The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Diary of a Resurrectionist, 1811-1812, by

James Blake Bailey

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Diary of a Resurrectionist, 1811-1812

To Which Are Added an Account of the Resurrection Men in

London and a Short History of the Passing of the Anatomy Act

Author: James Blake Bailey

Release Date: May 31, 2010 [EBook #32614]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DIARY OF A RESURRECTIONIST ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

“THE DISSECTING ROOM.” By Rowlandson.

The figure standing up above the rest is William Hunter; his brother John

is on his

right-hand side, and Matthew Baillie is the next figure to

William Hunter on the left;

Cruikshank is seated at the extreme left of

the picture, and Hewson is working on

the eye of the subject on the middle table.

TO WHICH ARE ADDED AN ACCOUNT OF

THE RESURRECTION MEN IN LONDON

AND A SHORT HISTORY OF THE PASSING OF

THE ANATOMY ACT

LONDON

SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., Lim.

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

1896

The “Diary of a Resurrectionist” here reprinted is only of a fragmentary character. It is, however, unique in being an actual record of the doings of one gang of the resurrection-men in London. Many persons have expressed a wish that so interesting a document should be published; permission having been obtained to print the Diary, an endeavour has been made to gratify this wish. To make the reprint more interesting, and to explain some of the allusions in the Diary, an account of the resurrection-men in London, and a short history of the events which preceded the passing of the Anatomy Act, have been prepared.

The great crimes of Burke and Hare drew especial attention to body-snatching in[Pg vi] Edinburgh, and consequently there have been published ample accounts of the resurrection-men in Scotland.[1] For this reason, Edinburgh has been omitted from the present work.

As to the genuineness of the Diary there can be no doubt. It was presented to the Royal College of Surgeons of England by the late Sir Thomas Longmore. In his early days, Sir Thomas was dresser to Bransby Cooper, and assisted him in writing the Life of Sir Astley Cooper.

At the suggestion of Lord Abinger, it was decided to introduce an account of the resurrection-men into the book. The information for this was partly obtained by Mr. Longmore from personal communication with some of the resurrection-men, who were then living in London. One of these handed over portions of a Diary he had kept during his resurrectionist days. This was preserved for some years at Netley, and was afterwards presented to the[Pg vii] College, as stated above. A few extracts from the Diary were printed in the Life of Sir Astley Cooper.

The information respecting the resurrection-men is very scattered; the two most useful works for getting up this subject are the Life of Astley Cooper before mentioned, and the Report of the Committee on Anatomy published in 1828. Most of the detailed information has to be sought for in the newspapers of the period. The accounts there given are, however, generally of such an exaggerated character that it is often very difficult to arrive at the truth. When any fresh scandal had given prominence to the doings of the resurrection-men, the newspapers saw “Burking” in every trivial case of assault. If a child were lost, the paragraph announcing the fact was headed, “Another supposed case of Burking.” Reports of the most ridiculous character were duly chronicled as facts by the newspapers of the day. Sometimes over a hundred bodies were supposed to have been found in some building, and it was expected that several persons of[Pg viii] eminence would be named in the subsequent proceedings. Search in the papers nearly always fails to find any further mention of the case.

In reading these accounts it must be remembered that “Burking” did not always mean killing a person for the purpose of selling the body, but it referred to the mode adopted by Burke and Hare in killing their victims, viz., suffocation. Elizabeth Ross is called a “Burker,” and may be found so described in Haydn’s Dictionary of Dates. She murdered an old woman named Catherine Walsh, but in the report of her trial there is no evidence of her having attempted to sell the body.

The broadside here printed is an excellent example of this exaggeration. The facts are so circumstantial, that it appears as though there could be no mistake. Enquiry at Edinburgh, however, shows that no such case occurred. Mr. A. D. Veitch, of the Justiciary Office, has very kindly made search, and can find no record of Wilson’s supposed crimes. Had the statements in the broadside been true,[Pg ix] there is no doubt that this case would have been referred to in books on Medical Jurisprudence. Poisoning by inhalation of arsenic is rare, and Wilson’s would have been a leading case. There would also have been great opportunities for studying post mortem appearances, as it is stated that three bodies were found in Wilson’s possession. Search through the chief books on the subject has failed in finding any reference whatever to this case.

“Burking by means of Snuff.

“The following Account is of so serious a Nature that no one can be too cautious how they receive Snuff from Strangers.

“It appears that, on Monday se’nnight, a man, named John Wilson, was apprehended at Edinburgh on a charge of Burking a number of persons by introducing arsenic into snuff kept by him. He had long excited the suspicion of the police of that place, but so deep-laid were his diabolical schemes that he eluded their vigilance for a considerable time, until Monday last. When, on the moors, on[Pg x] that day, between Lauder and Dalkeith, practising his dreadful trade, it appears that the victim of Wilson’s villainy was a poor man travelling over the moor, whom he accosted, and offered a pinch of snuff. He took it, and it had the desired effect. The next individual whom he accosted was a labouring-man breaking stones, who was asked the number of miles to Edinburgh; when answered, he then offered his snuff-box to the labourer, which was refused, alleging that he never used any. Wilson urged him again, which excited the man’s suspicions, but he took the snuff, and wrapped it up in paper, and carried it to a chemist at Dalkeith, who analysed it, when it proved to be mixed with arsenic. The police were then informed of Wilson’s villainies, who went in pursuit of him, and after a search of him for several days was at length apprehended at a place three miles from Edinburgh, driving rapidly in a vehicle like a hearse, which, on examination, contained three dead bodies. They were recognised from their dresses to be an elderly man, and his wife and son, who were seen travelling towards Lauder the day before.

“Wilson was immediately ironed and[Pg xi] conveyed to Edinburgh, and a sheriff’s inquest was held on the bodies. After an investigation of nearly two hours a verdict of Wilful Murder was returned against John Wilson, who was fully committed to the Calton gaol to take his trial at the ensuing sessions.

“Wilson is described as a desperate character, and of ferocious countenance. He is supposed to have been two or three years in this abominable practice, and to have realised a considerable sum in the course of that time. His career is now stopped, and that justice and doom which overtook a Burke and a Hare are his last and only portion.

“LINES ON THE OCCASION.

| Of Burke and of Hare we have heard much about, Yet Burking’s a trade that was lately found out— Their plans of despatching were wicked indeed, ’T was thought of all others that theirs did exceed; But the scheme first invented of Burking by snuff, May yet be prevented by taking the huff, For if strangers invite you to take of their dust, Decline their kind offers—refuse them you must; And would you be safe, and keep from all evil, Shun them as pests as you’d shun the d——l; By these means you’ll live, avoiding all strife, Shunning snuff takers all the days of your life. |

“Printed for the Publishers by T. KAY.”

[Pg xii]The difficulty of getting reliable information is increased by the incomplete nature of most of the newspaper records. In many cases there is an account of a preliminary examination of some of the men who were arrested for body-stealing. The report states that they were remanded, but further search fails to find any subsequent notice of the case. It is often impossible to fix who the men were who thus got into trouble, as they nearly always gave false names: unless they were too well-known to the police who arrested them, they invariably did this.

For the photographs, from which the illustrations of the house at Crail are taken, the writer is indebted to the kindness of Prof. Chiene, of Edinburgh.

The complaint as to the scarcity of bodies for dissection is as old as the history of anatomy itself. Great respect for the body of the dead has characterised mankind in nearly all ages; post mortem dissection was looked upon as a great indignity by the relatives of the deceased, and every precaution was taken to prevent its occurrence.

It would be beyond the scope of the present work to attempt a history of anatomical teaching; as will be pointed out later on, the resurrection-men did not come into existence until the early part of the eighteenth century.

In Great Britain the study of medicine and surgery was much hampered at this date by the[Pg 14] scarcity of opportunities by which the student might get a practical acquaintance with the anatomy of the human body. A knowledge of anatomy was insisted upon by the Corporation of Surgeons, as each student had to produce a certificate of having attended at least two courses of dissection. It is unnecessary to point out the wisdom of this condition in the case of men who were to go out into the world as surgeons, and, consequently, to have the lives of their fellow-men in their hands. The attendance on the two courses of dissection could be evaded, and this was frequently done. The Apothecaries’ Hall had no such restriction, and, consequently, many men went thither and received a qualification to practise, although they were quite unacquainted with human anatomy. The work of such ’prentice hands one trembles to think of; whatever experience these men did gain was obtained after they began to practise, and so must have been at the expense of their patients, who were generally those of the poorer class in life.

