The Project Gutenberg EBook of Atta Troll, by Heinrich Heine

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Atta Troll

Author: Heinrich Heine

Contributor: Oscar Levy

Illustrator: Willy Pogány

Translator: Herman Scheffauer

Release Date: February 17, 2010 [EBook #31305]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ATTA TROLL ***

Produced by Meredith Bach, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

| | page |

| FRONTISPIECE | ii |

| TITLE-PAGE | iii |

| ATTA TROLL | iv |

| INTRODUCTION (Half-Title) | 1 |

| ATTA TROLL (Half-Title) | 33 |

The headings and tail-pieces to the Cantos are by

Horace Taylor

AN INTERPRETATION OF

HEINRICH HEINE'S

"ATTA TROLL"

HE who has visited the idyllic isle of Corfu must

have seen, gleaming white amidst its surroundings

of dark green under a sky of the deepest blue, the

Greek villa which was erected there by Elizabeth,

Empress of Austria. It is called the Achilleion.

In its garden there is a small classic temple

in which the Empress caused to be placed a marble

statue of her most beloved of poets, Heinrich

Heine. The statue represented the poet seated,

his head bowed in profound melancholy, his

cheeks thin and drawn and bearded, as in his

last illness.

Elizabeth, Empress of Austria, felt a sentimental

affinity with the poet; his unhappiness,

his Weltschmerz, touched a responsive chord

in her own unhappy heart. Intellectual sympathy

with Heine's thought or tendencies there could

have been little, for no woman has ever quite

understood Heinrich Heine, who is still a riddle

to most of the men of this age.

After the assassination of the hapless Empress,

the beautiful villa was bought by the German

Emperor. He at once ordered Heine's statue

to be removed—whither no one knows. Royal

(as well as popular) spite has before this been

vented on dead or inanimate things—one need

only ask Englishmen to remember what happened

to the body of Oliver Cromwell. The Kaiser's

action, by the way, did not pass unchallenged.

Not only in Germany but in several other

countries indignant voices were raised at the

time, protesting against an act so insulting to

the memory of the great singer, upholding the

fame of Heine as a poet and denouncing the new

master of the Achilleion for his narrow and

prejudiced views on art and literature.

There was, however, a sound reason for the

Imperial interference. Heinrich Heine was in

his day an outspoken enemy of Prussia, a severe

critic of the House of Hohenzollern and of other

Royal houses of Germany. He was one who

held in scorn the principles of State and government

that are honoured in Germany, and elsewhere,

to this very day. He was one of those

poets—of whom the nineteenth century produced

only a few, but those amongst the greatest—who

had begun to distrust the capacity of the

reigning aristocracy, who knew what to expect

from the rising bourgeoisie, and who were nevertheless

not romantic enough to believe in the people

and the wonderful possibilities hidden in them.

These poets—one and all—have taken up a very

negative attitude towards their contemporaries

and have given voice to their anger and disappointment

over the pettiness of the society

and government of their time in words full of

satire and contempt.

Of course, the echo on the part of their

audiences has not been wanting. All these

poets have experienced a fate surprisingly similar,

and their relationship to their respective countries

reminds one of those unhappy matrimonial

alliances which—for social or religious reasons—no

divorce can ever dissolve. And, worse than

that, no separation either, for a poet is—through

his mother tongue—so intimately wedded to

his country that not even a separation can effect

any sort of relief in such a desperate case. All

of them have tried separation, all of them have

lived in estrangement from their country—we

might almost say that only the local and lesser

poets of the last century have stayed at home—and

yet in spite of this separation the mutual

recriminations of these passionate poetical

husbands and their obstinate national wives

have never ceased. Again and again we hear

the male partner making proposals to win his

spouse to better and nobler ways, again and

again he tries to "educate her up to himself" and

endeavours to direct her anew, pointing out to

her the danger of her unruly and stupid behaviour;

again and again his loving approaches

are thwarted by the well-known waywardness

of the feminine character, and so all his friendly

admonitions habitually turn into torrents of

abuse and vilification. There have been many

unhappy unions in the world, but the compulsory

mésalliances of such great nineteenth-century

writers as Heine, Byron, Stendhal, Gobineau,

and Nietzsche with Mesdames Britannia, Gallia,

and Germania, those otherwise highly respectable

ladies, easily surpass in grotesqueness anything

that has come to us through divorce court proceedings

in England and America. That, as

every one will agree, is saying a good deal.

The German Emperor, as I have said, had

some justification for his action, some motives

that do credit, if not to his intellect, at least

to what in our days best takes the place of

intellect; that is to say his character and his

principles of government. The German Emperor

appears at least to realize how offensive

and, from his point of view, dangerous, the

spirit of Heinrich Heine is to this very day, how

deeply his satire cuts into questions of religion and

State, how impatient he is of everything which

the German Emperor esteems and venerates in

his innermost heart. But the German people,

on the whole, and certainly all foreigners, have

long ago forgiven the poet, not because they have

understood the dead bard better than the Emperor,

but because they understood him less well.

It is always easier to forgive an offender if you

do not understand him too well, it is likewise

easier to forgive him if your memory be short.

And the peoples likewise resemble our womenfolk

in this respect, that as soon as they are widowed

of their poets, they easily forget all the unpleasantness

that had ever existed between them and their

dead husbands. It is then and only then that

they discover the good qualities of their dead

consorts and go about telling everybody "what

a wonderful man he was." Their behaviour

reminds me of a picture I once saw in a French

comic paper. It represented a widow who, in

order to hear her deceased husband's voice,

had a gramophone put at his empty place at the

breakfast table. And every morning she sat

opposite that gramophone weeping quietly into

her handkerchief, gazing mournfully at the

instrument—decorated with her dead hubby's

tasselled cap—and listening to the voice of the

dear departed. But the only words which came

out of the gramophone every morning were:

Mais fiche-moi donc la paix—tu m'empêches

de lire mon journal! (For goodness' sake,

leave me alone and let me read my paper.)

This, however, did not appear to disturb the

sentimental widow at all, as little indeed as a

good sentimental people resents being abused by

its dead poet.

And how our poet did abuse them during his

life! And not only during his life, for Heine

would not have been a great poet if his loves

and hatreds, his censure and his praise had not

outlasted his life, nay, had not come to real life

only after his death. Thus the shafts of wit

and satire which Heine levelled at his age and

his country will seem singularly modern to the

reader of to-day. It is this peculiar modern

significance and application that has been one

of the two reasons for presenting to the English

public the first popular edition of Heine's lyrico-satiric

masterpiece "Atta Troll." The other

reason is the fine quality of the translation,

made by one who is himself well known as a

poet, my friend Herman Scheffauer. I venture

to say that it renders in a remarkable degree

the elusive brilliance, wit, and tenderness of

the German original.

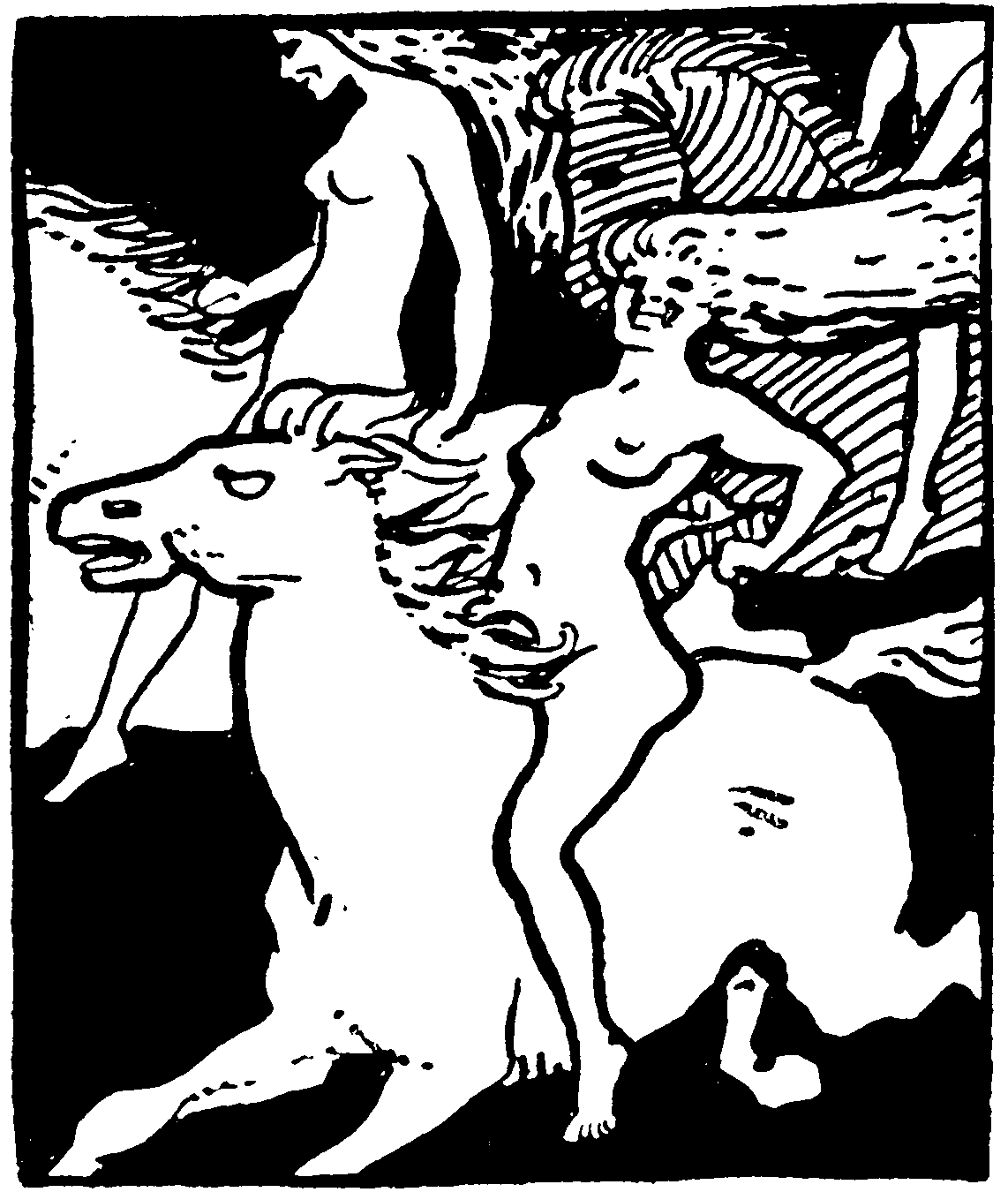

The poem begins in a sprightly fashion full

of airy mockery and romantic lyricism. The

reader is beguiled as with music and led on as

in a dance. Heine himself called it das letzte

freie Waldlied der Romantik ("The last free

woodland-song of Romanticism"); and so we

hear the alluring sound of flutes and harps, we

listen to the bells ringing from lonely chapels

in the forest, and many beautiful flowers nod to

us, the mysterious blue flower amongst them.

