The Project Gutenberg EBook of Happy Days for Boys and Girls, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Happy Days for Boys and Girls Author: Various Release Date: December 20, 2009 [EBook #30720] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HAPPY DAYS FOR BOYS AND GIRLS *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Sam W. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

136 ILLUSTRATIONS

CONTRIBUTIONS BY

LOUISA M. ALCOTT, ALICE AND PHŒBE CAREY, C. A. STEPHENS,

MARY N. PRESCOTT, WILLIAM M. THAYER, F. CHESEBORO,

J. G. WOOD, S. W. LANDER, and others.

PHILADELPHIA:

PORTER & COATES,

822 CHESTNUT STREET.

————

Copyright, 1877,

By Horace B. Fuller and Porter & Coates.

————

————

PRESS OF

HENRY B. ASHMEAD.

PHILADELPHIA.

————

YOUNG FISHERS.

| PAGE | ||

| Accident, The | Louisa M. Alcott | 280 |

| Adventure in the Life of Salvator Rosa | L. D. L. | 84 |

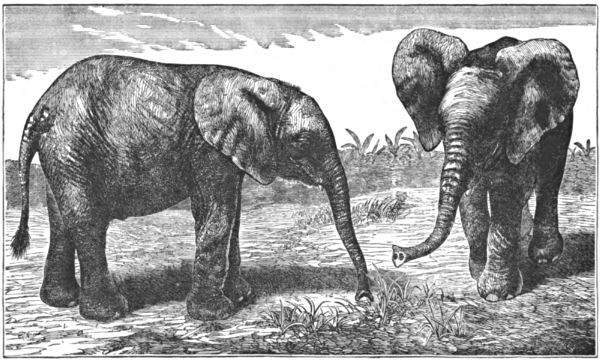

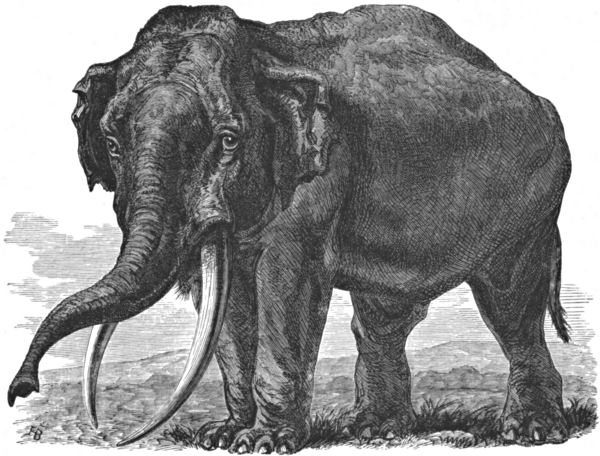

| African Elephant, The | J. G. Wood | 319 |

| Animal in Armor, The | 75 | |

| Aunt Thankful | M. H. | 253 |

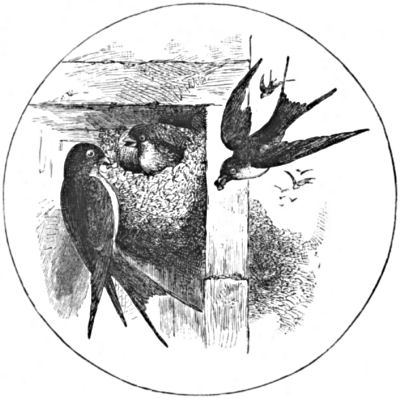

| Barn Swallows | W. Wander | 194 |

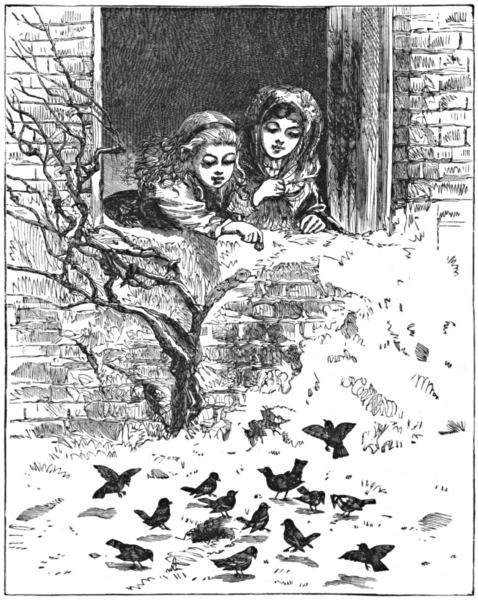

| Birds | F. F. E. | 25 |

| “Bitters” | 203 | |

| Books and Reading | 36 | |

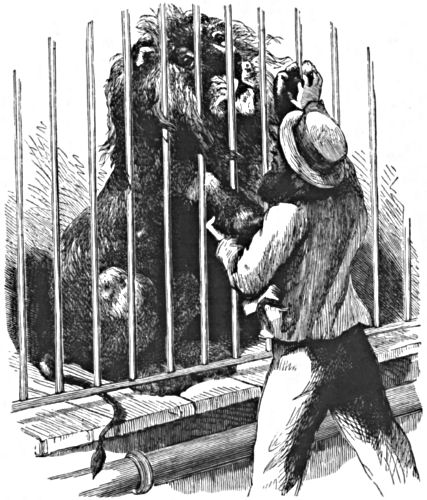

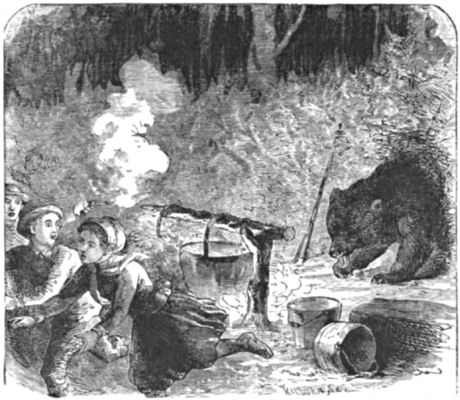

| Bruin at a Maple-Sugar Party | C. A. Stephens | 313 |

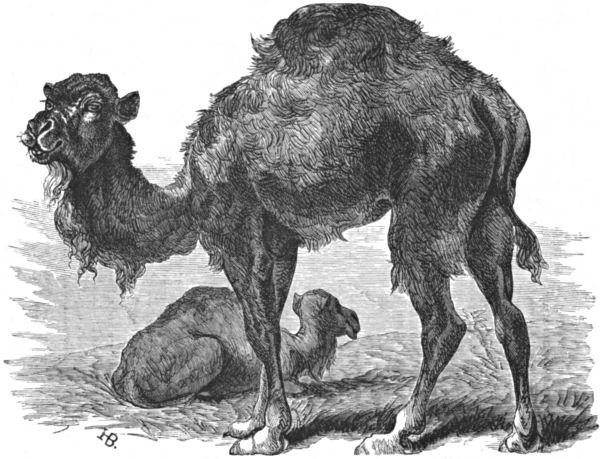

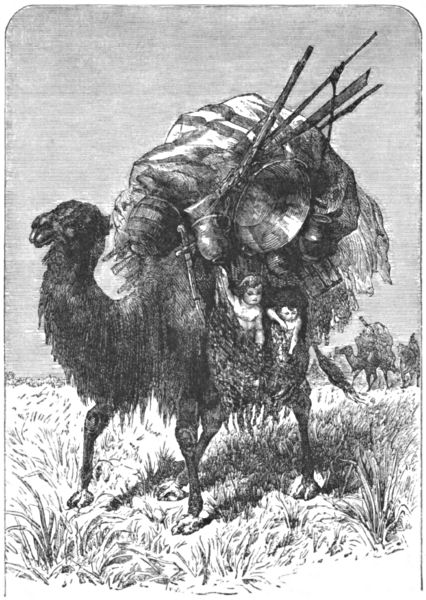

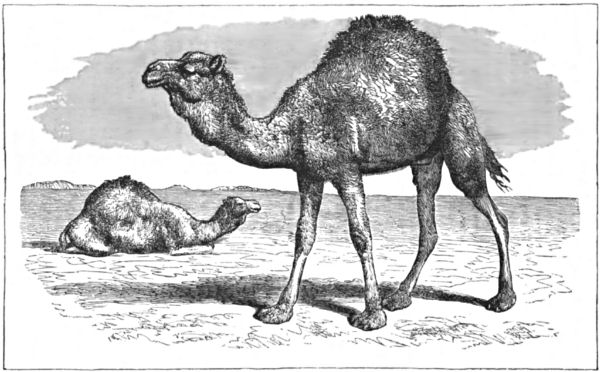

| Camels | J. G. Wood | 339 |

| Cave at Benton’s Ridge | F. E. S. | 350 |

| Charley | 368 | |

| Charlie’s Escape | 109 | |

| Charlie’s Christmas | 79 | |

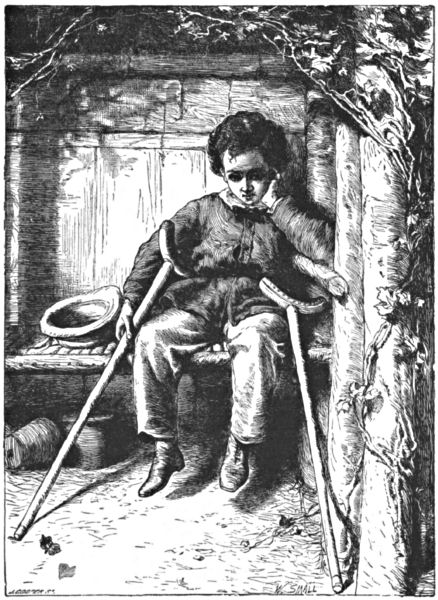

| Crippled Boy, The | S. W. Lander | 374 |

| Daisy’s Temptation | 111 | |

| Daring Feat | 183 | |

| Davy Boys’ Fishing-Pond | L. M. D. | 130 |

| Envy Punished | 271 | |

| Every Cloud has a Silver Lining | 31 | |

| Faithful Friends | X. | 237 |

| Fairy Bird, The | Louisa M. Alcott | 207 |

| Fred and Dog Stephen | 205 | |

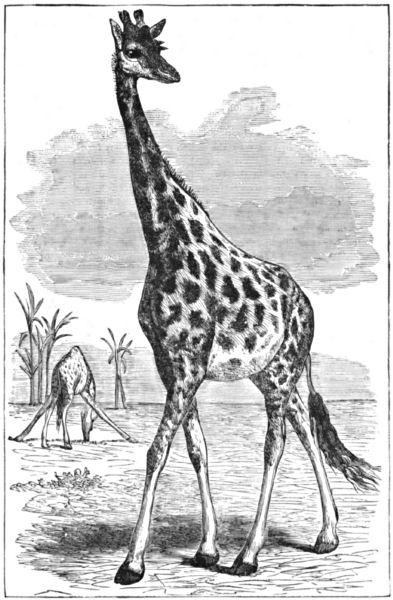

| Giraffe, The | J. G. Wood | 188 |

| Going for the Letters | 198 | |

| Good Word not Lost | 308 | |

| Gratitude of a Cow | 196 | |

| Haunts of Wild Beasts | C. A. Stephens | 355 |

| Help Yourselves | Wm. M. Thayer | 46 |

| Holiday Luck | Sara Conant | 296 |

| How a Good Dinner was Lost | Fannie Benedict | 256 |

| How Maggie paid the Rent | 227 | |

| [Pg 6] | ||

|

||

| How Sweetie’s “Ship came In” | Margaret Field | 96 |

| Hunting Adventure | 362 | |

| If; or, Bessie Green’s Holiday | 176 | |

| Iron Ring, The | A. L. O. E. | 76 |

| It takes Two to Make a Quarrel | 306 | |

| John Stocks and the Bison | Author of “Drifting to Sea” | 138 |

| Kindness Rewarded | 28 | |

| Kindness to Animals | Robert Handy | 284 |

| Lace-making | 44 | |

| Lame Susie | 261 | |

| Lion the Fire-dog | Benjamin Clarke | 38 |

| Lion on the Threshold | 190 | |

| Marcellin | 82 | |

| Merry Christmas | E. G. C. | 166 |

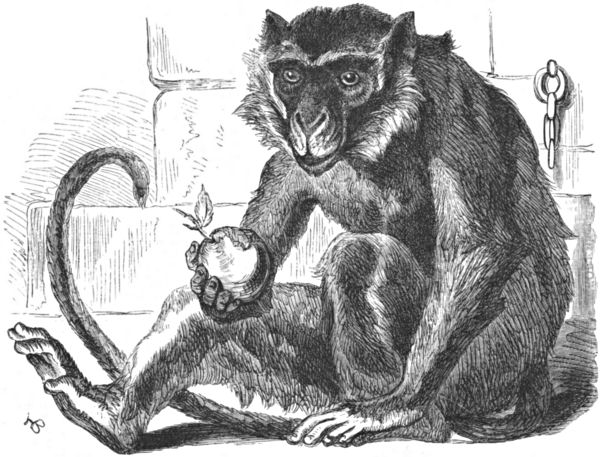

| Monkeys | L. B. U. | 301 |

| Motherless Boy, The | 49 | |

| Mouse and Canary, The | 287 | |

| Mrs. Pike’s Prisoners | M. R. W. | 123 |

| My Mother’s Stories | E. E. | 303 |

| My Story | S. P. Brigham | 332 |

| Nearly Lost | 365 | |

| Neddy’s Half Holiday | 121 | |

| Nicolo’s Little Friend | H. A. F. | 390 |

| Nino | Sara Conant | 244 |

| Orchard’s Grandmother | S. O. J. | 9 |

| Parsees, The | 371 | |

| Polly Arrives | Louisa M. Alcott | 282 |

| Ponto | 310 | |

| Puppet | Mary B. Harris | 162 |

| Puss | Robert Handy | 293 |

| Que | Mary B. Harris | 144 |