It was pointed out by Mr. Guthrie, that in the then state of the law a surgeon might be[Pg 15] punished in one Court for want of skill, and in another Court the same individual might also be punished for trying to obtain that skill. Before the Anatomy Committee, in 1828, Sir Astley Cooper narrated the case of a young man who was rejected at the College of Surgeons on account of his ignorance of the parts of the body; it was found, on enquiry, that he was a most diligent student, and that his ignorance arose entirely from his being unable to procure that which was necessary for carrying on this part of his education.

When bodies were obtained for dissection it was generally by surreptitious means; the newly-made grave was too often the source from whence the supply was obtained. At first there was no direct trade or traffic in subjects by men who devoted all their efforts to this mode of obtaining a livelihood. The students supplied their own wants as they arose. Mr. G. S. Patterson told the Committee that at St. George’s Hospital the students had to exhume bodies for their own use.

In the Diary of a Late Physician Samuel Warren has given us a chapter on this subject, which he calls “Grave Doings,” and which is[Pg 16] probably founded on fact. The object in the expedition here recorded was, however, rather to obtain a valuable pathological specimen, than to get a body for dissection. Writers of fiction have made use of body-snatching, and have given a gruesome turn to their stories by making the body, when uncovered, turn out to be that of a relation or friend of some one of the party engaged in the exhumation. Such a tale is recorded in the Monthly Magazine for April, 1827; there a sailor is pressed into the service of some students who were anxious to obtain a body. The subject was safely brought home, and, on being taken from the sack, turned out to be the sweetheart of the sailor, who had just returned from sea, and, not having heard of his girl’s decease, was on his way to greet her after a long absence from home. Truth and fiction often agree. There is a case on record of a child who had died of scrofula, and whose body was brought to St. Thomas’ Hospital by Holliss, a well-known resurrectionist. The body was at once recognised by one of the students as that of his sister’s child; on this being made known to the authorities at the hospital, the corpse[Pg 17] was immediately buried before any dissection had taken place.

In vols. 1 and 2 of the Medical Times there is a series of articles, entitled “The Confessions of Jasper Muddle, Dissecting-room Porter.” These papers are signed “Rocket,” but were written by Albert Smith.[2] One of the articles contains an account of a handsome young lady who came to the dissecting-room late at night, and begged for the body of a murderer executed the previous day, which was then being injected, ready for lecture purposes. In the Tale of Two Cities, Dickens has given us a good study of a resurrection-man in the person of Mr. Cruncher. Moir in Mansie Wauch, Lytton in Lucretia, Mrs. Crowe in Light and Darkness, and Miss Sergeant in Dr. Endicott’s Experiment, have also used the body-snatcher in fiction.

As long as the Barber Surgeons kept to their right of the exclusive teaching of anatomy, there was small need of bodies for dissection. This right the Company jealously guarded. On 21st May, 1573, the following entry occurs[Pg 18] in the records, “Here was John Deane and appoynted to brynge in his fyne xli for havinge an Anathomye in his howse contrary to an order in that behalf between this and mydsomer next.”[3] As late as 1714 this rule was put in force against no less a man than William Cheselden. The entry in the books of the Company runs as follows, “At a Court of Assistants of the Company of Barbers and Surgeons, held on the 25th March, 1714. Our Master acquainting the Court that Mr. William Cheselden, a member of this Company, did frequently procure the Dead bodies of Malefactors from the place of execution and dissect the same at his own house, as well during the Company’s Publick Lectures as at other times without the leave of the Governors and contrary to the Company’s By law in that behalf. By which means it became more difficult for the Beadles to bring away the Companies Bodies and likewise drew away the members of this Company and others from the Public Dissections and Lectures at the Hall. The said Mr. Cheselden was, therefore, called in.[Pg 19] But having submitted himself to the pleasure of the Court with a promise never to dissect at the same as the Company had their Lecture at the Hall, nor without leave of the Governors for the time being, the said Mr. Cheselden was excused for what had passed with a reproof for the same pronounced by the Master at the desire of the Court.”[4]

By the Act Henry VIII., xxii., cap. 12, provision was made for the Company of Barbers and Surgeons to have the bodies of malefactors for the purpose of dissection. This part of the Act was as follows: “And further be it enacted by thauctoritie aforesayd, that the sayd maysters or governours of the mistery and comminaltie of barbours and surgeons of Londō & their successours yerely for ever after their sad discrecions at their free liberte and pleasure shal and maie have and take without cõtradiction foure persons condempned adjudged and put to deathe for feloni by the due order of the Kynges lawe of thys realme for anatomies with out any further sute or labour to be made to the kynges highnes his heyres or successors[Pg 20] for the same. And to make incision of the same deade bodies or otherwyse to order the same after their said discrecions at their pleasure for their further and better knowlage instruction in sight learnyng & experience in the sayd scyence or facultie of Surgery.”

The “foure bodies” could not always be obtained without difficulty; despite the precautions of the Company private anatomy was, to a certain extent, carried on, and the bodies of malefactors had a market value. The following entries from the Annals of the Barber Surgeons are illustrative of this:

“6th March, 1711.[5] It is ordered that William Cave, one of the Beadles of this Company, do make Inquiry who the persons were that carryed away the last body from Tyburne, and that such persons be Indicted for the same.

“9th October, 1711. Richard Russell, one of the persons who stands Indicted for carrying away the last publick body applying himself to this Court and offering to be evidence against the rest of the persons concerned It is ordered that the Clerk do apply himself to Her Majesty’s[Pg 21] Attorney Generall for a Noli p’sequi as to the said Russell in order to make him an evidence upon the sd Indictment and particularly agst one Samuell Waters whom the Court did likewise order to be indicted for the said fact.”

Often there were riots caused by the Beadles of the Company going to Tyburn for the bodies of murderers. This rioting was carried to such an extent that it was found necessary to apply for soldiers to protect the Beadles.

“28th May, 1713. Ordered that the Clerk go to the Secretary at War for a guard in order to gett the next Body [from Tyburn.]”

The dissection of these bodies was made known by public advertisement. The following is from the Daily Advertiser of January 15th, 1742: “Notice is hereby given that there being a publick Body at Barbers and Surgeons Hall, the Demonstrations of Anatomy and the Operations of Surgery will be at the Hall this evening and to-morrow at six o’clock precisely in the Amphitheatre.”

In 1752 it was ordered that bodies of murderers executed in London and Middlesex should be conveyed to the Hall of the Surgeons Company to be dissected and anatomized, and[Pg 22] any attempt to rescue such bodies was made felony.

In 1745 the Barbers and Surgeons, who from 1540, until that date, had formed one Company, separated, and the latter were incorporated under the title of “The Masters, Governors, and Commonalty of the Art and Science of Surgery.” To the Surgeons naturally fell the duty of dissecting the bodies of the malefactors handed over for that purpose. The building of the Surgeons’ Company was in the Old Bailey; there was, therefore, no difficulty in removing the bodies from Newgate. In 1796 the Company came to a premature end through an improperly constituted Court having been held. It was attempted to put matters right by a Bill in Parliament, but there was so much opposition from those persons who were practising without the diploma of the Corporation, that the Bill, after passing safely through the Commons, was thrown out by the Lords. In the following year attempts were made to come to terms with the opponents of the Bill, and finally it was agreed to petition for a Charter from the Crown to establish a Royal College of Surgeons in London. These[Pg 23] negotiations were successfully carried out in 1800, and the old Corporation having disposed of their Old Bailey property to the City Authorities, the College took possession of a house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the site of part of the present building.

During the debate in the House of Lords on the Bill just mentioned, the Bishop of Bangor, who had charge of the measure, sent for the Clerk of the Company, and informed him that a strong opposition was expected to the Bill, on account of the inconvenience that would arise from the bodies of murderers being conveyed through the streets from Newgate to Lincoln’s Inn Fields. To remedy this a clause was proposed, giving the College permission to have a place near to Newgate, where the part of the sentence which related to the dissection of the bodies might be carried out.