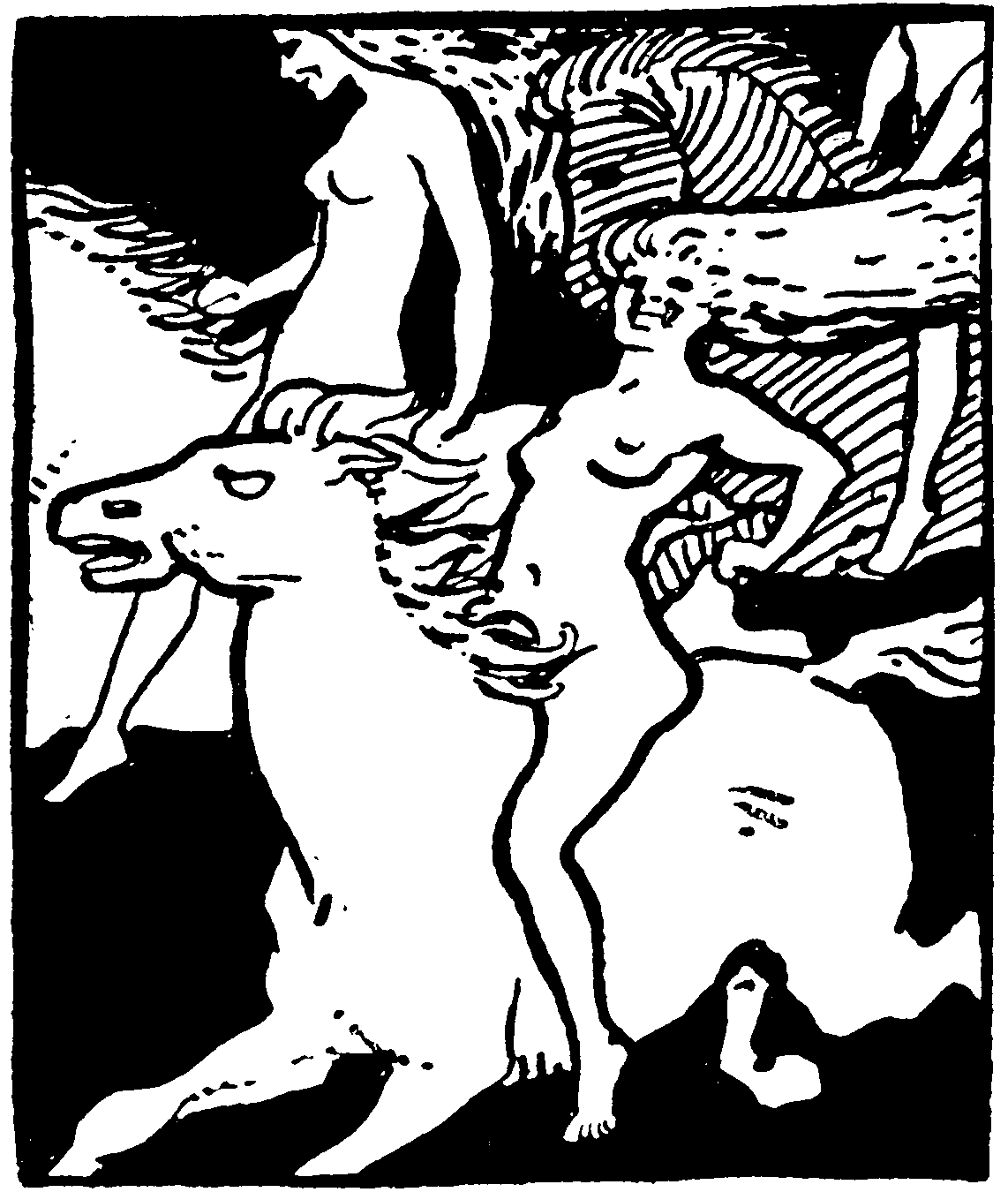

Then our eyes rejoice at the sight of fair maidens,

whose nude and slender bodies gleam from under

their floods of golden hair, who ride on white

horses and throw us provocative glances, that

warm and quicken our innermost hearts. But

just as we are on the point of responding to their

fond entreaties we are startled by the cracking

of the wild hunter's whip, and we hear the loud

hallo and huzza of his band, and see them

galloping across our path in the eerie mysterious

moonlight. Yes, in "Atta Troll" there is

plenty of that moonshine, of that tender sentimentality,

which used to be the principal stock-in-trade

of the German Romanticist.

But this moonshine and all the other paraphernalia

of the Romantic School Heine handled

with all the greater skill, inasmuch as he was no

longer a real Romanticist when he wrote "Atta

Troll." He had left the Romantic School long

ago, not without (as he himself tells us) "having

given a good thrashing to his schoolmaster."

He was now a Greek, a follower of Spinoza and

Goethe. He was a Romantique défroqué—one

who had risen above his neurotic fellow-poets

and their hazy ideas and wild endeavours. But

for this very reason he is able to use their mode of

expression with so much the greater skill, and,

knowing all their shortcomings, he could give to

his Dreamland a semblance of reality which they

could never achieve. Only after having left a town

are we in a position to judge the height of its

church steeple, only as exiles do we begin to see

the right relation in which our country stands

to the rest of the world, and only a poet who had

bidden farewell to his party and school, who had

freed himself from Romanticism, could give

us the last, the truest, the most beautiful poem of

Romanticism.

It is possible, even probable, that "Atta

Troll" will appeal to a majority of readers, not

through its satire, but through its wonderful

lyrical and romantic qualities—our age being

inclined to look askance at satire, at least at

true satire, at satire that, as the current phrase

goes, "means business." Weak satire, aimless

satire, humour, caricature—that is to say satire

which uses blank cartridges—this age of ours

will readily endure, nay heartily welcome;

but of true satire, of satire that goes in for

powder and shot, that does not only crack, but

kill, it is mortally, and, if one comes to think of

it rightly, afraid. But let even those who object

to powder and shot approach "Atta Troll"

without fear or misgiving. They will not be disappointed.

They will find in this work proof of

the old truth that a satirist is always and originally

a man of high ideals and imagination.

They will gain an insight into his much slandered

soul, which is always that of a great poet. They

will readily understand that this poet only

became a satirist through the vivacity of his

imagination, through the strength of his poetic

vision, through his optimistic belief in humanity

and its possibilities; and that it was precisely

this great faith which forced him to become a

satirist, because he could not endure to see all

his pure ideals and the possibilities of perfection

soiled and trampled upon by thoughtless mechanics,

aimless mockers and babbling reformers. The

humorist may be—and very often is—a sceptic,

a pessimist, a nihilist; the satirist is invariably

a believer, an optimist, an idealist. For let

this dangerous man only come face to face, not

with his enemies, but with his ideals, and you will

see—as in "Atta Troll"—what a generous friend,

what an ardent lover, what a great poet he is.

Thus no one will be in the least disturbed by

Heine's satire: on the contrary, those who

object to it on principle will hardly be aware of

it, so delighted will they be with the wonderful

imagination, the glowing descriptions, and the

passionate lyrics in which the poetry of "Atta

Troll" abounds. The poem may be and will

be read by them as "Gulliver's Travels" is

read to-day by young and old, by poet and

politician alike, not for its original satire, but

for its picturesque, dramatic, and enthralling tale.

But let those who still believe that writing is

fighting, and not sham-fighting only, those who

hold that a poet is a soldier of the pen and therefore

the most dangerous of all soldiers, those who feel

that our age needs a hailstorm of satire, let these,

I say, look closer at the wonderfully ideal figures

that pass before them in the pale mysterious

light. Let them listen more intently to the

flutes and harps and they will discover quite a

different melody beneath—a melody by no means

bewitching or soothing, nor inviting us to dreams,

sweet forgetfulness, soft couches, and tender

embraces, but a shrill and mocking tune that is

at times insolently discordant and that strikes

us as decidedly modern, realistic, and threatening.

As the poet himself expressed it in his dedication

to Varnhagen von Ense:

"Aye, my friend, such strains arise

From the dream-time that is dead

Though some modern trills may oft

Caper through the ancient theme.

"Spite of waywardness thou'lt find

Here and there a note of pain...."

Let their ears seek to catch these painful

notes. Let their eyes accustom themselves to

the deceitful light of the moon; let them

endeavour to pierce through the romanticism

on the surface to the underlying meaning of the

poem.... A little patience and we shall see

clearly....

Atta Troll, the dancing bear, is the representative

of the people. He has—by means of

the French Revolution, of course—broken his

fetters and escaped to the freedom of the mountains.

Here he indulges in that familiar ranting

of a sansculotte, his heart and mouth brimming

over with what Heine calls frecher Gleichheitsschwindel

("the barefaced swindle of equality").

His hatred is above all directed against the

masters from whose bondage he has just escaped,

that is to say against all mankind as a race. As

a "true and noble bear" he simply detests

these human beings with their superior airs and

impudent smiles, those arrogant wretches, who

fancy themselves something lofty, because they

eat cooked meat and know a few tricks and

sciences. Animals, if properly trained, if only

equality of opportunity were given to them,

could learn these tricks just as well—there is

therefore no earthly reason why

"these men,

Cursèd arch-aristocrats,

Should with haughty insolence

Look upon the world of beasts."

The beasts, so Atta Troll declares, ought not

to allow themselves to be treated in this wise.

They ought to combine amongst themselves, for

it is only by means of proper union that the

requisite degree of strength can ever be attained.

After the establishment of this powerful union

they should try to enforce their programme and

demand the abolition of private property and of

human privileges:

"And its first great law shall be

For God's creatures one and all

Equal rights—no matter what

Be their faith, or hide, or smell,

"Strict equality! Each ass

May become Prime Minister,

On the other hand the lion

Shall bear corn unto the mill."

This outrageous diatribe of the freed slave cuts

deeply into the poet's heart. He, the poet, does

not believe in equal, but in the "holy inborn"

rights of men, the rights of valid birth, the rights

of the man of ἁρετἡ. He, the poet, the

admirer of Napoleon, believes in the latter's

la carrière ouverte aux talents, but not in

opportunity given to every dunce or dancing

bear. He holds Atta Troll's opinion to be

"high treason against the majesty of humanity,"

and since he can endure this no longer, he sets

out one fine morning to hunt the insolent bear in

his mountain fastnesses.

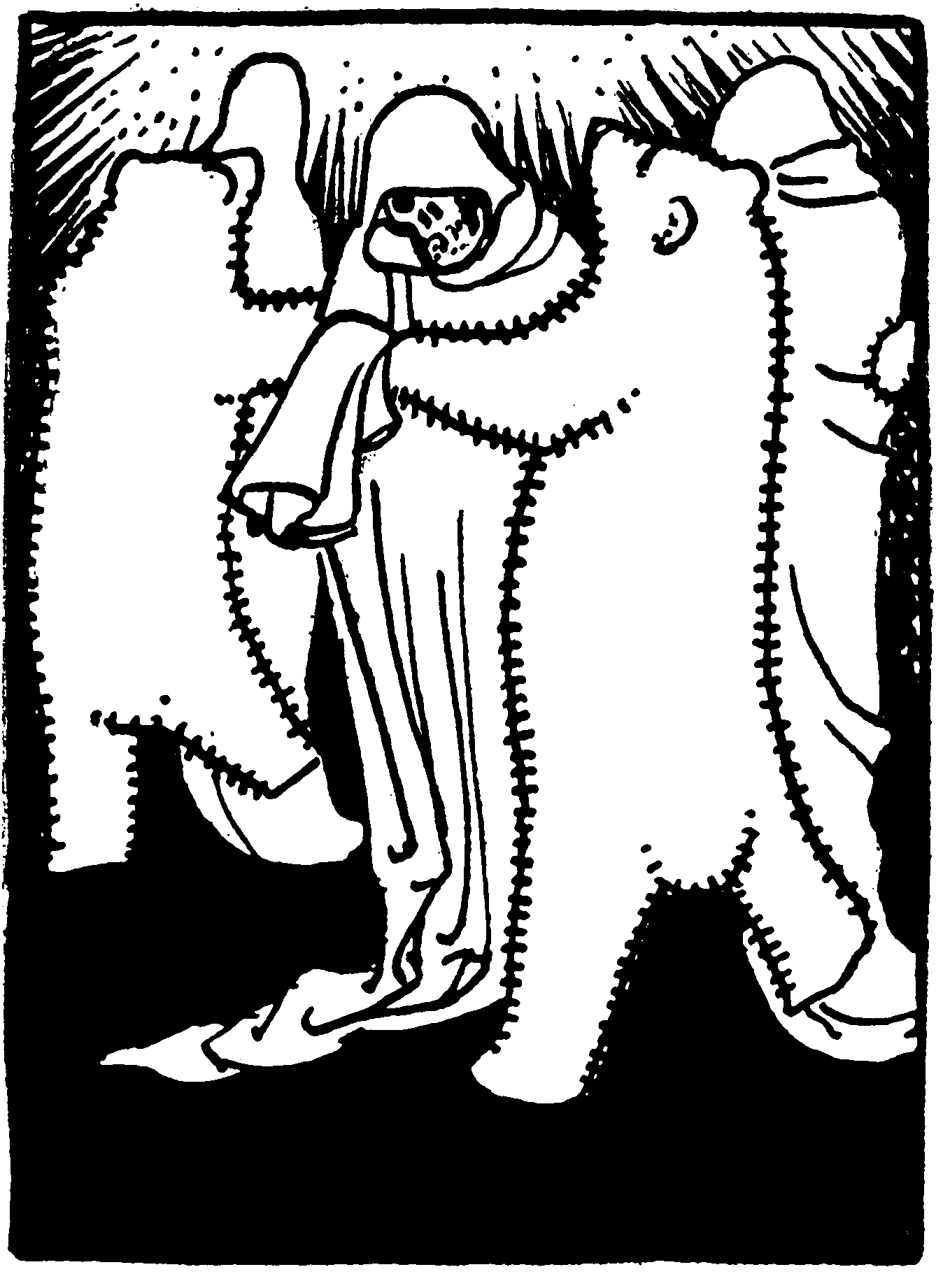

A strange being, however, accompanies him.

