Transcriber's Note

There are a few Greek words in this text, which may require adjustment of your browser settings to display correctly. Hover your mouse over words underlined with a faint red dotted line to see a transliteration.

There are a small number of characters with diacritical marks in the text, for example ǎ or ē; you may need to adjust your browser settings for them to display properly.

The original text indicated omitted text with varied numbers of spaced periods; this convention has been retained.

From 1579-1895.

A Comprehensive Review, with Copious Extracts

and Criticisms

FOR THE USE OF SCHOOLS AND THE GENERAL READER

Containing an Appendix with a Full List of Southern Authors

BY

——

ILLUSTRATED

——

RICHMOND, VA.

B. F. Johnson Publishing Company

1900

——————

Copyright, 1895, by

Louise Manly.

——————

THE primary object of this book is to furnish our children with material for becoming acquainted with the development of American life and history as found in Southern writers and their works. It may serve as a reader supplementary to American history and literature, or it may be made the ground-work for serious study of Southern life and letters; and between these extremes there are varying degrees of usefulness.

To state its origin will best explain its existence. This may furthermore be of some help to teachers in using the book, though each teacher will use it as best suits his classes and methods.

The study of History is rising every day in importance. Sir Walter Raleigh in his “Historie of the World” well said, “It hath triumphed over time, which besides it nothing but eternity hath triumphed over.” It is the still living word of the vanished ages.

The best way of teaching history has of late years received much attention. One excellent method is to read, in connection with the text-book, good works of fiction, dramas, poetry, and historical novels, bearing upon the different epochs, and also to read the works of the authors [Pg 4] themselves of these different periods. We thus make history and literature illustrate and beautify each other. The dry dates become covered with living facts, the past is peopled with real beings instead of hard names, fiction receives a solid basis for its airy architecture, and the mind of the pupil is interested and broadened. Even the difficult subjects of politics and institutions gradually assume a more pleasing aspect by being associated with individual human interests, and condescend to simplify themselves through personal relations.

To illustrate this method, which I have used with great success in teaching English History:

In connection with the times of the early Britons, read Tennyson’s “Idyls of the King.”

At the Norman Conquest, Bulwer’s “Harold.”

At the reign of Richard I. (Coeur de Lion), Scott’s “Ivanhoe” and “Talisman,” Shakspere’s “King John.”

At the reign of Elizabeth, Scott’s “Kenilworth,” the non-historical plays of Shakspere, as he lived at that epoch, Bacon’s Essays, and others.

I mention merely a few. The amount of reading can be increased almost indefinitely and will depend on the time of the pupil, the plan of the teacher, and the accessibility of the books. Most of the books necessary for English History are now published in cheap form and are within reach of every pupil.

A great deal of reading is very desirable; it is the only way to give our pupils any broad view of literature and [Pg 5] history, and to cultivate a taste for reading in those destitute of it. It is often the only opportunity for reading which some pupils will ever have, and it lasts them a life-time as a pleasure and a benefit.[1]

The reading may be done in the class or out of school hours. It is well to read as much as practicable in class, and to have some sketch of the outside reading given in class.

Geography must also go hand in hand with history, a point now well understood. But its importance can hardly be exaggerated and its practice is of the utmost value. One must use maps to study and read intelligently.

In American History pursue a similar course, as for example:

At the period of discovery and early settlement, read Irving’s “Columbus,” Simms’ “Vasconselos” (De Soto’s Expedition), and “Yemassee,” John Smith’s Life and Writings, Longfellow’s “Hiawatha” and “Miles Standish,” Kennedy’s “Rob of the Bowl,” Strachey’s Works, Mrs. Preston’s “Colonial Ballads,” &c.

In Revolutionary times, the Revolutionary novels of Simms and Cooper, Kennedy’s “Horse-Shoe Robinson;” the great statesmen of the day, as Jefferson, Adams, Patrick Henry, Hamilton, Washington; Cooke’s “Fairfax” in which Washington appears as a youthful surveyor, and “Virginia Comedians” in which Patrick Henry appears, Thackeray’s “Virginians;” and others.

[Pg 6] Each teacher will make his own list as his time and command of books allow. And each State or section of our great country will devote more time to its own special history and literature; this is right, for knowledge like charity begins at home, and gradually widens until it embraces the circle of the universe.

In collecting material for classes in American History to read in accordance with this plan, it was found easy to get cheap editions of Irving, Longfellow, Cooper, and other writers of the northern States, but almost impossible to get those of the southern, in cheap or even expensive editions. And the present volume has been prepared to supply in part this deficiency. To fit it to the plan suggested, the dates of the writers and the period and character of their works have been indicated, and some selections from them given for reading,—too little, it is feared, to be of much service, and yet enough to stimulate to further interest and study.

The materials have been found so abundant, even so much more abundant than I suspected when undertaking the work, that it has been a hard task to make a selection from the rich masses of interesting writing. I fear that the work is too fragmentary and contains too many writers to make a lasting impression in a historical point of view.

If, however, it leads to a sympathetic study of Southern life and literature, and especially if it makes young people acquainted with our writers of the past and with something of the old-time life and the spirit that controlled our ancestors, it will serve an excellent purpose.

[Pg 7] Our writers should be compared with those of other sections and other countries; and due honor should be given them, equally removed from over-praise and from depreciation. If we, their countrymen, do not know and honor them, who can be expected to do so? No people is great whose memory is lost, whose interest centres in the present alone, who looks not reverently back to true beginnings and hopefully forward to a grand future.

So I would urge my fellow-teachers to a fresh diligence in studying and worthily understanding the life and literature of our past, and in impressing them upon the minds of the rising generation, so as to infuse into the new forms now arising the best and purest and highest of the old forms fast passing away.

My sincere thanks are hereby tendered to the scholars who have aided me by their advice and encouragement, to living authors and the relatives of those not living who have generously given me permission to copy extracts from their writings, to the publishers who have kindly allowed me to use copyrighted matter, to Miss Anna M. Trice, Mr. Josiah Ryland, Jr., and the officials of the Virginia State Library where I found most of the books needed in my work, and to Mr. David Hutcheson, of the Library of Congress. My greatest indebtedness is to Professor William Taylor Thom and Professor John P. McGuire, for scholarly criticism and practical suggestions in the course of preparation.

1895.Louise Manly.

[1] See Professor Woodrow Wilson’s excellent article on the University study of Literature and Institutions, in the Forum, September, 1894.

Appleton: Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 6 vols.

Duyckinck: Cyclopaedia of American Literature, 2 vols.

Allibone: Dictionary of Authors, 3 vols.

Kirk: Supplement to Allibone, 2 vols.

Stedman: Poets of America.

Stedman and Hutchinson: Library of American Literature, 11 vols.

Poe: Literati of New York.

Griswold: Poets and Poetry of America.

Prose Writers of America.

Female Poets of America.

Hart: American Literature, Eldredge Bros., Phila.

Davidson: Living Writers of the South, (1869).

Miss Rutherford: American Authors, Franklin Publishing Company, Atlanta, Georgia.

Southern Literary Messenger, 1834-1863.

Southern Quarterly Review, 1842-1855.

De Bow’s Commercial Review.

The Land We Love, 1865-1869.

Southern Review, and Eclectic Review, Baltimore.

Southland Writers, by Ida Raymond (Mrs. Tardy).

Women of the South in Literature, by Mary Forrest.

Fortier: Louisiana Studies, F. F. Hansell, New Orleans.

Ogden: Literature of the Virginias, Independent Publishing Company, Morgantown, West Virginia.

C. W. Coleman, Jr.: Recent Movement in the Literature of the South, Harper’s Monthly, 1886, No. 74, p. 837.

T. N. Page: Authorship in the South before the War, Lippincott’s Magazine, 1889, No. 44, p. 105.

Professor C. W. Kent, University of Virginia: Outlook for Literature in the South.

People’s Cyclopedia (1894).

In Chronological Order.

