Project Gutenberg's The History of Dartmouth College, by Baxter Perry Smith This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The History of Dartmouth College Author: Baxter Perry Smith Release Date: April 30, 2009 [EBook #28641] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE HISTORY OF DARTMOUTH COLLEGE *** Produced by Stacy Brown, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Print project.)

OF

BY

BOSTON:

HOUGHTON, OSGOOD AND COMPANY.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge.

1878.

Copyright, 1878,

by Baxter Perry Smith.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge:

Printed by H. O. Houghton and Company.

In the preparation of this work the writer has deemed it better to let history, as far as possible, tell its own story, regarding reliability as preferable to unity of style.

The imperfect records of all our older literary institutions, limit their written history, in large measure, to a record of the lives and labors of their teachers.

To the many friends of the college, and others, who have kindly given their aid, the writer is under large obligations.

The following names deserve especial notice: Hon. Robert C. Winthrop, Hon. Charles L. Woodbury, Hon. R. R. Bishop, Wm. H. Duncan, Esq., Richard B. Kimball, Esq., Rev. Eden B. Foster, D.D., Hon. James Barrett, N. C. Berry, Esq., Dr. F. E. Oliver, Hon. J. E. Sargent, Dr. C. A. Walker, Hon. A. O. Brewster, Hon. A. A. Ranney, Dr. W. M. Chamberlain, Hon. James W. Patterson, Rev. Carlos Slafter, Hon. J. B. D. Cogswell, Gen. John Eaton, Rev. H. A. Hazen, Rev. S. L. B. Speare, H. N. Twombly, Esq., Caleb Blodgett, Esq., Hon. Benj. F. Prescott, Dr. C. H. Spring, Prof. C. O. Thompson, Hon. Frederic Chase, Rev. W. J. Tucker, D.D., L. G. Farmer, Esq., and N. W. Ladd, Esq.

With profound gratitude he mentions also the name of Hon. Nathan Crosby, but for whose valuable pecuniary aid the publication of the work must have been delayed; and the names of Hon. Joel Parker, Hon. William P. Haines, Hon. John P. Healy, Hon. Lincoln F. Brigham, John D. Philbrick, Esq., Dr. Jabez B. Upham, Hon. Harvey Jewell, and Hon. Walbridge A. Field, who have aided in a similar manner. Particular mention should also be made of the kindness of gentlemen connected with numerous libraries, especially that of Mr. John Ward Deane, and Mr. Albert H. Hoyt, and the late J. Wingate Thornton, Esq., of the New England Historic-Genealogical Society, by whose kindness the writer was furnished with the valuable letter from David McClure to General Knox, and Rev. Alonzo H. Quint, D.D., and Dr. Samuel A. Green, of the Massachusetts Historical Society, to whom he is indebted for the invaluable list of English donations given in the Appendix. Valuable aid has been rendered also by Messrs. Kimball and Secor, of the New Hampshire State and State Historical Society Libraries, at Concord. In this connection the well known names of W. S. Butler, Prof. F. B. Dexter, Hon. C. J. Hoadley, F. B. Perkins, Hon. J. Hammond Trumbull, and Hon. E. P. Walton also deserve notice.

The writer is deeply indebted to Hon. John Wentworth, of Chicago, for his kindness in examining the more important portions of the work previous to its publication.

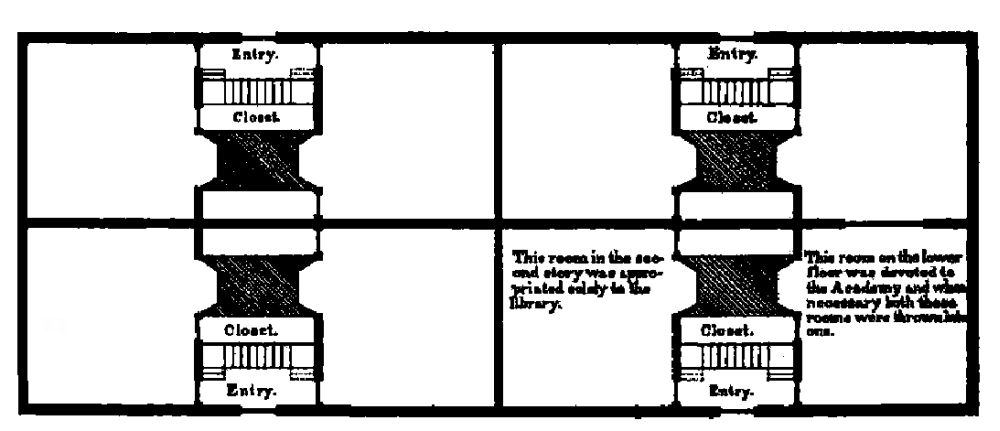

For the carefully-prepared draught of the original college edifice, the writer is indebted to the artistic skill of Mr. Arthur Bruce Colburn.

In closing, especial mention should be made of the kindness of Prof. Charles Hammond, Marcus D. Gilman, Esq., and others representing the family of the founder, of the family of Hon. Elisha Payne, an early and honored Trustee, of the Trustees and Faculty of the college, and the courteous liberality of the publishers.

BAXTER P. SMITH.

Brookline, Mass., June, 1878.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Ancestry and Early Life of Eleazar Wheelock.—His Settlement at Lebanon.—Establishment of the Indian Charity School.—Mr. Joshua More | 6 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Education in New Hampshire.—Action in Regard to a College.—Testimonial of Connecticut Clergymen.—Legislative Grant to Mr. Wheelock | 15 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| A College Contemplated by Mr. Wheelock.—Lord Dartmouth.—Occom and Whitaker in Great Britain | 23 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Sir William Johnson.—Explorations for a Location.—Advice of English Trustees | 29 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| A College Charter | 40 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| President Wheelock's Personal Explorations in New Hampshire.—Location at Hanover | 49 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Commencement of Operations.—Course of Study.—Policy of Administration | 57 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Progress to the Death of President Wheelock.—Prominent Features of his Character | 65 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Progress During the Administration of the Second President, John Wheelock | 76 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Lack of Harmony Between President Wheelock and Other Trustees.—Removal of the President From Office.—Estimate of His Character | 88 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Administration of President Brown.—Contest Between The College and the State.—Triumph of the College | 100 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Character of President Brown.—Tributes by Professor Haddock And Rufus Choate | 117 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Progress From 1820 to 1828.—Administrations of President Dana and President Tyler | 126 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Inauguration of President Lord | 143 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| The Policy of the College, its Progress and Enlargement under President Lord's Administration from 1828 to 1863 | 157 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Character of President Lord | 168 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Administration of President Smith | 177 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Inauguration of President Bartlett | 190 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Prof. John Smith.—Prof. Sylvanus Ripley.—Prof. Bezaleel Woodward | 211 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Prof. John Hubbard.—Prof. Roswell Shurtleff | 225 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Prof. Ebenezer Adams.—Prof. Zephaniah S. Moore.—Prof. Charles B. Haddock | 241 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Prof. William Chamberlain.—Prof. Daniel Oliver.—Prof. James Freeman Dana | 256 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Prof. Benjamin Hale.—Prof. Alpheus Crosby.—Prof. Ira Young | 276 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Prof. Stephen Chase.—Prof. David Peabody.—Prof. William Cogswell | 298 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Prof. John Newton Putnam.—Prof. John S. Woodman.—Prof. Clement Long.—Other Teachers | 316 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Medical Department.—Professors Nathan Smith, Reuben D. Mussey, Dixi Crosby, Edmund R. Peaslee, Albert Smith, and Alpheus B. Crosby—Other Teachers | 339 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| The Chandler Scientific Department.—The Agricultural Department.—The Thayer Department of Civil Engineering | 367 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Benefactors.—Trustees | 380 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| Labors of Dartmouth Alumni.—Conclusion | 395 |

INTRODUCTION.

The most valuable part of a nation's history portrays its institutions of learning and religion.

The alumni of a college which has moulded the intellectual and moral character of not a few of the illustrious living, or the more illustrious dead,—the oldest college in the valley of the Connecticut, and the only college in an ancient and honored State,—would neglect a most fitting and beautiful service, should they suffer the cycles of a century to pass, without gathering in some modest urn the ashes of its revered founders, or writing on some modest tablet the names of its most distinguished sons.