This is a man of the name of Lascaro, a somewhat

abnormal fellow, who is very thin, very pale,

and apparently in very poor health. He is

consequently not exactly a pleasant comrade

for the chase: he does not seem to enjoy the

sport at all, and his one endeavour is to get

through with his task without losing more of his

strength and health. Even now he is more of an

automaton than a human being, more dead than

alive, and yet—greatest of all miseries!—he is

not allowed to die. For he has a mother, the

witch Uraka, who keeps him artificially alive by

anointing him every night with magic salve and

giving him such diabolic advice as will be useful

to him during the day. By means of the sham

health she gives to her son, the magic bullets she

casts for him, the tricks and wiles she teaches him,

Lascaro is enabled to find the track of Atta

Troll, to lure him out of his lair and to lay him

low with a treacherous shot.

Who is this silent Lascaro and his mysterious

mother, whom the poet seems to hold in as slight

regard as the noisy Atta Troll? Who is this

Lascaro, whose methods he deprecates, whose

health he doubts, whose cold ways and icy smiles

make him shudder? Who is this chilliest of all

monsters? The chilliest of all monsters—we may

find the answer in "Zarathustra"—is the

State: and our Lascaro is nothing else than the

spirit of reactionary government, kept artificially

alive by his old witch-mother, the spirit

of Feudalism. The nightly anointing of Lascaro

is a parody on the revival of mediæval customs,

by means of which the frightened aristocracy of

Europe in the middle of the last century tried

to stem the tide of the French Revolution—the

anointed of the Lord becoming in Heine's poem

the anointed of the witch. But in spite of his

nightly massage, our Lascaro does not gain

much strength or spirit: no mediæval salves,

no feudal pills, no witch's spell, will ever cure him.

Not even a wizard's experiments (we may add,

with that greater insight bestowed upon us by

history) could do him any good, not even the

astute magic tricks that were lavished upon the

patient in Heine's time by that arch wizard, the

Austrian Minister Metternich. For we must

not forget the time in which "Atta Troll" was

written, the time of the omnipotent Metternich!

Let us recall to our memories this cool, clever,

callous statesman, who founded and set the

Holy Alliance against the Revolution, who

calmly shot down the German Atta Troll, who

skilfully strangled and stifled that promising

poetical school, "Young Germany," to which

Heine belonged. Let us recall this man, who

likewise artificially revived the old religion and

the old feudalism, who repolished and regilded

the scutcheons of the decadent aristocracy, and

who, despite all his energy, had at heart no belief

in his work, no joy in his task, no faith in the

anointed dummies he brought to life again in

Europe—and those puzzling personalities of

Uraka and Lascaro will be elucidated to us by

a real historical example.

Metternich is now part of history. But, alas!

we cannot likewise banish into that limbo of the

past those two superfluous individuals, the revolutionary

Atta Troll and the reactionary

Lascaro. Alas! we cannot join the joyful, but

inwardly so hopeless, band of those who sing the

pæan of eternal progress, who pretend to believe

that the times are always "changing for the

better." Let these good people open their eyes,

and they will see that Atta Troll was not shot

down in the valley of Roncesvalles, but that he

is still alive, very much alive, and making a

dreadful noise, and that not in the Pyrenees, but

just outside our doors, where he still keeps

haranguing about equality and liberty and

occasionally breaks his fetters and escapes from

his masters. And when this occurs, then that icy

monster Lascaro is likewise seen, with his hard,

pallid face and his joyless mouth, and his disgust

with his own task and his doubts and disbeliefs in

himself. He still carries his gun and he still

possesses some of that craftiness which his mother

the witch has taught him, and he still knows how

to entrap that poor, stupid Atta Troll, and to

shoot him down when the spirit of "order and

government," the spirit of a soulless capitalism,

requires it.

No, there is very little feeling in the man as

yet, and he seems as difficult to move as ever.

There is apparently only one thing that can rouse

him into action, and that is when a poet appears,

one who knows the truth and who dares to speak

the truth not only about Atta Troll, the people,

but also about its Lascaros, its leaders, its

emperors, and kings. Then and then only

his hard features change, and his affected self-possession

leaves him, then and then only his

mask of calmness is thrown off, and he waxes

very angry with the poet, and has his name

banished from his court and his statues turned

out of his cities and villas—nay, he would even

level his gun to slay the truth-telling poet as

he slew Atta Troll.

From which we may see that the modern

Lascaro has become a sort of Don Quixote—for,

truly is it not the height of folly for a mortal

emperor to shoot at an immortal poet?

OSCAR LEVY

London, 1913

PREFACE BY HEINE

"ATTA TROLL" was composed in the late

autumn of 1841, and appeared as a fragment in

The Elegant World, of which my friend Laube

had at that time resumed the editorship. The

shape and contents of the poem were forced to

conform to the narrow necessities of that periodical.

I wrote at first only those cantos which might be

printed and even these suffered many variations.

It was my intention to issue the work later in

its full completeness, but this commendable

resolve remained unfulfilled—like all the mighty

works of the Germans—such as the cathedral of

Cologne, the God of Schelling, the Prussian

Constitution, and the like. This also happened

to "Atta Troll"—he was never finished. In

such imperfect form, indifferently bolstered up

and rounded only from without, do I now set

him before the public, obedient to an impulse

which certainly does not proceed from within.

"Atta Troll," as I have said, originated in

the late autumn of 1841, at the time when

the great mob which my enemies of various

complexions, had drummed together against me,

had not quite ceased its noise. It was a very

large mob and indeed I would never have

believed that Germany could produce so many

rotten apples as then flew about my head!

Our Fatherland is a blessed country! Citrons

and oranges certainly do not grow here, and the

laurel ekes out but a miserable existence, but

rotten apples thrive in the happiest abundance,

and never a great poet of ours but could write

feelingly of them! On the occasion of that

hue and cry in which I was to lose both my head

and my laurels it happened that I lost neither.

All the absurd accusations which were used to

incite the mob against me have since then been

miserably annihilated, even without my condescending

to refute them. Time justified me,

and the various German States have even, as I

must most gratefully acknowledge, done me

good service in this respect. The warrants of

arrest which at every German station past the

frontier await the return of this poet, are

thoroughly renovated every year during the holy

Christmastide, when the little candles glow

merrily on the Christmas trees. It is this

insecurity of the roads which has almost destroyed

my pleasure in travelling through the German

meads. I am therefore celebrating my Christmas

in an alien land, and it will be as an exile in a

foreign country that I shall end my days.

But those valiant champions of Light and

Truth who accuse me of fickleness and servility,

are able to go about quite securely in the Fatherland—as

well-stalled servants of the State, as

dignitaries of a Guild, or as regular guests of a

club where of evenings they may regale themselves

with the vinous juices of Father Rhine

and with "sea-surrounded Schleswig-Holstein"

oysters.

It was my express intention to indicate in the

foregoing at what period "Atta Troll" was

written. At that time the so-called art of

political poetry was in full flower. The opposition,

as Ruge says, sold its leather and became

poetry. The Muses were given strict orders

that they were thenceforth no longer to gad about

in a wanton, easy-going fashion, but would be

compelled to enter into national service, possibly

as vivandières of liberty or as washerwomen of

Christian-Germanic nationalism. Especially

were the bowers of the German bards afflicted

by that vague and sterile pathos, that useless

fever of enthusiasm which, with absolute disregard

for death, plunges itself into an ocean of

generalities. This always reminds me of the

American sailor who was so madly enthusiastic

over General Jackson that he sprang from the

mast-head into the sea, crying out: "I die for

General Jackson!" Yes, even though we

Germans as yet possessed no fleet, still we had

plenty of sailors who were willing to die for

General Jackson, in prose or verse. In those

days talent was a rather questionable gift, for

it brought one under suspicion of being a loose

character. After thousands of years of grubbing

deliberation, Impotence, sick and limping Impotence,

at last discovered its greatest weapon

against the over-encouragement of genius—it

discovered, in fact, the antithesis between Talent

and Character. It was almost personally

flattering to the great masses when they heard it

said that good, average people were certainly

poor musicians as a rule, but that, on the other

hand, fine musicians were not usually good people—that

goodness was the important thing in this

world and not music. Empty-Head now beat

resolutely upon his full Heart, and Sentiment

was trumps. I recall an author of that day who

accounted his inability to write as a peculiar

merit in himself, and who, because of his wooden

style, was given a silver cup of honour.

By the eternal gods! at that time it became

necessary to defend the inalienable rights of the

spirit, above all in poetry. Inasmuch as I

have made this defence the chief business of my

life, I have kept it constantly before me in this

poem whose tone and theme are both a protest

against the plebiscite of the tribunes of the times.

And verily, even the first fragments of "Atta

Troll" which saw the light, aroused the wrath

of my heroic worthies, my dear Romans, who

accused me not only of a literary but also of a

social reaction, and even of mocking the loftiest

human ideals. As to the esthetic worth of my

poem—of that I thought but little, as I still do

to-day—I wrote it solely for my own joy and

pleasure, in the fanciful dreamy manner of that

romantic school in which I whiled away my

happiest years of youth, and then wound up by

thrashing the schoolmaster. Possibly in this

regard my poem is to be condemned. But thou

liest, Brutus, thou too, Cassius, and even thou,

Asinius, when ye declare that my mockery is

levelled against those ideals which constitute

the noble achievements of man, for which I

too have wrought and suffered so much. No, it

is just because the poet constantly sees these

ideas before him in all their clarity and greatness

that he is forced into irresistible laughter when he

beholds how raw, awkward, and clumsy these

ideas may appear when interpreted by a narrow

circle of contemporary spirits. Then perforce

must he jest about their thick temporal hides—bear

hides. There are mirrors which are ground

in so irregular a way that even an Apollo would

behold himself as a caricature in them, and invite

laughter. But we do not laugh at the god

but merely at his distorted image.

Another word. Need I lay any special

emphasis upon the fact that the parodying of

one of Freiligrath's poems, which here and there

somewhat saucily titters from the lines of "Atta

Troll," in no wise constitutes a disparagement

of that poet? I value him highly, especially

at present, and account him one of the most

important poets who have arisen in Germany

since the Revolution of 1830. His first collection

of poems came to my notice rather late, namely

just at the time when I was composing "Atta

Troll." The fact that the Moorish Prince

affected me so comically was no doubt due to my

particular mood at that time. Moreover, this

work of his is usually vaunted as his best. To

such readers as may not be acquainted with this

production—and I doubt not such may be found

in China and Japan, and even along the banks

of the Niger and Senegal—I would call attention

to the fact that the Blackamoor King, who at

the beginning of the poem steps from his white

tent like an eclipsed moon, is beloved by a black

beauty over whose dusky features nod white

ostrich plumes. But, eager for war, he leaves

her, and enters into the battles of the blacks,

"where rattles the drum decorated with skulls,"

but, alas! here he finds his black Waterloo, and

is sold by the victors unto the whites. They

take the noble African to Europe and here we

find him in a company of itinerant circus folk

who intrust him with the care of the Turkish

drum at their performances. There he stands,

dark and solemn, at the entrance to the ring,

and drums. But as he drums he thinks of his

erstwhile greatness, remembers, too, that he was

once an absolute monarch on the far, far banks of

the Niger, that he hunted lions and tigers:

"His eye grew moist; with hollow thunder

He beat the drum, till it sprang in sunder."