That this difficulty of moving the bodies was not a fancied one, the following extract from “Alderman Macaulay’s Diary” will show: “Dec. 6, 1796. Francis Dunn and Will. Arnold were yesterday executed for murder and the first malefactors conveyed to the new Surgeons’ Hall in the Lincoln’s Inn Fields.[Pg 24] They were conveyed in a cart, their heads supported by tea chests for the public to see: I think contrary to all decency and the laws of humanity in a country like this. I hope it will not be repeated.”[6]

Just at this date the Corporation were removing from their old premises to Lincoln’s Inn Fields; the last Court in the Old Bailey was held on October 6th, 1796, and the first at Lincoln’s Inn Fields on January 5th, 1797.

In July, 1797, it was reported to the Court that Mr. Chandler, one of their members, “had in the most polite and ready manner offered his stable for the reception of the bodies of the two murderers who were executed last month.” The thanks of the Court were voted to Mr. Chandler “for his polite attention to the Company upon that occasion.”

After the Bill had been lost in the Lords, the following resolution was passed by the Court in November, 1797: “Resolved that in order to evince the sincerity of the Court to remove all reasonable objections to the present situation in Lincoln’s Inn Fields the Clerk be directed, with proper assistance, to[Pg 25] look for a temporary dissecting-room at a place in or near the Old Bailey until a permanent one near the place of execution can be established.”

In June, 1800, a warehouse was taken in Castle Street, Cow Cross, West Smithfield, for eighteen months, as, owing to the labours of taking over the Hunterian Collection, there had been no time for obtaining a permanent place. A house in Duke Street, West Smithfield, was afterwards leased for the purpose, and arrangements were made for Pass, the Beadle, to reside there. This landed the College in a small expense, as in 1832 the Beadle was elected Constable of the Ward of Farringdon, and the Council had to pay a fine of £10 in place of his serving the office. At the expiration of the lease of the Duke Street house, so great an increase of rent was demanded that the College gave up the premises, and took a newly-built house in Hosier Lane, on a lease for twenty-one years. Here the dissections were carried on until the passing of the Anatomy Act, when the College had no longer to share with the hangman the duty of carrying out the sentence on[Pg 26] murderers who were condemned to be hanged and anatomized.

The bodies were not really dissected by the College Authorities; a sufficient incision was made to satisfy the requirements of the Act, and the body was then handed over to one of the Teachers of Anatomy. The following is a copy of an order authorizing the Secretary of the College to give up a body:

“Ordered.

“That the body of Mary Whittenbach executed this day at the Old Bailey for murder be delivered (after the necessary dissection by the College) to Mr. Joseph Henry Green.

“William Blizard

“Wm. Norris

“Anthy Carlisle.

“Royal College of Surgeons

“17th day of Sept. 1827

“To Mr. Belfour, Secy. to the College.”

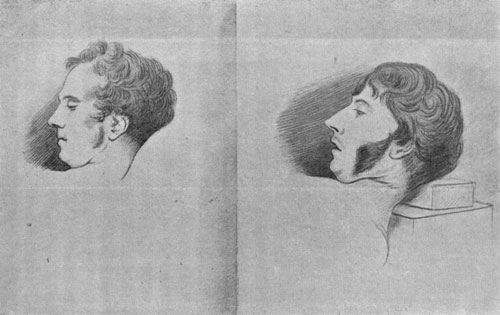

There is in the Library of the Royal College of Surgeons of England a series of drawings of the heads of murderers, made by the two Clifts, father and son, when the bodies were brought to the College for dissection. These drawings include Bishop and Williams (see p. 107),[7] and Bellingham, who was executed[Pg 27] in 1812 for the murder of Mr. Perceval in the lobby of the House of Commons.

Earl Ferrers, who suffered the extreme penalty of the law in 1760 for the murder of his steward, was taken to Surgeons’ Hall, where an incision was made in the body; instead of being further dissected it was given over to the relatives for burial.

At the execution of Bishop and Williams the Sheriffs of London felt that some means should be taken to show gratitude to Mr. Partridge, and the other officials of King’s College, for the way they had brought the murderers to justice. The following letter was therefore addressed to the College of Surgeons:

“Justice Hall,

“Dec. 5, 1831.

“To the Governors and Directors of the College of Surgeons.

“It is our particular desire and we do ask that it may be thought but a reasonable request that the bodies of the malefactors executed in the front of Newgate this morning should be sent to King’s College—by the vigilance of whose surgical establishment these offenders were detected and ultimately brought to justice, we shall therefore feel obliged by[Pg 28] your handing over these bodies to the King’s College.

| “We are, with great respect, “Your mo. ob. Servts., | ||

| “J. Cowan “John Pirie |

} | Sheriffs.” |

The body of Bishop was given to Mr. Partridge, and that of Williams went to Mr. Guthrie at the Little Windmill Street School of Anatomy.

The following account of the reception of one of the bodies is by Mr. T. Madden Stone, for many years an official at the College. It was printed in a series of articles, entitled “Echoes from the College of Surgeons.”[8]

“The executions generally took place at eight o’clock on Mondays, and the ‘cut down,’ as it is called, at nine, although there was no cutting at all, as the rope, with a large knot at the end, was simply passed through a thick and strong ring, with a screw, which firmly held the rope in its place, and when all was over, Calcraft, alias ‘Jack Ketch,’ would make his appearance on the scaffold, and by simply turning the screw, the body would fall down. [Pg 29]At once it would be placed in one of those large carts with collapsible sides, only to be seen in the neighbourhood of the Docks, and then preceded by the City Marshal in his cocked hat, and, in fact, all his war paint, with Calcraft and his assistant in the cart, the procession would make its way to 33 Hosier Lane, West Smithfield, in the front drawing room of which were assembled Sir William Blizard, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, and members of the Court desirous of being present, with Messrs. Clift (senior and junior), Belfour, and myself. On extraordinary occasions visitors were admitted by special favour. The bodies would then be stripped, and the clothes removed by Calcraft as his valuable perquisites, which, with the fatal rope, were afterwards exhibited to the morbidly curious, at so much per head, at some favoured public-house. It was the duty of the City Marshal to be present to see the body ‘anatomised,’ as the Act of Parliament had it. A crucial incision in the chest was enough to satisfy the important City functionary above referred to, and he would soon beat a hasty retreat, on his gaily-decked[Pg 30] charger, to report the due execution of his duty. These experiments concluded, the body would be stitched up, and Pearson, an old museum attendant, would remove it in a light cart to the hospital, to which it was intended to present it for dissection.”

These bodies of murderers were the only ones which could be legally used for dissection; it is therefore obvious that the number was quite insufficient for the wants of the Metropolitan Schools, and the teachers were thus forced to obtain a supply from other sources.

It was strongly urged, but urged in vain, that the whole difficulty would disappear if a short Act were passed, doing away with the dissection of murderers, and enacting that the bodies of all unknown persons who died in workhouses or hospitals, without friends, should be handed over, under proper control, to the different teachers of anatomy. That these would be sufficient was afterwards made clear by the Committee on Anatomy.[9] In their Report[Pg 31] it is stated that the returns obtained from 127 of the parishes situate in London, Westminster, and Southwark, or their immediate vicinity, showed that out of 3744 persons who died in the workhouses of these parishes in the year 1827, 3103 were buried at the parish expense, and that of these about 1108 were not attended to their graves by any relations. The number of bodies obtained from this source would have exceeded those supplied by the resurrection-men, and would have been adequate for the wants of the London Schools.

The newspapers of the day contain many proposed solutions of the difficulty. One correspondent gravely suggested that as prostitutes had, by their bodies during life, been engaged in corrupting mankind, it was only right that after death those bodies should be handed over to be dissected for the public good. Another correspondent proposed that all bodies of suicides should be used for dissection, and that all those persons who came to their death by duelling, prize-fighting, or drunkenness, should be handed over to the surgeons for a similar purpose.

