr. Franklin. "It is absurd for a boy like you to ask me for so much money. Incubators are of no good, anyhow. Give me a good old-fashioned hen."

"Perhaps, papa," said Cynthia, demurely, "Jack will give you a good old-fashioned hen if you let him buy an incubator to raise her with."

Mr. Franklin laughed. Then he grew very grave again.

"There's no doubt about my making something of it," persisted Jack. "I wish you would let me try, father! I'll pay back whatever you lend me. Indeed I will. It's only forty dollars for the machine."

Mr. Franklin was very determined. He could seldom be induced to change his mind, and his prejudices were very strong. Jack's face fell. It was of no use; he would have to give it up.

Presently Aunt Betsey spoke. She had been an attentive listener to the conversation, and now she settled herself anew in her rocking-chair, and folded her hands in the way she always did when she had something of especial importance to say.

"How much money do you need, Jackie? Forty dollars, did you say?"

"Forty for the incubator," said Jack, rather shortly. He felt like crying, though he was a boy, and he wished Aunt Betsey would not question him.[Pg 671]

"And then you must buy the eggs," put in Cynthia.

"And what do the chicks live in after they come out?" asked Miss Trinkett, who knew something about farming, and with all her eccentricities was very practical.

"They live in brooders," said Jack, warming to his beloved subject. "If I could buy one brooder for a pattern I could make others like it. I'd have to fence off places for the chicks to run in, and that would take a little money. I suppose I'd have to have fifty-five or sixty dollars to start nicely with and have things in good shape."

"Nephew John," said Miss Betsey, solemnly, turning to Mr. Franklin, "I don't wish to interfere between parent and child, it's not my way; but if you have no other objections to Jackie's hen-making machine—I forget its outlandish name—I am willing, in fact I'd be very pleased, to advance him the money. What do you say to it?"

Jack sprang to his feet, and Cynthia enthusiastically threw her arms about Aunt Betsey's neck.

"You dear thing!" she whispered. "And you look sweet in your new hair." Upon which Miss Trinkett smiled complacently.

Mr. Franklin expostulated at first, but he was finally persuaded to give his consent. So it was finally settled.

"I will lend you seventy-five dollars," said Miss Trinkett. "You may be obliged to pay more than you think, and it's well to have a little on hand in case of emergencies."

MISS TRINKETT TOOK AN AFFECTIONATE FAREWELL THE NEXT DAY.

MISS TRINKETT TOOK AN AFFECTIONATE FAREWELL THE NEXT DAY.

The next day Miss Trinkett took an affectionate farewell from her nieces and nephews, promising to send Jack the money by an early date.

"And a book on raising poultry that my father used to consult," she added; "I always keep it on the table in the best parlor. I'll send it by mail. It's wonderful what things can go through the post-office nowadays. These are times to live in, I do declare, what with chicks without a mother and everything else."

Aunt Betsey was true to her word. During the following week a package arrived most lightly tied up, and addressed in an old-fashioned, indefinite hand to "Jackie Franklin, Brenton, Mass." Within was an ancient book which described the methods of raising poultry in the early days of the century, and inside of the book were seventy-five dollars in crisp new bank-notes.

It was a week or two after the installation of the incubator that Edith was seized with what Cynthia called "one of her terribly tidy fits."

"I am going to do some house-cleaning," she announced one beautiful Saturday morning, when Cynthia was hurrying through her Monday's lessons in a wild desire to get to the river. "Cynthia, you must help me. We'll clear out all the drawers and closets in the 'north room,' and give away everything we don't need, and then have Martha clean the room."

"Oh no!" exclaimed Cynthia; "everything in this house is as neat as a pin. And we haven't got anything we don't need, Edith. And I can't. I must go on the river."

"You can go afterwards. You can spend all the afternoon on the river. This is a splendid chance for house-cleaning, with the children off for the morning. Come along, Cynthia—there's a dear."

Cynthia slowly and mournfully followed Edith up the stairs. She might have held out and gone on the river, but she knew Edith would do it alone if she deserted her, and Cynthia was unselfish, much as she detested house-cleaning.

"I am going to be very particular to-day," said Edith, as she wiped the ornaments of the room with her dusting-cloth and laid them on the bed to be covered, and took down some of the pictures.

"More particular than usual?"

"Yes, ever so much. I've been thinking about it a great deal. In all probability I shall always keep house for papa, and I mean to be the very best kind of a house-keeper. I am going to make a study of it. The house shall always be as neat as it can possibly be, and the meals shall be perfect. Then another thing," pursued Edith, from the closet where she was lifting down boxes and pulling out drawers. "I am going to be lovely with the children. They are to be taught to obey me implicitly, the very minute I speak. I am going to train them that way. I shall say one word, very gently, and that will be enough. I have been reading a book on that very subject. The eldest sister made up her mind to do that, and it worked splendidly."

"I hope it will this time, but things are so much easier in a book than out of it. Perhaps the children were not just like our Janet and Willy."