| Reason and Instinct | Flaneur | 60 |

| Reginald’s First School-Days | 384 | |

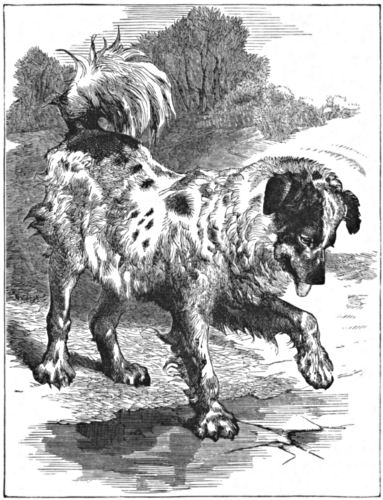

| Rough | M. R. O. | 17 |

| Sally Sunbeam | 251 | |

| Saved by a Fiddle | Sir Lascelles Wraxall | 211 |

| Song of the Bird | 323 | |

| Squanko | F. Cheseboro | 274 |

| Squirrels | 160 | |

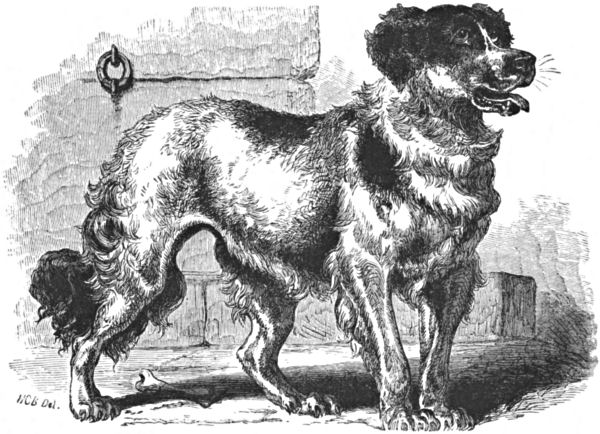

| St. Bernard Dog | 53 | |

| Stitching and Teaching | E. G. C. | 152 |

| Stories about Dogs | 137 | |

| Strange Combat, A | C. A. Stephens | 116 |

| Sweet One for Polly | Louisa M. Alcott | 277 |

| [Pg 7] | ||

|

||

| Thorns | 347 | |

| Tim the Match-Boy | 268 | |

| Truant, The | 393 | |

| Two Friends. A Story for Boys | 288 | |

| Two Gentlemen in Fur Cloaks | 107 | |

| Uncle John’s School-Days | 234 | |

| What Nelly gave Away | 115 | |

| White Butterfly | 63 | |

| Wings | 273 | |

| Working is Better than Wishing | 65 | |

| Young Artist, The | 218 | |

| All among the Hay | 286 | |

| Annie | 175 | |

| Answer to a Child’s Question | 113 | |

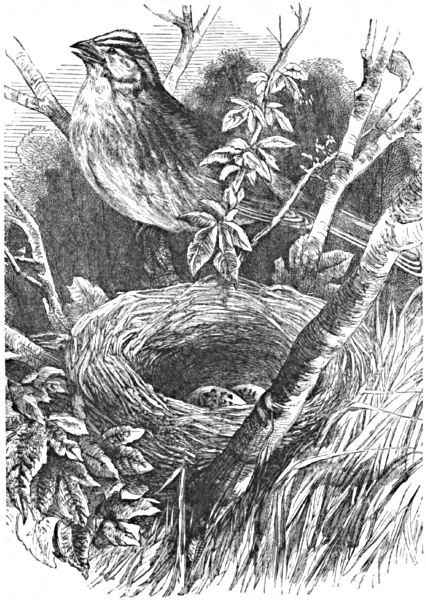

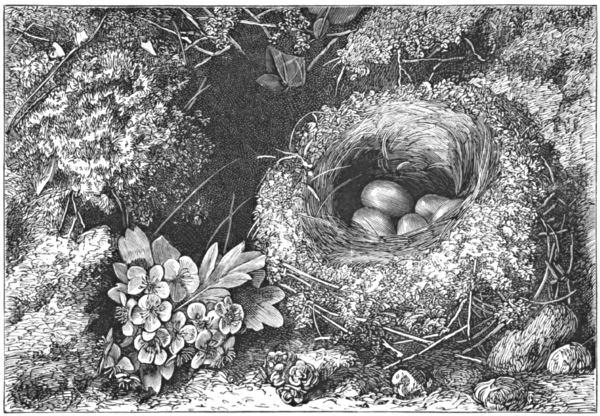

| Bird’s Nest, The | Mary. N. Prescott | 216 |

| C—A—T | 186 | |

| Cherry-Time | 128 | |

| Child’s Petition | 392 | |

| Child’s Prayer | 137 | |

| Children | 62 | |

| Children’s Song | 141 | |

| Cleopatra | Edgar Fawcett | 388 |

| Common Things | 249 | |

| Coral-Workers, The | 37 | |

| Counting Baby’s Toes | 345 | |

| Dinner and a Kiss | 381 | |

| Dream of Summer, A | Mary N. Prescott | 29 |

| Erl King | Mary N. Prescott | 241 |

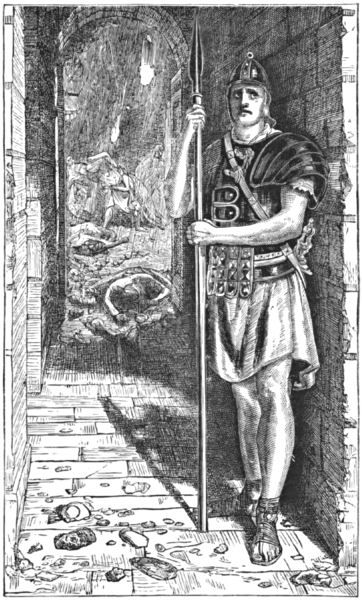

| Faithful unto Death; or, The Sentry of Herculaneum | W. B. B. Stevens | 230 |

| Flight of the Birds | 56 | |

| For the Children | 58 | |

| Forced Rabbit, The | 180 | |

| From Bad to Worse | Alice Cary | 331 |

| Frost, The | 22 | |

| Good-Humor | 35 | |

| Good Shepherd, The | 52 | |

| I am Coming | 110 | |

| Kind to Everything | 68 | |

| Let him Live | Mary R. Whittlesey | 300 |

| Little Helpers | 73 | |

| Little Home-body | Geo. Cooper | 119 |

| [Pg 8] | ||

|

||

| Little Red Riding-Hood | L. E. Landon | 224 |

| My Little Hero | 92 | |

| My Mother | 382 | |

| Minutes | 196 | |

| My Picture | 23 | |

| Music Lesson, The | 22 | |

| Nothing to Do | 105 | |

| Now the Sun is Sinking | 206 | |

| Our Daily Bread | 157 | |

| Preparing for Christmas | 143 | |

| Rich and Poor | Ellen M. H. Gates | 42 |

| Rigmarole about a Tea-Party | 206 | |

| Robin Redbreast | 95 | |

| Rustic Mirror, The | M. R. W. | 222 |

| Sailing the Boats | George Cooper | 305 |

| Secret | Mary R. Whittlesey | 264 |

| Shakspeare | Richard H. Stoddard | 389 |

| Sheep and the Goat | 328 | |

| Silly Young Rabbit, The | 242 | |

| Silver and Gold | Ellis Gray | 265 |

| Smiles and Tears | 390 | |

| Snow-Fall | 151 | |

| Snow-Man, The | Marian Douglas | 192 |

| Song of the Rose | T. E. D. | 41 |

| Sparrow, The | 122 | |

| Spring has Come | 202 | |

| Story of Johnny Dawdle | 47 | |

| Summer | 78 | |

| That Calf | Phœbe Cary | 70 |

| To the Cardinal Flower | M. R. W. | 40 |

| Touch Not | 61 | |

| Two Mornings | Mary N. Prescott | 267 |

| Under the Pear Trees | 349 | |

| Up and Doing | 182 | |

| Vacation | Beverly Moore | 232 |

| War and Peace | 126 | |

| Way to Walk | M. R. W. | 337 |

| We should hear the Angels singing | Kate Cameron | 91 |

| What so Sweet | Mary N. Prescott | 344 |

| What the Clock says | 149 | |

| Why | 24 | |

| Willie’s Prayer | 159 | |

| World, The | Lilliput Lectures | 185 |

| Worship of Nature | 361 | |

I MUST ask you to go back more than two hundred years, and watch two people in a quiet old English garden.