Mr. Dermott, the proprietor of the Gerrard[Pg 32] Street, or Little Windmill Street, School of Medicine, proposed a scheme by which a fund was to be raised by grants from Government, and from the College of Surgeons, and by voluntary contributions from the nobility and gentry. This fund was to be invested in the names of “opulent and respectable men,” not more than one-third of whom were to be members of the medical profession. It was proposed to expend the interest on this fund in paying a sum not exceeding seven pounds to those persons who were willing to contract for the sale of their bodies for dissection. Registers were to be kept of all such persons, and the Committee were to have the power of claiming the body six hours after death. Mr. Dermott also suggested that all medical men should leave their own bodies to be used for anatomical teaching. It is hardly necessary to point out the absurdity of the first part of this scheme; the Committee, after paying their seven pounds, would have had no control over the subsequent movements of the persons whose bodies they had thus purchased, and it was hardly to be expected that friends of the deceased would send notice to the Committee[Pg 33] that the body was ready for them. Both parts of the scheme would have required an Act of Parliament, as executors were not bound to give up a corpse, even though instructions had been left that it was a person’s wish that his body should be used for anatomical purposes. Many such bequests have been made, and in some instances the desire of the testator has been carried into effect. To try to do away with some of the prejudices against dissection, Jeremy Bentham left his body for this purpose; the dissection was duly carried out at the Webb Street School, and at the request of Dr. Southwood Smith, Mr. Grainger delivered the following oration over the body on June 9th, 1832:

“Gentlemen,—In presenting myself before you this day, at the request of my friend and colleague, Dr. Southwood Smith, I can assure you I do so strongly impressed with the high importance of the duty I have undertaken, and the responsibility I have thus assumed. Gentlemen, it is no ordinary occasion on which we are assembled. We are here collected to carry into execution the last wishes of one whose mortal career, prolonged far beyond the usual[Pg 34] limits of man’s existence, has been devoted with almost unexampled energy and perseverance to the establishment of those great moral and political truths, on which the happiness and the enlightenment of the human race are founded. Ill would it become me, however, to dwell on the genius, the philanthropy, or the integrity of the illustrious deceased. His eulogium has already been eloquently pronounced by one more fitted to do justice to such an undertaking than the humble individual who now addresses you. It would be more suitable to the object of the present meeting that I should consider in what manner the intentions of the late Mr. Bentham, regarding the disposition of his remains, can best be carried into effect. But before I do this, it may be proper to inform some of my auditors what those intentions were. This great man was an ardent admirer of the science of medicine, and his penetrating mind was not slow in perceiving that the safe and successful practice of the healing art entirely rests on a thorough knowledge of the natural structure and functions of the human body. He also perceived that there was but one method of obtaining[Pg 35] such knowledge, viz., dissection. In proceeding to inquire how it came to happen that in a country like England, justly proud of those numerous institutions in which science is so successfully cultivated, so little encouragement, or more correctly speaking, so much opposition, was offered to the advancement of so indispensable a branch of knowledge, Mr. Bentham discovered that this repugnance to dissection sprang from a feeling strongly implanted in the human breast—a feeling of reverence towards the dead. Far be it from me to condemn such a sentiment, for it has its source in some of the purest principles of our nature. But if it can be shown that an undue indulgence in this feeling produces incalculable mischief in society, it becomes the duty of all who are interested in the happiness of mankind to oppose the progress of such injurious opinions. Mr. Bentham, impressed with this idea, and thinking it unjust that the humbler classes of the community should alone be called upon to sacrifice those feelings which are cherished alike by the rich and poor, determined to devote his own body to the public good. He knew that this determination would[Pg 36] inflict pain on many of his dearest friends. An example of this character, emanating from a person so talented, so influential, and so esteemed, is calculated to operate a most beneficial effect on the public mind, and I cannot refrain from considering the dissection of the body now before us as an important era in the progress of anatomy, as it is one of the first that in this country has been employed for the purposes of science, under the direct sanction of the individual expressed during his lifetime; he also knew that obstacles would probably be offered to its fulfilment, but with an indifference to personal feeling rarely witnessed, he took effectual means to carry his resolution into effect. And thus, gentlemen, did the last act of this illustrious man’s existence accord with that leading principle of his well-spent life—the desire to promote the universal happiness and welfare of mankind.”

Bentham’s skeleton, clothed in his usual attire, is now in University College, London.

Messenger Monsey, the eccentric physician to the Chelsea Hospital, was exceedingly anxious that his body should be examined after death. He obtained a promise from[Pg 37] Mr. Forster, of Union Court, that he would perform this service for him. So anxious was Monsey for the post mortem to be carried out, that in May, 1787, he wrote to Cruikshank, the anatomist, as follows:

“Mr. Foster (sic) a Surgeon in Union Court, Broad Street, has been so good as to promise to open my Carcass and see what is the matter with my Heart, Arteries, Kidnies, &c. He is gone to Norwich and may not return before I am [dead]. Will you be so good as to let me send it to you, or if he comes will you like to be present at the dissection. I am now very ill and hardly see to scrawl this & feel as if I should live two days, the sooner the better. I am, tho’ unknown to you

“Your respectfull humble Servant

“Messr. Monsey.”

Monsey lived until December 20th, 1788; his wishes were duly carried out by Mr. Forster, at Guy’s Hospital, in the presence of the students.

Ninety-nine gentlemen of Dublin signed a document, in which the wish was expressed that their bodies, instead of being interred, should be devoted by their surviving friends “to the more rational, benevolent, and honourable[Pg 38] purpose of explaining the structure, functions and diseases of the human being.”

A Mr. Boys, who died in 1835, wished to be made into “essential salts” for the use of his female friends. In a letter to Dr. Campbell, written four years before his death, he asks: “Are you now disposed (without Burking) to accomplish my wish, when my breath or spirit shall have ceased to animate my carcase, to perform the operation of vitrifying my bones, and sublimating the rest, thereby cheating the Devil of his due, according to the ideas of some devotees among Christians? And, that I may not offend the delicate olfactory nerves of my female friends with a mass of putridity, if it be possible, let me rather fill a few little bottles of essential salts therefrom, and revive their drooping spirits. It may be irksome to you to superintend the business, but, perhaps, you have knowledge of some rising genius or geniuses who may be glad of a subject without paying for it. Let them slash and cut, and divide, as best please ’em.”

The following account, taken from a newspaper of 1810, shows that untoward[Pg 39] events sometimes followed a request of this kind. A journeyman tailor died at the Black Prince, in Chandos Street, and directed, in his will, that his body should be opened in the presence of Mr. Wood, the landlord. This instruction was carried out. The paragraph goes on to say that the dissection was scarcely concluded “when the landlord, a stranger to such exhibitions, was seized with sickness and vomiting; and, on reaching the bar, was prevailed upon by his wife to take a glass of brandy and water; in a few minutes he was obliged to be carried to bed, never to rise again; on Friday last, the third day from the attack, he died in a state of delirium, not from contagion, or a predisposition to disease, but solely from the impression made upon his mind by the anatomical performance, which, he observed, exceeded in horror any thing he had ever beheld.”

It was not an uncommon thing for persons to try to put into effect part of Dermott’s plan, by offering to leave their bodies for anatomical purposes, on the condition that they were paid a certain sum down. This was generally only a swindling dodge, and one[Pg 40] by which the teachers were not to be caught, as they could have no hold on the persons whose bodies they purchased, nor could they compel the friends to give them up after death. The following letter, preserved amongst Sir Astley Cooper’s papers, and now forming part of the Stone Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, is a specimen:

“Sir,—I have been informed you are in the habit of purchasing bodys and allowing the person a sum weekly; knowing a poor woman that is desirous of doing so, I have taken the liberty of calling to know the truth.

“I remain, your humble servant.”

[10]

On the back Sir Astley has written, “The truth is that you deserve to be hanged for such an unfeeling offer. A. C.”

The idea at the present day has not died out; quite recently a man called at the College of Surgeons, and offered to sell his body for a cash payment. It is a fairly common experience of Curators of Pathological Museums to have similar offers from persons suffering from a rare disease, or a curious deformity.

