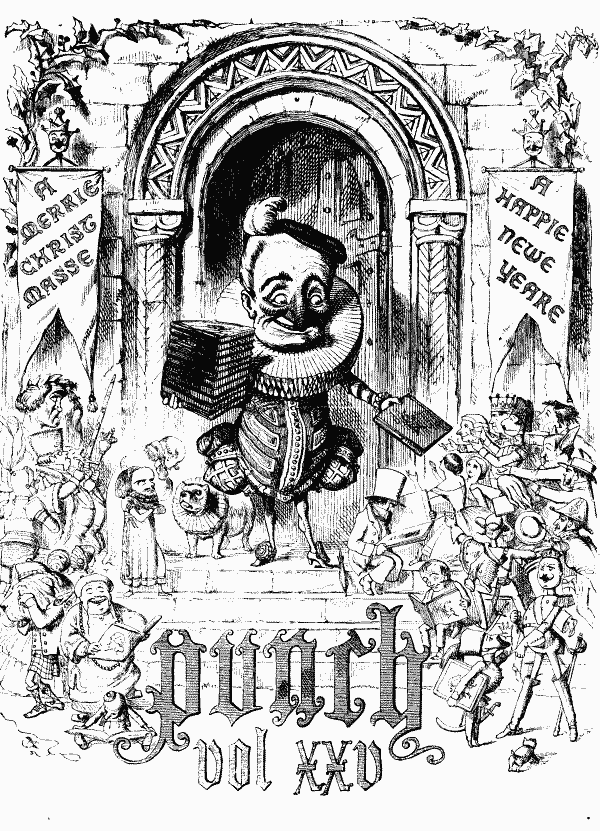

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch - Volume 25 (Jul-Dec 1853), by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch - Volume 25 (Jul-Dec 1853) Author: Various Release Date: May 12, 2010 [EBook #32352] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH - VOLUME 25 (JUL-DEC 1853) *** Produced by Neville Allen, Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net[Pg i]

On Christmas Eve, Mr. Punch, on the strength—or, rather, length—of a Message from President Pierce, visited her Majesty Queen Mab. He was received by a most courteous Dream-in-Waiting, who introduced him through the Gate of Horn, whence, as Colonel Sibthorp beautifully remarks,

Dream-World was merrily keeping its Yule-tide, with shadowy Sports and dissolving Pastimes. As Mr. Punch entered, the Game was

The Lady Britannia was enthroned, Mistress of the Revel, and her golden apron was heaped with Pledges. The owners, a miscellaneous group, awaited the sentence of penalties.

Down, at a smile-signal from the Lady in the Chair, down went the broad brow of Mr. Punch, to repose on her knee, while Kings, and Ministers, and Hierarchs, and Demagogues came rustling round to listen.

The magic formula was silverly uttered.

|

|

"Answer, dear Mr. Punch," said the Lady in the Chair. "You always say exactly what I wish said."

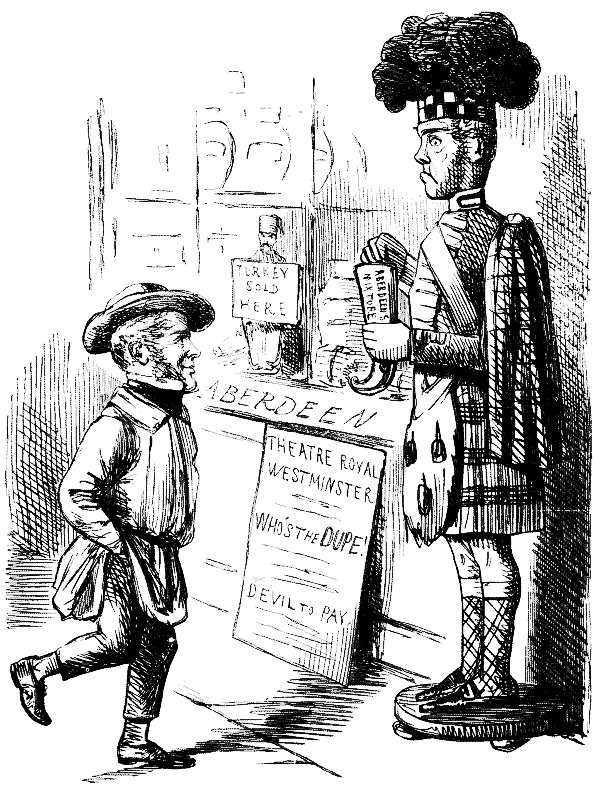

"The Owner," said Mr. Punch, "will retire." And the Earl of Aberdeen, who had forfeited Public Confidence, withdrew, and Britannia murmured her intense satisfaction with the proceeding.

The next forfeit was called. "The Owner," said the oracle, "will go down upon his knees, will, in all abjectness of humiliation, beg pardon of all the world, and will humbly deposit his purse at the foot of the Ottoman nearest to him." A heavy tread, and the Emperor of all the Russias sullenly stalked away, sooner than thus redeem his Honour.

The third forfeit. "The Owner will find a Lady, whose well-omened Christian name is Victoria, and to her he will recite some verses, of his own making, in praise of Chobham and Spithead." "I am not[Pg iii] much of a poet," said Mr. Cobden, "but if my Friend, Bright, will help me, I will gladly so redeem my Blunder."

The fourth. "A poor Foreigner," whispered the over-kindly Lady, but Mr. Punch sternly buttoned his pockets. "The Owner will behave with common honesty until further notice." A gentleman in a Spanish costume looked surprised at such a desire, and said that he did not care whether he did or did not redeem his Bonds.

The fifth was called, and a light step approached, and somebody was heard humming a melody of Tom Moore's. "The Owner," said Mr. Punch, "will carry three times through the chamber something to help you, Madam, to hear your own voice better." Lord John Russell smiled, and said that he hoped his Reform Bill would so redeem his Promise.

And the Dream—it is dream fashion—grew confused, but Mr. Punch thinks there was a scramble for the rest of the things, and that everybody snatched what he could. Mr. Gladstone, seizing, with tax-gatherer's gripe, what he thought was a work on Theology, got "The Whole Duty—off Paper." Emperor Louis Napoleon departed very happy with a Cradle. Lord Palmerston went out, angry with a Scotch Compass, which though only just out of the Trinity House, had an abominable bias to N.E. Pope Pius ran about most uncomfortably, apprehending the loss of a French Watch and Guard, to go without which would, His Holiness said, be his ruin. Mr. Disraeli made several vain grabs at a portfolio, which Britannia, laughing good-natured scorn, refused to let him have; and when the Earl of Derby tried for the same thing, she presented him with a Racing Game, as more suitable to his capabilities. Several Aldermen, who had presented specimens of Mendacity, received packets of tickets, inscribed Mendicity, to everybody's delight, and there was a cheer for a bold Bishop, who had put down a Carriage and was content to take up a little Gig. Another Bishop—he had a Fulham cut—found his mitre, but some one, in unseemly satire, had surmounted it with a golden and most vivacious Weathercock.

"And what would you put down, dear Mr. Punch," said the Lady of the Revel, "if we began again?"

"This, dear Lady," said Mr. Punch, gracefully bending, and proffering an object at which the eyes of Britannia sparkled like diamonds, "this—which—as your game is over, I will pray you to keep in pledge that, six months hence, I will present you with its still richer successor."

And Britannia—the smile at her heart reflected in her face—accepted

| First Lord of the Treasury | Earl of Aberdeen. |

| Lord Chancellor | Lord Cranworth. |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone. |

| President of the Council | Earl Granville. |

| Lord Privy Seal | Duke of Argyll. |

| Home Office | Viscount Palmerston. |

| Foreign Office | Earl of Clarendon. |

| Colonial Office | Duke of Newcastle. |

| Admiralty | Right Hon. J. R. G. Graham, Bart. |

| Board of Control | Right Hon. Sir C. Wood, Bart. |

| Secretary at War | Right Hon. Sidney Herbert. |

| First Commissioner of Works, &c. | Right Hon. Sir W. Molesworth, Bart. |

| Without Office | Lord John Russell |

| Without Office | Marquess of Lansdowne. |

The unjust demands of the Emperor of Russia on the Ottoman Porte, and his subsequent occupation of the Danubian Principalities, occupied the earnest attention of the Parliament and the people throughout the year, and was the occasion of much inquiry and discussion.

We cannot do better than add a summary of Lord John Russell's Speech, towards the close of the Session, in explanation of the position of affairs:—