One is an old lady reading. In her young days she was a famous beauty. That was very long ago, to be sure; but I think she is a beauty still—do not you?

She has such a lovely face, and her eyes are so sweet and bright! and better than that, they are the kind which see pleasant things in everybody, and something to like and be interested in. I hope with all my heart yours are that kind, too.

The other person is a little child. She was christened Mary Brenton, like her grandmother; but she was called Polly all her days, for short; and we will call her so.

She is sitting on the grass with a little cat in her arms, which she is trying [Pg 10] to put to sleep. But the kitten is not so accommodating as a doll would be, and just as Polly does not dare to move for fear of waking her, she makes up her mind that a run after a leaf and a play with any chance caterpillar which may be so unlucky as to cross her path, will be very preferable, and tries to get away.

It is one of the most delightful days that ever was. September, and almost too warm, if it were not for the breeze that brings cooler air from the sea. Once in a while some fruit falls from the heavily-laden trees, and the first dead leaves rustle a little on the ground. The bees are busy, making the most of the bright day; for they know of the stormy weather coming. The sky is very blue, and the flowers very bright. Two swallows are playing hide-and-seek through the orchard, and chasing each other in great races, now so close to the ground that it seems as if their feet might catch in the green grass, and now away up in the air over the high walls out towards the hills; and just as one loses sight of them, and turns away, here they are again. And in the kitchen the girls are clattering the dishes and laughing; and do you hear some one singing a doleful tune in a cheery, happy voice?

That is Dorothy, Polly’s dear Dorothy, who waits upon grandmother, with whom she has been to France, and Holland, and Scotland, and who can tell almost as charming stories as grandmother herself.

The house is large and old, with queer-shaped windows, all sizes and all heights from the ground, and a great many of them hidden by the ivy. That is the outside; and if you were to go in, you would find large, low rooms, filled with furniture that you would think queer and uncomfortable. And there are portraits in some of them, one of Polly, probably painted not very long before, in which she is attired after the fashion of those days, and looks nearly as old as she would now if she were living!

Now let us go back to the garden. The kitten has escaped, and Polly is wishing for something to do.

“Where’s Dolly?” says grandmother. “Find her, and then gather some apples and plums, and have a tea drinking.”

The doll had been very ill all day; it was strange in grandmother to forget it. She had fallen asleep just before dinner, and been put carefully in her bed; it would never do to wake her so soon. And besides, a tea party was not amusing when there was no one to sit at the other end of the table. This referred to Tom, Polly’s dearest cousin, who had just left her after a long visit; and she missed him sadly.

“And,” says Polly, “I do not think I should care for it if he were here, if I could have nothing but apples. I’m tired of them. I have eaten one of every kind in the garden to-day, even the great yellow ones by the lower gate. I think they’re disagreeable; but I left them till the very last, and then I was afraid they would feel sorry to be left out. I think I will eat another, though; and I will not have a party—it’s a trouble. Which kind would you take, grandmother?”

“One of the very smallest,” says the old lady, laughing; “but stop a moment. I have one I’ll give you;” and she took a beauty from her pocket, and threw it on the grass by Polly.

“That’s the very prettiest apple I ever saw,” says the child. “Where did you get it? Not off our trees. ‘Father gave it to you?’ and where did he find it?”

Grandmother did not know.

LITTLE POLLY.

After admiring her apple a little more, Polly eats it in a most deliberate manner, enjoying every bite as if it were the first she had eaten that day, and when she has finished it, gives a contented little sigh, and sits looking at the fine brown seeds [Pg 12] which she holds in her hand. Presently she says, earnestly,—

“Grandmother!”

“What now, Polly?”

“I wish I had that dear little apple’s two brothers and two sisters, and I would put them in the doll’s chest until to-morrow; I wouldn’t eat them to-day, you know.”

“I will tell you what you can do,” says grandmother. “Are those seeds in your hand? Go find Dorothy, and ask her to give you the empty flower-pot from the high shelf at my window; and then you can fill it with dark earth from one of the flower-beds, and plant them; then by and by you will have a tree, and can have plenty of your apple’s children.”

That was a happy thought. And Polly puts the seeds carefully on a leaf, and runs to find Dorothy. Now she comes back with a queer little Dutch china flower-pot, and sits down on the grass again, and makes a hole in the soft brown earth with her finger, and drops the fine seeds in.

For days she watered them, and carried them to sunny places; but at last she grew very impatient, and one morning, when she was all alone in the garden, very much provoked that they had not made their appearance, took a twig and explored; and the first poke brought to light the little seeds, as shiny and brown as when they left the apple. It was a great disappointment, and Polly caught them up, and threw them as far away as she could, and with tears in her eyes ran in to tell grandmother.

“Ah,” said the dear old lady, “it was not time! Thou hast not learned thy lesson of waiting; and no wonder, when there are few so hard, and thou art still so young.”

Then she sent Polly back to the garden, and the pot was put in its place, again. And a week or two after, as grandmother was just going to make room in the earth for a new plant, she saw growing there a little green sprig, which was not a weed. She listened a moment, and heard the child’s voice outside.

“Polly, my dear, are you sure you scattered all the seeds of your pretty apple the day you were so provoked at their not having begun to grow for you?”

The child reddened a little, and turned away.

“I don’t know, grandmother. I think so; I wished to then.”

How delighted she was when the old lady showed her the treasure, and how carefully it was watched and tended! For one little seed had been buried deeper than the rest, and now in the sunshine of grandmother’s wide window it had come up. Every pleasant day it was placed somewhere in the sun, and at night it was always carried to Polly’s own room. Her dolls and other old play-house friends, formerly much honored, and of great consequence, were quite neglected for “the apple tree,” as she always called the tiny thing with its few bits of leaves.

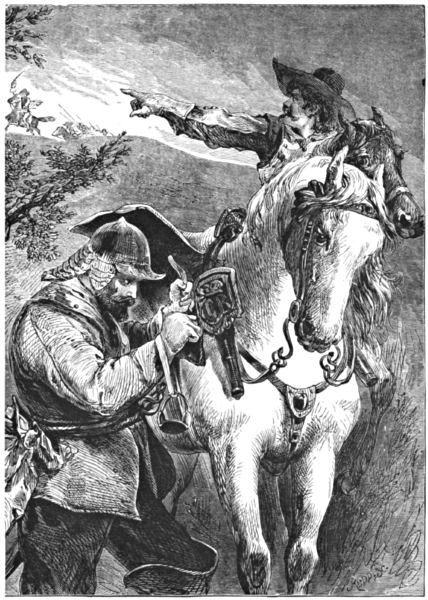

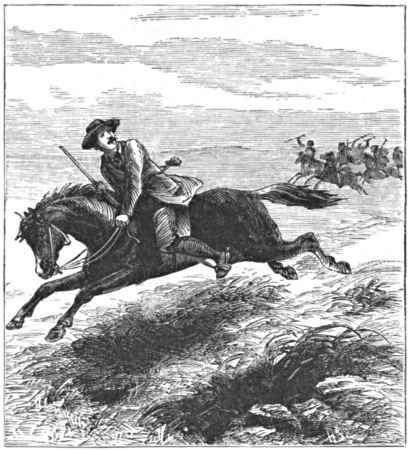

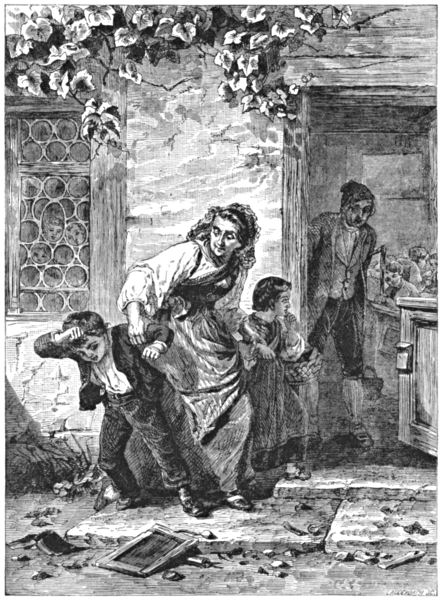

And now we must leave the Brentons’ old stone house and the garden. All this happened in the days of King Charles I., when there was a great war, and the country in a highly discordant state. Polly’s father was on the king’s side, and one day he did something which was considered particularly unpardonable by his enemies, and at night he came riding from Oxford in the greatest hurry he had ever been in; and riding after him were some of Cromwell’s men. It was bright moonlight, and as he rode in the paved yard the great dogs in their kennels began to bark, and that waked Polly’s mother, in a terrible fright at hearing her husband’s voice, and sure something undesirable had happened.

Squire Brenton hurried in to tell her, in as few words as possible, what he had [Pg 13] done, and that he was followed, and had just time to say good by, and take another horse, and rush on to the sea, where he hoped to find a fishing-boat, by means of which he could escape.

“And you,” said he, “had better take Polly and one of the men, and ride to your cousin Matthew’s; for in their rage at my escape, they may mean to burn my house. I little thought a month ago,—when he offered you ‘a safe home,’ and I laughed in his face, and said, ‘Give your good wife the same message; for she may not find your house so safe as mine by and by,’—that you would need to accept so soon.”

“But I cannot go there now,” said Mistress Brenton; “for cousin Matthew is away with the Roundhead army, and his wife and sister have gone to the north. I’ll go with you. Listen: I heard one of the maids say to-day that a ship sails to-morrow at daybreak from the bay by Dunner’s with a company of Puritans for Holland, on their way to one of the American colonies. We will go for a time to our friends in Amsterdam, and be quite safe.”

Anything was better than staying where he was; and Squire Brenton, bidding her hurry, went to the stables with his tired horse, and waking one of his men whom he could trust, told him why he was there, and to say, when the men came, that he was in Oxford yesterday, when they had a letter, and that Mistress Brenton had gone north to some friends. He gave him some messages for his brother, and then, sending him out to a field with the horse he had been riding, which would certainly have betrayed him, he went back to the yard, trying to keep the two fresh horses still, while he listened, fearing every moment to hear his pursuers coming down the road.