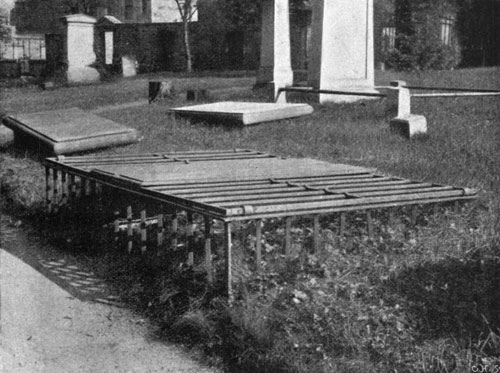

MORTSAFE IN GREYFRIARS CHURCHYARD, EDINBURGH.

As has been stated in the previous chapter, there was no need of the resurrection-men, so long as the teaching of anatomy was confined to the Company of Barbers and Surgeons. It has also been pointed out that, as late as 1714, Cheselden was reprimanded for having anatomical demonstrations at his private house. Soon after this date, however, began the establishment of private schools. Mr. Nourse, of St. Bartholomew’s, was one of the first to deliver public lectures at his own house. After a time this probably became inconvenient, as we find his advertisement, in 1739, worded thus:

“ANATOMY.

“Designing to have no more lectures at my own house, I think it proper to advertise that I shall begin a Course of Anatomy, Chirurgical Operations and Bandages on Monday, the 11th of Nov., at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

“Edw. Nourse, Assistant Surgeon

and Lithotomist to the said Hospital.”

[Pg 42]Percivall Pott, who was apprenticed to Nourse, followed his master’s example, and lectured on Surgery. In 1737 we find Dr. Fr. Nicholls advertising thus:

“On Wednesday, the 2nd of February, at the House below the Bull Head, in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, at five in the evening, will begin a Course of Anatomy and Physiology, introductory to the study and practice of Physick in all its branches by Fr. Nicholls, M.D. N.B. A compendium referring to the several matters, explain’d in these Lectures, is sold by John Clarke, under the Royal Exchange, and F. Woodward, at the Half Moon, within Temple Bar, Booksellers.”

The following is the advertisement of Cæsar Hawkins, from a newspaper of 1739:

“In Pall Mall Court, in Pall Mall. On Thursday, the 5th of February next, will begin a Course of Anatomy, with the principal Operations in Surgery and their suitable Bandages, by Cæsar Hawkins, Surgeon to St. George’s Hospital.”

Joshua Brookes’ advertisement, in 1814, ran as follows:

“THEATRE OF ANATOMY, BLENHEIM STREET,

GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

“The Summer Course of Lectures on Anatomy, Physiology, and Surgery, will be commenced on Monday, the 6th of June, at seven o’clock in the[Pg 43] morning. By Mr. Brookes.—Anatomical Converzationes will be held weekly, when the different Subjects treated of will be discussed familiarly, and the Students’ views forwarded. To these none but Pupils can be admitted. Spacious Apartments, thoroughly ventilated, and replete with every convenience, will be open at five o’clock in the morning, for the purposes of Dissecting and Injecting, when Mr. Brookes attends to direct the Students and demonstrate the various parts as they appear on Dissection.

“The inconveniences usually attending Anatomical Investigations, are counteracted by an antiseptic process. Pupils may be accommodated in the House. Gentlemen established in Practice, desirous of renewing their Anatomical Knowledge, may be accommodated with an apartment to dissect in privately.”

A very interesting account of the old Anatomical Schools, by Mr. D’Arcy Power, will be found in the British Medical Journal, 1895, vol. 2, p. 141. The paper is entitled “The Rise and Fall of the Private Medical Schools in London.” It has been reprinted, with other articles, in a pamphlet, entitled The Medical Institutions of London.

In Great Britain, as no licence was required for opening an Anatomical School, there was no limit to their number; there was also[Pg 44] no regular legal supply of subjects, except the bodies of murderers, executed in London and the county of Middlesex, which came to the schools through the College of Surgeons. In Paris a licence had to be obtained before opening an Anatomical School, and bodies were regularly supplied to the licensed places.

With the rise and competition of the Medical Schools in London, the difficulty of getting an adequate number of bodies increased. The absolute necessity of having a good supply for the use of students, so as to prevent them from going off to rival schools, caused the teachers to offer large prices, and thus made it worth while for men to devote themselves entirely to obtaining bodies for this purpose. At first the trade was carried on by a very few men, and without any public scandal, but the inducements mentioned above enticed others into the business; these were of the lowest class, often professed thieves, and the fights and disputes of these men, one with the other, in churchyards, often made really more scandal than the actual stealing of the bodies. It was stated[Pg 45] by the police in 1828 that the number of persons who, in London, lived regularly on the profits of exhumation, did not exceed ten; but there were, in addition to these, about two hundred who were occasionally employed. These latter individuals were thieves of the lowest grade, and the most desperate and abandoned class of the community. The men worked generally in gangs, and would do anything to spoil the success of their opponents in the business. If a body were bought by one of the teachers from an outside source, the regular men would sometimes break into the dissecting-room and cut the body in such a manner as to make it useless for anatomical purposes. If this could not be done, they would give information to the police that a stolen body was lying in a certain dissecting-room. Joshua Brookes, the proprietor of the Blenheim Street, or Great Marlborough Street, School, was a victim in this way; a body, for which he had paid 16 guineas, was taken away from his school through information of this kind, and the police officer who carried out the business was, as a reward for his efforts, presented with[Pg 46] a silver staff, purchased by public subscription. Brookes seems to have got on very badly with the resurrection-men; at one time, because he refused five guineas as a douceur at the beginning of the session, two dead bodies, in a high state of decomposition, were dropped at night close to his school by the men whom he had thus offended; one of these bodies was placed at the Poland Street end of Great Marlborough Street, and the other at the end of Blenheim Street. Two young ladies stumbled over one of these bodies, and at once raised such a commotion that, had it not been for the prompt assistance of Sir Robert Baker and the police, Brookes would have fared very badly at the hands of the mob which soon collected. The fact of his house being near to the Marlborough Police Court, on more than one occasion saved Brookes from the popular fury.

A subject was brought to him one day in a sack, and paid for at once; soon after it was discovered that the occupant of the sack was alive. This was not a case of attempted murder; the “subject” was a confederate of those from whom he had been purchased, and had, in all[Pg 47] probability, been thus introduced to the premises for purposes of burglary.

The competition of the schools had risen to such a height in the demand for bodies, that Brookes stated that for a subject, which would have cost two guineas in his student days, he had paid as much as sixteen guineas. Nor was the cost of the body the only expense to the teacher. At the beginning of each session he was waited upon by the resurrection-men, who offered to supply him regularly with bodies at a fixed price, on the condition that a douceur was paid down at once. The teachers were powerless in the matter, and had either to accede to the offered terms, or to lose their students through not having a sufficient supply of subjects. The scarcity of bodies was most keenly felt at the beginning of the session; the resurrection-men knew that they could command their own terms, and would not supply any subjects until the teachers had conceded all their demands. This was felt to be bad for the students, and Dr. James Somerville, who was assistant to Brodie at the Great Windmill Street School, in giving evidence before the Committee on Anatomy,[Pg 48] said that “the pupils not being able to proceed for a certain time lose their ardour, and get into habits of idleness.”

At the end of the session the resurrection-men again waited on the proprietors of the schools, and demanded “finishing money.” In some papers relating to Sir Astley Cooper, which were referred to in a letter published in the Medical Times, 1883, vol. 1, p. 343, we read: “May 10th, 1827, Paid Hollis, Vaughan, and Llewellyn, finishing money, £6 6s. 0d. 1829, June 18th, Paid Murphy, Wildes, & Naples, finishing money £6 6s. 0d.”

The cost of the bodies in this way to the teachers was more than they could charge to the students, and the deficiency thus created was made up by increased fees for the lectures. The expenses, moreover, did not end here. If one of the resurrection-men was unfortunate enough to get a term of imprisonment, the teacher had to partly keep the man’s wife and family whilst he was serving his sentence. A solatium was also expected on his release from gaol. Mr. R. D. Grainger spent £50 in this way for one man, and several guineas in keeping the family of another Resurrectionist[Pg 49] whilst the latter was in gaol. Sir Astley Cooper is known to have spent large sums of money for a similar purpose. The following may be cited as examples: “January 29th, 1828, Paid Mr. Cock to pay Mr. South half the expenses of bailing Vaughan from Yarmouth and going down £14 7s. 0d. 1829, May 6th, Paid Vaughan’s wife 6s. Paid Vaughan for twenty-six weeks’ confinement at 10s. per week, £13 0s. 0d.”

