The Project Gutenberg EBook of Diplomatic Immunity, by Robert Sheckley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Diplomatic Immunity Author: Robert Sheckley Illustrator: Ashman Release Date: April 18, 2010 [EBook #32040] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction August 1953. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

diplomatic immunity

By ROBERT SHECKLEY

Illustrated by ASHMAN

He said he wasn't immortal—but nothing could kill him. Still, if the Earth was to live as a free world, he had to die.

ome right in, gentlemen," the Ambassador waved them into the very special suite the State Department had given him. "Please be seated."

Colonel Cercy accepted a chair, trying to size up the individual who had all Washington chewing its fingernails. The Ambassador hardly looked like a menace. He was of medium height and slight build, dressed in a conservative brown tweed suit that the State Department had given him. His face was intelligent, finely molded and aloof.

As human as a human, Cercy thought, studying the alien with bleak, impersonal eyes.

"How may I serve you?" the Ambassador asked, smiling.

"The President has put me in charge of your case," Cercy said. "I've studied Professor Darrig's reports—" he nodded at the scientist beside him—"but I'd like to hear the whole thing for myself."

"Of course," the alien said, lighting a cigarette. He seemed genuinely pleased to be asked; which was interesting, Cercy thought. In the week since he had landed, every important scientist in the country had been at him.

But in a pinch they call the Army, Cercy reminded himself. He settled back in his chair, both hands jammed carelessly in his pockets. His right hand was resting on the butt of a .45, the safety off.

have come," the alien said, "as an ambassador-at-large, representing an empire that stretches half-way across the Galaxy. I wish to extend the welcome of my people and to invite you to join our organization."

"I see," Cercy replied. "Some of the scientists got the impression that participation was compulsory."

"You will join," the Ambassador said, blowing smoke through his nostrils.

Cercy could see Darrig stiffen in his chair and bite his lip. Cercy moved the automatic to a position where he could draw it easily. "How did you find us?" he asked.

"We ambassadors-at-large are each assigned an unexplored section of space," the alien said. "We examine each star-system in that region for planets, and each planet for intelligent life. Intelligent life is rare in the Galaxy, you know."

Cercy nodded, although he hadn't been aware of the fact.

"When we find such a planet, we land, as I did, and prepare the inhabitants for their part in our organization."

"How will your people know that you have found intelligent life?" Cercy asked.

"There is a sending mechanism that is part of our structure," the Ambassador answered. "It is triggered when we reach an inhabited planet. This signal is beamed continually into space, to an effective range of several thousand light-years. Follow-up crews are continually sweeping through the limits of the reception area of each Ambassador, listening for such messages. Detecting one, a colonizing team follows it to the planet."

He tapped his cigarette delicately on the edge of an ash tray. "This method has definite advantages over sending combined colonization and exploration teams obviously. It avoids the necessity of equipping large forces for what may be decades of searching."

"Sure." Cercy's face was expressionless. "Would you tell me more about this message?"

"There isn't much more you need know. The beam is not detectable by your methods and, therefore, cannot be jammed. The message continues as long as I am alive."

arrig drew in his breath sharply, glancing at Cercy.

"If you stopped broadcasting," Cercy said casually, "our planet would never be found."

"Not until this section of space was resurveyed," the diplomat agreed.

"Very well. As a duly appointed representative of the President of the United States, I ask you to stop transmitting. We don't choose to become part of your empire."

"I'm sorry," the Ambassador said. He shrugged his shoulders easily. Cercy wondered how many times he had played this scene on how many other planets.

"There's really nothing I can do." He stood up.

"Then you won't stop?"

"I can't. I have no control over the sending, once it's activated." The diplomat turned and walked to the window. "However, I have prepared a philosophy for you. It is my duty, as your Ambassador, to ease the shock of transition as much as possible. This philosophy will make it instantly apparent that—"

As the Ambassador reached the window, Cercy's gun was out of his pocket and roaring. He squeezed six rounds in almost a single explosion, aiming at the Ambassador's head and back. Then an uncontrollable shudder ran through him.

The Ambassador was no longer there!

ercy and Darrig stared at each other. Darrig muttered something about ghosts. Then, just as suddenly, the Ambassador was back.

