The Project Gutenberg EBook of Manual of Military Training, by James A. Moss

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Manual of Military Training

Second, Revised Edition

Author: James A. Moss

Release Date: September 26, 2008 [EBook #26706]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MANUAL OF MILITARY TRAINING ***

Produced by Brian Sogard, Chris Logan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Manual of

Military Training

(SECOND, REVISED EDITION)

BY

COLONEL JAMES A. MOSS

UNITED STATES ARMY

(Officially adopted by ONE HUNDRED AND FIVE [105] of our military

schools and colleges.)

Intended, primarily, for use in connection with the instruction and

training of Cadets in our military schools and colleges and of COMPANY

officers of the National Army, National Guard, and Officers' Reserve

Corps; and secondarily, as a guide for COMPANY officers of the Regular

Army, the aim being to make efficient fighting COMPANIES and to

qualify our Cadets and our National Army, National Guard and Reserve

Corps officers for the duties and responsibilities of COMPANY officers

in time of war.

Price $2.25

GENERAL AGENTS

GEORGE BANTA PUBLISHING COMPANY

Army and College Printers

MENASHA—WISCONSIN

Copyright 1917

By

Jas. A. Moss

| FIRST EDITION |

| First impression (October, 1914) |

10,000 |

| Second impression (September, 1915) |

10,000 |

| Third impression (March, 1916) |

10,000 |

| Fourth impression (July, 1916) |

10,000 |

| Fifth impression (February, 1917) |

3,000 |

| Sixth impression (April, 1917) |

4,000 |

| |

|

| SECOND EDITION |

| First impression (May, 1917) |

40,000 |

| Second impression (August, 1917) |

30,000 |

| Third impression (November, 1917) |

50,000 |

| Total |

167,000 |

Publishers and General Distributers

GEORGE BANTA PUBLISHING CO., MENASHA, WIS.

OTHER DISTRIBUTERS

(Order from nearest one)

Boston, Mass. The Harding Uniform and Regalia Co., 22 School St.

Chicago, Ill. A. C. McClurg & Co.

Columbus, Ohio. The M. C. Lilley & Co.

Fort Leavenworth, Kan.

U. S. Cavalry Association.

Book Dept., Army Service Schools.

Fort Monroe, Va. Journal U. S. Artillery.

Kalamazoo, Mich. Henderson-Ames Co.

New York.

Baker & Taylor Co., 4th Ave.

Army and Navy Coöperative Co., 16 East 42nd St.

Ridabock & Co., 140 West 36th St.

Warnock Uniform Co., 16 West 46th St.

Philadelphia, Pa. Jacob Reed's Sons, 1424 Chestnut.

Portland, Ore. J. K. Gill Co.

San Antonio, Tex. Frank Brothers Alamo Plaza.

San Francisco, Cal. B. Pasquale Co., 115–117 Post St.

Washington, D. C.

Army and Navy Register, 511 Eleventh St. N. W.

Meyer's Military Shops, 1331 F. St. N. W.

U. S. Infantry Association, Union Trust Bldg.

PHILIPPINE ISLANDS: Philippine Education Co., Manila, P. I.

HAWAIIAN ISLANDS: Hawaiian News Co., Honolulu, H. T.

CANAL ZONE: Post Exchange, Empire, C. Z.

NOTE

In order to learn thoroughly the contents of this manual it is

suggested that you use in connection with your study of the book the

pamphlet, "QUESTIONS ON MANUAL OF MILITARY TRAINING," which, by means

of questions, brings out and emphasizes every point mentioned in the

manual.

"QUESTIONS ON MANUAL OF MILITARY TRAINING" is especially useful to

students of schools and colleges using the manual, as it enables them,

as nothing else will, to prepare for recitations and examinations.

The pamphlet can be gotten from the publishers, Geo. Banta Publishing

Co., Menasha, Wis., or from any of the distributers of "MANUAL OF

MILITARY TRAINING." Price 50 cts., postpaid.