"When he entered office, he said, his attention was called to the question of the Holy Places; and he instructed Lord Cowley, at Paris, to give the subject his earnest attention. Soon after he, Lord John Russell, learned that a special Russian Minister would be sent to the Sultan, to put an end, by some solemn act, to the differences that existed with regard to the Holy Places. He did not object to that; and Prince Menschikoff arrived at Constantinople on the 2nd of March. From this point, Lord John Russell went over the subsequent events—the resignation of Fuad Effendi; the message of Colonel Rose To Admiral Dundas, sent at the request of the Grand Vizier, and subsequently retracted; and the notification by the Turkish Ministers to Lord Stratford, in April, that certain propositions had been made to them to which they were unwilling to accede. 'I should say,' continued he, 'that up to this time the Government of Her Majesty at home, and Her Majesty's Minister at St. Petersburg, had always understood that the demands to be made by Russia had reference to the Holy Places; and were all comprised, in one form or another, in the desire to render certain and permanent the advantages to which Russia thought herself entitled in favour of persons professing the Greek religion. Lord Stratford understood from the Turkish Ministers, that it had been much desired by the Russian Ambassador that the requests which were made on the part of Russia should be withheld from the knowledge of the representatives of the other Powers of Europe; and these fresh demands were as new to the Government of France as they were to the Government of Her Majesty.' The propositions were changed from time to time, until Prince Menschikoff gave in his ultimatum, and left Constantinople. 'I consider that this circumstance was one very greatly to be regretted. It has always appeared to me, that, on the one side and the other, there were statements that would be admitted, while there were others that might be the subject of compromise and arrangement. The Russian Minister maintained that Russia had, by certain treaties (especially by the treaties of Kainardji and Adrianople) the right to expect that the Christians in the Turkish territory would be protected; and he declared at the same time, that Russia did not wish in any manner to injure the independence or integrity of the Turkish Empire. The Sultan's Ministers, on their part, maintained that it was their duty, above all things, to uphold the independence of the Sultan, and to require that nothing should be acceded to which would be injurious to his dignity or would derogate from his rights; but at the same time, they declared that it was the intention of the Sultan to protect his Christian subjects, and to maintain them in the rights and privileges which they had enjoyed under the edicts of former Sultans. Such being the statements on the two sides, I own it appears to me that the withdrawal of the Russian mission from Constantinople, accompanied as that measure was by the preparation of a large Russian force, both military and naval, on the[Pg v] frontiers of Turkey, was a most unfortunate step, and has naturally caused very great alarm to Europe, while it has imposed great sacrifices both upon Turkey and upon the Turkish provinces adjoining Russia.' These appearances became so serious that the fleet was ordered to approach the Dardanelles; the French fleet advanced at the same time; and the Russians entered the Principalities. This, Turkey had an undoubted right to consider a casus belli; but France and England induced the Sultan to forego that right, thinking it desirable to gather up the broken threads of negotiation, and strive for some arrangement for maintaining peace. The French Minister for Foreign Affairs—'a gentleman whose talents, moderation, and judgment it is impossible too greatly to admire'—drew up a note, omitting what was objectionable on both sides. The Austrian Government, which had previously declined to enter on a conference, changed its views when the Russians occupied the Principalities, and Count Buol took the proposal of M. Drouyn de Lhuys as a basis for a note. This note was agreed to by the Four Powers; and the Emperor of Russia had accepted it, considering that his honour would be saved, and his objects attained, if that note was signed by the Turkish Minister.

"Supposing that note 'to be finally agreed upon by Russia and Turkey as the communication which shall be made by Turkey, there will still remain the question of the evacuation of the Principalities. It is quite evident, Sir, that no settlement can be satisfactory which does not include or immediately lead to the evacuation of those Principalities. (Cheers.) According to the declaration which has been made by the General commanding the Russian Forces, Prince Gortschakoff, the evacuation ought immediately to follow on the satisfaction obtained by Turkey from the Emperor of Russia. I will only say further, that it is an object which Her Majesty's Government consider to be essential: but with respect to the mode in which the object is to be obtained—with respect to the mode in which the end is to be secured—I ask the permission of Parliament to say nothing further upon this head, but to leave the means—the end being one which is certain to be obtained—to leave the means by which it is to be obtained in the Executive Government. With respect to the question which has been raised as to the fleets of England and France at Besika Bay, that of course need not be made any question of difficulty, because, supposing Turkey were in danger, we ought to have the power at all times of sending our fleets to the neighbourhood of the Dardanelles to be ready to assist Turkey in case of any such danger, and we ought not to consent to any arrangement by which it may be stipulated that the advance of the fleets to the neighbourhood of the Dardanelles should be considered as equivalent to an actual invasion of the Turkish territories. But, of course, if the matter is settled—if peace is secured, Besika Bay is not a station which would be of any advantage either to England or France.'

"In conclusion he said, he thought we had now a fair prospect, without involving Europe in hostilities, or exposing the independence and integrity of Turkey, that the object in view would be secured in no very long space of time. 'I will only say further, that this question of the maintenance of Turkey is one that must always require the attention—and I may say, the vigilant attention—of any person holding in his hands the foreign affairs of this country. This, however, can only be secured by a constant union between England and France—by a thorough concert and constant communication between those two great Powers."

In our next Volume we shall have to treat of the results of these difficulties.

One effect of these "rumours of wars" was the introduction of the Naval Coast Volunteers' Bill, a very necessary and important measure for the establishment of a Naval Militia, and by which 18,000 to 20,000 well-trained seamen are placed at the disposal of the country.

Other bills of considerable importance in themselves, though not of political interest, became Law, and have been productive of great good to the community. The Act for the Suppression of Betting Houses has saved many a thoughtless fool from ruin, and dispersed, though not destroyed, the bands of brigands who then preyed upon the unwary. The prisons of London gave abundant and conclusive testimony of the vast number of persons, especially the young, who had been led into crime by the temptation held out by Betting Houses.

Mr. Fitzroy's Act for the Better Prevention and Punishment of Aggravated Assaults upon Women and Children has done much, though not all that is required, to lessen the brutality of the lower orders, and the Smoke Prevention Act has removed in part one of the disgraces of our metropolis.

The Vaccination Extension Act was a sanitary measure of great importance, as the mortality from small-pox had long been greater in England than in any other country in Europe.

On the 16th of December Lord Palmerston resigned his office of Secretary of State for the Home Department, but he was subsequently induced to resume his position in the Government.

On the 20th of August the Parliament was prorogued by commission, and a Parliamentary Session of an unusually protracted and laborious character brought to an end. The year had been generally very prosperous, but the scanty harvest, and the unsettled condition of the labouring classes, who resorted to the desperate and suicidal agency of "strikes" for bettering their condition, added to the probability of a war with Russia, brought it to a gloomy close, and it was as much as Punch could do to sustain the nation in moderate cheerfulness.

| PAGE | |

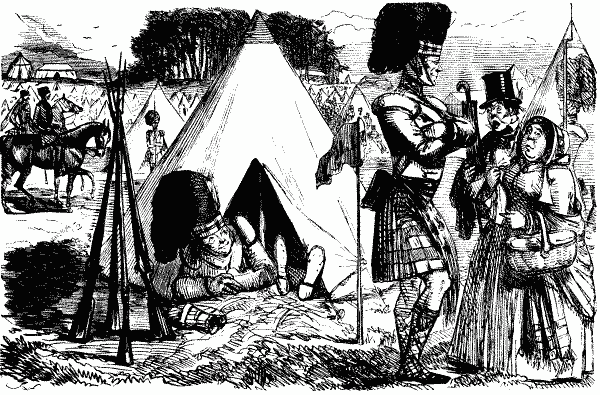

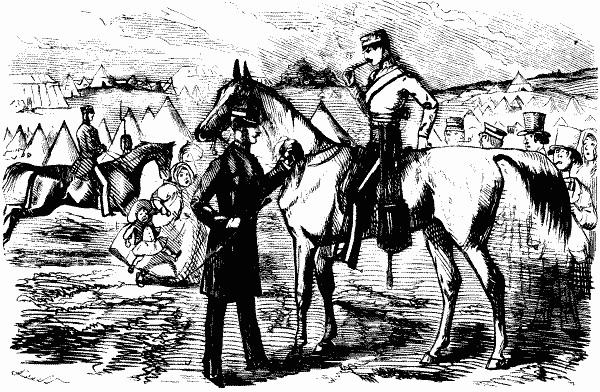

| The Camp at Chobham.—The July of 1853 was particularly wet. | 5 |

| " " | 8 |

| The Camp.—A fact. | 16 |

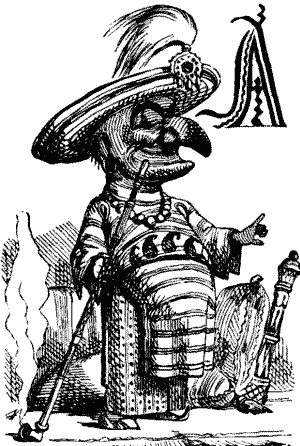

| Fancy Portrait.—Need we say of Mr. Charles Kean. | 13 |

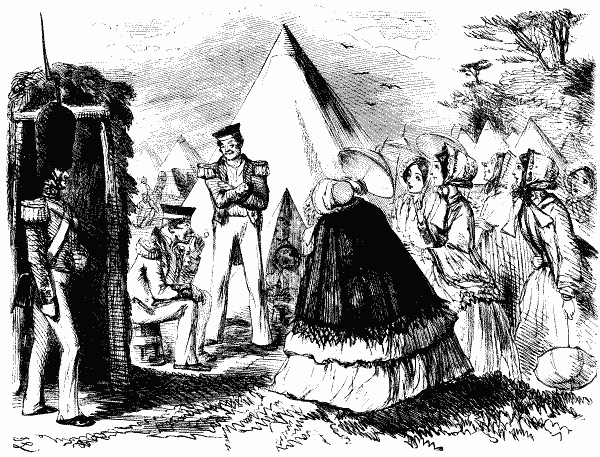

| A Genteel Reproof was really required to check the somewhat indelicate curiosity of lady-visitors to the camp. | 15 |

| Poisonous Puffs still disgrace many provincial papers and a few metropolitan ones. Newspaper readers have the remedy in themselves by adopting the advice given in this article. | 29 |

| A Startling Novelty in Shirts was barely an exaggerationin 1853. | 31 |

| A Determined Duellist.—See Note to p. 39. | 32 |

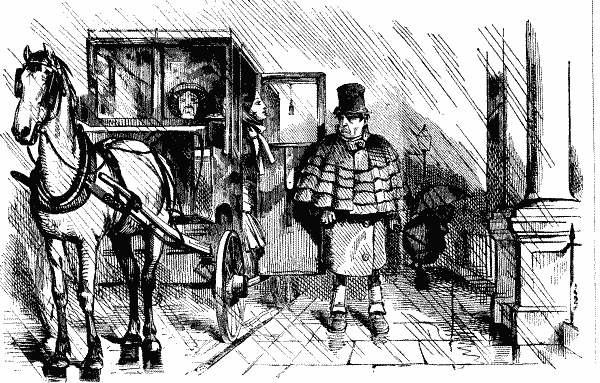

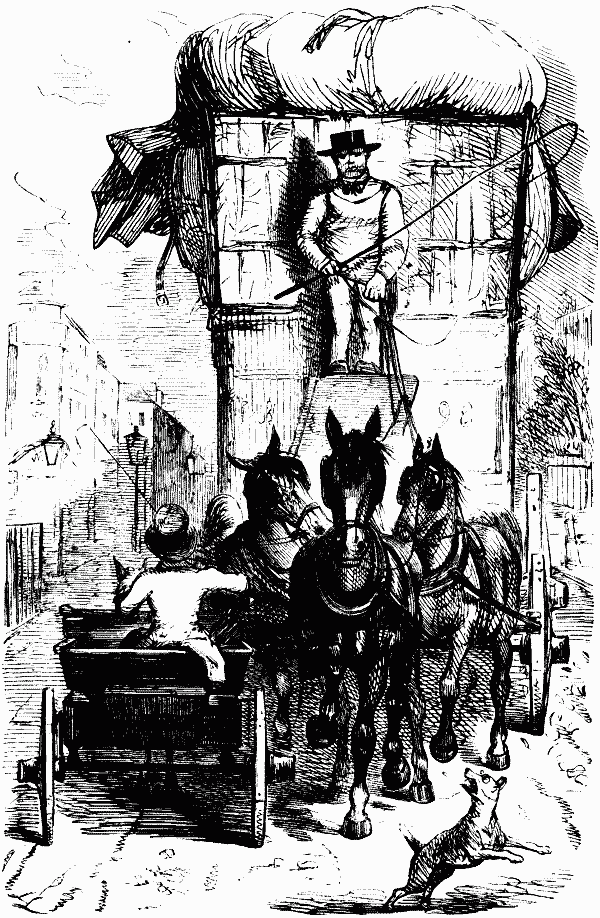

| The New Act.—The Cabman is the picture of a man then about town, and a member of a very respectable family, to annoy whom he drove a Hansom Cab. | 34 |