| Page | |

| John Smith, 1579-1631 | 33 |

| Rescue of Captain Smith by Pocahontas | 35 |

| Our Right to Those Countries | 38 |

| Ascent of the River James, 1607 | 42 |

| William Strachey, in America 1609-12 | 45 |

| A Storm Off the Bermudas | 45 |

| John Lawson, in America 1700-08 | 48 |

| North Carolina in 1700-08 | 49 |

| Harvest Home of the Indians | 53 |

| William Byrd, 1674-1744 | 54 |

| Selecting the Site of Richmond and Petersburg, 1733 | 58 |

| A Visit to Ex-Governor Spotswood, 1732 | 58 |

| Dismal Swamp, 1728 | 61 |

| The Tuscarora Indians and Their Legend of a Christ, 1729 | 65 |

| Henry Laurens, 1724-1792 | 67 |

| A Patriot in the Tower | 68 |

| George Washington, 1732-1799 | 71 |

| An Honest Man | 73 |

| [Pg 10]How to Answer Calumny | 74 |

| Conscience | 74 |

| On his Appointment as Commander-in-Chief, 1775 | 74 |

| A Military Dinner-Party | 76 |

| Advice to a Favorite Nephew | 76 |

| Farewell Address to the People of the United States, 1796 | 77 |

| Union and Liberty | 77 |

| Party Spirit | 79 |

| Religion and Morality | 81 |

| Patrick Henry, 1736-1799 | 82 |

| Remark on Slavery, 1788 | 84 |

| Not Bound by State Lines | 84 |

| If This Be Treason, 1765 | 84 |

| The Famous Revolution Speech, 1775 | 84 |

| William Henry Drayton, 1742-1779 | 87 |

| George III.’s Abdication of Power in America | 89 |

| Thomas Jefferson, 1743-1826 | 91 |

| Political Maxims | 94 |

| Religious Opinions at the Age of Twenty | 94 |

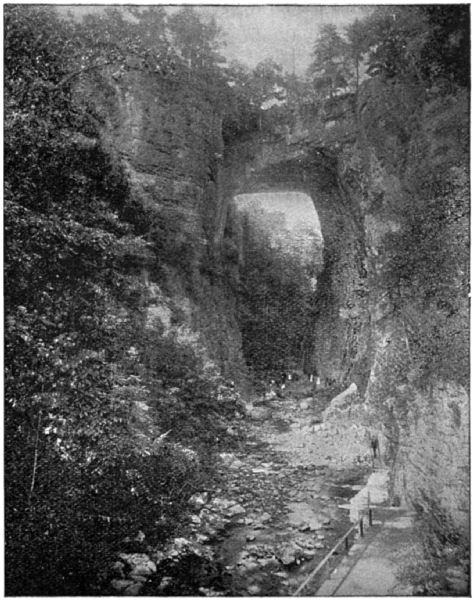

| Scenery at Harper’s Ferry, and at the Natural Bridge | 95 |

| On Freedom of Religious Opinion | 98 |

| On the Discourses of Christ | 98 |

| Religious Freedom (the Act of 1786) | 98 |

| Letter to his Daughter | 100 |

| Jefferson’s Last Letter, 1826 | 101 |

| David Ramsay, 1749-1815 | 103 |

| British Treaty with the Cherokees, 1755 | 105 |

| Sergeant Jasper at Fort Moultrie, 28 June, 1776 | 106 |

| Sumpter and Marion | 107 |

| James Madison, 1751-1836 | 109 |

| Opinion of Lafayette | 110 |

| Plea for a Republic | 111 |

| Character of Washington | 112 |

| St. George Tucker, 1752-1828 | 113 |

| Resignation, or Days of My Youth | 115 |

| [Pg 11]John Marshall, 1755-1835 | 116 |

| Power of the Supreme Court | 117 |

| The Duties of a Judge | 118 |

| Henry Lee, 1756-1818 | 119 |

| Capture of Fort Motte by Lee and Marion, 1780 | 120 |

| The Father of His Country | 124 |

| Mason Locke Weems, 1760-1825 | 126 |

| The Hatchet Story | 126 |

| John Drayton, 1766-1822 | 127 |

| A Revolutionary Object Lesson in the Cause of Patriotism 1775 | 128 |

| The Battle of Noewee, 1776 | 129 |

| William Wirt, 1772-1834 | 131 |

| The Blind Preacher (James Waddell) | 132 |

| Mr. Henry against John Hook | 135 |

| John Randolph, 1773-1833 | 137 |

| Revision of the State Constitution, 1829 | 138 |

| George Tucker, 1775-1861 | 140 |

| Jefferson’s Preference for Country Life | 142 |

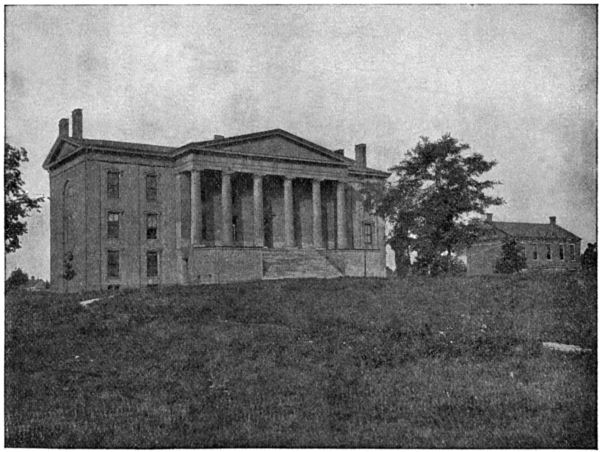

| Establishment of the University of Virginia | 143 |

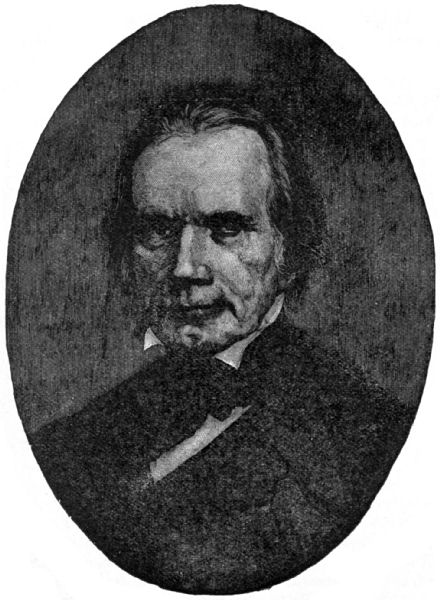

| Henry Clay, 1777-1852 | 147 |

| To Be Right above All | 148 |

| No Geographical Lines in Patriotism | 148 |

| Military Insubordination | 148 |

| Francis Scott Key, 1780-1843 | 151 |

| The Star-Spangled Banner | 151 |

| John James Audubon, 1780-1851 | 153 |

| The Mocking-Bird | 155 |

| The Humming-Bird | 157 |

| [Pg 12]Thomas Hart Benton, 1782-1858 | 158 |

| The Duel Between Randolph and Clay, 1826 | 159 |

| John Caldwell Calhoun, 1782-1850 | 161 |

| War and Peace | 164 |

| System of Our Government | 164 |

| Defence of Nullification | 164 |

| The Wise Choice | 166 |

| Official Patronage | 167 |

| Nathaniel Beverley Tucker, 1784-1851 | 167 |

| The Partisan Leader | 168 |

| David Crockett, 1786-1836 | 173 |

| Spelling and Grammar: Prologue To His Autobiography | 173 |

| On a Bear-hunt | 175 |

| Motto: Be Sure You Are Right | 178 |

| Richard Henry Wilde, 1789-1847 | 178 |

| My Life Is Like the Summer Rose | 179 |

| Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, 1790-1870 | 180 |

| Ned Brace at Church | 180 |

| A Sage Conversation | 182 |

| Robert Young Hayne, 1791-1839 | 185 |

| State Sovereignty and Liberty | 185 |

| Sam Houston, 1793-1863 | 189 |

| Cause of the Texan War of Independence | 190 |

| Battle of San Jacinto, 1836 | 193 |

| How To Deal With the Indians | 196 |

| William Campbell Preston, 1794-1860 | 199 |

| Literary Society in Columbia, S. C., 1825 | 201 |

| John Pendleton Kennedy, 1795-1870 | 204 |

| A Country Gentleman in Virginia | 205 |

| His Wife | 207 |

| How Horse-Shoe and Andrew Captured Five Men | 210 |

| Hugh Swinton Legaré, 1797-1843 | 217 |

| Commerce and Wealth vs. War | 217 |

| [Pg 13]Demosthenes’ Courage | 219 |

| A Duke’s Opinions of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia, in 1825 | 221 |

| Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, 1798-1859 | 223 |

| The Daughter of Mendoza | 223 |

| Francis Lister Hawks, 1798-1866 | 224 |

| The First Indian Baptism in America | 225 |

| Virginia Dare, the First English Child Born in America | 226 |

| The Lost Colony of Roanoke | 226 |

| George Denison Prentice, 1802-1870 | 228 |

| The Closing Year | 228 |

| Paragraphs | 231 |

| Edward Coate Pinkney, 1802-1828 | 231 |

| A Health | 232 |

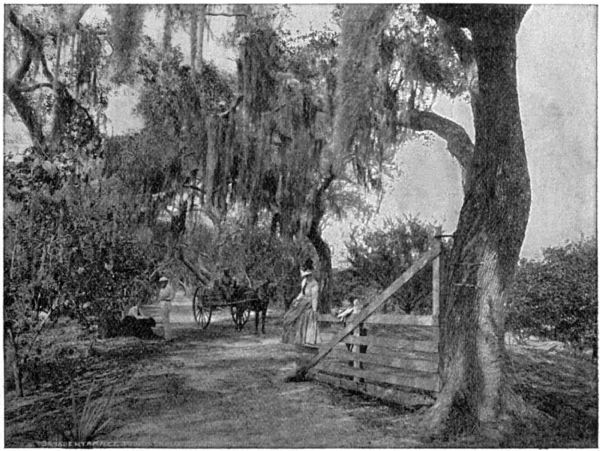

| Song: We Break the Glass | 233 |

| Charles Étienne Arthur Gayarré, 1805-1895 | 235 |

| Louisiana in 1750-1770 | 236 |

| The Tree of the Dead | 240 |

| Matthew Fontaine Maury, 1806-1873 | 243 |

| The Gulf Stream | 246 |

| Deep-Sea Soundings | 247 |

| Heroic Death of Lieutenant Herndon | 249 |

| William Gilmore Simms, 1806-1870 | 252 |

| Sonnet—The Poet’s Vision | 255 |

| The Doom of Occonestoga | 255 |

| Marion, the “Swamp-Fox” | 262 |

| Robert Edward Lee, 1807-1870 | 265 |

| Duty—To His Son | 266 |

| Human Virtue—At the Surrender | 266 |

| His Last Order, 1865 | 266 |

| Letter Accepting the Presidency of Washington College | 268 |

| Jefferson Davis, 1808-1889 | 269 |

| Trip To Kentucky at Seven Years of Age, and Visit to General Jackson | 271 |

| [Pg 14]Life of the President of the United States | 272 |

| Farewell to the Senate, 1861 | 274 |

| Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849 | 276 |

| To Helen | 279 |

| Israfel | 279 |

| Happiness | 281 |

| The Raven | 281 |

| Robert Toombs, 1810-1885 | 284 |

| Farewell to the Senate, 1861 | 286 |

| Octavia Walton Le Vert, 1810-1877 | 288 |

| To Cadiz from Havanna, 1855 | 289 |

| Louisa Susannah M’Cord, 1810-1880 | 291 |

| Woman’s Duty | 292 |

| Joseph G. Baldwin, 1811-1864 | 294 |

| Virginians in a New Country | 294 |

| Alexander Hamilton Stephens, 1812-1883 | 296 |

| Laws of Government | 297 |

| Sketch in the Senate, 1850 | 298 |

| True Courage | 301 |

| Alexander Beaufort Meek, 1814-1865 | 301 |

| Red Eagle, or Weatherford | 302 |

| Philip Pendleton Cooke, 1816-1850 | 305 |

| Florence Vane | 305 |

| Theodore O’Hara, 1820-1867 | 308 |

| Bivouac of the Dead | 308 |

| George Rainsford Fairbanks, 1820- | 311 |

| Osceola, Leader of the Seminoles | 311 |

| [Pg 15]Richard Malcolm Johnston, 1822- | 314 |

| Mr. Hezekiah Ellington’s Recovery | 315 |

| John Reuben Thompson, 1823-1873 | 317 |

| Ashby | 318 |

| Music in Camp | 319 |

| Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry, 1825- | 321 |

| Relations between England and America | 322 |

| Margaret Junkin Preston, 1825- | 324 |

| The Shade of the Trees | 324 |

| Charles Henry Smith, (“Bill Arp”), 1826- | 326 |

| Big John, on the Cherokees | 327 |

| St. George H. Tucker, 1828-1863 | 329 |

| Burning of Jamestown in 1676 | 330 |

| George William Bagby, 1828-1883 | 332 |

| Jud. Brownin’s Account of Rubinstein’s Playing | 332 |

| Sarah Anne Dorsey, 1829-1879 | 336 |

| A Confederate Exile on His Way to Mexico, 1866 | 338 |

| Henry Timrod, 1829-1867 | 341 |

| Sonnet—Life Ever Seems | 344 |

| English Katie | 344 |

| Hymn for Magnolia Cemetery | 345 |

| Paul Hamilton Hayne, 1830-1886 | 346 |

| The Mocking-Bird (At Night) | 348 |

| Sonnet—October | 349 |

| A Dream of the South Wind | 349 |

| John Esten Cooke, 1830-1886 | 350 |

| The Races in Virginia, 1765 | 351 |

| Zebulon Baird Vance, 1830-1894 | 358 |

| Changes Wrought by the War | 360 |

| The Country Gentlemen | 360 |

| The Negroes | 362 |

| [Pg 16]Albert Pike, 1809-1891 | 365 |

| To the Mocking-Bird | 365 |

| William Tappan Thompson, 1812-1882 | 367 |

| Major Jones’s Christmas Present | 368 |

| James Barron Hope, 1827-1887 | 370 |

| The Victory at Yorktown | 371 |

| Washington and Lee | 372 |

| James Wood Davidson, 1829- | 373 |

| The Beautiful and the Poetical | 373 |

| Charles Colcock Jones, Jr., 1831-1893 | 376 |

| Salzburger Settlement in Georgia | 376 |

| Mary Virginia Terhune (“Marion Harland”) | 379 |

| Letter Describing Mary [Ball] Washington When a Young Girl | 381 |

| Madam Washington at the Peace Ball | 381 |

| Augusta Evans Wilson, 1835- | 383 |

| A Learned and Interesting Conversation | 384 |

| Daniel Bedinger Lucas, 1836- | 387 |

| The Land Where We Were Dreaming | 388 |

| James Ryder Randall, 1839- | 389 |

| My Maryland | 390 |

| Abram Joseph Ryan, 1839-1886 | 392 |

| William Gordon McCabe, 1841- | 393 |

| Dreaming in the Trenches | 393 |

| Sidney Lanier, 1842-1881 | 394 |

| Song of the Chattahoochee | 396 |

| What is Music? | 397 |

| The Tide Rising in the Marshes | 397 |

| James Lane Allen | 398 |

| Sports of a Kentucky School in 1795 | 399 |

| [Pg 17]Joel Chandler Harris, 1848- | 401 |

| The Tar-Baby | 403 |

| Robert Burns Wilson, 1850- | 405 |

| Fair Daughter of the Sun | 406 |

| Dedication—A Sonnet | 407 |

| “Christian Reid,” Frances C. Tiernan | 407 |

| Ascent of Mt. Mitchell, N. C. | 409 |

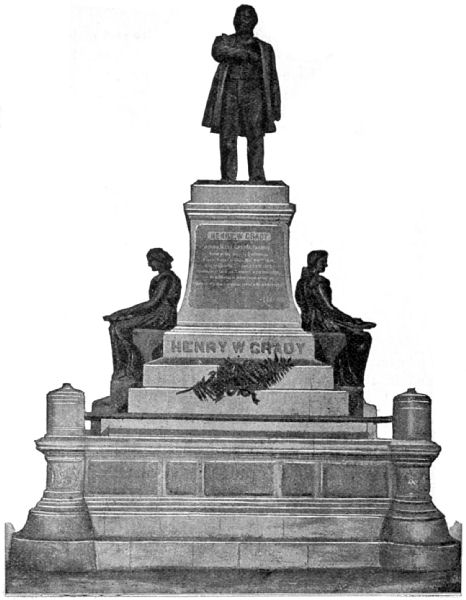

| Henry Woodfen Grady, 1851-1889 | 413 |

| The South before the War | 413 |

| Master and Slave | 413 |

| Ante-bellum Civilization | 416 |

| Thomas Nelson Page, 1853- | 419 |

| Marse Chan’s Last Battle | 421 |

| Mary Noailles Murfree, (“Charles Egbert Craddock”) | 423 |

| The “Harnt” that Walks Chilhowee | 423 |

| Danske Dandridge, 1859- | 429 |

| The Spirit and the Wood-Sparrow | 430 |

| Amélie Rives Chanler, 1863- | 431 |

| Tanis | 432 |

| Grace King | 437 |

| La Grande Demoiselle | 437 |

| Waitman Barbe, 1864- | 441 |

| Sidney Lanier | 442 |

| Madison Cawein, 1865- | 442 |

| The Whippoorwill | 443 |

| Dixie | 444 |

| List of Authors and Works omitted for lack of space | 445 |

| Page | ||

| A Confederate Exile on His Way to Mexico | Sarah A. Dorsey | 338 |

| Address in Congress, 1800, on the Death of Washington | Henry Lee | 124 |

| A Dream of the South Wind | Paul H. Hayne | 349 |

| Advice to His Nephew | George Washington | 76 |

| A Health | E. C. Pinkney | 232 |

| Alamo, Fall of the | 192 | |

| A Learned and Interesting Conversation | Augusta E. Wilson | 384 |

| Allen, James Lane | 398 | |

| Anecdotes of Alexander H. Stephens | 296, 297 | |

| An Honest Man | George Washington | 73 |

| Ante-bellum Civilization | Henry W. Grady | 416 |

| Arber, Professor, on John Smith’s Writings | 35 | |

| A Sage Conversation | A. B. Longstreet | 182 |

| Ascent of Mt. Mitchell, North Carolina | Christian Reid | 409 |

| Ascent of the James River, 1607 | John Smith | 42 |

| Ashby | John R. Thompson | 318 |

| Audubon, John James | 153 | |

| Bacon, Nathaniel | 330 | |

| Bagby, George William | 332 | |

| Baldwin, Joseph G. | 294 | |

| Barbe, Waitman | 441 | |

| Battle of Noewee, 1776 | John Drayton | 129 |

| Battle of San Jacinto, 1836 | Sam Houston | 193 |

| Battle of the Blue Licks, Ky., 1782 | 400 | |

| Battle of Tohopeka, or Horse-Shoe Bend, Ala. | 302 | |

| Bear Hunt | David Crockett | 175 |

| [Pg 19]Beauvoir | 270, 273 | |

| Beautiful and the Poetical, The, | Jas. Wood Davidson | 373 |

| Beauty is Holiness | 395 | |

| Benton, Thomas Hart | 158 | |

| “Be sure you are right,” | David Crockett | 178 |

| Big John, on the Cherokees | Bill Arp | 327 |

| Bill Arp (Charles Henry Smith) | 326 | |

| Bivouac of the Dead | Theodore O’Hara | 308 |

| Blind Preacher | William Wirt | 132 |

| Boone, Daniel | 401 | |

| British Treaty with the Cherokees, 1755 | David Ramsay | 105 |

| Burning of Jamestown, 1676 | St. George H. Tucker | 330 |

| Byrd, Evelyn | 56 | |

| Byrd, William | 54 | |

| Calhoun, John Caldwell | 161 | |

| Calhoun and the Union | 275 | |

| Calhoun, Death of | 300 | |

| Capture of Fort Motte | Henry Lee | 120 |

| Cause of the Texan War of Independence | Sam Houston | 190 |

| Cawein, Madison | 442 | |

| Changes Wrought by the War | Z. B. Vance | 360 |

| Chanler, Mrs. Amélie Rives | 431 | |

| Character of Washington | James Madison | 112 |

| Cherokees, Big John on the | Bill Arp | 327 |

| Clay, Henry | 147 | |

| Closing Year, The | George D. Prentice | 228 |

| Commerce and Wealth vs. War | Hugh S. Legaré | 217 |

| Conscience | George Washington | 74 |

| Cooke, Philip Pendleton | 305 | |

| Cooke, John Esten | 350 | |

| Corn-Shucking and Christmas Times | 362 | |

| Country Gentleman in Virginia and His Wife | John P. Kennedy | 205 |

| Country Gentlemen | 360 | |

| Cow-Boy’s Song | 339 | |

| Craddock, Charles Egbert, (Miss M. N. Murfree) | 423 | |

| Crockett, David | 173 | |

| [Pg 20]Curry, Jabez Lamar Monroe | 321 | |

| Dale, General Sam | 302 | |

| Dandridge, Mrs. Danske | 429 | |

| Daughter of Mendoza | M. B. Lamar | 223 |

| Davidson, James Wood | 373 | |

| Davis, Jefferson | 269 | |

| Davis, Winnie | 270 | |

| Davis, Mrs. Varina Jefferson | 271 | |

| Davy Crockett’s Motto | 178 | |

| Days of My Youth, or Resignation | St. George Tucker | 115 |

| Death of Calhoun | 300 | |

| Death of Lieutenant Herndon | 249 | |

| Dedication Sonnet (to his Mother) | Robert Burns Wilson | 407 |

| Deep-Sea Soundings | M. F. Maury | 247 |

| Defence of Nullification | John C. Calhoun | 164 |

| Demosthenes | Hugh S. Legaré | 219 |

| DeSaussure, Judge, and Social Dining in Columbia | 201 | |

| Discourses of Christ | Thomas Jefferson | 98 |

| Dismal Swamp | William Byrd | 61 |

| Dixie | 444 | |

| Dixie and Yankee Doodle | 319 | |

| Doom of Occonestoga | Wm. Gilmore Simms | 255 |

| Dorsey, Mrs. Sarah Anne | 336 | |

| Drayton, William Henry | 87 | |

| Drayton, John | 127 | |

| Dreaming in the Trenches | Wm. Gordon McCabe | 393 |

| Duel Between Randolph and Clay, 1826 | Thomas H. Benton | 159 |

| Duke of Saxe-Weimar in Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia, 1825 | Hugh S. Legaré | 221 |

| Duties of a Judge | John Marshall | 118 |

| Duty | Robert E. Lee | 266 |

| England and America, Relations between | J. L. M. Curry | 322 |

| English Katie | Henry Timrod | 344 |

| Ennui | 101 | |

| Establishment of the University of Virginia | George Tucker | 143 |

| [Pg 21]Fairbanks, George Rainsford | 311 | |

| Fair Daughter of the Sun | Robert Burns Wilson | 406 |

| Farewell Address to the American People, 1796 | George Washington | 77 |

| Farewell to the Senate, 1861 | Jefferson Davis | 274 |

| Farewell to the Senate, 1861 | Robert Toombs | 286 |

| Father of His Country | Henry Lee | 124 |

| First Indian Baptism in America | Francis L. Hawks | 225 |

| “First in War, first in Peace” | 124 | |

| Five Demands of the South | 286 | |

| Florence Vane | Philip Pendleton Cooke | 305 |

| Fort King, Florida | 311 | |

| Fort Motte, Capture of | Henry Lee | 120 |

| Freedom of Religious Opinion | Thomas Jefferson | 98 |

| Gayarré, Charles Étienne Arthur | 235 | |

| George the Third’s Abdication of Power in America | William Henry Drayton | 89 |

| Gladstone’s Opinion of the United States | 322 | |

| Goliad, Massacre at | 192 | |

| Grady, Henry Woodfen | 413 | |

| Grave of Dr. Elisha Mitchell | 411 | |

| Gulf Stream | M. F. Maury | 246 |

| Hampton at the Battle of Noewee, South Carolina, 1776 | 130 | |

| Happiness | Edgar Allan Poe | 281 |

| Harland, Marion (Mrs. M. V. Terhune) | 379 | |

| “Harnt” that Walks Chilhowee, The | Charles Egbert Craddock | 423 |

| Harper’s Ferry, Scenery at | 95 | |

| Harris, Joel Chandler | 401 | |

| Harvest Home of the Indians | John Lawson | 53 |

| Hatchet Story | Mason L. Weems | 126 |

| Hawks, Francis Lister | 224 | |

| Hayne, Robert Young | 185 | |

| Hayne, Paul Hamilton | 346 | |

| Hayne, William Hamilton | 346 | |

| Helen, To | Edgar Allan Poe | 279 |

| Henry, Patrick | 82 | |

| Hermitage, General Jackson at The | 271 | |

| [Pg 22]Heroic Death of Lieutenant Herndon | M. F. Maury | 249 |

| Hope, James Barron | 370 | |

| Horse-Shoe Bend, Battle of | 302 | |

| Houston, Sam | 189 | |

| How Horse-Shoe and Andrew Captured Five Men | John P. Kennedy | 210 |

| How Ruby Played | George William Bagby | 332 |

| How to Answer Calumny | George Washington | 74 |

| How to Deal with the Indians | Sam Houston | 196 |

| Human Virtue | R. E. Lee | 266 |

| Humming-Bird, The | J. J. Audubon | 157 |

| Hymn for Magnolia Cemetery | Henry Timrod | 345 |

| “If This Be Treason—” | Patrick Henry | 84 |

| “I’ll HAUNT you,” | 317 | |

| Indian Doom of Excommunication | 255 | |

| Israfel | Edgar Allan Poe | 279 |

| Jackson, General, at Home | 271 | |

| Jamestown, Burning of, 1676 | St. George H. Tucker | 330 |

| James Waddell, the Blind Preacher | William Wirt | 132 |

| Jefferson, Thomas | 91 | |

| Jefferson’s Last Letter, June 24, 1826 | Thomas Jefferson | 101 |

| Jefferson’s Preference for Country Life | George Tucker | 142 |

| Jefferson’s Religious Opinions at Twenty | Thomas Jefferson | 94 |

| John Hook, Patrick Henry against | William Wirt | 135 |

| Johnston, Richard Malcolm | 314 | |

| Jones, Charles Colcock, Jr. | 376 | |

| Jud. Brownin’s Account of Rubinstein’s Playing | George William Bagby | 332 |

| Kennedy, John Pendleton | 204 | |

| Key, Francis Scott | 151 | |

| King, Grace | 437 | |

| La Fayette, Madison’s Opinion of | James Madison | 110 |

| [Pg 23]La Grande Demoiselle | Grace King | 437 |

| Lamar, Mirabeau Buonaparte | 223 | |

| Land Where We Were Dreaming, The | D. B. Lucas | 388 |

| Lanier, Sidney | 394 | |

| Lanier, To Sidney | Waitman Barbe | 442 |

| La Rabida | 291 | |

| Last Letter of Jefferson, June 24, 1826 | Thomas Jefferson | 101 |

| Laurens, Henry | 67 | |

| Laurens, John, the “Bayard of the Revolution” | 67 | |

| Laws of Government | A. H. Stephens | 297 |

| Lawson, John | 48 | |

| Lee, Henry | 119 | |

| Lee, Robert Edward | 265 | |

| Lee’s Last Order | R. E. Lee | 266 |

| Lee’s Letter Accepting the Presidency of Washington College | R. E. Lee | 268 |