"You didn't think," he said, "that it would be as easy as all that, did you? We Ambassadors have, necessarily, a certain diplomatic immunity." He fingered one of the bullet holes in the wall. "In case you don't understand, let me put it this way. It is not in your power to kill me. You couldn't even understand the nature of my defense."

He looked at them, and in that moment Cercy felt the Ambassador's complete alienness.

"Good day, gentlemen," he said.

Darrig and Cercy walked silently back to the control room. Neither had really expected that the Ambassador would be killed so easily, but it had still been a shock when the slugs had failed.

"I suppose you saw it all, Malley?" Cercy asked, when he reached the control room.

The thin, balding psychiatrist nodded sadly. "Got it on film, too."

"I wonder what his philosophy is," Darrig mused, half to himself.

"It was illogical to expect it would work. No race would send an ambassador with a message like that and expect him to live through it. Unless—"

"Unless what?"

"Unless he had a pretty effective defense," the psychiatrist finished unhappily.

Cercy walked across the room and looked at the video panel. The Ambassador's suite was very special. It had been hurriedly constructed two days after he had landed and delivered his message. The suite was steel and lead lined, filled with video and movie cameras, recorders, and a variety of other things.

It was the last word in elaborate death cells.

In the screen, Cercy could see the Ambassador sitting at a table. He was typing on a little portable the Government had given him.

"Hey, Harrison!" Cercy called. "Might as well go ahead with Plan Two."

Harrison came out of a side room where he had been examining the circuits leading to the Ambassador's suite. Methodically he checked his pressure gauges, set the controls and looked at Cercy. "Now?" he asked.

"Now." Cercy watched the screen. The Ambassador was still typing.

Suddenly, as Harrison sent home the switch, the room was engulfed in flames. Fire blasted out of concealed holes in the walls, poured from the ceiling and floor.

In a moment, the room was like the inside of a blast furnace.

Cercy let it burn for two minutes, then motioned Harrison to cut the switch. They stared at the roasted room.

They were looking, hopefully, for a charred corpse.

But the Ambassador reappeared beside his desk, looking ruefully at the charred typewriter. He was completely unsinged.

"Could you get me another typewriter?" he asked, looking directly at one of the hidden projectors. "I'm setting down a philosophy for you ungrateful wretches."

He seated himself in the wreckage of an armchair. In a moment, he was apparently asleep.

ll right, everyone grab a seat," Cercy said. "Time for a council of war."

Malley straddled a chair backward. Harrison lighted a pipe as he sat down, slowly puffing it into life.

"Now, then," Cercy said. "The Government has dropped this squarely in our laps. We have to kill the Ambassador—obviously. I've been put in charge." Cercy grinned with regret. "Probably because no one higher up wants the responsibility of failure. And I've selected you three as my staff. We can have anything we want, any assistance or advice we need. All right. Any ideas?"

"How about Plan Three?" Harrison asked.

"We'll get to that," Cercy said. "But I don't believe it's going to work."

"I don't either," Darrig agreed. "We don't even know the nature of his defense."

"That's the first order of business. Malley, take all our data so far, and get someone to feed it into the Derichman Analyzer. You know the stuff we want. What properties has X, if X can do thus and thus?"

"Right," Malley said. He left, muttering something about the ascendancy of the physical sciences.

"Harrison," Cercy asked, "is Plan Three set up?"

"Sure."

"Give it a try."

While Harrison was making his last adjustments, Cercy watched Darrig. The plump little physicist was staring thoughtfully into space, muttering to himself. Cercy hoped he would come up with something. He was expecting great things of Darrig.

Knowing the impossibility of working with great numbers of people, Cercy had picked his staff with care. Quality was what he wanted.

With that in mind, he had chosen Harrison first. The stocky, sour-faced engineer had a reputation for being able to build anything, given half an idea of how it worked.

Cercy had selected Malley, the psychiatrist, because he wasn't sure that killing the Ambassador was going to be a purely physical problem.

Darrig was a mathematical physicist, but his restless, curious mind had come up with some interesting theories in other fields. He was the only one of the four who was really interested in the Ambassador as an intellectual problem.

"He's like Metal Old Man," Darrig said finally.

"What's that?"

"Haven't you ever heard the story of Metal Old Man? Well, he was a monster covered with black metal armor. He was met by Monster-Slayer, an Apache culture hero. Monster-Slayer, after many attempts, finally killed Metal Old Man."