| A Good Joke.—See Introduction. | 35 |

| Another Potato Blight, &c.—Mr. Serjeant Murphy, of facetious memory. | 37 |

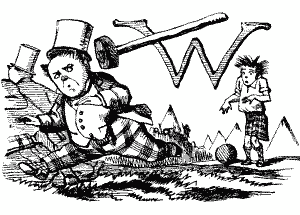

| Mornington's Challenge.—Lord Mornington, formerly Mr. Wellesley Tylney Long Pole, recently challenged Lord Shaftesbury, who declined the folly. Pop Goes the Weasel was the name of a popular tune. | 39 |

| East India House.—Mr. Hogg was a distinguished director of the East India Company and M.P. | 42 |

| The American Cupid.—Mr. Hobbs, the celebrated lock-picker, to whom reference has been frequently made in preceding Volumes. | 49 |

| Logic for Mr. Lucas.—See Notes to preceding Volumes. | 50 |

| Effect of the Cab Strike.—About this time the Cab Proprietors of London struck against the new Cab Act, and London for a day was left cabless. | 51 |

| Wanted, a Nobleman.—An Earl of Aldborough was advertised as a patron of Holloway's Pills, for whose real value, see Punch, No. 1126, February 7, 1863. | 61 |

| The Member for Lincoln as he will Appear at the Next General Election.—A Street Musician used to play several instruments in the manner here indicated. | 61 |

| The Battle of Spithead.—The Queen held a grand Naval Review at Spithead. | 73 |

| The Doom of Westminster Bridge was fulfilled in 1862 by the opening of the beautiful structure built by Mr. Page. | 79 |

| A Present for Aberdeen.—Lord Aberdeen was suspected of Russian tendencies. | 95 |

| " " | 238 |

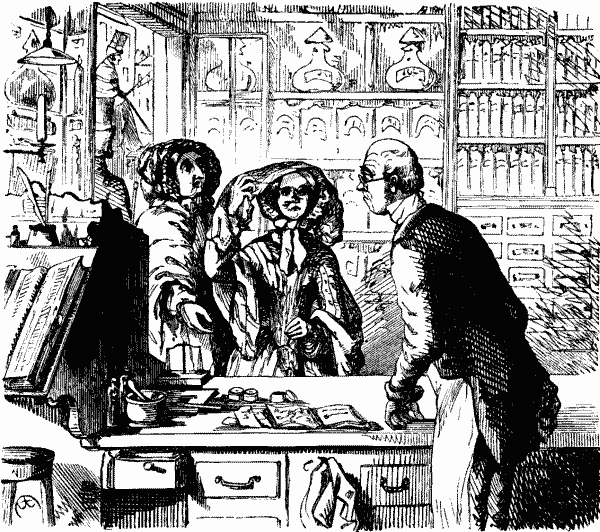

| Flowers of the Towzerey Plant.—The Towzerey Gang was a set of swindling warehousemen well exposed by the Times. | 104 |

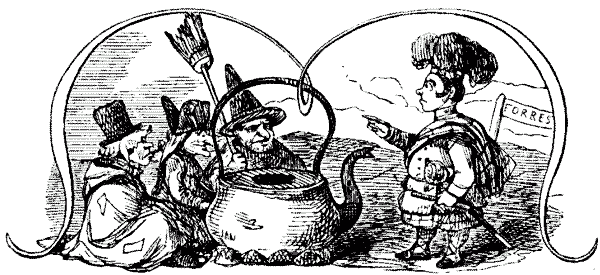

| A Consultation about the State of Turkey.—Turkey was described at this time as "the sick man." | 119 |

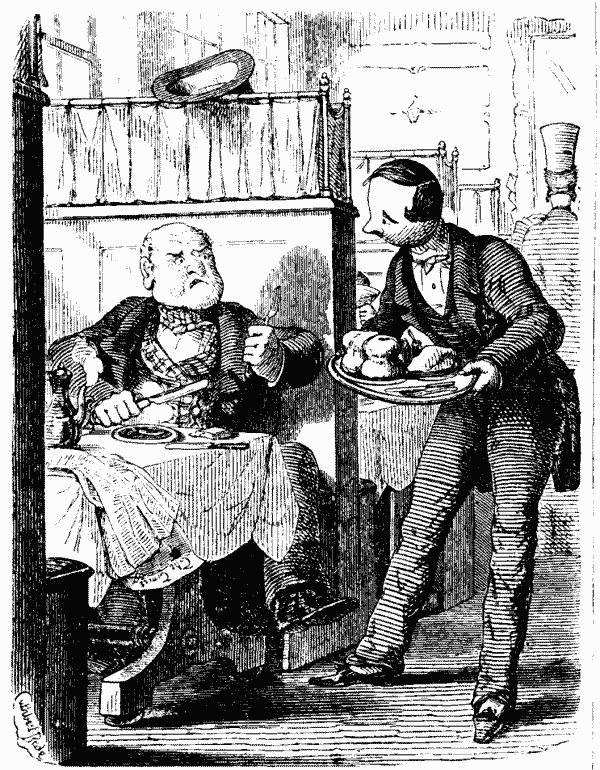

| Tavern Experience.—See large cut below. | 128 |

| The Institution of our Spectre of Chelsea.—An Apparition called the Lady of Salette was said to have appeared to a Shepherd boy, and was accredited by the Romish Church. | 131 |

| Memorial to Bellot.—A Monument to the memory of this gallant Frenchman, who perished during one of our Polar Expeditions, is erected opposite to Greenwich Hospital. | 186 |

| A Letter and an Answer.—The Cholera was rife at this time. | 197 |

| A Nuisance in the City, &c.—The Corporation of London strongly opposed the Health of Towns' Bill. | 199 |

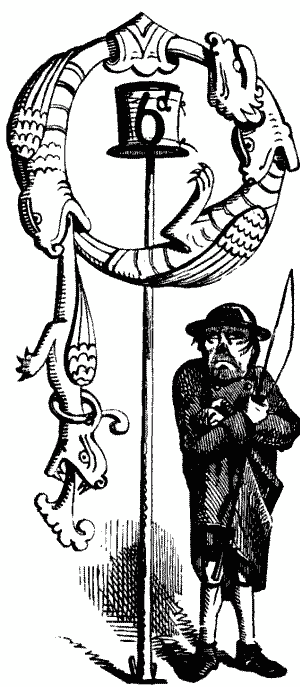

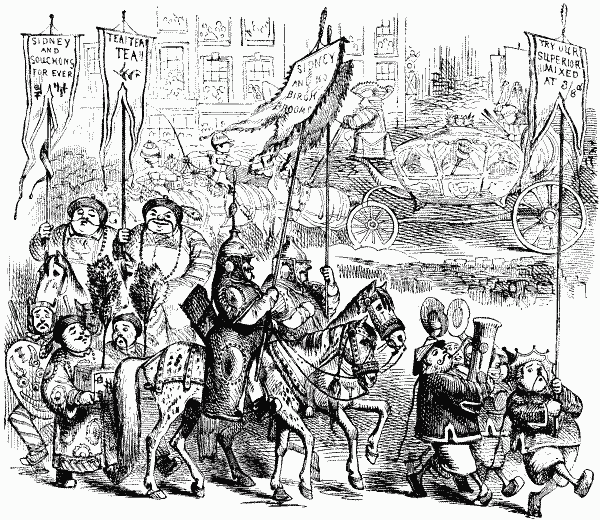

| Lord Sid-nee Show.—Sidney was a Tea-dealer. | 204 |

| A Bishop on Things Solid.—A most ridiculous movement was made in the City to obtain subscriptions for a Statue for Prince Albert. It was very properly discountenanced at Court. | 206 |

| " " | 208 |

| A Lonely Square.—This was the age of "stick-ups." | 222 |

| The Remonstrance, and A New Chime for Bow Bells.—The Lord Mayor and Corporation of London had fallen, sadly "fallen from their high estate" in public estimation. | 228 |

| Expostulation with Palmerston.—Lord Palmerston had left the Ministry at this time. See Introduction. | 258 |

"Yes, with much pleasure," said Mr. Punch, M.P. for England, as he entered the Octagon Hall in Parliament Palace; and, in his usual elegant and affable manner, extended his white-gloved hand to a courtly gentleman who had requested his presence.

"I was sure you would say so," said the gentleman, and he raised a finger. A watchful official at a door instantly turned to the electric dial, and Mr. Punch's gracious assent was known at Holyhead, before he had finished congratulating his companion, in the most truly charming style, on a promised knighthood, of which the Viceroy of Ireland had whispered something to Mr. Punch.

"No man ever earned his spurs better than the man who has been spurring railways into increased activity for so many years," said Mr. Punch, with a beautiful bow.