| Legaré, Hugh Swinton | 217 | |

| Letter to Martha Jefferson | Thomas Jefferson | 100 |

| Le Vert, Madame Octavia Walton | 288 | |

| Life Ever Seems—Sonnet | Henry Timrod | 344 |

| Life of the President of the United States | Jefferson Davis | 272 |

| Literary Society in Columbia in 1825 | Wm. C. Preston | 201 |

| Longstreet, Augustus Baldwin | 180 | |

| Lost Colony of Roanoke | F. L. Hawks | 226 |

| Louisiana in 1750-’70 | C. E. A. Gayarré | 236 |

| Lucas, Daniel Bedinger | 387 | |

| Madam Washington at the Peace Ball | Marion Harland | 381 |

| Madison, James | 109 | |

| Madison, Mrs. Dolly | 110 | |

| Madison’s Opinion of La Fayette | James Madison | 110 |

| Magnolia Cemetery, Hymn for Dedication | Henry Timrod | 345 |

| Major Jones’s Christmas Present | W. T. Thompson | 368 |

| Marion Harland, (Mrs. M. V. Terhune) | 379 | |

| [Pg 24]Marion, Sumpter and | David Ramsay | 107 |

| Marion, the “Swamp-Fox” | Wm. Gilmore Simms | 262 |

| Marquis de Vaudreuil, the “Great Marquis” | 237 | |

| Marse Chan’s Last Battle | Thomas Nelson Page | 421 |

| “Marseillaise of the Confederacy” | 389 | |

| Marshall, John | 116 | |

| Maryland, My Maryland | 390 | |

| Mary Washington When a Girl | Marion Harland | 381 |

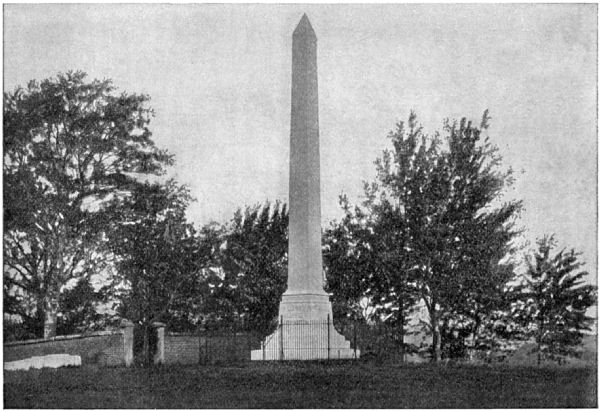

| Mary Washington’s Monument | Marion Harland | 379 |

| Master and Slave | 413 | |

| Maury, Matthew Fontaine | 243 | |

| Maxims of Jefferson | 94 | |

| McCabe, William Gordon | 393 | |

| M’Cord, Mrs. Louisa Susannah | 291 | |

| M’Cord, D. J. | 201, 291 | |

| Meek, Alexander Beaufort | 301 | |

| Military Dinner Party | George Washington | 76 |

| Military Insubordination | Henry Clay | 148 |

| “Millions for Defence” | 116 | |

| Mitchell’s Grave, Mt. Mitchell, N. C. | 411 | |

| Mocking-Bird, The | J. J. Audubon | 155 |

| Mocking-Bird (At Night) | Paul H. Hayne | 348 |

| Mocking-Bird, To The | Albert Pike | 365 |

| Mocking-Bird and Nightingale Compared | 100 | |

| Mr. Hezekiah Ellington’s Recovery | R. M. Johnston | 315 |

| Murfree, Mary Noailles, (Charles Egbert Craddock) | 423 | |

| Music in Camp | John R. Thompson | 319 |

| My Life Is Like the Summer Rose | R. H. Wilde | 179 |

| My Maryland | James R. Randall | 390 |

| Naming of Tallahassee, The | 288 | |

| Natural Bridge of Virginia | 97 | |

| Ned Brace at Church | A. B. Longstreet | 180 |

| No Geographical Lines in Patriotism | Henry Clay | 148 |

| North Carolina in 1700-1708 | John Lawson | 49 |

| Not Bound by State Lines | Patrick Henry | 84 |

| Nullification, Defence of | John C. Calhoun | 164 |

| [Pg 25]Object-Lesson in the Cause of Patriotism | John Drayton | 128 |

| Occonestoga, Doom of | Wm. Gilmore Simms | 255 |

| October—A Sonnet | Paul H. Hayne | 349 |

| Official Patronage | John C. Calhoun | 167 |

| O’Hara, Theodore | 308 | |

| Old Church at Jamestown | 39, 331 | |

| On a Bear Hunt | David Crockett | 175 |

| Osceola, Leader of the Seminoles | George R. Fairbanks | 311, 312 |

| Our Right to Those Countries | John Smith | 38 |

| Page, John, Letter to | 94 | |

| Page, Thomas Nelson | 419 | |

| Paragraphs | George D. Prentice | 231 |

| Partisan Leader | N. Beverley Tucker | 168 |

| Party Spirit | George Washington | 79 |

| Patrick Henry against John Hook | William Wirt | 135 |

| Patrick Henry’s Famous Revolution Speech | Patrick Henry | 84 |

| Patriot in the Tower | Henry Laurens | 68 |

| Payne, John Howard, among the Cherokees | 327 | |

| Pike, Albert | 365 | |

| Pinkney, Edward Coate | 231 | |

| Plea for a Republic | James Madison | 111 |

| Pocahontas,—Rescue of John Smith | John Smith | 35 |

| Poe, Edgar Allan | 276 | |

| Poet’s Vision.—A Sonnet | William Gilmore Simms | 255 |

| Political Patronage | John C. Calhoun | 167 |

| Power of the Supreme Court | John Marshall | 117 |

| Powhatan | 35 | |

| Preference for Country Life | George Tucker | 142 |

| Prentice, George Denison | 228 | |

| Preston, Mrs. Margaret Junkin | 324 | |

| Preston, William Campbell | 199 | |

| Prologue to Arms and the Man | James Barren Hope | 371 |

| Prologue to Autobiography | David Crockett | 173 |

| Races in Virginia, 1765 | John Esten Cooke | 351 |

| Ramsay, David | 103 | |

| [Pg 26]Randall, James Ryder | 389 | |

| Randolph, John, of Roanoke | 137 | |

| Raven, The | Edgar Allan Poe | 281 |

| Red Eagle, or Weatherford | A. B. Meek | 302 |

| Red Eagle and General Jackson | 304 | |

| Reid, Christian, (Frances C. Fisher, Mrs. Tiernan) | 407 | |

| Relations Between England and America | J. L. M. Curry | 322 |

| Religion and Morality | George Washington | 81 |

| Religious Freedom | Thomas Jefferson | 98 |

| “Remember the Alamo!” | 195 | |

| Rescue of Captain Smith by Pocahontas | John Smith | 35 |

| Resignation: or, Days of My Youth | St. George Tucker | 115 |

| Revision of the State Constitution | John Randolph | 138 |

| Revolutionary Object-Lesson | John Drayton | 128 |

| Revolution Speech, 1775 | Patrick Henry | 84 |

| Rives, Amélie (Mrs. Chanler) | 431 | |

| “Rope of sand” | 186 | |

| Rubinstein’s Playing | George William Bagby | 332 |

| Ryan, Abram Joseph, (Father Ryan) | 392 | |

| Sage Conversation, A | A. B. Longstreet | 182 |

| Salzburger Settlement in Georgia, 1734 | C. C. Jones, Jr. | 376 |

| Sang-Digger,[2] The | Amélie Rives | 432 |

| Savannah in 1735 | 378 | |

| Scenery at Harper’s Ferry and at the Natural Bridge | Thomas Jefferson | 95 |

| Selecting the Site of Richmond and of Petersburg, 1733 | William Byrd | 58 |

| Seminole War | 313 | |

| Sergeant Jasper at Fort Moultrie, 1776 | David Ramsay | 106 |

| Sergeant Jasper at Savannah, 1779 | 107 | |

| Sidney Lanier, To | Waitman Barbe | 442 |

| Siege of Fort Moultrie | David Ramsay | 106 |

| [Pg 27]Simms, William Gilmore | 252 | |

| Sketch in the Senate, February 5, 1850 | A. H. Stephens | 298 |

| Slavery, Remark on | Patrick Henry | 84 |

| Slave, Master and | 413 | |

| Smith, Charles Henry (Bill Arp) | 326 | |

| Smith, John | 33 | |

| Smith, John, Writings of | 35 | |

| Song of the Chattahoochee | Sidney Lanier | 396 |

| Sonnet: Dedication | R. B. Wilson | 407 |

| Song: We Break the Glass | E. C. Pinkney | 233 |

| Sonnet: Life ever seems | Henry Timrod | 344 |

| Sonnet: October | Paul H. Hayne | 349 |

| Sonnet: Poet’s Vision | William Gilmore Simms | 255 |

| South Before the War, The | Henry W. Grady | 413 |

| Southern Literary Messenger | 277, 317, 332 | |

| Southern “Mammy” and the Children | 363 | |

| Speaking of Clay in the Senate, 1850, The | 298 | |

| Spelling and Grammar (Prologue to Autobiography) | David Crockett | 173 |

| Spirit and Wood-Sparrow, The | Danske Dandridge | 430 |

| Sports of a Kentucky School in 1795 | James Lane Allen | 399 |

| Spotswood, Ex-Gov., and his Home in 1732 | 58 | |

| Star-Spangled Banner | Francis Scott Key | 151 |

| State Sovereignty and Liberty | Robert Y. Hayne | 185 |

| Stephens, Alexander Hamilton | 296 | |

| Stonewall Jackson’s Last Words | 324 | |

| Storm Off the Bermudas | Wm. Strachey | 45 |

| Strachey, William | 45 | |

| Sugar-Cane: Introduction into the United States | 236 | |

| Sumpter and Marion | David Ramsay | 107 |

| “Swamp-Fox,” The | 262 | |

| System of Our Government | John C. Calhoun | 164 |

| Tanis | Amélie Rives | 432 |

| Tar-Baby, The | Joel Chandler Harris | 403 |

| Terhune, Mrs. Mary Virginia (Marion Harland) | 379 | |

| Texas Prairie and Cow-Boy’s Song | 339 | |

| [Pg 28]The Land Where We Were Dreaming | D. B. Lucas | 388 |

| The Spirit and the Wood-Sparrow | Danske Dandridge | 430 |

| The South Before the War | Henry W. Grady | 413 |

| Thompson, John Reuben, | 317 | |

| Tide Rising in the Marshes | Sidney Lanier | 397 |

| Tiernan, Mrs. Frances C. (Christian Reid) | 407 | |

| Timrod, Henry | 341 | |

| To Be Right Above All | Henry Clay | 148 |

| To Cadiz from Havanna, 1855 | Madame Le Vert | 289 |

| To Helen | Edgar Allan Poe | 279 |

| Tohopeka, Battle of | 302 | |

| Toombs, Robert | 284 | |

| To the Mocking-Bird | Albert Pike | 365 |

| Tree of the Dead | C. E. A. Gayarré | 240 |

| Trip to Kentucky at Seven Years of Age | Jefferson Davis | 271 |

| True Courage | A. H. Stephens | 301 |

| Tucker, St. George | 113 | |

| Tucker, George | 140 | |

| Tucker, Nathaniel Beverley | 167 | |

| Tucker, St. George H. | 329 | |

| Tuscarora Indians and Their Legend of a Christ | William Byrd | 65 |

| Under the Shade of the Trees | Margaret J. Preston | 324 |

| Union and Liberty | George Washington | 77 |

| University of Virginia, Establishment of | George Tucker | 143 |

| Vance, Zebulon Baird | 358 | |

| Victory at Yorktown, 1781 | James Barren Hope | 371 |

| Virginia Dare | F. L. Hawks | 226 |

| Virginian or American? | Patrick Henry | 84 |

| Virginians in a New Country | Joseph G. Baldwin | 294 |

| Visit to Ex-Governor Spotswood, 1732 | William Byrd | 58 |

| Visit to the Hermitage | 271 | |

| War and Peace | John C. Calhoun | 164 |

| Washington, George | 71 | |

| [Pg 29]Washington and the Hatchet | 126 | |

| Washington’s Advice to His Nephew | George Washington | 76 |

| Washington, Character of | James Madison | 112 |

| Washington’s Farewell to the American People, 1796 | George Washington | 77 |

| Washington and Lee | James Barren Hope | 372 |

| Washington’s Mother When a Girl | 381 | |

| Washington’s Mother at the Peace Ball | 381 | |

| Washington’s Speech in Congress on his Appointment as Commander-in-Chief, 1775 | George Washington | 74 |

| Washington, Memorial Address in Congress, 1800, by Henry Lee | 124 | |

| Weatherford, or Red Eagle | 302 | |

| We Break the Glass,—Song | E. C. Pinkney | 233 |

| Weems, Mason Locke | 126 | |

| What is Music? | Sidney Lanier | 397 |

| Whippoorwill, The | Madison Cawein | 443 |

| Wilde, Richard Henry | 178 | |

| Wilson, Mrs. Augusta Evans | 383 | |

| Wilson, Robert Burns | 405 | |

| Wirt, William | 131 | |

| Wise Choice | John C. Calhoun | 166 |

| Woman’s Duty | Louisa S. M’Cord | 292 |

[2] Ginseng-Digger.