Presently out came Mistress Brenton, carrying some bundles of clothing, and a few little things besides, and wrapped in a great riding cloak; and at her side walked Polly, very sleepy, and looking wonderingly in the faces of the others, and asking all manner of childish questions.

Suddenly she ran back to the house, just as her father was going to lift her on his horse; and when she came back, what do you think she had? Together in a little bag were her doll and kitten, and one arm held tightly her little apple tree, wrapped in some garment of her own which she had found lying near it.

And then they rode away. The poor child, after begging them to go to her uncle’s, so she might say good by to grandmother, fell asleep, holding fast her treasures all the while.

There was a faint glimmer of light over the sea as they neared the shore, and they saw anchored at a little distance a small ship, and could see the men moving about her deck; for the wind had risen. Mr. Brenton found a man whom he knew, in whose charge he left the horses, and then a fisherman rowed them to the vessel.

The captain was nowhere to be seen, and the sailors paid no attention to them as they came on deck in the chilly morning twilight; and they went immediately below, and hid themselves in a dark corner, thinking they might have to go ashore if discovered, and that it was best to keep out of sight until it was too late to turn back. In the darkness they fell asleep. This may seem very strange; but remembering the long ride, and the fright they had been in, and that now they felt safe, we can hardly wonder. At any rate, it was the middle of the afternoon before Colonel Brenton—I think I have never given him his title before—made his appearance on deck, to the great astonishment of the captain and all the other people, who knew him more or less. He told the captain what had happened, saying at the end he would pay him double [Pg 14] the usual passage money to Holland, where he meant to stay for a while; and at this the rough man really turned pale.

“Holland, Holland!” said he; “do you not see we’re going down the Channel? We are bound direct for America.”

The story says that Colonel Brenton was almost beside himself, and offered large sums of money to be taken back, or to France; but the captain would not consent, saying that they had made good progress, and it was late in the year. The ship would come back in the spring, and he must content himself.

Those of the ship’s company who knew our friends had great wonderings at their having turned Puritans, until they knew the true state of affairs. Must not it have been dreadful news to Mistress Brenton, and was it not really a dreary prospect—a dreary journey in that frail ship, and at the end a cold, forlorn country? and all the stories of the Indians’ cruelties to the settlers came to her mind. They could not, in all probability, return for many months. No one whom she cared particularly for would be there to welcome them. Polly did not take it very much to heart, though she cried a little because she was not to go to Holland, which she had heard so much of from her grandmother and Dorothy. It was a great many days before they gave up their hope of falling in with some vessel to which they might be transferred; and the first two weeks were sunshiny and pleasant, with a good wind. But soon it grew bleaker and colder, and they suffered greatly. All through the pleasant days, Polly had been having a very enjoyable time. There were several children on board, and they had games around the deck and in the cabin.

It was delightful to have the kitten, who had a cord tied around her neck; and when she was not in Polly’s arms, she was generally anchored for safety in the cabin. Every day she had part of her little mistress’s dinner; and though she missed the garden, and the dead leaves that nestled about the walks, and made such nice playthings, and the sedate old family cat, her mother, and her mother’s numerous poor relations who lived in the stables, she was by no means unhappy. And the doll’s expression was as complacent as ever, though she had worn one gown an astonishing length of time. But if you could have seen the care the little tree received! It was carefully wrapped in the same little cloak Polly put round it the night they left home, and only on the warmest days it was taken on deck to have the sunshine; and every day it had part of Polly’s small allowance of water; and when the kitten had had its share, there would often be very little left.

The weary days went slowly by. The ship was slow at the best, and the winds were contrary. The provisions grew less and less, and the water was almost exhausted. Two people—a man, and a child Polly had grown very fond of—died, and were buried in the sea. The sky was cold and gray, and it snowed and rained, and every one looked sad and disheartened. It was terribly desolate. Polly could not often go on deck, for the frozen spray and rain made it very slippery and dangerous there; and her mother told story after story, and did her best to shorten the longest December days she had ever known. And soon there came a terrible bereavement. One night there was a great storm, and the dearly-beloved kitten, frightened to death by the things rolling about, and the pitching of the ship, broke the cord and rushed out in the darkness, and never was seen any more. I think a little cat has never been so mourned since the world began. That night, the Dutch flower-pot, with its leafless twig, went rolling about the cabin floor, and half the earth was scattered in [Pg 15] the folds of its wrappings, and carefully replaced next morning.

But at last the voyage was ended; they saw land, and finally came close to it and went ashore, Polly with her dear doll and something else rolled up in a little gray cloak. The ship was to stay until spring; and there seemed no hope of getting back to England until then. It was hard to decide what to do; but at last Colonel Brenton heard of some men whom he had known, who had been made prisoners in some of the battles in the north of England and sent to the Massachusetts colony by Cromwell, who had feared to imprison them. They had been sent to the settlement in York.

So the Brentons joined a party going there, or to places beyond. It was the last of January that they came to York, and were warmly welcomed at the great garrison, where they lived till spring. Polly found a very nice child to play with. There had been a good harvest, and the Indians were uncommonly peaceable. They had great log fires in the wide fireplace in the east room; and for a winter in those times, it was very comfortable. The flower-pot was deposited in a chink of the great chimney. Polly had insisted upon bringing it with her; and though “the tree” at that time was a slender little straight stick, she had firm faith that spring time would give it leaves again. And strange to say, she was not disappointed; for all the exposure had not destroyed it. The first of June came, and they were still living in the garrison-house, looking every day for a messenger to tell them the ship was ready to go back. Some people on their way to one of the eastern settlements, early in April, had told them there were no signs of her sailing; and since then they had heard nothing. How dismayed they were, early in June, to find the ship had sailed nearly two months before! It seemed as if everything was against them; and they could live no longer in the garrison. So the Brentons had a little log house near by, and “the squire” worked every day in the great field down towards the river. It must have been such a strange life for them! and I suppose their thoughts often went back to the dear English home. When Mistress Brenton looked from the small window in her log house out over half-cleared fields, and saw the garrison-house, and her husband working among the hills of corn with his gun close by, every now and then looking anxiously about him, she would remember the wide window, with its cushioned seat, in her own room at home, and the sunny garden, with the flowers and bees, and the maids and men singing and chattering in the distance, and the dear voice of grandmother singing the old church hymns. It was a great change; but days much more forlorn than these were yet to come.

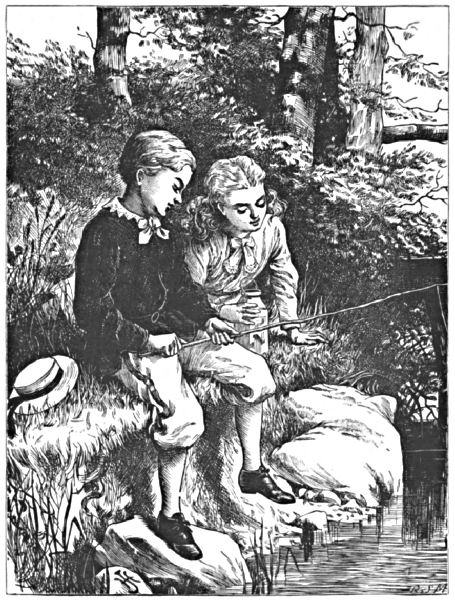

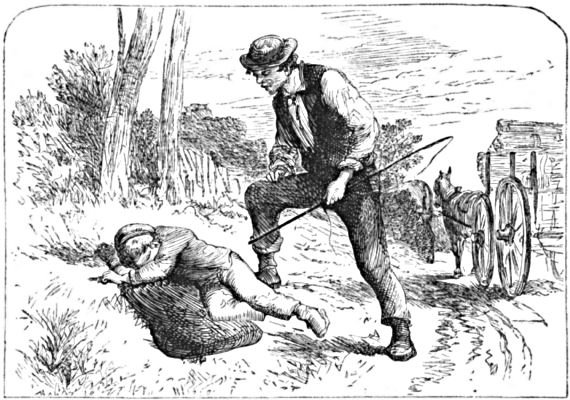

The Indians came around the settlement in large numbers, and no one dared to be out alone. At night the people waked in fear at the slightest noise; and in the daytime it was after the same fashion. News came of whole settlements having been murdered or made captives, and some of their own neighbors disappeared finally; and then the suspense was terrible. At last, one day Mrs. Brenton had gone up to the garrison to see one of the women, who was ill, and most of the men were in the field. Polly went with her mother; but the women were talking over something about the king and Parliament, which she found very uninteresting, and soon she unfastened the great outer door, and unwisely ran out with her doll in her arms, and went down to the field to see the men at work. But on her way, she bethought herself of a charming stump she had seen out at one side of the path, and went to visit it. None of the men happened to see her. [Pg 16] She talked to the doll, and made a throne for her of the soft moss growing around her, and had been playing there some time, when suddenly she heard shouts, and thought they must be killing a snake, and looked up to see all the men running up the hill to the garrison, with a great many Indians chasing them; and she heard a gun fired, and saw one of the men who had petted and been very kind to her, and told her stories, fall to the ground. Ah, how frightened she was!

The doll was snatched from her throne, and the poor little girl ran towards the garrison, too, right towards the Indians. It was weary work running over the rough ground,—and the tall grass was not much better,—and then on, up the hill. By this time the men had succeeded in getting in; and the wicked-looking Indians, after a yell of disappointment, turned to go back to the one who lay dead on the hill-side, and to escape the bullets which would come in a moment from the loopholes. O, if she could only get by them!

Up the hill she hurried as fast as the poor tired little feet could carry her, hugging the doll, almost breathless, with the great tears falling very fast, and still crying, “Wait, father!”

I am glad I know one kind thing the Indians of those days did. As they turned, they saw her coming, and some hurried forward a little to seize her; and it would have been so easy. But one spoke, and they all stopped, and laughed, and shouted, and the child got safely in.

Then the Indians went to the Brentons’ house, and some others, and burned them; but luckily the apple tree was at the play-house, by a large rock, at a little distance, and the wind was not in that direction; and after they disappeared, it was brought up to the fort, safe and sound.

It soon grew tall and strong, and in a little while was entirely too large for its pot; and finally Polly was forced to put it in the ground. It was hard to do it; for she had cared for it, and loved it so long, and this was giving it up, in a measure. And I think if she had understood that now it must be left behind, it would have been almost impossible to have persuaded her. Her father comforted her by telling her he could get quantities of the apples not very far from home, and she could plant more seeds as soon as she liked, or, far better than that, he would graft a tree.

In September, news came that a ship was going to the east coast of England; and they were all heartily glad, in spite of the long, dangerous voyage; and leaving the York friends, who had been so kind, and whom they would probably never see any more, Polly gave the little tree to a Masterson child, her great friend, who promised to wrap it in straw for winter, and to be very kind to it and fond of it. And I think she must have been faithful to her charge. Mistress Brenton laid some of the leaves in the little book she had had in her pocket that night, almost a year ago, when they left home. So they went to Boston, and sailed for the old country.