If any independence were shown by the teachers, and the demands of the men resisted, victory generally fell to the lot of the Resurrectionists. A teacher, perhaps, would refuse to pay the exorbitant demands, and would employ other men to obtain bodies for him. These were then watched by the regular gang, and information to the police was laid against them on every occasion. The bodies obtained by the irregular men were often taken from them by those who considered they had a monopoly in the business; these subjects were then hacked and cut about so as to make them quite useless for anatomical purposes. So the supply at this particular school would be very short, and great indignation would arise[Pg 50] amongst the students, who had paid their fees, and therefore demanded an adequate number of bodies for dissection. The teacher was thus obliged to give way, and to accede to the demands of the regular gang.

The teachers formed themselves into an Anatomical Club for their own protection; by this means it was hoped to regulate the price to be paid for bodies, by agreement amongst the members of the Club not to give more than a certain amount. This agreement does not seem, according to Mr. South, to have been very faithfully kept, and so, with new schools springing up and giving rise to still greater competition, the teachers were as much as ever in the hands of the resurrection-men.

It must not be supposed that all the bodies which were supplied to the schools were exhumed. Many of them were stolen or obtained by false pretences before burial. Glennon, the police officer, who has been before mentioned in connection with Joshua Brookes, told the Committee that he had recovered between fifty and a hundred bodies for persons who had had their houses broken open, and bodies stolen from them whilst in[Pg 51] the coffin awaiting burial. The following case, tried at the London Sessions in 1830, is an example of this:

“LONDON ADJOURNED SESSIONS.

“Tuesday.—Body-Snatching.—A well-known pilferer of graves, named Clarke, was tried upon an indictment, charging him with having stolen the body of a dead child, aged about four years, which had been under the care of a nurse named Mary Hopkins. The facts which came out in evidence are as follows: The deceased was the daughter of a woman of the town, residing in Shire Lane, and had been kept at the nurse’s lodging, which was in the same neighbourhood. She died on a Friday, and Clarke, whose ears were described as ‘quick to the toll of the passing bell,’ paid the nurse a visit the next morning, under pretence of hiring a cellar under the house. He took occasion to notice the poor woman’s son; said it was a pity to see the boy idle, and that he should have immediate employment, and called again with evidences of still stronger interest in favour of the family. ‘By the way,’ said he, ‘I understand you have had a death[Pg 52] lately.’ ‘Yes, sir,’ said the nurse, ‘a poor little girl is departed.’ ‘Poor little dear,’ cried the snatcher, ‘I should like to look at the little innocent.’ He was forthwith led into the front parlour, where the body lay in a coffin, and observing that its position was favourable to his intention, he sympathized with the nurse, and said, ‘We must all come to this sooner or later,’ and then he went to get a half-pint of summut to comfort them. The nurse disposed of a glass, which presently set her in a profound sleep, and when she awoke the body of the babe was gone. It appeared that the snatcher, after having quitted the house, as if for good, returned, and opening the parlour-window hooked out with a stick the corpse of the child, and went off with it towards a market that is open at all hours, near Bridgewater Square. However, a police officer, who knew his trade, laid hands upon him, telling him he was wanted. The snatcher then threw down the child and took to his heels, but was apprehended and lodged in the Compter. The nurse proved the identity of the body. Upon her cross-examination, by Mr. Payne, she stated that the mother had not been to see[Pg 53] the deceased for four or five days before the death. The Jury returned a verdict of Guilty, but some of them audibly spoke of recommending the prisoner to mercy, but made no appendage to that effect. The Recorder sentenced the prisoner to be imprisoned for the space of six calendar months.”

Sometimes these stolen bodies were claimed after payment had been made to the resurrection-men, but before any dissection had taken place. The following refers to Guy’s Hospital: “Returned to Vestry Clerk of Newington, by order of the Treasurer, one male and two females, purchased of Page, &c., on the 25th, who had broken open the dead-house to obtain them.”

Bodies of suicides, and of those who had met with an accidental death, were frequently stolen whilst they were awaiting the coroner’s inquest. Often in these cases the body-thieves, after selling the subject to a teacher of anatomy, secretly gave information to the police where the missing body might be found. It was then seized by the police, and, after the inquest, handed over to those who claimed to be relatives; these supposed relatives were[Pg 54] frequently confederates of the thieves, and by them the body was at once taken off and again sold to another teacher.

The following case is from a newspaper of 1823:

“Suicide and the Body Stolen.—Tuesday evening last a young woman of respectable and interesting appearance was observed for some time parading the banks of the Surrey Canal, Camberwell, in a melancholy mood, and at length she plunged into the water; on which a man rushed in after her and dived several times, but failed in recovering the body, which was not found till the following morning, when it was taken to the Albany Arms, near the Canal, for the Coroner’s inquest, which was to have taken place on Thursday. On the landlord proceeding to the shed on Wednesday morning, where the body had been deposited, he discovered, that in the course of the night, it had been broken open, and the corpse of the female stolen away. He instantly repaired to the Police Office, Union Street, and gave information of the circumstance to the Magistrates, who gave orders that immediate inquiry should [Pg 55]be made at Mr. Brookes’s, where the body has since been discovered and given up. The poor woman was unclaimed, and the verdict of the Coroner’s Jury was ‘Found Drowned.’”

A favourite trick, in the carrying out of which a woman was generally necessary, was that of claiming the bodies of friendless persons who died in workhouses, or similar institutions. Immediately it was found out that such an one was dead a man and woman, decently clad in mourning, in great grief, and often in tears, called at the workhouse to take away the body of their dear departed relative. If the trick proved successful, as it often did, the body was taken straight off to one of the schools and sold. The parish authorities, probably, were not over particular about giving up the body, if the deceased were a stranger, as by this means they saved the cost of burial.

Subjects, too, were obtained from cheap undertakers, who kept the bodies of the poor until the time for burial. The coffin was weighted so as to conceal the fraud, and the mockery of reading the Burial Service over it was gone through in the presence of the unsuspecting relatives.

[Pg 56]That some bodies were obtained by murder there can be no doubt. The exposure caused by the trials of Burke and Hare in Edinburgh, and Bishop and Williams in London, proves this.

The facts previously stated, however, go very far to exonerate the anatomists from the false charge (freely made at the time) of their being privy to these murders. It has been frequently stated that signs of murder could be easily seen, and that the fact of the body being fresh, and there being no evidence of its having been interred, ought to have at once suggested foul play, and to have caused the teacher to communicate with the police. But it must be remembered that the murders were generally very artfully contrived by suffocation, so as to leave no outward signs of ill-treatment. It was also no uncommon thing, for the reasons just given, to receive at the schools bodies in quite a fresh state, which had evidently never received sepulture.

An account of the post mortem on the Italian boy, for whose murder Bishop and Williams were hanged,[11] has been preserved by Mr.[Pg 57] Clarke.[12] The examination of the body was carried out by Mr. Wetherfield, of Southampton Street. There were also present Mr. Mayo, Lecturer on Anatomy at King’s College; Mr. Partridge, his demonstrator; Mr. Beaman, Parish Surgeon; and his Assistant, Mr. D. Edwards, and Mr. Clarke. The boy’s teeth had been removed and sold to a dentist, but beyond this there were no external marks of violence on any part of the body. The internal organs were carefully examined, but no trace of injury or poison could be found. Mr. Mayo, who had a peculiar way of standing very upright with his hands in his breeches’ pockets, said, with a kind of lisp he had, “By Jove! the boy died a nathral death.” Mr. Partridge and Mr. Beaman, however, suggested that the spine had not been examined, and after a consultation it was decided to do this. It was then found that one or more of the upper cervical vertebræ were fractured. “By Jove!” said Mr. Mayo, “this boy was murthered.” The conviction of Bishop and Williams was due, in a very great measure, to Mr. Partridge and Mr. Beaman.