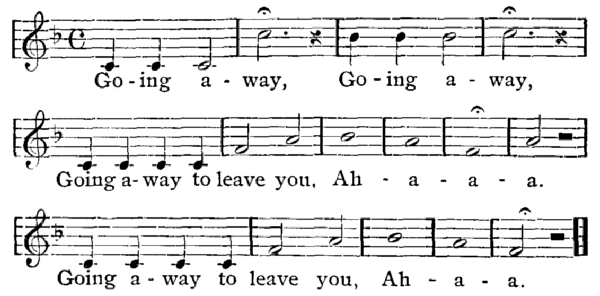

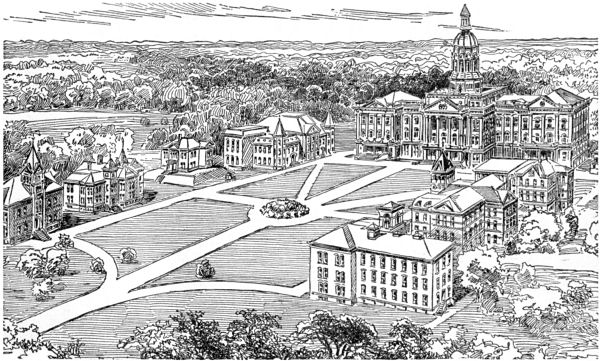

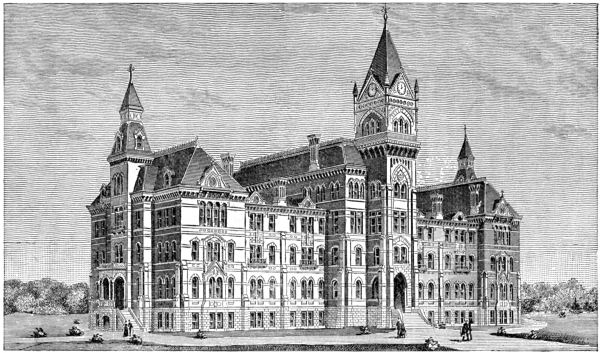

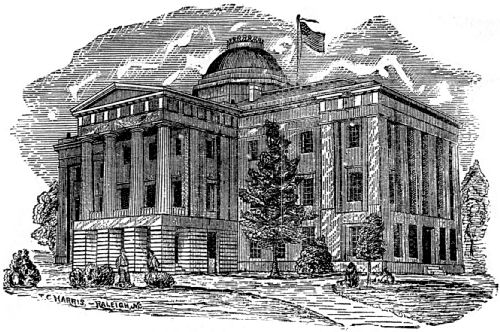

| Page | |

| Captain John Smith | 34 |

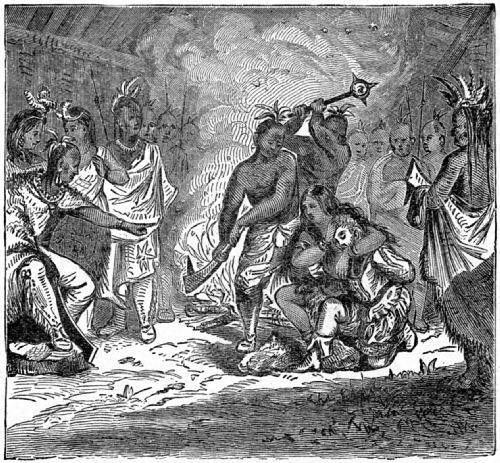

| Rescue of Captain Smith by Pocahontas | 36 |

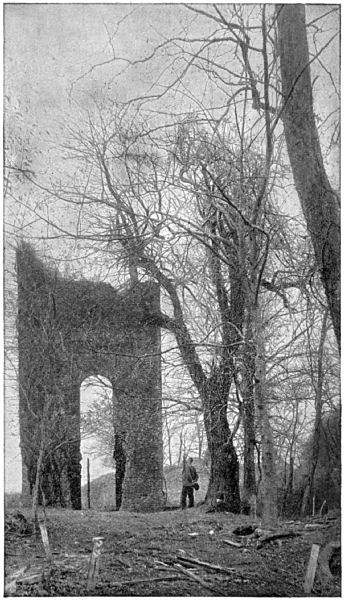

| Jamestown, Va. The first permanent English settlement in America | 39 |

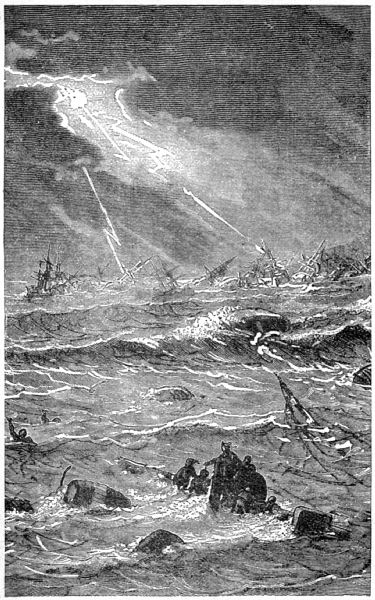

| Storm at Sea | 44 |

| Sir Walter Raleigh | 50 |

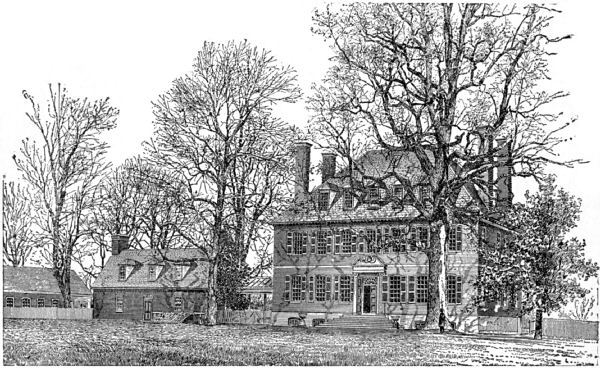

| Westover, the Home of William Byrd | 55 |

| Evelyn Byrd | 57 |

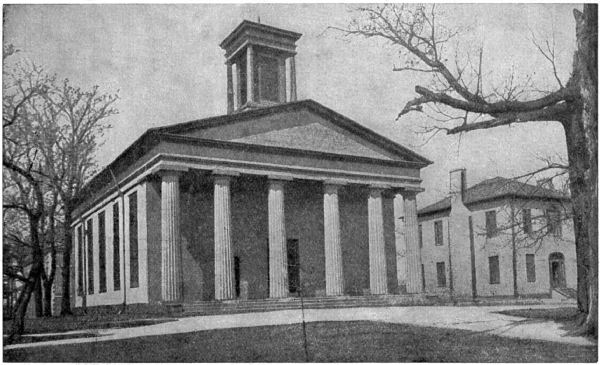

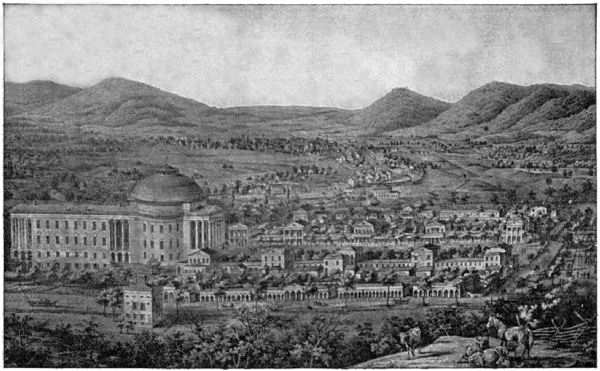

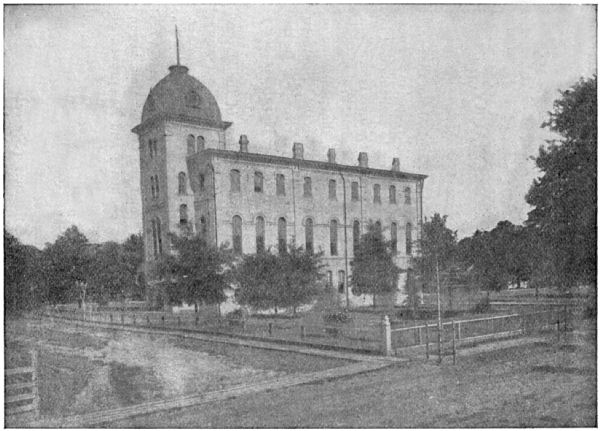

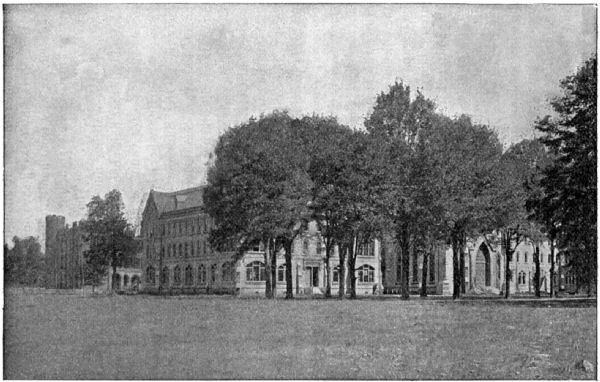

| The Chapel, University of Georgia, Athens | 62 |

| The Tower of London | 69 |

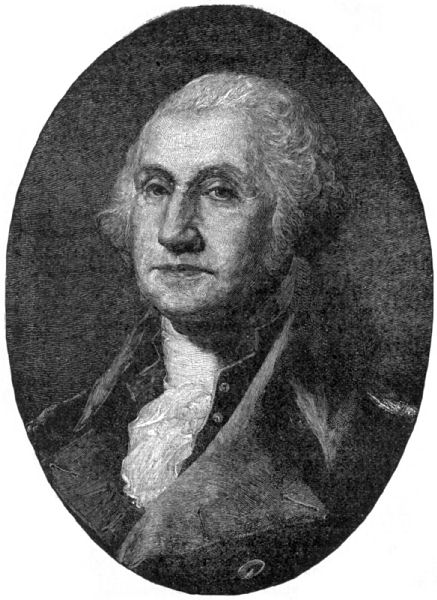

| George Washington | 72 |

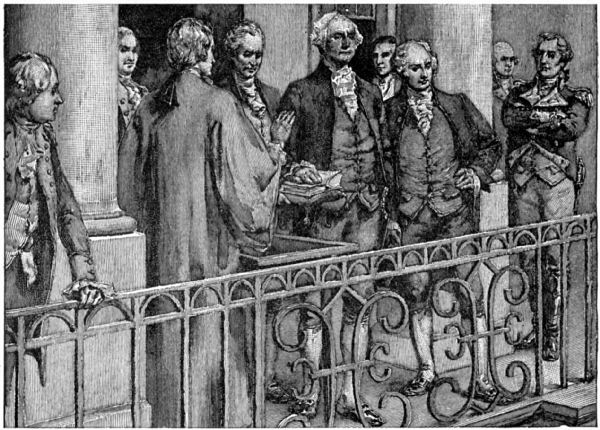

| Washington Taking the Oath of Office | 75 |

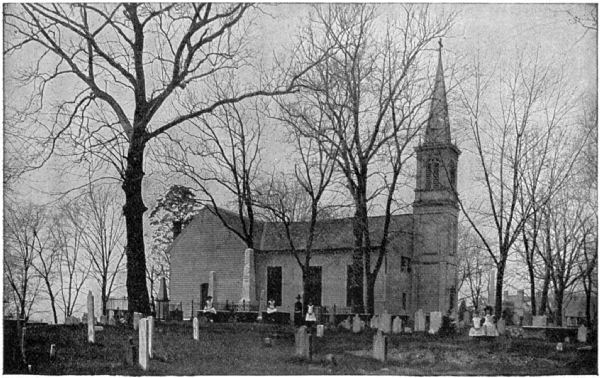

| Old St. John’s Church, Richmond, Va. | 83 |

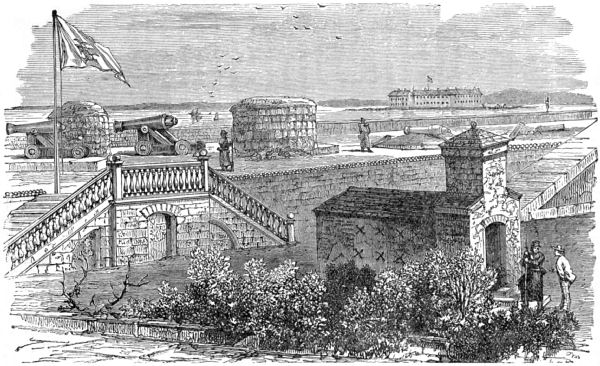

| Fort Moultrie, S. C. Fort Sumter in the Distance | 88 |

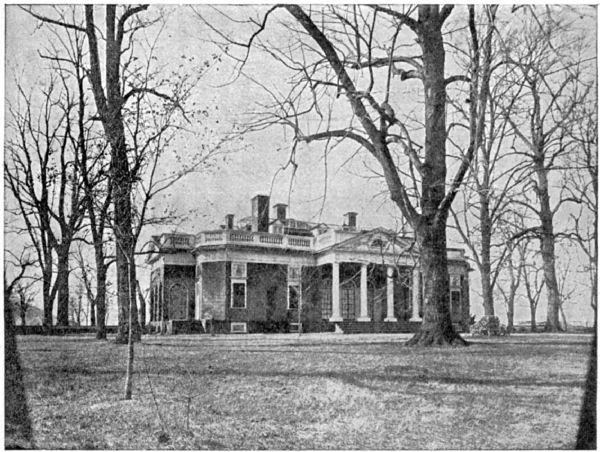

| Monticello, the Home of Jefferson | 92 |

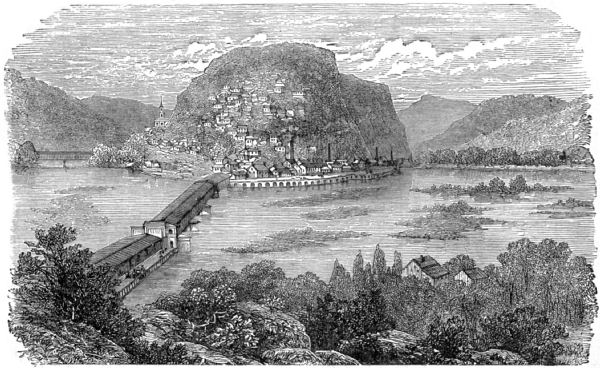

| Harper’s Ferry | 96 |

| Jasper Replacing the Flag | 104 |

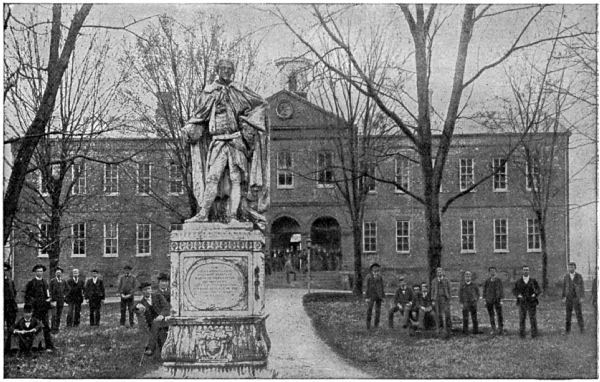

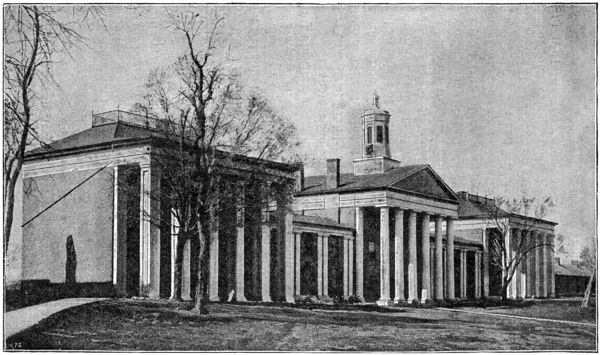

| William and Mary College, Williamsburg, Va. | 114 |

| University of Virginia | 141 |

| Henry Clay | 146 |

| Star-Spangled Banner and Seal of the United States | 152 |

| Scene in Louisiana | 154 |

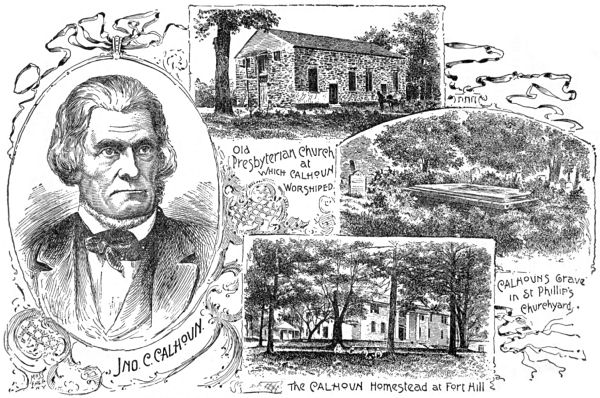

| John Caldwell Calhoun and His Home | 163 |

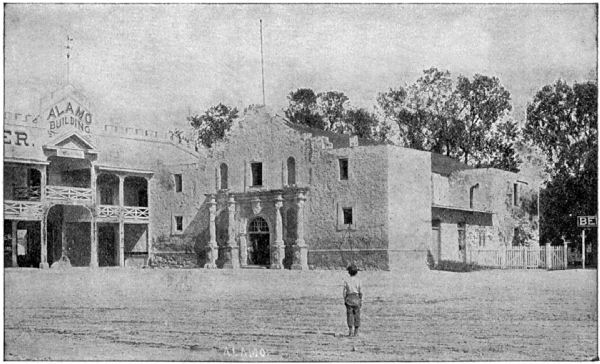

| [Pg 31]The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas | 174 |

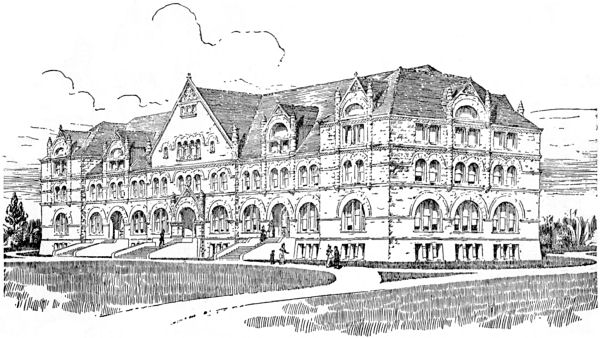

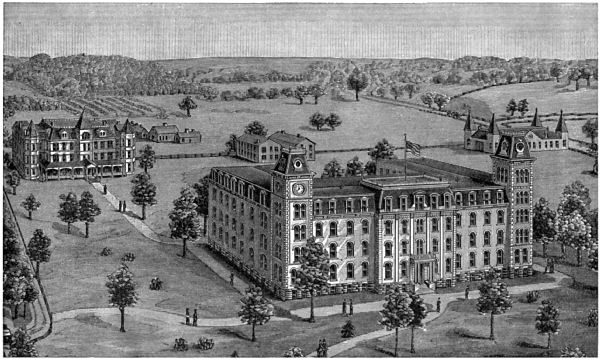

| University of North Carolina | 188 |

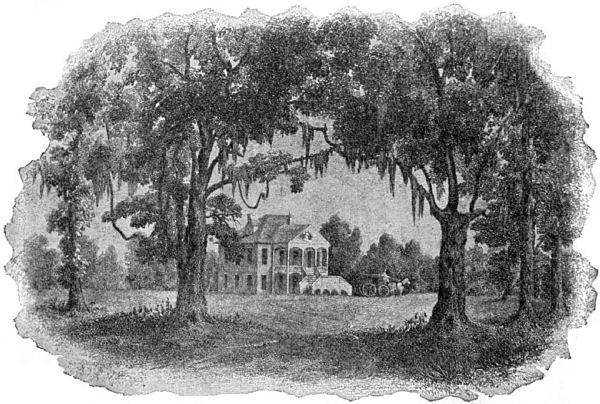

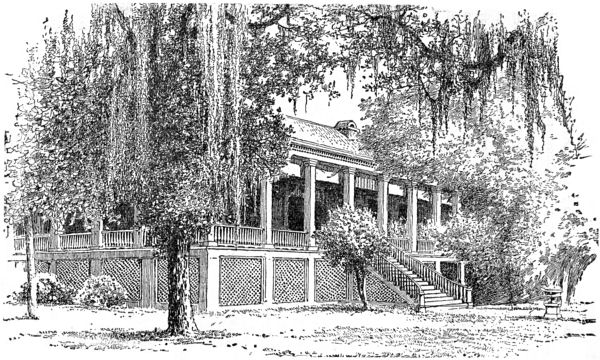

| Old Plantation Home | 200 |

| State House, Columbia, S. C. | Oppo. 211 |

| Tulane University, New Orleans | 234 |

| Florida State Agricultural College | 244 |

| “Woodlands,” the Home of W. Gilmore Simms | 253 |

| General R. E. Lee | Oppo. 265 |

| Washington and Lee University | 267 |

| Beauvoir, the Home of Jefferson Davis | 273 |

| Robert Toombs | 285 |

| University of Alabama | 299 |

| University of Kentucky | 307 |

| Osceola | 312 |

| Natural Bridge, Virginia | 325 |

| University of Mississippi | 337 |

| University of Texas (Main Building), Austin | 347 |

| State Capitol of North Carolina | 359 |

| Tomb of Mary, the Mother of Washington, Fredericksburg, Va. | 380 |

| General T. J. Jackson (Stonewall) | Oppo. 388 |

| Arkansas Industrial University | 402 |

| Mt. Mitchell, N. C. Above the Clouds | 408 |

| Grady Monument, Atlanta, Ga. | 414 |

| Agricultural and Mechanical College of Mississippi | 420 |

| University of Tennessee, Knoxville | 424 |

| Model School, Peabody Normal College | 433 |

| Mississippi Industrial Institute and College for Girls | Oppo. 446 |

1579=1631.

Captain John Smith, the first writer of Virginia, was born at Willoughby, England, and led a life of rare and extensive adventure. “Lamenting and repenting,” he says, “to have seen so many Christians slaughter one another,” in France and the Lowlands, he enlisted in the wars against the Turks. He was captured by them and held prisoner for a year, but escaped and travelled all over Europe. He finally joined the expedition to colonize Virginia, and came over with the first settlers of Jamestown in 1607. His life here is well known; he remained with the colony two years. He afterwards returned to America as Admiral of New England, but did not stay long. He spent the remainder of his life in writing accounts of himself and his travels, and of the colonies in America.

True Relation (1608).

Map of Virginia (1612).

Description of New England (1616).

New England’s Trials (1620).

Accidence for Young Seamen (1626).

Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles (1624).