I know nothing more of them; but we will hope their voyage was a short and easy one, and that they reached home on a pleasant, sunny day, and grandmother was there, and Dorothy, and all the people, and Polly had stories to tell as wonderful as Dorothy’s, and all true, and that they were all happy forever after.

A while ago I stood on the hill with an old farmer, eating one of a pocketful of apples he had given me, and said how very nice it was, and that I had never seen any like it.

“There are none of my apples sell half so well,” said he. “I’ve forty young trees that have been bearing a few years; and over to the right you see some old ones. Mine were grafted from those [Pg 17] and my father took his grafts from an old tree I’d like to show you;” and as we walked towards it, he said, “It looks, and I guess it is, as old as any around here. My father always said it was brought from England in a flower-pot by some of the first settlers. Perhaps you have heard the story. It’s very shaky. The high winds last fall were pretty hard on it. It will never bear again, I am afraid. I set a good deal by the old thing. The very first thing I can remember is my father’s lifting me up to one of the lower limbs, and I was frightened and cried. I believe I think more of that tree than of anything on my farm. My wife always laughs at me about it. Well, it has lasted my time. I’m old and shaky, too; and I suppose my sons won’t miss this much, and will like the young orchard best.”

“And you and I like your orchard’s grandmother,” said I.

S. O. J.

HE was a donkey, and we called him Rough. He belonged to Gerald and me. We didn’t keep him for his useful qualities, and we certainly didn’t keep him for his moral qualities; and I don’t know what we did keep him for, unless, for the best reason in the world, that we loved him.

He was always getting us into scrapes, the most renowned of which was one Rough’s enemies were fond of alluding to.

We were bidden to a christening one fair spring morning; and we not only accepted the invitation, but promised to bring apple-blossoms, to fill the font and make the church look gay. We had an old apple orchard, that bore beautiful blossoms, but worthless fruit; and of these blossoms we had leave to pick as many as we chose.

So we filled the donkey-cart with them, and set forth for the christening, which was to be at a little church about a mile or more distant from our farm. Rough’s enemies will tell how we arrived when the christening was all over, and our apple blossoms faded.

We were never so happy as when we had a whole leisure afternoon to go off with Rough in the donkey-cart, and our little sister Daisy by Gerald’s side, on the board that served as seat, and I lying on my back on the bottom of the cart, with my heels dangling out of it. So I would lie for hours, whistling and looking up at the drifting clouds, or with my hat over my eyes to keep out the sun.

One afternoon, early in March, when the roads were almost knee deep in mud, and the last of the melting snow made a running stream on either side of the road, we were slowly travelling along after the manner I have described. We were going to take a longing look at the skating pond, two miles from our farm. We were forbidden to try the dangerous ice, but meant only to look upon the scene of our winter’s delight.

“Some one’s in the pond!” cried Daisy.

“How do ye know?” said I, not removing my hat from my face.

You see Daisy was only six years old, and I hadn’t much faith in her observation.

“Cos I sees ’em with my own eyes.”

I jumped up and looked. It was only [Pg 18] a hat I saw. Gerald meanwhile said nothing, but had pulled up Rough (who not only stopped, but lay down in the mud), and looked. I watched him, to see what he thought, or proposed to do.

People had a way of trusting to Gerald’s judgment rather than their own, and were generally better off for it.

“It is some one in the pond,” said Gerald; and then followed a short discussion as to whether we should leave Daisy alone to the mercies of Rough, which resulted in our leaving Rough, and taking Daisy along with us down to the pond.

We could see a boy, apparently about Gerald’s age, swimming and striving to keep up, and catching at the ice, which broke as he clung to it. He swam feebly, as if benumbed and wearied.

“Keep a brave heart!” roared Gerald; “we’ll save you!” and then began to take off his boots and coat. The boy sank—under the ice, this time. We could see it bobbing up and down as he swam beneath it.

“Stay here till I call you,” said Gerald to me, as he stepped from the shore on to the ice, and walked out towards where the swimmer was hidden by the ice. I stood breathless, with my eye on Gerald.

The ice began to crack under him. He lay down on his stomach, and pulled himself forward with his hands. Up came the swimmer not far from him.

“Keep up! Gerald will save you!” cried Daisy.

The poor fellow cast one despairing look at Gerald, and sank again. Gerald had gone as far as was practicable on the ice. I could hear it cracking all over, [Pg 19] and see the white cracks darting suddenly over ice that had looked safe.

Up came the boy again.

“Keep up! keep up!” cried Daisy, in an excited treble. “Gerald will save you!”

But the boy could hear nothing. He had his eyes closed, and seemed to have fainted. Gerald reached out, and clutched him by the arm. How the ice cracked all about him! My heart was in my mouth; I thought he was in. I began to take my coat off.

“A scarf!” said Gerald, speaking for the first time.

I took off my own, and picked up Gerald’s from the ground, and tied them firmly together. I saw that they were too short. Daisy offered hers. I took it, with an inward fear, if the child should catch cold; it seemed paltry to think of it at such a moment. I stepped out on the ice, and went a few steps, when Gerald cried,—

“Stop!”

I obeyed like a soldier.

“Throw it now!”

I threw the long string of scarfs. Gerald dexterously caught it, and upholding the poor boy with one hand, with the other passed the string under his arms, and tied the ends of it to his own arm. Then he paused a moment before attempting the hazardous work of coming ashore, and looked at me speculatively. I knew what he meant. There was a shadow of trouble in his face that had nothing to do with his own danger. He was weighing the possibility of his falling in, and my doing the same in trying to save him, and Daisy alone on the shore. I gave a cheering “Go ahead, old fellow!” and he began to push himself back again, dragging his senseless burden after him by the scarf tied to his arm.

Crack! crack! crack! went the ice all about him, and little tides of water flooded it. At last it seemed a little firmer. Gerald rose to his feet, and dragging the boy still in the water after him, began to walk slowly towards the shore, not seeming to notice how the sharp edges of the ice cut the face and forehead of the poor half-drowned boy.

Again the ice began to crack and undulate. Gerald stood still for a moment, and the piece on which he stood broke away from the rest, and began to float out. He jumped to the next, which broke, and so to the next, and the next, till he neared the shore. Then he paused a moment, and looked at me.

“Go ashore!” he roared like a sea captain.

Then I noticed that I stood on a detached piece of ice, but nearer land than Gerald. I found no difficulty in gaining the shore.

“Now stand firm and give a hand!” said Gerald.

I grasped his hand, and he jumped ashore, and together we lifted the boy out of the water. Daisy burst into tears, crying,—

“O, Gerald, Gerald, I thought you’d be drowned!”

Gerald very gently put her clinging arms away from him, saying, firmly,—

“Don’t cry, Daisy. We have our hands full with this poor fellow.”

I got the skates off the “poor fellow,” and gave them to Daisy to hold. She, brave little woman, gulped down her tears, and only gave vent to her emotion, now and then, by a little suppressed sob. Gerald began beating the hands and breathing into the mouth and nostrils of the seeming lifeless form before us.

“Is he dead, Gery?” said I.

“No!” said Gerald, fiercely. It was evident that he wouldn’t believe he had gone through so much trouble to bring a dead man ashore. “Look for his handkerchief, and see if there’s a mark on it.”

[Pg 20] I fished a wet rag out of the wet trousers pocket, and found in one corner of it the name “Stevens.”

“There’s a farmer of that name two miles farther on. I don’t know any one else of that name. Must be his son. We’ll take him home;” and he began wrapping his coat about the poor boy; but I insisted on mine being used for the purpose, as Gerald was half wet, and his teeth were already chattering. “We must get him off this wet ground as soon as possible,” said Gerald; and together we lifted him, and slowly and laboriously bore him to the donkey-cart in the road.

By this time Gerald had only strength enough to hold the reins, and we set out forthwith for the Stevens farm, I, with what help Daisy could give, trying to bring some show of life back to the stranger. Perhaps the jolting of the cart helped,—I don’t know,—but by and by he began to revive, and at last we propped him up in one corner of the cart, with his head supported by Daisy’s knee.

I shall not soon forget how long the road seemed, and how I got out and walked in deep mud, and how, when poor Rough seemed straining every muscle to make the little cart move at all, Gerald insisted on getting out, too, and leading Rough; how the sun set as we were wading through a long road, where willow trees grew thick on either side, and Daisy said, “See; all the little pussies are out!” how, at last, we reached the Stevens farm, and restored the half-drowned boy to his parents. I remember, too, how they were so utterly absorbed, very naturally, in the welfare of their boy, as to forget all about us, and offer us no quicker means of return home than our donkey-cart.

They came to call on us the next day, and to thank us, and specially Gerald, with tears of gratitude. And Gerald was a hero in the village from that day forth.

I remember well how dark it grew as we waded slowly and silently home, and how poor little Rough did his very best, and never stopped once.

I think he understood the importance of the occasion; but those who were not Rough’s friends, believe it was a recollection, and expectation of supper, that made him acquit himself so honorably.

As we neared our home, we saw a tall figure looming up in the dark, and soon, by the voice, we knew it was Michael, one of the farm hands, sent to seek us.

“Bluder an nouns,” he exclaimed, “it is you, Mister Gery! An’ yer muther, poor leddy, destroyed wid the fright. An’ kapin’ the chilt out to this hair. Hadn’t ye moor sense?”

We explained briefly; and Daisy begged to be carried, as the cart was all wet.

With many Irish expressions of sympathy, Michael took the child in his arms; and so we arrived at home, and found father and mother half distracted with anxiety, and the farm hands sent in all directions to look for us. We were at once, all three of us, put to bed, and made to drink hot lemonade, and have hot stones at our feet, and not till then tell all our experiences, which were listened to eagerly.

Daisy escaped unhurt, I with a slight cold, but Gerald and poor little Rough were the ones who suffered. Gerald had a severe attack of pneumonia, from which we had much ado to bring him back to health, and Rough was ill. They brought us the news from the stable on the next morning. We couldn’t tell what was the matter; perhaps he had strained himself, perhaps had caught cold. We could not tell, nor could the veterinary surgeon we brought to see him. Poor Rough lay ill for weeks, and one bright spring morning he died.

They told us early in the morning, before we were out of bed, how, an hour ago, Rough had died.

THE MUSIC LESSON.

TOUCH the keys lightly,

Nellie, my dear:

The noise makes Johnnie

Impatient, I fear.

THE frost looked forth one still clear night,

And whispered, “Now I shall be out of sight;

So through the valley and over the height

In silence I’ll take my way:

I will not go on like that blustering train,

The wind and the snow, the hail and the rain,

Who make so much bustle and noise in vain,

But I’ll be as busy as they.”