"They were a great deal worse. Our children are perfect angels compared to them."

"Here they come now, speaking of angels," announced Cynthia, as the tramp of small but determined feet was heard on the stairs and the door burst open.

"Dear me, you don't mean to say you are back!" exclaimed Edith. "I thought you were going to play out-of-doors all the morning."

"We're tired of it, and we're terrible hungry."

"An' we want sumpun to do."

"If this isn't the most provoking thing!" cried Edith, wrathfully, emerging from the closet. "I thought you were well out of the way, and here I am in the midst of house-cleaning! You are the most provoking children—don't touch that!"

For Janet had seized upon a box and was investigating its contents.

"Go straight out of this room, and don't come near me till it is done."

"We won't go!" they roared in chorus; "we're going to stay and have some fun."

Edith walked up to them with determination written on her face, and grasped each child tightly by the hand. The roars increased, and Cynthia concluded that it was about time to interfere.

"Come down-stairs with me," she said, "and I'll give you some nice crackers. And very soon one of the men is going over to Pelham to take the farm-horses to be shod. Who would like to go?"

This idea was seized upon with avidity. The three departed in search of the crackers, and quiet reigned once more. When Cynthia came back Edith said nothing for a few minutes. Then she remarked:

"Those children in the book were not quite as provoking as ours, but I suppose I ought to have begun right away to be gentle. Somehow, Cynthia, you always seem to know just what to say to everybody. I wish I did! Janet and Willy both mind you a great deal better than they do me."

She was interrupted by a shout of joy from Cynthia.

"Edith, Edith, do look at this! Aunt Betsey's extra false front! She left it behind. Don't you know she told me to put it away? It's a wonder she hasn't sent for it. There, look!"

Edith turned with a brush in one hand and a dust-pan in the other, which dropped with a clatter when she saw her sister.

Cynthia had drawn back her own curly bang, and fastened on the smooth brown hair of her great-aunt. The puffs adorned either side of her rosy face, and she was for all the world exactly like Miss Betsey Trinkett, whose eyes were as blue and nose as straight as those of fourteen-year-old Cynthia, who was always said to greatly resemble her.

"You're the very image of her," laughed Edith. "No one would ever know you apart, if you had on a bonnet and shawl like hers."

"Edith," exclaimed Cynthia, "I have an idea! I'm going to dress up and make Jack think Aunt Betsey has come back. He'll never know me in the world, and it will be such fun to get a rise out of him."

Cynthia's enthusiasm was contagious, and Edith, leaving bureau drawers standing open and boxes uncovered, hurried off to find the desired articles.

Cynthia was soon dressed in exact reproduction of Aunt Betsey's usual costume, with a figured black-lace veil over her face, and, as luck would have it, Jack was at that moment seen coming up the drive. She hastily descended to the parlor, where she and Edith were discovered in conversation when Jack entered the house.

"Holloa, Aunt Betsey!" he exclaimed, as he kissed her unsuspectingly. "Have you come back?"

"Yes, Jackie," said a prim New England voice with a[Pg 672] slightly provincial accent. "I thought I'd like to hear about those little orphan chicks, and so I said to Silas, said I, Silas—"

Edith darted from her chair to a distant window, and Cynthia was obliged to break off abruptly, or she would have laughed aloud. Jack, however, took no notice. The mention of the chickens was enough for him.

"Don't you want to come down and see the machine? I say, Aunt Betsey, you were a regular brick to send me the money. Did you get my letter?"

"Yes, Jackie, and I hope you are reading the book carefully. You will learn a great deal from it, about hens."

"Yes. Well, I haven't got any hens yet. Look out for these stairs, Aunt Betsey. They're rather dangerous."

This was too much for Cynthia. To be warned about the cellar stairs, over which she gayly tripped at least a dozen times a day, was the crowning joke of the performance. She sat down on the lowest step and shouted with laughter. Jack, who was studying his thermometer, turned in surprise.

It was too good. Cynthia tossed up her veil, and turned her crimson face to her brother.

"Oh, Jack, Jack, I have you this time! Oh, oh, oh! I never dreamed you would be so taken in!" And she danced up and down with glee.

Jack's first feeling was one of anger. How stupid he had been! Then his sense of the ludicrous overcame him, and he joined in the mirth, laughing until the tears rolled down his face.

"It's too good to be wasted," he said, as soon as he could speak. "Why don't you go and see somebody? Go to those dear friends of Aunt Betsey's, the Parkers."

"I will, I will!" cried Cynthia. "I'll go right away now. Jack, you can drive me there."

"Oh no!" exclaimed Edith. "They would be sure to find you out, and it would be all over town. You sha'n't do it, Cynthia."

"They'll never find me out. If Jack, my own twin brother, didn't, I'm sure they wouldn't. I'm going! Hurry up, Jack, and harness the horse."