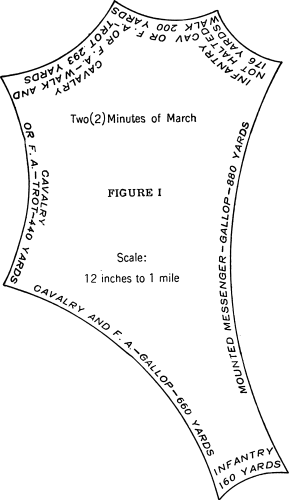

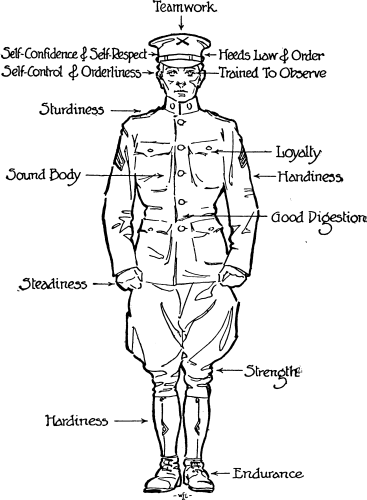

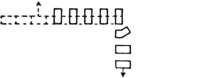

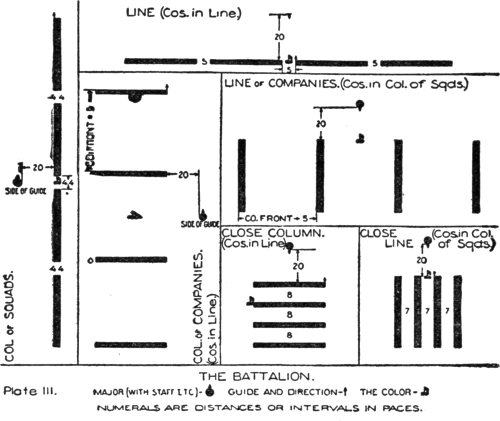

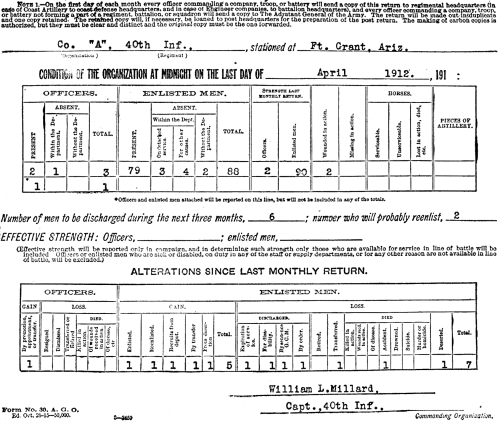

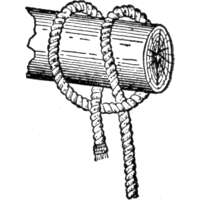

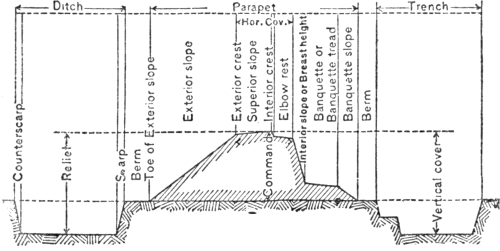

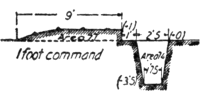

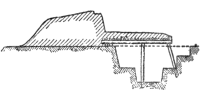

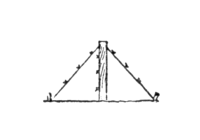

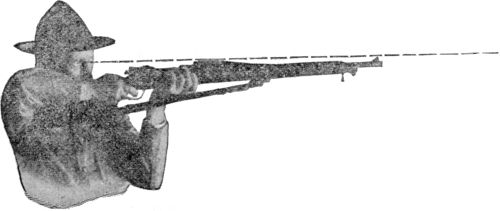

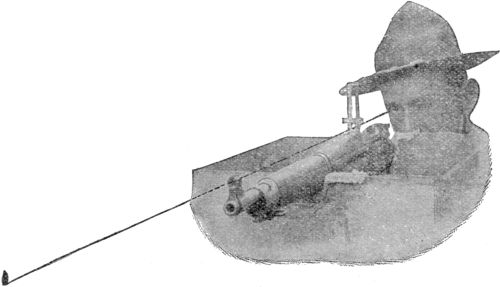

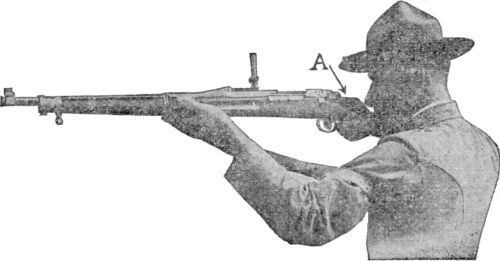

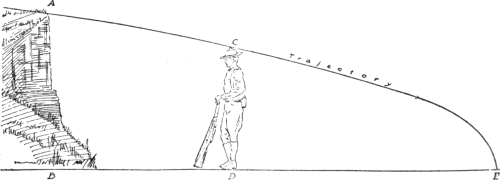

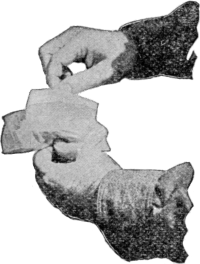

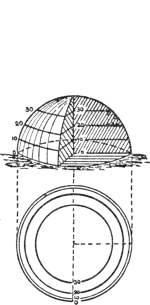

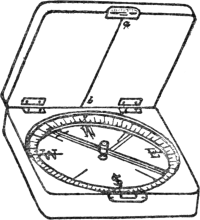

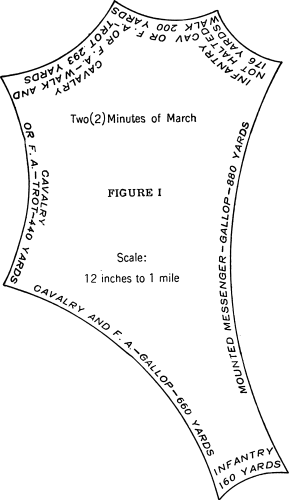

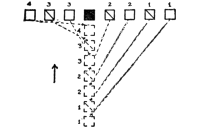

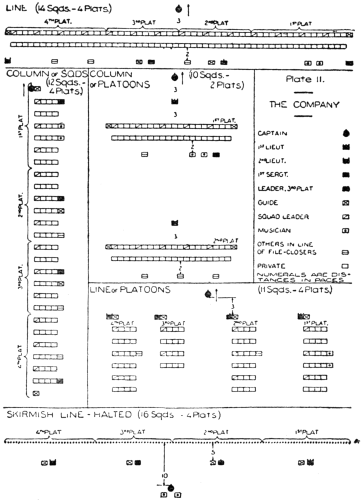

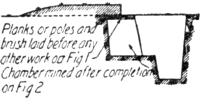

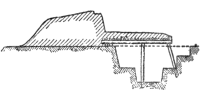

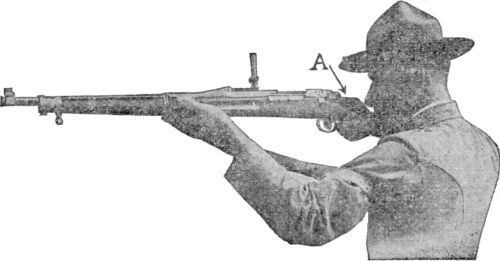

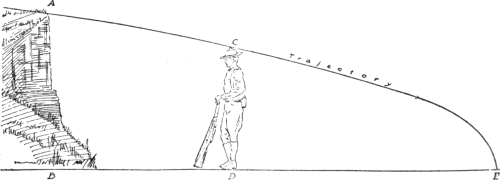

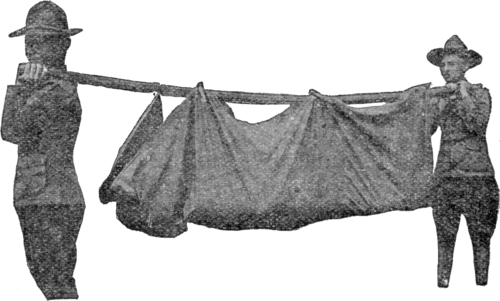

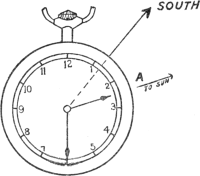

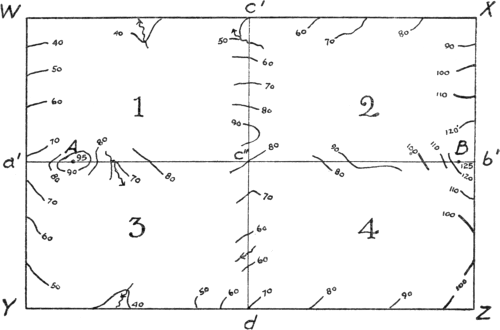

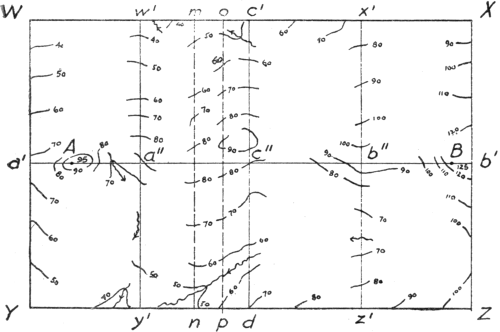

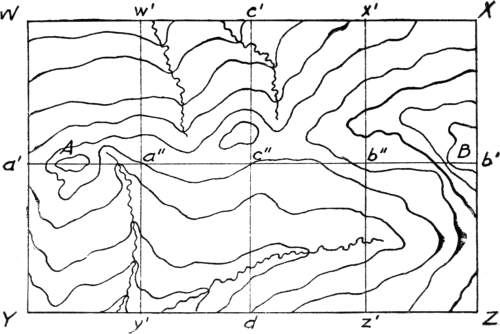

Cover Insert Fig. I

Cover Insert Fig. I

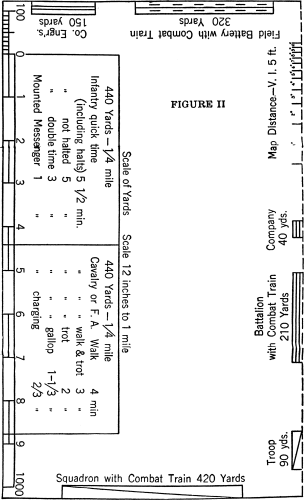

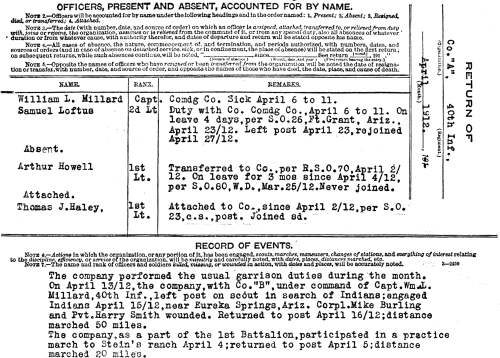

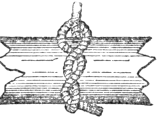

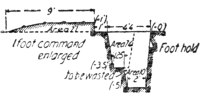

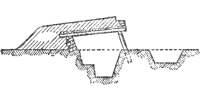

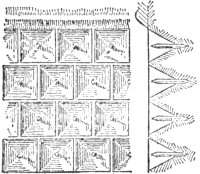

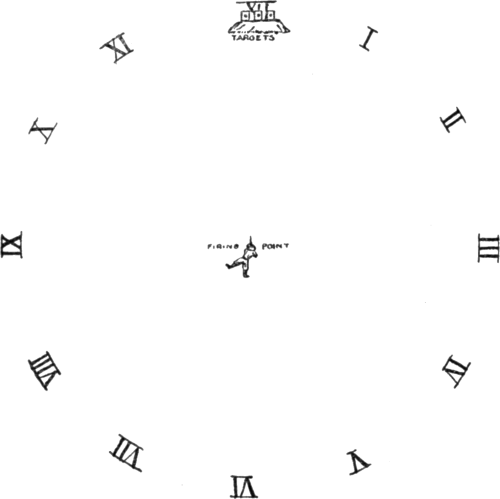

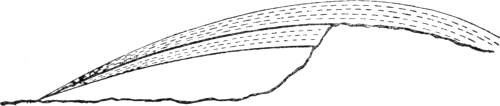

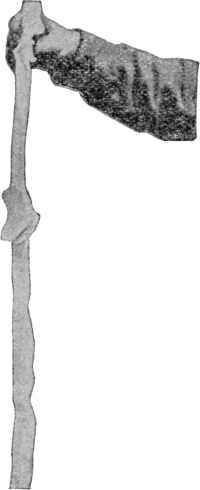

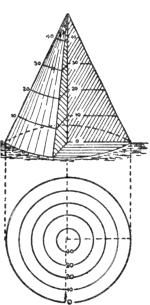

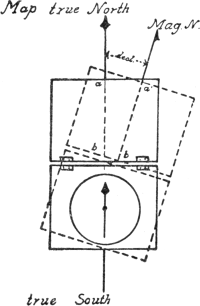

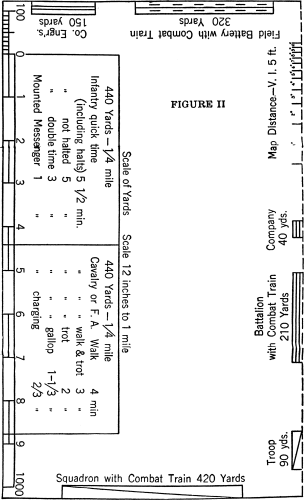

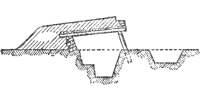

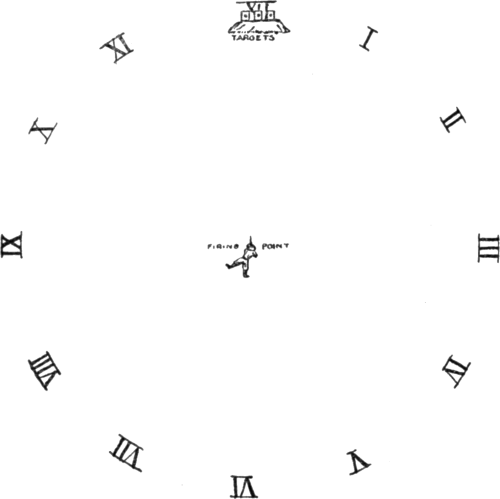

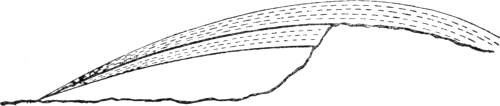

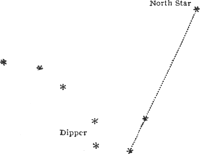

Cover Insert Fig. II

Cover Insert Fig. II

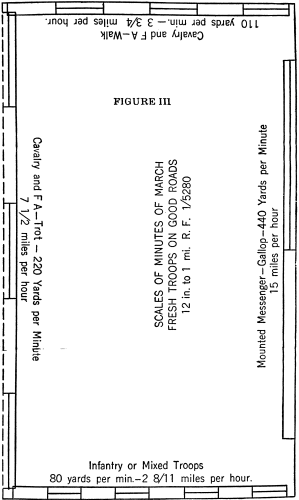

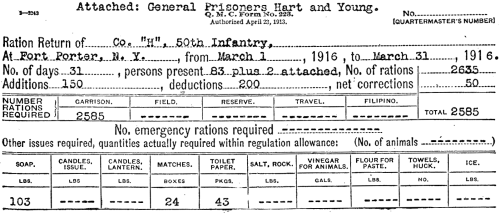

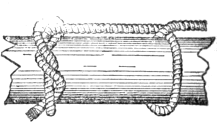

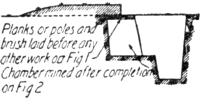

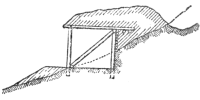

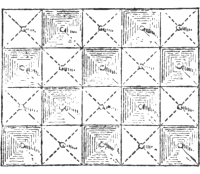

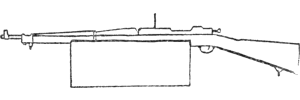

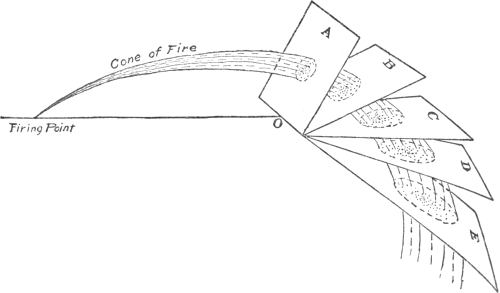

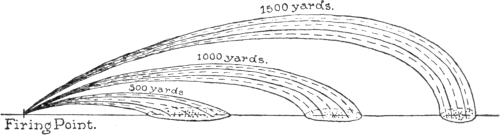

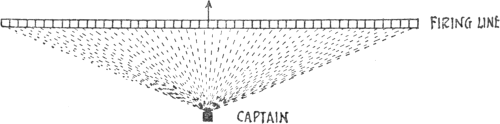

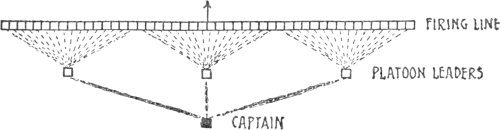

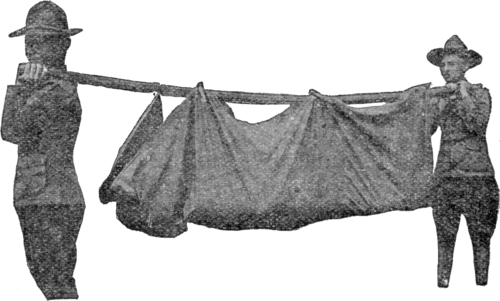

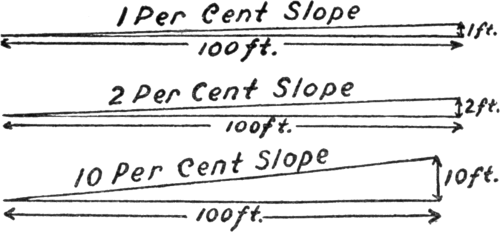

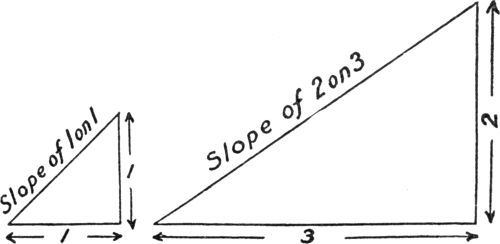

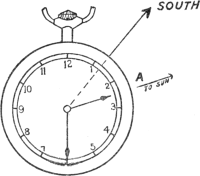

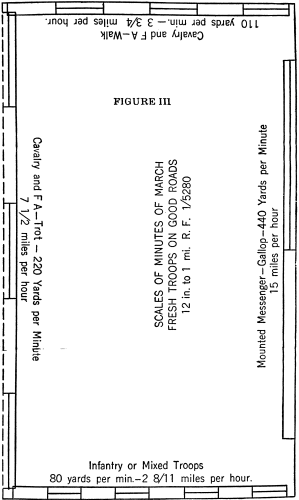

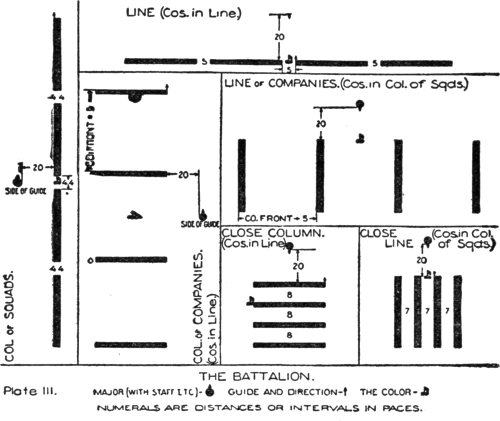

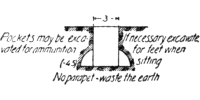

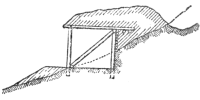

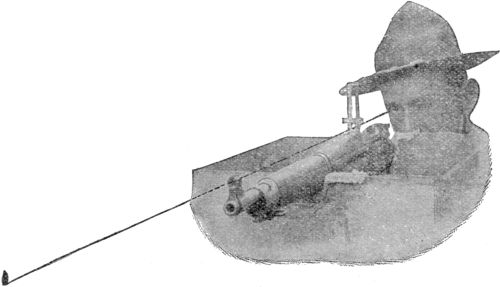

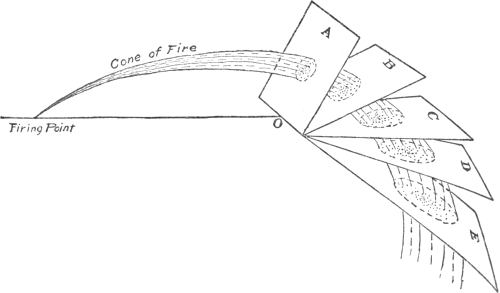

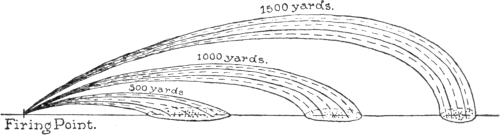

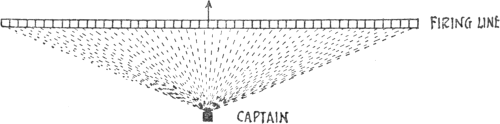

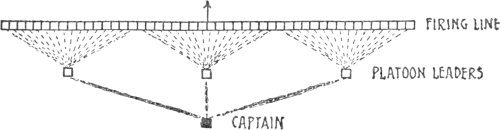

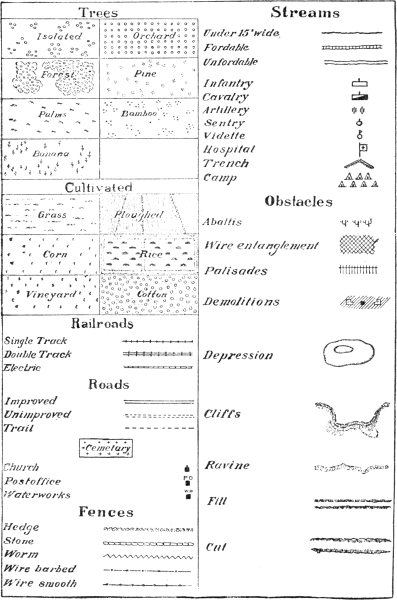

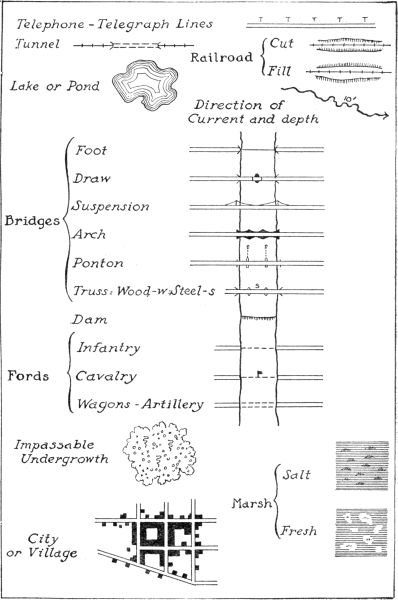

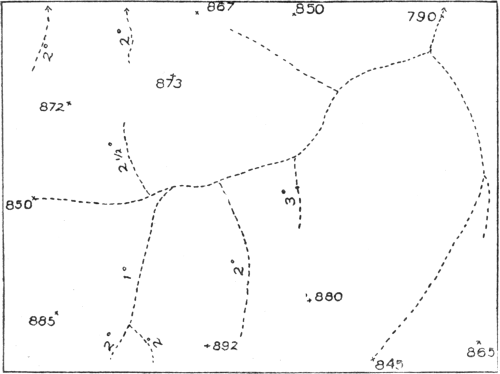

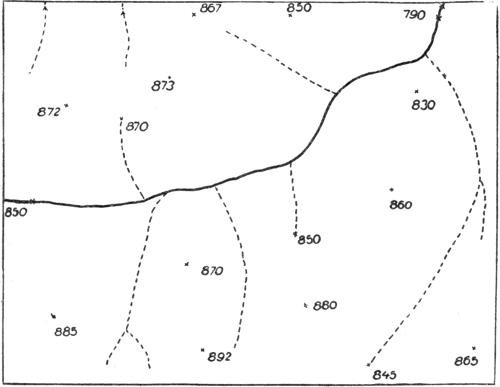

Cover Insert Fig. III

Cover Insert Fig. III

PREFATORY

Not only does this manual cover all the subjects prescribed by War

Department orders for the Junior Division, and the Basic Course,

Senior Division, of the Reserve Officers' Training Corps, but it also

contains considerable additional material which broadens its scope,

rounding it out and making it answer the purpose of a general,

all-around book, complete in itself, for training and instruction in

the fundamentals of the art of war.

The Company is the basic fighting tactical unit—it is the

foundation rock upon which an army is built—and the fighting

efficiency of a COMPANY is based on systematic and thorough training.

This manual is a presentation of MILITARY TRAINING as manifested in

the training and instruction of a COMPANY. The book contains all the

essentials pertaining to the training and instruction of COMPANY

officers, noncommissioned officers and privates, and the officer who

masters its contents and who makes his COMPANY proficient in the

subjects embodied herein, will be in every way qualified, without the

assistance of a single other book, to command with credit and

satisfaction, in peace and in war, a COMPANY that will be an

efficient fighting weapon.

This manual, as indicated below, is divided into a Prelude and nine

Parts, subjects of a similar or correlative nature being thus grouped

together.

| PRELUDE. |

The Object and Advantages of Military Training. |

| PART I. |

Drills, Exercises, Ceremonies, and Inspections. |

| PART II. |

Company Command. |

| PART III. |

Miscellaneous Subjects Pertaining to Company Training and Instruction. |

| PART IV. |

Rifle Training and Instruction. |

| PART V. |

Health and Kindred Subjects. |

| PART VI. |

Military Courtesy and Kindred Subjects. |

| PART VII. |

Guard Duty. |

| PART VIII. |

Military Organization. |

| PART IX. |

Map Reading and Sketching. |

A schedule of training and instruction covering a given period and

suitable to the local conditions that obtain in any given school or

command, can be readily arranged by looking over the TABLE OF

CONTENTS, and selecting therefrom such subjects as it is desired to

use, the number and kind, and the time to be devoted to each,

depending upon the time available, and climatic and other conditions.

It is suggested that, for the sake of variety, in drawing up a program

of instruction and training, when practicable a part of each day or a

part of each drill time, be devoted to theoretical work and a part to

practical work, theoretical work, when possible, being followed by

corresponding practical work, the practice (the doing of a thing)

thus putting a clincher, as it were, on the theory (the explaining of

a thing). The theoretical work, for example, could be carried on in

the forenoon and the practical work in the afternoon, or the

theoretical work could be carried on from, say, 8 to 9:30 a. m., and

the practical work from 9:30 to 10:30 or 11 a. m.

Attention is invited to the completeness of the Index, whereby one is

enabled to locate at once any point covered in the book.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author wishes to acknowledge the assistance received in the

revision of this Manual in the form of suggestions from a large number

of officers on duty at our military schools and colleges, suggestions

that enabled him not only to improve the Manual in subject-matter as

well as in arrangement, but that have also enabled him to give our

military schools and colleges a textbook which, in a way, may be said

to represent the consensus of opinion of our Professors of Military

Science and Tactics as to what such a book should embody in both

subject-matter and arrangement.

Suggestions received from a number of Professors of Military Science

and Tactics show conclusively that local conditions as to average age

and aptitude of students, interest taken in military training by the

student body, support given by the school authorities, etc., are so

different in different schools that it would be impossible to write a

book for general use that would, in amount of material, arrangement

and otherwise, just exactly fit, in toto, the conditions, and meet the

requirements of each particular school.

Therefore, the only practical, satisfactory solution of the problem is

to produce a book that meets all the requirements of the strictly

military schools, where the conditions for military training and

instruction are the most favorable, and the requirements the greatest,

and then let other schools take only such parts of the book as are

necessary to meet their own particular local needs and requirements.

"MANUAL OF MILITARY TRAINING" is such a book.

Camp Gaillard, C. Z.,

March 4, 1917.

[Pg 6]

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| |

|

Par. No. |

| PRELUDE |

| OBJECT AND ADVANTAGES OF MILITARY TRAINING |

| |

Object of: Setting-Up Exercises, Calisthenics,

Facings and Marchings, Saluting,

Manual of Arms, School of the Squad,

Company Drill, Close Order, Extended

Order, Ceremonies, Discipline—Advantages:

Handiness, Self-Control, Loyalty,

Orderliness, Self-Confidence, Self-Respect,

Training Eyes, Teamwork, Heeding Law

and Order, Sound Body. |

1–23 |

| PART I |

| CHAPTER I. |

INFANTRY DRILL REGULATIONS—Definitions—General

Remarks—General

Rules for Drills and Formations—Orders,

Commands, and Signals—School of the

Soldier—School of the Squad—School of

the Company—School of the Battalion—Combat—Leadership—Combat

Reconnaissance—Fire

Superiority—Fire Direction

and Control—Deployment—Attack—Defense—Meeting

Engagements—Machine

Guns—Ammunition Supply—Mounted

Scouts—Night Operations—Infantry

Against Cavalry—Infantry Against Artillery—Artillery

Supports—Minor Warfare—Ceremonies—Inspections—Muster—The

Color—Manual of the Saber—Manual of

Tent Pitching—Appendices A and B. |

24–710 |

| CHAPTER II. |

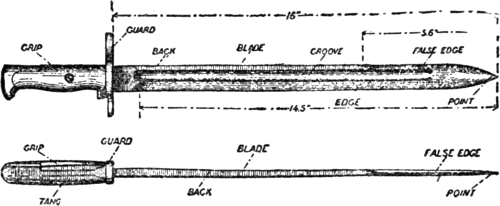

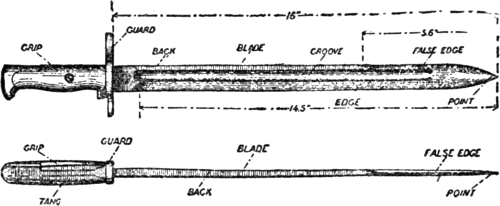

MANUAL OF THE BAYONET—Nomenclature

and Description of the Bayonet—Instruction

without the Rifle—Instruction

with the Rifle—Instruction without the

Bayonet—Combined Movements—Fencing

Exercises—Fencing at Will—Lessons of

the European War—The "Short point"—The "Jab." |

711–824 |

| CHAPTER III. |

MANUAL OF PHYSICAL TRAINING—Methods—Commands—Setting-Up

Exercises—Rifle Exercises. |

825–860 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

SIGNALING—General Service Code—Wigwag—The

Two-Arm Semaphore Code—Signaling with Heliograph, Flash Lanterns,[Pg 7]

and Searchlight—Sound Signals—Morse

Code. |

861–866 |

| PART II |

| COMPANY COMMAND |

| CHAPTER I. |

GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION

OF A COMPANY—Duties and

Responsibilities of the Captain and the

Lieutenants—Devolution of Work and

Responsibility—Duties and Responsibilities

of the First Sergeant and other Noncommissioned

Officers—Contentment and

Harmony—Efficacious Forms of Company

Punishment—Property Responsibility—Books

and Records. |

867–909 |

| CHAPTER II. |

DISCIPLINE—Definition—Methods of

Attaining Good Discipline—Importance—Sound

Discipline—Punishment—General

Principles. |

910–916 |

| PART III |

| MISCELLANEOUS SUBJECTS PERTAINING TO COMPANY

TRAINING AND INSTRUCTION |

| CHAPTER I. |

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF COMPANY

TRAINING AND INSTRUCTION—Object

of Training and Instruction—Method

and Progression—Individual Initiative—The

Human Element—Art of Instruction

on the Ground—Ocular Demonstration. |

917–941 |

| CHAPTER II. |

GENERAL COMMON SENSE PRINCIPLES

OF APPLIED MINOR TACTICS—Art

of War Defined—Responsibilities

of Officers and Noncommissioned Officers

in War—General Rules and Principles of

Map Problems, Terrain Exercises, the

War Game, and Maneuvers—Estimating

the Situation—Mission. |

942–953 |

| CHAPTER III. |

GENERAL PLAN OF INSTRUCTION

IN MAP PROBLEMS FOR NONCOMMISSIONED

OFFICERS AND PRIVATES—INSTRUCTION

IN DELIVERING

MESSAGES. |

954–958 |

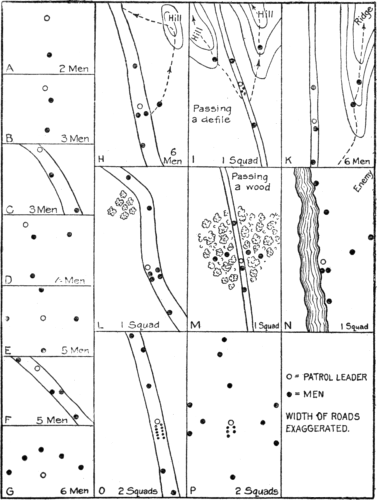

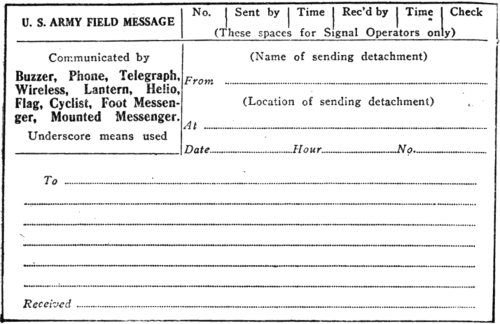

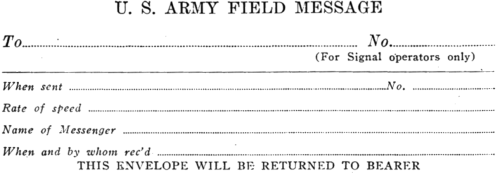

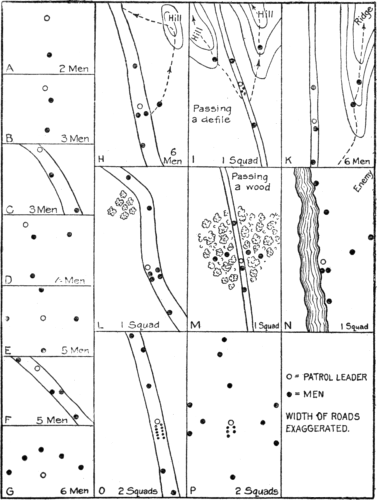

| CHAPTER IV. |

THE SERVICE OF INFORMATION—General

Principles of Patrolling—Sizes of[Pg 8]