I HAVE a little picture;

Perchance you have one too.

Mine is not set in frame of gold;

’Tis first a bit of blue,

And then a background of dark hills—

A river just below,

Along whose broad, green meadow banks

The wreathing elm trees grow.

WHY are the blossoms

Such different hues?

And the waves of the sea

Such a number of blues?

So many soft greens

Flit over the trees?

And little gray shadows

Fly out on the breeze?

THE wisdom of God is seen in every part of creation, and especially in the different kinds of birds. The beauty displayed in their graceful forms and varied colors strikes every beholder, while the adaptation of their organs for the purposes of flight, their peculiar habits and modes of living, are a constant source of admiration to the student of nature.

Almost everything about the shape of a bird fits it for moving rapidly in the air, and all parts of its body are arranged so as to give it lightness along with strength. The soft and delicate plumage of birds protects them from cold or moisture; their wings, though so delicate, are furnished with muscles of such power as to strike the air with great force, whilst their tails act like the rudder of a ship, so that they can direct their course at pleasure with the utmost ease.

The internal structure of a bird also is such as to help it to sustain itself in, and to fly quickly through, the air. Its lungs are pierced with large holes, which allow air to pass into cavities in the breast, and even into the interior of the bones. It is thus not only rendered buoyant, but is enabled to breathe even while in rapid motion. Two sparrows, it is said, require as much air to maintain their breathing properly as a guinea pig.

In many other ways the skill and goodness of God are seen in the “fowl of the air.” Their necks and beaks are long, and very movable, so that they may readily pick up food and other objects from the ground. The muscles of their toes are so arranged that the simple weight of the body closes them, and they are able, in consequence, to sit on a perch a long time without fatigue. Even in a violent wind a bird easily retains its hold of the branch or twig on which it is sitting. Their bills are of almost all forms: in some kinds they are straight; in others curved, sometimes upwards and sometimes downwards; in others they are flat; in some they are in the form of a cone, wedge-shaped, or hooked. The bill enables a bird to take hold of its food, to strip or divide it. It is useful also in carrying materials for its nest, or food to its young; and in the birds of prey, such as the owl, the hawk, the falcon, eagle, etc., the beak is a formidable weapon of attack.

The nostrils of birds are usually of an oval form, and are placed near the base of the beak. Their eyes are so constructed that they can see near and distant objects equally well, and their sight is very acute. The sparrow-hawk discerns the small birds which are its prey at an incredible distance. No tribe of birds possesses an outward ear, except those which seek their food by night; these have one in the form of a thin, leathery piece of flesh. The inside ear, however, is very large, and their hearing is very quick.

BIRD’S NEST.

Another admirable feature in the structure of birds consists in their feathers. These are well adapted for security, warmth, and freedom of motion. The larger feathers of the body are placed over each other like the slates on the roof of a house, so that water is permitted to run off, and cold is kept out. The down, which is placed under the feathers, is a further protection against the cold; and hence it is most abundant in those species that are found in northern climates. The feathery covering of birds forms their peculiar beauty: on this, in [Pg 27] the warm climates, Nature bestows her most delicate and brightest colors.

Another point which sets forth the resources of Infinite Wisdom is the structure and uses of the wings of birds. The size of the wings is not always in proportion to the bulk of their bodies, but is accommodated to their habits of living. Accordingly, birds of prey, swallows, and such birds as are intended to hover long in the air, have much longer wings, in proportion to their size, than hens, ducks, quails, etc. In some, such as the ostrich, the cassiowary, and the penguin, the largest quill-feathers of the wing are entirely wanting.

Then, again, how varied is the flight of birds! The falcon soars above the clouds, and remains in the air for many hours without any sign of exertion. The swallow, the lark, and other species, sail long distances with little effort. Others, like the sparrow and the humming-bird, have a fluttering flight. Some, as the owl, fly without any noise; and some, like the partridge, with a loud whir.

How graceful are the motions of the hawk, sweeping higher and higher in circles, as he surveys far and wide the expanse of fields and meadows below, in which he hopes to espy his prey. Our [Pg 28] paper would be too long were we to say even a little about the roosting, the swimming, or running, the migration, the habits and instincts, the varied notes and pleasant songs, of the endless species of birds.

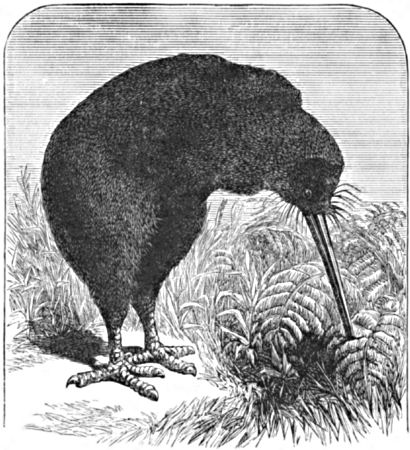

All these subjects are well worthy of being carefully studied; for they all show the design of their Creator. The extraordinary creature represented in the engraving is the “Apteryx,” or “wingless bird” of New Zealand. It was not known to European naturalists till of late years, and for a long time the accounts which the natives of New Zealand gave of it were discredited. A specimen of it, preserved in brine, was, however, brought to this country, and a full description of the bird given.

The kirvi-kirvi, as the New Zealanders call it, stands about two feet high. Its wings are so small that they can scarcely be called wings, and are not easy to find under the general plumage of the body. Its nostrils, strange to say, are at the tip of the beak. The toes are strong, and well adapted for digging, the hind one being a thick, horny spur. To add to the singularity of this creature, it has no tail whatever. The kirvi-kirvi conceals itself among the extensive beds of fern which abound in the middle island of New Zealand, and it makes a nest of fern for its eggs in deep holes, which it hollows out of the ground. It feeds on insects, and particularly worms, which it disturbs by stamping on the ground, and seizes the instant they make their appearance. Night is the season when it is most active; and the natives hunt it by torchlight. When pursued, it elevates its head, like an ostrich, and runs with great swiftness. It defends itself, when overtaken, with much spirit, inflicting dangerous blows with its strong spur-armed feet.

In this instance, as in all others, God has wisely adapted the very shape and limbs of the creature to the habits by which it was intended to be distinguished.

F. F. E.

WHEN Agrippa was in a private station, he was accused, by one of his servants, of having spoken injuriously of Tiberius, and was condemned by that emperor to be exposed in chains before the palace gate. The weather was very hot, and Agrippa became excessively thirsty. Seeing Thaumastus, a servant of Caligula, pass by him with a pitcher of water, he called to him, and entreated leave to drink. The servant presented the pitcher with much courtesy; and Agrippa, having allayed his thirst, said to him,—

“Assure thyself, Thaumastus, that if I get out of this captivity, I will one day pay thee well for this draught of water.”

Tiberius dying, his successor, Caligula, soon after not only set Agrippa at liberty, but made him king of Judea. In this high situation Agrippa was not unmindful of the glass of water given to him when a captive.

He immediately sent for Thaumastus, and made him controller of his household.

WEST wind and sunshine

Braided together,

What is the one sign

But pleasant weather?

Mary N. Prescott.

SUMMER FLOWERS.

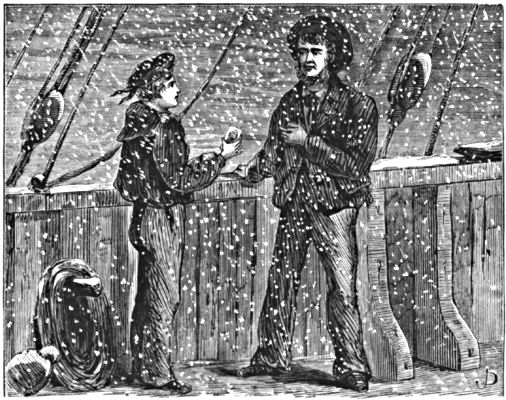

PLEASE, Mr. Mate has that cloud a silver lining?”

The question was asked by little Kate Vale, the daughter of an emigrant, who, with her mother, was following her father, who had gone before to New York. Katie was a quiet, gentle little child, who gave trouble to no one. She had borne the suffering of seasickness at the beginning of the voyage so patiently, and now took the rough sea-fare so thankfully, that she had made a fast friend of Tom Bolton, the mate. Bolton had a warm, kindly heart, and one of the children whom he had left in England was just the age of Katie; this inclined him all the more to show her kindness. Katie often had a piece of Bolton’s sea-biscuit; he told her tales which he called “long yarns,” and sometimes in rough weather he would wrap his thick jacket around her, to keep the chill from her thinly-clad form. Katie was not at all afraid of Bolton, or “Mr. Mate,” as she called him, and she took hold of his hard brown hand as she asked the question,—

“Has that cloud a silver lining?”

Bolton glanced up at a very black, lowering cloud, which seemed to blot the sun quite out of that part of the sky.

“Why do you ask me, Kate?” said the sailor.

“Because mother often says that every cloud has a silver lining, and that one looks as if it had none.”

Tom Bolton gave a short laugh.

“None that we can see,” he replied; “for the cloud is right atween us and the sun. If we could look at the upper part, where the bright beams fall, we should see yon black cloud like a great mass of silvery mother-o’-pearl, just like those that you yesterday called shining mountains of snow.”

Katie turned round, and raising her eyes, watched for some minutes the gloomy cloud. It was slowly moving towards the west, and as it did so, the sun behind it began to edge all its dark outline with brightness.

“See, see!” exclaimed Katie; “it is turning out the edge of its silver lining. If I were up there in the sky, I suppose that all would look beautiful then. But I don’t know why mother should take comfort from talking of the clouds and their linings.”

The mother, Mrs. Vale, who was standing near, leaning against the bulwarks, heard the last words of her child, and made reply,—

“Because we have many clouds of sorrow here to darken our lives, and our hearts would often fail us but for the thought, ‘There is a bright side to every trial sent to the humble believer.’”

And Mrs. Vale repeated the beautiful lines,—

Katie did not quite understand the verse, but she knew how patiently and meekly her mother had borne sudden poverty, the sale of her goods, and the bitter parting from her beloved husband. Bolton also had been struck by the pious courage of one who had had a large share of earthly trials.

“Your clouds at least seem to be edged with silver,” he observed, with a smile; and as he spoke, the glorious beams of the sun burst from behind the black mass of cloud, making widening streams of light up the sky, which, as Katie remarked, looked like paths up to heaven.

The vessel arrived at New York, after [Pg 32] rather a rough voyage, and Mrs. Vale, to her great delight, found her husband ready at the port to receive her. He brought her good tidings also. A fortnight before her landing he had procured a good situation, and he was now able to take her and their child to a comfortable home. Past sorrows now seemed to be almost forgotten.