True Travels (1630).

Advertisements for Inexperienced Planters of New England (1631).

Captain John Smith.

Captain Smith’s style is honest and hearty in tone, picturesque, often amusing, never tiresome. It is involved and ungrammatical at times, but not obscure. The critics have professed to find many inaccuracies of historical statement; [Pg 35] but the following, from Professor Edward Arber, the editor of the English Reprint of Smith’s Works, will acquit him of this charge:

“Inasmuch as the accuracy of some of Captain Smith’s statements has, in this generation, been called in question, it was but our duty to subject every one of the nearly forty thousand lines of this book to a most searching criticism; scanning every assertion of fact most keenly, and making the Text, by the insertion of a multitude of cross-references, prove or disprove itself.

“The result is perfectly satisfactory. Allowing for a popular style of expression, the Text is homogeneous; and the nine books comprising it, though written under very diverse circumstances, and at intervals over the period of twenty-two years (1608-1630), contain no material contradictions. Inasmuch, therefore, as wherever we can check Smith, we find him both modest and accurate, we are led to think him so, where no such check is possible, as at Nalbrits in the autumn of 1603, and on the Chickahominy in the winter of 1607-’8.” See Life, by Simms, by Warner, and by Eggleston in “Pocahontas.”

(From Generall Historie.)

[This extract from his “Generall Historie” is in the words of a report by “eight gentlemen of the Jamestown Colony.” It is corroborated by Captain Smith’s letter to the Queen on the occasion of Pocahontas’ visit to England after her marriage to Mr. John Rolfe. Matoaka, or Matoax, was her real name in her tribe, but it was considered unlucky to tell it to the English strangers.]

Rescue of Captain Smith by Pocahontas.

At last they brought him [Smith] to Meronocomoco, where was Powhatan their Emperor. Here more than two hundred of those grim Courtiers stood wondering at him, as he had beene a monster; till Powhatan and his trayne had put themselues in their greatest braveries. Before a fire vpon a seat like a bedstead, he sat covered with a great robe, made of Rarowcun skinnes, and all the tayles hanging by. On either hand did sit a young wench of 16 or 18 yeares; [Pg 37] and along on each side the house, two rowes of men, and behind them as many women, with all their heads and shoulders painted red; many of their heads bedecked with the white downe of Birds; but every one with something; and a great chayne of white beads about their necks.

At his entrance before the King, all the people gaue a great shout. The Queene of Appamatuck was appointed to bring him water to wash his hands, and another brought him a bunch of feathers, in stead of a Towell to dry them; having feasted him after their best barbarous manner they could, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan; then as many as could layd hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs, to beate out his braines, Pocahontas, the Kings dearest daughter, when no intreaty could prevaile, got his head in her armes, and laid her owne vpon his to saue him from death: whereat the Emperour was contented he should liue to make him hatchets, and her bells, beads, and copper; for they thought him as well of all occupations as themselues. For the King himselfe will make his owne robes, shooes, bowes, arrowes, pots; plant, hunt, or doe anything so well as the rest.

Two dayes after, Powhatan having disguised himselfe in the most fearefullest manner he could, caused Captain Smith to be brought forth to a great house in the woods, and there vpon a mat by the fire to be left alone. Not long after from behinde a mat that divided the house, was made the most [Pg 38] dolefullest noyse he ever heard; then Powhatan, more like a devill than a man, with some two hundred more as blacke as himselfe, came vnto him and told him now they were friends, and presently he should goe to James towne, to send him two great gunnes, and a gryndstone, for which he would giue him the Country of Capahowosick, and for ever esteeme him as his sonne Nantaquoud.

