The Project Gutenberg EBook of Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Author: Various Release Date: September 1, 2009 [EBook #29882] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ASTOUNDING STORIES *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, Greg Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

W. M. CLAYTON, Publisher HARRY BATES, Editor DR. DOUGLAS M. DOLD, Consulting Editor

That the stories therein are clean, interesting, vivid, by leading writers of the day and purchased under conditions approved by the Authors' League of America;

That such magazines are manufactured in Union shops by American workmen;

That each newsdealer and agent is insured a fair profit;

That an intelligent censorship guards their advertising pages.

The other Clayton magazines are:

ACE-HIGH MAGAZINE, RANCH ROMANCES, COWBOY STORIES, CLUES, FIVE-NOVELS MONTHLY, ALL STAR DETECTIVE STORIES, RANGELAND LOVE STORY MAGAZINE, and WESTERN ADVENTURES.

More than Two Million Copies Required to Supply the Monthly Demand for Clayton Magazines.

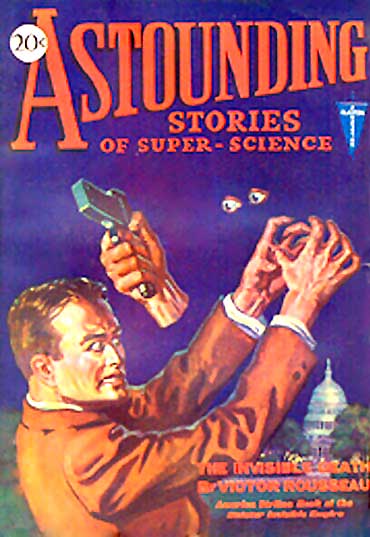

| COVER DESIGN | H. W. WESSOLOWSKI | ||

| Painted in Oils from a Scene in "The Invisible Death." | |||

| STOLEN BRAINS | CAPTAIN S. P. MEEK | 7 | |

| Dr. Bird, Scientific Sleuth Extraordinary, Goes After a Sinister Stealer of Brains. | |||

| THE INVISIBLE DEATH | VICTOR ROUSSEAU | 24 | |

| With Night-Rays and Darkness-Antidote America Strikes Back, at the Terrific and Destructive Invisible Empire. (A Complete Novelette.) | |||

| PRISONERS ON THE ELECTRON | ROBERT H. LEITFRED | 75 | |

| Fate Throws Two Young Earthians into Desperate Conflict with the Primeval Monsters of an Electron's Savage Jungles. | |||

| JETTA OF THE LOWLANDS | RAY CUMMINGS | 94 | |

| Into Remote Lowlands, in an Invisible Flyer, Go Grant and Jetta—Prisoners of a Scientific Depth Bandit. (Part Two of a Three-Part Novel.) | |||

| AN EXTRA MAN | JACKSON GEE | 118 | |

| Sealed and Vigilantly Guarded Was "Drayle's Invention, 1932"—for It Was a Scientific Achievement Beyond Which Man Dared Not Go. | |||

| THE READERS' CORNER | ALL OF US | 130 | |

| A Meeting Place for Readers of Astounding Stories. | |||

Single Copies, 20 Cents (In Canada, 25 Cents) Yearly Subscription, $2.00

Issued monthly by Publishers' Fiscal Corporation, 80 Lafayette St., New York, N. Y. W. M. Clayton, President; Nathan Goldmann, Secretary. Application for entry as second-class mail pending at the Post Office at New York, under Act of March 3, 1879. Title registered as a Trade Mark in the U. S. Patent Office. Member Newsstand Group—Men's List. For advertising rates address E. R. Crowe & Co., Inc., 25 Vanderbilt Ave., New York; or 225 North Michigan Ave., Chicago.

Two long arms shot silently down and grasped the

motionless figure.

Two long arms shot silently down and grasped the

motionless figure.hope, Carnes," said Dr. Bird, "that we get good fishing."

"Good fishing? Will you please tell me what you are talking about?"

"I am talking about fishing, old dear. Have you seen the evening paper?"

"No. What's that got to do with it?"

Dr. Bird tossed across the table a copy of the Washington Post folded so as to bring uppermost an item on page three. Carnes saw his picture staring at him from the center of the page.

"What the dickens?" he exclaimed as he bent over the sheet. With growing astonishment he read that[8] Operative Carnes of the United States Secret Service had collapsed at his desk that afternoon and had been rushed to Walter Reed Hospital where the trouble had been diagnosed as a nervous breakdown caused by overwork. There followed a guarded statement from Admiral Clay, the President's personal physician, who had been called into conference by the army authorities.

The Admiral stated that the Chief of the Washington District was in no immediate danger but that a prolonged rest was necessary. The paper gave a glowing tribute to the detective's life and work and stated that he had been given sick leave for an indefinite period and that he was leaving at once for the fishing lodge of his friend, Dr. Bird of the Bureau of Standards, at Squapan Lake, Maine. Dr. Bird, the article concluded, would accompany and care for his stricken friend. Carnes laid aside the paper with a gasp.

o you know what all this means?" Carnes demanded.

"It means, Carnsey, old dear, that the fishing at Squapan Lake should be good right now and that I feel the need of accurate information on the subject. I didn't want to go alone, so I engineered this outrage on the government and am taking you along for company. For the love of Mike, look sick from now on until we are clear of Washington. We leave to-night. I already have our tickets and reservations and all you have to do is to collect your tackle and pack your bags for a month or two in the woods and meet me at the Pennsy station at six to-night."

"And yet there are some people who say there is no Santa Claus," mused Carnes. "If I had really broken down from overwork, I would probably have had my pay docked for the time I was absent, but a man with official pull in this man's government wants to go fishing and presto! the wheels move and the way is clear. Doctor, I'll meet you as directed."

"Good enough," said Dr. Bird. "By the way, Carnes," he went on as the operative opened the door, "bring your pistol."

Carnes whirled about at the words.

"Are we going on a case?" he asked.

"That remains to be seen," replied the Doctor enigmatically. "At all events, bring your pistol. In answer to any questions, we are going fishing. In point of fact, we are—with ourselves as bait. If you have a little time to spare this afternoon you might drop around to the office of the Post and get them to show you all the amnesia cases they have had stories on during the past three months. They will be interesting reading. No more questions now, old dear, we'll have lots of time to talk things over while we are in the Maine woods."

ate the next evening they left the Bangor and Aroostook train at Mesardis and found a Ford truck waiting for them. Over a rough trail they were driven for fifteen miles, winding up at a log cabin which the Doctor announced was his. The truck deposited their belongings and jounced away and Dr. Bird led the way to the cabin, which proved to be unlocked. He pushed open the door and entered, followed by Carnes. The operative glanced at the occupants of the cabin and started back in surprise.

Seated at a table were two figures. The smaller of the two had his back to the entrance but the larger one was facing them. He rose as they entered and Carnes rubbed his eyes and reeled weakly against the wall. Before him stood a replica of Dr. Bird. There was the same six feet two of bone and muscle, the same beetling brows and the same craggy chin and high forehead surmounted by a shock of unruly black hair. In face and figure the stranger was a replica of the famous scientist until he glanced at their hands. Dr. Bird's hands were long and slim with tapering fingers, the hands of a thinker and an artist despite the acid stains[9] which disfigured them but could not hide their beauty. The hands of his double were stained as were Dr. Bird's, but they were short and thick and bespoke more the man of action than the man of thought.

The second figure arose and faced them and again Carnes received a shock. While the likeness was not so, striking, there was no doubt that the second man would have readily passed for Carnes himself in a dim light or at a little distance. Dr. Bird burst into laughter at the detective's puzzled face.

"Carnes," he said, "shake yourself together and then shake hands with Major Trowbridge of the Coast Artillery Corps. It has been said by some people that we favor one another."

"I'm glad to meet you, Major," said Carnes. "The resemblance is positively uncanny. But for your hands, I would have trouble telling you two apart."

he Major glanced down at his stubby fingers.

"It is unfortunate but it can't be helped," he said. "Dr. Bird, this is Corporal Askins of my command. He is not as good a second to Mr. Carnes as I am to you but you said it was less important."

"The likeness is plenty good enough," replied the Doctor. "He will probably not be subjected to as close a scrutiny as you will. Did you have any trouble in getting here unobserved?"

"None at all, Doctor. Lieutenant Maynard found a good landing field within a half mile of here, as you said he would, and he has his Douglass camouflaged and is standing by. When do you expect trouble?"