HEINRICH HEINE

Written at Paris, 1846

Out of the gleaming, shimmering tents of white

Steps the Prince of the Moors in his armour bright—

So out of the slumbering clouds of night,

The moon in its dark eclipse takes flight.

"The Prince of Blackamoors,"

by Ferdinand Freiligrath.

|

CANTO I

Ringed about by mountains dark,

Rising peak on sullen peak,

And by furious waterfalls

Lulled to slumber, like a dream

White within the valley lies

Cauterets. Each villa neat

Sports a balcony whereon

Lovely ladies stand and laugh.

Heartily they laugh and look

Down upon the crowded square

Where unto a bag-pipe's drone

He- and she-bear strut and dance.

Atta Troll is dancing there

With his Mumma, dusky mate,

While in wonderment the Basques

Shout aloud and clap their hands.

Stiff with pride and gravity

Dances noble Atta Troll,

Though his shaggy partner knows

Neither dignity nor shame.

I am even fain to think

She is verging on the can-can,

For her shameless wagging hints

Of the gay Grande Chaumière

Even he, the showman brave,

Holding her with loosened chain,

Marks the immorality

Of her most immodest dance.

So at times he lays the lash

Straight across her inky back,

Till the mountains wake and shout

Echoes to her frenzied howls.

On the showman's pointed hat

Six Madonnas made of lead

Shield him from the foeman's balls

Or invasions of the louse.

And a gaudy altar-cloth

From his shoulders hanging down,

Makes a proper sort of cloak,

Hiding pistol and a knife.

In his youth a monk was he,

Then became a robber chief;

Later, in Don Carlos' ranks,

He combined the other two.

When Don Carlos, forced to flee,

Bade his Table Round farewell,

All his Paladins resolved

Straight to learn an honest trade.

Herr Schnapphahnski turned a scribe,

And our staunch Crusader here

Just a showman, with his bears

Trudging up and down the land.

And in every market-place

For the people's pence they dance—

In the square at Cauterets

Atta Troll is dancing now!

Atta Troll, the Forest King,

He who ruled on mountain-heights,

Now to please the village mob,

Dances in his doleful chains.

Worse and worse! for money vile

He must dance who, clad in might,

Once in majesty of terror

Held the world a sorry thing!

When the memories of his youth

And his lost dominions green,

Smite the soul of Atta Troll,

Mournful sobs escape his breast.

And he scowls as scowled the black

Monarch famed of Freiligrath;

In his rage he dances badly,

As the darkey badly drummed.

Yet compassion none he wins,—

Only laughter! Juliet

From her balcony is laughing

At his wild, despairing bounds.

Juliet, you see, is French,

And was born without a soul—

Lives for mere externals—but

Her externals are so fair!

Like a net of tender gleams

Are the glances of her eye,

And our hearts like little fishes,

Fall and struggle in that net.

|

|

|

CANTO II

When the dusky Moorish Prince

Sung by poet Freiligrath

Beat upon his mighty drum

Till the drumskin crashed and broke—

Thrilling must that crash have been—

Likewise hard upon the ear—

But just fancy when a bear

Breaks away from captive chains!

Swift the laughter and the pipes

Cease. What yells of fear arise!

From the square the people rush

And the gentle dames grow pale.

Yea, from all his slavish bonds

Atta Troll has torn him free.

Suddenly! With mighty leaps

Through the narrow streets he runs.

Room enough is his, I trow!

Up the jagged cliffs he climbs,

Flings down one contemptuous look,

Then is lost within the hills.

Lone within the market-place

Mumma and her master stand—

Raging, now he grasps his hat,

Cursing, casts it on the earth,

Tramples on it, kicks and flouts

The Madonnas, tears the cloak

Off his foul and naked back,

Yells and blasphemes horribly

'Gainst the base ingratitude

Of the race of sable bears.

Had he not been kind to Troll?

Taught him dancing free of charge?

Everything this monster owed him,

Even life. For some had bid,

All in vain! three hundred marks

For the hide of Atta Troll.

Like some carven form of grief

There the poor black Mumma stands

On her hind feet, with her paws

Pleading with the raging clown.

But on her the raging clown

Looses now his twofold wrath;

Beats her; calls her Queen Christine,

Dame Muñoz—Putana too....

All this happened on a fair

Sunny summer afternoon.

And the night which followed, ah!

Was superb and wonderful.

Of that night a part I spent

On a small white balcony;

Juliet was at my side

And we viewed the passing stars.

"Fairer far," she sighed, "the stars

Which in Paris I have seen,

When upon a winter's night

In the muddy streets they shine."

|

|

CANTO III

Dream of summer nights! How vain

Is my fond fantastic song.

Quite as vain as Love and Life,

And Creator and Creation.

Subject to his own sweet will,

Now in gallop, now in flight,

So my Pegasus, my darling,

Revels through the realms of myth.

Ah, no plodding cart-horse he!

Harnessed up for citizens,

Nor a ramping party-hack

Full of showy kicks and neighs.

For my little wingèd steed's

Hoofs are shod with solid gold

And his bridle, dragging free,

Is a rope of gleaming pearls.

Bear me wheresoe'er thou wouldst—

To some lofty mountain-trail

Where the torrents toss and shriek

Warnings over folly's gulf.

Bear me through the silent vales

Where the solemn oaks arise

From whose twisted roots there well

Ancient springs of fairy lore.

There, oh, let me drink—mine eyes

Let me lave—Oh, how I thirst

For that flashing wonder-spring,

Full of wisdom and of light.

All my blindness flees. My glance

Pierces to the dimmest cave,

To the lair of Atta Troll,

And his speech I understand!

Strange it is—this bearish speech

Hath a most familiar ring!

Once, methinks, I heard such tones

In my own dear native land.

|

|

CANTO IV

Roncesvalles, thou noble vale!

When thy golden name I hear,

Then the lost blue flower blooms

Once again within my heart!

All the glittering world of dreams

Rises from its hoary gulf,

And with great and ghostly eyes

Stares upon me till I quake!

What a stir and clang! The Franks

Battle with the Saracens,

While a thin, despairing wail

Pours like blood from Roland's horn.

In the Vale of Roncesvalles,

Close beside great Roland's Gap—

So 'twas named because the Knight

Once to clear himself a path.

Now this youngest was the pet

Of his mother. Once in play

Chewing off his tiny ear—

She devoured it for love.

A most genial youth is he,

Clever in gymnastic tricks,

Throwing somersaults as clever

As dear Massmann's somersaults.

Blossom of the pristine cult,

For the mother-tongue he raves,

Scorning all the senseless jargon

Of the Romans and the Greeks.

"Fresh and pious, gay and free,"

Hating all that smacks of soap

Or the modern craze for baths—

Verily like Massmann too!

Most inspired is this youth

When he clambers up the tree

Which from out the hollow gorge

Rears itself along the cliff,

Rears and lifts unto the crest

Where at night this jolly band

Squat and loll about their sire

In the twilight dim and cool.

Gladly there the father bear

Tells them stories of the world,

Of strange cities and their folk,

And of all he suffered too,

Suffered like Ulysses great—

Differing slightly from this brave

Since his black Penelope

Never parted from his side.

Loudly too prates Atta Troll

Of the mighty meed of praise

Which by practice of his art

He had wrung from humankind.

Young and old, so runs his tale,

Cheered in wonder and in joy,

When in market-squares he danced

To the bag-pipe's pleasant skirl.

And the ladies most of all—

Ah, what gentle connoisseurs!—

Rendered him their mad applause

And full many a tender glance.

Artists' vanity! Alas,

Pensively the dancing-bear

Thinks upon those happy hours

When his talents pleased the crowd.

Seized with rapture self-inspired,

He would prove his words by deeds,

Prove himself no boaster vain

But a master in the art.

Swiftly from the ground he springs,

Stands on hinder paws erect,

Dances then his favourite dance

As of old—the great Gavotte.

Dumb, with open jaws the cubs

Gaze upon their father there

As he makes his wondrous leaps

In the moonshine to and fro.

|

|

CANTO V

In his cavern by his young,

Atta Troll in moody wise

Lies upon his back and sucks

Fiercely at his paws, and growls:

"Mumma, Mumma, dusky pearl

That from out the sea of life

I had gathered, in that sea

I have lost thee once again!

"Shall I never see thee more?

Shall it be beyond the grave

Where from earthly travail free

Thy bright spirit spreads its wings?

"Ah, if I might once again

Lick my darling Mumma's snout—

Lovely snout as dear to me

As if smeared with honey-dew.

"Might I only sniff once more

That aroma sweet and rare

Of my dear and dusky mate—

Scent as sweet as roses' breath!

"But, alas! my Mumma lies

In the bondage of that tribe

Which believes itself Creation's

Lords and bears the name of Man!

"Death! Damnation! that these men—

Cursèd arch-aristocrats!

Should with haughty insolence

Look upon the world of beasts!

"They who steal our wives and young,

Chain us, beat us, slaughter us!—

Yea, they slaughter us and trade

In our corpses and our pelts!

"More, they deem these hideous deeds

Justified—particularly

Towards the noble race of bears—

This they call the Rights of Man!

"Rights of Man? The Rights of Man!

Who bestowed these rights on you?

Surely 'twas not Mother Nature—

She is ne'er unnatural!

"Rights of Man! Who gave to you

All these privileges rare?

Verily it was not Reason—

Ne'er unreasonable she!

"Is it, men, because you roast,

Stew or fry or boil your meat,

Whilst our own is eaten raw,

That you deem yourselves so grand?

"In the end 'tis all the same.

Food alone can ne'er impart

Any worth;—none noble is

Save who nobly acts and feels!

"Are you better, human things,

Just because success attends

All your arts and sciences?

No mere wooden-heads are we!

"Are there not most learnèd dogs!

Horses, too, that calculate

Quite as well as bankers?—Hares

Who have skill in beating drums?

"Are not beavers most adroit

In the craft of waterworks?

Were not clyster-pipes invented

Through the cleverness of storks?

"Do not asses write critiques?

Do not apes play comedy?

Could there be a greater actress

Than Batavia the ape?

"Do the nightingales not sing?

Is not Freiligrath a bard?

Who e'er sang the lion's praise

Better than his brother mule?

"In the art of dance have I

Gone as far as Raumer quite

In the art of letters—can he

Scribble better than I dance?

"Why should mortal men be placed

O'er us animals? Though high

You may lift your heads, yet low

In those heads your thoughts do crawl.

"Human wights, why better, pray,

Than ourselves? Is it because

Smooth and slippery is your skin?

Snakes have that advantage too!

"Human hordes! two-legged snakes!

Well indeed I understand

That those flapping pantaloons

Must conceal your serpent hides!

"Children, Oh, beware of these

Vile and hairless miscreants!

O my daughters, never trust

Monsters that wear pantaloons!"

But no further will I tell

How this bear with arrogant

Fallacies of equal rights

Raved against the human race

For I too am man, and never

As a man will I repeat

All this vile disparagement,

Bound to give most grave offence.

Yes, I too am man, am placed

O'er the other mammals all!

Shall I sell my birthright?—No!

Nor my interest betray.

Ever faithful unto man,

I will fight all other beasts.

I will battle for the high

Holy inborn rights of man!

|

|

|

CANTO VI

Yet for man who forms the higher

Class of animals 'twere well

That betimes he should discover

What the lower thinks of him.

Verily within those drear

Strata of the world of brutes,

In those lower social layers

There is misery, pride and wrath.

Laws which Nature hath decreed,

Customs sanctioned long by Time,

And for centuries established,

They deny with pertest tongue.

Grumbling, there the old instil

Evil doctrines in the young,

Doctrines which endanger all

Human culture on the Earth.

"Children!" grunts our Atta Troll,

As he tosses to and fro

On his hard and stony couch,

"Future time we hold in fee!

"If each bear, each quadruped,

Held with me a like ideal,

With our whole united force

We the tyrant might engage.

"Compact then the boar should make

With the horse—the elephant

Curve his trunk in comradeship

Round the valiant ox's horns.