"I have not called you from the House at an unfortunate time, I trust, Sir," said the other. "Not that you can ever be spared, but—"

"William Gladstone is quite up to his work," replied the great patriot. "He has but a couple of dozen of the Brigade in hand at present, and he is tossing up one after the other, cup-and-ball fashion, cupping or spiking him to taste, with the precision of a Ramo Samee. I can leave William. Let us go."

"You will take care that no other passenger is put into Mr. Punch's coupé, guard," said the gentleman, as the Euston whistle sounded.

"No masculine passenger, please tell him, Mr. Roney," said Mr. Punch, facetiously. "Good night."

"This Irish journey is capitally done, certainly," said Mr. Punch, as, thirteen hours later, he found himself over his coffee and prawns in Sackville Street, on a radiant morning, and all the bright eyes of Dublin sparkling round the door of his hotel, eagerly glancing towards his balcony. Mr. Punch rushed forth, serviette in hand. His large heart beat high at the sight of so much loveliness, and at the sound of those angel-voices, rising into musical cheering.

"Bless you, my darlings!" Mr. Punch could say no more, but finished his prawns, and, throwing his manly form upon a jaunting car, he dashed over the bridge, and to Merrion Square.

"An' it's for luck I'll be takin' your honour's sixpence, and not for the dirthy money," said the excited driver, as he rattled round the corner, and into the Square, and the gigantic cylinders of the Exhibition burst upon Mr. Punch's gaze.

"My Irish friend," said Mr. Punch, gravely, but not severely, "do not talk nonsense. Your carriage is clean, your horse is rapid, you are civil, and your fare is certain. In London, we have as yet neither clean carriages, rapid horses, civil drivers, nor certain fares. We may learn those lessons of you. Learn two from us. Do not believe in luck, but practice perseverance; and do not call that money dirty which is the well-earned pay of honest service. To sweeten the advice, there is a shilling." And Mr. Punch entered the Exhibition building, and was drawing out his purse at the turnstile. But two gigantic policemen, in soldierly garb, welcomed him with a respectful smile, and the turnstile suddenly spun him into the building gratis, but a little too fast for dignity. What a sight was that before him! The vast hall, with its blue lines and red labels, looked a handsome instalment of Paxtonia. Plashing fountains, murmuring organs, a Marochetti Queen high pedestalled, white statues, glistering silver-blazoned banners. A fine and a noble sight, and worthy of all plaudit; but it was not that which almost bewildered the great patriot, as he was shot into Dargania. Those eyes again—two thousand pairs at least—Irish diamonds, worth mines of Koh-i-noors, suddenly flashing and sparkling and melting upon him. That telegraph message from the Octagon Hall—and, as they say in the Peers' House, "and the Ladies summoned." Staggered though he was, you do not often see such a bow as that with which Mr. Punch did homage to his lovely hostesses.

Two of the fairest stepped forward gracefully, and blushingly proffered themselves as his guides through the building.

"Chiefly, that I may set them in my prayers," murmured Mr. Punch, "if you happen to have names——"

Those blue eyes belong to Honora, and those violet eyes to Grace, and all to Mr. Punch's heart henceforth and until further notice. They proceeded, and there was a sound as of a great rustling, as of a world of feminine garments forming into procession and following, but it was vain for Mr. Punch to think of looking round, for he never got further than the face of one or other of his companions. They paraded the building.

Grace bade him look from her, and observe the five halls, in the central and greatest of which they stood. She showed him that Royalty had contributed a gorgeous temple, rich in gems and gold, richer in an artist-thought of the Prince who designed it. And, standing[Pg 2] on the platform, she pointed out that the forge and the loom and the chisel had all been busy for that huge hall, whose area offered a series of bold general types of the work to be seen in detail around it. And China was near with her carvings, and India with her embroideries, and Japan with a hundred crafts (now for the first time revealed, thanks to our brother, the King of Holland), and Belgium with her graceful ingenuity, and France with her artistic luxury, and the Zollverein with its bronzes, and Austria with her maps, and flowers, and furniture. And then Grace led him on to the Fine Arts Hall, where the original thoughts of a thousand painters, new and old, glowed upon him from walls which the Devonshires, and Lansdownes, and Talbots, and Portarlingtons, and Yarboroughs, and Charlemonts, and others, had joined to enrich with the choicest treasures of their castles and mansions. And amid the priceless display, Mr. Punch felt justly proud of his aristocratic friends, who could at once trust and teach the people.

Honora bade him look from her, and they passed from an exquisite Mediæval Court, its blue vault studded with golden stars, crossed the hall, and observed a long range of machinery doing its various restless work, and doing it noiselessly, thanks to a silent system and a tremendous rod, sent from Manchester by Fairbairn, through whose Tubular Bridge Mr. Punch had flown at dawn. And Honora showed him where Ireland had put forth her own strength, and thrown down her linens and her woollens in friendly challenge, and with her hardware, her minerals, her beautiful marbles, and her admirable typography. They ascended, and passing through long lines of galleries, Mr. Punch's adorable guides pointed out, amid a legion of wares, things more graceful and useful than he had seen assembled since the bell (on that 11th of October last but one) tolled for the fall of Paxtonia.

"And now, dear Mr. Punch," said Honora, "you have looked round our Dublin Exhibition, and—and—"

"And," said Grace, "you know that you sometimes say rather severe things about Ireland—"

"Never," said Mr. Punch, dropping upon his knees. "Never. But here I register a vow."

The whole assembly was suddenly hushed, and had Mr. Punch's words been literal, instead of only metaphorical, pearls and diamonds, you might have heard them fall on those boards.

"That for your sakes here present, and for the sake of all the wise, and energetic, and right-hearted men of Ireland who have to do with this building, and with your roads, and railways, and schools, and the like, I will henceforth wage even more merciless and exterminating war than hitherto with the humbug Irish patriots (dupes or tools), who tarnish the name of a nation which can rear and fill an edifice like this."

A shout which made the good Sir John Benson's broad arches ring again and again. And, as it subsided, there came forth from the crowd of ladies, whose eyes all turned affectionately on the new comer, a stalwart presence. Mr. Punch sprang up.

"This is your work!" he exclaimed. "Don't say it is not, William Dargan, because I know it is, and because England knows it too, and holds your name in honour accordingly."

That day's proceedings are not reported further. But all Mr. Punch's friends who wish to please him will have the goodness to run over to Dublin, and see the finest sight which will be seen between this and the First of May next.

A real, genuine, out-and-out Teetotaller says he likes this Table-turning vastly; for, though it keeps folks to the table, still it keeps them from the bottle. "The table may go round," he says, "but the wine does not circulate." There may be more in this teetotaller's chuckle than wine-bibbers imagine. We ourselves have heard an instance of a wealthy City man, who is nearly as mean as the Marquis Of Northminster, who spares his Port regularly, by proposing to his company, as soon as the cloth is removed, that "they should try a little of this table-moving that is so much talked about." The decanters are removed, and he keeps his company with their fingers fixed upon the mahogany, until Coffee is announced. We warn all persons who are in the habit of dining out, against lending their hands to this favourite trick.

Though, perhaps, not strictly within our province to attend to the Commissariat of any but ourselves, we beg leave to announce that we have undertaken to supply the whole of the Camp at Chobham with chaff.

The Author of Scotch Beer.—We lately read an advertisement of a book entitled The Scottish Ale-Brewer. The author's name is Roberts; but it ought to have been Mac Entire.

Ye reverend Fathers, why make such objection,

Why raise such a cry against Convents' Inspection?

Is it not just the thing to confound the deceivers,

And confute all the slanders of vile unbelievers?

It strikes me that people in your situation

Should welcome, invite, and court investigation,

As much as to say, "Come and see if you doubt us;

We defy you to find any evil about us."

For my part I think, if I held your persuasion,

That I should desire to improve the occasion,

And should catch at the chance, opportunely afforded,

Of showing how well Nuns are lodged, used, and boarded.

That as to the notion of cruel inflictions

Of penance, such tales are a bundle of fictions,

And that all that we hear of constraint and coercion

Is, to speak in mild language, mere groundless assertion.

That an Abbess would not—any more than a Mayoress—

Ever dream of inveigling an opulent heiress,

That each convent's the home of devotion and purity,

And that nothing is thought about, there, but futurity.

That no Nuns exist their profession regretting,

Who kept in confinement are pining and fretting;

And to fancy there might be one such, though a rarity,

Implies a most sad destitution of charity.

That all sisters are doves—without mates—of one feather,

In holy tranquillity living together,

Whose dovecote the bigots have found a mare's nest in,

Because its arrangements are rather clandestine.

Nay, I should have gone, out of hand, to Sir Paxton,

As a Frenchman would probably call him, and "axed 'un,"

As countrymen say—his ingenious noddle

Of a New Crystal Convent to scratch for a model.

Transparent and open, inquiry not shirking,

Like bees you might watch the good Nuns in it, working;

And study their habits, observe all their motions,

And see them performing their various devotions.

This is what I should do, on a sound cause relying,

Not run about bellowing, raving, and crying;

I shouldn't exhibit all that discomposure,

Unless in the dread of some startling disclosure.

What makes you betray such tremendous anxiety

To prevent the least peep into those haunts of piety?

People say there's a bag in your Convents—no doubt of it,

And you are afraid you'll have Pussy let out of it.

Our contemporary, Household Words, has given an account of Canvas Town in the new world, but we doubt whether a description of one of the Canvas Towns—or Towns under Canvas—in the old world, would not reveal a greater amount of depravity and corruption than anything that exists even in Australia. A Canvas Town in England is no less bent on gold discovery than a Canvas Town at Port Phillip—the only difference being that the candidate's pocket, instead of the earth, is the place that the electors or gold diggers are continually digging into. In the Colonies the inhabitants of a Canvas Town are huddled together irrespective of rank, and frequently the best educated persons are found doing the dirtiest work, just as may be seen in a Canvas Town in England before election time. The inhabitants of a Colonial Canvas Town think only of the gold and the quartz, just as at home the inhabitants of a Canvas Town think of nothing but filthy dross and drink—the quarts taking of course precedence of the pints in the estimation of the "independent" voters.