"How did he do it?"

"Shot him in the armpit. He didn't have any armor there."

"Fine," Cercy grinned. "Ask our Ambassador to raise his arm."

"All set!" Harrison called.

"Fine. Go."

In the Ambassador's room, an invisible spray of gamma rays silently began to flood the room with deadly radiation.

But there was no Ambassador to receive them.

"That's enough," Cercy said, after a while. "That would kill a herd of elephants."

But the Ambassador stayed invisible for five hours, until some of the radioactivity had abated. Then he appeared again.

"I'm still waiting for that typewriter," he said.

ere's the Analyzer's report." Malley handed Cercy a sheaf of papers. "This is the final formulation, boiled down."

Cercy read it aloud: "The simplest defense against any and all weapons, is to become each particular weapon."

"Great," Harrison said. "What does it mean?"

"It means," Darrig explained, "that when we attack the Ambassador with fire, he turns into fire. Shoot at him, and he turns into a bullet—until the menace is gone, and then he changes back again." He took the papers out of Cercy's hand and riffled through them.

"Hmm. Wonder if there's any historical parallel? Don't suppose so." He raised his head. "Although this isn't conclusive, it seems logical enough. Any other defense would involve recognition of the weapon first, then an appraisal, then a countermove predicated on the potentialities of the weapon. The Ambassador's defense would be a lot faster and safer. He wouldn't have to recognize the weapon. I suppose his body simply identifies, in some way, with the menace at hand."

"Did the Analyzer say there was any way of breaking this defense?" Cercy asked.

"The Analyzer stated definitely that there was no way, if the premise were true," Malley answered gloomily.

"We can discard that judgment," Darrig said. "The machine is limited."

"But we still haven't got any way of stopping him," Malley pointed out. "And he's still broadcasting that beam."

Cercy thought for a moment. "Call in every expert you can find. We're going to throw the book at the Ambassador. I know," he said, looking at Darrig's dubious expression, "but we have to try."

uring the next few days, every combination and permutation of death was thrown at the Ambassador. He was showered with weapons, ranging from Stone-Age axes to modern high-powered rifles, peppered with hand grenades, drowned in acid, suffocated in poison gas.

He kept shrugging his shoulders philosophically, and continued to work on the new typewriter they had given him.

Bacteria was piped in, first the known germ diseases, then mutated species.

The diplomat didn't even sneeze.

He was showered with electricity, radiation, wooden weapons, iron weapons, copper weapons, brass weapons, uranium weapons—anything and everything, just to cover all possibilities.

He didn't suffer a scratch, but his room looked as though a bar-room brawl had been going on in it continually for fifty years.

Malley was working on an idea of his own, as was Darrig. The physicist interrupted himself long enough to remind Cercy of the Baldur myth. Baldur had been showered with every kind of weapon and remained unscathed, because everything on Earth had promised to love him. Everything, except the mistletoe. When a little twig of it was shot at him, he died.

Cercy turned away impatiently, but had an order of mistletoe sent up, just in case.

It was, at least, no less effective than the explosive shells or the bow and arrow. It did nothing except lend an oddly festive air to the battered room.

After a week of this, they moved the unprotesting Ambassador into a newer, bigger, stronger death cell. They were unable to venture into his old one because of the radioactivity and micro-organisms.

The Ambassador went back to work at his typewriter. All his previous attempts had been burned, torn or eaten away.

"Let's go talk to him," Darrig suggested, after another day had passed. Cercy agreed. For the moment, they were out of ideas.

ome right in, gentlemen," the Ambassador said, so cheerfully that Cercy felt sick. "I'm sorry I can't offer you anything. Through an oversight, I haven't been given any food or water for about ten days. Not that it matters, of course."

"Glad to hear it," Cercy said. The Ambassador hardly looked as if he had been facing all the violence Earth had to offer. On the contrary, Cercy and his men looked as though they had been under bombardment.

"You've got quite a defense there," Malley said conversationally.

"Glad you like it."

"Would you mind telling us how it works?" Darrig asked innocently.

"Don't you know?"

"We think so. You become what is attacking you. Is that right?"

"Certainly," the Ambassador said. "You see, I have no secrets from you."

"Is there anything we can give you," Cercy asked, "to get you to turn off that signal?"