Jack went up the stairs like lightning, and was off to the barn. All Edith's pleadings and expostulations were in vain. Cynthia could be very determined when she pleased, and this time she had made up her mind to pay no attention to the too-cautious Edith.

She waved farewell to her sister in exact imitation of Aunt Betsey's gesture, and drove away by Jack's side in the old buggy.

They drew up at the Parkers' door, and Jack politely assisted "Aunt Betsey" from the carriage. He ran up the steps and rang the bell for her, and then, taking his place again in the buggy, he drove off to a shady spot, and waited for his supposed aunt to reappear.

"Don't be too long," he had whispered at parting.

It seemed hours, but it was really only twenty minutes later, when the front door opened, and the quaint little figure descended the steps amid voluble good-byes.

"So glad to have seen you, my dear Miss Trinkett! I never saw you looking so well or so young. You are a marvel. And you won't repeat that little piece of news I told you, will you? You will probably hear it all in good time. Good-by!"

It was a very quiet and depressed Aunt Betsey who got into the carriage and drove away with Jack, very different from the gay little lady who had entered the Parkers' gates.

"Well, was it a success? Did she know you? Tell us about it," said Jack, eagerly.

"Jack, don't ask me a word."

"Why? I say, what's up? What's the matter? Did she find you out?"

"No, of course not. She never guessed it. But—but—oh, Jack, she told me something."

"But what was it?"

"I—I don't believe I can tell you!"

Characters:

| Queen of Clubs. |

| Queen of Hearts. |

| Queen of Spades. |

| Queen of Diamonds. |

| King of Spades. |

| King of Diamonds. |

| Joker. |

| King of Hearts. |

| King of Clubs. |

| Knave of Hearts. |

| Knave of Spades. |

| Knave of Diamonds. |

| Knave of Clubs. |

Scene.—Audience-chamber in the palace of the King of Hearts. The thrones of the King and Queen in the centre of the stage at back. Near the King's throne a small gilded three-legged stool. Entrances R. and L. Three arm-chairs R. A bench L. At the rising of the curtain the Joker is discovered seated on the King's throne, leaning on one elbow, his rattle hanging idly in the other hand. He is apparently meditating. He speaks slowly, with a pause between each sentence.

Joker. Peradventure it may seem improper for a fool to leave his lowly place and climb upon the throne. But no one's here to say me nay; and by my faith fools have sat on thrones before. What odds, then, if there's one fool more or one fool less beneath the dais? To be sure, my crown's a fool's cap and my sceptre's a rattle, and so, perhaps, not imposing; but it pleases me to sit here and fancy myself a King. Nay, laugh not. It's the province of a fool to be foolish. And verily am I not a king? Am I not monarch of all I survey? In truth I am, for I survey nothing, and am therefore King of Nothing. There's a title for you—his Majesty the King of Nothing! (Yawns and stretches and rises from the throne; picks up his stool, places it near the front, and sits down.) In faith the throne's no softer than the stool, and perhaps it is best for me to cling to this. It affords at least one advantage over the King. If he falls—and I fall—he gets the greater injury, for he tumbles from a higher place. (Laughs softly, and then sings:)

"For it's nonny, hey nonny, the Jester's song,

It's nonny, hey nonny, hey oh!

For it's nonny, hey nonny, no life is long;

Oh, merry be ye here below!"

[As he sings the last line there is a loud noise of exploding fire-crackers behind the scenes, and the four Knaves come tumbling in at the door L. in great confusion, all talking at once. The Knave of Hearts holds a lighted taper in his hand, and the other Knaves carry fire-crackers and other fireworks under their arms.]

Knave of Spades. Thou didst it.

Knave of Hearts. Thou speakest false. 'Twas he.

"HEARTS DID IT!"

"HEARTS DID IT!"

Knave of Diamonds. Never. Hearts did it.

Knave of Clubs. Hearts held the taper. He did it. Thou didst it.

Knave of Spades. Ay, ay, 'twas he.

Knave of Hearts. I say thee nay.

Knave of Diamonds. He gives him the lie direct.

Knave of Clubs. I saw him. I saw him.

Joker (rising, shakes the stool in one hand, the rattle in the other, and shouts). Silence! silence, ye riotous varlets! What is this now? What is it? Why all this noise and debate?

Knave of Hearts. Nay, Sir Joker, but it was the Knave of Spades.

Knave of Spades. Thou speakest false.

Knave of Diamonds and Knave of Clubs. Ay, ay, Hearts held the taper.

[The Knave of Hearts quickly blows out the taper and throws it away. The Knaves all begin to talk to the Joker at once. He stops his ears and shouts.]

Joker. Silence, I beg of ye! Silence! What is it, I say?

The four Knaves (speaking all together). Good Sir Joker, let me explain.

Joker. One at a time, I pray of ye! Now speak thou, Spades. What is this alarum? Whither go ye? And what bear ye? And bearing what, whither do you bear it?

Knave of Spades. Good Sir Joker, if you would ask but one question, and that direct, making it simple too, it were the easier to give a reply.