Patrols—Patrol Leaders—Patrol Formations—Messages

and Reports—Suggestions

for Gaining Information about the

Enemy—Suggestions for the Reconnaissance

of Various Positions and Localities—Demolitions—Problems

in Patrolling. |

959–1019 |

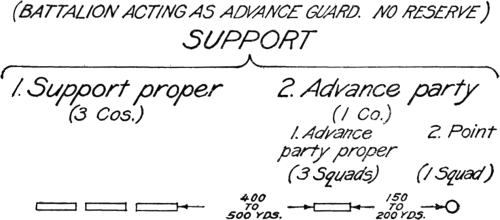

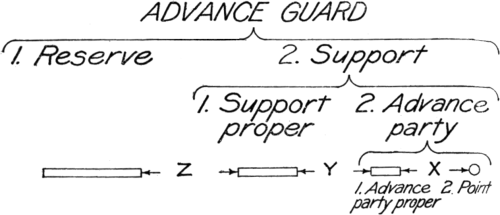

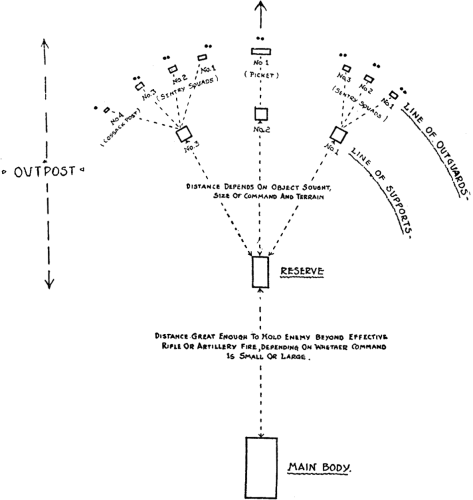

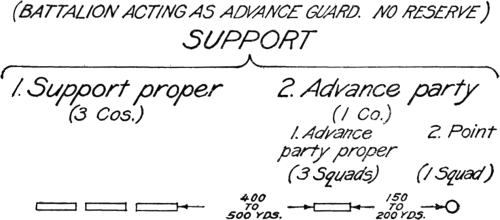

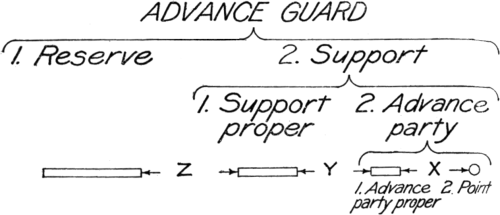

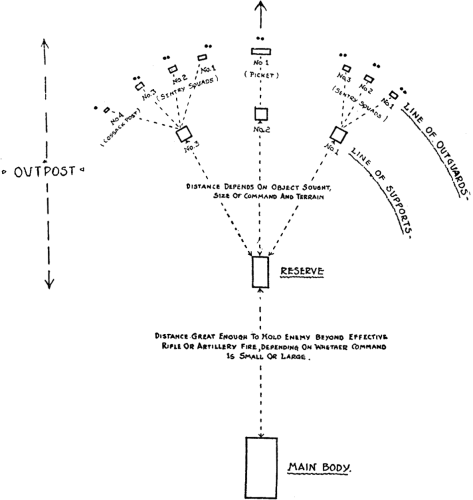

| CHAPTER V. |

THE SERVICE OF SECURITY—General

principles—Advance Guard—Advance

Guard Problems—Flank Guards—Rear

Guard—Outposts—Formation of Outposts—Outguards—Flags

of Truce—Detached

Posts—Examining Posts—Establishing

the Outpost—Outpost Order—Intercommunication—Outpost

Problems. |

1020–1079 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

THE COMPANY ON OUTPOST—Establishing

the Outpost. |

1080 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

THE COMPANY IN SCOUTING AND

PATROLLING—Requisites of a Good

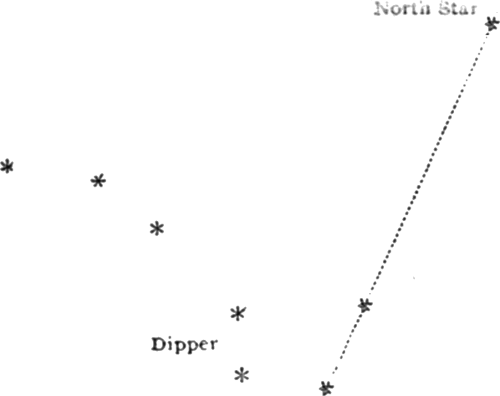

Scout—Eyesight and hearing—Finding

Way in Strange Country—What to do

when Lost—Landmarks—Concealment

and Dodging—Tracking—The Mouse and

Cat Contest—Flag Stealing Contest. |

1081–1090 |

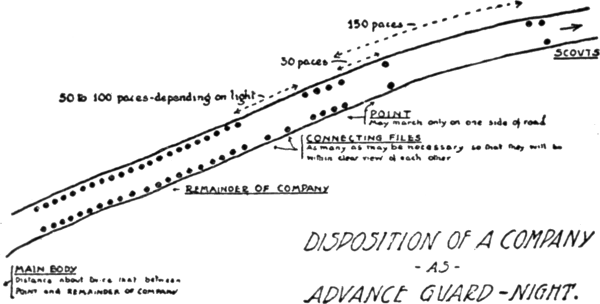

| CHAPTER VIII. |

NIGHT OPERATIONS—Importance—Training

of the Company—Individual

Training—Collective Training—Outposts. |

1091–1108 |

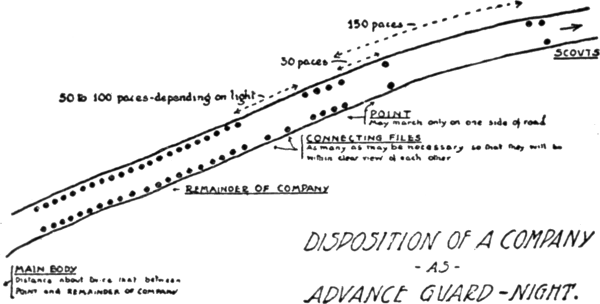

| CHAPTER IX. |

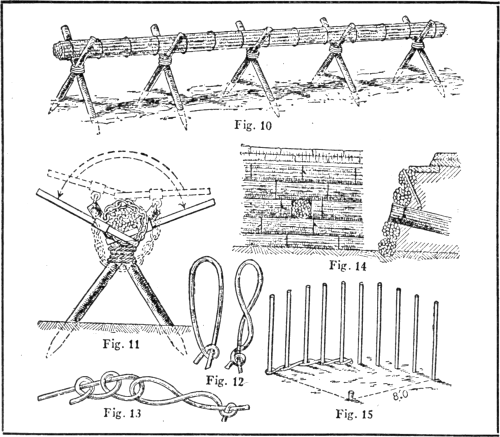

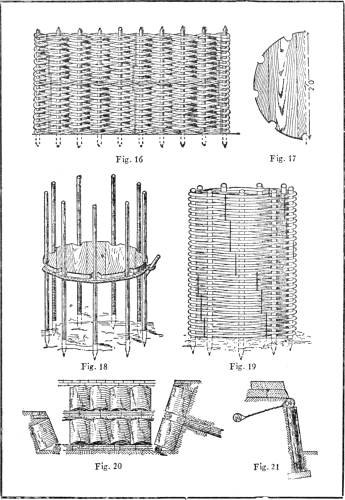

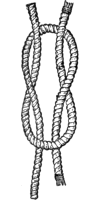

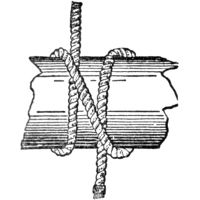

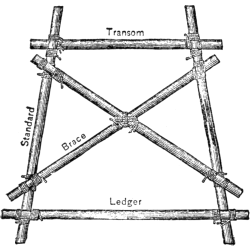

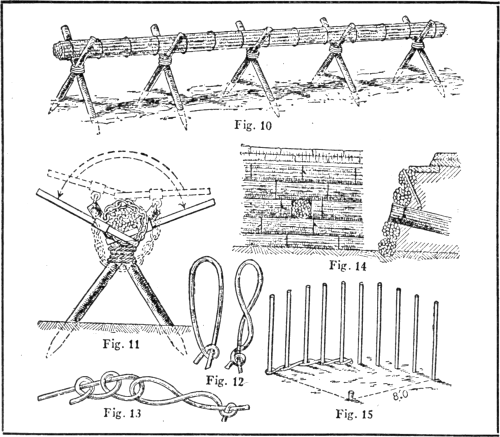

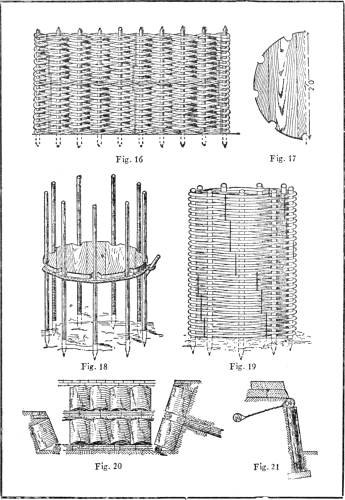

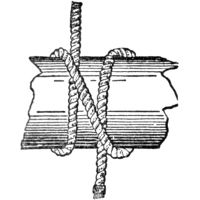

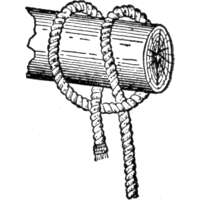

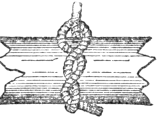

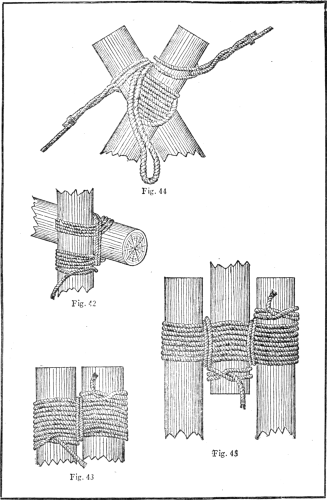

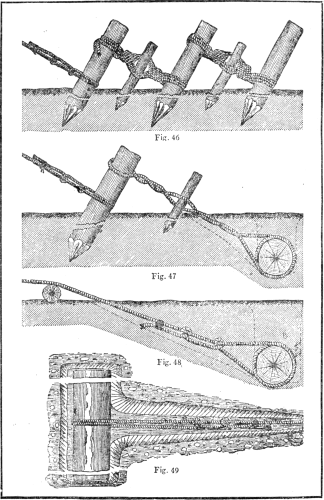

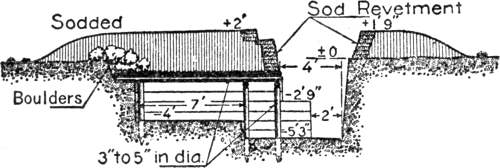

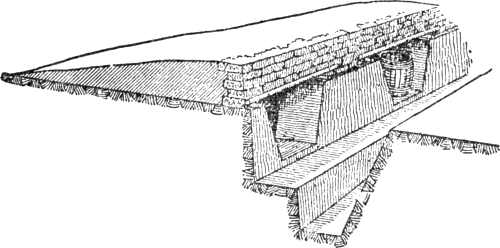

FIELD ENGINEERING—Bridges—Corduroying—Tascines—Hurdles—Brush

Revetment—Gabions—Other

Revetments—Knots—Lashings. |

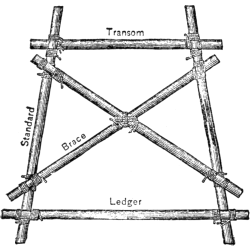

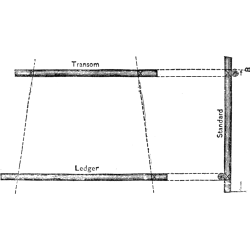

1109–1139 |

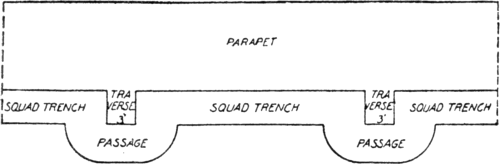

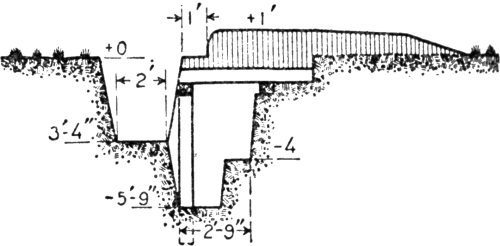

| CHAPTER X. |

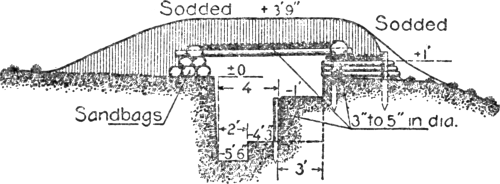

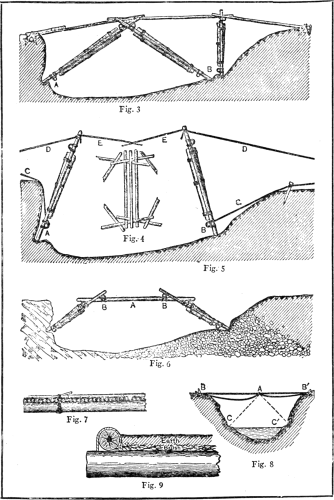

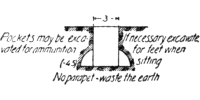

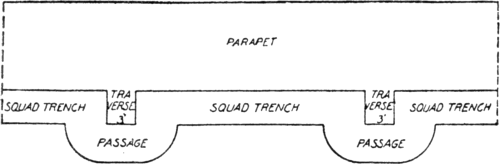

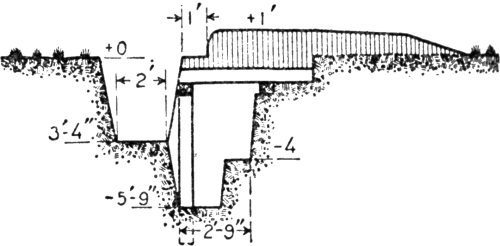

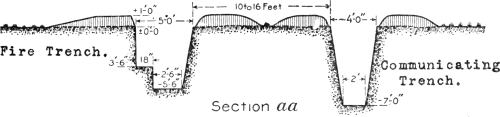

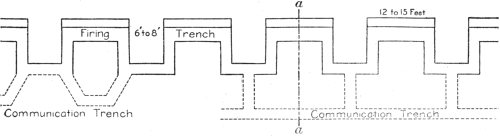

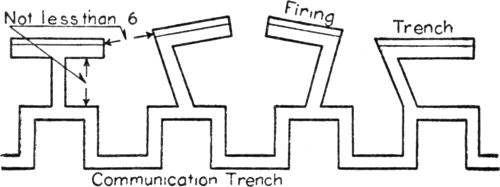

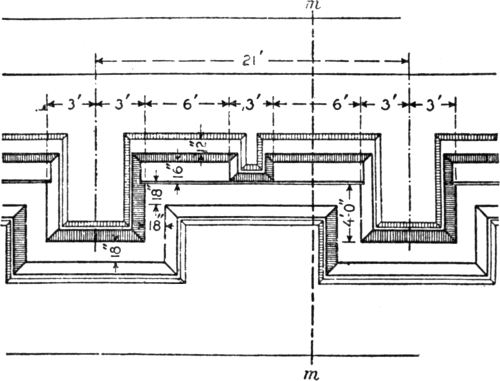

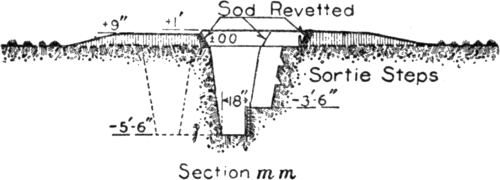

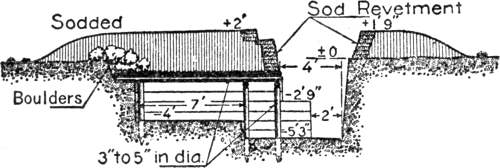

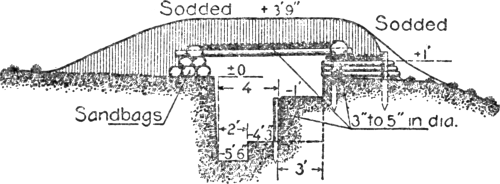

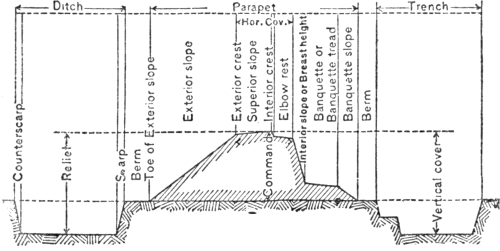

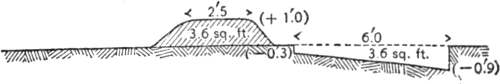

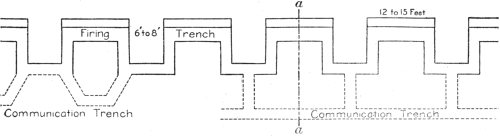

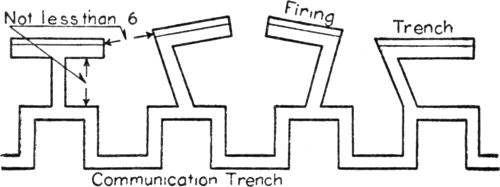

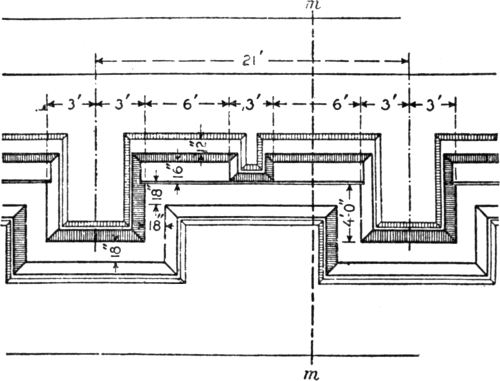

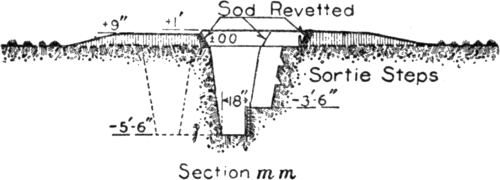

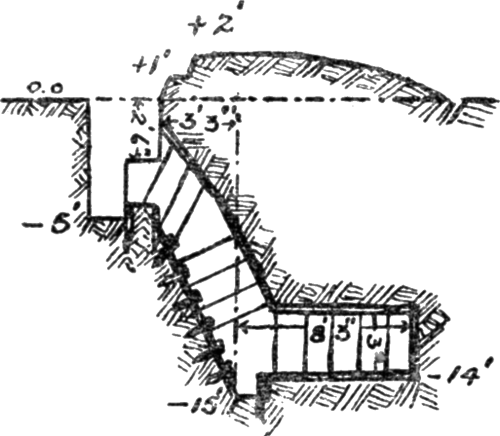

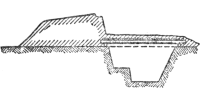

FIELD FORTIFICATIONS—Object—Classification—Hasty

Intrenchments—Lying

Trench—Kneeling Trench—Standing

Trench—Deliberate Intrenchments—Fire

Trenches—Traverses—Trench recesses;