So to James towne with 12 guides Powhatan sent him. That night, they quartered in the woods, he still expecting (as he had done all this long time of his imprisonment) every houre to be put to one death or other; for all their feasting. But almightie God (by his divine providence) had mollified the hearts of those sterne Barbarians with compassion. The next morning betimes they came to the Fort, where Smith having vsed the Salvages with what kindnesse he could, he shewed Rawhunt, Powhatan’s trusty servant, two demi-Culverings and a millstone to carry Powhatan; they found them somewhat too heavie: but when they did see him discharge them, being loaded with stones, among the boughs of a great tree loaded with Isickles, the yce and branches came so tumbling downe, that the poore Salvages ran away halfe dead with feare. But at last we regained some conference with them, and gaue them such toyes: and sent to Powhatan, his women, and children such presents, as gaue them in generall full content.

(From Advertisements for the Inexperienced.)

Many good religious devout men have made it a great question, as a matter in conscience, by what warrant they might goe to possesse those Countries, which are none of theirs, but the poore Salvages.

Jamestown, Va.

The first permanent English settlement in America.

[Pg 40] Which poore curiosity will answer it selfe; for God did make the world to be inhabited with mankind, and to have his name knowne to all Nations, and from generation to generation: as the people increased, they dispersed themselves into such Countries as they found most convenient. And here in Florida, Virginia, New-England, and Cannada, is more land than all the people in Christendome can manure [cultivate], and yet more to spare than all the natives of those Countries can use and culturate. And shall we here keepe such a coyle for land, and at such great rents and rates, when there is so much of the world uninhabited, and as much more in other places, and as good or rather better than any wee possesse, were it manured and used accordingly?

If this be not a reason sufficient to such tender consciences; for a copper knife and a few toyes, as beads and hatchets, they will sell you a whole Countrey [district]; and for a small matter, their houses and the ground they dwell upon; but those of the Massachusets have resigned theirs freely.

Now the reasons for plantations are many. Adam and Eve did first begin this innocent worke to plant the earth to remaine to posterity; but not without labour, trouble, and industry. Noah and his family began againe the second plantation, and their seed as it still increased, hath still planted new Countries, and one Country another, and so the world to that estate it is; but not without much hazard, travell, mortalities, discontents, and many disasters; had those worthy Fathers and their memorable offspring not beene more diligent for us now in those ages, than wee are to plant that yet unplanted for after-livers: Had the seed of Abraham, our Saviour Christ Jesus and his Apostles, exposed themselves to no more dangers to plant the Gospell [Pg 41] wee so much professe, than we; even we our selves had at this moment beene as Salvages, and as miserable as the most barbarous Salvage, yet uncivilized.

The Hebrewes, the Lacedemonians, the Goths, Grecians, Romans, and the rest; what was it they would not undertake to enlarge their Territories, inrich their subjects, and resist their enemies? Those that were the founders of those great Monarchies and their vertues, were no silvered idle golden Pharisees, but industrious honest hearted Publicans; they regarded more provisions and necessaries for their people, than jewels, ease, and delight for themselves; riches was their servants, not their masters; they ruled as fathers, not as tyrants; their people as children, not as slaves; there was no disaster could discourage them; and let none thinke they incountered not with all manner of incumbrances; and what hath ever beene the worke of the best great Princes of the world, but planting of Countries, and civilizing barbarous and inhumane Nations to civility and humanity; whose eternall actions fils our histories with more honour than those that have wasted and consumed them by warres.

Lastly, the Portugals and Spaniards that first began plantations in this unknowne world of America till within this 140. yeares [1476-1616], whose everlasting actions before our eyes, will testifie our idlenesse and ingratitude to all posterity, and neglect of our duty and religion we owe our God, our King, and Countrey, and want of charity to those poore Salvages, whose Countries we challenge, use and possesse: except wee be but made to marre what our forefathers made; or but only tell what they did; or esteeme our selves too good to take the like paines where there is so much reason, liberty, and action offers it selfe. Having as much power and meanes as others, why should English men [Pg 42] despaire, and not doe as much as any? Was it vertue in those Hero[e]s to provide that [which] doth maintaine us, and basenesse in us to do the like for others to come? Surely no: then seeing wee are not borne for ourselves but each to helpe other; and our abilities are much alike at the howre of our birth and the minute of our death: seeing our good deeds or bad, by faith in Christs merits, is all wee have to carry our soules to heaven or hell: Seeing honour is our lives ambition, and our ambition after death to have an honourable memory of our life; and seeing by no meanes we would be abated of the dignitie and glory of our predecessors, let us imitate their vertues to be worthily their successors; or at least not hinder, if not further, them that would and doe their utmost and best endeavour.

(From Newes from Virginia.)

The two and twenty day of Aprill [or rather May, 1607], Captain Newport and myself with diuers others, to the number of twenty two persons, set forward to discouer the Riuer, some fiftie or sixtie miles, finding it in some places broader, and in some narrower, the Countrie (for the moste part) on each side plaine high ground, with many freshe Springes, the people in all places kindely intreating vs, daunsing, and feasting vs with strawberries, Mulberies, Bread, Fish, and other their Countrie prouisions whereof we had plenty; for which Captaine Newport kindely requited their least fauors with Bels, Pinnes, Needles, beades, or Glasses, which so contented them that his liberallitie made them follow vs from place to place, and euer kindely to respect vs. In the midway staying to refresh our selues in a little Ile foure or five sauages came vnto vs which described vnto vs the course of the Riuer, and after in our [Pg 43] iourney, they often met vs, trading with vs for such prouision as wee had, and arriuing at Arsatecke, hee whom we supposed to bee the chiefe King of all the rest, moste kindely entertained vs, giuing vs in a guide to go with vs vp the Riuer to Powhatan, of which place their great Emperor taketh his name, where he that they honored for King vsed vs kindely.

But to finish this discouerie, we passed on further, where within an ile [a mile] we were intercepted with great craggy stones in the midst of the riuer, where the water falleth so rudely, and with such a violence, as not any boat can possibly passe, and so broad disperseth the streame, as there is not past fiue or sixe Foote at a low water, and to the shore scarce passage with a barge, the water floweth foure foote, and the freshes by reason of the Rockes haue left markes of the inundations 8. or 9. foote: The south side is plaine low ground, and the north side high mountaines, the rockes being of a grauelly nature, interlaced with many vains of glistring spangles.

That night we returned to Powhatan: the next day (being Whitsunday after dinner) we returned to the fals, leauing a mariner in pawn with the Indians for a guide of theirs, hee that they honoured for King followed vs by the riuer. That afternoone we trifled in looking vpon the Rockes and riuer (further he would not goe) so there we erected a crosse, and that night taking our man at Powhatans, Captaine Newport congratulated his kindenes with a Gown and a Hatchet: returning to Arsetecke, and stayed there the next day to obserue the height [latitude] thereof, and so with many signes of loue we departed.

Storm at Sea.

William Strachey[3] was an English gentleman who came over to Virginia with Sir Thomas Gates in 1609, and was secretary of the Colony for three years. Their ship, the Sea Venture, was wrecked on the Bermudas in a terrible tempest, of which he gives the account that follows. It is said to have suggested to Shakspere the scene of the storm and hurricane in his “Tempest.”

A True Repertory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates upon and from the Islands of the Bermudas.

Historie of Travaile into Virginia Brittania.

Edited Lawes Divine, Morall, and Martiall.

William Strachey’s writings show a thoughtful and cultivated mind. His style abounds in the long involved and often obscure sentences of his times, but his subject matter is usually very interesting. Compare the following selection with Shakspere’s “Tempest,” Act I., scene 1 and 2, to “Ariel, thy charge.” Notice the reference to Bermoothes (Bermudas).

(From A True Repertory of the Wracke and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates.)

On St. James his day, July 24, being Monday (preparing for no less all the black night before) the clouds gathering thick upon us, and the winds singing and whistling most unusually, which made us to cast off our Pinnace, towing the same until then asterne, a dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from out the Northeast, which, swelling and roaring as it were by fits, some hours with more violence than others, at length did beat all light from heaven, which, like an hell of darkness, turned black upon [Pg 46] us, so much the more fuller of horror, as in such cases horror and fear use to overrun the troubled and overmastered senses of all, while (taken up with amazement) the ears lay so sensible to the terrible cries, and murmurs of the winds and distraction of our Company, as who was most armed and best prepared, was not a little shaken. . .

For four and twenty hours the storm, in a restless tumult, had blown so exceedingly, as we could not apprehend in our imaginations any possibility of greater violence, yet did we still find it, not only more terrible, but more constant, fury added to fury, and one storm urging a second, more outrageous than the former, whether it so wrought upon our fears, or indeed met with new forces. Sometimes strikes in our Ship amongst women, and passengers not used to such hurly and discomforts, made us look one upon the other with troubled hearts, and panting bosoms, our clamors drowned in the winds, and the winds in thunder. Prayers might well be in the heart and lips, but drowned in the outcries of the Officers,—nothing heard that could give comfort, nothing seen that might encourage hope. . . . .

Our sails, wound up, lay without their use, and if at any time we bore but a Hollocke, or half forecourse, to guide her before the Sea, six and sometimes eight men, were not enough to hold the whip-staffe in the steerage, and the tiller below in the Gunner room; by which may be imagined the strength of the storm, in which the Sea swelled above the Clouds and gave battle unto heaven. It could not be said to rain, the waters like whole Rivers did flood in the ayre. And this I did still observe, that whereas upon the Land, when a storm hath poured itself forth once in drifts of rain, the wind as beaten down, and vanquished therewith, not long after endureth,—here the glut of water (as if throatling the wind ere while) was no sooner a little emptied [Pg 47] and qualified, but instantly the winds (as having gotten their mouths now free and at liberty) spake more loud, and grew more tumultuous and malignant. What shall I say? Winds and Seas were as mad as fury and rage could make them. . . . . . .

Howbeit this was not all; it pleased God to bring a greater affliction yet upon us, for in the beginning of the storm we had received likewise a mighty leak, and the ship in every joint almost having spewed out her Okam, before we were aware (a casualty more desperate than any other that a Voyage by Sea draweth with it) was grown five feet suddenly deep with water above her ballast, and we almost drowned within, whilest we sat looking when to perish from above. This, imparting no less terror than danger, ran through the whole Ship with much fright and amazement, startled and turned the blood, and took down the braves of the most hardy Mariner of them all, insomuch as he that before happily felt not the sorrow of others, now began to sorrow for himself, when he saw such a pond of water so suddenly broken in, and which he knew could not (with present avoiding) but instantly sink him. . . .

Once so huge a Sea brake upon the poop and quarter, upon us, as it covered our ship from stern to stem, like a garment or a vast cloud. It filled her brimful for a while within, from the hatches up to the spar deck. . .

Tuesday noon till Friday noon, we bailed and pumped two thousand tun, and yet, do what we could, when our ship held least in her (after Tuesday night second watch) she bore ten feet deep, at which stay our extreme working kept her one eight glasses, forbearance whereof had instantly sunk us; and it being now Friday, the fourth morning, it wanted little but that there had been a general determination, to have shut up hatches and commending our sinful souls to God, [Pg 48] committed the ship to the mercy of the sea. Surely that night we must have done it, and that night had we then perished; but see the goodness and sweet introduction of better hope by our merciful God given unto us. Sir George Summers, when no man dreamed of such happiness, had discovered and cried, “Land!” Indeed, the morning, now three-quarters spent, had won a little clearness from the days before, and it being better surveyed, the very trees were seen to move with the wind upon the shore-side.

[3] Pronounced Strǎk´ey.

Died 1712.

John Lawson was a Scotch gentleman who came to America in 1700. In his own words: “In the year 1700, when people flocked from all parts of the Christian world, to see the solemnity of the grand jubilee at Rome, my intention being at that time to travel, I accidentally met with a gentlemen, who had been abroad, and was very well acquainted with the ways of living in both Indies; of whom having made inquiry concerning them, he assured me that Carolina was the best country I could go to; and, that there then lay a ship in the Thames in which I might have my passage.” He resided in Carolina eight years. As “Gent. Surveyor-General of North Carolina,” he wrote his History of North Carolina, which is an original, sprightly, and faithful account of the eastern section of the State, and contains valuable matter for the subsequent historian. It is dedicated to the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, and was published in 1714.