The germ of Dartmouth College was a deep-seated and long-cherished desire, of the foremost of its founders, to elevate the Indian race in America.

The Christian fathers of New England were not unmindful of the claims of the Aborigines. The well-directed, patient, and successful labors of the Eliots, Cotton, and the Mayhews, and the scarcely less valuable labors of Treat and others, fill a bright page in the religious history of the seventeenth century. To numerous congregations of red men the gospel was preached; many were converted; churches were gathered, and the whole Bible—the first printed in America—was given them in their own language.

This interest in the Indian was not confined to our own country, in the earlier periods of our history. In Great Britain, sovereigns, ecclesiastics, and philosophers recognized[2] the obligations providentially imposed upon them, to aid in giving a Christian civilization to their swarthy brethren, who were sitting in the thickest darkness of heathenism in the primeval forests of the New World. Societies, as well as individuals, manifested a deep and practical interest in the work.

We can only touch upon some of the more salient points of this subject. But it is especially worthy of note, that the elevation of the Indian race, by the education of its youth, was not an idea of New England, nor indeed of American, birth.

In Stith's "History of Virginia" (p. 162), we find in substance the following statements: At an early period in the history of this State, attempts were made to establish an institution of learning of a high order. In 1619, the treasurer of the Virginia Company, Sir Edwin Sandys, received from an unknown hand five hundred pounds, to be applied by the Company to the education of a certain number of Indian youths in the English language and in the Christian religion. Other sums of money were also procured, and there was a prospect of being able to raise four or five thousand pounds, for the endowment of a college. The king favored the design, and recommended to the bishops to have collections made in their dioceses, and some fifteen hundred pounds were gathered on this recommendation. The college was designed for the instruction of English, as well as Indian, youths. The Company appropriated ten thousand acres of land to this purpose, at Henrico, on James River, a little below the present site of Richmond. The plan of the college was, to place tenants at halves on these lands, and to derive its income from the profits. The enterprise was abandoned in consequence of the great Indian massacre, in 1622, although operations had been commenced, and a competent person had been secured to act as president. This is believed to have been the first effort to found a college in America.

Passing to the middle of the century, we find the distinguished Christian philosopher, Robert Boyle, appointed governor of "a company incorporated for the propagation of the gospel among the heathen natives of New England, and the parts adjacent in America," and that, after his decease, in[3] 1691, a portion of his estate was given, by the executors of his will, to William and Mary's College, which was possibly, in a measure, the outgrowth of the efforts of Mr. Sandys and his coadjutors, for the support of Indian students.

In 1728, Col. William Byrd, in writing upon this subject, laments "the bad success Mr. Boyle's charity has had in converting the natives," which was owing in part, at least, to the fact, that the interest of their white brethren in their welfare was confined chiefly to their residence at college.

Pursuing these researches, we come to the name of another distinguished British scholar and divine, George Berkeley, who has been styled "the philosopher" of the reign of George II.

We quote a portion of a letter relating to his educational plans, from Dean Swift to Lord Carteret, Lieutenant of Ireland, dated Sept. 3, 1724, in which he says:

"He showed me a little tract which he designs to publish, and there your Excellency will see his whole scheme of a life academico-philosophic, of a college at Bermuda for Indian scholars and missionaries. I discourage him by the coldness of courts and ministers, who will interpret all this as impossible and a vision, but nothing will do. And therefore I do humbly entreat your Excellency either to use such persuasions as will keep one of the first men in this kingdom for learning and virtue quiet at home, or assist him by your credit to compass his romantic design, which, however, is very noble and generous, and directly proper for a great person of your excellent education to encourage."

The pamphlet alluded to begins, as one of his biographers informs us, by lamenting "that there is at this day little sense of religion and a most notorious corruption of manners in the English colonies settled on the continent of America, and the islands," and that "the Gospel hath hitherto made but very inconsiderable progress among the neighboring Americans, who still continue in much the same ignorance and barbarism in which we found them above a hundred years ago." After stating what he believes to be the causes of this state of things, he propounds his plan of training young natives, as missionaries to their countrymen, and educating "the youth of our English plantations," to fill the pulpits of the colonial churches. His[4] biographer is doubtless correct in the opinion, that "it was on the savages, evidently, that he had his heart."

He obtained a charter from the crown for his proposed college, and a promise, never fulfilled, of large pecuniary aid from the government, and early in 1729 he arrived in America, settling temporarily at Newport, R. I. Failing to accomplish his purpose, he remained in this country but two or three years, yet long enough to form the acquaintance of many eminent men, and among them President Williams, of Yale College.

Finding that there was no prospect of receiving the promised aid for his college, Berkeley returned to England in 1731. Soon after, in addition to a large and valuable donation of books for the library, he sent as a gift, to Yale, a deed of his farm in Rhode Island, the rents of which he directed to be appropriated to the maintenance or aid of meritorious resident graduates or under-graduates.

Although he failed to carry out his plan of establishing a college himself, in America, perhaps he "builded better than he knew." Most fitting is it, as we shall see hereafter, for the current literature of our day to place in intimate association, the names of Boyle, Berkeley, and Dartmouth.

Passing to 1734, we find Rev. John Sergeant commencing missionary labor among the Indians at Stockbridge, Mass. After a trial of a few years, he writes in a manner showing very plainly that he believes civilization essential to any permanent success. In one of his letters to Rev. Dr. Colman, of Boston, he says: "What I propose, in general, is, to take such a method in the education of our Indian children as shall in the most effectual manner change their whole manner of thinking and acting, and raise them as far as possible into the condition of a civil, industrious, and polished people, while at the same time the principles of virtue and piety shall be instilled into their minds in a way that will make the most lasting impression, and withal to introduce the English language among them instead of their own barbarous dialect."

"And now to accomplish this design, I propose to procure an accommodation of 200 acres of land in this place (which may be had gratis of the Indian proprietors), and to erect a[5] house on it such as shall be thought convenient for a beginning, and in it to maintain a number of children and youth." He proposes "to have their time so divided between study and labor that one shall be the diversion of the other, so that as little time as possible may be lost in idleness," and, "to take into the number, upon certain conditions, youths from any of the other tribes around." His plan included both sexes. Mr. Sergeant died in 1749. Besides accomplishing much himself, he laid the foundations for the subsequent labors of Jonathan Edwards.

This rapid glance at the earlier efforts in behalf of the Aborigines of our country, shows that the next actor upon the stage, undaunted by any lack of success on their part, measurably followed in the footsteps of learned and philanthropic predecessors.

ANCESTRY AND EARLY LIFE OF ELEAZAR WHEELOCK.—HIS SETTLEMENT AT LEBANON, CONN.—ESTABLISHMENT OF THE INDIAN CHARITY SCHOOL.—MR. JOSHUA MORE.

Eleazar Wheelock, the leading founder of Dartmouth College, was a great-grandson of Ralph Wheelock, a native of Shropshire, in England, through whom Dartmouth traces her academic ancestry to the ancient and venerable Clare Hall, at Cambridge, where he graduated in 1626, the contemporary of Thomas Dudley, Samuel Eaton, John Milton, John Norton, Thomas Shepard, and Samuel Stone.

Coming a few years later to this country, he became a useful and an honored citizen of the then new, but now old, historic town of Dedham, from which place he removed to Medfield, being styled "founder" of that town, where he remained till his death. He devoted his time largely to teaching, although, having been educated for the ministry, he rendered valuable service to the infant community as an occasional preacher. His name is also conspicuous among the magistrates and legislators of that period.[1]

[1] His daughter Rebecca married John Craft, whose birth is the earliest on record among the pioneer settlers at Roxbury. Some of his descendants (by another marriage) are conspicuous in history. Medfield records connect the names of Fuller, Chenery, and Morse with the Wheelock family.

In the character of his son, Eleazar Wheelock, of Mendon, we are told there was a union of "the Christian and the soldier." Having command of a corps of cavalry, he was "very successful in repelling the irruptions of the Indians," although he treated them with "great kindness," in times of peace. From him, his grandson and namesake received "a handsome legacy for defraying the expenses of his public education," and from him, too, he doubtless acquired, in some[7] measure, that peculiar interest in the Indian race which so largely moulded his character and guided the labors of his life.