sortie steps—Parados—Head Cover—Notches

and Loopholes—Cover Trenches—Dugouts—Communicating

Trenches—Lookouts—Supporting

Points—Example

of Trench System—Location of Trenches—Concealment

of Trenches—Dummy

Trenches—Length of Trench—Preparation

of Foreground—Revetments—Drainage—Water

Supply—Latrines—Illumination

of the foreground—Telephones—Siege

Works. |

1140–1172 |

| [Pg 9]CHAPTER XI. |

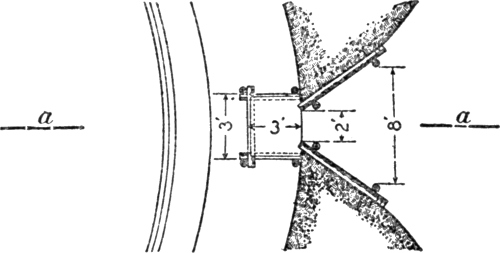

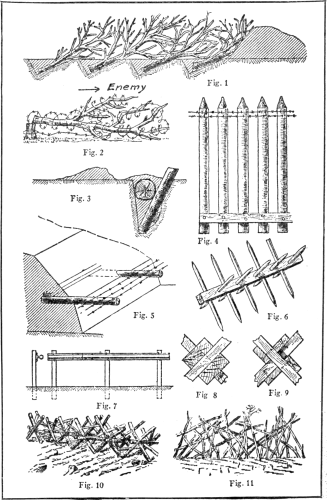

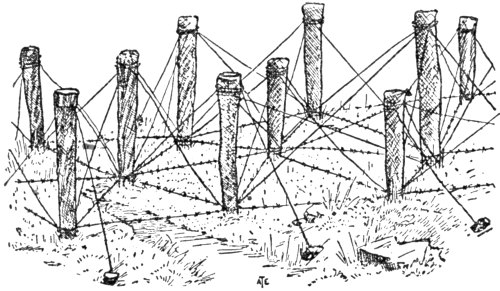

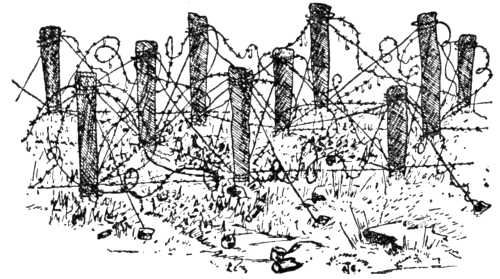

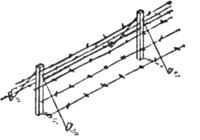

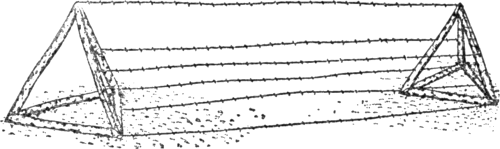

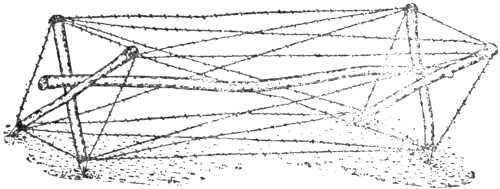

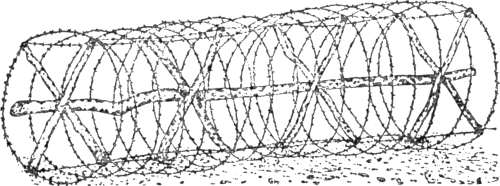

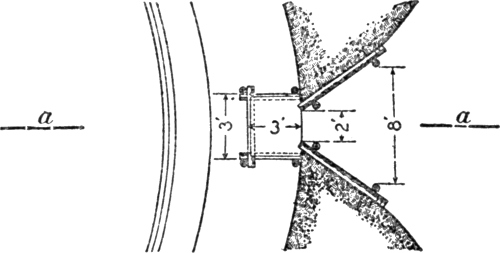

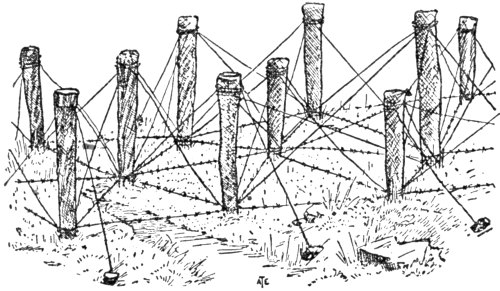

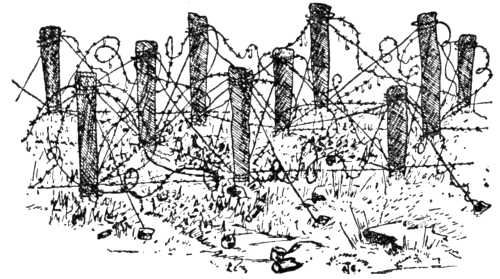

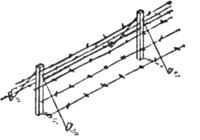

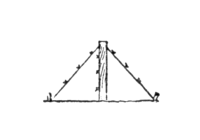

OBSTACLES—Object—Necessity for Obstacles—Location—Abatis—Palisades—Fraises—Cheveaux

de Frise—Obstacles

against Cavalry—Wire Entanglements—Time

and Materials—Wire Fence—Military

Pits or Trous de Loup—Miscellaneous

Barricades—Inundations—Obstacles

in Front of Outguards—Lessons from the

European War—Wire Cheveaux de Frise—Guarding

Obstacles—Listening Posts—Automatic

Alarms—Search Lights. |

1173–1193 |

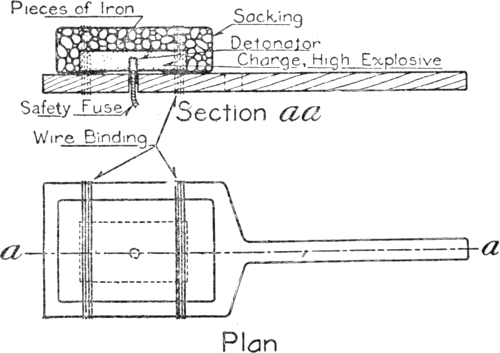

| CHAPTER XII. |

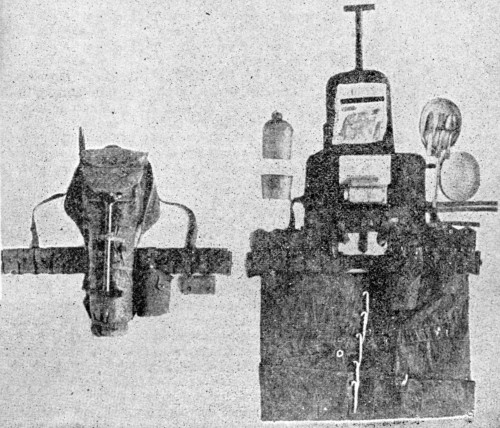

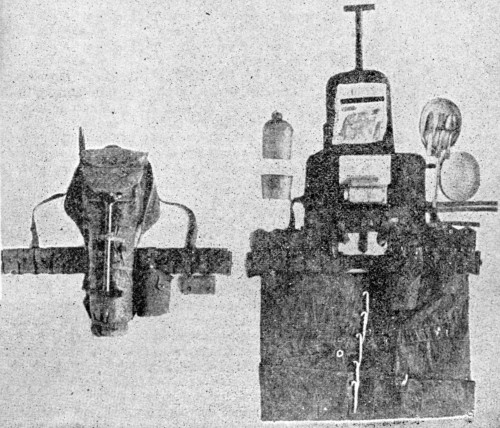

TRENCH AND MINE WARFARE—Asphyxiating

Gases—Protection against

Gases—Liquid Fire—Grenades—Bombs—Aerial

Mines—Winged Torpedoes—Bombs

from Air-Craft—Protection against Hand

Grenades—Tanks—Helmets—Masks—Periscopes—Sniperscopes—Aids

to Firing—Mining—Countermining. |

1194–1211 |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

MARCHES—Marching Principal Occupation

of Troops in Campaign-Physical

Training Hardening New Troops—Long

Marches Not to Be Made with Untrained

Troops—A Successful March—Preparation—Starting—Conduct

of March—Rate—Marching

Capacity—Halts—Crossing

Bridges and Fords—Straggling and

Elongation of Column—Forced Marches—Night

Marches—No Compliments Paid

on March—Protection on March—Fitting

of Shoes and Care of Feet. |

1212–1229 |

| CHAPTER XIV. |

CAMPS—Selection of Camp Sites—Desirable

Camp Sites—Undesirable Camp

Sites—Form and Dimensions of Camps—Making

Camp—Retreat in Camp—Parade

Ground—Windstorms—Making Tent Poles

and Pegs Fast in Loose Soil—Trees. |

1230–1240 |

| CHAPTER XV. |

CAMP SANITATION—Definition—Camp

Expedients—Latrines—Urinal Tubs—Kitchens—Kitchen

Pits—Incinerators—Drainage—Avoiding

Old Camp Sites—Changing

Camp Sites—Bunks—Wood—Water—Rules

of Sanitation—Your Camp,

Your Home. |

1241–1255 |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

INDIVIDUAL COOKING—Making Fire—Recipes—Meats—Vegetables—Drinks—Hot

Breads—Emergency Ration. |

1256–1275 |

| [Pg 10]CHAPTER XVII. |

CARE AND PRESERVATION OF

CLOTHING AND EQUIPMENT—Clothing—Pressing—Removing

Stains—Shoes—Cloth Equipment—Washing—Shelter

Tent—Mess Outfit—Leather Equipment—Points

to Be Remembered. |

1276–1320 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

CARE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE

RIFLE—Importance—Care of Bore—How

to Remove Fouling—Care of Mechanism

and Various Parts—How to Apply Oil—Army

Regulation Paragraphs About Rifle—Nomenclature

of Rifle. |

1321–1343 |

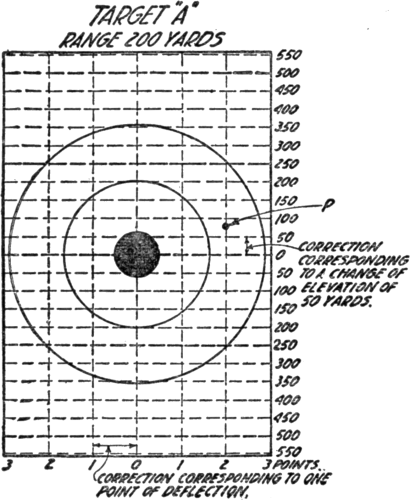

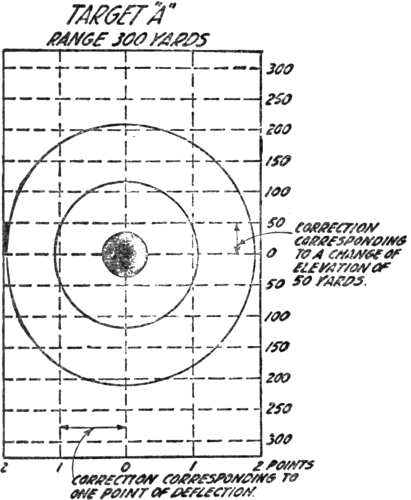

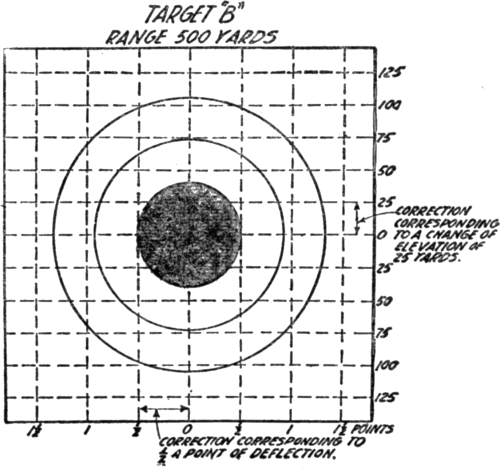

| PART IV |

| RIFLE TRAINING AND INSTRUCTION |

| |

Object and Explanation of Our System of

Instruction—Individual Instruction—Theory

of Sighting—Kinds of Sights—Preliminary

Drills—Position and Aiming

Drills—Deflection and Elevation Correction

Drills—Gallery Practice—Range

Practice—Use of Sling—Designation of

Winds—Zero of Rifle—Estimating Distances—Wind—Temperature—Light—Mirage—Combat

Practice—Fire Discipline—Technical

Principles of Firing—Ballistic

Qualities of the Rifle—Cone of

Fire—Shot Group—Center of Impact—Beaten

Zone—Zone of Effective Fire—Effectiveness

of Fire—Influence of

Ground—Grazing Fire—Ricochet Shots—Occupation

of Ground—Adjustment of

Fire—Determination of Range—Combined

Sights—Auxiliary Aiming Points—Firing

at Moving Targets—Night Firing—Fire

Direction and Control—Distribution of

Fire—Individual Instruction in Fire Distribution—Designation

of Targets—Exercises

in Ranging, Target Designation

Communication, etc. |

1344–1450 |

| PART V |

| CARE OF HEALTH AND KINDRED SUBJECTS |

| CHAPTER I. |

CARE OF THE HEALTH—Importance

of Good Health—Germs—The Five Ways

of Catching Disease—Diseases Caught by

Breathing in Germs—Diseases Caught by[Pg 11]