"I have no idea. It may come to-night or it may come later. Personally I hope that it comes later so that we can get in a few days of fishing before anything happens."

"What do you expect to happen, Doctor?" demanded Carnes. "Every time I have asked you anything you told me to wait until we were in the Maine woods and we are there now. I read up everything that I could find on amnesia victims during the past three months but it didn't throw much light on the matter to me."

"How many cases did you find, Carnes?"

"Sixteen. There may have been lots more but I couldn't find any others in the Post records. Of course, unless the victim were a local man, or of some prominence, it wouldn't appear."

"You got most of them at that. Did any points of similarity strike you as you read them?"

"None except that all were prominent men and all of them mental workers of high caliber. That didn't appear peculiar because it is the man of high mentality who is most apt to crack."

"Undoubtedly. There were some points of similarity which you missed. Where did the attacks take place?"

"Why, one was at—Thunder, Doctor! I did miss something. Every case, as nearly as I can recall, happened at some summer camp or other resort where they were on vacation."

"Correct. One other point. At what time of day did they occur?"

"In the morning, as well as I can remember. That point didn't register."

"They were all discovered in the morning, Carnes, which means that the actual loss of memory occurred during the night. Further, every case has happened within a circle with a diameter of three hundred miles. We are near the northern edge of that circle."

arnes checked up on his memory rapidly.

"You're right, Doctor," he cried. "Do you think—?"

"Once in a while," replied Dr. Bird dryly, "I think enough to know the futility of guesses hazarded without complete data. We are now located within the limits of the amnesia belt and we are here to find out what did happen, if anything, and not to make wild guesses about it. You have the tent set up for us, Major?"[10]

"Yes, Doctor, about thirty yards from the cabin and hidden so well that you could pass it a dozen times a day without suspecting its existence. The gas masks and other equipment which you sent to Fort Banks are in it."

"In that case we had better dispense with your company as soon as we have eaten a bite, and retire to it. On second thought, we will eat in it. Carnes, we will go to our downy couches at once and leave our substitutes in possession of the cabin. I trust, gentlemen, that things come out all right and that you are in no danger."

Major Trowbridge shrugged his heavy shoulders.

"It is as the gods will," he said sententiously. "It is merely a matter of duty to me, you know, and thank God, I have no family to mourn if anything does go wrong. Neither has Corporal Askins."

"Well, good luck at any rate. Will you guide Carnes to the tent and then return here and I'll join him?"

uddled in the tiny concealed tent, Dr. Bird handed Carnes a haversack on a web strap.

"This is a gas mask," he said. "Put it on your neck and keep it ready for instant use. I have one on and one of us must wear a mask continually while we are here. We'll change off every hour. If the gas used is lethane, as I suspect, we should be able to detect it before its gets too concentrated, but some other gas might be used and we must take no chances. Now look here."

With the aid of a flash-light he showed Carnes a piece of apparatus which had been set up in the tent. It consisted of two telescopic barrels, one fitted with an eye-piece and the other, which was at a wide angle to the first, with an objective glass. Between the two was a covered round disc from which projected a short tube fitted with a protecting lens. This tube was parallel to the telescopic barrel containing the objective lens.

"This is a new thing which I have developed and it is getting its first practical test to-night," he said. "It is a gas detector. It works on the principle of the spectroscope with modifications. From this projector goes out a beam of invisible light and the reflections are gathered and thrown through a prism of the eye-piece. While a spectroscope requires that the substance which it examines be incandescent and throw out visible light rays in order to show the typical spectral lines, this device catches the invisible ultra-violet on a fluorescent screen and analyzes it spectroscopically. Whoever has the mask on must continually search the sky with it and look for the three bright lines which characterize lethane, one at 230, one at 240 and the third at 670 on the illuminated scale. If you see any bright lines in those regions or any other lines that are not continually present, call my attention to it at once. I'll watch for the first hour."

t the end of an hour Dr. Bird removed his mask with a sigh of relief and Carnes took his place at the spectroscope. For half an hour he moved the glass about and then spoke in a guarded tone.

"I don't see any of the lines you told me to look for," he said, "but in the southwest I get wide band at 310 and two lines at about 520."

Dr. Bird advanced toward the instrument but before he reached it, Carnes gave an exclamation.

"There they are, Doctor!" he cried.

Dr. Bird sniffed the air. A faint sweetish odor became apparent and he reached for his gas mask. Slowly his hands drooped and Carnes grasped him and drew the mask over his face. Dr. Bird rallied slightly and feebly drew a bottle from his pocket and sniffed it. In another instant he was shouldering Carnes aside and staring through the spectroscope. Carnes watched him for an instant and then a low whirring noise attracted his attention and he looked up. Silently he[11] caught the Doctor's arm in a viselike grip and pointed.

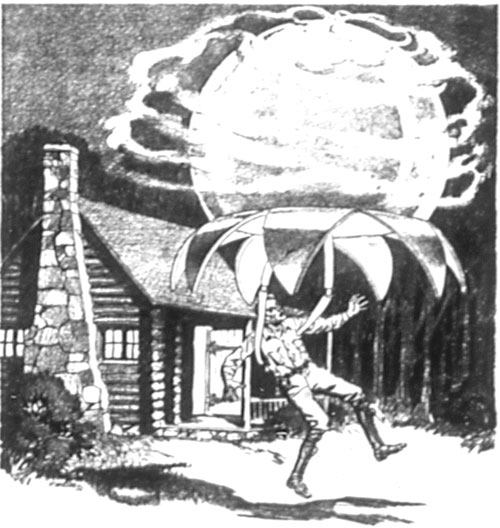

Hovering above the cabin was a silvery globe, faintly luminous in the moonlight. From its top rose a faint cloud of vapor which circled around the globe and descended toward the earth. The globe hovered like a giant humming bird above the cabin and Carnes barely stifled an exclamation. The door of the cabin opened and Major Trowbridge, walking stiffly and like a man in a dream, appeared. Slowly he advanced for ten yards and stood motionless. The globe moved over him and the bottom unfolded like a lily. Two long arms shot silently down and grasped the motionless figure and drew him up into the heart of the globe. The petals refolded, and silently as a dream the globe shot upward and disappeared.

"Gad! They lost no time!" commented Dr. Bird. "Come on, Carnes, run for your life, or rather, for Trowbridge's life. No, you idiot, leave your gas mask on. I'll take the spectroscope; it'll be all we need."

Followed by the panting Carnes, Dr. Bird sped through the night along an almost invisible path. For half a mile he kept up a headlong pace until Carnes could feel his heart pounding as though it would burst his ribs. The pair debouched from the trees into a glade a few acres in extent and Dr. Bird paused and whistled softly. An answering whistle came from a few yards away and a figure rose in the darkness as they approached.

"Maynard?" called Dr. Bird. "Good enough! I was afraid that you might not have kept your gas mask on."

"My orders were to keep it on, sir," replied the lieutenant in muffled tones through his mask, "but my mechanician did not obey orders. He passed out cold without any warning about fifteen minutes ago."

"Where's your ship?"

"Right over here, sir."

"We'll take off at once. Your craft is equipped with a Bird silencer?"

"Yes, sir."

"Come on, Carnes, we're going to follow that globe. Take the front cockpit alone, Maynard; Carnes and I will get in the rear pit with the spec and guide you. You can take off your gas mask at an elevation of a thousand feet. You have pack 'chutes, haven't you?"

"In the rear pit, Doctor."

"Put one on, Carnes, and climb in. I've got to get this spec set up before he gets too high."

The Douglass equipped with the Bird silencer, took the air noiselessly and rapidly gained elevation under the urging of the pilot. Dr. Bird clamped the gas-detecting spectroscope on the front of his cockpit and peered through it.

"Southwest, at about a thousand more elevation," he directed.

"Right!" replied the pilot as he turned the nose of his plane in the indicated direction and began to climb. For an hour and a half the plane flew noiselessly through the night.

"Bald Mountain," said the pilot, pointing. "The Canadian Border is only a few miles away."

"If they've crossed the Border, we're sunk," replied the doctor. "The trail leads straight ahead."

or a few minutes they continued their flight toward the Canadian Border and then Dr. Bird spoke.

"Swing south," he directed, "and drop a thousand feet and come back."

The pilot executed the maneuver and Dr. Bird peered over the edge of the plane and directed the spectroscope toward the ground.