Near the time of Ralph Wheelock's arrival in America, were two other arrivals worthy of notice: that of Thomas Hooker, at Cambridge, "the one rich pearl with which Europe more than repaid America for the treasures from her coasts," and that of the widowed Margaret Huntington, at Roxbury, of which there is still a well-preserved record, in the handwriting of John Eliot. The guiding and controlling influence of Hooker's masterly mind upon all, whether laymen or divines, with whom he came in contact, must be apparent to those who are familiar with the biography of one, to whom the learned and religious institutions of New England are more indebted, perhaps, than to any other single person. Hooker's settlement at Hartford is fitly styled "the founding of Connecticut."

When a little later the family of Margaret Huntington settled at Saybrook, their youthful pastor, who was just gathering a church, was James Fitch, a worthy pupil of Thomas Hooker. Not satisfied with their location, pastor and people sought an inland home, and in 1660 laid the foundations of what is now the large and flourishing town of Norwich. From this time Huntington and Fitch are honored names in the history of Connecticut.

A quarter of a century after the settlement of Norwich, an English refugee from religious oppression began the settlement of the neighboring town of Windham. To this place, Ralph Wheelock the younger, a grandson of the Dedham teacher and preacher, was attracted, marrying about the same time, Ruth, daughter of Dea. Christopher Huntington, of Norwich. Mr. Ralph Wheelock was a respectable farmer, universally esteemed for his hospitality, his piety, and the virtues that adorn the Christian character, and in his later years was an officer of the church.

Of Mrs. Wheelock, it is said:[2] "Every tradition respecting her makes her a woman of unusual intelligence and rare piety. Her home, the main theatre of her life, was blessed equally by her timely instructions, her holy example, and the administration[8] of a gentle yet firm discipline." Their son Eleazar was born at Windham, April 22, 1711.

[2] Huntington Family Memoir, p. 78.

The first minister of this honored town was Rev. Samuel Whiting, a native of Hartford, and trained in the "Hooker School." For a helpmeet he had secured a lineal descendant of that noble and revered puritan, Gov. Wm. Bradford. The labors of this worthy pair were largely blessed to their people. At one period, in a population of hundreds, it is said "the town did not contain a single prayerless family."

Thus kindly and wisely did the Master arrange, by long and closely blended lines of events, that the most genial influences should surround the cradle of one for whom He designed eminent service and peculiar honor.

The mother of Eleazar Wheelock having died in 1725, for a second wife his father married a lady named Standish, a descendant of Myles Standish, whose heroic character she perhaps impressed, in some measure, upon her adopted son. "Being an only son," says his biographer,[3] "and discovering, at an early age, a lively genius, a taste for learning, with a very amiable disposition, he was placed by his father under the best instructors that could then be obtained." At "about the age of sixteen, while qualifying himself for admission to college, it pleased God to impress his mind with serious concern for his salvation. After earnest, prayerful inquiry, he was enlightened and comforted with that hope in the Saviour, which afterwards proved the animating spring of his abundant labors to promote the best interests of mankind." At the time of his admission to the Windham church, the distinguished Thomas Clap was its pastor.

[3] Memoirs of Wheelock, by McClure and Parish.

Having made the requisite preparation, he entered Yale College, of which President Williams was then at the head, "with a resolution to devote himself to the work of the Gospel ministry." Among his college contemporaries were Joseph Bellamy and President Aaron Burr.

"His proficiency in study, and his exemplary deportment, engaged the notice and esteem of the rector and instructors, and the love of the students. He and his future brother-in-law, the late Rev. Doctor Pomeroy of Hebron, in Connecticut, were the first who received the interest of the legacy, generously[9] given by the Rev. Dean Berkeley," for excellence in classical scholarship.

Soon after his graduation, in 1733, he commenced preaching. Having declined a call from Long Island, to settle in the ministry, he accepted a unanimous invitation from the Second Congregational Society in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was ordained in June, 1735.

This town occupies a conspicuous place in American history; for, whoever traces the lineage of some of the most illustrious names that grace its pages, finds his path lying to or through this "valley of cedars," in Eastern Connecticut. Here the patient, heroic Huguenot aided in laying foundations for all good institutions. Here the learned, indefatigable Tisdale taught with distinguished success. Here lived those eminent patriots, the Trumbulls. By birth or ancestry, the honored names of Smalley, Ticknor, Marsh, and Mason, are associated with this venerable town.

Mr. Wheelock's parish was in the northern and most retired part of the town, and the least inviting, perhaps, in its physical aspects and natural resources. The products of a rugged soil furnished the industrious inhabitants with a comfortable subsistence, but left nothing for luxury. It was at that period a quiet agricultural community, living largely within itself. As at the present day, there was but one church within the territorial limits of the parish. The "council of nine," selected from the more discreet of the male members, somewhat in accordance with Presbyterian usage, aided in the administration of a careful and thorough discipline.

There can be no doubt that Mr. Wheelock was accounted one of the leading preachers and divines of his day. Both as a pastor, and the associate of the eminent men who were prominent in the great revival which marked the middle of the last century, his labors were crowned with large success. Rev. Dr. Burroughs, who knew him intimately, says: "As a preacher, his aim was to reach the conscience. He studied great plainness of speech, and adapted his discourse to every capacity, that he might be understood by all." His pupil, Dr. Trumbull, the historian, says: "He was a gentleman of a comely figure, of a mild and winning aspect, his voice smooth[10] and harmonious, the best by far that I ever heard. He had the entire command of it. His gesture was natural, but not redundant. His preaching and addresses were close and pungent, and yet winning beyond almost all comparison."[4] By an intermarriage of their relatives, he was allied to the family of Jonathan Edwards, whose high regard for him is sufficiently indicated in a letter dated Northampton, June 9, 1741, from which we make brief extracts. "There has been a reviving of religion of late amongst us, but your labors have been much more remarkably blessed than mine. May God send you hither with the like blessing as He has sent you to some other places, and may your coming be a means to humble me for my barrenness and unprofitableness, and a means of my instruction and enlivening. I want an opportunity to concert measures with you, for the advancement of the kingdom and glory of the Redeemer."

[4] The venerable Prof. Stowe states that, when a professor in the College, he was informed by an aged man, living in the vicinity, that President Wheelock's earnestness in preaching at times led him to leave the pulpit, and appeal to individuals in his audience.

We are fortunate in having the testimony of a member of his own family, in regard to the beginning of Mr. Wheelock's more practical interest in the unfortunate Aborigines. His grandson, Rev. William Patten, D.D., says,[5] "One evening after a religious conference with a number of his people at Lebanon, he walked out, as he usually did on summer evenings, for meditation and prayer; and in his retirement his attention was led to the neglect [from lack of means] of his people in providing for his support. It occurred to him, with peculiar clearness, that if they furnished him with but half a living, they were entitled to no more than half his labors. And he concluded that they were left to such neglect, to teach him that part of his labors ought to be directed to other objects. He then inquired what objects were most in want of assistance. And it occurred to him, almost instantaneously, that the Indians were the most proper objects of the charitable attention of Christians. He then determined to devote half of his time to them."

[5] Memoirs of Wheelock, p. 177.