"A bribe?"

"Sure," Cercy said. "Anything you—?"

"Nothing," the Ambassador replied.

"Look, be reasonable," Harrison said. "You don't want to cause a war, do you? Earth is united now. We're arming—"

"With what?"

"Atom bombs," Malley answered him. "Hydrogen bombs. We're—"

"Drop one on me," the Ambassador said. "It wouldn't kill me. What makes you think it will have any effect on my people?"

he four men were silent. Somehow, they hadn't thought of that.

"A people's ability to make war," the Ambassador stated, "is a measure of the status of their civilization. Stage one is the use of simple physical extensions. Stage two is control at the molecular level. You are on the threshold of stage three, although still far from mastery of atomic and subatomic forces." He smiled ingratiatingly. "My people are reaching the limits of stage five."

"What would that be?" Darrig asked.

"You'll find out," the Ambassador said. "But perhaps you've wondered if my powers are typical? I don't mind telling you that they're not. In order for me to do my job and nothing more, I have certain built-in restrictions, making me capable only of passive action."

"Why?" Darrig asked.

"For obvious reasons. If I were to take positive action in a moment of anger, I might destroy your entire planet."

"Do you expect us to believe that?" Cercy asked.

"Why not? Is it so hard to understand? Can't you believe that there are forces you know nothing about? And there is another reason for my passiveness. Certainly by this time you've deduced it?"

"To break our spirit, I suppose," Cercy said.

"Exactly. My telling you won't make any difference, either. The pattern is always the same. An Ambassador lands and delivers his message to a high-spirited, wild young race like yours. There is frenzied resistance against him, spasmodic attempts to kill him. After all these fail, the people are usually quite crestfallen. When the colonization team arrives, their indoctrination goes along just that much faster." He paused, then said, "Most planets are more interested in the philosophy I have to offer. I assure you, it will make the transition far easier."

He held out a sheaf of typewritten pages. "Won't you at least look through it?"

Darrig accepted the papers and put them in his pocket. "When I get time."

"I suggest you give it a try," the Ambassador said. "You must be near the crisis point now. Why not give it up?"

"Not yet," Cercy replied tonelessly.

"Don't forget to read the philosophy," the Ambassador urged them.

The men hurried from the room.

ow look," Malley said, once they were back in the control room, "there are a few things we haven't tried. How about utilizing psychology?"

"Anything you like," Cercy agreed, "including black magic. What did you have in mind?"

"The way I see it," Malley answered, "the Ambassador is geared to respond, instantaneously, to any threat. He must have an all-or-nothing defensive reflex. I suggest first that we try something that won't trigger that reflex."

"Like what?" Cercy asked.

"Hypnotism. Perhaps we can find out something."

"Sure," Cercy said. "Try it. Try anything."

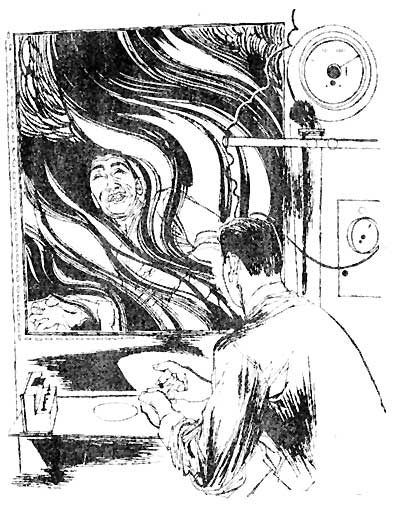

Cercy, Malley and Darrig gathered around the video screen as an infinitesimal amount of a light hypnotic gas was admitted into the Ambassador's room. At the same time, a bolt of electricity lashed into the chair where the Ambassador was sitting.

"That was to distract him," Malley explained. The Ambassador vanished before the electricity struck him, and then appeared again, curled up in his armchair.

"That's enough," Malley whispered, and shut the valve. They watched. After a while, the Ambassador put down his book and stared into the distance.

"How strange," he said. "Alfern dead. Good friend ... just a freak accident. He ran into it, out there. Didn't have a chance. But it doesn't happen often."

"He's thinking out loud," Malley whispered, although there was no possibility of the Ambassador's hearing them. "Vocalizing his thoughts. His friend must have been on his mind for some time."