"Half a mile east," he said, "and drop another thousand. Carnes, get ready to jump when I give the word."

"Oh, Lord!" groaned Carnes as he fumbled for the rip cord of his parachute, "suppose this thing doesn't open?"

"They'll slide you between two barn doors for a coffin and bury you that way," said Dr. Bird grimly. "You know your orders, Maynard?"[12]

"Yes, sir. When you drop, I am to land at the nearest town—it will be Lowell—and get in touch with the Commandant of the Portsmouth Navy Yard if possible. If I get him, I am to tell him my location and wait for the arrival of reenforcements. If I fail to get him on the telephone, I am to deliver a sealed packet which I carry to the nearest United States Marshal. When reenforcements arrive, either from the Navy Yard or from the Marshal, I am to guide them toward the spot where I dropped you and remain, as nearly as I can judge, two miles away until I get a further signal or orders from you."

"That is right. We'll be over the edge in another minute. Are you ready, Carnes?"

"Oh, yes, I'm ready, Doctor, if I have to risk my precious life in this contraption."

"Then jump!"

ide by side, Carnes and the doctor dropped toward the ground. The Douglass flew silently away into the night. Carnes found that the sensation of falling was not an unpleasant one as soon as he got accustomed to it. There was little sensation of motion, and it was not until a sharp whisper from Dr. Bird called it to his attention that he realized that he was almost to the ground. He bent his legs as he had been instructed and landed without any great jar. As he rose he saw that Dr. Bird was already on his feet and was eagerly searching the ground with the spectroscope which he had brought with him in the jump.

"Fold your parachute, Carnes, and we'll stow them away under a rock where they can't be seen. We won't use them again."

Carnes did so and deposited the silk bundle beside the doctor's, and they covered them with rocks until they would be invisible from the air.

"Follow me," said the doctor as he strode carefully forward, stopping now and then to take a sight with the spectroscope. Carnes followed him as he made his way up a small hill which blocked the way. A hiss from Dr. Bird stopped him.

Dr. Bird had dropped flat on the ground, and Carnes, on all fours, crawled forward to join him. He smothered an exclamation as he looked over the crest of the hill. Before him, sitting in a hollow in the ground, was the huge globe which had spirited away Major Trowbridge.

"This is evidently their landing place," whispered Dr. Bird. "The next thing to find is their hiding place."

e rose and started forward but sank at once to the ground and dragged Carnes down with him. On the hill which formed the opposite side of the hollow a line of light showed for an instant as though a door had been opened. The light disappeared and then reappeared, and as they watched it widened and against an illuminated background four men appeared, carrying a fifth. The door shut behind them and they made their way slowly toward the waiting globe. They laid down their burden and one of them turned a flash-light on the globe and opened a door in its side through which they hoisted their burden. They all entered the globe, the door closed and with a slight whirring sound it rose in the air and moved rapidly toward the northeast.

"That's the place we're looking for," muttered Dr. Bird. "We'll go around this hollow and look for it. Be careful where you step; they must have ventilation somewhere if their laboratory is underground."

Followed by the secret service operative, the doctor made his way along the edge of the hollow. They did not dare to show a light and it was slow work feeling their way forward, inch by inch. When they had reached a point above where the doctor thought the light had been he paused.

"There must be a ventilation shaft somewhere around here," he whispered,[13] his mouth not an inch from Carnes' ear, "and we've got to find it. It would never do to try the door; if any of them are still here it is sure to be guarded. You go up the hill for five yards and I'll go down. Quarter back and forth on a two hundred yard front and work carefully. Don't fall in, whatever you do. We'll return to this point every time we pass it and report."

The operative nodded and walked a few yards up the hill and made his way slowly forward. He went a hundred yards as nearly as he could judge and then stepped five yards further up the hill and made his way back. As he passed the starting point he approached and Dr. Bird's figure rose up.

"Any luck?" he whispered.

Dr. Bird shook his head.

"Well try further," he said. "I think it is probably beyond us, so suppose you go fifteen yards up and quarter the same as before."

arnes nodded and stole silently away. Fifteen yards up the hill he went and then paused. He stood on the crest of the hill and before him was a steep, almost precipitous slope. He made his way along the edge for a few yards and then paused. Faintly he could detect a murmur of voices. Inch by inch he crept forward, going over the ground under foot. He paused and listened intently and decided that the sound must come from the slope beneath him. A glance at his watch told him that he had spent ten minutes on this trip and he made his way back to the meeting place.

Dr. Bird was waiting for him, and in a low whisper Carnes reported his discovery. The doctor went back with him and together they renewed the search. The slope of the hill was almost sheer and Carnes looked dubiously over the edge.

"I wish we had brought the parachutes," he whispered to the doctor. "We could have taken the ropes off them and you could have lowered me over the edge."

Dr. Bird chuckled softly and tugged at his middle. Carnes watched him with astonishment in the dim light, but he understood when Dr. Bird thrust the end of a strong but light silk cord into his hands. He looped it under his arms and the doctor with whispered instructions, lowered him over the cliff. The doctor lowered him for a few feet and then stopped in response to a jerk on the free end. A moment later Carnes signaled to be drawn up and soon stood beside the doctor.

"That's the place all right," he whispered. "The whole cliff is covered with creepers and there is a tree growing right close to it. If we can anchor the cord here, I think that we can slide down to a safe hold on the tree."

A tree stood near and the silk cord was soon fastened. Carnes disappeared over the cliff and in a few moments Dr. Bird slid down the cord to join him. He found the detective seated in the crotch of a tree only a few feet from the face of the cliff. From the cliff came a pronounced murmur of voices. Dr. Bird drew in his breath in excitement and moved forward along the branch. He touched the stone and after a moment of searching he cautiously raised one corner of a painted canvas flap and peered into the cliff. He watched for a few seconds and then slid back and silently pulled Carnes toward him.

ogether the two men made their way toward the cliff and Dr. Bird raised the corner of the flap and they peered into the hill. Before them was a cave fitted up as a cross between a laboratory and a hospital. Almost directly opposite them and at the left of a door in the farther wall was a ray machine of some sort. It was a puzzle to Carnes, and even Dr. Bird, although he could grasp the principle at a glance, was at a loss to divine its use. From a set of coils attached to a generator was connected a tube of the Crookes tube type with the rays from it gathered and thrown by a parabolic[14] reflector onto the space where a man's head would rest when he was seated in a white metal chair with rubber insulated feet, which stood beneath it. An operating table occupied the other side of the room while a gas cylinder and other common hospital apparatus stood around ready for use.

Seated at a table which occupied the center of the room were three men. The sound of their voices rose from an indistinct murmur to audibility as the flap was raised and the watchers could readily understand their words. Two of them sat with their faces toward the main entrance and the third man faced them. Carnes bit his lip as he looked at the man at the head of the table. He was twisted and misshapen in body, a grotesque dwarf with a hunched back, not over four feet in height. His massive head, sunken between his hunched shoulders, showed a tremendous dome of cranium and a brow wider and even higher than Dr. Bird's. The rest of his face was lined and drawn as though by years of acute suffering. Sharp black eyes glared brightly from deep sunk caverns. The dwarf was entirely bald; even the bushy eyebrows which would be expected from his face, were missing.

hey ought to be getting back," said the dwarf sharply.

"If they get back at all," said one of the two figures facing him.

"What do you mean?" growled the dwarf, his eyes glittering ominously. "They'll return all right; they know they'd better."

"They'll return if they can, but I tell you again, Slavatsky, I think it was a piece of foolishness to try to take two men in one night. We got Bird all right, but it is getting late for a second one, and they had to take Bird over a hundred miles and then go nearly three hundred more for Williams. The news about Bird may have been discovered and spread and others may be looking out for us. Carnes might have recovered."

"Didn't he get a full dose of lethane?"

"So Frick says, and Bird certainly had a full dose, but I can't help but feel uneasy. Our operations were going too nicely on schedule and you had to break it up and take on an extra case in the same night as a scheduled one. I tell you, I don't like it."

"I'm sorry that I did it, Carson, but only because the results were so poor. We had planned on Williams for a month and I wanted him. And Bird was so easy that I couldn't resist it."

"And what did you get? Not as much menthium as would have come from an ordinary bookkeeper."

"I'll admit that Bird is a grossly overrated man. He must have worked in sheer luck in his work in the past, for there was nothing in his brain to show it above average. We got barely enough menthium to replace what we used in capturing him."