We will now allow this eminent Christian philanthropist to speak for himself. In his "Narrative," for the period ending[11] in 1762, after referring to the too general lack of interest in the Indian, he says:

"It has seemed to me, he must be stupidly indifferent to the Redeemer's cause and interest in the world, and criminally deaf and blind to the intimations of the favor and displeasure of God in the dispensations of His Providence, who could not perceive plain intimations of God's displeasure against us for this neglect, inscribed in capitals, on the very front of divine dispensations, from year to year, in permitting the savages to be such a sore scourge to our land, and make such depredations on our frontiers, inhumanly butchering and captivating our people, not only in a time of war, but when we had good reason to think (if ever we had) that we dwelt safely by them. And there is good reason to think that if one half which has been expended for so many years past in building forts, manning, and supporting them, had been prudently laid out in supporting faithful missionaries and schoolmasters among them, the instructed and civilized party would have been a far better defence than all our expensive fortresses, and prevented the laying waste so many towns and villages; witness the consequence of sending Mr. Sergeant to Stockbridge, which was in the very road by which they most usually came upon our people, and by which there has never been one attack made upon us since his going there." After referring to the ordinary obligations of humanity, patriotism, and religion, he says:

"As there were few or none who seemed to lay the necessity and importance of Christianizing the natives so much to heart as to exert themselves in earnest and lead the way therein, I was naturally put upon consideration and inquiry what methods might have the greatest probability of success; and upon the whole was fully persuaded that this, which I have been pursuing, had by far the greatest probability of any that had been proposed, viz.: by the mission of their own [educated] sons in conjunction with the English; and that a number of girls should also be instructed in whatever should be necessary to render them fit to perform the female part, as house-wives, school-mistresses, and tailoresses. The influence of their own sons among them will likely be much greater than[12] of any Englishmen whatsoever. There is no such thing as sending English missionaries, or setting up English schools among them, to any good purpose, in most places, as their temper, state, and condition have been and still are." In illustration of his theory, he refers to the education, by the assistance of the "Honorable London Commissioners,"[6] of Mr. Samson Occom, "one of the Mohegan tribe, who has several years been a useful school-master and successful preacher of the Gospel."[7]

[6] Agents of the Corporation in London referred to on page 2, of which Robert Boyle was governor.

[7] See Appendix.

"After seeing the success of this attempt," he continues, "I was more encouraged to hope that such a method might be very successful, and above eight years ago I wrote to Rev. John Brainerd [brother of the distinguished David Brainerd], missionary in New Jersey, desiring him to send me two likely boys for this purpose, of the Delaware tribe. He accordingly sent me John Pumpshire in the fourteenth, and Jacob Woolley in the eleventh years of their age. They arrived December 18, 1754.

"Sometime after these boys came, the affair appearing with an agreeable aspect, I represented it to Col. Elisha Williams, late Rector of Yale College, and Rev. Messrs. Samuel Moseley, of Windham, and Benjamin Pomeroy, of Hebron, and invited them to join me. They readily accepted the invitation. And Mr. Joshua Moor,[8] late of Mansfield, deceased, appeared, to give a small tenement in this place [Lebanon], for the foundation, use and support of a charity school, for the education of Indian youth, etc." Mr. More's grant contained "about two acres of pasturing, and a small house and shop," near Mr. Wheelock's residence.

[8] Mr. M.'s own orthography is More.

This gentleman was one of the more prominent of the early settlers at Mansfield. He owned and resided upon a large estate on the Willimantic river, a few miles north of the present site of the village bearing that name. There is sufficient evidence to warrant the belief, that the first husband of Mr. More's mother was Mr. Thomas Howard (or Harwood),[13] of Norwich, who was slain in the memorable fight at Narragansett Fort, in December, 1675, and that her maiden name was Mary Wellman. From the church records, he appears to have been of a professedly religious character, as early as 1721. As his residence was in the neighborhood of Mr. Wheelock's early home, and but little farther removed from Lebanon "Crank," as the north parish in that town was styled, Mr. More had ample opportunities for a thorough acquaintance with the person to whom he now generously extended a helping hand. It is not known that this worthy man left any posterity, to perpetuate a name which will be cherished with tender regard, so long as the institution to which he furnished a home, in its infancy, shall have an existence.

In a summary of his work for the eight years, Mr. Wheelock says: "I have had two upon my hands since 1754, four since April, 1757, five since April, 1759, seven since November, 1760, and eleven since August, 1761. And for some time I have had twenty-five, three of the number English youth. One of the Indian lads, Jacob Woolley, is now in his last year at New Jersey College."

There is reason to believe that Occom would have taken a collegiate course, but for the partial failure of his health. On the whole, we are fully warranted in the opinion that, from the outset, Mr. Wheelock designed to have all his missionaries, whether Indian or English, "thoroughly furnished" for their work.

Before closing the "Narrative," he gives an interesting account of material resources.

"The Honorable London Commissioners, hearing of the design, inquired into it, and encouraged it by an allowance of £12 lawful money, by their vote November 12, 1756. And again in the year 1758 they allowed me £20; and in November 4, 1760, granted me an annual allowance of £20 for my assistance; and in October 8, 1761, they granted me £12 towards the support of Isaiah Uncas, son of the Sachem of Mohegan, and £10 more for his support the following year. In October, 1756, I received a legacy of fifty-nine dollars of Mrs. Ann Bingham, of Windham. In July, 1761, I received[14] a generous donation of fifty pounds sterling from the Right Hon. William, Marquis of Lothian; and in November, 1761, a donation of £26 sterling from Mr. Hardy, of London; and in May, 1762, a second donation of £50 sterling from that most honorable and noble lord, the Marquis of Lothian; and, at the same time, £20 sterling from Mr. Samuel Savage, merchant in London; and a collection of ten guineas from the Rev. Dr. A. Gifford, in London; and £10 sterling more from a lady in London, unknown, which is still in the hands of a friend, and to be remitted with some additional advantage, and to be accounted for when received. And, also, for seven years past, I have, one year with another, received about £11 lawful money, annually, interest of subscriptions. And in my journey to Portsmouth last June, I received, in private donations, £66 17s. 7¼d., lawful money. I also received, for the use of this school, a bell of about 80 lb. weight, from a gentleman in London. The Honorable Scotch Commissioners,[9] in and near Boston, understanding and approving of the design of sending for Indian children of remote tribes to be educated here, were the first body, or society, who have led the way in making an attempt for that purpose. While I was in Boston they passed a vote, May 7, 1761, 'that the Reverend Mr. Wheelock, of Lebanon, be desired to fit out David Fowler, an Indian youth, to accompany Mr. Samson Occom, going on a mission to the Oneidas; that said David be supported on said mission for a term not exceeding four months; and that he endeavor, on his return, to bring with him a number of Indian boys, not exceeding three, to be put under Mr. Wheelock's care and instruction, and that £20 be put into Mr. Wheelock's hands to carry this design into execution.' In November, 1761, the Great and General Court or Assembly of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, voted that I should be allowed to take under my care six children of the Six Nations, for education, clothing, and boarding, and be allowed for that purpose, for each of said children, £12 per annum for one year."[10]

[9] Agents of the Scotch "Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge."

[10] For tribes represented in the school, and other donors to the school and college, see Appendix.

EDUCATION IN NEW HAMPSHIRE.—ACTION IN REGARD TO A COLLEGE.—TESTIMONIAL OF CONNECTICUT CLERGYMEN.—LEGISLATIVE GRANT TO MR. WHEELOCK.

The importance of education to the welfare of any community, has been duly appreciated by the people of New Hampshire from the earliest periods of her history.

Such an item as the following is worthy of notice:

"At a publique Town Meeting held the 5: 2 mo. 58 [1658,] It is agreed that Twenty pounds per annum shall be yearly rayzed for the mayntenance of a School-master in the Town of Dover."[11] Harvard College being in need of a new building in 1669, the inhabitants of Portsmouth "subscribed sixty pounds, which sum they agreed to pay annually for seven years to the overseers of Harvard College. Dover gave thirty-two pounds, and Exeter ten pounds for the same purpose."[12] Very few towns at the present day are as liberal, in proportion to their ability.

[11] Dover Town Records.

[12] Adams's Annals of Portsmouth, p. 50.

Classical schools were established in all the more populous towns, and these were furnished with competent teachers, who were graduates of Harvard College, or European universities.

In 1758, in the midst of the din and tumult of the French war, we find the clergy—ever among the foremost in laudable enterprise—making an earnest effort for increased facilities for liberal education.