Mr. Disraeli calls "invective a great ornament in debate." According to this species of decoration, Billingsgate ought to be the most ornamental place of debate in the world; and Mr. Disraeli himself, than whom few orators deal more largely in invective, deserves taking his rank as the most ornamental debater that ever was born.

THE gallant fellows now assembled under arms and over ankles in the mud and dust of Chobham, were on Tuesday, the 21st of June, led—or rather guided—into one of the most civil wars to be found in the pages—including the fly-leaves—of history.

It having been understood that a battle was to be fought, every one seemed animated with the spirit of contention, and the struggle commenced at the Railway Station, where a company of heavy Cockneys, several hundred strong, besieged with great energy the few flys, omnibuses, and other vehicles, that were to be met with. The assault was vigorously carried; but the retaliation was complete; for the cads, drivers, and other marauders, having allowed the besiegers to fall into the snare, drove them off to the field, and exacted heavy tribute as the price of their ransom. Some few took refuge by trusting to their heels, rather than undergo the severe charge to which they would have been exposed; and they arrived, after a fatiguing march of nearly five miles, much harassed by the ginger-beer picquets and tramps that always lie on the outskirts of an army.

It was, however, on the field, or rather among the furze-bushes of Chobham, that the battle was really to be fought; and in the afternoon, the Guards, the 1st and 2nd Brigades, with the Artillery and Cavalry, took up a sheltered position under a hill, to conceal themselves from the enemy. This "concealment" was rather dramatic than real; for the enemy had already determined not to see, and as none are so blind as those who won't see, the "concealment" was quite effectual. When the force had had full time to get itself snugly out of sight, the "foe" poured down with immense vehemence from Flutter's Hill, and began squeezing into ditches, or hiding behind mud walls, to avoid the "observation" of the enemy, who knowing from signals where it was proper to look without the possibility of seeing anything, kept up the spirit of this truly "civil" war in the politest manner.

The moment of action was now eagerly looked for on all sides, and particularly by our old friend the British Public, who had perched himself on all the available eminences commanding a view of those who were about to give—and take—battle. Aides-de-camp were now seen flying about in all directions with breathless speed, delivering "property" despatches, similar to those with which the gallant officers at Astley's are in the habit of prancing over the platformed planes of Waterloo. Suddenly the skirmishers of the 42nd made a sally from the heights, and poured an incessant volley of blank cartridge into the ears of the Highlanders; who, after one decisive struggle—though we defy anybody to say what the gallant fellows really struggled with—dislodged the foe, who had on the previous day received regular notice to quit their lodging at the time agreed on. The Guards now came on from the O. P. side, Upper Entrance, of the Common, and turning back the wing, made for an adjoining flat, marching fearlessly over the set pieces under a heavy fire—of nothing—from the muskets of the enemy. Victory seemed hesitating on which side to declare herself, when a rush of cavalry turned the scale, scattered the weights, and upset the barrow of a seller of sweet-stuff, who had incautiously—as a camp follower—ventured too near the flanks of the horse on the field of battle.

The mélée now became general, and it being impossible to discriminate between friend and foe, the Guards, seeing a large assemblage of the public on Flutter's Hill, were immediately "up and at 'em." This put the Hill in a more than usual flutter, for the British public having been given to understand there was "nothing to pay" for their position, were not prepared to expect there would be any charge whatever, and still less a charge at the point of the bayonet. It was here that the war assumed its most civil aspect, for the public, though vigorously charged, were most civilly requested to get out of the way, and the request was met on all sides with the most civil compliance. Thus ended the battle of Chobham of the 21st of June, in which several fell on both sides; but of all who fell every one happily jumped up again. A few lost their balance, but as these kept no banker's account the loss did not signify. We annex a spirited drawing of

At the Metropolitan Free Hospital Dinner, the Lord Mayor in the Chair, we find it reported that Miss M. Wells obtained great applause by the spirit and feeling with which she sang the ballad of "Annie Laurie." Is the Reporter sure that it was Annie? Is he quite certain it wasn't Peter?

There is one objection to the Bill for the Recovery of Personal Liberty in Certain Cases. That is, its title. False imprisonment, in certain cases, is remediable by Habeas Corpus. What inspection of nunneries is chiefly needed for, is the recovery of personal liberty in uncertain cases.

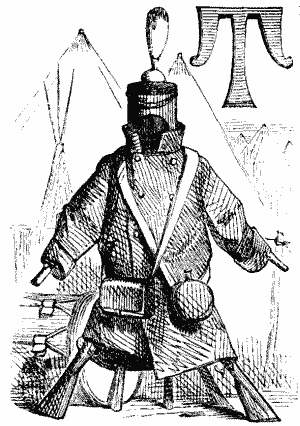

Mr. Muggins. "What! Fourteen on ye sleep under that Gig Umbereller of a thing? Get along with yer!"

Two attorneys quarrel about a matter of business; one of them accuses the other of trickery; the latter retorts on the former by calling him a liar and a scoundrel: and the first attorney brings an action for slander against the second. Whereon, according to the report of the case:—

"The Lord Chief Justice, in summing up, said it was not actionable to say of a man personally, 'you are a liar,' or 'you are a scoundrel;' nor was it actionable to combine the epithets, and say, 'you are a lying scoundrel;' but, if said of an attorney in his professional character, those words would be actionable."

What the law—speaking by the Lord Chief Justice—means to say, is, that abuse, in order to be actionable, must be injurious; that to call an attorney a lying and scoundrelly man does him no injury; whereas, calling him a lying and scoundrelly attorney tends to injure him in his profession. The law, therefore, presumes, that you may esteem a man to be a true and honest attorney, whilst in every other capacity you consider him a false and mean rascal; so that you may be willing to confide the management of your affairs to him, although you will not trust him with anything else.

It is curious that the rule applied to the defamation of lawyers is reversed in its application to invective against legislators. Members of Parliament are censurable if they impute falsehood and scoundrelism to each other in a personal sense, but not censurable for making those imputations in a Parliamentary sense. The theory of this anomaly seems to be, that the affairs of political life cannot be conducted without deceit and baseness, and accordingly that there is no offence in accusing an honourable gentleman of evincing those qualities in labouring at his vocation, that is to say for his country's good, for which it is necessary that he should cheat and deceive.

The law of slander, partially applied to attorneys, ought perhaps to be wholly inapplicable in the case of barristers. If a counsel may suggest to a jury a supposition which he knows to be false, and particularly one, which at the same time tends to criminate some innocent person; and if he is to be allowed to make such a suggestion for his client's benefit, he is allowed to be base and deceitful for the benefit of his client. To charge him with deception and villainy in his character of advocate, is to accuse him of professional zeal; to advantage him, not injure him, in his business. It ought to be lawful to call him a liar and a scoundrel in a forensic sense, as well as in every other.

When Lord Brougham, the other evening, was presenting some petition for the abolition of oaths, there were certain oaths in particular which he might have taken the opportunity of recommending the Legislature to do away with. They are alluded to in the following passage from a letter signed Censor in the Times:—

"As a condition of admission, the Head and Fellows of all Colleges are enjoined to take oaths to the inviolable observance of all the enactments of the statutes. These oaths, to use the words of the commission, increase in stringency and solemnity, in proportion as the statutes become more minute and less capable of being observed. These oaths are not only required but actually taken. Men of high feeling, refinement, education, and, for the most part, dedicated in an especial manner to God's service, are called on suddenly to swear that they will obey enactments incapable of being obeyed."

Oaths such as these are enough to make any man turn Quaker—at least by quaking as he swallows them. Any amount of swearing that ever disgraced a cabstand is preferable to such shocking affidavits; and there is something much more horrible in the oaths of college Fellows than there is in the imprecations of such fellows as coster-mongers. Our army once "swore terribly in Flanders," but never at such a rate as officers of the Church Militant appear to be in the habit of swearing at the Universities: and although there is said to be an awful amount of perjury committed in the County Courts, it is probable that the individuals forsworn at those halls of justice are far exceeded in number by the Reverend Divines who kiss the book to untruth at the temples of learning. It is a strange kind of consistency that objects to rapping out an oath, and yet obstinately retains such oaths at Oxford and Cambridge.

The Plain Truth of it.—There is NO "medium" in Spirit Rapping; for, in our opinion, it is all humbug from beginning to end.

Jones (a Batman.) "DID YOU SOUND, SIR?"

Officer. "YES, JOLES. BRING ME MY BUCKET OF GRUEL AS SOOL AS I'VE TALLOWED MY LOZE." (Catarrhic for Nose.)

A GREAT fact in India—nay, why should we not throw affected modesty on one side, and say at once, the great fact in that great country—is the position occupied in the most flourishing Indian communities by our humble—pooh! why blink the truth—our noble selves!

India is a country of contrasts—of wealth and want, of prosperity and and decay, of independence and servility, of self-government and despotism.

The want, the decay, the servility, and the despotism are to be found among all the native races—Bengalee and Madrassee, Maratta and Telinga, Canarese and Tamul, Bheel and Ghoorka, Khoond and Rohilla, Sikh and Aheer—it will be seen that we too have been getting up our India;—under all sorts of authorities—Potails and Zemeendars, Kardars and Jagheerdars, Ameers and Mokaddams, and Deshmucks; with all kinds of tenures—Zemeendaree and Ryotwaree and Jagheerdaree. But the wealth, the prosperity, the independence, and the self-government, are to be met with in one class of communities, under one form of authorities, among one kind of holders only. These oases in the desert of Indian native existence are those in which Punch—the Punch—the Mr. Punch—in one word the Indian representative of OURSELVES—bears sway!

This remarkable circumstance—so deeply gratifying to us of course—is no imagination of our own brain, no dream of our self-satisfaction, no figment of any of our numerous flatterers and admirers; but an historical truth, recorded in his distinctest and dryest manner by one of the distinctest and dryest writers upon India—Mr. Campbell, whose work has been much bought, much read, and unblushingly cribbed from by pillars of the state in the House of Commons, and by leading columns of the morning papers.