Swallowing Germs—Disease Caught by

Touching Germs—Diseases Caught from

Biting Insects. |

1451–1469 |

| CHAPTER II. |

PERSONAL HYGIENE—Keep the Skin

Clean—Keep the Body Properly Protected

against the Weather—Keep the Body

Properly Fed—Keep the Body Supplied

with Fresh Air—Keep the Body well

Exercised—Keep the Body Rested by

Sufficient Sleep—Keep the Body Free of

Wastes. |

1470–1477 |

| CHAPTER III. |

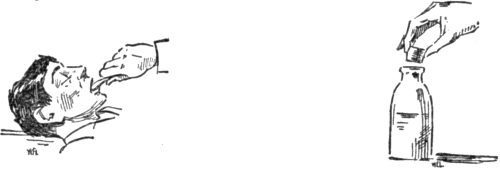

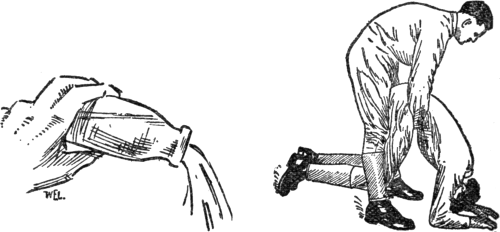

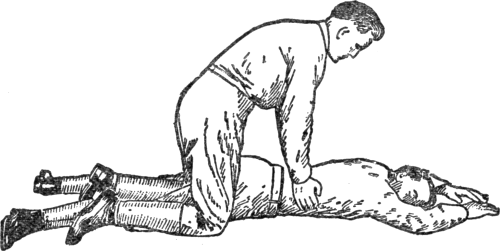

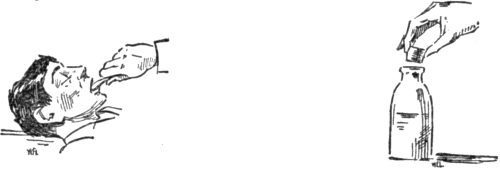

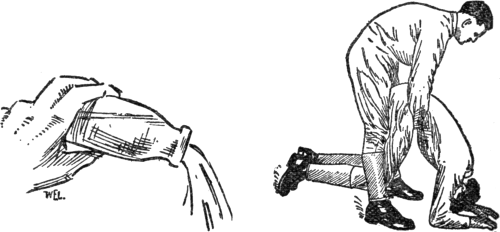

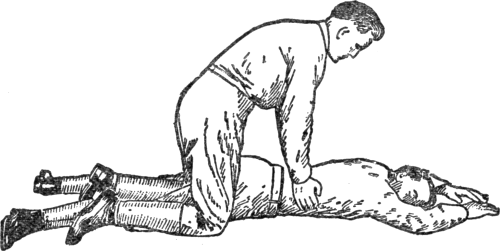

FIRST AID TO THE SICK AND INJURED—Object

of Teaching First Aid—Asphyxiation

by Gas—Bite of Dog—Bite

of Snake—Bleeding—Broken Bones

(Fractures)—Burns—Bruises—Cuts—Dislocations—Drowning—Electric

Shock—Fainting—Foreign

Body in Eye, in Ear—Freezing—Frost

Bite—Headache—Heat

Exhaustion—Poison—Sprains—Sunburn—Sunstroke—Wounds—Improvised

Litters. |

1478–1522 |

| PART VI |

| MILITARY COURTESY AND KINDRED SUBJECTS |

| CHAPTER I. |

MILITARY DEPORTMENT AND APPEARANCE—PERSONAL

CLEANLINESS—FORMS

OF SPEECH—DELIVERY

OF MESSAGES. |

1523–1531 |

| CHAPTER II. |

MILITARY COURTESY—Its Importance—Nature

of Salutes and Their Origin—Whom

to Salute—When and How to

Salute—Usual Mistakes in Saluting—Respect

to Be Paid the National Anthem,

the Colors and Standards. |

1532–1575 |

| PART VII |

| GUARD DUTY |

| |

Importance—Respect for Sentinels—Classification

of Guards—General Rules—The

Commanding Officer—The Officer of the

Day—The Commander of the Guard—Sergeant

of the Guard—Corporal of the

Guard—Musicians of the Guard—Orderlies

and Color Sentinels—Privates of the

Guard—Countersigns and Paroles—Guard

Patrols—Compliments from Guards—Gen[Pg 12]eral

Rules Concerning Guard Duty—Stable

Guards—Troop Stable Guards—Reveille

and Retreat Gun—Formal Guard Mounting—Informal

Guard Mounting. |

1576–1857 |

| PART VIII |

| MILITARY ORGANIZATION |

| |

Composition of Infantry, Cavalry and

Field Artillery Units up to and Including

the Regiment. |

1858 |

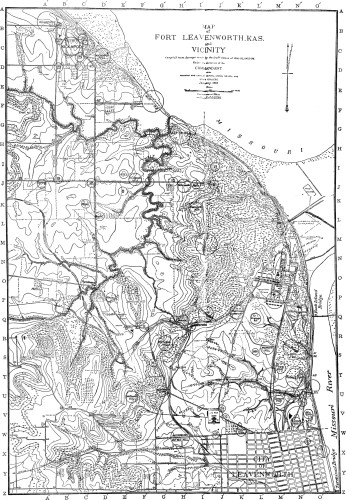

| PART IX |

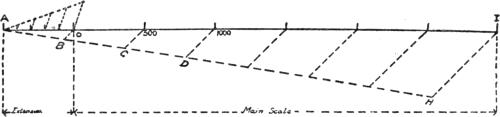

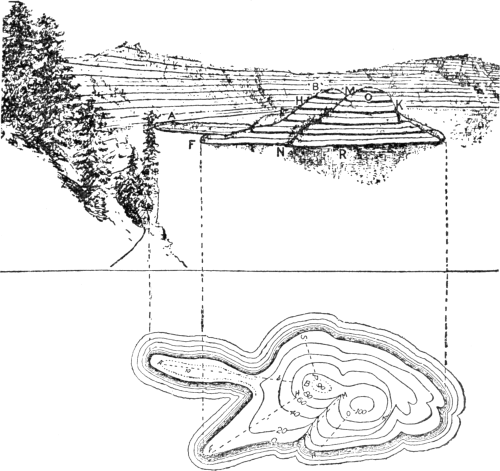

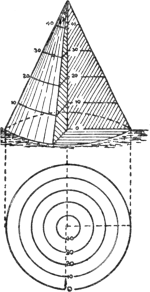

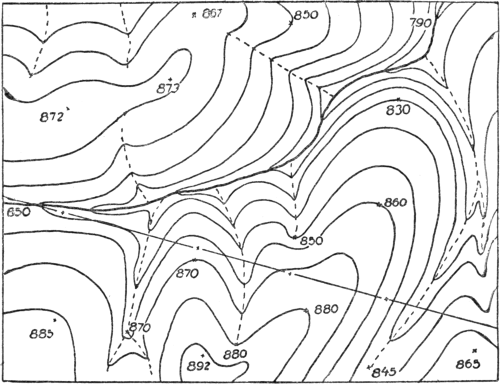

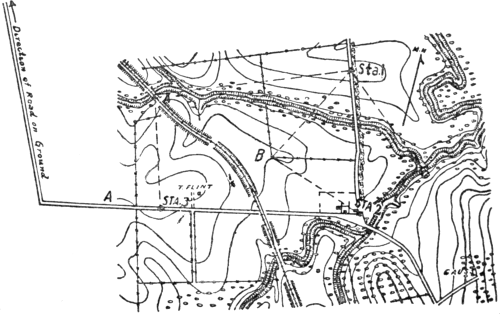

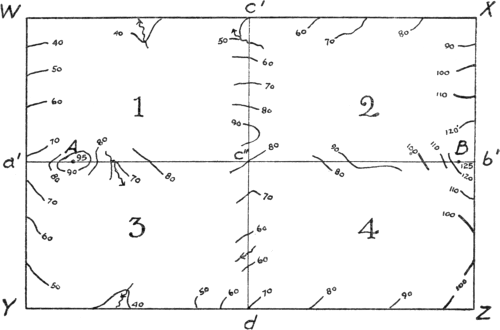

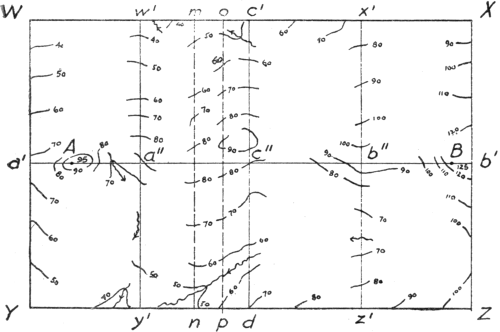

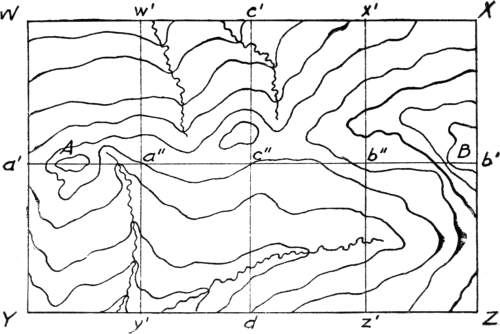

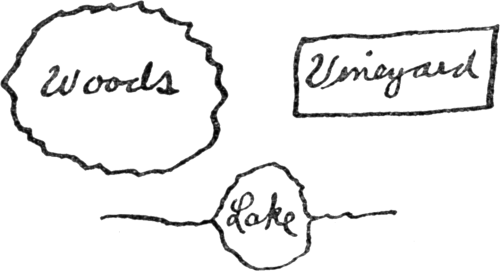

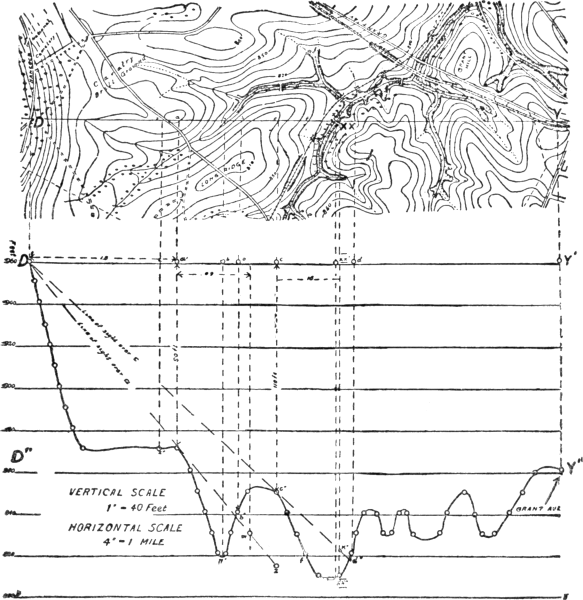

| MAP READING AND SKETCHING |

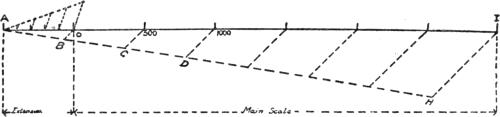

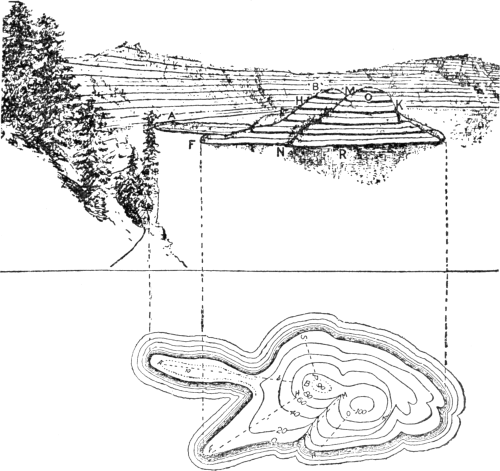

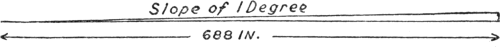

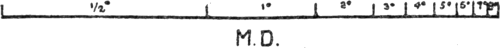

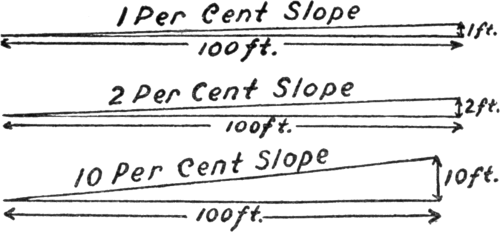

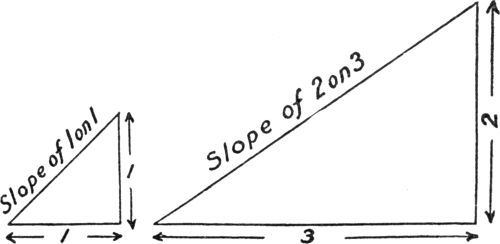

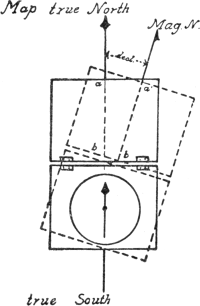

| CHAPTER I. |

MAP READING—Definition of Map—Ability

to Read a Map—Scales—Methods

of Representing Scales—Construction of

Scales—Scale Problems—Scaling Distances

from a Map—Contours—Map Distances—Slopes—Meridians—Determination

of Positions of Points on Map—Orientation—Conventional

Signs—Visibility. |

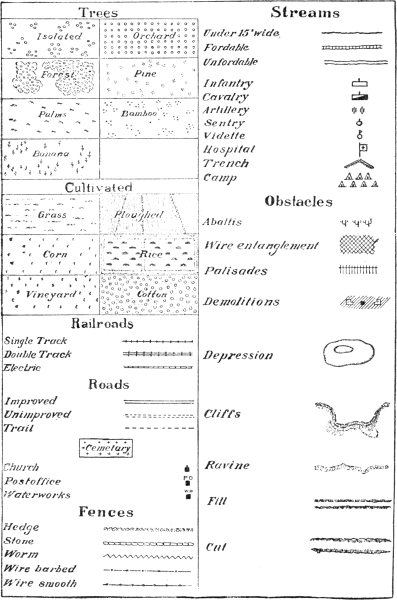

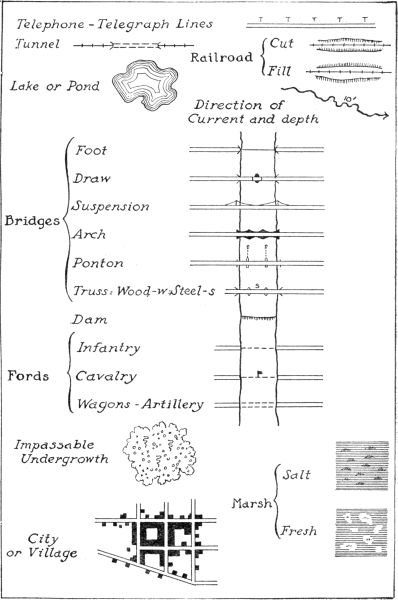

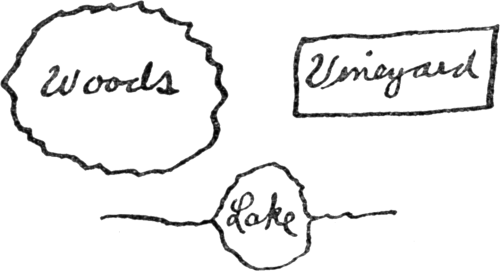

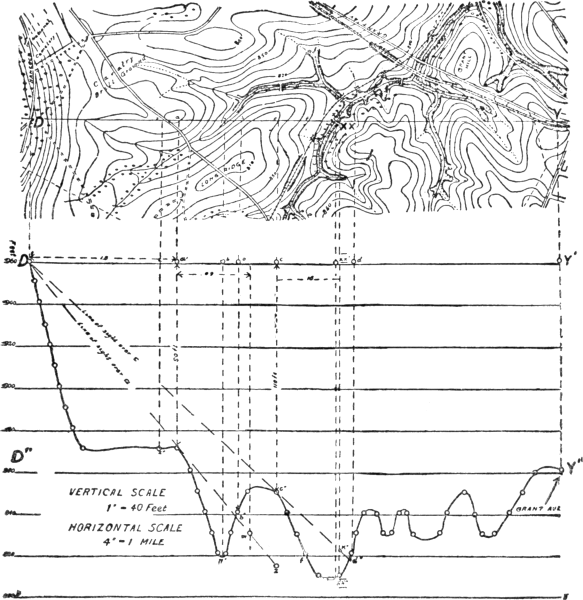

1859–1877 |

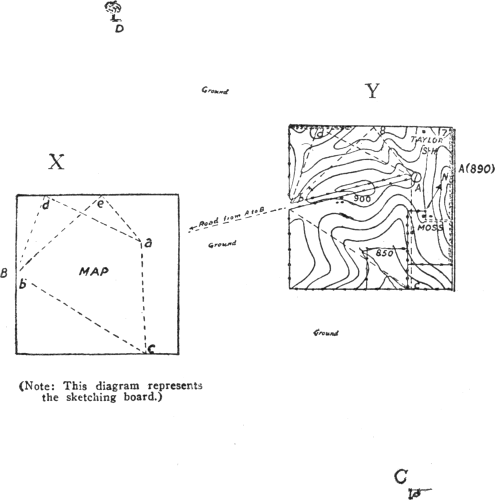

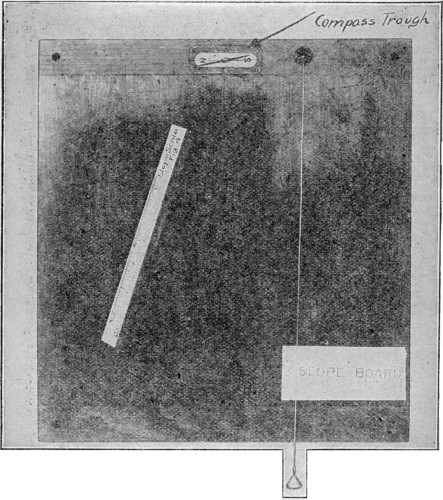

| CHAPTER II. |

MILITARY SKETCHING—The Different

Methods of Sketching—Location of

Points by Intersection—Location of

points by Resection—Location of Points

by Traversing—Contours—Form Lines—Scales—Position

Sketching—Outpost

Sketching—Road Sketching—Combined

Sketching—Points for Beginners to

Remember. |

1878–1893 |

[Pg 13]

PRELUDE

THE OBJECT AND ADVANTAGES OF MILITARY TRAINING

1. Prelude. We will first consider the object and advantages of

military training, as they are the natural and logical prelude to the

subject of military training and instruction.

Object

2. The object of all military training is to win battles.

Everything that you do in military training is done with some

immediate object in view, which, in turn, has in view the final

object of winning battles. For example:

3. Setting-up exercises. The object of the setting-up exercises, as

the name indicates, is to give the new men the set-up,—the bearing

and carriage,—of the military man.

In addition these exercises serve to loosen up his muscles and prepare

them for his later experiences and development.

4. Calisthenics. Calisthenics may be called the big brother, the

grown-up form, of the setting-up exercise.

The object of calisthenics is to develop and strengthen all parts and

muscles of the human body,—the back, the legs, the arms, the lungs,

the heart and all other parts of the body.

First and foremost a fighting man's work depends upon his physical

fitness.

To begin with, a soldier's mind must always be on the alert and equal

to any strain, and no man's mind can be at its best when he is

handicapped by a weak or ailing body.

The work of the fighting man makes harsh demands on his body. It must

be strong enough to undergo the strain of marching when every muscle

cries out for rest; strong enough to hold a rifle steady under fatigue

and excitement; strong enough to withstand all sorts of weather, and

the terrible nervous and physical strain of modern battle; and more,

it must be strong enough to resist those diseases of campaign which

kill more men than do the bullets of the enemy.

Hence the necessity of developing and strengthening every part and

muscle of the body.

5. Facings and Marchings. The object of the facings and marchings is

to give the soldier complete control of his body in drills, so that he

can get around with ease and promptness at every command.

The marchings,—the military walk and run,—also teach the soldier how

to get from one place to another in campaign with the least amount of

physical exertion.

Every man knows how to walk and run, but few of them how to do so

without making extra work of it. One of the first principles in

training the body of the soldier is to make each set of muscles do its

own work and save the strength of the other muscles for their work.

Thus the soldier marches in quick time,—walks,—with his legs,

keeping the rest of his body as free from motion as possible. He

marches in double[Pg 14] time,—runs,—with an easy swinging stride which

requires no effort on the part of the muscles of the body.

The marchings also teach the soldier to walk and run at a steady gait.

For example, in marching in quick time, he takes 120 steps each

minute; in double time, he takes 180 per minute.

Furthermore, the marchings teach the soldier to walk and run with

others,—that is, in a body.

6. Saluting. The form of salutation and greeting for the civilian

consists in raising the hat.

The form of salutation and greeting for the military man consists in

rendering the military salute,—a form of salutation which marks you

as a member of the Fraternity of Men-at-arms, men banded together for

national defense, bound to each other by love of country and pledged

to the loyal support of its symbol, the Flag. For the full

significance of the military salute see paragraph 1534.

7. Manual of Arms. The rifle is the soldier's fighting weapon and he

must become so accustomed to the feel of it that he handles it

without a thought,—just as he handles his arms or legs without a

thought,—and this is what the manual of arms accomplishes.

The different movements and positions of the rifle are the ones that

experience has taught are the best and the easiest to accomplish the

object in view.

8. School of the Squad. The object of squad drill is to teach the

soldier his first lesson in team-work,—and team-work is the thing

that wins battles.

In the squad the soldier is associated with seven other men with whom

he drills, eats, sleeps, marches, and fights.

The squad is the unit upon which all of the work of the company

depends. Unless the men of each squad work together as a single

man,—unless there is team-work,—the work of the company is almost

impossible.

9. Company Drill. Several squads are banded together into a

company,—the basic fighting unit. In order for a company to be able

to comply promptly with the will of its commander, it must be like a

pliable, easily managed instrument. And in order to win battles a

company on the firing line must be able to comply promptly with the

will of its commander.

The object of company drill is to get such team-work amongst the

squads that the company will at all times move and act like a pliable,

easily managed whole.

10. Close Order. In close order drill the strictest attention is paid

to all the little details, all movements being executed with the

greatest precision. The soldiers being close together,—in close

order,—they form a compact body that is easily managed, and

consequently that lends itself well to teaching the soldier habits of

attention, precision, team-work and instant obedience to the voice of

his commander.

In order to control and handle bodies of men quickly and without

confusion, they must be taught to group themselves in an orderly

arrangement and to move in an orderly manner. For example, soldiers

are grouped or formed in line, in column of squads, column of files,

etc.

In close order drill soldiers are taught to move in an orderly[Pg 15] manner

from one group or formation to another; how to stand, step off, march,

halt and handle their rifles all together.

This practice makes the soldier feel perfectly at home and at ease in

the squad and company. He becomes accustomed to working side by side

with the man next to him, and, unconsciously, both get into the habit

of working together, thus learning the first principles of

team-work.

11. Extended Order. This is the fighting drill.

Modern fire arms have such great penetration that if the soldiers were

all bunched together a single bullet might kill or disable several men

and the explosion of a single shell might kill or disable a whole

company. Consequently, soldiers must be scattered,—extended

out,—to fight.

In extended order not only do the soldiers furnish a smaller target

for the enemy to shoot at, but they also get room in which to fight

with greater ease and freedom.

The object of extended order drill is to practice the squads in

team-work by which they are welded into a single fighting machine that

can be readily controlled by its commander.

12. Parades, reviews, and other ceremonies. Parades, reviews and other

ceremonies, with their martial music, the presence of spectators,

etc., are intended to stimulate the interest and excite the military

spirit of the command. Also, being occasions for which the soldiers

dress up and appear spruce and trim, they inculcate habits of

tidiness,—they teach a lesson in cleanliness of body and clothes.

While it is true it may be said that parades, reviews and other

ceremonies form no practical part of the fighting man's training for

battle, they nevertheless serve a very useful purpose in his general

training. In these ceremonies in which soldiers march to martial music

with flags flying, moving and going through the manual of arms with

perfect precision and unison, there results a concerted movement that

produces a feeling such as we have when we dance or when we sing in

chorus. In other words, ceremonies are a sort of "get-together"

exercise which pulls men together in spite of themselves, giving them

a shoulder-to-shoulder feeling of solidity and power that helps to

build up that confidence and spirit which wins battles.