We give official records:

"The Convention of the Congregational Ministers in the Province of New Hampshire, being held at the house of the[16] Rev. Mr. Pike in Somersworth on the 26th day of Sept. 1758: The Rev. Joseph Adams was chosen Moderator." After the sermon and transaction of some business:

"The Convention then taking into consideration the great advantages which may arise, both to the Churches and State from the erecting [an] Academy or College in this Province, unanimously Voted that the following Petition shall be preferred to the Governor, desiring him to grant a Charter for said purpose:

"To his Excellency, Benning Wentworth, Esq., Capt.-General and Governor-in-Chief in and over his Majesty's Province of New Hampshire in New England. May it please your Excellency,—

"We, the Ministers of the Congregational Churches in this Province of New Hampshire under your Excellency's Government now assembled in an Annual Convention in Somersworth, as has been our custom for several years past, the design of which is to pray together for his Majesty and Government, and to consult the interests of religion and virtue, for our mutual assistance and encouragement in our proper business: Beg leave to present a request to your Excellency in behalf of literature, which proceeds, not from any private or party views in us, but our desire to serve the Government and religion by laying a foundation for the best instruction of youth. We doubt not your Excellency is sensible of the great advantages of learning, and the difficulties which attend the education of youth in this Province, by reason of our distance from any of the seats of learning, the discredit of our medium, etc. We have reason to hope that by an interest among our people, and some favor from the Government, we may be able in a little time to raise a sufficient fund for erecting and carrying on an Academy or College within this Province, without prejudice to any other such seminary in neighboring Colonies, provided your Excellency will be pleased to grant to us, a number of us, or any other trustees, whom your Excellency shall think proper to appoint, a good and sufficient charter, by which they may be empowered to choose a President, Professors, Tutors, or other officers, and regulate all matters belonging[17] to such a society. We therefore now humbly petition your Excellency to grant such a charter as may, in the best manner, answer such a design and intrust it with our Committee, viz.: Messrs. Joseph Adams, James Pike, John Moody, Ward Cotton, Nathaniel Gookin, Woodbridge Odlin, Samuel Langdon, and Samuel Haven, our brethren, whom we have now chosen to wait upon your Excellency with this our petition, that we may use our influence with our people to promote so good a design, by generous subscriptions, and that we may farther petition the General Court for such assistance, as they shall think necessary. We are persuaded, if your Excellency will first of all favor us with such a charter, we shall be able soon to make use of it for the public benefit; and that your Excellency's name will forever be remembered with honor. If, after trial, we cannot accomplish it, we promise to return the charter with all thankfulness for your Excellency's good disposition. It is our constant prayer that God would prosper your Excellency's administration, and we beg leave to subscribe ourselves your Excellency's most obedient servants.

Joseph Adams, Moderator.

"Proceedings attested by Samuel Haven, Clerk."

"The Convention of Congregational Ministers in the Province of New Hampshire being held at the house of the Rev. Mr. Joseph Adams in Newington on the 25th of September, 1759, the Rev. Mr. Adams was chosen Moderator. We then went to the house of God. After prayer and a sermon:

"A draught of a charter for a college in this Province being read: Voted, That the said charter is for substance agreeable to the mind of the Convention. Whereas a committee chosen last year to prefer a petition to his Excellency the Governor for a charter of a college in this Province have given a verbal account to this Convention of their proceedings and conversation with the Governor upon said affair, by which, notwithstanding the Governor manifests some unwillingness, at present, to grant a charter agreeable to the Convention, yet there remains some hope, that after maturer consideration and advice of Council, his Excellency will grant such a charter as will be agreeable to us and our people, therefore, Voted, that[18] Rev. Messrs. Joseph Adams, James Pike, Ward Cotton, Samuel Parsons, Nathaniel Gookin, Samuel Langdon, and Samuel Haven, or a major part of them, be and hereby are a Committee of this Convention, to do everything which to them shall appear necessary, in the aforesaid affair, in behalf of this Convention; and, moreover, to consult upon any other measures for promoting the education of youth, and advancing good literature in the Province, and make report to the next Convention.

Attested by Samuel Haven, Clerk."

The Convention was holden at Portsmouth, September 30, 1760, and at the same place in September, 1761, but nothing appears in the proceedings of those years concerning the charter. But at the convention held at Portsmouth, September 28, 1762, the Rev. Mr. John Rogers having been chosen moderator, after prayer and sermon, the following testimonial was laid before the Convention:

"Chelsea, Norwich, July 10, 1762.

"We ministers of the gospel and pastors of churches hereafter mentioned with our names, having, for a number of years past, heard of or seen with pleasure the zeal, courage, and firm resolution of the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon, to prosecute to effect a design of spreading the gospel among the natives in the wilds of our America, and especially his perseverance in it, amidst the many peculiar discouragements he had to encounter during the late years of the war here, and upon a plan which appears to us to have the greatest probability of success, namely, by a mission of their own sons; and as we are verily persuaded that the smiles of Divine Providence upon his school, and the success of his endeavors hitherto justly may, and ought, to encourage him and all to believe it to be of God, and that which he will own and succeed for the glory of his great name in the enlargement of the kingdom of our divine Redeemer, as well as for the great benefit of the crown of Great Britain, and especially of his Majesty's dominions in America; so we apprehend the present openings in Providence ought to invite Christians of every denomination to unite their endeavors and to lend a[19] helping hand in carrying on so charitable a design; and we are heartily sorry if party spirit and party differences shall at all obstruct the progress of it; or the old leaven of this land ferment upon this occasion, and give a watchful adversary opportunity so to turn the course of endeavors into another channel as to defeat the design of spreading the gospel among the heathen. To prevent which, and encourage unanimity and zeal in prosecuting the design, we look upon it our duty as Christians, and especially as ministers of the gospel, to give our testimony that, as we verily believe, a disinterested regard to the advancement of the Redeemer's kingdom and the good will of His Majesty's dominions in America, were the governing motives which at first induced the Rev. Mr. Wheelock to enter upon the great affair, and to risk his own private interest, as he has done since, in carrying it on; so we esteem his plan to be good, his measures to be prudently and well concerted, his endowments peculiar, his zeal fervent, his endeavors indefatigable, for the accomplishing this design, and we know no man, like minded, who will naturally care for their state. May God prolong his life, and make him extensively useful in the kingdom of Christ. We have also, some of us, at his desire examined his accounts, and we find that, besides giving in all his own labour and trouble in the affair, he has charged for the support, schooling, etc., of the youth, at the lowest rate it could be done for, as the price of things have been and still are among us; and we apprehend the generous donations already made have been and we are confident will be laid out in the most prudent manner, and with the best advice for the furtherance of the important design: and we pray God abundantly to reward the liberality of many upon this occasion. And we hope the generosity, especially of persons of distinction and note, will be a happy lead and inducement to still greater liberalities, and that in consequence thereof the wide-extended wilderness of America will blossom as the rose, habitations of cruelty become dwelling places of righteousness and the blessing of thousands ready to perish come upon all those whose love to Christ and charity to them has been shown upon this occasion. Which[20] is the hearty prayer of your most sincere friends and humble servants:

Ebenezer Rosetter Pastor of ye 1st Chh: in Stonington.

Joseph Fish Pastor of ye 2d Chh: in Stonington.

Nathl Whitaker Pastor of ye Chh: in Chelsea in Norwich.

Benja Pomeroy Pastor of ye 1st Chh: in Hebron.

Elijah Lothrop Pastor of ye Chh: of Gilead in Hebron.

Nathl Eells Pastor of a Chh: in Stonington.

Mather Byles Pastor of ye First Chh: in New London.

Jona. Barber Pastor of a Chh: in Groton.

Matt. Graves Missionary in New London.

Peter Powers Pastor of the Chh: at Newent in Norwich.

Daniel Kirtland Former Pastor of ye Chh: in Newent Norwich.

Asher Rosetter Pastor of ye 1st Chh: in Preston.

Jabez Wight Pastor of ye 4 Chh: in Norwich.

David Jewett Pastor of a Chh: in New London.

Benja Throop Pastor of a Chh: in Norwich.

Saml Moseley Pastor of a Chh: in Windham.

Stephen White Pastor of a Chh: in Windham.

Richard Salter Pastor of a Chh: in Mansfield.

Timothy Allen Pastor of ye Chh: in Ashford.

Ephraim Little Pastor of ye 1st Chh: in Colchester.

Hobart Estabrook Pastor of a Chh: in East Haddam.

Joseph Fowler Pastor of a Chh: in East Haddam.

Benja Boardman Pastor of a Chh: in Middletown.

John Norton Pastor of a Chh: of Christ in Middletown.

Benja Dunning Pastor of a Chh: of Christ in Marlborough."