[Pg 58]At the present day it is well-nigh impossible to understand the relations between men of honour and education, such as the teachers of anatomy were, and the ruffians who carried on this ghastly trade. It must, however, be borne in mind that, until the passing of the Anatomy Act in 1832, there was no provision for supplying the means by which the student might be taught this necessary part of his professional education; the only way in which teachers could get material for giving instruction was by dealing with the resurrection-men.

It would have been quite impossible for the resurrection-men to have obtained the number of bodies they frequently did, had they not been able to bribe the custodians of the different burial-grounds. Sometimes they met with a difficulty in the shape of a keeper newly appointed to replace one who had been dismissed for being privy to these depredations. In most instances this was soon overcome; if, at the outset, the custodian could not be bribed, he could generally be induced to drink, and then, whilst he was in a state of intoxication, the body which the resurrection-men wished to obtain could be easily removed.[Pg 59] After this first step there was generally very little difficulty in the future.

Sometimes, too, the grave-diggers not only gave information to the Resurrectionists, but acted as principals themselves. In Benson’s Remarkable Trials is recorded the case of John Holmes, Peter Williams, and Esther Donaldson. Holmes was grave-digger at St. George’s, Bloomsbury; Williams was his assistant, and Donaldson was charged as an accomplice. They were prosecuted before Sir John Hawkins at the Guildhall, Westminster, in December, 1777, for stealing the body of Mrs. Jane Sainsbury, who died in the previous October, and was buried in the St. George’s burial-ground. Holmes and Williams were sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, and to be whipped on their bare backs from the end of Kingsgate Street, Holborn, to Dyot Street, St. Giles. The sentence, says Benson, was duly carried out amidst crowds of well-satisfied and approving spectators. The woman Donaldson was acquitted.

The ranks of the resurrection-men were largely recruited from the keepers of burial-grounds. When these men had lost their[Pg 60] situations for connivance at the stealing of bodies, they naturally joined their old associates, and became part of the regular gang.

The bribery of the custodians will account for the large number of bodies often obtained in one night. Had there been the slightest vigilance on the part of the authorities, it would have been absolutely impossible for the resurrection-men to have spent the time necessary for their work without detection. The amount of time required for the work depended greatly on the soil. One man told Bransby Cooper that he had taken two bodies from separate graves of considerable depth, and had restored the coffins and the earth to their former positions in an hour and a half. Another man said that he had completed the exhumation of a body in a quarter of an hour; but in this instance the grave was extremely shallow, and the earth loose and without stones. If much gravel had to be dug through, the resurrection-men had a peculiar way of using their spades, so that the gravel was thrown out of the grave quite noiselessly.

On Thursday, February 20th, 1812, the Diary tells us that 15 large bodies and one[Pg 61] small one were obtained from St. Pancras. No doubt this was simplified by the custom of burying several paupers in one grave. To obtain these it was necessary to dig all the earth out, so that each coffin could be dealt with; the men generally worked very soon after a funeral, and so the earth was much more easily moved than it would have been if they had been obliged to dig through undisturbed ground. When only one body was to be had, a small opening was dug down to the head of the coffin, which was then broken open, and the body was pulled up with a rope, fastened either round the neck or under the armpits.

In a memoir of Thomas Wakley, the founder of The Lancet,[13] the following account of the modus operandi of the resurrection-men is given: “In the case of a neat, or not quite new grave, the ingenuity of the Resurrectionist came into play. Several feet—fifteen or twenty—away from the head or foot of the grave, he would remove a square of turf, about eighteen or twenty inches in diameter. This he would carefully put by, and then commence to mine. Most pauper graves were[Pg 62] of the same depth, and, if the sepulchre was that of a person of importance, the depth of the grave could be pretty well estimated by the nature of the soil thrown up. Taking a five-foot grave, the coffin lid would be about four feet from the surface. A rough slanting tunnel, some five yards long, would, therefore, have to be constructed, so as to impinge exactly on the coffin head. This being at last struck (no very simple task), the coffin was lugged up by hooks to the surface, or, preferably, the end of the coffin was wrenched off with hooks while still in the shelter of the tunnel, and the scalp or feet of the corpse secured through the open end, and the body pulled out, leaving the coffin almost intact and unmoved.

“The body once obtained, the narrow shaft was easily filled up and the sod of turf accurately replaced. The friends of the deceased, seeing that the earth over his grave was not disturbed, would flatter themselves that the body had escaped the Resurrectionist; but they seldom noticed the neatly-placed square of turf, some feet away.”

A somewhat similar account is given in[Pg 63] the Memorials of John Flint South.[14] This method is also referred to by Bransby Cooper,[15] who states that it was told him by one “who fancied he had found out their secret, but had, no doubt, been deceived by some of them purposely.” Bransby Cooper also says that he asked one of the principal resurrection-men as to the feasibility of this method, and the man showed him several objections to it, and stated that “it would never do.” This statement was made after the resurrection-days were over, when there could be no advantage in keeping the true plan secret. It must be remembered that there were some amateur body-snatchers, and that it was not at all unlikely that the regular men would tell to them a plan as full of difficulties as that quoted above. To make the tunnel as described, would be impossible, and it is somewhat difficult to see how grappling-irons were fastened to the coffin; a man could hardly get down a tunnel 18 in. in diameter and 15 feet in length to do this; if he did succeed, his difficulties in returning must have[Pg 64] been still greater. To pull a body out of the head or foot of a coffin, as described, is an impossibility. No allowance is made, either, in digging the tunnel for obstacles, in the shape of intervening graves or grave-stones. As regards the evidence on the surface of a grave having been disturbed, it would be greater in one opened in this manner than if the recently-disturbed earth had been again dug out. It would be impossible to get back into the tunnel all the earth dug out in the course of its construction, and this loose earth would at once attract attention. Generally, bodies were removed before the graves were finally tidied up, so that it was difficult to notice a fresh disturbance.

The writer of the Diary was a cemetery-keeper when he first began his resurrection proceedings; his modus operandi, in some cases, was to take the body out of the coffin, and place it in a sack, before he began to fill in the grave. Then, as he gradually threw the earth in, he kept pulling the sack to the surface, so that when his work of filling in was completed, he had the sack close to the top of the grave. He had then only to wait until[Pg 65] night, when he was able, under cover of the darkness, to remove the body without fear of detection. When the resurrection-men had been successful in their night’s work, they were glad to find a temporary shelter for the bodies, as near at hand as possible. This was generally an out-house belonging to one of the schools which they regularly supplied; the men were permitted to place the bodies there for the night, and to fetch them away the next day. This explains some of the entries in the Diary, such as “Took the whole to ——,” and the next day, “Removed the whole from ——.” Before removing any of the bodies, the men would find out exactly where they were wanted, and so would save much risk of being arrested with the bodies in their possession.

If the following broadside could be believed, the resurrection-men sometimes performed a valuable service to those who had been buried—

“MIRACULOUS CIRCUMSTANCE:

“Being a full and particular account of John Macintire, who was buried alive, in Edinburgh, on the 15th day of April, 1824, while in a [Pg 66]trance, and who was taken up by the resurrection-men, and sold to the doctors to be dissected, with a full account of the many strange and wonderful things which he saw and felt while he was in that state, the whole being taken from his own words.