"We ought to have taken Carnes and left Bird alone," snorted Carson. "Even a wooden-headed detective ought to have given us a better supply than Bird yielded."

"We are bound to meet with disappointments once in a while. I had marked Bird down long ago as soon as I could get a chance at him."

"Well, you ran that show, Slavatsky, but I'll warn you that we aren't going to let you pull off another one like it. I take no more crazy chances, even on your orders."

he hunchback rose to his feet, his eyes glittering ominously.

"What do you mean, Carson?" he asked slowly, his hand slipping behind him as he spoke.

"Don't try any rough stuff, Slavatsky!" warned Carson sharply. "I can pull a tube as fast as you can, and I'll do it if I have to."

"Gentlemen, gentlemen!" protested the third man rising, "we are all too deep in this to quarrel. Sit down and let's talk this over. Carson is just worried."[15]

"What is there to be worried about?" grunted the dwarf as he slid back into his chair. "Everything has gone nicely so far and no suspicion has been raised."

"Maybe it has and then again maybe it hasn't," growled Carson. "I think this Bird episode to-night looks bad. In the first place, it came too opportunely and too easily. In the second place Bird should have yielded more menthium, and in the third place, did you notice his hands? They weren't the type of hands to expect on a man of his type."

"Nonsense, they were acid stained."

"Acid stains can be put on. It may be all right, but I am worried. While we are talking about this matter, there is another thing I want cleared up."

"What is it?"

"I think, Slavatsky, that you are holding out on us. You are getting more than your share of the menthium."

Again the dwarf leaped to his feet, but the peace-maker intervened.

"Carson has a right to look at the records, Slavatsky," he said. "I am satisfied, but I'd like to look at them, too. None of us have seen them for two months."

The dwarf glared at first one and then the other.

"All right," he said shortly and limped to a cabinet on the wall. He drew a key from his pocket and opened it and pulled out a leather-bound book. "Look all you please. I was supposed to get the most. It was my idea."

"You were to get one share and a half, while Willis, Frink and I got one share each and the rest half a share," said Carson. "I know how much has been given and it won't take me but a minute to check up."

e bent over the book, but Willis interrupted.

"Better put it away, Carson," he said, "here come the rest and we don't want them to know we suspect anything."

He pointed toward a disc on the wall which had begun to glow. Slavatsky looked at it and grasped the book from Carson and replaced it in the cabinet. He moved over and started the generator and the tube began to glow with a violet light. A noise came from the outside and the door opened. Four men entered carrying a fifth whom they propped up in the chair under the glowing tube.

"Did everything go all right?" asked the dwarf eagerly.

"Smooth as silk," replied one of the four. "I hope we get some results this time."

The dwarf bent over the ray apparatus and made some adjustments and the head of the unconscious man was bathed with a violet glow. For three minutes the flood of light poured on his head and then the dwarf shut off the light and Carson and Willis lifted the figure and laid it on the operating table. The dwarf bent over the man and inserted the needle of a hypodermic syringe into the back of the neck at the base of the brain. The needle was an extremely long one, and Dr. Bird gasped as he saw four inches of shining steel buried in the brain of the unconscious man.

Slowly Slavatsky drew back the plunger of the syringe and Dr. Bird could see it was being filled with an amber fluid. For two minutes the slow work continued, until a speck of red appeared in the glass syringe barrel.

"Seven and a half cubic centimeters!" cried the dwarf in a tone of delight.

"Fine!" cried Carson. "That's a record, isn't it?"

"No, we got eight once. Now hold him carefully while I return some of it."

lavatsky slowly pressed home the plunger and a portion of the amber fluid was returned to the patient's skull. Presently he withdrew the needle and straightened up and held it toward the light.

"Six centimeters net," he announced. "Take him back, Frink. I'll give Car[16]son and Willis their share now and we'll take care of the rest of you when you return. Is the ship well stocked?"

"Enough for two or three more trips."

"In that case, I'll inject this whole lot. Better get going, Frink, it's pretty late."

The four men who had brought the patient in stepped forward and lifted him from the table and bore him out. Dr. Bird dropped the canvas screen and strained his ears. A faint whir told him that the globe had taken to the air. He slid back along the limb of the tree until he touched the rope and silently climbed hand over hand until he gained the crest. He bent his back to the task of raising Carnes, and the operative soon stood beside him on the ledge surmounting the cliff.

"What on earth were they doing?" asked Carnes in a whisper.

"That was Professor Williams of Yale. They were depriving him of his memory. There will be another amnesia case in the papers to-morrow. I haven't time to explain their methods now: we've got to act. You have a flash-light?"

"Yes, and my gun. Shall we break in? There are only three of them, and I think we could handle the lot."

"Yes, but the others may return at any time and we want to bag the whole lot. They've done their damage for to-night. You heard my orders to Lieutenant Maynard, didn't you?"

"Yes."

"He should be somewhere in these hills to the south with assistance of some sort. The signal to them is three long flashes followed in turn by three short ones and three more long. Go and find them and bring them here. When you get close give me the same light signal and don't try to break in unless I am with you. I am going to reconnoitre a little more and make sure that there is no back entrance through which they can escape. Good luck. Carnes: hurry all you can. There is no time to be lost."

he secret service operative stole away into the night and Dr. Bird climbed back down the rope and took his place at the window. Willis lay on the operating table unconscious, while Slavatsky and Carson studied the now partially emptied syringe.

"You gave him his full share all right," Carson was saying. "I guess you are playing square with us. I'll take mine now."

He lay down on the operating table and the dwarf fitted an anesthesia cone over his face and opened the valve of the gas cylinder. In a moment he closed it and rolled the unconscious man on his face and deftly inserted the long needle. Instead of injecting a portion of the contents of the syringe as Dr. Bird had expected to do, he drew back on the plunger for a minute and then took out the needle and held the syringe to the light.

"Well, Mr. Carson," he said with a malignant glance at the unconscious figure, "that recovers the dose you got a couple of weeks ago while Willis watched me. I don't think you really need any menthium; your brain is too active to suit me as it is."

He gave an evil chuckle and walked to the far side of the cave and opened a secret panel. He drew from a recess a flask and carefully emptied a portion of the contents of the syringe into it. He replaced the flask and closed the panel, and with another chuckle he limped over to a chair and threw himself down in it. For an hour he sat motionless and Dr. Bird carefully worked his way back along the branch and climbed the rope and started for the hollow.

faint whirring noise attracted his attention, and he could see the faintly luminous globe in the distance, rapidly approaching. It came to a stop at the spot where it had previously landed and four men got out. Instead of going toward the cave, they towed the globe, which floated a few inches from the earth, toward the side[17] of the hill farthest from where the doctor stood. Three of them held it, while the fourth went forward and bent over some controls on the ground. A creaking sound came through the night and the men moved forward with the globe. Presently its movement stopped and men reappeared. Again came the creaking sound and the glow faded out as though a screen had been drawn in front of it. The four men walked toward the door of the cave.

Dr. Bird dropped flat on the ground and saw them pause a few yards below him on the hill and again work some hidden controls. A glare of light showed for an instant and they disappeared and everything was again quiet. Dr. Bird debated the advisability of returning to the window but decided against it and moved down the face of the hill.

Inch by inch he went over the ground, but found nothing. In the darkness he could not locate the door and he made his way around to the back of the hill. The precipice loomed above him and he swept it with his gaze, but he could locate no opening in the darkness and he dared not use a flash-light. As he turned he faced the east and noted with a start of surprise that the sky was getting red. He glanced at his watch and found that Carnes had been gone for nearly three hours.

"Great Scott!" he exclaimed in surprise. "Time has gone faster than I realized. He ought to be back at any time now."

e mounted the highest point of the hill and sent three long flashes, followed in turn by three short and three more long to the south and watched eagerly for an answer. He waited five minutes and repeated the signal, but no answering flashes came from the empty hills. With a grunt which might have meant anything, he turned and made his way toward the opposite side of the hollow where the globe had disappeared. Here he met with more luck. He had marked the location with extreme care and he had not spent over twenty minutes feeling over the ground before his hand encountered a bit of metal. As he pulled on it his eyes sought the side of the hill.

The dawn had grown sufficiently bright for him to see the result of his action. A portion of the hill folded back and the faintly glowing ship became visible. With a muttered exclamation of triumph he approached it.