"Voted, the Rev. Messrs. Moody, Langdon, Haven, and Foster be a Committee of this Convention to consider and report on the above. Said committee laid the following draft before the Convention, which was unanimously voted and signed by the moderator:

"We, a Convention of Congregational Ministers assembled at Portsmouth, September 28, 1762, having read and considered the foregoing attestation from a number of reverend gentlemen in Connecticut, taking into consideration the many obligations the Supreme Ruler has laid upon Christian churches to promote his cause and enlarge the borders of his[21] kingdom in this land, the signal victories he has granted to our troops, the entire reduction of all Canada, so that a way is now open for the spreading of the light and purity of the gospel among distant savage tribes, and a large field, white unto the harvest, is presented before us; considering the infinite worth of the souls of men, the importance of the gospel to their present and everlasting happiness, and the hopeful prospect that the aboriginal natives will now listen to Christian instruction; considering also the great expense which must unavoidably attend the prosecution of this great design, think ourselves obliged to recommend, in the warmest manner, this subject to the serious consideration of our Christian brethren and the public. It is with gratitude to the Great Head of the Church, who has the hearts of all in his hands, that we observe some hopeful steps taken by the societies founded for the gospelizing the Indians, and the hearts of such numbers, both at home and in this land, have been disposed to bestow their liberalities to enable such useful societies to effect the great ends for which they are founded. But as we wish to see every probable method taken to forward so benevolent and Christian a design, we, therefore, rejoice to find that the Rev. Mr. Wheelock has such a number of Indian youths under his care and tuition; and in that abundant testimony which his brethren in the ministry have borne to his abilities for, and zeal and faithfulness in, this important undertaking. And we do hereby declare our hearty approbation of it, as far as we are capable of judging of an affair carried on at such a distance; and think it our duty to encourage and exhort all Christians to lend a helping hand towards so great and generous an undertaking. We would not, indeed, absolutely dictate this, or any other particular scheme, for civilizing and spreading the gospel among the Indians; but we are persuaded that God demands of the inhabitants of these colonies some returns of gratitude, in this way, for the remarkable success of our arms against Canada, and that peace and security which he has now given us; we must, therefore, rely on the wisdom and prudence of the civil authority to think of it as a matter in which our political interests as well as the glory of God are deeply concerned; and we refer to our churches and[22] all private Christians as peculiarly called to promote the Redeemer's kingdom everywhere, to determine what will be the most effectual methods of forwarding so noble and pious a design, and to contribute, to the utmost of their power, either towards the execution of the plan which the Rev. Mr. Wheelock is pursuing, or that of the corporation erected in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, or any other which may be thought of here or elsewhere, for the same laudable purpose.

John Rogers, Moderator."

The first Legislative action in New Hampshire relative to Mr. Wheelock's work is also worthy of notice. The following is from the Journal of the House of Representatives:

"June 17, 1762, Voted, that the Hon. Henry Sherburne and Mishech Weare, Esquires, Peter Gilman, Clement March, Esq., Capt. Thomas W. Waldron, and Capt. John Wentworth be a committee to consider of the subject-matter of Rev. Mr. Eleazar Wheelock's memorial for aid for his school." This committee made a favorable report, saying: "We think it incumbent on this province to do something towards promoting so good an undertaking," and recommending a grant of fifty pounds sterling per annum for five years. The action of the Legislature was in accordance with this report. Later records, however, indicate that the grant was not continued after the first, or possibly the second, year. Gov. Benning Wentworth, after careful investigation, gave his official sanction to the action of his associates, in aid of Mr. Wheelock.

A COLLEGE CONTEMPLATED BY MR. WHEELOCK.—LORD DARTMOUTH.—OCCOM AND WHITAKER IN GREAT BRITAIN.

Mr. Wheelock held relations more or less intimate with the leading educational institutions of the country. But his favorite college was at Princeton, New Jersey, far removed from his own residence. A warm friendship subsisted between him and many of its officers, and thither he sent most of his students for a considerable period. The inconvenience of doing this, may have suggested the idea of a college in connection with his school. However this may have been, nothing short of a college could satisfy him. The following letter, written in April, 1763, needs no further preface:

"TO HIS EXCELLENCY GENERAL JEFFREY AMHERST, BARONET.

"May it please your Excellency,—The narrative herewith inclosed, gives your Excellency some short account of the success of my feeble endeavors, through the blessing of God upon them, in the affair there related.

"Your Excellency will easily see, that if the number of youth in this school continues to increase, as it has done, and as our prospects are that it will do, we shall soon be obliged to build to accommodate them and accordingly to determine upon the place where to fix it, and I would humbly submit to your Excellency's consideration the following proposal, viz.: That a tract of land, about fifteen or twenty miles square, or so much as shall be sufficient for four townships, on the west side of Susquehannah river, or in some other place more convenient in the heart of the Indian country, be granted in favor of this school: That said townships be peopled with a chosen number of inhabitants of known honesty, integrity, and such as love and will be kind to, and honest in their dealings with Indians. That a thousand acres of, and within said grant, be given to[24] this school, and that the school be an academy for all parts of useful learning; part of it to be a college for the education of missionaries, interpreters, schoolmasters, etc.; and part of it a school to teach reading, writing, etc., and that there be manufactures for the instruction both of males and females, in whatever shall be necessary in life, and proper tutors, masters, and mistresses be provided for the same. That those towns be furnished with ministers of the best characters, and such as are of ability, when incorporated with a number of the most understanding of the inhabitants, to conduct the affairs of the school, and of such missions as they shall have occasion and ability for, from time to time. That there be a sufficient number of laborers upon the lands belonging to the school; and that the students be obliged to labor with them, and under their direction and conduct, so much as shall be necessary for their health, and to give them an understanding of husbandry; and those who are designed for farmers, after they have got a sufficient degree of school learning, to labor constantly, and the school to have all the benefit of their labor, and they the benefit of being instructed therein, till they are of an age and understanding sufficient to set up for themselves, and introduce husbandry among their respective tribes; and that there be a moderate tax upon all the granted lands, after the first ten or fifteen years, and also some duty upon mills, etc., which shall not be burdensome to the inhabitants, for the support of the school, or missionaries among the Indians, etc. By this means much expense, and many inconveniences occasioned by our great distance from them, would be prevented, our missionaries be much better supported and provided for, especially in case of sickness, etc. Parents and children would be more contented, being nearer to one another, and likely many would be persuaded to send their children for an education, who are now dissuaded from it only on account of the great distance of the school from them.

"The bearer, Mr. C. J. S.,[13] is able, if your Excellency desires it, to give you a more full and particular account of the present state of this school, having been for some time the master and instructor of it, and is now designed, with the leave of Providence, the ensuing summer, to make an excursion[25] as a missionary among the Indians, with an interpreter from this school.

"And by him your Excellency may favor me with your thoughts on what I have proposed.

"I am, with sincerest duty and esteem, may it please your Excellency, your Excellency's most obedient and humble servant,

Eleazar Wheelock."

[13] Charles J. Smith.

In 1764, the Scotch Society, already referred to, manifested increasing interest in Mr. Wheelock's work, by appointing a Board of Correspondents, selected from gentlemen of high standing, in Connecticut, to coöperate with him.

We here insert entire, Mr. Wheelock's first letter to Lord Dartmouth:

"TO THE RIGHT HON. THE EARL OF DARTMOUTH.

"Lebanon, Connecticut, New England, March 1, 1764.

"May it please your Lordship,—

"It must be counted amongst the greatest favors of God to a wretched world, and that which gives abundant joy to the friends of Zion, that among earthly dignities there are those who cheerfully espouse the sinking cause of the great Redeemer, and whose hearts and hands are open to minister supplies for the support and enlargement of His kingdom in the world.

"As your Lordship has been frequently mentioned with pleasure by the lovers of Christ in this wilderness, and having fresh assurance of the truth of that fame of yours, by the Rev. Mr. Whitefield, from his own acquaintance with your person and character, and being encouraged and moved thereto by him, I am now emboldened, without any other apology for myself than that which the nature of the case itself carries in its very front, to solicit your Lordship's favorable notice of, and friendship towards, a feeble attempt to save the swarms of Indian natives in this land from final and eternal ruin, which must unavoidably be the issue of those poor, miserable creatures, unless God shall mercifully interpose with His blessing upon endeavors to prevent it.