"Bear and wolf of every shade,

Goat and ape, the rabbit, too.

Let them for the common cause

Labour—and the world is ours!

"Union! union! is the need

Of our times! For singly we

Fall as slaves, but joined as one

We shall overcome our lords.

"Union! union! Victory!

We shall overthrow the reign

Of such tyranny and found

One great Kingdom of the Brutes.

"And its first great law shall be

For God's creatures one and all

Equal rights—no matter what

Be their faith, or hide or smell.

"Strict equality! Each ass

May become Prime Minister;

On the other hand the lion

Shall bear corn unto the mill.

"And the dog? Alas, 'tis true

He's a very servile cur,

Just because for ages man

Like a dog has treated him.

"Yet in our Free State shall he

Once again enjoy his rights—

Rights most unassailable—

Thus ennobled be the dog.

"Yea, the very Jews shall win

All the rights of citizens,

By the law made equal with

Every other mammal free.

"One thing only be denied them!

Dancing in the market-place;

This amendment I shall make

In the interests of my art.

"For they lack all sense of style;

All plasticity of limb

Lacks that race. Full surely they

Would debauch the public taste."

|

|

|

CANTO VII

Gloomy in his gloomy cave,

In the circle of his home,

Crouches Troll, the Foe of Man,

As he growls and champs his jaws.

"Men, O crafty, pert canaille!

Smile away! That mighty hour

Dawns wherein we shall be freed

From your bondage and your smiles!

"Most offensive was to me

That same twitching bitter-sweet

Of the lips—the smiles of men

I found unendurable!

"When in every visage white

I beheld that fatal spasm,

Then did anger seize my bowels

And I felt a hideous qualm.

"For the smiling lips of men

More insultingly declare,

Even than their lips avouch,

All their insolence of soul.

"And they smile forever! Even

When all decency demands

Gravity—as in the moments

Of love's solemn mysteries.

"Yea, they smile forever. Even

In their dances!—desecrate

Thus this high and noble art

Which a sacred cult should be.

"Ah, the dance in olden days

Was a pious act of faith,

When the priests in solemn round

Turned about their holy shrines.

"Thus before the Covenant's

Sacred Ark King David danced.

Dancing then was worship too,—

It was praying with the legs!

"So did I regard my dance

When before the people all

In the market-place I danced

And was cheered by every soul.

"This applause, I grant you, oft

Made me feel content at heart;

Sweet it is from grudging foes

Admiration thus to win!

"Yet despite their rapture they

Still would smile and smile! My art—

Even that proved vain to save

Them from base frivolity!"

|

|

|

CANTO VIII

Many a virtuous citizen

Smells unpleasantly the while

Ducal knaves are lavendered

Or a-reek with ambergris.

There are many virgin souls

Redolent of greenest soap;

Vice will often lave herself

In rose attar top to toe.

Therefore, gentle reader, pray,

Do not lift your nose in air

Should Troll's cavern fail to rouse

Memories of Arabia's spice.

Bide with me within this reek,

'Mid these turbid odours foul,

Whence unto his son our hero

Speaks, as from a misty cloud:

"Child, my child, the last begot

Of my loins, thy single ear

Snuggle close against the snout

Of thy father, and give heed!

"Oh, beware man's mode of thought;

It destroys both flesh and soul,

For amongst all mankind never

Shalt thou find one worthy man.

"E'en the Germans, once the best,

Even Tuiskion's sons,

Our dear cousins primitive,

Even they have grown effete.

"Godless, faithless have they grown;

Atheism now they preach.

Child, my child, oh, guard thee 'gainst

Feuerbach and Bauer too!

"Never be an atheist!

Monster void of reverence!

For a great Creator reared

All the mighty Universe!

"And the sun and moon on high,

And the stars—the stars with tails

Even as the tailless ones—

Are reflections of His power.

"In the depths of sea and land

Ring the echoes of His fame,

And each creature yields Him praise

For His glory and His might.

"E'en the tiny silver louse

Which within some pilgrim's beard

Shares his earthly pilgrimage,

Sings to Him a song of praise!

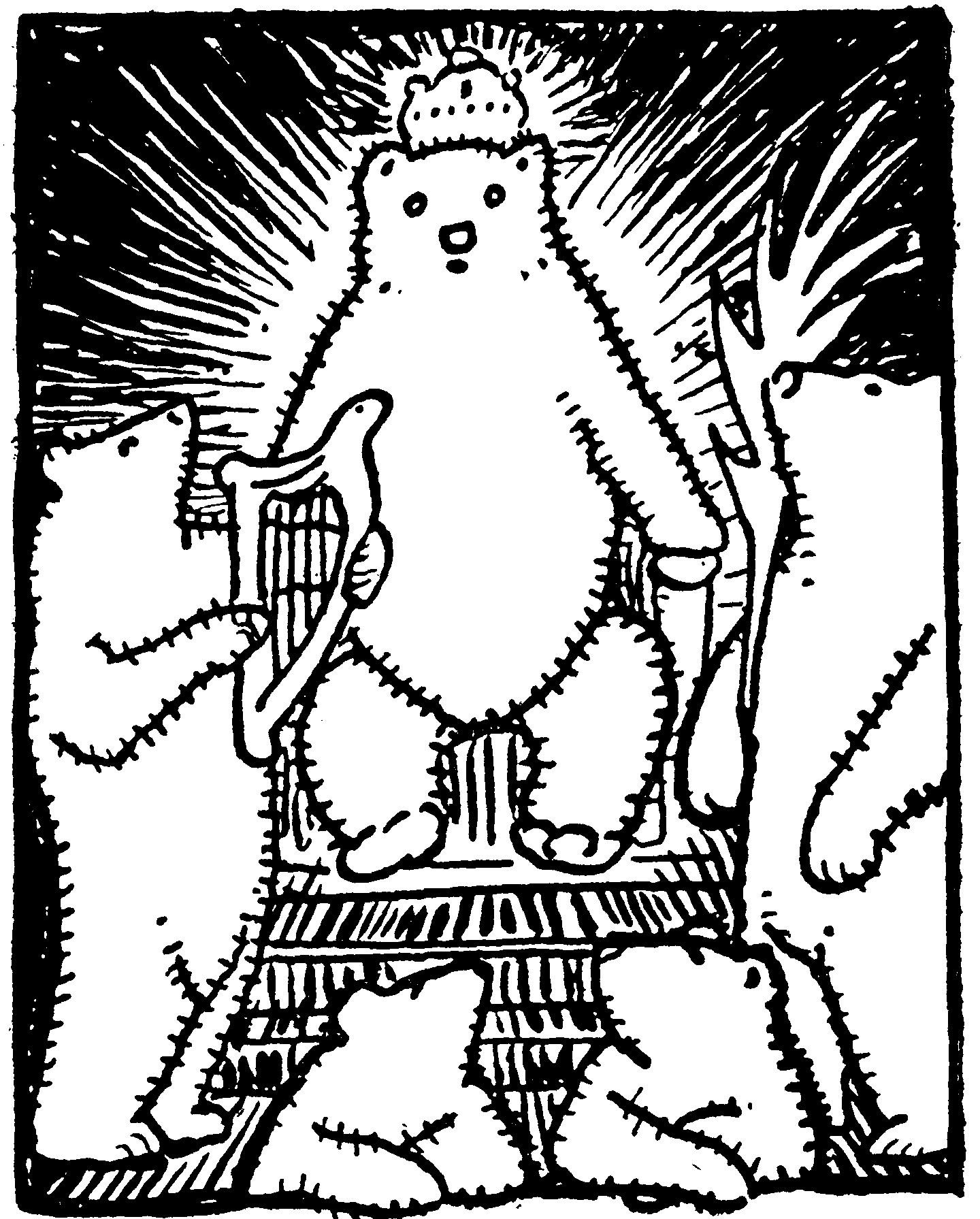

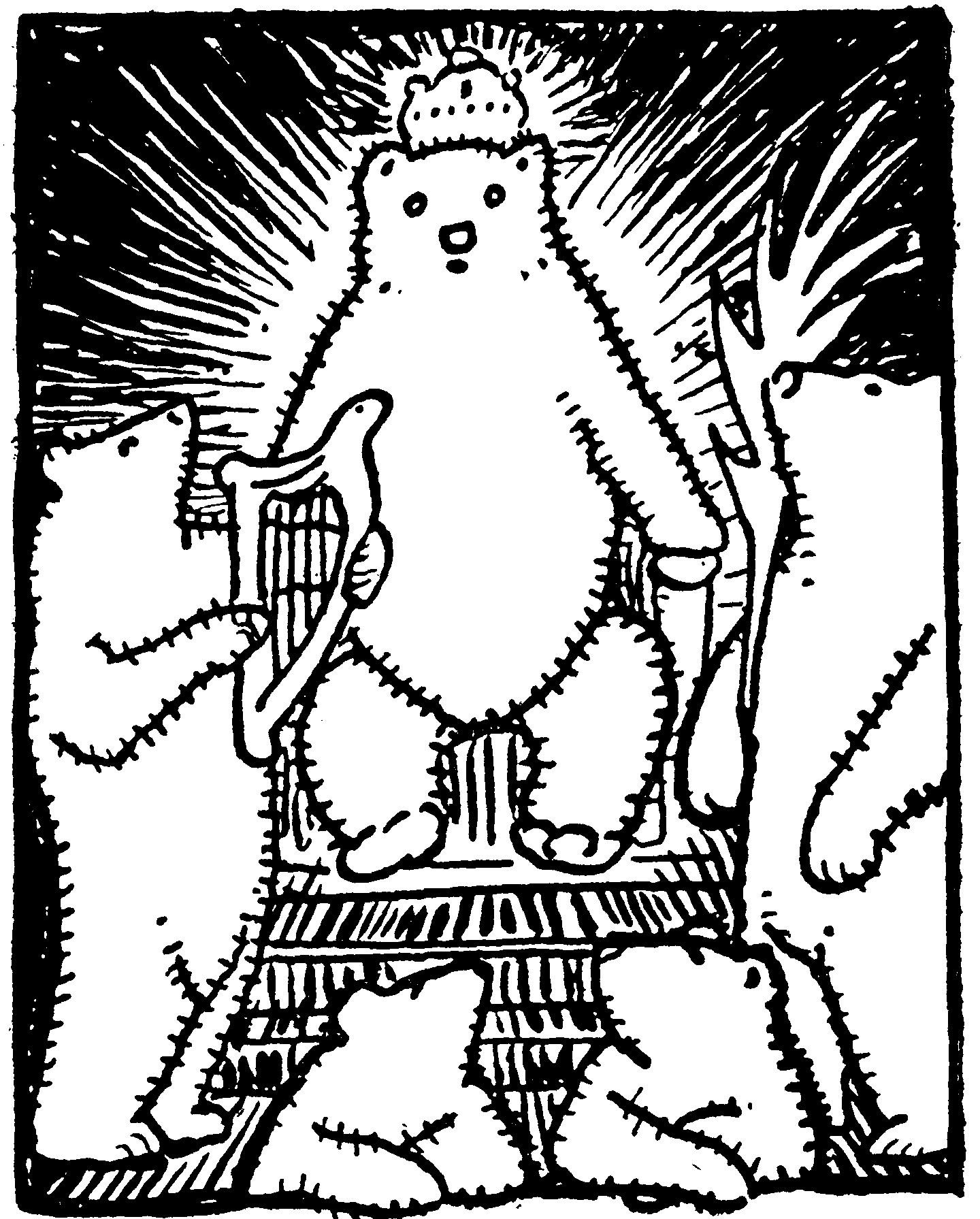

"High upon his golden throne

In yon splendid tent of stars,

Clad in cosmic majesty,

Sits a titan polar bear.

"Spotless, gleaming white as snow

Is his fur; his head is decked

With a crown of diamonds

Blazing through the central vault.

"In his face bide harmony

And the silent deeds of thought,

And obedient to his sceptre

All the planets chime and sing.

"At his feet sit holy bears,

Saints who suffered on the Earth,

Meekly. In their paws they hold

Splendid palms of martyrdom.

"Ever and anon they leap

To their feet as though aroused

By the Holy Ghost, and lo!