Hear then upon this great fact Mr. Campbell—of the Bengal Civil Service—whose civil service to Punches in general, and Indian Punches in particular, Punch is glad here to acknowledge. Hear Mr. Campbell, on the nature and effects of the authority and administration of Punch in India. Where Punches preside, "the system" he tells us "is infinitely better than anything we have hitherto seen." The revenue is larger and more easily collected; the condition of the cultivator more flourishing; property more secure, and the police better administered. Each village, under the beneficent and equal rule of its Punch, "is one community, composed of a number of families, all possessing rights in the soil, and responsibilities answering to their rights." Still Punch is no tyrant. "The Democratic Punch has no official power or authority except as representing this body of proprietors"—- like ourselves, who have no authority except in so far as we represent the people of Great Britain, which we flatter ourselves we do in most things.

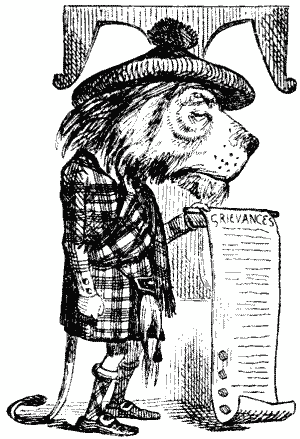

"The Punch," Mr. Campbell tells us (page 88), "is as a rule of the plural number"—(that is, there are several contributors);—"a clever well-spoken man, who has a good share of land" (we substitute brains), "and is at the head of a number of relatives and friends" (in our case, readers and admirers), "becomes one of the Punch, which office he holds for life, if he continues to give satisfaction to his constituents" (the public and proprietors are enough for us); "but if he becomes very old, or incompetent, or unpopular, some one else, probably, revolutionises himself into the place" (and serve the old, incompetent, unpopular contributor right). "The office of Punch is much coveted" (we should think it was), "and all arrangements are by the Punch collectively" (if the gentle reader could be present at one of our Saturday dinners, he would see what very small beer we think of the Editor). "They act not as persons having authority over the community, but always as representatives, and on many subjects they consult their constituencies before deciding." (When did we not consult public opinion, and when did we claim any other authority than as representing the country at large?) "There is generally in the village a leader of opposition," (poor creature!) "perhaps the defeated candidate for the last Punchship" (obviously a rejected contributor), "who leads a strong party" (oh, dear no! Mr. Campbell, you are misinformed on that point), "accuses the Punch of malversation, and, sometimes, not without reason, of embezzlement" (not on this side the water), "and insists on their being compelled to render an account of their stewardship" (our proprietors' books are open to all the world); "for there are abuses and grievances in all corporations, in all parts of the world" (i.e. "even Punches are not perfect"—a truth, probably, though we trust we shall never exemplify it in our own case).

Such is the rule of the Punches of India—and now for its effect. It produces communities, "strong, independent, and well-organized" (page 90). It is established over what Mr. Campbell styles "a perfect democratic community."

In short, this rule of Punch is the only one Mr. Campbell is able to rest on with entire satisfaction, as the model to which all the other native organizations of India ought to be, as far as possible, assimilated.

Yes—give every community its Punch, and India would be something like what it ought to be—something like what England has become since the rule of Punch was firmly established here—something which would render altogether unnecessary these dreadful Indian debates, and the immense amount of Indian "cram" which members, journalists, and conscientious persons, who follow the Parliamentary reports, are obliged to bolt, and of which we have disgorged a sample, with great relief to ourselves, at the beginning of this article.

I'm a free indepent Brish Elector—I swear—

And I'll have s'more bremwarra—anbanish dullcare!—

I know I've a trustodischarge in my vote,

And my countryexpex—I shall getfipunnote!

At 'lecksh'n shey 'n vied me to come up anget

Some breakf'st—so I did—an' I drank—an' I eat—

At the Chequers this was—zhere was morebesides me—

And not one blessed shixpence—to forkout had we.

Dropowhisky I had; bein' indishpo—posed—

Sha truth and sha whole truth I 'clare I'vedisclosed—

I feel almosasleep—I've been trav'linallnight—

Had but one smallglass gin—and you know tha's not right.

I have had a shov give me—to come uptatown,

An' shey paid my fareup—and shey paid myfare down—

Who shey was—I donow—any more than an assh—

But I hadmyplacepaidfor an' comebyfirsclassh.

I'm a true tenpun householder—noways a snob—

Though I did sell myself for the shummofivebob—

They wanted myvote—which I toldem theysh'd have,

If they'd give sunthink for it—and tha's what they gave.

While I'm shtoppinintown, I has ten bobaday,

Witch that money's mylowance myspenses to pay,

For peachin' on myside byzh 'tother I'm paid,

And a preshusgood thingouto' boshsides I've made.

I don't feel no 'casion for 'idinmyface,

Don't consider sh' I'm kivver'd wizh shameandisgrace,

I don't unstand what you should 'sfranchise me for—

And 'tis my 'termination to have s'more bremwarr'!

The Russian Minister has long been connected by name and parentage with one of the nicest puddings to be found in the receipts of Soyer, or in the carte of the Trois Frères. We must, however, protest against the Russian Diplomatist's endeavouring to combine with the practice of cookery the science of medicine, for though we always eat with pleasure Nesselrode pudding, we cannot undertake to swallow Nesselrode's recent draught.

The thunder of war turns the milk of human-kindness sour. Moreover, it may be said to spoil the beer of brotherly love.

The Sublime Porte and the Emperor of Russia, regarded in an æsthetical point of view, present examples of the Sublime and the Ridiculous.

Literature for the Camp.—There are not many books to read at the Chobham encampment; but, besides going through all the Reviews, the Camp will, doubtless, take in a great many numbers of this periodical.

The following Indexes have been compiled by a gentleman who is rather strong in that useful, but much-snubbed and little-read, department of literature. They are intended to keep in countenance the well-known "face," which is said to be "the Index of the Mind."

Cold Soup is the Index of a Bad Dinner.

A Bang of the door is the Index of a Storm.

A "Button off" is the sure Index of a Bachelor.

An Irish Debate is the Index of a Row.

A Popular Singer is the Index of a Cold.

A bright Poker is the Index of a Cold Hearth.

A Servant standing at the door is the Index of a Wasteful House.

A Shirt with ballet-girls is the Index of "a Gent."

The Painted Plate is the Index of the Hired Fly.

Duck, or Goose, is the Index of "a Small Glass of Brandy."

A Baby is the Index of a Kiss.

A Toast (after dinner) is the Index of Butter.

Cold Meat is, frequently, the Index of a Pudding.

A Favour is, more frequently, the Index of Ingratitude.

A Governess is the Index of suffering, uncomplaining, Poverty.

A Puseyite is the Index of a Roman Catholic.

Home is the Index Expurgatorius of Liberty; and lastly,

Mismanagement is the Index (at least the only one published yet) of the Catalogue of the British Museum.

Whether, in the event of Mr. Sands being subject, like Amina, to fits of somnambulism, it would be likely that he would walk in his sleep head downwards with his feet on the ceiling?

THURSDAY, MAY 23, 18—

"It would be something to say, Fred, that we'd been to France."—

"To be sure," replied Fred. "And yet only to have something to say and nothing to show, is but parrot's vanity."

"But that needn't be. We might learn a great deal. And I should like to see Normandy; if only a bit of it. One could fancy the rest, Fred. And then—I've seen 'em in pictures—the women wear such odd caps! And then William the Conqueror—papa says we came in with him; so that we were Normans once; that is on papa's side—for mamma won't hear that she had anything to do with it—though papa has often threatened to get his arms. And now I think of it, Fred, what are your arms?"

"Don't you know?" asked Fred, puckering his mouth—well, like any bud. "Don't you know?"

"No, I don't;" and I bit my lip and would be serious. "What are they?"

"It's very odd," said he, "very odd. And you are Normans! To think now, Lotty, that I should have made you flesh of my flesh, without first learning where that flesh first came from. You must own, my love, it was very careless of me. A man doesn't even buy a horse without a pedigree."

(I did look at him!)

"Nevertheless"—and he went on, as if he didn't see me—"nevertheless, my beloved, I must say it showed great elevation of mind on your part to trust your future fate to a man, without so much as even a hint about his arms. But it only shows the beautiful devotion of woman! What have arms to do with the heart? Wedlock defies all heraldry."

"I thought"—said I—"that, for a lawful marriage, the wedding ring must have the Hall mark?"

"I don't think it indispensable. I take it, brass would be as binding. Indeed, my love, I think according to the Council of Nice, or Trent, or Gretna Green—I forget which—a marriage has been solemnised with nothing more than a simple curtain-ring."

"Nonsense," said I; "such a marriage could never hold. Curtain-rings are very well in their way; but give me the real gold."

"True, my love, that's the purity of your woman's nature. In such a covenant we can't be too real. Any way"—and he took my wedding-finger between his—"any way, Lotty, yours seems strong enough to hold, ay, three husbands."

"One's enough," said I, looking and laughing at him.

"At a time"—said Fred; "but when we're about buying a ring, it's as well to have an article that will wear. Bless you," and he pressed his thumb upon my ring, "this will last me out and another."—

"Frederick," I cried very angrily; and then—I couldn't help it—I almost began to weep. Whereupon, in his kind, foolish manner he—well, I didn't cry.

"Let us, my darling," said Fred, after a minute, "let us return to our arms. And you came in with the Normans?"

"With William the Conqueror, papa says, so we must have arms."—

"I remember"—said Fred, as grave as a judge—"once, a little in his cups, your father told me all about it. I recollect. Very beautiful arms: a Normandy pippin with an uplifted battle-axe."

"I never heard that"—said I—"but that seems handsome."

"Yes; your ancestor sold apples in the camp. A fact, I assure you. It all comes upon me now. Real Normandy pippins. They show a tree at Battle—this your father told me as a secret; but as man and wife are one, why it's only one half talking to the other half—a tree at Battle grown from your ancestor's apple-pips. Something like a family tree, that."

"I don't believe a word of it," said I.

"You must. Bless you"—said Fred—"arms come by faith, or how many of the best of people would be without 'em. There's something innocent in the pippin: besides it would paint well. And with my arms"—

"Yes;" I cried; "and what are they, Fred?"

"Well, it's odd: we were—it's plain—made for one another. I came from Normandy too."