"The Indian Charity School, under my care (a narrative of which, herewith transmitted, humbly begs your Lordship's[26] acceptance), has met with such approbation and encouragement from gentlemen of character and ability, at home and abroad, and such has been the success of endeavors hitherto used therein, as persuade us more and more that it is of God, and a device and plan which, under his blessing, has a greater probability of success than any that has yet been attempted. By the blessing and continual care of heaven, it has lived, and does still live and flourish, without any other fund appropriated to its support than that great one, in the hands of Him, whose the earth is, and the fullness thereof.

"And I trust there is no need to mention any other considerations to prove your Lordship's compassions, or invite your liberality on this occasion, than those which their piteous and perishing case does of itself suggest, when once your Lordship shall be well satisfied of a proper and probable way to manifest and express the same with success. Which I do with the utmost cheerfulness submit to your Lordship, believing your determination therein to be under the direction of Him who does all things well. And, if the nature and importance of the case be not esteemed sufficient excuse for the freedom and boldness I have assumed, I must rely upon your Lordship's innate goodness to pardon him who is, with the greatest duty and esteem, my lord,

"Your Lordship's most obedient,

"And most humble servant,

"Eleazar Wheelock."

It is interesting to observe here the agency of Mr. Wheelock's old and intimate friend, Whitefield. As early as 1760, after alluding to efforts in his behalf in Great Britain, he wrote to Mr. Wheelock:

"Had I a converted Indian scholar, that could preach and pray in English, something might be done to purpose."

After much deliberation, Mr. Wheelock determined to send Mr. Occom and Rev. Nathaniel Whitaker of Norwich, who was deeply interested in his work, to solicit the charities of British Christians, with a purpose of more extended operations.

They left this country late in 1765, carrying testimonials from a large number of eminent civilians and divines.[27]

The following letter indicates that they were cordially welcomed in England:

"London, February 2, 1766.

My dear Mr. Wheelock,—This day three weeks I had the pleasure of seeing Mr. Whitaker and Mr. Occom. On their account, I have deferred my intended journey into the country all next week. They have been introduced to, and dined with the Daniel of the age, viz., the truly noble Lord Dartmouth. Mr. Occom is also to be introduced by him to his Majesty, who intends to favor their design with his bounty. A short memorial for the public is drawn, which is to be followed with a small pamphlet. All denominations are to be applied to, and therefore no mention is made of any particular commissioners or corresponding committees whatsoever. It would damp the thing entirely. Cashiers are to be named, and the moneys collected are to be deposited with them till drawn for by yourself. Mr. Occom hath preached for me with acceptance, and also Mr. Whitaker. They are to go round the other denominations in a proper rotation. As yet everything looks with a promising aspect. I have procured them suitable lodgings. I shall continue to do everything that lies in my power. Mr. S.[14] is providentially here,—a fast friend to your plan and his dear country.

"I wish you joy of the long wished for, long prayed for repeal, and am, my dear Mr. Wheelock,

"Yours, etc., in our glorious Head,

"George Whitefield."

[14] Mr. John Smith, of Boston.

We are now introduced to Mr. Wheelock's most valuable coadjutor, the son of Mark Hunking Wentworth,—another active and earnest friend:

"Bristol, [England,] 16th Dec., 1766.

"The Rev. Mr. Whitaker having requested my testimony of an institution forming in America, under the name of an Indian School, for which purpose many persons on that continent and in Europe have liberally contributed, and he is now soliciting the further aid of all denominations of people in this kingdom to complete the proposed plan, I do therefore[28] certify, whomsoever it may concern, that the said Indian School appears to me to be formed upon principles of extensive benevolence and unfeigned piety; that the moneys already collected have been justly applied to this and no other use. From repeated information of many principal gentlemen in America, and from my own particular knowledge of local circumstances, I am well convinced that the charitable contributions afforded to this design will be honestly and successfully applied to civilize and recover the savages of America from their present barbarous paganism.

"J. Wentworth,

"Governor of New Hampshire."

The annals of philanthropy unfold few things bolder or more romantic in conception, or grander in execution, or sublimer in results than this most memorable, most successful pilgrimage. The unique, but magnetic, marvelous eloquence of this regenerated son of the forest, as he passed from town to town, and city to city, over England and Scotland, engaged the attention and opened the hearts of all classes—the clergy, the nobility, and the peasantry. The names of the men and women and children, who gave of their abundance or their poverty, primarily and apparently to civilize and evangelize their wild and savage brethren across the sea, but ultimately and really to found one of the most solid and beautiful temples of Christian and secular learning, in the Western hemisphere, deserve affectionate and perpetual remembrance, along with those of their kindred, who in a preceding century dedicated their whole treasure upon Plymouth Rock.

With sincere regret that we have not the name of every donor, yet with devout gratitude for the preservation of so full a record, we append the original list of donors in England, as prepared and published at the time, by Lord Dartmouth and his associates.[15]

[15] See Appendix.

Never was more timely aid given to a worthy cause. When Mr. Wheelock's agents went abroad he had a school of about thirty, and an empty treasury. These funds gave him present comfort, and enabled him to effect the long-desired removal.

SIR WILLIAM JOHNSON.—EXPLORATIONS FOR A LOCATION. ADVICE OF ENGLISH TRUSTEES.

Mr. Wheelock was in friendly correspondence, for several years, with Sir William Johnson, the distinguished Indian agent and superintendent, who resided in the province of New York, near the Six Nations. Through his agency, the famous Mohawk, Joseph Brant, was sent to Mr. Wheelock's school. After enjoying some opportunities for an estimate of his abilities and character, Mr. Wheelock speaks of him in highly complimentary terms, as a gentleman, "whose understanding and influence in Indian affairs, is, I suppose, greater than any other man's, and to whose indefatigable and successful labors to settle and secure a peace with the several tribes, who have been at war with us, our land and nation are under God chiefly indebted."

In September, 1762, Mr. Wheelock writes to Sir William: "I understand that some of our people are about to settle on a new purchase on Susquehannah river. It may be a door may open for my design on that purchase." He also intimates that he desires to set up the school in his neighborhood. This plan does not meet Sir William's approval, but in January, 1763, Mr. Wheelock addresses him again, saying: "Gov. Wentworth has offered a tract of land in the western part of the province of New Hampshire which he is now settling, for the use of the school if we will fix it there, and there has been some talk of fixing it in one of the new townships in the province of the Massachusetts which lie upon New York line near Albany. I much want to consult your Honor in the affair." Mr. Wheelock's confidence in his friend having been strengthened by the receipt of several cordial letters,[30] and other circumstances, he writes to him, July 4, 1766: "I apprehend you are able above any man in this land to serve the grand design in view," desiring to "act in every step" agreeable to his mind, and informing him that he has sent his son, with Dr. Pomeroy, to confer with him about a location for the school. He also refers to "arguments offered to carry it into the Southern governments." But Mr. Johnson did not see fit to invite the settlement of the school in the neighborhood of the Six Nations, deeming it unwise, apparently, to encourage a movement which might be regarded by them as an invasion of their territory, especially if they were asked to give lands to the school. This decision virtually determined the location. If Mr. Wheelock could not follow his old neighbors and friends to the westward, and plant himself beside the great Indian Confederacy, he must turn his attention to the northward, where other neighbors and friends were settling within easy reach of the far-extended Indian tribes of Canada. Other localities, as we shall see hereafter, presented some inducements, but they were all of minor importance. Hence, when his agents returned from Great Britain placing the long-desired funds for the accomplishment of his purposes in his hands, we may well imagine that Mr. Wheelock gladly turned toward that worthy magistrate, who had already shown "a willing heart," for more aid.

In the meantime, Mr. Wheelock was giving the matter of a location his most earnest and careful attention. In a letter to Mr. Whitefield, dated September 4, 1766, he says: "We cannot get land enough on Hudson river." Nor has he any more hope of success on the Mohawk. "Large offers have been made in the new settlements on Connecticut river. It is likely that near twenty thousand acres would be given in their several towns." After stating that "Col. Willard" has made generous offers of lands, "on Sugar river," he says: "that location would be the most inviting of any part of that country. Samuel Stevens, Esq., offers two thousand acres to have it at No. 4. Col. Chandler offers two thousand acres in the centre of the town of Chester, opposite to No. 4, nine miles from the River. The situation of Wyoming, on Susquehannah river, is very convenient."[16] A few months later,[31] General Schuyler earnestly advocated the claims of Albany as a favorable location.