Joker (sitting down again). Troth, for a fat Knave thou speakest plainly. 'Tis to be hoped thou canst hear as well. Now listen. Whither go ye?

Knave of Spades. To the banquet hall.

Joker. And what bear ye?

Knave of Spades. Fireworks.

Joker. Fireworks?

Knave of Spades. Indeed, fireworks.

"ART BLIND? CANST NOT SEE?"

"ART BLIND? CANST NOT SEE?"

Knave of Hearts (poking a large fire-cracker into the Joker's face). Art blind? Canst not see?

Joker (much alarmed). Away there, varlet, away!

Knave of Spades. Ay, fireworks, Sir Joker, for to-day 'tis the glorious Fourth.

Joker. To-day the Fourth of July?

Knave of Diamonds (to the other Knaves in a mocking tone). He was well named "Fool."[Pg 674]

Knave of Clubs. In truth he was; yet no name was necessary. 'Tis plain writ upon his face.

[The Knaves laugh loudly.]

Joker. Marry, for a pack of rowdy varlets ye four do verily hold first claim, although you rotund Knave of Spades doth possibly deserve exemption. I prithee, Spades, whyfore all this preparation? Why these fireworks? And why so many large red fire-crackers?

Knave of Spades. Have you not heard of the King's banquet?

Knave of Hearts (sitting down on the bench and shaking his head wearily). Nay, Spades, ask him not. He has the ass's ears, but hears naught.

Knave of Diamonds. Or hearing, understands naught.

Joker. By my halidame an ye ruffians bridle not your tongues, I will even on this torrid night fall to and smite ye till ye whine like hounds for mercy!

[Threatens them with his rattle.]

The four Knaves. Oh, but that is a fierce threat!

[They nod their heads to one another in mock seriousness, and point at the Joker with the big fire-crackers.]

Joker. And now, Spades—?

Knave of Spades. Ay, Sir Joker, to-night the King and Queen of Hearts do hold a sumptuous feast, and afterward there are to be fireworks galore. To the banquet have been invited the King and Queen of Spades, the King and Queen of Diamonds, and the King and Queen of Clubs.

Joker. A right royal company, Spades.

Knave of Spades. Indeed right royal. And the feast too shall be right royal. My liege the King of Spades brings with him his fiddlers three.

Joker. So, so! Ha, ha! [Sings.]

"Old King Kole

Was a merry old soul.

A merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe,

He called for his bowl,

And he called for his fiddlers three."

Knave of Hearts. Nay, but methinks the Joker hath his rhyming mood to-day. Sit thee down, Diamonds, and be a comfortable listener.

[The Knave of Diamonds sits down on the bench beside the Knave of Hearts.]

Joker. It is meet that I should have my rhyming mood to-day; for at the feast will there not be mirth and rhyme and wit?

Knave of Hearts. Ay, mirth and doggerel, Joker; but what wit there may be thou'lt not answer for 't.

Joker (rising and shaking his fist). I can answer for thee, though, thou churl!

Knave of Hearts [bowing]. Gramercy, but I can answer for myself.

Joker. And 'twill not be the first time. Methinks, as a thief thou hast already been called upon to answer once. (Sits down again.) And now, Spades, I beg of thee, proceed.

Knave of Spades. There is little more to tell, Sir Joker, save that the Queen of Hearts herself did fashion these huge fire crackers—eight of them, that there should be one for a salute to each guest. We bear them now to the banquet hall.

Knave of Diamonds. Ay, and the quicker we go hence the wiser; for time moves on apace, and the guests will soon be here.

Joker (rising from his stool and making a mock obeisance). My gratitude, gentle Knaves, for your varied courtesies. (The Knaves bow and exeunt, R., in single file. Joker puts his stool back in its place, beside the throne.) Of two misfortunes, rather let me suffer that of being a fool than a knave. The one knows nothing of the evil he does; the other knows nothing of the evil he does not do. And methinks whether of evil or of good those Knaves know but little of what they now perform. They bear those explosive bombs to the banquet hall? Surely they err. But of my affair it is none, and so I shall sagely hold my peace upon it, and—tap my wit! For here come the King and Queen.

[Music. Enter the King and Queen of Hearts, L., the Joker bowing and dancing before them as they come. They take their seats upon the thrones.]

King of Hearts. Well, Sir Joker, what was this riot that I lately heard? What this odor of powder and saltpetre?

Joker. The Knaves, my lord, the Knaves, the sorry Knaves. They did but even pass this way toward the banquet hall, bearing fireworks. (Sits down in one of the arm-chairs, and juggles with his rattle.) They did by mischance set off several of the pieces, and wellnigh scared me of the possession of my wits.

King of Hearts (laughing). Yet thou hast thy fool's cap still well on, I hope?

Joker. That I have, sire. So well on that even should you wish to borrow it, you could not get it off.