“I had been some time ill of a low and lingering fever. My strength gradually wasted, and I could see by the doctor that I had nothing to hope. One day, towards evening, I was seized with strange and indescribable quiverings. I saw around my bed, innumerable strange faces; they were bright and visionary, and without bodies. There was light and solemnity, and I tried to move, but could not; I could recollect, with perfectness, but the power of motion had departed. I heard the sound of weeping at my pillow, and the voice of the nurse say, ‘He is dead.’ I cannot describe what I felt at these words. I exerted my utmost power to stir myself, but I could not move even an eyelid. My father drew his hand over my face and closed my eyelids. The world was then darkened, but I could still hear, and feel and suffer. For three days a number of friends called to see[Pg 67] me. I heard them in low accents speak of what I was, and more than one touched me with his finger. The coffin was then procured, and I was laid in it. I felt the coffin lifted and borne away. I heard and felt it placed in the hearse; it halted, and the coffin was taken out. I felt myself carried on the shoulders of men; I heard the cords of the coffin moved. I felt it swing as dependent by them. It was lowered and rested upon the bottom of the grave. Dreadful was the effort I then made to exert the power of action, but my whole frame was immovable. The sound of the rattling mould as it covered me, was far more tremendous than thunder. This also ceased, and all was silent. This is death, thought I, and soon the worms will be crawling about my flesh. In the contemplation of this hideous thought, I heard a low sound in the earth over me, and I fancied that the worms and reptiles were coming. The sound continued to grow louder and nearer. Can it be possible, thought I, that my friends suspect that they have buried me too soon? The hope was truly like bursting through the gloom of death. The sound ceased. They dragged me out of the[Pg 68] coffin by the head, and carried me swiftly away. When borne to some distance, I was thrown down like a clod, and by the interchange of one or two brief sentences, I discovered that I was in the hands of two of those robbers, who live by plundering the grave, and selling the bodies of parents, and children, and friends. Being rudely stripped of my shroud, I was placed naked on a table. In a short time I heard by the bustle in the room that the doctors and students were assembling. When all was ready the Demonstrator took his knife, and pierced my bosom. I felt a dreadful crackling, as it were, throughout my whole frame; a convulsive shudder instantly followed, and a shriek of horror rose from all present. The ice of death was broken up; my trance was ended. The utmost exertions were made to restore me, and in the course of an hour I was in full possession of all my faculties.

“STEPHENSON, PRINTER, GATESHEAD.”

It was quite necessary for the Committee on Anatomy to adopt some means to protect the resurrection-men who gave evidence before it;[Pg 69] this was done by suppressing their names, and using letters of the alphabet to distinguish the witnesses one from another. Popular feeling was so bitter against these men that they were often severely handled by the mob. Sometimes the mob made a mistake, and the innocent suffered for the guilty. In 1823 a coach containing an empty coffin was being drawn along the streets of Edinburgh; the people, suspecting that it was intended to convey a body, taken from some churchyard, seized the coach; it was with great difficulty that the police rescued the driver from the fury of the mob. The coach they could not save; it was taken through the streets, thrown over a mound, and smashed; the people then kindled a fire with the fragments, and danced round it. It turned out that the coffin was intended to convey to his house, in Edinburgh, the body of a physician who had died in the country.

On another occasion two American gentlemen, who were looking at the Abbey of Linlithgow after nightfall, were mistaken for resurrection-men, and assaulted by the mob.

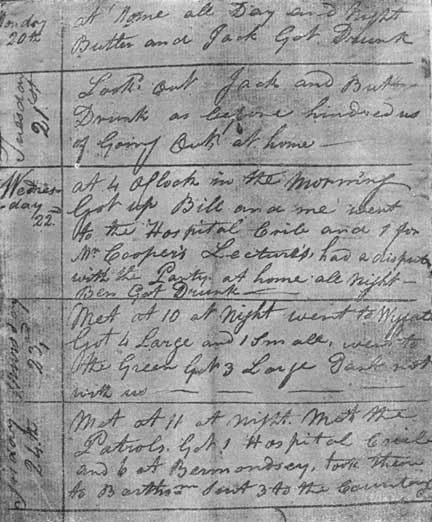

One of the witnesses, called “A. B.,” but who was probably Ben Crouch himself, stated that[Pg 70] twenty-three in four nights was the greatest number he had ever obtained. He added, “When I go to work, I like to get those of poor people buried from the workhouses, because instead of working for one subject, you may get three or four. I do not think, during the time I have been in the habit of working for the schools, I got half a dozen of wealthier people.” Another witness, who is called “C. D.,” but who was, without doubt, the writer of the Diary, stated that, “according to my book,” in 1809 and 1810 the number of bodies disposed of in England was 305 adults and 44 small; but the same year 37 were sent to Edinburgh, and the gang had 18 in hand, which were never used at all. In 1810-11, 312 adults were disposed of in the regular session, and 20 in the summer, in addition to 47 smalls. In the Report of the Committee in 1828, it was pointed out that, at that time, there were over 800 students attending the Schools of Anatomy in London, but of these not more than 500 actually worked at dissection. The number of subjects annually available for instruction amounted to between 450 and 500, or rather less than one for each student.

[Pg 71]The average price of an adult body was stated to be £4 4s. 0d. It may be here explained that a “small” was a body under three feet long; these were sold at so much per inch and were generally classified as “large small,” “small,” and “fœtus.” The earnings of the resurrection-men may be gathered from the above entry. To take the year 1810-11, the receipts for bodies alone come to 1328 guineas; this is exclusive of “smalls,” and probably also of the teeth, in which these men did a large trade. Teeth, in those days, were very valuable; the amounts received by some of the men for teeth only will be dealt with in the chapter containing biographical notices of some of the principal London resurrection-men. It may be here mentioned that on one occasion Murphy obtained the entry to a vault belonging to a meeting-house, on the pretence of selecting a burial-place for his wife. Whilst in there he managed to slip back some bolts, so that he could easily gain an entrance at another time; this he did at night, and got possession of teeth by which he made £60.

From the statements of the teachers it is[Pg 72] most likely that £4 4s. 0d. is under the average price paid for bodies. It must be remembered, too, that this amount does not include the retaining-fee paid at the beginning of the session, nor the “finishing-money” which was demanded at its close. The 1328 guineas spoken of above would be divided amongst six or seven persons, and this, for men in their position, was a large income. The biographical notes of the chief workers in this horrible trade will show that some few of them did save money. Taking them, however, as a whole, they were a dissolute and ruffianly gang; reference to the Diary proves their drunken habits, and there is more than one entry to show that they were often in pecuniary difficulties; so much so that on one occasion they were obliged to have recourse to Mordecai, the Jew.

It was quite useless for those who had just buried a relative or friend to depend either upon the custodian of the burial-ground, or upon the watch, to see that the newly-made grave was not violated. The resurrection-men often met with a guard, instituted by the friends of the deceased, who would take it in turns to watch by the grave-side through the[Pg 73] whole night; these friends were frequently armed, and were not afraid to use their arms if the resurrection-men gave them an opportunity. As a rule the body-snatchers made off when they found a guard in the cemetery; it was to their interest not to create a riot, and if they were strong enough to drive off the watchers, the latter could soon raise a tumult, whereby the bodily safety of the thieves would be endangered.

Matters did not always pass off so peaceably, particularly in Ireland, as the following extract from an Irish newspaper for 1830 shows:

“Desperate Engagement with Body-snatchers.—The remains of the late Edward Barrett, Esq., having been interred in Glasnevin churchyard on the 27th of last month (January), persons were appointed to remain in the churchyard all night, to protect the corpse from ‘the sack ’em-up gentlemen,’ and it seems the precaution was not unnecessary, for, on Saturday night last, some of the gentry made their appearance, but soon decamped on finding they were likely to be opposed. Nothing daunted, however, they returned on Tuesday morning with augmented force, and well armed. [Pg 74]About ten minutes after two o’clock three or four of them were observed standing on the wall of the churchyard, while several others were endeavouring to get on it also. The party in the churchyard warned them off, and were replied to by a discharge from fire-arms. This brought on a general engagement; the sack ’em-up gentlemen fired from behind the churchyard wall, by which they were defended, while their opponents on the watch fired from behind the tomb-stones. Upwards of 58 to 60 shots were fired. One of the assailants was shot—he was seen to fall; his body was carried off by his companions. Some of them are supposed to have been severely wounded, as a great quantity of blood was observed outside the churchyard wall, notwithstanding the ground was covered with snow. During the firing, which continued for upwards of a quarter of an hour, the church bell was rung by one of the watchmen, which, with the discharge from the fire-arms, collected several of the townspeople and the police to the spot—several of the former, notwithstanding the severity of the weather, in nearly a state of nakedness; but the assailants were by this [Pg 75]time defeated, and effected their retreat. Several of the head-stones bear evident marks of the conflict, being struck with the balls, &c.”

MORTSAFE IN GREYFRIARS CHURCHYARD, EDINBURGH.

Most of the disgraceful riots which took place in the burial-grounds, were not between resurrection-men and friends guarding a grave, but between two gangs of body-snatchers. In cases of this kind one gang would do all in its power to bring its rival into disrepute; the stronger party, after driving the weaker one away, would put the burial-ground into a most disgraceful state, and then give information against their opponents.