In a festal dance they join!

"'Tis a dance where saintly gifts

Cover up defects of style,—

Dance in which the very soul

Seeks to leap from out its skin!

"I, unworthy Troll, shall I

Ever such salvation share?

Shall I ever from this drear

Vale of tears ascend to joy?

"Shall I, drunk with Heaven's draught,

In that tent of stars above,

Dance before the Master's throne

With a halo and a palm?"

|

|

|

CANTO IX

As the noble negro king

Of our Freiligrath protrudes

From his dusky mouth his long

Scarlet tongue in scorn and rage,—

Even so the moon now peers

Out of darkling clouds. The sad,

Sleepless waterfalls forever

Roar into the brooding night.

Atta Troll upon the crest

Of his well-beloved cliff

Stands alone, and now he howls

Down the wind and the abyss:

"Yea, a bear am I—even he,

Even he whom you have named

Bruin, growler, shag-coat too,

And such other titles vile.

"Yea, a bear am I—that same

Boorish animal you know;

That gross, trampling brute am I

Of your sly and crafty smiles!

"Of your wit am I the mark;

I'm the bugbear—him with whom

Every wicked child you frighten

In the silence of the night.

"Yea, I am that clumsy butt

Of your nursery tales—aloud

Will I shout that name forever

Through the scurvy world of men.

"Oyez! Oyez! I'm a bear

Unashamed of my descent,

Just as proud as if my forbear

Had been Moses Mendelsohn."

|

|

CANTO X

Lo, two figures, wild and sullen,

Gliding, sliding on all fours,

Break a path at dead of night

Through a wood of gloomy pines.

It is Atta Troll the Sire,

One-Ear too, his youngest son,

And they halt within a clearing

By a stone of bloody rites.

"This same stone," growled Atta Troll,

"Is a shrine where Druids once

Slaughtered wretched human wights

In dark Superstition's days.

"Oh! what frightful horrors these!

When I think of them, my fur

Lifts along my back! To praise

God they drenched the soil in blood!

"Certes, men have now become

More enlightened. Now no more

Do they slaughter in their zeal

For celestial interests.

"'Tis no longer holy rage,

Ecstasy nor madness sheer,

But self-love alone that urges

Them to slaughter and to crime.

"Now for worldly goods they strive,

Day by day and year by year.

It is one eternal war;

Each goes robbing for himself.

"When the common goods of all

Fall into the hands of one,

Straight of Rights of Property

He will prate and Ownership.

"Property! Just Ownership?

Property is theft! O lies!

Craft and folly!—such a mixture

Man alone would dare invent.

"Never yet did Nature make

Properties, for pocketless

We are born into the world—

Who hath pockets in his pelt?

"None of us was ever born

With such little sacks devised

In our outer hides and skins

To enable us to steal!

"Only man, that creature smooth

Who in alien wool is garbed

Artfully, in artful wise

Made himself such pockets too.

"Pockets! as unnatural

As is property itself,

Or that law of have-and-hold.

Men are only pocket-thieves!

"Flamingly I hate them! Thee

All my hatred I bequeath.

Oh, my son, upon this shrine

Shalt thou swear eternal hate!

"Be the mortal foeman thou

Of th' oppressor, unforgiving

To thy very end of days!

Swear it—swear it here, my son!"

And the youngster swore as once

Hannibal. The moonbeams bleak

Yellowed on the bloodstone hoary

And that brace of misanthropes.

Later shall our harp record

How the young bear kept his faith

And his plighted oath,—for him

Shall our epic strings be strung.

With regard to Atta Troll,

Let us leave him for a space,

So we may the surer smite

Him with our unerring ball.

Traitor to Humanity!

Thou art judged, the sentence writ.

Of lèse-majesté thou'rt guilty,

And to-morrow sees the chase.

|

|

CANTO XI

Like to sleepy dancing-girls

Lift the mountains white and cold,

Standing in their skirts of mist

Flaunted by the winds of morn.

Yet full soon their breasts shall glow

To the sun-god's burning kiss,

He shall tear the clinging veils

And illume their beauty nude.

In the early dawn had I

With Lascaro sallied forth

On a bear-hunt and the noon

Saw us at the Pont d'Espagne.

Thus is named the bridge that leads

From the land of France to Spain,

To barbarians of the West,

Centuries behind the times.

Full ten centuries they lie

From all modern thought removed,

And my own barbarians

Of the East—not more than two.

Lingering and loth I left

The all-hallowed soil of France,

Left great Freedom's motherland

And the women that I love.

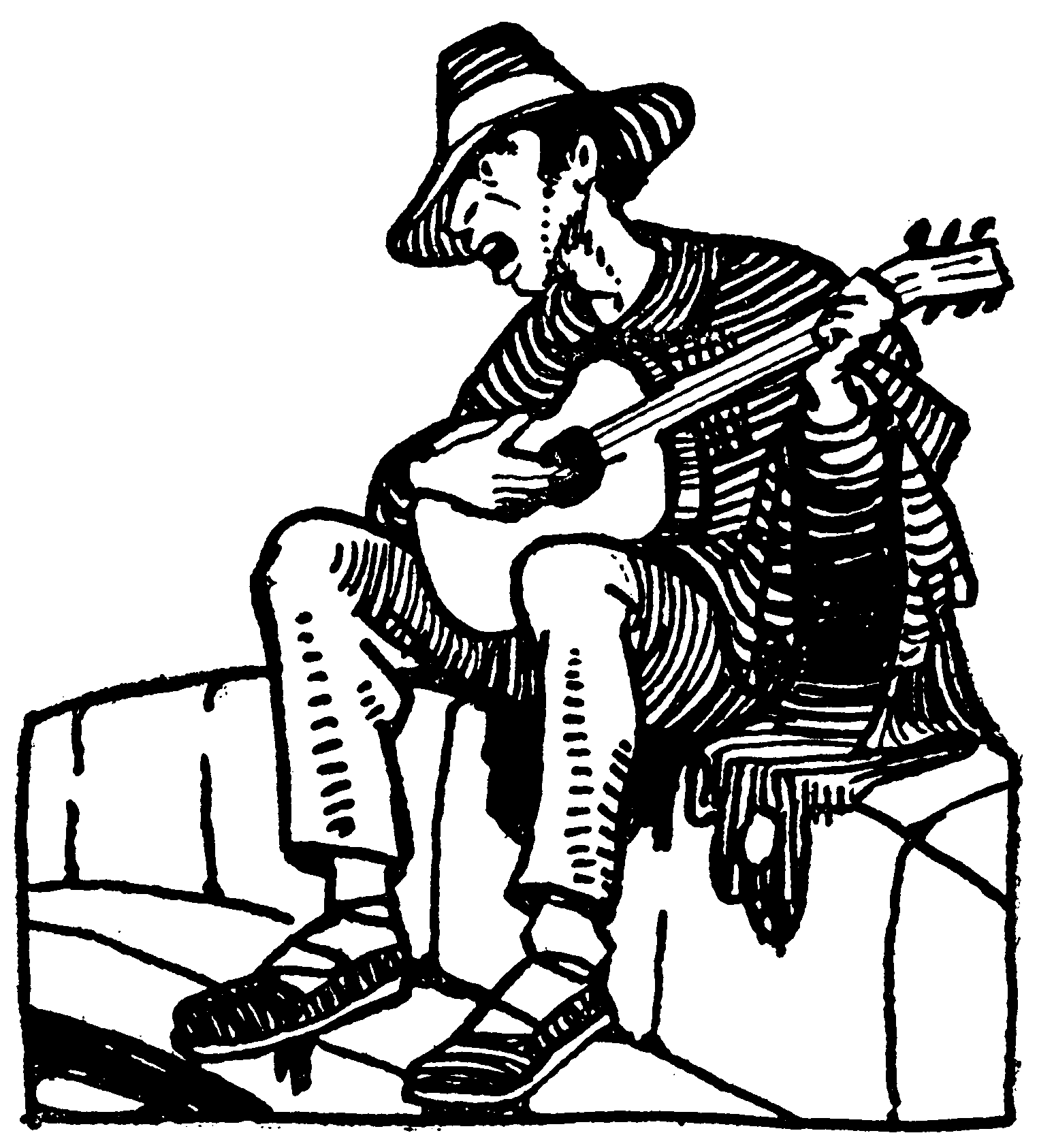

Midmost of the Pont d'Espagne

Sat a Spaniard. Misery

Lurked within his tattered cape;

Misery lurked within his eyes.

With his bony fingers he

Plucked an ancient mandolin

Full of discord shrill which echoed

Mockingly from out the gulch.

Then betimes he leaned aslant

O'er the depths and laughed aloud,

Tinkled then in maddest wise

As he sang his little song:

"In my very heart of heart

There's a tiny golden table,

And about this golden table

Four small golden chairs are set.

"Seated on these golden chairs,

Little dames with darts of gold

In their hair are playing cards—

Clara wins at every game.

"Yes, she wins and smiles in glee.

Clara, oh, within my heart,

Thou can'st never fail to win,

For thou holdest all the trumps!"

On I wandered and I spoke

Thus unto myself. How strange!

Lunacy itself sits there

Singing on the road to Spain.

Is this madman not a sign

Of how nations trade in thought?

Or is he his native land's

Wild and crazy title-page?

Twilight sank before we came

To a wretched old posada

Where podrida—favourite dish!

Steamed within a dirty pot.

There garbanzos did I eat

Huge and hard as musket-balls,

Which not e'en a native Teuton,

Bred on dumplings, could digest.

And my bed was of a piece,

With the cooking. Insects vile

Dotted it. Oh, surely these

Are the grimmest foes of man!

Far more fearful than the wrath

Of a thousand elephants,

Is one small and angry bug

Crawling o'er thy lowly couch.

Helpless thou against its bite—

That is bad enough!—but worse

Evil comes if it be crushed

And its horrid smell released.

All Life's terrors we may taste

In the war with vermin waged,

Vermin well-equipped with stinks,

And in duels with a bug.

|

|

|

CANTO XII

How they rave, the blessèd bards—

Even the tamest! how they sing,—

How they do protest that Nature

Is a mighty fane of God!

One great fane whose splendours all

Of the Maker's glory tell;

Sun and moon and stars they vow

Hang as lamps within the dome.

Yet concede, most worthy folk,

That this mighty temple hath

Most uncomfortable stairs,

Stairs most villainously bad!

All this climbing up and down,

Escalading, jumping o'er

Boulders—how it tires me

Both in spirit and in legs!

By my side Lascaro strode,

Like a taper long and pale—

Never speaks he, never laughs—

He the witch's lifeless son.

For they say Lascaro died

Many years ago—his mother's,—

Old Uraka's,—magic draughts

Gave to him a seeming life.

These confounded temple steps!

How it chanced that I escaped

With whole vertebræ will puzzle

Me until my dying day.

How the torrents foamed and roared!

Through the pines how lashed the wind

Till they groaned! Then suddenly

Burst the clouds! O weather vile!

In a fisherman's poor hut

Close by Lac de Gaube we gained

Shelter and a mess of trout—

Dish divine and glorious!

In his padded arm-chair there

Sat the ancient ferryman,

Ill and grey. His nieces sweet

Like two angels tended him.

Plumpest angels, Flemish quite,

As if out of Rubens' frame

They had leaped, with golden locks,

Sparkling eyes of limpid blue,

Dimples in each ruddy cheek

Where bright mischief peered and hid,

And with limbs robust and lithe,

Waking both desire and fear.

Sweet and bonny creatures they

Who disputed prettily

Which might prove the sweetest draught

To their ancient, ailing charge.

If one proffers him a brew

Made of linden-flower tea,

Then the other tempts him with

Possets made of elder-blooms.

"I will swallow none of this!"

Cried the greyhead, sorely tried,

"Bring me wine so that my guest

May have worthy drink with me!"

If this stuff was really wine

Which I drank at Lac de Gaube—

Who can tell? My countrymen

Would have dubbed it sweetish beer.

Vilely smelled the wine-skin too,

Fashioned from a black goat's hide.

But the old man drank and drank

And grew jubilant and gay.