King of Hearts. Thou needst have no fear that I shall care to deprive thee of that honor.

Joker. Nay, but Kings have played the fool before.

King of Hearts. True. And thou mayst well add—many a fool has played the King.

Joker. But do not accuse me, sire. I never played you. I do but play upon you.

King of Hearts. Thou playest upon me?

Joker. Only to hear your sweet notes, my liege.

Queen of Hearts. Thou hast a well-turned speech to-day, Joker.

Joker. Well turned, my Queen? Yet not so well turned as those giant fire-crackers which you have fashioned for the feast. Those indeed are royal bombs!

Queen of Hearts. Bombs? They are indeed harmless. There is nothing in them, but I warned the Knaves to handle[Pg 675] them carefully, saying they might unexpectedly explode. [Laughs.]

Joker. And so, if they exploded, 'twould in truth be unexpected!

[As the Joker finishes his speech, enter Knave of Diamonds, L. He holds the portières up and announces in loud and formal tones,]

ARRIVAL OF THE ROYAL GUESTS.

ARRIVAL OF THE ROYAL GUESTS.

Knave of Diamonds. Their Majesties the King and Queen of Diamonds.

[Music. Enter the King and Queen of Diamonds, L.]

King of Hearts. Welcome, my cousin of Diamonds. Welcome this glorious July day.

Queen of Hearts. Welcome, fair lady. "First come, best loved," is the saying, you know—and ye are the first come. Pray be seated.

[At the entrance of the King and Queen of Diamonds the King and Queen of Hearts rise to greet them. The King of Diamonds bows to the King of Hearts and kisses the hand of the Queen of Hearts. The Queen of Diamonds courtesies. She then sits down in an arm-chair, R., and the King of Diamonds takes his stand behind her. The Knave of Diamonds drops the portière and sits on the bench.]

Joker (to Queen of Diamonds). Even the sun, fair lady—which is said by the poets to shine brightest this fair month of July—even the sun fails to outsparkle your priceless precious stones.

Queen of Diamonds. Ah, you have a pretty wit, Sir Joker. But are they not truly the most brilliant of jewels?

Joker. The most brilliant of jewels, yes; but they pale before their wearer's beauty.

[Takes his seat on the stool near the throne.]

[Enter, L., Knave of Clubs, who announces,]

Knave of Clubs. Their Majesties the King and Queen of Clubs.

[Music. Enter the King and Queen of Clubs, L.]

King of Hearts. Welcome, welcome, good Clubs. My best wishes, fair lady, my best wishes!

Queen of Hearts (to Queen of Clubs). Greeting to you, and pray take seat beside our cousin of Diamonds.

[At the entrance of the King and Queen of Clubs, the King and Queen of Hearts arise, as before. The King of Clubs bows to the King of Hearts, and kisses the hand of the Queen of Hearts. The Queen of Clubs courtesies. She then sits down in an arm-chair next to the Queen of Diamonds, the King of Clubs stands behind her, and the Knave of Clubs takes his place on the bench.]

Queen of Hearts. It is indeed a pleasure to have you here again. 'Tis now many a long day since I have seen you.

Queen of Clubs (fanning herself, and affecting an air of great weariness). Ah, dear lady of Hearts, you cannot conceive of my perplexities. What with tournaments and levees and audiences at large, the days do slip so swiftly by, giving me no pause for rest or recovery, that I do find myself ending the week ere I realize it to have begun.

Joker. Yet time, fair Queen, seems to have touched your comely brow with a light finger. The winged hours fly swiftly past you, but yourself dwell at the one sweet station of constant youthfulness.

Queen of Clubs (haughtily). So graceful a speech, Sir Joker, were worthy of a knight rather than of a fool.

Joker. It is for the listener to detect when the fool speaks foolishly. For he himself is too great a fool to judge of the burden of his speech.

Queen of Diamonds (superciliously, to Queen of Clubs). Methinks his words have a double edge.

Joker (to Queen of Diamonds). You wrong me, good lady, for he that playeth with edged tools is most apt to cut himself.

[Enter, L., Knave of Spades, who announces,]

Knave of Spades. Their Majesties the King and Queen of Spades.

[Music. Enter, L., in great haste, the King and Queen of Spades.]

King of Spades (breathlessly). Ah, I so greatly feared, my lord—

King of Hearts. A hand to thee, cousin of Spades, a hand to thee, and welcome.

Queen of Hearts. And a fair day to you, good dame of Spades.

"WE DID HASTEN BEYOND ALL REASON!"

"WE DID HASTEN BEYOND ALL REASON!"

Queen of Spades (panting). Sweet cousin, we did so greatly fear to be behindhand that we did hasten beyond all reason. I am quite forlorn of breath.

Queen of Hearts. Seat you, seat you, good lady.