He was taken captive by the Tuscarora Indians, while on a surveying trip, and was by them put to death in 1712 on [Pg 49] the Neuse River in North Carolina, because, said they, “he had taken their land,” by marking it off into sections.

History of North Carolina [rare].

(From History of North Carolina, 1714.)

The first discovery and settlement of this country was by the procurement of Sir Walter Raleigh, in conjunction with some public spirited gentlemen of that age, under the protection of queen Elizabeth; for which reason it was then named Virginia, being begun on that part called Ronoak Island, where the ruins of a fort are to be seen at this day, as well as some old English coins which have been lately found; and a brass gun, a powder horn, and one small quarter-deck gun, made of iron staves, and hooped with the same metal; which method of making guns might very probably be made use of in those days for the convenience of infant colonies. . . . . .

I cannot forbear inserting here a pleasant story that passes for an uncontested truth amongst the inhabitants of this place; which is, that the ship which brought the first colonies does often appear amongst them, under sail, in a gallant posture, which they call Sir Walter Raleigh’s ship. And the truth of this has been affirmed to me by men of the best credit in the country.

Sir Walter Raleigh.

A second settlement of this country was made about fifty years ago, in that part we now call Albemarl county, and chiefly in Chuwon precinct, by several substantial planters from Virginia and other plantations; who finding mild winters, and a fertile soil beyond expectation, producing everything that was planted to a prodigious increase; . . . . so that everything seemed to come by nature, the [Pg 51] husbandman living almost void of care, and free from those fatigues which are absolutely requisite in winter countries, for providing fodder and other necessaries; these encouragements induced them to stand their ground, although but a handful of people, seated at great distances one from another, and amidst a vast number of Indians of different nations, who were then in Carolina.

Nevertheless, I say, the fame of this new discovered summer country spread through the neighboring colonies, and in a few years drew a considerable number of families thereto, who all found land enough to settle themselves in (had they been many thousands more), and that which was very good and commodiously seated both for profit and pleasure.

And, indeed, most of the plantations in Carolina naturally enjoy a noble prospect of large and spacious rivers, pleasant savannas and fine meadows, with their green liveries interwoven with beautiful flowers of most glorious colors, which the several seasons afford; hedged in with pleasant groves of the ever famous tulip tree, the stately laurels and bays, equalizing the oak in bigness and growth, myrtles, jessamines, woodbines, honeysuckles, and several other fragrant vines and evergreens, whose aspiring branches shadow and interweave themselves with the loftiest timbers, yielding a pleasant prospect, shade and smell, proper habitations for the sweet singing birds, that melodiously entertain such as travel through the woods of Carolina.

The Planters possessing all these blessings, and the produce of great quantities of wheat and indian corn, in which this country is very fruitful, as likewise in beef, pork, tallow, hides, deer skins, and furs; for these commodities the new England men and Bermudians visited Carolina in their barks and sloops, and carried out what they made, bringing [Pg 52] them in exchange, rum, sugar, salt, molasses, and some wearing apparel, though the last at very extravagant prices.

As the land is very fruitful, so are the planters kind and hospitable to all that come to visit them; there being very few housekeepers but what live very nobly, and give away more provisions to coasters and guests who come to see them than they expend amongst their own families. . .

The easy way of living in that plentiful country makes a great many planters very negligent, which, were they otherwise, that colony might now have been in a far better condition than it is, as to trade and other advantages, which an universal industry would have led them into. The women are the most industrious sex in that place, and, by their good housewifery, make a great deal of cloth of their own cotton, wool and flax; some of them keeping their families, though large, very decently appareled, both with linens and woolens, so that they have no occasion to run into the merchants’ debt, or lay their money out on stores for clothing.

. . . As for those women that do not expose themselves to the weather, they are often very fair, and generally as well featured as you shall see anywhere, and have very brisk, charming eyes which sets them off to advantage. . . . .

Both sexes are generally spare of body and not choleric, nor easily cast down at disappointments and losses, seldom immoderately grieving at misfortunes, unless for the loss of their nearest relations and friends, which seems to make a more than ordinary impression upon them. Many of the women are very handy in canoes and will manage them with great dexterity and skill, which they become accustomed to in this watery country. They are ready to help their husbands in any servile work, as planting, when the season of the weather requires expedition; pride seldom [Pg 53] banishing good housewifery. The girls are not bred up to the wheel and sewing only, but the dairy and the affairs of the house they are very well acquainted withal; so that you shall see them, whilst very young, manage their business with a great deal of conduct and alacrity. The children of both sexes are very docile and learn any thing with a great deal of care and method, and those that have the advantages of education write very good hands, and prove good accountants, which is most coveted, and, indeed, most necessary in these parts. The young men are commonly of a bashful, sober behaviour; few proving prodigals to consume what the industry of their parents has left them, but commonly improve it.

(From History of North Carolina.)

They have a third sort of feasts and dances, which are always when the harvest of corn is ended, and in the spring. The one to return thanks to the good spirit for the fruits of the earth; the other, to beg the same blessings for the succeeding year. And to encourage the young men to labour stoutly in planting their maiz and pulse, they set up a sort of idol in the field, which is dressed up exactly like an Indian, having all the Indians habit, besides abundance of Wampum and their money, made of shells, that hangs about his neck. The image none of the young men dare approach; for the old ones will not suffer them to come near him, but tell them that he is some famous Indian warrior that died a great while ago, and now is come amongst them to see if they work well, which if they do, he will go to the good spirit and speak to him to send them plenty of corn, and to make the young men all expert hunters and mighty warriors. All this while, the king and old men sit around the image and seemingly pay a profound respect to the same. One great [Pg 54] help to these Indians in carrying on these cheats, and inducing youth to do as they please, is, the uninterrupted silence which is ever kept and observed with all the respect and veneration imaginable.

At these feasts which are set out with all the magnificence their fare allows of, the masquerades begin at night and not before. There is commonly a fire made in the middle of the house, which is the largest in the town, and is very often the dwelling of their king or war captain; where sit two men on the ground upon a mat; one with a rattle, made of a gourd, with some beans in it; the other with a drum made of an earthen pot, covered with a dressed deer skin, and one stick in his hand to beat thereon; and so they both begin the song appointed. At the same time one drums and the other rattles, which is all the artificial music of their own making I ever saw amongst them. To these two instruments they sing, which carries no air with it, but is a sort of unsavory jargon; yet their cadences and raising of their voices are formed with that equality and exactness that, to us Europeans, it seems admirable how they should continue these songs without once missing to agree, each with the others note and tune.

1674=1744.

William Byrd, second of the name, and the first native Virginian writer, was born at Westover, his father’s estate on the James below Richmond.

Westover, Home of William Byrd.

The following inscription on his tomb at Westover gives a sketch of his life and services well worth preserving:

“Here lies the Honourable William Byrd, Esq., being born to one of the amplest fortunes in this country, he was sent [Pg 56] early to England for his education, where under the care and direction of Sir Robert Southwell, and ever favoured with his particular instructions, he made a happy proficiency in polite and various learning. By the means of the same noble friend, he was introduced to the acquaintance of many of the first persons of that age for knowledge, wit, virtue, birth, or high station, and particularly contracted a most intimate and bosom friendship with the learned and illustrious Charles Boyle, Earl of Orrery.

“He was called to the bar in the Middle Temple, studied for some time in the Low Countries, visited the Court of France, and was chosen Fellow of the Royal Society. Thus eminently fitted for the service and ornament of his country, he was made receiver-general of his Majesty’s revenues here, was then appointed public agent to the Court and Ministry of England, being thirty-seven years a member, at last became president, of the Council of this Colony.

“To all this were added a great elegancy of taste and life, the well-bred gentleman, and polite companion, the splendid economist and prudent father of a family, with the constant enemy of all exorbitant power, and hearty friend to the liberties of his country. Nat. Mar. 28, 1674. Mort. Aug. 26, 1744. An. aetat. 70.”

His daughter Evelyn was famous both in England and Virginia for her beauty, wit, and accomplishments. She died at the age of thirty, 1737.—See Century Magazine, 1891, Vol. 20, p. 163.

Westover Manuscripts:

(1) History of the Dividing Line [the survey to settle the line between Virginia and North Carolina, 1728.]

(2) A Journey to the Land of Eden [North Carolina, of which Charles Eden was governor 1713-19.]

(3) A Progress to the Mines [Iron mines in Virginia which Ex-Governor Alexander Spotswood and others were beginning to open and work.]

Evelyn Byrd.

Considered one of the most beautiful women in Virginia, or of her time.

[FROM AN OLD PAINTING.]

His writings are among the most interesting that we have, being remarkable for their wit and culture, a certain [Pg 58] poetic vein, a keen interest in nature, a simple religious faith, a fund of cheerful courage and good sense, and a fine consideration for others.

(From A Journey to the Land of Eden.)

When we got home, we laid the foundations of two large Citys. One at Shacco’s, to be called Richmond, and the other at the Point of Appamattuck River, to be nam’d Petersburgh. These Major Mayo offered to lay out into Lots without Fee or Reward. The Truth of it is, these two places being the uppermost Landing of James and Appamattux Rivers, are naturally intended for Marts, where the Traffick of the Outer Inhabitants must Center. Thus we did not build Castles only, but also Citys in the Air.

(From A Progress to the Mines.)

Then I came into the Main County Road, that leads from Fredericksburgh to Germanna, which last place I reacht in Ten Miles more. This famous Town consists of Colo. Spotswood’s enchanted Castle on one Side of the Street, and a Baker’s Dozen of ruinous Tenements on the other, where so many German Familys had dwelt some Years ago; but are now remov’d ten Miles higher, in the Fork of Rappahannock, to Land of their Own. There had also been a Chappel about a Bow-Shot from the Colonel’s house, at the End of an Avenue of Cherry Trees, but some pious people had lately burnt it down, with intent to get another built nearer to their own homes.

Here I arriv’d about three o clock, and found only Mrs. Spotswood at Home, who receiv’d her Old acquaintance [Pg 59] with many a gracious Smile. I was carry’d into a Room elegantly set off with Pier Glasses, the largest of which came soon after to an odd Misfortune. Amongst other favourite Animals that cheer’d this Lady’s Solitude, a Brace of Tame Deer ran familiarly about the House, and one of them came to stare at me as a Stranger. But unluckily Spying his own Figure in the Glass, he made a spring over the Tea Table that stood under it, and shatter’d the Glass to pieces, and falling-back upon the Tea Table, made a terrible Fracas among the China. This Exploit was so sudden, and accompany’d with such a Noise, that it surpriz’d me, and perfectly frighten’d Mrs. Spotswood. But twas worth all the Damage to shew the Moderation and good humour with which she bore this disaster.

In the Evening, the noble Colo. came home from his Mines, who saluted me very civilly, and Mrs. Spotswood’s Sister, Miss Theky, who had been to meet him en Cavalier, was so kind too as to bid me welcome. We talkt over a Legend of old Storys, supp’d about 9, and then prattl’d with the Ladys, til twas time for a Travellour to retire. In the mean time I observ’d my old Friend to be very Uxorious, and exceedingly fond of his Children. This was so opposite to the Maxims he us’d to preach up before he was marryed, that I cou’d not forbear rubbing up the Memory of them. But he gave a very good-natur’d turn to his Change of Sentiments, by alleging that whoever brings a poor Gentlewoman into so solitary a place, from all her Friends and acquaintance, wou’d be ungrateful not to use her and all that belongs to her with all possible Tenderness.

We all kept Snug in our several apartments till Nine, except Miss Theky, who was the Housewife of the Family. At that hour we met over a Pot of Coffee, which was not quite strong enough to give us the Palsy. After Breakfast [Pg 60] the Colo. and I left the Ladys to their Domestick Affairs, and took a turn in the Garden, which has nothing beautiful but 3 Terrace Walks that fall in Slopes one below another. I let him understand, that besides the pleasure of paying him a Visit, I came to be instructed by so great a Master in the Mystery of Making of Iron, wherein he had led the way, and was the Tubal Cain of Virginia. He corrected me a little there, by assuring me he was not only the first in this Country, but the first in North America, who had erected a regular Furnace. . . That the 4 Furnaces now at work in Virginia circulated a great Sum of Money for Provisions and all other necessarys in the adjacent Countys. That they took off a great Number of Hands from Planting Tobacco, and employ’d them in Works that produced a large Sum of Money in England to the persons concern’d, whereby the Country is so much the Richer. That they are besides a considerable advantage to Great Britain, because it lessens the Quantity of Bar Iron imported from Spain, Holland, Sweden, Denmark, and Muscovy, which us’d to be no less than 20,000 Tuns yearly. . .