"Of course," the Ambassador went on, "Alfern had to die sometime. No immortality—yet. But that way—no defense. Out there in space they just pop up. Always there, underneath, just waiting for a chance to boil out."

"His body isn't reacting to the hypnotic as a menace yet," Cercy whispered.

"Well," the Ambassador told himself, "the regularizing principle has been doing pretty well, keeping it all down, smoothing out the inconsistencies—"

Suddenly he leaped to his feet, his face pale for a moment, as he obviously tried to remember what he had said. Then he laughed.

"Clever. That's the first time that particular trick has been played on me, and the last time. But, gentlemen, it didn't do you any good. I don't know, myself, how to go about killing me." He laughed at the blank walls.

"Besides," he continued, "the colonizing team must have the direction now. They'll find you with or without me."

He sat down again, smiling.

hat does it!" Darrig cried. "He's not invulnerable. Something killed his friend Alfern."

"Something out in space," Cercy reminded him. "I wonder what it was."

"Let me see," Darrig reflected aloud. "The regularizing principle. That must be a natural law we knew nothing about. And underneath—what would be underneath?"

"He said the colonization team would find us anyhow," Malley reminded them.

"First things first," Cercy said. "He might have been bluffing us ... no, I don't suppose so. We still have to get the Ambassador out of the way."

"I think I know what is underneath!" Darrig exclaimed. "This is wonderful. A new cosmology, perhaps."

"What is it?" Cercy asked. "Anything we can use?"

"I think so. But let me work it out. I think I'll go back to my hotel. I have some books there I want to check, and I don't want to be disturbed for a few hours."

"All right," Cercy agreed. "But what—?"

"No, no, I could be wrong," Darrig said. "Let me work it out." He hurried from the room.

"What do you think he's driving at?" Malley asked.

"Beats me," Cercy shrugged. "Come on, let's try some more of that psychological stuff."

First they filled the Ambassador's room with several feet of water. Not enough to drown him, just enough to make him good and uncomfortable.

To this, they added the lights. For eight hours, lights flashed in the Ambassador's room. Bright lights to pry under his eyelids; dull, clashing ones to disturb him.

Sound came next—screeches and screams and shrill, grating noises. The sound of a man's fingernails being dragged across slate, amplified a thousand times, and strange, sucking noises, and shouts and whispers.

Then, the smells. Then, everything else they could think of that could drive a man insane.

The Ambassador slept peacefully through it all.

ow look," Cercy said, the following day, "let's start using our damned heads." His voice was hoarse and rough. Although the psychological torture hadn't bothered the Ambassador, it seemed to have backfired on Cercy and his men.

"Where in hell is Darrig?"

"Still working on that idea of his," Malley said, rubbing his stubbled chin. "Says he's just about got it."

"We'll work on the assumption that he can't produce," Cercy said. "Start thinking. For example, if the Ambassador can turn into anything, what is there he can't turn into?"

"Good question," Harrison grunted.

"It's the payoff question," Cercy said. "No use throwing a spear at a man who can turn into one."

"How about this?" Malley asked. "Taking it for granted he can turn into anything, how about putting him in a situation where he'll be attacked even after he alters?"

"I'm listening," Cercy said.

"Say he's in danger. He turns into the thing threatening him. What if that thing were itself being threatened? And, in turn, was in the act of threatening something else? What would he do then?"

"How are you going to put that into action?" Cercy asked.

"Like this." Malley picked up the telephone. "Hello? Give me the Washington Zoo. This is urgent."

The Ambassador turned as the door opened. An unwilling, angry, hungry tiger was propelled in. The door slammed shut.

The tiger looked at the Ambassador. The Ambassador looked at the tiger.

"Most ingenious," the Ambassador said.

At the sound of his voice, the tiger came unglued. He sprang like a steel spring uncoiling, landing on the floor where the Ambassador had been.

The door opened again. Another tiger was pushed in. He snarled angrily and leaped at the first. They smashed together in midair.

The Ambassador appeared a few feet off, watching. He moved back when a lion entered the door, head up and alert. The lion sprang at him, almost going over on his head when he struck nothing. Not finding any human, the lion leaped on one of the tigers.

The Ambassador reappeared in his chair, where he sat smoking and watching the beasts kill each other.

In ten minutes the room looked like an abattoir.