[The King and Queen of Spades are very much out of breath, and very warm. The King and Queen of Hearts arise in their entrance to greet them, but the King and Queen of Spades are so overcome with excitement that they forget the conventionalities, and the Queen of Spades flops into the third arm-chair without making any courtesy. The King of Spades takes his stand behind her, wiping his brow vigorously with his handkerchief, then suddenly remembers he has omitted to kiss the hand of his hostess. He hastens across the stage falling as he goes, and makes up for the omission. The Knave of Spades sits on the bench.]

Queen of Hearts. There, now, rest you easily, for there is small haste for the feast.

King of Spades (still mopping his face and puffing). I am much relieved that we were not late on the banquet, King of Hearts. The banquet should have waited on you, cousin.

King of Spades (pacing about the stage, nervously fanning himself; occasionally he stumbles and falls). Ay, but I might not so well have waited on the banquet.

Queen of Spades. True, he hungers mightily.

[Fans herself vigorously with her handkerchief.]

Queen of Hearts (to Joker). Sir Joker, the Queen of Spades suffereth of her exertions. I beg of you seek a fan.

[Joker bows, and exit R.]

Queen of Clubs (aside to Queen of Diamonds). I marvel at the rapacity of some folk.

Queen of Diamonds. Verily one might think that there lacked meat and cooks and scullions in the land of Spades.

Queen of Clubs. Nay, but I dare say they be short two scullions at the present hour. [They laugh.]

Queen of Hearts (to Queen of Diamonds). What say you?

Queen of Clubs. I was saying that if haste might always so trim our cheeks with color as that which now blooms upon the fair face of our cousin of Spades, it were worth the discomfort of so great an energy.

[Enter Joker, R. He presents fan to Queen of Spades, who fans herself boisterously.]

Joker. Would I were a fan, that even my whispers might be of such grateful reception to a lady's ear![Pg 676]

Queen of Spades. Not my ear, Sir Joker, not my ear. It is my nose that reddens from my efforts.

King of Spades (wiping his brow and neck with his handkerchief). And as to me, it is my neck. 'Tis the pity of being stout.

Joker. The neck, Sir King? Aha, but I warrant that even if it be moist without, it is dry within.

King of Spades (with asperity). Ay, marry, fool; but not so dry as thy wit.

King of Hearts. Come, come, cousin, heed him not. (The Joker moves over to the throne of the Queen of Hearts, and enters into earnest conversation with her.) It pleases me to hear you say you bring a good appetite to the feast.

King of Spades. Verily I feel as though I were one vast incarnation of appetite.

King of Hearts. All the more honor will you do us, and we shall ever recall this Fourth of July as one that pleased you. And the good lady of Spades, has she too—

Queen of Hearts (screams). Ah, me! Ah, lackaday, lackaday! [Faints.]

King of Hearts. What is this? What is this? The Queen faints! A cup! a cup!

Queen of Diamonds, Queen of Clubs, Queen of Spades (rising and rushing to the Queen of Hearts' seat. They pat her hands and fan her). Yes, a cup, a cup!

[The three Knaves rush out, R., tumbling over one another and shouting "Water, water!" The Knaves return, one at a time, bearing glasses of water, but they are met each time by the King of Spades, who takes the glass, goes half-way to the Queen of Hearts, and then, in his excitement, drinks the water himself. This "business" can be carried on while the ensuing dialogue is being spoken.]

Queen of Hearts (recovering herself). Nay, nay, trouble not. I am myself again. It was merely the Joker.

[The three Queens resume their seats.]

King of Hearts (angrily). The Joker?

Queen of Hearts. Ay, he spake in my ear, and said—

King of Hearts (threatening the Joker). What, Sir Joker! Hast thou dared to frighten or disturb the Queen?

Queen of Hearts (expostulating). Nay, nay, the Joker is good! Good Sir Joker, tell the King. Tell them all, that they may know!

"WHAT IS THIS MYSTERY?"

"WHAT IS THIS MYSTERY?"

King of Hearts (sternly). Come, Sir Joker, what is this mystery?

Joker. There is no mystery, my lord. It is all but too plain. Her Majesty the Queen, as you know, did fashion eight large fire-crackers of fine red paper, the which were placed upon the board for the banquet. I went to seek a fan for her Majesty of Spades, and in passing the banquet hall curiosity did impel me to look in upon the tables. The fire-crackers are not there, my liege. They have been purloined. They have been stolen.

[Great excitement. The Kings and Queens talk and gesticulate with one another.]

King of Hearts. What? The fire-crackers are stolen?

Joker. Ay, my lord, stolen.

King of Spades. And will there be no fireworks after the feast?

King of Hearts. And the thief?

Joker. It is but left for us to guess.

King of Hearts. And thou hast suspicion?

Joker. True, my lord, I have.

King of Hearts. Name him, Sir Joker.

All. Ay, name him—name him!

Joker. Nay, nay, my liege. 'Twere unjust falsely to accuse—

King of Hearts. Name him, Sir Joker!

All. Ay, name him!

Joker. My lord—

King of Hearts. Name him. I command thee!

Joker. Hath no man stolen before?