"You did?" and I was pleased.

"Yes," said he. "I wonder what terms our families were on a thousand years ago? To be sure, I came to England later than you; and I can't exactly say who I came with: but then—for I'm sure I can trust my grandmother—my descent is very historical. I assure you that your family pippin will harmonize with my bearings beautifully."

[Pg 9]"We'll have the hall-chairs painted," said I, and I felt quite pleased.

"And the gig of course," said Fred.

"Of course; for what is life if one doesn't enjoy it?" said I.

"Very true, love. And the stable-bucket," continued Fred.

"Just as you please, dear," said I; "but certainly the hall-lamp."—

"Yes: and if we could only get—no, but that's too much to expect," said Fred.

"What's too much?" I asked; for Fred's manner quite excited me.

"Why, I was thinking, if we could get your great aunt merely to die, we might turn out a very pretty hatchment."—

"Now, Frederick!"—for this was going too far.

"I assure you, my love"—said Fred—"'twould give us a great lift in the neighbourhood: and as you say, what's existence without enjoying it?—What's life without paint?"

"Well, but"—for he hadn't told me—"but your descent, love? Is it so very historical?"

"Very. I come in a direct line—so direct, my darling, you might think it was drawn by a ruler—a direct line from Joan of Arc."

"Is it true?" I cried.

"When we cross over to Dieppe, it isn't far to Rouen. You'd like to see Rouen?"

"Very much, indeed," I answered. "I always wanted to see Normandy; the home of my ancestors;" and I did feel a little elevated.

"It's very natural, Lotty"—said Fred. "A reasonable, yes, a very reasonable ambition. Well, at Rouen, I have no doubt I can show you my family tree; at the same time, I shouldn't wonder if we could obtain some further authentic intelligence about your pippin."—

"Nothing more likely," said I; for I did want to see France. "Nothing more likely."

"I'm afraid there's no regular packet across"—said Fred—"but we can hire a boat."—

"A boat? Why, my dear, a boat is"—

"Yes; in a nice trim sea-boat we can cross admirably; and, my love," said Fred, moving close and placing his arm about me—"my love, the matter grows upon me. Let us consider it. Here we are about to begin the world. In fact, I think I may say, we have begun it."—

"Mamma always said marriage wasn't beginning, but settling."

"Let us say the beginning of the settling. Well, we are at a very interesting point of our history; and who knows what may depend upon our voyage?"—

"Still, you'll never go in a boat that"—but he put his hand over my mouth, and went on.

"I declare, beloved Lotty, when I look upon ourselves—two young creatures—going forth upon the waters to search for and authenticate our bearings—when I reflect, my darling, that not merely ourselves, but our unborn great grandchildren"—

"Don't be foolish, Fred," said I; but he would.

"That our great grandchildren, at this moment in the dim regions of probability, and in the still dimmer limbo of possibility"—

"Now, what are you talking about?" I asked; but he was in one of his ways, and it was of no use.

"Are, without being awake to the fact, acutely interested in our discovery; why our voyage becomes an adventure of the deepest, and the most delicate interest. Open your fancy's eye, my love, and looking into futurity, just glance at that magnificent young man, your grandson"—

"Now, I tell you what, Fred, don't be foolish; for I shall look at nothing of the sort," and with the words, I shut my eyes as close as shells.

"Or that lovely budding bride, your grand-daughter"—

"No," said I, "nor any grand-daughter, either; there's quite time enough for that."

"Any way, my love, those dearest beings are vitally interested in the matter of our voyage. Therefore, I'll at once go and charter a boat. Would you like it with a deck?"—

"Why, my love, my dearest—as for a boat, I"—and I felt alarmed.

"Columbus found America almost in a punt," said Fred; "then surely we may seek our arms in"—

"But stop," I cried; for he was really going. "After all, love," and I resolutely seated myself on his knee, and held him round the neck—"after all, you have not told me what are your arms? I mean your arms from Joan of Arc."

"Why, you know, my love, that Joan of Arc was a shepherdess?"

"I should hope I knew as much as that," said I.

"Very good. Well, in order to perpetuate the beautiful humility of her first calling, Charles the Seventh magnificently permitted her and all her descendants, to carry in her shield—a lamb's fry!"

"Now, Frederick!"

"Such are my bearings, inherited in a direct line—I say in a direct line—from the Maid of Orleans!"—

"From the Maid of—" and then I saw what a goose he had made of me; and didn't I box his ears, but not to hurt him; and didn't we afterwards agree that the hall-chairs should remain as they were, and that life might be beautiful and bright enough without a touch of herald's paint.

How we did laugh at the family pippin!

A well-founded objection has been raised against the Zoological Gardens; one objection: and that the only one that we can think of. It is complained, with truth, that no proper liquor is provided for the children to drink there. Ginger-beer, soda-water, and lemonade are not fit for children at all times, if they are fit at any, and cherry-brandy is good for nobody; not even for the young ladies who alone drink it; for it neither quenches thirst, nor causes hilarity: which are the sole valid reasons for drinking anything whatever, except physic. It appears that the only juvenile taps in the Gardens are those which supply water to the gardeners. If these afforded the pure element, it would be all very well; but their contents are much more suitable for the nourishment of plants than for the refreshment of little boys and girls. Numerous and interesting as are the varieties of the animal creation contained in these Gardens, the collection does not include that useful individual of the mammalia, the common cow, to produce a drop of milk for the little ones.

Even if children could drink soda-water and cherry-brandy, it would be, for many a father of a family which he takes to the Zoological Gardens for a holiday, much too heavy a disbursement to treat his progeny with soda-waters and cherry-brandies all round. If the Society cannot manage to add an ordinary milch cow to their quadrupeds, they might, at least, establish the cow with an iron tail. They have evinced great solicitude for the comforts of all the specimens of the inferior orders of animals on their grounds; and doubtless, now that their attention has been directed to the subject, they will make the requisite provision for a very pressing want experienced by the young of the genus Homo. With such a fact before them as the Camp at Chobham, they would indeed be inexcusable if they were not immediately to rectify a glaring deficiency in their Commissariat for the Infantry.

The gin-shop keepers and Sabbatarians ought to get up a petition to the Queen, praying Her Majesty to remove Sir William Molesworth from her councils, because the Right Hon. Baronet has directed the Royal Pleasure Grounds at Kew, and the Royal Botanic Gardens also, to be opened on Sundays; which must cause a shocking desecration of Sunday to be committed in the enjoyment of flowers and fresh air, accompanied by an equally awful decrease in the consumption of "Cream of the Valley."

The House of Nesselrode and Co. has issued a Circular Note—which, however, is a very different thing from a Letter of Credit. We don't think they are very likely to get it discounted.

Her Majesty's Drawing Room was remarkable for the carriage of every lady who attended it; and it may be observed that each one came in a special train.[Pg 10]

Mr. Punch observes that his friends the parliamentary reporters did a sensible thing lately. An Irish faction-fight was detaining the House of Commons from its bed at the unseemly hour of three in the morning, and seemed likely to last until six. As the dawn broke, the gentlemen of the gallery, wearied with the gesticulations of Lord Claude Clamourous—for the best Peter Waggey that ever came out of the Lowther Arcade ceases to amuse after a time—wearied with the iterations of Lord Chaos, for a man cannot always have an eminent statesman, or an old friend, to carp at—wearied with what Mr. Gladstone gently called the "freshness" of Mr. Connoodle, fresh as dew from the mountain—the reporters, we say, suddenly shut up their note-books, and retired into their own apartment. The tongues of the Irish orators faltered, they looked up piteously at the long row of empty benches, murmured that it was unreasonable that the reporters should think that eleven hours and a half of talk was as much as the journals for which they work could conscientiously republish, and the profitless squabble was brought to a speedy close. Mr. Punch cordially approves of the remedy, and suggests that on another and a similar occasion it be tried a little earlier.

A few more such showers as we have had lately, and the Camp at Chobham will become a flotilla.

A history of England for young ladies remains yet to be written. The usual ingredients of a reign cannot be interesting to the youthful female mind. Battles, with the number of killed and wounded; party feuds, with the names of the ministers who succeed one another in place; the slow march of public events, and the men who march slowly with them; the eternal round of diplomatic and political relations—which, as they never marry, are the last relations a lady cares for; these, we say, are not exactly the subjects that would engage the sympathies or the attention of a young girl. What romance, what possible interest is there in any one of them? No! we would change all that, and have our English History written in a style popular, easy, and graceful, and alluding only to such subjects as ladies understand, or can best appreciate.

Our proposal, however, will be at once apparent by the nature of the following questions, which we have extracted from a History supposed to be written according to our sensible plan;—

What do you mean by the "Crush-Room of the Opera;" and why is it so called?

When did gigot sleeves go out of fashion, and did such sleeves have anything to do with the popular French phrase of "Revenons à nos Moutons?"

What do you mean by "Crochet Work"? and can you set the pattern for ladies of "How to make a purse for your brother?"

Who edited the "Book of Beauty?" and mention a few of the aristocratic names whose portraits have had the honour of appearing in its splendid pages.

Can you describe the habits and haunts of the "Swedish Nightingale?" and can you mention the highest note it ever reached, and also why it sang in a Haymarket?

State the name of the "Bohemian nobleman" who first brought over the Polka to England.

In what year of Victoria's reign was the celebrated Bal Costumé given at Buckingham Palace? and describe the dress that Her Majesty wore on that interesting occasion.

Give the names of the principal singers who distinguished themselves at the two Italian Operas during the rival administrations of Gye and Lumley, and describe the nature of the feud that existed between those two great men.

Give a description of "Pop Goes the Weasel," and state all you know about the "Weasel," and what was the origin of his going "Pop."

Who succeeded Wigan in the Corsican Brothers?

Mention the names of the principal watering-places, and say which was considered the more fashionable of the two—Margate, or Gravesend?

When did flounces come into fashion, and state the lowest and the highest number a lady could wear?

Describe the position of Chiswick—and give a short account of its Gardens, and the Fêtes that were held there every year.

What were the duties of the Ladies of the Bedchamber, and in what respects did they differ from the Maids of Honour at Richmond?