But by then the Ambassador had tired of the spectacle, and was reclining on his bed, reading.

give up," Malley said. "That was my last bright idea."

Cercy stared at the floor, not answering. Harrison was seated in the corner, getting quietly drunk.

The telephone rang.

"Yeah?" Cercy said.

"I've got it!" Darrig's voice shouted over the line. "I really think this is it. Look, I'm taking a cab right down. Tell Harrison to find some helpers."

"What is it?" Cercy asked.

"The chaos underneath!" Darrig replied, and hung up.

They paced the floor, waiting for him to show up. Half an hour passed, then an hour. Finally, three hours after he had called, Darrig strolled in.

"Hello," he said casually.

"Hello, hell!" Cercy growled. "What kept you?"

"On the way over," Darrig said, "I read the Ambassador's philosophy. It's quite a work."

"Is that what took you so long?"

"Yes. I had the driver take me around the park a few times, while I was reading it."

"Skip it. How about—"

"I can't skip it," Darrig said, in a strange, tight voice. "I'm afraid we were wrong. About the aliens, I mean. It's perfectly right and proper that they should rule us. As a matter of fact, I wish they'd hurry up and get here."

But Darrig didn't look certain. His voice shook and perspiration poured from his face. He twisted his hands together, as though in agony.

"It's hard to explain," he said. "Everything became clear as soon as I started reading it. I saw how stupid we were, trying to be independent in this interdependent Universe. I saw—oh, look, Cercy. Let's stop all this foolishness and accept the Ambassador as our friend."

"Calm down!" Cercy shouted at the perfectly calm physicist. "You don't know what you're saying."

"It's strange," Darrig said. "I know how I felt—I just don't feel that way any more. I think. Anyhow, I know your trouble. You haven't read the philosophy. You'll see what I mean, once you've read it." He handed Cercy the pile of papers. Cercy promptly ignited them with his cigarette lighter.

"It doesn't matter," Darrig said. "I've got it memorized. Just listen. Axiom one. All peoples—"

Cercy hit him, a short, clean blow, and Darrig slumped to the floor.

"Those words must be semantically keyed," Malley said. "They're designed to set off certain reactions in us, I suppose. All the Ambassador does is alter the philosophy to suit the peoples he's dealing with."

"Look, Malley," Cercy said. "This is your job now. Darrig knows, or thought he knew, the answer. You have to get that out of him."

"That won't be easy," Malley said. "He'd feel that he was betraying everything he believes in, if he were to tell us."

"I don't care how you get it," Cercy said. "Just get it."

"Even if it kills him?" Malley asked.

"Even if it kills you."

"Help me get him to my lab," Malley said.

hat night Cercy and Harrison kept watch on the Ambassador from the control room. Cercy found his thoughts were racing in circles.

What had killed Alfern in space? Could it be duplicated on Earth? What was the regularizing principle? What was the chaos underneath?

What in hell am I doing here? he asked himself. But he couldn't start that sort of thing.

"What do you figure the Ambassador is?" he asked Harrison. "Is he a man?"

"Looks like one," Harrison said drowsily.

"But he doesn't act like one. I wonder if this is his true shape?"

Harrison shook his head, and lighted his pipe.

"What is there of him?" Cercy asked. "He looks like a man, but he can change into anything else. You can't attack him; he adapts. He's like water, taking the shape of any vessel he's poured into."

"You can boil water," Harrison yawned.

"Sure. Water hasn't any shape, has it? Or has it? What's basic?"

With an effort, Harrison tried to focus on Cercy's words. "Molecular pattern? The matrix?"

"Matrix," Cercy repeated, yawning himself. "Pattern. Must be something like that. A pattern is abstract, isn't it?"

"Sure. A pattern can be impressed on anything. What did I say?"

"Let's see," Cercy said. "Pattern. Matrix. Everything about the Ambassador is capable of change. There must be some unifying force that retains his personality. Something that doesn't change, no matter what contortions he goes through."

"Like a piece of string," Harrison murmured with his eyes closed.

"Sure. Tie it in knots, weave a rope out of it, wind it around your finger; it's still string."

"Yeah."

"But how do you attack a pattern?" Cercy asked. And why couldn't he get some sleep? To hell with the Ambassador and his hordes of colonists, he was going to close his eyes for a moment....

ake up, Colonel!"