King of Hearts. Thou meanest—

Joker. The Knave of Hearts.

All (lifting their hands). The Knave of Hearts!

King of Hearts. The rascal Knave! Where is he? Come, come, I must have him! He is not here? Then hale me hither that churlish lout, and heavily shall he pay his sins! (Exeunt the three Knaves, L.) Aha! but there is no cause for laughter here!

King of Spades (very much excited, throws himself in an exhausted condition on the bench, L.). Laughter—laughter? Well, I should say thee nay! Is the larder robbed?

Queen of Hearts. Nay, he has but taken the fire-crackers.

King of Spades. The crackers—the crackers! Did he take the cheese too?

Joker. Nothing else is gone.

King of Spades. Ah, fortune be praised!

Queen of Clubs (to Queen of Hearts). And did you fashion these fire-crackers?

King of Hearts. With her own hands she fashioned them.

Joker. One for each guest.

Queen of Clubs. Indeed—indeed! And is the Queen as dexterous at the fashioning of fire-crackers as she is at the baking of water-crackers and other light confections?

Queen of Hearts. You are sweet so to flatter me.[Pg 677]

Queen of Clubs. But I so well remember the Christmas pie.

King of Spades. Pie! Where is the pie?

Joker. It was eaten last Christmas, the pie.

King of Spades. Oh, alack!

Joker. But it was a noteworthy pie. I have rhymed upon it. Pray listen. [Sings.]

"Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye,

Four-and-twenty blackbirds baked in a pie;

When the pie was opened

The birds began to sing;

Was not that a dainty dish to set before the King?"

King of Spades. Indeed that must have been a toothsome dish.

[Noise and commotion without. Enter the Knaves, L., two dragging, one pushing the Knave of Hearts. He is forced to his knees in front of the King of Hearts' throne.]

King of Hearts (sternly). There be severe accusations against thee, Knave.

Knave of Hearts. Oh, my King! I pray—

"DIDST THOU STEAL THE FIRE-CRACKERS?"

"DIDST THOU STEAL THE FIRE-CRACKERS?"

King of Hearts. Silence, churl! Answer but my questions. Didst thou steal the fire-crackers?

Knave of Hearts. Not "steal," my lord.

King of Hearts. Didst thou steal the fire-crackers?

Knave of Hearts. I did but take them from the table.

King of Hearts. Thou makest confession, then?

Knave of Hearts. My lord, my lord, I would but say one word in explanation.

King of Hearts. Thou shalt say nothing. This is the second time thou art taken a thief. Last summer thou didst steal the Queen's tarts, and now thou takest the fire-crackers. Thou shalt pay for it with thine head! Thou shall be blown up to-night upon a monster pile of fireworks.

Knave of Hearts. Mercy, my lord—mercy! Let me explain.

King of Hearts (to the other Knaves). Remove him.

[The Knave of Hearts is dragged out, L.]

Queen of Diamonds. And did he steal once before?

King of Hearts. That he did, and was therefore severely punished. I myself did beat him full sore.

King of Spades (slapping King of Hearts on the back). Do it again, cousin—do it again!

King of Hearts (approvingly). That shall I! Thou speakest well. I beg your patience, ladies; but I will beat this Knave before he dies.

[Exit King, L., rolling up his sleeves.]

King of Spades (to Queen of Spades). 'Tis fortunate he did but take the fire-crackers. I should have grieved surely had they been tarts; for tarts one may eat, but fire-crackers they be somewhat indigestible, I fear.

Queen of Clubs. I had not heard of this previous theft.

Queen of Hearts. It was similar to this, fair cousin. And the Joker hath likewise rhymed upon it.

Queen of Clubs. Indeed. And may we hear the verse, Sir Joker?

Joker. It is a pleasure to sing it. [Sings]

"The Queen of Hearts

She baked some tarts

All on a summer's day—"

[Sounds of beating without, and loud cries by the Knave of Hearts of "Ow!" "Ow!" "Mercy, my lord!" "Hold!" "Hear me!"][Pg 678]

Queen of Spades. 'Tis evident the punishment hath begun.

Queen of Clubs. Oh, the poor Knave! the poor Knave!

[More sounds of beating and more cries. The King of Spades becomes very much excited.]

King of Spades (shaking his fist in the direction of the cries). Have at him, good cousin of Hearts, have at him! Ah, but those are lusty blows! By my halidame, I would fain witness that controversy! [Slaps his knee.]

Joker. A most one-sided controversy, my lord.

King of Spades. Nay, but I warrant the King doth lay it on both sides. [More beating and cries.]

Joker. Ay, from the sounds, he doth lay it on. But, doubtless, it will whet his appetite.

King of Spades. His appetite? Now, by St. Dagobert, I have already an appetite as I had beaten an hundred knaves!

Joker. Then will it also be a one-sided controversy when you meet the banquet board.