[16] See Appendix.

But Mr. Wheelock's friends were very unwilling that he should leave Connecticut. Windham and Hebron[17] made earnest efforts to obtain the school. We quote from Lebanon parish records:

[17] See Appendix.

"At a legal and full meeting of the Inhabitants, legal voters of the second society in Lebanon [now Columbia], in Connecticut, held in said society on the 29th day of June, Anno Domini 1767, We made choice of Mr. James Pinneo to be moderator of said meeting, and passed the following votes, nemine contradicente:

"1. That we desire the Indian Charity School now under the care of the Rev. Mr. Eleazar Wheelock, may be fixed to continue in this society: provided it may consist with the interest and prosperity of said School.

"2. That as we have a large and convenient house for public and divine Worship, we will accommodate the members of said school with such convenient seats in said house as we shall be able.

"3. That the following letter be presented to the Rev. Mr. Eleazar Wheelock, by Messrs. Israel Woodward, James Pinneo, and Asahel Clark, Jun., in the name and behalf of this society; and that they desire him to transmit a copy of the same, with the votes foregoing, to the Right Honorable the Earl of Dartmouth, and the rest of those Honorable and Worthy Gentlemen in England who have condescended to patronize said school; and to whom the establishment of the same is committed.

"The Inhabitants of the Second Society in Lebanon in Connecticut to the Rev. Mr. Eleazar Wheelock, Pastor of said Society.

"Rev. and ever dear Pastor,—As you are witness to our past care and concern for the success of your most pious and charitable undertaking in favor of the poor perishing Indians on this continent, we are confident you will not be displeased at our addressing you on this occasion; but that you would rather think it strange if we should altogether hold our peace[32] at such a time as this; when we understand it is still in doubt both with yourself and friends where to fix your school; whether at Albany or more remote among the Indian tribes, in this society where it was first planted, or in some other part of this colony proposed for its accommodation.

"We have some of us heard most of the arguments offered for its removal, and however plausible they appear we are not at all convinced of their force, or that it is expedient, everything considered, it should be removed, nor do we think we have great reason to fear the event, only we would not be wanting as to our duty in giving such hints in favor of its continuance here as naturally and easily occur to our minds, for we have that confidence in you and the friends of the design, that you will not be easily carried away with appearances: but will critically observe the secret springs of those generous offers, made in one place and another, (some of which are beyond what we can pretend to,) whether some prospect of private emolument be not at the bottom; or whether they will finally prove more kind to your pious institution as such considered, (whatever their pretenses may be,) than they have been or at present appear to be to the Redeemer's Kingdom in general. We trust this institution, so well calculated to the advancement of its interest, will flourish best among the Redeemer's friends; and although with respect to ourselves we have little to boast as to friendship to our divine Redeemer or his interest, yet this we are sure of, that he has been very kind to us, in times past, and we trust has made you the instrument of much good to us, and to lay a foundation for it to succeeding generations; we humbly hope God has been preparing an habitation for himself here, and has said of it, this is my resting place, here will I dwell forever, (not because they deserved it,) but because I have desired it, and where God is pleased to dwell, under his influence your institution (which we trust is of Him) may expect to live and thrive. We desire it may be considered that this is its birth place, here it was kindly received, and nourished when no other door was set open to it—here it found friends when almost friendless, yea when despised and contemned abroad—its friends are now increased here as well as elsewhere, and[33] although by reason of our poverty and the hardness of the times, our subscriptions are small compared with what some others may boast, being at present but about £810 lawful money, yet there are here some other privileges which we think very valuable and serviceable to the design, viz. 400 acres of very fertile and good land, about forty acres of which are under improvement, and the remainder well set with choice timber and fuel, and is suitably proportioned for the various branches of Husbandry which will much accommodate the design as said land is situated within about half a mile of our Meeting House, and may be purchased for fifty shillings lawful money per acre. There is also several other small parcels of land suitably situate for building places for the use of the school to be sold at a reasonable rate. We have also a beautiful building place for said school within a few rods of said meeting house, adjacent to which is a large and pleasant Green: and we are confident that wood, provisions, and clothing, etc., which will be necessary for the school, may be had here not only now, but in future years, at as low a rate as in any place in the colony, or in any other place where it has been proposed to settle your school. These privileges, we think, are valuable and worthy your consideration, and also of those honourable and worthy gentlemen in England to whom you have committed the decision of the affair, and from the friendly disposition which has so many years past and does still reign in our breasts towards it, we think it may be presumed we shall from time to time be ready to minister to its support as occasion shall require and our circumstances permit. We take the liberty further to observe that such has hitherto been the peace and good order (greatly through your instrumentality), obtaining among us that the members of your school have all along been as free from temptations to any vicious courses or danger of fatal error as perhaps might be expected they would be on any spot of this universally polluted globe.

"Here, dear sir, your school has flourished remarkably. It has grown apace; from small beginnings how very considerable has it become; an evidence that the soil and climate suit the institution—if you transplant it you run a risk of stinting[34] its growth, perhaps of destroying its very life, or at least of changing its nature and missing the pious aim you have all along had in view; a danger which scarce needs to be hinted, as you are sensible it has been the common fate of institutions of this kind that charitable donations have been misapplied and perverted to serve purposes very far from or contrary to those the pious donors had in view; such is the subtilty of the old serpent that he will turn all our weapons against ourselves if possible. Aware of this, you have all along appeared to decline and even detest all such alliances and proposals as were calculated for, or seemed to promise any private emolument to your self or your friends. This, we trust, is still your prevailing temper, and rejoice to hear that your friends and those who are intrusted with the affair in England are exactly in the same sentiments, happy presage not only of the continuance of the institution itself but we hope of its immutability as to place. One thing more we beg leave to mention (not to tire your patience with the many that occur), viz. if you remove the school from us, you, at the same time, take away our Minister, the light of our eyes and joy of our hearts, under whose ministrations we have sat with great delight; whose labors have been so acceptable, and we trust profitable, for a long time; must, then, our dear and worthy Pastor and his pious institution go from us together? Alas, shall we be deprived of both in one day? We are sensible that we have abused such privileges and have forfeited them; and at God's bar we plead guilty—we pray Him to give us repentance and reformation, and to lengthen out our happy state; we own the justice of God in so heavy losses, if they must be inflicted; and even in the removal of our Candlestick out of its place, but we can't bear the thought that you our Dear Pastor and the dear friends to your pious institution should become the executioners of such a vengeance. However, we leave the matter with you, and are with much duty and filial regard, dear sir, Your very humble servants or rather obedient children.

"By order of said Society,

Israel Woodward,

James Pinneo,

Asahel Clark, Jr."

"June 29, 1767."

[35]This interesting document bears the same date with Mr. Wheelock's Doctorate in Divinity, from the University of Edinburgh.

Dr. Wheelock, appreciating the importance of a better knowledge of the comparative advantages of the various proposed locations, finally determined to commission trustworthy agents, to make thorough explorations. We give his language, in substance:

"Lebanon, Connecticut, July 20, 1768.

"Whereas the number in my Indian Charity School is now, by the blessing of God, become so large as that it is necessary the place where to fix it should be speedily determined, and so many and generous have been the offers made for that purpose by gentlemen of character and distinction in several neighboring governments, I do, therefore, hereby authorize and appoint the Rev. Mr. Ebenezer Cleaveland, of Gloucester, in the province of the Massachusetts Bay, and my son, Ralph Wheelock (while the Rev. Dr. Whitaker is performing the like part in Pennsylvania) in my name and stead, to wait upon his Excellency John Wentworth, Esq., Governor of New Hampshire, and his associates in office, to know what countenance and encouragement they will give to accommodate and endow said school, in case it should be fixed in the western part of that province."

Deep interest in Dr. Wheelock's work being manifested by Rev. Thomas Allen and others, at Pittsfield; Timothy Woodbridge and others, at Stockbridge;[18] and Abraham J. Lansing, the founder of Lansingburg,[19] and many others in that Province, they were also instructed to extend their explorations to Western Massachusetts and to New York.

[18] See Appendix.

[19] See Appendix.