Cercy pried his eyes open and looked up at Malley. Besides him, Harrison was snoring deeply. "Did you get anything?"

"Not a thing," Malley confessed. "The philosophy must've had quite an effect on him. But it didn't work all the way. Darrig knew that he had wanted to kill the Ambassador, and for good and sufficient reasons. Although he felt differently now, he still had the feeling that he was betraying us. On the one hand, he couldn't hurt the Ambassador; on the other, he wouldn't hurt us."

"Won't he tell anything?"

"I'm afraid it's not that simple," Malley said. "You know, if you have an insurmountable obstacle that must be surmounted ... and also, I think the philosophy had an injurious effect on his mind."

"What are you trying to say?" Cercy got to his feet.

"I'm sorry," Malley apologized, "there wasn't a damned thing I could do. Darrig fought the whole thing out in his mind, and when he couldn't fight any longer, he—retreated. I'm afraid he's hopelessly insane."

"Let's see him."

They walked down the corridor to Malley's laboratory. Darrig was relaxed on a couch, his eyes glazed and staring.

"Is there any way of curing him?" Cercy asked.

"Shock therapy, maybe." Malley was dubious. "It'll take a long time. And he'll probably block out everything that had to do with producing this."

Cercy turned away, feeling sick. Even if Darrig could be cured, it would be too late. The aliens must have picked up the Ambassador's message by now and were undoubtedly heading for Earth.

"What's this?" Cercy asked, picking up a piece of paper that lay by Darrig's hand.

"Oh, he was doodling," Malley said. "Is there anything written on it?"

Cercy read aloud: "'Upon further consideration I can see that Chaos and the Gorgon Medusa are closely related.'"

"What does that mean?" Malley asked.

"I don't know," Cercy puzzled. "He was always interested in folklore."

"Sounds schizophrenic," the psychiatrist said.

Cercy read it again. "'Upon further consideration, I can see that Chaos and the Gorgon Medusa are closely related.'" He stared at it. "Isn't it possible," he asked Malley, "that he was trying to give us a clue? Trying to trick himself into giving and not giving at the same time?"

"It's possible," Malley agreed. "An unsuccessful compromise—But what could it mean?"

"Chaos." Cercy remembered Darrig's mentioning that word in his telephone call. "That was the original state of the Universe in Greek myth, wasn't it? The formlessness out of which everything came?"

"Something like that," Malley said. "And Medusa was one of those three sisters with the horrible faces."

Cercy stood for a moment, staring at the paper. Chaos ... Medusa ... and the organizing principle! Of course!

"I think—" He turned and ran from the room. Malley looked at him; then loaded a hypodermic and followed.

n the control room, Cercy shouted Harrison into consciousness.

"Listen," he said, "I want you to build something, quick. Do you hear me?"

"Sure." Harrison blinked and sat up. "What's the rush?"

"I know what Darrig wanted to tell us," Cercy said. "Come on, I'll tell you what I want. And Malley, put down that hypodermic. I haven't cracked. I want you to get me a book on Greek mythology. And hurry it up."

Finding a Greek mythology isn't an easy task at two o'clock in the morning. With the aid of FBI men, Malley routed a book dealer out of bed. He got his book and hurried back.

Cercy was red-eyed and excited, and Harrison and his helpers were working away at three crazy looking rigs. Cercy snatched the book from Malley, looked up one item, and put it down.

"Great work," he said. "We're all set now. Finished, Harrison?"

"Just about." Harrison and ten helpers were screwing in the last parts. "Will you tell me what this is?"

"Me too," Malley put in.

"I don't mean to be secretive," Cercy said. "I'm just in a hurry. I'll explain as we go along." He stood up. "Okay, let's wake up the Ambassador."

hey watched the screen as a bolt of electricity leaped from the ceiling to the Ambassador's bed. Immediately, the Ambassador vanished.

"Now he's a part of that stream of electrons, right?" Cercy asked.

"That's what he told us," Malley said.

"But still keeping his pattern, within the stream," Cercy continued. "He has to, in order to get back into his own shape. Now we start the first disrupter."

Harrison hooked the machine into circuit, and sent his helpers away.