King of Spades. I would fain go out and beat the Knave for causing this delay. (Sounds and cries.) Have at him! Have at him, sir! Now, a good one for me, sir, a good one!

[The sounds and cries gradually cease.]

Queen of Clubs. Prithee, Sir Joker, finish your rhyme; you did but sing the first lines.

Joker (sings).

"The Queen of Hearts

She baked some tarts

All on a summer's day;

The Knave of Hearts

He stole those tarts,

And bore them far away.

"The King of Hearts

Called for those tarts,

And beat the Knave full sore—"

Enter the King of Hearts, L., somewhat out of breath, rolling down his sleeves, and followed by the Knaves of Diamonds, Clubs, and Spades.

King of Hearts. Ah, but I did ply the rod right lustily! I am quite aweary. [Sits down.]

King of Spades (rubbing his hands). We did much enjoy the music!

Queen of Hearts. Good spouse, I would beg one thing of thee. It being the Fourth of July, and so our nation's birthday, spare the rogue his life. Let him come before us again. You heard him say he would make explanation. Let him come and speak. Perchance it is not too late for him to make restitution.

King of Hearts (in astonishment). Dost thou truly desire that the varlet should be spared?

Queen of Hearts (pleading). Ay, truly, my lord. And I do especially yearn for the return of the fire-crackers.

King of Spades. Ay, cousin, if he would but return the fire-crackers, hear him, I urge, hear him.

King of Hearts (to the three Knaves). Hale me hither that Knave again. (Exeunt the Knaves, L.) I greatly doubt me, sweet lady, that the thieving churl will return the crackers. He did not return the tarts. But if he can and does return the fire-crackers, then at your request will I spare him his life.

Queen of Hearts. You make me promise of that, my King?

King of Hearts. You have my word upon it.

[Enter, L., the three Knaves escorting the Knave of Hearts, who is very sore as a result of his beating.]

King of Hearts. Knave, the Queen hath begged of me to let thee speak ere the headsman seals thy lips forever.

Knave of Hearts. A blessing upon you, good lady.

King of Hearts. And now speak what thou hast to say, and may thy words be brief.

Knave of Hearts. My liege, I did not steal the fire-crackers. I did but see them near the tapers, and I did fear lest they catch fire and explode upon the table. Methought they were the daintier did they hold some sweet contents, and so I took them and bore them off, and found them void. So then I was about to bring them back to the banquet board, when yon messengers did seize me and hale me roughly before your Majesties.

King of Hearts. And thou didst have intention to return them?

Knave of Hearts. Ay, verily, my liege. Verily I did. I plead now that I be allowed to bring them to the board.

King of Hearts. Speakest thou the truth, Knave?

Knave of Hearts. Every word is truth, sire.

King of Hearts. Then go thou and seek the fire-crackers. (To the other Knaves.) And go ye with him. (To the Knave of Hearts.) The Queen holds my word that if thou bringest them back, I spare thy life. Now look to thyself. Away!

[Exeunt, L., the four Knaves.]

Joker. It is a cheap life that costeth but eight fire-crackers!

King of Spades. Ay, but the fire-crackers be worth more than yon Knave's life.

Queen of Hearts. Come, speak no more of his life. It is no longer forfeit. He hath promised restitution, and the King will bestow plenary pardon.

King of Spades. Well, as for me, I am more anxious as to the crackers than as to any Knave's life.

[Music. Enter, L., the four Knaves, each bearing two large fire-crackers. There are tarts in each. The Knaves sand side by side along the wall, L.]

King of Spades. Aha, the fire-crackers, the fire-crackers!

Queen of Spades. And most wondrous, wondrous are they!

Queen of Diamonds. Truly they be most marvellously fashioned.

King of Hearts. Now, Knave, according to my promise, and because of the gracious intercession of the Queen, thy life is spared, for thou hast brought back the fire-crackers. Take them to the board. And if ever again thou art taken a thief, thou needst not reckon thy life at the hundredth part of a farthing.

King of Spades. But, Sir King, the Knave did say he took the fire-crackers that he might place somewhat therein.

King of Hearts. True, I remember he said so. Hast thou placed aught within them, Knave?

Knave of Hearts. Ay, my lord. When I did first purloin the Queen's tarts last summer, methought to eat them. But being so sorely beaten by your Majesty, I did refrain, and so kept the tarts uneaten. To-day I return the tarts in the fire-crackers, thereby making double restitution to her most charitable and generous Majesty the Queen of Hearts.

[The Knaves open the fire-crackers and shake out the tarts into a tray held by the Joker.]

Queen of Hearts. The tarts?

"THE IDENTICAL TARTS!"

"THE IDENTICAL TARTS!"

Knave of Hearts. Ay, my Queen, the identical tarts.

Queen of Clubs. But they must be stale of the last summer?

Joker. Nay, fair lady. These be royal tarts, and not of the general. Age cannot stale them, nor can human possibility limit their infinite variety.

Queen of Hearts. Taste them, fair cousins, taste them.