Bolton, who, during a trying voyage, had shown much kindness to Mrs. Vale as well as to Katie, was invited during his stay at New York to make their house his home. He had much business to do as long as he remained in the great city, so saw little of the Vales except in the evenings, when he shared their cheerful supper, and then knelt down with them at family prayers. The mate learned much of the peace and happiness which piety brings while he dwelt under the emigrant’s roof.

But ere long the day arrived when Bolton’s vessel, the Albion, was to start for England. She was to weigh anchor at one o’clock, and at midday the mate bade good by to his emigrant friends.

“A pleasant journey to you, and a speedy return; we’ll be glad to see you back here,” said Henry Vale, as he shook the mate by the hand.

Bolton’s journey was to be much shorter, and his return much more speedy than he wished, or his friends expected. He was hastening down to the pier to join his vessel, when he saw hanging up in a shop window a curious basket, made of some of the various nuts of the country prettily strung together.

“That’s just the thing to take my Mary’s fancy,” said the mate to himself. “I’ve a present for every one at home but for her; it won’t take two minutes to buy that basket.”

Great events often hang upon very small hooks. If Bolton had not turned [Pg 33] back to buy the basket, he would not have been passing a house on which masons were working at the very moment when a ladder, carelessly placed against it, happened to fall with a crash. The ladder struck Bolton, and he fell on the pavement so much stunned by the shock, that he had to be carried in a senseless state into the shop of an apothecary.

Happily no bones were broken, but it was nearly an hour before the mate recovered the use of his senses. He then opened his eyes, raised his head, and stared wildly around him, as if wondering to find himself in a strange place, and trying to think how he came to be there. Bolton pressed his aching forehead, seeking to recall to his memory what had happened, for he felt like one in a dream. Soon his glance fell on the clock in the apothecary’s shop, and at the same instant the clock struck one! Bolton started to his feet, as if the chime of the little bell had been the roar of a cannon.

“The Albion sails at one!” cried the mate; and without so much as stopping to look for his oilskin cap, with bandaged brow and bareheaded, Bolton rushed forth into the street, and, dizzy as he felt, staggered on towards the pier from which the vessel was to sail.

It was not to be expected that the sailor’s course should be a very straight one, or that with all his haste he should manage to make good speed. The streets of New York seemed to be more full of traffic than usual, and twice the mate narrowly escaped being knocked down again by some vehicle rapidly driven along the road. At last, breathless and faint, and scarcely able to keep his feet, poor Bolton arrived at the wharf to which his ship had been moored but an hour before. But the Albion was there no longer—the vessel had started without the mate—he could see her white sails in the distance; she was already on her way back to Old England, and she had left him behind!

This was a greater shock to poor Bolton than the blow from the falling ladder had been. He stood for several minutes gazing after the ship with a look of despair, then slowly the sailor returned to the house of the Vales.

“Nothing more unlucky could possibly have happened,” muttered the mate to himself. “Here’s a pretty scrape that I shall get into with my employers; the mate of their vessel absent just at the time when he ought to have been at his post! Then I’ve nothing with me—nothing, save the clothes that I stand in! All my luggage is now on the waves, and a precious long time it will be before I shall see it again. But I don’t care so much for the luggage; what I can’t bear to think of is my wife and my children looking out eagerly for the arrival of the good ship Albion, and then, when she reaches port, finding that no Tom Bolton is in her! I wish that that stupid basket had been at the bottom of the sea before ever I set eyes on it!”

Pale, haggard, and looking—as he was—greatly troubled, Bolton entered the house of the Vales, which he so lately had quitted. The family were just finishing their dinner; and not a little astonished were they to see one whom they had believed to be on the wide sea.

“Here I am again, like a bad half-penny,” said the sailor; and sitting down wearily on a chair which Katie placed for him directly, Bolton gave a short account of what he called the most unlucky mischance that had ever happened to him in the course of his life.

The Vales felt much for his trouble, and begged him to remain with them until he could get a passage in some other vessel bound for England.

THE MAN AT THE WHEEL.

“And don’t take your accident so much [Pg 35] to heart,” softly whispered little Katie; “you know mother’s favorite proverb—‘Every cloud has a silver lining.’”

“Sometimes, even in this life, we can see the silver edge round the border,” observed Mrs. Vale.

Bolton had too brave a heart and too sensible a mind to give way long to fretting, though he did not see how so black a cloud as that which hung over his sky could possibly have anything to brighten its gloom. He tried to make the best of that which he could not prevent, and retired to rest that night with a tolerably cheerful face, though with a violent headache, and a heartache which troubled him more.

Bolton slept very little that night, nor indeed did any one else in the house; for with the close of day there came on a violent storm which raged fiercely until the morning. Katie trembled in her little cot to hear how the gale roared and shrieked in the chimneys, and rattled the window-frames, and threatened to burst open the doors. The child raised her head from the pillow, and thanked the Lord that her sailor friend was not tossing then on the waves.

But far more thankful was Katie when tidings reached New York of what the storm had done on that terrible night. Bolton was sitting at breakfast with his friends on the third day after the tempest, when Vale, who was reading the newspaper, turned to the part headed “Shipping Intelligence.”

“Any news?” inquired Tom Bolton, struck by the expression on the face of his friend.

Instead of replying, Vale exclaimed, “How little we can tell in this life what is really for our evil or our good! You called that accident which prevented your sailing in the Albion an ‘unlucky mischance.’”

“Of course I did. My wife and children are impatient to see me—”

“Had you sailed in that ship,” interrupted Vale, “they would never have seen you again. The Albion went down in that storm!”

What was the regret of Tom Bolton on hearing of the disaster, and what was his thankfulness for his own preservation, I leave the reader to guess. Often in after days did the little American basket remind him in his own home of what others might have called the chance that led him to turn back on his way to the ship, and so caused the accident which vexed him so much at the time.

I AM a first-rate fairy—

“Good-Humor” is my name;

I use my wand where’er I go,

And make the rough ways plain;

I REALLY am in doubt whether or not the young folks ought to be congratulated in consequence of the great number of juvenile books which are being placed before them about this time. An excellent book is certainly excellent company; but there is a limit to all things; and so we may have too many books, taking it for granted that all are good ones.

You all know, that, as a general rule, people in America read too much, and think too little. Reading is a benefit to us only when it leads to reflection. It is useless when it leaves no lasting impression on the mind; it is worse than useless if the lesson it conveys be not a really good one.

Suppose you sit down to a well-furnished table at a hotel to eat your dinner. The waiter hands you a bill of fare, upon which is printed a long list of good and wholesome dishes, and then quietly waits until you order what you wish. You are not expected to eat of every one, however attractive they may be, but rather to select what you like best,—enough to make a modest meal,—and let that suffice.

But the selection is not all. If you expect to gain health and strength by your dinner, you must eat it in a proper manner; that is, slowly. Otherwise nature’s work will be imperfectly done, and your food become a source of bodily harm, instead of a benefit.

Now, it is precisely so with the food of the mind, which comes to you through books. You are not expected to read everything which comes within your reach. You should rather select the best, and, having done so, read them slowly and carefully. You may read too much as well as eat too much; and while the one will injure your body, the other will as certainly harm your mind.

One of the worst evils which too much reading leads to is a habit of reading to [Pg 37] forget. You know what a bad habit is, how it clings to us, when once contracted, and how hard it is to be shaken off. Some boys and girls read a book entirely through in a single evening, and the next day are eagerly at work on another, to be as quickly mastered. No mind, however strong, can stand such a strain. You see at once that it would be absolutely impossible for them to remember what they read. And so they read for a momentary enjoyment, and gradually fall into the habit I have spoken of—reading to forget. I need not tell you that such a habit is fatal to any very high position in life.

How often we hear parents boast that their children are “great readers,” just as if their intelligence should, in their opinion, be measured by the number of books and papers which they had read! Need I say, that, on the contrary, they are objects of pity?

But how much may we read with profit? That is a question not always easy to answer. Some can read a great deal more than others. Yet, if young people read slowly, and think a great deal about the subject, there is very little danger of their reading too much, provided they select only good books; because good books are very scarce—much more so in proportion to the number printed than they were twenty years ago; and there are very few young persons who have too great a supply of good works placed within their reach.

I have mentioned one evil which results from too much reading, and will only briefly allude to another equally important. Children who attend school have no time to devote to worthless books. Their studies consume many hours. If, aside from the time which should be devoted to play, to their meals, and the various duties of home, they will read a useless book every day or two, their health is sure to suffer. The evil consequences may not be at once apparent, but in later years the penalty will certainly have to be paid. This reflection alone, if there were no other reason, should induce the young to discard all useless books, and read only such as shall have a tendency to make them wiser and better.

THE little coral-workers,

By their slow but constant motion,

Have built those pretty islands

In the distant dark-blue ocean;

And the noblest undertakings

Man’s wisdom hath conceived

By oft-repeated efforts

Have been patiently achieved.

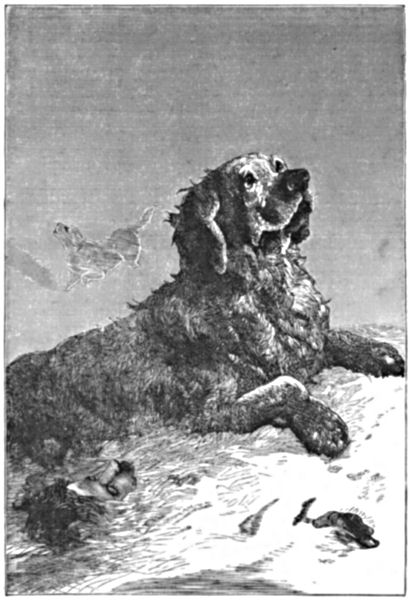

LION, who was a cross between a Great St. Bernard and a Newfoundland dog, came into the possession of the superintendent of the London fire brigade when he was but twelve months old. His first retreat was in the engine-house, where, on some old hose and sacking, he made himself as comfortable as he could, and coiled himself up, like the tubing on which he lay. Considering that he was thus placed in charge of the engine-house, he resented the first occasion on which a fire occurred at night. The fire bell rang, and the firemen crowded to the spot, prepared to draw forth the engine, when a decided opposition was made on the part of Lion, who showed a determination to fasten himself on the first fireman who dared to enter the house. In this way the faithful dog kept them all at bay until the arrival of his master, whom he instantly recognized and obeyed. As soon as the horses were harnessed, and the engine was in motion, Lion bounded along in company, and was present at his first fire. After that time, he attended no less [Pg 39] than three hundred and thirty-two fires, and not only attended, but assisted at them, always useful, and sometimes doing work and saving life, which, but for him, would have been lost.

His chief friends, the firemen, say it would take a long while to tell all his acts of daring and sagacity; but we must, in justice to his memory, record some of the most notable.