"Here's a running graph of the electron stream," Cercy said. "See the difference?" On the graph there was an irregular series of peaks and valleys, constantly shifting and leveling. "Do you remember when you hypnotized the Ambassador? He talked about his friend who'd been killed in space."

"That's right," Malley nodded. "His friend had been killed by something that had just popped up."

"He said something else," Cercy went on. "He told us that the basic organizing force of the Universe usually stopped things like that. What does that mean to you?"

"The organizing force," Malley repeated slowly. "Didn't Darrig say that that was a new natural law?"

"He did. But think of the implications, as Darrig did. If an organizing principle is engaged in some work, there must be something that opposes it. That which opposes organization is—"

"Chaos!"

"That's what Darrig thought, and what we should have seen. The chaos is underlying, and out of it there arose an organizing principle. This principle, if I've got it right, sought to suppress the fundamental chaos, to make all things regular.

"But the chaos still boils out in spots, as Alfern found out. Perhaps the organizational pattern is weaker in space. Anyhow, those spots are dangerous, until the organizing principle gets to work on them."

e turned to the panel. "Okay, Harrison. Throw in the second disrupter." The peaks and valleys altered on the graph. They started to mount in crazy, meaningless configurations.

"Take Darrig's message in the light of that. Chaos, we know, is underlying. Everything was formed out of it. The Gorgon Medusa was something that couldn't be looked upon. She turned men into stone, you recall, destroyed them. So, Darrig found a relationship between chaos and that which can't be looked upon. All with regard to the Ambassador, of course."

"The Ambassador can't look upon chaos!" Malley cried.

"That's it. The Ambassador is capable of an infinite number of alterations and permutations. But something—the matrix—can't change, because then there would be nothing left. To destroy something as abstract as a pattern, we need a state in which no pattern is possible. A state of chaos."

The third disrupter was thrown into circuit. The graph looked as if a drunken caterpillar had been sketching on it.

"Those disrupters are Harrison's idea," Cercy said. "I told him I wanted an electrical current with absolutely no coherent pattern. The disrupters are an extension of radio jamming. The first alters the electrical pattern. That's its purpose: to produce a state of patternlessness. The second tries to destroy the pattern left by the first; the third tries to destroy the pattern made by the first two. They're fed back then, and any remaining pattern is systematically destroyed in circuit ... I hope."

"This is supposed to produce a state of chaos?" Malley asked, looking into the screen.

For a while there was only the whining of the machines and the crazy doodling of the graph. Then, in the middle of the Ambassador's room, a spot appeared. It wavered, shrunk, expanded—

What happened was indescribable. All they knew was that everything within the spot had disappeared.

"Switch it off" Cercy shouted. Harrison cut the switch.

The spot continued to grow.

"How is it we're able to look at it?" Malley asked, staring at the screen.

"The shield of Perseus, remember?" Cercy said. "Using it as a mirror, he could look at Medusa."

"It's still growing!" Malley shouted.

"There was a calculated risk in all this," Cercy said. "There's always the possibility that the chaos may go on, unchecked. If that happens, it won't matter much what—"

The spot stopped growing. Its edges wavered and rippled, and then it started to shrink.

"The organizing principle," Cercy said, and collapsed into a chair.

"Any sign of the Ambassador?" he asked, in a few minutes.

The spot was still wavering. Then it was gone. Instantly there was an explosion. The steel walls buckled inward, but held. The screen went dead.

"The spot removed all the air from the room," Cercy explained, "as well as the furniture and the Ambassador."

"He couldn't take it," Malley said. "No pattern can cohere, in a state of patternlessness. He's gone to join Alfern."

Malley started to giggle. Cercy felt like joining him, but pulled himself together.

"Take it easy," he said. "We're not through yet."

"Sure we are! The Ambassador—"

"Is out of the way. But there's still an alien fleet homing in on this region of space. A fleet so strong we couldn't scratch it with an H-bomb. They'll be looking for us."

He stood up.

"Go home and get some sleep. Something tells me that tomorrow we're going to have to start figuring out some way of camouflaging a planet."

—ROBERT SHECKLEY

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Diplomatic Immunity, by Robert Sheckley

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK DIPLOMATIC IMMUNITY ***

***** This file should be named 32040-h.htm or 32040-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/3/2/0/4/32040/

Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at http://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

http://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at http://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit http://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: http://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart is the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

http://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.