13. Discipline. By discipline we mean the habit of observing all

rules and regulations and of obeying promptly all orders. By observing

day after day all rules and regulations and obeying promptly all

orders, it becomes second nature,—a fixed habit,—to do these things.

Of course, in the Army, like in any other walk of life, there must be

law and order, which is impossible unless everyone obeys the rules and

regulations gotten up by those in authority.

When a man has cultivated the habit of obeying,—when obedience has

become second nature with him,—he obeys the orders of his leaders

instinctively, even when under the stress of great excitement, such as

when in battle, his own reasoning is confused and his mind is not

working.

In order to win a battle the will of the commander as expressed

through his subordinates down the line from the second in command to

the squad leaders, must be carried out by everyone. Hence the vital[Pg 16]

importance of prompt, instinctive obedience on the part of everybody,

and of discipline, which is the mainspring of obedience and also the

foundation rock of law and order.

And so could we go on indefinitely pointing out the object of each and

every requirement of military training, for there is none that has no

object and that answers no useful purpose, although the object and

purpose may not always be apparent to the young soldier.

And remember that the final object of all military training is to win

battles.

Advantages of Military Training

The following are the principal advantages of military training:

14. Handiness. The average man does one thing well. He is more or less

apt to be clumsy about doing other things. The soldier is constantly

called upon to do all sorts of things, and he has to do all of them

well. His hands thus become trained and useful to him, and his mind

gets into the habit of making his hands do what is required of

them,—that is to say, the soldier becomes handy.

Handy arms are a valuable asset.

15. Self-control. In the work of the soldier, control does not stop

with the hands.

The mind reaches out,—control of the body becomes a habit. The feet,

legs, arms and body gradually come under the sway of the mind. In the

position of the soldier, for instance, the mind holds the body

motionless. In marching, the mind drives the legs to machine-like

regularity. In shooting, the mind assumes command of the arms, hands,

fingers and eye, linking them up and making them work in harmony.

Control of the body, together with the habit of discipline that the

soldier acquires, leads to control of the mind,—that is, to

self-control.

Self-control is an important factor in success in any walk of life.

16. Loyalty. Loyalty to his comrades, to his company, to his

battalion, to his regiment becomes a religion with the soldier. They

are a part of his life. Their reputation is his; their good name, his

good name; their interests, his interests,—so, loyalty to them is but

natural, and this loyalty soon extends to loyalty in general.

When you say a man is loyal the world considers that you have paid him

a high tribute.

17. Orderliness. In the military service order and system are

watchwords. The smooth running of the military machine depends on

them.

The care and attention that the soldier is required to give at all

times to his clothes, accouterments, equipment and other belongings,

instill in him habits of orderliness.

Orderliness increases the value of a man.

18. Self-confidence and self-respect. Self-confidence is founded on

one's ability to do things. The soldier is taught to defend himself

with his rifle, and to take care of himself and to do things in almost

any sort of a situation, all of which gives him confidence in

himself,—self-confidence.

Respect for constituted authority, which is a part of the soldier's

creed, teaches him respect for himself,—self-respect.

[Pg 17]Self-confidence and self-respect are a credit to any man.

19. Eyes trained to observe. Guard duty, outpost duty, patrolling,

scouting and target practice, train both the eye and the mind to

observe.

Power of observation is a valuable faculty for a man to possess.

20. Teamwork. In drilling, patrolling, marching, maneuvers and in

other phases of his training and instruction, the soldier is taught

the principles of team-work,—coöperation,—whose soul is loyalty, a

trait of every good soldier.

Teamwork,—coöperation,—leads to success in life.

21. Heeding law and order. The cardinal habit of the soldier is

obedience. To obey orders and regulations is a habit with the soldier.

And this habit of obeying orders and regulations teaches him to heed

law and order.

The man who heeds law and order is a welcome member of any community.

22. Sound body. Military training, with its drills, marches, and other

forms of physical exercise, together with its regular habits and

outdoor work, keeps a man physically fit, giving him a sound body.

A sound body, with the physical exercise and outdoor life of the

soldier, means good digestion, strength, hardiness and endurance.

A sound body is, indeed, one of the greatest blessings of life.

The Trained Soldier

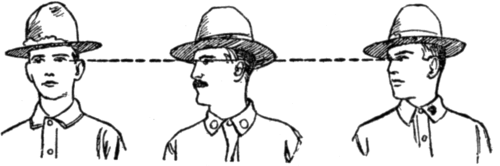

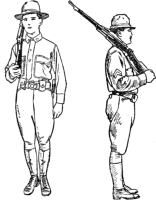

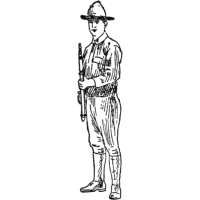

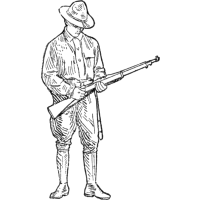

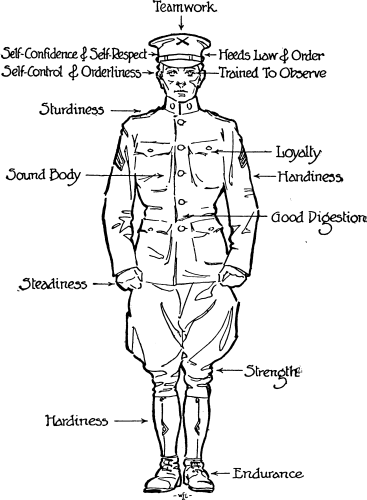

23. Look at the trained soldier on the following page; study him

carefully from top to bottom, and see what military training does for

a man.

[Pg 18]

THE TRAINED SOLDIER

WHAT DO YOU THINK OF HIM, EH?

WHAT DO YOU THINK OF HIM, EH?

[Pg 19]

PART I

DRILLS, EXERCISES, CEREMONIES AND INSPECTIONS

[Pg 20]

CHAPTER I

INFANTRY DRILL REGULATIONS

(To include Changes No. 20, Aug. 18, 1917.)

DEFINITIONS

(The numbers following the paragraphs are those of the Drill

Regulations, and references in the text to certain paragraph

numbers refer to these numbers and not to the numbers preceding

the paragraphs.)

(Note.—Company drills naturally become monotonous. The monotony,

however, can be greatly reduced by repeating the drills under

varying circumstances. In the manual of arms, for instance, the

company may be brought to open ranks and the officers and

sergeants directed to superintend the drill in the front and rear

ranks. As the men make mistakes they are fallen out and drilled

nearby by an officer or noncommissioned officer. Or, the company

may be divided into squads, each squad leader drilling his squad,

falling out the men as they make mistakes, the men thus fallen out

reporting to a designated officer or noncommissioned officer for

drill. The men who have drilled the longest in the different

squads are then formed into one squad and drilled and fallen out

in like manner. The variety thus introduced stimulates a spirit of

interest and rivalry that robs the drill of much of its monotony.

It is thought the instruction of a company in drill is best

attained by placing special stress on squad drill. The

noncommissioned officers should be thoroughly instructed,

practically and theoretically, by one of the company officers and

then be required to instruct their squads. The squads are then

united and drilled in the school of the company.—Author.)

DEFINITIONS

24. Alignment: A straight line upon which several elements are formed,

or are to be formed; or the dressing of several elements upon a

straight line.

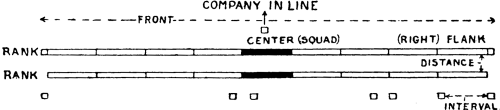

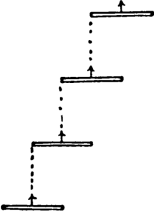

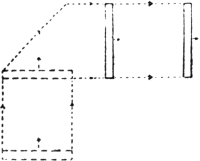

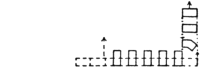

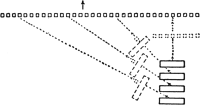

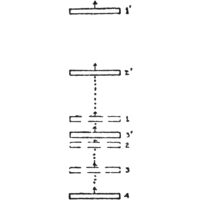

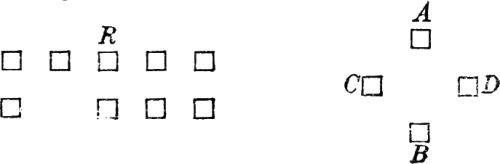

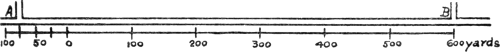

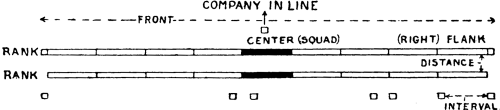

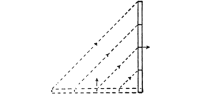

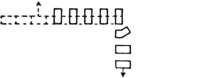

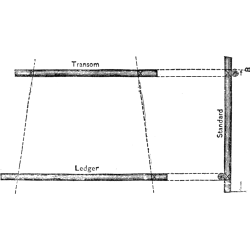

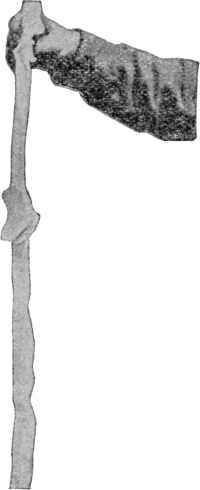

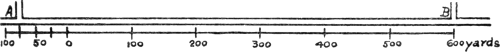

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Note.—The line A-B, on which a body of troops is formed or is to be

formed, or the act of dressing a body of troops on the line, is called

an alignment.—Author.

25. Base: The element on which a movement is regulated.

26. Battle sight: The position of the rear sight when the leaf is laid

down.

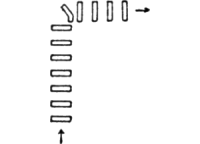

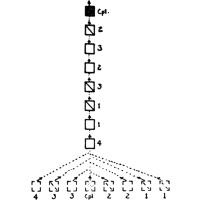

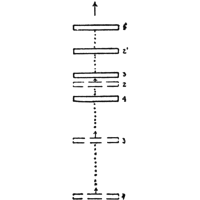

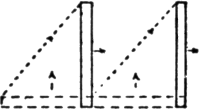

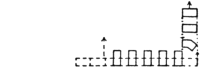

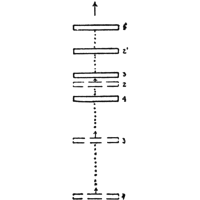

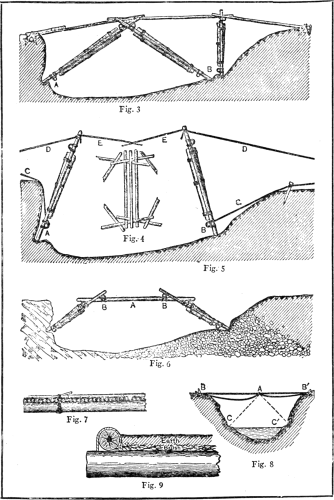

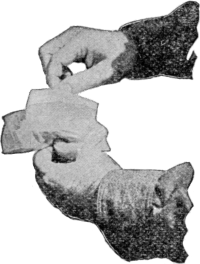

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

27. Center: The middle point or element of a command. (See Figs. 2, 3

and 5.) (The designation "center company," indicates the right center

or the actual center company, according as the number of companies is

even or odd.—Par. 298.)

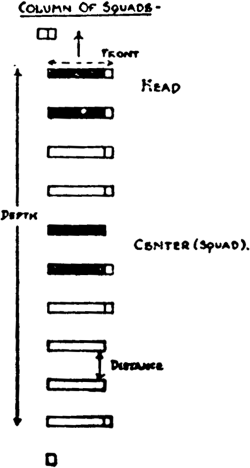

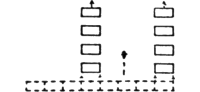

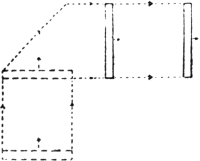

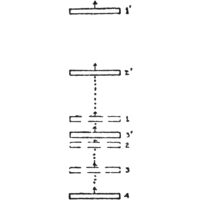

[Pg 21]28. Column: A formation in which the elements are placed one behind

another. (See Figs. 4, 5, 6.)

29. Deploy: To extend the front. In general to change from column to

line, or from close order to extended order.

30. Depth: The space from head to rear of any formation, including the

leading and rear elements. The depth of a man is assumed to be 12

inches. (See Figs. 4, 5, 6.)

31. Distance: Space between elements in the direction of depth.

Distance is measured from the back of the man in front to the breast

of the man in rear. The distance between ranks is 40 inches in both

line and column. (See Figs. 4, 5, 6.)

32. Element: A file, squad, platoon, company, or larger body, forming

part of a still larger body.

33. File: Two men, the front-rank man and the corresponding man of the

rear rank. The front-rank man is the file leader. A file which has no

rear-rank man is a blank file. The term file applies also to a single

man in a single-rank formation.

34. File closers: Such officers and noncommissioned officers of a

company as are posted in rear of the line. For convenience, all men

posted in the line of file closers.

35. Flank: The right or left of a command in line or in column; also

the element on the right or left of the line. (See Figs. 2, 3 and 4.)

36. Formation: Arrangement of the elements of a command. The placing

of all fractions in their order in line, in column, or for battle.

37. Front: The space, in width, occupied by an element, either in line

or in column. The front of a man is assumed to be 22 inches. Front

also denotes the direction of the enemy. (See Figs. 2, 3 and 5).

38. Guide: An officer, noncommissioned officer, or private upon whom

the command or elements thereof regulates its march.

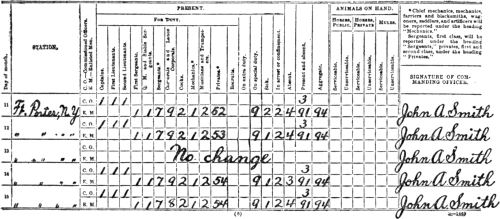

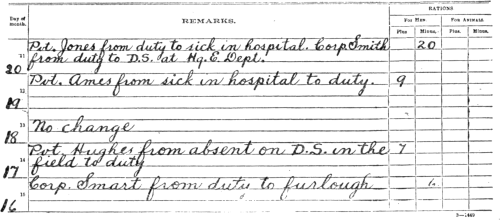

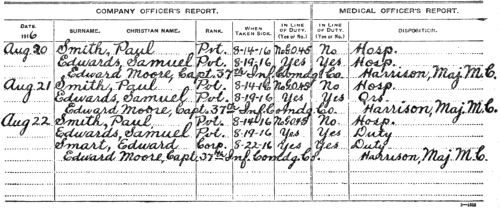

39. Head: The leading element of a column. (See Figs. 4, 5 and 6.)

[Pg 22]40. Interval: Space between elements of the same line. The interval

between men in ranks is 4 inches and is measured from elbow to elbow.

Between companies, squads, etc., it is measured from the left elbow of

the left man or guide of the group on the right, to the right elbow of

the right man or guide of the group on the left. (See Fig. 3.)

41. Left: The left extremity or element of a body of troops.

42. Line: A formation in which the different elements are abreast of

each other. (See Figs. 2 and 3.)

43. Order, close: The formation in which the units, in double rank,

are arranged in line or in column with normal intervals and distances.

44. Order, extended: The formation in which the units are separated by

intervals greater than in close order.

45. Pace: Thirty inches; the length of the full step in quick time.

46. Point of rest: The point at which a formation begins.

Specifically, the point toward which units are aligned in successive

movements.

47. Rank: A line of men placed side by side.

48. Right: The right extremity or element of a body of troops.

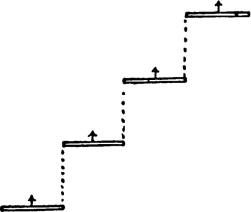

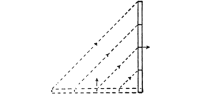

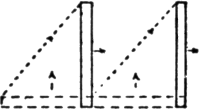

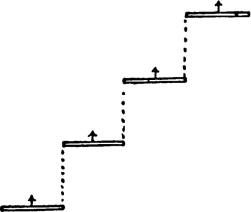

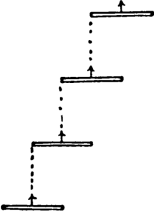

49. Note. In view of the fact that the word "Echelon" is a term of

such common usage, the following definition is given: By echelon we

mean a formation in which the subdivisions are placed one behind

another, extending beyond and unmasking one another either wholly or

in part.—Author.

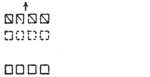

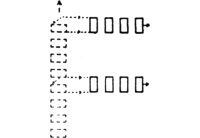

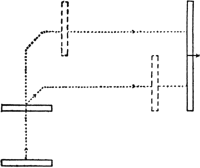

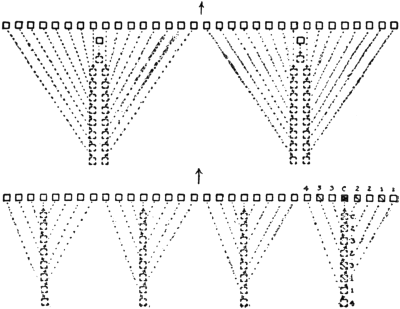

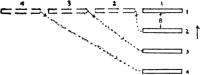

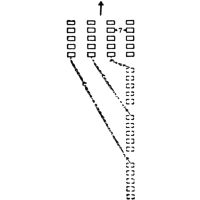

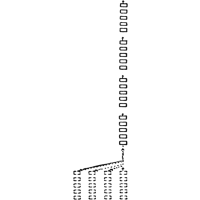

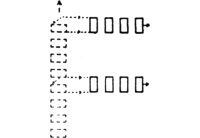

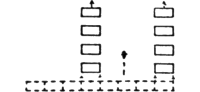

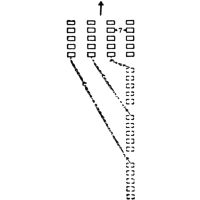

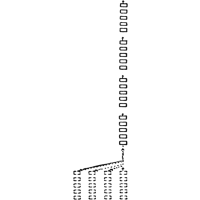

| BATTALION IN ECHELON |

COMPANIES UNMASKING WHOLLY

COMPANIES UNMASKING WHOLLY

|

COMPANIES UNMASKING IN PART

COMPANIES UNMASKING IN PART

|

INTRODUCTION

50. Object of military training. Success in battle is the ultimate

object of all military training; success may be looked for only when

the training is intelligent and thorough. (1)

51. Commanding officers accountable for proper training of

organizations; field efficiency; team-work. Commanding officers are

accountable for the proper training of their respective organizations

within the limits prescribed by regulations and orders. (2)

The excellence of an organization is judged by its field efficiency.

The field efficiency of an organization depends primarily upon its

effectiveness as a whole. Thoroughness and uniformity in the training

of the units of an organization are indispensable to the efficiency of

the whole; it is by such means alone that the requisite team-work may

be developed.

[Pg 23]52. Simple movements and elastic formations. Simple movements and

elastic formations are essential to correct training for battle. (3)

53. Drill Regulations a Guide; their interpretation. The Drill

Regulations are furnished as a guide. They provide the principles for

training and for increasing the probability of success in battle. (4)

In the interpretation of the regulations, the spirit must be sought.