Of banditti tales he told

And of smugglers, merry men

Who still ply their goodly trades

Freely in the Pyrenees.

Many ancient stories, too,

He recited, as of wars

'Twixt the giants and the bears

In the grey primeval days.

For it seems the bears and ogres

Waged a war for mastery

Of these ranges and these vales

Long ere man came wandering in.

Startled then at sight of men

All the giants fled the land;—

Only tiny brains were housed

In their huge, unwieldy heads!

It is also said these dolts,

When they reached the ocean-shore

Where the azure skies lay glassed

In the watery plains below,

Fondly fancied that the sea

Must be Heaven. In they plunged

All in reckless confidence,

And in watery graves were gulfed.

Now the bears are slain by man,

And each year their number grows

Smaller, smaller, till at last

None shall roam within the hills.

"And," the old man cackled, "thus

On this Earth must one yield room

To the other—after man

We shall have a reign of dwarfs.

"Tiny and most clever wights

Toiling in the bowels of Earth,

Busy little folk that gather

Riches from Earth's golden veins.

"I have seen their rounded heads

Peering out of rabbit-holes

In the moonlight—and I shook

As I thought of coming days.

"Yes, I dread the golden power

Of these mites. Our sons, I fear,

Will like stupid giants plunge

Straight into some watery heaven."

|

|

CANTO XIII

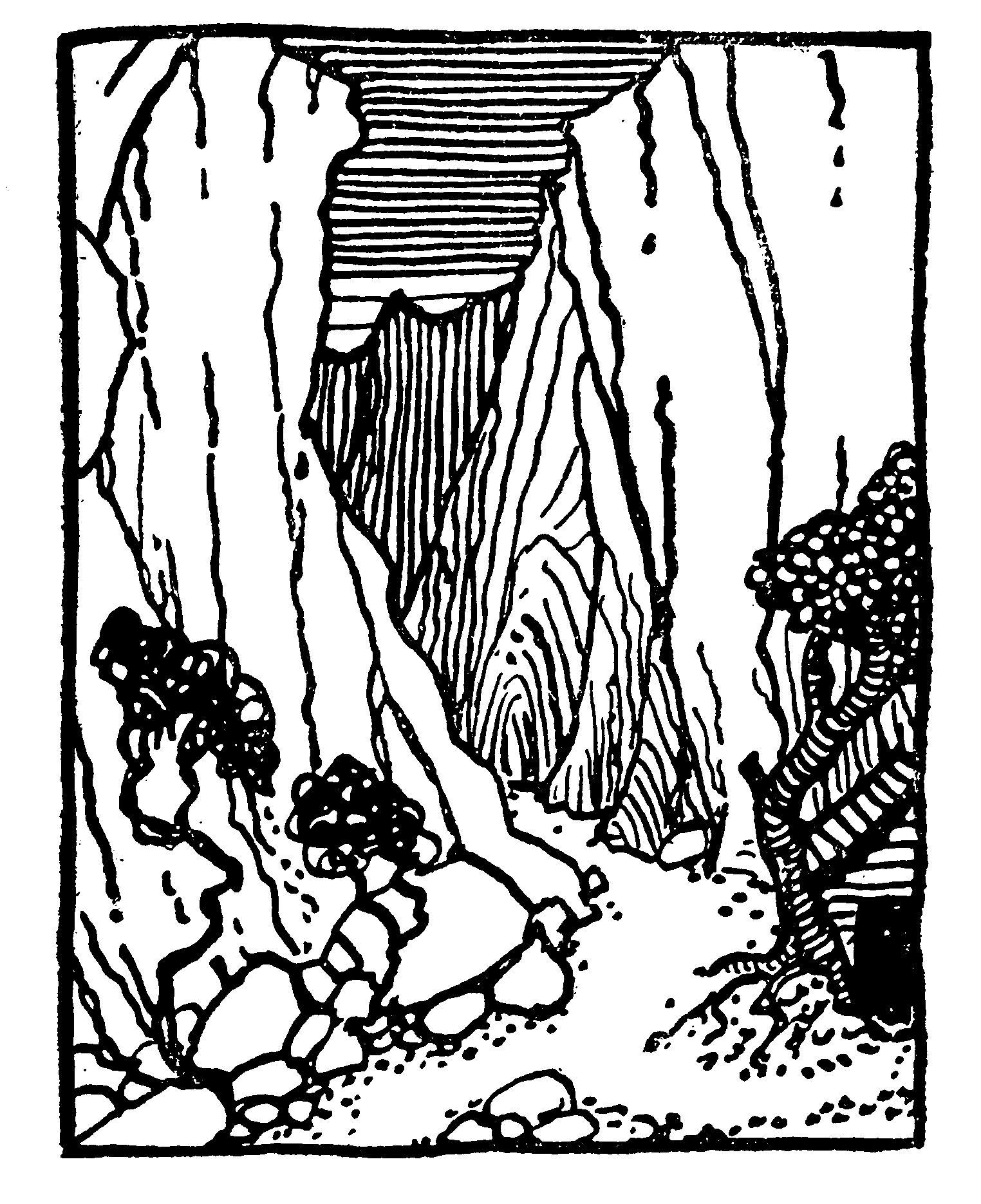

In the cauldron of the cliffs

Lies the deep and inky lake.

And from heaven the solemn stars

Peer upon us. Night and stillness.

Night and stillness. Beat of oars.

Like a rippling mystery

Swims our boat. The nieces twain

Serve in place of ferrymen.

Swift and blithe they row. Their arms

Sometimes shine from out the night,

And on their white skins the stars

Gleam and on large eyes of blue.

At my side Lascaro sits

Pale and mute as is his wont,

And I shudder at the thought:

Is Lascaro really dead?

Or perchance 'tis I am dead?

I, perchance, am drifting down

With these spectral passengers

To the icy realm of shades?

Can this lake be Styx's dark,

Sullen flood? Hath Proserpine,

In the absence of her Charon

Sent her maids to fetch me down?

Nay, not yet my days are done!

Unextinguished in my soul

Still the living flame of life,

Leaps and blazes, glows and sings.

And these girls who swing their oars

Merrily, and splash me too,

Laugh and grin with mischief rare

As the drops upon me flash.

Ah, these wenches fresh and strong,

Surely they could never be

Ghostly hell-cats, nor the maids

Of the dark queen Proserpine.

So that I might be assured

Of the girls' reality,

And unto myself might prove

My own honest flesh and blood,—

On their rosy dimples I

Swiftly pressed my eager lips,

And to this conclusion came:

Lo, I kiss; therefore I live!

When we reached the shore, again

Did I kiss these bonny maids,—

Kisses were the only coin

Which in payment they would take.

|

|

|

CANTO XIV

Joyous in the golden air

Lift the purple mountain heights

Where a daring hamlet clings

Like a nest against the steep.

Wearily I climbed and climbed.

When at last I stood aloft,

Then I found the old birds flown

And the fledglings left behind.

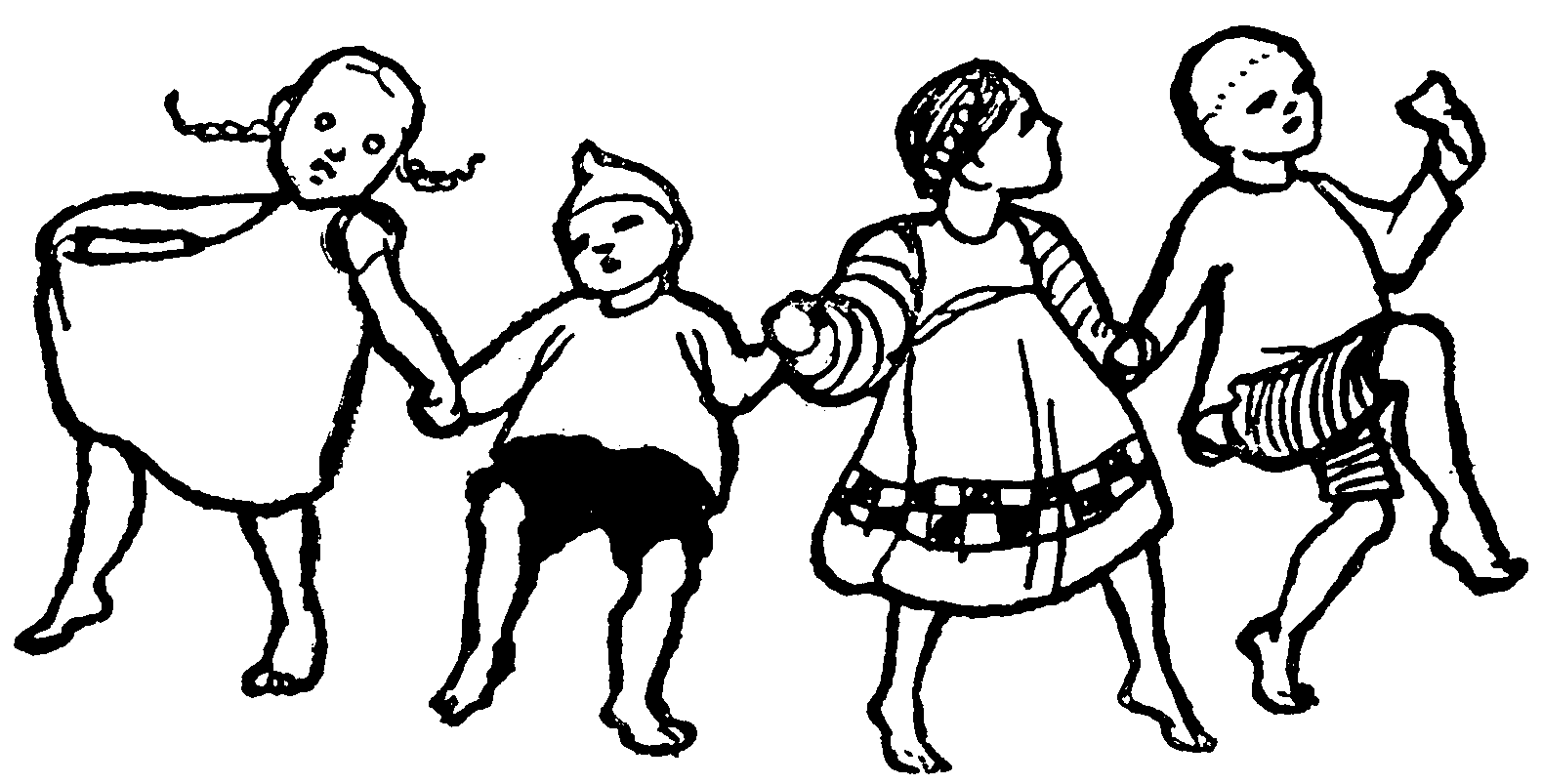

Pretty lads and lassies small

With their little heads half hid

In their white and scarlet caps,

Played at bridals in the mart.

Neither stay nor halt they brooked,

And the little love-lorn Prince

Of the Mice knelt down at once

To the Cat-King's daughter fair.

Hapless Prince! At last he's wed

To the Princess. How she scolds!

Bites him and devours him—

Hapless mouse!—thus ends the play.

That entire day I spent

With the children, and we talked

Cosily. They longed to know

Who I was? and what my trade?

"Germany, my dears," I spoke,

"Is my native country's name—

Bears are all too common there,

So I took to hunting bears!

"Many a bear-pelt have I pulled

Over many a bearish head,

Though, 'tis true, I sometimes got

Damage from their bearish paws.

"But at last I felt disgust

Of this strife with ill-licked boors

In my blessèd land—I grew

Weary of these daily moils.

"So in quest of nobler game,

I at last have come to you;

I shall try my little strength

'Gainst the mighty Atta Troll.

"Worthy of me is this noble

Foe. In Germany, alas!

Many a battle did I win,

Most ashamed of victory."

When I left, the little folk

Danced about me in a ring,

And in sweetest wise they sang:

"Girofflino! Girofflett'!"

And the youngest of them all

Stepped before me quick and pert,

And four times she curtsied low

As she sang in silver tones:

"Curtsies two I give the King,

Should I meet him. And the Queen,

Should I meet her, then I give

Curtsies three unto the Queen.