Mention the names of the most delicious novels that were published between the years 1840 and 1853, and name the character and scene that pleased you the most.

Whose gloves do you consider were the best?

What was the last elopement that created any sensation at Gretna Green?

State who was Jullien? also, whether he had anything to do with the soup that bears his celebrated name?

A lady living at Peckham Rise has nearly ruined her husband by the enormous prices she has been giving for Cochin-China fowls. The poor fellow is always pointed at in the neighbourhood, so the story goes, as "the Cochin-China-pecked husband."

A gentleman at a party, where table-turning was the principal amusement of the evening, upon hearing that the power of turning mainly depended upon the will, instantly recommended his wife, as he "begged to assure the company she had a very strong one, and he had never known anything able to resist it."

It is pleasant to find that the Commissioners of Sewers are stirring; notwithstanding the result proverbially ascribed to stirring in such matters: and we hope we shall soon be enabled to expect that the Metropolis will be drained with some degree of rational assewerance. If this great object is successfully accomplished, we take the liberty of recommending that the Chairman of the Commission should be raised to the Peerage, by the title of Lord Scavenger.

Test of Good Humour.—Wake a man up in the middle of the night, and ask him to lend you five shillings.

We were wet as the deuce; for like blazes it poured,

And the sentinels' throats were the only things dry;

And under their tents Chobham's heroes had cowered,

The weary to snore, and the wakeful to sigh.

While dozing that night in my camp-bed so small,

With a Mackintosh over to keep out the rain—

After one glass of grog, cold without—that was all—

I'd a dream, which I hope I shall ne'er have again.

Methought from damp Chobham's mock battle-array,

I had bowled off to London, outside of a hack;

'Twas the season, and wax-lights illumined the way

To the balls of Belgravia that welcomed me back.

I flew to the dancing-rooms, whirled through so oft

With one sweet little partner, who tendril-like clung,

I saw the grim chaperons, perched up aloft,

And heard the shrill notes Weippert's orchestra flung.

She was there—I would "pop"—and a guardsman no more,

From my sweet little partner for life ne'er would part,

When sudden I saw—just conceive what a bore—

A civilian—by Jove—laying siege to her heart!

"Out of sight, out of mind!" It was not to be borne—

To cut her, challenge him I was rushing away—

When sudden the twang of that vile bugle-horn

Scared my visions, arousing the Camp for the day.

It seems that Dr. Paul Cullen and the Ultramontanists have procured the rejection, from the Irish National Schools, of the Archbishop of Dublin's Evidences of Christianity. Hence it may be presumed that the "Evidences" of Archbishop Whately are favourable specimens of Whately's logic, and afford some really sensible and satisfactory reason for believing in the Christian religion.

FRIDAY, MAY 24, 18—.

I am not superstitious—certainly not: but when I woke this morning, I felt as if something would happen; though I said nothing to Fred. With the feeling that came upon me, I wouldn't have thought of going to France for worlds. I felt as if a war must break out, or something.

"I knew it; I was certain of it," said I, when I'd half read the letter from home.

"In that case," said Fred, in the most unconcerned way, which he will call philosophy, whereas I think it downright imprudence—but I fear dear Mamma's right; all men are imprudent—"In that case, we might have saved postage."

"Now Fred, don't be frivolous. But I see, there'll be nothing right at home till we get fairly back. Everything will be sacrificed."—

"Is that your serious belief, my love?" said Fred, finishing his tea; and I nodded very decidedly.—"Well, then, suppose we pack up our traps and return to-day. And talking of home, you can't think, Lotty, what a present you've made me without knowing it."

"Have I indeed? What present, love?"—

"It was in my sleep; but then, it was one of those dreams that always forerun the reality. Do you know I dreamt that we'd returned home, and somehow when I tried to sit down in my chair, up I jumped again; and so again and again. Whenever I tried to be quiet and stretch my legs out at my fireside, I seemed possessed with a legion of imps that would lift me from my seat and pull me towards the door."—

"Hm! That's a very ugly dream, Fred," said I; and I know I looked thoughtful.

"Very: but it's wonderful how, like a tranquillizing spirit, you appeared upon the scene. I thought, my dear, you looked more beautiful than is possible."—

"Frederick!"—

"Not but what I'm quite content as it is. You know, my love, it might have been worse."—

"Well," said I, "Mamma needn't have written to me that my honeymoon was nearly ended. It seems I'm not likely to forget that."

"And when it was impossible for me to remain in the chair—when I continued to get up and sit down, and run here and run there—- then, as I say, you appeared like a benevolent fairy—bearing across one arm what seemed to me a rainbow turned to silk; and in the other hand carrying a pair of slippers."

"Well; and then?"—

"And then, with a thought, I had put on the morning-gown;—for it was that you carried—and placed my feet in the slippers. There never were more beautiful presents; never richer gifts for a wife to make her husband. For would you think it, Lotty? No sooner had I wrapped the dressing-gown about me, than I became settled in the sweetest repose in my chair: and the very walls of the room seemed to make the softest music. And then the slippers! Most wonderful! Would you believe it, Lotty—wherever the slippers touched, a flower sprang up; flowers and aromatic herbs! The very hearth seemed glowing and odorous with roses and thyme. But then, you know, it was only a dream, Lotty. There's no such dressing-gown—and in this world no such slippers;" and then—I could see it—he looked in his odd way at me.

"I suppose not, Fred," said I; for I wouldn't seem to understand him. "And then, if such slippers could be found, where's the husband's feet to fit 'em? 'T would be another story of the glass slipper."

"Who knows when we get home? But what's happened?" and he pointed to the letter.

"Well, then, the pigeon-house has blown down; and Rajah's flown away; and a strange cat has killed the gold-fish; and, in fact, Fred—as dear Mamma writes to me; not, as she says, she'd have me worry myself about the matter—in fact the house wants a mistress."

"I have no doubt your excellent mother is right," said Fred; "and as you won't go to France, suppose we make way for The Flitch. Do you know, Lotty, I'm curious to know if—after all—those slippers mayn't be found there."

"I'll take care of that," said I; "but you know, Fred, we can't go back yet."

"Why not?"—

"Why, you know our honeymoon isn't quite out; and"—

"And what of that? We needn't burn all the moon from home. What if we put the last fragment on a save-all, and see it out at The Flitch?"[Pg 12]

"It isn't to be done, Fred," said I; for I knew how people would talk. "Of course, 'twould be said we were tired of our own society, and so got home for company."

"Nevertheless," said Fred; "you take the flight of Rajah, that dear bird, with wondrous serenity."

And it then struck me that I did not feel so annoyed as I ought. "Ha, Fred," said I, "you don't know what my feelings may be; don't misjudge me because I don't talk. I can assure you, I am very much disturbed;" and I was vexed.

"Perhaps, then"—said Fred—"you'll take a little walk towards the Steyne; and recover yourself? I've some letters to write, my love: and—'twill do you good—I'll join you."

"Certainly"—said I—"of course; if you wish it," and then I wondered why he should wish to get rid of me. It never happened before. Yes—and the thought came again very forcibly upon me—it's plain the honeymoon's nearly out; and then I left the room; and as I left it, didn't I nearly bang the door?

"Why should he wish to get rid of me?" I seemed quite bewildered with this question. Everything seemed to ask it. He could have written his letters without my leaving the house. However, I felt glad that I contained myself; and especially glad that I didn't bang the door.

Well, I ran and put on my bonnet; and then just peeping in at the door to Fred, said, "I'm going;" and in another minute was taking my way towards the Steyne. It was such a beautiful day; the sky so light; and the air so fresh and sweet, that—yes, in a little minute, my bit of temper had all passed away—and I did well scold myself that, for a moment, I had entertained it. I walked down upon the beach. Scarcely a soul was there: and I fell into a sort of dreamy meditation—thinking about that morning-gown and those slippers. "I'll get 'em for Fred, that I will;" I resolved within myself. "Roses shall grow at the fireside; and repose shall be in his arm-chair. That I'm determined:" and as I resolved this with myself, everything about me seemed to grow brighter and more beautiful. And then I wished that we were well at home, and the slippers had, for once and all, been tried and fitted. The gulls flying about reminded me of Rajah: and I did wonder at myself that I could think of his loss—that would have nigh killed me at one time—so calmly. But then, as Mamma said, and as I've since discovered,—it's wonderful what other trifles marriage makes one forget.

There was nobody upon the beach: so I sat down, and began a day-dreaming. How happy we should be at home, and how softly and sweetly all things would go with us! And still, as the waves ran and burst in foam upon the beach, I thought of the slippers.

I hardly knew how long I'd been there, when a little gypsey girl stood at my side, offering a nosegay. I looked and—yes, it was one of the gypsies, at whose tent Fred and I took shelter in the thunderstorm. However, before I could say a word, the little creature dropt the nosegay in my lap; and laughing, ran away.

Such a beautiful bouquet! Had it been a thing of wild or even of common garden flowers—but it was a bouquet of exotics—and how were gypsies to come by such things? Then something whispered to me—"stole them."

I didn't like to throw the thing away; and as I remained meditating, Fred came up. "Pretty flowers, Lotty," said he.

"Yes: selected with taste—great taste, an't they?" said I; and I cannot think what whim it was possessed me to go off in such praise of the bouquet.

"Pretty well," said Fred.

"Pretty well! my dear Fred; if you'll only look and attend, you'll own that the person who composed this bouquet must have known all the true effect of colours."

"Indeed," said Fred; as I thought very oddly; so I went on.

"Every colour harmonizes; the light, you see, falling exactly in the right place; and yet everything arranged so naturally—so harmoniously. The white is precisely where it should be, and"—

"Is it truly?" and saying this, Fred twitched from among the flowers a note that like a mortal snake as I thought it lay there.

"Why, it's a letter!" I cried.

"It looks like it," said Fred.

"It was brought by a gypsey," said I; and I felt my face burning, and could have cried. "It's a mistake."

"Of course," said Fred: "what else, my love? Of course, a mistake."

And then he gave me his arm, and we returned towards the Inn. Fred laughed and talked; but somehow I felt so vexed: yes, I could have cried; and still Fred was so cool—so very cool.