The globe was about nine feet in diameter and was without visible doors or windows. Around and around it the doctor went, searching for an entrance. The ship now rested solidly on the ground. He failed to find what he sought and his sensitive hands began to go over it searching for an irregularity. He had covered nearly half of it before his finger found a hidden button and pressed it. Silently a door in the side of the craft opened and he advanced to enter.

"Keep them up!" said a sharp voice behind him.

Dr. Bird froze into instant immobility and the voice spoke again.

"Turn around!"

Dr. Bird turned and looked full into the eye of a revolver held by the man the dwarf had addressed as Frink. Behind Frink stood the dwarf and three other men.

As his eye fell on Dr. Bird, Frink turned momentarily pale and staggered back, the revolver wavering as he did so. Dr. Bird made a lightning-like grab for his own weapon, but before he could draw it Frink had recovered and the revolver was again steady.

"Dr. Bird!" gasped Slavatsky. "Impossible!"

"Get his gun, Harris," said Frink.

ne of the men stepped forward and dextrously removed the doctor's automatic and frisked him expertly to insure himself that he had no other weapon concealed.

"Bring him to the cave," directed Slavatsky, who, though obviously still[18] shaken, had just as obviously recovered enough to be a very dangerous man. Two of the men grasped the doctor and led him along toward the entrance to the laboratory cave which stood wide open in the gathering daylight. Frink paused long enough to shut the side of the hill and conceal the ship, and then followed the doctor. In the cave the door was shut and the doctor placed against the wall under the window through which he had peered earlier in the night. Slavatsky took his seat at the table, his malignant black eyes boring into the Doctor. Carson and Willis sat on the edge of the operating table, evidently still partially under the effects of the anesthetic that had been administered to them.

"How did you get back here?" demanded Slavatsky.

"Find out!" snapped Dr. Bird.

The dwarf rose threateningly.

"Speak respectfully to me; I am the Master of the World!" he roared in an angry voice. "Answer my questions when I speak, or means will be found to make you answer. How did you get back here?"

Dr. Bird maintained a stubborn silence, his fierce eyes answering the dwarf's, look for look, and his prominent chin jutting out a little more squarely. Carson suddenly broke the silence.

"That's not the Bird we had here earlier," he cried as he staggered to his feet.

"What do you mean?" demanded Slavatsky whirling on him.

"Look at his hands!" replied Carson pointing.

lavatsky looked at Dr. Bird's long mobile fingers and an evil leer came over his countenance.

"So, Dr. Bird," he said slowly, "you thought to match wits with Ivan Slavatsky, the greatest mind of all the ages. For a time you fooled me when your double was operated on here, but not for long. I presume you thought that we had no way of detecting the substitution? You have discovered differently. Where is your friend, Mr. Carnes?"

"Didn't your men leave him in the cabin when you kidnapped me?"

Slavatsky looked at Frink inquiringly.

"He stayed in the cabin if he was in it when we got there," the leader of the kidnapping gang replied. "He got a full shot of lethane and he's due to be asleep yet. I don't know how this man recovered. I left him there myself."

"Fool!" shrieked Slavatsky. "You brought me a double, a dummy whom I wasted my time in operating on. Was the other a dummy, too?"

"I didn't enter the cabin."

Slavatsky shrugged his shoulders.

"If that is all the good the menthium I have injected has done you, I might as well have saved it. It doesn't matter, however: we have the one we wanted. Dr. Bird, it was very thoughtful of you to come here and offer your marvelous brain to strengthen mine. I have no doubt that you will yield even more menthium than Professor Williams did this evening especially as I will extract your entire supply and reduce you to permanent idiocy. I will have no mercy on you as I have on the others I have operated on."

Dr. Bird blanched in spite of himself at the ominous words.

"You have the whip-hand for the moment, Slavatsky, but my time may come—and if it does, I will remember your kindness. I saw your operation on Professor Williams this evening and know your power. I also know that you stole the idea and the method from Sweigert of Vienna. I saw you inject the fluid you drew into Willis' brain. Shall I tell what else I saw?"

It was the dwarf's turn to blanch, but he recovered himself quickly.

"Into the chair with him!" he roared.

hree of the men grasped the doctor and forced him into the chair and Slavatsky started the generator. The violet light bathed Dr.[19] Bird's head and he felt a stiffness and contraction of his neck muscles, and as he tried to shout out his knowledge of Slavatsky's treachery, he found that his vocal chords were paralyzed. Through a gathering haze he could see Carson approaching with an anesthesia cone and the sweet smell of lethane assailed his nostrils. He fought with all his force, but strong hands held him, and he felt himself slipping—slipping—slipping—and then falling into an immense void. His head slumped forward on his chest and Slavatsky shut off the generator.

"On the table," he said briefly.

Four men picked up the herculean frame of the unconscious doctor and hoisted him up on the table. Carson seized his head and bent it forward and the dwarf took from a case a syringe with a five-inch needle. He touched the point of it to the base of the doctor's brain.

"Slavatsky! Look!" cried Frink.

With an exclamation of impatience the dwarf turned and stared at a disc set on the wall of the cave. It was glowing brightly. With an oath he dropped the syringe and snapped a switch, plunging the cave into darkness. A tiny panel in the door opened to his touch and he stared out into the light.

"Soldiers!" he gasped. "Quick, the back way!"

As he spoke there came a sound as of a heavy body falling at the back of the cave. Slavatsky turned the switch and flooded the cave with light. At the back of the cave stood Operative Carnes, an automatic pistol in his hand.

"Open the main door!" Carnes snapped.

lavatsky made a move toward the light, and Carnes' gun roared deafeningly in the confined space. The heavy bullet smashed into the wall an inch from the dwarf's hand and he started back.

"Open the main door!" ordered Carnes again.

The men stared at one another for a moment and the dwarf's eyes fell.

"Open the door, Frink," he said.

Frink moved over to a lever. He glanced at Slavatsky and a momentary gleam of intelligence passed between them. Frink raised his hand toward the lever and Carnes gun roared again and Frink's arm fell limp from a smashed shoulder.

"Slavatsky," said Carnes sternly, "come here!"

Slowly the dwarf approached.

"Turn around!" said Carnes.

He turned and felt the cold muzzle of Carnes' gun against the back of his neck.

"Now tell one of your men to open the door," said the detective. "If he promptly obeys your order, you are safe. If he doesn't, you die."

Slavatsky hesitated for a moment, but the cold muzzle of the automatic bored into the back of his neck and when he spoke it was in a quavering whine.

"Open the door, Carson," he whimpered.

There was moment of pause.

"If that door isn't open by the time I count three," said Carnes, "—as far as Slavatsky is concerned, it's just too bad. I'll have four shots left—and I'm a dead shot at this range. One! Two!"

His lips framed the word "three" and his fingers were tightening on the trigger when Carson jumped forward with an oath. He pulled a lever on the wall and the door swung open. Carnes shouted and through the opened door came a half dozen marines followed by an officer.

"Tie these men up!" snapped Carnes.

n a trice the six men were securely bound and Frink's bleeding shoulder was being skilfully treated by two of the marines. Carnes turned his attention to the unconscious doctor.

He rolled him over on his back and began to chafe his hands. An officer in a naval uniform came through the door and with a swift glance around, bent[20] over Dr. Bird. He raised one of the doctor's eyelids and peered closely at his eye and then sniffed at his breath.

"It's some anesthetic I don't know," he said. "I'll try a stimulant."

He reached in his pocket for a hypodermic, but Carnes interrupted him.

"Earlier in the evening Dr. Bird said they were using lethane," he said.

"Oh, that new gas the Chemical Warfare Service has discovered," said the surgeon. "In that case I guess it'll just have to wear off. I know of nothing that will neutralize it."

Without replying, Carnes began to feverishly search the pockets of the unconscious scientist. With an exclamation of triumph he drew out a bottle and uncorked it. A strong smell as of garlic penetrated the room and he held the opened bottle under Dr. Bird's nose. The doctor lay for a moment without movement, and then he coughed and sat up half strangled with tears running down his face.

"Take that confounded bottle away, Carnes!" he said. "Do you want to strangle me?"

He sat up and looked around.

"What happened?" he demanded. "Oh, yes, I remember now. That brute was about to operate on me. How did you get here?"

"Never mind that, Doctor. Are you all right?"

"Right as a trivet, old dear. How did you get here so opportunely?"