"But should I the devil meet

With his fiery eyes and horns,

I will make him curtsies four—

Girofflino! Girofflett'!"

"Girofflino! Girofflett'!"

Shouts once more the mocking band,

And around me swings the gay

Ring-o'-roses with its song.

As I scrambled down the slopes,

After me in echoes sweet,

Came these words in bird-like strains:

"Girofflino! Girofflett'!"

|

|

|

CANTO XV

Hulking and enormous cliffs

Of deformed and twisted shapes

Look on me like petrified

Monsters of primeval times.

Strange! the dingy clouds above

Drift like doubles bred of mist,

Like some silly counterfeit

Of these savage shapes of stone.

In the distance roars the fall;

Through the fir trees howls the wind!

'Tis a sound implacable

And as fatal as despair.

Lone and dreadful lies the waste

And the black daws sit in swarms

On the bleached and rotten pines,

Flapping with their weary wings.

At my side Lascaro strides

Pale and silent—I myself

Must like sorry madness look

By dire Death accompanied.

'Tis a wild and desert place.

Curst perchance? I seem to see

On the crippled roots of yonder

Tree a crimson smear of blood.

This tree shades a little hut

Cowering humbly in the earth,

And the wretched roof of thatch

Pleads for pity in your sight.

Cagots are the denizens

Of this hut—the last remains

Of a tribe which sunk in darkness

Bides its bitter destiny.

In the heart of every Basque

You will find a rooted hate

Of the Cagots. 'Tis a foul

Relic of the days of faith.

In the minster at Bagnères

You may see a narrow grille,

Once the door, the sexton told me,

Which the herded Cagots used.

In that day all other gates

Were forbidden them. They crawled

Like to thieves into the blest

House of God to worship there.

There these wretched beings sat

On their lowly stools and prayed,

Parted as by leprosy,

From all other worshippers.

But the hallowed lamps of this

Later century burn bright,

And their light destroys the black

Shadows of that cruel age!

While Lascaro waited there,

Entered I the lonely hut

Of the Cagot, and I clasped

Straight his hand in brotherhood.

Likewise did I kiss his child

Which unto the shrivelled breast

Of his wife clung fast and sucked

Like some spider sick and starved.

|

|

|

CANTO XVI

Shouldst thou see these mountain peaks

From the distance thou wouldst think

That with gold and purple they

Flamed in splendour to the sun.

But at closer hand their pomp

Vanishes. Earth's glories thus

With their myriad light-effects

Still beguile us artfully.

What to thee seemed blue and gold

Is, alas, but idle snow,

Idle snow which, lone and drear,

Bores itself in solitude.

There upon the heights I heard

How the hapless crackling snow

Cried aloud its pallid grief

To the cold and heartless wind:

"Ah," it sobbed, "how slow the hours

Crawl within this awful waste!

All these many endless hours,

Like eternities of ice!

"Woe is me, poor snow! I would

I had never seen these peaks—

Might I but in vales have fallen

Where a myriad flowers bloom!

"To some little brook would I

Then have melted, and some maid—

Fairest of the land! with smiles

Would in me have laved her face.

"Yea, perchance, I might have fared

To the sea and changed betimes

To a pearl and gleamed at last

In some royal coronet!"

When I heard this plaint, I spake:

"Dearest Snow, indeed I doubt

Whether such a brilliant fate

Had been thine within the world.

"Comfort take. Few, few, indeed,

Ever grow to pearls. No doubt

Thou hadst fallen in the mire

And become a clod of mud."

As in kindly wise I spoke

Thus unto the joyless snow,

Came a shot—and from the skies

Plunged a hawk of brownish wing.

It was just a hunter's joke

Of Lascaro's. But his face

Was as ever stark and grim,

And his rifle barrel smoked.

Silently he tore a plume

From the hawk's erected tail,

Stuck it in his pointed hat

And resumed his silent way.

'Twas an eerie sight to see

How his shadow black and thin

With the nodding feather moved

O'er the slopes of drifted snow.

|

|

CANTO XVII

Lo, a valley like a street!

'Tis the Hollow Way of Ghosts:

Dizzily the cloven crags

Tower up on every side.

There upon the sheerest slope

Hangs Uraka's little shack

Like some outpost over chaos—

Thither fared her son and I.

In a secret dumb-show speech

He took counsel with his dam,

How great Atta Troll might best

Be ensnared and safely slain.

We had found his mighty spoor.

Never more canst thou escape

From our hands! thine earthly days

All are numbered—Atta Troll!

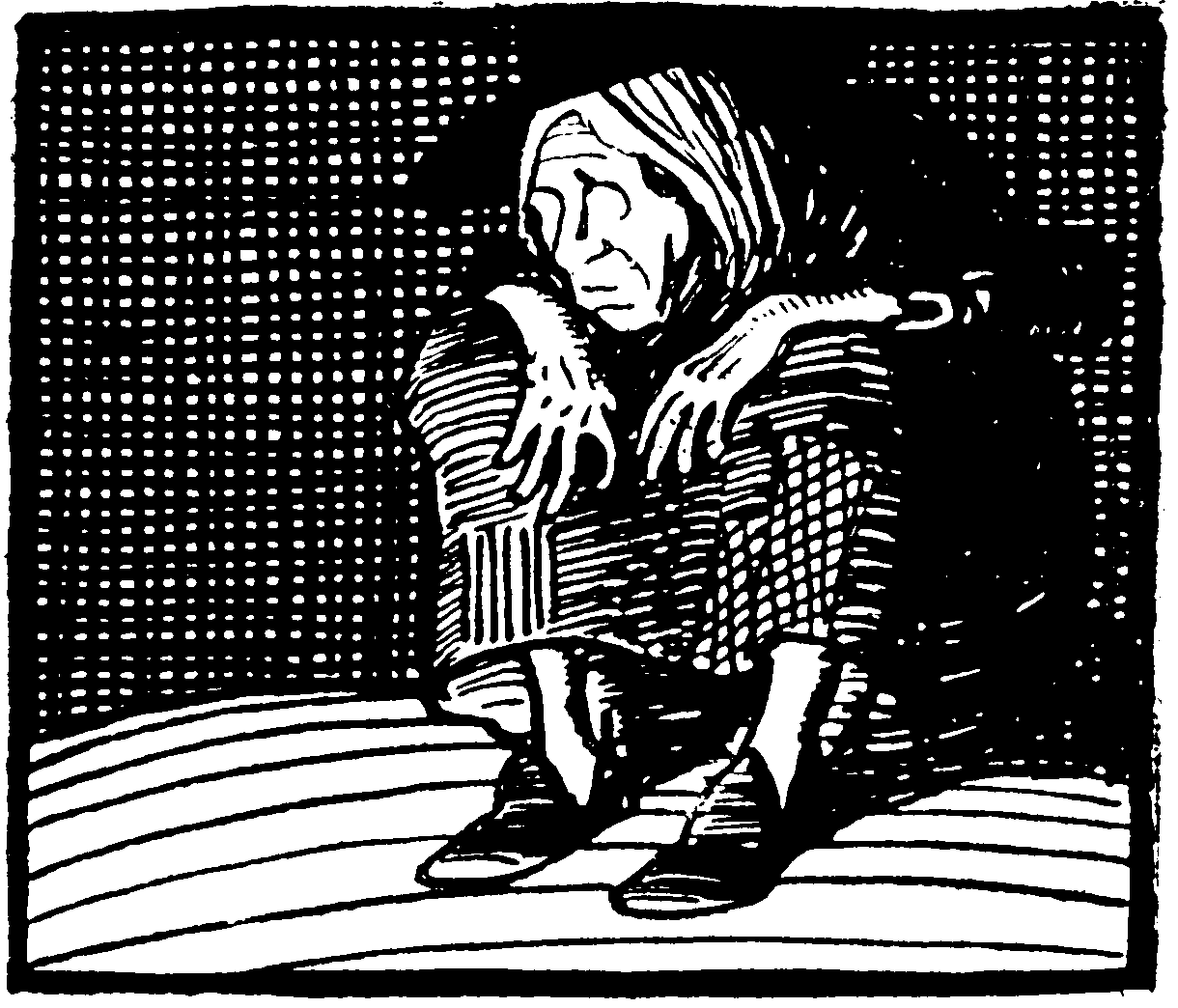

Never could I well determine

If Uraka, ancient hag,

Was in truth a potent witch,

As within these Pyrenees

It was rumoured. But I know

That in truth her very looks

Were suspicious. Most suspicious

Were her red and running eyes.

Evil is her look and slant.

It is said whene'er she stares

At some hapless cow, its milk

Dries, its udder withers straight.

It is said that stroking with

Her thin fingers, many a kid

She had slaughtered, many a huge

Ox had stricken unto death.

Oft within the local court

For such crimes arraigned she stood,

But the Justice of the Peace

Was a true Voltairean.

Quite a modern worldling he,

Shallow and devoid of faith,—

So the plaintiffs he dismissed

Both in mockery and scorn.

The alleged official trade

Of Uraka's honest quite,

For she deals in mountain-herbs

And in birds that she has stuffed.

Her entire hut was crammed

With such relics. Horrible

Was the smell of cuckoo-flowers,

Fungi, henbane, elder-blooms.

There a fine array of hawks

To advantage was displayed,

All with pinions stretching wide

And with grim enormous bills.

Was it but the breath of these

Maddening plants that turned my brain?

Still the vision of these birds

Filled me with the strangest thoughts.

These perchance are mortal wights,

Bound by sorcery in this

Miserable state as birds

Stuffed and most disconsolate.

Sad, pathetic is their stare,

Yet it hath impatience too,

And, methinks at times they cast

Sidelong glances at the witch.

She, Uraka, ancient, grim,

Crouches low beside her son,

Mute Lascaro near the fire

Where the twain are casting slugs.

Casting that same fateful ball

Whereby Atta Troll was slain.

How the lurching firelight flares

O'er the witch's features gaunt!

Ceaselessly, yet silently

Move her thin and quivering lips.

Are those magic spells she murmurs

That the balls may travel true?

Now and then she nods and titters

To her son. But he is deep

In the business of the casts

And sits silently as Death.

Overcome by fevered fears,

Yearning for the cooler air,

To the window then I strode

And looked down the gulches dim.

All that in that midnight hour

I beheld, all that will I

Faithfully and featly tell

In the canto that shall follow.

|

|

|

CANTO XVIII

'Twas the night before Saint John's,

In the fullness of the moon,

When that wild and spectral hunt

Fills the Hollow Way of Ghosts.

From the window of Uraka's

Little cabin I could see

All that mighty host of wraiths

As it drifted through the gorge.

Yea, a goodly place was mine

Wherefrom I might well behold

The tremendous spectacle

Of the raised, carousing dead.

Cracking whips, hallo! hurrah!

Neigh of horses, bark of dogs,

Laughter, blare of huntsmen's horns—

How the tumult echoed there!

Dashing in advance there came

Stags and boars adventurous

In a solid pack; behind

Charged a wild and merry rout.

Huntsmen come from many zones

And from many ages too.

Charles the Tenth rode close beside

Nimrod the Assyrian.

High upon their snowy steeds

They charged onward. Then on foot

Came the whips with hounds in leash

And the pages with the links.

Many in that maddened horde

Seemed familiar—yon knight

Gleaming all in golden mail,—

Surely was King Arthur's self!

And Lord Ogier the Dane

In chain-armour shining green,

Truly close resemblance bore

To some mighty frog forsooth!

Many a hero I beheld

Of the gleaming world of thought;

Wolfgang Goethe straight I knew

By the sparkling of his eyes.

Being damned by Hengstenberg,

In his grave no peace he finds,

So with pagan blazonry

Gallops down the chase of Life.

By the glamour of his smile

Did I know the mighty Will

Whom the Puritans once cursed

Like our Goethe,—yet must he,

Luckless sinner, in this host

Ride a charger black as coal.

Close beside him on an ass

Rode a mortal and—great heavens!

By the weary mien of prayer

And the snowy night-cap too,

And the terror of his soul,

Francis Horn I recognized.

Commentaries he composed

On that great and cosmic child,