Quibbling over the minutiae of form is indicative of failure to grasp

the spirit.

54. Combat principles. The principles of combat are considered in

Pars. 50–363. They are treated in the various schools included in Part

I of the Drill Regulations only to the extent necessary to indicate

the functions of the various commanders and the division of

responsibility between them. The amplification necessary to a proper

understanding of their application is to be sought in Pars. 364–613.

(5)

55. Drills at attention, ceremonies, extended order, field exercises

and combat exercises. The following important distinctions must be

observed:

(a) Drills executed at attention and the ceremonies are disciplinary

exercises designed to teach precise and soldierly movement, and to

inculcate that prompt and subconscious obedience which is essential to

proper military control. To this end, smartness and precision should

be exacted in the execution of every detail. Such drills should be

frequent, but short.

(b) The purpose of extended order drill is to teach the mechanism of

deployment of the firing, and, in general, of the employment of troops

in combat. Such drills are in the nature of disciplinary exercises and

should be frequent, thorough, and exact, in order to habituate men to

the firm control of their leaders. Extended order drill is executed at

ease. The company is the largest unit which executes extended order

drill.

(c) Field exercises are for instruction in the duties incident to

campaign. Assumed situations are employed. Each exercise should

conclude with a discussion, on the ground, of the exercise and

principles involved.

(d) The combat exercise, a form of field exercise of the company,

battalion, and larger units, consists of the application of tactical

principles to assumed situations, employing in the execution the

appropriate formations and movements of close and extended order.

Combat exercises must simulate, as far as possible, the battle

conditions assumed. In order to familiarize both officers and men with

such conditions, companies and battalions will frequently be

consolidated to provide war-strength organizations. Officers and

noncommissioned officers not required to complete the full quota of

the units participating are assigned as observers or umpires.

The firing line can rarely be controlled by the voice alone; thorough

training to insure the proper use of prescribed signals is necessary.

The exercise should be followed by a brief drill at attention in order

to restore smartness and control. (6)

56. Imaginary, outlined and represented enemy. In field exercises the

enemy is said to be imaginary when his position and force are merely

assumed; outlined when his position and force are indicated by a few

men; represented when a body of troops acts as such. (7)

[Pg 24]

General Rules for Drills and Formations

57. Arrangement of elements of preparatory command. When the

preparatory command consists of more than one part, its elements are

arranged as follows:

(1) For movements to be executed successively by the subdivisions or

elements of an organization: (a) Description of the movement; (b) how

executed, or on what element executed.

(For example: 1. Column of Companies, first company, squads right. 2.

March.—Author.)

(2) For movements to be executed simultaneously by the subdivisions of

an organization: (a) The designation of the subdivisions; (b) The

movement to be executed. (For example: 1. Squads right. 2.

March.—Author.) (8)

58. Movements executed toward either flank explained toward but one

flank. Movements that may be executed toward either flank are

explained as toward but one flank, it being necessary to substitute

the word "left" for "right," and the reverse, to have the explanation

of the corresponding movement toward the other flank. The commands are

given for the execution of the movements toward either flank. The

substitute word of the command is placed within parentheses. (9)

59. Any movement may be executed from halt or when marching unless

otherwise prescribed. Any movement may be executed either from the

halt or when marching, unless otherwise prescribed. If at a halt, the

command for movements involving marching need not be prefaced by

forward, as 1. Column right (left), 2. MARCH. (10)

60. Any movement may be executed in double time unless specially

excepted. Any movement not specially excepted may be executed in

double time.

If at a halt, or if marching in quick time, the command double time

precedes the command of execution. (11)

61. Successive movements executed in double time. In successive

movements executed in double time the leading or base unit marches in

quick time when not otherwise prescribed; the other units march in

double time to their places in the formation ordered and then conform

to the gait of the leading or base unit. If marching in double time,

the command double time is omitted. The leading or base unit marches

in quick time; the other units continue at double time to their places

in the formation ordered and then conform to the gait of the leading

or base unit. (12)

62. To hasten execution of movement begun in quick time. To hasten the

execution of a movement begun in quick time, the command: 1. Double

time, 2. MARCH, is given. The leading or base unit continues to march

in quick time, or remains at halt, if already halted; the other units

complete the execution of the movement in double time and then conform

to the gait of the leading or base unit. (13)

63. To stay execution of movement when marching, for correction of

errors. To stay the execution of a movement when marching, for the

correction of errors, the command: 1. In place, 2. HALT, is given. All

halt and stand fast without changing the position of the pieces. To[Pg 25]

resume the movement the command: 1. Resume, 2. MARCH, is given. (14)

64. To revoke preparatory command or begin anew movement improperly

begun. To revoke a preparatory command, or, being at a halt, to begin

anew a movement improperly begun, the command, AS YOU WERE, is given,

at which the movement ceases and the former position is resumed. (15)

65. Guide. Unless otherwise announced, the guide of a company or

subdivision of a company in line is right; of a battalion in line or

line of subdivisions or of a deployed line, center; of a rank in

column of squads, toward the side of the guide of the company.

To march with guide other than as prescribed above, or to change the

guide: Guide (right, left, or center).

In successive formations into line, the guide is toward the point of

rest; in platoons or larger subdivisions it is so announced.

The announcement of the guide, when given in connection with a

movement follows the command of execution for that. Exception: 1. As

skirmishers, guide right (left or center), 2. MARCH. (16)

66. Turn on fixed and moving pivots. The turn on the fixed pivot by

subdivisions is used in all formations from line into column and the

reverse.

The turn on the moving pivot is used by subdivisions of a column in

executing changes of direction. (17)

67. Partial changes of direction. Partial changes of direction may be

executed:

By interpolating in the preparatory command the word half, as Column

half right (left), or Right (left) half turn. A change of direction of

45° is executed.

By the command: INCLINE TO THE RIGHT (LEFT). The guide, or guiding

element, moves in the indicated direction and the remainder of the

command conforms. This movement effects slight changes of direction.

(18)

68. Line of platoons, companies, etc. The designations line of

platoons, line of companies, line of battalions, etc., refer to the

formations in which the platoons, companies, battalions, etc., each in

column of squads, are in line. (19)

69. Full distance in column of subdivisions; guide of leading

subdivision charged with step and direction. Full distance in column

of subdivisions is such that in forming line to the right or left the

subdivisions will have their proper intervals.

In column of subdivisions the guide of the leading subdivision is

charged with the step and direction; the guides in rear preserve the

trace, step, and distance. (20)

70. Double rank, habitual close order formation; uniformity of

interval between files obtained by placing hand on hip. In close

order, all details, detachments, and other bodies of troops are

habitually formed in double rank.

To insure uniformity of interval between files when falling in, and in

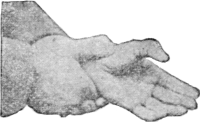

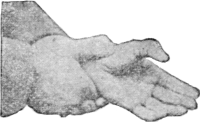

alignments, each man places the palm of the left hand upon the[Pg 26] hip,

fingers pointing downward. In the first case, the hand is dropped by

the side when the next man on the left has his interval; in the second

case, at the command front. (21)

71. Posts of officers, noncommissioned officers, and special units;

duties of file closers. The posts of officers, noncommissioned

officers, special units (such as band or machine-gun company), etc.,

in the various formations of the company, battalion, or regiment, are

shown in plates.

In all changes from one formation to another involving a change of

post on the part of any of these, posts are promptly taken by the most

convenient route as soon as practicable after the command of execution

for the movement; officers and noncommissioned officers who have

prescribed duties in connection with the movement ordered, take their

new posts when such duties are completed.

As instructors, officers and noncommissioned officers go wherever

their presence is necessary. As file closers it is their duty to

rectify mistakes and insure steadiness and promptness in the ranks.

(22)

72. Special units have no fixed posts except at ceremonies.

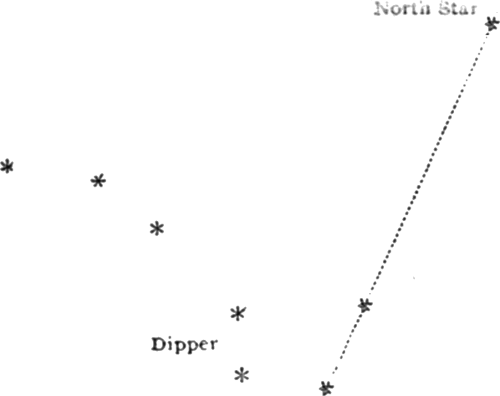

Except at ceremonies, the special units have no fixed places. They

take places as directed; in the absence of directions, they conform as

nearly as practicable to the plates, and in subsequent movements

maintain their relative positions with respect to the flank or end of

the command on which they were originally posted. (23)

73. General, field and staff officers habitually mounted; formation of

staff; drawing and returning saber. General, field, and staff officers

are habitually mounted. The staff of any officer forms in single rank,

3 paces in rear of him, the right of the rank extending 1 pace to the

right of a point directly in rear of him. Members of the staff are

arranged in order from right to left as follows: General staff

officers, adjutant, aids, other staff officers, arranged in each

classification in order of rank, the senior on the right. The flag of

the general officer and the orderlies are 3 paces in rear of the

staff, the flag on the right. When necessary to reduce the front of

the staff and orderlies, each line executes twos right or fours right,

as explained in the Cavalry Drill Regulations, and follows the

commander.

When not otherwise prescribed, staff officers draw and return saber

with their chief. (24)

74. Mounted officer turns to left in executing about; when commander

faces about to give commands, staff and others stand fast. In making

the about, an officer, mounted, habitually turns to the left.

When the commander faces to give commands, the staff, flag, and

orderlies do not change position. (25)

75. Saluting when making and receiving reports; saluting on meeting.

When making or receiving official reports, or on meeting out of doors,

all officers will salute.

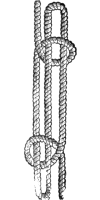

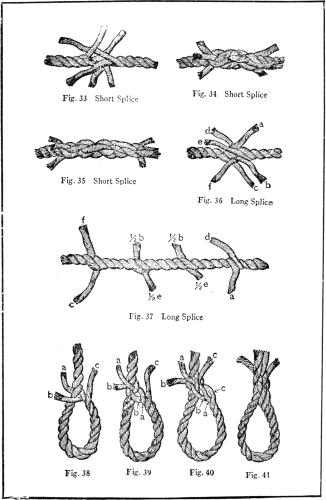

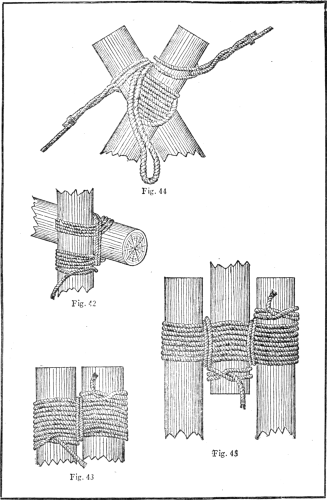

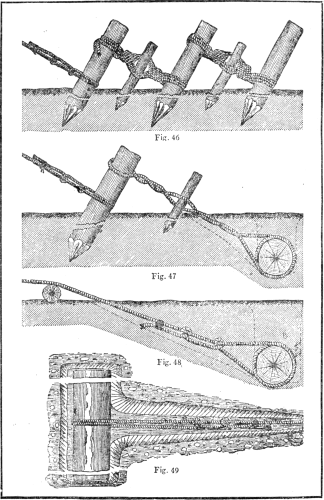

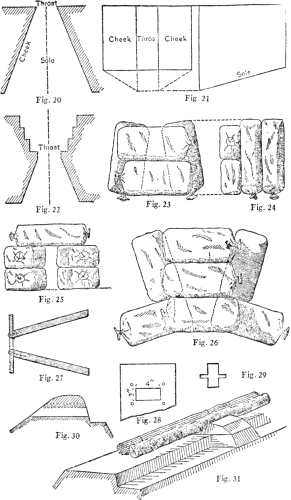

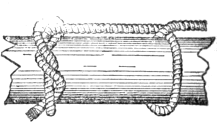

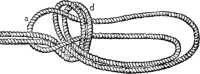

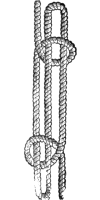

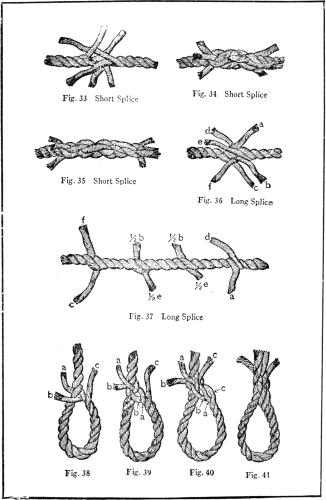

Military courtesy requires the junior to salute first, but when the

salute is introductory to a report made at a military ceremony or[Pg 27]

formation, to the representative of a common superior (as, for

example, to the adjutant, officer of the day, etc.), the officer

making the report, whatever his rank, will salute first; the officer

to whom the report is made will acknowledge by saluting that he has

received and understood the report. (26)

76. Formation of mounted enlisted men for ceremonies. For ceremonies,

all mounted enlisted men of a regiment or smaller unit, except those

belonging to the machine-gun organizations, are consolidated into a

detachment; the senior present commands if no officer is in charge.

The detachment is formed as a platoon or squad of cavalry in line or

column of fours; noncommissioned staff officers are on the right or in

the leading ranks. (27)

77. Post of dismounted noncommissioned staff officers for ceremonies.

For ceremonies, such of the noncommissioned staff officers as are

dismounted are formed 5 paces in rear of the color, in order of rank

from right to left. In column of squads they march as file closers.

(28)

78. Post of noncommissioned staff officers and orderlies other than

for ceremonies. Other than for ceremonies, noncommissioned staff

officers and orderlies accompany their immediate chiefs unless

otherwise directed. If mounted, the noncommissioned staff officers are

ordinarily posted on the right or at the head of the orderlies. (29)

79. Noncommissioned officer commanding platoon or company, carrying of

piece and taking of post. In all formations and movements a

noncommissioned officer commanding a platoon or company carries his

piece as the men do, if he is so armed, and takes the same post as an

officer in like situation. When the command is formed in line for

ceremonies, a noncommissioned officer commanding a company takes post

on the right of the right guide after the company has been aligned.

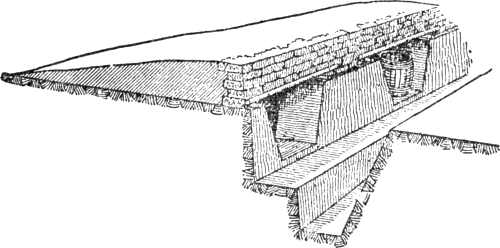

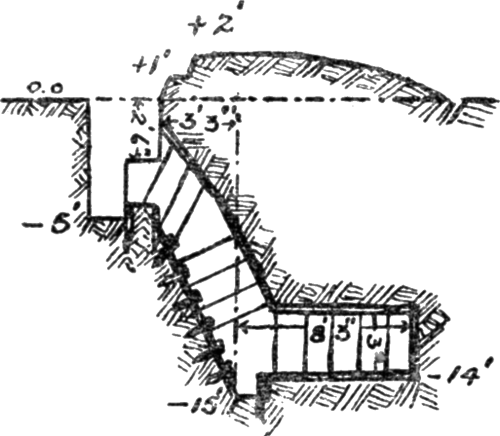

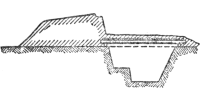

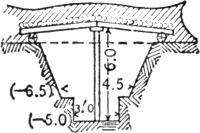

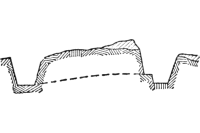

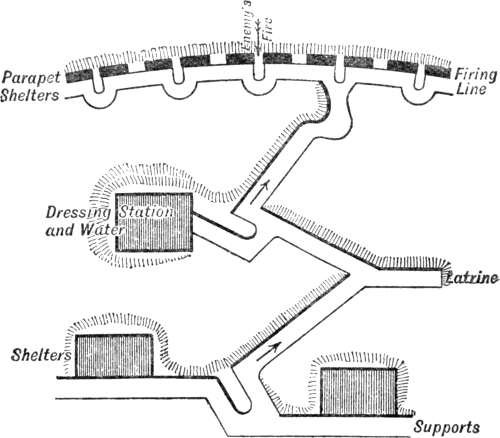

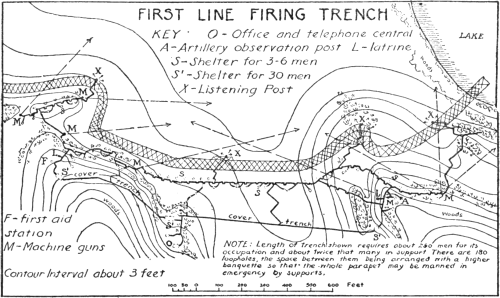

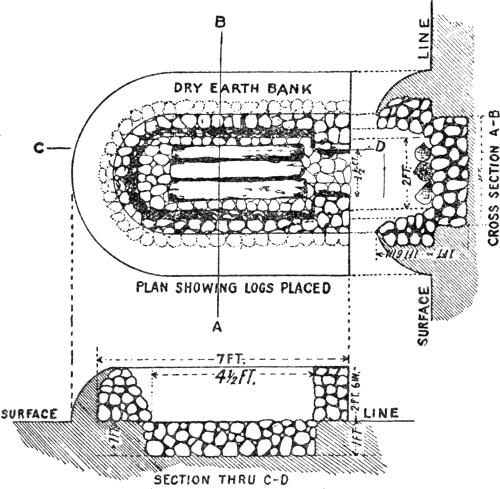

(30)

ORDERS, COMMANDS, AND SIGNALS

80. When commands, signals, and orders are used. Commands only are

employed in drill at attention. Otherwise either a command, signal, or

order is employed, as best suits the occasion, or one may be used in

conjunction with another. (31)

81. Instruction in use of signals; use of headdress, etc., in making

signals. Signals should be freely used in instruction, in order that

officers and men may readily know them. In making arm signals, the

saber, rifle, or headdress may be held in the hand. (32)

82. Fixing of attention; a signal includes command of preparation and

of execution. Officers and men fix their attention at the first word

of command, the first note of the bugle or whistle, or the first

motion of the signal. A signal includes both the preparatory command

and the command of execution; the movement commences as soon as the

signal is understood, unless otherwise prescribed. (33)

83. Repeating orders, commands and signals; officers, platoon leaders,

guides and musicians equipped with whistles; whistles with different

tones. Except in movements executed at attention, commanders or

leaders of subdivisions repeat orders, commands, or signals whenever

such repetition is deemed necessary to insure prompt and correct

execution.

[Pg 28]Officers, battalion noncommissioned staff officers, platoon leaders,

guides, and musicians are equipped with whistles.

The Major and his staff will use a whistle of distinctive tone; the

captain and company musicians a second and distinctive whistle; the

platoon leaders and guides a third distinctive whistle. (34)

84. Limitation of prescribed signals; special prearranged signals.

Prescribed signals are limited to such as are essential as a

substitute for the voice under conditions which render the voice

inadequate.