"I was a little slow in locating Lieutenant Maynard and the marines. When we got here I was afraid that we couldn't find the door, so I took Maynard and a detail around to the back and I went up to the top and slid down our cord and looked in the window. You were unconscious and Slavatsky was bending over you with a needle in his hand. I was about to try a shot at him when something called their attention to the men in front and I squeezed through the window and dropped in on them. They didn't seem any too glad to see me, but I overlooked that and insisted on inviting the rest of my friends in to share in the party. That's all."

"Carnes," said the Doctor, "you're probably lying like a trooper when you make out that you did nothing, but I'll pry the truth out of you sooner or later. Now I've got to get to work. Send for Lieutenant Maynard."

ne of the marines went out to get the flyer, and Dr. Bird stepped to the cabinet from which Slavatsky had taken his record book earlier in the evening and took out the leather-bound volume. He opened it and had started to read when Lieutenant Maynard entered the cave.

"Hello, Maynard," said the Doctor, looking up. "Are the rest of the party on their way?"

"They will be here in less than two hours, Doctor."

"Good enough! Have some one sent to guide them here. In the meanwhile, I'm going to study these records. Keep the prisoners quiet. If they make a noise, gag them. I want to concentrate."

For an hour and a half silence reigned in the cave. A stir was heard outside and Admiral Clay, the President's personal physician, entered leading a stout gray-haired man. Dr. Bird whistled when he saw them and leaped to his feet as another figure followed the admiral.

"The President!" gasped Carnes as the officers came to a salute and the marines presented arms.

The President nodded to his ex-guard, acknowledged the salute of the rest and turned to Dr. Bird.

"Have you met with success, Doctor?" he asked.

"I have, Mr. President; or, rather, I hope that I have. At the same time, I would rather experiment on some other victim of their deviltry than the one you have brought me."

"My decision that the one I have brought shall be the first to be experimented on, as you term it, is unalterable."[21]

r. Bird bowed and turned to the dwarf who had been a sullen witness of what had gone on.

"Slavatsky," he said slowly, "your game is up. I have witnessed one of your brain transfusions and I know the method. I gather from your notes that the menthium you have hidden in that cabinet is still as potent as when it was first extracted from a living brain, but in this case I am going to draw it fresh from one of your gang. Some of the details of the operation are a little hazy to me, but those you will teach me. I am going to restore this man to the condition he was in before you did your devil's work on him and you will direct my movements. Just what is the first step in removing the menthium from a brain?"

The dwarf maintained a stubborn silence.

"You refuse to answer?" asked the Doctor in feigned surprise. "I thought that you would rather instruct me and have me try the operation first on other men. Since you prefer that I operate on you first, I will be glad to do so."

He stepped to the opposite wall and in a few moments had opened the dwarf's hiding place and taken out the flask of menthium.

"Carson," he said, "after you had watched Slavatsky inject menthium into Willis, you took lethane and expected him to inject menthium into your brain. Instead of doing so he withdrew a portion from your brain and put it in this flask. I have reason to believe from his secret records which I found in the cabinet with this flask that he has done so regularly. Are you willing to instruct me while I remove the menthium from him?"

"The dirty swine!" shouted Carson. "I'll do anything to get even with him, but I have never performed the operation. Only Slavatsky and Willis have operated."

"Will you help me, Willis? asked Dr. Bird.

"I'll be glad to, Doctor. I am sick of this business anyway. At first, Slavatsky just planned to give us abnormally keen brains, but lately he has been talking of setting himself up as Emperor of the World, and I am sick of it. I think I would have broken with him and told all I know, soon, anyway."

"Throw him in that chair," said Dr. Bird.

espite the howlings and strugglings of the dwarf, three of the marines strapped him in the chair beneath the tube. The dwarf howled and frothed at the mouth and directed a final appeal for mercy to the President.

"Spare me, Your Excellency," he howled. "I will put my brains at your service and make you the greatest mentality of all time. Together we can conquer and rule the world. I will show you how to build hundreds of ships like mine—"

The President turned his back on the dwarf and spoke curtly.

"Proceed with your experiments, Dr. Bird," he said.

Slavatsky directed his appeals to the doctor, who peremptorily silenced him.

"I told you a few hours ago, Slavatsky, that the time might come when I would remember your threats against me. I will show you the same mercy now as you promised me then. Carnes, put a cone over his face."

Despite the howls of the dwarf, the operative forced an anesthesia cone over his face and Dr. Bird turned to the valve of the lethane cylinder. With Willis directing his movements, he turned on the ray for three minutes and removed the unconscious dwarf to the operating table. He took the long-needled syringe from a case and sterilized it and then turned to the President.

"I am about to operate," he said, "but before I do so, I wish to explain to all just what I have learned and what I am about to do. With that data, the decision of whether I shall proceed will rest with you and Admiral Clay. Have I your permission to do so?"[22]

he President nodded.

"When I first read of these amnesia cases, I took them for coincidences—until you consulted me and gave me an opportunity to examine one of the victims. I found a small puncture at the base of the brain which I could not explain, and I began to dig into old records. I knew, of course, of Sweigert of Vienna, and the extravagant claims he had put forward in 1911. He was far ahead of his time, but he mixed up some profound scientific discoveries with mysticism and occultism until he was discredited. Nevertheless, he continued his experiments with the aid of his principal assistant, a man named Slavatsky.

"Sweigert's theory was that intellectuality, brain power, intelligence, call it what you will, was the result of the presence of a fluid which he called 'menthium' in the brain. He thought that it could be transferred from one person to another, and with the aid of Slavatsky, he experimented on himself. He removed the menthium from an unfortunate victim, who was reduced to a state of imbecility, and Slavatsky injected the substance into Sweigert's brain. The experiment resulted fatally and Slavatsky was tried for murder. He was acquitted of intentional murder but was imprisoned for a time for manslaughter. He was released when the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken up, and for a time I lost track of him.

"I found translations of both the records of the trials and of Sweigert's original reports, and the thing that attracted my attention was that the puncture I found in the victim corresponded exactly with the puncture described by Sweigert as the one he made in extracting the menthium. I asked the immigration authorities to check over their records and they found that a man named Slavatsky whose description corresponded with the ill-fated Sweigert's assistant had entered the United States under Austria's quota about a year ago. The chain of evidence seemed complete to me, and it only remained to find the man who was systematically robbing brains.

"If such a thing was really going on, I felt that my reputation would make me an attractive bait and I secured a double, as you know, and placed him in a position where his kidnapping would be an easy matter. I was sure that the victims were being taken away by air and that lethane was being used to reduce the neighborhood to a state of profound somnolence, so I hid myself near my double with a gas detector which would find even minute traces of lethane in the air.

"My fish rose to the lure and came after the bait last night. When his ship arrived, I found a strange gas in the air, and followed the ship by the trail of the substance which it left behind it. Carnes was with me, and we got here in time to witness the extraction of the menthium from my friend, Professor Williams of Yale, and to see it injected into one of Slavatsky's gang. I sent Carnes for help and messed around until I was captured myself—and help arrived just in time. That's about all there is to tell. I am now about to reverse the process and try to remove the stolen brains from the criminals and restore them to their rightful owners. I have never operated and the result may be fatal. Shall I proceed?"

The President and Admiral Clay consulted for a moment in undertones.

"Go on with your experiments, Dr. Bird," said the President, "and we will hold you blameless for a failure. You have worked so many miracles in the past that we have every confidence in you."

Dr. Bird bowed acknowledgment to the compliment and bent over the unconscious dwarf. With Willis directing every move, he inserted the needle and drew back slowly on the plunger. Twenty-three and one-half cubic centimeters of amber fluid flowed into the syringe before a speck of blood appeared.[23]

"Enough!" cried Willis. Dr. Bird withdrew the syringe and motioned to Admiral Clay. The man the Admiral had brought in was placed in the chair and lethane administered. He was laid on the table, and, with a silent prayer, Dr. Bird inserted the needle and pressed the plunger. When five and one-quarter centimeters had flowed into the man's brains, he withdrew the needle and held the bottle which Carnes had used to revive him under the man's nose. The patient coughed a moment and sat up.

"Where am I?" he demanded. His gaze roved the cave and fell on the President. "Hello, Robert," he exclaimed. "What has happened?"

With a cry of joy the President sprang forward and wrung the hand of the man.

"Are you all right, William?" he asked anxiously. "Do you feel perfectly normal?"

"Of course I do. My neck feels a little stiff. What are you talking about? Why shouldn't I feel normal? How did I get here?"