Whenever the fire bell rang, Lion was immediately on the alert, barking loudly, as if to spread the dire alarm. Then, as soon as his master had taken his place on the engine, and before the horses were off, he led the way, clearing the road and warning every one of the approach of the engine, and spreading the news of the fire by his loud voice.

On one occasion, when the horses were tearing along the streets as fire engine horses alone can, a little child was seen just in front of the engine. To stop the horses in time was impossible, though the driver did his best. The brave hearts of the firemen sank within them as they felt they must drive over the little body. Bystanders raised their arms and shrieked as they witnessed an impending catastrophe which they could do nothing to avert. No human help could avail, and it must needs be that the engine of mercy, on its way to save life, must sacrifice the life of an innocent, helpless child!

But stay! Human eyes were not the only ones that took in that sad scene, and that saw the impending doom of the little one. Brave, sagacious, and fleet, Lion saw at a glance the danger that threatened the child, and springing forward, he knocked him down; then seizing him firmly in his jaws, he made for the pavement obliquely, and gently deposited his charge in the gutter just as the engine went tearing by.

But this was only an incident by the way; Lion’s real work began when the scene of the fire was reached. As soon as the door was opened, or dashing through the window if there was a delay in opening the door, the noble animal would run all over the burning house, barking, so as to arouse the inmates if they were unaware of the danger; and never would he leave the fire until he had either aroused them or had drawn the attention of the firemen to them.

Once the firemen could not account for his conduct. Darting into the burning house,—the ceilings of which had given way,—and then out again to the firemen, he howled and yelled most loudly. It was believed that no one was in the house, but Lion’s conduct made his master feel uneasy.

Still nothing could be done by way of entering the house, as the fire was raging fiercely, and the house would soon fall in. Finding that his entreaties were not regarded, and suffering from burns and injuries, the noble animal discontinued his efforts, but ran uneasily round the engine, howling in a piteous manner; nor would he leave the spot after the fire was put out until search was made, when beneath the still smouldering embers, the firemen discovered the charred body of an old man, whom he had done his utmost to save.

Lion’s noble efforts, however, were often crowned with success; and many a one has to bless the wondrous qualities with which God had endowed him.

At one fire, after the inmates had made their escape, a cry was raised that “the baby had been left behind in the cradle up stairs,” though no one seemed to be able to indicate the room. The fire had so far got hold of the dwelling, such dense volumes of flame and smoke were issuing from every opening, that it was impossible for any fireman to enter, and the crowd stood horror-stricken at the thought of the perishing babe.

[Pg 40] The crisis was a terrible one; an effort was made, an entry was effected, and some of the men ventured some distance within the burning pile, only to retrace their steps.

At this emergency, Lion dashed past the men, disappeared amid the flames, but returned in a minute into the street with the empty cradle in his powerful jaws. The consequence of this almost incredible feat—which was witnessed by many—may be better imagined than described.

The fact that Lion did not re-enter the house—which, though badly burned, he would doubtless have done had he left the child behind—was sufficient to convince the dullest intellect that the child was secure; and it was very soon ascertained that the object of search was safe in a neighboring house.

No wonder, then, that this noble animal endeared himself to all who knew him; and those who knew him best loved him the most. For fourteen years Lion continued his noble and useful career as public benefactor, as friend and companion to the firemen, and as mourner at their graves; for he attended the funerals of no less than eleven of them.

Death came to him at length; for last year he died from injuries received in the discharge of his self-imposed duties.

There are few of our readers who would not have liked to pat that brave old dog; there are fewer still who may not learn useful and valuable lessons from the speaking testimony of that dumb animal.

Benjamin Clarke.

O, MY princely flower, shall I never win

To your moated citadel within,

To your guarded thought?

M. R. W.

I COME not when the earth is brown, and gray

The skies; I am no flower of a day,

No crocus I, to bloom and pass away;

T. E. D.

MY dear little girl, with the flowers in your hair,

Stop singing a moment, and look over there;

While you are so safe in the sheltering fold,

With treasures of silver, and treasures of gold,

Just a few steps away, in a dark, narrow street,

With no pure, cooling drink, and no morsel to eat,

A poor girl is dying, no older than you;

Her lips were as red, and her eyes were as blue,

Her step was as light, and her song was as sweet,

And the heart in her bosom as merrily beat.

Ellen M. H. Gates.

RICH AND POOR.

SEE, mamma what is the woman doing? She looks as if she was holding a pin-cushion in her lap and was sticking pins in it.”

“So she is, my dear,” Ellen’s mother remarked. “But that is not all she is doing. There is a cluster of bobbins hanging down one side of the cushion which are wound with threads, and these threads she weaves around the pins in such a manner as to make lace.”

“I never saw anybody make lace that way. I have seen Aunt Maria knit it with a crochet-hook.”

“This is a different kind of lace altogether from the crocheted lace. They do not make it in the United States. The woman whom you see in the picture lives in Belgium in Europe. In that country, and in some parts of France and Germany, many of the poorer people earn a living at lace-making. The pattern which in making the lace it is intended to follow is pricked with a pin on a strip of paper. This paper is fastened on the cushion, and then pins are stuck in through all the pin-holes, and then the thread from these bobbins is woven around the lace.”

“Can they work fast?”

“An accomplished lace-maker will make her hands fly as fast as though she were playing the piano, always using the right bobbin, no matter how many of them there may be. In making the pattern of a piece of nice lace from two hundred to eight hundred bobbins are sometimes used. In such a case it takes more than one person—sometimes as many as seven—at a single cushion.”

“It must be hard to do.”

“I dare say it would be for you or me. Yet in those countries little children work at lace-making. Little children, old women and the least skilful of the men make the plainer and coarser laces, while experienced women make the nicer sorts.”

“What do they do with their lace when it is finished?”

“All the lace-makers in a neighborhood bring in their laces once a week to the ‘mistress’—for women carry on the business of lace-making—then this ‘mistress’ packs them up and takes them to the nearest market-town, where they are peddled about from one trading-house to another until they are all sold.”

“Do they get much for them?”

“The poor lace-makers get hardly enough to keep them from starvation for their fine and delicate work; but the laces, after they have passed through the hands of one trader after another, and are at last offered to the public, bring enormous prices. A nice library might be bought for the price of a set of laces, or a beautiful house built at the cost of a single flounce.”

“I think I should rather have the house, mamma.”

“So should I. But the people who buy these laces probably have houses already. There is over four million dollars’ worth of lace sold every year in Belgium alone.”

Ellen thought she should never see a piece of nice lace without thinking of these wonderful lace-makers, who produce such delicate work and yet are paid so little for it; and while she was thus thinking over the matter, mamma went quietly on with her sewing.

LACE-MAKERS.

MANY boys and girls make a failure in life because they do not learn to help themselves. They depend on father and mother even to hang up their hats and to find their playthings. When they become men and women, they will depend on husbands and wives to do the same thing. “A nail to hang a hat on,” said an old man of eighty years, “is worth everything to a boy.” He had been “through the mill,” as people say, so that he knew. His mother had a nail for him when he was a boy—“a nail to hang his hat on,” and nothing else. It was “Henry’s nail” from January to January, year in and out, and no other member of the family was allowed to appropriate it for any purpose whatever. If the broom by chance was hung thereon, or an apron or coat, it was soon removed, because that nail was “to hang Henry’s hat on.” And that nail did much for Henry; it helped make him what he was in manhood—a careful, systematic, orderly man, at home and abroad, on his farm and in his house. He never wanted another to do what he could do for himself.

Young folks are apt to think that certain things, good in themselves, are not honorable. To be a blacksmith or a bootmaker, to work on a farm or drive a team, is beneath their dignity, as compared with being a merchant, or practising medicine or law. This is PRIDE, an enemy to success and happiness. No necessary labor is discreditable. It is never dishonorable to be useful. It is beneath no one’s dignity to earn bread by the sweat of the brow. When boys who have such false notions of dignity become men, they are ashamed to help themselves as they ought, and for want of this quality they live and die unhonored. Trying to save their dignity, they lose it.

Here is a fact we have from a very successful merchant. When he began business for himself, he carried his wares from shop to shop. At length his business increased to such an extent, that he hired a room at the Marlboro’ Hotel, in Boston, during the business season, and thither the merchants, having been duly notified, would repair to make purchases. Among all his customers, there was only one man who would carry to his store the goods which he had purchased. The buyers asked to have their goods carried, and often this manufacturer would carry them himself. But there was one merchant, and the largest buyer of the whole number, who was not ashamed to be seen carrying a case of goods through the streets. Sometimes he would purchase four cases, and he would say, “Now, I will take two, and you take two, and we will carry them right over to the store.” So the manufacturer and the merchant often went through the streets of Boston quite heavily loaded. This merchant, of all the number who went to the Marlboro’ Hotel for their purchases, succeeded in business. He became a wealthy man when all the others failed. The manufacturer, who was not ashamed to help himself, is now living—one of the wealthy men of Massachusetts, ready to aid, by his generous gifts, every good object that comes along, and honored by all who know him.

You have often heard and read the maxim, “God helps those who help themselves.” Is it not true?

William M. Thayer.

HERE, little folks, listen; I’ll tell you a tale,

Though to shock and surprise you I fear it won’t fail;

Of Master John Dawdle my story must be,

Who, I’m sorry to say, is related to me.

JOHNNY DAWDLE.

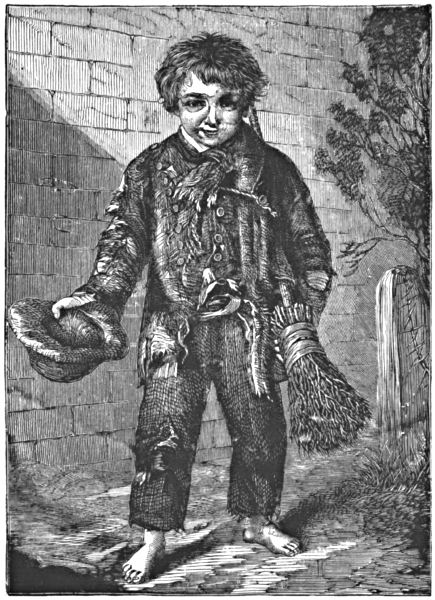

ONE day, about a year ago, the door of my sitting-room was thrown suddenly open, and the confident voice of Harvey thus introduced a stranger:

“Here’s Jim Peters, mother.”

I looked up, not a little surprised at the sight of a ragged, barefoot child.

Before I had time to say anything, Harvey went on:

“He lives round in Blake’s Court and hasn’t any mother. I found him on a doorstep feeding birds.”

My eyes rested on the child’s face while my boy said this. It was a very sad little face, thin and colorless, not bold and vicious, but timid and having a look of patient suffering. Harvey held him firmly by the hand with the air of one who bravely protects the weak.