Before or during an engagement special signals may be agreed upon to

facilitate the solution of such special difficulties as the particular

situation is likely to develop, but it must be remembered that

simplicity and certainty are indispensable qualities of a signal. (35)

Orders

85. Orders defined; when employed. In these regulations an order

embraces instructions or directions given orally or in writing in

terms suited to the particular occasion and not prescribed herein.

Orders are employed only when the commands prescribed herein do not

sufficiently indicate the will of the commander.

Orders are more fully described in paragraphs 378 to 383, inclusive.

(36)

Commands

86. Command defined. In these regulations a command is the will of the

commander expressed in the phraseology prescribed herein. (37)

87. Kinds of commands; how given. There are two kinds of commands:

The preparatory command, such as forward, indicates the movement that

is to be executed.

The command of execution, such as MARCH, HALT, or ARMS, causes the

execution.

Preparatory commands are distinguished by italics; those of execution

by CAPITALS.

Where it is not mentioned in the text who gives the commands

prescribed, they are to be given by the commander of the unit

concerned.

The preparatory command should be given at such an interval of time

before the command of execution as to admit of being properly

understood; the command of execution should be given at the instant

the movement is to commence.

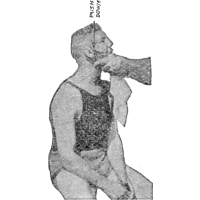

The tone of command is animated, distinct, and of a loudness

proportioned to the number of men for whom it is intended.

Each preparatory command is enunciated distinctly, with a rising

inflection at the end, and in such manner that the command of

execution may be more energetic.

The command of execution is firm in tone and brief. (38)

88. Battalion and higher commanders repeat commands of superiors;

battalion largest unit executing movement at command of its commander.

Majors and commanders of units larger than a battalion repeat such

commands of their superiors as are to be executed by their units,

facing[Pg 29] their units for that purpose. The battalion is the largest

unit that executes a movement at the command of execution of its

commander. (39)

89. Facing troops and avoiding indifference when giving commands. When

giving commands to troops it is usually best to face toward them.

Indifference in giving commands must be avoided as it leads to laxity

in execution. Commands should be given with spirit at all times. (40)

Bugle Signals

90. Bugle signals that may be used on and off the field of battle. The

authorized bugle signals are published in Part V of these regulations.

The following bugle signals may be used off the battlefield, when not

likely to convey information to the enemy:

- Attention: Troops are brought to attention.

- Attention to orders: Troops to fix their attention.

- Forward, march: Used also to execute quick time from double time.

- Double time, march.

- To the rear, march: In close order, execute squads right about.

- Halt.

- Assemble, march.

The following bugle signals may be used on the battlefield:

- Fix bayonets.

- Charge.

- Assemble, march.

These signals are used only when intended for the entire firing line;

hence they can be authorized only by the commander of a unit (for

example, a regiment or brigade) which occupies a distinct section of

the battlefield. Exception: Fix bayonet. (See par. 355.)

The following bugle signals are used in exceptional cases on the

battlefield. Their principal uses are in field exercises and practice

firing.

Commence firing: Officers charged with fire direction and control open

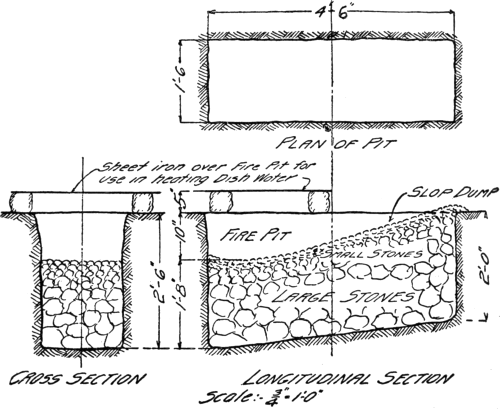

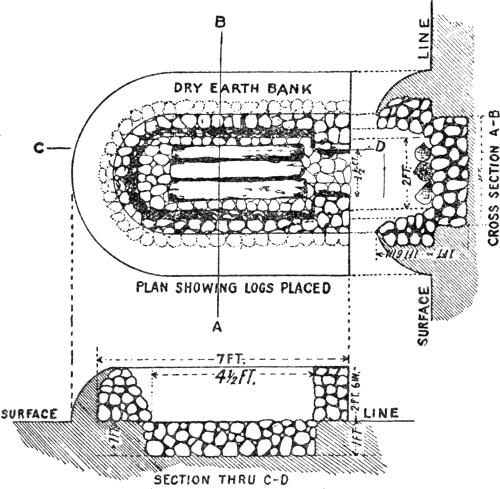

fire as soon as practicable. When given to a firing line, the signal

is equivalent to fire at will.

Cease firing: All parts of the line execute cease firing at once.

These signals are not used by units smaller than a regiment, except

when such unit is independent or detached from its regiment. (41)

Whistle Signals

91. Attention to orders. A short blast of the whistle. This signal is

used on the march or in combat when necessary to fix the attention of

troops, or of their commanders or leaders, preparatory to giving

commands, orders, or signals.

When the firing line is firing, each squad leader suspends firing and

fixes his attention at a short blast of his platoon leader's whistle.

The platoon leader's subsequent commands or signals are repeated and

enforced by the squad leader. If a squad leader's attention is

attracted by a whistle other than that of his platoon leader, or if

there are no orders or commands to convey to his squad, he resumes

firing at once.

Suspend firing. A long blast of the whistle. All other whistle signals

are prohibited. (42)

[Pg 30]

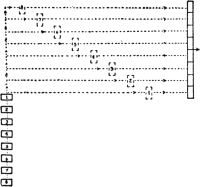

Arm Signals

92. The following arm signals are prescribed. In making signals either

arm may be used. Officers who receive signals on the firing line

"repeat back" at once to prevent misunderstanding.

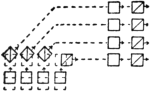

Forward

Forward

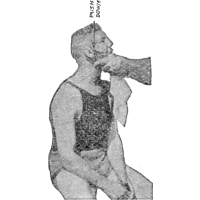

Forward, MARCH. Carry the hand to the shoulder; straighten and hold

the arm horizontally, thrusting it in the direction of march.

This signal is also used to execute quick time from double time.

Halt—arm held stationary

Halt—arm held stationary

Double Time— arm moved up and down several times

Halt. Carry the hand to the shoulder; thrust the hand upward and hold

the arm vertically.

Double time, MARCH. Carry the hand to the shoulder; rapidly thrust the

hand upward the full extent of the arm several times.

Squads Right

Squads Right

Squads right, MARCH. Raise the arm laterally until horizontal; carry

it to a vertical position above the head and swing it several times

between the vertical and horizontal positions.

Squads Left

Squads Left

Squads left, MARCH. Raise the arm laterally until horizontal; carry it

downward to the side and swing it several times between the downward

and horizontal positions.

Squads Right About

Squads Right About

To the Rear

[Pg 31]Squads right about, MARCH (if in close order) or, To the rear, MARCH

(if in skirmish line). Extend the arm vertically above the head; carry

it laterally downward to the side and swing it several times between

the vertical and downward positions.

Change Direction

Change Direction

Change direction or Column right (left), MARCH. The hand on the side

toward which the change of direction is to be made is carried across

the body to the opposite shoulder, forearm horizontal; then swing in a

horizontal plane, arm extended, pointing in the new direction.

As Skirmishers

As Skirmishers

As skirmishers, MARCH. Raise both arms laterally until horizontal.

As Skirmishers, Guide Center

As Skirmishers, Guide Center

As skirmishers, guide center, MARCH. Raise both arms laterally until

horizontal; swing both simultaneously upward until vertical and return

to the horizontal; repeat several times.

As Skirmishers, Guide Right

As Skirmishers, Guide Right

[Pg 32]As skirmishers, guide right (left), MARCH. Raise both arms laterally

until horizontal; hold the arm on the side of the guide steadily in

the horizontal position: swing the other upward until vertical and

return it to the horizontal; repeat several times.

Assemble

Assemble

Assemble, March. Raise the arm vertically to full extent and describe

horizontal circles.

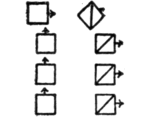

To Announce Range—Battle Sight

To Announce Range—Battle Sight

Range or Change elevation. To announce range, extend the arm toward

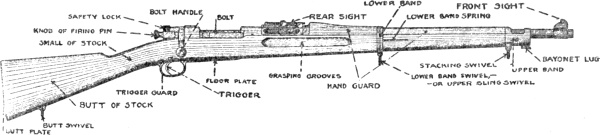

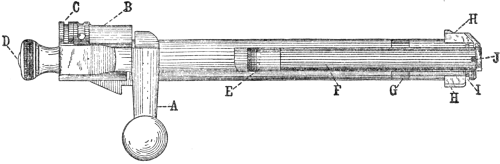

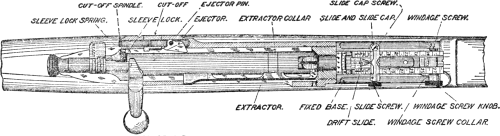

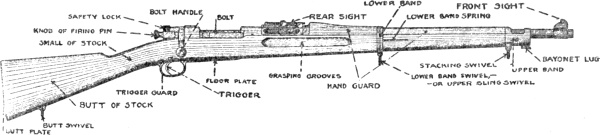

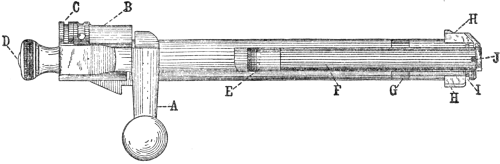

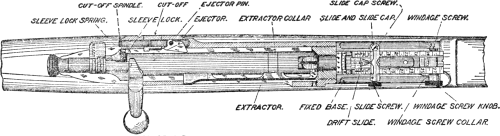

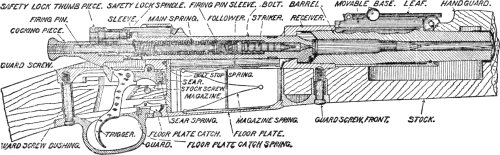

the leaders or men for whom the signal is intended, fist closed; by

keeping the fist closed battle sight is indicated;

Range 300—Or Increase By 300

Range 300—Or Increase By 300

by opening and closing the fist, expose thumb and fingers to a number

equal to the hundreds of yards;

Add 50 Yards

Add 50 Yards

(Top View)

to add yards describe a short horizontal line with forefinger.

Decrease By 300

Decrease By 300

To change elevation, indicate the amount of increase or decrease by

fingers as above; point upward to indicate increase and downward to

indicate decrease.

What Range Are You Using?

What Range Are You Using?

[Pg 33]What range are you using? or What is the range? Extend the arms toward

the person addressed, one hand open, palm to the front, resting on the

other hand, fist closed.

Are You Ready?

Are You Ready?

Are you ready? or I am ready. Raise the hand, fingers extended and

joined, palm toward the person addressed.

Commence Firing

Commence Firing

Commence firing. Move the arm extended in full length, hand palm down,

several times through a horizontal arc in front of the body.

Fire faster. Execute rapidly the signal, "Commence Firing."

Fire slower. Execute slowly the signal, "Commence Firing."

Swing the Cone of Fire to the Right

Swing the Cone of Fire to the Right

Swing the cone of fire to the right, or left. Extend the arm in full

length to the front, palm to the right (left); swing the arm to right

(left), and point in the direction of the new target.

Fix Bayonet. Simulate the movement of the right hand in "Fix bayonet."

(See par. 142.)

Suspend Firing

Suspend Firing

Cease Firing—Swing Arm Up And Down Several Times

[Pg 34]Suspend firing. Raise and hold the forearm steadily in a horizontal

position in front of the forehead, palm of the hand to the front.

Cease firing. Raise the forearm as in suspend firing and swing it up

and down several times in front of the face.

Platoon

Platoon

Platoon. Extend the arm horizontally toward the platoon leader;

describe small circles with the hand. (See par. 93.)

Squad

Squad

Squad. Extend the arm horizontally toward the platoon leader; swing

the hand up and down from the wrist. (See par. 93.)

Rush. Same as double time. (43)

93. Use of signals "platoon" and "squad." The signals platoon and

squad are intended primarily for communication between the captain and

his platoon leaders. The signal platoon or squad indicates that the

platoon commander is to cause the signal which follows to be executed

by platoon or squad.

Note.—The following signals, while not prescribed, are very

convenient:

Combined Sights. Extend the arm toward the leaders for whom the signal

is intended, hand open and turn hand rapidly from right to left a

number of times. Then indicate ranges in the manner prescribed, giving

the mean of the two ranges. (For example: If the combined sights are

1050 and 1150, indicate a range of 1100 yards. The leaders who give

the oral commands, give the command, "Range 1050 and 1150," whereupon

every man in the front rank, before deployment, fixes his sight at

1150, and every man in the rear rank, before deployment, fixes his

sight at 1050.)

Company. Bring the hand up near the shoulder and then thrust to the

front, snapping fingers in usual way; repeat several times.

Contract fire. Extend both arms horizontally, fingers extended, arms

parallel, palms facing each other; bring hands together once, and hold

them so and look at the leader concerned.

Disperse fire. Bring hands together, fingers extended, pointing in

direction of leader concerned, arms extended horizontally; swing arms

outward once, and hold them so and look at the leader concerned.

Platoon column. Raise both arms vertically, full length, arms

parallel, fingers joined and extended, palms to the front.

[Pg 35]Prepare to rush. Cross the arms horizontally several times.

Squad Column. Raise both arms vertically from elbows, elbows at side

of body, fingers joined and extended, palms to the front.—Author.

(44)

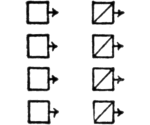

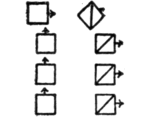

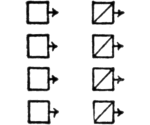

Flag Signals

94. Signal flags carried by company musicians; description of flags.

The signal Hags described below are carried by the company musicians

in the field.

In a regiment in which it is impracticable to make the permanent

battalion division alphabetically, the flags of a battalion are as

shown; flags are assigned to the companies alphabetically, within

their respective battalions, in the order given below.

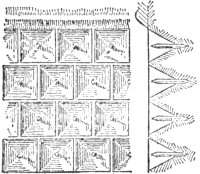

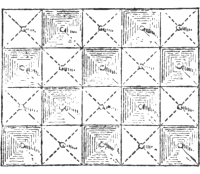

First battalion:

- Company A. Red field, white square.

- Company B. Red field, blue square.

- Company C. Red field, white diagonals.

- Company D. Red field, blue diagonals.

Second battalion:

- Company E. White field, red square.

- Company F. White field, blue square.

- Company G. White field, red diagonals.

- Company H. White field, blue diagonals.

Third battalion:

- Company I. Blue field, red square.

- Company K. Blue field, white square.

- Company L. Blue field, red diagonals.

- Company M. Blue field, white diagonals.

Note.—An analysis of the above system of signal flags will show:

1. The color of the field indicates the battalion and the colors

run in the order that is so natural to us all, viz: Red, White and

Blue. Hence red field indicates the first battalion; white field,

the second; blue field, the third.

2. The squares indicate the first two companies of each battalion,

and the diagonals, the second two. Hence,

| Companies |

Indicated by |

| A |

E |

I |

Squares |

| B |

F |

K |

| C |

G |

L |

Diagonals |

| D |

H |

M |

[Pg 36]3. The colors of the squares and diagonals in combination with

those of the fields, run in the order that is so natural to us

all, viz.: Red, White and Blue, the color of any given field

being, of course, omitted from the squares and diagonals, as a

white square for instance, would not show on a white field, nor

would a blue diagonal show on a blue field. For example, with a

red field we would have white and blue for the square and diagonal

colors; with a white field, red and blue for the square and

diagonal colors; with a blue field, red and white for the square

and diagonal colors.

4. From what has been said, the following table explains itself:

| Battalion |

Field |

Co. |

Squares |

Diagonals |

| First |

Red |

A |

White |

|

| B |

Blue |

|

| C |

|

White |

| D |

|

Blue |

| Second |

White |

E |

Red |

|

| F |

Blue |

|

| G |

|

Red |

| H |

|

Blue |

| Third |

Blue |

I |

Red |

|

| K |

White |

|

| L |

|

Red |

| M |

|

White |

Note how the square and diagonal colors always follow in the

natural order of red, white, and blue, with the color of the field

omitted.—Author. (45)

95. Signal flags used to mark assembly point of company, etc. In

addition to their use in visual signaling, these flags serve to mark

the assembly point of the company when disorganized by combat, and to

mark the location of the company in bivouac and elsewhere, when such

use is desirable. (46)

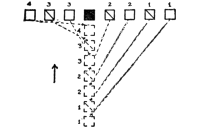

96. Signals used between firing line and reserve or commander in rear.

(1) For communication between the firing line and the reserve or

commander in the rear, the subjoined signals (Signal Corps codes) are

prescribed and should be memorized. In transmission, their concealment

from the enemy's view should be insured. In the absence of signal

flags, the headdress or other substitute may be used. (See par. 863

for the semaphore code and par. 861 for the General Service, or

International Morse Code.) (47)

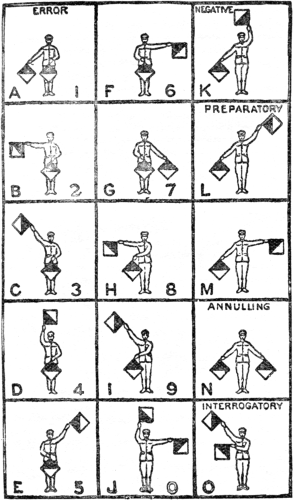

[Pg 37]

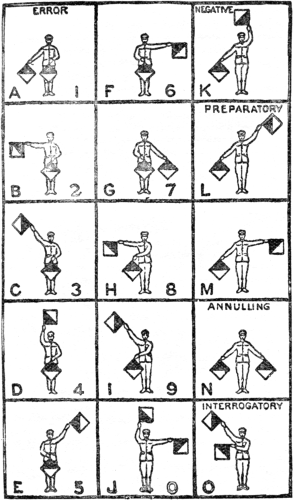

| Letter of alphabet |

If signaled from the rear to the firing line |

If signaled from the firing line to the rear |

| A M |

Ammunition going forward. |

Ammunition required. |

| C C C |

Charge (mandatory at all times). |

Am about to charge if no instructions to the contrary. |

| C F |

Cease firing. |

Cease firing. |

| D T |

Double time or "rush." |

Double time or "rush." |

| F |

Commence firing. |

Commence firing. |

| F B |

Fix bayonets. |

Fix bayonets. |

| F L |

Artillery fire is causing us losses. |

Artillery fire is causing us losses. |

| G |

Move forward. |

Preparing to move forward. |

| H H H |

Halt. |

Halt. |

| K |

Negative. |

Negative. |

| L T |

Left. |

Left. |

O

(Ardois and semaphore only.) |

What is the (R. N. etc.)? Interrogatory. |

What is the (R. N. etc.)? Interrogatory. |

| (All methods but ardois and semaphore.) |

What is the (R. N. etc.)? Interrogatory. |

What is the (R. N. etc.)? Interrogatory. |

| P |

Affirmative. |

Affirmative. |

| R |

Acknowledgment. |

Acknowledgment. |

| R N |

Range. |