"Take him outside, Admiral, and explain to him," said the President.

Admiral Clay led the puzzled man outside and the President turned to Dr. Bird.

"Doctor," he said, "I need not tell you that I again add my personal gratitude to the gratitude of a nation which would be yours, could the miracles you work be told off. If there is ever any way that can serve you, either personally or officially, do not hesitate to ask. The other victims will be brought here to-day. Will you be able to restore them?"

"I will, Mr. President. From Slavatsky's records I find that I will have enough if I reduce all of his men to a state of imbecility except Willis. In view of his assistance, I propose to leave him with enough menthium to give him the intelligence of an ordinary schoolboy."

"I quite approve of that," said the President as Willis humbly expressed his gratitude. "Have you had time to make an examination of that ship of Slavatsky's, yet?"

"I have not. As soon as the work of restoration is completed, I will go over it, and when I master the principles I will be glad to take them up with the Army-Navy General Board."

"Thank you, Doctor," said the President. He shook hands heartily and left the cave. Carnes turned and looked at the Doctor.

"Will you answer a question, Doctor?" he asked. "Ever since this case started, I have been wondering at your extraordinary powers. You have ordered the army, the navy, the department of justice and everyone else around as though you were an absolute monarch. I know the President was behind you, but what puzzles me is how he came to be so vitally interested in the case."

Dr. Bird smiled quizzically at the detective.

"Even the secret service doesn't know everything," he said. "Evidently you didn't recognize the man whose memory I restored. Besides being one of the most brilliant corporation executives in the country, he has another unique distinction. He happens to be the only brother of the President of the United States."

Far overhead a luminous shape appeared.

Far overhead a luminous shape appeared.

ou speak," said Von Kettler, jeering, "as if you really believed that you had the power of life and death over me."

The Superintendent of the penitentiary frowned, yet there was something of perplexity in the look he gave the prisoner. "Von Kettler, I think it is time that you dropped this absurd pose of yours," he said, "in view of the fact that you are scheduled to die by hanging at eight o'clock to-morrow night. Your life and death are in your own hands."

Von Kettler bowed ironically. Standing in the[25] Superintendent's presence in the uniform of the condemned cell, collarless, bare-headed, he yet seemed to dominate the other by a certain poise, breeding, nonchalance.

"Your life is offered you in consideration of your making a complete written confession of the whole ramifications of the plot against the Federal Government," the Superintendent continued.

"Rather a confession of weakness, my dear Superintendent," jeered the prisoner.

h don't worry about that! The Government has unravelled a good deal of the conspiracy. It knows that you and your international associates are planning to strike at civilized government throughout the world, in the effort to restore the days of autocracy. It knows you are planning a world federation of states, based on the principles of absolutism and aristocracy. It is aware of the immense financial resources behind the movement. Also that you have obtained the use of certain scientific discoveries[26] which you believe will aid you in your schemes."

"I was wondering," jeered the prisoner, "how soon you were coming to that."

"They didn't help you in your murderous scheme," the Superintendent thundered. "You were found in the War Office by the night watchman, rifling a safe of valuable documents. You shot him with a pistol equipped with a silencer. You shot down two more who, hearing his cries, rushed to his aid. And you attempted to stroll out of the building, apparently under the belief that you possessed mysterious power which would afford you security."

"A little lapse of judgment such as may happen with the best laid plans," smiled Von Kettler. "No, Superintendent, I'll be franker with you than that. My capture was designed. It was decided to give the Government an object lesson in our power. It was resolved that I should permit myself to be captured, in order to demonstrate that you cannot hang me, that I have merely to open the door of my cell, the gates of this penitentiary, and walk out to freedom."

"Have you quite finished?" rasped the Superintendent.

"At your disposal," smiled the other.

"Here's your last chance, Von Kettler. Your persistence in this absurd claim has actually shaken the expressed conviction of some of the medical examiners that you are sane. If you will make that complete written confession that the Government asks of you, I pledge you that you shall be declared insane to-night, and sent to a sanitarium from which you will be permitted to escape as soon as this affair has blown over."

he United States Government has sunk pretty low, to involve itself in a deal of this character, don't you think, my dear Superintendent?" jeered Von Kettler.

"The Government is prepared to act as it thinks best in the interests of humanity. It knows that the death of one wretched murderer such as yourself is not worth the lives of thousands of innocent men!"

"And there," smiled Von Kettler, without abating an atom of his nonchalance, "there, my dear Superintendent, you hit the nail on the head. Only, instead of thousands, you might have said millions."

Von Kettler's aspect changed. Suddenly his eyes blazed, his voice shook with excitement, his face was the face of a fanatic, of a prophet.

"Yes, millions, Superintendent," he thundered. "It it a holy cause that inspires us. We know that it is our sacred mission to save the world from the drabness of modern democracy. The people—always the people! Bah! what are the lives of these swarming millions worth when compared with a Caesar, a Napoleon, an Alexander, a Charlemagne? Nothing can stop us or defeat us. And you, with your confession of defeat, your petty bargaining—I laugh at you!"

"You'll laugh on the gallows to-morrow night!" the Superintendent shouted.

Again Von Kettler was the calm, superior, arrogant prisoner of before. "I shall never stand on the gallows trap, my dear Superintendent, as I have told you many times," he replied. "And, since we have reached what diplomacy calls a deadlock, permit me to return to my cell."

The Superintendent pressed a button on his desk; the guards, who had been waiting outside the office, entered hastily. "Take this man back," he commanded, and Von Kettler, head held high, and smiling, left the room between them.

he Superintendent pressed another button, and his assistant entered, a rugged, red-haired man of forty—Anstruther, familiarly known as "Bull" Anstruther, the man who had in three weeks reduced the penitentiary[27] from a place of undisciplined chaos to a model of law and order. Anstruther knew nothing of the Superintendent's offer to Von Kettler, but he knew that the latter had powerful friends outside.

"Anstruther, I'm worried about Von Kettler," said the Superintendent. "He actually laughed at me when I spoke of the possibility of another medical examination. He seemed confident that he could not be hanged. Swore that he will never stand on the gallows trap. How about your precautions for to-morrow night?"

"We've taken all possible precautions," answered Anstruther. "Special armed guards have been posted at every entrance to the building. Detectives are patrolling all streets leading up to it. Every car that passes is being scrutinized, its plate numbers taken, and forwarded to the Motor Bureau. There's no chance of even an attempt at rescue—literally none."

"He's insane," said the Superintendent, with conviction, and the words filled him with new confidence. It had been less Von Kettler's statements than the man's cool confidence and arrogant superiority that had made him doubt. "But he's not too insane to have known what he was doing. He'll hang."

"He certainly will," replied Anstruther. "He's just a big bluff, sir."

"Have him searched rigorously again to-morrow morning, and his cell too—every inch of it, Anstruther. And don't relax an iota of your precautions. I'll be glad when it's all over."

He proceeded to hold a long-distance conversation with Washington over a special wire.

n his cell, Von Kettler could be seen reading a book. It was Nietzsche's "Thus Spake Zarathusta," that compendium of aristocratic insolence that once took the world by storm, until the author's mentality was revealed by his commitment to a mad-house. Von Kettler read till midnight, closely observed by the guard at the trap, then laid the word aside with a yawn, lay down on his cot, and appeared to fall instantly asleep.

Dawn broke. Von Kettler rose, breakfasted, smoked the perfecto that came with his ham and eggs, resumed his book. At ten o'clock Bull Anstruther came with a guard and stripped him to the skin, examining every inch of his prison garments. The bedding followed; the cell was gone over microscopically. Von Kettler, permitted to dress again, smiled ironically. That smile stirred Anstruther's gall.

"We know you're just a big bluff, Von Kettler," snarled the big man. "Don't think you've got us going. We're just taking the usual precautions, that's all."

"So unnecessary," smiled Von Kettler. "To-night I shall dine at the Ambassador grill. Watch for me there. I'll leave a memento."

Anstruther went out, choking. Early in the afternoon two guards came for Von Kettler.

"Your sister's come to say good-by to you," he was told, as he was taken to the visitors' cell.

This was a large and fairly comfortable cell in a corridor leading off the death house, designed to impress visitors with the belief that it was the condemned man's permanent abode; and, by a sort of convention, it was understood that prisoners were not to disabuse their visitors' minds of the idea. The convention had been honorably kept. The visitor's approach was checked by a grill, with a two-yards space between it and the bars of the cell. Within this space a guard was seated: it was his duty to see that nothing passed.

s soon as Von Kettler had been temporarily established in his new quarters, a pretty, fair-haired young woman came along the corridor, conducted by the Superintendent himself. She walked with dignity, her bearing was proud, she smiled at her[28] brother through the grill, and there was no trace of weeping about her eyes.

She bowed with pretty formality, and Von Kettler saluted her with an airy wave of the hand. Then they began to speak, and the German guard who had been selected for the purpose of interpreting to the Superintendent afterward, was baffled.

It was not German—neither was it French, Italian, or any of the Romance languages. As a matter of fact, it was Hungarian.

Not until the half-hour was up did they lapse into English, and all the while they might have been conversing on art, literature, or sport. There was no hint of tragedy in this last meeting.

"Good-by, Rudy," smiled his sister, "I'll see you soon."

"To-night or to-morrow," replied Von Kettler indifferently.

The girl blew him a kiss. She seemed to detach it from her mouth and extend it through the grill with a graceful gesture of the hand, and Von Kettler caught it with a romantic wave of the fingers and strained it to his heart. But it was only one of those queer foreign ways. Nothing was passed. The alert guard, sitting under the electric light, was sure of that.

They searched Von Kettler again after he was back in the death house. The other cells were empty. In three of them detectives were placed. In the yard beyond the hangman was experimenting with the trap. He himself was under close observation. Nothing was being left to chance.

t seven o'clock two men collided in the death-house entrance. One was a guard, carrying Von Kettler's last meal on a tray. He had demanded Perigord truffles and paté de foie gras, cold lobster, endive salad, and near-beer, and he had got them. The other was the chaplain, in a state of visible agitation.

"If he was an atheist and mocked at me it wouldn't be so bad," the good man declared. "I've had plenty of that kind. But he says he's not going to be hanged. He's mad, mad as a March hare. The Government has no right to send an insane man to the gallows."

"All bluff, my dear Mr. Wright," answered the Superintendent, when the chaplain voiced his protest. "He thinks he can get away with it. The commission has pronounced him sane, and he must pay the penalty of his crime."

By that mysterious process of telegraphy that exists in all penal institutions, Von Kettler's boast that he would beat the hangman had become the common information of the inmates. Bets were being laid, and the odds against Von Kettler ranged from ten to fifteen to one. It was generally agreed, however, that Von Kettler would die game to the last.

"You all ready, Mr. Squires?" the prowling Superintendent asked the hangman.

"Everything's O. K., sir."

The Superintendent glanced at the group of newspaper men gathered about the gallows. They, too, had heard of the prisoner's boast. One of them asked him a question. He silenced him with an angry look.

"The prisoner is in his cell, and will be led out in ten minutes. You shall see for yourselves how much truth there it in this absurdity," he said.

e looked at his watch. It lacked five minutes of eight. The preparations for an execution had been reduced almost to a formula. One minute in the cell, twenty seconds to the trap, forty seconds for the hangman to complete his arrangements: two minutes, and then the thud of the false floor.

Four minutes of eight. The little group had fallen silent. The hangman furtively took a drink from his hip-pocket flask. Three minutes! The Superintendent walked back to the[29] door of the death house and nodded to the guard.

"Bring him out quick!" he said.

The guard shot the bolt of Von Kettler's cell. The Superintendent saw him enter, heard a loud exclamation, and hurried to his side. One glance told him that the prisoner had made good his boast.

Von Kettler's cell was empty!

aptain Richard Rennell, of the U. S. Air Service, but temporarily detached to Intelligence, thought that Fredegonde Valmy had never looked so lovely as when he helped her out of the cockpit.

Her dark hair fell in disorder over her flushed cheeks, and her eyes were sparkling with pleasure.

"A thousand thanks, M'sieur Rennell," she said, in her low voice with its slight foreign intonation. "Never have I enjoyed a ride more than to-day. And I shall see you at Mrs. Wansleigh's ball to-night?"

"I hope so—if I'm not wanted at Headquarters," answered Dick, looking at the girl in undisguised admiration.

"Ah, that Headquarters of yours! It claims so much of your time!" she pouted. "But these are times when the Intelligence Service demands much of its men, is it not so?"

"Who told you I was attached to Intelligence?" demanded Dick bluntly.

She laughed mockingly. "Do you think that is not known all over Washington?" she asked. "It is strange that Intelligence should act like the—the ostrich, who buries his head in the sand and thinks that no one sees him because it is hidden."

Dick looked at the girl in perplexity. During the past month he had completely lost his head and heart over her, and he was trying to view her with the dispassionate judgment that his position demanded.

As the niece of the Slovakian Ambassador, Mademoiselle Valmy had the entry to Washington society. The Ambassador was away on leave, and she had appeared during his absence, but she had been accepted unquestionably at the Embassy, where she had taken up her quarters, explaining—as the Ambassador confirmed by cable—that she had sailed under a misconception as to the date of his leave.

runette, beautiful, charming, she had a score of hearts to play with, and yet Dick flattered himself that he stood first. Perhaps the others did too.

"Of course," the girl went on, "with the Invisible Emperor threatening organized society, you gentlemen find yourselves extremely busy. Well, let us hope that you locate him and bring him to book."

"Sometimes," said Dick slowly, "I almost think that you know something about the Invisible Emperor."

Again she laughed merrily. "Now, if you had said that my sympathies were with the Invisible Emperor, I might have been surprised into an acknowledgment," she answered. "After all, he does stand for that aristocracy that has disappeared from the modern world, does he not? For refinement of manners, for beauty of life, for all those things men used to prize."

"Likewise for the existence of the vast body of the nation in ignorance and poverty, in filth and squalor," answered Dick. "No, my sympathies are with law and order and democracy, and your Invisible Emperor and his crowd are simply a gang of thieves and hold-up men."

"Be careful!" A warning fire burned in the girl's eyes. "At least, it is known that the Emperor's ears are long."

"So are a jackass's," retorted Dick.

He was sorry next moment, for the girl received his answer in icy silence. In his car, which conveyed them from the tarmac to the Embassy, she received all his overtures in the same si[30]lence. A frigid little bow was her farewell to him, while Dick, struggling between resentment and humiliation, sat dumb and wretched at the wheel.

Yet the idea that Fredegonde Valmy had any knowledge of the conspiracy or its leaders never entered Dick's head. He was only miserable that he had offended her, and he would have done anything to have straightened out the trouble.

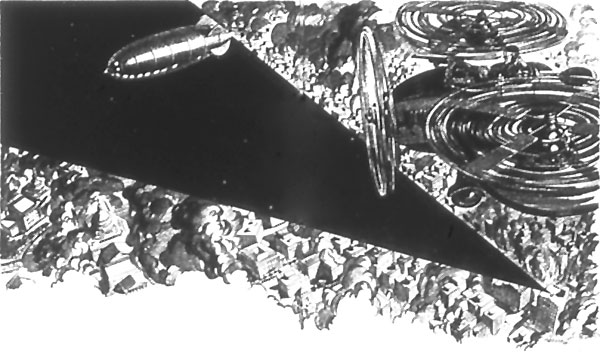

t seemed impossible that in the year 1940 the peace of the civilized world could be threatened by an international conspiracy bent on restoring absolutism, and yet each day showed more clearly the immense ramifications of the plot. Each day, too, brought home to the investigating governments more clearly the fact that the things they had discovered were few in number in comparison with those they had not.

The headquarters of the conspirators had never been discovered, and it was suspected that the powerful mind behind them was intentionally leading the investigators along false trails.

The conspiracy was world-wide. It had been behind the revolution that had recreated an absolutist monarchy in Spain. It had plunged Italy into civil war. It had thrown England into the convulsions of a succession of general strikes, using the communist movement as a cloak for its activities.

But nobody dreamed that America could become a fertile field for its insidious propaganda. Yet it was behind the millions of adherents of the so-called Freemen's Party, clamoring for the destruction of the constitution. Upon the anarchy that would follow the absolutist regime was to be erected.

Already the mysterious powers had struck. Departments of State had been entered and important papers abstracted. The Germania had mysteriously disappeared in mid-Atlantic, and a shipping panic had ensued. There were tales of mysterious figures materializing out of nothingness. It was known that the conspirators were in possession of certain chemical and electrical devices with which they hoped to achieve their ends.